Travel reports of lecturers and members of the Jan Hus Educational Foundation are embodied in six volumes. In terms of time, they cover the period from 1983 to December 1989, mainly from Prague, Brno and Bratislava. The reports include the length and main purpose of the stay, a description of the trip including possible complications in crossing borders, meetings with other people and subjects of their interviews, information on specific activities of the state police, etc. Visitors of Czechoslovakia also proposed other forms of cooperation in their reports. There are unique and very specific documents mapping the concrete forms of the Czechoslovak dissent linked with underground universities, efforts of the foreign organisation and important Western representatives of science to support the unofficial educational environment, and documents describing the contemporary social and political conditions in Czechoslovakia including the activities of the state police.

The collection, which is the private property of István Viczián, illustrates the history of the Calvinist youth organization of Pasarét under socialism. The collection includes letters and photographs, which provide insights into the aspirations of the group to create an active religious community in an era when such communities were a threat to and contradiction of official communist youth policy.

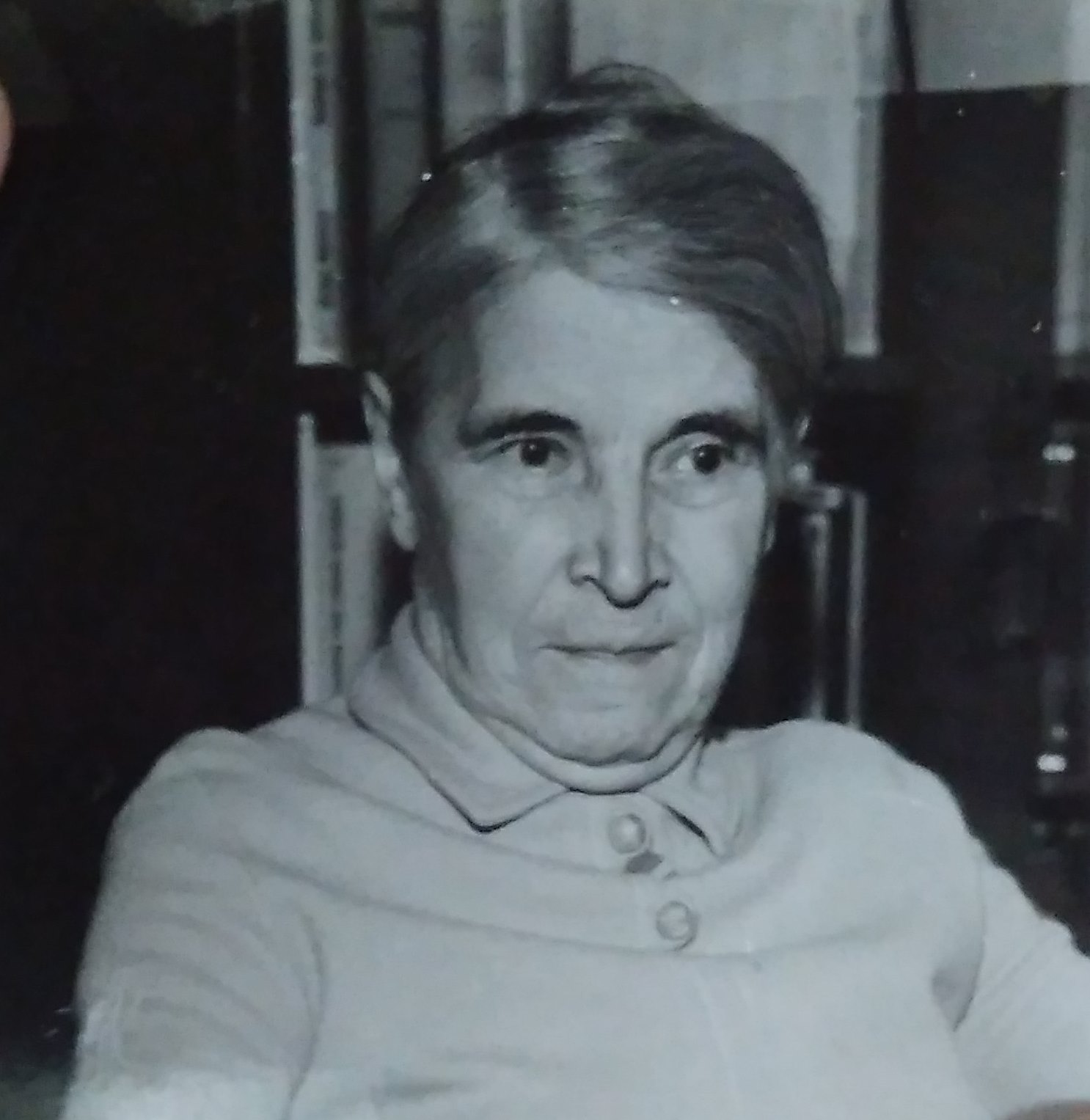

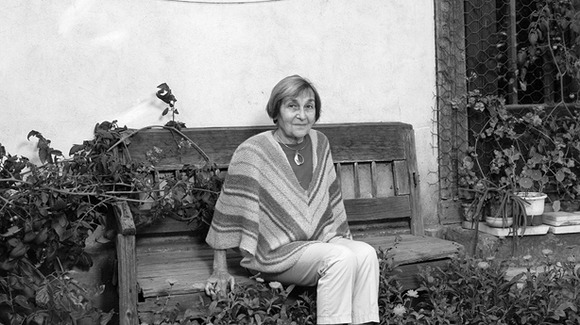

The private collection, established in 2016, presents the life and work of Sevdalina Panayotova. It shows this literature teacher, theater director, public figure, and citizen daily and consistent opposition to the hypocrisy of the structures of state socialism and against the status quo. Sevdalina Panayotova, a teacher and cultural activist, was neither a well-known writer, director, nor a popular dissident, but her whole life and creativity was a rebellion against the attempt of the socialist state to impose narrow standards and norms on everyday life and thinking, a rebellion against pseudo-morals and pseudo-arts, against the principles of socialist realism in literature and theatrical art.The collection of books, scripts, photos from theatrical productions, interviews given by Sevdalina Panayotova and interviews with her, published articles, among others, shows an "ordinary" life of civil and cultural opposition. Sevdalina Panayotova pursued opposition through critical themes in literature and theater as well as through the use of innovative means of expression by resisting against imposed artistic forms. The collection highlights individual estrangement from the socialist state, the dynamics of criticism, and the risks criticism entailed for "ordinary" people. The collection shows the attempt of a "life of truth" and of repeated defiance borne out of a strong moral stance. It is also a good example of a small family collection that maintains personal memories without having a grand political agenda.

Personal notes of the Founder, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1984-1985’, 1985. Publication

Personal notes of the Founder, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1984-1985’, 1985. Publication

“The Founder’s personal notes”

In: The Yearbook of the Soros Foundation, Hungary 1984–1985

“It was not my choice that I was born in Hungary in 1930. However, it was my own deliberate decision, one of the most important ones in my life, that 17 years later I left this country. And my return with this foundation is but a late consequence of this early age choice.” These opening sentences are the most “personal” notes in the founder’s preface to the first yearbook of the Soros Foundation, Hungary (HSF) 1984–1985.

Soros used this opportunity to address the public freely (i.e. without much risk of being censored) and share authentic information and assert the principles on which his recently established foundation was based.

The was important in part simply because in the first few years the foundation was given hardly any press coverage in communist Hungary except for some short official statements published in dailies, according to which a New York stock investor had signed a contract with the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS) and opened a small office in the Buda Castle district to receive applications for grants and other forms of support. Apart from this, no reports were printed and no interviews were done in the print and broadcast media. Even in 1987, Soros and his secretary staff still had to fight for the right to publish lists of successful grantees at least in HVG (the three-letter abbreviation used for an earlier title of the same periodical, Heti Világgazdaság, or “Weekly World Economy”), an economic weekly. The first principle Soros insisted on, thus, was the importance of free and permanent control by the pubic (instead of by the party and the secret police) of the operations of his foundation. Similarly, he asserted a number of other safeguards as a founder. He maintained the right to choose his personal colleagues, to decide on his own on the amount of his yearly donations to be spent (which began at one million dollars and grew to nine million dollars by 1990), and to exercise a veto in all strategic or personnel decisions, i.e. decisions concerning curators, projects, grants, prizes, etc.

As for the applications and projects, Soros readily informed the public about ongoing practice and plans for the future. The foundation wished to maintain the individual system of both dollar-based and forint-based grants and support. The Literary and Social Science grant systems were running successfully, but they also planned to test and introduce some new projects which offered support for study abroad and research grants and support for conferences, as well as funding for filmmakers, theater groups, and artists active in the fine arts. Applicants who fell in other categories were equally welcome to submit inventive workplans and new, creative initiatives.

Finally, Soros sought and offered a confident partnership to all: “We need the help of the larger public, after, all the success of our foundation can only be ensured by the applicants’ talent and inventiveness, and the reactions of Hungarian society.”The Jan Hus Educational Foundation's collection presents an extraordinary set of materials documenting a work of a British organization focusing on supporting of cultural opposition in Czechoslovakia, mainly through underground university, scholarships, and the publication and translation of forbidden or unaccessable books.

The Doina Cornea Private Collection is an invaluable historical source for those researching the biography and especially the dissident activities of the person labelled by the Western mass media as the “emblematic figure” of the Romanian resistance to Ceauşescu’s dictatorship. This collection comprises manuscripts of her open letters of protest, her diary, samizdat translations, correspondence, drafts of her academic works, photos, paintings, video recordings, and her personal library. This private collection is by far one of the most significant and valuable collections reflecting the cultural opposition to the Romanian communist regime.

The Jan Patočka Archives (AJP) studies and interprets the philosophical heritage of the Czech philosopher and dissident Jan Patočka (1907-1977). AJP is led by Patočkaʼs pupils and is a unique institute working with Patočkaʼs original texts and also with the attendees of his lectures.

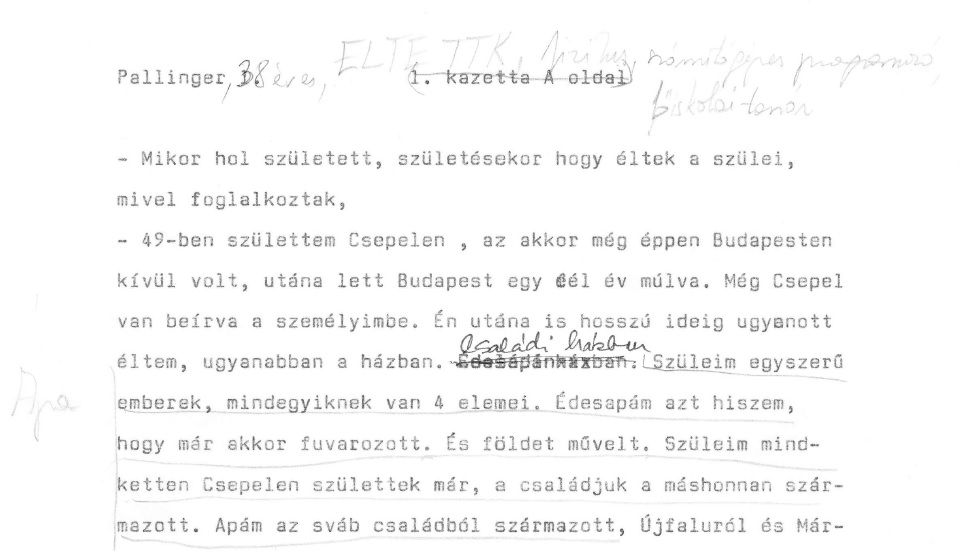

The machine-read transcript of the audio recorded interviews from the secret meetings which took place in Božena Komárková´s flat, comprised of 42 pages. She discusses her life, reflection of T. G. Masaryk, St. Augustine, relationship to democracy, Christian faith, Socialism and Christianity, church affairs after the Communist coup in 1948, etc. The transcription is crossed out and supplemented by Božená Komárková´s comments. Part of the collection is also the original audio record. This document shows authentic and original views from the meetings and a wide range of views from the prominent figure of Protestant dissent - Božena Komárková.

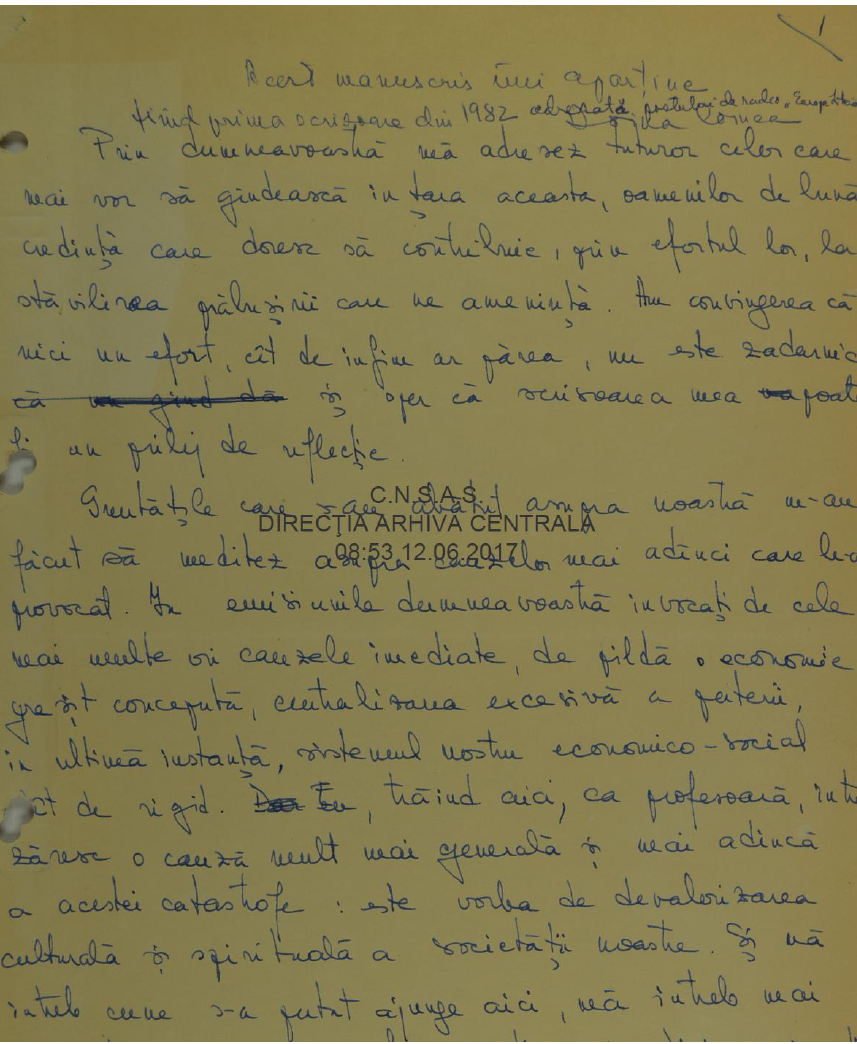

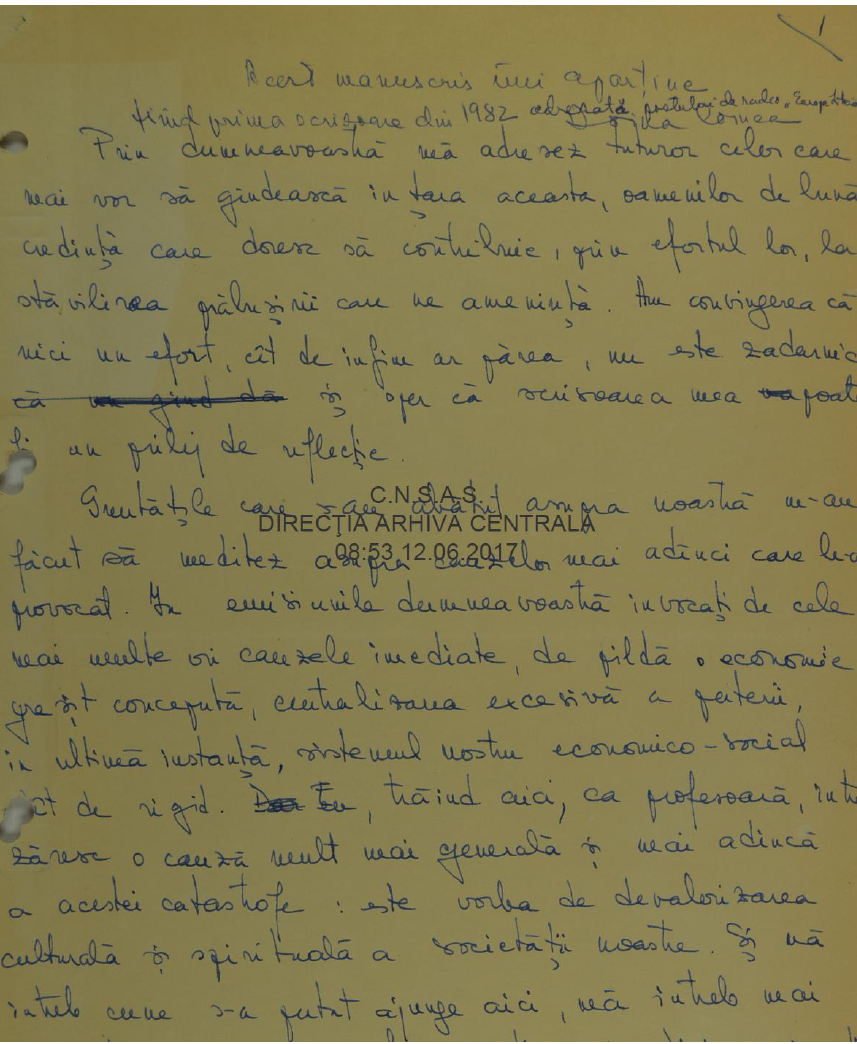

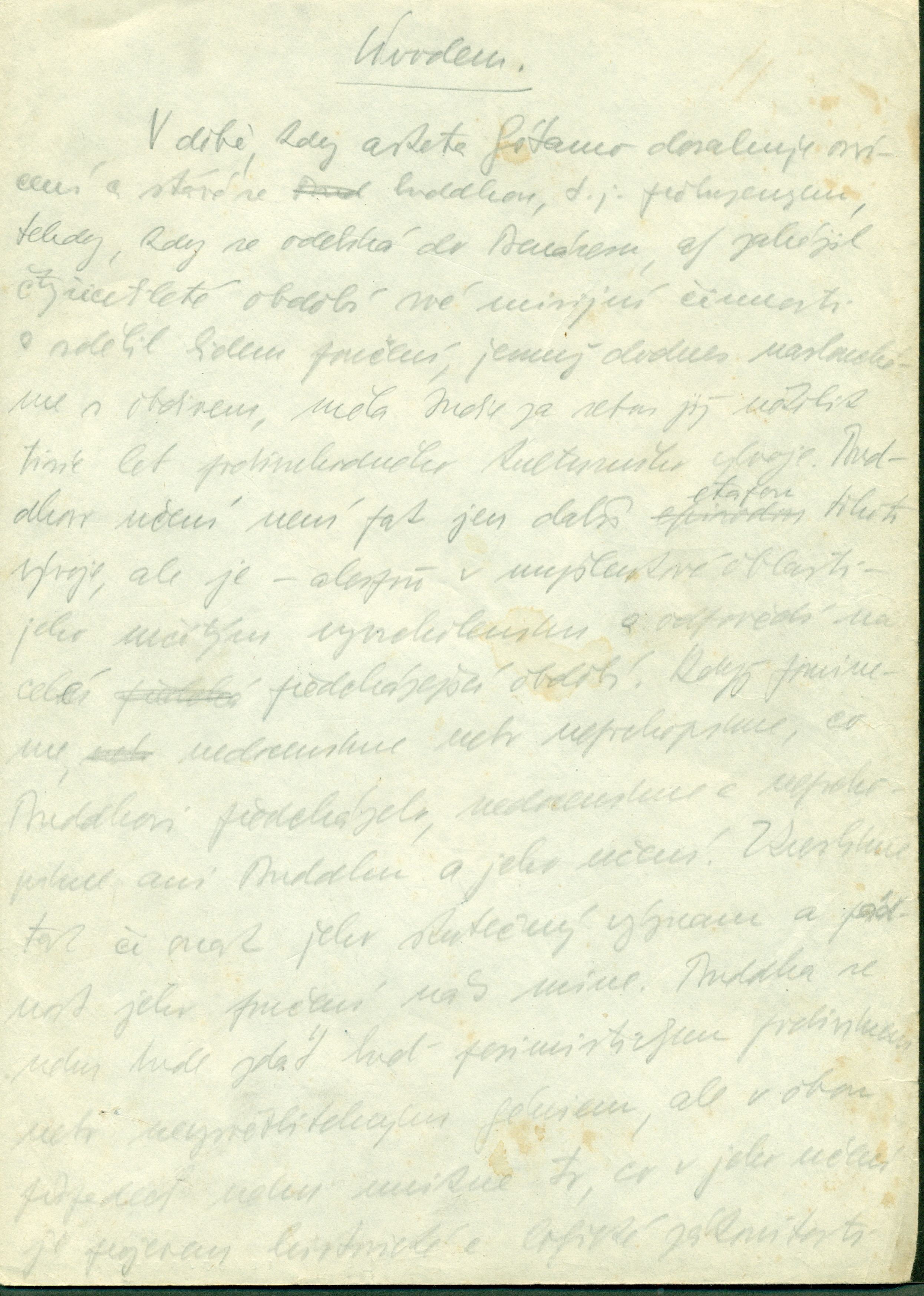

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

After listening in November 1987 to the news broadcast by Radio Free Europe (RFE) about the anti-communist revolt of the workers in the factories of the city of Braşov, Doina Cornea openly displayed her solidarity with the protesters. On 18 November 1987, she drafted 160 manifestos, which were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in several public spaces in Cluj (Cornea 2009, 194–195). Consequently, on 19 November 1987, she and her son were arrested by the Securitate after a detailed home search (Cornea 2006, 203). During home searches on 19 and 23 November 1987, the Securitate confiscated many documents from Cornea’s private dwelling, including all the drafts of her letters to RFE.

Among these documents, the Securitate confiscated the handwritten draft of the first letter she sent to RFE entitled: “Letter to those from home who have not given up thinking with their heads.” According to interviews granted by Doina Cornea, this letter was drafted by Cornea and her daughter Ariadna Combes in July 1982 (Cornea 2009, 169-170). The document was smuggled to the West and sent to RFE with the help of her daughter, who chose to remain in France in 1976 and visited her mother in July 1982 (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, f. 11). In August 1982, the letter was broadcast by RFE during the radio programme “Talking with RFE listeners.” It was the first letter in a series of twenty open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE in the period from 1982 to 1989, through which she asserted herself as one of the most prominent Romanian dissidents (Cornea 2009, 195–196). The open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE intensified the surveillance and repressive actions of the Securitate, which had already been monitoring her closely since 1981. Due to the fact that the strict surveillance in communist Romania did not allow the development of a samizdat and tamizdat milieu, RFE played a key role in conveying the messages of Romanian dissidents to their fellow citizens (Petrescu 2013, 277).

The letter starts with a reference to radio programmes of RFE that had been previously broadcast. During these radio programmes, journalists specialising in East European issues had dealt with the crisis that affected communist Romania during 1980s and identified political and economic factors as the immediate causes. Instead of these causes, Doina Cornea emphasises in her letter causes relating to moral and cultural values. By idealising interwar Romania, she brings into discussion the destruction of the Romanian intellectual elite during the first two decades of communist rule and the decay of the educational system. In Cornea’s opinion, this “spiritual crisis” is illustrated by the everyday “compromises” and “lies” that citizens living under a communist dictatorship have to “accept and circulate” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f.1). Her argumentation in this respect is similar to that developed by Vaclav Havel’s essays and epitomised by his principle of “living in truth” (Havel 1990). Cornea argues that “the people is fed only with slogans,” which stifle all openness towards “truth, revival, and creativity” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 2–3). She criticises the conformism of Romanian intellectuals and state policies which limit theoretical education (especially the humanities) and promote technical education in order to fill the need for cadres in the rapidly growing heavy industry.

She concludes her text by asking for a reform in the educational system and encourages those working in this field at least to take advantage of the limited possibilities available to them to promote what she considers to be authentic cultural and moral values. According to Cornea, those working with students should not teach them “things in which they themselves do not believe” and they should “encourage the creativity of young people and not be afraid to say what they think” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 4–5). At the end of the letter, Doina Cornea inserted her name with the mention: “for the messengers of RFE listeners” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 5). She did not intend to reveal her real identity to the listeners of RFE, but just to prove the authenticity of the document to the editors of the radio programme. Due to a misunderstanding, her real identity was revealed during the radio show.

In November 1987, after the draft of this document was confiscated by the Securitate, the secret police used it as an argument of accusation during Cornea’s interrogation. This focused especially on the channels used by Cornea to send the letter to RFE. Although she did not mention it during the interrogation, the Securitate suspected that her daughter Ariadna Combes had helped her in this respect. For this reason, Cornea’s daughter thereafter did not receive a permit to enter the country to visit her family until the fall of the communist regime.

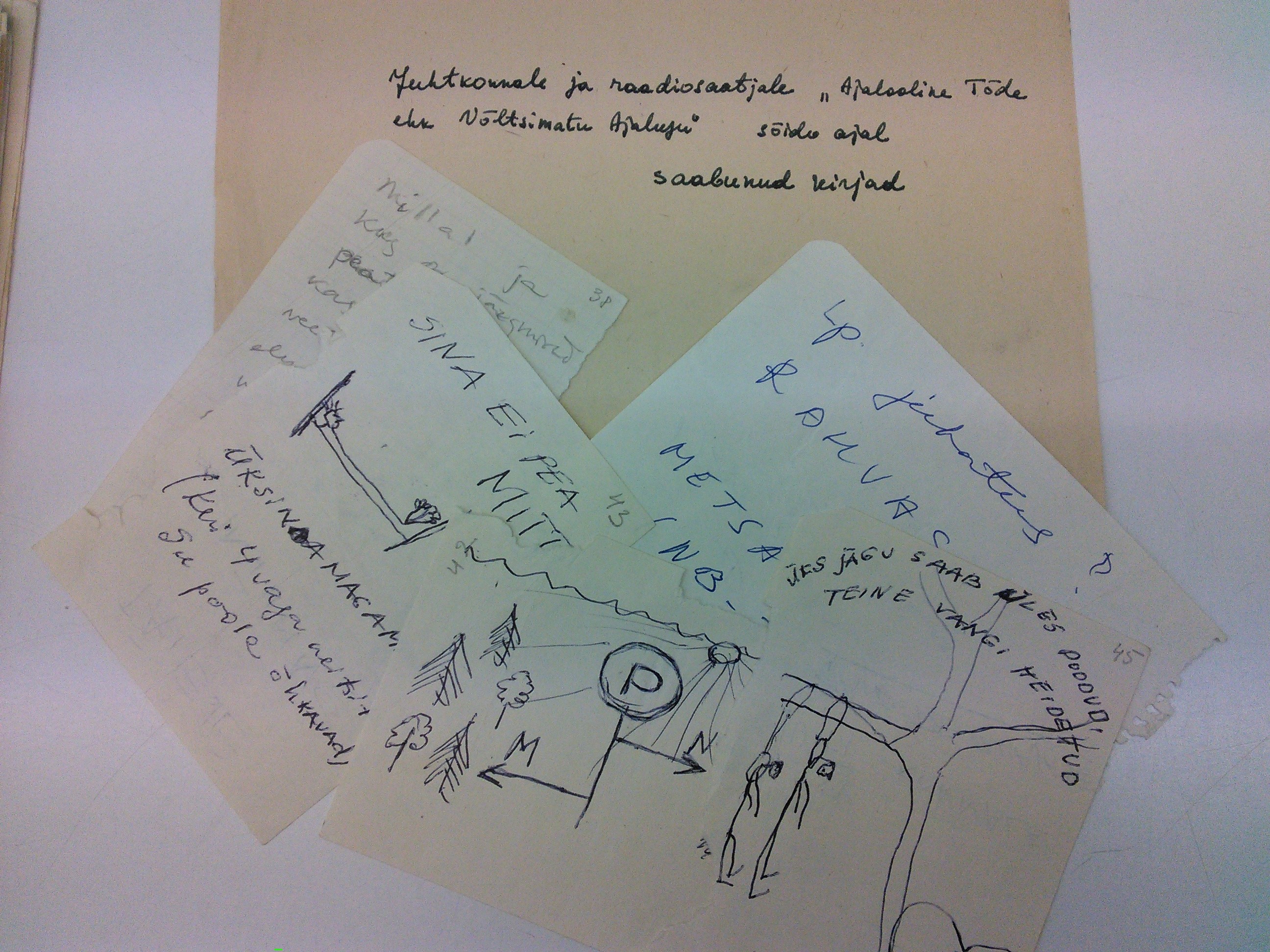

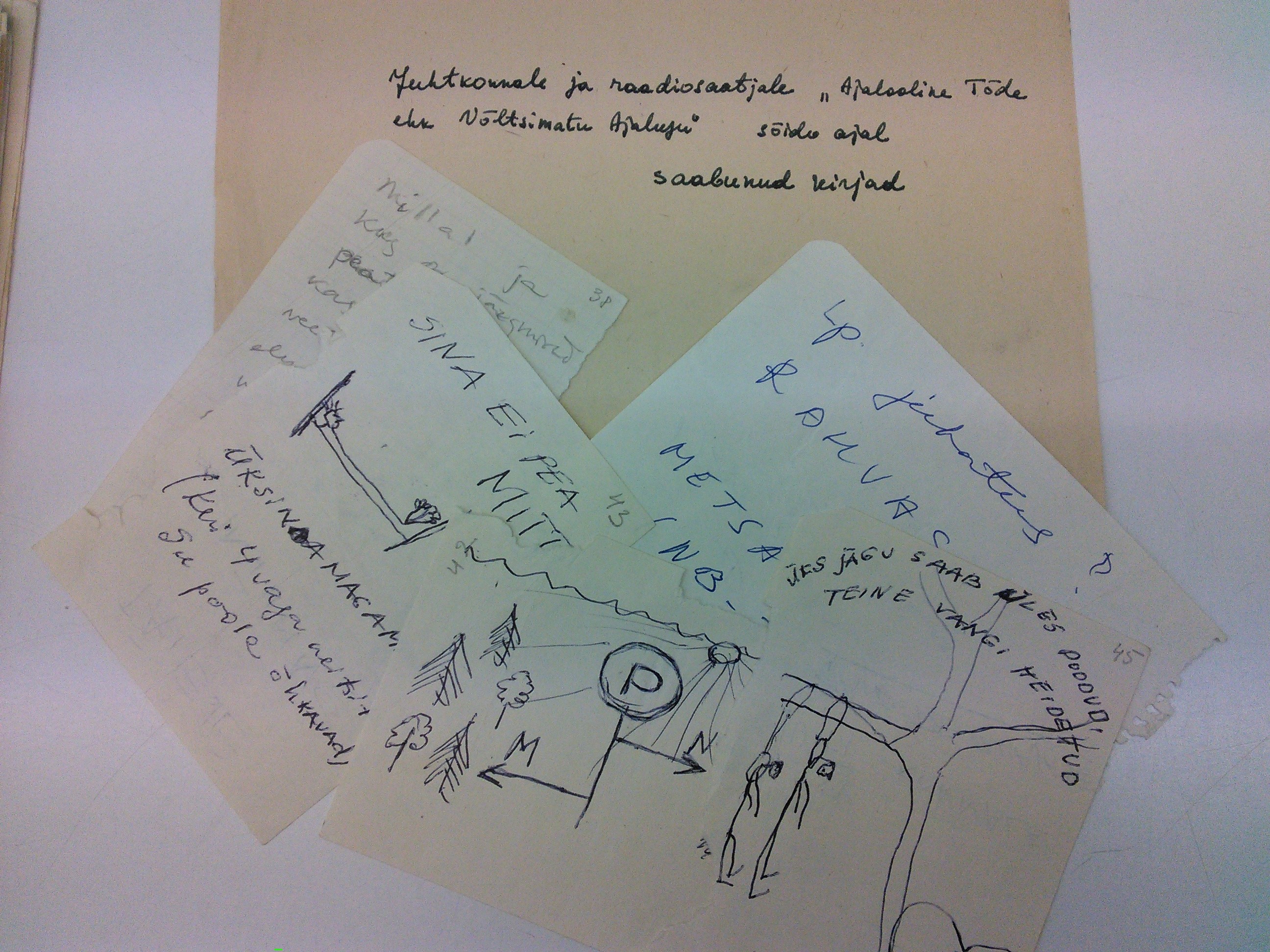

The Circle of History Students was a society for history students and lecturers at the University of Tartu during Soviet times which was officially part of the Students' Scientific Union. Although it was an official organisation, the Circle of History Students offered space for relatively free discussions between students and lecturers. It was a breeding ground for the growing protest spirit in the late 1980s. The Circle of History Students archive, which is preserved today in the National Archives of Estonia, contains various documents about its activities. Although it followed the formal rules for Soviet public speaking, these documents also display ironic and critical attitudes towards the regime, and reflect the free atmosphere for research and communication in the society.

Ferenc Erős’s interview collection includes in-depth interviews with second-generation Holocaust survivors. This project was one of the first which seeks to revive suppressed memories of the Holocaust and the effects of the psychological strategies used to grapple with these memories and the ways in which trauma are transmitted within families.

The Memory of Nations is an extensive online collection of the memories of witnesses, which is being developed throughout Europe by individuals, organizations, schools and institutions. It preserves and makes available the collections of memories of witnesses who have agreed that their testimony should serve to explore modern history and be publicly accessible. The collection includes testimonies of communism resistance, holocaust survival, artists of alternative culture and underground and many others.

The collection includes documents (archival material) stored in the archive of the "Commission for the Disclosure of Documents and Announcing Affiliation of Bulgarian Citizens with the State Security and the Intelligence Services of the Bulgarian People's Army", commonly called "Commission for Dossiers" (Comdos) in Bulgarian.

The collection documents developments among the Bulgarian intelligentsia during the communist regime through the perspective of the secret police and reveals their strategies of observation and persecution of critical intellectuals.

Ferenc Fejtő was an original, democratic leftist thinker. His library is a unique trace of the criticism of Eastern European rightist, authoritarianist, socialist dictatorship, and Western European leftist romanticism. Fejtő, who maintained strong connections with European intellectual elites, left Hungary for France in 1938, yet remained deeply committed to the fate of freedom-lacking Eastern Europe.

Juretić, Augustin. “Suština sukoba Kominform – Tito” [The essence of the Cominform conflict – Tito] (Hrvatski dom), 1950. Article

Juretić, Augustin. “Suština sukoba Kominform – Tito” [The essence of the Cominform conflict – Tito] (Hrvatski dom), 1950. Article

The Croatian expatriate magazine Hrvatski dom, edited and published by Augustin Juretić in Switzerland, carried the article "The essence of the Cominform conflict – Tito," in its issue of 15 November 1950. The article is unsigned, and as with most unsigned articles in the magazine, its author is probably Juretić. The article described the essence of the conflict between Tito and Stalin, considering it through the prism of Marxist theory and practice. Juretić concluded that Tito carried out the last communist revolution in the world, which according to Marxist theory made him the leader of the world communist movement, i.e. placed him ahead of Stalin. As a warning to Western leaders, Juretić stated that in the future Tito could become more dangerous than Moscow, and that “the destruction of world communism will required Tito’s destruction as well” (Hrvatski dom, 15 November 1950, 3-6)

The manuscript of the article is held in the Augustin Juretić Collection at the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome. The collection also contains a printed version of the article published in Hrvatski dom.

The Praxis and Korčula Summer School Collection includes significant books and articles by the Praxis thinkers and a complete set of all editions of the journal Praxis. It represents a first-class cultural legacy because it is the most comprehensive collection of the phenomenon, widely recognised not only in (the former) Yugoslavia but also internationally. During the socialist period, philosophers and sociologists of a predominantly Marxist orientation actively participated in the promotion of the culture of critical thought by writing for the journal, and by attending the summer school.

The János Dobri Collection of the Reformed Congregation of Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund contains materials covering the confessional life and activity of the eponymous pastor, which alongside proofs of his individual stand and sacrifice, in the course of the official and private correspondence with the Romanian authorities and private individuals, and beyond the struggle for survival of the Reformed church, also provides an insight into the details of the fight for minority and human rights in the twentieth century.

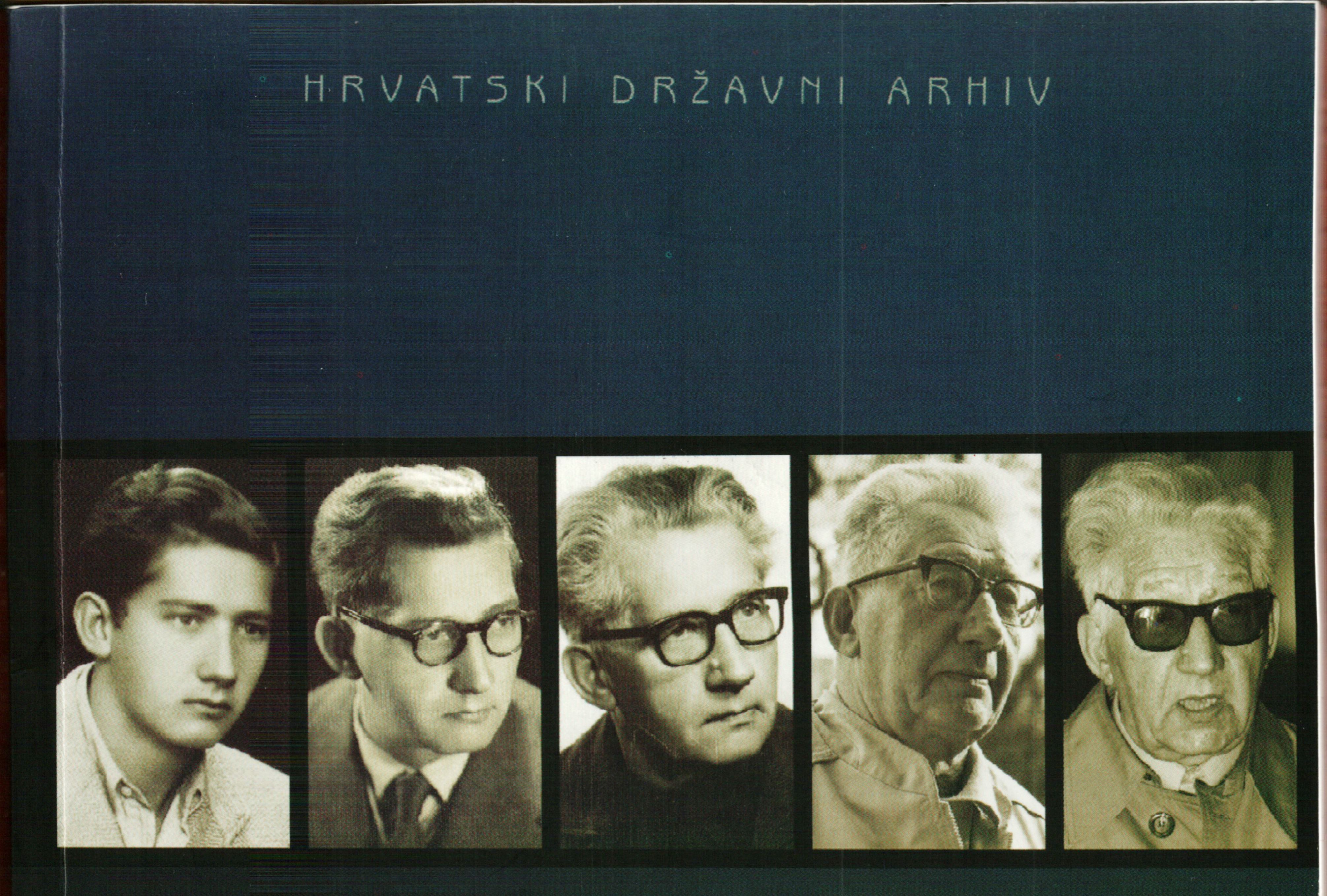

The website illustrates the life path and evolution of Franjo Tuđman’s ideas. Tuđman was a historian and politician who was twice sentenced to prison and banned from engaging in any public activity because he published and defended the results of his historical research, which contradicted the prevailing narrative promoted by the regime. The website contains digitised photographs, excerpts from Tuđman's diary, manuscripts and published works. The material testifies to his academic and political activities and his transformation from a relatively high-level communist official to a party dissident and finally the leader of the political opposition which overthrew the communist regime in Croatia.

The digital collection of the Oral History Center contains more than 2000 interviews with twentieth-century witnesses, which are divided into different themes and topics, thus presenting a unique collection of professionally created interviews and memories, many of which are related to the theme of cultural opposition.

This is the collection of the prominent intellectual and dissident of the SFR Yugoslavia, Zoran Đinđić. During his studies at the beginning of the 70s, Đinđić was active in a leftist oppositional student movement. After being tried for attempting to organize an alternative independent student union, he left Yugoslavia for Germany and only returned at the beginning of the 90s. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia, Đinđić was one of the most important leaders of the opposition movement during the 1990s, and between 2001 and 2003 he served as prime minister of Serbia. The collection consists of books which Đinđić accumulated from his student days up until his assassination.

Cornea, Doina. Regarding the reform of the Romanian educational system (open letter), in Romanian, 1986. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina. Regarding the reform of the Romanian educational system (open letter), in Romanian, 1986. Manuscript

This document drafted in December 1986 is one of a series of open letters sent by Doina Cornea to Nicolae Ceaușescu. A copy of the letter was also sent to Radio Free Europe (RFE) and broadcast in January 1987 (Cornea 2006, 198). As Cornea confessed in her post-1989 interviews, despite the repression and the strict censorship, she tried to think and behave under communism as if living in a free society (Liiceanu 2006, 8–9). She considered that this behaviour was in accordance with her moral values, but also might play a transformative role in a society under dictatorship, because others would be encouraged to follow her example. Her strategy of opening a free dialogue with the authorities also illustrates also the profoundly democratic character of her inner convictions.

The ethical and cultural background of her open letters draws on two main sources: 1. the tradition of the Greek-Catholic Church (of which she was a member), banned by the communist regime in 1948, which functioned underground under communism despite the state repression directed at priests and parish members; 2. the influence exercised by the works of Mircea Eliade and Constantin Noica, both members of the so-called “generation of 1927” (Petrescu 2013, 309). During her teaching activity at the University of Cluj in the late 1970s and early 1980s, she tried to introduce a non-conformist bibliography that promoted different cultural models from those approved by the regime and encouraged free thinking among her students. Due to these attempts she lost her position in the Faculty of Letters in June 1983 (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, ff. 51–52).

If in other open letters she identified among the causes of the general crisis in Ceaușescu’s Romania the decay of cultural and moral values (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 73), in this letter Cornea drafts a plan to solve some of these problems by proposing a reform of the educational system. Thus, she starts her open letter by mentioning the fact that in her opinion some of the main problems of Romanian society under communism (“corruption”, “negligence,” and hypocrisy are caused by the “progressive degradation of the educational system” after 1948. Her criticism targets especially the following aspects of the Romanian educational system during the 1980s: the focus of the state authorities on technical education and the lack of investment in the humanities, the emphasis on memorisation and the failure to encourage critical thinking, and the lack of exigency and the encouraging of mediocrity due to the pressure on teachers from the state authorities (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 73).

She ends her open letter by proposing several measures for a future reform of the educational system: 1. depoliticising education; 2. “reconsidering all curriculums in the disciplines that have suffered deformations caused by the intrusion of the official ideology, such as history, social sciences, literature, and philosophy”; 3. university autonomy; 4. more academic exchanges with foreign universities; 5. reform of teaching methods by paying more attention to “quality” and less to “quantity”; 6. “the re-establishment of those theoretical high-schools transformed into technical secondary schools”; 7. the reintroduction of the humanities in all secondary schools; 8. “the establishment of schools for ethnic minorities in proportion to their percentage in the total population” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 76).

During the home search in November 1987 when the letter was confiscated by the Securitate officers, Doina Cornea was asked to write on the recto side of the first leaf: “I am the author of this text,” and to sign for authentication (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 73). Like other letters confiscated during the home searches, this document was invoked during her interrogations at the Securitate in November and December 1987.

The Czechoslovak Students’ Movement of the 1960s Collection (Ivan Dejmal Collection) at the Libri Prohibiti Library contains valuable sources documenting Czechoslovak students’ movement in the 1960s, and especially during the years 1968 and 1969. Materials, which were collected by the leading Czechoslovak student activist Ivan Dejmal, illustrate, among other things, students’ activities during the so-called “Prague Spring” or reactions of students’ milieu to Jan Palach’s self-immolation in 1969.

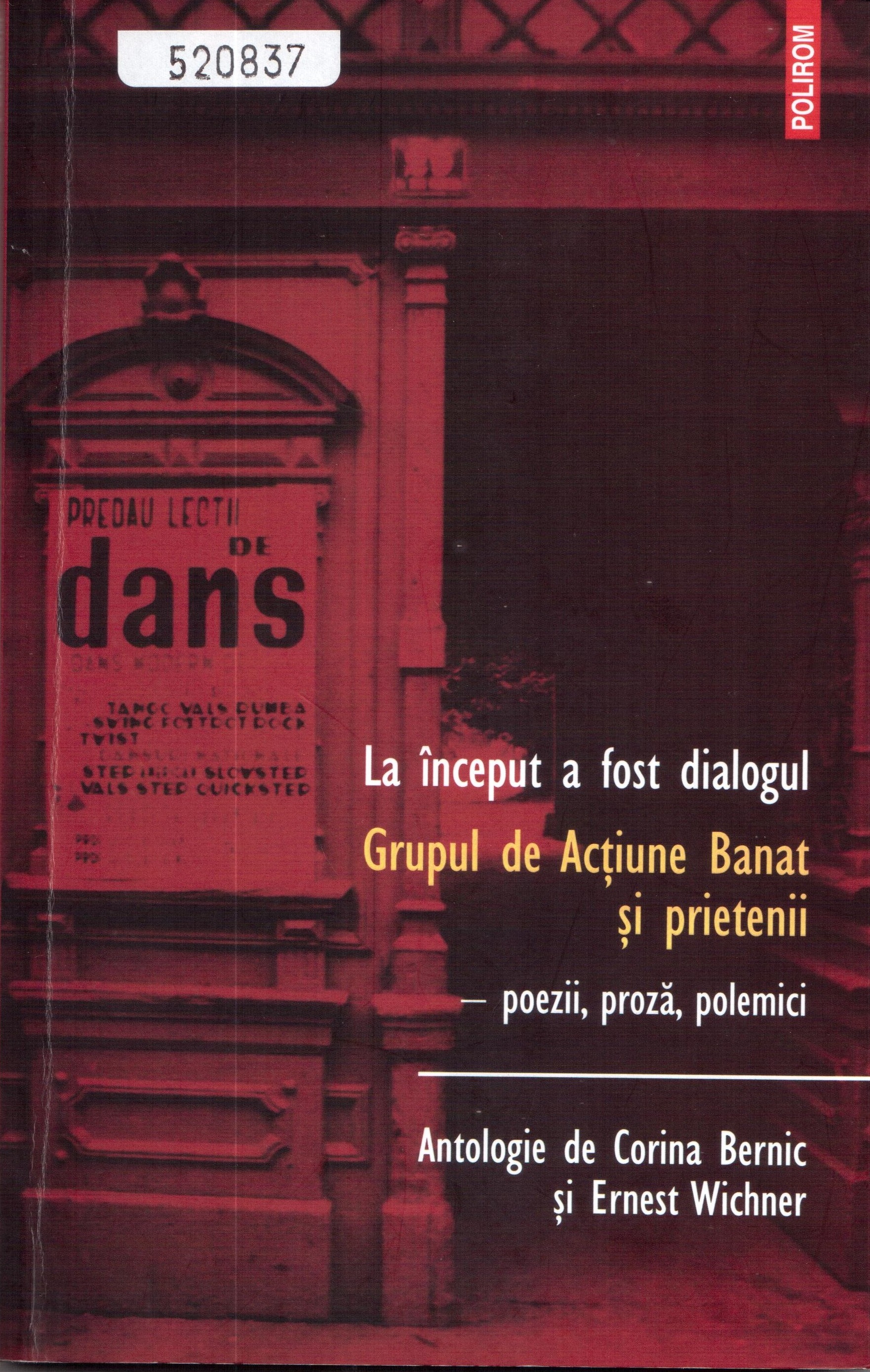

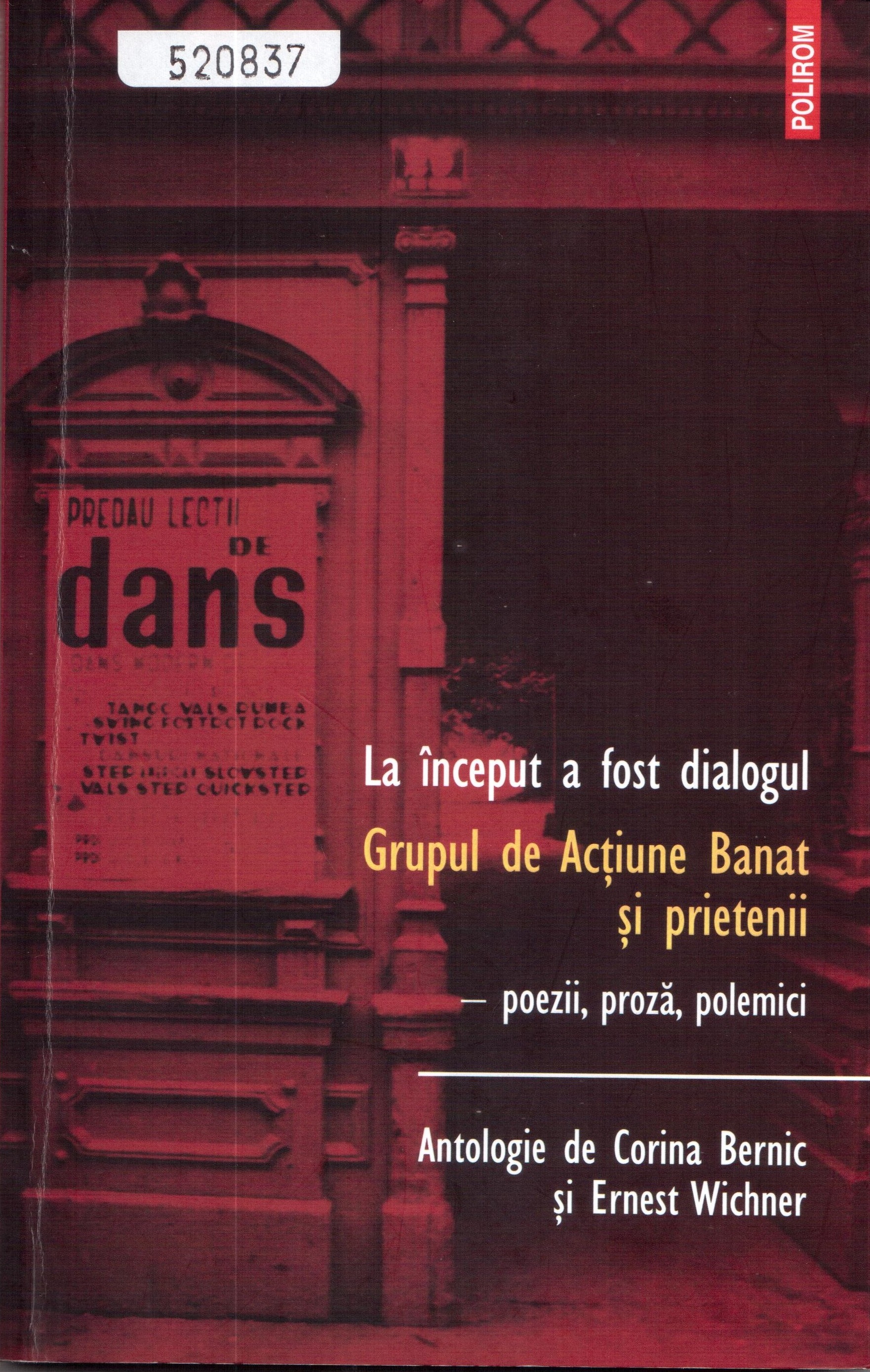

The Aktionsgruppe Banat Ad-hoc Collection reflects the type of cultural opposition represented by a group of Romanian-German writers, who founded together the literary circle Aktionsgruppe Banat and developed a neo-Marxist criticism of “really existing socialism.” The collection comprises two types of items: (1) manuscripts and other materials confiscated by the Securitate from these writers, (2) documents issued by the Securitate concerning their cultural activity, which the communist regime perceived as dangerous.

The Marian Zulean personal collection is an illustration of the fact that any act of cultural opposition is dependent on the societal context that generates it. It implicitly highlights the fundamental difference between Romania and other communist states in the last years of the period 1980–1989. The more than 400 newspapers, magazines, brochures and books, originating especially from the Soviet Union in the Gorbachev period, epitomise a reformist political discourse that had become relatively official in the rest of the Soviet bloc, but was considered dangerous by the Romanian Securitate.

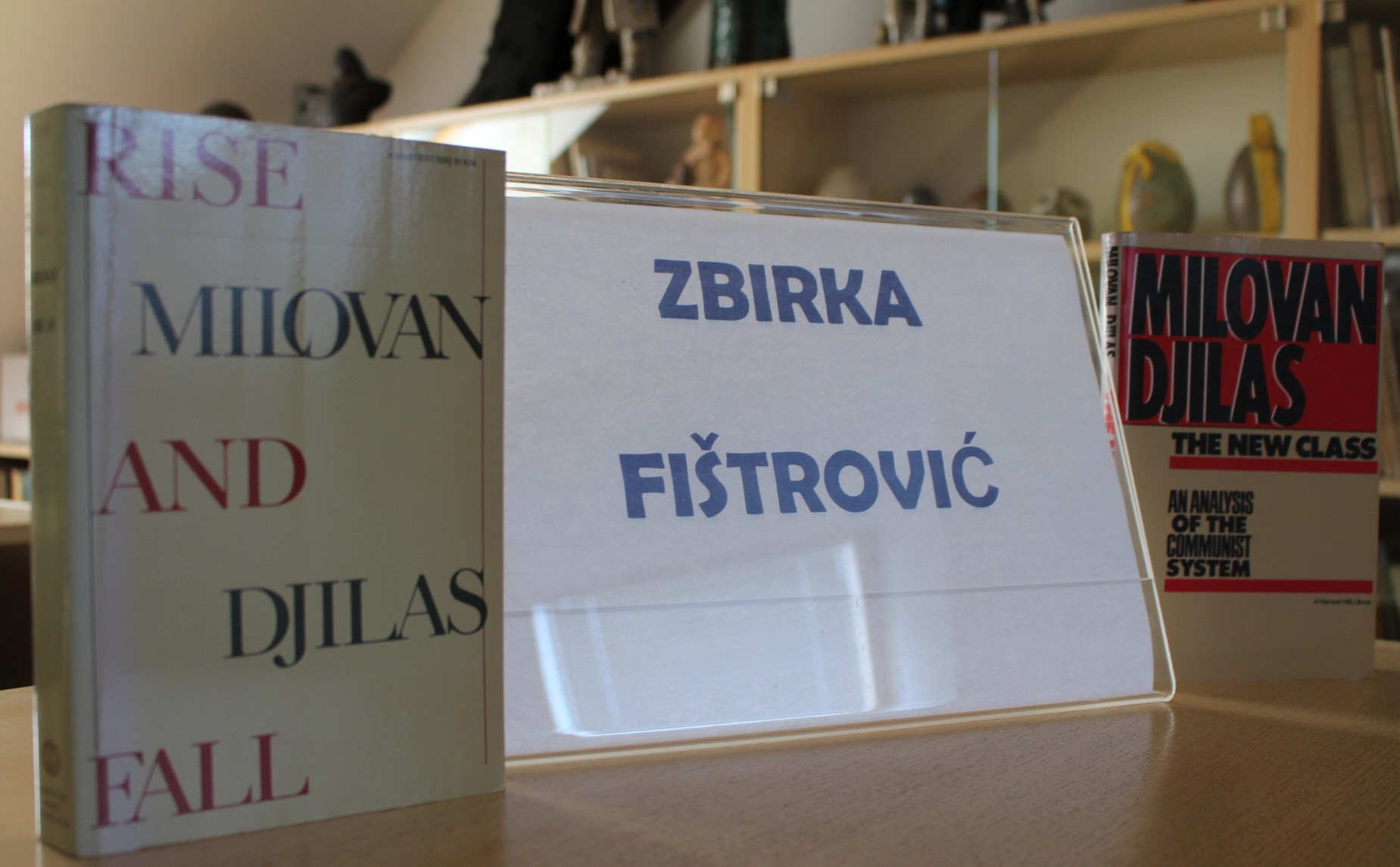

The Fištrović Collection of the Fran Galović Library and Reading Room in Koprivnica contains about 1,300 historical, political, economic and cultural books in English, many of which are the only copies in Croatia. The books were used by a group of Croatian intellectuals in Chicago in the 1990s to address the American public and advocate for a democratic and independent Croatia, which can be considered a final act of resistance to the Yugoslav socialist regime. The authors of some of the books are also intellectuals from the former Yugoslav republics, and their work, published in English, is evidence of their dissent against the Yugoslav system of government.

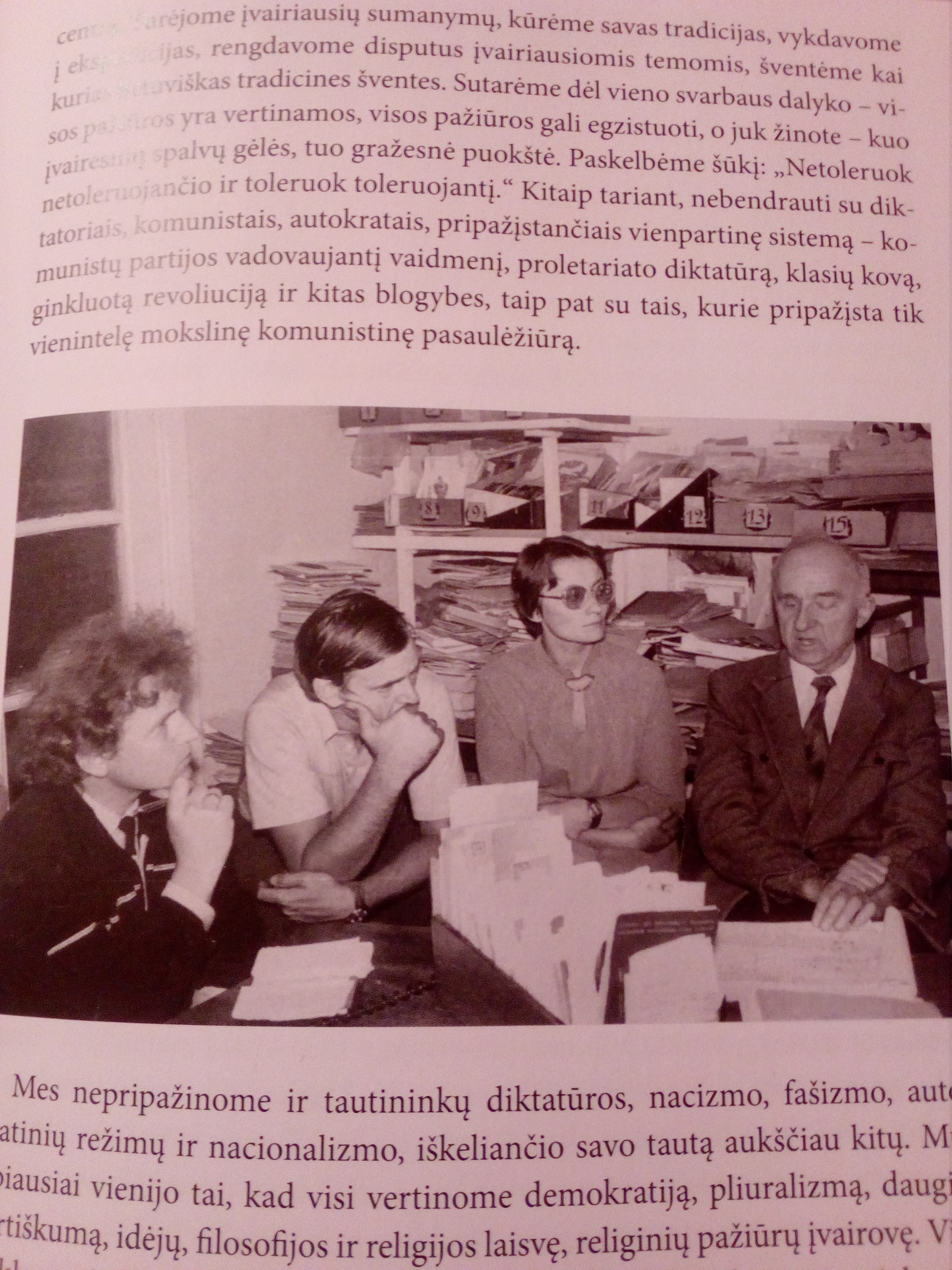

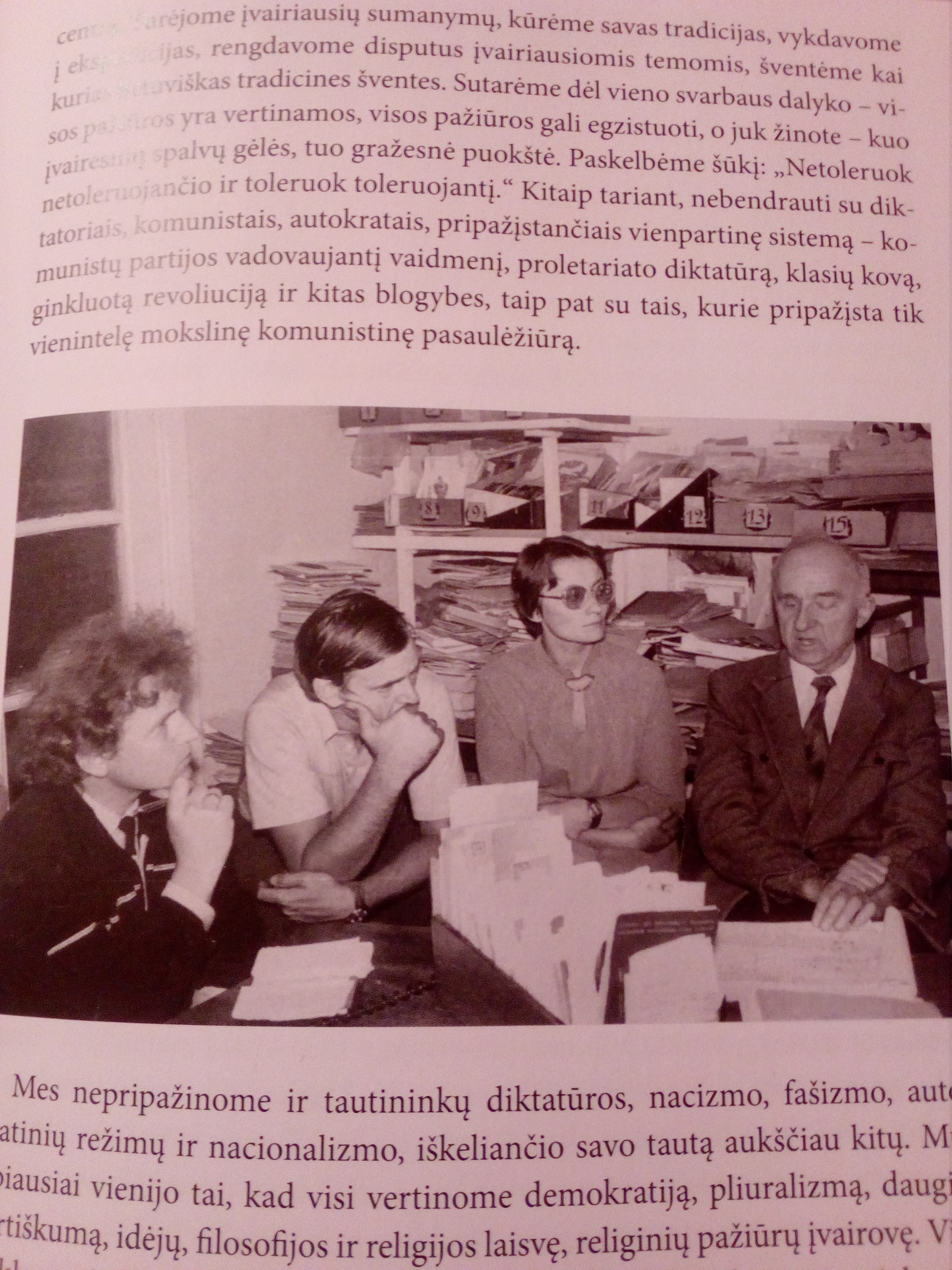

The collection holds documentation on the activities of the Strazdelis University, which operated underground in Lithuania in the 1970s. The aim of the Strazdelis University was to provide alternative education on a voluntary basis, organising and inspiring self-education in the humanities and social sciences. Much attention was paid to ethnography and the study of Karl Marx, interpreting his works differently to how Soviet ideology did. The Strazdelis University was the first step in anti-Soviet or non-Soviet actions for a group of people who later, during the period of Sąjūdis (the Lithuanian national movement, 1988-1990), became activists and founders of modern political parties. The collection is stored in the private papers of Vytenis Povilas Andriukaitis, the EU commissioner, who was a member and dean of the university.

In the GDR, child care and education were firmly in the hands of the ruling SED party, but in 1950 the protestants were allowed to open a seminary on the Island of Hermannswerder, near Potsdam. First, it offered men, and from the 1950s women banned from attending regular secondary schools, the opportunity to obtain their secondary school leaving qualification (Abitur), enabling them to study theology or church music. In the GDR pupils were often prohibited from attending secondary schools for religious and/or political reasons. It was particularly common for the children of clergy members to attend the seminary.

In addition to a growth in the school size during the 1970s, the curriculum also changed. It then included more subjects that were not part of theological education, for example the possibility to focus on modern languages. From 1982, the school even adopted the curriculum of North Rhine–Westphalia (West Germany) as part of their leaving qualifications.

The State Security Service (Stasi) constantly had their eyes on the institute and commonly conducted searches for forbidden material. “Youth Sundays”, taking place yearly from 1949, were a huge thorn in the government’s side. During these events, young people discussed, away from the official socialist apparatus, how to lead a Christian life. Even an eventual ban could not stop the meetings as even without official announcements, meeting times were simply passed on by word-of-mouth.

Apart from “Youth Sundays”, the island was also home to church synods and later environmental gatherings and bicycle “star rides”. These are events in which the participants start at different locations, all meeting at the same spot in the centre thus forming a star. In Germany they have taken place since the 1970s to bring attention to different causes, such as the environment.

After reunification, anyone who graduated from the school was retroactively granted the right to study anything, not just theology and church music. Today it is a Protestant secondary school.

Ljubomir Tadić was a professor of philosophy, academic, and politically active intellectual over many decades. During the socialist period in Yugoslavia he was a prominent opposition figure and critically minded intellectual who struggled against the Yugoslav system. Ljubomir Tadić’s collection is located in the Archives of Yugoslavia in Belgrade.

Augustinas Janulaitis was a famous Lithuanian national activist, an active member of the Social Democratic Party, a lawyer and historian. In 1945, he became dean of the Faculty of History at Vilnius University, and later a member of the Academy of Sciences. The Augustinas Janulaitis collection, which is kept in the Wróblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, holds various manuscripts of Janulaitis' work, and documents relating to his career and life in Soviet Lithuania. His letter to the president of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences reflects the difficult situation in 1946, when he was attacked by the Soviet authorities for bourgeois nationalism. To students, he was an example of an intellectual and a scholar of interwar independent Lithuania.

The Áron Márton Memorial Collection in Alba Iulia contains the materials that represent the most complete coverage of the bishop’s life and activity, which offers countless proofs of individual courage and spirit of sacrifice, in the light of his official and private correspondence carried on with the Holy See, the Romanian public authorities, and private persons, and insight not only into his struggle for the survival of the Church and the Catholic faith, but also into the details of the fight for minority and human rights in the twentieth century.

The Alexandru Călinescu private collection epitomises the trajectory of an intellectual in an important university city who began to practise a camouflaged contestation, published in local student magazines, with a limited readership, and ended up in unequivocal public opposition, disseminated transnationally through foreign radio stations. The collection marks some of the key episodes in the movement of resistance to and contestation of the communist regime as it manifested itself in Iaşi, the historical capital of the region of Moldavia and the city with the oldest university in the Old Kingdom of Romania. At the same time, the collection and the personal story of Alexandru Călinescu illustrate a lesson in dignity in very difficult times, when there were few who had the courage to speak openly against the Ceaușescu regime.

The Audiovisual Section of the Libri Prohibiti library contains recordings of non-conformist music and spoken word, underground lectures and seminars. It also contains video-documents and amateur film productions. The unavailability of the original recordings and total content consisting of thousands of exemplars makes the collection unique in the Czech context.

This collection of the historian, teacher and politician Milan Hübl consists of a unique collection of archive materials, which includes the correspondence and documentation of the Political University of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and a large collection of ego documents, samizdat volumes and materials related to Charter 77, the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS).

The collection of Ilona Liskó is the legacy of the oeuvre of a sociologist who tried to shed light on the problems in Hungarian society which, according to the official stance of the regime, did not exist. Liskó felt a sense of solidarity with the poor and marginalized in part thanks to her family upbringing, and her desire to shed light on their sufferings came from her deep sense of social obligation.

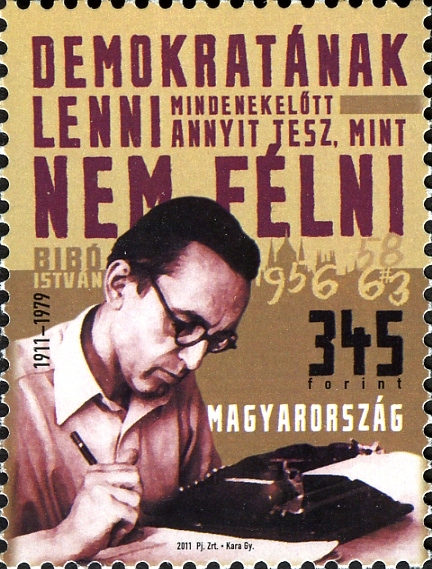

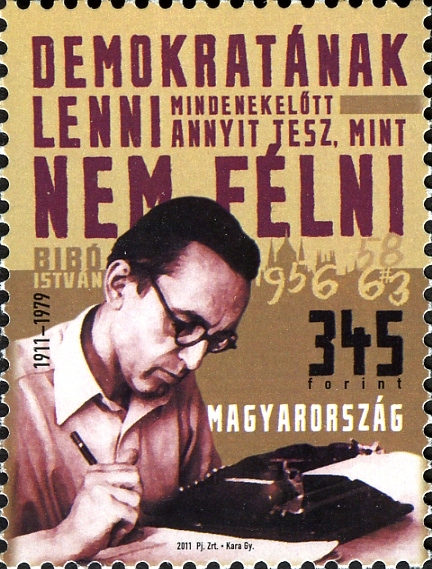

István Bibó (1911–1979) was a Hungarian political scientist, sociologist, and scholar on the philosophy of law. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Bibó acted as the Minister of State for Imre Nagy’s second government. When the Soviets invaded and crushed the revolution, he was the last minister left at his post in the Hungarian parliament building. Rather than flee, he remained in the building and wrote his famous proclamation, “For Freedom and Truth,” until he awaited arrest. Bibó became a role model for dissident intellectuals in the late communist era and a symbol of non-violent civilian resistance based on a firm moral stand. Since Bibó’s death in 1979, the family collection of his bequest, which includes personal documents, photos, manuscripts, books, and video and sound recordings, has been in the care of art historian and educator István Bibó Jr., who keeps the materials in his home in Budapest.

Vaclovas Aliulis (1921-2015) was a Lithuanian Catholic priest. During Soviet times he participated actively in underground catechisation, and was a lecturer with the Underground Catholic Seminary, which was established to train priests for Catholic parishes in Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and other Soviet republics. Aliulis is the author of a number of books and other publications; and during the times of Sąjūdis (the Lithuanian national movement), he was the initiator and organiser of Catholic publishing. He started to collaborate with the Lithuanian Central State Archives from 2003, transferring files from his private papers to the state archives. The documents in the collection show the situation of the Catholic Church and the community of believers in Soviet Lithuania, and Soviet policy on religion.

One of the documents in the Alexandru Călinescu private collection reflects the perspective from which this critical intellectual in Iaşi was regarded by the authorities in the last years of communism, when the dissidents in the city, including Alexandru Călinescu, became radicalised in their attitude towards the Ceaușescu regime. The document was discovered on 23 December 1989, in the cabinet of the person who had been propaganda secretary for Iaşi county up until the previous day, and thus came into the possession of Alexandru Călinescu. It had also been sent, as Alexandru Călinescu recalls, to the then rector of A.I. Cuza University of Iaşi, “so he would work on me, but without success, of course,” he adds. This document was published by the former dissident in 2018 under the suggestive title “My life told by the Securitate,” together with other documents of the same type and an article summarising the context of the last two years of communism in Romania.

The Securitate informative note begins by recalling the intellectual origins of the person in question and emphasising that “he has always manifested a particular interest in entering into relations with foreign citizens of all categories, especially language assistants, diplomats, reporters, journalists, writers, etc., but with many of these he exceeded the official context, […] repeatedly transgressing in a flagrant and ostentatious manner the provisions regulating relations with foreigners.” Because he had “cosmopolitan” ideas and implicitly a “communion of ideas” with some of these foreigners, “he particularised the relations in such a manner that they developed from simple friendship to seriously affecting the interests of the Romanian state,” the document continues. The informative note on Alexandru Călinescu emphasises his role as the leader of the oppositional group around the magazine Dialog: “He has been considered the mentor of a group of young people with literary ambitions, launched by the above-mentioned publication, and has appointed himself a ‘school leader’ of the so-called ‘1980 generation,’ to whom he has passed on his harmful ideas.” The articles published in Dialog under the direction of Alexandru Călinescu by him and his disciples are characterised as being ‚ “of a contestatory character, which has attracted the attention of reactionary circles in the West, who provided them with publicity through the ill-famed radio station Free Europe.” As the leader of the new generation at Dialog, which he directed towards “hostile activities,” Alexandru Călinescu was considered to have “arrived at the threshold of treason,” resulting – according to the note – in no more than a sanction through Party structures with a “vote of blame.” The note goes on to emphasise that the individual in question “has not drawn appropriate conclusions from the measures taken in 1983. Making a mockery of the good advice and disregarding the clemency that was shown in his case, he has continued to maintain the same position, at first more prudently, then more and more openly and ostentatiously.” The document then recounts how Alexandru Călinescu “has gone further down the slope of treason,” by facilitating Dan Petrescu’s and Liviu Cangeopol’s meetings with French journalists to whom they granted interviews “with a particularly hostile content,” and thus becoming “the coordinator from the shadows of the alleged Iaşi dissidence.” Moreover, the document states, Alexandru Călinescu has shown solidarity with the dissidents in Bucharest, who have taken a public position in defence of Mircea Dinescu. The conclusion of the informative note with regard to the individual under surveillance is that “he more and more often exteriorises ideas inciting opposition to the socialist regime in our country, […] letting himself be influenced by what is happening in other socialist countries.” It is interesting to observe the interpretive key in which the Securitate informative note narrates all these real actions of contestation of the regime, as a result of which Alexandru Călinescu had become at the end of the 1980s one of the most heavily surveilled critical intellectuals in Iaşi and indeed in the whole of Romania. In the words of the secret police documents, “by the hostile actions he has carried out, especially in the last two years, […] Alexandru Călinescu has proved [...] that he has crossed the threshold of treason to the country and has become a tool of reactionary circles in the West, through which he has seriously compromised his status as citizen, Party member, and university teacher.” In other words, all that after 1989 became an act of courage was considered an act of treason before 1989.

The collection holds various documents (manuscripts, letters, etc) relating to the Lithuanian historian Ignas Jonynas. His works written in the interwar period laid the foundations for modern Lithuanian national historiography. During Soviet times, Jonynas was a professor of history at Kaunas and Vilnius universities. In 1949, he was severely criticised by Party activists for ‘bourgeois objectivism’ and nationalism. However, Jonynas was still very popular among students, and had a huge influence on the younger generation of Lithuanian historians.

Since there were no underground organisations or networks of Soviet Lithuanian philosophers, Lithuanian lecturers and scholars of philosophy accommodated Soviet ideology, and used legal forms of activity in order to pursue the aims of cultural opposition. Philosophers played an important role in Sąjūdis (the Lithuanian national movement) in 1988-1990. One of the key figures among Lithuanian philosophers was Romualdas Ozolas. During Soviet times, he occupied nomenklatura positions, such as adviser to the deputy chair of the Council of Ministers, but at the same time he was deeply involved in various cultural initiatives that went far beyond the Soviet ideological line. Being a very scrupulous collector, Ozolas left extensive papers that are still waiting for investigation by researchers.

The collection reflects, on the one hand, the oppositional activity of the Romanian Greek Catholic (Uniate) Church towards the communist regime, and, on the other hand, the intense surveillance and harsh repression of this Church carried out by the repressive apparatus of the communist authorities. The Romanian Greek Catholic Church Ad-hoc Collection represents the most comprehensive collection of documents, which illustrates the multilayered resistance to dictatorship of one of the most repressed religious groups in communist Romania and its vivid underground religious activity from 1948 to 1989.

Limes was a circle of Hungarian dissident intellectuals which operated more or less actively from 1985 until the 1989 Romanian revolution. The aim of the circle was to provide a pluralist platform of cooperation for Hungarian intellectuals, which meant holding monthly/bimonthly organized meetings and publishing a journal dealing with the history and actual situation of the Hungarian minority from Romania, as well as other outstanding research work pertaining to other domains. The circle was also devoted to maintaining high standards of scientific work in Romania. As there was no chance of getting anything past the censors in Romania, the plan was to smuggle manuscripts to Hungary and to publish the journal there.

The initiator was Gusztáv Molnár, who mostly due to his job as a literary editor at the Bucharest-based Kriterion publishing house had a large personal network among Transylvanian Hungarian critical intellectuals. The core of the group was represented by the following individuals: Vilmos Ágoston, Béla Bíró, Gáspár Bíró, Ernő Fábián, Károly Vekov, Levente Salat, Csaba Lőrincz, Ferenc Visky, András Visky, Péter Visky, Levente Horváth, Sándor Balázs, Sándor Szilágyi N., and Éva Cs. Gyímesi. Through the process of editing the journal, many more intellectuals became acquainted with the activity of the Limes group.

Between September 1985 and November 1986, six meetings were held in four different localities in Romania in the homes of members of the group. The meetings encompassed a presentation (usually of a manuscript) followed by a debate, and all proceedings were recorded. The series of meetings was interrupted by a search and seizure performed by the Securitate in Molnár’s apartment in Bucharest. All documents related to Limes were taken and later studied by the authorities. By this time, the plan to make four Limes issues had already been completed, and the manuscripts for the first two issues had already been collected. The contents included transcripts of the Limes debates and studies and documents covering topics such as “national minorities,” “nationalism,” “totalitarianism,” “autonomy,” and “Transylvanianism” as a guiding ideology for the Hungarian minority in Romania. The topics also included the situation of the Csángó Catholic (Hungarian-speaking) population in Romania.

The Limes group ceased its activity after the intervention of the Romanian secret police, and in 1987, summons and warnings were issued to the members of the group. Though no more meetings were organized, after a while, Limes members resumed work on the texts. Molnár moved to Hungary in 1988, but the editorial work was continued in Romania by Éva Cs. Gyímesi Éva and Péter Cseke in Cluj. The first issues of Limes was published by Molnár in Budapest in late 1989. The content does not coincide with the initial first volume of the Limes, but the issues did contain excerpts from the debates which were held at the first two meetings.

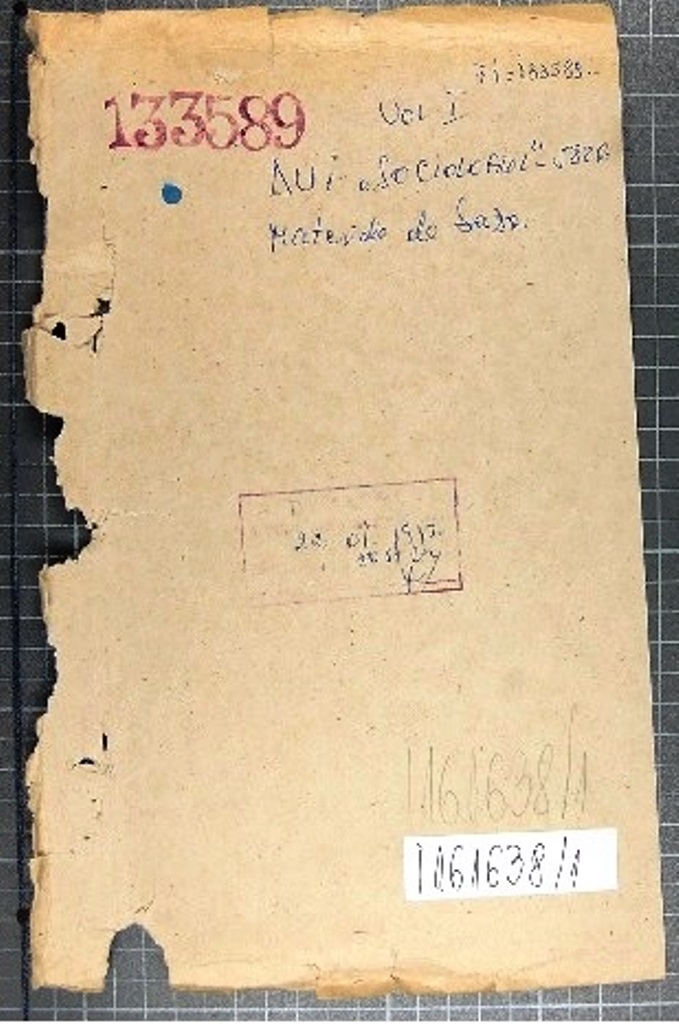

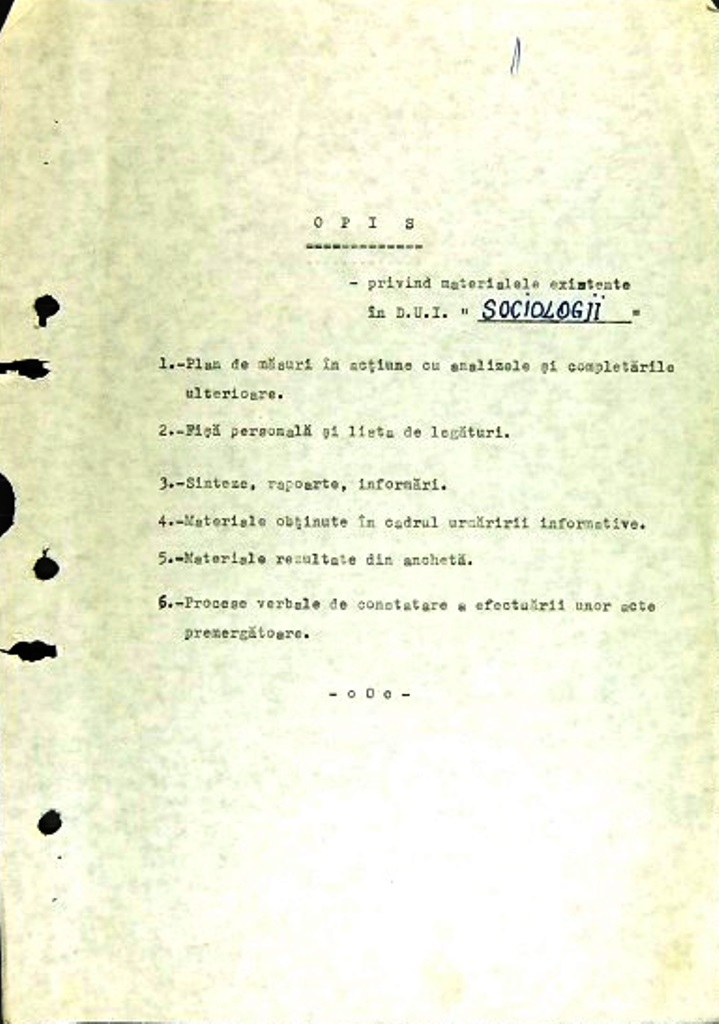

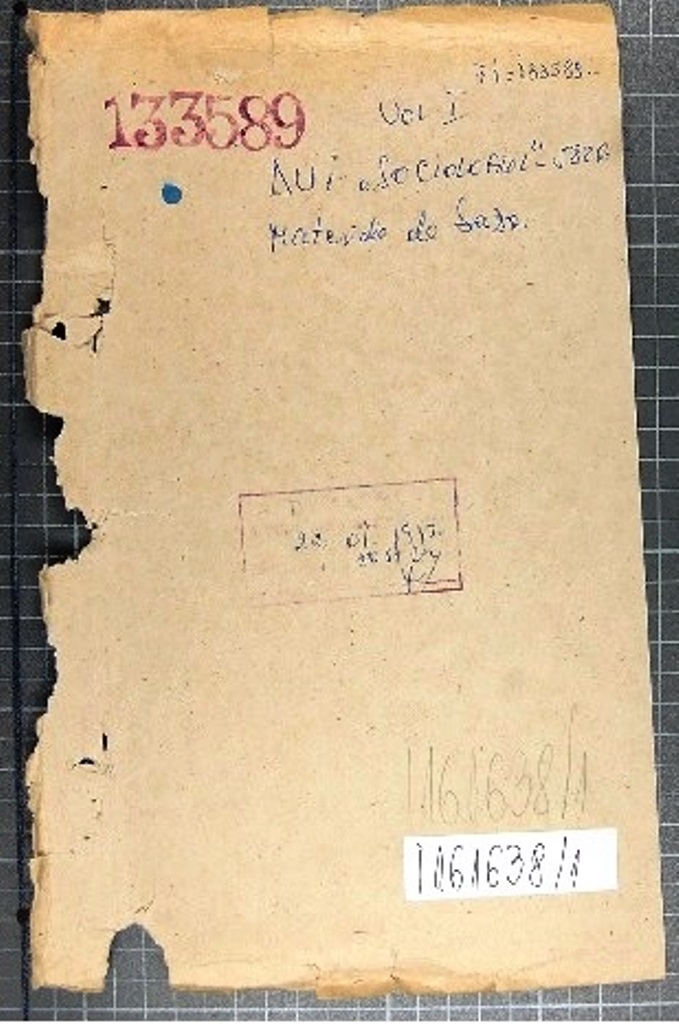

Invaluable insights into the details of the Limes story and other events in the lives of outstanding Hungarian intellectuals are provided by the Securitate files on professor of philosophy at the Babes Bolyai University Sándor Balázs (1928–), which are available for research in the Historical Collection of the Jakabffy Elemér Foundation. This is because the Limes activities in Cluj were recorded by the county agency of the Securitate as part of the information surveillance files on Sándor Balázs. His code name was “the Sociologist” (Sociologul), but the table of contents at the beginning of the dossier refers to “the Sociologists” (Sociologii), the code name used to denote the Limes group.

The dossier was opened at the beginning of 1987, and the version handed over by the CNSAS for research has three volumes which consist of some 800 folios. The files represent various types of documents: 1. strategic plans, analyses, and annexes to these plans; 2. characterizations and personal networks; 3. Syntheses, reports, and notes; 4. Information and materials obtained from surveillance; 5. Results of the monitoring activity; 6. Minutes. As noted already, the dossier contains copies of documents considered important originating from the surveillance files of other people involved in the Limes group: Éva Cs. Gyímesi (code name Elena), Péter Cseke, Gusztáv Molnár (Editorul), Lajos Kántor Lajos (Kardos), Ernő Gáll (Goga), Sándor Tóth (Toma), and Edgár Balogh (Bartha).

Sociology, along with other social sciences, was under a strong political pressure in the socialist era. After the foundation of the Sociological Research Group (1963), sociologists tried to make room for more autonomous academic activities. “Critical sociology” formed in part because many sociologists refused to legitimize the communist regime through their work. This collection gives insights into this controversial dynamic, i.e. the struggle between scholars on the one hand and political institutions on the other.

The personal collection of Croatian philosopher and sociologist Rudi Supek contains documents and photographs that testify to Supek's intellectual activity, which had been prevented in some phases of his life. Supek was the editor of two critically-oriented Marxist journals, Pogledi and Praxis, and as one of the main protagonists of the Korčula Summer School of Philosophy, he expressed views that did not align with those promoted by the Communist authorities. Supek's disagreement with the practices of the communist regime stemmed from his understanding of the position of intellectuals in society and his stance that there is no socialism without democracy. This collection also illustrates Supek's work as one of the pioneers of the environmental movement in Yugoslavia.

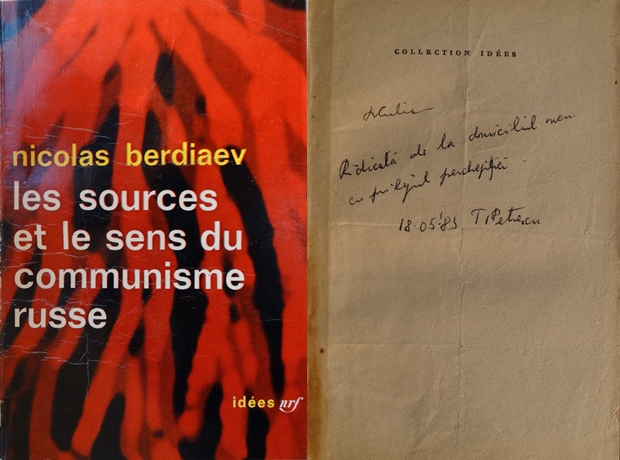

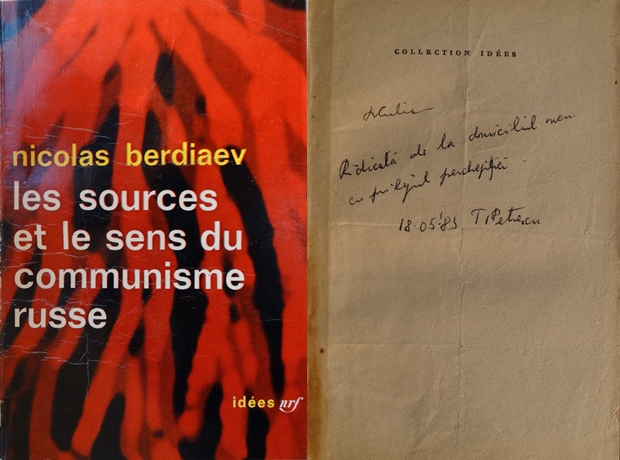

The document that records the extent of the search carried out at the home of the Petrescus on 18 May 1983 is in the family’s private collection in an original copy, made out by the officers who took part in the event. Another two copies were kept by the communist authorities of the time. The minute records that the Petrescus were present at the search, as were two witnesses. It consists of four pages, very clearly written, and is made out in the name of the Iaşi County Inspectorate of the Securitate. Each page is signed both by the representatives of the forces of control and repression and by the witnesses and the couple themselves. The document lists the objects that were kept by the Securitate on this occasion: books; audio cassettes, including one containing a recording of Virgil Ierunca’s broadcast on Radio Free Europe in which he highly praised Dan Petrescu and other young intellectuals in Iaşi for their articles in the student magazines Dialog and Opinia Studenţească; rolls of recording tape; photographs; letters from various people; pages of notes; and a folder labelled “Furrows across the baulks – feuilleton novel of the collectivisation,” containing forty-five leaves of the manuscript of this collective novel. Among the books confiscated were some that later became classic works of critical analysis of the communist system, but which were very recent publications at the time, for example La Nomenklatura, les privilégiés en URSS by Mikhail Voslensky (1980) and L'Union soviétique survivra-t-elle en 1984? by Andrei Amalrik (1977). There were also critical works on Romanian communism published by Romanian writers in exile, such as La Cité totale by Constantin Dumitrescu (1980). The couple managed to save some books from confiscation, but of those removed from their home by the Securitate only one was given back to them, though it is not clear on which criteria this particular book, Les Sources et le sens du communisme russe by Nikolai Berdyaev, was returned – perhaps because it dated from 1938, so was much older than the others. Thérèse Culianu-Petrescu recalls how they managed to hide some of the most critical, and implicitly the most incriminating books: “The next day, 18 May 1983, at six o’clock sharp in the morning, the guys burst in. […] At first they were very pleasant. They gave us time to get dressed, and those minutes gave us a chance to remove some books, to give them to my aunt, who stuck them under her jacket, under her overcoat. Solzhenitsyn, for example. We saved the Gulag and a few others. My aunt took them into her room, where they had no mandate to enter and where they didn’t think of entering. [… Wherever they had a mandate,] they left nothing untouched. Nothing, nothing. You realised that you could hide something anywhere, in the garden, in the house, in the woodshed, and they would rummage around and they could find it. They were capable of moving everything, of going through everything.” And regarding the immediate consequence of the search, interrogation at the Securitate headquarters, she adds: “The search lasted approximately five hours. From six in the morning to eleven. […] Then they took us up – ‘up’ meaning to the Securitate. It was on a street named Triumfului. Now after 1989, the gangs of Securitate people have built a district of apartment blocks that they own.” Dan Petrescu adds, with regard to the manner in which those who came conduct the search acted in order to find what interested them, underlining that the Securitate was particularly interested in a cassette with the recording of a Radio Free Europe broadcast, in which some young Iaşi writers had been highly praised, among them himself, and in the manuscript of the collective novel: “They had come on the basis of information, for they were looking for certain things. They were looking for a recording of a broadcast on Radio Free Europe where [Virgil] Ierunca praised us and… they were looking for books […] They confiscated a lot of books from us. Only one was given back to us, after the search. Berdyaev – his book about the sources and the meaning of communism. At the same time they asked me about the novel [“Furrows Across the Baulks” revisited]. I said to them: ‘Why are you still looking for it? Because you’ve already got it.’ They had taken it from George Pruteanu. […] It didn’t exist in more than one manuscript. There were no copies. It passed from one to the next and each one added to it. They were also looking for letters in the search.” Dan Petrescu adds, to give a clearer picture of those months, another detail that casts a new light on that moment: “The search took place, at our home, in May 1983. In March, I found out later in documents at CNSAS, the Securitate guys had made new recruits in literary circles in Iaşi. Ten new names. In editorial boards of periodicals, publishing houses, that sort of thing.”

Problemos (Problems) is a Lithuanian academic philosophical journal published by Vilnius University. The journal was reorganised during the 1960s and 1970s, when the community of Soviet Lithuanian philosophers made attempts to produce a serious academic journal, with critical articles, reviews and translations of Western authors. This initiative was seen very negatively by cultural administrators at that time. The minutes of a meeting on 27 November 1972 demonstrates the attempts of the government to direct Problemos the ‘right way’. Philosophers, the authors of papers in Problemos, were criticised at the meeting for their passive ideological stance, and their lack of publications on communist ideology. After the meeting, the control of Problemos became stronger, and the content of its volumes was thematically limited. According to the philosopher Algimantas Jankauskas, after strengthening the controls, a core group of Lithuanian philosophers, including Romualdas Ozolas, started to think of producing an underground samizdat philosophy journal. But they later decided to keep to legal cultural opposition. They initiated and established a series of books on the history of philosophy ‘Filosofijos istorijos chrestomatija’ (Chrestomatia of the History of Philosophy), which resulted in a number of volumes being published in 1974-1987.

Márton, Áron. 2016. Egyház – Állam (Church – State). Drawn-up and notes added by József Marton. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print Könyvkiadó

Márton, Áron. 2016. Egyház – Állam (Church – State). Drawn-up and notes added by József Marton. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print Könyvkiadó

The thirteenth volume of the series entitled Áron Márton’s Legacy comprises those of the bishop’s writings that had been addressed to the state authorities. As a bishop, Áron Márton represented the diocese of Alba Iulia for forty-two years and on occasion the other Transylvanian Roman Catholic dioceses as well. His episcopate was not free of cares; following the years of royal dictatorship, he remained in Southern Transylvania after the Second Vienna Award to offer hope for his congregation members, who held a minority status. Then, following the Second World War, the much-awaited peace failed to arrive and the religion-persecuting dictatorship inherent in the Romanian version of Soviet power came instead. Throughout these years, the supreme power in Bucharest proved helpful or tolerant for only very short periods as there was a twofold pressure on the Hungarian Roman Catholic congregation members, clergy, and bishop, as a minority both through confessional otherness and through differences in mother tongue.

In the four years between 1948 and 1951, besides the nationalisation of ecclesiastical schools, the conversion of Greek Catholics to Orthodoxy by force, and the abolition of monastic orders, priests and monks had to face imprisonment, forced labour, and persecution. After Áron Márton’s release in 1955 he was the only active Roman Catholic bishop in Romania. He had to establish contact with both the local and central authorities, and, considering the correlation of forces, this relationship was a subordinating one and, consequently, marked by struggle and compromises. In this struggle the bishop had only two instruments to resort to: asking and protesting. Surrender was not possible as he had to undergo all the hardships for his priests and congregation. His letters are classic examples for minority leaders regarding the nature of their attitude toward the government. The letters in which he asked for something were written in such a manner that he never humiliated himself; at all times he maintained his human dignity and his episcopal stance and remained unbiased. The official letters published in the volume represent testimonies to the bishop’s straightforwardness, honesty, sense of responsibility, empathy, and regard towards the authorities. They speak about people who suffered, in whose interests he intervened before the local authorities or the Ministry of Religious Affairs and later before the competent authorities of the Office of Religious Affairs. He had to defend his congregation members against national oppression, rather than against purely religious offences. The letters arranged in chronological order according to the changes in history reflect the serious problems characteristic of the period and reveal the relationship between State and Church through time. The bishop’s official writings and letters published in the volume help readers to “get acquainted with and make out” the laws regulating the ecclesiastical life of the time, considering that their application produced mostly negative effects and led to restrictive consequences.

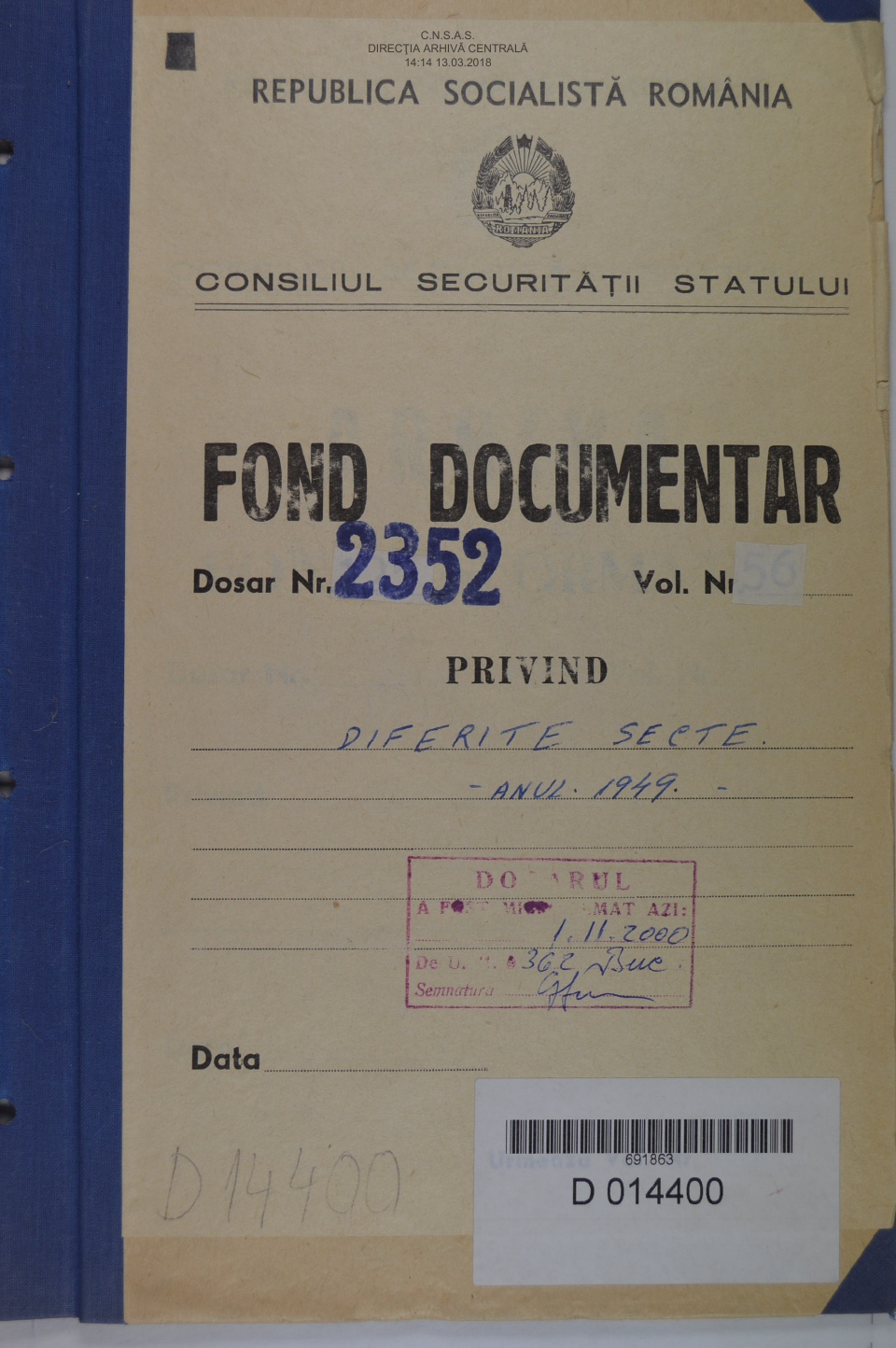

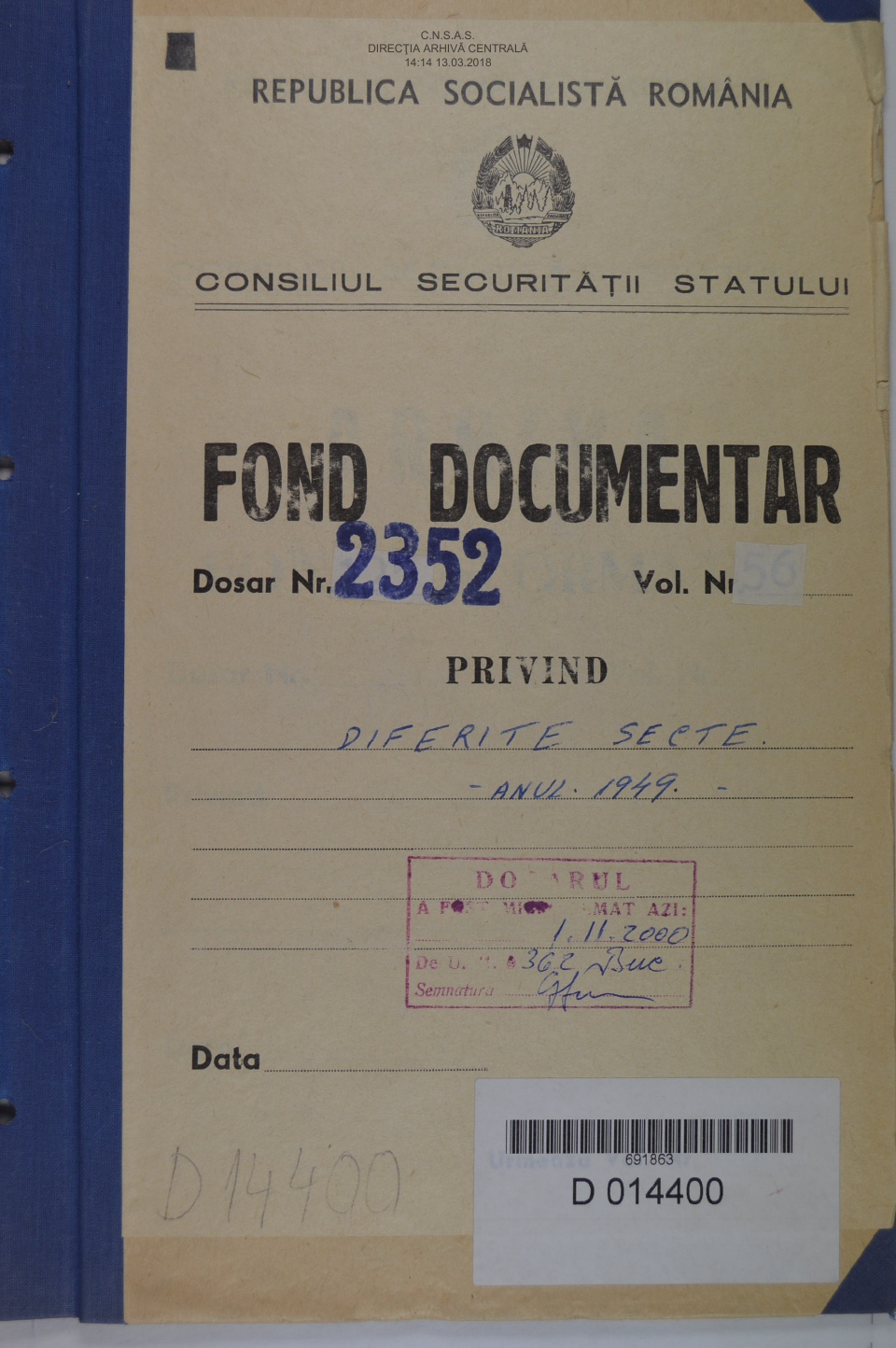

The collection reflects the variety of religious dissent in communist Romania, and illustrates the underground religious practices and overt religious oppositional activities from the late 1940s until the 1980s. The collection comprises, on the one hand, documents and other cultural artefacts created by various religious denominations and confiscated by the Securitate and, on the other hand, documents created by the secret police. The latter illustrate the intense surveillance and the repressive policies of the secret police directed towards those religious activities that opposed the policies of the communist regime in Romania.

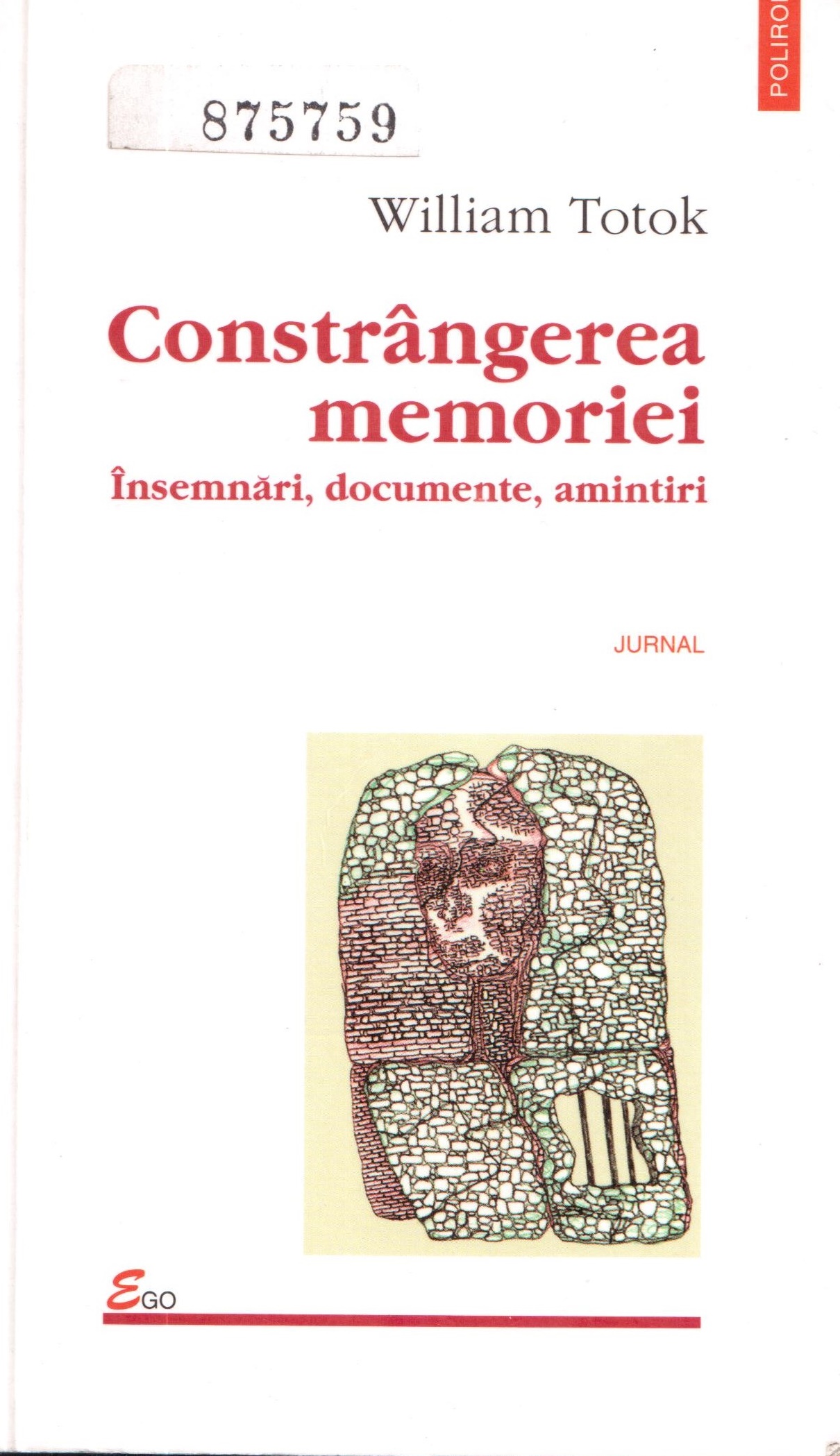

Totok, William. Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (A project for an intellectual extermination), in German, 1976-1977. Manuscript

Totok, William. Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (A project for an intellectual extermination), in German, 1976-1977. Manuscript

In the period from 1975 to 1976, William Totok spent more than eight months in arrest at the Securitate for his involvement in the Aktionsgruppe Banat literary group, considered subversive by the authorities,and for his criticism of Ceaușescu’s political regime. Totok was released in June 1976 after the publication in the newspapers Frankfurter Rundschau and Le Monde of articles presenting the abuses of the communist authorities in his case. After his release, Totok drew up a manuscript of memoirs entitled Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (A project for an intellectual extermination), in which he recounted his experience as political prisoner. In May 1982, the Securitate carried out a search at his domicile and at that of one of his friends, the Romanian-German writer Horst Samson. On this occasion several documents were confiscated, including one copy of the manuscript of these memoirs (ACNSAS, I 210 845, vol. 2, 265–66; Totok 2001, 107–108).

In this manuscript, Totok recounts in detail the conditions in the political prison in Timișoara, the interrogations carried out by the Securitate, and the story of a letter drawn up between the two periods of arrest (Totok was released for a short period in October 1975, only to be arrested again in November 1975). In this letter, sent by his mother to the Federal Republic of Germany after his second arrest, Totok related the dramatic events of the abusive arrest of his colleagues and himself in October 1975 and all the harassments of the secret police. Fortunately, the copy of the manuscript of this memoirs that was confiscated by the Securitate was not the only one. Totok managed to hide a copy and to smuggle it out of the country to the Federal Republic of Germany after his emigration in March 1987. In 1988, Totok published a revised and extended version of this manuscript under the title: Die Zwänge der Erinnerung: Aufzeichnungen aus Rumänien (The constraint of memory: Recollections from Romania).

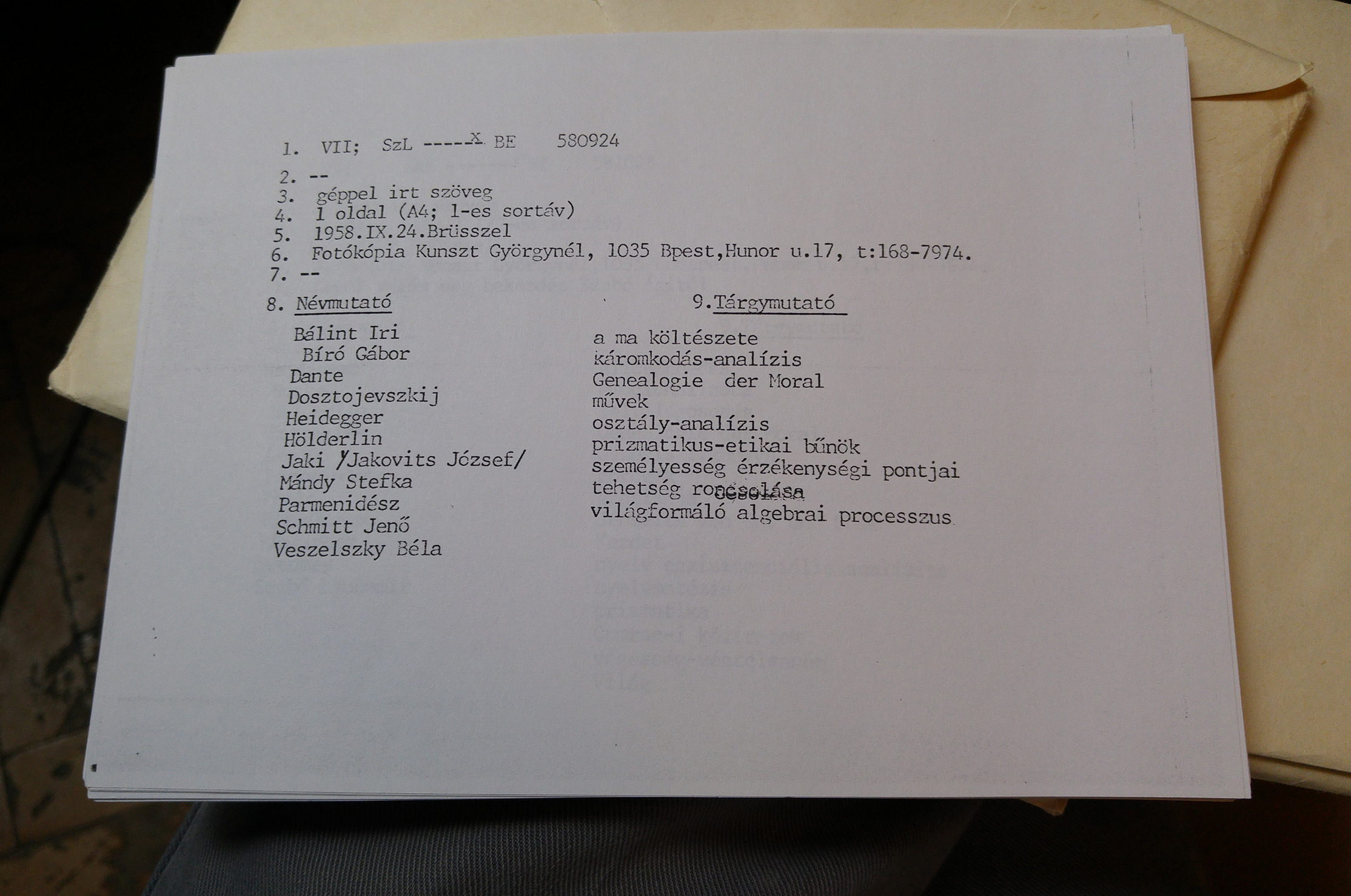

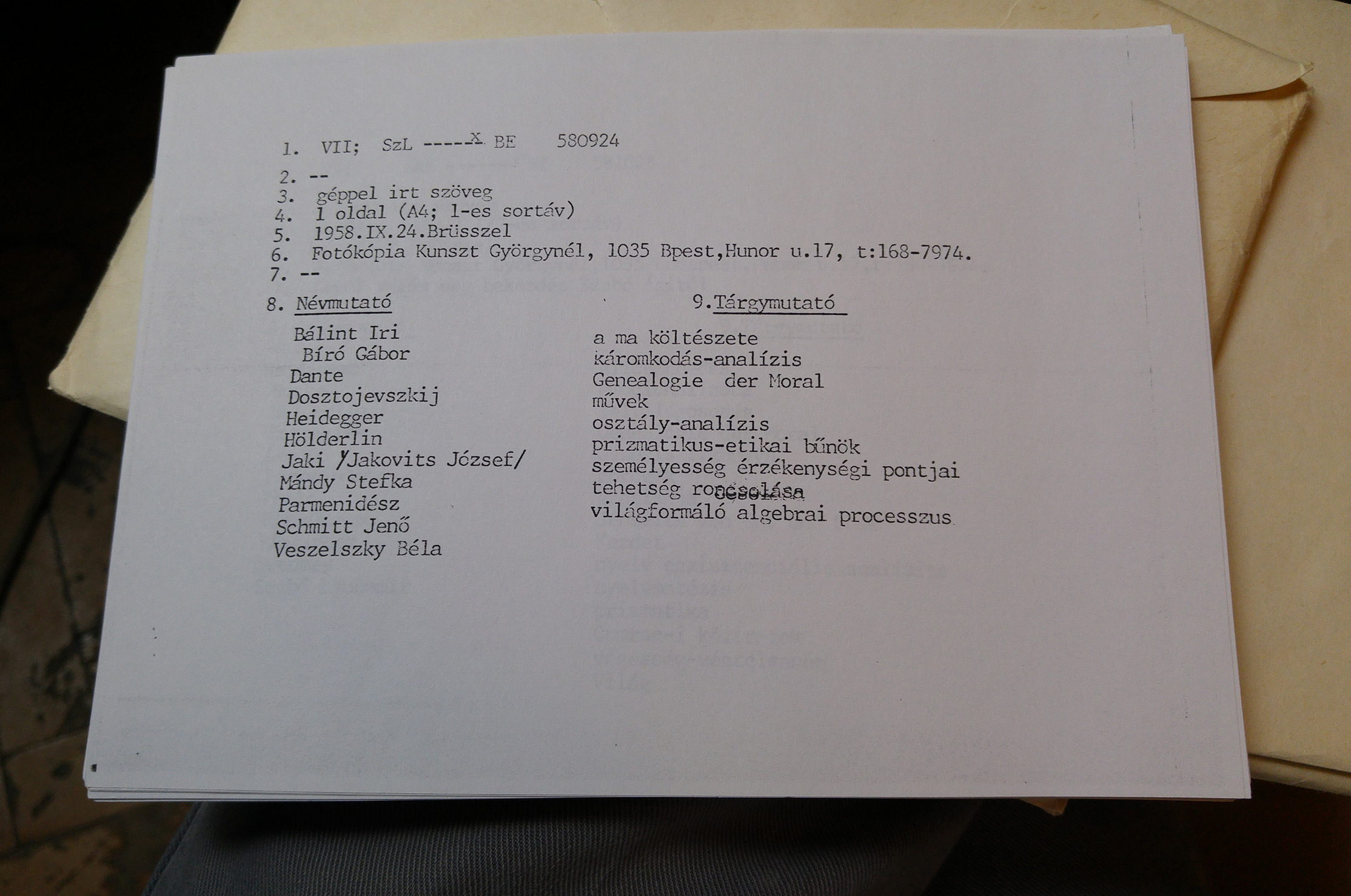

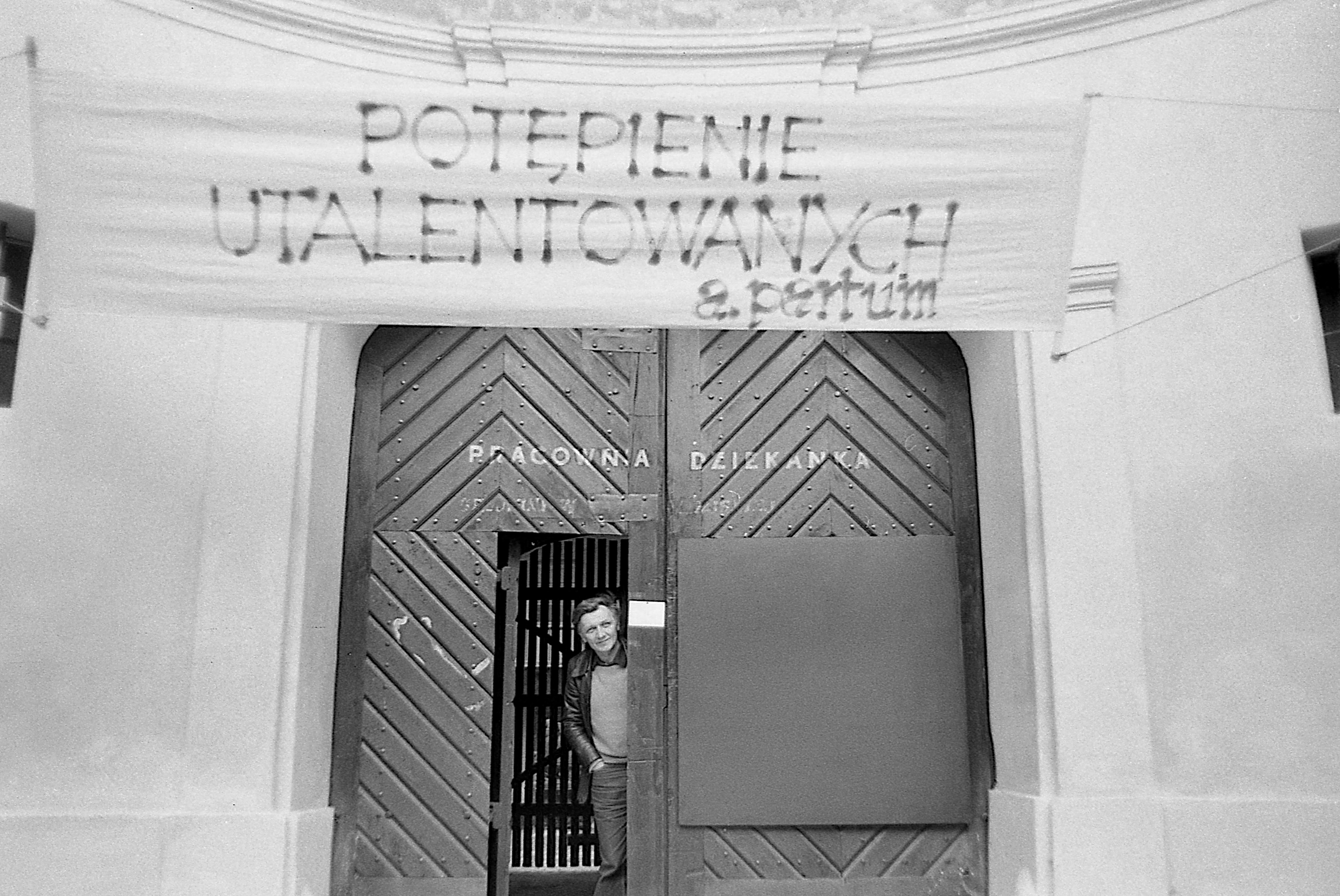

This index was created during the systematization of the oeuvre of Lajos Szabó, following the principles worked out by György Kunszt. It specifies a surprisingly long list of names and subjects compared to the length of the whole document, one typed page, created during the second year in emigration. It lists many names from their circle of friends in Budapest (but not only them). The list of subjects includes promising items, as “analysis of damnation” and “Genealogie der Moral.” It is a nice coincidence that the word “destruction” appears smudgy on the paper.

The Czecho-Slovak poet, novelist, playwright, philosopher and “guru” of the Czechoslovak underground, Egon Bondy (real name Zbyněk Fišer, 1930–2007), is well known as the author of dozens of collections of poems and novels. His philosophical texts, however, are an equally significant part of his work. Bondy, who graduated in philosophy from the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, was also interested in Eastern philosophy, in particular Buddhism. He wrote several academics studies on this topic in the first half of the 1960s, and published the book “Buddha” under his real name in 1968 through the publishing house Orbis. This significant study on the founder of Buddhism and his teachings caused a sensation in Czechoslovakia. The book was later republished twice (1995, 2006) in the Czech Republic and still remains topical.Bondy’s manuscript of his study of Buddha and his teachings was bought by the Museum of Czech Literature (PNP) in 1986 and is now part of the Egon Bondy collection deposited in the Literary Archive of PNP.

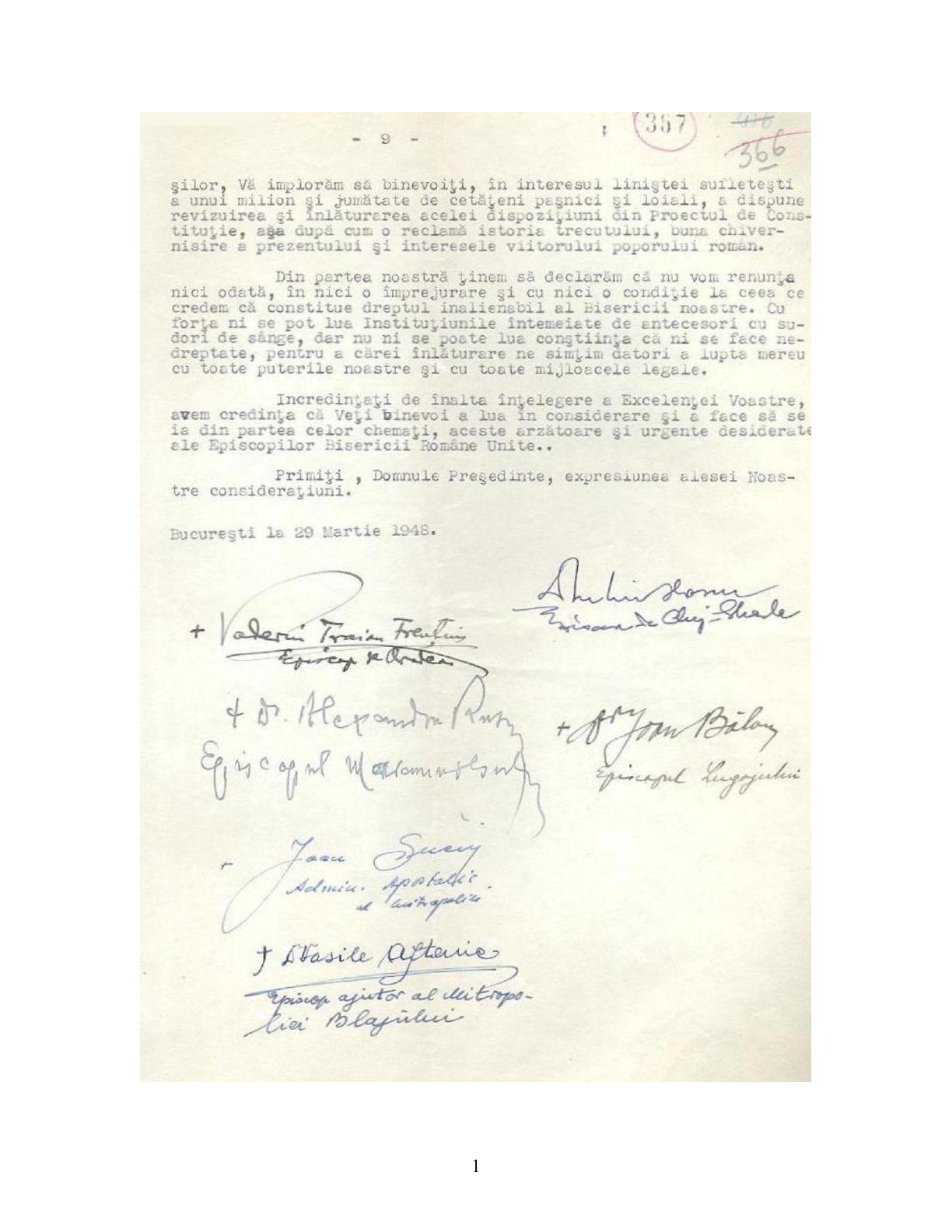

Memorandum addressed to the president of the Presidium of the Great National Assembly, in Romanian, 1948. Manuscript (copy)

Memorandum addressed to the president of the Presidium of the Great National Assembly, in Romanian, 1948. Manuscript (copy)

The Memorandum addressed to the president of the Presidium of the Great National Assembly on 29 March 1948 by the six Romanian Greek Catholic bishops concerns those aspects of the project of the 1948 Romanian Constitution which hampered religious freedom in Romania. The six Romanian Greek Catholic bishops who signed the document and assumed the risk of being arrested were: Valeriu Traian Frenţiu (Bishop of Oradea), Iuliu Hossu (Bishop of Cluj-Gherla), Alexandru Rusu (Bishop of Maramureş), Ioan Bălan (Bishop of Lugoj), Ioan Suciu (Auxiliary Bishop of Oradea) and Vasile Aftenie (Auxiliary Bishop and Vicar Bishop of Bucharest and the Old Kingdom.This risk was materialised in the autumn of 1948 when they were arrested and imprisoned by the Securitate for their obstinate resistance to the abusive policies of the communist regime towards their church (Vasile 2002).

In the introduction of the Memorandum the leadership of the Church emphasise the importance of the new Constitution and the real need for social reforms in the country, which the 1948 Constitution included. After this captatio benevolentiae, the six bishops bring to the fore those stipulations which in their opinion could “violate natural and perennial human rights” and the international obligations assumed by the Romanian state through international treaties (ACNSAS, Fond Documentar, dosar FD 8792, ff. 359–360). Their criticism targets especially article 28, the third part of the project of the 1948 Constitution, which stated: “No congregation or religious denomination may establish and administrate institutions of general education, but only special schools aimed at training the staff of the religious denomination under the control of the state” (f. 361).

The argument of the Memorandum is that the stipulations of the third part of article 28 is in contradiction with another part of the same article, which stipulated freedom of religion. By these limitations concerning the education system, the Greek Catholic bishops considered that an important aspect of the freedom of religion was violated. Thus, in their opinion the third part “suppresses those generous stipulations proclaimed previously” (f. 362).

The Memorandum emphasises the natural right of citizens to educate their children according to their values and convictions. The bishops invoke the long tradition not only of Greek Catholic but also of Orthodox confessional schools in Transylvania, and emphasise their importance in the affirmation of Romanian national culture and identity in Transylvania (f. 363). The bishops also emphasise that the confessional schools were attended during the nineteenth century mainly by children of peasant origin and represented a lever for social emancipation for the Romanian population of this region.

In conclusion, the text points out that the decision to abolish the confessional educational system in Romania will be an act of injustice from many points of view and states that: “For our part, we stand firm to declare that we will never give up, in any circumstances and on any conditions, what we believe is the inalienable right of our Church.” All the six Greek Catholic Bishops signed the document, which was addressed to the communist authorities. A copy of this document was attached to the files of the Documentary Fonds, created by the Securitate in order to document the “Greek Catholic issue”.

Doina Cornea was a leading dissident in communist Romania, who started by criticising the educational and cultural policies of Ceaușescu’s regime and issuing some modest samizdat materials, and ended up as the driving force behind several collective actions against the arbitrary actions of Ceaușescu’s regime and the trigger of the most significant transnational network in defence of the Romanian villages menaced with destruction by the regime. Accordingly, the Doina Cornea Ad-Hoc Collection at CNSAS constitutes one of the largest collections of documents referring to one single individual and includes not only records created by the secret police while trying to counter her actions, but also materials confiscated as evidence of those actions.

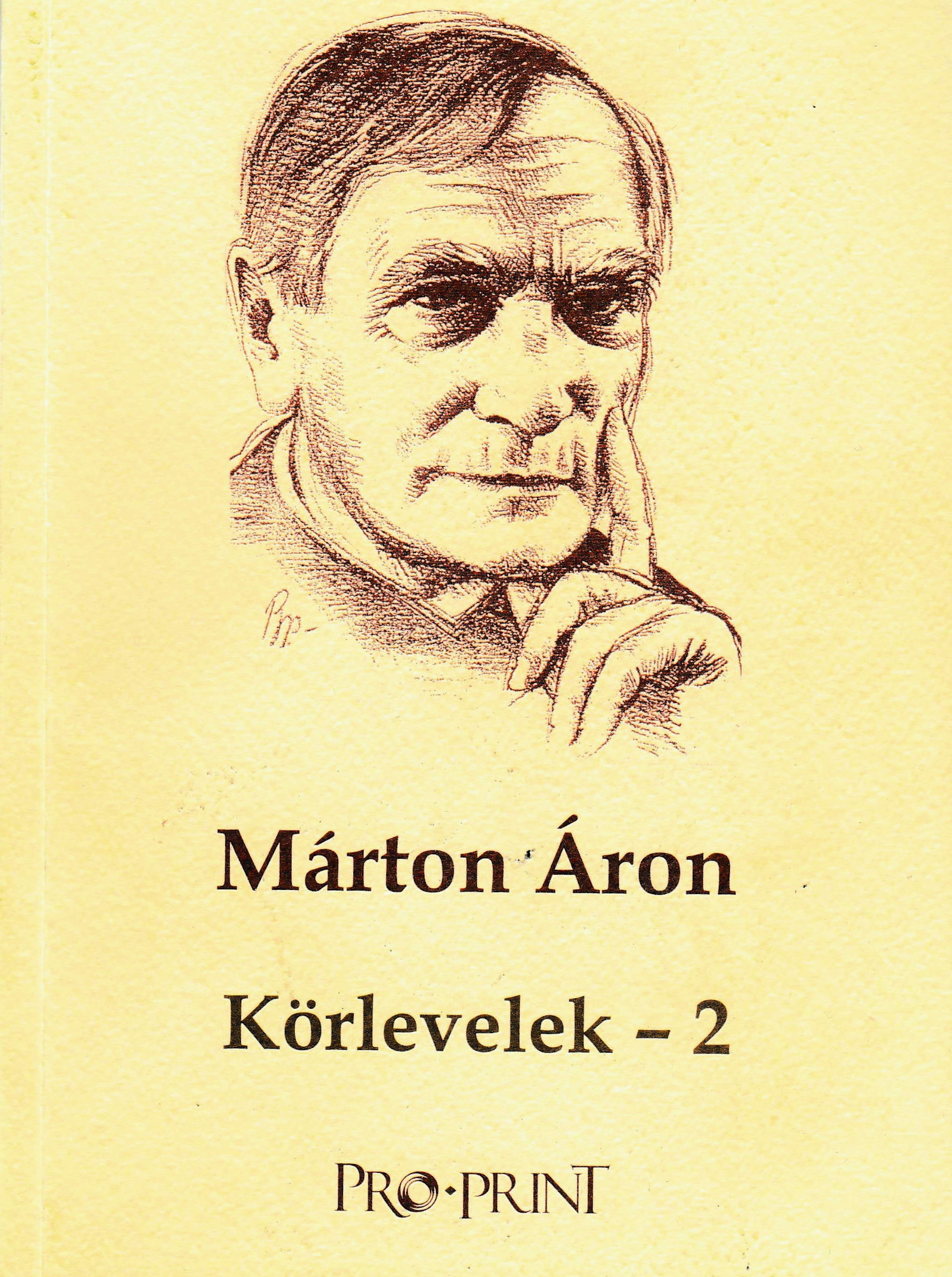

Márton, Áron. 2015. Körlevelek – 2 (Circulars – 2). Drawn-up and notes added by József Marton. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print Könyvkiadó

Márton, Áron. 2015. Körlevelek – 2 (Circulars – 2). Drawn-up and notes added by József Marton. Csíkszereda: Pro-Print Könyvkiadó

As a continuation of the eleventh volume covering the time interval between 1938–1947, the twelfth volume of the Áron Márton’s Legacy series, based on the materials stored in the Archiepiscopal and Capitular Archives within the Archdiocesan Archives in Alba Iulia, respectively, in the Áron Márton Museum, contains the bishop’s circulars written during the communist era, between 1948–1980.

Despite the guarantee of “freedom of conscience and of religion” laid down in the text of the new Constitution published in 1948, laws and decrees restricting the rights of churches were passed one after the other. In attacking the Catholic Church the Party first eliminated the formal obstacle: on 19 July 1948 the Presidential Council of the Romanian People’s Republic unilaterally cancelled the concordat concluded with the Holy See in 1927. Then they proclaimed the so-called “School Law” no. 175 of 3 August 1948 and the associated Decree no. 176, which was followed by the so-called “Law of Religious Denominations” of 4 August. The latter law, beside imposing a strict control over religious denominations, prohibited, by its Article 41, the enforcement of papal jurisdiction in the Romanian People’s Republic, thus rendering the existence of the Catholic church impossible. As opposed to the other thirteen denominations operating on the basis of rules of organisation and operation, this article of the law was immediately responsible for the “tolerated” status of the Catholic church until 1990. Already from the very beginning the communist system closely monitored persons and institutions that held different views, and these included, apart from the Catholic clergy considered as an enemy of popular democracy, also the Catholic church, which lacked a Statute.

In these hard times, amidst the attacks and warnings, Áron Márton could resort only to his circulars in order to encourage and spiritually strengthen his priests and congregation, as he had no alternative than to deal with the existing laws. In 1948 – according to the twelfth volume – he issued twenty circulars, the contents of which shed light on the violent nature of the dictatorship and its anti-religious manifestations. After the nationalisation of church schools, the operation of the Seminary was also of pressing concern to the bishop, as due to the elimination of financial support, the maintenance of the institution became the task of the diocese. He successfully asked for help from congregation members: “Please be of help in our poverty even amidst your own poverty.” Religious teaching is, after the preaching of the Gospel, the most important field of pastoral service. The new system primarily targeted young people with its materialistic teachings and it was not accidental that by means of the law of public education it banned religious education from the institutional curriculum, finding ways and means to interfere also in extracurricular education. Áron Márton recognised and put on paper the road to escape: “After the elimination of religious education from the school curriculum, Catholic families are facing a new task,” and called upon parents asking them to undertake the religious education of their children in a conscientious and responsible manner. He also used circulars to indicate the proper Christian conduct for the difficult times that awaited his priests and congregation members, preparing them for the challenges and all the while cautioning them against opportunism. At the same time in his circular from 6 October 1948 he adopted an adequately strict tonality: “I hereby inform all Catholic congregation members, that any Catholic priest or believer, irrespective of Catholic ritual, who participates in any assembly held with the purpose to promote his/her break-away from the Catholic church, shall be immediately ostracised from the Church without the need for any further measures.” The same circular stipulated the support to be offered to the Greek Catholics, too: “I hereby call upon and ask my R[espected]. Priests, to display courteous love in offering the greatest possible religious support and help to our Greek Catholic brothers, and whenever necessary, to readily put our churches, chalices, and ecclesiastical equipment at their disposal so that they can officiate masses according to the Eastern rite. Let us pray for them!” On 20 October 1948, the bishop repeated the issue of support, clarifying things: “My R[espected]. Priests may only grant permission to Greek Catholic priests to officiate masses in our churches, if the Greek Catholic priests in question are prevented by external circumstances from officiating masses in their own churches and if they have indisputable, positive knowledge of the fact that they had not signed the declaration of schism, or that they have received final absolution from ostracism, and in case of suspicion in this respect, we must await the up-to-date certificate issued by the competent Ordinarius regarding the fact that the persons in question are not under ecclesiastical punishment.”

During the six years following Áron Márton’s arrest his circulars ceased too. On 25 March 1955, a day after his return from prison to Alba Iulia, the bishop issued a new circular. In order to eliminate the atmosphere of distrust generated by the lack of priests and by the authorities he asked for two things from his priests: discipline and work. He received authorisation from the state authorities to turn to the pope first in a telegram, then in a letter. However, the maintenance of contact with Rome was rather difficult as in 1955 official records were delivered only haltingly. The bishop who animated even dormant souls continued to be not particularly welcome, and by virtue of the government decree of 5 June 1957 they restricted his free movement and office administrative work, confining the bishop to his room for eleven years by force. They supplemented this “punishment” by imposing a restriction on the subject-matter of his circulars, too. The bishop was only allowed to communicate measures regarding official matters to his priests: retirement, tax and financial rules, provisions concerning the preservation and restoration of monuments, dispositions regarding the liturgy and spiritual exercises for the clergy, priest training, chorister training, issues pertaining to religious education, etc. However, beyond this, the preparations for the second Vatican Council (1962–1965), his works and the implementation of his objectives, and the announcements of the holy years (1965–1975) encouraged him to write circulars. These circulars expressly contain ecclesiastical notifications and calls for prayer.

The volume also contains several draft circulars and documents written upon “request,” which can be explained by political historical factors. One of the manifestations of the political elite in Bucharest in its rapprochement efforts towards the West was that already from the early 1960s it sought the favours of churches, as with their mediation they could approach the more important countries and thus they could obtain the abolition of certain economic restrictions. It may be no accident that Áron Márton’s house arrest was also suspended precisely in November 1967. In February 1968 Ceaușescu summoned the Romanian religious leaders and in August 1968, at the time of the invasion of Czechoslovakia, he initiated the issue of a common circular which Áron Márton also complied with. At the same time, grabbing the opportunity, the bishop also submitted a separate declaration to the government, in which he expressed his views regarding the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. In 1973, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the proclamation of the Romanian Socialist Republic, and in 1974, on the thirtieth anniversary of the liberation from German occupation, which was then the Romanian national day, the communist authorities also asked for festive manifestations from the bishop. However, these remained only drafts, as their contents (the bishop raised his voice in the interest of his people living with a minority status) prevented them from obtaining authorisation for distribution. In 1974, following a serious surgical intervention, Áron Márton decided to adopt a more restrained work schedule and assigned part of his duties to his suffragan. From then on the number of his circulars decreased; he issued only a few of them in a year. His last circular, in which he said goodbye to his diocese, was drawn-up in 1980 by the suffragan Antal Jakab, theology professor József Huber, and office director Lajos Erőss on the basis of the bishop’s earlier circulars. However, it was still signed by Áron Márton himself.

The collection reflects the activity of the Romanian-German writer and journalist William Totok, persecuted by the communist authorities for the criticism towards Ceaușescu’s political regime expressed in his literary texts. The William Totok private collection comprises mainly books, literary manuscripts, drafts of academic papers, audio and video documents, and correspondence.

The High Consistory Collection includes mostly of documents issued by the High Consistory of the Evangelical Church of Augustan Confession of Romania in the period 1922–1990, together with the minutes of meetings of the High Consistory and documents concerning institutional communication with parishes and with the state authorities. The collection illustrates the opposition of the Evangelical Church A.C. of Romania to the policies of the communist regime in certain domains, such as religious education.

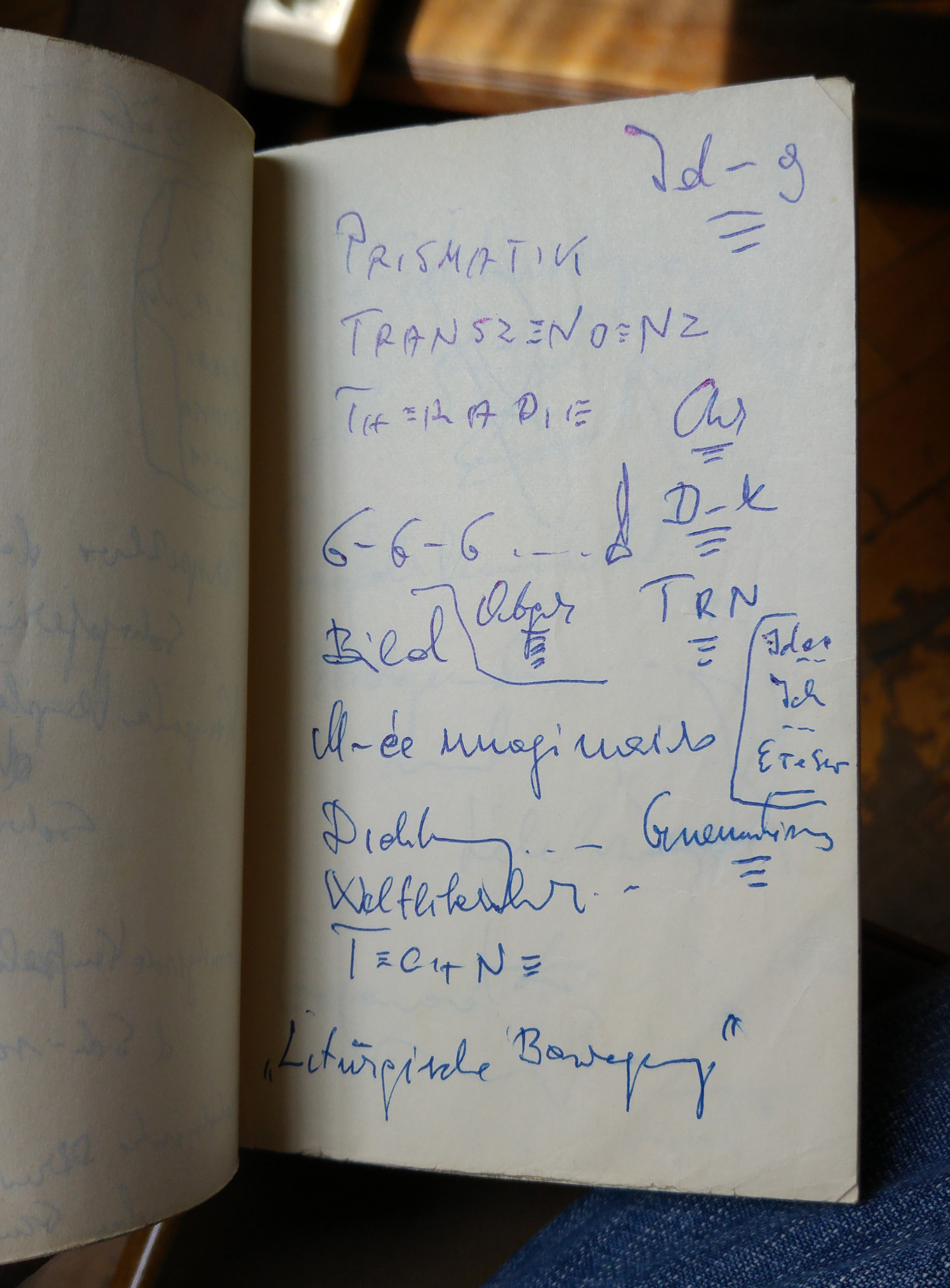

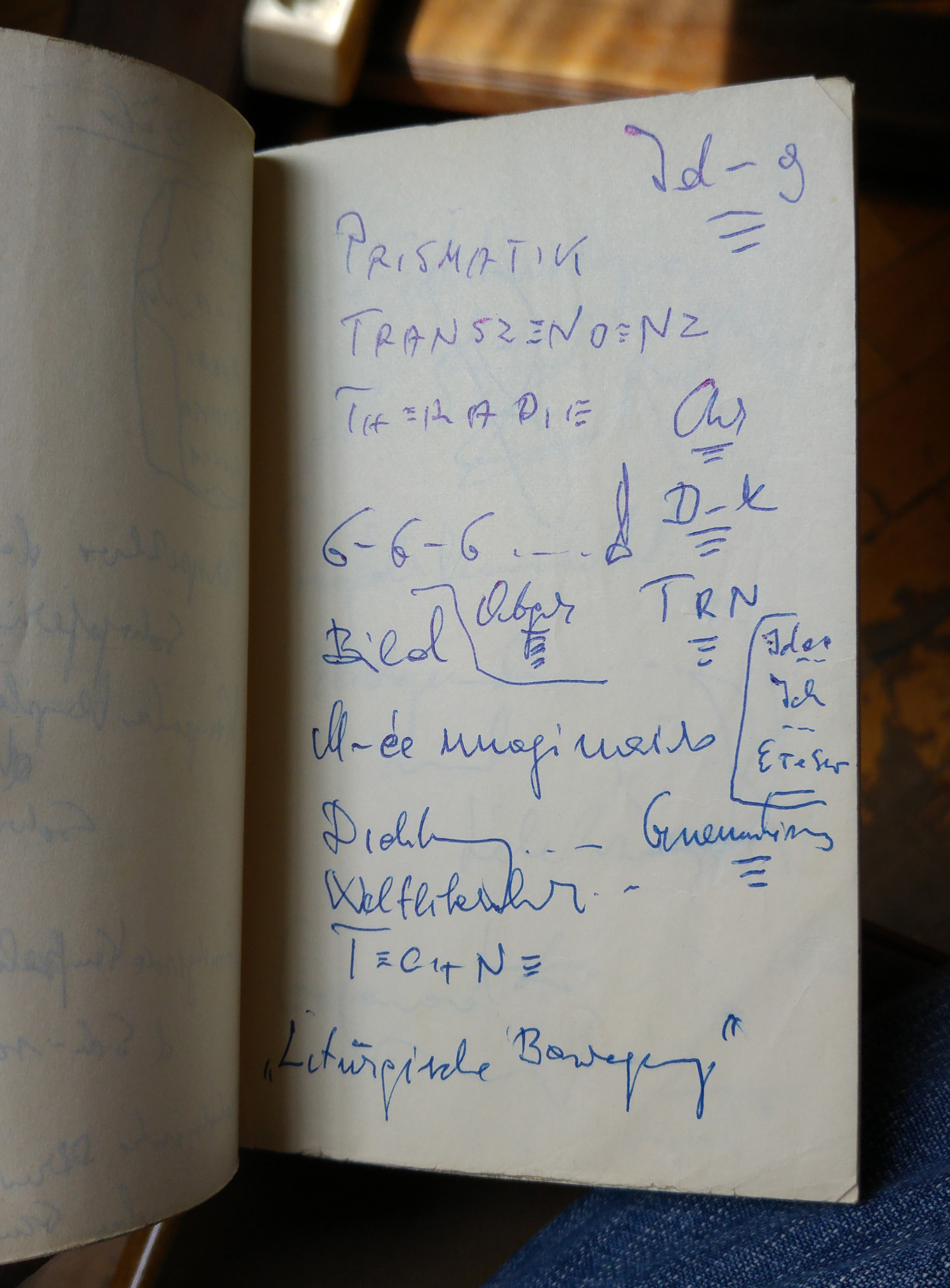

The philosophical notes of Lajos Szabó made in the years he spent abroad (between 1956 and 1967) fill more than one hundred and sixty notebooks. These notes in most cases are not contiguous texts, but groups of keywords and names, as Attila Kotányi drafted it, “systematizing scalings marked by abbreviations, paths of the branching correlations.” Szabó considered exact wording important, so he worked continuously on the purgation of language.

This concrete page was written in German. The first keyword, prismatic, refers to the interrelation of logic, ethics, and aesthetics (they relate as the prism makes colors visible). This concept has great significance in his thought. According to Kotányi, “this triple interrelation is the central dome of his philosophy.” As he worded it, “Prismatic research reveals the vortex motion of beauty, good, and true, in contrast with the dimness of ‘spirit’. The spirit is the unity, movement and energy of this three motifs.”

The Krunoslav Draganović Collection on World War II and Post-war Victims is an archive collection whose original collector was the priest Krunoslav Draganović, who, relying primarily on the testimonies of survivors and other witnesses, planned to publish a book on the crimes of the Yugoslav communists.

The collection includes the documents of the Danube Circle Association, which was a non-governmental organization in opposition to the government’s project to construct a River Barrage Dam near Nagymaros (Hungary) in the 1980s. The Danube Circle movement tried to prevent the construction of the dam with samizdats, public debates, and protests. The Circle was one of the new types of alternative movements, which expanded the base of the “traditional” intellectual opposition.

Szabolcs Vajay’s collection is the bequest of a Hungarian scholar who represented classic European erudition. It also documents the efforts to save a marginalized culture. The collection offers insights into a way of life in exile which is centered around efforts to preserve heritage abroad, a lifestyle which arose in part as a response to political assault on culture.

Totok, William. Wieland durch die Lorgnette gelesen (Wieland seen through the lorgnette), in German, n.d. Manuscript

Totok, William. Wieland durch die Lorgnette gelesen (Wieland seen through the lorgnette), in German, n.d. Manuscript