The University Library of Pula initiated the digitization of regional Istrian newspapers in 2005, and a digital page containing 22 digitized newspapers and seven digitized journals, two of which are related to Istrian Fighter (Istrian Fighter and IBOR), was launched in 2010. A total of 64 issues of Istrian Fighter and nine issues of IBOR have been digitized. Istrian Fighter was digitized and posted on the repository page in 2015.

The digital version of Istrian Fighter/IBOR is an important step in promoting research into issues related to the journal itself as well as the presentation of the cultural-opposition activity of the Literary Club and its members in the socialist period.

The exhibition, which was based on scientific research done by the members of the AnBlokk Kulturális Egyesület (AnBlokk Cultural Association), bore the title Pedagogic Opposition during the Kádár era. In the course of the research, dozens of oral history interviews were recorded with former participants (including Ferenc Fábri, Ferenc Háber, and János Zsolnay). In the exhibition, the forty years were represented through the prism of four notions (community, continuity, cult, and conflict). All the materials on display came from private collections (after the museum had classified them, they were returned to the owners). The curatorial program paid particular attention to the integration of the former participants as a “living source community”. Thanks to this ambition, space was handed over to them temporarily during the opening ceremony (the Bánk anthem was sung and speeches were held), and later, as a positive result, the community also started to use the space where the exhibition was held to organize meetings and guided tours.

Croatian Film Days are one of the most important film events in Croatia, which includes the presentation of current domestic production of all forms, with special emphasis on short and medium durations.

In the accompanying program of the 24th Croatian Film Days on April 24, 2015, a retrospective of Nikša Fulgosi's films entitled "Educational Ephemera" was presented. The following films were screened: Dangerous Games (47 min), Two Letters - Worldwide (12 min), Take Care of the Cups (17 Min), The Road Isn’t Just Yours (13 Minutes), Women and Choice of Occupation (20 min), His Way to Life (21 min).

In collaboration with the HTV’s Channel 3, Fulgosi's documentary film 100 Beauties per Day from 1971 was shown on April 18, while the author himself was presented in the documentary film by director Danko Volarić, Who is that Niksa Fulgosi?

The main organizer was the production company Spiritus movens, but the event was organised jointly with representatives of these professional film associations: the Academy of Dramatic Arts, the Croatian Film Critics Association, the Croatian State Archives - Croatian Cinematheque, Croatian Association of Filmmakers, the Zagreb University Student Centre, the Croatian Film Association, Croatian Broadcasting Company, directors, the Croatian Association of Producers and the Croatian Association of Filmmakers.

The steering committee for Croatian Film Week: Festival Director Zdenka Gold, Artistic Director Željko Luketić, Executive Producers Vlatka Jeh and Ivan Tofing, Production Assistant Dunja Bovan.

On the occasion of its 60th anniversary, the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA) declared year 2015 Hardijs Lediņš Year, highlighting his importance to Latvian contemporary art, his multifaceted and interdisciplinary activities, and his expansion of the boundaries of Latvian culture. The idea to mark this anniversary was a critical commentary on the tendency to create cultural cannons in which contemporary alternative culture was not taken into account. The opinion of the LCCA was that Hardijs Lediņš was also a part of the cannon of Latvian culture. A number of events took place during Hardijs Lediņš Year: reconstructions of performances (Binocular Dance Lessons, Walk to Bolderāja, the Kosmoss discotheque ), exhibitions of contemporary art, literary readings, multimedia performances, concerts, actions in parts of Riga that were important in the life of Hardijs Lediņš, and publications about him. The events were widely popularized by the media, and had a much greater impact on cultural milieus than was initially expected by the LCCA.

The collection of Art on the Streets in Poland 1962-2015 is a unique collection of photos documenting various manifestations of creative activities in public space from the last few decades. The creator of the collection, Tomasz Sikorski has accumulated an extensive photographic collection, which also includes photographs made available by other artists. The concept of "art on the streets" allows you to juxtapose self-employed graffiti and happenings, performances and installations created in the public space by avant-garde and neo-avant-garde since the 1960s.

The Women’s Activism in Kosovo collection belongs to the Kosovo Oral History Initiative, and contains Kosovan women's vivid personal stories, which often intersect with broader historic events within Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1999. It depicts women's specific forms of engagement and resistance in protests against the Yugoslav regime, as well as their fight for women’s rights. The Women’s Activism collection offers a unique online archive of oral records, giving visibility and permanence to a history of women’s experience, which has been consistently marginalized, if not forgotten. To date, the collection contains thirty interviews with women activists, of which twenty-five are Albanian, three are Serbian, and two are of other nationality.

Márton, Áron. 2015. Körlevelek – 2 (Circulars – 2). Drawn-up and notes added by József Marton. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print Könyvkiadó

Márton, Áron. 2015. Körlevelek – 2 (Circulars – 2). Drawn-up and notes added by József Marton. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print Könyvkiadó

As a continuation of the eleventh volume covering the time interval between 1938–1947, the twelfth volume of the Áron Márton’s Legacy series, based on the materials stored in the Archiepiscopal and Capitular Archives within the Archdiocesan Archives in Alba Iulia, respectively, in the Áron Márton Museum, contains the bishop’s circulars written during the communist era, between 1948–1980.

Despite the guarantee of “freedom of conscience and of religion” laid down in the text of the new Constitution published in 1948, laws and decrees restricting the rights of churches were passed one after the other. In attacking the Catholic Church the Party first eliminated the formal obstacle: on 19 July 1948 the Presidential Council of the Romanian People’s Republic unilaterally cancelled the concordat concluded with the Holy See in 1927. Then they proclaimed the so-called “School Law” no. 175 of 3 August 1948 and the associated Decree no. 176, which was followed by the so-called “Law of Religious Denominations” of 4 August. The latter law, beside imposing a strict control over religious denominations, prohibited, by its Article 41, the enforcement of papal jurisdiction in the Romanian People’s Republic, thus rendering the existence of the Catholic church impossible. As opposed to the other thirteen denominations operating on the basis of rules of organisation and operation, this article of the law was immediately responsible for the “tolerated” status of the Catholic church until 1990. Already from the very beginning the communist system closely monitored persons and institutions that held different views, and these included, apart from the Catholic clergy considered as an enemy of popular democracy, also the Catholic church, which lacked a Statute.

In these hard times, amidst the attacks and warnings, Áron Márton could resort only to his circulars in order to encourage and spiritually strengthen his priests and congregation, as he had no alternative than to deal with the existing laws. In 1948 – according to the twelfth volume – he issued twenty circulars, the contents of which shed light on the violent nature of the dictatorship and its anti-religious manifestations. After the nationalisation of church schools, the operation of the Seminary was also of pressing concern to the bishop, as due to the elimination of financial support, the maintenance of the institution became the task of the diocese. He successfully asked for help from congregation members: “Please be of help in our poverty even amidst your own poverty.” Religious teaching is, after the preaching of the Gospel, the most important field of pastoral service. The new system primarily targeted young people with its materialistic teachings and it was not accidental that by means of the law of public education it banned religious education from the institutional curriculum, finding ways and means to interfere also in extracurricular education. Áron Márton recognised and put on paper the road to escape: “After the elimination of religious education from the school curriculum, Catholic families are facing a new task,” and called upon parents asking them to undertake the religious education of their children in a conscientious and responsible manner. He also used circulars to indicate the proper Christian conduct for the difficult times that awaited his priests and congregation members, preparing them for the challenges and all the while cautioning them against opportunism. At the same time in his circular from 6 October 1948 he adopted an adequately strict tonality: “I hereby inform all Catholic congregation members, that any Catholic priest or believer, irrespective of Catholic ritual, who participates in any assembly held with the purpose to promote his/her break-away from the Catholic church, shall be immediately ostracised from the Church without the need for any further measures.” The same circular stipulated the support to be offered to the Greek Catholics, too: “I hereby call upon and ask my R[espected]. Priests, to display courteous love in offering the greatest possible religious support and help to our Greek Catholic brothers, and whenever necessary, to readily put our churches, chalices, and ecclesiastical equipment at their disposal so that they can officiate masses according to the Eastern rite. Let us pray for them!” On 20 October 1948, the bishop repeated the issue of support, clarifying things: “My R[espected]. Priests may only grant permission to Greek Catholic priests to officiate masses in our churches, if the Greek Catholic priests in question are prevented by external circumstances from officiating masses in their own churches and if they have indisputable, positive knowledge of the fact that they had not signed the declaration of schism, or that they have received final absolution from ostracism, and in case of suspicion in this respect, we must await the up-to-date certificate issued by the competent Ordinarius regarding the fact that the persons in question are not under ecclesiastical punishment.”

During the six years following Áron Márton’s arrest his circulars ceased too. On 25 March 1955, a day after his return from prison to Alba Iulia, the bishop issued a new circular. In order to eliminate the atmosphere of distrust generated by the lack of priests and by the authorities he asked for two things from his priests: discipline and work. He received authorisation from the state authorities to turn to the pope first in a telegram, then in a letter. However, the maintenance of contact with Rome was rather difficult as in 1955 official records were delivered only haltingly. The bishop who animated even dormant souls continued to be not particularly welcome, and by virtue of the government decree of 5 June 1957 they restricted his free movement and office administrative work, confining the bishop to his room for eleven years by force. They supplemented this “punishment” by imposing a restriction on the subject-matter of his circulars, too. The bishop was only allowed to communicate measures regarding official matters to his priests: retirement, tax and financial rules, provisions concerning the preservation and restoration of monuments, dispositions regarding the liturgy and spiritual exercises for the clergy, priest training, chorister training, issues pertaining to religious education, etc. However, beyond this, the preparations for the second Vatican Council (1962–1965), his works and the implementation of his objectives, and the announcements of the holy years (1965–1975) encouraged him to write circulars. These circulars expressly contain ecclesiastical notifications and calls for prayer.

The volume also contains several draft circulars and documents written upon “request,” which can be explained by political historical factors. One of the manifestations of the political elite in Bucharest in its rapprochement efforts towards the West was that already from the early 1960s it sought the favours of churches, as with their mediation they could approach the more important countries and thus they could obtain the abolition of certain economic restrictions. It may be no accident that Áron Márton’s house arrest was also suspended precisely in November 1967. In February 1968 Ceaușescu summoned the Romanian religious leaders and in August 1968, at the time of the invasion of Czechoslovakia, he initiated the issue of a common circular which Áron Márton also complied with. At the same time, grabbing the opportunity, the bishop also submitted a separate declaration to the government, in which he expressed his views regarding the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. In 1973, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the proclamation of the Romanian Socialist Republic, and in 1974, on the thirtieth anniversary of the liberation from German occupation, which was then the Romanian national day, the communist authorities also asked for festive manifestations from the bishop. However, these remained only drafts, as their contents (the bishop raised his voice in the interest of his people living with a minority status) prevented them from obtaining authorisation for distribution. In 1974, following a serious surgical intervention, Áron Márton decided to adopt a more restrained work schedule and assigned part of his duties to his suffragan. From then on the number of his circulars decreased; he issued only a few of them in a year. His last circular, in which he said goodbye to his diocese, was drawn-up in 1980 by the suffragan Antal Jakab, theology professor József Huber, and office director Lajos Erőss on the basis of the bishop’s earlier circulars. However, it was still signed by Áron Márton himself.

The Fourth Conference of the same name was held in September 2018. The conferences bring together researchers from various disciplines – religion, literature and literary history, history, archival, and documentary studies, political science, culture, pedagogy, etc. They include university and school lecturers as well as Ph.D. students, esoteric researchers, writers, poets, musicians, psychologists and others.

Facebook conference page: https://www.facebook.com/konferenciyauchitelya/ (24.08.2018)

Until recently, the concert posters in the Mihai Manea collection were, to a large extent, for private use; they were accessible only to their owner and a few of his friends. The appearance and development of social media lifted some of the documents in this collection out of their condition of exclusively private objects. A part, so far a small part, of these posters have been scanned, uploaded, and distributed on Mihai Manea’s Facebook account and those of his friends. “It is my intention, in time, to upload all the concert posters that are still in my possession. I hope that by giving them another body – an electronic one, so to speak – their life will perhaps be longer than it would have been if they had remained only in paper format. Of course I’m not going to give up the paper ones, the originals. I’ll keep them as well as I can. But I think it’s better that they should be in two places than in just one place,” says Mihai Manea.

The aim of the digitization is not purely utilitarian, however, but at the same time emotional-evocative and rational-educative. “It is, of course, also a form of nostalgia, because, ultimately, these concert posters are about my life, about my youth, about my passions. But I think there is also something about them, in them, that goes beyond my person. They are documents, perhaps not very spectacular, but in any case, I’m convinced, quite rare out of all that has been preserved from the 1970s and 1980s of music in Romania. Why shouldn’t I hand them on to others?” Thus, from a collection developed out of passion and conserved only in the private space, the Mihai Manea collection has become one that is disseminated completely free to the public, basically an online exhibition through which the passion of a collector brings its contribution to enriching the collective memory of communism in Romania. As in other cases, the springboard of this dissemination is the desire to share with future generations a part of the past that is not only that of the collector, but that of a whole generation who made the transition from communism to democracy. The address at which Mihai Manea’s Facebook account can be found is: https://www.facebook.com/manea.mihaicroco

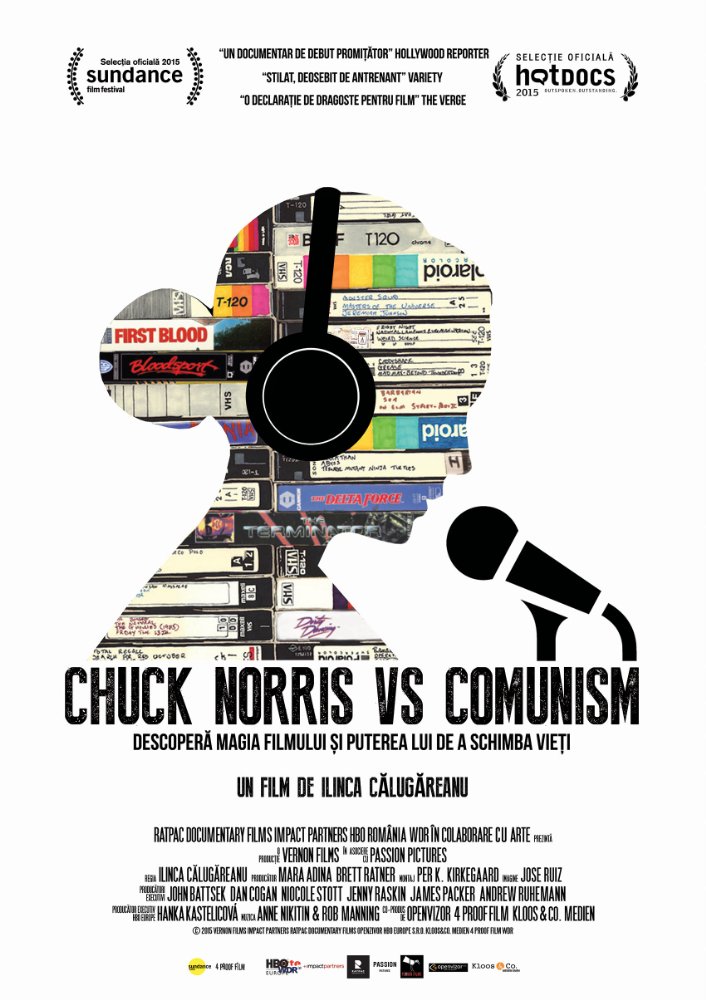

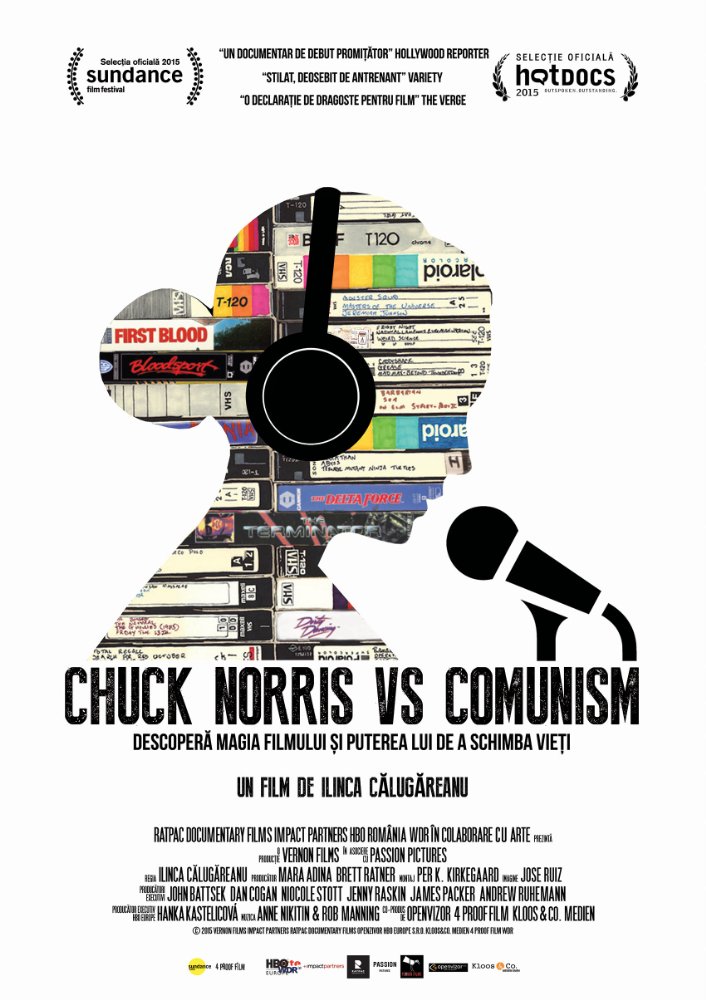

Chuck Norris versus Communism is a documentary film made in 2015 as a Romanian–British co-production. Written and directed by Ilinca Călugăreanu, the film suggests that the films brought from the West and distributed (semi)clandestinely on video cassettes contributed to the fall of the regime of the dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu. Indeed on the IMDb website, the film is summed up in the words: “The VHS revolution that brought down a communist government!” Of course this claim, which essentialises the clandestine activity of procuring, translating, and distributing Western films, but neglects the complex of internal and external factors that led to the fall of communism in Romania and in five other communist states in 1989, is an exaggeration. More appropriate is the promotion of the film using the formula: “A documentary about the magic of film and the power it has to change lives.” This obviously paraphrases the comment made by Tom Hanks about this film, in a note on his Facebook page that went viral: “See this documentary! The power of film! To change the world.”

Better even than the advertising slogan, this succinct commentary synthesises the essence of the activity of cultural opposition reconstructed in the documentary. More exactly, the film tells the story of the entire circuit of the video cassettes, as it became routine and turned into a mass phenomenon in the last years of the communist period. The video cassettes were first imported clandestinely from the West. Films also procured clandestinely from the West were recorded onto them, then dubbed in Romanian, and, finally they were multiplied and distributed (semi)clandestinely throughout Romania. The film gives the comments of many of those who watched these films in the 1980s about the significance they give to this activity that absorbed very diverse categories of people who were in search of an alternative cultural space. The principal character of the film is, however, Irina Margareta Nistor, who translated and dubbed with her own voice the vast majority of the Western films that circulated on video cassettes. For this reason, her voice constitutes a symbol of this whole cultural activity, which appeared as an alternative to the official television schedule, which was reduced in the late 1980s to just two hours per day of broadcasts, principally connected to the political activity of the party and of Nicolae Ceauşescu. In the film, Irina Margareta Nistor is played by the actress Ana Maria Moldovan. In an interview she gave for a publication in the field, the actress says: “I tried to represent Irina as I perceived her and felt her then. Her voice is indeed known to many Romanians and it is not easy to imitate. It is possible to learn, to exercise her way of phrasing, the pauses that she uses naturally and certain words that she uses more often.”

The intrigue of this documentary film is summed up by the director Ilinca Călugăreanu in an article in the newspaper Adevărul de Cluj-Napoca: “In 1985, Irina Margareta Nistor, a young translator at the national television, met a mysterious entrepreneur. He was smuggling, copying, and distributing films on VHS cassettes. This was the start of a working relationship that lasted for more than a decade. In total, Mrs Nistor says that she dubbed more than 3,000 films. Thanks to her, Chuck Norris, Jean-Claude Van Damme, and Bruce Lee became popular heroes in Romania. At a time when the Romanian state controlled every aspect of the lives of its citizens – including food, heat, transport, and information – people found through the power of films a way to escape and to resist the oppressive regime of the state.” And she adds, with reference to the title of her film: “Chuck Norris wins in the end – of course: it’s a film with a happy ending. The pirated cassettes turned Irina’s voice into a symbol of freedom, and Chuck Norris, Van Damme, and Bruce Lee into national heroes, and they helped a whole country to stand up to a brutal regime.” It is interesting to note that the films with Chuck Norris were not typical of this cultural phenomenon, but his name is an allusion to the martial arts films, which were one of the types of “consumer” films that circulated on video cassettes. In other words, the title suggests that it was not the message of the films that was subversive, so much as their Western provenance itself and the (semi)clandestine circulation of the cassettes.

Since 2006, BCU Cluj-Napoca has organised each year in March, the month of Adrian Marino’s death, commemorative exhibitions in the lobby of the institution. These events have been targeted especially at the current users of the library, students of the universities in Cluj-Napoca. The exhibitions have focused on different aspects of Marino’s activity: his work as literary historian and critic, as reflected by the manuscripts in his collection, his activity as publicist and ideologist of Romanian liberalism after 1989, and his correspondence with Romanian and foreign intellectuals of that time. As far as this last topic is concerned, in March 2015, when we commemorated 10 years since the author’s death, BCU Cluj-Napoca organised the exhibition “Din corespondenţa lui Adrian Marino” (From Adrian Marino’s correspondence). This exhibition designed by Florina Ilis included elements of the author’s correspondence with Romanian intellectuals in exile, such as Matei Călinescu and Mircea Carp, as well as photographs from the collection. The exhibited letters illustrated Marino’s capacity to carry on an ample international dialogue in the difficult conditions of correspondence control in communist Romania, and to turn his correspondence into a genuine cultural act. The March 2015 exhibition also highlighted the role the correspondence played in Marino’s intellectual development.

April 8, 2015 Wiener Secession, Vienna

Beginning in the 2000s, the materials of the “IMAGINATION/IDEA” project (organized privately by László Beke in 1971) have been featured at several exhibitions, both in Hungary and internationally, and were also published as a book.

This comprehensive collection of conceptual art, after its initial appearance in Hungarian (Budapest: OSAS – tranzit. hu, 2008), has been published as facsimiles with English translations along with Eszter Szakács's interview with László Beke and his essay describing the context of the project and updated biographical data regarding the participants (tranzit. hu – JRP|Ringier, 2014).

The event is held on the occasion of the publication of the English version of the book. Participants in the discussion were Georg Schöllhammer (critic and curator from Vienna), László Beke (art historian from Budapest) and Dóra Hegyi (curator from Budapest).

Laszlo Beke's 1971 Collection in an International Context, Tranzitdisplay Prague, 23.03. 2017–21. 05. 2017.

The Istrian Fighter Digital Collection is available at the University Library of Pula website. It is the collection of the first Croatian youth journal Istrian Fighter/IBOR, which was published in Pula from 1953 to 1979 (with two minor interruptions). The journal was published by the Istrian Fighter Literary Club with the objective of preserving the Croatian language in Istria. The journal developed a reputation as a critical media in the 1970s, covering more and more cultural, local and social themes whose tone was not well-received by the socialist authorities, so the financing of the journal was cancelled in 1979 after which it ceased publication.

The main goal of the Society for Queer Memory for the year 2015 was to open a multi-purpose space that would function as a facility for works on recording elderly LGBT generation memories, research on LGBT history, preservation of collections from this field, presentation of these outcomes to the public, as well as a place for LGBT seniors meetings. A suitable premise was found in an office building Na Strži 40, which is property of the Municipal District of Prague 4. Following the resolution of this district’s council, the Society, as a non-profit organization, obtained a reduced rent that it could afford to pay. The Society furnished the interior with basic furniture and stored its library and collections there. Then, over several months they started cataloguing and inventorying the items. A temporary exhibition of the LGBT history and memory (author: Jan Seidl, technical director: Pavel Bílek) was installed. The exhibition consists of pictorial-textual panels and copies of significant sources to the history of sexual minorities in the Czech context and presents the main outcomes of previous Czech research about the history of the queer community.

In June 2015, the Centre for Queer Memory was opened to public. Several dozen visitors, representatives of the Society’s Research Board, members of Society as well as delegates from the Prague 4 municipality attended the opening ceremony. Besides the opening ceremony, a higher attendance was also recorded in 2015 during two Open Doors Days within Prague Pride and on two social-discussion intergeneration evenings.

KOHI interviewed Shukrije Gashi in two sessions, on 14 February and 21 March, 2015. Gashi was born on 22 May 22 1960 in Pristina. A former political prisoner during Yugoslav times, she worked to promote peace for more than twenty years, and took part in around 400 cases of conflict resolution. Gashi studied law at the University of Pristina, and currently directs the “Partners Kosova Center for Conflict Management”.

In 1983, she was arrested and charged as an accessory to “the perpetration of criminal acts against the people and the state of Yugoslavia,” the official charges according to the country’s penal code, and spent two years in prison. Shukrije Gashi was found guilty of being a member of the then-illegal Albanian national movement, a loose network of small groups advocating the Republic of Kosovo. As a prisoner of conscience, she was given drugs, forced to work, and subjected to physical and psychological torture, which included being told that her boyfriend and fellow activist had been killed (which was true).

Gashi’s story is a young woman’s gripping account of determination (she was 21 when she was finally arrested after an adventurous escape from the Yugoslav secret police), in order to take a leadership role in the underground Albanian national movement. Gashi drew courage and will from her grandmother, a charismatic local figure who was involved in the “Campaign to Reconcile Blood Feuds” and national mobilization efforts – acts of feminism before the term was globally recognized. Because of their political opinions and activities, Gashi and other members of her family were under constant surveillance, which involved police harassment, pressure to change jobs, and difficulty to navigate the Yugoslav system, in which Albanian demands in Kosovo – for more autonomy and improved living conditions – were considered sedition.

The items stored by the museum – from its launch in 2010 until 2017 – represented the material of sixteen travelling exhibitions. The collection of objects was displayed in the form of more or less extensive travelling exhibitions outside of Răscruci, not only in Romania (2011, Călugăreni, Mureș county, where the furnishings of the Răscruci clean room was displayed), but also abroad, in Hungary (2013, Sárospatak) and in the Republic of Moldova (2014, Chișinău), where the ensemble of objects from the Transylvanian Plain was exhibited. In recent years exhibitions in Hungary have gained more significance. First, in 2016, there was a one-month exhibition in Berettyóújfalu, featuring photos and various objects from the Transylvanian Plain, followed by a display of textiles originating from Zoltán Kallós’s collection areas in Dunaújváros.

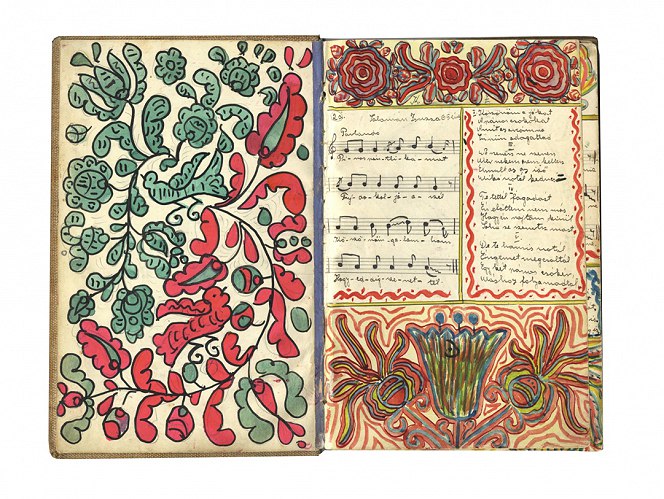

The most significant among the travelling exhibitions in Hungary is the exhibition encompassing Kallós’s entire career, launched in March 2015 in Szentendre (Hungary) and bearing the title Indulj el egyúton... Kallós Zoltán (Set off on a Road... Zoltán Kallós), financed by the Hungarian Ministry of Human Resources, the Research Institute for National Strategy in Budapest, and the Hungarian Open-Air Museum in Szentendre. The exhibition presented the life and work of Kallós on three locations in three parts. The materials on display in the Skanzen Gallery, featuring folk costumes, objects, photos, and documents in the context of the Set off on a Road… Zoltán Kallós Life-work Exhibition were lent by the Hungarian Heritage House, the Janus Pannonius Museum of Pécs, the Zoltán Kallós Foundation, the Ethnographic Museum, the Institute of Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and the Transylvanian Ethnographic Museum of Cluj-Napoca, among others. In parallel to the exhibition, the Pont Itt Gallery of the same institution housed a display of selected photos entitled With the Camera in the Hand – A Selection of Zoltán Kallós’s Transylvanian Photographs. Beginning on5 April, the above-mentioned exhibitions, which opened to the public on 13 March 2015 were joined by the Tánccsűr/Dancers’ Barn in Sonkád in the Upper-Tisza Region, which evoked the atmosphere of the folk music and folk dance camps at Răscruci.

The exhibition presents the life span of an identity-building personality who did his best to rescue the system of values pertaining to a disappearing era, and, along with other representatives of the dance-house movement revived this spirit and lifestyle. The exhibition focused on the scholar behind the regions, buildings, and interiors, placed the researcher in the centre of attention. Kallós’s career revolved around service, which implied the saving, preservation, and passing on of numerous spiritual and material assets. Early on, he became aware of the accelerating changes undergone by traditional culture and dedicated his whole life to research.

Invited to Romania, the exhibition bearing the title Set off on a Road... Zoltán Kallós was made accessible to the public in several locations: in 2016 in the Székely National Museum of Sfântu Gheorghe, in 2017 in the Haáz Rezső Museum of Odorheiu Secuiesc, and later in the Csíki Székely Museum of Miercurea-Ciuc. The organisation of the exhibitions in these localities enjoyed considerable support from the Zoltán Kallós Foundation, both in terms of personal and material support. The travelling exhibitions were accessible in these localities for a three-month period.

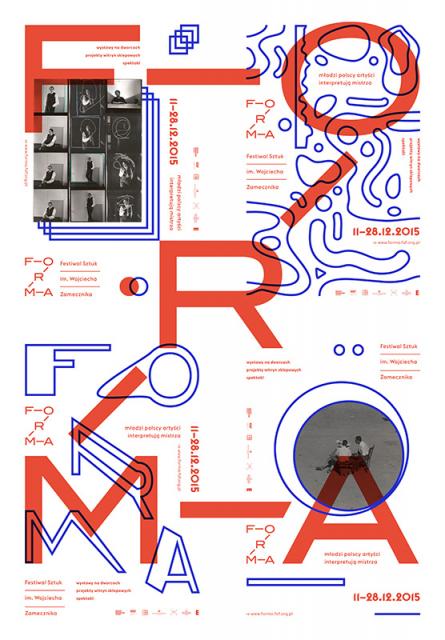

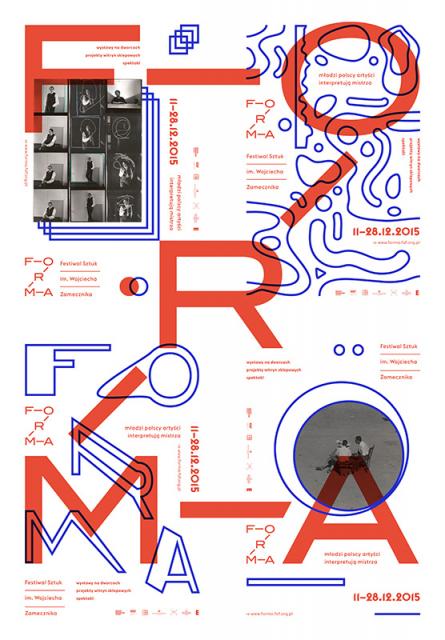

Polish artists and circles involved in performance art were in many ways critical of Polish People's Republic authorities. They would often be involved in the so-called “second circuit” of publishers and galleries that functioned without public support and independently from national institutions. Performers’ actions themselves were also loaded critically not only towards the authoritarian practices of the “people’s” government, but also the patriarchal and hierarchical aspects of Polish culture. The Archive of Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw presents the history of Polish performance art. It uses an attractive web portal to publish photographic and video recordings of artistic actions along with commentaries from curators. The Archive is also engaged in research and promotion activities, and is participating in the preparation of Museum’s permanent exhibition.

The exhibition “My Youth in Communism” aimed at providing a comprehensive image of the everyday life of young people in communist Romania during the 1970s and 1980s. Given the specific nature of the institution which organised the event, the CNSAS, the exhibition highlighted the methods and techniques used by the Securitate in monitoring young people’s leisure activities, such as staking out, informative surveillance, phone-tapping, and illegal interception of private correspondence. The exhibition also described the preventive measures, such as warnings, so-called positive influencing talks, public debates on their alleged deviant behaviour, and forceful dissolution of groups, which the secret police used to employ in order to limit the influence of Western culture on Romanian youth. Many young people came under surveillance after they listened to Cornel Chiriac’s programmes and attempted to get in touch with him through letters. As a result, the exhibition contained documents from the informative file on Cornel Chiriac and also letters that Romanian young people sent to him at the address of the Romanian desk of Radio Free Europe. For more on the exhibition, see http://www.cnsas.ro/documente/evenimente/2018.06.05%20Comunicat%20de%20presa.pdf

Vratislav Brabenec is a well-known Czech musician, poet, and a representative of the underground movement. He was born in Prague on April 28, 1943 and he grew up in Horní Počernice. After graduating from the Secondary Technical School of Agriculture in Mělník, he studied theology at the Comenius Protestant Theological Faculty in Prague, but he did not complete his studies and instead began earning his living as a garden designer. From 1972 he was a member of the music band The Plastic People of the Universe and he wrote many lyrics for them, such as “The Passion Play”. In 1976 he was sentenced in the trial against independent artists and culture activists to eight months of imprisonment. He served his sentence as part of his detention pending trial. Shortly after his release from prison he became a signatory to Charter 77 and after that time he lived under constant surveillance by the StB Security Police. In 1982 he was subjected to a number of interrogations which were accompanied by blackmail and physical violence. Based on these incidents, he eventually decided to emigrate together with his wife Marie Benetková, with whom he was raising their daughter Nikola. He returned to his homeland only in 1997. He now lives in Prague and his activities include concert performances, poetry and other literary pursuits.

The testimony includes a 2.15-hour recording, a transcript of the interview, links to interviews about the author and some of his works, as well as contemporary and present-day photographs, all online and accessible to researchers after signing up.

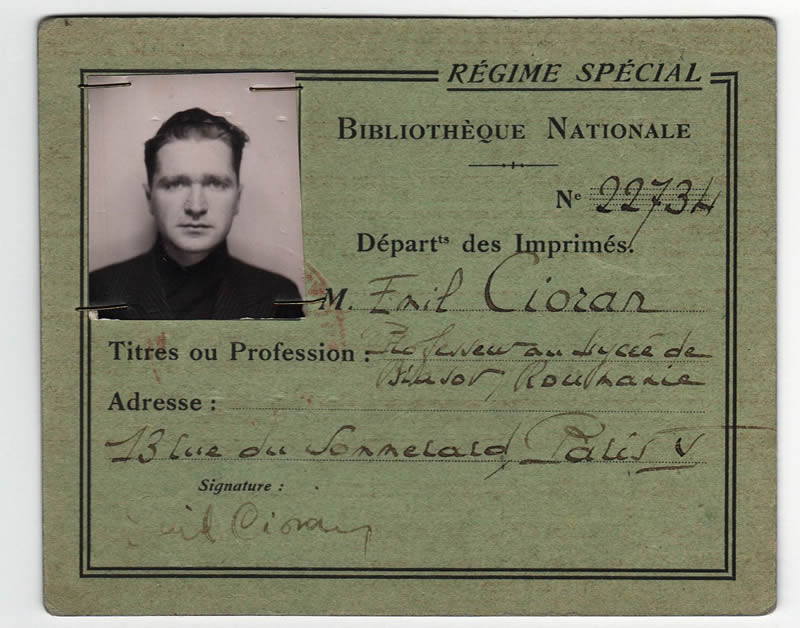

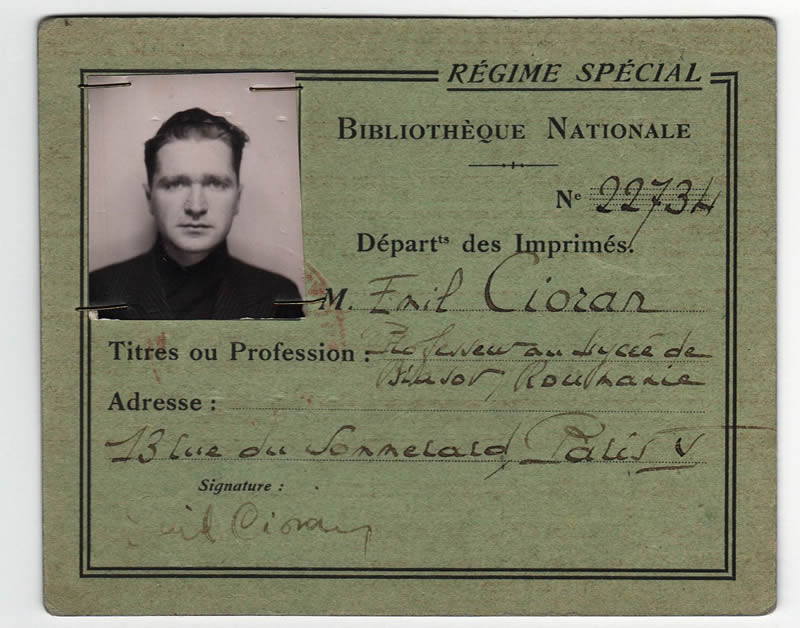

On 14 November 2015, ASTRA Sibiu County Library held the opening of the exhibition: “The Correspondence of Emil Cioran in the Collections of the ASTRA Sibiu County Library” (Corespondența Emil Cioran în colecțiile Bibliotecii Judeţene ASTRA Sibiu). The exhibition displayed letters from Emil Cioran’s correspondence ofthe 1930s. It is worth mentioning that among the items exhibited were three unpublished letters sent by Constantin Noica to Emil Cioran. In these letters Noica reacts to articles published by the Cioran in the Romanian cultural press in 1933. Through these documents, visitors were introduced to the cultural atmosphere of interwar Romania, and to the intellectual milieu that shaped Emil Cioran’s personality. The exhibition was part of a broader initiative involving the Faculty of Letters and Arts of Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu and the National Foundation for Science and Arts, which comprised a conference dedicated to Emil Cioran and the launching of the two volumes of Emil Cioran’s works published by the Romanian Academy.

The first was dedicated to the life and work of Božidar Mandić in Novi Sad in the late 1960s and during the 1970s. Bottle with milk (Flaša s mlekom), an artistic action originally performed in 1969 was reconstructed. There was a screening of the movie Maniac 7001 (Manijak 7001) shot on 8mm film by the brothers Miroslav Mandić and Božidar Mandić and of Gregor Zupanac’s documentary Lestvica about Božidar Mandić. Božidar Mandić's first solo exhibition on display in the Youth Tribune venue entitled One evening called evening (Jedno veče zvano veče) was also presented. A review published in Index magazine made its reconstruction possible. Extensive photo documentation was also a part of the exhibition.

The second part of the exhibition is a presentation of Božidar's life and work in the Family of Clear Streams commune. Exhibited items are made of natural materials: wood, straw, dung and stone. By using these materials, the artist is, in the words of the curator and author of the exhibition, “trying to evoke the energy of nature, and of pagan and mystic elements within the gallery”. Some of them are Stones without inscriptions, potatoes without pesticide (Kamenje bez citata, krompiri bez pesticida; 2013), Volition (Htenje; 2010), Identity (Identitet; 1997), Sculpture of the wind (Skulptura vetral; 1980), Iron and dung (Gvožđe i balega; 1987), and Trace (Trag; 1979). They are permanently exhibited in the commune. Fourteen issues of the Breza family magazine, which was published until 1981, were also exhibited. All issues are one of a kind and they can only be read at the Family of Clear Streams commune.

The Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina purchased the movies Maniac 7001 and Horses (Konji) made by the urban commune in Novi Sad, but they are still not on permanent display due to a lack of exhibition space. Some of the material, available in DVD format, was provided by The Public Broadcasting Service of Vojvodina, as because Božidar has only the VHS.

In 2015, a book came out of Liobytė's letters to cultural figures. It was dedicated to the 100th anniversary of her birth, and its launch was accompanied by various events to mark her activities among the cultural intelligentsia. For example, the Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore held the conference ‘Aldona Liobytė ir jos laikas' (Aldona Liobytė and her Times) about her life and work (see: http://slaptas.nzidinys.lt/a/2015/07/16/aldona-liobyte-ir-jos-laikas/). Many of the letters published in the book illustrate the everyday life of the intelligentsia under the Soviet regime. While her correspondence does not express strong anti-Soviet statements, readers may find many sarcastic and satirical comments on Soviet policy and Soviet cultural managers in the publication.

The collection consists of more than 500 recorded interviews with national (Sąjūdis), dissident and ex-Soviet figures, and from the cultural opposition and informal groups, conducted during two research projects in 2009-2015. It is the biggest database of oral history on the Soviet past in Lithuania.

Publication: Mircea Udrescu, Metronom’70: Cornel Chiriac în documentele Securității (Metronom 1970: Cornel Chiriac in the Securitate documents), 2015. Book

Publication: Mircea Udrescu, Metronom’70: Cornel Chiriac în documentele Securității (Metronom 1970: Cornel Chiriac in the Securitate documents), 2015. Book

The volume Metronom’70: Cornel Chiriac în documentele Securității by Cornel Chiriac’s best friend, Mircea Udrescu, was launched on 23 May 2015, on the occasion of the annual international book fair in Bucharest, BOOKFEST. This is the third volume that Mircea Udrescu has published about Cornel Chiriac. While the other two volumes approached the subject of his childhood and his activity at Radio Free Europe, the present volume reconstructs step by step the Securitate’s investigation of Cornel Chiriac, which began in 1963 and ended with his death in 1975. In fact, the volume is a combination of memoirs and archival documents that sheds light on Cornel Chiriac’s personality and explains how his rebellious nature brought him into trouble with the Romanian authorities and especially the Securitate. Mircea Udrescu’s analysis of the Securitate documents shows how the Romanian secret police approached the “Chiriac problem,” identified their sources of information, and assigned them specific roles in the informative surveillance of Cornel Chiriac in Romania and in the Federal Republic of Germany. The book launch was attended by a large audience, which included former listeners of Cornel Chiriac’s musical shows, musicians, and young people equally interested in finding out more about the life and activity of one of well-known radio voices during the 1960s and 1970s.