The collection, which is the private property of István Viczián, illustrates the history of the Calvinist youth organization of Pasarét under socialism. The collection includes letters and photographs, which provide insights into the aspirations of the group to create an active religious community in an era when such communities were a threat to and contradiction of official communist youth policy.

The bequest of György Martin contains his folk dance films and documents about them. Martin started to shoot films in the 1950s, and he wanted to use the best technical facilities for his work. He worked together with his wife Jolán Borbély and his stepson Péter Éri. They collected folk music and folk dances among Roma and travelled to Transylvania regularly. They remained in regular contact with Transylvanian dancers. Films were made by Martin, Jolán Borbély documented the collections, and Péter Éri recorded sounds on tapes. In the years which followed, he began to work with Ernő Pesovár, Ferenc Pesovár, and László Maácz. Later, Bertalan Andrásfalyv also joined these tours. The trips were supported by the Folk Art Institute. Its head, Jenő Széll, provided his car and chauffeur. The Hungarian Academy of Sciences also supported these research trips. Martin, however, used his own equipment during the collecting and research work. These folk dance films provide essential and in many respects unparalleled insights into peasant culture in socialist Hungary. Martin and his friends started their work as collectors in an extraordinary era, when the political elite launched programs to transform traditional peasant culture radically. Private farmers lost their land due to collectivization, and many members of the younger generations had to find jobs in industry. Martin was an inventive researcher and active traveler. Several anecdotes tell of how they used organized state tourist agency (IBUSZ) trips to Transylvania.

His films about István Mátyás “Mundruc” (1911–1977) are the most famous of all. Martin always wanted to make films about the famous Transylvanian dance known as the “legényes” (lad’s dance) from Kalotaszeg (the aforementioned region in Transylvania, known as Țara Călatei in Romanian), so he travelled to Magyarvista (or Viștea by its Romanian name), where he met with Mundruc (Mundruc means nice or slim in Romanian). Martin thought that Mundruc was the most talented dancer in East Central Europe. He was not a just talented dancer, he was also very conscientious about drawing a clear distinction between traditional and modern dances. Martin stayed in touch with Mundruc for twenty years, and he studied the photos and films about him. Martin’s cooperative endeavor with Mundruc adhered to the principles of the research school established by Gyula Ortutay, which focused on personal character. Unfortunately, Martin was unable to finish his book about Mundruc because of his untimely death. His work was published in 2004 as a posthumous volume.

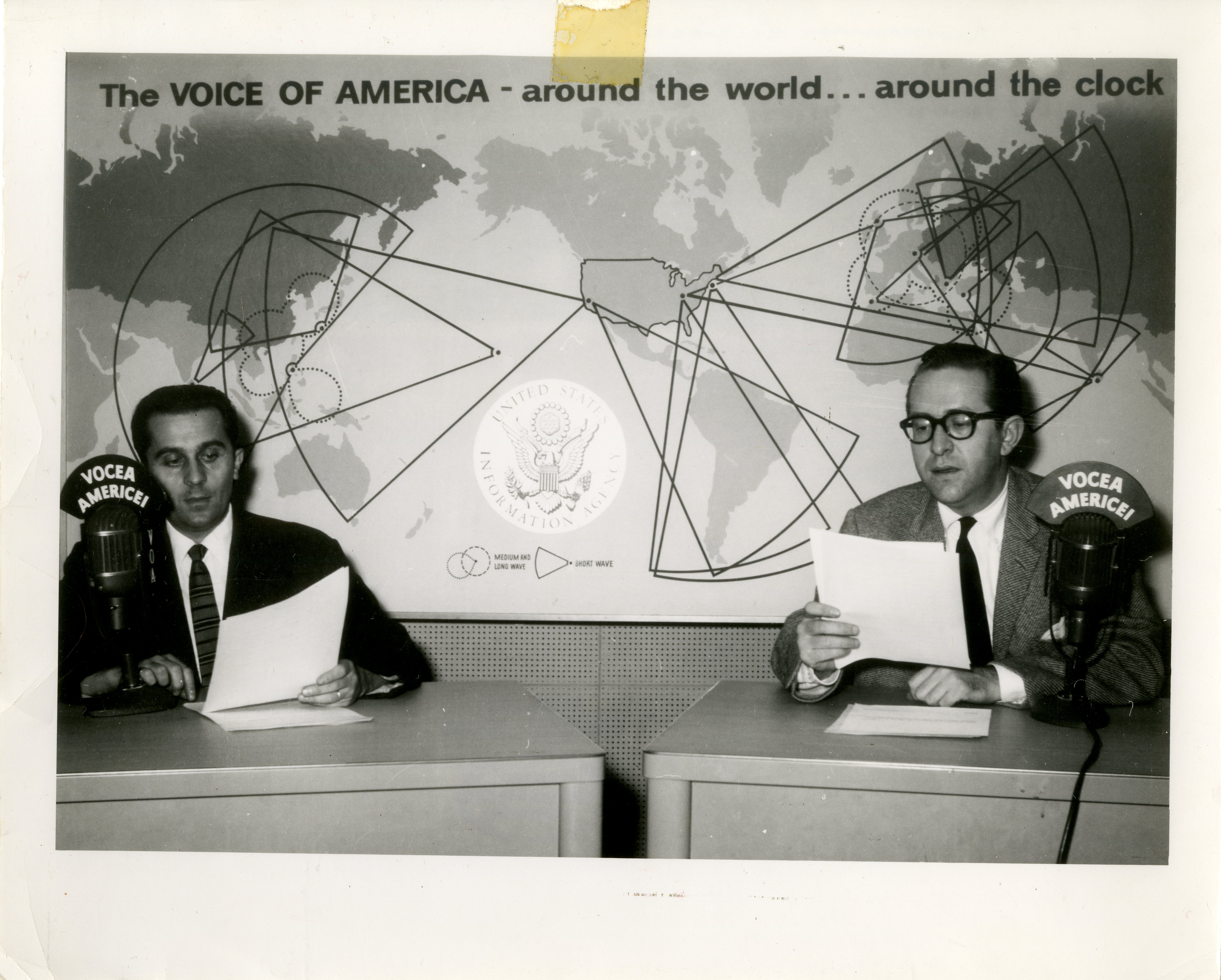

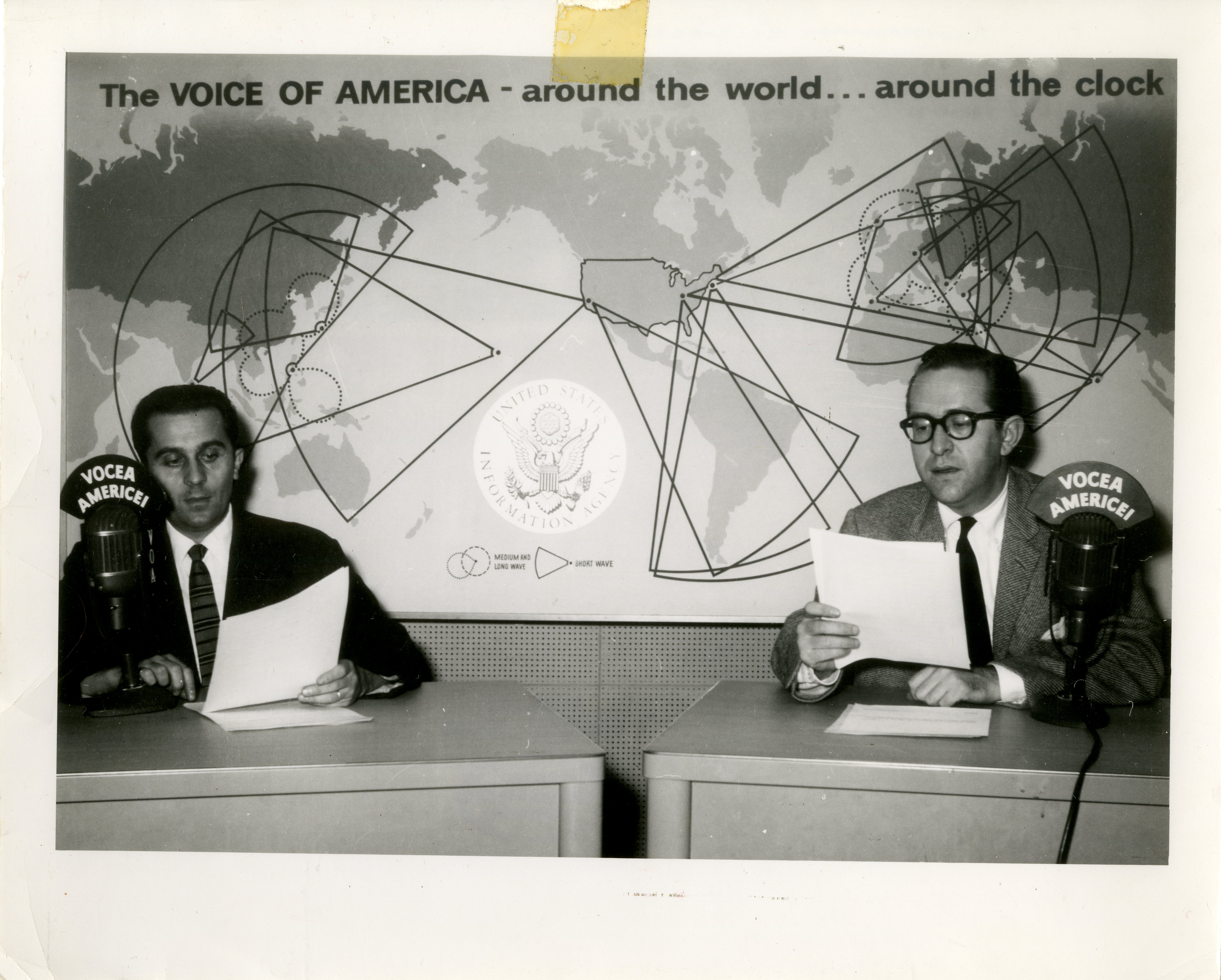

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 had a strong echo in Romania, especially among young people. As a result of the news about the revolt of the Hungarian students, there were student protests especially in the university centres of Timişoara, Cluj, and Bucharest, which were nipped in the bud by the repressive institutions of the communist state. These initiatives would not have happened if Voice of America and RFE had not broadcast detailed information about the Hungarian Revolution. The Mircea Carp Collection includes a black and white photo which illustrates the moment in the autumn of 1956 when Voice of America radio station became an alternative source of news to the official one concerning events in the Eastern Block. The photo was taken in the studio of the Romanian section of Voice of America during the Hungarian Revolution. In the foreground can be seen two employees of the radio station, Mircea Carp and Michael A. Hanu, reading typed materials live. In the background there is a map of the world covered by the motto: “The Voice of America – around the world ... around the clock”. On the back of the photo the creator of the collection, Mircea Carp, noted: “October 1956: Mircea Carp (commentator) and Michael A. Hanu (editor) commenting on the Hungarian Revolution”. In his memoirs, Mircea Carp mentioned about this moment that, although the Romanians who had emigrated to the West expected the USA to adopt a stronger position towards the Soviet intervention in Hungary in 1956, the American political class took a step back, thus disappointing the supporters of the Hungarian Revolution (Carp 2012, 169).

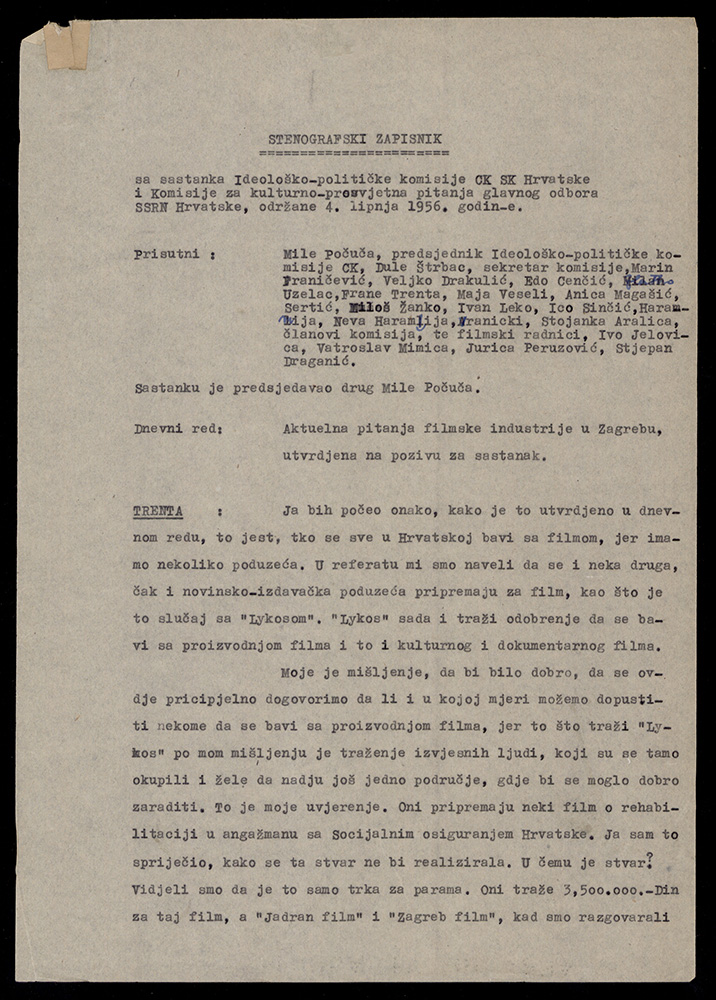

Stenographic Minutes from the Meeting of the Ideological Commission and the Commission on Cultural and Educational Issues of the CC of the SAWPC, 1956

Stenographic Minutes from the Meeting of the Ideological Commission and the Commission on Cultural and Educational Issues of the CC of the SAWPC, 1956

These are elaborate minutes of the session in which the current issues in the film industry in Zagreb were on the agenda. At the session, Ivo Jelovica, Vatroslav Mimica, Jurica Peruzović and Stjepan Draganić also participated along with the members of the Ideological Commission of the CC LCC and the Commission for Cultural and Educational Issues of the Central Committee of the Socialist Alliance of the Working People of Croatia (SAWPC). The document is important because it shows how the members of the Commission steered the film industry in Croatia, the production of films, and how they managed recruitment and staff within that industry. The participants in the meeting analysed the situation in Croatia: who is engaged in the film business, the need for two art centers/production companies; Jadran film and Zagreb, and the related issue of finances, staff and quality of achievement. The role of the Film Council was also emphasized as the authoritative body for quality, but also the ideological "regularity" of productions, whose role was to approve screenplays. In addition to this, the question was raised as to whether such "socialistic morality" could be ensured in the film company. Particularly interesting was the part of the discussion on the staff in film companies, when Dule Štrbac, a member of the Commission, noted that the problem surrounding Jadran film was the accumulation of personnel who were politically and morally problematic, but who were professionals of the highest quality. He appointed Branko Marjanovic as such, saying that he was considered an irreplaceable film director and expert, but also mentioned his film The Watch on Drina (Straža na Drini) from the time of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), and emphasized how he "brings together people who fit his understanding and concepts." Branko Belan was appointed as a troublemaker, as he was the screenwriter of the film Odnarođeni, whose screenplay was awarded the highest Ustasha prize at the beginning of January 1945. The third person featured in a negative context was Krešo Golik, who "declares himself as an Ustasha dorojnik" and wrote that the Ustasha "will never surrender alive." The members of the Commission wondered how such people had the ability to work, and on the other hand "our staff" has failed to hold on. An example in Zagreb Film was Zvane Črnja, a playwright, as an imposing cadre, although it was said that he should not be engaged in certain duties.

Frane Trenta emphasized that "strong political and party personnel should be placed in these companies," and Milos Zanko supported him by saying that the Council should not appoint people who are not "on course" and that the Film Council should also provide the appropriate staff.

It is interesting to note that the record also mentions the work of the party organization in the company and that in past years opposing to them meant to be left out of work and to starve, to be without social security, to remain without any protection, to be silent or to obey ... This especially very clearly shows the role of LC organization in directing the work of film companies, censorship and monitoring the "ideological correctness" of the personnel and policies of the companies themselves.

Mile Počuča finally concluded that sit the enemies of socialism or at least the problematic people were sitting in both companies, and advocated a special meeting to see who should be thrown out and who should stay. It was concluded that the meeting should be held.

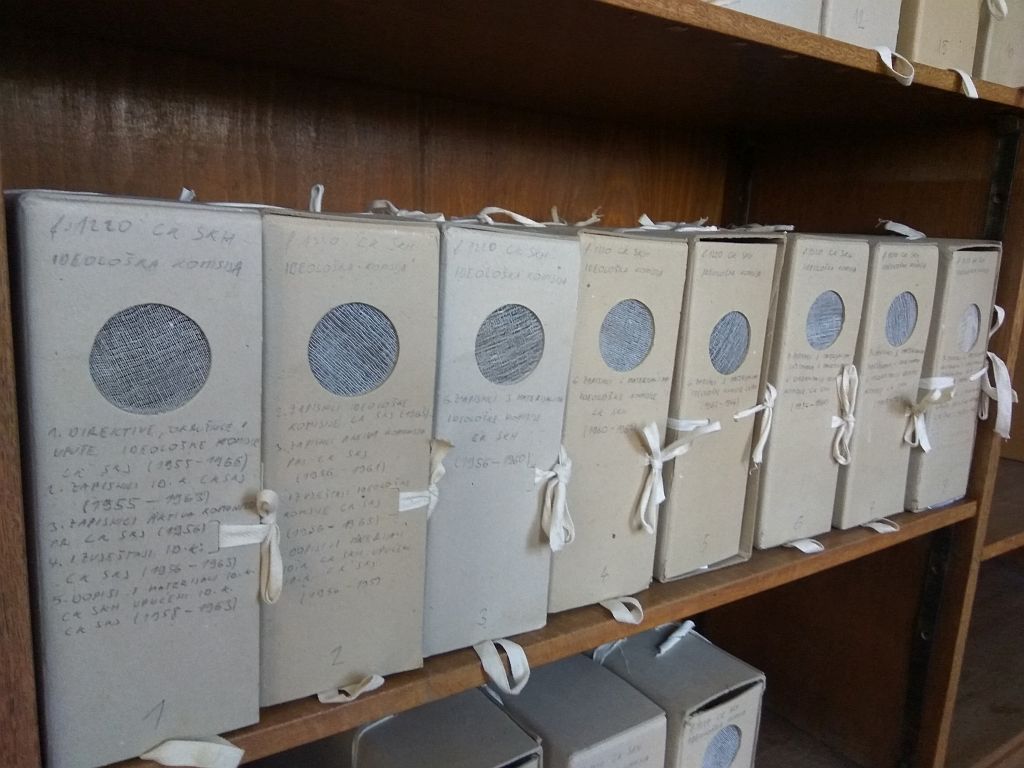

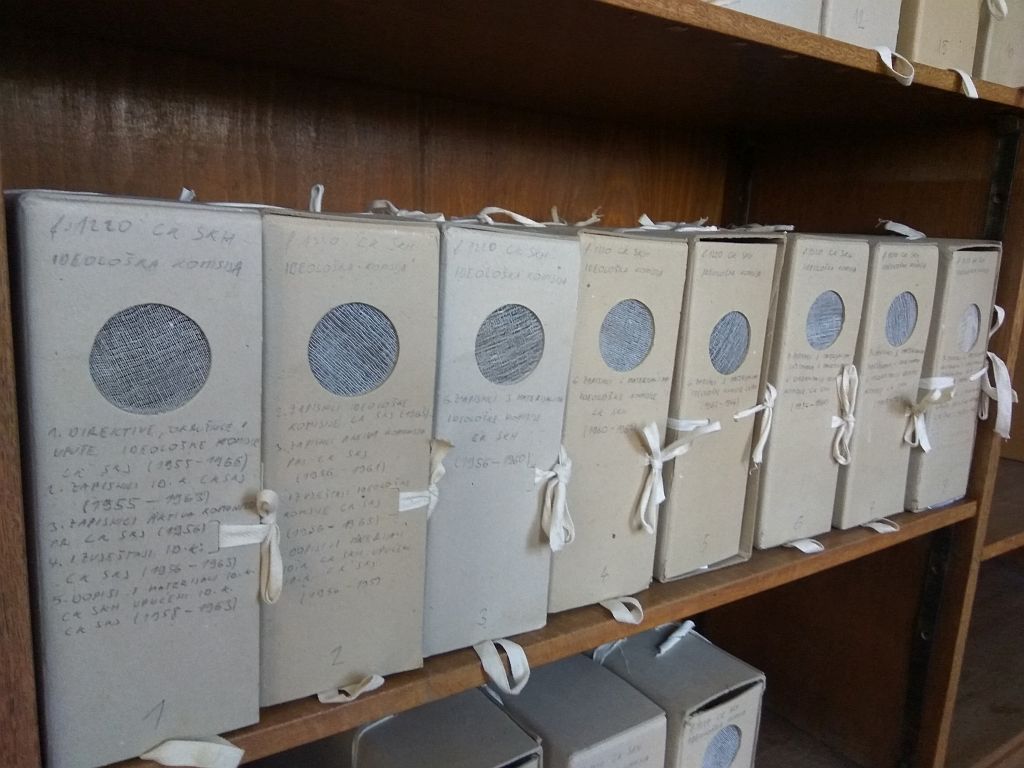

By 1995, the document was, along with the other records of socio-political organisations, a part of the Archive of the Institute of History of the Labour Movement of Croatia/Institute of Contemporary History. That year, in July, it was handed over to the Croatian State Archives (CSA) where it is kept today. The documents are accessible for use without any restrictions.

Collection of the Ideological Commission of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia (1956 - 1965)

Collection of the Ideological Commission of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia (1956 - 1965)

In the collection of the Ideological Commission of the League of Communists of Croatia (IC LCC) (1956-1965), a number of documents illustrate the IC LCC's view of ideologically inappropriate occurrences in cultural creativity (art, literature, film), the media (the press, radio and television), education and science in Croatia. This commission had the task of monitoring, analysing and directing overall activity in these areas, issuing its directives and establishing staffs in all major institutions and organizations. In this way, it also reacted to ideological currents that did not align with the accepted direction, and it thereby became the deciding factor in cultural policy in Croatia.

Vladislavs Urtāns devoted a lot of energy to training schoolchildren in the Madona district to research local history, and to encouraging an interest in the past. In April 1956, the first meeting of young local historians of the Madona district was held in the Madona Museum.

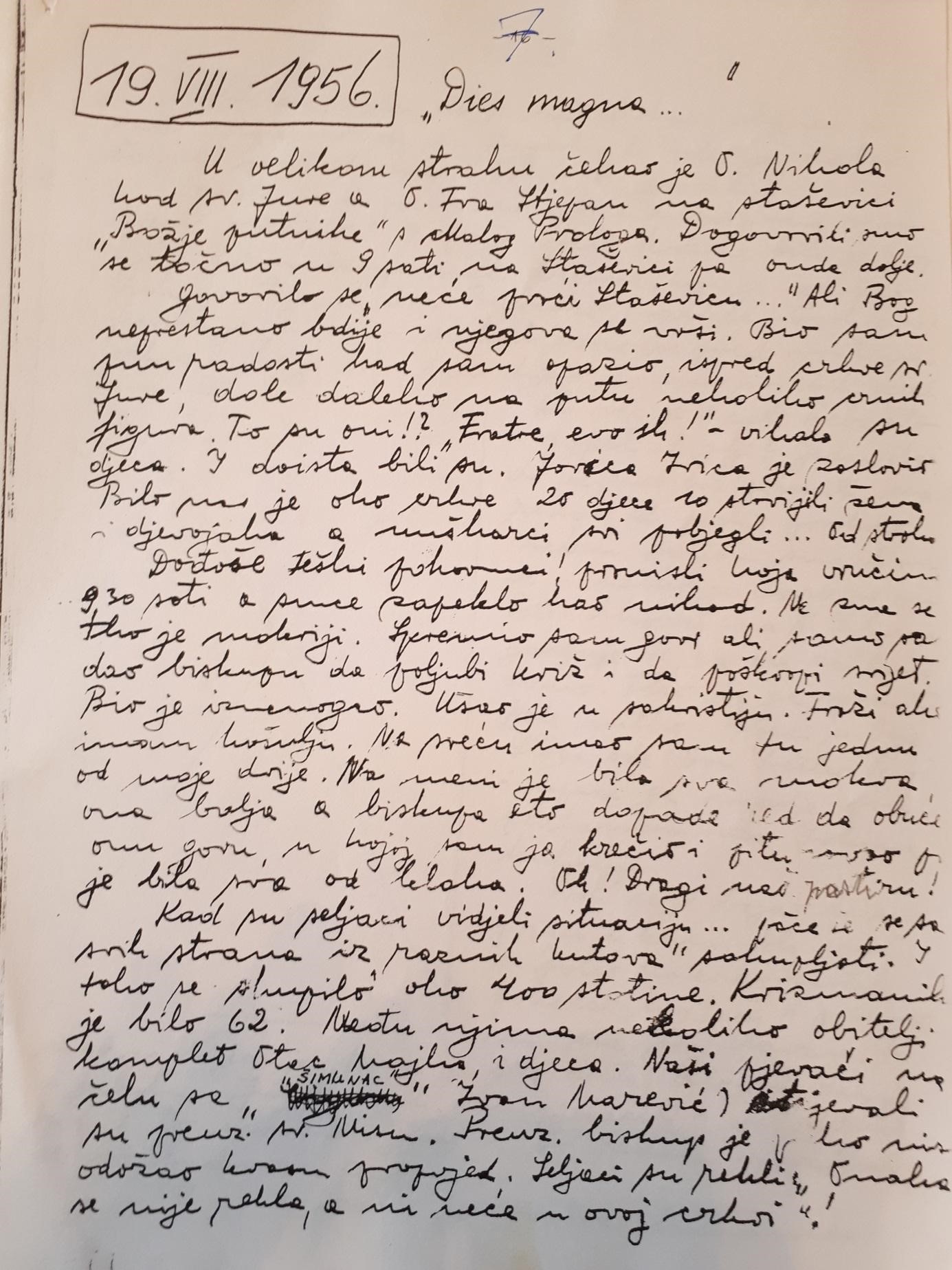

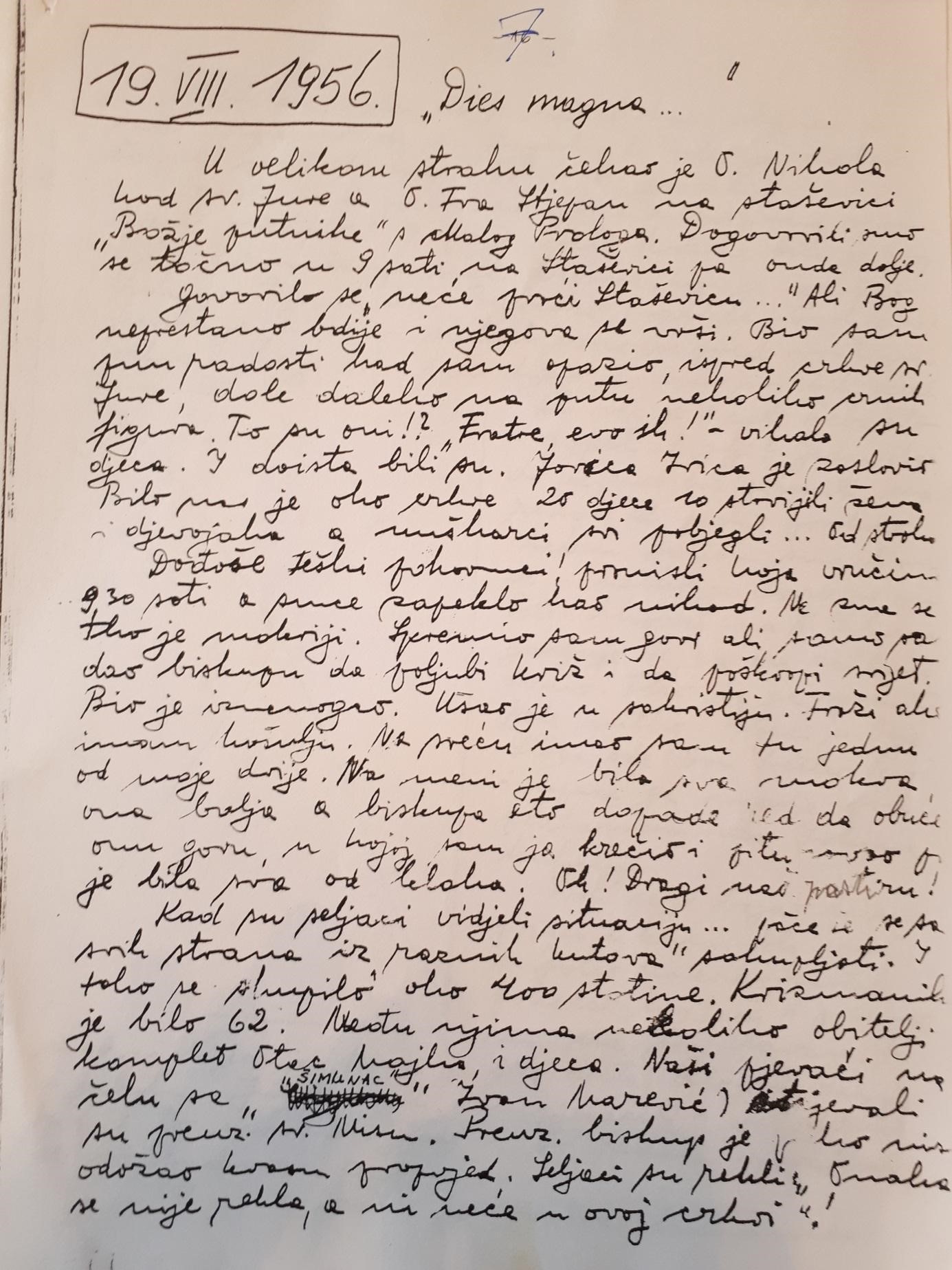

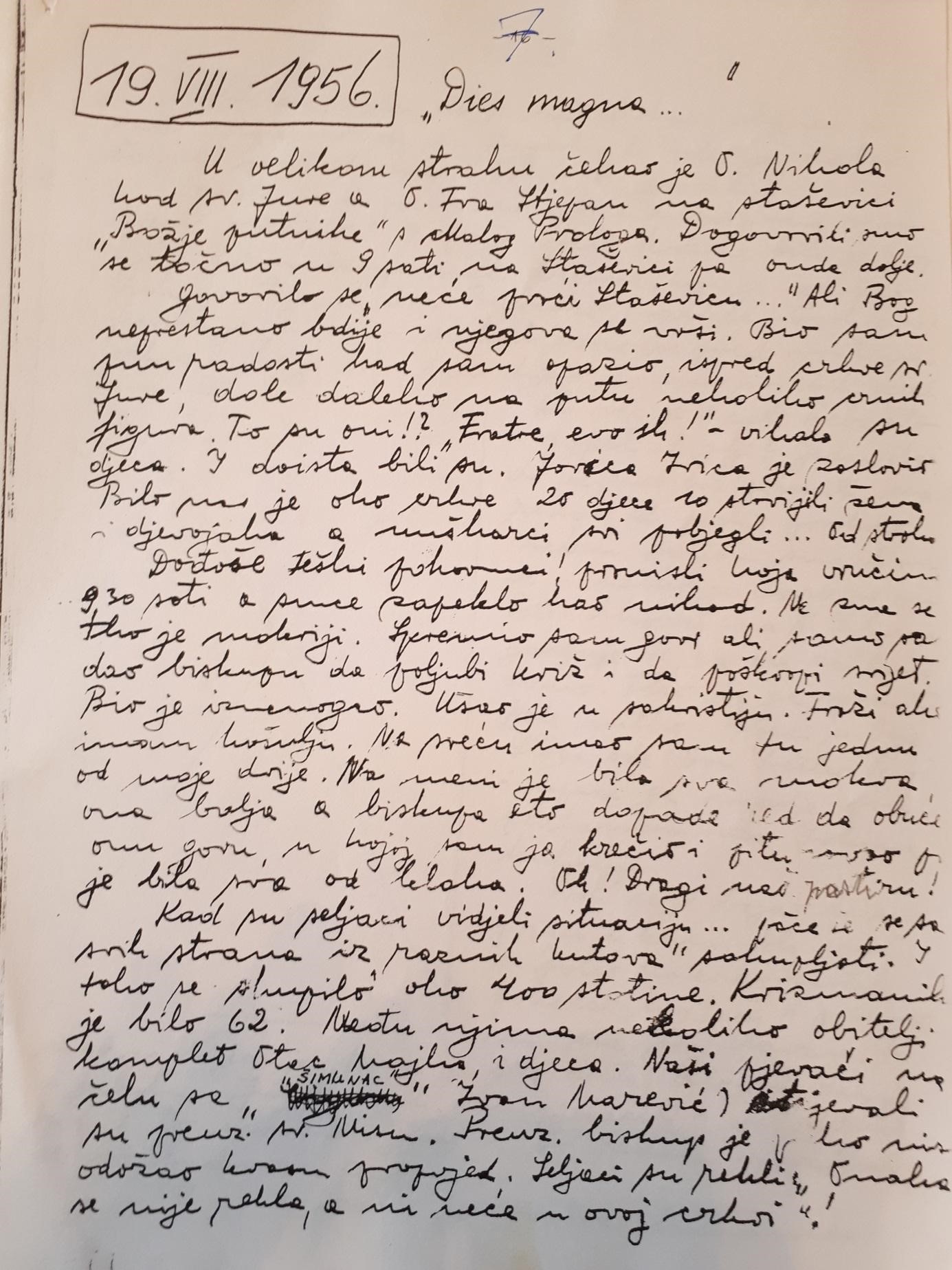

This record is from the Chronicle of the parish of Stasevica dated August 19, 1956, when Franić went on a pastoral visit to parishes in the area around the Neretva River, more precisely in the small village Staševica. Local communists attempted to prevent the arrival of Archbishop Franić in their parish through their Party organizations by physically stopping him on the road to the village, which he was visiting to share the sacrament of the confirmation to young people. The event testified to the total effort to de-Christianize society by the regime at the time. In that sense, Franić's diary is a genuine source of testimony about similar processes throughout his archdiocese.

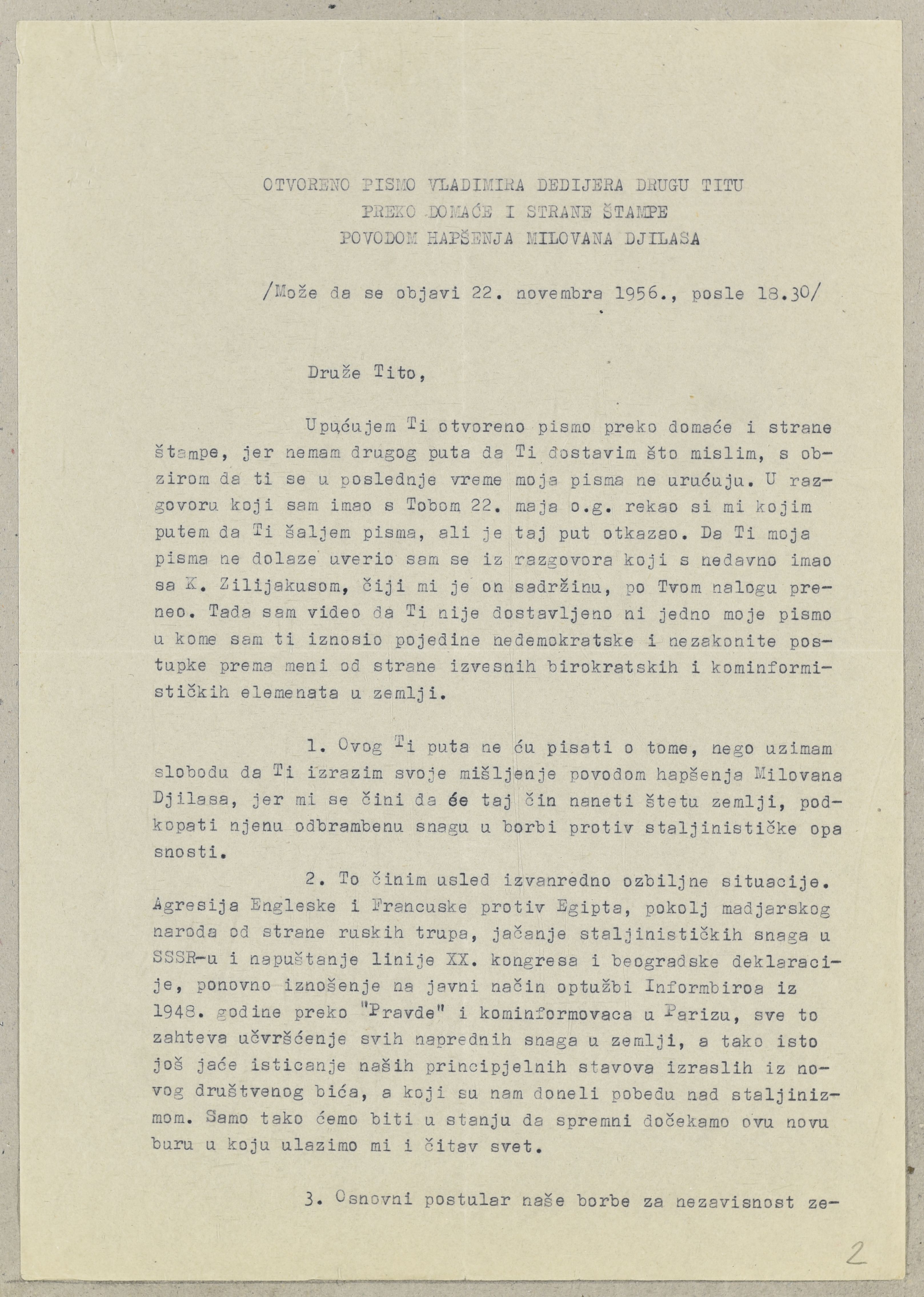

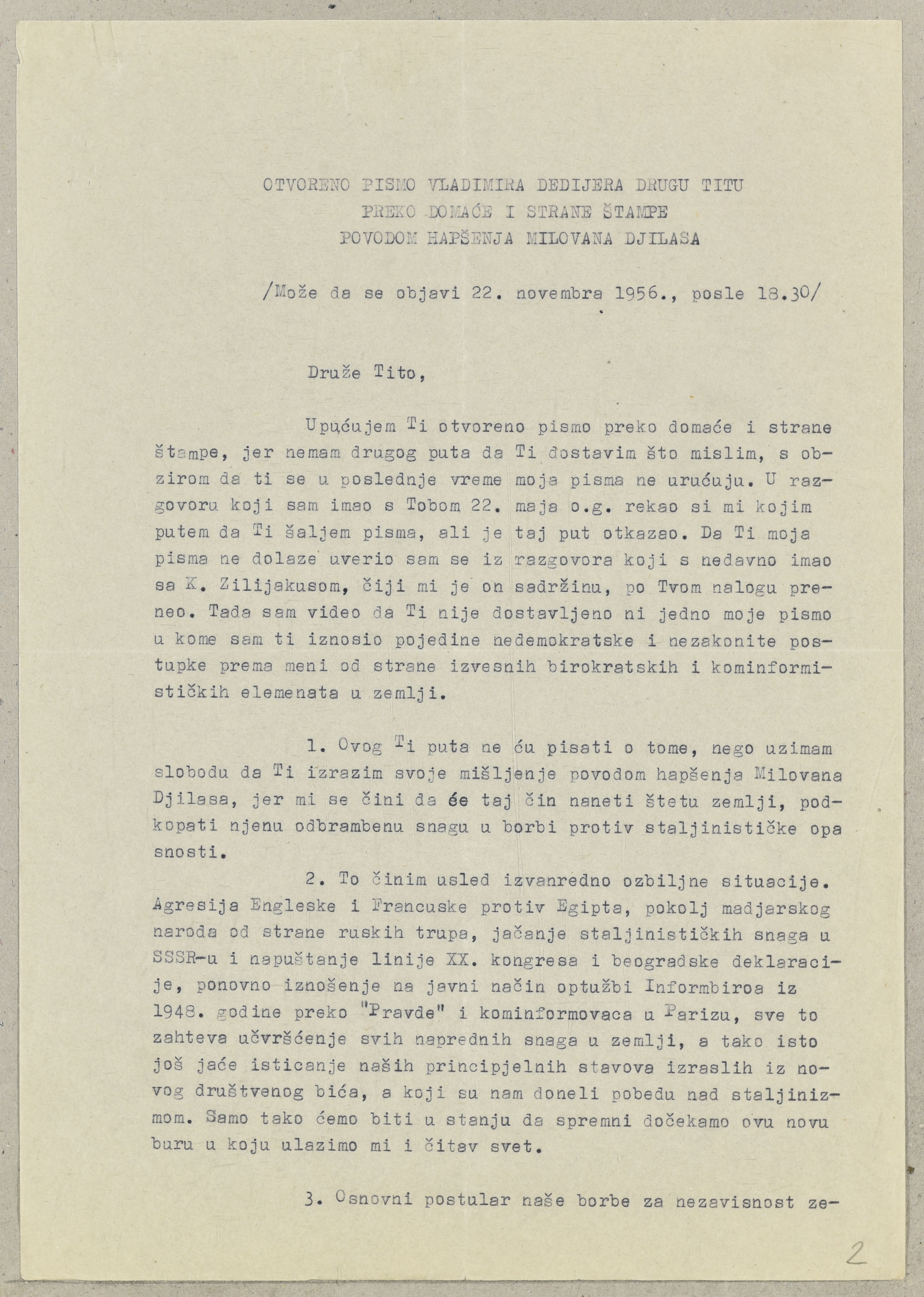

Vladimir Dedijer's open letter to Josip Broz Tito on the arrest of Milovan Djilas. 1956. Archival document

Vladimir Dedijer's open letter to Josip Broz Tito on the arrest of Milovan Djilas. 1956. Archival document

The Croatian State Security Service's operational data from the mid-1950s contain descriptions of the connections of Djilas supporters in Zagreb (the group around the banned weekly newspaper Naprijed) to the brothers Stevan and Vladimir Dedijer. Vladimir was editor-in-chief of the newspaper Borba at the time of publication of the Djilas articles. After a suspended year and a half sentence, he withdrew from political life and in 1955 emigrated to the United States. From 1950 to 1957, Stevan was director of the Nuclear Research Institute in Belgrade and the Rudjer Bošković Institute in Zagreb. Because of his public criticism of the Yugoslav nuclear programme, he was expelled from the Rudjer Bošković Institute, and in 1961 managed to emigrate to Sweden.

The documents in the Croatian State Security Service's file on the Djilas case and Djilas supporters in Croatia include a transcript of Vladimir Dedijer's open letter to Josip Broz Tito. Dedijer protested against the prosecution and arrest of Milovan Djilas due to an interview in which he criticised the neutral position of Yugoslavia on the Soviet army’s intervention in Hungary, which he saw as tacit support for that action. He was arrested on 19 November, and on 12 December 1956 convicted to 3 years of strict imprisonment for “anti-Yugoslav activities.ˮ Dedijer wrote, inter alia, that he is not defending Milovan Djilas as his personal friend, but rather because he has to stay “consistent in his conviction that they have to promote more democratic and humane forms” in Yugoslav society, that he cannot act against his conscience, defending in this way his personal integrity as a writer and intellectual.

The document is available for research and copying.

“Gediegenes Erz” (Solid ore) is the manuscript of a short story about the life of young Saxons in Romania in the first half of the 1950s. Under the influence of the German literary circle in Cluj, Eginald Schlattner started to question himself about the future of the Transylvanian Saxons. The author’s intention was to deliver a message for the integration of the German community in the new socialist society. This short story was published in 1956 and even received the prize of the official German-language newspaper in Romania, Neuer Weg. After Schlattner read this text during a youth meeting in Braşov in the autumn of 1956, the Securitate became interested in him and, contrary to the intentions of the author, interpreted the respective literary work as an appeal for the preservation of the German national identity in spite of the official emphasis on internationalism. The short story was banned in 1957, and was used by the Securitate against Schlattner during his interrogations in 1957–1959. The manuscript was confiscated in 1957 and was returned upon its author’s release in 1959. In 2012, Michaela Nowotnick edited the volume Odem, which included this short story together with other pre-1989 texts by Eginald Schlattner.