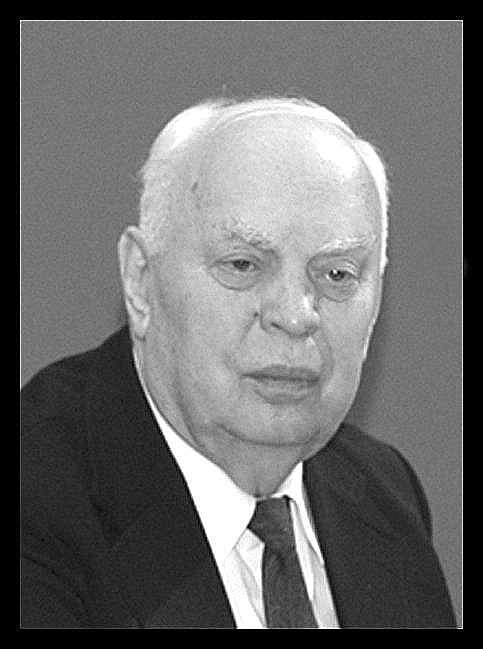

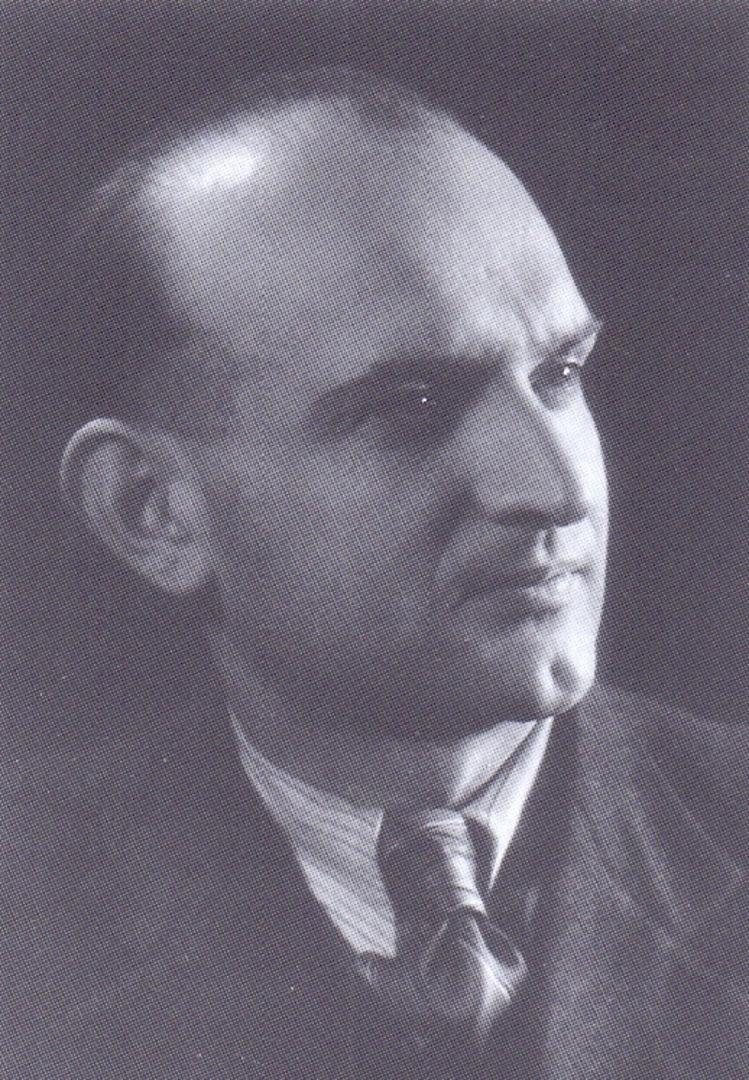

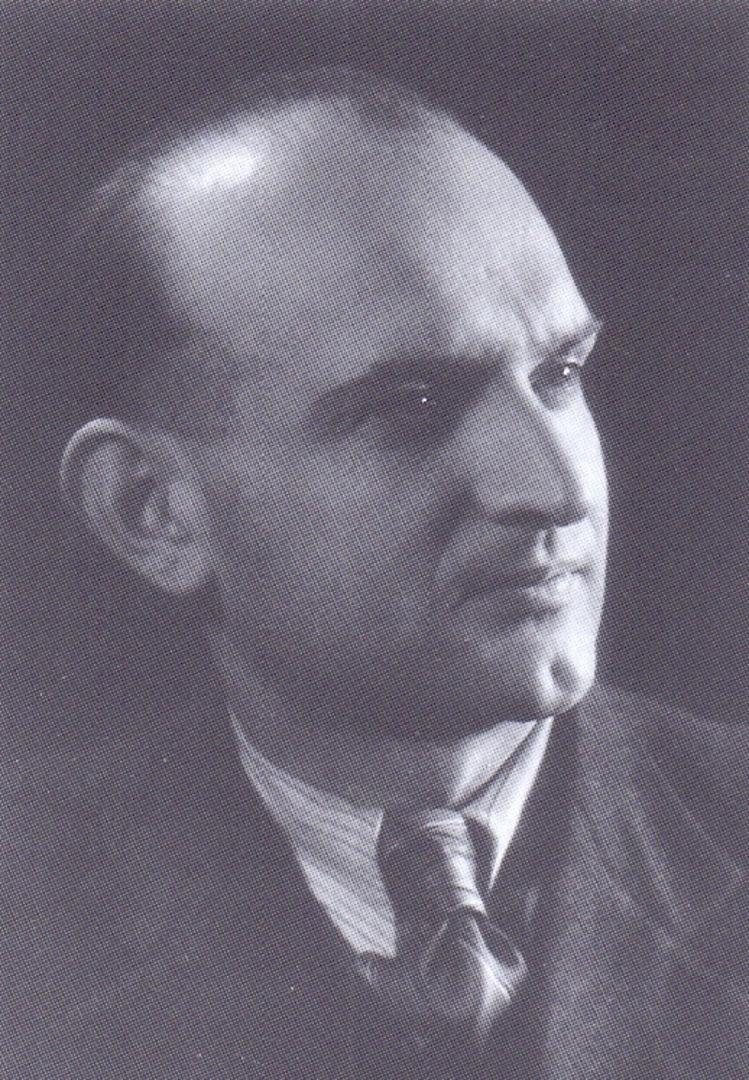

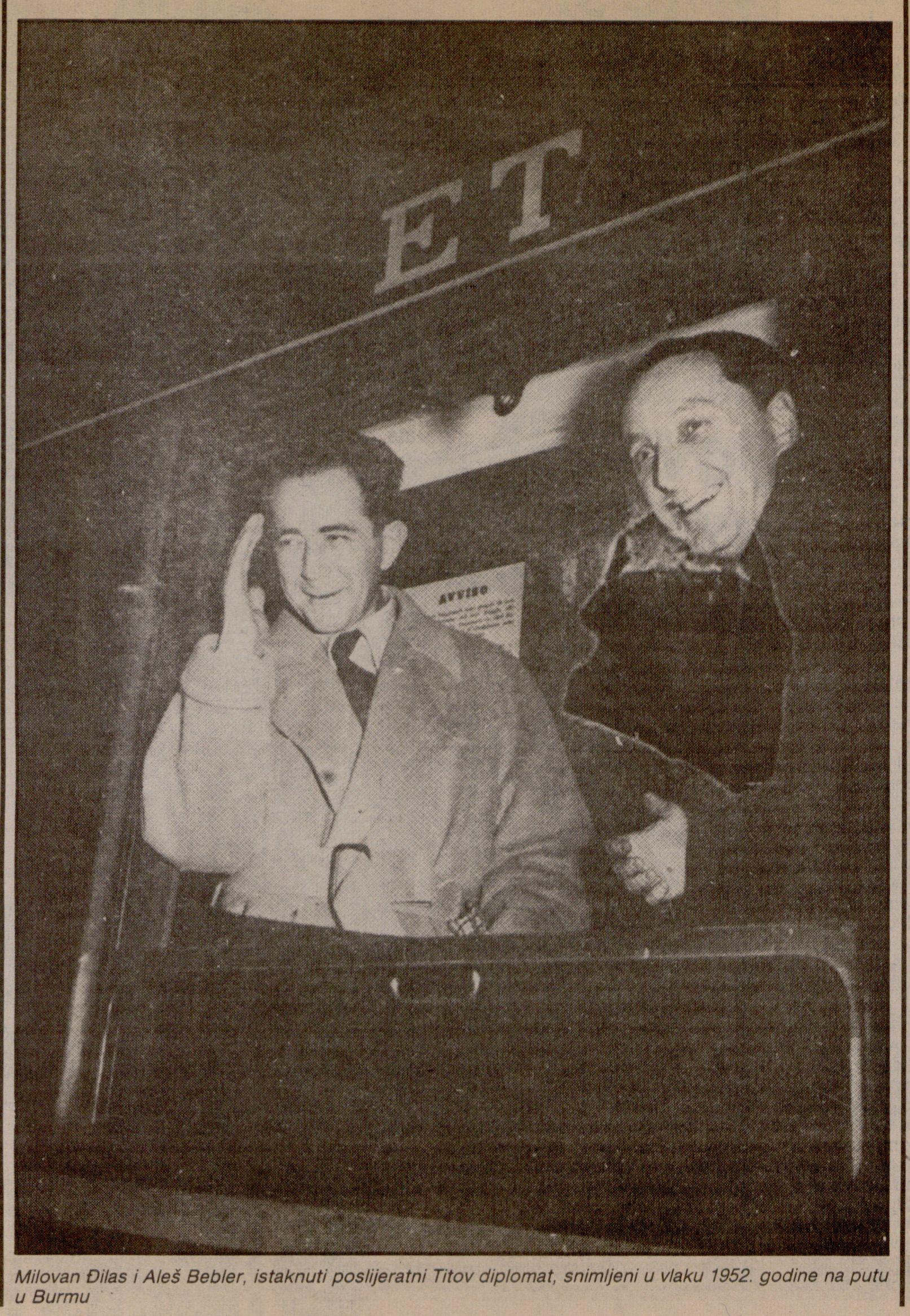

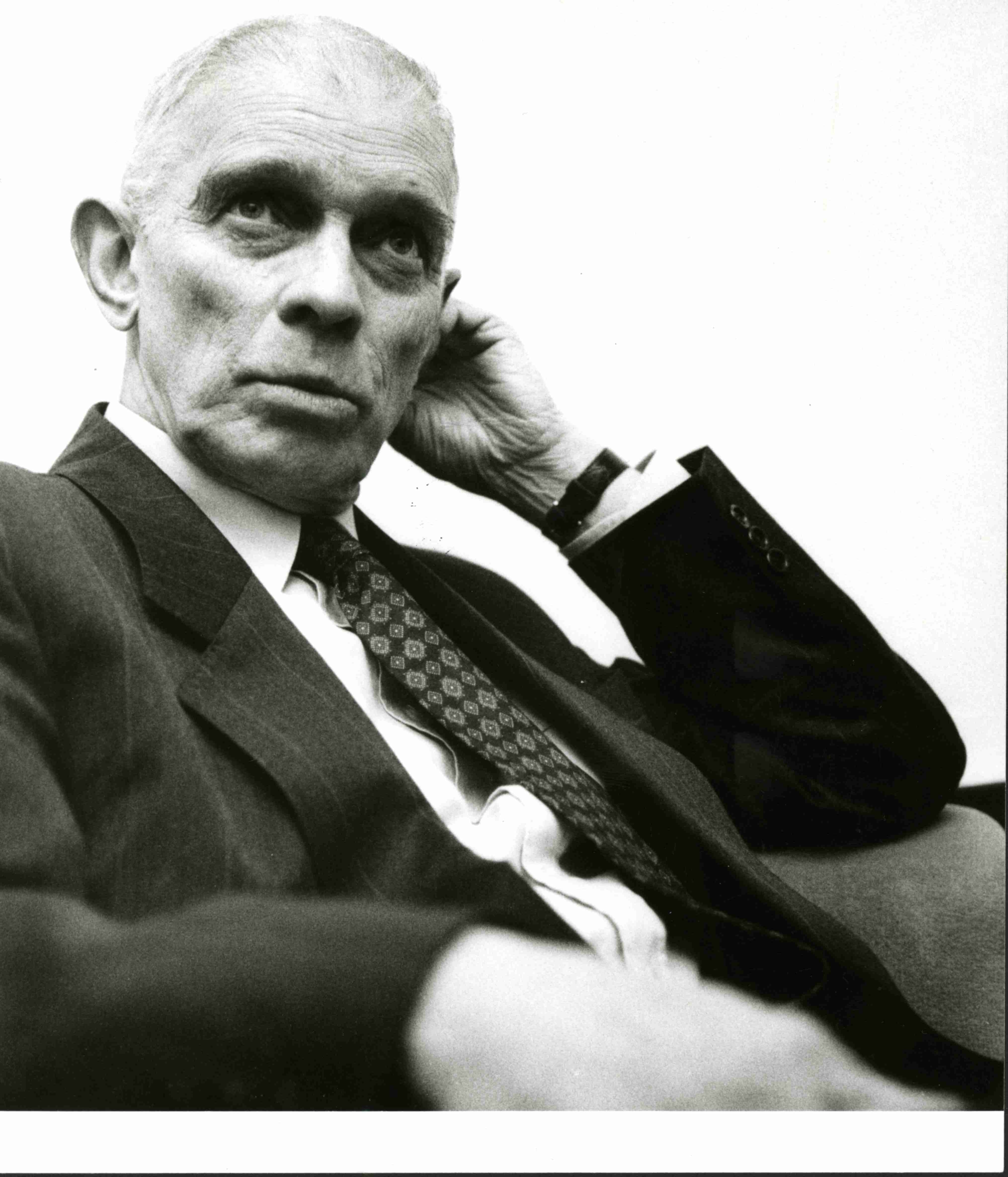

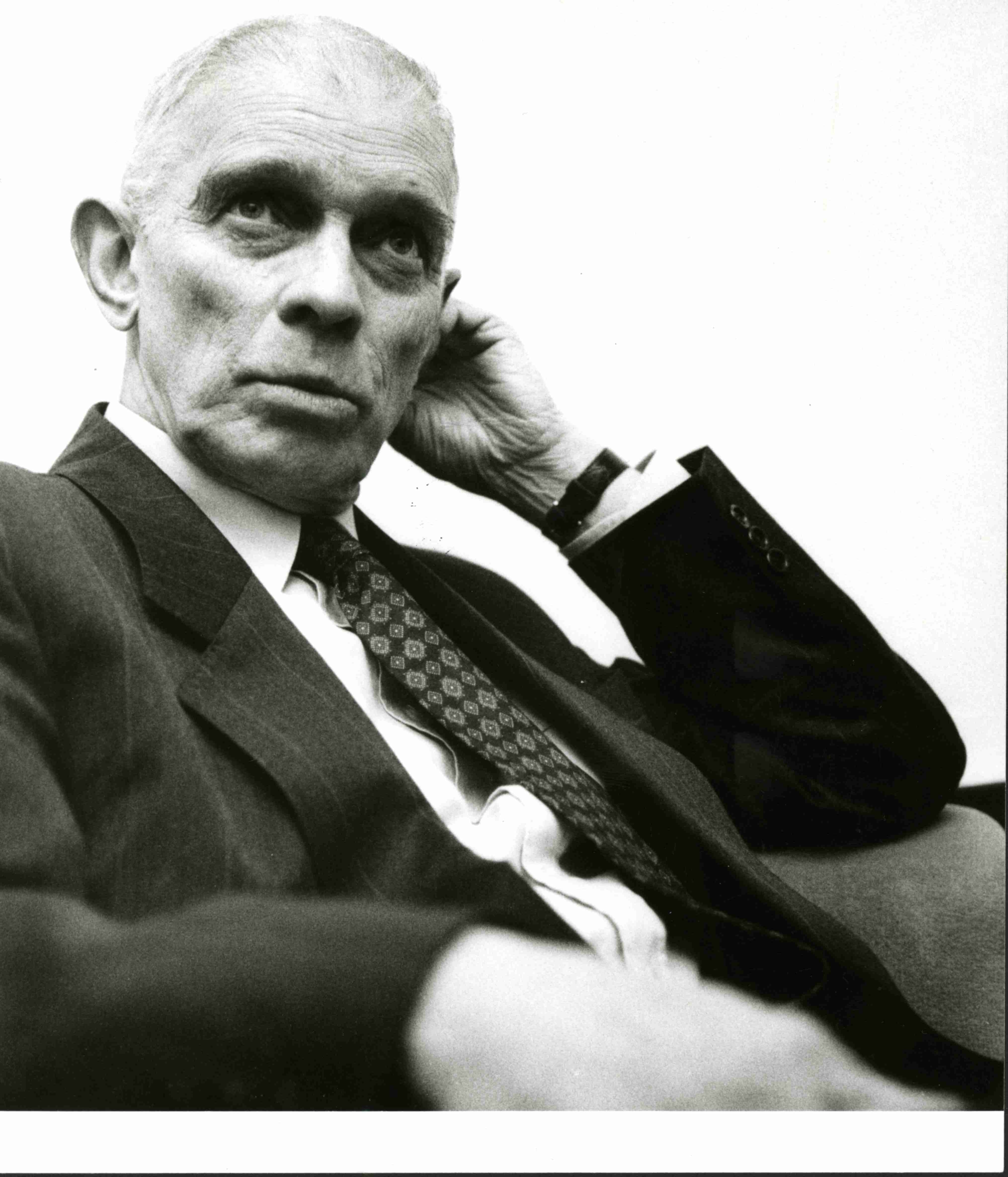

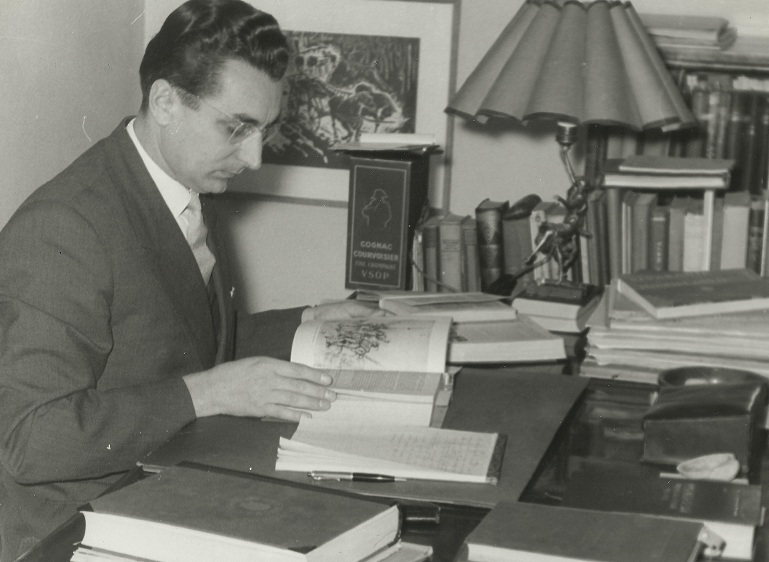

The Milovan Djilas collection is deposited at the Hoover Institute Library & Archives, located at Stanford University in the United States. It offers an important insight into the life and work of the first and most prominent dissident in Yugoslavia, who was also one of the most notable dissidents anywhere in communist Europe. Djilas had been the main ideologue of the Yugoslav Communist Party and one of the Tito's closest associates when he confronted the Party and Tito in the mid-1950s.

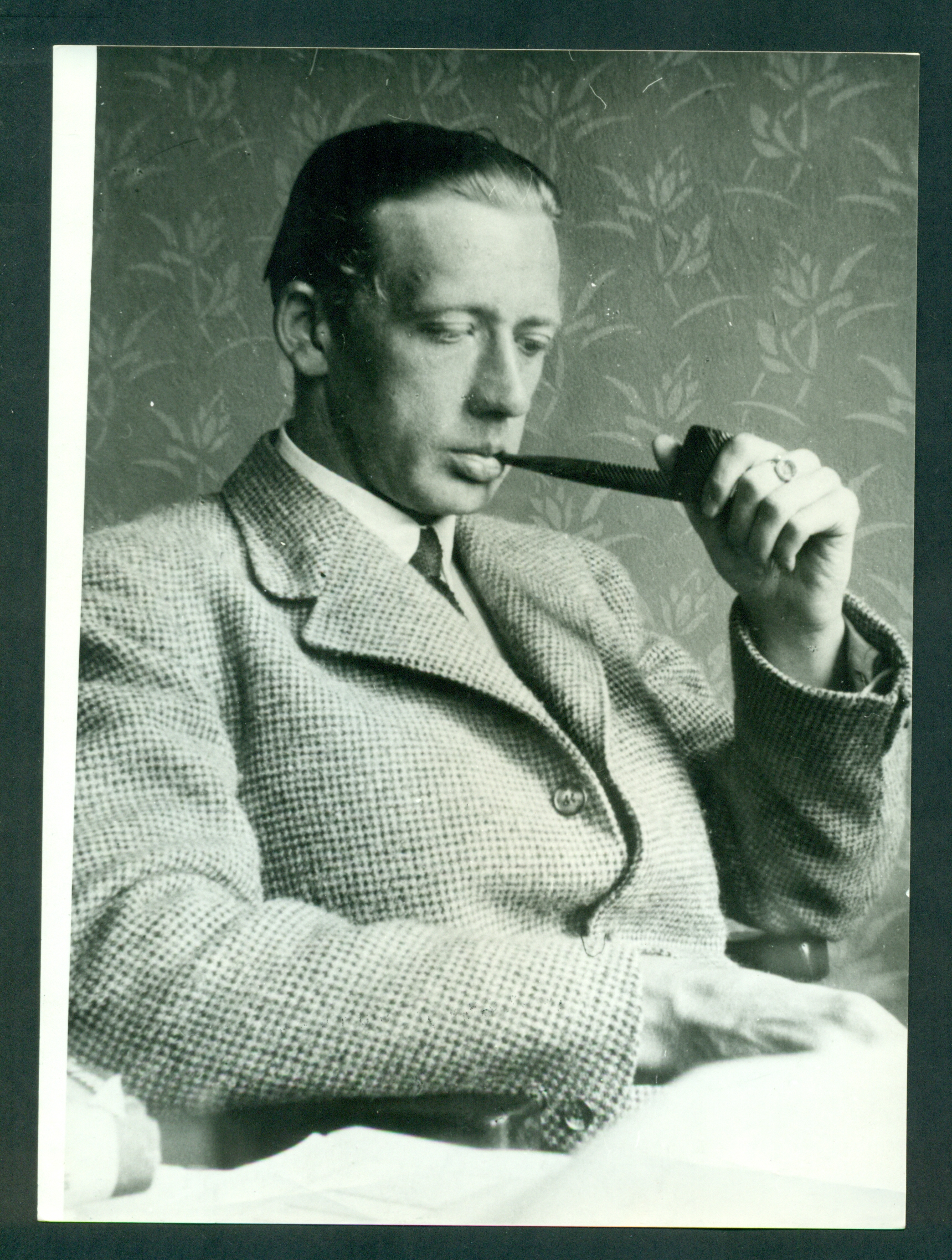

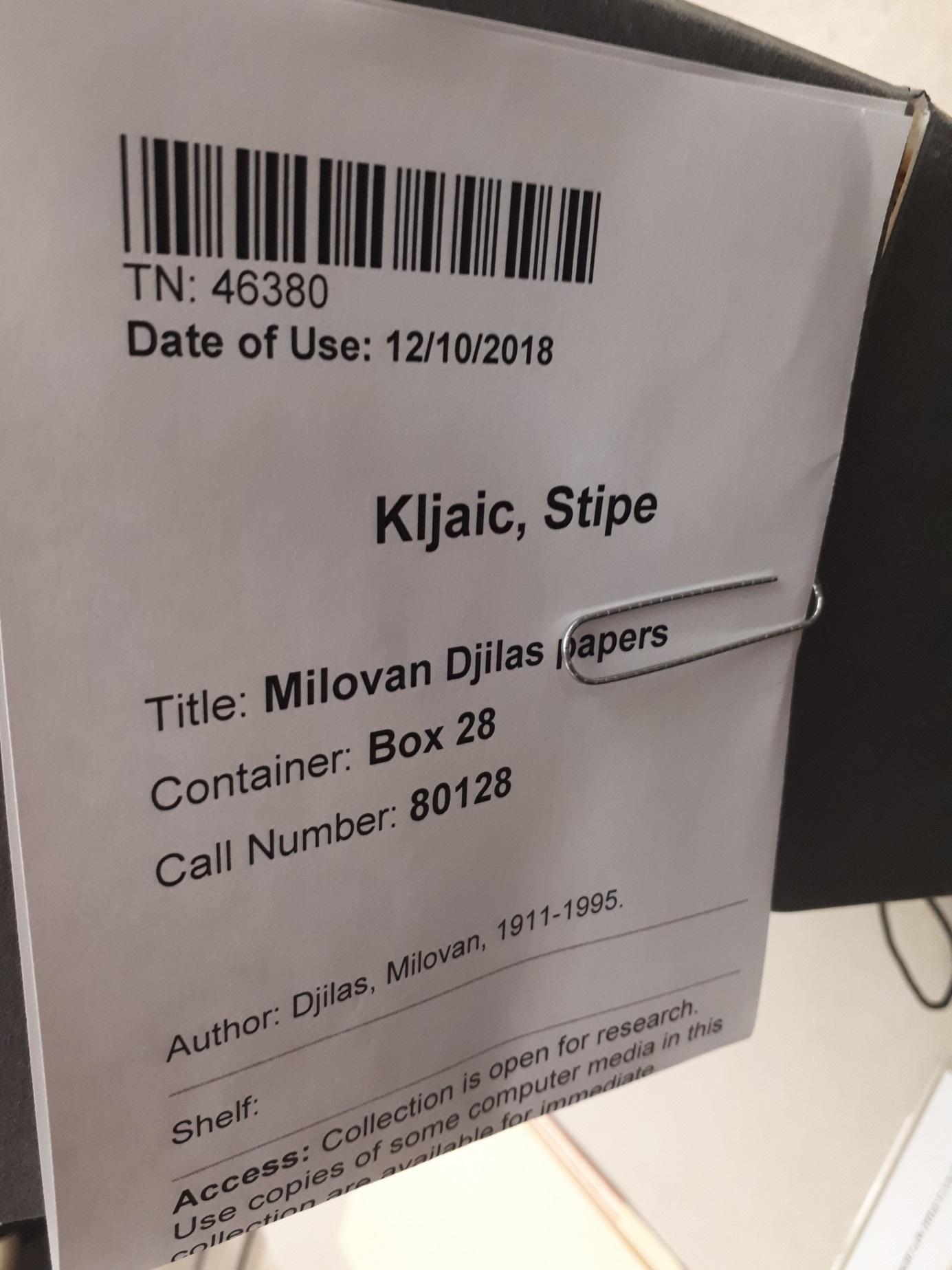

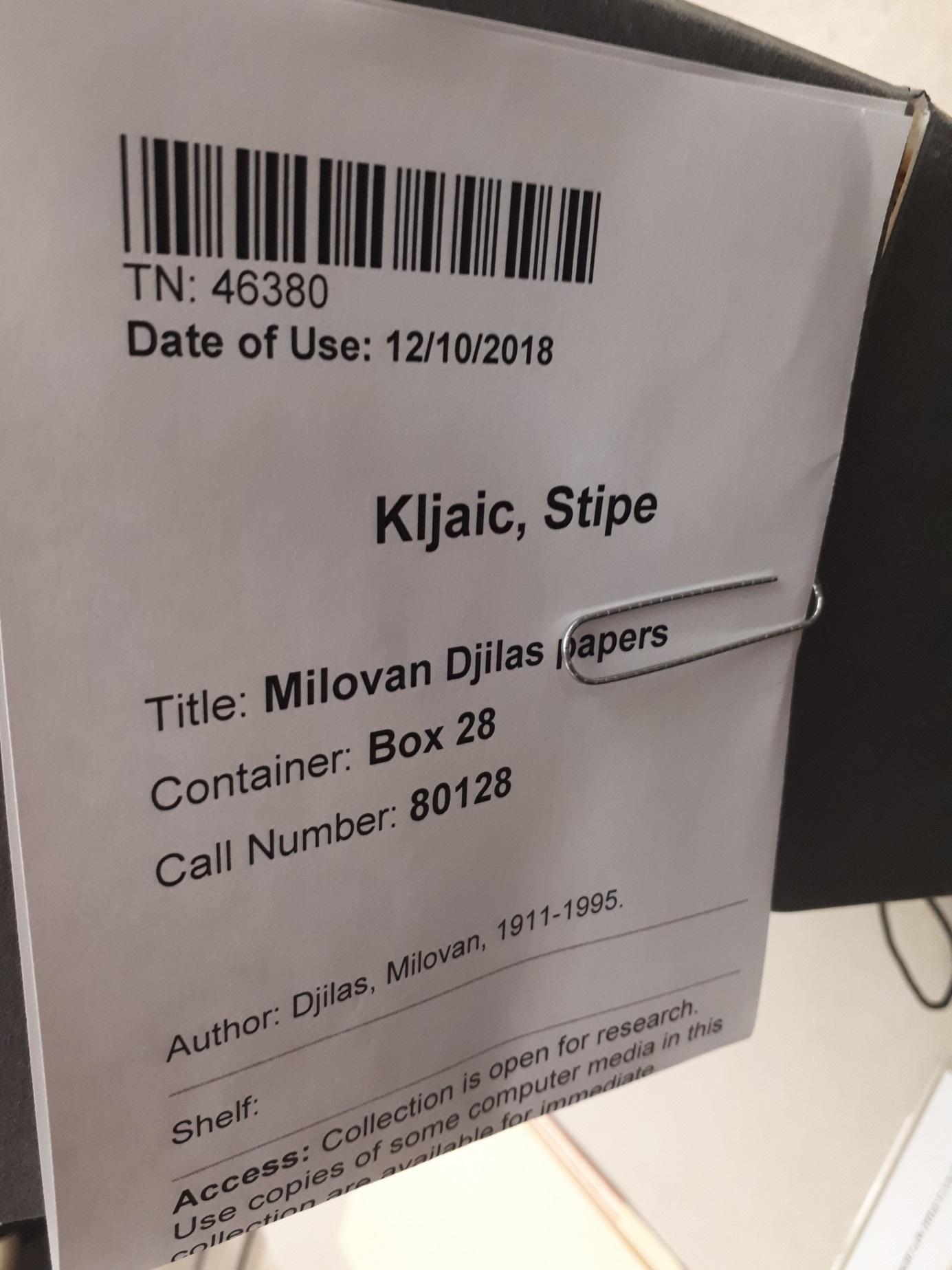

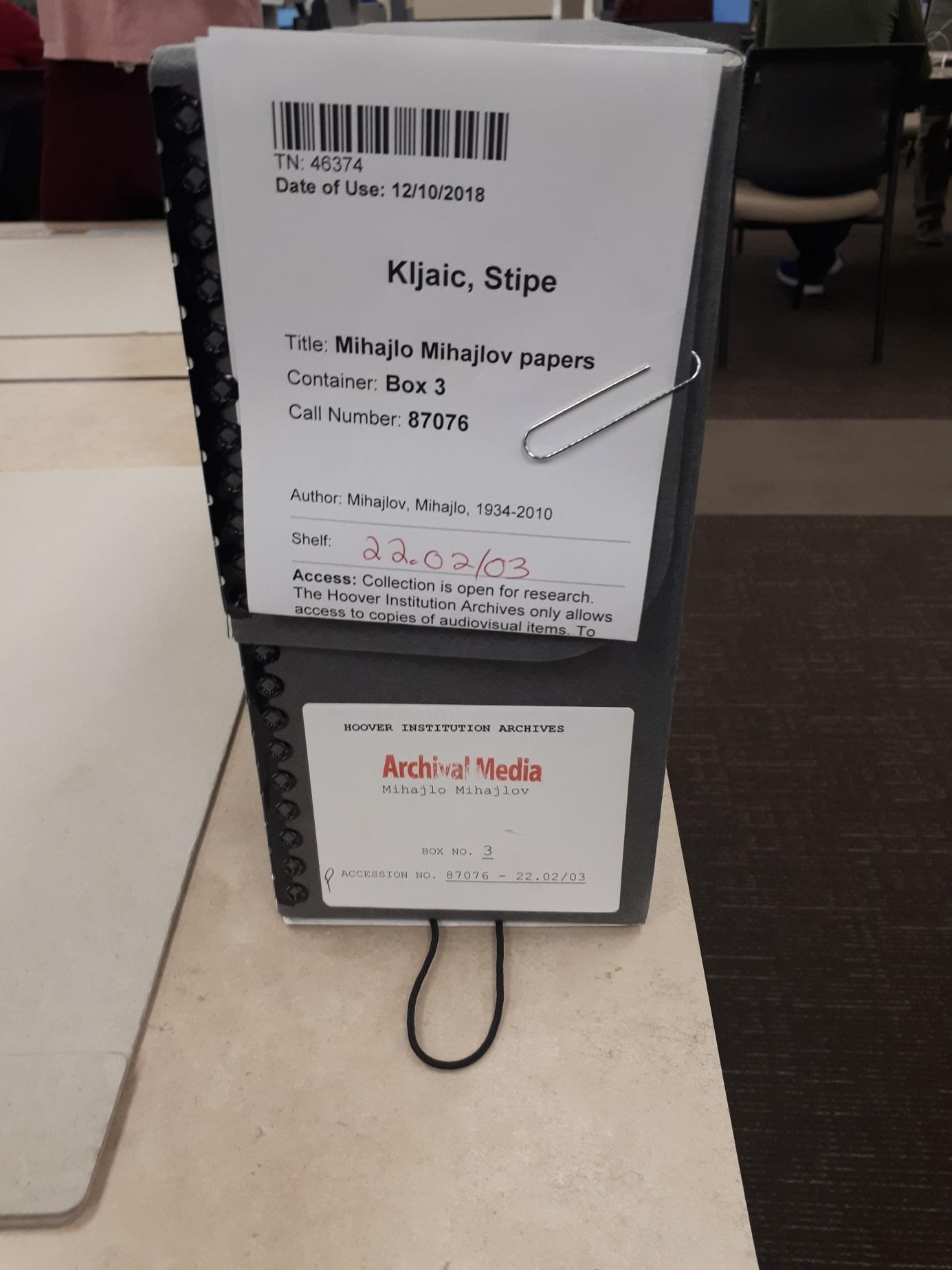

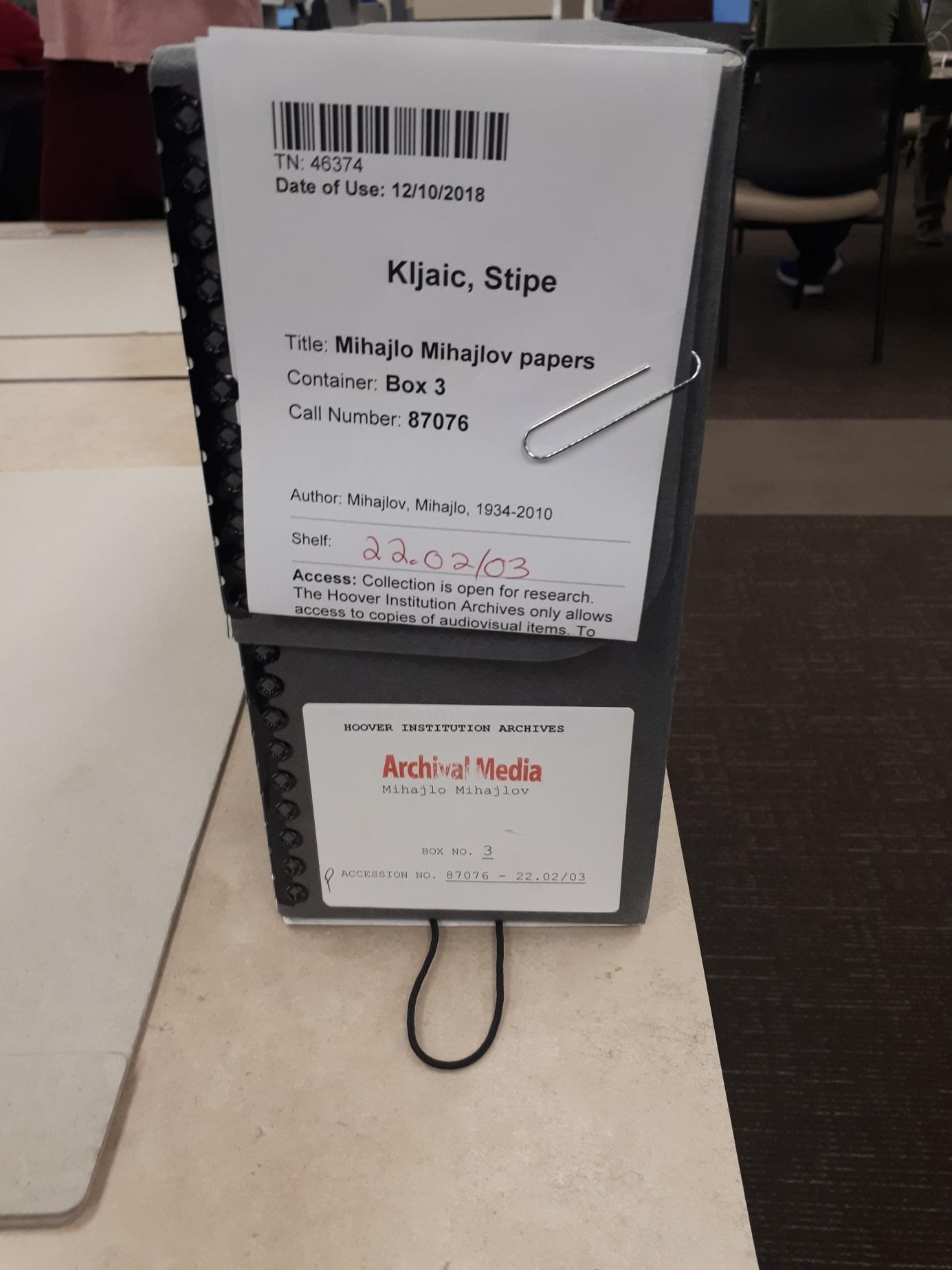

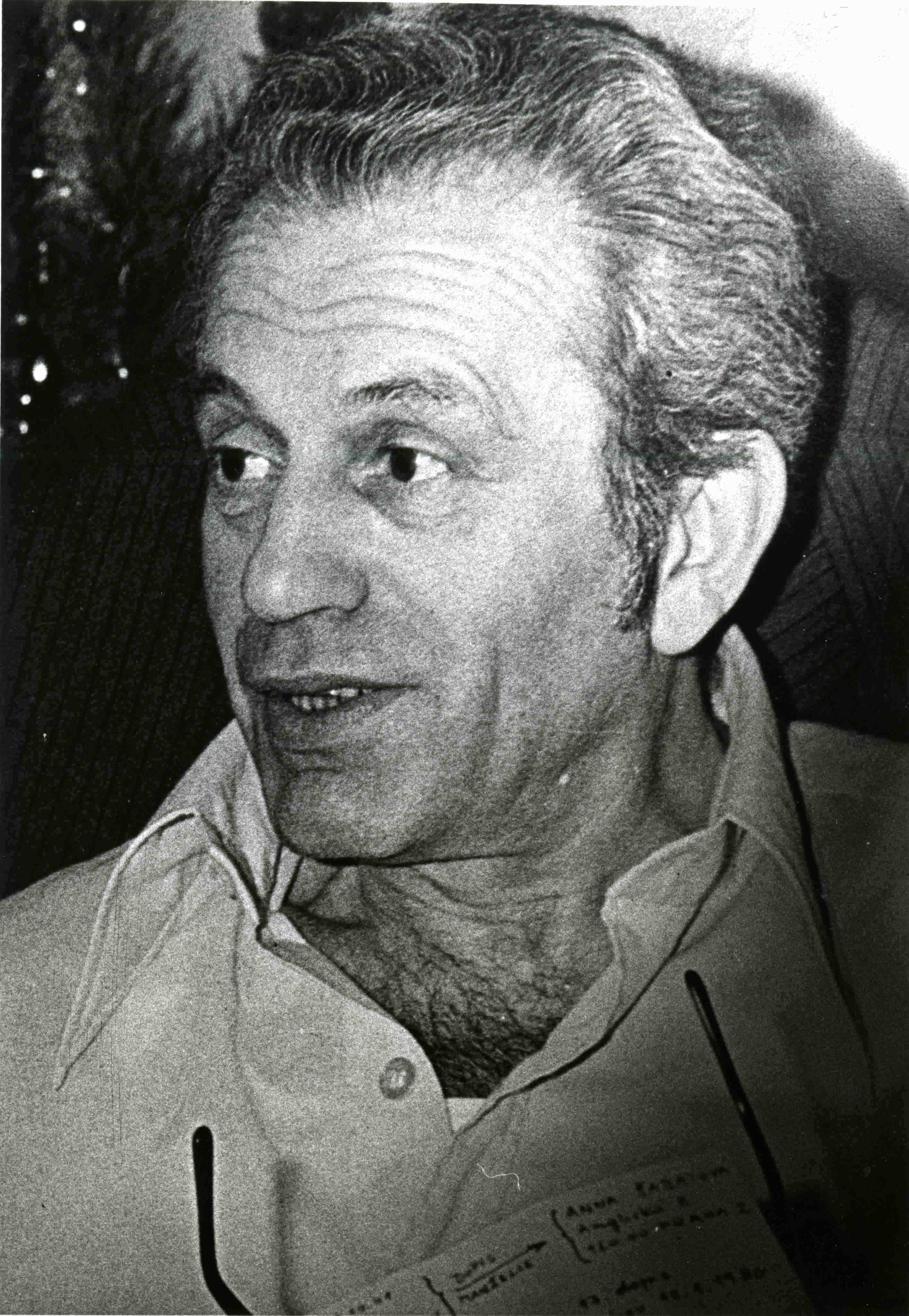

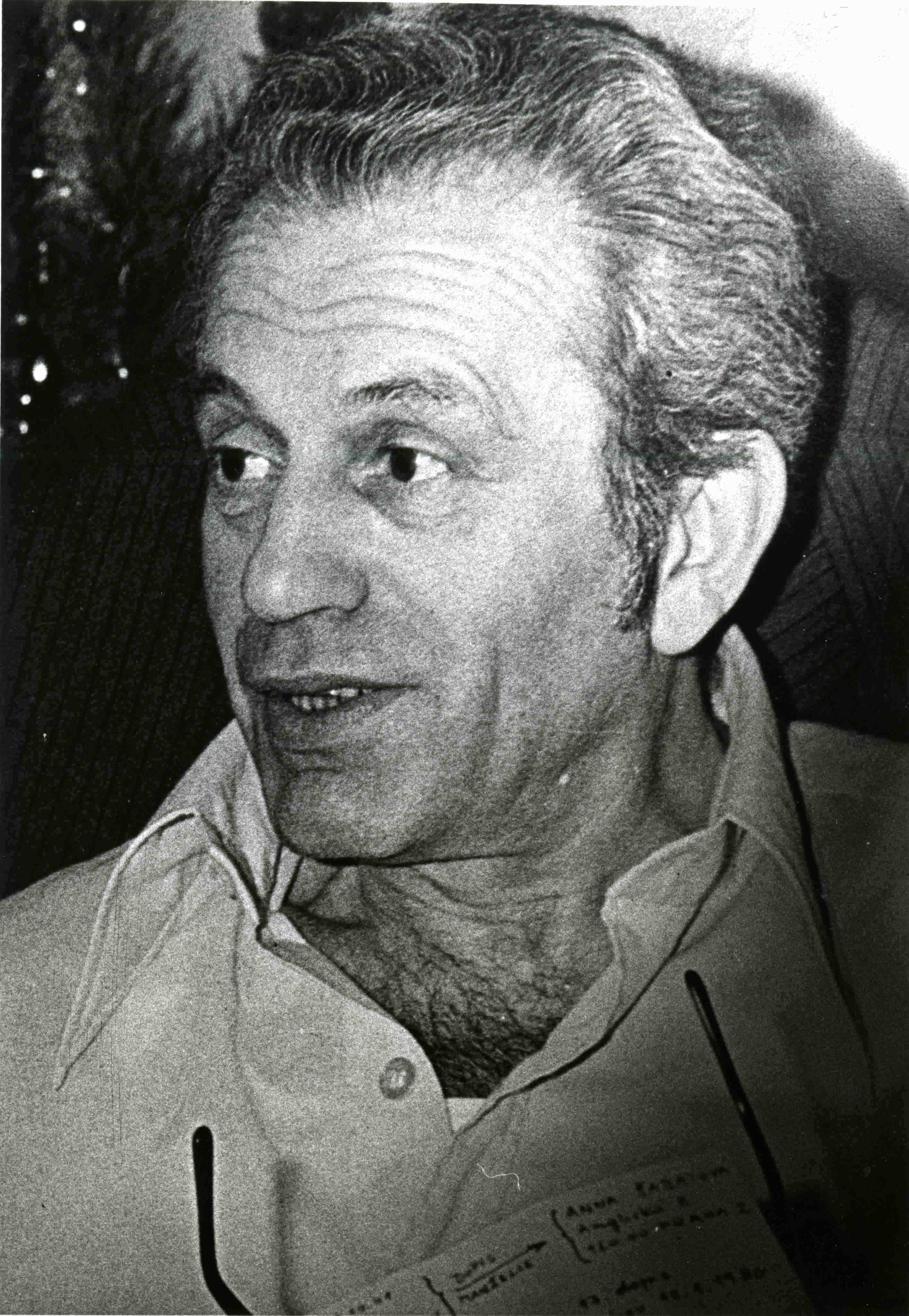

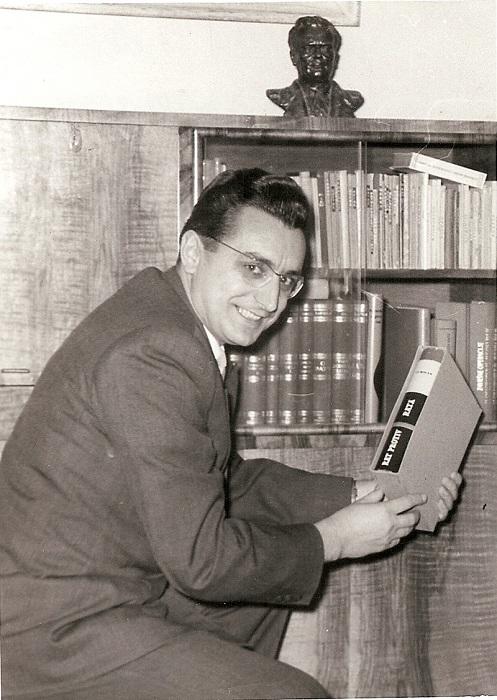

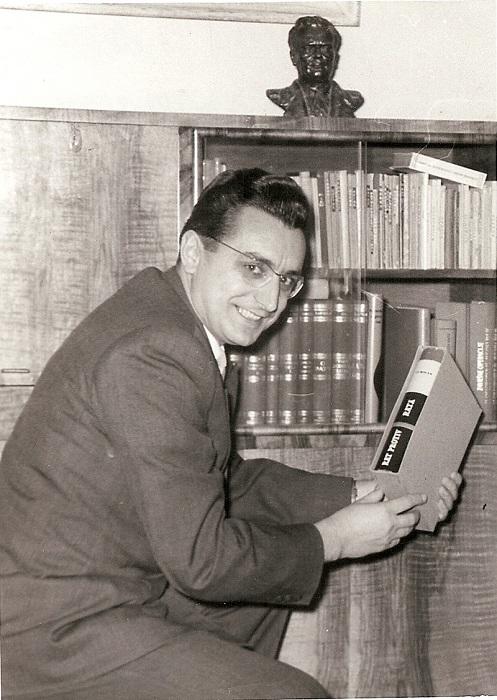

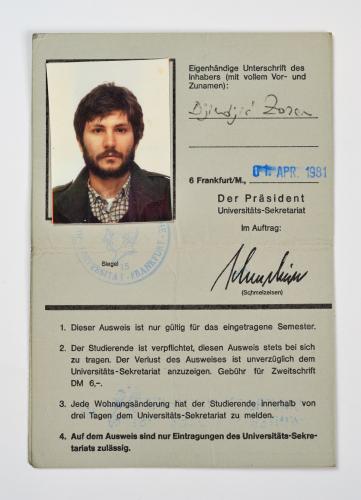

The Mihajlo Mihajlov collection gives an overview of his life and work as a Yugoslav dissident who lived in exile in the USA since 1978. Due to his efforts to democratize Tito's Yugoslavia and introduce political, economic and cultural pluralism, he became a political prisoner, first in the period from 1966 to 1970 and later from 1974 to 1977. After the “Mihajlov case” in Yugoslavia in 1966, a wave of dissident movements emerged in the Eastern bloc countries. Together with Milovan Đilas, Mihajlov became one of the most famous figures of the dissident movement in the Cold War world in general. The collection is stored at the Hoover Institution, located at Stanford University in the USA.

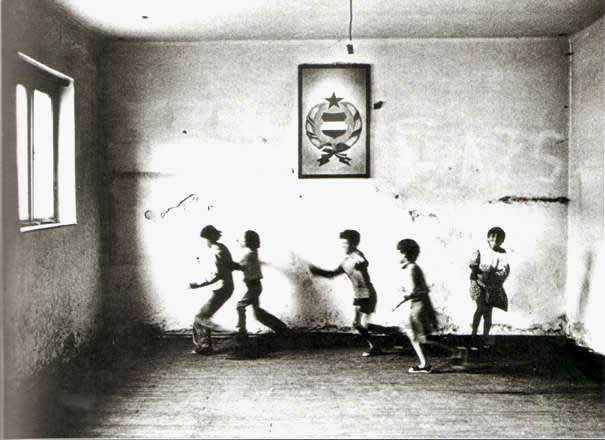

Some of the photographs taken by Lucian Ionică are snapshots of moments of high drama. Among them, those “hard to look at” images from the Paupers’ Cemetery, with the bodies of those killed by the repressive forces of the communist regime, hastily buried by the representatives of those forces, and then disinterred in order to be laid to rest in a fitting manner. There are also in the collection some photographs with portraits of children wounded during the Revolution of December 1989 in Timişoara. They were taken in the Timişoara Children’s Hospital on 24 December. The photographs show the wounded children in bed; the three snapshots include portraits of two boys and a girl. “For a few years after I took those photos I tried to trace the children I had photographed. I couldn’t find them, although I tried repeatedly. In the confusion and the strong emotions of the events back then, I didn’t have the inspiration to make a note of their names. Today I don’t know what has become of them, what they are doing,” says Lucian Ionică, confessing his regret at being unable to follow the story of those whose drama he immortalized in December 1989. “In the Timişoara Revolution, there were a lot of teenagers in the street. However the repressive forces had no compunction about firing at them. They were victims of the Army in the first place. Opening fire on minors is impossible to accept. Of course it is not justified against adults either, but the brutal actions of the soldiers against the children show how faithful those in the forces of repression were to Nicolae Ceauşescu,” is the comment of Gino Rado, the vice-president of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, summing up the tragic consequences of the involvement of forces loyal to the communist regime in the repression of the demonstrators, including minors (Szabo and Rado 2016). According to research carried out at the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, as well as other official statistics documenting the scale of the repression in the city in December 1989, at least six children or adolescents under the age of 18 were killed in this symbolic city of the Romanian Revolution. The youngest hero-martyr was Cristina Lungu; when she was fatally shot in December 1989, she was only two years old.

One of the most imposing rooms of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara is dedicated to the tricolour flags that were in the street or in various institutions during the very tense days of December 1989. It houses some fifteen flags, all original. “They are flags that have, in a sense, been to war; people came out to demonstrations with them in the days from 15 to 22 December; some of them were shot at; some were discoloured by the weather on those days; they are important symbolic objects that had very important trajectories for the revolutionary movements of 1989, in those heated and bloody days in Timişoara,” says Gino Rado. The majority have a hole where the communist emblem was removed – the flag with a hole in the middle became one of the emblematic images of the Romanian Revolution of December 1989. Of all these flags, only one is of the Communist Party: it was taken down from the building of the Party Committee in Timişoara. They came to the Memorial as donations over a number of years, mostly in the period 1990–1994.

The Foreign Croatica Collection is the largest collection of books and periodicals published by Croatian authors in foreign countries. The Collection includes publications in many languages covering numerous issues on Croatia and the Croatian people, including those related to the socialist period. It is the most important collection in Croatia containing books by Croatian émigrés banned during the time of socialist Yugoslavia.

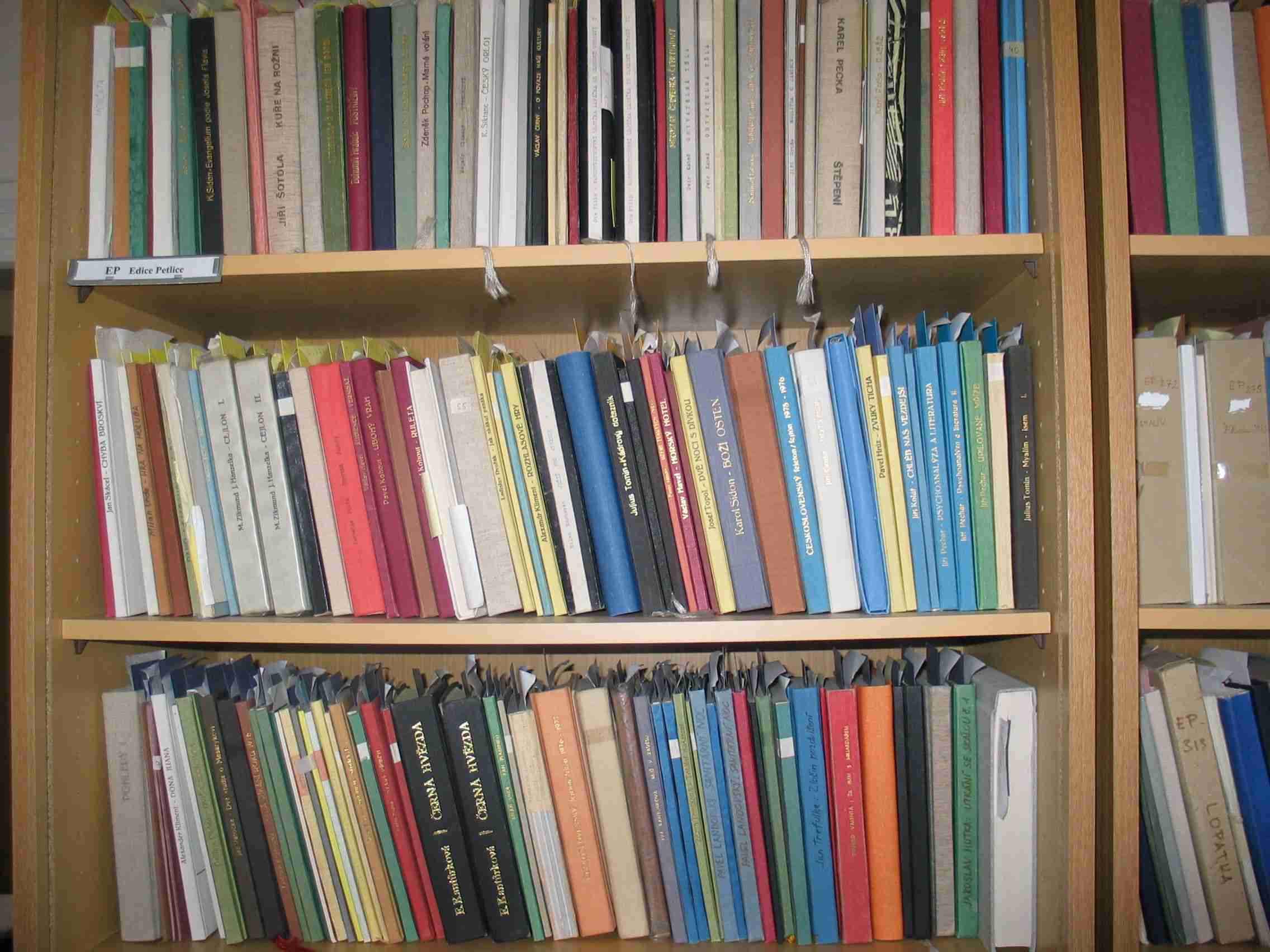

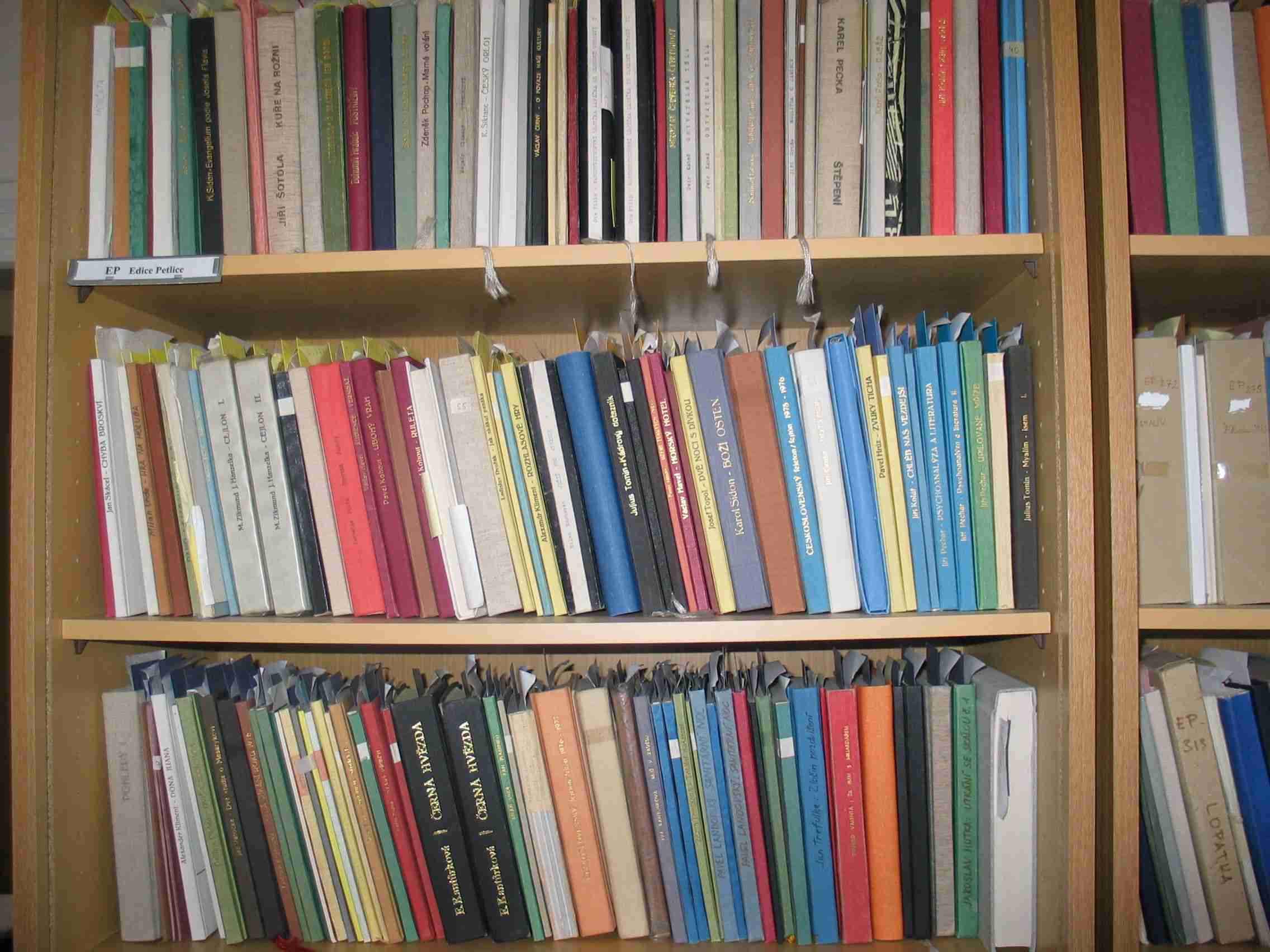

This unique collection of samizdat literature (1972-1989) contains samizdat books by Czech and Slovak authors whose works could not officially be published in socialist Czechoslovakia, as well as a collection of samizdat periodicals and individual texts.

Cristina Lungu was the youngest hero-martyr of the Revolution of December 1989 in Timişoara. When shed died, shot in the heart by one of the bullets fired from the roof of the Research Centre on Calea Girocului, Cristina Lungu was only two and a half years old. She died on Str. Ariş in Timişora, at the crossing with Calea Girocului, in her father’s arms with her mother beside her. Her destiny is symptomatic for the fate of most of the over 1,000 victims of the Romanian Revolution of 1989, who lost their lives not in a direct clash with the apparatus of repression, but because they happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when a stray or ricocheting bullet cut short their lives.

The tragic moment is recounted as follows in one of the books published by the publishing house of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara: “There was a moment of respite, around 10 pm, after intense shooting close by, on Calea Girocului. They came out at the crossing of Str. Negoi with Str. Arieş and Calea Girocului. At a certain moment, Cristina fell. Her father thought she had tripped, because there had been no particular noise. When he picked her up, Doru Lungu noticed that blood was flowing from her mouth. Then he ran with her to the County Emergency Hospital: “And it was only in the morning, about 4 am, that I found out, someone told me, that in fact she had been shot and had died on the spot. I wanted, because someone there had told me, to run quickly to the Morgue to take her, because otherwise I would never be able to get her.” Because he was afraid that her body would disappear for ever in the criminal action of erasing the traces of the repression of the popular revolt, her father was determined to take her from the Morgue, although it would have been almost impossible to bury her officially, because he had no documents. But he did not reach her, because he was given advice to take care and not to put himself in danger, because two people from the Securitate were at the Morgue, carrying out investigations into the deceased. It was only in the afternoon of Thursday 21 December that he managed to recover her body, his good fortune (if one can speak of good fortune in these circumstances) being that she had not been put in the batch that would arrive in Bucharest for incineration.” (Szabo 2014)

On the ground floor of the building of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişora there is a thematic corner dedicated to this heroine-martyr. Her portrait, donated by her family to the institution in 2001, is covered by a pane of glass pierced in the middle by the impact of a bullet. The pane comes from a shop in the centre of Timişoara, in Opera Square, a place where there were violent exchanges of fire between 17 and 22 December 1989. In connection with the tragic case of this youngest victim of the December 1989 events in Timişoara, the portfolio of the Memorial also contains some testimonies by her parents and information that helps to place Cristina Lungu in both her historical and her family context.

Film Notations of European Solidarity Centre are biographical interviews, conducted with democratic opposition activists and creators of independent culture in socialist Poland. They are first-hand testimonies of people who organised illegal gatherings, demonstrations, art exhibitions, film screenings, literature circulation etc. Collection includes rare interviews that cannot be seen anywhere else.

Croatian scholars made important contributions to the work of the Pugwash Movement by gathering primarily around the Institute for the Philosophy of Science and Peace of the Yugoslav (after 1991 Croatian) Academy of Sciences and Arts (JAZU/HAZU). In 1966, a group of Croatian intellectuals from the Institute, led by Ivan Supek, in 1966 launched the journal Encyclopaedia moderna: časopis za sintezu znanosti, umjetnosti i društvene prakse. It was published in all Yugoslav languages and dialects, but there were also articles in English. In addition to the central editorial office in Zagreb, it had editorial staffs in Belgrade, Ljubljana, Sarajevo, Skopje and Titograd. It was issued quarterly, although occasionally deviated from this schedule. The editor in chief was Ivan Supek (except in 1975, when the editor was Eugen Pusić). Since the mid-1980s, Supek was assisted by Nikola Zovko and Bojan Marotti (interview with Marotti, Bojan).

As a multidisciplinary journal, it promoted universalism and a humanistic orientation for science and the arts, as well as the complete disarmament and the creation of world peace. The first issue began with the “A Word from the Editors,” in which they stress: “we stand between military, economic and ideological blocs, and it is clear that in the event of a [global] conflict there can be no victory, but only a general disaster” (p. 1). They insisted on the universality of humankind: “Although the world is so fatally disunited, in every corner of it peaceful, humane and progressive thought is smouldering" (p. 3).

The goals of the journal were almost identical to the goals of the Pugwash Movement, and Supek insisted that every issue must contain something about the movement. “Pugwash” or “Peace Studies” or some column with a similar name was published in almost every issue. It would usually convey information, documents, declarations, or reports from Pugwash Conferences and other meetings. All of the contributions in the column were in English, in attempt to make the journal accessible to international scientific currents.

In the 1960s, Encyclopaedia moderna was relatively popular due to the prominent intellectuals who contributed articles to it. The journal strived for academic freedom and was even open to topics that the communist government considered undesirable, as was the case with religion (Kolarić 1973). The Yugoslav communist authorities did not like such intellectual independence, and the government reduced the funding for all of Yugoslavia's Pugwash organisations and publications. In 1976, Encyclopaedia moderna was forced to shut down because the government completely severed its funding (Knapp 2013, 99). In the 1980s, the very existence of the Pugwash organisation in Yugoslavia was questionable, mainly because Supek was out of favour with the communist regime. Still, the movement survived those trying years.

The journal was re-launched after the fall of communism in 1991, with Nikola Zovko as editor-in-chief, but its scope was oriented more towards Central Europe. It was published until 1998, and Marotti believes the journal was "naturally extinguished" because the themes of the journal were no longer as current as during the Cold War (interview with Marotti, Bojan).

The video periodical Black Box was the first independent film production studio during the last years of communist rule in Hungary. It reported on demonstrations and civilian initiatives that the official media passed over in silence or reported on with disinformation. With its film reports, and portraits distributed in samizdat channels, at the beginning Black Box managed to create the largest film collection documenting the events of the transitional period and the change of political system both in Hungary and in other communist countries.

The Victor Frunză Collection is an important historical source for understanding and writing the history of that part of the Romanian exile community which was actively involved in supporting dissidents in the country and in publicising in the West the repressive or aberrant policies of the Ceaușescu regime. In particular, the collection illustrates the activity of the collector and other personalities of the exile community for respecting human rights in Romania. Also, the documents of this collection reflect the involvement of Romanians from abroad in the reconstruction of democracy in their country of origin.

It is estimated that the film archive of the Institute of National Remembrance in Poland consists of over 1500 archival units and includes videos made by civil and military departments of the State Security. The biggest part of the collection are the materials from different surveillance actions, including training materials for employees of state security. In the collection we can find: - videos from manifestations in March 1968 and December 1970 – materials from invigilation of dissidents: Jan Józef Lipski, Jacek Kuroń, Adam Michnik, Leszek Kołakowski and organisations such as Workers' Defence Committee or "Solidarity" - materials documenting foreigners in Poland - both diplomatic residents and representatives of foreign governments, official visits of Fidel Castro, Josip Broz Tito or Richard Nixon.

The Edvard Kocbek Collection is located in the depot of the National and University Library in Ljubljana. It is actually his personal bequest to that same library. Kocbek was the greatest Slovenian poet and writer of the 20th century, who, as a Christian Socialist, joined the Slovene National Liberation Front under the control of the communists during the Second World War. Due to his divergent opinions about the war and the policies of the new communist regime, immediately after the war he was placed under the surveillance of the secret police (known as the UDBA). After that, he was very soon placed under a kind of public isolation, which implied limited movement and restricted access to intellectual life.

This collection expresses the artistic tendencies in the last decades of Polish reality under socialist regime. It includes a huge number of graphics, posters, paintings and drawings, as well as some items produced by opposition members held under detention.

Krzysztof Skiba's archive is a private collection of photos, movies, zines, books, articles, and leaflets documenting the alternative culture phenomena that Skiba participated in during the 1980s. The majority of the collection covers the street happenings created by the Gallery of Maniacal Activities in Łódź, the activities of anarchist Alternative Society Movement in Gdańsk, the very first years of the punk cabaret Big Cyc, and the first exhibition of the third circuit papers and magazines co-organized by Skiba in 1989.

The Karl Laantee collection at the Estonian Cultural History Archive is part of the large archival legacy of Karl Laantee, an émigré Estonian religious activist, and announcer with the Voice of America radio station.

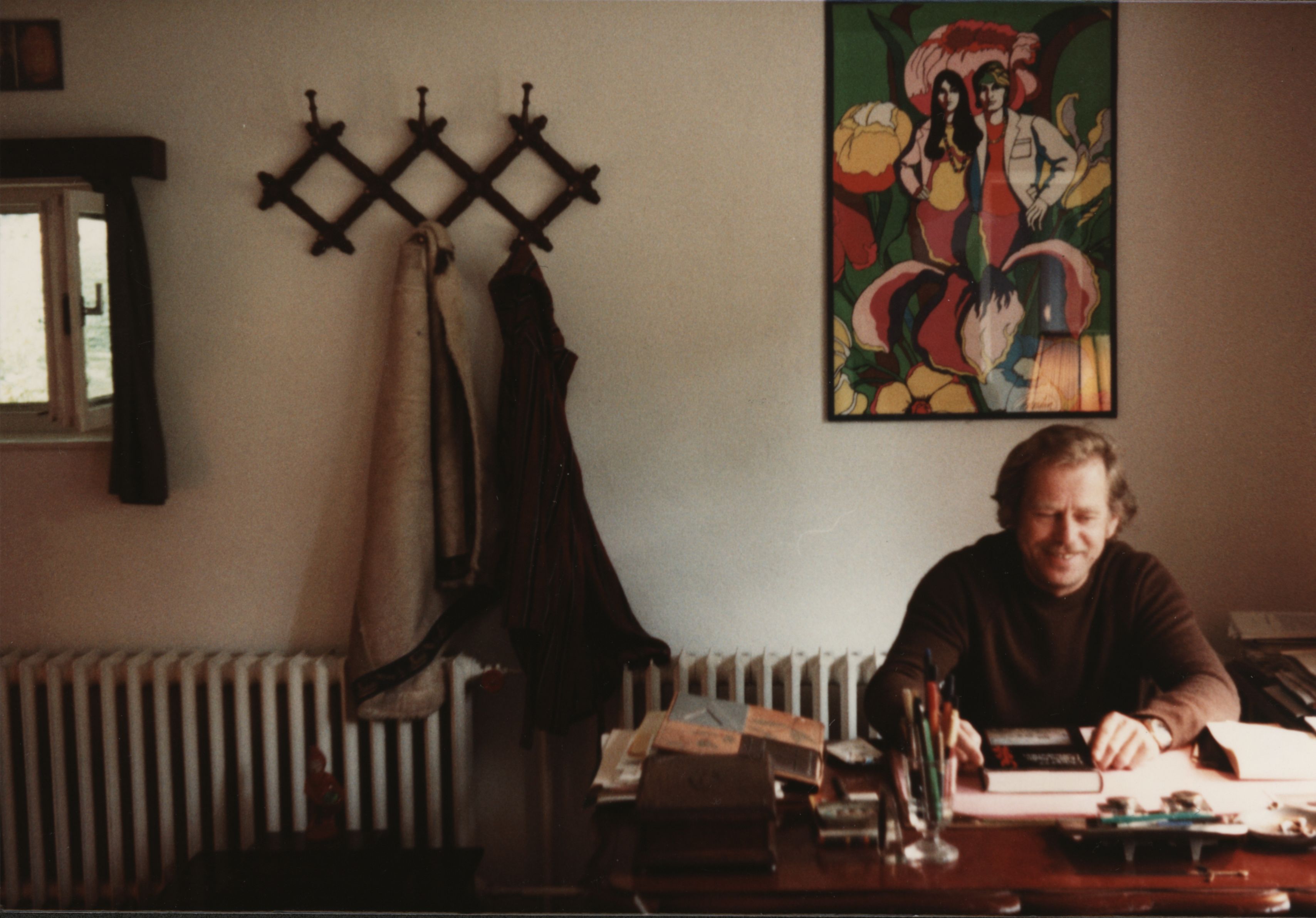

Petko Ogoyski - one of the few living artists who survived socialist prisons and labor camps, was an important figure in the Bulgarian cultural opposition against the communist regime. As a member of the Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union-Nikola Petkov (BZNS-Nikola Petkov) and poet/writer, Ogoyski was imprisoned twice (1950-1953 and 1962-1963) by the socialist state for writing “hostile” poems, texts and aphorisms and for “conspiracy”.

The Tower-Museum was established as a private initiative of the family Petko and Yagoda Ogoyski. The exhibition is partly a national and local ethnographic one, including household appliances, costumes, and weapons from the 19th and 20th centuries. At the same time, this was a way to circumvent the censorship of the communist regime. Among the ethnographic materials, Petko Ogoyski kept and preserved evidence from the periods of his imprisonment in six prisons and two forced labour camps; as also notes, books and poems written by him during and after the discharge from prison. The materials of the Tower Museum have been collected by Petko Ogoyski since his first imprisonment in 1950.

The collection of Petko Ogoyski documents the repressions of the socialist state over dissidents and is a valuable source of the forms of asserting political principles and moral positions by intellectuals.

The Jan Patočka Archives (AJP) studies and interprets the philosophical heritage of the Czech philosopher and dissident Jan Patočka (1907-1977). AJP is led by Patočkaʼs pupils and is a unique institute working with Patočkaʼs original texts and also with the attendees of his lectures.

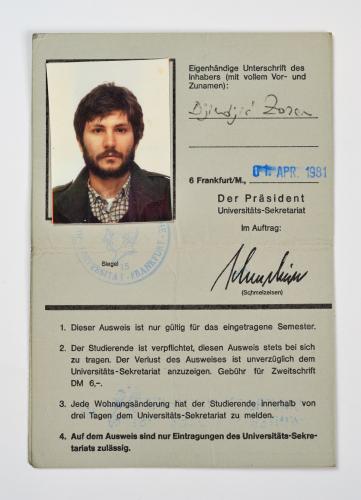

The manuscript of Mihajlov's travels, “Moscow Summer,” written in English is in the box 28. The text was the fruit of Mihajlov's visit to the Soviet Union in the summer months of 1964. Mihajlov supported Nikita Khrushchev's reforms and the program of de-Stalinisation, and he criticized the changes in the Soviet leadership after Kruschev’s fall. This criticism alarmed those in charge of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy, since it could once more undermine Soviet-Yugoslav relations, which had normalized in the mid-1950s.

Referring to the publication of the first two essays of this book, Tito himself called out Mihajlov in February 1965 as a result of pressure from the Soviet ambassador due to his criticism of the new political course following the fall of Khrushchev in the autumn of 1964. Despite censorship of Mihajlov’s essays in Yugoslavia, American politicians and the public were interested in Mihajlov's case precisely because of his stance on the Soviet Union during the political upheavals in the upper echelons of the Soviet party in those years.

The beginnings of the Video Studio Gdansk are connected to the I National Congress of “Solidarity”, organised in Gdansk in 1981. At first, the independent “Solidarity” filmmakers documented the union’s most important events, however soon the first documentaries were produced. Video Studio Gdansk has been operating for almost 40 years, and its archive today consists of several thousands of video materials. It mostly comprises own videos, created by the Studio: raw footages (of the most important oppositional events, like strikes, clashes, protests), documentaries, reportages, few feature films, and numerous recordings of television theatre, public debates, cultural events, etc.

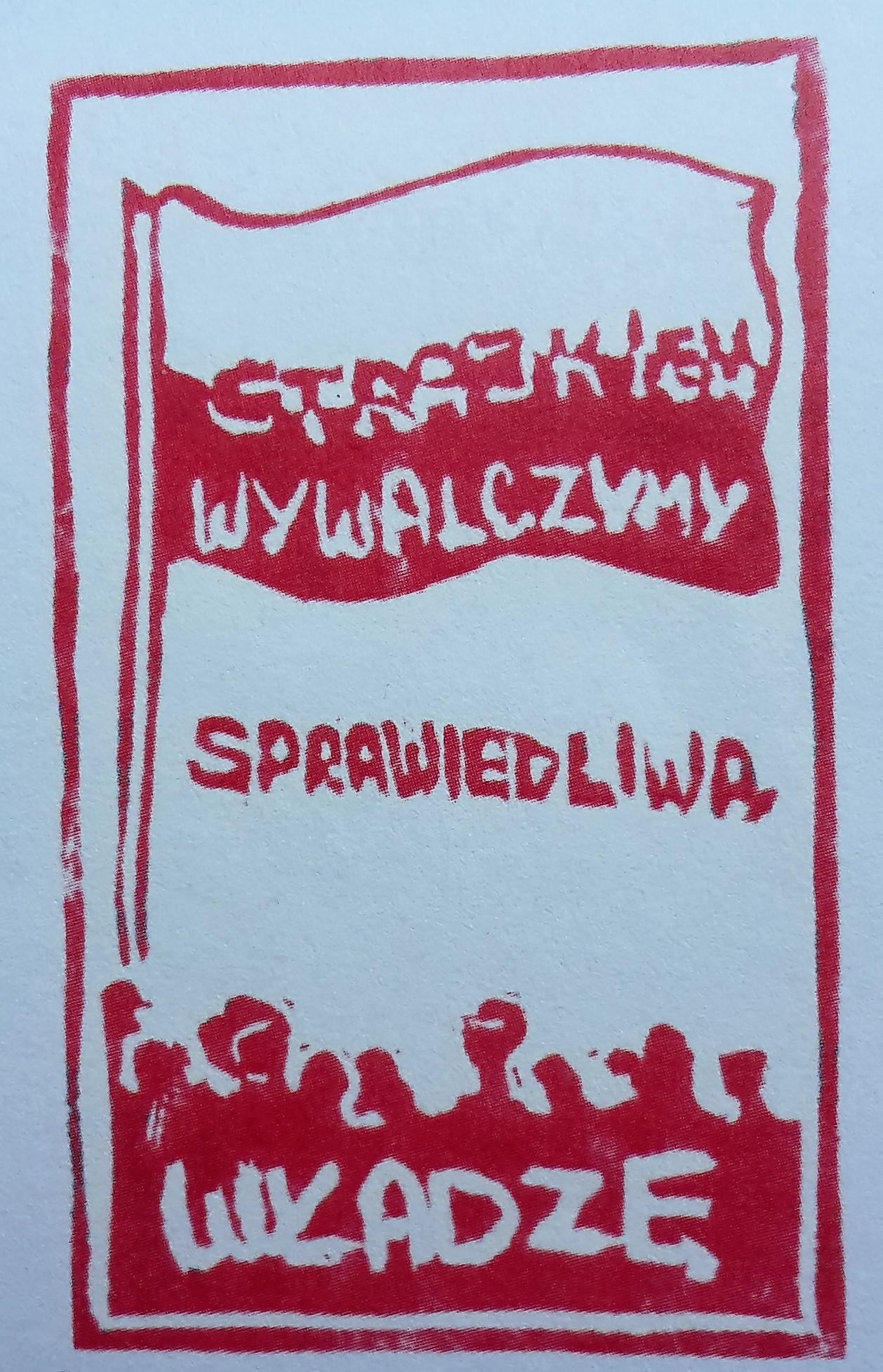

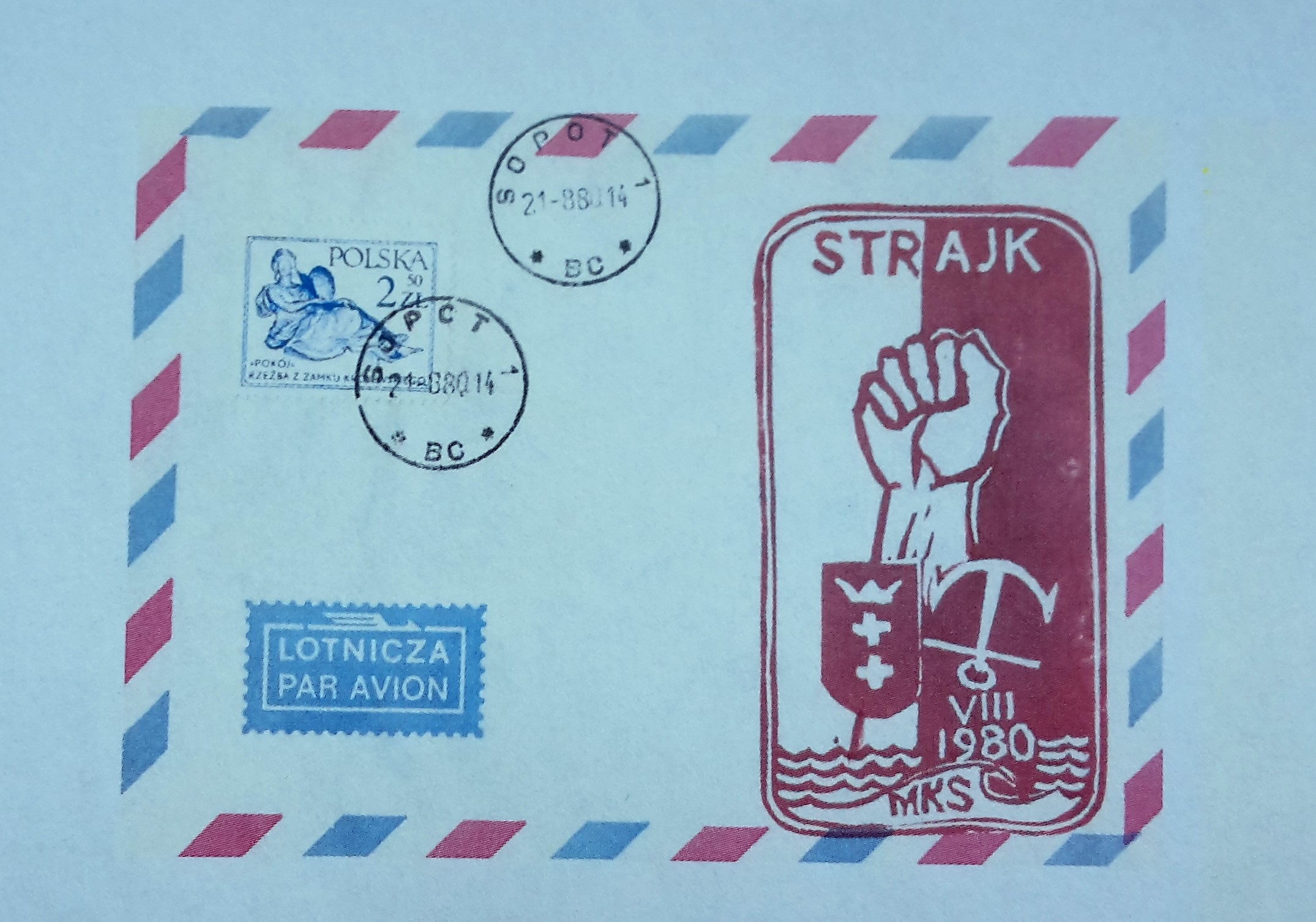

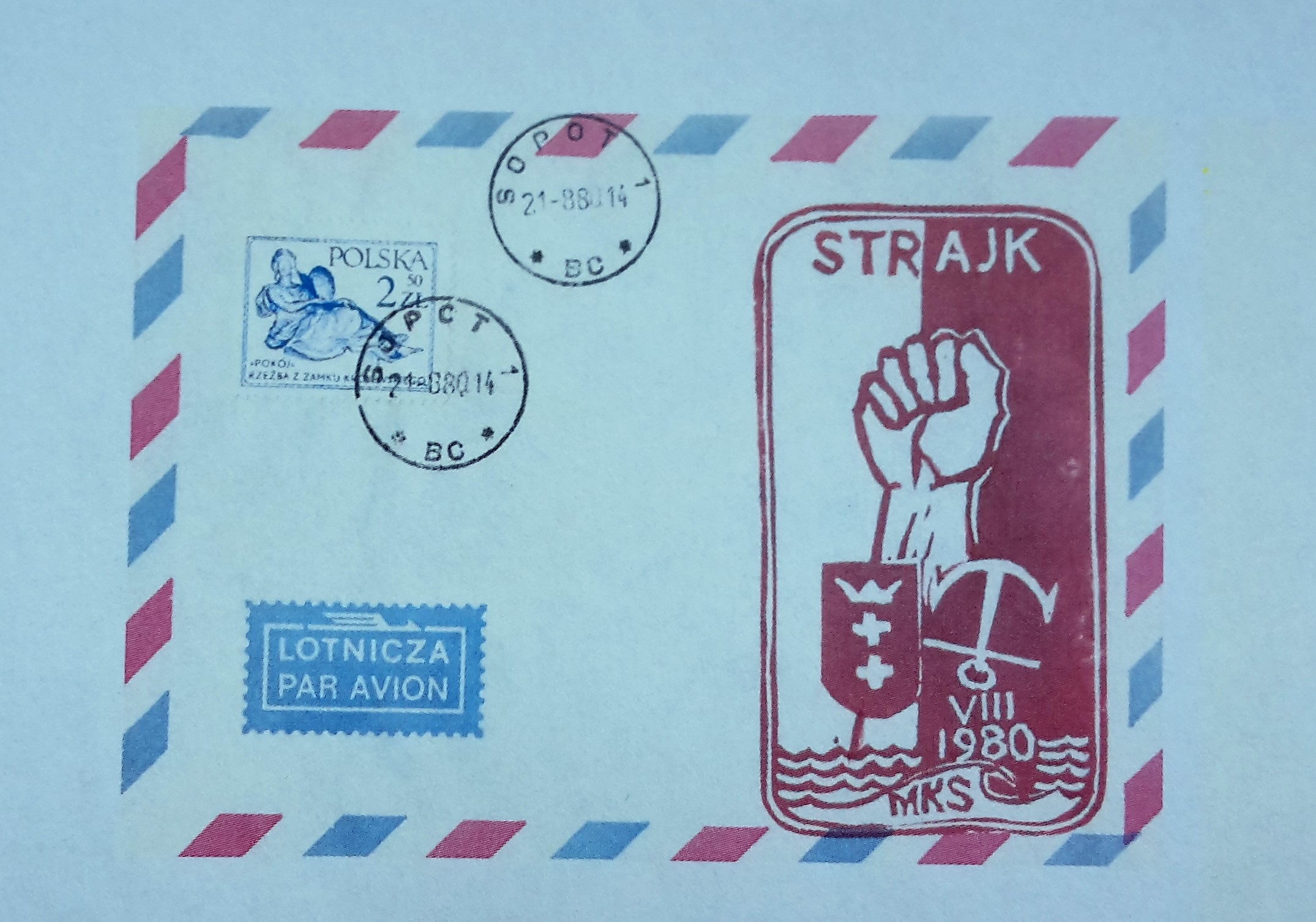

The seals and stamps created by Józef Figiela are an interesting visual representation of the strikes in the Gdansk Shipyard of the August 1980. They are also a testimony of an incredible engagement and effort put in sharing the strike’s ideals by a person who used his artistic abilities for this purpose, as well as a talent and enthusiasm of his teenage daughter. Józef Figiela is both a sailor and an artist by profession, and he has alternately practiced both of them throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In August 1980 he had already been signed in for another cruise when the strike in the Gdansk Shipyard broke. His ship was stuck in the harbour and he used this opportunity to support the protesters. He became a member of the Inter-Factory Strike Committee as a delegate of the Association of the Polish Fine Artists of the Gdansk Region, and as a graphic artist he joined the fight for changes. On 20 August 1980 he created his first seal of the strike’s underground post. It shows a hand clenched into a fist (symbolising the fight), Gdansk’s coat of arms, and some nautical motifs (an anchor, sea waves), as well as a sign: “strike”. The original linocut is a part of the collection of Michał Guć, who is also in the possession of the authentic copies in the form of stamps on the envelopes.

The seals in the form of stamps were copied in the Polish national colours onto the envelopes and specially prepared postcards. During the strikes, Figiela prepared 4 linocuts, which as copies were disseminated among the strikers. Figiela’s seals stand out from other underground stamps with their precise execution and interesting graphic design. However, their content is quite typical for this type of philatelist: it refers to the Polish patriotic emblems, fight symbols, and the shipyard itself. There are also some religious (Catholic) motifs.

It is worth mentioning that with his activity Figiela inspired to action his daughter Dąbrówka, who as a just 15-year-old girl created her own seal, as well as she helped her father in creating copies. Every day Dąbrówka would cut out the postcards and glue on them the official state stamps, and in the evenings she would go to the post office, asking the workers to mark the papers with tomorrow’s date. Next, her father and her pressed their seals onto the envelopes, and the next day Figiela took them to the shipyard and shared them among the strikers. Thus, the materials have always had the current date.

The last seal Figiela created just before the end of the strike. It shows the Polish flag and a hand holding some flowers – it symbolised the peacefulness of the protests. The text says: “victory”.

Michał Guć estimates that altogether there were around 300-400 paper copies of Józef and Dąbrówka Figiela’s stamps disseminated in August 1980. It is a relatively small number which was caused by the fact that making copies was a very time-consuming activity and that only two people were involved in their production. Low number of existing stamps makes every original copy a valuable item.

Source:

Stocznia Gdańska im. Lenina, Michał Guć, Gdynia 2017 (unpublished text, shared by the author in July 2017).

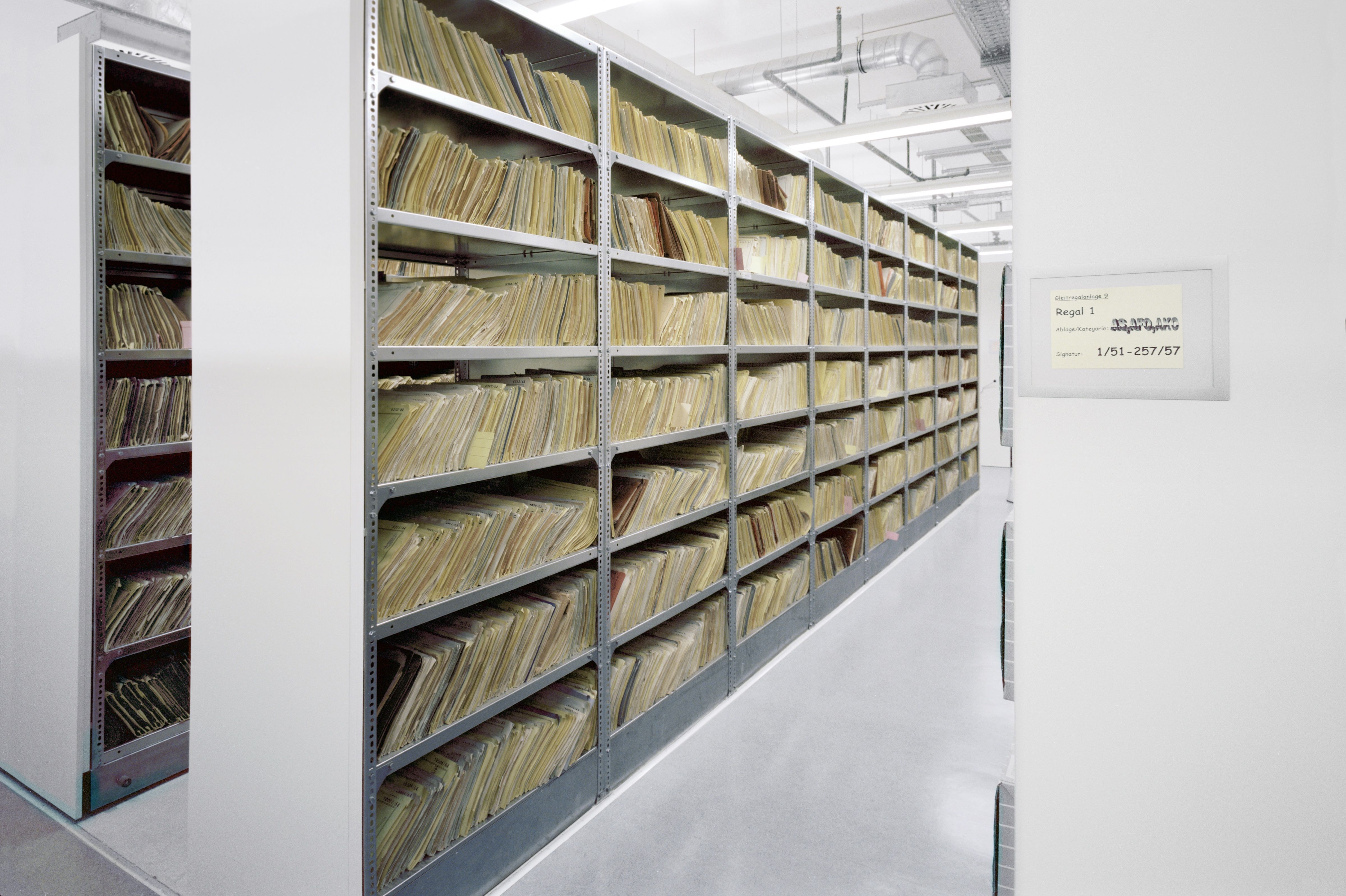

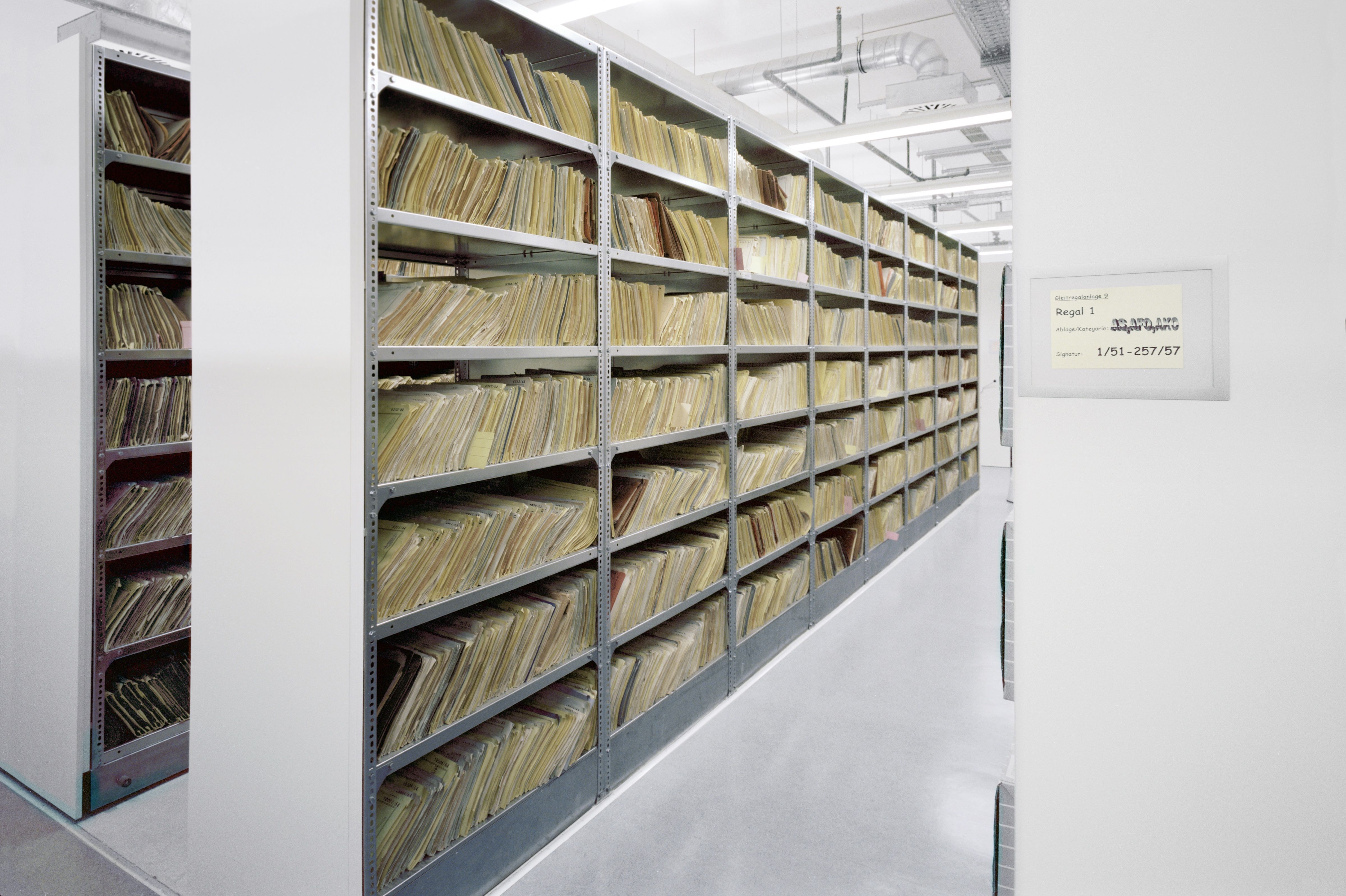

This collection contains the files of the State Security Service of the GDR that are preserved and administered by the Federal Commissioner for Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR (BstU). The surveillance records of the secret police represent a singular body of sources that offer unique glimpses into the cultural opposition to the GDR. The destruction of large numbers of these documents could only be averted in 1989/90 owing to the spirited actions of “Civil Committees”.

Judging from the level of difficulty of the twenty-two questions contained in it, the target group of the document identified as a questionnaire included the most sophisticated members of the Hungarian elite in Romania, who did not necessary work in the cultural sphere, but who had presumably been selected as a result of previous inquiries. The questionnaire, made up of three major sets of questions, first assesses the social status, qualification level, and general culture of the subject, then examines the subject’s sense of identity, and finally investigates, also out of a need for identifying a solution, the nature of the connections and relationships between Romanians and Hungarians, as well as experiences regarding coexistence.

I. The first set of questions focuses on the subject’s social status. It begins by examining the social background of the subject – family, origin – and then inquires about his/her age to further turn to a direct reference to the “small Hungarian world” in Northwestern Transylvania during the Second World War (Sárándi and Tóth-Bartos, 2015), which suggests that the questionnaire focuses primarily on mature individuals holding well-defined views on the Transylvanian issue. Questions four and five address the length and possibilities of past education in the mother tongue in the family of the subject, respectively, in his/her “range of vision.”

The Questions:

1. What kind of family do you come from?

2. What type of social environment do you come from? (rural, urban, peasant, worker, bourgeois, aristocrat, etc.)

3. How old are you? Were you alive between 1940 and 1944?

4. How long and what were you able to study in your mother tongue?

5. What about your family and /or “range of vision”?

II. The second set of questions – questions 6 to 14 – is directed at the subject’s sense of identity. The assessment of collective memory is followed by a nostalgic question, which, beside the inventory of violations of human rights experienced in the present, makes the subject draw a comparison with the rights undoubtedly held in the past. The question about general knowledge of Hungarian history is followed more emphatically by that about self-declared knowledge of post-1918 Transylvanian history and of the public figures related to it. Then the author of the questionnaire moves on to the mapping of reading habits and needs in the mother tongue, of cultural life and religion. The question referring to the level of Romanian language skills is still relevant. As the knowledge of language represents a prerequisite for social integration, this also means that as long as the coexisting nations are unable to eliminate language barriers, their cultures cannot get closer to each other, cannot coexist in harmony. Radio listening habits provide answers regarding the need for information of Hungarians in Transylvania, but also about their possible resignation and indifference. The inquiry about connections in Hungary presupposes the existence of a current network of contacts in the “mother country,” including relatives, friends, and acquaintances. The thirteenth question, about the new situation in Hungary – which offers a clue about the date of the document – presumably hints at the changes that took place during the official mandate of the moderate reformer Károly Grósz, appointed president of the Council of Ministers in June 1987. On May 1988, the reform wing of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP) obtained the long-awaited goal of removing the old and ill János Kádár from the party leadership and elected Grósz as his successor upon a programme of transition to a market economy and political decentralisation. However, it cannot be excluded that allusion was made to symbolic events of 1989 relating to the commemoration of the Revolution of 1956, such as the reburial of Imre Nagy and his comrades, or the radio speech by the senior party official Imre Pozsgay about the re-evaluation of this tragic event in Hungary’s recent past (Romsics 2013). The last question in this section, referring to a “prominent Transylvanian personality” takes into consideration the greater political events and perhaps it looks ahead in allowing for an unpredictable political turn in Romania.

The Questions:

6. What can you recall, or how far back does your collective (family, workplace, etc.) memory extend?

7. Would you like to regain anything from the past? If yes, what?

8. Are you familiar with Hungarian history, and with the history of Transylvania in particular? (What do you know about the events following 1918? Are you familiar with the operation of the Hungarian National Party [Bárdi 2014, Horváth 2007, György 2003]? Are you familiar with figures such as Ct. Bethlen György [1888–1968, president of the Hungarian National Party representing the Hungarian minority in Romania in the interwar period (ACNSAS, I185019)], Jakabffy Elemér [1881–1963, Hungarian, later Romanian Hungarian politician, lawyer, publicist (Balázs 2012, Csapody 2012)], Makkai Sándor [1890–1951, Transylvanian Hungarian writer, pedagogue, Reformed bishop (Veress 2003)], Mailáth [Majláth] Gusztáv Károly [1864-1940, Transylvanian Roman Catholic bishop, member of the nobility, honorary archbishop (Marton and Jakabffy 1999)], Domokos Pál Péter [1901-1992, teacher, historian, ethnographer, one of the pioneers of research into the Csangos (Jánosi 2017, Domokos 1988)] etc.?

9. Do you own Hungarian books? Do you read in Hungarian? If yes, how much? How do you gain access to Hungarian books? Do you go to the theatre? Are you a church-goer? (Is the use of the Hungarian language or the fact that you are a believer behind church attendance?) 10. How well do you speak the Romanian language?

11. Which radio station do you listen to? That of Budapest or that of Bucharest? And which Radio Free Europe broadcast do you listen to: the Romanian or the Hungarian one?

12. Do you have contacts in Hungary?

13. What do you think of Hungary in this new situation?

14. Is there a prominent Transylvanian personality you know about and consider worth paying attention to?

III. The third set of questions – questions 15 to 22 – analyses the relationship between Romanians and Hungarians. Thus, beside inquiring about the nature of relationships maintained by the subject and his/her environment with his/her ethnic Romanian fellow citizens, these questions focus also on the ethnic characteristics of the coexisting population, whether the demographic balance in a given settlement, which was centuries ago favourable to the Hungarian community, has been subject to modifications by the communist regime by attracting inhabitants from other regions populated mostly by Romanians. Having future coexistence in view, question 17 is aimed at learning the “lacking needs” of the subject, so it inquires about the required minimum conditions in terms of human rights that allow him/her to live as a Hungarian there, in that given place. Amidst the measures aimed at the assimilation of the Hungarian minority in Transylvania, such as the continuous diminishing of educational opportunities in the Hungarian language, the closing down of Transylvanian Hungarian theatres, the potential destruction of villages, the phenomenon of emigration, which affected the Romanian citizens too, in the context in which the nationalism of Ceaușescu’s regime was become more and more radical, when politics-fuelled intolerance towards ethnic otherness was a daily presence, the question about individual views regarding the future of the minority community might have seemed surreal. Thoughts referring to the renewal of the indigenous minority were closer to utopia as the flagrant violation of human and minority rights provided no realistic grounds for this. The last two questions of the questionnaire – questions 21 and 22 – about positive experiences as a Hungarian living in Romania, positive experiences concerning the Romanian–Hungarian relationship – illustrate, even in their choice of words – “have you ever,” “accompany or would accompany” – the perspicacity with which the author of the questionnaire acknowledges the situation of the Transylvanian Hungarian minority of the period preceding the change of regime.

The Questions:

15. What is the nature of your (your personal and your community) relationship with Romanians?

16. Are you surrounded mostly by Romanians or by Hungarians in your living environment? If you live predominantly surrounded by Romanians, when was this situation installed? Is it a result of incoming settlement or is it the indigenous population?

17. What is it that you lack most in living there as a Hungarian?

18. What is your opinion about your own future, the future of your family, and that of Transylvanian Hungarians?

19. Do you see any possibilities of renewal?

20. If you are a church-goer, what do you know and what can you witness from the Greek Catholic movement?

21. Have you ever had any positive experiences as a Hungarian? If yes: when and what kind of experience was it?

22. List the positive experiences that accompany or would accompany the relationship between Romanians and Hungarians?

There is no doubt that Gyimesi is the author of this document. In numerous places her works include analyses of the given situation and sense of identity of the Hungarian minority in Transylvania (Gyimesi 1993). Most probably the document escaped the attention of secret police officers conducting the home search on 20 June 1989 due to the absence of title and date. The physical existence of a questionnaire examining minority life in the darkest days of Romanian Communist dictatorship is startling in itself. Research conducted in the form of questionnaires presupposes the subject’s right to free opinion and is interpreted as an accessory of democratic systems. However, the existence of the document does not mean that the intended survey was actually conducted. For Gyimesi, who was the subject of informative surveillance, in a world abounding in collaborators with the secret police, this questionnaire must have meant a handhold which should have helped her in identifying persons with similar views on whom she could have counted in the struggle against the violation of human and minority rights. This may have served as a basis – as a possible interpretation – for her efforts to recruit reliable colleagues for the editing and distribution of the Cluj-based samizdat paper known as Kiáltó Szó, which she conceived in the fall of 1988 together with Sándor Balázs, a philosopher and university professor. Out of the nine edited issues of the samizdat – which was little known even by the Securitate – only two were published, though this had nothing to do with the editors: the publishing of further issues was rendered unnecessary under the circumstances following the fall of the Ceaușescu-dictatorship.

The Lucian Ionică private collection is one of the few collections of snapshots taken during the tensest and most feverish days of the Romanian Revolution of December 1989 in the city of Timişoara, the place where the popular revolt against the communist dictatorship first broke out. The photographic documents in this collection preserve the memory both of the dramatic moments before the change of regime and of the days immediately after the fall of Nicolae Ceauşescu, when sudden freedom of expression produced moments no less significant for the recent history of Romania.

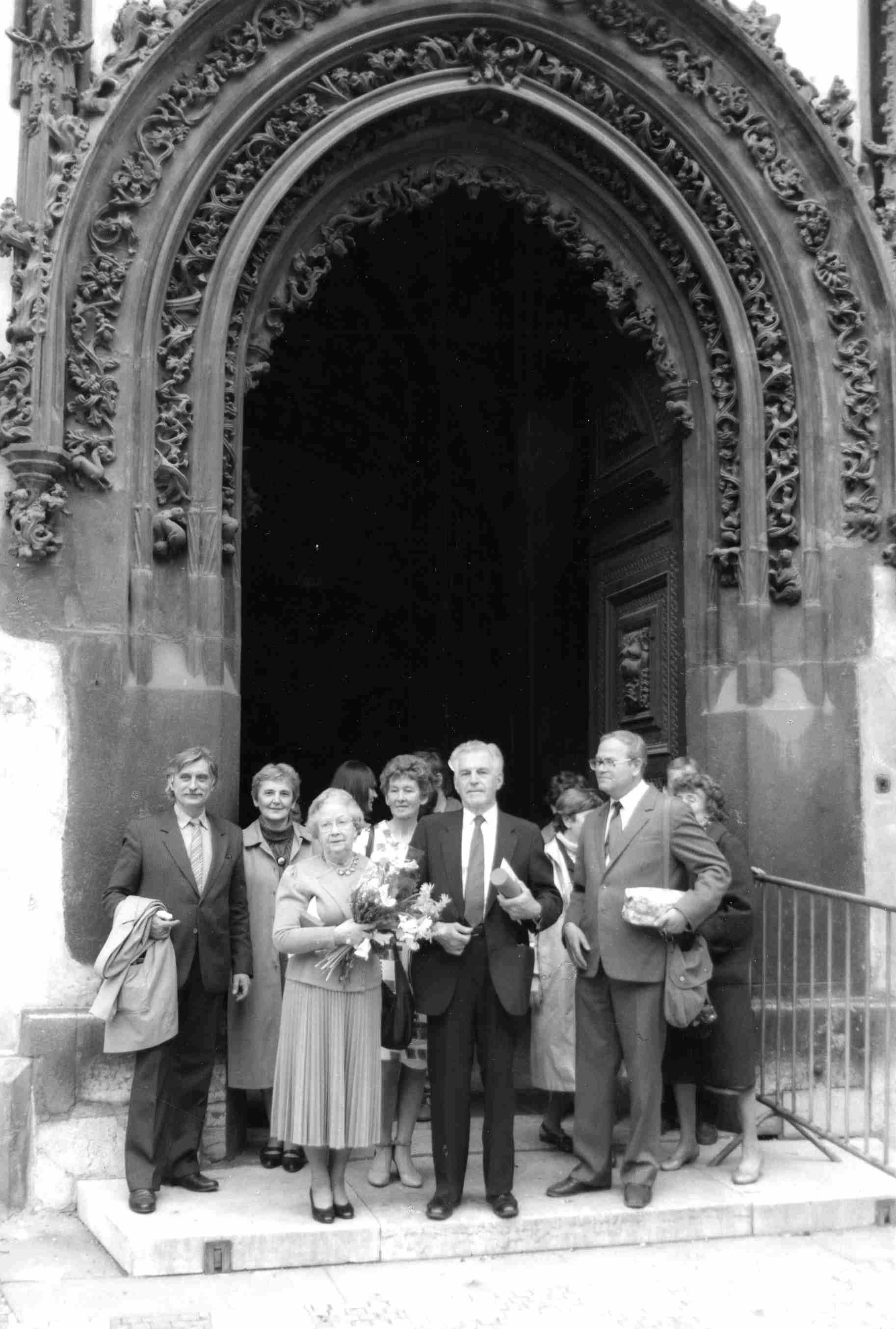

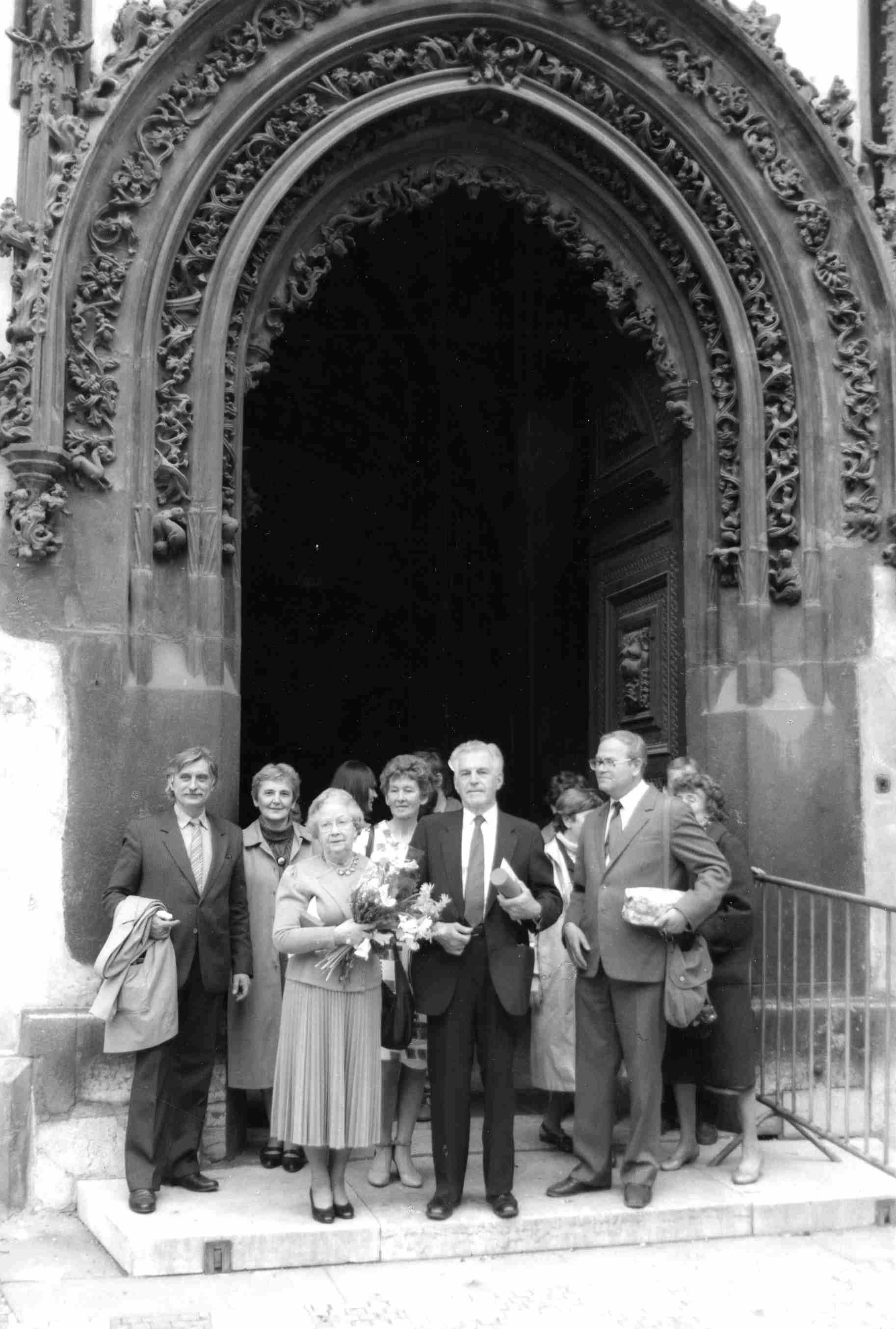

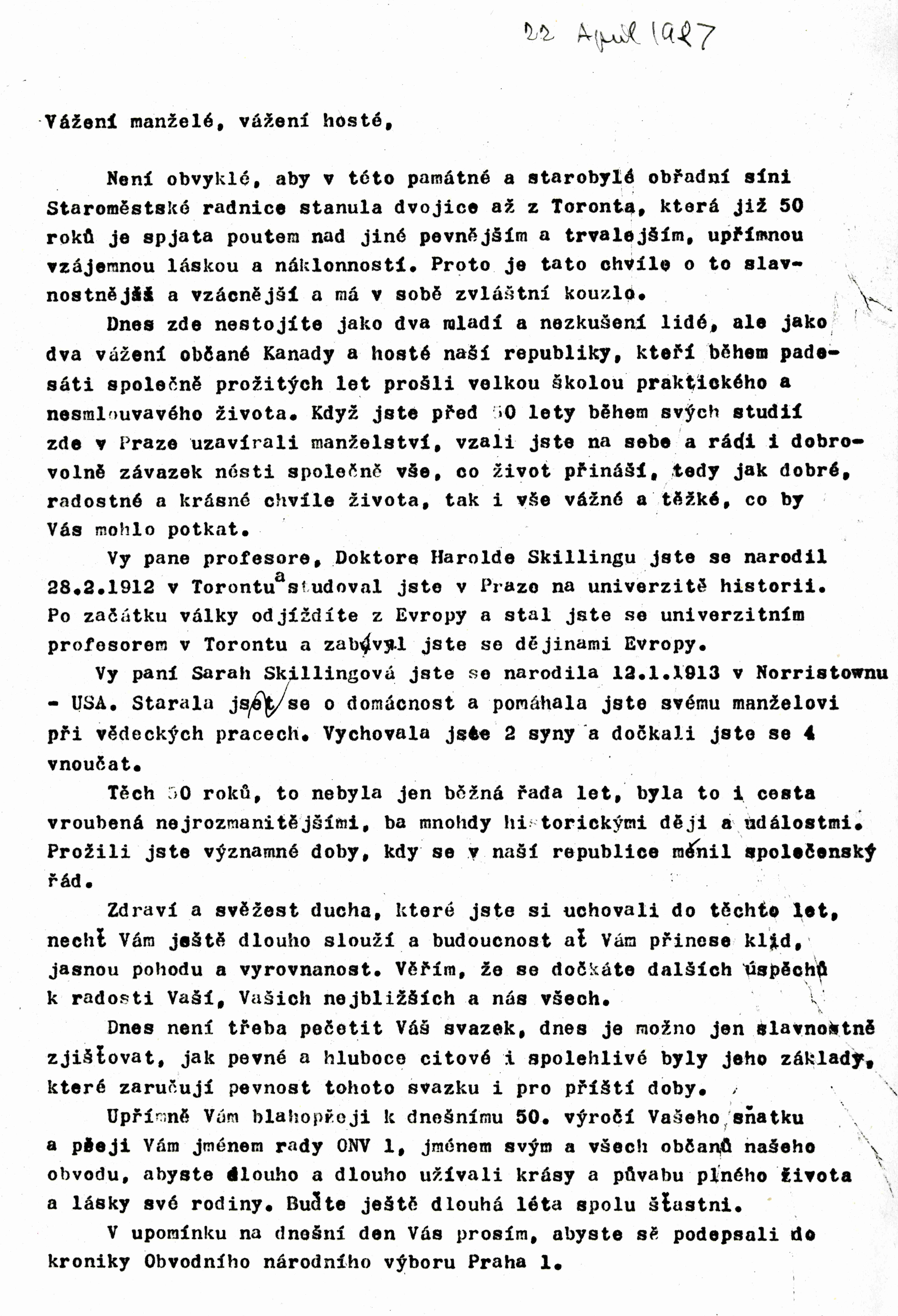

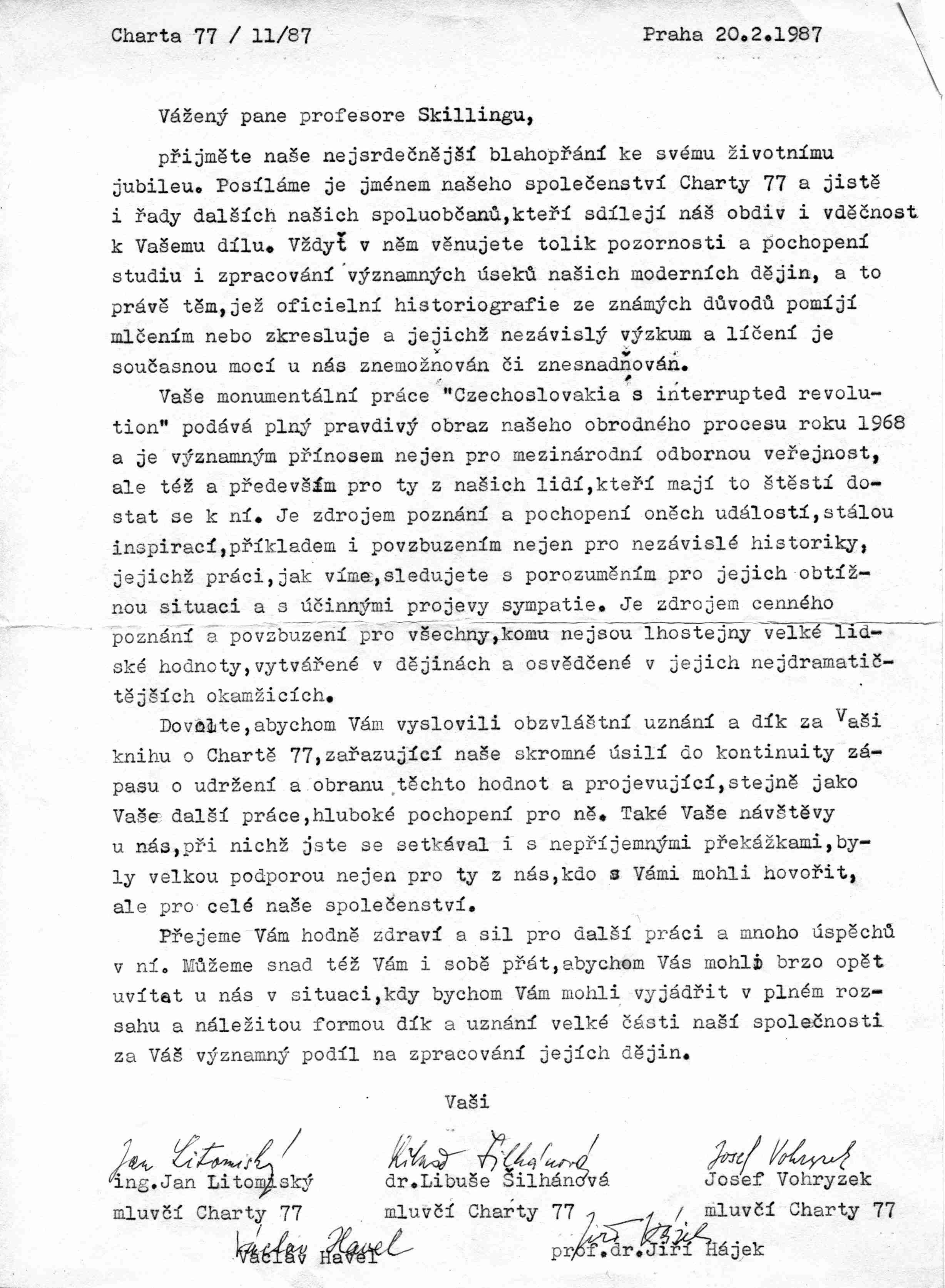

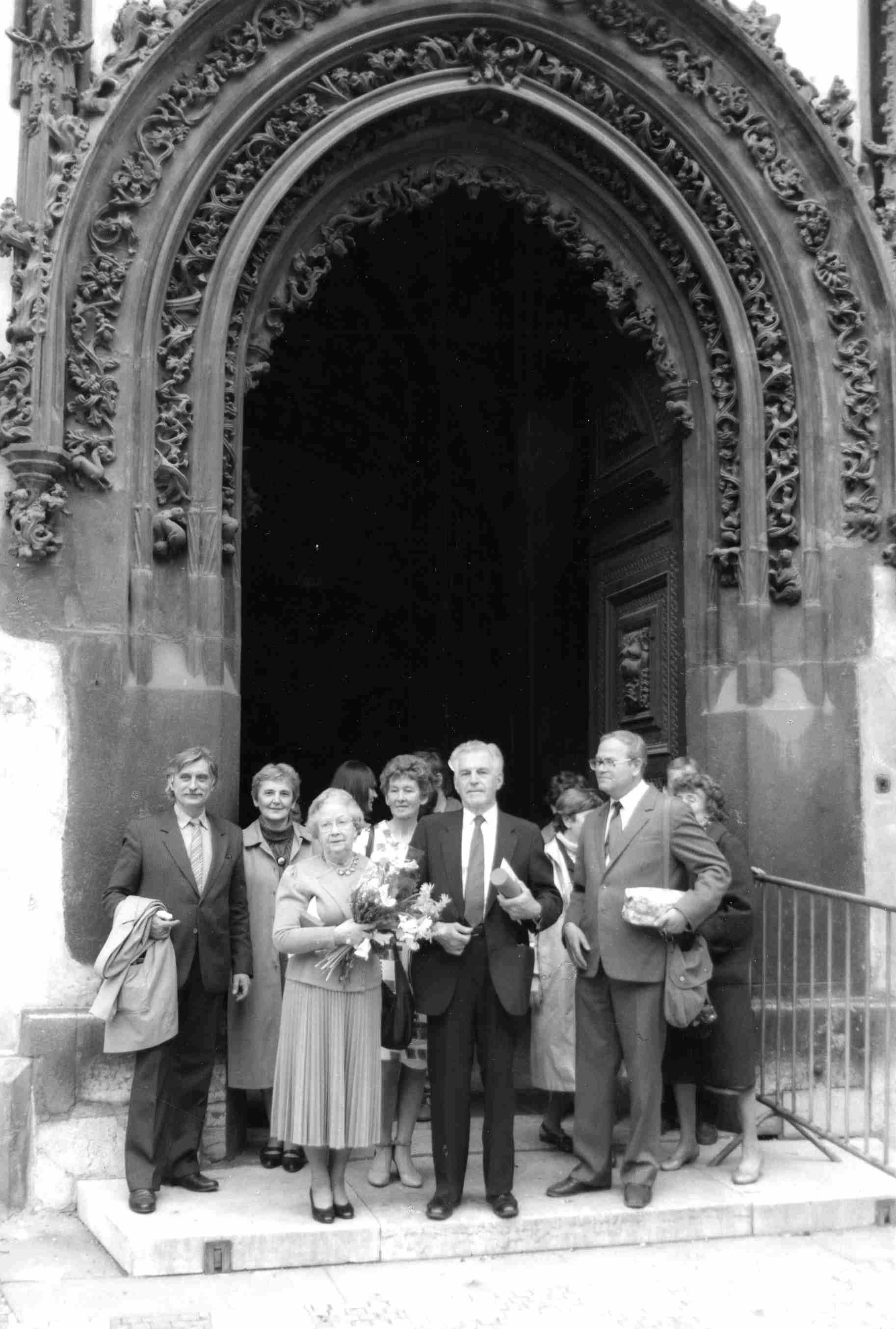

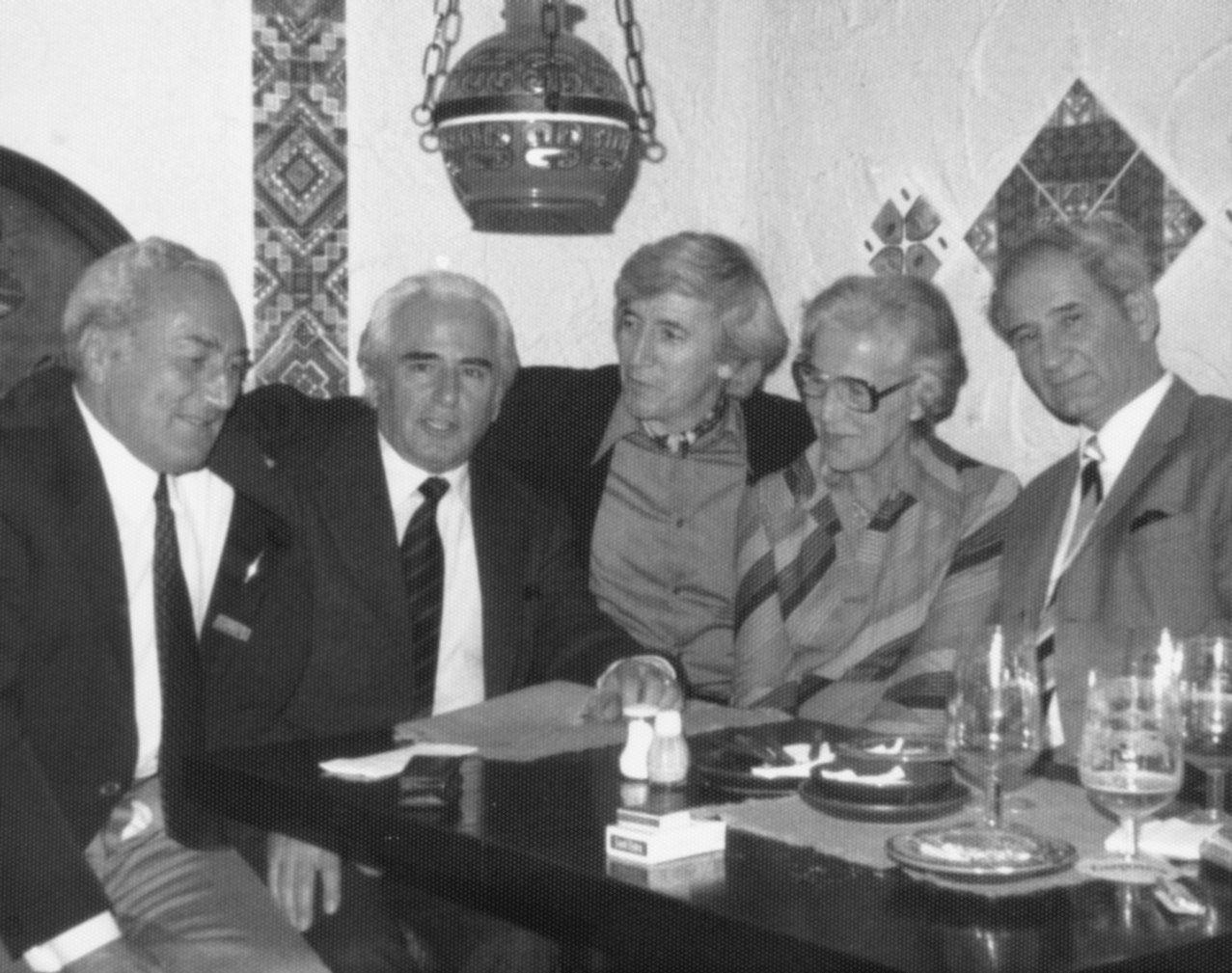

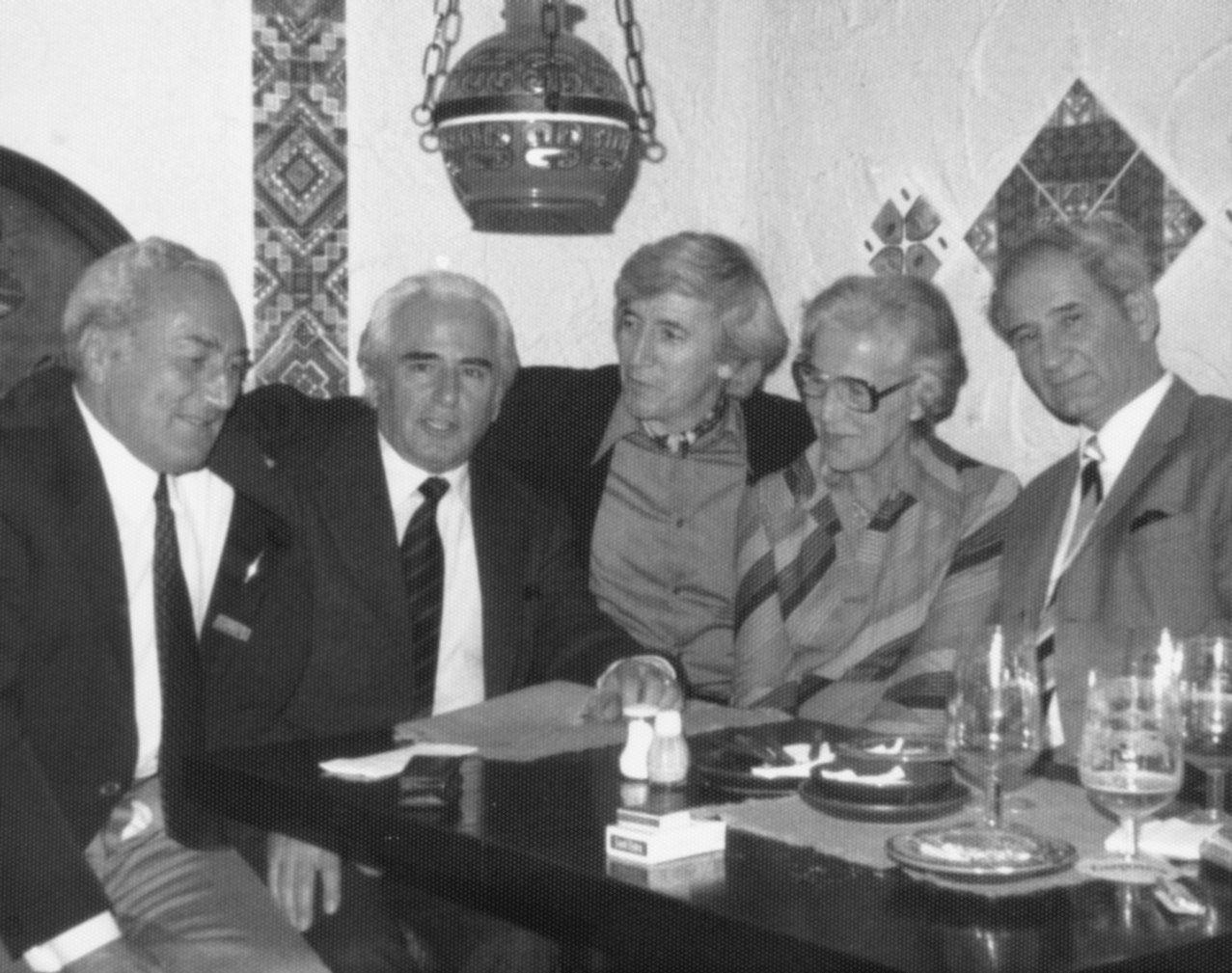

Skilling’s Golden Wedding anniversary, was at the Old Town Hall in April 1987. The journey Gordon Skilling made to Prague in April 1987, marked the celebration of Skilling's 75th birthday and the 50th anniversary of his marriage to Sally. The wedding ceremony was arranged by his dissident friends in the Old Town Hall, which was also the same ceremonial hall where they were married in 1937 (their wedding in October 1937 took place during G. Skilling’s first time in Czechoslovakia, where he studied the History of Central Europe as a student of London University). The anniversary celebration was a delicate irony in which the guests were fond of - a tribute to the "enemy of the state" because the Communists had released a number of dissidents which they had not known about. The next day in the Prague Evening, the news appeared, with a somewhat funny title, "Wedding Overseas". Jiřina Šiklová gained a great credit for this, because she paid the newspaper editors with the make-up from Tuzex at that time.

Gordon Skilling himself remembers this after years in an interview with Lidove Noviny in June 1993: "It was an interesting ceremony because perhaps all Czech dissidents - Havel, Pithart, Dienstbier and others - were present. It was strange that, in this honest ceremony, the chairman of the National Committee for Prague 1 spoke about what I did for Czech history. But he did not know that I also wrote a book about the Prague Spring, a book on Charter 77 and other things. He did not know it, and so he was very glad. Absurd situation. But the dissidents liked it. They were smiling internally. And then we had a gala dinner at the Municipal House. I like to recall the event."

The Libri Prohibiti’s collection of foreign samizdat monographs and periodicals contains mainly Slovak and Polish samizdat literature. Russian samizdat and periodicals from the former German Democratic Republic are marginally represented.

The Polish Underground Library was set up in 2009 in collaboration with the The Karta Center Foundation in Warsaw. It is comprised of Polish underground and exile publications, Polish flyers, posters, sound and visual recordings that are part of the Libri Prohibiti’s collections.

The Memory of Nations is an extensive online collection of the memories of witnesses, which is being developed throughout Europe by individuals, organizations, schools and institutions. It preserves and makes available the collections of memories of witnesses who have agreed that their testimony should serve to explore modern history and be publicly accessible. The collection includes testimonies of communism resistance, holocaust survival, artists of alternative culture and underground and many others.

The collection illustrates Adrian Marino’s intellectual evolution as a historian and literary critic who chose to pursue his activity outside the institutions controlled by the communist regime. The Marino Collection includes books, original manuscripts, and the author’s correspondence, which reflects a critical perspective on Romanian literary life in the period 1964–1989.

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Offences against the Polish Nation (IPN) was created under parliament act of 1998 and is a state body authorised to carry out research, educational, archival, investigative, and vetting activities. The head office is located in Warsaw and there are 11 branch offices in larger cities, as well as 7 delegations. The historical scope of Institute’s activities is very ample, as its operations concern the period from 1944 to 1989. Its tasks include collecting and managing national security services’ documents created between 22 July 1944 and 31 July 1990, as well as investigating Nazi and communist crimes - against Polish nationals or Polish citizens of other nationalities - committed between 8 November 1917 and 31 July 1990. Other important activities include scientific research and public education. Institute of National Remembrance collaborates closely with State Archives, veteran organisations, historical associations and foreign agendas involved in research and commemoration of the recent history, in particular history of Central-Eastern Europe.

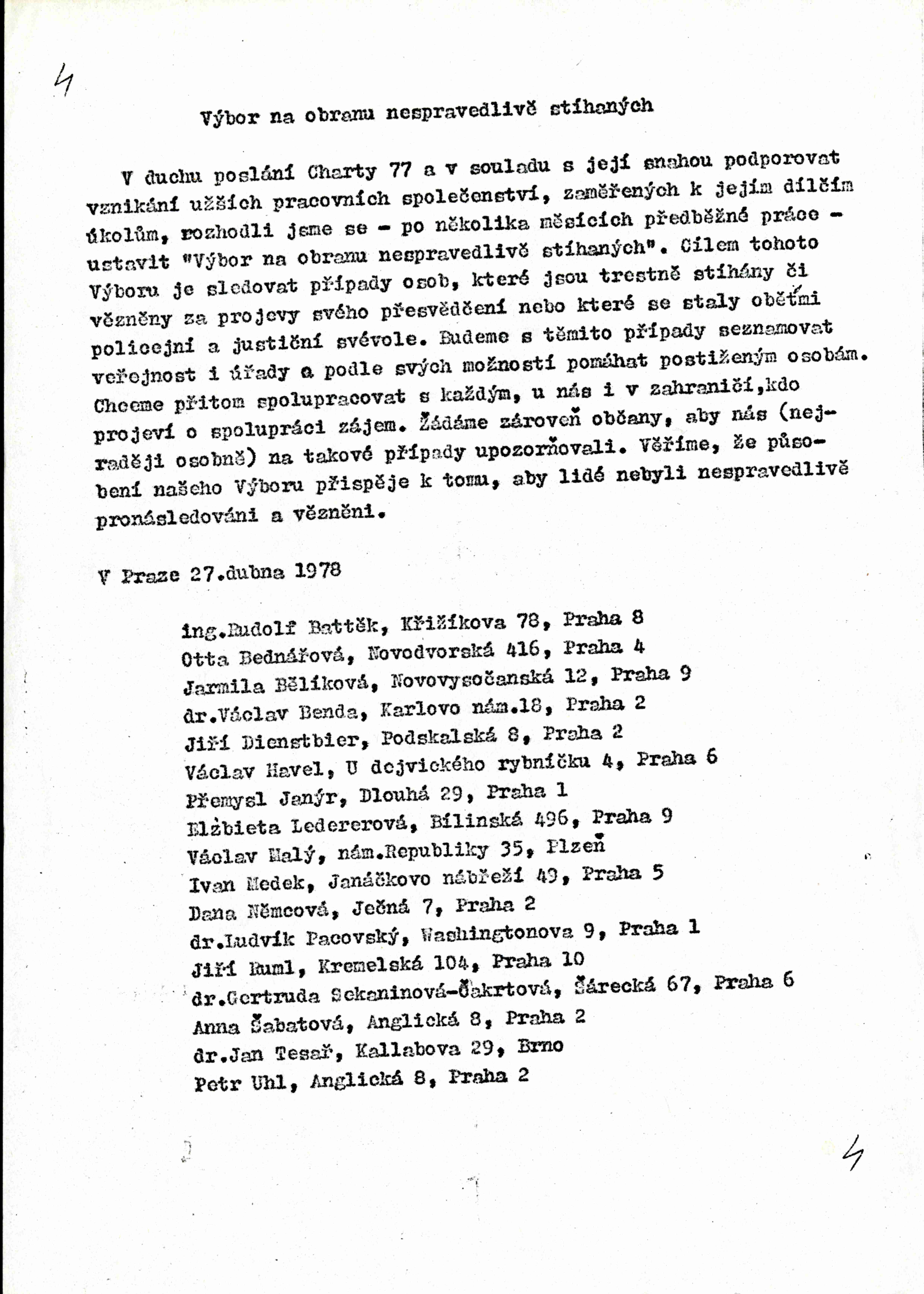

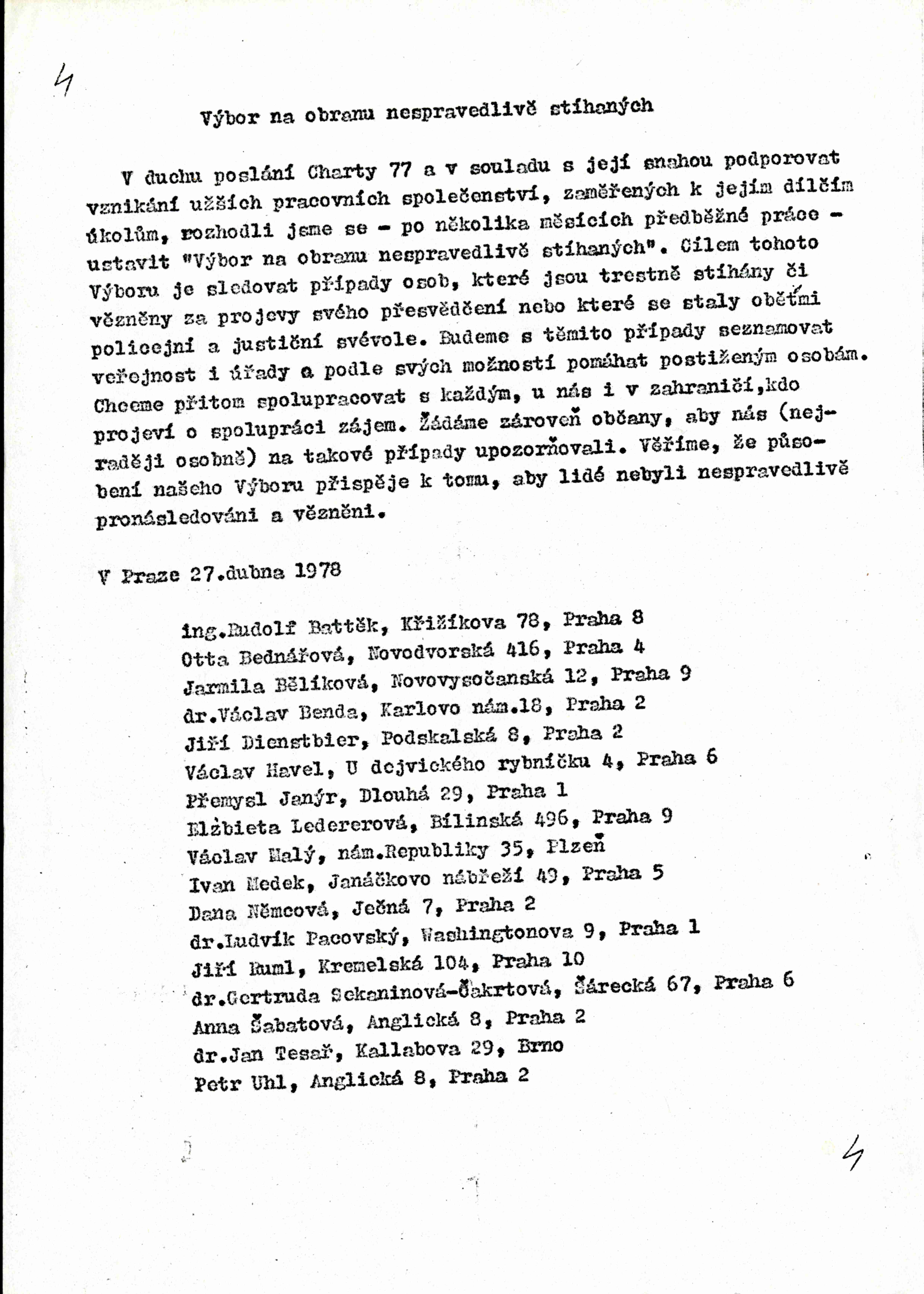

The founding statement of the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS) of April 27th, 1978, signed by seventeen signatories on the Charter 77, who posted their addresses so that people could find them. VONS's goal was to track the cases of people who had been prosecuted or imprisoned for their opinions and beliefs or who had become victims of police and judicial arbitrariness. VONS, by means of numbered communications, familiarised the domestic and international public with these cases and asked the Czechoslovak authorities for remedy. They helped to provide legal representation and mediate financial assistance to the unjustly persecuted and imprisoned.

The impulse for the creation of VONS was, among other things, the events associated with the Railroad Ball in January 1978, in which the signatories of the Charter 77 wanted to attend to. However, three of them were detained by the state security. In support of them, the Defence Committee was formed by Václav Havel, Pavel Landovský and Jaroslav Kukal, who gathered documents for their defence and informed the Czech and foreign public about the whole case. The accusations were released after six weeks and the prosecution was halted. This was a great success for committee members and other dissidents, so VONS was founded in May 1978.

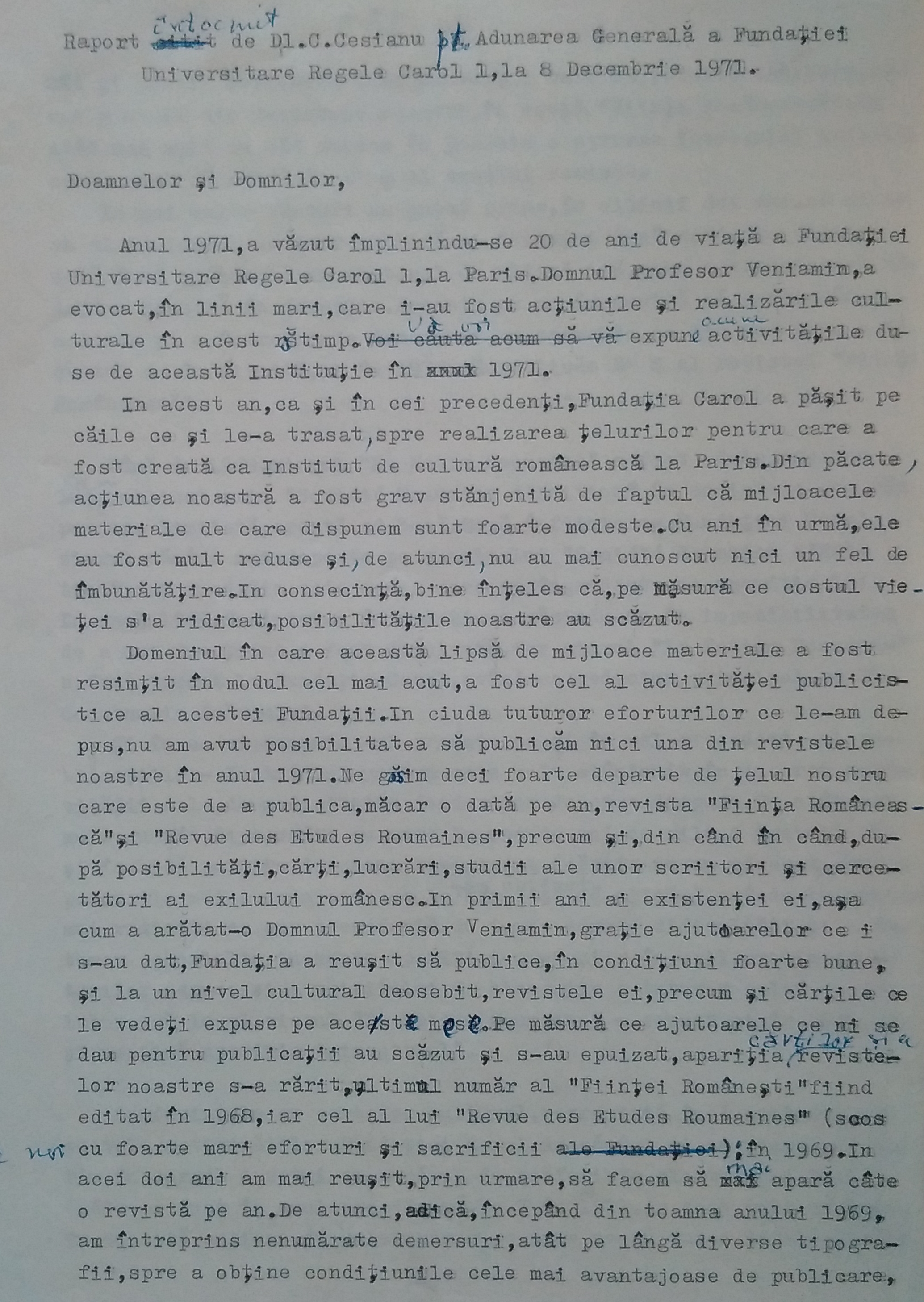

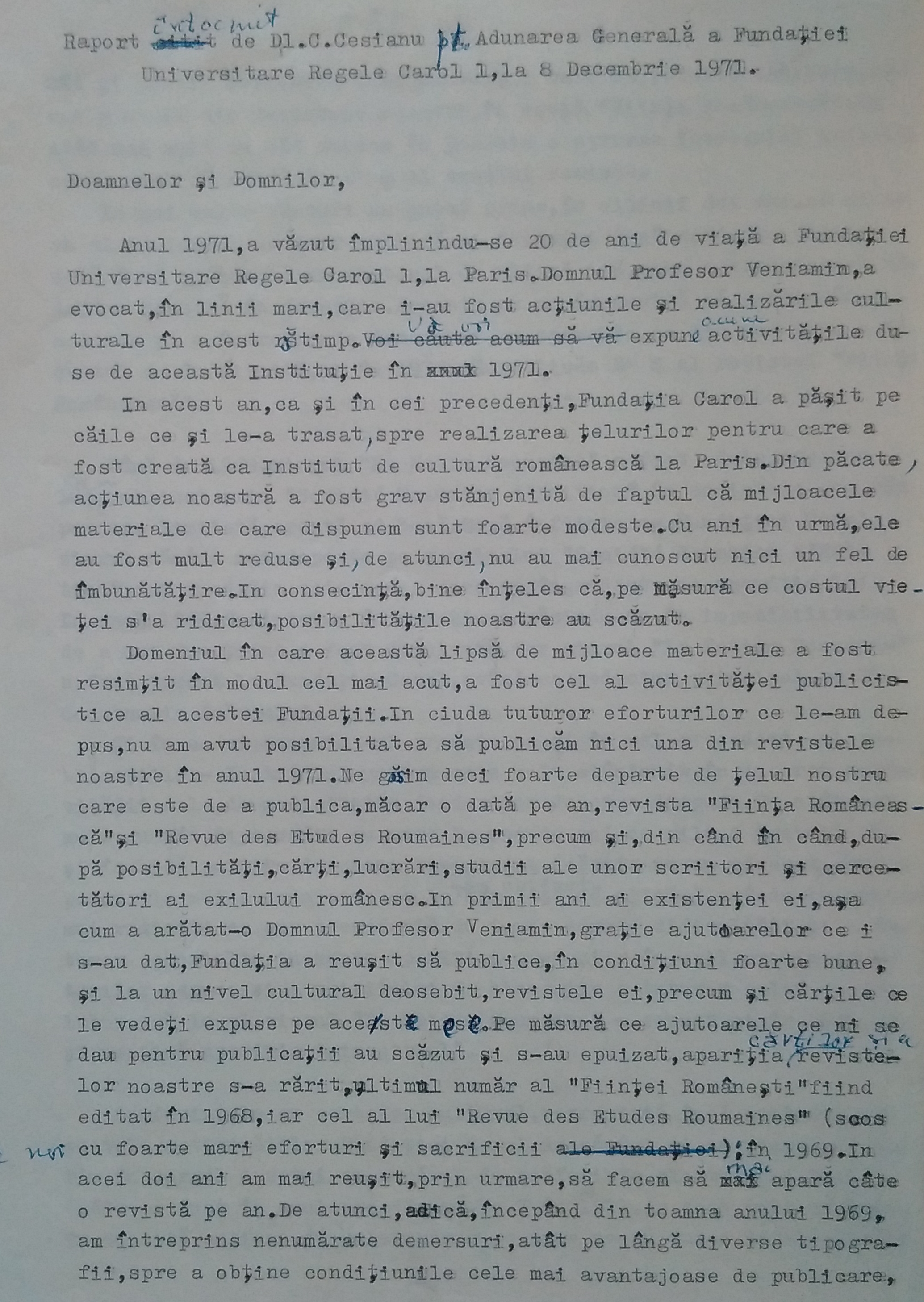

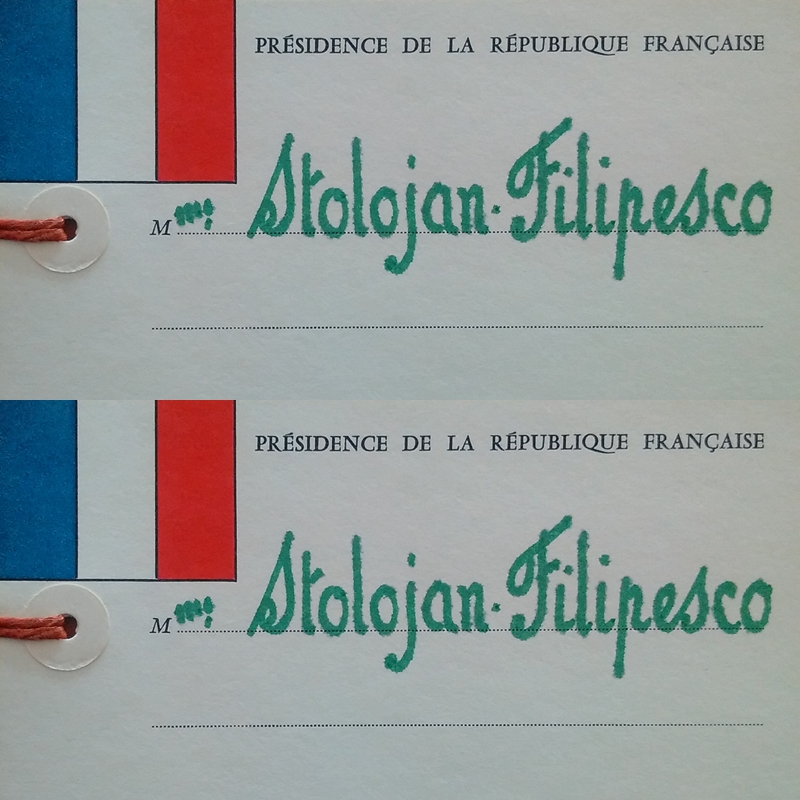

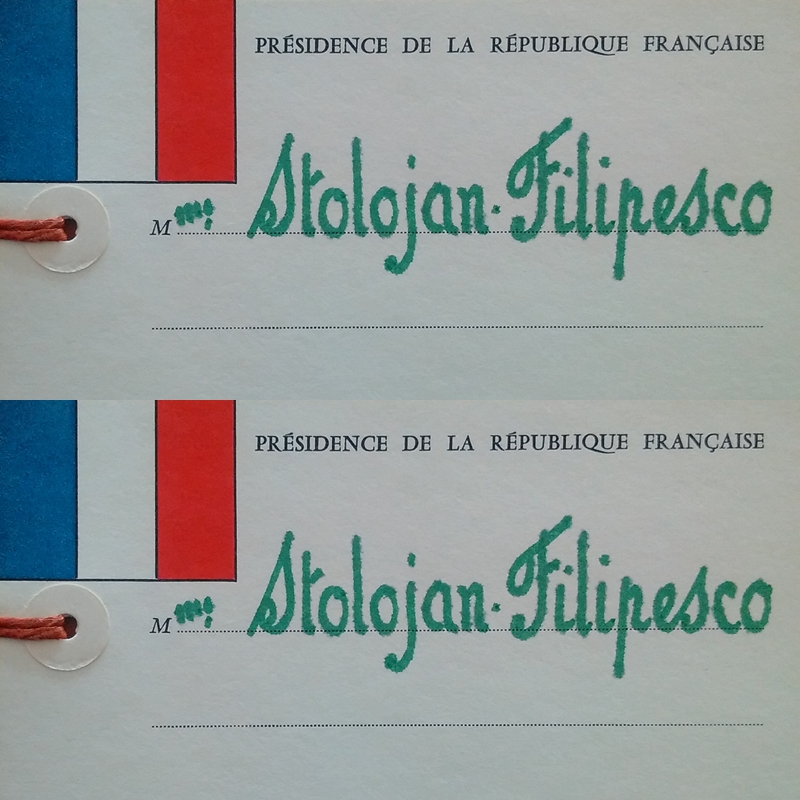

Report by Constantin Cesianu for the General Assembly of Carol I Royal University Foundation, in Romanian, Paris, 1971

Report by Constantin Cesianu for the General Assembly of Carol I Royal University Foundation, in Romanian, Paris, 1971

This document reflects the manner of organisation and activity of the Romanian postwar exile community, as well as a series of major problems that it encountered: the lack of material means and of the unity of Romanians. The Romanian exile community, although a form of opposition of Romanians from several historical periods, reached a significant dimension during the communist regime. The postwar Romanian exile community manifested itself over an expanded geographical area, spread across several continents: Europe, North America, South America, Australia, and Africa. There were, however, a number of states where the Romanian exile community was particularly active: France, the USA, the UK, West Germany, Spain, and Canada. Determined by the domestic political context and influenced by shifts on the international political scene, the Romanian exile after the Second World War must be understood as a reaction to the establishment and domination of the communist regime in Romania and as a form of opposition to it. Romanians abroad tried to organise themselves by setting up foundations, associations, institutions, institutes, and publications with the purpose of: representing the Romanian nation and defending its interests until its liberation; carrying out actions that would lead to the restoration of the democratic system in Romania; coordinating the activity of Romanians outside the country for the fulfilment of this common cause; establishing links with Western governments and international organisations; representing the exile community and solving its problems; and collaborating in joint activities with representatives of the other "captive nations" in Central and Eastern Europe.

The report in question, which amounts to five pages, presents the situation of one of the most important cultural organisations of the exile community, the Carol I Royal University Foundation. A university level institution, the Carol I Royal University Foundation (1950–1974) was initially founded in Paris on 3 May 1881 by King Carol I, but was abolished by the communist regime in Bucharest. Later, on December 8, 1950, out of a desire to continue the old royal family tradition, it was re-established by King Michael I in exile, with the support of the Romanian National Committee, which was in the view of the founders the government of Romanians in exile. The Foundation began to function effectively on 1 January 1951. The purpose of the Foundation was: to present the values of Romanian culture to the West; to affirm and develop the traditional ties between French and Romanian cultures; to establish and maintain relations with cultural and educational institutions and with the French administrative authorities; to ensure a Romanian presence in international cultural forums and events; to safeguard the national cultural heritage; to study the cultural and technical problems that Romania would face after liberation from the communist regime; to support and guide Romanian students in exile; to encourage scholarly research; to build up a library at the headquarters of the Foundation, transforming it into the House of Romanian Culture abroad. Every year, the Foundation's leaders drew up an activity report. Such a document can be found in the collection of Sanda Stolojan, who was involved in the Foundation's activities and published poetry and prose in its two literary publications: Ființa Românească (Romanian being) and Revue des Etudes Roumaines. A copy of this document is in Sanda Stolojan's private archive due to the fact that she was a close friend of the person who wrote the material, Constantin Cesianu, and was directly involved in the Foundation's actions. Regarding the personality of Constantin Cesianu (1886–1983), he was a political detainee in communist Romania between 1956 and 1963. A few years after his release, he emigrated to France, where he published the book Salvat din infern (Saved from the inferno), in which he reported his experience as a political prisoner in communist Romania. The volume originally appeared in French. It was translated into Romanian and published in Romania in 1992, and is an indispensable part of any specialised bibliography on the subject. In Paris, he actively participated in the activities of Romanians in exile for the promotion of Western media coverage of the repressive and aberrant policies of the communist regime in Romania.

The report that Constantin Cesianu wrote in 1971 draws attention to the situation of the Foundation in that year, when its annual activity balance was not a positive one. The explanation was the lack of the material means to achieve its goals. In fact, all organisations of the exile community were confronted with this problem. On a different line of thought, beyond the Foundation's poor financial situation, the report presented some of the activities the Foundation carried out in 1971: cultural conferences and the celebration of Romania's historic days (1 December – Great Union Day, 24 January – Little Union Day, 10 May – Independence Day). Furthermore, the paper presented the situation of the Foundation’s library and the profile of the researchers who had come there for documentation. Finally, the unity of Romanians abroad was called for – the supreme desideratum of all the organisations of the exile community, though it never materialised between 1948 and 1989.

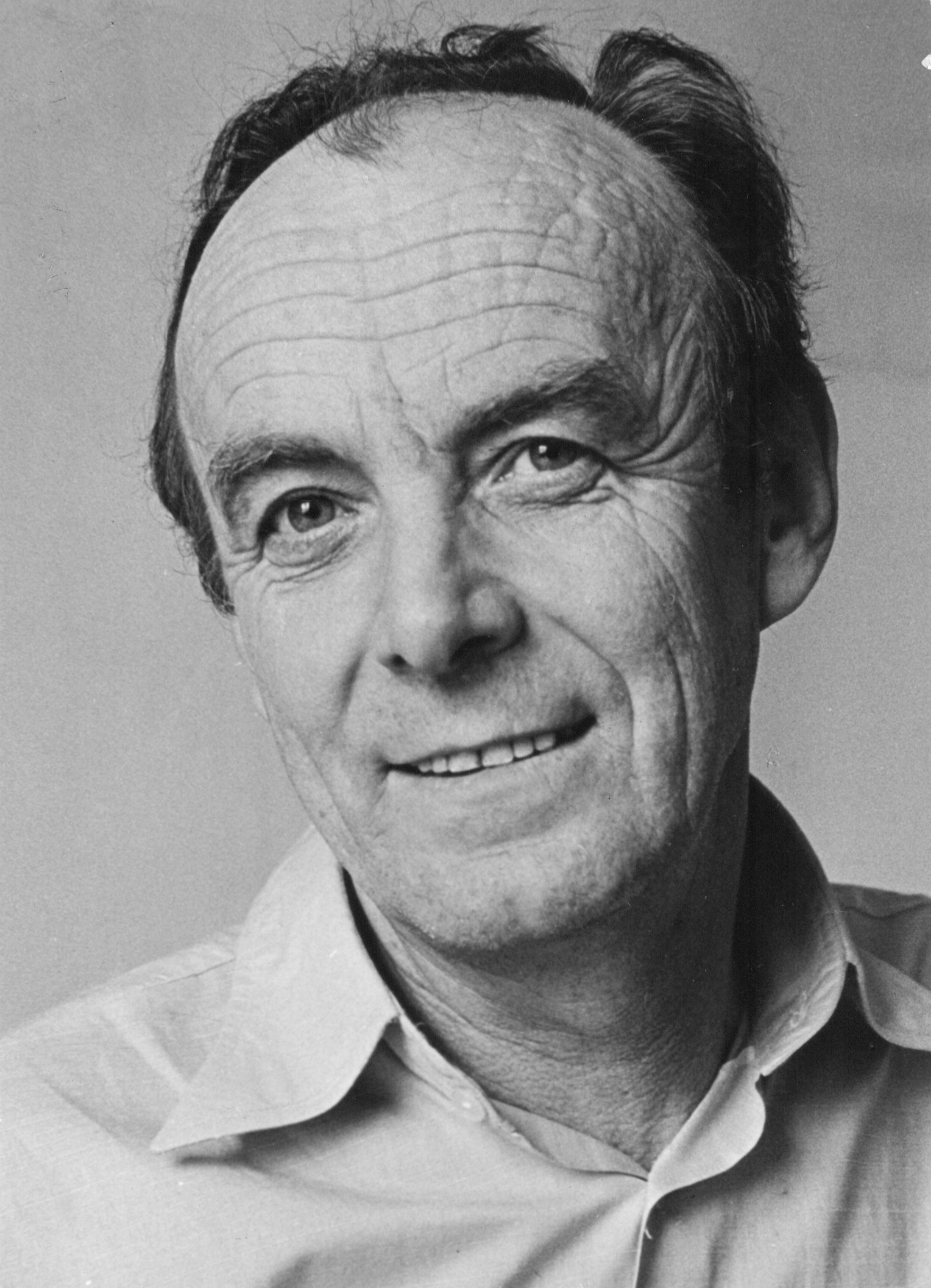

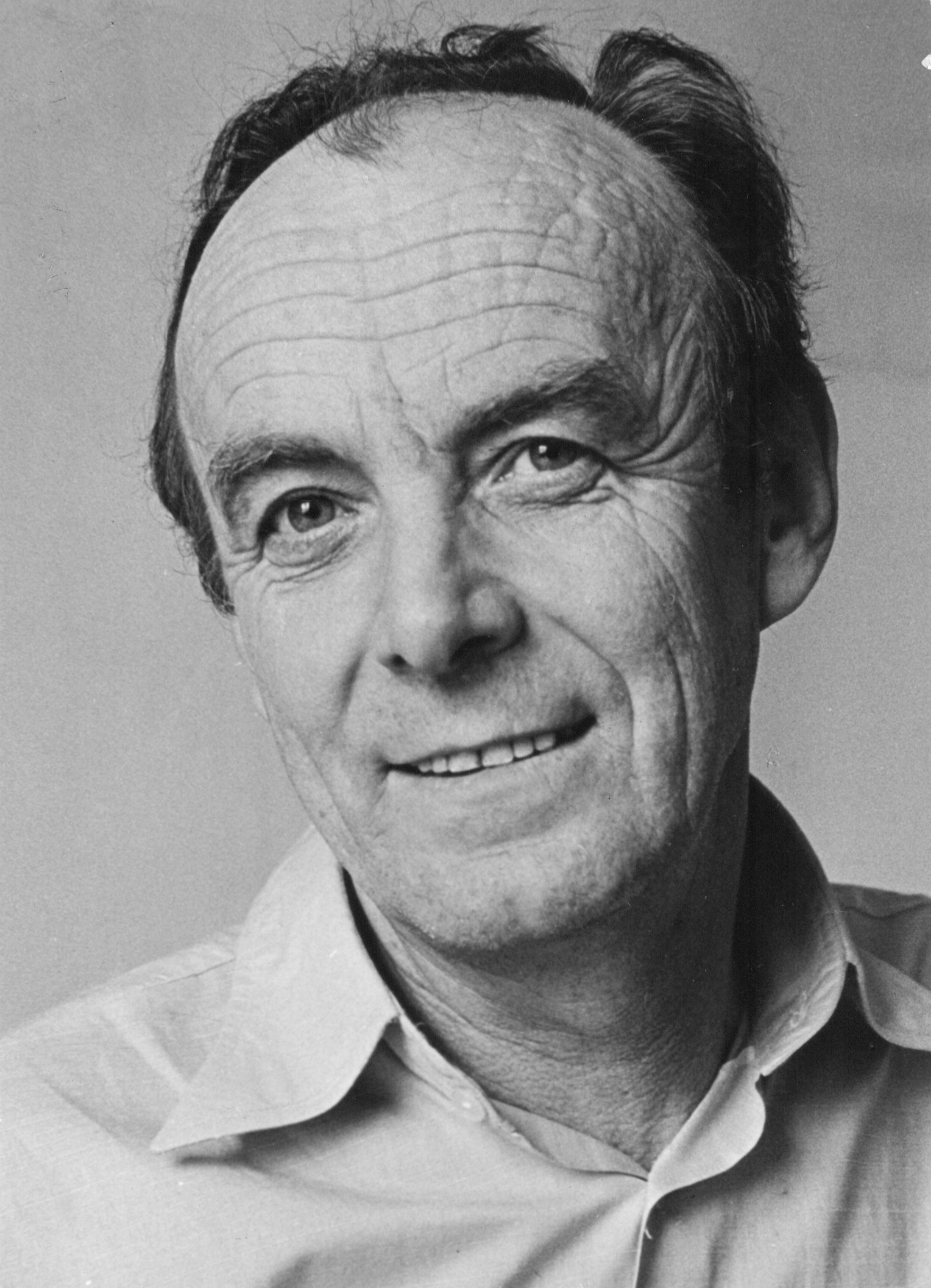

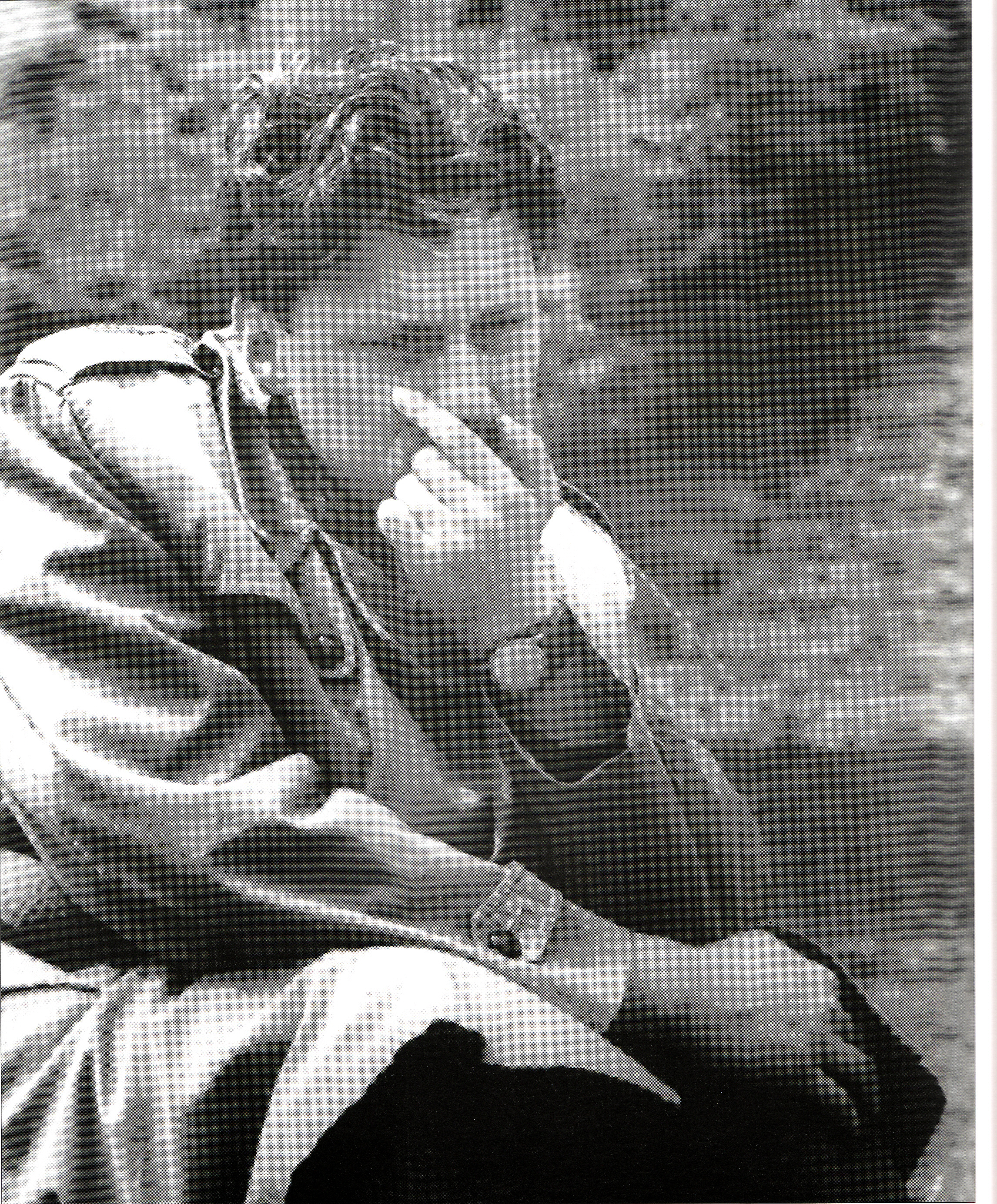

Skilling H. Gordon (1912-2001) was a prominent Canadian historian, political scientist and Slavist. His life and work were closely linked to the dramatic fate of Czechoslovakia from the late 1930s to the 1989 Velvet Revolution.

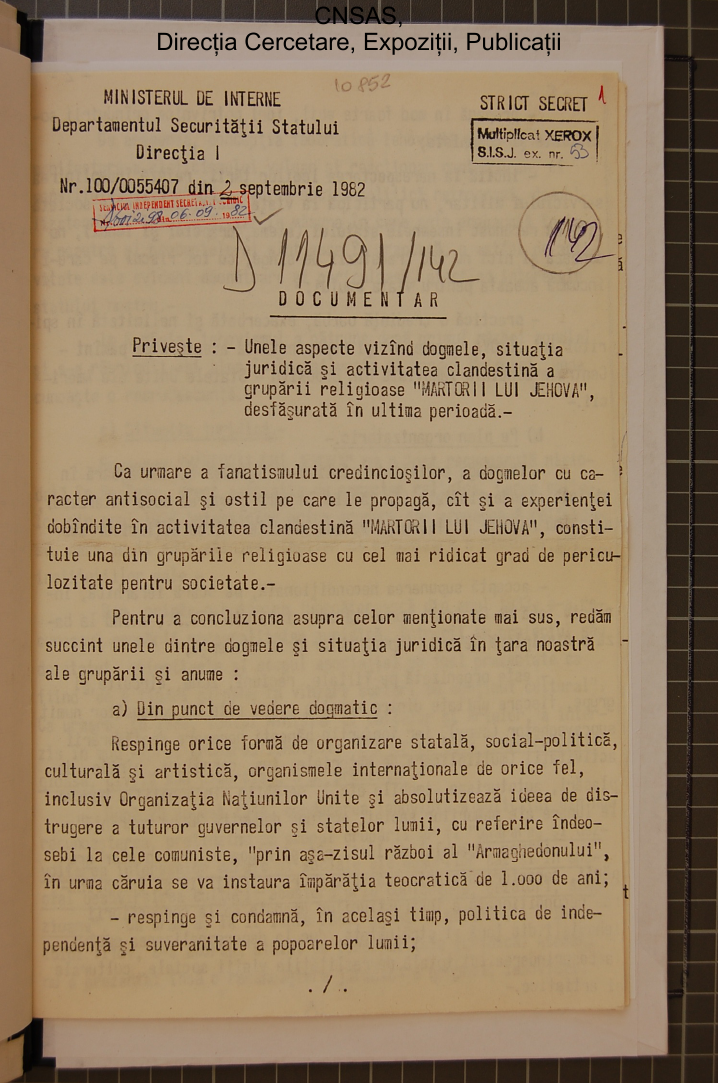

The legal situation and the clandestine activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses religious group, in Romanian, 1982. Report

The legal situation and the clandestine activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses religious group, in Romanian, 1982. Report

The report on “the legal situation and the clandestine activities of the religious group entitled Jehovah’s Witnesses” was drafted by the First Directorate of the Securitate (in charge of gathering information within the country). This report synthesised the evolution of the religious community of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Romania, their legal status during the past and at the time of its issuance, and the policies of the Securitate regarding this religious denomination.

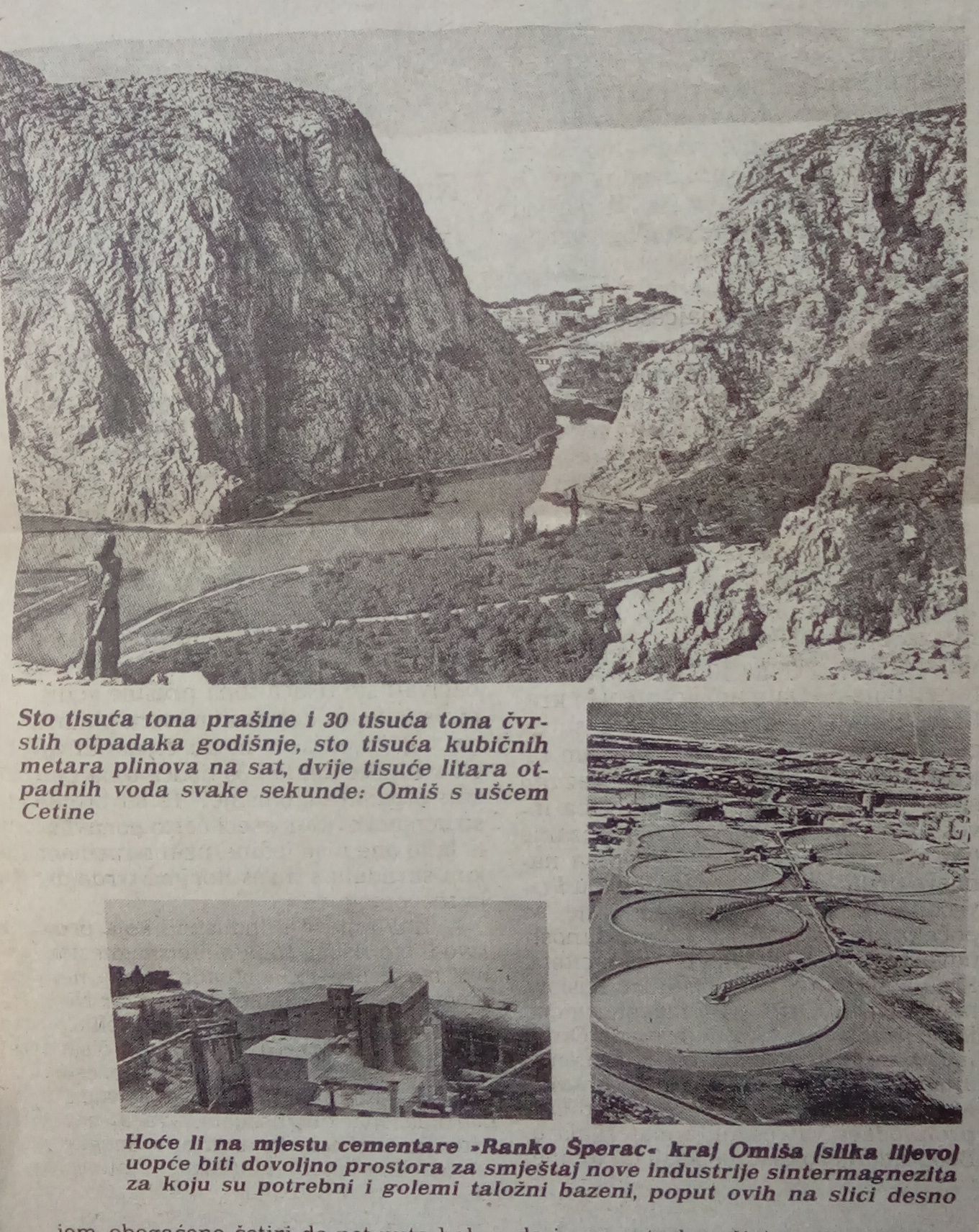

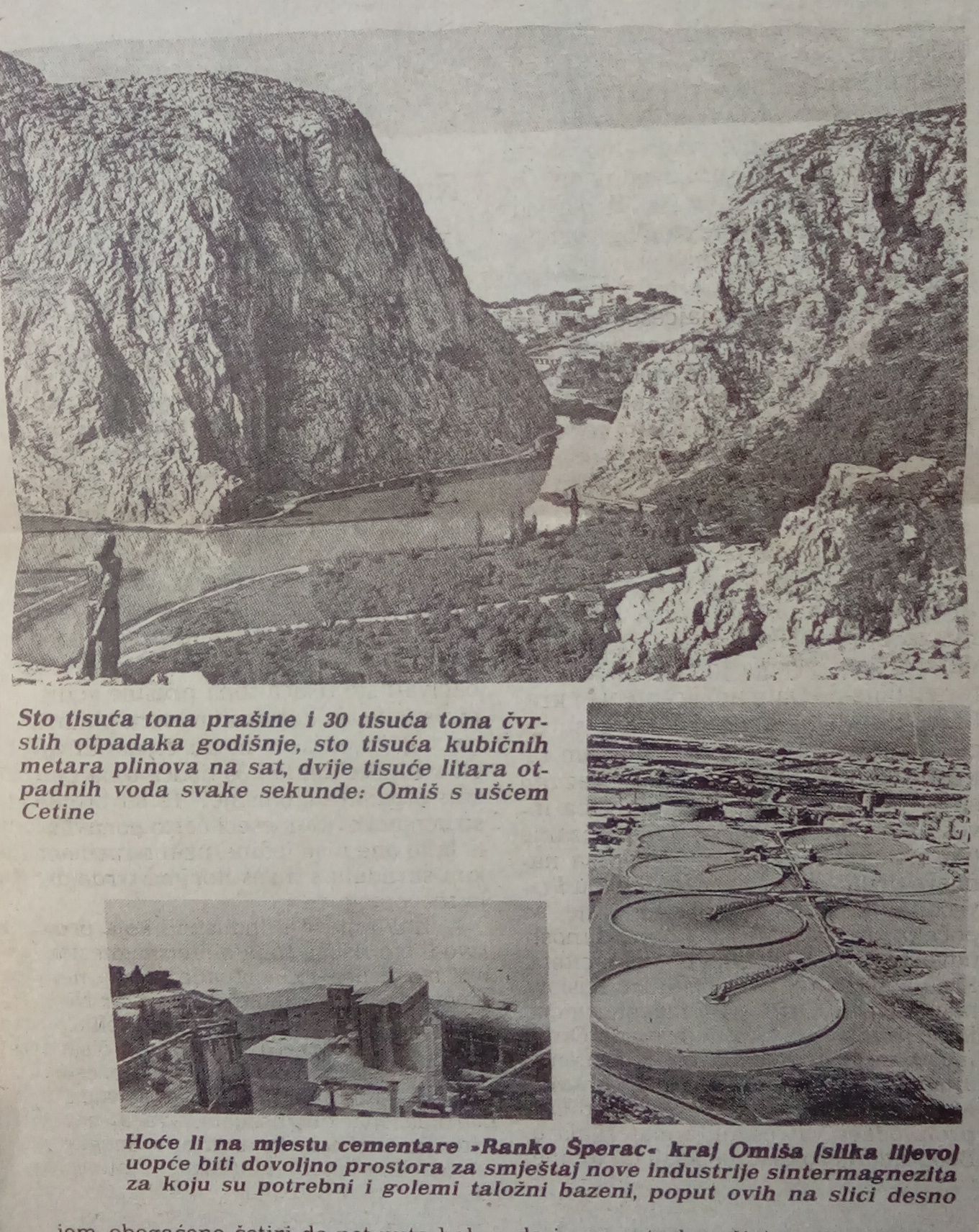

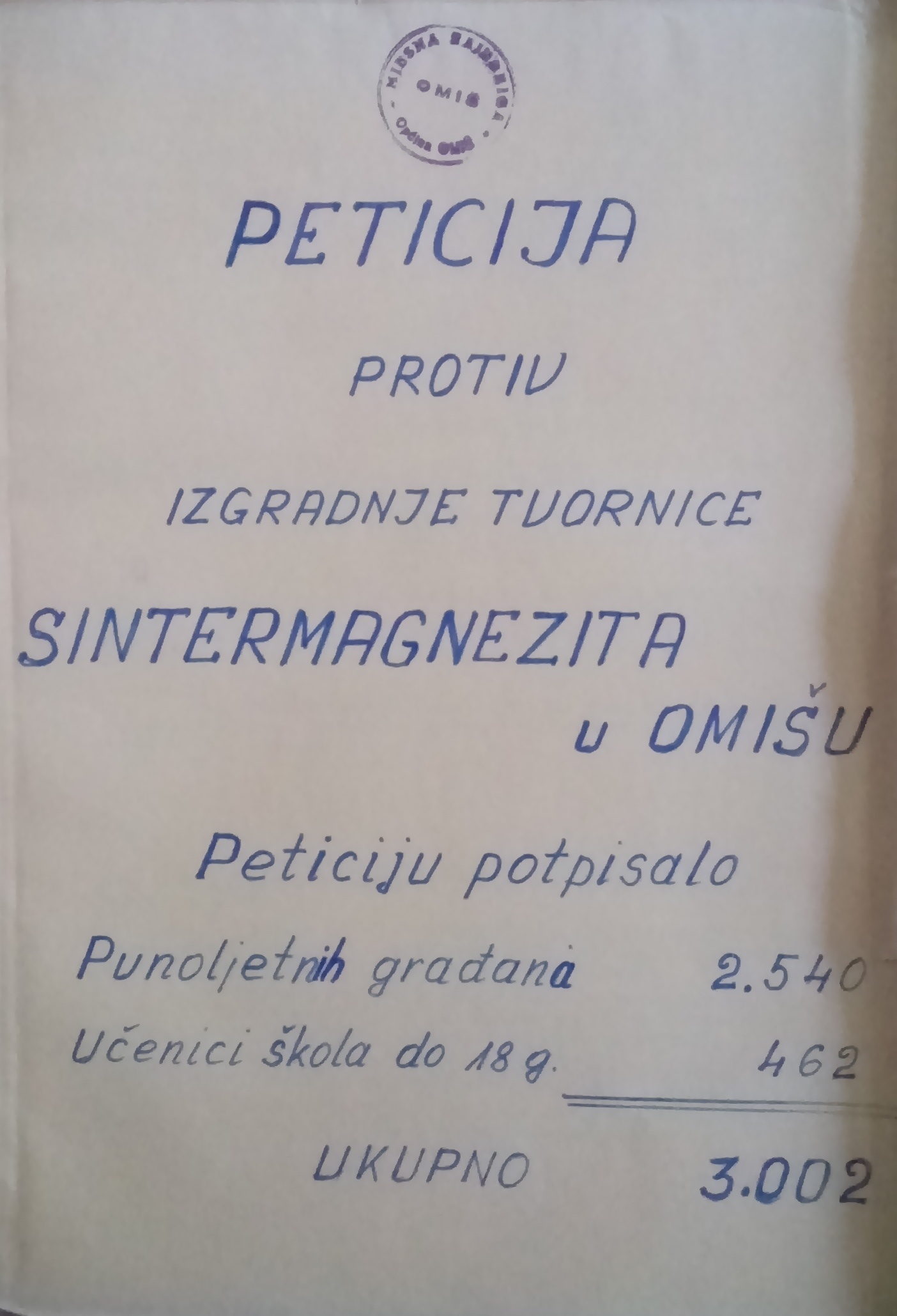

The ad hoc collection contains archival documents and newspaper articles from the period 1979-1984, which testify to local organising and protests by several thousand citizens of Omiš against the construction of a sintered magnesia factory in that area, to prevent pollution and maintain the local tourism potential. The collection combines documents from two archival collections which are held in the Croatian State Archives in Zagreb: the records of the Parliament of the Socialist Republic of Croatia and press clippings from the newspaper publishing house Vjesnik.

The Bogdan Radica Collection is a personal archival fund which Radica founded in the late 1940s. His daughter Bosiljka Raditsa and Professor Ivo Banac delivered the entire collection to the Croatian State Archives (CSA) on three occasions in 1996, 2001 and 2006. It contains vital records related to the history of Croatian political emigration and constitutes an integral part of the cultural opposition to the Yugoslav communist regime.

The Ellenpontok Ad-hoc Collection stored in the CNSAS Archives comprises, besides the records of the Securitate, the written evidences of the system-criticising activity of the samizdat editors and their struggle against the violation of human rights and ethnic discrimination. In addition to the life courses of Transylvanian Hungarian intellectuals monitored during the 1970s and 1980s, the collection offers insight into the working methods applied by the secret police in compliance with the policies of the Party, which envisaged the surveillance of individuals in opposition even after their emigration.

The Matica hrvatska Collection is an excellent historical source for Croatia's cultural and political history. It is an archival collection created by the work of Matica hrvatska, a non-profit and non-governmental cultural organisation which became the central Croatian cultural institution in the Croatian national reform movement – the Croatian Spring. Matica gathered the Croatian intelligentsia that was dissatisfied with the status of Croatia within the Yugoslav federation. That is why the communist government began to treat Matica as an oppositional institution, a driver of oppositional political ideas and a rival to the League of Communists.

The János Dobri Collection of the Reformed Congregation of Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund contains materials covering the confessional life and activity of the eponymous pastor, which alongside proofs of his individual stand and sacrifice, in the course of the official and private correspondence with the Romanian authorities and private individuals, and beyond the struggle for survival of the Reformed church, also provides an insight into the details of the fight for minority and human rights in the twentieth century.

This letter is an important document for the history of the post-war Romanian exile community because it is a proof of the attempt of a Romanian dissident to establish a connection with the emigration. The purpose was to gain the support of Romanians abroad. If their situation was publicised in the West, then there were chances that once returned to their country they would not suffer the reprisals of the communist regime. Also, such actions were meant to trigger the support of international public opinion in criticising Nicolae Ceausescu's dictatorship. One such example was the action of the Romanian writer and journalist Victor Frunză during a tour in France in 1978. In Paris, he wrote a letter to Eugène Ionesco (Eugen Ionescu), a French-language writer originally from Romania, a representative of the theatre of the absurd and a member of the French Academy. In this document, sent on 8 September 1978, Victor Frunză informed Eugène Ionesco that, in France, he criticised openly the situation in communist Romania, especially the personal power and personality cult of Nicolae Ceaușescu. Starting from the idea that he was not the first Romanian and hopefully not the last to do so, Frunză told Ionesco that his approach was deliberately chosen, in full awareness of the possible consequences for him: "When I did this, I knew what I could expect, but I have defeated my fear (...). The sense of the justice of my criticisms gives me the strength to resist. There is no fear of the reprisals that will come anyway, but in the face of the fears of others who can in my mind support me, and in fact will leave me. Immense is the fear of staying alone, as in a desert." In conclusion, Victor Frunză asked Eugène Ionesco to publicly support his action of criticising the dictatorship and personality cult of Nicolae Ceaușescu.

The collection includes various pieces of documentation about the ‘Phosphorite War’ that took place in Estonia in 1987, and material about the Estonian television programme ‘Panda’ in the second half of the 1980s. The collector of the material is Juhan Aare, the journalist and politician who unleashed the Phosphorite War. The most valuable part of the collection is made up of the letters written by people in Estonia and sent to Juhan Aare or to Estonian Television. These letters refer to the environmental situation and the national question in Estonia.

The collection of Pavel Kohout is an extraordinary set of materials documenting a transformation of the author's personality from a prominent literary into a representative of the cultural opposition engaging in the Charter 77 and then being in exile.

Gojko Đogo was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for publishing a collection of poems entitled Vunena vremena [Woollen Times] in which he “metaphorically alluded to Tito’s rule as one of tyranny, indolence and ignorance” (Dragović-Soso 2002, 54). It was the first time that “poetry was being tried” and thus support for Đogo was considered to be a principled defence of the freedom of literary and artistic creation and brought together intellectuals from across the political spectrum (nationalists, the “New Left”, and liberals).

The Đogo case was significant in that it led to the first institutional base of intellectual activism since the crackdowns of the early 1970s. This is reflected in the formation of the Committee for the Protection of Artistic Freedom at the Association of Serbian Writers in May 1982.

In the first two years of its work, the Committee raised its voice against Đogo’s persecution and imprisonment, the ban of the book Slučaj Đogo – dokumenti [The Case of Đogo - Documents] by Dragan Antić, the ban of the play Golubnjača in Novi Sad, the broadcast Beograde, dobro jutro [Belgrade, Good Morning] by Dušan Radović, the ban of Ljubomir Simović’s collection of poems Istočnice, the sentencing to seven months’ imprisonment of the Dubrovnik poet Milan Milišić, the closure of the Zapis publishing house, the ban on the regular publication of the newspaper Književne novine, the ban of Nebojša Popov’s book Društveni sukobi – izazov sociologiji [Social Conflicts: A Challenge to Sociology], the illegal detention of the writer Borislav Pekić in Belgrade, the ban of Aleksandar Popović’s play Mrešćenje šarana [The Spawn of the Carp] in Pirot, and the ban of Živojin Pavlović’s book Ispljuvak pun krvi [Spit Full of Blood], among others (Kljakić 2015).

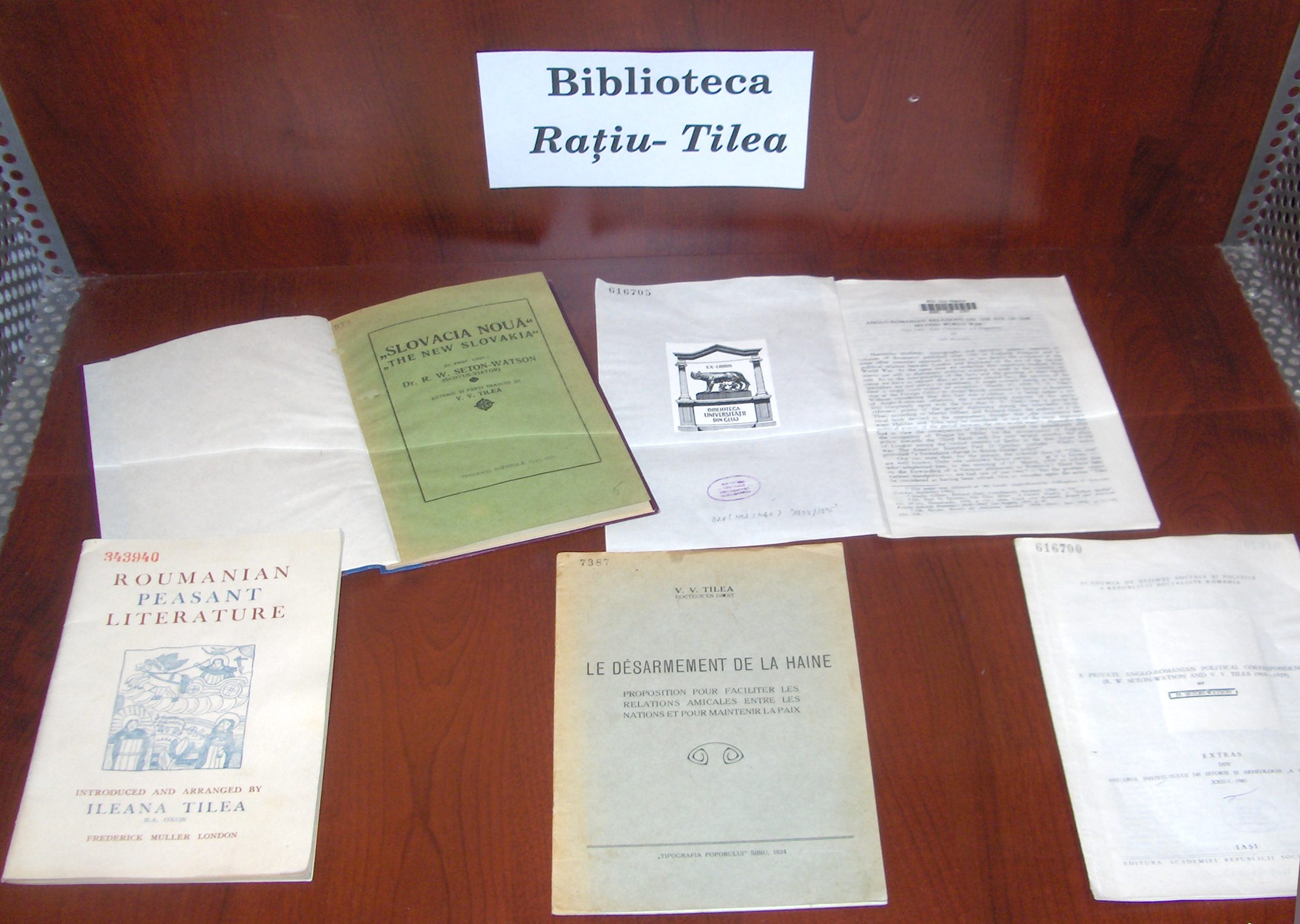

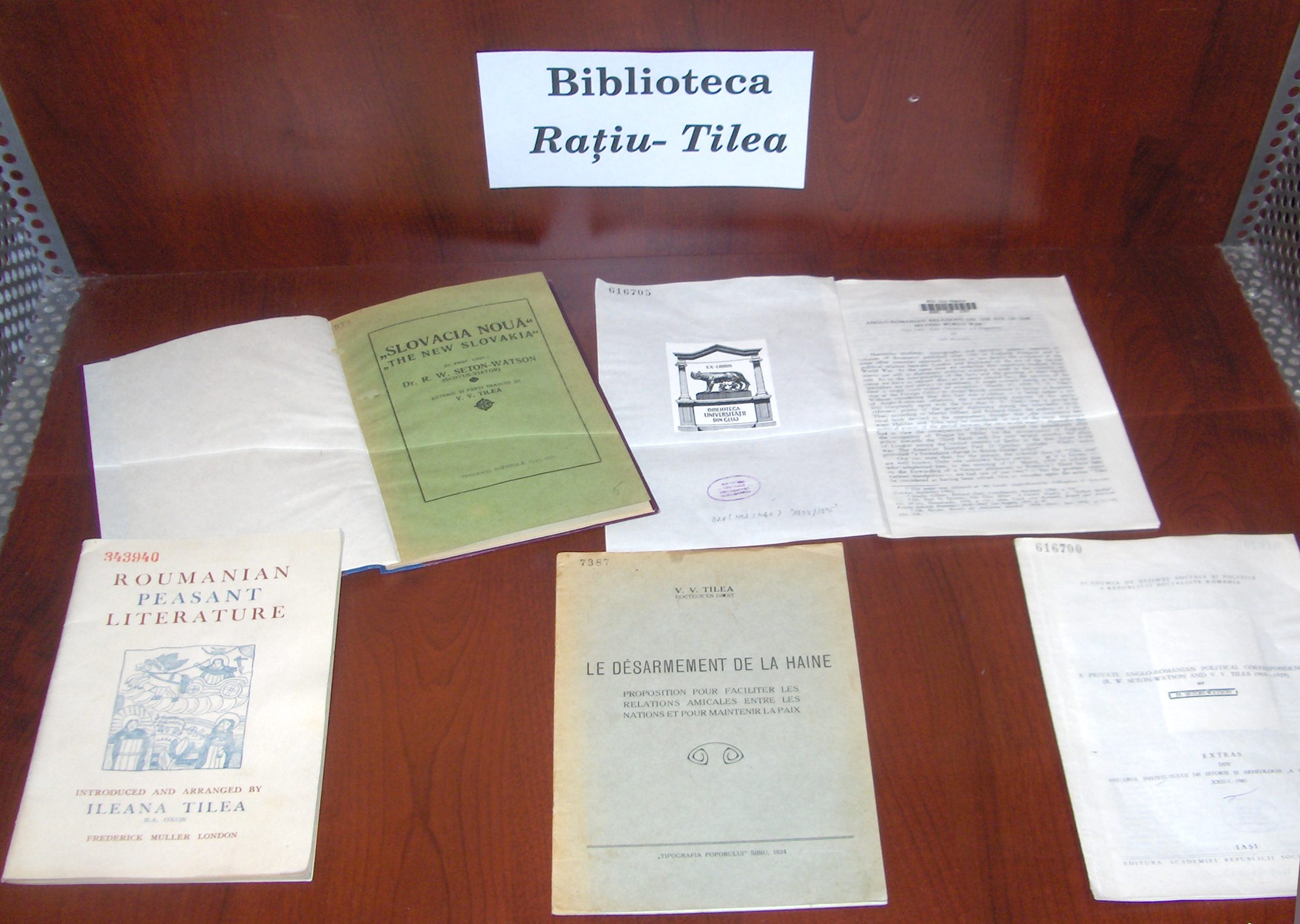

The collection comprising the documents collected by Ion Raţiu and Viorel V. Tilea gives detailed insights into the activities of its two creators, who were key political and cultural personalities of the Romanian diaspora. It represents one of the most valuable sources of documentation for the history of the Romanian exile community in the West during the Cold War period.

Photographic collection of European Solidarity Centre documents the most important political events from the 1970s and 1980s in Northern Poland. They are a testimonial of suppression, fight and victory, but they also tell little histories: of alternative lifestyles and artistic sensibility. The still-growing archive resources contain over 63.000 items.

The Ion Dumitru Collection is the richest and most diverse of all the private archives of the Romanian exile community, which makes it indispensable for the study of the history of postwar Romanian exile. The collection is also a fundamental source for documenting and understanding Romania's (domestic and foreign) political, cultural, economic, and social evolution during both the communist and post-communist periods. At the same time, this private archive is a historical source both for understanding how the Bucharest authorities acted to divide the Romanians abroad and to counteract their actions aimed at unmasking the wrondoings of the communist regime between 1948 and 1989 in the West and for how Romanians within the country perceived the emigrant community.

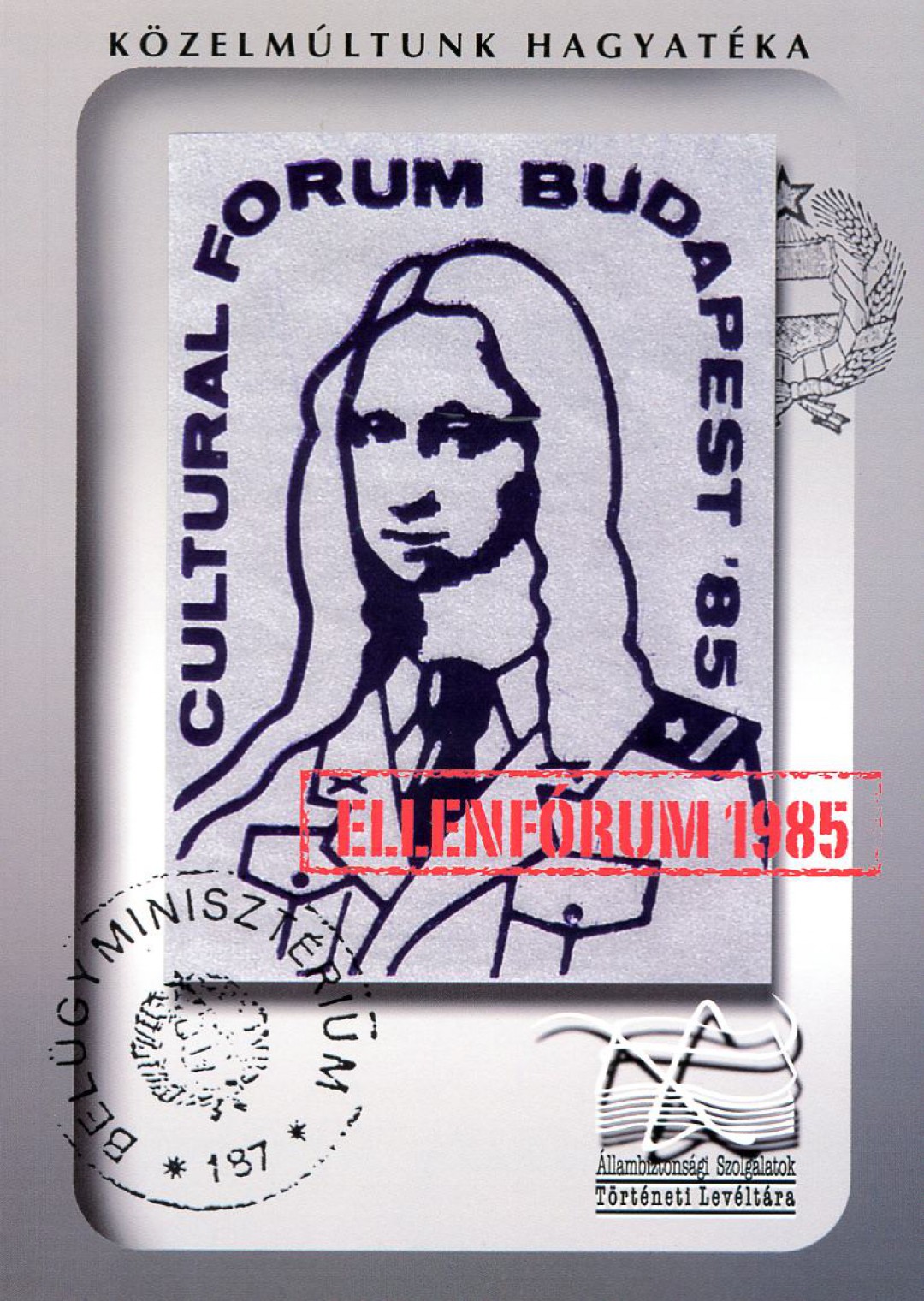

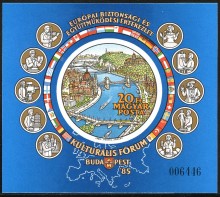

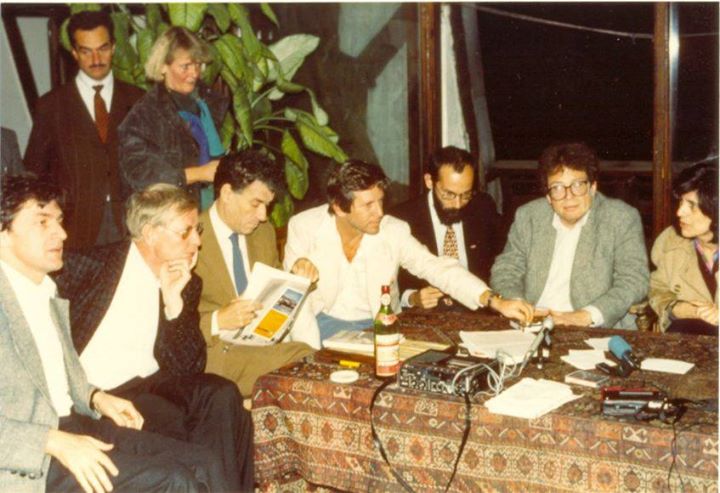

The documents of the Cultural Forum and Counter-Forum of Budapest in late 1985 reflected on the major changes which had just begun at the time in East-West relations, politics, and diplomacy, together with the challenging concept of cultural freedom as a basic part of human rights. For the official Forum, some 850 participants were accredited to Budapest, thus the city was home for six weeks to a legion of diplomats and experts. However, instead of the protocol-like program of the official Forum, the real novelty which caught the attention of the world, the samizdat press, the Western public, and dissidents from the East (not to mention the Hungarian secret police, who were busier than ever) was an open dispute among writers and intellectuals from both East and West that was held at a poet’s flat and then at a film director’s apartment, and which lasted three days. The rich and versatile sub-collection contains many exciting documents which are of potential interest both to Hungarian and international visitors.

The Augustin Juretić Collection in the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome consists of written (manuscripts and printed matter) legacy collected by Croatian Catholic intellectual Msgr. Juretić during his life as an émigré from 1942 until his death in 1954. The collection attests to Msgr. Juretić’s cultural-opposition activities against the Ustasha regime and communist ideology until 1945, and against the communist government until his death. Msgr. Juretić, in his cultural-opposition activities, advocated the liberation of Croatia from the totalitarian systems of the Ustasha and communist regimes, and ultimately for the creation of an independent Croatian state based on the Christian tradition and democratic principles.

Andrej Aplenc’s testimony of captivity on the island of Goli was held in front of a young audience in Ljubljana on August 27, 2014. Aplenc was detained twice on Goli. The first time, he went to Goli otok in 1949 for a year, and the second time was in 1952 for two years. The reason for his first imprisonment was his criticism of the lack of freedom of speech in Yugoslavia, as he advocated greater freedom of expression for young people. The second time he was imprisoned for refusing to cooperate with the state security service, which tried to recruit him as an informer.

The event was organized by the Study Centre for National Reconciliation and is listed in their Archive of Testimonies as one of the testimonies about the post-war rigidity of the communist system that also impacted young people, resulting in disillusionment with this system and Aplenc's emigration. The testimony is publicly available by prior arrangement but has not yet been used.

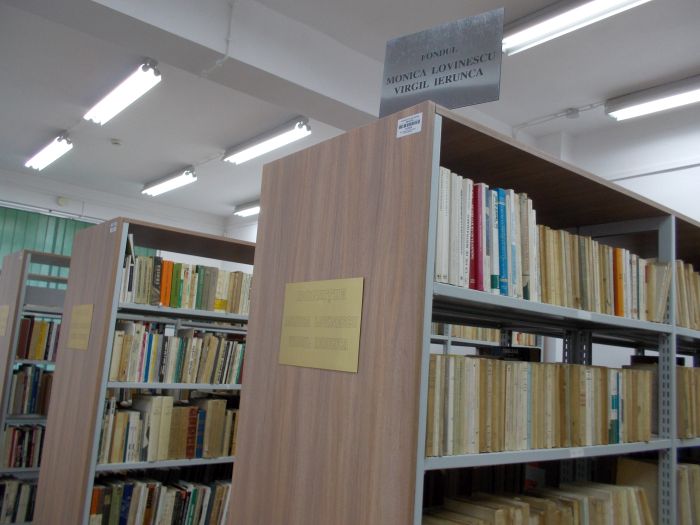

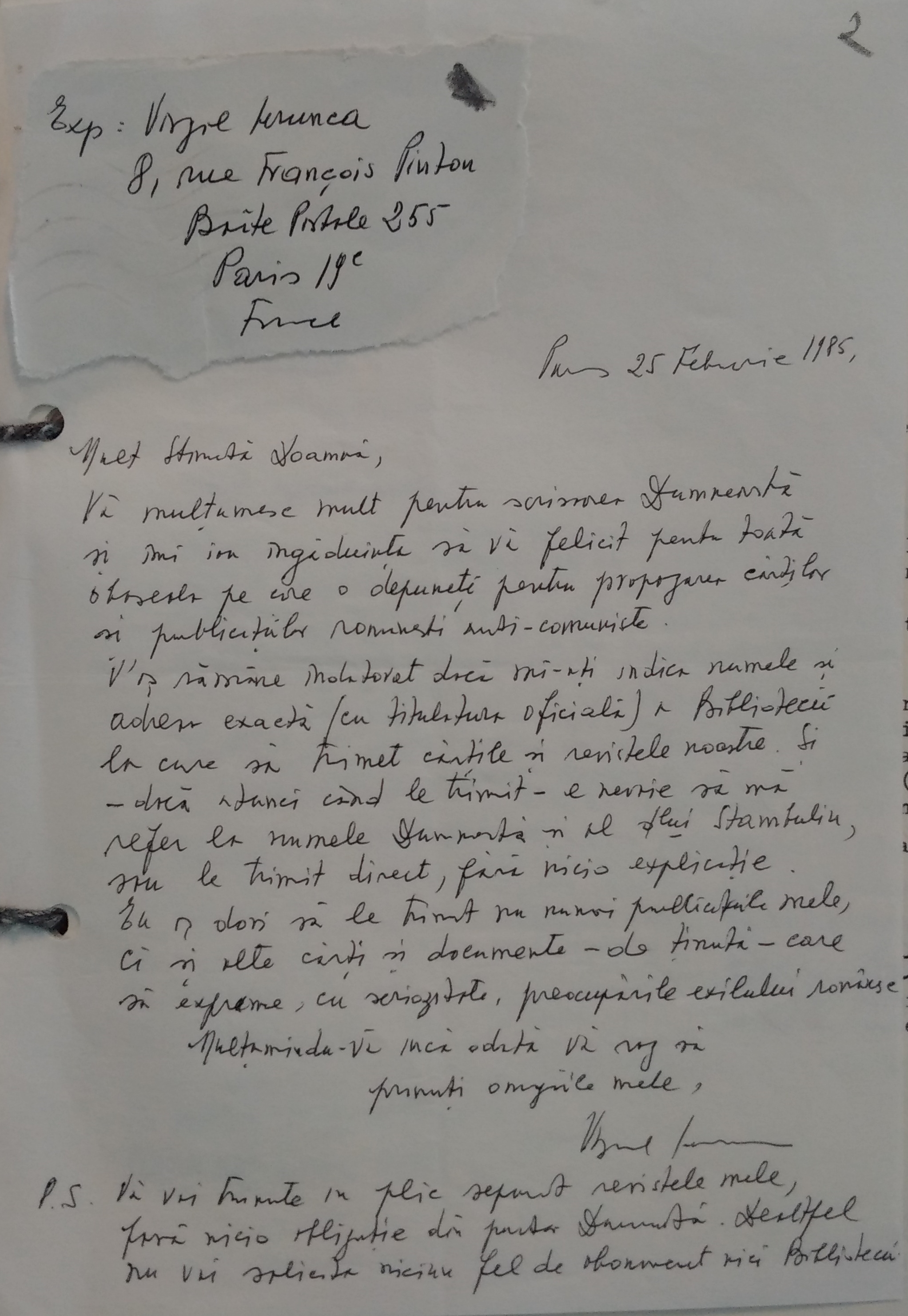

The collection is illustrative for the documentation work that lay behind the broadcasting activities of two prominent members of the Romanian exile community in Paris who worked with Radio Free Europe (RFE), Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca. Their programmes focused mainly on presenting the cases of dissidents in the then Soviet Bloc. The need to understand the dissidence phenomenon and the main ideas behind its criticism of the communist regimes required diverse readings from different subject areas. Thus, the Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca Collection in Oradea testifies to the interest of its creators in subjects relating more or less to cultural opposition in the fields of literature, philosophy, sociology, history, art, and religion.

The collection "Only the Forbidden Newspapers Remain in History!" (Stefan Prodev) is one of the many collections of funds of the National Library "St. Cyril and St. Methodius "(NBCM), containing rich and diverse materials for and from the socialist period.

The newspapers and magazines presented in the collection show the possible forms of opposition by journalists and authors; the ways in which questions of freedom of the press were raised; the attempts to circumvent censorship and to rise critical issues on the regime; to develop new insights into artistic and genre diversity.

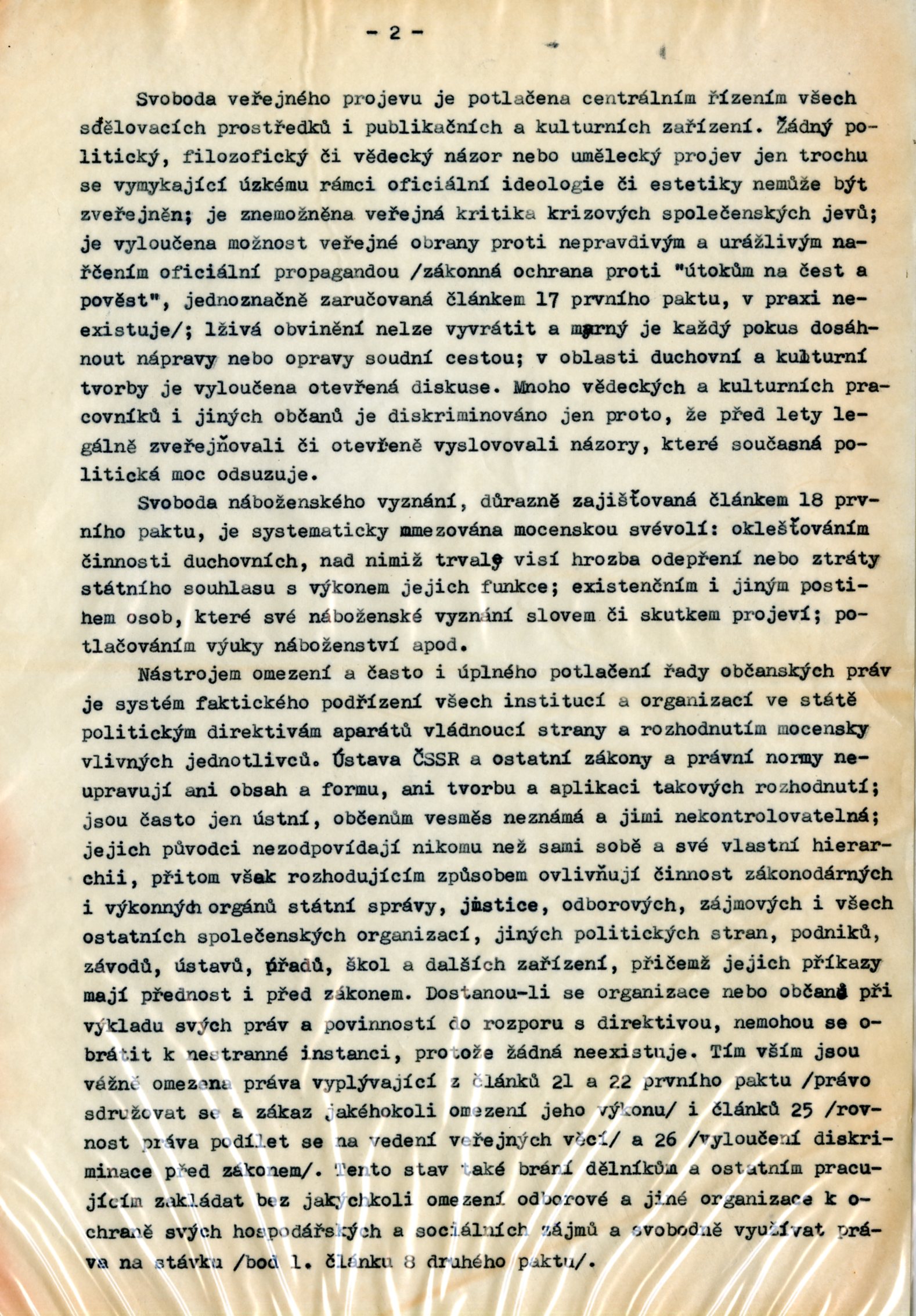

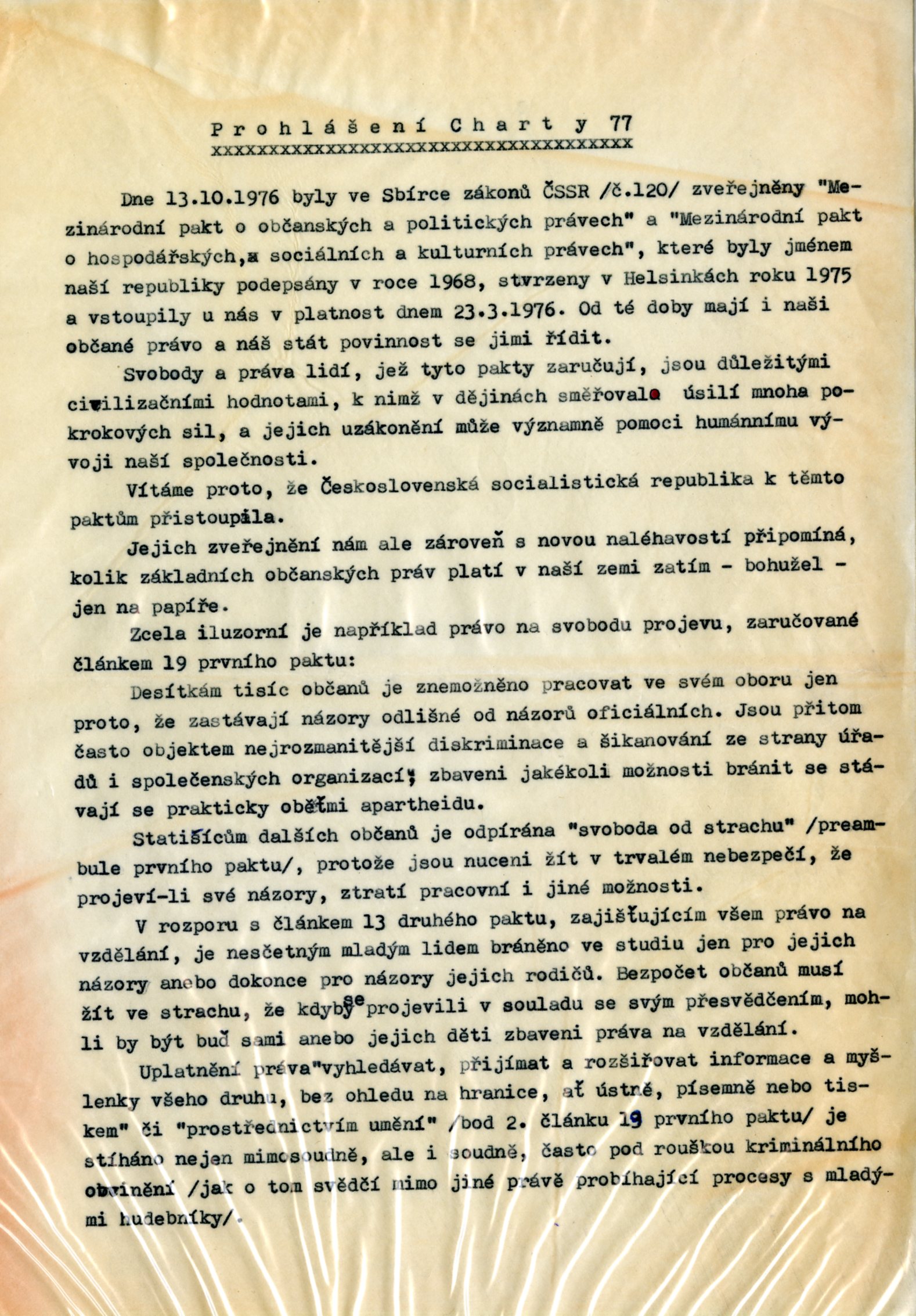

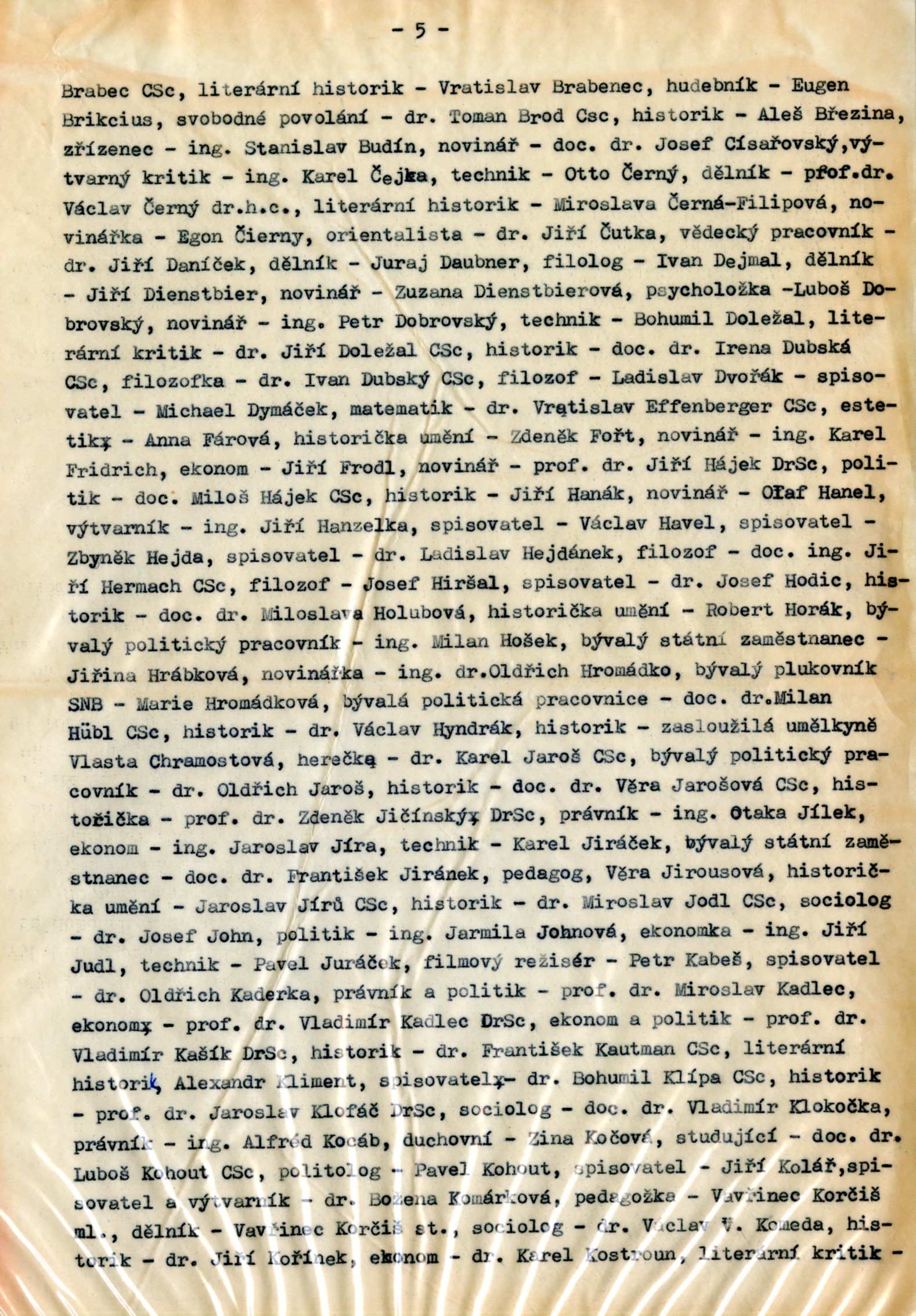

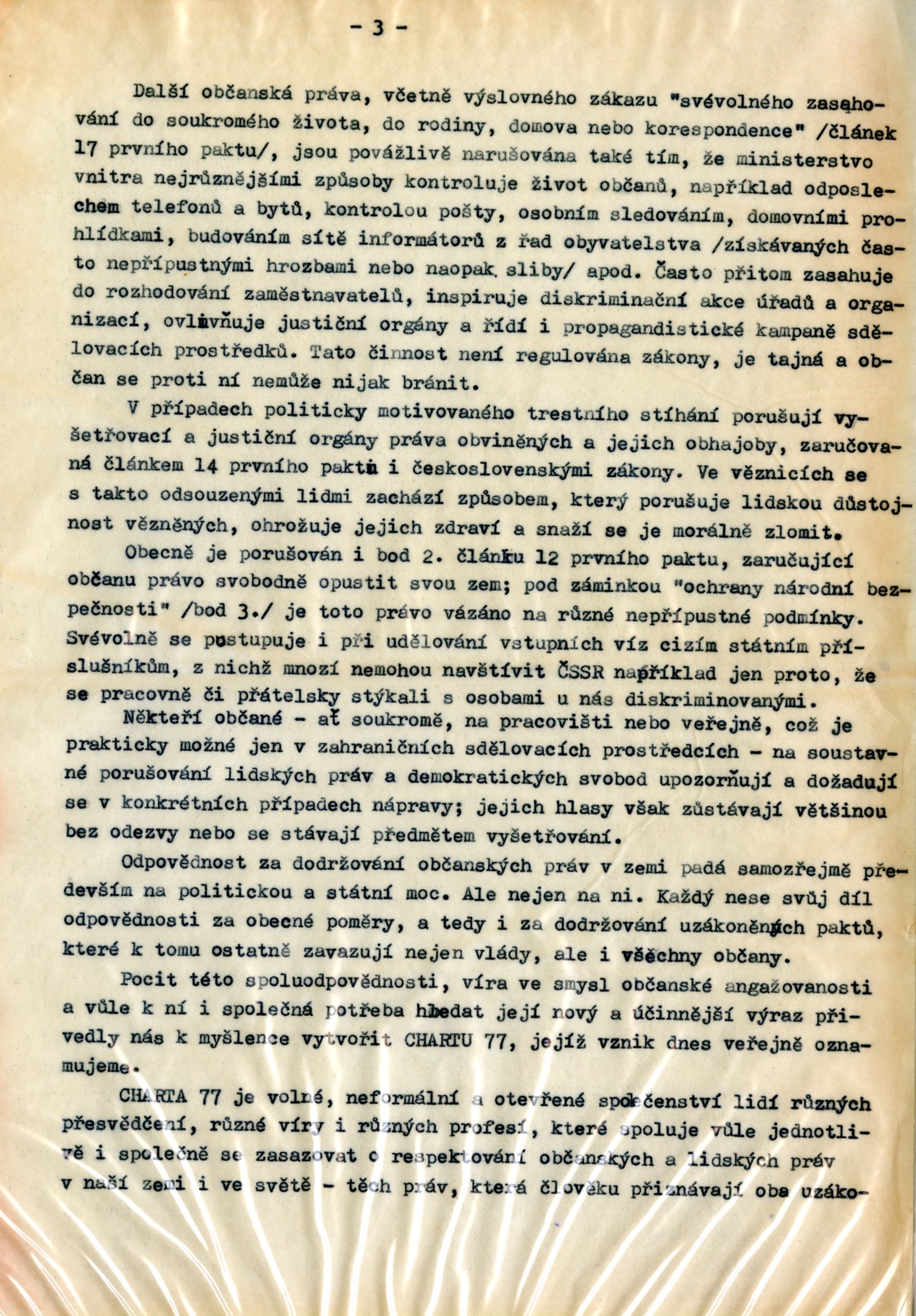

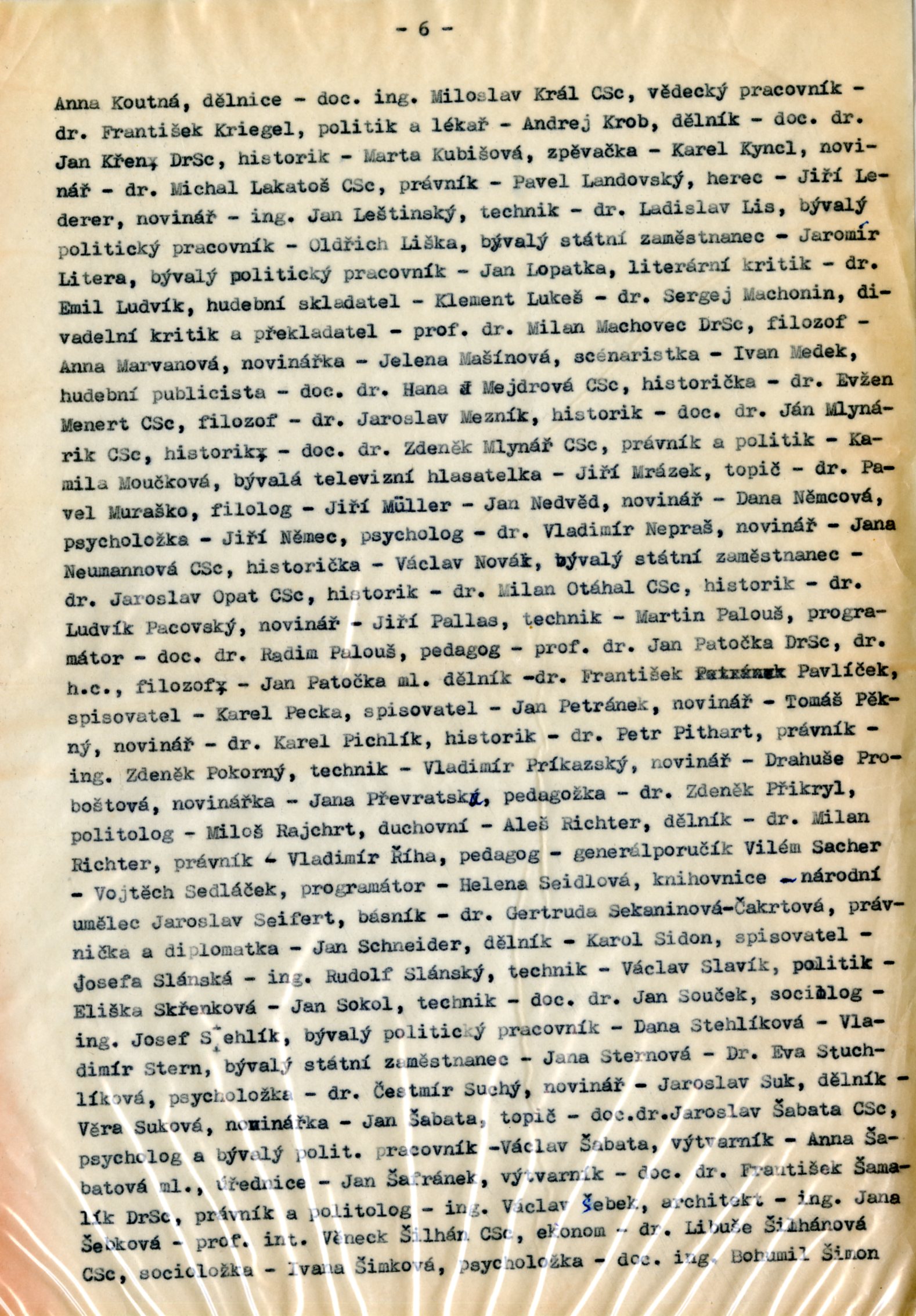

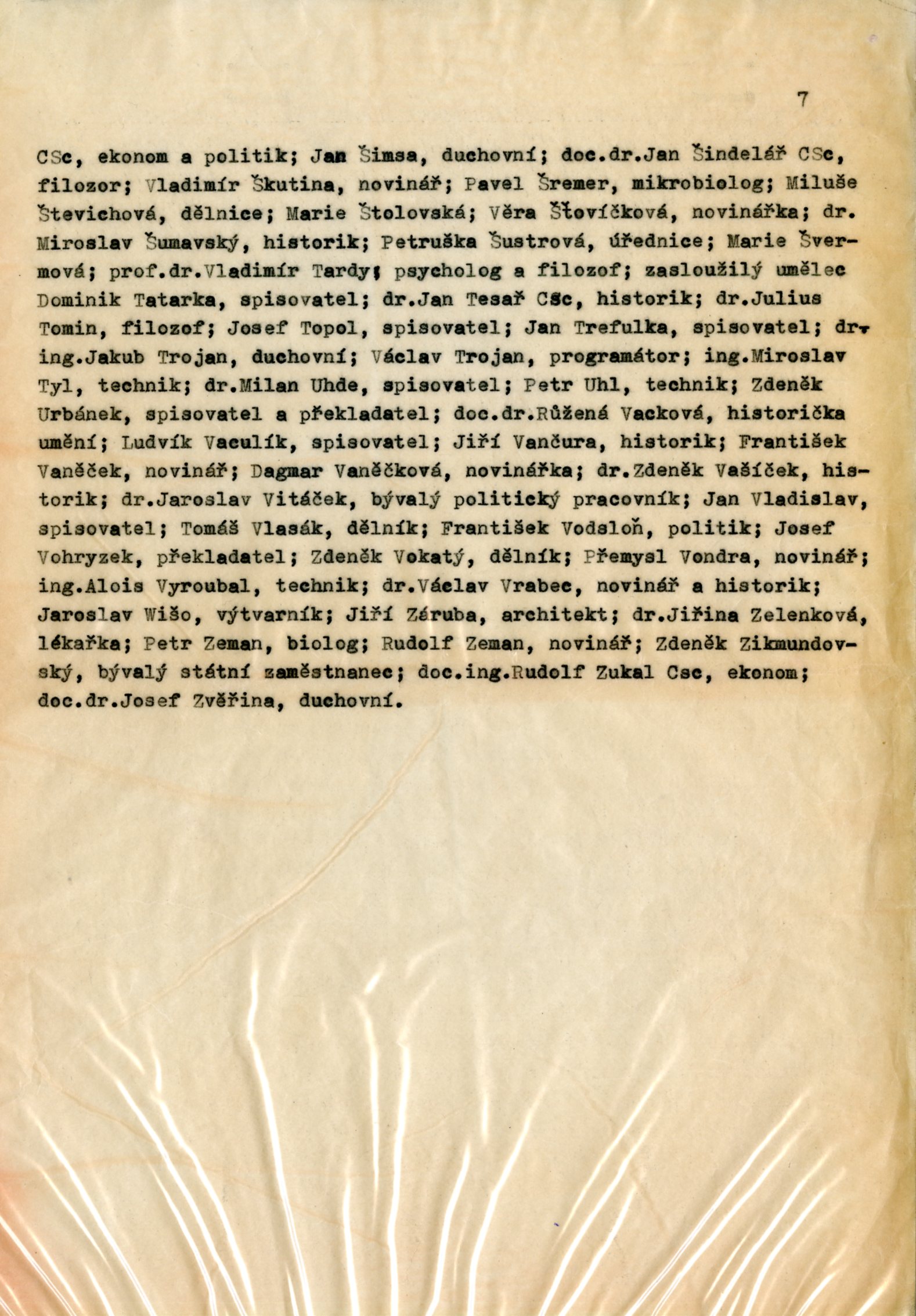

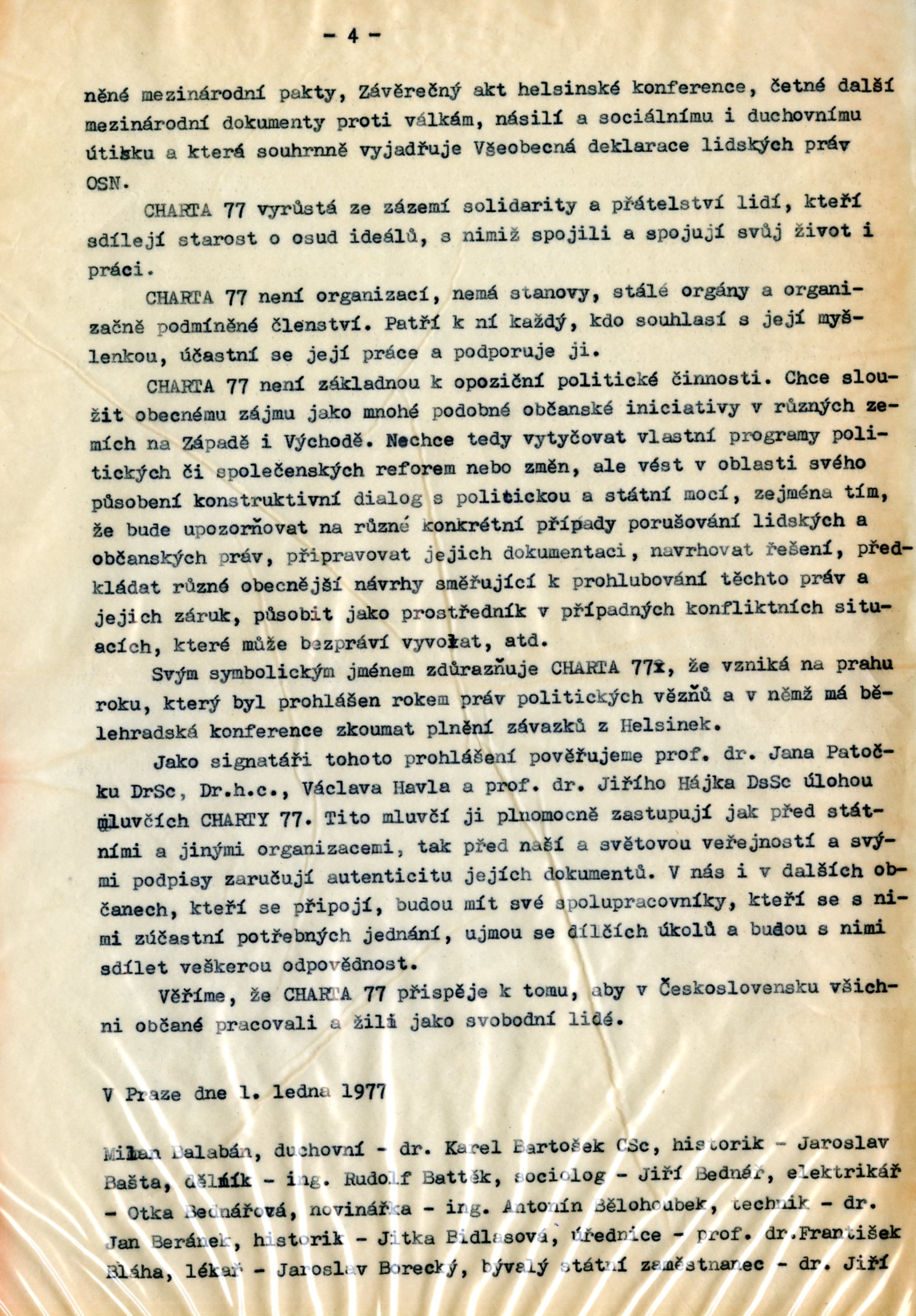

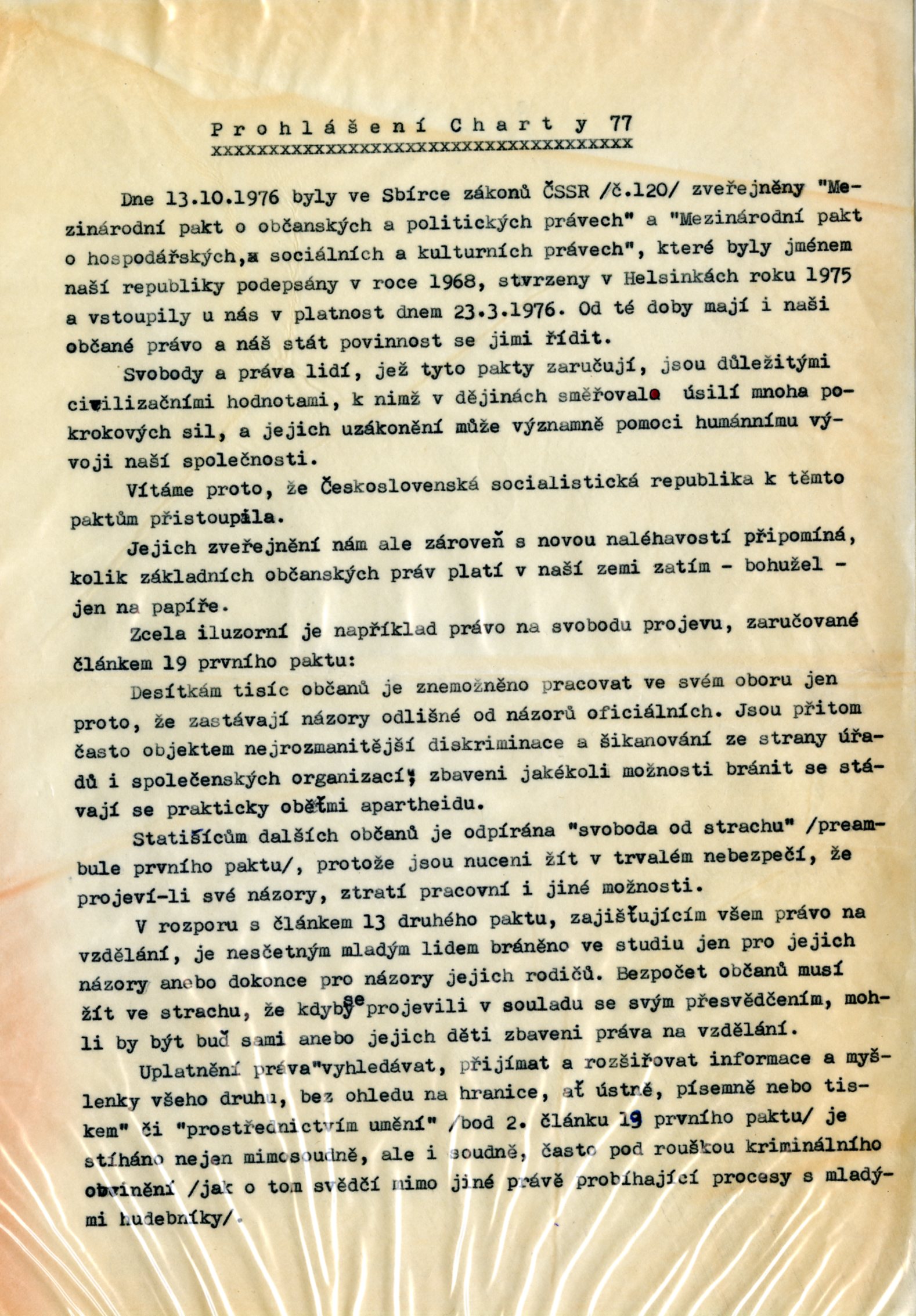

The Basic Declaration of Charter 77 of 1st January 1977 on the Causes of the Origin, Purpose and Targets of Charter 77, which on the Holiday of the Three Kings on January 6th, 1977, the playwright Václav Havel, the actor Pavel Landovský and the writer Ludvík Vaculík were issued to the Office of the Federal Assembly, Czechoslovakia and the Czechoslovak Press Office. On the way to Prague's Dejvice, their chase was ended, and the StB members caught up with them and they were then, detained by state security. The three were released later in the evening, apparently in response to the news which travelled abroad. The published Declaration of Charter 77 had given rise to a number of restrictive measures by the Czechoslovak regime. Its signatories were subjected to a constant persecution of the regime through police surveillance, house searches, job cuts, seizure of passports, detention, physical violence, imprisonment or expulsion from the country.

The Alenka Puhar Collection on the Human Rights Movement in Slovenia/Yugoslavia was mostly created in the 1980s and testifies to the struggle of Slovenian and Yugoslav activists to promote and protect human rights in Yugoslavia. Alenka Puhar was one of the key people in the 1983 campaign to abolish the death penalty in Yugoslavia, and in the organization of mass protests in Ljubljana in 1988 and in the Slovenian spring in the late 1980s. The collection documents the struggle and connections between Slovenian activists and other Yugoslav activists and dissidents who had the common goal of promoting and protecting human rights in Yugoslavia and ultimately the collapse of the communist regime.

The Mojmír Vaněk collection is a unique collection of materials that relate to the life and activities of Mojmír Vaněk. The activities of this distinctive, albeit unknown, Czechoslovak exile was very important for the dissemination of Czech music abroad, as well as his activities within the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences, the Swiss branch of which he presided over for many years. The collection is at the Comenius Museum in Přerov.

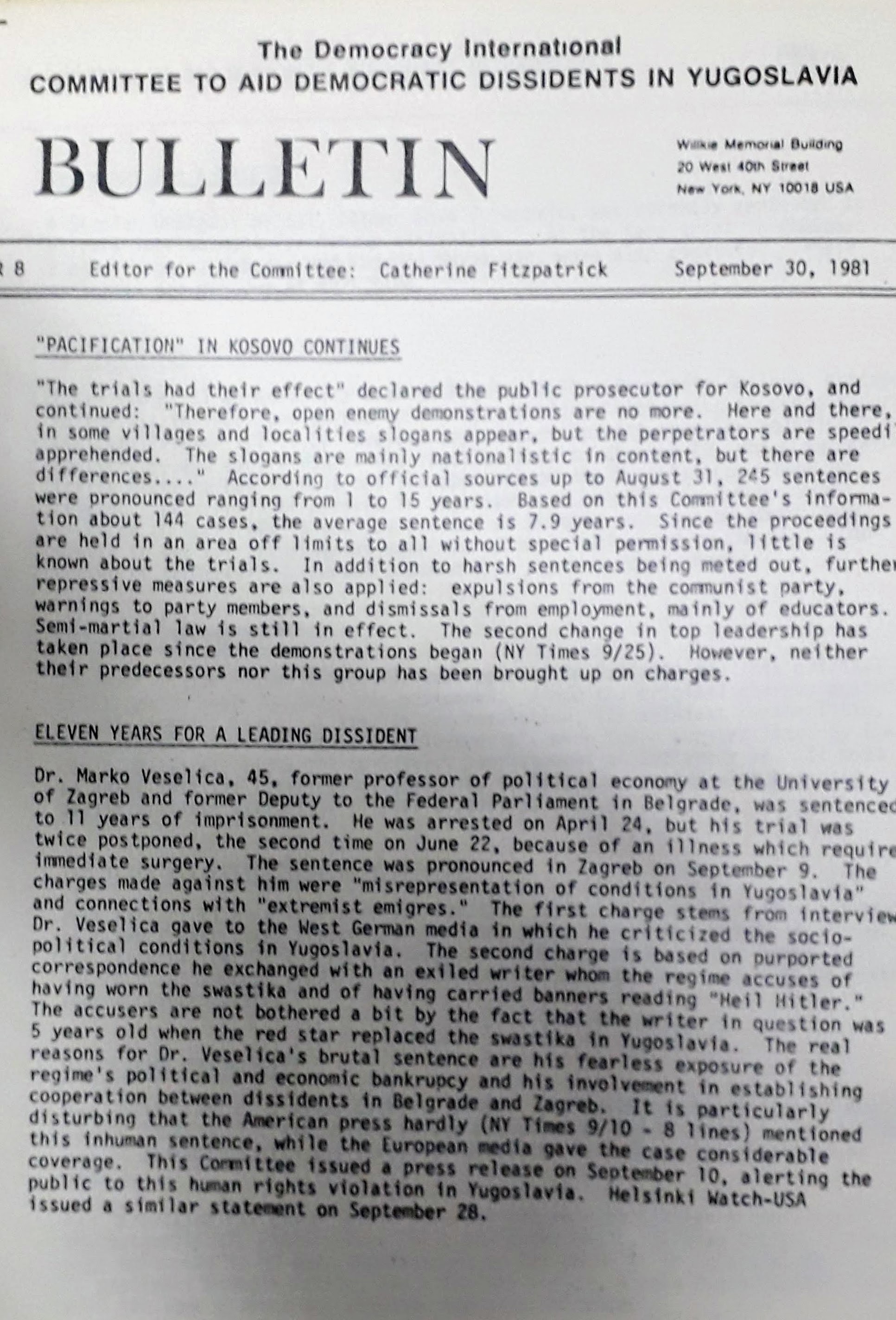

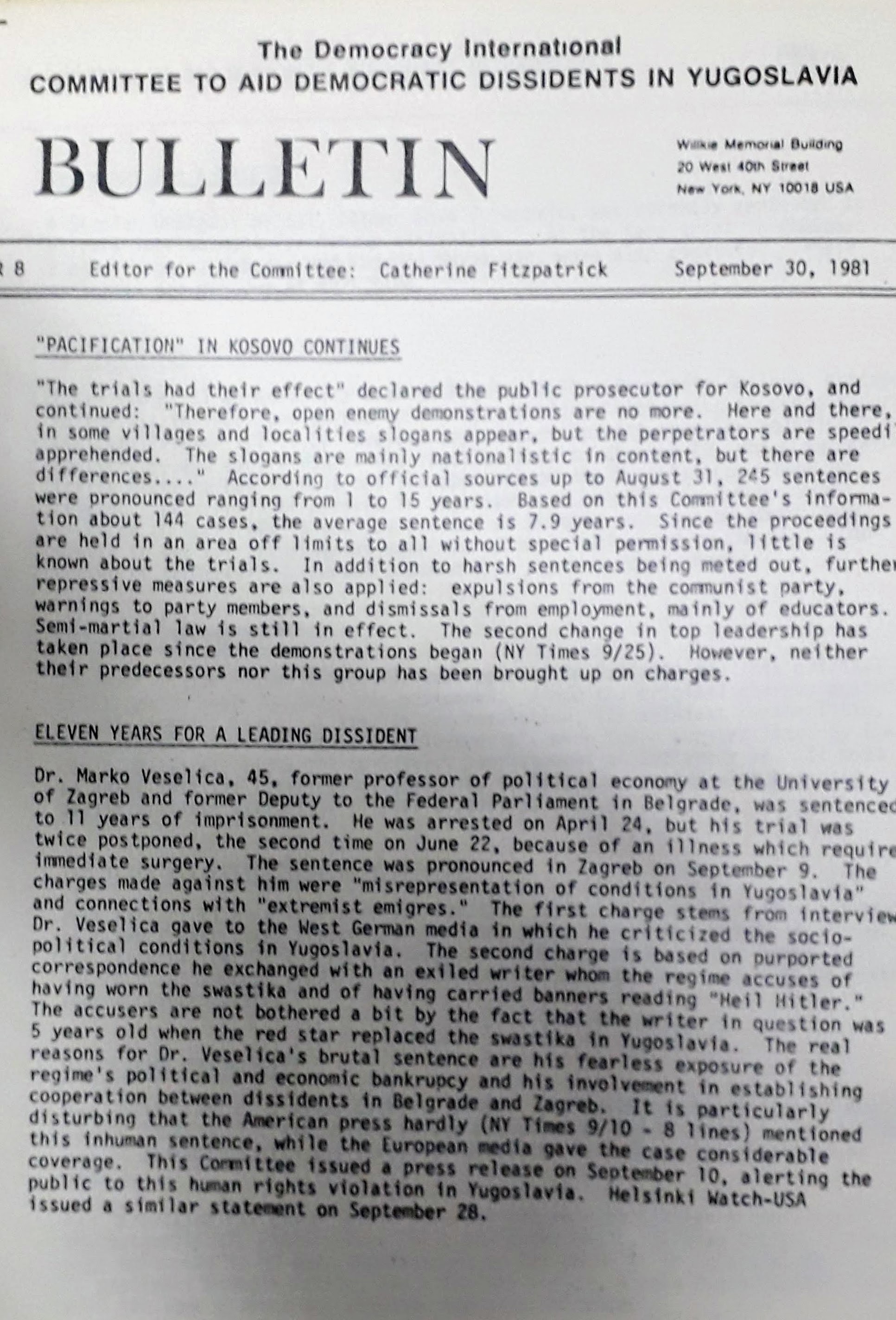

The Bulletin of the Democracy International Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia, 1985

The Bulletin of the Democracy International Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia, 1985

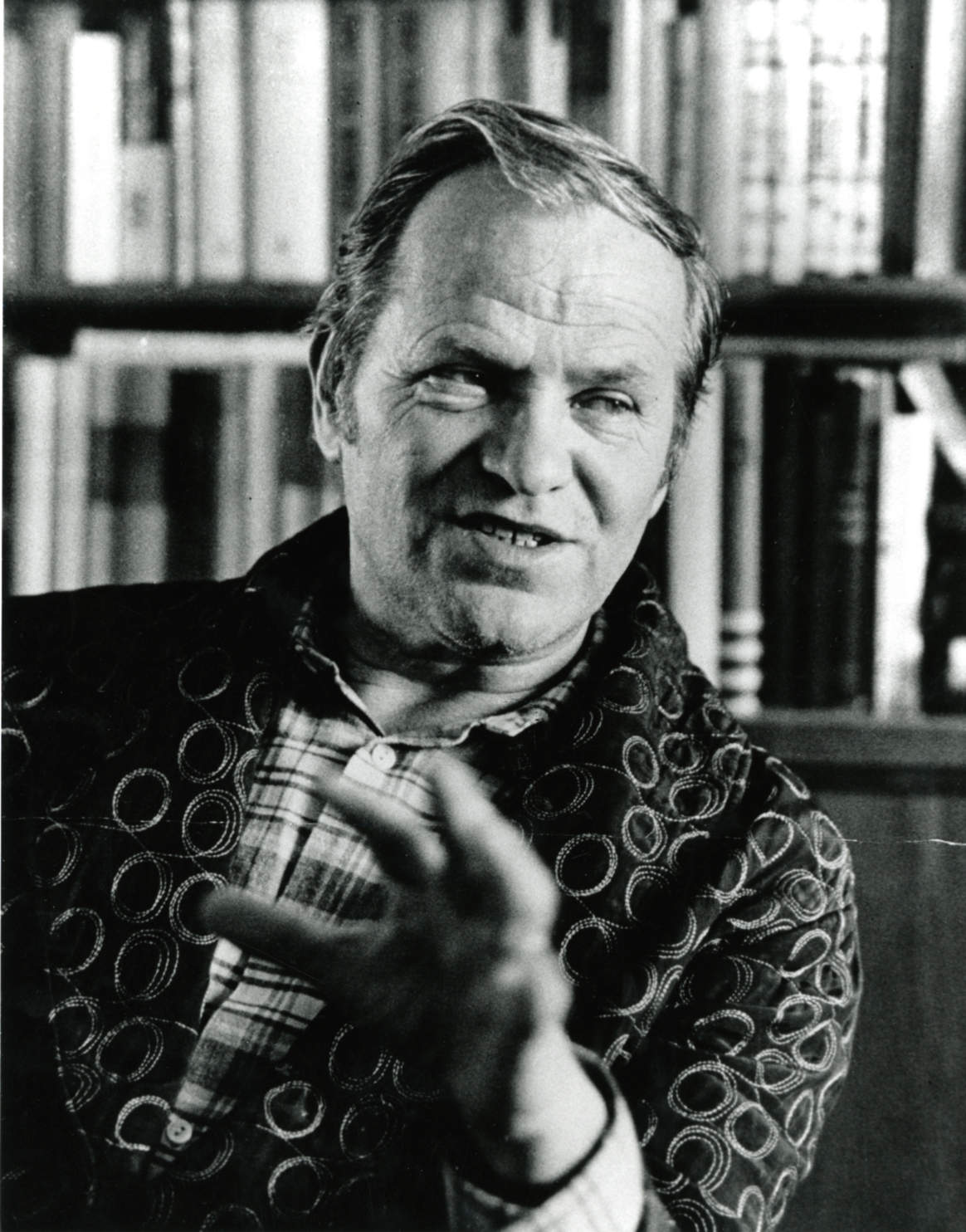

The Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia was the organization which Mihajlo Mihajlov founded in May 1980, in New York. The vice-presidents at the time were Franjo Tuđman and Milovan Đilas. The Committee bulletin was printed monthly, and covered issues on Yugoslavia, the repression by the regime, arrests and trials of its political opponents. It dealt with the status of human rights in Yugoslavia during 1980s. This bulletin is kept at the redaction of the Democracy International.

This collection of the historian, teacher and politician Milan Hübl consists of a unique collection of archive materials, which includes the correspondence and documentation of the Political University of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and a large collection of ego documents, samizdat volumes and materials related to Charter 77, the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS).

This photo reflects the way in which the Romanian exile organised itself and acted to present in the West the urban systematisation project of the Ceaușescu regime, which involved the demolition, mutilation, or destruction of the national heritage. The photo captures the moment when the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania was set up in Paris in 1985. On that occasion, the Association organised a protest on the streets of Paris, during which it displayed a series of placards with texts about Communist Romania, accompanied by photographs of historic monuments destroyed by the Communists or about to be demolished or moved. These details are captured in the photograph in question, which can be found in the Ștefan Gane collection in the original, 10x15 cm, printed on colour paper. The purpose of the Association was to draw the attention of political decision-makers and international public opinion to the project of the communist regime in Romania for the demolition of the architectural and urban heritage. The actions undertaken by the Association focused in particular on drawing media attention to the demolition of the city centre of Bucharest, which was planned by the authorities of the totalitarian regime so that they could reconstruct it according to the communist architectural vision.

In 1958, a group of 55 Latvian scientists and cultural figures signed a petition against the Pļaviņas Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP) project, because it envisaged the flooding of part of the Daugava valley, one of the most beautiful areas in Latvia, which was rich in archaeological and historic monuments. It also had a symbolic value as part of the Latvian nation-building narrative. Due to the efforts of the Soviet authorities to suppress the protest, very few documents are available, some of which are in the Museum of the River Daugava.

The bequest of Rusko Matulić, an American engineer and writer of Yugoslav origin, is held in the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The collection largely encompasses Matulić's activities as a political émigré in the United States of America, when he mainly dealt with the publication of the bi-monthly bulletin of the Committee Aid to Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia (CADDY). The bulletin and organization acted as a part of the Democratic International, established in New York in 1979. Mihajlo Mihajlov, one of the most prominent Yugoslav dissidents, was a member and the main initiator of launching the CADDY organization and its bulletin. Rusko Matulić was Mihajlov's main collaborator in the overall CADDY project.

The Pavao Tijan Collection is deposited in the Archives of the Croatian Academy of Science and Arts in Zagreb. It demonstrates the cultural-oppositional activities of the Croatian émigré Pavao Tijan, who lived in Madrid after the Second World War. There, Tijan organized anti-communist activities against the Yugoslav regime and also against global communism during the time of the Cold War. This collection is very important to the little known Croatian cultural history of the émigré colony of Spain.

Jiří Lederer (1922-1983) was a Czech journalist and publicist, one of the most prominent journalists during the "Prague Spring" in 1968. In the 1970s he participated in the work of the Czechoslovak opposition and was one of the first signatories of Charter 77. During the 1970s he was imprisoned several times. In 1980 he went into exile. The collection mainly contains materials and notes from the period around the Prague Spring.

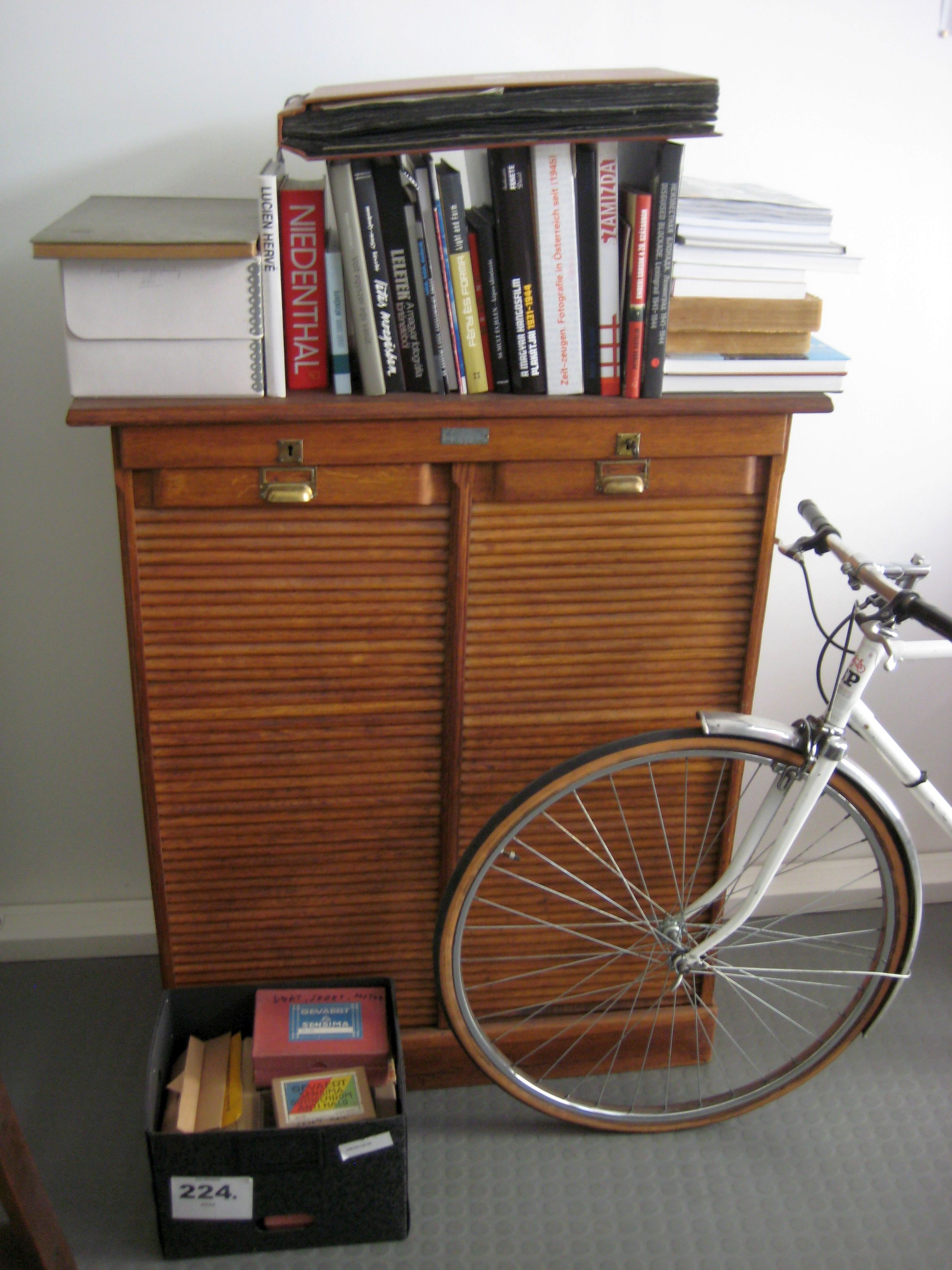

This letter is an important document for the history of the post-war Romanian exile community because it is proof of the activity of fighting communist propaganda outside the country, as well as of the integration of Romanian culture into Western culture. Such activity was also carried out by Sanda Budiș, an exile community personality, who emigrated to Switzerland in 1973. One of her actions, alongside another representative of the Romanian exile community in Switzerland, the lawyer Dumitru Stambuliu, consisted in supplying the Swiss Library for Eastern Europe in Bern with publications of the Romanian exile community. The starting point of Sanda Budiș’s project was a book donation from Romania, which the Romanian ambassador to Switzerland made to the Cantonal and University Library of Lausanne in 1984. This donation took place during a festivity advertised in the local press. In response, Sanda Budiș took the initiative to donate publications of the Romanian exile community from her personal library to this library, but her donation was denied "for political reasons." Consequently, she addressed the leadership of another institution – the Swiss Library for Eastern Europe in Bern – which served at the time as a documentary fonds for the Swiss Eastern Institute (Institut suisse de recherche sur les pays de l'Est–ISE/Schweizerische Ostinstitut–SOI), an institute that carried out research on communist countries. At the Institute, both the management and the members were Swiss personalities with authority in their field of expertise. The management of this library accepted her donation “with great satisfaction, especially as it is literally flooded by propaganda publications sent free and regularly by the various propaganda officers of the Ceaușescu regime.” In order to counteract the propaganda of the Romanian communist authorities, Sanda Budiș continued her efforts by sending letters to the management of important and representative publications of the Romanian exile community. Among the recipients of such letters was Virgil Ierunca, who accepted her invitation and sent to the library not only newspapers and magazines of the exile community, but also books published by Romanians abroad. Ierunca also responded to Sanda Budiș in a letter in which he congratulated and thanked her for the action she had initiated. The original handwritten letter is to be found today in the Sanda Budiş Collection at IICCMER.

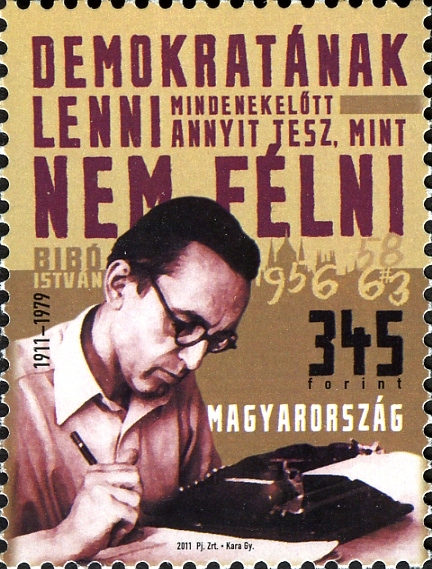

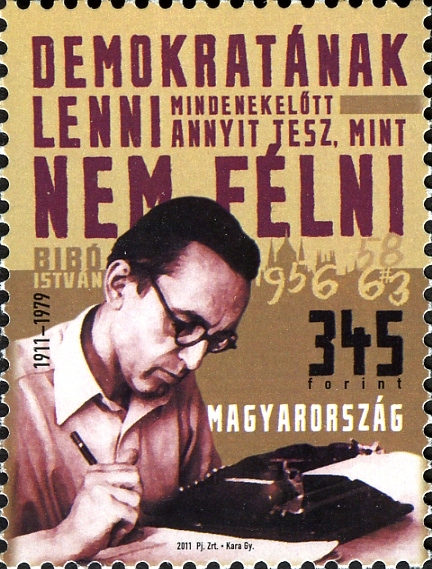

István Bibó (1911–1979) was a Hungarian political scientist, sociologist, and scholar on the philosophy of law. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Bibó acted as the Minister of State for Imre Nagy’s second government. When the Soviets invaded and crushed the revolution, he was the last minister left at his post in the Hungarian parliament building. Rather than flee, he remained in the building and wrote his famous proclamation, “For Freedom and Truth,” until he awaited arrest. Bibó became a role model for dissident intellectuals in the late communist era and a symbol of non-violent civilian resistance based on a firm moral stand. Since Bibó’s death in 1979, the family collection of his bequest, which includes personal documents, photos, manuscripts, books, and video and sound recordings, has been in the care of art historian and educator István Bibó Jr., who keeps the materials in his home in Budapest.

Vjesnik Newspaper Documentation is an archival collection created in the Vjesnik newspaper publishing enterprise from 1964 to 2006. It includes about twelve million press clippings, organized into six thousand topics and sixty thousand dossiers on public persons. Inter alia, it documents various forms of cultural opposition in the former Yugoslavia, but also in other communist countries in Europe and worldwide.

This letter is an important document for the history of dissidence in Romania, being a proof of the open opposition of a Romanian living in the country to the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu. In this case the writer was Victor Frunză, a Romanian writer and journalist, who in 1978 went as tourist to Paris. On this occasion, he contacted a representative of the Reuters Agency, to whom he handed a letter addressed to Nicolae Ceaușescu. He wrote the text of the letter in Romania and memorised its content in order not to carry it and be discovered at customs control. So he rewrote it from memory after he arrived in France. The material in question was published by Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung and broadcast by Radio Free Europe. Also, a copy of the letter was sent by Victor Frunză, by post, to Nicolae Ceaușescu. Essentially, his letter was a criticism of Ceausescu's dictatorship: "I want to manifest deep disagreement with the revival of the cult of personality, today is an improved version, decorated with the national flag." Frunză's conclusion was that "the type of socialist democracy in Romania is nothing more than a parody of discussions through speeches, even if these are not written by those who speak them." The document is in the IICCMER archive and is an original copy of the German letter published in 1978 in Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung. The letter was subsequently published by Victor Frunză in Romanian, at the publishing house he founded after the emigration, in the pages of the book For Human Rights in Romania (1982). The second edition of this volume appeared in 1990, in Bucharest, under the aegis of Victor Frunză Publishing House.

Frantisek Starek was one of the leading figures of the Czechoslovak underground movement and culture. Due to his long-lasting activity, he has built a very rich and interesting collection. In this collection, a lot of material – often unique – about Czechoslovak counterculture and personal resistance can be found. The collection covers the time period from the seventies to the nineties.

The private collection of Tamás Csapody (1960–) includes documents related to movements for the reform of the compulsory military service and the introduction of alternative civilian service. Refusal to perform military service was an illegal act in the countries of the Warsaw Pact. Csapody’s collection, as the only collection focusing this specific topic, contributes to remembering the stories of people who were penalized by the laws of the Kádár regime because of freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

Personal notes of the Founder, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1984-1985’, 1985. Publication

Personal notes of the Founder, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1984-1985’, 1985. Publication

“The Founder’s personal notes”

In: The Yearbook of the Soros Foundation, Hungary 1984–1985

“It was not my choice that I was born in Hungary in 1930. However, it was my own deliberate decision, one of the most important ones in my life, that 17 years later I left this country. And my return with this foundation is but a late consequence of this early age choice.” These opening sentences are the most “personal” notes in the founder’s preface to the first yearbook of the Soros Foundation, Hungary (HSF) 1984–1985.

Soros used this opportunity to address the public freely (i.e. without much risk of being censored) and share authentic information and assert the principles on which his recently established foundation was based.

The was important in part simply because in the first few years the foundation was given hardly any press coverage in communist Hungary except for some short official statements published in dailies, according to which a New York stock investor had signed a contract with the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS) and opened a small office in the Buda Castle district to receive applications for grants and other forms of support. Apart from this, no reports were printed and no interviews were done in the print and broadcast media. Even in 1987, Soros and his secretary staff still had to fight for the right to publish lists of successful grantees at least in HVG (the three-letter abbreviation used for an earlier title of the same periodical, Heti Világgazdaság, or “Weekly World Economy”), an economic weekly. The first principle Soros insisted on, thus, was the importance of free and permanent control by the pubic (instead of by the party and the secret police) of the operations of his foundation. Similarly, he asserted a number of other safeguards as a founder. He maintained the right to choose his personal colleagues, to decide on his own on the amount of his yearly donations to be spent (which began at one million dollars and grew to nine million dollars by 1990), and to exercise a veto in all strategic or personnel decisions, i.e. decisions concerning curators, projects, grants, prizes, etc.

As for the applications and projects, Soros readily informed the public about ongoing practice and plans for the future. The foundation wished to maintain the individual system of both dollar-based and forint-based grants and support. The Literary and Social Science grant systems were running successfully, but they also planned to test and introduce some new projects which offered support for study abroad and research grants and support for conferences, as well as funding for filmmakers, theater groups, and artists active in the fine arts. Applicants who fell in other categories were equally welcome to submit inventive workplans and new, creative initiatives.

Finally, Soros sought and offered a confident partnership to all: “We need the help of the larger public, after, all the success of our foundation can only be ensured by the applicants’ talent and inventiveness, and the reactions of Hungarian society.”

Milan Šimečka (1930-1990) was a Czech and Slovak philosopher, essayist and publicist. He was one of the prominent personalities of the Czechoslovak opposition from 1968. He published in samizdat and exile, and for this he was detained illegally for a year. The collection contains mainly texts and correspondence.

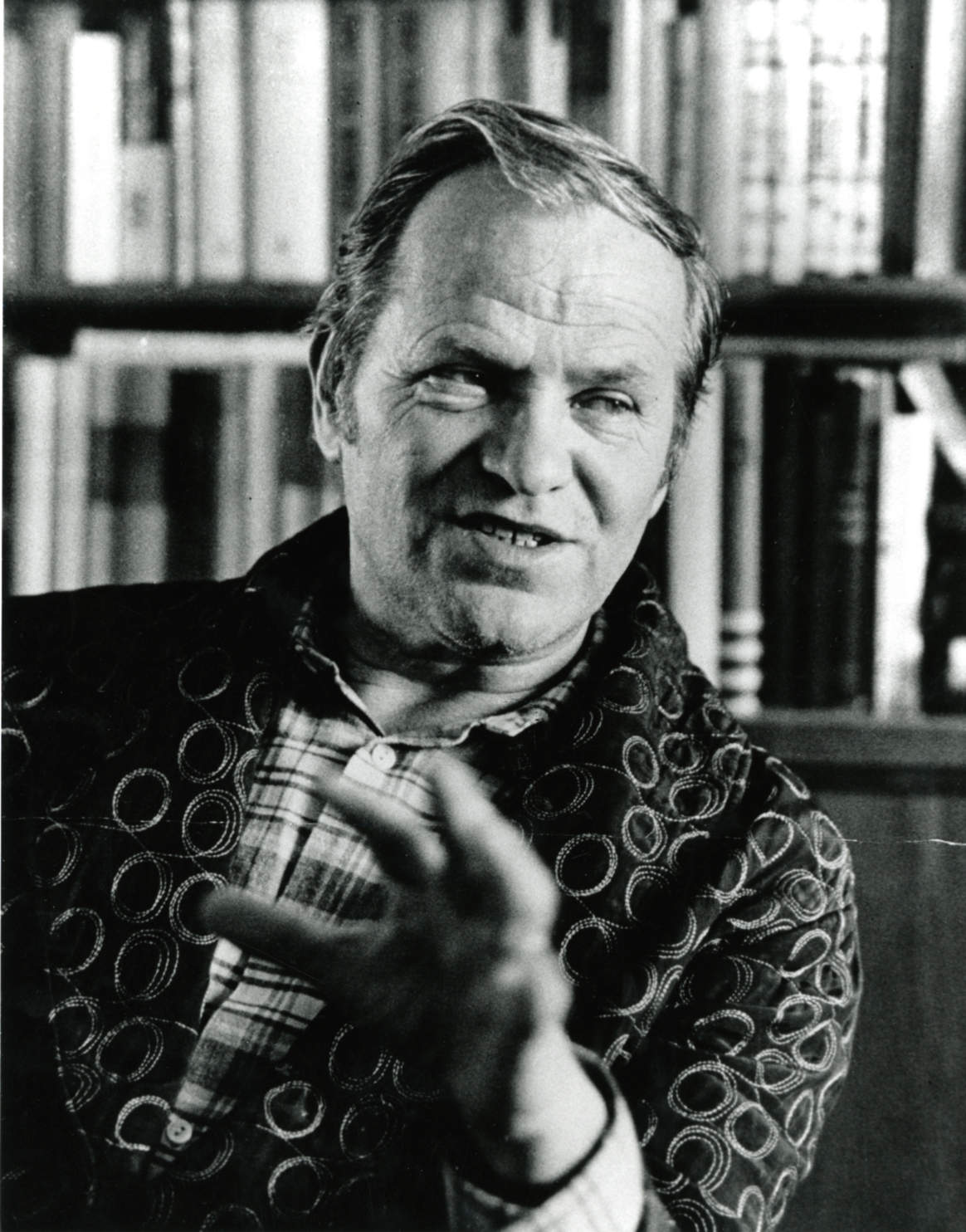

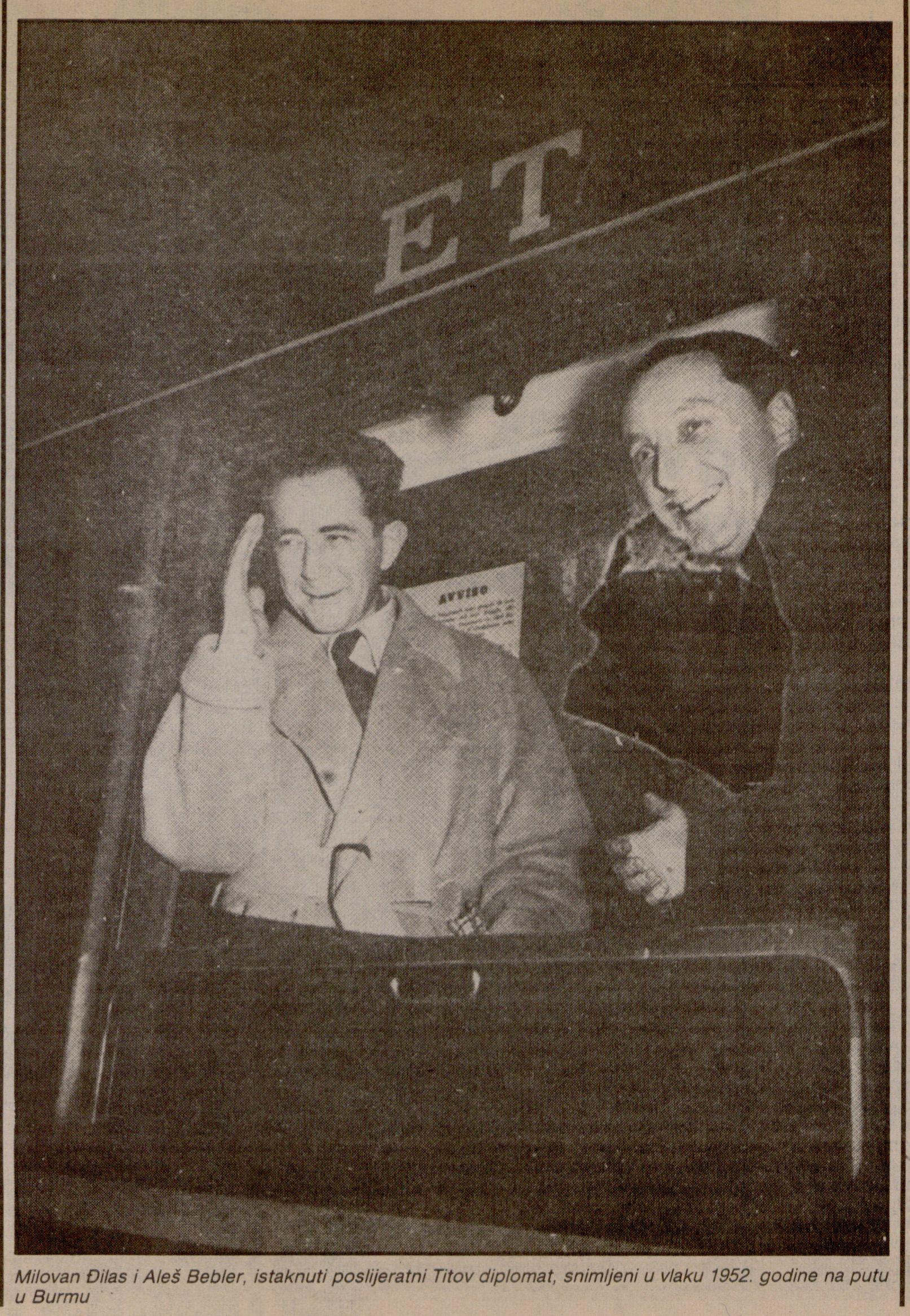

The collection includes Croatian State Security Service's file on the case of first and best known Yugoslav dissident, Milovan Djilas, and its reception in Croatia. During 1953, Djilas published a series of articles in the newspaper Borba on the need for democratization and liberalization of Yugoslav society, which led to his condemnation at Party forums and expulsion from the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. In Croatia, similar ideas were mainly manifested in the weekly Naprijed, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Croatia. It led to open conflict with Party leaders and the suppression of the newspaper, while its journalists were forced to halt their careers in journalism. The collection includes different analysis and reports on operational measures conducted by the Croatian State Security Service against the Naprijed group and other Djilas supporters (Djilasovci) in Croatia until the beginning of 1960s.

The events that transpired alongside the fall of the Romanov monarchy in February 1917, the takeover of the Winter Palace by the Bolsheviks in October 1917, and the dissolution of the Constitutional Assembly in January 1918 are immensely significant for understanding Ukrainian history and cultural opposition to communism. During that year of upheaval, many divergent visions for the future were articulated throughout the Russian Empire. In the Imperial Southwest, the Bolsheviks battled monarchists, nationalists, socialists, greens and anarchists over how to move forward during and after the collapse of empire.

The Ukrainian Museum-Archives has in its possession an original broadside of the Third Universal, issued by the Central Rada on November 20, 1917, in the four major languages used in the Imperial Southwest—Ukrainian, Russian, Polish and Yiddish. This document is reflective of efforts by the Central Rada to appeal to various communities living on the territory, while negotiating with the Provisional Government for greater autonomy. As historian George Liber notes, the first two proclamations of Rada did not define the borders of Ukraine, but the Third Universal asserted that the nine provinces in the Imperial Southwest with Ukrainian majorities belonged to the Ukrainian National (or People’s) Republic. The document also claimed parts of Kursk, Kholm/Chelm and Voronezh provinces, where Ukrainians also constituted the majority. The Central Rada also pledged to defend the interests of all national groups living in these territories and articulated a law protecting personal and national autonomy for Russians, Poles, Jews and others.

Shortly after this, the UNR established diplomatic ties with a number of European countries and even the United States. Britain and France tried to persuade the UNR leadership to side with them against the Central Powers, which they refused as they were determined to stay neutral. The Soviet Russian Republic initially recognized the UNR, but this was short-lived as the Red Army soon moved in from the north and east. This prompted the Rada to issue the Fourth Universal on January 25, 1918, which declared independence of the UNR as defined by the Third Universal. This made the push for greater autonomy within the context of empire a war of nationalist secession. (Liber, 62-63)