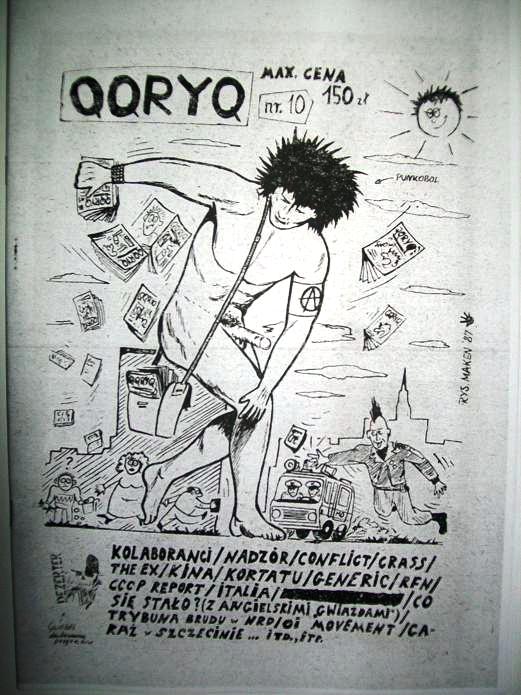

The majority of the editions of ‘QQRYQ’ was printed on Xerox from one hundred to two hundred copies. The matrices were made by hand, in a collage technique, from scraps of official newspapers and magazines, small text lines prepared on typewriter, hand written articles, photos, graphics, and comics. The first issue published on the offset appeared in 1990. It was also the first issue prepared with a usage of a computer. Against this background of Xerox and offset techniques of printing, the tenth edition of ‘QQRYQ’ seems to be very original. This edition was published by screen print, which was hardly ever practiced as a way of bringing out punk fanzines. The screen printing technique was extremely labour-intensive and took a lot of time to print even a relatively small number of copies. Another unusual fact about the tenth number of ‘QQRYQ’ was a usage of the official foolscap because of lack of different kinds of paper. The content of the issue did not vary so much from the rest of the editions, but worth mentioning were the graphics by Mirosław ‘Maken’ Dzięciołowski, reggae DJ, promoter, and alternative scene activist in the late 1980s in Poland. Dzięciołowski was one of a few regular contributors of ‘QQRYQ’.

During the first half of 1987, personal and ideological tensions within the MWU were rampant. These tensions came to a head early in the year, when the long-serving Chairman of the MWU, Pavel Boțu, committed suicide. This tragic event reflected not only the unprecedented degree of personal animosities and rivalries among the writers, but also a sharpening ideological divide along national-cultural lines. The Writers’ Conference organised on 18 May 1987 became the stage for heated and acrimonious debates. These debates reflected not only a generational rupture between the “generation of the 1960s” and the writers born in the interwar period, but also the radically changed ideological circumstances during Perestroika. Some members of the MWU did not hide their open dissatisfaction with the organisation’s leaders and used the context of Perestroika to voice radical demands. Aside from the journalist and publicist Valentin Mândâcanu’s incisive speech on the “language issue,” the speech made by Grigore Vieru attracted widespread attention due to its virulence and radicalism. At the time, Vieru was a well-known poet and author of children’s books, whose texts reached a wider audience compared to most of his colleagues. Vieru was frequently attacked for “nationalism” and “ideological deviations” by the MWU’s “old guard,” most notably Andrei Lupan. Vieru thus used the conference to mount a violent attack on Lupan personally and on the “old style of leadership” within the MWU more generally. However, Vieru’s speech is notable not because of the settling of personal scores, but due to the wider issues it raised. First, he responded to the accusations of emulating and “aping” the Romanian model by “looking beyond the Prut.” He rhetorically wondered: “Why wouldn’t I look in that direction, after all? Why do I have the right to look toward Turkey, but not beyond the Prut? What harm did Sadoveanu, Călinescu, Arghezi, Blaga, Stănescu do to me?” These cultural references only emphasised his pro-Romanian position in contemporary debates. Second, while attacking Lupan for his ostensible pro-Stalinism and his earlier ”ideological sins,” as well as for his ambiguous position toward the regime, Vieru used an openly oppositional language, going far beyond the prudent rhetoric of early Perestroika. He mentioned a number of “hot” issues that made his speech subversive in the eyes of the authorities. Vieru spoke about “the disastrous situation in which the speech of our children finds itself, the pollution of our folklore, the intentional and offensive neglect of our native language on national television,” but he also emphasised the ecological crisis, the consequences of the 1946–47 mass famine, as well as the “physical and spiritual inebriation of the common man.” All these topics were to be exploited by the fledgling national movement in the following years and served as mobilising slogans for the anti-regime opposition. Toward the end of his speech, Vieru launched a rhetorical tirade against his opponent, using this pretext in order to voice a number of social and political grievances:

“Do you know that, behind our literary distinctions and prizes, we are witnessing, in broad daylight, a real linguistic disaster? Do you know how distorted and ugly is today the speech of our children, youth and even older people? Do you know that the few Moldavian kindergartens in Chișinău are full to the brim and it is impossible to enrol your child there? Do you know that, out of seventeen hours of TV broadcast every day, barely two or three, and sometimes even fewer, are reserved for TV shows in our native language?!...Do you know that our villages, which preserved our national being, are being depleted of their people and their soul?”

This radical and impassioned speech was met by the audience “with applause,” marking a change of tone and atmosphere that foreshadowed the later role played by the writers in the national mobilisation against the Soviet regime. The Writers’ Conference of May 1987 represented a turning point in the radicalisation of political discourse, with Vieru and some of his nationally oriented colleagues positioning themselves at the forefront of the emerging oppositional movement.

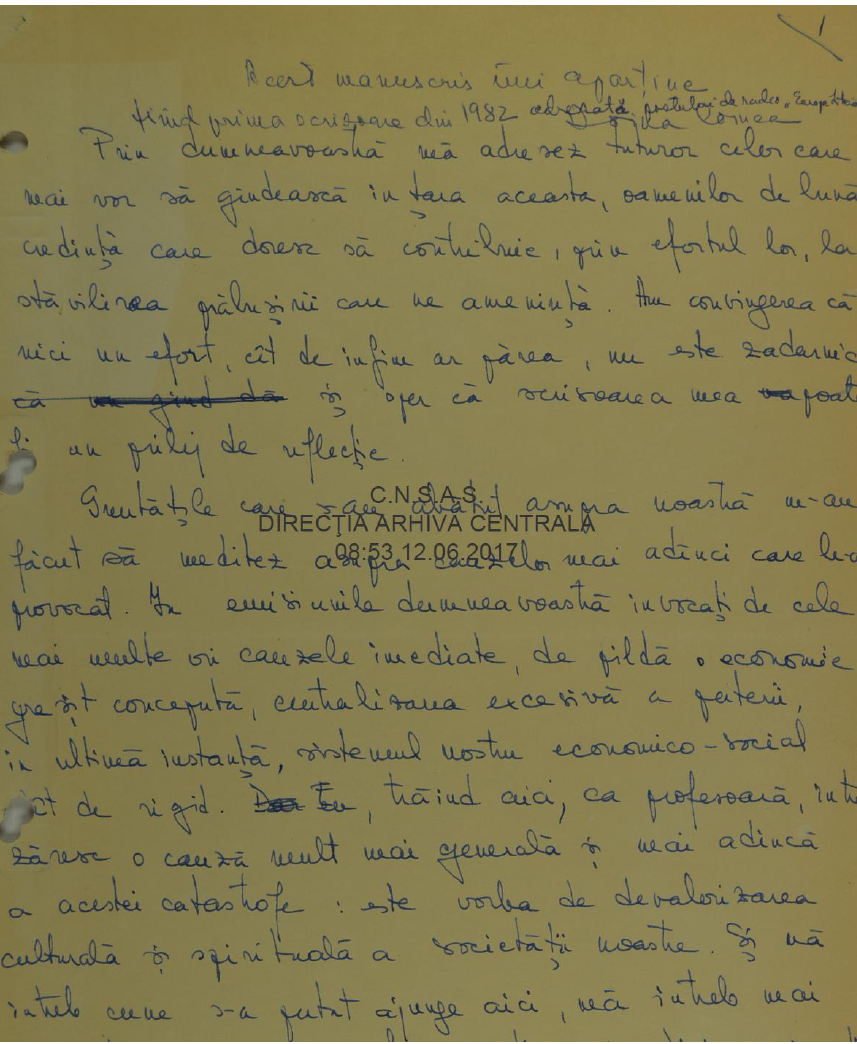

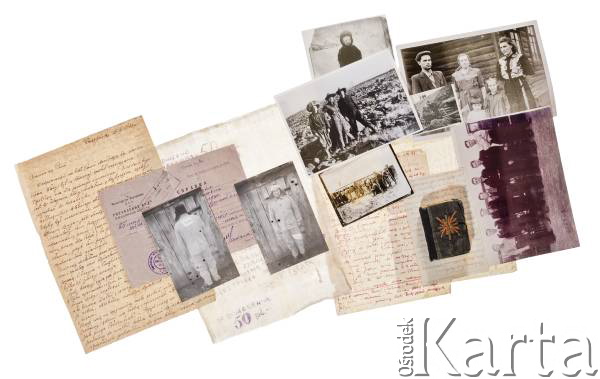

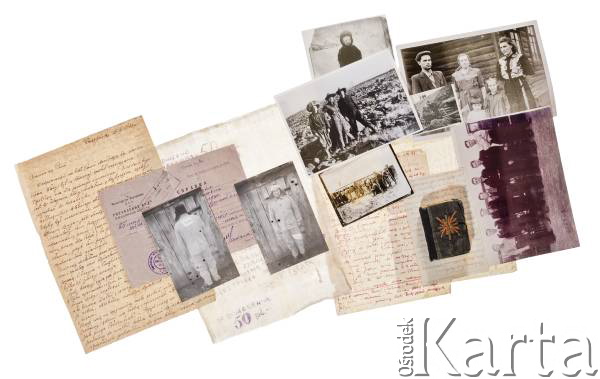

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

After listening in November 1987 to the news broadcast by Radio Free Europe (RFE) about the anti-communist revolt of the workers in the factories of the city of Braşov, Doina Cornea openly displayed her solidarity with the protesters. On 18 November 1987, she drafted 160 manifestos, which were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in several public spaces in Cluj (Cornea 2009, 194–195). Consequently, on 19 November 1987, she and her son were arrested by the Securitate after a detailed home search (Cornea 2006, 203). During home searches on 19 and 23 November 1987, the Securitate confiscated many documents from Cornea’s private dwelling, including all the drafts of her letters to RFE.

Among these documents, the Securitate confiscated the handwritten draft of the first letter she sent to RFE entitled: “Letter to those from home who have not given up thinking with their heads.” According to interviews granted by Doina Cornea, this letter was drafted by Cornea and her daughter Ariadna Combes in July 1982 (Cornea 2009, 169-170). The document was smuggled to the West and sent to RFE with the help of her daughter, who chose to remain in France in 1976 and visited her mother in July 1982 (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, f. 11). In August 1982, the letter was broadcast by RFE during the radio programme “Talking with RFE listeners.” It was the first letter in a series of twenty open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE in the period from 1982 to 1989, through which she asserted herself as one of the most prominent Romanian dissidents (Cornea 2009, 195–196). The open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE intensified the surveillance and repressive actions of the Securitate, which had already been monitoring her closely since 1981. Due to the fact that the strict surveillance in communist Romania did not allow the development of a samizdat and tamizdat milieu, RFE played a key role in conveying the messages of Romanian dissidents to their fellow citizens (Petrescu 2013, 277).

The letter starts with a reference to radio programmes of RFE that had been previously broadcast. During these radio programmes, journalists specialising in East European issues had dealt with the crisis that affected communist Romania during 1980s and identified political and economic factors as the immediate causes. Instead of these causes, Doina Cornea emphasises in her letter causes relating to moral and cultural values. By idealising interwar Romania, she brings into discussion the destruction of the Romanian intellectual elite during the first two decades of communist rule and the decay of the educational system. In Cornea’s opinion, this “spiritual crisis” is illustrated by the everyday “compromises” and “lies” that citizens living under a communist dictatorship have to “accept and circulate” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f.1). Her argumentation in this respect is similar to that developed by Vaclav Havel’s essays and epitomised by his principle of “living in truth” (Havel 1990). Cornea argues that “the people is fed only with slogans,” which stifle all openness towards “truth, revival, and creativity” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 2–3). She criticises the conformism of Romanian intellectuals and state policies which limit theoretical education (especially the humanities) and promote technical education in order to fill the need for cadres in the rapidly growing heavy industry.

She concludes her text by asking for a reform in the educational system and encourages those working in this field at least to take advantage of the limited possibilities available to them to promote what she considers to be authentic cultural and moral values. According to Cornea, those working with students should not teach them “things in which they themselves do not believe” and they should “encourage the creativity of young people and not be afraid to say what they think” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 4–5). At the end of the letter, Doina Cornea inserted her name with the mention: “for the messengers of RFE listeners” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 5). She did not intend to reveal her real identity to the listeners of RFE, but just to prove the authenticity of the document to the editors of the radio programme. Due to a misunderstanding, her real identity was revealed during the radio show.

In November 1987, after the draft of this document was confiscated by the Securitate, the secret police used it as an argument of accusation during Cornea’s interrogation. This focused especially on the channels used by Cornea to send the letter to RFE. Although she did not mention it during the interrogation, the Securitate suspected that her daughter Ariadna Combes had helped her in this respect. For this reason, Cornea’s daughter thereafter did not receive a permit to enter the country to visit her family until the fall of the communist regime.

Judging from the level of difficulty of the twenty-two questions contained in it, the target group of the document identified as a questionnaire included the most sophisticated members of the Hungarian elite in Romania, who did not necessary work in the cultural sphere, but who had presumably been selected as a result of previous inquiries. The questionnaire, made up of three major sets of questions, first assesses the social status, qualification level, and general culture of the subject, then examines the subject’s sense of identity, and finally investigates, also out of a need for identifying a solution, the nature of the connections and relationships between Romanians and Hungarians, as well as experiences regarding coexistence.

I. The first set of questions focuses on the subject’s social status. It begins by examining the social background of the subject – family, origin – and then inquires about his/her age to further turn to a direct reference to the “small Hungarian world” in Northwestern Transylvania during the Second World War (Sárándi and Tóth-Bartos, 2015), which suggests that the questionnaire focuses primarily on mature individuals holding well-defined views on the Transylvanian issue. Questions four and five address the length and possibilities of past education in the mother tongue in the family of the subject, respectively, in his/her “range of vision.”

The Questions:

1. What kind of family do you come from?

2. What type of social environment do you come from? (rural, urban, peasant, worker, bourgeois, aristocrat, etc.)

3. How old are you? Were you alive between 1940 and 1944?

4. How long and what were you able to study in your mother tongue?

5. What about your family and /or “range of vision”?

II. The second set of questions – questions 6 to 14 – is directed at the subject’s sense of identity. The assessment of collective memory is followed by a nostalgic question, which, beside the inventory of violations of human rights experienced in the present, makes the subject draw a comparison with the rights undoubtedly held in the past. The question about general knowledge of Hungarian history is followed more emphatically by that about self-declared knowledge of post-1918 Transylvanian history and of the public figures related to it. Then the author of the questionnaire moves on to the mapping of reading habits and needs in the mother tongue, of cultural life and religion. The question referring to the level of Romanian language skills is still relevant. As the knowledge of language represents a prerequisite for social integration, this also means that as long as the coexisting nations are unable to eliminate language barriers, their cultures cannot get closer to each other, cannot coexist in harmony. Radio listening habits provide answers regarding the need for information of Hungarians in Transylvania, but also about their possible resignation and indifference. The inquiry about connections in Hungary presupposes the existence of a current network of contacts in the “mother country,” including relatives, friends, and acquaintances. The thirteenth question, about the new situation in Hungary – which offers a clue about the date of the document – presumably hints at the changes that took place during the official mandate of the moderate reformer Károly Grósz, appointed president of the Council of Ministers in June 1987. On May 1988, the reform wing of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP) obtained the long-awaited goal of removing the old and ill János Kádár from the party leadership and elected Grósz as his successor upon a programme of transition to a market economy and political decentralisation. However, it cannot be excluded that allusion was made to symbolic events of 1989 relating to the commemoration of the Revolution of 1956, such as the reburial of Imre Nagy and his comrades, or the radio speech by the senior party official Imre Pozsgay about the re-evaluation of this tragic event in Hungary’s recent past (Romsics 2013). The last question in this section, referring to a “prominent Transylvanian personality” takes into consideration the greater political events and perhaps it looks ahead in allowing for an unpredictable political turn in Romania.

The Questions:

6. What can you recall, or how far back does your collective (family, workplace, etc.) memory extend?

7. Would you like to regain anything from the past? If yes, what?

8. Are you familiar with Hungarian history, and with the history of Transylvania in particular? (What do you know about the events following 1918? Are you familiar with the operation of the Hungarian National Party [Bárdi 2014, Horváth 2007, György 2003]? Are you familiar with figures such as Ct. Bethlen György [1888–1968, president of the Hungarian National Party representing the Hungarian minority in Romania in the interwar period (ACNSAS, I185019)], Jakabffy Elemér [1881–1963, Hungarian, later Romanian Hungarian politician, lawyer, publicist (Balázs 2012, Csapody 2012)], Makkai Sándor [1890–1951, Transylvanian Hungarian writer, pedagogue, Reformed bishop (Veress 2003)], Mailáth [Majláth] Gusztáv Károly [1864-1940, Transylvanian Roman Catholic bishop, member of the nobility, honorary archbishop (Marton and Jakabffy 1999)], Domokos Pál Péter [1901-1992, teacher, historian, ethnographer, one of the pioneers of research into the Csangos (Jánosi 2017, Domokos 1988)] etc.?

9. Do you own Hungarian books? Do you read in Hungarian? If yes, how much? How do you gain access to Hungarian books? Do you go to the theatre? Are you a church-goer? (Is the use of the Hungarian language or the fact that you are a believer behind church attendance?) 10. How well do you speak the Romanian language?

11. Which radio station do you listen to? That of Budapest or that of Bucharest? And which Radio Free Europe broadcast do you listen to: the Romanian or the Hungarian one?

12. Do you have contacts in Hungary?

13. What do you think of Hungary in this new situation?

14. Is there a prominent Transylvanian personality you know about and consider worth paying attention to?

III. The third set of questions – questions 15 to 22 – analyses the relationship between Romanians and Hungarians. Thus, beside inquiring about the nature of relationships maintained by the subject and his/her environment with his/her ethnic Romanian fellow citizens, these questions focus also on the ethnic characteristics of the coexisting population, whether the demographic balance in a given settlement, which was centuries ago favourable to the Hungarian community, has been subject to modifications by the communist regime by attracting inhabitants from other regions populated mostly by Romanians. Having future coexistence in view, question 17 is aimed at learning the “lacking needs” of the subject, so it inquires about the required minimum conditions in terms of human rights that allow him/her to live as a Hungarian there, in that given place. Amidst the measures aimed at the assimilation of the Hungarian minority in Transylvania, such as the continuous diminishing of educational opportunities in the Hungarian language, the closing down of Transylvanian Hungarian theatres, the potential destruction of villages, the phenomenon of emigration, which affected the Romanian citizens too, in the context in which the nationalism of Ceaușescu’s regime was become more and more radical, when politics-fuelled intolerance towards ethnic otherness was a daily presence, the question about individual views regarding the future of the minority community might have seemed surreal. Thoughts referring to the renewal of the indigenous minority were closer to utopia as the flagrant violation of human and minority rights provided no realistic grounds for this. The last two questions of the questionnaire – questions 21 and 22 – about positive experiences as a Hungarian living in Romania, positive experiences concerning the Romanian–Hungarian relationship – illustrate, even in their choice of words – “have you ever,” “accompany or would accompany” – the perspicacity with which the author of the questionnaire acknowledges the situation of the Transylvanian Hungarian minority of the period preceding the change of regime.

The Questions:

15. What is the nature of your (your personal and your community) relationship with Romanians?

16. Are you surrounded mostly by Romanians or by Hungarians in your living environment? If you live predominantly surrounded by Romanians, when was this situation installed? Is it a result of incoming settlement or is it the indigenous population?

17. What is it that you lack most in living there as a Hungarian?

18. What is your opinion about your own future, the future of your family, and that of Transylvanian Hungarians?

19. Do you see any possibilities of renewal?

20. If you are a church-goer, what do you know and what can you witness from the Greek Catholic movement?

21. Have you ever had any positive experiences as a Hungarian? If yes: when and what kind of experience was it?

22. List the positive experiences that accompany or would accompany the relationship between Romanians and Hungarians?

There is no doubt that Gyimesi is the author of this document. In numerous places her works include analyses of the given situation and sense of identity of the Hungarian minority in Transylvania (Gyimesi 1993). Most probably the document escaped the attention of secret police officers conducting the home search on 20 June 1989 due to the absence of title and date. The physical existence of a questionnaire examining minority life in the darkest days of Romanian Communist dictatorship is startling in itself. Research conducted in the form of questionnaires presupposes the subject’s right to free opinion and is interpreted as an accessory of democratic systems. However, the existence of the document does not mean that the intended survey was actually conducted. For Gyimesi, who was the subject of informative surveillance, in a world abounding in collaborators with the secret police, this questionnaire must have meant a handhold which should have helped her in identifying persons with similar views on whom she could have counted in the struggle against the violation of human and minority rights. This may have served as a basis – as a possible interpretation – for her efforts to recruit reliable colleagues for the editing and distribution of the Cluj-based samizdat paper known as Kiáltó Szó, which she conceived in the fall of 1988 together with Sándor Balázs, a philosopher and university professor. Out of the nine edited issues of the samizdat – which was little known even by the Securitate – only two were published, though this had nothing to do with the editors: the publishing of further issues was rendered unnecessary under the circumstances following the fall of the Ceaușescu-dictatorship.

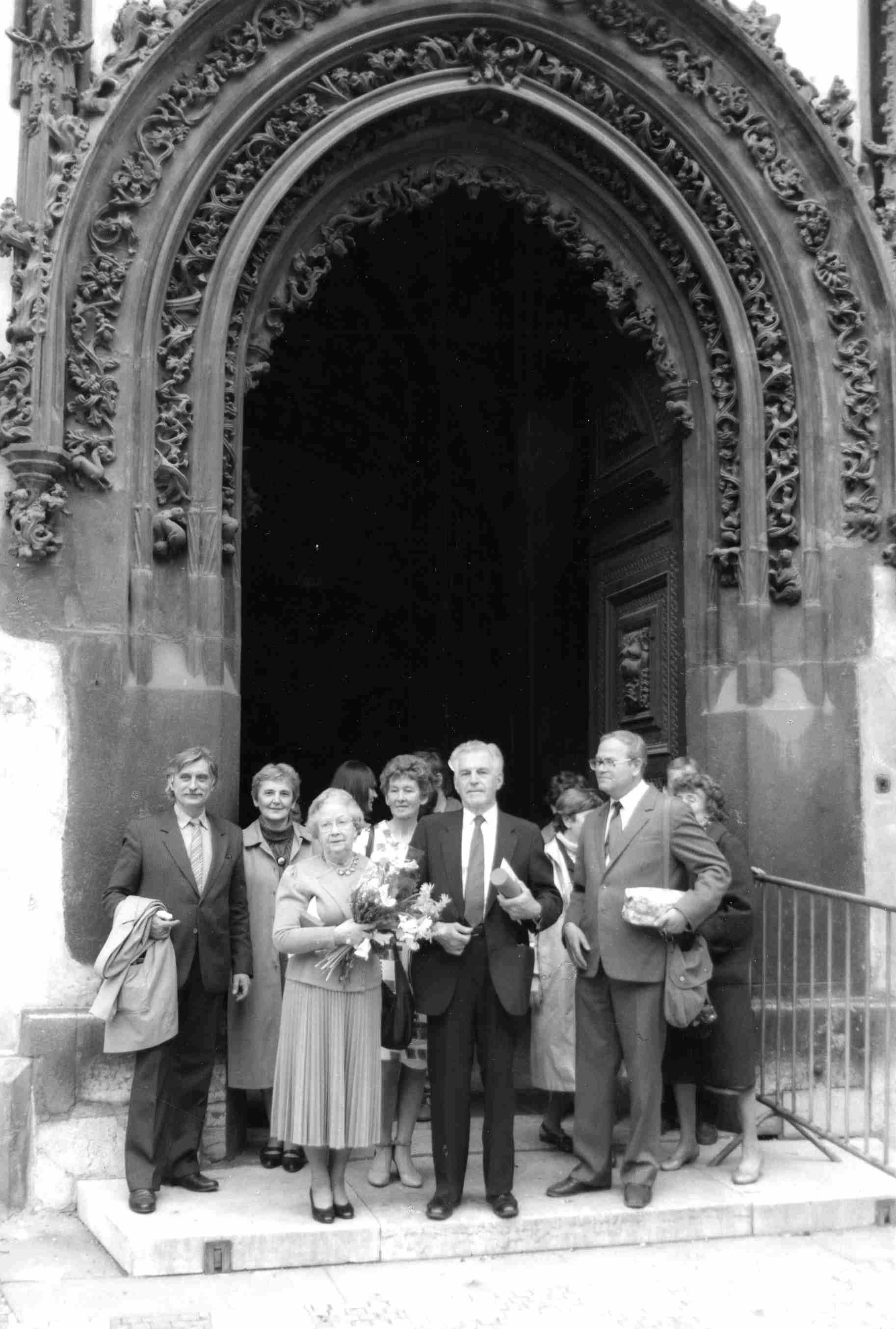

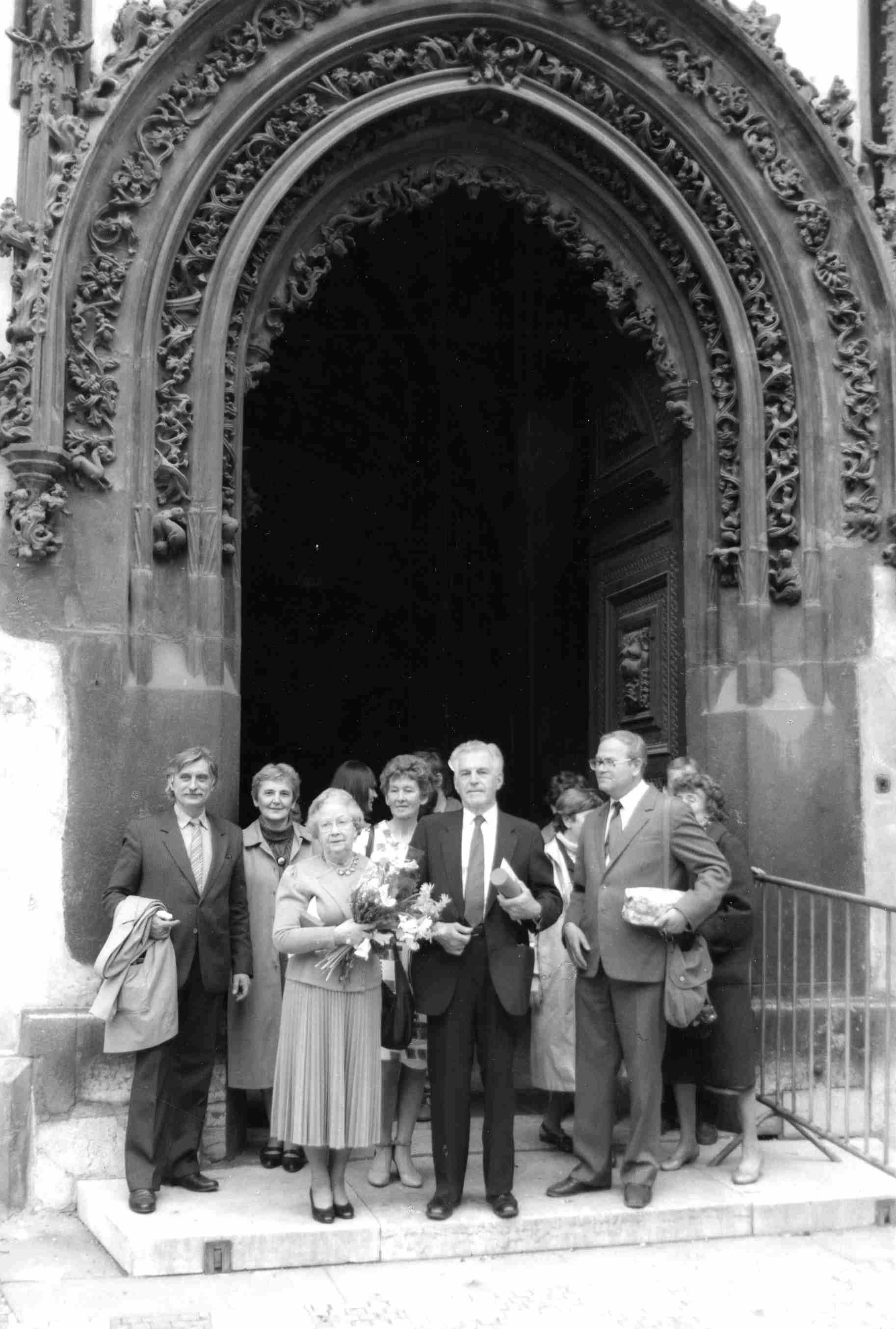

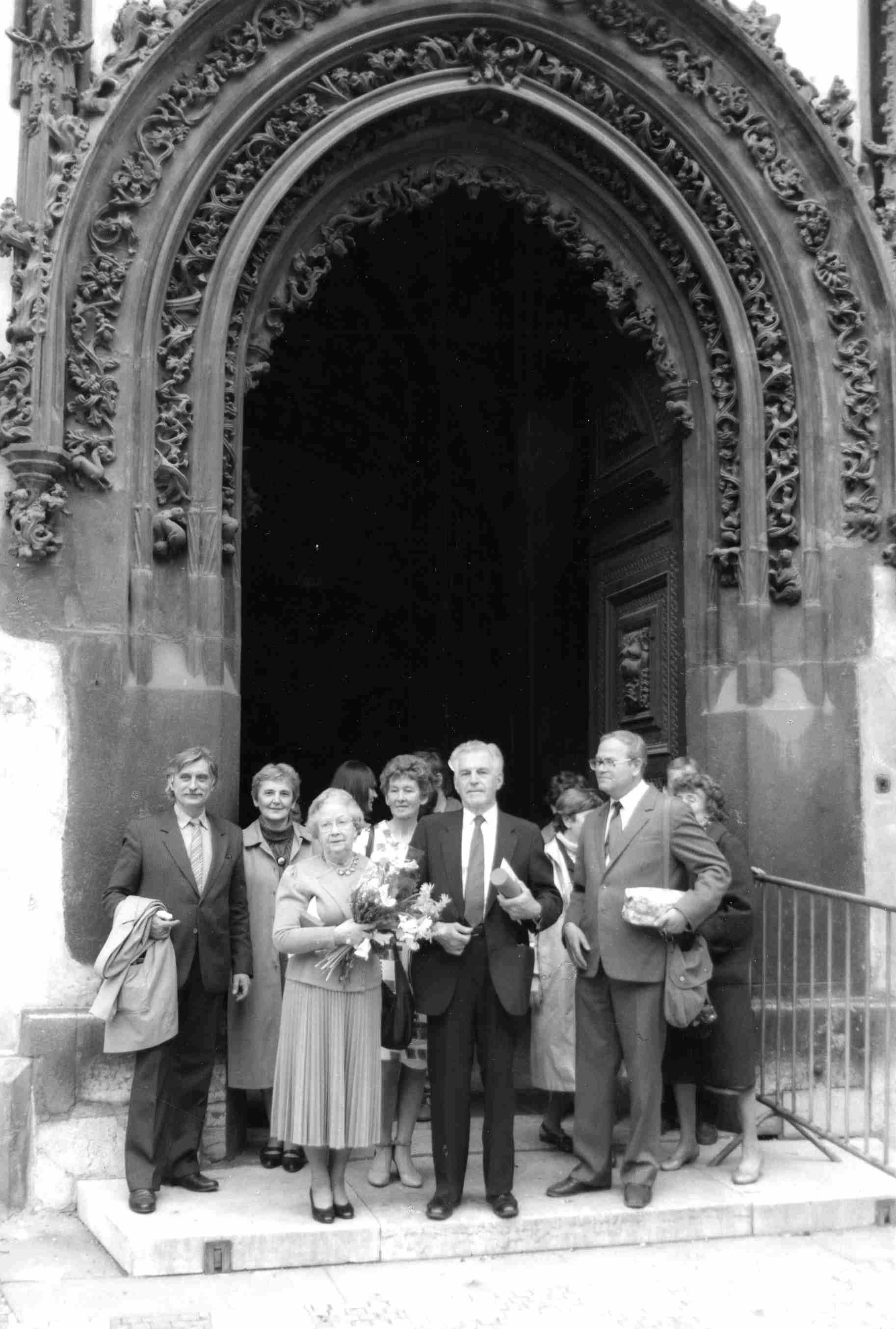

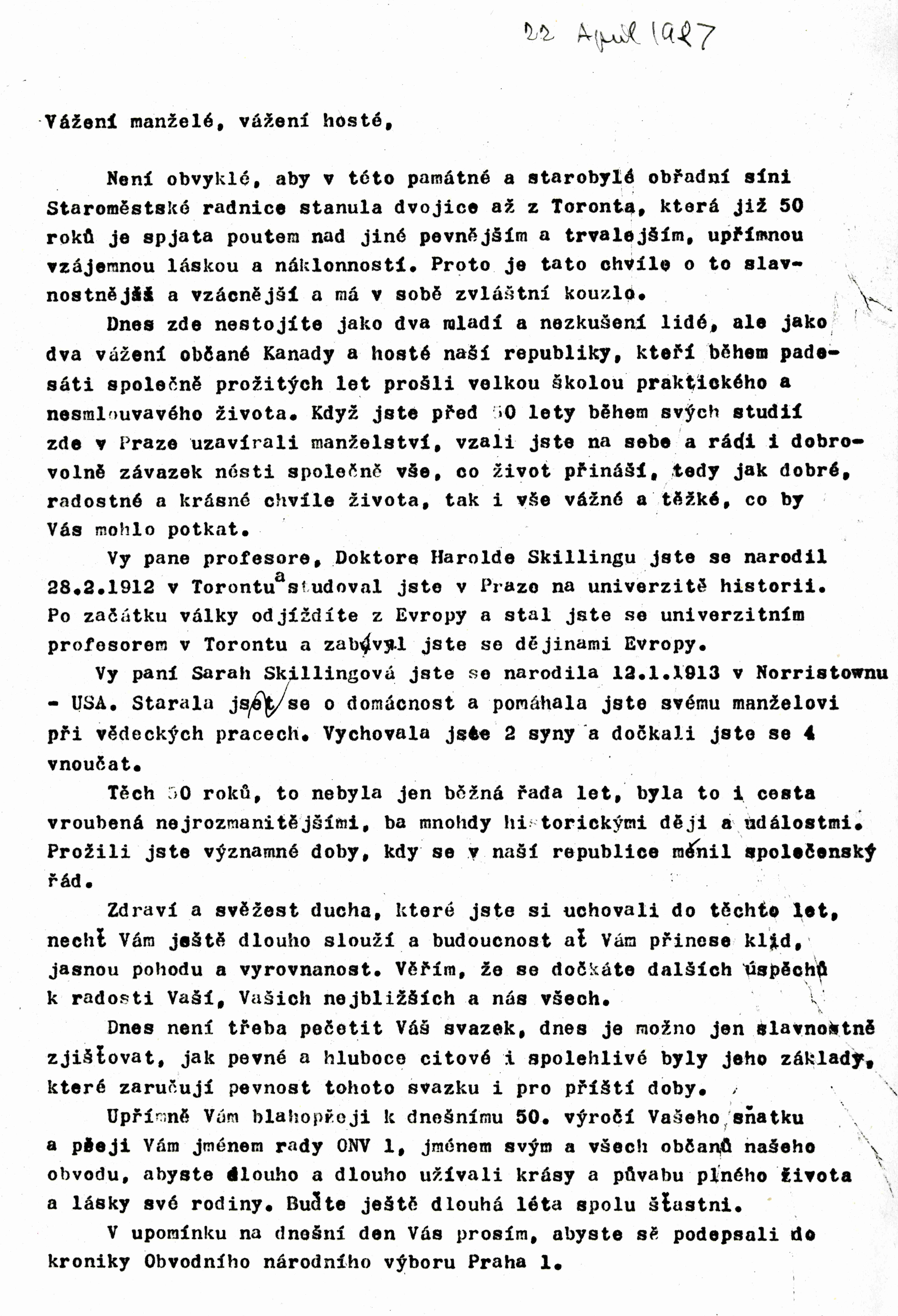

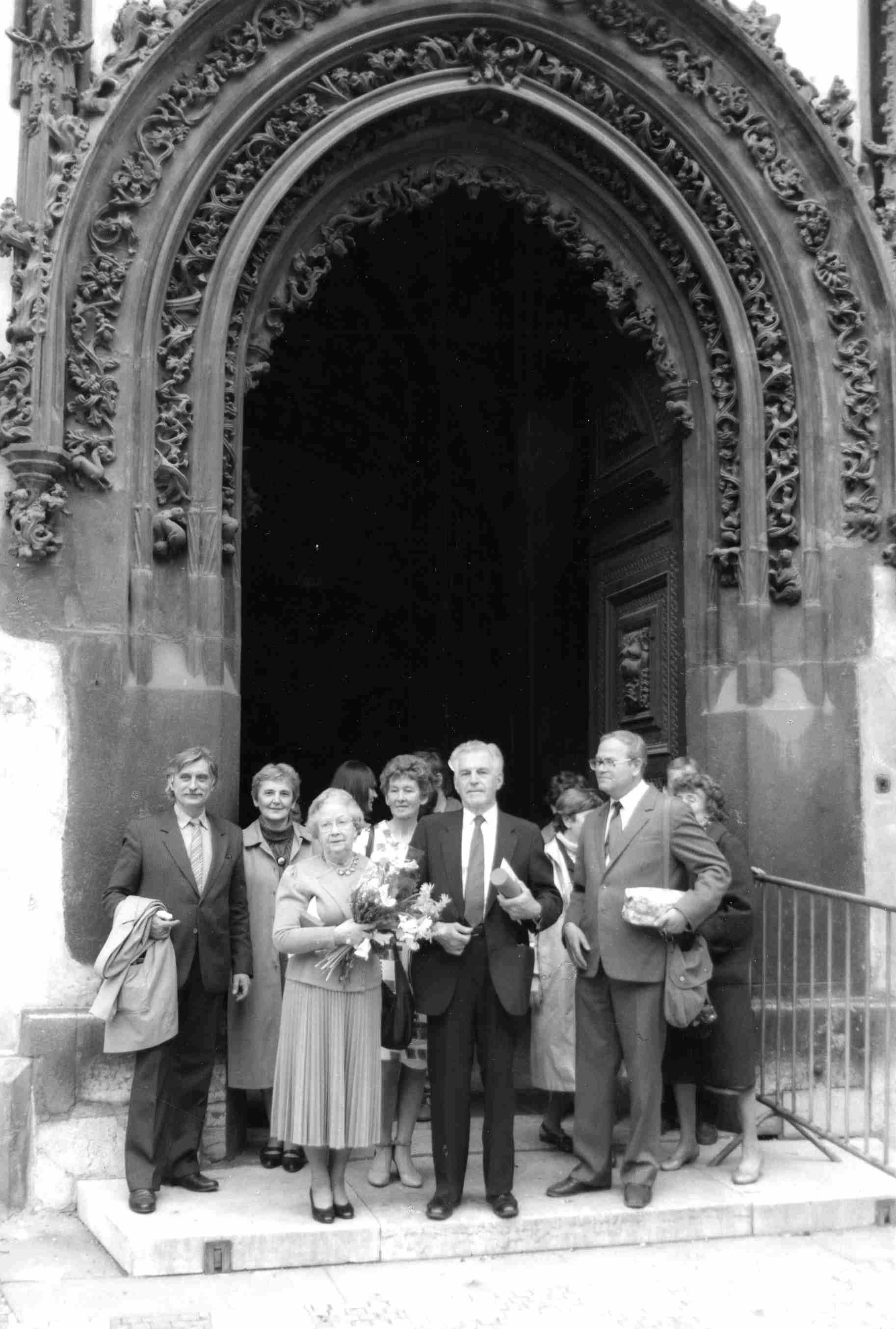

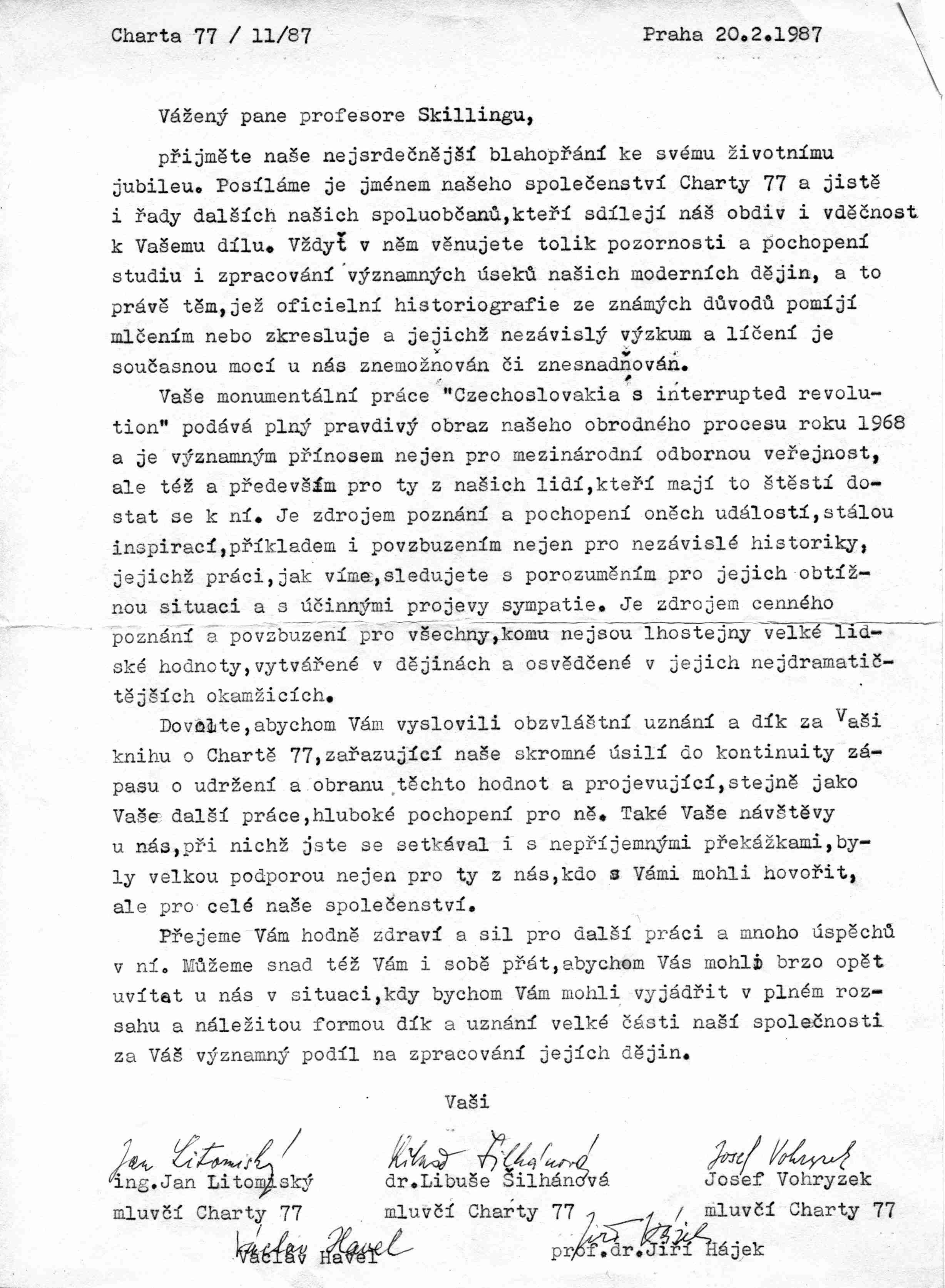

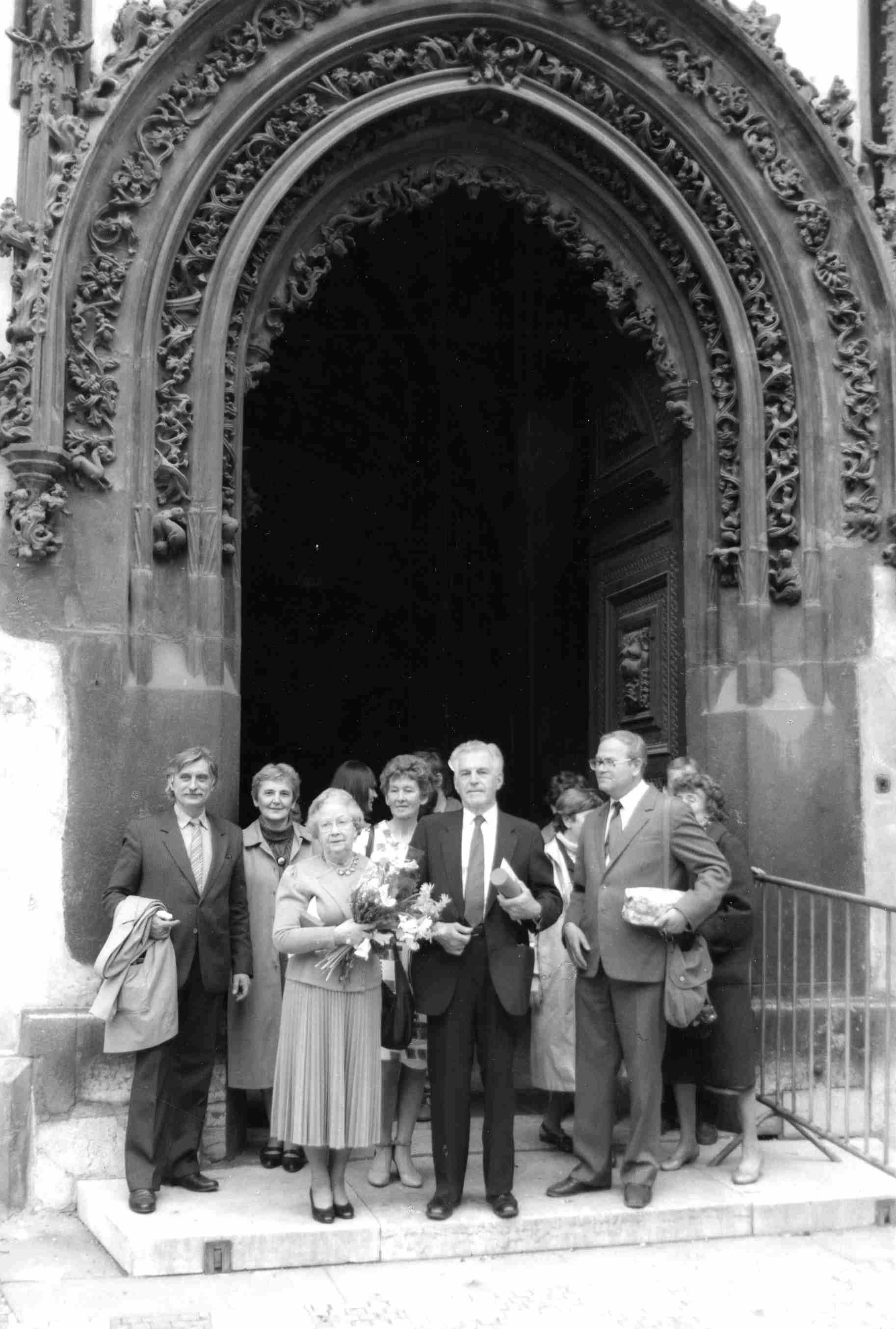

Skilling’s Golden Wedding anniversary, was at the Old Town Hall in April 1987. The journey Gordon Skilling made to Prague in April 1987, marked the celebration of Skilling's 75th birthday and the 50th anniversary of his marriage to Sally. The wedding ceremony was arranged by his dissident friends in the Old Town Hall, which was also the same ceremonial hall where they were married in 1937 (their wedding in October 1937 took place during G. Skilling’s first time in Czechoslovakia, where he studied the History of Central Europe as a student of London University). The anniversary celebration was a delicate irony in which the guests were fond of - a tribute to the "enemy of the state" because the Communists had released a number of dissidents which they had not known about. The next day in the Prague Evening, the news appeared, with a somewhat funny title, "Wedding Overseas". Jiřina Šiklová gained a great credit for this, because she paid the newspaper editors with the make-up from Tuzex at that time.

Gordon Skilling himself remembers this after years in an interview with Lidove Noviny in June 1993: "It was an interesting ceremony because perhaps all Czech dissidents - Havel, Pithart, Dienstbier and others - were present. It was strange that, in this honest ceremony, the chairman of the National Committee for Prague 1 spoke about what I did for Czech history. But he did not know that I also wrote a book about the Prague Spring, a book on Charter 77 and other things. He did not know it, and so he was very glad. Absurd situation. But the dissidents liked it. They were smiling internally. And then we had a gala dinner at the Municipal House. I like to recall the event."

In the 1980s an entire area of Braşov was demolished in order for a new district to be built in its place, namely the Civic Centre, supposedly the city’s new socialist centre. The building of “civic centres” (centre civice) was an intrinsic part of the urban systematisation policy that was promoted during the 1970s and 1980s. This policy was meant to implant a new urban identity in the cities, one that would reflect the “greatness” of the “Golden Age,” as the official propaganda presented Ceauşescu’s regime. The buildings depicted in the pictures are part of a district called Strungul (The Lathe), which was the name of the factory in the vicinity. The buildings were private houses of one or two storeys, mostly built at the beginning of the twentieth century or in the interwar period by middle-class or working-class families. The demolished buildings were replaced in the second half of the 1980s by a cluster of ten- to fifteen-storey buildings. In the background of the picture can be seen a building that took shape in the 1960s, belonging to the Hidromecanica Factory, on which a propagandistic slogan can be seen: “Long live the Romanian Communist Party.” The juxtaposition of this slogan suggesting the greatness of the communist era with the apocalyptic setting of the demolition gives this image an ironic meaning. Taking these pictures was an act of cultural opposition because photographing the demolition processes implied political risks for the photographer. The simple act of immortalising the demolition processes could have been considered as a critical stance towards the official policies of urban systematisation.

The poster is one of the first hand-made materials, used in the initial protest in the autumn of 1987. The protest actions at that time were cautious due to the possible regime response, and contained no explicit political statements or requests. Their main appeal was directed towards the resolution of the severe pollution problem. Requests were articulated towards the need of pressing the Romanian state for the closure of the “Verachim” Chemical Factory in Giurgiu. The poster is a donation by Zlatko Elenski, participant in the protests and one of the creators of the poster, to the Rousse Regional Museum of History in 2014. He kept it until he heard the news in 2014 of the Rousse Museum’s participation in the international exhibition “Roads to 1989”, and decided to donate it to the museum.

The collection consists of three photographed copies of the periodical Auseklis (October-November 1987; January 1988; April 1988). It is not at present exhibited in the display of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia in its temporary location, but it will be shown in the permanent exhibition after the renovation of the museum's permanent building. The Auseklis review is a brilliant example of what the focus of public interest and discussion was in the early years of the development of the pro-independence movement.

The work of Adriena Šimotová that is in Jindřich Štreita’s collection is one of the many large-scale paper works that the artist has created since the 1970s. This is a body print imprinted in several layers of paper, highlighted with a blue pigment. Like the Polish sculptor Magdalen Abakanowicz, Simot formed her own body with touch. In many of her works she has attempted to wipe out the difference between the creator and his work. She wanted a physical gesture, such as a print of the body, the face or the limbs, to literally be incorporated into the work. Therefore, the traditional canvas was replaced with fine laminated paper or linen sheets. The paper, which symbolized vulnerable and sensitive skin, layered, crackled and jerked directly on her body or the bodies of her friends. Printed bodies and their torso became the symbol of a man wounded during the ‘normalization’ period of the 1970s and 1980s.

According to Jindřich Štreit, this work of Adriena Šimotová is the most valuable work in his collection; the estimated price is more than half a million euro.

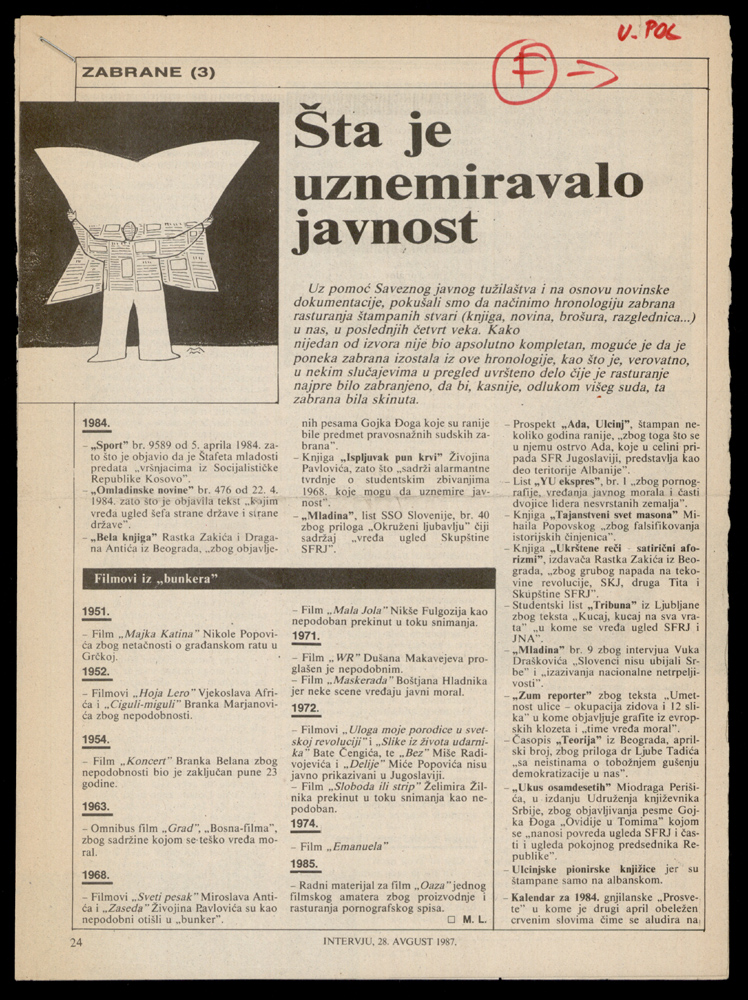

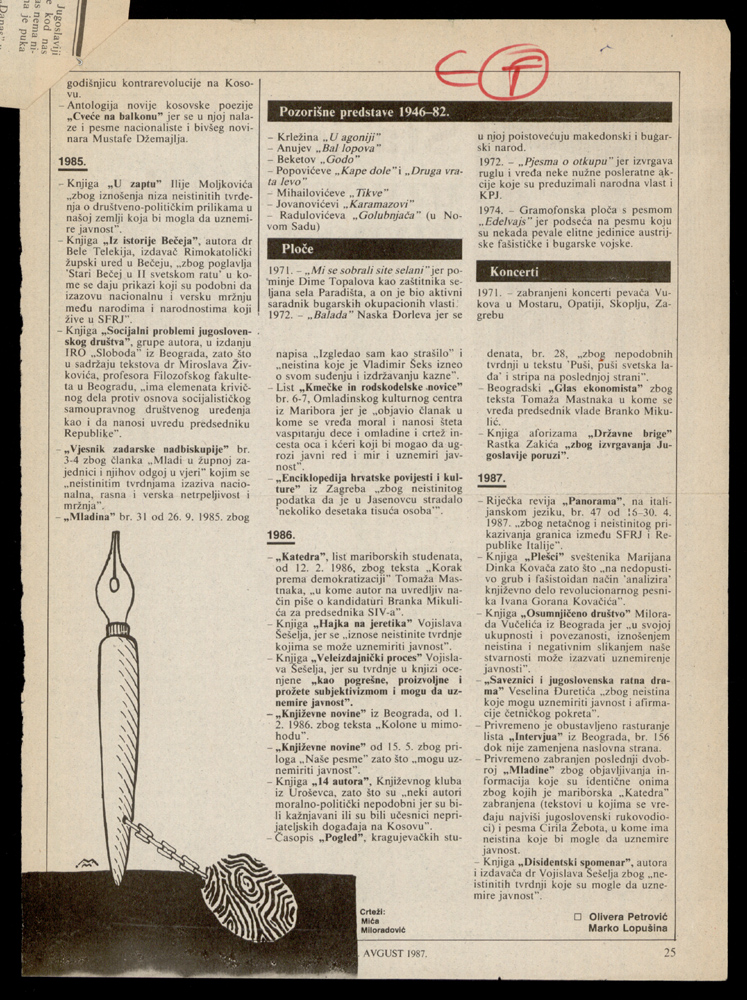

Petrović, Olivera and Marko Lopušina. Šta je uznemiravalo javnost (What disturbed the public), Intervju, 1987. Press clipping

Petrović, Olivera and Marko Lopušina. Šta je uznemiravalo javnost (What disturbed the public), Intervju, 1987. Press clipping

A feuilleton in three parts, published in the magazine Intervju on 31 July, 14 and 28 August 1987, shows the extent of censorship in Yugoslavia in different fields of artistic production. It contains a chronological overview of banned publications (books, newspapers, brochures, postcards) in the period 1963-1987, banned movies in the period 1951-1985, theatrical productions in the period 1946-1982, as well as concerts and phonorecords from 1971-1972. According to the authors, the list is based on the records of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office and newspaper documentation. The authors note that none of the sources were complete, and why it is possible that some of banns were left out, either because the list included a work that was initially banned but then later, by a of a higher court, had the ban lifted. Along with the title of work, the rationale for the ban is also cited. The list is structured by years and, inter alia, shows that most publications were banned in the early 1970s (1970 – 9, 1971 – 19, 1972 – 28, 1973 – 8, 1974 – 15, 1975 – 4) and in the mid-1980s (1984 – 17, 1985 – 7, 1986 – 9, 1987 – 7). The document is available for research and copying.

Marko Lopušina, co-author of the feuilleton, has systematically researched censorship practices in the former Yugoslavia and published two books on that subject: Crna knjiga - cenzura u Jugoslaviji 1945-91. [Black Book – censorship in Yugoslavia 1945-91] published in 1991, and Crna knjiga – cenzura u Srbiji 1945-2015. [Black book – censorship in Serbia 1945-2015], published in 2015.

Materials of the Original Videojournal collection constitute hundreds of hours of uncut videos that captured fragments of alternative culture, dissent movements and news reports about developments in Czechoslovakia in the late 1980s. Samizdat audiovisual magazine was founded in 1987 at the instigation of Václav Havel. The Original Videojournal aesthetic and style remotely resembled television news in state media. This established form of news allowed it to target a wide audience while at the same time criticising the restricted view of the official media.

Confiscation of the drafts of the open letters authored by Doina Cornea by the Securitate, November 1987

Confiscation of the drafts of the open letters authored by Doina Cornea by the Securitate, November 1987

After listening on RFE to the news news regarding the harsh repression of the anti-communist revolt of the workers in the factories of the city of Braşov in November 1987, Doina Cornea openly manifested her solidarity with the protesters. She displayed a placard in front of her house in Cluj and on 18 November 1987 she drafted 160 manifestos, which were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in the main squares and factories of Cluj (Cornea 2009, 194–195). The Securitate, which closely monitored all her movements, arrested her and her son on 19 November 1987 (Cornea 2006, 203). In order to collect proofs of her guilt, the secret police made two home searches of her private dwelling on 19 and 23 November 1987. On these occasions the Securitate confiscated many documents authored by Doina Cornea, including all the drafts of her letters sent to RFE. These documents were archived in the criminal file created on Doina Cornea. As in many other cases of similar confiscations, the Securitate archives thus ironically became an important repository institution for artefacts of the cultural opposition in Romania.

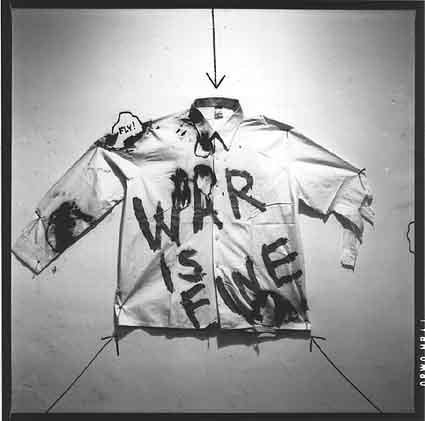

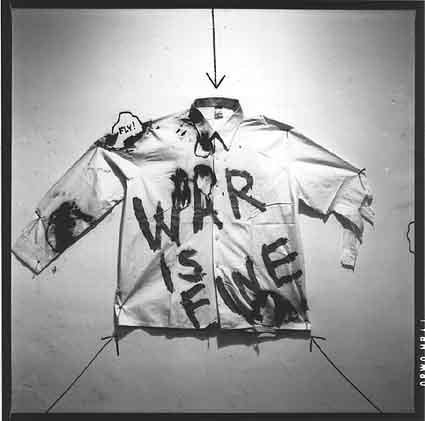

Milan Knížák is an artist associated with Fluxus and the organiser of the first Happenings in Czechoslovakia. Together with Jan Mach, Vít Mach, Sonia Švecová, Jan Trtílek, and Robert Wittmann, he founded the group Aktuální umění (Actual Art) in 1963, but the group removed the word “art” from its name in 1966 and was known as Aktual from then on. Aktual proclaimed a complete union of art and life, and it strove to awakening people’s awareness of life in art and art in life.

Liget Gallery invited Knížák to hold a solo show in 1987. The exhibition was thoroughly documented, because the gallerist knew that he would not have been able to hold a similar exhibition in Czechoslovakia. Novotny Miklós and Székelyhidi Sándor made photographs, as did Tibor Várnagy and István Halas, and György Durst made a video (the video unfortunately has been lost). Many local artists joined the action, and all participants were given a shirt for the occasion, and Knížák painted the shirts and the faces and hands of the participants.

The next day, Knížák showed his films in the Kassák Club. This was followed by a talk-show conversation between Knížák and art historian László Beke. At one point, someone ran into the room from the office with the news that Tamás Szentjóby, a well-known artist in exile, was on the phone. Knížák went to the office to take the call, and Szentjóby told him that “the greatest Czechoslovak artist has died today.” He was referring to Andy Warhol, whose death was in the news only one or two days later. Knížák had known Andy personally, so the rest of the evening became a personal commemoration.

A couple of weeks later, the gallerist brought the materials from the exhibition to Knížák in Prague, with the exception of the shirts, which Knížák had asked him not to bring. The gallerist donated the shirts to Artpool, and the documentation remained in the Liget archive.Blažena Despot published a monograph, The Woman Question and Self-Management, in 1987, the book is a result of the age-old consideration of the issue of women's rights and the genesis of the woman question in history, which was reflected in the social relations in socialist Yugoslavia, to which Marxism gave the final seal. In this book, Despot placed the woman question into the context of Marxism and socialist self-management, that is, within the theoretical concept of "Marxist feminism," whose role she sees as a struggle for more women to work on jobs that are not poorly paid and require higher or high qualifications, jobs and salaries that would enable them to support themselves.

In the Woman and Society Feminist Collection there is a presentation by Blaženka Despot, entitled "Marxist Feminism," which forms one of the earlier foundations for the book The Woman Question and Self-Management.

The red star dress was originally displayed in the short movie by the architect Gábor Bachmann: Eastern European Alarm (“Kelet-európai riadó”). The movie is an abstract critique of the late Kádár regime, focusing on social and aesthetical tensions. A woman in the red star plays an important role. Her outlook and attitude serve as a counterpoint to other characters in the middle of the breakdown. Like many of Király’s works, the red star dress has also been destroyed. Still, the photograph of the dress has been archived.

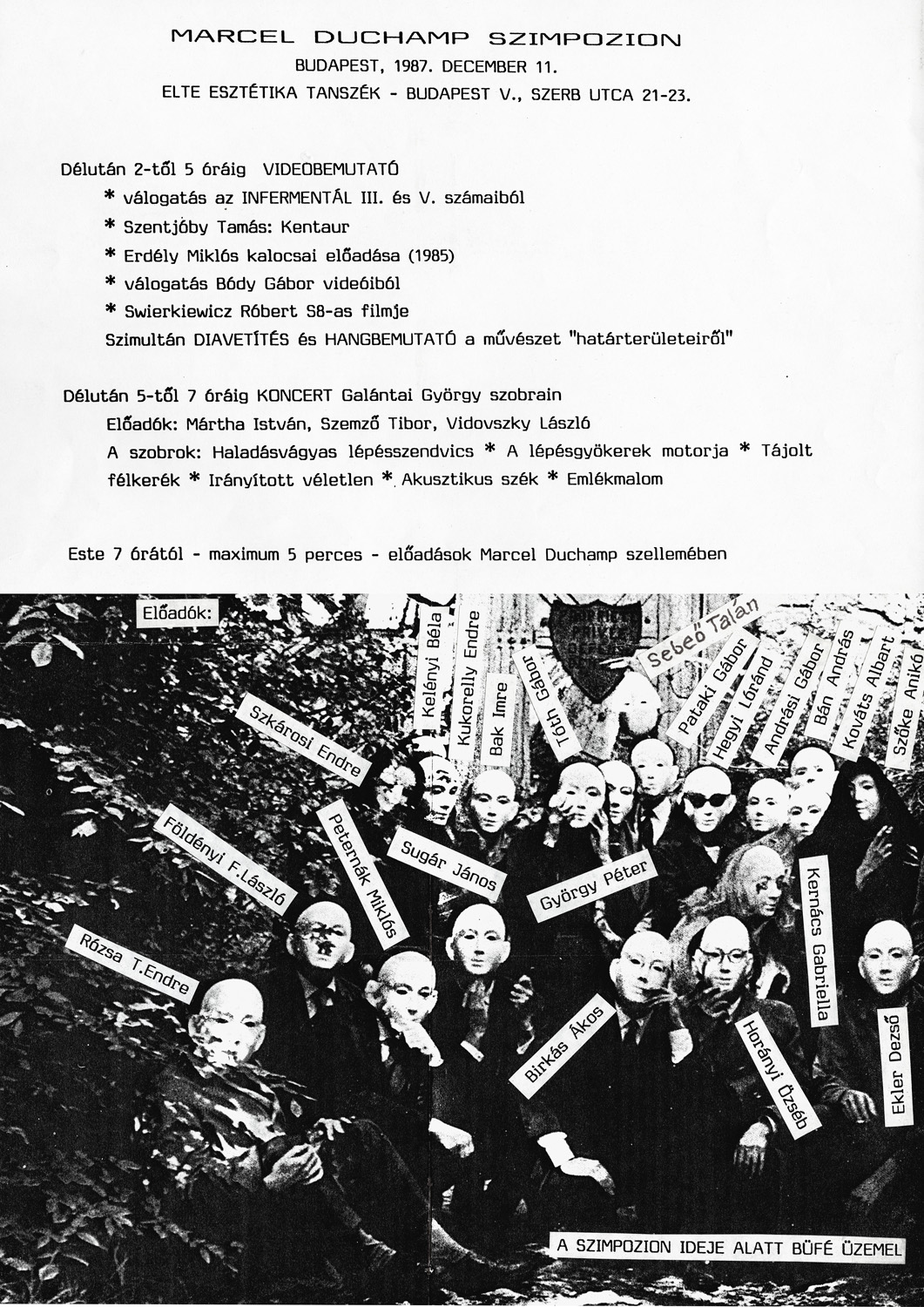

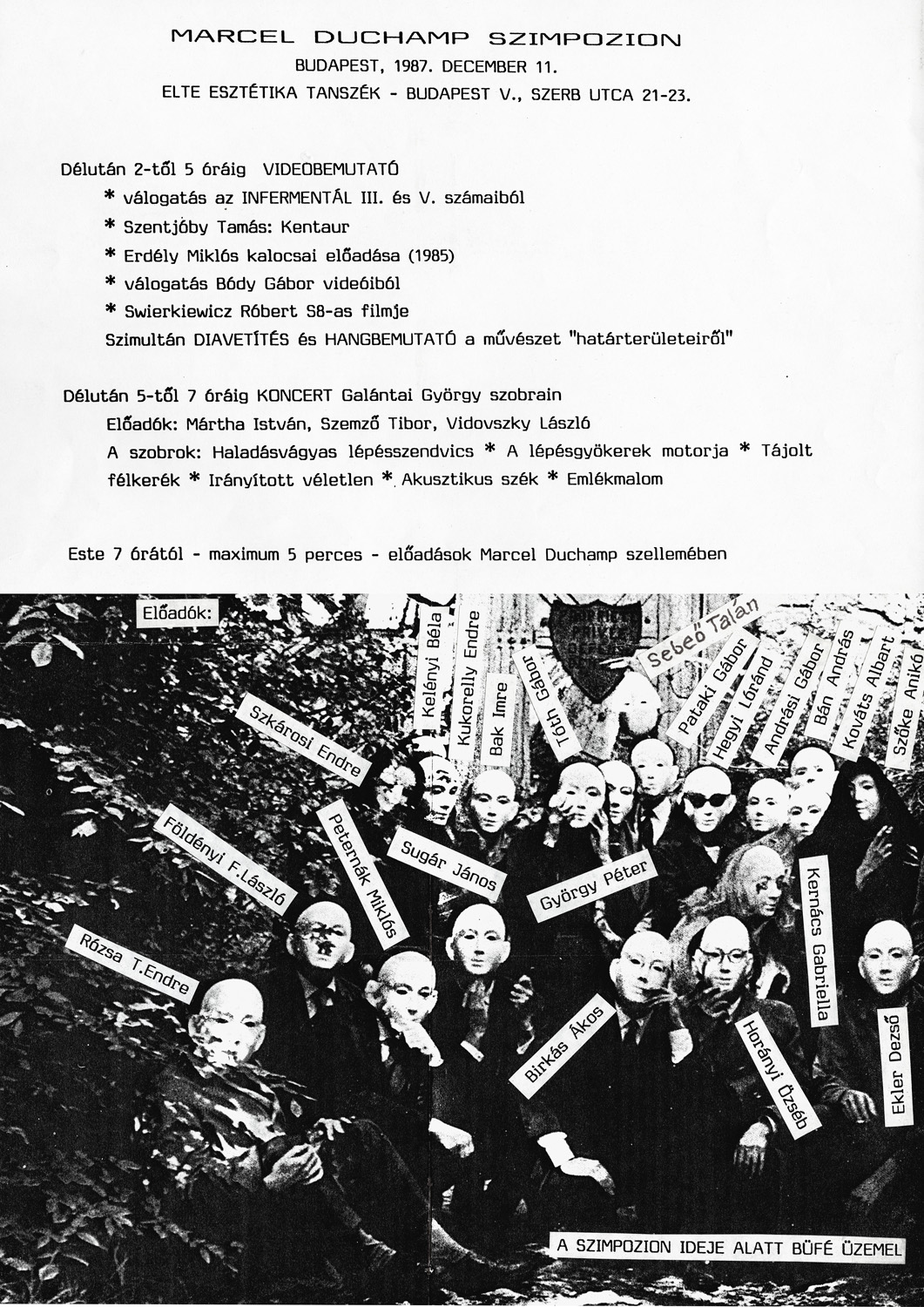

Artpool organized a symposium to commemorate the 100th birthday of Marcel Duchamp in cooperation with the Department of Aesthetics at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest (organizers: György Galántai and Péter György). The symposium was preceded by a call for applications announced by Artpool for international artists to cooperate in the event by sending artworks, documents, projects related to the spirit of Duchamp. Among the participants, one finds artists like Vittore Baroni, Robin Crozier, Christo, Klaus Groh, Ruth Wolf Rehfeldt, etc. Artpool organized an exhibition based on the received materials entitled In the spirit of Marcel Duchamp. Concerts, sound presentations, video-screenings, slide projections and short presentations were parts of the program of the symposion. Tibor Szemző (piece for Directed Chance), András Wilhelm & Zoltán Rácz (concert on five sculptures) and István Márta (Multimedia sound improvisation on two sculptures and a video) gave concerts on György Galántai’s sound sculptures. Tamás Szentjóby’s Centaur, Miklós Erdély’s Lecture in Kalocsa and András Szirtes’ Diary were being screened. Ray Johnson’s letters, mail art and sound materials were projected from slides. The following lecturers held five minute-long talks, evoking Duchamp by measuring time with a chess clock: Gábor Andrási, Imre Bak, László Beke, Ákos Birkás, Dezső Ekler, László Földényi F., Péter György, Lóránd Hegyi, Özséb Horányi, Gabriella Kernács, Albart Kováts, Endre Kukorelly, Gábor Pataki, Miklós Peternák, Endre Rózsa T., Talán Sebeő, János Sugár, Endre Szkárosi, Annamária Szőke, Ádám Tábor, Gábor Tóth.

http://www.artpool.hu/Duchamp/MDspirit/index.htmlDifferent kinds of letters were sent to Juhan Aare. One of the most beautiful was written by artists in calligraphic writing. It shows that in some cases, letters were not just a quick response to a pressing problem, but rather works of art that were carefully composed and designed. It is a typical joint letter, signed mainly by artists from the advertising group of the Trade Administration in Tartu. The letter was signed by 34 people altogether, many of whom were related to artists. It is relatively short, like most letters in the collection, but like many of them, it also connects environmental problems with the national question. Although it is not directly mentioned in the letter, it was feared that foreign labour for the planned phosphorite mines would settle in Estonia, which would threaten the survival of the Estonian nation. In the letter, the phrase ‘Our children, grandchildren need [...] the persistence of the nation’ is used. The letter was sent to Estonian Television, but it was actually in the possession of Juhan Aare until he deposited his collection with the Estonian History Museum.

Krzysztof Skiba's archive is a private collection of photos, movies, zines, books, articles, and leaflets documenting the alternative culture phenomena that Skiba participated in during the 1980s. The majority of the collection covers the street happenings created by the Gallery of Maniacal Activities in Łódź, the activities of anarchist Alternative Society Movement in Gdańsk, the very first years of the punk cabaret Big Cyc, and the first exhibition of the third circuit papers and magazines co-organized by Skiba in 1989.

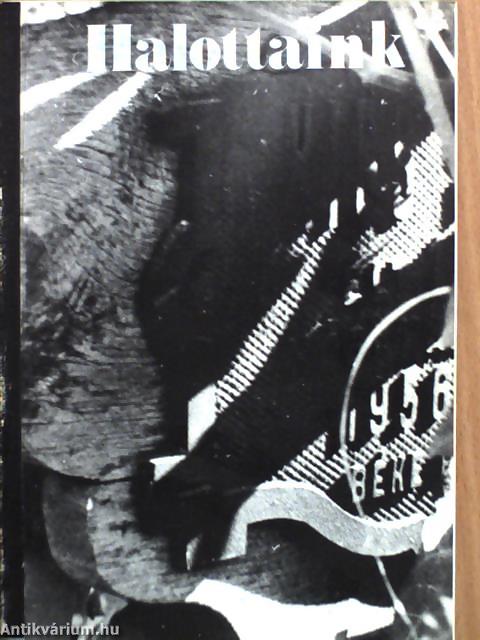

![Halottaink [Our Dead], 1987. Book](/courage/file/n74231/halottaink-12144397-eredeti.jpg)

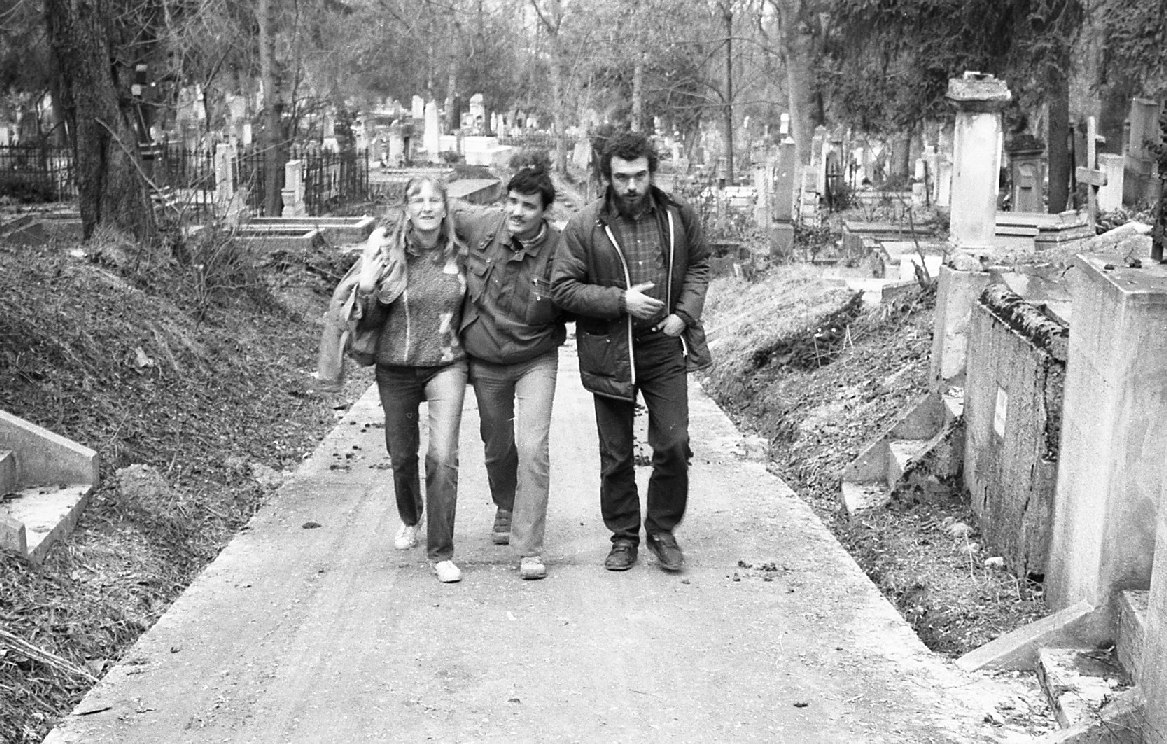

The members of Katalizátor Iroda visited Plot 301 in New Public Cemetery in Budapest a couple of times since 1987. They then published the first edition of this book as a commemoration of the victims of the Revolution of 1956. The book contains the names and the biographies of those involved. In 1989, the second edition of this book became the first legally published work of Katalizátor Iroda.

Limes was a circle of Hungarian dissident intellectuals which operated more or less actively from 1985 until the 1989 Romanian revolution. The aim of the circle was to provide a pluralist platform of cooperation for Hungarian intellectuals, which meant holding monthly/bimonthly organized meetings and publishing a journal dealing with the history and actual situation of the Hungarian minority from Romania, as well as other outstanding research work pertaining to other domains. The circle was also devoted to maintaining high standards of scientific work in Romania. As there was no chance of getting anything past the censors in Romania, the plan was to smuggle manuscripts to Hungary and to publish the journal there.

The initiator was Gusztáv Molnár, who mostly due to his job as a literary editor at the Bucharest-based Kriterion publishing house had a large personal network among Transylvanian Hungarian critical intellectuals. The core of the group was represented by the following individuals: Vilmos Ágoston, Béla Bíró, Gáspár Bíró, Ernő Fábián, Károly Vekov, Levente Salat, Csaba Lőrincz, Ferenc Visky, András Visky, Péter Visky, Levente Horváth, Sándor Balázs, Sándor Szilágyi N., and Éva Cs. Gyímesi. Through the process of editing the journal, many more intellectuals became acquainted with the activity of the Limes group.

Between September 1985 and November 1986, six meetings were held in four different localities in Romania in the homes of members of the group. The meetings encompassed a presentation (usually of a manuscript) followed by a debate, and all proceedings were recorded. The series of meetings was interrupted by a search and seizure performed by the Securitate in Molnár’s apartment in Bucharest. All documents related to Limes were taken and later studied by the authorities. By this time, the plan to make four Limes issues had already been completed, and the manuscripts for the first two issues had already been collected. The contents included transcripts of the Limes debates and studies and documents covering topics such as “national minorities,” “nationalism,” “totalitarianism,” “autonomy,” and “Transylvanianism” as a guiding ideology for the Hungarian minority in Romania. The topics also included the situation of the Csángó Catholic (Hungarian-speaking) population in Romania.

The Limes group ceased its activity after the intervention of the Romanian secret police, and in 1987, summons and warnings were issued to the members of the group. Though no more meetings were organized, after a while, Limes members resumed work on the texts. Molnár moved to Hungary in 1988, but the editorial work was continued in Romania by Éva Cs. Gyímesi Éva and Péter Cseke in Cluj. The first issues of Limes was published by Molnár in Budapest in late 1989. The content does not coincide with the initial first volume of the Limes, but the issues did contain excerpts from the debates which were held at the first two meetings.

Invaluable insights into the details of the Limes story and other events in the lives of outstanding Hungarian intellectuals are provided by the Securitate files on professor of philosophy at the Babes Bolyai University Sándor Balázs (1928–), which are available for research in the Historical Collection of the Jakabffy Elemér Foundation. This is because the Limes activities in Cluj were recorded by the county agency of the Securitate as part of the information surveillance files on Sándor Balázs. His code name was “the Sociologist” (Sociologul), but the table of contents at the beginning of the dossier refers to “the Sociologists” (Sociologii), the code name used to denote the Limes group.

The dossier was opened at the beginning of 1987, and the version handed over by the CNSAS for research has three volumes which consist of some 800 folios. The files represent various types of documents: 1. strategic plans, analyses, and annexes to these plans; 2. characterizations and personal networks; 3. Syntheses, reports, and notes; 4. Information and materials obtained from surveillance; 5. Results of the monitoring activity; 6. Minutes. As noted already, the dossier contains copies of documents considered important originating from the surveillance files of other people involved in the Limes group: Éva Cs. Gyímesi (code name Elena), Péter Cseke, Gusztáv Molnár (Editorul), Lajos Kántor Lajos (Kardos), Ernő Gáll (Goga), Sándor Tóth (Toma), and Edgár Balogh (Bartha).

The Eastern Archive, initiated in 1987, is a collection of testimonies gathered from former Polish citizens, repressed by the Soviet Union after the 1939, imprisoned, resettled, etc. Their remembrance was excluded from the official view of the past during the communist era. At the end of the Polish Peoples’ Republic it became possible to make it more public.

After sending two open letters to RFE in the period 1982–1983 and discussing with her students texts by Paul Goma and Mircea Eliade which were not officially published in Romania, Doina Cornea was put under close surveillance and threatened by the Securitate, in order to make her give up her oppositional activities. In June 1983, she lost her teaching position at the University of Cluj because she had refused to cede to these pressures. Despite these repressive measures against her, Cornea continued to send open letters of protests and to show solidarity with other dissidents in Romania (Cornea 2009, 176–177). Among these acts displaying solidarity with other oppositional activities, those supporting the 1987 workers revolt from Braşov attracted the most violent reactions on the part of the Securitate.

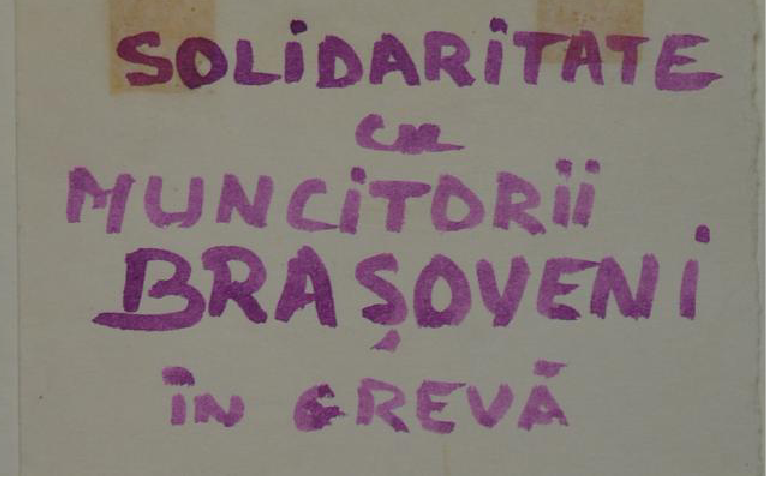

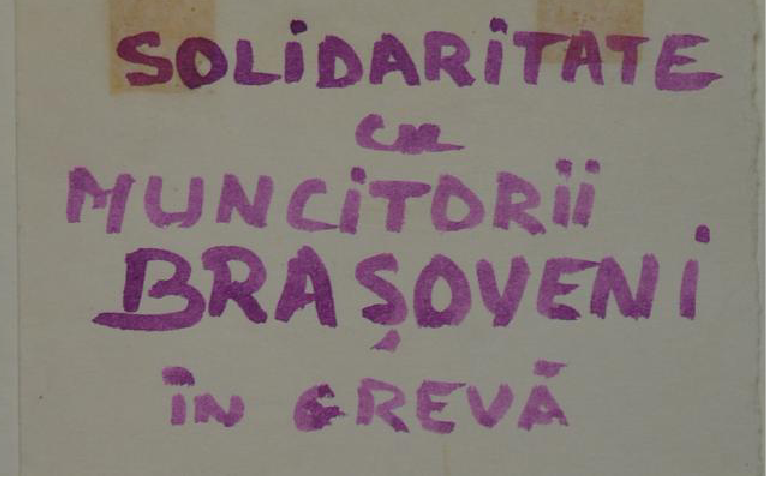

In November 1987, Cornea learned of the Braşov workers’ revolt from RFE radio programmes. Immediately afterwards she displayed a placard in front of her house in Cluj through which she expressed her solidarity with the workers. On 18 November 1987, she drafted 160 manifestos written in violet ink on sheets of paper similar to A5 format with the text: “Solidarity with the workers from Braşov” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 109). These manifestos were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in various public spaces in Cluj, namely in the main squares and in factories (Cornea 2009, 194–195). On 19 November 1987, Cornea and her son were arrested by the Securitate and its employees conducted a detailed home search (Cornea 2006, 203). On this occasion the ink with which these documents were written and some copies of the manifestos were confiscated. The latter would be attached to the criminal file and invoked as proofs of the accusation during Doina Cornea’s interrogation by the Securitate in late November 1987 (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 109).

The collection includes various pieces of documentation about the ‘Phosphorite War’ that took place in Estonia in 1987, and material about the Estonian television programme ‘Panda’ in the second half of the 1980s. The collector of the material is Juhan Aare, the journalist and politician who unleashed the Phosphorite War. The most valuable part of the collection is made up of the letters written by people in Estonia and sent to Juhan Aare or to Estonian Television. These letters refer to the environmental situation and the national question in Estonia.

Suddenly, the director of the museum called the curator and said that two particular works could not be shown (the painting by András Wahorn, to which they objected because of its explicit sexual references, and the installation by Imre Bukta because of his use of manure as one of the materials).

This decision created controversy among the exhibiting artists, and eleven of them (members of the Vajda Lajos Studio) decided to withdraw their works from the exhibition to protest the challenge to the jury’s decision and to express their solidarity with the artists who had created the banned works.

At the same time, they decided to arrange a parallel exhibition in their cellar gallery around the corner, which would open at the same time as the official opening. This became the “Open Space Exhibition” (the title in Hungarian refers also to the legendary open air exhibitions held unofficially from the late 1960s on, which created the community which later became the VLS).

The removal of the works by eleven artists created large gaps in the official exhibition arrangement, so the curator decided to put empty black frames in these gaps, together with a large apostrophe. The issue was addressed in the official opening speech, in which it was referred to as the “expressive gesture of young artists.” Later, the black frames and the apostrophe disappeared, and the gaps were filled with stored works from the museum collection.The 11th Congress of the Union of Artists, which took place on 13-14 November 1987, was a significant event not only for artists, but also for other groups among the Soviet Lithuanian intelligentsia, which started to raise more vociferously questions about the historical memory, greater modernism, the historical heritage, and others. During the congress, speakers spoke about the necessity for the National Gallery and the Directorate of Art Exhibitions to apply more flexibility in managing this sphere of culture, and they also spoke about the need to democratise the work of art critics, about the necessary avoidance of pitching Soviet art against modernism, the importance of the integration of contemporary art into the global context, and a broader dialogue with foreign countries. During the congress, all the old Board of the Union of Artists was changed for new people (such as Bronius Leonavičius and Arvydas Šaltenis), who a few months later became leaders of the Sąjūdis national movement. Arvydas Šaltenis, one of the leaders of contemporary artists, called this congress a 'revolutionary congress, which was noticed by a public audience' (see http://www.bernardinai.lt/straipsnis/2016-07-25-arvydas-saltenis-nereikia-meluoti-grazinti-pudruoti-tikroves/146626), and which had an impact on Sąjūdis.

Radojević Danilo. “The Point of the Disputes Between Historians about Sources on Old Montenegrin History”, in Serbian, 1987. Journal Article

Radojević Danilo. “The Point of the Disputes Between Historians about Sources on Old Montenegrin History”, in Serbian, 1987. Journal Article

In the article “The Point of the Disputes Between Historians about Sources on Old Montenegrin History”, Danilo Radojević criticized interpretations of medieval Byzantine historians’ texts on Dioclea [Serbian: Duklja] by contemporary Serbian and Croatian historians. Dioclea was a medieval state, which roughly encompassed the territories of present-day south-eastern Montenegro. Radojević claims that the interpretations of medieval Byzantine historical texts had been “conveniently” incomplete, imprecise, and in some cases tendentious. He further stated that contemporary Serbian and Croatian historians were taking into account only the parts of those texts that they found suitable for confirming certain preconceived theories, which always supported Serbian and Croatian nationalist agendas. In order to explain why Dioclea was the focus of disputes among historians, Radojević asserted the following:

“[…] Dioclea like crossroads, where Orthodoxy and Catholicism coincide, has become current [in debate], especially since the identification of individuals with a particular religious affiliation took place. Therefore, the negligence of the fact that Dioclea is an old Montenegrin state and the Diocleans are predecessors of Montenegrins is transpiring, and thus arises an unrealistic question – to whom does this place belong.” (Radojević 1987, 46)Although criticizing other historians’ interpretations of historical texts on Dioclea and Diocleans, Radojević in this text does not provide evidence for his allegations about the equivalence of Diocleans and Montenegrins, which is still considered a rather contentious statement.

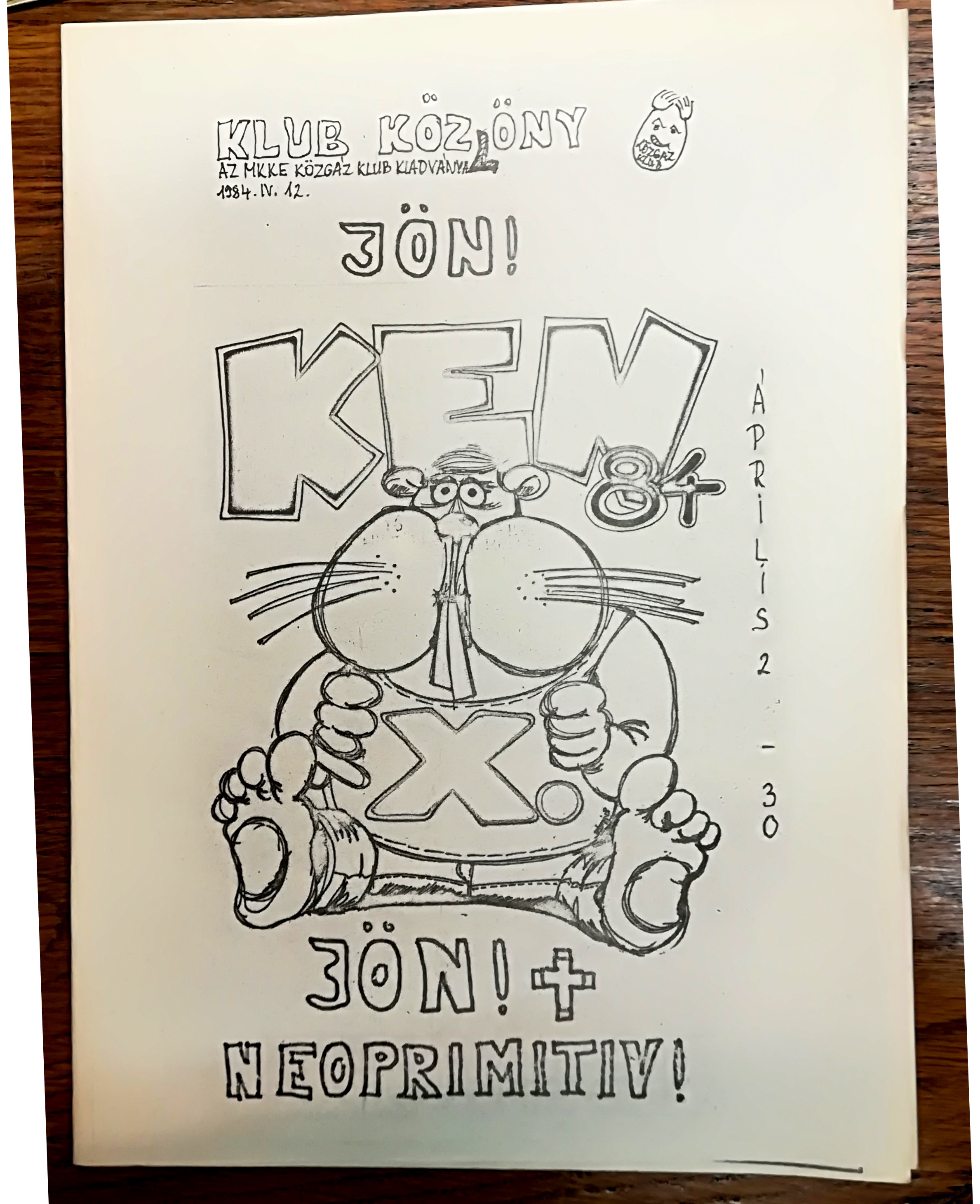

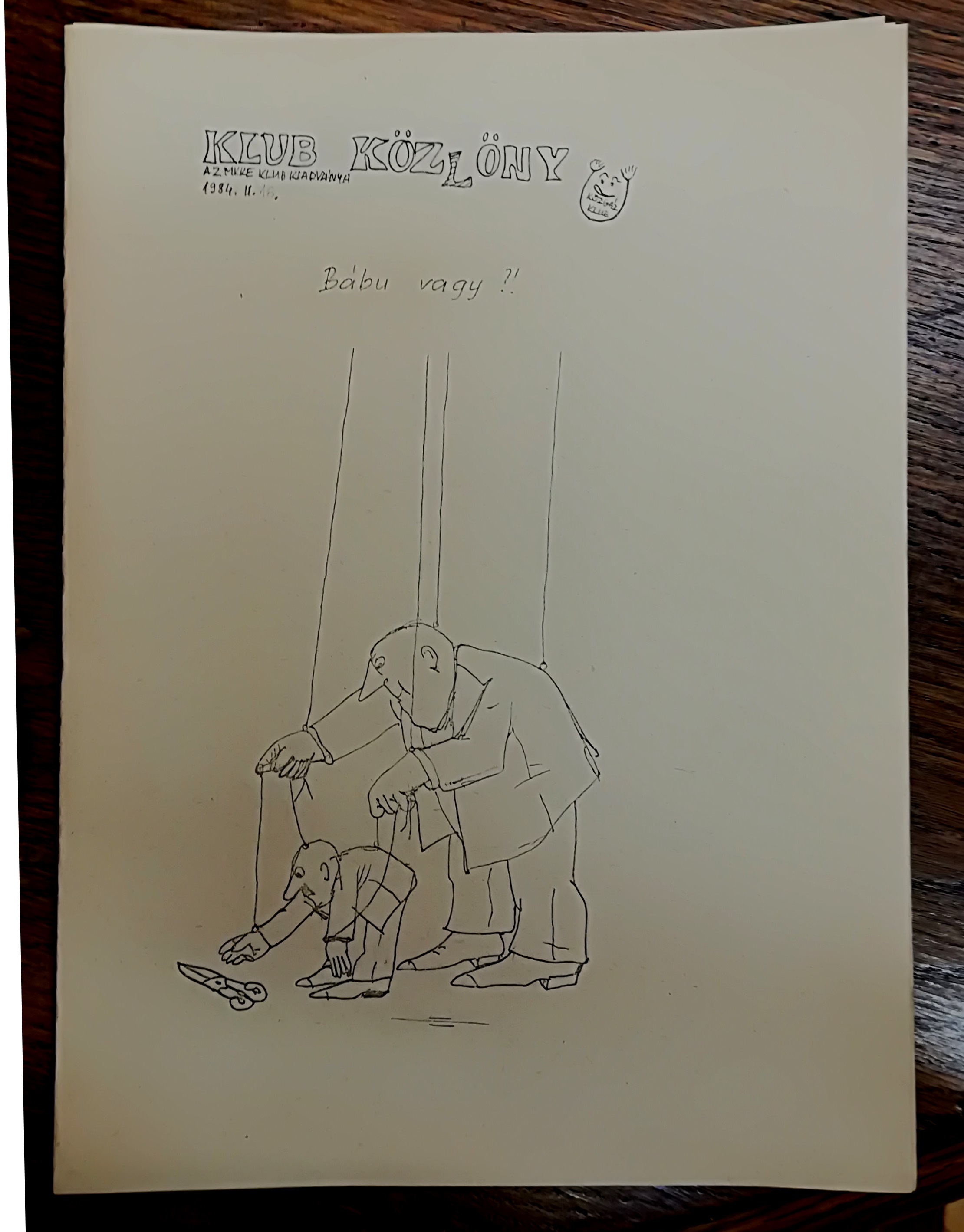

The Klub Közlöny (Club Gazette) was the self-published newspaper of the Közgáz-klub (Economics Club) at the Karl Marx University of Economic Sciences (MKKE) between 1976–1987. In the newspaper, articles were published about the club’s activities and also cultural and political topics. In contrast to the official organ of the Communist Youth League (KISZ) titled Közgazdász, there were more direct and honest writings about life at the university in the uncensored Klub Közlöny, and its tone was many times more critical of the party leadership of the university. The aim of its creators was to galvanize the students and to develop the culture of debate. The issues are preserved in the archive of the Corvinus University and in the National Széchényi Library.