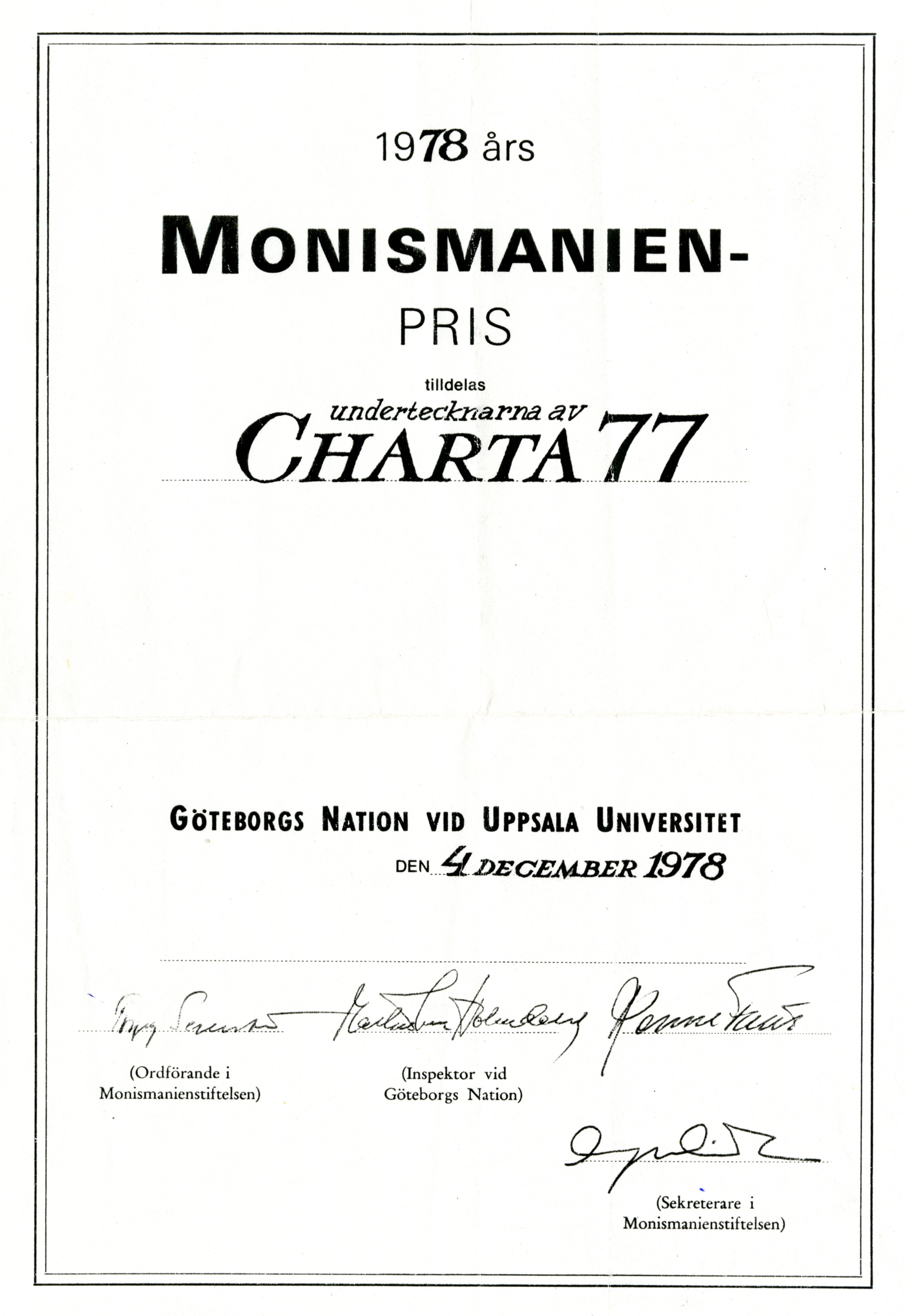

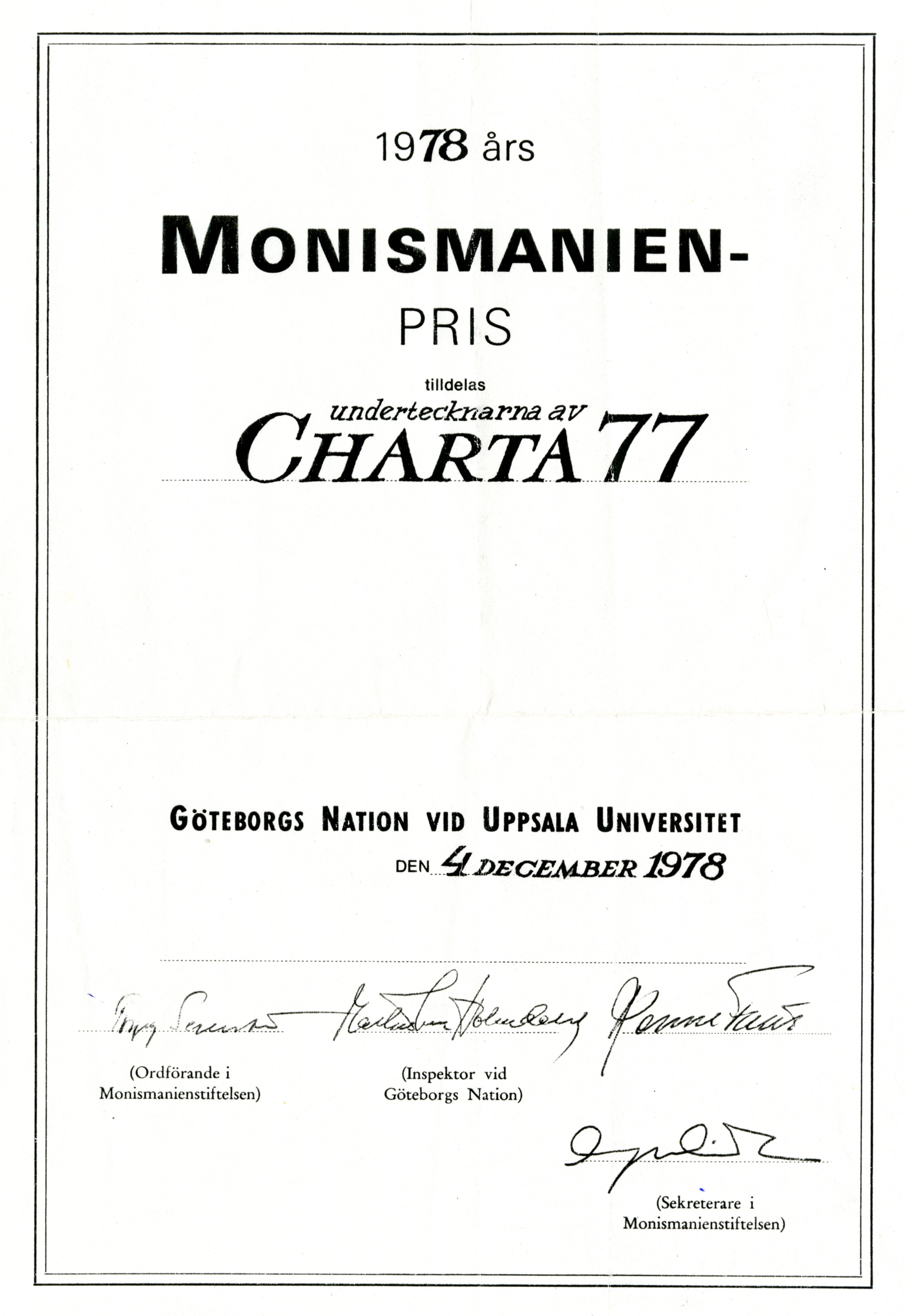

This collection of the historian, teacher and politician Milan Hübl consists of a unique collection of archive materials, which includes the correspondence and documentation of the Political University of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and a large collection of ego documents, samizdat volumes and materials related to Charter 77, the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS).

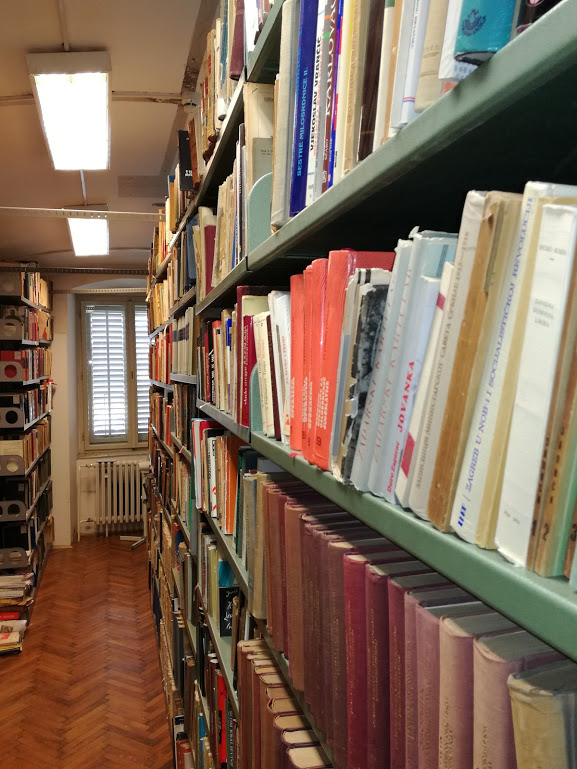

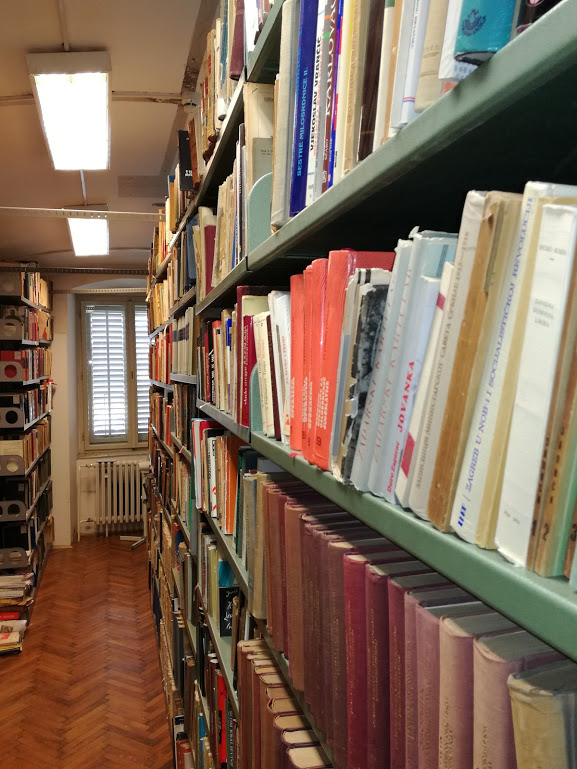

The Foreign Croatica Collection is the largest collection of books and periodicals published by Croatian authors in foreign countries. The Collection includes publications in many languages covering numerous issues on Croatia and the Croatian people, including those related to the socialist period. It is the most important collection in Croatia containing books by Croatian émigrés banned during the time of socialist Yugoslavia.

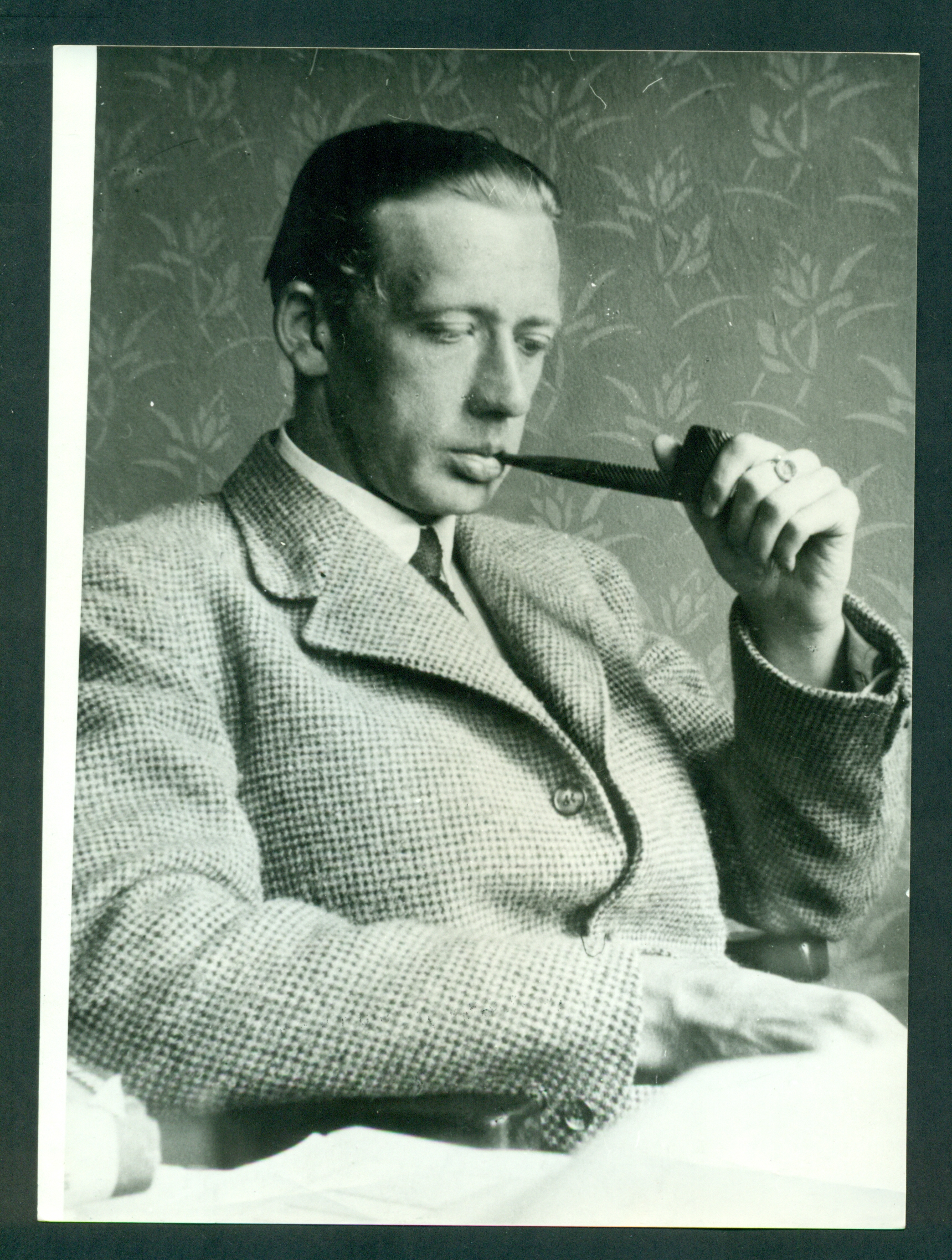

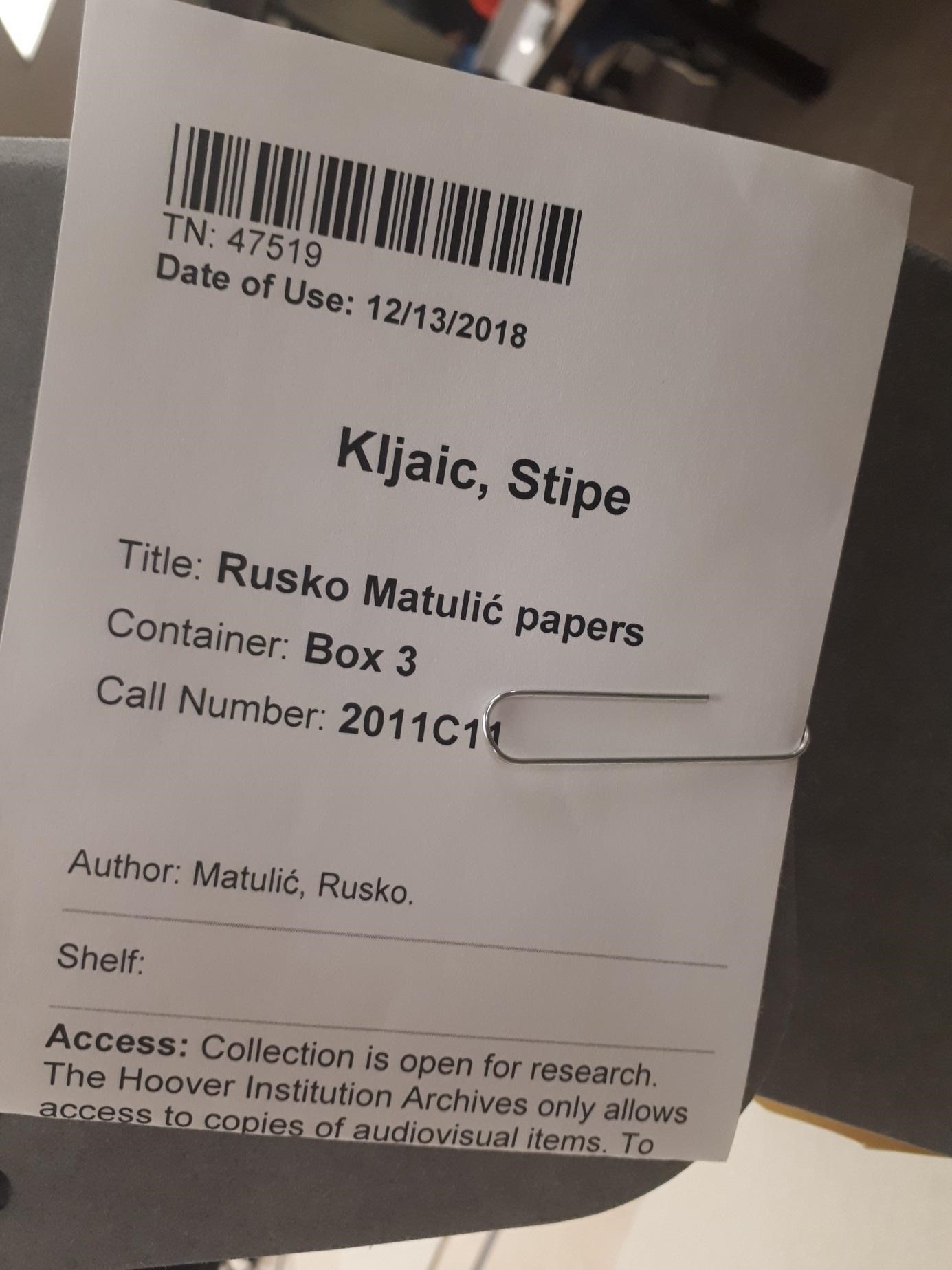

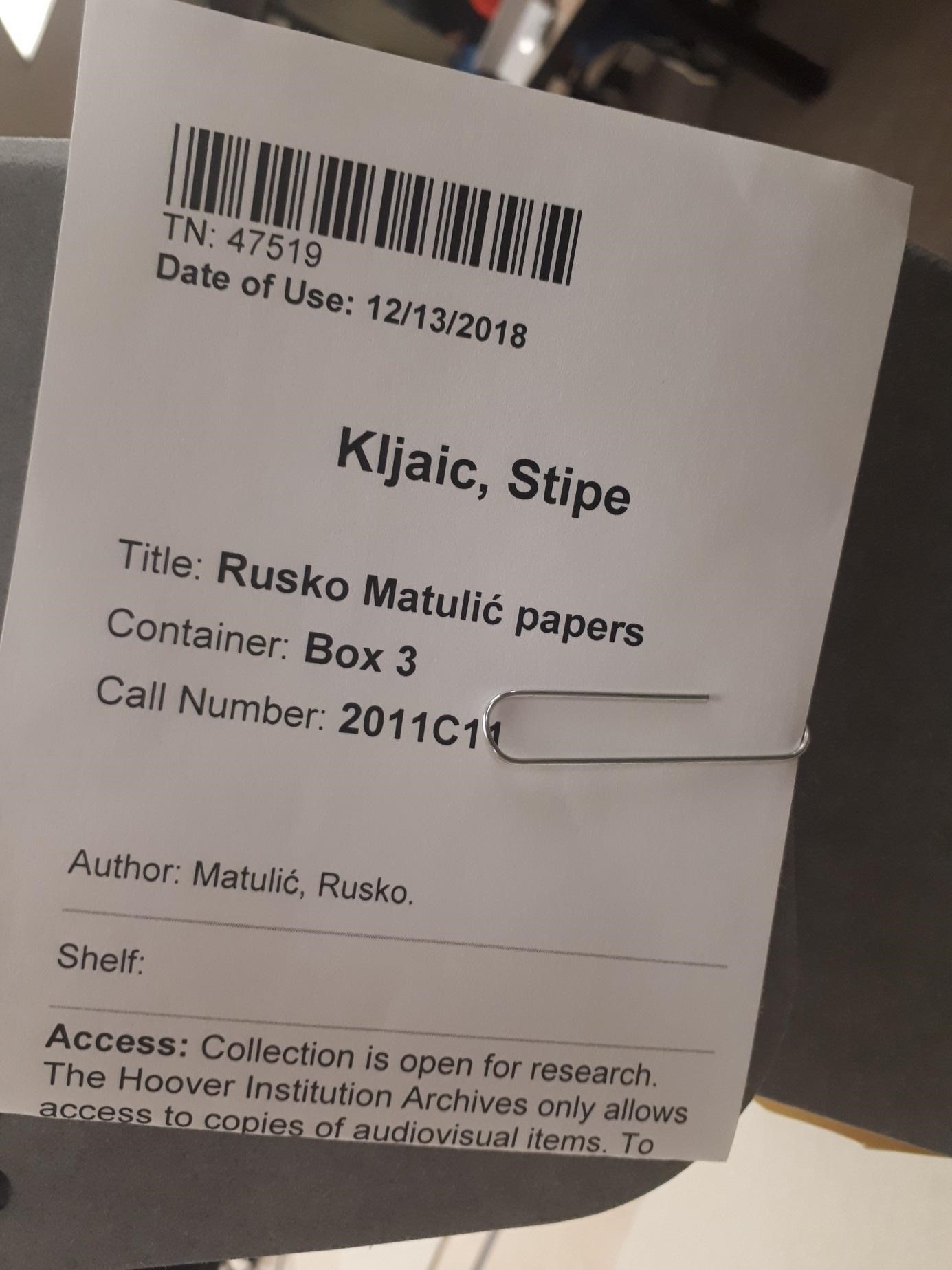

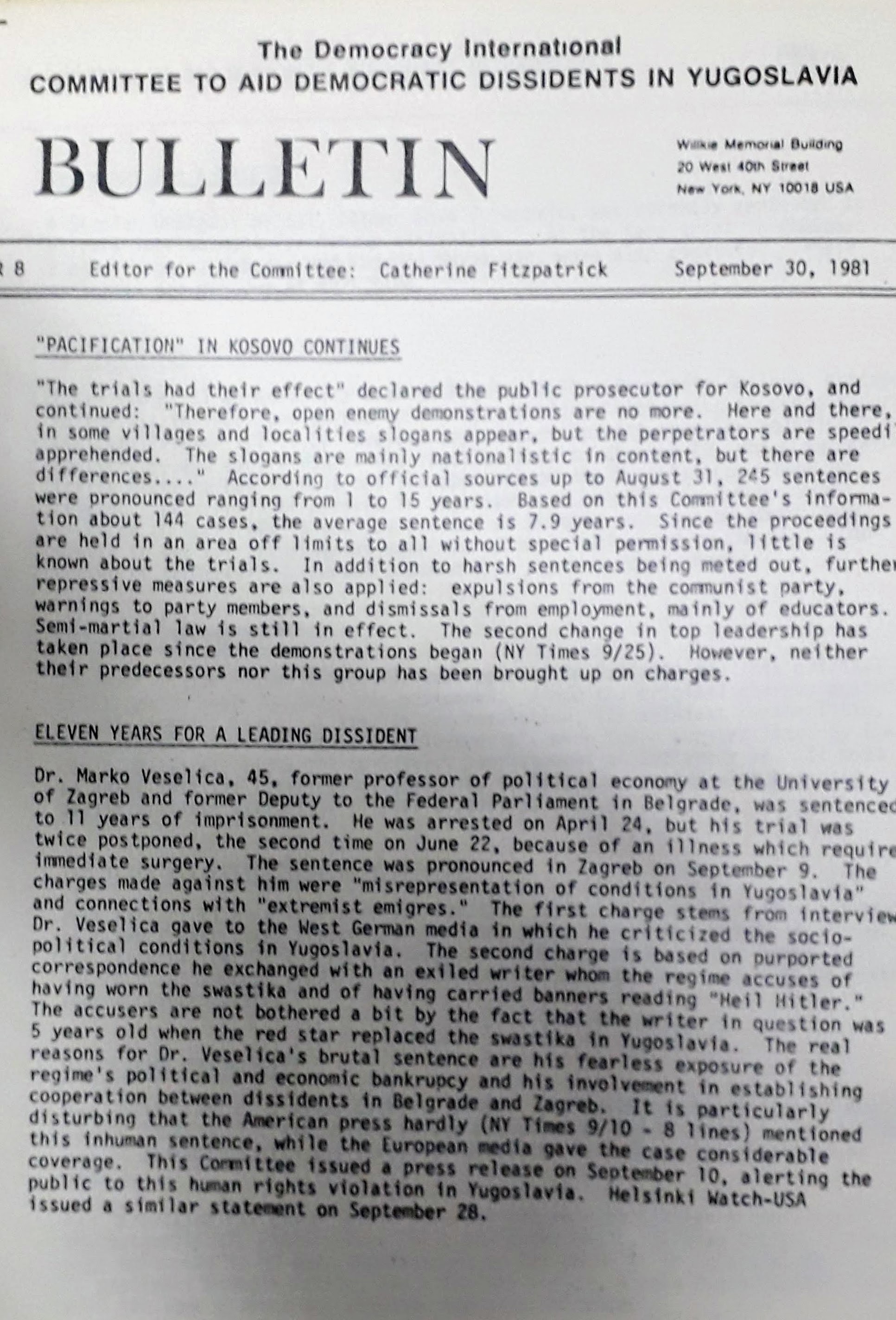

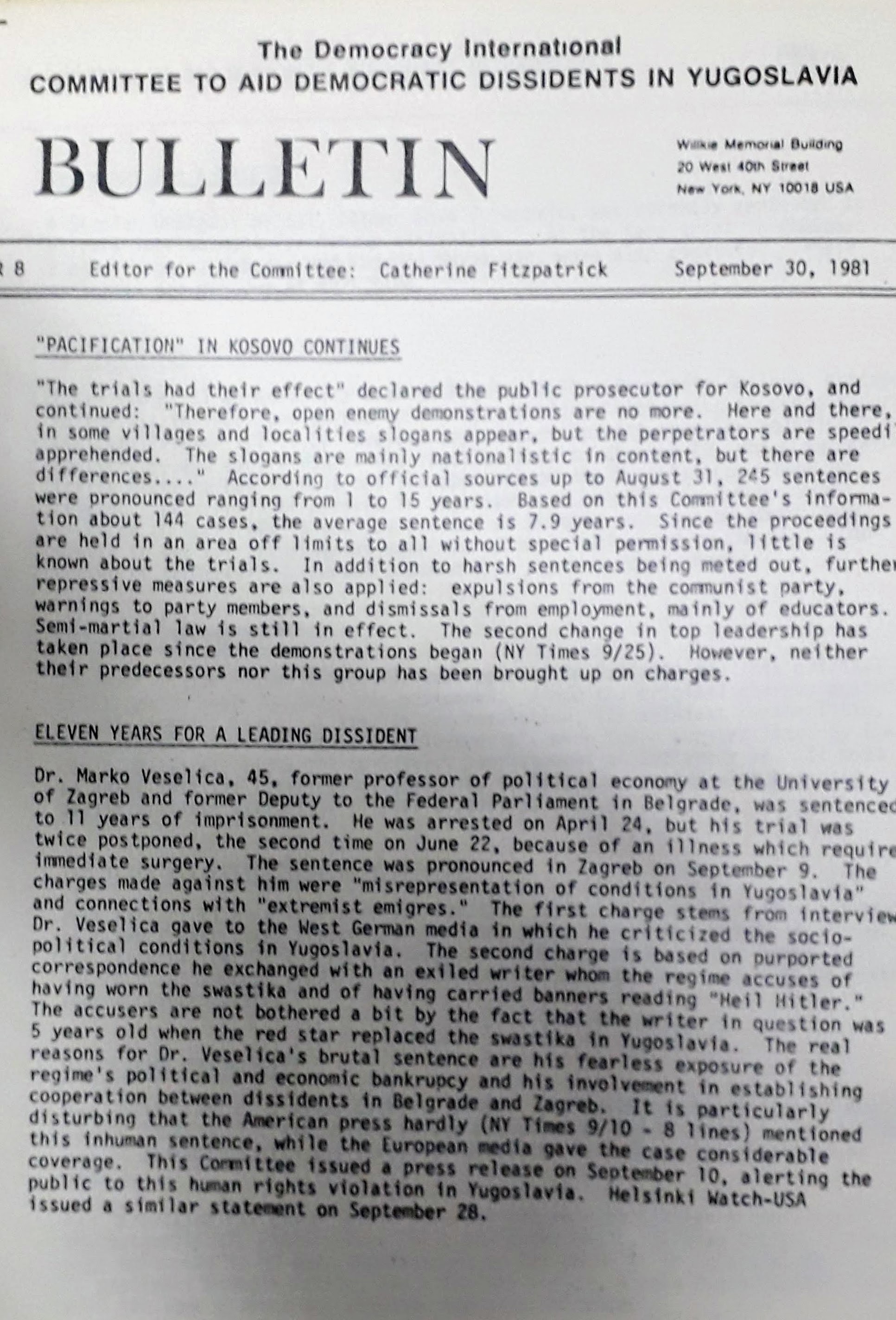

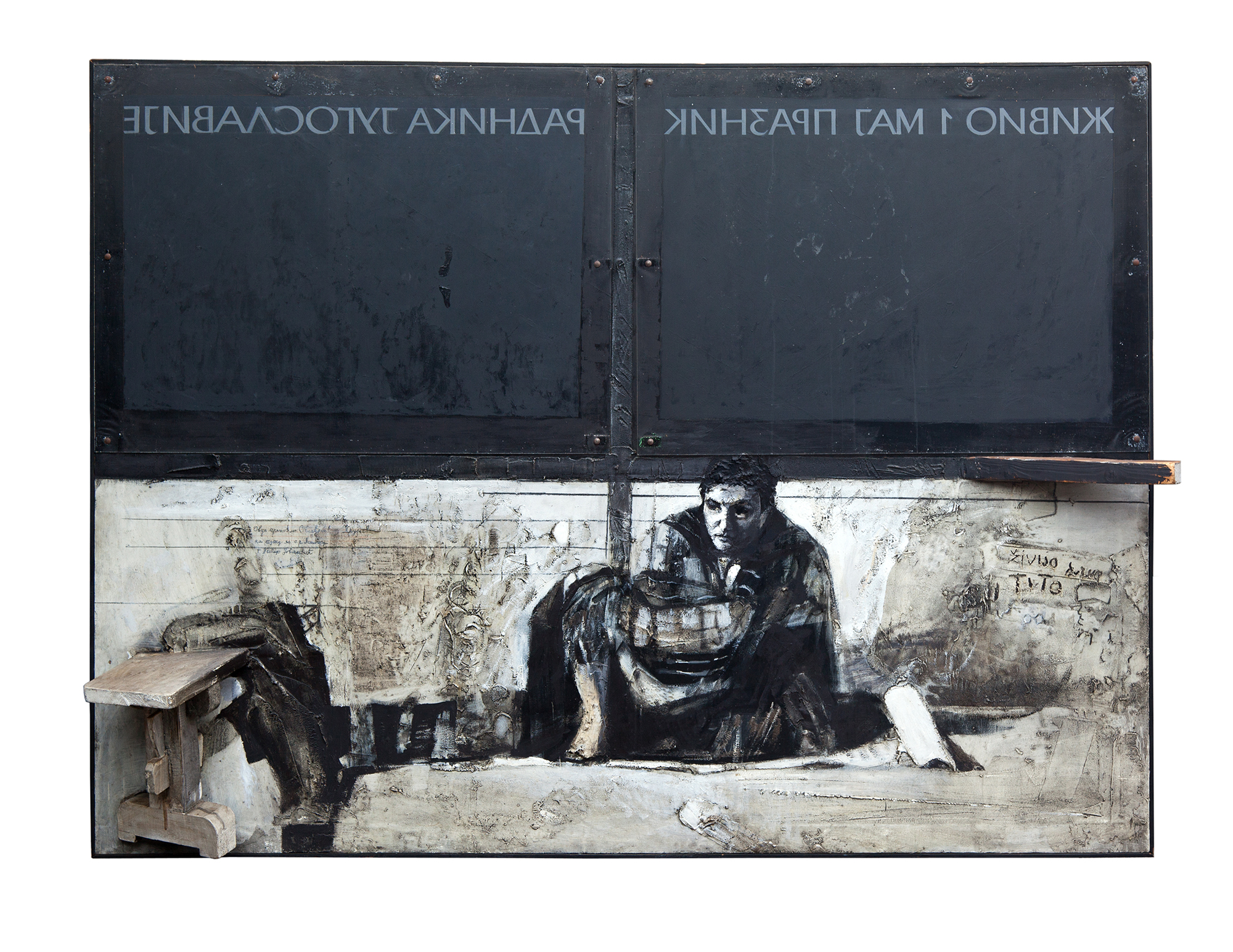

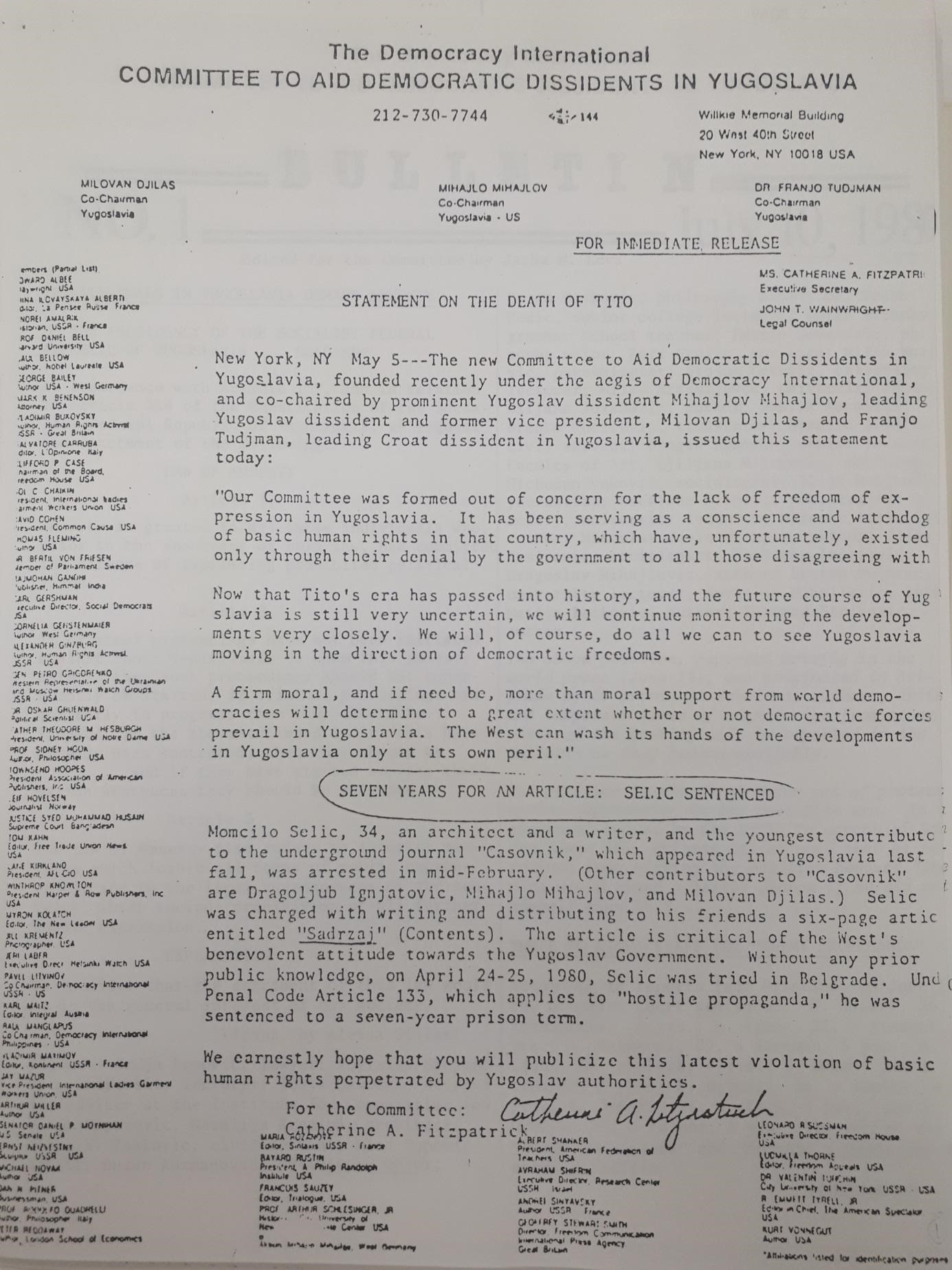

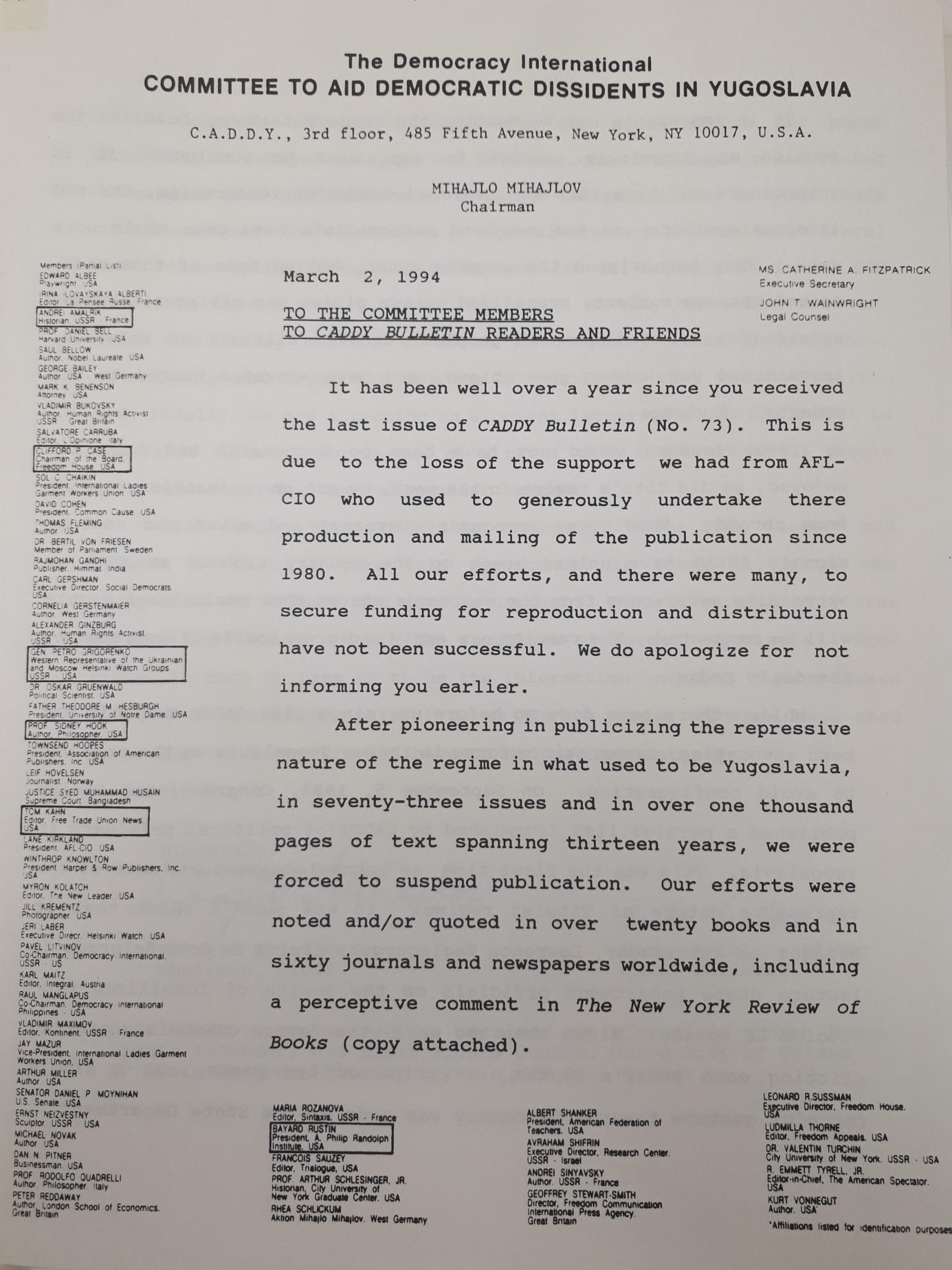

The bequest of Rusko Matulić, an American engineer and writer of Yugoslav origin, is held in the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The collection largely encompasses Matulić's activities as a political émigré in the United States of America, when he mainly dealt with the publication of the bi-monthly bulletin of the Committee Aid to Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia (CADDY). The bulletin and organization acted as a part of the Democratic International, established in New York in 1979. Mihajlo Mihajlov, one of the most prominent Yugoslav dissidents, was a member and the main initiator of launching the CADDY organization and its bulletin. Rusko Matulić was Mihajlov's main collaborator in the overall CADDY project.

Drábek, Jaroslav. A Contribution to the History of the Beginning of the Czechoslovak Resistance (in Czech), 1960. Manuscript

Drábek, Jaroslav. A Contribution to the History of the Beginning of the Czechoslovak Resistance (in Czech), 1960. Manuscript

Jaroslav Drábek Jr (1901–1996), a Czech lawyer, journalist and member of the Czechoslovak resistance movement during the Second World War, was the author of a lecture entitled “A Contribution to the History of the Beginning of the Czechoslovak Resistance”, which was presented on 9 December 1960 as part of the series “Contributions to the Development of the Idea of the Czechoslovak State” organized by the Czechoslovak Society for Arts and Science. The 33-page article includes descriptions of Drábek’s memories of his resistance activities, his escapes, interrogations, the Gestapo, and his colleagues in exile in London. Drábek also described other experiences from the postwar period, such as the arrest and torture of his colleague after the Communist coup. After February 1948, Drábek emigrated from Czechoslovakia. The document also includes a letter from the Czech scientist and prominent member of the anti-Nazi resistance, Professor Vladimír Krajina, who also emigrated after 1948. In his letter, Krajina mentions the fact that it was Jaroslav Drábek Jr who persuaded him to be active in the resistance during the Second World War.

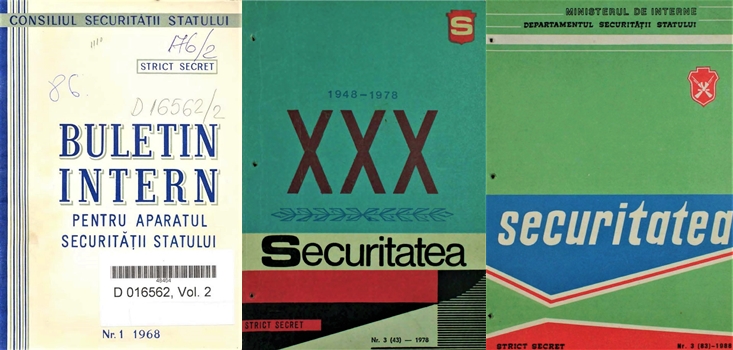

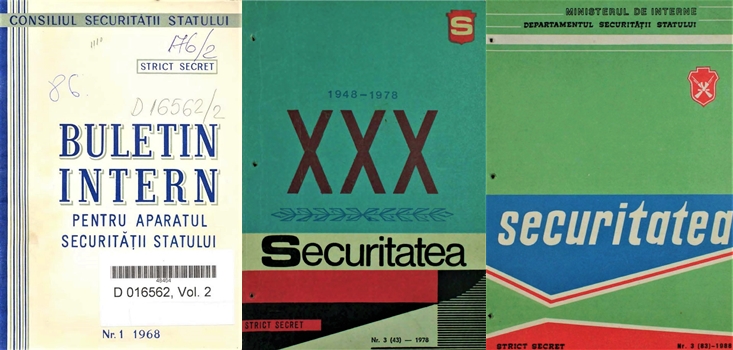

About the relations of the Romanian citizens with some capitalist radio stations. In Securitatea, 41 (1978): 38-49, in Romanian. Article

About the relations of the Romanian citizens with some capitalist radio stations. In Securitatea, 41 (1978): 38-49, in Romanian. Article

Securitatea was a quarterly aimed at improving the training of Securitate operative personnel. Its articles were written by Securitate officers for Securitate officers and thus they touched upon practical problems faced during their specific mission of preventing and neutralising any actions that potentially threatened the communist regime. Among the many dangers that were outlined in the pages of the quarterly as undermining “state security” were foreign radio stations, and especially Radio Free Europe (RFE). The article chosen as a featured item of the collection presents under the title “Cu referire la relațiile cetățenilor români cu unele posturi de radio capitaliste” (About the relations of Romanian citizens with some capitalist radio stations) the perspective of the Securitate upon the activity of RFE and evaluates its contribution in providing an alternative source of information for Romanians. In the absence of underground publications, RFE represented the main source of alternative information in communist Romania. Thus, the Securitate regarded RFE and contacts between Romanian citizens and employees of the Romanian desk of this radio station as dangerous to the communist regime. Accordingly, the entire article focuses on revealing how RFE allegedly acts in order to undermine “state security.” Starting from the premise that RFE is the locus “of espionage, ideological diversion, and hostile propaganda,” the anonymous author traces the connection between this radio station and the American espionage machine, namely the CIA. The Central Intelligence Agency was credited with financing RFE and setting its agenda even after the American Congress officially took responsibility for financially supporting its functioning. The control of the CIA over RFE was underlined once again when discussing its organisation. The two management structures in the United States and Europe were allegedly infiltrated by CIA agents who engaged the radio station in their “ungentlemanly” war against communist countries and used it to collect information about them. As a result, the CIA used the microphone of RFE to proffer slanders and shamefully distort the realities of the communist countries, according to the Securitate’s interpretation of the broadcasting of news and other political programmes by this radio station. Even worse from the point of view of the Securitate was that people travelling abroad were an easy prey for “agents” working at the Romanian desk of RFE. After underlining the connection between its director, deputy director, and programme producers with the CIA, the article describes how they allegedly succeeded in manipulating Romanian tourists in order to collect valuable information about the country, its leadership, and the impact of its social and economic policies on the mood of the population. In other cases, they even managed to trick their “victims” and persuade them to emigrate. The narrative of blaming RFE for these “unpatriotic” deeds was an ideologically convenient explanation for the fact that the great majority of Romanians listened to and trusted RFE, in spite of the fact that this might have caused problems. At the same time, such a narrative was meant to highlight the vital role played by the Securitate as a guardian of the communist regime in Romania.

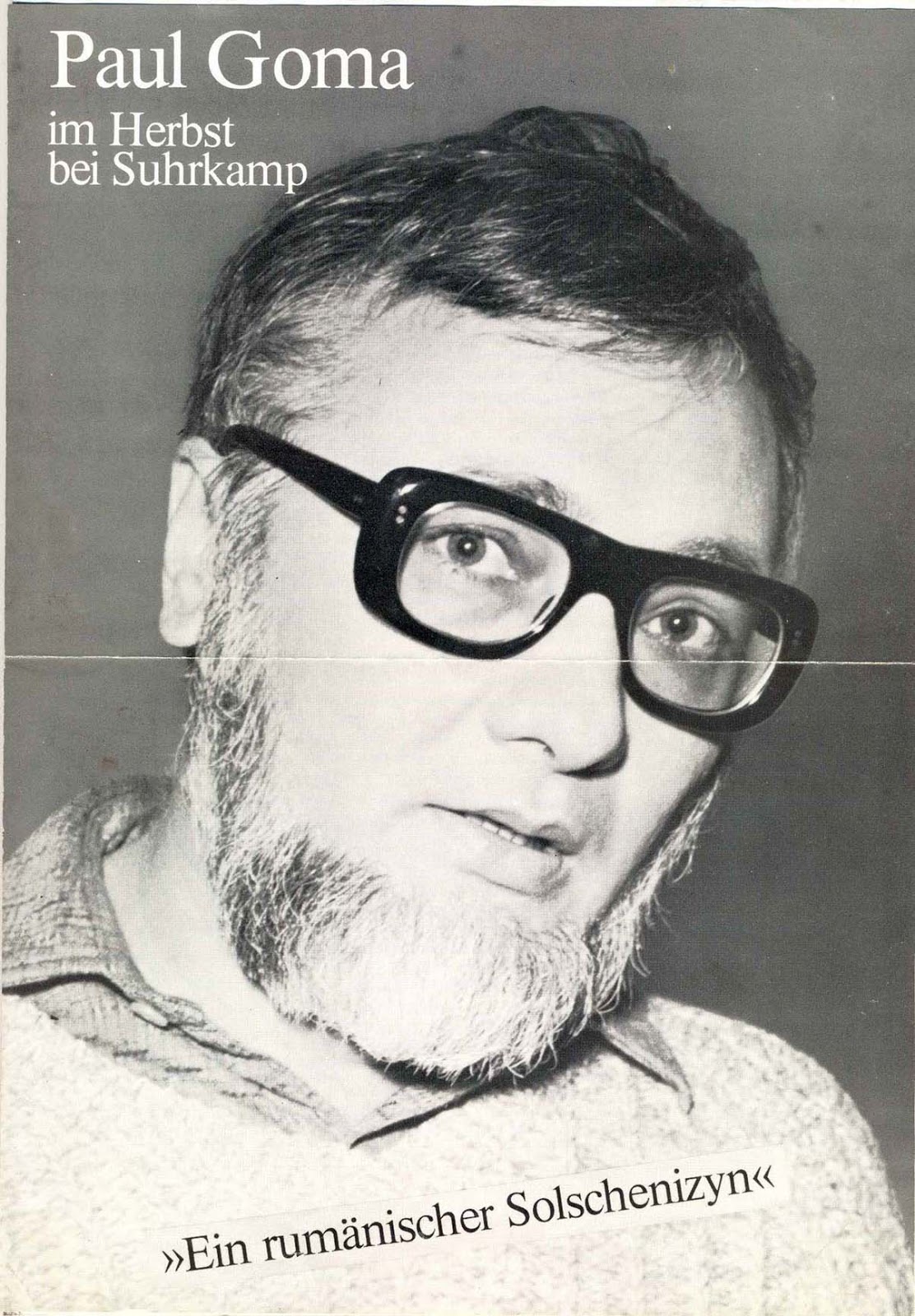

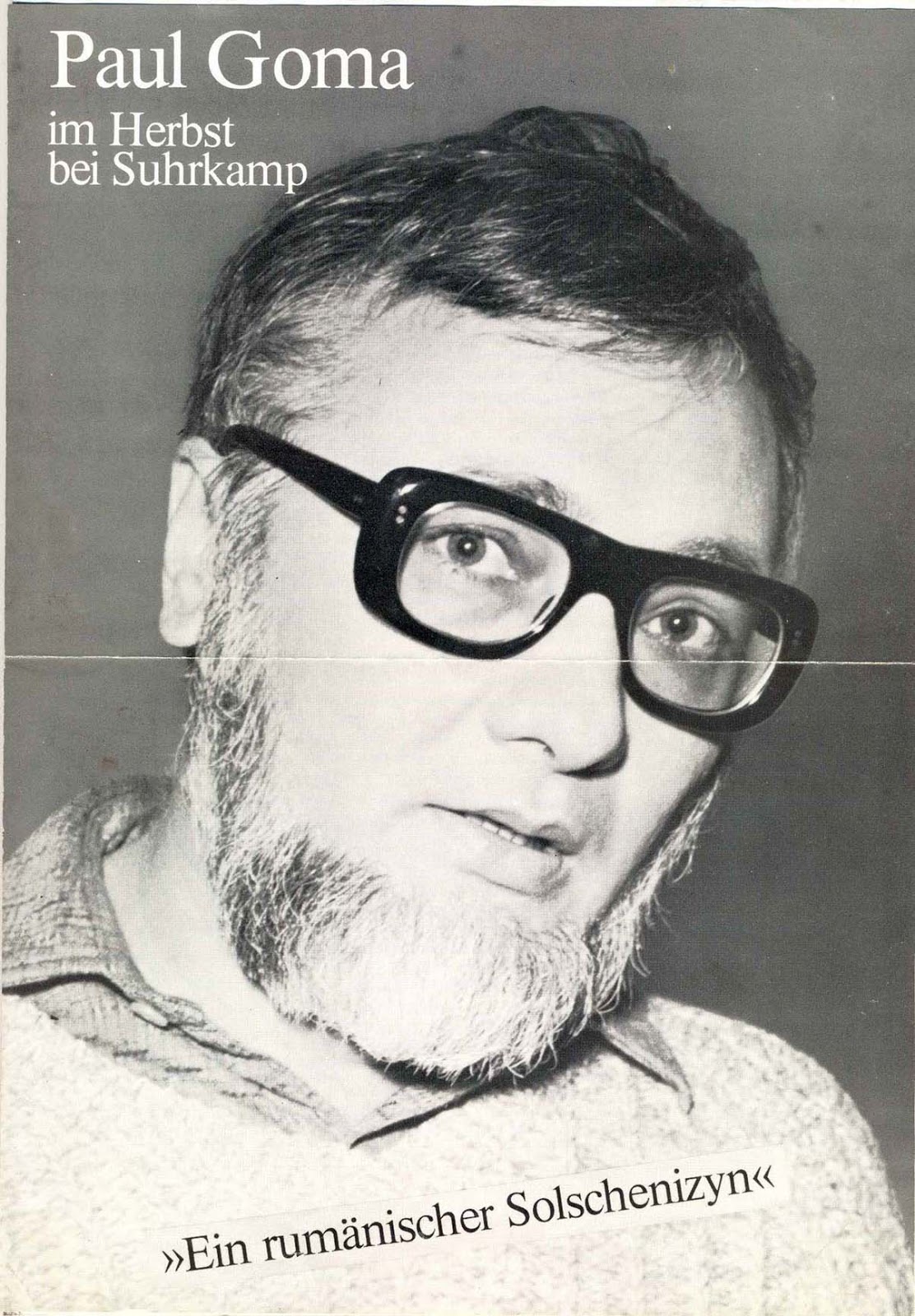

This collection consists primarily of the items confiscated by the Securitate on 1 April 1977, on the occasion of the house search and arrest of the driving force behind an emerging movement in defence of human rights in Romania, Paul Goma, a writer censored in Romania but successful abroad. A particular feature of this collection is that the confiscated items were not destroyed, but were preserved by the Securitate and finally transferred to CNSAS in 2002, from where they were returned to Goma in 2005. Thus, the collection is one of the few which travelled after 1989 from Romania into exile and is now to be found in Paris, where Goma was forced to emigrate a few months after his arrest and the confiscation of the collection.

The Victor Frunză Collection is an important historical source for understanding and writing the history of that part of the Romanian exile community which was actively involved in supporting dissidents in the country and in publicising in the West the repressive or aberrant policies of the Ceaușescu regime. In particular, the collection illustrates the activity of the collector and other personalities of the exile community for respecting human rights in Romania. Also, the documents of this collection reflect the involvement of Romanians from abroad in the reconstruction of democracy in their country of origin.

This letter is an important document for the history of dissidence in Romania, being a proof of the open opposition of a Romanian living in the country to the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu. In this case the writer was Victor Frunză, a Romanian writer and journalist, who in 1978 went as tourist to Paris. On this occasion, he contacted a representative of the Reuters Agency, to whom he handed a letter addressed to Nicolae Ceaușescu. He wrote the text of the letter in Romania and memorised its content in order not to carry it and be discovered at customs control. So he rewrote it from memory after he arrived in France. The material in question was published by Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung and broadcast by Radio Free Europe. Also, a copy of the letter was sent by Victor Frunză, by post, to Nicolae Ceaușescu. Essentially, his letter was a criticism of Ceausescu's dictatorship: "I want to manifest deep disagreement with the revival of the cult of personality, today is an improved version, decorated with the national flag." Frunză's conclusion was that "the type of socialist democracy in Romania is nothing more than a parody of discussions through speeches, even if these are not written by those who speak them." The document is in the IICCMER archive and is an original copy of the German letter published in 1978 in Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung. The letter was subsequently published by Victor Frunză in Romanian, at the publishing house he founded after the emigration, in the pages of the book For Human Rights in Romania (1982). The second edition of this volume appeared in 1990, in Bucharest, under the aegis of Victor Frunză Publishing House.

Jan Čep (1902-1974) was one of the most prominent representatives of modern Czech prose. His collection contains his manuscripts of radio reflections, which he wrote for Czechoslovak Radio Free Europe. Through his reflections, he tried to face totalitarianism and spiritually strengthen people "at home".

The events that transpired alongside the fall of the Romanov monarchy in February 1917, the takeover of the Winter Palace by the Bolsheviks in October 1917, and the dissolution of the Constitutional Assembly in January 1918 are immensely significant for understanding Ukrainian history and cultural opposition to communism. During that year of upheaval, many divergent visions for the future were articulated throughout the Russian Empire. In the Imperial Southwest, the Bolsheviks battled monarchists, nationalists, socialists, greens and anarchists over how to move forward during and after the collapse of empire.

The Ukrainian Museum-Archives has in its possession an original broadside of the Third Universal, issued by the Central Rada on November 20, 1917, in the four major languages used in the Imperial Southwest—Ukrainian, Russian, Polish and Yiddish. This document is reflective of efforts by the Central Rada to appeal to various communities living on the territory, while negotiating with the Provisional Government for greater autonomy. As historian George Liber notes, the first two proclamations of Rada did not define the borders of Ukraine, but the Third Universal asserted that the nine provinces in the Imperial Southwest with Ukrainian majorities belonged to the Ukrainian National (or People’s) Republic. The document also claimed parts of Kursk, Kholm/Chelm and Voronezh provinces, where Ukrainians also constituted the majority. The Central Rada also pledged to defend the interests of all national groups living in these territories and articulated a law protecting personal and national autonomy for Russians, Poles, Jews and others.

Shortly after this, the UNR established diplomatic ties with a number of European countries and even the United States. Britain and France tried to persuade the UNR leadership to side with them against the Central Powers, which they refused as they were determined to stay neutral. The Soviet Russian Republic initially recognized the UNR, but this was short-lived as the Red Army soon moved in from the north and east. This prompted the Rada to issue the Fourth Universal on January 25, 1918, which declared independence of the UNR as defined by the Third Universal. This made the push for greater autonomy within the context of empire a war of nationalist secession. (Liber, 62-63)

These early conflicts helped shape Soviet Ukraine’s relationship to Moscow for decades to come. In fact, Ukraine’s cultural, political and economic leadership struggled to define the parameters of engagement. Figures who were at the forefront of creating Soviet culture in the political and creative domains had to contest with the complex legacies of the Civil War of 1917-1922, which were never really fully resolved. Republican officials in particular (first in Kharkiv and later Kyiv) found it difficult to strike the right balance between autonomy and central control, regularly finding themselves on the wrong side of cultural policy after major shift in the priorities of Moscow.

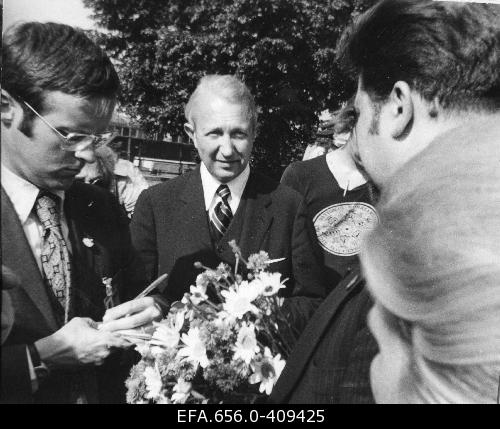

The Karl Laantee collection at the Estonian Cultural History Archive is part of the large archival legacy of Karl Laantee, an émigré Estonian religious activist, and announcer with the Voice of America radio station.

This sheepskin coat is one of the featured items of the Hnatiuk Collection at the Ukrainian Museum-Archives (UMA) in Cleveland, OH. The collection consists of more than 450 examples of Ukrainian textiles, which were produced for ritual ceremonies, for home use and as garments worn in the 19th and 20th centuries. Myroslav and Anna Hnatiuk compiled this vast collection of textiles over a number of decades. The first items were brought with them as they fled to the West along with hundreds of thousands of their compatriots toward the end of WWII. Though not classically representative of cultural opposition or resistance to communism, the motivations of the Hnatiuks make clear that their intention was to preserve pieces of Ukrainian culture until they were able to return home. As with other collections described in the COURAGE registry, folk art anchored Ukrainian resistance to communism within certain communities, more traditional forms of expression and clothing pushing back against the internationalism and uniformity that underpinned Soviet socialism.

Myroslav and Anna grew up in Galicia, part of the Western Ukrainian territories clandestinely annexed by the Soviets in 1939 as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The war disrupted his medical studies, which he resumed in Austria, eventually becoming a physician. He worked for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation in Germany before moving with his wife Anna and their sons to the US in 1949. They kept in touch with family and friends living in Soviet Ukraine, sending packages of food and clothing and receiving in return textiles and costumes. In the 1980s, they began traveling regularly to Ukraine, continuing to augment their collection with authentic leather, textiles, ceramics, and other folk items from Galicia and the Hutsul mountain regions.

The UMA published a volume about the Hnatiuk Collection (financed with a generous grant from the Ohio Humanities Council), which not only demonstrates the value of the Hnatiuk Collection as a whole, but also reveals a lot about the priorities of the museum’s leadership. When it came time for the Hnatiuks to find a new home for their collection, they invited (with help from Congresswoman Marci Kaptur) interested parties from Ukrainian museums and archives throughout North America. Many of those institutions tried to pick and choose the very best pieces for their own collections, while Andrew Fedynsky and Aniza Kraus of the UMA argued “the collection is an artifact in itself, a monument to a family’s dedication to Ukrainian culture.” As with many émigré communities, cultural preservation was an important part of life in the new world, nearly impossible to disentangle from the larger mission of diaspora institutions, which for a long time was to inculcate future generations with a sense of mission that contributes to the eventual liberation of Ukraine. The preservation of cultural heritage was part of a larger sphere of activism that included attending benefit concerts, church services, parades and demonstrations that both marked important turning points in history and supported Ukrainian independence.

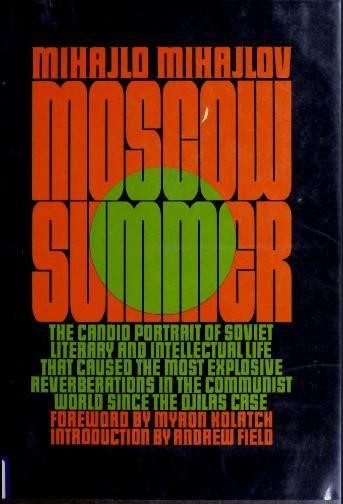

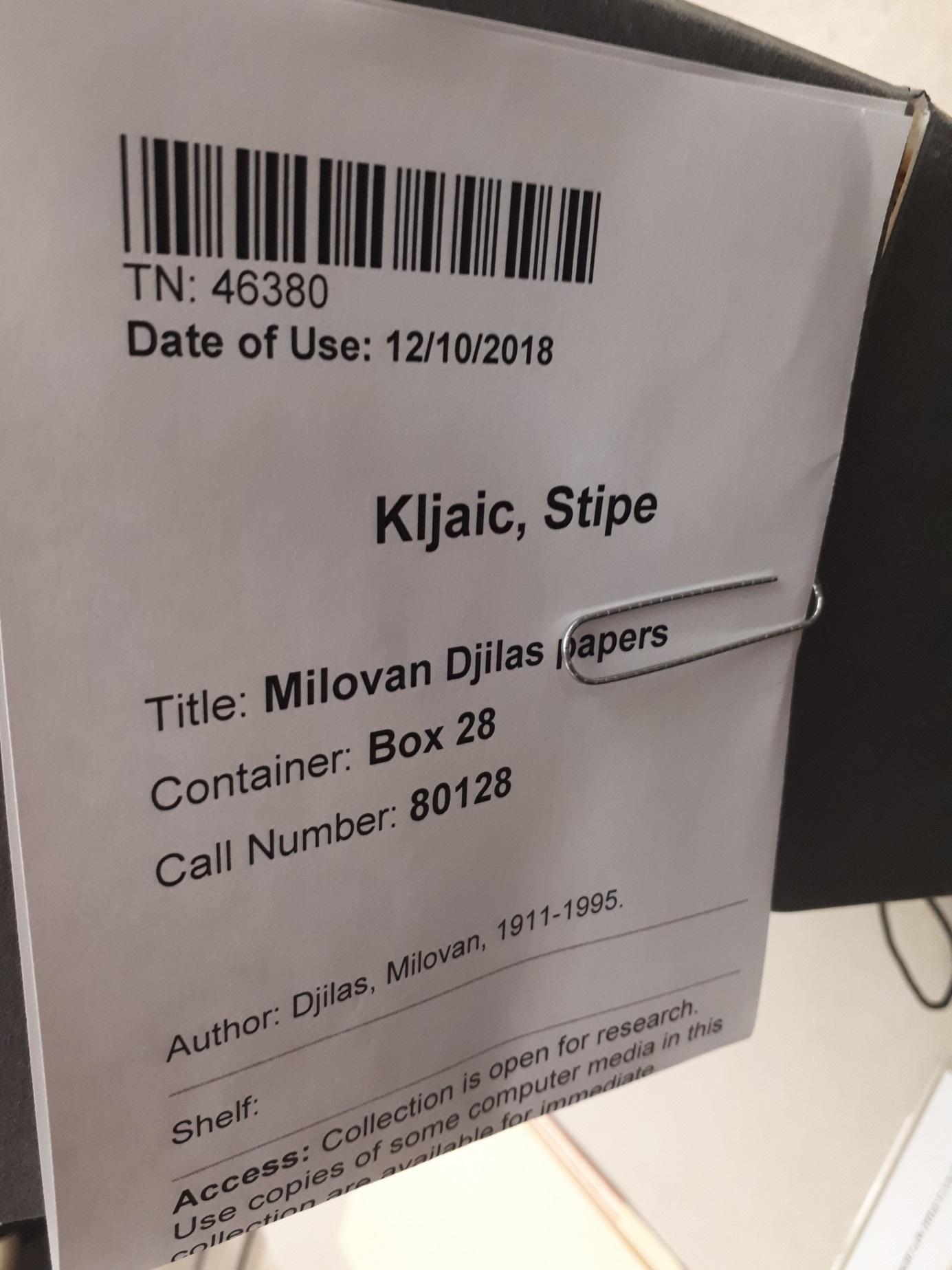

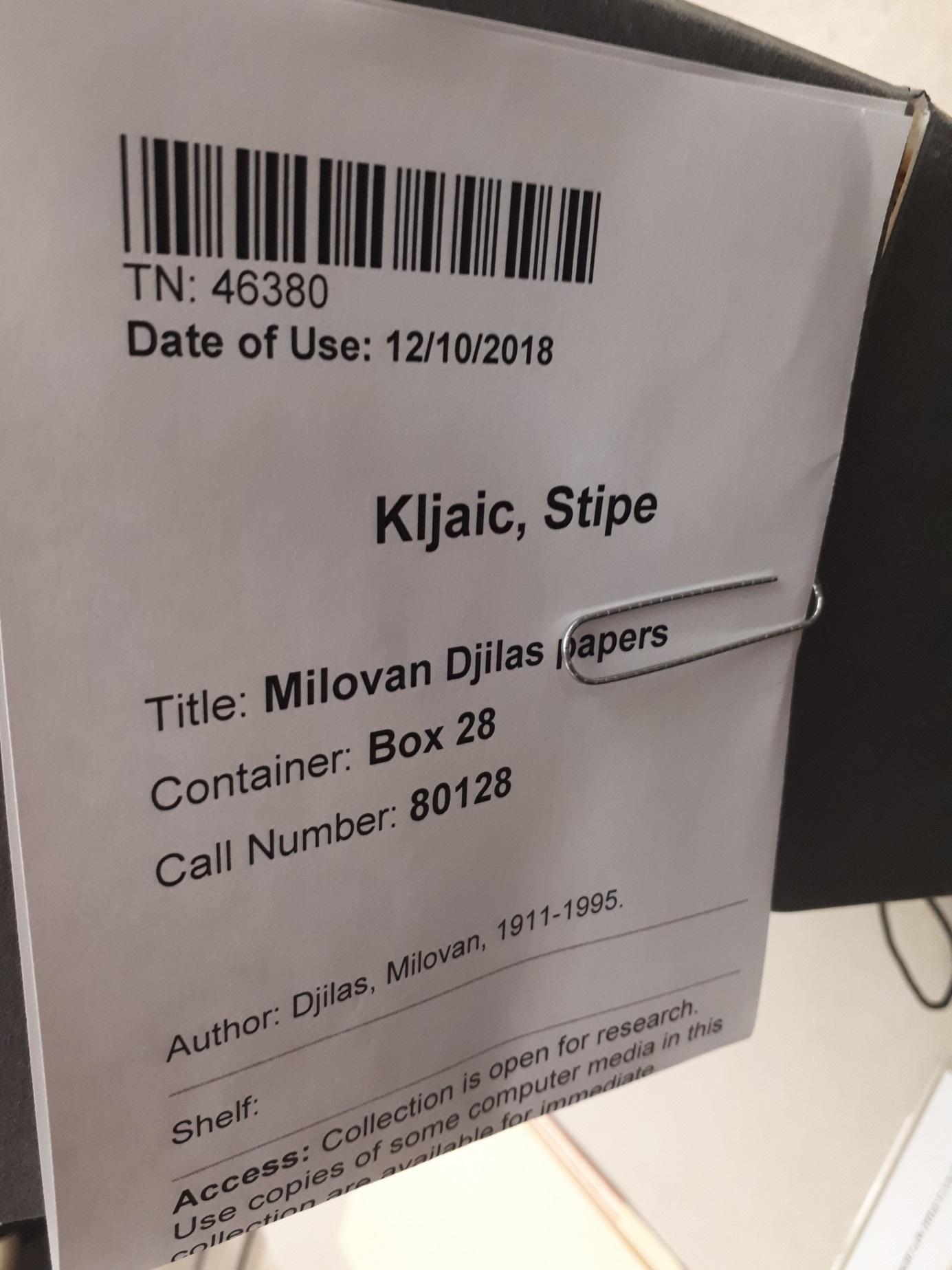

The manuscript of Mihajlov's travels, “Moscow Summer,” written in English is in the box 28. The text was the fruit of Mihajlov's visit to the Soviet Union in the summer months of 1964. Mihajlov supported Nikita Khrushchev's reforms and the program of de-Stalinisation, and he criticized the changes in the Soviet leadership after Kruschev’s fall. This criticism alarmed those in charge of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy, since it could once more undermine Soviet-Yugoslav relations, which had normalized in the mid-1950s.

Referring to the publication of the first two essays of this book, Tito himself called out Mihajlov in February 1965 as a result of pressure from the Soviet ambassador due to his criticism of the new political course following the fall of Khrushchev in the autumn of 1964. Despite censorship of Mihajlov’s essays in Yugoslavia, American politicians and the public were interested in Mihajlov's case precisely because of his stance on the Soviet Union during the political upheavals in the upper echelons of the Soviet party in those years.

Ivan Medek (1925-2010) was a prominent Czech music publicist, a signatory of Charter 77 and a founding member of VONS. In 1978 he went into exile, where he founded the Press Service and worked with Voice of America and Radio Free Europe. This collection contains unique documents from his exile activity.

The Libri Prohibiti’s collection of Czech exile monographs and periodicals contains over 8100 publications including the complete works of many publishers. More than 940 titles of Czechoslovak exile periodicals, some of them complete editions, are part of this collection as well.

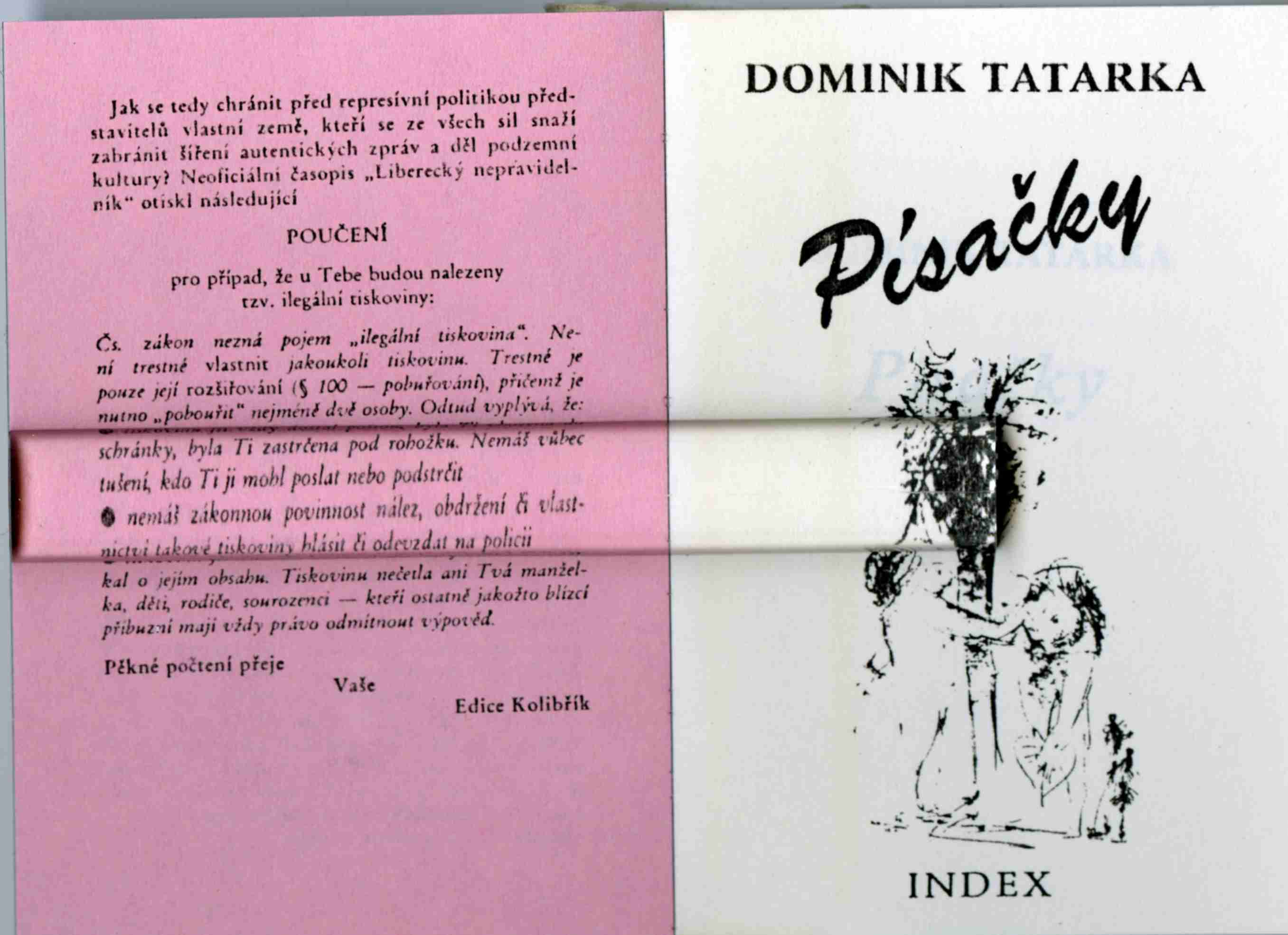

Ivan Blatný (1919–1990), an important Czech poet, lived and died in exile in the United Kingdom after 1948. Upon arrival in the UK, he applied for political asylum and became a “banned” poet in Czechoslovakia as a result of his emigration and openly talking on BBC radio about political pressure against artists in Czechoslovakia. Despite being banned, his work circulated in Czechoslovakia through both samizdat and official printings.

The Memory of Nations is an extensive online collection of the memories of witnesses, which is being developed throughout Europe by individuals, organizations, schools and institutions. It preserves and makes available the collections of memories of witnesses who have agreed that their testimony should serve to explore modern history and be publicly accessible. The collection includes testimonies of communism resistance, holocaust survival, artists of alternative culture and underground and many others.

The collection includes documents (archival material) stored in the archive of the "Commission for the Disclosure of Documents and Announcing Affiliation of Bulgarian Citizens with the State Security and the Intelligence Services of the Bulgarian People's Army", commonly called "Commission for Dossiers" (Comdos) in Bulgarian.

The collection documents developments among the Bulgarian intelligentsia during the communist regime through the perspective of the secret police and reveals their strategies of observation and persecution of critical intellectuals.

Ferdinand Peroutka, who represented the democratic past of Czechoslovakia, and mainly the First Czechoslovak Republic, became the director of the Czechoslovak section of Radio Free Europe (RFE) in New York on 6 April 1950. The Czechoslovak service of the RFE began its regular broadcasting from Munich on 1 May 1951 with the famous phrase “This is the voice of Free Czechoslovakia, Radio Free Europe.” One of the first speakers was also Ferdinand Peroutka, who stated, besides other things: “One magazine would mean little in a country where freedom reigns. But one free magazine, one radio station in a dictatorial regime – that is a revolution, because such a system is based on the fact that only the government can speak and nobody can answer back, that anyone can be charged, but nobody can defend themselves. However, once even a fraction of freedom enters that rigid and artificial system, from anywhere, once it is again possible to set argument against argument, once it is no longer possible to act without criticism, once there is a place to call untruths into question, then this whole proud system quavers.”

The Literary Archives of the Museum of Czech Literature possesses a mimeograph copy of the typescript of this speech.

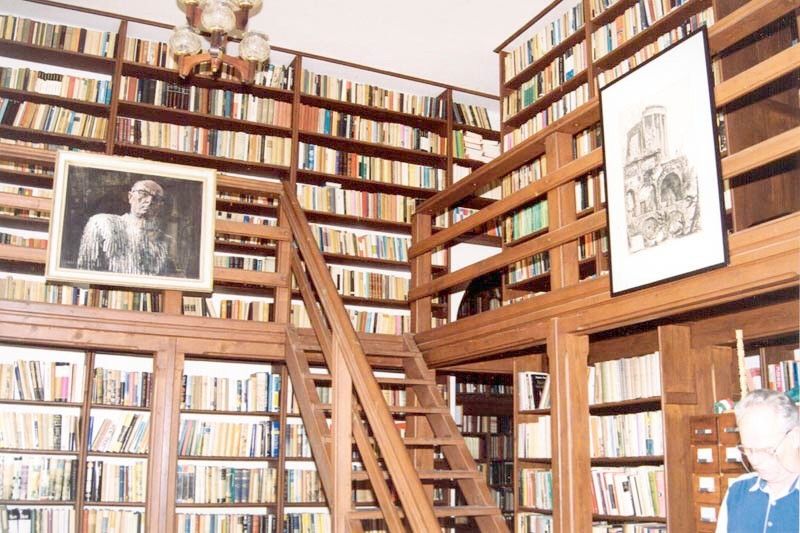

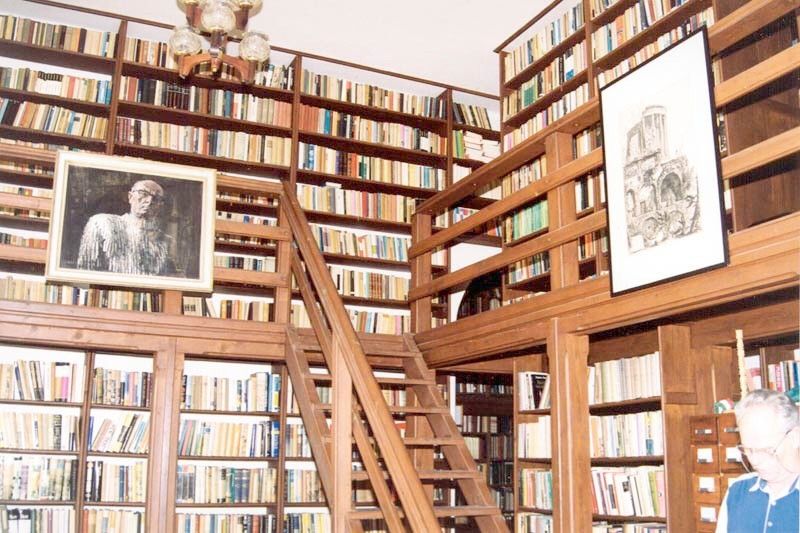

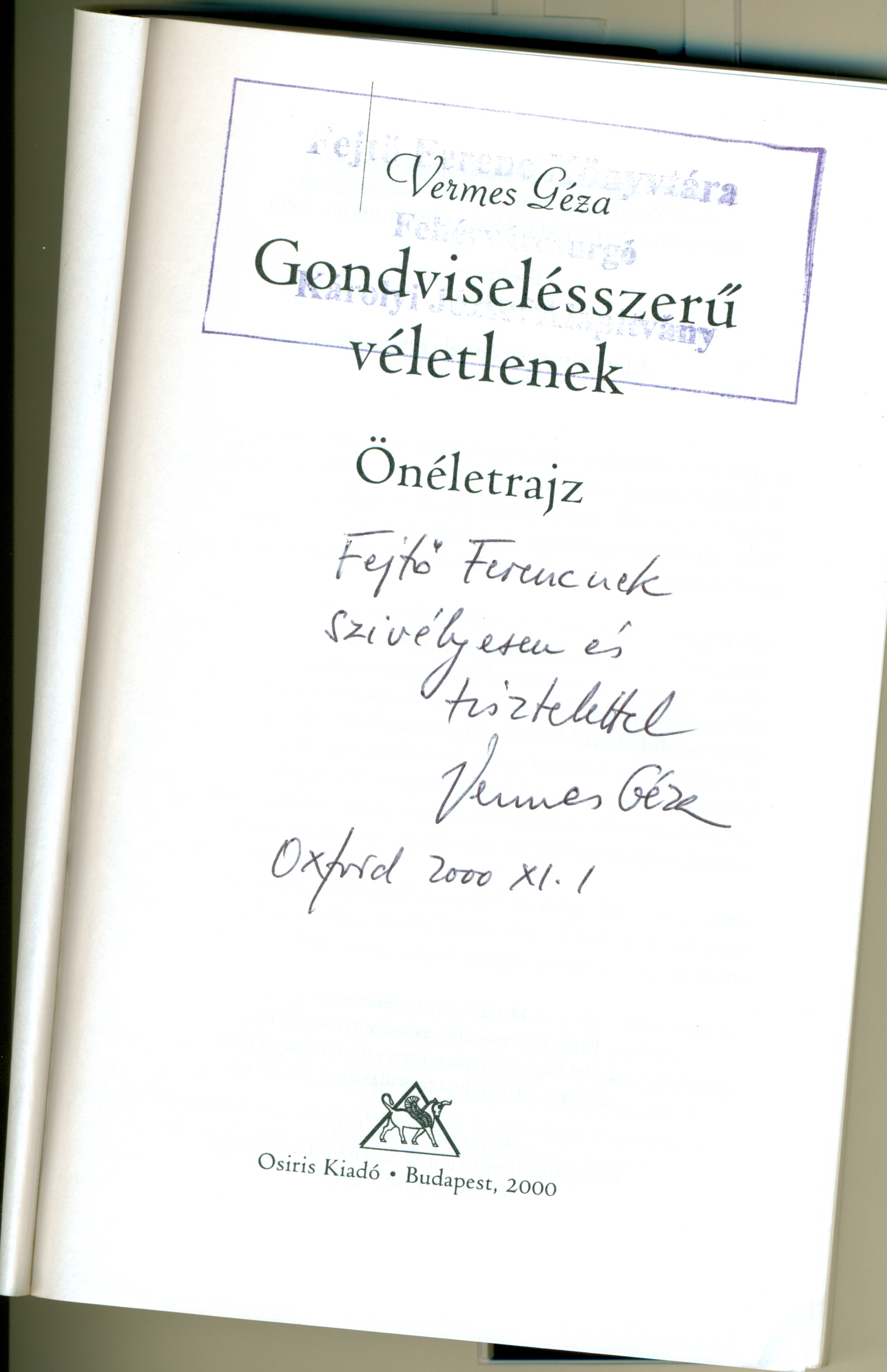

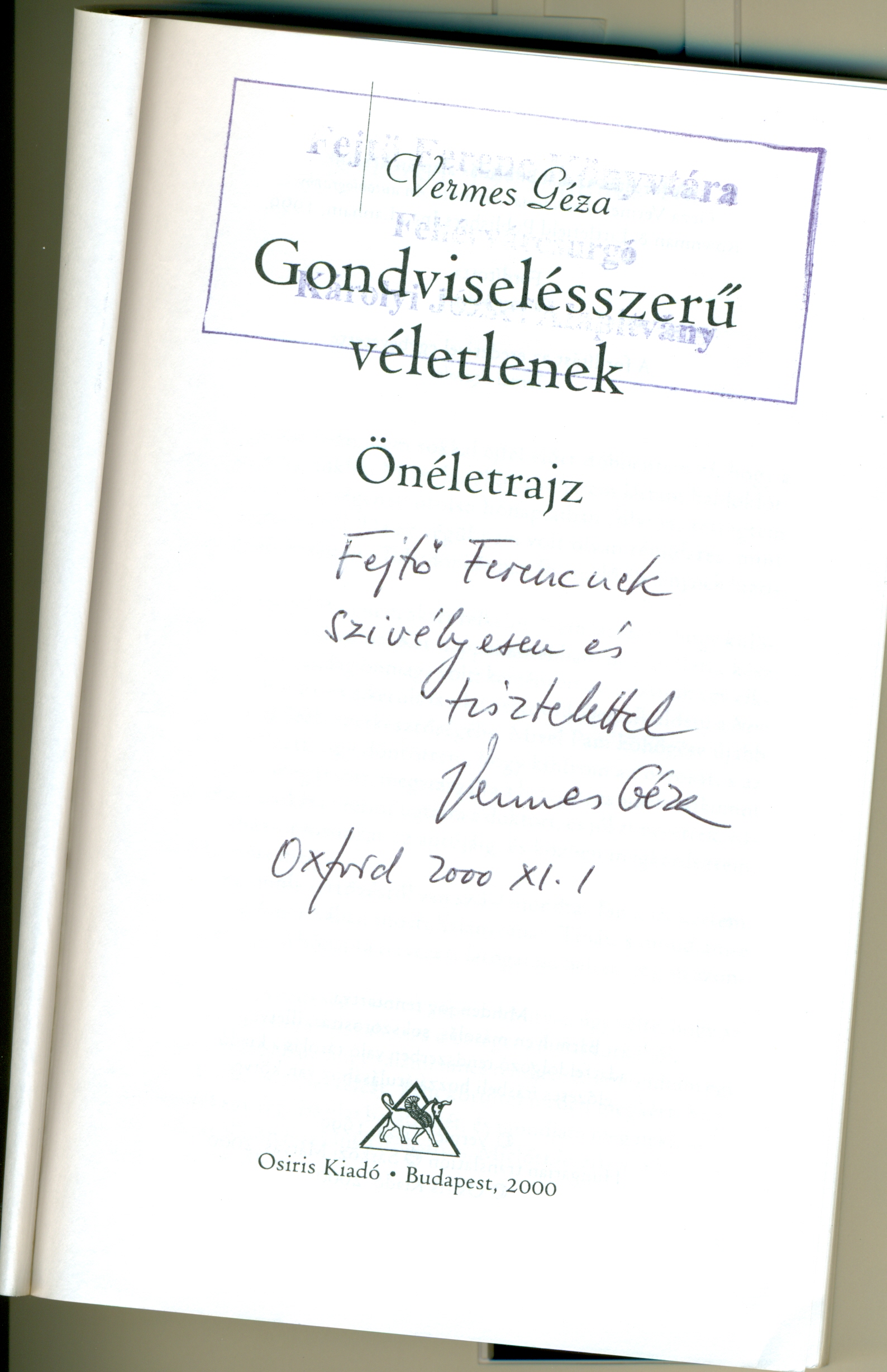

Ferenc Fejtő was an original, democratic leftist thinker. His library is a unique trace of the criticism of Eastern European rightist, authoritarianist, socialist dictatorship, and Western European leftist romanticism. Fejtő, who maintained strong connections with European intellectual elites, left Hungary for France in 1938, yet remained deeply committed to the fate of freedom-lacking Eastern Europe.

Čengić, Aziz. National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence, 1950. Article

Čengić, Aziz. National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence, 1950. Article

In the issue from 15 December 1950, the Croatian expatriate magazine Hrvatski dom published the article “Nacionalna politika Komunističke partije Jugoslavije u svijetlu borbe hrvatskog naroda za samostalnost” [National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence] by émigré Adil Zulfikarpašić, written under the pseudonym Aziz Čengić. Zulfikarpašić was a friend of Augustin Juretić and his associate until Juretić's death in 1954. It was Zulfikarpašić, together with Msgr. Pavao Jesih, who took over the magazine Hrvatski dom after Juretić’s death. The two of them edited the magazine until the last issue in October 1958.

In the article, Zulfikarpašić (Čengić) described the development of the national policies of the CPY since its establishment after World War I until after World War II, and concluded that "the theory of free nations of Yugoslavia, even with the constitutional right to secession from the union, is a façade – in reality it is rigid centralism carried out from Belgrade through the Central Committee of the CPY (Hrvatski dom, 15 December 1950, 2-3). Zulfikarpašić published a similar article, "Political report on the situation in Yugoslavia," in the newspaper Hrvaska riječ a month later (No 1-2, January-February, 1951). Similar analytical articles dealing with the issues of communist ideology and criticism of the communist government in Yugoslavia were published in Hrvatski dom continually in an attempt to influence the attitude of Western countries and their public opinion of Tito's Yugoslavia.

The manuscript of the article " National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence " is held in the Augustin Juretić Collection at the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome. The collection also contains a printed version of the article published in Hrvatski dom.

The collection belongs to the group of the most relevant archival resources for researching the communist regime’s relationship with and repression against religious communities in Croatia, and their organisations, priests and other religious officials. It contains documents collected or produced by the State Security Service of the Republic Internal Affairs Secretariat of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, the civilian security and intelligence service in Croatia in the period from 1946 to 1990. Different cultural opposition activities of certain religious communities and their members can be studied on the basis of its documents. Criticism (concealed and public) of communist rule and its social and political system, i.e. the official doctrine of atheism, is especially visible.

Securitate. Plan of Action against Goma and his supporters at RFE and in the Romanian emigration, 17 March 1977

Securitate. Plan of Action against Goma and his supporters at RFE and in the Romanian emigration, 17 March 1977

The Goma Movement Ad-hoc Collection includes numerous plans of action against the individuals involved in supporting the open letter of protest against the violation of human rights in Romania which was to be addressed to the CSCE Follow-Up Conference in Belgrade. Each Securitate informative surveillance file contains periodically updated plans of action, but these usually required only the approval of the high-ranking Securitate officer in charge of the case of the person in question. What is remarkable about this plan of action, which is part of Goma’s personal file, is its endorsement by the highest possible office holders in the Ministry of the Interior, to which the Direction of State Security was directly subordinated in 1977: the plan was countersigned by Nicolae Pleșiță, first deputy minister, and finally approved by Teodor Coman, the minister of the interior himself. Obviously, the hierarchical level of those who endorsed this plan indicates the great importance attached to this case. It is worth noting that the “successful” handling of the Goma Movement, in which Pleșiță involved himself and acted as Goma’s head interrogator, led to his promotion to the rank of lieutenant general in 1977. The same year, he coordinated the repressive measures taken by the regime in the aftermath of the Jiu Valley miners’ strike of August. Pleșiță remains notorious, however, for his actions while head of the Centre for Foreign Intelligence between 1980 and 1984, in particular for the 1982 failed attempt at suppressing Goma while in exile in Paris, and for the 1981 bomb attack on the RFE headquarters in Munich, for which the Securitate seems to have hired the infamous terrorist known as Carlos the Jackal. After 1989, Pleșiță showed no remorse for his misdeeds, and all attempts to hold him legally responsible for these wrongdoings eventually failed.

To return to this particular Securitate plan, its content and date of issuance illustrate that it was just an intermediate stage in the devising of actions meant to disintegrate the emerging movement. Chronologically, the date of issuance, 17 March 1977, is over a month after the open letter of protest against the violation of human rights was made public by Radio Free Europe, and thus it is entitled “plan of action for continuing the actions for annihilating and neutralising the hostile activities which Paul Goma initiated, being instigated and supported by Radio Free Europe and other reactionary centres in the West.” At the same time, it is a plan one step short of Goma’s arrest, which occurred two weeks later, on 1 April 1977. The document includes four separate types of action. The first type consists of the so-called “actions of discouragement, disorientation and intimidation,” which were directed mainly against Goma, but the necessity of tackling his supports separately is also mentioned. This type of action consists mostly of various forms of harassment up to the level of deporting him outside Bucharest in order to seclude him from his channels of communication across the border. These actions of rather soft repression were to be accompanied by attempts bring this problematic episode for the Securitate to a faster and neater end by convincing Goma to either give up or emigrate. The second category of actions included the use of the foreign press and publications in the attempt to compromise Goma and implicitly the movement for human rights initiated by him among the Romanian emigration and the Western audience. The third category referred to actions of counterbalancing the denigrating messages broadcast by Radio Free Europe, which was the radio agency that helped Goma the most. Finally, the fourth category consisted of actions to compromise Goma among the personnel of Western embassies in Bucharest, with the aim of depriving him of his channels of communication with RFE or other members of the exile community (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/6, f. 109-112). All these measures failed, and thus Goma was eventually arrested and brutally interrogated, including by First Deputy Minister Pleșită himself, but liberated approximately a month later, on 6 May 1977, due to the massive protests of the Romanian emigration in Paris, which managed to convince many outstanding personalities to sign a petition for his release. This plan of action testifies to the Securitate practice of spreading calumnious rumours about all those who spoke against the regime in order to defame and isolate them. As Goma himself observes, “a document of great importance for me. (…) I knew that (…) the [calumnious] rumours and gossip (…) were inspired by the Securitate. Now I have the proof that the Securitate was not only inspiring, but also authoring them” (Goma 2005, 397).

The Bogdan Radica Collection is a personal archival fund which Radica founded in the late 1940s. His daughter Bosiljka Raditsa and Professor Ivo Banac delivered the entire collection to the Croatian State Archives (CSA) on three occasions in 1996, 2001 and 2006. It contains vital records related to the history of Croatian political emigration and constitutes an integral part of the cultural opposition to the Yugoslav communist regime.

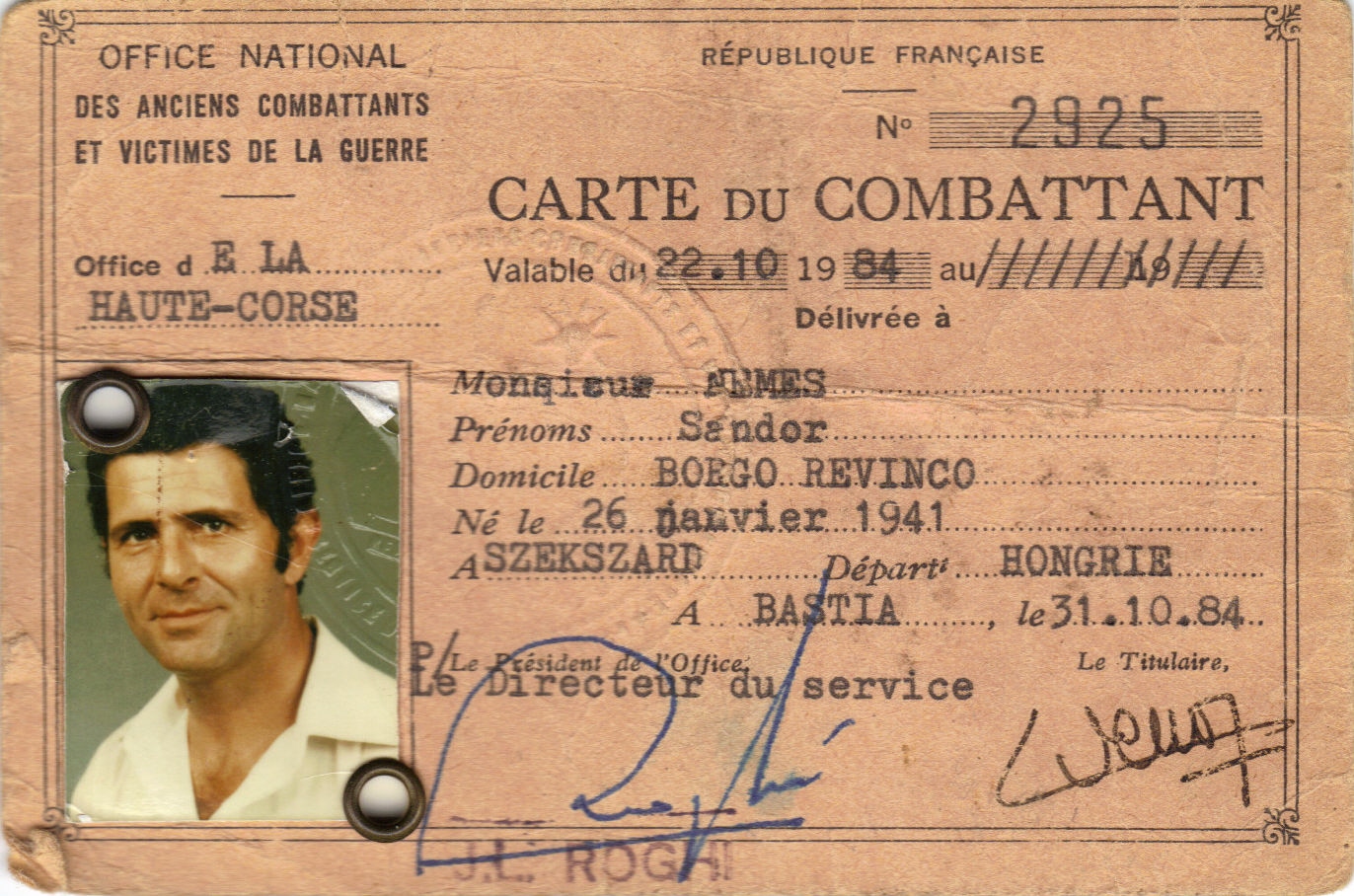

The multiethnic, multilingual, and multicultural world of the French Foreign Legion, that throughout its almost two century long past has recruited its volunteers from among 150 nations, is well reflected by the manuscript “The Slang Vocabulary of the Legionnaires,” edited by Sándor Nemes, a Hungarian veteran residing in Course for close to 50 years now. It provides an authentic insight into the odd group identity of its many Hungarian recruits throughout the twentieth century. To better understand this, one needs to become acquainted with some basic facts of the Legions’ history. The French Foreign Legion, founded in 1831 by King Louis Philippe in Algeria, is still an active and legitimate French armed force, today with some 9,000 mercenaries, that still preserves much of its traditions, although since the 1960s it has been transformed from an old-fashioned colonial army into a modern elite force specialized for international missions of peace maintenance, humanitarian and anti-terrorist tasks, both in France and worldwide.

Ironically enough, the French Foreign Legion, due to several grave economic, political, and war crises, preserved for more than a century the traditional dominance of its German-speaking recruits (from Switzerland, Austria, Germany, and elsewhere), who left behind far-reaching effects even on the language use of the Legion’s command and its folklore, e.g., the military marches, which all used to be German songs. Therefore, it is not at all surprising that following 1945 and 1956, when more than 4,000 Hungarians joined the Legion, this newly arrived ethnic group also began to strengthen its cohesion against the challenging dominance of the “German mafia,” as Sándor Nemes and his fellow Hungarian veterans recalled in their accounts. This was, of course, but a limited and rather informal rivalry given the strict hierarchy and the wartime conditions (in Indochina, and Algeria!). Still a “two-front” cultural resistance emerged ever more markedly among the Hungarian volunteers, on the one hand against the mostly native French officers, and the German warrant officers on the other. In fact, at a closer look the Hungarian recruits (who were called “Huns,” “kicsis,” or “Attilas” in the common slang used by the Legion) were not homogenous either, especially as far as their cultural and political identity was concerned. Although the age difference between them was hardly more than 10–15 years, they belonged to two markedly different generations: the ’45-ers, or the “Horthy’s hussars,” recruited mostly from POW and refugee camps after the end of WWII, and the ’56-ers, who fled to the West when the Hungarian revolution was violently suppressed. The main difference between the active ’56-ers and the rest of the Hungarian legionnaires could be felt most in their attitudes and group identity, since the former were much more united in their common engagement in the revolutionary events and battles that they experienced as very young men or even minors. As members of the Hungarian veterans’ circle in Provence, they were the ones who kept in contact for decades and preserved the memory of the revolution up to the present day with their special group rituals (like banquets, memorial meetings, and the sharing of their revolutionary experiences and relics).

These can be best illustrated with a number of funny, original, and telling entries in Sándor Nemes’s “The Slang Vocabulary of the Legionnaires,” especially in its Forward and in Chapters 2–6. (2. Slang and loanwords used by legionnaires; 3. Figures of speech, idioms, and proverbs; 4. The most common German phrases; 5. The most common Arabic loanwords; 6. Bynames of ethnicities and nationalities in the slang used by legionnaires.)

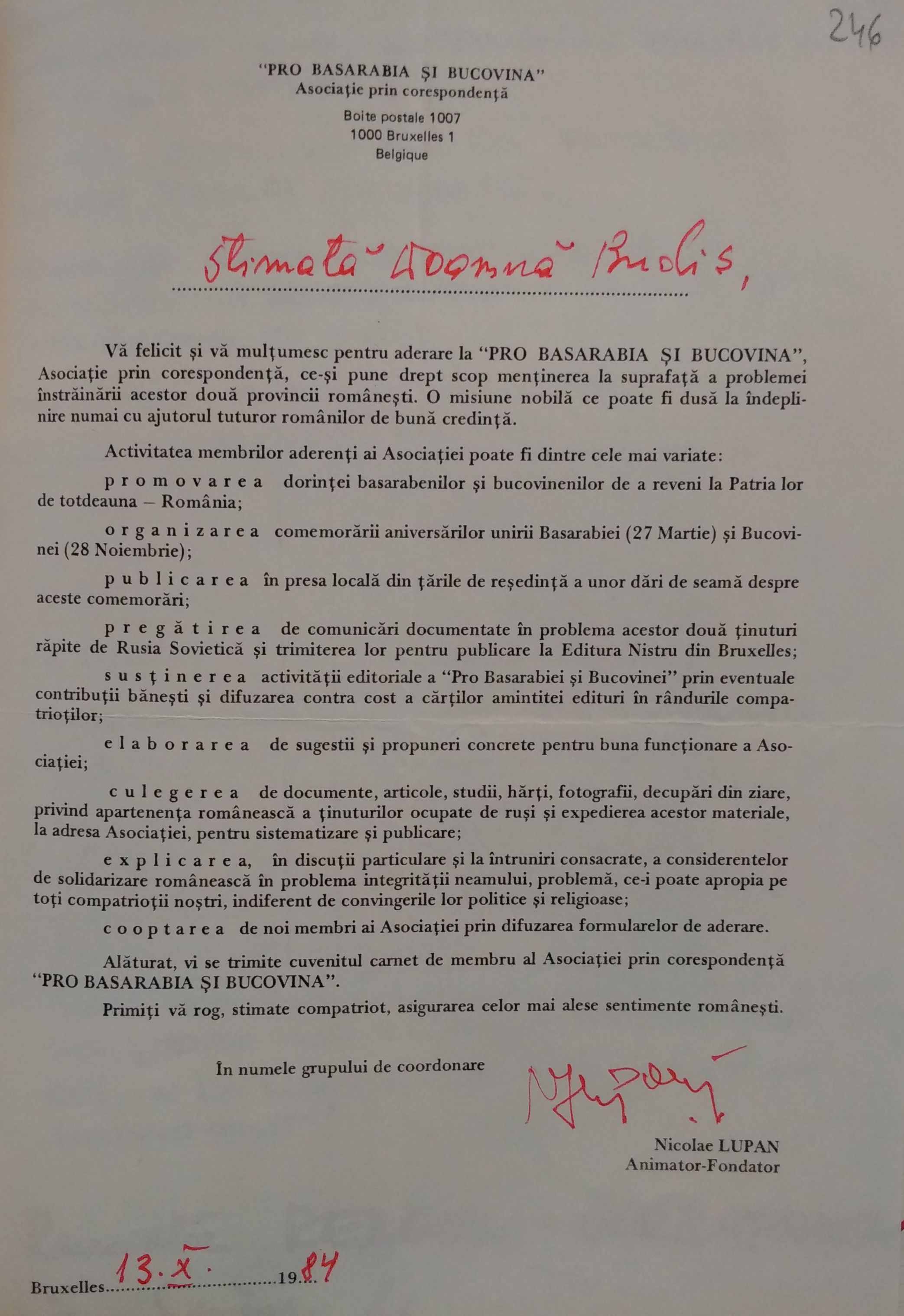

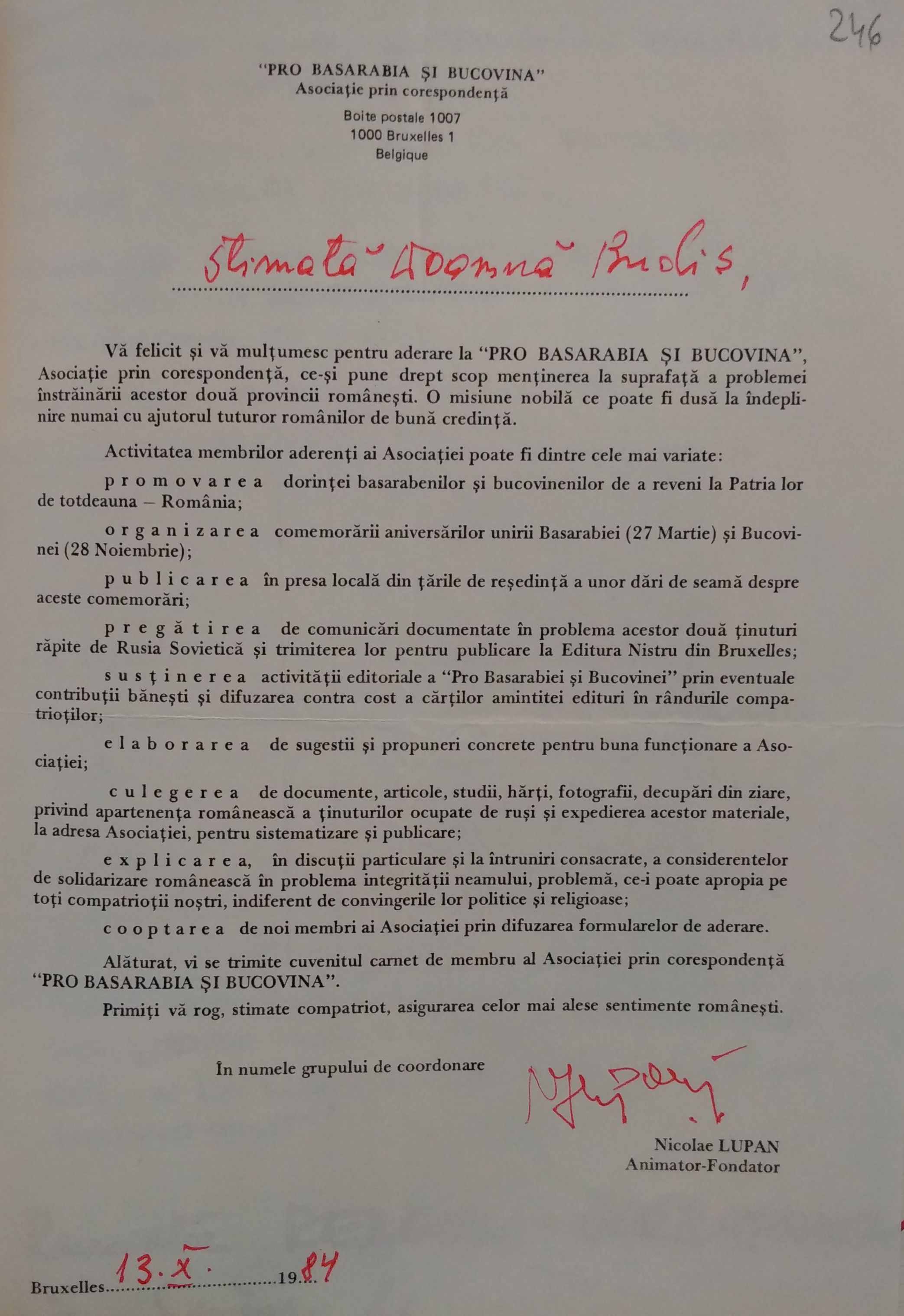

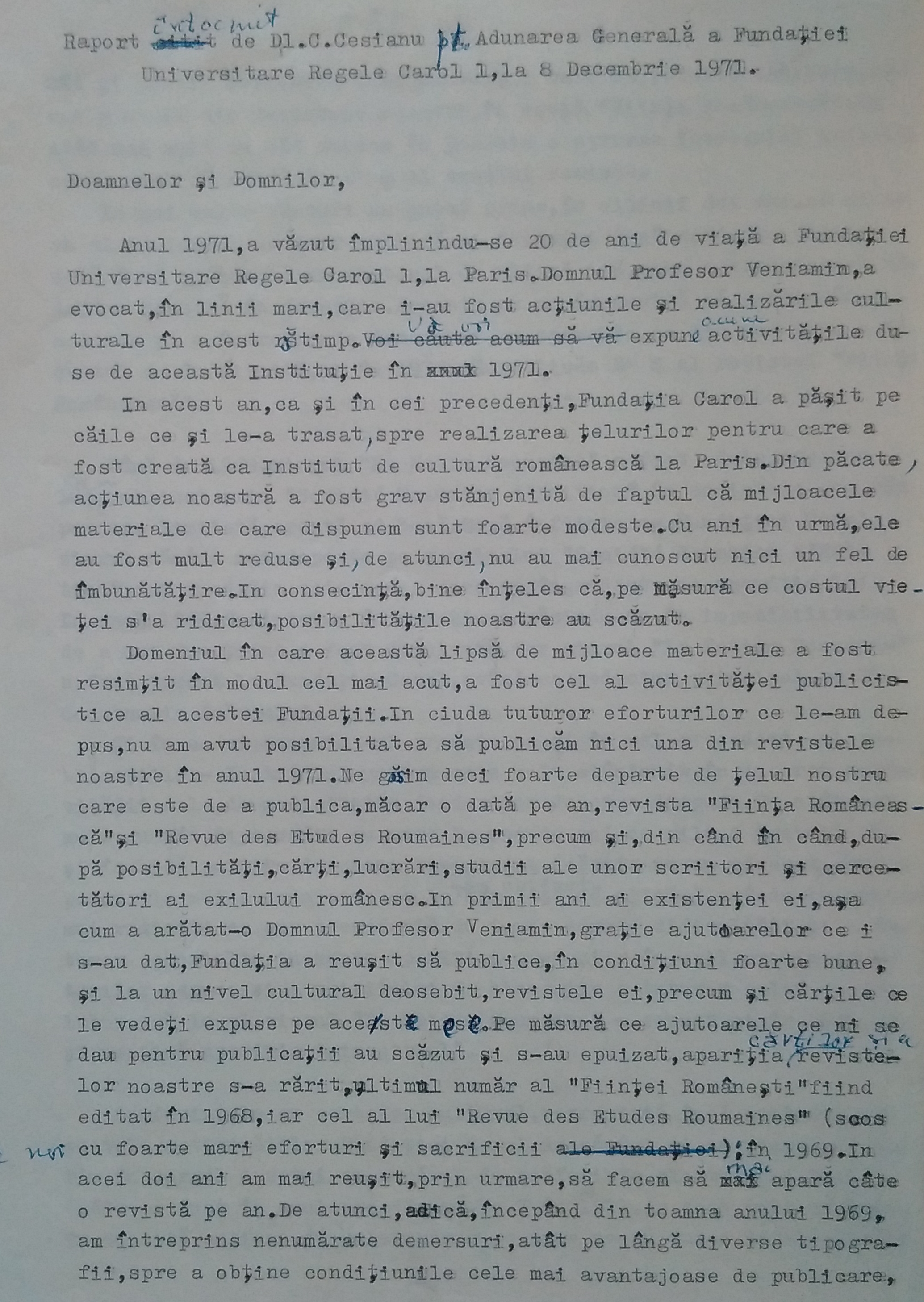

This document is an important source of documentation for the understanding and writing of the history of the Romanian exile community in the 1980s. It concerns the organisation that Romanians of the emigration established to unmask the wrongdoings of the communist regime in their native country to the West in the hope that they would find external support for the removal of communism in Romania. In particular, the document illustrates exile actions for the observance of human rights in Romania, as it testifies to the existence of a political body set up for this purpose, namely Liga Românilor din Exil pentru Drepturile Omului (The League of Romanians in Exile for Human Rights). It had its headquarters in Paris and was coordinated by Virgil Veniamin, who was a personality of the exile. A graduate of the Law Faculty of the University of Paris in 1930, he was a professor of international law and a lawyer, as well as being a distinguished member of a Romanian political party, the National Peasant Party. The establishment of the communist regime found him at home in Romania, which he left clandestinely in February 1948, settling in Paris. In exile, he was particularly noted for his activity as president of the Carol I Royal University Foundation and as a member of the Romanian National Committee, considered by its founders as the Romanian government in exile. In the 1970s he was involved in a major scandal in the Romanian exile community when he was accused of collaborating with the Securitate in Bucharest. Today, based on the documents contained in the file on him created by the former Romanian secret police, it can be ascertained that he was indeed an agent of influence of the communist regime within the exile community. The document kept in the Ion Dumitru Collection is a request sent by the collector to Virgil Veniamin on 23 February 1980, asking him to accept affiliation to the central section in Paris of Liga Românilor din Exil pentru Drepturile Omului (The League of Romanians in Exile for Human Rights) of a newly established West German section based in Munich, in which Ion Dumitru had been elected chairman. In response to this request, Ion Dumitru received a favorable reply from Virgil Veniamin. Both documents, in A4 format, can be found in the private archive of Ion Dumitru at IICCMER.

The Oral History Collection at CNSAS is a unique collection of this kind as it includes only interviews with individuals who are the subjects of personal files in the CNSAS Archives, and who after studying these personal files created by the Securitate agreed to narrate their own experience of entanglement with the secret police. The interviewees include not only individuals who were under surveillance and thus victims of the Securitate, but also individuals who collaborated with the secret police to provide information on others: family, friends, and colleagues. Both types of interviews represent the response of the interviewees to the narrative created about them by the Securitate.

The Ștefan Gane Collection documents in photographs and slides the extent of the demolitions imposed by the so-called systematisation programme in Bucharest following the devastating earthquake of 4 March 1977, which the communist regime used as a pretext for destroying or mutilating numerous historic monuments. The Ștefan Gane Collection is also an important source for understanding and writing the history of that particular segment of the Romanian exile community which was extremely active in disseminating in Western countries information about the aberrant policies of the Ceaușescu regime. In particular, this personal archive illustrates the efforts of the collector and of other personalities from the exile community to stop the systematisation of Bucharest.

The collection contains material about Sergei Soldatov, one of Estonia's most notable dissidents, who was culturally most active when living in exile after 1981. There are different types of documents and photographs in the collection, which describe not only Soldatov's life, but also the activities of dissident movements in the Soviet Union. Soldatov also used this material in his numerous books, which he published himself.

The collection testifies to the thirty-six-year activity of Croatian journalist and writer Jakša Kušan (1931), who propagated the idea of a democratic, pluralistic and free Croatia in exile from 1955 to 1990. By editing and publishing the non-partisan magazine Nova Hrvatska, he tried to inform the Croatian and global public about the suppression of human rights and civil liberties in socialist Croatia and Yugoslavia.

The collection contains approximately 68,800 intelligence files produced by the State Security Service of the Republic Internal Affairs Secretariat of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, the civilian security and intelligence service in Croatia in the period from 1946 to 1990. The Service monitored all persons whose activities were assessed as a threat to the state's political and security system. A significant number of files pertain to members of religious communities, political émigrés, participants in the Croatian Spring, as well as other political and intellectual dissidents.

The Ion Dumitru Collection is the richest and most diverse of all the private archives of the Romanian exile community, which makes it indispensable for the study of the history of postwar Romanian exile. The collection is also a fundamental source for documenting and understanding Romania's (domestic and foreign) political, cultural, economic, and social evolution during both the communist and post-communist periods. At the same time, this private archive is a historical source both for understanding how the Bucharest authorities acted to divide the Romanians abroad and to counteract their actions aimed at unmasking the wrondoings of the communist regime between 1948 and 1989 in the West and for how Romanians within the country perceived the emigrant community.

Ivana Tigridová (1925-2008) was a journalist and human rights activist. She was one of the most distinguished personalities of Czechoslovak exile. In Paris, she founded two organisations supporting prisoners and persecuted opponents of the regime in Czechoslovakia and other countries of the Eastern Bloc.

The digital collection of the Oral History Center contains more than 2000 interviews with twentieth-century witnesses, which are divided into different themes and topics, thus presenting a unique collection of professionally created interviews and memories, many of which are related to the theme of cultural opposition.

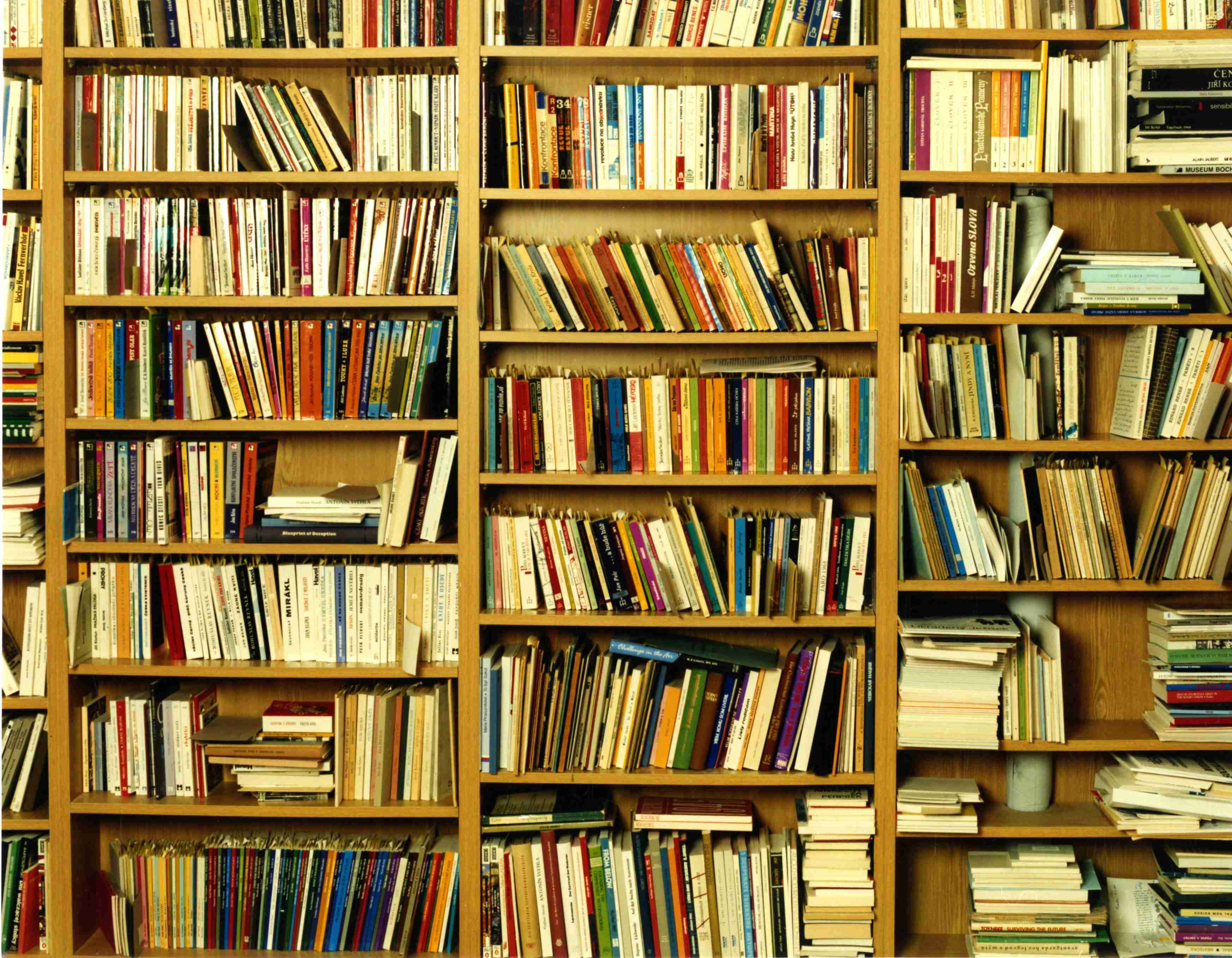

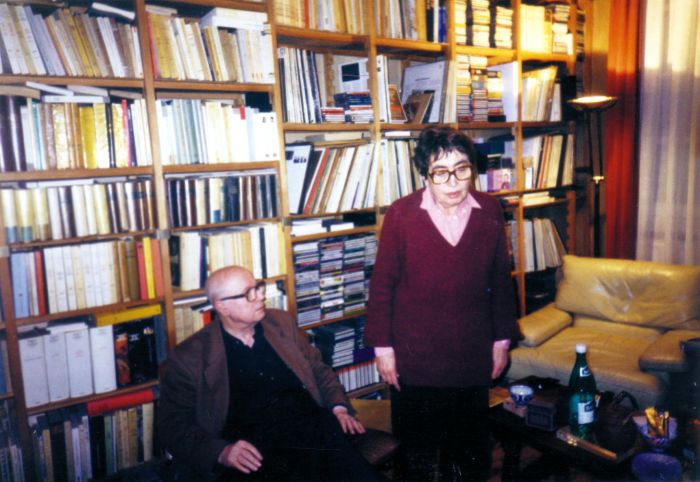

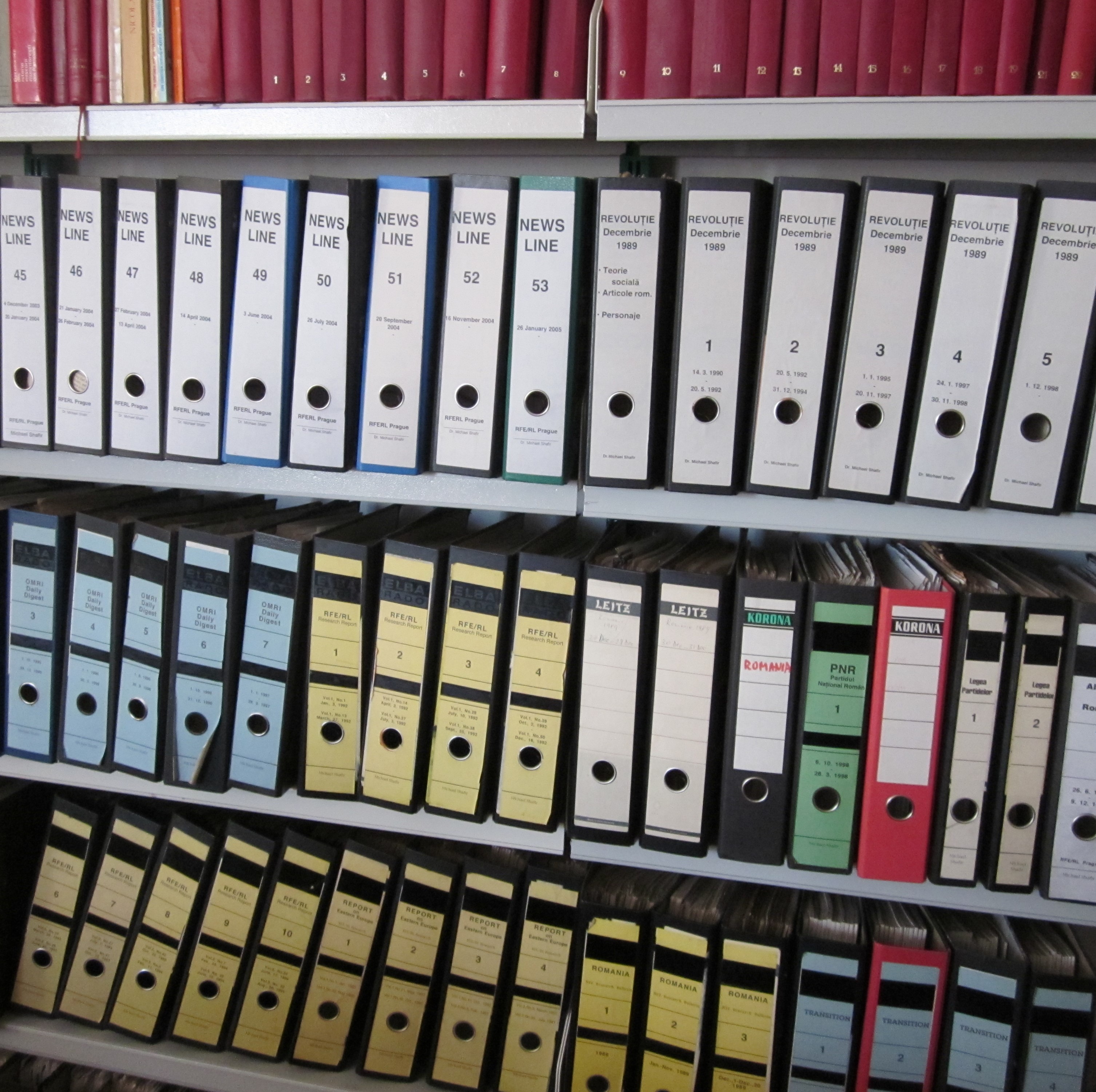

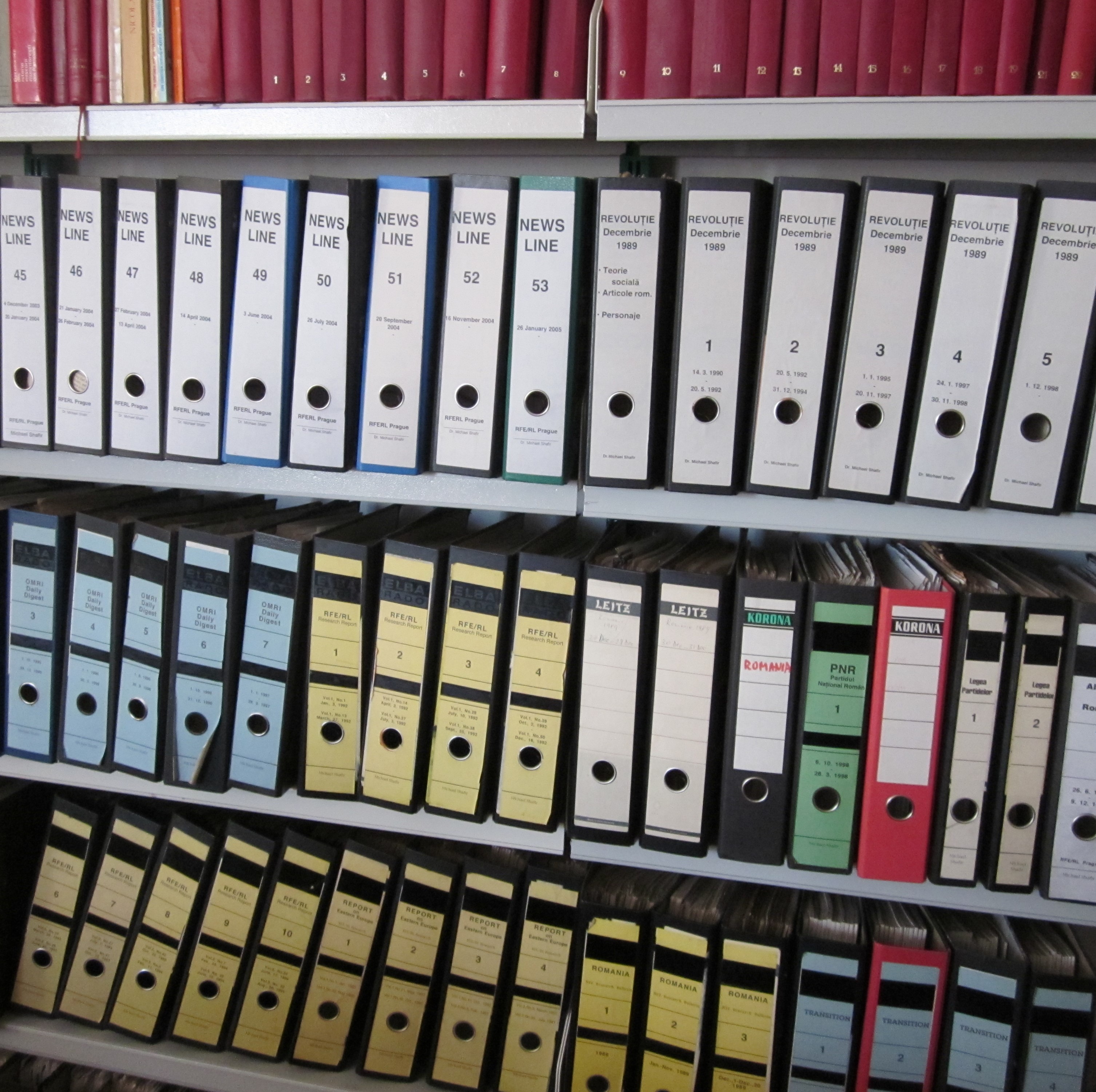

The collection is illustrative for the documentation work that lay behind the broadcasting activities of two prominent members of the Romanian exile community in Paris who worked with Radio Free Europe (RFE), Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca. Their programmes focused mainly on presenting the cases of dissidents in the then Soviet Bloc. The need to understand the dissidence phenomenon and the main ideas behind its criticism of the communist regimes required diverse readings from different subject areas. Thus, the Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca Collection in Oradea testifies to the interest of its creators in subjects relating more or less to cultural opposition in the fields of literature, philosophy, sociology, history, art, and religion.

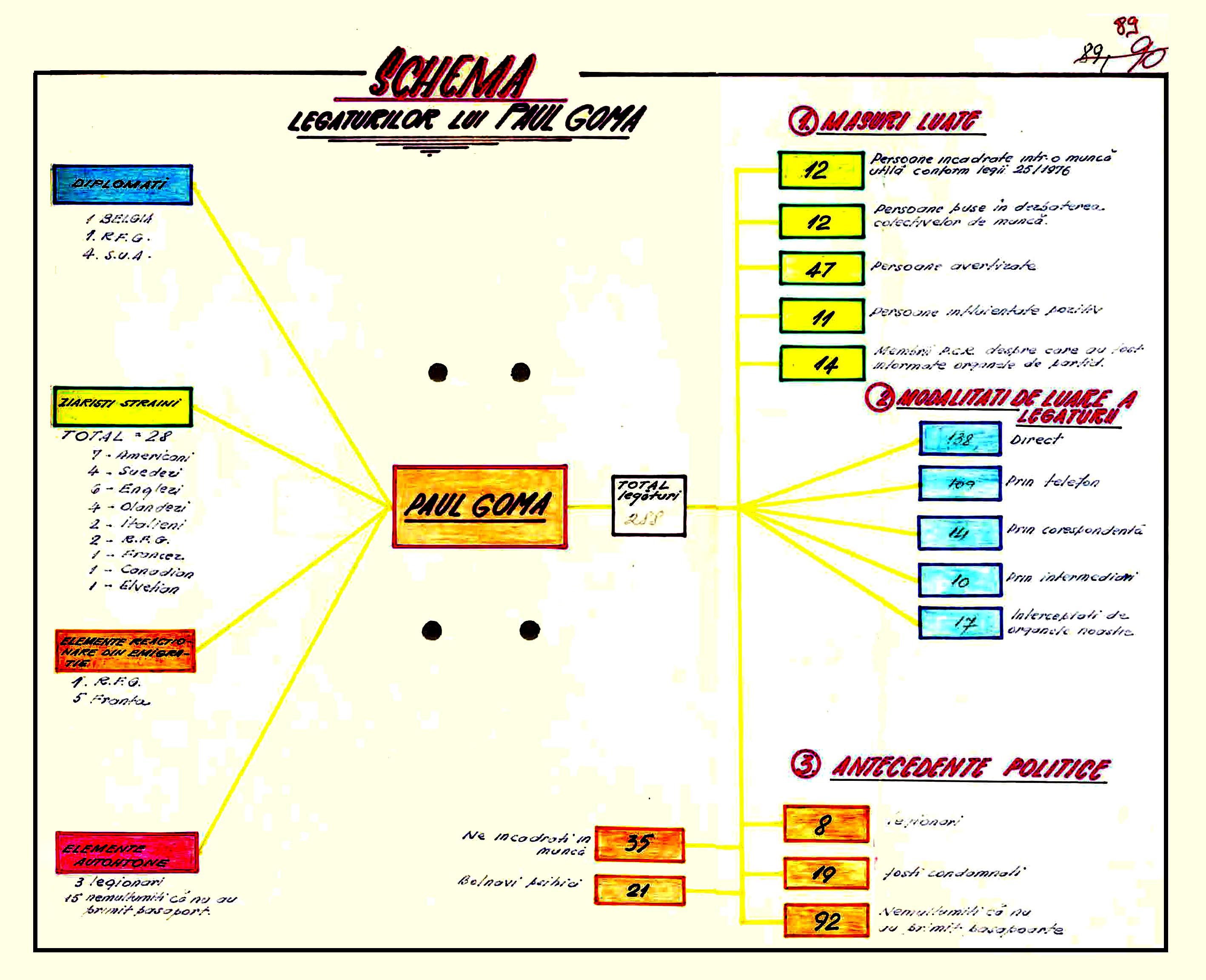

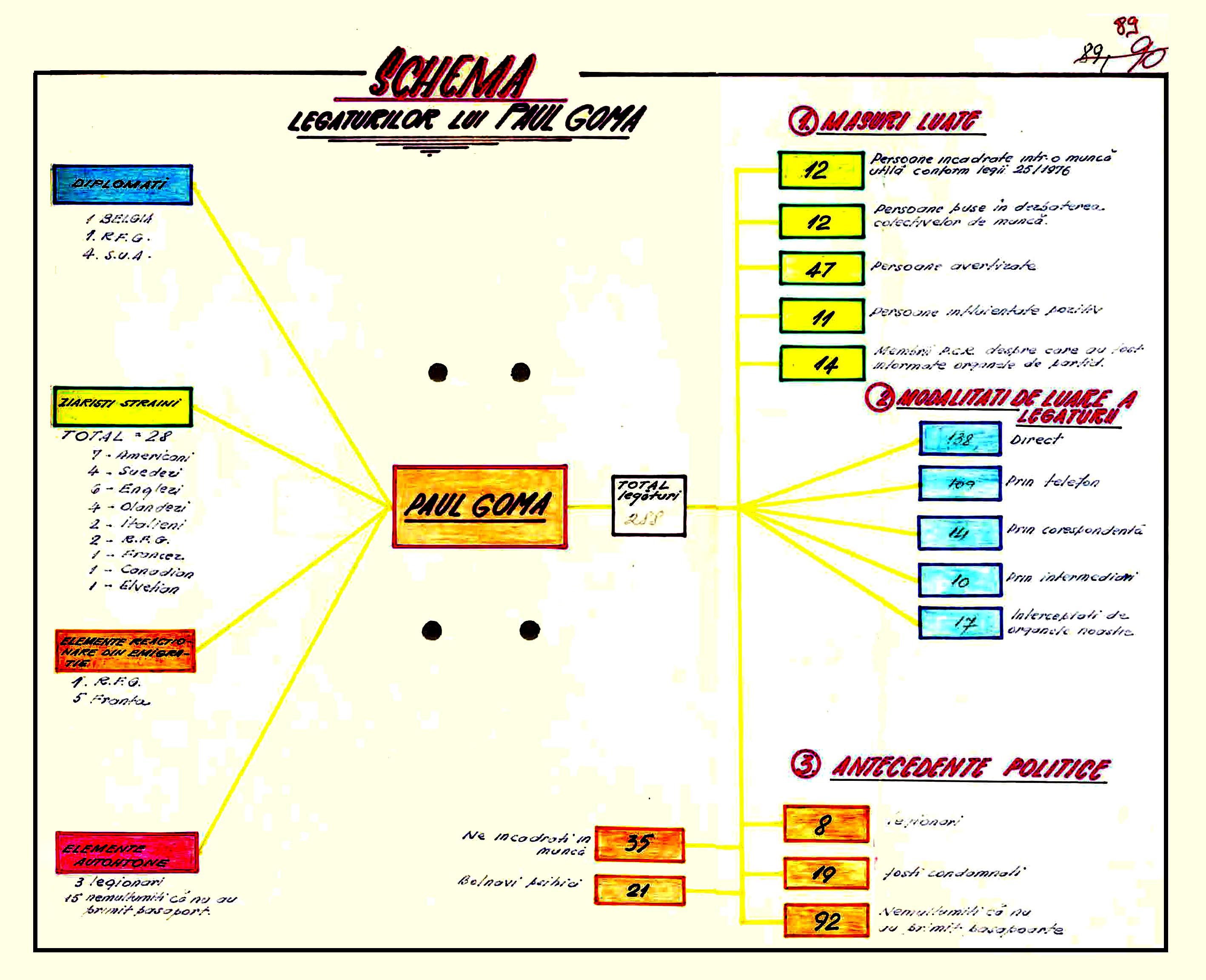

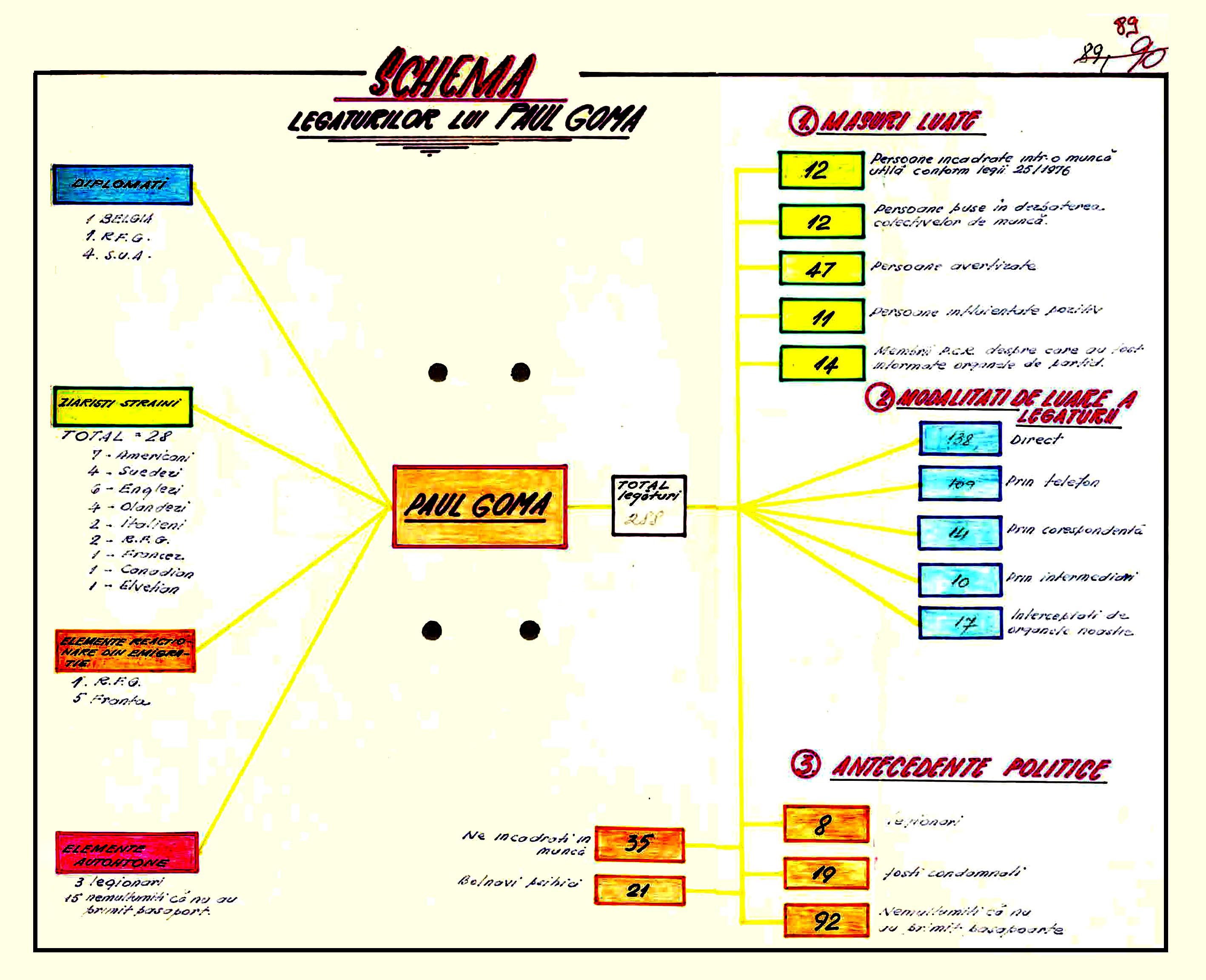

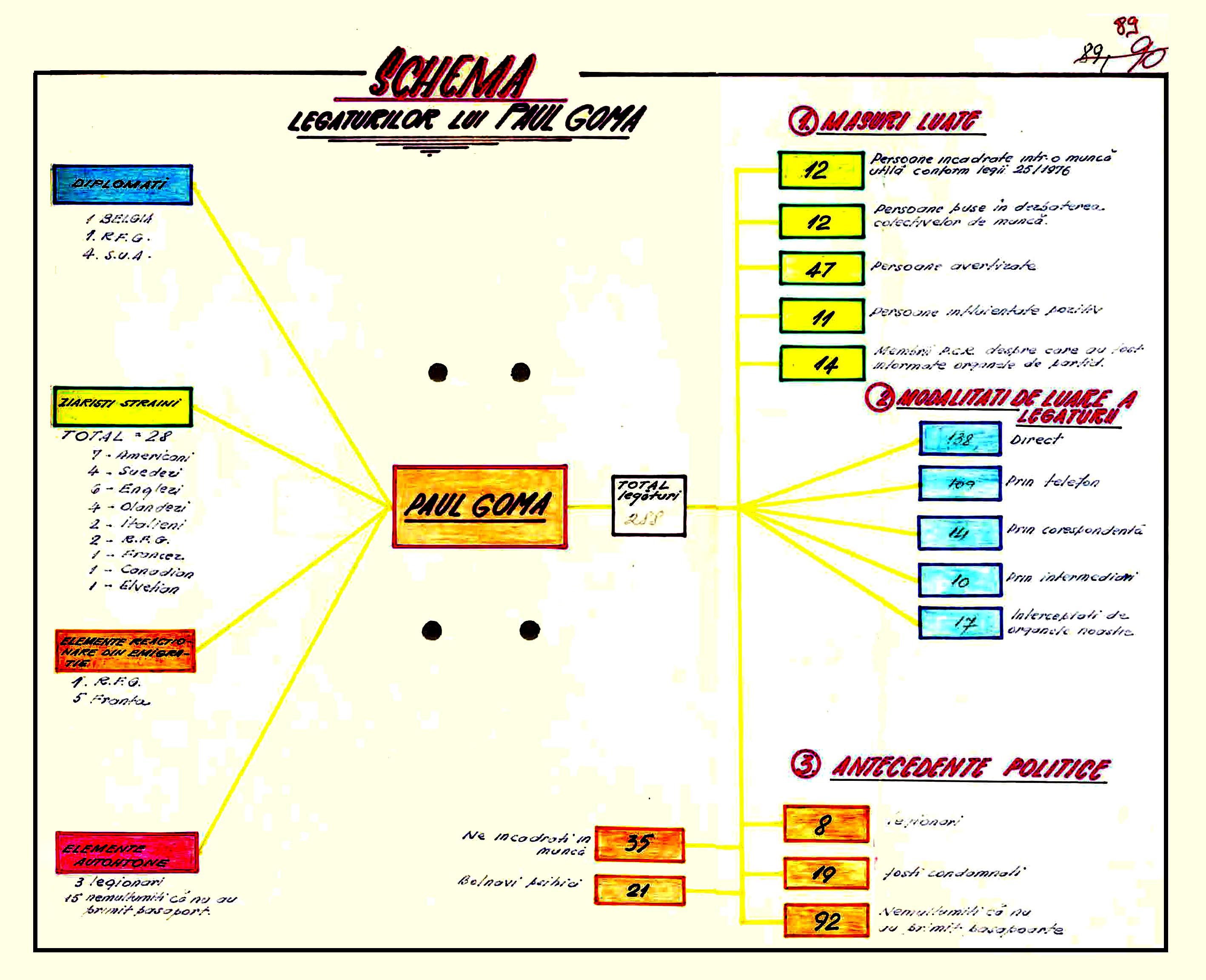

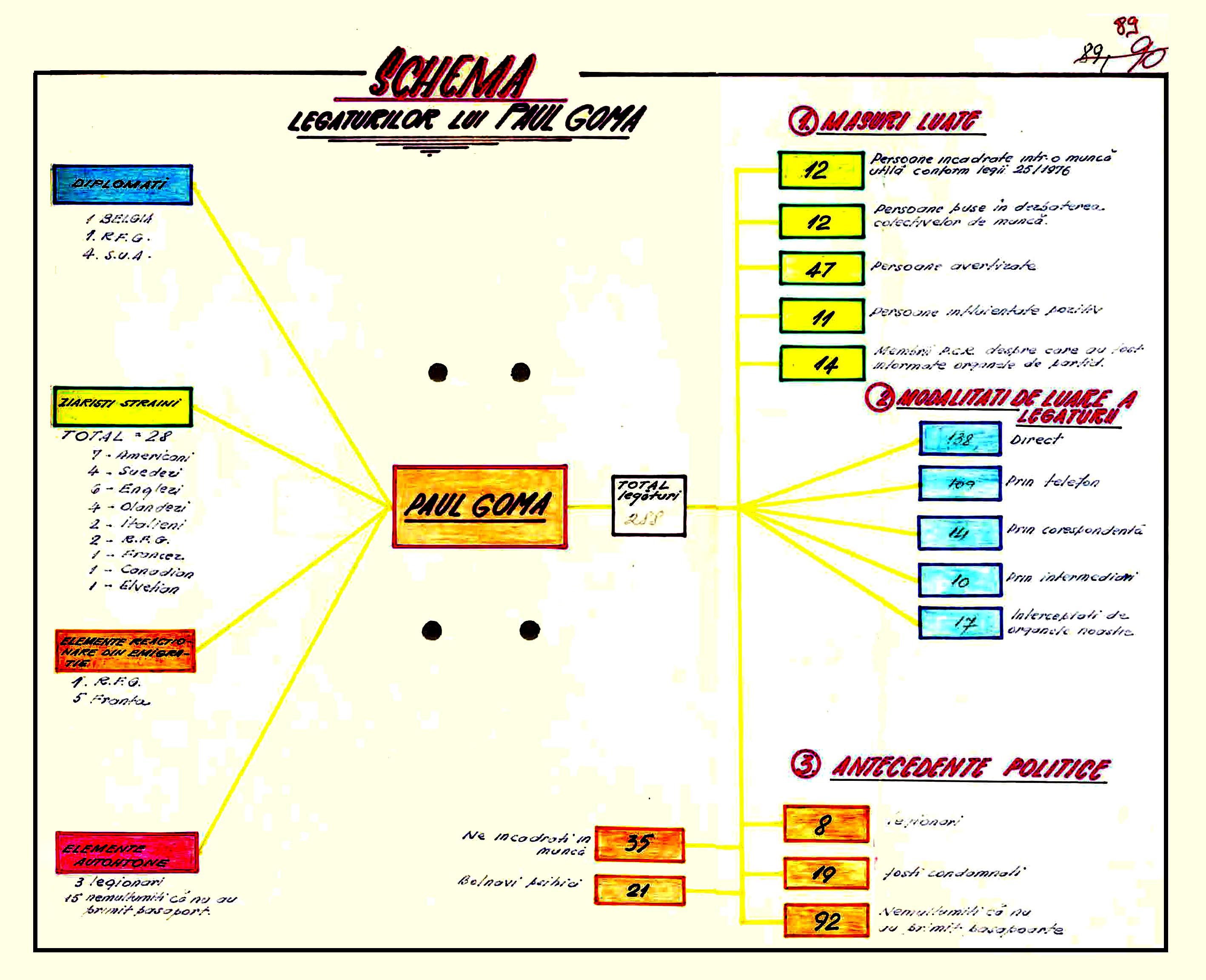

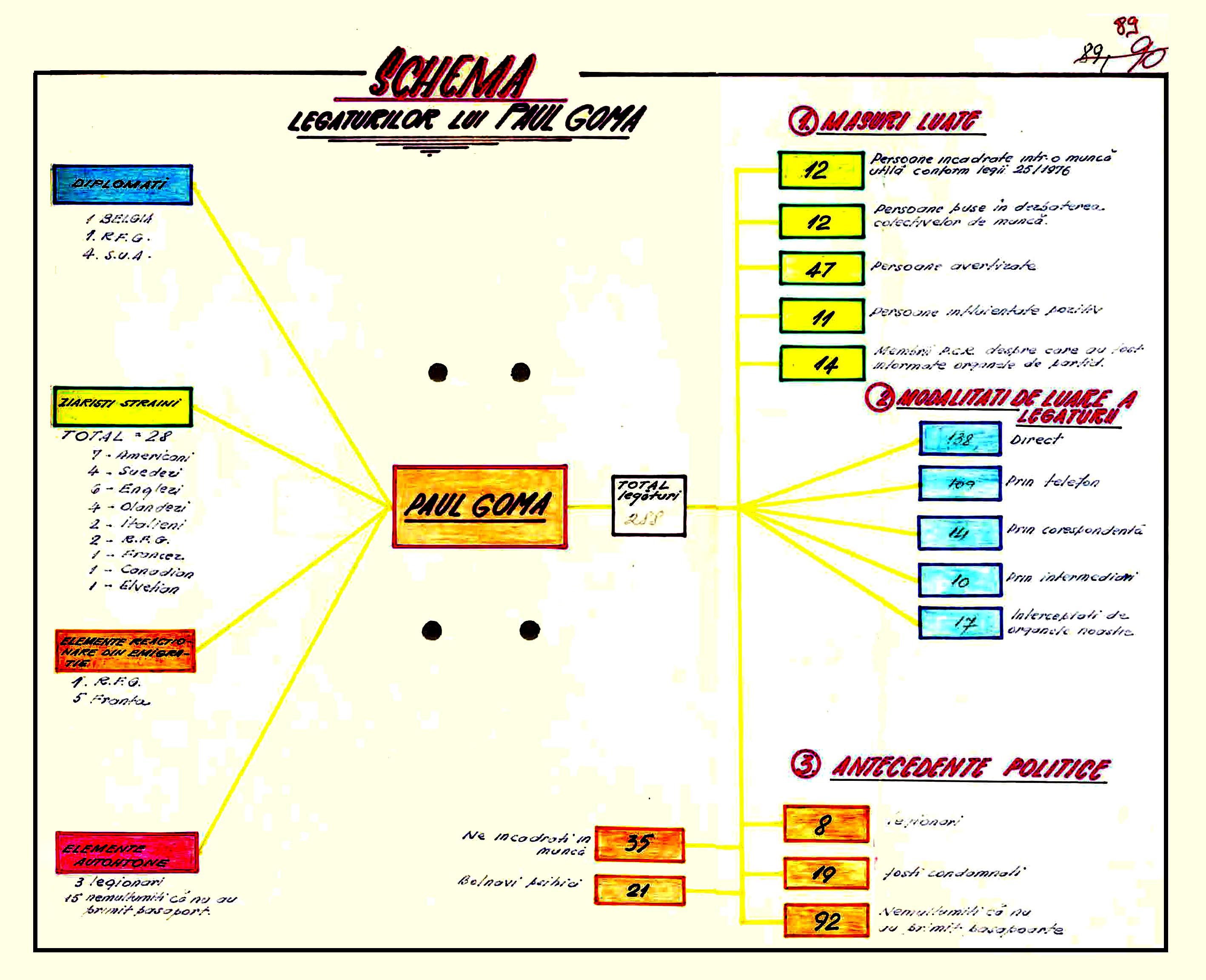

This chart epitomises the typical and efficient method which the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, used against those who attempted to establish networks of dissent in Romania. It seems to have been drafted for the Securitate officers who prepared the operative decision-making process regarding an emerging human rights movement in Romania, inspired by Charter 77. The driving force behind this movement was the writer Paul Goma, who initiated the movement in February 1977 by drafting a collective letter of protest against the violation of human rights in Romanian, which he and more than 200 other individuals eventually endorsed and addressed to the CSCE (Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe) Follow-Up Meeting in Belgrade. It was the first time that the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, had faced such an enormous challenge, and thus it had to react quickly in order to curtail the spread of the movement. In order to counteract this movement, the secret police had to collect in two months complex information about all those involved.

This chart and its annexes epitomise the collection of these complex data in the short time span between 9 February, when the collective letter was first broadcast by Radio Free Europe, and 1 April 1977, the day when the secret police arrested Paul Goma. The first thing one notices about this chart is its resemblance to the drawings made by high school teachers to facilitate a better understanding of a topic. The chart actually highlights Goma’s connections with the internal and external supporters of this movement which at that time constituted a collective action of unprecedented magnitude in communist Romania and implicitly a novel challenge for the Securitate. The chart only contains a schematic representation of Paul Goma’s relations with other persons (schema legăturilor lui Paul Goma). The central field, which features Paul Goma, is connected left and right with two columns of differently coloured fields. The left-hand column seems to represent a typology of individuals whom Goma had contacted in order to send documents relating to the activity of the emerging movement across the border to a Western country. They are divided into four categories: diplomats, foreign journalists, “reactionary elements from the emigration” and “autochthonous elements.” The right-hand column seems to categorise all those who had contacted Goma with the purpose of endorsing the movement. At the time when this chart was drawn, the Securitate had been able to scrutinise only 288 persons out of 430; the number of those identified to date is added in pencil. About these persons, there are three types of information offered: the actions taken (against them), their method of contacting Goma, and their political background (antecedente politice). The complex data collected about all these, which is included in annexes to this chart, included age, ethnicity, profession, education, place of residence and political background, meaning information about previous anti-regime activities.

The chart is an unusual type of document in the archives of the Securitate. Its unique character is directly related to the novelty of the challenge which the Securitate had to confront with Paul Goma’s attempt to establish a Romanian Charter 77. The novelty was twofold: it consisted both in the network established and the ideas expressed by this movement. Such a rapid solidarisation of individuals around a common purpose did not occur in communist Romania either before or after the Goma movement. At the same time, the defence of human rights was a totally alien idea and ideal in the political traditions of Eastern Europe in general, and of Romania in particular, even considering the period before the communist takeover. Thus, this emerging movement which implied the defence of a political idea (and not a material benefit) must have been really puzzling for the Securitate officers, who did their best to grasp the situation and understand the “real” motivations of the individuals protesting for the observance of such an “abstract” issue as human rights. This coloured chart and its annexes testify to the methods used by the Securitate in order to disaggregate a collective action for a common interest, the observance of human rights, into a multitude of individual actions, driven by personal interests and thus easier to break apart. In Goma’s words, “this is the use of statistics in the house of terror” (Goma 2005, 412).

The Mojmír Vaněk collection is a unique collection of materials that relate to the life and activities of Mojmír Vaněk. The activities of this distinctive, albeit unknown, Czechoslovak exile was very important for the dissemination of Czech music abroad, as well as his activities within the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences, the Swiss branch of which he presided over for many years. The collection is at the Comenius Museum in Přerov.

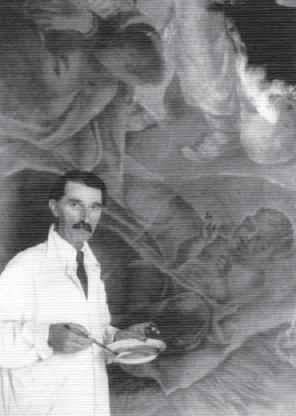

The émigré manuscripts of the painter Joze Kljaković are located at the archives of the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome. The collection is a source for the study of Kljaković's prose and current affairs writing during his émigré life in Italy and Argentina. Kljaković stands out as an example of the culture of dissent, having written a handful of manuscripts at the time of exile, in which he heavily criticized the socialist regime in Croatia and Yugoslavia.

The Lovinescu–Ierunca Collection at the Central National Historical Archives (ANIC) in Bucharest is arguably the most important collection created by the Romanian Diaspora in Paris. The collection illustrates not only Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca’s interest in the subject of dissent in Romania but also how their activity at Radio Free Europe (RFE) created a transnational network of support for those who decided to speak against the regime.

This document contributes to the understanding of the activity of the postwar Romanian exile community in the 1980s, especially regarding the correspondence and interaction between its most active members. During the communist period in Romania, the Romanians of the emigration were in general located at significant distances from each other, being settled on several continents: Europe, North America, South America, Australia, and Africa. The most active of them founded organisations, associations, institutions, institutes, foundations, publications, and publishing houses in their countries of residence. The purposes of their efforts were to: represent the Romanian nation, its democratic values and principles, and to defend its interests until the collapse of the communist regime; to coordinate the activity of Romanians abroad to carry out activities that would help to restore the democratic system in Romania; to represent the exile community within democratic societies and solve its problems; to establish links with Western governments and international organisations; to collaborate with representatives of the other "captive nations" in Central and Eastern Europe to form a common front to unmask and remove communism. Such an approach was also that of Ion Dumitru, a personality of the exile community, who set up in the mid-1960s one of the most important publishing houses of the Romanian emigration. It was founded in Munich, where he settled in 1961, and was officially registered in 1976 as a printing company. The Ion Dumitru Publishing House published over eighty books by exiled Romanians, many of them extremely valuable for national culture and history. To acquire such volumes, the owner of the publishing house, Ion Dumitru, maintained an ample correspondence with those interested. A proof of these relationships is this letter, which Ion Dumitru addressed to Leonid Mămăligă on 8 August 1982. Leonid Mămăligă, who wrote under the name L.M. Arcade , was a personality of the Romanian exile community, in which he made a name for himself, in particular, through the establishment and coordination for more than thirty years (1958–1989) of the Neuilly-sur-Seine Cenacle. The purpose of this cenacle, unique in France during those years of exile, was respond to the need for a Romanian place to offer Romanian intellectuals outside the country the possibility of thematic meetings and discussions. Also, the cenacle represented a platform of expression for Romanian intellectuals in exile, which helped them to keep alive the Romanian identity abroad and to put Romanian culture in communication with that of France. At the same time, the cenacle stimulated the act of creation both in Romanian and in French, by supporting and promoting Romanian writing, as it had its own publishing house, Caietele Inorogului (The unicorn notebooks). As or the subject of the letter that Ion Dumitru addressed to Leonid Mămăligă, in it he talks about sending a package of books published by his publishing house for another well-known Romanian exile, Aurel Răuţă, a professor at the University of Salamanca, Spain. Aurel Răuţă was a notable personality of the exile community because of his publishing activity and the founding, among others, of the Asociația Hyperion (Hyperion Association) in Paris. This was a distribution platform for books by Romanians in exile. In ten years of activity, he distributed to Romanian emigrants more than 10,000 volumes, published at more than 130 publishing houses. The document in the Ion Dumitru Collection in the IICCMER archive is a copy in A4 format.

Group of Yugoslav Communists. Comparing Nationalism in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia , in Croatian, 1973. Leaflet

Group of Yugoslav Communists. Comparing Nationalism in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia , in Croatian, 1973. Leaflet

The collection is an extensive set of materials documenting the culturally opposed activities of its author: a writer, a signatory of The Charter 77 and later a diplomat who was deprived of Czechoslovak citizenship during the Communist regime.

The Tóth Private Collection in Göteborg comprises the most comprehensive materials related to Ellenpontok (Counterpoints), the Hungarian-language samizdat publication which gained international reputation in the early 1980s due to its resolute fight for human and minority rights in communist Romania. At the same time, the items resulting from the different stages of the Tóth family’s emigrant life (Hungary, Canada, Sweden), such as official documents, manuscripts, sound recordings, photos, private correspondence, and books on minorities, shed light on the cultural efforts undertaken by the collectors in order to improve the situation of those left behind.

The CNSAS Online Collection (CNSAS – Romanian acronym for the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives) illustrates how the communist secret police, the Securitate, conceptualised: (1) oppositional groups and individuals in communist Romania; (2) the forms in which this opposition manifested against the party-state; and (3) the transnational support it received from the exile community and foreign organisations. It also encompasses an impressive amount of invaluable information about the inner mechanisms of the Securitate, its institutional development and relationship with the Communist Party, the use of repression against any form of opposition, and the use of surveillance to avoid the development of oppositional groups and networks during its over forty years of functioning. In brief, this collection offers a comprehensive image of the means and methods used by the communist secret police, the Securitate, to deal with the anti-communist opposition between 1948 and 1989, and the response it received from oppositional groups and individuals.

The Zina Genyk-Berezovska Collection at the T.H. Shevchenko Institute of Literature in Kyiv is crucial for understanding the transnational networks underpinning cultural opposition in Ukraine and the Ukrainian diaspora community in Prague. The latter was largely composed of anti-Bolshevik émigrés that had fled to Czechoslovakia in the 1920s, after their failed attempt to establish the Ukrainian National Republic amid the chaos of the First World War. Genyk-Berezovska was born and raised in this community, studied Slavic languages and literatures at Charles University in Prague, later teaching and translating Ukrainian literature into Czech. Through personal connections, Genyk-Berezovska was also deeply involved in the cultural renaissance in Soviet Ukraine known as the sixtiers movement.

In addition to the more than 800 letters Genyk-Berezovska received from her many correspondents in Ukraine, her archive contains her own works as a scholar of Ukrainian and Czech literature, translator, and prominent community figure, as well as those of her husband Kost’ Genyk-Berezovsky, a philologist who taught Ukrainian at Charles University in Prague. Their family archive served as a repository for materials about prominent members of the Ukrainian émigré community in Czechoslovakia, including the Ukrainian sculptor Mykhailo Brynsky, the Czech writer František Hlaváček, the Ukrainian chemist and statesman Ivan Horbachevskyi, and Petro Krytskyi, a former colonel in the Ukrainian National Republican army, among others. This unique collection highlights both the transnational and the intergenerational dimensions of Ukrainian cultural opposition to communism.

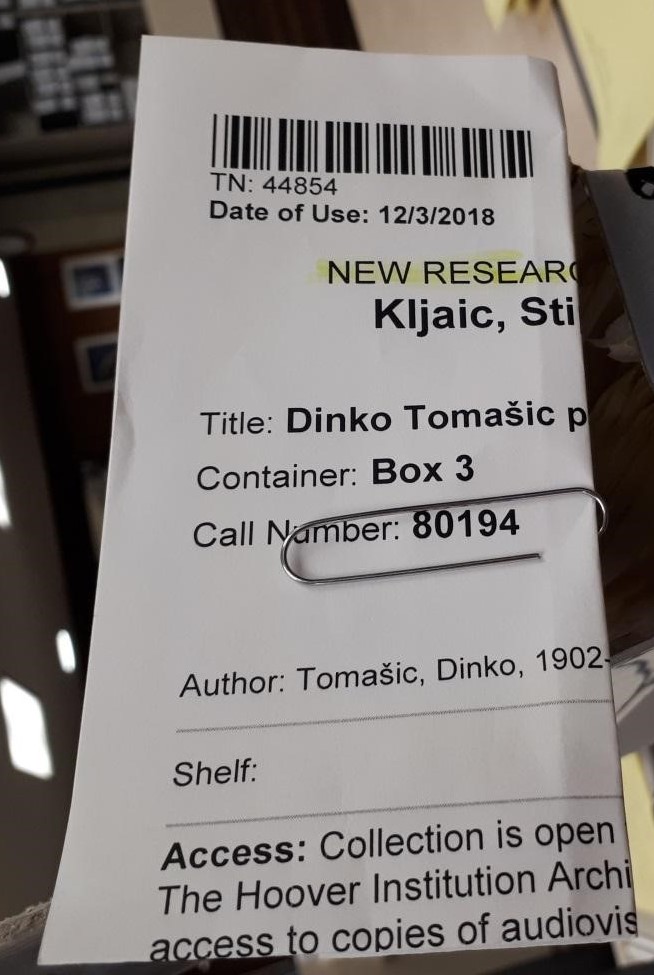

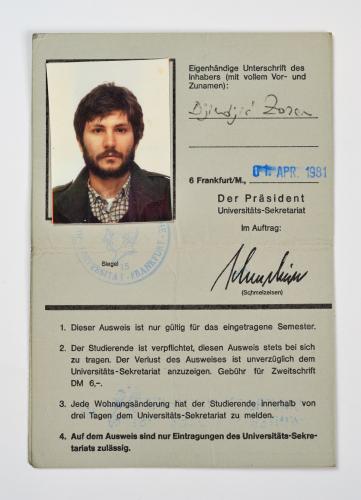

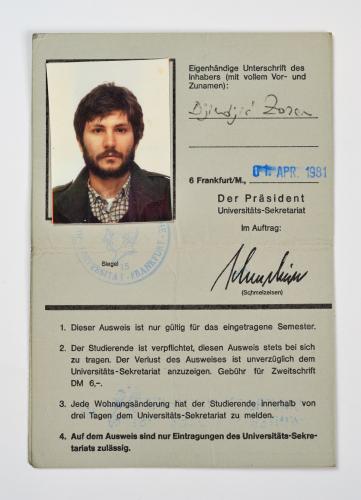

The records of Croatian-American sociologist Dinko Tomašić are deposited at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford University. In accordance with its own themes and periodization, it covers Tomašić's public work after the Second World War, when he settled in the United States as a political émigré. The collection testifies to Tomašić's sociological research, in which he critically examined political and social phenomena of post-war communist society in Croatia and Yugoslavia. The main thesis of Tomašić's sociological theory was that the revolutionary transformation of society and the huge growth of the party-state’s power destroyed political, economic, social and cultural pluralism in the public life of the Yugoslav nations. Based on his sociological methods, and making use of results the fields of ethnography and anthropology, he believed that the source of the Yugoslav revolution derived from the specific Dinaric culture, which belonged to economically passive territories, regions where the Partisan movement secured the great support, such as Montenegro, Dalmatia, Lika, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

This collection contains lectures and papers prepared and organized by the Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU), a prominent organization in exile which brought together scientists and artists originally from Czechoslovakia. It contains unique manuscripts and publications from 1957 to 1977, including the series entitled “The Czechoslovak State Idea 1938-1948”. The authors of these papers were important representatives from the Czech and Slovak community in exile – former politicians and diplomats from before the Communist coup of 1948.

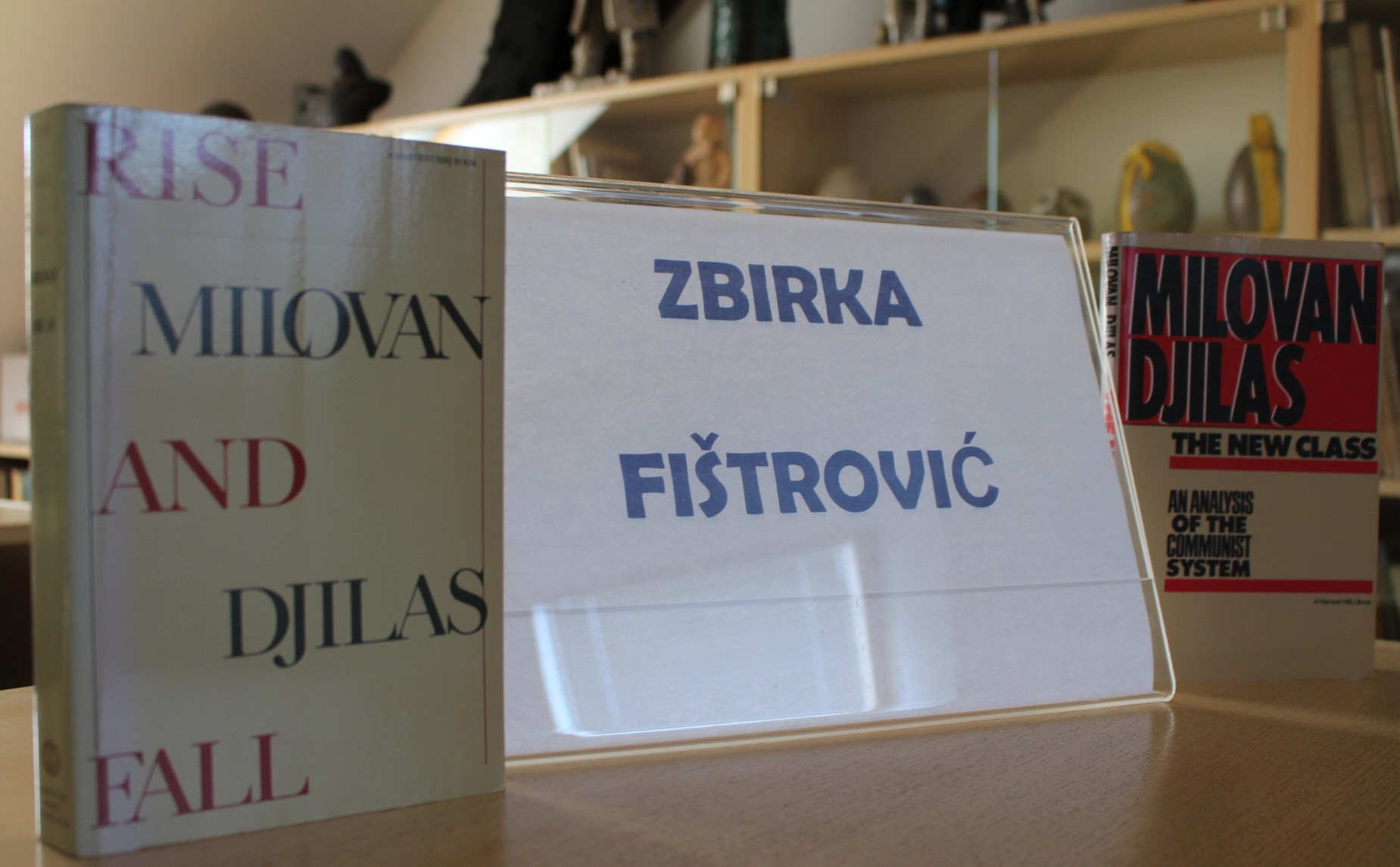

The Fištrović Collection of the Fran Galović Library and Reading Room in Koprivnica contains about 1,300 historical, political, economic and cultural books in English, many of which are the only copies in Croatia. The books were used by a group of Croatian intellectuals in Chicago in the 1990s to address the American public and advocate for a democratic and independent Croatia, which can be considered a final act of resistance to the Yugoslav socialist regime. The authors of some of the books are also intellectuals from the former Yugoslav republics, and their work, published in English, is evidence of their dissent against the Yugoslav system of government.

The Krunoslav Draganović Collection on World War II and Post-war Victims is an archive collection whose original collector was the priest Krunoslav Draganović, who, relying primarily on the testimonies of survivors and other witnesses, planned to publish a book on the crimes of the Yugoslav communists.

The German journalist and writer Jürgen Serke (b. 1938) dealt with persecuted and silenced artists. At the beginning of the 1980s, he was researching a book about life and work of Polish, Russian, East German, and Czechoslovak poets and writers living in exile. Thus, Jürgen Serke, accompanied by photographer Wilfried Bauer and Czech poet in exile, Jiří Gruša, visited Blatný in Ipswich in October 1981. Then, Serke wrote a report about Blatný and his life in exile entitled “Escape to the Madhouse” (Flucht ins Irrenhaus), which was published in the West German magazine Stern in December 1981. The following year, Serke’s book “Expelled Poets” (Die verbannten Dichter), which also included the report about Ivan Blatný, was issued. Serke’s article about Ivan Blatný in Stern found an echo. After its publication, Ivan Blatný received many letters and gifts, mainly from Czechoslovak emigrants. Some people also came to Ipswich to visit Blatný personally. Then, in 1982, British and Norwegian televisions made a documentary film about Ivan Blatný. Hence, Jürgen Serke, or specifically his article, “Escape to the Madhouse”, significantly contributed to the rediscovery of this almost forgotten exiled poet.

The Ivan Blatný Collection at the Museum of Czech Literature contains Blatný’s copy of Serke’s article.

In the autumn 2011, veteran legionnaire and military historian Dr. Tibor Szecskó was the first to return his questionnaire of 50 questions, covering his whole life career. As the main organizer of the Hungarian veterans’ circle in Provence, he was the also one who managed to get many of his comrades involved in their shared memory research work (questionnaires, oral history interviews, memoirs, film shootings, archival research at the Headquarters of the French Foreign Legion in Aubagne, etc.)

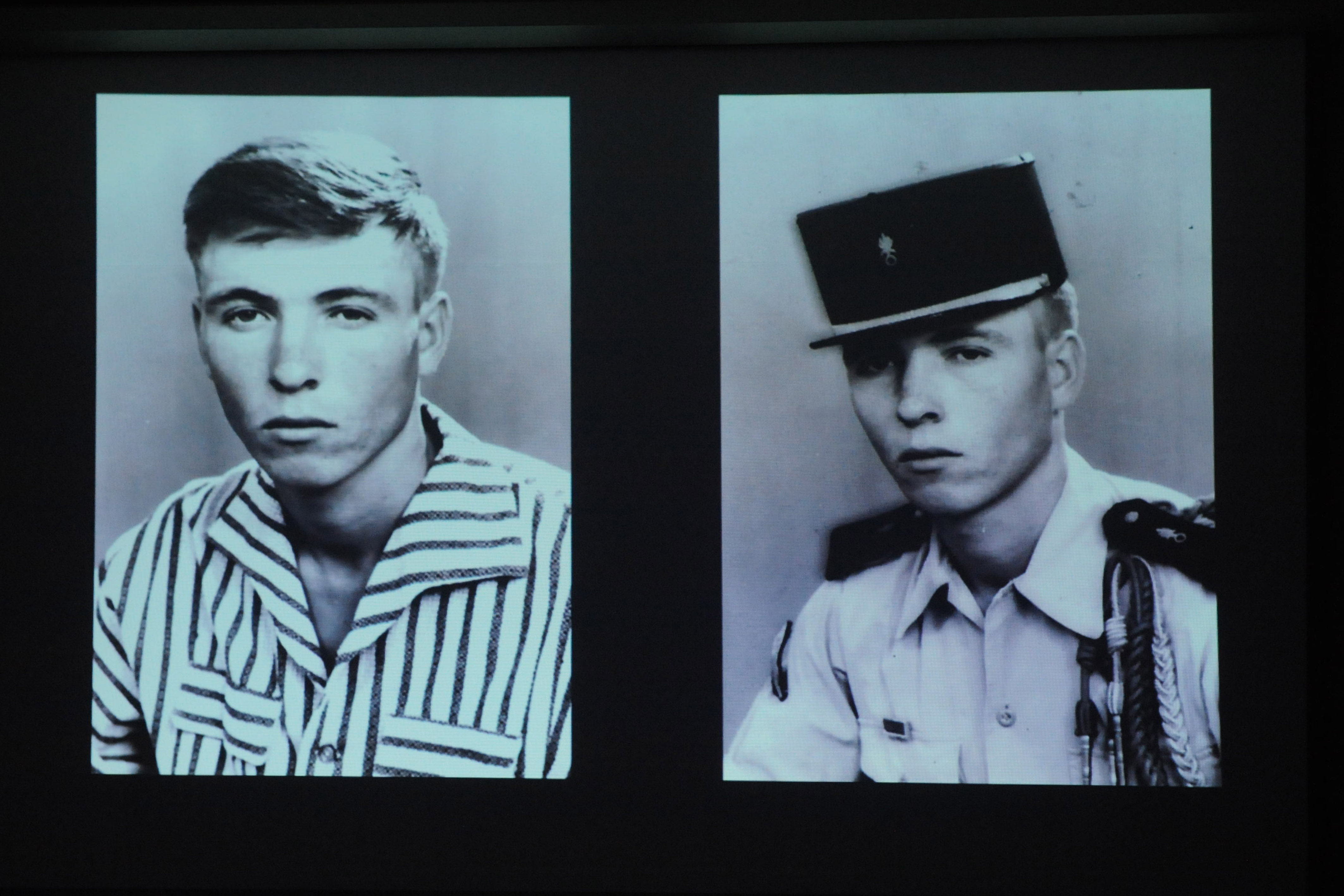

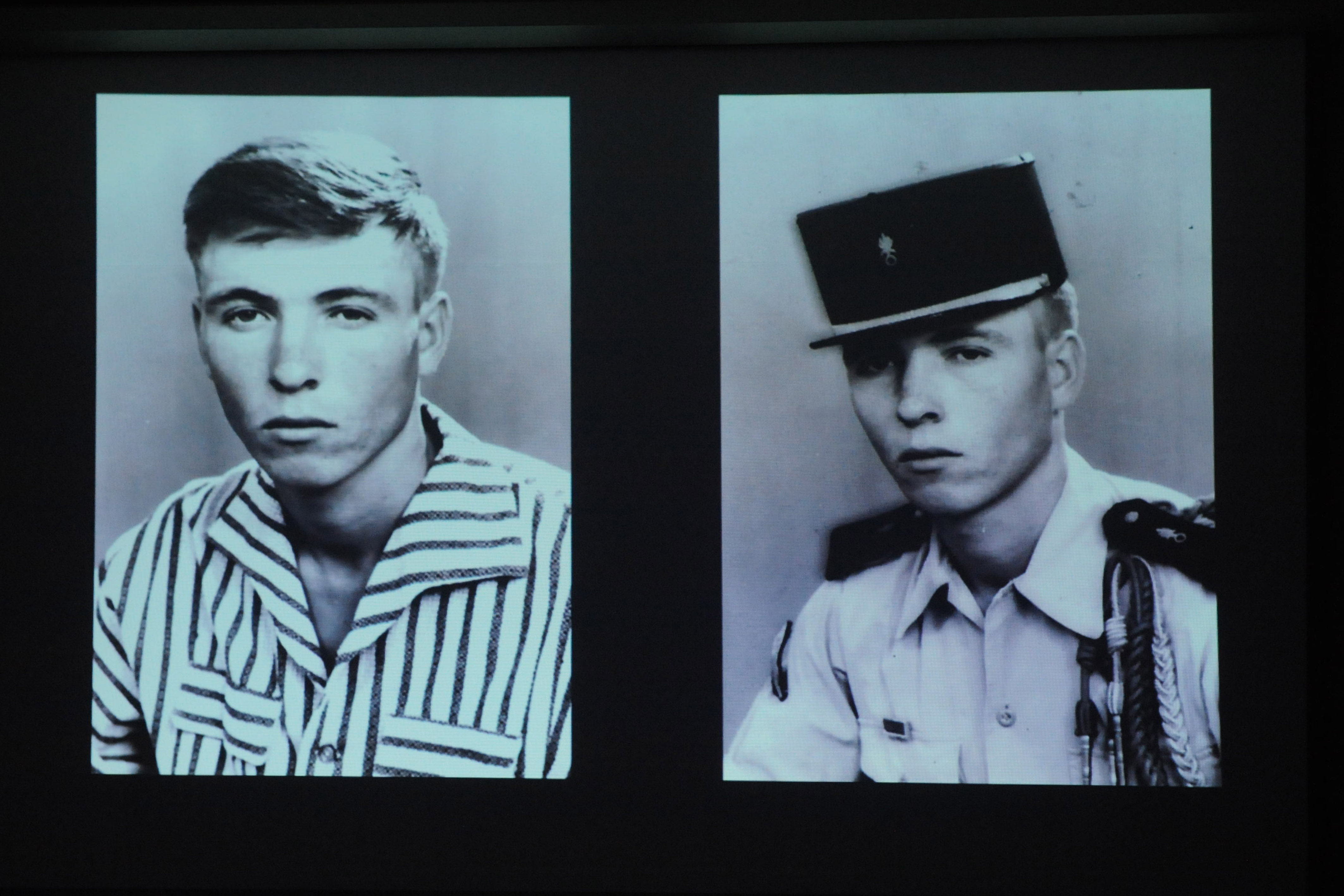

He was born in 1939 in the rural town of Gyöngyös, Hungary, as the third and youngest child of a working-class family. His father was a mason working for a state farm. As a second-year student of a vocational school in the autumn of 1956, he took part enthusiastically in local events of the revolution. Together with a friend, they then hitched a ride with a lorry and travelled to Budapest, where they joined the largest group of insurgents at Corvin-köz, and took part in the battles in several parts of the city. In late November, without saying goodbye to his family, he escaped to Austria with other teenage boys. For a few weeks he stayed in the Eisenstadt refugee camp, then he was transported to France and given the status of “réfugier politique.”

As soon as he arrived in the city of Rouen, he signed up at the Legion’s recruitment office, but being only 16 years old, he was rejected. For two years he shared all the misery of the tramps in Lille and Paris, sleeping in the “Draft Hotel” (Hôtel de Curant Air) under bridges, living off of aid for refugees and poorly paid, sporadic work. Hunger and misery pushed him to try his fortune again with the Legion in the autumn of 1958, this time with much success. He was shipped as an 18-year-old recruit from Marseille to Oran, and soon found himself on the military training base of Saida. Another two years passed, and he was promoted to sergeant at the age of 20, and became the training warrant of hundreds of young Hungarian recruits arriving at that time in North Africa. Afterward, as a warrant of the 3rd Infantry Regiment, he also took part in the offensives in the Sahara and Madagascar, was injured twice, and then was commanded to the 1st Cavalry (Warship) Regiment.

After the Algerian war ended in 1962, the main base of the Legion was moved from Sidi-bel-Abbes to the town of Aubagne, South of France, and Szecskó held his new post here at the Headquarters of the Legion. In the 1970s and 1980s, he became the Director of the Museum and the Archives of the French Foreign Legion, and edited its monthly magazine Képi blanc. In the meantime, he received his MA and then PhD degree in history from the University of Montpelier. He finished his military career in 1986 after close to 29 years of service in the Legion; however, he kept active in his field of science and in organizing circles of veteran legionnaires (AALE). He published a number of articles and a dozen books on the history of French Foreign Legion in French, English, and German.

Before 1990, based on rumors fostered by the communist secret police, he, together with his fellow patriots, thought for decades that all active legionnaires had been deprived of their Hungarian citizenship. He became a French citizen in 1974, and lived together with his Spanish-French wife, children, and grandchildren in Aix-en-Provence for half a century. Among his many prizes and decorations, he was most proud of the “Knight of Arts and Literature,” a prestigious French prize established for civilians, that no active military man ever received, except him. Though he felt all through his life a strong homesickness, and managed to preserve his traditional Hungarian patriotism, he never had the chance to return to Hungary after 1956—for a long time due to his political anathema, and then his poor state of health. He passed in Aix-en-Provence in late 2017 following years of struggle with his fatal illness. His parting was not only a painful loss to his family but also to his friends and the Hungarian circle of veteran legionnaires in Provence, of which he had been a devoted organizer for decades.

His straightforward, and emotive answers to his questionnaire lay bare his life career and frame of mind. He also reflected on his feelings toward his native land, the Legion, and his host country. Though his loyalty to the former two seems to remain firm, similarly to his stubborn anticommunism rooted in his early life experience of 1956, he felt much more reserved and often critical of the French public affairs and way of life, as both are lacking “the real” patriotic loyalty and altruism. Thus, keeping alive the regular meetings and traditional community rituals, with their strong 1956 engagement, served to strengthen the Hungarian legionnaires’ moral and cultural resistance.

List of completed veteran questionnaires, 2011–2017

(Place and date of birth, residence in France, and year of completion)

1. A., Domokos (Budapest, 1939) Paris, 2012

2. Bubla, István Miklós (Keszthely, 1936) Paulhan, 2017

3. Huber, Béla (Sopron, 1942) Aubagne, 2012

4. Spátay, János (Budapest, 1943) Puyloubier, 2011

5. Soós, Sándor (Budapest, 1939) Septémes les Vallons, 2012

6. Sorbán, Gyula Elek (Budapest, 1940) Toulon, 2011

7. Szecskó, Tibor (Gyöngyös, 1939) Aix-en-Provence 2017, 2011

8. Morvay, Tamás (Budapest, 1938) Vins sur Caramy, 2012

9. Nemes, Sándor (Szekszárd-Zomba, 1941) Borgo (Corsica), 2011

10. Pápai, Lajos (Öcsöd, 1937) Montrichard, 2014

Protest message of the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania, in French and English, Paris, 1985

Protest message of the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania, in French and English, Paris, 1985

This document reflects the way in which the Romanian exile community organised itself and acted to promote media coverage in the West of the urban systematisation project of Ceaușescu's regime, which tacitly involved the demolition, mutilation, or destruction of the national heritage. The protest message was shared when the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania was founded in 1985, in Paris. The purpose of the association was to draw the attention of political decision-makers and international public opinion to the communist regime's plan for the demolition of the architectural and urban heritage of Romania. The actions undertaken within the Association focused particularly on the promotion of media coverage of the demolition of the city centre of Bucharest, which the communist authorities planned to reorganise according to their architectural vision. On the occasion of its foundation, the association organised a protest on the streets of Paris, during which it distributed a protest message to participants and passers-by with texts about communist Romania accompanied by photographs of historic monuments destroyed by the communists or scheduled to be demolished or moved. A copy of this protest message was sent by post to several Romanian exiles in order to convince them to join the Association and get involved in unmasking the communist regime in Romania and, in particular, the urban systematisation project of the Ceaușescu regime. This document was sent by the president of the Association, the architect Ștefan Gane, to Sanda Stolojan, a personality of the Romanian exile, who kept it in her private archive. The document, which can be consulted in the IICCMER collection, was written in English and French, in A4 format. The material, titled "Protest: Romania's historical and spiritual heritage is in danger," briefly outlines the consequences of the Bucharest systematisation project undertaken by the Communist authorities since 1977 and some examples of monuments from the historical and spiritual heritage of the Romanians that had been destroyed, demolished, or mutilated by the Ceaușescu regime. Against this background, the association protested, asking for: a stop to the demolition of historic monuments and sites in the country; the re-establishment of the Romanian Historic Monuments Commission, abolished in 1977; and the rebuilding, under the aegis of this Commission and with the help of the International Council for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites and other international organisations, of the demolished historic monuments and sites.

The collection documents the work of Croatian historian and political émigré Nikola Čolak (1914-1996). In 1966, he belonged to a group of academics and thinkers from Zadar, who officially sought to break the Communist Party's monopoly on truth by establishing the first journal not controlled by the Party. After the suppression of this initiative, Čolak was forced into exile in Italy. The so-called Movement of Independent Intellectuals represented the first attempt to create a formal cultural opposition circle not only in Croatia, but in Yugoslavia as a whole, which is recorded through this collection.

The collection portrays the life and work of two Romanian intellectuals separated by the Iron Curtain, the brothers Aurel and Emil Cioran. While Aurel Cioran experienced imprisonment and then lived in Sibiu, Romania, his brother lived in Paris from 1941, where he became an internationally known French essayist. The collection comprises original manuscripts, correspondence, books, photos, and personal documents from the period 1911–1996.

The Milovan Djilas collection is deposited at the Hoover Institute Library & Archives, located at Stanford University in the United States. It offers an important insight into the life and work of the first and most prominent dissident in Yugoslavia, who was also one of the most notable dissidents anywhere in communist Europe. Djilas had been the main ideologue of the Yugoslav Communist Party and one of the Tito's closest associates when he confronted the Party and Tito in the mid-1950s.

The Mihajlo Mihajlov collection gives an overview of his life and work as a Yugoslav dissident who lived in exile in the USA since 1978. Due to his efforts to democratize Tito's Yugoslavia and introduce political, economic and cultural pluralism, he became a political prisoner, first in the period from 1966 to 1970 and later from 1974 to 1977. After the “Mihajlov case” in Yugoslavia in 1966, a wave of dissident movements emerged in the Eastern bloc countries. Together with Milovan Đilas, Mihajlov became one of the most famous figures of the dissident movement in the Cold War world in general. The collection is stored at the Hoover Institution, located at Stanford University in the USA.

This photo reflects the way in which the Romanian exile organised itself and acted to present in the West the urban systematisation project of the Ceaușescu regime, which involved the demolition, mutilation, or destruction of the national heritage. The photo captures the moment when the International Association for the Protection of Monuments and Historic Sites in Romania was set up in Paris in 1985. On that occasion, the Association organised a protest on the streets of Paris, during which it displayed a series of placards with texts about Communist Romania, accompanied by photographs of historic monuments destroyed by the Communists or about to be demolished or moved. These details are captured in the photograph in question, which can be found in the Ștefan Gane collection in the original, 10x15 cm, printed on colour paper. The purpose of the Association was to draw the attention of political decision-makers and international public opinion to the project of the communist regime in Romania for the demolition of the architectural and urban heritage. The actions undertaken by the Association focused in particular on drawing media attention to the demolition of the city centre of Bucharest, which was planned by the authorities of the totalitarian regime so that they could reconstruct it according to the communist architectural vision.

The Pavao Tijan Collection is deposited in the Archives of the Croatian Academy of Science and Arts in Zagreb. It demonstrates the cultural-oppositional activities of the Croatian émigré Pavao Tijan, who lived in Madrid after the Second World War. There, Tijan organized anti-communist activities against the Yugoslav regime and also against global communism during the time of the Cold War. This collection is very important to the little known Croatian cultural history of the émigré colony of Spain.

Jiří Lederer (1922-1983) was a Czech journalist and publicist, one of the most prominent journalists during the "Prague Spring" in 1968. In the 1970s he participated in the work of the Czechoslovak opposition and was one of the first signatories of Charter 77. During the 1970s he was imprisoned several times. In 1980 he went into exile. The collection mainly contains materials and notes from the period around the Prague Spring.

The collection of Ladislav Mňačko (1919–1994), a Slovak writer and former prominent Czechoslovak journalist, consists of unique correspondence, manuscripts, prints and clippings which help to describe the life of this significant writer, who after August 1968 was a critic of the communist regime and a representative of Czechoslovak exile literature.

This letter is an important document for the history of the post-war Romanian exile community because it is proof of the activity of fighting communist propaganda outside the country, as well as of the integration of Romanian culture into Western culture. Such activity was also carried out by Sanda Budiș, an exile community personality, who emigrated to Switzerland in 1973. One of her actions, alongside another representative of the Romanian exile community in Switzerland, the lawyer Dumitru Stambuliu, consisted in supplying the Swiss Library for Eastern Europe in Bern with publications of the Romanian exile community. The starting point of Sanda Budiș’s project was a book donation from Romania, which the Romanian ambassador to Switzerland made to the Cantonal and University Library of Lausanne in 1984. This donation took place during a festivity advertised in the local press. In response, Sanda Budiș took the initiative to donate publications of the Romanian exile community from her personal library to this library, but her donation was denied "for political reasons." Consequently, she addressed the leadership of another institution – the Swiss Library for Eastern Europe in Bern – which served at the time as a documentary fonds for the Swiss Eastern Institute (Institut suisse de recherche sur les pays de l'Est–ISE/Schweizerische Ostinstitut–SOI), an institute that carried out research on communist countries. At the Institute, both the management and the members were Swiss personalities with authority in their field of expertise. The management of this library accepted her donation “with great satisfaction, especially as it is literally flooded by propaganda publications sent free and regularly by the various propaganda officers of the Ceaușescu regime.” In order to counteract the propaganda of the Romanian communist authorities, Sanda Budiș continued her efforts by sending letters to the management of important and representative publications of the Romanian exile community. Among the recipients of such letters was Virgil Ierunca, who accepted her invitation and sent to the library not only newspapers and magazines of the exile community, but also books published by Romanians abroad. Ierunca also responded to Sanda Budiș in a letter in which he congratulated and thanked her for the action she had initiated. The original handwritten letter is to be found today in the Sanda Budiş Collection at IICCMER.

Vjesnik Newspaper Documentation is an archival collection created in the Vjesnik newspaper publishing enterprise from 1964 to 2006. It includes about twelve million press clippings, organized into six thousand topics and sixty thousand dossiers on public persons. Inter alia, it documents various forms of cultural opposition in the former Yugoslavia, but also in other communist countries in Europe and worldwide.

The video and audio library of the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature consists of audio and video recordings of Czech poets and writers from 1932 until 2013; the collection also covers the literary scene in Czechoslovakia before 1989, including the activities of unofficial or “banned” writers and artists and their work in exile. One important part of the collection are recordings made between 1990 and 2013 as part of the Authentic project, which focused on recording videos and audios from various spheres of the Czech literary scene.

In 1977, English nurse Frances Meacham began to collect Ivan Blatný’s manuscripts of poems. She also sent some poems to Josef Škvorecký, a Czech writer living in exile in Toronto, Canada. Škvorecký decided to publish Blatný’s poems and thus, the collection of poems Old Addresses (Stará bydliště) was issued by the Czechoslovak exile publishing house Sixty-Eight Publishers in 1979. The collection was compiled during years 1978 and 1979 by Czech poet Antonín Brousek, who emigrated to West Germany in 1969. In accordance with Josef Škvorecký’s request, Brousek intentionally did not include multilingual and “modern” poems. On the contrary, he chose rather lyrical poems that resembled Ivan Blatný’s texts from the beginning of the 1940s. Josef Škvorecký justified this decision stating that their clients (readers of books issued by the publishing house Sixty-Eight Publishers) are usually “elder emigrants, who already had preconceived notions about poetry”. Although Old Addresses did not reflect Blatný’s modern style, the issue of this collection in 1979 was crucial. It resulted in better knowledge of Blatný and his work in exile, and Blatný was rediscovered by Czechoslovak readers, mainly those in exile and dissent circles. This book circulated in Czechoslovakia, where it was disseminated through illegal typescript copies. As Czech literary historian Jiří Rambousek stated later, it “created a small literary sensation.” Thus, it was not surprising that Old Addresses was also published by the Czechoslovak samizdat edition “Czech Expedition”. Moreover, it encouraged Blatný himself to continue in his literary work. Since 1989, this collection has officially been published in Czechoslovakia, and later in the Czech Republic, four times (1992, 1997, 2002 and 2014).

The Museum of Czech Literature possesses a copy of the typescript of the collection Stará bydliště (Old Addresses) with handwritten notes.

The collection exists thanks to Kolář’s friendships with artists and reflects his personal taste. Kolář bought works directly from the artists and thus he supported them. Along with works from the second half of the twentieth century, Kolář also collected older works, which are part of the collection.

This photograph from the Ștefan Gane Collection is a testimony to the Ceaușescu regime's policy of transforming the urban landscape and destroying everything that was opposed to its vision. An example of this is the almost total destruction in 1985 of the Mihai Vodă Monastery, of which only the church and the bell tower were preserved and moved to another site down an incline.

The church of the former Mihai Vodă Monastery is an emblem of premodern Bucharest and one of the oldest buildings that have been preserved in Bucharest. Built in 1594, over time it had several destinations, including Princely Residence, Military Hospital, Medical School, and headquarters of the State Archives. It was founded by one of the most important rulers in the Romanians' national history: Mihai Viteazul (Michael the Brave). He was the ruler of Wallachia between 1593 and 1601 and the only leader of one of the premodern states existing in the modern perimeter of modern Romania that unified, for the period 1600–1601, a territory roughly equal to that of today's Romania. Thus Mihai Viteazul was considered from the nineteenth century an important figure in national history. Under the communist regime, historiography of gave Mihai Viteazul a much more important place in national history than he had had before. He was named as the prefigurer of the so-called "Union of 1918". This historical event consisted of the annexation of the historical regions of Austro-Hungary, inhabited mostly by Romanians to the so-called Old Kingdom of Romania and was materialised in the Peace Treaties of Saint-Germain (1919) and Trianon (1920). This image of Mihai Viteazul as anticipator of the “Union of 1918” was strongly promoted under the Ceauşescu regime not only through textbooks and historical works, but also through the historical film Mihai Viteazul, made in 1970.