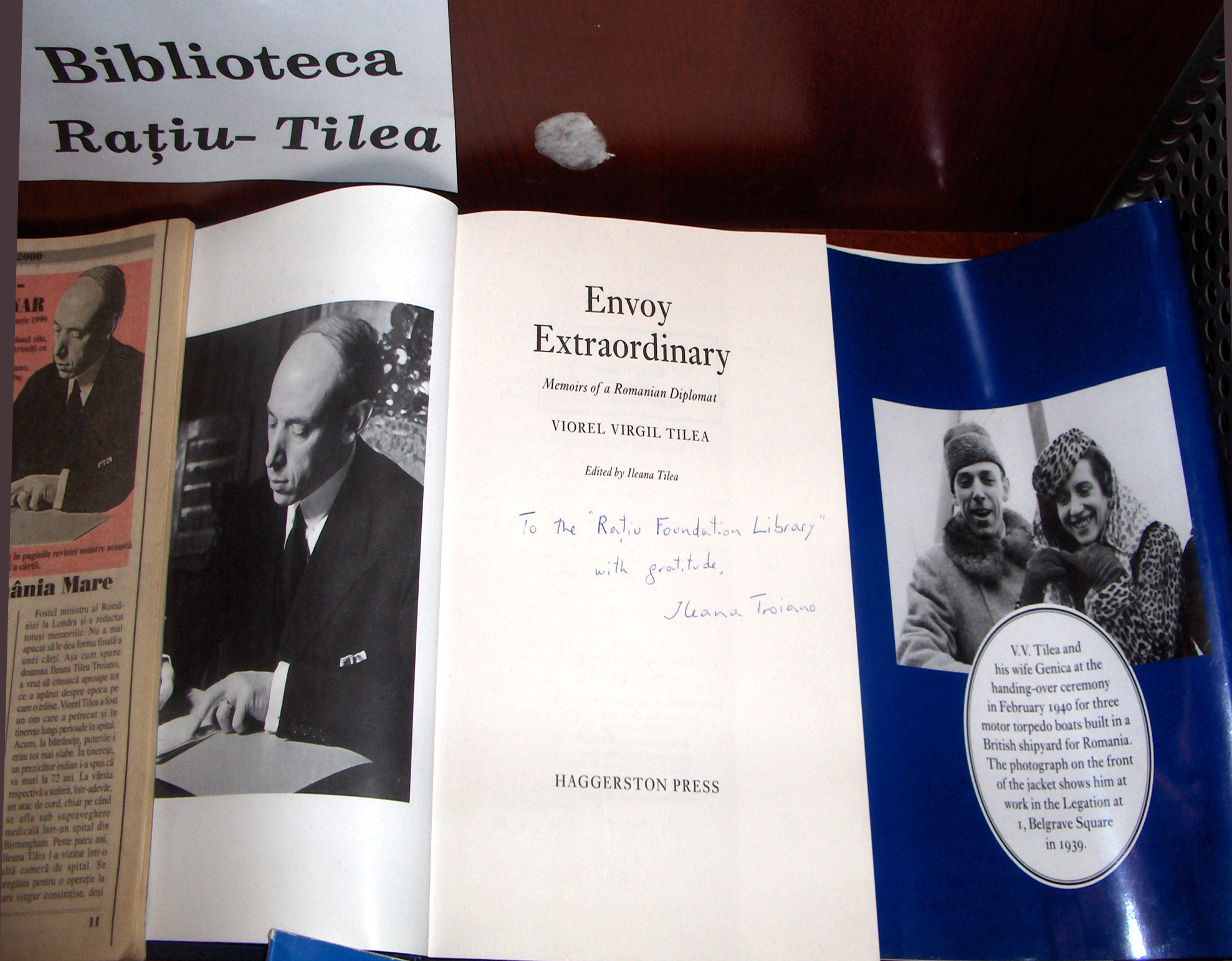

After Ion Raţiu’s death in 2000, the family decided to donate his personal library, including Viorel Virgil Tilea’s library, which Raţiu had previously inherited, to BCU Cluj-Napoca. In the period from 2006 to 2008, the books gradually came into the custody of BCU and were registered. On 5 June 2009, the Raţiu–Tilea reading room at BCU Cluj-Napoca, which became the repository space for the collection, was opened to the public in the presence of members of the Raţiu family. The festivity marked thirty years since the opening of the Raţiu Foundation in London. In his speech, Nicolae Raţiu, the son of Ion Raţiu, emphasised the symbolic component of the transfer of the collection to BCU Cluj-Napoca, the place where his father gave his first speech about democracy in Romania in January 1990. During this festive opening, the members of the Raţiu family gave the donation deed to Professor Doru Radosav, the head of BCU Cluj-Napoca.

The Museum of Contemporary Art moved to a newly built building in 2009. The new Museum was opened on December 9, and with its opening the Museum also presented its permanent display. The permanent display bears the name Collections in Motion, and it also includes works/work from the "Exploitation of the Dead" cycle by Mladen Stilinović.

The presentation of works/work from "Exploitation of the Dead" in the permanent display at the Museum of Contemporary Art gives him a continuous presence on the art scene and thus increases its availability to a wider audience and popularity.

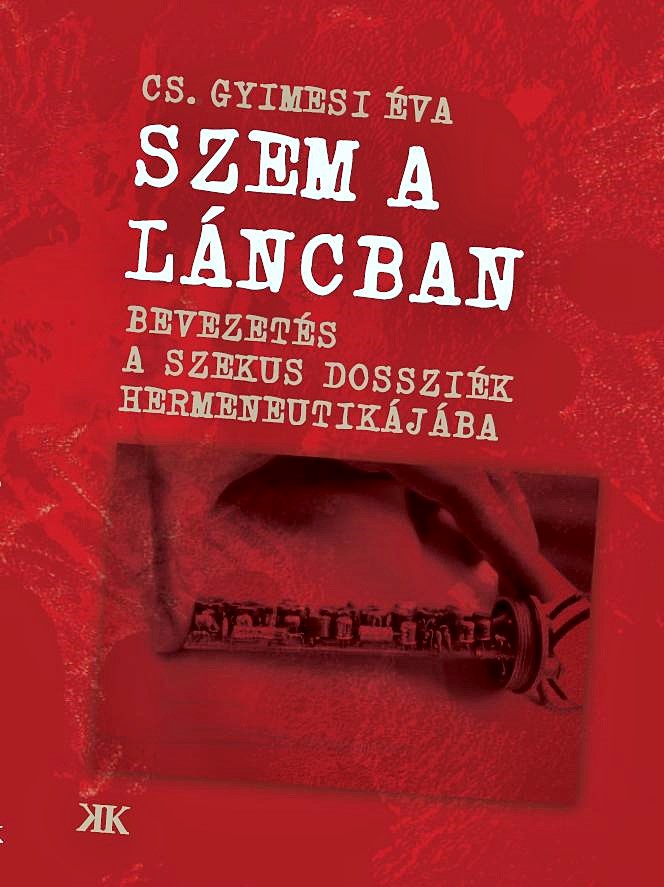

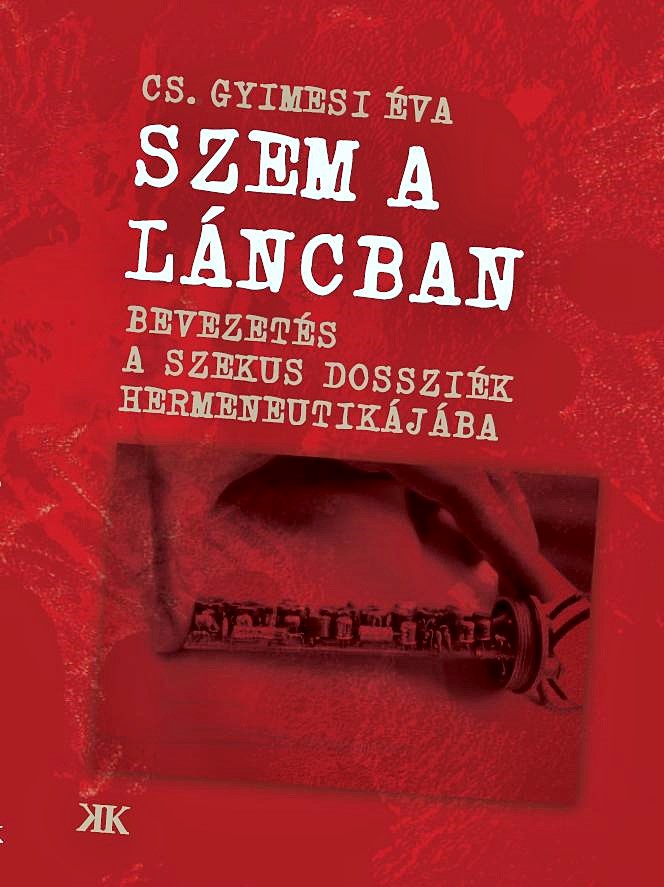

Publication: Cs. Gyimesi, Éva. Piece in a Chain: An Introduction to the Hermeneutics of Securitate Files, 2009

Publication: Cs. Gyimesi, Éva. Piece in a Chain: An Introduction to the Hermeneutics of Securitate Files, 2009

The publication of this book marked the moment when Gyimesi opened up about her experiences of being confronted with, reading, and processing the secret police “collection” of files on her person. The book launch event took place on 18 November 2009 in the Tranzit House in Cluj-Napoca, within the framework of a series of events called “The Human Pyramid: Discussions about Party State Dictatorship.” Gyimesi tries to understand the mechanisms of the dictatorship in her capacity as a piece in a chain, as the subject of a top-down system. She tries to offer insight into the secret police mode of operation outlined in the texts of the first volume of her informative file, presenting the victims of a society totally controlled by the party-state, as well as the collaboration with the system, trying to locate herself and other figures in the larger picture. The selected word is hermeneutical in the broadest sense of the word with the author refraining from a closer, more in-depth study of the texts on file. At the same time the secret police files are not reliable from the hermeneutical point of view, because the secret police officers in question interpreted things in such a manner as to offer their superiors the materials they liked to receive. Gyimesi was interested to learn what factual and literary theoretical points of view can be identified upon a subsequent reading of such a material. Obviously she takes into consideration their value as documents, however, her particular way of thinking and approach drives her to also use this material professionally. Her volume is an attempt at doing this and it is also interesting from the point of view of reading theory to see how she returns to these, how she finds her way in them and, practically, the levels at which she creates connections in the meantime (István Berszán’s statement). When reconstructing the past, Gyimesi avoids being trapped in those points of view the Securitate set out to follow, and tries to keep the Securitate from determining what should be said and remembered even decades after the events. By making comments, Gyimesi relates to these records, introduces subsequent knowledge and references to their interpretation, thus questioning also the set of criteria applied in these documents; this is another aspect of relating hermeneutics to the documents (József Imre Balázs’s statement). Gyimesi’s undisguised aim with this book was to set an impediment in the way of nationwide oblivion which ultimately eliminates responsibility on the part of those supporting and serving dictatorship. Last but not least, she tries to raise some empathy in the reader towards those who were once monitored and harassed, and to bring the younger generations who have not known dictatorship, closer to understanding the degree of past “freedom.” According to her, the files are unsuitable for granting access to the “truth” about the secret police as an institution. Their language is defined by the ideologically biased, “official” image of reality of the actors involved (officers, collaborators, informers, etc.), the “robot image” created of the target person and the flesh-and blood person are not identical (Cs. Gyimesi 2009).

The event was organised by Braşov Art Museum for the 125th anniversary of the birth of the artist. On this occasion the museum displayed sixty–four works of art (sculptures, paintings, and graphic works) created by Mattis-Teutsch, gathered from several Romanian museums (the Brukenthal National Museum Sibiu, the Székely National Museum in Sfântu Gheorghe, the Criş Country Museum in Oradea, and the Arad Museum Complex) and various private collections. The exhibition illustrated the artistic evolution of Hans Mattis-Teutsch in the period from 1910 to 1939 by emphasising his connections with the artistic avant-garde movements in Europe. Special attention was paid to his collaborations with the Hungarian avant-garde movement associated with the magazine Ma, the Romanian avant-garde movements of Contimporanul and Integral, and German Der Sturm.

Müller, Herta. Cristina and her dummy. What is (not) written in the Securitate’s files. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2009. Book

Müller, Herta. Cristina and her dummy. What is (not) written in the Securitate’s files. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2009. Book

Herta Müller’s book Cristina und ihre Attrappe oder Was (nicht) in den Akten der Securitate steht (Cristina and her dummy: What is (not) written in the Securitate’s files) was published in 2009. The book contains her thoughts regarding the informative file that the Securitate created against her name in 1983. “Cristina,” as Herta Müller was code-named by the Securitate, came to the unwanted attention of Romanian secret police because her literary works allegedly distorted “the social-economic realities (…) especially in rural areas” and misrepresented and sometimes openly mocked the local state and Party authorities. After introducing the foreign reader to the legal and political constraints that for ten years prevented her from reading the file created on her by the Romanian secret police, Herta Müller underlines that the documents included in her three-volume informative file do not capture all the facets of the surveillance organised by the Securitate against her. Moreover, some of the abuses committed against her by its officials, such as bullying, beatings, or home violations are not even mentioned in her file. Using as a starting point the content of her informative file, Herta Müller engages in a discussion at length about the persecutions she was subjected to by the Securitate and how these episodes were reflected or not even mentioned in the documents it created. She describes how her problems with the Romanian secret police began at the end of the 1970s when, while working as a German-language translator at a factory in Timișoara, she turned down the Securitate’s proposal to become its informer. As a result of her refusal she was fired and the Romanian secret police continued to harass her and prevented her from finding a job. None of these events left traces in her file. Herta Müller also approaches the topic of her direct surveillance by the Securitate prior to and after the publication of her first book Niederungen (Nadirs) at a publishing house in West Berlin in 1984 and how the Securitate supplemented their physical abuse against her with psychological abuse. Again she underlines the fact that the documents in her informative file mention none of these episodes. Also omitted from her Securitate file are other events that could be used as incriminating evidence against Securitate officials, such as the beating of a German journalist who tried but failed to visit her, the death of one of her close friends, the organisation of their surveillance of her while she was abroad, etc. Herta Müller also expresses her anger at the Securitate’s violation of her private life through the installation of microphones in her house (even in the bedroom) and her mixed feelings about the recruitment of some of her friends as sources and informers of the Romanian secret police.

Greek Church Exhibition Hall, 1. May - 14. June 2009.

The reception of art is based on the dynamics of perception, or in some cases, on the conscious deception of perception. It is not only an aesthetic-optical, but an art historical and philosophical question: shall we put emphasis on the “seen” or on the “known”?

Art in the Middle Ages visualized the “known.” Later, until modernism, art presented the empirical, the “seen” world. Following this categorization, we can say the abstract and conceptual tendencies in modernist and contemporary art are related to the spirit of medieval art.

The relation of images to one another adds to the relation of reality and art: the cases of the simple epigone, the hyperrealist painter working on the basis of a photo, the artwork quoting other artworks, the artist mimicking the style of other artists, etc.

Through the parallel presentation of positive and negative examples, the exhibition gave an opportunity to viewers to think about differences between valid art of the pictorial age and products of the identity-crisis of postmodern culture.

These temporary exhibitions are important for the collection, which lacks a permanent show, as they offer a chance to display important works from the expanding repository and provide an opportunity to influence public opinion on the notion of “mimesis.”

Authors of the works on display: Andor Boruth - Diego Velázquez; Unknown master - Rembrandt; József Mányai - Van Dyck; Henrik Papp - Frans Hals, Ákos Birkás, Pál Gerber, Gábor Gerhes, Károly Kelemen, Frigyes Kőnig, Dániel László, Tamás Szentjóby, Ernő Tolvaly, Ákos Wechter, Dénes Wächter.

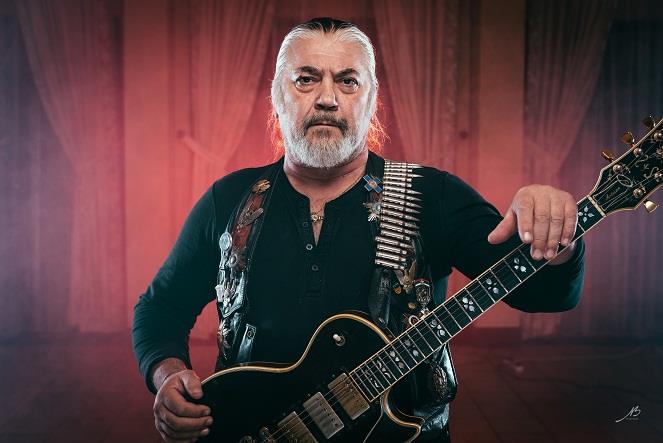

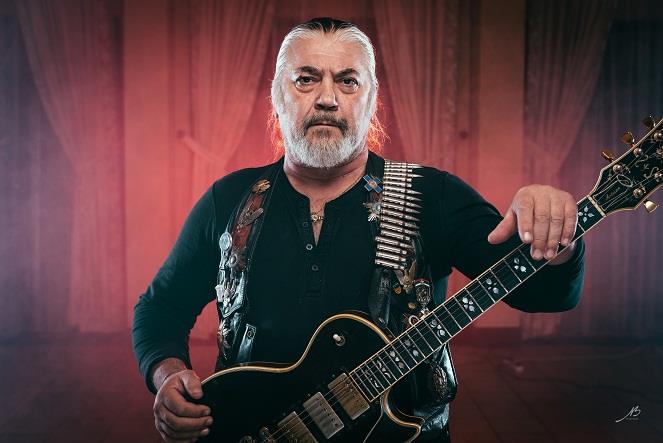

The founder and member of one of the most well-known Romanian rock bands, Phoenix, Nicolae (Nicu) Covaci granted a video-recorded interview to the researchers of the Centre of Oral History at the CNSAS (Romanian acronym for the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives) on 5 May 2009. The interview was recorded after Covaci read the personal file about him created by the former Romanian secret police, the Securitate, and expressed his discontent regarding its content, which covered only parts of the artistic life of the band. The interview follows a semi-structured format and falls into the category of life-story interviews. Nicu Covaci spoke about his early life in Timișoara, his educational background, his family and friends, how he became interested in music, and the beginnings of his band Sfinții (The Saints), later renamed Phoenix. Special attention was given to his relations with the communist authorities, especially the Securitate and the communist Militia, given his public profile and non-conformist stance as the leader of Phoenix. Consequently, Nicu Covaci spoke about how surveillance by the Securitate and Militia intensified as the band gained popularity among young people and how he and other members of Phoenix felt their presence during concerts, and he underlined the fact that authorities feared that their concerts might trigger young people’s revolt against the communist regime. Regarding this last aspect, he spoke about the influence Phoenix had on Romanian teenagers and how they filled the concert halls and stadiums where the band played. Moreover, Nicu Covaci described how Phoenix concerts were used by the same young Romanians to carve out a space for personal freedom and self-expression through nonconformist dressing style and behaviour, and especially through singing lyrics that contained hidden messages against the communist regime and its restrictive policies regarding the consumption of Western music. Censorship was another subject of the interview and the leader of Phoenix remembered their complicated relations with it. Sometimes they managed to trick the censors by coating the anti-regime messages of their lyrics in figures of speech, but in other instances, some of Phoenix’s songs could not be included on their albums. The non-conformist stances of Nicu Covaci also brought him into direct conflict with the authorities, as he refused publicly to became a member of the Romanian Communist Party and play an obedient role in relation to the communist authorities. The frequent harassment he was subjected to by the Militia and the Securitate influenced his decision to emigrate in 1976. After the earthquake of 4 March 1977, Nicu Covaci returned to Romania to participate in a fundraising concert for the numerous victims of the natural disaster that had devastated the southern part of the country. In fact, he took advantage of his return home to help the other members of the Phoenix to flee the country. In his interview, Covaci recounts in great details the movie-like story of how he helped the rest of the Phoenix band to get out of the country illegally, hidden in huge loudspeakers.

Doina Cornea kept a diary from the late 1940s up to the 2000s, which reflects the inner life of a Romanian intellectual under communism who embarked on a courageous opposition to Ceauşescu’s dictatorship. The manuscript offers a valuable insight into the intellectual atmosphere in which Cornea’s open letters and samizdat translations were created. In 2009, the Civic Academy Foundation published those notebooks which cover the period from 1988 to 1989, when Doina Cornea intensified her oppositional activities and sent several of her famous open letters of protest, such as that opposing the demolition of Romanian villages or the “Letter of 23 August,” which synthesised her criticism of Ceauşescu’s regime. In June 2009, the book was launched at the French Cultural Institute in Bucharest. Henri Lebreton, the head of the French Cultural Institute in Bucharest, chaired the discussion and the Romanian poet Ana Blandiana presented the book to the public.

The Museum of Contemporary Art moved to its new premises in 2009. The new Museum was opened on December 9, and with its opening the Museum also presented its permanent display. The permanent display carries the name Collections in Motion, and it also includes a photograph of the performances from Braco Dimitrijević’s cycle “Casual Passer-by’’ performed on Marshal Tito Square (today's Republic of Croatia Square) in Zagreb in 1971, as well as a poster used in the performance. As a part of the Museum’s permanent exhibition, "Casual Passer-by" is available daily to a wide audience, especially to organized visits by schoolchildren.

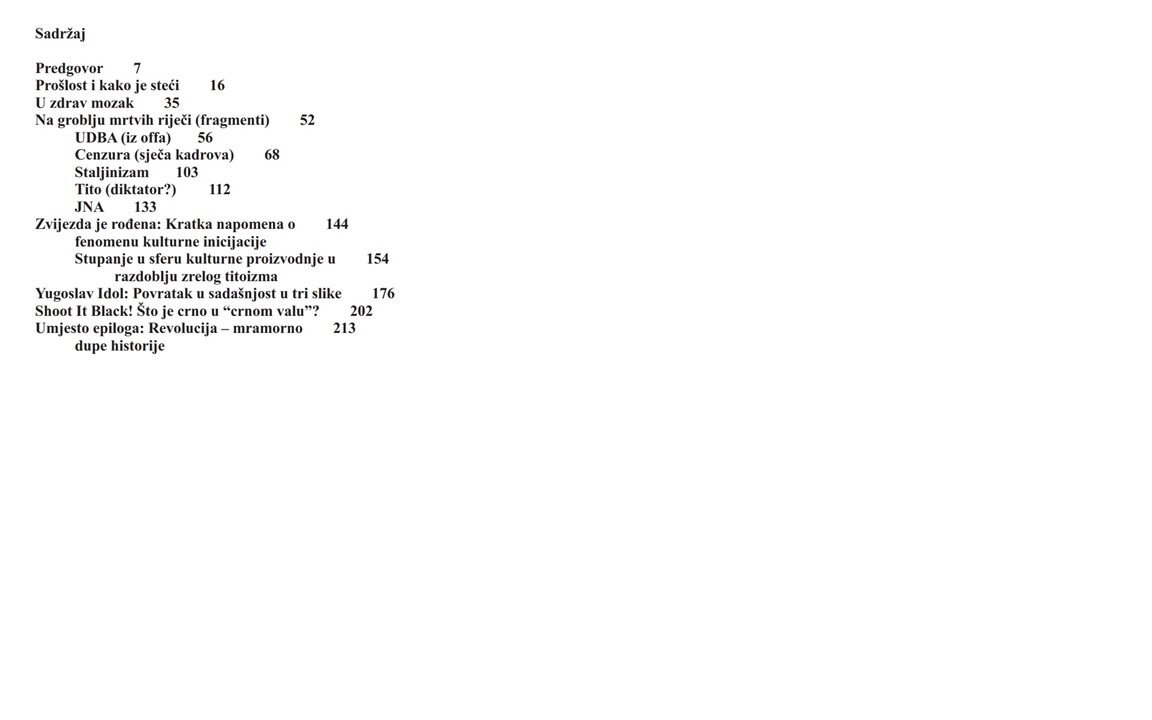

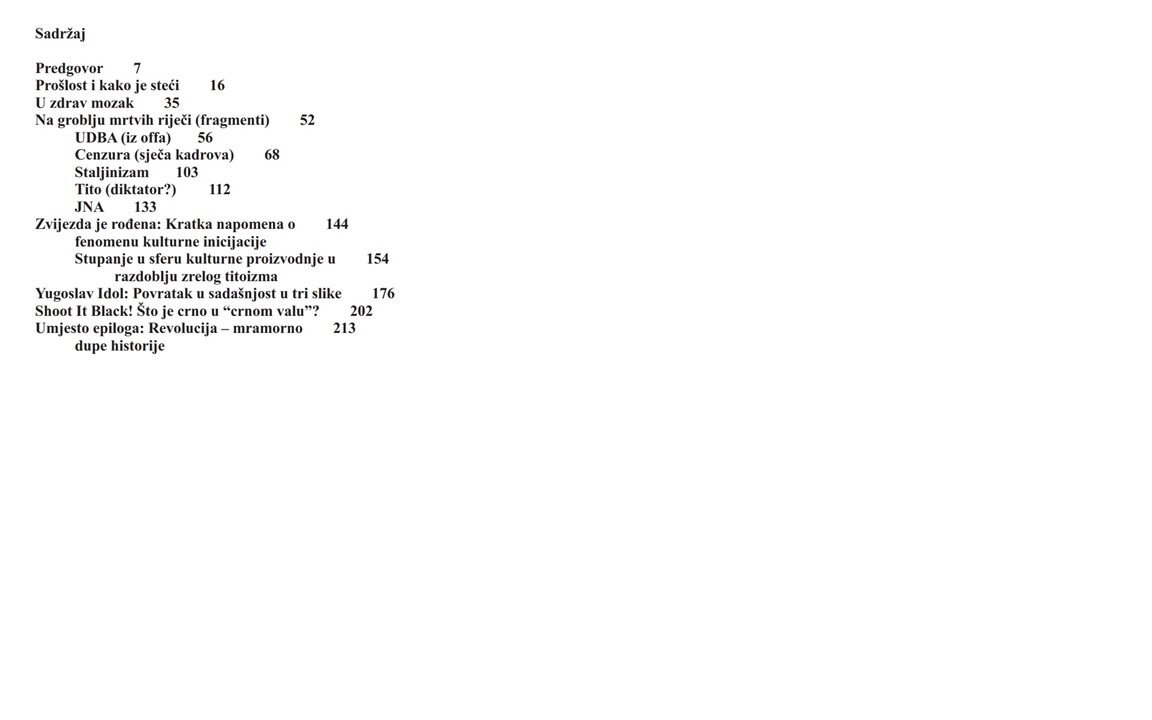

The book An Introduction to the Past (Uvod u prošlost) is published only in Serbian/Croatian, while the intent is also to publish an English version. A lengthy 22-hour interview with Želimir Žilnik was recorded; Boris Buden took excerpts from it and used them as “initial triggers” for his essays, creating a pseudo-dialogue and extending it with his analysis. Kuda.org regards Buden as an important partner.The table of content translates as follows: Preface 7The Past and How to Acquire It 16Into the Healthy Brain 35At the Cemetery of Dead Words (Fragments) 52UDBA (From Off) 56Censorship (Cutting Cadres) 68Stalinism 103Tito (Dictator?) 112JNA 133The Star is Born: Brief Note on the Phenomenon of Cultural Initiation 144Entering into the Sphere of Cultural Production in the Period of the Late Titoism 154Yugoslav Idol: Return to the Present in Three Images 176Shoot it Black! What is Black in the “Black Wave”? 202Instead of the Epilogue: Revolution – A Marble Ass of History 213

In December 2009, the CNSAS (Romanian acronym of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives) organized in Munich, with the support of the Institute for German Culture and History in South-Eastern Europe (Institut für deutsche Kultur und Geschichte Südosteuropas e.V.),which is affiliated to Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, an exhibition under the title “Romanian-German Writers in the Securitate Files.” On this occasion the CNSAS returned to William Totok the two notebooks with drafts of poems which had been confiscated illegally by the secret police in June 1975 and archived in the criminal file created by the Securitate on his case. This restitution was based on a post-communist legal framework which aimed at rectifying the wrongdoings of the communist regime (D. Petrescu 2017, 125–136).

Ljubomir Tadić was a professor of philosophy, academic, and politically active intellectual over many decades. During the socialist period in Yugoslavia he was a prominent opposition figure and critically minded intellectual who struggled against the Yugoslav system. Ljubomir Tadić’s collection is located in the Archives of Yugoslavia in Belgrade.

“Without a Trace? The Camp Belene 1949-1959 and After…”, 2009. Exhibition, round table and publication

“Without a Trace? The Camp Belene 1949-1959 and After…”, 2009. Exhibition, round table and publication

Kustić's columns (about one-fifth of the total number) were released in the form of a book in 2009, covering his writings in Glas Koncila over nearly forty years from the 1960s to the beginning of this century. Kustić dealt with various topics in addition to religion and theology, and he often delved into socio-political themes. Kustić's writing and editing in Glas Koncila under constant surveillance by the Commission for Relations with Religious Communities of the Socialist Republic of Croatia.

For example, the communist authorities had banned Glas Koncila no. 21 of 22 October 1972, in which they singled out among other things Kustić's article under the headline “Seventeen Centuries of Sacred Defiance.” In this article, Kustić took the example of St. Pollio, who preferred death because he did not want to forsake Christianity before the Roman prefect Probus. Kustić pointed out in this context the following: "St. Pollio claimed in particular that there are just laws that Christians are obliged to obey, but that the same authority could issues decrees that are not righteous, laws that a believer cannot accept" (Kustić 1972: 1). The communist authorities suggested, although he did not write it literally, that with these allusions Kustić had, in fact, "invited citizens to disobey and disrespect of the Constitution and laws of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Socialist Republic of Croatia" (Mikić 2016: 445).

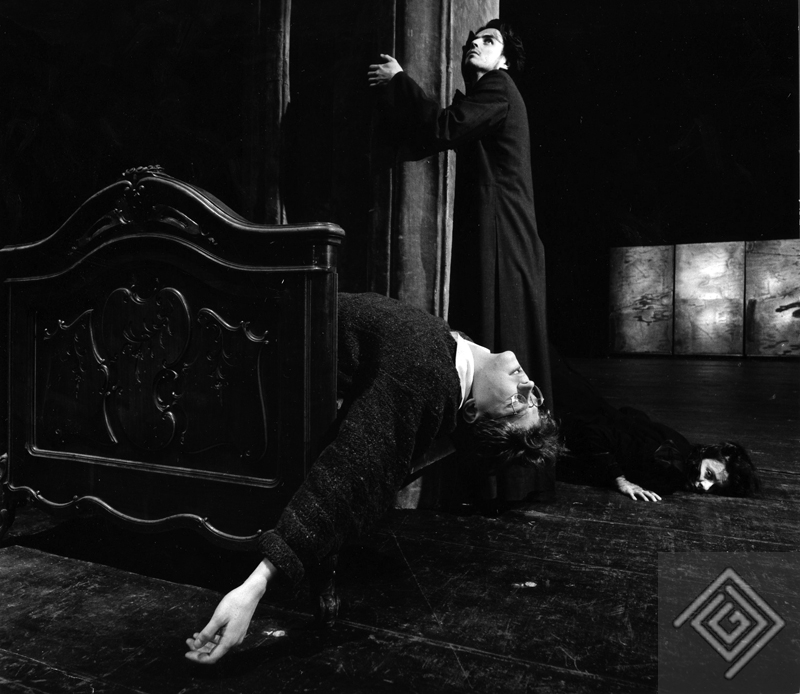

![By Hans van Dijk / Anefo (Nationaal Archief) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](/courage/file/n14683/Jerzy_Grzegorzewski_%281982%29.jpg)

The Alternative Theatre Archive is a research and archival project led by the Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute in Warsaw with support of the KARTA Center Foundation. Its aim is to collect, gather in one location and digitize documents, prints, recordings, photographs and all other archival materials on the alternative theatre movement in Poland in the 1970s and the 1980s.

As a result of special cooperation with Central European University, a course was held entitled Approaches to Counter-Cultural Movements in East Central Europe, 1960-1990, which examined the counter-cultural initiatives in the region. The course dealt with several topics in the research area of Artpool (including new wave, performance art, and underground culture), and the recorded lectures are available in the video archive.

The collection is about the life, work and activities of the famous Lithuanian humanist Meilutė Lukšienė. Although she is well known in Lithuania as the initiator and creator of the concept of the Lithuanian National School, and as an active member of Sąjūdis (the national movement) in the late 1980s, Lukšienė was also involved in cultural opposition during Soviet times. She was a key figure who promoted lithuanianisation at Vilnius University as early as the 1950s. Accused of 'bourgeois nationalism', she was dismissed from the post of head of the Department of Lithuanian Literature in 1958.

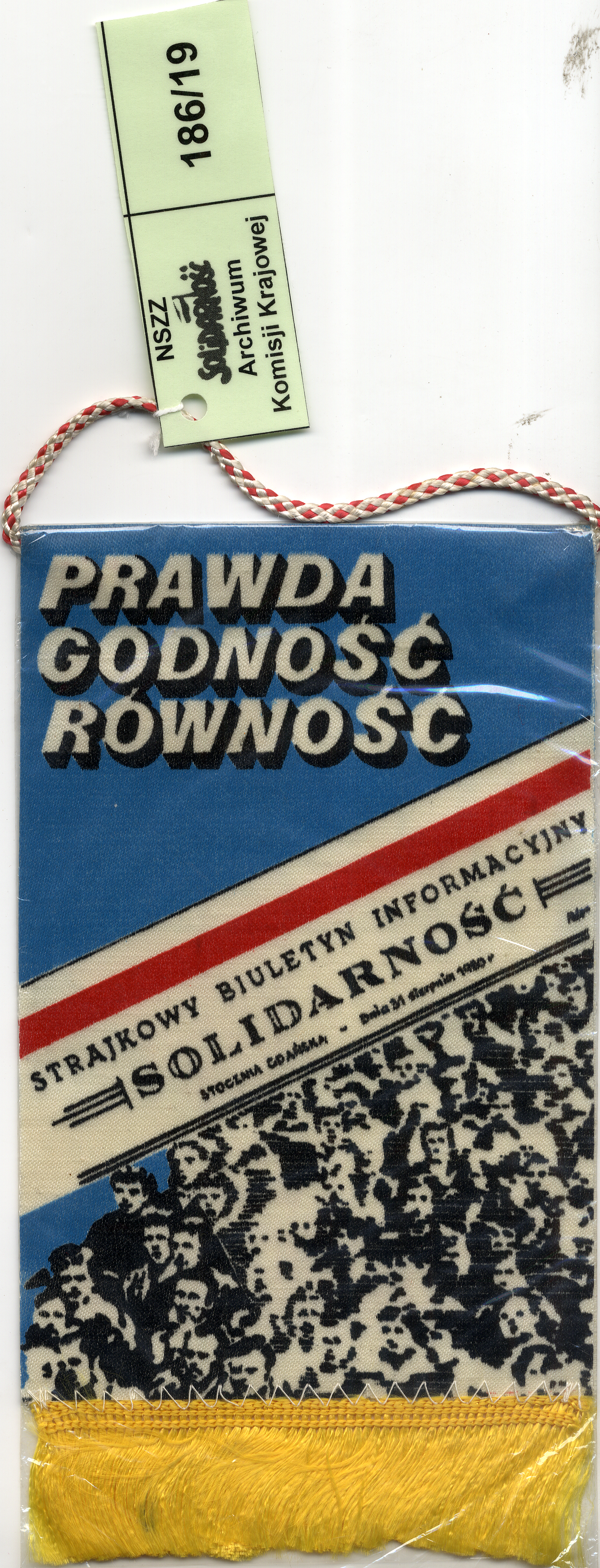

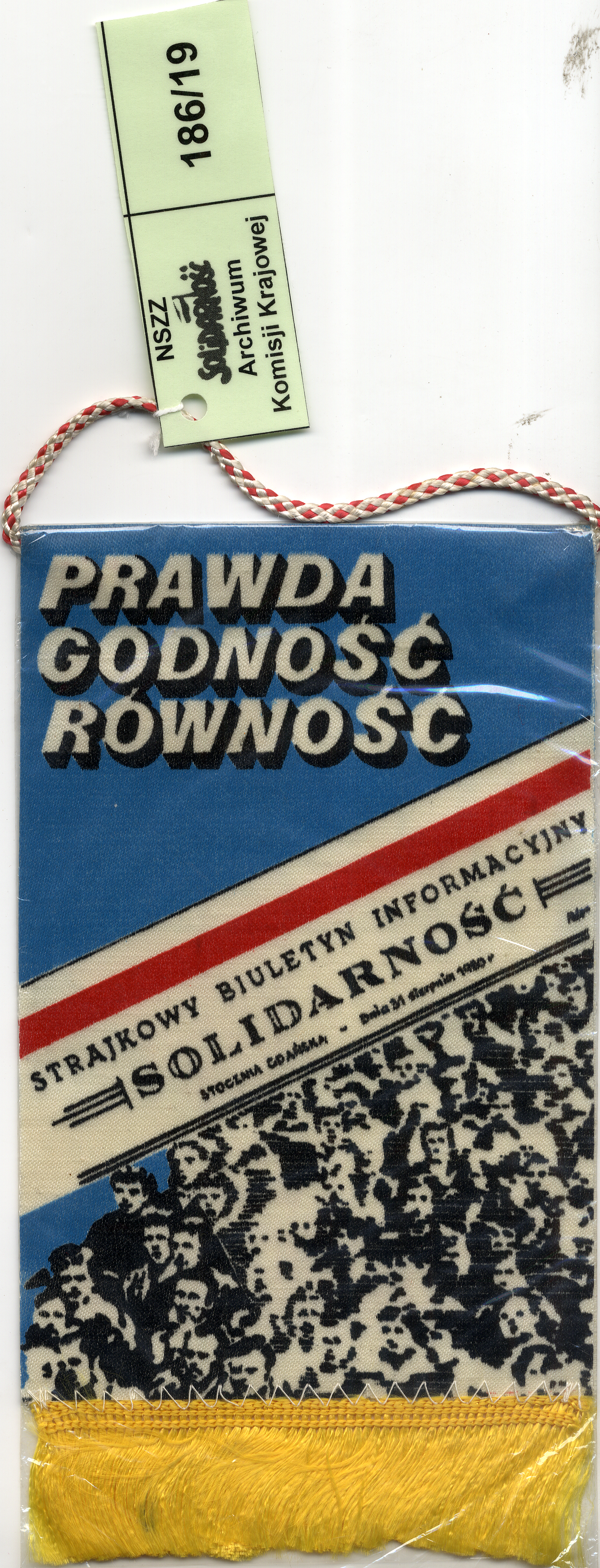

The Polish Underground Library was set up in 2009 in collaboration with the The Karta Center Foundation in Warsaw. It is comprised of Polish underground and exile publications, Polish flyers, posters, sound and visual recordings that are part of the Libri Prohibiti’s collections.

The Václav Havel Library’s permanent exhibition, “Havel in a Nutshell”, located on the ground floor of the library on Ostrovní street in Prague, introduces visitors to the life of Václav Havel through a collage of photographs and quotations. The exhibition also uses touchscreens that provide more detailed information and sound recordings. The exhibition focuses on the main chapters of Havel’s life: family, theatre, dissident life and presidency, which are presented in a broad cultural-historical context. Part of the exhibition is also a large interactive map of Václav Havel’s global “footsteps”. The exhibition, originally entitled “Václav Havel - the Czech Myth, or Havel in a Nutshell”, was first opened in April 2009 at the Montmartre Gallery in Prague’s Old Town, the former location of the Václav Havel Library. It expanded from the temporary exhibition “Václav Havel - the Czech Myth”, which had been exhibited at Hergetova cihelna in Prague from December 2007.

The project For an idea – against the status quo: Analysis and Systematization of Želimir Žilnik’s Artistic Practice is part of two research projects: The Continuous Art Class by New Media Center_kuda.org, the subject of which is the art practices of the neo-avantgarde movement in Novi Sad, and the regional project Political Practices in (Post–) Yugoslav Art, in which kuda.org participates in partnership with other organizations: WHW from Zagreb,

Prelom Kolektiv from Belgrade and SCCA/pro.ba from Sarajevo.

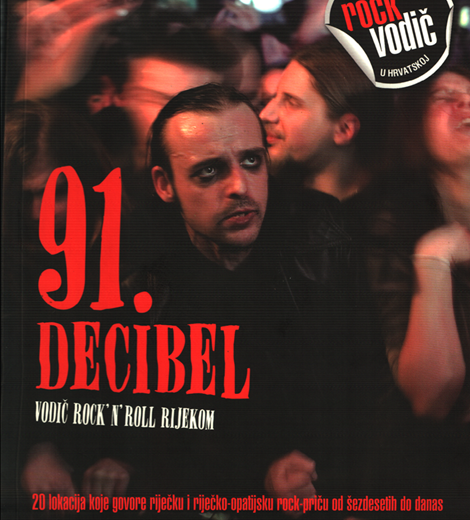

Đekić, Velid. 91 decibel: vodič rock’ n’roll Rijekom (91 decibels: A guide through the rock 'n' roll scene of Rijeka), 2009. Publication

Đekić, Velid. 91 decibel: vodič rock’ n’roll Rijekom (91 decibels: A guide through the rock 'n' roll scene of Rijeka), 2009. Publication

Velia Đekić's book 91 decibel is a sort of rock guide to the well-known locations of Rijeka's rock scene. In the book, Đekić covers the period from the late 1950s until the end of the 1990s, and takes us through the locations where many of today's cult Rijeka bands began their careers. Thus, the guide mentions Uragani as the first rock band in the then socialist Yugoslavia, as well as Paraf, which, along with the Slovenian band Pankrti, are considered the first punk bands in the socialist countries in Europe. Throughout the book we can keep track of how rock 'n'roll evolved over the years into numerous subgenres. Youth hangouts evolved together with rock 'n'roll.

Rijeka entered the rock 'n'roll revolution with small and crowded spaces, where it was possible to listen to music for "dances from LP records," which then gave way to several larger and smaller concert venues by the beginning of the new millennium. The stages of the Youth Hall, Palach, Circolo or Hartera are venues where domestic and international rock performers play regularly. The author published numerous photographs in the book that show the spirit of rock 'n' roll that has been in Rijeka for over fifty years.

Alexanderplatz is one of the most well-known and frequented squares in Berlin. On the 4 November 1989, it was the scene of one of the largest demonstrations in the history of the GDR. 20 years hence, the Robert-Havemann Society memorialized the events, people and unfolding of the revolutionary years of 1989/90. An open-air exhibition covering some 300 meters presented 700 photos and textual documents. Tom Sello, a former GDR dissident and now member of the Robert-Havemann Society curated the project. The exhibition was financed in great part by the German Lottery Foundation. 85 additional events were held in conjunction with the exhibition. Over its one and a half years of staging, the exhibition attracted more than 2 million visitors. On 15 June 2016, the expanded and in part, newly conceived exhibition was reopened as a permanent exhibition in the courtyard of the former GDR State Security Headquarters in Berlin-Lichtenberg.

The virtual Museum of the Orange Alternative is an Internet archive containing full documentation, i.e. photographs, posters, leaflets, articles, films, and other testimonies of the activities of the Orange Alternative in Wrocław and other cities, as well as its predecessor the New Culture Movement and the alternative graffiti in Polish People's Republic. Orange Alternative was a youth movement whose street happenings in the 1980s gathered hundreds and sometimes thousands of people dressed as dwarfs, singing songs for children, and ostentatiously chanting slogans expressing support for the police and the government.

The exhibition “Requiem for the Romanian Peasant: The Peasants and Communism” was held to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the beginnings of collectivisation in Romania, announced through the Plenary of the Central Committee of the Romanian Workers’ Party on 3–5 March 1949. Organised by the International Centre for Studies into Communism, part of the Memorial to the Victims of Communism and to the Resistance – Civic Academy Foundation, in partnership with the Dimitrie Gusti National Village Museum, the exhibition was initially displayed at this museum dedicated to the rural world of Romania from 17 March to 30 May 2009. The exhibition then travelled to Sighet, Oradea, Arad, Timișoara, Drobeta Turnu Severin, Iași, Alexandria, Baia Mare, Alba Iulia, Satu Mare, and Cluj. It presented archive documents, photographs from the period, and oral history testimonies relating to the traditional village world that collapsed as a consequence of the destruction of the system of private land ownership as a result of forced collectivisation – a process initiated by the communist regime at the end of the 1940s, interrupted after the death of Stalin, and then vigorously resumed after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and completed by 1962. The process of forced collectivisation gave rise to desperate reactions on the part of the peasants, who rebelled in numerous localities. A map showing the places where peasants rebelled against collectivisation and the imposition of quotas was one of the central elements of the exhibition. The creation of the exhibition involved the collaboration of the Timiş and Arad county branches of the Association of Former Political Prisoners in Romania, the County History Museum in Alexandria, and many witnesses to the events. The opening of the exhibition was also the occasion for the launch of the audio-book Ţăranii şi comunismul (The peasants and communism), comprising ten accounts by peasants who participated in the rebellions of the years 1949–1962, selected from the over 5,000 hours of recordings accumulated in the Oral History Archive of the International Centre for Studies into Communism.

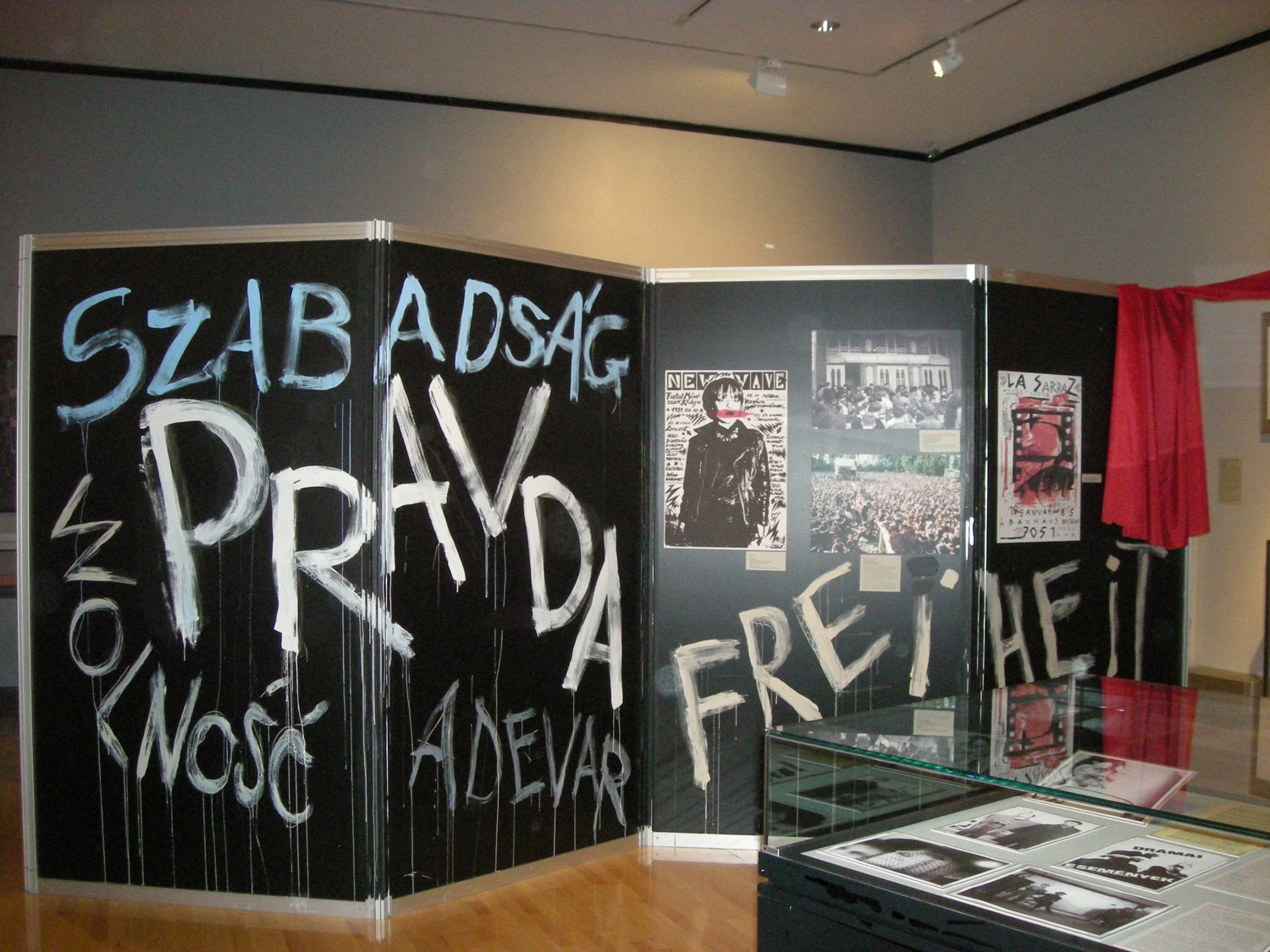

The five-month festival was organized at the the New York Public Library. It included theater performances, music, dance programs, exhibitions, and roundtable discussions. As a cooperating partner, Artpool participated in the event with exhibited materials and research assistance. Posters of concerts and photo documentation from the Artpool collection were on display at the show. They touched on the bands Europa Kiadó, Kontroll Csoport, and archive materials of the Budapest-Vienna-Berlin telephone concert.

In recent years, there has been increased interest in the materials in the Artpool sound archive. Various international exhibition-cooperative endeavors have been organized. At these exhibitions, (sound) documents and posters related to the underground art scene represented the collection.

The public memory regarding what Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti meant before 1989 has undergone significant improvement in recent years. After the passage of twenty years since the fall of Romanian communism, journalists rediscovered the topic of the holidays spent in the youth resort of Costinești as part of an emerging public interests in the pre-1989 personal experiences of common people. This interest in issues of everyday life under communism has grown steadily in Romania during the last decade. This is partly due to Romania’s accession to the European Union in 2007, which made communism suddenly seem forever gone and its remembrance a quest to avoid oblivion, and partly due to the economic crisis of 2008, which made past communism seem preferable to present “capitalism.” Radio Vacanța-Costinești occupies a special place among such issues, probably because it epitomises a past and mythicised life experience, which was free of the often-insurmountable problems of the present. In other words, the summer holidays in Costinești represent a common memory for many young people of yesterday, which the adults of today remember with nostalgia (C. Petrescu 2014).

Evocations concerning Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti in the mass media are currently taking place almost on a yearly basis. In the past decade, journalists from several daily newspapers with large circulation have reiterated the way young people used to have a lot of fun at a time when Romania was undergoing a deep economic crisis and an increasing isolation not only from Western countries, but also from other communist states. As a rule, it is Andrei Partoş who is responsible for the content of these evocations, as the principle presenter of the programmes of Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti. “Whenever I am asked, I talk about what happened then, on the radio in Costineşti,” he says. “It is my believe that it was something very important. Others who were directly involved in what happened then also talk about it. We are a sort of living memory, a portable memory. But there are fewer and fewer of us.” And he adds: “It would have been good if there had been a public event dedicated specifically to the Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti phenomenon. But there hasn’t been anything of that sort, at least not so far.” Although the interest in publicly remembering those summer holidays has remained constant in recent years, there has indeed been no special event dedicated to Radio Vacanța-Costinești apart from these recurring media articles. The extraordinary story of experiencing a life as if free during summer time in the 1980s in Costinești, Romania, still awaits its narrator. Until then, a new summer festival, which is scheduled for 25-26 August 2017 under the title FolkFest Remember Costinești, aims at reviving the bohemian atmosphere specific to the pre-1989 Golden Age of Costinești.