The collection of Ilona Liskó is the legacy of the oeuvre of a sociologist who tried to shed light on the problems in Hungarian society which, according to the official stance of the regime, did not exist. Liskó felt a sense of solidarity with the poor and marginalized in part thanks to her family upbringing, and her desire to shed light on their sufferings came from her deep sense of social obligation.

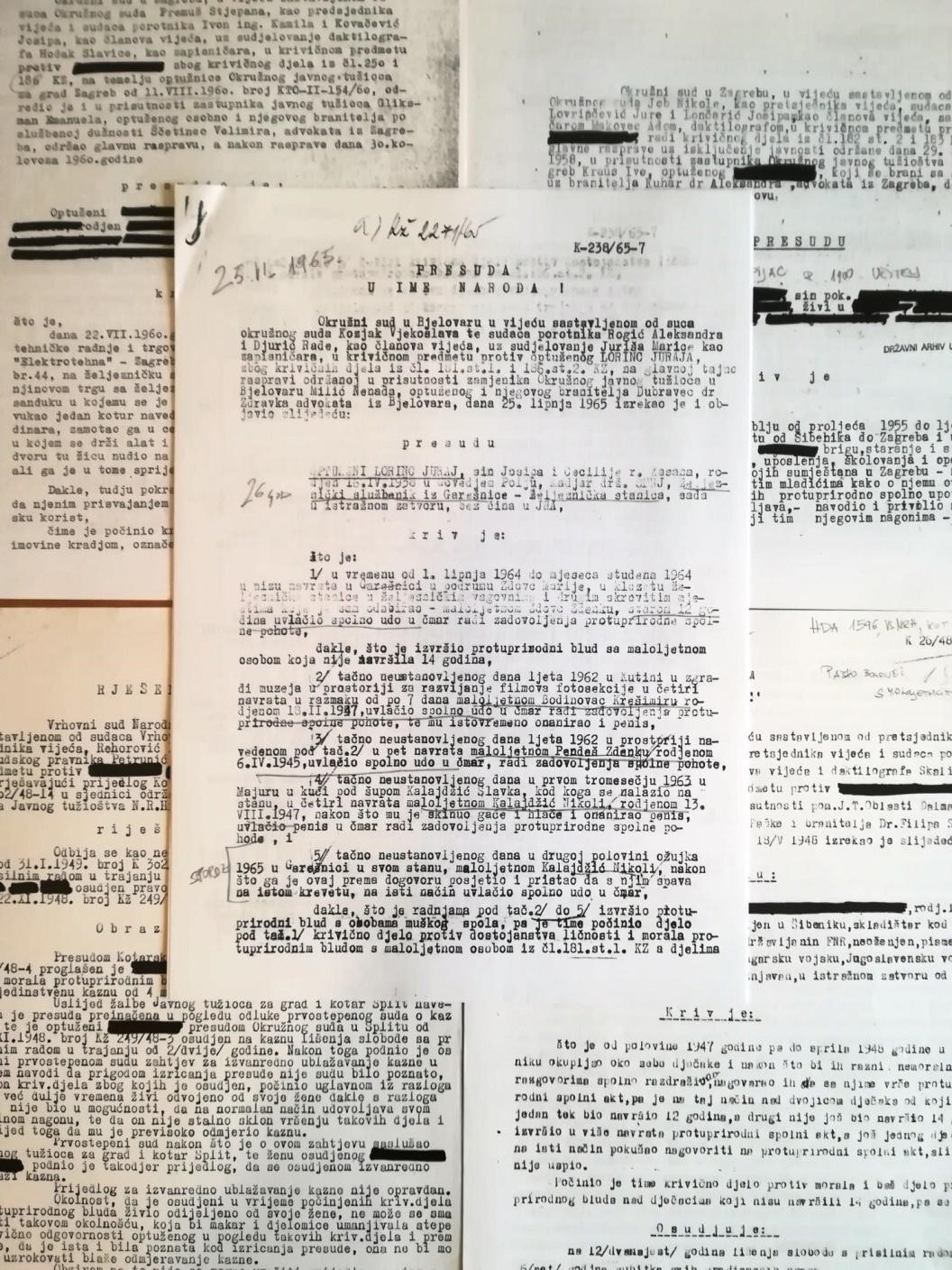

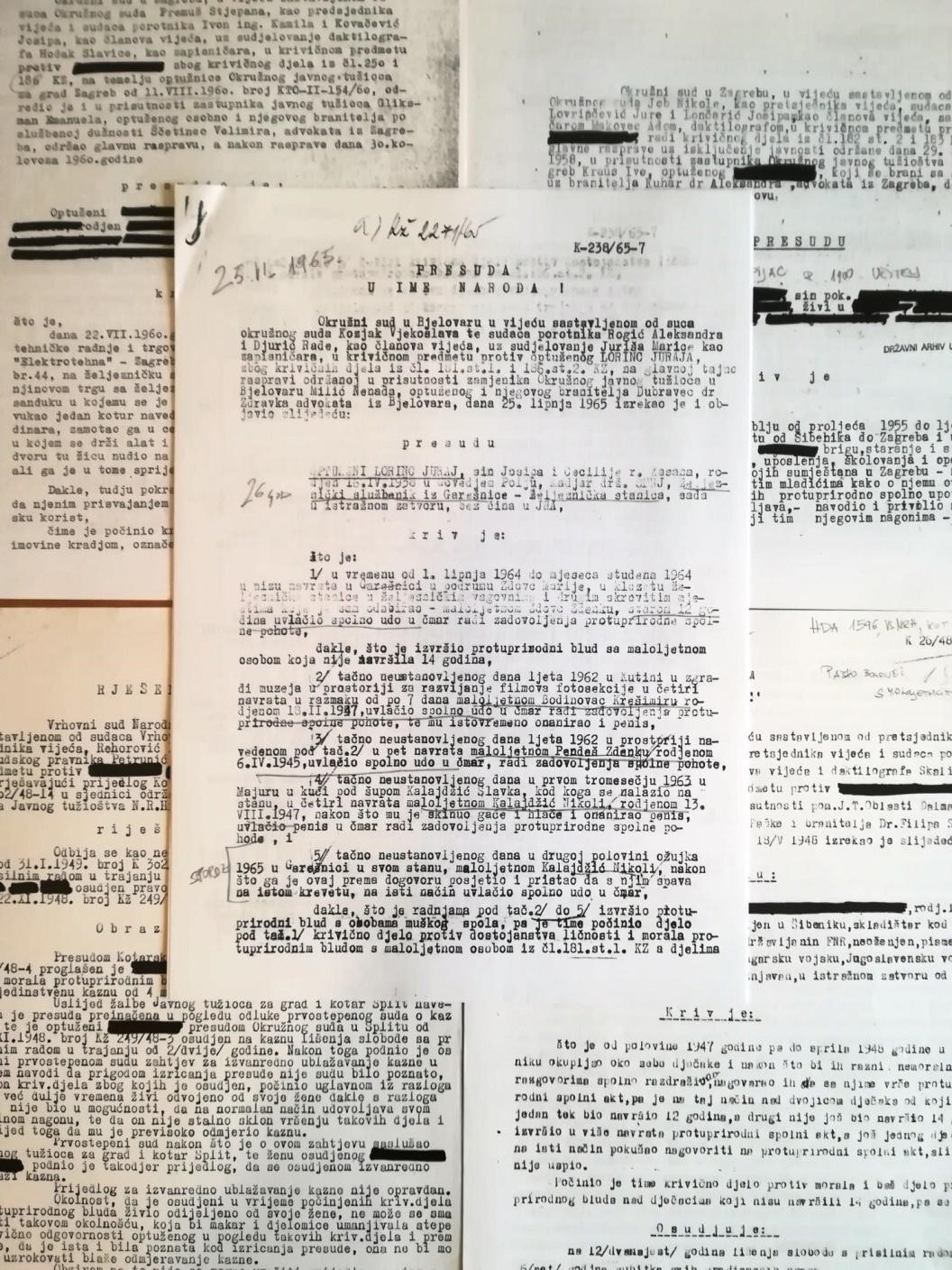

Round table: “In the Name of the People! – Trials against Homosexuals and Lesbians in Croatia, 1945-1977”

Round table: “In the Name of the People! – Trials against Homosexuals and Lesbians in Croatia, 1945-1977”

The round-table discussion “In the Name of the People! – Trials against Homosexuals and Lesbians in Croatia, 1945-1977”, on the first cluster of sentences for homosexual behaviour found in the Croatian archives. Knowing that male same-sex sexual relations in Croatia were criminalized until 1977, the Domino Association began to search for sentences that would demonstrate the severity and scope of the persecution of homosexuality in socialist Croatia. In 2009, with the help of volunteers, and under professional guidance of a historian, research was conducted in the Croatian State Archives (HDA), in the Supreme Court of Croatia archival collection (HR-HDA 1596, VS NRH). During this first phase, a dozen sentences for “unnatural fornication” were found, mostly verdicts dating back to the initial post-war years. These sentences showed that by the mid-1950s in socialist Yugoslavia, homosexuality was branded as a “corruptor of youth” and a “decadent, rotten remnant of the old, overthrown bourgeois regime.” The authorities were convinced that the homosexuals came from the ranks of “decadent intellectuals,” the urban middle class and the clergy, all of whom were perceived as “corruptors of healthy working-class youth.” Especially important was the finding of the complete materials from the probably largest trial against homosexuals ever held in post-war Yugoslavia, when in February 1950, seven men were found guilty of “unnatural fornication.” Moreover, their full names were published in the press where they were called out as enemies – and even saboteurs – of socialism. All of this indicates that the entire proceeding had elements of a show trial, with a clear ideological message (Dota 2017, 167-177). The materials from the trial contained statements that were given by the accused themselves, and even complaints they wrote against the verdict. These documents bear witness to the forms of resistance some men engaged in against the anti-homosexual policies to which they were subjected. Some argue that homosexuality does not pose any kind social peril but is rather a natural predisposition that should not be punishable in a socialist country. Others cited progressive sexological and other scientific works in order to prove they were neither sick nor perverted. In January 2010, following the initial phase of research in the Croatian State Archives, a roundtable discussion was held under the title “In the Name of the People! –Trials Against Homosexuals and Lesbians in Croatia, 1945-1977.” This event presented the public with copies of retrieved sentences and summarized the preliminary results of the research project. The speakers were Gordan Bosanac, the director of Domino and research project coordinator, two historians working on the history of homosexuality in socialism, Dean Vuletic and Franko Dota, and Andrea Zlatar-Violić, a literary theorist and, later, Minister of Culture. Furthermore, an article on trials against homosexuals in socialist Croatia was published in the press (Dota 2010a). Subsequently, the research was expanded to the State Archives in Zagreb (DAZG), where 30 more sentences for “unnatural fornication” were found, mostly from the 1950s and the 1960s.

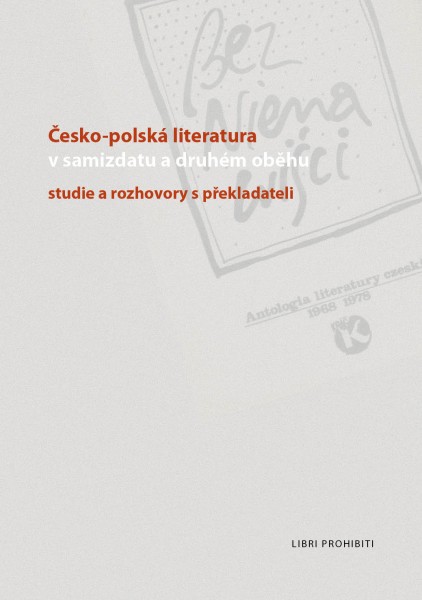

Publication: Česko-polská literatura v samizdatu a druhém oběhu (Czech-Polish Literature in Samizdat and Underground), 2010. Book

Publication: Česko-polská literatura v samizdatu a druhém oběhu (Czech-Polish Literature in Samizdat and Underground), 2010. Book

The compendium “Czech-Polish Literature in Samizdat and Underground: A Study, Interviews with Translators” accompanied the Polish Underground Library in Prague project, supported by the Czech-Polish Forum of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic, and was published by the Prague library Libri Prohibiti in 2010. This publication analyses Poland and Poles within the Czech samizdat in the 1970s and 1980s. It includes interviews with Czech and Polish translators, a study of Polish literature in the context of the Czech samizdat and of Czech literature in the context of the Polish underground. Moreover, the exhibition “Polish Underground Library in Prague in Libri Prohibiti’s Collections” took place from December 2009 to January 2010. The exhibition presented materials of the Polish Underground Library that are part of Libri prohibiti’s collections – mainly Polish underground and exile publications.

Gabriel (Dinu) Zamfirescu is one of the most representative figures of the Romanian exile community. Imprisoned for his anti-communist convictions at the end of the 1940s, he was continuously harassed until his emigration in 1975 by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, due to his “bourgeois” family background, political sympathies, and connections with former National Liberal Party. The interview with Dinu Zamfirescu included in The Oral History Collection at CNSAS has three parts. Each of these video recordings has a duration of almost 120 minutes and they were made on three different days of July 2010. Following the logic of a life-story interview, Dinu Zamfirescu draws a comprehensive image of his early life, his family, and its connections with the most important political figures of interwar Romania. Special attention is given to his anti-communist activities, which influenced his decision to join the ranks of the National Liberal Party and provided the Securitate with another reason to put him under informative surveillance after the establishment of the communist regime in Romania. Harassment by the secret police and finally imprisonment prevented him from completing his university education. After his release, his many requests for a passport to visit his relatives only intensified his surveillance by the Securitate. In 1975 he was finally granted an exit visa and he settled in Paris, one of the most important centres of the Romanian anti-communist exile community. In his interview, Dinu Zamfirescu remembers how he met well-known figures of the Romanian exile community in Paris, such as Monica Lovinescu, Virgil Ierunca, and Sanda Stolojan, and joined their collective effort of organising opposition to the communist regime at home. As a member of the Romanian exile community, he used every opportunity to raise the awareness of international public opinion about the Ceaușescu regime. As a result, Dinu Zamfirescu signed and sent memoranda to Western governments that continued to consider Nicolae Ceaușescu a “good communist” in view of his anti-Soviet stance, ignoring his disastrous internal policies. He also participated in conferences and programmes broadcast by the Romanian department of Radio Free Europe and used his position as a BBC correspondent in Paris for fourteen years to denounce the abuses and the repeated violations of human rights by the communist regime in Romania. More importantly, Dinu Zamfirescu joined Operation Villages Roumains, a transnational network of support for the Romanian villages whose existence was endangered by Ceaușescu’s systematisation plans. As a result, between 1988 and 1989 he contacted mayors and local communities in France, Belgium, Italy and Switzerland and asked them to “adopt” Romanian rural settlements as a means of preventing their destruction by the Ceaușescu regime.

The Brașov–Orașul Memorabil Collection gathers more than 4,500 scanned copies of personal and official photos illustrating the history of this Transylvanian city, everyday life in Romania under communism, the programme of so-called urban systematisation conducted during Ceaușescu’s regime, and the popular resistance to this arbitrary policy.

The collection includes the documents of the Danube Circle Association, which was a non-governmental organization in opposition to the government’s project to construct a River Barrage Dam near Nagymaros (Hungary) in the 1980s. The Danube Circle movement tried to prevent the construction of the dam with samizdats, public debates, and protests. The Circle was one of the new types of alternative movements, which expanded the base of the “traditional” intellectual opposition.

The collection of Milan Uhde documents the life of an important writer, later a signatory of the Charter 77, who at the time of normalisation could not officially publish, and after 1989 a parliamentary deputy and a minister of culture. The collection is composed of Milan Uhde's sequencing material, covering the period predominantly from the 1960s to the present.

The first year of the Prize of Memory of Nations, directed by Václav Marhoul, took place in 2010 in Žofín Palace in Prague.

The Prize of Memory of Nations are awards for persons who have shown in their lives that honor, freedom and human dignity are not just empty words. People of the Czech and Slovak Republics who spent years in communist prisons have taken over the People's Memory Award. The organizers of the gala evening are Post Bellum, Czech Television, Czech Radio and Television of Slovakia and the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. Each of the winners can state their wishes and the organizers will try to grant them.

The winners of the first year of the Prize of Memory of Nations were Tomáš Sedláček, Věra Roubalová-Kostlánová, Jan Pecka and Šimon Pánek. From that year to the present (2017), 29 people have been awarded prizes. Among them are war veterans, political prisoners, resistance fighters, Holocaust survivors, persecuted writers or underground people, scouts, church members, and many others.

Since 2010, when was the first prize was awarded, the Prize of Memory of Nations has been awarded annually

The Husar Club was founded by the Club of Friends of Popular Music Rijeka in 1957. In the Husar, young people gathered to "dance to music from LP records." Beginning in 1962, the first rock bands in Rijeka performed in the club. The club operated until 1964 and is considered as the first disco club in Croatia and one of the first in Europe. The establishment of this club heralded the creation of the rock and disco culture movement as a counterculture in socialist Yugoslavia.

Already in the 1990s, Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca decided that their impressive collection in Paris was going to be donated to the Romanian state after their death. Consequently, in 1998 they named two of their close friends, Gabriel Liiceanu and Mihnea Berindei, as executors of their will. The two were thus entrusted with bringing Lovinescu and Ierunca’s collection (composed of books, documents, and vinyl discs) to Romania (Lovinescu 2010, 477). After the death of the owners and creators, Gabriel Liiceanu and Mihnea Berindei divided the collection between them. A part, composed mainly of manuscripts, memoirs, clippings from newspapers, copies of press articles, magazines and other foreign press publications, was donated in 2012 to the National Archive of Romania. The books were divided among three institutions: The Union of Writers in Romania in Bucharest (about 1,250 rare books), The Faculty of Political Sciences in Bucharest (around 1,500 books),and the University of Oradea. On September 6, 2011, the Humantis Aqua Forte Foundation donated the rest of the documents and manuscripts to the Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of the Romanian Exile (IICCMER) (Meseșan 2015, 14–15).

The person who intermediated the donation to the University Library in Oradea was Lilian Zamfiroiu. A PhD candidate in history at the University of Oradea, Lilian Zamfiroiu was also the deputy of the Romanian ambassador at UNESCO, Nicolae Manolescu. Thus, Zamfiroiu persuaded Manolescu to contact Mihnea Berindei, and ask him to donate a part of the Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca collection to Oradea University Library. Thus, on April 27, 2010 a large truck full of books from the house of the two collectors in Paris arrived in Oradea. The books were unloaded from the truck and stored in the new modern building of Oradea University Library in (Matica 2010, 3; Editorial Jurnal bihorean 2013, 3). Since 2011 the Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca collection has been housed in a special room at Oradea University Library and is open for research to students, scholars, and other people interested in the history of the Romanian exile community and cultural dissident movement.

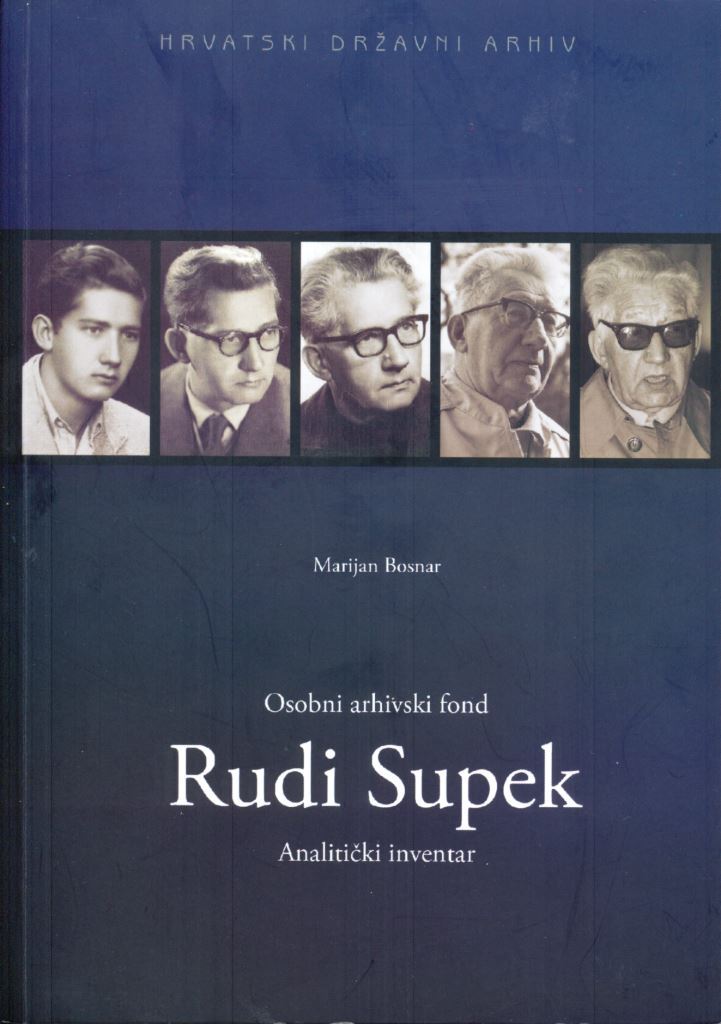

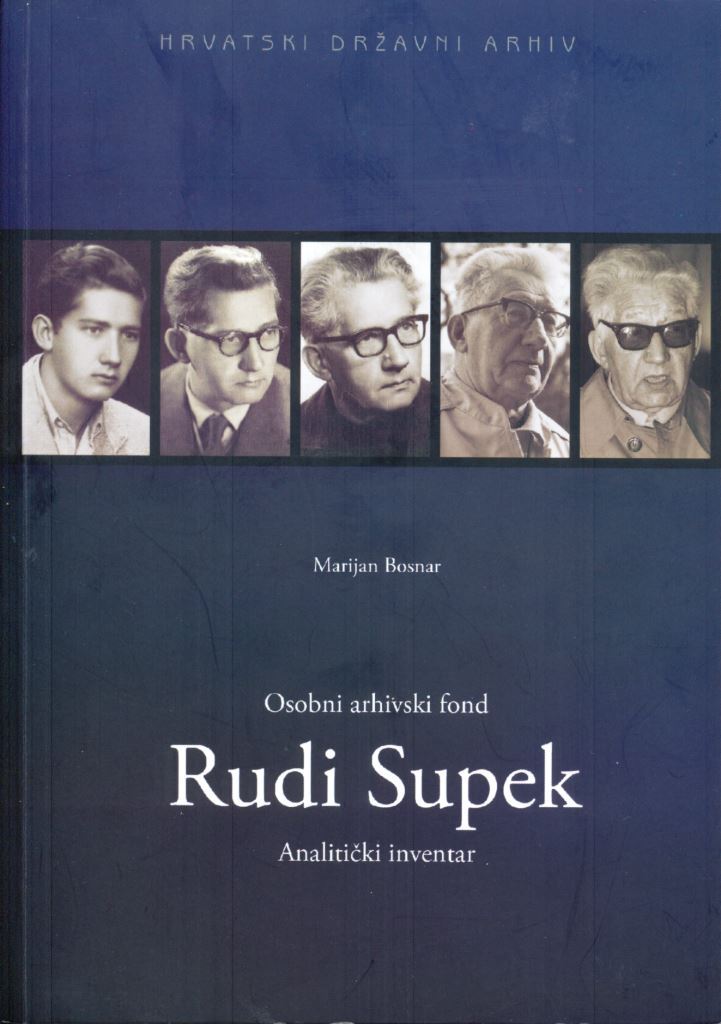

Publication: Osobni arhivski fond Rudi Supek. Analitički inventar (Rudi Supek Personal Papers. Analytical Inventory), 2010. Book

Publication: Osobni arhivski fond Rudi Supek. Analitički inventar (Rudi Supek Personal Papers. Analytical Inventory), 2010. Book

During his life, Croatian philosopher, sociologist and psychologist Rudi Supek (1913-1993), systematically collected a personal archive which his granddaughter, Bojana Zupan, donated to the Croatian State Archives more than a decade after his death. His archive illustrates his life and work, which often did not fit into the dogmatic-ideological frameworks of the communist authorities in Yugoslavia. After the acquisition of the materials (2005), archivist and historian Marijan Bosnar started to archivally organise the papers at the end of 2006. He arranged the collection in 17 series and created a finding aid (analytical inventory) in 2008 which was later published as a book with introductory text, photographs and facsimiles (Bosnar 2010). Ms. Olga Supek, Rudi’s daughter, provided great assistance to Marijan Bosnar in identifying the persons on the photographs in the collection.

The Oral History Collection at CNSAS is a unique collection of this kind as it includes only interviews with individuals who are the subjects of personal files in the CNSAS Archives, and who after studying these personal files created by the Securitate agreed to narrate their own experience of entanglement with the secret police. The interviewees include not only individuals who were under surveillance and thus victims of the Securitate, but also individuals who collaborated with the secret police to provide information on others: family, friends, and colleagues. Both types of interviews represent the response of the interviewees to the narrative created about them by the Securitate.

On October 29, 2010, the Study Centre for National Reconciliation organized a trip to the island of Goli for the interested public, students, professors and journalists. The purpose of the trip was to familiarize the public with the events that took place on Goli during the period of socialist rule, and the main eyewitness of those events was Andrej Aplenc. Aplenc was detained on Goli as a student on two occasions and as a part of the excursion, he talked about life and survival on the island.

![I, Ondřej Žváček [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], from Wikimedia Commons](/courage/file/n32314/%C4%8Cesk%C3%A1_televize.jpg)

Czech Television (the transferee) and the Original Videojournal Ltd. (the transferor) made a contract for the transfer of the ownership rights as well as the rights of the audiovisual record producer on 13 October 2010. The subject of the contract was uncut material on VHS cassette tapes which was shot between 1987 and 1989 for the purpose of Original Videojournal production. Because of this agreement, the archive of CT could digitise the material and preserve it for future use. The contract also allowed Czech Television to use the content of video cassette tapes in a documentary series about OVJ, which included previously unpublished shots.

Vanda Zaborskaitė (1922-2010) was a professor of Lithuanian literature. In 1961, she was dismissed from her position as a lecturer at Vilnius University because of her 'nationalism'. After that, she found a position at the Lithuanian Institute of History. While she had other research topics at the institute, she also worked on Lithuanian literature, researching a very disapproved of topic at the time, the work and activities of the Lithuanian poet Jonas Mačiulis-Maironis (1862-1932). Maironis was a Catholic priest, who used strong patriotic and nationalist expression in his works, and the Soviet regime had to consider how to interpret his legacy, what parts of his work should be available to society, and what should be seen as religious.