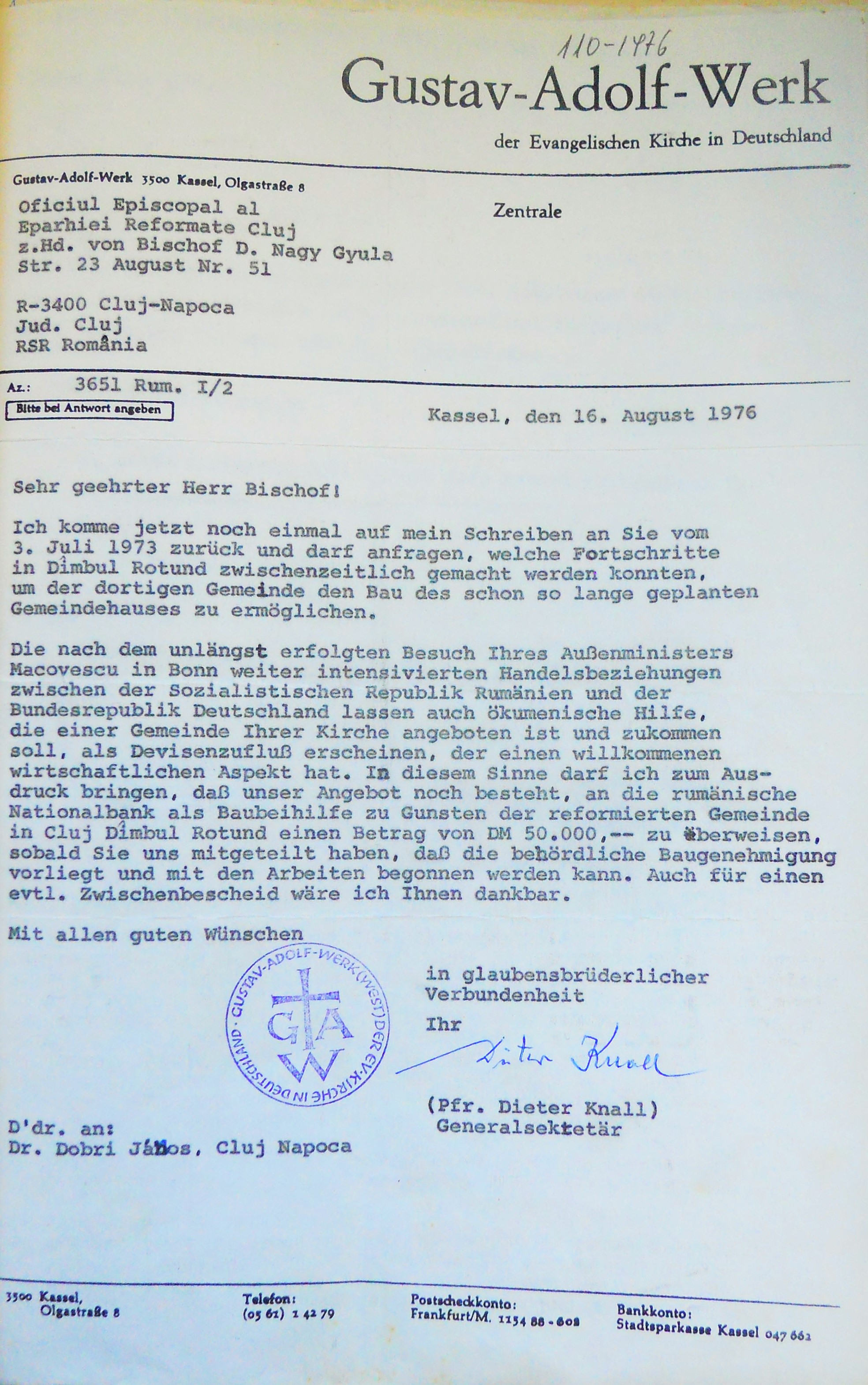

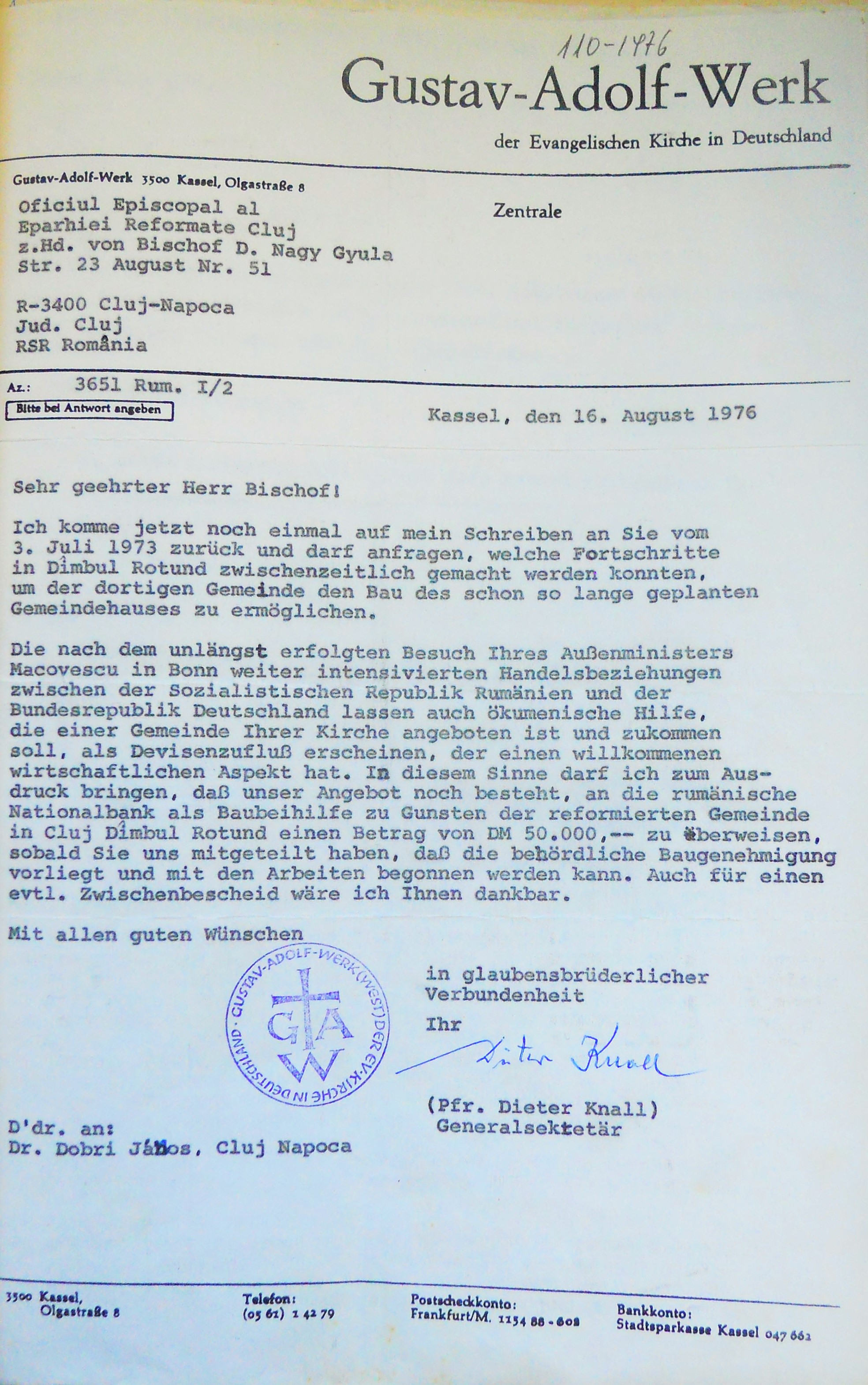

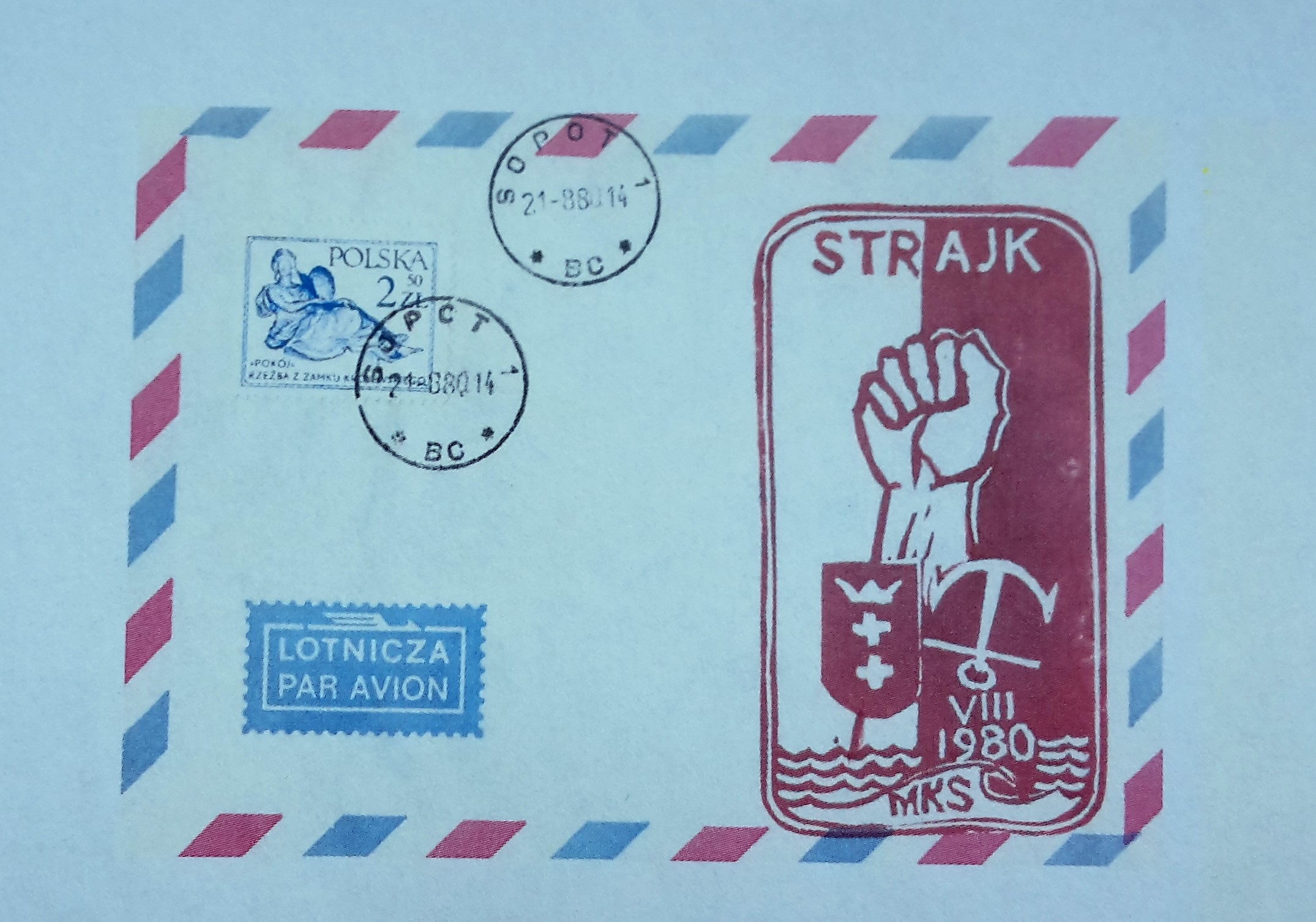

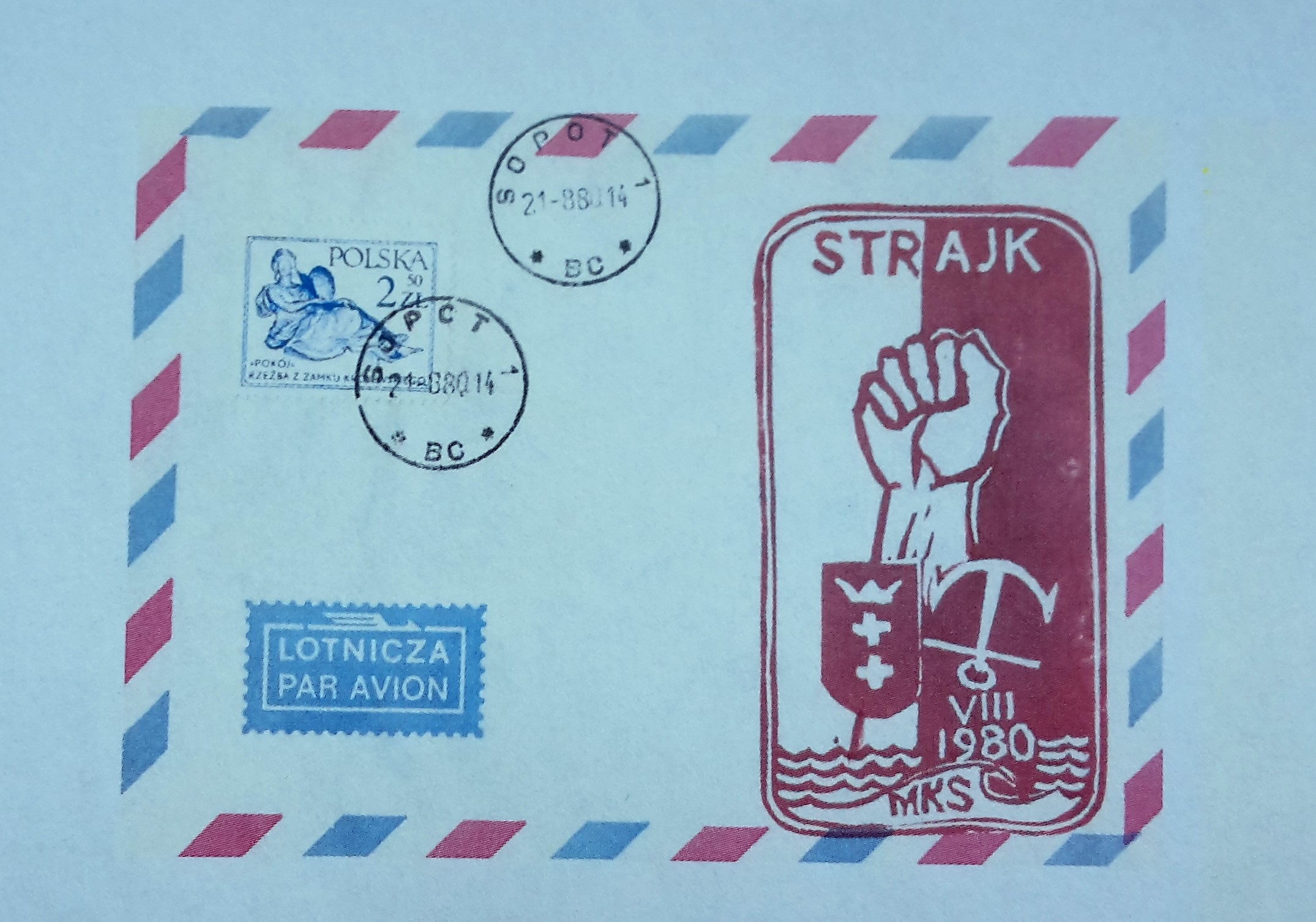

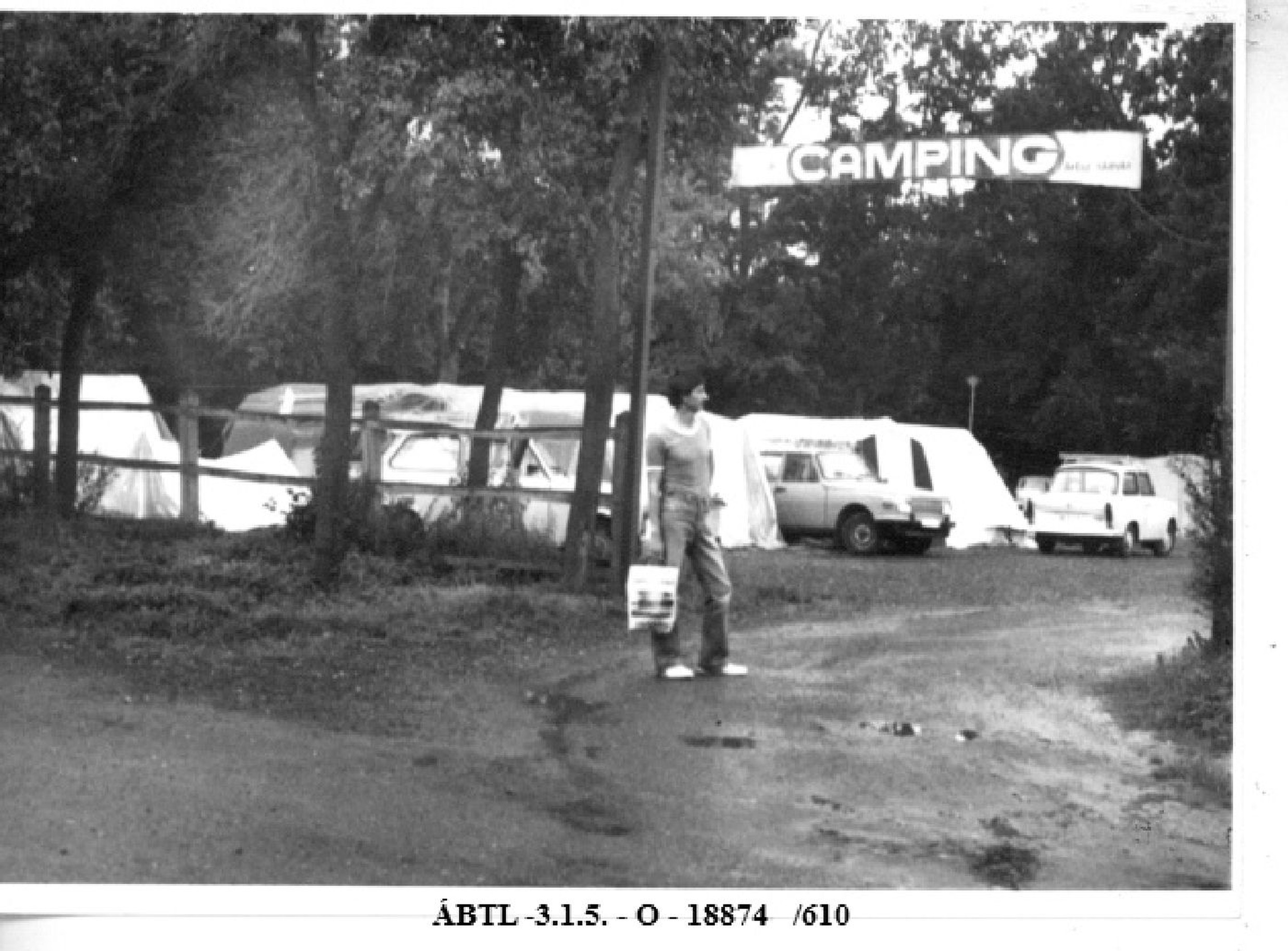

According to documents in the Reformed Congregation of Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund's Collection, on 13 March 1971 the West German foundation Gustav-Adolf-Werk offered a donation of 50,000 deutschmarks as ecumenical help for church construction (KKREL 1971/7, Report no. 28). This turned out to be of major importance in the process of constructing the church building. The fact that the state could benefit from foreign currency on the construction site counted as a very strong argument and played a huge role in the history of the reluctantly issued building permit. Between 1971 and 1976 there existed mostly only correspondence between the foundation and the pastor of Dâmbul Rotund, János Dobri on the question of when they would take over this sum of money, with the parish having to answer that they had not yet obtained approval for it. In the communist regime, any donation in money or of a different nature coming from abroad could be accepted and taken over only with "religious affairs departmental" permission from Bucharest. Regulation no. 16455/1971 of the Department of Religious Affairs (Departamentul Cultelor), referring to Decree-Law No. 334/1971 paragraph 5 point “r”, stated that gifts and bequests given or accepted by clerical organisations could be made only with the approval of the Department of Religious Affairs. Furthermore, any inventory objects, with or without historical or artistic value, books, manuscripts, musical instruments, money, material, or producs, regardless of their value could only be donated or accepted with the prior approval of the Department of Religious Affairs (KKREL 1971/7, Rescript no. 1420). Eventually, in addition to approving the construction of the church building, the Department granted permission for the use of the donation. According to the knowledge of Reformed pastor András Dobri and cantor Anna Jankó, only the first half of the amount was transferred officially to the Romanian National Bank, while the other half was transmitted through other "gates." In those times foreign exchange was not permitted for Romanian citizens living in the country. Only foreigners could change foreign currency and thus deliver the donated money. As the exchange rate was very unfavourable, those concerned decided to change the foreign currency with the willing help of Polish tourists. The greater amount obtained this way could be used properly during the construction. Because of the large amount involved, almost all members of the presbytery, which was then made up of about twenty-eight members took a part of it, which they then offered as donations in their own names for the church construction. In fact, based on oral history interviews, the possibility is not to be excluded that the second part of the West German donation was transferred officially in a similar way to the first, while the church members were used to collect other foreign cash donations, as the Gustav-Adolf-Werk donation was not enough on its own to pay for the construction (statement of Anna Jankó; statement of András Dobri).

The Securitate materials on János Dobri also give information about the donation. Based on the documents contained in the informative file, on 5 March 1971 Reformed Bishop Gyula Nagy was informed in a letter from the West German donor – through Pastor-Secretary General Dieter Knall – that the sum of money destined for the church construction in Dâmbul Rotund had been prepared, and he was asked to accept the donation in the name of the Reformed Church District of Cluj. A positive response was preceded by the consent of the Department of Religious Affairs in Bucharest (ACNSAS, 211500/4, 147). Since August 1972 the counter-intelligence in Cluj led by Colonel Sándor Peres had dealt specially with the case. When the Securitate learned that a considerable sum had been allocated by the Gustav-Adolf-Werk foundation for church construction, Peres had stated that in order to receive the money, the Church officials would have to talk with the county religious affairs inspector, "studying the possible modes of coordination." This statement is significant especially in the light of a later declaration of the county religious affairs inspector Hoinărescu Țepeș Horia, according to which no Hungarian churches or chapels were to be built in Cluj as long as he held that position in the city. (ACNSAS, I211500/5, 152–153). The later actions involved in the church construction prove the success of the "coordination," bearing in mind the interests of the single-party state.

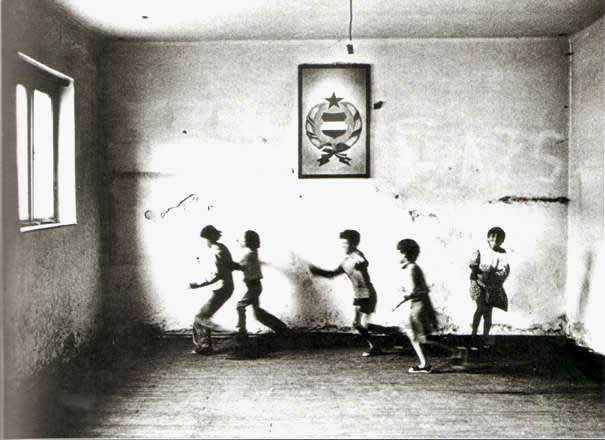

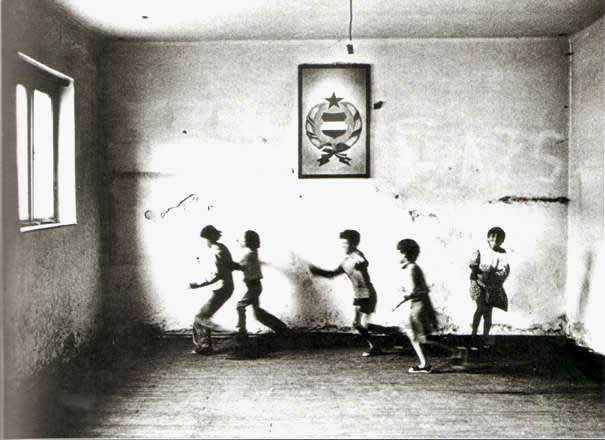

Some of the photographs taken by Lucian Ionică are snapshots of moments of high drama. Among them, those “hard to look at” images from the Paupers’ Cemetery, with the bodies of those killed by the repressive forces of the communist regime, hastily buried by the representatives of those forces, and then disinterred in order to be laid to rest in a fitting manner. There are also in the collection some photographs with portraits of children wounded during the Revolution of December 1989 in Timişoara. They were taken in the Timişoara Children’s Hospital on 24 December. The photographs show the wounded children in bed; the three snapshots include portraits of two boys and a girl. “For a few years after I took those photos I tried to trace the children I had photographed. I couldn’t find them, although I tried repeatedly. In the confusion and the strong emotions of the events back then, I didn’t have the inspiration to make a note of their names. Today I don’t know what has become of them, what they are doing,” says Lucian Ionică, confessing his regret at being unable to follow the story of those whose drama he immortalized in December 1989. “In the Timişoara Revolution, there were a lot of teenagers in the street. However the repressive forces had no compunction about firing at them. They were victims of the Army in the first place. Opening fire on minors is impossible to accept. Of course it is not justified against adults either, but the brutal actions of the soldiers against the children show how faithful those in the forces of repression were to Nicolae Ceauşescu,” is the comment of Gino Rado, the vice-president of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, summing up the tragic consequences of the involvement of forces loyal to the communist regime in the repression of the demonstrators, including minors (Szabo and Rado 2016). According to research carried out at the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, as well as other official statistics documenting the scale of the repression in the city in December 1989, at least six children or adolescents under the age of 18 were killed in this symbolic city of the Romanian Revolution. The youngest hero-martyr was Cristina Lungu; when she was fatally shot in December 1989, she was only two years old.

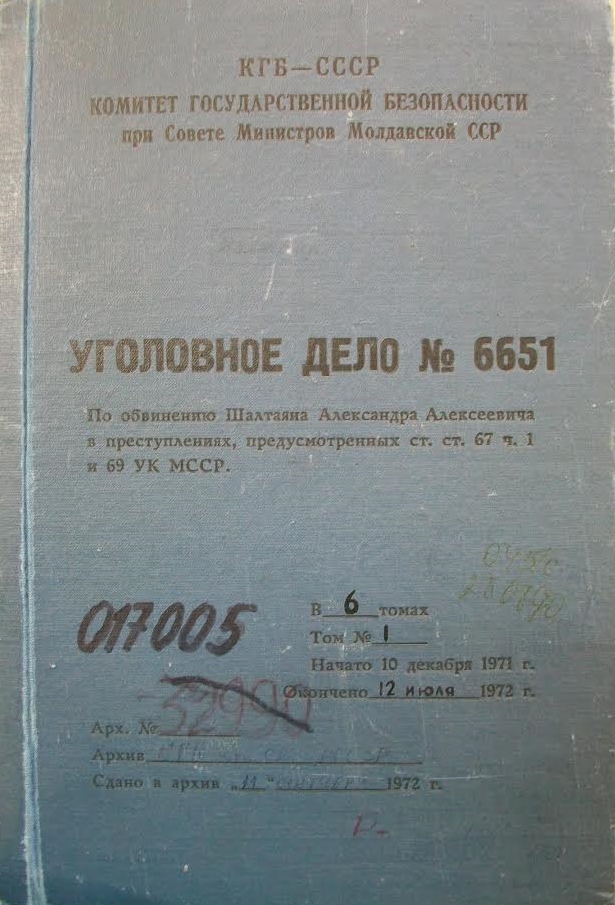

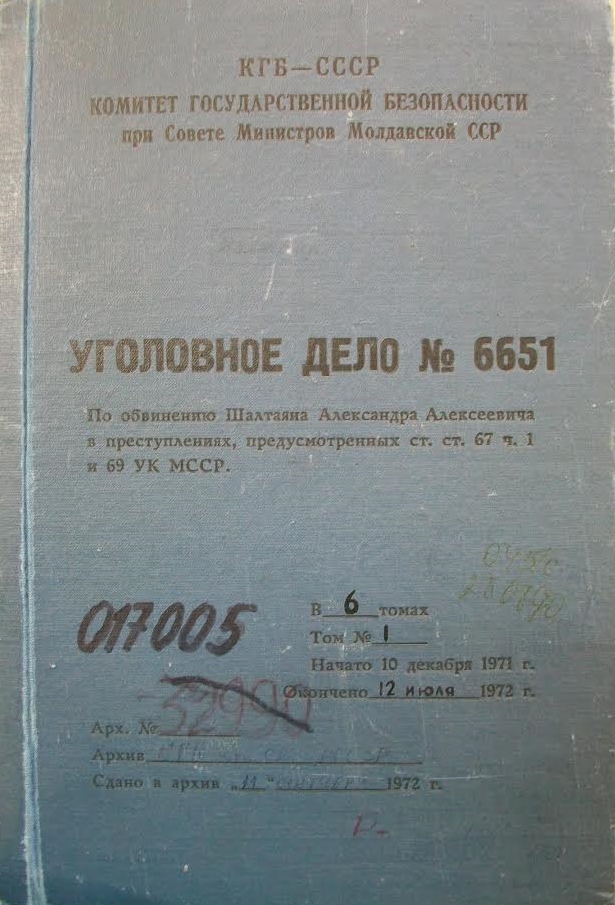

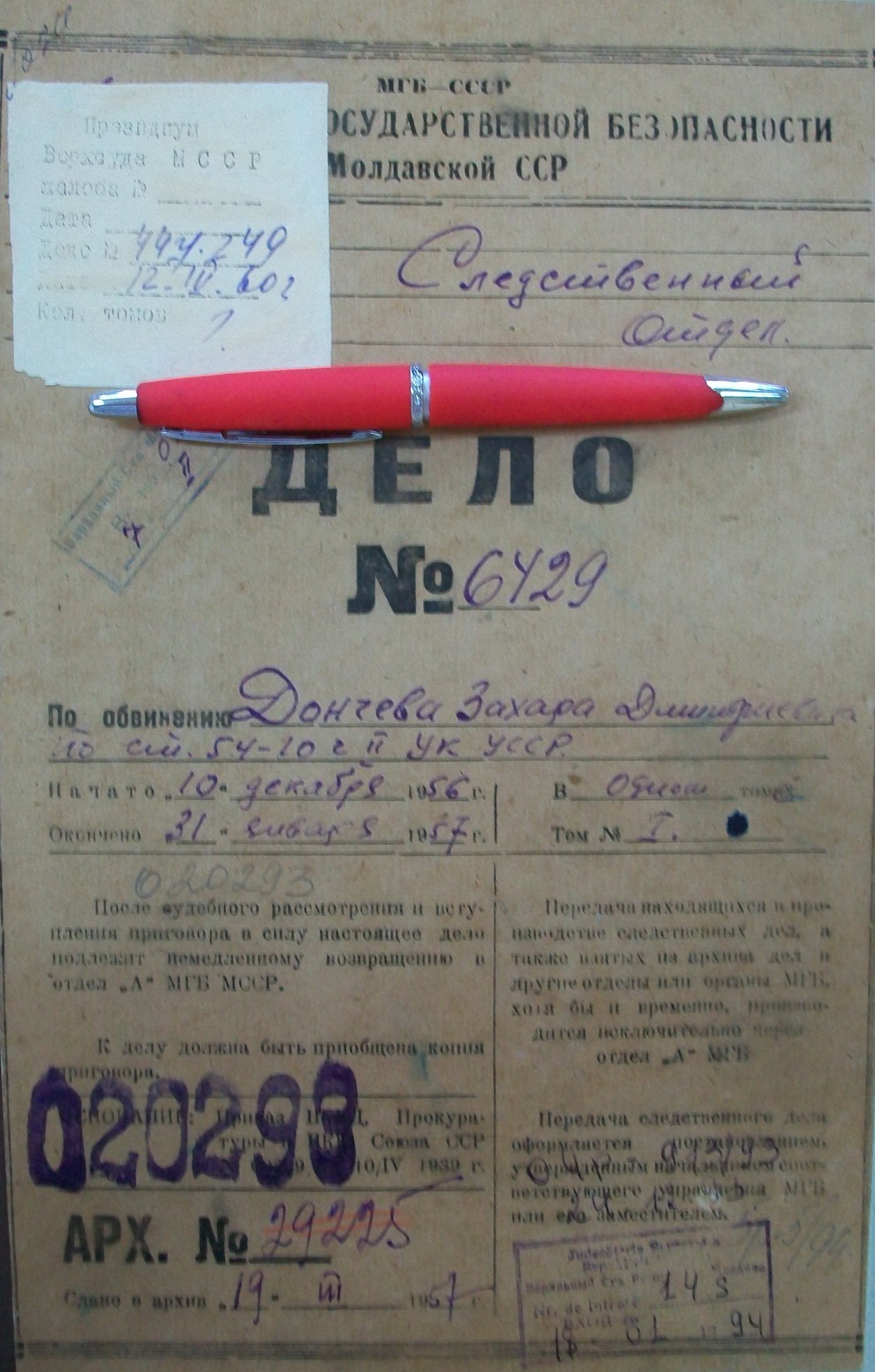

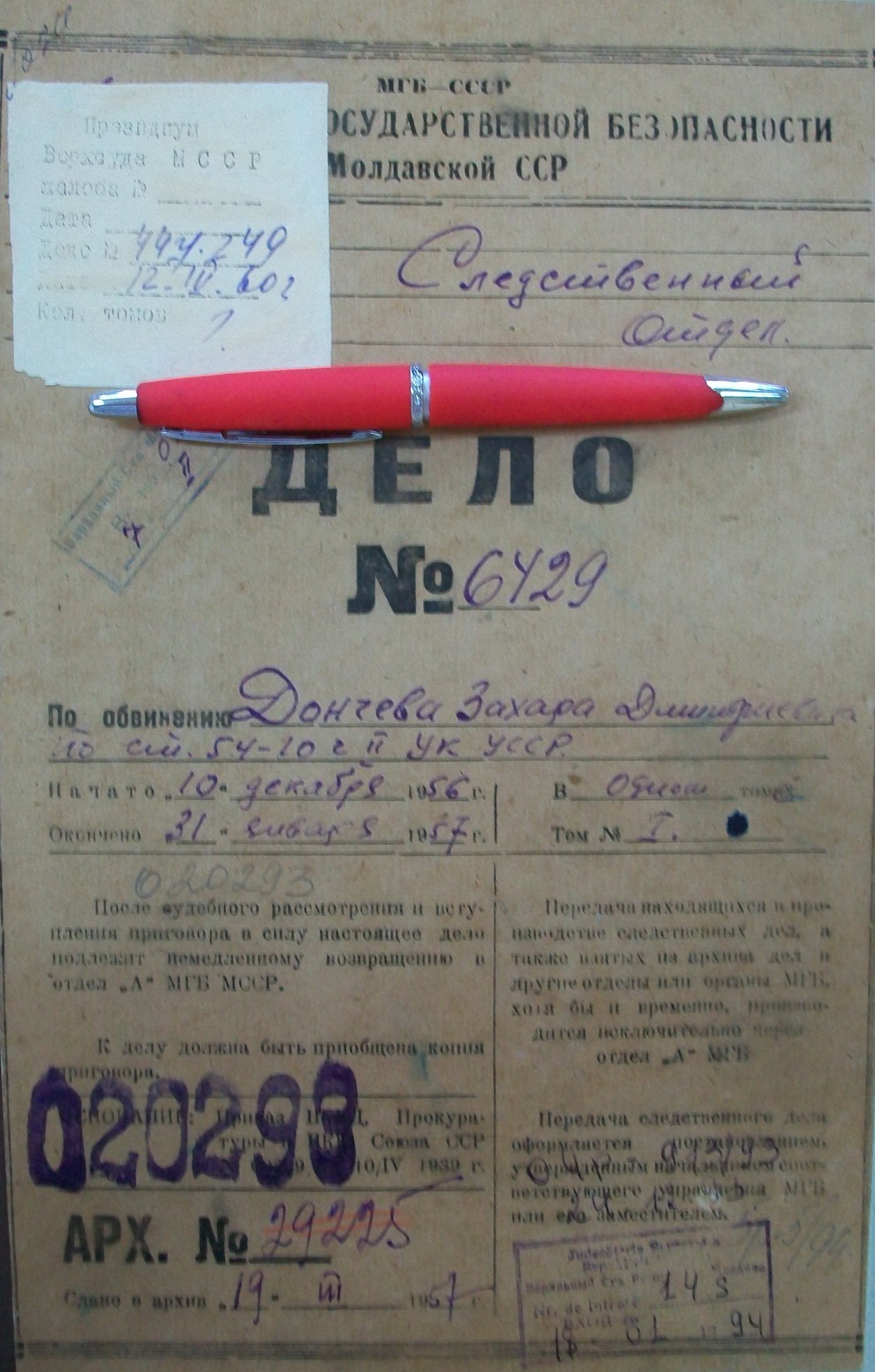

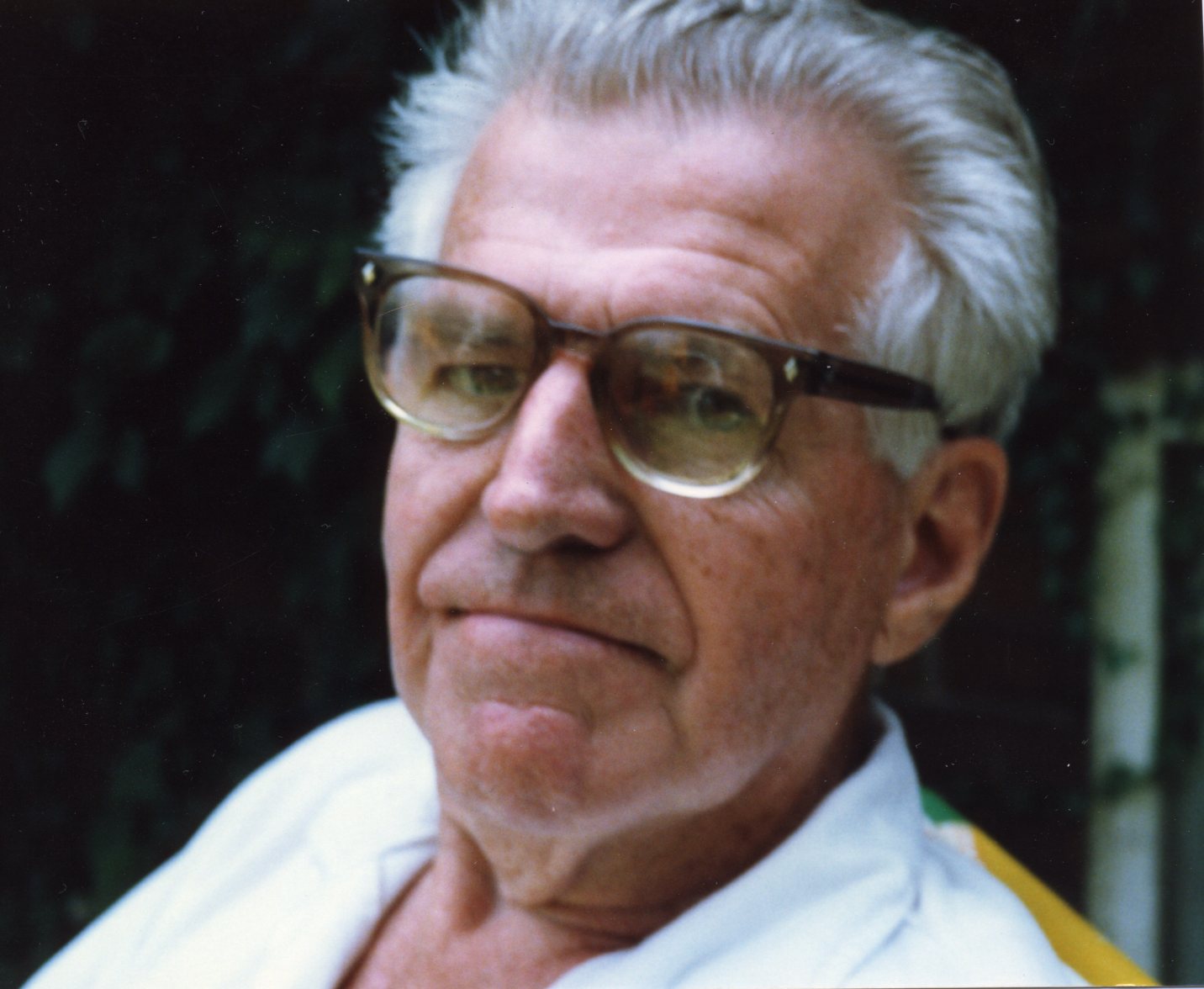

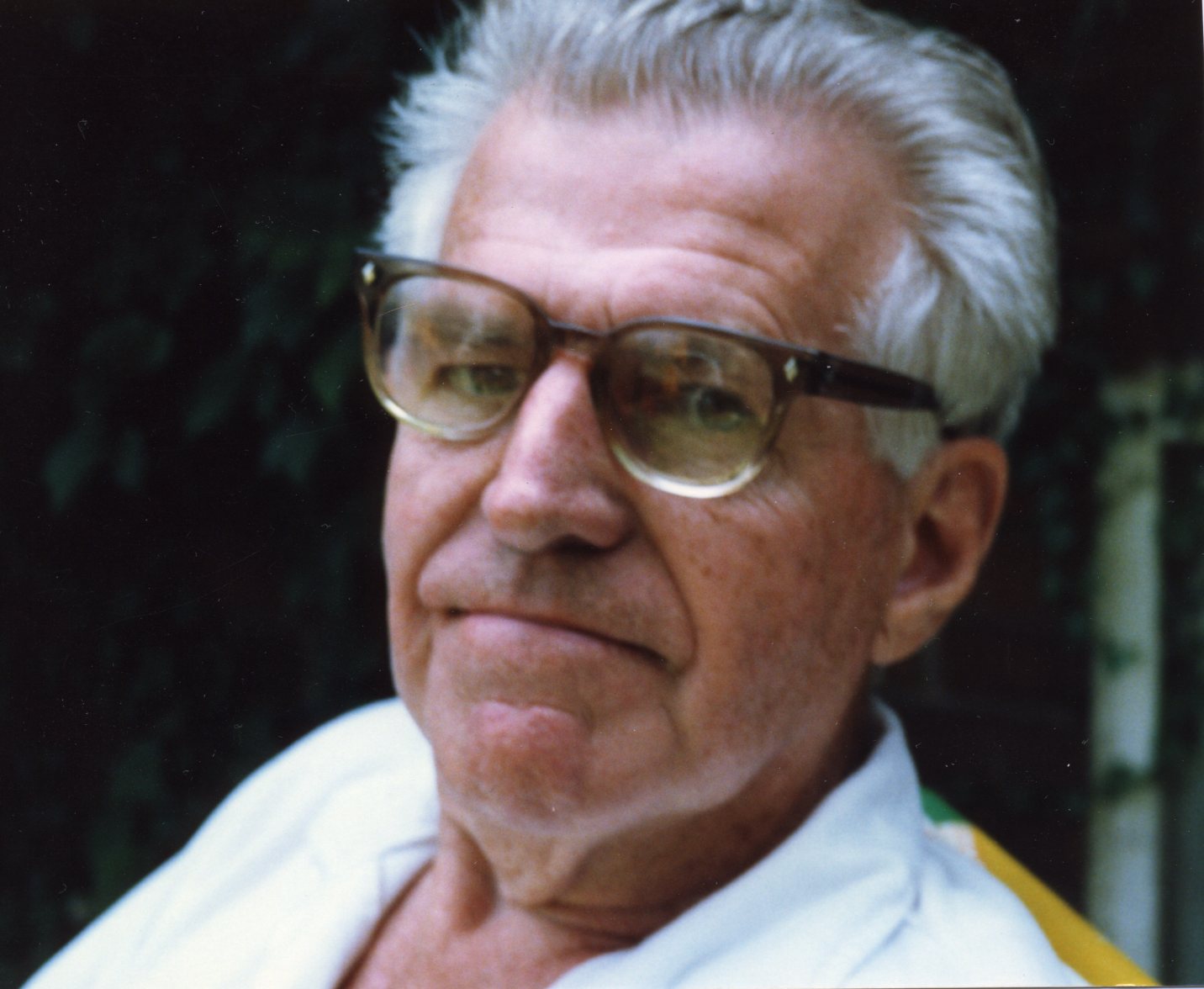

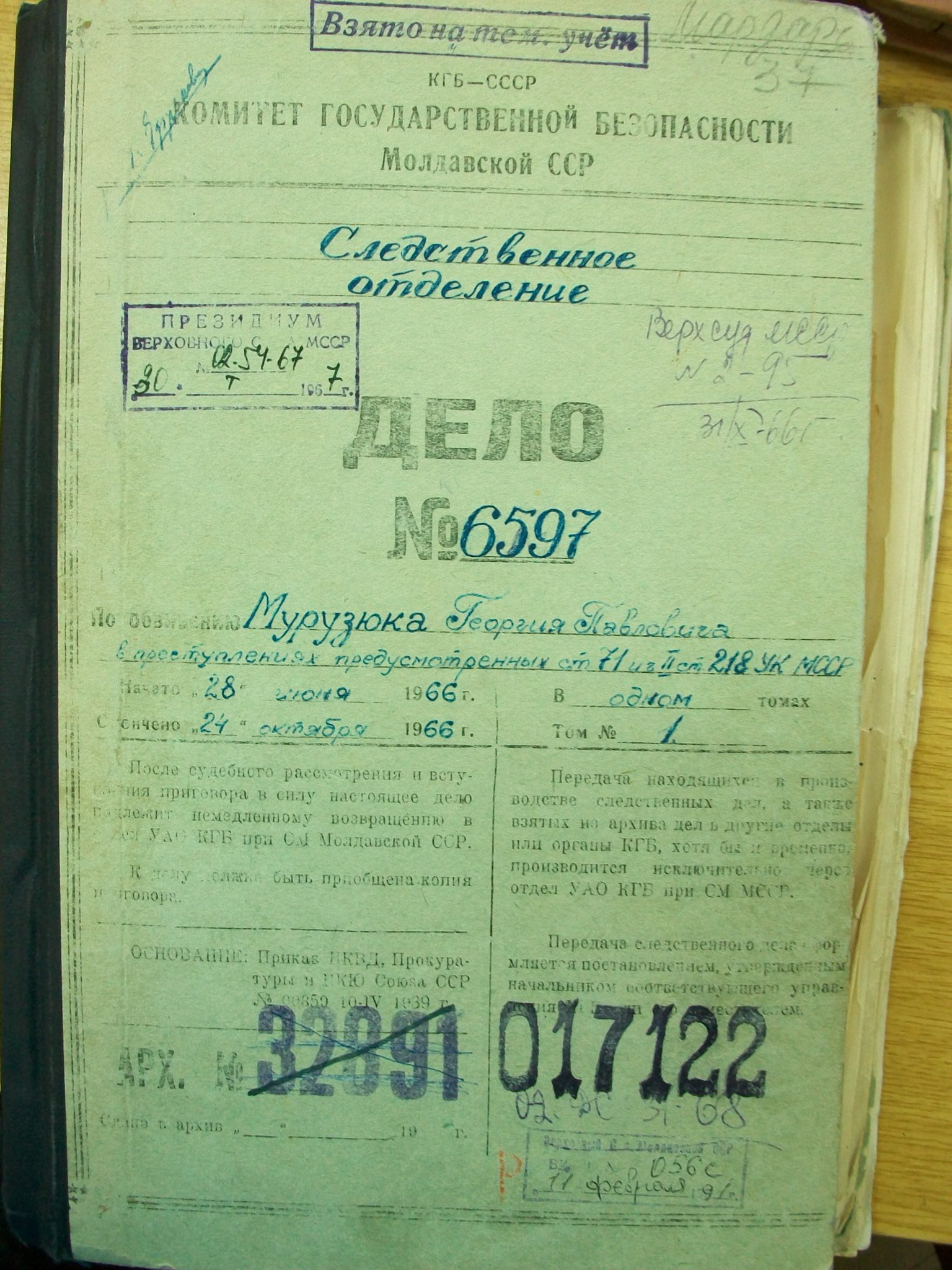

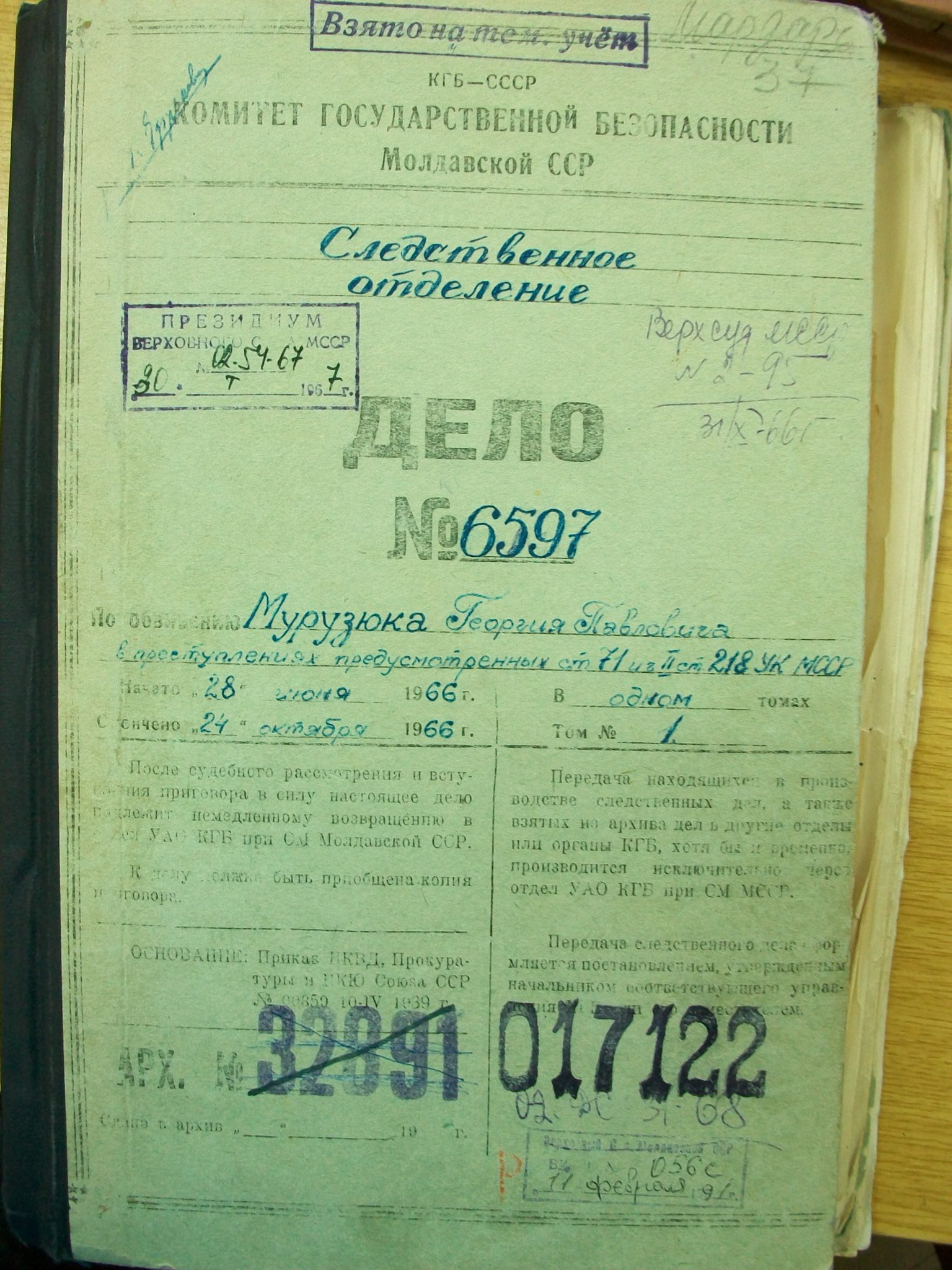

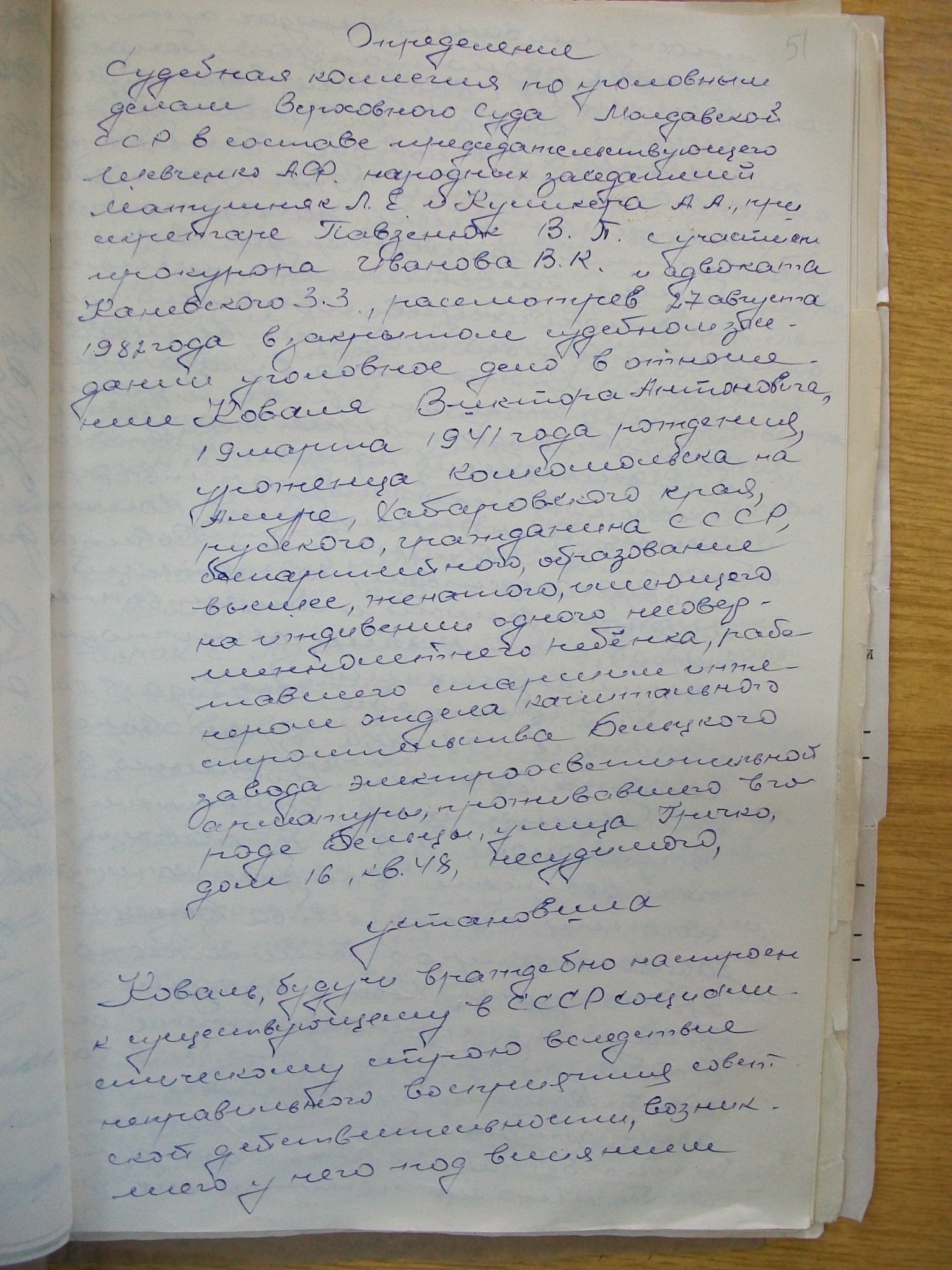

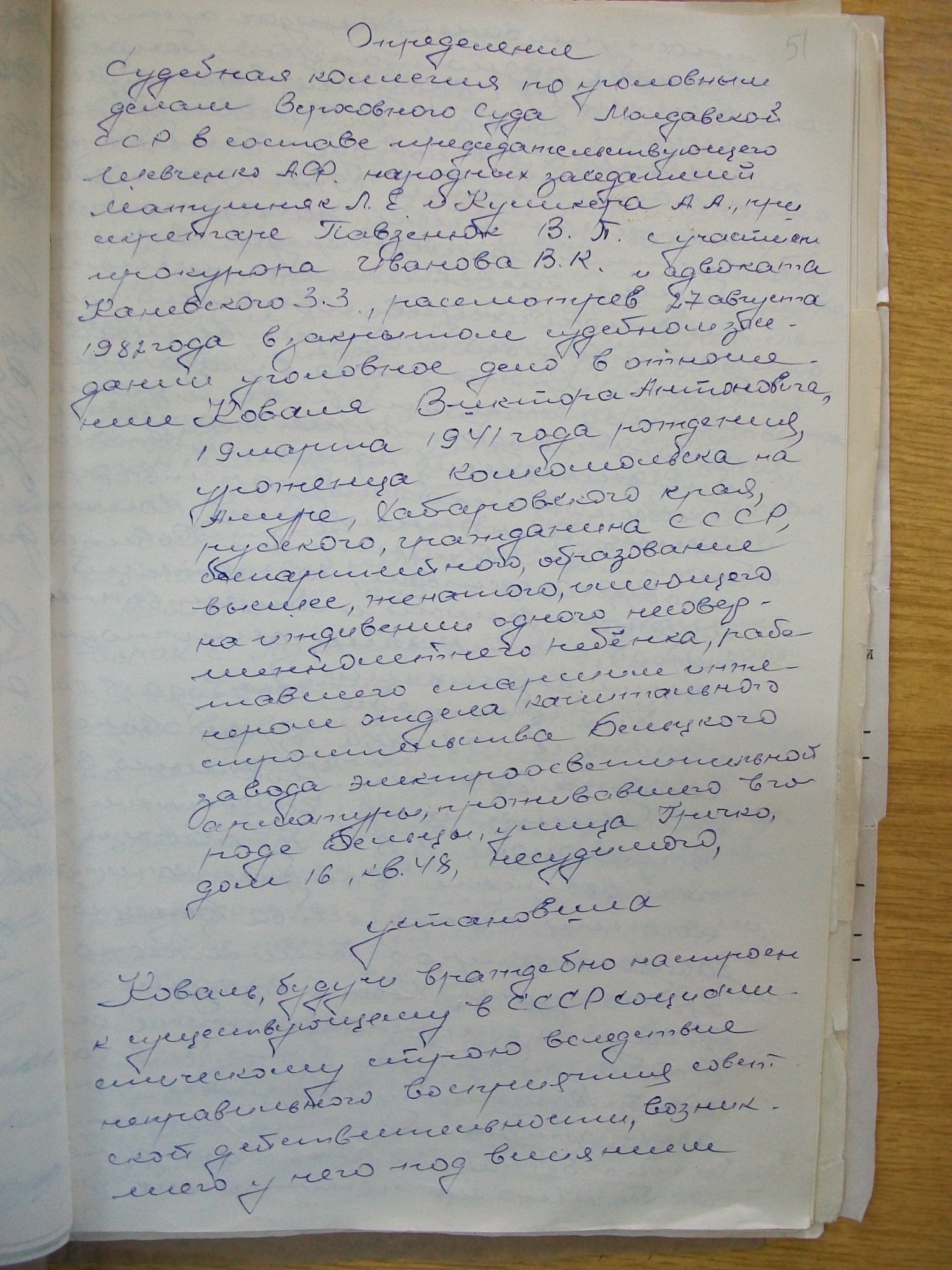

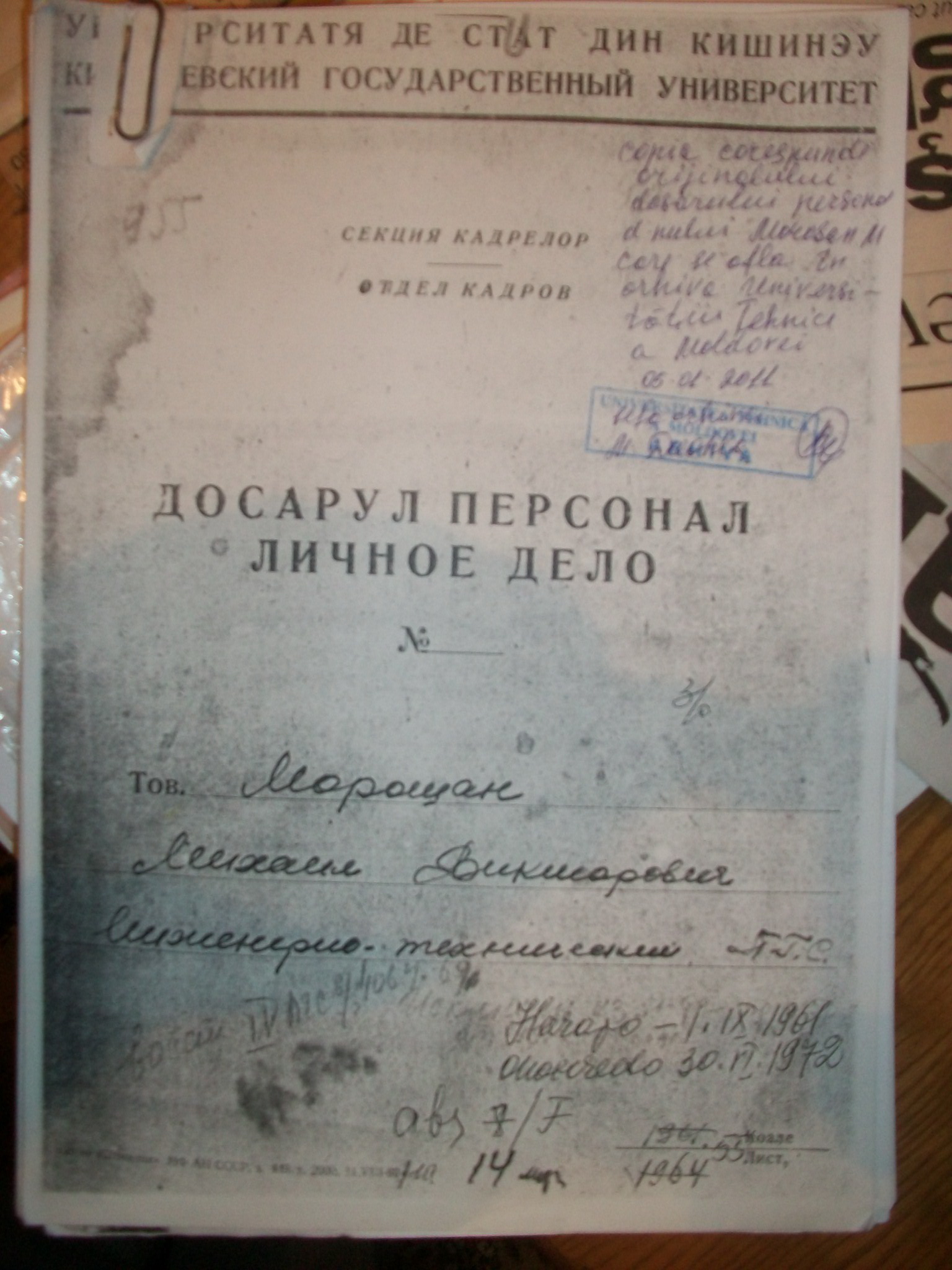

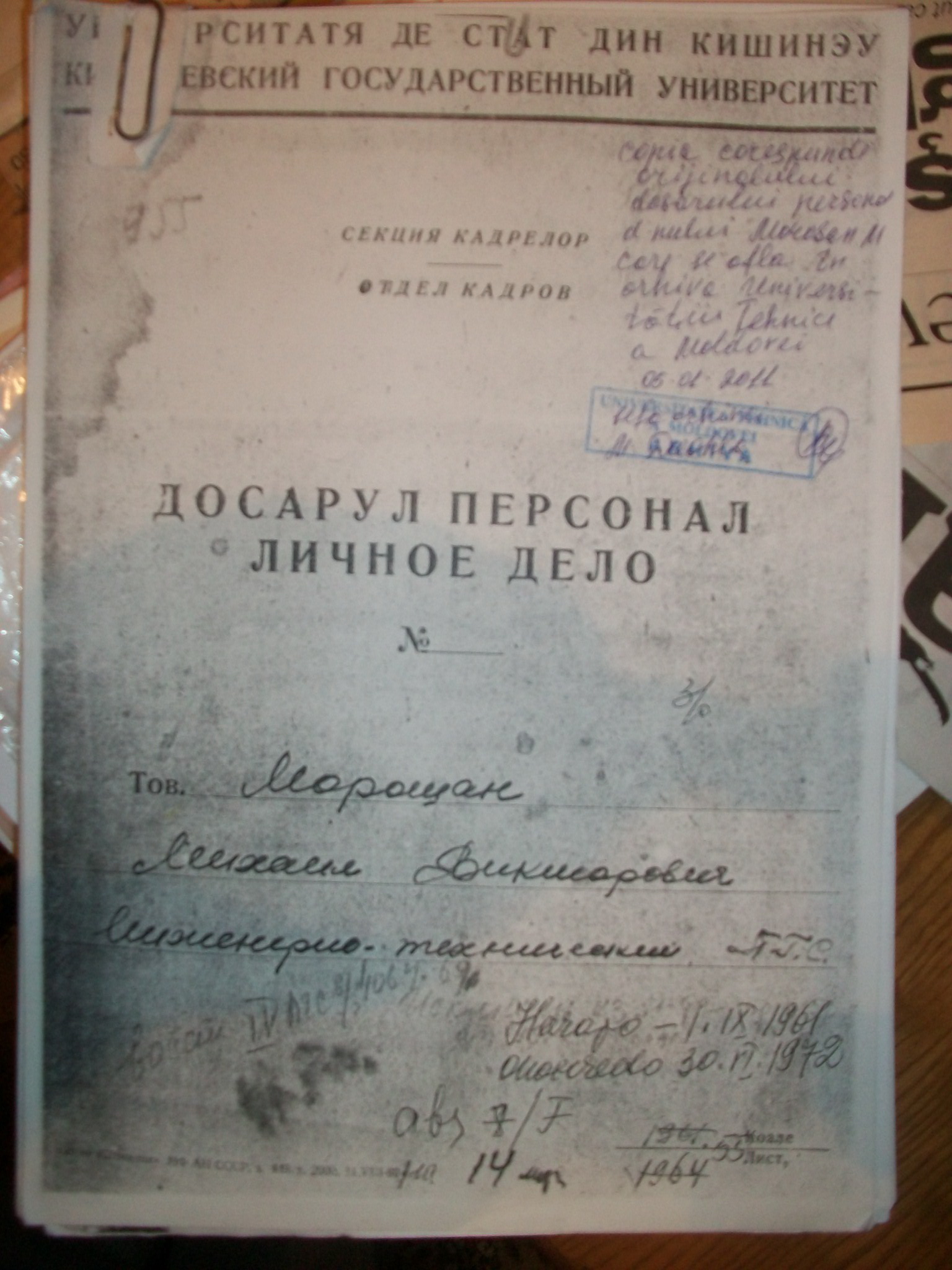

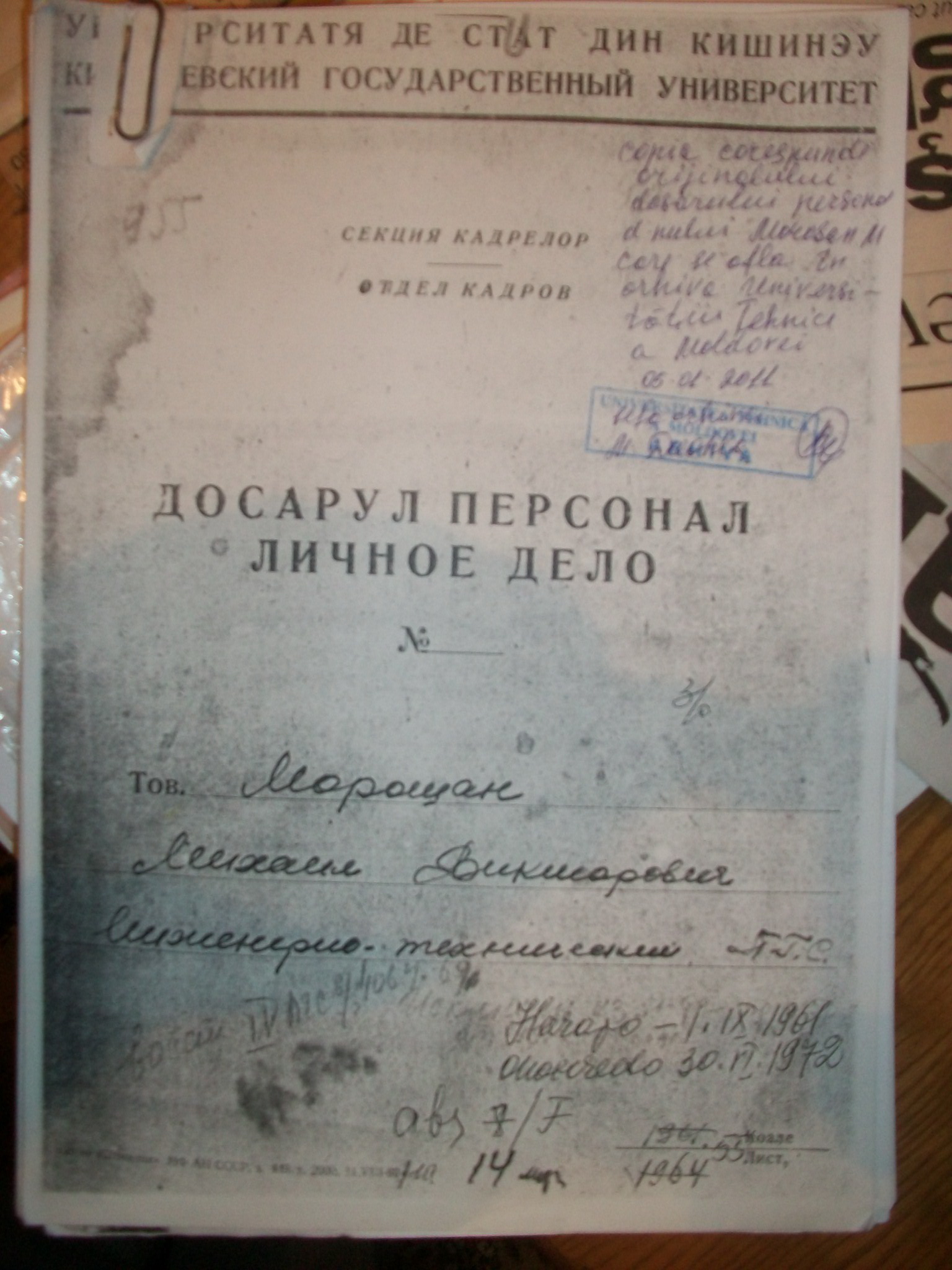

This collection comprises various documents (including trial records) relating to the activities of Alexandru Șoltoianu, a well-known oppositional figure in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) in the late 1960s and 1970s. Closely linked to the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group, Șoltoianu pursued a parallel project of creating a mass nationally oriented anti-Soviet political party known as National Rebirth of Moldavia (Renașterea Națională a Moldovei), to be based upon a broad network of student associations. Șoltoianu’s case files are currently held in the National Archive of the Republic of Moldova (ANRM). These materials were transferred to the ANRM from the Archive of the Intelligence and Security Service of the Republic of Moldova (formerly the KGB Archive).

Decision of the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR Concerning the Case of Gheorghe Zgherea. 9 June 1955 (in Russian)

Decision of the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR Concerning the Case of Gheorghe Zgherea. 9 June 1955 (in Russian)

Almost two years after his condemnation, in the spring of 1955, Zgherea filed a petition addressed to the General Prosecutor of the Moldavian SSR, requesting the revision of his sentence. In this petition, Zgherea again admitted his guilt, but emphasised that his conversion to Inochentism was mainly caused by the influence of his parents. He claimed that, due to his young age and to the unsatisfactory level of his education, he did not fully understand the implications of his actions at the time. He also declared that, during his detention in the labour camp, he “fully realised the mistaken nature of his views” and therefore was ready to “cut all his ties to the sect of the Inochentists.” This remarkable example of repentance and apparently successful “re-education” should not be taken at face value, especially given the fact that during the trial Zgherea refused to abjure and renounce his faith. However, in the post-Stalinist Soviet context, this proved an effective strategy for alleviating his plight and for receiving a reduction of the sentence and, ultimately, a full amnesty. In his review of Zgherea’s case, one of the employees of the MSSR’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, Major Rogachev, noted the defendant’s partial admission of guilt and his apparent repentance as alleviating circumstances. In the Resolution he sent to the General Prosecutor of the MSSR, A. Kazanir, on 28 April 1955, Rogachev concluded that, although Zgherea’s “guilt” was not in doubt, the punishment was “too severe and did not correspond to the seriousness of his actions.” Therefore, Rogachev recommended that the prosecutor’s office file a formal protest to the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the MSSR in order to request a revision of Zgherea’s case, which the prosecutor did in due course. As a result of this protest, after reviewing the case, on 9 June 1955 the Supreme Court issued a special decision which reduced Zgherea’s sentence to five years of hard labour and a further three-year suspension of civil rights. The main argument of the court was that Zgherea “did not have a leading position within the sect.” This motivation points to a shift in the authorities’ perception of the social danger of the Inochentists and similar religious movements and to a more differentiated approach to the individual guilt of their members. Moreover, Zgherea was amnestied according to the provisions of the Decree of 27 March 1953, which ended the main wave of Stalinist repressions and secured a legal basis for the gradual release of political prisoners. He was to be released from the labour camp as soon as possible, while his penal conviction was dropped. This case certainly did not illustrate an entirely new attitude of the regime toward religious dissent, which continued to be viewed with suspicion and repressed. However, there was a marked shift in the authorities’ repressive strategies, which became subtler and more differentiated. The case of Gheorghe Zgherea is thus a fascinating example of essential ideological continuity uneasily combined with changing methods of addressing and dealing with dissent and opposition in the religious sphere.

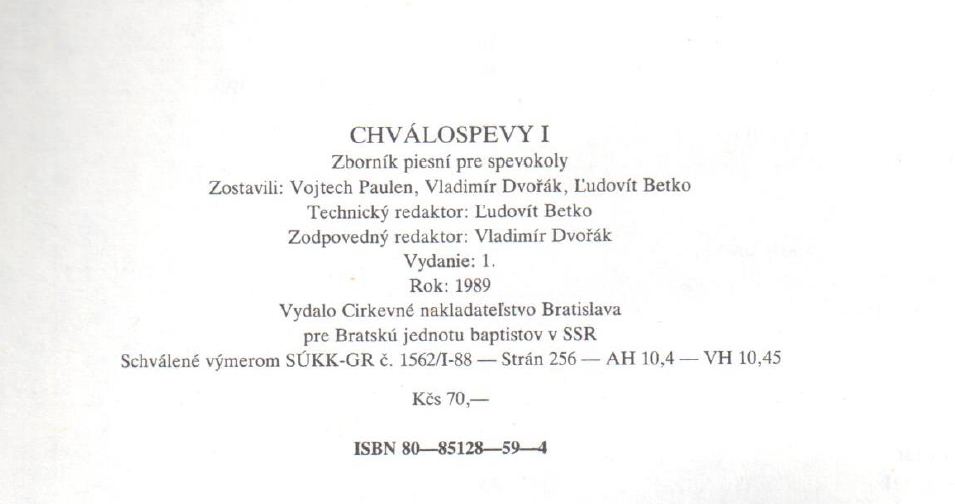

The Nádosy bequest is an exceptional collection of materials documenting the daily work done by a Christian samizdat author and his efforts to establish a network of contacts. It also contains materials concerning the organization of the missionary working group, international communication, and the process of samizdat production.

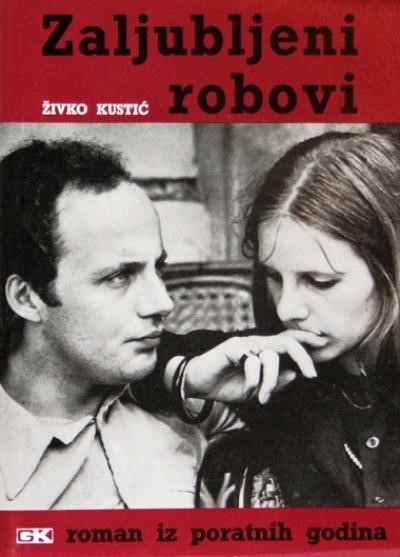

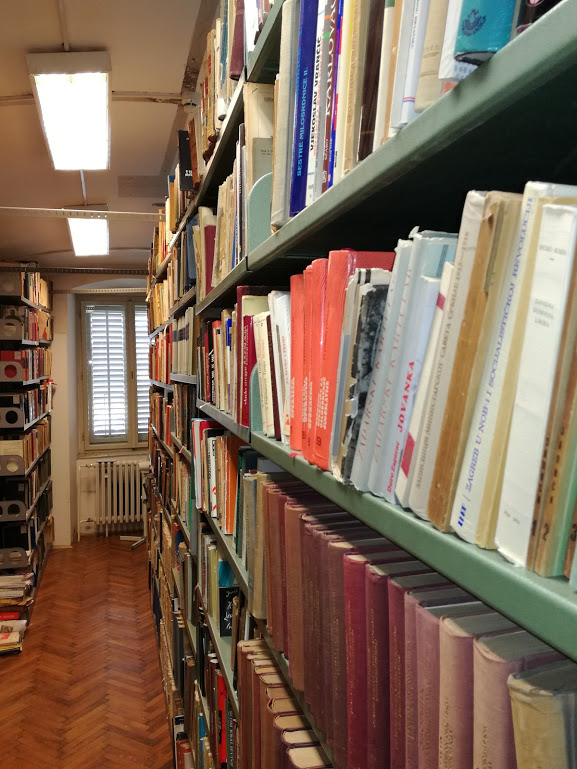

The Foreign Croatica Collection is the largest collection of books and periodicals published by Croatian authors in foreign countries. The Collection includes publications in many languages covering numerous issues on Croatia and the Croatian people, including those related to the socialist period. It is the most important collection in Croatia containing books by Croatian émigrés banned during the time of socialist Yugoslavia.

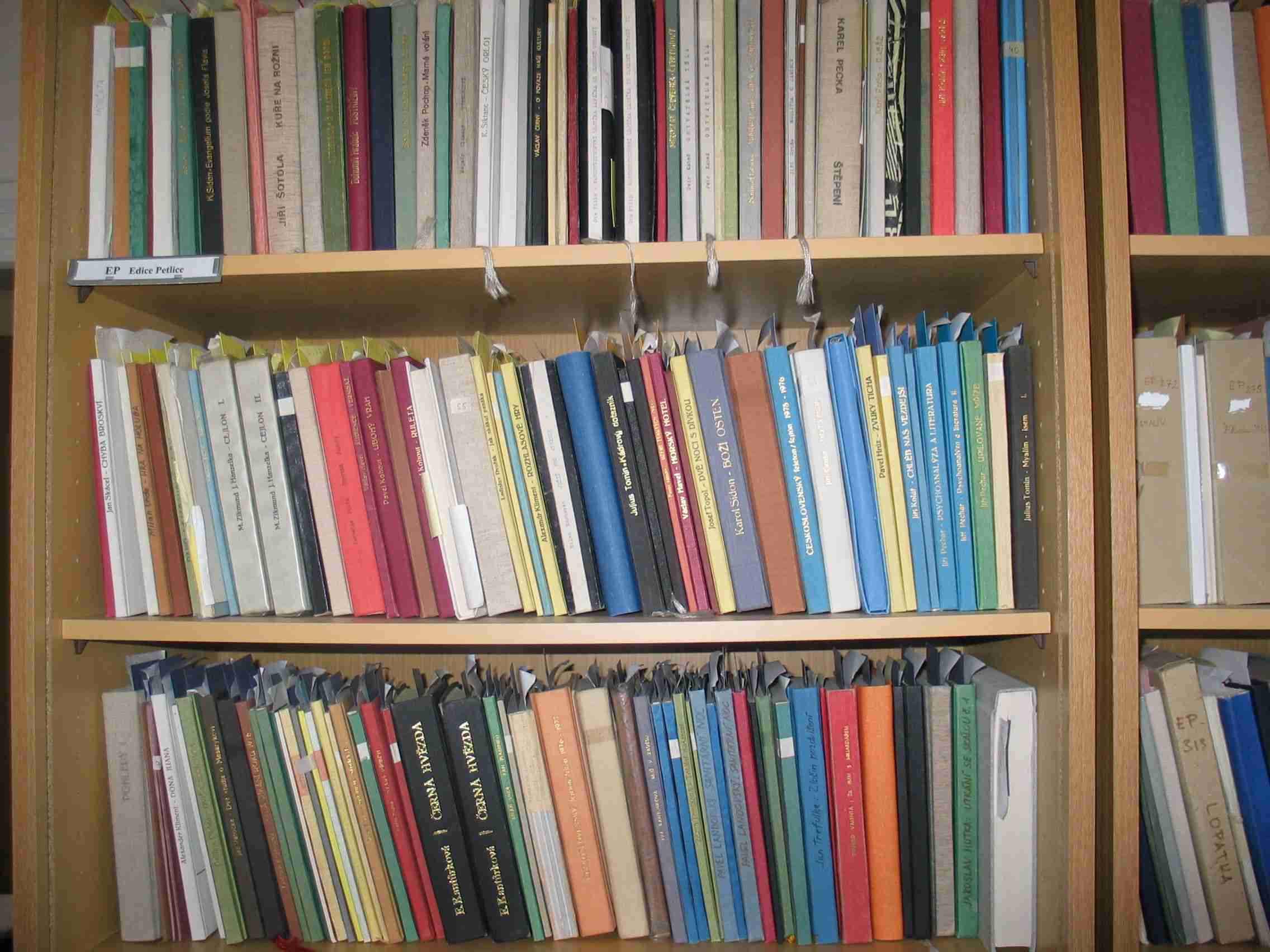

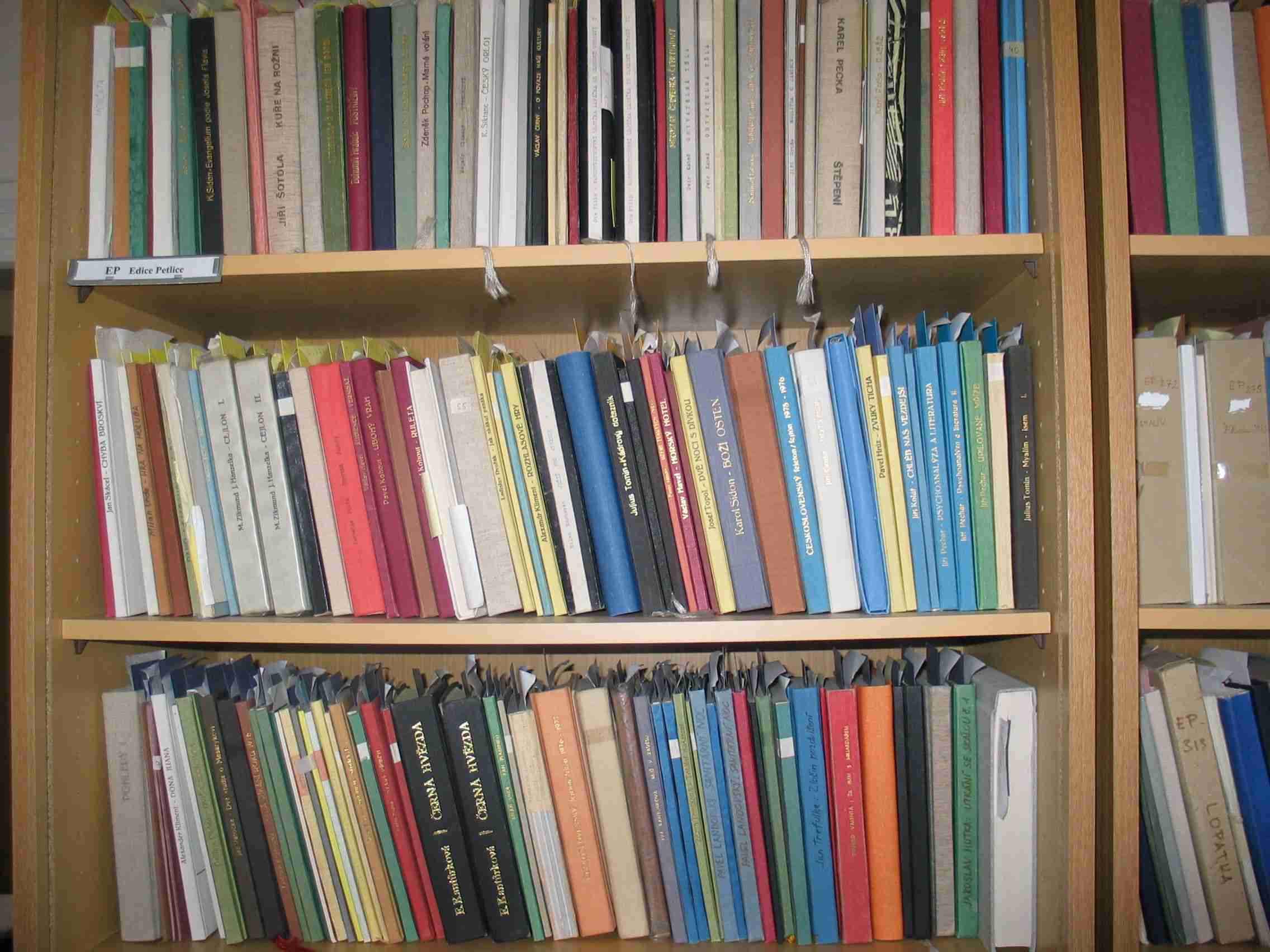

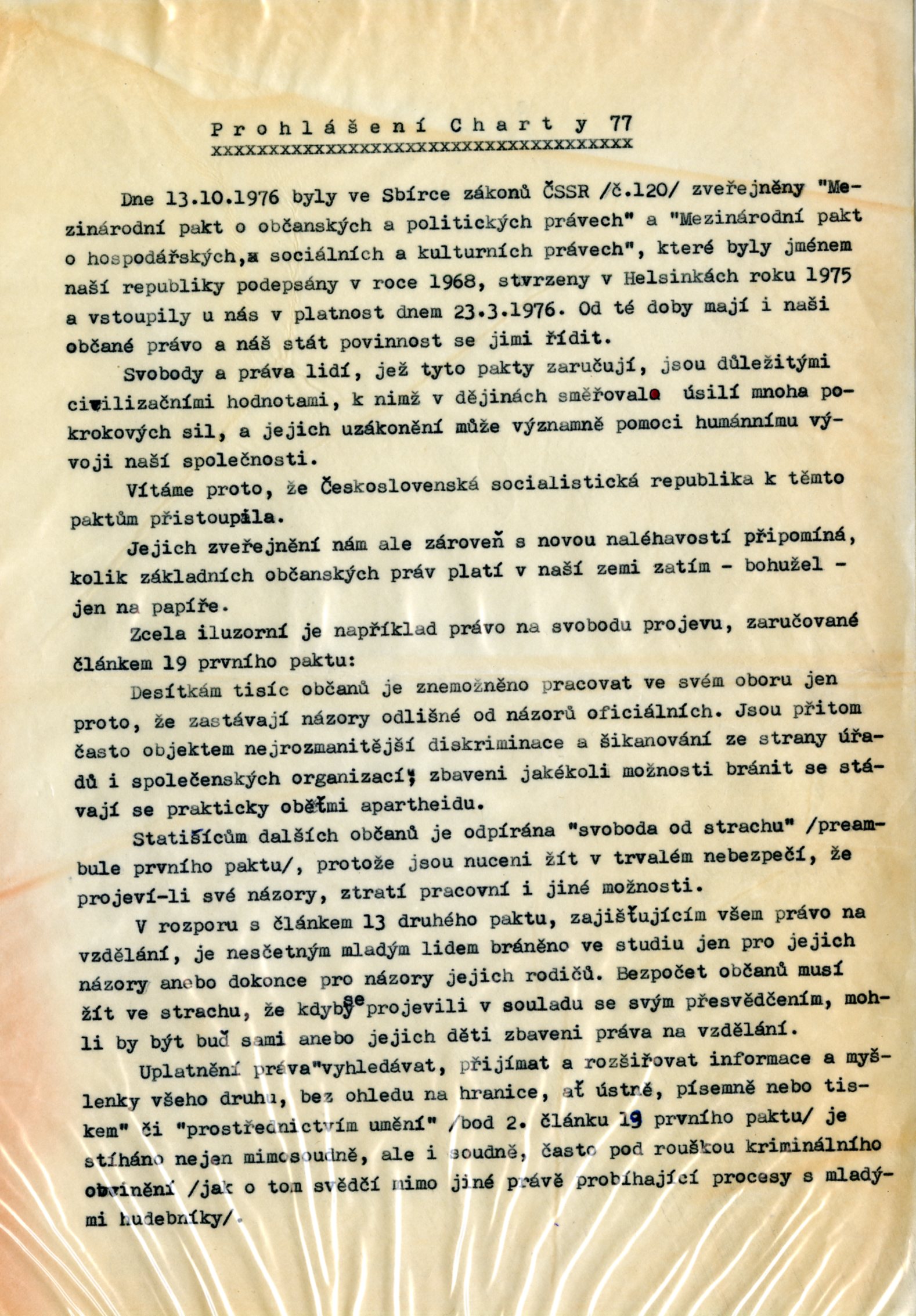

This unique collection of samizdat literature (1972-1989) contains samizdat books by Czech and Slovak authors whose works could not officially be published in socialist Czechoslovakia, as well as a collection of samizdat periodicals and individual texts.

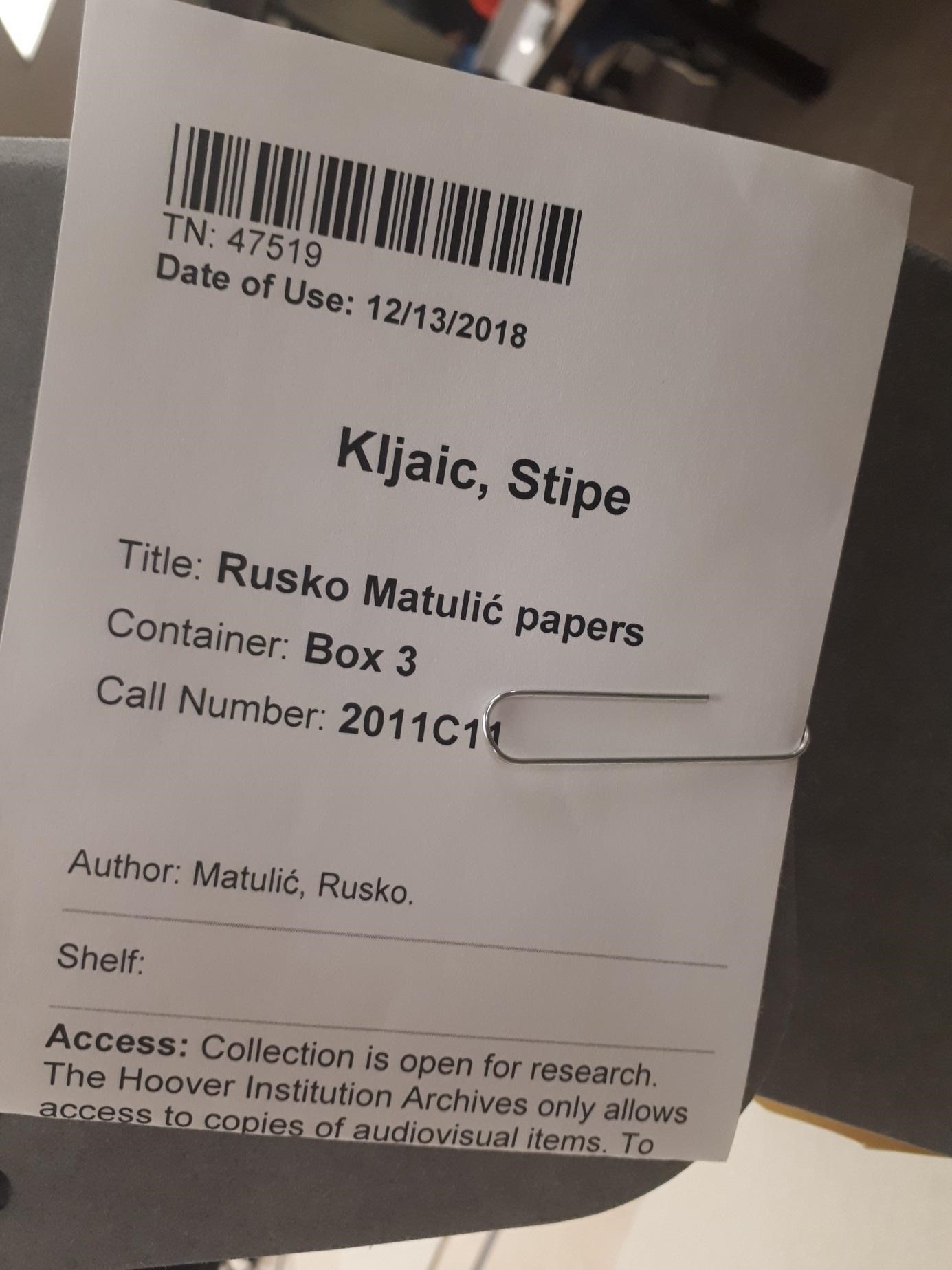

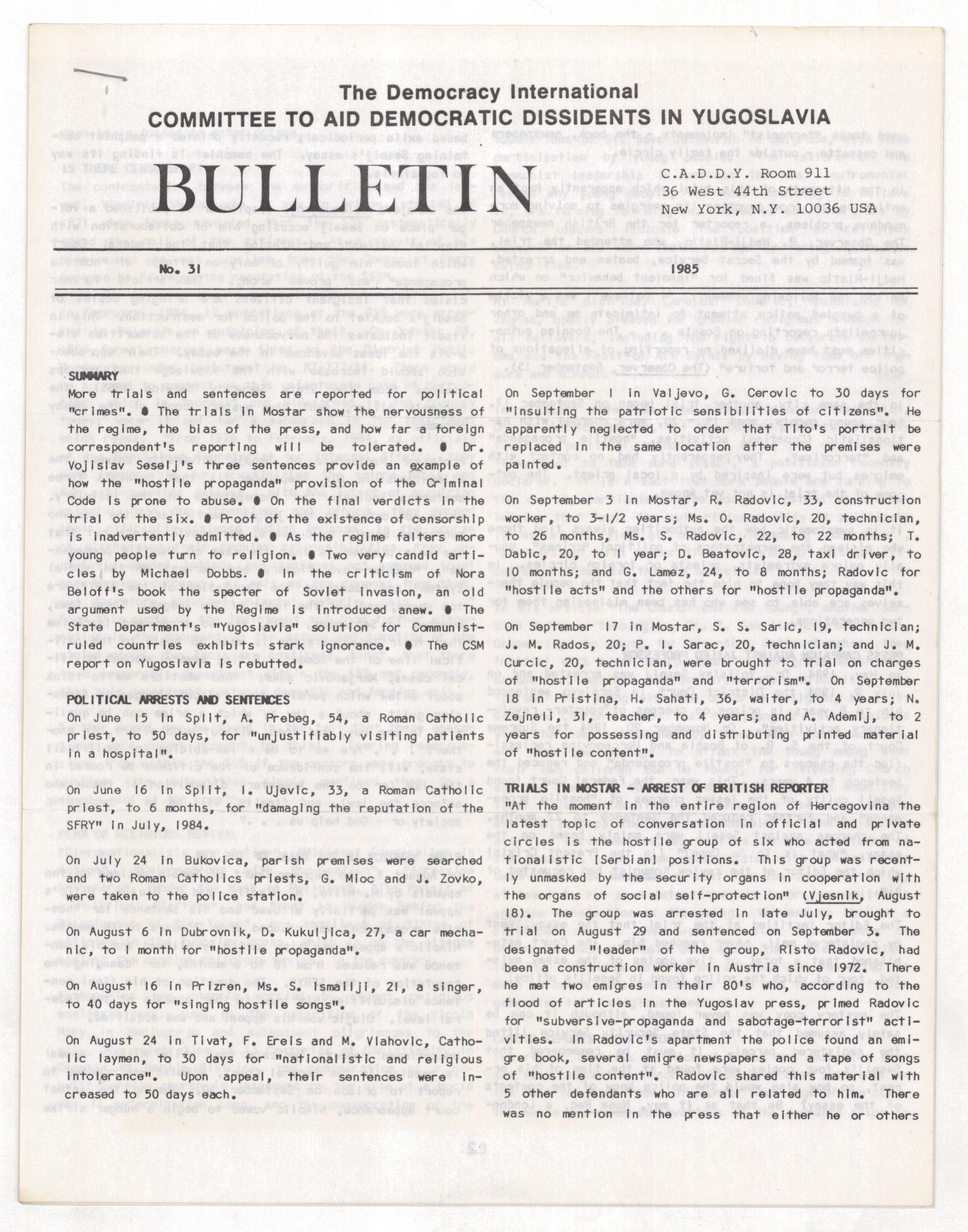

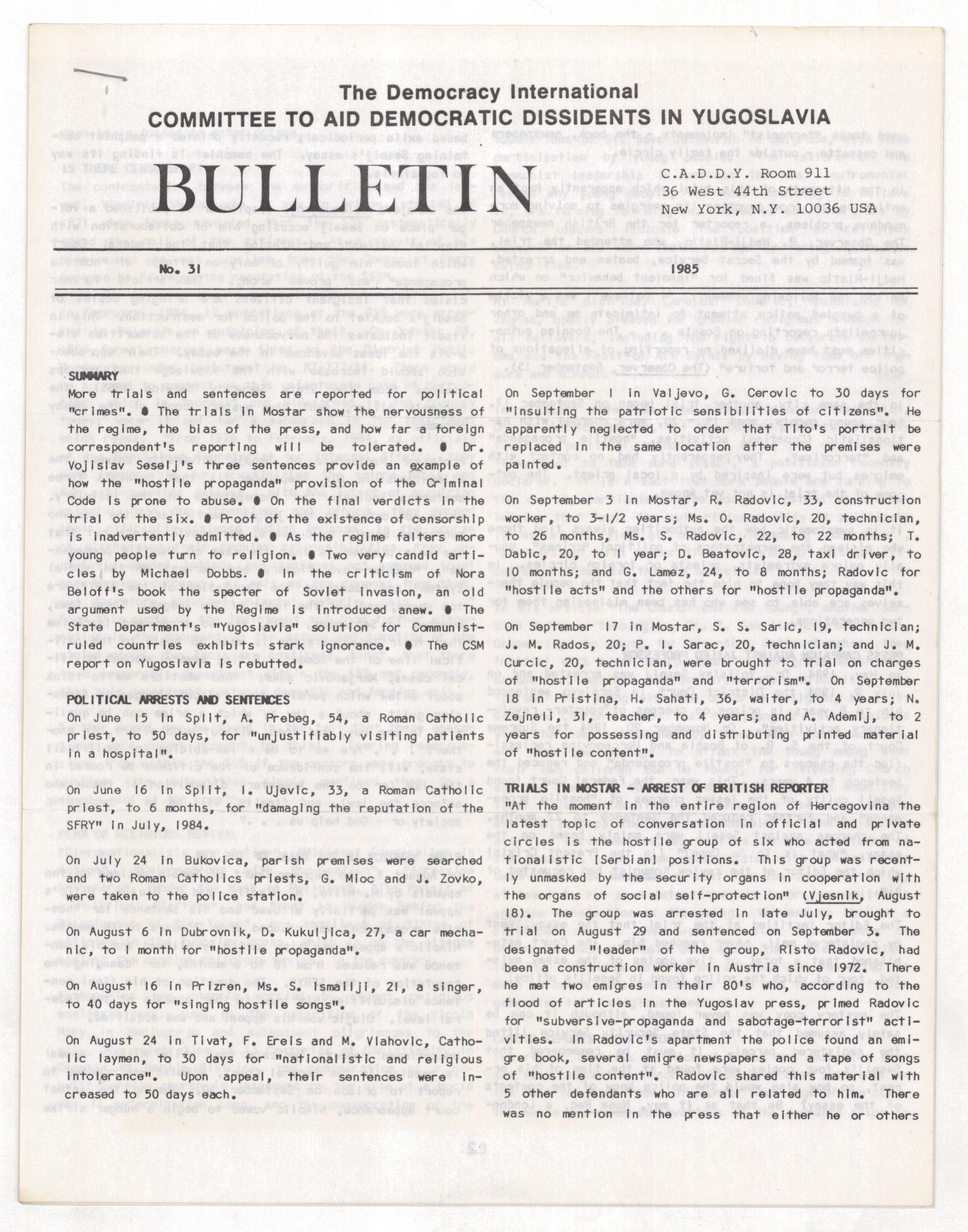

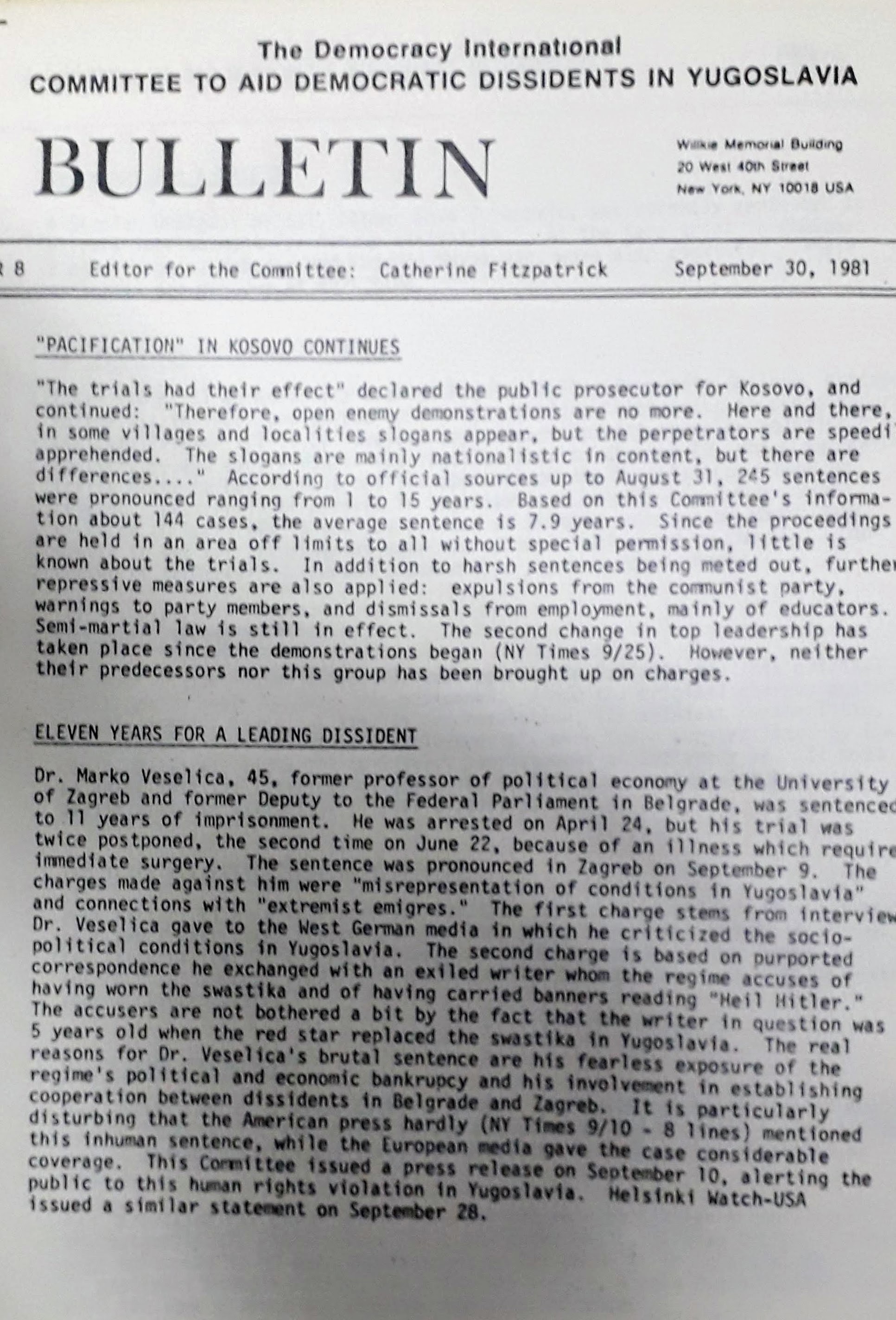

The bequest of Rusko Matulić, an American engineer and writer of Yugoslav origin, is held in the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The collection largely encompasses Matulić's activities as a political émigré in the United States of America, when he mainly dealt with the publication of the bi-monthly bulletin of the Committee Aid to Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia (CADDY). The bulletin and organization acted as a part of the Democratic International, established in New York in 1979. Mihajlo Mihajlov, one of the most prominent Yugoslav dissidents, was a member and the main initiator of launching the CADDY organization and its bulletin. Rusko Matulić was Mihajlov's main collaborator in the overall CADDY project.

The Pavao Tijan Collection is deposited in the Archives of the Croatian Academy of Science and Arts in Zagreb. It demonstrates the cultural-oppositional activities of the Croatian émigré Pavao Tijan, who lived in Madrid after the Second World War. There, Tijan organized anti-communist activities against the Yugoslav regime and also against global communism during the time of the Cold War. This collection is very important to the little known Croatian cultural history of the émigré colony of Spain.

The Jan Zahradníček Collection at the Museum of Czech Literature is an important resource documenting the literary and Catholic opposition to the communist regime in post-war Czechoslovakia. It includes Jan Zahradníčekʼs poetry manuscripts, written illegally in the 1950s, in Pankrác Prison.

This manuscript was written on 2 April, 1969. Rendić raises the question of the position of the Catholic Church and Catholics after the so-called "liberalization" of the Yugoslav regime. She came to the conclusion that after ceasing the policy of open force, nothing had substantially changed in their position. She added that both the Church and Catholics live together in a sort of social ghetto isolated from the mainstream of socialist society, since "as it is with all liberalization, the Church remained in a ghetto, the Church is not moving from the ghetto at all" (Rendić 1969: 12). For this state of affairs, Rendić pointed to, as she said, the "totalitarian atheism" of the then socialist regime in Croatia and Yugoslavia, who taught that the progress of time would necessarily lead to the disappearance of religious consciousness throughout socialist society (Rendić 1969: 10).

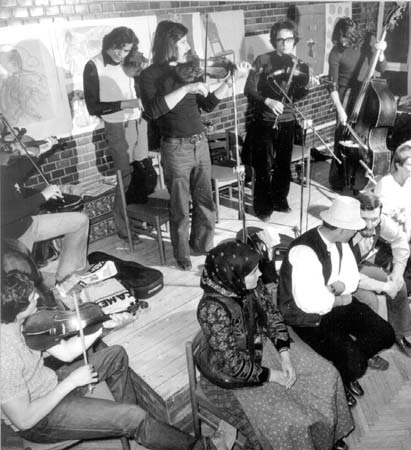

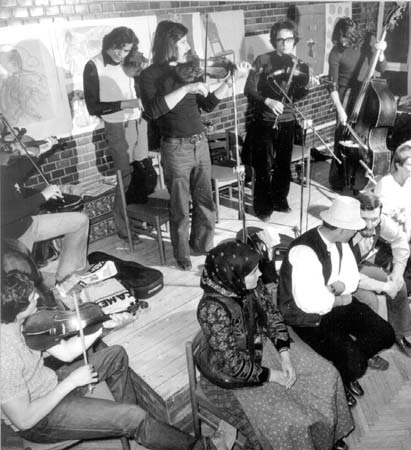

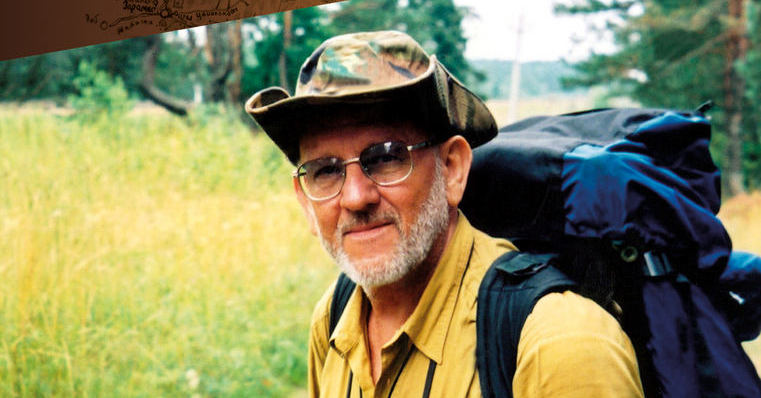

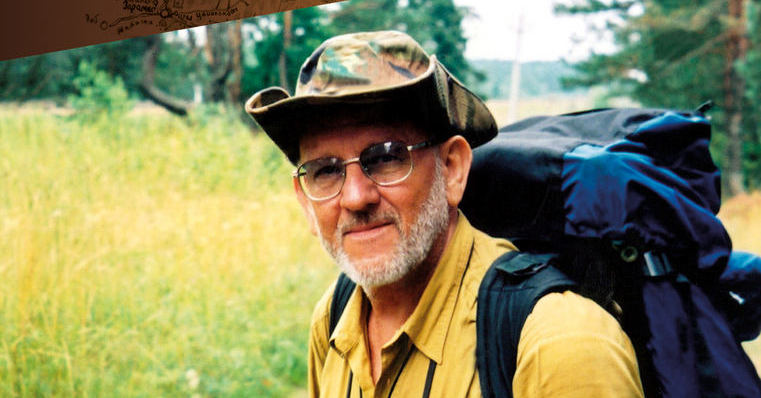

The founder of the Folk Dance House Movement was Béla Halmos. Halmos, as a musician, a folklorist, an instructor, an organizer and the leader of the Hungarian revival movement, supported the Hungarian folk culture and Dance House Movement. The Folk Dance House Archives started to function in 1999. The root of the Archives was the private collection of Béla Halmos, and it continuosly grew thanks to gifts and donations.

This ad-hoc collection was separated from the fonds of judicial files concerning persons subject to political repression during the communist regime which is currently stored in the Archive of the Intelligence and Security Service of the Republic of Moldova (formerly the KGB Archive). It focuses on the case of Gheorghe Zgherea, a person of peasant background who was a member of the Inochentist religious community, a millenarian and eschatological movement active in Bessarabia and Transnistria mostly during the first half of the twentieth century. The collection materials are revealing for the repressive policy of the Soviet regime in the religious sphere, showing the Soviet authorities’ hostile attitude toward non-mainstream and marginal denominations, which were perceived as a particularly serious threat. Zgherea, a preacher within his community starting from late 1950, was accused of “roaming the villages” of the Moldavian SSR and spreading “anti-Soviet ideas” among the local populace by “using their religious prejudices.” Arrested on 2 May 1953, he received a harsh sentence of twenty-five years of hard labour. His sentence was reduced to five years of hard labour in June 1955, when he was also amnestied according to a special decree of March 1953. Zgherea’s case thus points to the changing strategies of the regime applied after Stalin’s death, but also to the continuity of repression and to the shifting practices of stifling dissent in post-Stalinist Soviet society.

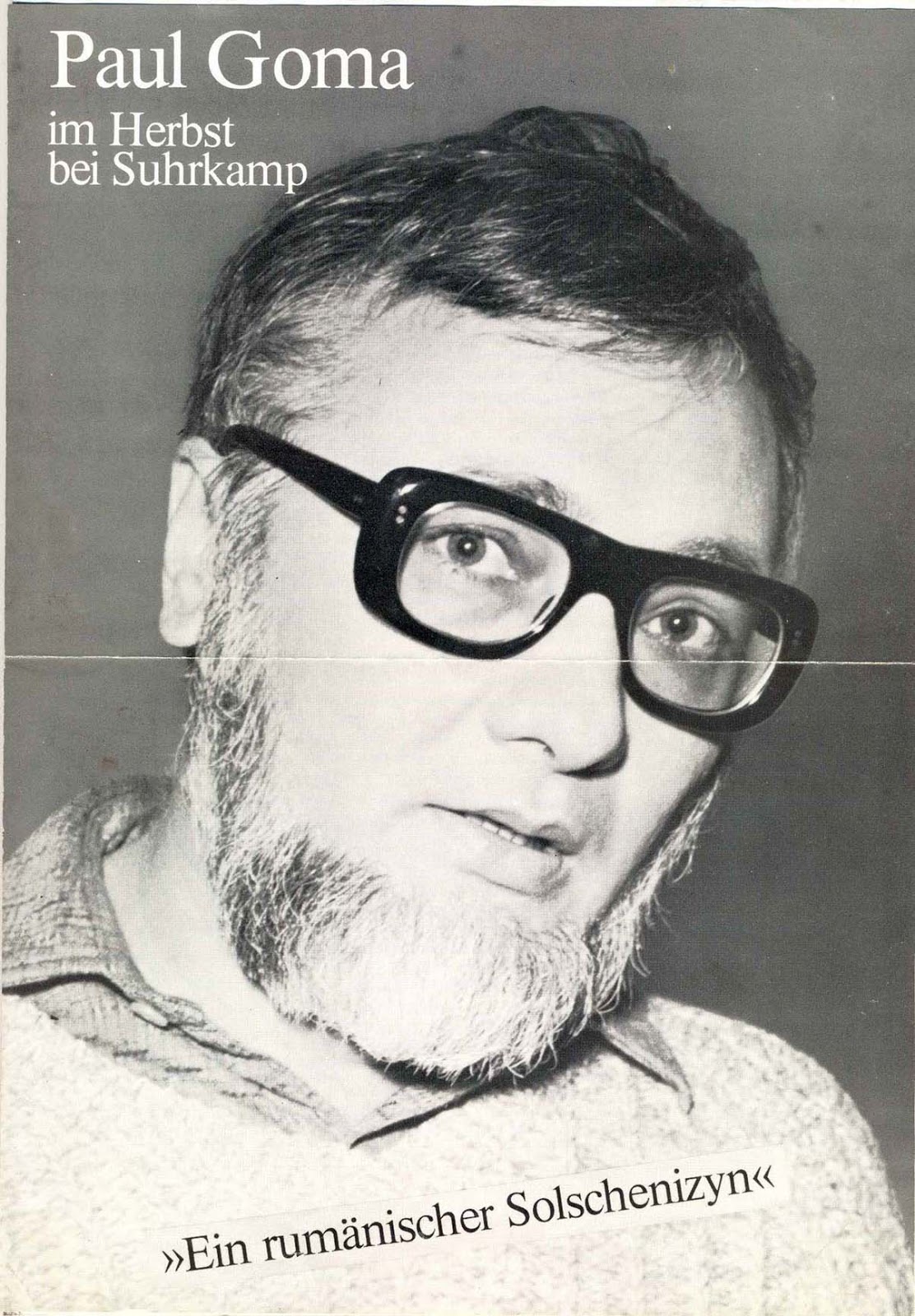

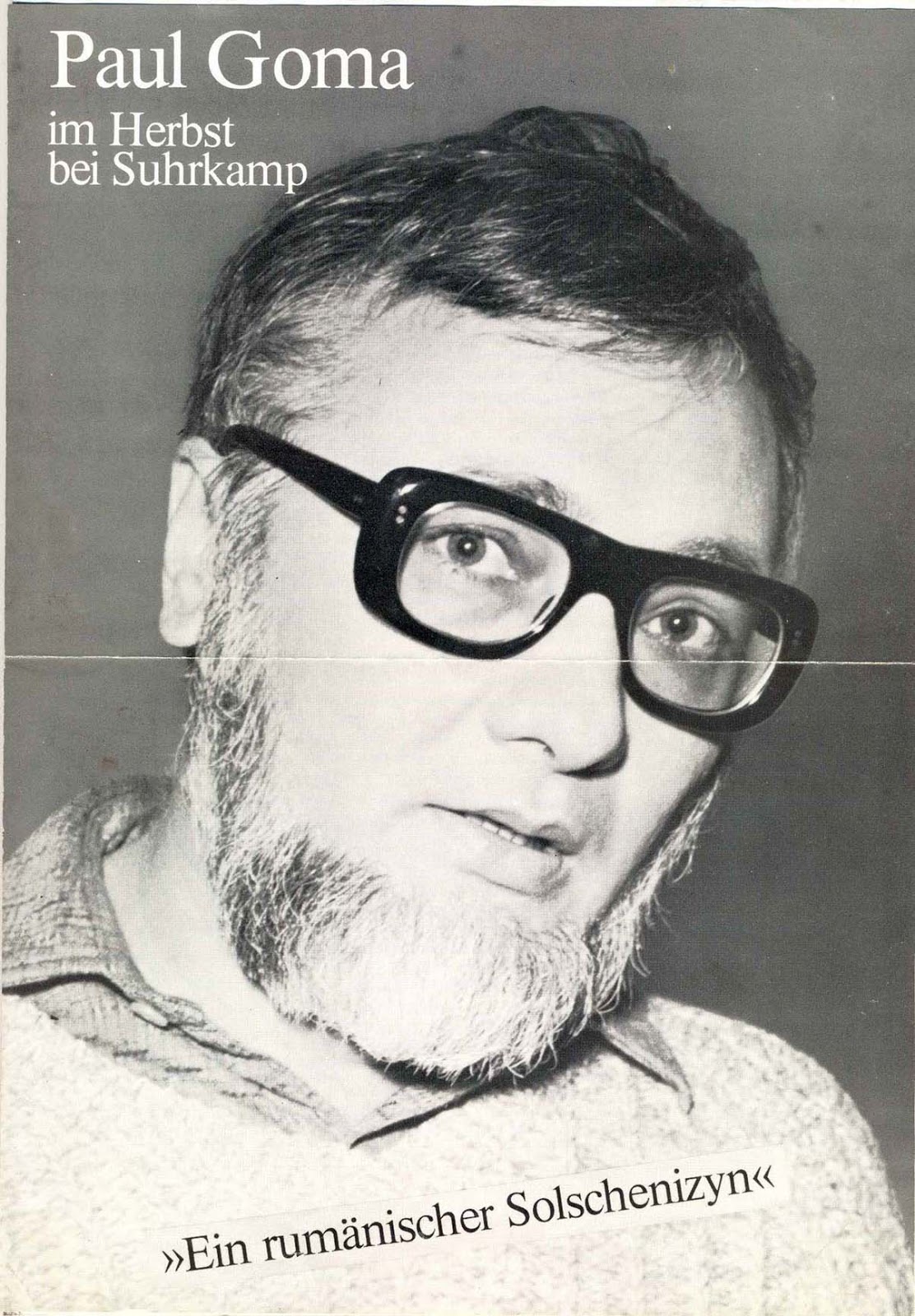

This collection consists primarily of the items confiscated by the Securitate on 1 April 1977, on the occasion of the house search and arrest of the driving force behind an emerging movement in defence of human rights in Romania, Paul Goma, a writer censored in Romania but successful abroad. A particular feature of this collection is that the confiscated items were not destroyed, but were preserved by the Securitate and finally transferred to CNSAS in 2002, from where they were returned to Goma in 2005. Thus, the collection is one of the few which travelled after 1989 from Romania into exile and is now to be found in Paris, where Goma was forced to emigrate a few months after his arrest and the confiscation of the collection.

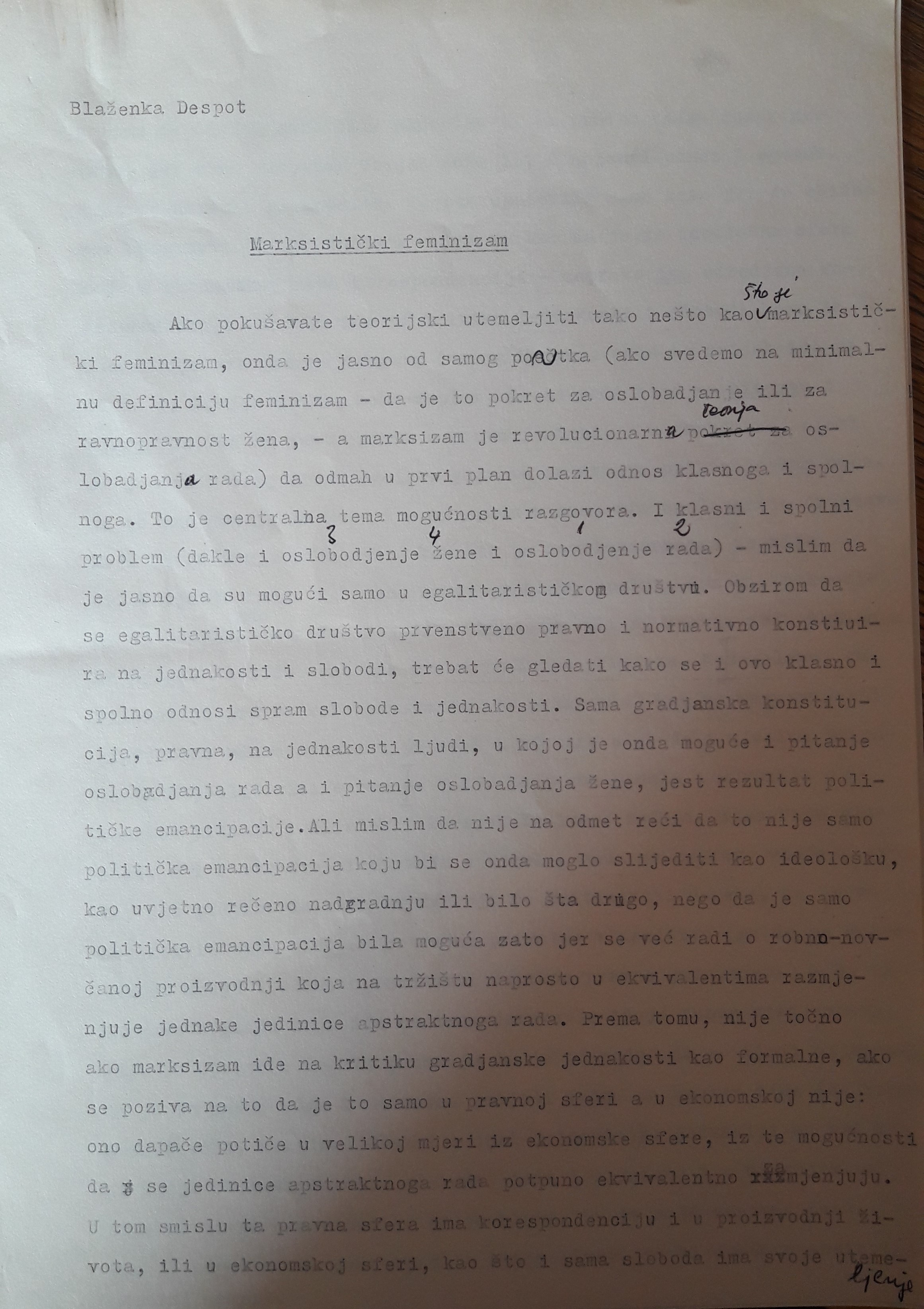

The Woman and Society Feminist Collection at the Centre for Women's Studies in Zagreb consists of one register containing the manuscripts from the lecture cycle which was organized by the "Woman and Society" Section in 1982/83. The lectures dealt with the “woman question” in the historical context, as well as the “woman question” issues in socialist self-management and Marxist theory. The Collection testifies to the engagement of a smaller number of intellectuals who sought to put the “woman question” into public focus, thus affecting the improvement of the status of women in Yugoslavia, while the authorities argued that it was unnecessary because they thought that the ˝woman question˝ was resolved within Marxism.

The collection, which is the private property of István Viczián, illustrates the history of the Calvinist youth organization of Pasarét under socialism. The collection includes letters and photographs, which provide insights into the aspirations of the group to create an active religious community in an era when such communities were a threat to and contradiction of official communist youth policy.

The Declaration on the Name and Status of the Croatian Literary Language was proclaimed by Croatian linguists published in the weekly Telegram on March 17, 1967, with the signatures of eighteen Croatian scholarly and cultural institutions. Croatian linguists and writers gathered around Matica hrvatska and the Association of Writers of Croatia were dissatisfied with published dictionaries and orthographies in which the language, according to the Novi Sad Agreement (1954), was called Serbo-Croatian. In late 1966 and early 1967, they had decided to write an amendment to the new Constitution which was being prepared in the late 1960s. They secretly prepared a text about the name and status of the language that was officially used in the Socialist Republic of Croatia (SRH) as part of the then Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). The text of the Declaration was drafted in Matica hrvatska's premises by a group of academics, literary and cultural workers (Miroslav Brandt, Dalibor Brozović, Radoslav Katičić, Tomislav Ladan, Slavko Mihalić, Slavko Pavešić, Vlatko Pavletić). The Steering Committee of Matica hrvatska approved the content of the Declaration on March 13, 1967, and sent it to other Croatian cultural and academic institutions. In the next few days, the Declaration was signed by a total of eighteen Croatian academic and cultural institutions which directly dealt with the Croatian language, and by a significant number of prominent intellectuals.

The publication of the Declaration was not only a cultural but also a political affair. It had additional weight because of Miroslav Krleža, probably the most prominent left-wing intellectual not only in Croatia but all of Yugoslavia, was one of the intellectuals who signed the document. Despite the fact that the writers of the Declaration were cautious in attempting to avoid any boundaries set by the League of Communists (they used the usual communist phraseology and the style of "self-managing socialism" and the Yugoslav slogan of "fraternity and unity"), the publication of the Declaration triggered strong political reactions and set the repressive apparatus in motion. The Croatian language was a litmus test through which the overall economic, political and cultural subordination of Croatia within Yugoslavia was revealed (Kovačec 2017), and the appearance of the Declaration is considered the practical beginning of the Croatian national movement – the Croatian Spring.

The Matica hrvatska Collection at the Croatian State Archives contains the original document of the Declaration with accompanying materials (the manuscript of the Declaration, multiple typescript versions with and without signatures and stamps, Dalibor Brozović's telegrams, letters of the signatory institutions of the Declaration that give their support to its contents).

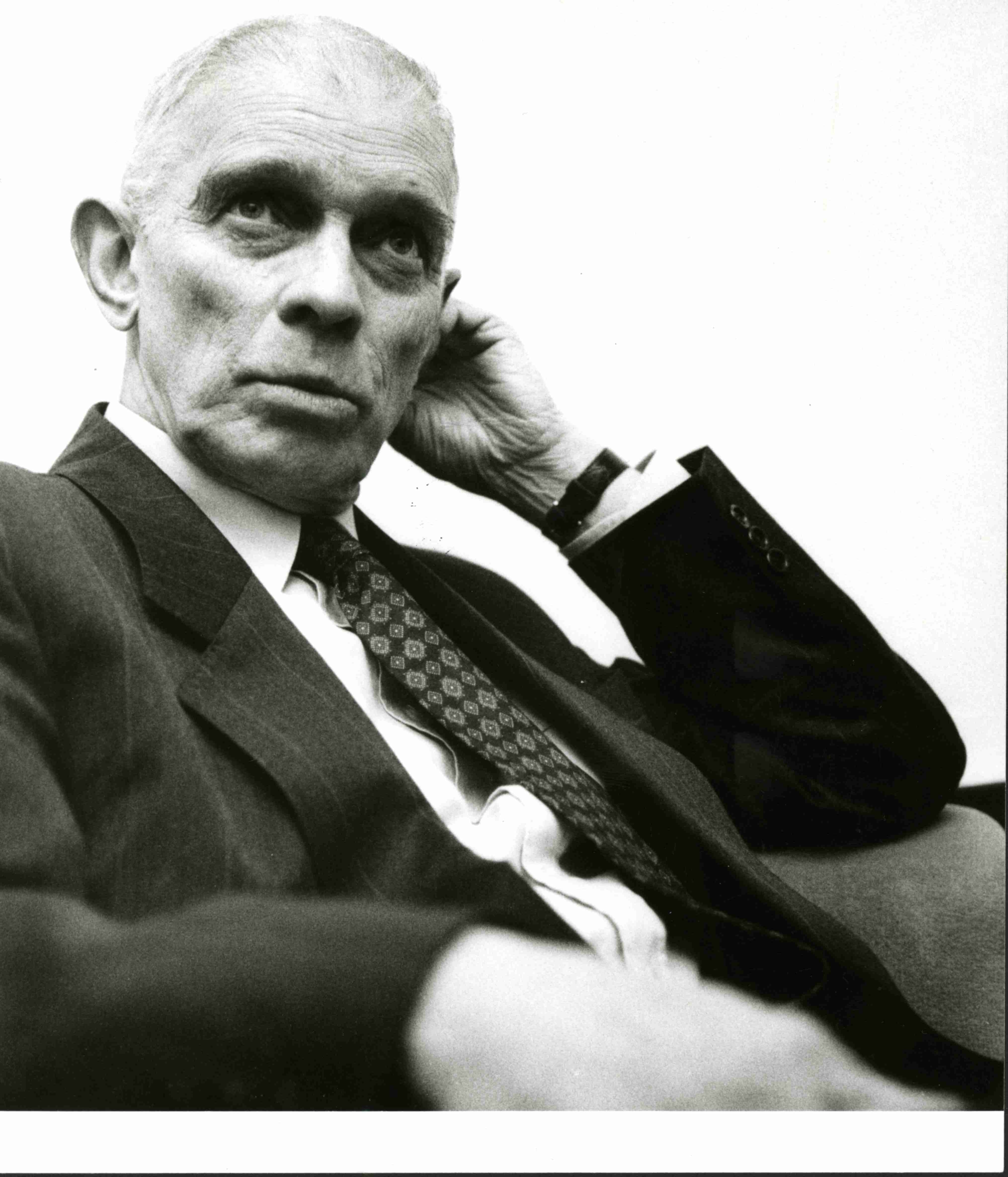

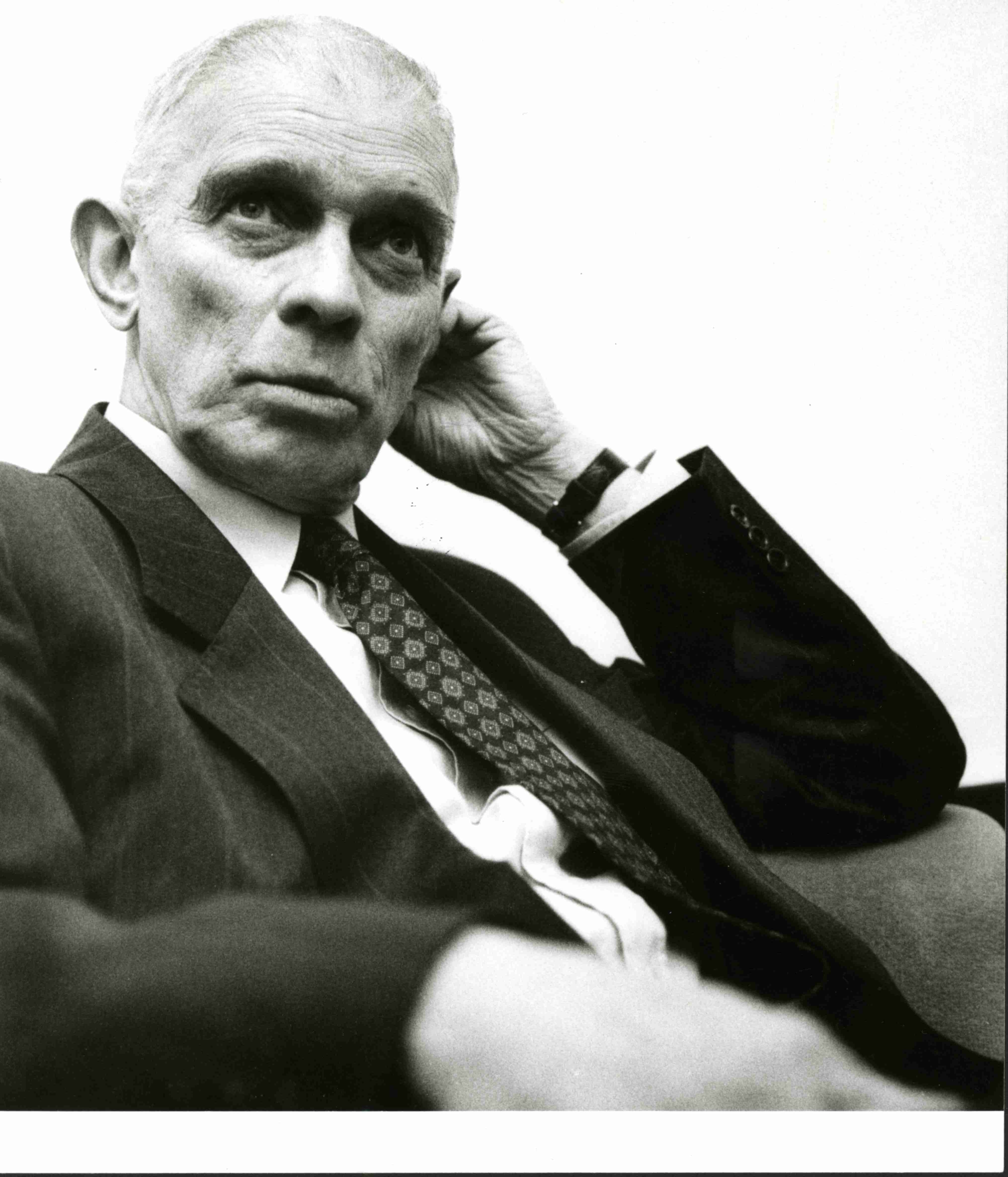

István Bibó (1911–1979) was a Hungarian political scientist, sociologist, and scholar on the philosophy of law. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Bibó acted as the Minister of State for Imre Nagy’s second government. When the Soviets invaded and crushed the revolution, he was the last minister left at his post in the Hungarian parliament building. Rather than flee, he remained in the building and wrote his famous proclamation, “For Freedom and Truth,” until he awaited arrest. Bibó became a role model for dissident intellectuals in the late communist era and a symbol of non-violent civilian resistance based on a firm moral stand. Since Bibó’s death in 1979, the family collection of his bequest, which includes personal documents, photos, manuscripts, books, and video and sound recordings, has been in the care of art historian and educator István Bibó Jr., who keeps the materials in his home in Budapest.

The Victor Frunză Collection is an important historical source for understanding and writing the history of that part of the Romanian exile community which was actively involved in supporting dissidents in the country and in publicising in the West the repressive or aberrant policies of the Ceaușescu regime. In particular, the collection illustrates the activity of the collector and other personalities of the exile community for respecting human rights in Romania. Also, the documents of this collection reflect the involvement of Romanians from abroad in the reconstruction of democracy in their country of origin.

The private collection of Tamás Csapody (1960–) includes documents related to movements for the reform of the compulsory military service and the introduction of alternative civilian service. Refusal to perform military service was an illegal act in the countries of the Warsaw Pact. Csapody’s collection, as the only collection focusing this specific topic, contributes to remembering the stories of people who were penalized by the laws of the Kádár regime because of freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

The Edvard Kocbek Collection is located in the depot of the National and University Library in Ljubljana. It is actually his personal bequest to that same library. Kocbek was the greatest Slovenian poet and writer of the 20th century, who, as a Christian Socialist, joined the Slovene National Liberation Front under the control of the communists during the Second World War. Due to his divergent opinions about the war and the policies of the new communist regime, immediately after the war he was placed under the surveillance of the secret police (known as the UDBA). After that, he was very soon placed under a kind of public isolation, which implied limited movement and restricted access to intellectual life.

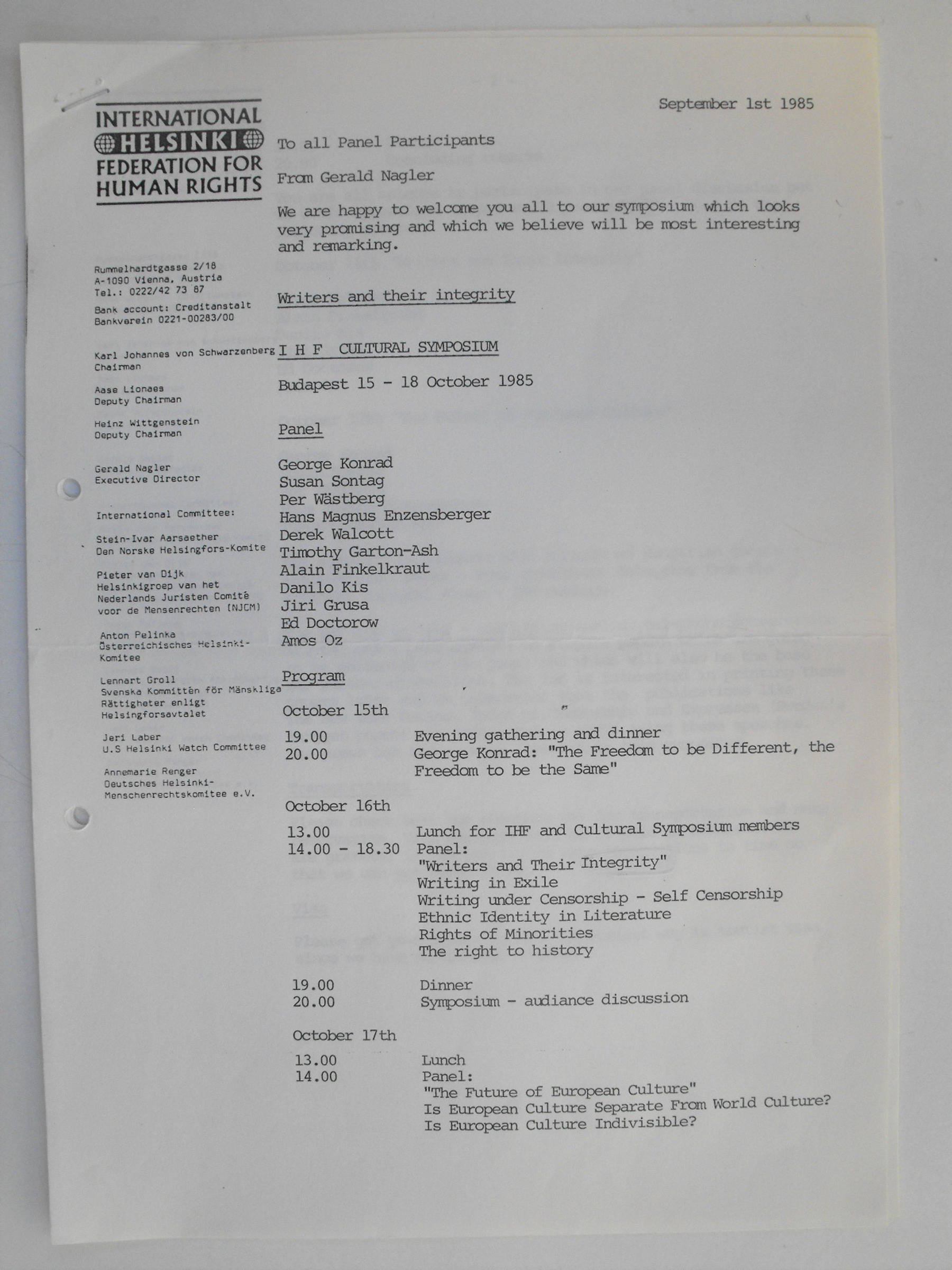

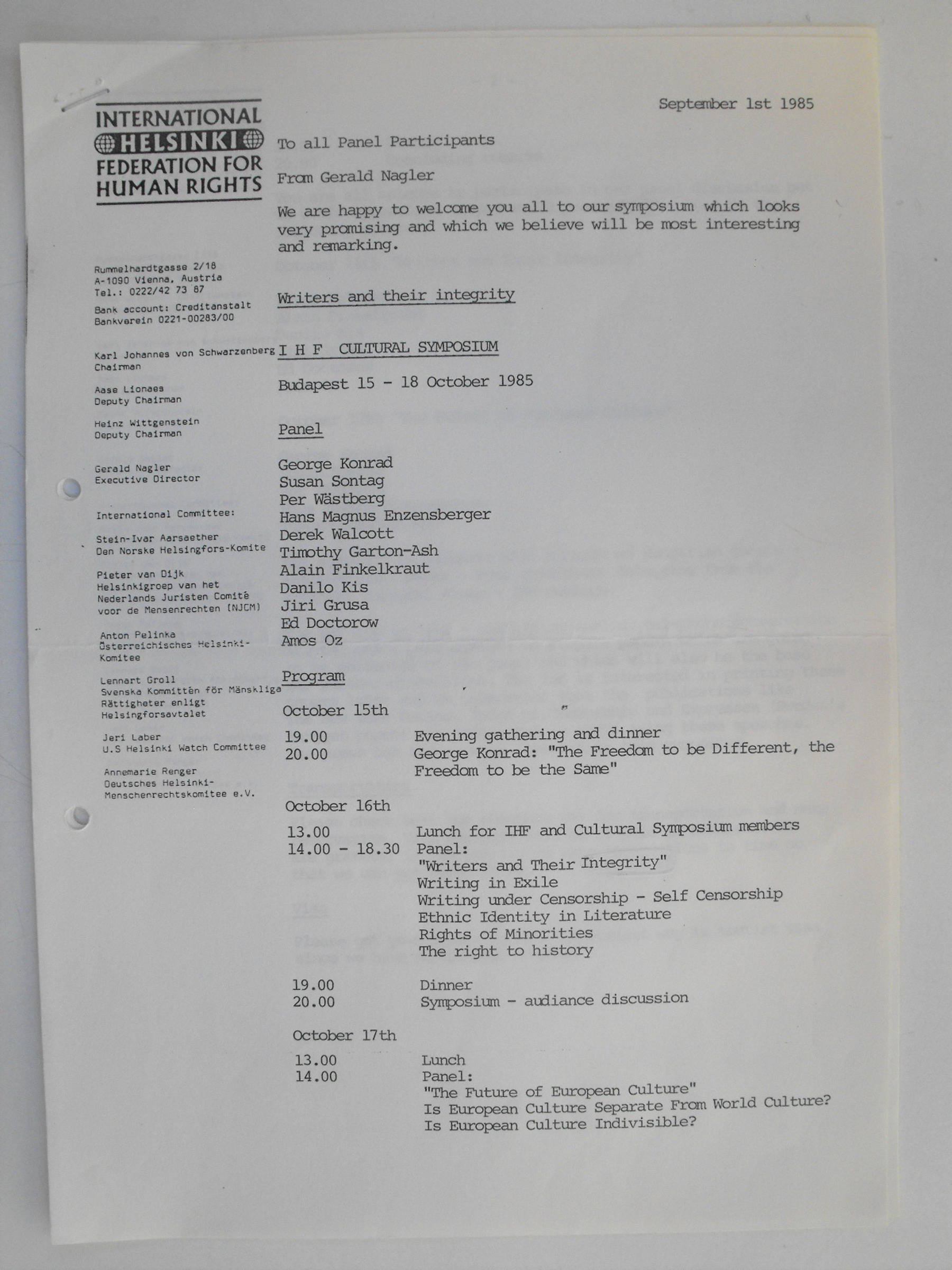

Invitation and program schedule for the IHF Cultural Symposium, Budapest 15–18 October 1985

Although the plans and practical preparations for the alternative programs of the Budapest Cultural Forum 1985 had been started more than a year earlier, it was this invitation letter and program schedule sent to all Western participants by the International Helsinki Federation from its Vienna Office, an invitation signed by Chairman Karl Joachim Schwarzenberg on 1 September 1985, that proved the success of devoted efforts made by the IHF staff to organize a three-day East-West Cultural Symposium in Budapest in parallel with the official opening session of the CSCE European Conference.

The main subjects of the alternative forum were much more challenging. They included “Writers and their Integrity” and “The Future of European Culture,” and they offered a good opportunity for free and stimulating exchange of ideas for participants from both East and West. The list of authors invited seemed quite imposing, as it included prominent figures such as György Konrád, Susan Sontag, Per Wἃstberg, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Derek Walcott, Timothy Garton Ash, Alain Finkelkraut, Danilo Kis, Jirzi Grusa, Ed Doctorow, and Amos Oz. This forum was perhaps the first chance since 1945 for writers from both East and West to enter free public debates on sensitive cultural and political issues such as exile, censorship, self-censorship, the role of national identity in literature, the rights of minorities, the right to history, or the basic question of whether European culture is separate from world culture. And is European culture really one indivisible culture? These questions and issues represented an utterly new approach which regarded cultural freedom as a vitally important and integral part of the overall realm of human rights.

How did the Budapest “Cultural Counter-Forum” manage to implement the promising plans made by the IHF? Not quite as was expected. Apart from Hungarians, no other participants from Eastern Bloc countries could attend the symposium, either because they could not get passports or because of the were forced to live under police surveillance or under house arrest, or they had been interned or jailed, like many Russian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, and Romanian writers at the time. They were partly represented by some Western writers with Eastern origins, e.g. Jirzi Grusa, Danilo Kis, and Amos Oz, and Timothy Garton Ash, who came from Warsaw to Budapest, spoke for the Polish writers who at the time were still suffering from the harsh measures of martial law. Things were similar in the case of writers who belonged to ethnic minorities. Hungarian participants, like poet Sándor Csoóri and philosopher Gáspár Miklós Tamás, spoke on their behalf, as did two of the most harassed writers and samizdat makers, Géza Szőcs, who was originally from Cluj / Kolozsvár / Klausenburg, and Miklós Duray from Bratislava / Pozsony / Pressburg. Szőcs and Duray addressed open letters to the participants in the Counter-Forum

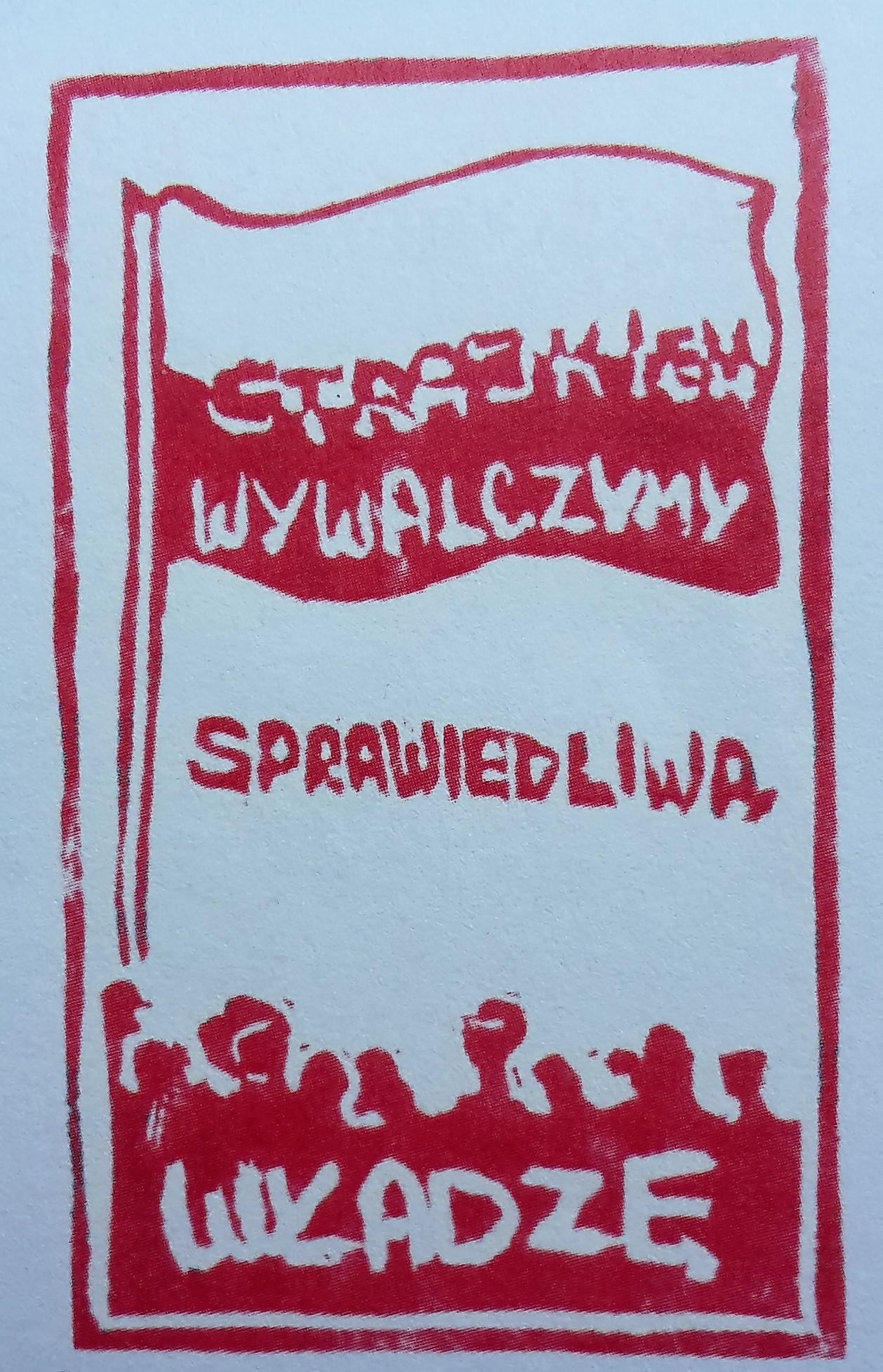

How many people took part in the forum? As many people (120–150) as could fit in the crowded private Budapest flats provided for the event by poet István Eörsi and film director András Jeles. These people were IHF representatives, writers, journalists, Western diplomats, Hungarian intellectuals, and students. This constituted an unanticipated change which gave the Counter Forum a fairly informal and non-conformist feel. The Hungarian authorities refused to allow the group to hold its gathering in any public place, and the reservation made by the IHF for a conference room in a downtown Budapest hotel was cancelled at the last moment by the Hungarian secret police. On the very first day of the six-week-long official Forum, this scandal, which was reported on by the world press and some Western delegates, all of a sudden drew attention to the Counter-Forum, highlighting the fact that cultural affairs are still sensitive political issues in the eastern part of Europe.This collection expresses the artistic tendencies in the last decades of Polish reality under socialist regime. It includes a huge number of graphics, posters, paintings and drawings, as well as some items produced by opposition members held under detention.

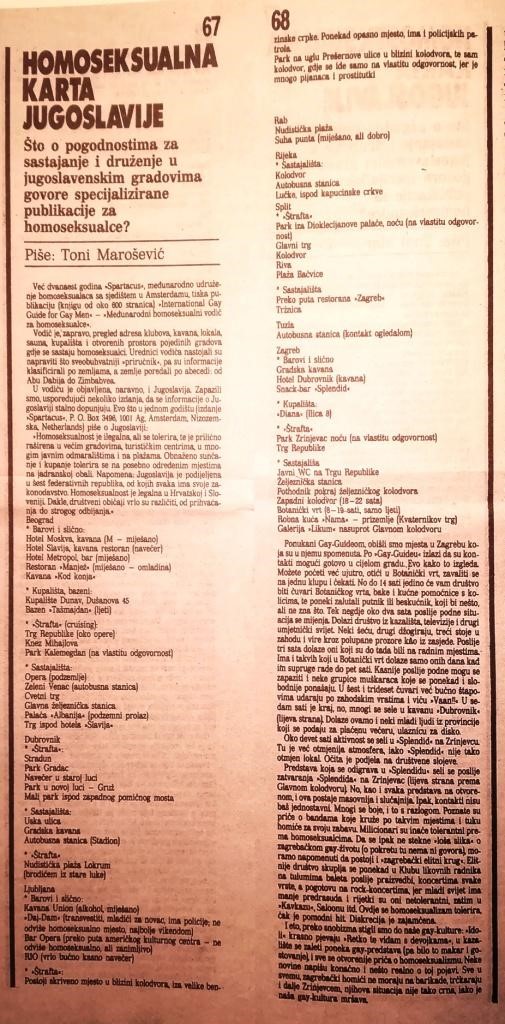

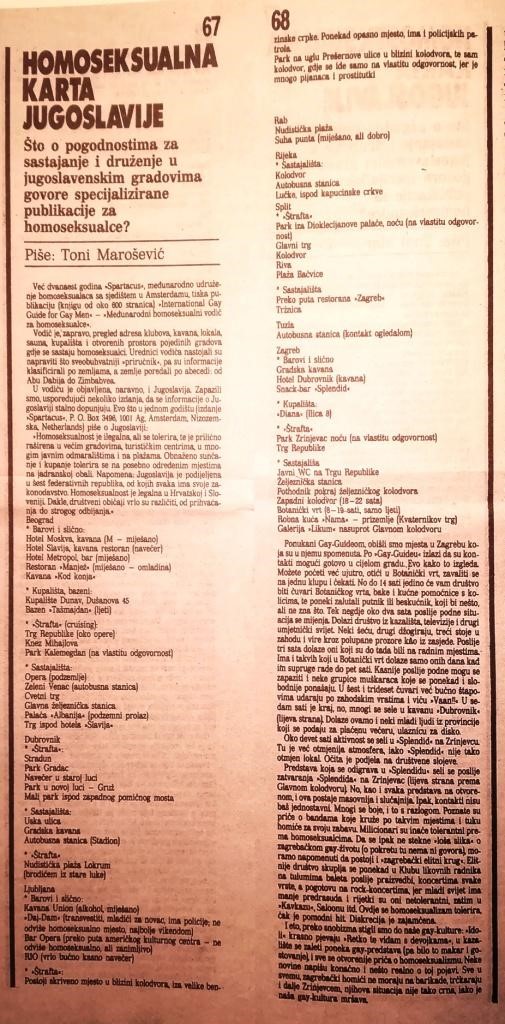

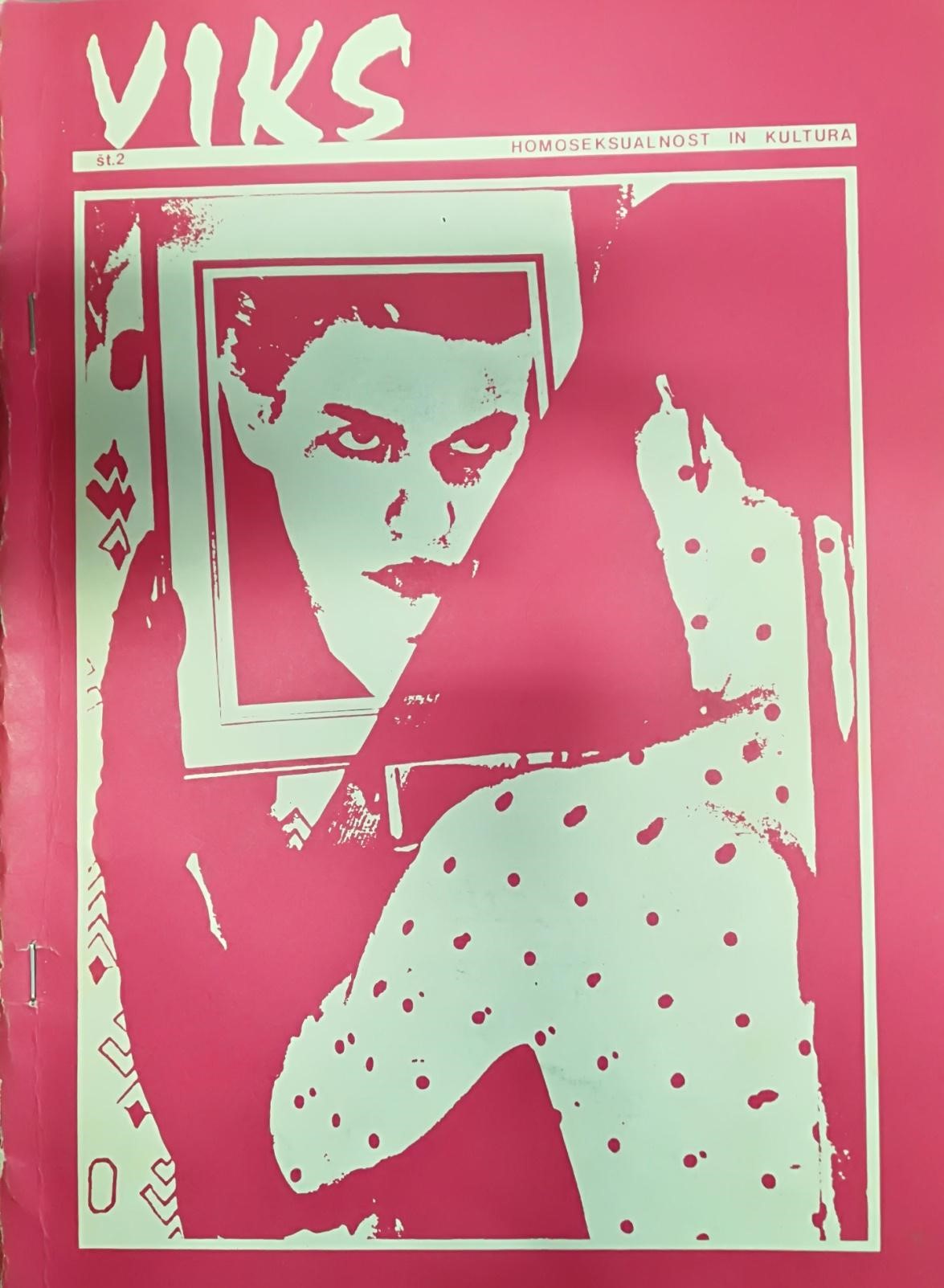

The History of Homosexuality in Croatia Collection covers some of the most salient aspects of Croatian gay and lesbian private and public life in the socialist period (1945-1990). Court verdicts for same-sex sexual relations testify to the active institutional persecution of homosexuality, mostly in the immediate post-war period, in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Personal memories and oral history recollections illustrate the harsh everyday life reality of homosexuals in socialist Yugoslavia, but they also tell amazing stories of individual or collective resistance to institutional and social homophobia.

The events that transpired alongside the fall of the Romanov monarchy in February 1917, the takeover of the Winter Palace by the Bolsheviks in October 1917, and the dissolution of the Constitutional Assembly in January 1918 are immensely significant for understanding Ukrainian history and cultural opposition to communism. During that year of upheaval, many divergent visions for the future were articulated throughout the Russian Empire. In the Imperial Southwest, the Bolsheviks battled monarchists, nationalists, socialists, greens and anarchists over how to move forward during and after the collapse of empire.

The Ukrainian Museum-Archives has in its possession an original broadside of the Third Universal, issued by the Central Rada on November 20, 1917, in the four major languages used in the Imperial Southwest—Ukrainian, Russian, Polish and Yiddish. This document is reflective of efforts by the Central Rada to appeal to various communities living on the territory, while negotiating with the Provisional Government for greater autonomy. As historian George Liber notes, the first two proclamations of Rada did not define the borders of Ukraine, but the Third Universal asserted that the nine provinces in the Imperial Southwest with Ukrainian majorities belonged to the Ukrainian National (or People’s) Republic. The document also claimed parts of Kursk, Kholm/Chelm and Voronezh provinces, where Ukrainians also constituted the majority. The Central Rada also pledged to defend the interests of all national groups living in these territories and articulated a law protecting personal and national autonomy for Russians, Poles, Jews and others.

Shortly after this, the UNR established diplomatic ties with a number of European countries and even the United States. Britain and France tried to persuade the UNR leadership to side with them against the Central Powers, which they refused as they were determined to stay neutral. The Soviet Russian Republic initially recognized the UNR, but this was short-lived as the Red Army soon moved in from the north and east. This prompted the Rada to issue the Fourth Universal on January 25, 1918, which declared independence of the UNR as defined by the Third Universal. This made the push for greater autonomy within the context of empire a war of nationalist secession. (Liber, 62-63)

These early conflicts helped shape Soviet Ukraine’s relationship to Moscow for decades to come. In fact, Ukraine’s cultural, political and economic leadership struggled to define the parameters of engagement. Figures who were at the forefront of creating Soviet culture in the political and creative domains had to contest with the complex legacies of the Civil War of 1917-1922, which were never really fully resolved. Republican officials in particular (first in Kharkiv and later Kyiv) found it difficult to strike the right balance between autonomy and central control, regularly finding themselves on the wrong side of cultural policy after major shift in the priorities of Moscow.

The Karl Laantee collection at the Estonian Cultural History Archive is part of the large archival legacy of Karl Laantee, an émigré Estonian religious activist, and announcer with the Voice of America radio station.

This sheepskin coat is one of the featured items of the Hnatiuk Collection at the Ukrainian Museum-Archives (UMA) in Cleveland, OH. The collection consists of more than 450 examples of Ukrainian textiles, which were produced for ritual ceremonies, for home use and as garments worn in the 19th and 20th centuries. Myroslav and Anna Hnatiuk compiled this vast collection of textiles over a number of decades. The first items were brought with them as they fled to the West along with hundreds of thousands of their compatriots toward the end of WWII. Though not classically representative of cultural opposition or resistance to communism, the motivations of the Hnatiuks make clear that their intention was to preserve pieces of Ukrainian culture until they were able to return home. As with other collections described in the COURAGE registry, folk art anchored Ukrainian resistance to communism within certain communities, more traditional forms of expression and clothing pushing back against the internationalism and uniformity that underpinned Soviet socialism.

Myroslav and Anna grew up in Galicia, part of the Western Ukrainian territories clandestinely annexed by the Soviets in 1939 as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The war disrupted his medical studies, which he resumed in Austria, eventually becoming a physician. He worked for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation in Germany before moving with his wife Anna and their sons to the US in 1949. They kept in touch with family and friends living in Soviet Ukraine, sending packages of food and clothing and receiving in return textiles and costumes. In the 1980s, they began traveling regularly to Ukraine, continuing to augment their collection with authentic leather, textiles, ceramics, and other folk items from Galicia and the Hutsul mountain regions.

The UMA published a volume about the Hnatiuk Collection (financed with a generous grant from the Ohio Humanities Council), which not only demonstrates the value of the Hnatiuk Collection as a whole, but also reveals a lot about the priorities of the museum’s leadership. When it came time for the Hnatiuks to find a new home for their collection, they invited (with help from Congresswoman Marci Kaptur) interested parties from Ukrainian museums and archives throughout North America. Many of those institutions tried to pick and choose the very best pieces for their own collections, while Andrew Fedynsky and Aniza Kraus of the UMA argued “the collection is an artifact in itself, a monument to a family’s dedication to Ukrainian culture.” As with many émigré communities, cultural preservation was an important part of life in the new world, nearly impossible to disentangle from the larger mission of diaspora institutions, which for a long time was to inculcate future generations with a sense of mission that contributes to the eventual liberation of Ukraine. The preservation of cultural heritage was part of a larger sphere of activism that included attending benefit concerts, church services, parades and demonstrations that both marked important turning points in history and supported Ukrainian independence.

Resolution of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Moldavian SSR concerning Viktor Koval’s petition (in Russian). October 1988

Resolution of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Moldavian SSR concerning Viktor Koval’s petition (in Russian). October 1988

On the occasion of the nineteenth Party conference, held in Moscow in late June 1988, in the context of the increasingly obvious reformist tendencies of the late Perestroika period, Viktor Koval filed a petition requesting the revision of his case, his full rehabilitation, and his release from the psychiatric hospital. This petition was examined by the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Moldavian SSR in early October 1988. On 6 October, the special prosecutor responsible for supervising KGB investigations, M. V. Prodan, issued a special resolution denying Koval’s request and upholding the earlier decision of the Supreme Court. This resolution was approved by the General Prosecutor of the Moldavian SSR, N. K. Demidenko, six days later, on 12 October. This document is especially significant as it shows the reluctance of the Soviet justice system to acknowledge the repressive character of punitive psychiatry (and thus its own subservience to the regime) even as late as 1988, despite the general atmosphere of liberalisation. The prosecutor based his decision on the fact that Koval’s purported “socially dangerous acts” were confirmed by “the witness accounts, the material evidence, the conclusions of the psychiatric assessment, and the evaluation of the defendant’s handwriting,” as well as by other documents from the KGB file. After reviewing these materials, the prosecutor concluded that Koval’s assertions and papers comprised “certain well-founded critical remarks concerning the imperfections of our socialist society. At the same time, the essence of his activity did not focus on the criticism of the existing flaws in order to remove them from society. Rather, he constantly emphasised the advantages of the capitalist system and the Western way of life, and used rude and insulting expressions in connection with the role of the ruling communist party. He also stated demagogically that the people lacked any rights, that the country was ruled through fascist methods, and that the people were exploited. His main goal is obvious – to discredit the socialist order and the system of state power.” This assessment provided a glimpse into the logic of the regime’s actions and into the reasons for qualifying Koval’s case of political opposition as particularly dangerous. Although ritualistically invoking the results of the psychiatric assessment, the prosecutor in fact synthesised the regime’s attitude toward Koval’s and other similar examples of “ideological deviance.” It is not surprising that the official found the decision to subject Koval to forced medical treatment to be “correct” and rejected his petition for rehabilitation as “unfounded.” However, the prosecutor’s arguments seem more sincere and less euphemistic than earlier instances of comparable legal documents, probably reflecting a slight change in emphasis (if not in essence). Koval’s release from hospital only occurred in May 1990, when the article incriminating him was excluded from the Penal Code. His final rehabilitation followed in November 1991, when the Moldovan Supreme Court annulled the previous judicial decisions and openly admitted that Koval had suffered for his political opinions. However, even on that occasion punitive psychiatry as such was not officially condemned by the Moldovan justice system. It was only following a recommendation of the Presidential Commission for the Study and Evaluation of the Communist Regime in Moldova that the government officially condemned the use of psychiatric hospitals as a major strategy for the repression of dissent during the later stages of the Soviet regime.

The manuscript of Mihajlov's travels, “Moscow Summer,” written in English is in the box 28. The text was the fruit of Mihajlov's visit to the Soviet Union in the summer months of 1964. Mihajlov supported Nikita Khrushchev's reforms and the program of de-Stalinisation, and he criticized the changes in the Soviet leadership after Kruschev’s fall. This criticism alarmed those in charge of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy, since it could once more undermine Soviet-Yugoslav relations, which had normalized in the mid-1950s.

Referring to the publication of the first two essays of this book, Tito himself called out Mihajlov in February 1965 as a result of pressure from the Soviet ambassador due to his criticism of the new political course following the fall of Khrushchev in the autumn of 1964. Despite censorship of Mihajlov’s essays in Yugoslavia, American politicians and the public were interested in Mihajlov's case precisely because of his stance on the Soviet Union during the political upheavals in the upper echelons of the Soviet party in those years.

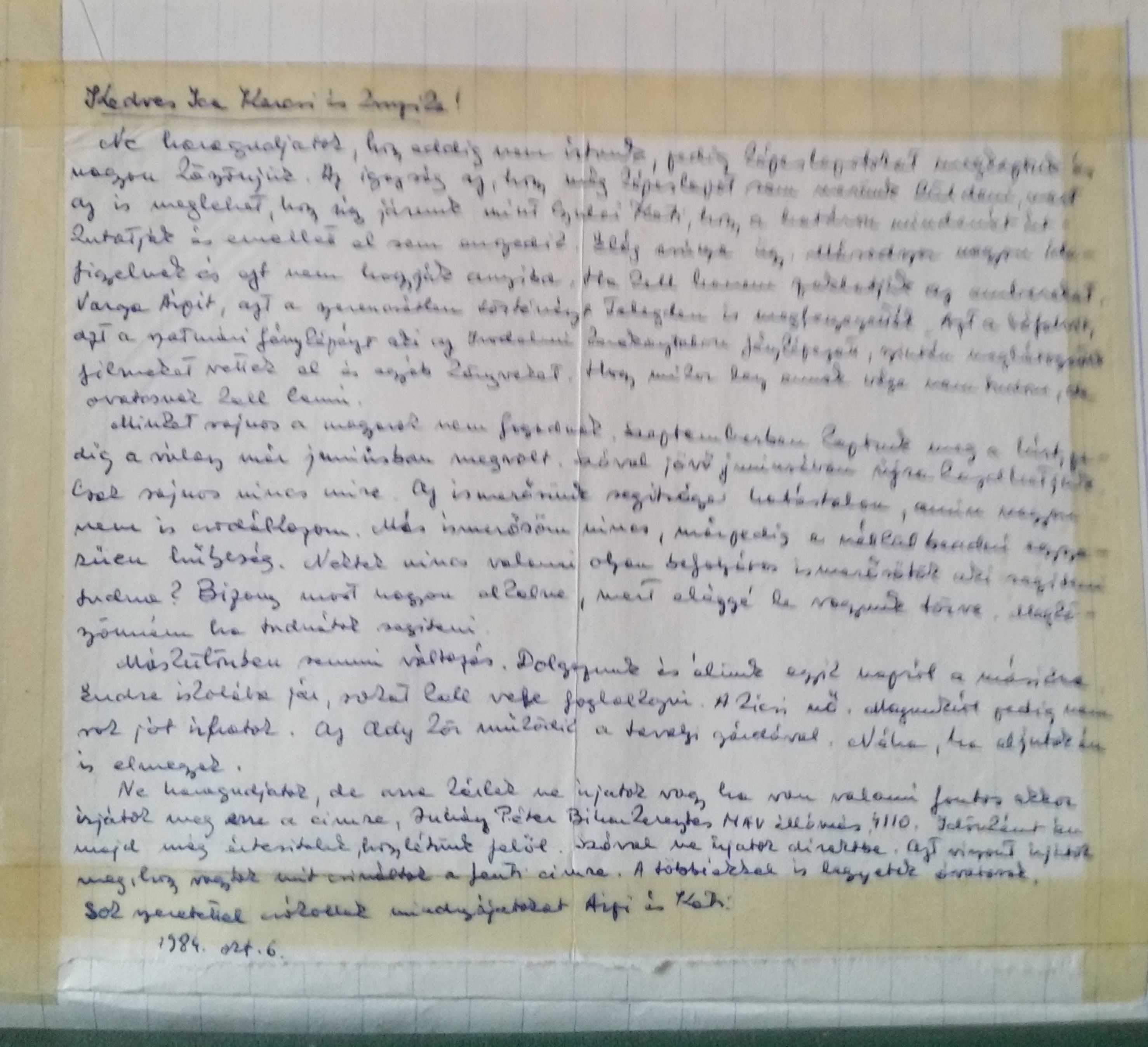

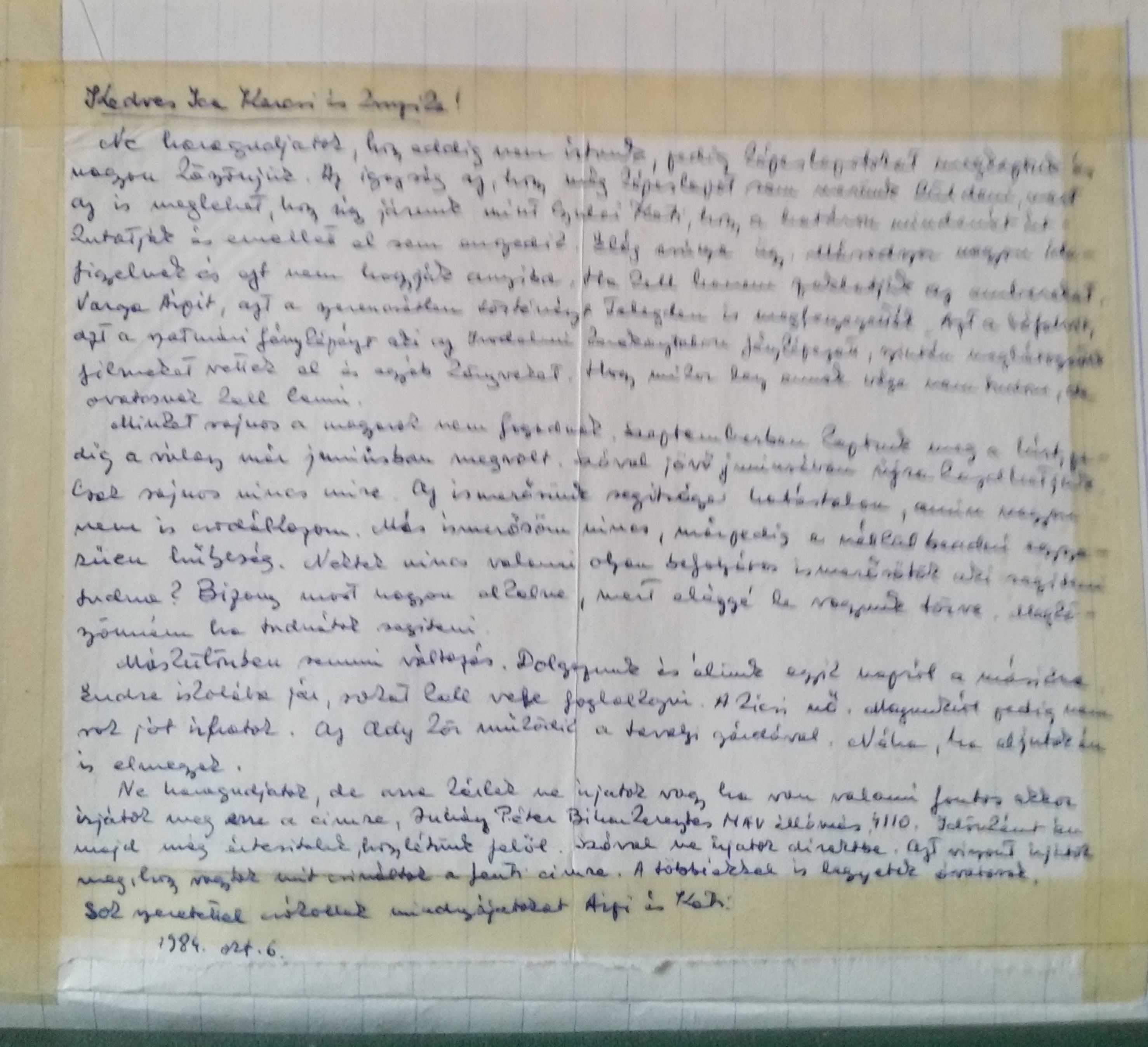

Letter “Smuggled” Across the Romanian-Hungarian Border, in Hungarian, 6 October 1984 (Letter Size: 15 cm x 14cm)

Letter “Smuggled” Across the Romanian-Hungarian Border, in Hungarian, 6 October 1984 (Letter Size: 15 cm x 14cm)

The Ellenpontok – Tóth Private Collection includes several hundred letters dating from that time. Especially interesting are the letters and notes of various shapes and sizes, smuggled primarily across the Romanian–Hungarian border by individuals during the eighties. In that time the relevant Transylvanian events had news value. Measures taken against the Hungarian minority were hardly talked about in the press, so it was essential to spread information to the broader public, partly with the purpose of protecting the victims of such measures, and partly in the hope that the situation of the minority would be improved by drawing the attention to these atrocities occurring under the Romanian communist regime.

This smuggled letter, size 15 cm x 14 cm, was delivered to the Tóth family in October 1984 while they lived in Budapest. The senders were the Spaller couple, old friends of the Tóths living in Oradea. Both Árpád Spaller and his wife Katalin obtained their degrees at Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, in 1970 and 1971 respectively, in special education (health pedagogy) and Romanian language and literature. After graduating they both worked as teachers in Oradea (Spaller and Spaller 2006).

The text of the letter is as follows:

”Dear Ica, Karcsi and Zsuzsika!

Excuse us for not having written so far, although we were glad to receive your postcard. The truth is that we hesitate to even send a postcard for fear we might end up like Kati Gyulai [Gyulai Katalin, verse performer from Oradea (Molnár 1993)], who underwent a thorough customs control only to be refused entry to the country. Quite an unfortunate case. On the other hand, they keep a close eye on us and they mean it seriously. They keep harassing people. Árpi Varga, [Árpád Varga, 1951-1994 (Sipos 1995)], that miserable historian from Tileagd was also threatened. They also showed up in the home of Sófalvi, that photographer from Satu Mare who took photos at the Literary Round Table, and confiscated some of his films and books. We have no idea when this will end but we ought to be cautious.

Unfortunately, we were denied entry to Hungary. We were informed about this in September, although the decision was already made in June. So, we can apply again next June. Unfortunately, we cannot expect much. The help from our acquaintance hasn’t been efficient which doesn’t surprise us. We do not have any other contacts to turn to, so applying under such circumstances is totally pointless. Do you happen to know anyone influential who could help us? To be honest, it would mean a lot to us now, because we are rather disappointed. We would appreciate your help.

Otherwise, everything is the same. We are working and living from one day to the other. Endre attends school, he pretty much needs our assistance. The little one is growing. As for us, not much good news to tell. The Ady Circle is still active with the old members. Sometimes, when we have time, we also attend.

If you don’t mind we need to ask you to stop writing to us, or if there is anything important, address your letter to Péter Juhász [railway worker] Biharkeresztes MÁV station 4110. From time to time, we shall send you news about us. So, please don’t write directly to us. But please let us know how you are in a letter sent to the above address. And please be cautious in the case of the others, too.

With love, Árpi and Kati.

October 6, 1984”.

The letter of the Spaller family perfectly illustrates the fear present in those times, affecting both the public sphere and the everyday life of the individual. People, afraid they might be observed and harassed by the Securitate, in the constant climate of insecurity, chose to be silent, avoiding any form of public manifestation. It also says a lot that the senders of the letter did not give a Romanian address for direct correspondence, but that of the railway station in Biharkeresztes, a Hungarian settlement 6 km from the Hungarian-Romanian border, which is also a border crossing point.

The reasons behind emigration did not require much explanation back then. Beginning with January 1983 it became increasingly difficult to obtain a residence permit from the Hungarian authorities, as the application involved the presentation of a letter of invitation. This seemingly insignificant administrative obstacle – as revealed also in the above letter – could represent an enormous impediment for families who planned to emigrate, though emigration did not prove to be an impossible endeavour on the whole: in 1987 the Spaller family moved to Hungary where they managed to find jobs that suited their qualifications. At present they live in Budapest (Spaller and Spaller 2006).

Ivan Medek (1925-2010) was a prominent Czech music publicist, a signatory of Charter 77 and a founding member of VONS. In 1978 he went into exile, where he founded the Press Service and worked with Voice of America and Radio Free Europe. This collection contains unique documents from his exile activity.

The machine-read transcript of the audio recorded interviews from the secret meetings which took place in Božena Komárková´s flat, comprised of 42 pages. She discusses her life, reflection of T. G. Masaryk, St. Augustine, relationship to democracy, Christian faith, Socialism and Christianity, church affairs after the Communist coup in 1948, etc. The transcription is crossed out and supplemented by Božená Komárková´s comments. Part of the collection is also the original audio record. This document shows authentic and original views from the meetings and a wide range of views from the prominent figure of Protestant dissent - Božena Komárková.

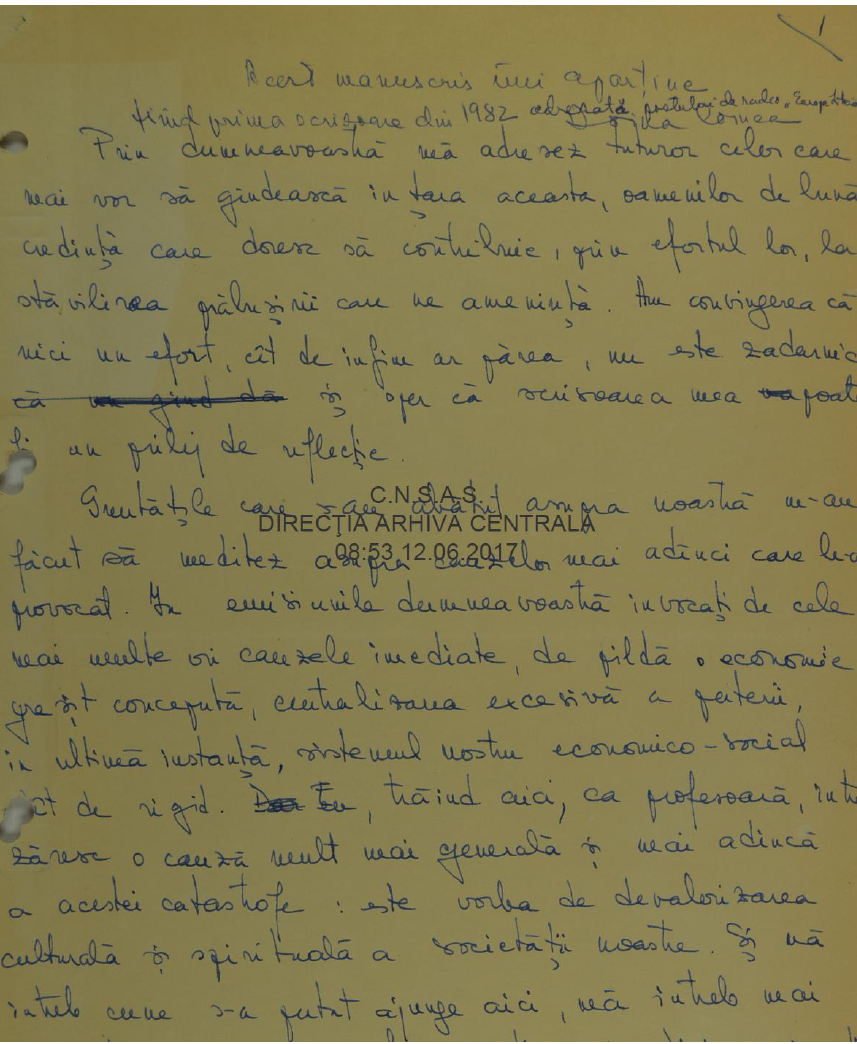

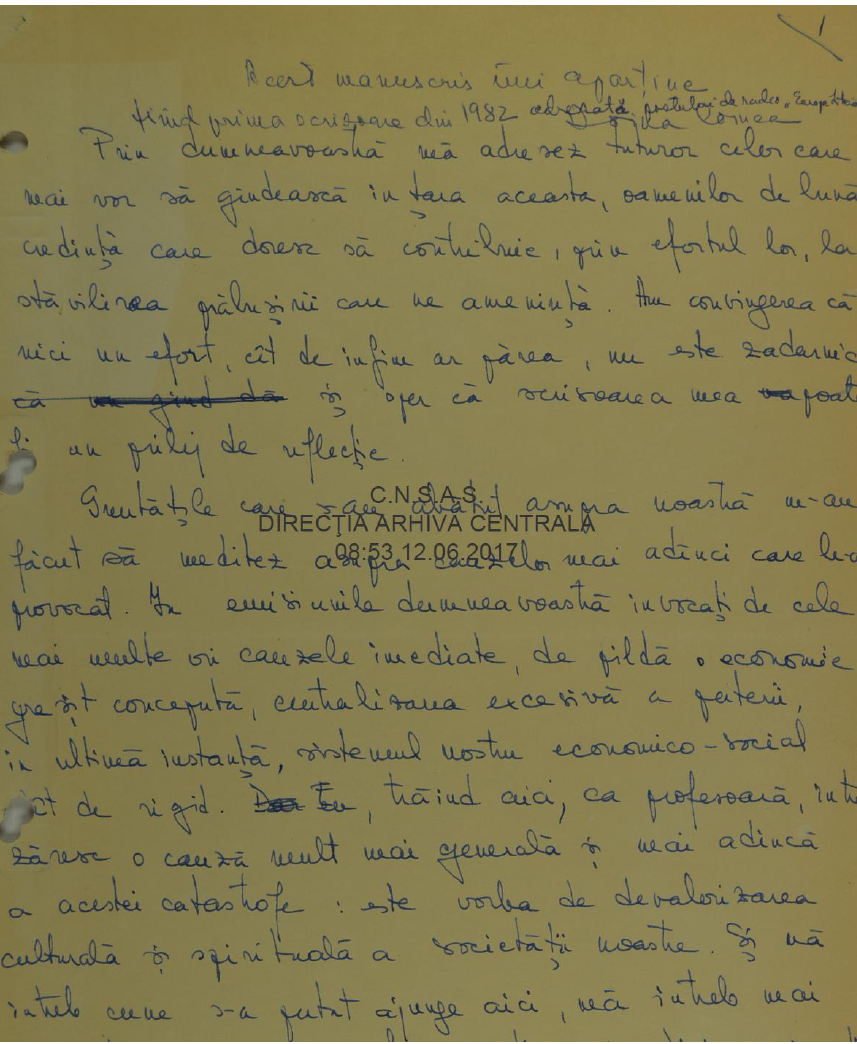

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

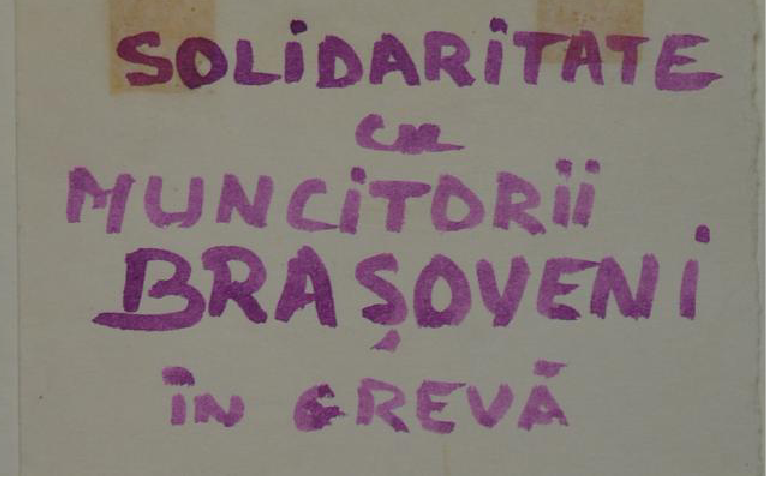

After listening in November 1987 to the news broadcast by Radio Free Europe (RFE) about the anti-communist revolt of the workers in the factories of the city of Braşov, Doina Cornea openly displayed her solidarity with the protesters. On 18 November 1987, she drafted 160 manifestos, which were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in several public spaces in Cluj (Cornea 2009, 194–195). Consequently, on 19 November 1987, she and her son were arrested by the Securitate after a detailed home search (Cornea 2006, 203). During home searches on 19 and 23 November 1987, the Securitate confiscated many documents from Cornea’s private dwelling, including all the drafts of her letters to RFE.

Among these documents, the Securitate confiscated the handwritten draft of the first letter she sent to RFE entitled: “Letter to those from home who have not given up thinking with their heads.” According to interviews granted by Doina Cornea, this letter was drafted by Cornea and her daughter Ariadna Combes in July 1982 (Cornea 2009, 169-170). The document was smuggled to the West and sent to RFE with the help of her daughter, who chose to remain in France in 1976 and visited her mother in July 1982 (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, f. 11). In August 1982, the letter was broadcast by RFE during the radio programme “Talking with RFE listeners.” It was the first letter in a series of twenty open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE in the period from 1982 to 1989, through which she asserted herself as one of the most prominent Romanian dissidents (Cornea 2009, 195–196). The open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE intensified the surveillance and repressive actions of the Securitate, which had already been monitoring her closely since 1981. Due to the fact that the strict surveillance in communist Romania did not allow the development of a samizdat and tamizdat milieu, RFE played a key role in conveying the messages of Romanian dissidents to their fellow citizens (Petrescu 2013, 277).

The letter starts with a reference to radio programmes of RFE that had been previously broadcast. During these radio programmes, journalists specialising in East European issues had dealt with the crisis that affected communist Romania during 1980s and identified political and economic factors as the immediate causes. Instead of these causes, Doina Cornea emphasises in her letter causes relating to moral and cultural values. By idealising interwar Romania, she brings into discussion the destruction of the Romanian intellectual elite during the first two decades of communist rule and the decay of the educational system. In Cornea’s opinion, this “spiritual crisis” is illustrated by the everyday “compromises” and “lies” that citizens living under a communist dictatorship have to “accept and circulate” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f.1). Her argumentation in this respect is similar to that developed by Vaclav Havel’s essays and epitomised by his principle of “living in truth” (Havel 1990). Cornea argues that “the people is fed only with slogans,” which stifle all openness towards “truth, revival, and creativity” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 2–3). She criticises the conformism of Romanian intellectuals and state policies which limit theoretical education (especially the humanities) and promote technical education in order to fill the need for cadres in the rapidly growing heavy industry.

She concludes her text by asking for a reform in the educational system and encourages those working in this field at least to take advantage of the limited possibilities available to them to promote what she considers to be authentic cultural and moral values. According to Cornea, those working with students should not teach them “things in which they themselves do not believe” and they should “encourage the creativity of young people and not be afraid to say what they think” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 4–5). At the end of the letter, Doina Cornea inserted her name with the mention: “for the messengers of RFE listeners” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 5). She did not intend to reveal her real identity to the listeners of RFE, but just to prove the authenticity of the document to the editors of the radio programme. Due to a misunderstanding, her real identity was revealed during the radio show.

In November 1987, after the draft of this document was confiscated by the Securitate, the secret police used it as an argument of accusation during Cornea’s interrogation. This focused especially on the channels used by Cornea to send the letter to RFE. Although she did not mention it during the interrogation, the Securitate suspected that her daughter Ariadna Combes had helped her in this respect. For this reason, Cornea’s daughter thereafter did not receive a permit to enter the country to visit her family until the fall of the communist regime.

The collection is important proof of the activities of a left-thinking historian, a "spiritual father" and co-founder of the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS), a co-publisher of unofficial periodic Dialogy, who was imprisoned several times and forced to go to exile, where he collaborated with dissidents from other socialist countries.

The collection of files of political prisoners contains the criminal cases against people who were charged by Soviet security institutions (NKVD/MGB/KGB) of real or imaginary crimes against the Soviet state from 1940 to 1986, including many intellectuals and religious activists. The files of visual artist Kurts Fridrihsons and poet Knuts Skujenieks, participants in the Action of Light, and many others, are in this collection.

Judging from the level of difficulty of the twenty-two questions contained in it, the target group of the document identified as a questionnaire included the most sophisticated members of the Hungarian elite in Romania, who did not necessary work in the cultural sphere, but who had presumably been selected as a result of previous inquiries. The questionnaire, made up of three major sets of questions, first assesses the social status, qualification level, and general culture of the subject, then examines the subject’s sense of identity, and finally investigates, also out of a need for identifying a solution, the nature of the connections and relationships between Romanians and Hungarians, as well as experiences regarding coexistence.

I. The first set of questions focuses on the subject’s social status. It begins by examining the social background of the subject – family, origin – and then inquires about his/her age to further turn to a direct reference to the “small Hungarian world” in Northwestern Transylvania during the Second World War (Sárándi and Tóth-Bartos, 2015), which suggests that the questionnaire focuses primarily on mature individuals holding well-defined views on the Transylvanian issue. Questions four and five address the length and possibilities of past education in the mother tongue in the family of the subject, respectively, in his/her “range of vision.”

The Questions:

1. What kind of family do you come from?

2. What type of social environment do you come from? (rural, urban, peasant, worker, bourgeois, aristocrat, etc.)

3. How old are you? Were you alive between 1940 and 1944?

4. How long and what were you able to study in your mother tongue?

5. What about your family and /or “range of vision”?

II. The second set of questions – questions 6 to 14 – is directed at the subject’s sense of identity. The assessment of collective memory is followed by a nostalgic question, which, beside the inventory of violations of human rights experienced in the present, makes the subject draw a comparison with the rights undoubtedly held in the past. The question about general knowledge of Hungarian history is followed more emphatically by that about self-declared knowledge of post-1918 Transylvanian history and of the public figures related to it. Then the author of the questionnaire moves on to the mapping of reading habits and needs in the mother tongue, of cultural life and religion. The question referring to the level of Romanian language skills is still relevant. As the knowledge of language represents a prerequisite for social integration, this also means that as long as the coexisting nations are unable to eliminate language barriers, their cultures cannot get closer to each other, cannot coexist in harmony. Radio listening habits provide answers regarding the need for information of Hungarians in Transylvania, but also about their possible resignation and indifference. The inquiry about connections in Hungary presupposes the existence of a current network of contacts in the “mother country,” including relatives, friends, and acquaintances. The thirteenth question, about the new situation in Hungary – which offers a clue about the date of the document – presumably hints at the changes that took place during the official mandate of the moderate reformer Károly Grósz, appointed president of the Council of Ministers in June 1987. On May 1988, the reform wing of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP) obtained the long-awaited goal of removing the old and ill János Kádár from the party leadership and elected Grósz as his successor upon a programme of transition to a market economy and political decentralisation. However, it cannot be excluded that allusion was made to symbolic events of 1989 relating to the commemoration of the Revolution of 1956, such as the reburial of Imre Nagy and his comrades, or the radio speech by the senior party official Imre Pozsgay about the re-evaluation of this tragic event in Hungary’s recent past (Romsics 2013). The last question in this section, referring to a “prominent Transylvanian personality” takes into consideration the greater political events and perhaps it looks ahead in allowing for an unpredictable political turn in Romania.

The Questions:

6. What can you recall, or how far back does your collective (family, workplace, etc.) memory extend?

7. Would you like to regain anything from the past? If yes, what?

8. Are you familiar with Hungarian history, and with the history of Transylvania in particular? (What do you know about the events following 1918? Are you familiar with the operation of the Hungarian National Party [Bárdi 2014, Horváth 2007, György 2003]? Are you familiar with figures such as Ct. Bethlen György [1888–1968, president of the Hungarian National Party representing the Hungarian minority in Romania in the interwar period (ACNSAS, I185019)], Jakabffy Elemér [1881–1963, Hungarian, later Romanian Hungarian politician, lawyer, publicist (Balázs 2012, Csapody 2012)], Makkai Sándor [1890–1951, Transylvanian Hungarian writer, pedagogue, Reformed bishop (Veress 2003)], Mailáth [Majláth] Gusztáv Károly [1864-1940, Transylvanian Roman Catholic bishop, member of the nobility, honorary archbishop (Marton and Jakabffy 1999)], Domokos Pál Péter [1901-1992, teacher, historian, ethnographer, one of the pioneers of research into the Csangos (Jánosi 2017, Domokos 1988)] etc.?

9. Do you own Hungarian books? Do you read in Hungarian? If yes, how much? How do you gain access to Hungarian books? Do you go to the theatre? Are you a church-goer? (Is the use of the Hungarian language or the fact that you are a believer behind church attendance?) 10. How well do you speak the Romanian language?

11. Which radio station do you listen to? That of Budapest or that of Bucharest? And which Radio Free Europe broadcast do you listen to: the Romanian or the Hungarian one?

12. Do you have contacts in Hungary?

13. What do you think of Hungary in this new situation?

14. Is there a prominent Transylvanian personality you know about and consider worth paying attention to?

III. The third set of questions – questions 15 to 22 – analyses the relationship between Romanians and Hungarians. Thus, beside inquiring about the nature of relationships maintained by the subject and his/her environment with his/her ethnic Romanian fellow citizens, these questions focus also on the ethnic characteristics of the coexisting population, whether the demographic balance in a given settlement, which was centuries ago favourable to the Hungarian community, has been subject to modifications by the communist regime by attracting inhabitants from other regions populated mostly by Romanians. Having future coexistence in view, question 17 is aimed at learning the “lacking needs” of the subject, so it inquires about the required minimum conditions in terms of human rights that allow him/her to live as a Hungarian there, in that given place. Amidst the measures aimed at the assimilation of the Hungarian minority in Transylvania, such as the continuous diminishing of educational opportunities in the Hungarian language, the closing down of Transylvanian Hungarian theatres, the potential destruction of villages, the phenomenon of emigration, which affected the Romanian citizens too, in the context in which the nationalism of Ceaușescu’s regime was become more and more radical, when politics-fuelled intolerance towards ethnic otherness was a daily presence, the question about individual views regarding the future of the minority community might have seemed surreal. Thoughts referring to the renewal of the indigenous minority were closer to utopia as the flagrant violation of human and minority rights provided no realistic grounds for this. The last two questions of the questionnaire – questions 21 and 22 – about positive experiences as a Hungarian living in Romania, positive experiences concerning the Romanian–Hungarian relationship – illustrate, even in their choice of words – “have you ever,” “accompany or would accompany” – the perspicacity with which the author of the questionnaire acknowledges the situation of the Transylvanian Hungarian minority of the period preceding the change of regime.

The Questions:

15. What is the nature of your (your personal and your community) relationship with Romanians?

16. Are you surrounded mostly by Romanians or by Hungarians in your living environment? If you live predominantly surrounded by Romanians, when was this situation installed? Is it a result of incoming settlement or is it the indigenous population?

17. What is it that you lack most in living there as a Hungarian?

18. What is your opinion about your own future, the future of your family, and that of Transylvanian Hungarians?

19. Do you see any possibilities of renewal?

20. If you are a church-goer, what do you know and what can you witness from the Greek Catholic movement?

21. Have you ever had any positive experiences as a Hungarian? If yes: when and what kind of experience was it?

22. List the positive experiences that accompany or would accompany the relationship between Romanians and Hungarians?

There is no doubt that Gyimesi is the author of this document. In numerous places her works include analyses of the given situation and sense of identity of the Hungarian minority in Transylvania (Gyimesi 1993). Most probably the document escaped the attention of secret police officers conducting the home search on 20 June 1989 due to the absence of title and date. The physical existence of a questionnaire examining minority life in the darkest days of Romanian Communist dictatorship is startling in itself. Research conducted in the form of questionnaires presupposes the subject’s right to free opinion and is interpreted as an accessory of democratic systems. However, the existence of the document does not mean that the intended survey was actually conducted. For Gyimesi, who was the subject of informative surveillance, in a world abounding in collaborators with the secret police, this questionnaire must have meant a handhold which should have helped her in identifying persons with similar views on whom she could have counted in the struggle against the violation of human and minority rights. This may have served as a basis – as a possible interpretation – for her efforts to recruit reliable colleagues for the editing and distribution of the Cluj-based samizdat paper known as Kiáltó Szó, which she conceived in the fall of 1988 together with Sándor Balázs, a philosopher and university professor. Out of the nine edited issues of the samizdat – which was little known even by the Securitate – only two were published, though this had nothing to do with the editors: the publishing of further issues was rendered unnecessary under the circumstances following the fall of the Ceaușescu-dictatorship.

Justas Paleckis (1899–1980) was a chairman of the presidium of the Supreme Council of Soviet Lithuania from 1940 to 1974. Paleckis’ collection holds his personal papers, various manuscripts, notebooks, correspondence with Lithuanian writers and scholars, and letters from victims of Stalinist repressions. The documents reflect the aspirations and the ambitions of the Lithuanian cultural elite to preserve and develop the Lithuanian cultural heritage.

The records of the Commission on Religious Matters of the Vinkovci Municipal Assembly in the State Archives in Vukovar (at present situated in the Archival Collection Centre in Vinkovci) is a part of the archival fund of the Vinkovci Municipal Assembly covering the period from 1963 until 1993. The collection contains materials that testify to the local oppositional activity of different religious institutions from the area under the jurisdiction of the Vinkovci Municipal Assembly and also to the state control over them.

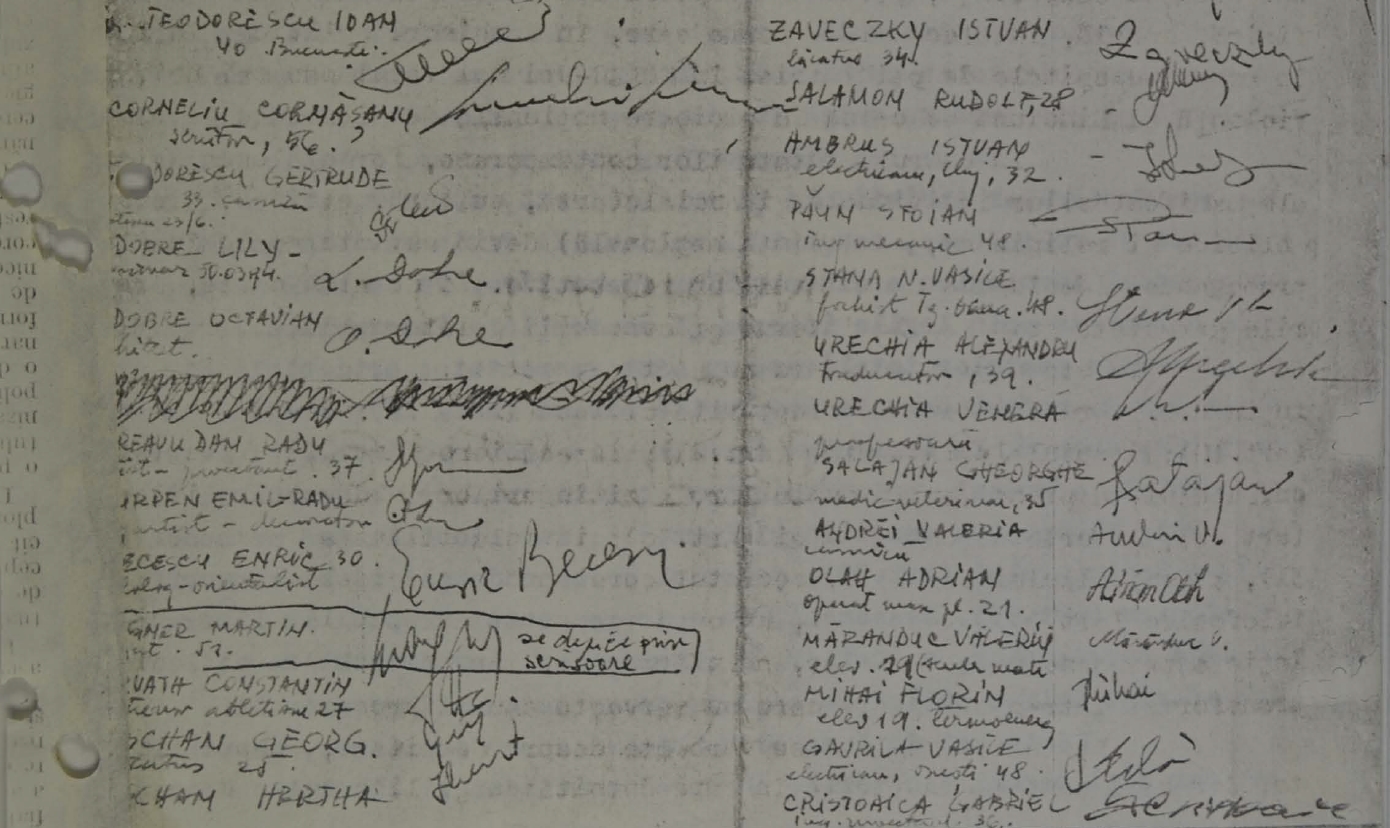

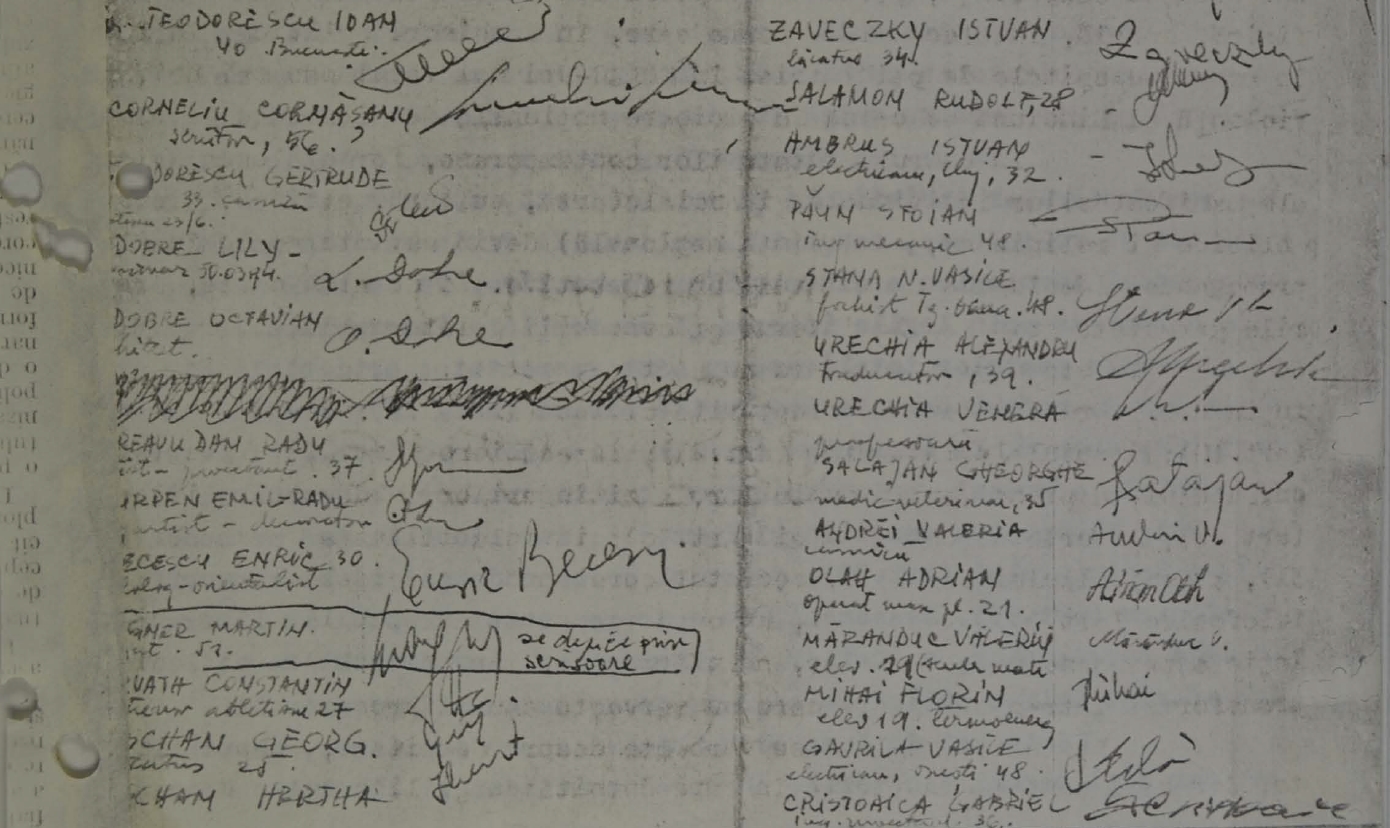

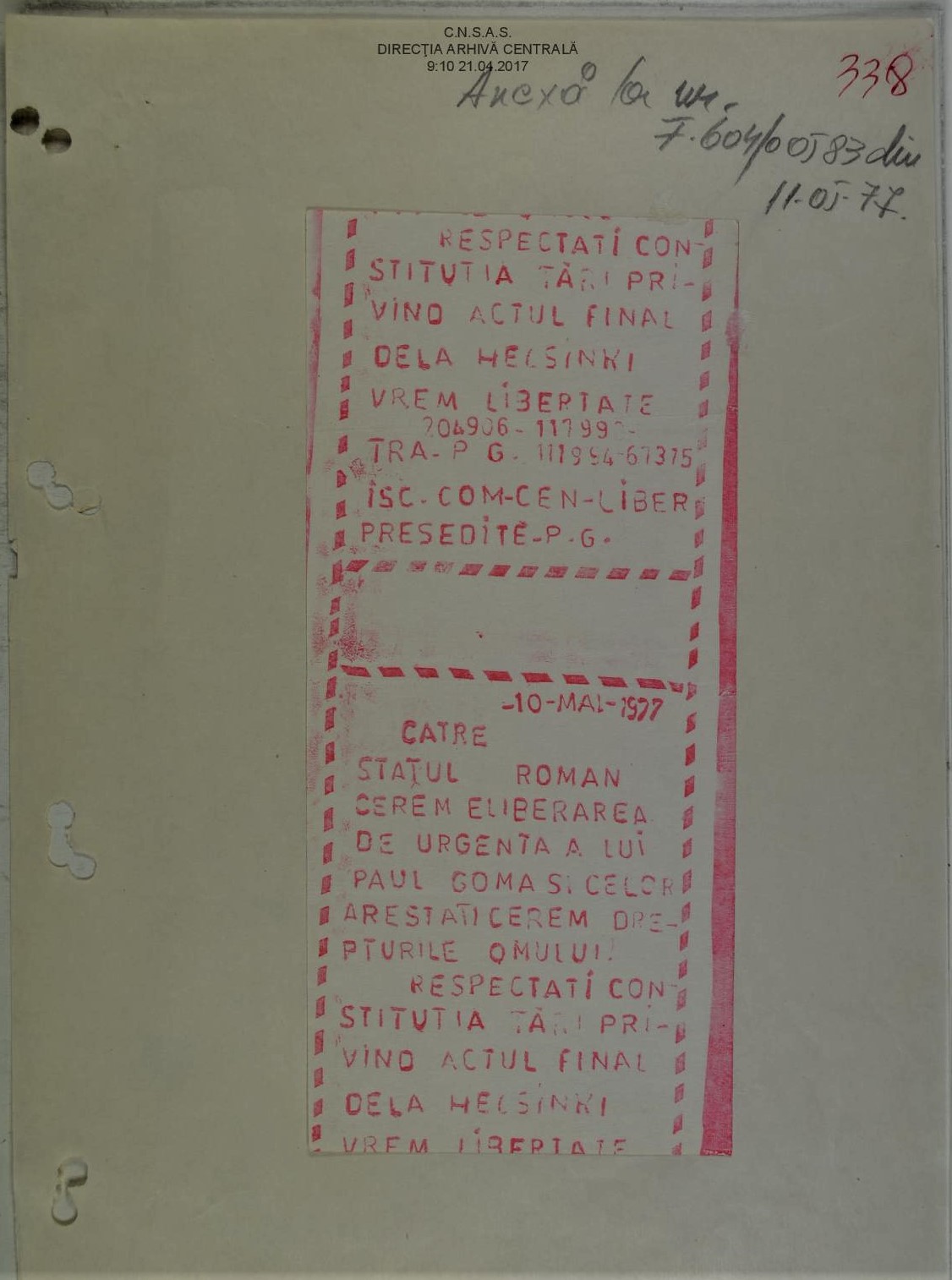

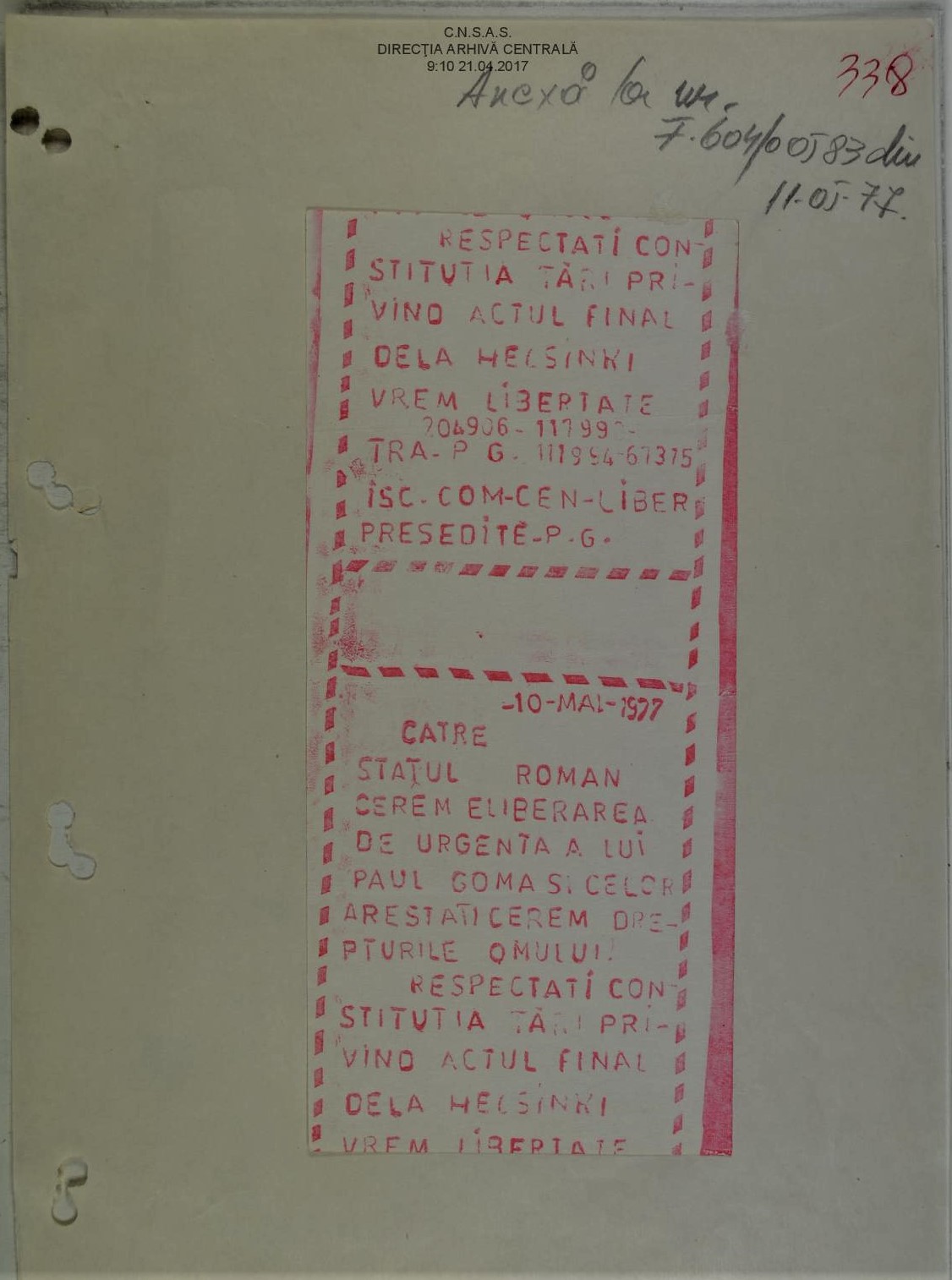

The trigger of the struggle for human rights in this region, which was considered by many analysts a fundamental factor in the collapse of communism in 1989, was the Helsinki Agreements of 1975. The very idea of monitoring human rights abuses, which the Charter 77 grasped from these agreements and promoted until 1989, also inspired Goma and perhaps others in the Soviet bloc. This idea, however, was entirely novel in the countries of East-Central Europe, including Romania. Most individuals in this region lacked the necessary background to fully grasp a problem which was central in Western political thinking, but absent or distorted in local politics even before communism. Nonetheless, due to the transnational travel of ideas, movements for human rights gradually emerged after 1975. In Romania, the ephemeral movement arose around an arid letter addressed to the First Follow-Up Meeting of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), which was to take place in Belgrade beginning in 1977. This letter was initially signed only by Goma, his wife Ana Maria Năvodaru and six other persons: Adalbert Feher, a worker; Erwin Gesswein and Emilia Gesswein, a couple of instrumentalists with the Bucharest Philharmonic Orchestra; Maria Manoliu and Sergiu Manoliu, mother and son, both painters; and Şerban Ştefănescu, a draftsman. However, by the day of Goma's arrest, 192 individuals had endorsed this collective letter of protest. The list of signatures was confiscated from Paul Goma's residence at the moment of his arrest, but he had managed to send it to Radio Free Europe in advance. The lists confiscated by the secret police in 1977 were returned to Paul Goma in 2005. Thus, the document listing all these persons is now part of Paul Goma Private Collection in Paris, but copies can be found in the CNSAS Archives in Bucharest (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7), as the secret police preserved them in Goma’s informative surveillance file, and in the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives in Budapest (OSA/RFE Archives, Romanian Fond, 300/60/5/Box 6, File Dissidents: Paul Goma).

Cornea, Doina. Stop the demolition of the Romanian villages (open letter), in Romanian, July 1988. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina. Stop the demolition of the Romanian villages (open letter), in Romanian, July 1988. Manuscript

Among the open letters addressed by Doina Cornea to Ceauşescu himself, that entitled “Stop the demolition of the villages” (Opriți dărâmarea satelor) was among the most significant and certainly the one that aroused the greatest international reaction. The letter opposed the programme of “rural systematisation,” which entailed the planned demolition of more than 7,000 Romanian villages (Ceaușescu 1989, 395). Cornea drafted the open letter in July 1988 in a period when the demolitions had been intensified. The letter was also broadcast by RFE in September 1988 and published later by the French newspaper Le Monde (Cornea 2006, 220).

In comparison with other open letters that focused more on future-oriented reforms (such as those dealing with the educational system), this letter is “nostalgic and past-oriented,” and deals with the protection of the Romanian peasants’ habitat and way of life, which she argues is the core of Romanian national identity (Petrescu 2013, 314). This approach was based on her readings of Romanian philosophers and writers such as Lucian Blaga, Constantin Noica, and Nicolae Steinhardt, who dedicated many of their works to the “spirituality” of the Romanian village. She thus places herself in a cultural tradition which since the end of the nineteenth century had emphasised peasant culture as a key element for defining Romanian national identity (Hitchins 1994, 298–299). Consequently, she considers Ceauşescu’s plan to restructure most of the Romanian villages as a malicious attempt to destroy “the soul of the nation.” She also invokes the fact that the rural habitat is a part of world cultural heritage and criticises the demolitions from a preservationist perspective. Thus, she asks Ceauşescu to stop the demolition of the villages and to consult of the will of the Romanian people concerning the future of the national programme of “rural systematisation.”

At the end of the letter, Doina Cornea mentions another twenty-seven persons who had expressed their solidarity with the open letter of protest and agreed that their names could be included on the list. Most of them were either Cluj-based supporters of her oppositional activity, such as the dissident Iulius Filip (who in 1981 had addressed an open letter of support to the Polish free union Solidarity), or part of a group of workers in the town of Zărneşti (Braşov county, Romania), who had initiated a local free union. This open letter, together with her interviews granted to Western journalists, inspired the collective initiative Opération Villages Roumains (OVR), “the largest ever network of transnational support against the abuses of Ceausescu’s regime,” which opposed the demolition of Romanian villages by encouraging a symbolic adoption of the endangered Romanian rural sites by Western communes (Petrescu 2013, 317).

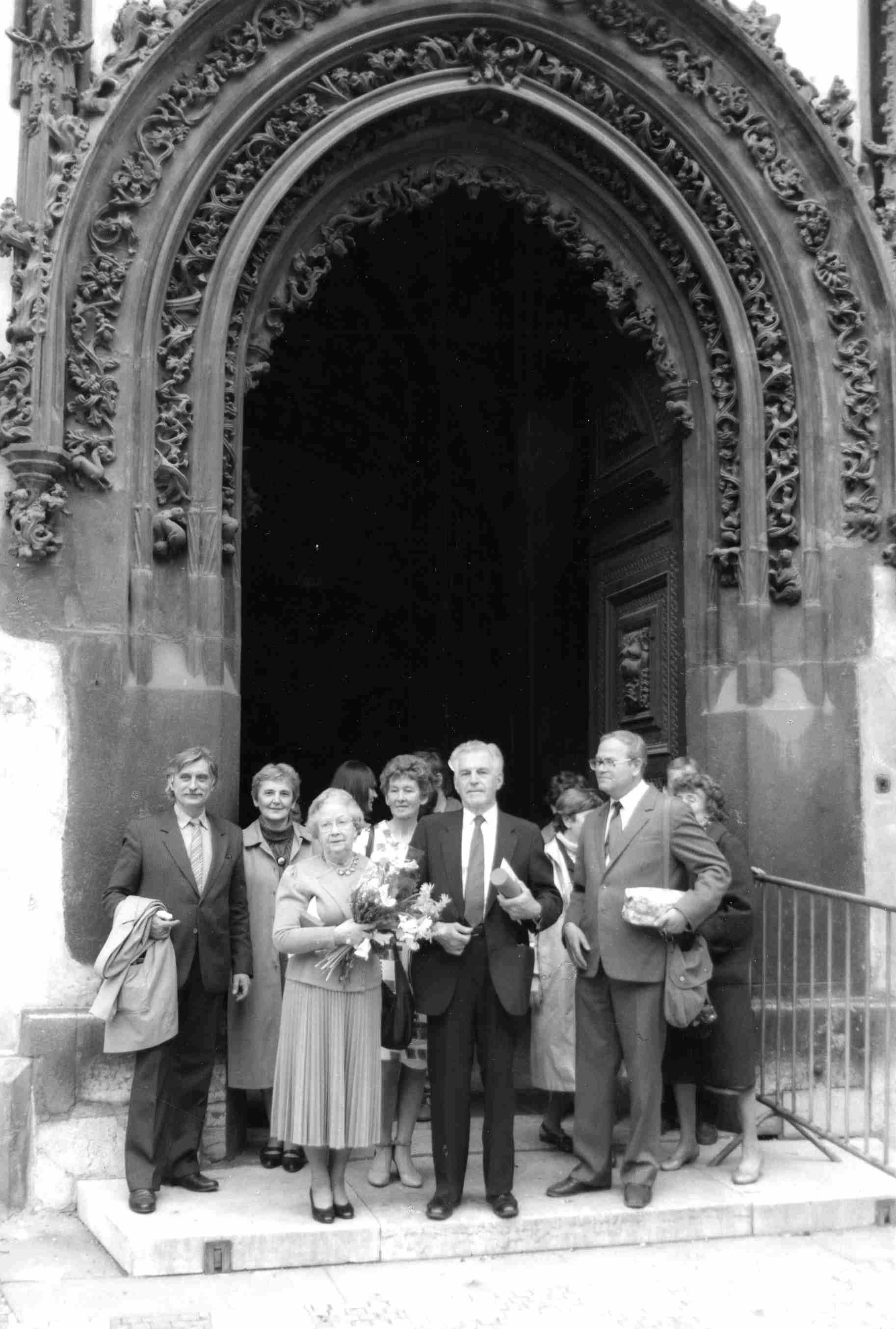

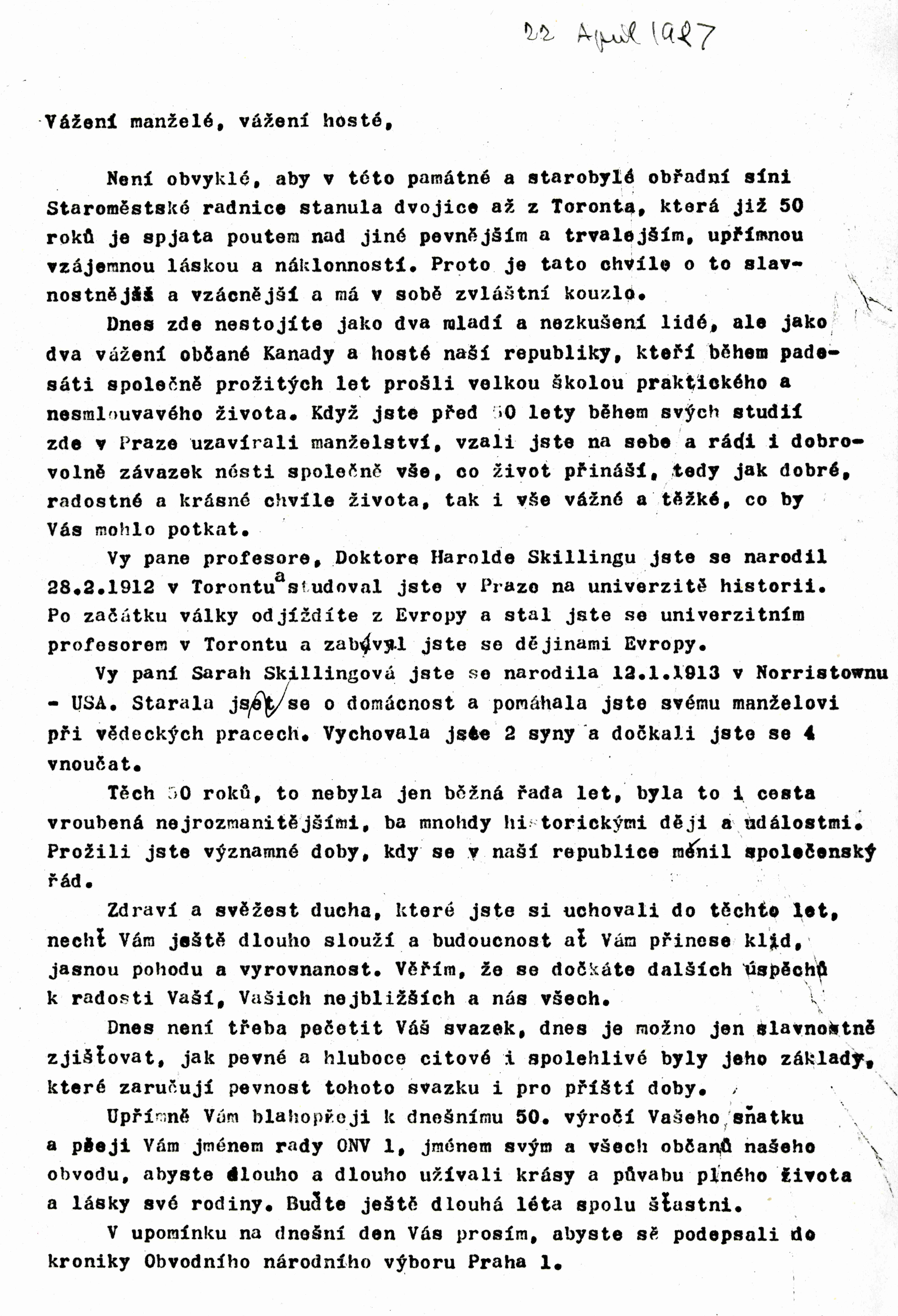

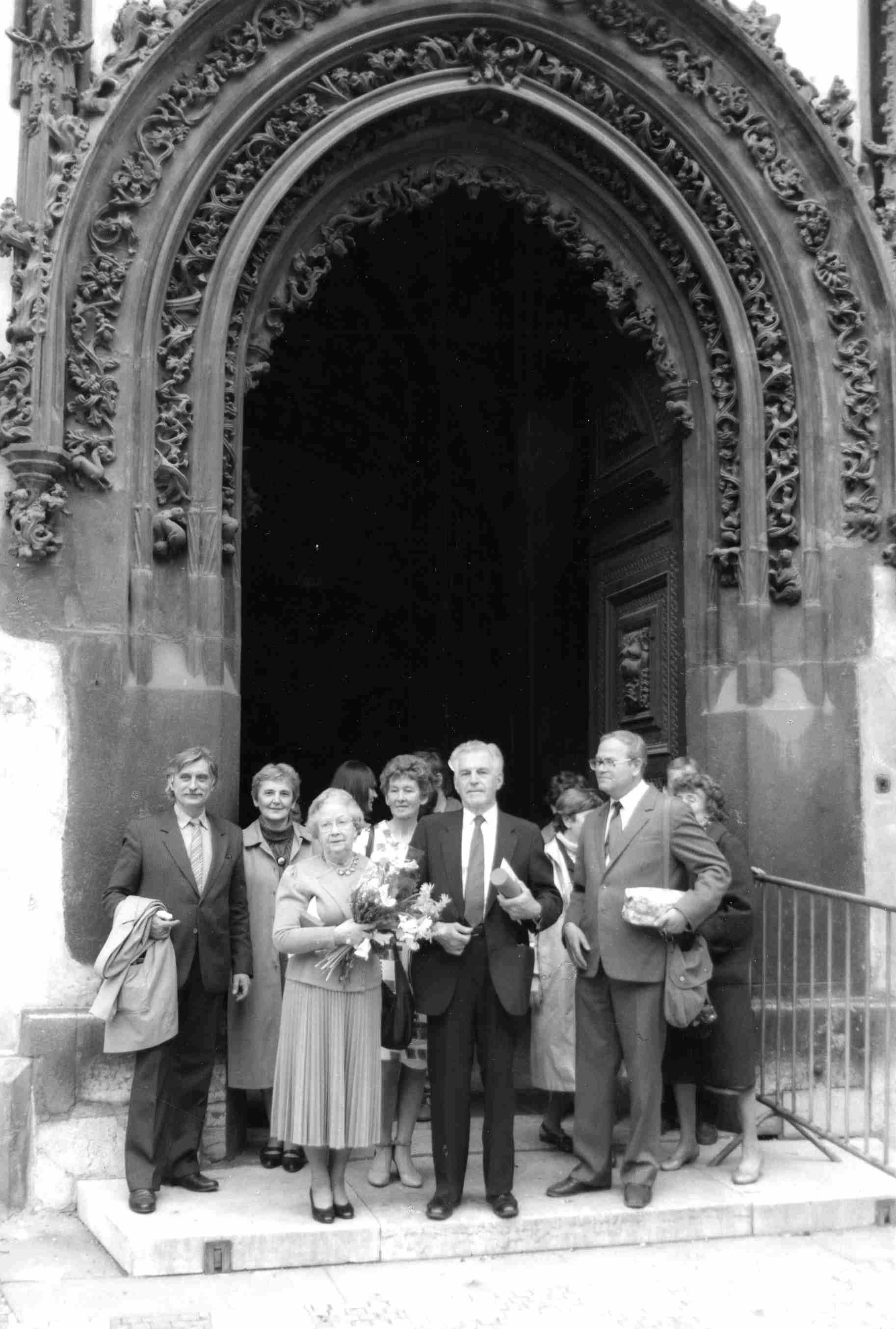

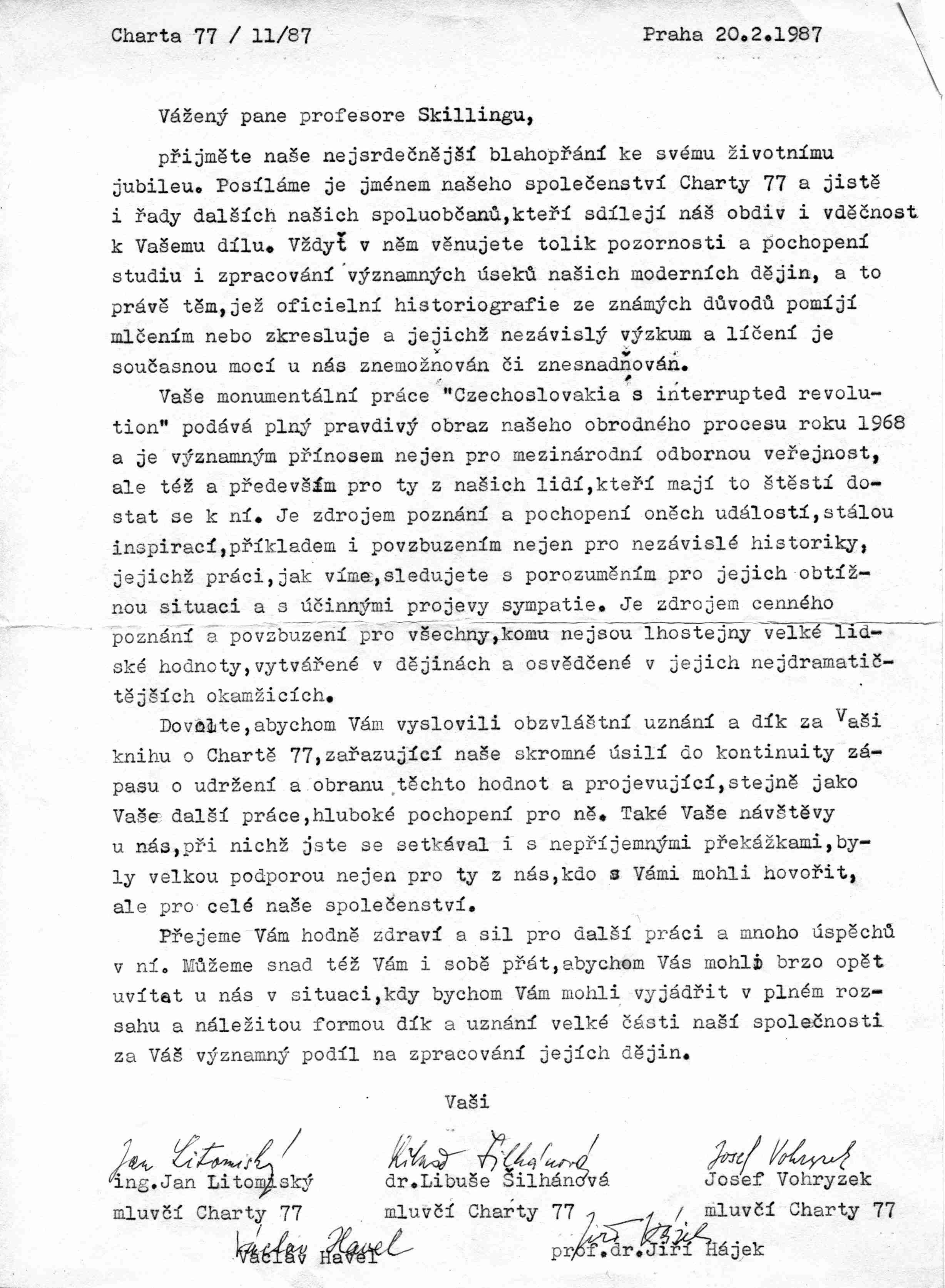

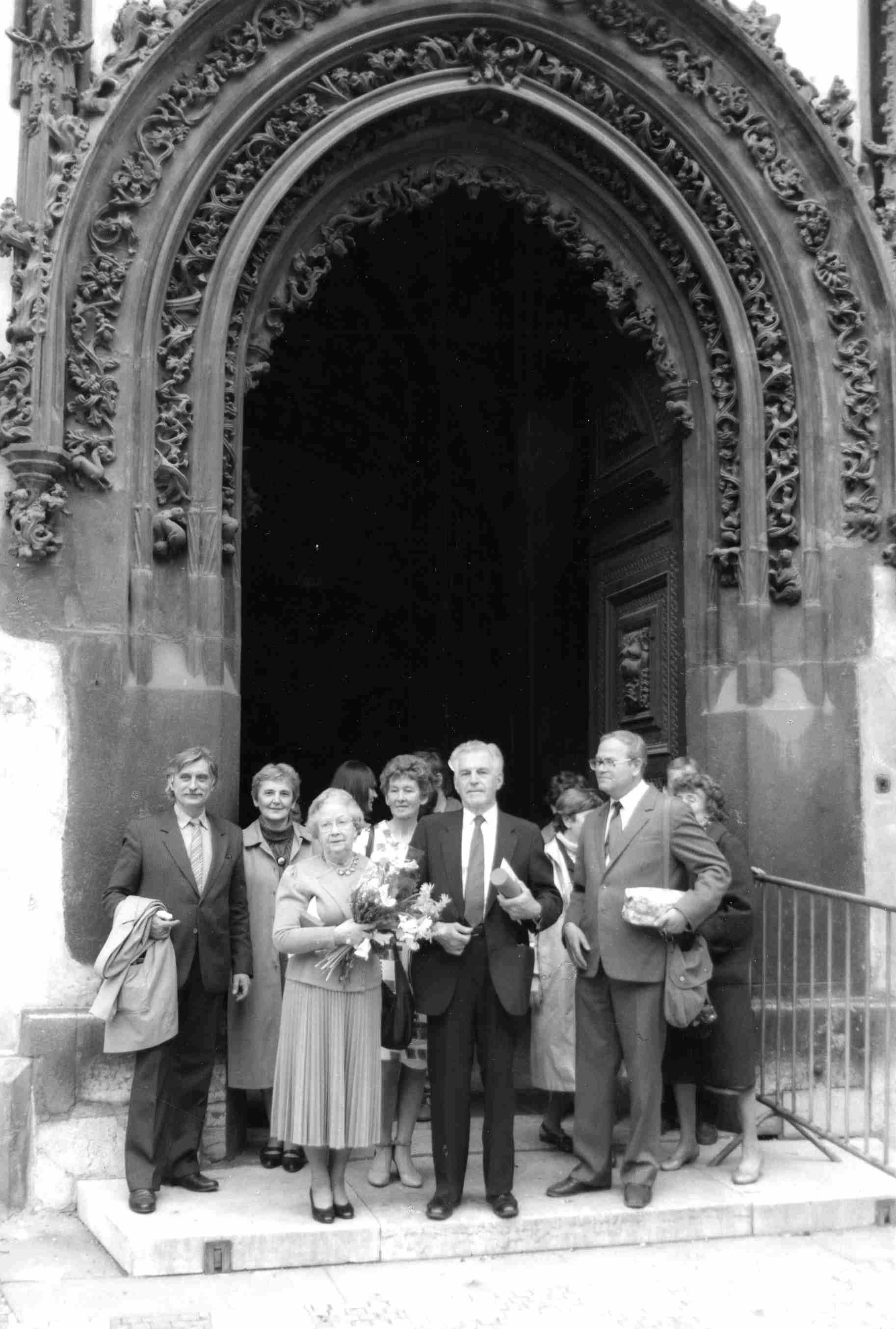

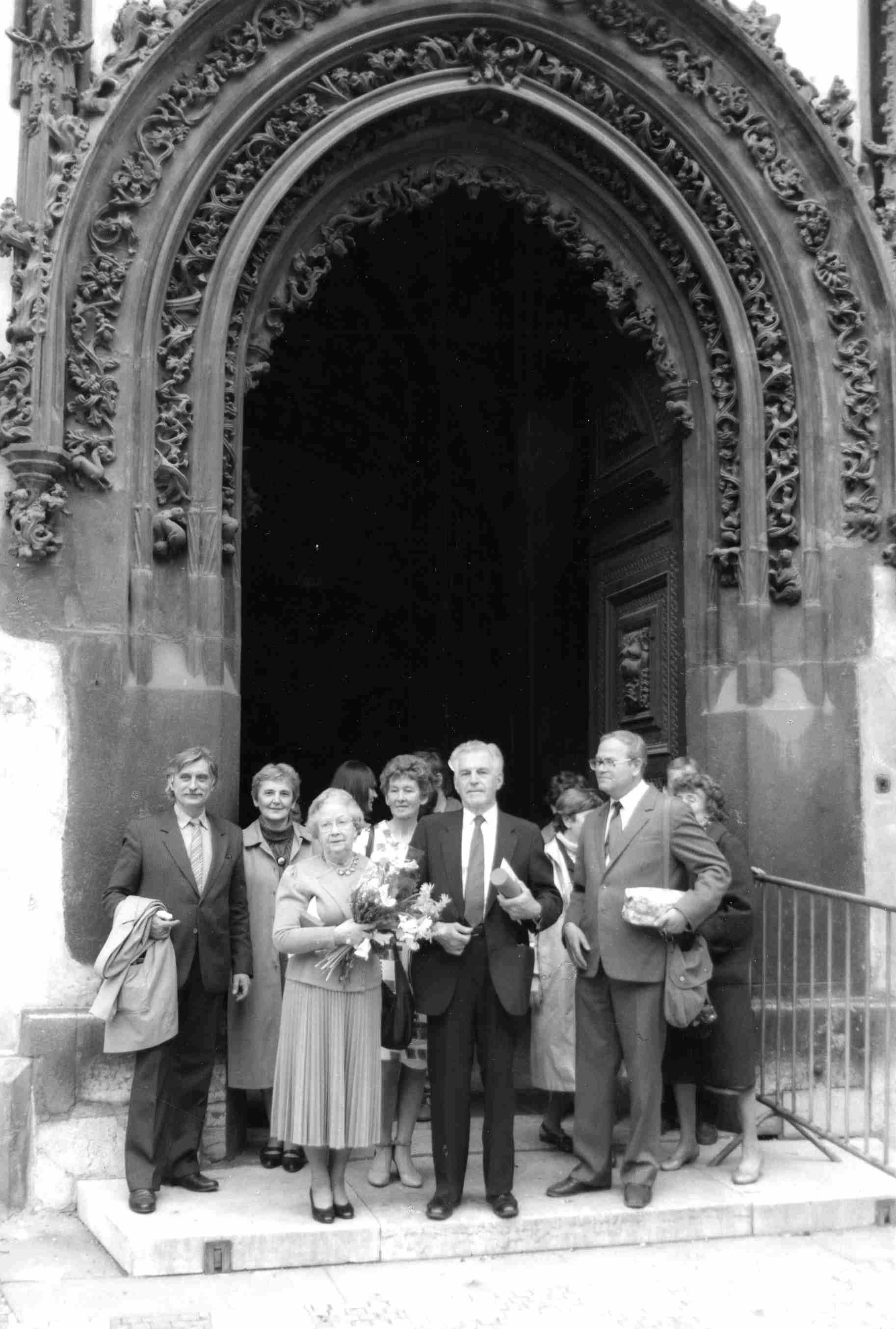

Skilling’s Golden Wedding anniversary, was at the Old Town Hall in April 1987. The journey Gordon Skilling made to Prague in April 1987, marked the celebration of Skilling's 75th birthday and the 50th anniversary of his marriage to Sally. The wedding ceremony was arranged by his dissident friends in the Old Town Hall, which was also the same ceremonial hall where they were married in 1937 (their wedding in October 1937 took place during G. Skilling’s first time in Czechoslovakia, where he studied the History of Central Europe as a student of London University). The anniversary celebration was a delicate irony in which the guests were fond of - a tribute to the "enemy of the state" because the Communists had released a number of dissidents which they had not known about. The next day in the Prague Evening, the news appeared, with a somewhat funny title, "Wedding Overseas". Jiřina Šiklová gained a great credit for this, because she paid the newspaper editors with the make-up from Tuzex at that time.

Gordon Skilling himself remembers this after years in an interview with Lidove Noviny in June 1993: "It was an interesting ceremony because perhaps all Czech dissidents - Havel, Pithart, Dienstbier and others - were present. It was strange that, in this honest ceremony, the chairman of the National Committee for Prague 1 spoke about what I did for Czech history. But he did not know that I also wrote a book about the Prague Spring, a book on Charter 77 and other things. He did not know it, and so he was very glad. Absurd situation. But the dissidents liked it. They were smiling internally. And then we had a gala dinner at the Municipal House. I like to recall the event."

The collection of the significant Czech journalist, dissident, signatory to Charter 77 and politician, Jiří Ruml, contains both published and as yet unpublished texts from 1967 to 1989, correspondence, Czech and foreign samizdat and exile publications. There are also writings by his friends, many of whom were also important signatories of Charter 77.

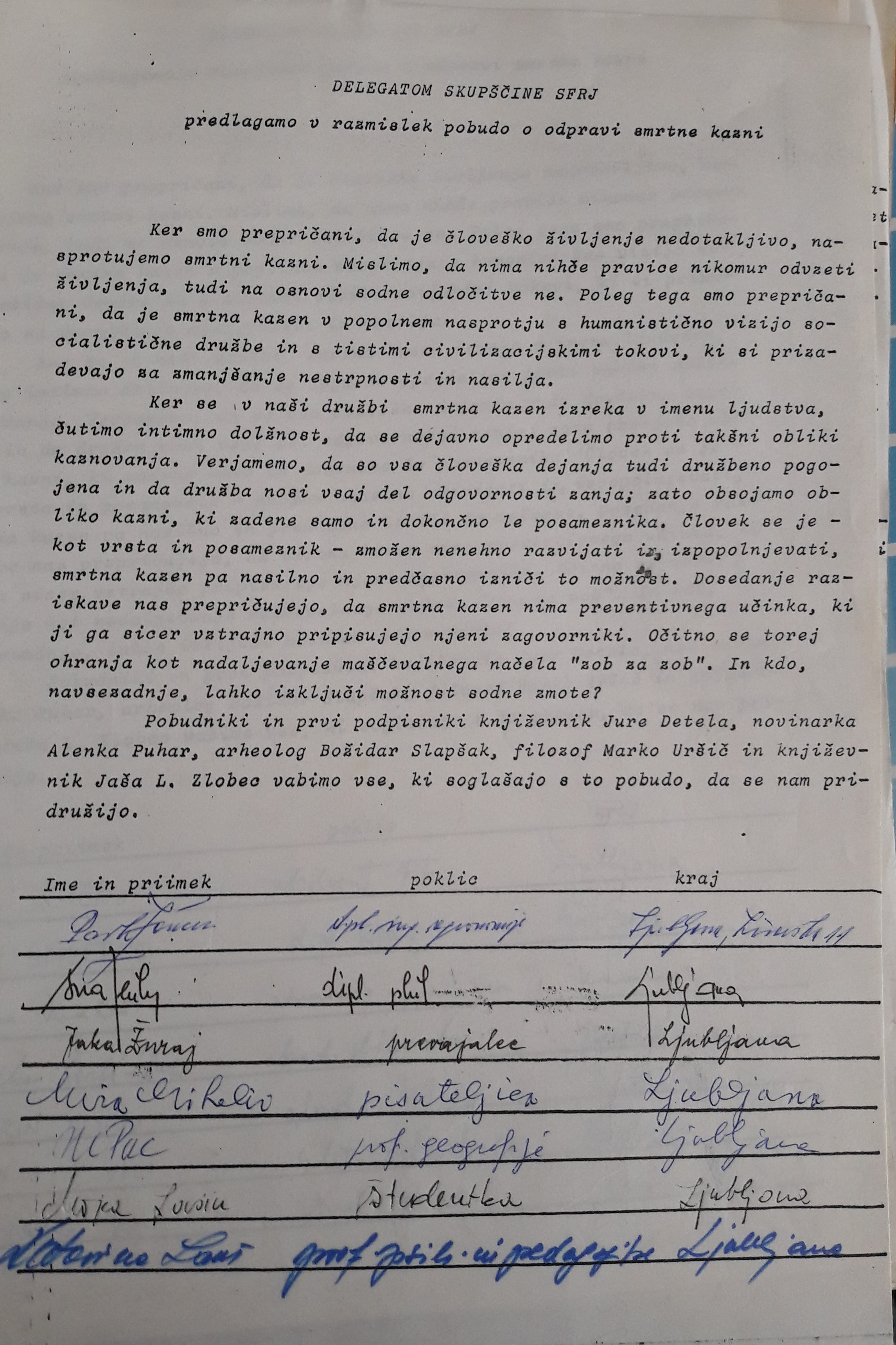

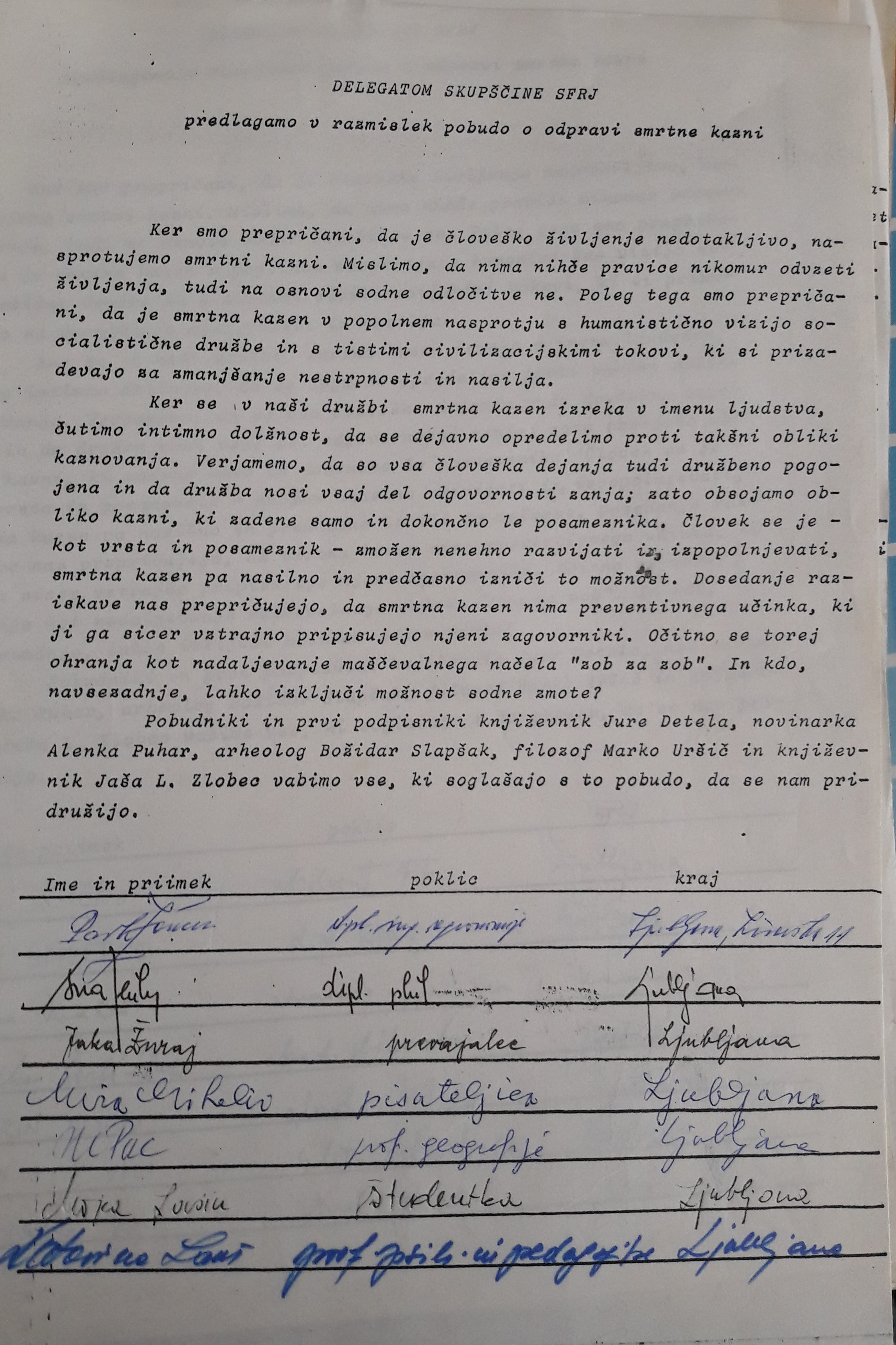

At the beginning of the 1980s, citizens in Slovenia became more aware of the need for their involvement in decision-making processes and that brought about the first initiatives to protect human rights. One of those initiatives was a petition for the abolition of the death penalty in Yugoslavia. A group of activists, including Alenka Puhar, collected signatures for the abolition of the death penalty and sent them to several institutions on November 23, 1983: to the Assembly of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY/SFRJ), the League of Communists of Slovenia (LCS/SKS), the League of Communist Youth of Slovenia (LCYS/SKOS) and others. The petition was discussed in public and among the political leadership, and it was published in Ljubljana’s magazine Mladina on December 1, 1983. However, the petition did not produce any results at the time. The death penalty in Slovenia was abolished only in 1989 at the time of the Slovenian Spring.

Alenka Puhar's collection contains the original petition with signatures that were collected in that campaign. Puhar testifies that over 1,500 signatures were collected. She wrote about her experience working on this petition in the book Peticije, pisma in tihotapski časi (Petitions, Letters and a Time of Smuggling) which she published two years later. (Puhar 1985: 152)

Vytautas Skuodis (1929-2016) was a Lithuanian scientist, Soviet dissident and former political prisoner. From 1979, he was a member of the dissident organisation the Lithuanian Helsinki Group. In 1978, he initiated and edited the journal Perspektyvos (Perspectives), the most recognised underground publication among the Lithuanian intelligentsia. The Vytautas Skuodis collection holds various manuscripts of Skuodis’ monograhs, a PhD dissertation, articles, lectures, letters, reviews of diploma works by students, notes, memoirs and diaries. These documents are relevant to the topic of cultural opposition, because they reveal personally the involvement of Skuodis and other people in anti-Soviet activities.

The Ante Ciliga Collection is deposited at the Collection of the Old Books and Manuscripts at the National and University Library in Zagreb. It testifies to cultural opposition activities of the Croatian political émigré Ante Ciliga, who made the transition from high-ranking member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia to an anticommunist and critic of the one party system and the totalitarian form of socialism.

This eighty-eight-page manuscript contains the texts of eight sermons and seems to have been prepared to be sent abroad for publication. The author was a priest and professor at the Theological Institute in Bucharest, and was imprisoned between 1948 and 1964. While in the notorious prison of Pitești, he was forced to take part in the infamous re-education experiment in that prison, which turned a part of the prisoners into the torturers of the others. Tormented by such a terrible sin, Calciu-Dumitreasa tried, according to his own confession, to write about this prison experience in order to come to terms with it. However, he changed his priorities when, in the aftermath of the earthquake of 1977, the demolition of churches in Bucharest began while the hierarchy of the Romanian Orthodox Church kept quiet. It was then that Calciu-Dumitreasa conceived this series of non-conformist sermons, in which he argued against atheist education and reminded his students of fundamental Christian values, of their mission as priests who must build, and not destroy, churches in order to take care of their parish communities. Seven of the sermons were delivered by the author in the Radu Vodă Church in Bucharest between 8 March and 19 April 1978. Particularly important is the sermon of 15 March 1978, in which Calciu-Dumitreasa explicitly condemned the demolition of the Enei Church, the first church demolished in Bucharest. The sixth sermon, of 12 April 1978, was no longer delivered in the church but in front of it, for the authorities had closed the church and locked the students in their dormitories in order to impede them from attending what had turned in the meantime into an increasingly popular event. The eighth sermon was supposed to open a new cycle entitled “Christianity and Culture” on 17 May 1978, but it was never delivered due to the author’s removal from his teaching position. Continuously harassed by the secret police, in 1979 Calciu-Dumitreasa endorsed the establishment of the Free Trade Union of the Working People of Romania, which caused his arrest and imprisonment for another five years. He was released only in 1985, after intense international lobbying, especially by the United States administration, which threatened the Romanian communist regime with the withdrawal of Most Favoured Nation status. A year later, he went into exile in the United States, where he remained until his death. This manuscript was probably confiscated on the occasion of his arrest in 1979. This version of the sermons differs slightly from the post-communist published volume because it mentions the persons who were responsible for the interruption of his cycle of sermons in 1978.

At the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara may be seen Lorenţ Fecioru’s vest with the holes made by the bullets that killed him and the traces left by their victim’s blood. This object with a profound emotional charge was donated in 1999 by the mother of the hero-martyr. The material traces of the violent death of this young man are symbolic for all the young people who, with the recklessness and courage of youth, took part in the Revolution of 1989. At the same time, the manner in which he met his death is illustrative of the repression that followed in the days immediately after the outbreak of the popular revolt in Timişoara. Along with over 1,000 others, Lorenţ Fecioru is a martyr of the bloody events that led to the change of regime in 1989 and one of those to whom all Romanians are indebted for the freedom that they enjoy today. It is a civic duty of all Romanian citizens to preserve their memory, a duty that the Memorial has taken upon itself to pass on to generations who did not experience the Revolution of 1989.

Lorenţ Fecioru was one of those who, alongside the poet Ion Monoran, took part in the stopping of trams in Maria Square on 16 December. He died in the night of 17–18 December from the effects of a bullet fired by a sniper straight into his heart. In the public documents issued after the Revolution of 1989, it was initially stated that Lorenţ Fecioru was shot on the steps of the Cathedral of Timişoara. The facts, however, are otherwise, albeit equally tragic. Two decades after the tragedy played out, Lorenţ Fecioru’s youngest son related for a national newspaper what actually happened to his father: “My father was shot by a sniper in the night of 17–18 December. In the Securitate files photographs have been found that were taken during the day, when my father and some of his colleagues from work went out into the street and climbed onto tramcars, onto buses. I understand that in the file is written ‘mission accomplished.’ He was on the balcony with his friends that evening, telling them that he had seen when the photographer took pictures of them and that he was afraid to go out onto the balcony. The moment he went out onto the balcony he was shot. I saw the bullet that killed him, because he was shot in the heart and the bullet came out through his back and ricocheted off two walls in the house. His friends took him to the morgue, and by ‘good fortune’ they found a coffin, otherwise he would have been incinerated like the others.” This version is confirmed by researchers at the Memorial to the Revolution. Gino Rado, the vice-president of the Memorial, mentions that Lorenţ Fecioru was on the balcony at his home on Calea Şagului in Timişoara when he was fatally shot. The vest donated by the family of the hero-martyr Lorenţ Fecioru is on the same ground-floor level of the building of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, very close to the corner dedicated to the child-martyr Cristina Lungu.

Cseke-Gyimesi, Éva. Levél egy erdélyi menekülthöz (Letter to a Transylvanian Refugee), 1988. Manuscript

Cseke-Gyimesi, Éva. Levél egy erdélyi menekülthöz (Letter to a Transylvanian Refugee), 1988. Manuscript