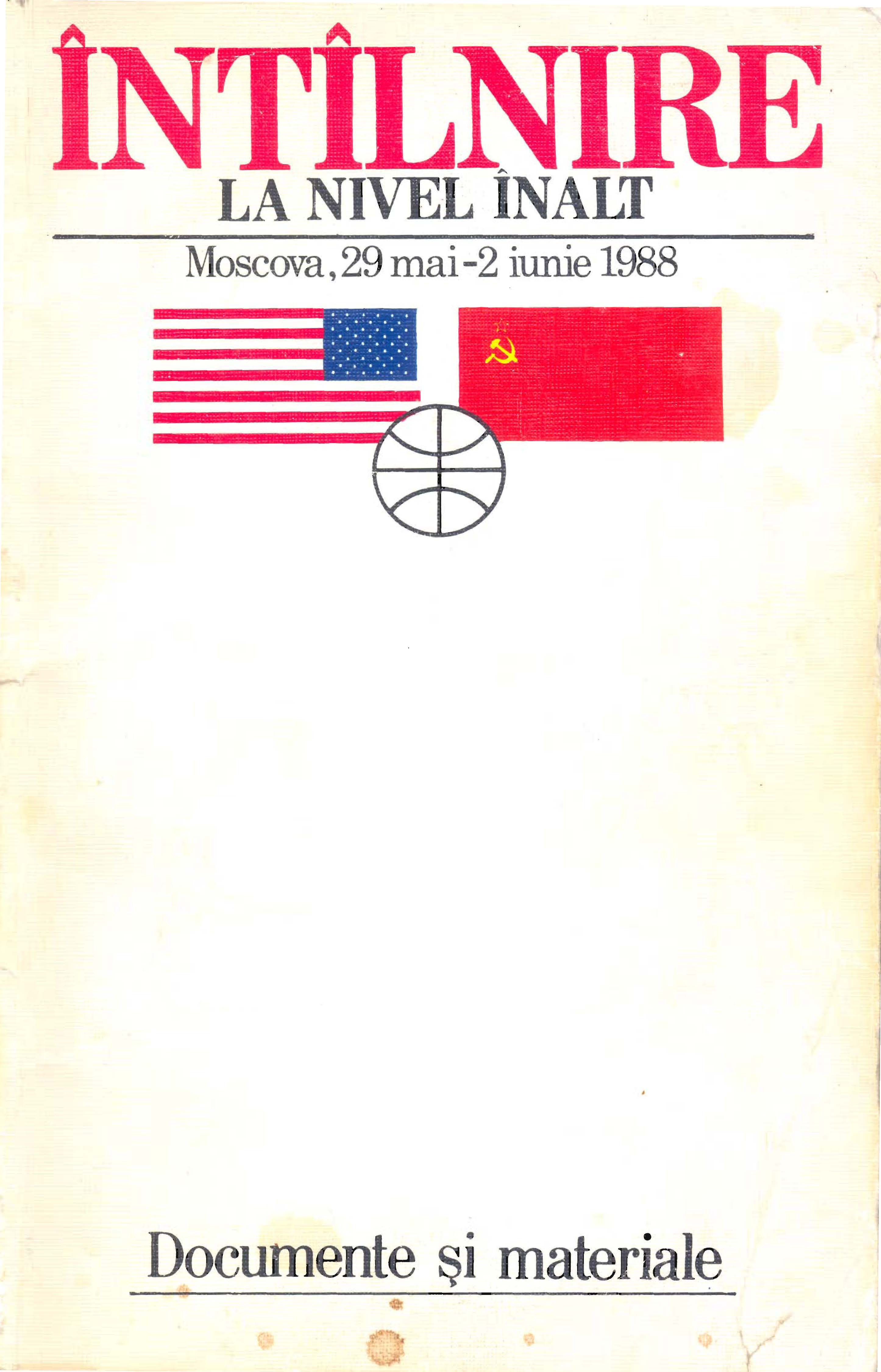

The full title of this central document in the Marian Zulean collection is Întîlnire la nivel înalt: Moscova, 29 mai – 2 iunie 1988. Documente și materiale (Summit meeting: Moscow, 29 May – 2 June 1988: Documents and materials). The book documents in detail the content of the visit to the USSR made by US President Ronald Reagan in the early summer of 1988, at the invitation of Mikhail Gorbachev.

The volume consists of a series of transcriptions of the public moments of the meetings of the leaders of the two states, four speeches by each of them, press statements and addresses by Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan, transcriptions of question and answer sessions in front of the press, and the answers given by the Soviet leader in an extensive interview granted to the newspaper The Washington Post and the magazine Newsweek prior to the visit. The book also gives details of the ceremony of exchanging instruments of ratification with the reference to the coming into force of the treaty eliminating medium-and shorter-range missiles, and the text of the joint statement made at the Moscow summit. Not least among the interesting features of the book is a substantial photographic archive of the state visit.

In order to understand why such a book constituted an alternative source of information, it must be recalled that, in comparison, the reflection of this visit in the Romanian press was minimal. Marian Zulean remarks: “I remember that it was just mentioned briefly in short news items. Because in fact what was happening then between the USSR and the USA did not suit the leaders of the communist regime here at all. Once I read this book, to which I added what I heard on Radio Free Europe, I really understood what had happened during those days in the USSR.”

The book is preserved in good condition in the Marian Zulean collection. It has 128 pages and was published, directly translated into Romanian, by Novosti Press Agency in 1988. The book was purchased at the International Trade Fair for Consumer Goods (TIBCO), where the USSR had a very large stand.

A valuable part of the Doina Cornea private collection is made up of photographs. Some of these photographs (more than a dozen), which were taken by the Securitate in the late 1980s, ended up in Cornea’s possession in a strange way that illustrates the contradictions of the turbulent Romanian exit from Ceaușescu’s dictatorship. In the late 1980s, the Securitate put Doina Cornea under strict surveillance and she became the target of harsh repressive measures on the part of the state authorities due to her oppositional activity. These photographs were taken by the Securitate during the complex operation of keeping Cornea under surveillance and were aimed at analysing her daily activity and social network. Later, the photographs were archived by the secret police in their “informative surveillance file” (dosar de urmărire informativă) on her and were usually attached to an “informative” report drafted by Securitate employees for the higher echelons of the secret police. The items remained in the possession of the secret police until December 1989. During the Romanian Revolution of 1989, Doina Cornea became a leader of the population of Cluj in revolt and acted as their unofficial representative. The Romanian army changed sides on 22 December 1989 and joined the population in revolt. In this turbulent period, the Ministry of National Defence became the institution with custody of the Securitate archives.

According to her son, Leontin Horațiu Iuhas, after 22 December 1989, Doina Cornea, as a representative of the local population, had several meetings with the leadership of the Romanian Fourth Army, which had its headquarters in Cluj. During one of these meetings, in order to show their support for the population in revolt and as a gesture of benevolence, the leadership of the Romanian Fourth Army gave Cornea several photographs from her Securitate files (Interview with Leontin Horațiu Iuhas). This gesture could be understood as an attempt of the leadership of the local military to gain the sympathy of the dissident after they had been involved in the repression of the local uprising of 21 December 1989 (Adevărul 2009).

One of these photographs shows Doina Cornea, her son Leontin Horațiu Iuhas, and two members of the French Embassy staff in Bucharest, talking in front of her home in Cluj. The Securitate was monitoring all her social contacts and tried its best to stop all contacts that were important for her oppositional activity, such as those with Western journalists and diplomats. However, after she was released from arrest in December 1987 due to international pressure, the secret police was put in the situation of having to tolerate her contacts with the staff of Western embassies in Bucharest in order to avoid international scandals. This photograph reflects the paradoxical situation of Doina Cornea, who was practically forced into house arrest, but was able to meet the diplomatic staff of Western embassies due to her international reputation.

Resolution of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Moldavian SSR concerning Viktor Koval’s petition (in Russian). October 1988

Resolution of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Moldavian SSR concerning Viktor Koval’s petition (in Russian). October 1988

On the occasion of the nineteenth Party conference, held in Moscow in late June 1988, in the context of the increasingly obvious reformist tendencies of the late Perestroika period, Viktor Koval filed a petition requesting the revision of his case, his full rehabilitation, and his release from the psychiatric hospital. This petition was examined by the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Moldavian SSR in early October 1988. On 6 October, the special prosecutor responsible for supervising KGB investigations, M. V. Prodan, issued a special resolution denying Koval’s request and upholding the earlier decision of the Supreme Court. This resolution was approved by the General Prosecutor of the Moldavian SSR, N. K. Demidenko, six days later, on 12 October. This document is especially significant as it shows the reluctance of the Soviet justice system to acknowledge the repressive character of punitive psychiatry (and thus its own subservience to the regime) even as late as 1988, despite the general atmosphere of liberalisation. The prosecutor based his decision on the fact that Koval’s purported “socially dangerous acts” were confirmed by “the witness accounts, the material evidence, the conclusions of the psychiatric assessment, and the evaluation of the defendant’s handwriting,” as well as by other documents from the KGB file. After reviewing these materials, the prosecutor concluded that Koval’s assertions and papers comprised “certain well-founded critical remarks concerning the imperfections of our socialist society. At the same time, the essence of his activity did not focus on the criticism of the existing flaws in order to remove them from society. Rather, he constantly emphasised the advantages of the capitalist system and the Western way of life, and used rude and insulting expressions in connection with the role of the ruling communist party. He also stated demagogically that the people lacked any rights, that the country was ruled through fascist methods, and that the people were exploited. His main goal is obvious – to discredit the socialist order and the system of state power.” This assessment provided a glimpse into the logic of the regime’s actions and into the reasons for qualifying Koval’s case of political opposition as particularly dangerous. Although ritualistically invoking the results of the psychiatric assessment, the prosecutor in fact synthesised the regime’s attitude toward Koval’s and other similar examples of “ideological deviance.” It is not surprising that the official found the decision to subject Koval to forced medical treatment to be “correct” and rejected his petition for rehabilitation as “unfounded.” However, the prosecutor’s arguments seem more sincere and less euphemistic than earlier instances of comparable legal documents, probably reflecting a slight change in emphasis (if not in essence). Koval’s release from hospital only occurred in May 1990, when the article incriminating him was excluded from the Penal Code. His final rehabilitation followed in November 1991, when the Moldovan Supreme Court annulled the previous judicial decisions and openly admitted that Koval had suffered for his political opinions. However, even on that occasion punitive psychiatry as such was not officially condemned by the Moldovan justice system. It was only following a recommendation of the Presidential Commission for the Study and Evaluation of the Communist Regime in Moldova that the government officially condemned the use of psychiatric hospitals as a major strategy for the repression of dissent during the later stages of the Soviet regime.

Cornea, Doina. Stop the demolition of the Romanian villages (open letter), in Romanian, July 1988. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina. Stop the demolition of the Romanian villages (open letter), in Romanian, July 1988. Manuscript

Among the open letters addressed by Doina Cornea to Ceauşescu himself, that entitled “Stop the demolition of the villages” (Opriți dărâmarea satelor) was among the most significant and certainly the one that aroused the greatest international reaction. The letter opposed the programme of “rural systematisation,” which entailed the planned demolition of more than 7,000 Romanian villages (Ceaușescu 1989, 395). Cornea drafted the open letter in July 1988 in a period when the demolitions had been intensified. The letter was also broadcast by RFE in September 1988 and published later by the French newspaper Le Monde (Cornea 2006, 220).

In comparison with other open letters that focused more on future-oriented reforms (such as those dealing with the educational system), this letter is “nostalgic and past-oriented,” and deals with the protection of the Romanian peasants’ habitat and way of life, which she argues is the core of Romanian national identity (Petrescu 2013, 314). This approach was based on her readings of Romanian philosophers and writers such as Lucian Blaga, Constantin Noica, and Nicolae Steinhardt, who dedicated many of their works to the “spirituality” of the Romanian village. She thus places herself in a cultural tradition which since the end of the nineteenth century had emphasised peasant culture as a key element for defining Romanian national identity (Hitchins 1994, 298–299). Consequently, she considers Ceauşescu’s plan to restructure most of the Romanian villages as a malicious attempt to destroy “the soul of the nation.” She also invokes the fact that the rural habitat is a part of world cultural heritage and criticises the demolitions from a preservationist perspective. Thus, she asks Ceauşescu to stop the demolition of the villages and to consult of the will of the Romanian people concerning the future of the national programme of “rural systematisation.”

At the end of the letter, Doina Cornea mentions another twenty-seven persons who had expressed their solidarity with the open letter of protest and agreed that their names could be included on the list. Most of them were either Cluj-based supporters of her oppositional activity, such as the dissident Iulius Filip (who in 1981 had addressed an open letter of support to the Polish free union Solidarity), or part of a group of workers in the town of Zărneşti (Braşov county, Romania), who had initiated a local free union. This open letter, together with her interviews granted to Western journalists, inspired the collective initiative Opération Villages Roumains (OVR), “the largest ever network of transnational support against the abuses of Ceausescu’s regime,” which opposed the demolition of Romanian villages by encouraging a symbolic adoption of the endangered Romanian rural sites by Western communes (Petrescu 2013, 317).

Gediminas Ilgūnas was a well-known Lithuanian writer, journalist, ethnographer and traveller. In the 1950s, he was accused of anti-Soviet activity and imprisoned. On being released from prison, he and his close friends started to organise ethnographic expeditions, collecting material about important personalities in Lithuanian national history. The collection holds various manuscripts, including documents relating to his activities in the Sąjūdis movement and his political activities as a member of the Supreme Council, short memories about the Stalinist period, and material collected for a biography of Vincas Pietaris. The collection shows the actions of a Soviet-period cultural activist who tried to collect and preserve Lithuania's past culture.

In 1988, Berlin became the cultural capital of Europe. For the occasion, the German fashion designer Claudia Skoda was asked to create a fashion show by inviting artist from different corners of Europe. Skoda invited Király, who was the only representative of the Eastern Bloc. His collection was strongly inspired by Oskar Schlemmer’s costumes at the Triadic ballet in that he created his dresses using only circles, triangles, and squares from the perspective of design and only red and black colours separately from the perspective of colour. In the end, he created 40 dresses, of which three have survived as part of his bequest.

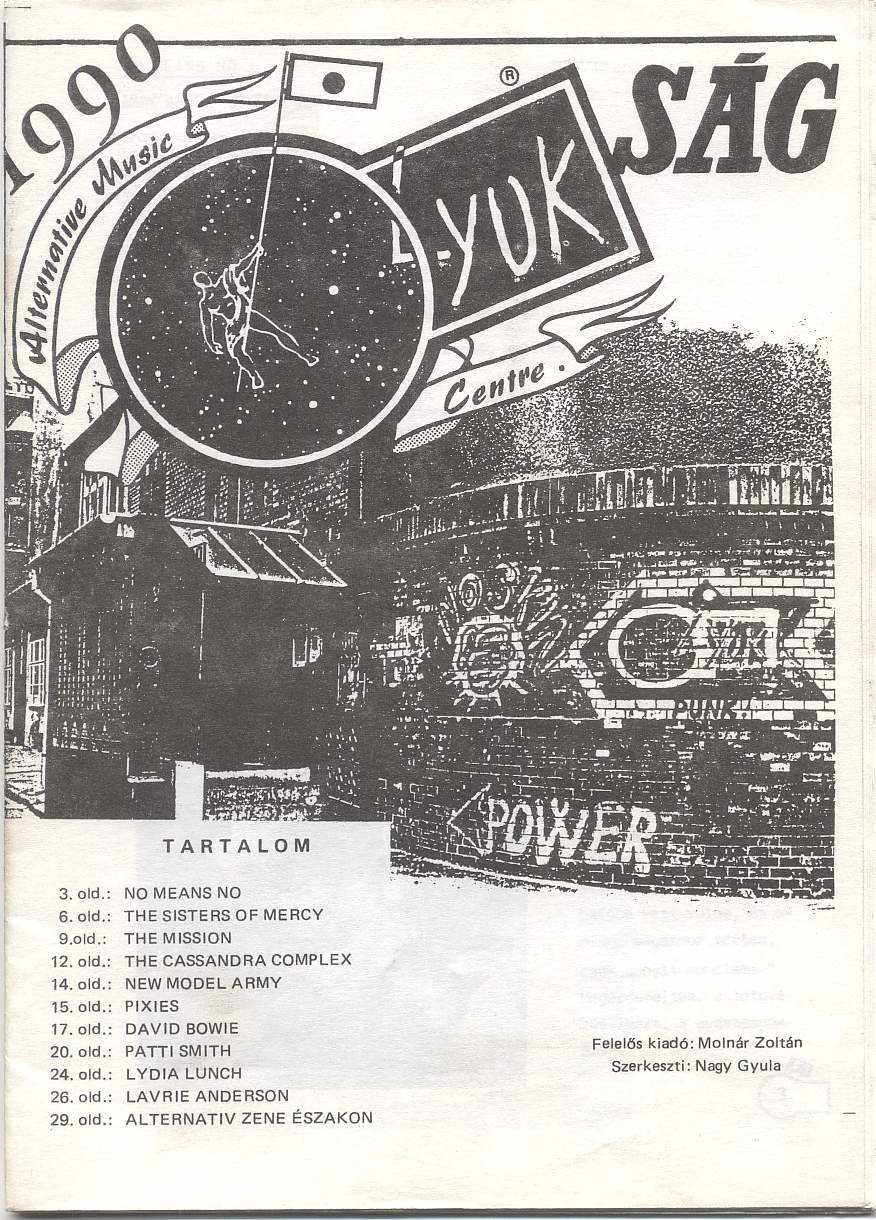

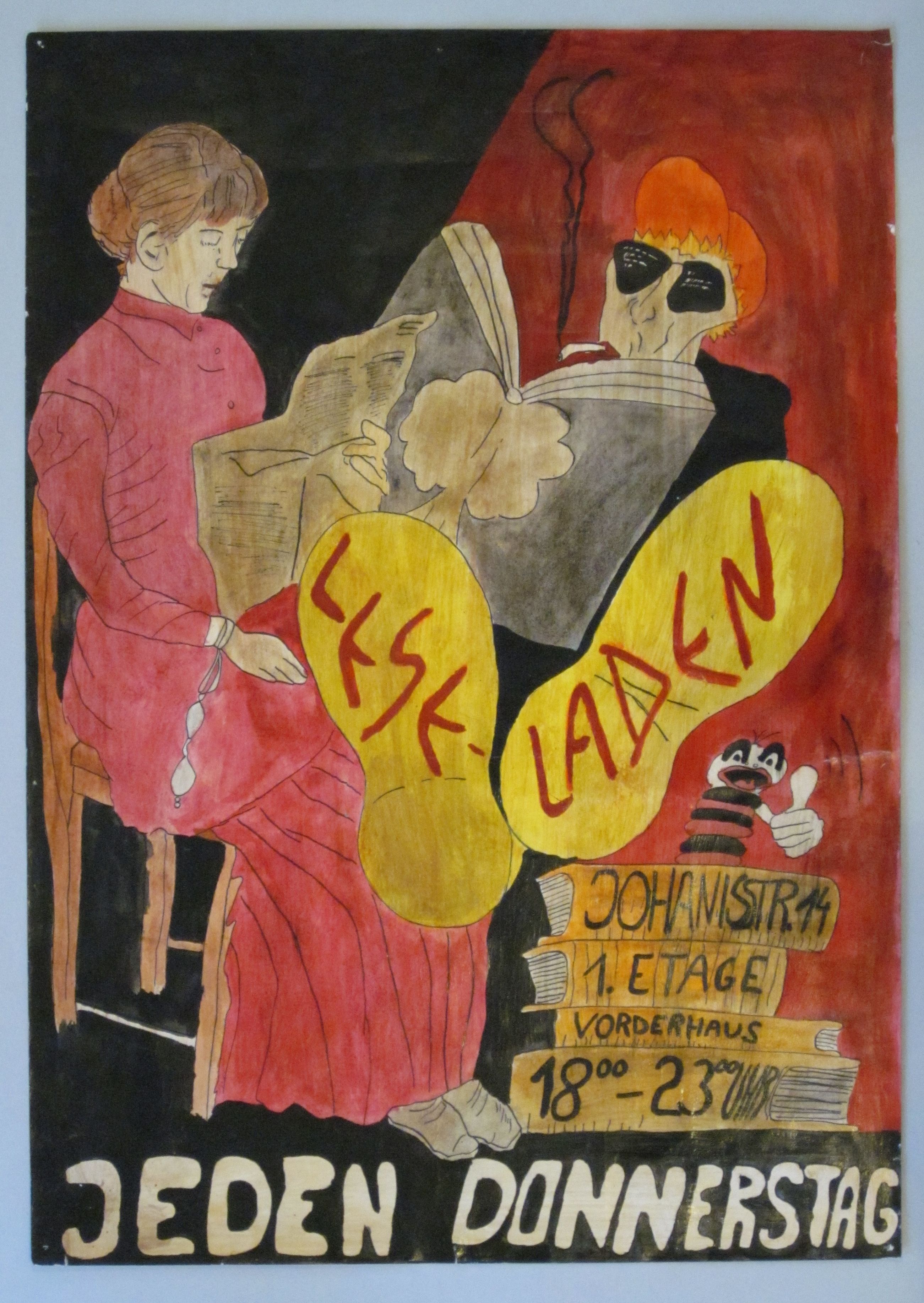

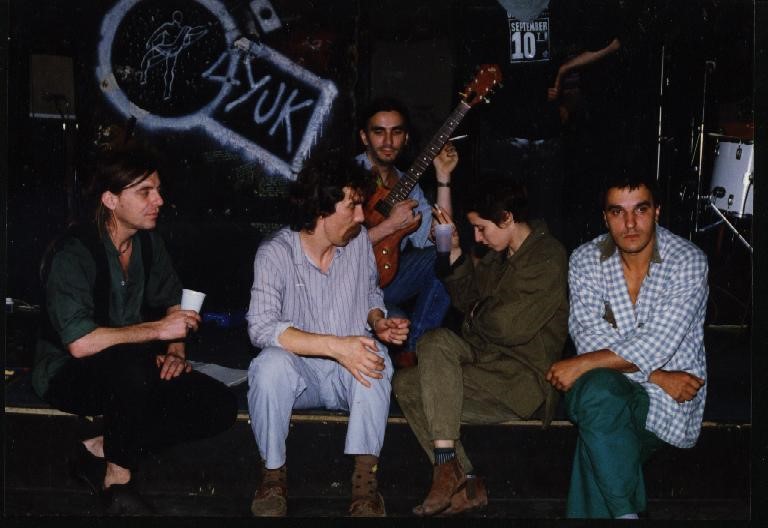

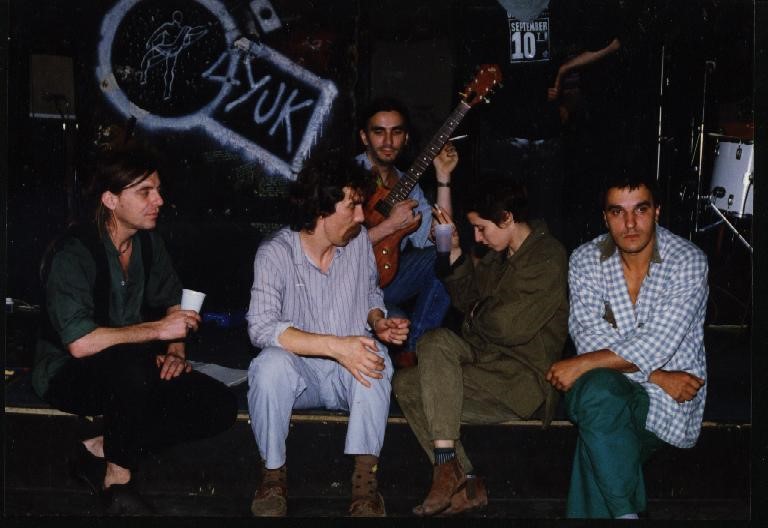

The former Black Hole (Fekete Lyuk) in Budapest had become a legend already in its first few years of existence as the most important underground nightclub of the transition period. The building in Golgota Street originally was a community center at the residential area for the workers of the Ganz-MÁVAG machine factory. After 1945, it was operating under the name Vörösmarty House of Culture (it was a kind of a “community center”) under the oversight of VASAS, the Hungarian Metalworkers’ Federation. The basement, which served as a community bath until 1969, was transformed into a center of contemporary alternative and independent music in just a few weeks in 1988. The Black Hole opened its gates relatively late, in February 1988: perhaps this could not have taken place at any other time. Club life in Budapest was just beginning to take root, and while the plans to open the place had been drawn up in 1985, permission was granted only in 1988, when the party-state eased the pressure it had been putting on this kind of undertaking. “Adult educator” (népművelő) Gyula Nagy, the leader of the community center, ran the place.

In the initial period, the target audience was primarily a narrow circle of young intellectuals, but when a frequented punk club in the working class district Kispest closed, the repertoire of the Black Hole expanded. The club became a kind of home to several subcultures: young intellectuals who sought ways of expressing dissent, path-seeking artists, punks, skinheads, and a variety of nonconformists mingled in the smoky basement. The performers were similarly diverse. The Hole provided a platform for all sorts of upcoming bands, which was extraordinary during an age of censorship and “blacklisted” performers. In this sense, the name alternative music center stood not for a single music genre, but for the diversity of the featured genres. Numerous bands started their careers at Black Hole, and some of them even managed to acquire national or international reputations. From Auróra to F.O. System to Pál utcai Fiúk, almost everybody performed at some point in Black Hole. The place remained popular in the first few years after the transition too: a diverse array of bands performed there, such as Kispál és a Borz and VHK. Foreign bands also came to perform at the club, such as No Means No, Chumbawamba, and Fugazzi. The club quickly acquired an international reputation. In 1989, the club was on Rolling Stones magazine’s list of the 50 best clubs of the world. The core members also edited a fanzine entitled Lyukság (Hole-ness), and the constant rehearsals were complemented with other cultural programs. In addition to film screenings, literary evenings, readings, and various performances, the club also served as a site for exhibitions. Later, a studio was added to the Hole, and the Voice of the Black Hole Cultural Association helped countless bands publish and distribute cassettes.

It was essential to the spirit of the club to reject all formalities, which was evident in the looks of the club. There was not attempt to change the labyrinth of the former community bath. On the contrary, during the process of renovation, the holes and cracks were either left in the walls or even deliberately emphasized. The walls were covered with graffiti, and there were very few pieces of furniture, and they were not of a particularly high quality. People could sit on the floor or on discarded train seats. The same principles applied to rules of politeness. People could casually dance on the table, pogo, or take a quick nap on the floor, and a passing sickness did not mean much of a problem either. Prices were low and the opening hours were long. The place was tremendously popular, and with popularity came trouble. There were fights, drug use, and deviant behaviors. Nonetheless, Black Hole was a kind of home for many young people, and in this sense, the club was not the cause of these problems. It was a place where people could find refuge from their problems, and it was also a place where they could take their problems. In addition to the many cultural programs, the Black Hole also ran a drug monitoring program. Meanwhile, in 1989, the Faith Church held ceremonies in the community center right above Black Hole for six months.

The outsider nature of the club, both in terms of content and form, drew a considerable amount of attention. The night club was presented by the press as the “gates of hell” and a “rathole.” The reputation of Black Hole as a dangerous place spread rapidly. This negative presentation was a kind of advertisement for the club, and it was also a sign of softening. While police presence was constant, it consisted mostly of a single officer, László Kerti, who spend most of his time at Black Hole as a kind of “indoor major.” The club also had to maintain daily contact with the cultural department of the Budapest Police Headquarters. It had to submit the lyrics to the songs performed by the bands, and the files on the bands under observation (Sziámi, Európa Kiadó, Bizottság, and more) and their activities at the Black Hole grew. The very existence of Black Hole was in many ways a matter of sheer luck.

This spirit of this vibrant, unique, and sometimes frightening sphere was captured by Tamás Urbán, the well-known forensic and social documentary photographer. Urbán began taking photographs there at the request of Youth Magazine (Ifjúsági Magazin, IM) at the end of the 1980s. IM was the first periodical to publish a report on Black Hole legally, and Urbán took photographs there several times after that, not so much because of the music, but because of the atmosphere. Black Hole was connected to Urbán’s major topics in several ways, not just through the various subcultures and junkies, but also through personal relationships. His photo series offers portraits of the performing musicians and snapshots of the carefree parties, offering insights into an unrepeatable, unique sphere of the age.

After the transition, Black Hole remained open for another four years, but under the changed circumstances, it began to lose some of its significance. More and more nightclubs with similar profiles were opened, and the people who had frequented the club either dispersed or, as they grew older, their interests changed. The new wave lost its influence. The club also faced financial problems and an evolving conflict between the club manager and the director of the community house. After having been in operation for six years and have hosted almost 600 performers on its stage, Black Hole closed its doors in 1994. Several attempts were made to reopen it, but they all failed. Black Hole was part of a unique time and sphere, and it had a distinctive influence in part simply because of the historical context in which it functioned. It remains a subject of interest for the historian precisely because of its uniqueness. More recently, it was opened for guided tours on an occasional basis to let latecomers and nostalgic “survivors” travel back in time.

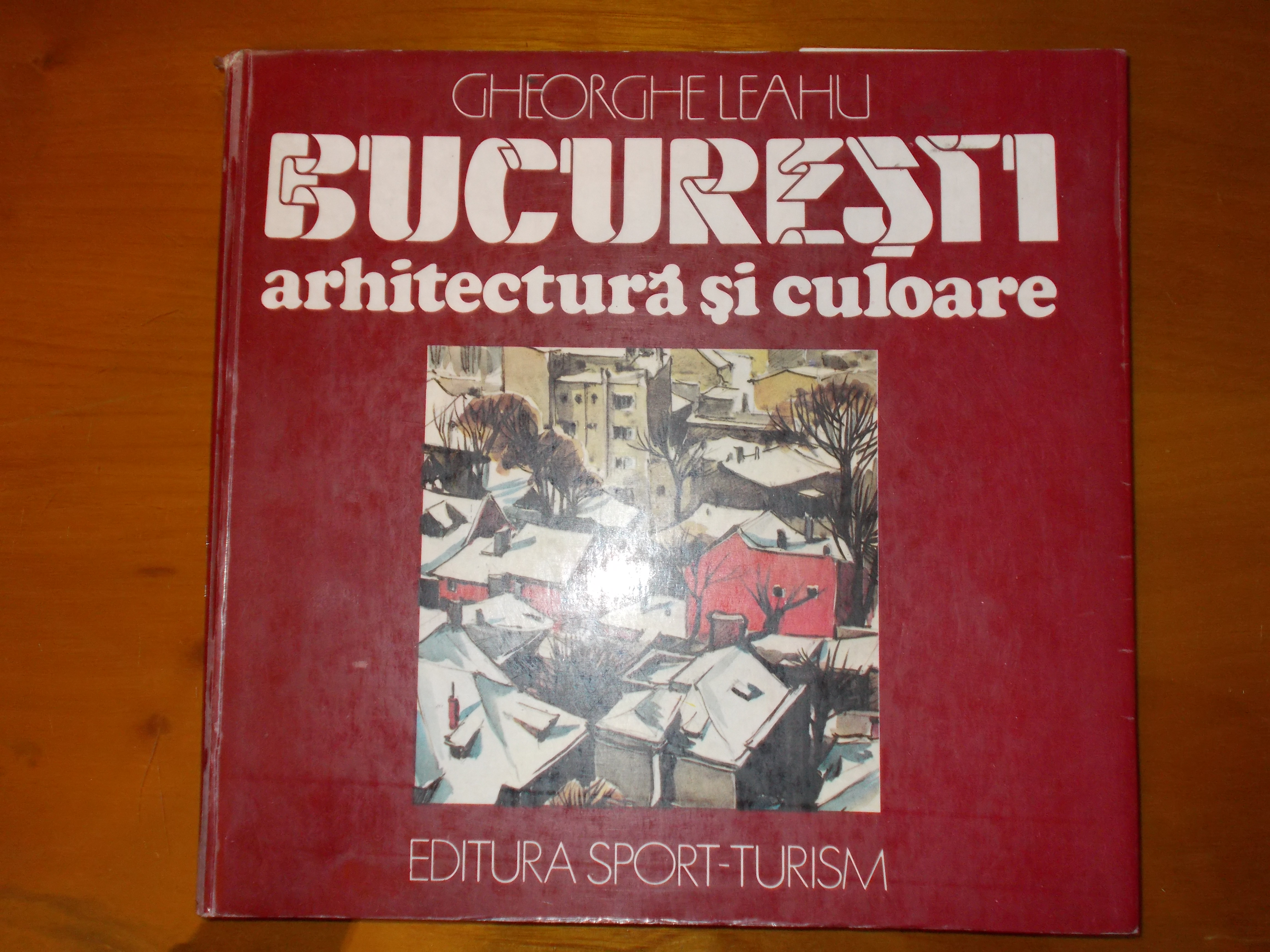

Watercolour painting was for Gheorghe Leahu a form of escape from the constraints imposed on the activity of architects under communism, which became more severe in the last decade of the regime. In the 1980s, Ceauşescu intensified the process of urban restructuring of Bucharest, which entailed the demolition of entire areas in the centre of the Romanian capital to make room for new boulevards. These actions were legitimised by the concept of “urban systematisation,” which was presented in the official discourse as a process of modernisation through which the city would acquire a new socialist identity. The watercolours painted by Leahu in the 1970s and 1980s portray urban landscapes, especially in the old centre of Bucharest. In addition to their artistic value, these watercolours represent, according to their author, a “source of documentation” concerning the architecture of the Romanian capital before the demolitions brought about by the so-called “urban systematisation.” A selection of these watercolours was included in an album that Gheorghe Leahu sent in 1986 to the Sport Turism Publishing House, entitled: Bucureşti – arhitectură şi culoare (Bucharest – Architecture and Colour). The album was passed by the censors, even though its introduction made no mention of Nicolae Ceauşescu. (Although this was not an official requirement of the publishing houses, most authors did refer to various quotations from the Secretary General in order to get their books published, so in the end, this reference became the norm, while its absence was seen as an ideological failing on the part of the author in question.) After the album was printed in 1988, the 4,500 copies were withdrawn before reaching the bookshops and destroyed. In addition to the failure to mention Ceaşescu’s name, another cause for the withdrawal of the album was the fact that it contained watercolours representing many old churches. Their presence contradicted the policy of the communist regime of discouraging the protection of the architectural heritage of the capital. Some employees of the printing house managed to rescue several copies, which they delivered to the author. The volume was republished in 1989 in a censored edition, and again in 1991, this time in an edition free of any censorship constraints. This volume, as well as others published by Leahu after 1989, represented an important component of the post-communist visual identity, and promoted in the public space a nostalgic approach to the old centre of Bucharest.

The documentary entitled, “Parcel 301” (1988) brought Black Box fame. The film presents the inauguration of a memorial designed by László Rajk in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, on the 16th of June 1988, and the commemoration ceremony of the 1956 revolution and Imre Nagy that turned into an anti-dictatorship demonstration in Budapest on that same day. It is based on reports and interviews with 1956 revolutionaries, relatives of those executed for their involvement in the revolution, as well as political opposition figures. On the 16th of June 1988, the 30th anniversary of the execution of Imre Nagy and other martyrs of the revolution, there was an unveiling of a monument for the victims of the 1956 Hungarian revolution in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. That same day, in Budapest, a commemoration of the revolution began at the unmarked graves of Parcel no. 301 in the Rákoskeresztúr Cemetery. The commemoration turned into an anti-dictatorship demonstration that continued at the Batthyány eternal flame and Heroes’ Square. The victims’ relatives and ’56 revolutionaries recalled 1956 and what this day meant to them.

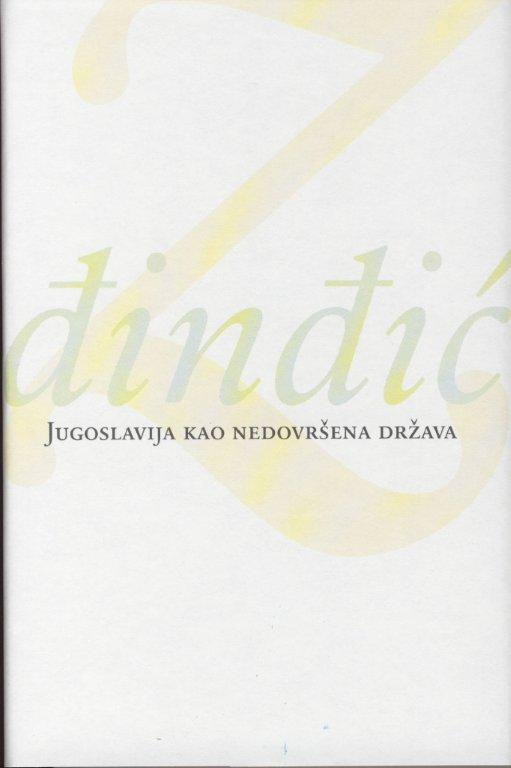

The most important among the books of Đinđić’s collection is his analysis of the political and constitutional system of Yugoslavia and its key shortcomings in “Yugoslavia as an Incomplete State”. The book was published in 1988 out of a series of essays Đinđić had published in “Literary News” [Književne novine] between 1986 and 1988. Using theoretical analysis, Đinđić criticized the ruling ideological paradigm of the time and “affirmed for the first time, on a theoretically relevant basis, liberal thought on the level of the individual, society and politics.” (N. Dmitrijević, Kontinuitet nedovršene državnosti (Foreword) in: Đinđić, 1998, IX).

Đinđić wrote on Yugoslavia: “Not even the more sober-minded observers will be able to escape the impression that the most fundamental matters are, indeed, contested here. The impression that Yugoslavia is, as a matter of fact, an unfinished state. So to say, it is an open option, which withstands any final definition... In the vacuum spreading with the communist term (or, more precisely, non-term) of statehood, a variety of herbs grew, which turned the lack of premises for life in its own premise for life.“ Đinđić also analysed key problems in Yugoslavia, anticipating its dissolution, the victory of nationalism, and warned about the far-reaching consequences. This book is considered among the most important works in political theory during the 1980s in Serbia.

![Photo: Josip MihaljevićSource: Kulundžić, Zvonimir. Tajne i kompleksi Miroslava Krleže: koje su ključ za razumijevanje pretežnog dijela njegova opusa (Secrets and Complexes of Miroslav Krleža: which are the key to understanding the overwhelming part of his opus), 2nd edition. Ljubljana / Zagreb: [samizdat], 1988.](/courage/file/n1222/20170609_173650.jpg)

Publishers did not want to release some of Zvonimir Kulundžić's polemic books. On the other hand, Kulundžić himself was not ready to make compromises which some publishers were demanding. Therefore, Kulundžić published some of his most important books in his edition, without any institutional support. Nevertheless, some of his books were printed in a large number and were even sold out, such as the book Tragedija hrvatske historiografije (Tragedy of Croatian Historiography) (Zagreb, samizdat, 1970). Kulundžić gained readers quickly because of his controversial attitudes, subjects he dealt with and the thesis he offered, but also because he communicated directly with readers. In his books, he invited readers to buy his books directly from him. Most of Kulundžić's readers were subscribers of his self-published editions. This featured item - "Call for Pre-Order" - is the last page of the 2nd edition of the book Tajne i kompleksi Miroslava Krleže: koje su ključ za razumijevanje pretežnog dijela njegova opusa (Secrets and Complexes of Miroslav Krleža: which are the key to understanding the overwhelming part of his opus) (Ljubljana: Emonica, 1988). In this book author announces the release of his new book Odgonetavanje zagonetke Rakovica (Unriddle of Rakovica's Riddle) (Zagreb: Multigraf, 1994) and invites readers to ask for a copy of the book, saying "Let you become patriots and preachers on the cultural site of the Croatian people". He instructs the reader to cut off a part of the book (order form) write his home address with the text: "Please ensure a copy of your book Unriddle of Rakovica's Riddle, and send it to me when the book comes out."

Cross-border solidarity and global networking with progressive movements was at the core of Slovene peace movement’s activity. The regular information bulletins in English were published and widely distributed to convey a strong message to the international community concerning the dedication of the movement to the values of global solidarity, non-violent action and peaceful resolution of conflicts. The network of recipients of the papers ranged from political actors, the media, action groups and NGOs. This is why opposition political groups that appeared in Slovenia in late 1988 entrusted the peace movement with promotion of the “Slovenian spring” abroad. It was this movement that published news about democratic movements and organised the first political missions abroad. It was also instrumental in promoting the rights of the four opposition personalities put before a court martial in 1988 (Janša, Borštner, Tasič Zavrl) which triggered a massive resistance movement against the Yugoslav regime and finally led to independence.

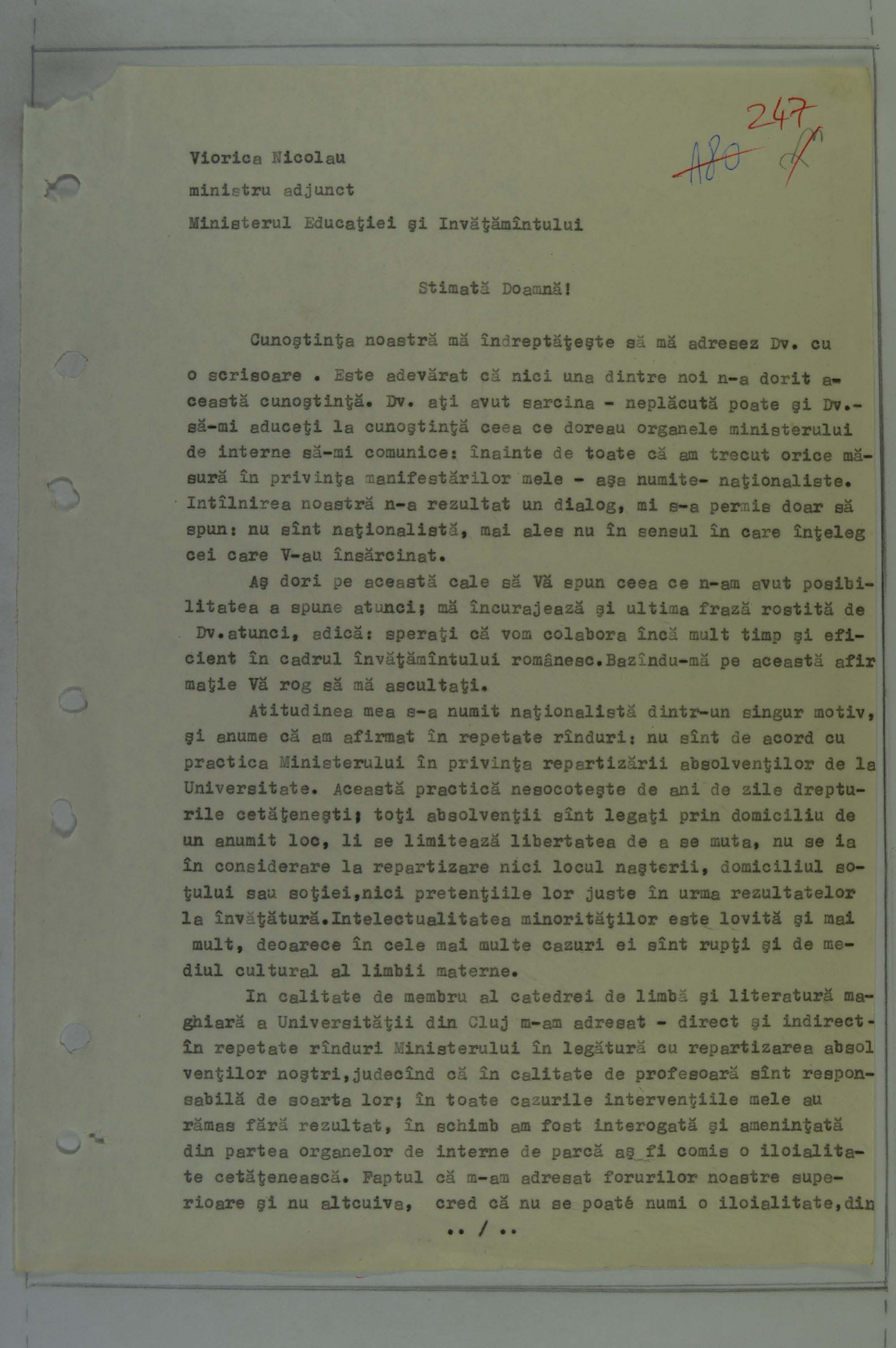

The Memorandum of 8 March 1988 addressed to Deputy Education Minister Viorica Nicolau concerning the “Repartition” of Students of Babeș-Bolyai University

The Memorandum of 8 March 1988 addressed to Deputy Education Minister Viorica Nicolau concerning the “Repartition” of Students of Babeș-Bolyai University

The term “repartition” – the act of assigning a professional job to university graduates requires some explanation. Prior to 1989, university graduates in Romania were assigned to a workplace by the Ministry of Education through a centralised system. The position assigned as a result of “repartition” could not be abandoned by the new graduate for three years (or two years in the case of those who had an overall grade over 9 out of 10), otherwise the person in question could not continue working in his/her field. “Repartitions” were carried out in accordance with a list of workplaces compiled by the Ministry, and fresh graduates could choose a place of work upon consideration of their accomplishments and other points of view. Quite often this led to the destruction of projected marriages, as couples could not get places together unless they were already married before the “repartition.” (Cs. Gyimesi 2009).

In order to understand the importance of the selected feature item it is necessary to provide details regarding the context. Hungarian students of Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, Faculty of Philology, almost exclusively opted for Hungarian paired with a foreign language, or for a foreign language as major paired with a minor in Hungarian language. In 1985, graduates in Hungarian and a foreign language (English, German, French, Russian) were offered five places in Transylvania (two of these in cities) and sixteen positions in the other regions of Romania, all of them in the severely deprived countryside. In fact, most teaching positions for university graduates in communist Romania were in remote places in the countryside, since all major cities were “closed,” which means that no working place in those cities was available in the 1980s. When it came to occupying the two more advantageous positions in Transylvanian cities it turned out that these were listed only as a trick, as these positions were not made available to Hungarian candidates on the grounds that they were “high responsibility positions” that fell within the competence of the Securitate. The nominal list of advertised positions shows that graduates majoring in Hungarian were assigned to posts exclusively in schools located in the so-called Old Kingdom of Romania (i.e. Wallachia and Moldavia, regions where there was not a significant Hungarian element in the population) or in Romanian-medium schools in Transylvania, where they were forced to teach their secondary academic discipline (Russian, German, etc.) to Romanian children. Not a single position was offered to these graduates in the counties of the overwhelmingly Hungarian-populated Székely Land in eastern Transylvania, although there was a clear shortage of Hungarian teachers and also despite the fact that schools in these counties forwarded their demand for about 30-40 newly-graduated Hungarian teachers to the central authorities. It would have served as an alleviating circumstance in this respect if the Hungarian graduates had been given the possibility of teaching the foreign languages they had studied as a secondary academic discipline subordinate to Hungarian in the settlements they were sent off to. However, most of them did not have this opportunity, as the schools of the listed localities beyond the Carpathians did not even have departments for the foreign languages these graduates had been forced to accept, or they were given only a few classes of foreign languages together with classes of gymnastics, handicrafts, music, etc. in order to make up the twenty-two weekly classes required for a full-time position.

Encouraged by their tutor, Gyimesi, the 1985 graduates issued a protest against the official procedure by collective absence from the place-selection meeting. They submitted their complaint to the Ministry of Education in a memorandum signed by all of them, requesting the modification of repartitions that had in the meantime been resolved ex officio. Many prominent Hungarian personalities in Romania also protested against the discriminatory repartitions in a joint petition (Edgár Balogh, Sándor Kányádi, György Beke, etc.); nevertheless, collective action yielded no results whatsoever. Freshly graduated teachers were vigorously called upon to compulsorily occupy the jobs imposed on them – failing to do so leading to their dismissal and the payment of a fine.

The extensive repartition manipulations had repercussions on Romanian higher education in Hungarian. As a result of the repartitions, the number of university applicants for Hungarian language and literature saw a considerable decrease, as the Hungarian teaching profession had no future under the given circumstances. At the same time the number of advertised university places was also reduced. By the academic year 1985–1986 the number of available places sank to just seven, a third of the number in previous years. Beginning with 1986, Romanian grammar was introduced as a compulsory subject at the entrance examination, which made things even harder for candidates from purely Hungarian-inhabited regions who had a poor command of Romanian. Moreover, after the entrance examination, at the start of the academic year it was announced that instead of the foreign language – which had also been a subject at the examination – the Romanian language would be the secondary discipline subordinate to Hungarian, and, similarly, a foreign language as a major was paired with Romanian instead of Hungarian as a minor. This practically meant that Hungarian students majoring or minoring in Hungarian language had no possibility of becoming qualified in a foreign language. A Hungarian student could only study English, German, French or Russian if he/she chose Romanian as a major.

Repartitions in the Old Kingdom of Romania affected not only philology graduates. In the same way hundreds of teachers of other subjects, engineers, doctors, etc. were placed in settlements beyond the Carpathians. The most striking case in this respect was that of the graduates of the University of Medical Studies of Târgu Mureș, predominantly Hungarians, who could only occupy jobs outside Transylvania, according to a centrally established territorial placement plan. The equivalent of this process in the opposite direction was that many graduates from the Universities of Bucharest, Iași, or Craiova received often repartitions in Transylvania. The undisguised trend unfolded according to the so-called homogenisation concept that was promoted nationwide. It was evident that the chances of students wishing to continue their studies in Hungarian gradually diminished, since their background of increasing educational deprivation in the Hungarian language represented a serious disadvantage in higher education. As a consequence of the central dispositions, many Hungarian teacher positions were occupied by unqualified substitutes lacking a degree. Children of Hungarian nationality were offered a single chance for advancement: if they stopped using their mother tongue. All this foreshadowed the disappearance of Hungarian intellectuals, the marginalisation of Hungarian language and culture, and gradual assimilation (ACNSAS, I017980/6, 136–144).

Under the given circumstances Gyimesi, who had endured harassment on multiple occasions, turned to Deputy Minister of Education Viorica Nicolau, with whom she had made acquaintance after the latter – along with the Cluj university rector and the central party secretary – had attended the disciplinary meeting on 10 October 1987. In the three-page memorandum deliberately dated 8 March 1988, the International Day of Women, Gyimesi tried to win over the deputy education minister as an ally in her efforts to find a more just and equitable solution to the repartition of graduates while making an appeal to the empathy of a women/mother in defending innocence (ACNSAS, I017980, vol. 1, 247–249; I017980/5, 70–73). The letter was broadcast on Radio Free Europe as well, with the obvious intention of drawing the attention of foreign forums to the defence of minority rights in Romania. Several Romanian colleagues expressed their feelings of sympathy to Gyimesi and conveyed their congratulations (Cs. Gyimesi 2009).

The eight-page text written by the Czechoslovak historian and dissident Milan Hübl introduces its readers to the issue of convicts and their language. At the beginning are some brief but very interesting statistics comparing the sentences and records of criminal offences (regardless of length of sentence) in the years 1925, 1928, 1978, 1979 and 1980. Hübl goes on to write about prison structures and prisoners. The main focus of the text is prisoners’ slang. Hübl was familiar with this topic because he had also been imprisoned for several years. His own correspondence, written during his imprisonment between 1972 and 1976, is among the sources for this chapter, which focuses on the prison slang in the Brno region, the so-called “plotňáčina”. The text ends with following sentences: “While browsing through my letters, I realised that they would be a valuable source when I started writing my memoirs. A lot of information has been preserved that would have been difficult to recall without them. At least something positive came from being in jail.”

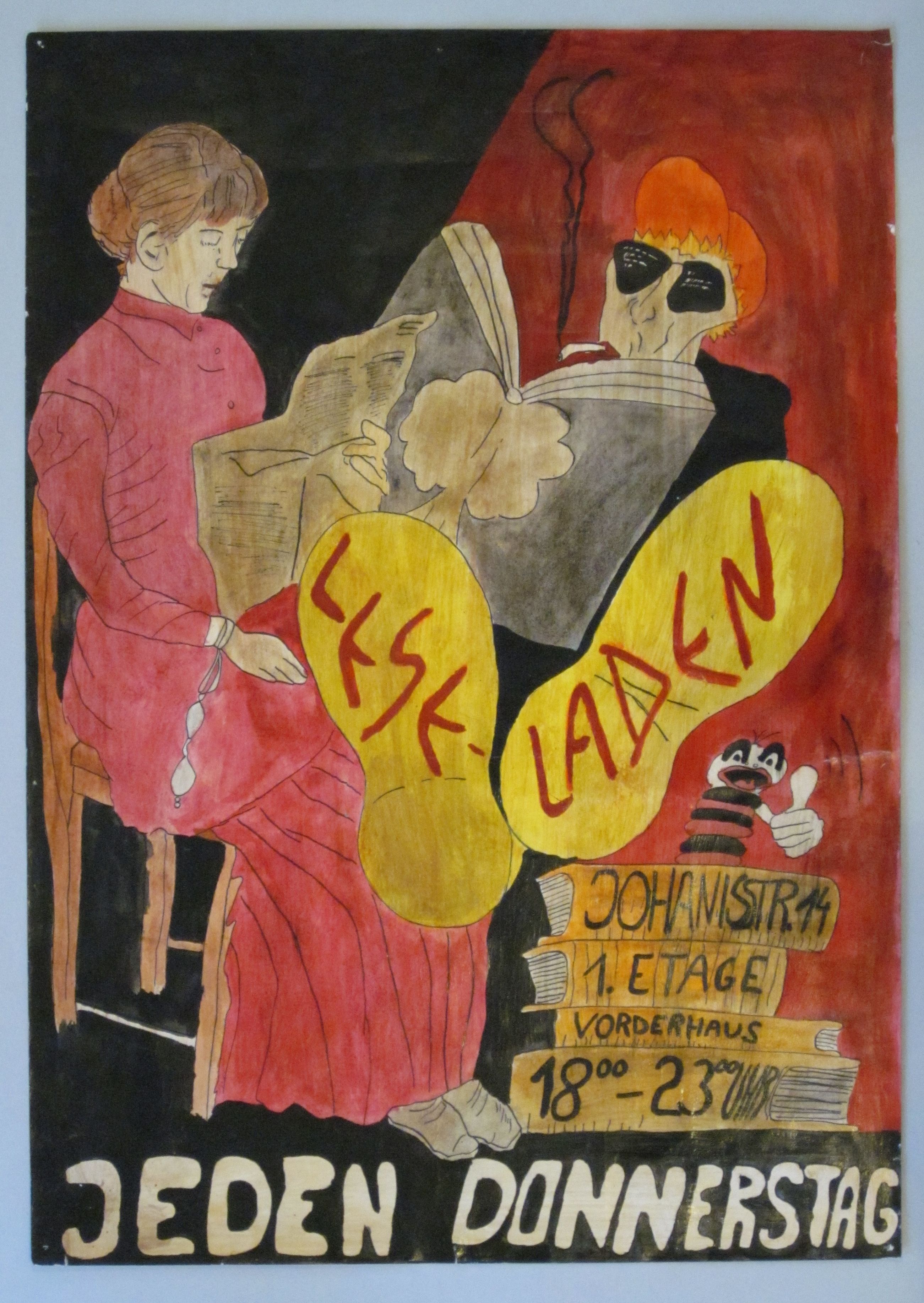

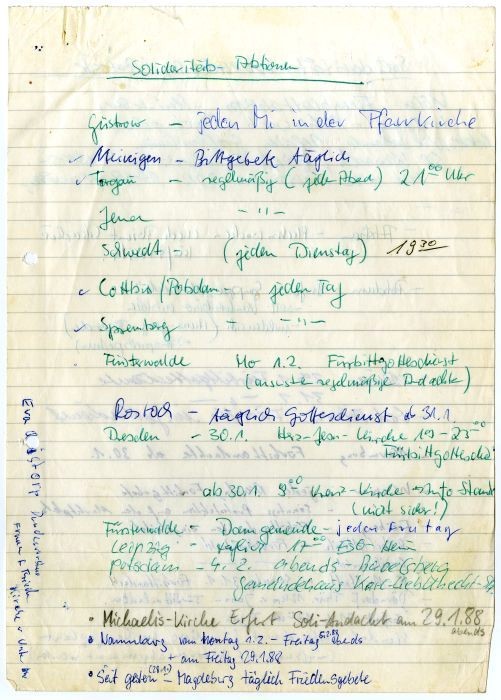

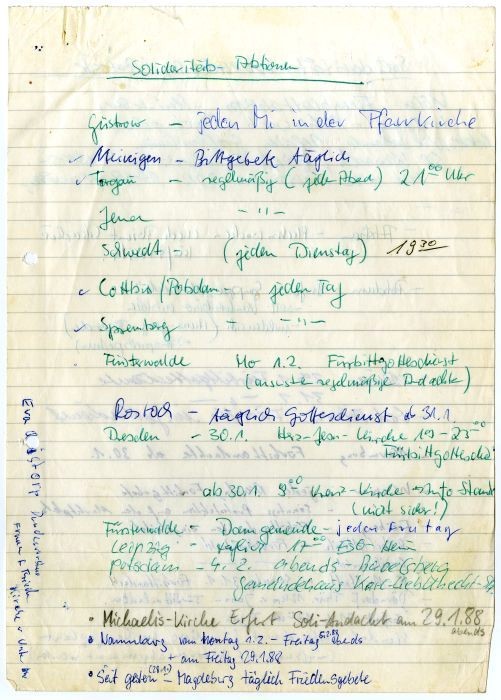

On 17 January 1988, around the periphery of the traditional march commemorating Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, which had long since become a mere ritual, a group of protestors unfurled a banner with the famous words of Luxemburg “Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who think differently.” They, along with many other protestors were arrested at the end of the demonstration, with some being forcibly extradited from the GDR against their will. This measure and its consequences are a key element in the prehistory of the “Wende” of 1989. Owing to the lack of publicity, little was known about the events or the protests and solidarity demonstrations which followed it. As a result, the so-called “Telephone Contact group” was created in Berlin. They distributed their number across the GDR via the structures of the church. Similar to an autonomous investigation committee, the group gathered information on the reactions (and mood) in the country. The notes which have been preserved here pinpoint where and when demonstrations and other acts of solidarity with the “Luxemburg-Liebknecht demonstrators” could be found. Marianne Birthler, who would later go on to become the Federal Commissioner for the Documents of the State Security Service of the former GDR, also belonged to the “Telephone Contact Group” and passed this on to the Robert-Havemann Society.

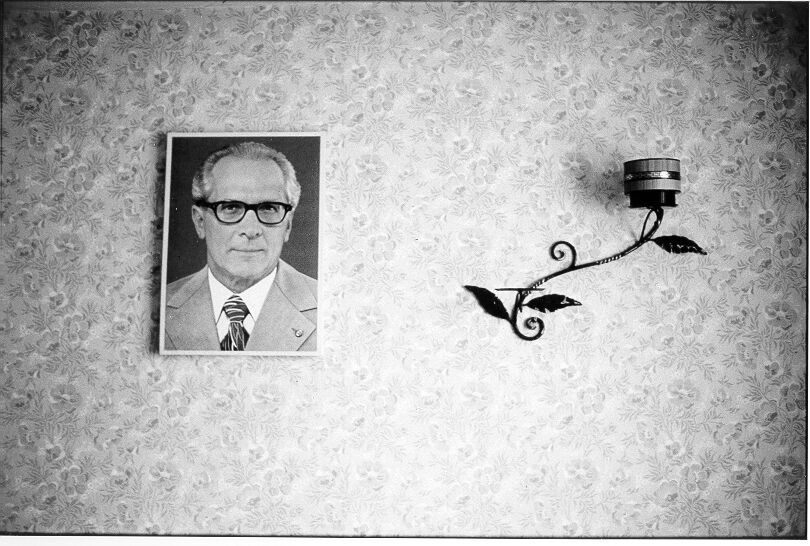

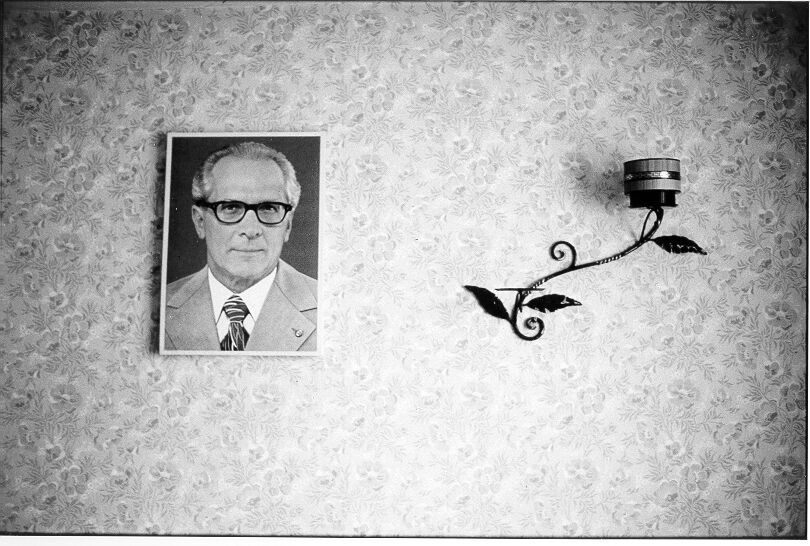

The black and white image (20,3 x 30,3, on paper) belongs to a series of images capturing everyday life in the GDR and in particular motifs which Nagel encountered on the daily basis in the village of Severin. These images have been taken over a long period between 1982 and 1988.

The image capturing the portrait of Erich Honecker reflects Nagels witty approach to symbols depicting the presence of the regime in the public space. Honecker portrait is not the focus of attention of the picture, but rather it is captured symmetrical to the banal decorative floral element on the wall same sized as the portrait of Honecker. The floral decoration seems to rather take over the entire image also on the background of the floral wallpaper, thus making Honecker presence in the image rather peripheral.

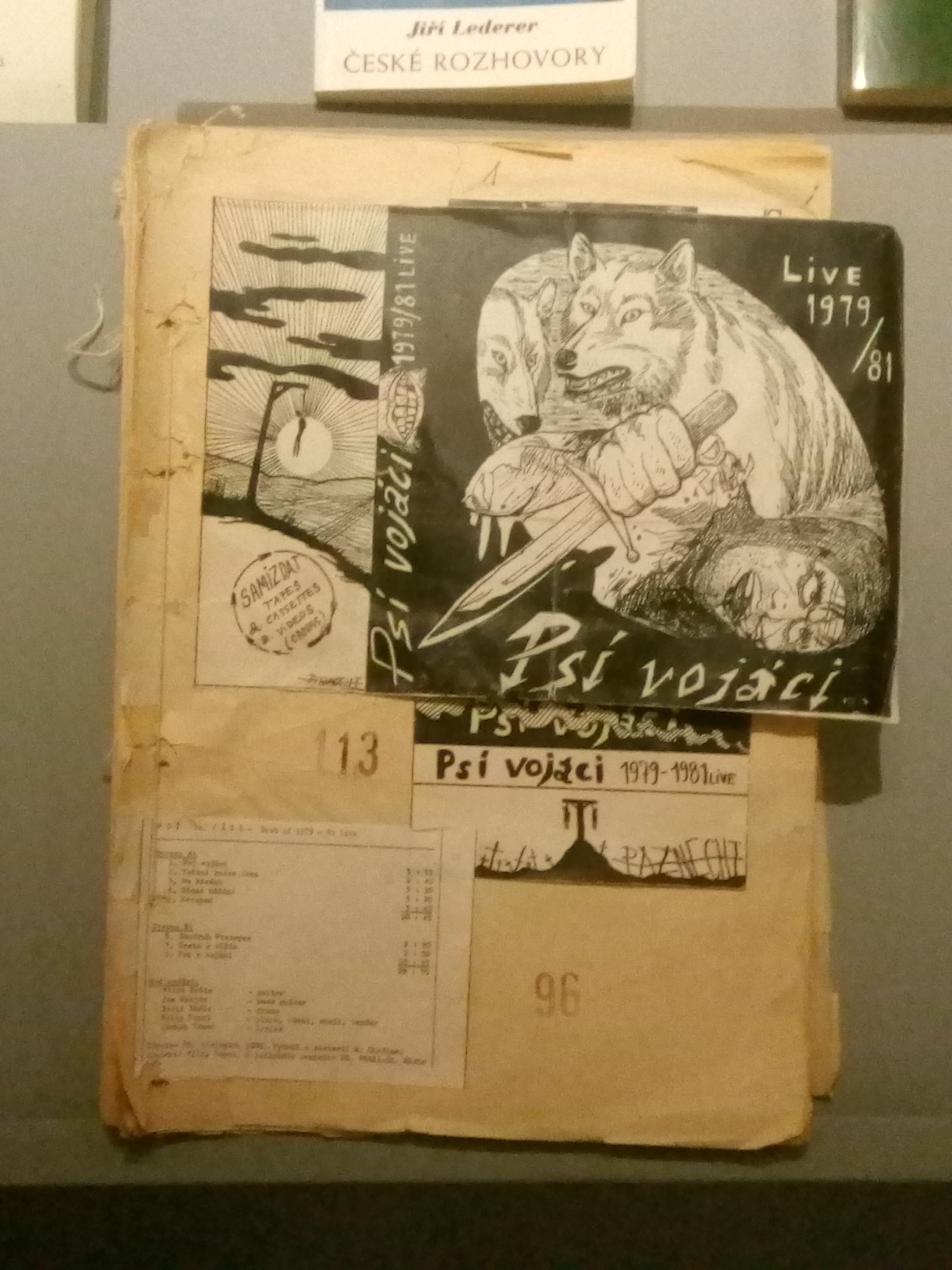

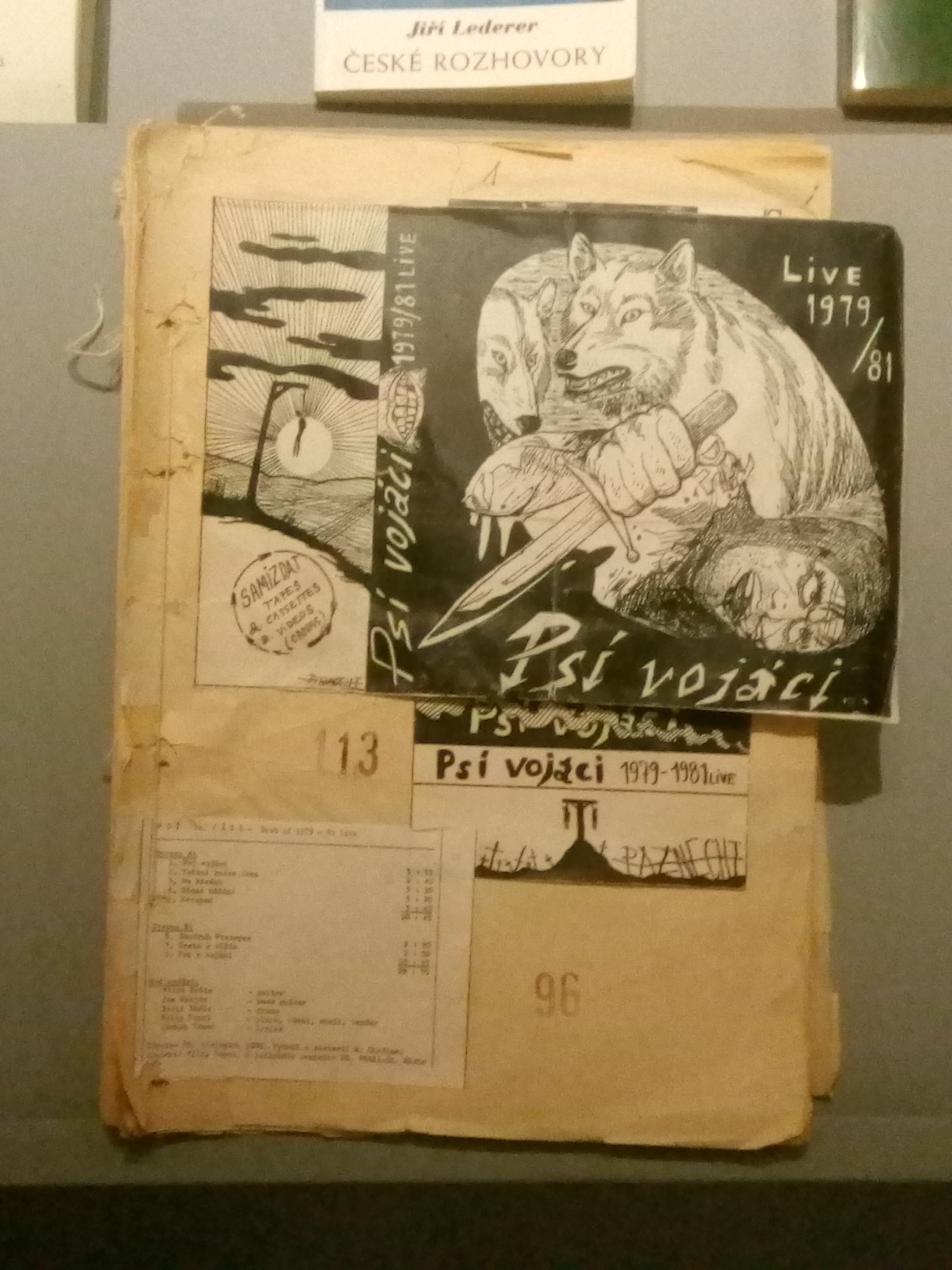

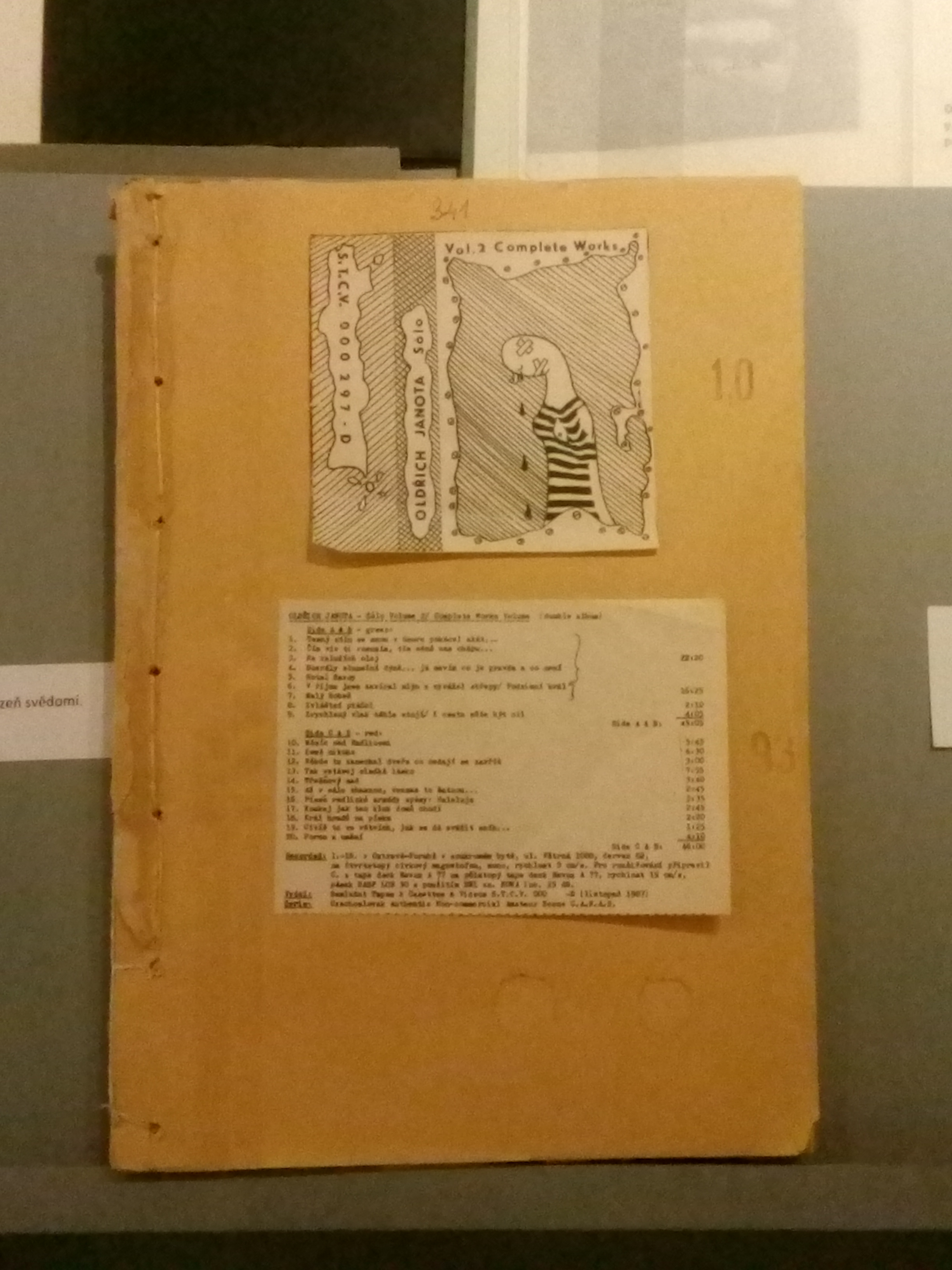

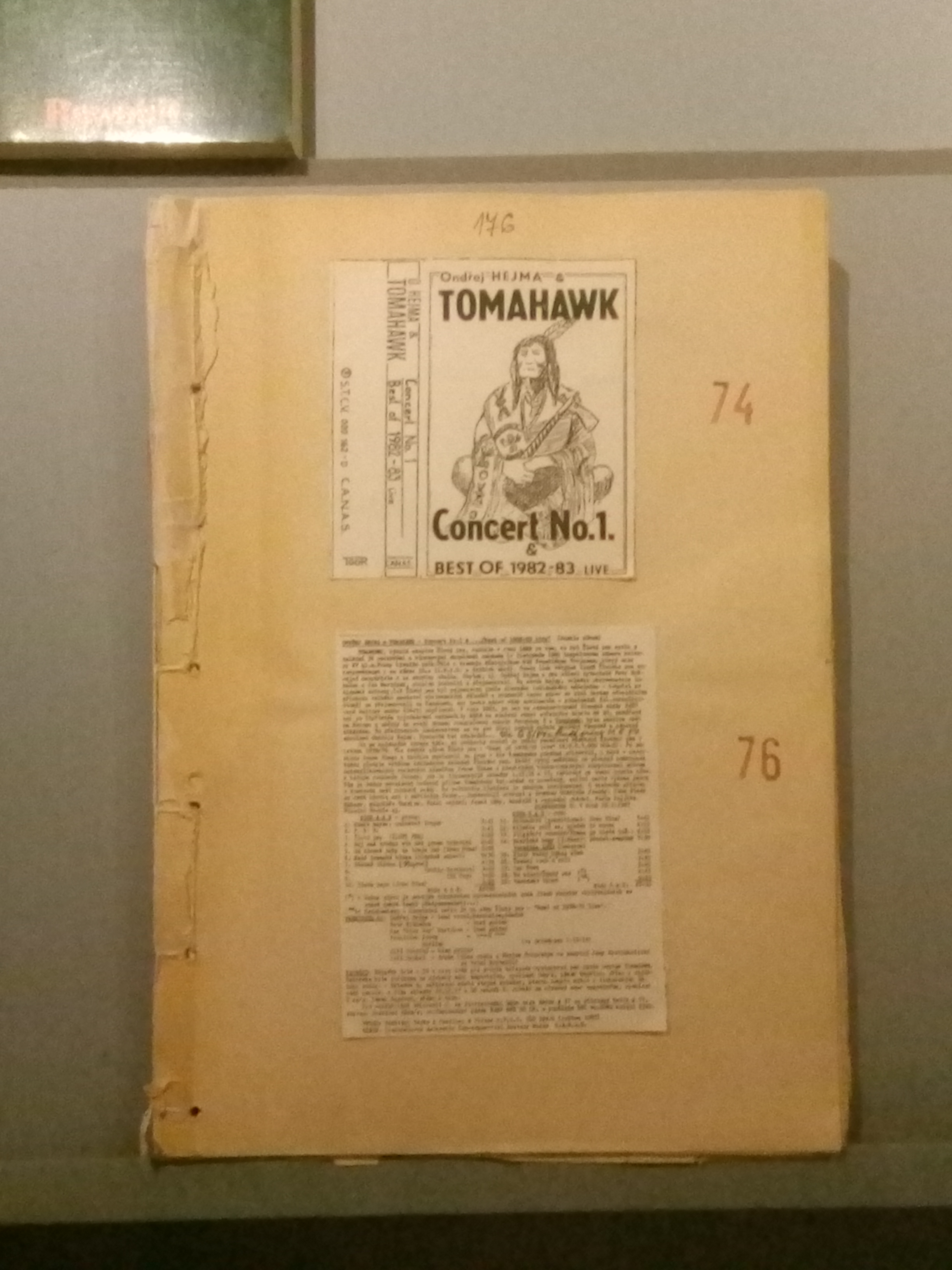

The Audiovisual Section of Libri Prohibiti contains three “books” – sheaves of paper – made from covers of cassettes of unofficial music groups from 1980s Czechoslovakia. The sheaves were made by the State Security (StB) from items confiscated during the prosecution of Petr Cibulka, a political activist and collector. During the 1980s, Cibulka recorded both concerts and amateur studio recordings, which he then produced and distributed in his samizdat record label S.T.C.V. (Samizdat Tapes & Cassettes & Video). Cibulka’s collection – hundreds of recordings and covers – was probably the biggest private collection before 1989. Cibulka was, because of these activities, sued in 1988 and imprisoned for “unjust enrichment” and his collection was confiscated by StB. The sheaves should have been evidence of his activities. A lot of original cassette covers were made from photo paper. The “books” therefore testify to the originality of producers of samizdat recordings. The item was presented on the travelling exhibition COURAGE “Risk Factors: Collections of Cultural Opposition” between 21 September and 28 October 2018 in the National Monument in Vítkov, Prague.

Gorbachev, Mikhail. Revolutionary restructuring - An ideology of renewal, in Romanian. Moscow: Novosti, 1988

Gorbachev, Mikhail. Revolutionary restructuring - An ideology of renewal, in Romanian. Moscow: Novosti, 1988

The Marian Zulean collection contains a brochure by Mikhail Gorbachev that summarises the main lines of the vision of the new Soviet leadership regarding the policies of glasnost and perestroika. The title of this little book in Romanian is Restructurări revoluționare: O ideologie a înnoirilor (the English edition is entitled The ideology of renewal for revolutionary restructuring) and it was published in 1988 by the Novosti Press Agency. Its presence on the market of publications in Romania was mediated by the International Trade Fair for Consumer Goods (TIBCO), an event held annually in Romania during the communist period, at which the USSR had a prominent stand.

The document, which is preserved in good condition in the Marian Zulean collection, gives a Romanian translation of the speech delivered by the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at its plenary meeting on 18 February 1988. Of this event, Mikhail Gorbachev says: “Our plenary is taking place in a period of responsibility for restructuring. The democratisation of social life and radical economic reform demand from the party a clear perspective on actions” (Gorbaciov 1988, 3).

A first observation that can easily be made after reading this document concerns the abundance of references to the key concepts of Gorbachev’s policy, perestroika and glasnost. They are mentioned dozens of times in the sixty-two pages of the document, but not in the original Russian forms in which they enjoyed an international career, including in English, but translated into Romanian as “restructurare/reconstrucţie” and “transparenţă”. On the basis of these key concepts of Gorbachevism, the brochure makes many suggestions for actions that obviously undermined the strictest rules of communism. Here, for example, is a single quotation in which the idea of egalitarianism is undermined, from the podium of the greatest communist party in the world and from the mouth of its supreme leader: “In general, comrades, we must deal thoroughly with the problem of eradicating egalitarian approaches. This one of the most important social-economic and ideological problems. Egalitarianism, in its essence, exercises a destructive influence not only over the economy, but also over morality over people’s whole way of thinking and acting. It diminishes the prestige of conscientious and creative work, weakens discipline, stifles interest in increasing qualification and the spirit of emulation, of competition in work” (Gorbaciov 1988, 34).

In Marian Zulean’s assessment: “This brochure authored by Mikhail Gorbachev was a precious book at the time.” It’s value came from the discrepancy between the ideas promoted by means of it and those that characterised official discourses in Romania. “While the URSS was becoming more open and had a discourse that was less and less in contradiction to the ideas of the West, in Romania, it was exactly the opposite. They were becoming more open; we were becoming more closed. You could try to read from this booklet in public, but it was safer to think well a few times before doing so. There were a lot of risky pages in it.” In other words, in the conditions of cultural isolation in which Romania found itself at the end of the 1980s, a brochure like this was one of the few sources of exposure to alternative ideas and a precious help to those who wanted to emancipate themselves from the dogmatic constraints in Romania and to be able to think critically and freely.

Vytautas Skuodis (1929-2016) was a Lithuanian scientist, Soviet dissident and former political prisoner. From 1979, he was a member of the dissident organisation the Lithuanian Helsinki Group. In 1978, he initiated and edited the journal Perspektyvos (Perspectives), the most recognised underground publication among the Lithuanian intelligentsia. The Vytautas Skuodis collection holds various manuscripts of Skuodis’ monograhs, a PhD dissertation, articles, lectures, letters, reviews of diploma works by students, notes, memoirs and diaries. These documents are relevant to the topic of cultural opposition, because they reveal personally the involvement of Skuodis and other people in anti-Soviet activities.

Cseke-Gyimesi, Éva. Levél egy erdélyi menekülthöz (Letter to a Transylvanian Refugee), 1988. Manuscript

Cseke-Gyimesi, Éva. Levél egy erdélyi menekülthöz (Letter to a Transylvanian Refugee), 1988. Manuscript

This work was finished in February 1988. It was published in Budapest on 17 July 1988 in the twenty-fifth issue of the weekly national youth magazine Magyar Ifjúság (Hungarian Youth), the periodical of the Hungarian Union of Communist Youth. In her writing Gyimesi condemns the fact that a Hungarian intellectual who had suffered no harm as a result of his/her previous actions should declare himself/herself a “Transylvanian refugee.” She understands the existential insecurity of the individual in question, the fear of losing one’s job in the near future, the worries about one’s children’s possibilities of further studying in Hungarian and also the fear that one’s children might be placed in faraway Romanian regions after graduation. In spite of this, besides the numerous arguments in support of emigration, Gyimesi calls for remaining in the home country. She points to the fact that leaving the country only results in a greater reduction of the already thinned and weakened Hungarian minority and the space voluntarily given up by the addressee only increases the control the communist regime has on those left behind. Gyimesi even passes a judgment on the person embracing the role of the “poor Transylvanian refugee.” She reproaches that he or she is not hit harder by the disadvantageous situation than what is generally implied by minority existence in Romania. She goes on to reproach that the addressee never – either individually or jointly – stood up publicly – by means of petitions or memoranda –, never did anything in order to ensure that constitutional rights regarding the use of the mother tongue, education, and cultural life were respected. The consequences of these efforts would have been labelling as “nationalist” at most, but “having to put up a daily fight for the rights stipulated in the constitution is not a natural thing and is also very tiring.” She states that the “refugee” did not only flee from the common disadvantageous situation but also from the responsibility he/she as an intellectual owed to the Hungarian ethnic minority and indirectly to the nation (ACNSAS, I017980/1, 138–141).

This text published in Hungary in July 1988 rendered Gyimesi’s situation at the time even more difficult as she mentioned the violation of human rights in Romania in various respects, thus adding to the series of accusations brought against her. Already in 1987, the Cluj county Securitate had transmitted her case to the directory board of Babeș-Bolyai University and instructed the rector to commence disciplinary procedure against her. In this regard mention must be made of the disciplinary meeting of 26 July 1988 when the Executive Board of the University Senate issued a last warning to Gyimesi, and disposed that a three-member committee should supervise the conduct and professional activity of the professor, suspending her academic status until a decision was reached (Cs. Gyimesi 2009).

At the end of the 1980s, the “letter” and such writings in general had the value of a gesture; standing up for one’s views, expressing one’s opinion was in itself an irregular act – their main merit was the disruption of the silence of dictatorship (Király 1993). Relatively few people could hear about or read the critical writings of the final years of dictatorship. In an attempt to compensate for this public ignorance, Gyimesi published in 1993 her volume Homesickness in the Home Country containing her works written in the 1980s, considered in the context of that time as dissident, including studies, private and public correspondence, and texts of lectures and conversations, along with her shorter works written after the collapse of the Communist regime up to the summer of 1992 (Cs. Gyimesi 1993).

Csapody felt that it was not enough simply to research and document acts and fates of individuals who refused to perform compulsory military service. He sought to make the decisions and fates of these individuals familiar to wider audiences, as well. He began shooting the film with great enthusiasm but without any financial support or filmmaking experience. His technical supporter was cameraman László Pesty. Almost all of the raw material, including interviews and discussions, was preserved in the collection.

The ‘Fuck 89’ collection is an archive of Warsaw anarchistic movement from the last years of state socialism and the beginning of capitalism. It documents activities of groups such as A-Cykliści (A-Cyclists), Alternative Society Movement, Wolność i Pokój (Freedom and Peace), Intercity Anarchist Federation, and others.

"Monty Cantsin is a multiple personality pseudoname, an open-pop-star project. Anybody can be Monty Cantsin.

Neoism has no definition, and it doesn't mean anything specific. You can become a neoist by doing everything in the name of Neoism and by calling yourself Monty Cantsin."

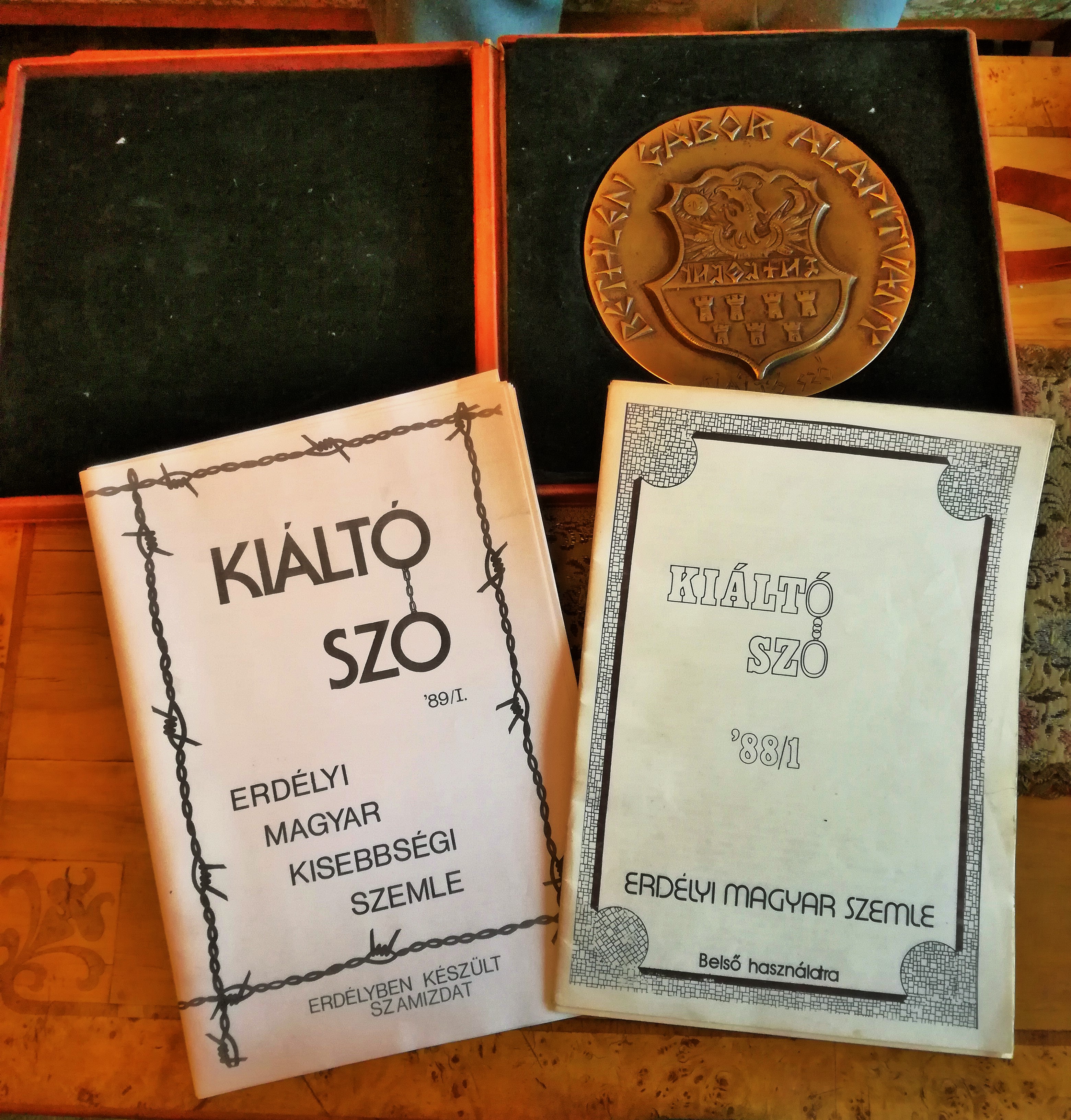

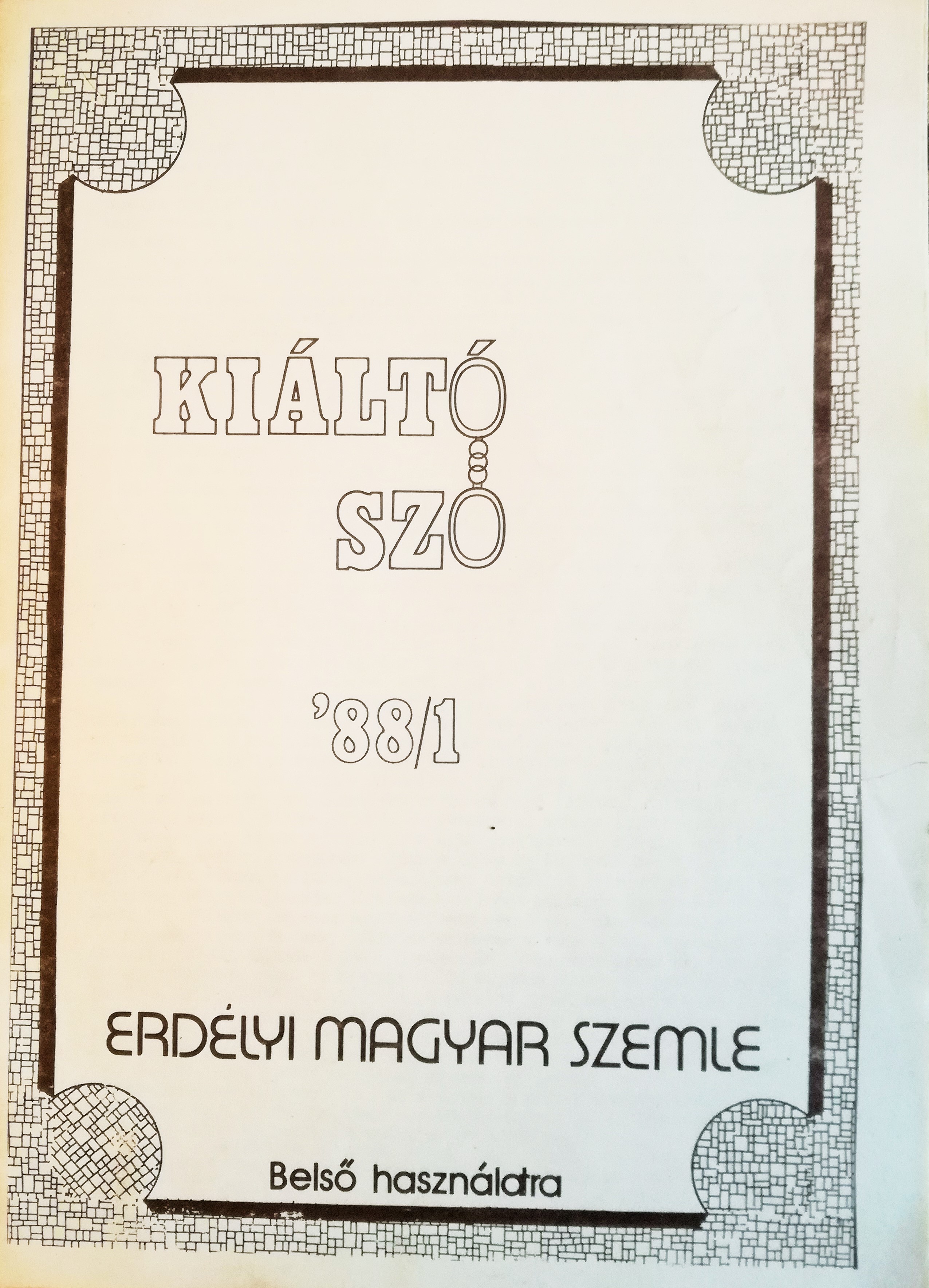

The Kiáltó Szó – Balázs Sándor Private Collection in Cluj-Napoca contains the second Transylvanian Hungarian samizdat magazine issued under Ceaușescu’s regime and offers insight into the democratic resistance and the human rights struggle of the time. At the same time the samizdat is an example of the pre-1989 Hungarian–Romanian rapprochement, in which the idea of shared destiny secured a common ground for minorities and the majority alike.

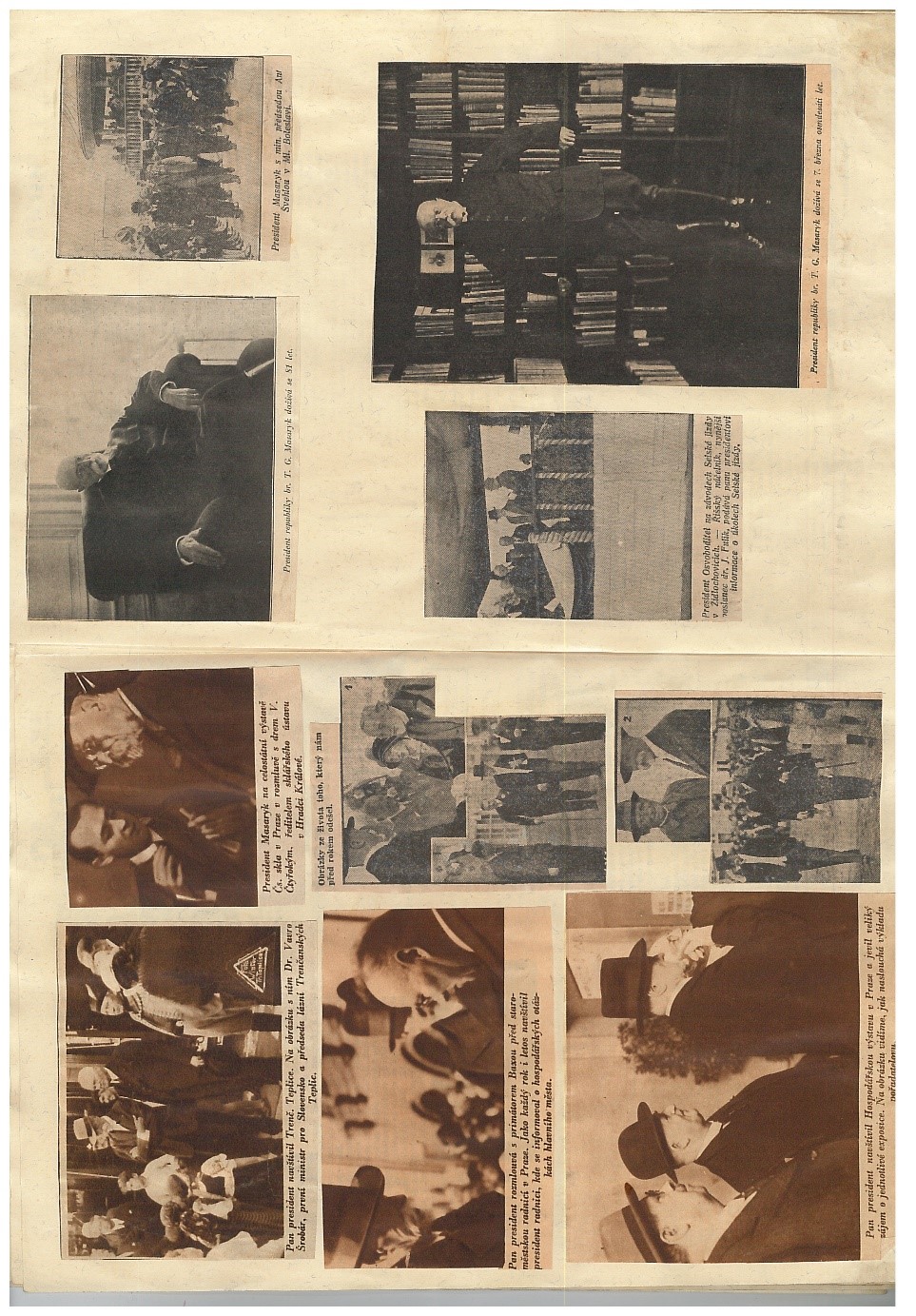

An album composed of clippings of period texts, pictures, photographs and graphics. Its author, nor the exact date of origin, is known. Perhaps his creator was one of the founding members of the Masaryk Society in Brno. Its foundations can be found in the 1930s, since the greatest amount of material came from this time - mainly newspaper clippings about TGM’s death (in 1937). The album was probably used as a pictorial accompaniment to lectures that took place at the time of socialism as an unofficial event in private flats. At this time, no articles with references to the personality or the work of the first Czechoslovak president were officially rooted and there was a lack of available photographs of President Tomas G. Masaryk and other illustrative documents. This album offered a rich visual accompaniment to the stages of his life and topics related to his personality. The pictures accompany published texts, for example, by Edvard Beneš. Owning such an album and its public presentation could have had unpleasant consequences for the owner during socialism. It is good to note this context at the moment, because all controversies of this kind have disappeared, the visual material about TGM is more than enough and the old album with clippings from newspapers would not attract any attention.

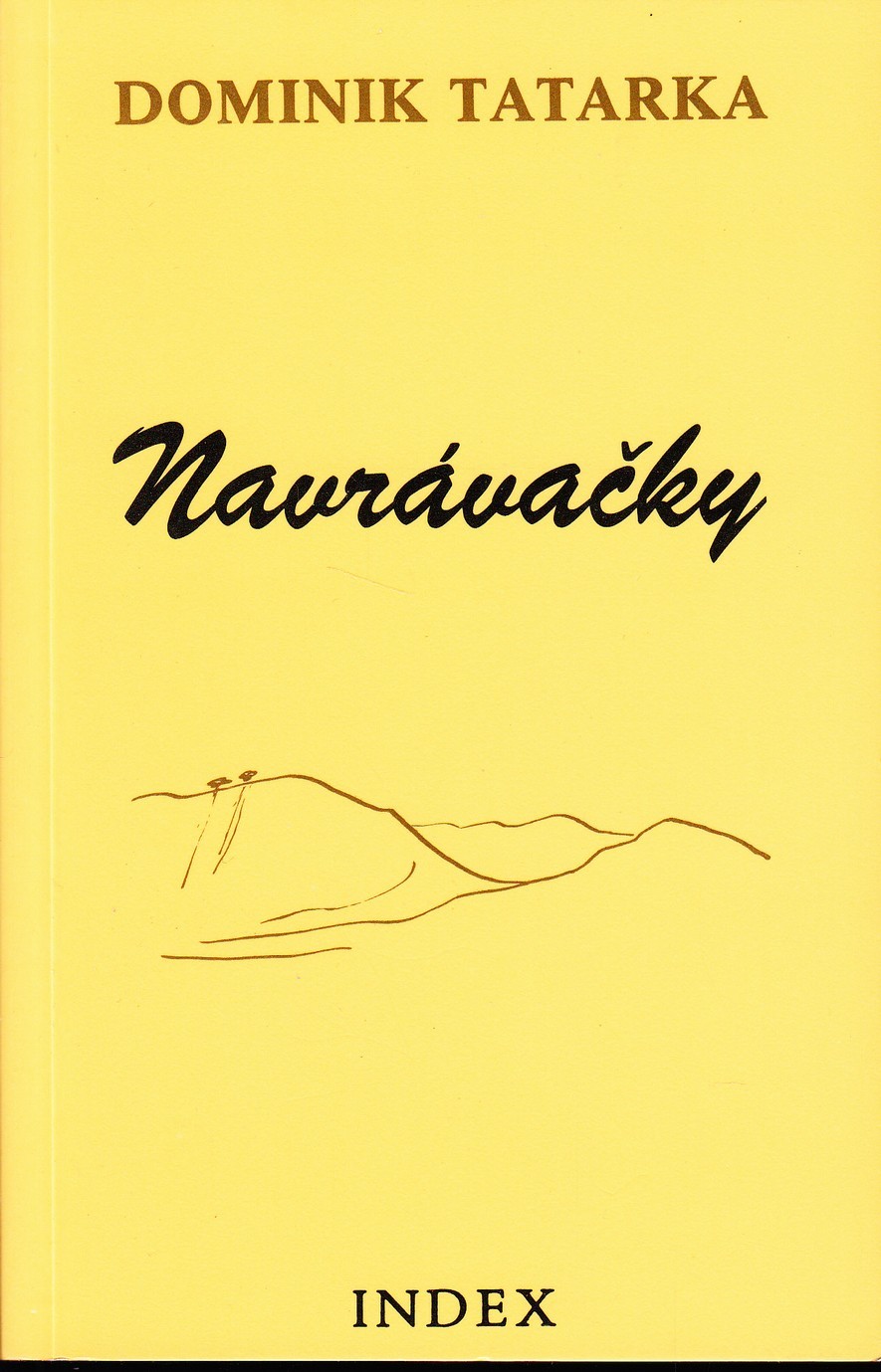

Dominik Tatarka was a famous Slovak writer that became a “banned author” after 1968. He criticized Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and he was the first Slovak signatory to Charter 77. Thus, some of his books were published as samizdat or in exile. Tatarka’s book “Navrávačky” was first published in the samizdat journal “Fragment K” in 1986 (the first part) and 1987 (the second part). In 1987, this book was published in the samizdat edition “Petlice”. Then, this text was issued in exile – “Navrávačky” was published in 1988 in Western Germany in Cologne within the exile edition “Index”. These samizdat and exile editions of “Navrávačky” were prepared by Martin Šimečka and Ján Langoš. “Navrávačky” are book of Tatarka’s memories, opinions, and messages about culture, society or his life. This book is based on Eva Štolbová’s interviews with Tatarka that were recorded on twenty tapes during years 1985 and 1986. However, the text of these samizdat and exile editions was modified and rewritten as Tatarka’s monologue (in prose), without Štolbová’s questions. Later, in 2000 and 2013, “Navrávačky” was published in an original and complete version, as a transcription of interviews from tapes without any modification.

Tymoteusz Onyszkiewicz claimed that the most important artefacts from the Fuck 89 Collection are photographs of youth demonstrations from 1988 and 1989. He argued that mass demonstrations that occurred one after another in two-three weeks period were essential for the anarchist movement in the late 1980s. Anarchists, socialists, punks, Rastafarians, pacifists, ecologists, and other alternative youth groups used to regularly gather together in the streets of Warsaw to manifest their disagreement with the state policy and socio-economic situation in Poland. What they showed was also the solidarity among different groups of young people, when the whole movement fought for rights of small parts of itself. Exemplification of this united fight of the youth opposition is given by unique photography which captured one of the demonstrations demanding the legalization of Independent Students’ Union (ISU) in 1988. The photo shows a mob of people with flags and banners of ISU as well as anarchistic, marching through Krakowskie Przedmieście street nearby university’s gate, in spite of ideological differences between liberal-democratic ISU and radical anarchists and socialists. The author of the picture is unknown, but the message about the solidarity of rebellious youth movement is very clear.

At the launch of the underground magazine the first challenge the editors were faced with was the political embedding of the product. This was done in the editors’ note (“Beköszöntő”) of the 29-page first edition and in Balázs Sándor’s programmatic article (“A Ceaușescu-korszak után” – After the Ceaușescu era). The title of the magazine was borrowed from a post-Trianon publication of the Hungarian community in Transylvania, which had found itself turned into a minority. Although the social-political circumstances in the interwar period differed in several aspects from the situation of the 1980s in Romania, the similarity between the existential situation of the minority in the two periods was considered more important. The editors revealed an analogy between the former outstanding personalities of Transylvanism and their own strivings. At the same time, they saw a resemblance between the post-Trianon mood and the spirit of hopelessness which existed during the decades of communism, characterised by: “despair, hesitation, idleness, the lack of creative energy, paralysis, turning away from politics, shattered self-confidence, escape fever, etc.” However, beside the words with negative meaning, the editors made use of the positive message of the 1921 Kiáltó Szó, which they tried to incorporate in their political statement with expressions like: “urge to act,” “restoring shattered self-confidence,” “work for the survival of the community instead of lamentation,” “developing the sense of reality instead of dreaming.”

They believed that the Romanian state had to take into consideration an ethno-cultural community as numerous as the Hungarian minority. They considered it important to establish a party on the basis of nationality which would represent the interests of the ethnic minority but in the context of Party-state dictatorship this called for a fundamental prerequisite, namely, the abolition of the one-party system. Organising a party was thus not an immediate option; they merely wanted to imprint the idea of this necessity in public awareness. By raising the issue, they implicitly adopted a position in favour of a multi-party system and of “real (not mocked as socialist) democracy.” As they could not imagine the implementation of multi-party democracy in the near future, they separated tactical (immediate) goals from strategic (long-term) tasks. The strategic task, that is, the abolition of the totalitarian regime, could not be formulated as an objective considering that this depended on the coordinated action of the entire Romanian society; therefore they only alluded to it. Thus, the emphasis was laid on the tactical goals, on preserving the Hungarian ethno-cultural community in Romania “until the time comes to participate in change.”

Continuing the tradition of their predecessors, the editors believed in the direct proportionality between fairness and loyalty, according to which the state could expect only as much loyalty as was justified by the degree of fairness it displayed towards minorities. The editors did not act against the Romanian state, but strove to put an end to discrimination against the Hungarian minority and to achieve a real democracy where loyalty too could be fully expressed. They were not against the state, and, as they expressed in their programme objective, they did not want a revision of borders. The distributed writings and the attached interpretations illustrated that the target of their criticism was the Party dictatorship. In particular, they tried to dispel the misconception according to which the dictatorial couple was responsible for everything, as they were fully aware that even if the dictators were eliminated, the Party apparatus would remain, and so their replacement would not solve the problem.

The editors of this samizdat doubted the idea shared by many according to which the Hungarian minority in Romania would play the role of a bridge not only between Hungarians and Romanians, but implicitly, between Hungary and Romania. Therefore they formulated and applied their threefold slogan towards Romanians: form an alliance with the Romanian democratic forces, win over the misled Romanians, consistently fight against Romanian nationalism. They tried to nourish the sense of interdependence and made efforts using their modest means to promote the necessity of a joint Romanian–Hungarian action. When presenting their political creed the editors strove to show their sympathy with those who held similar or identical views; in this regard they sympathised with the authors of the previous samizdat – Ellenpontok (Counterpoints) – as well as with Károly Király who at that time was a legendary figure of political resistance.

In his optimistic piece entitled “A Ceaușescu-korszak után” (After the Ceaușescu Era) Balázs dedicates seven paragraphs to the discussion of the tasks, the tactics, and the clarification of the legal status of the minority in the period up to the establishment of plural democracy, “preserving ourselves for the future.” The key point of his conception is, among general democratic rights, the need for collective rights to be granted to the minority, and further on, the securing of various forms of autonomy for the national minority. In the paragraph dealing with politics he speaks up for the political representation of the minority, where the nationality-based party separately representing itself at the elections is a political grouping guided primarily by the minority point of view in a multi-party social system. Nevertheless, this party will voice its opinion not only about minority problems, but also with reference to general issues concerning the country. In economic policy he argues in favour of unimpeded private initiative, stating that minority initiatives, both individual and group-level – cooperatives, economic associations, private companies – must be made possible in places densely populated by Hungarians. As far as culture is concerned, he stresses the importance of a licence accorded to the community (at the time referred to as either nationality, national minority or Romanians of Hungarian origin) that will enable them to manage their own affairs, especially cultural issues, independently. This requires a proper institutional framework which means, in fact, cultural autonomy. The article discussing the tasks underlines that this autonomy – be it cultural or not – is not meant to serve disconnection and that the editors of the samizdat have no intention of using the potential autonomy for purposes of boundary revision.

The part dedicated to education discusses the prospective restoration of the Hungarian-language Bolyai University and of the old Hungarian school network as well as the possibility of carrying out scholarly work in the Hungarian language in own institutions. When touching upon the free use of the mother tongue as one of the most essential minority rights, Balázs asks the state for guarantees as regards the validation of this abstractly stipulated and theoretically acknowledged “constitutional right.” He thinks that this right should be concretely included in several laws, as well as in the constitution. Thus there should be laws to regulate the introduction of multilingual signs in places also inhabited by minorities, the use of the Hungarian language in court and during official procedures, etc. He also argues in favour of the re-launch of Hungarian television programmes and local radio broadcasts. All this could have been considered as an act of revendication since the Romanian nationalist policy strove to restrict the use of the minority mother tongue most of all. The tactical measures include an inventory of clerical complaints, including problems linked to clergy training and difficulties concerning the bringing out of church publications. This last paragraph of the article asks for an elimination of discrimination between the domineering Orthodox religion of the Romanians and the so-called “Hungarian” religions the minority adheres to. The articles discussing the political statement as well as the “draft political programme,” besides representing a proof of civil courage, belong to one of the most significant historical documents of the years preceding the change of regime in 1989.

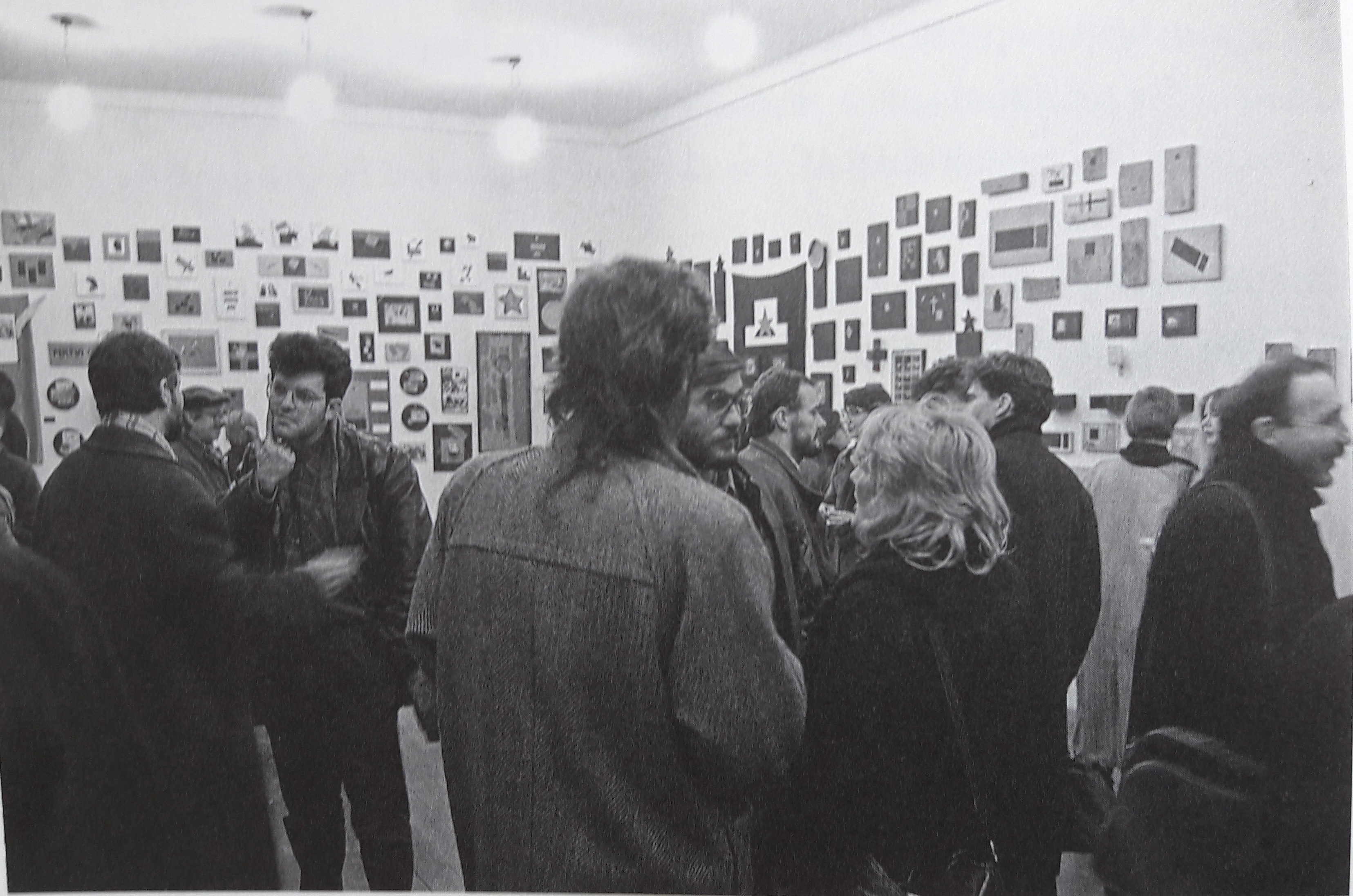

The first presentation of works from the "Exploitation of the Dead" cycle took place in the Extended Media Gallery in Zagreb in January/February 1988. About 350 small-format works which summarize Stilinović's four-year work were shown at the exhibition.

The exhibition was well attended by the public, and received sound media coverage. The main Croatian newspapers (Vjesnik, Večernji list, Oko, Studentski list, Danas) ran positive reviews on the exhibition. Especially interesting is the review by the well-known art critic Ana Lendvaj, who emphasised Stilinović's courage to play with the symbols of the star or the cross and generally with - according to Stilinović - dead ideologies that still impress people.

She noted: "It is clear that Stilinović - by touching upon the network of ideology, the network of religion, and the network of art, and doing this in a courageous world-building attempt - explores how the process of repetition vibrates as the one that either leaves things as they were or radically changes them at the expense of (lethal) consequences for the person who engages in this perilous task. It is dangerous because all these used signs, artistic or historical directions to which the author refers have not been emptied of emotion, and we are still tragically sensitive over them, but only when they are thrown into our faces in a pure, direct and non-derivative form. If they are transmitted through pictures, it will be harder for us to notice them" (Večernji list, 26 January 1988, p. 11).

The collection contains documents of the Masaryk Society, citizens' illegal initiatives, which originated in Brno and Prague in 1988. The society organized events for the return of Masaryk's name to the public space and cultivated the regime of suppressed knowledge and awareness of the philosopher and first president of Czechoslovakia, Tomas Garrigue Masaryk.