Before the fall of the communist regime led by Nicolae Ceaușescu in December 1989, performance art appeared only sporadically in basements and in private apartments. The birth of Romanian and Transylvanian performance art is closely linked to the artistic work of Imre Baász. The Burial of the Suitcase is one of the earliest of the very few performances carried out in Romania before 1989. Its message is linked to Chances of Survival, prompting people to discover the possibility of staying in Romania, softly accusing those who had left, but without pointing fingers.

The performance was carried out in 1979, near the town of Sfântu Gheorghe. Baász used his grandfather’s old suitcase, which he had taken with him when he had moved to America. He did not make a fortune and he did not stay there though: he returned home and continued his life where he had left off. This story showed that the time spent in a foreign place can more easily turn out to be wasted than time spent at home, even if it is spent struggling. Baász put everything in the suitcase which would be necessary for a real emigration, walked out of the town, asked for a saw, and buried the suitcase. In a way, the performance had a double goal: to symbolically protest against leaving the country and to give final peace to the ancestor’s suitcase in the soil of his homeland.

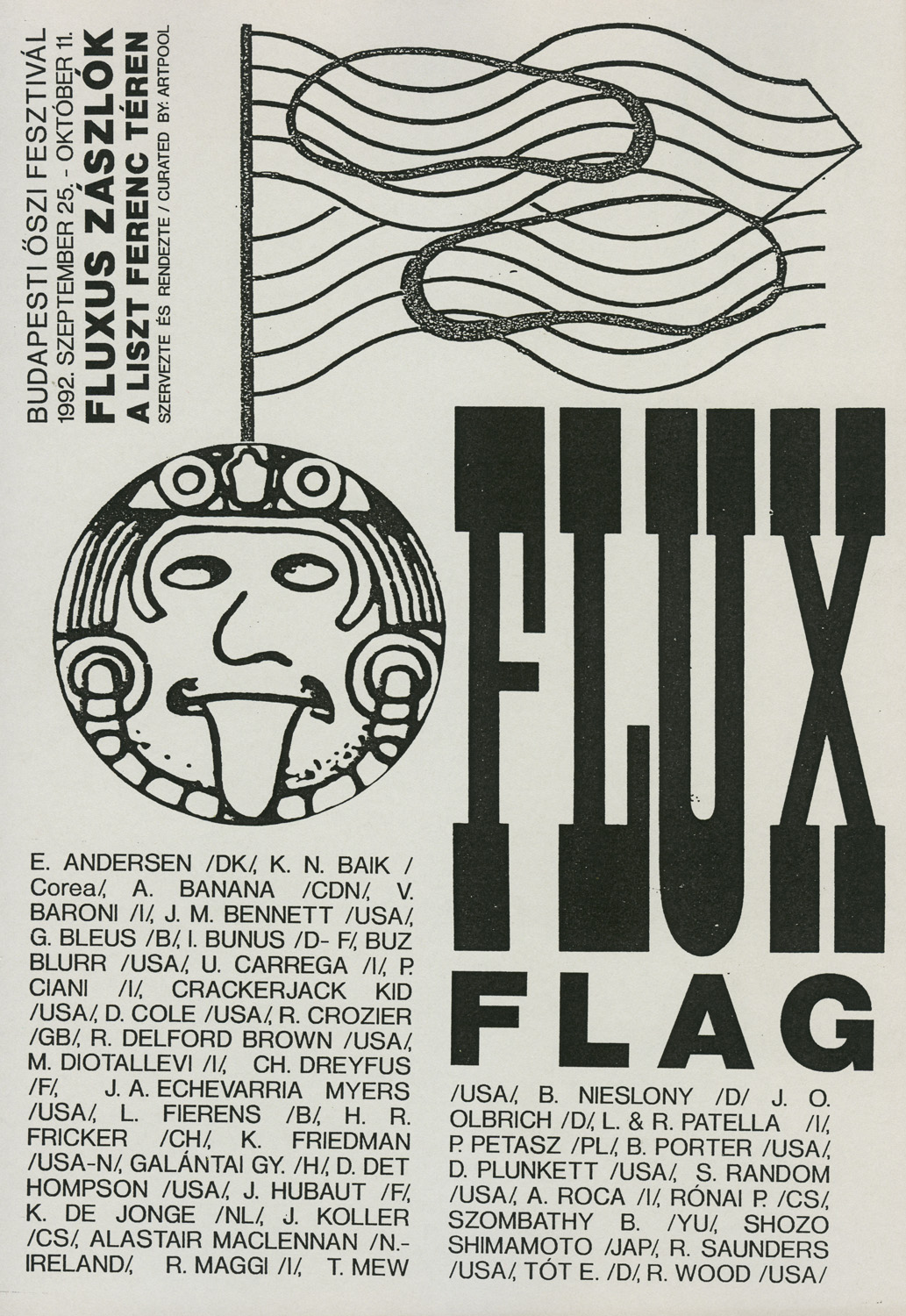

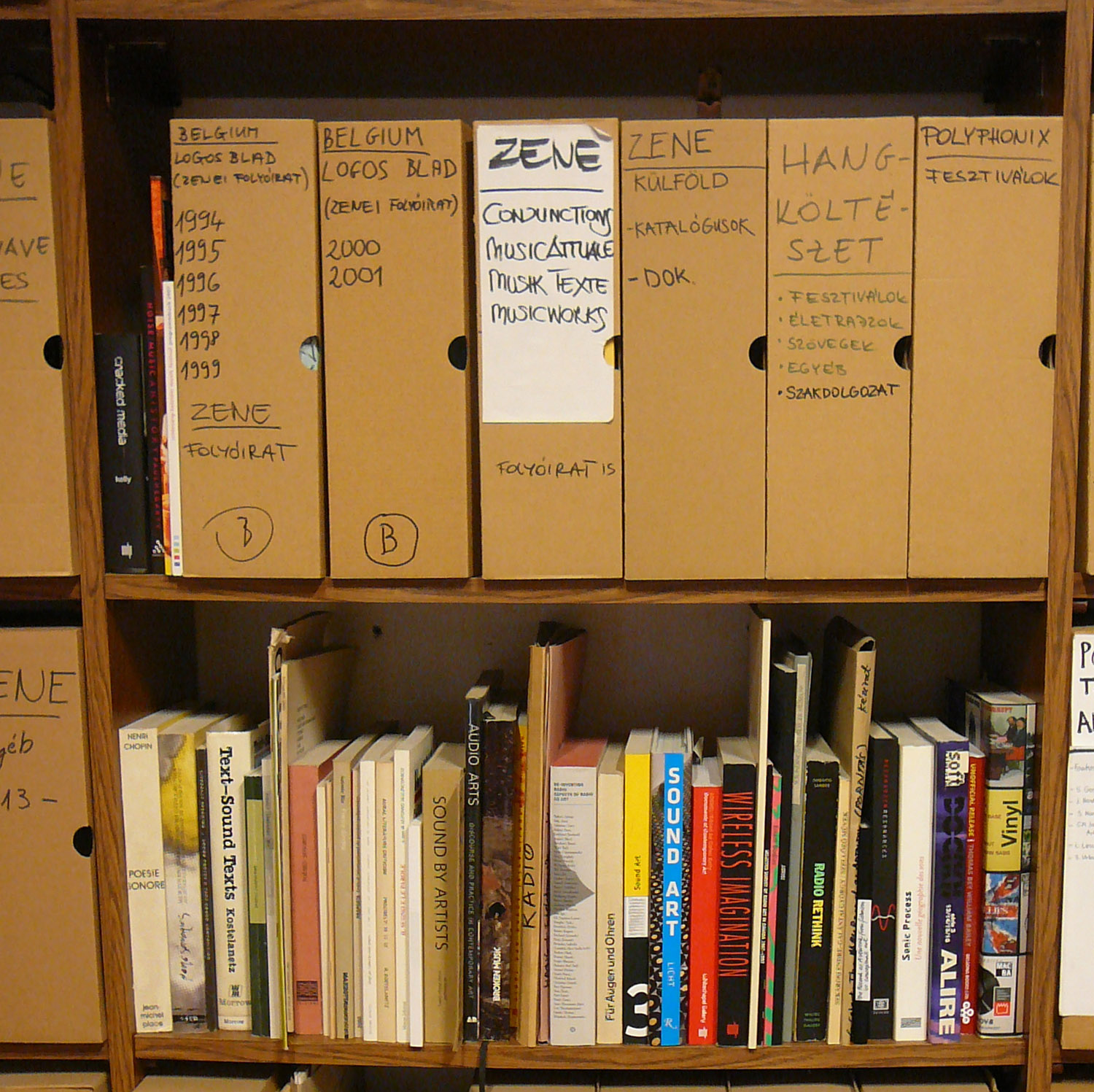

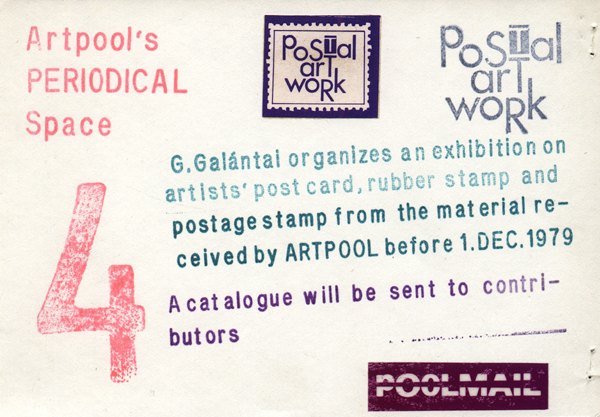

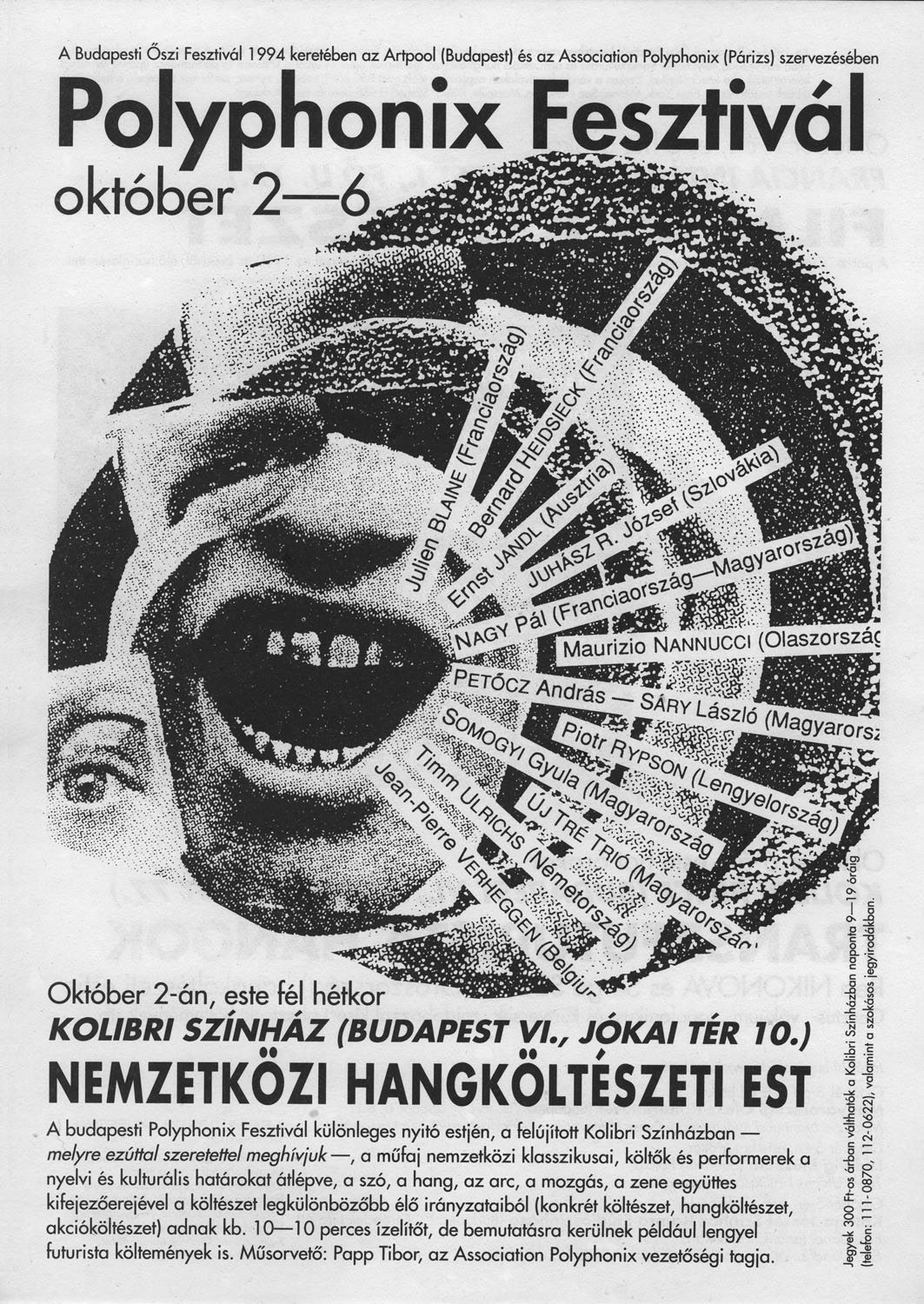

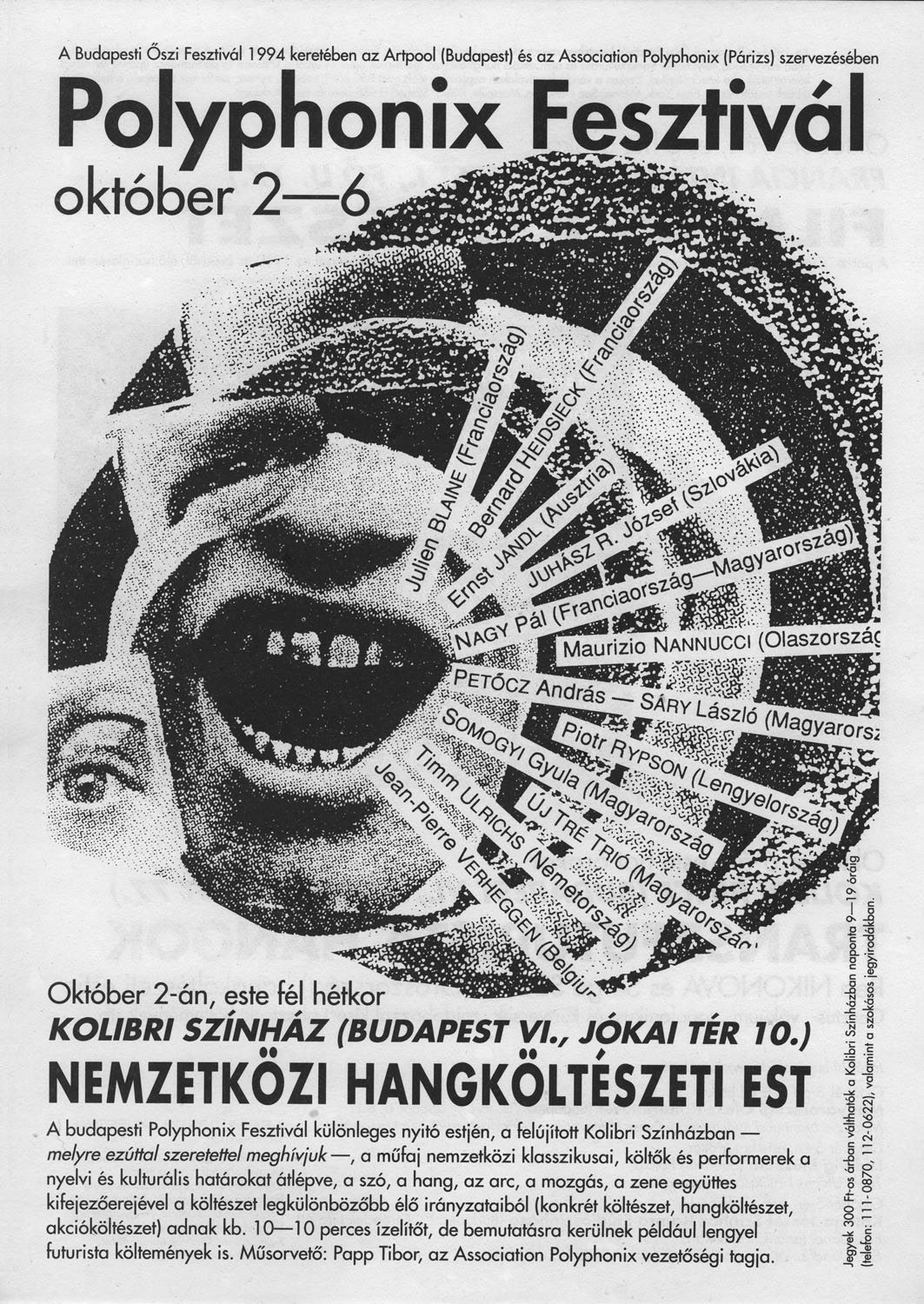

Artpool Art Research Center collects, archives, and makes available documents for researchers regarding marginalized art practices of Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary international art tendencies. Topics in the archive include progressive, unofficial Hungarian art movements (such as underground art events, venues, groups, and samizdat publications between 1970 and 1990) and new tendencies in international art beginning in the 1960s.

In addition to functioning as a research center, Artpool considers itself an active archive. It organizes events in search of new forms of social activity, participates in the process in a formative way, and simultaneously documents and archives these process in order to promote the free flow of information.

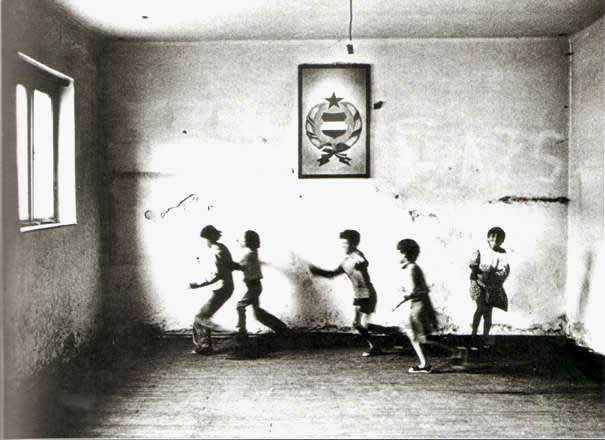

The For the Democratization of Art Collections contains six photographs representing the activist work (i.e. performances) of the Croatian conceptual artist Marijan Molnar from 1979 to 1983. The work consists of a series of performances in which the author drew graffiti and hung banners with the message "For the Democratization of Art" in Zagreb, Belgrade and Ljubljana, collected signatures for a 'petition' on Republic Square in Zagreb, had his picture taken dressed as a terrorist for the student newspaper and presented an installation at the Koprivnica Gallery. Through this work, Molnar tried to point out the influence of politics on art in socialist Yugoslavia, at the same time seeking freedom of action for artists.

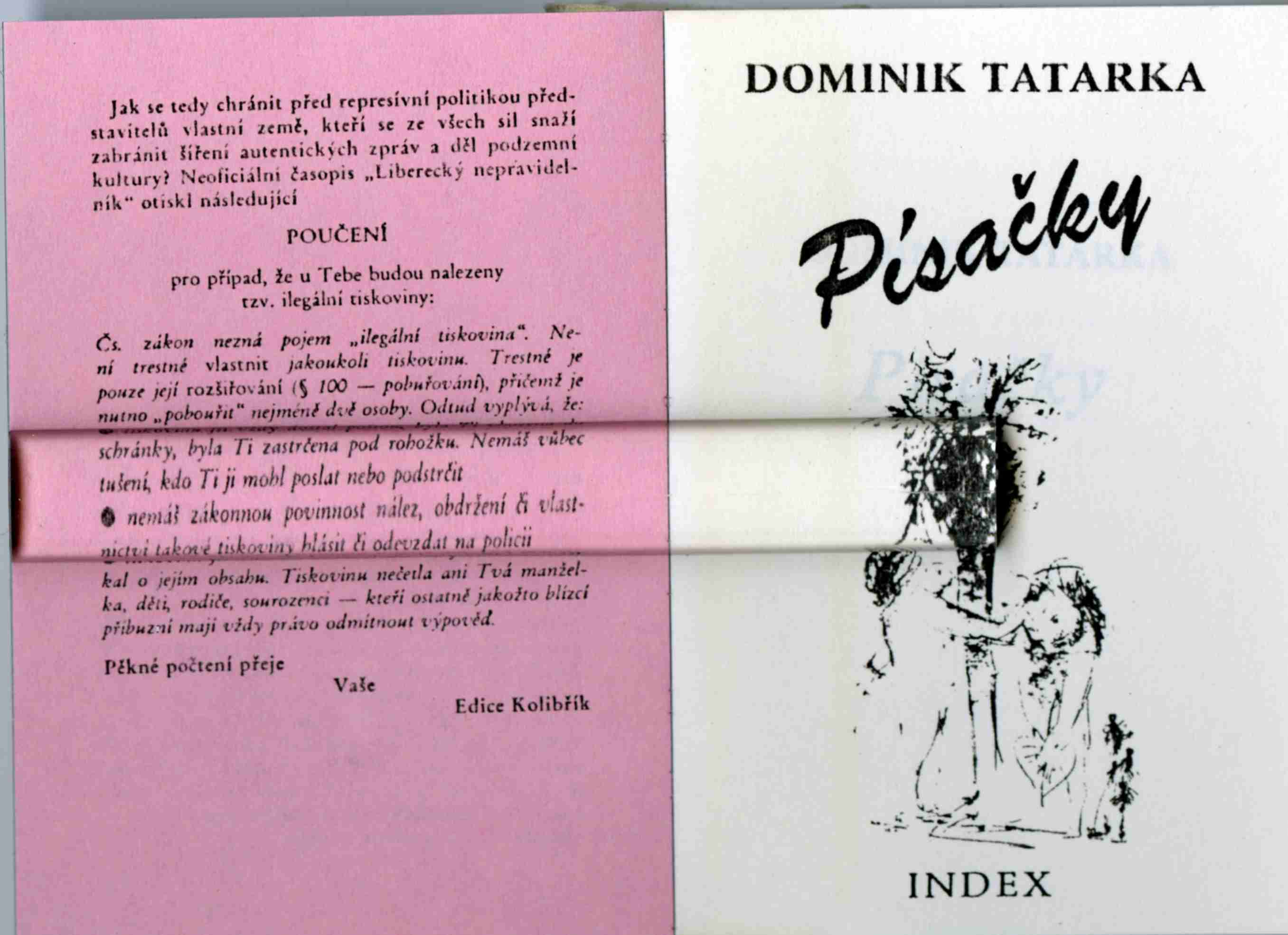

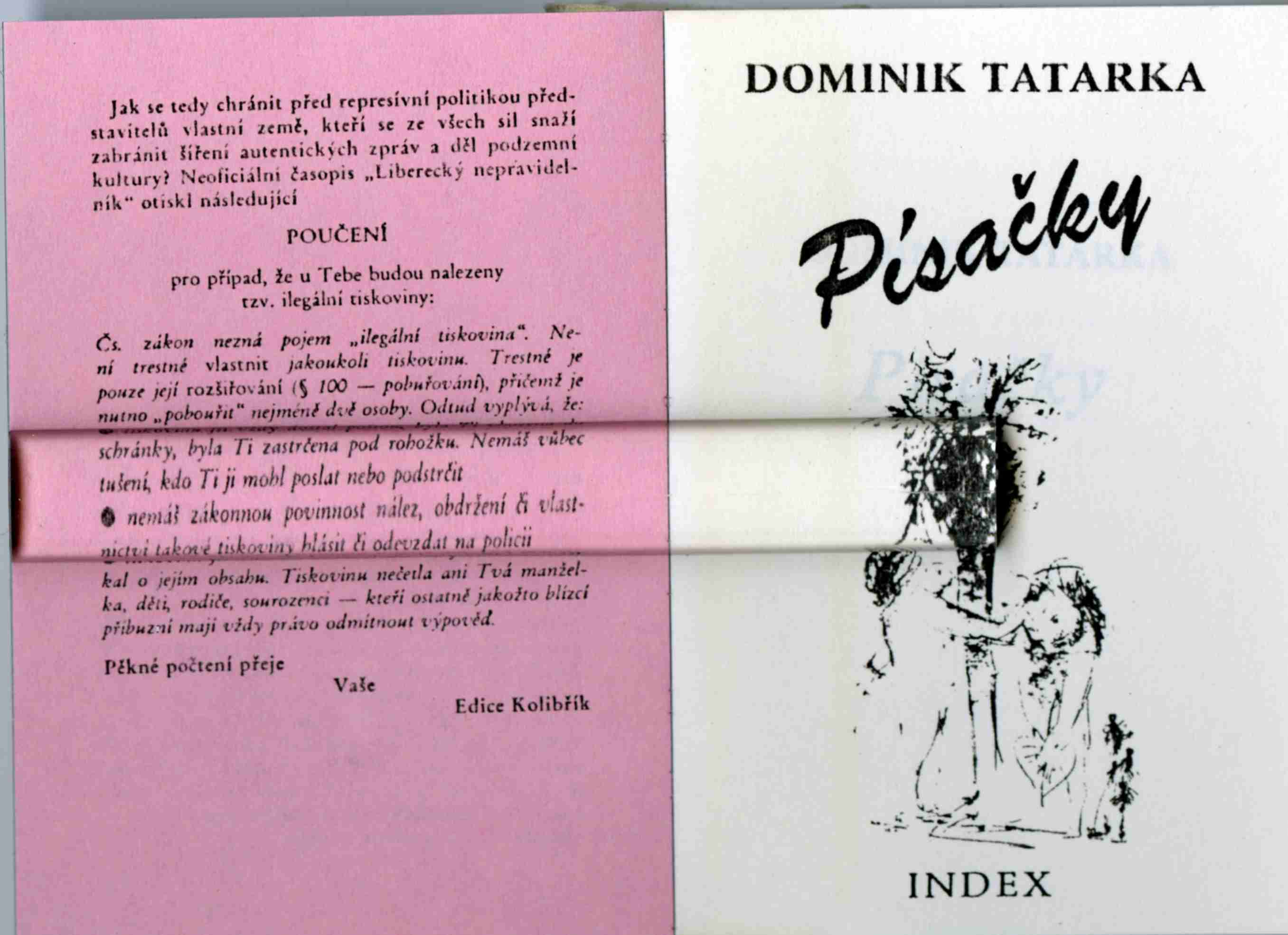

In 1979 the Museum of Czech Literature bought first part of the Dominik Tatarka collection. These materials included his correspondence (22 letters), and manuscripts of his works (more than 1000 pages). This acquisition was mediated by Slovak historian and dissident Ján Mlynárik in cooperation with the employee of the acquisition department of the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature Marie Krulichová. However, direct purchase from Dominik Tatarka was not possible. That is why the Museum of Czech Literature officially purchased materials from the antiquarian bookshop in Karlova street in Prague that had previously bought them from Tatarka. The Slovak writer then obtained from the bookshop two thirds of the price paid by the Museum of Czech Literature and it was a significant sum. Thus, the willingness and courage of the employees of the Museum of Czech Literature and the above-mentioned antiquarian bookshop significantly helped to improve living conditions of Dominik Tatarka, who was at that time oppressed by the Czechoslovak communist regime.

The most valuable piece of the entire collections is probably Kata Bethlen’s mortar. The original owner, Countess Kata Bethlen de Bethlen, also known as Katherine Bethlen (1700-1759), was a writer and a patron of arts. She supported the Transylvanian Hungarian Reformed parishes and schools. Talented students were sent on her own expense abroad for further learning. She bequeathed her precious library to the reformed college of Aiud. She was buried in Făgăraș in the Reformed Church.

The acquisition of this item has a very interesting story and represent an event in the development of this collection because it stirred the interest in similar objects. In fact, following this acquisition, the countess started to collect mortars as well. These mortars and their pestles represented objects of everyday life from the past, used for crushing ingredients in the processes of cooking or medicine preparation. They had lost their practical use in the meantime due to the advancement in food and pharmaceutical industries, so they turned into decorative art objects. The acquisition of Kata Bethlen’s mortar by her descendant Anikó Bethlen represented, on the one hand, an act which corresponded to the philosophy of collecting as understood by the latter, i.e., the preservation of all these small but significant traditional items, which were about to disappear due to the communist modernisation. On the other hand, this acquisition represented an act of safeguarding the heritage of the Bethlen noble family of Transylvania, which had once played crucial historical, cultural and social roles in this multicultural region.

Turning to the story of the acquisition, Anikó Bethlen remembers that “in an autumn night in 1979, four local Gypsies temporarily working in Făgăraș visited me with the purpose of selling a mortar. They encouraged me to buy it because as they said it ’belonged to someone wealthy, and I have to buy it.’ The huge mortar bore the inscription ‘Gr. Bethlen Kata 1758.’ I knew that she died in 1759, so it was cast a year before her death. They did not know that I am also a Bethlen. They asked 4000 lei for it, but I had only 900 lei, and had gathered it for the summer. I told them that the mortar is a little bit cracked and worth only 900 lei. They thought a bit about what to answer, then sold it me at that price.”

The mortar is made of bronze and consist of two parts. The actual mortar is high twenty-two cm, has a diameter of twenty-two cm and weighs fourteen kg. The length of the breaker is thirty-two cm and it weighs one kg. The two pieces weight a total of fifteen kg.

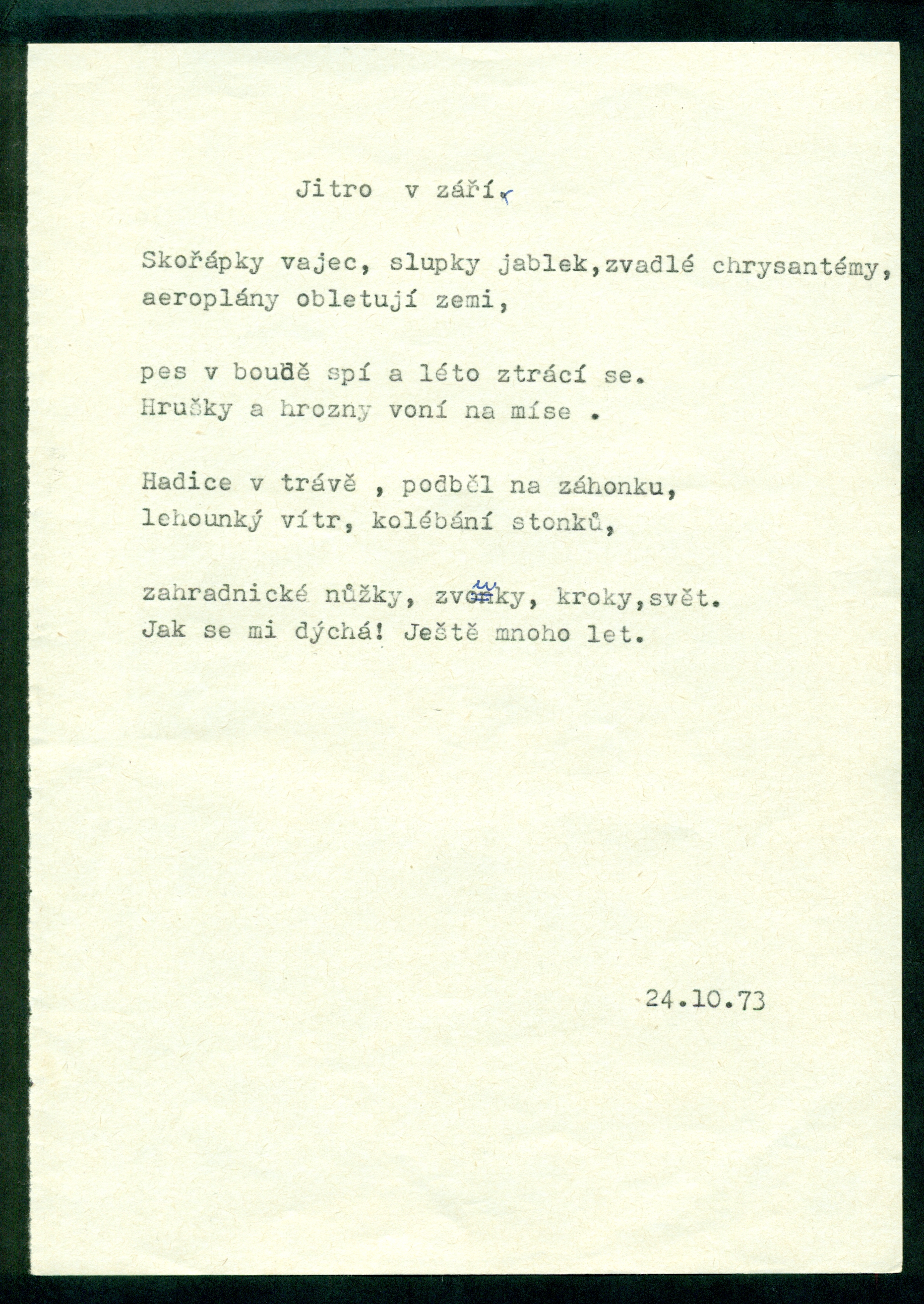

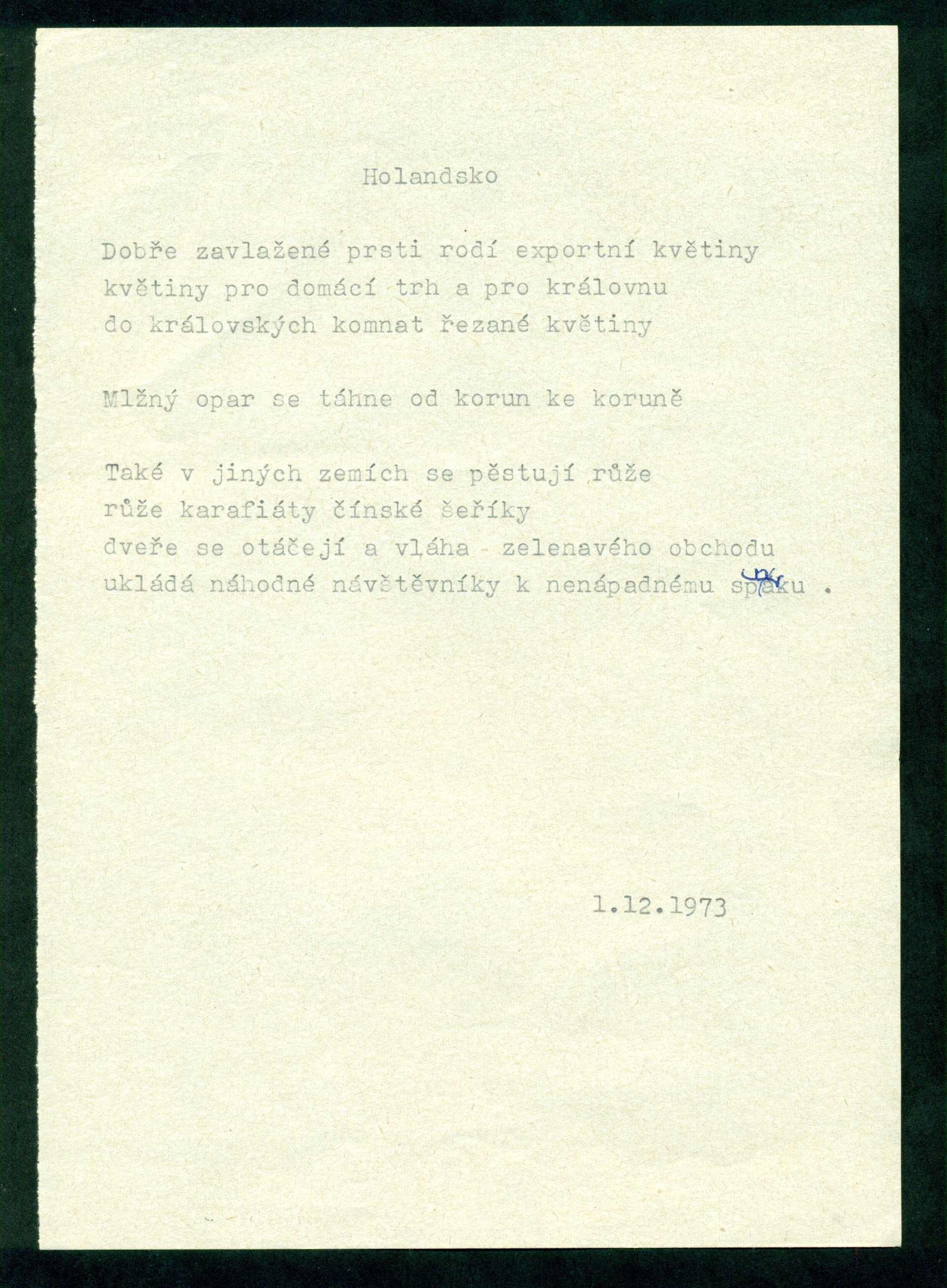

In 1977, English nurse Frances Meacham began to collect Ivan Blatný’s manuscripts of poems. She also sent some poems to Josef Škvorecký, a Czech writer living in exile in Toronto, Canada. Škvorecký decided to publish Blatný’s poems and thus, the collection of poems Old Addresses (Stará bydliště) was issued by the Czechoslovak exile publishing house Sixty-Eight Publishers in 1979. The collection was compiled during years 1978 and 1979 by Czech poet Antonín Brousek, who emigrated to West Germany in 1969. In accordance with Josef Škvorecký’s request, Brousek intentionally did not include multilingual and “modern” poems. On the contrary, he chose rather lyrical poems that resembled Ivan Blatný’s texts from the beginning of the 1940s. Josef Škvorecký justified this decision stating that their clients (readers of books issued by the publishing house Sixty-Eight Publishers) are usually “elder emigrants, who already had preconceived notions about poetry”. Although Old Addresses did not reflect Blatný’s modern style, the issue of this collection in 1979 was crucial. It resulted in better knowledge of Blatný and his work in exile, and Blatný was rediscovered by Czechoslovak readers, mainly those in exile and dissent circles. This book circulated in Czechoslovakia, where it was disseminated through illegal typescript copies. As Czech literary historian Jiří Rambousek stated later, it “created a small literary sensation.” Thus, it was not surprising that Old Addresses was also published by the Czechoslovak samizdat edition “Czech Expedition”. Moreover, it encouraged Blatný himself to continue in his literary work. Since 1989, this collection has officially been published in Czechoslovakia, and later in the Czech Republic, four times (1992, 1997, 2002 and 2014).

The Museum of Czech Literature possesses a copy of the typescript of the collection Stará bydliště (Old Addresses) with handwritten notes.

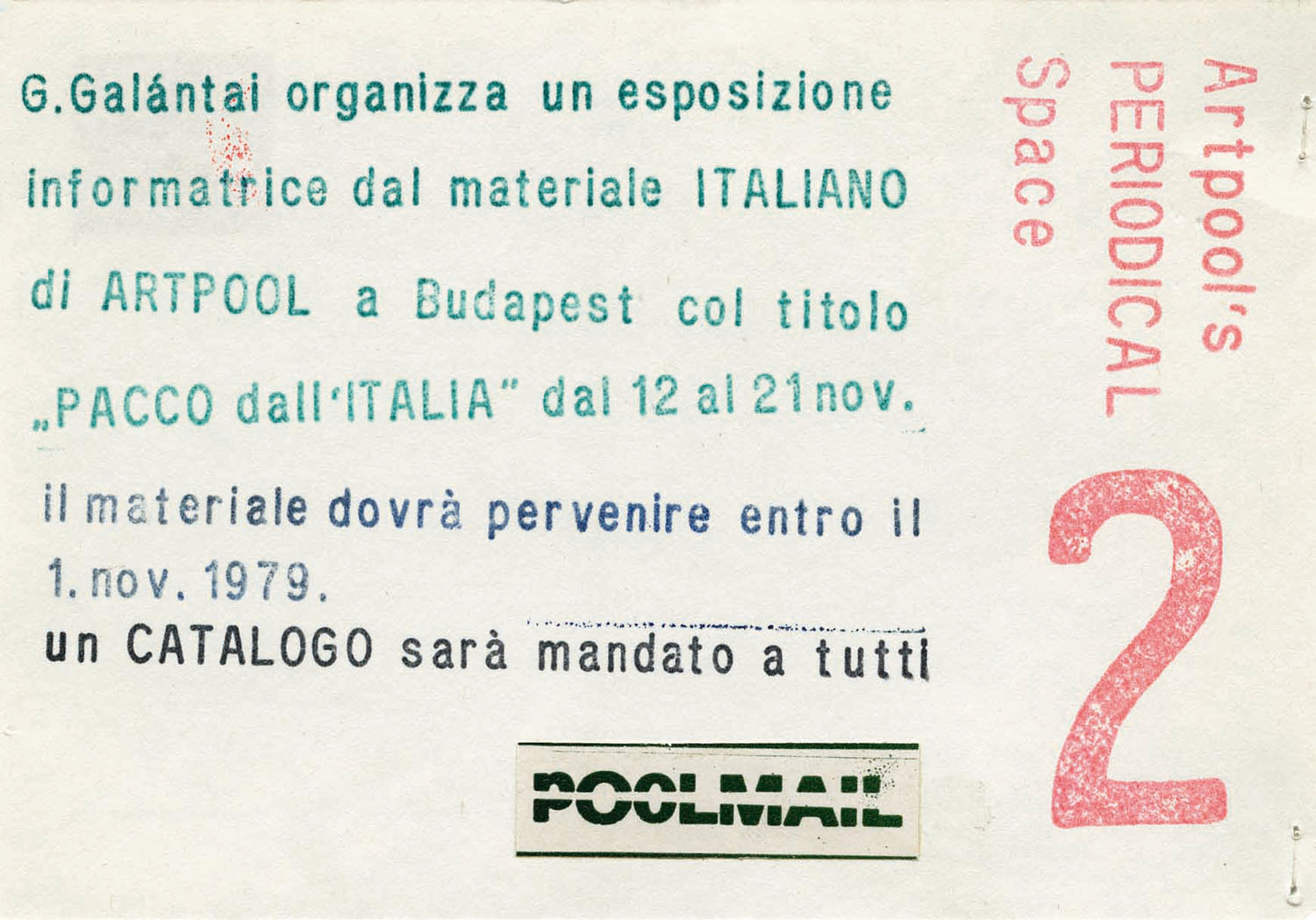

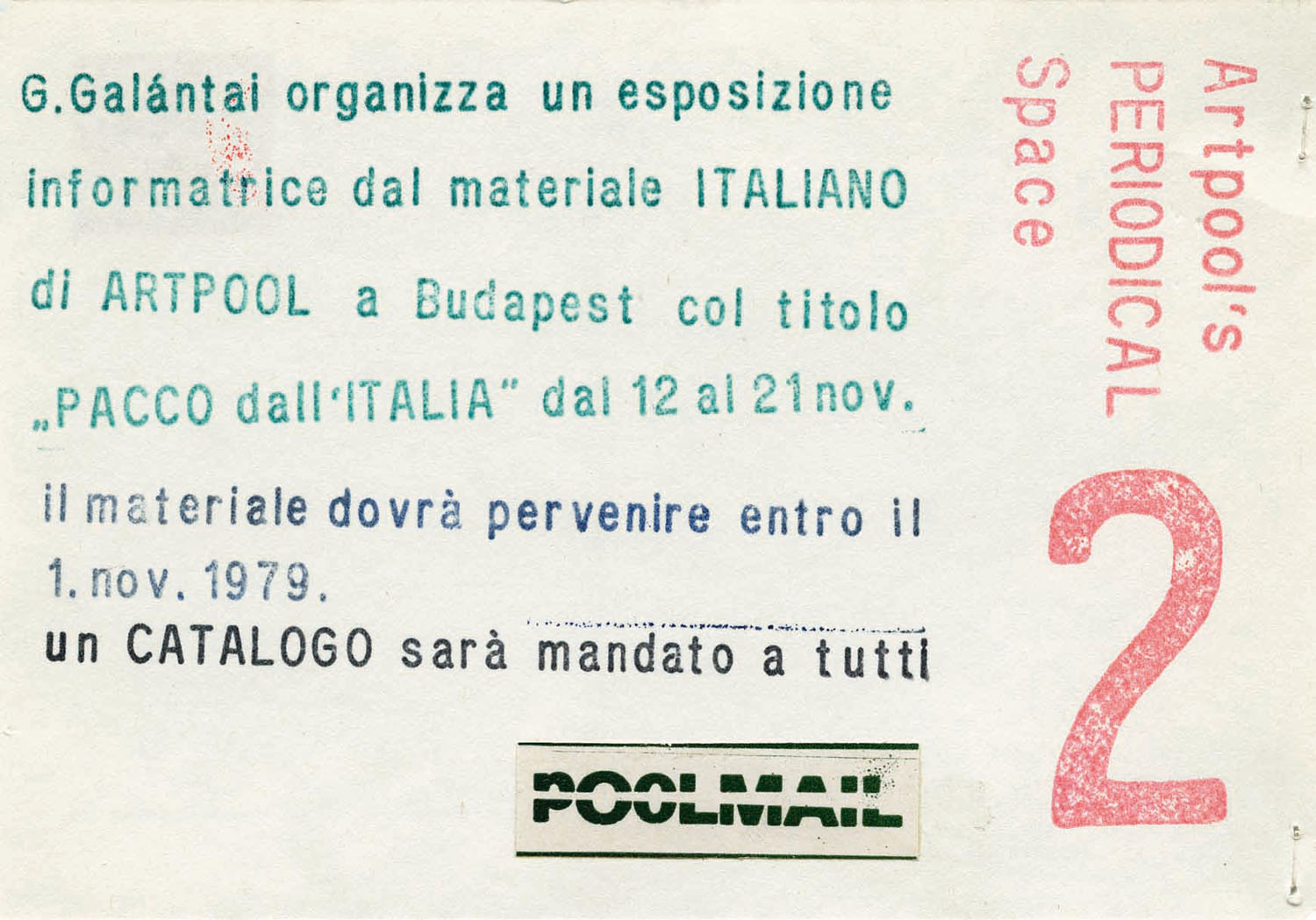

Artpool organized several shows presenting visual poetic tendencies in other venues and in its own exhibition space (Artpool P60): Pacco dall’Italia (1979 APS no.2, PACCO dall'ITALIA (Italian Package) PIK Galéria, Csepel, Budapest): the exhibition material would have been made up of the visual and sound poetry works collected during the Italian Art Tour (of the previous year), combined with mail art works. The show was banned by the state cultural authorities.

In 1979, the Museum of the River Daugava (then the Dole History Museum) decided to organise the River Daugava Festival. The event was a great success, thanks to the involvement of many creative and competent personalities. Afterwards, the director of the museum was reprimanded by the authorities, because the festival did not have any Soviet content. Items in the collection reflect the festival and its political aftermath. The museum was formed in the 1970s in order to preserve the archaeological and cultural heritage of this part of the River Daugava, as well as Dole Island, which was partly flooded after the construction of the Riga HPP. It is located at the former Dole manor building.

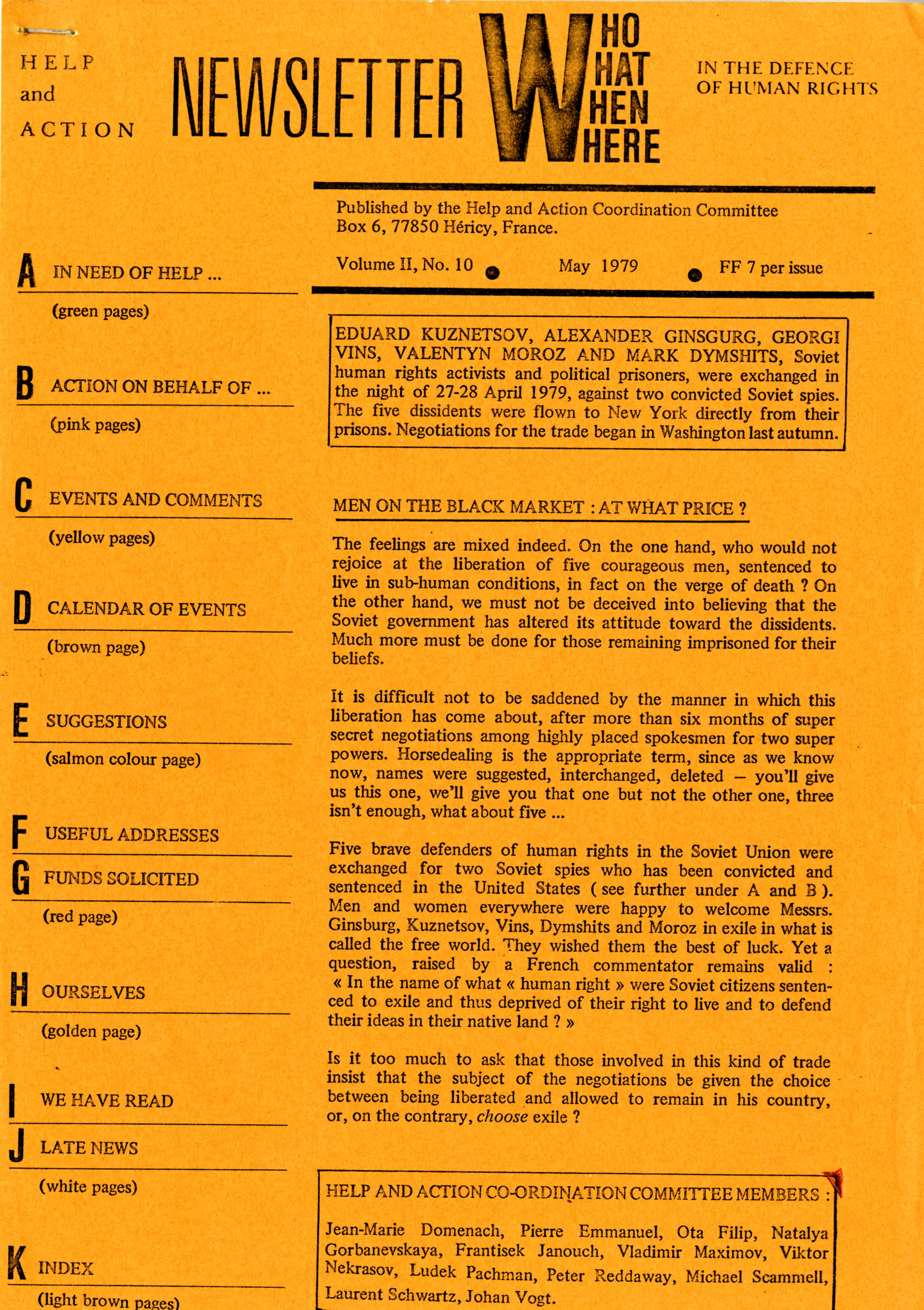

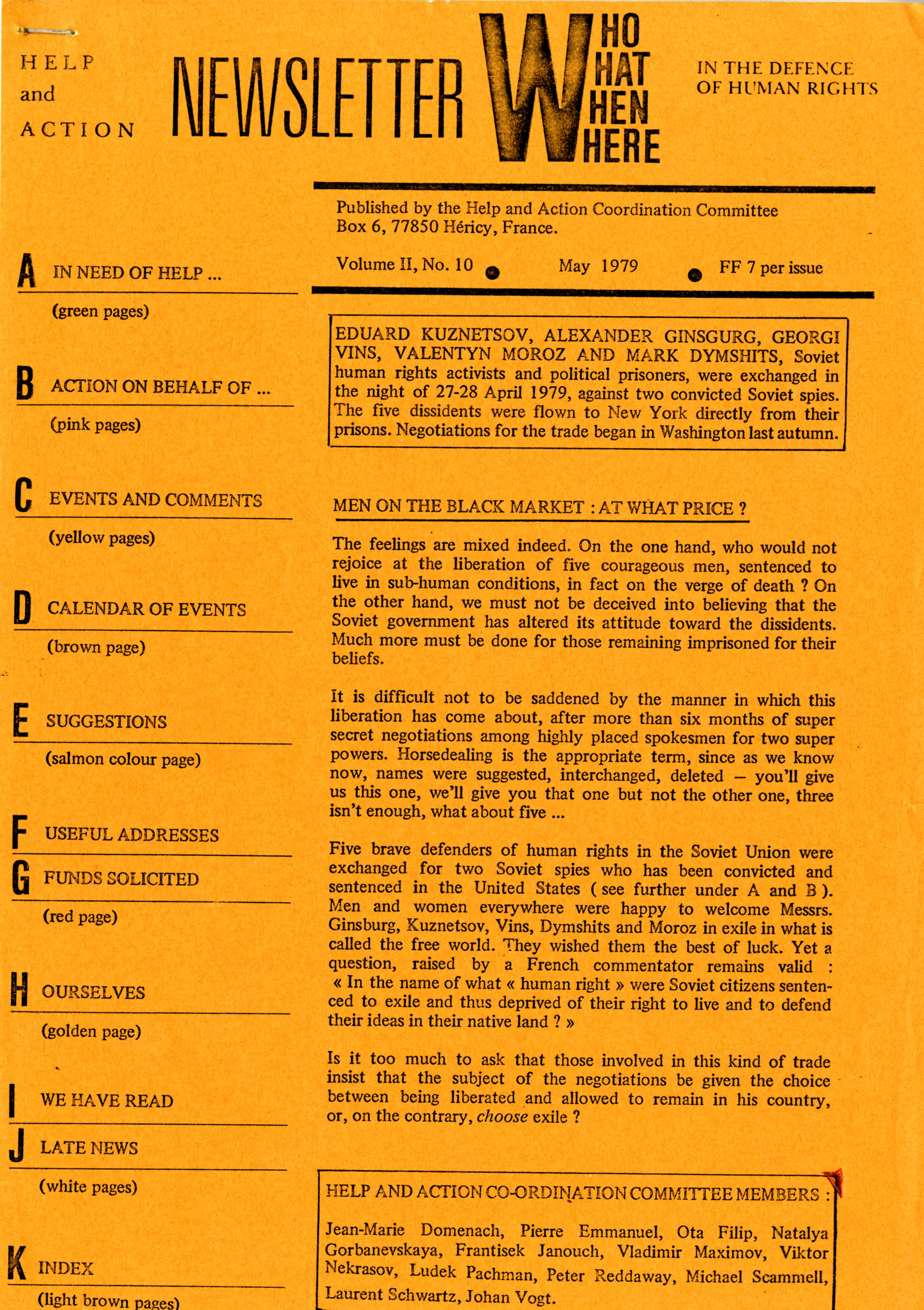

The Help and Action newsletter was launched in 1977. It was published by the same organisation Help and Action, founded in Paris in 1974, dealing with the protection of human rights and civil liberties in the Soviet Union and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The Newsletter regularly published information on individual cases of human rights violations guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other internationally recognised conventions. The first issue was published on 15th January 1977, shortly after the establishment of Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia. The rapporteur was based on the English and French versions, initially as a bimonthly, and was published quarterly from 1987 onwards.

The Help and Action newsletter regularly reported on all types of persecution behind the Iron Curtain. They published the names of the persecuted and imprisoned opponents of the regime in the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia, East Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania and Albania. It spoke about protest actions organised in the West by human rights organisations to help the oppressed opponents of the regime. There were various demonstrations, campaigns and concerts to support persecuted dissidents, open letters to representatives of totalitarian regimes, but also exhibitions of forbidden samizdat books by authors and conferences on human rights issues. The aim of these actions was primarily the release of political prisoners and the administration of fair trials in the countries of Eastern Europe. The leadership of the committee and the issue of Help and Action was organized by Ivana Tigridová, the wife of Pavel Tigrid, who was one of the most prominent representatives of Czechoslovakian anti-Communist exile.

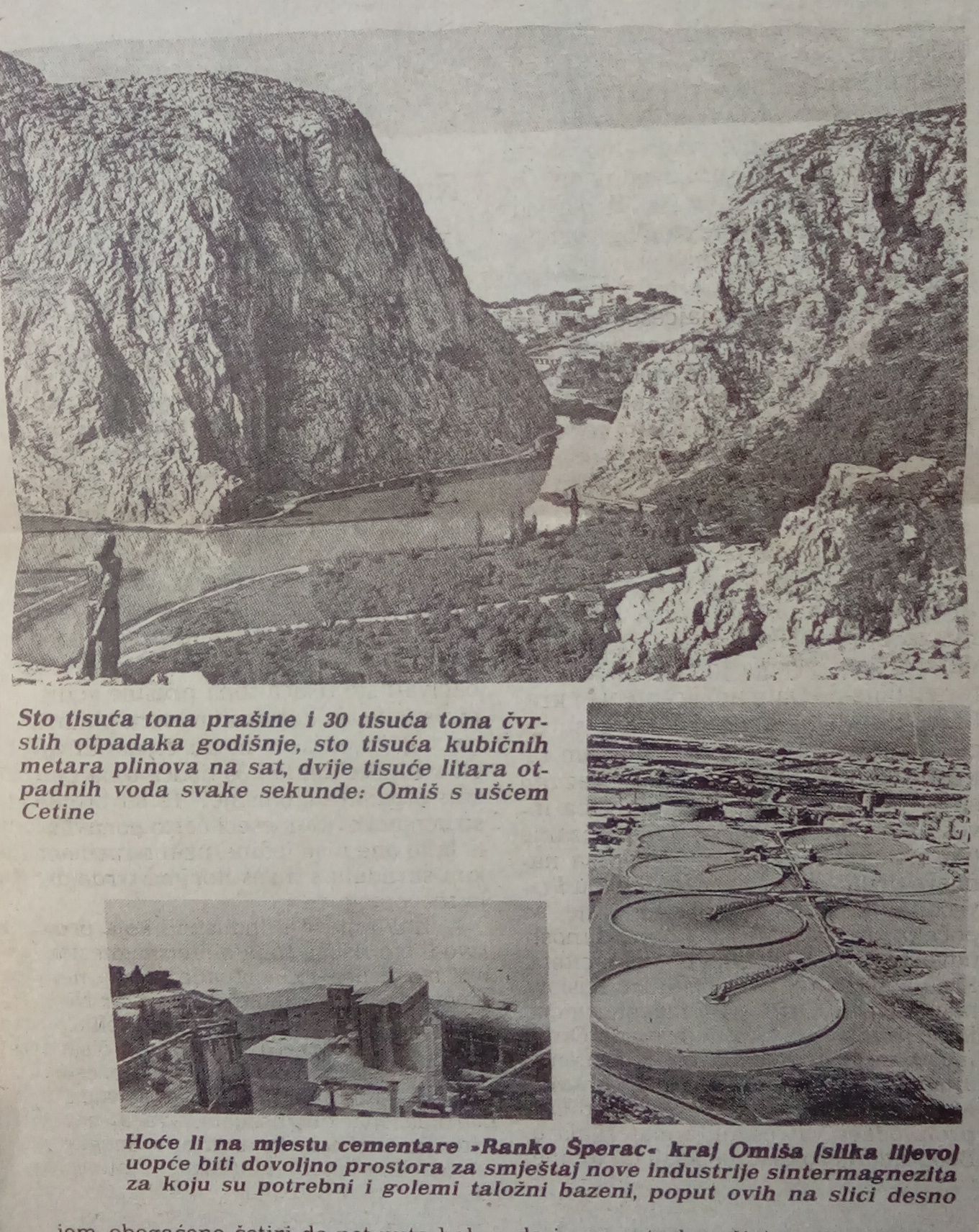

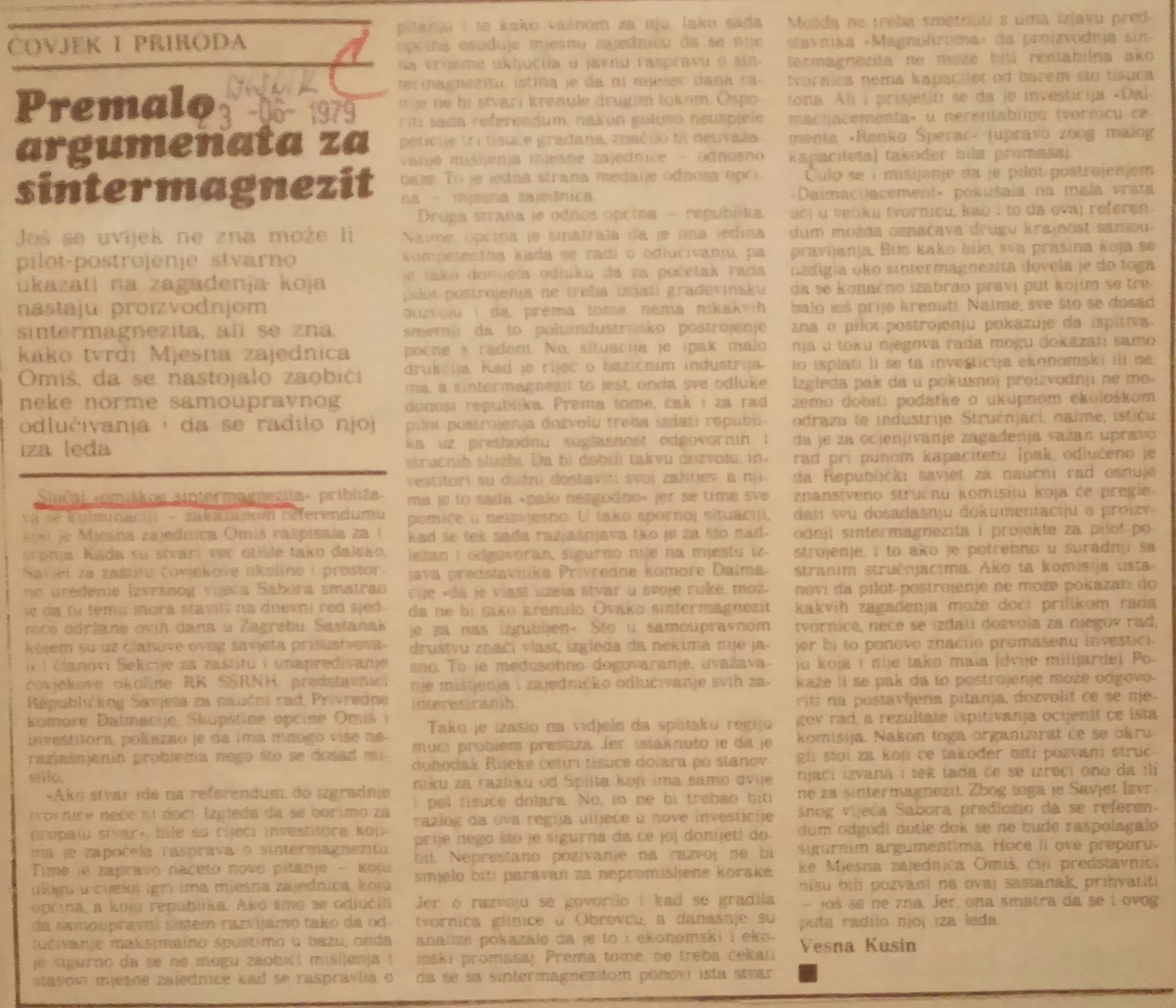

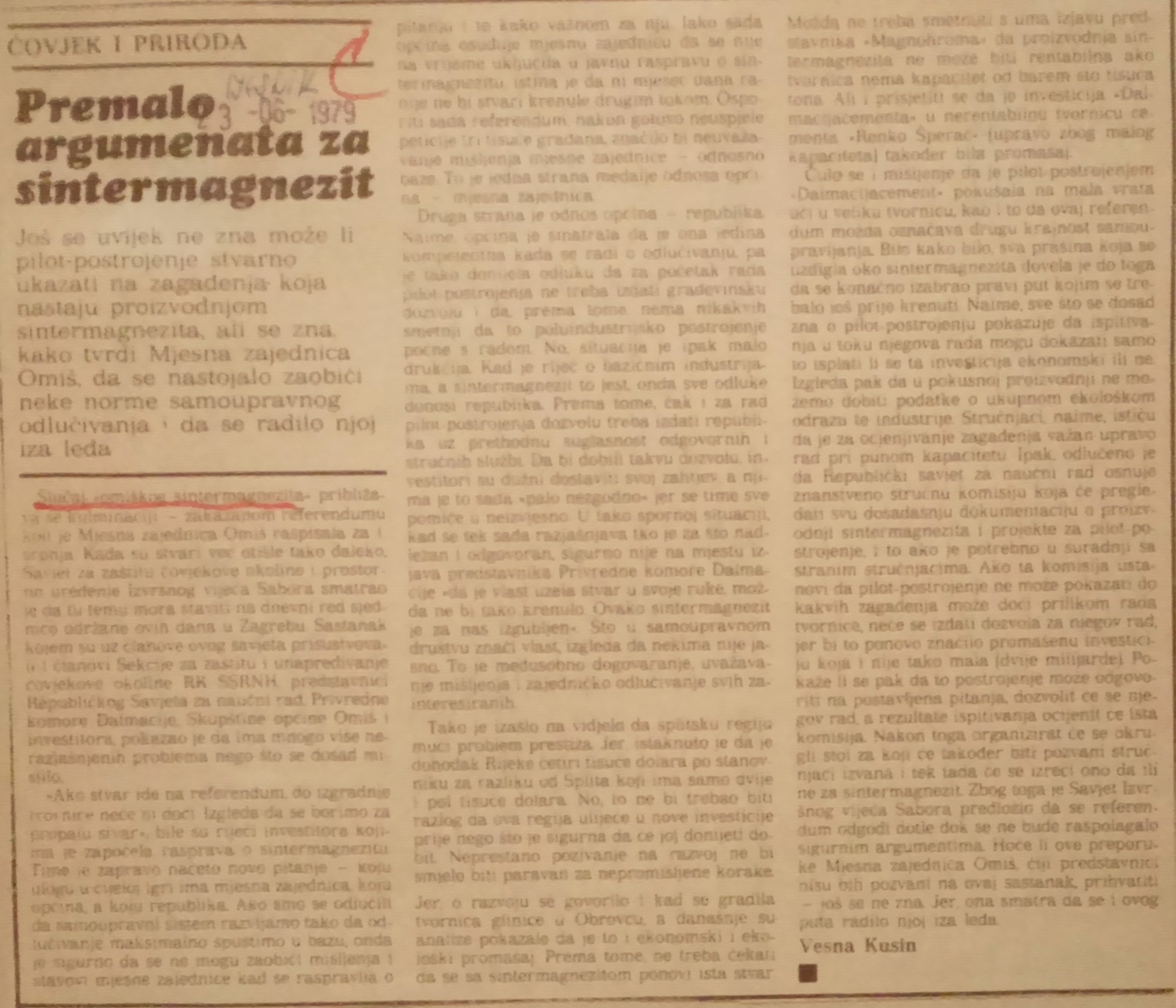

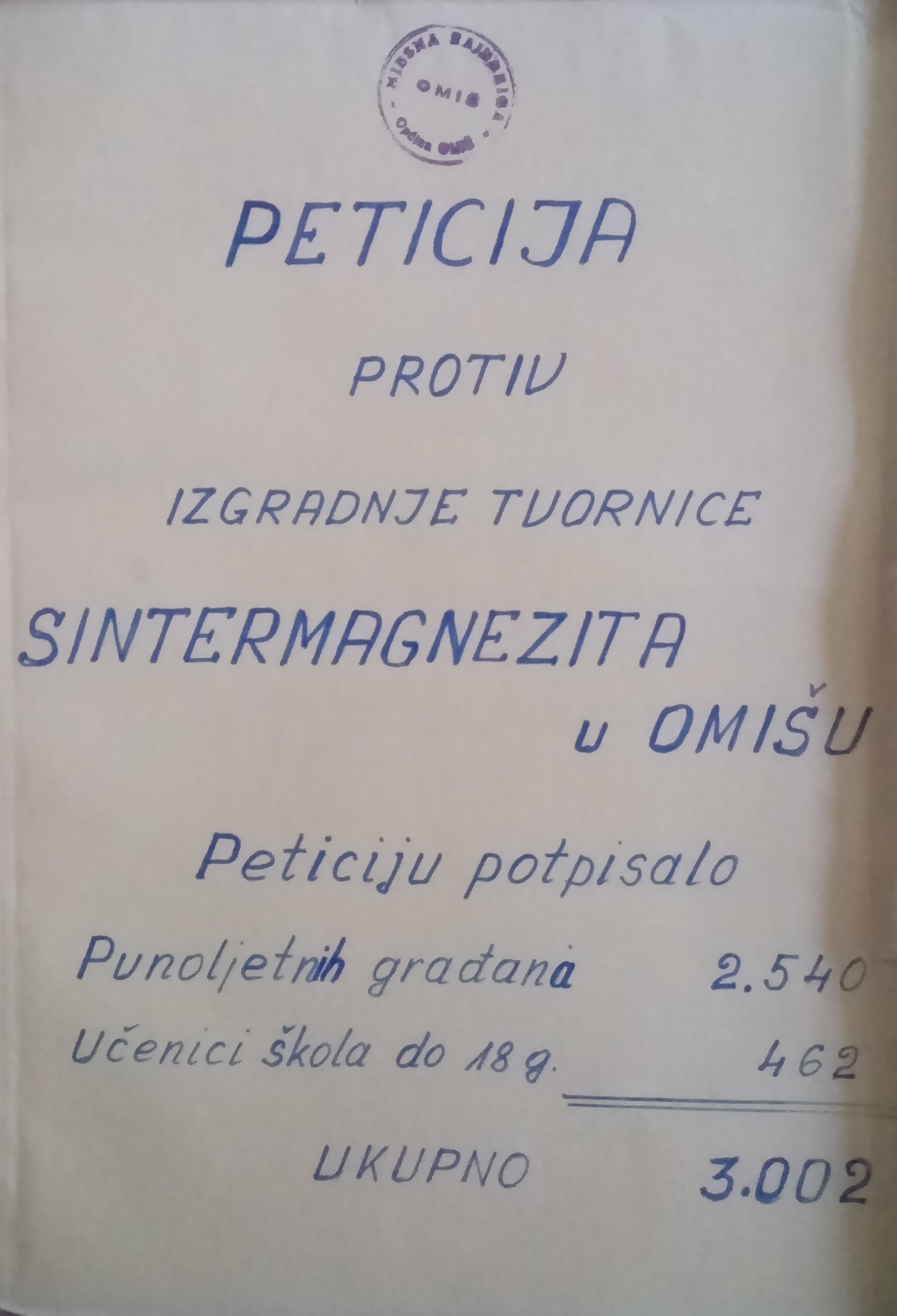

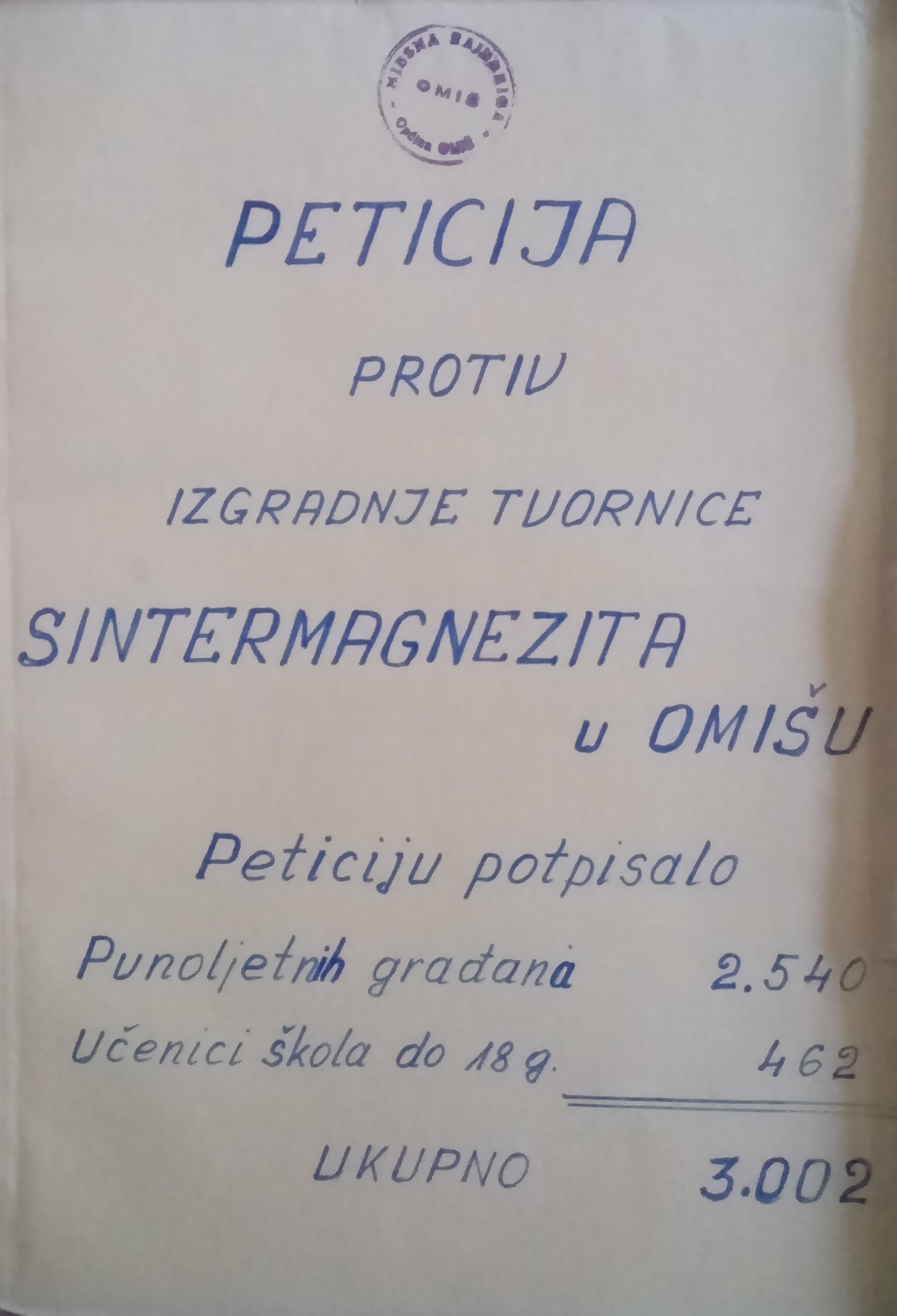

The ad hoc collection contains archival documents and newspaper articles from the period 1979-1984, which testify to local organising and protests by several thousand citizens of Omiš against the construction of a sintered magnesia factory in that area, to prevent pollution and maintain the local tourism potential. The collection combines documents from two archival collections which are held in the Croatian State Archives in Zagreb: the records of the Parliament of the Socialist Republic of Croatia and press clippings from the newspaper publishing house Vjesnik.

L’Alternative : Pour les droits et les libertés démocratiques en Europe de l’Est, no. 1 (November – December 1979)

L’Alternative : Pour les droits et les libertés démocratiques en Europe de l’Est, no. 1 (November – December 1979)

After his growing involvement in the support for the sporadic acts of dissent and anti-regime opposition in Romania was triggered by the case of Paul Goma and the “Goma movement” in February 1977, Mihnea Berindei became a central figure within the Romanian exile community in France. He was associated, in particular, with several editorial projects initiated in exile but specifically designed to give a voice to dissidents and opposition figures from Eastern Europe. The journal L’Alternative was perhaps the most important initiative of this kind. Founded by editor and journalist François Maspero, this publication included in its editorial board several expatriates from among the East European intellectuals and public figures who had settled in the West (e.g., Efim Etkind, Viktor Fainberg, Paul Goma, Miklos Haraszti, Jan Kavan, Jiri Pelikan, Leonid Pliushch, Krzysztof Pomian, etc.). The journal was conceived as a trans-national endeavour aimed at reflecting “the struggle […] for democratic freedoms, both individual and collective, and against their repression.” In a special declaration of the journal’s founders, published in its first issue, the aims of the new publication were defined as “gathering information, documents, and opinions originating with different groups or individuals who take part in these struggles or who, to put it simply, are victims of this repression; giving to the mass of the anonymous, of the workers, the opportunity to be heard; stimulating journalistic inquiries, dossiers and reports; being a place of dialogue”. The priorities of the new journal were thus the “concrete and systematic defence” of the opponents and victims of the communist regimes and an “active solidarity” with the “struggle for democratic rights.” Ideologically, although it declared itself “independent,” the journal was closest to the anti-communist and “anti-totalitarian” left that was increasingly visible on the French political stage at the time. It emphasised the role of public opinion and its attempt to “bring the first elements of a dialogue” between East European dissidents /opponents of the regimes and their supporters in the West. The first issue had at its core a special file (dossier) on “free workers and trade unions” (travailleurs et syndicats libres), featuring various reports from the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. The section about Romania focused on the case of Paul Goma. An essay by Goma on the relationship between the workers and the communist state – The “Workers’ State” and the Working Class (« Etat ouvrier » et classe ouvrière) – was published. This essay presented certain aspects of the Romanian workers’ everyday life and reminded the reader about the main stages of workers’ protest, starting with February 1977. This section also discussed the formation of the first “free” trade union in Romania – The Free Trade Union of the Working People of Romania (Sindicatul Liber al Oamenilor Muncii din România, SLOMR), emphasising the solidarity of the main French unions with their Romanian counterpart. Under the “Documents” section, the journal published important pieces by Jacek Kuron on the Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR), as well as Vaclav Havel’s famous essay Living in Truth, the most significant text associated with the Charter 77 movement in Czechoslovakia. Other materials discussed developments in East Germany, Hungary, and the USSR, with a particular emphasis on the cultural sphere. Special attention was devoted to initiatives for the defence of persecuted anti-regime activists in the context of the growing repressions in Czechoslovakia (such as the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted, VONS). A separate subject concerned the upcoming 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow, including several appeals for a boycott of the event on political and moral grounds. Finally, a “chronicle of current events” focusing on the reporting of recent developments in the Eastern bloc countries was inaugurated as a regular item in the journal. L’Alternative became one of the most important French-language publications dealing with Eastern Europe. During its existence (1979–1985) it published numerous reports and texts relating to communist Romania. In the early 1980s, Mihnea Berindei became closely associated with the journal, providing a vital link between the French readership and Romanian authors criticising the regime, either in Romania or in exile.

Noor-Tartu (Young-Tartu) was a non-institutional student movement in Tartu between 1979 and 1984 (from 1979-1981 it was called Kodulinn, or Hometown). It was formed mostly by history students who wanted to do something useful for their city, without being connected to any official institution. Arranging urban space, collecting antiquities and organising cultural events were the main activities of the movement. Various pieces of material (announcements, newspapers, overviews, photographs) about these activities have been preserved. Today, this material forms an unofficial private collection owned by the core group of the Noor-Tartu movement.

Artpool Art Research Center collects, archives, and makes available documents for researchers regarding marginalized art practices of Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary international art tendencies. Topics in the archive include progressive, unofficial Hungarian art movements (such as underground art events, venues, groups, and samizdat publications between 1970 and 1990) and new tendencies in international art beginning in the 1960s.

In addition to functioning as a research center, Artpool considers itself an active archive. It organizes events in search of new forms of social activity, participates in the process in a formative way, and simultaneously documents and archives these process in order to promote the free flow of information.

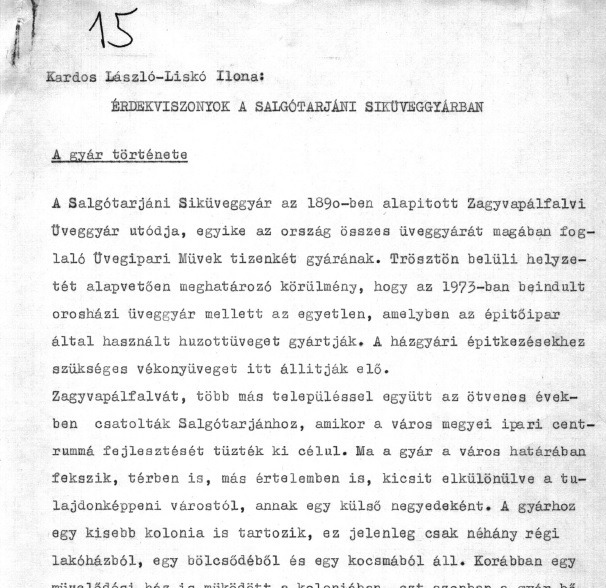

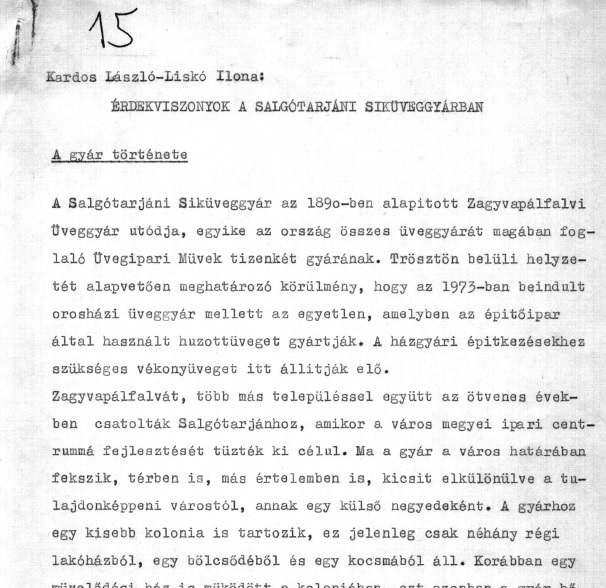

László Kardos - Ilona Liskó. Vested Interests in the Factory of Flat Glass at Salgótarján, 1979. Manuscript

László Kardos - Ilona Liskó. Vested Interests in the Factory of Flat Glass at Salgótarján, 1979. Manuscript

![Kusin, Vesna. Too few good reasons for sintered magnesia [Premalo argumenata za sintermagnezit], Vjesnik, 23. June 1979. Press clipping](/courage/file/n107342/%C4%8Clanak%2BVesna%2BKusin%2B23_6_1979%2Bcrop.jpg)

Kusin, Vesna. Too few good reasons for sintered magnesia [Premalo argumenata za sintermagnezit], Vjesnik, 23. June 1979. Press clipping

Kusin, Vesna. Too few good reasons for sintered magnesia [Premalo argumenata za sintermagnezit], Vjesnik, 23. June 1979. Press clipping

The project on construction of a sintered magnesia factory and protests by the local population in Omiš were covered extensively by several Croatian and wider Yugoslav newspapers (Borba, Večernje novosti, Večernji list, Vjesnik). Articles written by Vesna Kusin in the daily newspaper Vjesnik during that and subsequent years are particularly noteworthy. Along with demands for environmental protection, the public statements from the local population and newspaper articles also contained criticism of local and republic institutions, as well as the investor, Dalmacijacement, because of they “went behind [the people’s] back,ˮ i.e. bypassed “the principle of self-governmentˮ and the opinion of the local community in the decision-making process. An example of this is the article “Too few good reasons for sintered magnesia [‘Premalo argumenata za sintermagnezit’]ˮ published in Vjesnik on 23 June 1979. . In an interview in the newsmagazine Globus in 2015, she recall that at that time she “consistently travelled to Omiš, where the demonstrations occurred, and wrote a plethora of articles on this matter, and ultimately the plant wasn't builtˮ (Museums of Hrvatsko Zagorje, Media report 08.04.2015).

The documents are available for research and copying.

Artpool Art Research Center collects, archives, and makes available documents for researchers regarding marginalized art practices of Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary international art tendencies. Topics in the archive include progressive, unofficial Hungarian art movements (such as underground art events, venues, groups, and samizdat publications between 1970 and 1990) and new tendencies in international art beginning in the 1960s.

In addition to functioning as a research center, Artpool considers itself an active archive. It organizes events in search of new forms of social activity, participates in the process in a formative way, and simultaneously documents and archives these process in order to promote the free flow of information.The Museum of the River Daugava (then the Dole History Museum) was established in order to preserve archaeological and historical items from areas that were to be flooded after the construction of the Riga HPP. The staff of the museum saw their mission as being custodians of the local identity, which was under pressure from the indifferent, at best, and often negligent and hostile environment created by the influx of thousands of construction workers from other Soviet republics, which caused substantial changes to the composition of residents of Salaspils and its environs. In 1979, the museum decided to organise the River Daugava Festival. The idea of the festival was to show how the biggest river in Latvia was portrayed in Latvian folklore. Folklore in any explicitly non-Soviet form was looked on with suspicion by the authorities of the Latvian SSR as a potential source of ‘bourgeois nationalism’, and the situation in Latvia differed in this respect from the situations in Estonia and Lithuania, where the ideologues were more lenient. The event was a great success, due to the involvement of many creative and competent personalities. Nevertheless, the director of the museum was afterwards reprimanded by the authorities. The exact reason for their discontent was never explained, there is only speculation in this regard. It could also be explained in part by the fact that the former political prisoner and poet Knuts Skujenieks wrote the script for the event and participated in the festival. Also, the participation of Skandinieki, an authentic folk group, as well as the repertoire of choirs, was considered to be inappropriate. Among the audience were young people from the Latvian diaspora. Although they participated with the approval of the authorities, the authorities probably believed that the festival was not Soviet enough. Despite the reprimand, the museum continued to be a centre for cultural activity, and with the start of perestroika, it became actively involved in the pro-independence movement. Items in the collection show how the festival was prepared and implemented, as well as its political aftermath.

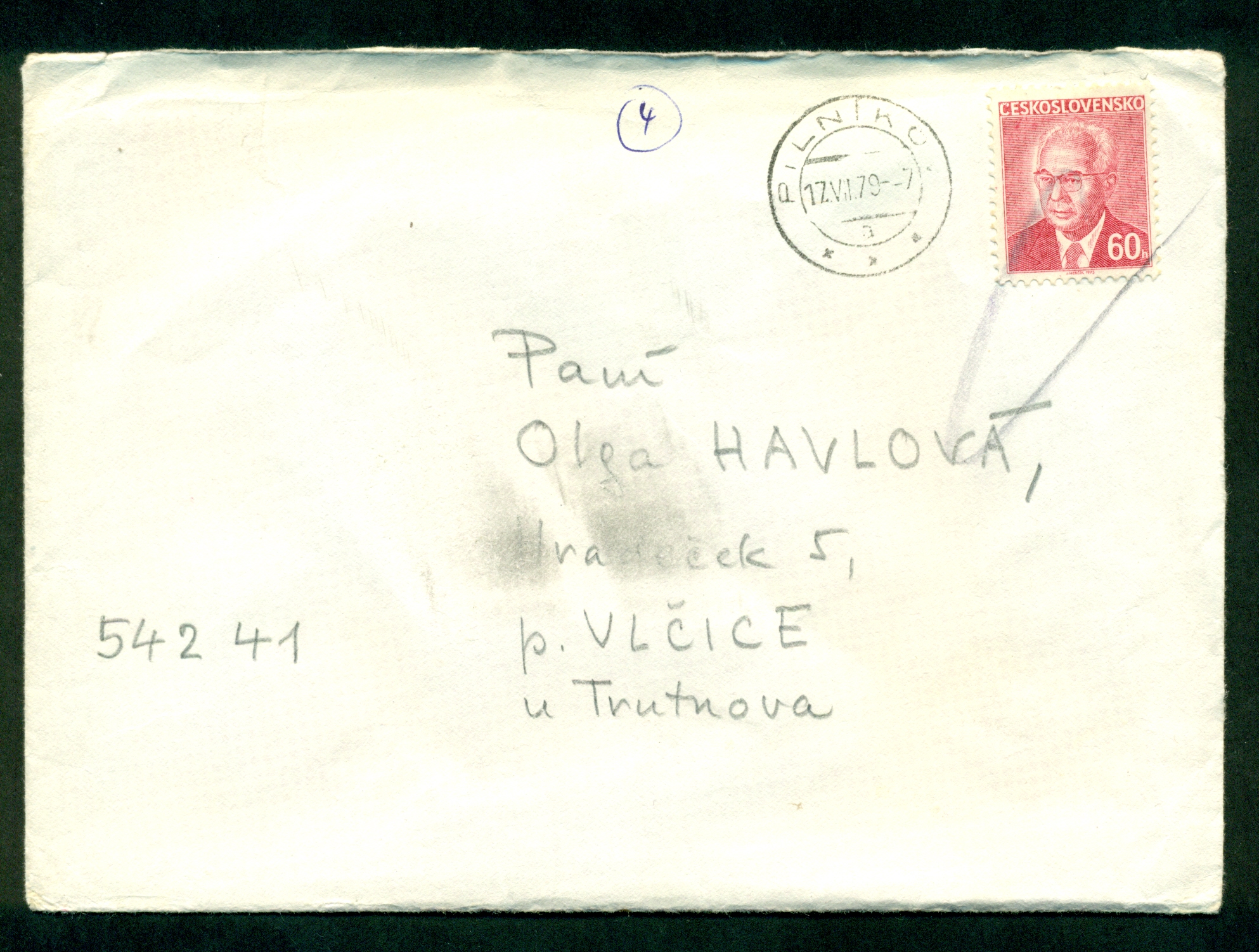

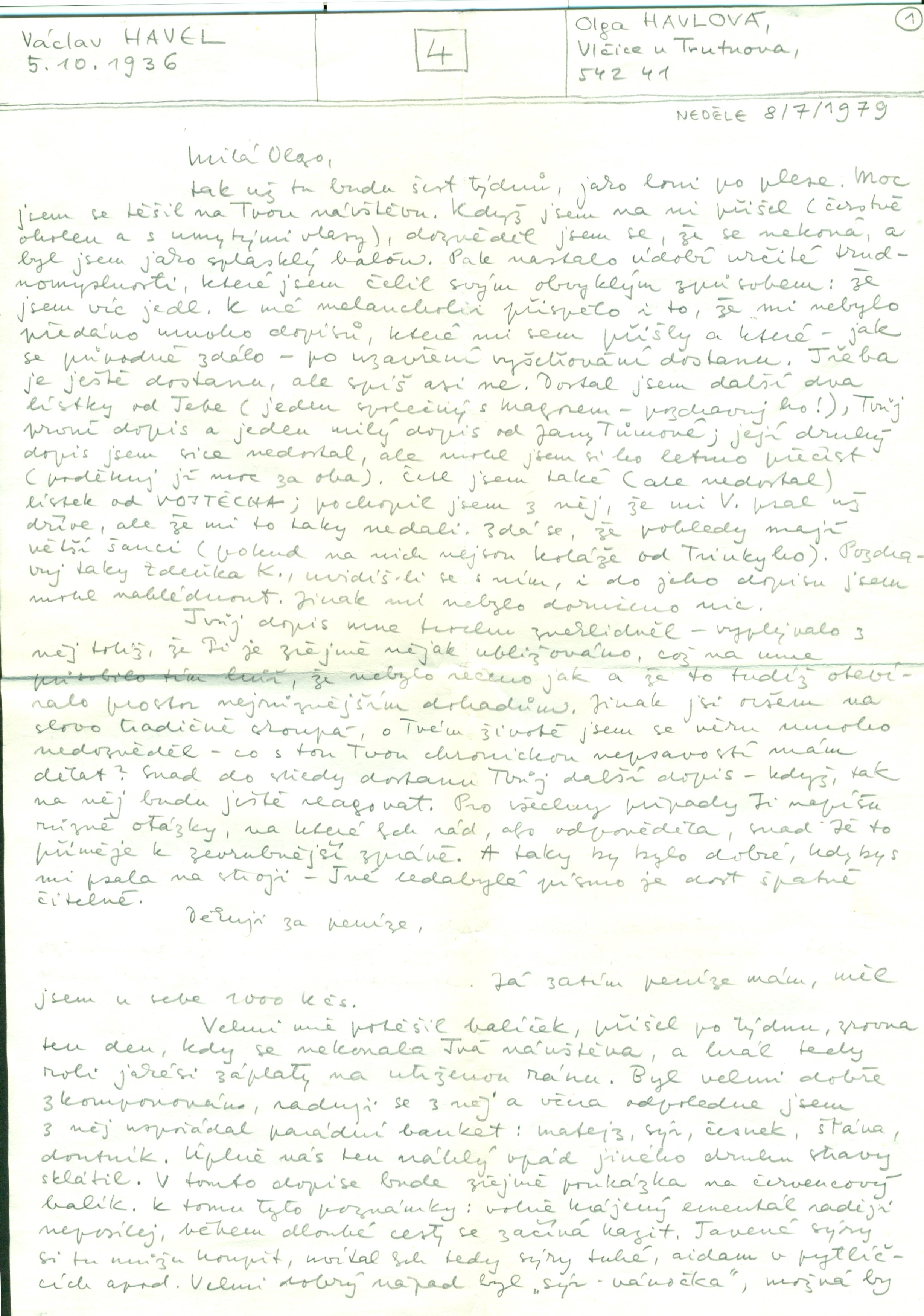

The Václav Havel Collection at the Museum of Czech Literature contains letters of the dramatist, poet and president of the Czech Republic Václav Havel (1936–2011) to his wife Olga, written from prison between 1979 and 1983. Havel’s unique prison correspondence documents the life of this significant artist and philosopher, as well as the life of his wife before 1989.

The performance or action from the "For the Democratization of Art" cycle, in which the artist collected signatures for a petition. The performance took place on Republic Square in Zagreb on October 19, 1979. In this action, Molnar asked passers-by to sign under his work and collected 45 signatures in five hours. A large number of passers-by refused to sign the petition. According to Tihomir Milovac, this was a petition that advocated for the democratization of art, but in a subversive way:- "a subversive form in which an artist, in a way urges the public and fellow citizens to even agree to something like that. To sign a petition like that.”

Artpool Art Research Center collects, archives, and makes available documents for researchers regarding marginalized art practices of Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary international art tendencies. Topics in the archive include progressive, unofficial Hungarian art movements (such as underground art events, venues, groups, and samizdat publications between 1970 and 1990) and new tendencies in international art beginning in the 1960s.

In addition to functioning as a research center, Artpool considers itself an active archive. It organizes events in search of new forms of social activity, participates in the process in a formative way, and simultaneously documents and archives these process in order to promote the free flow of information.

The photo showed Zofia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek during their presentation on the documentation of the artistic initiatives. The presentation took place in the Student Center for Artistic Communities Dziekanka as a part of the exhibition and theoretical session Dokumentacja i autodokumentacja w sztuce (Documentation and Self-Documentation in Art), March 5-6, 1979. The photographer Tomasz Sikorski was also the organizer of the event as a co-director of the P.O. Box 17 Gallery. The participants of the event, besides Kulik and Kwiek, were Peter van Beveren, Andrzej Jórczak, Tomasz Konart, Jerzy Olek, Jerzy Onuch, Andrzej Partum, Andrzej Paruzel, Józef Robakowski, and Tomasz Sikorski.

In 1978, Tomasz Konart invited Tomasz Sikorski to have a talk about independent galleries. The condition of the talk was that both participants had to take ten photographies of the interlocutor. The very photographies are the only evidence of the conversation. Also, the time of the discussion was strictly fixed to 30 minutes.The documentation of the action Conversation and Photography was published in the catalog of the P.O. Box 17 Gallery. The catalog was edited by both Sikorski and Konart in 1979. It was made of the loose pages of A4 format. One of the pages showed exactly the action carried on by Konart. The work is a proper example of both the ephemeral nature of the neo-avant-garde art and its intellectual ambitions to analyze its own status.

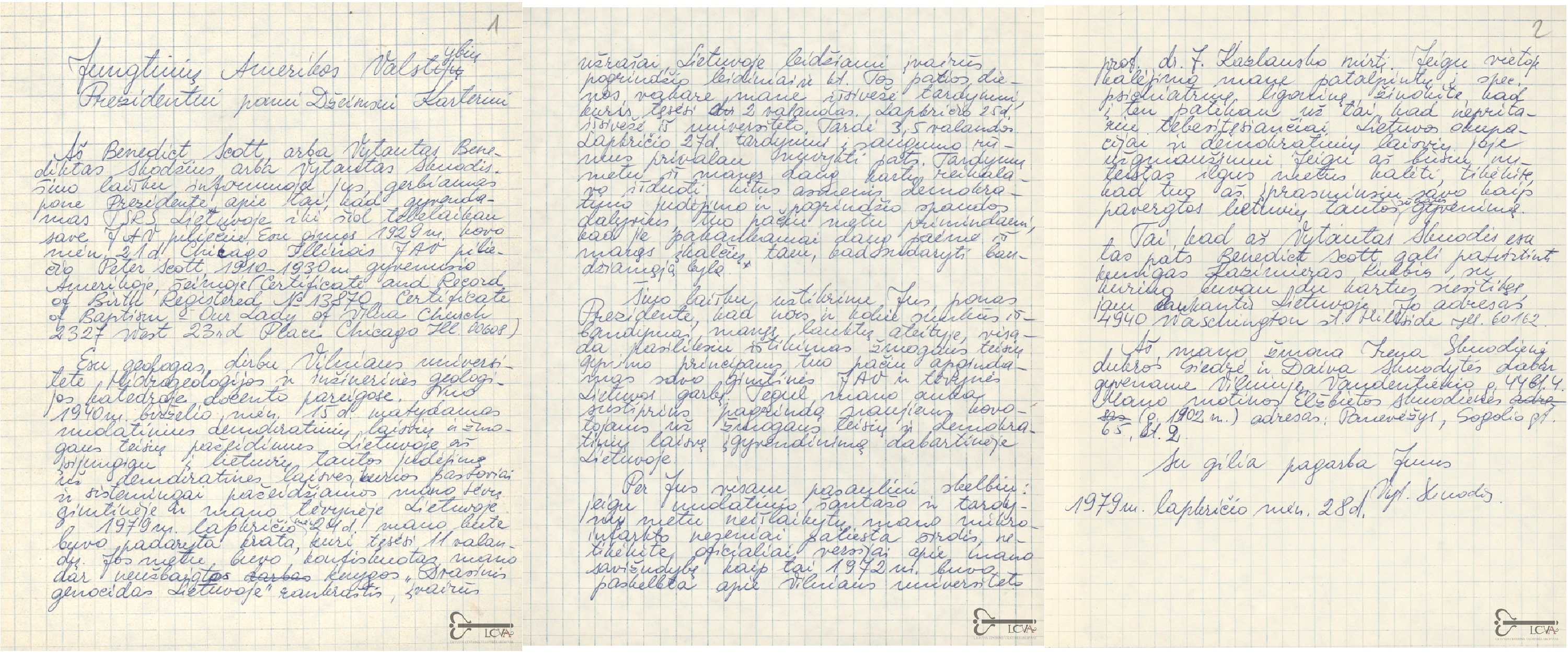

Skuodis’ letter to the US president Jimmy Carter was written on 28 November 1979. In the letter, Skuodis presented himself as a citizen of the USA (Benedict Scott, born in Chicago in 1929). He reveals the human rights situation in Soviet Lithuania. In the letter, he blames the Soviet regime for the violation of the democratic rights of citizens. He mentions the KGB search of his house in 1979, when many drafts and manuscripts were taken by KGB investigators. One of these was the manuscript of his book Dvasinis genocidas Lietuvoje (Spiritual Genocide in Lithuania). The book is a detailed survey of the KGB’s persecution of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, and Skuodis planned to send it to the West. It was published in Lithuania only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1996.

The book was written by Ljubo Sirc, a Slovenian émigré and economist of liberal orientation and is devoted to criticism of Yugoslav self-management socialism. Sirc's economic analysis proved that the Yugoslav economy led by a self-management model was doomed, since it was led by profoundly utopian and anti-economic thought.

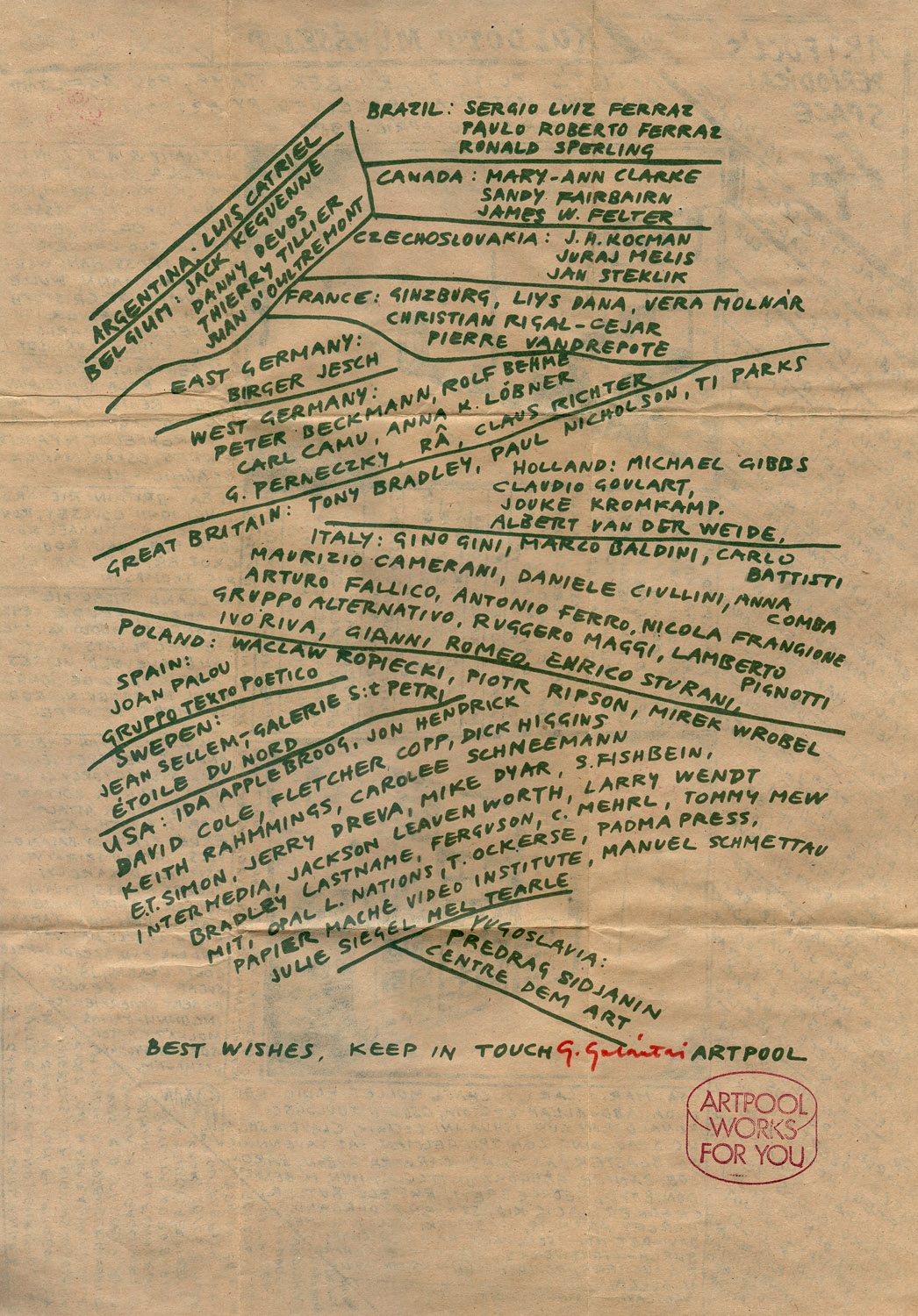

The collection presents photos and other documentation of the annual activity of Gallery P.O. Box 17, run by Tomasz Sikorski and Tomasz Konart from the beginning of 1979 to November of the same year. This gallery was a continuation of the activities of the Mospan Gallery, closed in December 1978. It had no localization - it only had a mailbox. Gallery, by courtesy, were using the space of Dziekanka Students' Art Center and Stodoła Club. At the same time, Sikorski and Konart planned to use the form of mail art. The collection, preserved and developed by Sikorski, is a unique testimony, characteristic for neo-avant-garde art in Poland in the late 1970s.

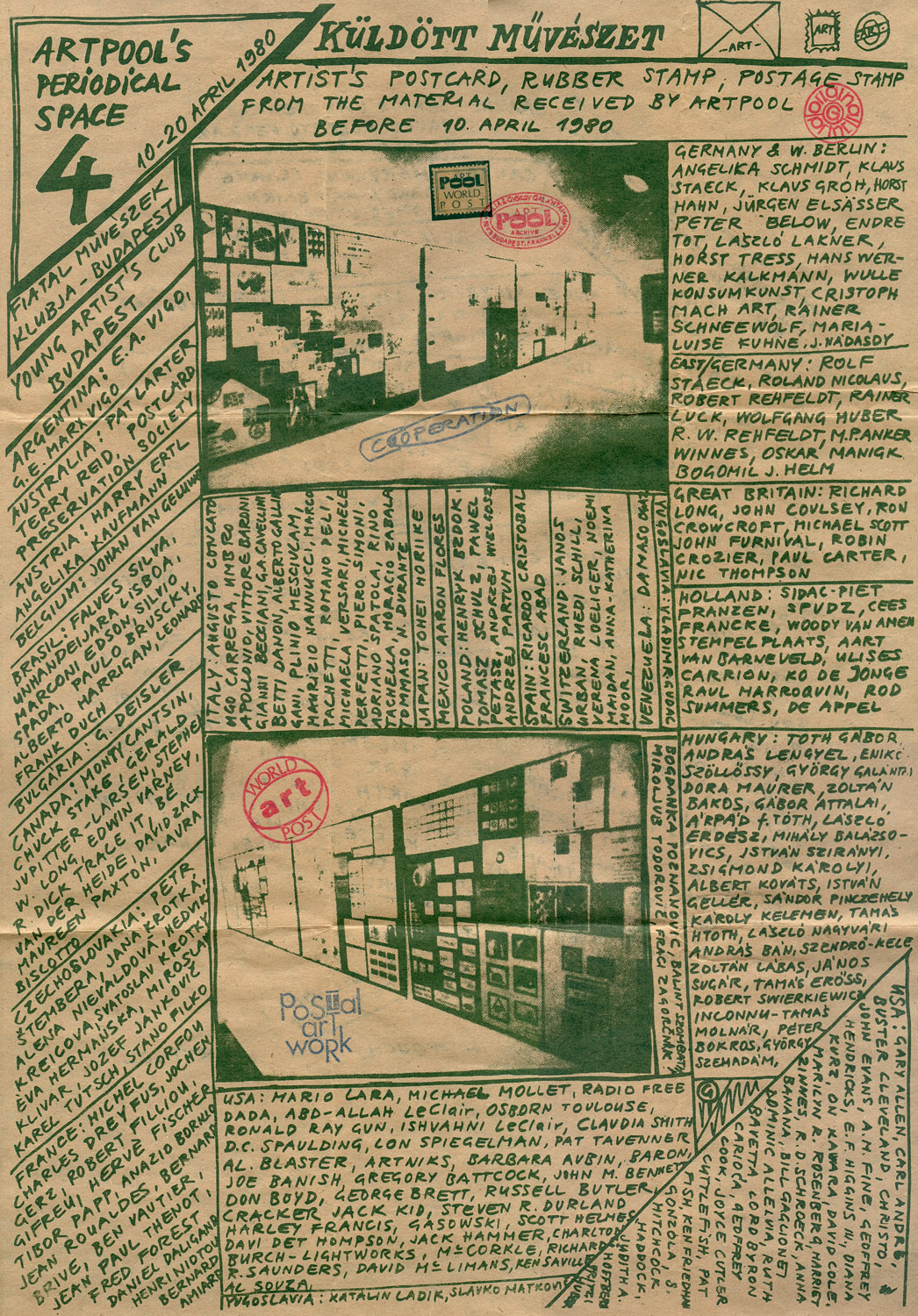

As Artpool did not have a permanent art space during the years when it was functioning illegally, most of the events which were organized at the time were held at different locations, such as clubs and small galleries. These sites were referred to as the Artpool Periodical Spaces (APS). These exhibition events were always accompanied by documentation materials of some kind, including posters, artists’ books and publications, and catalogues in which theoretical texts and translations on correspondence art, mail art, and artists’ stamps were first available in Hungary. Along with György Galántai’s own network art, these publications formed the essential exchange material when it came to the expansion of the archive.

The APS project was inspired by a request made by Robert Filliou. The APS series had 14 events each of which dealt with various aspects of publication in space. Exhibitions, performances, screenings, actions, concerts, and performance pieces were held on a range of themes. The events included several network projects which made Artpool known all over the world. For instance, an exhibition was organized for G. A. Cavellini in 1980, together with a joint performance on Heroes’ Square in Budapest, Hommage à Vera Muhina, and in 1982 an artistamp exhibition (World Art Post) was held of a collection which has grown to be one of the largest in the world thanks to the work of the “Eternal Network.”

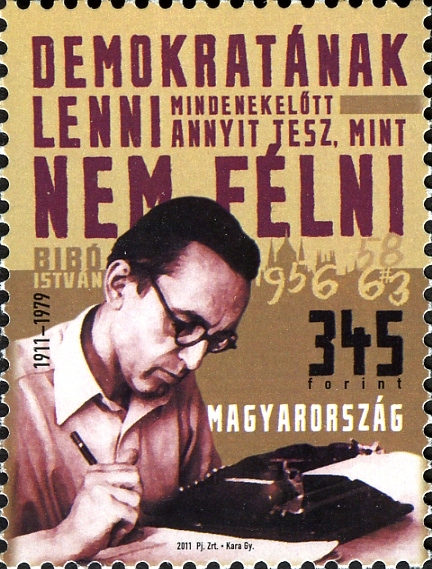

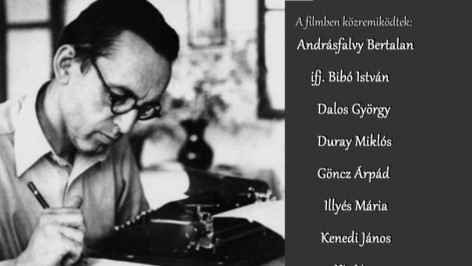

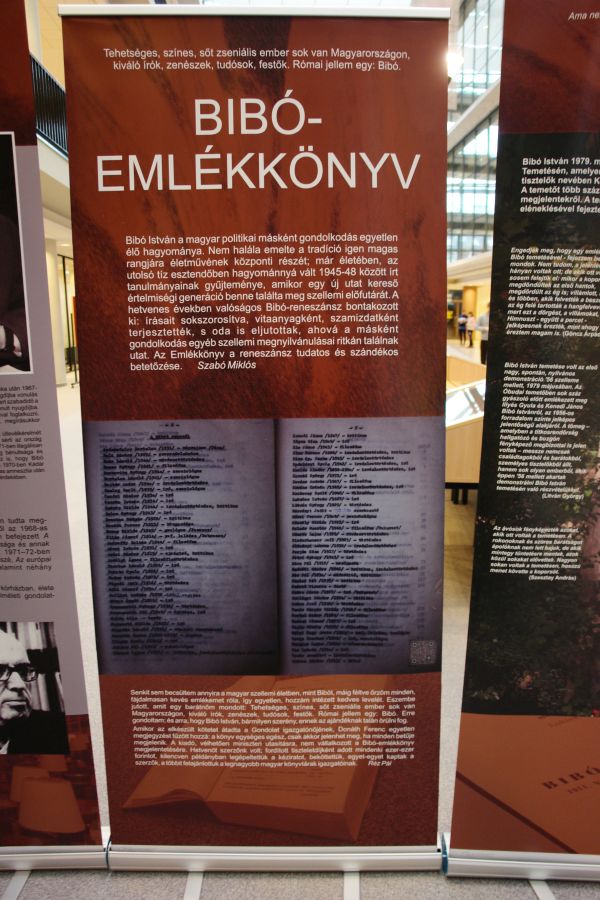

István Bibó (1911–1979) was a Hungarian political scientist, sociologist, and scholar on the philosophy of law. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Bibó acted as the Minister of State for Imre Nagy’s second government. When the Soviets invaded and crushed the revolution, he was the last minister left at his post in the Hungarian parliament building. Rather than flee, he remained in the building and wrote his famous proclamation, “For Freedom and Truth,” until he awaited arrest. Bibó became a role model for dissident intellectuals in the late communist era and a symbol of non-violent civilian resistance based on a firm moral stand. Since Bibó’s death in 1979, the family collection of his bequest, which includes personal documents, photos, manuscripts, books, and video and sound recordings, has been in the care of art historian and educator István Bibó Jr., who keeps the materials in his home in Budapest.

The article 'Religinė atributika Justino Marcinkevičiaus knygoje "Gyvenimo švelnus prisiglaudimas"' (Religious Attributes in Justinas Marcnkevičius’ book ‘The Gentle Touch of Life’). The article analyses new trends in works by Lithuanian authors. It argues that a sort of trend for religious and sacral moments could be seen in Lithuanian poetry in that time, especially in Justinas Marcinkevičius’ poems, that contradicted Soviet ideology and materialism.

All roads in the Ukrainian archives seem to lead to Vasyl Stus, one of the most prominent poets of the sixtiers generation. He was a central figure in samizdat circles, though his works were largely unknown to the larger public until the late 1980s. This item has a particularly unusual trajectory, as it was smuggled out of Soviet Ukraine by Raisa Moroz. Liuba Vozniak-Lemyk copied by hand five of Stus’ poems on two pieces of cloth and then Moroz sewed them into the wide skirt she would wear as she left the Soviet Union. Vozniak-Lemyk was a member of the Ukrainian underground, sentenced in 1948 to 25 years of hard labor in Siberia, but was amnestied in 1956. Moroz was a human rights activist married to one of the most prominent Ukrainian political prisoners of the Brezhnev era—Valentyn Moroz. On April 27, 1979, he was released unexpectedly from a Mordovian prison, as part of a spectacular exchange of five political prisoners for two Soviet spies that took place at JFK Airport in New York. None of the prisoners knew about the planned exchange nor been asked for their consent. They thought they were having their citizenship revoked and being deported. Raisa was also allowed to leave the Soviet Union as part of this exchange. These poems were published in the Munich-based émigré journal Suchasnist in Ukrainian in December 1979.

Report about "Agency-operational work of the organs of the State Security to prevent the attempts of the enemy to carry out ideological diversion and other subversive activities among the intelligentsia and forthcoming tasks", Sofia, April 10, 1979. The report identifies weaknesses in the work of the State Security. It emphasizes the need to focus on preventive measures and "prophylactic work". For the past two years, the number of agents working with respect to the intelligentsia has doubled. However, the report stresses that the Unions of Artists, Actors and Journalists, and some institutes of the Bulgarian Academy of Science and the Ministry of People’s Health are still weakly covered. Thus, the report not only gives a vivid illustration of the work of the State Security in the late 1970s and of its assessment of the political attitudes of intellectuals; it also shows how the state security evaluated its own work and what rhetoric they used to demand more resources.

An explanatory letter from Daina Lasmane, the director of the Dole History Museum, to an official at the Latvian SSR Ministry of Culture about the First River Daugava Festival was written in 1979. It alludes to some accusations against the organisers of the festival, but also the fact that the authorities did not want to voice any official accusations, which was rather typical in the 1970s and 1980s, when repressions against cultural personalities were often covert, or were based on the belief that a reprimand was enough to correct the behaviour of the people involved.

The last issue of IBOR dealing with the topic of total institutions or comprehensive institutions, with special emphasis on psychiatric institutions, came out in September 1979. Using the deductive approach, starting with the profiling of totalitarian institutions, focusing on psychiatric institutions and their patients, the editorial draws conclusions, referring to eminent historical personalities from the fields of philosophy, historiography and culture, that an artist can only be a person who is either on the border of madness or has already passed that boundary. This is backed up by a series of texts and poems, the most provocative among them being "Please Master" by American poet Allen Ginsberg. The poem deals about a paedophiliac-homosexual relationship between a pupil and a teacher and is accompanied by a photo of a child named after the poem.

The poem aroused great controversy in Pula's Party and youth circles, and in republic, local and youth publications, and it was the formal reason for abolishing the journal’s funding. Speaking of topics that were considered undesirable in conservative Pula, but also about the social circumstances in Yugoslavia that bothered the state-party leadership, the IBOR editorial board’s notable cultural-opposition activity was what ultimately led to the cessation of its funding.

The film and television work of the unconventional screenplay writer and director Nikša Fulgosi (1919-1996) is a component of the cultural heritage, which in a peculiar way testifies to the culture of dissent in the period of socialism in Croatia and Yugoslavia. Many of Fulgosi's film works remained unfinished or were "put in the vault" after their completion because the censors considered them unfit for the public. Fulgosi made the first television documentary series about sex for the Zagreb Radio Television in the late 1970s, which was only partially aired.

Artpool Art Research Center collects, archives, and makes available documents for researchers regarding marginalized art practices of Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary international art tendencies. Topics in the archive include progressive, unofficial Hungarian art movements (such as underground art events, venues, groups, and samizdat publications between 1970 and 1990) and new tendencies in international art beginning in the 1960s.

In addition to functioning as a research center, Artpool considers itself an active archive. It organizes events in search of new forms of social activity, participates in the process in a formative way, and simultaneously documents and archives these process in order to promote the free flow of information.

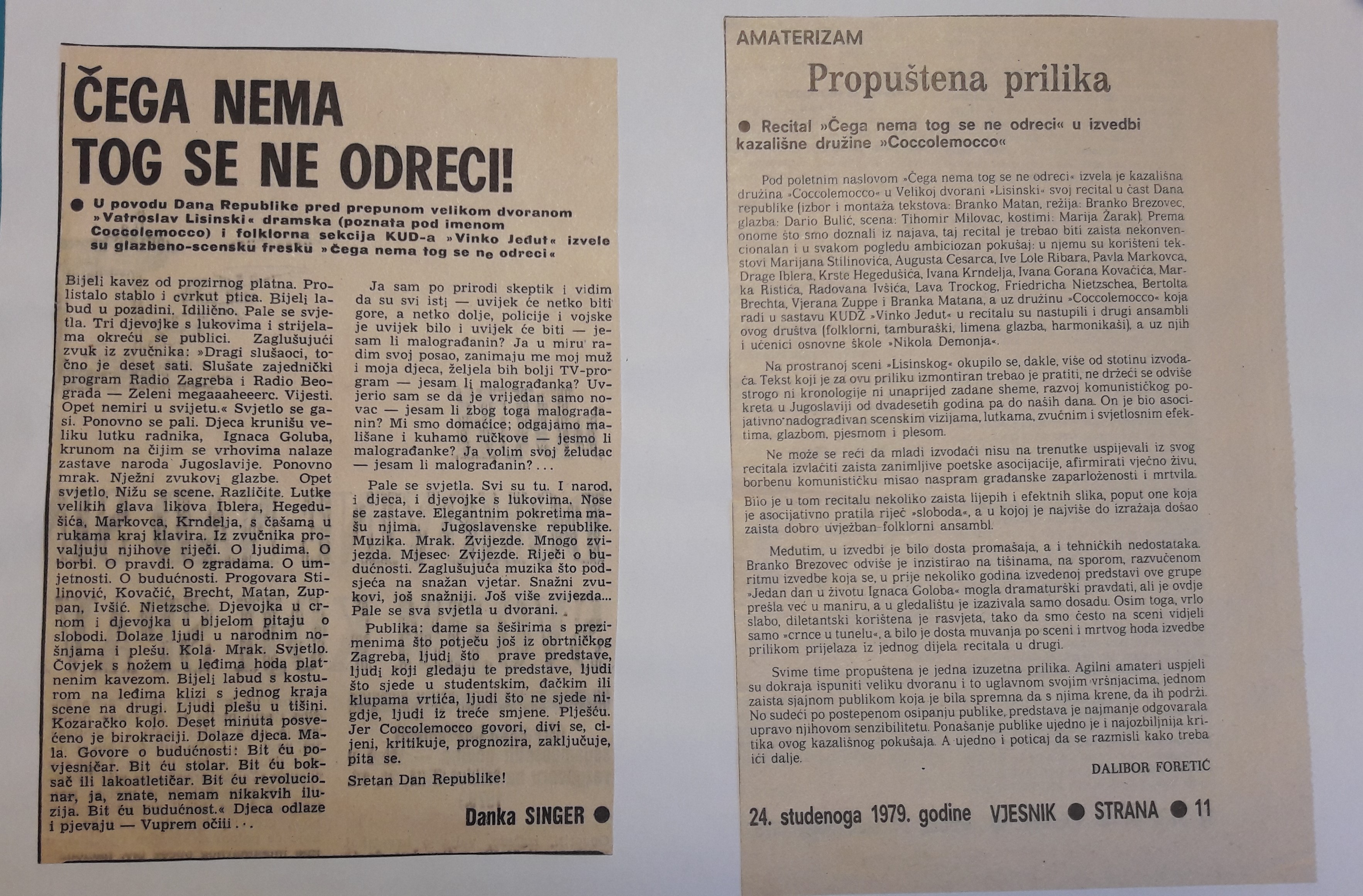

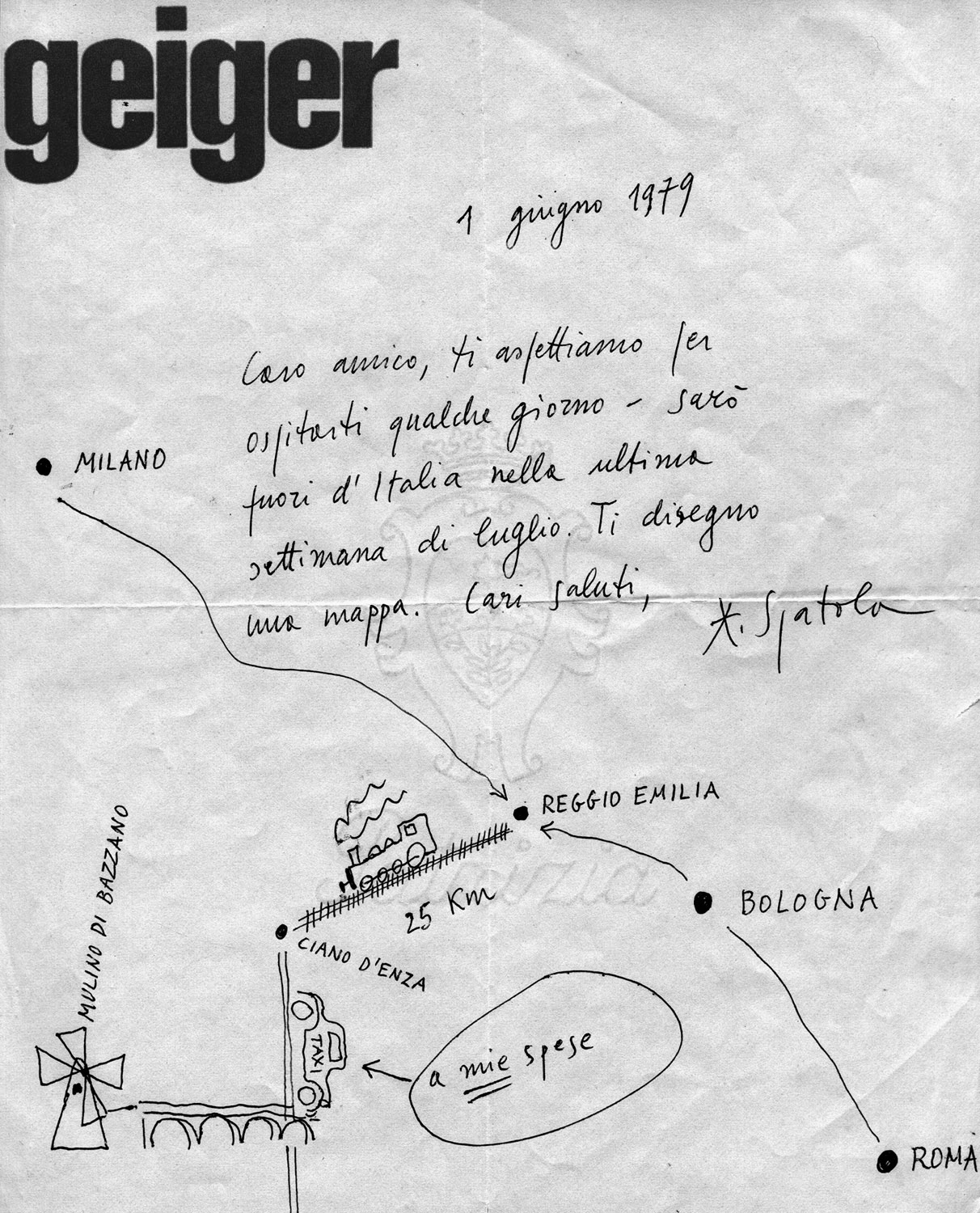

The premiere of the mega-recital You Don't Renounce What You Haven't Got! by the theatre company Coccolemocco, then operating as a theatre section of the Society of Amateurs in Culture and Arts Vinko Jeđut, was held at the Vatroslav Lisinski Concert Hall in Zagreb as part of Republic Day celebrations, on November 18, 1979. Later, the recital toured festivals in Yugoslavia (Skopje and Young People’s Theatre Days of Dubrovnik) and performed on the Republic Square (today Ban Josip Jelačić Square) on the anniversary of the liberation of Zagreb on the 8th of May.

In their pursuit of an authentic theatre language, the company continued to explore the forms that were usually ridiculed by professional bel-esprit theatres such as socialist rallies and parades, choral recitations and alike, performed on the occasions of important anniversaries (Republic Day, May Day, Veterans Day, Antifascist Revolt Day) which were staged in a hurry and without any creativity. The performance You Don't Renounce What You Haven't Got! against any conventions, followed the development of the communist movement in Yugoslavia from the twenties to the late 1970s. The performance consists of texts dealing with the revolution from the position of unrealized left-wing forces, as Brecht sang: revolution’s "mountain hardships" but also "lowland hardships." Writings, poems and quotations by Marijan Stilinović, August Cesarec, Ivo Lola Ribar, Pavao Markovac, Drago Ibler, Krsto Hegedušić, Ivan Krndelj, Ivan Goran Kovačić, Marko Ristić, Radovan Ivšić, Karl Marx, Leon Trotsky, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertolt Brecht, Vjeran Zuppa, Branko Matan and others were used. All sections of the Society of Amateurs in Culture and Arts Vinko Jeđut with more than a hundred participants appeared on stage. The show included, in addition to the members of Coccolemocco, a folklore ensemble, orchestras of accordions, brass instruments, tamboura, a wind orchestra, the Jeđutovke Choir, and a group of children from the Nikola Demonja Elementary School.

According to Gordana Vnuk, the recital You Don't Renounce What You Haven't Got! was critical of some aspects in self-managing socialism, such as state-sponsored public events omnipresent at the time. The performance was a persiflage which pointed to the totalitarian aspect of social realism and its forms of public representation. It could have been described as a collage of visually spectacular images characterized by poetic anarchy and subversion outside any protocols (Vnuk, interview, January 26, 2018). Performing this event during official celebrations was probably the greatest persiflage they could have done, and not be punished for it.

Gordana Vnuk cut the newspaper articles about the recital and stored them in her collection, along with the program leaflets, theatre tickets, and other documentation related to the recital You Don't Renounce What You Haven't Got!

Artpool Art Research Center collects, archives, and makes available documents for researchers regarding marginalized art practices of Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary international art tendencies. Topics in the archive include progressive, unofficial Hungarian art movements (such as underground art events, venues, groups, and samizdat publications between 1970 and 1990) and new tendencies in international art beginning in the 1960s.

In addition to functioning as a research center, Artpool considers itself an active archive. It organizes events in search of new forms of social activity, participates in the process in a formative way, and simultaneously documents and archives these process in order to promote the free flow of information.

Artpool is an archive, library, documentation center and place of research concerning the progressive, non-official trends in Hungarian art in the 1970s and 1980s (including alternative art scenes and groups, underground art magazines, samizdat publications etc.) and contemporary avant-garde tendencies.

Artpool – beside being a research institute - defines itself as an active archive: seeks out new forms of societal activity, takes a formative role in processes, organizes events, documents, archives them and freely distributes information.

Veljo Tormis wrote his Kurvameelsed laulud (Melancholy Songs) in 1979, and dedicated it to the conductor Neeme Järvi, who was persona non grata in the Soviet Union since 1978. Thus, Tormis was told to cross out the dedication on the first page of the manuscript. However, he refused to do so, and covered it up with a strip of dark paper instead. The dedication is faintly visible through the paper. The manuscript was accepted, and later archived in this form. On a later copy, which also belongs to the same collection, the dedication is rewritten and formulated as a dedication to Neeme Järvi's leaving the homeland. Järvi emigrated to the United States in 1980. Kurvameelsed laulud is not the most famous work by Tormis, but the manuscript is a unique and notable rarity as a reflection of the struggle with Soviet censorship.

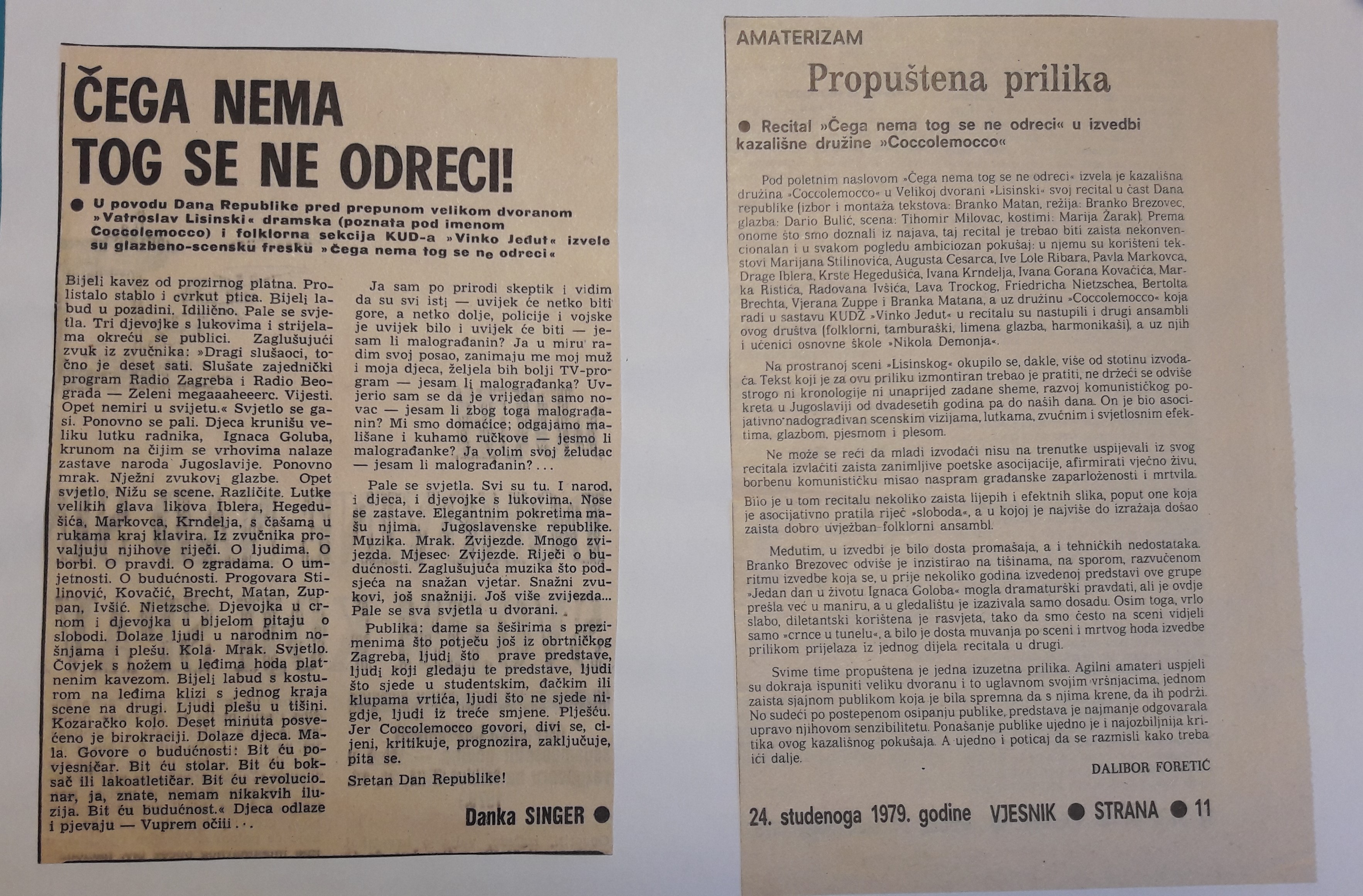

The founders of Artpool organized two Artpool’s Art Tours, one in 1979 and one in 1982, with the aim of meeting first some of their Italian and then some of their Western European network correspondents, including Romano Peli, Vittore Baroni, Adriano Spatola, Cavellini, Rod Summers, Julien Blaine, and Ben Vautier. They returned with a bunch of new connections, publications, and plans.

The first tour in 1979 resulted in the organization of the successful Cavellini exhibition (APS no. 5), which was held in the Young Artists’ Club, and the joint performance Hommage à Vera Muhina, which was held on Heroes’ Square, Budapest.

Work was underway on another exhibition entitled Package from Italy (Pacco dall’Italia), but the exhibition was banned before it could be held. The plan was to show visual and sound poetry works collected during Artpool’s first art tour.

The second art tour project in 1982 was a huge European trip by car through six countries. The goal was to make possible personal meetings with networkers already known from the Mail Art network, further the exchange of ideas and publications, collect documentation and addresses, make photographic and audio documentations, etc. The final result of the collecting activity was eight boxes of precious archive material. The audio recordings were used for Artpool Radio 5’s program. The travel diary was used for a sheet of stamps and some illustrated reports the following year for the first four issues of the samizdat art magazine entitled AL (Artpool Letter).

Pop culture, mediation, gender roles, and the image of the self were the basic motifs of Péter Sarkadi’s art in the late 1970s. He analysed the image of the star in his compositions: on the one hand, he performatively personified the character (using makeup even in normal life situations), while on the other hand he photographed and then drew or painted them in a distancing, hyperrealist manner.

Rainbow belongs to the series of these works. In this composition, the black and white photograph is directly blown onto the canvas, together with its attributes (perforation, brand), emphasizing the mediating process. The protagonist’s jewellery shimmers, while his flowing makeup is counterpointed with the colorful painted rainbow motif over the eyes.

Before 1989, the Czech dramatist and dissident Václav Havel was imprisoned several times for his beliefs and activities, his longest prison term lasting from 1979 to 1983. This period is reflected in Havel’s letters to his wife, later published as “Dopisy Olze” (“Letters to Olga”). Already in prison Václav Havel began to design these letters as a future book and tried to develop within them a more general reflection on human identity and responsibility. Especially after the summer of 1980, Havel’s letters to his wife Olga gradually turned into philosophical essays. On the other hand, the letters from the first year of imprisonment, written from June 1979, contained, besides philosophical, literary and other reflections, also more practical passages, including concrete instructions to Olga concerning their household or Havel’s everyday needs. This is also the case of letter “number 4”, which was written by Václav Havel on 8 July 1979 while in custody in Prague – Ruzyně. In this letter, Václav Havel informed Olga about the letters he had so far received, he described how he had been spending his time in custody and wrote that despite his imprisonment he was “sure of his truth” and did not regret anything. This letter was in an abridged version (without passages about practical matters and specific instructions to Olga) published in “Letters of Olga” issued by the samizdat Expedition Edition in 1983. It has appeared in subsequent samizdat, exile, and after 1989, official editions of “Letters to Olga” as well.

In 1998, this letter, along with 160 other letters from 1979 to 1983 and 11 letters from 1989, was donated by Václav Havel to the Museum of Czech Literature.

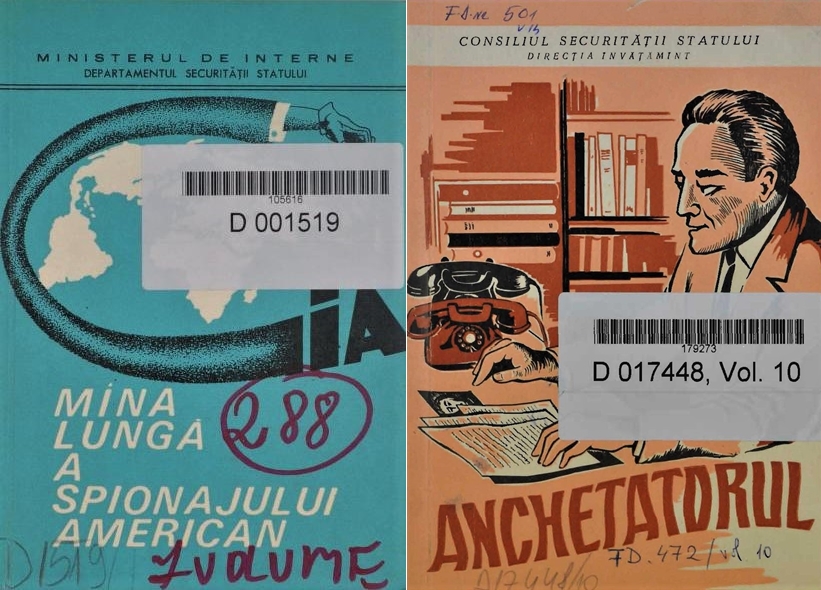

The brochure Infiltrarea: Cazuri de folosire a acestei metode ofensive de muncă pentru cunoașterea, prevenirea și contracararea acțiunilor îndreptate împotriva securității statului (Infiltration: Cases of the use this offensive method of work for the knowledge, prevention, and countering of actions directed against state security) is a top-secret publication of the Ministry of the Interior that was used for the professional training of Securitate personnel. The booklet deals with one of the main methods used by the Romanian secret police in its mission of annihilating the potential actions of all those who were suspected of “hostile attitudes” towards the communist regime: the so-called infiltration of an informer. Infiltration basically means the insertion of an informer (or an undercover officer) into the immediate personal entourage and/or the professional milieu of the targeted victim. According to the definition included in the brochure, infiltration refers to establishing a relation between the informer and his/her target that aimed at winning the trust of the latter in order to fulfil the former’s “informative-operative tasks.” The brochure also describes how the Securitate officer should prepare the infiltration by paying attention to the personality of the target, selecting the most appropriate informer in accordance to the profile of the target, and carefully preparing him/her for a successful infiltration. Another section deals with the practical problems that might occur during the infiltration. These refer to the supervision of the infiltration by the Securitate officer and the collection of information from his/her “source.” The last part of the brochure focuses on the cases in which not an informer but an undercover Securitate officer is required to infiltrate a particular target. These theoretical notes were followed by four annexes in which four cases corresponding to four different methods of infiltration are described in detail. One of these cases refers to the successful infiltration of a group of young Romanian German writers who in 1972 in Timișoara established the literary circle known as Aktionsgruppe Banat. Although the text used pseudonyms and omitted the name of the group, the general information provided allows a researcher to discern that the case under debate is that of Aktionsgruppe Banat. The brochure describes the problem faced by the Securitate, which directly derived from the functioning of this informal circle without formal approval that led to the production and dissemination of writings critical of the “realities of socialist Romania,” as some sources interpreted these for the secret police. Following a failed attempt at recruiting two of the literary group members as informants, the Securitate decided to infiltrate an outside informer into the group. The text describes how the officers carefully selected the informer, nicknamed “Gruia,” on the basis of his common professional background and interests to the target, “Otto Wilhelm,” one of the members of the non-conformist literary group. The text also underlines how the informer was trained to initiate the first contact with his “victim,” and how they became friends given their shared interest in literature and the alleged common experience of being marginalised by the communist regime due to their non-conformist stances. The success of the infiltration was unquestionable as not only did the target, “Otto Wilhelm,” invite “Gruia” to attend the meetings of the literary circle, but he also entrusted some of his manuscripts to him to read. The brochure does not state this, but this informer must have decisively contributed to the formal dismemberment of Aktionsgruppe Banat after the arrest of four members in 1975.

http://www.cnsas.ro/documente/materiale_didactice/D%20008712_001_p21.pdf

The collection of the Slovak writer and publicist Dominik Tatarka (1913–1989) contains unique correspondence, manuscripts and audio recordings illustrating life of this leading Czechoslovak writer, who had been critical to the communist regime since 1950s and became a “banned author” and dissident after 1968.

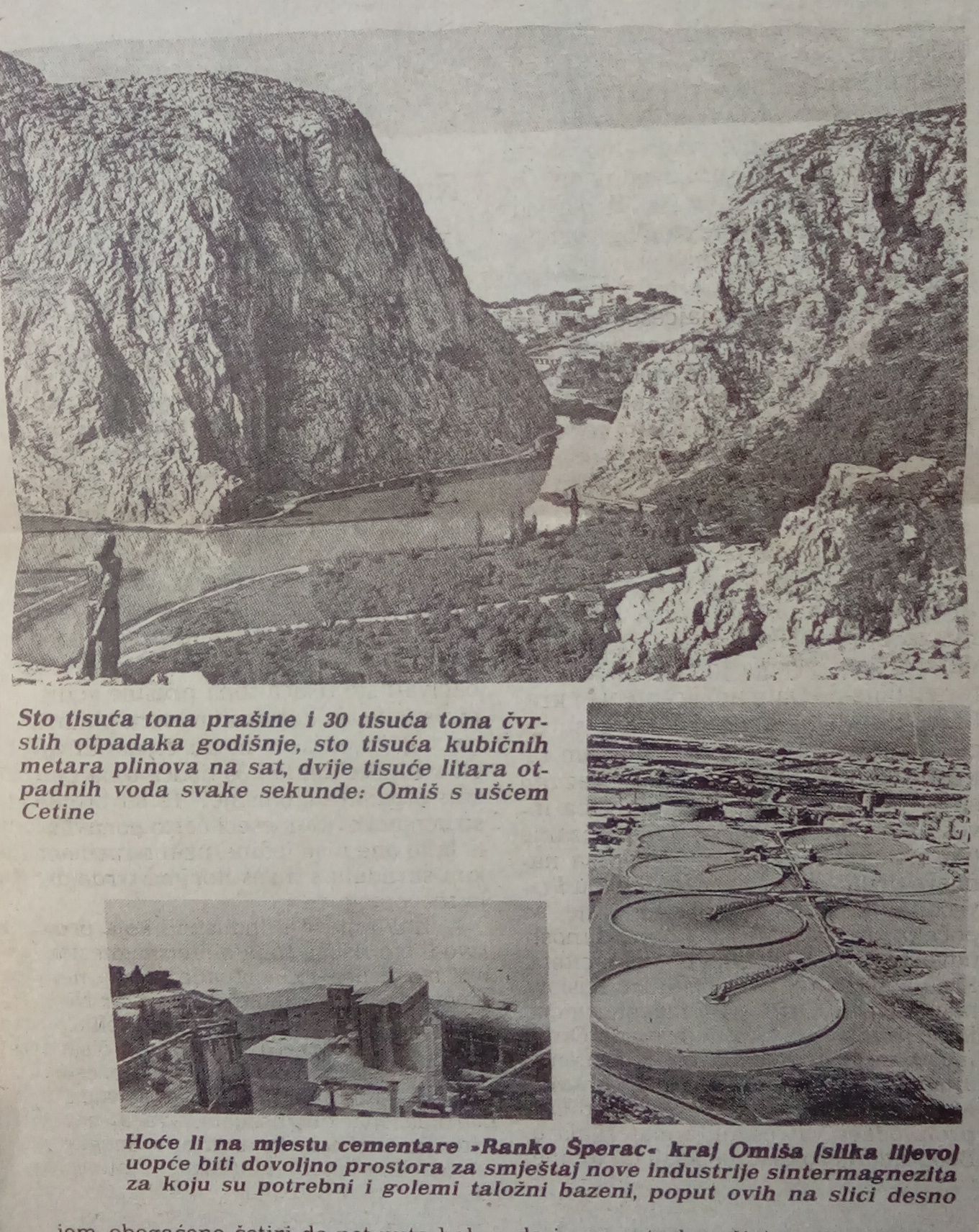

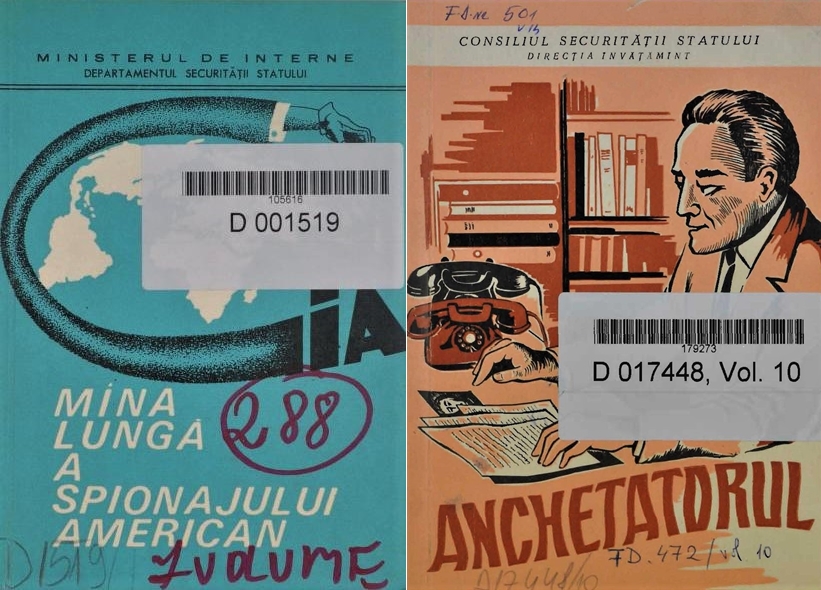

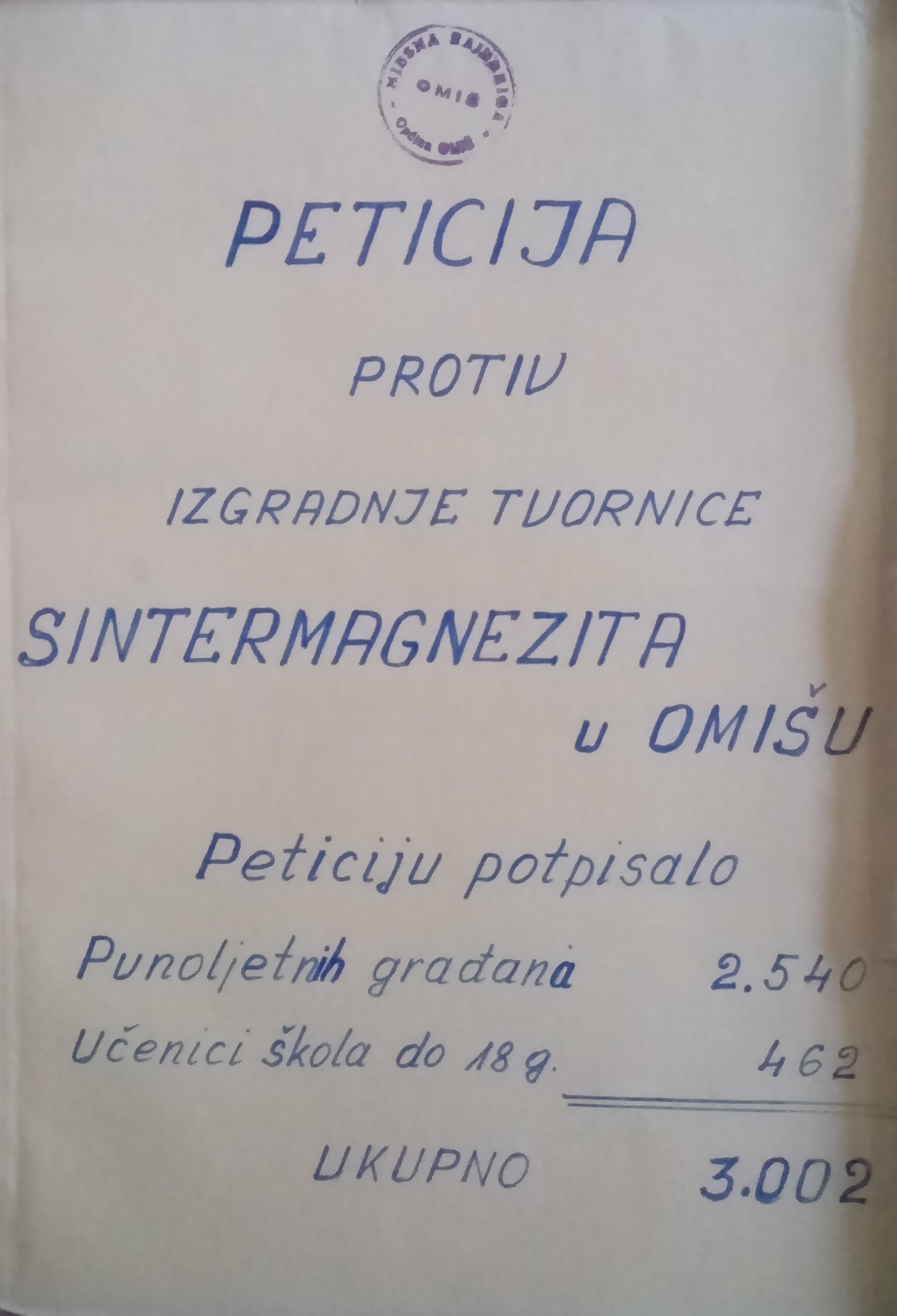

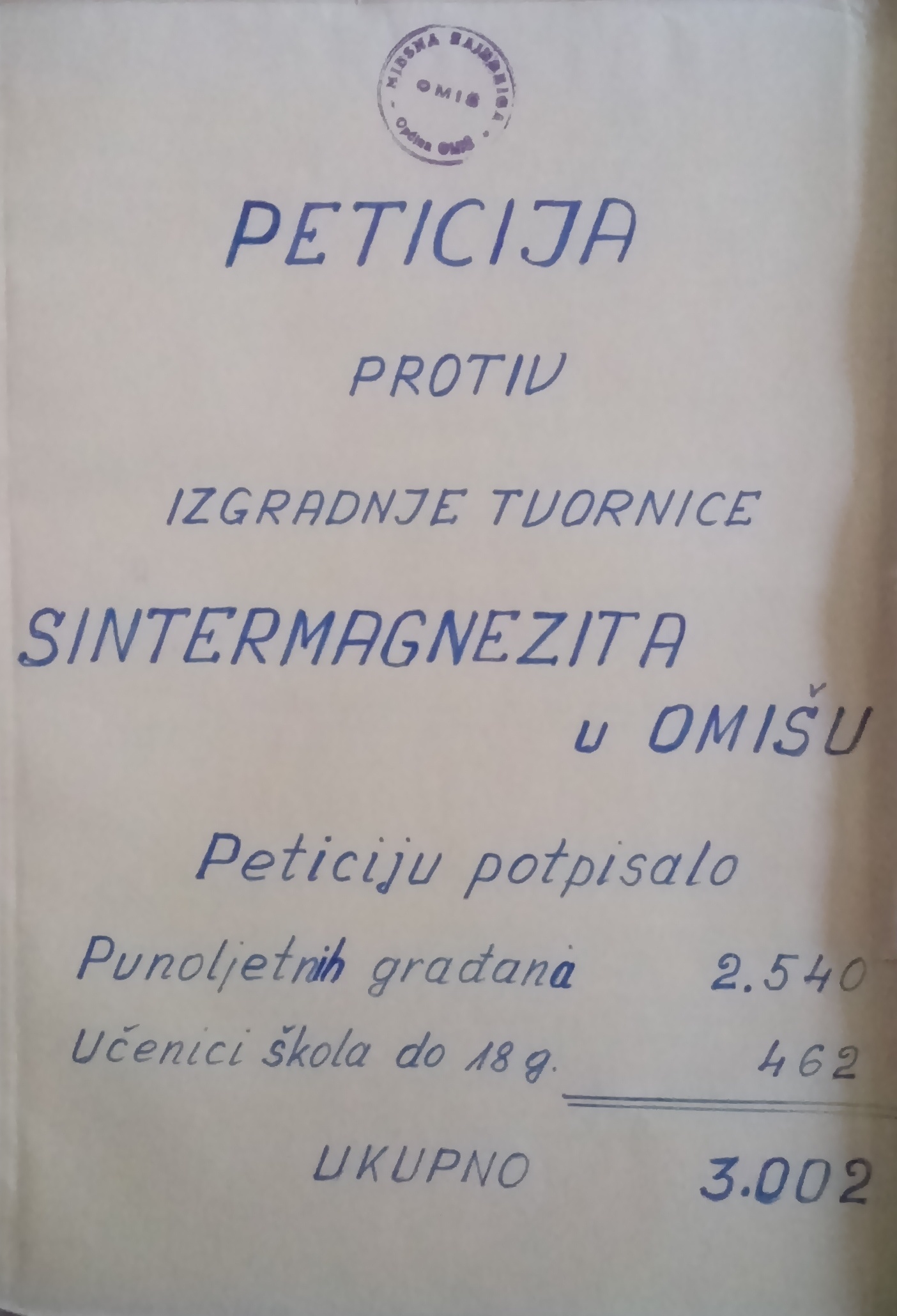

Petition letter against construction of sintered magnesia factory in Omiš sent to Parliament of Socialist Republic of Croatia. 12 April 1979. Archival document

Petition letter against construction of sintered magnesia factory in Omiš sent to Parliament of Socialist Republic of Croatia. 12 April 1979. Archival document

The files of the Office of the President of the Parliament of the Socialist Republic of Croatia in the period 1978-1982 include the preserved petition with copies of 3,002 signatures from Omiš residents opposing construction of a sintered magnesia factory in that area. The petition drive in Omiš was organised on 7 April 1979. It was signed by 3,002 persons: 2,540 eligible voters and 462 students under 18 years of age. According to the file cover, Parliament received the petition on 12 April 1979, and placed it ad acta ten days later, on 24 April. Besides Parliament, the conclusions from the town meeting and the petition with copies of all 3,002 signatures were also sent to the Omiš Municipal Assembly and to a range of republic-level institutions, and to participants in the Second Conference on Adriatic Protection, held at that time on the island of Hvar. That campaign resulted in further debate on the matter by the professional and general public.

The document is available for research and copying.

“The only live tradition of Hungarian alternative political thinking today is that of István Bibó,” said historian Miklós Szabó, a prominent theorist of democratic opposition at the beginning of his review of the Bibó memorial book, published in the first issue of Beszélő (Speaker), a prominent Hungarian samizdat periodical launched in December 1981. As Szabó argues a few lines below, “in the 1970s, there was a real Bibó revival in Hungary; his earlier studies were copied and distributed in samizdat and then discussed by many young intellectuals, and they found new devoted readers even among people who otherwise rarely read similar sources of alternative thinking. (…) Now, the Bibó Memorial Book represents a conscious and intended culmination of this unique revival.”

In early 1979, at the initiative of János Kenedi, a voluntary editorial team of intellectuals was formed to prepare a tribute anthology on the occasion of István Bibó’s 70th birthday. However, as Bibó died in May 1979, the book became something of a post mortem homage, as it was published a year later in a samizdat edition. (Bibó’s funeral developed into a silent protest demonstration against the communist regime, as thousands of people gathered in a Budapest cemetery, with hundreds of secret policemen among them.)

This imposing anthology, which consisted of contributions by 76 authors in three thick volumes of more than 1,200 typewritten pages, was no doubt the first important venture with a significant influence in the history of the Hungarian samizdat movement. Furthermore, as an example of united political strivings on the part of all democratic opposition forces in Hungary, it also seemed to set a promising precedent, and it was perceived by the onetime communist party leaders as a real challenge. This is why they tried to prevent any further escalation of a resistance movement organized partly by the former ’56 tradition and partly according to the Polish patterns of self-organized Solidarity.

The ten-member editorial team included both ’56-ers and ’68-ers, “populists” and “urban” intellectuals, but the list of the 76 authors who contributed was even more diverse: old and young, prominent and hardly-known dissidents, writers, artists, scholars, etc. all readily contributed writings. The contributors included Gyula Illyés, György Petri, István Csurka, György Konrád, Sándor Bali, Sándor Weöres, Lajos Vargyas, and Piroska Szántó, just to name a few. Many of their memoirs, essays, and studies revolved around the relevant traditions of Hungarian national democratic movements and the chances of reviving these traditions. For all their differences, the authors equally shared sincere respect for István Bibó’s personality and his ideas. They also shared the belief that the only solution for the miseries of the Eastern Bloc countries, including Hungary, was real democratic changes in the principle of self-determination. In other words, both the sinister “heritages” of Stalinism and extreme right-wing nationalism should be rejected once and for all.

This kind of common consensus was a real revelation at the time, and in fact the main result of the collective venture of the book published in commemoration of Bibó was that it helped further a rediscovery of the real tradition of the independent, democratic spirit of Hungarian resistance movements, which had been suppressed and forgotten for a long time, together with the 1956 revolution. However, this was not the only positive effect of the book. It also helped break several taboos, making sensitive and long-suppressed issues, like the real heritage of 1956, the historical trauma of the Trianon Peace Treaty of 1920, and the Hungarian Holocaust in 1944 subjects in the public discourse again, along with the latent survival of anti-Semitism in the country and the forced assimilation of ethnic Hungarian minorities in the neighboring states.