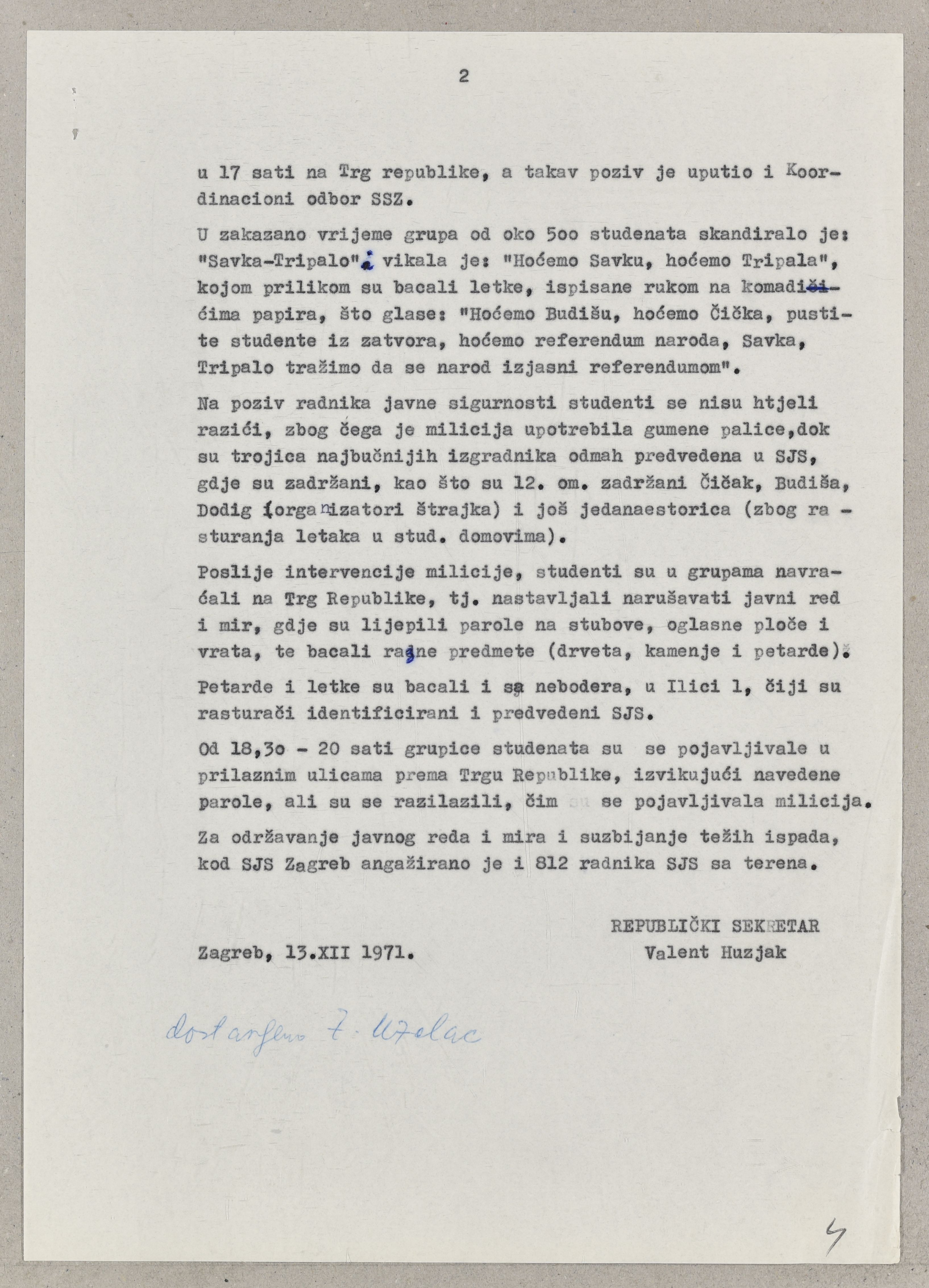

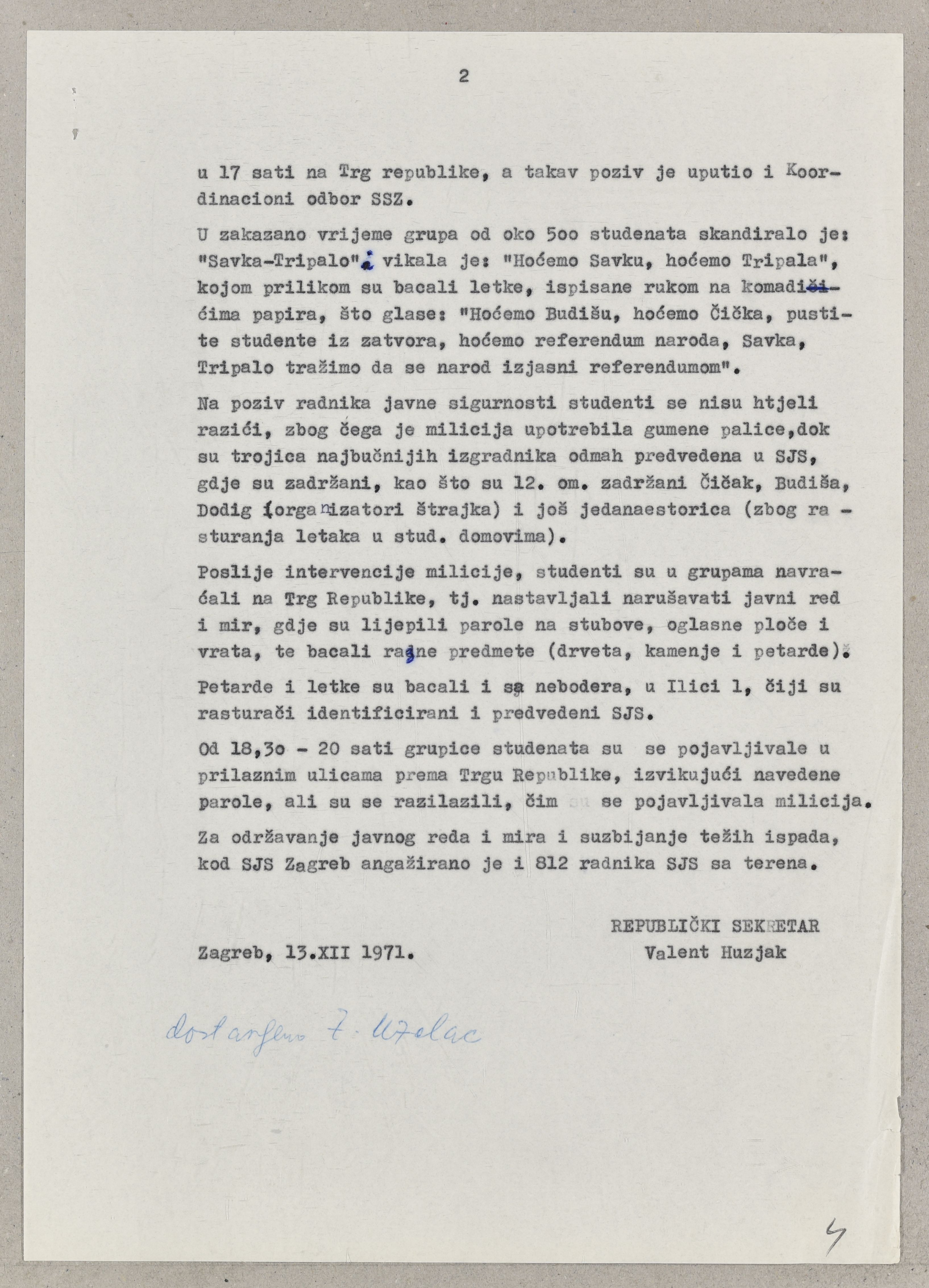

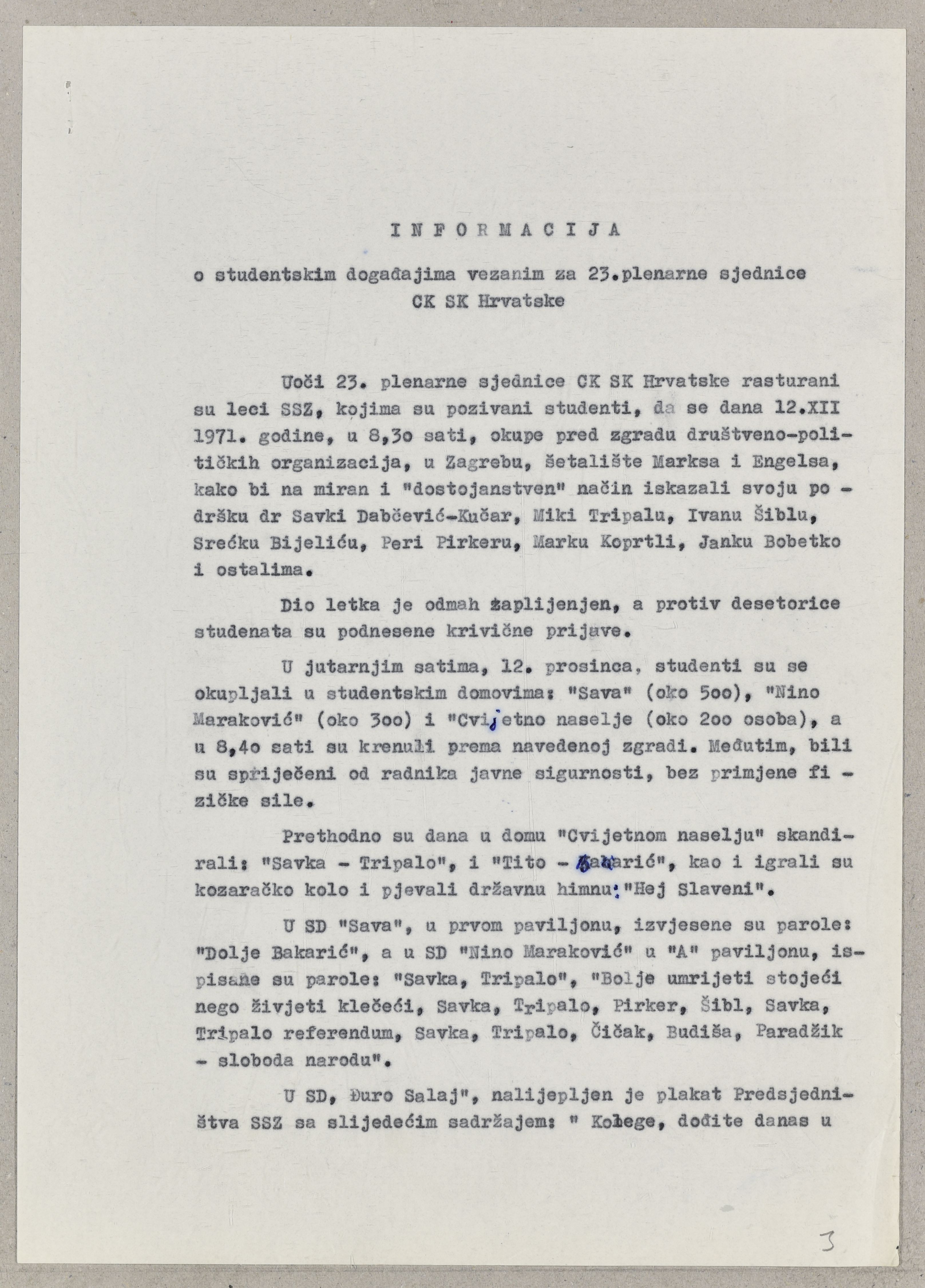

Information on student activities related to the 23rd plenary session of the Central Committee of the League of Croatia. 13 December 1971. Archival document

Information on student activities related to the 23rd plenary session of the Central Committee of the League of Croatia. 13 December 1971. Archival document

The crackdown on the Croatian Spring and the repression against its members came in December 1971, after the twenty-first session of the Presidium of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, held in Tito's residence in Karađorđevo. Croatian political leaders were removed from their posts and banned from engaging in any public work. On the eve of the twenty-third session of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia held in Zagreb on 12 December 1971, where they formally resigned, as a show of support students organised various activities. According to the report written by Valentin Huzjak, secretary of the Republic Internal Affairs Secretariat of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, early in the morning on that day, approximately 1,000 students gathered in three student dormitories in Zagreb and then went to demonstrate in front of the Central Committee's headquarters, but were halted by police forces. In the student dormitories they shouted and wrote slogans on the walls in support of Savka Dabčević-Kučar, Miko Tripalo, Pero Pirker and other political leaders dismissed from their posts. Huzjak also reported that later in the afternoon, approximately 500 students demonstrated, shouted and posted slogans and distributed handwritten pamphlets on Zagreb’s main square. According to the report, a few dozen people were arrested, and while breaking up the demonstrations, the “police used nightsticks.ˮ Besides the staff of the Public Security Service in Zagreb, 812 police officers from other towns and cities were engaged to suppress the demonstrations.

The document is available for research and copying.

Era Milivojević first carried out the work ‘Taping the Slave’ in 1969, followed by ‘Taping the Mirror’, while his first performance, ‘Taping the Artist’, was staged at the exhibition in 1971. In the words of the artist, a performance is created by including the person in the work itself. This is a photograph of the performance enacted in the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade. The photograph records the creation of a living sculpture produced by the artist himself, Era Milivojević, in collaboration with another artist, Marina Abramović – the taped artist.

The work was incorporated into the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in 2007 thanks to funding provided by the City Assembly of Belgrade.

This is a reprint of a Ukrainian underground samizdat journal published by Smoloskyp and P.I.U.F. Ukrainskyi visnyk was the first samizdat literary journal in Ukraine, founded in 1970 and edited by Viacheslav Chornovil until his arrest in 1972 (issues 1-6). Iaroslav Kendzior, Mykhailo Kosiv, Atena Pashko were among the journal’s main contributors. In 1975, after Chornovil’s arrest, Stepan Khmara,Vitalii Shevchenko, and Oles Shevchenko published one more issue of the journal (7-8). In 1987, the journal reappeared again, this time as the main publication of the Ukrainian Helsinki group. The journal published information about political repression and cases of violations of human rights in Ukraine, as well as literary criticisms, poetry, and socio-political articles.

Smoloskyp and P.I.U.F. published nearly all the issues of the journal (except no. 5) that were smuggled from Ukraine to the West. Reprinted issues of the Ukrainskyi visnyk played a key role in making the case of political repression in Ukraine and the Ukrainian liberation movement internationally known. Soon after its first publication by Smoloskyp, materials of Ukrainskyi visnyk were widely circulated by Western media, including Radio Freedom, which of course did not go unnoticed by the Soviet authorities.

Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca had an intense correspondence with Romanian intellectuals in exile and a part of this correspondence is preserved in the collection housed by the National Archives in Bucharest. Among the letters preserved here there is one signed by the well-known historian of religions, Mircea Eliade. Eliade left Romania in 1940 and dedicated his entire intellectual activity in exile to the study of history of religions and the history and philosophy of culture.

In his letter of 27 March 1971, which was read by Monica Lovinescu in her broadcast on RFE under the suggestive title of Refutation, Mircea Eliade speaks about the interview he granted to Adrian Păunescu and published in the Romanian magazine Contemporanul (The contemporary) on 10 and 17 March 1971. The historian of religion underlines the fact that he agreed to answer Păunescu’s questions on condition that the interview would be published in full. To his unpleasant surprise, the conversation was drastically censored and according to Eliade, the cuts dramatically altered the meaning of the interview. Specifically, the Romanian censorship removed those parts in which Eliade mentioned autobiographical details connected to his youth in interwar Romania, such as the impact that Nae Ionescu, a very influential right-wing-oriented journalist and professor of philosophy, had on his intellectual development. Also, the names of other renowned Romanian exiles such as Emil Cioran and Eugène Ionesco were removed, as was any reference to his co-generationist, Mircea Vulcănescu, who ended his life in a communist prison. Finally, any mention of his writings about the history of religion and philosophy of culture, which were central in Eliade’s work, were absent from the published interview. Consequently, Eliade bitterly concluded that: "As for the memories of the nights spent together in the winter of 1971, they are evoked by the poet and journalist Adrian Păunescu and belong to him entirely. When we were talking, I thought we were speaking the same language: the old, honest Romanian language that I learned in my childhood and which I am still speaking now, in my old age. I admit with immense sadness that I was wrong."

The censorship of the interview can be easily understood if one considers the political and cultural context in Romania at the beginning of the 1970s. The nationalist turn of the Ceaușescu regime (Petrescu 2009, 523–544) did not result in the rehabilitation of Nae Ionescu, Emil Cioran, Eugène Ionesco, or Mircea Vulcănescu whose names were still on the list of the Romanian censorship. Moreover, the ending of the liberalisation period, marked by the so-called Theses of July 1971 on improving political-ideological education, made even more problematic the publishing of any reference to religion and history of religions. The paradox that Mircea Eliade accepted an interview with Adrian Păunescu only on the basis of the latter’s assurance that the text was going to be published uncensored in Romania can be understood if one takes into consideration the situation of the two protagonists involved. Since Mircea Eliade left Romania in 1940, he had lost touch with what was really going on in the country, and he seems to have been unaware about what censorship really meant and how it actually worked. As for Adrian Păunescu, at that time a young man of only twenty-eight and without any obvious connection with the communist regime, he had come to the United States at the invitation of several Romanian writers. Enticed by the young poet’s genuine interest in his person and work, Mircea Eliade not only agreed to grant him an interview, but also answered wholeheartedly the provocative questions asked by Adrian Păunescu, at that time a promising and uncommitted young writer (Manolescu 2014).

The collection is made up of the papers of the avant-garde multimedia conceptual artist Hardijs Lediņš (1955-2004). It reflects his activities, and those of his collaborator Juris Boiko (1954-2002), as well as a number of their friends who were at the centre of alternative culture in Latvia in the 1970s and 1980s.

Rendić, Smiljana. “Izlazak iz genitiva ili drugi hrvatski preporod” (Departure from the genitive or the second Croatian national revival), 1971. Manuscript

Rendić, Smiljana. “Izlazak iz genitiva ili drugi hrvatski preporod” (Departure from the genitive or the second Croatian national revival), 1971. Manuscript

This manuscript was created at the time of the Croatian Spring, and was published in the journal Kritika in its June issue in 1971. Rendić discussed the Croatian national question under Yugoslavian socialism, with particular emphasis on the status of Croatian language and Croatian statehood within a common state. In this respect, Rendić negatively assessed the developmental logic of Yugoslav socialism, which according to her view was based on the negation of the Croatian national identity and language. The main reason for Rendić's thesis was that the “radical colonization of the Croatian language” was carried out in socialist Yugoslavia by the introduction of numerous words from the Serbian language. Precisely because of that, the “Declaration on the Name and Status of the Croatian Language” arose to resist such efforts in 1967. According to Rendić, apart from linguistic policy, the unequal status of Croatia in the Yugoslav federation was reflected politically in the fact that all republic institutions were written in the genitive case, "Croatia has been wholly reduced to a certain administrative-territorial term, so that it could only be expressed as: Republic of Croatia, Parliament of Croatia, Executive Council of the Parliament of Croatia…"(Rendić 1971: 14). This prompted the Supreme Court to rule against her, after which she was forced to retire.

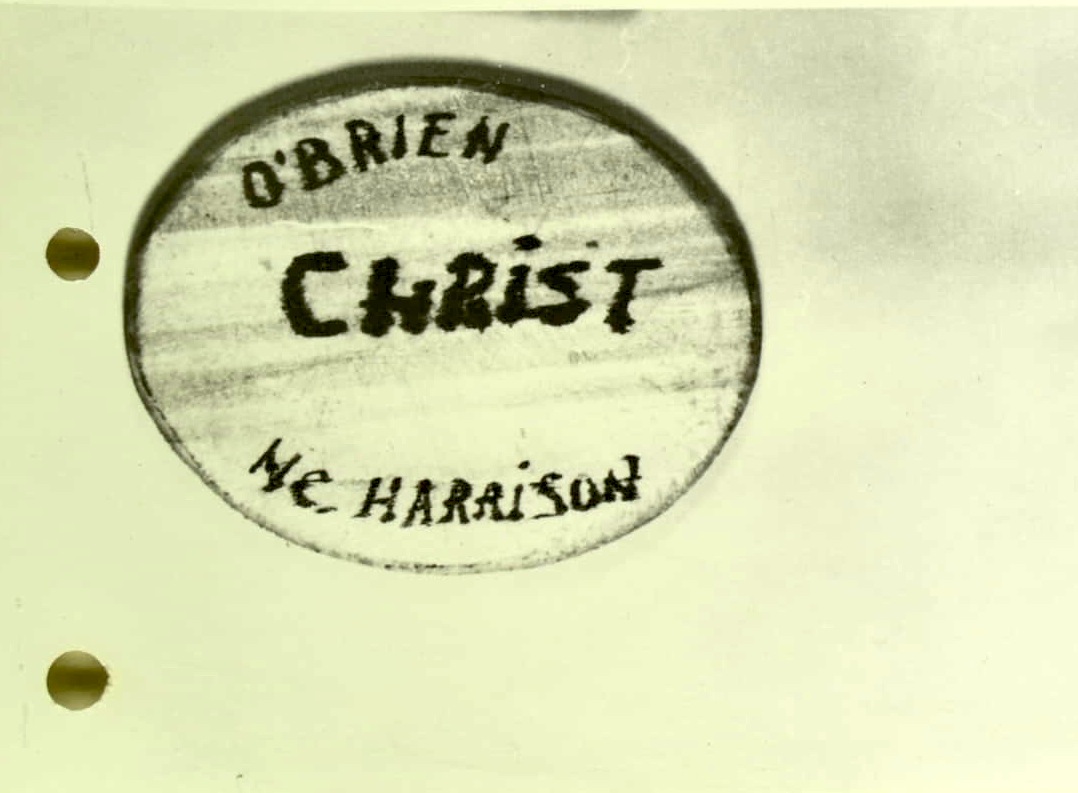

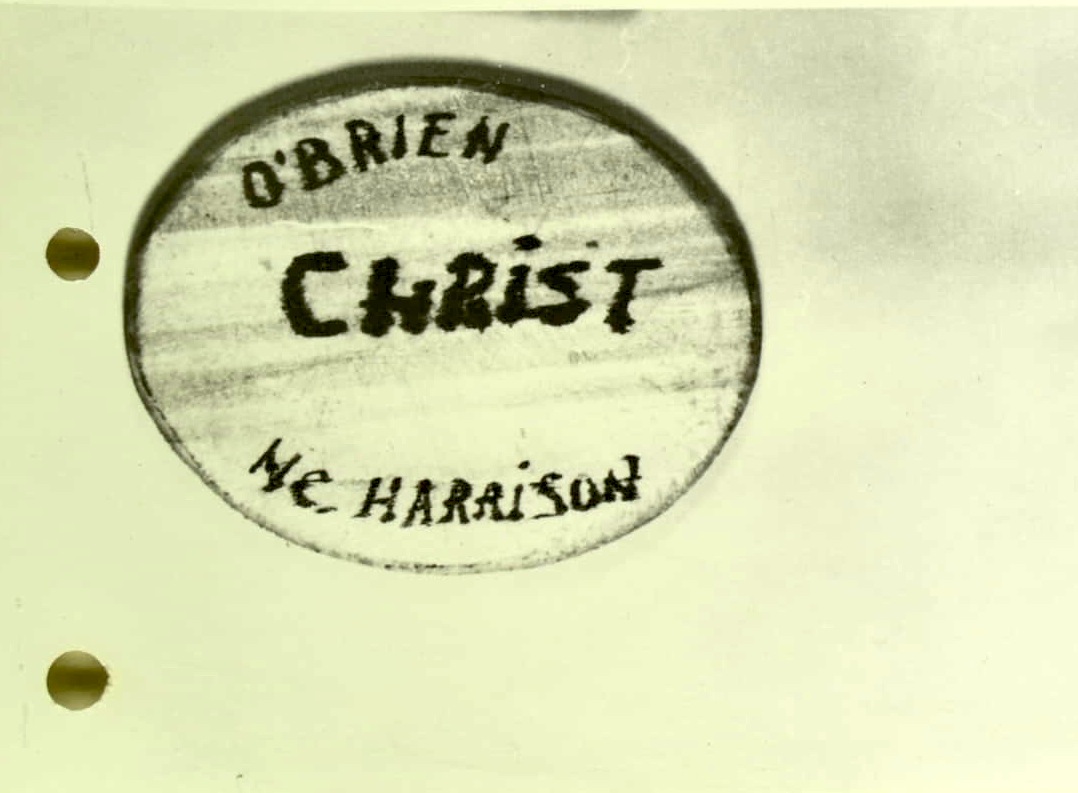

Wood-carved badges of the members of Clubul Regilor Liberi (The Club of the Free Kings), 1971. Photograph

Wood-carved badges of the members of Clubul Regilor Liberi (The Club of the Free Kings), 1971. Photograph

The informative file on the creator of The Club of the Free Kings, Puiu Apostolescu, contains five photographs of two badges made of wood. They were carved by Apostolescu and sent to his friend, Eugen Mircea, in Târgoviște. The insignia were confiscated by the Dâmbovița county branch of the Securitate on the occasion of a search at Eugen Mircea’s home. The badges were one of the distinctive elements of a member of The Club of the Free Kings. They were supposed not only to differentiate the Free Kings from their peers but also to underline the hippy character of the group. Thus, on one side, the badges contained the name of the group, and the word “hippy.” The word “free” is written twice in the combination, with “The Free Kings” and “The Free Club.”On the reverse, the badges are individualised, as they contain the English nicknames of Eugen Mircea (Christ) and Puiu Apostolescu (O’Brien McHarrison) as a way of stressing their friendship and membership of the group (ACNSAS I 3032, ff. 128–132).

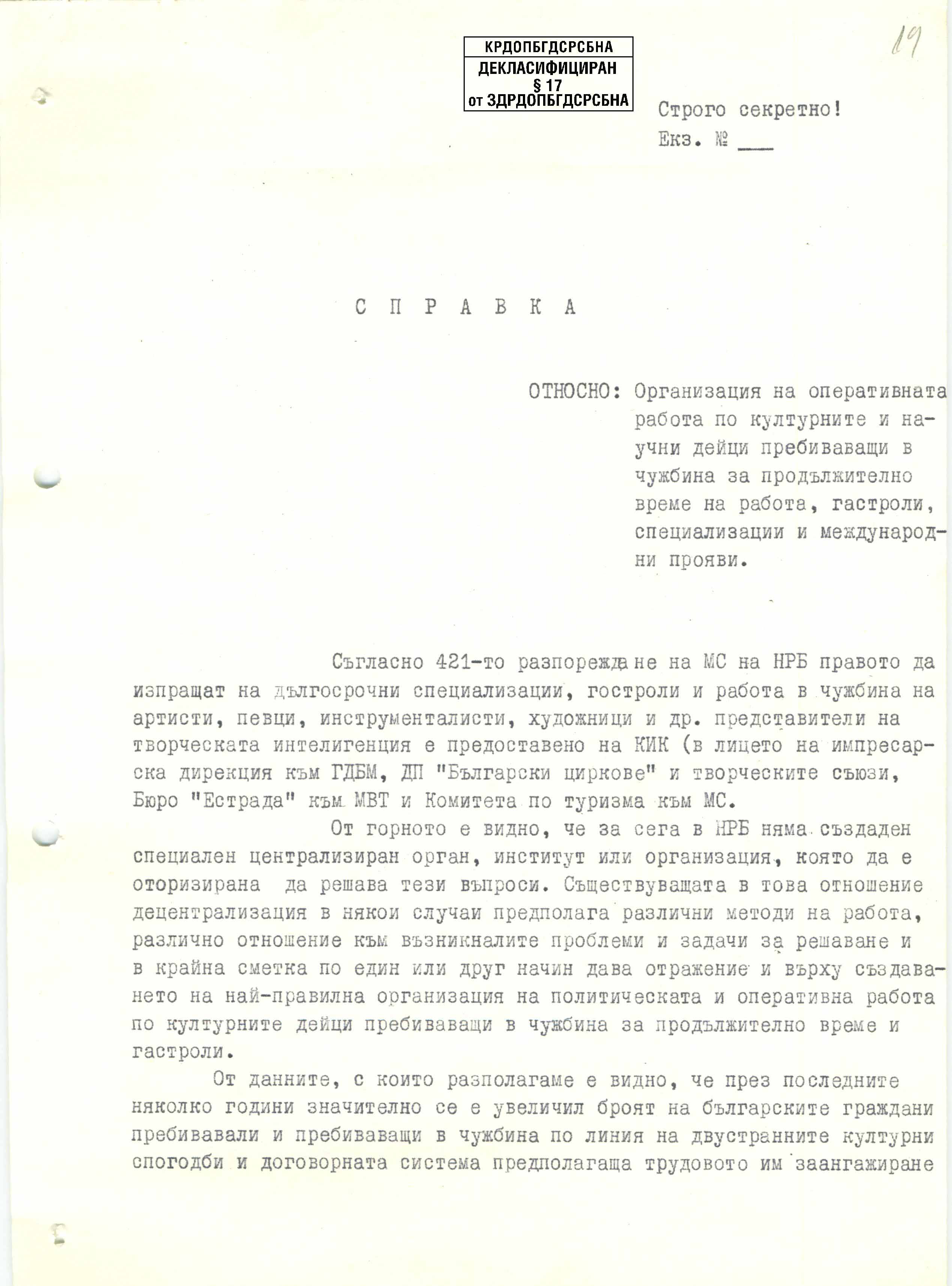

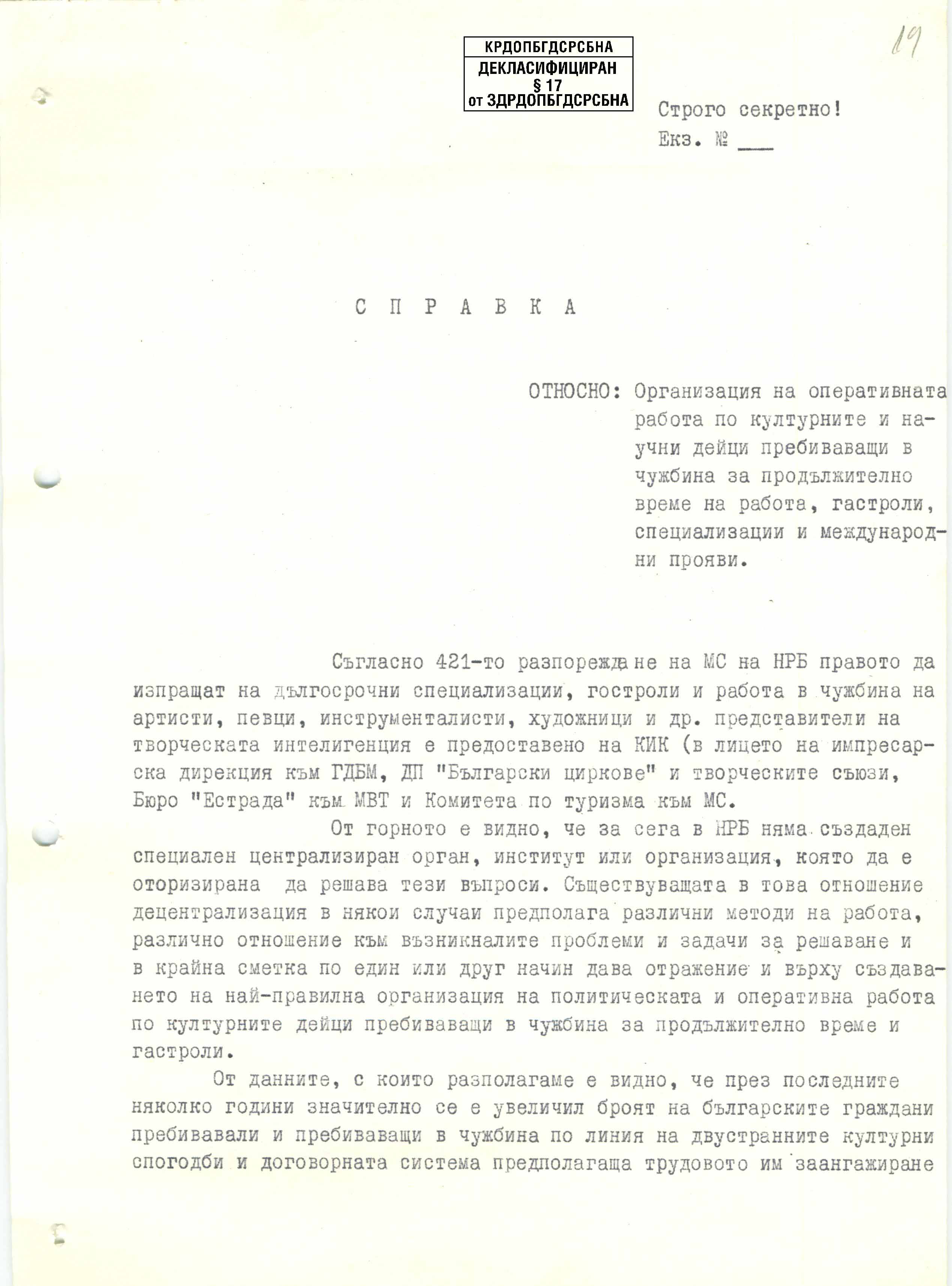

Report about "The organization of the operational work with regard to cultural and scientific figures who reside abroad for a long time for the purpose of work, tours, fellowships and international events", Sofia, June 9, 1971. The report gives a good idea of the work of the State Security among (and against) Bulgarian figures of cultural life, who for different reasons lived abroad. It highlights, among others, that "Among the intelligentsia, there is an increasing desire for escape to the capitalist countries in order to gain material benefits and a desire for 'creative expression and recognition' in the West. As a consequence, there are many cases of non-return. Strengthening the operational work on the selection of candidates for exit abroad is proposed." Hence, the document also reveals the strategies used by the regime to control international travel to the West of personalities from cultural life.

Acquisition of two book manuscripts about the "Aktual" group activities by the Museum of Czech Literature

Acquisition of two book manuscripts about the "Aktual" group activities by the Museum of Czech Literature

In March 1971, two manuscripts of unique books describing the events of Aktual, created by a Czech artist, musician and performer Milan Knížák, were bought by the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature (LA PNP). The books, containing scripts of happenings organised by a nonconformist art group Aktual in 1962–1969 as well as manuscripts and typescripts with illustrations and photographs, were sold to LA PNP by Knížák himself after a deal with its employee, PhDr. Jaromír Loužil. This acquisition was interesting for PNP mainly because it documents the artistic and literary effort in the 1960s. By similar purchases, PNP not only gained materials created by “unofficial” authors, but at the same time financially supported them.

The collection includes different operational reports, transcripts of conversations, anonymous letters and pamphlets, as well as other written materials collected by the Croatian State Security Service during Operation Tuškanac, conducted against students and professors at the University in Zagreb in the early 1970s, based on charges of nationalist and hostile activities against the communist regime in Croatia. It was one of several operations conducted by the Croatian State Security Service against members of the Croatian Spring, a national movement which included student reform demands among its essential elements.

Minutes of the SCA Prosvjeta meeting and and its Conclusions (Executive Committee and the Commission on Conclusion)

Minutes of the SCA Prosvjeta meeting and and its Conclusions (Executive Committee and the Commission on Conclusion)

The documents present the continuing tendency of Prosvjeta’s leadership to expand Serbian influence in society and insure equality with the Croats, but they also reflect an attempt to justify this tendency, denying any oppositional activity by the Association (so-called counter-revolutionary activity) and rejecting comparisons with Matica hrvatska. The Conclusions of the Executive Committee and the Commission on Conclusions were in fact the working agenda the SCA Prosvjeta i.e., a list of priorities: reviving passive subcommittees and establishing new ones, launching a weekly magazine to cover cultural and social issues Srpska riječ, implementation of a scholarship and research work plan, restoring the museum of Serbs in Croatia, activation of the Documentation Department under the Prosvjeta SCA Main Comittee, the Association's active participation in deliberations on amendments to the Constitution of the SRC and the proposal for constitutional and legal regulation of the status of Serbs in Croatia (equality of languages and scripts in all segments of society, education of Serbian children in special school programs), the establishment of a roughly a dozen commissions with the Main Comittee, and enhanced funding. A change in the Association's name was also proposed: to Prosvjeta – Serbian Union of Croatia, also the convening of the Second Congress of Serbs in Croatia and re-establishment of a Serbian caucus which was supposed to have been decided at the next, twelfth, annual assembly, which, however, was never held because the association’s further work was halted.

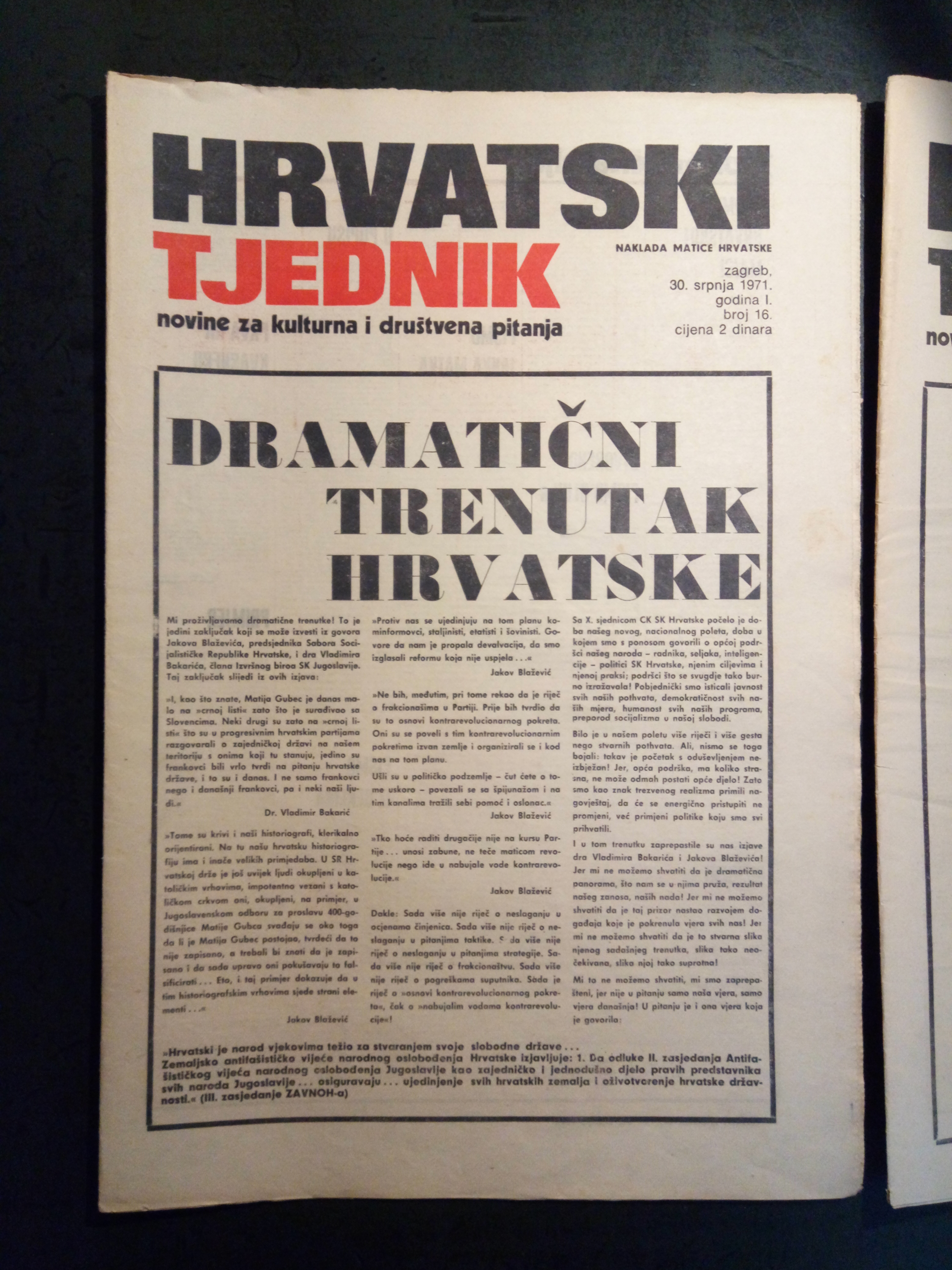

The performance presented on Marshal Tito Square (today's Republic of Croatia Square) in Zagreb in 1971 was, together with the performance on Republic Square (today's Ban Jelačić Square), the first work from the "Casual Passer-by" cycle. The poster (portrait) ˝Casual passer-by I met at 12:15 p.m.˝ was used for the performance. This poster (portrait) and two photographs of the event are owned by the Museum of Contemporary Art and are part of its permanent display. This performance aroused both the interest and confusion of Zagreb’s citizens, just as the one on Republic Square did.

It was a subversive performance in a public area, otherwise intended for officials, where the artist hung portraits of random passers-by and in that way questioned the established forms of communication in the public space of a socialist state.

Ewa Partum was one of the pioneers of the art in the public space in Poland. From the beginning she was interested in the new means of artistic expression, new genres, such as mail art, performance art, photography; also very early she started to create the installations beyond a gallery space. The installation Legalność przestrzeni (Legality of the Space) was constructed in 1971 in the Freedom square in Łódź – the city where the artist was living those days. Partum gathered and put in the one place the collection of dozens of street signs and boards indicating ban of something. The meaning of the gesture was clear: the artist let see the limits of the public spaces and regulations regarding the use of this space in the Polish People’s Republic. The space of the street, at first glance freely accessible and egalitarian, turned out to be severely restricted and under surveillance. The Legality of the Space was an important piece especially in the context of the apparent openness and liberty of the first years of Edward Gierek rules in Poland. The photography of the installation came from the archive of the Artum Foundation.

Sociology was the official periodical of the Sociological Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (1972–1990). It was the first journal in Hungary devoted entirely to sociology. It opened a new chapter in the history of Hungarian sociology. Although the conservative ideological campaign led by orthodox Communist leaders made some changes in the editorial staff, Sociology was published continuously until 1990. The manuscript of the first issue from 1972, with the archival documents from 1971, inform us of the beginnings of this important journal. The authors of the first issue –included Zsuzsa Ferge (“Social Structure and the School System”), István Kemény (“Stratification of the Hungarian Working Class”), Iván Szelényi (“Housing System and Social Structure”), and others.

The Alexandru Călinescu private collection epitomises the trajectory of an intellectual in an important university city who began to practise a camouflaged contestation, published in local student magazines, with a limited readership, and ended up in unequivocal public opposition, disseminated transnationally through foreign radio stations. The collection marks some of the key episodes in the movement of resistance to and contestation of the communist regime as it manifested itself in Iaşi, the historical capital of the region of Moldavia and the city with the oldest university in the Old Kingdom of Romania. At the same time, the collection and the personal story of Alexandru Călinescu illustrate a lesson in dignity in very difficult times, when there were few who had the courage to speak openly against the Ceaușescu regime.

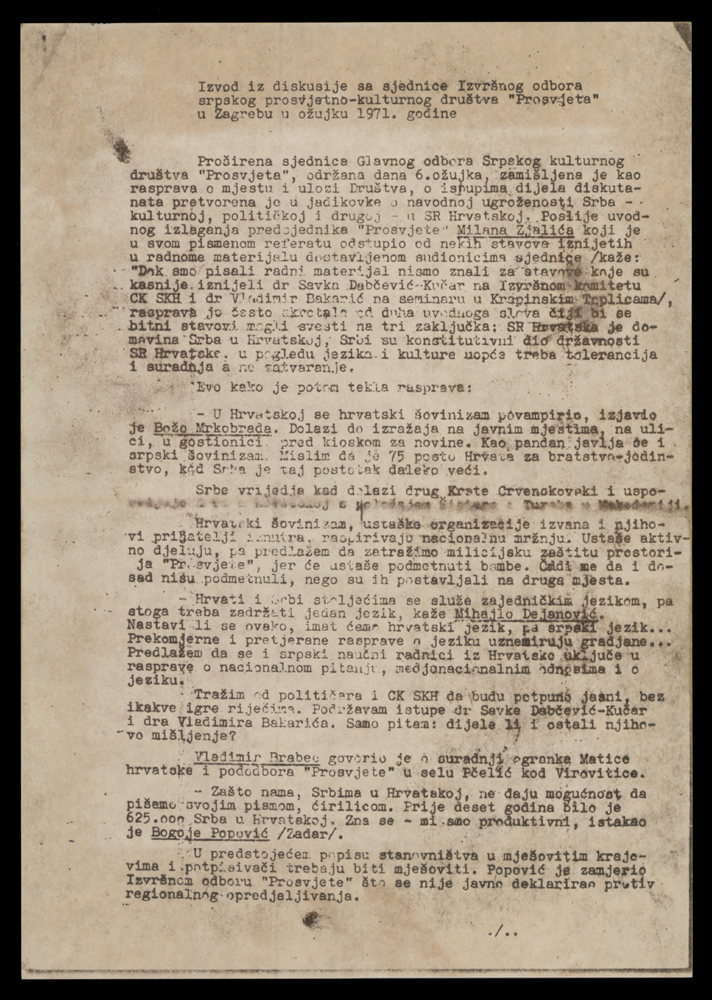

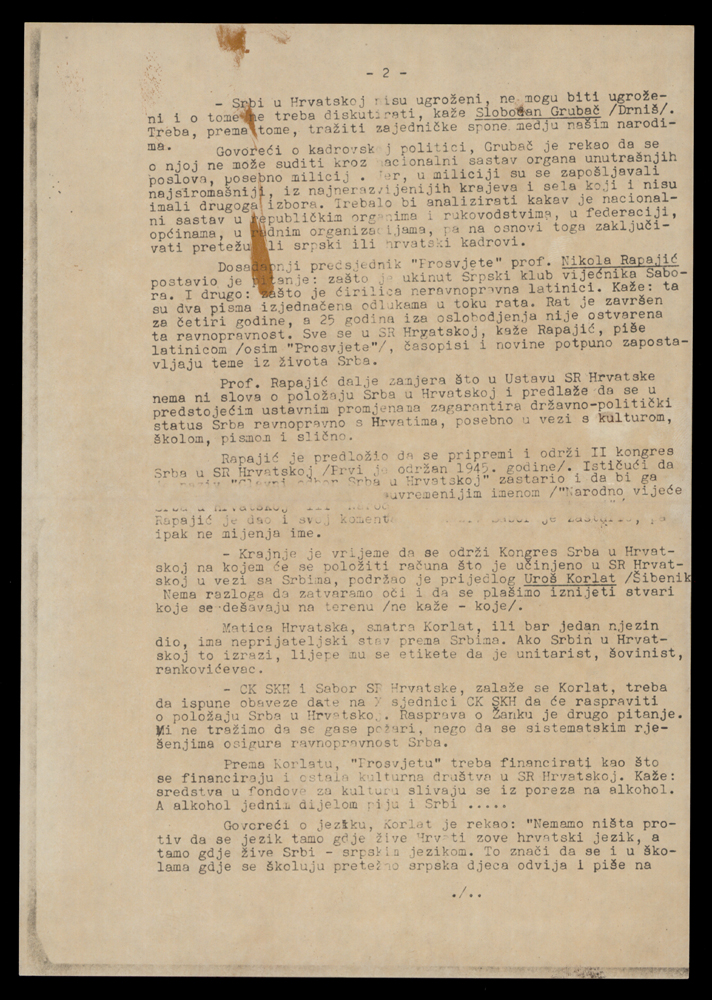

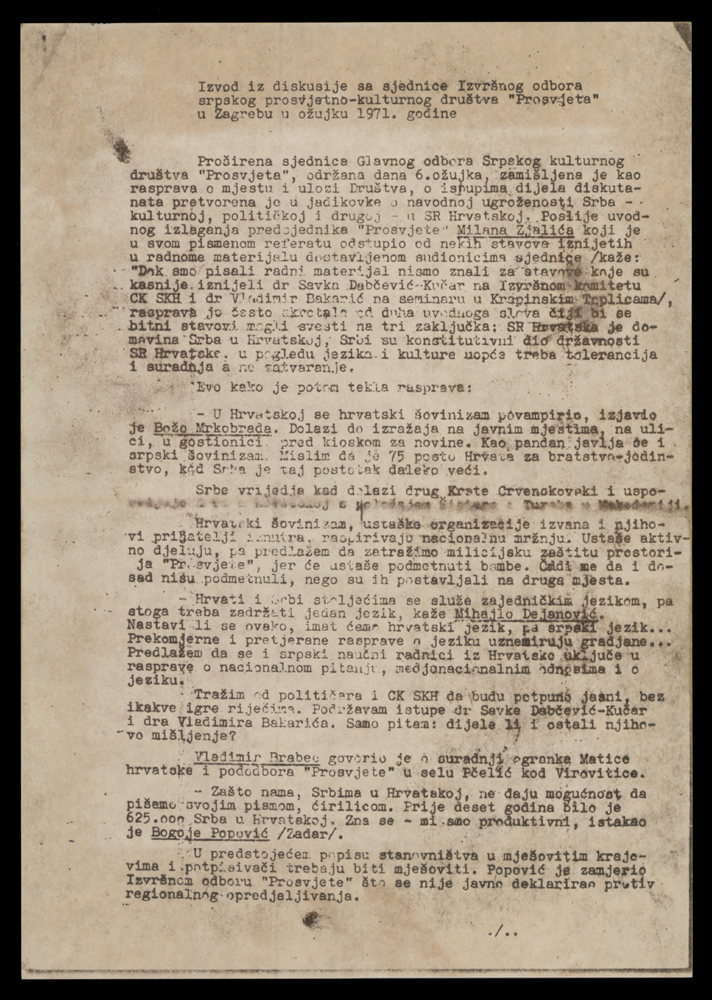

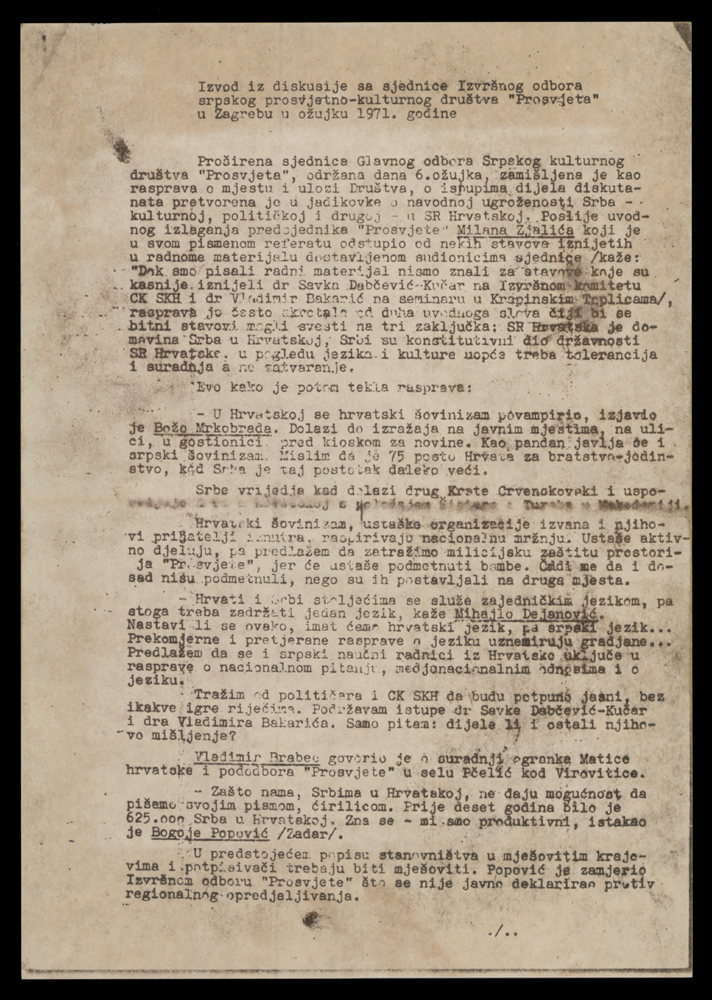

Document excerpt from the discussion of the meeting of the Executive Committee of the SCA Prosvjeta in Zagreb in March 1971

Document excerpt from the discussion of the meeting of the Executive Committee of the SCA Prosvjeta in Zagreb in March 1971

The document presents an excerpt of the important points expressed at the meeting of Prosvjeta’s Executive Comittee, held in Zagreb in March 1971. It documents the aspirations of Prosvjeta’s leadership , which exceeded accepted boundaries and whereby the authorities deemed them oppositional. The debate clearly reflected dissatisfaction with Prosvjeta’s status in society and the evident tendency toward a broader Serbian influence. The demands detailed in the document include a constitutional guarantee of equal treatment of Serbs and Croats, the convening of a Congress of Serbs in Croatia, more state funding, equal status of languages and scripts, the renaming of the periodical Prosvjeta to Srpska riječ, the establishment of the Museum of Serbs in Croatia and other Serbian institutions as well. But not all participants were of the same opinion, so various disagreement were recorded in the document, especially when it came to Prosvjeta’s political engagement.

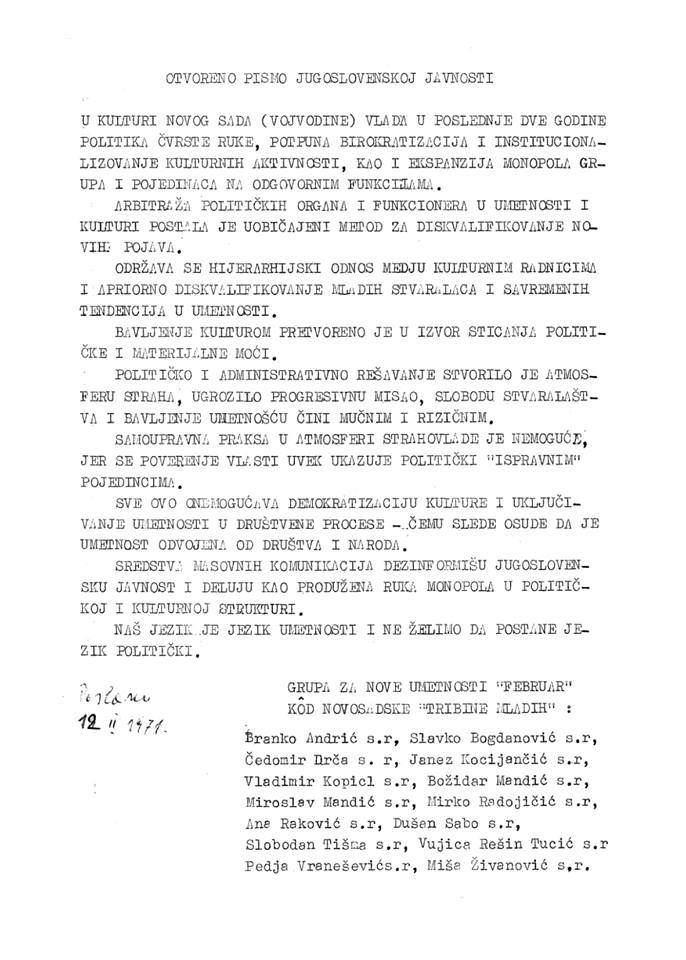

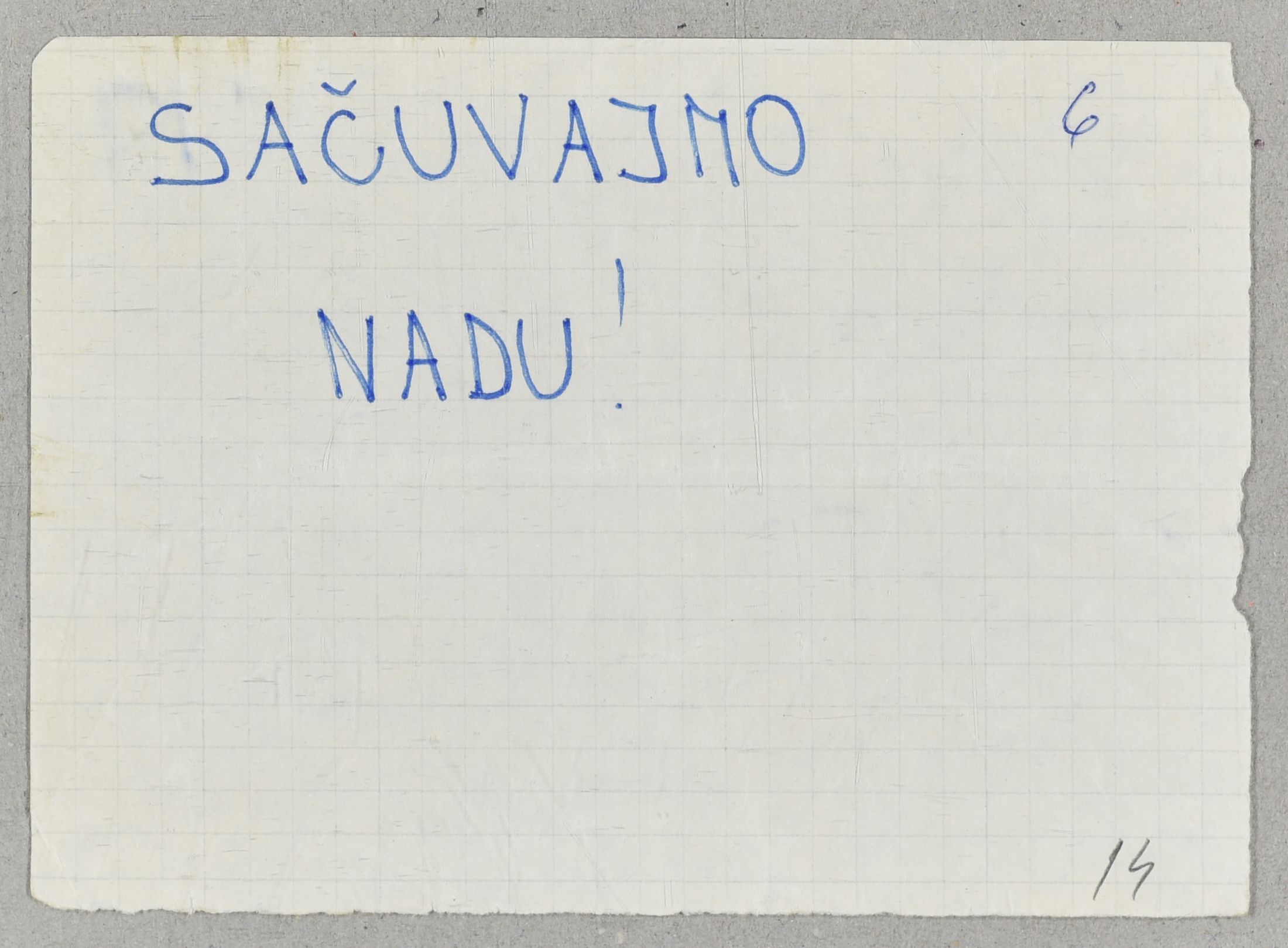

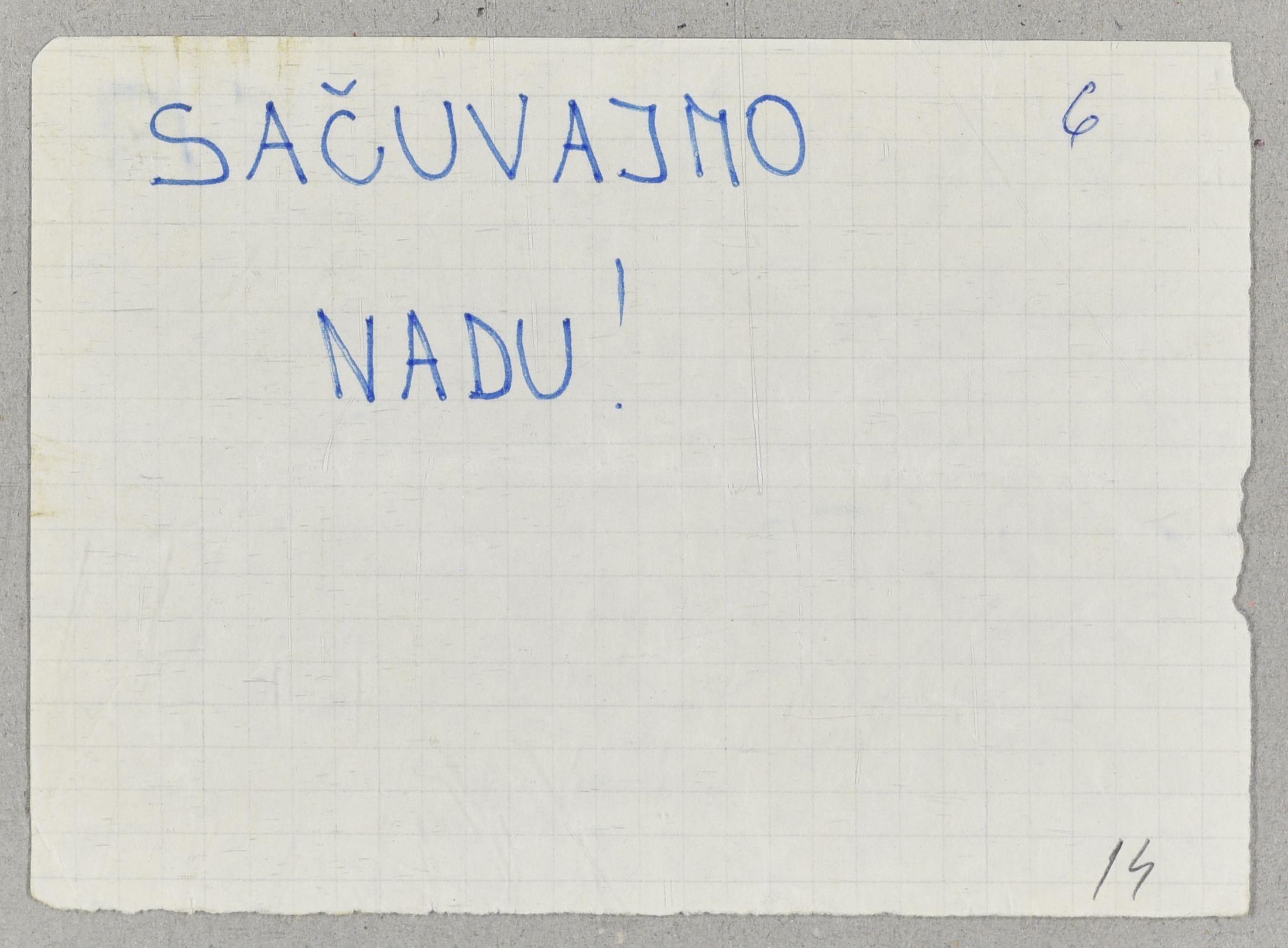

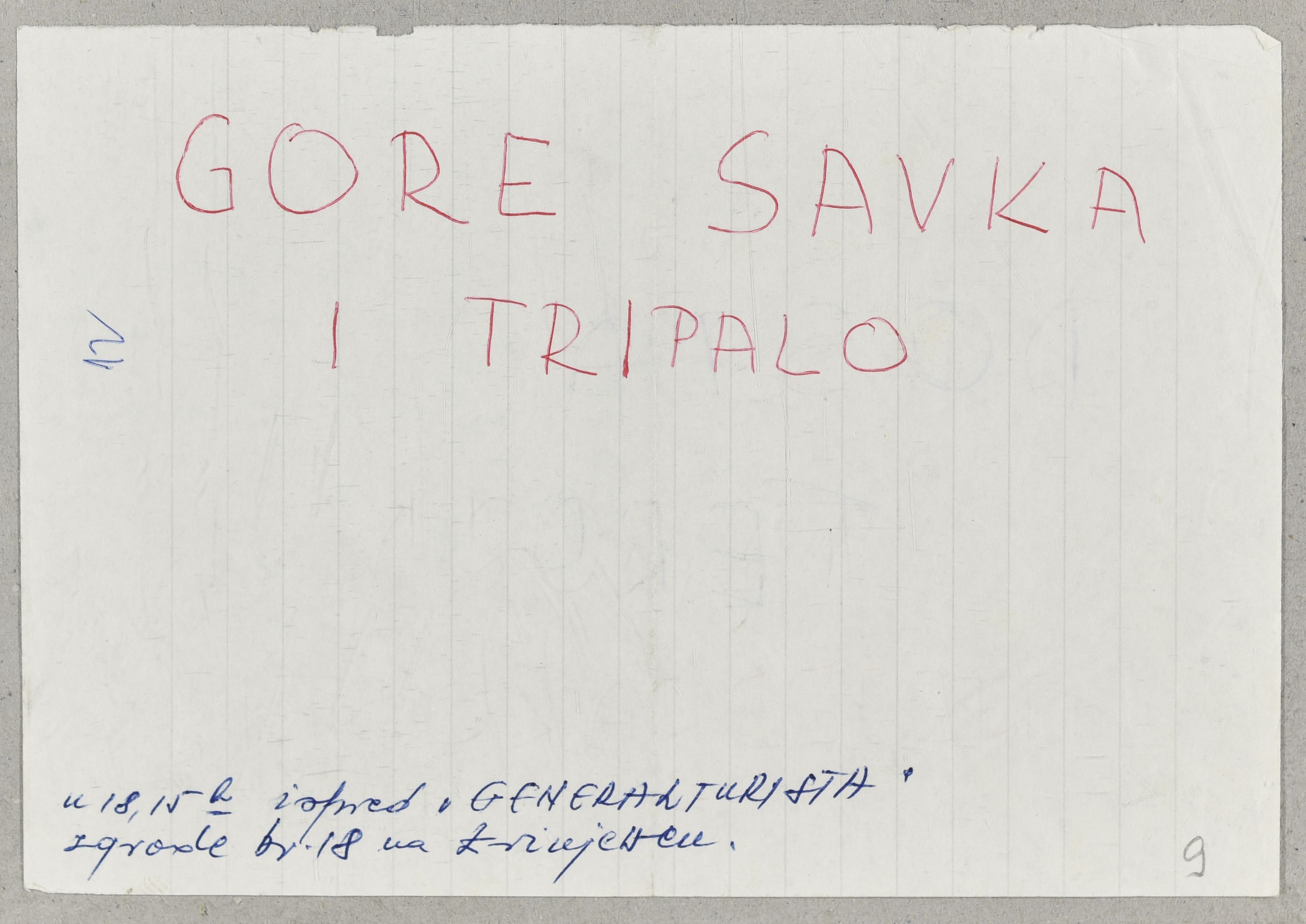

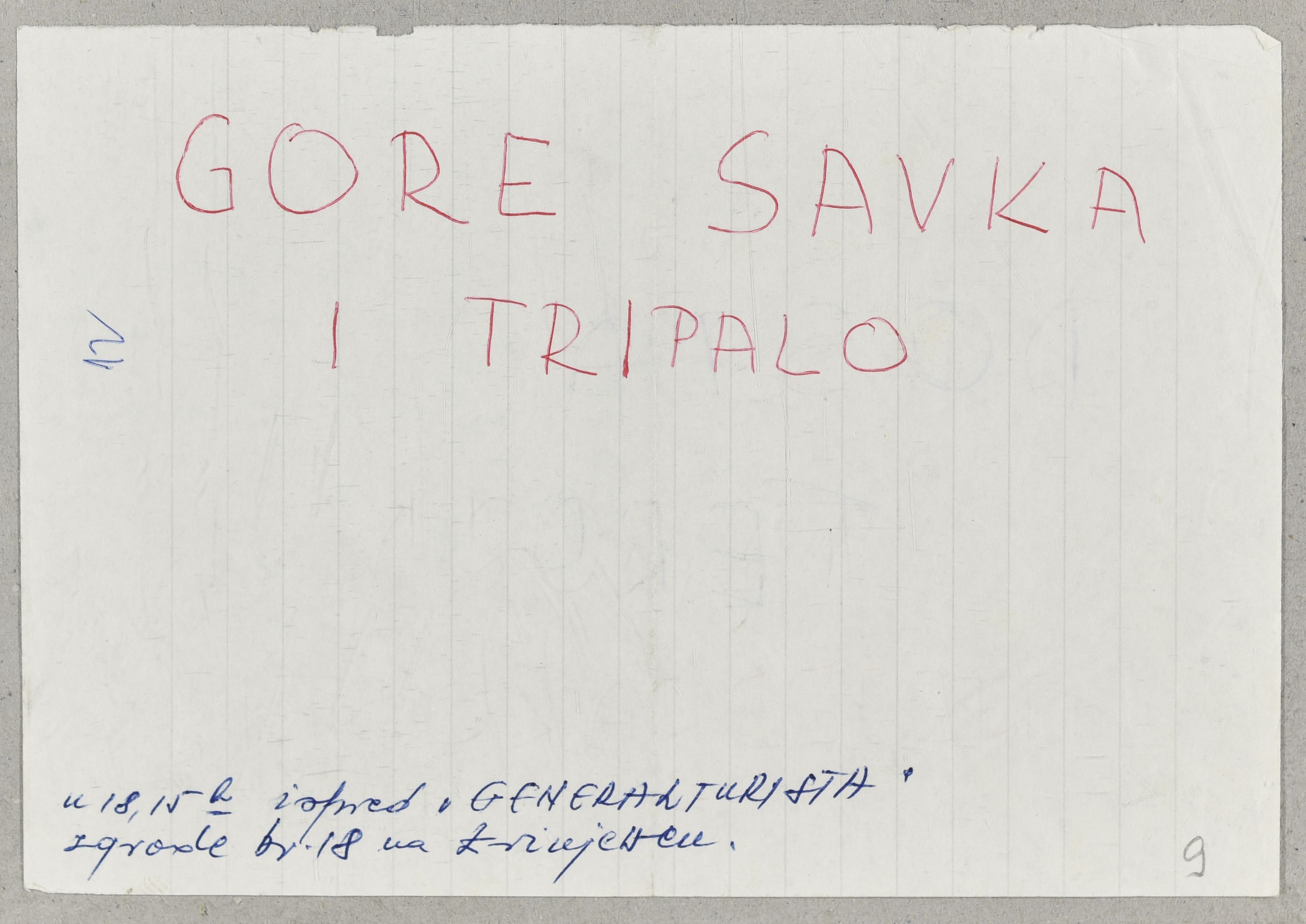

Pamphlet of support for Croatian reformist and nationally-oriented political leaders. 1971. Archival document

Pamphlet of support for Croatian reformist and nationally-oriented political leaders. 1971. Archival document

Students also demonstrated their support for Croatian reformist and nationally-oriented political leaders by distributing handwritten pamphlets on different types of paper. This collection includes several examples of such pamphlets, and one mentions Savka Dabčević-Kučar and Mika Tripalo, both removed from their posts in December 1971. On the pamphlets themselves or in separate notes, the State Security Service recorded where and when the pamphlets were found. Together with other materials collected during Operation Tuškanac, these pamphlets were used in the prosecution of participants in the student movement.

The documents are available for research and copying.

In some film and television works, director and screenwriter Niksa Fulgosi developed a subversive critical discourse that has the features of opposition. Sto ljepotica na dan [A Hundred Beauties per Day] is one of three films from his critical- feuilletonist trilogy of 1971 (which also includes Sto kletvi na sekundu [A Hundred Curses per Second] and Sto zaduženja Betike Gumbas [The Hundred Duties of Betika Gumbas]). It was broadcasted in abridged versions "approved for presentation." Sto ljepotica na dan is a satirical and multi-layered presentation of Yugoslav society, which presents the novelty of beauty contests in a humorous way. The film is characterized by the sharp social and political satire of socialist society; under the guise of an event, the author critically interprets the current social problems such as faulty administration, social differences, backwardness, low standards and so forth. The original film is held in the Documentation Centre of Croatian Television in Zagreb.

This document is a copy of a memorandum written by Gheorghe Ghimpu at the end of 1971 and addressed to Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. This thirteen-page typed text is part of volume 10 of the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur file stored at the SIS Archive . The version preserved in this archive represents a literal Russian translation of a handwritten Romanian-language document. The Romanian version was copied by Valeriu Graur from the initial typed draft of the memorandum authored by Gheorghe Ghimpu. The handwritten Romanian text, confiscated from Graur’s apartment, constituted one of the main pieces of evidence during the trial. This text was to be smuggled by Graur to Romania and subsequently sent to the RFE/RL headquarters in Munich (by clandestine means), but Graur’s arrest hampered this. The document synthesises the main arguments and views of the members of the National Patriotic Front. The text begins by deploring the fate of the “ancient Romanian lands” of Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and Transnistria under the “most cruel and despotic tyranny” of the Soviet regime. This regime is accused of “chauvinism” and of large-scale repressive policies in the post-war period. The author acknowledges that during the 1960s the situation had improved and that the Moldavian population had more opportunities to receive a better education. However, the MSSR’s position within the USSR is described as that of a “colony of the Russian Empire” (the anti-imperialist rhetoric is pervasive). The document then presents and purports to analyse various strategies used by the Soviet regime to Russify and “de-nationalise” the local Romanian-speaking population. Aside from mentioning the isolation of the USSR Romanians from Romania proper and the attempt to create a separate linguistically based Moldavian national identity, the author points to several other concrete manifestations of the Russification policy, e.g.: 1) the attempt to further assimilate the local population by appointing to leading and managerial positions Russian speakers or Russified Moldavians, who were in reaction labelled ”outsiders” (venetici) or Russian collaborators, and who consolidated the colonial relationship between Soviet Moldavia and the Russian centre; 2) the ”expulsion” of the Romanians to Siberia’s ”virgin lands” and their replacement by a wave of Slavic migrants, 3) compulsory service in the Soviet army; 4) the encouragement of mixed marriages; 5) the ubiquitous use of Russian as a state language (despite the provisions of the Soviet Constitution) and the marginalisation of Romanian; 6) the Russification of education at all levels; 7) the purposeful Russification of proper names (both family names and geographic locations). The author further argues that the Romanian population has not accepted the policies of the “Russian colonisers,” and invokes a number of individual examples of resistance, mainly from intellectual circles. Although stating that the “struggle will continue,” the text concludes on a rather pessimistic note, emphasising that the Romanians of the MSSR are isolated and ignored by the wider world due to the Russification policies pursued by the regime. The dominant nationalistic language and overtones, which are probably inspired from the interwar rhetoric specific to Greater Romania, make this document one of the most eloquent examples of Moldovan national opposition in the Soviet period. The attention given to the cultural sphere is especially revealing. It is worth mentioning that Graur reconstructed a version of this document from memory, so it was thus able finally to reach its destination ten years later, in 1982, when it was broadcast by Radio Free Europe.

Tamás Szentjóby: Parallel-course Study Track, July 1, 1971 (Initiation ritual. Designed and moderated by Tamás Szentjóby and János Baksa-Soós. Contributors: Eleni Taxidu, Zója Karandata, Gábor Bene)

As part of his project Parallel-course Study Track, Tamás Szentjóby realized his action entitled A-B happening at the Chapel Studio in Balatonboglár. Regarding his concept, the term “parallel-course” had multi-layered references. On the one hand, it reflected on the activities of avantgarde artists parallelly and at the same time opposing the socialist regime. On the other hand, the parallel aspect referred to the parallel attitudes of Eastern and Western avantgarde artists, as well. Szentjóby also used the term to describe his self-established “pedagogical system” operating in parallel with the official educational institutions, which provided the frameworks of new artistic strategies inspired by the attitude of fluxus and the new leftist ideas he regarded as exemplars, like the activity of Joseph Beuys and Robert Filliou. The A-B happening as an initiation ritual reflected on the sacral space of the chapel and its environment in term of initiating the chapel for avantgarde art. The act of breathing in and out as part of the happening could be regarded as a symbol of the system’s operation as both a reciprocal and a power relation.

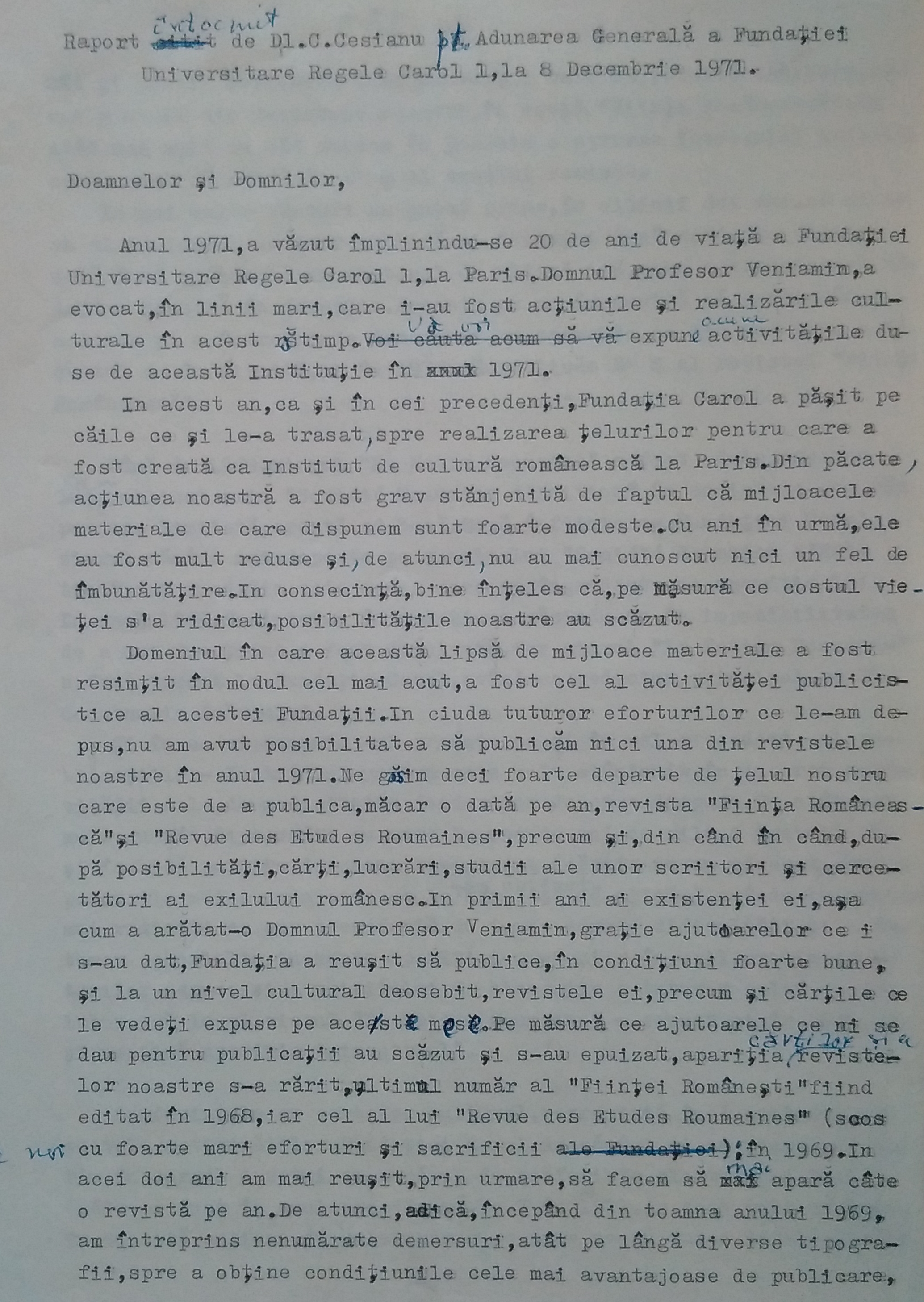

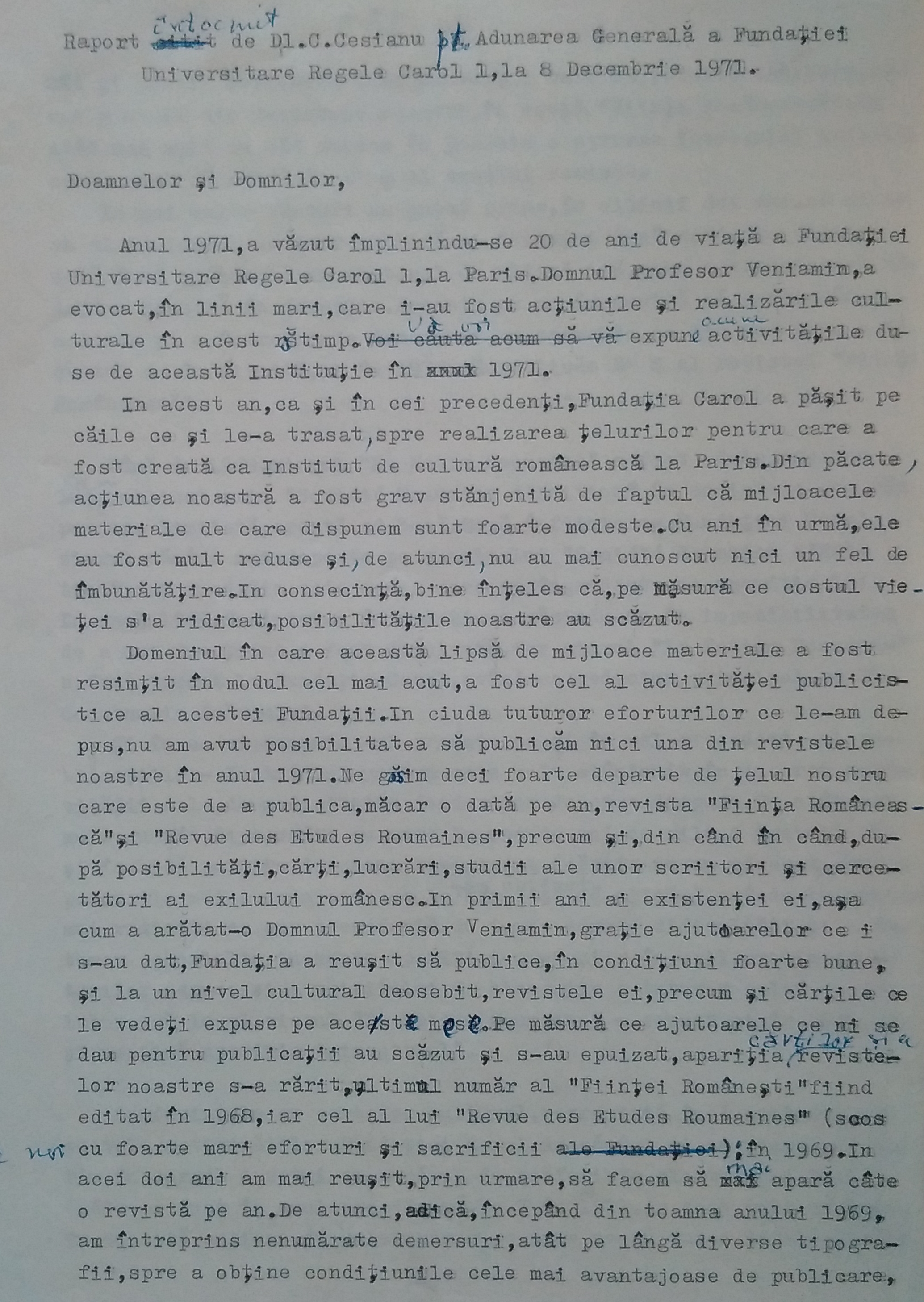

Report by Constantin Cesianu for the General Assembly of Carol I Royal University Foundation, in Romanian, Paris, 1971

Report by Constantin Cesianu for the General Assembly of Carol I Royal University Foundation, in Romanian, Paris, 1971

This document reflects the manner of organisation and activity of the Romanian postwar exile community, as well as a series of major problems that it encountered: the lack of material means and of the unity of Romanians. The Romanian exile community, although a form of opposition of Romanians from several historical periods, reached a significant dimension during the communist regime. The postwar Romanian exile community manifested itself over an expanded geographical area, spread across several continents: Europe, North America, South America, Australia, and Africa. There were, however, a number of states where the Romanian exile community was particularly active: France, the USA, the UK, West Germany, Spain, and Canada. Determined by the domestic political context and influenced by shifts on the international political scene, the Romanian exile after the Second World War must be understood as a reaction to the establishment and domination of the communist regime in Romania and as a form of opposition to it. Romanians abroad tried to organise themselves by setting up foundations, associations, institutions, institutes, and publications with the purpose of: representing the Romanian nation and defending its interests until its liberation; carrying out actions that would lead to the restoration of the democratic system in Romania; coordinating the activity of Romanians outside the country for the fulfilment of this common cause; establishing links with Western governments and international organisations; representing the exile community and solving its problems; and collaborating in joint activities with representatives of the other "captive nations" in Central and Eastern Europe.

The report in question, which amounts to five pages, presents the situation of one of the most important cultural organisations of the exile community, the Carol I Royal University Foundation. A university level institution, the Carol I Royal University Foundation (1950–1974) was initially founded in Paris on 3 May 1881 by King Carol I, but was abolished by the communist regime in Bucharest. Later, on December 8, 1950, out of a desire to continue the old royal family tradition, it was re-established by King Michael I in exile, with the support of the Romanian National Committee, which was in the view of the founders the government of Romanians in exile. The Foundation began to function effectively on 1 January 1951. The purpose of the Foundation was: to present the values of Romanian culture to the West; to affirm and develop the traditional ties between French and Romanian cultures; to establish and maintain relations with cultural and educational institutions and with the French administrative authorities; to ensure a Romanian presence in international cultural forums and events; to safeguard the national cultural heritage; to study the cultural and technical problems that Romania would face after liberation from the communist regime; to support and guide Romanian students in exile; to encourage scholarly research; to build up a library at the headquarters of the Foundation, transforming it into the House of Romanian Culture abroad. Every year, the Foundation's leaders drew up an activity report. Such a document can be found in the collection of Sanda Stolojan, who was involved in the Foundation's activities and published poetry and prose in its two literary publications: Ființa Românească (Romanian being) and Revue des Etudes Roumaines. A copy of this document is in Sanda Stolojan's private archive due to the fact that she was a close friend of the person who wrote the material, Constantin Cesianu, and was directly involved in the Foundation's actions. Regarding the personality of Constantin Cesianu (1886–1983), he was a political detainee in communist Romania between 1956 and 1963. A few years after his release, he emigrated to France, where he published the book Salvat din infern (Saved from the inferno), in which he reported his experience as a political prisoner in communist Romania. The volume originally appeared in French. It was translated into Romanian and published in Romania in 1992, and is an indispensable part of any specialised bibliography on the subject. In Paris, he actively participated in the activities of Romanians in exile for the promotion of Western media coverage of the repressive and aberrant policies of the communist regime in Romania.

The report that Constantin Cesianu wrote in 1971 draws attention to the situation of the Foundation in that year, when its annual activity balance was not a positive one. The explanation was the lack of the material means to achieve its goals. In fact, all organisations of the exile community were confronted with this problem. On a different line of thought, beyond the Foundation's poor financial situation, the report presented some of the activities the Foundation carried out in 1971: cultural conferences and the celebration of Romania's historic days (1 December – Great Union Day, 24 January – Little Union Day, 10 May – Independence Day). Furthermore, the paper presented the situation of the Foundation’s library and the profile of the researchers who had come there for documentation. Finally, the unity of Romanians abroad was called for – the supreme desideratum of all the organisations of the exile community, though it never materialised between 1948 and 1989.

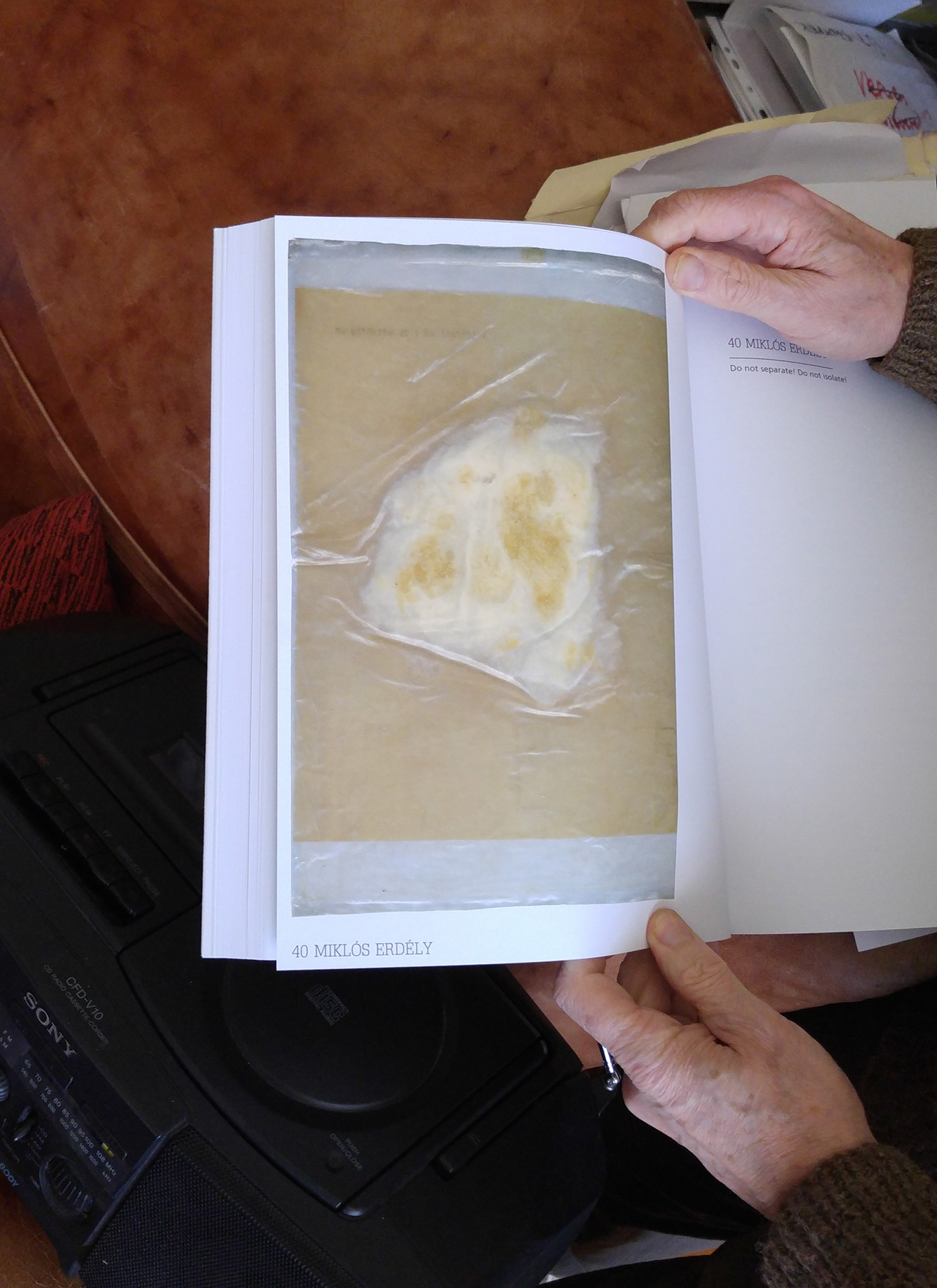

Cotton-wool dipped into goose grease on standing A4 format paper. Typed text on the upper left corner: “Do not separate! Do not isolate!”

Miklós Erdély intended this work to be part of the concept collection initiated by László Beke called “Imagination/Idea,” which consisted of paper works arranged into a dossier. Erdély formulated the text with this in mind and handled the work to the collector without wrapping it. László Beke was compelled to find a solution in order to protect the other works, so after some pondering he placed the work of Erdély into a nylon folder.

The utilized material has a layer of meaning beyond the concrete situation as well: the use of goose grease is a reference to spiritism, which had a materialization phenomenon—the emanation of ectoplasm from the mouth or the ear of the medium in a state of trance—was faked with cotton-wool dipped into goose grease in the 1920s. In this respect, it is interesting to note that the goose grease appears in the work in its own right, providing an example for its real and meaningful use.

Hrvatski pravopis (Croatian Orthography) written by Stjepan Babić, Božidar Finka and Milan Moguš, published in 1971, was banned by the Yugoslav authorities on political grounds shortly after its printing. However, the editorial board of Nova Hrvatska, headed by Jakša Kušan, succeeded in obtaining a copy and published it in a phototype edition in London in 1972. This is why the book is popularly called the "Londoner."

Its first edition in Croatia was a part of the endeavours of Croatian reform-oriented intellectuals in the Croatian Spring movement. In the cultural sphere, the Croatian Spring was most evident in the struggle of Croats for the equality of the Croatian language in Yugoslavia. To eliminate the disagreement between the previous orthography and contemporary language practices in Croatia, Matica hrvatska has entrusted the task of drafting the principle of a new orthography to the linguists Babić, Finka and Moguš. All of the relevant vocational, scholarly and educational institutions in the Socialist Republic of Croatia agreed with this orthography. This was one of the last acts in the struggle for the equality of Croatian literary language, which began in 1967 with the publication of the Declaration on the Name and Status of the Croatian Literary Language. The book (Hrvatski pravopis) was printed in September 1971, but for political reasons, the entire print run of 40,000 copies was withdrawn and destroyed in a paper mill. Only a few internal copies were preserved. This act of censorship was a part of the crackdown by the Yugoslav authorities against the Croatian Spring at the end of 1971. Moreover, the authors of the book were members of Matica hrvatska, the essential cultural-oppositional institution in Croatia.

Jakša Kušan learned out that several copies of the book had been salvaged and he decided to try to obtain a copy to print it abroad. He learned that a proofreader, Roman Turčinović, had a copy and somehow Turčinović managed to send the book to Kušan in the UK. The editorial board of Nova Hrvatska added a short introduction to the book, in which they explained that in Croatia the book was destroyed and labelled a "nationalistic diversion." This introduction was printed in Croatian, English, German and Spanish (Kušan 2000, 96-97).

Announcing the publishing of the Croatian orthography in May 1972, the editorial board of Nova Hrvatska emphasised that it was the most significant victory over Yugoslav censorship (Kušan 2000, 93). Five thousand ordered copies were printed in December 1972. Large quantities were sent immediately by aeroplane, and in April 1973 3,000 more copies were printed, and at the beginning of 1984 two thousand copies of the second edition were printed. Several hundred copies were also sent to Croatia, and many copies were sent to foreign journalists, and to all Slavic institutes at universities around the world. Kušan pointed out that they sent the book with the desire to show how broad Yugoslav censorship in Croatia was and to show how Croats could not exercise their constitutional rights to their (Croatian) language (Kušan 2000, 97). He also said that many Croatian emigrants bought the book, even people who never used it, simply to participate in the “all-Croatian defiance and defence of Croatian culture" (Kušan 2000, 97). Hrvatski pravopis was first exhibited at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1973, and Kušan stated that they did not expect such great success. The "Londoner" became a best-seller in Croatian emigrant communities because it symbolised the Croatian Spring. The financial success of the book enabled the editorial board of Nova Hrvatska to purchase a house in London, where they set up their new offices to continue their work. After the fall of communism in Croatia in 1990, Hrvatski pravopis was published freely again.

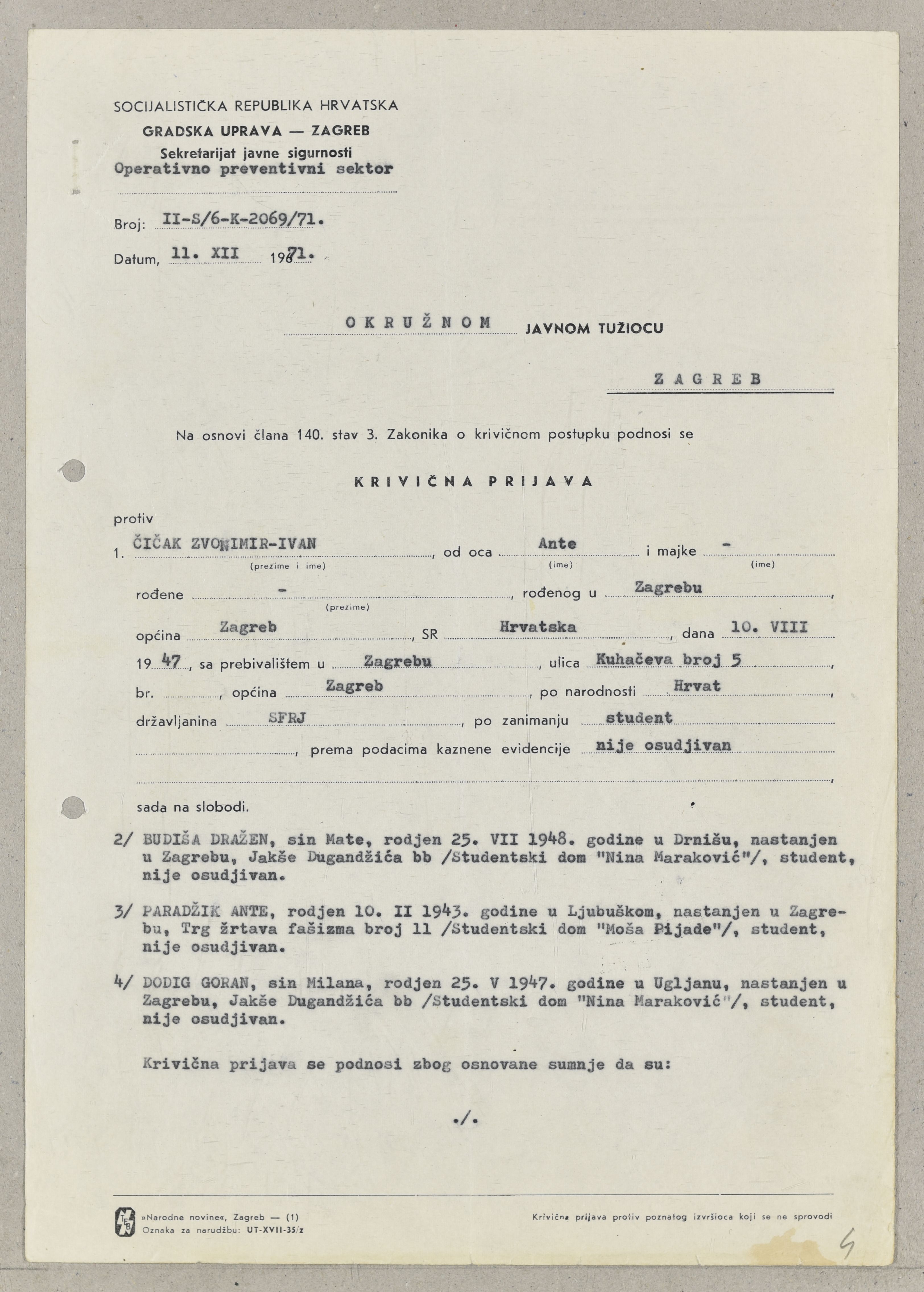

On 11 December 1971, the Public Security Secretariat in Zagreb filed criminal charges with the District Public Prosecutor in Zagreb against student leaders Ivan Zvonimir Čičak, Dražen Budiša, Ante Paradžik and Goran Dodig on grounds of enemy propaganda and “criminal offences against the people and state by a counter-revolutionary attack on the state and social order.ˮ They were charged, inter alia, for incitement by “speeches and textsˮ calling for “violent and unconstitutional changes to the state and social order,ˮ “disrupting the fraternity and unity of Yugoslav nationalities,ˮ as well as “undermining the economic basis of socialist development.ˮ All four were convicted: Dražen Budiša to four years in prison, Ivan Zvonimir Čičak and Ante Paradžik to three, and Goran Dodig to one. Their prosecution is an example of the repression at the end of 1971 and in 1972 against members of the student movement, and participants in the Croatian national movement and the Croatian Spring in general. It resulted in several hundred convictions for political offences and the purge of several thousand members of the League of Communists of Croatia (Croatian Encyclopaedia online. “Hrvatsko proljećeˮ. Accessed on 30 May 2018). This collection includes over 1,000 pages pertaining to such indictments and criminal indictments.

The documents are available for research and copying.

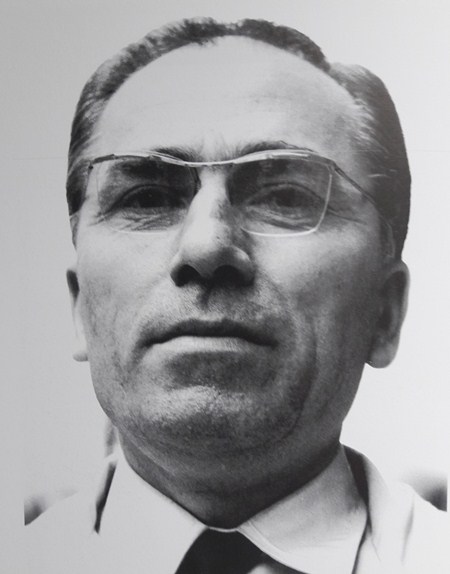

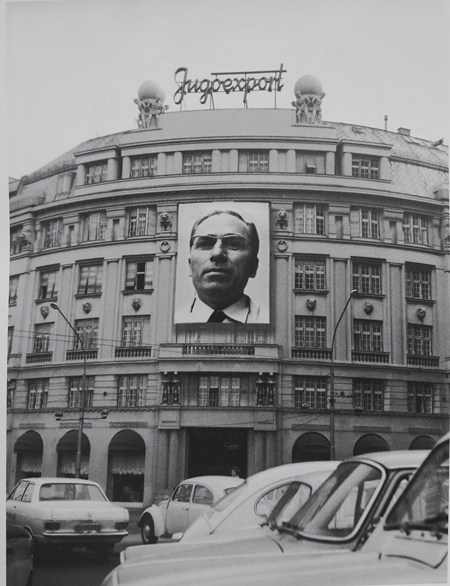

One of the first performances from the "Causal Passer-by" cycle (after those in Zagreb) was the one in Belgrade in 1971, in which the poster (portrait) ˝Casual passer-by I met at 2:29 p.m.“ was used. The poster (portrait) was placed on the façade of the Jugoexport building on Belgrade’s central square (today's Kolarčeva 1). It is safe to assume that the reaction of Belgrade's citizens was similar to that of the citizens of Zagreb - confusion and suspicion concerning the identity of the depicted figures.

It was a subversive performance in a public area, otherwise intended for officials, where the artist hung portraits of random passers-by and in that way questioned the established forms of communication in the public space of a socialist state.

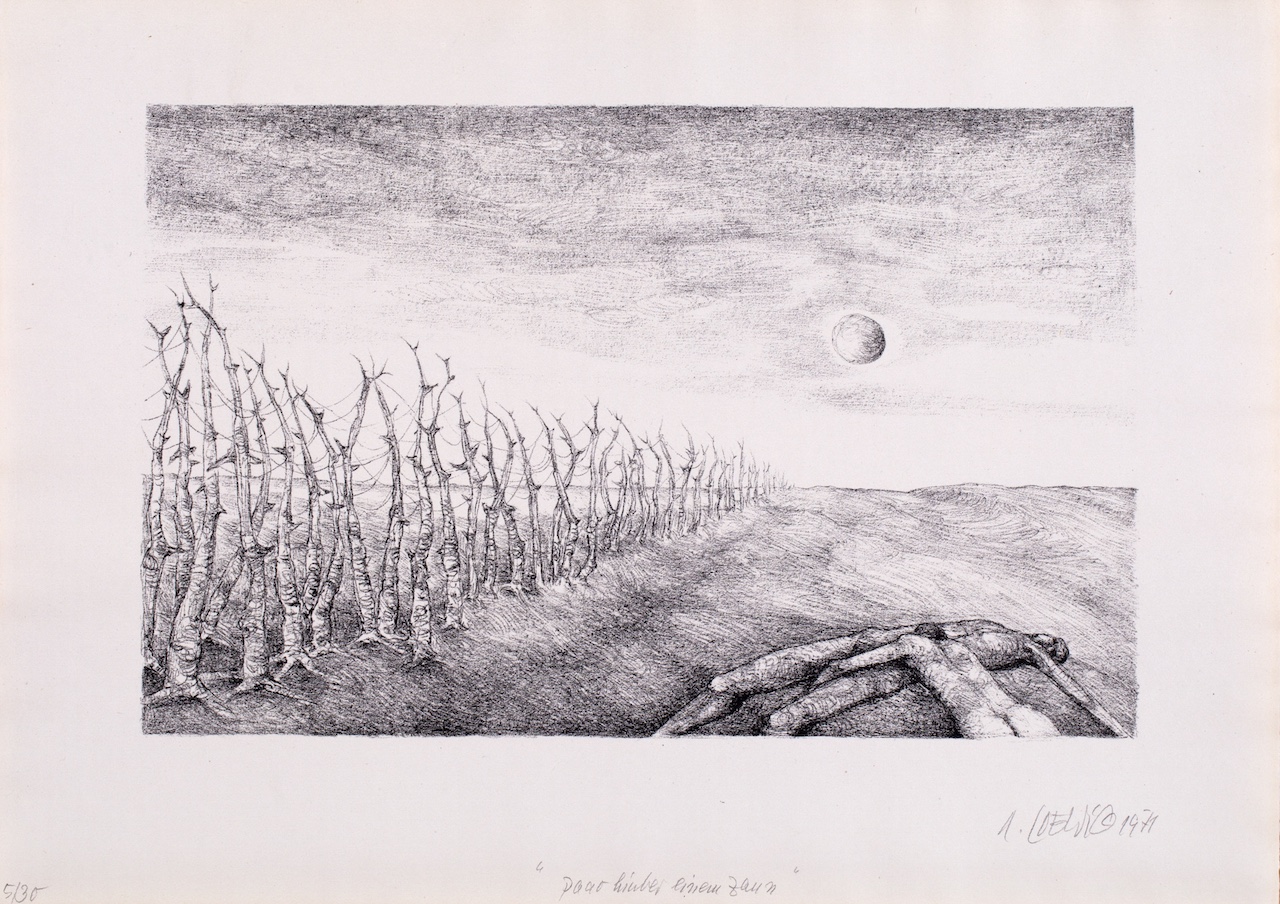

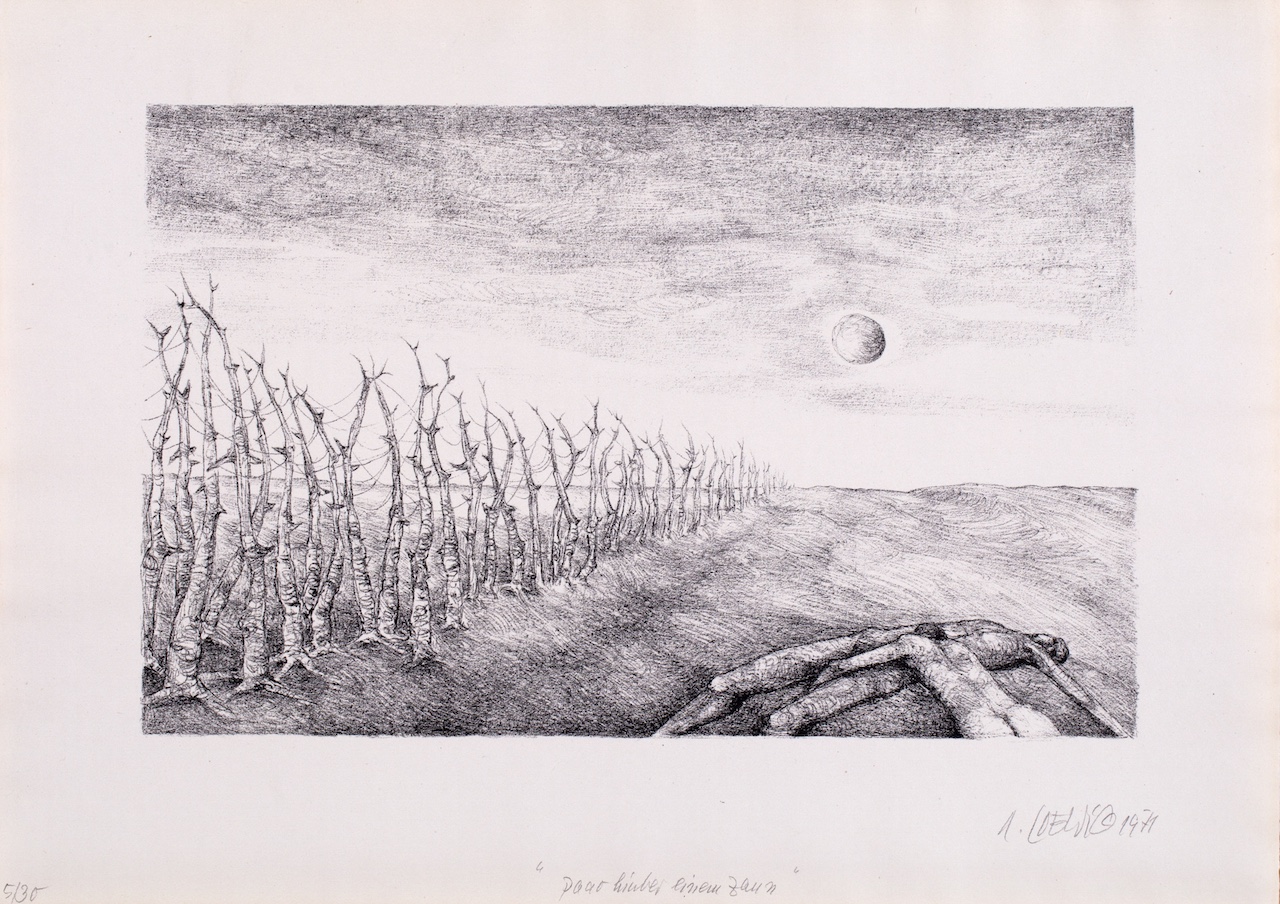

Recurrent motifs addressed by Roger Loewigs artworks are walls, rivers, fences, broken bridges, injured or dead bodies. These representations draw inspiration from the personal experiences of the Second World War, making a clear statement against any form of violence and repression.

The lithography 'Paar hinter einem Zaun' [Couple behind a fence], 30 x 42 cm, created in 1971, is the fourth sheet of the series 'Mein Mund webt ein Fangnetz für den Tod' [My mouth forms a catch net for death]. The series, including eight sheets, was created shortly before the artist's departure from the GDR. It accounts for the artworks created illegally during the period when the artist access to the printing machines was prohibited. 1971 it is also the year when his request to leave the GDR for West Berlin was granted. Thus one can account these series among Loewig's last productions while still in the GDR.

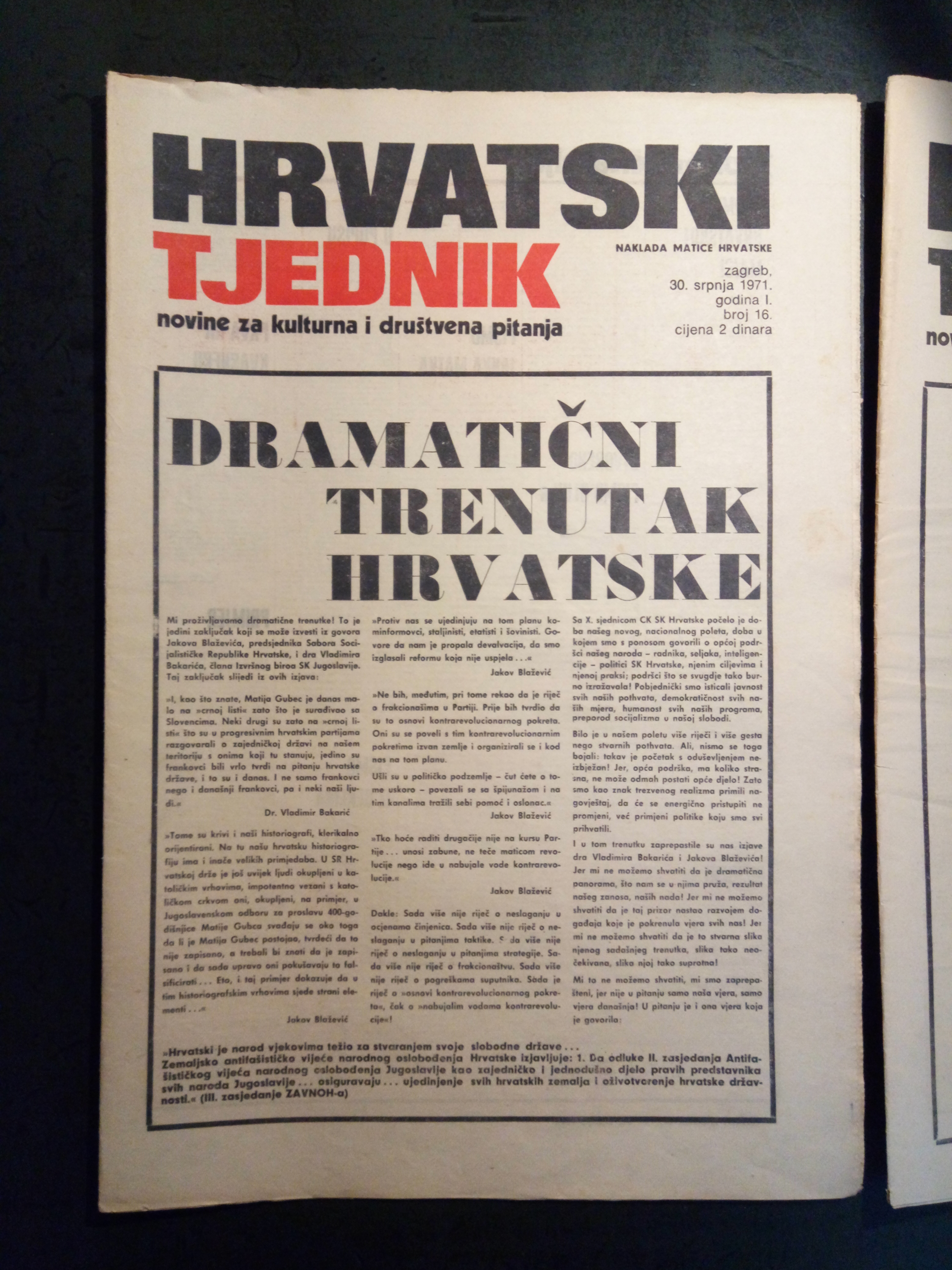

Hrvatski tjednik (in its sub-title it was defined as a newspaper for cultural and social issues) was a periodical published by Matica hrvatska (MH) in 1971 (from April 16 to December 3). It was launched at the peak of the Croatian Spring and soon became the primary media through which the MH and a circle of intellectuals gathered around it spread the ideas of this national reform movement. In advocating for Croatian cultural integration and equality within the Yugoslav federation, the paper openly criticised the socialist regime due to its economic-political, demographic and cultural failures. It was the most vocal media of the Croatian Spring that shared the destiny of the movement. After a precipitous ascent, the government extinguished it.

The first editor-in-chief was Igor Zidić (no. 1-13), who was succeeded by Vlado Gotovac (no. 14- 33), while the managing editor was Jozo Ivičević. The editors and authors of Hrvatski tjednik were prominent Croatian intellectuals (Stjepan Babić, Zvonimir Berković, Dubravko Horvatić, Tomislav Ladan, Srećko Lipovčan, Zvonimir Lisinski, Petar Selem, Tvrtko Šercar, Ivo Škrabalo, Hrvoje Šošić, Franjo Tuđman and others). The paper, which was published every Friday on 24 pages, had a circulation of 35,000, which increased over time. The last issue reached a number of 130,000 copies, which was an incredible number for that time.

The rapid spread of the newspaper provoked a reaction by the regime, which began to see it and its publisher as political opposition. Soon the regime declared them a focal point of counterrevolutionary politics and Croatian nationalism. The paper was censored in July (No. 16, July 30), and after issue number 33 of December 3, and the fall of Croatian political leadership at a meeting in Karađorđevo a day earlier, the regime shut down the paper and its publisher. The regime also launched various types of persecution against the most prominent members of Matica hrvatska and its newspaper, from harassment at work, dismissals, to court trials and prison sentences. In 1972, editor-in-Chief Vlado Gotovac was accused of conducting hostile activity against the state and was sentenced to four years of strict imprisonment with an additional three-year loss of civil rights. The editorial board had also prepared issue no. 34 , which was ready to print, but it was never released during communist rule. This unpublished issue with the editorial ("Maintaining Hope") written by Vlado Gotovac, was obtained by émigrés and came to the hands of Jakša Kušan, who published it in the newspaper Nova Hrvatska.

The Matica hrvatska Collection at the Croatian State Archives contains copies of Hrvatski tjednik, including the censored issue of July 30, 1971, and the one with the text of the Supreme Court's decision to censor the issue on the cover. The Supreme Court's decision was printed on the cover instead of the disputed article "A Dramatic Moment for Croatia." In this article, statements by Vladimir Bakarić and Jakov Blažević on the issue of counterrevolutionary activity and the rise of nationalism in Croatia were cited. These statements were followed by critical comments by an anonymous author who rejected

The performances presented on Republic Square (today's Ban Jelačić Square) in Zagreb in 1971 are the first work from the "Casual Passer-by" cycle. Another performance was done separately on Marshal Tito Square (today's Republic of Croatia Square) on the same day, when a large poster (portrait) of a random passer-by was mounted. Three large posters (portraits) showing photographs of an older man, an older woman and a young girl were hung on Republic Square. The posters (portraits) aroused great interest and confusion among the passers-by waiting for a tram.

It was a subversive performance in a public area, otherwise intended for officials, where the artist hung portraits of random passers-by and in that way questioned the established forms of communication in the public space of a socialist state.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb owns five photographs on one background that testify to this event - called the "Casual passers-by I met at 1:15, 4:23, 6:11 p.m.".

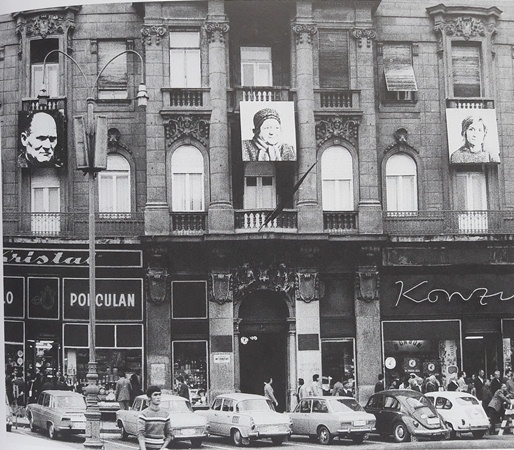

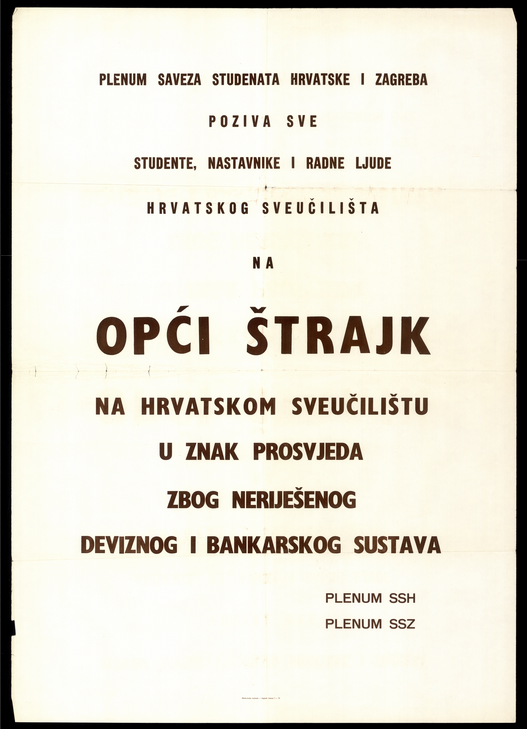

Poster with an invitation for a students' general strike at the University of Zagreb, 1971. Publication

Poster with an invitation for a students' general strike at the University of Zagreb, 1971. Publication

The Croatian Spring is the best example of cultural opposition in the period of the communist regime in Croatia. Students were an important part of this reform movement and were very decisive in their requested reforms. They started a strike at the University of Zagreb (a.k.a. the Croatian University) and invited the entire public sphere to join. Their messages were distributed on leaflets and posters, pinned at the University and in other public spaces. Many such examples are found in the collection, and the masterpiece is a big poster with an invitation to a “general strike at the Croatian University”. The poster was confiscated and handed in to the Public Prosecutor’s Office in Zagreb (December 1971). The poster remained unknown to the public.

Iljko Karaman took the document illegally from the Public Prosecutor's Office and stored it in his home collection, which ended up in the Croatian State Archives in 1992. The material is available for research and copying.

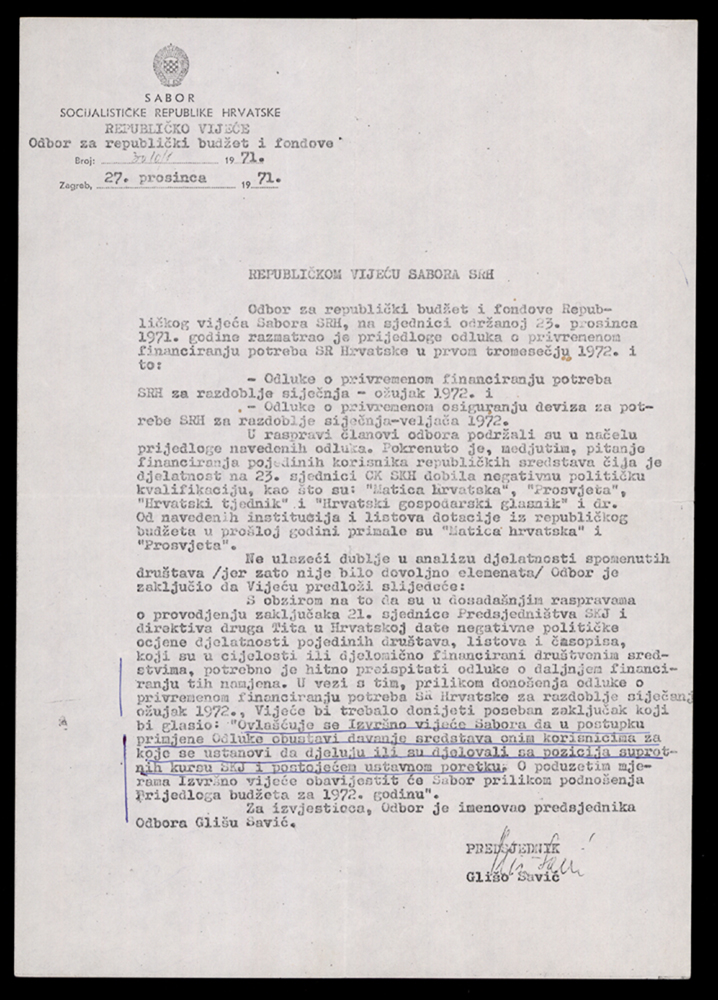

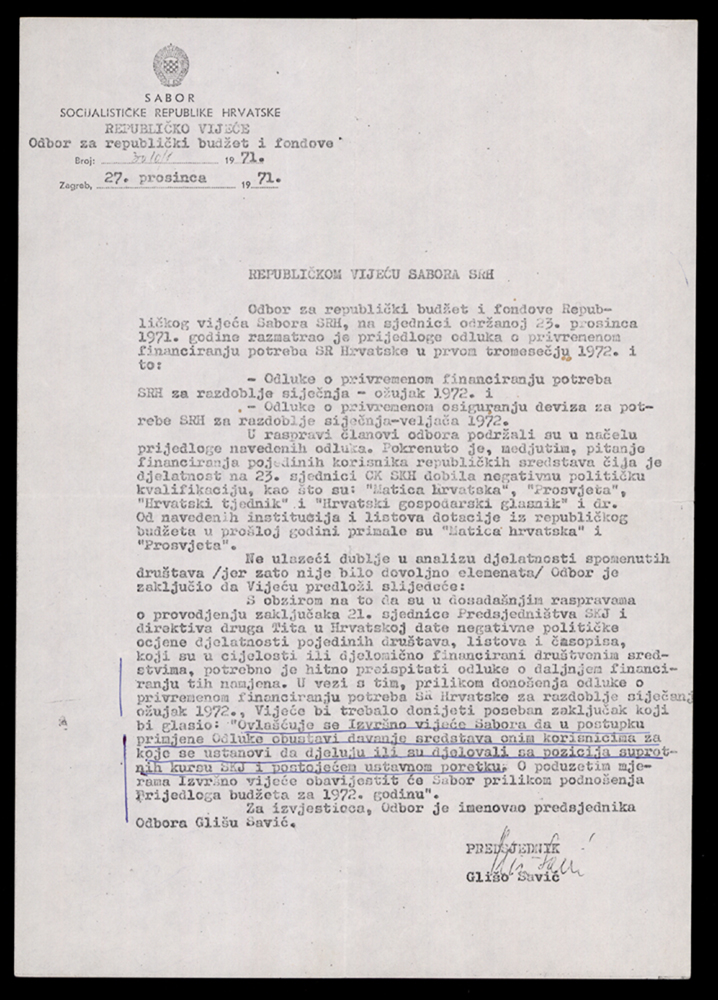

Letter of the State Budget and Funding Committee on the termination of funding for the SCA Prosvjeta

Letter of the State Budget and Funding Committee on the termination of funding for the SCA Prosvjeta

The document clearly states that Prosvjeta’s activities received a "negative political assessment" by the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia, with the recommendation that the Executive Council of Parliament suspend the allocation of funds to those users "who are found to act or have acted in a manner that oppose course set forth by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and the existing constitutional order". The document is evidence that in that period on the basis of its activities Prosvjeta was considered an opposition organization.

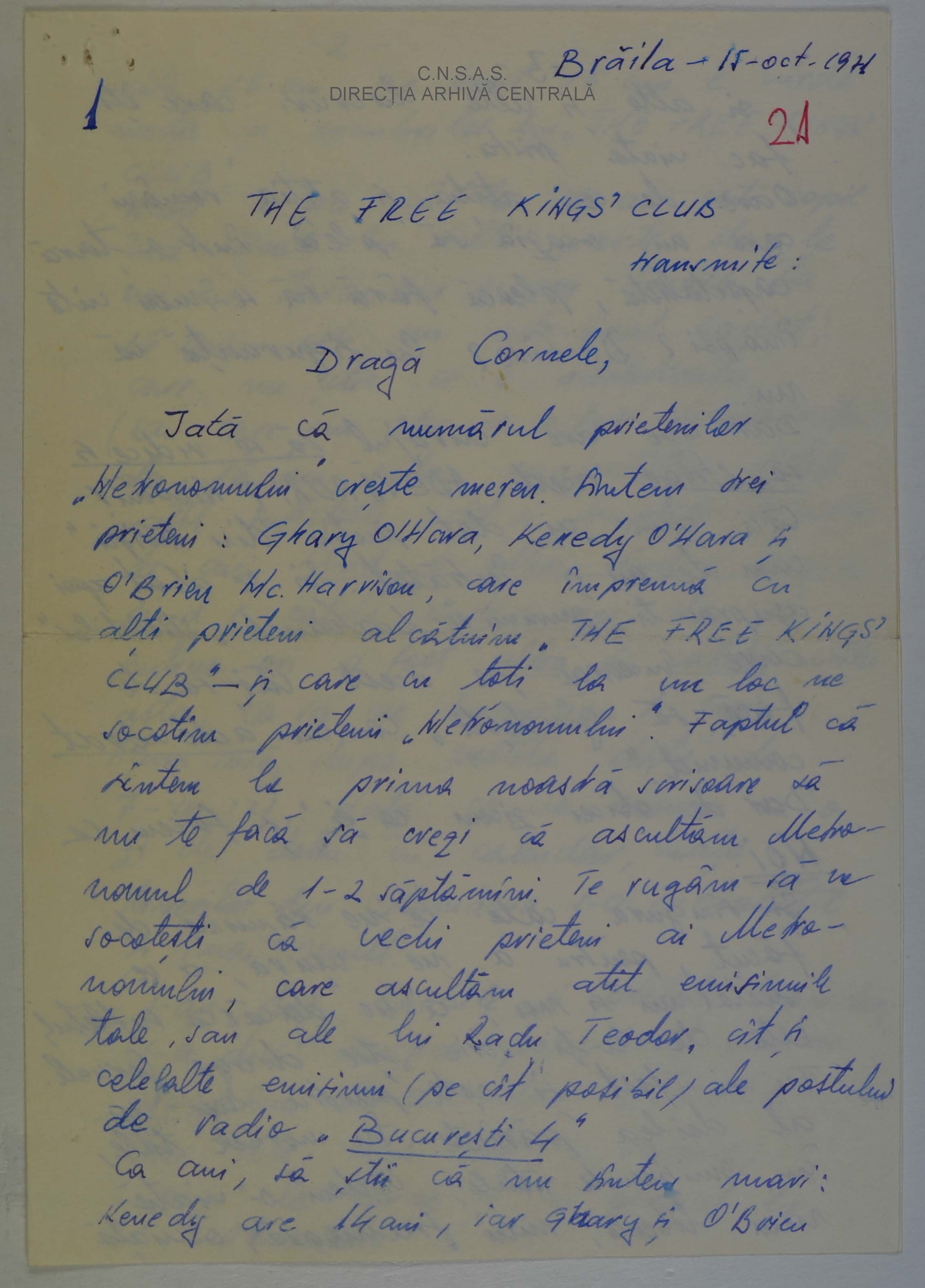

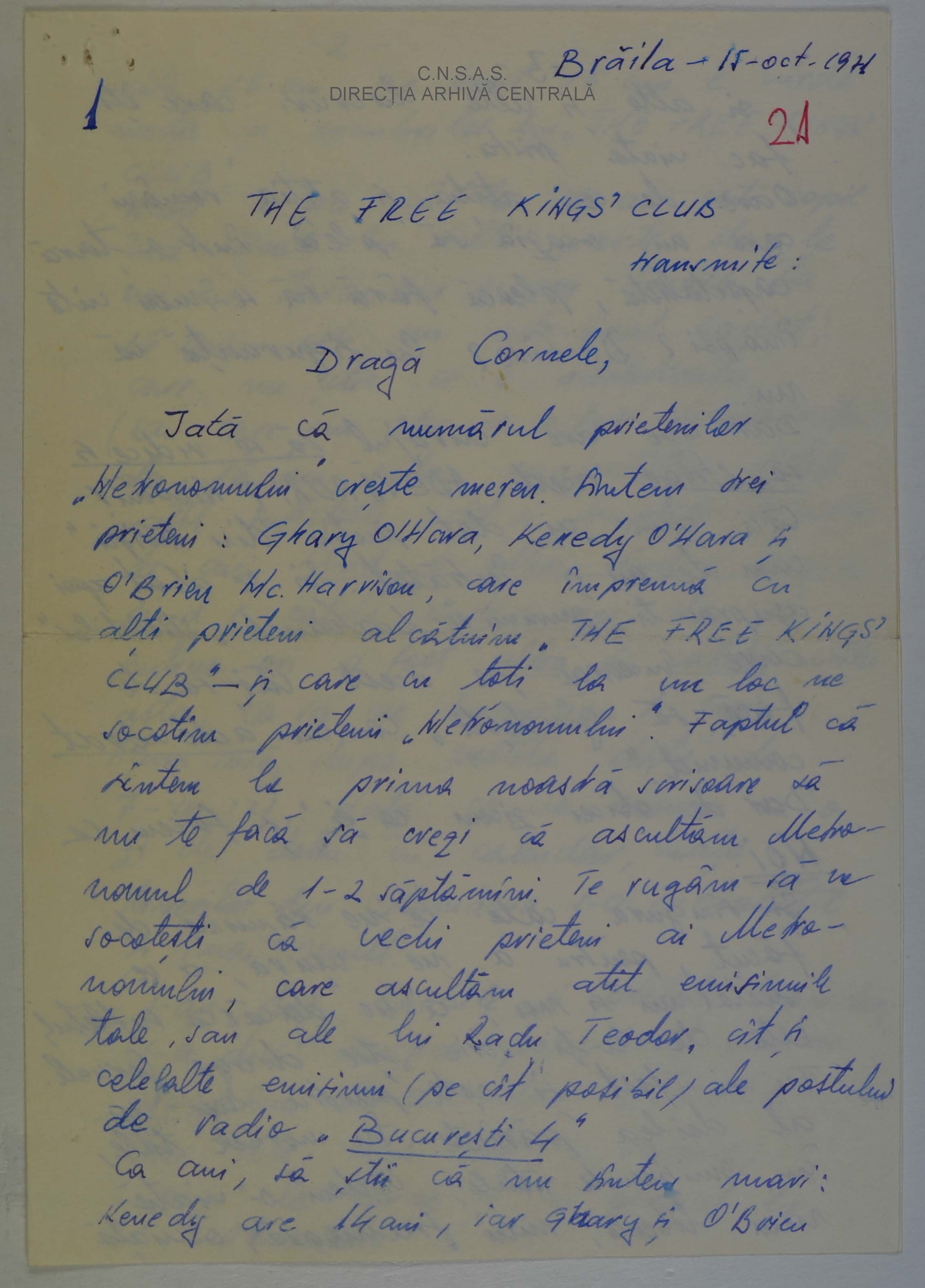

Dated on 15 October 1971, the letter was signed by three members of The Club of the Free Kings. The club was in fact a group of teenagers, fourteen to sixteen years old, who gathered occasionally in order to listen to foreign music. In order to distinguish themselves from their peers, each member of the group took an English nickname and decided to wear a yellow T-shirt with the group’s initials and a flower imprinted on it. They also made badges for themselves with the name of the club, their nicknames, and the word “hippy,” as they wanted to be identified as a hippy group. Because their favourite music programme at RFE was Cornel Chiriac’s programme Metronom, they decided to write him a letter on behalf of the group. In their message, these young people described the impact of Theses of July 1971, which imposed an embargo on foreign cultural products of all kinds: “After the famous date of 7 July 1971 [actually, Ceaușescu delivered his speech on 6 July], a date that will remain forever inscribed in the calendar as a day of mourning, the lives of young people in Romania worsened even more: gone were the beards and the long hair, gone was pop, beat or progressive music. Everything was gone!” (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, file 3032 vol. 1, f.21). Their letter represented a quite radical criticism of the cultural policies of Ceaușescu’s regime and the economic difficulties the Romanians had to face in their daily life. Moreover, they considered Cornel Chiriac’s show Metronom to be an escape from the grim reality of their lives and a window to “a freer, more beautiful life, a life you would like to live.” In the final part of the letter, the signatories asked Cornel Chiriac to broadcast their favourite songs. Unfortunately for them, the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, intercepted the letter and subjected its authors to an investigation. In the end, the members of The Club of the Free Kings received a warning from the Securitate and had to sign a declaration in which they recognised their guilt and pledged not to get involved in similar activities in the future.