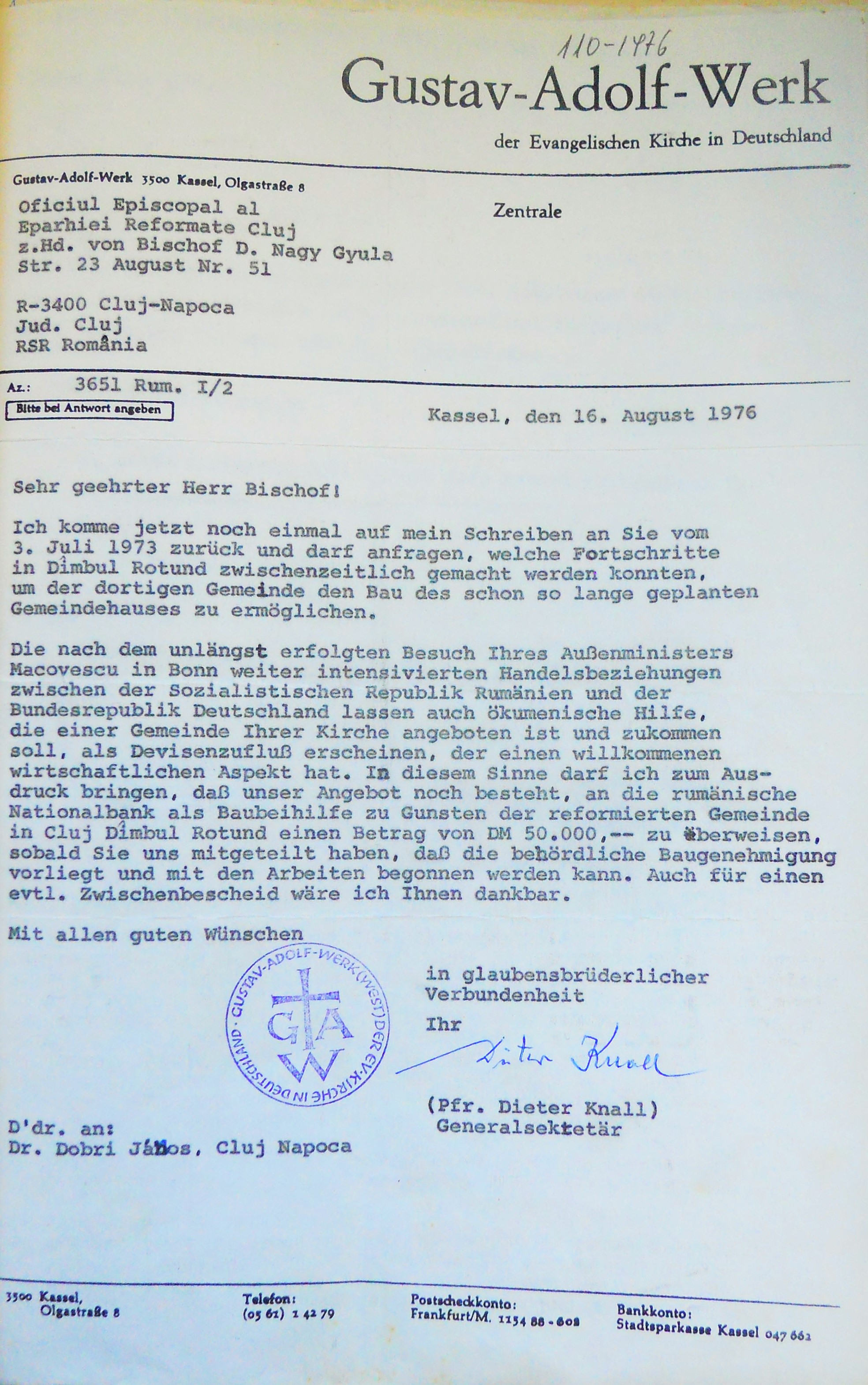

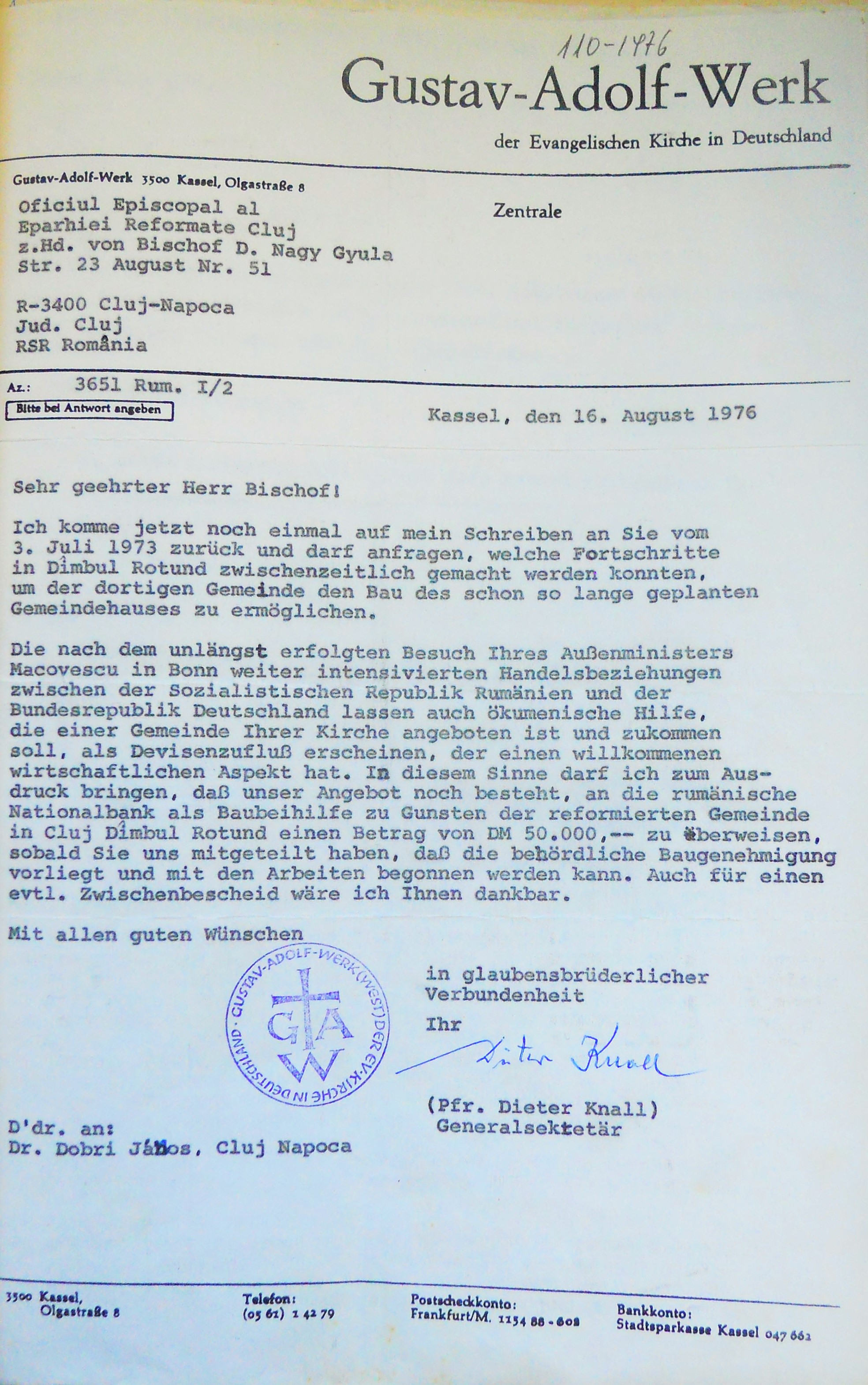

According to documents in the Reformed Congregation of Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund's Collection, on 13 March 1971 the West German foundation Gustav-Adolf-Werk offered a donation of 50,000 deutschmarks as ecumenical help for church construction (KKREL 1971/7, Report no. 28). This turned out to be of major importance in the process of constructing the church building. The fact that the state could benefit from foreign currency on the construction site counted as a very strong argument and played a huge role in the history of the reluctantly issued building permit. Between 1971 and 1976 there existed mostly only correspondence between the foundation and the pastor of Dâmbul Rotund, János Dobri on the question of when they would take over this sum of money, with the parish having to answer that they had not yet obtained approval for it. In the communist regime, any donation in money or of a different nature coming from abroad could be accepted and taken over only with "religious affairs departmental" permission from Bucharest. Regulation no. 16455/1971 of the Department of Religious Affairs (Departamentul Cultelor), referring to Decree-Law No. 334/1971 paragraph 5 point “r”, stated that gifts and bequests given or accepted by clerical organisations could be made only with the approval of the Department of Religious Affairs. Furthermore, any inventory objects, with or without historical or artistic value, books, manuscripts, musical instruments, money, material, or producs, regardless of their value could only be donated or accepted with the prior approval of the Department of Religious Affairs (KKREL 1971/7, Rescript no. 1420). Eventually, in addition to approving the construction of the church building, the Department granted permission for the use of the donation. According to the knowledge of Reformed pastor András Dobri and cantor Anna Jankó, only the first half of the amount was transferred officially to the Romanian National Bank, while the other half was transmitted through other "gates." In those times foreign exchange was not permitted for Romanian citizens living in the country. Only foreigners could change foreign currency and thus deliver the donated money. As the exchange rate was very unfavourable, those concerned decided to change the foreign currency with the willing help of Polish tourists. The greater amount obtained this way could be used properly during the construction. Because of the large amount involved, almost all members of the presbytery, which was then made up of about twenty-eight members took a part of it, which they then offered as donations in their own names for the church construction. In fact, based on oral history interviews, the possibility is not to be excluded that the second part of the West German donation was transferred officially in a similar way to the first, while the church members were used to collect other foreign cash donations, as the Gustav-Adolf-Werk donation was not enough on its own to pay for the construction (statement of Anna Jankó; statement of András Dobri).

The Securitate materials on János Dobri also give information about the donation. Based on the documents contained in the informative file, on 5 March 1971 Reformed Bishop Gyula Nagy was informed in a letter from the West German donor – through Pastor-Secretary General Dieter Knall – that the sum of money destined for the church construction in Dâmbul Rotund had been prepared, and he was asked to accept the donation in the name of the Reformed Church District of Cluj. A positive response was preceded by the consent of the Department of Religious Affairs in Bucharest (ACNSAS, 211500/4, 147). Since August 1972 the counter-intelligence in Cluj led by Colonel Sándor Peres had dealt specially with the case. When the Securitate learned that a considerable sum had been allocated by the Gustav-Adolf-Werk foundation for church construction, Peres had stated that in order to receive the money, the Church officials would have to talk with the county religious affairs inspector, "studying the possible modes of coordination." This statement is significant especially in the light of a later declaration of the county religious affairs inspector Hoinărescu Țepeș Horia, according to which no Hungarian churches or chapels were to be built in Cluj as long as he held that position in the city. (ACNSAS, I211500/5, 152–153). The later actions involved in the church construction prove the success of the "coordination," bearing in mind the interests of the single-party state.

The item is part of the photograph series comprised in the Braşov–Oraşul Memorabil Collection that portrays school under communism. The perception of the school uniforms of this period in post-1989 Romania reflects a sort of nostalgia for childhood under communism (Marin 2013, 10–12). This nostalgia is particularly related to objects such as toys, sweets, and children’s books that disappeared after 1989 or, in this case, school uniforms that marked affiliation to a form of political regimentation, such as Șoimii patriei (Falcons of the Motherland) and Organizaţia pionierilor (The Pioneers’ Organisation). Those who spent their childhood under communism do not necessarily remember the political regimentation part, but rather certain details that now bear an emotional value, namely, uniforms, festive moments, participation in competitions, etc. This photograph features two types of uniforms: the pioneer uniform worn by the student on the left and that of the falcons worn by the two children on the right. The photograph was taken in the Steagul Roşu (Red Flag) district in Braşov, which was one of the iconic proletarian districts, built at the end of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1950s.

![Imre Baász: Bar breaker [A rácstörő/ Spărgătorul de gratii], linocut, 1976](/courage/file/n129077/5.+R%C3%A1cst%C3%B6r%C5%91.jpg)

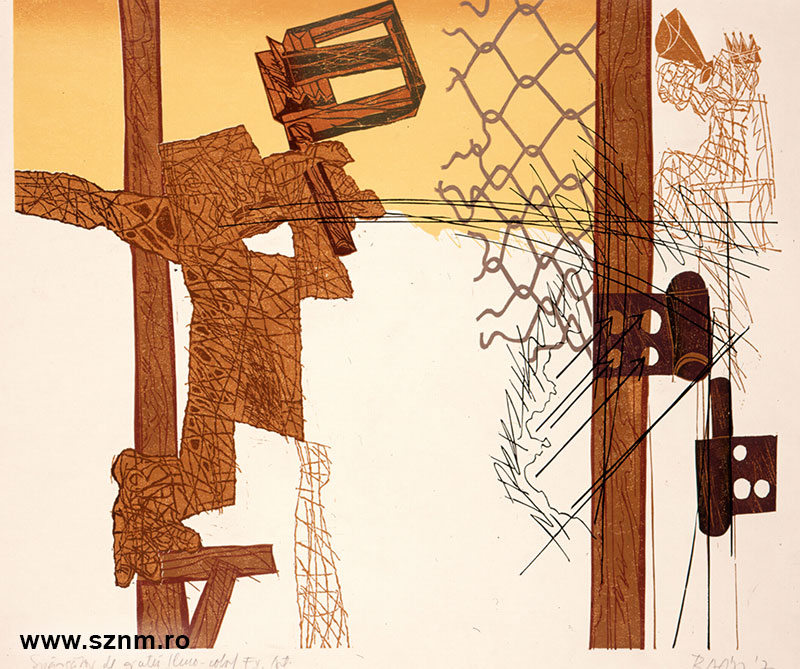

Bar Breaker is one of Baász’s most iconic works, compressing his virtuoso graphic world and his oppositional attitude into one piece of art. Although now famous for his workshops and performances, Imre Baász was primarily a graphic artist. His aim of destroying familiar forms in art is paired with a constant search for new forms. He only kicks the rules if he has news to offer. Bar Breaker dates back to the period right after he moved to Sfântu Gheorghe from Cluj-Napoca. The county first offered him a house in Arcuș/Árkos, a nearby village. This was the period when he discovered objects which later become key elements in his work, like the clapper, the nelson, and the loudspeaker.

Bar Breaker features a standing figure with a clapper in his hands disrupting a grid. On the other side of the grid, there is another figure sitting on a crowned chair, holding a loudspeaker. The abstract style and the geometrical figure perception are very typical of the Baász’s early period.

Atanas Vasilev Patsev was a Bulgarian painter and illustrator. As a secondary-school boy, Patsev joined the communist revolutionary movement and became a partisan.

In 1949, he graduated from the State Academy of Arts, in the class of Prof. Dechko Uzunov.

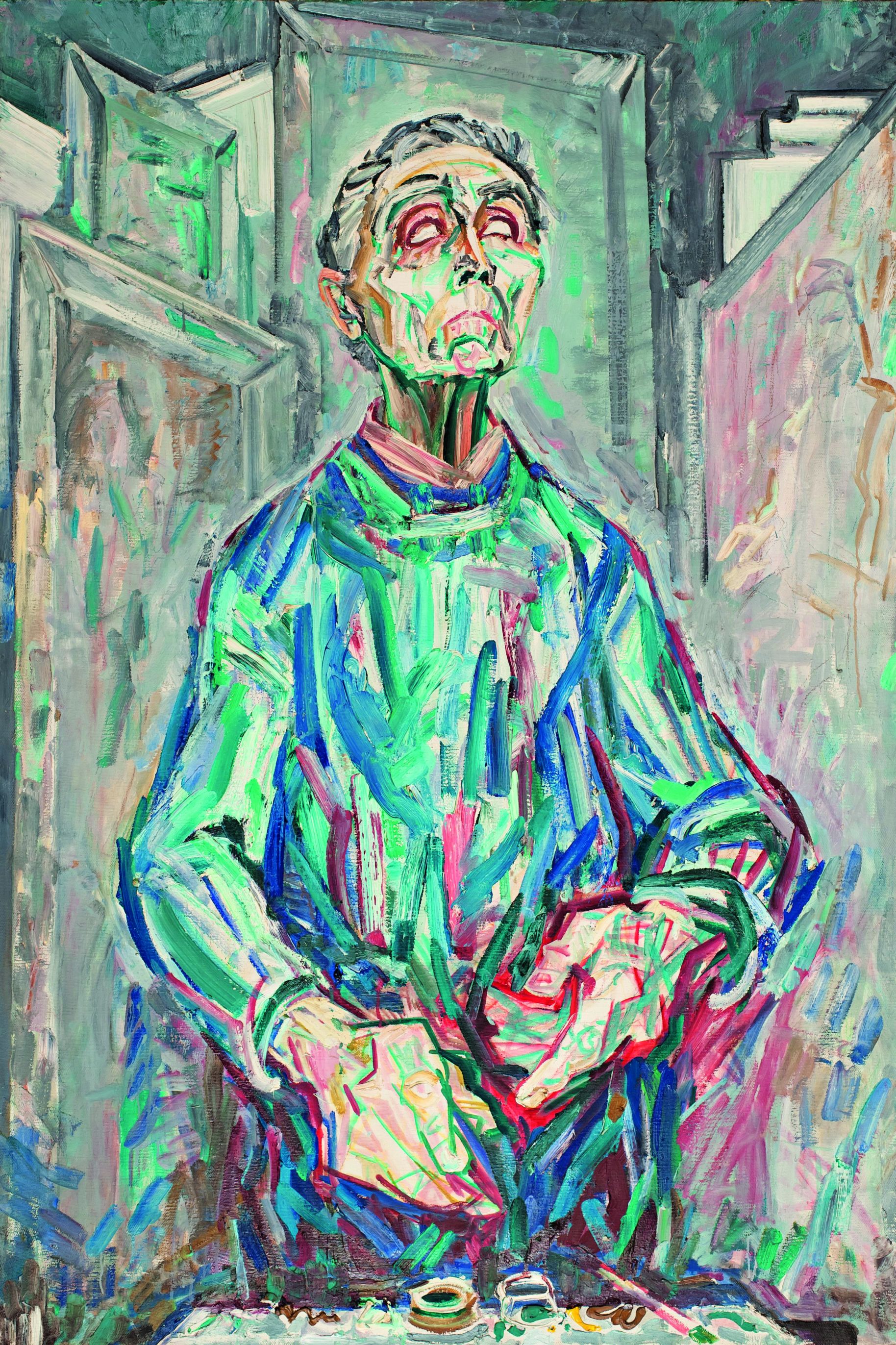

During the 1960s, his method of work changed in favour of the modern means of the expressive sculpture and painting. In 1968, his exhibition "Weightlessness" provoked confusion among the authorities responsible for the ideological correctness of art. The exhibition was accompanied by a small brochure containing text by the author as well defining weightlessness as a leading principle of the composition. "The form has no weight. It becomes unstable, transparent. The familiar silhouette loses shape. As if the inner construction of the body becomes visible. As if the range of visibility expands. The motion becomes six-way, rotary, supple and undulating" (Patsev, quoted after Iliev 2016: 153). The exhibition took place in a time when the situation in Paris was revolutionary and the Prague Spring was at its height.

Patsev's call for plastic revolution was initially wrapped in silence but afterwards defeating reviews were published: "roughly deformed bodies and practices", "a mixture of styles". The exhibition was attacked for "not containing any new problems" and the author was accused of "discrepancy between theory and practice" (Iliev 2016: 153). The philosophy of weightlessness was perceived as a threat to the regime whose ideology was based on the theorem of control of the Party-state over all processes. "The deprivation of gravity of the person represented is determined as theoretical vandalism similar to anarchism because the concept of the place of the particular individual puts him in a strict rank, together, united, in the group, in the team, at the meeting, at a manifestation. The idea of the different points of view is opposite to the only true uniform line represented by the Party" (Iliev 2016: 153).

Paradoxically, Patsev was simultaneously accused of secession, cubism and expressionism – styles defined by the party ideologists as "noxious", "decadent", "effete" bourgeois forms of plastic thinking.

In the next years, Atanas Patsev created big cycles of paintings on subjects related to the anti-fascist resistance ("Partisan Recollections"). The themes were ideologically orthodox – the events were promoted to mythologized heroism. However, the plastic language did not correspond to the pattern. The paintings of the cycle "The Man and the Things" were perceived as an attack of Patsev on the communist ruling crust tempted by gaining.

The portraits painted by Atanas Patsev combine "analytical mind and emotional expression" (Iliev 2016: 156). The portrait of Kiril Petrov (1976, Kiril Petrov – a painter who spent many years in estrangement and self-isolation from the public art life after being accused of "formalism") is created with dynamic contrasting colours so that the view of the head is from below and that of the arms is from above. Using the means of perspective, Patsev upsets the balance of the viewer's static contemplation. "Kiril Petrov forecasts through the hatches of Patsev [...] The resistance of Atanas Patsev against the System is the resistance of a man religiously believing in its ideological righteousness, on the one hand, but on the other hand, of a painter who sees its visible ugliness. The painter fights against its main principle – the submission to the rules, standards and instructions. And sometimes, flying on the wings of the subconscious sense of the divine, he manages to escape the locked room of the ideologized mind" (Iliev 2016: 156-157).

There is no monograph published.

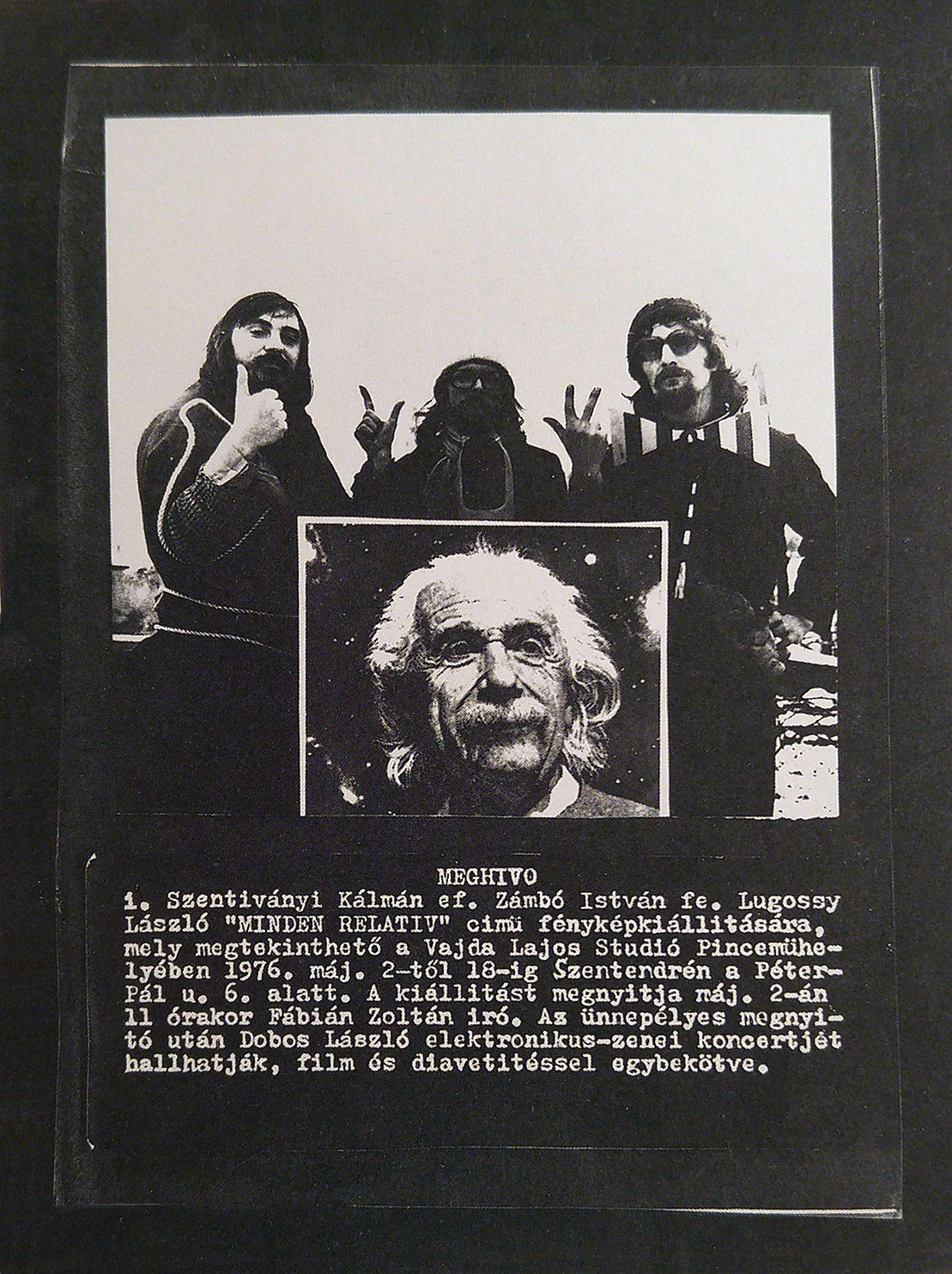

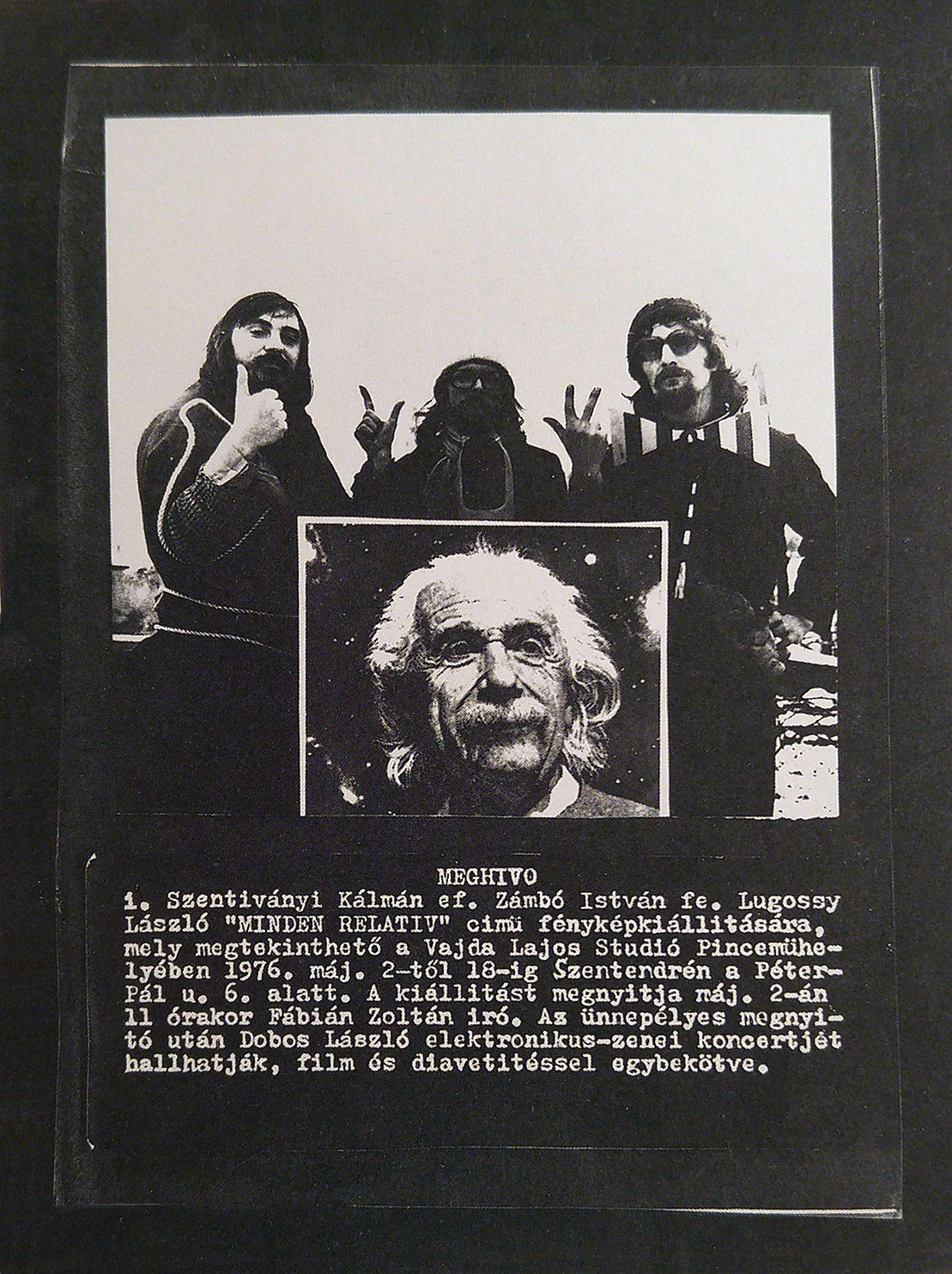

The collection contains mainly documentation, primarily photographic, of the Mospan Gallery operating in the years 1976-1978 at the Mospan Club at Warsaw University of Technology. Initially, it was run by Tomasz Sikorski, and then by Sikorski together with Tomasz Konart. The gallery during three years of its existence was one of few independent places (together with Gallery Remont and Repassage) of presentation neo-avant-garde art in Warsaw. The profile of the Mospan Gallery focused on ephemeral works, meetings, performances, not permanent objects, and therefore archive contains mostly pictures from current events that used to take places there.

Totok, William. Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (A project for an intellectual extermination), in German, 1976-1977. Manuscript

Totok, William. Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (A project for an intellectual extermination), in German, 1976-1977. Manuscript

In the period from 1975 to 1976, William Totok spent more than eight months in arrest at the Securitate for his involvement in the Aktionsgruppe Banat literary group, considered subversive by the authorities,and for his criticism of Ceaușescu’s political regime. Totok was released in June 1976 after the publication in the newspapers Frankfurter Rundschau and Le Monde of articles presenting the abuses of the communist authorities in his case. After his release, Totok drew up a manuscript of memoirs entitled Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (A project for an intellectual extermination), in which he recounted his experience as political prisoner. In May 1982, the Securitate carried out a search at his domicile and at that of one of his friends, the Romanian-German writer Horst Samson. On this occasion several documents were confiscated, including one copy of the manuscript of these memoirs (ACNSAS, I 210 845, vol. 2, 265–66; Totok 2001, 107–108).

In this manuscript, Totok recounts in detail the conditions in the political prison in Timișoara, the interrogations carried out by the Securitate, and the story of a letter drawn up between the two periods of arrest (Totok was released for a short period in October 1975, only to be arrested again in November 1975). In this letter, sent by his mother to the Federal Republic of Germany after his second arrest, Totok related the dramatic events of the abusive arrest of his colleagues and himself in October 1975 and all the harassments of the secret police. Fortunately, the copy of the manuscript of this memoirs that was confiscated by the Securitate was not the only one. Totok managed to hide a copy and to smuggle it out of the country to the Federal Republic of Germany after his emigration in March 1987. In 1988, Totok published a revised and extended version of this manuscript under the title: Die Zwänge der Erinnerung: Aufzeichnungen aus Rumänien (The constraint of memory: Recollections from Romania).

A special music collection was created by two librarians in a public library in Budapest. This unique repository was established in the branch library of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library (Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár, FSZEK). The librarians maneuvered among the barriers of the regime and utilized a loophole which allowed them to copy music recordings. The collection consists of recordings of contemporary Western music and alternative Hungarian bands. The materials reflect the tastes of the librarians.

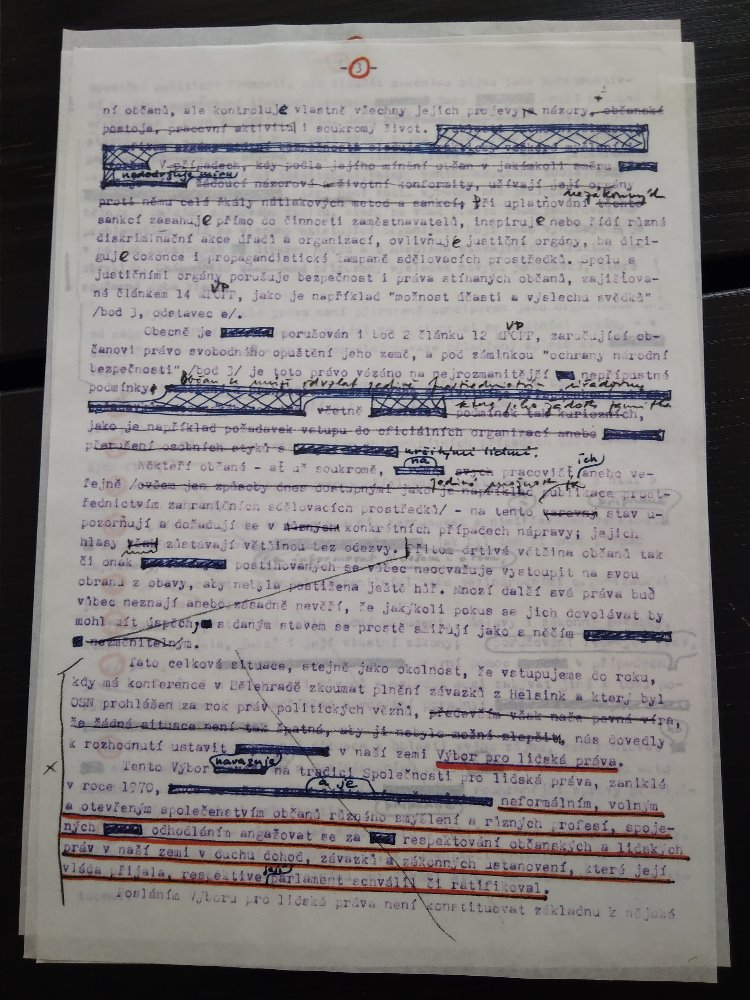

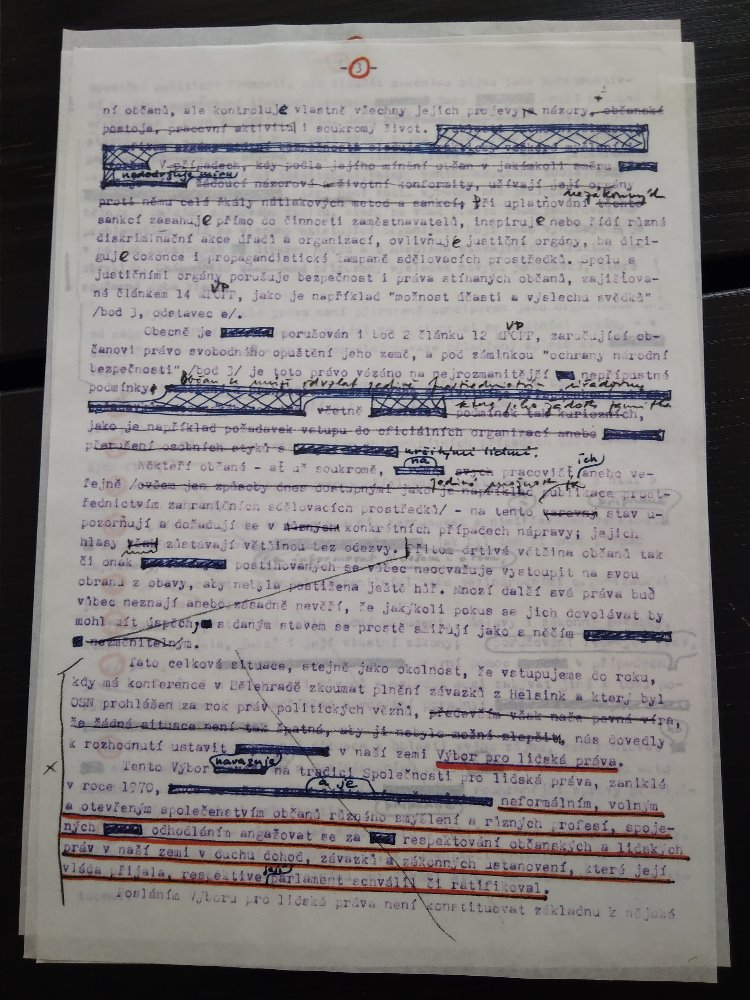

The five-page first version of the Charter 77 Declaration was established in the second half of December 1976 (date 26 December 1976), its basic content was agreed on the 11th December of the same year. Red notes were from Václav Havel, pencil notes from Paul Kohout. The declaration is a founding document of the Charter 77, which criticised state power for the non-observance of human and civil rights in Czechoslovakia. Originals of three drafts of this Declaration was handed over by Pavel Kohout to the contemporary Swiss Ambassador and after Kohout´s forced exile the texts were returned to him. About next 25 years these versions were deposited in Vienna and in Prague and since 2012 have become a part of the Moravian Museum´s collections. Because of the material’s high value, a copy of the Declaration is very often exhibited, illustrating the mapping of the Communist regime.

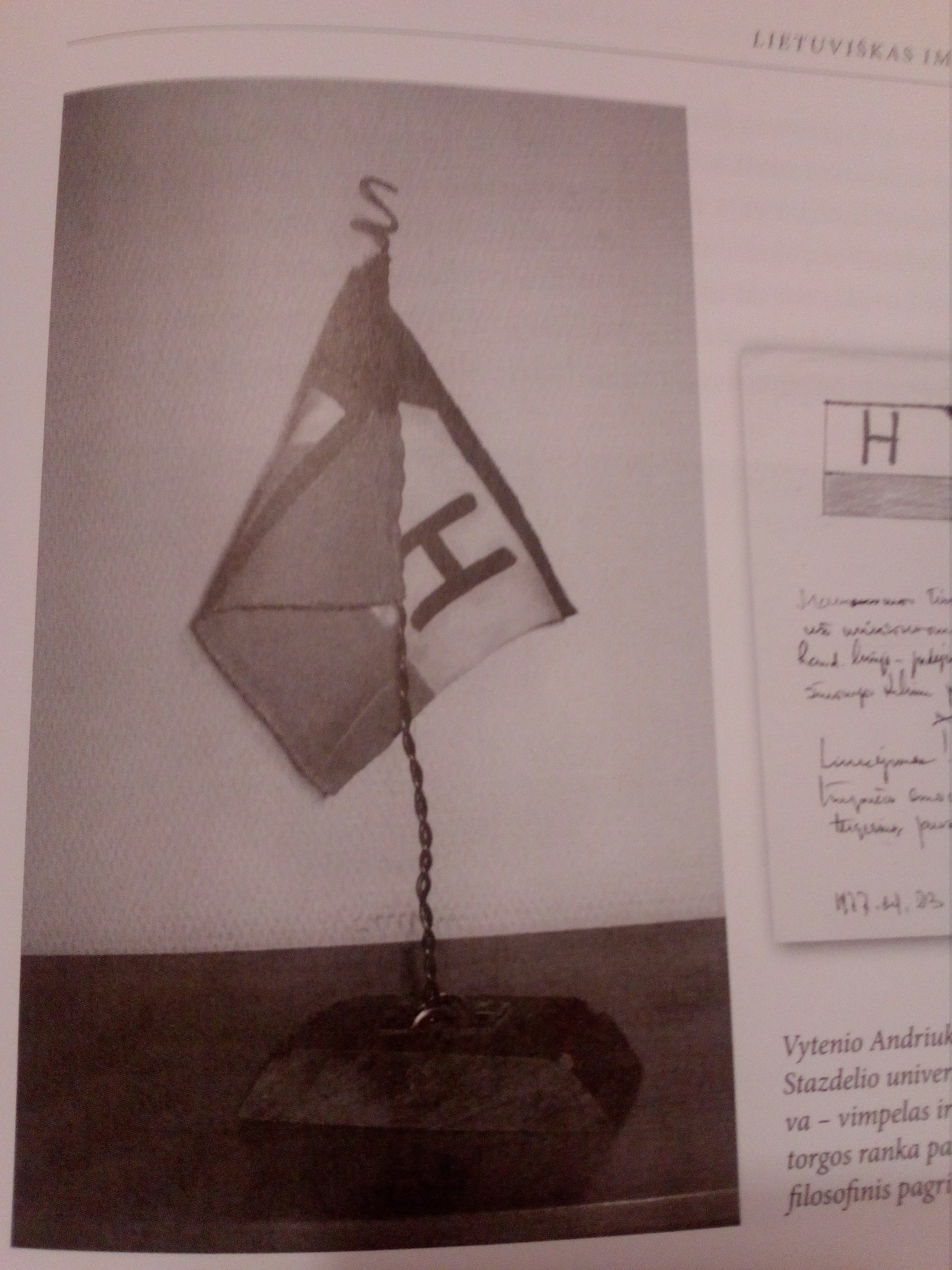

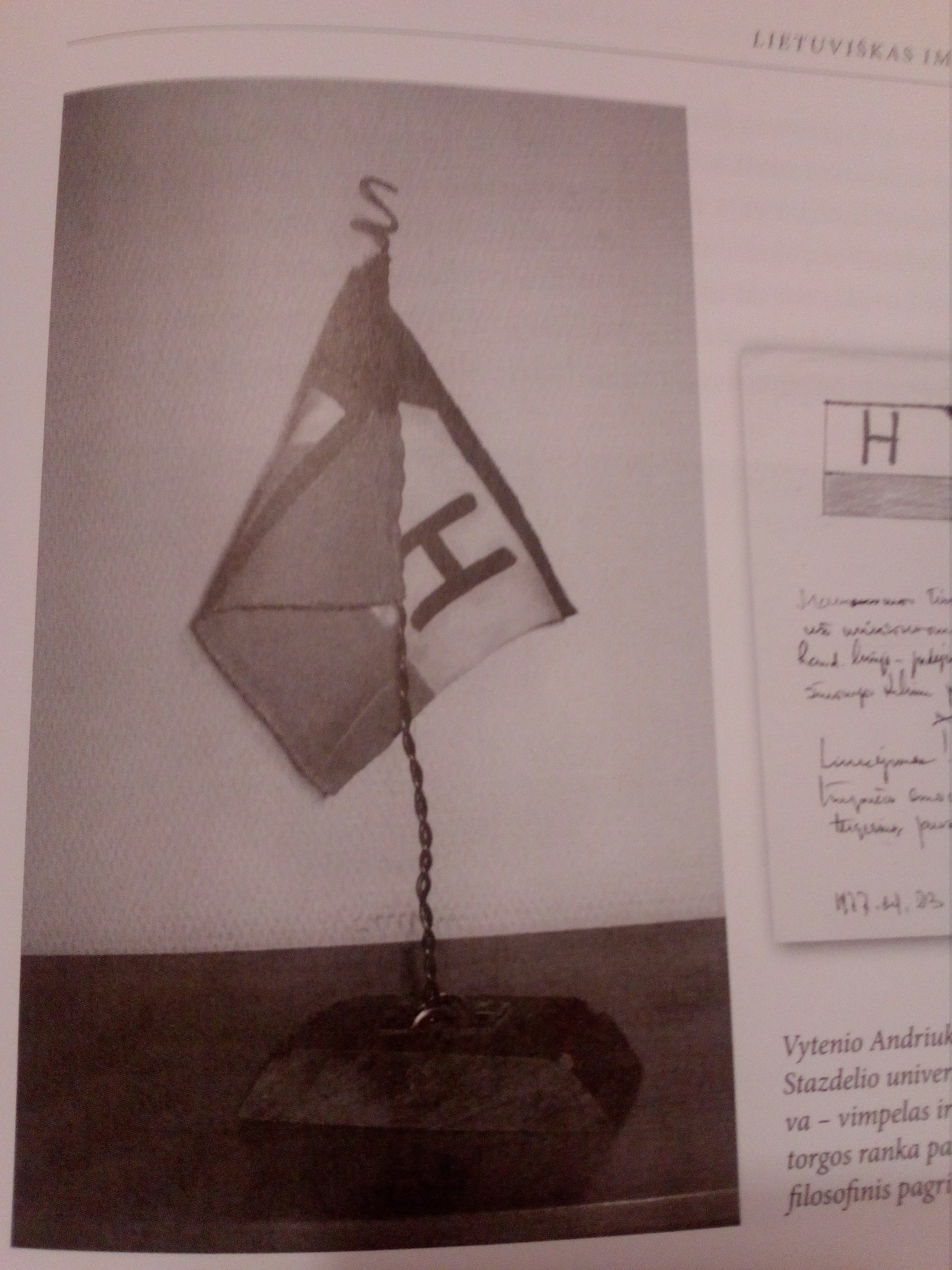

Vytenis Andriukaitis made the university’s flag according to a description by Viktoras Kutorga. All the parts of the flag, like the colour and the emblems, had a meaning, and the composition had a philosophical basis. The colour yellow symbolised a microcosm, and black symbolised a macrocosm. The colour green meant harmony and ecology, and red symbolised the people’s humanistic altruism. The flag has survived until today. Vytenis Andriukaitis keeps it in his office in the EU Commission in Brussels.

[Šagi Bunić, Tomislav]. “Thirteen centuries of Christianity among the Croats.” Epistle of Bishops, 1976. Publication

[Šagi Bunić, Tomislav]. “Thirteen centuries of Christianity among the Croats.” Epistle of Bishops, 1976. Publication

The text of the epistle of bishops entitled Trinaest stoljeća kršćanstva u Hrvata (Thirteen centuries of Christianity among the Croats) was published during Lent in 1976, and it was signed by 23 bishops in Croatia and Yugoslavia. Although its author was not specified, according to the testimony of Fr. Živko Kustić, it is known that it was written by Capuchin friar Tomislav Šagi-Bunić, a prominent theologian in Zagreb and the founder of the theological society Kršćanska sadašnjost (Christian Modernity) (Hudelist 2015, 370). According to Darko Hudelist, it is "one of the most inspired and highest-quality texts ever written in the Catholic Church in Croatia" (Hudelist 2015, 370), a sort of a programmatic text, which served as a guideline for the Church at the time. Although a part of the text was dedicated to (critically examined) Catholic national history, because the reason for the celebration itself was the thirteen centuries of the Christianisation of the Croats, Šagi Bunić directed it to the present time and the future of Christian life following the teachings of the Second Vatican Council. The letter served as an announcement for the celebration of the Grand Jubilee in Solin on 12 June 1976.

Šagi Bunić encouraged believers to live their Christian faith more deeply. However, this automatically meant exclusion from political life under a socialist order, because practical believers could not be members of the League of the Communists of Croatia and thus have careers at higher-level posts.

Czech poet, writer and Nobel Prize holder Jaroslav Seifert sold the manuscript of his memoirs “Všecky krásy světa” (All Beauties of the World), altogether 784 pages written between 1970 and 1975, to the Museum of Czech Literature in 1978. The sale, which was in negotiation since 1976, was realised based on an agreement with Marie Krulichová, the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature acquisition staffer, and with the help of an antiquarian book shop on Wenceslas Square 41 in Prague. The manuscript “Všecky krásy světa” became the foundation of the Jaroslav Seifert Collection in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature, which expanded in the following years and now includes 63 boxes.

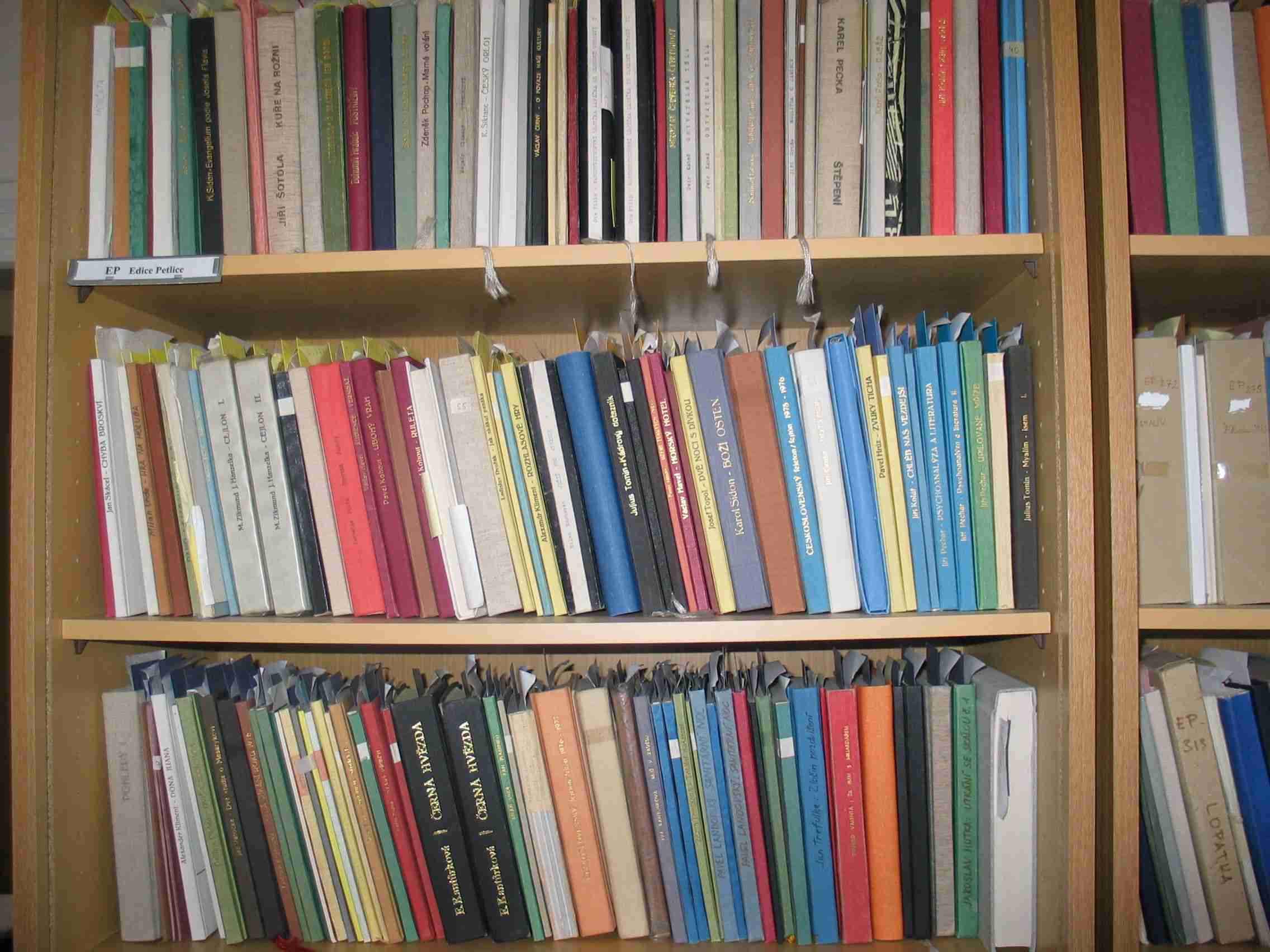

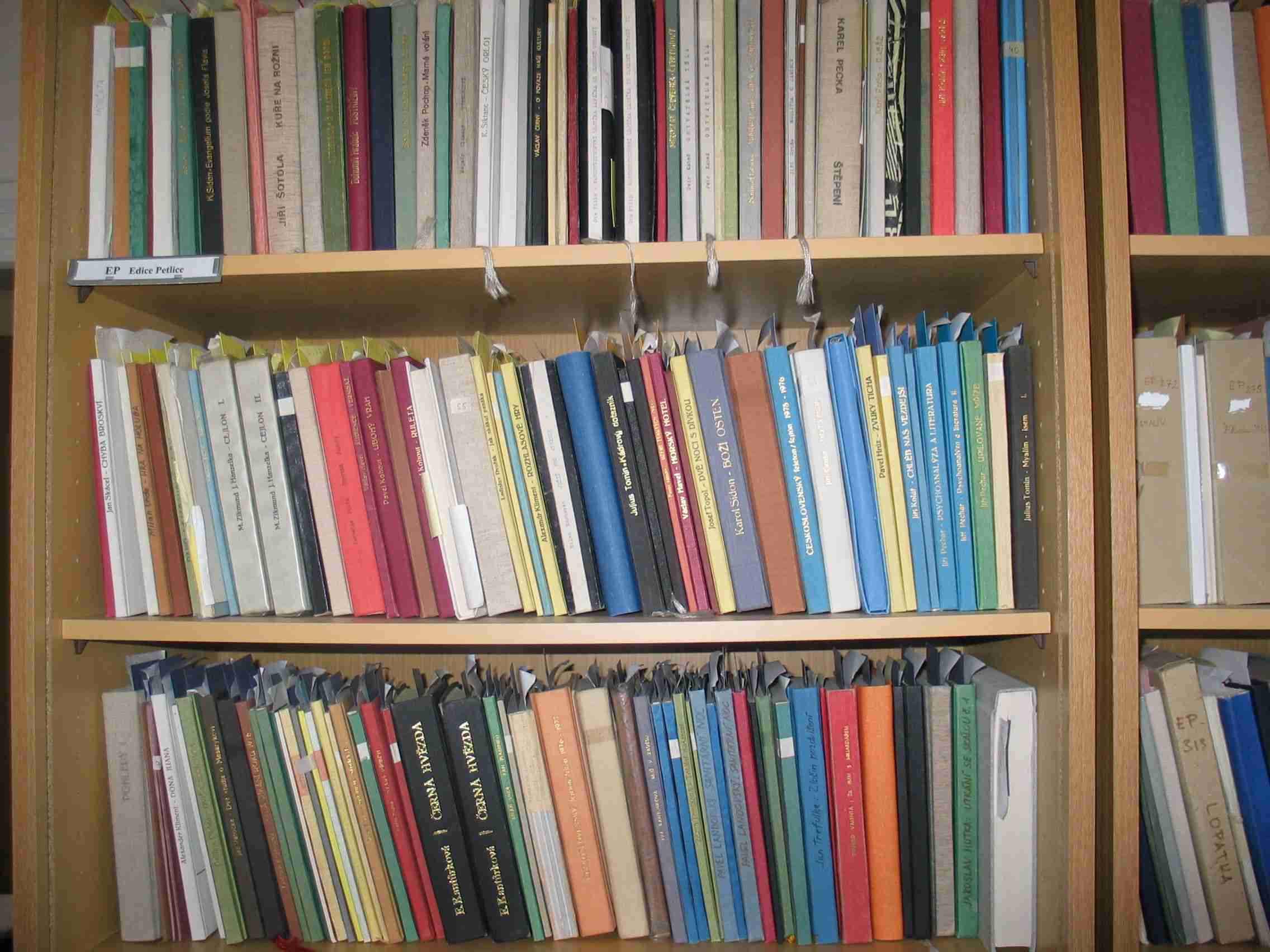

This unique collection of samizdat literature (1972-1989) contains samizdat books by Czech and Slovak authors whose works could not officially be published in socialist Czechoslovakia, as well as a collection of samizdat periodicals and individual texts.

The “Black Book” collection contains documents from the first seven days of the occupation of Czechoslovakia by five Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968, which served as a basis for Seven Prague Days 21-27 August 1968, also called the “Black Book”. The “Black Book” was edited by Milan Otáhal and Vilém Prečan, academics from the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, and all materials were collected during or shortly after the occupation.

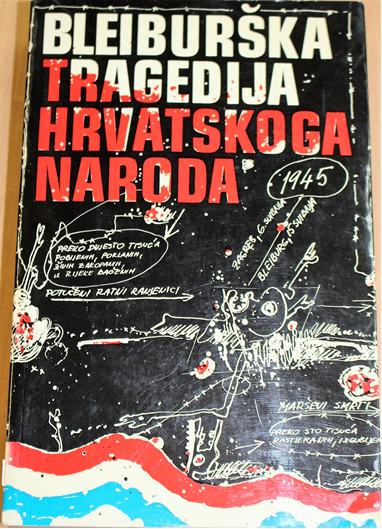

Nevistić, Franjo and Nikolić, Vinko. Bleiburška tragedija hrvatskoga naroda (The Bleiburg Tragedy of the Croatian People). Munich: Hrvatska revija, 1976. Book

Nevistić, Franjo and Nikolić, Vinko. Bleiburška tragedija hrvatskoga naroda (The Bleiburg Tragedy of the Croatian People). Munich: Hrvatska revija, 1976. Book

The subject of Bleiburg was banned in Yugoslavia, both in public discourse and in the scientific community (scientific research was forbidden). The topic was treated freely only in the diaspora, and the book The Bleiburg Tragedy of the Croatian People presents the most systematic treatment of the subject. An additional fact is that it was originally published in the Spanish language (1963).

Václav Havel (1936-2011) was an important Czech playwright and essayist, a critic of the communist regime, one of the initiators of Charter 77, a founding member of VONS (The Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted), a political prisoner and later president of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic. The collection consists mainly of materials of his dramatic creation and its dissenting effect.

The photography made by Tomasz Sikorski documented Edward Dwurnik’s painting action Wykonanie portretów psychologicznych studentów D.S. „Babilon” (Making of psychological portraits of the students from ‘Babylon’ Dormitory) at the Mospan Gallery. The action took place on May 31, 1976. Between 6 PM and 9 PM, Edward Dwurnik painted 28 images of the students living in the dormitory which the Mospan Gallery was associated with. The portraits were made by acrylic paints on the one huge canvas. The canvas was at the end cut into 28 pieces so every participant of the action could take his or her psychological image with his or her name and surname. Dwurnik’s performance was an exceptional event at the Mospan Gallery, one of a few that were addressed directly to the students from the ‘Babylon’ Dormitory of the Warsaw University of Technology.

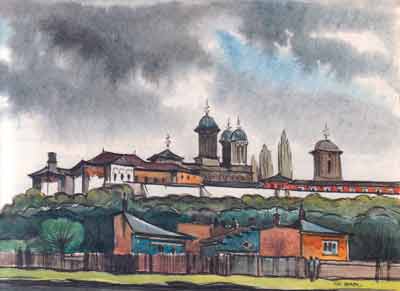

Given the severe constraints that the political authorities imposed on the activity of architects in the communist period, for Gheorghe Leahu watercolours became a form of escape. According to his testimony, Leahu was attracted by “architectural watercolour” painting because this activity allowed him to choose both the topics and his approach to them, thus offering him a creative freedom which was not possible in his professional activity. Being passionate about the architectural heritage of Bucharest, he chose to paint mainly picturesque landscapes in the old centre of the Romanian capital, and in other cities in Romania as well. He believed that painting “architectural watercolours” was also a way of leaving behind a testimony to the urban heritage which was in danger during those years. Because of Ceauşescu’s megalomaniac ambitions of reshaping the Romanian capital according to his vision of what a socialist city should look like, entire areas of the city were demolished during the 1980s.Several of Leahu’s watercolours depict the Văcăreşti Monastery, one of the most important historic monuments in Bucharest, demolished in 1986. One of these watercolours, painted in 1976, is entitled “The Văcăreşti Monastery before the Storm.” The painting presents a panoramic view of the monastery complex built at the beginning of the eighteenth century. The title given by the painter to this watercolour contains an unintentional allusion to the monument’s tragic destiny. As head of the Bucharest Project Institute, a state company in charge of architectural projects in the Romanian capital, Leahu was appointed in 1984 to coordinate a team of architects in designing the new Bucharest court of law, which Ceauşescu wanted to build on the site of the Văcăreşti Monastery. Together with his team, he supplied the authority with twelve different plans for the future building which preserved most of the monastery complex. Their efforts were unsuccessful because in 1986 the authorities decided to demolish the entire monument. Thus, the watercolour became a source of information about one of the most valuable historical monuments destroyed by the urban policies of Ceauşescu’s regime. It was reproduced in some of the architect’s albums and books. One of these books, published in 1997, was dedicated to the demolition of the monument: Distrugerea Mănăstirii Văcăreşti (The Destruction of the Văcăreşti Monastery).

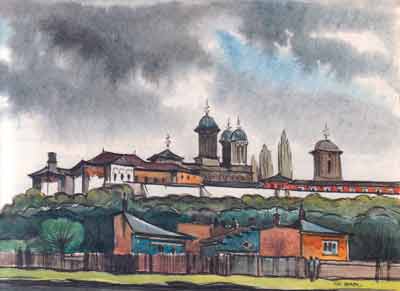

Professor Kathy Hillman highlighted autographed volumes by Alexander Solzhenitsyn as rare items in the Keston Collection. They require special handling and are not digitized. The publication is the 1974 London Book Club Associates edition translated from the Russian by Thomas P. Whitney. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn personally inscribed the book to Jane Ellis on February 26, 1976. Ms. Ellis worked for the Keston Institute for nearly 20 years, serving on the editorial board of Keston’s journal Religion in Communist Lands (later titled Religion, State & Society), including 5 years as editor. She also founded Aid to Russian Christians (ARC).According to her obituary published by Philip Walters in Religion, State & Society in 1998, the ARC was the first organisation with the aim of systematically supplying material aid and spiritual support to Orthodox Christians in Russia. She remained the organization’s director until 1986. For the first four years of its existence, Jane Ellis ran the organization alone, operating out of a tiny bedsit in London. She wrote hundreds of letters asking for support for faith communities in the Soviet Union. She joined the Keston Center immediately after graduating from the university in 1973, where she translated documents, gave lectures, wrote articles for scholarly journals and edited volumes, and broadcast for the BBC in both Russian and English. She travelled widely within the USSR and wrote two monographs about the Russian Orthodox Church, which were received with acclaim in Russia. She also promoted interfaith discussions and cooperative projects.

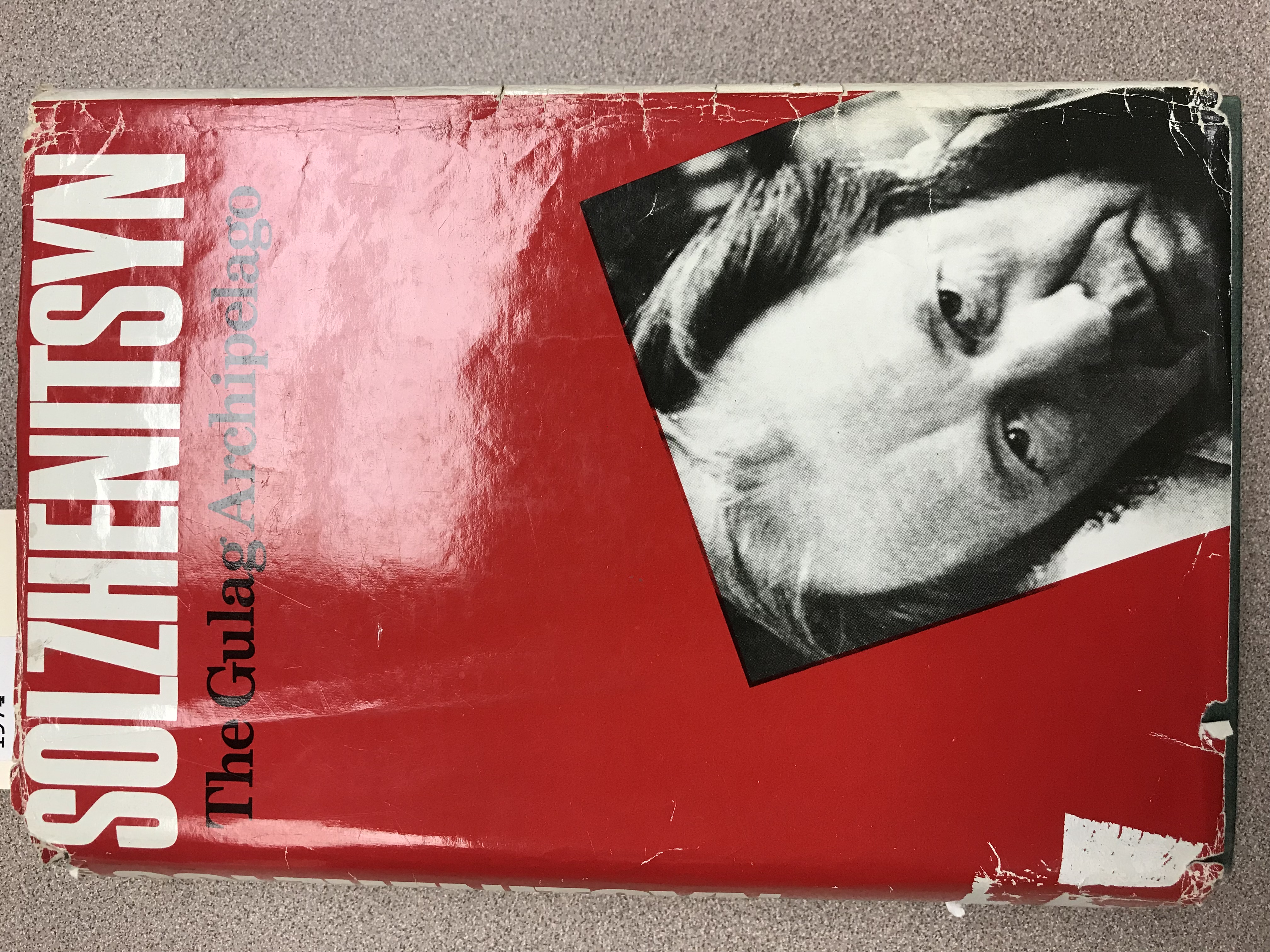

The collection holds documentation on the activities of the Strazdelis University, which operated underground in Lithuania in the 1970s. The aim of the Strazdelis University was to provide alternative education on a voluntary basis, organising and inspiring self-education in the humanities and social sciences. Much attention was paid to ethnography and the study of Karl Marx, interpreting his works differently to how Soviet ideology did. The Strazdelis University was the first step in anti-Soviet or non-Soviet actions for a group of people who later, during the period of Sąjūdis (the Lithuanian national movement, 1988-1990), became activists and founders of modern political parties. The collection is stored in the private papers of Vytenis Povilas Andriukaitis, the EU commissioner, who was a member and dean of the university.

The collection is a private documentary collection of documents concerning one of the most successful Hungarian American advocacy organizations in the field of minority and human rights. Founded in 1976 by second-generation Hungarian American intellectuals and professionals and referred to until 1984 as the CHRR–Committee for Human Rights in Romania, HHRF addressed the advocacy on behalf of Hungarian minorities in Central and Eastern Europe.

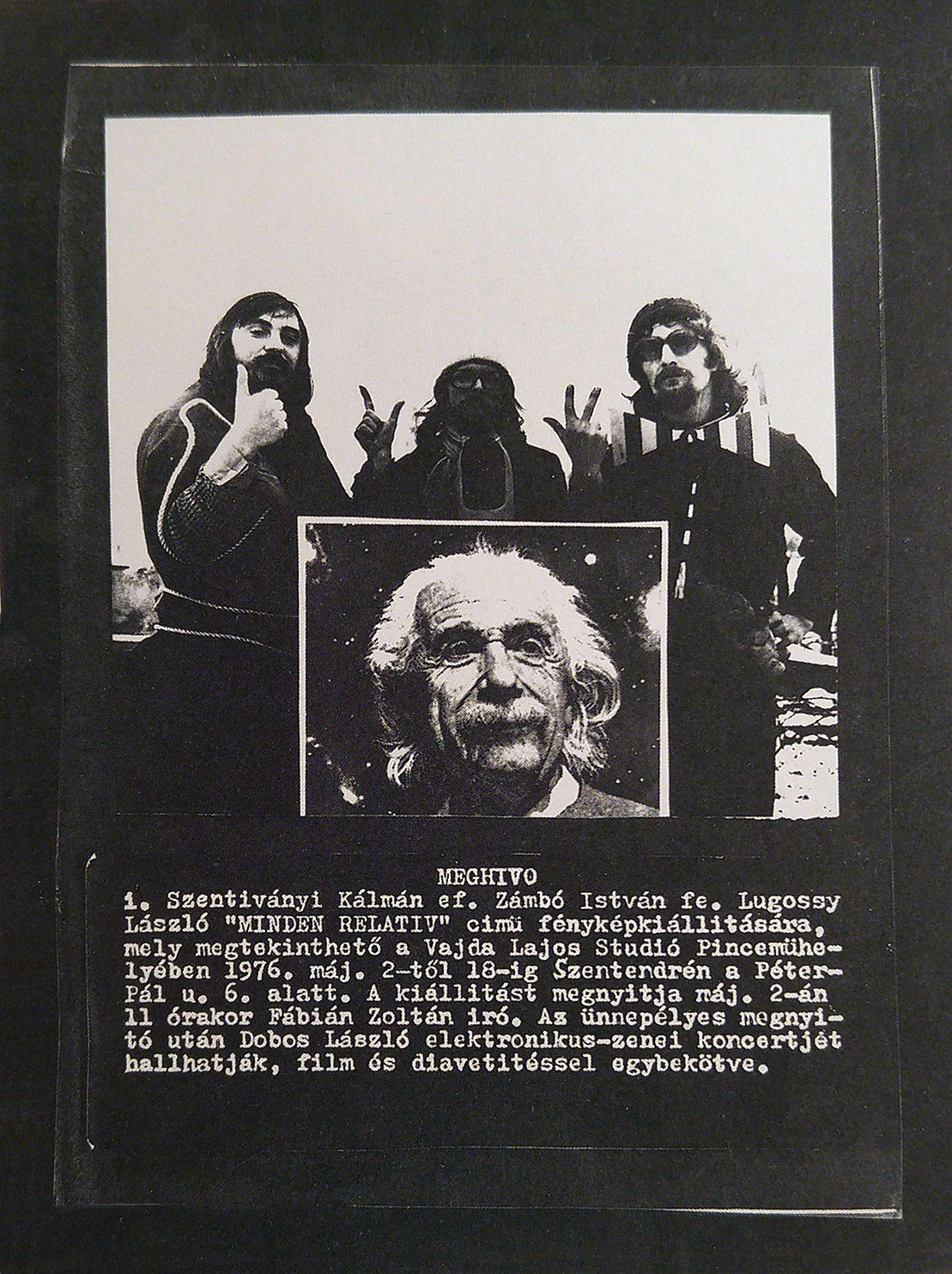

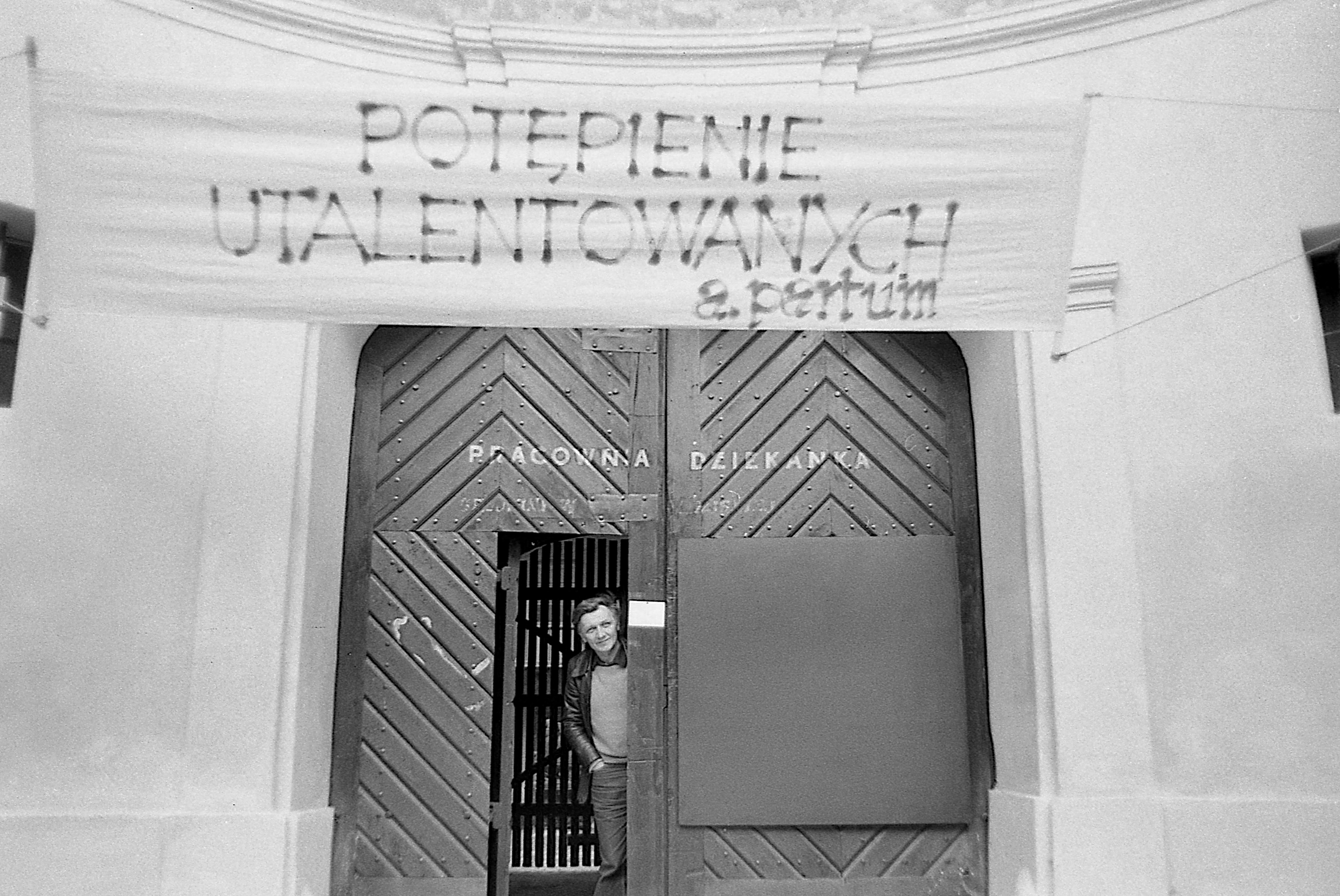

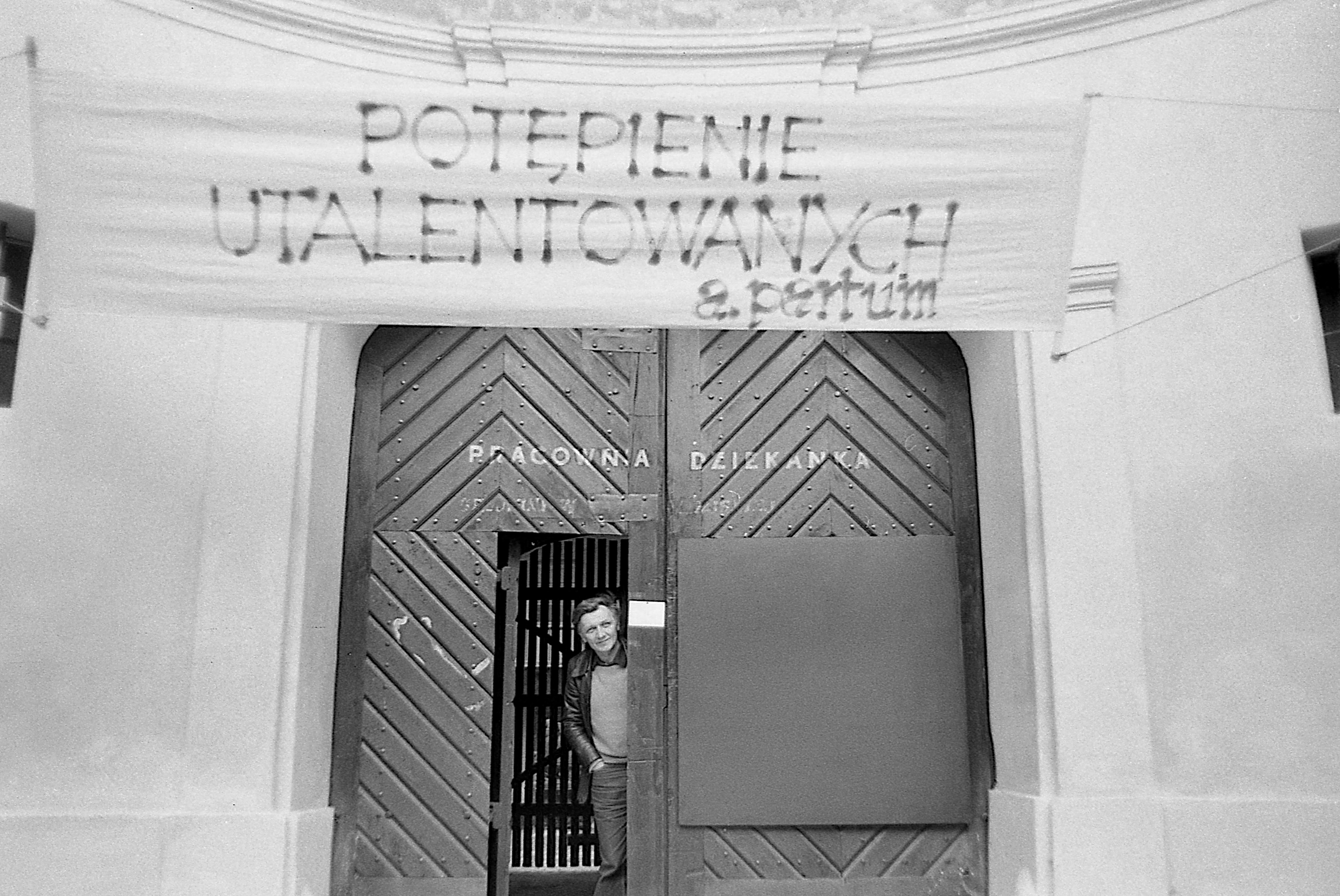

The collection is about the activities of the Dziekanka Students' Art Center and Dziekanka Workshop (Pracownia Dziekanka) in the years 1976-1987. Under these two names was the same place, an extraordinary interdisciplinary artistic and educational laboratory, combining the debuting students of Warsaw's art academies and outstanding artists from Poland and abroad. Around the studio, a unique milieu was created, combining post-Fluxus artists interested in new media and avant-garde theatre ventures, but also painters and sculptors of new expression or punk music bands. The years 1976-1987 is the most intense, though the heterogeneous period in the history of Dziekanka, filled with exhibitions, performances, shows, discussions and social life. During this time Tomasz Sikorski was an active participant in events at Dziekanka, and from 1979 he was the co-director of the institution. Owing to his constant presence and managerial function, Sikorski gathered an extensive collection of photos and other materials documenting the functioning of the initiative, going beyond the definitions of independent galleries.