The section entitled Collisions presents open confrontations with the system, including individual and group initiatives and brave and daring acts (protests, strikes, and the at times shockingly bold acts committed by individuals) which had unambiguous political messages and which were very clearly visible to the regime and the public.

The reason for the protest movement was air pollution caused by an industrial chemical complex in Giurgiu, on the Romanian side of the River Danube opposite Ruse. This plant was built in the early 1980s, and its emissions caused a serious pollution problem in the neighbouring city of Ruse, in Bulgaria. Since the factory was part of the military-industrial complex of the Warsaw Pact, its work could not be halted. Chemical plants in Ruse also contributed to high levels of air pollution, which created serious health problems for the local inhabitants. This was well known to the Communist party and the state leadership in both countries. Yet, the governments sought to conceal the problem; it became a taboo subject not to be debated in public (although at that time, in both countries laws for the protection of the environment were already in place).

On 28th September 1987, more than 300 people protested in Ruse against the unbearable quality of the air in the city, which suffered from the emission of toxic gases. The protest is considered the first street demonstration during communist rule in the People's Republic of Bulgaria. The first relatively limited protest was followed by a second one in November 1987, where several thousand people gathered. Neither radio nor television or the press reported on these protests.

The poster is one of the first hand-made materials, used in the initial protest in the autumn of 1987. The protest actions at the time were cautious due to the possible regime response, and contained no explicit political statements or requests.

The years of continuing chlorine pollution of Ruse, as well as the lack of visible results from the actions of the local authorities in cooperation with the Romanian authorities, were sometimes interpreted by the locals as a purposeful act against their home town.

In this respect, the call for ceasing the “ecological genocide” does not appear as a dramatic overstate, but rather as an expression of the citizen’s desperation.

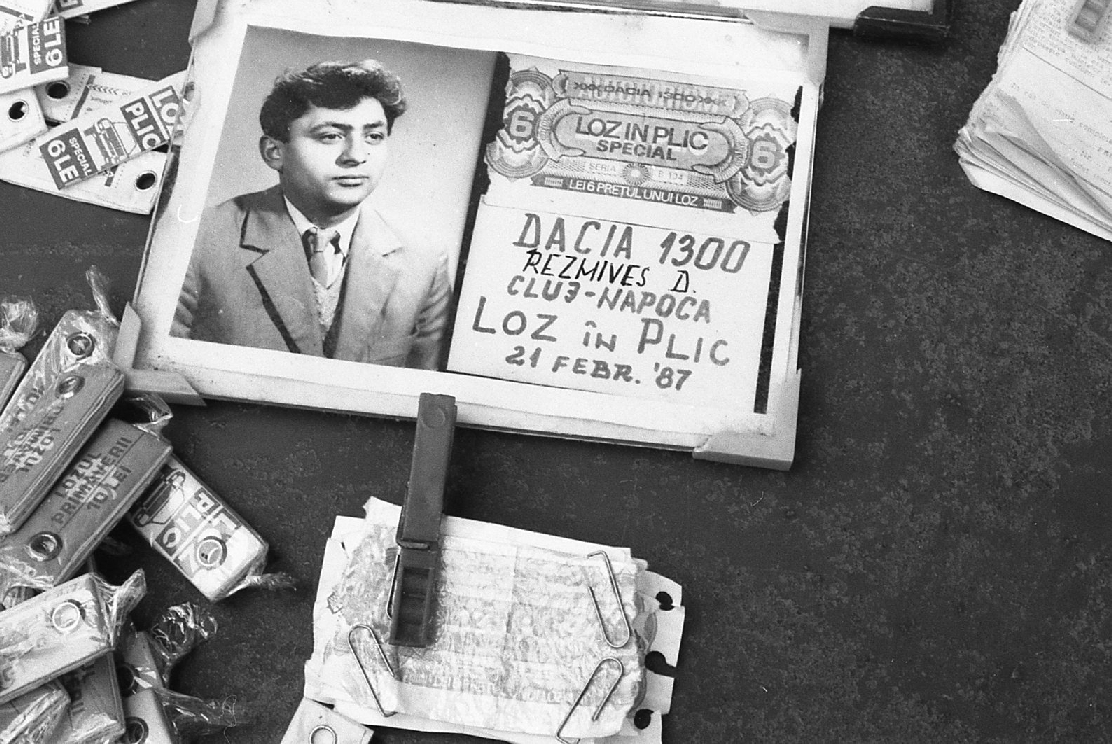

Romania was increasingly isolated under Ceauşescu’s rule, and became the most oppressive communist police state by the 1980s. Great need, starvation on the one hand, and mass abuse of human rights, forced assimilation, endangered multicultural heritage on the other, forced thousands of people, including ethnic Hungarians from Transylvania, to flee the country. This mobilised groups of volunteers in Hungary to provide help, and to regularly inform the Hungarian and international public of the grave situation. To this end, one of the most active humanitarian and human rights movements, ETE was established in 1985 (the group was renamed Transcar in 1990). ETE/Transcar organised several relief trips to Romania, and printed samizdat publications distributed in Hungary, Romania and in the West.

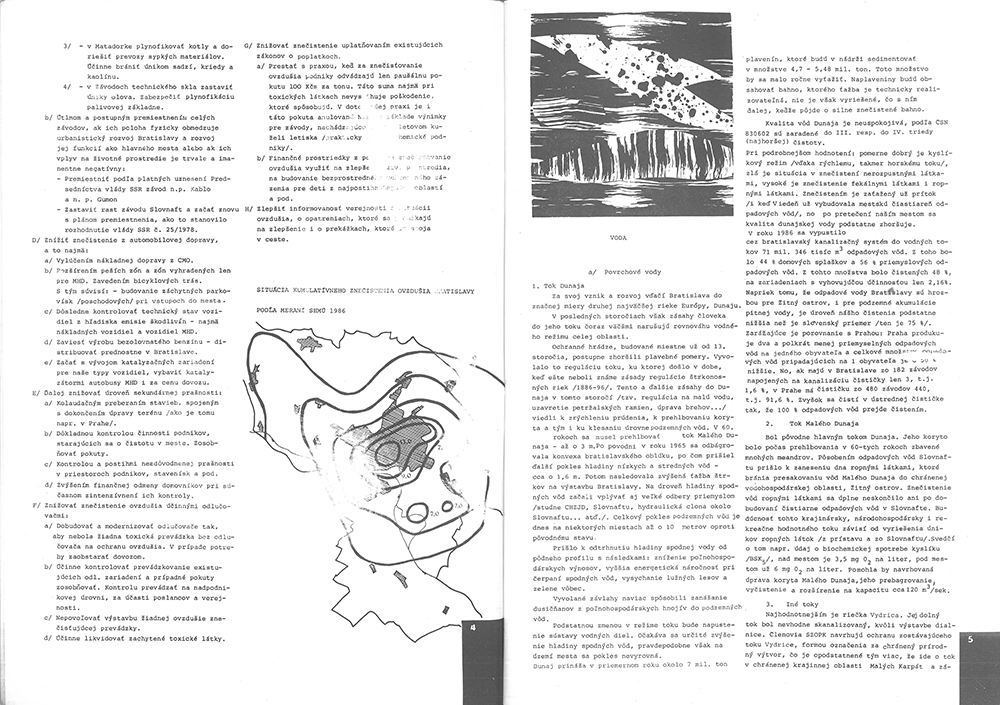

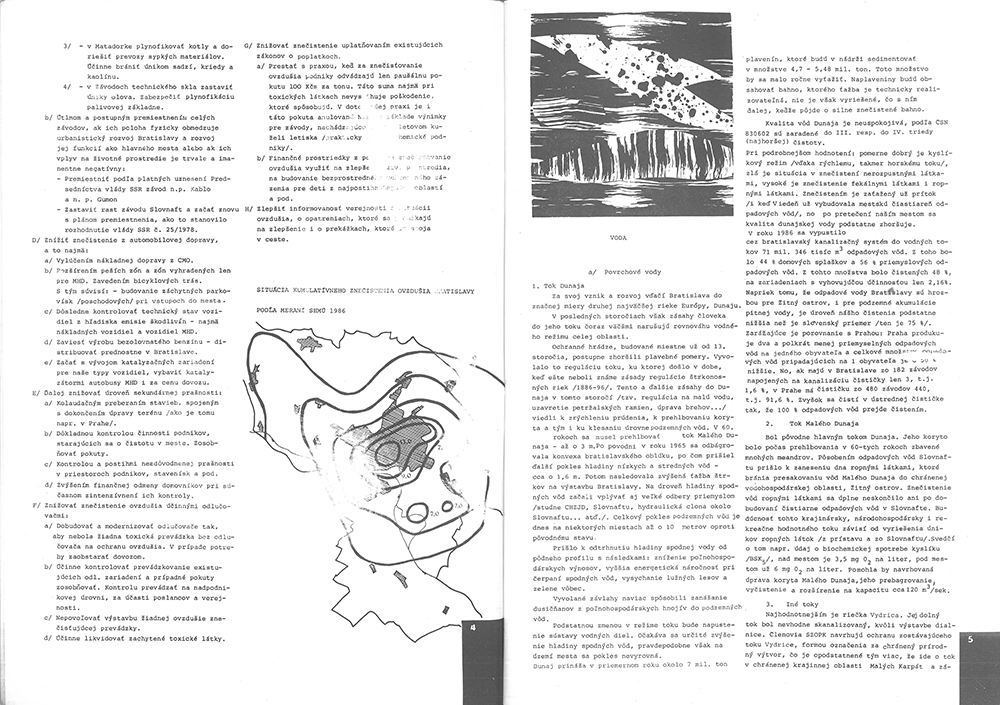

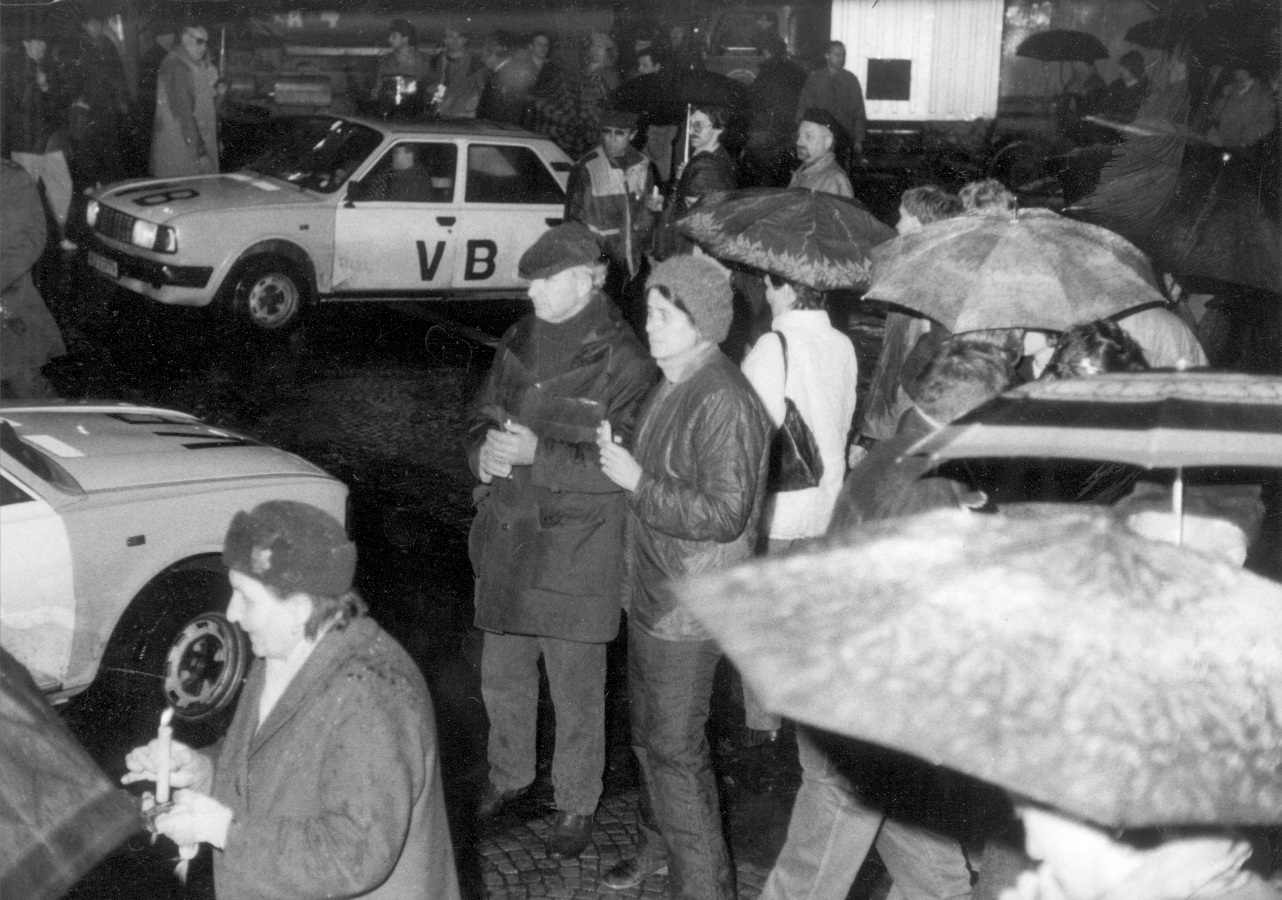

Environmentalists played an important role in the opposition movement in Slovakia. Their critical views on the situation of the environment in the Slovak capital were summarized in the samizdat Bratislava/nahlas [Bratislava Aloud]. This was published (officially as an addendum to the records of a regular meeting of the Association of Environmentalists) in October 1987 with a print run of 2000 copies and announced on 25 October 1987 on Voice of America. A group of around 80 people highlighted the air pollution in Bratislava, which proved to have the highest level of contamination in Czechoslovakia (figure on p. 4). Attention was also drawn to the contamination of water by the oil-processing industry. Another point concerned the catastrophic condition of Bratislava’s Old Town monuments, the majority of which, were destined to fall into decay, since renovation either did not take place at all or was delayed. The initiative of young environmentalists, who became active participants in the Velvet Revolution shortly after, was hailed as the „Slovak Charter 77“.

The collection “Slovak Association of Environmentalists” is based mainly on the private archive of Professor Mikuláš Huba. Slovak environmentalists were among the protagonists of civil opposition in Slovakia in the 1970s and 1980s. They published their critical views on the alarming situation of the environment in Slovakia, protested against the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros dams project, and, as volunteers, they preserved nature and also renovated historical buildings and saved old cemeteries.

On 5th January 1990, two Hungarian opposition parties the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ) and Fidesz (Alliance of Young Democrats) prosecuted the Ministry of Interior because it pursued illegal covert operations against opposition politicians. The incident soon became known as the Danube (Duna) gate and accelerated the transformation of state security organisations into national intelligence services and the police records into historical documents. The Minister of Interior ordered the suspension of covert operations in mid-January 1990, which was soon to be followed by the release of the relevant records, too.

The secret service archives that operated from 1997 as Historical Office, and then from 2003 as the Historical Archives of the State Security Services represents the imprint of the relationship of dissidence and the party-state. Its foundation has clarified that the former police records have been turned into historical evidence. The archives caution that the act of turining autonomous and critical thinking into political or police matters is symptomatic of oppression.

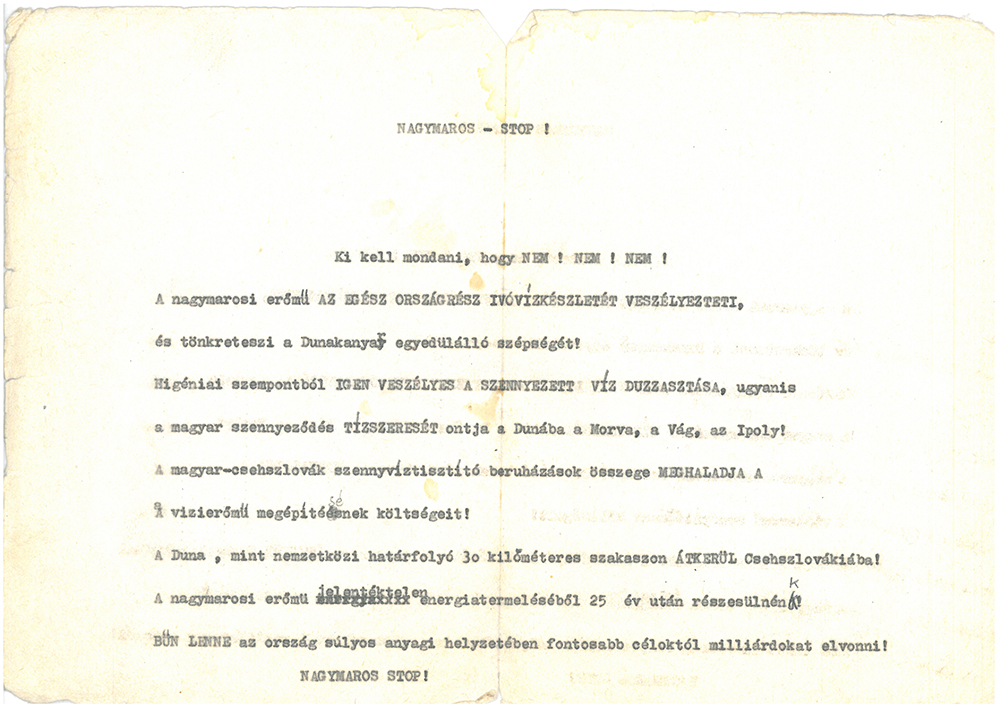

In the fall of 1988, ten thousands protested against the Communist government in Hungary in demonstrations comparable only to the mass protests of 1956. This demonstration was organized by the Danube Circle founded in 1984, as a group of private individuals dedicated to protect the river Danube. Members of the organization feared that the Gabčikovo-Nagymaros water dam, which had been initiated as a joint project of socialist Czechoslovakia and Hungary, would destroy traditional natural and human livelihoods in the area leading to an ecological disaster and the dispersal of Hungarian village communities in the area called the „Csallóköz”.

The Danube Circle highlighted the lack of intention and incapacity of socialist governments to protect the natural environment and their deep indifference to the interests of local communities and minority cultures. The genuine grass-roots civic movement that raised serious ecological concerns, and quickly turned into firm political criticism of the party-state.

Born in Yalta, Crimea in 1929 to prominent Soviet officials, Alla Horska led a privileged life, but one that was marked by tragedy and shaped by the vicissitudes of Soviet cultural policy. She and her mother survived the Nazi siege of Leningrad in 1941-1943, after which the family moved to Kyiv to avoid mounting political pressure on her father.

Like many artists of her generation, Horska embraced Khrushchev’s Thaw, experimenting with cultural forms stamped out by socialist realism. She worked with others to locate unmarked mass graves of NKVD victims near Kyiv. She was radicalized by her many run-ins with the authorities, a turn reflected in her later work. She refused to testify at a number of trials of friends and colleages, citing the illegality of the proceedings.

On December 2nd, 1970, Horska was found murdered in the village of Vasylkiv. After a brief investigation, the Kyiv Procuracy determined her death the result of a domestic dispute, while contemporaries saw in the gruesome details the hand of the KGB. Photos of Alla capture not only her indomitable spirit, but also urge the viewer to reflect on what might have been.

Shukrije Gashi’s life is the gripping story of a woman determined to prove herself in the battlefield of politics. Early on, she joined the Albanian national movement which was an illegal network of groups advocating the Republic of Kosovo. In 1983, Shukrije was 21 when she was charged with having been accessory to “the perpetration of criminal acts against the people and the state of Yugoslavia,” as read the official charge. She was eventually arrested after an adventurous escape from the Yugoslav secret police and spent two years in prison. As a prisoner of conscience, Shukrije was given drugs, forced to work, and subject to physical and psychological tortures, including being told derisively that her boyfriend and fellow activist had been killed (which he was).

Shukrije drew her courage and will from her grandmother, a charismatic local figure engaged in blood feuds reconciliation. They were feminist before anyone spoke of feminism. Because of their political opinions and activities, Shukrije and other members of her family were constantly under surveillance, were harassed by the police, and often had to often change jobs, just because they demanded more autonomy for Kosovo and better living conditions.

Shukrije Gashi studied law at the University of Pristina and today directs the Center for Conflict Management – Partners Kosova.

The Law on Stasi Records entered into force from 29th December 1991, and provides a framework for the processing of files of the secret police of the GDR. It offers a basis for the activities of the Federal Commissioner for Stasi Records (BStU) and is a direct result of pressure from the civil committees which illegally occupied offices of the Ministry for State Security across the GDR in December 1989. As a result of hunger strikes by members of the civil committees in September 1990, a proposal for the administration and preservation of Stasi documentation was added to the German Treaty, creating in the process, a Special Commissioner of the German Federal Government for Stasi Records. Since the passing of the Law on Stasi Records, the employees of the BStU (as of 2016) have processed more than 6.5 million requests to view Stasi documents.

Süleyman Saadettinov resisted the so-called “Revival Process” implemented by the Communist Party and its campaign of forced name-changing in 1984 and refused to change his Turkish name to Bulgarian. His resistance was peaceful; he attended a small protest against the “Revival Process”. He was arrested and sent to prison and the forced labour camp in Belene, on the island Persin on the Danube.

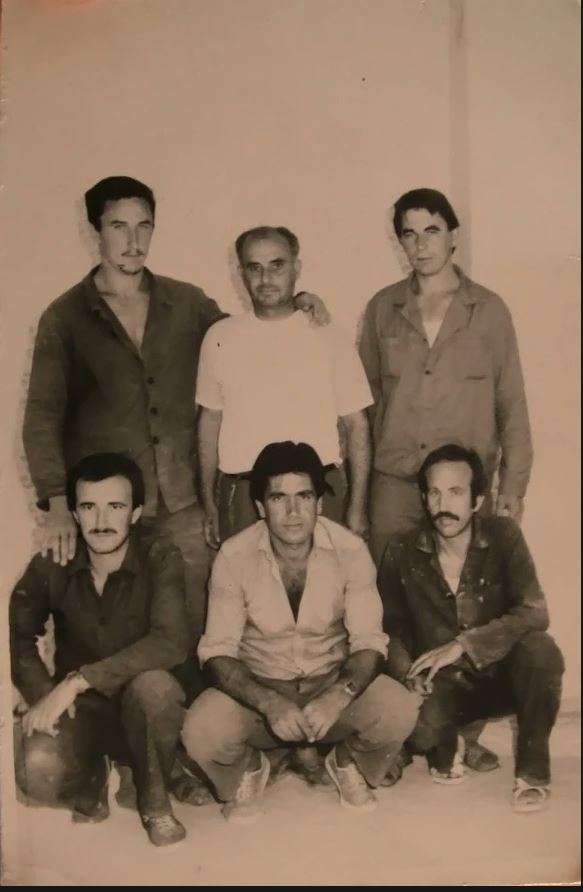

According to the account of Süleyman, the photograph was secretly taken at a moment when camp prisoners were removed from the camp to work outside of the camp area, near to ordinary workers. They saw a photographer taking photos of ordinary workers. They asked the unknown photographer to take a photo of them. The photographer secretly took the photo of a group of prisoners and a week later brought them the developed photograph. Süleyman is on the right of the picture, the man crouching and with a moustache. According to the testimonies of the victims, this is the only photo from 1985 to 1986 taken in the forced labour camp in Belene.

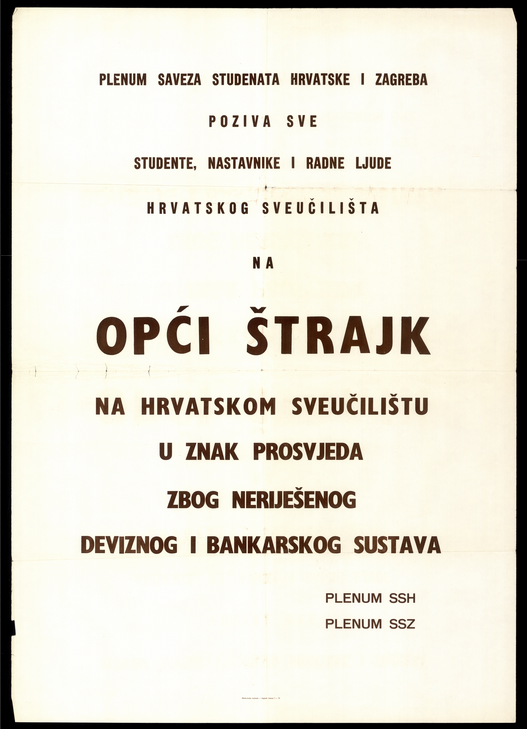

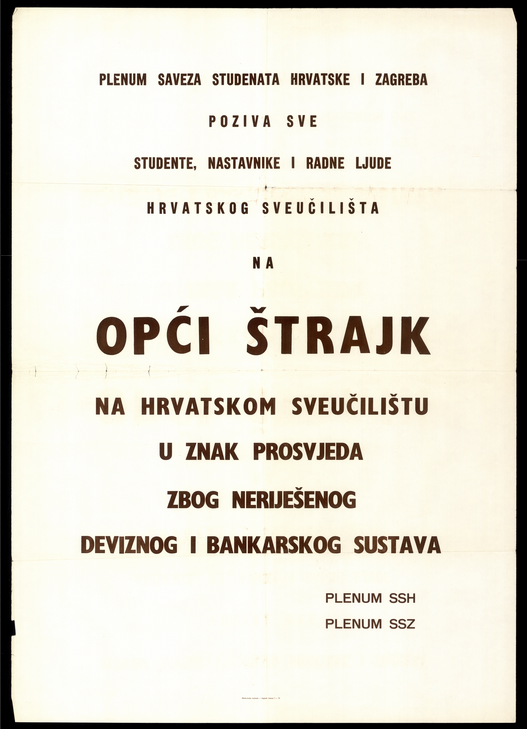

The Croatian Spring is the best example of cultural opposition in the period of the communist regime in Croatia. Students were an important part of this reform movement and were very decisive in their requested reforms. They started a strike at the University of Zagreb (a.k.a. the Croatian University) and invited the entire public sphere to join. Their messages were distributed on leaflets and posters, pinned at the University and in other public spaces. Many such examples are found in the collection, and the masterpiece is a big poster with an invitation to a “general strike at the Croatian University”. The poster was confiscated and handed in to the Public Prosecutor’s Office in Zagreb (December 1971). The poster remained unknown to the public.

Iljko Karaman took the document illegally from the Public Prosecutor's Office and stored it in his home collection, which ended up in the Croatian State Archives in 1992. The material is available for research and copying.

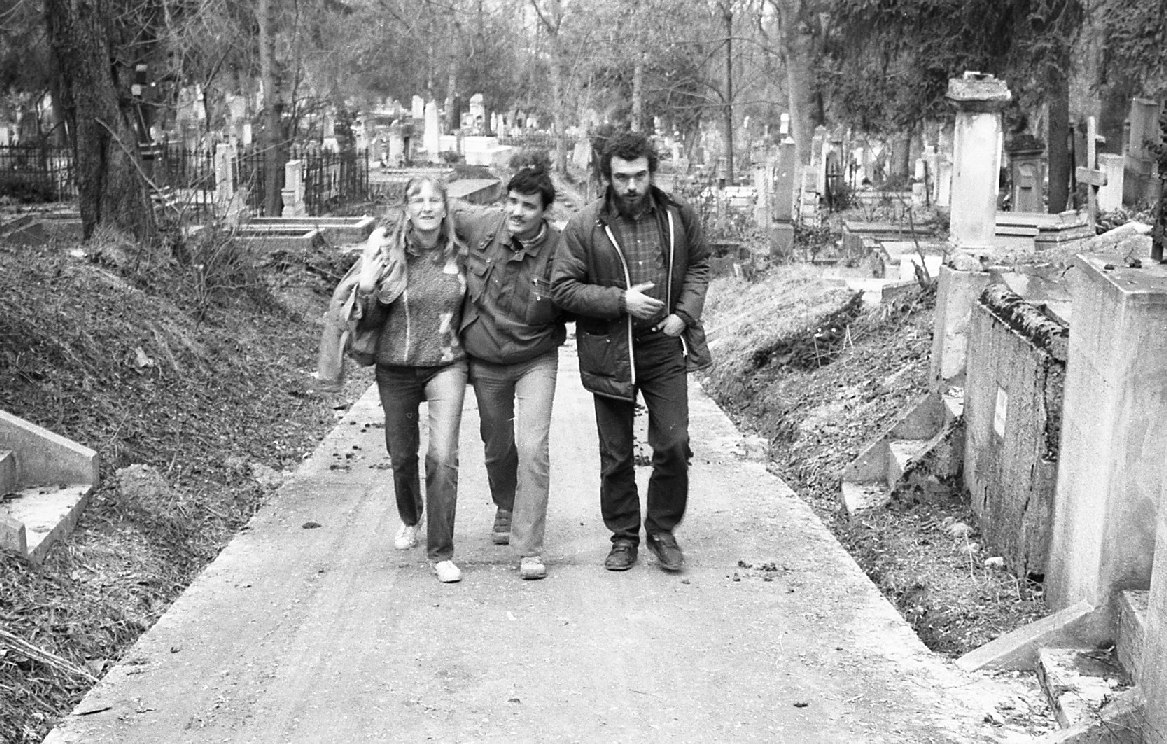

On 30 May 1990, just a few months after Ceausescu’s tyranny was overthrown by desperate street fights, a severe earthquake hit the counties of Vrancea and Covasna (Háromszék) in central Romania. Among the losses were fifty heavily-damaged, older church buildings (many built before AD 1300) in Háromszék, the easternmost region of Transylvania with an 80% Hungarian majority. A group of volunteers formed among the activists of the relief organization, ETE-Transcar, and the architects of the National Historical Monuments Protection Authority. They made an overall survey of the damaged churches in order to inform the wider public and acquire the help needed for repairs. An international relief campaign was launched, and detailed documentation of the damages was published as “Pro Domo Dei”. It was edited by Budapest-based monument architect István Varga, with the collaboration of Hungarian co-authors and specialists: János Gyurkó, József Sebestyén, Béla Nóvé, László Nagy and others. The illustrated report contained a number of case studies, lists, maps and photo documentation of the damages, together with English and French summaries.

The aims and spirit of the relief campaign were much the same as those of Deadline Diaries – Transylvanian Monitor, ETE-Transcar, S.O.S Transylvania, and Hopes and Doubts by Bálint Homoród (Béla Nóvé); helping people in need and helping traditional cultural values survive. This profoundly humanitarian and democratic spirit is reflected in the forward to Pro Domo Dei:

Pro Domo Dei is a neutral project from the point of view of religious and ethnic groups. TRANSCAR relief organization will help both the Hungarian Catholic and Protestant parishes, in their grave situation, as well as the Orthodox Romanian parishes in Covasna (Háromszék) County. […] The ‘Pro Domo Dei’ project is organized first and foremost for monument protection. Our main focus of support is for the historical value; among the heavily damaged churches in the county there are some which are more than 700 years old. […] In addition to financial assistance, it is also important that, after the failure of communism, this region in Europe that has suffered so much has some moral support from the international community and readiness to help.

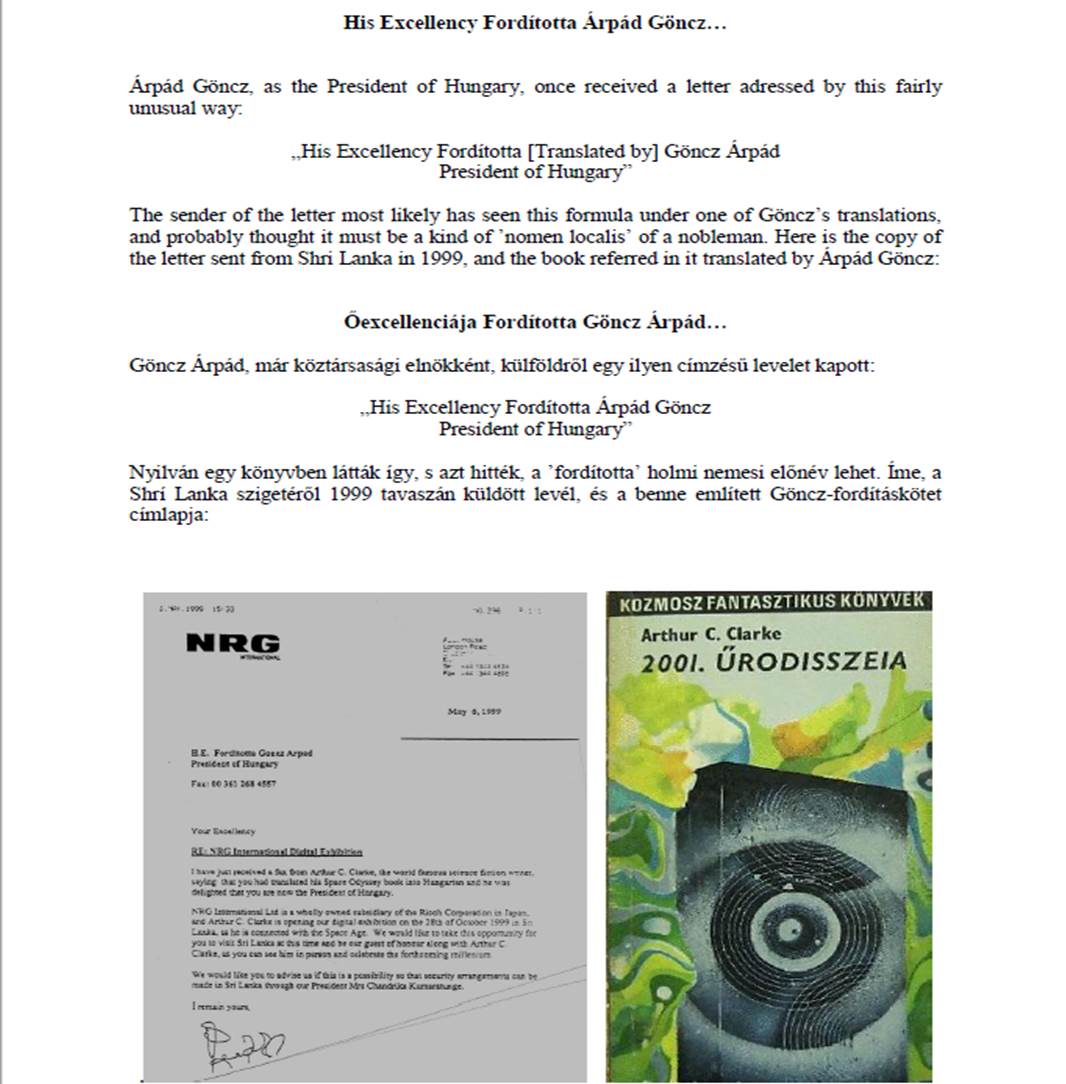

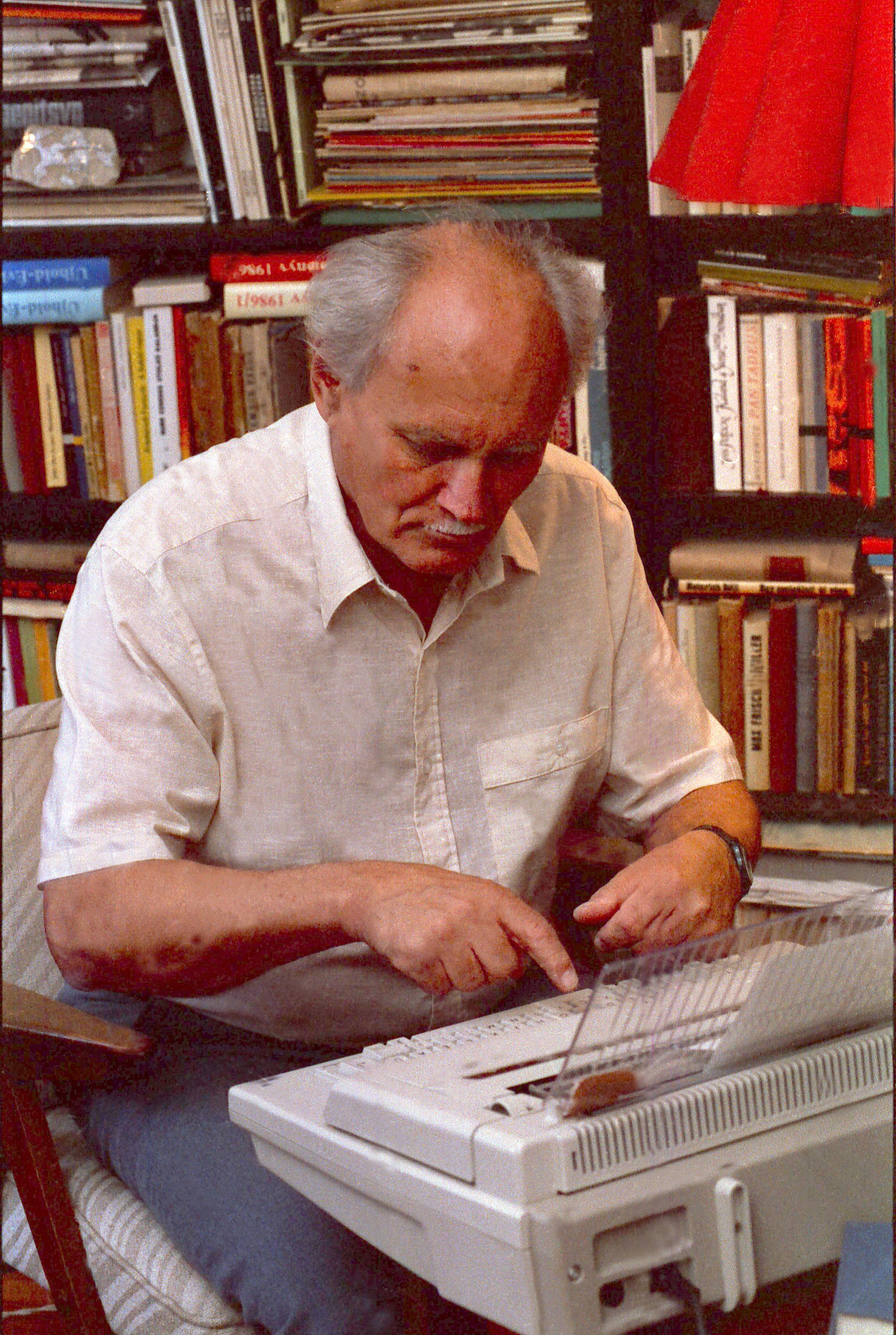

Árpád Göncz (1922-2015) was a writer, translator, politician, and the first freely elected President of Hungary from 1990 to 2000.

He had been a devoted protagonist of freedom, civil liberties and social justice ever since his early youth until the end of his long life. He bravely fought against both the Nazi and the Communist regimes, and after the Hungarian revolution of 1956 he suffered a six year imprisonment for taking an active part in the resistance movement.

He learned English on his own in prison, and following his release, he became one of the best Hungarian interpreters of modern English and American prose. He produced more than 250 translations of the works of prominent authors such as Faulkner, Hemingway, Tolkien, Updike, Golding, and Doctorow.

He died at the age of 94 in 2015, but he remained for many a positive symbol of the 1956 revolution and the free, democratic Hungarian Republic established in 1989-1990.In Autumn 2013 the four adult children of Árpád Göncz created a foundation in order to promote the presentation of their father’s life and work and to preserve the authentic heritage of the 1956 revolution as well as the democratic traditions in Hungary. Since then the Árpád Göncz Foundation has opened its website, organized conferences, exhibitions, and other public events, like placing memorial plates and a bust of the late President. As a plan for the near future, the Foundation also wishes to display Árpád Göncz’s personal memorabilia in a small museum to be opened in the same residential building, where the Göncz family once lived for almost half a century in the city of Budapest (III. Bécsi út 88-90.). The family collection of photos, papers, books and documents left behind him would serve as the core material of the future Árpád Göncz Memorial Exhibition.

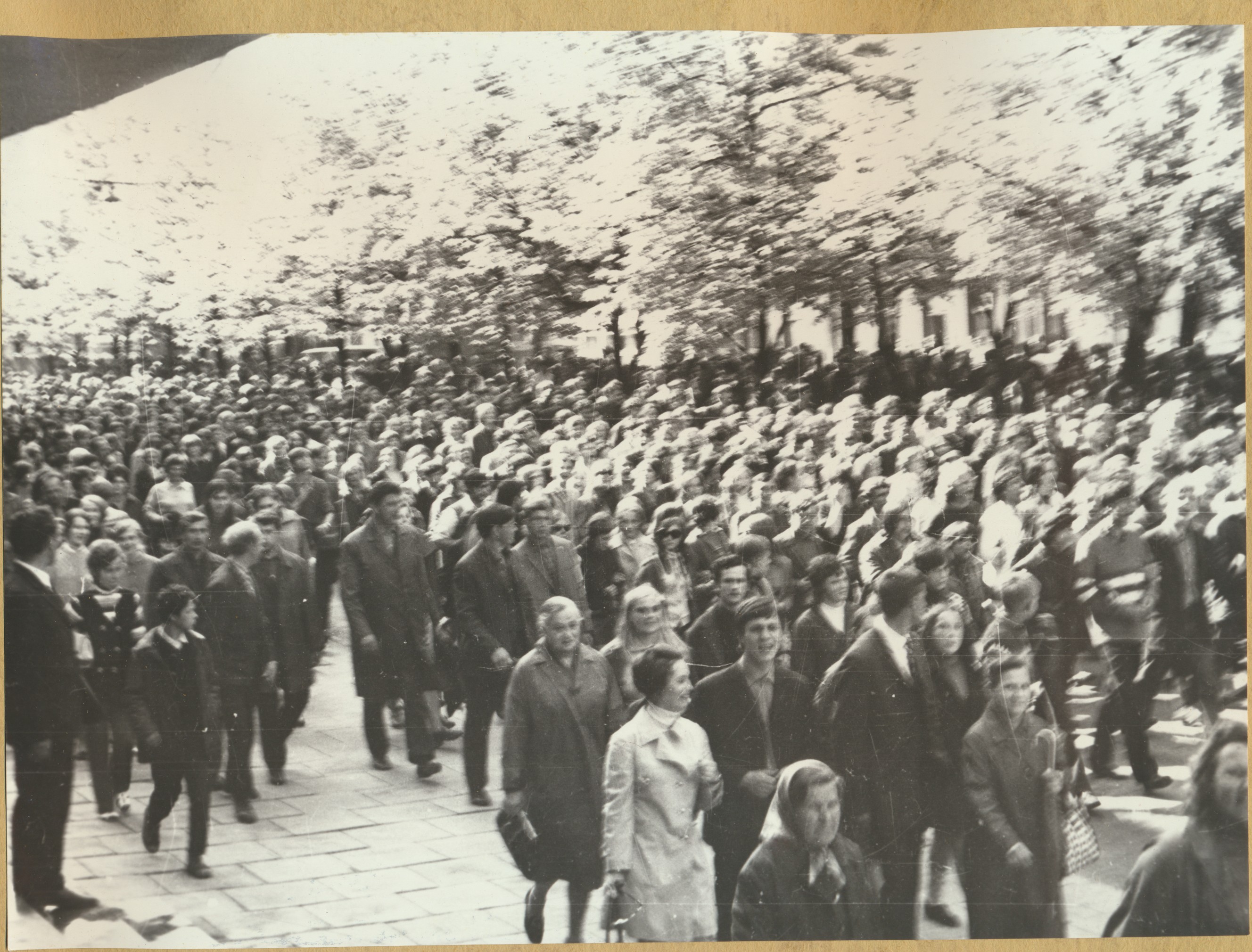

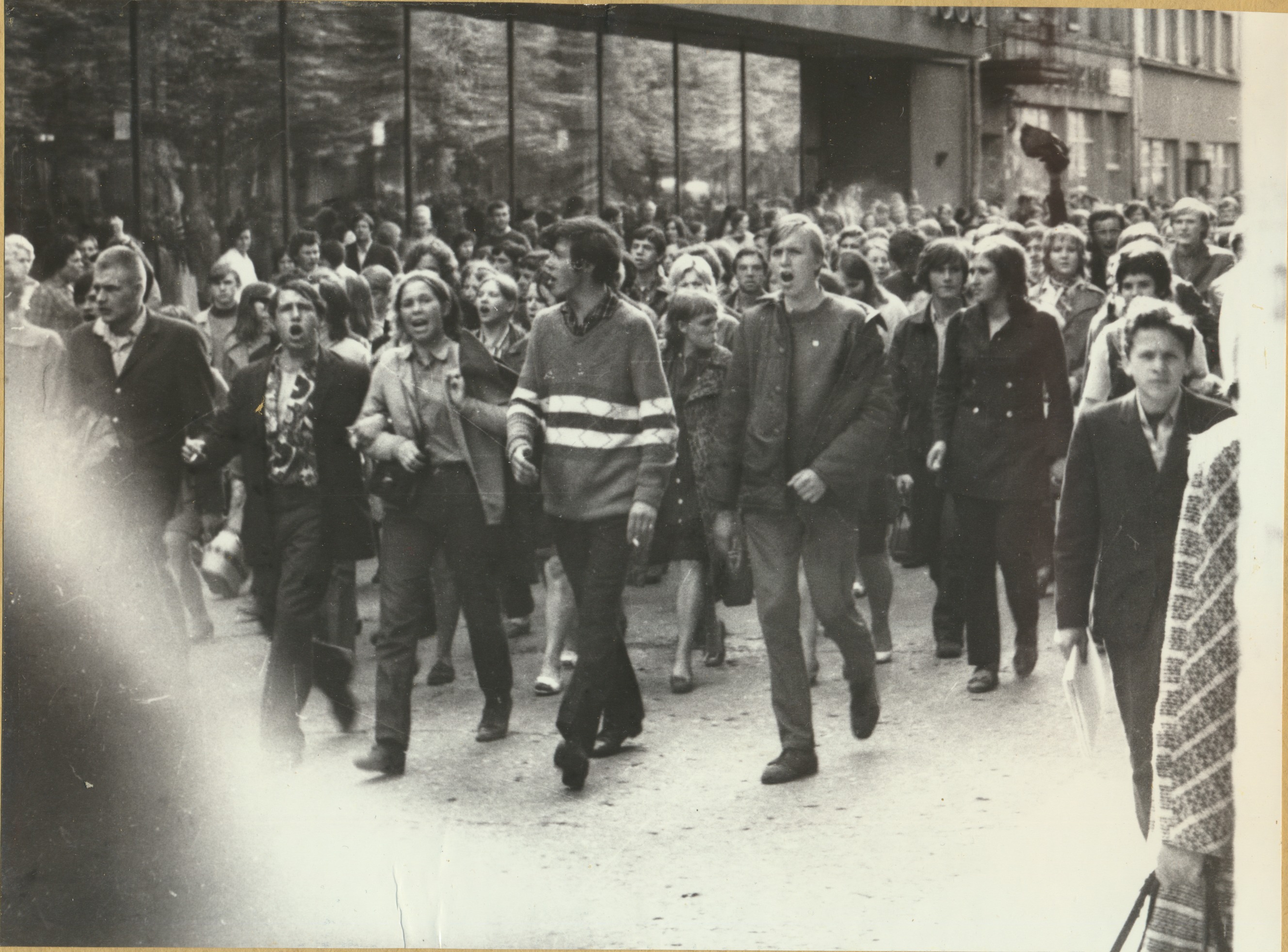

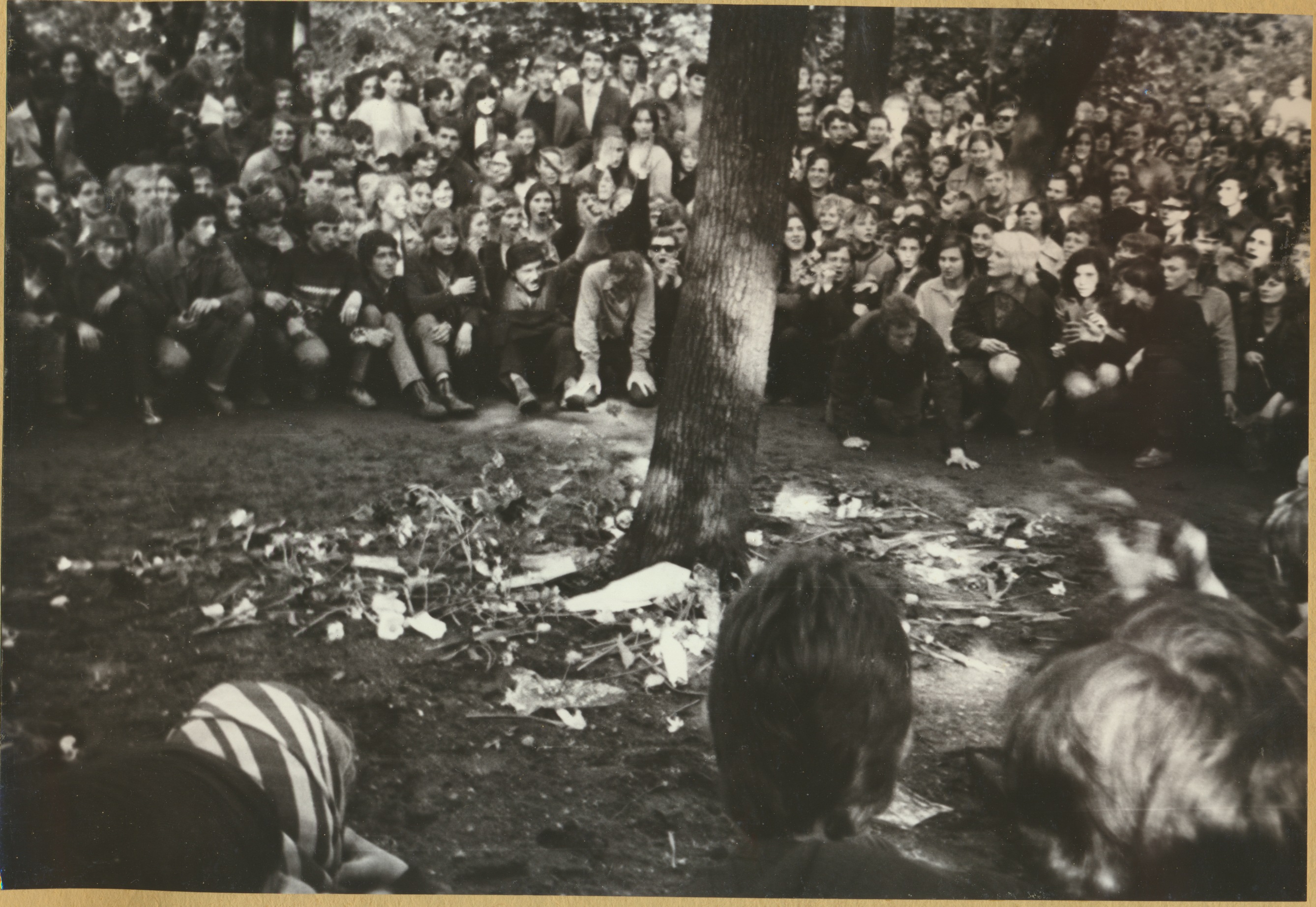

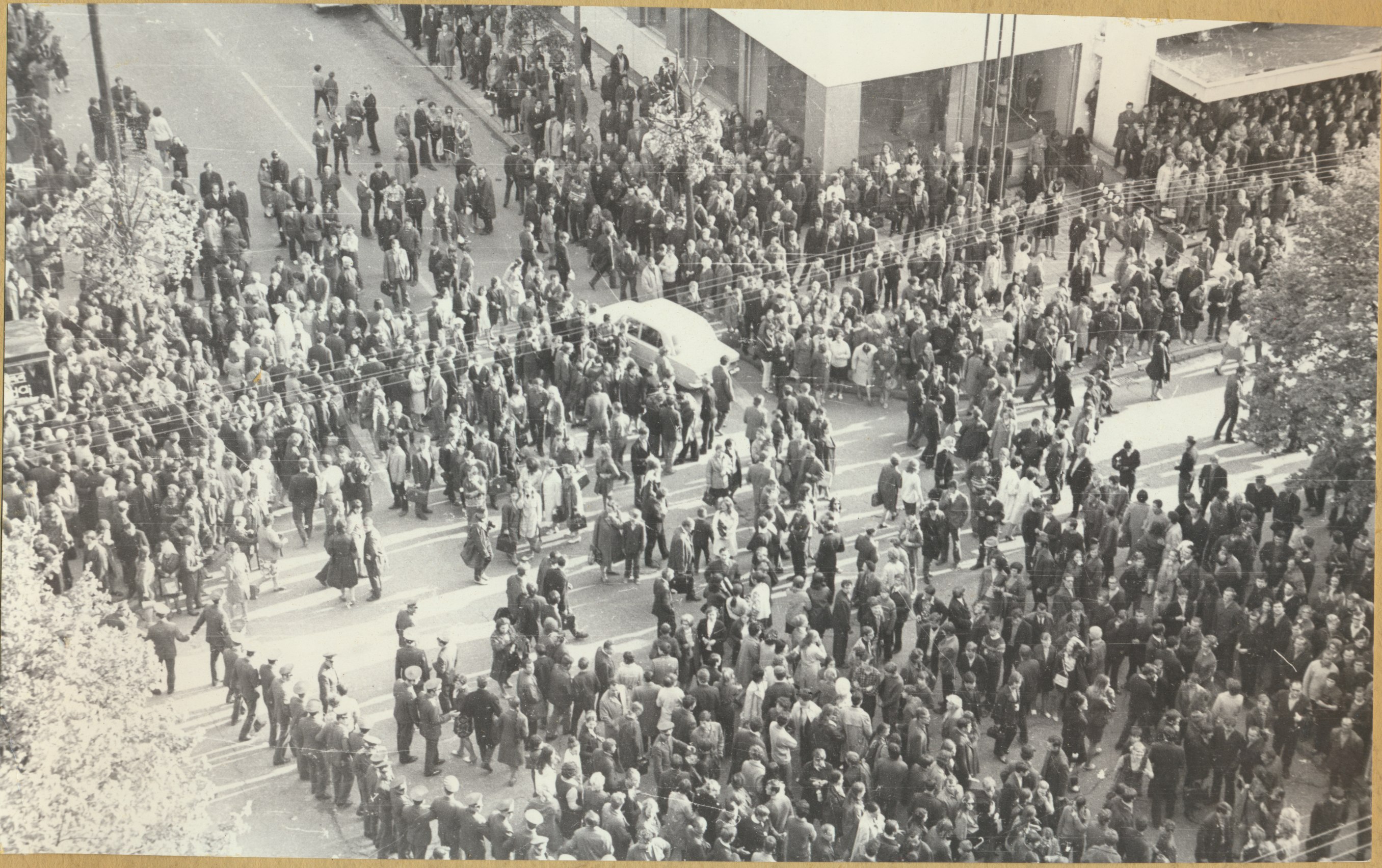

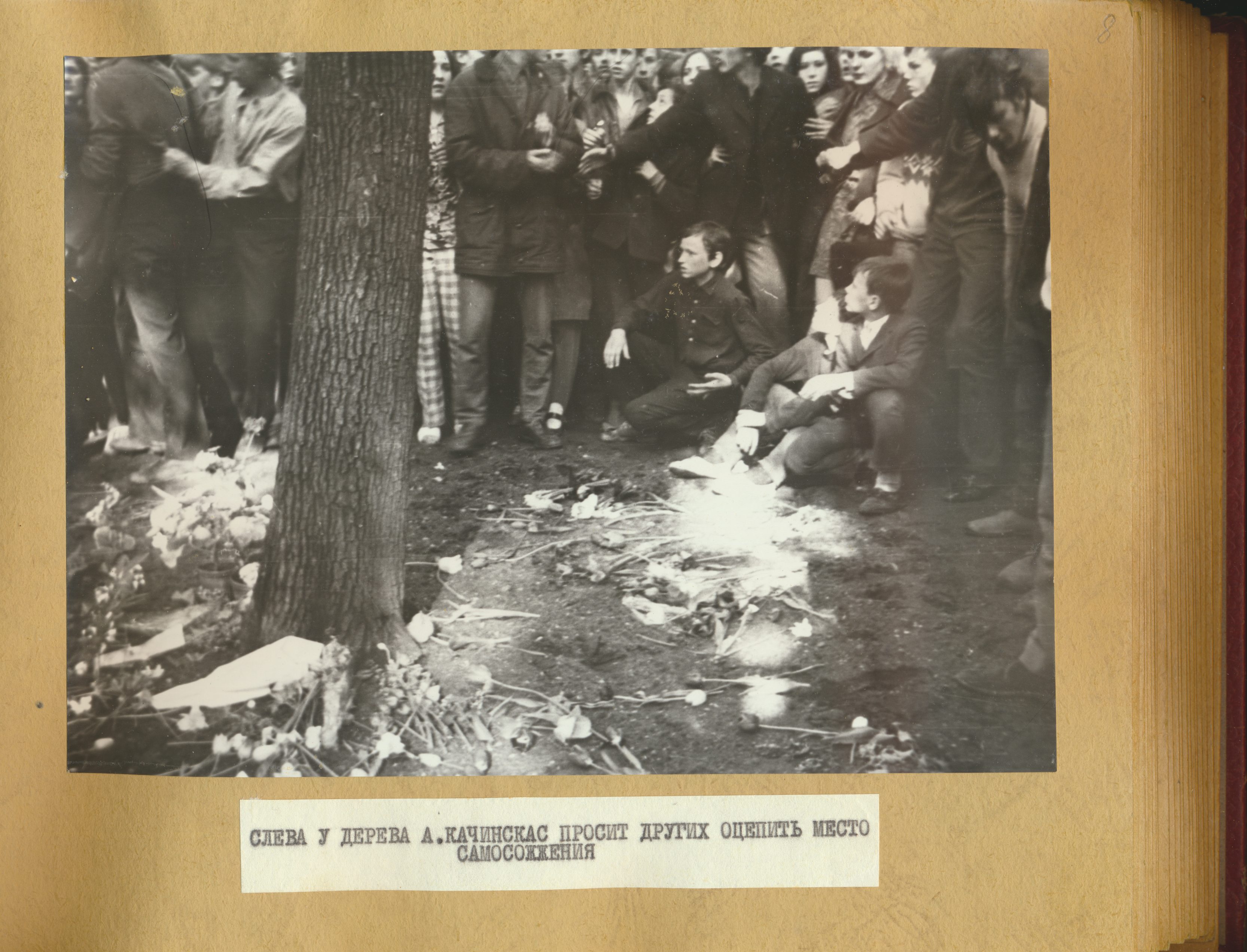

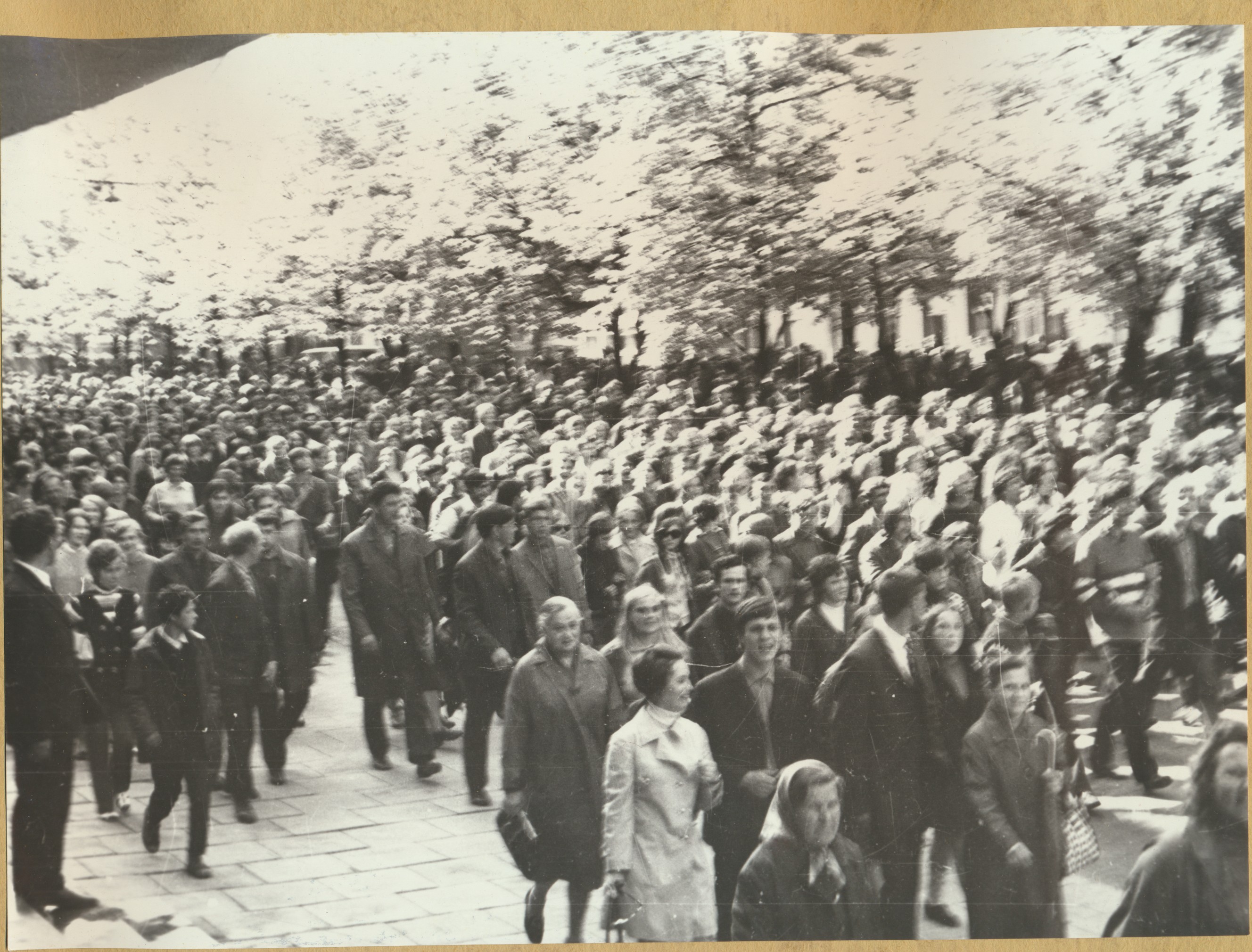

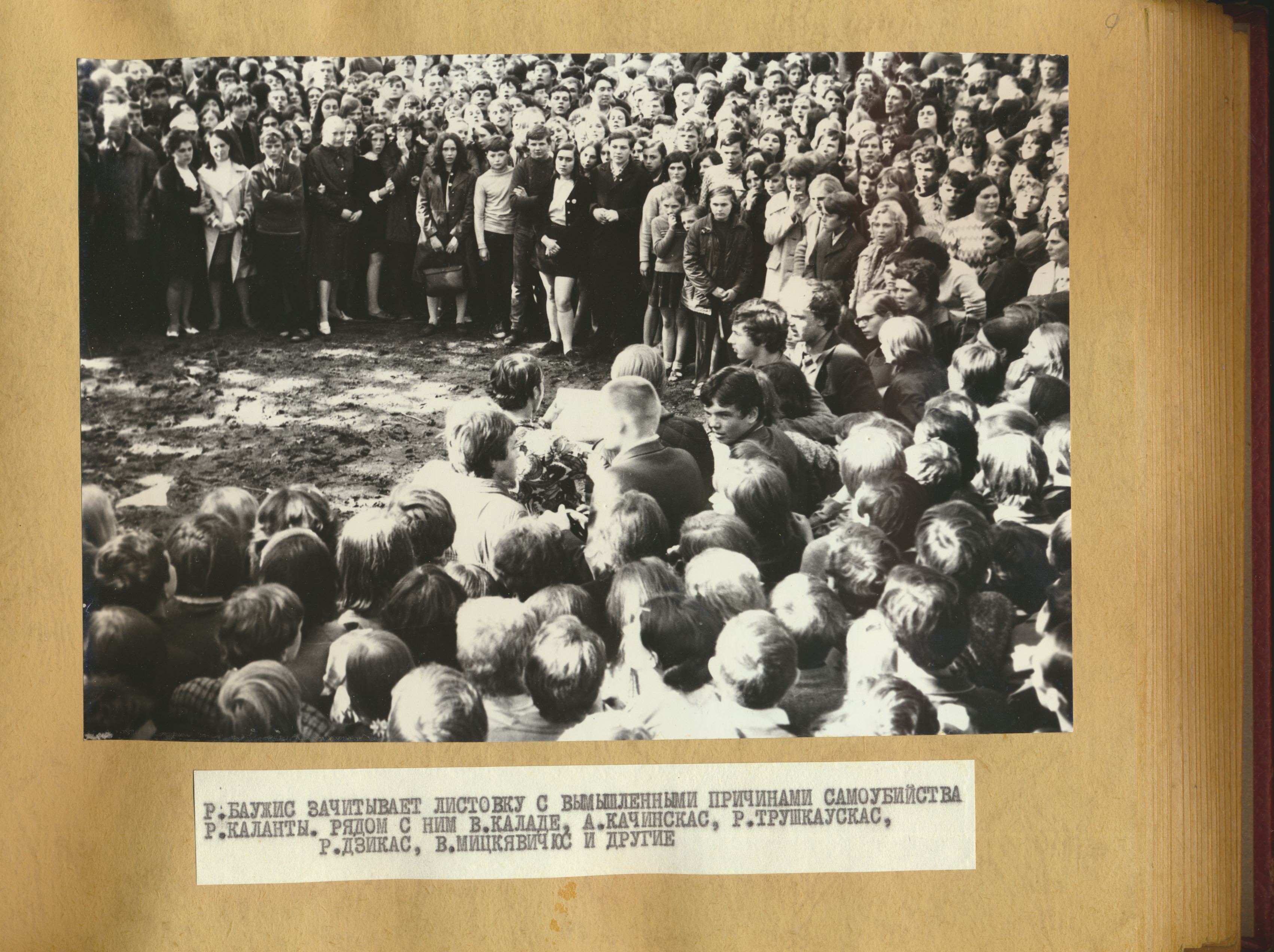

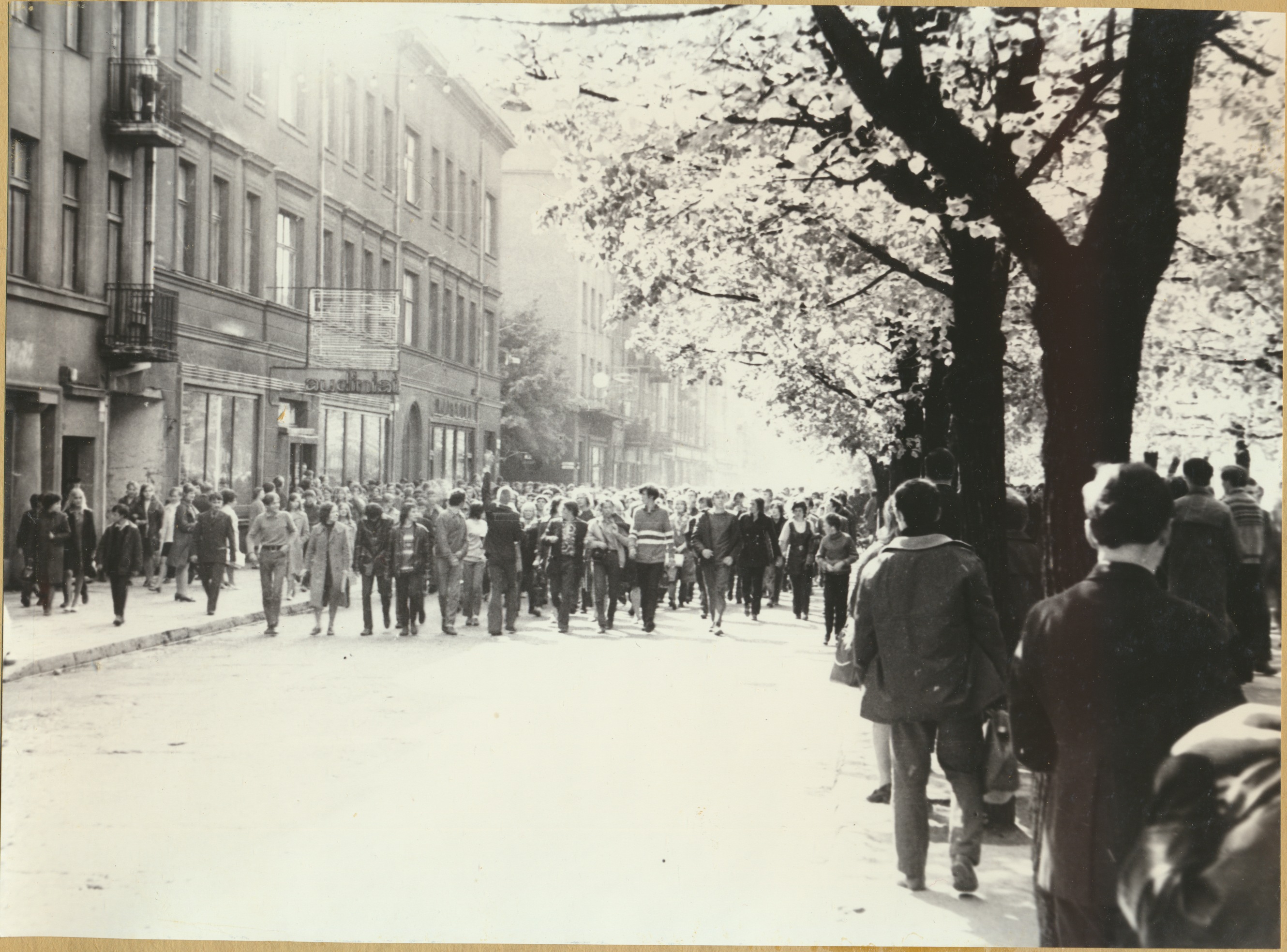

The collection was created by the KGB during mass protests by young people in Kaunas in 1972. The protests started on 15th May 1972, when a student set himself on fire in Kaunas. Mass protests broke out after the Soviet administration buried Kalanta secretly. Anti-Soviet poetry and leaflets dedicated to him were disseminated during the protests. The KGB followed the protests closely, secretly taking the photographs presented in the album. It reveals not only the event, but also how the KGB saw and interpreted it: every photograph has a short description.

Another important point is how this collection was created and finally appeared in the Lithuanian Institute of History. It was taken from the office by a KGB operative in the early 1990s, and, after keeping it in his own home for a long time, he gave it to a researcher. This circumstance allows us to make the assumption that there are still many more KGB files among the personal papers of ex-KGB officers.

The poster is one of the first hand-made materials, used in the initial protest in the autumn of 1987. The protest actions at that time were cautious due to the possible regime response, and contained no explicit political statements or requests. Their main appeal was directed towards the resolution of the severe pollution problem. Requests were articulated towards the need of pressing the Romanian state for the closure of the “Verachim” Chemical Factory in Giurgiu. The poster is a donation by Zlatko Elenski, participant in the protests and one of the creators of the poster, to the Rousse Regional Museum of History in 2014. He kept it until he heard the news in 2014 of the Rousse Museum’s participation in the international exhibition “Roads to 1989”, and decided to donate it to the museum.