The State Archive of Literature and Art was established in 1968, when a branch of the Central State Archive was made into a separate archive. All the documents relating to literature and art (including the Union of Writers collection) were transferred to the new archive.

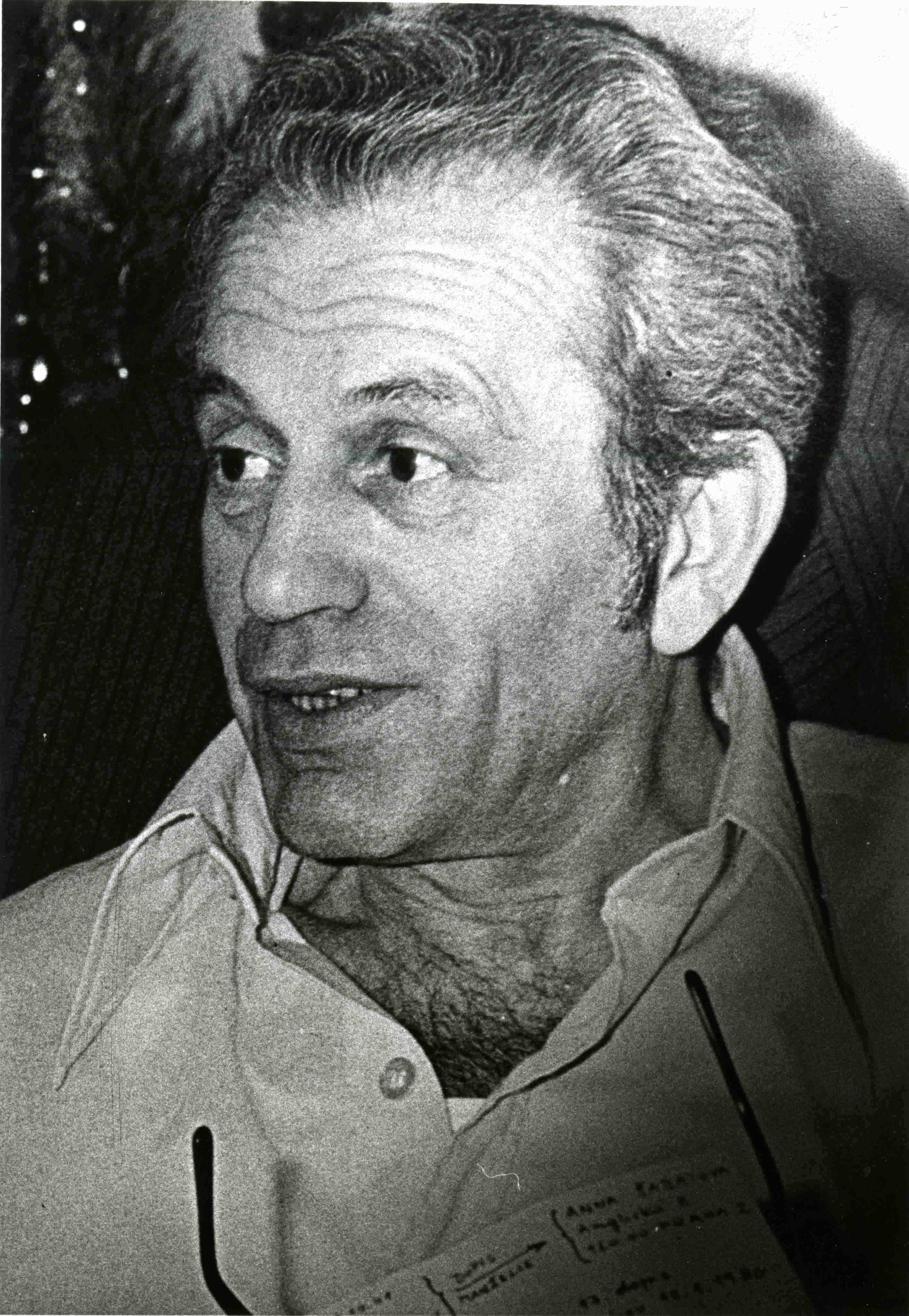

This photograph is from the ‘Red University’ series that shows scenes of the clashes between militia and students in 1968. On June 3, 1968, students from Belgrade University set off from New Belgrade towards the building of the rector’s office located in the old part of the city with the intention of demonstrating and stating their demands. They were soon stopped by a militia cordon. Veljko Vlahović and Miloč Minić, top officials in the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, spoke to the students and tried to convince them not to rally. However, militia and students clashed, resulting in injuries to at least four people. The following day, the students occupied the building of the rector’s office and proclaimed their programme. One of their demands called for changing the university’s name to the ‘Karl Marx Red University’. The occupation lasted seven days, while the protests spread to Yugoslavia’s larger university centres. It was ended by a television address by Josip Broz Tito in which he allegedly supported the students, acknowledging that irregularities did exist and should be removed. At that time a photo reporter with the Belgrade weekly ‘NIN’, Tomislav Peternek recorded the shocking scenes of the riots at the overpass in New Belgrade.

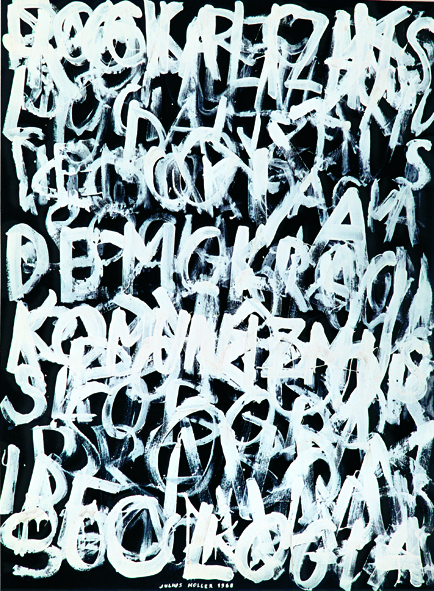

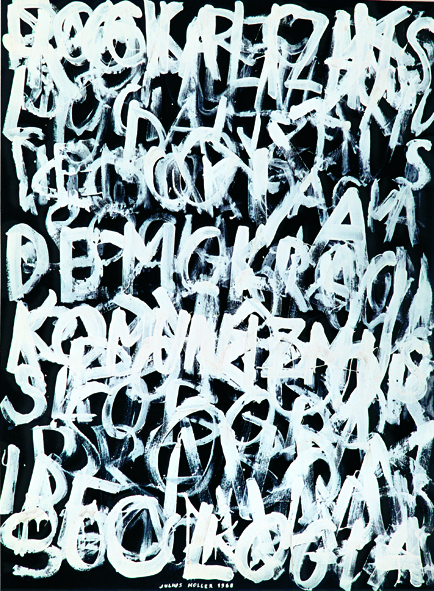

The Jan and Meda Mládek collection is the core of Museum Kampa exhibition. Besides works by František Kupka, an “undesirable artist” during the communist era, there is a broad collection of other works by artists from Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland that do not follow the official socialist style.

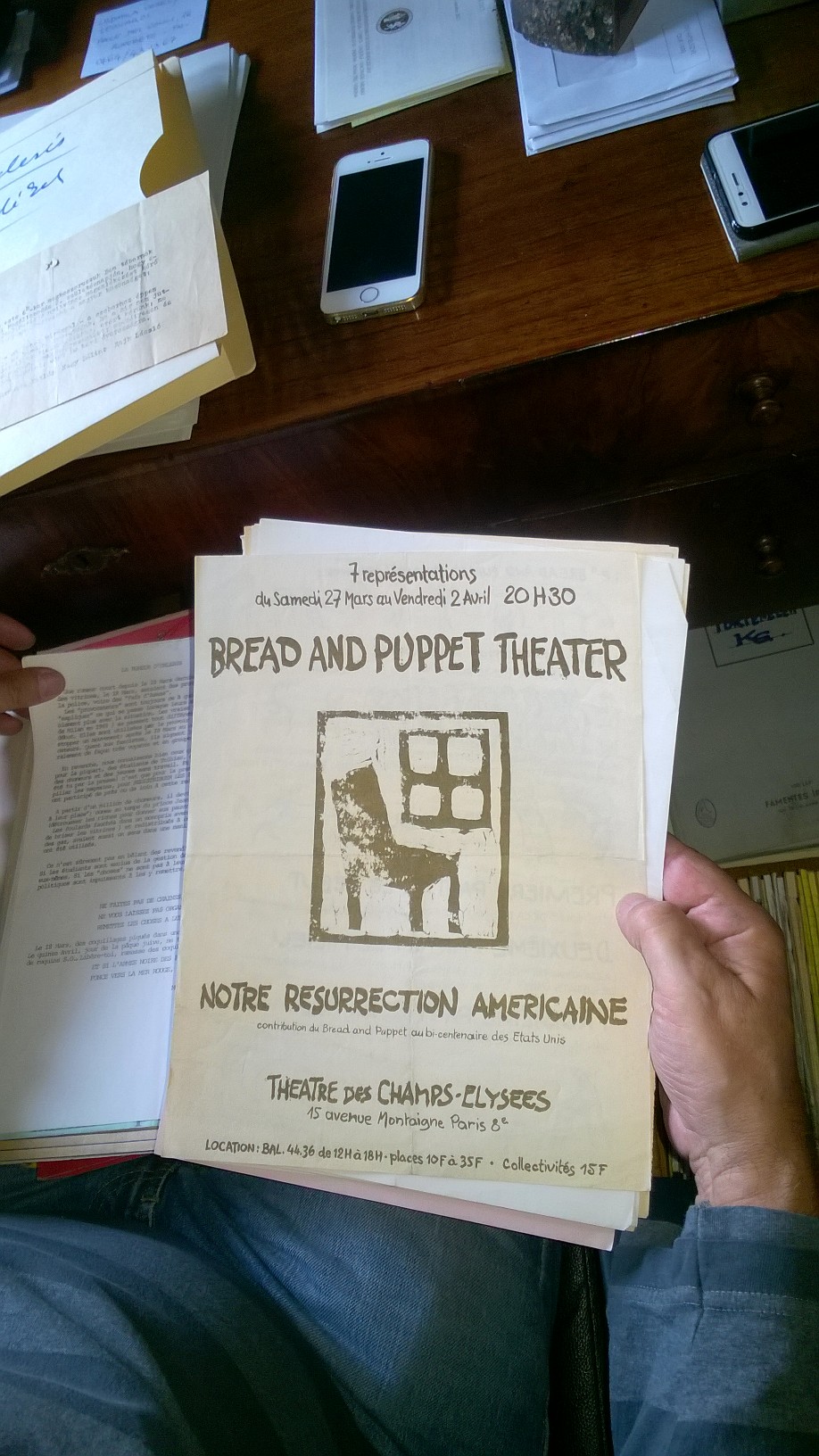

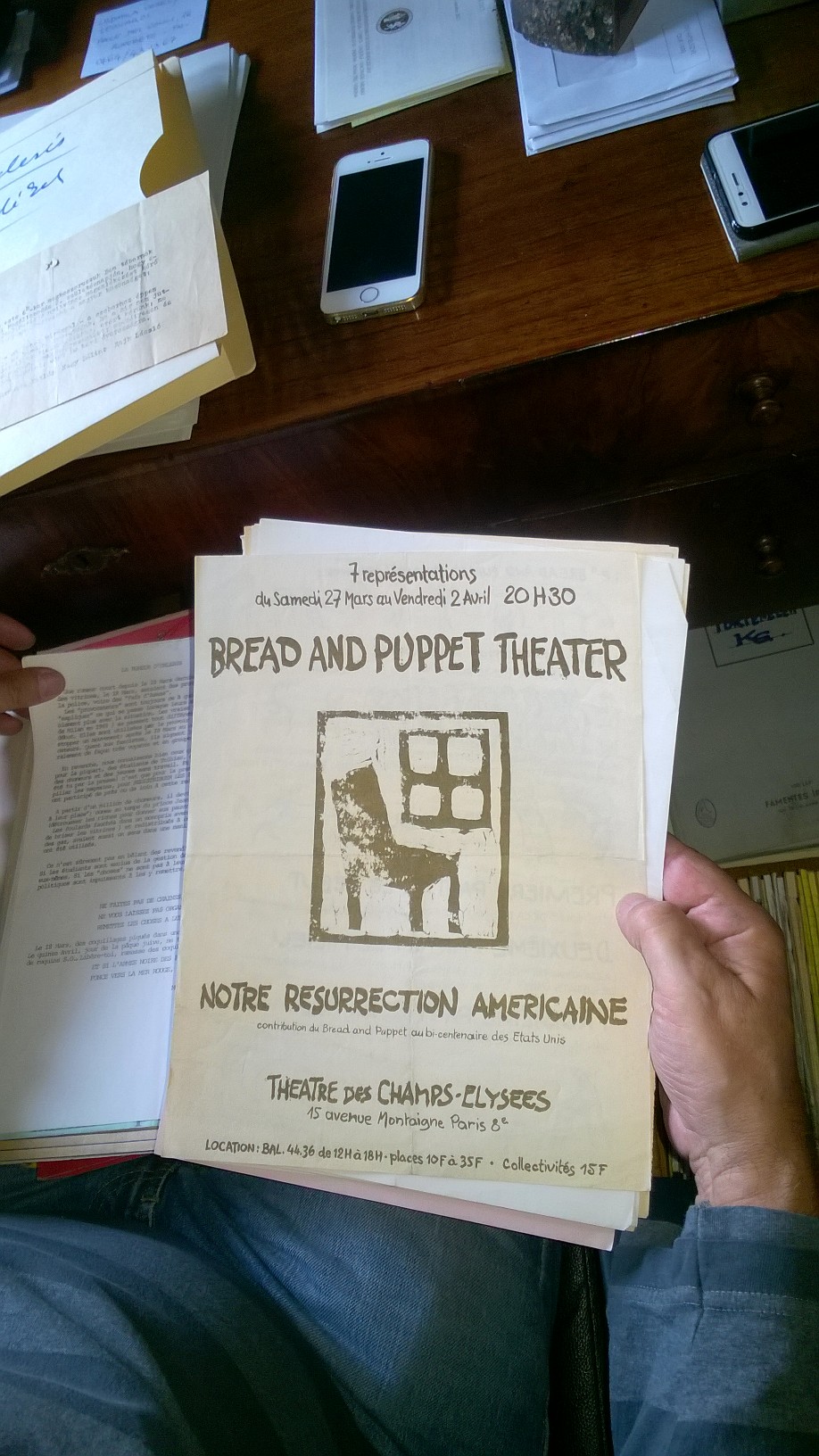

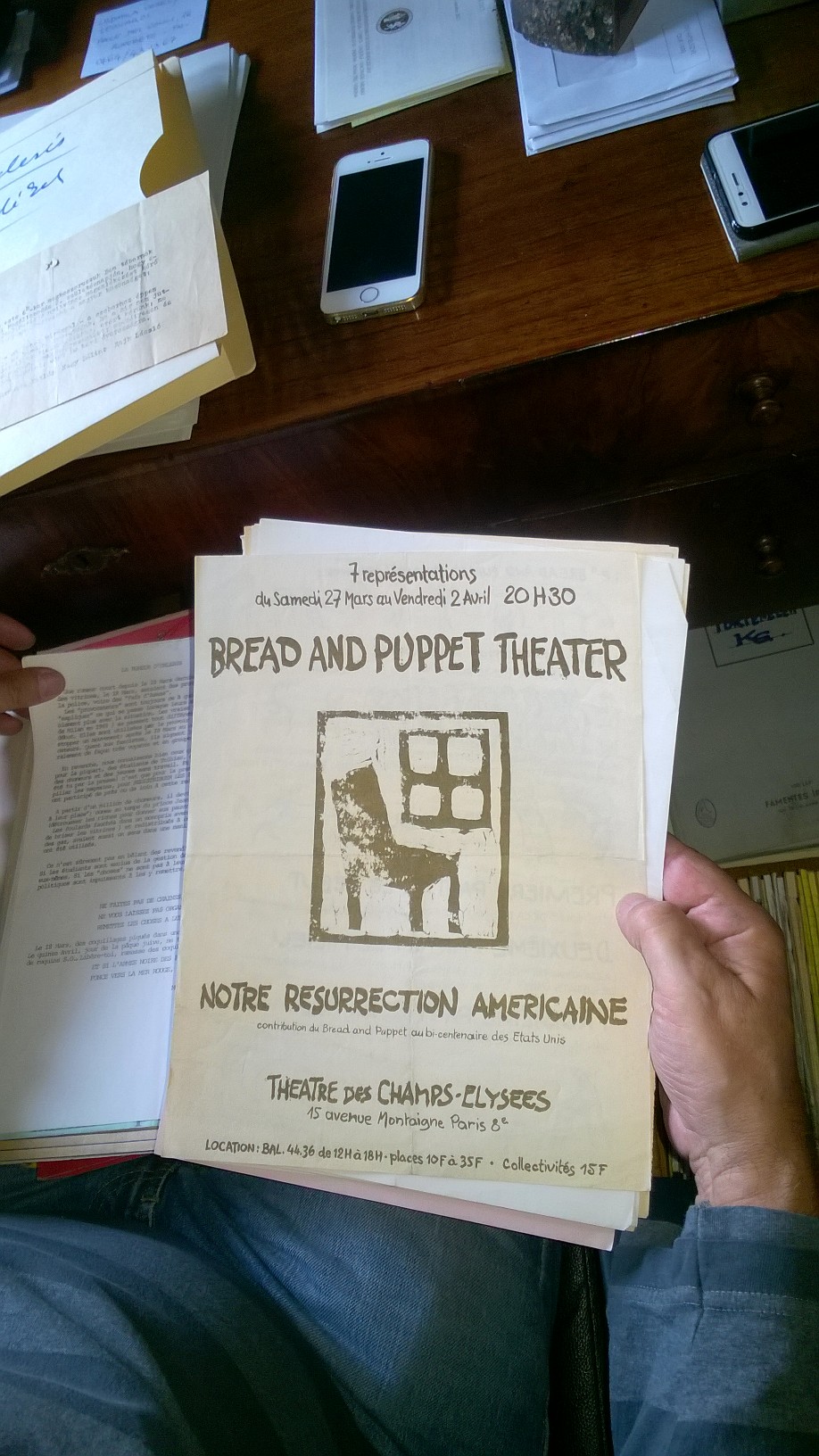

Gábor Klaniczay traveled to Paris for the first time in 1967, when he spent one year in the city. This journey was followed by more. During his travels, he collected an array of different material: leaflets, proclamations, and posters about alternative cultural life and student movements. These documents reveal the kind of ideas, trends, performances, and exhibitions he was interested in at the time. This particular item is a leaflet of Bread and Puppet Theater’s performance in Paris, entitled “Notre résurrection américaine.”

Ivan Blatný emigrated to England in 1948. In Czechoslovakia, he was labelled a “traitor” and became a banned author. Later, the Czechoslovak Radio even falsely announced that Blatný had died in England. In 1968, during the era of the “Prague Spring”, the interest in Blatný and his poetry grew in Czechoslovakia. An example of this increasing interest, there was a programme dedicated to Blatný’s poetry called “The Smells of Brno”. This programme, advertised by a small poster from the Ivan Blatný Collection, was organised by the Czech director and artist Karel Fuksa in the Brno House of Arts. Blatný’s poems were recited by Czech actors Ladislav Lakomý and Helena Kružíková. According to Fuksa, the hall was full. In the same year, the Blok publishing house issued the second edition of Ivan Blatný’s “Melancholic Walks”, and Blatný’s poems sporadically appeared in Czechoslovak press or on the Radio. Then, Blatný’s texts could be officially published in Czechoslovakia only after 1989.

Adrian Marino had an ample correspondence with Romanian intellectuals in exile, a correspondence that is preserved in his collection. It is worth noting the volume and content of his correspondence with the literary historian and critic Matei Călinescu, who defected to the USA in 1973, and went on to teach at Indiana University Bloomington. The letters received by Marino from Matei Călinescu can be found in the original in the files of his personal archive donated to BCU Cluj, while those received by the Călinescu from Marino were copied after 1989 and archived carefully in the collection. In these letters, Marino criticised Romanian literary life, the fierce competition among writers for positions in state cultural institutions in Romania, and the censorship practised by the publishing houses of the time. As their correspondence was monitored by the Securitate, Marino avoided formulating any critical political opinions and confined himself to cultural topics.

In the letter sent by Adrian Marino to Matei Călinescu on February 26, 1968, the former congratulates the latter for not being in the country to witness a literary life which he characterises as being “increasingly convulsive and thus sterile” (Marino 2010, 32). The “convulsiveness” was caused by the intensification at the end of the 1960s of the competition between various literary groups for positions which allowed the allocation of financial resources. In this case, the letter addressed to Matei Călinescu (who was in London) is written in the context of the departure of Eugen Barbu – one of the most controversial Romanian writers of the communist period – from the position of editor in chief of the literary magazine Luceafărul (The Evening Star), which was issued by the Writers’ Union of Romania and aimed at promoting young talents. Marino deplored the fact that literary life was “unpredictable” because of the frequent changes of the people who occupied leadership positions in publishing houses and literary magazines, which threatened the prospects of certain of his editorial projects. Dissatisfied with the tense atmosphere within the cultural institutions, Marino proposed withdrawal from public life and wished to emerge himself in his own cultural projects stating that: “We need the passion for study in itself, for itself” (Marino 2010, 32).

The Czecho-Slovak poet, novelist, playwright, philosopher and “guru” of the Czechoslovak underground, Egon Bondy (real name Zbyněk Fišer, 1930–2007), is well known as the author of dozens of collections of poems and novels. His philosophical texts, however, are an equally significant part of his work. Bondy, who graduated in philosophy from the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, was also interested in Eastern philosophy, in particular Buddhism. He wrote several academics studies on this topic in the first half of the 1960s, and published the book “Buddha” under his real name in 1968 through the publishing house Orbis. This significant study on the founder of Buddhism and his teachings caused a sensation in Czechoslovakia. The book was later republished twice (1995, 2006) in the Czech Republic and still remains topical.Bondy’s manuscript of his study of Buddha and his teachings was bought by the Museum of Czech Literature (PNP) in 1986 and is now part of the Egon Bondy collection deposited in the Literary Archive of PNP.

Lika Yanko was a Bulgarian painter, daughter of Albanian immigrants. She studied at the French College in Sofia. In 1946, Lika Yanko enrolled in the State Academy of Arts studying painting in the classes of Prof. Dechko Uzunov and Prof. Iliya Petrov but she was not allowed to do a diploma work. Her first independent exhibition in 1967 in Sofia was closed down prematurely. Lika Yanko continued to draw, choosing isolation and refusing to take part in art exhibitions and to be dependent on juries determining the limits of the permissible. Until 1981 when she received an invitation for exhibition by Lyudmila Zhivkova, her paintings had never been exhibited publicly. She managed to subsist due to the redemption of her paintings by foreign embassies and diplomats. Since those were "unauthorized contacts", Lika Yanko was under constant surveillance, observed and eavesdropped by the structures of the State Security; however, her record was destroyed.

At the beginning of her career, Lika Yanko drew landscapes, portraits, figured compositions. After the closing of her exhibition, she completely laid aside any restrictions in her painting. In the 1960s, Lika relinquished the landscapes and embraced the mythopoetic composition: she stylized the forms, shortened the spatial plans and distanced herself more and more from the principles of nature-resemblance defended by the authorities. Her self-portrait of 1968 shows a face half-covered by bars, a symbol of interdiction. Her paintings of the 1970s are dominated by themes from Christianity seen through the eyes of the author. Lika Yanko used the rope as a contour, incrusted beads, buttons, nuts, splinters, and pebbles interweaving astrology, Christianity, reflections on eternity and the initial things.

In the course of her entire life, Yanko had only 7 exhibitions; she died (of pneumonia) only a few days after the opening of the last one at the Cavalet Gallery in the city of Varna. While still living, Lika Yanko presented the National and the Sofia City Art Gallery with paintings.

In the absence of an organized rebellion which was present even among the Soviet artists, the most common form of resistance in Bulgaria, according to Iliev, was the self-isolation. Lika Yanko was an example of such type of opposition to the regime.

In 1989, Lika Yanko received the Sofia Award.

Rudolf Mihle (1937-2008) was one of the most important Czech amateur filmmakers. Some of his films were critical of the communist regime and society, and so could not be publicly screened. This was also the case for the film “The First Hours of Occupation”, which was filmed during the first days of the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968. The images of the dramatic events from the streets of Prague are accompanied by Czechoslovak Radio broadcasts from the time. The film was banned and could not be publicly screened until 1990. In the same year, Rudolf Mihle received several awards for this film, including at the World Nonprofessional Film Festival UNICA 90 in Sweden, and at the Amateur Film Festival in Hradec Králové, Czech Republic. In August 2018, the film with English subtitles was published on YouTube by Czech Radio as part of its “Project ʼ68”.

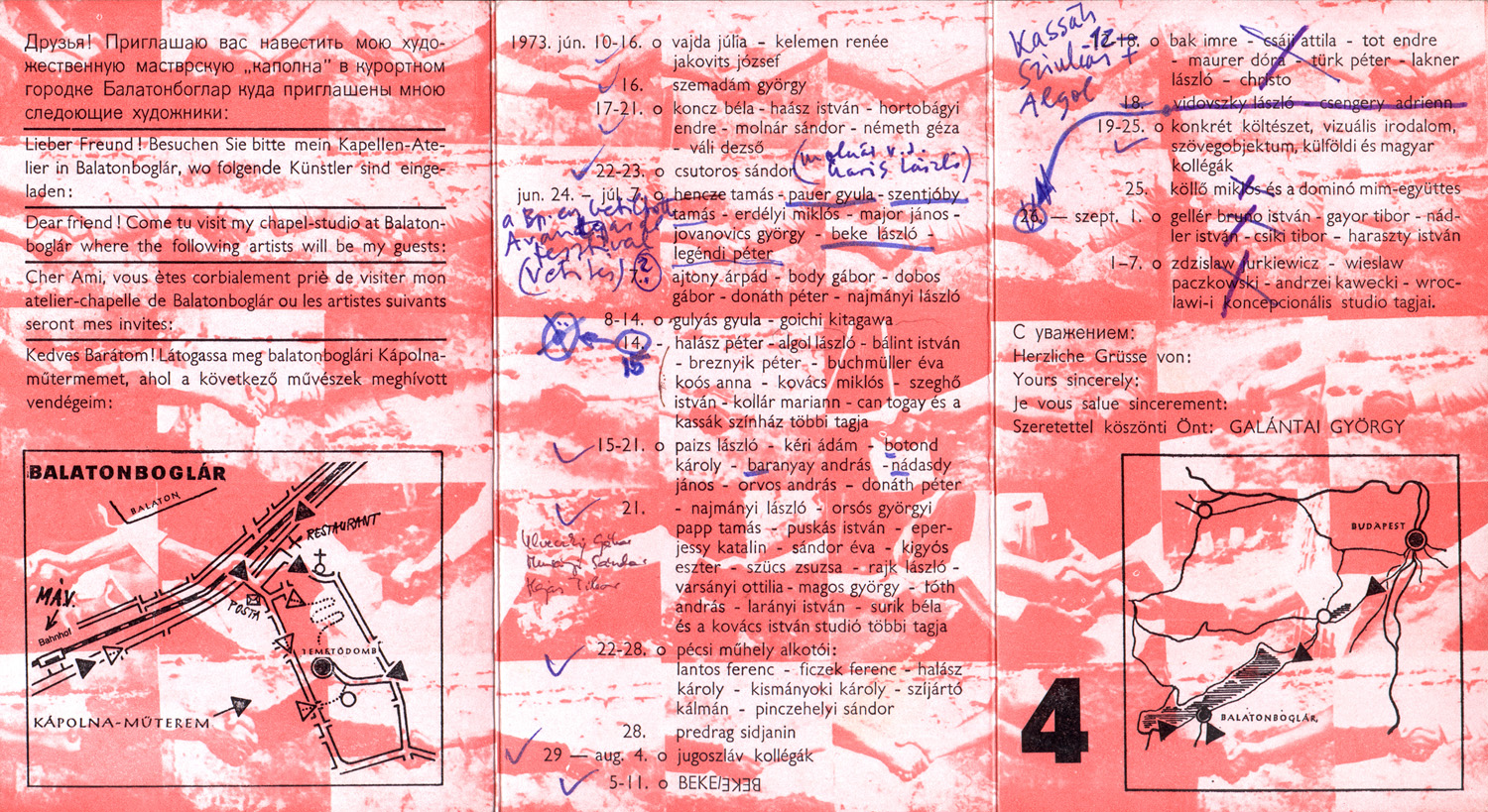

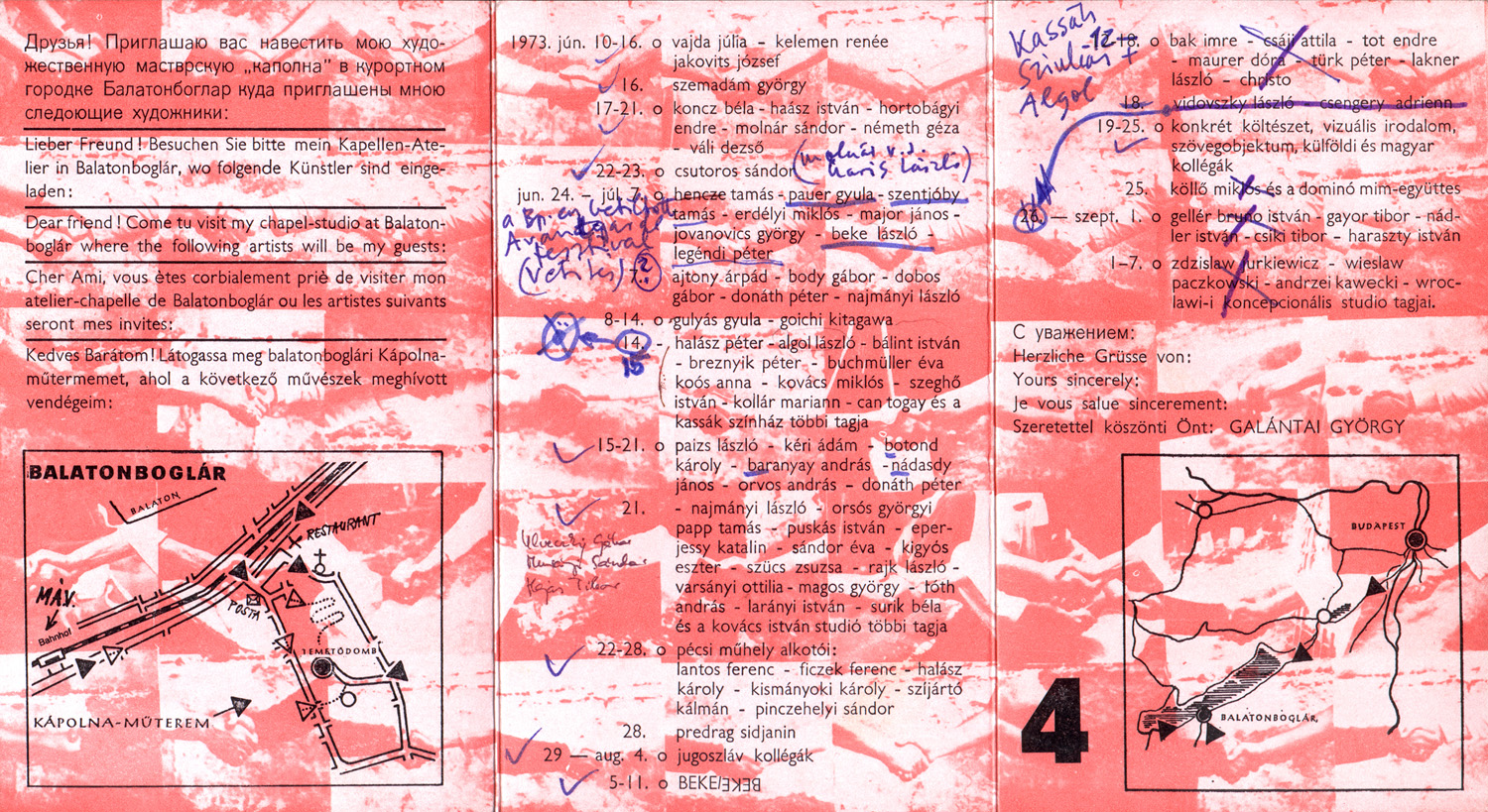

Artpool Art Research Center collects, archives, and makes available documents for researchers regarding marginalized art practices of Hungary in the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary international art tendencies. Topics in the archive include progressive, unofficial Hungarian art movements (such as underground art events, venues, groups, and samizdat publications between 1970 and 1990) and new tendencies in international art beginning in the 1960s.

In addition to functioning as a research center, Artpool considers itself an active archive. It organizes events in search of new forms of social activity, participates in the process in a formative way, and simultaneously documents and archives these process in order to promote the free flow of information.

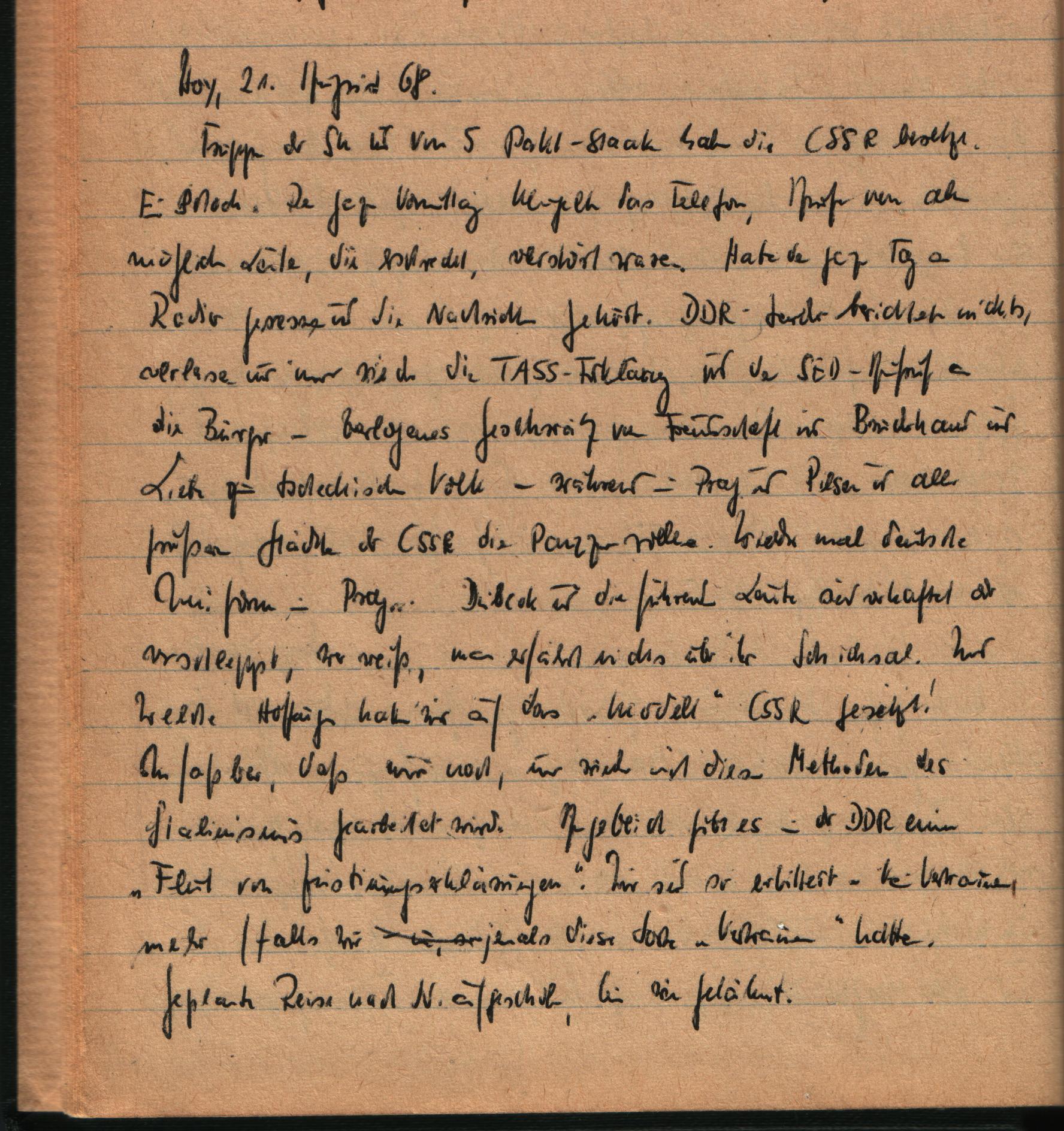

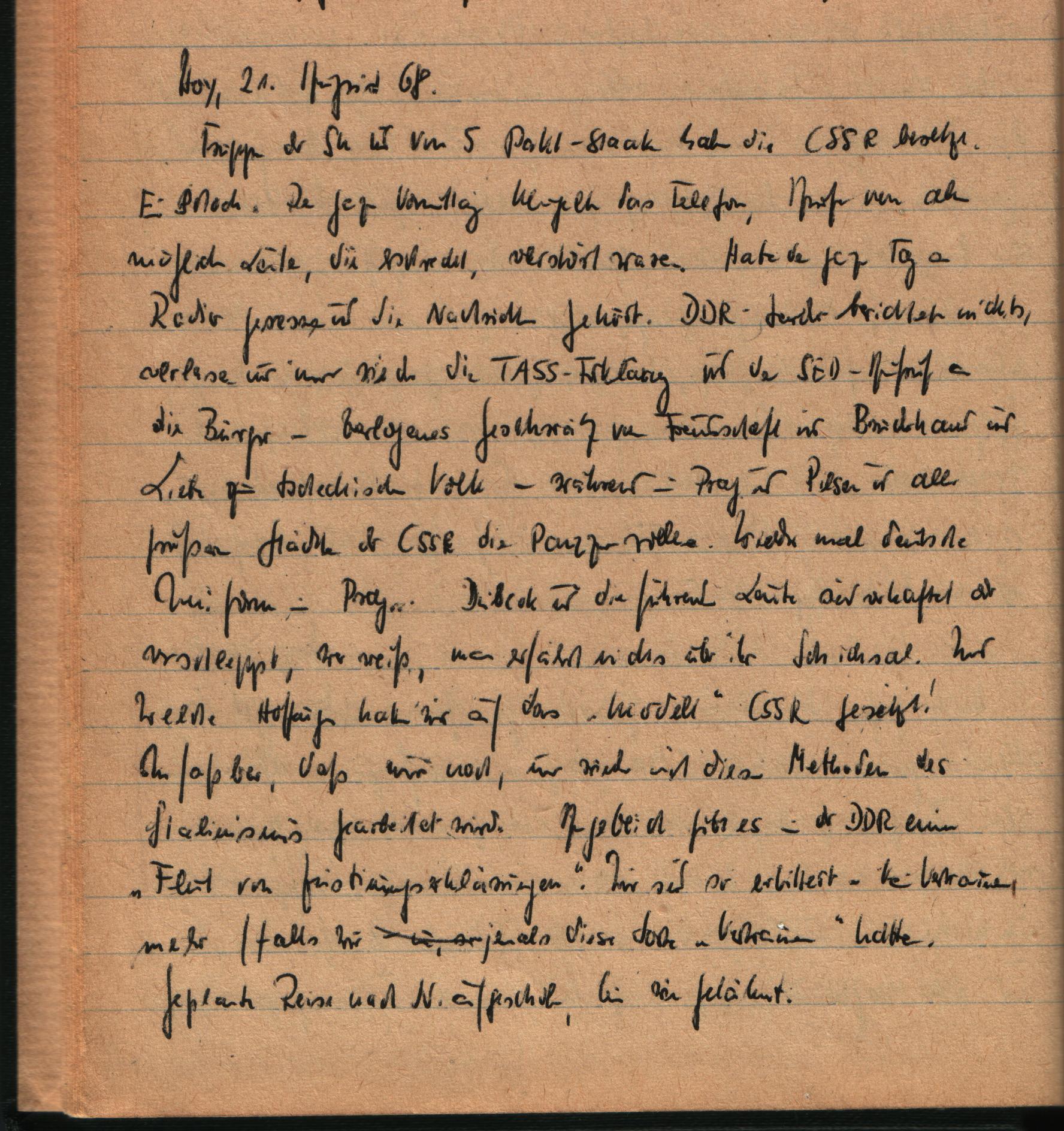

The invasion of Warsaw-Pact troops and the defeat of the Prague Spring shocked Brigitte Reimann. At precisely this moment, she lost all trust in the leadership of the GDR. Reimann noted in her diary on the 21st of August 1968:

[Transcription of the scanned masterpiece] Hoy[erswerda], 21. August 68. Troops of the SU [Soviet Union] and five members of the Warsaw Pact have occupied the CSSR [Czechoslovak Socialist Republic]. Shocking. My phone has been ringing the entire morning, calls from all sorts of people who are horrified and drained. All day, I have sat next to the radio listening to the news. GDR-channels have not said a thing, repeating only the official TASS-release and the deceitful appeal of the SED-government to its citizens to show friendship, brotherhood and love to the Czech people, while at the same time tanks are rolling through Prague and Plzen and all of the other large cities of the CSSR. Once again German uniforms in Prague. Dubcek and the ringleaders have either been arrested or carried off, who knows, we have heard nothing about their fate. And what hopes we had for the ‚Model‘ CSSR! Unbelievable that Stalinism is still enforced with these methods. Supposedly, there is an “Outpouring of Declarations of Support” emanating from the GDR. We are so bitter, no longer able to trust (supposing we were ever able to trust this ‚sort‘.) My trip to N[eubrandenburg] has been delayed, I feel paralyzed.

The fourth New Tendencies event was held in Zagreb from August 1968 to August 1969. Tošo Dabac visited the event, where he took a photograph of one of the meetings of participants. The photograph shows Dušan Džamonja, Marija Braut, Božo Beck, Ivan Picelj and Victor Vasarely.

A samizdat book by György Bulányi entitled Seek the Country of the Lord! /Keressétek az Isten Országát! - KIO/ includes the theological background of the Bokor base movement. The author summarized the ideals which needed to be followed as the New Testament Gospel: the values of poverty, nonviolence, and love. Bokor’s theology focused on Jesus’s love, which can never be replaced by ceremonies. It required social, practical action from people, such as making donations, performing useful services, and maintaining a commitment to nonviolence. 6 volumes of KIO were published legally in 1991.

Jiří Lederer (1922-1983) was a Czech journalist and publicist, one of the most prominent journalists during the "Prague Spring" in 1968. In the 1970s he participated in the work of the Czechoslovak opposition and was one of the first signatories of Charter 77. During the 1970s he was imprisoned several times. In 1980 he went into exile. The collection mainly contains materials and notes from the period around the Prague Spring.

Rudolf Mihle (1937-2008) was one of the most important Czech amateur filmmakers and an active member of the Czech Club of Amateur Filmmakers (Český klub kinoamatérů). In 1968, he filmed a six-minute documentary film “The Time of Accumulating Stones” (Čas shromažďování kamení), which depicts the Berlin Wall in June 1968. The film was featured in 2011 at the 15th International Documentary Film Festival in Jihlava, Czech Republic, as part of the project “Amateur Filmmakers” (Kinoamatéři).

Immediately after the founding of the Society of Students of the Faculty of Arts of UJEP Brno, the first issue of the magazine "Ruch" was published (15 March 1968). The magazine provided the information on the reasons for establishing the association and its internal structure. It gave information about events at the university, petitions, public letters, and contacts with other universities in the Czechoslovakia and abroad. In addition to the predominant political focus of this paper, poems, parodic texts, illustrations appeared. The first issue was followed by the second after three weeks. The print had not been published regularly (was published about once a month), and was officially referred to as an interviewer. It was printed in hundreds of copies (400-600) and was sold at the faculty for CZK 1. The authors of texts and graphics were a changing group of students - usually members of the association.

During his detention in Mordovia in 1963-1969, Knuts Skujenieks wrote several hundred poems. He was allowed to send two letters a month, and sent poems in letters to his wife which were read by his colleagues. After his release, he composed a collection of poetry, but it could not be published until 1990, and was only published in its entirety in his complete works in 2002. As Skujenieks said, this poetry ‘is not "gulag" poetry, but poetry written in the gulag [...] The initial shock and protest gradually turned into a fight in prison within myself' (Bitite Vinklers. Introduction. In: Seed in Snow. Poems by Knuts Skujenieks. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2016, p. 9).

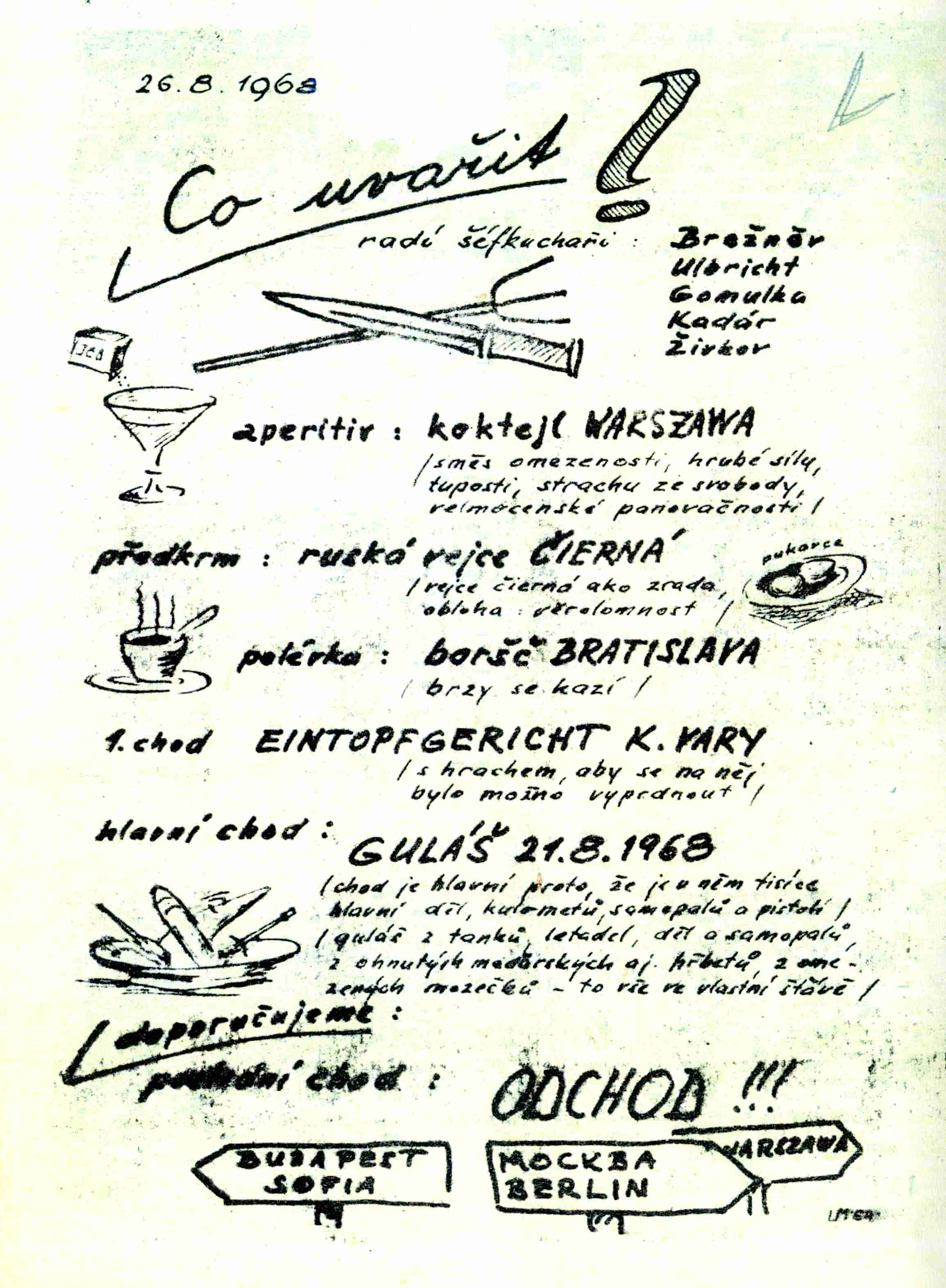

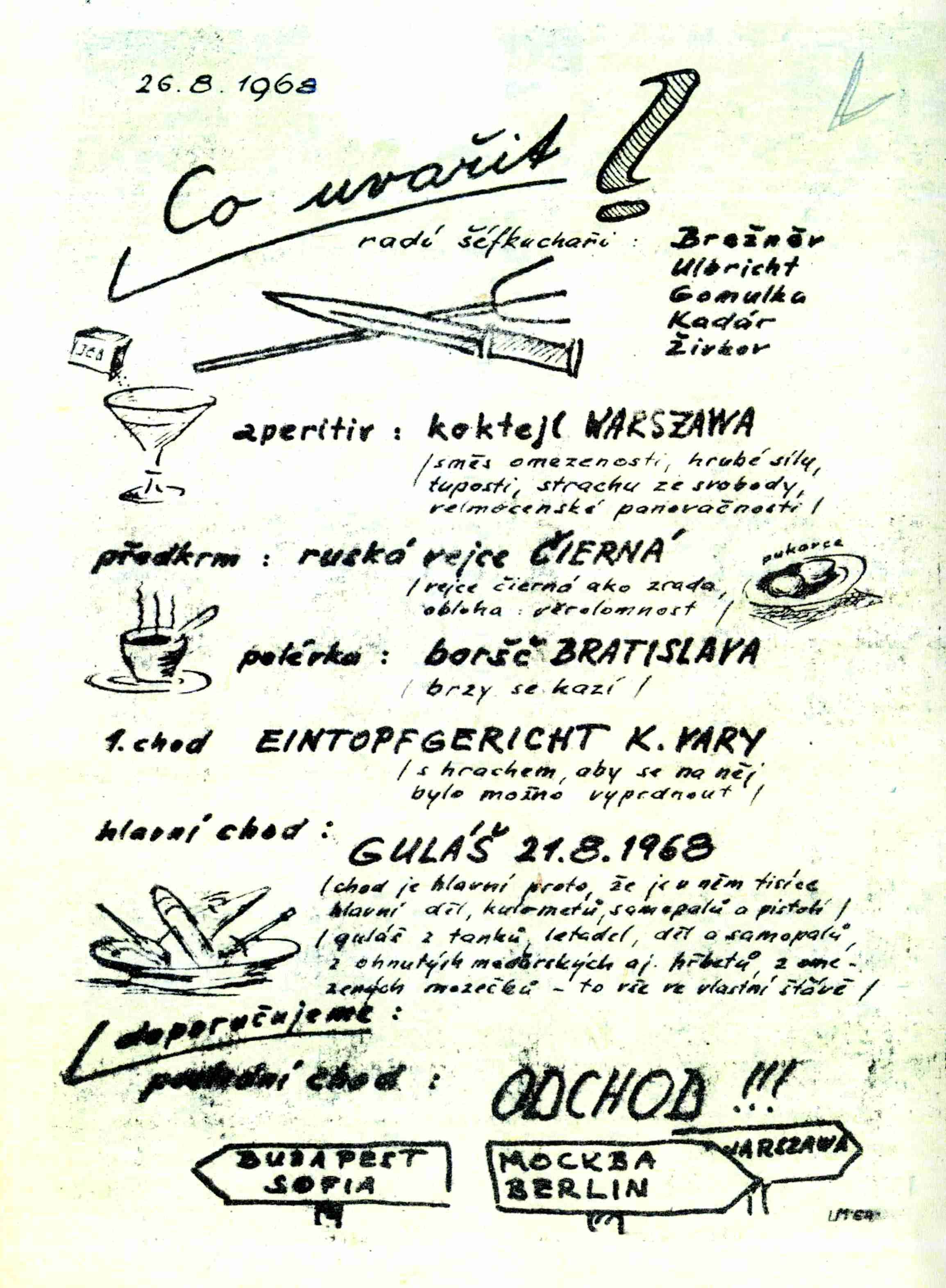

The leaflet was created in August 1968 after the occupation of Czechoslovakia by five armies of the Warsaw Pact. From the beginning of the invasion on August 21, 1968, spontaneous demonstrations of resentment and opposition to the occupation took place. One of the demonstrations of resistance was the display of hundreds of posters, passwords and banners on walls, showcases, trams and buses, calling on the occupants to leave.

The leaflet proves that the population opposed the occupation openly and that even in this tedious and difficult situation, a sense of humor was not lost.

The flyer was exhibited at the exhibition, “…And tanks arrived/” Prague, National Museum, 2008.

The edition of the magazine Marm was published in 1968. It was the first samizdat magazine to be compiled outside an institution. For example, the magazines HEES and HEES 2 were partly related to the Young Authors Association, which was related to the Writers' Union. These first publications created the samizdat tradition in Estonia, which continued until the restoration of independence. Kersti Unt describes Marm as follows: ‘Many poems in both publications talk about headlessness, an aimless existence without meaning, and about suffering, hypocritically being related to all of this, even about living in the wrong times.’ The cover of Marm magazine was designed by Kaljo Põllu, who was the head of the Art Department at the University of Tartu, an avant-garde artist, and the founder of the Visarid group of artists. Many leading figures in the almanac movement in Tartu consider this publication to be the most prominent. Marm magazine also published poems by the resistance fighter Jaan Isotamm (Johnny B. Isotamm).

![Lešaja, Ante. 2014. Praksis orijentacija, časopis Praxis i Korčulanska ljetna škola [građa] (Praksis Orientation, Journal Praxis and The Korčula Summer School [collection]). Beograd: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, p. 224.](/courage/file/n25045/okupacija+1968.jpg)

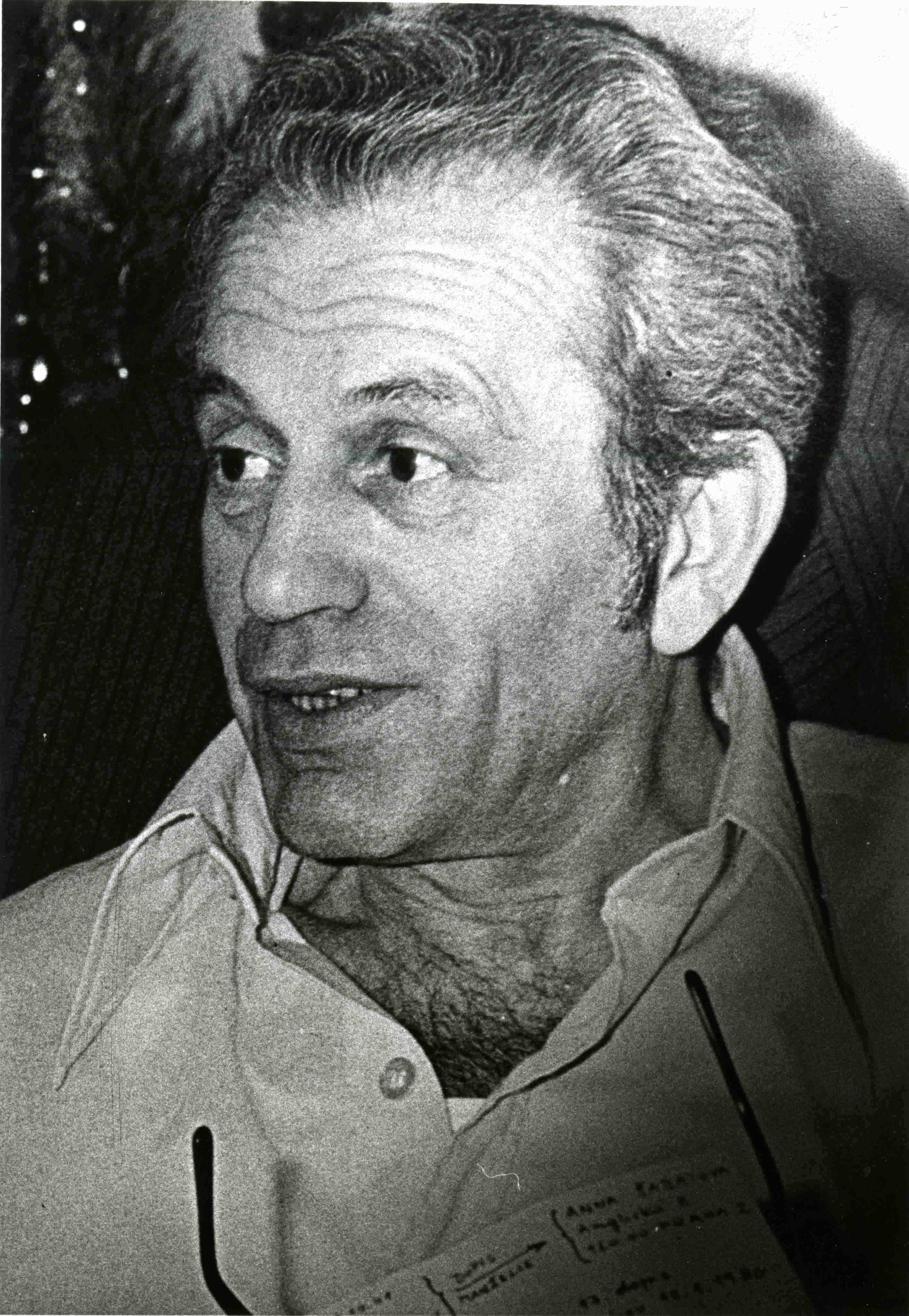

Participants in the Korčula Summer School discussing the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia, 1968. Photo

Participants in the Korčula Summer School discussing the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia, 1968. Photo

The photograph shows participants in the Korčula Summer School discussing the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and preparing an official protest. About 70 prominent non-conformist Marxist and left-wing philosophers from Western and Eastern countries attending a symposium on "Marx and Revolution" at the Korcula (philosophical) Summer School, fiercely condemned the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet-led Warsaw Pact forces in August 1968. According to a Western journalist who took part in the symposium, the protest was expressed in the form of an appeal "to all Communist, Socialist and progressive forces all over the world to condemn this aggressive act." The appeal compares "the situation of Czechoslovakia with that of Vietnam," and the Soviet aggression "with that committed by Hitler's Germany.” One of the declarations was issued by the editorial board of Praxis and sent to Yugoslav President Tito, urging him to "defend the cause of Communism and Socialism against any kind of hegemony, and against a revival of conservative forces." The declaration also urged Tito to fully "utilise the authority of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia to support Czechoslovak progressive forces."

The society of students of Faculty of Arts, UJEP Brno Collection at the Archive of Masaryk University

The society of students of Faculty of Arts, UJEP Brno Collection at the Archive of Masaryk University

Collection of documents from the independent association of students and graduates of the Faculty of Arts, UJEP. The Collection of artefacts includes: handwritten posters, prints and typography documents, collated from a dramatic period, 1968, and the beginning of the normalisation (mainly at the Faculty of Arts in the City Brno and all of Czechoslovakia).

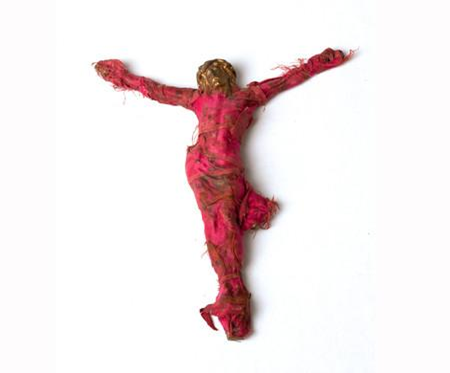

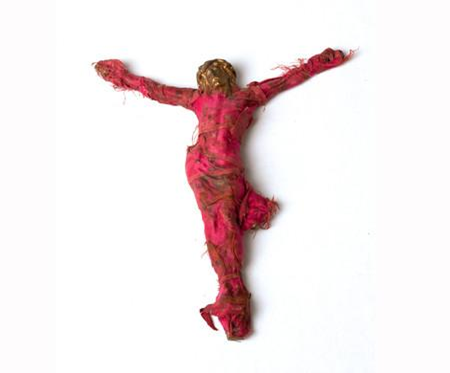

Trokut’s sculpture Red Corps from 1968 is a work that connects the symbolic universalism of the crucifixion and material suffering (playing with the word corpus). The symbolism of the colour red represents the revolutionary spirit, both in art and politics. The conceptual performances in which Trokut was involved reflected criticism of the communist regime from the standpoint of the left avant-garde (Red Peristyle intervention, the Red Sea action).

The Czechoslovak Students’ Movement of the 1960s Collection (Ivan Dejmal Collection) at the Libri Prohibiti Library contains valuable sources documenting Czechoslovak students’ movement in the 1960s, and especially during the years 1968 and 1969. Materials, which were collected by the leading Czechoslovak student activist Ivan Dejmal, illustrate, among other things, students’ activities during the so-called “Prague Spring” or reactions of students’ milieu to Jan Palach’s self-immolation in 1969.

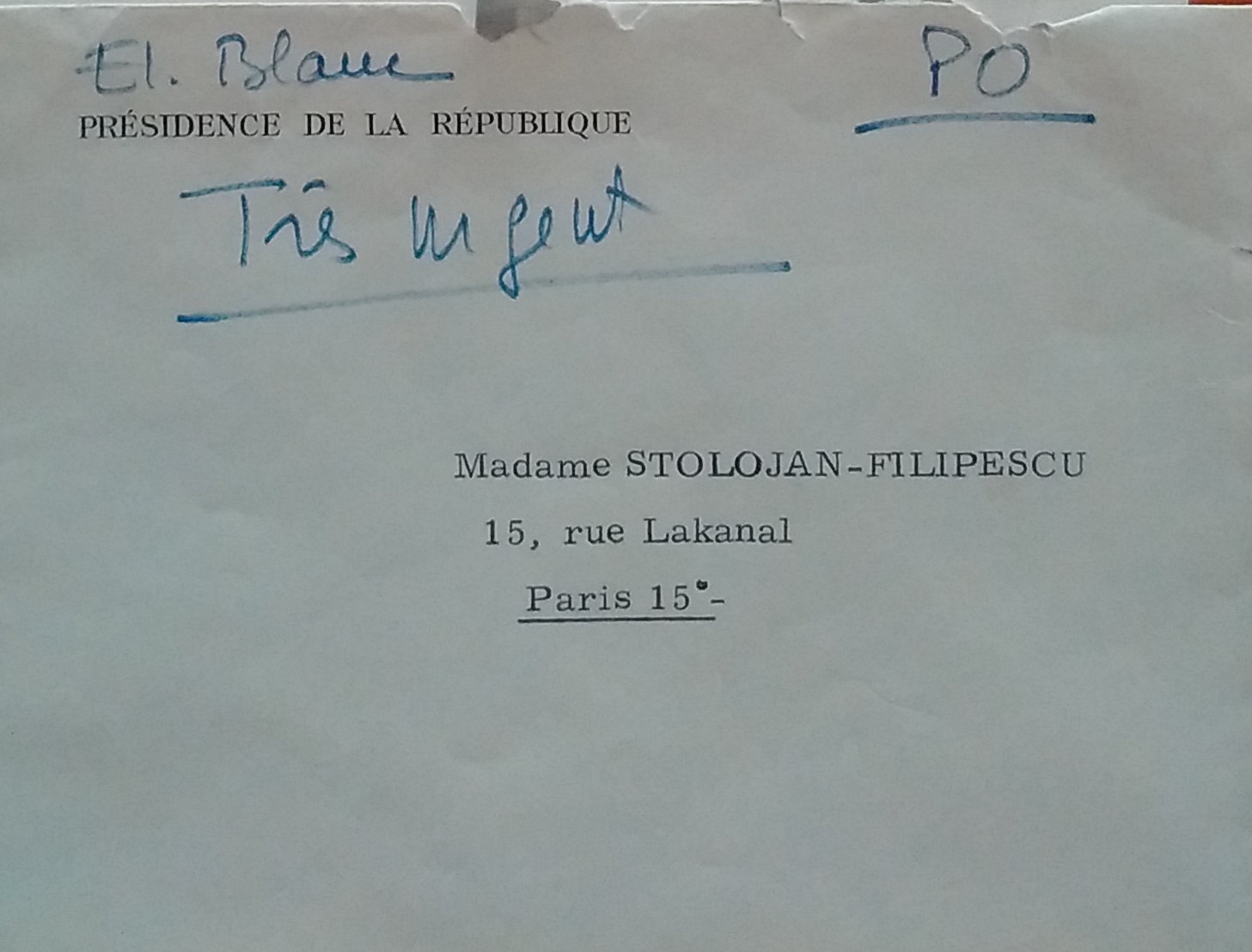

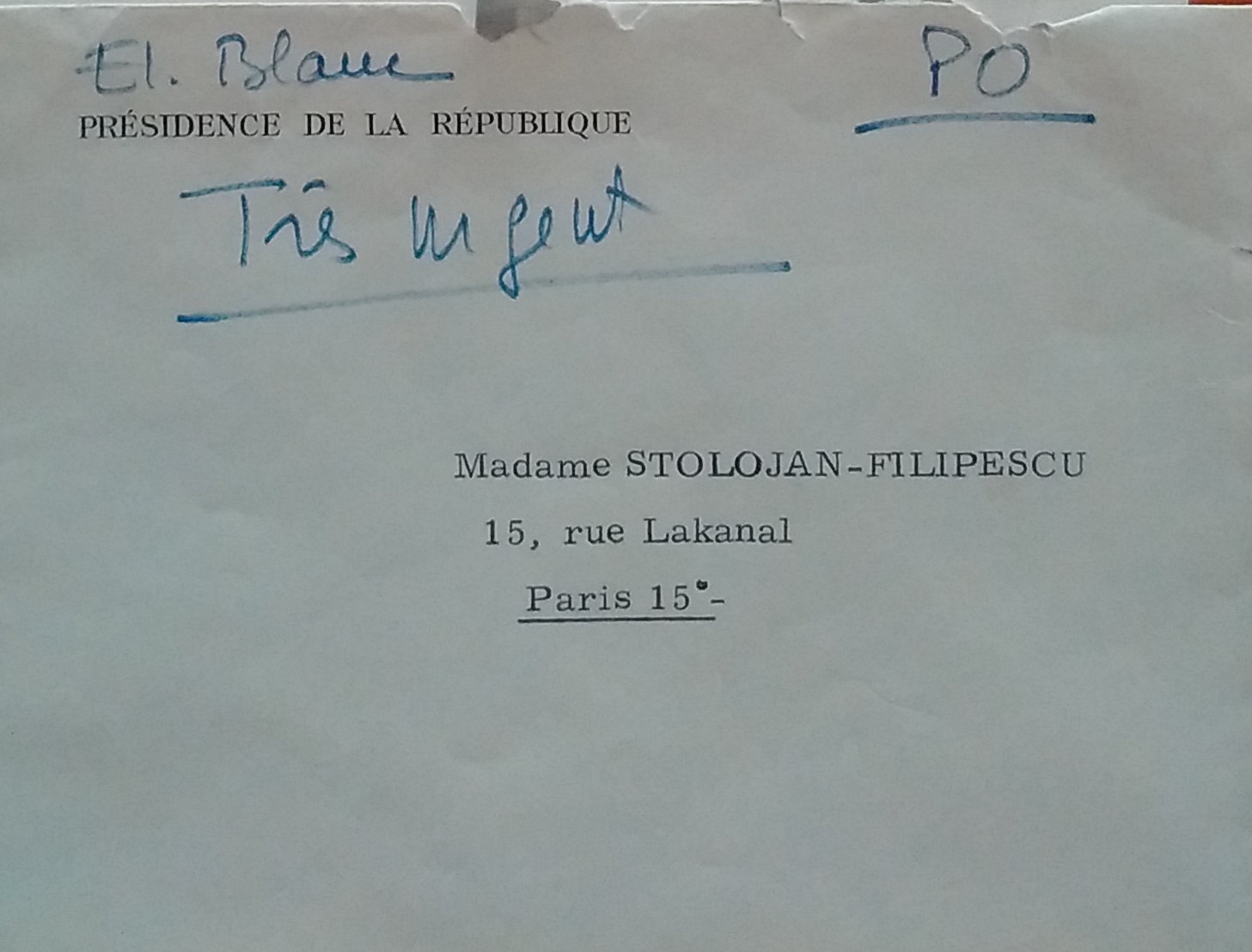

Letter of invitation from the French Foreign Ministry to Sanda Stolojan, in French, Paris, 9 May 1968

Letter of invitation from the French Foreign Ministry to Sanda Stolojan, in French, Paris, 9 May 1968

The collection of the writer Vincas Mykolaitis-Putinas holds various documents: notes, correspondence and manuscripts. The documents illustrate very well the situation of intellectuals and writers in Soviet Lithuania. The government considered Mykolaitis-Putinas to be a famous Lithuanian writer, but on the other hand it tried to control his creative work. During the Late Stalinist period, the writer was often criticised by Party officials.