The section entitled Hidden Paths examines alternative forms of connection in what was known as the second public sphere, including samizdat, writings which were smuggled out of prisons, and ironic or satirical criticisms of the system. It also presents several of the responses that were made by the regime to these forms of cultural opposition, such as imprisonment, censorship, and exile.

Petko Ogoyski in his collection with a piece of bread, the daily ration in the forced labour camp in Belene on the island Persin, he received on the day of his liberation from the camp in August 1953 and preserved. Petko Ogoyski - one of the few living artists who survived socialist prisons and labor camps, was an important figure in the Bulgarian cultural opposition against the communist regime. As a member of the Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union-Nikola Petkov (BZNS-Nikola Petkov) and poet/writer, Ogoyski was imprisoned twice (1950-1953 and 1962-1963) by the socialist state for writing “hostile” poems, texts and aphorisms and for “conspiracy”.

The Tower-Museum was established as a private initiative of the family Petko and Yagoda Ogoyski. The exhibition is partly a national and a local ethnographic one, including household appliances, costumes, and weapons from the 19th and 20th centuries. At the same time, this was a way to circumvent the censorship of the communist regime. Among the ethnographic materials, Petko Ogoyski kept and preserved evidence from the periods of his imprisonment in six prisons and two forced labour camps, as well as notes, books and poems written by him during and after the discharge from prison.

Petko Ogoyski in his collection holding the wooden shoe with a secret hiding-place for medicine and a small pencil, perserved from the forced labour camp in Belene on the island Persin. Petko Ogoyski - one of the few living artists who survived socialist prisons and labor camps, was an important figure in the Bulgarian cultural opposition against the communist regime. As a member of the Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union-Nikola Petkov (BZNS-Nikola Petkov) and poet/writer, Ogoyski was imprisoned twice (1950-1953 and 1962-1963) by the socialist state for writing “hostile” poems, texts and aphorisms and for “conspiracy”.

The Tower-Museum was established as a private initiative of the family Petko and Yagoda Ogoyski. The exhibition is partly a national and a local ethnographic one, including household appliances, costumes, and weapons from the 19th and 20th centuries. At the same time, this was a way to circumvent the censorship of the communist regime. Among the ethnographic materials, Petko Ogoyski kept and preserved evidence from the periods of his imprisonment in six prisons and two forced labour camps, as well as notes, books and poems written by him during and after the discharge from prison.

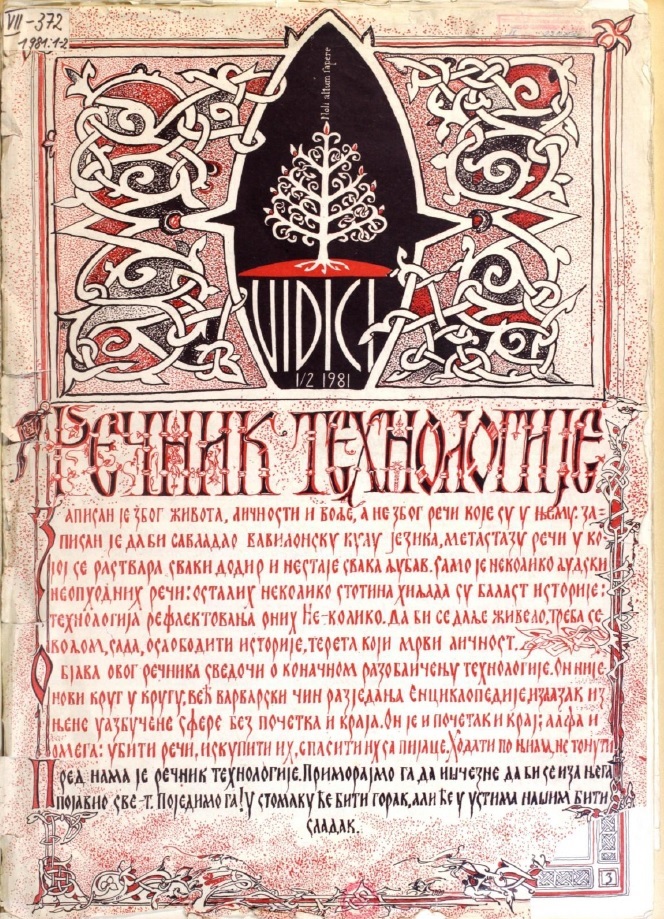

A special issue of the magazine “Vidici” [Horizons] came out in the spring of 1981 under the title “The Glossary of Technology”. It is one of the most significant dissenting publications in Yugoslavia that directly relied on the then subversive press trends in Czechoslovakia and Poland, which some of the journalists were in contact with.

“The Glossary of Technology” was modelled on a manuscript from mediaeval times with illustrations and used a calligraphic style. It was completely handmade and crafted with old-fashioned technology. Another specificity was that this issue was conceived as a dictionary with carefully selected samples. The entries had a symbolic meaning. „The Glossary” was a protest against the modern technology-based social systems.

The political authorities did not understand what was behind this coded edition. The special issue was banned, and its subversive nature was discussed before the University Commitee of the Union of Communists. Eventually, it was concluded that "The Glossary" was anti-humanist and anti-socialist-oriented, which was enough of a reason to ban it. Soon afterwards, the party agencies launched a broader backlash against dissident groups following Tito’s death (1980).

"Plastic Jesus” (1971) stands as a masterpiece of the Lazar Stojanović collection and is one of the most famous cases of cultural opposition in socialist Yugoslavia. On the surface, the film has a simple plot depicting a strayed director (Tom Gotovac) in his attempt to make a movie while being financially supported by his lovers. However, the film represents a scathing attack on the society of the time, invoking almost all taboos of the era – from the political to the sexual. Stojanović used archival material, showing original footage of Nazis, Chetniks (radical Serbian nationalists), Ustashe (Croatian fascists) and socialist Yugoslavia. The film juxtaposed the totalitarian practices of Nazism and socialism, comparing them in the process. A sharp albeit indirect, satire of Josip Broz Tito rests at the heart of the film.

„Plastic Jesus” was Stojanović’s graduate final project at the Film Academy. It was banned before any public screening and led to Stojanović being brought to trial. The film remained banned until the end of 1990 in Yugoslavia. In 1991, “Plastic Jesus” received the FIPRESCI award at the Montreal film festival.

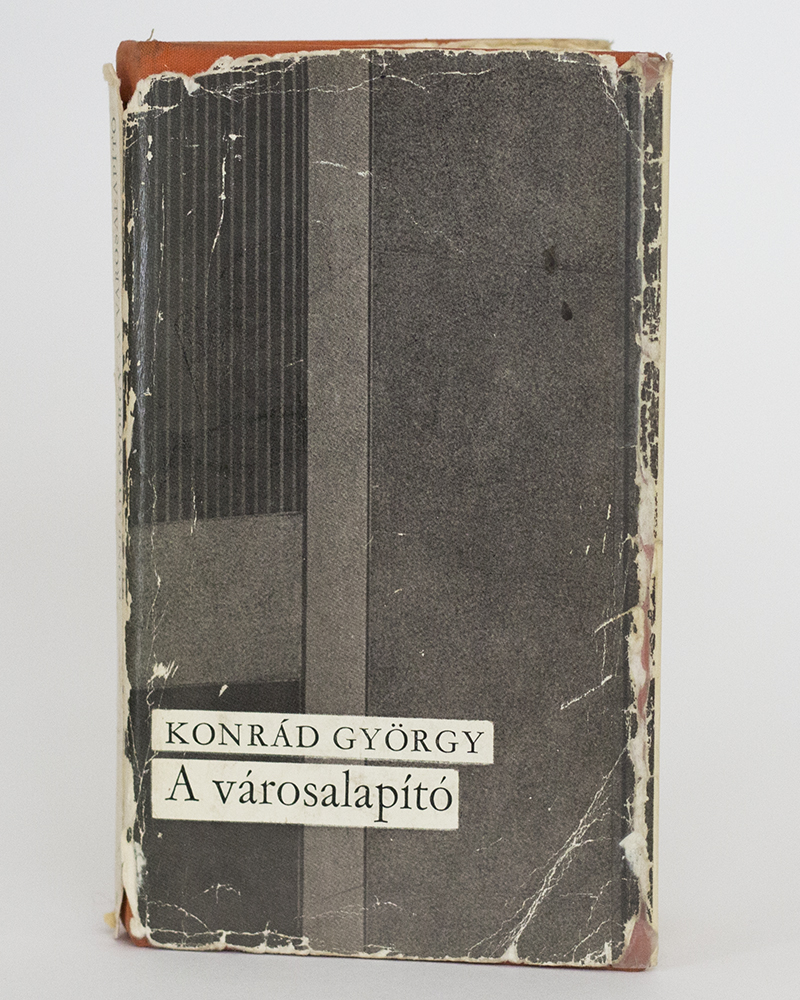

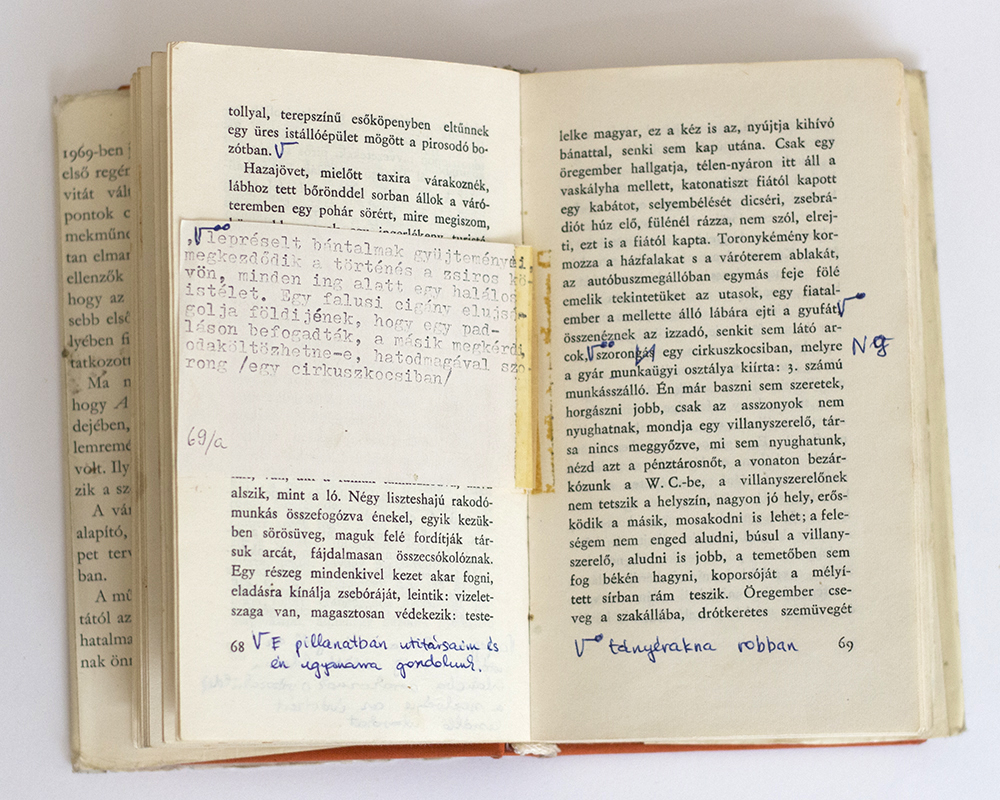

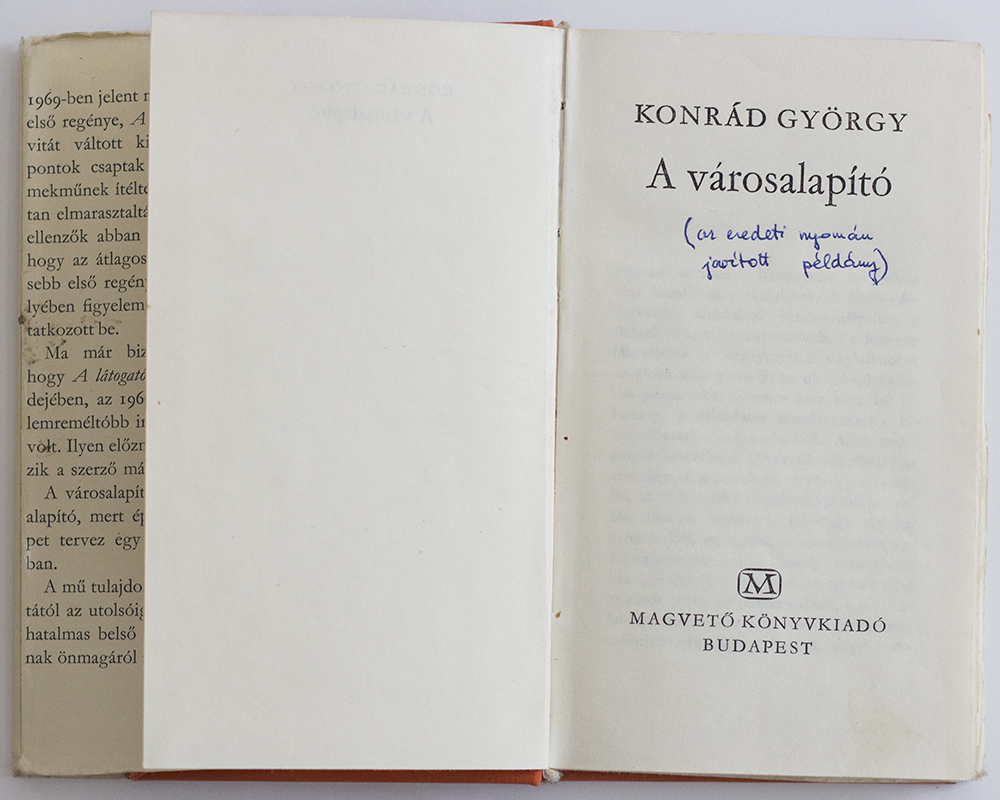

“I write what I write, state publishers publish from me what they want, and I, however, publish my work as I can.” In 1974, György Konrád summarized the functioning of censorship in an interview given to the West German periodical Die Zeit. The dissident author and activist Konrád was regularly persecuted by the state authorities from the early 1970s. His works were either not published or printed only following thorough censuring. His novel, The City-Builder could be published in Hungary in 1977 only with substantial cuts and modifications forced by the censor.Gábor Klaniczay, the young intellectual interested in counter-culture preserved one copy of Konrád’s novel. This book is unique, however: in his own copy, Klaniczay corrected by himself the parts that were cut or modified by the censor. At that time, the original texts of forbidden or censured works were shared in manuscript or homemade copies among oppositional networks. The book displayed here documents both the intention of suppressing culture and the individual act of resisting it.

The prison record of the Yugoslavian film director Lazar Stojanović contains material from his imprisonment between 1972 and 1975, such as the verdicts, complaints, personal notes and psychological evaluation of the case. Stojanović was on trial twice – first at the end of 1972, during his compulsory military service when he was brought before the military court for lambasting the Yugoslav People’s Army and Tito. It was a sensitive historical moment, as in 1971 and 1972, clashes between the central and national leadership seriously threatened the legitimacy of the Yugoslavian Communist Party. The military court charged Stojanović with “hostile propaganda” and sentenced him to one year in prison.

During this trial, the film „Plastic Jesus” - Stojanović’s graduate final project at the Film Academy (1971) caught the attention of censors. The director was then sentenced additionally by a civil court for “Plastic Jesus”. The verdict from 1973 states that the author “represented the socio-political situation in the country maliciously and falsely”, that he depreciated the socialist revolution, its fighters, and self-governing socialist system, and that he had insulted the figure of the President, Tito. All copies were confiscated due to their ‘criminal offense’ and the movie was barred from screening until December 1990.

The trial of Lazar Stojanović and the treatment of “Plastic Jesus” were meant to set examples for other artists, ending the so-called “Black Wave” in Yugoslavian cinematography and a relatively free phase of cultural production.

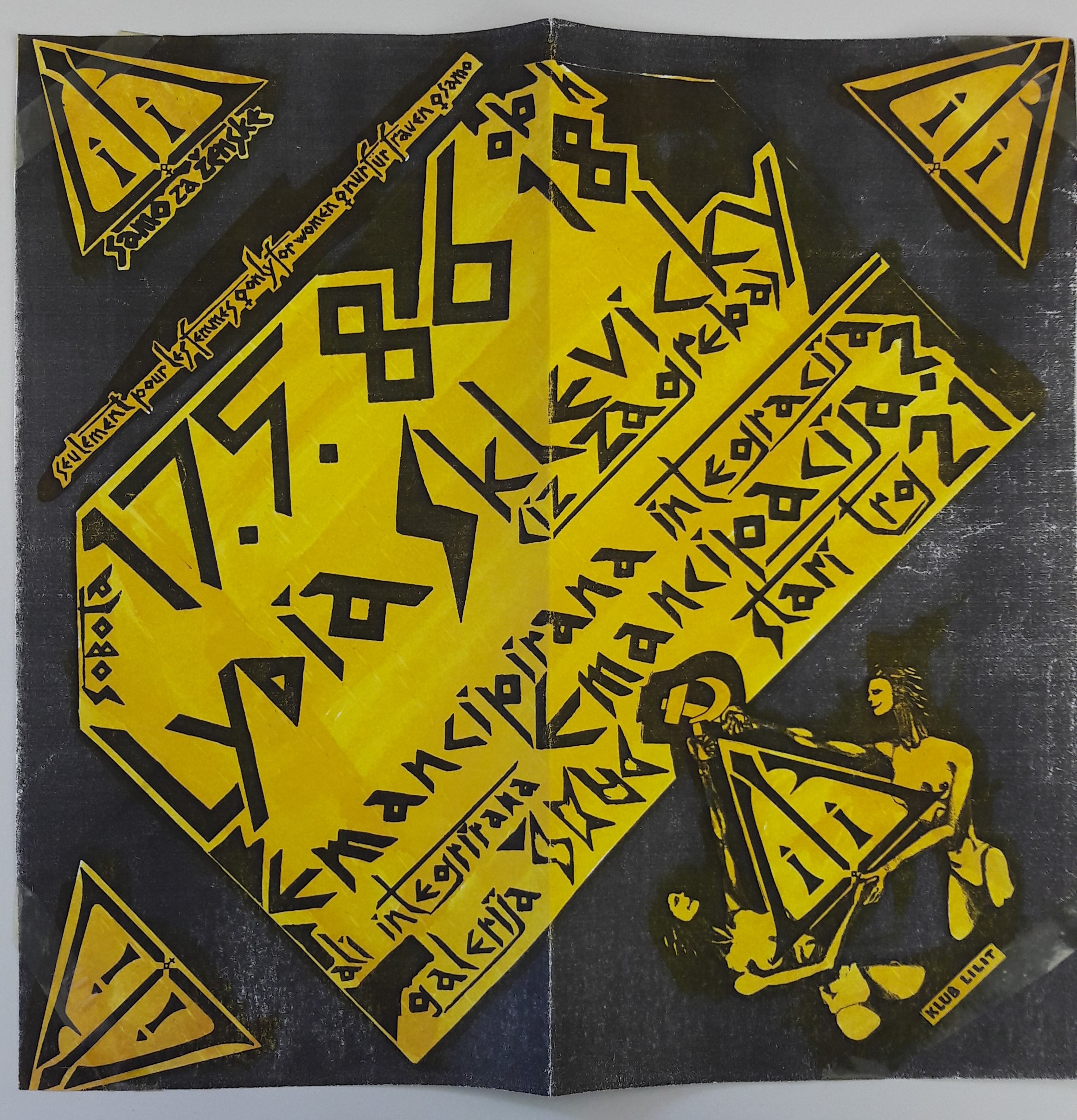

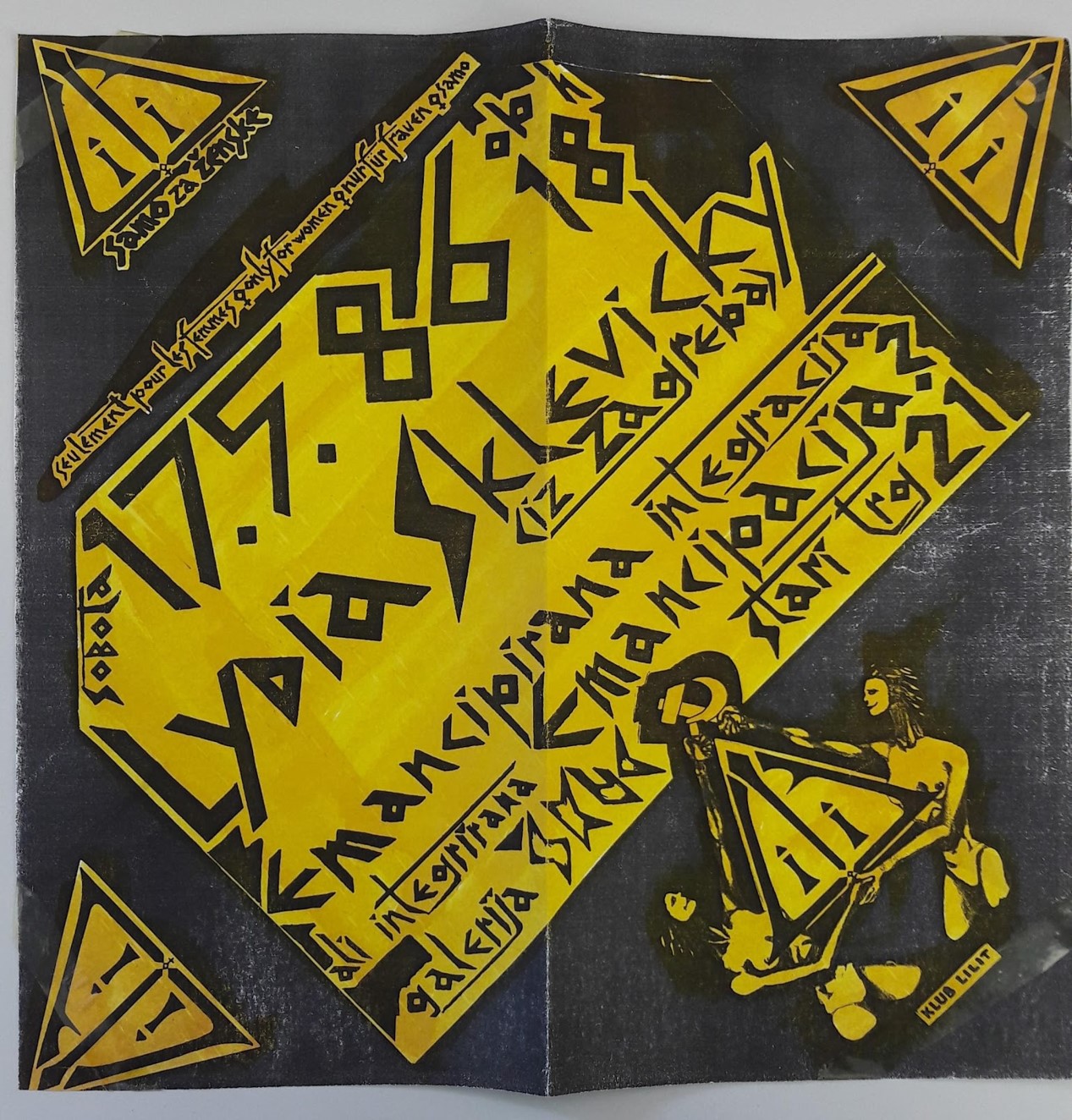

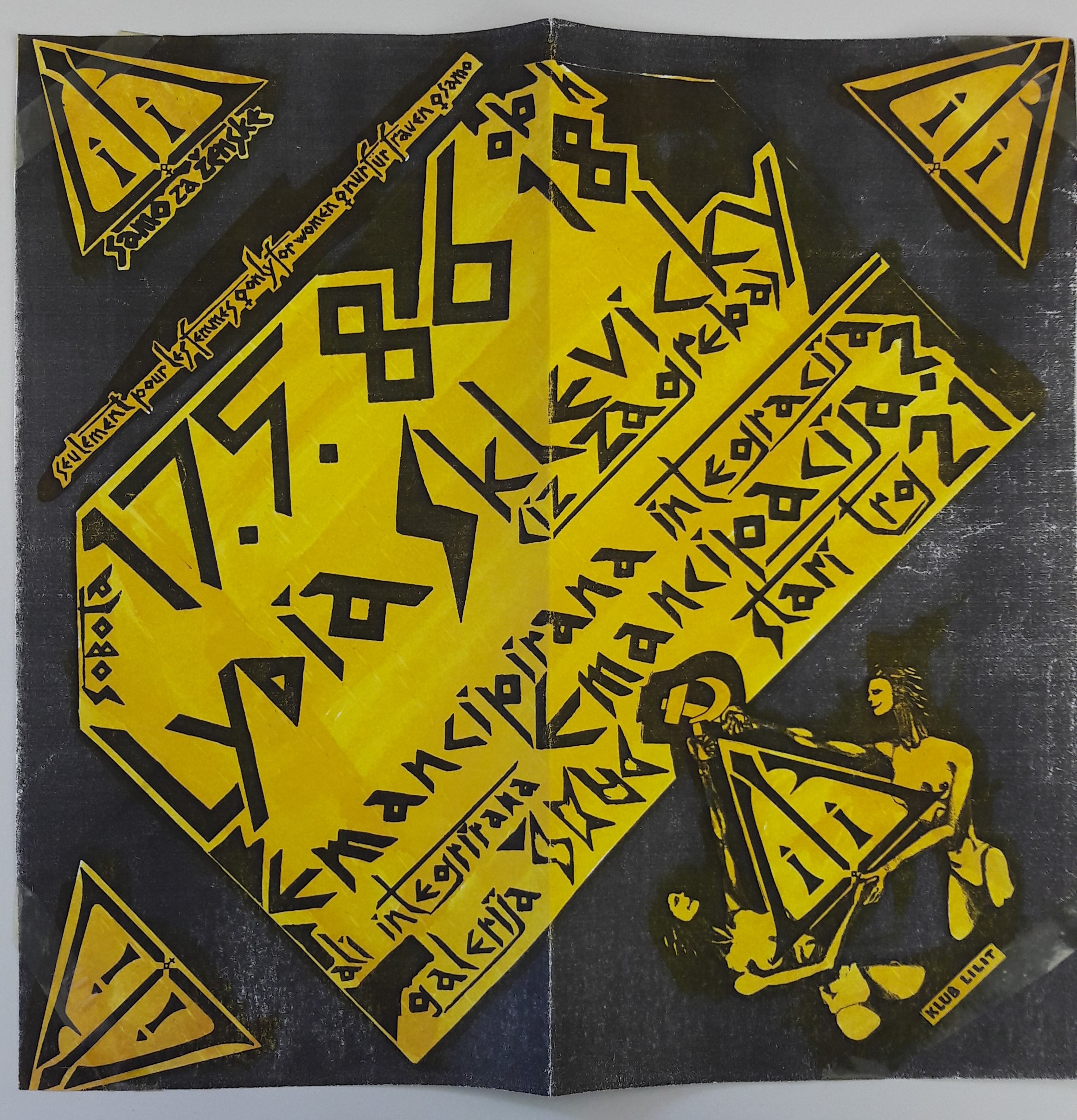

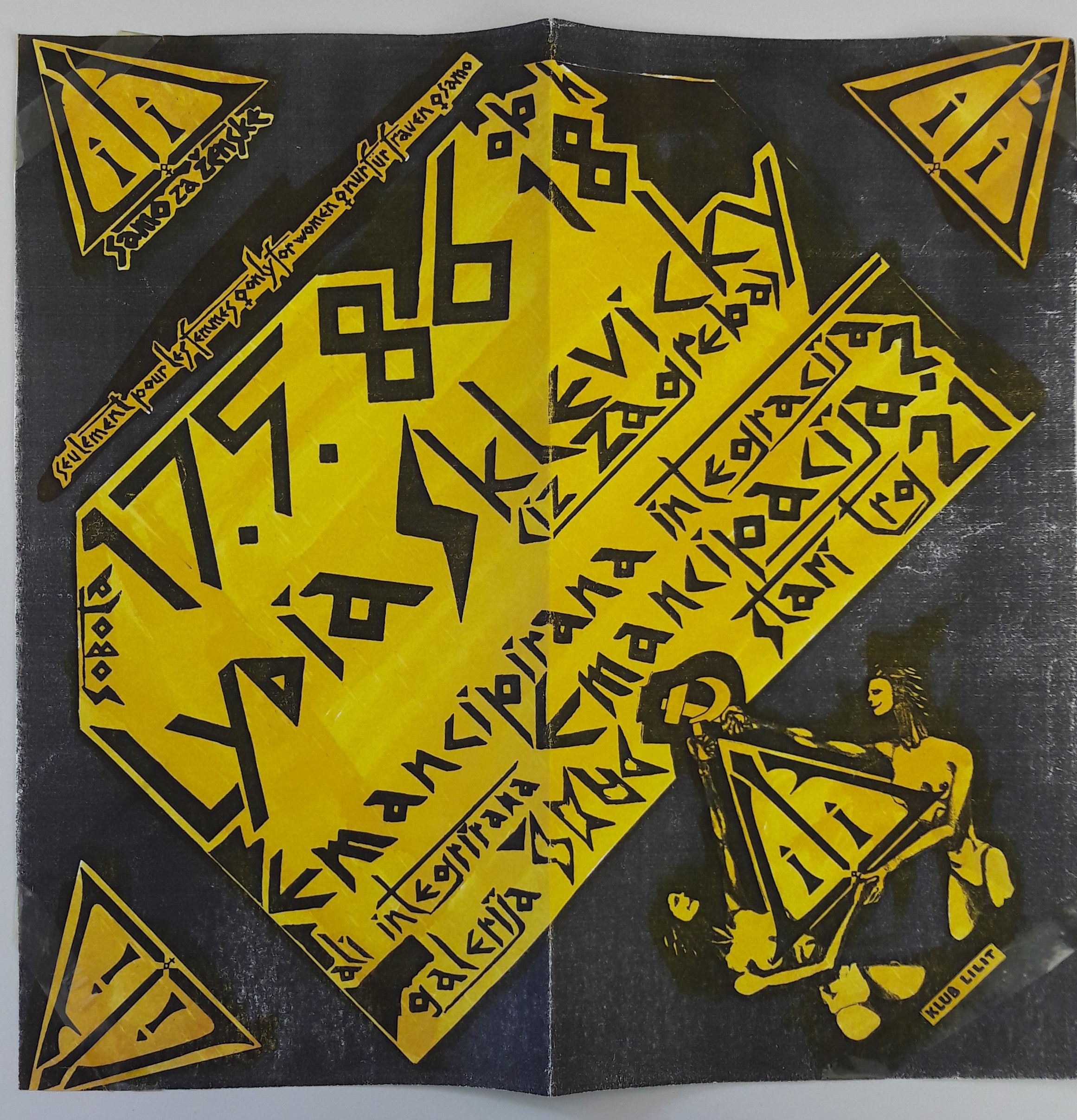

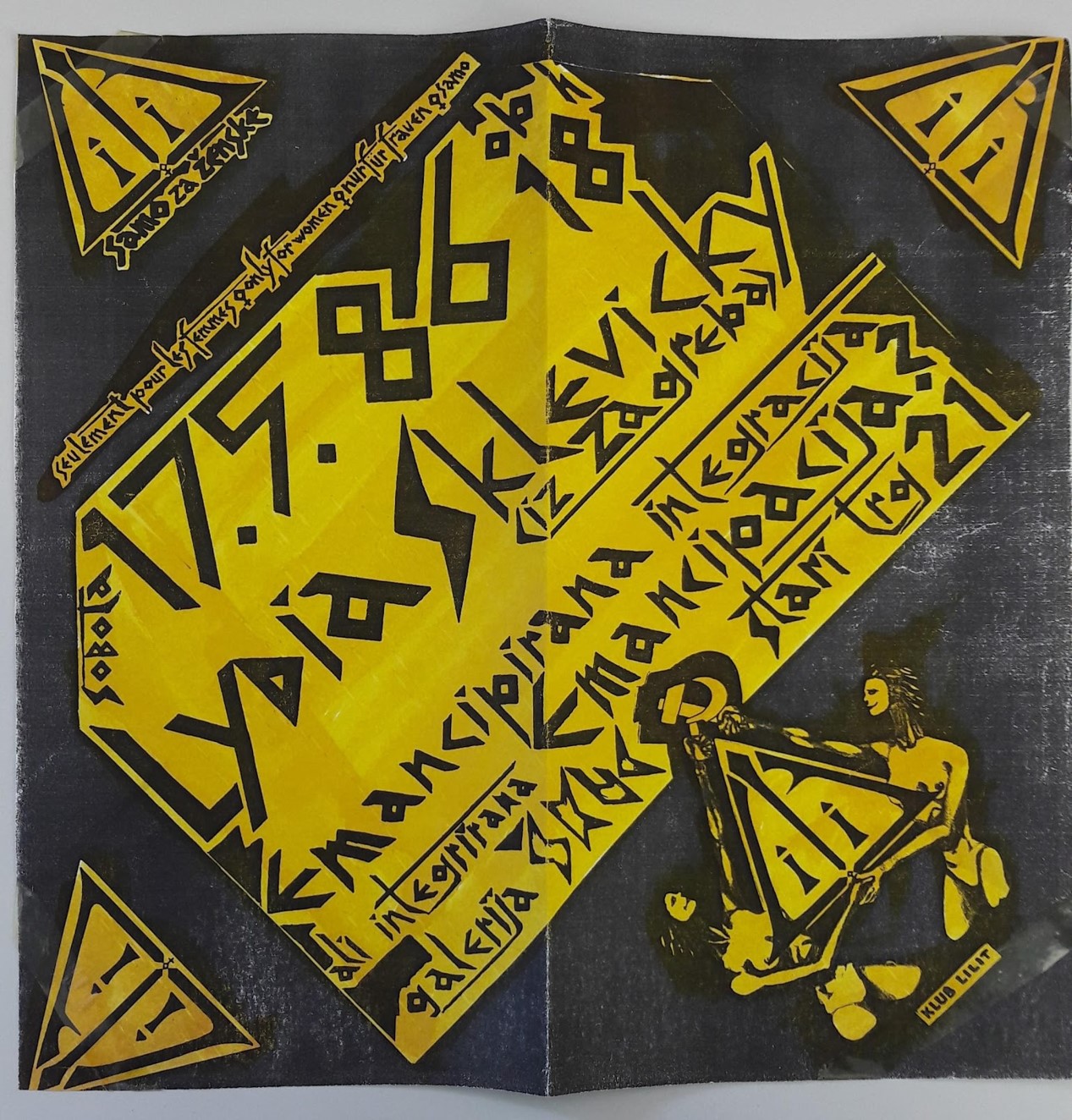

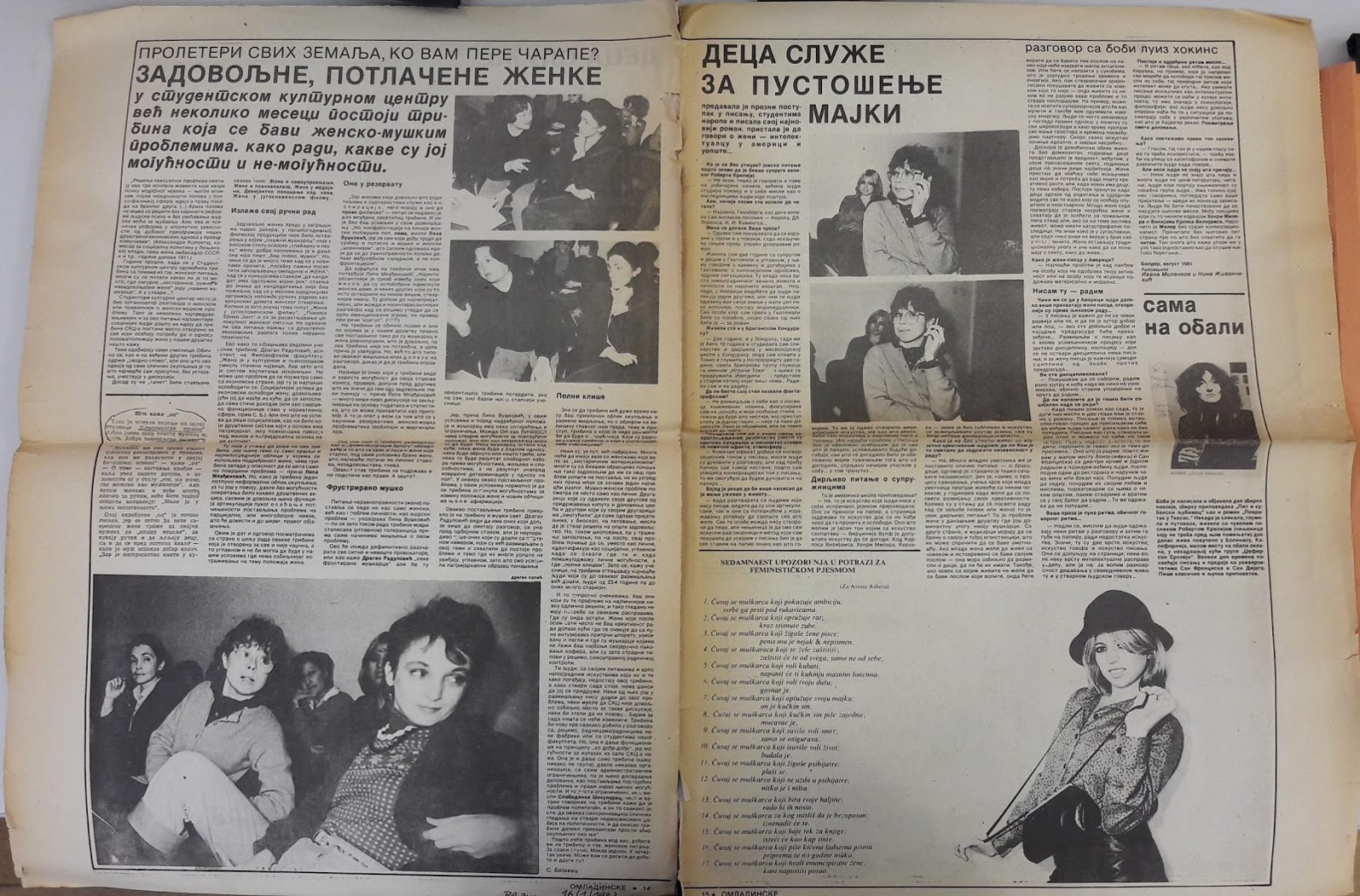

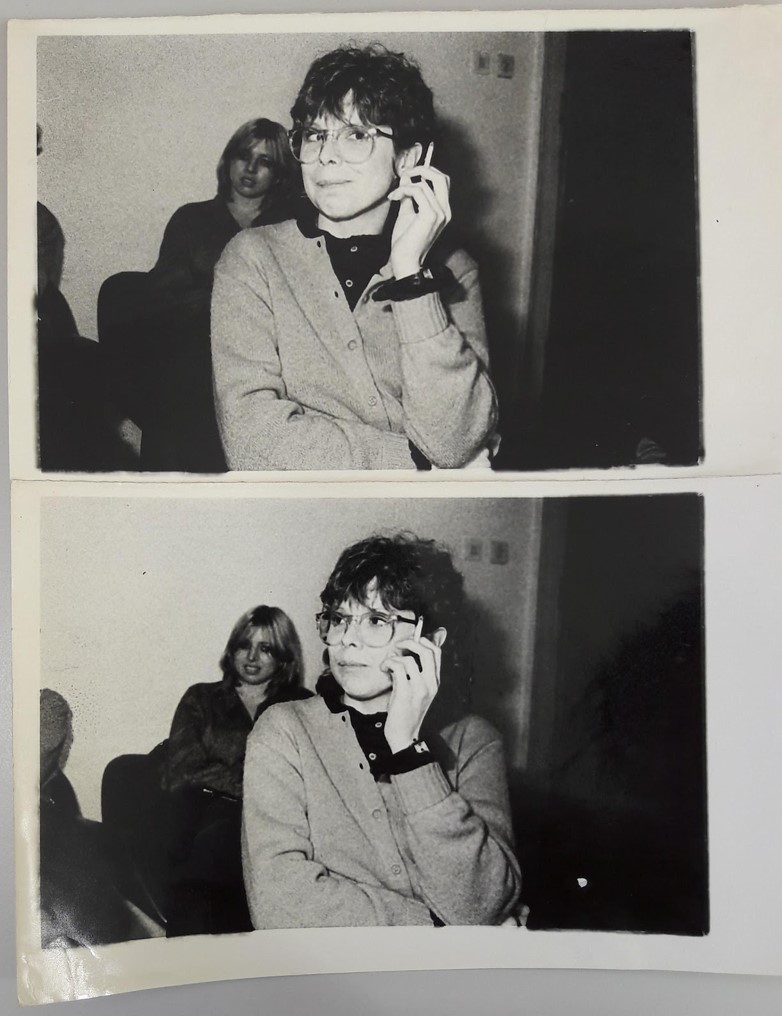

The origin of the feminist movement in Yugoslavia is linked to the international feminist conference ˝DRUG-CA žena˝ (Women) held in 1978 in Belgrade. After the conference, a further initiative took placein Zagreb, as a result of which the first feminist group "Woman and Society" was founded in 1979. The Belgrade group of the same name was founded in 1980, and the first Ljubljana group Lilith in 1985. The feminist Lydia Sklevicky, who was active in Zagreb, Ljubljana and Belgrade according to the poster which announced her lecture at the ŠKUC Gallery in Ljubljana held on May 17, 1986, organized by the feminist group Lilith. The two photos were taken on January 7th 1982 (photographer: Dragan Savić) at the forum on women's issues held in the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade. The article published in Belgrade newspaper Omladinski (Youth) states that there is no serious research on the subject of the status of women in Yugoslavia (because in scientific circles it is ˝bypassed and marginalized˝). On the other hand, Lydia Sklevicky is one of the few scientists who both scientifically and popularly (in the media) speaks about the position of women in Yugoslavia in the form of human rights, emphasizing their institutional marginalization in Yugoslav society from the mid-1950s.

Lydia Sklevicky is one of the protagonists of the late 1970s and 1980s who puts women's issues in focus, emphasizing the discrepancy between their contribution fighting in World War II and a prominent role in the post-war period with their marginalization since the mid-1950s. The Lydia Sklevicky Feminist Collection at the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research in Zagreb testifies Sklevicky’s professional work and interests, as well as her connection with the Yugoslav feminist scene.

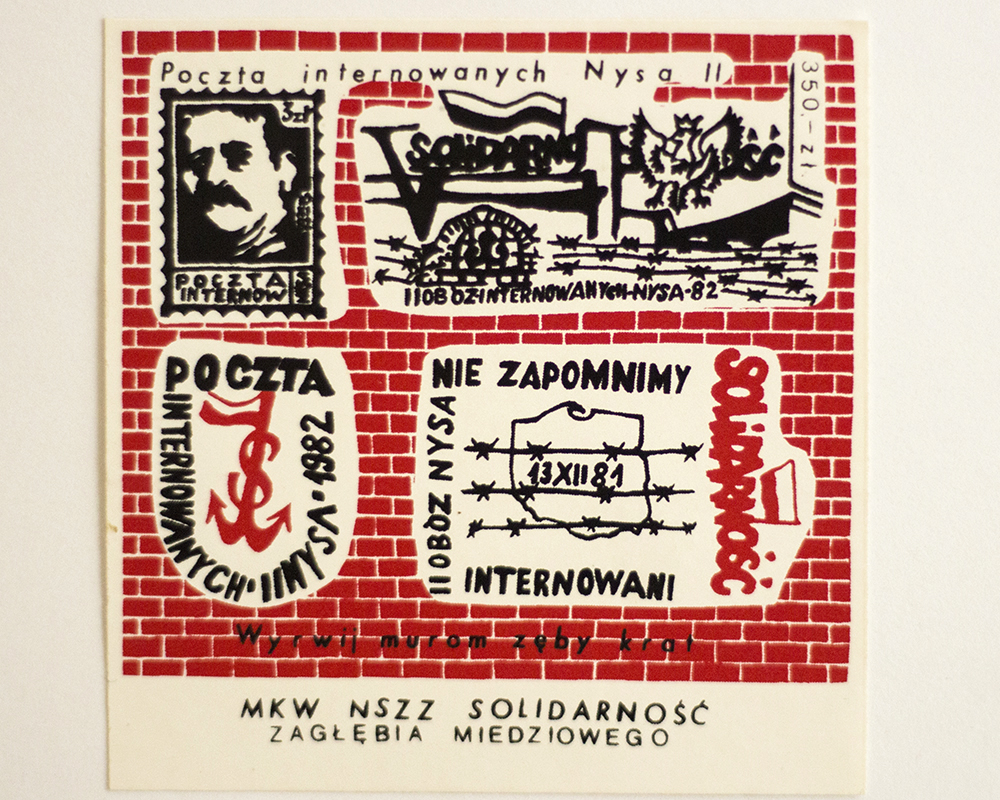

The Fund to Support the Poor (SZETA) was a unique feature of the early activities of the Hungarian democratic opposition, whereby some counter-cultural initiatives in the fields of art and literature, and increased social responsibility aimed to help those in need. The grassroots movement, inspired partly by the Polish Solidarity, was initiated in late 1979 by sociologist Ottília Solt. Together with her seven fellow-founders, most of whom had already been involved for years in extensive field research among the poor, workers, and Roma under the guidance of István Kemény, a devotee of modern empirical sociology, who in 1977 was forced into Western exile. Within the prevailing socialist system of that time, poverty, unemployment, homelessness and ethnic discrimination were all considered taboo, therefore the founders of SZETA did not even try to make it a legal entity. With their couragous public appeals and charity actions they soon challenged the Communist authorities, who counter-reacted in various ways. The party agencies, administration and the police used all means possible to try to block SZETA’s independent activities: the charity concerts, exhibitions, auctions, presentations, etc. Its samizdat prints were confiscated, its main activists were fined, dismissed or prohibited from research work and publishing. Even so, its large network of volunteers kept on supporting hundreds of the needy families for years by regularly sending them money and relief packages, providing them with free legal, medical and educational service, and sometimes even bying or building cheap homes for them, if the donations of a successful campaign or auction made that possible. In 1984, with no notice or formal disbandment, SZETA stopped working, however many of its volunteers kept on supporting families in need. After 1989-1990, its social role was taken over by several new NGOs with a similar mission, and their one-time organisers took key positions either in research work or policy-making as devoted protagonists of equal opportunities and social justice. This followed the principles of SZETA’s founder Ottilia Solt, who, in one of her last articles claimed and demanded no less than: „Dignity for all!”

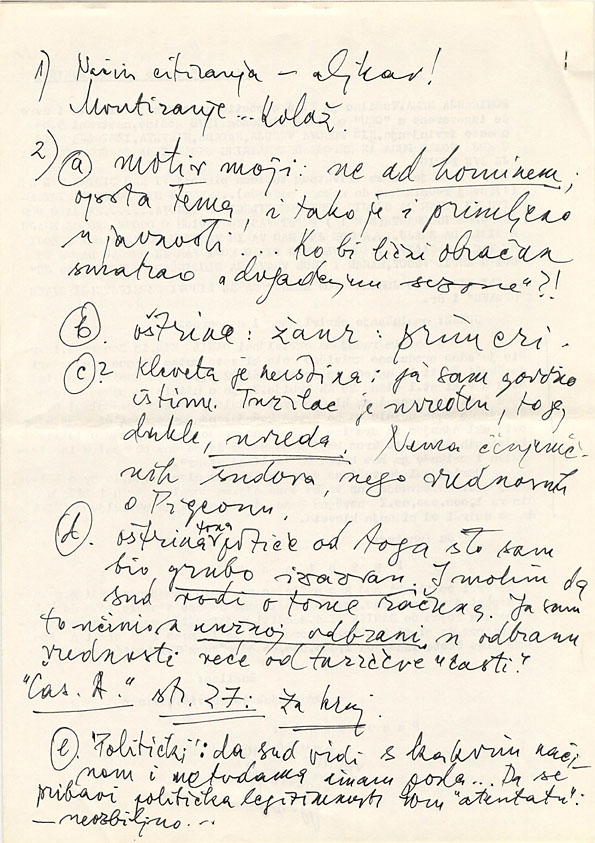

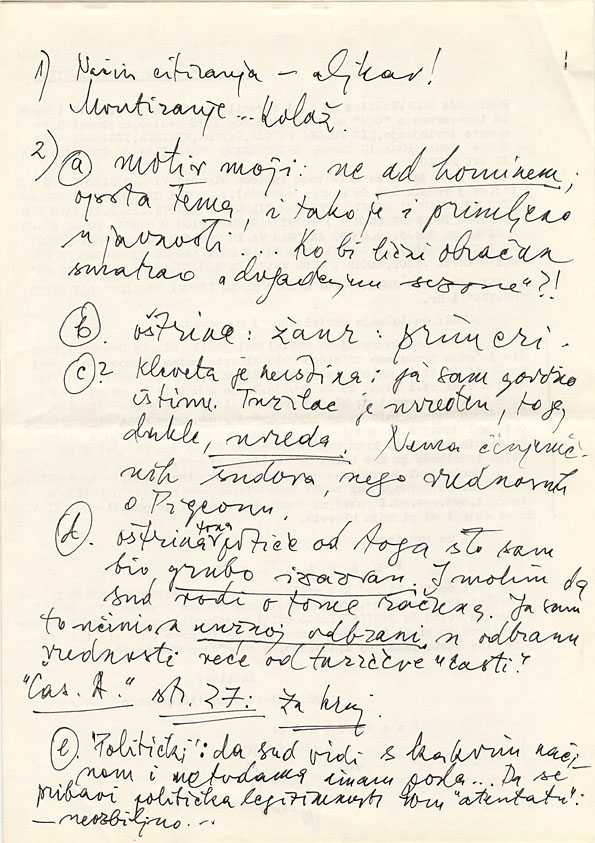

1) The form of quoting – sloppy!

Mounting ... collage.

2)a) my motive: not ad hominem; general topic, and that is how it is received in public.. Who would a personal reckoning perceive as „[not readable]“ ?!

b) severity: genre: examples.

c)? „Libel is untrue: I have said the truth. The prosecutor is insulted, it is therefore an insult. There are no factual judgements, but valuable [judgements] about Pigeon[1].“

d) The sharpness of the attack derives from that I was bluntly challenged. And I request the court to pay attention to this. I acted in indispensable defense to defend values greater than the prosecutor's „honour“!

„Anatomy Lesson“, p. 27, to the end.

e) Politically: that the court may see with which form and methods it is faced.. That it caters the political legitimacy of this assassination!:

- immature...“

[1] Pigeon is a „freshly graduated literary examiner“in the book „The Anatomy Lesson“.

The origin of the feminist movement in Yugoslavia is linked to the international feminist conference ˝DRUG-CA žena˝ (Women) held in 1978 in Belgrade. After the conference, a further initiative took placein Zagreb, as a result of which the first feminist group "Woman and Society" was founded in 1979. The Belgrade group of the same name was founded in 1980, and the first Ljubljana group Lilith in 1985. The feminist Lydia Sklevicky, who was active in Zagreb, Ljubljana and Belgrade according to the poster which announced her lecture at the ŠKUC Gallery in Ljubljana held on May 17, 1986, organized by the feminist group Lilith. The two photos were taken on January 7th 1982 (photographer: Dragan Savić) at the forum on women's issues held in the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade. The article published in Belgrade newspaper Omladinski (Youth) states that there is no serious research on the subject of the status of women in Yugoslavia (because in scientific circles it is ˝bypassed and marginalized˝). On the other hand, Lydia Sklevicky is one of the few scientists who both scientifically and popularly (in the media) speaks about the position of women in Yugoslavia in the form of human rights, emphasizing their institutional marginalization in Yugoslav society from the mid-1950s.

Lydia Sklevicky is one of the protagonists of the late 1970s and 1980s who puts women's issues in focus, emphasizing the discrepancy between their contribution fighting in World War II and a prominent role in the post-war period with their marginalization since the mid-1950s. The Lydia Sklevicky Feminist Collection at the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research in Zagreb testifies Sklevicky’s professional work and interests, as well as her connection with the Yugoslav feminist scene.

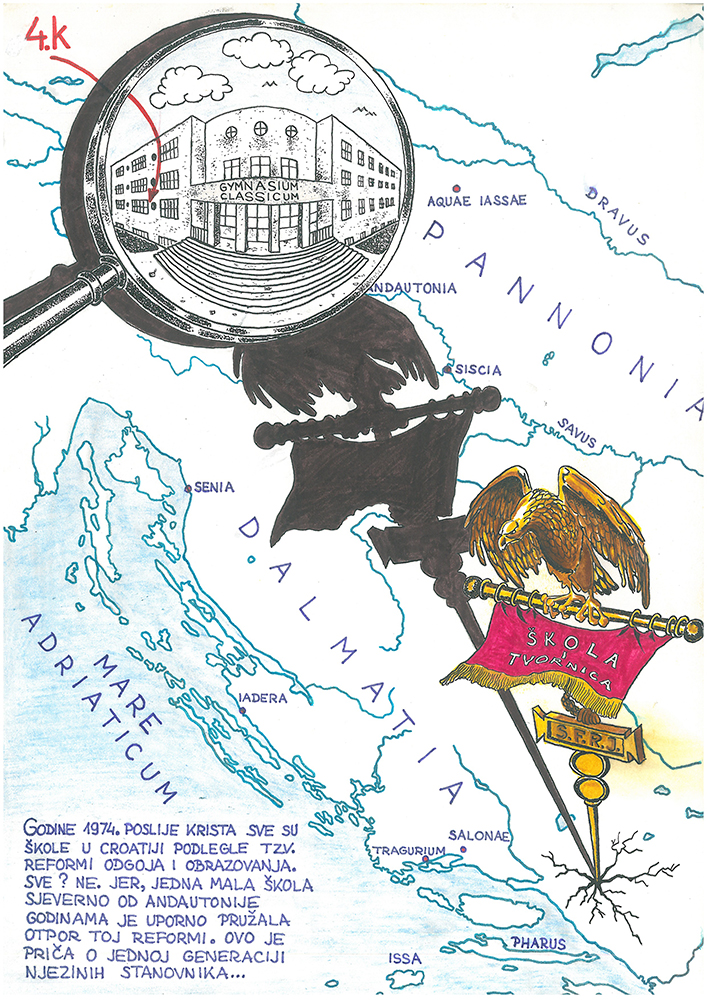

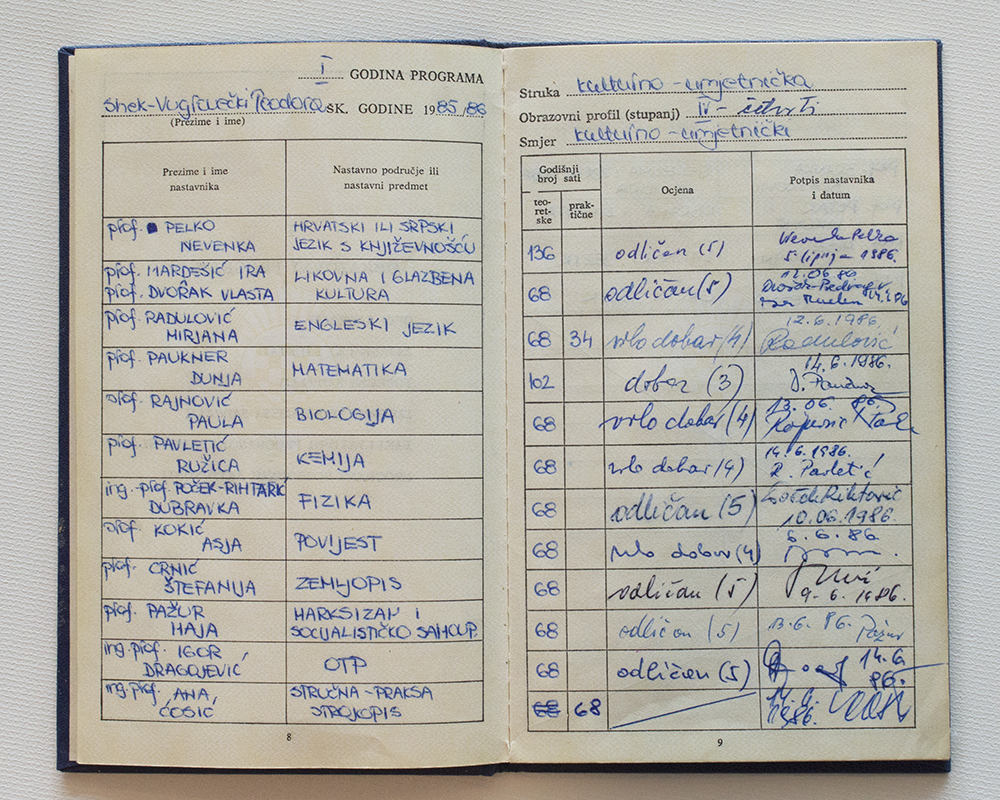

In 1974 the Minister of Education of the Socialist Republic of Croatia Stipe Šuvar implemented educational reforms of secondary schools, which turned them into vocational schools with specialised and limited vocational training. Such schools were supposed to provide pupils with immediate employment, preferably in factories. In 1977 the name „gymnasium“ was forbidden, and among others, the Classical Gymnasium in Zagreb was re-named the Educational Centre for Languages. Thanks to the courage of its director Marijan Bručić, the classical curriculum was saved providing general (universal) humanistic knowledge with emphasis on classical languages. In addition, this school was among the very few schools, which kept four years of Latin and Greek and had philosophy alongside Marxism, according to the student record book. The cover of the classroom samizdat which was put together by pupils from grade 4K on the occasion of matriculation in 1989 makes a parody of this exceptional case by using a comic strip Asterix, which was very popular at the time. The Roman eagle carries a flag with the inscription „School and factory“ and beneath there is a plate, which instead of the Latin SPQR carries the abbreviation for Yugoslavia, that is, SFRY.