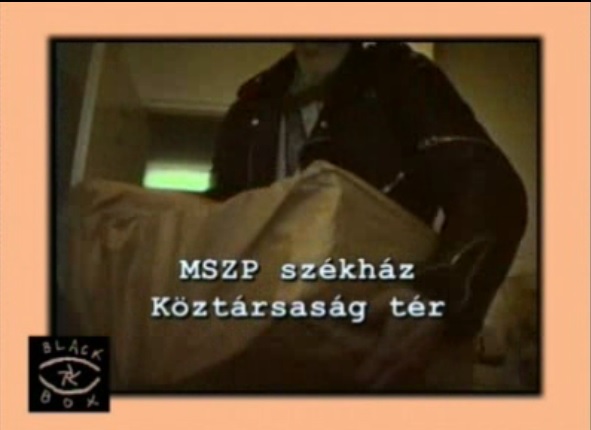

The 34-minute long documentary film ‘Danube-gate’ by Black Box is an event tracking documentation of the secret spying scandal that exploded in Hungary in January 1990. Police Major József Végvári, an active member of the infamous III/3 secret department, in late 1989 called on the cameraman of Black Box to help to reveal the fact that months before the free elections, the ex-communist ruling party, renamed MSZP, was still surveilling the activists of the democratic opposition, just as it did for several prior decades.

In one of her interviews, Márta Elbert recalled her memories about the discovery and its effects: “In January, with the Danube-gate scandal exploding because of our recordings, we practically managed to remove the Interior Minister from his position. In our days, the activities of Department III/3 of the Hungarian secret police were well known. However, at that time no one had any idea about its staff, and how it worked in secret operations; it was our film ‘Danube-gate’ that shed light on these aspects for the first time, informing a wider public. It is no wonder then that these revelatory shots immediately made Black Box known and esteemed not only in Hungary, but also abroad, as the world’s major TV companies tried to come in contact with us. […] Nowadays, in the media, spectacular expositions follow each other at such speed that they often extinguish each other’s effect. But at that time it was different. And just a few months before the first free elections, it was really shocking for most of the public to be informed that the secret police went on surveilling the democratic opposition in much the same way as it had been doing before, although the National Roundtable Negotiations of 1989 concluded in an agreement between the ruling communist party and the opposition to stop all those antidemocratic secret operations. In fact, the Danube-gate scandal set off by our film was the very first case that publicly identified by face and name those hidden and high-ranking apparatchiks who were in charge of operating the secret spying and reporting system in Hungary.”

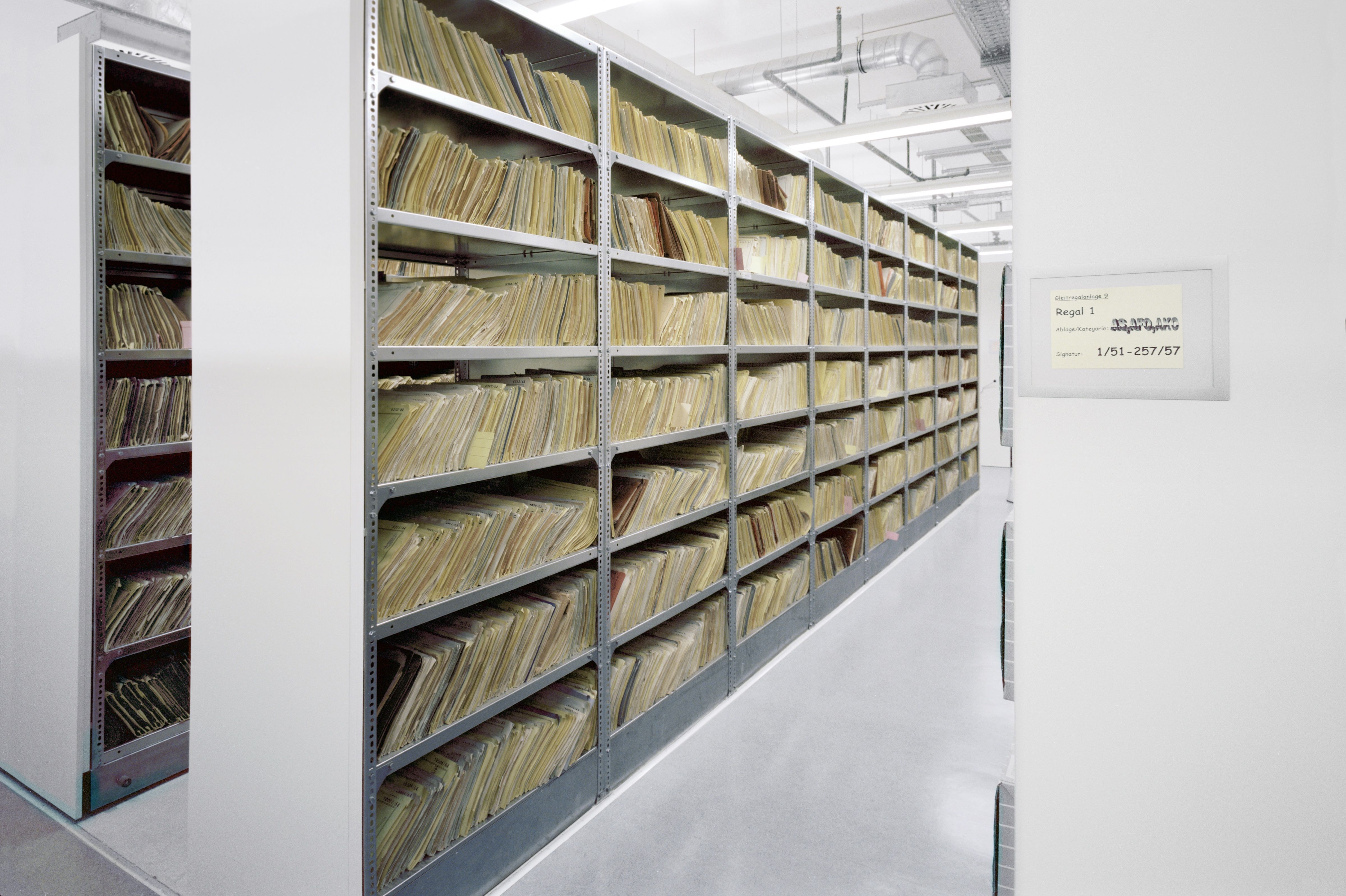

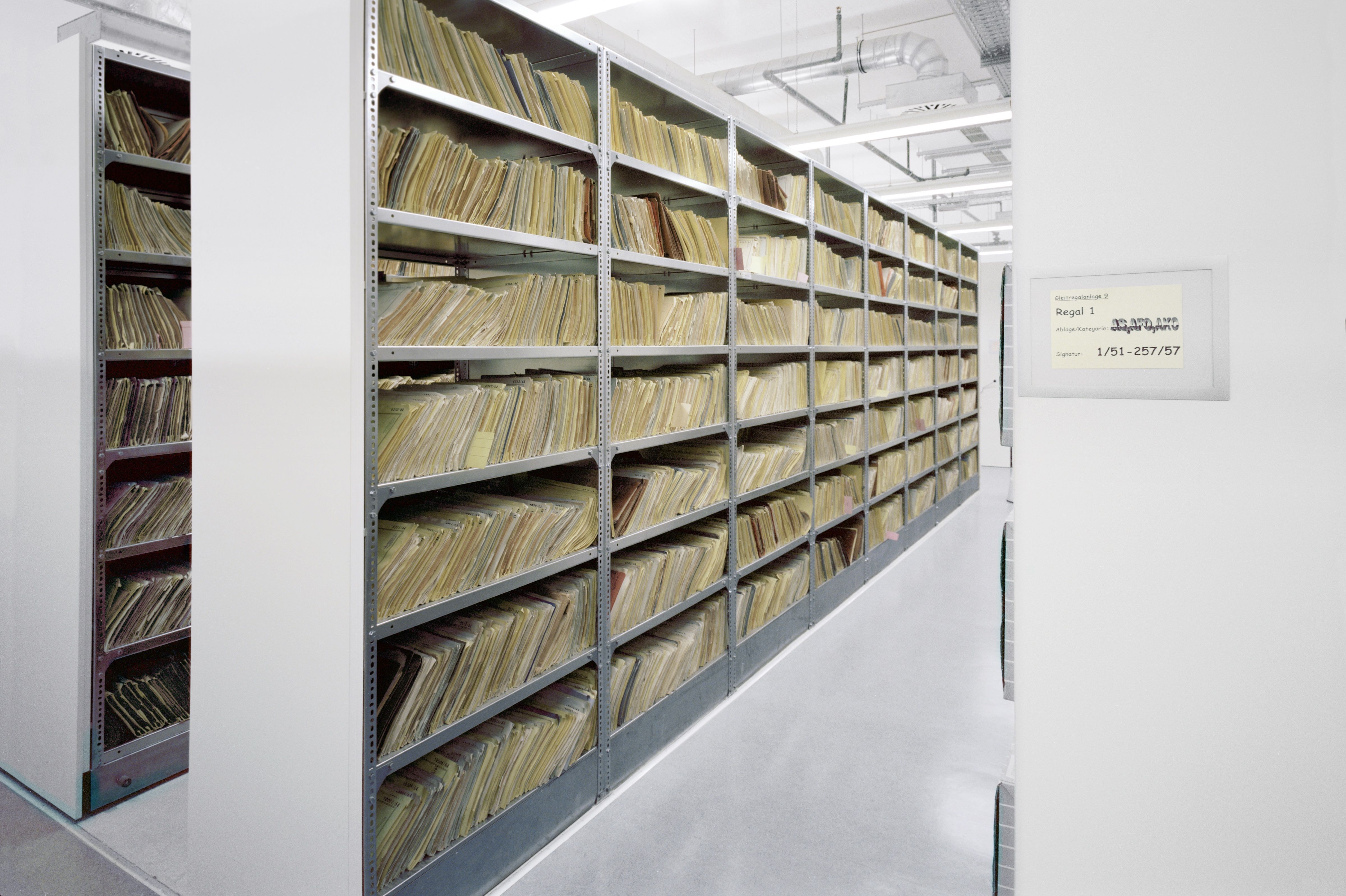

This collection contains the files of the State Security Service of the GDR that are preserved and administered by the Federal Commissioner for Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR (BstU). The surveillance records of the secret police represent a singular body of sources that offer unique glimpses into the cultural opposition to the GDR. The destruction of large numbers of these documents could only be averted in 1989/90 owing to the spirited actions of “Civil Committees”.

In 1990-1991, the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation put on an exhibition about student organizations before the Soviet occupation in 1940. Artefacts were displayed in the exhibition that could not be displayed before for political reasons: flags and other attributes of fraternities and other student organizations, as well as many photographs showing their traditions and activities, including pictures from the collection of photographic negatives of Krišs Rake (1897-1965), which was acquired by the museum at the beginning of the 1970s.

27 September - 10 November 1990

Franklin Furnace, New York

The exhibition presented 32O Hungarian, Polish, Czechoslovak, East-German, and Romanian publications from the period between 1956-199O. Since the selection was not confined to political publications in the literal sense, it included a remarkably rich array of materials from the perspective of artistic forms: self-publishing, political, cultural, and art books, book series, reviews (AL, AB HIRMONDO, BESZÉLŐ, Cseresorozat, TANGO, Világnézettségi Magazin etc., and publishers: ABC, ARTPOOL, HITEL Független Kiadó, KRAG, M.O, SzNOB International, SNTL, WSH etc./ and a number of cassettes, stickers, posters, pins, badges, T-shirts, arm badges, documention of various illegal street actions, etc.)

Curators: John P. Jacob and Tibor Várnagy

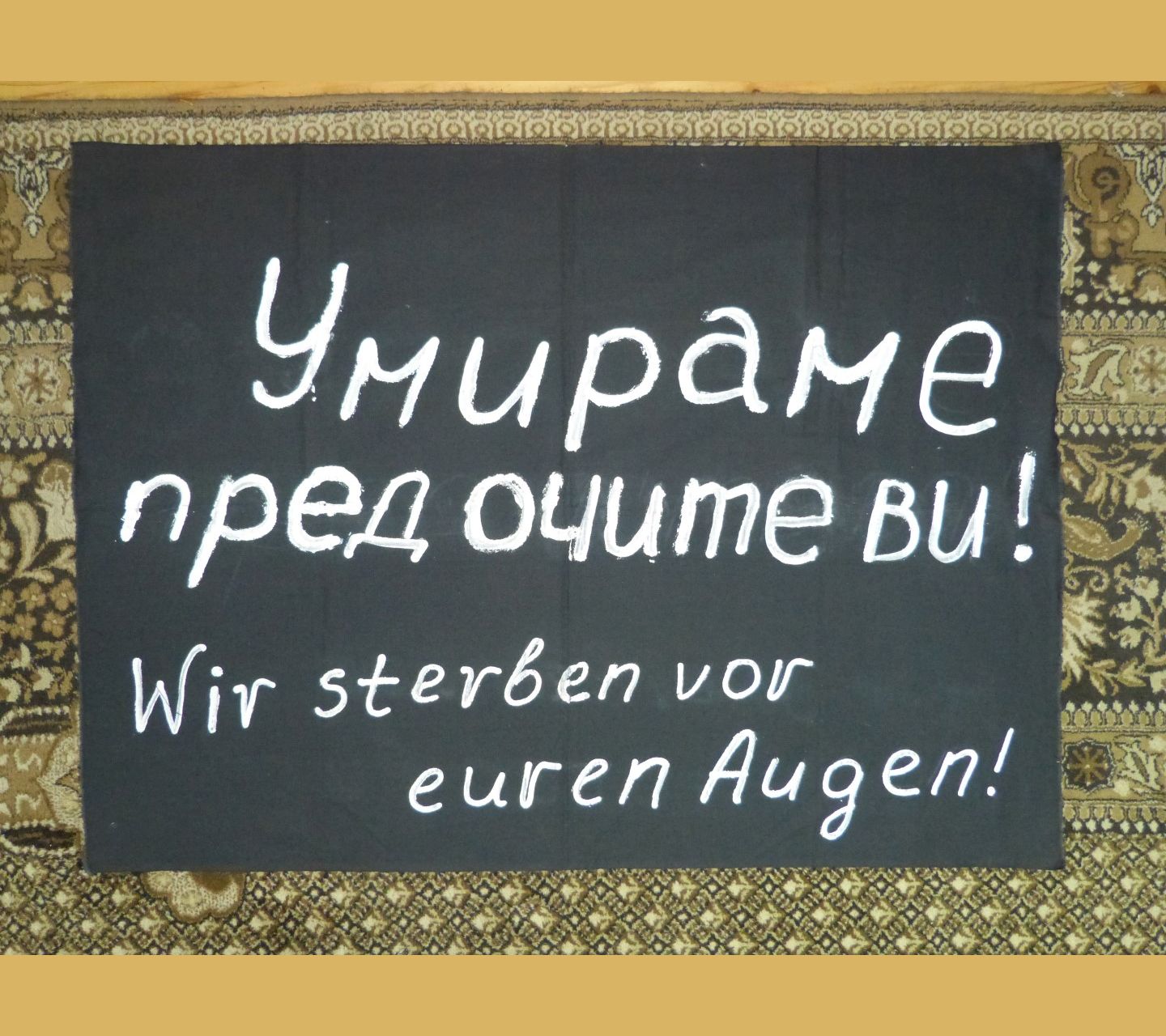

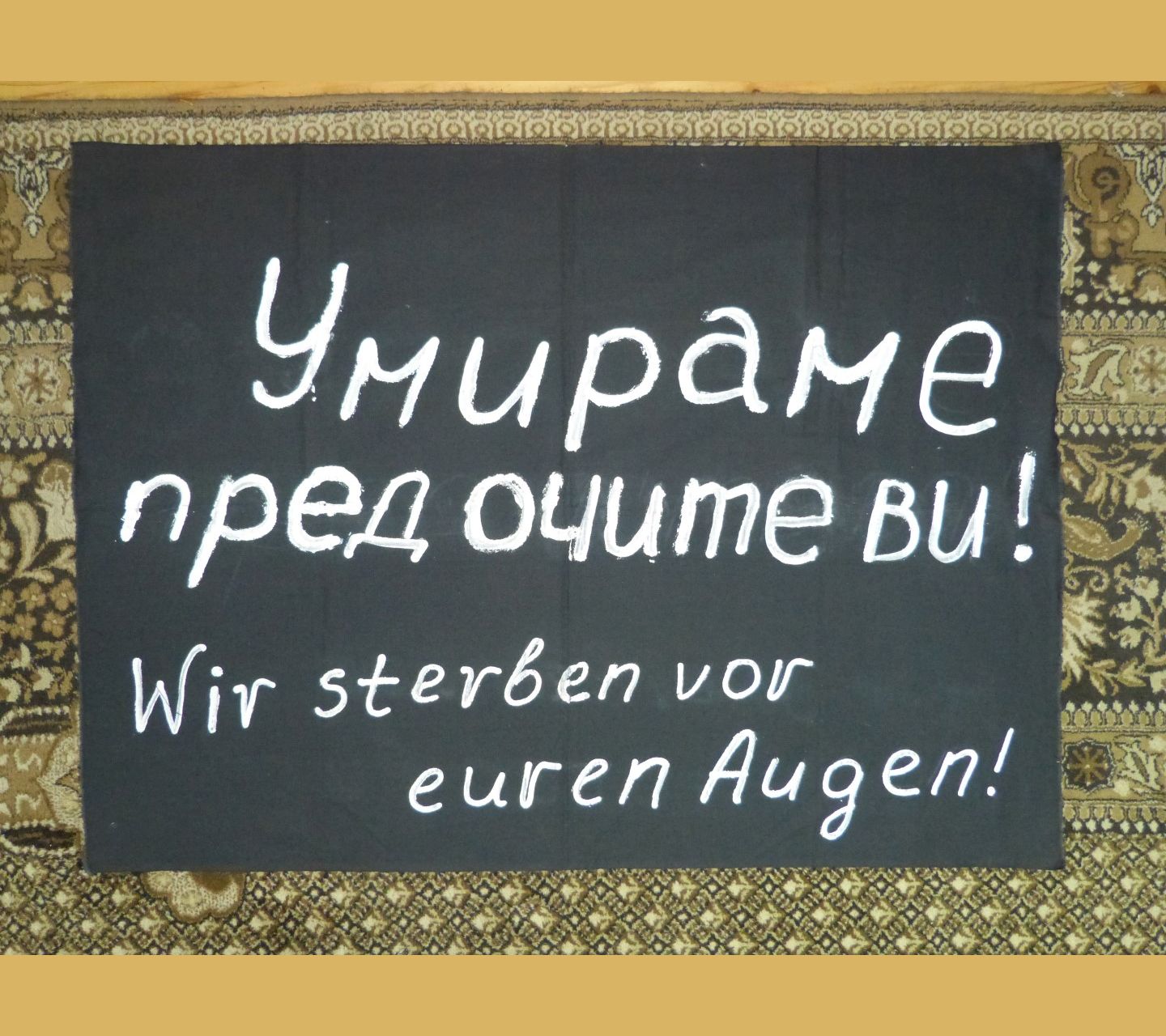

The material belongs to the final stages of the ecological protests – in 1990 and 1991. The request for international assistance on resolving the environmental problem was one of the ways, sought by the citizens of Ruse in finding a solution to their predicament. Along with numerous petitions to international organizations and media that covered the issue, this bilingual black banner with white-paint letters was one of the most direct expressions of the desire for international help. The banner was donated by Iskra Pencheva, a participant of the ecological protests, to the Rousse Regional Museum of History in 1991.

Already during the Velvet Revolution, students of the archives at the Faculty of Arts, UJEP in Brno started to create an archive of documents, photographs, posters, banners and other items of this important time. The collection grew, not only through their efforts but also spontaneously grew as the collection began to be organised by many students, and in the end, during 1990 it was also completely finished and prepared. The basement of its organisation has become an inventory, which are summarising the individual parts of the collection. There is, for example, an inventory of documents, photographs, newspapers, etc. They are hand written in exercise books, and they are still key in locating the huge amount of documents and charters.

Publication: Petrescu, Dan and Liviu Cangeopol. What remains to be said: Free conversations in an occupied country, in Romanian, 1990 (rev. ed. 2000). Book

Publication: Petrescu, Dan and Liviu Cangeopol. What remains to be said: Free conversations in an occupied country, in Romanian, 1990 (rev. ed. 2000). Book

The volume written by Dan Petrescu together with Liviu Cangeopol is, beyond doubt, one of the key books of Romanian dissidence. Its subject matter is extremely wide-ranging but, either explicitly or implicitly comes under the general theme of the values of liberal democracy and the “open society.” The book was begun in the spring of 1988 and finished the same year, in the autumn. Shortly after it was finished, its content was recorded on five audio cassettes. Later, the tapes were removed from their plastic housings and transported, after a tense journey, to the West by the Italian language assistant Anna Alassio, who had been attached to the University of Iaşi. “An audio-book avant la lettre. From the time of communism. The book, in its read form, was the length of five cassettes. But it wasn’t enough just to do that. We then took the cassettes apart and removed the tapes, so that, for transport, they would occupy as little volume as possible and not resemble anything we had sent out before. The rolls of tape occupied a very small space, and could be easily hidden and then remounted very easily. Which is what happened later, thanks to Dan Alexe. But not before further adventures. The Italian woman went with the cassettes to some members of the Romanian exile community and at first they told her that nothing could be done. She got angry, and reproached them that the language assistants were taking risks and when they reached their destination nothing could be done with what they brought. Finally they discovered Dan Alexe and he managed to mount the tapes.” Parts of the book were broadcast on Voice of America, but the whole book could unfortunately only be published after the fall of communism, in the February 1990 edition of the periodical Agora, the first and only alternative cultural journal in Romanian published in the United States. After the fall of communism, the book was also published in Romania, in two editions, 1990 and 2000. The second edition appeared in the “Societatea politică” (Political society) series at the Nemira publishing house, and in addition to the initial text, it also included all the other dissident texts of Dan Petrescu and Liviu Cangeopol, the minute of the 1983 search, the notices of fines issued for Dan Petrescu’s interviews on 10 October 1989 on Radio Free Europe and Voice of America, and the lists of signatures in support of Dan Petrescu collected by Ioan Petru Culianu in November 1989, when the former was on hunger strike. Like the first edition of 1990, the volume includes a preface by Vladimir Tismăneanu, an explanatory note on the context that gave rise to the book, a letter from Dan Alexe telling of the process by which the book went from audio tape to text transcribed for publication, and a letter of support from the poet Mariana Marin. In addition, the second edition has a postface by Cristina Petrescu.

András Kisfaludy’s collection suggests ways of interpreting retrospective gazes on the alternative culture of the socialist period. While Kisfaludy is the owner of a sizable private collection that concerns alternative and dissent culture of the era, he is more a creator than a collector of documents. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, he was a member of the famous youth gang called "Kalef" (in 2006, he made a film about the gang). From 1968 to 1971, he was the percussionist of the underground band "Kex.” Kisfaludy began to make documentary films on cultural opposition in the 1990s. The core of his oeuvre was done between the early 1990s and early 2000s. The status of the collection is special because the rights of the movies belong exclusively to András Kisfaludy, so the collection exists only as a private collection. However, the majority of his films are accessible via Youtube.

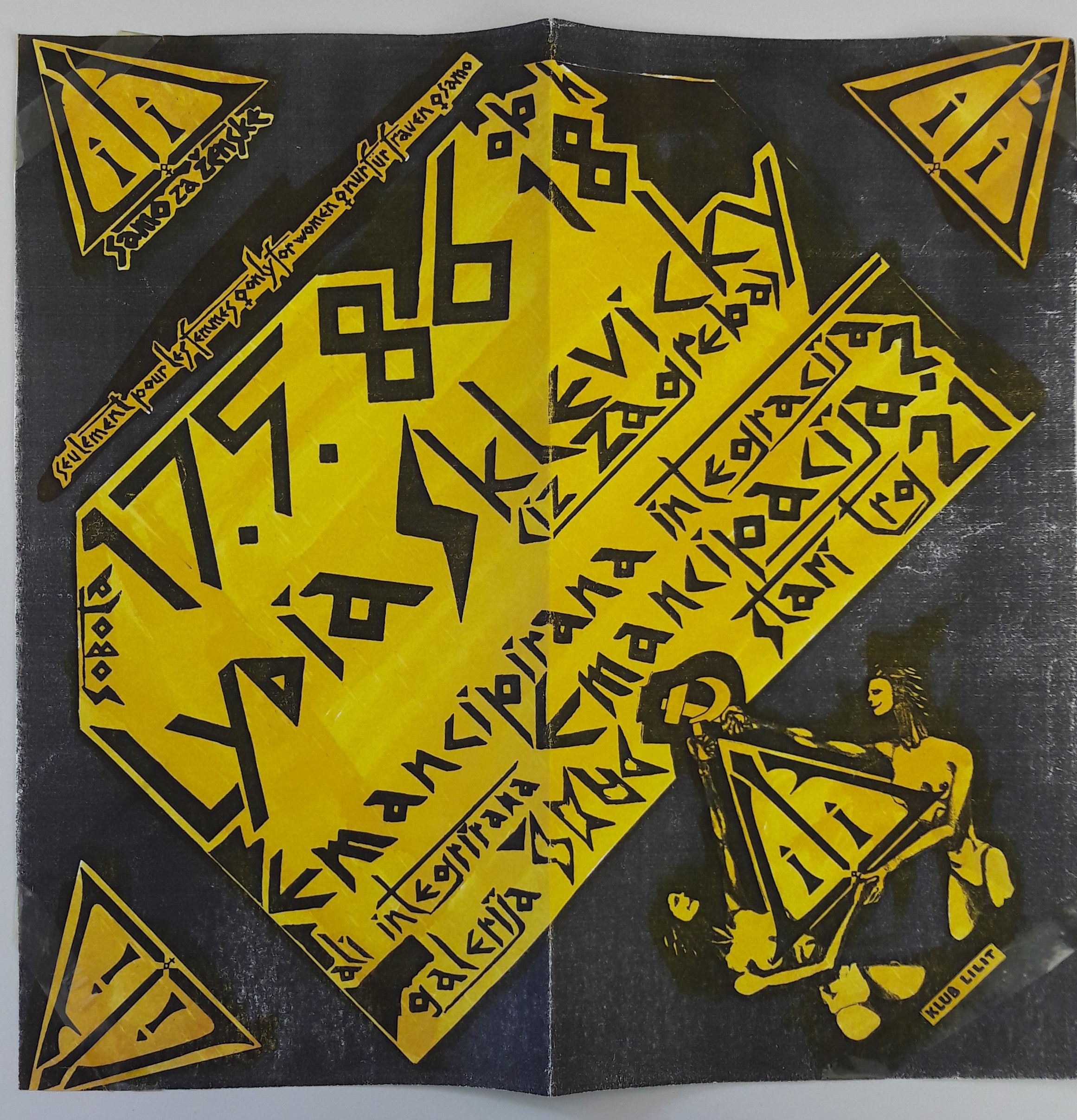

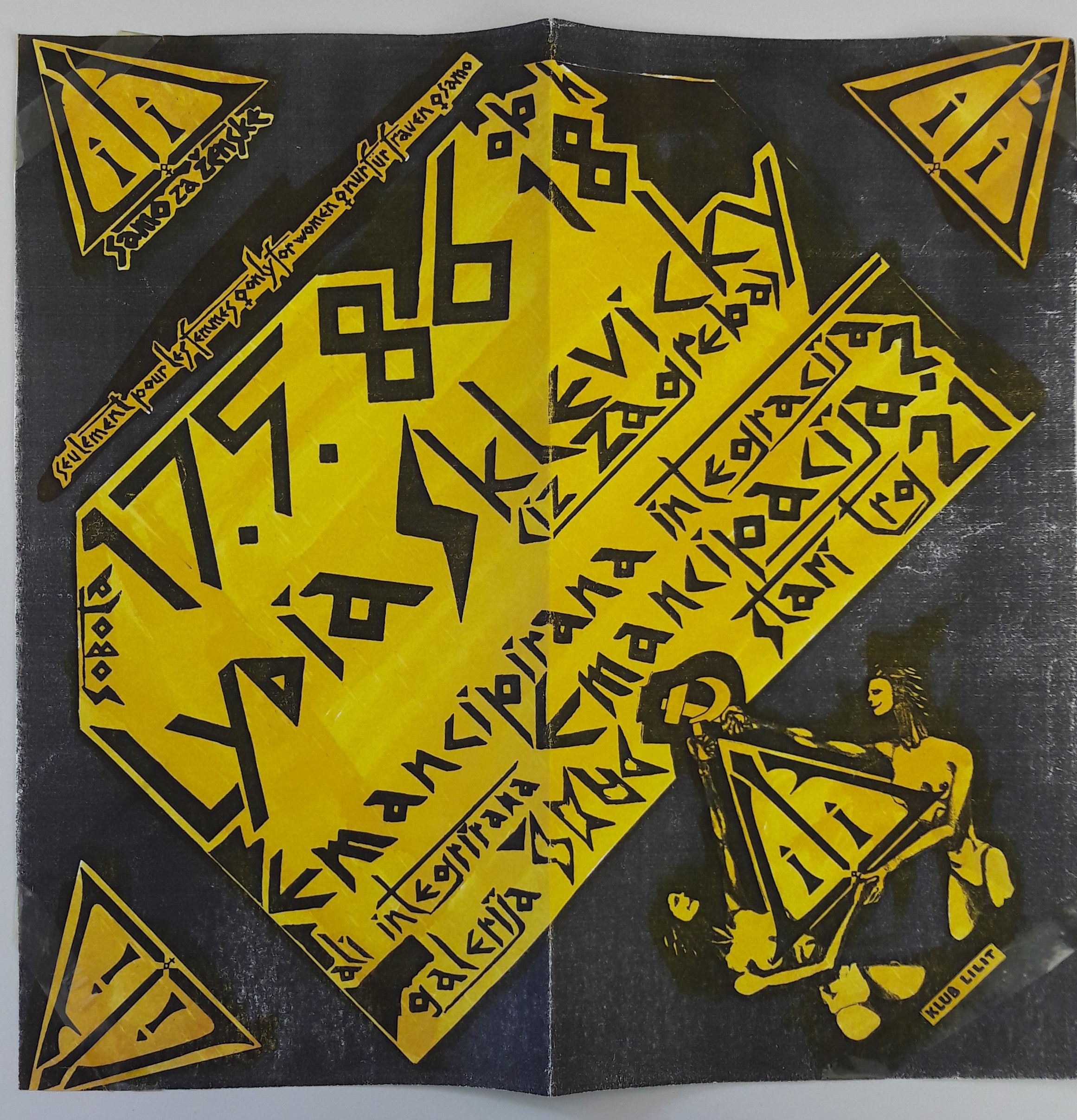

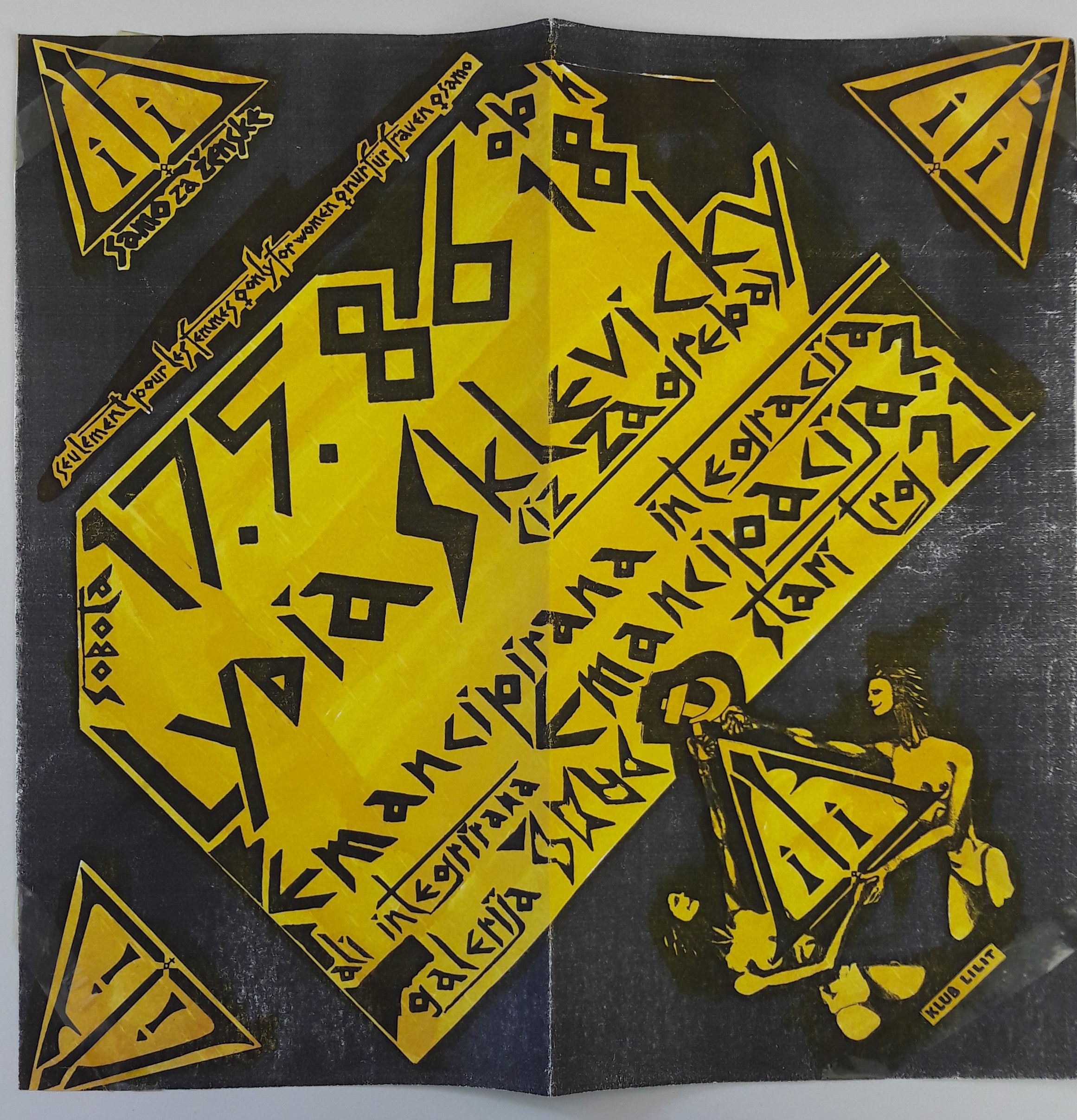

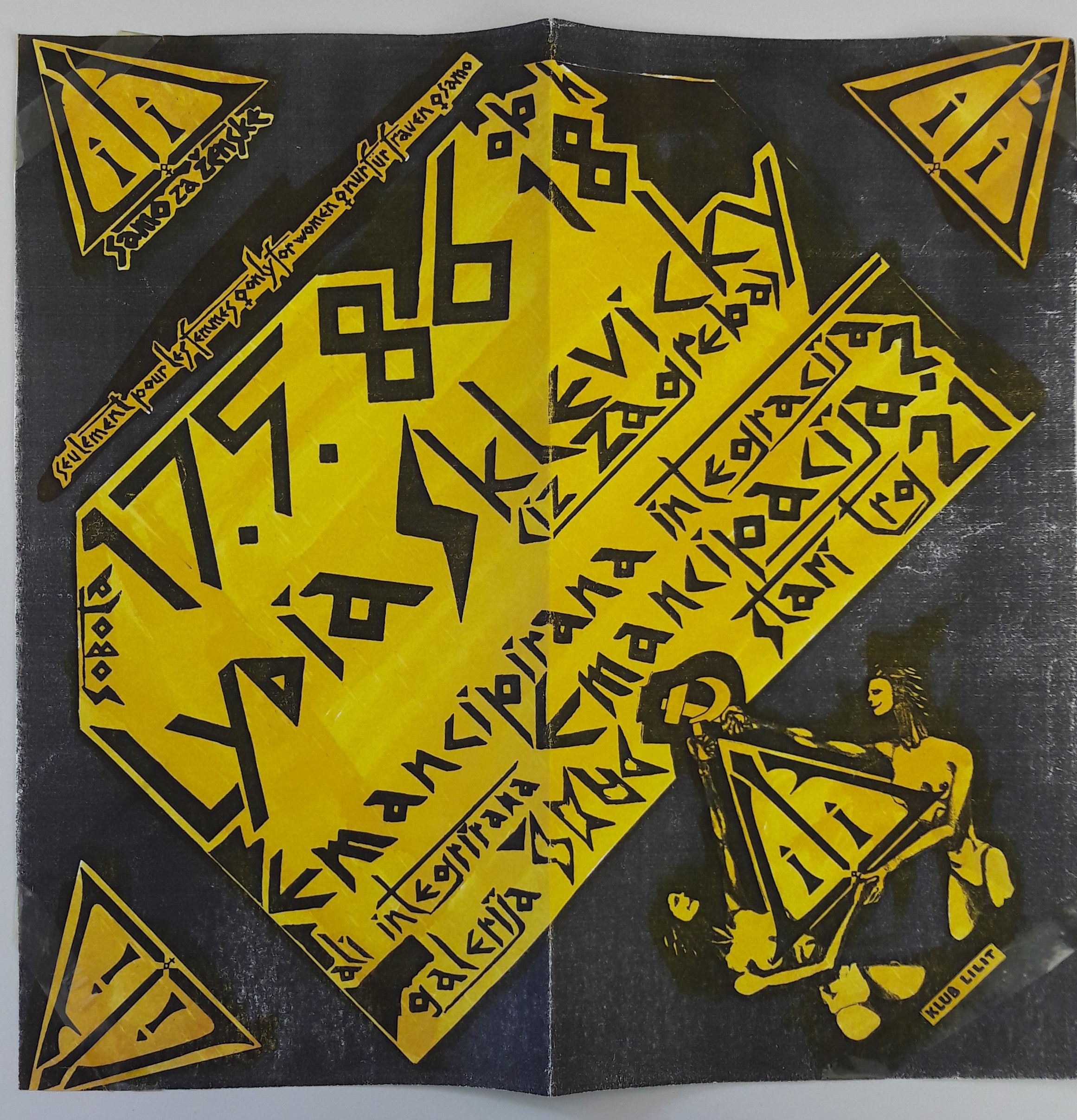

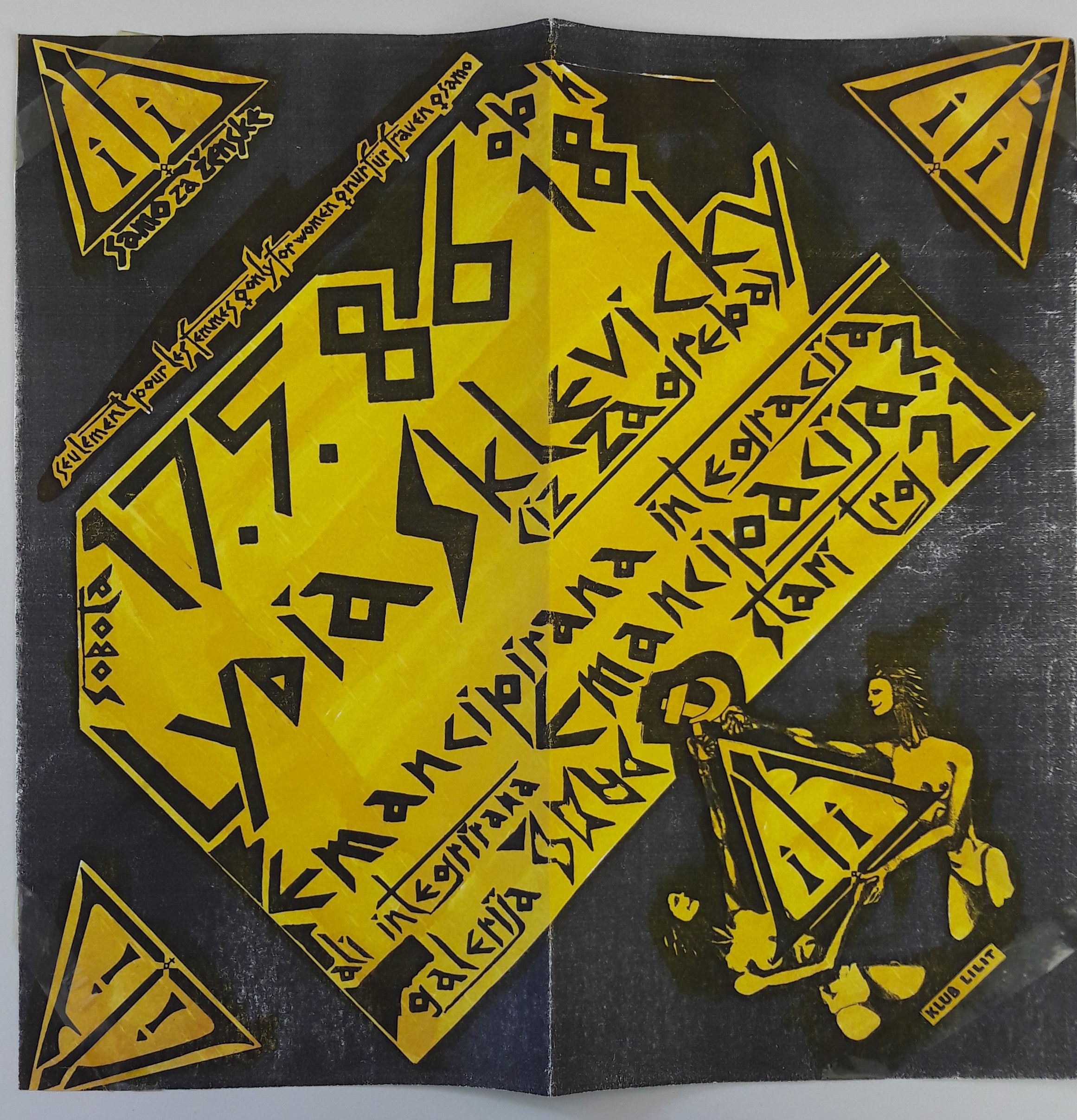

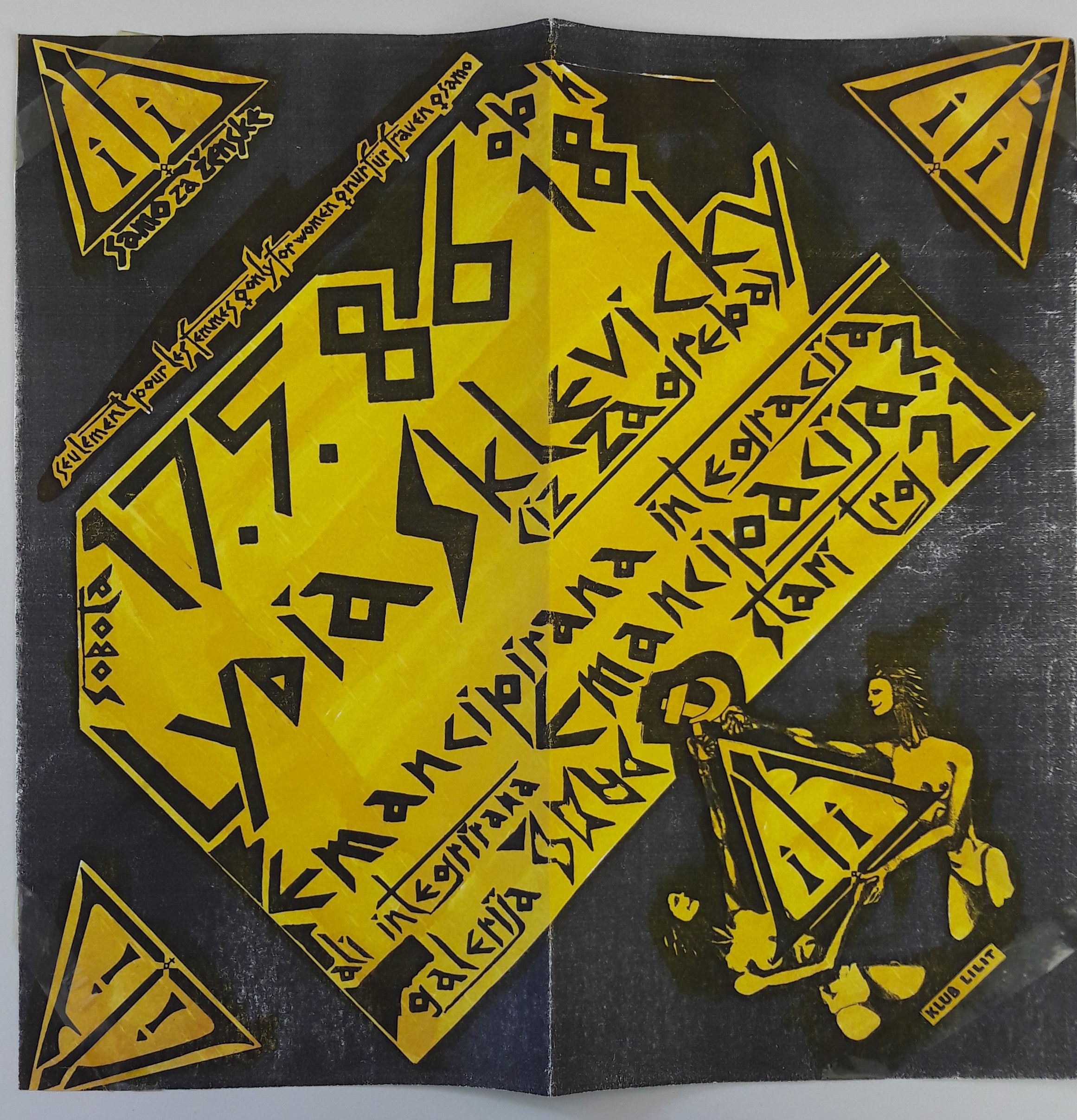

Lydia Sklevicky's Feminist Collection at the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research in Zagreb consists of a newspaper and periodicals collection, documentation and a library that testify to Sklevicky’s professional work and interests, primarily related to feminism and the issues of women's rights in Yugoslavia and the world. Sklevicky was one of the protagonists of the late 1970s and 1980s who put women's issues in focus and criticized the unenviable position of women in Yugoslavia, particularly by pointing out the discrepancy between their contribution in World War II and their prominent role in the post-war period on the one hand, and their re-marginalization since the mid-1950s on the other.

One of Árpád Göncz’s first trips abroad in May 1990 as newly-elected President of the Hungarian Republic was to Indianapolis, US in order to receive a Honorary Doctorate from the Senate of Butler University. On this occasion, he first read his essay “The nameless Hungarian,” a brief historical overview of twentieth century in Hungary and East Central Europe. (The speech held at the ceremony was somewhat longer than the essay, but only the Hungarian draft survived in a later book publication, without the final English version. Here, all the three texts can be read attached.) This somewhat “bitterly optimistic” summary reflects Göncz’s charmingly brave and honest character, his wisdom, his deep empathy, and his sense of humor, as well as his sincere conviction that all the pains, failures, and losses of a horrible century can only be surpassed by the powerful collective reserves of freedom and liberty.

Just few days after he was elected president, Václav Havel travelled to Ostrava on 3 January 1990. The so-called “Steel Heart of the Republic” therefore became the first city (besides Prague) visited by Havel as the president. Havel’s first steps led to Jaromír Šavrda’s grave at the Ostrava-Hrabová cemetery. There he paid tribute, by taking a bow and laying flowers, to the significant Ostrava writer, journalist, dissident and his own friend who died in May 1988 shortly before the Velvet Revolution. Havel’s symbolic gesture helped to spread awareness of Jaromír Šavrda; many Ostrava citizens first heard of him thanks to Václav Havel’s visit. The iconic pictures of the event are now part of the Jaromír and Dolores Šavrda Collection in the Ostrava City Archive.

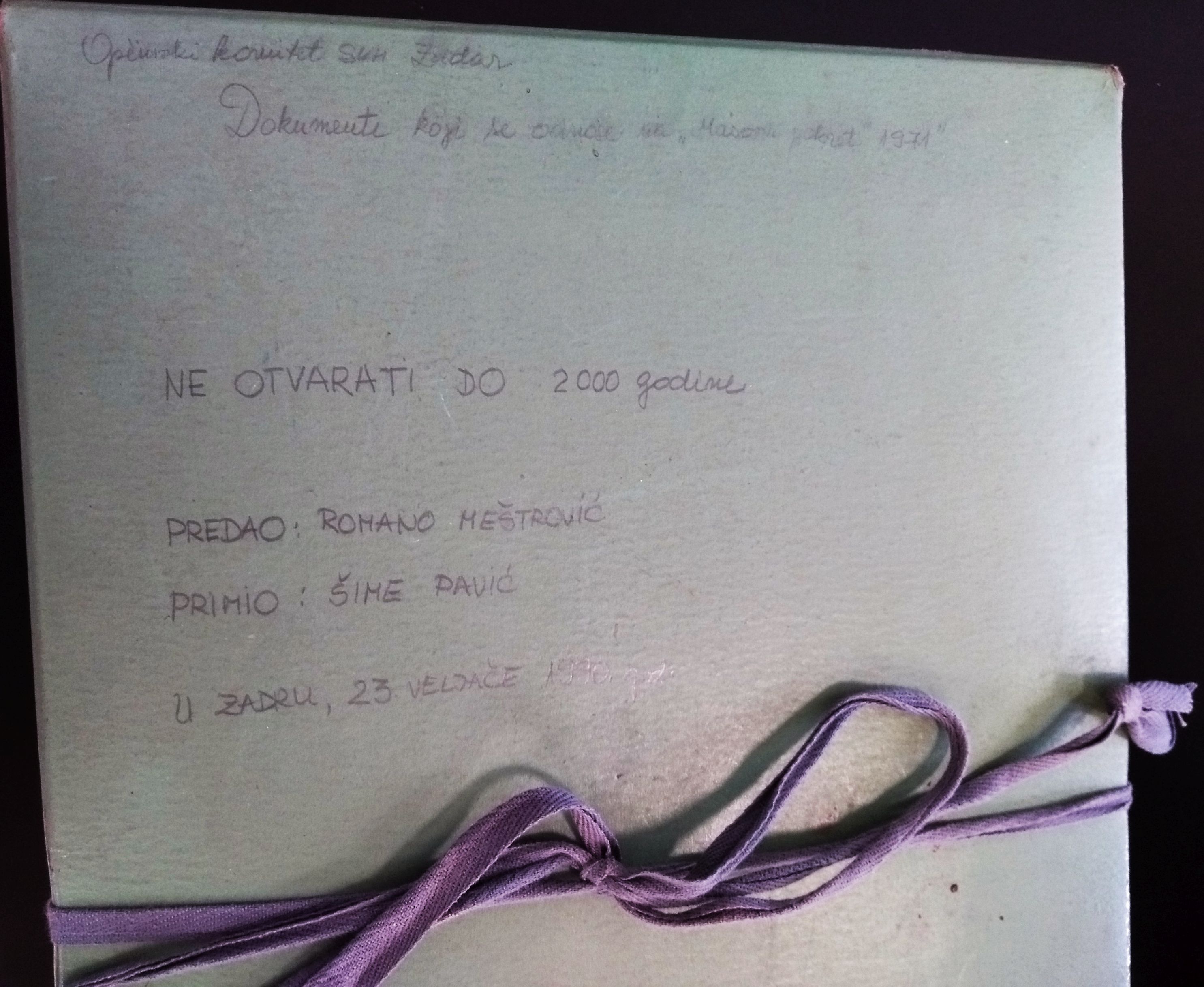

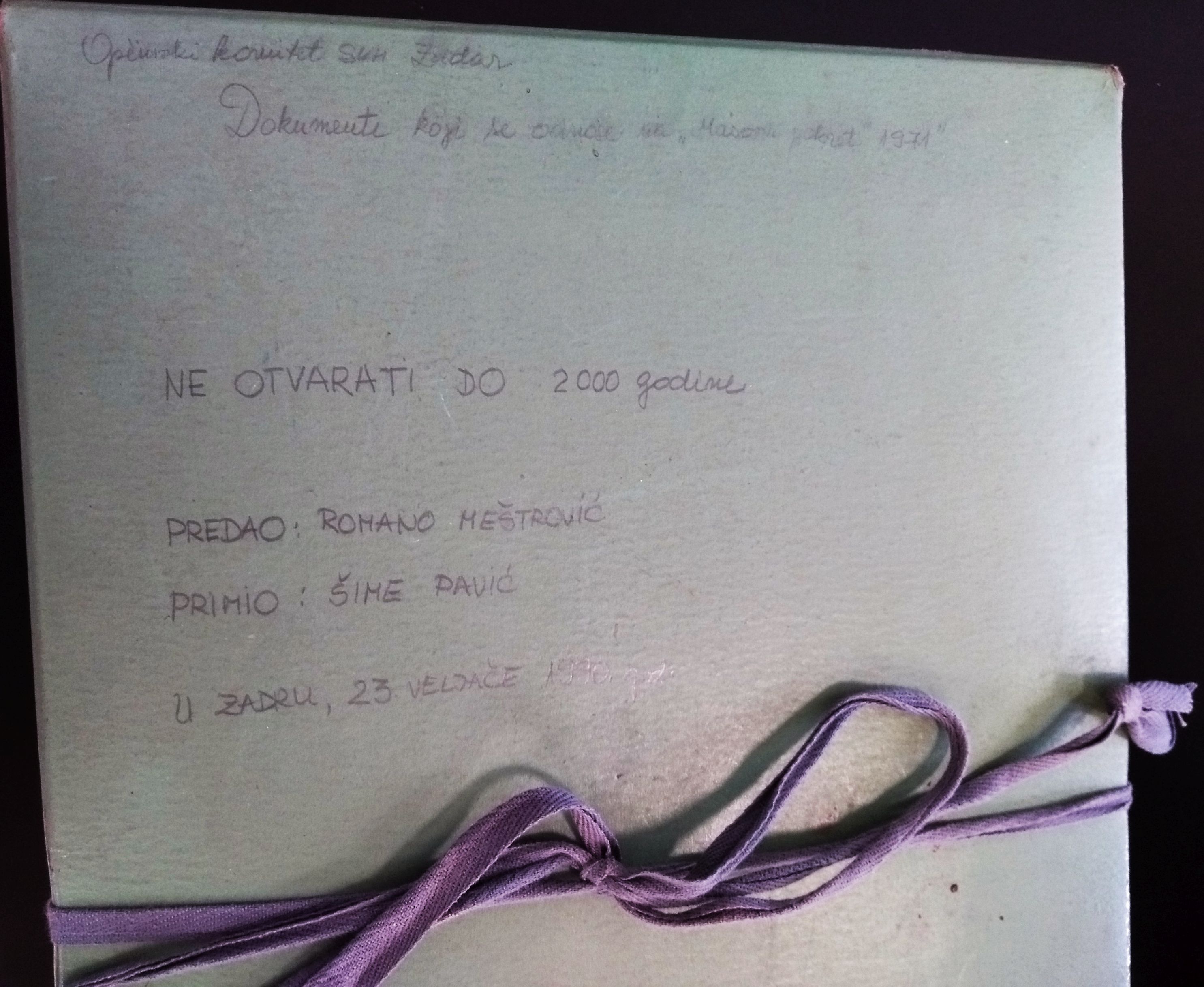

The former chairman of the Zadar municipal committee, Romano Meštrović, extracted the documents on the mass movement of 1971 in Zadar as an ad hoc collection already in 1990. The archival materials testify to the local communist purges after the quelling of the Croatian national liberal movement known as the Croatian Spring. It mainly consists of different reports, assessments and the minutes of the inquiry panel, which investigated and accused the reformist Party members for nationalist, i.e., anti-socialist activities also in the cultural field. The city of Zadar and its communist leadership was considered one of the epicentres of the Croatian Spring, heavily criticised by Josip Broz Tito at the Karađorđevo meeting at the end of 1971.

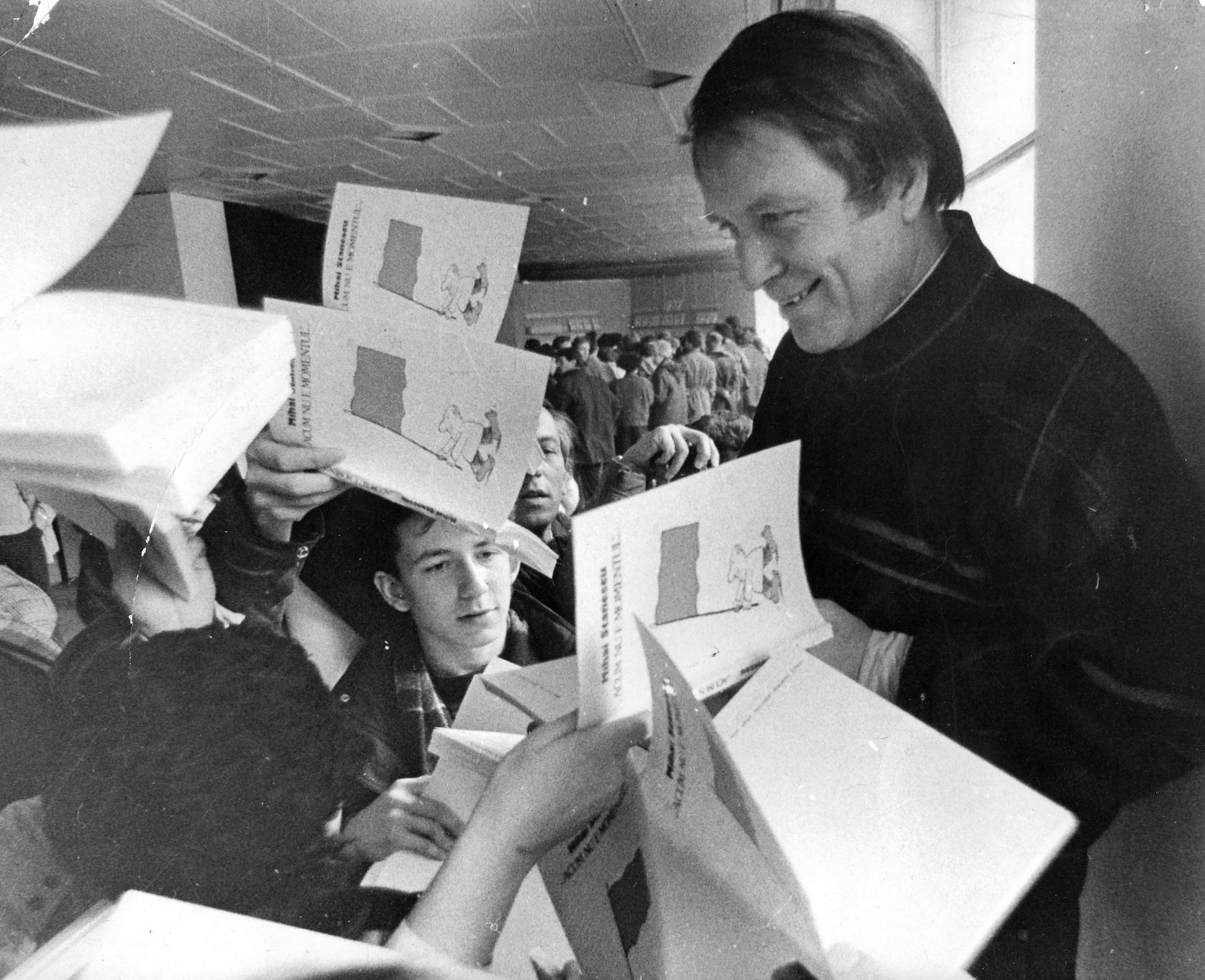

Just a few weeks after the fall of communism in Romania, in February 1990, at the Dalles Hall in the centre of Bucharest, Mihai Stănescu’s exhibition “Now Is Not the Time” was opened in the presence of the artist. The album that accompanied the works assembled in the exhibition was printed in a spectacular print run of 100,000 copies, after the artist had multiplied it by his own efforts and put it into circulation among his friends as a samizdat. However, although the print run was huge, Mihai Stănescu says that it was insufficient for that moment, in which his exhibition drew a quite remarkable number of visitors. Mihai Stănescu also recalls the short history of the samizdat album that preceded the exhibition, ensuring its extraordinary success later: “I also created an album called Now Is Not the Time in June 1989, and I multiplied [the drawings] at the American Library, at the Fine Mechanics Factory, where they had photocopiers. And that’s why people knew about it, and after the Revolution the first book that appeared in Romania was mine, at the beginning of January, because all the writers had withdrawn their books, to remove from them the compromises that they had made. I had mine ready and I had nothing to remove, so [I took advantage of the fact that] the whole House of the Spark was free, and I printed [the album] in 100,000 copies. And it wasn’t enough. I held a launch at the Dalles Hall, but I only too about 5,000 copies to sign for the launch, because I didn’t know there would be so many people. And many people were left without, but they bought it afterwards.”

The Jan Patočka Archives (AJP) studies and interprets the philosophical heritage of the Czech philosopher and dissident Jan Patočka (1907-1977). AJP is led by Patočkaʼs pupils and is a unique institute working with Patočkaʼs original texts and also with the attendees of his lectures.

The Libri Prohibiti’s collection of Czech exile monographs and periodicals contains over 8100 publications including the complete works of many publishers. More than 940 titles of Czechoslovak exile periodicals, some of them complete editions, are part of this collection as well.

On 30 May 1990, just a few months after Ceausescu’s tyranny was overthrown by desperate street fights, a severe earthquake hit the counties of Vrancea and Covasna (Háromszék) in central Romania. Among the losses were fifty heavily-damaged, older church buildings (many built before AD 1300) in Háromszék, the easternmost region of Transylvania with an 80% Hungarian majority. A group of volunteers formed among the activists of the relief organization, ETE-Transcar, and the architects of the National Historical Monuments Protection Authority. They made an overall survey of the damaged churches in order to inform the wider public and acquire the help needed for repairs. An international relief campaign was launched, and detailed documentation of the damages was published as “Pro Domo Dei”. It was edited by Budapest-based monument architect István Varga, with the collaboration of Hungarian co-authors and specialists: János Gyurkó, József Sebestyén, Béla Nóvé, László Nagy and others. The illustrated report contained a number of case studies, lists, maps and photo documentation of the damages, together with English and French summaries.

The aims and spirit of the relief campaign were much the same as those of Deadline Diaries – Transylvanian Monitor, ETE-Transcar, S.O.S Transylvania, and Hopes and Doubts by Bálint Homoród (Béla Nóvé); helping people in need and helping traditional cultural values survive. This profoundly humanitarian and democratic spirit is reflected in the forward to Pro Domo Dei:

Pro Domo Dei is a neutral project from the point of view of religious and ethnic groups. TRANSCAR relief organization will help both the Hungarian Catholic and Protestant parishes, in their grave situation, as well as the Orthodox Romanian parishes in Covasna (Háromszék) County. […] The ‘Pro Domo Dei’ project is organized first and foremost for monument protection. Our main focus of support is for the historical value; among the heavily damaged churches in the county there are some which are more than 700 years old. […] In addition to financial assistance, it is also important that, after the failure of communism, this region in Europe that has suffered so much has some moral support from the international community and readiness to help.

This documentary was filmed in 1990, in the context of the collapse of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe. While former members of the underground opposition were celebrated as heroes of the fight for freedom in countries like Poland, Hungary, and former Czechoslovakia, in Romania – a country where only a few intellectuals had dared to stand up against the Ceaușescu regime – the most troublesome question was: “Why did we not have a Havel?” In other words, why was dissent in Romania weak in comparison to any other country of the Soviet bloc. Romanian intellectuals found themselves socially compelled to formulate a convincing answer to this question, and argued that the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, was so efficient that it destroyed any attempt at organising an opposition movement. This documentary was among the first to challenge this interpretation and thus trigger an ongoing public debate, for it argued that the feeble criticism of the former communist regime was rather the effect of co-optation than of oppression.

The director Benny Brunner focused on an interview that he conducted in Munich with the founder of the collection Michael Shafir and the late dissident Mihai Botez. Images depicting Romania during the 1980s support the arguments of the two interviewees. The main assumption of the documentary, which both Shafir and Botez had previously developed in their works, is that Romanian intellectuals were co-opted by the communist regime and became an instrument for the preservation of political power. In this respect, the regime used, on the one hand, financial incentives and career opportunities and, on the other, the manipulation of the nationalist discourse. The case of the poet Adrian Păunescu was given particular attention, for he represented the most striking example of a talented young intellectual who nonetheless submitted himself willingly to the communist regime. He started his career as a nonconformist intellectual in the late 1960s, only to end up as a pillar of Nicolae Ceauşescu’s cult of personality in the 1980s and a manipulator of the underground culture of the young generation.

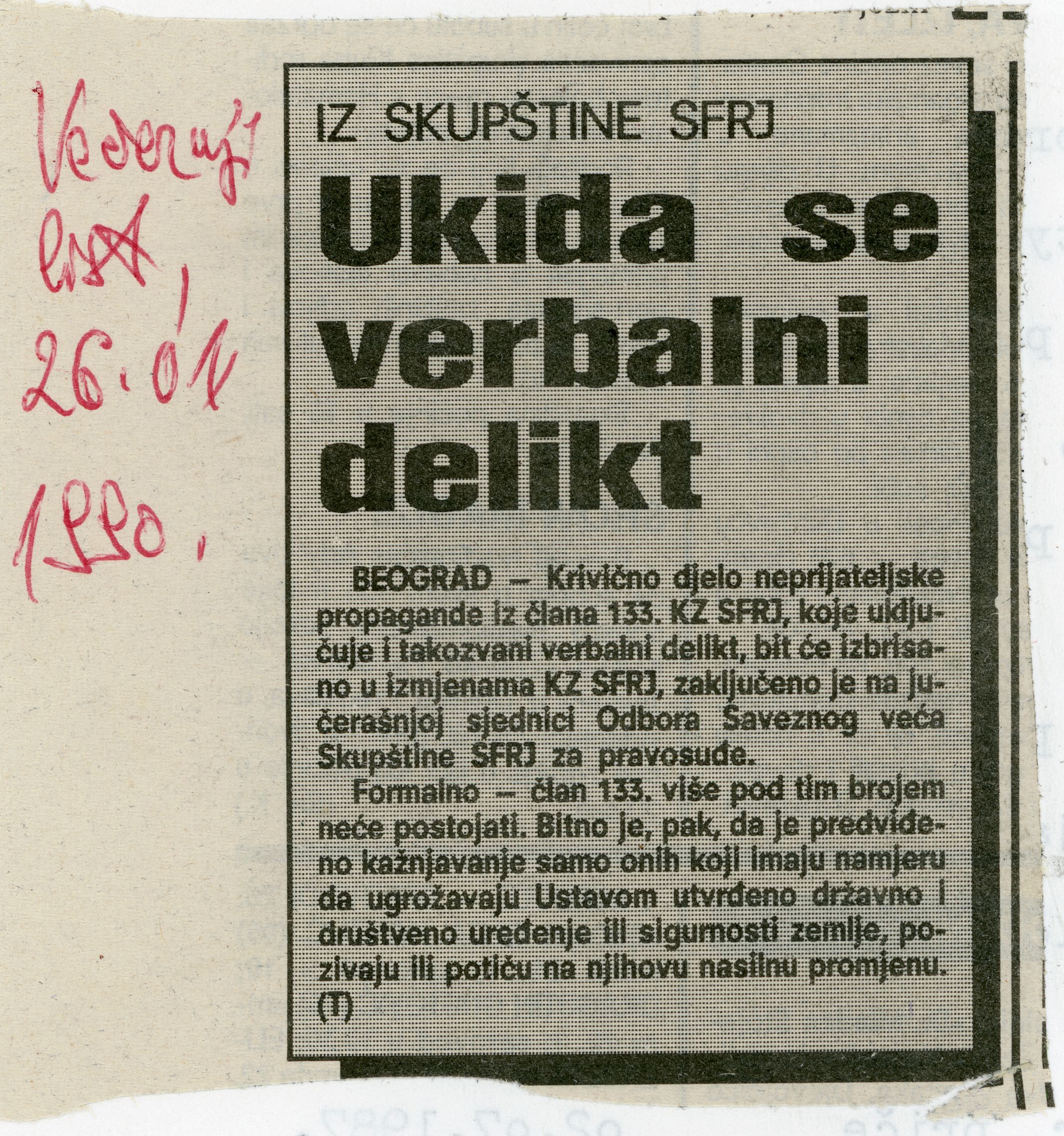

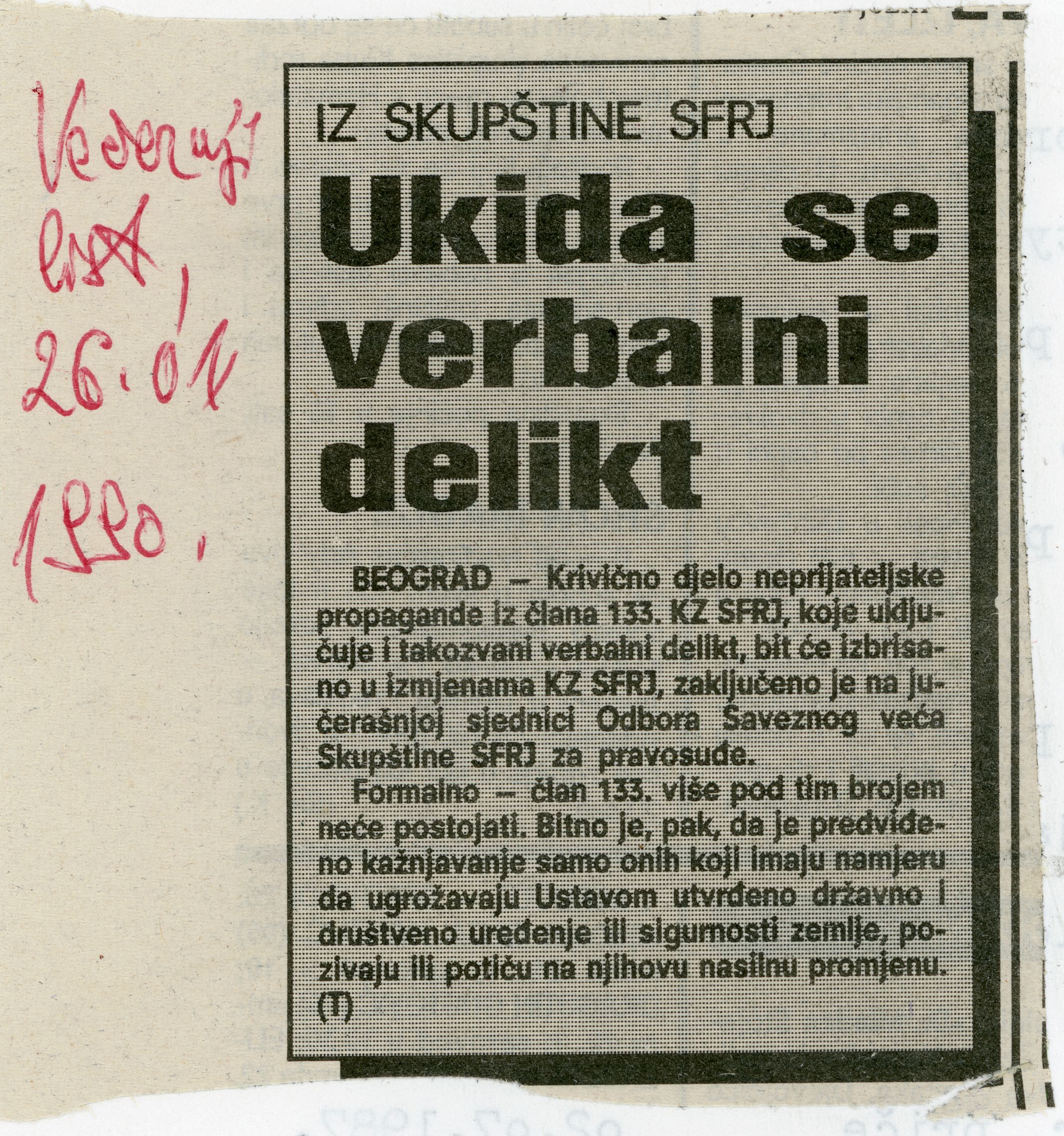

Freedom of conscience officially existed in Yugoslavia, but not freedom of expression. The ‘verbal delict’ was punishable as a crime of "hostile propaganda" as stipulated in Article 133 of the Criminal Code of the SFRY. It was abolished only at the beginning of 1990, which was reported as news in this press clipping. Singing nationalist songs, socialising with émigrés or the approbation of "hostile statements" were once grounds for a jail sentence. During the 1970s and 1980s, approximately 500 lawsuits were filed against ‘verbal delinquents’ every year. In Croatia, the most famous among them were Franjo Tuđman, Marko Veselica, Ivan Zvonimir Čičak, Dobroslav Paraga and Vladimir Šeks.

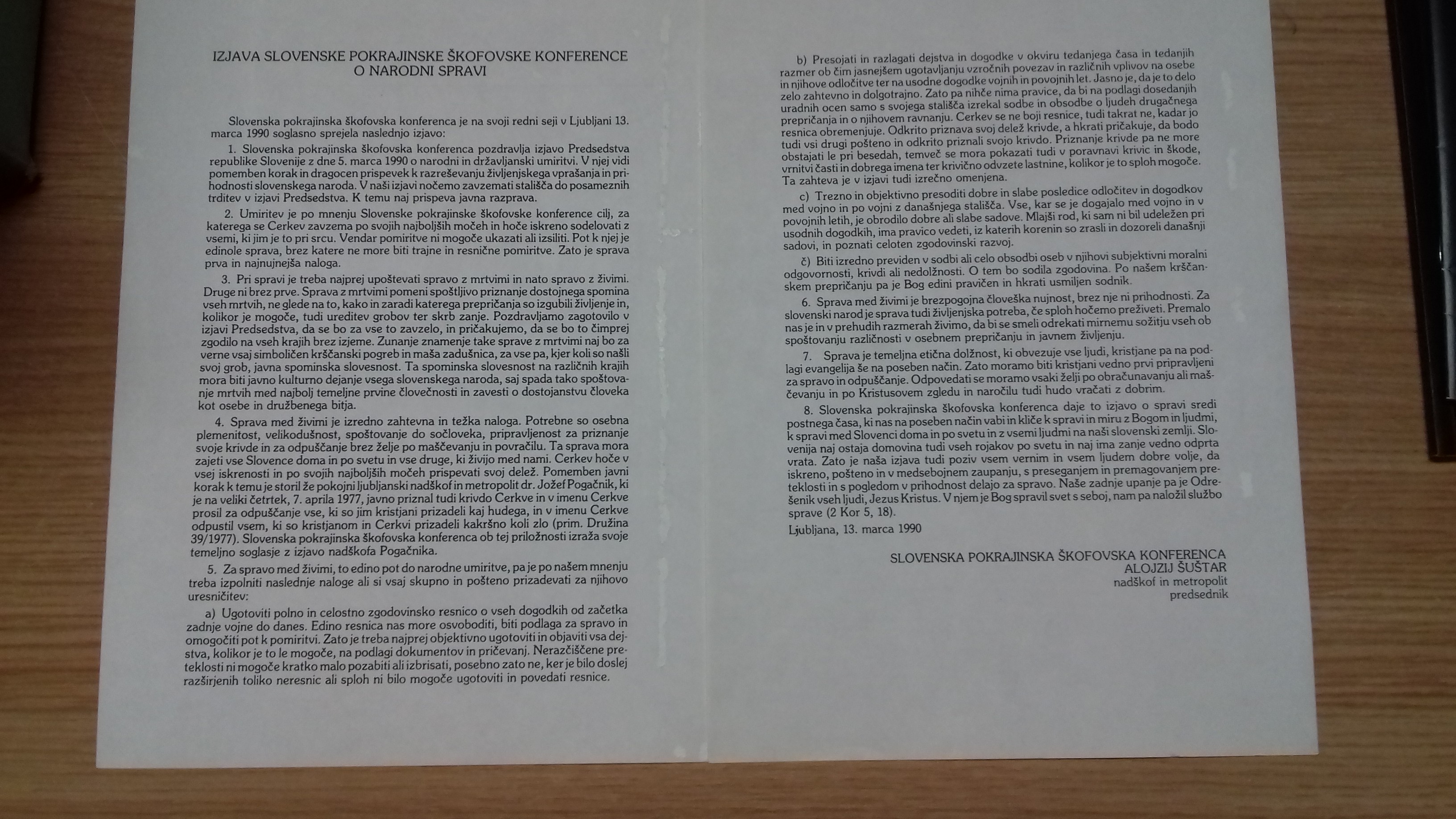

Declaration of the Slovenian Catholic Conference of Bishops on national reconciliation, 13 March 1990. Manuscript

Declaration of the Slovenian Catholic Conference of Bishops on national reconciliation, 13 March 1990. Manuscript

The role of the document was to address the Slovenian public on the question of national reconciliation. It was a very critical message questioning the basic premises of the 45 year-long policy of the communist government on the civil war fought between the Slovenians between 1941 and 1945 and the post-war mass killings committed by them. The authorities did nothing, because the Declaration was published on March 13, 1990 and in April of 1990 there were free elections after many decades of communist dictatorship. The Slovenian public was immensely interested in the Declaration. Already in July the Slovenian authorities, including the chairman of the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia, Milan Kučan, participated in the memorial service on Kočevski Rog led by Archbishop Šuštar. It was a major step toward a public break with the communist monopoly on truth and rehabilitation of the victims of the post-war mass killings perpetrated by the communist government. The document is used in publications and exhibitions. Historians as well as the Catholic Church in Slovenia consider it a symbol of cultural opposition. It is located in box 38 of the Alojzij Šuštar Collection and it is provisionally available.

The collection belonging to the Memorial to the Revolution of 16–22 December 1989 in Timişoara brings a distinct and quite remarkable civic and ethical dimension to the institutionalization of the memory of the recent past of Romania. The monuments, exhibition spaces, objects, documents, photographs, and personal testimonies included in this collection illustrate the authenticity of the popular revolt that began in the city of Timișoara. To be more precise, the collection illustrates both the huge scale of the armed repression in those days and the extraordinary citizen resistance that the authorities were faced with in this key city for the fall of communism in Romania. The Memorial also includes a research centre and a publishing house, ensuring that there is constant scholarly and editorial activity aimed at developing the potential of the historical resource that it administers.

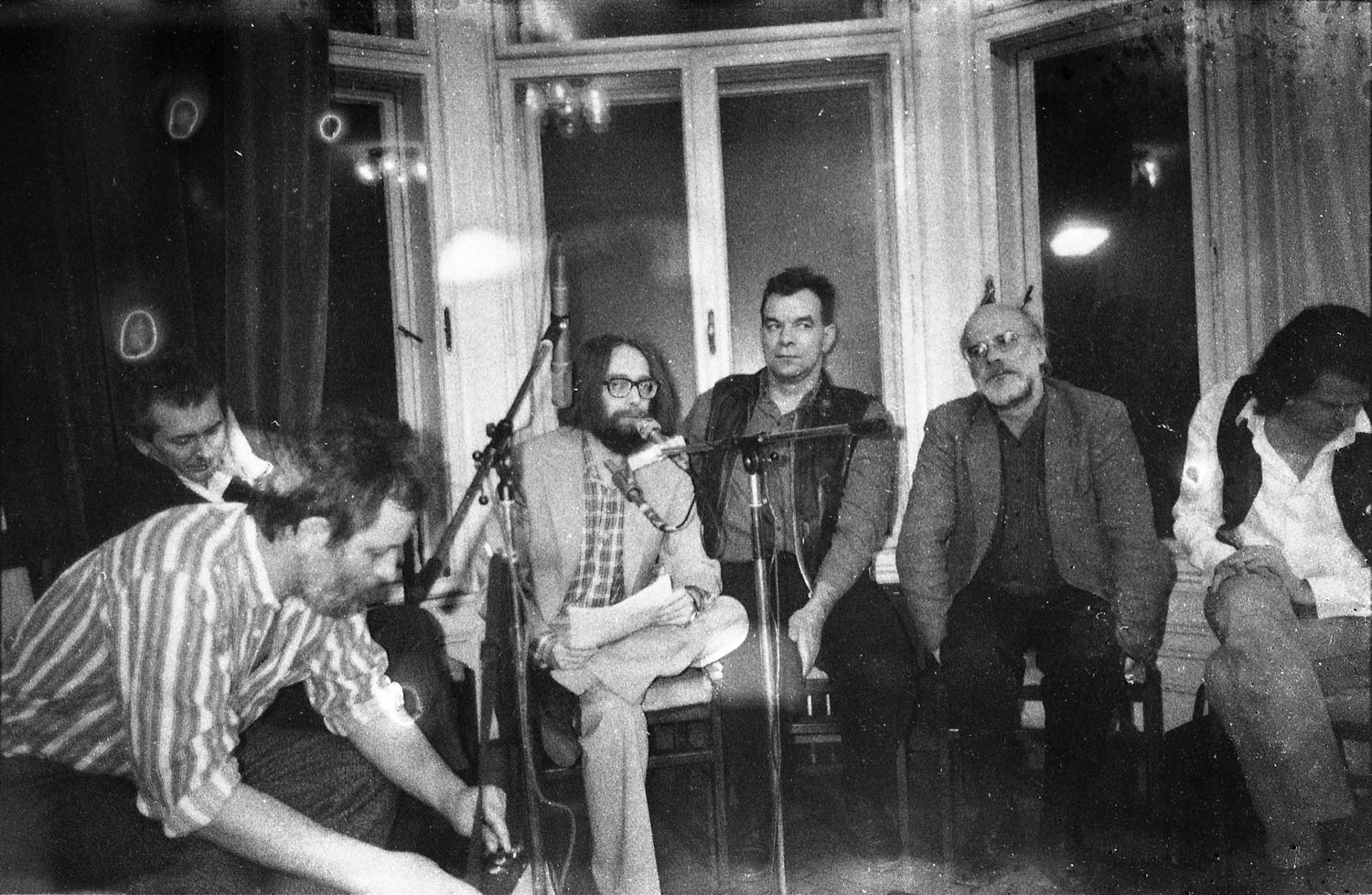

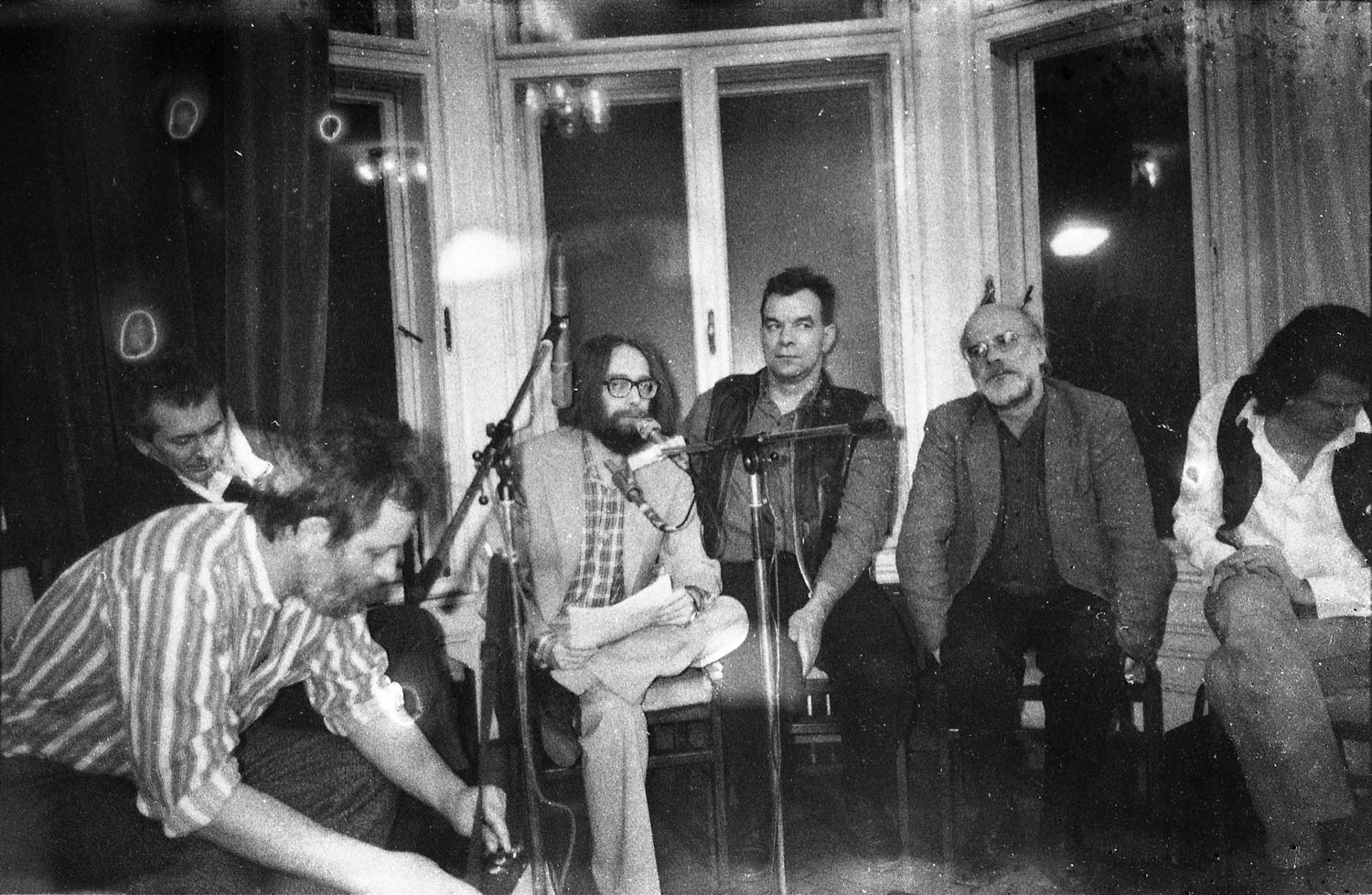

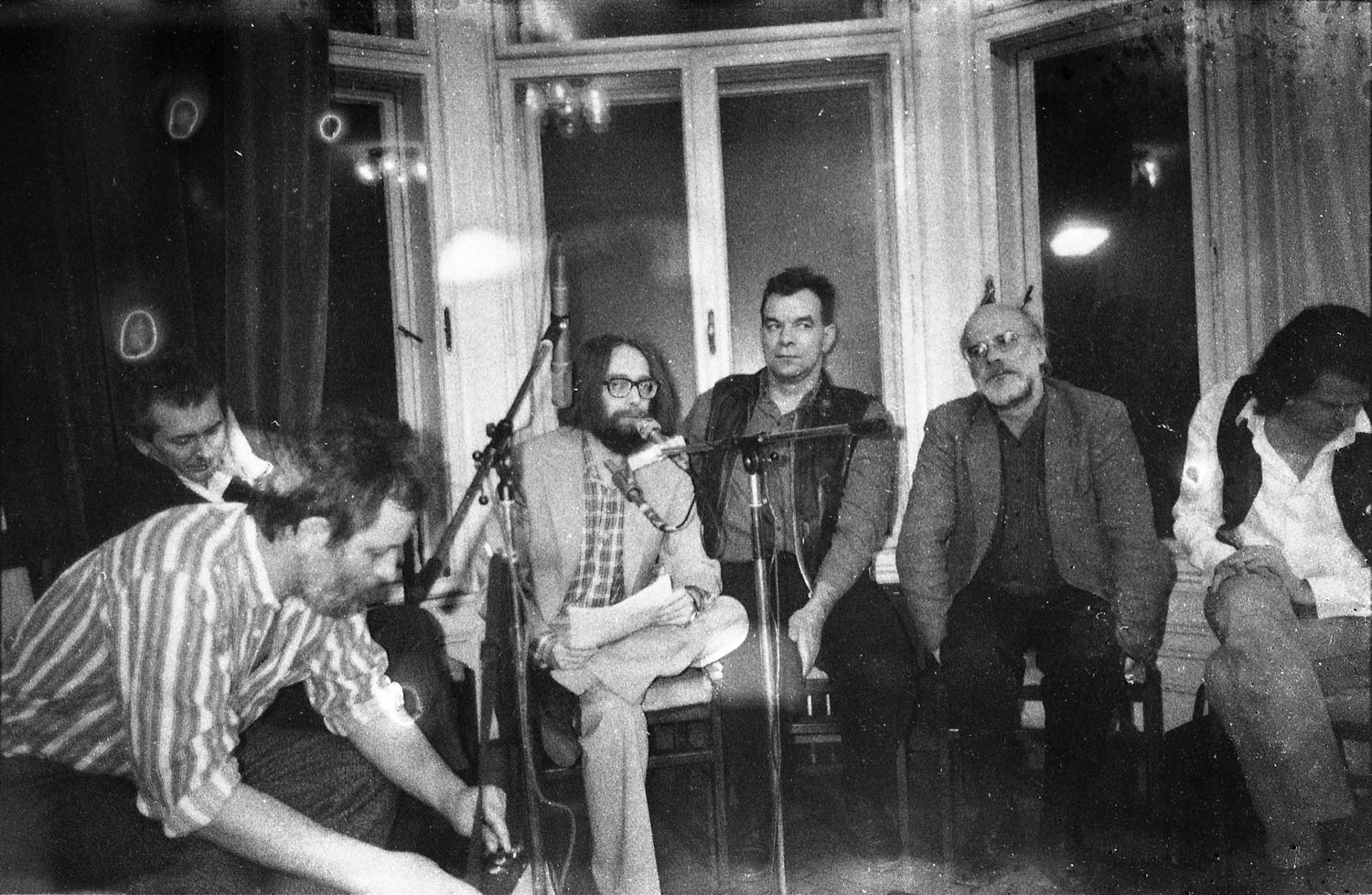

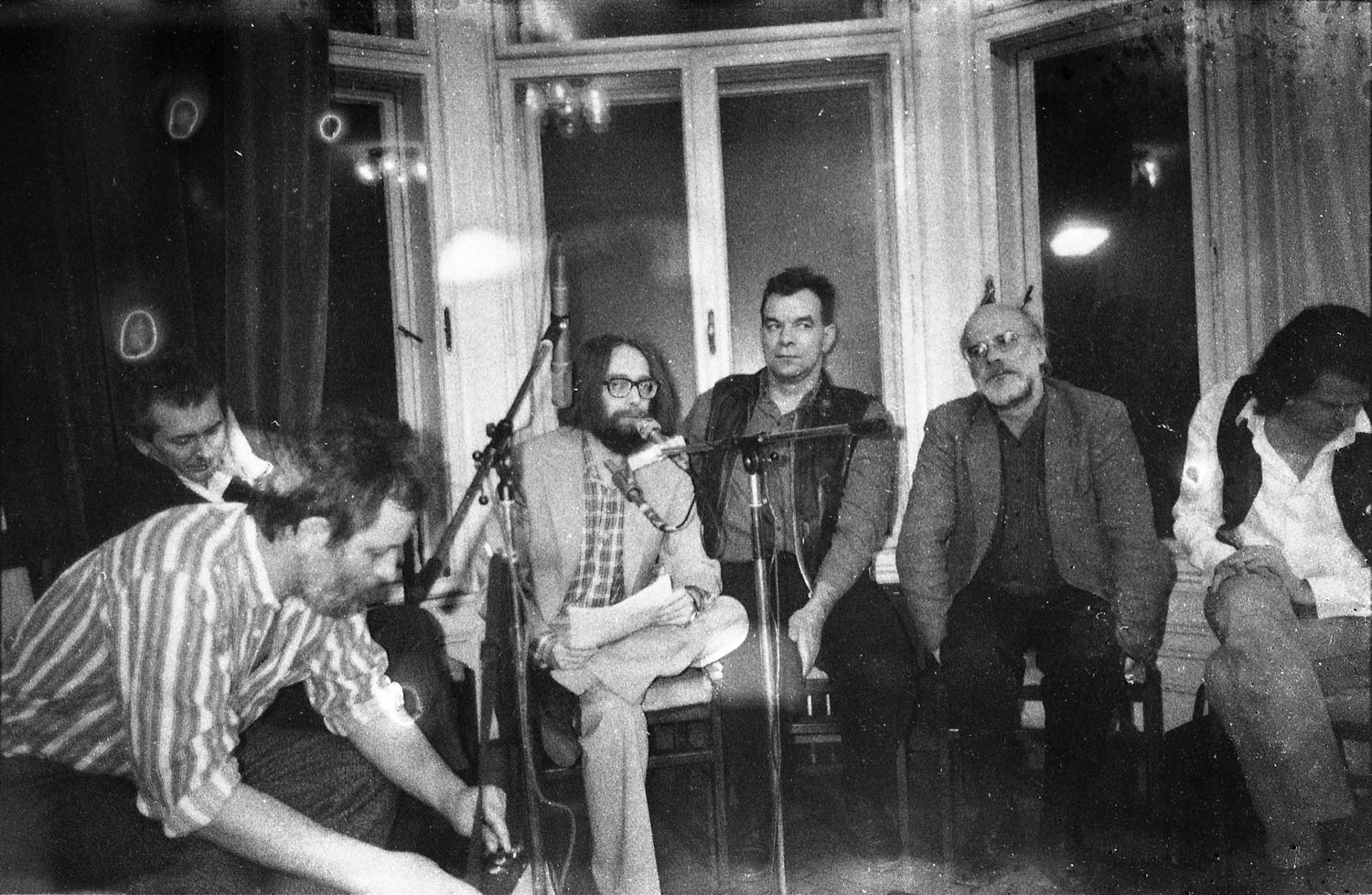

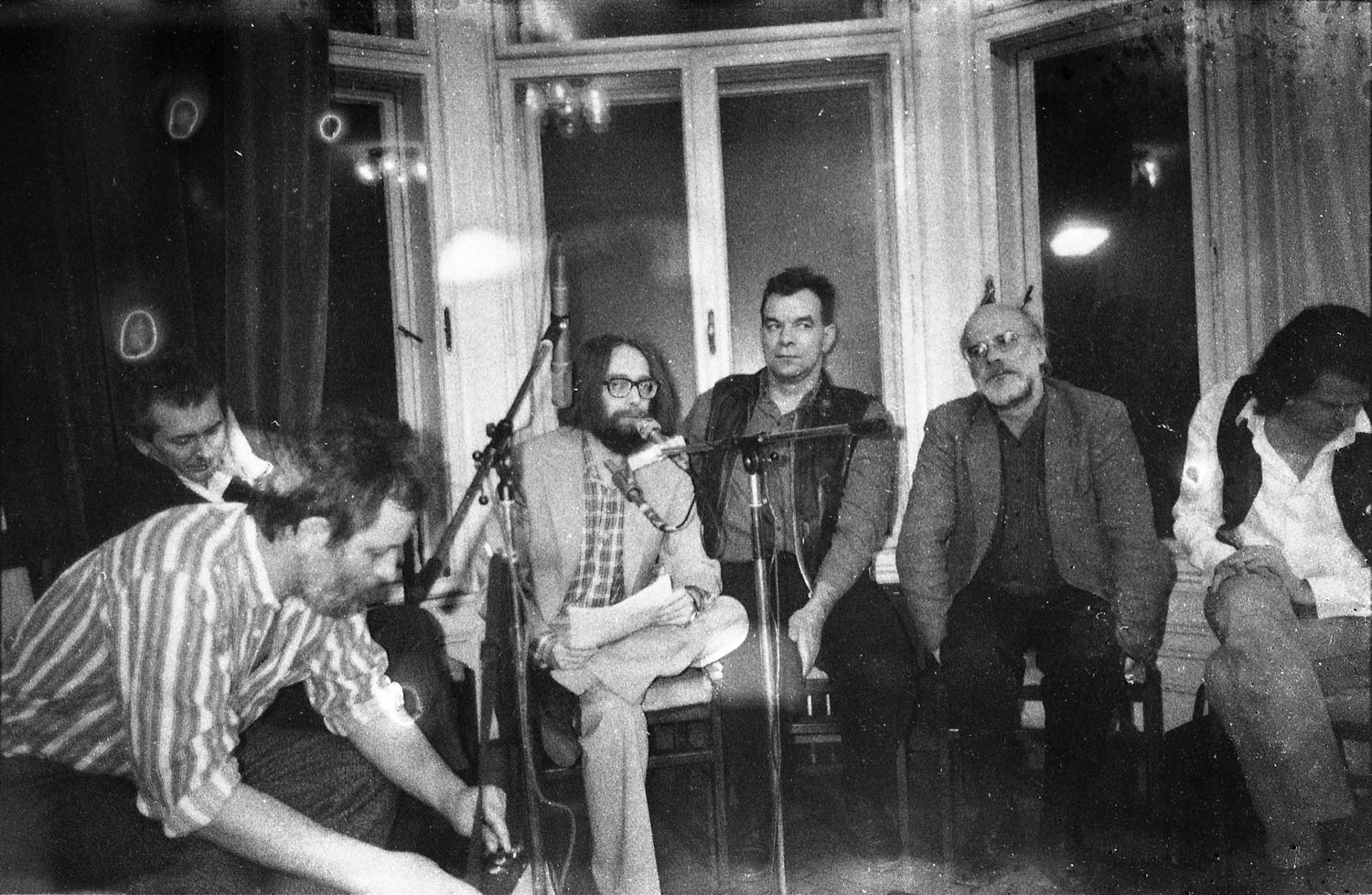

Documentary exhibition in the framework of the “Liberal Nights” cultural series of SZDSZ (Alliance of Free Democrats). Exhibition and slide-show of documents and artworks of non-official art of the 1970s in Hungary from the Artpool Archive, curated by György Galántai. (The title of the event referred to the dark period under the “regime” of György Aczél, the key figure of Hungarian cultural policy from the 1960s to the mid-1980s.) After the opening: Literary Program (organized by Ádám Tábor) followed by a discussion with people who had been active during the period.