Opanas Zalyvakha's "Zone" ("Zona") is a featured item of the permanent exhibition at the Sixtiers Museum in Kyiv, Ukraine. This painting depicts a crystalline labyrinthine construction, with figures passing in front and outside the enclosure, while others are only able to peer over the tops of volumetric poles, resembling wooden fences that surrounded hard labor camps in Siberia and also the pipes of an organ. Some of these figures blend more readily into the background, while others stand out. The narrow slats between the poles obscure the central figure, who seems to be peering out with eyes downcast and despondent demeanor and is, most probably, a prisoner in the zone. A flurry of figures moves around him in complete anonymity, without the least bit of contact. Art historian Myroslava Mudrak notes that the colors are on the bluish-gray side to underscore the effects of being closed in, and the orange of a setting sun also gives the sense of finality and denouement. The sharp verticality and harsh, repetitive linearity of its component forms gives the painting a sense of tactility—a kind of physicality to the experience of being cut off from everything.Fellow dissident Mykhailo Horyn' considers the verticality of Zalyvakha's paintings to be an indicator of the latter's general philosophy. "There is almost no horizontality to his work...the vertical rays produce a rhythmic-energetic pulse... giving his canvasses a sense of higher meaning and purpose." Another fellow dissident, the literary critic Yevhen Sverstiuk, compares Zalyvakha's approach to that of the poet and political prisoner Vasyl Stus, who always sought "to dig deeper rather than wider." What Stus expressed semantically, Zalyvakha portrayed visually, "hands and forms outstretched, reaching toward the heavens to a higher power, the only force that could defend the individual against tyranny."

The Nelu Stratone collection is one of the most impressive collections of rock, jazz, and folk records created in communist Romania, as a result of the happy combination between its owner’s exceptional passion for alternative music and his ability to acquire records that were not imported officially. The collection is important not only for its size, but even more for the significant number of albums of Western provenance, which were unavailable in shops in Romania but could nevertheless be obtained due to the existence of an alternative market for such products. The creation and preservation of such a collection were activities regarded with suspicion by the communist authorities in Romania, because they proved the younger generation’s fascination with Western cultural products, in contravention of the spirit of Nicolae Ceauşescu’s Theses of July 1971.

From the record it is visible that Stojanović was on trial twice – first at the end of 1972, during his compulsory military service when he was brought before the military court. Stojanović served as a conscript amidst political infighting between the highest Party leadership and President Tito on the one side, and Croatian communist leadership (1971) as well as Serbian communist leadership (1972) on the other. The clashing between the central and national leaderships led to a complete purging of both national leaderships in the wake of which, the legitimacy of the Yugoslav Communist Party was seriously threatened. In the first six months of 1972, about 3,500 individuals were imprisoned as 'political criminals', 60% of which were from Croatia (Marković 2011, 119). Tito’s Letter from October 1972, in which he called for a “more assertive Party” was the trigger for a more direct confrontation with what had until then been accepted liberties, particularly in the arts. Exactly at the end of October 1972, during Stojanović’s final month of military service, a captain denounced him to the military authorities for his lambasting of the Yugoslav People’s Army and Tito’s Letter. While awaiting trial, he was threatened and the police searched his house and found “anarchistic” materials which were confiscated (Solomun 2012, 15). Apart from his films, all student papers, samizdat issues, émigré press and the majority of the publications distributed among politically active youth were confiscated. At first, Stojanović was accused of espionage, however, in the end, he was charged only with “hostile propaganda.” His film “Plastic Jesus” was used as evidence against him during the trial but he was not judged for the movie during this first proceeding. The military court sentenced him to one year of prison.

In the meantime a civil trial commenced for “Plastic Jesus”. The majority of Stojanović’s file concerns the verdict from June 1973 in which “Plastic Jesus” and its “hostile” agency were analyzed in detail. The verdict states that in the work, the author “represented the socio-political situation in the country maliciously and falsely”, that he depreciated the socialist revolution, its fighters, and self-governing socialist system, and that he had insulted the figure of the President, Tito, “the most distinguished representative of the Revolution and of the construction of the socialist social relations.” The civil court sentenced Stojanović to one and a half years of prison. This sentence, combined with the previous sentence of the military court equated to two years in prison. As the verdict was issued, all copies of the film were confiscated due to their ‘criminal offense’ and the movie was barred from screening until December 1990.

The record also contains the verdict of the Supreme Court in Serbia from November 1973 which stated that owing to the severity of the act, the sentence would be increased to three years of prison. The verdict stated that the lower court did not evaluate the level of criminal irresponsibility of the accused and that the sentence of (only) two years would not achieve the purpose of providing adequate punishment. The reasoning behind this act was to ensure that others would refrain from engaging in similar criminal offences.

Article 118 of the Criminal law of Yugoslavia, which judicated against “hostile propaganda” was used as the basis for trial in both cases against Stojanović. Article 118 stated: “Whoever uses propaganda, with the intention to pull down the authority of the working people, the power of the state to defend, or the economic basis of socialist upbuild, or the fraternity and unity of the peoples in the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia with a drawing, inscription, speech at a gathering or any other way uses propaganda against the state or social organization or against political, economic, military or any other important measures of the people’s rule, will be punished with rigorous confinement.”

The trial of Stojanović and the treatment of “Plastic Jesus” were meant to set examples for other artists, ending the so-called “Black Wave” in Yugoslav cinematography.

Official memorandum in Vlado Gotovac's intelligence file on personal correspondence seized during a search of his home. 4 February 1972. Archival document.

Official memorandum in Vlado Gotovac's intelligence file on personal correspondence seized during a search of his home. 4 February 1972. Archival document.

The State Security Service's collection of intelligence files also includes the files of intellectuals and other participants in the Croatian Spring. A significant number of documents in such files is related to criminal prosecution of these persons which followed the suppression of that reform movement in Croatia at the end of 1971.

This group also included Vlado Gotovac, a prominent Croatian poet, journalist, philosopher and politician (Imotski, 18 September 1930 – Rome, 7 December 2000). From July to December 1971, he was editor-in-chief of the magazine Hrvatski tjednik (Croatian Weekly), the newspaper of the Matrix Croatica, which advocated the programme of the national reform movement. As one of its leaders, together with ten other members of the Croatian spring, Gotovac was arrested on 11 January 1972 on charges of a “counter-revolutionary attack against the state and social order ,” “conspiring against the people and state,” and “other offences against the people and state.”A search of their homes followed. In an annex to the report from 6 February 1972 “based on a review of written, published and other material temporarily sequestered during the search of Vlado Gotovac's home and office,” there is a listed of 158 books (by émigré and other authors), Gotovac's writings, letters, poems, notes, notebooks and other items. On the basis of “friendly or business” correspondence, a list of 76 persons with whom Gotovac was in contact was drawn up. A significant number of the documents in Gotovac's intelligence file pertain to written records of hearings before the District Court in Zagreb and other documents related to proceedings in which, on 26 October 1972, he was sentenced to four years in prison, deprived of civil liberties for three years and the right to employment in the civil service, and his publishing and public activities were restricted. Ignoring the ban on public activities, after granting an interview to foreign journalists in 1977, he was again indicted and, after a trial in 1981, sentenced to two years in prison and loss of civil liberties for four years. He returned to public life at the end of the 1980s, but could only find employment after the restoration of democracy in 1990. The content of the file reveals that Gotovac was under the surveillance of the State Security Service since the mid-1950s. Among other things, the operational notes from that time contain the observation that Gotovac was “noticed as a very active young voice” of writers gathered around the journal Krugovi (Circles), whence a thread of Croatian nationalism began to spread” (HR-HDA-1561. SDS RSUP SRH. Intelligence files, Vlado Gotovac's file, no. 204605, Operational note, 30 July 1963).

Vlado Gotovac was the author of about twenty collections of poems and prose works. Additionally, he published criticism, essays, stories, radio dramas and engaged non-fiction texts in newspapers and magazines. It is interesting to note that Gotovac wrote even during his imprisonment in Stara Gradiška and Lepoglava. Such writings are preserved in his prison file, now also in the CSA in Zagreb. Referring to them at the meeting “Encounter with Gotovac” held in the Petit Local Library in Pula on 7 December 2015 on the 15th anniversary of Gotovac's death, his daughter Ana Gotovac said that they reflect “the immense efforts of a man, who was thrown into a place unthinkable to someone who wasn't there, to remain normal and to maintain his spirit and soul” (Angeleski, Z. 2015. “Svog sam oca doživljavala kao tatu, ali i kao heroja.” GlasIstre.hr, 8 December).

The Croatian State Security Service file on Vlado Gotovac is registered under number 204605 and preserved on microfiche. It includes roughly 530 pages of documents. All of them are available for research and copying. So far they have been used by several researchers. It should be noted that Filip Zoričić from the Institute Mediterran is writing a doctoral thesis on Vlado Gotovac's life and work.

The collection stores about 250 photos made by Tomasz Sikorski during the Fifth Biennial of Spatial Forms known as Kino Laboratorium (Cinema Laboratory), in 1973. The pictures documented the 1973’s sculptures, objects, and performances, as well as artworks created in the earlier years. There are also some photos from 1972 when Sikorski came to Elbląg to document the preparations for the event. The Biennial, organized in Elbląg from 1965, was one of the crucial neo-avantgarde events in Poland. Cinema Laboratory was the last edition of Biennial in Elbląg; soon after its end Gerard Blum-Kwiatkowski, initiator and founder of the event, moved abroad to Germany.

This document is an internal informative note addressed by the Deputy Chairman of the Moldavian KGB, F. Krulitskii, to the Head of the Enquiry Section of the KGB, A. V. Kulikov, and dated 26 May 1972. This item was produced in the context of the intentions expressed by the members of the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group to send a number of the documents produced by the organisation to the RFE/RL headquarters in Munich. The radio station is labelled as “one of the imperialist propaganda tools” aimed at the USSR and the “socialist camp.” The note analyses the organisational structure of RFE/RL, and emphasises that its employees “originate from various East European countries ([being] renegades, defectors, repatriated persons, traitors to the Motherland etc.”). The document states that the bulk of the RFE/RL annual budget (approx. 20 million US$) is provided by “CIA subsidies.” It is clear that the Soviet secret services were alarmed by the impact of RFE/RL broadcasts on the population of the USSR and the satellite states, while the radio station’s “subversive activities” were taken rather seriously. Describing the content of the broadcasts and the operational procedures, the KGB official notes that “during the last five years” (i.e. since 1967) RFE has intensified its activities, aiming to ‘subvert the unity, cohesion, and friendship between the peoples of the USSR and those of the socialist countries, foment nationalism, incite tendencies towards emigration, and spread anti-Soviet hysteria.” Specifically, the document asserts that during 1968–1971, RFE/RL broadcasts were paying increasing attention to the “Bessarabian question,” mentioning Romania’s “purported claims to the territory of Soviet Moldavia and the rebirth of nationalist tendencies within the [Moldavian] republic.” These trends provoked the apprehension of KGB officials, which partly explains the harsh sentences meted out to the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group and the repression against “local nationalism” that intensified throughout the USSR during the early 1970s. The document also points towards the sensitivity of Soviet officials concerning the international context and the USSR’s image abroad.

The first private dance house was opened on 6 May 1972 in the Book Club at Liszt Ferenc Square in Budapest, where Ferenc Novák and his followers showed the simple form of the “széki” dance (Szék, Sic is a Romanian village). The event was organized by dancers of the Bihari Dance Ensemble, Jolán Foltin, Lajos Lelkes, and Antal Stoller. The dancers of the Bartók, the Vadrózsák, and the Vasas Dance Ensembles also took part in it; the music was provided by Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, and Péter Éri. The main supporter of the event was György Martin. He helped Béla Halmos and Ferenc Sebő too. Martin showed them the Collection of Szék by László Lajtha and other records what later became the music collection of the dance house movement. Halmos and Sebő learnt from Sándor Tímár in 1971 how to play music for dancers.

“Music and dance like in Szék” was written on the invitation for the first private dance house in 1972. Opposite the entrance, there was a photo by Péter Korniss who also spent a lot of time in Szék and documented traditional Transylvanian peasant culture. At the door, Lajos Lelkes and Antal Stoller gave the guests a welcome similar to the welcome they would get in Szék. Originally the organizers wanted to reconstruct the traditional dance house of Szék, but later there were also ethnographical and sociological lectures at the dance houses.

In 1972, there were three more private dance houses at the Book Club.

At the end of 1972, Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, and Mihály Sipos traveled to Szék because they wanted to learn about the dance house. Here Béla Halmos heard the band of István Ádám "Icsán,” and he started to learn folk songs from them. In Budapest, when Béla Halmos organized the dance houses, the model for him was the dance house of Szék, where that was a natural event every time.

Over the course of the years, the dance houses in Budapest became more and more popular. Young people had chances to learn and hear about that information and ideas which were not allowed at schools or universities. The HVDSZ, VDSZ, VASAS, ÉPÍTŐK were the main Ensembles at the dance houses. From 1973 the members of the Bartók Dance Ensembles taught folk dances at Fővárosi Művelődési Ház. New folk music bands were founded which resembled Muzsikás, and the dance house movement became popular at all around Hungary.

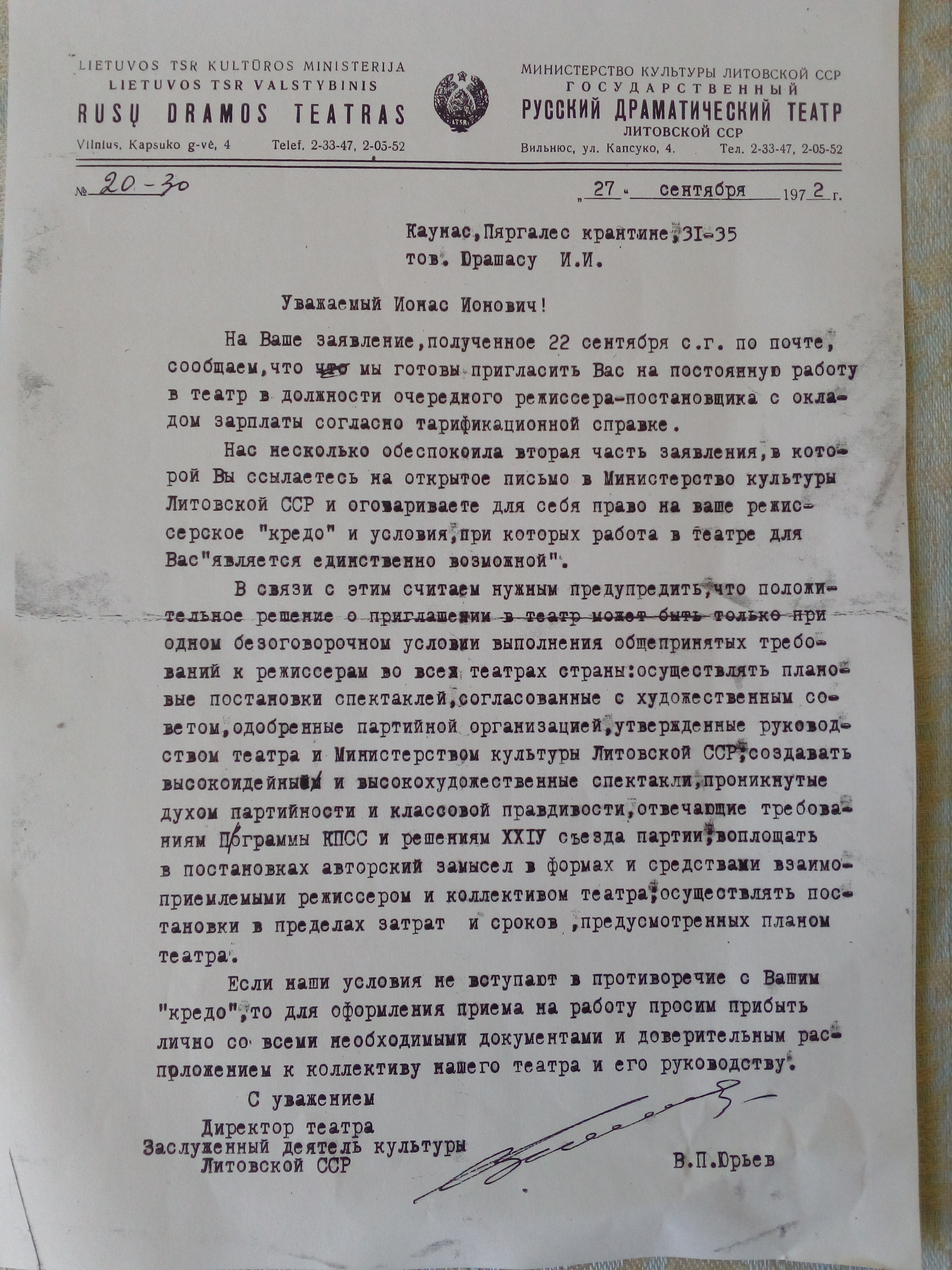

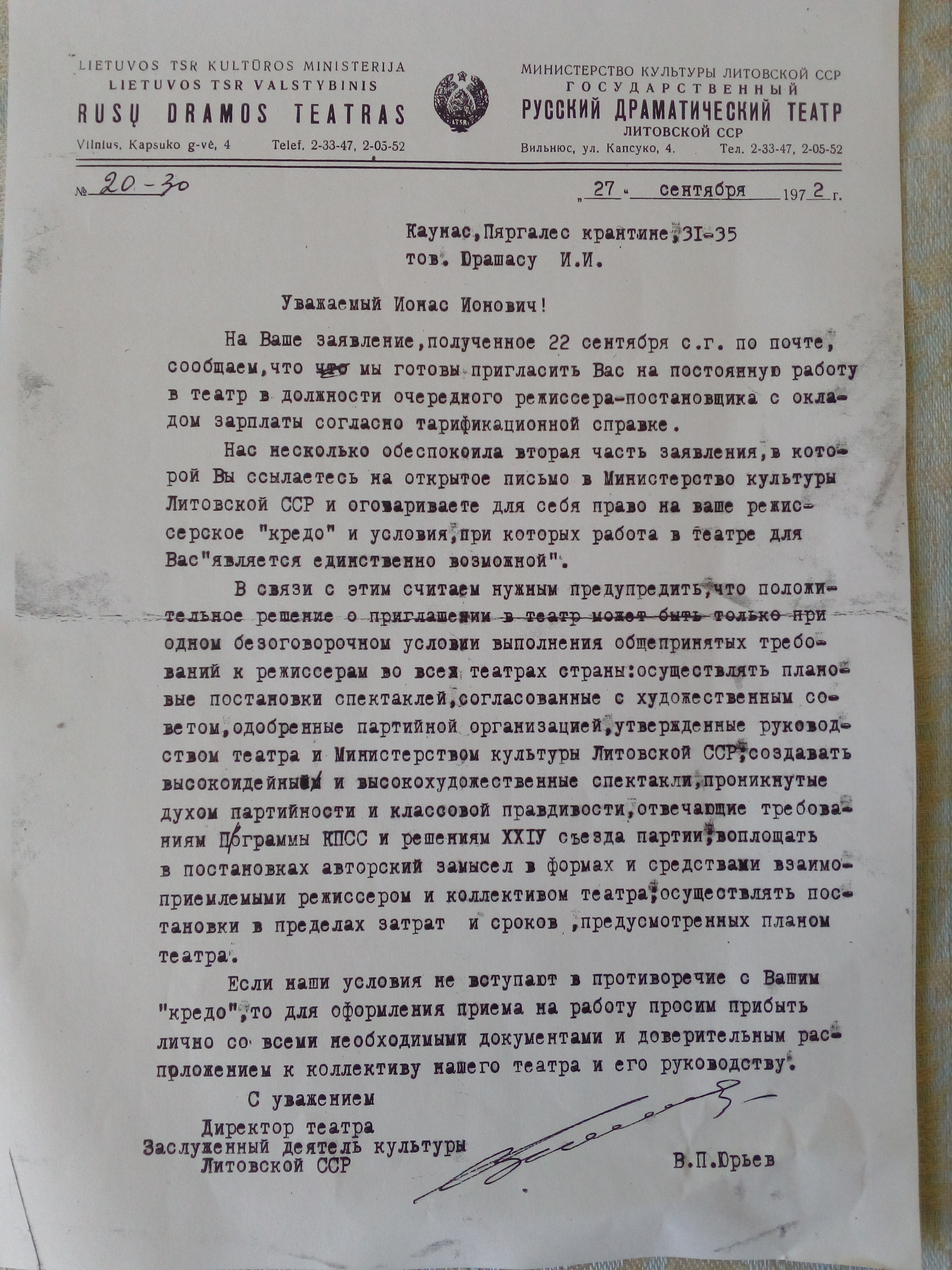

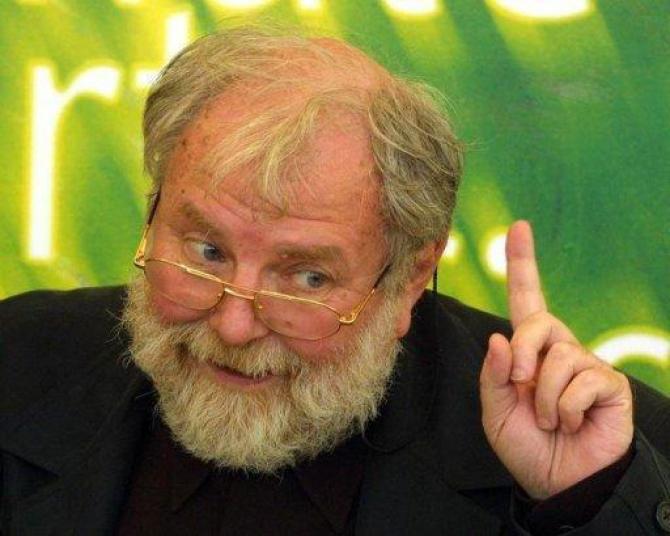

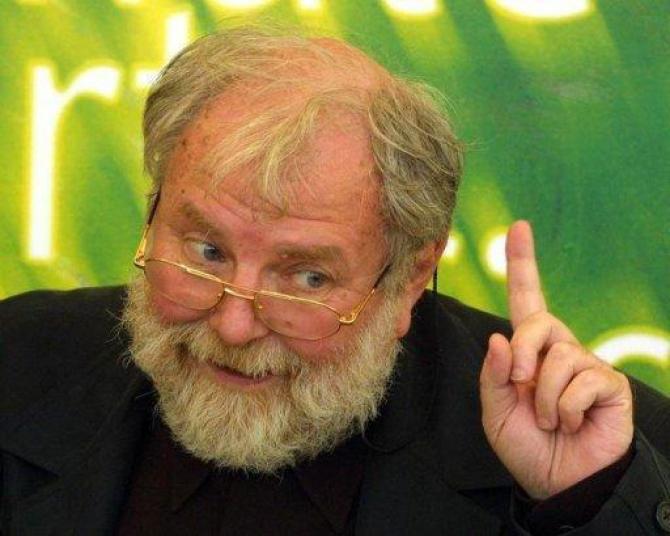

After the intervention of Soviet cultural managers following the discussions about Jurašas' production Barbora Radvilaitė, Jurašas wrote an open letter. In the letter, he expressed his dissatisfaction with the limitations to creative freedom. The letter became the reason for his dismissal from his position as theatre director. An order from the culture minister of Soviet Lithuania said that Jurašas was dismissed from his director's position, and suggests he apply to the Lithuania Russian Theatre for a new possition as an ordinary theatre director. Jurašas put forward his requirements about creative freedom for theatre directors in a letter to the Russian Drama Theatre. He soon received an answer from the theatre that he should follow the rules of the Soviet theatre director and Communist Party decisions, otherwise he would not get a job (see attached document). Jurašas declined this proposal, and became an unemployed artist.

A main figure of the Romanian cultural opposition to the communist regime, Paul Goma began to write his book Gherla during his first trip abroad (between June 1972 and June 1973). The title refers to the name of the Transylvanian town where he was imprisoned between 1957 and 1958 due to his failed attempt to stir up unrest among the students of the University of Bucharest in the context of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. The book which represents a personal account of Goma’s experience as a political prisoner in Gherla was published in 1976 and managed to raise the interest of the Western public in what had happened in Romanian communist prisons (Petrescu 2013, 124–125, 121).

Gherla takes the form of a passionate dialogue of the author with himself and focuses on the last two days he spent in prison. The main event of those days was the atrocious beatings Goma received from the prison’s authorities due to his involvement in a quarrel between two inmates. Consequently, he and another prisoner whose side he had taken against one of the prison’s informers were called for questioning. Things escalated and the two were tortured by the prison’s associate director, under the watchful eyes of the prison’s doctor and another guard renowned for his torturing procedures. Upon further instigation by the prison informers, the same two inmates received a second and more brutal beating in the old section of the prison, built in the time of Empress Maria Theresa. During his beating, in which the prison’s associate director and the guards gladly participated once again, the narrator reached the end of his capacity to endure and thus, he promised to himself that he would never forget or keep silent about his torture.

The episodes of Goma’s punishment are retold with many interruptions and deviations that help to describe the larger context of the events: the worsening of prison conditions after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the ruthless repression of an inmates’ rebellion and the increased terror that prisoners were forced to endure from torturers who creatively learned from the Soviet experience. The detours are glimpses into the narrator’s life before his imprisonment to Gherla prison, starting with his time as a pioneer instructor and ending with his trial and conviction.

Beyond the personal drama of the narrator, the book Gherla is also a convincing account of the inner workings of the prison system and of the uncountable abuses that inmates had to endure from the guards and other prison’s officials. Paul Goma is also a fine observer of the little and apparently insignificant details of everyday life in prison, such as personality traits, gestures, reactions, responses, mispronounced words, different behaviours that not only coloured but also disturbed the strict order in Gherla prison.

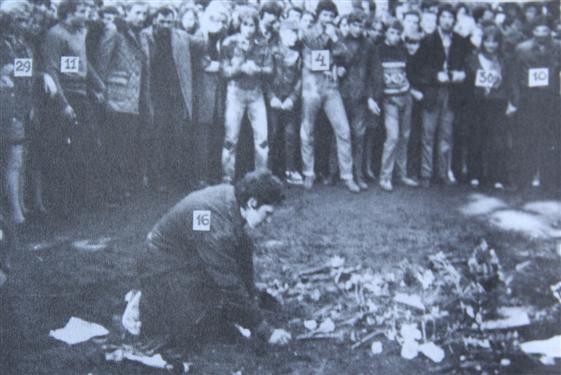

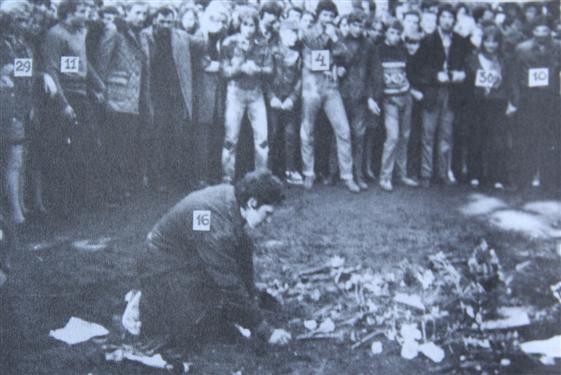

The collection is an album of 24 photographs made by a KGB officer (or secret informer) about the youth protests after the self-immolation of Romas Kalanta in Kaunas in the spring of 1972. The album shows the attitude of the KGB towards the anti-Soviet event and youth protests. On the other hand, it also shows the attitude of the younger generation of Lithuanians towards the regime.

In early 1972, the Municipal Conference of League of the Communists of Croatia (LCC) in Zadar appointed a separate working group with the task of interrogating and assessing the political responsibility of 16 party members accused for escalating the “mass movement” in the city of Zadar. As most of the reformist communist leaders at the republic (Miko Tripalo and Savka Dapčević Kučar) and local level (those who were supporters of Tripalo and Dapčević-Kučar), Ivan Aralica resigned from his post as deputy chairman of the Municipal Conference of LCC - municipality of Zadar in the course of December 1971. Although not a single incriminating word was found in his texts and statements, the working group of the Municipal Conference conducted an inquiry and found evidence against him:

A) as a deputy chairman of the Conference of LCC of the municipality of Zadar, Aralica did nothing to prevent nationalist-chauvinist discussions at conferences, he participated in discussions in which he positively emphasized the activities of Matica hrvatska (MH), he did not condemn individual nationalist outbursts, he submitted papers in which he supported the endeavours of the [Croatian] national movement;

B) at the event “Croatia Yesterday and Tomorrow,” he persuaded the organisers to invite the writer Petar Šegedin regardless of his political qualifications; did not see anything negative in the “politicization of the masses,” although it was clear that this was the heart of the ideology of the mass movement;

C) as president of the MH branch in Zadar, he actively participated in its work and in the creation of its policies, and in the establishment of the special committee of MH in Nin and other villages. Although he knew that MH was turning into a political organisation, he positively assessed its work, although he should not have done so as a political leader;

D) he actively participated in the organisation of the event “Croatia Yesterday and Today” together with representatives of the League of Socialist Youth. The political consequences of this event are very well known;

E) he supported the student newspaper Zoranić and those standpoints in line with the mass movement;

F) he was engaged in overcoming the resistance of the editorial board of the weekly Narodni tjednik (People’s Weekly) in order to subordinate them to the attitudes and needs of the political forces in power;

G) he was an active member of the committee to rename streets and squares, which also had political consequences (Aralica 2014, 128-129).

Although the party cell of the organisation where he worked (the Pedagogy Gymnasium in Zadar) did not find any culpability in his actions, the working group concluded that “his contribution to the escalation of the ‘mass movement’ was immense” (Aralica 2014, 129). Because of this, Aralica was suspended from the League of the Communists of Croatia in May 1972.

Juozas Keliuotis (1902-1983) was a famous Lithuanian intellectual in the Catholic movement. He was founder of the journal Naujoji Romuva in 1930, and its editor-in-chief until 1940. After the beginning of the Soviet occupation, he was sent to Siberia as a political prisoner. After his return to Lithuania, the KGB still followed his every move, trying to force him to collaborate with the Soviet regime. Keliuotis refused to collaborate, becoming a well-known figure in the cultural opposition in Lithuania. KGB documents from the collection demonstrate the efforts by Soviet state security to break his anti-Soviet network. The KGB finally succeeded in 1972, and he agreed to make a public denunciation of his past ‘bourgeois’ activity. It was even presented to the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party by Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB of the USSR, as a clear victory against the ‘nationalist intelligentsia’. Keliuotis’ case shows clearly the limits to freedom and self-expression under the Soviet regime. The document is the KGB operational plan for working against Juozas Keliuotis.

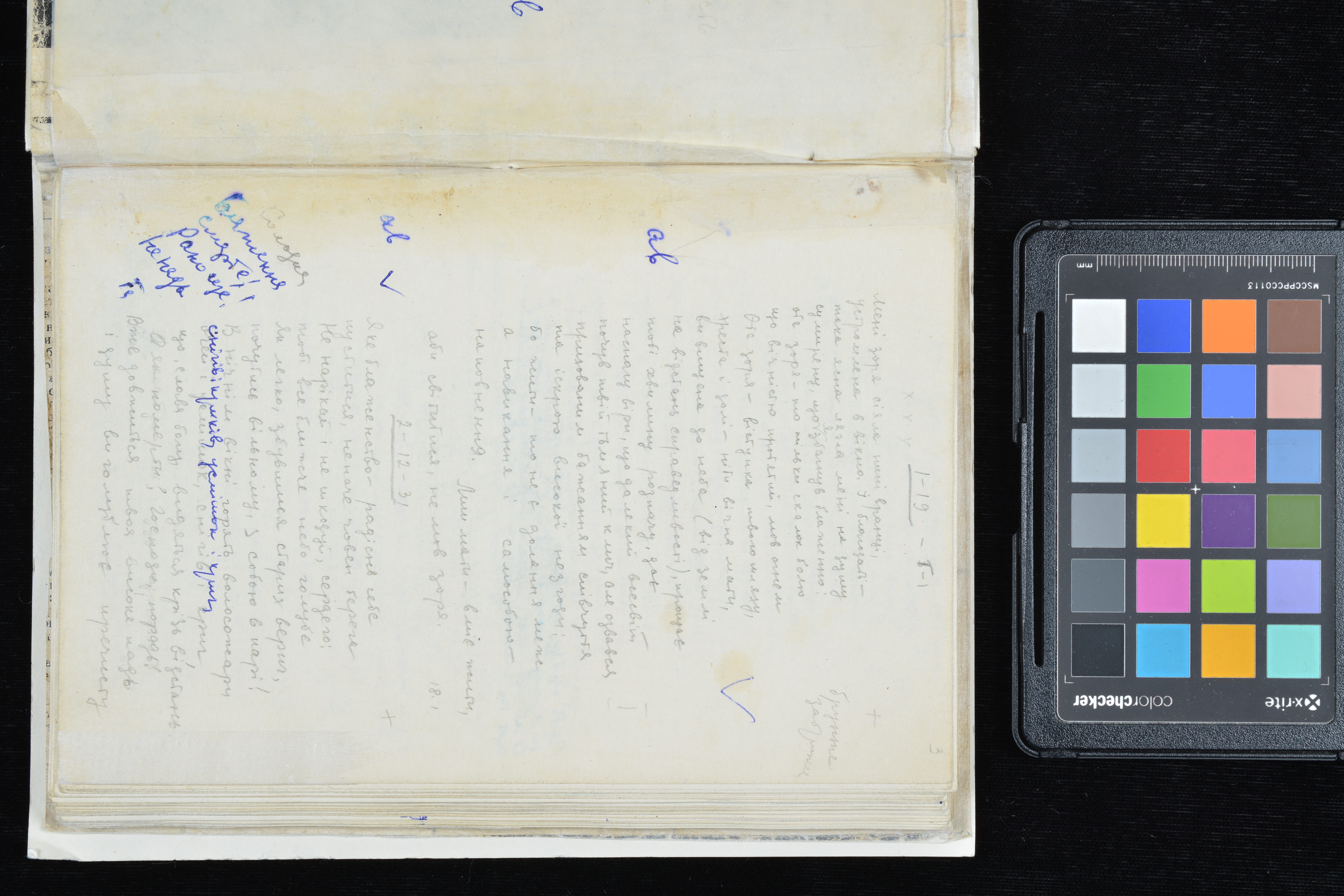

Vasyl Stus’ fourth volume of poetry was written under particularly difficult and unusual circumstances, during a nine month period in 1972, when he was held in isolation prior to his trial and sentencing. The poems were written in pencil (as he was forbidden from using pens) into a single notebook from January to September. Despite the austere conditions and near total isolation, Stus himself and literary scholars point to this period as one of explosive creativity in which he wrote nearly 200 poems and 100 translations. This notebook captures not only the circumstances under which these poems were written, but also Stus’ own extraordinary gifts as a poet and his strength of character.

![https://www.arhivaskc.org.rs/foto-arhiva/velike-manifestacije/i-as/12383-1972-04-05-ias-tucic-resin-pobesnela-krava-a1-3-02.html#prettyPhoto[%201972-04-05%20ias%20tucic%20resin%20pobesnela%20krava]/6/](/courage/file/n48915/SKC+1972+cut.jpg)

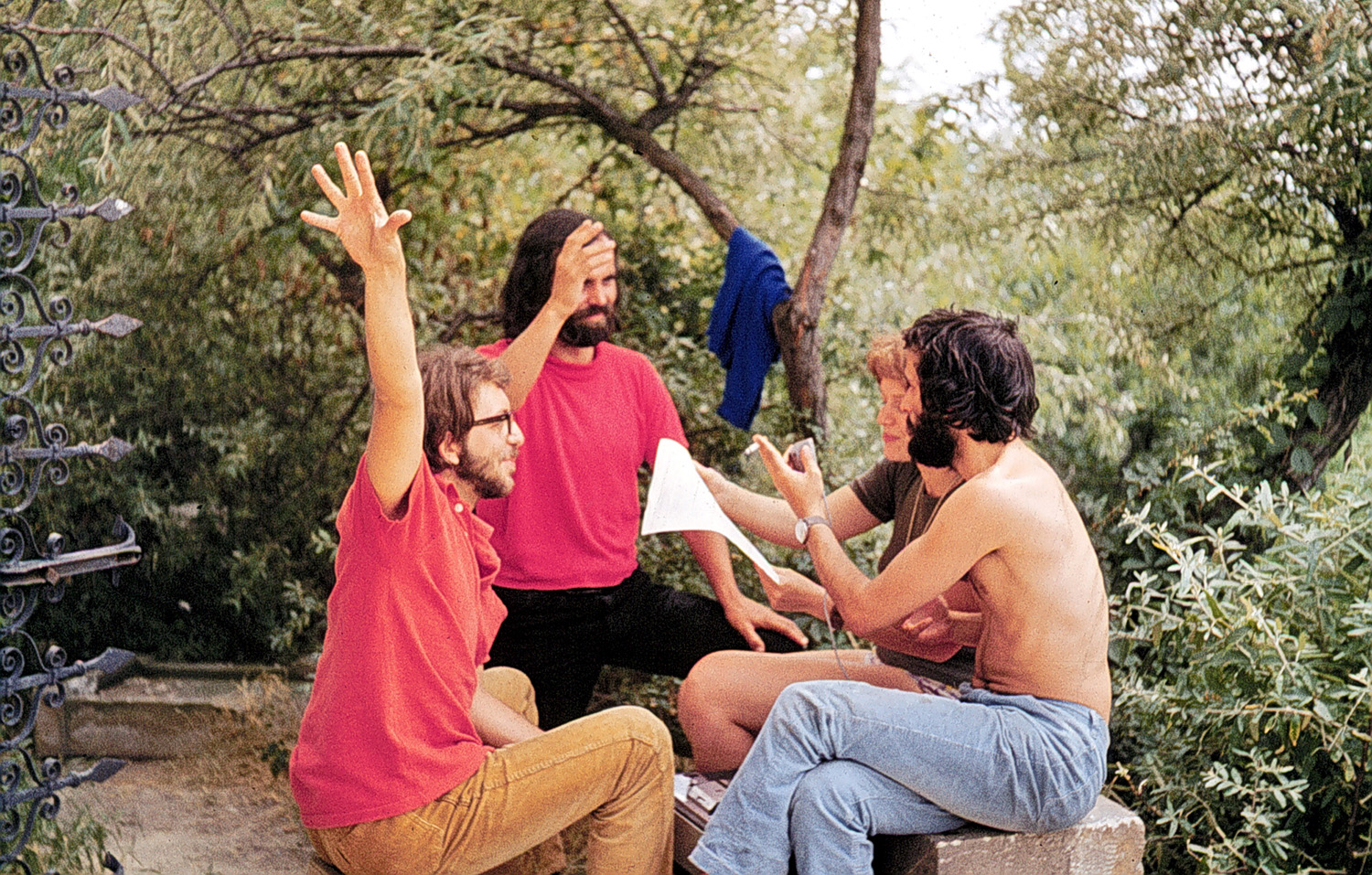

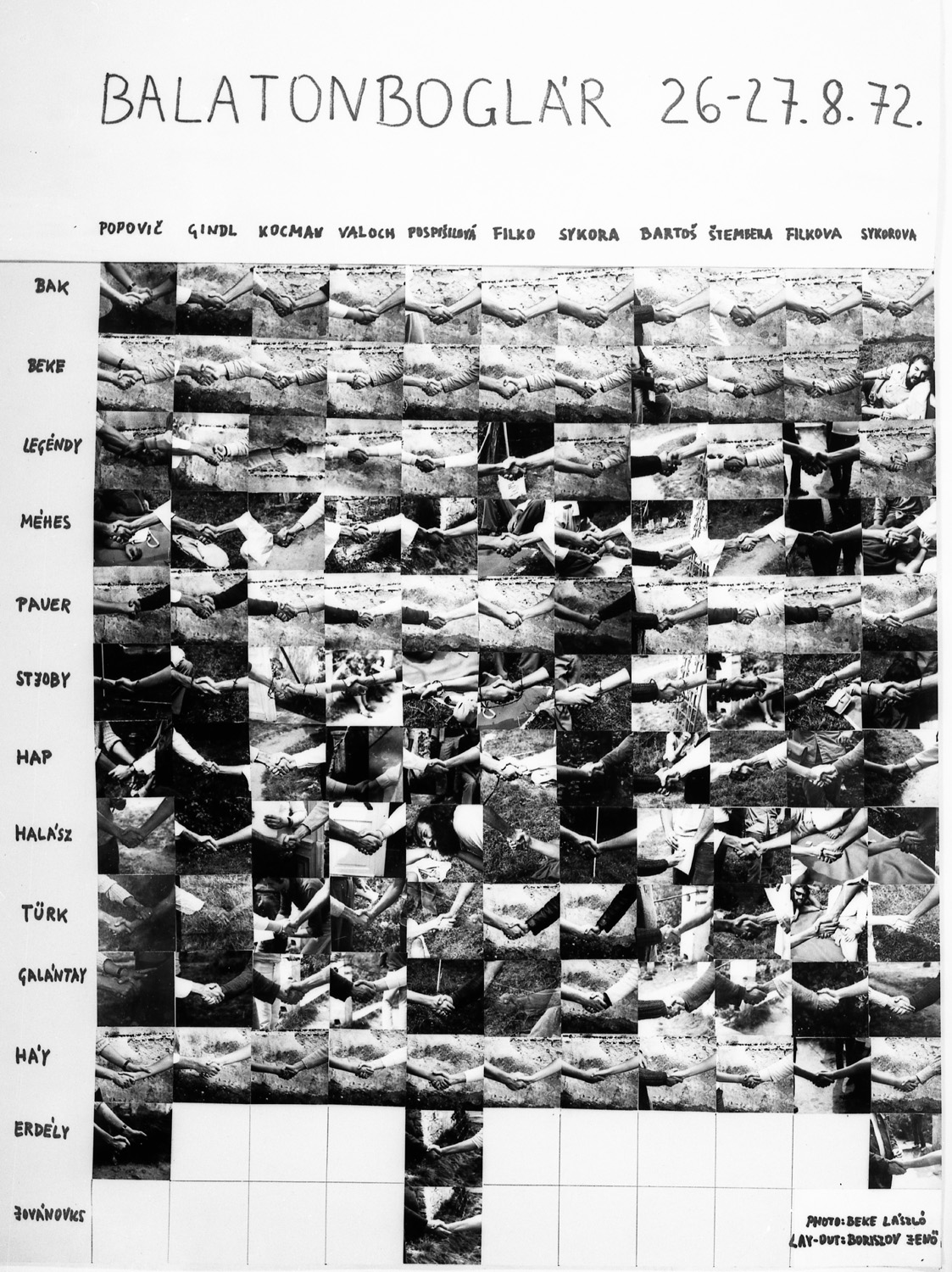

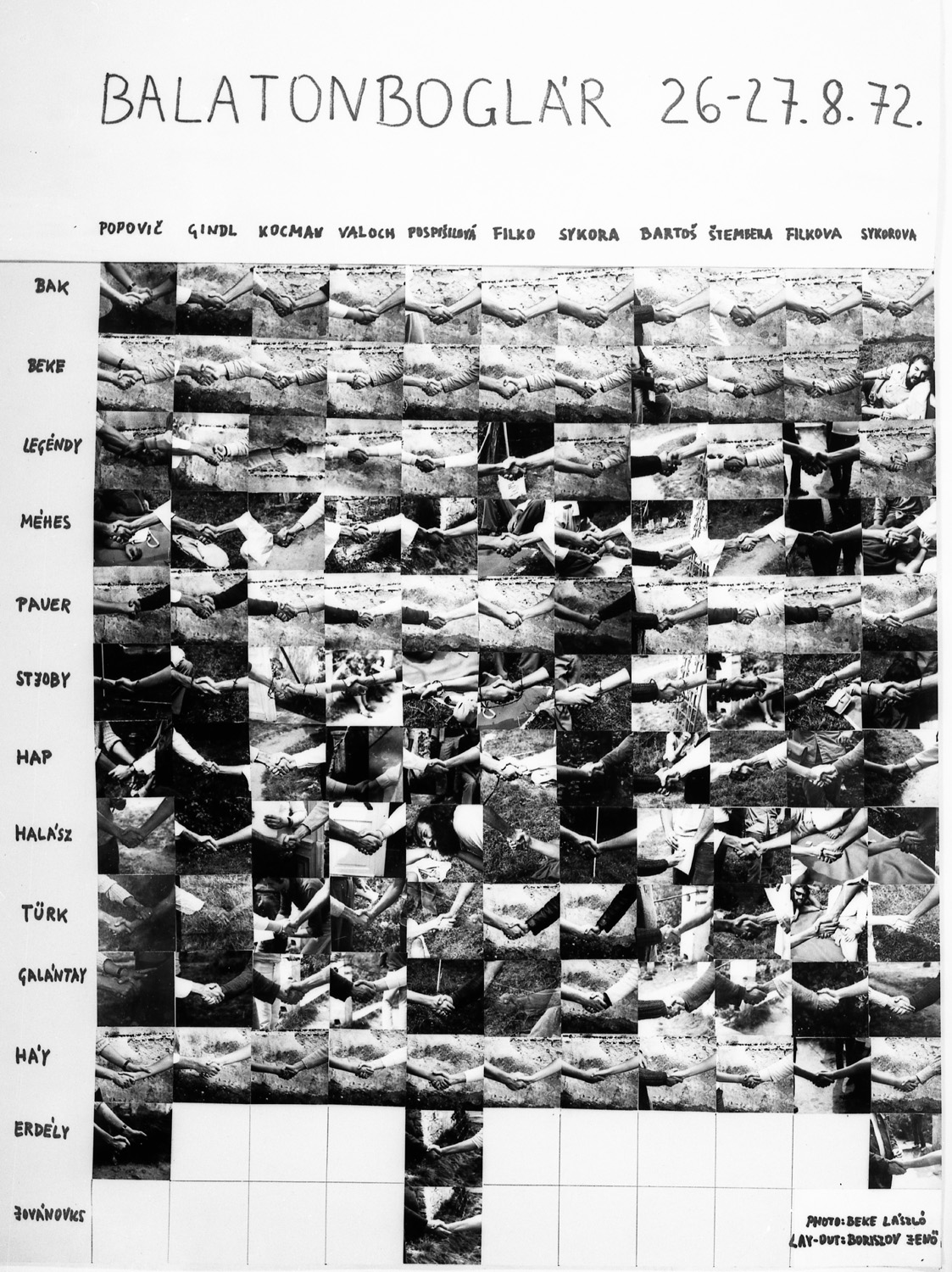

Action Tableau of shaking hands during the Meeting of Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian artists, August 26–27, 1972, organized by László Beke

As the organizer of the event Meeting of Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian artists, László Beke intended to reflect on the possibilities of cooperation between artists from the three (at that time two) countries in the past and present, while examining and reconsidering the problems around the case of 1968, when Hungarian troops invaded Czechoslovakia in alliance with the Soviet Union. In addition to the handshakes of artists from different countries, which resulted in the tableau work documenting the meeting, the event included a tug of war action, which recalled the memories of 1968 by tearing up a photo showing the united forces playing tug of war after marching in the former Czechoslovakia in 1968; and an exhibition including a list of words which are similar in all three languages (Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian). Participants: Imre Bak, Peter Bartos, László Beke, Miklós Erdély, Stano Filko, György Galántai, Péter Halász, Béla Hap, Ágnes Háy, Tamás Hencze, György Jovánovics, J. H. Kocman, Péter Legéndy, János Major, László Méhes, Gyula Pauer, Vladjimir Popovic, Petr Stembera, Rudolf Sikora, Tamás Szentjóby, Anna Szeredi, Endre Tót, Péter Türk, Jiri Valoch.

The Securitate’s informative surveillance of Lucian Pintilie also resulted in the recording of his private conversations. This was the case of his discussion with the actor Paul Sava on 15 November 1972 in one of the halls of the Lucia Sturdza Bulandra Theatre, where Pintilie worked at the time. During their dialogue Lucian Pintilie complains about the fact that the Romanian cultural authorities are making his life difficult as they are trying to prevent him from continuing his film projects in Yugoslavia on the grounds that “no one knows what I’m going to do there.” Without their approval, he could not get the service passport that would have allowed him to travel and work in neighbouring Yugoslavia. Asked by Paul Sava why he does not want to work in Romania, Pintilie replies that he wants to work at home and has already approached the authorities with a plan to stage Chekhov’s play The Seagull. However the censors are reluctant to agree to his project as they are afraid of a new scandal after the banning of his theatrical production of Gogol’s The Inspector General in 1971. Pintilie denies that he had any sort of hidden and subversive agenda in staging Gogol’s play and says that he chose this play because it represented his “moral and aesthetic creed.” He adds that he will use his personal contacts with some of the highest Party leaders in order to speed up the issuing of his passport and to get official endorsement for the staging of Chekhov’s play. At this point in the conversation, Paul Sava intervenes and asks him why he does not want to accept any kind of compromise with the political authorities, why he does not try to “understand some interests, some political points of view” given that no one can “survive outside politics, without the knowledge of it.” Pintilie’s reply contains the argument behind his refusal to compromise with the political authorities and his determination to oppose them in the cultural sphere. He mentions that the only politics he understands is “the art of the performance through which I serve the people.” Paul Sava goes on to ask if his artistic work can be called politics and if indeed it serves the interests of the people as he claims. Pintilie replies that he does not want to know anything about politics because he considers his artistic work to be separated from it. From his point of view, Nicolae Ceaușescu is “a political genius and he deals with politics” while he (Pintilie) has “a genius for the performance” and he deals with that. He also adds that he is sure that the Romanian communist leader does not even know about his work. Consequently, those who are to be blamed for banning his work are cultural activists seeking to please the leader in order to avoid losing their positions. The two interlocutors leave the theatre and before saying good-bye Sava wishes Pintilie would gain “a bit of wisdom” and reconsider his uncompromising position in cultural matters and in his relation with the authorities (ACNSAS, Informative Fond, File 52 vol. 1, ff. 107-110, 111 f-v).

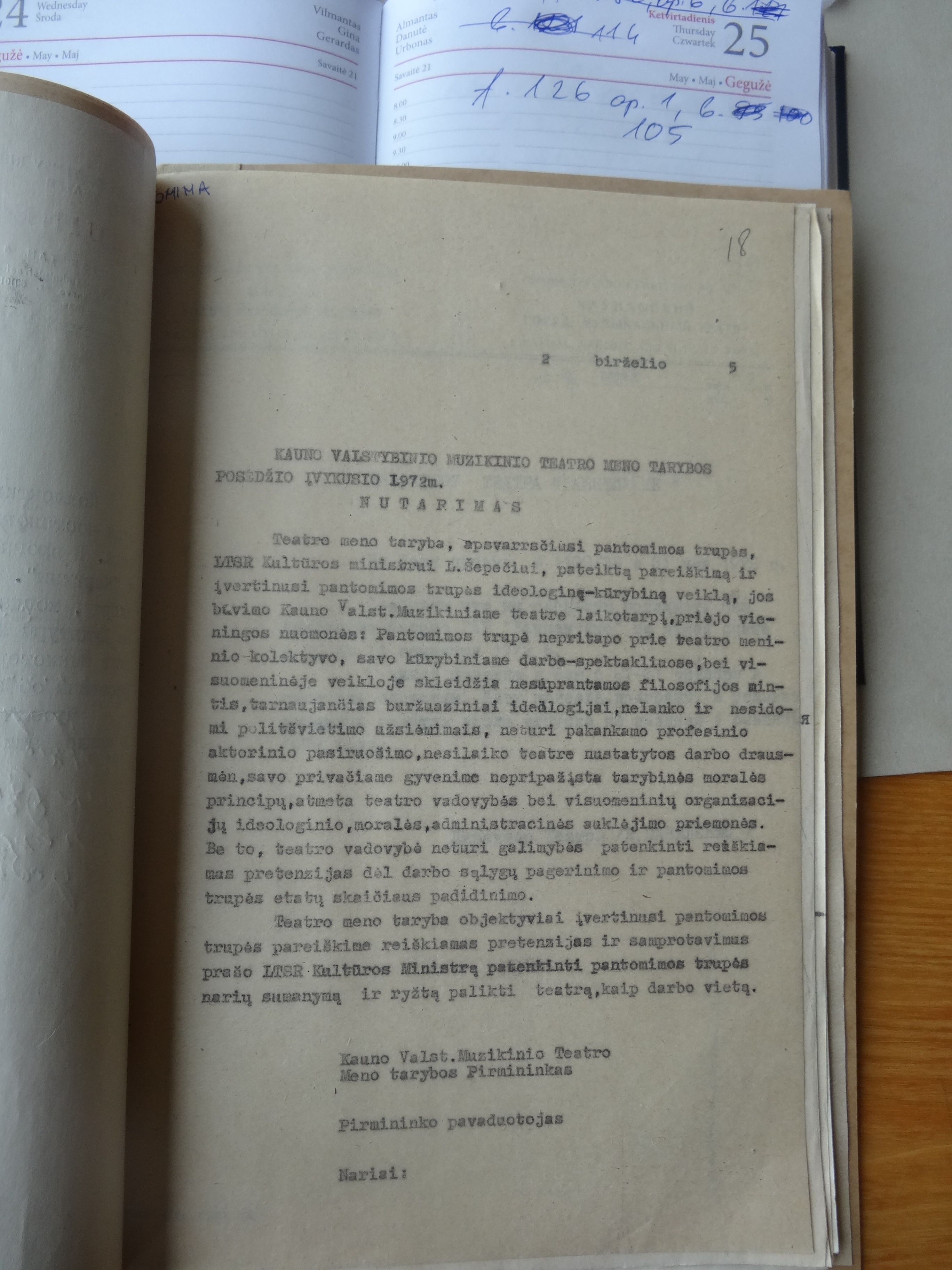

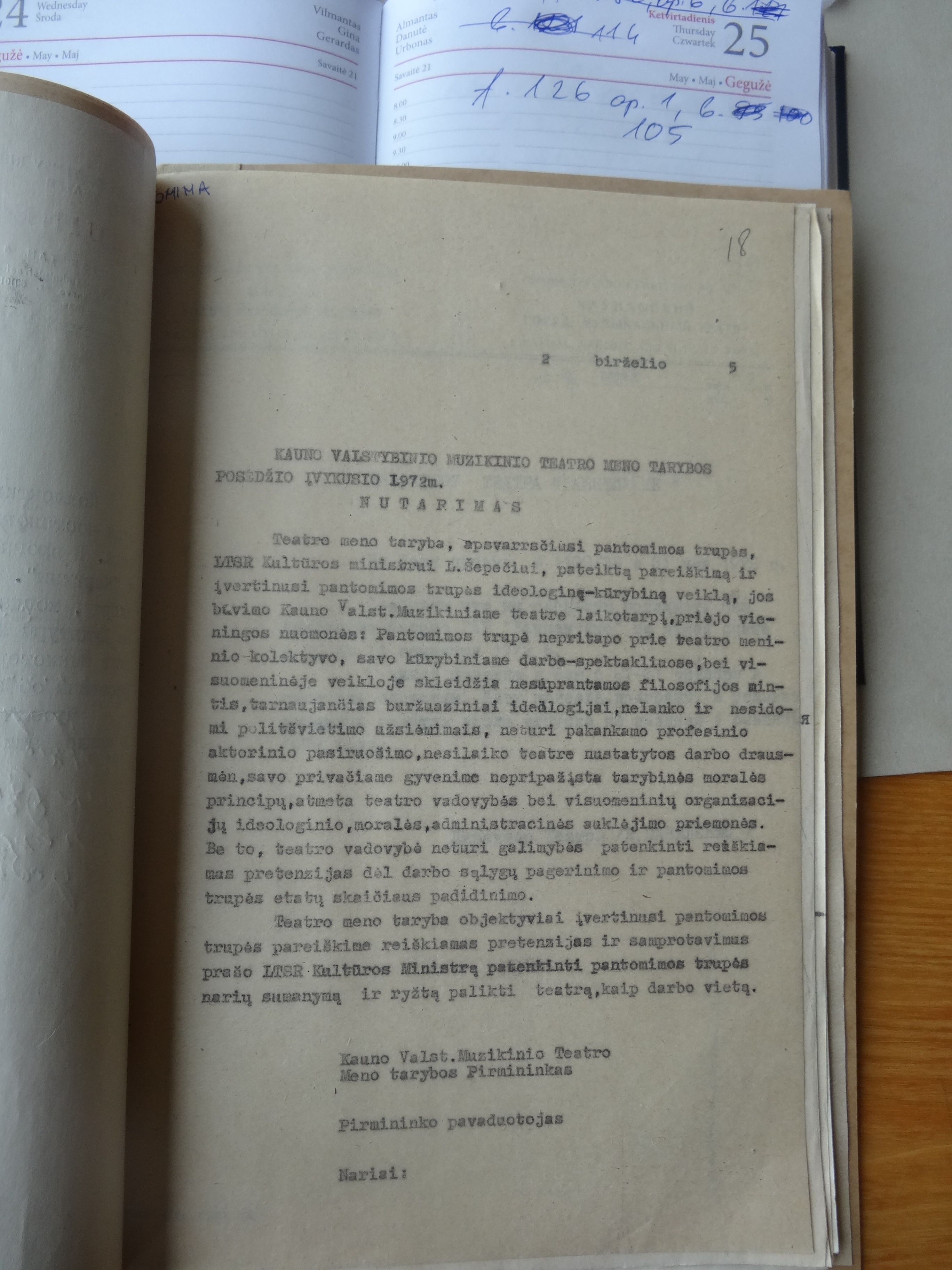

Modris Tenisons’ troupe worked in Kaunas Musical Theatre for only two years, between 1970 and 1972. During this short time, it received many invitations from cultural institutions in other Soviet republics. It is obvious from the documents in the collection that people’s opinions of the performances by the troupe were always high, and theatre managers received many letters about the good and interesting pieces that held the attention of audiences in various places. But the situation changed in the middle of 1972, after the self-immolation of Romas Kalanta and youth protests in Kaunas. In a resolution by the theatre's council, Tenisons and his troupe are accused of leading an un-Soviet way of life. The document makes a reference to the minister of culture Lionginas Šepetys, and says that the troupe had not found its place in the theatre company, and it disseminated strange ideas of bourgeois ideology. Thus, in a very short period of time, we can see a sharp change in opinions about the troupe expressed by theatre managers . The document is the last in the collection. After its dismissal from Kaunas Musical Theatre, no more documents were produced about Tenison's troupe.

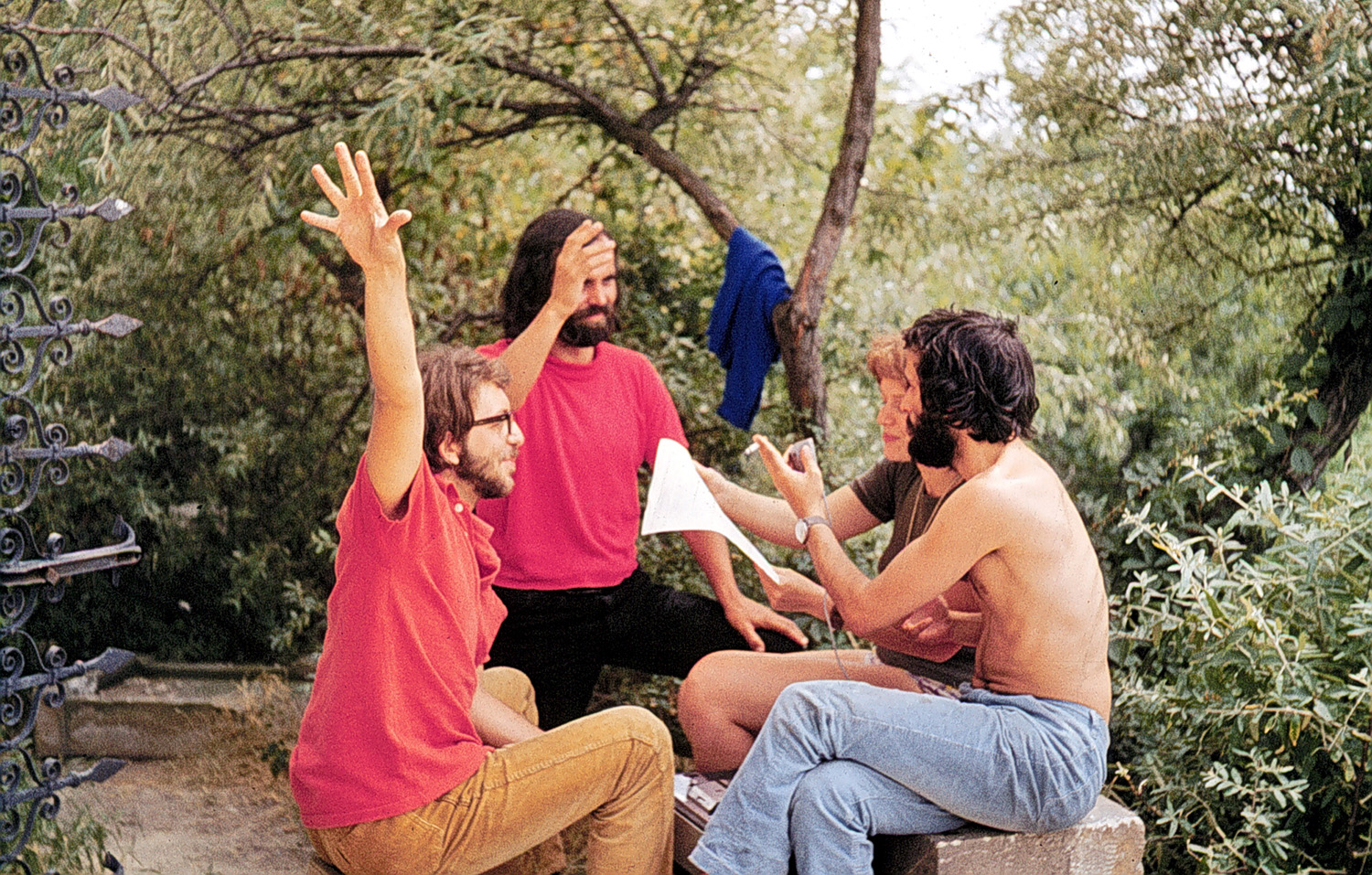

The members of Orfeo built a semi-detached house in Pilisborosjenő (15 kilometers from Budapest) between 1972 and 1974, when they wanted to improve the conditions under which they worked. The first house became the home of the actors of the Orfeo Studio. The Orfeo Group constructed a commune, while also holding theatrical and musical performances and creating artwork and photos. The creation of a collection on their work is the result of ordinary activities and an alternative, opposition-cultural lifestyle, which was, in turn, embodied in a house and objects. The inner spaces, the furniture in the house, and the uses of the furniture themselves are artistic works. The houses were spaces of the alternative theatre work and alternative lifestyle of Orfeo, which was condemned by the state authorities as violating the norms and morals of social coexistence.

Initially, the case against Alexandru Șoltoianu was part of the larger Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur affair. Șoltoianu was arrested on 13 January 1972, together with the other protagonists in the affair. However, on 29 April 1972 his case was separated from the others, as the Soviet authorities found no compelling evidence of a direct link between Șoltoianu’s activities and those of the National Patriotic Front. The accusations against Șoltoianu were based on the claim that “he systematically pursued certain organisational activities aimed at the creation of an underground nationalist organisation with the goal of fighting the social order currently in existence in the USSR and of undermining Soviet power.” An especially damning count of indictment referred to “spreading, among his immediate entourage, of calumnies and lies that discredited the Soviet state and social order,” which included “producing, depositing, and spreading certain documents of an inimical character [to Soviet power].” Interestingly, the specific accusation of advocating the “secession of the Moldavian SSR and a part of the Ukrainian SSR” from the Soviet Union and their unification with Romania does not figure prominently in this document. The special severity of Șoltoianu’s treatment and his harsh sentence owed much to his intention to create a widespread network of anti-Soviet resistance with clear ethno-national aims based on recruits from among the “student youth and intelligentsia of Moldavian nationality”. Although the materials of the inquiry clearly show that Șoltoianu’s circle of supporters never exceeded fifteen to twenty people at best, he was punished much more for his intentions and the audacity of his unfulfilled plans than for the actual outcome of his activity. Șoltoianu’s training in international relations and Oriental studies also led to his sensitivity to historical literature and to his extensive ruminations on the “colonial” nature of Russian–Moldavian relations in the USSR, which he systematically compared to the Russian imperial experience. During his trial, Șoltoianu attempted to convince the judges that he never intended his activity to be “anti-Soviet” or “anti-communist,” i.e., that he never targeted the system as a whole, but only the domination of ethnic Russians and the alleged discrimination against his fellow Moldavians. It seems, however, that the ethnic framework of his arguments convinced the authorities of the potential danger of his activities, given that local nationalism was perceived as the most serious challenge on the Soviet periphery. Certain of Șoltoianu’s papers seemed to incite to open revolt against the Soviet regime, while his open and radical criticism of Soviet foreign policy (especially of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia) completed the picture. Perhaps the most troubling element for the Soviet authorities was his project of creating a wide network of student associations in Moscow, Leningrad and a number of western Soviet cities (Kiev, Odessa, Kharkov, Lvov, Ismail, Chernivtsi / Cernăuți and Belgorod-Dnestrovskii). The “bourgeois nationalism” and “radical anti-Soviet leanings” that Șoltoianu displayed in the drafts of his projected political treatise, while serious enough, paled in comparison with his organisational ambitions (despite the extremely modest outcomes). The speech that he made in front of a group of Moldavian students visiting Moscow in January 1963 seemed to have confirmed the potential danger of his propaganda efforts. The accusatory act carefully summarised Șoltoianu’s “subversive” activities, tracing the emergence and growth of his informal network and apparently proving the grave nature of his ideological deviations through ample citations from his personal notebooks. The accusatory act was issued on 12 July 1972, five days before the delivery of the final sentence. This document is revealing not only concerning Șoltoianu’s own views, but also regarding the hierarchy of danger that the Soviet regime perceived and constructed on its “national” peripheries. Șoltoianu was accused (and correspondingly sentenced) according to art. 67, part I and art. 69 of the Penal Code of the MSSR: anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda / participation in an anti-Soviet organisation aiming at committing dangerous state crimes. His radical “anti-imperialist” and anti-Russian agenda, while in many respects similar to the aims and strategy of the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group, was unique in its sophistication and wide-ranging ambition.

The Lajos Vajda Studio was officially established in 1972 as a circle of visual artists interested in experimental practices. The origins of the cohesiveness of the group lie in the spirit of the place and the group’s attachment to Szentendre and its artistic traditions. At the end of the 1960s, a vital, informal counterculture-cell came into existence in Szentendre in part because of the activities of young artists who inspired one another. The archive documents the history and the activities of the studio and its members.

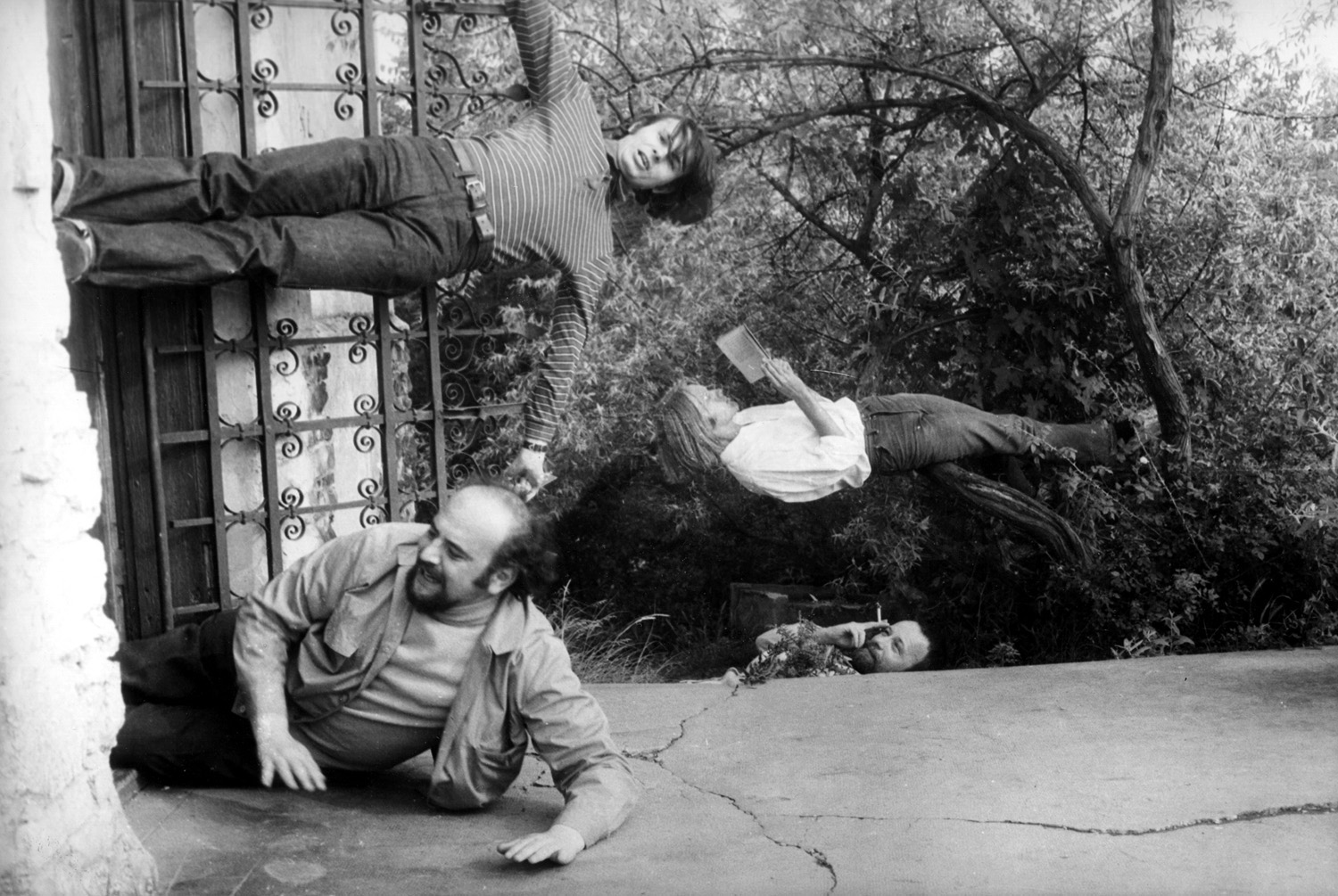

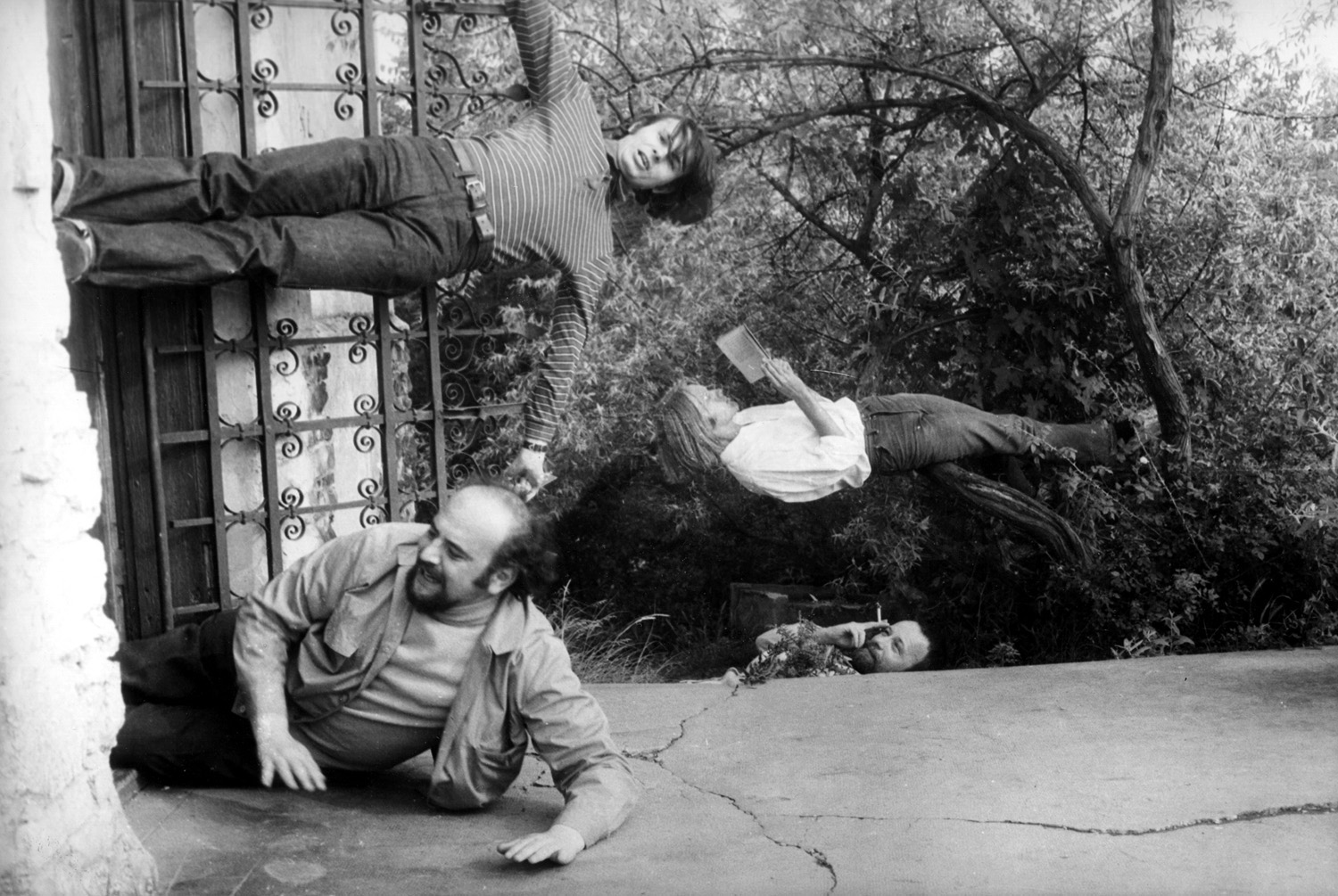

Photo series of spontaneous actions at the chapel: Once we went, May, 1972 (Photo: Dóra Maurer, participants: Miklós Erdély, György Jovánovics, Tamás Szentjóby, Tibor Gáyor)

“There was a grid put across the chapel door, originally from a fence, but applied horizontally and not vertically. Jován stood on it, and the others automatically began to find their places, too. Szentjóby lay down on a branch and stuffed his long hair into his shirt, so his hair was not floating like Jován’s in the photo. Erdély placed himself in the door, bent over, as if he had been glancing out from there, while Tibor lay on the ground, as if that had been another direction, too, and only the smoke of his cigarette revealed which direction was up. Erdély held up a poppy and said that if we photographed it, it might look as if it were the chapel bell. Then they were jumping down from a bench, Erdély, Tibor, and I think Jován, too, as if they were jumping on top of the Badacsony, i.e. as if they had been touching the mountain with the shape of their bodies.” (Dóra Maurer, 1998)

The first private dance house was on 6 May 1972, at Könyvklub at Liszt Ferenc Square in Budapest, where Ferenc Novák and his followers showed the simple form of széki dance (Szék, Sic is a Romanian village). The event was organized by dancers of the Bihari Dance Ensemble, Jolán Foltin, Lajos Lelkes, Antal Stoller. The dancers of the Bartók, the Vadrózsák, the Vasas Dance Ensembles also took part in it; the music was provided by Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, Péter Éri. The main supporter of the event was György Martin who helped to Béla Halmos and Ferenc Sebő too. Martin showed them the Collection of Szék by László Lajtha and other records what later became the music collection of dance house movement. Halmos and Sebő learnt by Sándor Tímár in 1971 how to play music for dancers.

"Music and dance like in Szék” was read on the invitation for the first private dance house in 1972. Opposite the entrance, there was a photo by Péter Korniss who also spent a lot of time in Szék and documented the traditional Transylvanian peasant culture. At the door, Lajos Lelkes and Antal Stoller welcomed the guest like in Szék. Originally the organizers wanted to organize the traditional dance house of Szék, but later there were ethnographical, sociological lectures at the dance houses.

During the year 1972, there were three more private dance houses at the Könyvklub.

The end of the 1972 Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, Mihály Sipos travelled to Szék because they wanted to learn about the dance house of Szék. Here Béla Halmos heard the band of István Ádám "Icsán” and started to learn folk songs by them. At Budapest when Béla Halmos organized the dance houses, the idol for him was the dance house of Szék where that was a natural event every time.

During the years the dance houses at Budapest became more and more popular where the youth had possibilities to learn and hear about that information and interest which were not allowed at school or universities. The HVDSZ, VDSZ, VASAS, ÉPÍTŐK were the main Ensembles at the dance houses. From 1973 the members of the Bartók Dance Ensembles taught folk dances at Fővárosi Művelődési Ház. New folk music bands were founded like the Muzsikás and the dance house movement became popular at all around Hungary.

Problemos (Problems) is a Lithuanian academic philosophical journal published by Vilnius University. The journal was reorganised during the 1960s and 1970s, when the community of Soviet Lithuanian philosophers made attempts to produce a serious academic journal, with critical articles, reviews and translations of Western authors. This initiative was seen very negatively by cultural administrators at that time. The minutes of a meeting on 27 November 1972 demonstrates the attempts of the government to direct Problemos the ‘right way’. Philosophers, the authors of papers in Problemos, were criticised at the meeting for their passive ideological stance, and their lack of publications on communist ideology. After the meeting, the control of Problemos became stronger, and the content of its volumes was thematically limited. According to the philosopher Algimantas Jankauskas, after strengthening the controls, a core group of Lithuanian philosophers, including Romualdas Ozolas, started to think of producing an underground samizdat philosophy journal. But they later decided to keep to legal cultural opposition. They initiated and established a series of books on the history of philosophy ‘Filosofijos istorijos chrestomatija’ (Chrestomatia of the History of Philosophy), which resulted in a number of volumes being published in 1974-1987.

A diagram The Stages of the Evolution of Art from 1972 is a graphic extension of the idea which Ludwiński presented two years earlier in the text Art in the Post-art Epoch. Ludwiński often used images and diagrams to better explain his thoughts on history and future of art. As a man of a spoken word, he rarely wrote and rather talked, discussed, and argued in an oral way, helping himself with some notes and sketches. On the other hand, Ludwiński’s drawings are a testimony for his visual imagination. In this case, the evolution of art is presented through overlapping of next rings, analogically to the rings visible in the tree’s section.

The Stages of the Evolution of Art in a suggestive way show the dependencies and development directions between the main genres in the modern art, as well as design its forthcoming tendencies, through the conceptual and impossible art (thus the streams developed at the turn of the 1960s and the 1970s, all to the phase 0, when art is supposed to disappear in the reality of science, technology, and social life, acting through empathy and over-intellectual understanding).

Diagram is a repository of Zacheta Lower Silesian Fine Arts Association in the Modern Museum Wroclaw and it is presented on the exhibition in two languages: the original (Polish) and in English translation.

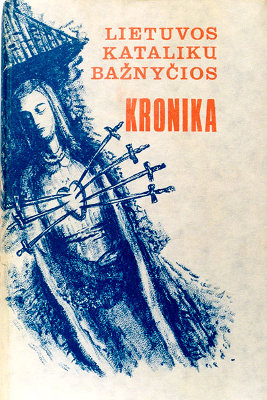

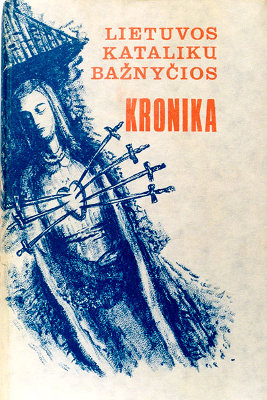

Catholic newspapers published underground were a well-organised and conceptually grounded form of samizdat. The collection consists of two underground publications: Lietuvos Katalikų Bažnyčios Kronika (The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania) and Rūpintojėlis (The Sorrowing Christ). The Chronicle was the longest-surviving samizdat publication in Soviet Lithuania, providing alternative news to that coming from Soviet institutions. It was initiated by a group of Catholic priests; while Rūpintojėlis was a publication from the Catholic community that became known for being intellectual and cultivated. The collection is made up of several sources: the Lithuanian Special Archives, which holds issues of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania and Rūpintojėlis confiscated during KGB searches; and the internet page http://www.lkbkronika.lt/ containing digitalised issues of the Chronicle, with comments and introductions.

The Ion Monoran Collection documents the intellectual profile of one of the leaders of the underground cultural movements in the Banat, who, thanks to his ability to catalyse the action of the crowd gathered in the streets of Timişoara on 16 December 1989, became one of the figures who incontestably made a mark on the Romanian Revolution.

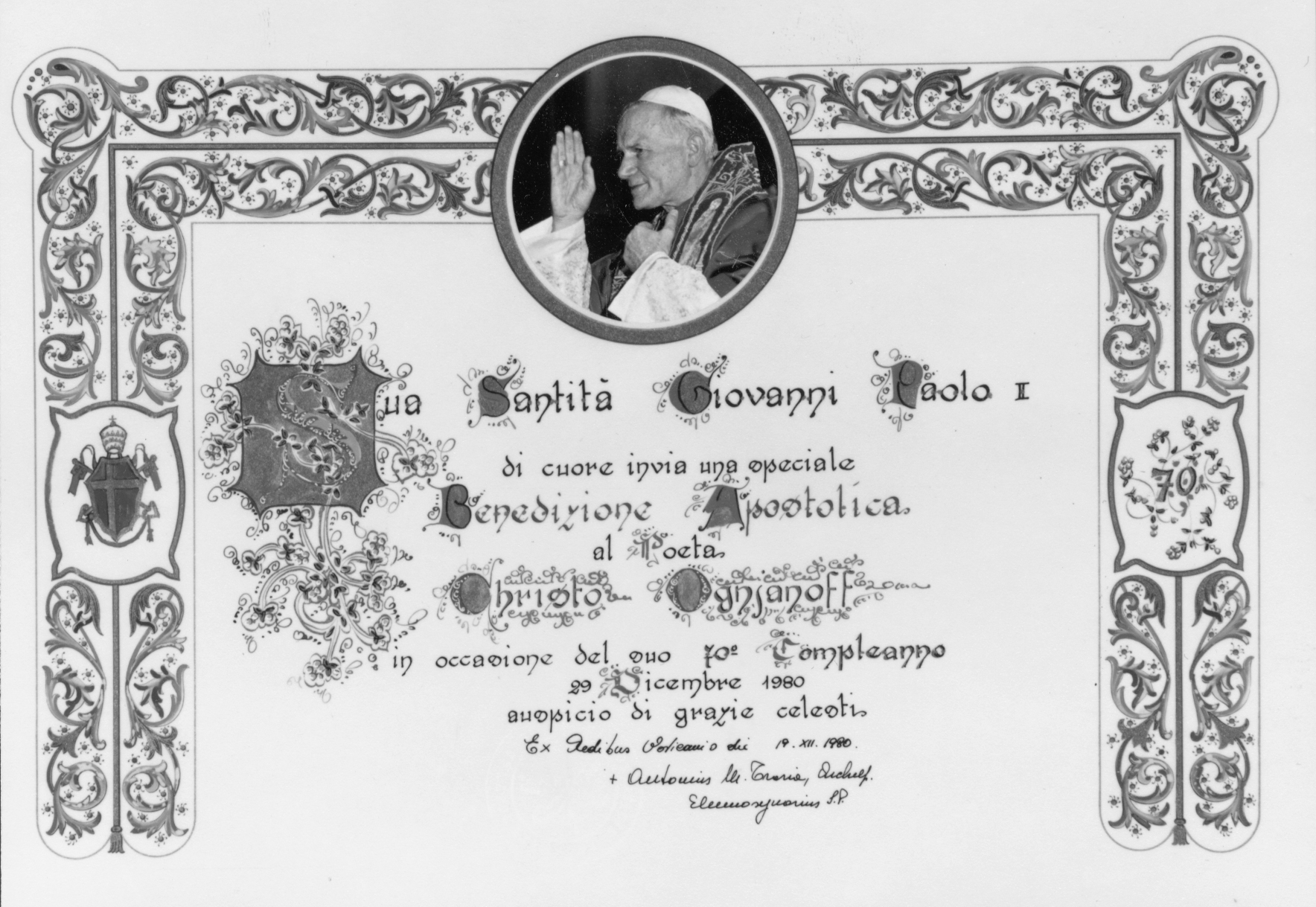

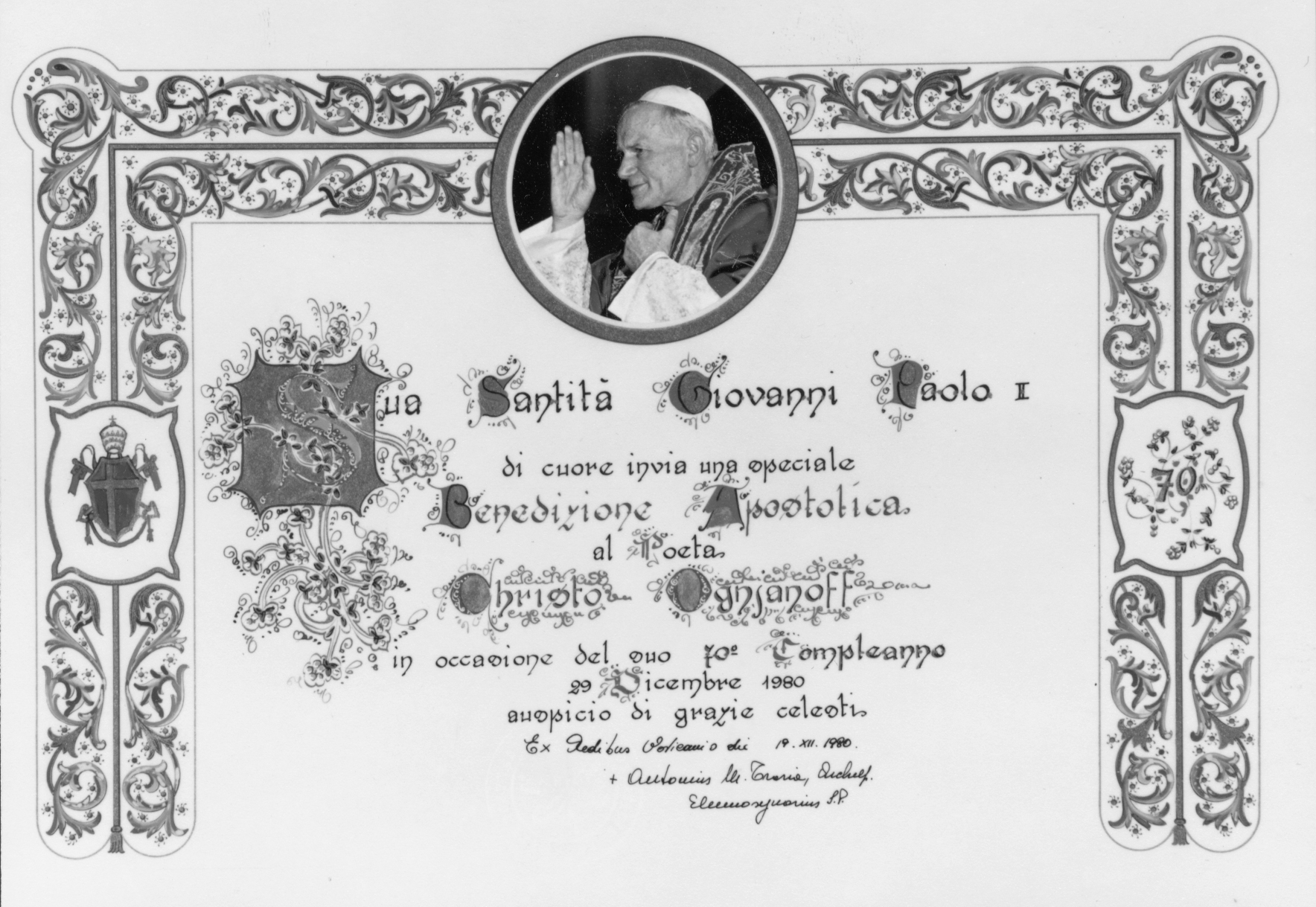

This picture shows the honorary diploma given to Hristo Ognyanov by Pope Saint John Paul II in 1981 on the occasion Ognyanov’s 70th birthday and in gratitude for his activities defending freedom of religion (Source: CSA, F. 1264). It is associated with the History of the Bulgarian Church, written by Hristo Ognyanov for broadcasts on Voice of America in the period 1953–1957 (CSA F. 1264, op. 1, a.e. 249–251). In this and in programs on Radio Free Europe, Ognyanov critically discussed communist propaganda against religion. Ognyanov’s program "Eleven Centuries of Christianity in Bulgaria" received an award by The Catholic Broadcasters Association of America. Under the name "Religion and Atheism in Bulgaria under Communism," he delivered a series of lectures in 1974. In Bulgaria, Ognyanov's activities, including those on religious subjects, were considered by the authorities as "subversive propaganda".

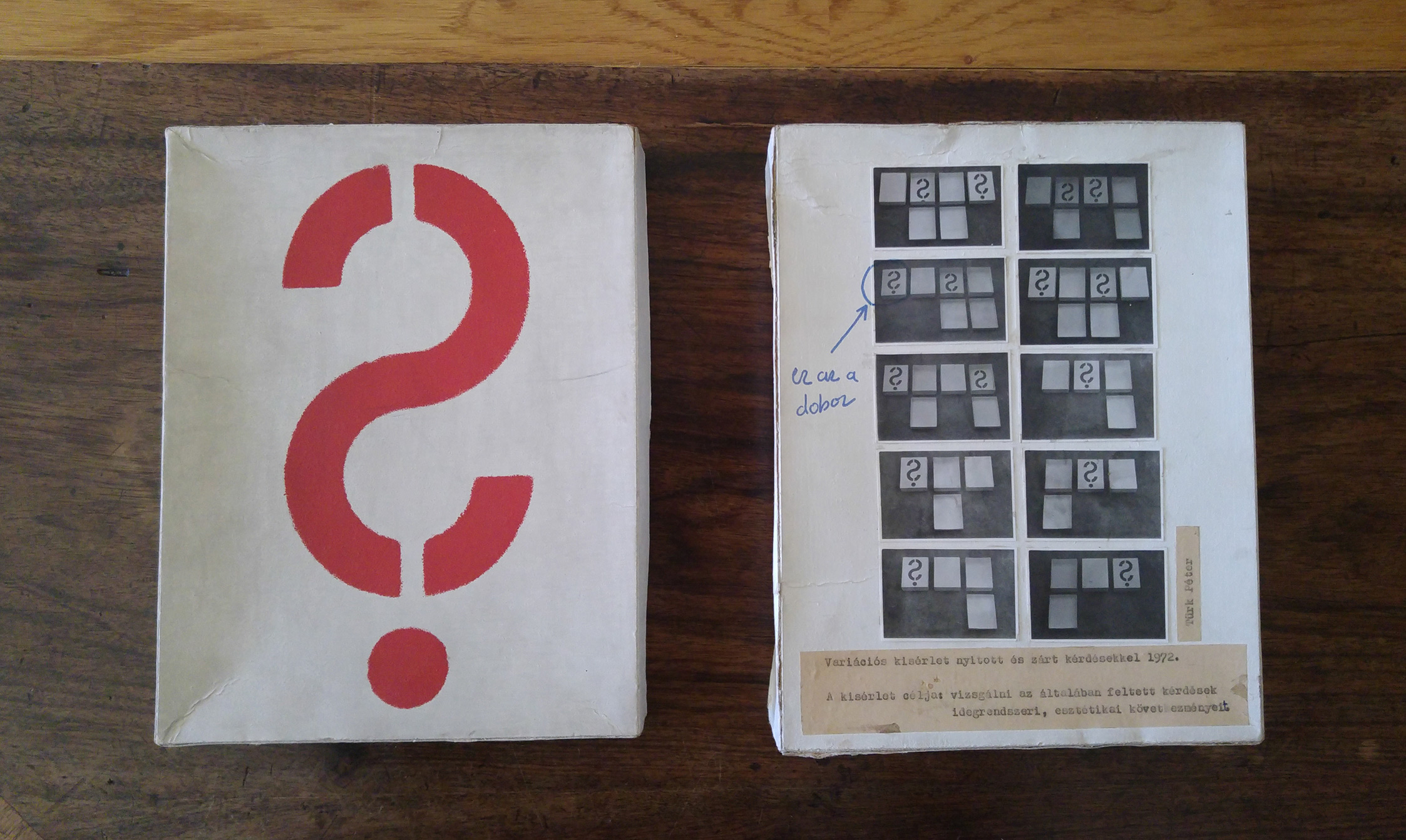

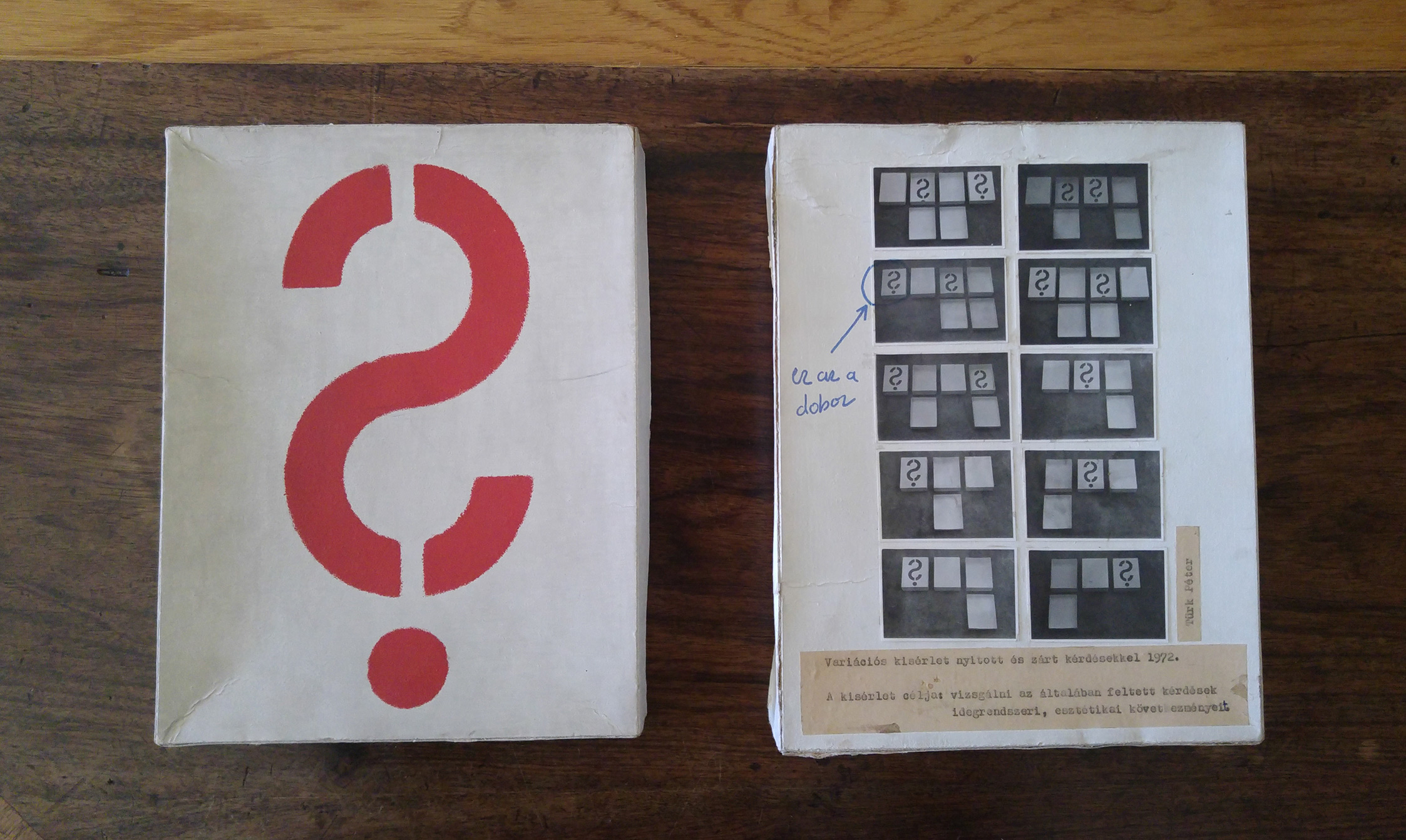

Cardboard box with a large, red, stenciled, symmetrical question mark on the outer top of one side and the inner bottom of the other side. On the outer back side, a series of ten photos arranged in a grid demonstrating the possible combinations of similar boxes in an open and closed state.

On the third photo the box on the left is marked with an arrow pointing to a handwritten caption reading “that is this box.” Under the photo appears the typewritten title of the work and the following sentence: “The aim of the experiment is to examine the sensory and esthetic effects of generally asked questions.” Beside the photos, above the label the typewritten name of the author is visible.

The handwritten commentary suggests that a box can be interpreted alone as well (this concrete example incorporates two differently positioned, painted question marks). Looking at the photos, one can conclude that more—though not necessarily identical—copies exist, which were given away (as this example got to the archive).

Politics did not constitute the primary context of Péter Türk’s oeuvre, but a subtle, sometimes ironic, criticism of the system can be observed in his works produced during the first half of the 1970s. During this period, he created geometric, but more and more conceptually oriented works, pursuing visual, semantic-logical investigations, which formed an implicit statement in the eyes of cultural politics at the time.

The question marks appearing in several series of his works are “visual conundrums,” which come into play via their color, position, material, constellation and, last but not least, their variations. Contemplating the object, the viewer becomes involved in a conceptual-associative process.

During our visit, we first wanted to define what is a generally asked question. According to professor Beke, “how are you?” or rather “what’s up?” is a good example. Hearing (or reading) a question of this type it is worth noting that this still concerns the sensory effect.

The object bears the marks of time and the consequences of its storage conditions. Dedicated wood crates or humidity control could not be provided for an item kept in a private archive, but it did not lose any of its authenticity and conceptual clarity even in its current condition.

This collection comprises documents (including trial records) relating to the group known as the “National Patriotic Front,” which are currently held in the National Archive of the Republic of Moldova (ANRM). These materials were transferred to the ANRM from the Archive of the Intelligence and Security Service of the Republic of Moldova (formerly the KGB Archive). This group operated in the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) in the late 1960s and the early 1970s as the only significant organisation in the MSSR with a clear-cut and coherent oppositional message.

The cantata Lenini sõnad (Lenin's Words) is a purely ironic work. It was formally dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the Soviet Union. Tormis used extracts of texts by Vladimir Lenin. The irony lies in the fact that these were extracts which demanded equality between nations and the right of self-determination. Since the author was Lenin himself, the authorities could not blame Tormis for anything. Whether the authorities understood the irony or not remains unknown. It has not been widely performed, and even not at all since the restoration of independence, but it is often quoted in the press as a curious case. This cantata is definitely not forgotten. For example, Lenini sõnad was one of the works mentioned in the obituaries of Tormis. The original manuscript and a later written copy are currently stored in the Estonian Theatre and Music Museum.

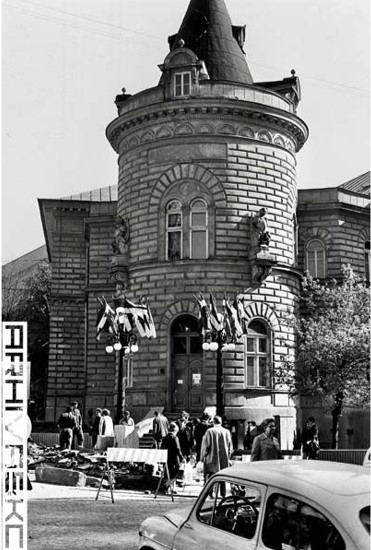

Meeting of Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian artists, August 26–27, 1972, organized by László Beke.

The event was organized by László Beke with the intention of reflecting on the possibilities of cooperation among Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian artists, especially after 1968, when Hungarian troops also took part in the invasion of Czechoslovakia. As part of the event, Beke organized a Handshaking-action among artists from the three countries, which resulted in a tableau work documenting the connections; In addition to the handshakes, the event included a Tug of War action, which recalled the memories of 1968 by tearing up a photo showing the united forces playing tug of war after marching into the former Czechoslovakia in 1968; and an exhibition, the Czech, Slovak and Hungarian Words, including a list of words which are closely similar in all three languages. Participants: Imre Bak, Peter Bartos, László Beke, Miklós Erdély, Stano Filko, György Galántai, Péter Halász, Béla Hap, Ágnes Háy, Tamás Hencze, György Jovánovics, J. H. Kocman, Péter Legéndy, János Major, László Méhes, Gyula Pauer, Vladjimir Popovic, Petr Stembera, Rudolf Sikora, Tamás Szentjóby, Anna Szeredi, Endre Tót, Péter Türk, Jiri Valoch.The Saulė Kisarauskienė collection contains documents relating to the life and work of the Lithuanian painter Saulė Kisarauskienė, her family, and her husband, the famous artist and nonconformist painter Vincas Kisarauskas. She is a well-known representative of the Lithuanian school of exlibris, and the collection contains originals of her works. During Soviet times, Saulė Kisarauskienė adhered to the principles of her creative vision and free thinking, and was marginalised for this in the 1960s by the Soviet regime.

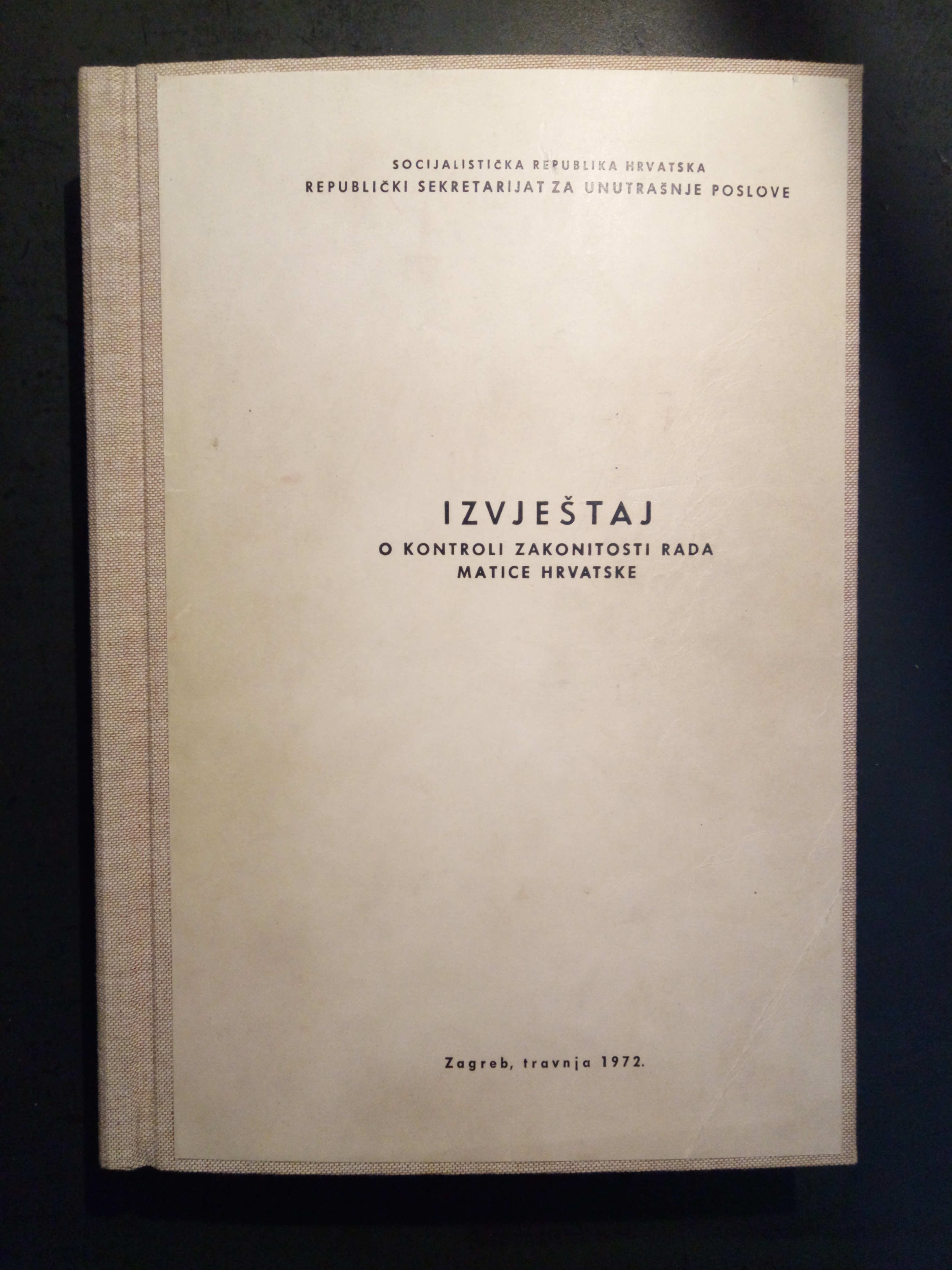

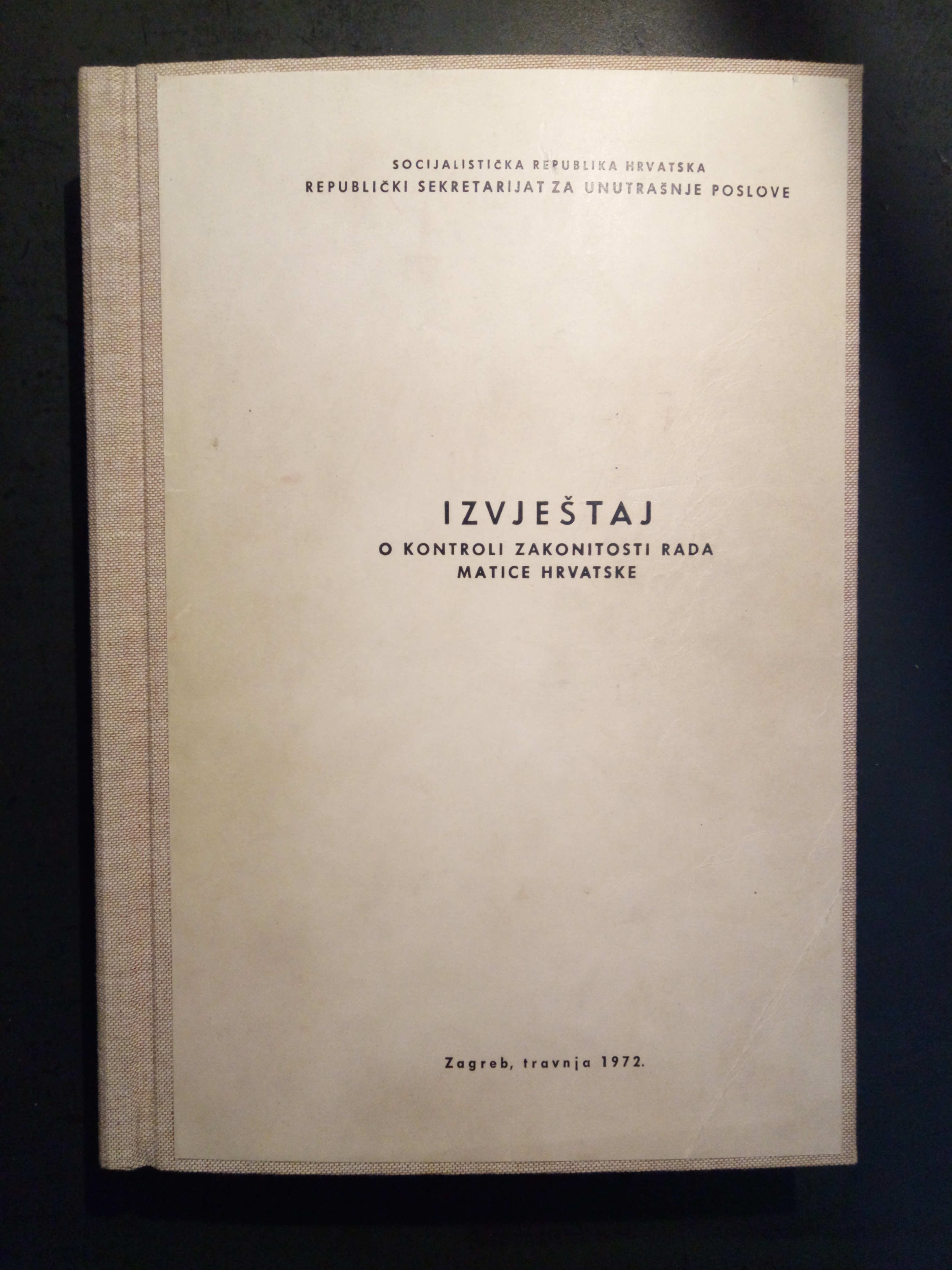

Matica hrvatska (MH) became the central Croatian cultural institution during the Croatian Spring, gathering the Croatian intelligentsia that was dissatisfied with the position of Croatia within the Yugoslav federation, especially with the attitude of the federal government toward Croatian national identity. For this reason, the communist government began to look at it as an institution that spread oppositional political ideas. By the fall of the Croatian Spring in 1972, Matica was practically abolished, and many of its prominent members came under attack by state repression under the accusations of "Croatian nationalism." The bearer of all actions against MH was the Republic Internal Affairs Secretariat (RSUP) of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, which also collected information about the work of Matica and its branches years before the quashing of the Croatian Spring. Following the political decision in Karađorđevo in December 1971, the RSUP was tasked with filing a report on the work of MH that was supposed to serve as a basis for future indictments and the court prosecution of Matica hrvatska’s members.

The RSUP inspectors compiled a report on oversight of the legality of the work of the Matica hrvatska on five hundred typed pages. The first 150 pages refer to the history of Matica and the work of its centre in Zagreb, while the rest of the report is dedicated to its branches in numerous cities. The history, structure and the activities of the institution were given, as well as data on the most prominent individuals and their activities. A special section is devoted to the links of Matica with Croatian émigrés, which the communist regime usually characterised as "hostile political emigration." The report ends with a brief conclusion (on one page) that Matica "has grown into an association for achieving counter-revolutionary goals" (Hekman 2002, 484). Based on this report, indictments were written, and trials against Croatian intellectuals were conducted.

The Matica hrvatska Collection at the Croatian State Archives maintains the original copy of the Report on oversight of the legality of the work of Matica hrvatska, based on which Matica published a reprint (Hekman 2002) with an accompanying foreword by Josip Bratulić. One copy of the 1972 Report is also stored at the National and University Library in Zagreb.

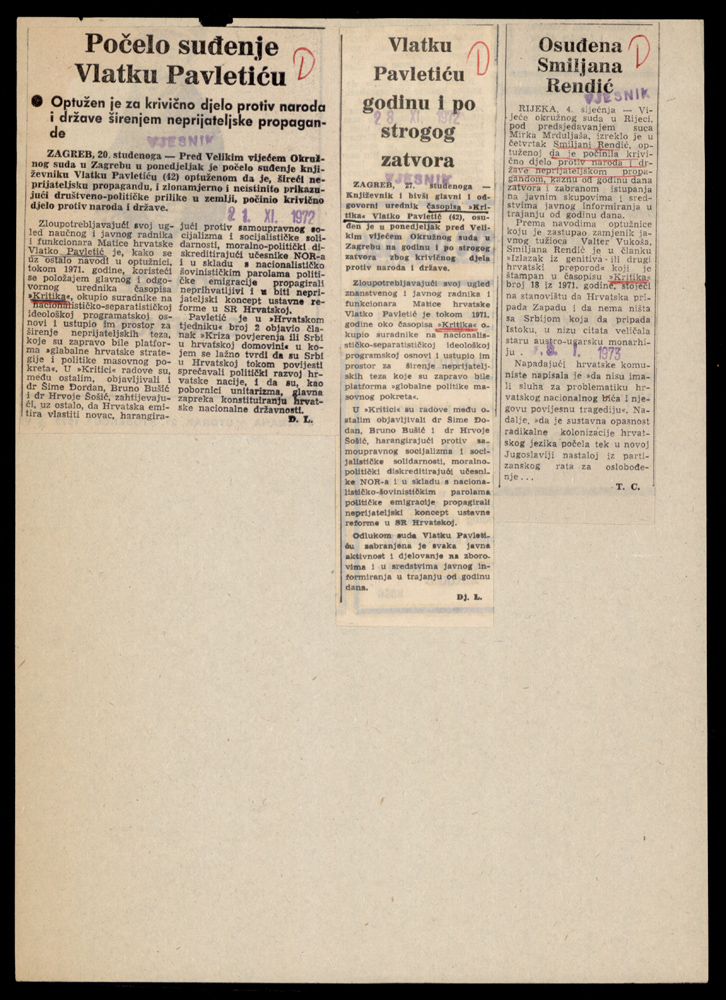

A newspaper reports on court trials for the offences against the people and the State by enemy propaganda, Vjesnik, 1972-1973. Press clipping

A newspaper reports on court trials for the offences against the people and the State by enemy propaganda, Vjesnik, 1972-1973. Press clipping

The card contains three cut and glued press clippings containing reports on trials for “offences against the people and the State by enemy propaganda.” As a criminal act aimed against the people and the State, enemy propaganda was defined in the 1951 Criminal Code as propaganda by illustration, writing, or public speech at rallies or otherwise, aimed against the state structure and social system, and against political, economic, military or other important institutions of the people’s government. Strict imprisonment was stipulated as punishment for the perpetration of such a crime.

Two press clippings refer to trials against Vlatko Pavletić (Zagreb, 2 December 1930 – Zagreb, 19 September 2007), the then editor-in-chief of the magazine Kritika, a publication of the literary organization Matica hrvatska and the Croatian Association of Writers. The third clipping refers to a trial against journalist Smiljana Rendić (Split, 1926 – Trsat, 1994), because of her article “Izlazak iz genitiva ili drugi hrvatski preporod” [‘Exit from the genitive or the second Croatian revival’], published in 1971 in the issue no. 18 of the same magazine, which was therefore banned. Together with a group of officials of Matica hrvatska, Pavletić was arrested in 1972 and then sentenced to a year and a half of strict imprisonment as a Croatian nationalist on charges of “attempting to overthrow and alter the state structure.” Rendić was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment and was banned from public activity for one year after her release. They demonstrate a number of cases of prosecution against members of the Croatian Spring that followed the suppression of that reform movement in Croatia at the end of 1971. A significant part of this prosecution encompassed cultural institutions and humanist intellectuals. The work of Matica hrvatska and its magazine Kritika were banned by the communist authorities. The collection includes a number of press clippings about these events, grouped in several topics in the categories for Culture (filing folders KUL 320 and KUL 491) and Domestic affairs (filing folder UP 27 and UP 28), and in the dossiers Public Persons category. The documents are available for research and copying.