The third section of the exhibition, Exits and Parallel Worlds, presents the alterative spaces and communities of cultural production and consumption and the everyday modes of a life which had been made bearable. Here, attention is given to activities and forms of expressions which went largely unnoticed by the regime and which defined themselves not on the basis of specific political stances, but rather on the basis of their cultural, artistic, religious, ethnographic, or popular music tastes. For many people, the theater productions which were held in private apartments, the dance houses, the concerts, and the fashion walks offered a creative setting in which they could be sincere, liberated, and at times even willful and rebellious. These spaces of creative engagement also made it possible for them to create and maintain culturally vibrant lives.

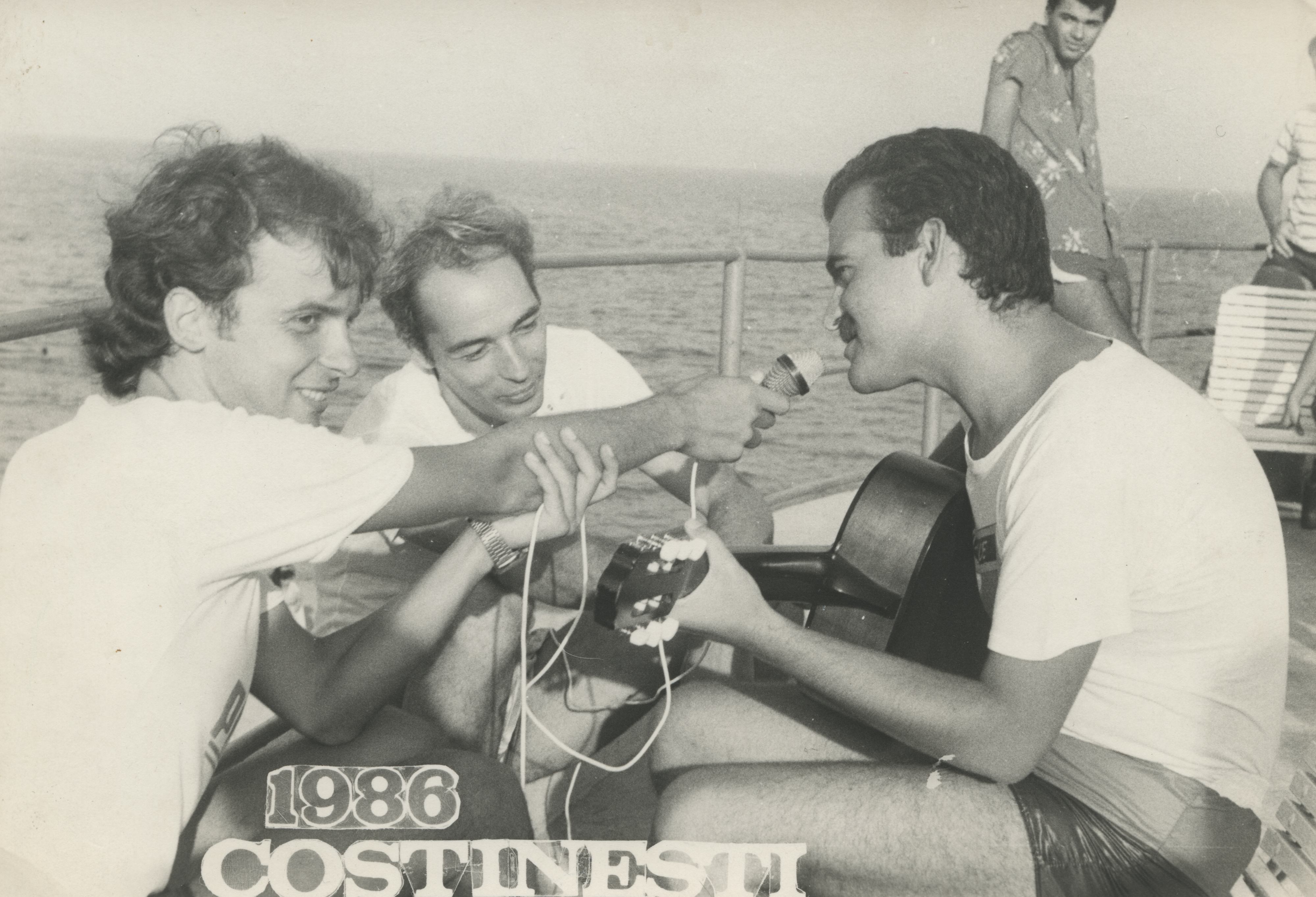

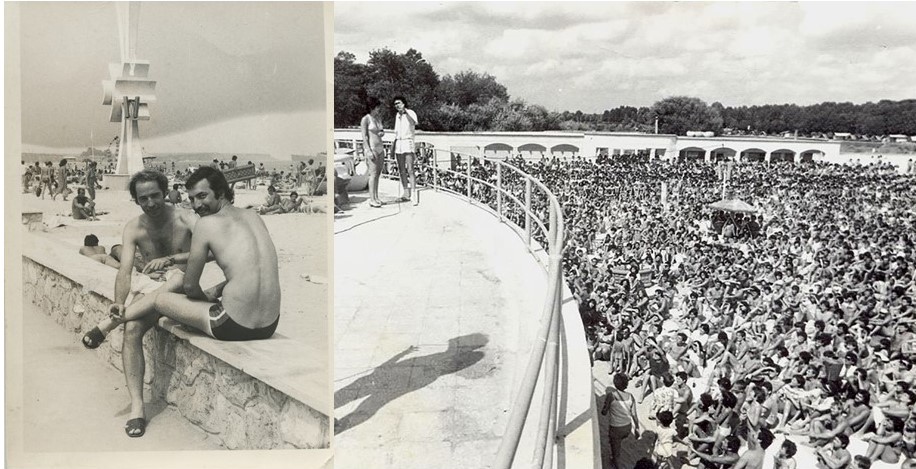

Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti was a semi-professional radio station, a radio-amplification station that only broadcast via loudspeakers within the bounds of the Costineşti resort. Due to its limited audience, the programmes could be broadcast without prior censorship, as the routine procedure in a “normal” radio station required. While all radio programmes in communist Romania were prerecorded in order to get approval for broadcast, all Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti programmes were live.

Its first broadcasts began in 1979, but those that gave shape to this phenomenon began to be transmitted regularly starting in the summers of 1981 and 1982. Initially, it operated in an improvised form, in a doughnut shop, with two tape recorders, and a microphone within a space of 1 metre by 1.5 metres. Thus, the first broadcasts could be heard within a radius of a few dozen metres. In its heyday, the loudspeakers of Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti were mounted on around 100 posts, and its broadcasts could be heard practically everywhere in the resort.

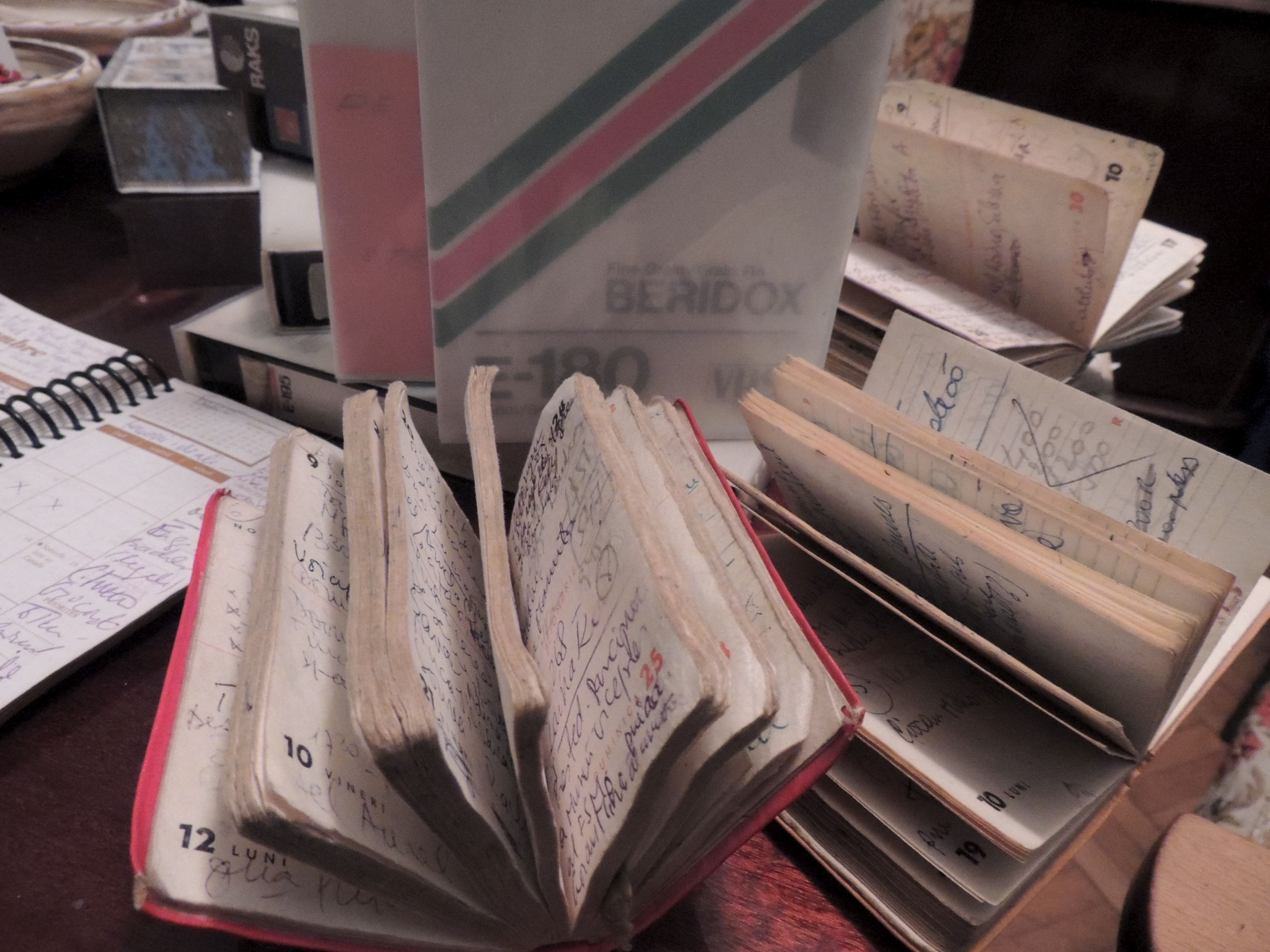

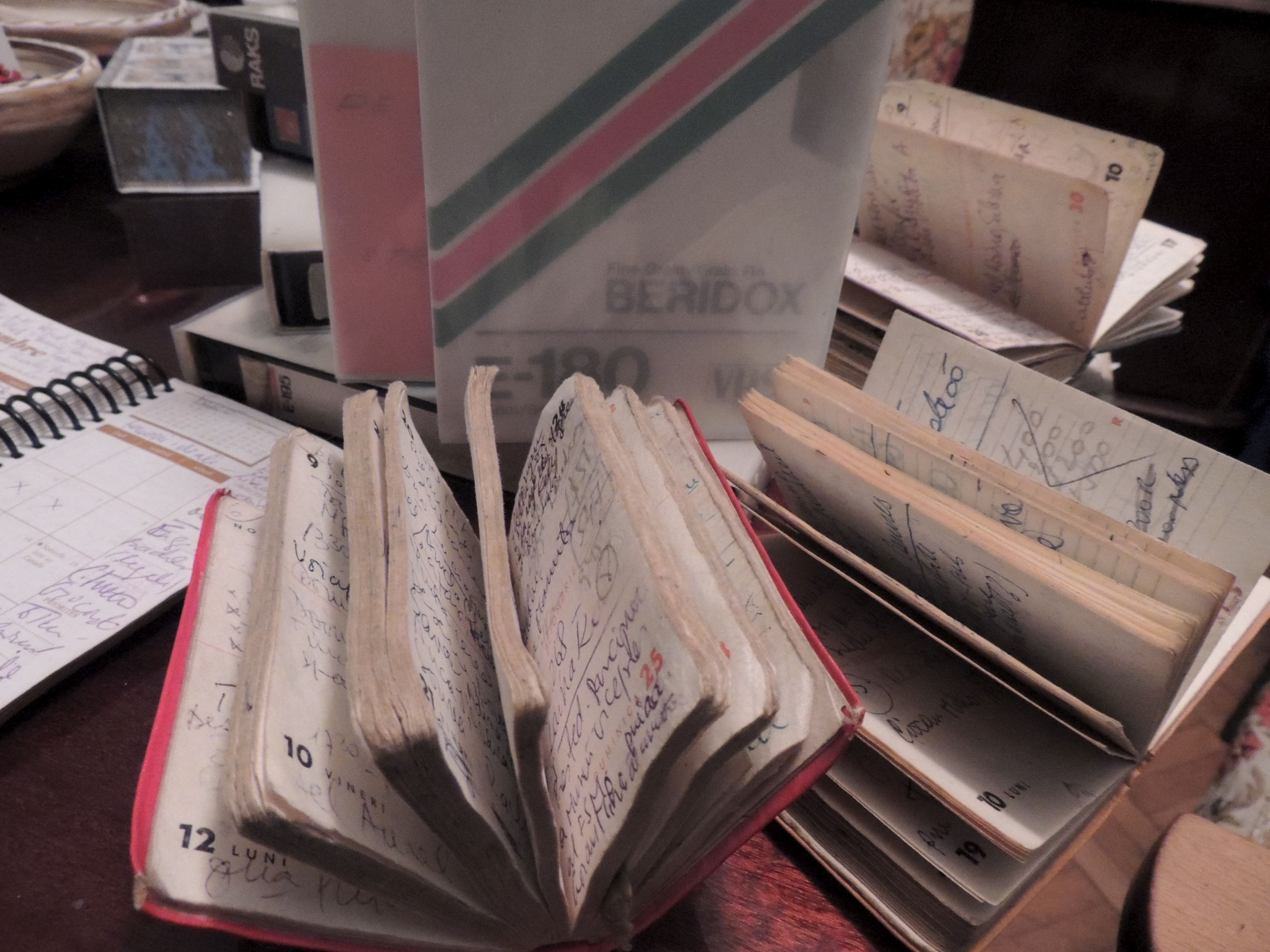

The Andrei Partoş–Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti Private Collection includes photographs, publications, and various documents regarding a (semi)clandestine seasonal radio station that operated during the summer holiday period in Costineşti, which was officially and popularly considered to be the seaside resort for young people. This radio station and its associated activities in Costineşti constituted a social phenomenon without comparison in the Romania of the 1980s, an epitome of the alternative culture of the younger generation under later Romanian communism and a formative experience for the generation who supports the democratic consolidation in present day Romania.

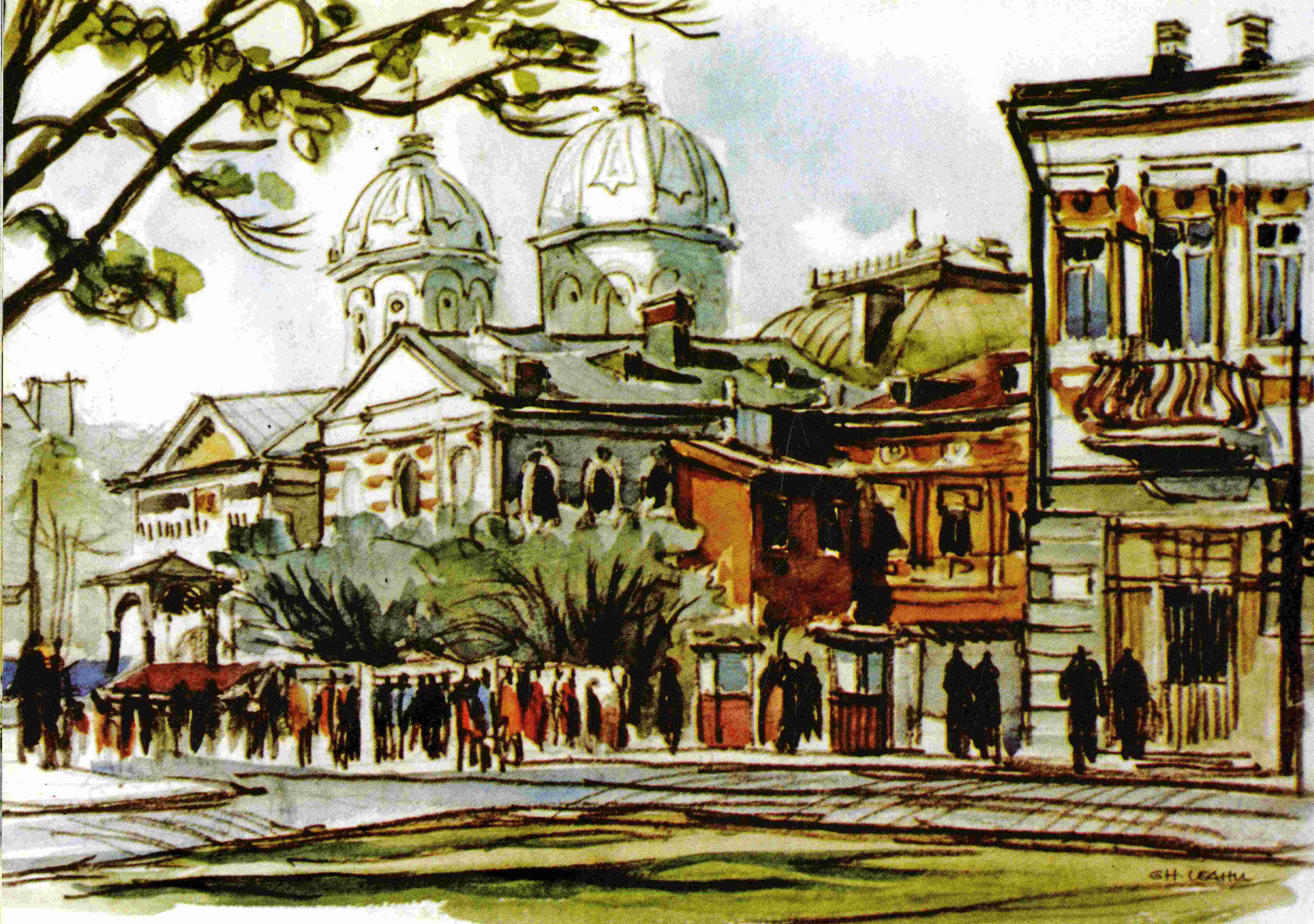

These watercolors capture two historical landmarks in Bucharest prior to their destruction as a result of Ceaușescu’s urban systematization plan, which envisaged large-scale demolitions in the center of the city for the sake of building new, communist-style, massive, apartment blocks. Between 1977 and 1989, about twenty churches and many other historical monuments became the victims of this absurd policy, while some 10,000 private homes were demolished and over 50,000 people were forcefully moved out. One watercolor represents the Church of Sfânta Vineri (Saint(e) Friday), which was totally demolished in 1987, in spite of the human chain that tried to protect this very popular church. No worker wanted to contribute to its destruction, so convicts were brought to tear it down. The second watercolor represents the Mihai Vodă monastery, an emblem of premodern Bucharest and the first home of the State Archives after the establishment of the modern Romanian state. Its founder in 1594 was prince Michael the Brave, a key hero of the Romanians’ national history. This complex of buildings was partially demolished and partially transported to a new location in 1985, while its central and dominent location in Bucharest was taken by the so-called House of the People, the enormous building that should have become Ceaușescu’s office. The church and the bell-tower were moved down the slope a distance of 289 metres, descending by 6.2 metres, to the foot of the hill, where they remained hidden behind the new apartment blocks.

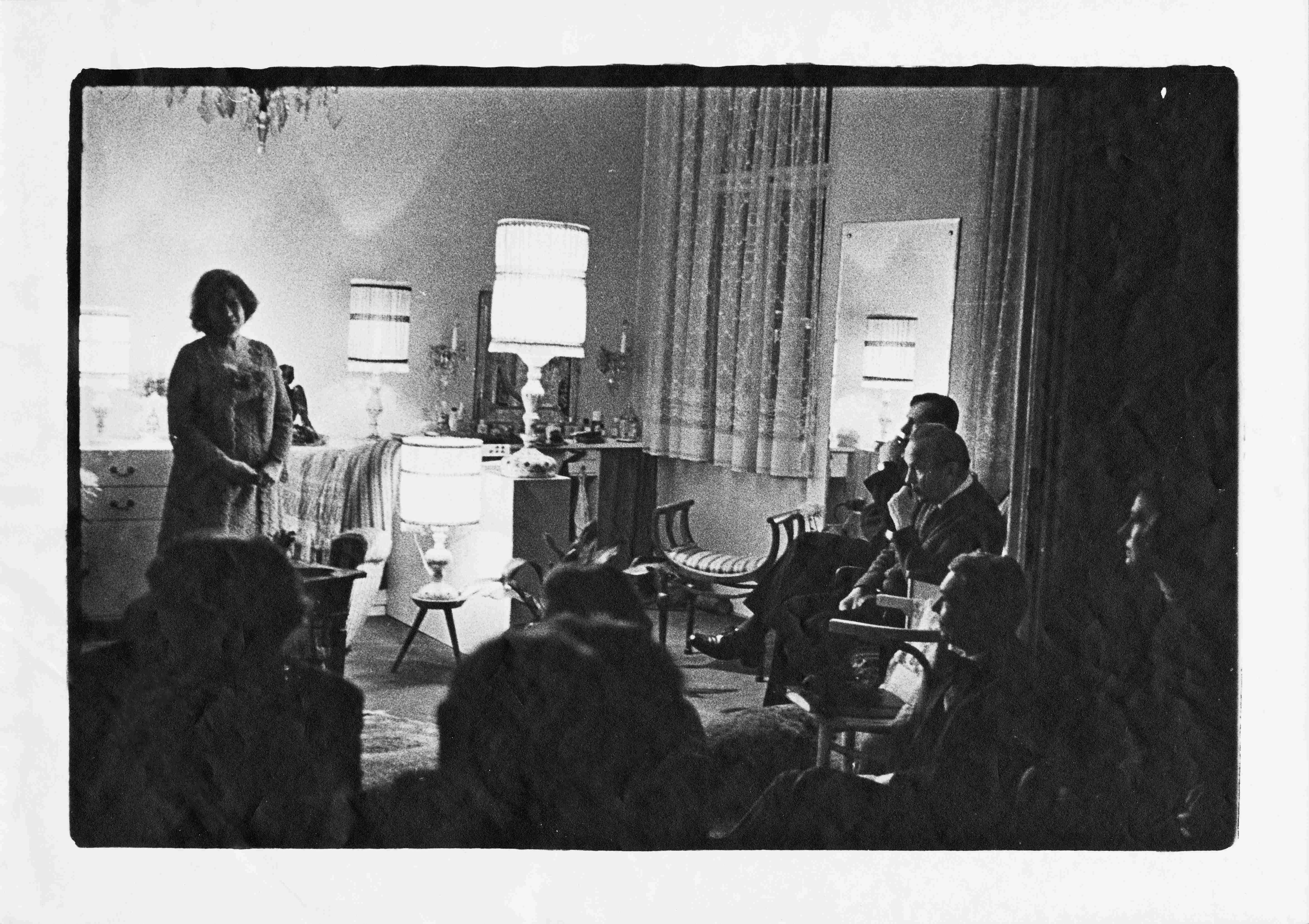

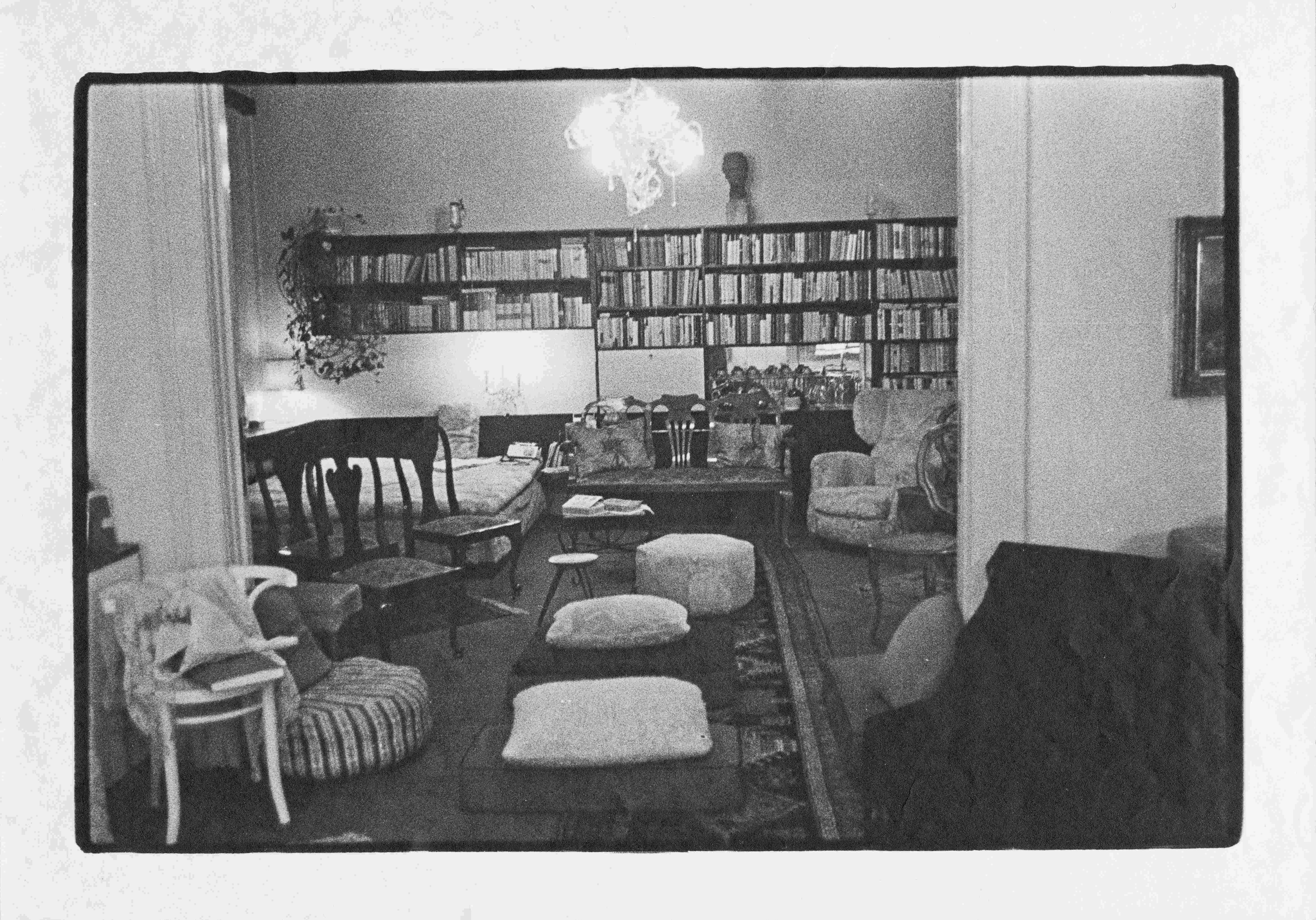

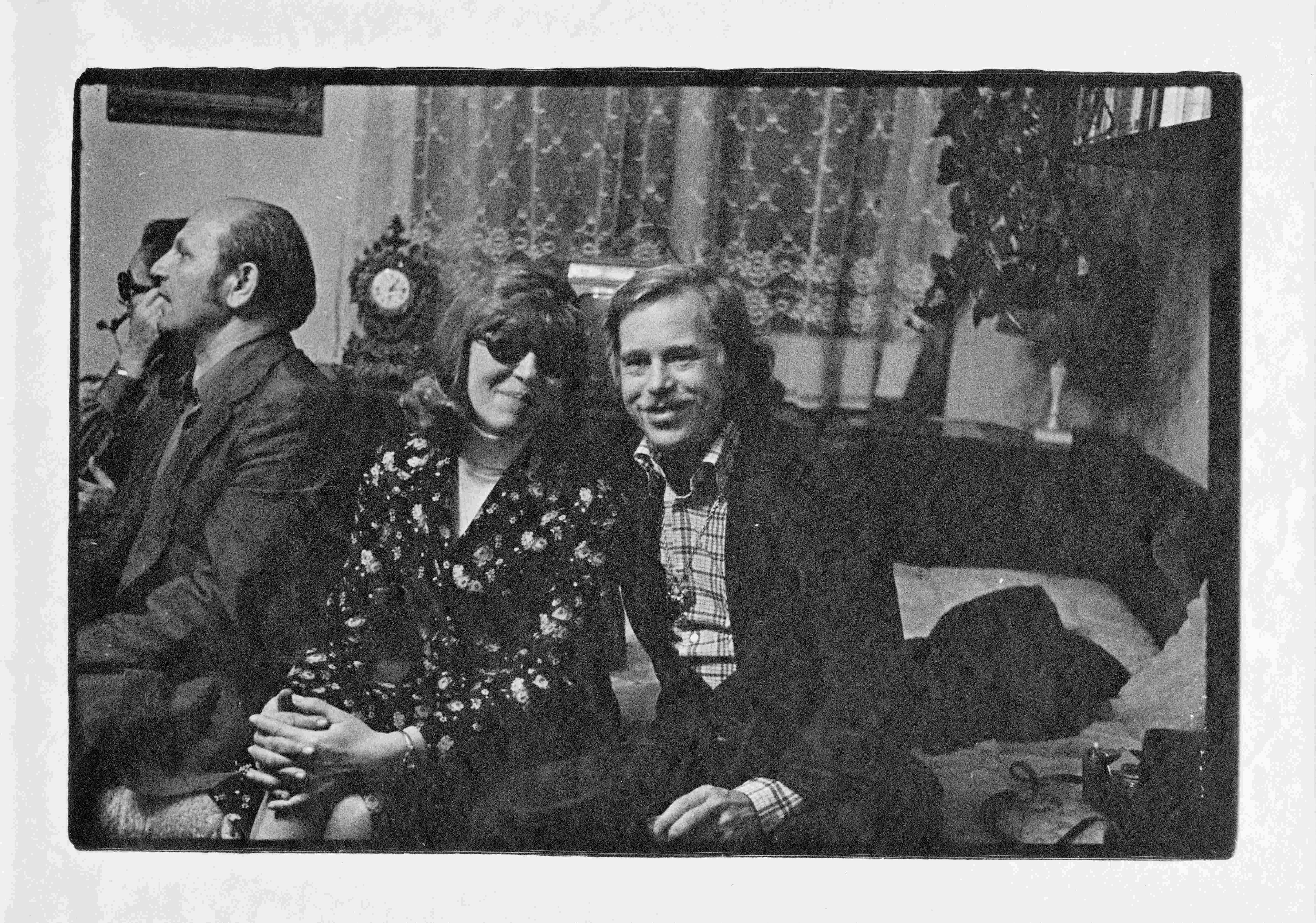

The Apartment Theater: performances at Vlasta Chramostová´s apartment, 1976-1978.The “apartment theater” was a unique cultural phenomenon in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and was a way of presenting independent and oppositional theater activity and the work of artists that were forbidden due to their critical attitudes towards the regime. The performances were of a non-public nature and took place secretly in private flats and residences. Despite their hidden nature, such forms of theater productions became quite popular within the independent intellectual milieu of the 1970s. Most art groups emerged spontaneously during the first half of the decade. Probably the best-known was the Apartment Theater initiated by Vlasta Chramostová, who was a famous Czech film and theater actress in the 1950s and 1960s. The theater was originally created on the occasion of the 75th birthday of poet Jaroslav Seifert. Thanks to the enthusiastic response of the audience, a private celebration became a popular tradition and the original performance Všecky krásy světa (All beauty in the world), based on Seifert’s book, was repeated more than twenty times in Prague, Brno, and Olomouc. This unexpected success inspired Chramostová to continue with other productions. One of them was inspired by current events such as the trial of the signatories of the Charter 77 (Appelplatz II.), another (Play Macbeth) was an adaptation of classical works, modified for the conditions of apartment performance. The perfomers and their audiences were composed of personalities from diverse cultural milieus including established intellectual elites and emerging independent artists such as the writer and musician Vlasta Třešňák.

Copyright: Vlasta Chramostová collection, National Theatre Archive, Czech Republic, Prague

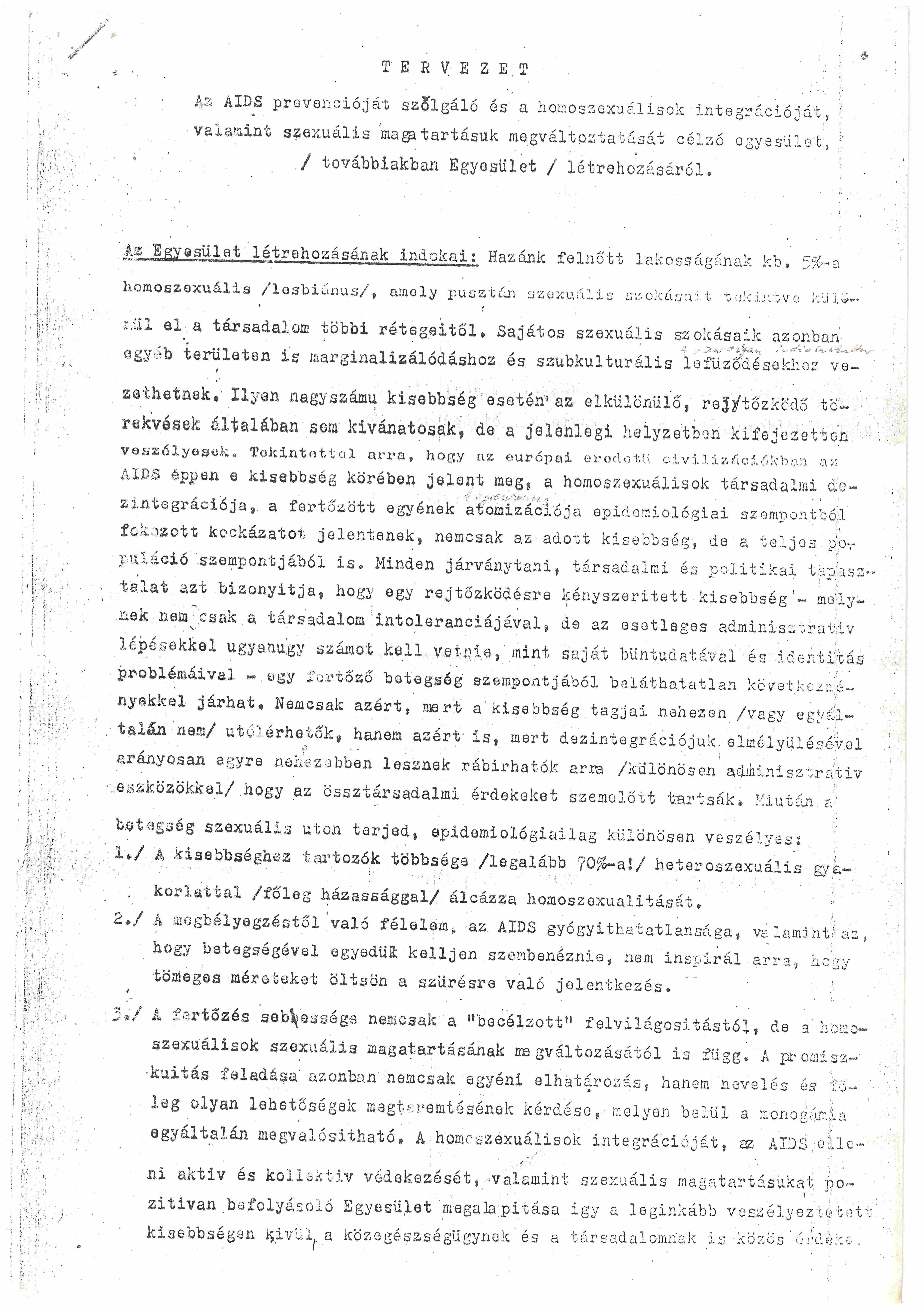

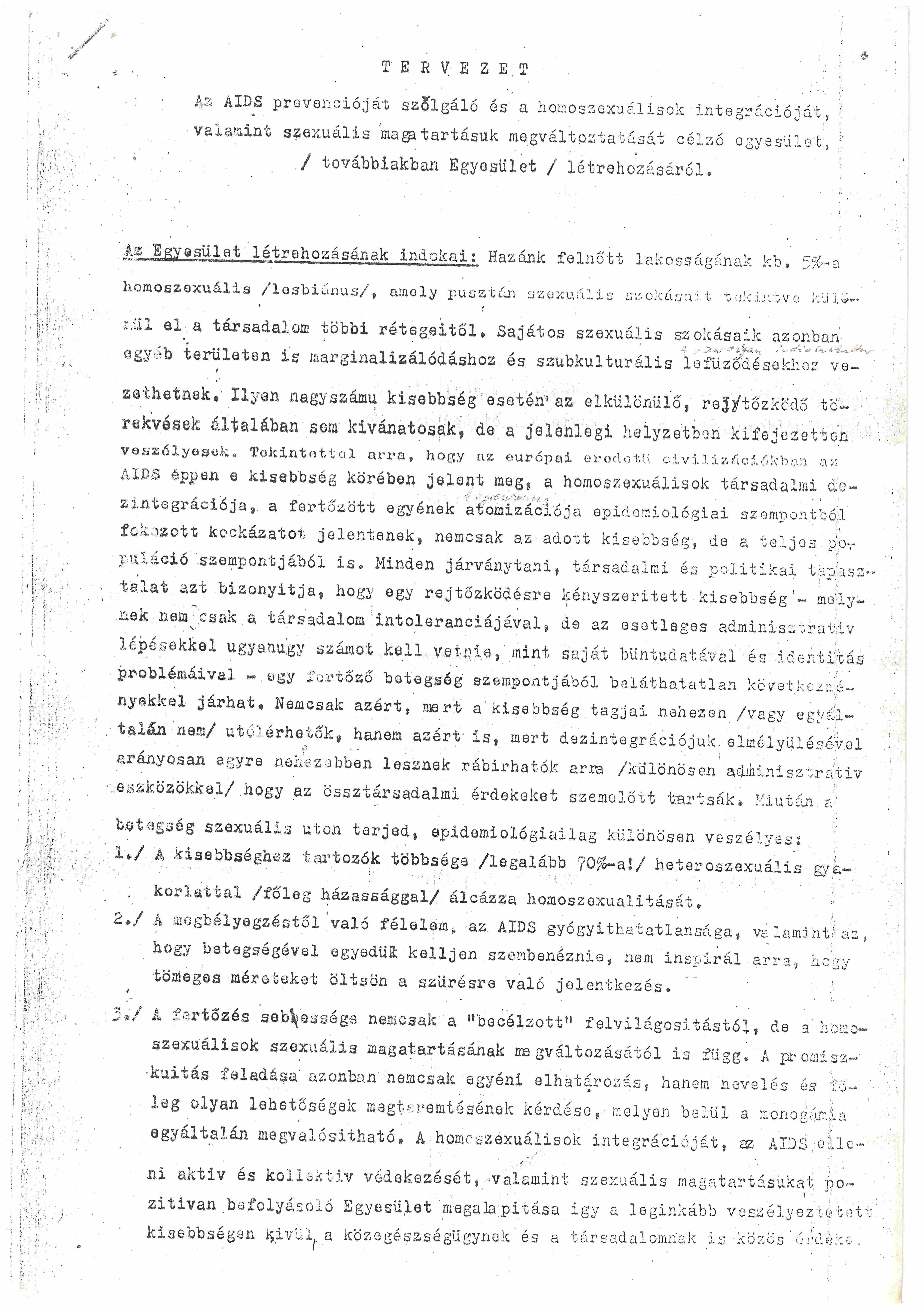

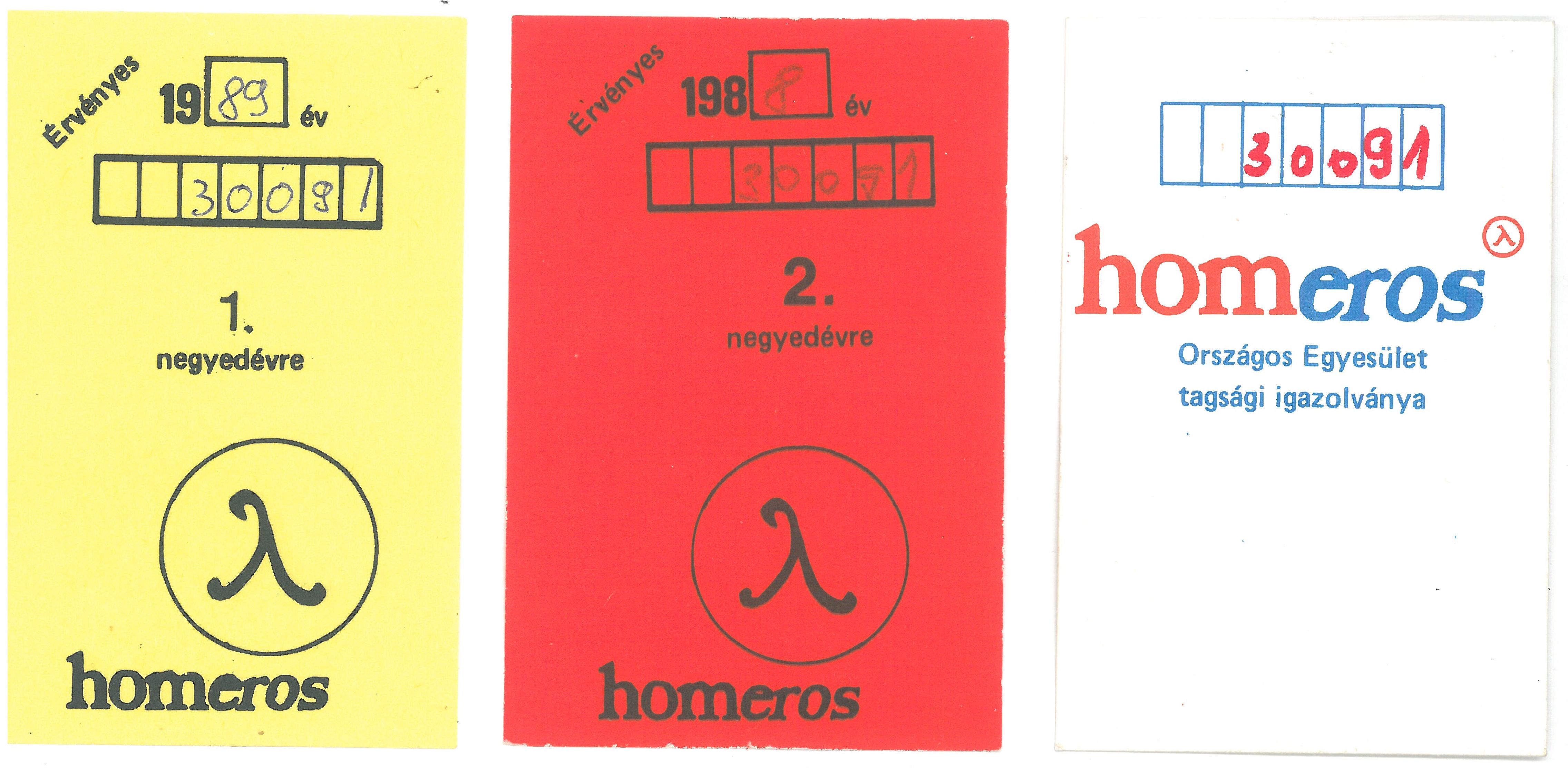

The records of the first Hungarian LMBTQ association provide unique insights into the opportunities for self-organisation and collective identity, beyond official and popular misrepresentation. The archiving activities of gay subcultures in Hungary is firmly linked to the modalities of institutionalization of homosexuality and the accompanying cultural and political debates. The first successful initiative in homosexual self-organisation in Hungary occurred with the latent assistance of the state authorities. In 1985, initiated by Lajos Romsauer (who later served as president) and sociologist Péter Ambrus (who later served as general secretary), a network of friends began to consider founding an LMBTQ association or organisation in the country. The foundation of the association, however, proceeded very slowly. Only in 1987 did the Ministry of Health give the green light to an organisation known by the acronym Homérosz (‘Homer-Lambda’ Association of Hungarian Homosexuals). Homosexuality was decriminalized in 1962 in Hungary, but the authorities made considerable efforts to keep the gay community under surveillance.

Květa Fulierová Private Collection, Bratislava, Slovakia. Courtesy: Květa Fulierová

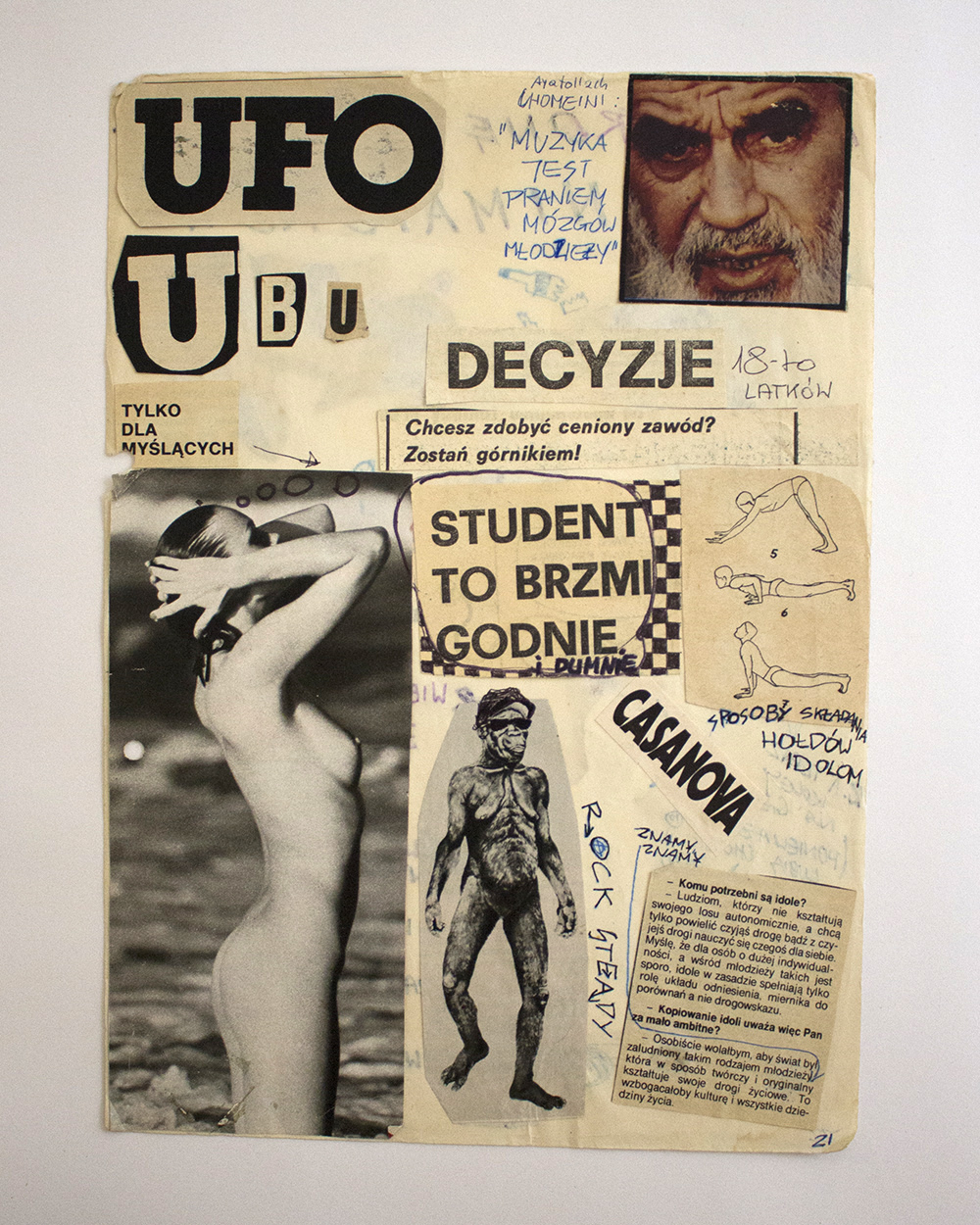

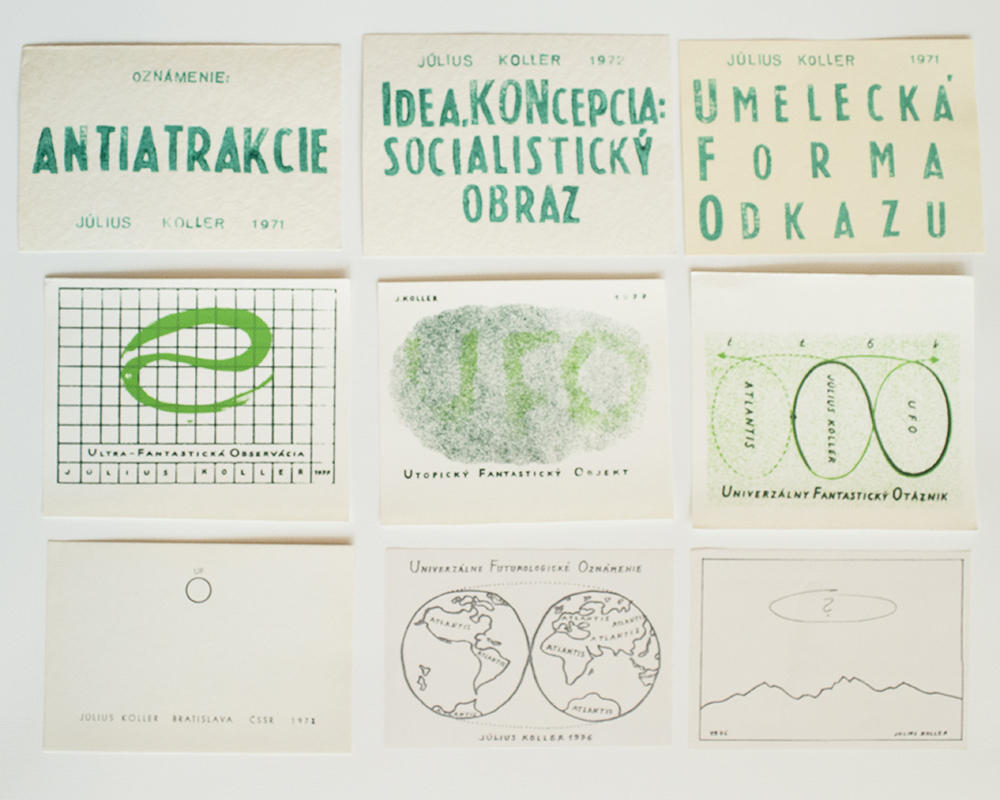

Július Koller (1939 – 2007), a prominent and internationally renowned Slovak conceptual artist, found original ways to communicate the absurdity he experienced every day in socialist Czechoslovakia. His text cards, which he sent to his friends and acquaintances, are a playful and ironic reaction to the circumstances of the time. Through a simple verbal and visual form (e.g. the question mark) he commented on the then-current situation in arts and culture (e.g. Idea, Concept: Socialist Image; The Artistic of Form of the Message). The motif of the question mark is a symbol of Kollerʼs ceaseless questioning of dogmatic truths. In his works, the mystery, the secret, and the fascination with the unknown mingle with absurdity. He used the U.F.O. abbreviation and assigned various words to it (Utopian Fantastic Object; Universal Fantastic Question Mark). Kollerʼs interest in fiction and his fascination with the mysterious are also a form of intellectual play and an escape from everyday worries. His artistic attitude does not harbour illusion; he connected art with lived experience.

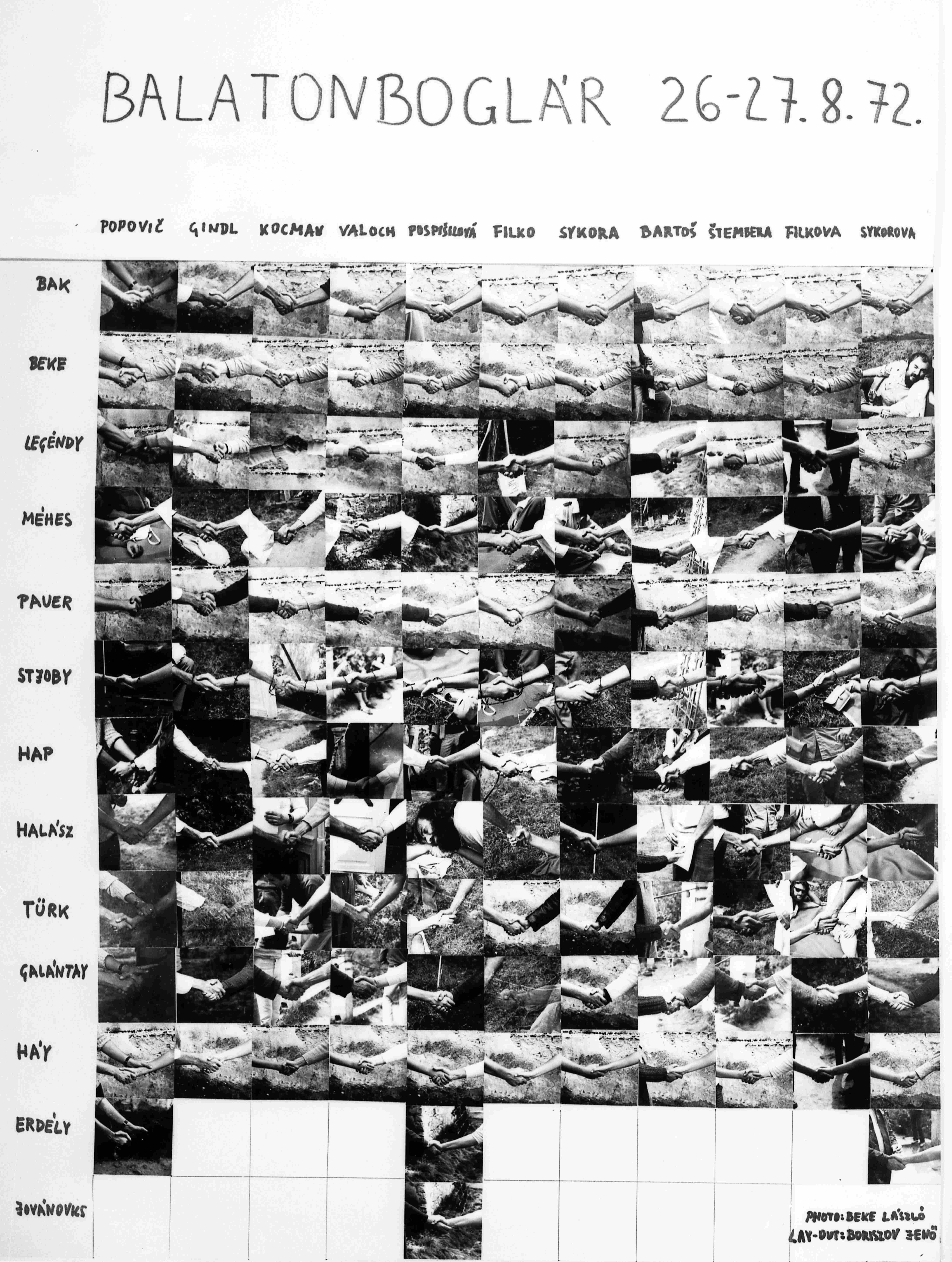

In the summer of 1972, László Beke organized a meeting of Czech, Slovak and Hungarian artists in the Chapel Studio of Balatonboglár. This event was held in a historical context where the state-socialist discourses emphasized the fraternity and solidarity of Eastern Bloc countries, but spontaneous attempts of communication between them were usually discouraged. It was especially true for the meeting of Czech, Slovak and Hungarian artists that were organized only four years after the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, in which Hungarian troops also participated.

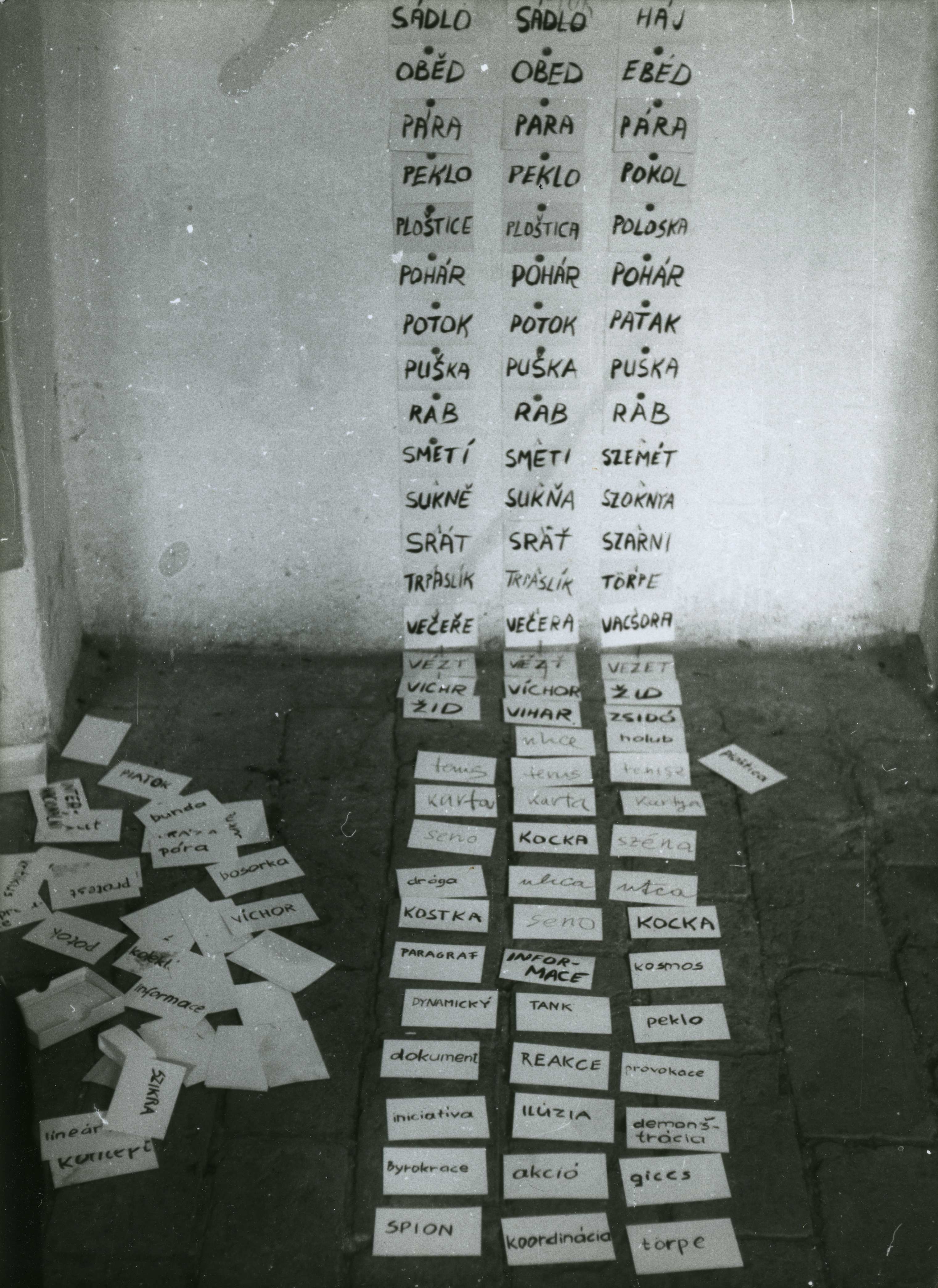

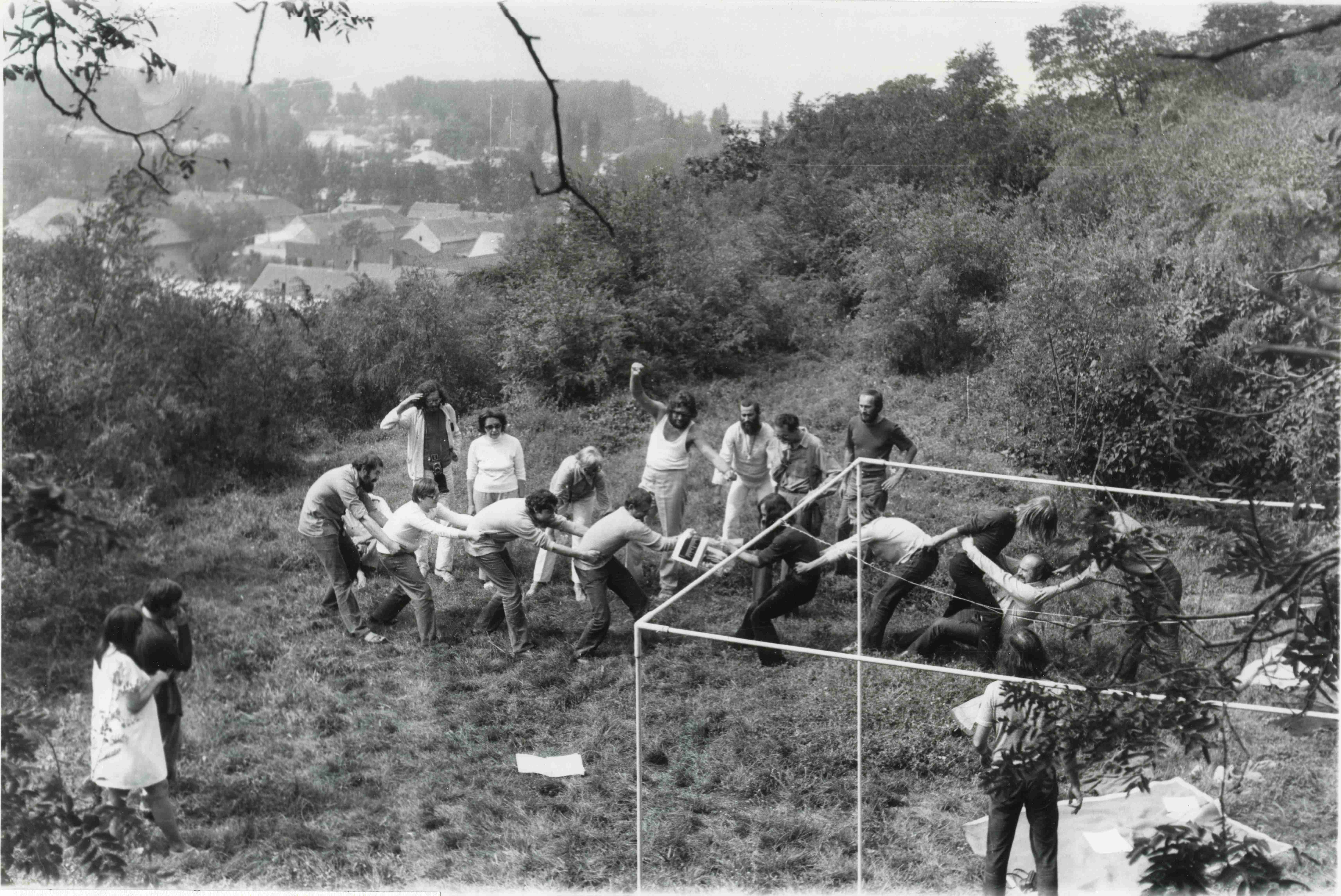

The artists’ meeting was organized around an exhibition with Beke’s conceptual installation of Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian words, which built a coalition between the three languages against the keywords of the dominant ideological setting. The Tug of war action was a reenactment of a photo from 1968 in which Hungarian occupational troops were playing the game in Czechoslovakia. In the action in Balatonboglár, the artists were tearing apart the photo, this way they jointly annihilated both the photography and the aggressors. The Handshaking Action continued this track of building solidarity and alliance between artists by creating a tableau in which all the Hungarian artists were shaking hands with all of their Czechoslovakian colleagues.The Chapel Studio of Balatonboglár was run by the artist György Galántai between 1970 and 1973 and it became a central node of avant-garde and underground artistic activities in Hungary. During the summers of these years, the Chapel Studio functioned as an alternative institution in a context, in which artists working outside of this field had no exhibition possibilities and were excluded from the state support system. It was more than an exhibition space, as it became a real meeting point and melting pot of different artist groups and artistic trends. Having been banned already in 1971, Galántai was forced to use his creativity to advertise the exhibitions. Using a semiotic action he painted the sign of the nearby passing red trail (do you mean trail?) on the tower of the chapel, and with a stencil he produced, visitors were able to print T-shirts that directly promoted the exhibitions of the Chapel Studio.

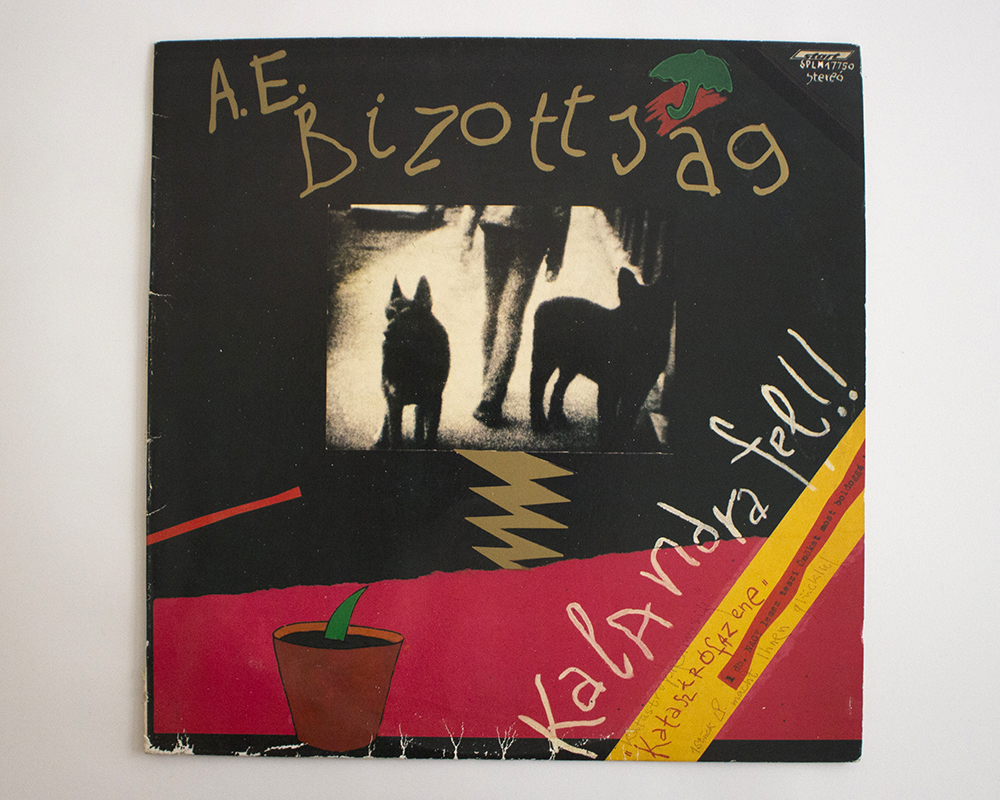

At the turn of the 1980s, bands appeared on the Hungarian music scene which did not heed the status quo of the so called “pop-business.” They represented a grassroots new wave, which meant a turn to elementary music sources and the development of a poetically elevated world of lyrics. They soon became popular among the urban youth, but at the same time they were strategically marginalized by the monopolized channels of exposure of the time.

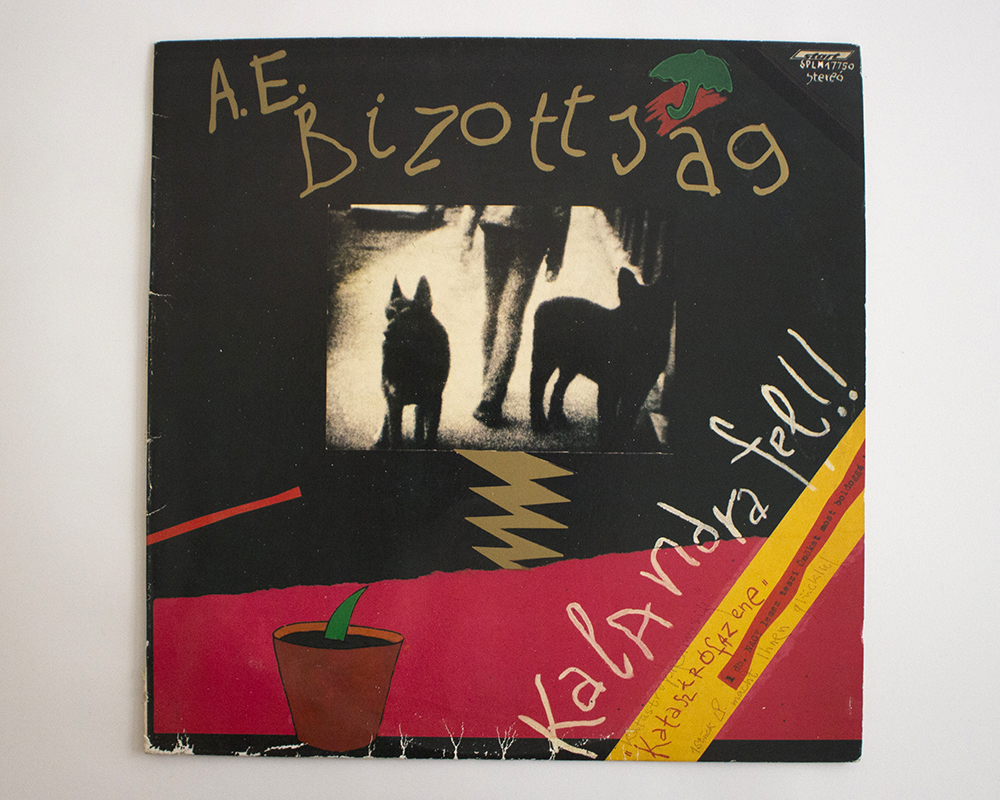

In this climate, it came as something of a surprise that one of these bands, Bizottság (Comittee), was able to release an album in 1983. The story has become a familiar anecdote. Due to the issue of popularity, a radio reporter asked one of the decision makers at the state record company if they would release some music by the new wave bands. He routinely replied that they had already discussed the matter with Wahorn from Bizottság. This was not true, but Wahorn just happened to be listening to the radio, and he sought out the decision-maker to discuss the matter.

After awhile, they agreed to make a concert album under the condition that the band change its name (from Bizottság to A. E. Bizottság in reference to Albert Einstein). The album was popular, and it sold out within days. However, the numbers were manipulated. It was released in only 14,000 copies, so the officials could later argue that only a small number of copies had been sold, it had not been popular enough and represented merely a niche type of music (a “gold standard” for success at the time was 100,000 copies sold).

The album presents several of the characteristics that made Bizottság (Comittee) special: the surreal lyrics fit the times, since in many cases the words were not used in their usual meanings in public discourses (though the lyrics remain poetic even today); the funny, improvised dialogues between songs; the special sound (for example the distinctive breaks developed by their female drummer, the peculiar riffs played by the guitarist, the sharp sound of the organ made in GDR, etc.); the remarkable post-production work (it is worth noting that the song Bestia (Beast) was altered by the censors: the word “siege” is made inaudible with the use of sound effects).

Altogether, it was an impressive debut album, and despite the limited number of copies made (a year later, another 10,000 copies were released, and twelve years later it came out on cd as well), it is regularly included to this day on the lists of the most remarkable Hungarian records ever made.

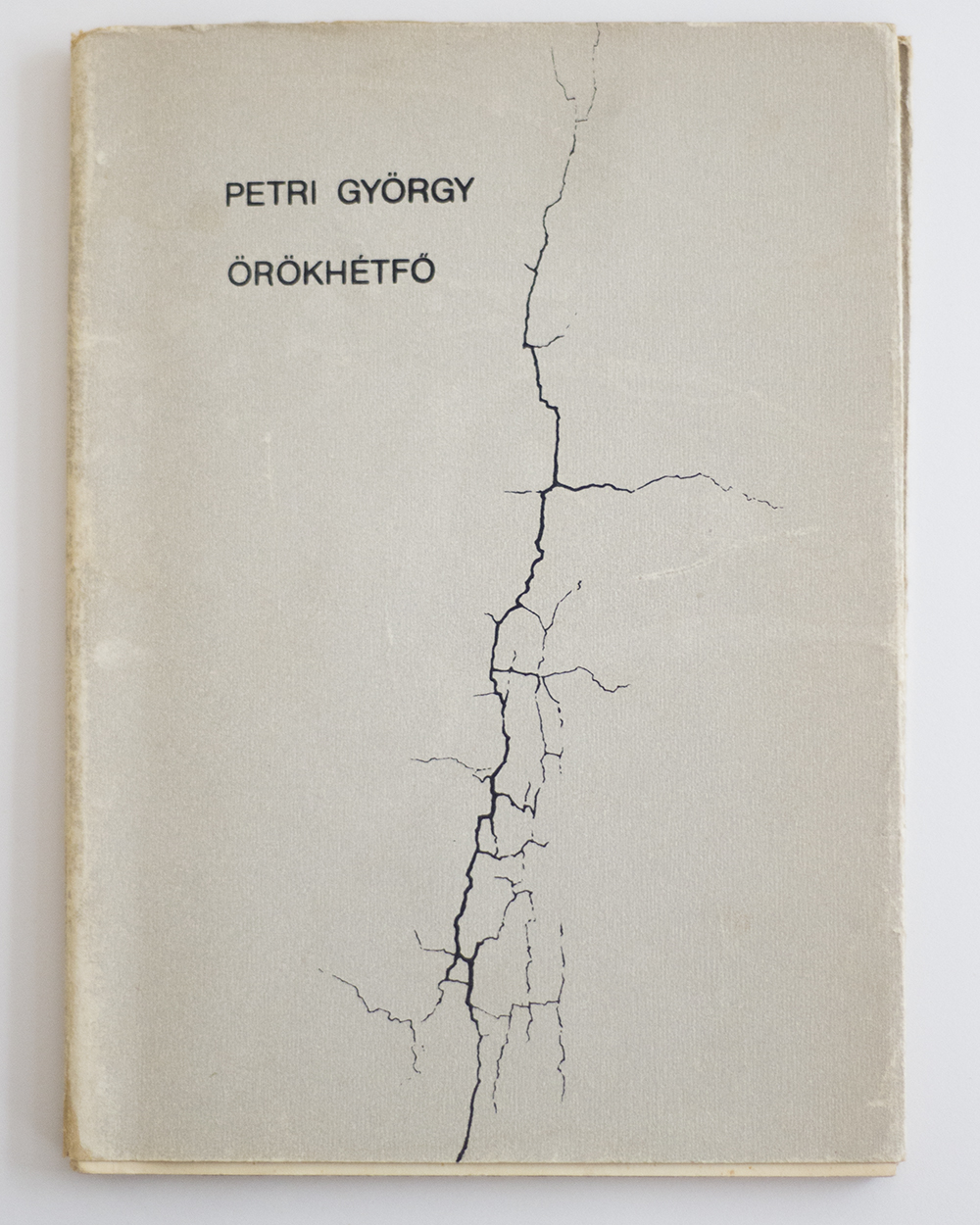

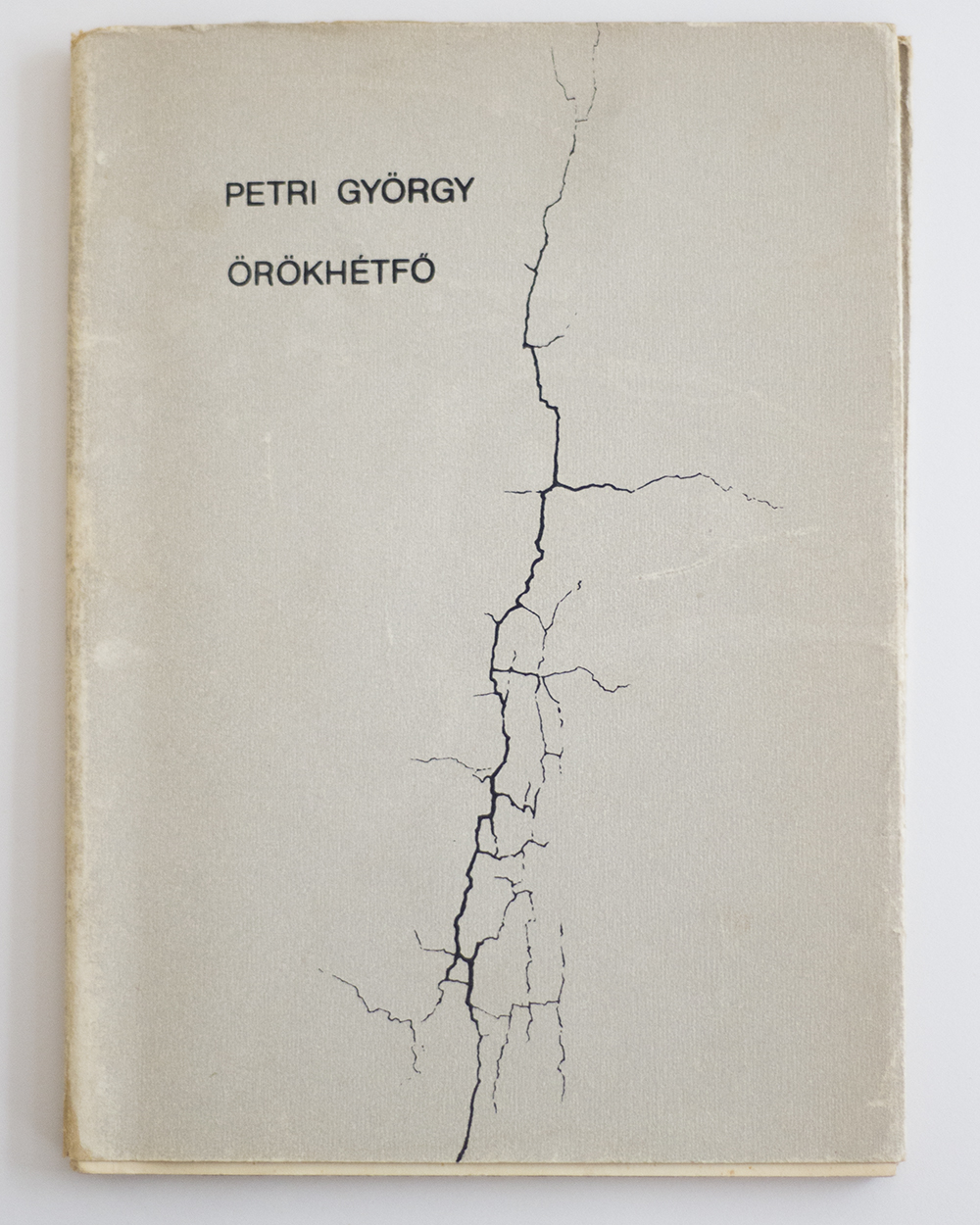

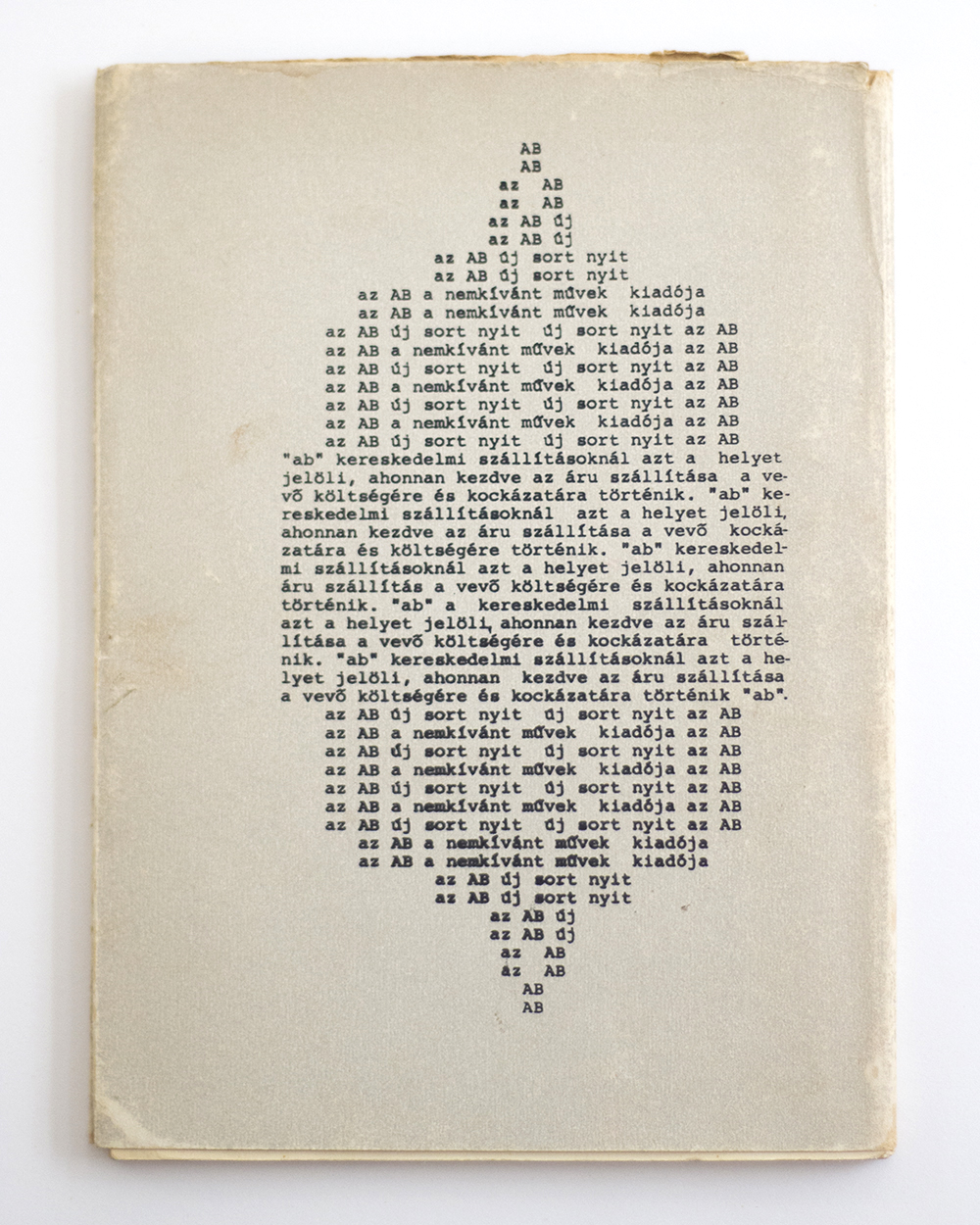

The poet György Petri was a towering figure of Hungarian literature working in the tradition of T. S. Eliot, C. P. Cavafy and the domestic classic Attila József. He was also one of the most active members of the democratic opposition: he was distributing samizdat, involved in organizing nonconformist events, and from 1981 edited the most significant samizdat journal Beszélő. In the 1970s, he was still tolerated by the regime: his two books of highly sophisticated, philosophically inspired poems were allowed to be printed. His third book of poems, however, that eventually became a Hungarian classic of political poetry by the title Örökhétfő (Eternal Monday) was to be censored to such an extent that he decided to publish it in samizdat instead in 1981. After that, he remained in firm opposition to the regime. In a 1984 volume published as tamizdat in New York, he included a satirical verse on the occasion of Brezhnev’s death. This eliminated his chances to publish officially until the regime change.

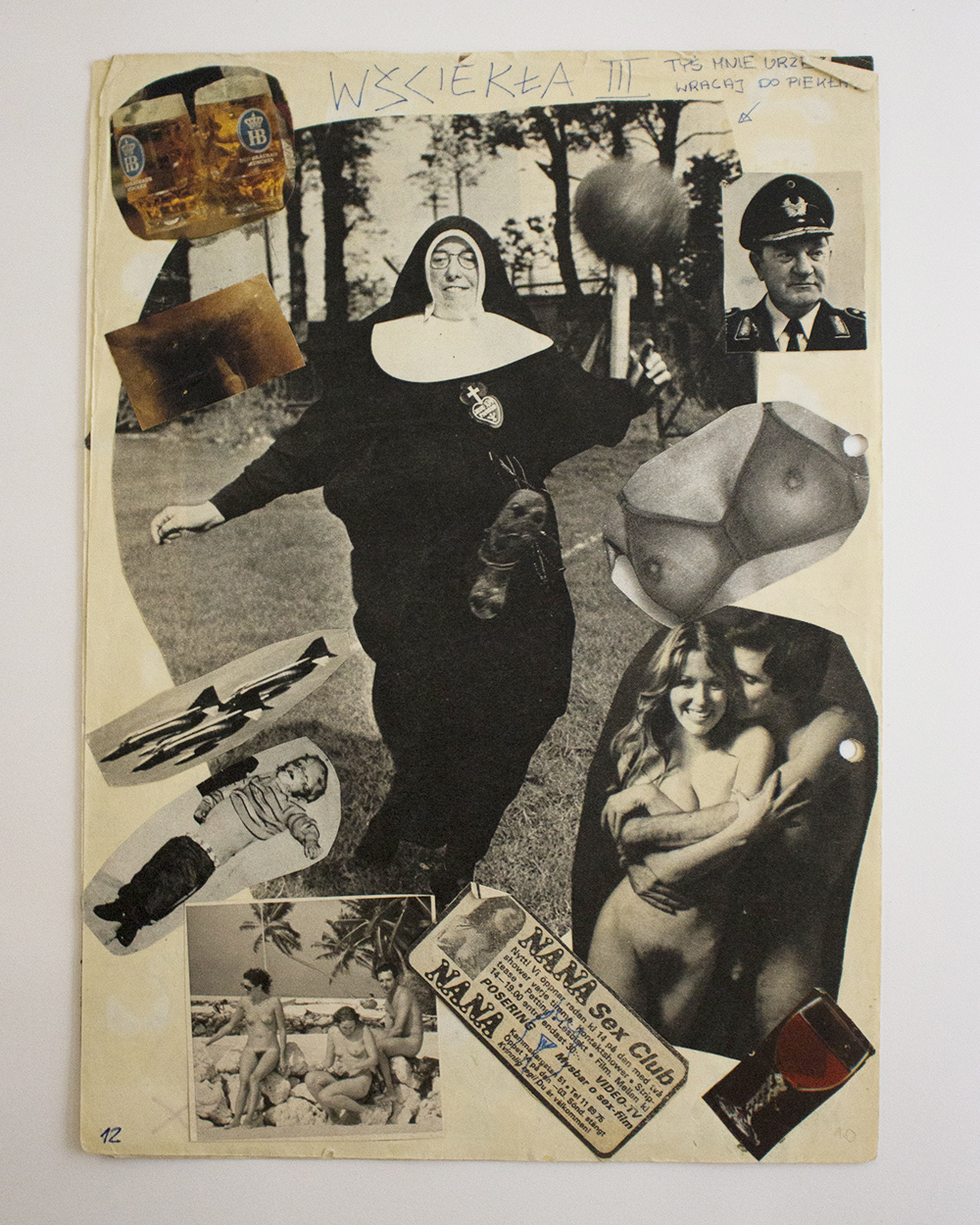

Group FV 112/15 started to work in 1980 as an amateur theatre group, which built in Ljubljana the alternative spaces for the expression of social, artistic and cultural difference. In 1983, the members of the FV group established the music band Borghesia, which engaged in the critique of socialist ideological construct. At the same time, they ran events in three clubs: Disco Študent/Disco FV (1981–1983), Šiška Youth Centre (1983–1984), Kersnikova 4 (K4) (1984–). As a home of underground music and sub-cultural and gay movements, K4 club had a stylistically very diverse weekly programme, which is visible in the K4 poster (1984). At Šiška Youth Centre the group staged performances and events, which are represented through two xeroxed posters. The event Kaj je alternative? (What is the alternative?) was advertised by a poster, combining aspects of the aesthetics of the FV group and the band Laibach, with elements appropriated from socialist aesthetics mixed ambiguously with elements of petit-bourgeois romanticism. The poster contained Laibach’s name, which was prohibited at that time because of a crossed-out swastika and slogans, and this is why its designer Dušan Mandić was visited by the police. In 1983, the performance Kdo je ugasnil luč (Who turned out the lights?) was staged by the members of the FV theatre, who generally sought inspiration in topics from art history and society. The poster was designed with the help of a reproduced photograph taken at a political trial and combined with the title of the performance, clearly suggesting that socialism had found itself in the dark.

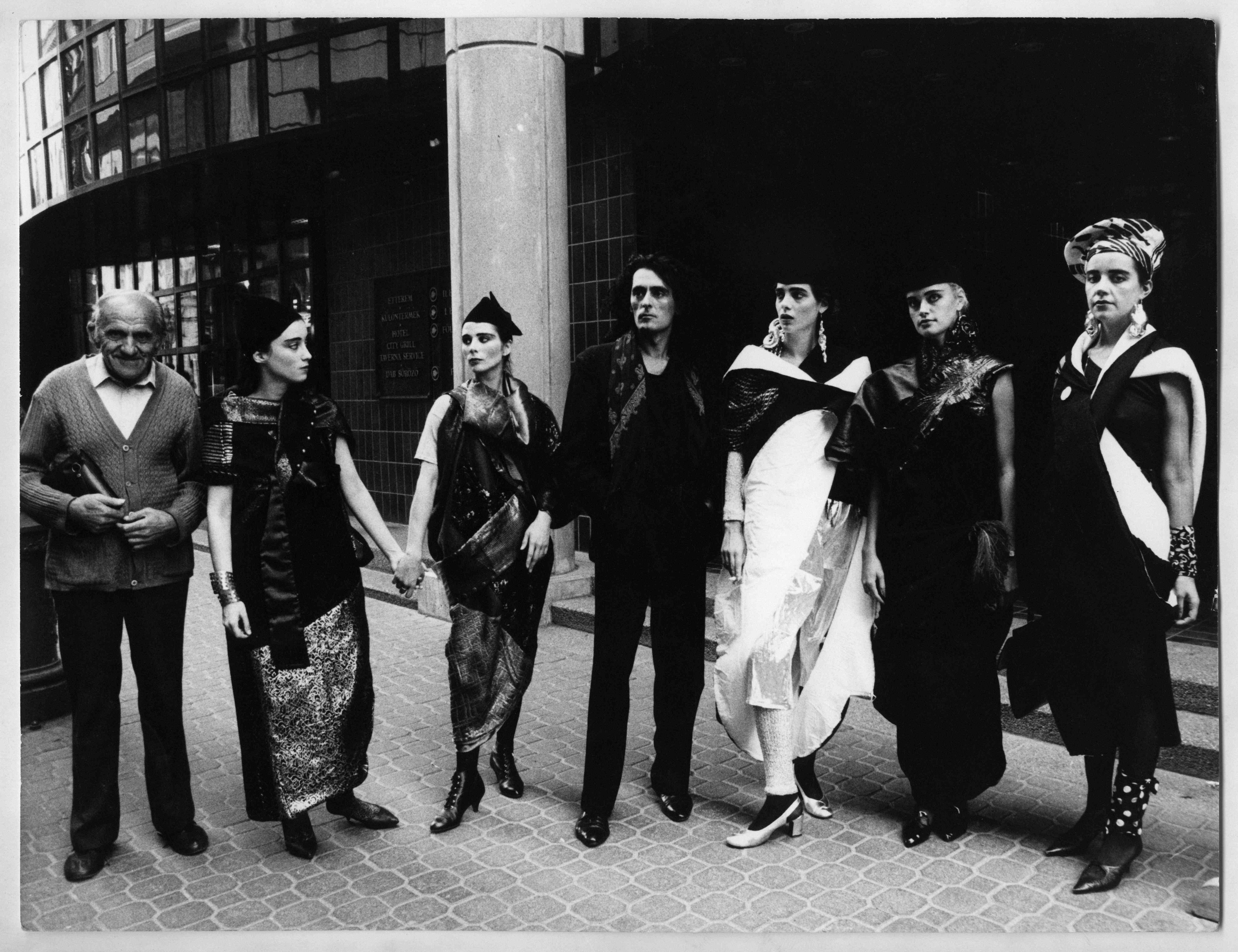

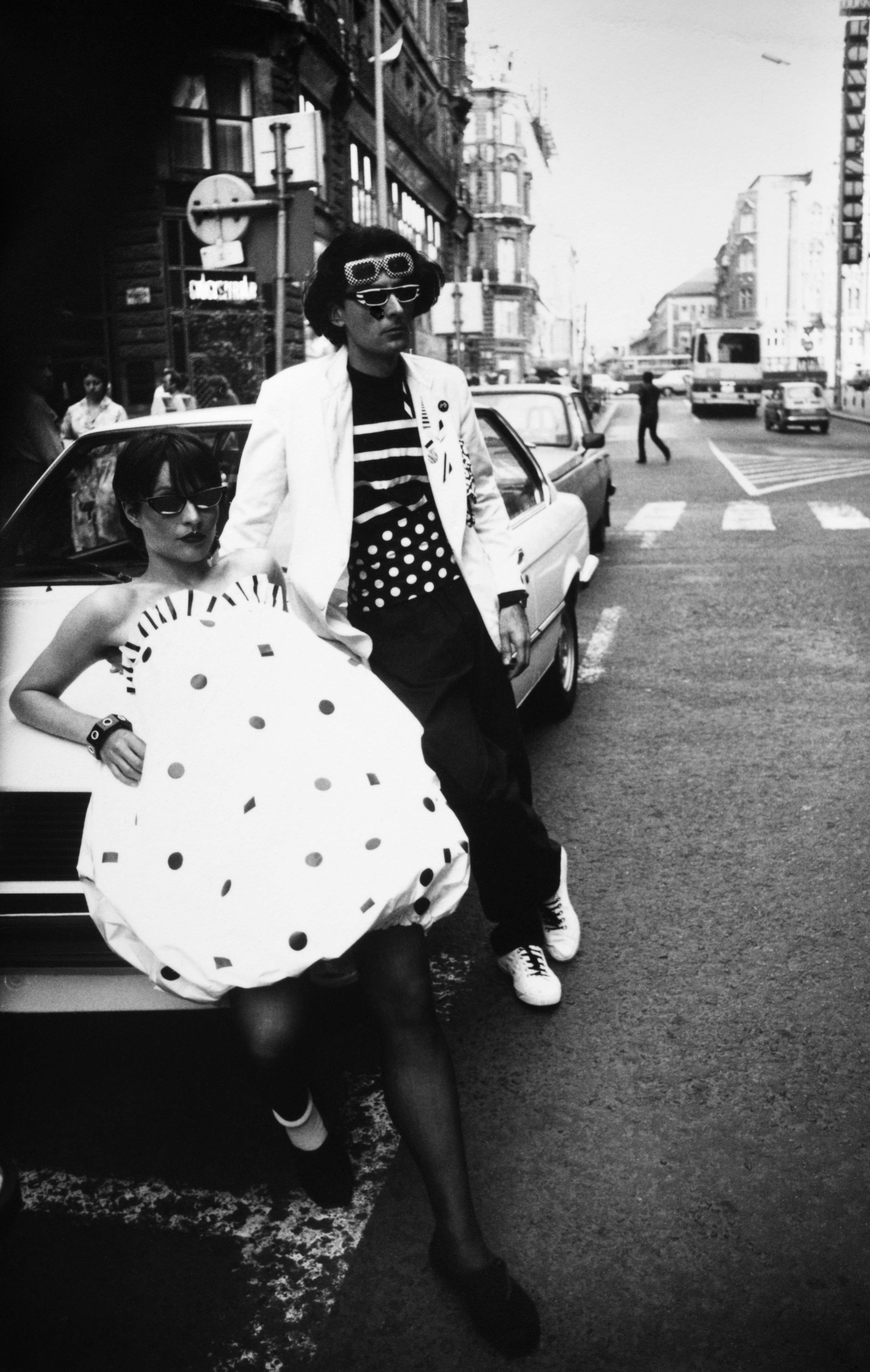

Tamás Király constantly challenged the boundaries of fashion design, performance and, visual arts which, were strongly influenced by the cultural and social context of the 1980s, when new cultural trends (e.g. “new wave” bands and the Albert Einstein Committee, which represented a new kind of Gesamtkunstwerk) had emerged. His oeuvre was not related to politics and ideology directly, but the act of reusing, or re-appropriating political symbols (for example in the case of the Red star dress, etc.) and his subversive performances always contained critical elements. In 1981, he staged his first “fashion walk” (followed by many others), crossing the downtown area of Budapest to FMK (Fiatal Művészek Klubja, “Club for Young Artists”), of which Király was also a member. During these tours, professional models and his acquaintances took a walk wearing flashy and extravagant clothes designed by him. According to Király, these walks also served as a counterpoint to the grey, boring visual appearance of the city and its inhabitants (the socialist clothing industry provided only a poor assortment of garments).

Beginning in the middle of the 1980s, Király also started to organize shows in Berlin (1984, 1988) and New York (1985), and he gained international fame. Even the magazine Stern called him the “Gautier of Eastern Europe”. Simultaneously, Király created four different thematic fashion shows at the Petőfi Hall (Baby’s Dreams 1985, Boy’s Dreams 1986, Animal’s Dreams 1987 and Király’s Dreams 1989). During the performances, underground bands like URH, Kontroll Csoport, and Sziámi played music, and the “unwearable” clothes were presented by ordinary people of Budapest. Additionally, beginning in the 1980s, Király extended his activities by creating costumes for theatre plays and movies.

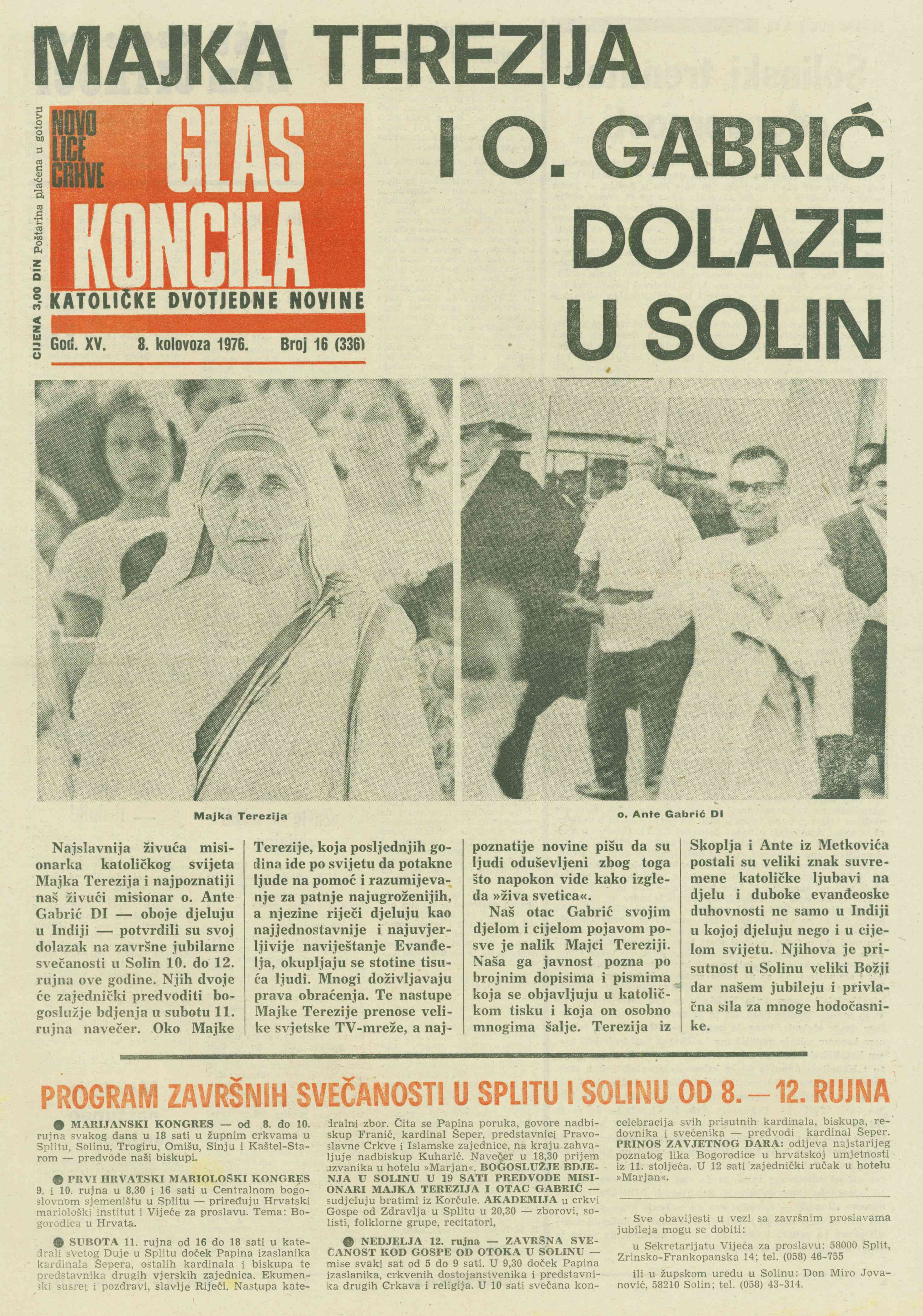

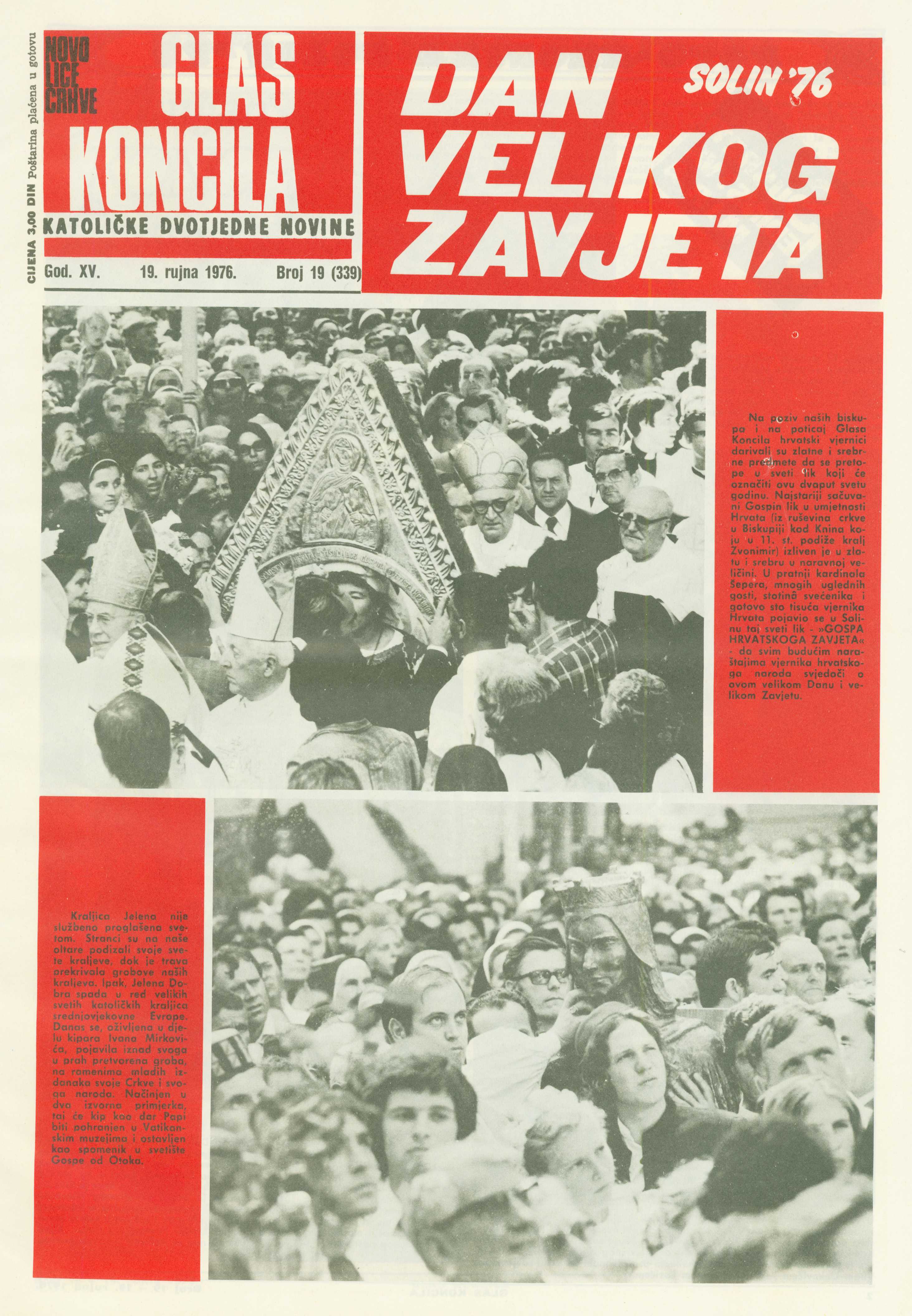

In September 1976, the Catholic Church in Croatia celebrated a thousand year anniversary of the death of the Croatian Queen Jelena, who had built the oldest known Croatian Church of Our Lady of the Islet and St. Stephen’s church, the mausoleum of the Croatian royal family, in Solin. On this occasion 100,000 people of Catholic faith from Croatia and abroad (including Mother Teresa) gathered in Solin. The event was covered by the church’s fortnightly newspaper Glas koncila (the Voice of the Council) with a lot of photos, which can be seen on the cover of 19th September 1976. The celebration took place in 1965. First, only the information about the celebration of the anniversary of the church building was released. In 1975, on the eve of the Jubilee year the intention to celebrate thirteen centuries of Christianity in Croatia was announced together with the proclamation of the Year of the Great Vow, which is documented by the brochure and the cover of GK of 26th October 1975. The reaction of the regime was silence, and the manifestation was ignored in the official press. In the end, the Jubilee turned out to be a great national celebration of the whole history of the Croatian people, which in civilisational, cultural, identity, and other respects was marked by Christianity. It is assumed that the Church “tactics” of being cautious contributed to the fact that the authorities did not prohibit anything, and that, in fact, did not know what to prohibit. Most probably, the regime did not want to have further problems with the world publicity.

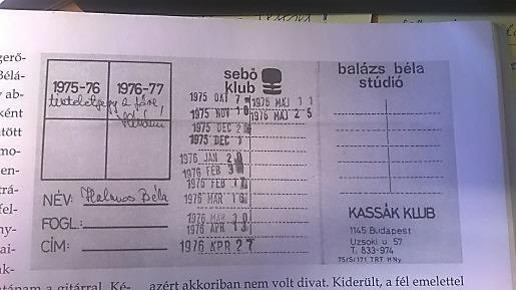

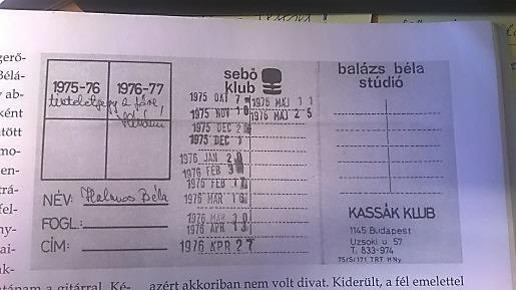

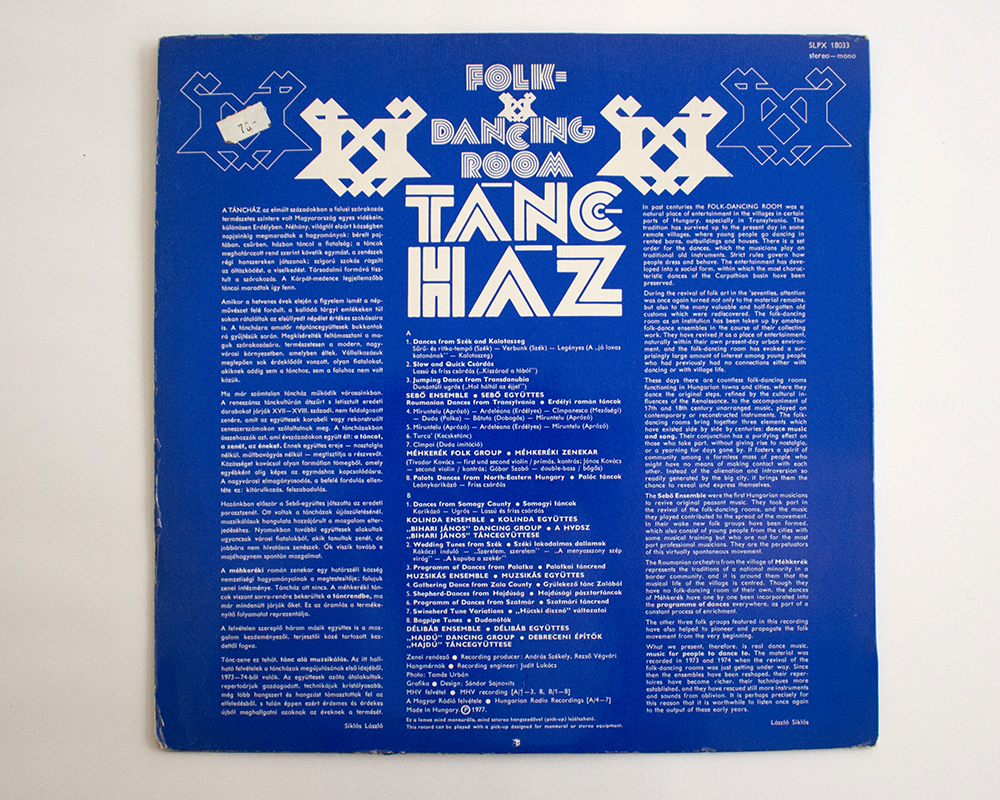

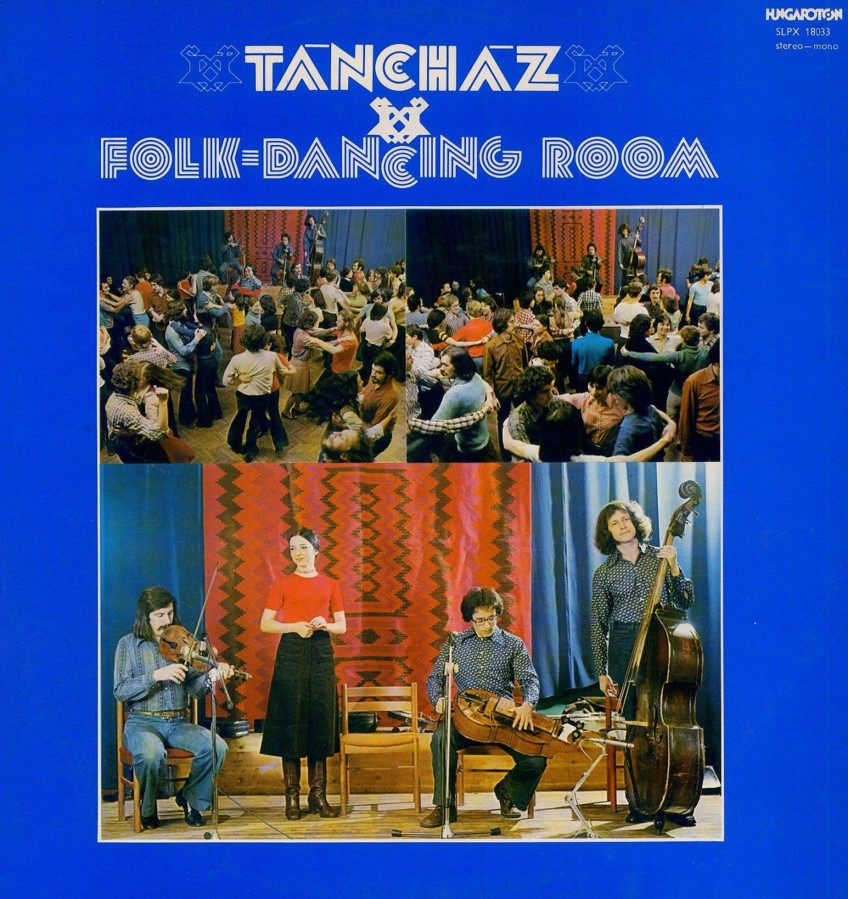

The “Dance House Movement,” which began to emerge in 1972, was a kind of trend in the world of folklore in Hungary which was rather distinctive of the Hungarian context. It was very much part of the international youth and folk movements of the late 1960s. Essentially, it was a call for a “return to roots,” i.e. to peasant culture, and for the use of folk music and folk dance as a way of building community and identity in the modern world. On the palette of cultural life in Hungary under socialism, the Dance House Movement constituted an alternative form of entertainment and even education, and from time to time, various elements of this movement were grouped by the people in charge of culture policy in the Kádár regime in the “tolerated” or “forbidden” categories of cultural practices.

As Imre Marczi has observed, “this culture exerted an influence on a receptive group among the younger generations of the 1970s and 1980s which gave rise to the emergence of a distinctive lifestyle. It offered forms [of culture and entertainment] which were expressive of an identity opposed to the vapid socialist cultural platitudes and the entertainment industry. […] It offered a genuine alternative to the forms which had become rigid in their dominance: the freedom of one’s existence, self-organization, and self-expression.”

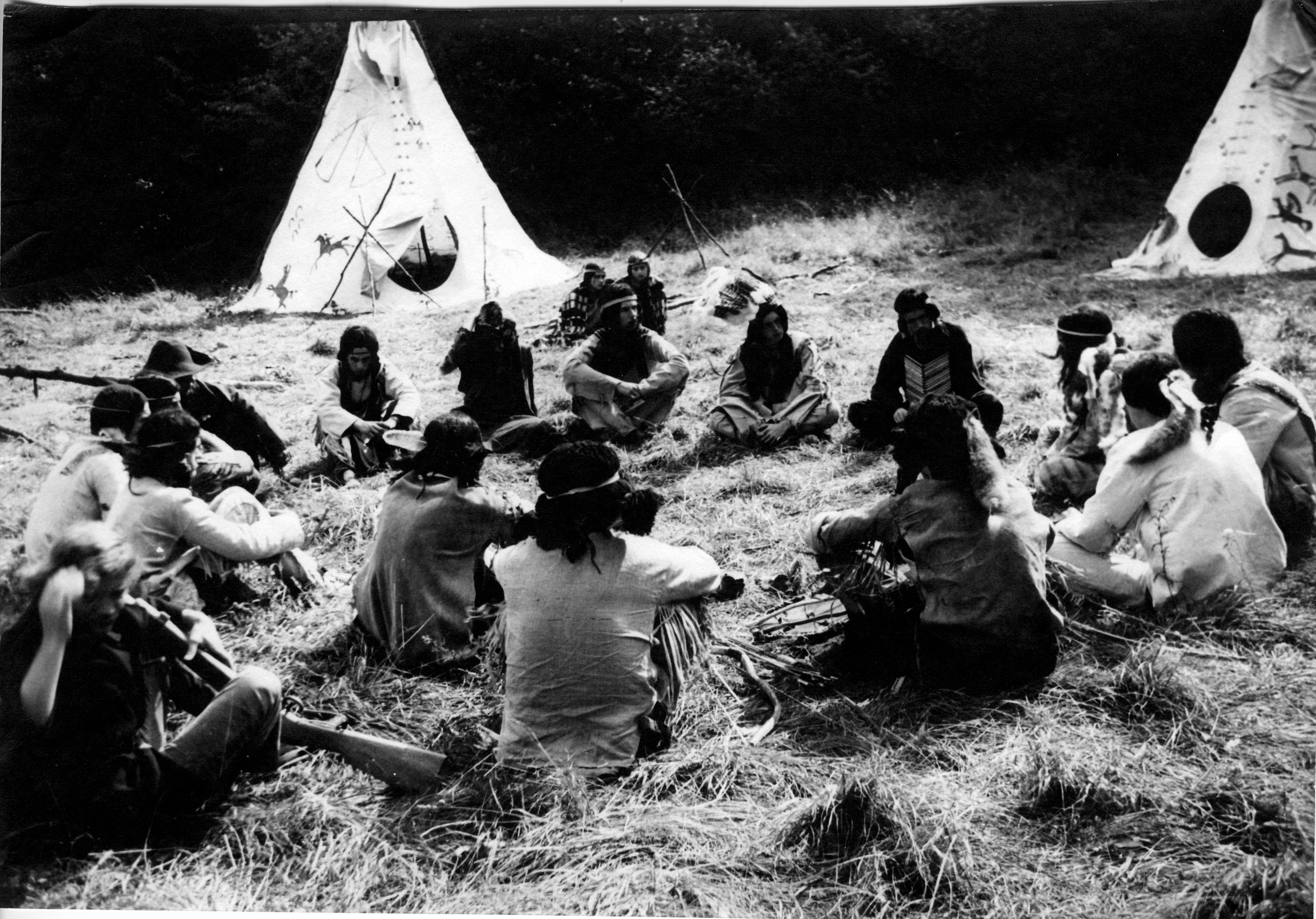

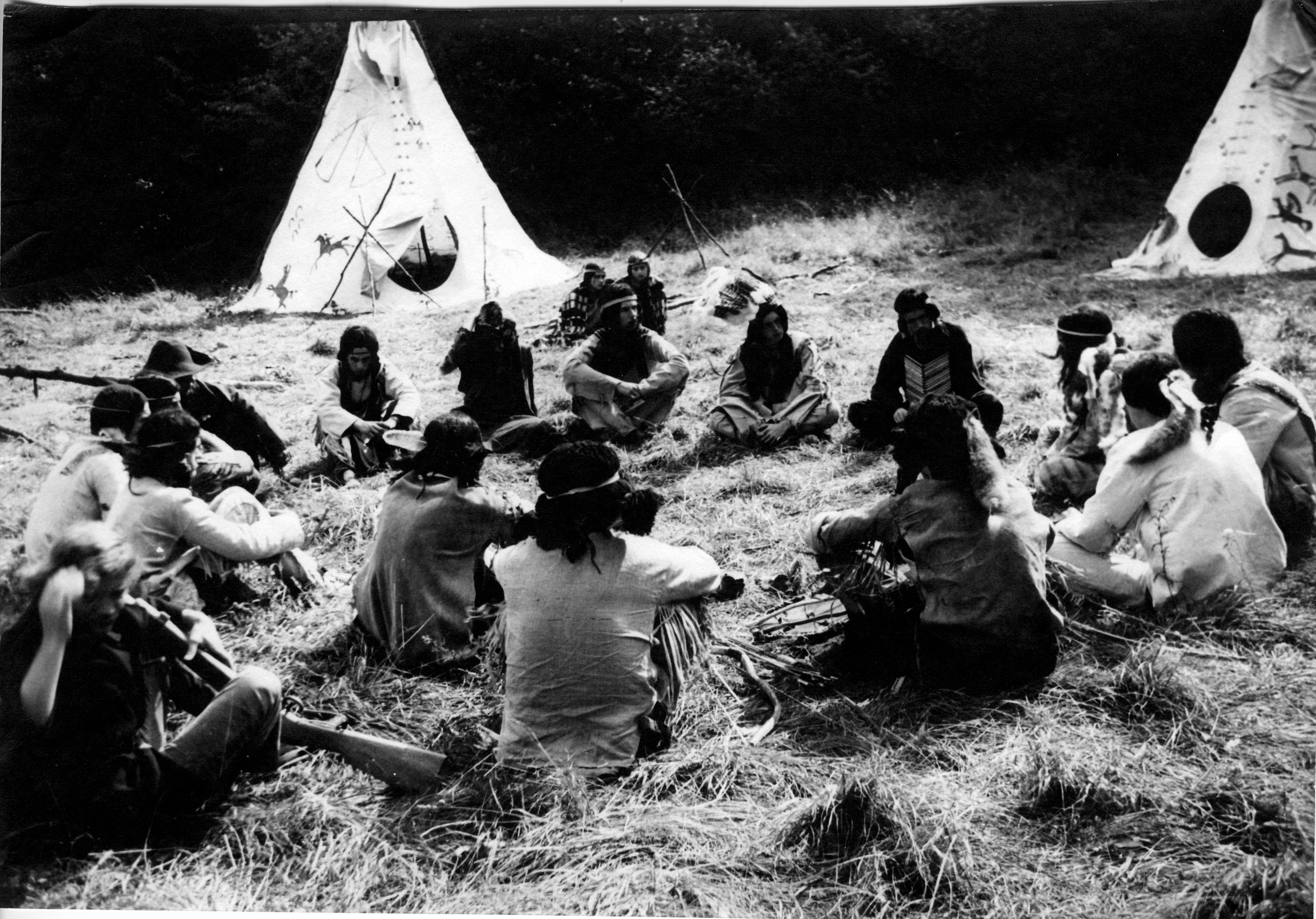

At the very beginning of the sixties, four teenagers decided to "fight with each other in american indian style". That's how the story of the Native American games played in the forests of Bakony, Hungary, started, involving hundreds of participants today. The goals of the game (cultivating appreciation, revealing courage, and learning skilfulness and endurance) and the methods (playing a war-game based on commonly accepted rules) have remained unchanged ever since. Over the course of the years, women and children also started to take part in the activities, which originally were enjoyed exclusively by men.

The participants strove from the outset for ethnographic authenticity in camps with home-made accessories and props. They divided themselves into tribes once or twice each year in the same location in a valley and the nearby plateau. The weapons used for the game had blunt edges, and the ways in which they could be used were governed by strict, self-imposed rules. The war dimension of their game is unique, as this is the only Native American roleplay camp worldwide where a war game is played.,

Initially, the State Security services automatically connected the games to the scout movement, which was forbidden, so they considered them “counter-revolutionary” in spirit, fearing they could turn into an "anti-state conspiracy". Later, the good relationship that developed with locals and positive publicity provided by magazines took the wind out of the "sails of mistrust", meaning that in the long run, the camps were eventually left alone.