Publication: Alenka Puhar. Peticije, pisma in tihotapski časi (Petitions, Letters and a Time of Smuggling). Maribor, 1985.

Publication: Alenka Puhar. Peticije, pisma in tihotapski časi (Petitions, Letters and a Time of Smuggling). Maribor, 1985.

Based on the materials from her collection, Alenka Puhar published the book Peticije, pisma in tihotapski časi (Petitions, Letters and a Time of Smuggling) in Maribor in 1985. The book was based on her experience of participation in the petition for the abolition of the death penalty in Yugoslavia, which was conducted at the end of 1983. A group of citizens, including Alenka Puhar, sent the petition to various institutions, including the Assembly of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The petition was not successful because the death penalty was abolished only in 1989, but it paved the way for new civil society campaigns in Slovenia, which had their peak in the Slovenian spring at the end of the 1980s, and in the collapse of the communist regime followed by the establishment of the independent Republic of Slovenia.

The book was first published in 1985 and it had two reprints in 2005 and 2009.

Károly Hetényi Varga. Those who persecuted for the Truth. Clerical Fates in the Shadow of the Swastika and Arrow Cross, 1985. Manuscript

Károly Hetényi Varga. Those who persecuted for the Truth. Clerical Fates in the Shadow of the Swastika and Arrow Cross, 1985. Manuscript

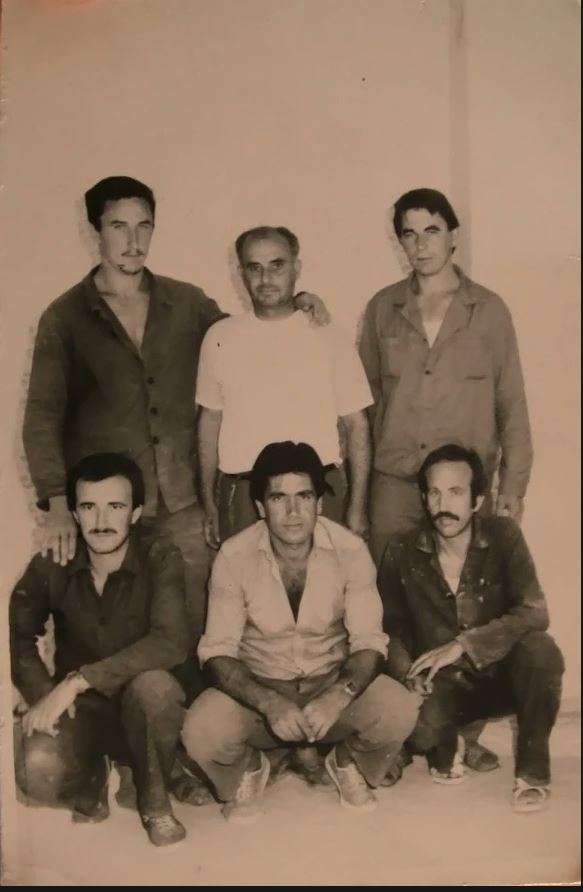

Süleyman Kazımov Saadettinov was born on 9 April 1951, in the village of Bashevo, Kardzhali province, Bulgaria. He worked as a mechanical engineer. Süleyman Saadettinov resisted against the so-called “Revival Process” implemented by Communist Party and its campaign of forced name-changing in December 1984 and refused to change his Turkish name to Bulgarian. His resistance was peaceful; he attended a small protest against the “Revival Process”. Because of his resistance, he was arrested and sent to prison and the forced labour camp or the ”concentration camp’, as the collectors define it, in Belene, on the island Persin on Danube river. After about one year he was released and kept on probation until deportation from the country during the summer of 1989. Süleyman Kazımov Saadettinov was expelled with his family from Bulgaria in the summer of 1989, before the collapse of the socialist regime. He and his family found refuge in Turkey. He took the Turkish citizenship. Now he lives in Bursa and has double citizenship – Bulgarian and Turkish.

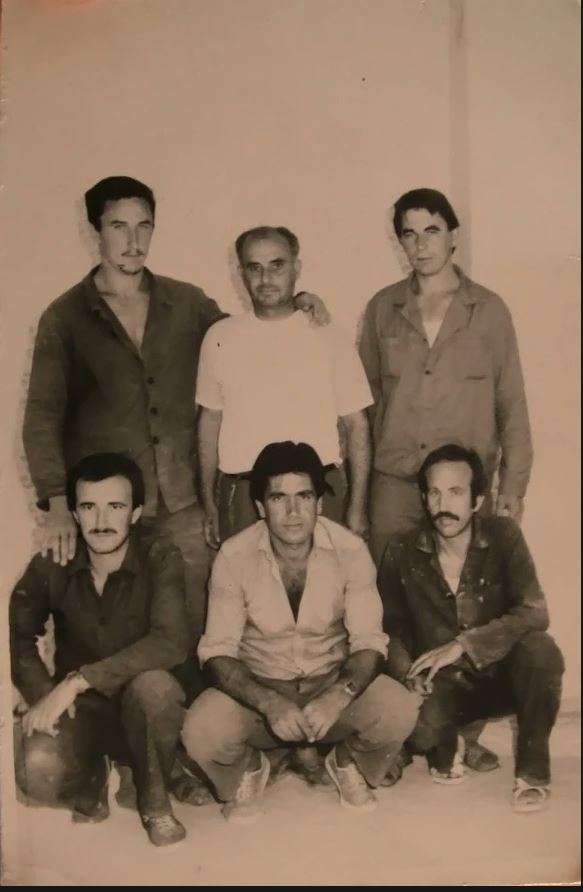

According to the account of Süleyman, the photograph was secretly taken at a moment when camp prisoners were removed from the camp to work outside of the camp area, near to ordinary workers. In the working area, Süleyman and his friends saw a photographer, taking photos of ordinary workers. They asked the unknown photographer to take a photo of them. The photographer secretly took the photo of the group of prisoners and a week later brought them the developed photograph. When Süleyman was set free from the camp, he took the photo with him.

Süleyman is on the right of the picture, the man crouching and with a mustache.

According to the testimonies of the victims, this is the only photo from 1985 to 1986 period of the forced labour camp in Belene.

Personal notes of the Founder, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1984-1985’, 1985. Publication

Personal notes of the Founder, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1984-1985’, 1985. Publication

“The Founder’s personal notes”

In: The Yearbook of the Soros Foundation, Hungary 1984–1985

“It was not my choice that I was born in Hungary in 1930. However, it was my own deliberate decision, one of the most important ones in my life, that 17 years later I left this country. And my return with this foundation is but a late consequence of this early age choice.” These opening sentences are the most “personal” notes in the founder’s preface to the first yearbook of the Soros Foundation, Hungary (HSF) 1984–1985.

Soros used this opportunity to address the public freely (i.e. without much risk of being censored) and share authentic information and assert the principles on which his recently established foundation was based.

The was important in part simply because in the first few years the foundation was given hardly any press coverage in communist Hungary except for some short official statements published in dailies, according to which a New York stock investor had signed a contract with the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS) and opened a small office in the Buda Castle district to receive applications for grants and other forms of support. Apart from this, no reports were printed and no interviews were done in the print and broadcast media. Even in 1987, Soros and his secretary staff still had to fight for the right to publish lists of successful grantees at least in HVG (the three-letter abbreviation used for an earlier title of the same periodical, Heti Világgazdaság, or “Weekly World Economy”), an economic weekly. The first principle Soros insisted on, thus, was the importance of free and permanent control by the pubic (instead of by the party and the secret police) of the operations of his foundation. Similarly, he asserted a number of other safeguards as a founder. He maintained the right to choose his personal colleagues, to decide on his own on the amount of his yearly donations to be spent (which began at one million dollars and grew to nine million dollars by 1990), and to exercise a veto in all strategic or personnel decisions, i.e. decisions concerning curators, projects, grants, prizes, etc.

As for the applications and projects, Soros readily informed the public about ongoing practice and plans for the future. The foundation wished to maintain the individual system of both dollar-based and forint-based grants and support. The Literary and Social Science grant systems were running successfully, but they also planned to test and introduce some new projects which offered support for study abroad and research grants and support for conferences, as well as funding for filmmakers, theater groups, and artists active in the fine arts. Applicants who fell in other categories were equally welcome to submit inventive workplans and new, creative initiatives.

Finally, Soros sought and offered a confident partnership to all: “We need the help of the larger public, after, all the success of our foundation can only be ensured by the applicants’ talent and inventiveness, and the reactions of Hungarian society.”

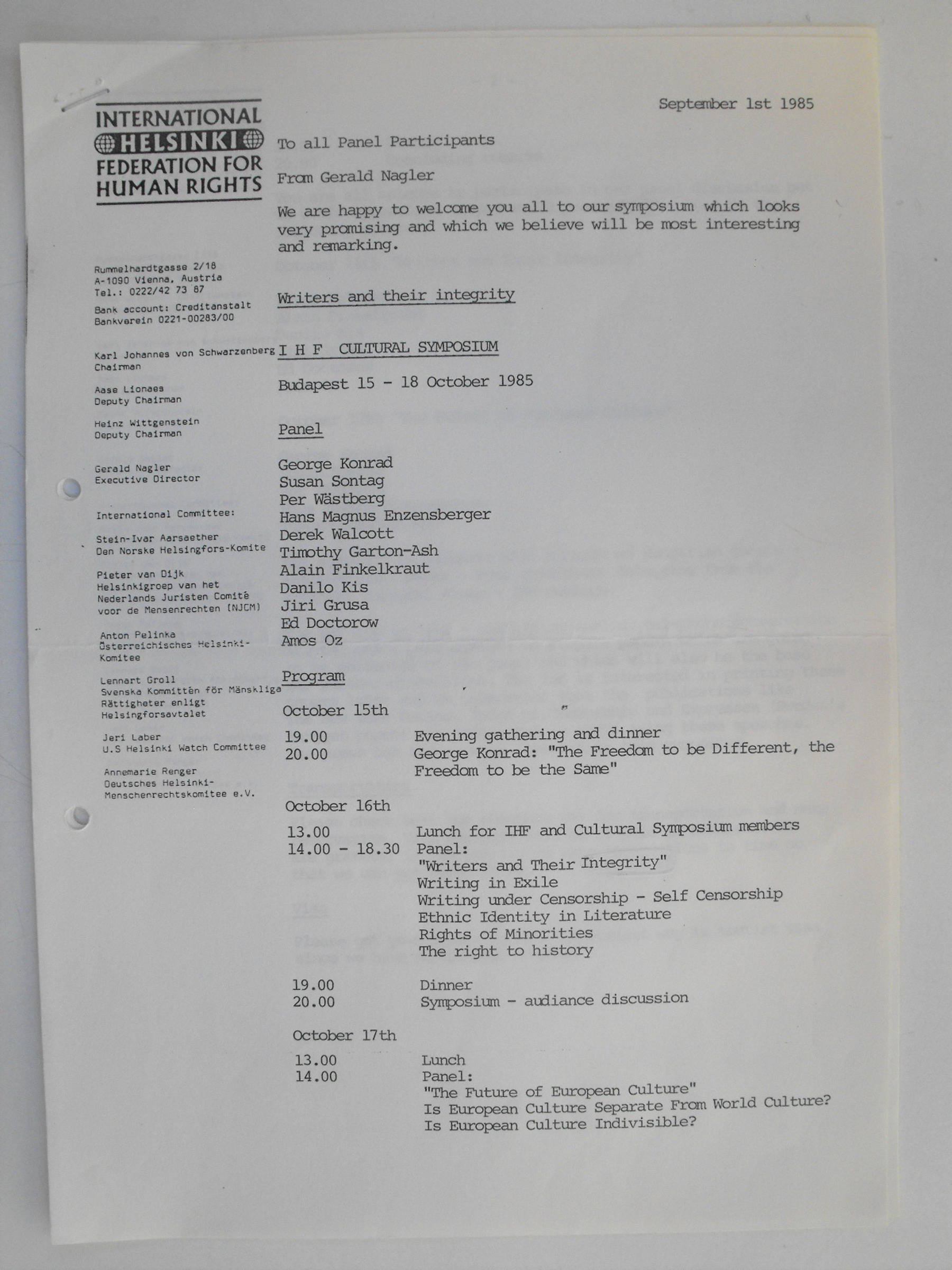

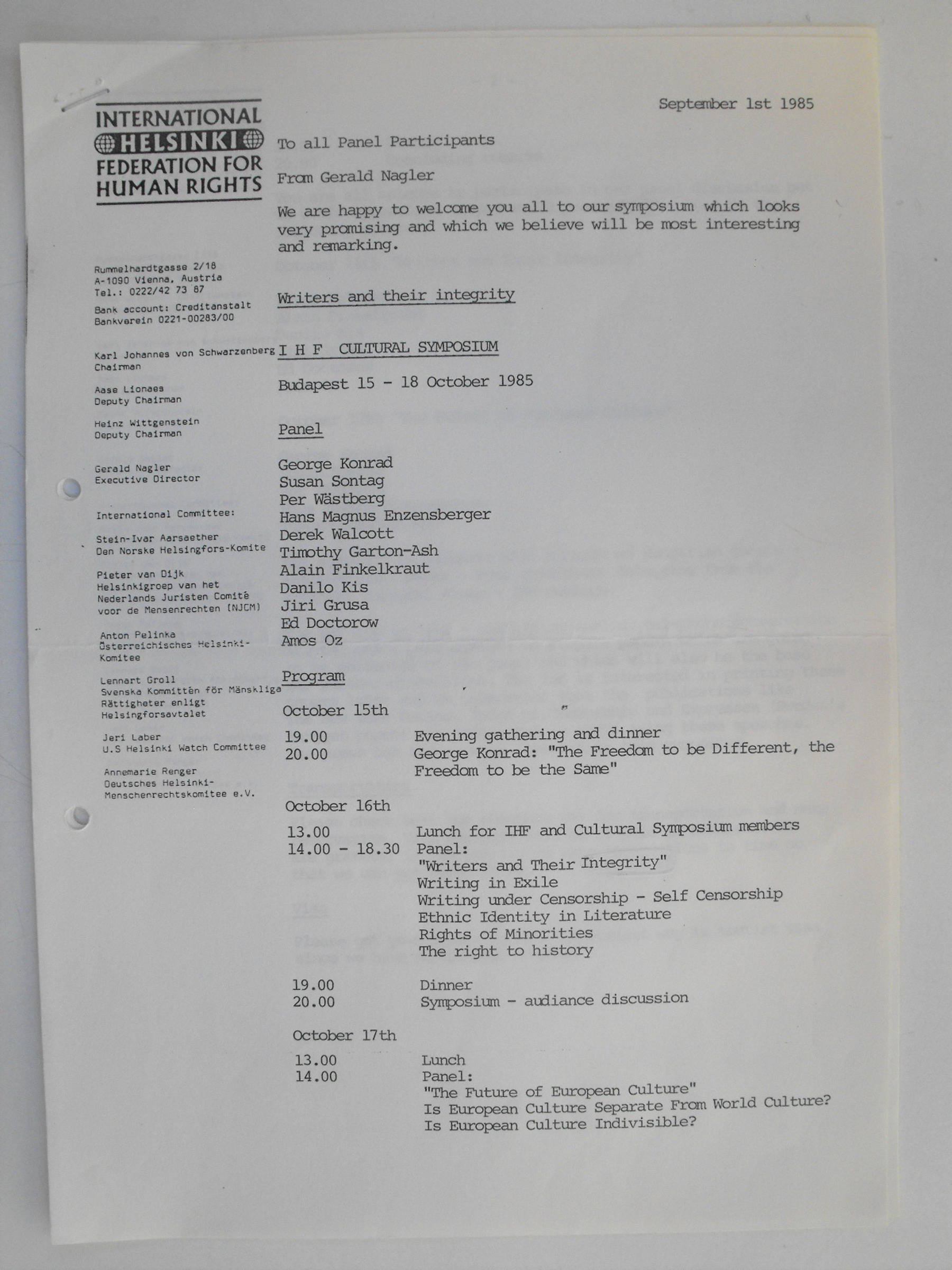

Invitation and program schedule for the IHF Cultural Symposium, Budapest 15–18 October 1985

Although the plans and practical preparations for the alternative programs of the Budapest Cultural Forum 1985 had been started more than a year earlier, it was this invitation letter and program schedule sent to all Western participants by the International Helsinki Federation from its Vienna Office, an invitation signed by Chairman Karl Joachim Schwarzenberg on 1 September 1985, that proved the success of devoted efforts made by the IHF staff to organize a three-day East-West Cultural Symposium in Budapest in parallel with the official opening session of the CSCE European Conference.

The main subjects of the alternative forum were much more challenging. They included “Writers and their Integrity” and “The Future of European Culture,” and they offered a good opportunity for free and stimulating exchange of ideas for participants from both East and West. The list of authors invited seemed quite imposing, as it included prominent figures such as György Konrád, Susan Sontag, Per Wἃstberg, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Derek Walcott, Timothy Garton Ash, Alain Finkelkraut, Danilo Kis, Jirzi Grusa, Ed Doctorow, and Amos Oz. This forum was perhaps the first chance since 1945 for writers from both East and West to enter free public debates on sensitive cultural and political issues such as exile, censorship, self-censorship, the role of national identity in literature, the rights of minorities, the right to history, or the basic question of whether European culture is separate from world culture. And is European culture really one indivisible culture? These questions and issues represented an utterly new approach which regarded cultural freedom as a vitally important and integral part of the overall realm of human rights.

How did the Budapest “Cultural Counter-Forum” manage to implement the promising plans made by the IHF? Not quite as was expected. Apart from Hungarians, no other participants from Eastern Bloc countries could attend the symposium, either because they could not get passports or because of the were forced to live under police surveillance or under house arrest, or they had been interned or jailed, like many Russian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, and Romanian writers at the time. They were partly represented by some Western writers with Eastern origins, e.g. Jirzi Grusa, Danilo Kis, and Amos Oz, and Timothy Garton Ash, who came from Warsaw to Budapest, spoke for the Polish writers who at the time were still suffering from the harsh measures of martial law. Things were similar in the case of writers who belonged to ethnic minorities. Hungarian participants, like poet Sándor Csoóri and philosopher Gáspár Miklós Tamás, spoke on their behalf, as did two of the most harassed writers and samizdat makers, Géza Szőcs, who was originally from Cluj / Kolozsvár / Klausenburg, and Miklós Duray from Bratislava / Pozsony / Pressburg. Szőcs and Duray addressed open letters to the participants in the Counter-Forum

How many people took part in the forum? As many people (120–150) as could fit in the crowded private Budapest flats provided for the event by poet István Eörsi and film director András Jeles. These people were IHF representatives, writers, journalists, Western diplomats, Hungarian intellectuals, and students. This constituted an unanticipated change which gave the Counter Forum a fairly informal and non-conformist feel. The Hungarian authorities refused to allow the group to hold its gathering in any public place, and the reservation made by the IHF for a conference room in a downtown Budapest hotel was cancelled at the last moment by the Hungarian secret police. On the very first day of the six-week-long official Forum, this scandal, which was reported on by the world press and some Western delegates, all of a sudden drew attention to the Counter-Forum, highlighting the fact that cultural affairs are still sensitive political issues in the eastern part of Europe.

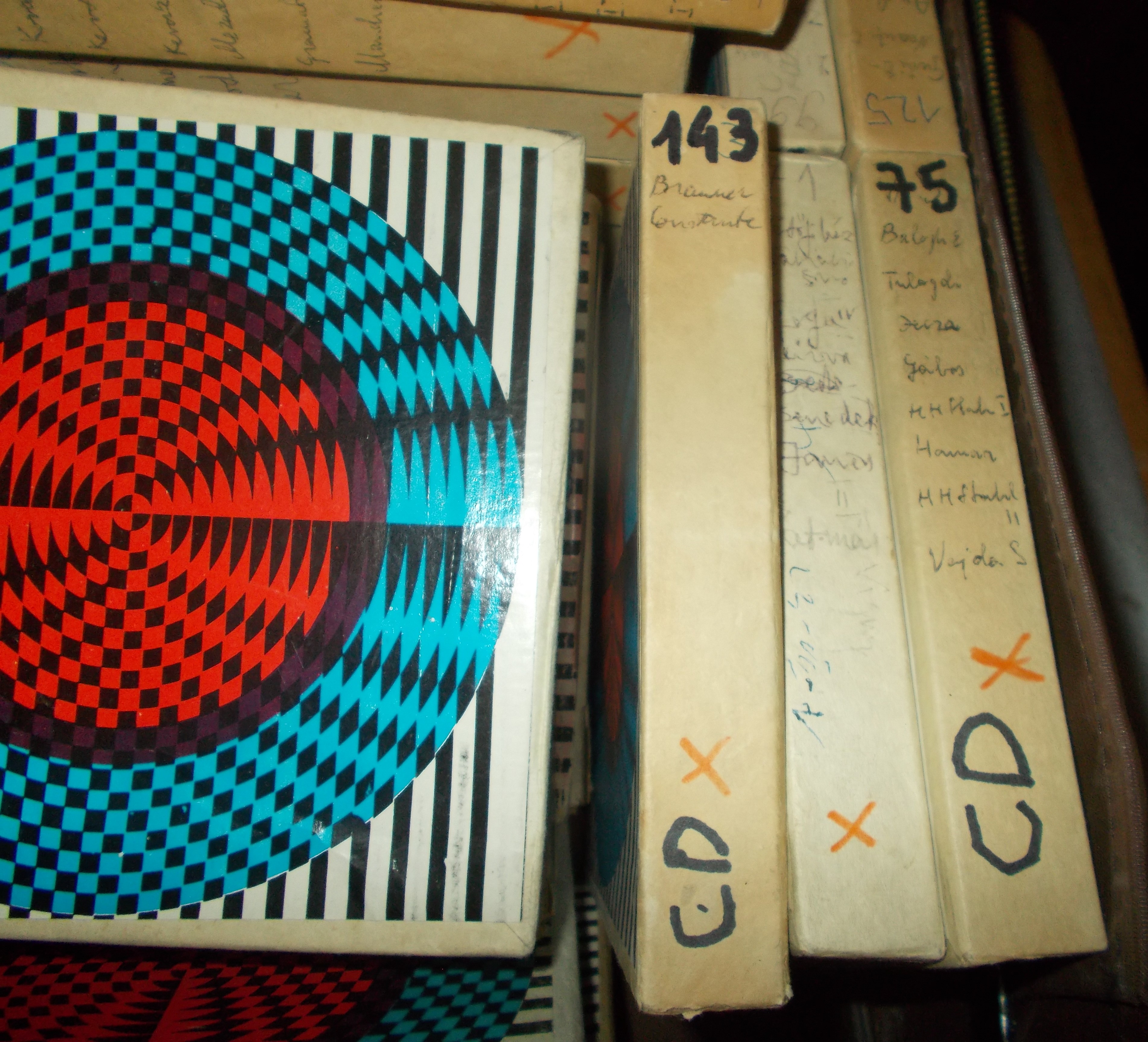

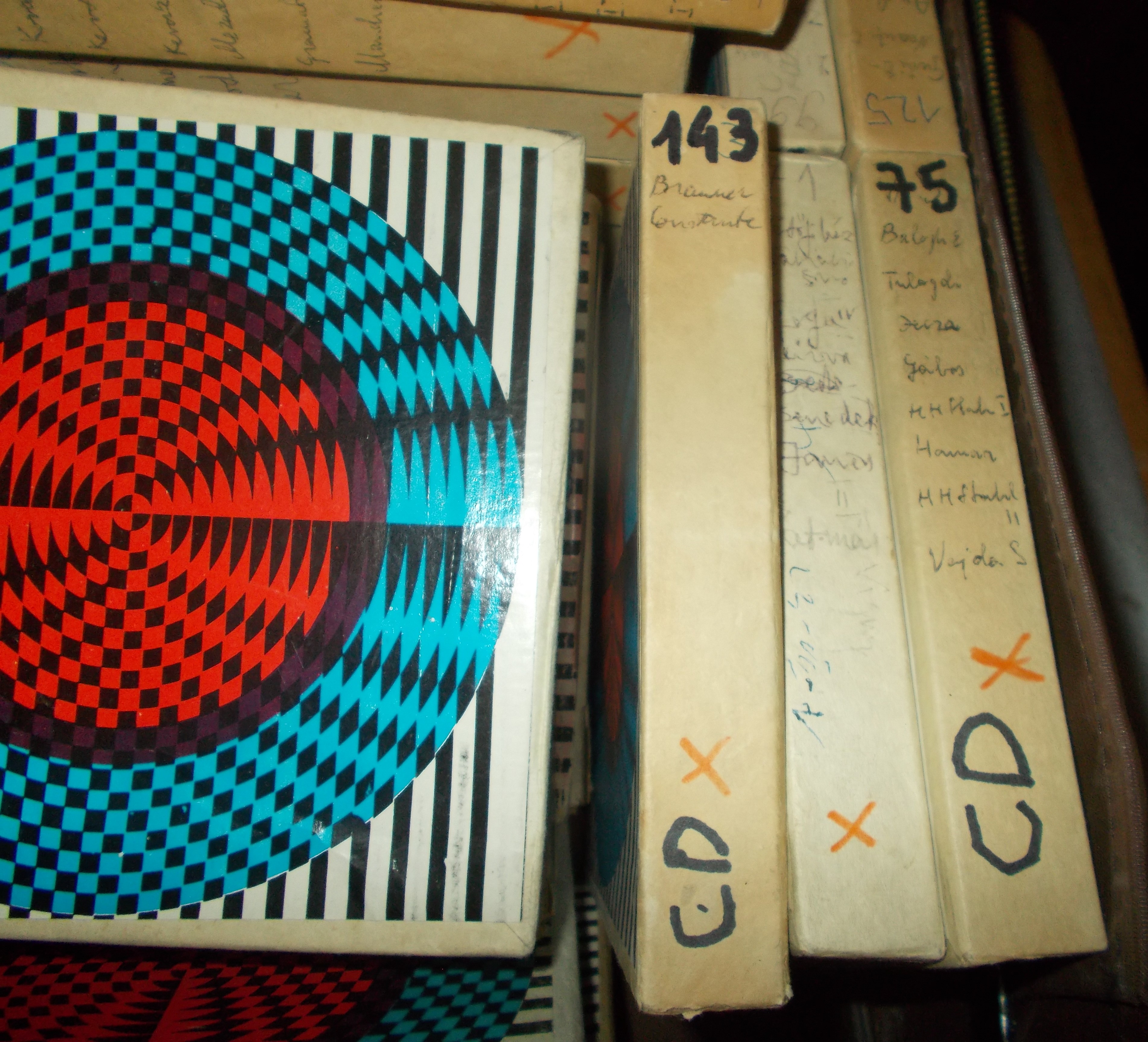

The Irina Margareta Nistor Private Collection includes a series of written documents, together with a few dozen VHS video cassettes preserving a small part of the Western films that were introduced clandestinely into Romania between 1985 and 1989, to be translated and dubbed and then distributed on video cassettes (semi)clandestinely. This collection epitomises a popular culture phenomenon without any equivalent in Eastern Europe, which emerged in Romania as a reaction to the reduction of the official programme broadcast on television channels to just two hours per day and to news broadcasts about the activity of Nicolae Ceauşescu and the leadership of the Romanian Communist Party.

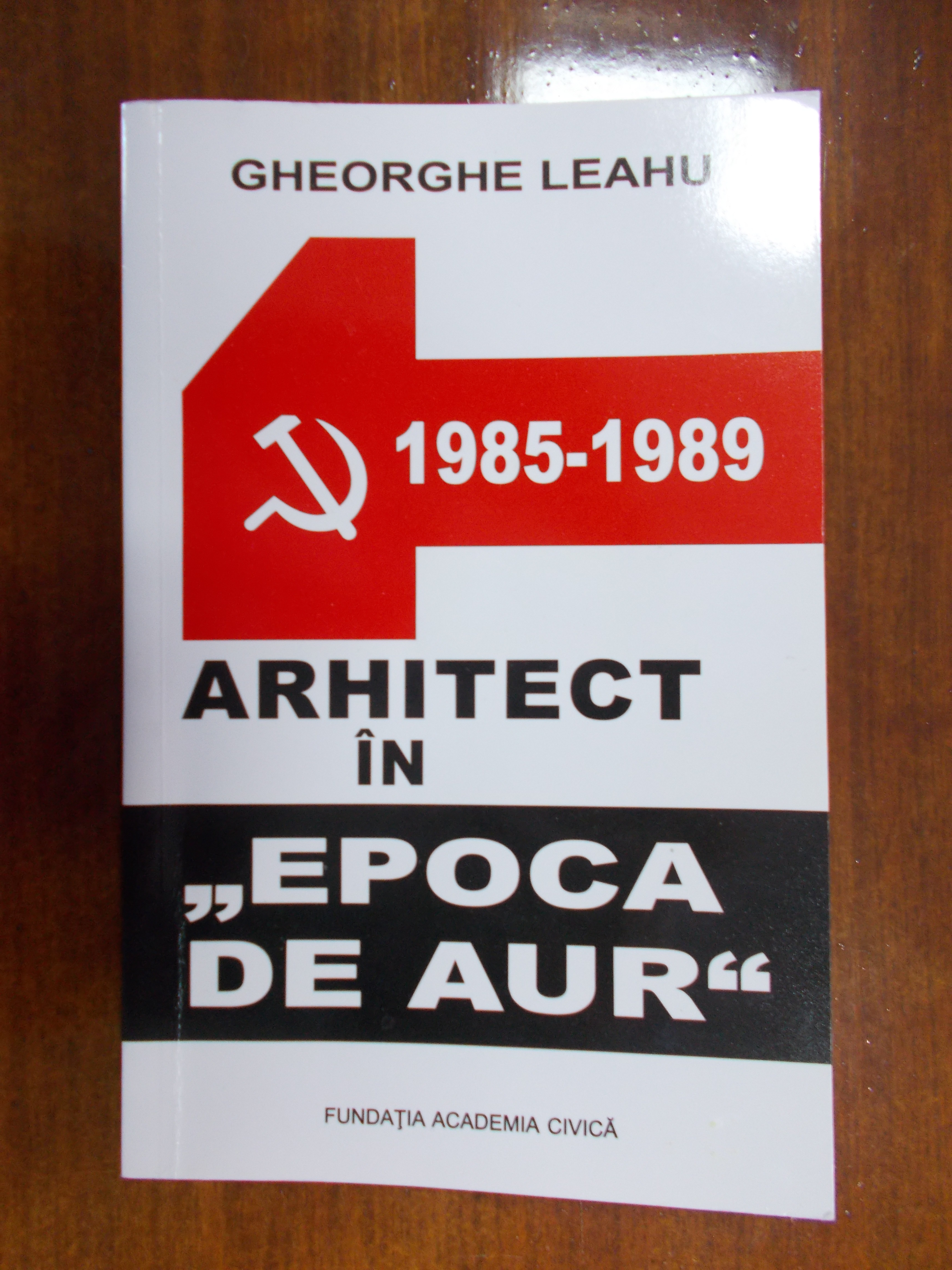

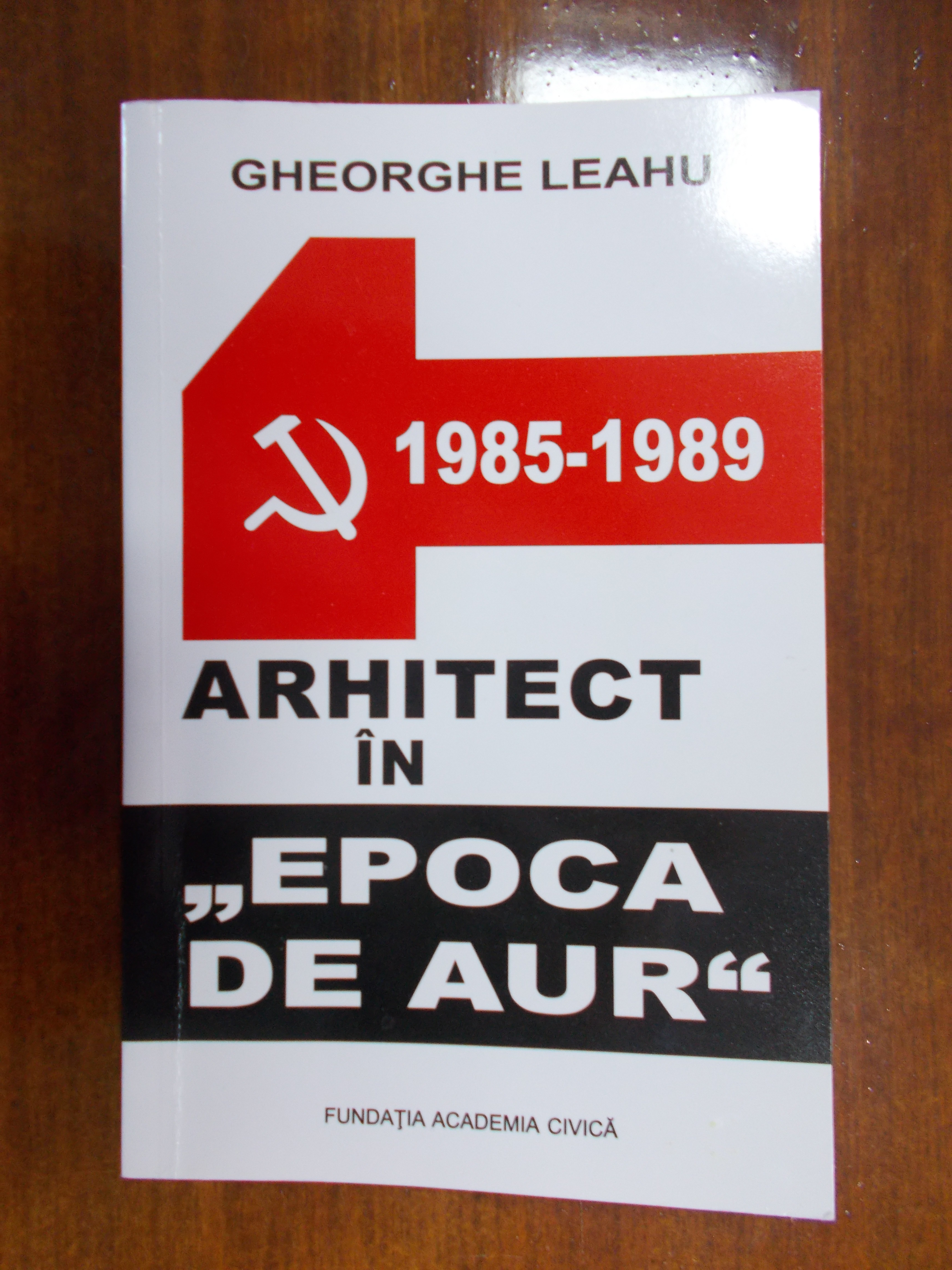

The architect Gheorghe Leahu kept a secret diary in the period 1985–1989. In view of the risk of being arrested if the diary was discovered by the Securitate, he stored it in his garage, in a black cover, under some spare tires. After work, Leahu would write in this diary about aspects of his daily life and personal impressions. In the context of an increasingly repressive regime during the 1980s, this was a way of venting an intellectual’s resentments in communist Romania. In his diary, Leahu reported in detail on the severe shortages which affected everyday life in Romania in the 1980s, on the absurdity of the policies of Ceauşescu’s regime, and on the ridiculous nature of the official propaganda, especially the cult of the dictator’s personality.Leahu was very critical of the regime in the pages of his diary. According to these notes, day to day life in Romania in the 1980s had become a fight for survival, a desperate struggle for food and other consumer goods, and professional activity, a long line of humiliations, caused by the arbitrary and absurd interventions of the holders of political power in the activity of architects. He also constantly criticised the policies of urban restructuring of the capital. In one of the passages dealing with this topic, Leahu noted the effects these policies were having on the identity of the city, but also on everyday life: “Old buildings are being demolished at an infernal pace, many new low-quality buildings are taking their place, the city is losing its personality, it is being completely transformed, the blocks of flats are steamrolling over entire neighbourhoods with gardens and backyards and decades– or centuries-old trees. Instead of life in a quiet backyard, we squeeze into blocks of flats like worms on the vertical, subject to barbarous austerity measures, with hot running water only five times a week, for two hours, always in the cold during the winter, we are becoming depersonalised like soldiers of a blind army of workers” (Leahu 2013, 56). The diary, published in 2005 by the Civic Academic Foundation under the title: Arhitect în “Epoca de Aur” (Architect in the “Golden Age”), constitutes a valuable historical source of information concerning everyday life in Romania in the 1980s. The content of the diary and the conditions in which it was written reflect the atmosphere of generalised fear, frustration, and helplessness in which many Romanian intellectuals were living in the 1980s.

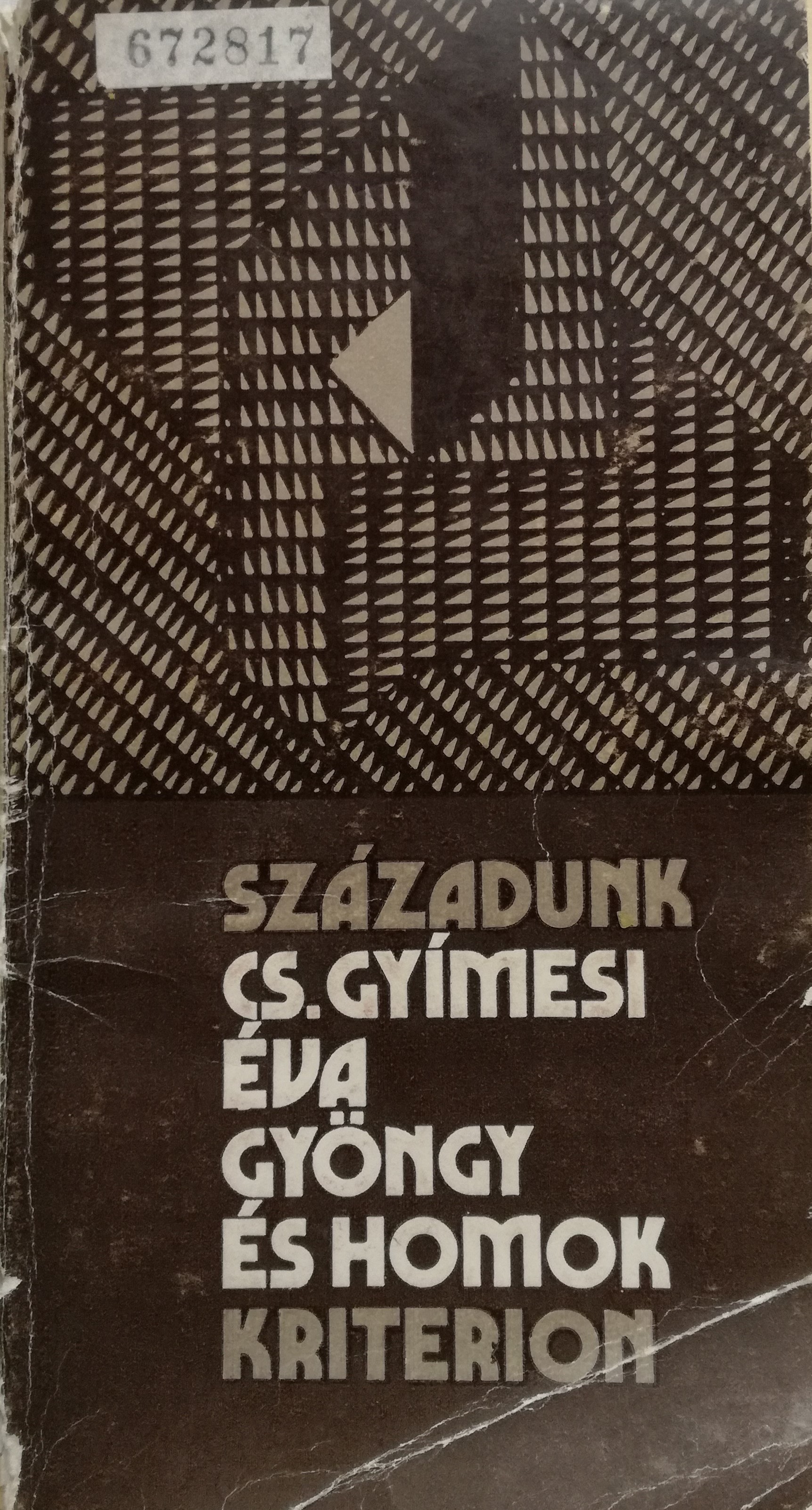

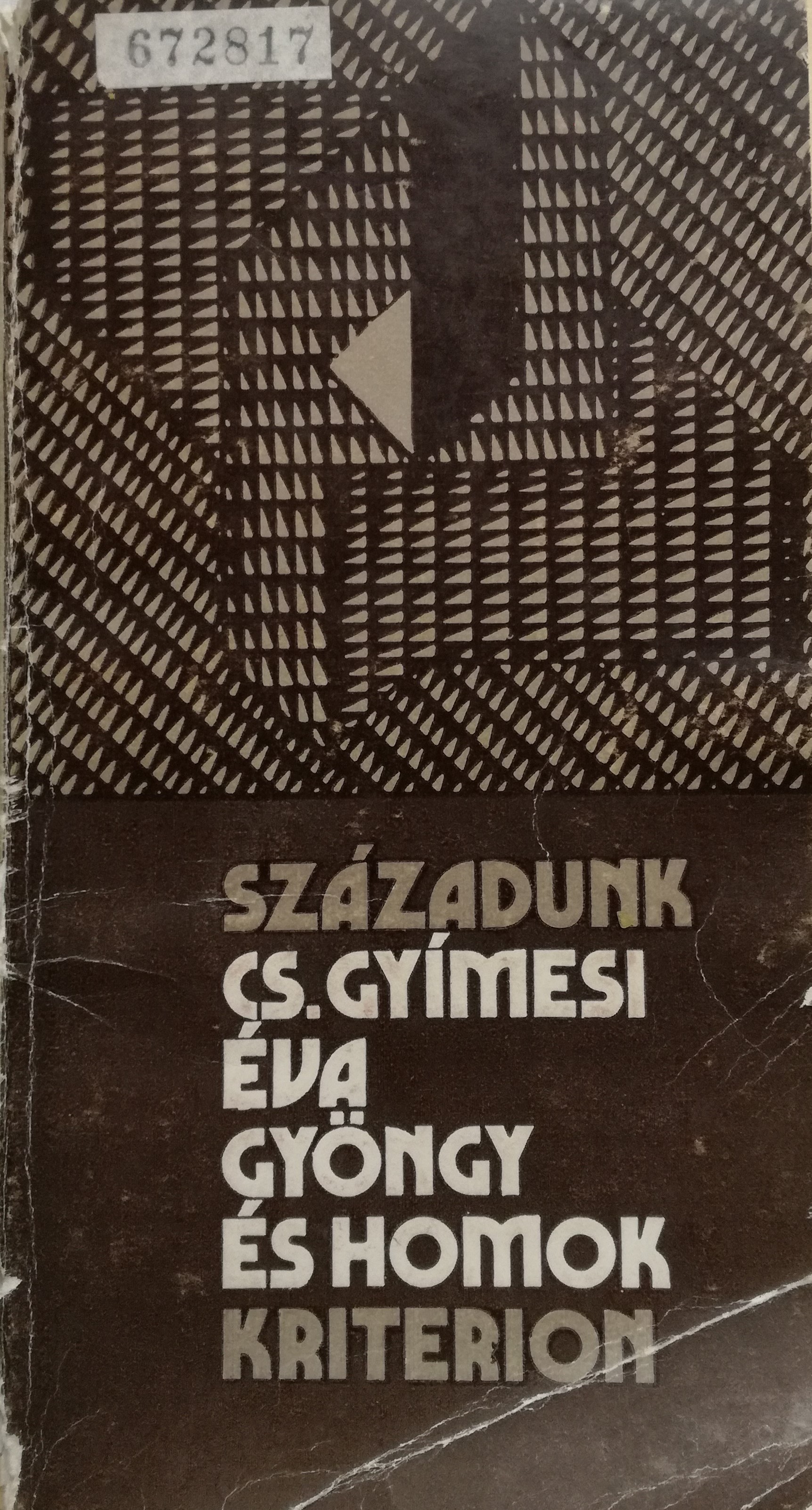

Cs. Gyimesi, Éva. Pearls and Sand: Ideological Value-Symbols in Hungarian Literature, 1992, in Hungarian. Book

Cs. Gyimesi, Éva. Pearls and Sand: Ideological Value-Symbols in Hungarian Literature, 1992, in Hungarian. Book

Gyöngy és homok: Ideológiai értékjelképek a magyar irodalomban (Pearls and Sand: Ideological Value-Symbols in Hungarian Literature) is a literary historical-aesthetic study of the so-called "pearl-mussel motif” so popular in the Transylvanian lyrical creation of the 1920s and the 1930s, also present in the subsequent periods. Beyond this, it is also an analysis of the underlying ideology behind the poetic image, that is, of Transylvanism. This work did not originally express an explicit ideological challenge to the communist regime, but its fate of being confiscated by the secret police transformed it into a significant part of Gyimesi’s intellectual legacy directly linked to her dissident activity, as József Imre Balázs points out. At the same time, in its cultural meaning, Pearls and Sand was a genuine “oppositional” work, whose critical understanding of Transylvanism brought a refreshing critique of the dominant tradition of the Hungarian minority culture before 1990. The reframing of the concept of Transylvanism after the First World War focused on the idea of a federal Transylvania within Romania consisting of ethnically diverse independent cantons organised after the Swiss model. Even if the enormous demographic changes in Transylvania brought about by the Romanian political leadership during the last decades of communism would have thwarted all real chances of seeing this implemented, Transylvanism remained an influential ideology among the members of the Hungarian community and a fertile ground for literary and artistic creation.

Early Transylvanism of the Hungarian community was a response to the traumatic territorial changes that culminated with the 1920 Trianon Peace Treaty and created a de facto, formerly inexistent minority community, which was separated from its “mother country.” Under these circumstances there was a need to define the self-awareness of the Hungarian minority and to strengthen its national identity. This “strategy” of survival was much needed as the political-moral collapse of the Hungarian ruling elites following the military defeat in 1918 drove many people to suicide, alcoholism, or emigration. By 1924 as many as 200,000 people emigrated from Transylvania to Hungary. Transylvanism was a spiritual-moral defence, a positive response to the negative consequences of the Trianon Treaty which facilitated the moral acceptance of the situation the Hungarians in Transylvania found themselves confronted with. Its primary ideological function was to turn necessity into virtue: presenting disadvantage as an advantage, regarding the self-reliance of the minority as a beautiful possibility for independence, as a chance for creating specific values. This is how Transylvanism compensated for the sense of loss generated by the new situation. In the light of survival this ideology played a positive part, as in the so-called heroic era it helped Hungarians in Romania to recover from the post-Trianon trauma. It must be mentioned that this ideology was shared by a rather small group of people whose members undertook the mission, the sacrifice, mainly out of Christian faith; however, it is evident that this personal belief could not be turned into the ideology of one and a half million people.

The criticism of Transylvanism started already in the second half of the 1930s with the so called “populist” writers. They reached the conclusion that Transylvanism was not the sober conscientisation of the minority situation and of fundamental Hungarian interests, but a mere “faith and aspiration,” or wishful thinking, which created a false image of reality. The historical facts used as arguments represented, according to these critics, half-truths that were over generalised by writer-ideologists to cover up other mainly negative historical facts. This illusory image of reality proved to be necessary in the further stages of minority life as well and it fulfilled a similar role. After the Second World War both proletarian internationalism and the illusion of the “Danube basin” fraternity aimed at mitigating the conflicts of interest between winners and losers, between majority and minority. After many writers and cultural activists officially rejected the “dual commitment” in 1968, Transylvanian regionalism regained its former prestige, also strengthened by the newly established minority institutions. The manipulations of the Ceaușescu regime and the cooperative attitude displayed by certain Transylvanian Hungarian representatives towards a more liberal version of Romanian communism seemed to facilitate the validation of this illusory regional self-esteem. Accordingly, Transylvanian ideology revived again in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, when the need for redefining the collective identity of the Hungarian minority re-emerged, while its existence as minority was still unsolved. This appeared primarily in the conscious revival of tradition, as in Ernő Gáll’s historical works and in his ideology focused on the “dignity of the individual.” The publications of György Beke and the poetry of the second Forrás-generation poets also maintained the illusion of positive possibilities of coexistence, that of the decisive role played by Transylvanian historical traditions and the myth of the moral surplus inherent in the human character of minority individuals, which derives from the need to play roles such as “coping,” “service,” and “readiness to sacrifice” which paralyse the need for formulating real interests.

Gyimesi was preoccupied with Transylvanism – the interwar minority ideology – because she recognised that such a moral-centred ideological phenomenon holds the possibility of continuous political compromise from the outset. It is very difficult to draw the line between the morality of standing one’s ground and resignation. She raised the question whether the ideology of intellectuals heroically embracing minority destiny is a self-justification for not doing anything to change their situation? While writing her work she considered that the political tradition of compromise also contributed to the fact that her generation found itself in a minority situation even worse than that of the interwar period. It was her admitted purpose to point at the utopian, mythical features of this ideology that hid the real political interests of the minority and, instead of a strategy aimed at the satisfactory solution of the situation, compensated Transylvanian Hungarians with illusions. The manuscript was finished in the early months of 1985 when it seemed that an emotion-free, adequately abstract set of concepts was suitable to carry out a critique of the leading ideology of the interwar period in publishable form. She tried to avoid all those pathetic symbols and metaphors that – in the Romanian Hungarian spiritual life of the 1980s – defined in a concealed form the sense of identity among the Hungarians in Transylvania, and, by highlighting the positive values of the Transylvanian spirit and of the minority destiny, she tried to cope with the “double oppression” under the dictatorship.

The view of Transylvanism expressed in Pearls and Sand is characterised by a rather harsh critical voice. However, this is not performed in a direct manner. Criticism is primarily targeted at the clarification of concepts, determined by the need to grab the values polished into myths in their real essence. The detached dissection of the ideology components led to reactions that included labelling the author as destructive and describing the effects of the manuscript as damaging, on grounds that this merciless uncovering of the contradictory value structure of Transylvanism could easily discourage the reader from further accepting this seemingly hopeless minority situation. Beside the rather self-critical view of the past which was at the same time directed at the present, Gyimesi was unable to offer arguments in support of hope, and could not offer a perspective regarding the future, as between 1985 and 1987 she saw no real chances of a change in the deprivation of rights which the Hungarians in Transylvania had to endure. She considered it important to perform an accurate assessment of the situation and of minority awareness, to express the need for reflection, the desire for spiritual detachment, the system of analytical concepts by which she could identify even the most delicate contradictions.

The study could not be published. It was confiscated by the Securitate for the first time on 1 October 1985, during a home search conducted at the author’s residence. Gyimesi had to provide translations of random excerpts from her study to her interrogators. Almost a year later, on 30 August 1986, the Limes circle organised by Gusztáv Molnár provided the occasion for discussing the manuscript during a meeting in Ilieni, Covasna county. Sándor Balázs, Béla Bíró, Ernő Fábián, and Levente Salat were the authors of comments (I236674/4). They intended to publish this debate material along with the study “later on, when times turn more favourable.” On 7 February 1987 the Securitate conducted a home search at Gusztáv Molnár’s flat in Bucharest and seized this work along with the Limes circle materials (I236674/1). However, by that time one copy was already in a “safe place.” The study was confiscated for the third time during the home search at Gyimesi’s residence on 20 June 1989 (Cs. Gyimesi 2009).

Gyimesi intended her study – finally published in 1992 after the regime change – to be a “warning mirror,” which would prevent Transylvanian Hungarians from falling into the traps of self-deception inherent in interwar ideology. The idealising moral view characteristic of Transylvanism, the patience exaggerated to the point of helplessness, the tendency to embrace suffering could get in the way of the struggle for human rights. Gyimesi held the opinion that a balance had to be found between the Transylvanist ideology of survival and the legal and political guidelines of the struggle. Furthermore, she believed that there was a need not only for emotional-moral reconciliation but, first of all, for a legal framework to ensure a humane, worthy life so that Hungarians in Transylvania could lead a harmonious, full-fledged life in Romania despite their minority status.

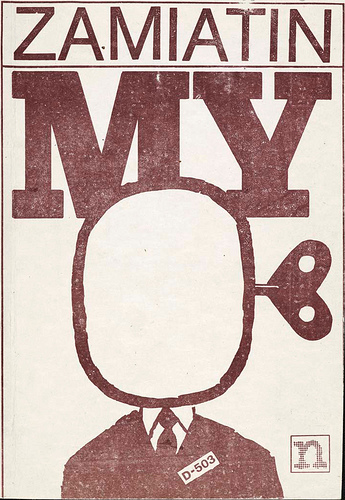

Vincas Pietaris (1850–1902) was a Lithuanian national activist and writer. He is famous for writing Algimantas, the first historical novel in Lithuanian. The novel was published for the first time in the United States in 1904–1906. (It was published for the second time in interwar Lithuania.) The novel takes a popular approach to the formation of the Medieval Lithuanian state, and the heroic struggles between the Lithuanian dukes and their enemies. By glorifying Lithuania's past, it influenced Romantic nationalism. Because of this, Algimantas became very popular in interwar Lithuania.

However, the novel and its author were practically unknown in Soviet Lithuania. Gediminas Ilgūnas started to work on his biography of Pietaris in about 1980. He travelled twice to Russia, where Pietaris had lived and died. The biography was published during Gorbachev's perestroika in 1987. At that time, various historical studies and popular works about the history of the Lithuanian state were becoming more popular among different sections of the population. Various historical issues relating to the Medieval and modern state were being discussed in the Sąjūdis press. The biography of Vincas Pietaris was part of this growing movement. The novel Algimantas was published later in 1989, and became very popular with the Lithuanian public.

‘Aldona Liobytė. Smiling Resistance' was the title of one of the first books about the writer, publicist and interpreter Aldona Liobytė. Being a very active person with a strong sense of humour, Liobytė initiated and led informal networks among the Lithuanian intelligentsia. She kept up social ties and correspondence with many artists, discussing and making suggestions about creative work and everyday life, as well as supporting the ideas of the younger generation of artists. Through her personal ties and networks, she expressed an outlook (usually in the form of humour, irony or sarcasm) that had a sense of the existence beyond official Soviet ideology. While she was forced to leave her job at the Literary Fiction publishers because of her un-Soviet attitudes, she continued to work in the cultural sphere, writing for children and the younger generation. Translating from other languages was also an important activity and a reliable source of income for Liobytė's family . The collection consists of the papers of Aldona Liobytė, which are split between the Maironis Lithuanian Literature Museum and Liobytė’s daughter Gintarė Paškevičiūtė-Breivienė.

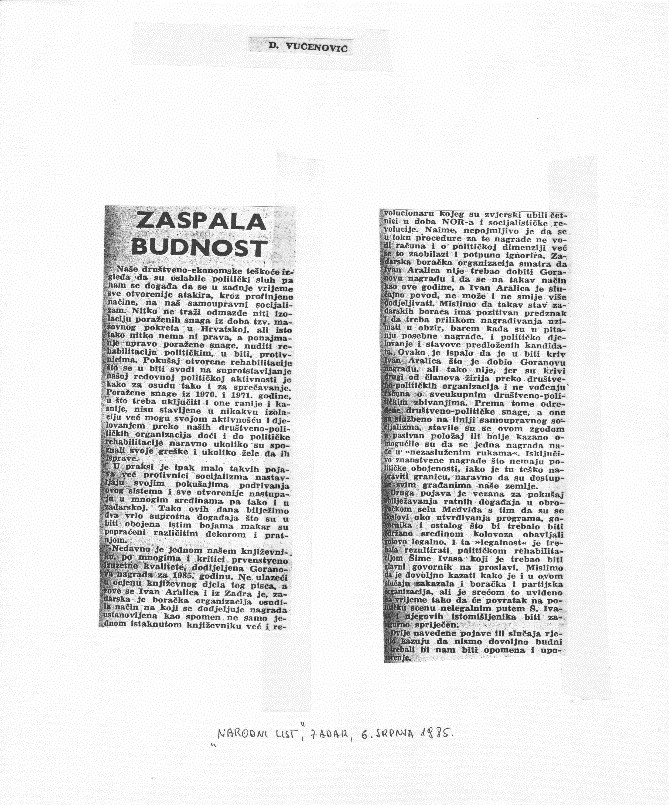

After Ivan Aralica had been granted the Vjesnik literary Ivan Goran Kovačić Award for literature, members of the Zadar branch of SUBNOR condemned this act. This was first commented by the local weekly Narodni list in a lead under headline “Vigilance fell asleep” written by the editor-in-chief Dane Vučenović. In the article, the frequency of attacks on self-management socialism is mentioned and the attempts of “defeated groups from the era of the so-called ‘massive movement in Croatia’.” Vučenović stressed that in that period the opponents of socialism increasingly came out openly in many centres, and so in Zadar, where the writer Ivan Aralica lives, the winner of the Ivan Goran Kovačić Award for the novel The Souls of Slaves (1984). He agreed with the SUBNOR Zadar branch, which criticized the Vjesnik jury for giving the award to a writer whose profile was inadequate because of his participation in the Croatian Spring in Zadar. “We think that such an attitude of the Zadar veterans has a positive significance, and that in the process of giving awards, the political profiles of candidates should be taken into account, at least when special awards are at stake,” Dane Vučenović concluded, indirectly pleading for interventionism in the assessment of literary works.

Ivan Aralica himself stated in his letter of 26 July 1985 to Zlatko Crnković that this lead was an overture for the attacks on him: “It has been a long time since I wanted to write to you, ever since I came to Zagreb at the beginning of July, because right on the eve of my departure from Zadar the campaign against me started with the lead in Narodni list (Aralica and Crnković 1998, 123).

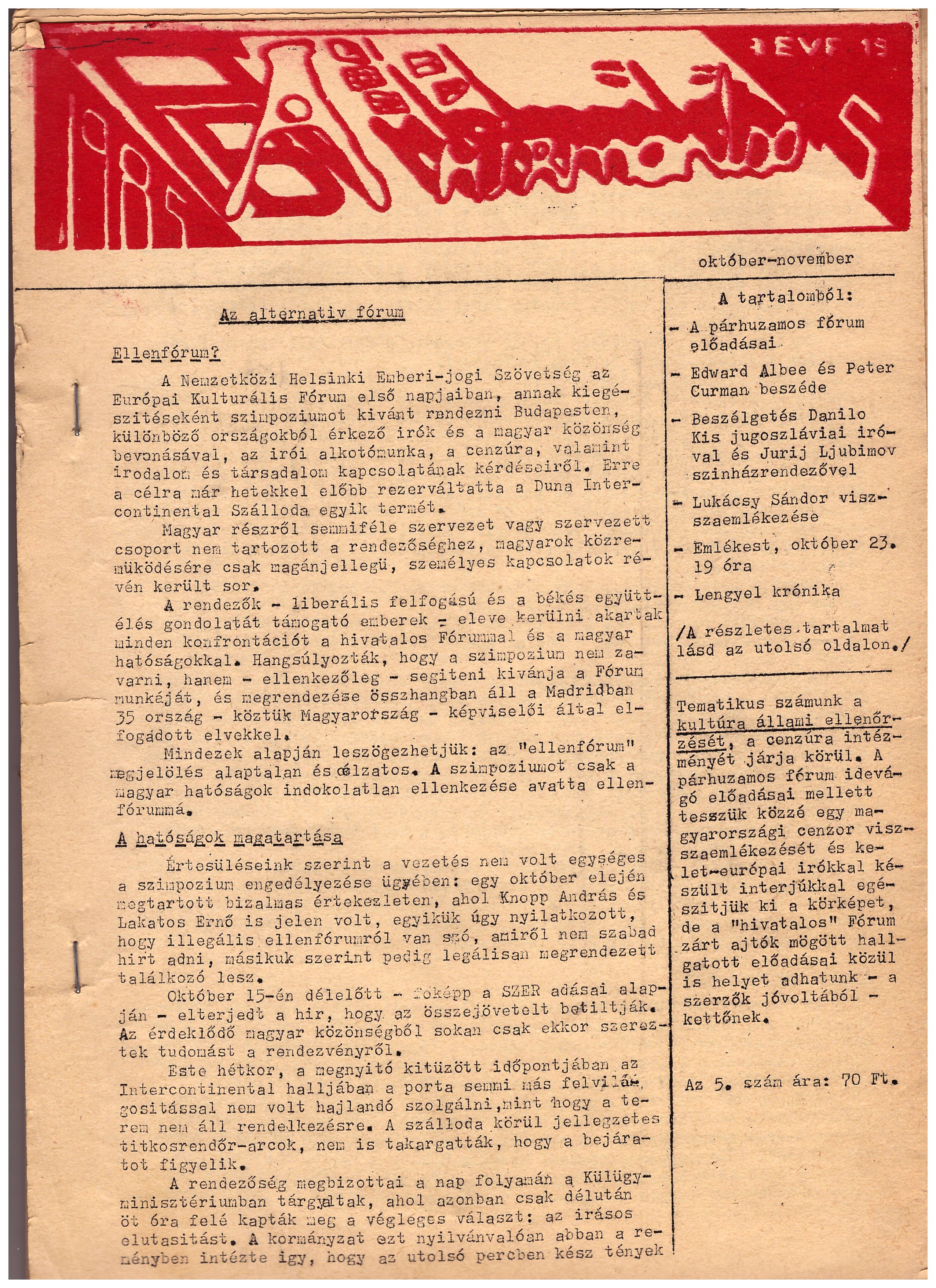

Special issue of the Hungarian samizdat paper ’Hírmondó’ on the debates of Cultural Forum and Counter-Forum held in Budapest, October–November 1985

Special issue of the Hungarian samizdat paper ’Hírmondó’ on the debates of Cultural Forum and Counter-Forum held in Budapest, October–November 1985

Special issue of the Hungarian samizdat paper Hírmondó on the debates at the Counter-Forum in Budapest, October–November 1985

The Hungarian samizdat periodical Hírmondó (“Messenger”) was launched in 1993 by Gábor Demszky, also the founder of AB Independent Publishing House and from 1990 to 2010 the Mayor of Budapest, and hardly more than a year later also the founder of Beszélő (“Speaker” or “Prison visitor”). Soon, other samizdat papers were also launched, such as Demokrata (“Democrat”) which was founded by Jenő Nagy, and Máshonnan Beszélő (“Speaker from Elsewhere”), an East European Monitor which reflected the increasing interest among the public in the uncensored press and the Hungarian samizdat press. Hírmondó was published as a screen-printed bimonthly; by the Autumn of 1985, it had been published in 15 issues, each of which sold well. Its profile, style and character were somewhat different compared to other free press products, such as Hírmondó, which preferred to publish shorter articles and interviews. Its greatest asset was rather the fresh news blocs based on many sources.

Well over of one third of its October–November 1985 issue was dedicated to the debates which had just taken place at the Budapest Cultural Forum and the Counter-Forum. This issue included 10 documents, interviews, essays, and articles, for instance conference papers by Danilo Kis, Amos Oz, Edward Albee, and Peter Curman, open letters by Géza Szőcs and Miklós Duray, interviews with Jurij Ljubimov and Danilo Kis, US Congressman D’Amato’s speech, etc. Hungarian readers were also given a detailed introduction to the principles and activities of International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, which had been founded three years earlier. Though the articles and comments were published with no names, the issue nonetheless seems to be the product of good teamwork among the authors, editors, translators, and interviewers. Two of the authors who published anonymously in the issue were editors Miklós Haraszti and Gábor Demszky. Their witty styles and challenging statements make their writings easy to identify.

This special issue of Hírmondó, a Hungarian samizdat periodical, was dedicated to the debates which took place at the Counter-Forum. These debates were fresh and provocative, and they evinced a clear commitment to engagement in human rights. Thus, the issue stands out from among the tired, routine news and reports which appeared in the professional press, both in the East and in the West.

The Dziekanka Workshop was the space of intersection of many domains: visual arts, theatre, music, philosophy. Among music groups that gave concerts in Dziekanka, one might mention punk bands TZN Xenna and Dezerter, intuitive Ossian, and ephemeral projects set by Krzysztof Knittel, Marcin Krzyżanowski, Mieczysław Litwiński, Andrzej Przybielski, and other avant-garde musicians. Familja Radio Warszawa was related with Dziekanka as well. The group was established by Jerzy Caryk, Kuba Pajewski, and Libero Petrič with the participation of many other musicians, artists, and actors. The group combined musical improvisation with electronic experiments and joyful atmosphere while their performances were enriched with elements of theatre and astonishing scenographies. The photography made by Tomasz Sikorski presented the installation-environment created by Familja Radio Warszawa in Dziekanka, December 28-31, 1985.

Secret report of the Hungarian State Security Service, 16 October 1985

The state security services of communist Hungary began to follow the preparations underway for the Counter-Forum Budapest 18 months earlier, i.e. as early as March 1984, by gathering regular information and agent reports on the informal meetings of IHF representatives and some Hungarian dissident intellectuals in Budapest. By the opening of the official CSCE Cultural Forum in mid-October 1985, the entire staff of the Hungarian secret police had been mobilized with the main task of preventing any potential conflict or open scandal before, after, or during the six-week-long prestigious East-West diplomatic conference, as a “top secret” daily information report dated 16 October 1985 (just one day after the grand opening of the CSCE Conference) clearly proves. It seems to be a telling sign of flurry and an excess of caution or paranoia that on that day this was the second report submitted by the secret service on the same subject: reporting on all suspicious signs and information concerning the efforts of the IHF to find public places: restaurants, conference rooms in downtown Budapest for the use of the Counter Forum. This brief report, which contained both false and misleading information, also illustrates the incompetence of the Hungarian secret police, as they do not seem to have been aware of the latest news, according to which the Counter-Forum had been refused permission to hold its session in a public place a day before and so was hosted by Hungarian dissident poet István Eörsi and film director András Jeles, who offered their private residences for the sessions.

Gyula Horn, Head of Department of Foreign Affairs in the Communist Party’s Central Committee and Hungarian Prime from 1994 to 1998, was responsible for conducting and ensuring the smooth operations of the CSCE Conference in Budapest. He must have known about the parallel preparations of the IHF’s Counter Forum, and he might also have had a decisive role in the official refusal of the IHF demand for public space, which was issued in written form by the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Years later, after 1990, when he was asked about this by reporters, he replied with an obscure allusion to the fact that there were far too many high-ranking Soviet and Eastern Bloc delegates who expected Hungary, the host country, to adopt firm measures in order to resist “the pressure of Western countries.”

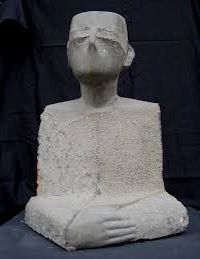

Ziyatin Nuriev was born in the village of Most, municipality of Kardzhali (1955). He graduated from the High School of Arts in Kazanlak and then studied painting at the National Academy of Arts in Sofia. During his second year at the Academy, he changed his speciality to sculpture in the class of Prof. Iliya Iliev. Nuriev graduated from the Academy in 1982.

Initially, Ziyatin Nuriev worked with basalt, one of the hardest materials. His favourite themes are the figure and the portrait. He took the human figure to abstract form using various materials – marble, bronze, wood, ceramics. Even his first participations in national exhibitions were noticed – in 1985, in the National Youth Exhibition, he won the prize of the Union of Bulgarian Painters and two years later, he received the annual prize in sculpture of the Union of Bulgarian Painters. Some of his works were bought by the National Art Gallery, the Sofia City Art Gallery and other leading galleries in the country.

During the so-called Revival Process (an attempt of the Bulgarian Communist Party to forcibly assimilate the Muslim population – Turks, Pomaks, Tatars, Roma), the name of Ziyatin Nuriev was changed to Zlatin Norev. The Revival Process began in the early 1970s and continued until the end of state socialism. The measures for the implementation of this policy included forced change of the Arabic-Turkish names with Bulgarian, restrictions in the use of the mother tongue by representatives of the above-mentioned groups, forced restraint of their traditional customs and rituals and of the use of their religion. The assimilation policy of the socialist authorities provoked a wave of resistance which played a significant role in the development of open civil opposition to the communist regime.

Until 1990, Ziyatin Nuriev worked in Bulgaria but afterwords he moved to Istanbul.

When often asked if he feels distressed about Bulgaria because of the "Revival Process" and the change of names, Ziyatin Nuriev answers: "I was distressed about the country not as people but, let's say, as government. How could I be distressed and offended by my friends, acquaintances, neighbours? It wasn't their fault. They were even more surprised and frightened than us. Because we were in a way prepared in advance. Something was telling us it was going to happen. I remember many people, colleagues and friends, who literally broke into tears. But these are other things – ethnical affiliation, this and that; that's not a problem for me. This is a wholly different story. If you ask me if I'm offended or distressed about Bulgaria – no, absolutely not. Because Bulgaria is my home. I'm glad that I was not alone at the exhibition last night. [...] I'm not a patriot, neither Bulgarian nor Turkish." (Dzhambazov 2016)

"The changes in Bulgaria in the 1990s enabled my departure for the megalopolis [Istanbul – A.K.]. But it wasn't planned. I didn't want to leave my own country. Remember the insanity of 1989 when many people were expelled or forced to leave the homeland. Not that I didn't want to see the world and live in it but I didn't want it to happen that way. That's why I arrived in Istanbul as an ordinary tourist, not an exile (1990). It was summertime and with a friend of mine went to see the museums. We walked along the İstiklal Avenue and then entered the trade centre for textiles and fashion. We were filled right away with a sense of luxury and glitter, felt the smell of incredible scents. I introduced myself to the manager and showed her my brochure. It turned out that we were at "Vakko", chain stores with galleries located in the biggest Turkish cities – Istanbul, Ankara, İzmir... My first exhibition in Turkey was at Vakko in Ankara in 1991. The same year, I was offered a lecturer's position at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Marmara University. For 16 years now, I lead there the workshop on stone-cutting which I actually founded. [...]

Do you remember the Revival Process?

- We all have to remember it so that we won't repeat the same savagery. But I must also forget about it because of the relations with my friends, fellow-citizens, compatriots" (Cesur 2006).

Ziyatin Nuriev participated in international symposia and exhibitions in Poland, Turkey, Japan, the Canary Islands and others. He never broke his connection with Bulgaria; he had exhibitions in Burgas (Prolet Gallery, 2006??), Varna (Gallery 8, 2014), Plovdiv (Resonance Gallery, 2015), Kardzhali and Sofia (2016). His sculptures can be seen in many Bulgarian towns and cities.

The sculpture "Window" was created in 1985, the year when the campaign for a large-scale change of the Arabic-Turkish names with Bulgarian was at its height; all administrative structures, the repressive apparatus and the state organizations of the totalitarian regime were engaged; in only two months, the names of over 800 000 people were changed. The assimilation policy of the socialist authorities provoked a wave of resistance which played a significant role in the development of open civil opposition to the communist regime.

Although the author says that they are not directly related to the "Revival Process", the works of Ziyatin Nuriev express his protest. Despite the similarity in material and technique between "Window" and his earlier works ("Dream", 1982; "White Light", 1983; "Head", 1984), the difference in the message of the sculpture is considerable: "The wound of unbearable violence is engraved in this sculpture; a wound on the person's morals, on the family, the society. The window of Ziyatin Nuriev gives us the possibility and the impossibility to touch what we won't ever experience. The possibility – because he has brought out to the surface the iceberg of pain; the impossibility – because he has locked up all external expressions of pain.

The eyes are missing.

The lips are missing.

In the place of the eyes, from the meandering edge of the eyelid line, depending on the light, the shadows casted could call the look of sorrow from which a sigh slips out whispering.

In the place of the lips, on the border where the two halves of the face meet, the concealed lamentation passes over, the red vertical line of the silence.

Ziyatin chooses for the first and may be for the last time the bust, the most used pattern for heroization of the character. He deprives his character of individual characteristics but presents him with plastic uniqueness – he takes from the crown, prolongs the scull, flattens the body, marks the nose and cuts the volumes by sharp edges. He includes the clasped hands which emphasize the geometry of the forms as well as the delicacy of the details. At first, the sculpture looks deceivably fragile but it has the mighty hardness of the basalt. The differences in the texture of the basalt cause differences in the shades of grey. This is particularly visible in the place of the eyes; the tangle of dark and light spots begins from the area of the eyes, runs through the temples and reaches the back of the head. The grief is transformed into enlightenment. The shades of grey are not enough and Ziyatin uses brick-red to wound particular edges or places of the head and the body.

The window is blocked up for those who observe and open for those who can sympathize." (Iliev 2011: 34-35)

The Zagreb Gymnasium private collection consists of memorabilia from the 1985-89 period. The school was then named as the Educational Centre for Languages, and two of its classes, which retained the classical curriculum, were considered a peculiarity. It was highly exceptional at the time, because in the framework of the secondary school reform implemented by Stipe Šuvar in 1975-76, which promoted so-called “directed education,” all gymnasia in Croatia were transformed into some manner of vocational schools with the aim of preparing the students for the labour market. From the communist perspective, the classical education was deemed unnecessary petty bourgeois elitism, which prepared select students for the university and enhanced class inequality.

The typewriten manuscript of a petition calling for religious freedom, an predecessor of the so-called "Moravian Challenges"

The typewriten manuscript of a petition calling for religious freedom, an predecessor of the so-called "Moravian Challenges"

The two-page typed petition Petice Podněty katolíků k řešení situace věřících občanů v ČSR was written by Augustin Navrátil in 1985, preceding the most famous petition from 1988 called the "Moravian Challenge" signed by over half a million people. The petition is in Jan Tesař’s collection, and is the second petition of Augustin Navrátil, with 20 signatures on religious freedom. It includes the requirements of a free study in theology, an autonomous church administration, a separation of the Church from the state, an end to the discrimination of believers, etc. The petition was distributed in Czechoslovakia and also in exile. Jan Tesař and Navrátil were in contact, so the petition has been saved in his collection. It is an important material illustrating the forms of discrimination against believers and churches, as well as a historical documentary on the breakthrough of the "Moravian challenge".

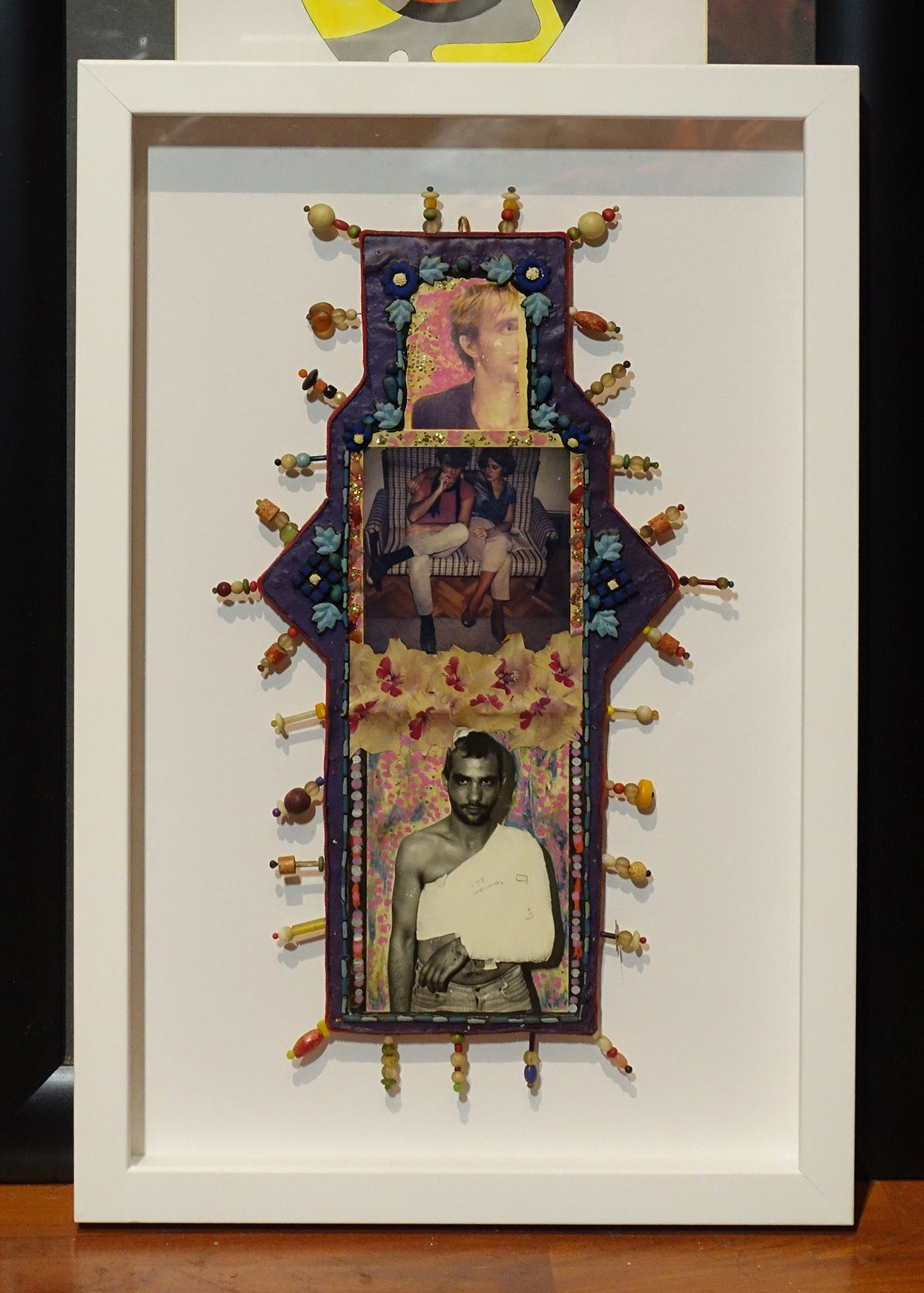

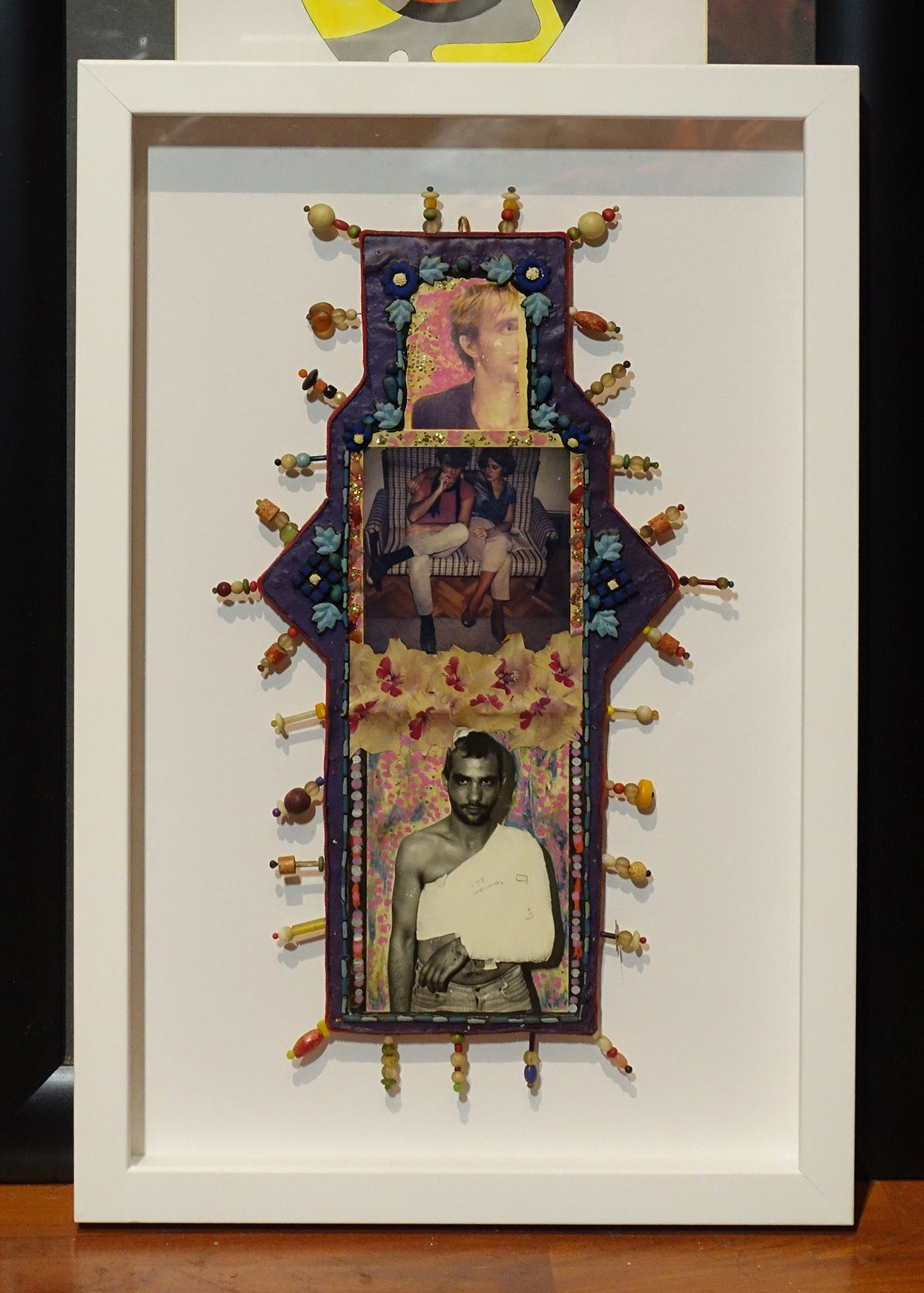

This was the very first album created by the artist Lóránt Méhes from the photos accumulating in his box, incorporating the best photos from his collection. In this sense it differs from the rest of the compilations, which are all arranged in chronological order (these photos are featured exclusively here and are missing from those other chronologies).

Its exterior is also different: while the later albums are in portrait format and the photographs are fixed on black cardboard, this one is in landscape format, and the photos are compartmentalized.

In the last decades of Romanian communism, queues for various foodstuffs or common consumer goods were an everyday sight. Images of queues are common to all the former communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe. However Andrei Pandele’s photographs are different because they illustrate a period of decay and degradation of human life that was unparalleled in the Soviet bloc. They show the absurdity of the arbitrary measures taken by the Ceaușescu regime, which reintroduced food rationing on the pretext of so-called “rational nutrition.” The severe shortage of food products was the direct result of the decision to be able to pay off Romania’s foreign debt and so become less dependent on the West, thus implicitly being under less pressure to release dissidents who had been arrested for the crime of criticising the regime’s policies. Andrei Pandele’s photographs are impressive because they show not only a dark and dirty Bucharest with interminable queues, but also people completely without hope. “It took me years to notice what I wasn’t interesting in noticing. People look, and as a rule, they only see what interests them. It’s absolutely natural. It was a question of practice, of education of the eye, to which, I must acknowledge, my architectural training had also contributed. Why do I say this? Because I was not, at first, in real time, conscious of exactly what I was photographing. Some places, their hidden, grave symbolism, I myself discovered long after I had taken the pictures. Often we see what we are able to see…,” says Andrei Pandele, with regard to what he calls a “rabid abnormality.” In this connection, he mentions that: “in my photographs of everyday life during communism, implicit, but visible when you look carefully at the photographs, is the abnormality that is/was represented by the small details. Buckets of cheese on the pavement. Or shopping backs lined up on the pavement, empty bags. Or bottles of milk frozen in the street. And many other things. It was, as I say, a rabid abnormality.”

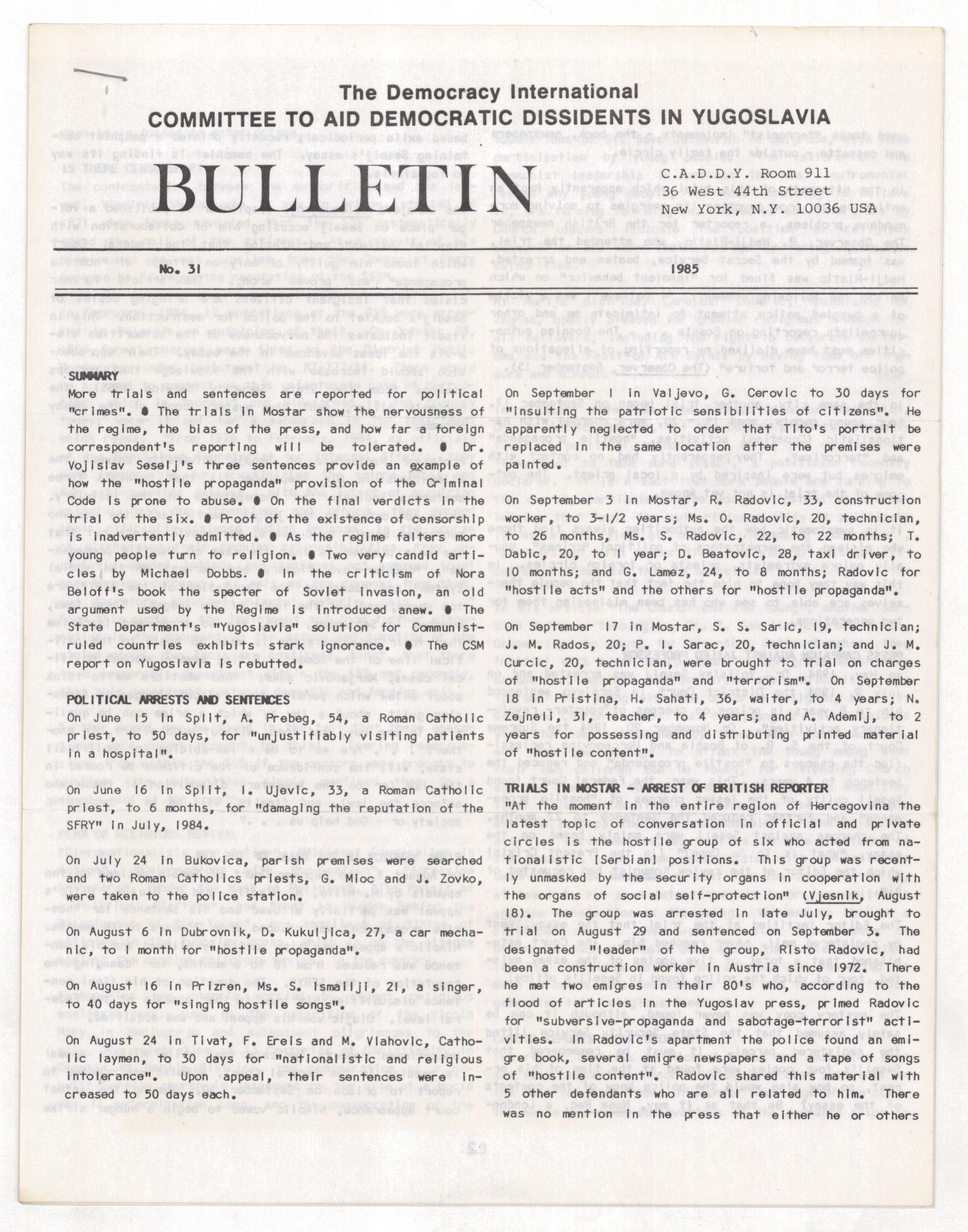

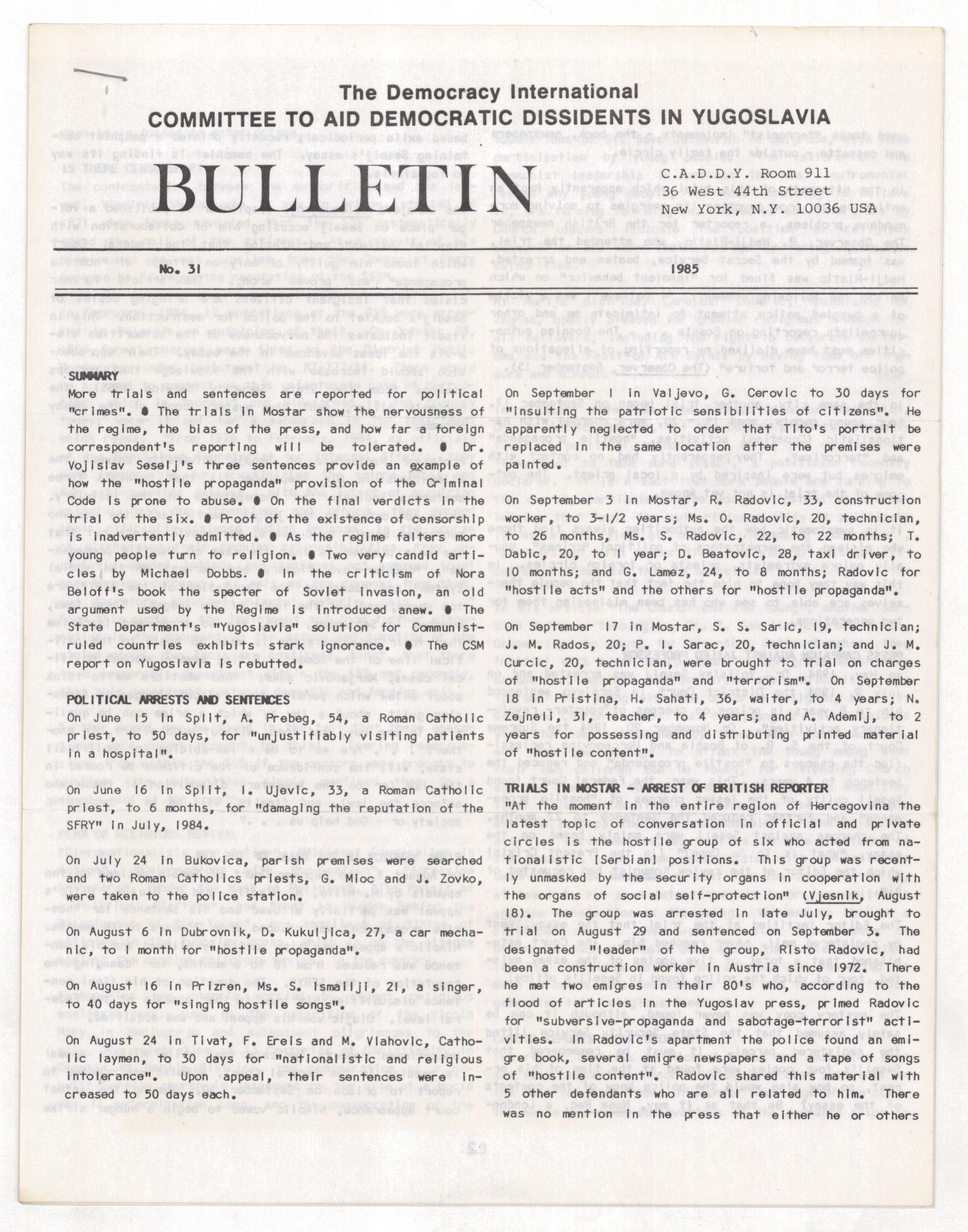

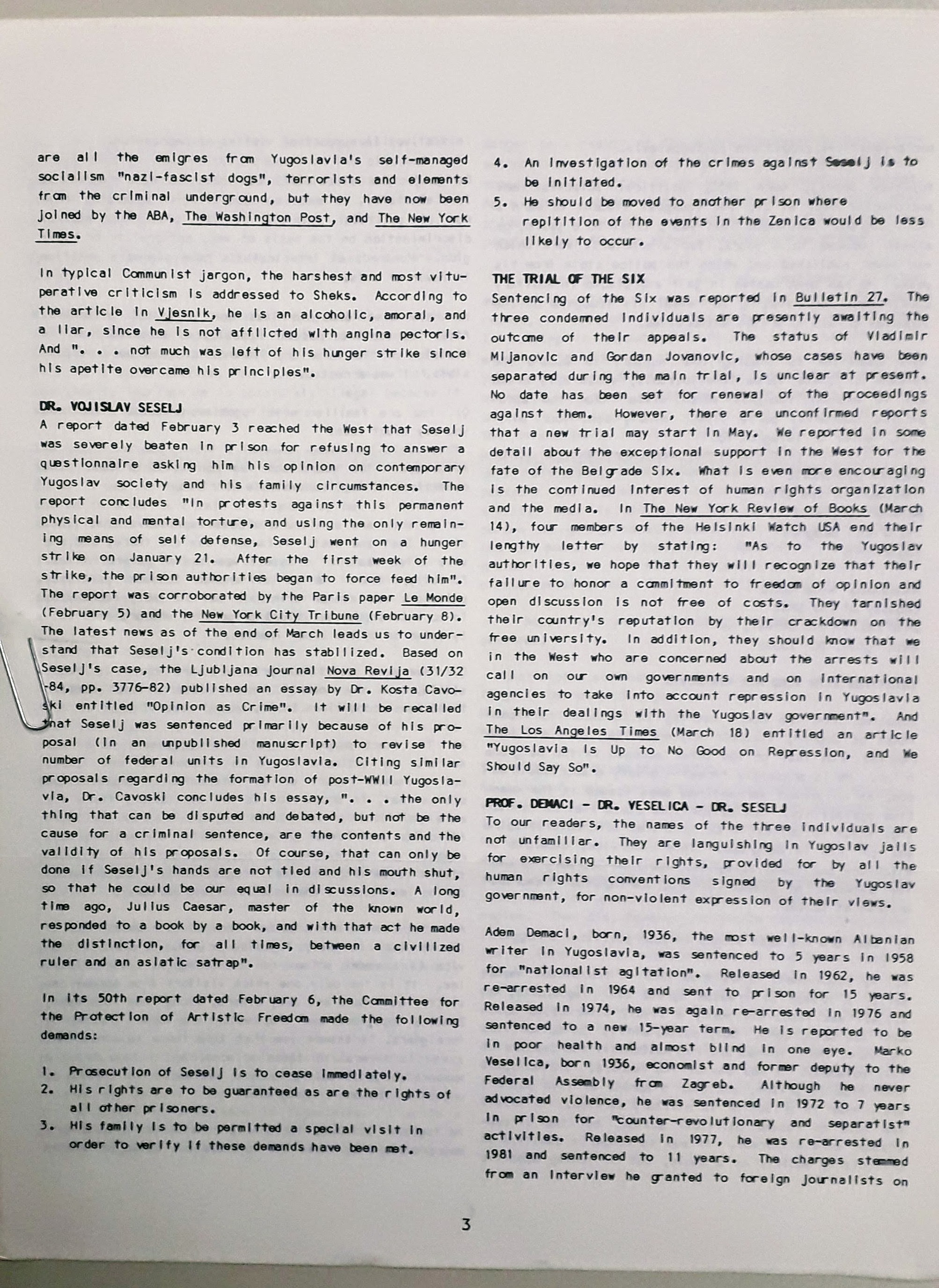

The Bulletin of the Democracy International Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia, 1985

The Bulletin of the Democracy International Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia, 1985

The Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia was the organization which Mihajlo Mihajlov founded in May 1980, in New York. The vice-presidents at the time were Franjo Tuđman and Milovan Đilas. The Committee bulletin was printed monthly, and covered issues on Yugoslavia, the repression by the regime, arrests and trials of its political opponents. It dealt with the status of human rights in Yugoslavia during 1980s. This bulletin is kept at the redaction of the Democracy International.

This photo reflects the way in which the Romanian exile organised itself and acted to present in the West the urban systematisation project of the Ceaușescu regime, which involved the demolition, mutilation, or destruction of the national heritage. The photo captures the moment when the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania was set up in Paris in 1985. On that occasion, the Association organised a protest on the streets of Paris, during which it displayed a series of placards with texts about Communist Romania, accompanied by photographs of historic monuments destroyed by the Communists or about to be demolished or moved. These details are captured in the photograph in question, which can be found in the Ștefan Gane collection in the original, 10x15 cm, printed on colour paper. The purpose of the Association was to draw the attention of political decision-makers and international public opinion to the project of the communist regime in Romania for the demolition of the architectural and urban heritage. The actions undertaken by the Association focused in particular on drawing media attention to the demolition of the city centre of Bucharest, which was planned by the authorities of the totalitarian regime so that they could reconstruct it according to the communist architectural vision.

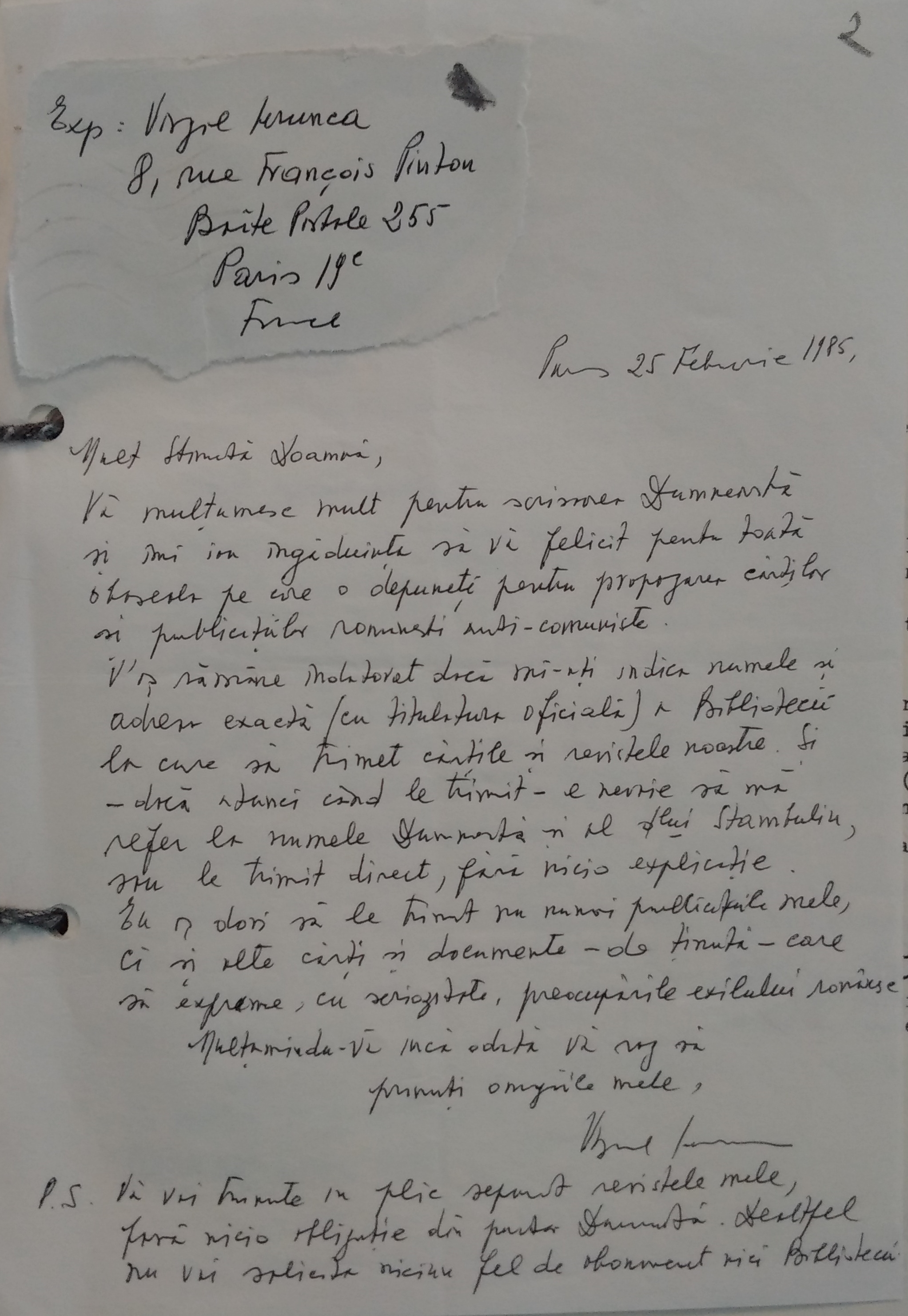

This letter is an important document for the history of the post-war Romanian exile community because it is proof of the activity of fighting communist propaganda outside the country, as well as of the integration of Romanian culture into Western culture. Such activity was also carried out by Sanda Budiș, an exile community personality, who emigrated to Switzerland in 1973. One of her actions, alongside another representative of the Romanian exile community in Switzerland, the lawyer Dumitru Stambuliu, consisted in supplying the Swiss Library for Eastern Europe in Bern with publications of the Romanian exile community. The starting point of Sanda Budiș’s project was a book donation from Romania, which the Romanian ambassador to Switzerland made to the Cantonal and University Library of Lausanne in 1984. This donation took place during a festivity advertised in the local press. In response, Sanda Budiș took the initiative to donate publications of the Romanian exile community from her personal library to this library, but her donation was denied "for political reasons." Consequently, she addressed the leadership of another institution – the Swiss Library for Eastern Europe in Bern – which served at the time as a documentary fonds for the Swiss Eastern Institute (Institut suisse de recherche sur les pays de l'Est–ISE/Schweizerische Ostinstitut–SOI), an institute that carried out research on communist countries. At the Institute, both the management and the members were Swiss personalities with authority in their field of expertise. The management of this library accepted her donation “with great satisfaction, especially as it is literally flooded by propaganda publications sent free and regularly by the various propaganda officers of the Ceaușescu regime.” In order to counteract the propaganda of the Romanian communist authorities, Sanda Budiș continued her efforts by sending letters to the management of important and representative publications of the Romanian exile community. Among the recipients of such letters was Virgil Ierunca, who accepted her invitation and sent to the library not only newspapers and magazines of the exile community, but also books published by Romanians abroad. Ierunca also responded to Sanda Budiș in a letter in which he congratulated and thanked her for the action she had initiated. The original handwritten letter is to be found today in the Sanda Budiş Collection at IICCMER.

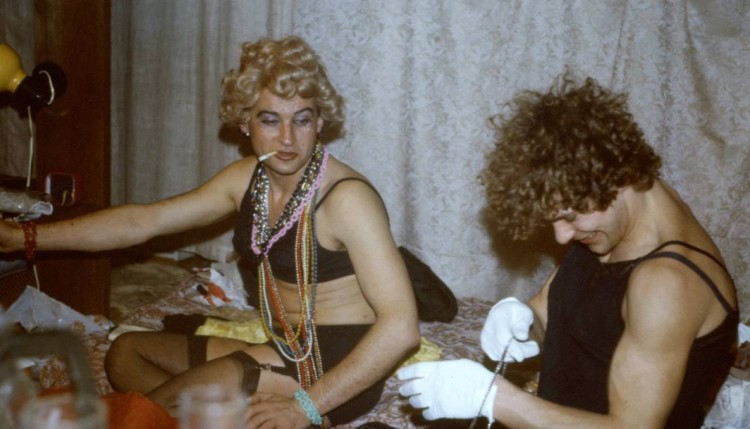

Artists István Ef Zámbó, László Fe Lugossy, and András Wahorn were members of both the Lajos Vajda Stúdió in Szentendre and the important art punk band of the 1980s, Bizottság (Committee). They performed as the occasional band Neoszarvasbika [NeoStag] before the opening of their exhibition in Pécs. The photo shows Fe Lugossy singing and Wahorn playing the guitar. In the center of the picture, there sits Péter Hardy among the audience. He is recording the concert on tape. Live recordings of underground bands were disseminated on amateur tape recordings, in part because there was no other means of spreading music in the 1980s. Péter Hardy (1964-2008) was a well-known figure of the Pécs underground art scene. He was a singer and the author of lyrics for songs played by several bands, including Bizonytalanság (Uncertainty), Gruppensex, and later the Pécsi Underground Forum (PUF). Hardy was also active in theater, particularly, alternative and street performance.

20 x 34 cm (29 x 43 cm framed), photos, cardboard, velour, acrylic, pearls

Three photos underlie the composition, arranged onto one surface, decorated with paint and pearls. The main members of the circle of friends are shown in the photos: Prince January (János Baksa Soós) in the upper section, Zuzu (Lóránt Méhes) and his girlfriend, Kriszta Kecskés, in the middle, and János Vető below.

The composition evokes an ideal situation where companionship is complete. Prince January lived in Berlin, visited Budapest only once a year, mostly in autumn, stayed usually for a month. He sent the featured photo by mail, an intentionally decomposed snapshot made with an instant camera; only half of his face is seen in the frame.

Zuzu and Kriszta are in synch with each other in terms of clothes and attitude. The selection criterion for the photo was that it emanates the atmosphere of the era. Zuzu smokes on his joint, Kriszta embraces him, as the love seat embraces them too.

The photo of János Vető is dramatic, not only because it is black and white: the image was taken after a serious car accident (a couple of years ago), his shoulder, chest, and left arm are in cast. Appropriate to the situation, his face is serious, and he is the only one looking into the camera.

According to the author’s comment, it is a spontaneously created, handcrafted composition. First the photos were attached to the cardboard, then the paint, pearls, glass, and velour were added. “I felt like a folk artist during production,” commented Zuzu, “like a shepherd, decorated as much as possible.”

The finished picture was then hanged in the hall of his apartment. January was moved a bit by seeing it. Later he also made a composition in response, with an image of Zuzu also sent to him in the mail. He too cultivated a craftsman’s attitude. They were following the work of each other. He even depicted Zuzu as a duke for his drawing series, “Primeval Light – Pathway.”

The poster gives details of two extraordinary concerts held on 10 and 11 May 1985 by some of the most appreciated rebel artists and rock groups of that period. Among the participants were the bands Roșu și Negru (“Red and Black”), Hardton, Post Scriptum, Celelalte cuvinte (“The Other Words”), Compact, Progresiv TM, Vali Sterian și Compania de Sunet, (“Vali Sterian and the Sound Company”), and the soloists Florian Pittiș and Alexandru Andrieș. All these participants were in the grey zone of tolerance admitted by the communist regime in Romania, and numbered among those that the younger generation considered nonconformist in comparison with the musical landscape of the period. The poster is not spectacular: on a white background, the text is printed in two colours, red and blue. The rock concerts announced by this poster were held in the Polyvalent Hall. Completed in 1974 and inaugurated under the name of “Palace of Sport and of Culture,” this hall was the largest performance space in Romania at the time, with a capacity of over 5,000 places. At both concerts, the auditorium was completely packed, due to the fact that they brought together an unusually large number of stars of nonconformist music. Such concerts with a very large audience posed a particular problem for the communist authorities, who were afraid that any crowd gathered at a performance might turn into a collective protest against the economic crisis, which was weighing more and more heavily on the population of Romania. The moment at which the concerts took place is also significant, because 1985 marked a turning point. On the one hand, for fear of revolt, such shows with large numbers of stars were not organised again after this event. On the other, the years that followed up until 1989 were the most difficult for the majority of people in communist Romania, who saw the growing discrepancy between their daily lives and those of people not only in the West but also in all the other communist countries.

At the beginning of August 1985, Ivan Aralica wrote a statement to the editorial board of Vjesnik regarding the campaign and accusations that were levelled against him due to the Ivan Goran Kovačić Award. In the text, he did not refute the political qualifications concerning his former activities at the time of the Croatian Spring, after which he had realised that political work is not for a writer. Aralica pointed out that in the scholarly and colloquial terminology there was no distinction between the term “nationalism” and “chauvinism.” He noted that the term “national” replaces “nationalist,” and that “nationalist” is the same as “chauvinist,” and that the latter qualification had been imposed upon him, which he could not accept because any hatred toward man or a nation was totally foreign to him.

He stressed that to him it is quite strange that the author is separated from his literary work and concluded his defence by saying: “Should I say that I do not demand any political rehabilitation for myself […] I am horrified with the idea that I would hate someone, I feel deep regret for those who hate someone. Hatred makes me unhappy, even when I am not involved” (Vjesnik, 3 August 1985).

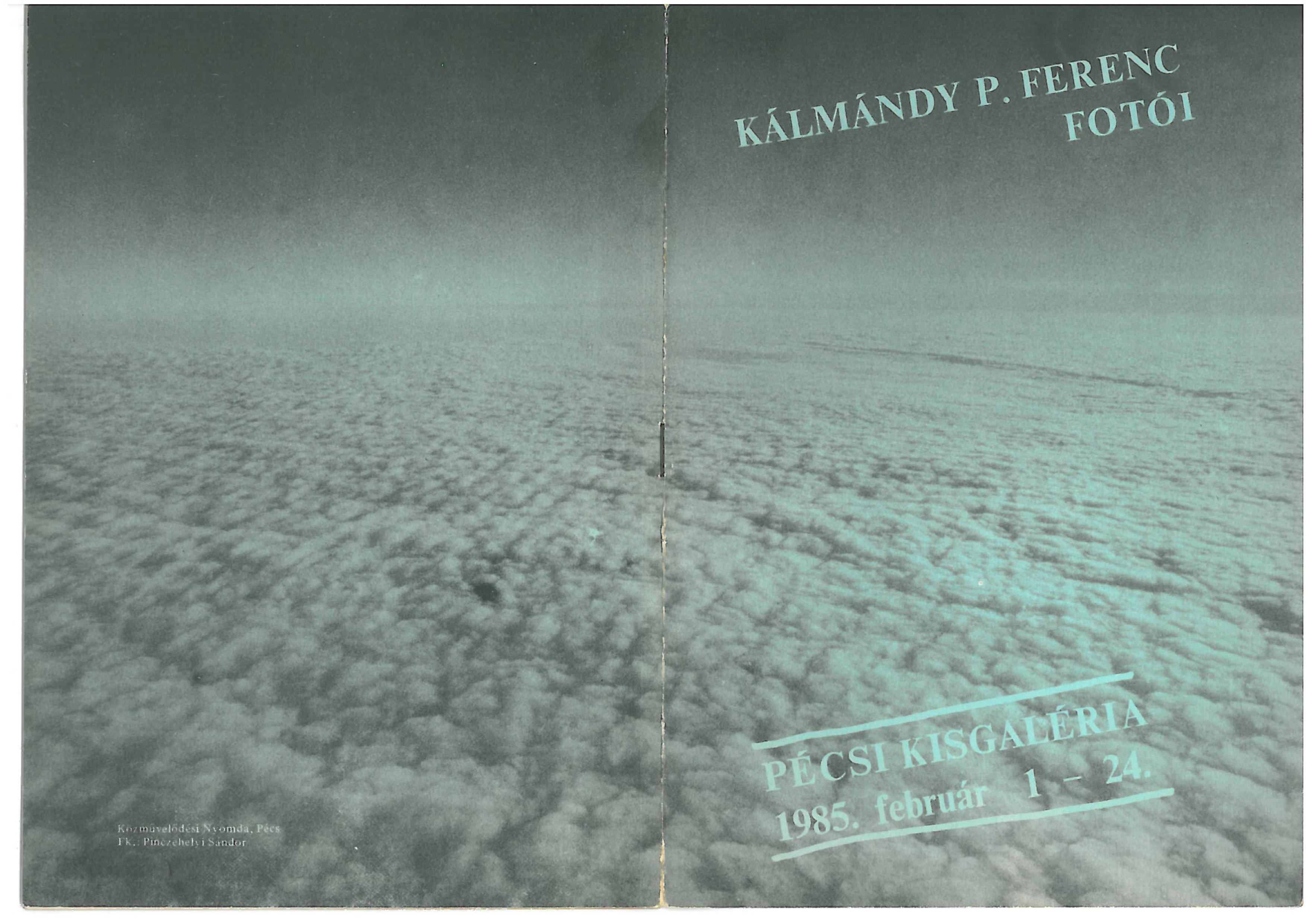

The exhibition that was installed in the Gallery of Pécs in 1985 represented the photographic oeuvre of Kálmándy. The portrait images depict representatives of the Pécs and Budapest underground scene: composer Kristóf Wéber, architect and artist János Rauschenberger, puppet theater and cartoon director Károly Papp, photo artist Ferenc Kálmándy, and others. The exhibition represented the language of “preset photography” among contemporary versions of photo art. Its relevance was that it showed young intellectuals close to the Pécs underground scene as a closed, insider, subcultural micro-community. It also highlighted their dress codes, which confronted both conventional street fashions and mainstream rock-punk fashion and what contemporaries associated with the new wave style. At the time, János Vető and Lenke Szilágyi adopted similar approaches to art.

The poster for the first feminist-lesbian cultural night, organized by the Lilith Women’s Club, was made by the artist known under the pseudonym Jona Veronika Rev. This event, held in Ljubljana April 1984, is considered the first public lesbian gathering in Yugoslavia. The poster is a unique piece of art, currently exhibited at the Lesbian Library and Archive in Ljubljana. The painter, Jona Veronika Rev, was a frequent collaborator of Lilit and, later on, Section LL of the ŠKUC Association. Since 1984, Rev has made several posters and visuals for their events, including the front-page illustration for the special issue of Mladina, dedicated to lesbianism with the title ”We Love Women“ (”Ljubimo ženske,” Mladina, no. 37, Oct. 30, 1987, Ljubljana). The poster, alongside an invitation for the event and a round table discussion on sexuality, contains feminist and lesbian visual cues and symbols, decorated with a hammer and sickle, the symbol of the international workers’ and communist movement. A leaflet, lost since then, was handed out with a copy of the poster. It referred to various modes of lesbian gender expression so as to communicate the nature of the event clearly to lesbians, without explicitly calling it lesbian. Such semi-clandestine means of communication demonstrate the necessity of keeping lesbian identity hidden in the then predominantly homonegative social context.

The photo collection of the painter Lóránt Méhes (“Zuzu”) portrays the personalities and events of the Budapest alternative art scene from the beginning of the seventies. The images arranged into scrap books in chronological order can be called social albums on the analogy of family albums, and present a composed, personal, visual imprint of the style of living of the nonconformist community.

András Hegedűs B. (1930–2001) had a twofold role in the history of OHA. He was one of its two founders and main interviewers and he had also been an active participant in the revolution, with whom detailed interviews were done to record his testimony. In the spring of 1956, economist and sociologist Hegedűs B. became one of the secretaries of the Petőfi Circle, and in the autumn he became an activist of the Revolutionary Committee of Hungarian Intellectuals. Two interviews with him are found in the holdings of OHA, one recorded in 1985 and another one in 1992–1993. The total typed transcripts of these interviews are almost two-million characters long.

Rise and Fall, a book by the Communist dissident Milovan Đilas, originally published under the title Vlast (Power) in the Serbian language in London in 1983 and in Croatia under the title Vlast i Pobuna (Power and Rebellion) in 2009, is one in the series of Đilas’ memoirs covering the years from the end of World War II until his release from prison in 1966.

In addition to the other books Đilas published in English about the Yugoslav socialist regime and the nature of its rule, the book Rise and Fall contributes to the understanding of the complexity of relations inside the Yugoslav party leadership and its methods of dealing with political enemies, and illustrates the personal transformation of a fierce communist into a democrat and liberal, demonstrating his personal courage, thereby contributing to the culture of dissent under the socialist regime.

The first text reminds of the prison mistreatment of Šešelj, sentenced in 1984 to eight years’ imprisonment for “counterrevolutionary activity” (Dragović-Soso 2002, 58). For years he was known for challenging local Bosnian authorities and intellectuals. Consequently, he was dismissed from the University of Sarajevo where he worked as an assistant and was expelled from the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. However, Šešelj was sentenced primarily due to “his proposal (in an unpublished manuscript) to revise the number of federal units in Yugoslavia” (C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin no. 28 1985, 3). Here Šešelj suggested that Serbia be unified with Montenegro and that Bosnia and Herzegovina be partitioned between Serbia and Croatia, while denying Muslim and Montenegrin nationhood (Dragović-Soso 2002, 57).

The featured item communicates arguments which defend Šešelj’s right to freedom of expression. C.A.D.D.Y. argued that Šešelj’s proposal could be subject to debate; however, it is not grounds for criminal prosecution.

The text concludes with proposals of the Committee for Protection of Artistic Freedom, calling for an end to Šešelj’s persecution and to respect his human rights as a prisoner.

The second text discussed the previous C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin issue (no. 27), which reported on the sentences of the Belgrade Six. The text reported that Western countries are aware of the crackdown on the “Free University” and other arrests and sought to communicate to the Yugoslav government that repression of freedom of opinion and expression is “not free of costs” (C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin no. 28 1985, 3).

The case of the Belgrade Six took place in 1984 when twenty-eight members of the “Free University” were arrested while attending a presentation given by “Yugoslav dissident no.1” Milovan Đilas. They were interrogated and some were subjected to physical abuse resulting in one suicide attempt and one case of death under mysterious circumstances. Afterwards six members of the “Free University” were indicated in court (Vladimir Mijanović, Miodrag Milić, Dragomir Olujić, Pavluško Imširović, Milan Nikolić, and Gordan Jovanović).

The two cases of Šešelj and the Belgrade Six, both taking place in 1984, were crucial to the radicalisation of the intellectual opposition in Yugoslavia. The Belgrade intelligentsia, now accompanied by colleagues in Zagreb and Ljubljana, undertook a series of protest actions such as calling for high officials to resign from their positions, writing petitions, forming new dissident committees, with the Committee for the Defence of Freedom of Thought and Expression being the most important. The committee went as far as opposing the entire legitimacy of the Yugoslav regime and demanding the abolition of the one-party system, free elections, a free press, and an independent judiciary (Dragović-Soso 2002, 60).

The cartoon “The Future,” which was included in the censored volume Umor 50% (Humour 50%), suggests through four successive images the story of a shipwrecked man longing in vain for rescue. In the first image, a huge ship on which is written “The Future” seems to be approaching a desert island to rescue a man; in the next three, however, it may be observed that this approaching ship becomes smaller and smaller, so that in the last image, the viewer’s eye can no longer even make out the inscription alluding to the long-awaited future of communist society, in which everyone should finally live happily. Beyond the ideological disillusion that was general in the whole Soviet Bloc, Mihai Stănescu captures that state of mind specific to communism in Romania in this final period, and suggests the hopelessness and lack of expectations. In this sense, the cartoon is not only a subtle criticism of Marxism-Leninism, but also a parable of the gradual disappearance of hope as the twilight of the communist regime in Romania approached.

The Ivan Aralica Collection of Press Clippings contains articles, documents and letters presenting the heated polemics in the Yugoslav press in 1985 and 1986. Members of the Association of Veterans of the People's Liberation War (SUBNOR) tried to proclaim award-winning author Ivan Aralica as politically unfit for literary work in a socialist society due to his involvement in the "counter-revolutionary" Croatian Spring (1967-71). The collection contains outstanding materials to studying the microhistory of censorship through pressure on public opinion.

A small group of devoted researchers began to do interviews in 1981 with people who had been active in the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. The aim of people who did the interviews was to reveal, by giving people chances to share personal memories, the real story of this decisive set of events, which were taboo under the Kádár regime, which had violently suppressed the revolution and which was eager to make up for its lack legitimacy in the eyes of the population by spreading false propaganda. These early interviews later served as the core collection of the Oral History Archives, which was founded in Budapest in 1985.

The private collection created and owned by Piotr ‘Pietia’ Wierzbicki contains hardcore punk fanzines, articles, and papers from the 1980s, including the original matrices of ‘QQRYQ’ fanzine edited and published by Wierzbicki from 1985. ‘QQRYQ’ was the leading Polish magazine about the underground punk scene and Wierzbicki became an influential author and promoter on that scene.

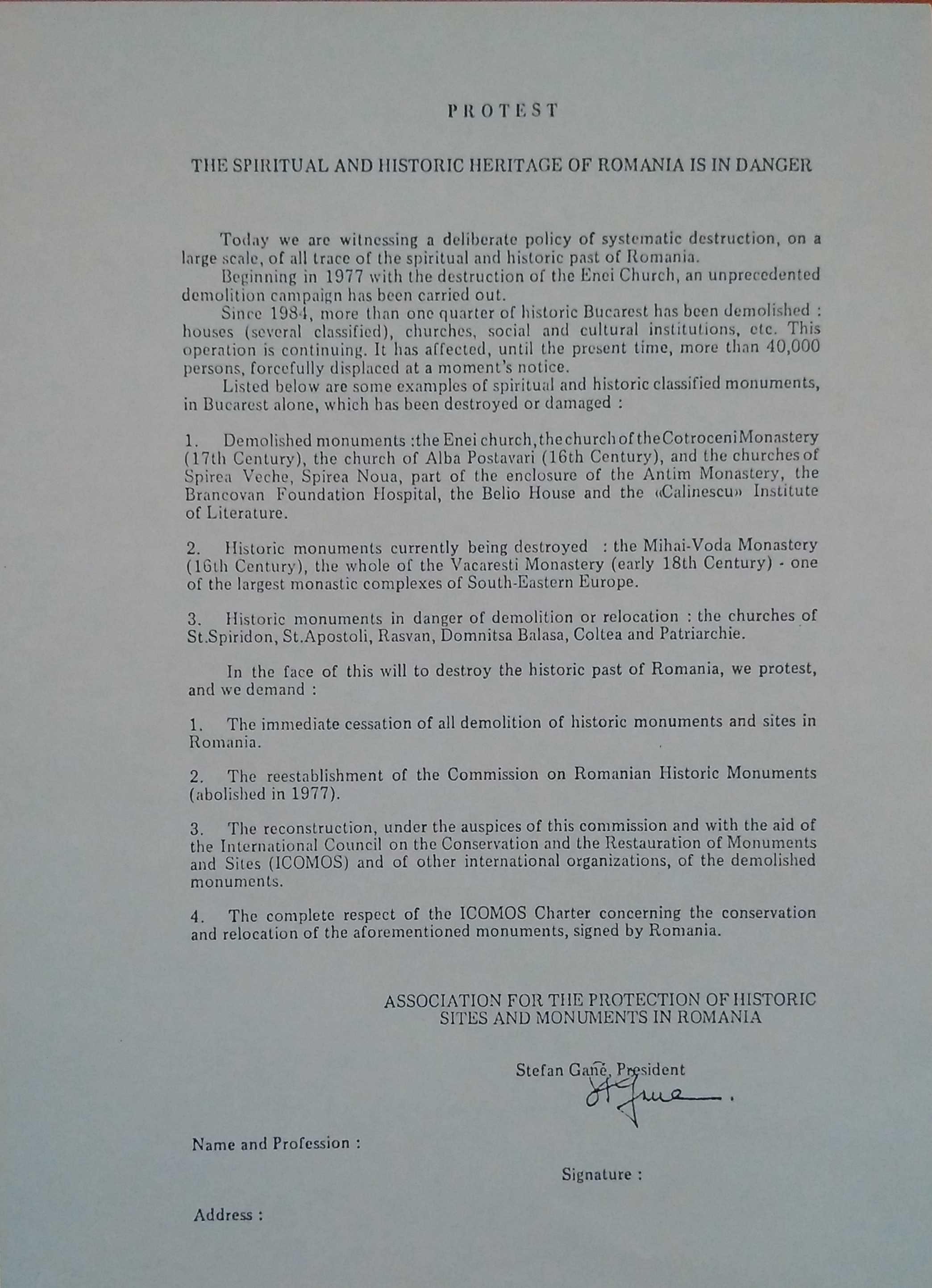

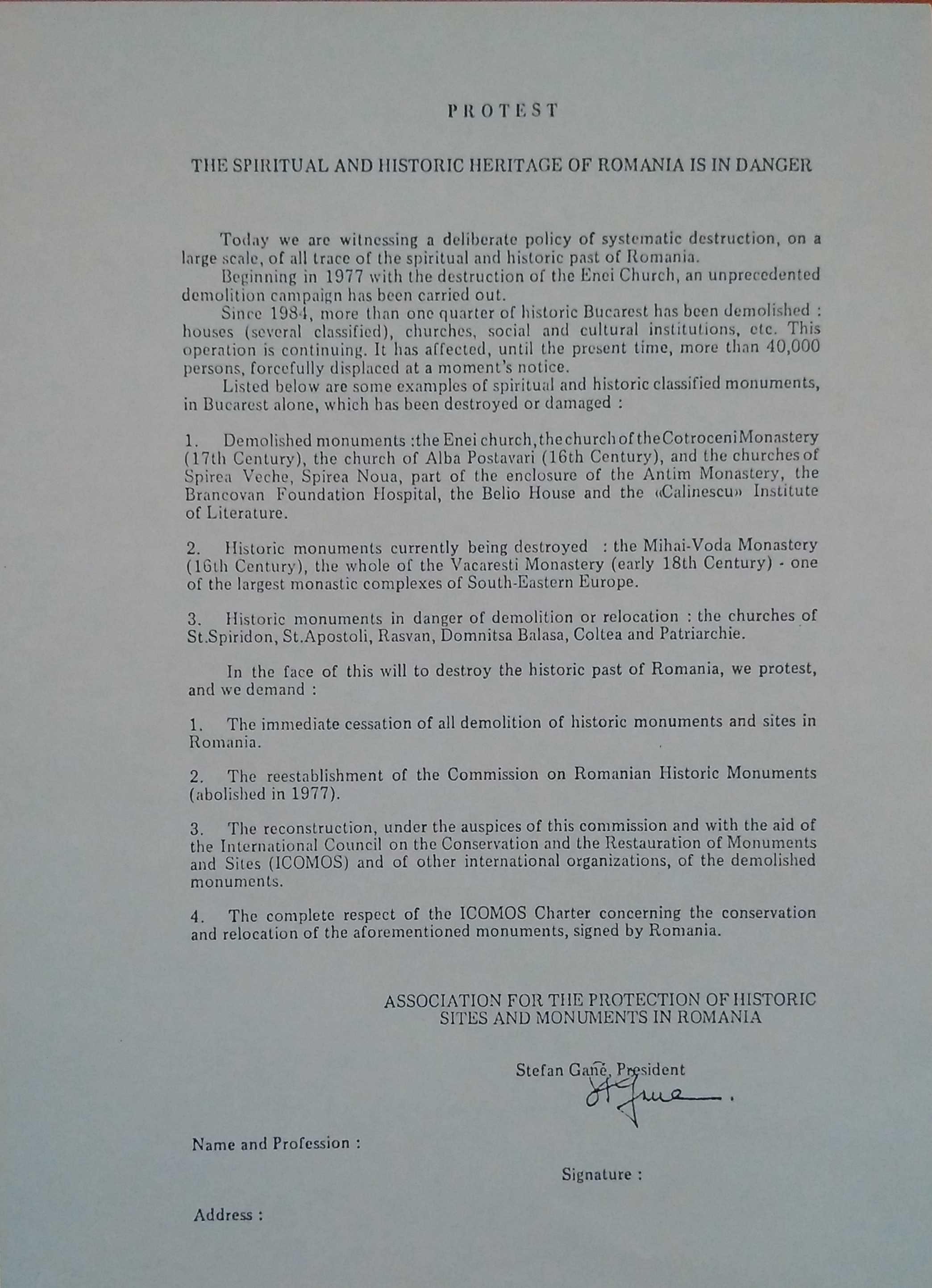

Protest message of the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania, in French and English, Paris, 1985

Protest message of the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania, in French and English, Paris, 1985

This document reflects the way in which the Romanian exile community organised itself and acted to promote media coverage in the West of the urban systematisation project of Ceaușescu's regime, which tacitly involved the demolition, mutilation, or destruction of the national heritage. The protest message was shared when the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania was founded in 1985, in Paris. The purpose of the association was to draw the attention of political decision-makers and international public opinion to the communist regime's plan for the demolition of the architectural and urban heritage of Romania. The actions undertaken within the Association focused particularly on the promotion of media coverage of the demolition of the city centre of Bucharest, which the communist authorities planned to reorganise according to their architectural vision. On the occasion of its foundation, the association organised a protest on the streets of Paris, during which it distributed a protest message to participants and passers-by with texts about communist Romania accompanied by photographs of historic monuments destroyed by the communists or scheduled to be demolished or moved. A copy of this protest message was sent by post to several Romanian exiles in order to convince them to join the Association and get involved in unmasking the communist regime in Romania and, in particular, the urban systematisation project of the Ceaușescu regime. This document was sent by the president of the Association, the architect Ștefan Gane, to Sanda Stolojan, a personality of the Romanian exile, who kept it in her private archive. The document, which can be consulted in the IICCMER collection, was written in English and French, in A4 format. The material, titled "Protest: Romania's historical and spiritual heritage is in danger," briefly outlines the consequences of the Bucharest systematisation project undertaken by the Communist authorities since 1977 and some examples of monuments from the historical and spiritual heritage of the Romanians that had been destroyed, demolished, or mutilated by the Ceaușescu regime. Against this background, the association protested, asking for: a stop to the demolition of historic monuments and sites in the country; the re-establishment of the Romanian Historic Monuments Commission, abolished in 1977; and the rebuilding, under the aegis of this Commission and with the help of the International Council for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites and other international organisations, of the demolished historic monuments and sites.

The neo-avant-garde duo of Zofia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek was frequently performing in Dziekanka in the 1970s and 1980s. In the space of Dziekanka, KwieKulik made performances, showed their art on exhibitions and presentations, took part in discussions and symposiums. As a good example of their activity in Dziekanka could serve the performance Festiwal Inteligencji i Kraty (Festival of Intelligence and Bars) from March 4, 1985. The attached photography showed the artists making the performance.

The tape on which are imprinted the voices of two personalities of Romanian culture, Lena Constante and Harry Brauner, is today in the Zoltán Rostás private collection and contains an extensive interview taken with the couple in 1985. Harry Brauner (1908–1998) was a Romanian folklorist and ethnomusicologist of Jewish origin, who came from a family that included other notable intellectuals: his brothers were the surrealist painter Victor Brauner and the photographer Theodore (Teddy) Brauner. Lena Constante (1909–2005) was an artist and folklorist of Aromanian origin, and the author of a number of well-known postcommunist volumes, which were well received by readers of memorialistic literature. The couple were involved in a famous political trial, which had as its central figure Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu, an intellectual of Marxist orientation and an important political leader after 1945, arrested in 1948 and executed in 1954. This political trial was to have been a show trial, like those of László Rajk in Hungary and Rudolf Slánský in Czeschoslovakia, but in the end it was orchestrated behind closed doors, on the basis of false testimonies squeezed out of some of those included among the accused, as in similar cases in the Soviet bloc. In 1954, Harry Brauner was sentenced by the communist authorities to 15 years in prison and Lena Constante to 12. Both were released in 1962, after 12 years, but Brauner had to remain in “obligatory domicile” on the Bărăgan plain until 1964, when all political prisoners were released. The two only got married after their time in prison, while Brauner was still in forced domicile. In 1968, both were politically rehabilitated by Nicolae Ceauşescu, who had initiated a belated de-Stalinization and was reviewing some of the political trials orchestrated by his predecessor, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, in order to gain political capital. After 1989, the Pătrăşcanu trial was one of the most visited subjects out of the whole period of Romanian communism, owing to the political and intellectual eminence of those included among the accused. The interview carried out in 1985 by Zoltán Rostás also includes the couple’s testimonies about political imprisonment and forced domicile, subjects that were and still are of maximum interest for the majority of historians of postcommunist Romania. Here is an extract from Harry Brauner’s reflection on the significance of his experience of incarceration, remarkable for the way in which he synthesizes the essence of the absence of the rule of law under communism in a period in which there was effectively no access to professional analyses of undemocratic regimes: “ZR: Were you really so dangerous that after you had come out of prison they also gave you obligatory domicile? HB: Yes, it seems that I was very dangerous. Much more dangerous than I imagined. But at the same time, I was a good example for all the others, don’t you think? ZR: In what sense? HB: Ah, you haven’t understood what I mean. I was a good example for intellectuals, for artists, for all those who could see an example of what could happen to a man who had done nothing.” The aim of the 1985 interview was broader, however. The recording includes discussions referring to the beginnings of the couple’s relationship, to intellectual life in the interwar and postwar periods, and above all to many details of their contribution to the researches of the Gustian sociological school. “It was, I remember, a single meeting, but quite a long one. Lena Constante spoke significantly more than Harry Brauner, as he preferred to be very concise in the answers he gave me. By the way, he was a character in himself, with a voice and a ceremony of speaking that were quite distinctive. Indeed he is the character in a well-known novel by Marin Preda,” says Zoltán Rostás, recalling the meeting of which the dialogues are preserved on the magnetic tape in his private collection.

Clearly dated 1983, the cartoon “Working Visit” was probably among those withdrawn from the exhibition at the Eforie Gallery that year. It was subsequently omitted from the volumes later prepared by Mihai Stănescu before 1989, but it was included in the volume Best of Stănescu, which comprises works from the period 1979–1989 and was published in 2009 on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the fall of communism. The cartoon “Working Visit” shows a crowd of people drawn like parquet pieces on which footprints can be seen. The drawing mocks in a tragic-comic key the so-called “working visits” made by the secretary general of the Party, Nicolae Ceauşescu, together with his suite of communist officials, to various cities, to factories, building sites, and cultivated fields. These working visits, unknown in the time of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej but introduced and intensely promoted by Ceauşescu, followed broadly the same pattern: the Party delegation, led by Ceauşescu himself and in most cases also including his wife Elena, travelled to various “objectives.” There they were greeted by the local authorities and frenetically applauded by crowds of people specially mobilised to give the distinguished guests a long ovation. During these visits, Ceauşescu formulated so-called “precious indications” regarding what ought to be done in the factory, building site, or agricultural cooperative that he was visiting. Once launched, these “indications” became the letter of the law, no matter how absurd they were, and those on whom they had been bestowed dared not contradict them, even when specialists understood that they could produce disastrous effects. In essence, the “indications” symbolised the arbitrary character of decisions in a dictatorial regime. At the same time, for the presidential couple as for the rest of the officials of the communist regime, these “working visits” constituted what we would today call an image-building exercise. At the time, they were an obligatory element in the complex arsenal of the personality cult. For the crowds of people brought to attend these working visits, they were an exercise in accepted humiliation. This is what Mihai Stănescu manages to show through the cartoon “Working Visit.” This cartoon is one of the most well-known works in his portfolio, and indeed in the history of Romanian cartoons under communism.