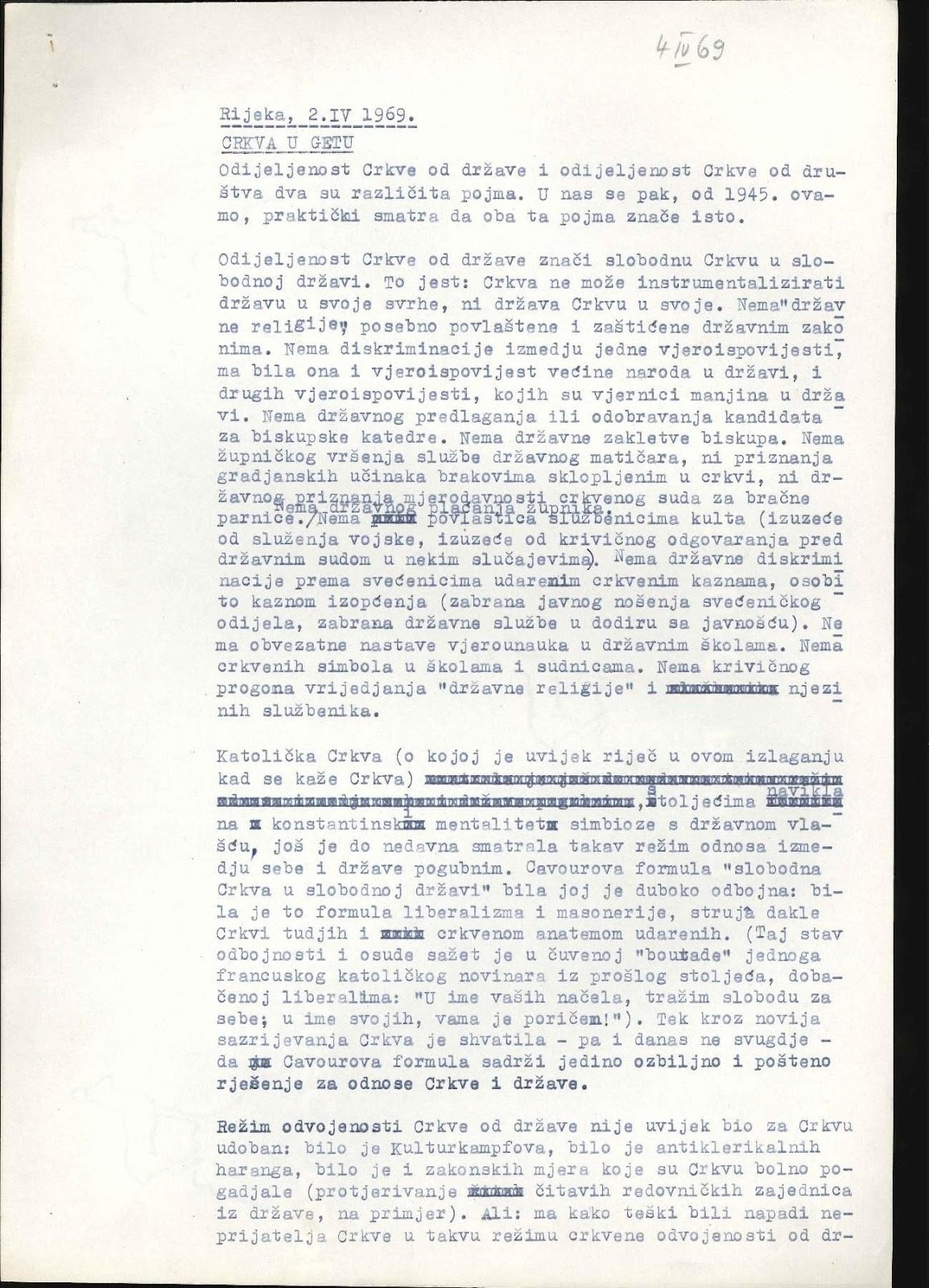

This manuscript was written on 2 April, 1969. Rendić raises the question of the position of the Catholic Church and Catholics after the so-called "liberalization" of the Yugoslav regime. She came to the conclusion that after ceasing the policy of open force, nothing had substantially changed in their position. She added that both the Church and Catholics live together in a sort of social ghetto isolated from the mainstream of socialist society, since "as it is with all liberalization, the Church remained in a ghetto, the Church is not moving from the ghetto at all" (Rendić 1969: 12). For this state of affairs, Rendić pointed to, as she said, the "totalitarian atheism" of the then socialist regime in Croatia and Yugoslavia, who taught that the progress of time would necessarily lead to the disappearance of religious consciousness throughout socialist society (Rendić 1969: 10).

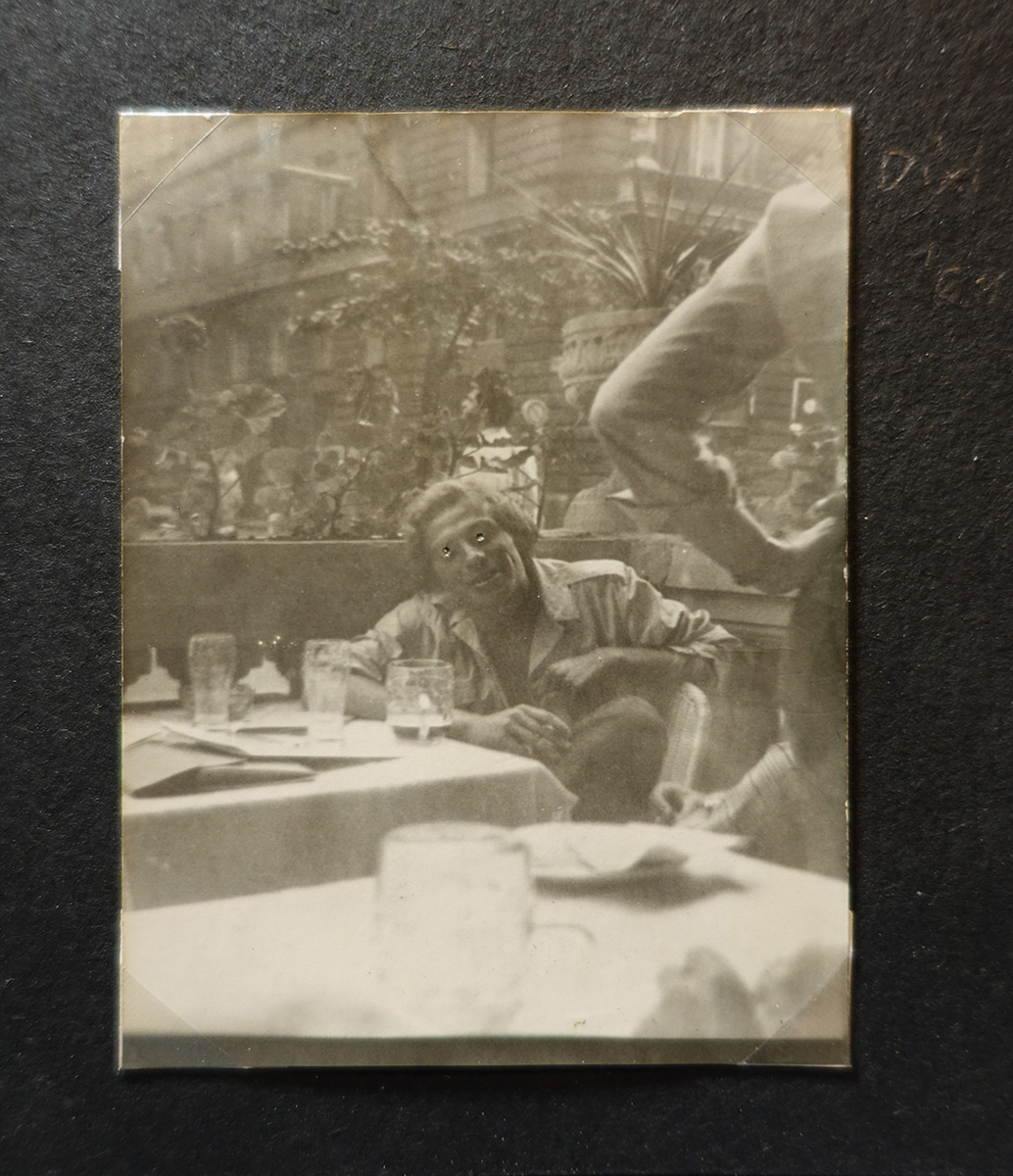

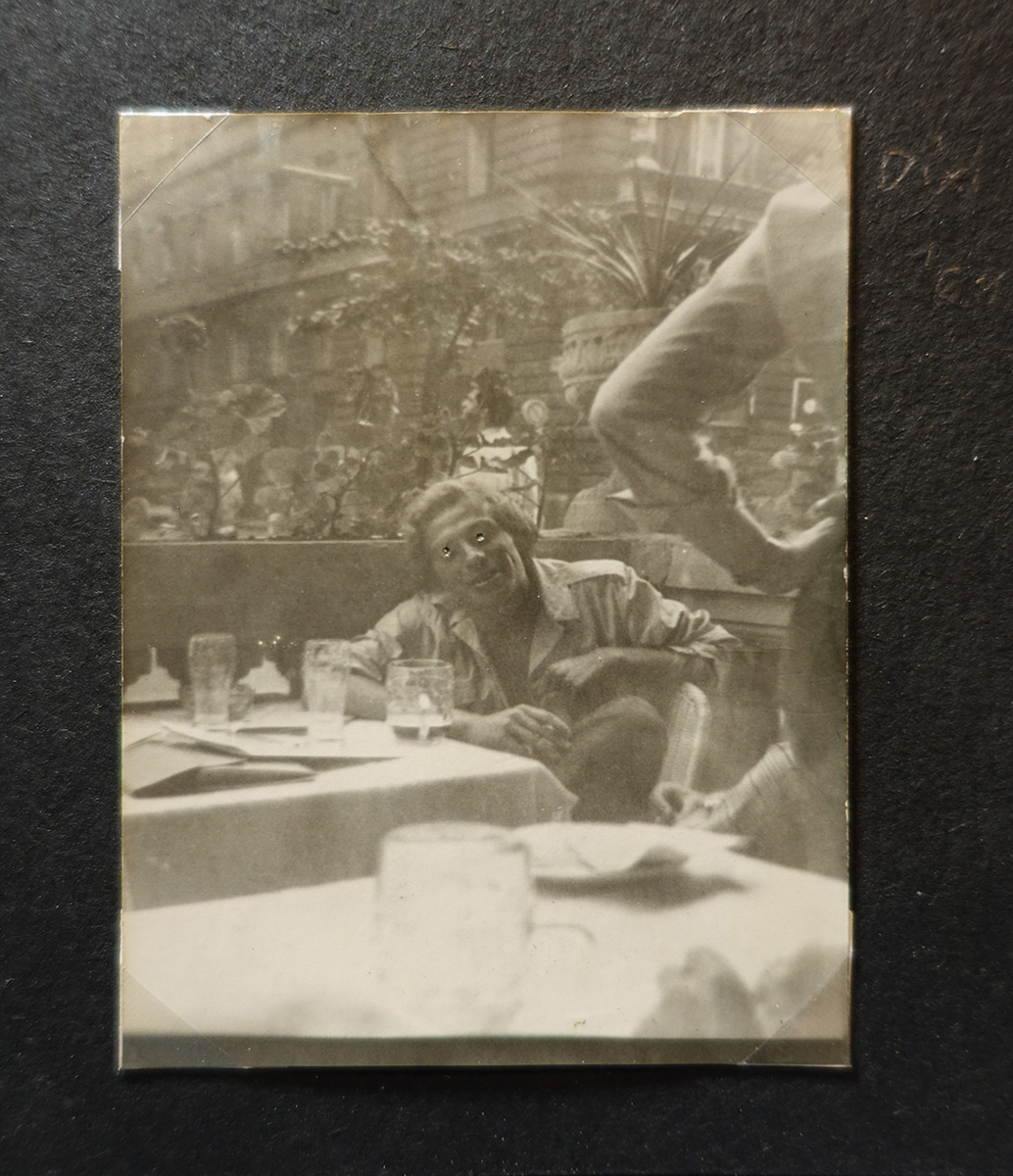

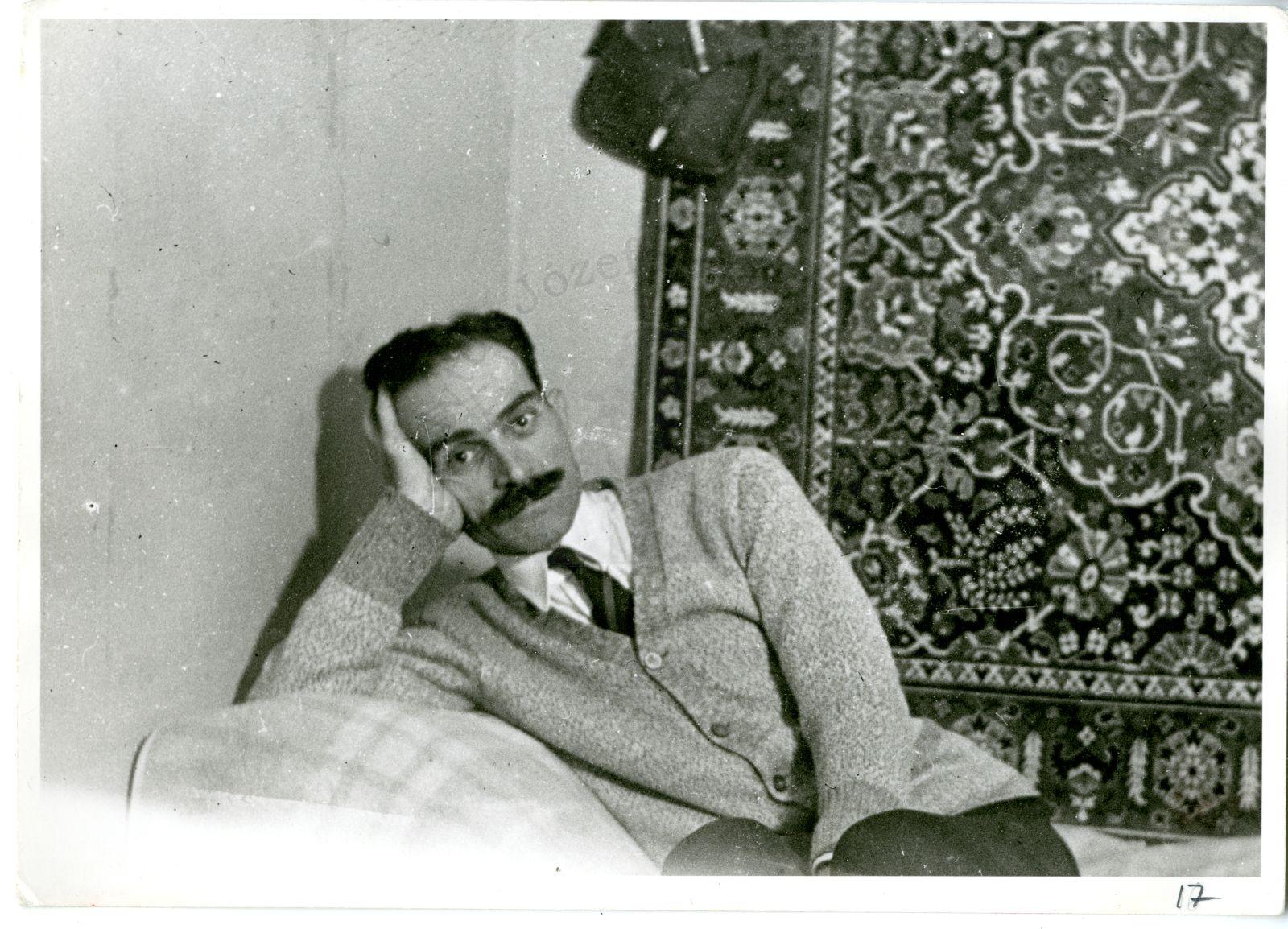

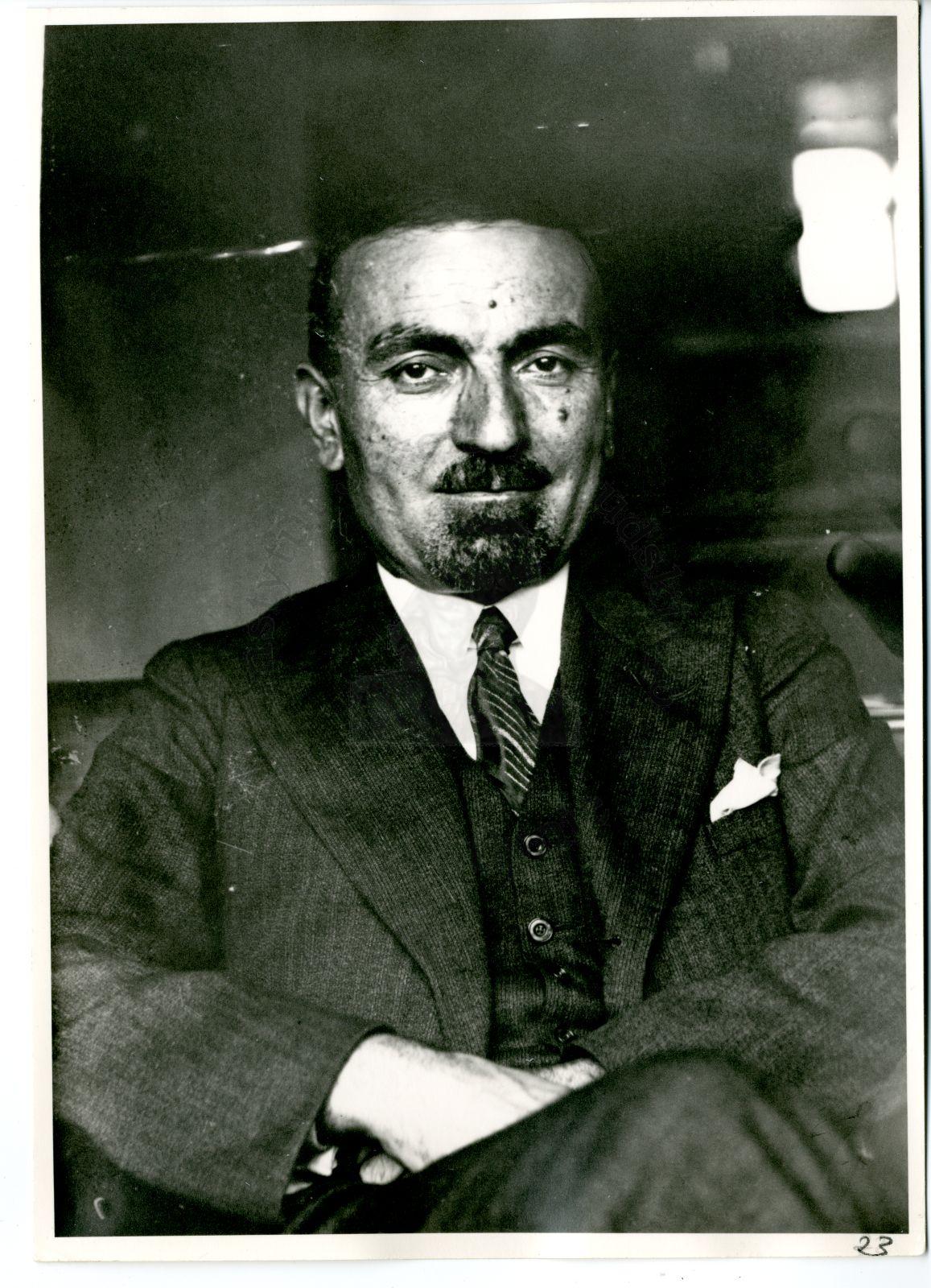

János Gémes (“Dixi”), the poet. Here he is in live speech, constantly provoking situations around him, like it is depicted in the photo, on the terrace of the Kárpátia restaurant, most probably in 1969. Dixi was a well-known, ubiquitous persona of the Budapest nightlife for decades.

He delivered endless monologues, orated in an associative manner, creating connections between the beginning and the end of a sentence with word play, twirling a few times the texture. He was a baffling personality, often grandiose, many times provocative, sometimes aggressive. He saw through people and never cared about the consequences.

The author of the photo is unknown. It is probably cut out from a larger photograph, as the edge is jagged. The most interesting feature of the photograph is that someone pegged out the eye of the protagonist with a needle. According to Zuzu this gesture is feminine.

Gábor Bódy introduced Dixi to Zuzu in 1971. At that time Dixi lived temporarily across the street from Zuzu at a guy’s apartment who was in the business of tailoring blue jeans—a hot, rare commodity at that time. He was a habitué at the Kárpátia, and people favored his company. He usually sat on the terrace, close to the entrance, from where it was possible to look into the restaurant as well as onto the street. He was older than them (they were still in high school, Bódy a university student).

Many students, artists, writers, poets, and musicians were hanging out at Kárpátia in those times, practically forming a regular audience. Zuzu, together with his friend Gomba (Erzsébet Gombás, one of the main characters of the film The Third by Gábor Bódy), went there often after school. This photo has preserved the familiar setting.

The figure of Dixi (1943–2002) is preserved in some photos and stories, appearances in six feature films, and a few videos and music recordings. Together with Zuzu they impersonated the characters Antoine and Désiré on the record cover of Tamás Cseh. He also provided inspiration for Géza Bereményi as one of the main protagonists of the novel Baby Vadnai.

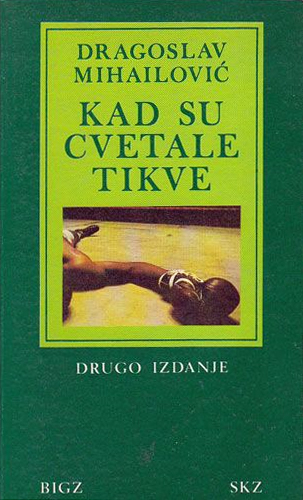

A file belonging to the ‘Ideological trends’ section contains valuable material for the investigation of political pressure and prohibitions in relation to cultural and artistic work in Yugoslavia. The featured item of the collection consists of documents gathered under the heading, ‘Information on the performance “When Pumpkins Blossomed” at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre by Dragoslav Mihailović’ (KPR II-4-a/73), which encompass party material from 1969 relating to the performance. At issue is a play based on the novel of the Serb and Yugoslav writer, Dragoslav Mihailović. The novel appeared one year earlier but did not generate much controversy. However, the inclusion of the play in the programme of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre in Belgrade alarmed the communist party. ‘The novel was not suited for a theatre production, so I rewrote half the text,’ explained Dragoslav Mihailović in an interview with the Večernje Novosti newspaper (Matović 2016). The play’s story of a Belgrade boxer addressed the topic of violence and for the first time publicly broke the silence about the Goli Otok camp and the political and police torture of dissidents in Yugoslavia at that time. Mihailović, who himself had been an inmate of Goli Otok in the beginning of the 1950s, confirmed that ‘I did not mention Goli Otok in the novel. I only mentioned Bakar, which was the last stop for Goli Otok. Later I mentioned it in the play, maybe because when we were developing the performance, it was openly talked about’ (Matović 2016).

The mentioned documents disclose that the intelligence service of the Central Committee of the Serbian League of Communists reacted straight after the first few performances. The record reveals that criticism was directed at the ideological and ethical messages sent by the play; then objection was made to the inacceptable political attitudes professed by the protagonist, ‘that led to doubt in the policies of the SKJ and our country during the period of resistance to Cominform’. Criticism was expressed about ‘the pessimistic conclusions regarding the fate of the human personality in whatever system, and naturally also in this, our own’, while the insertion of sentences that were not in the novel drew special attention, such as: ‘They are worse than the Germans’ (implying the communist authorities), uttered by the protagonist’s father on leaving the prison. The documents show that all this disturbed the City Committee of the League of Communists which called on the organization of the League of Communists of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre to discuss ‘the ideological content of this drama and the political implications that challenge, in the socio-political and cultural life of the city, putting this work on stage’.

Directly following this criticism, the Belgrade press began to attack the play and leading newspapers consequently wrote about it being, ‘a political pamphlet according to the taste of the likes of the Cominform’. Several documents that in fact represent an analysis of the press by the intelligence service of the Central Committee of the Serbian League of Communists, allow us to follow the development of the situation chronologically from day to day, culminating in Tito’s remarks regarding the play. At the congress in Zrenjanin at the end of October 1969, he said, ‘It seems there is something shadowy in the head of the author who in every way attempts to prove that our society is no good. And who says so. That’s written by someone who was at Goli Otok. The number of those who think and talk like that is very small. (...) There are individuals who spit on the accomplishments of our revolution and on the victims who fell in that struggle, but not once have shown that they do not love this country. They do not love this society; they do not love socialism and don’t belong to it with their being. But, once again the same ones are popping up who at the time of the Informbiro [the break from Cominform] revealed who and what they are. We will not undertake administrative measures. I don’t think that arrests are necessary now, but it is the responsibility of the communists to disenable those who deal with such affairs. The voice of our public must be strong and decisive in relation to such incidents’.

Soon after this speech by Tito, the play was removed from the programme of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre. In their analysis about how institutions like the Yugoslav Drama Theatre remember the dark sides of their history, Dragićević Šešić and Stefanović proposed the term “institutional trauma” when referring to “censorship and self-censorship, rejection of creative dissident personalities, etc.” (Dragićević Šešić and Stefanović 2014, 13). They also maintained that “the trauma in Serbian theatrical censorship was linked to the fact that there was no official censorship. That message would be transmitted mostly by telephone to theater managers, and then through a complex procedure the collective "decided" to remove the performance from the stage. Therefore, it was more traumatic than as it would have been in the situation of real state censorship.” (Dragićević Šešić and Stefanović 2014, 19).

The János Dobri Collection of the Reformed Congregation of Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund contains materials covering the confessional life and activity of the eponymous pastor, which alongside proofs of his individual stand and sacrifice, in the course of the official and private correspondence with the Romanian authorities and private individuals, and beyond the struggle for survival of the Reformed church, also provides an insight into the details of the fight for minority and human rights in the twentieth century.

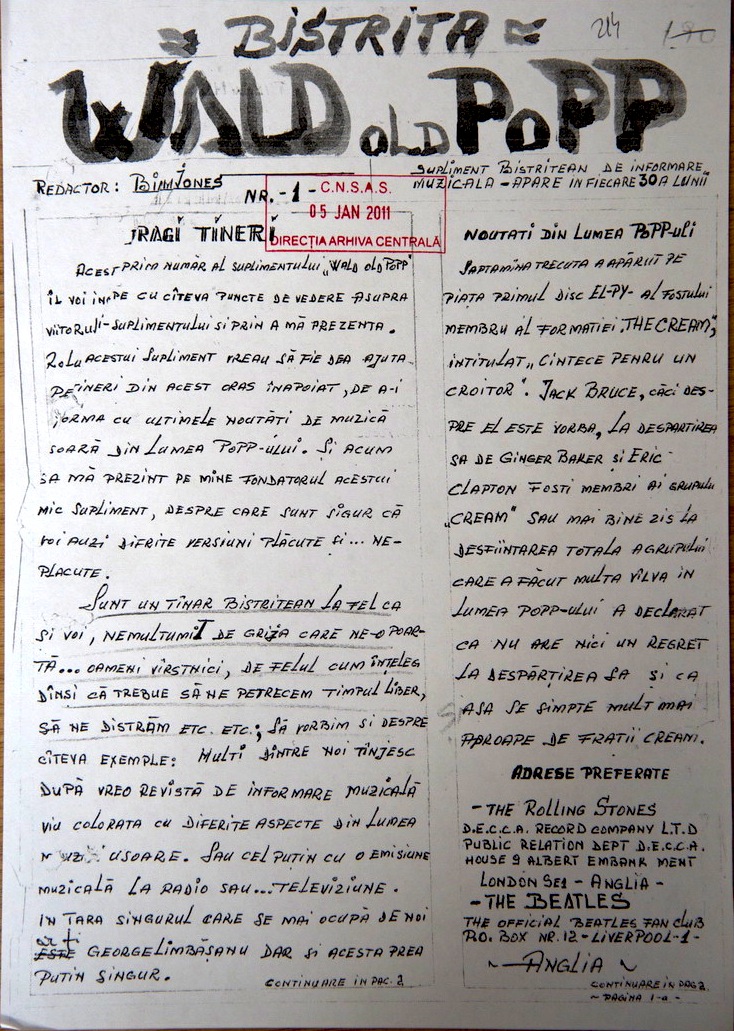

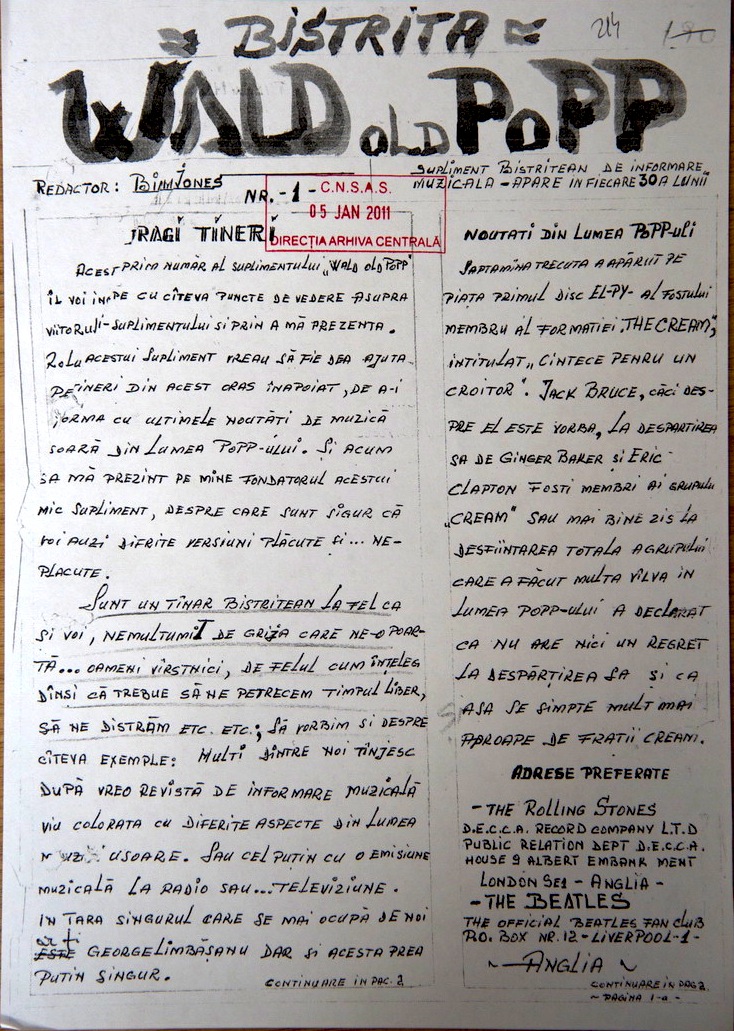

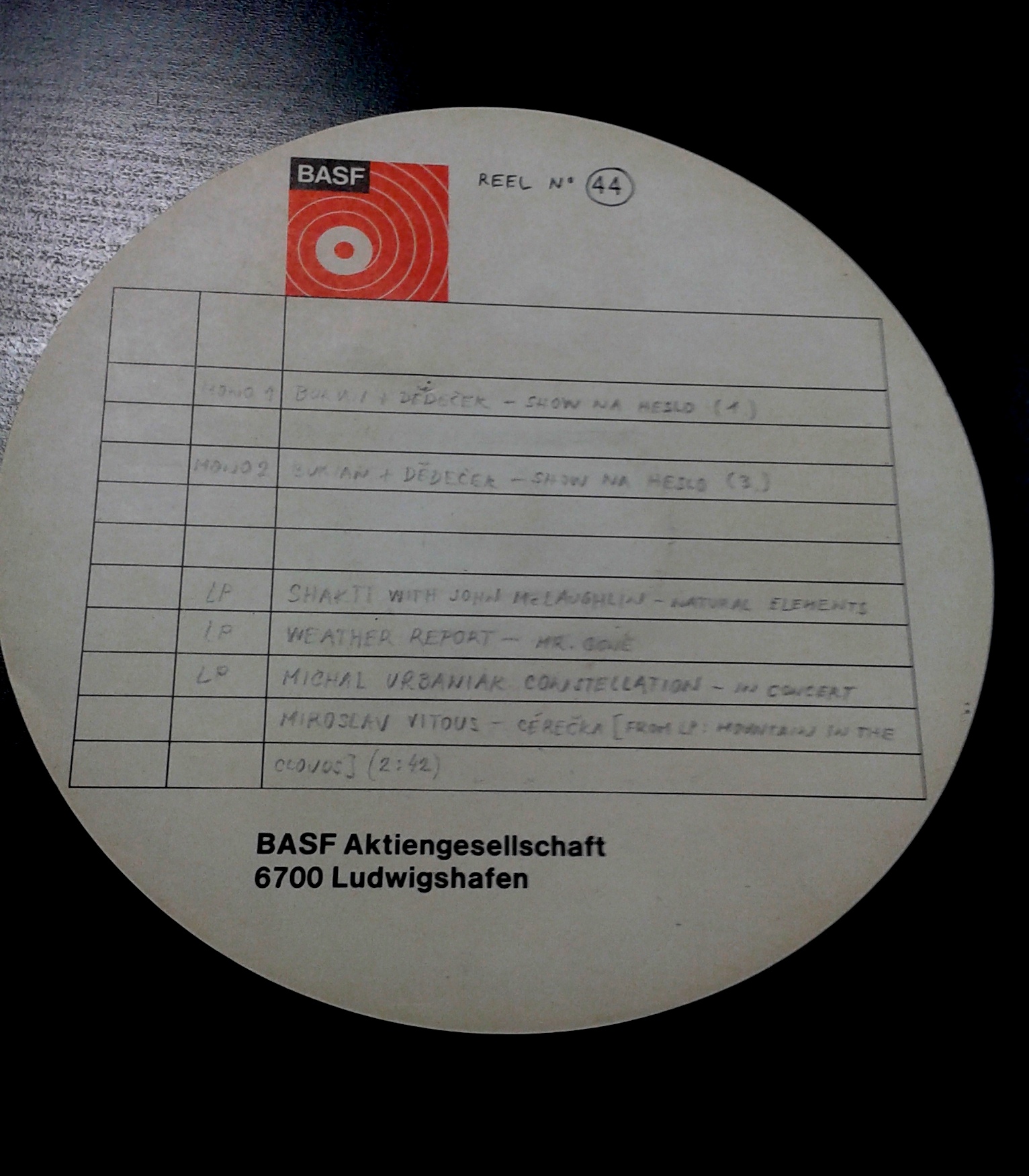

Wald old popp was one of the few musical samizdat publications in communist Romania. It was created in 1969 by Emil Hidoș, a twenty-year-old man from the town of Bistrița, who was passionate about foreign music. He was a faithful listener to Cornel Chiriac’s musical programme Metronom, broadcast by the Romanian department of Radio Free Europe (RFE). The copies of Wald old popp were confiscated by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, in June 1970, after a search at Hidoș’s home. The Securitate used the samizdat as the main evidence against him and for his prosecution under the charge of “propaganda against the socialist order,” and copies of the publication were included in his penal file.

The musical samizdat Wald old popp was a handwritten publication whose chief editor was “Braim Iones,” the nickname used by Emil Hidoș. The copies were made using carbon paper. The subtitle of the samizdat, The Bistrița supplement of musical information, gives a hint as to the purpose of the editor: “to help the young people of this backward town, to inform them about the latest musical news from the world of popp (sic!).” Very interesting is Emil Hidoș’s short self-description, which illustrates his revolt against the limitations the communist regime put on the consumption of foreign cultural goods, which were nonetheless highly interesting to young people: “I am a young man in Bistrița just like you, unhappy with the care shown to us… by the older people, with the way in which they understand how we should spend our free time, have fun etc.” After stating that Romanian youth needed a magazine, a radio or a television programme to get information about the latest musical developments, Emil Hidoș underlined once again his personal revolt against this state of affairs and the fact that he was forced to create “such miserable supplements, which resemble more closely a manifesto than a supplement of music information.” From his point of view, the forced isolation of youth from the outside Western musical world would only increase their revolt against the communist regime to the point where things would get out of hand and the authorities would not be able to silence the young people’s revolt.

This editorial was followed by several articles about the latest developments in “popp” music, as Emil Hidoș misspelled and mistakenly labelled all music played at RFE and other foreign radio stations at that time. The entries concerned the latest “El-PY” (LP or Long Play) of a former member of the British rock band Cream and new releases of albums. Other columns contained the addresses of fan clubs of the most popular bands of that time, such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and a musical chart. A special feature was dedicated to “Events in Bistrița,” where Hidoș described how the authorities had reacted negatively to the exaltation displayed by young people during the concert of Cromatic Group, a rock band from the nearby city of Cluj-Napoca. He used the event as pretext for fresh criticism of the communist regime, which labelled as “hooliganism” the patterns of spending their free time that many young people adopted in revolt against the older generation and implicitly the communist regime. From Hidoș’s point of view, the critical stance of the authorities toward this issue was unfounded, as the officially-sponsored relevant organisations failed to take into consideration alternative and more appealing modes of entertainment. He ended his article by wondering when youth in Romanian would enjoy “total freedom” (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 1, ff. 215–223 f–v).

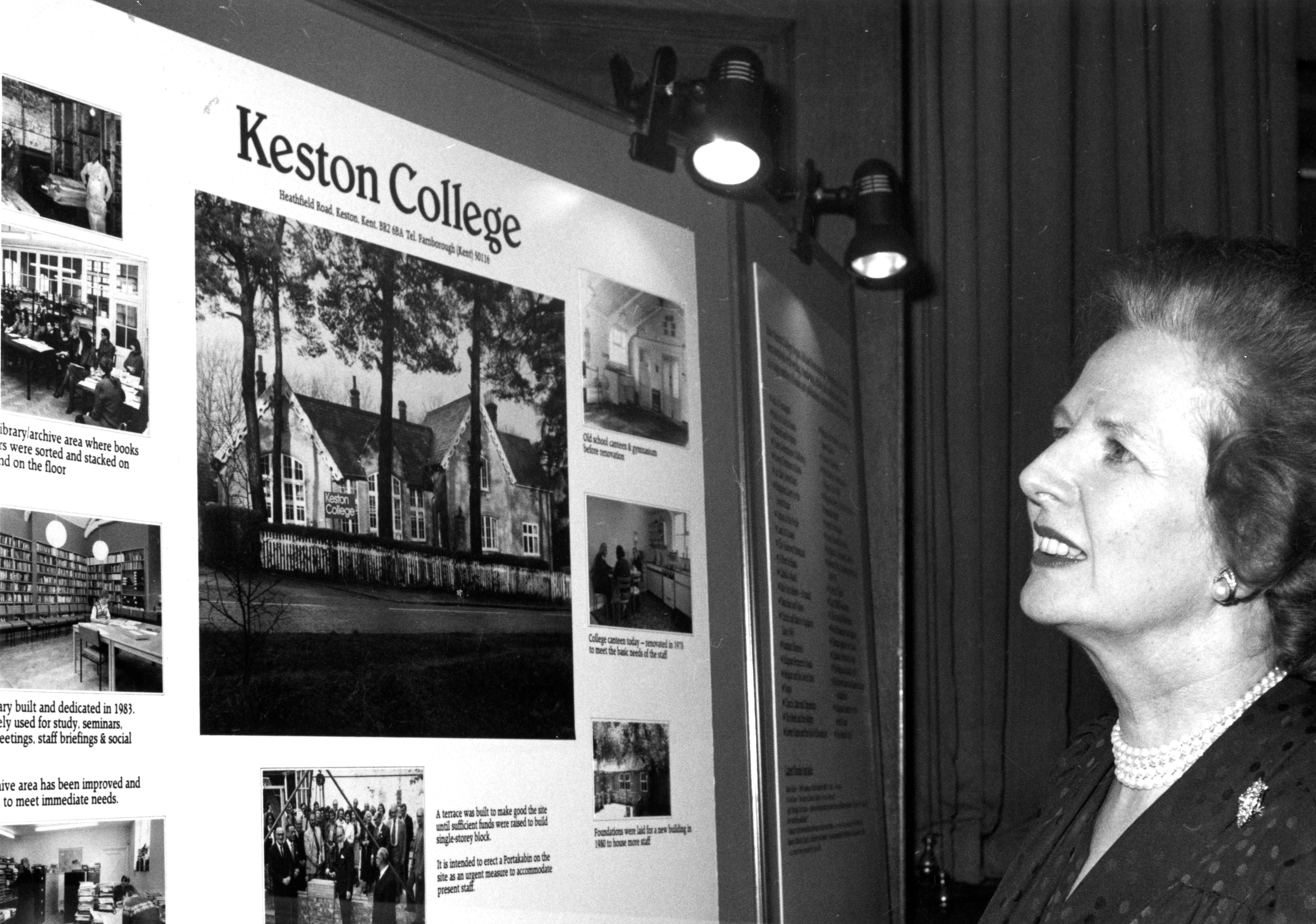

In 1969, Reverend Canon Dr. Michael Bourdeaux, along with political scientist Peter Reddaway, diplomat and writer Sir John Lawrence and Soviet historian Leonard Schapiro, set up the Center for the Study of Religion and Communism, later known as Keston College and Keston Institute. It soon grew into a widely known British human rights organization and a resource center, unique in a way, as its field of expertise focused on church-state relations and persecutions of religious believers behind the Iron Curtain. From its foundation, the creation and development of an archive of documentation was a primary aim for Keston. Today, the Keston Archive and Library remains a unique collection of primary-source material on religious life and religious persecutions in socialist countries, containing, among other things, the world’s most extensive collection of religious samizdat. The Keston collection fills an important gap between state historical records and official church histories, giving voices to ordinary believers in their everyday struggle to freely express their faith.

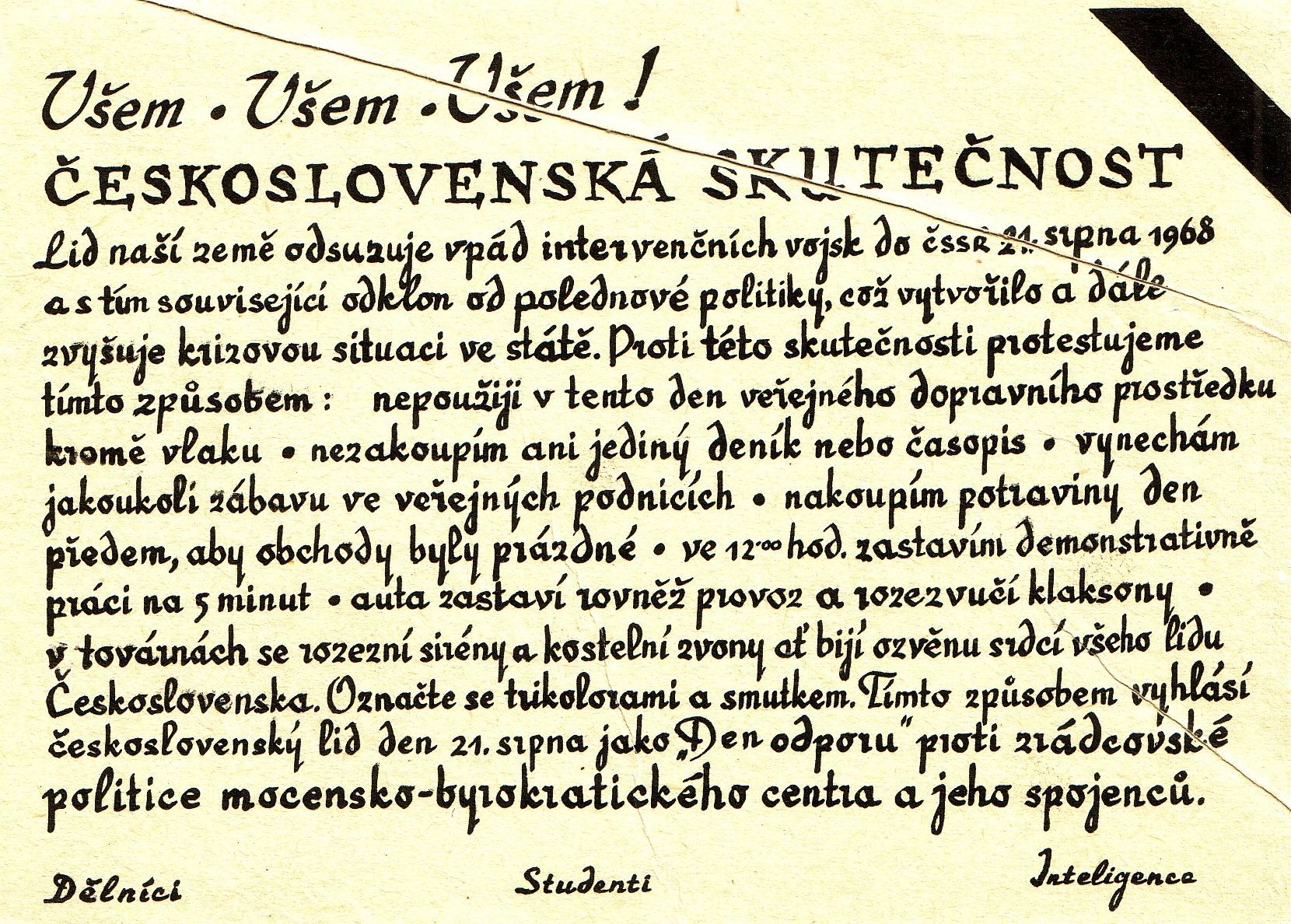

The Movement of Revolutionary Youth (HRM) was a predominantly student group with a radical left orientation that was founded at the beginning of December 1968 and that stood up against the upcoming Normalization until it was broken by the State Security during the winter of 1969 to 1970. Members of the HRM organised intense activity ahead of the first anniversary of the August occupation when they wanted to mobilize people against the Normalization regime. They published several leaflets for this occasion, one of them being the leaflet “To all – to all – to all!” which was signed by “workers, students, intelligentsia” and that urged non-violent protests on 21 August 1969, such as to boycotting public transportation, the press and shops. Pavel Šremer and Radan Baše from the Movement, and in cooperation with a printing trade union in Prague, saw to the printing of 200-thousand small leaflets. Initially, poet Jaroslav Seifert was asked to write up the text of the leaflet by the students. He thanked them for their trust but he declined their request arguing that they would manage to write the right text themselves. The final version was written collectively under the supervision of Petr Uhl. The whole event was finally called the Black Coffee Operation after two men in the printing trade union, Černý and Turek, and also as an allusion to the statement of the First Secretary of the SED Walter Ulbricht about the “coffee sediment of intellectuals in Prague”. The leaflets were also distributed beyond Prague, predominantly in North Bohemia and scattered by an engine driver, who was an acquaintance of Pavel Šremer, and his colleagues.

This ceramic piece was created by Halyna Sevruk. She titled it "Ivan Svitlychny" in order to show her deep love and respect for this leader of the Ukrainian sixtiers movement. Her portrayal meant to underscore his importance in forming the Ukrainian national consciousness and civic bravery of the sixtiers, who were persecuted for their words and their pursuit of truth. The martyred figure is winged and crucified. Quite importantly, at the very center of the piece is a book, as Svitlychny was a soul who thrived on knowledge. The curator of the Sixtiers Museum, Olena Lodzynska, noted during our interview that the date of creation (1969) is also significant, as it was well before the mass arrests that happened in the winter of 1972, when Svitlychny and many other sixtiers were taken by the Soviet authorities. This gives the piece an unsettling and prescient quality.

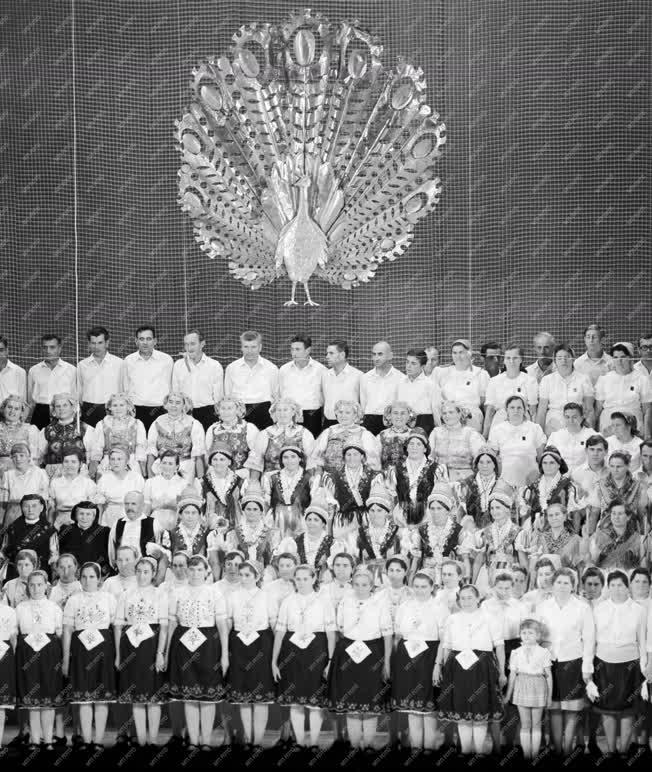

Hungarian researchers began studying the traditional culture of the city of Szék and the surrounding area in Romania in the 1940s, but their findings were only published in the 1970s. It was striking that Romanian folk dance groups did not include dances from Szék in their shows, and the locals from Szék did not present dances at national folklore festivals and competitions before 1969. Szék became popular among professional and amateur researchers because of a monograph on the region on which planning began at the end of the 1950s. Hungarian researchers, therefore, started to travel to Szék in the second half of the 1950s. In this period, travel was not easy, but it was possible. In 1965, Ferenc Novák wrote a paper about the dance culture of Szék. For a long time, only silent films were available about the dance culture of Szék. The turning point came in 1969, when Zoltán Kallós, György Martin, and Pál Sztanó cooperated with the Romanian Academy of Sciences and shot sound films about the Szék folk dances. This constituted an important breakthrough in the research, because the music could be heard while audiences saw the dances, so it became possible to learn the steps. Between 1959 and 1969, six sound dance films were made by Ferenc Novák, Gyula Varga, Jolán Borbély, Gabriella Böröcz, László Gurka, László Vásárhelyi, Zoltán Kallós, and György Martin. In the middle of the 1960s, photographer Péter Korniss also travelled to Szék and took thousands of photos of traditional folk dance houses. The interest in the folk dances of Szék grew thanks to the sound films, and soon, more and more ethnographers, folklorists, photographers, amateur researchers, and people with an interest in traditional folk culture traveled to the city. These events are closely linked to the new wave of folklorism in Hungary, the so-called “Fly Peacock Festivals.” In the first dance house, which was held on 6 May 1972, the participants could imitate the style and atmosphere of a traditional dance house in Szék thanks to the work done by the people who had compiled collections on the music and dances of Szék. Today, these films are available in color and digital versions.

The concert poster giving details of the concerts that were to be held as part of the first Jazz Festival in communist Romania is one of the earliest in the Mihai Manea collection. It is almost half a century old; it dates from 1969 and is preserved in very good condition. The poster provides concert information for the days of 4, 5, and 6 April 1969, when a series of jazz performances took place in the Philharmonic Hall in Ploieşti. Among the participants were a number of prestigious groups and artists in the genre from various places in Romania, who gathered for an exceptional show at a jazz festival that was very well-known and appreciated in communist Romania. Among them were the Richard Oschanitzki quartet and the Ștefan Berindei sextet, both from Bucharest, Jazz Club from Roman, Big Band from Cluj-Napoca (at the time simply named Cluj), the Choralys octet from Constanţa, the Robert Kovacs trio and the Robert Movsessian trio, both from Ploiești, the Free Jazz trio from Timișoara, and the soloists Elena Constantinescu and Aura Urziceanu. The concert poster is printed on thick paper and has a white background on which horizontal yellow lines are discretely traced. The text is placed within a well marked frame and is in the two colours that are most common in the Mihai Manea collection: red and blue. The quality of the poster, even if it is not extraordinary, contrasts with that of those from later years, which were printed on paper of worse and worse quality and became less and less elaborate from an aesthetic point of view.

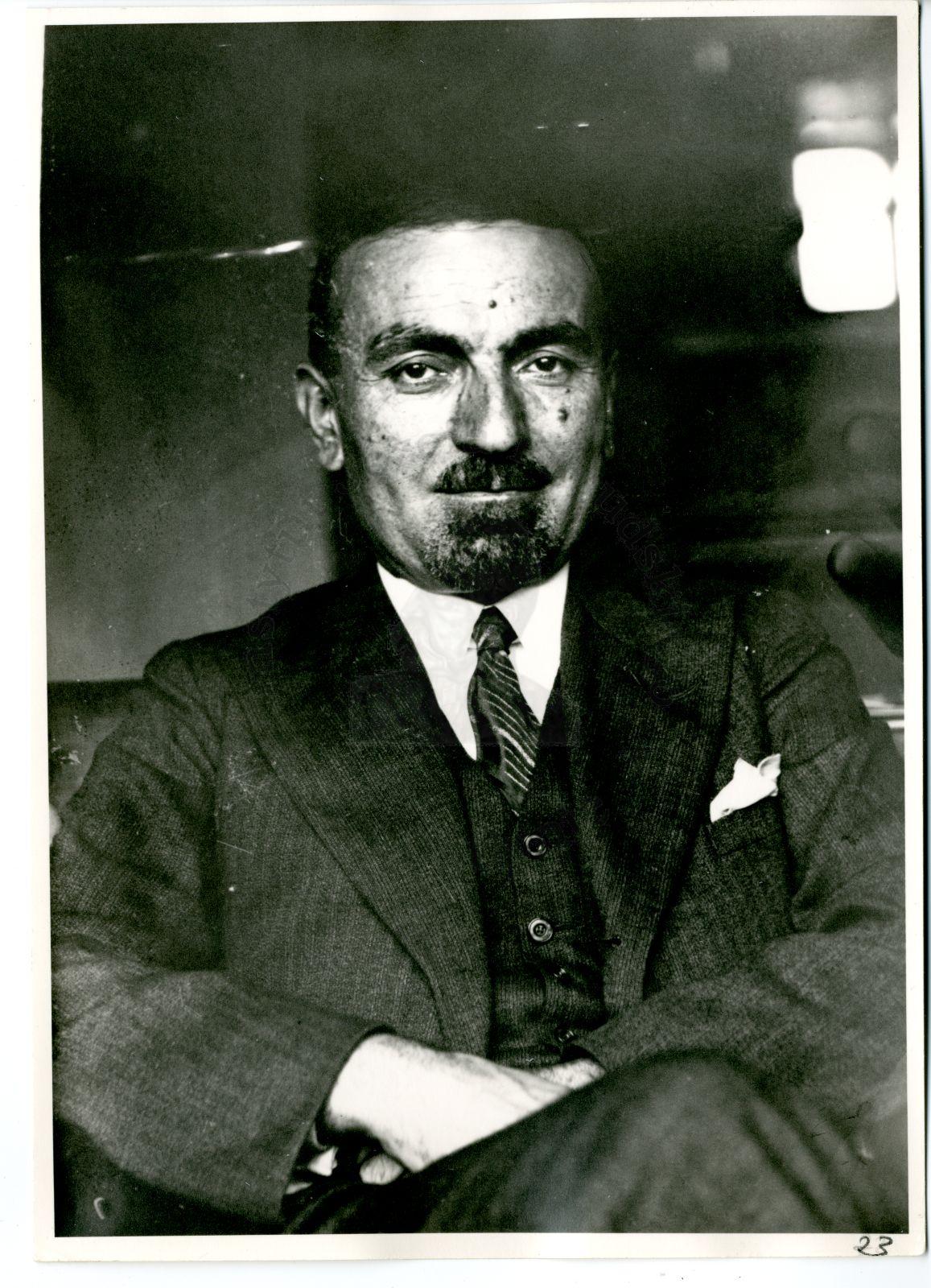

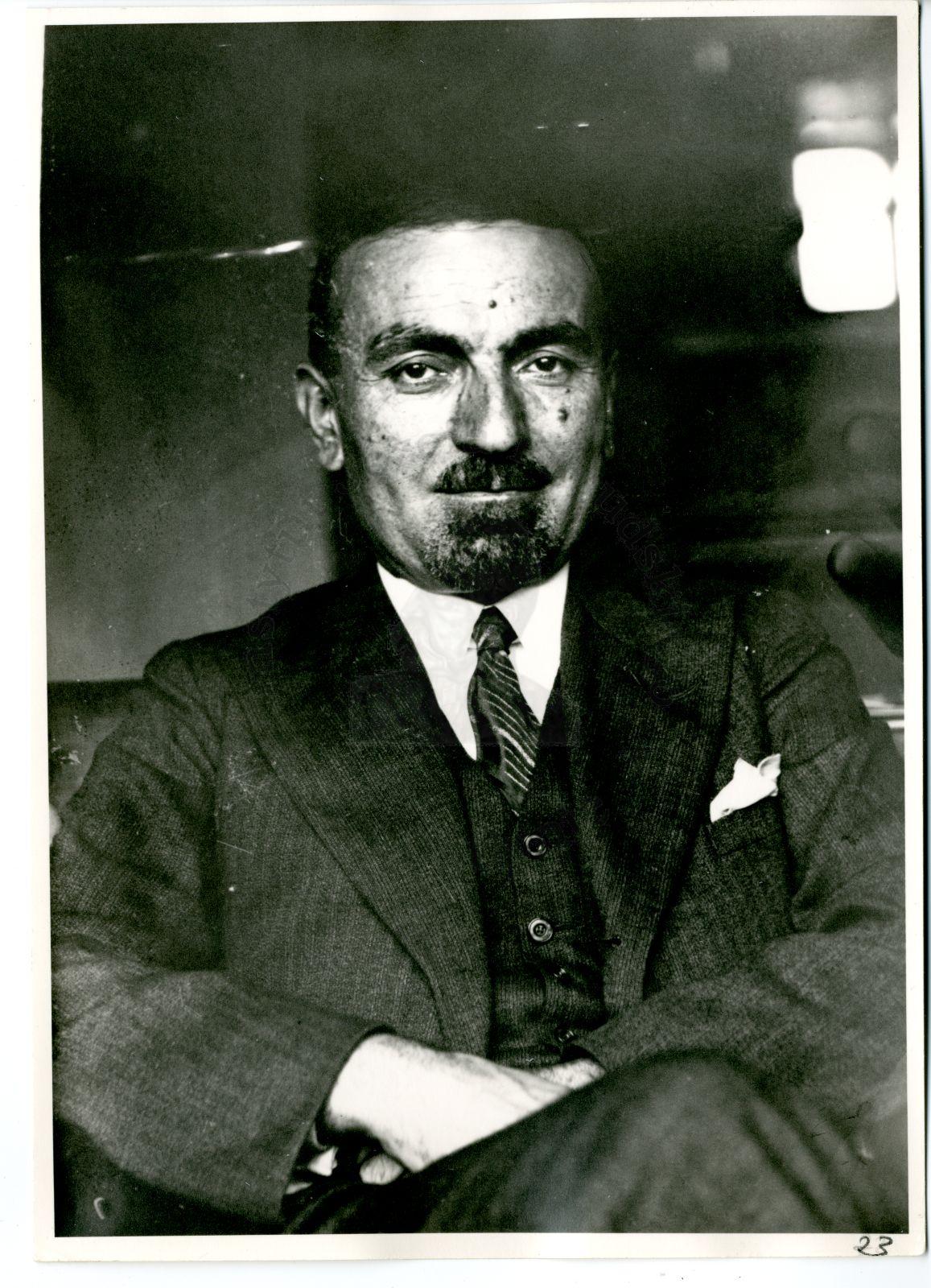

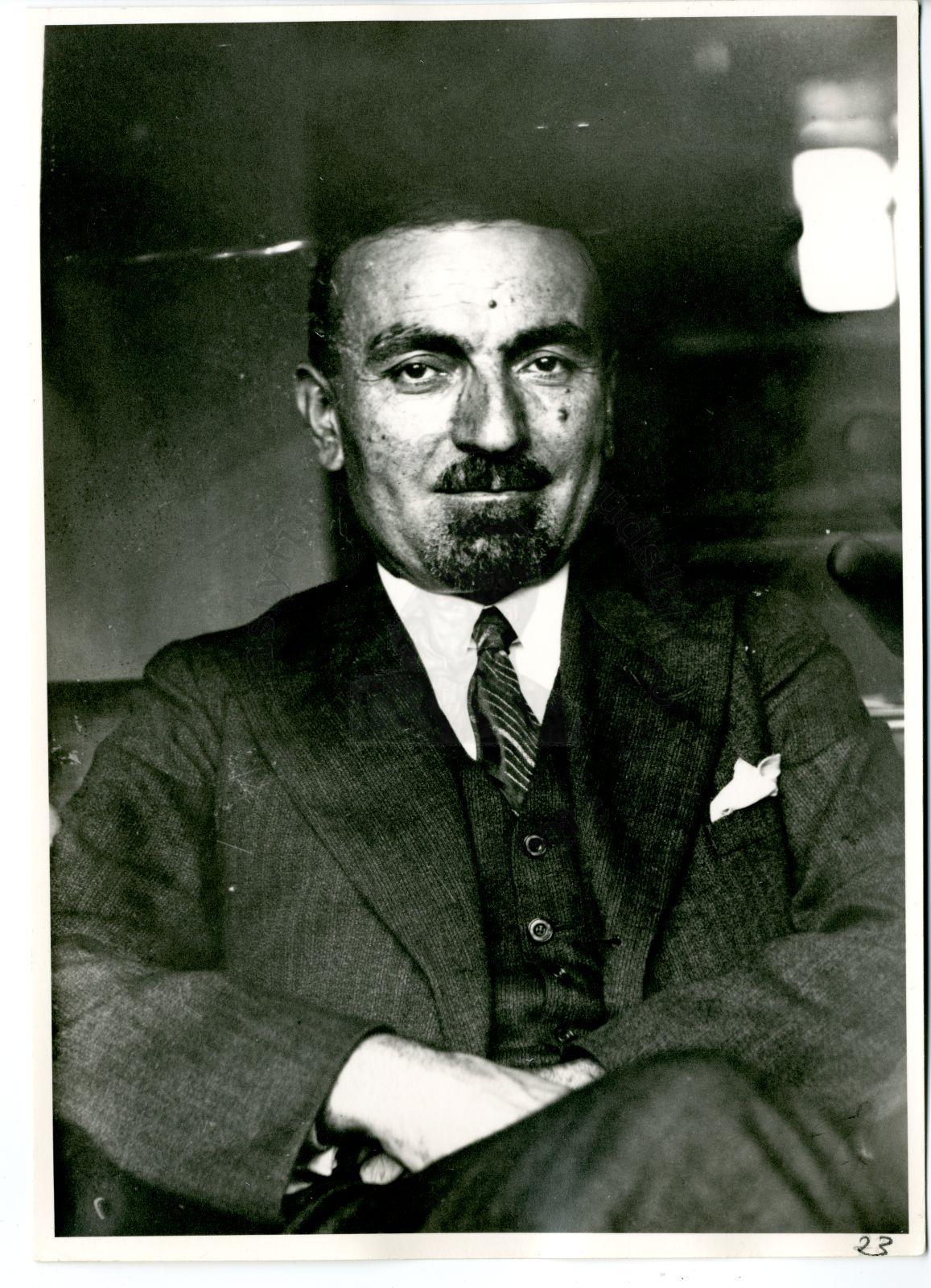

Made as part of the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, which emerged following the collapse of the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy in 1919, the film offers a complex overview of revolutionary practice and the psychology of terror.

Dezső Magyar and Gábor Bódy, the director and the writer created a multi-layered narrative by using diverse literary sources, actual news footage, and references to current events. The main source of inspiration was Ervin Sinkó’s novel Optimists and the memoirs of József Lengyel and the wife of Tibor Szamuely. Georg Lukacs’s account on the subject was also used for references in some cases, as well as quotations from the writings of Mao and Che Guevara.

The film presents a general model of revolution through talking heads reflecting on their own interpretations and ideas. Though the story is based on actual events, the characters are all fictional. The protagonists, however, in addition to being professional actors, were members of radical intellectual and neoavantgarde circles. They pursued intense theoretical debates on the possibilities of revolutionary action, the dilemma of violence, the criticism of new bureaucracy, and the essence of working class culture.

In part as a consequence of the experiences of the Prague Spring and student movements in the West, the terms of the discussions were changed. The 68er radicals dropped Marxist-Leninist concepts and debated the meaning of leftist politics, the future, and the potentials of revolution and social autonomy. They developed an allegorical reading of the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, which provided a pretext for the filmmakers to discuss 1968. Due to its subversive approach, the film was banned for decades.

Produced by BBS (Béla Balázs Studio), MAFILM (Hungarian Film Producing Company) and the Hungarian Film and Theatre Academy in 1969. Published on dvd by Műcsarnok Non-profit Ltd, Hungarian National Film Archive and BBSA in 2006. Available online: https://youtu.be/vH4N_MJ2vvE

The Mirel Leventer private collection of photographs and films is the richest archive of images from the period of glory of Club A, 1969–1989, when it operated as a (semi-) clandestine and exclusive club, founded and administered by students of the Institute of Architecture in Bucharest (today the Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism). Club A was an oasis of freedom created in a basement in the middle of the historic area of the capital of communist Romania for the purpose of being able to organise shows, debates, and concerts that would be an alternative to the officially promoted culture, and to offer young people a place where they could behave as if they were free. In short, the Mirel Leventer private collection preserves the memory of an essential place for the alternative culture of young people in the last two decades of Romanian communism.

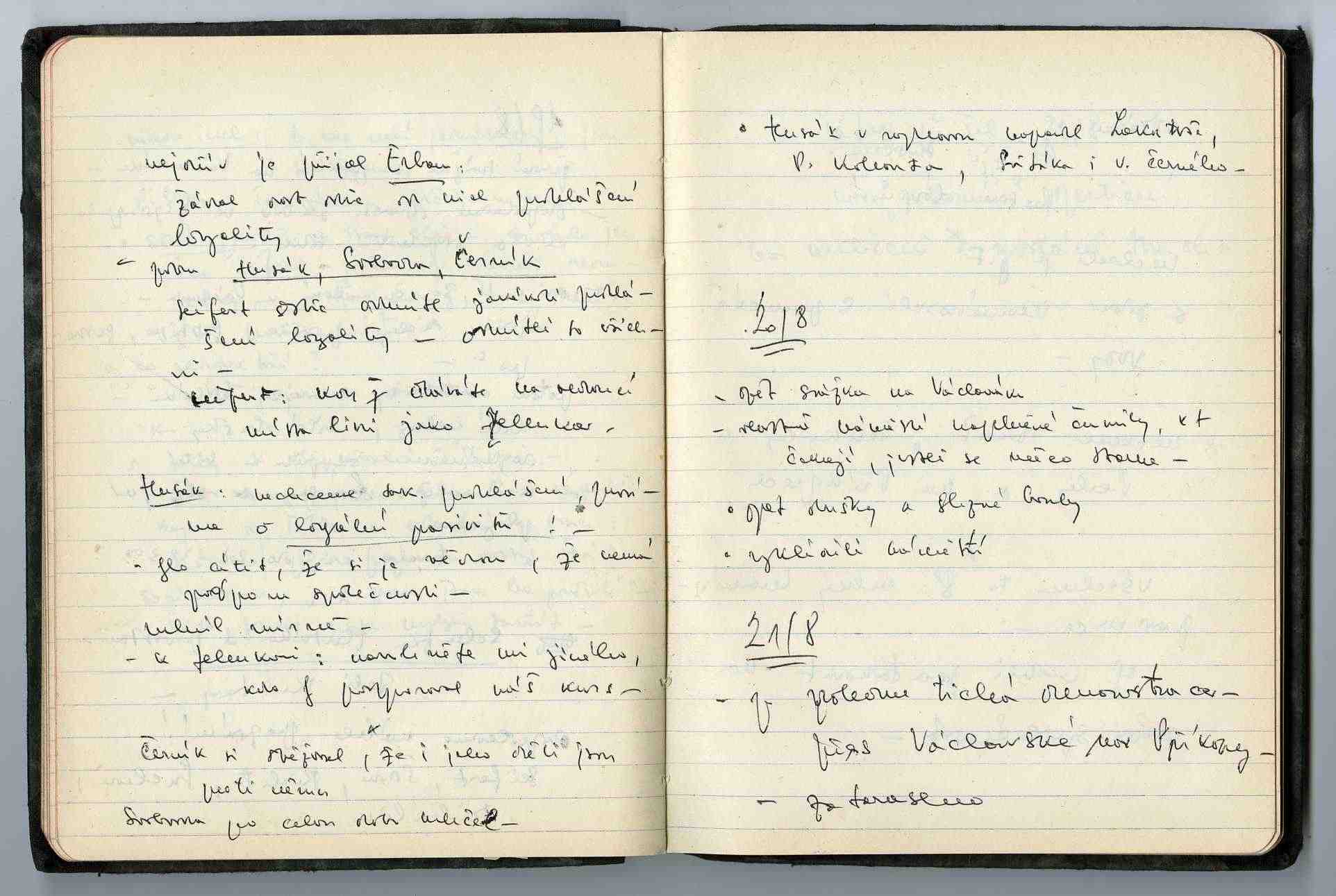

Jiří Lederer's personal memos are from the meetings, consultations and sessions, especially from the Union of Czech Journalists from 18 April 1969 to 22 August1969. The book ends with notes from the events of the 1st anniversary of the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops.

These notes capture the thoughts and encounters with various people during these dramatic days, as well as the feelings of Jiří Lederer, a prominent journalist, dissident and eventually an exile.

In the notebook remarks on Husak, Svoboda and Cernik, as well as known Czech writer Seifert, can be found in addition to short notes on the "silent demonstration" on Wenceslas Square on August 21. These notes serve as a unique example of journalist scriptures from the dramatic August events of 1968.

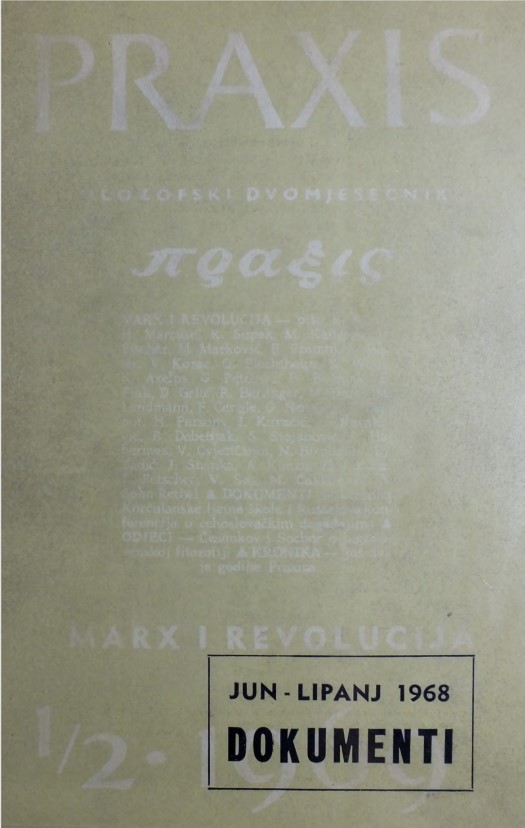

One of the historically most interesting materials related to the journal Praxis consists of the documents about student events in Yugoslavia in June 1968. The proceedings contain original documentation that closely cover events associated with the student movement in many Yugoslav cities. Along with the editorial notes, anti-Vietnam protests were documented, different views of the demonstrators regarding the relationship with student protests in the world, but also issues of social antagonisms as well as government reactions, including investigations and trials. The documentation was underscored as a precursor to sociological research into social conflicts. The primary purpose was to collect these authentic documents into a publication and to testify to the significance of events of 1968 to the development of socialism in Yugoslavia. This publication was published as a Volume 1-2 for 1969. The editors-in-chief were Gajo Petrović and Rudi Supek.

Sorin Costina’s private collection is illustrative of the visual art that evaded the official aesthetic canons of the communist regime in Romania. The collection is all the more valuable as the artists represented in it, who were marginal in the last two decades of communism, when ideological control became stricter and stricter, received due recognition both nationally and internationally after 1989.

Speech by Ivan Bodiul, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPM, at the Second Congress of the MUC, 23 December 1969, in Russian

Speech by Ivan Bodiul, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPM, at the Second Congress of the MUC, 23 December 1969, in Russian

The Second Congress of the MUC marked, on the one hand, the apex of the cinematic production and professional creativity of Soviet Moldavian filmmakers. Emboldened by the international success of such recently released films as Poslednii mesiats oseni / Ultima lună de toamnă (The Last Month of Autumn), the MUC was optimistic about its future perspectives and the mass impact of its productions. On the other hand, this Congress also foreshadowed the future ideological crackdown that was to be initiated in the early 1970s. The speech by Ivan Bodiul, the highest-ranking Party dignitary of the MSSR, was ominous in this regard. Bodiul openly attacked the “ideological mistakes and flaws” that apparently characterised many of the recent productions, accusing the MUC members of focusing too much on “form” instead of “ideological content.” Bodiul argued that, while certain movies might suffer from a “formal,” i.e., artistic, point of view, they could be quite useful ideologically, and vice versa. To illustrate a negative example of an “ideologically flawed” film that nevertheless was well received by critics, he referred to The Last Month of Autumn, released in 1965 and awarded several international prizes. In Bodiul’s opinion, the film suffered from “two political inaccuracies that cause a lot of harm.” The first concerned the contrast between modern technology and the depiction of poor peasants, which for Bodiul meant a “distortion of the Party’s policy.” The second problem was more serious: the director was accused of “sympathy for a kulak woman” featuring as a character in the movie. Bodiul openly stated that such flaws – which were to be “uncovered and firmly swept away” – were contributing to “bourgeois propaganda” and called for a much more careful political screening of films at the Party level before their release, which amounted to an argument for direct Party interference in the creative process. In his final remarks, Bodiul stated that he would be “opposed” to any nomination of the film for a state prize, as long as these “ideological flaws” persisted. The priorities of the Party leadership were thus outlined unequivocally by the first secretary and would lead to an increasingly harsh and intolerant attitude on the part of the regime in the years to come. This hardening “Party line” was supported and reinforced by two subsequent speakers who elaborated on Bodiul’s theses. The first was the secretary of the USSR Union of Cinematographers, Alexandr Karaganov, who emphasised the lack of a social and “revolutionary” dimension in recent Soviet films and the losing of the ideological battle with Western “film propaganda” that this entailed. Karaganov also discussed the Czechoslovak example of “ideological deviation” and the successful Western “infiltration” of the profession there, interpreting it as a dangerous warning against any ideological relaxation. The second speaker was Dumitru Cornovan, the secretary of the CC of the CPM responsible for ideology, who focused on the threat of “bourgeois nationalism” and attempted to define the Party’s interpretation of the acceptable “national form and national specificity in art.” He condemned the “exaggeration of national differences” and attacked any artistic forms “extolling archaic national traditions”, viewing such themes as examples of the “ideological war” waged by the West against the USSR. He also referred to the particular attention that “Western propaganda” devoted to the Moldavian SSR, emphasising the “distortion of the history of the Moldavian people, the denial of our peculiarity, our independence and even the right of our republic to exist.” He also inveighed against the Western “fomenting of nationalist tendencies” and against attempts to “undermine the friendship between various Soviet peoples.” This amounted to a full-scale agenda of repressing any forms of opposition, which was applied under Bodiul’s leadership in the early 1970s and connected alternative forms of cultural expression to open displays of political dissidence.

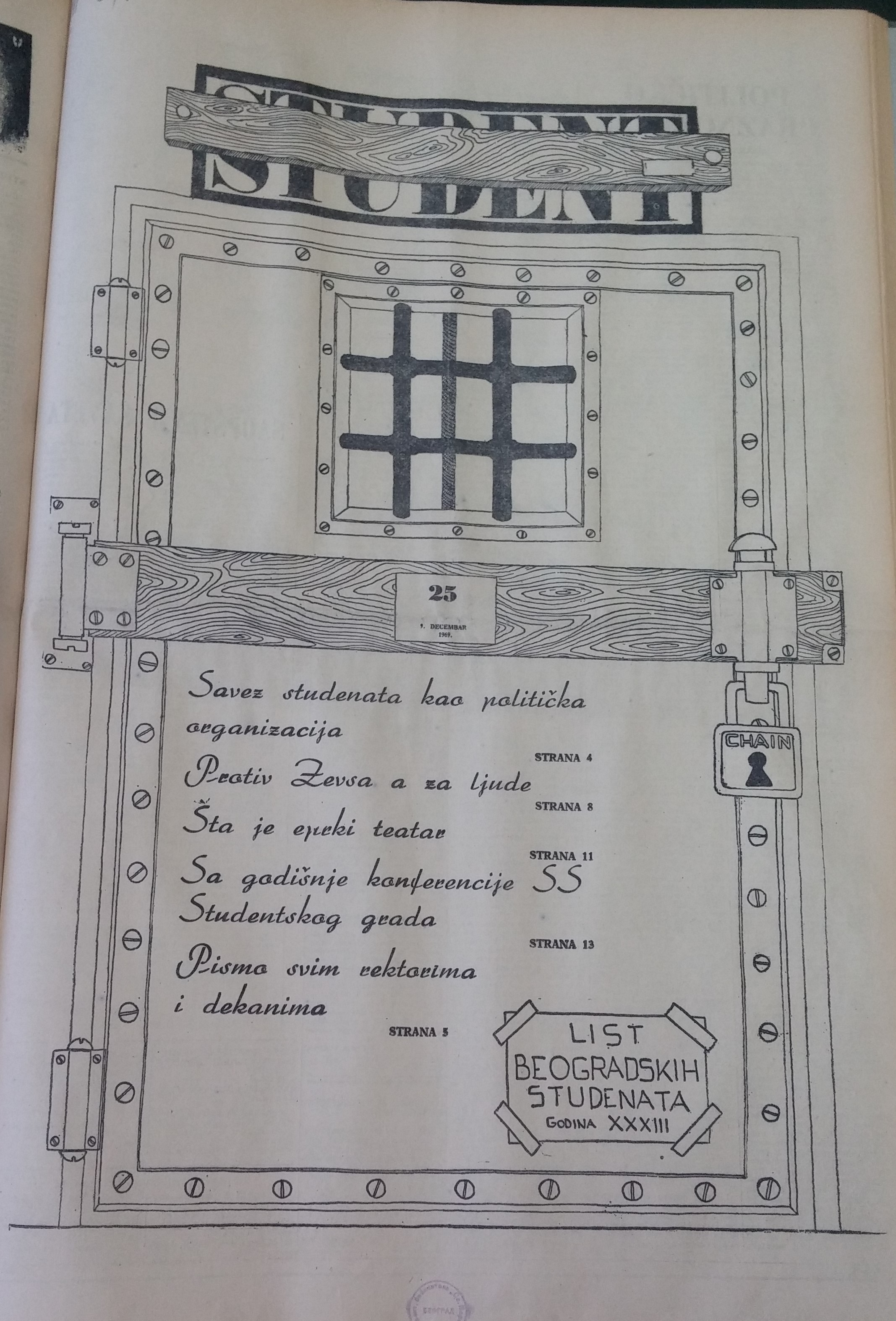

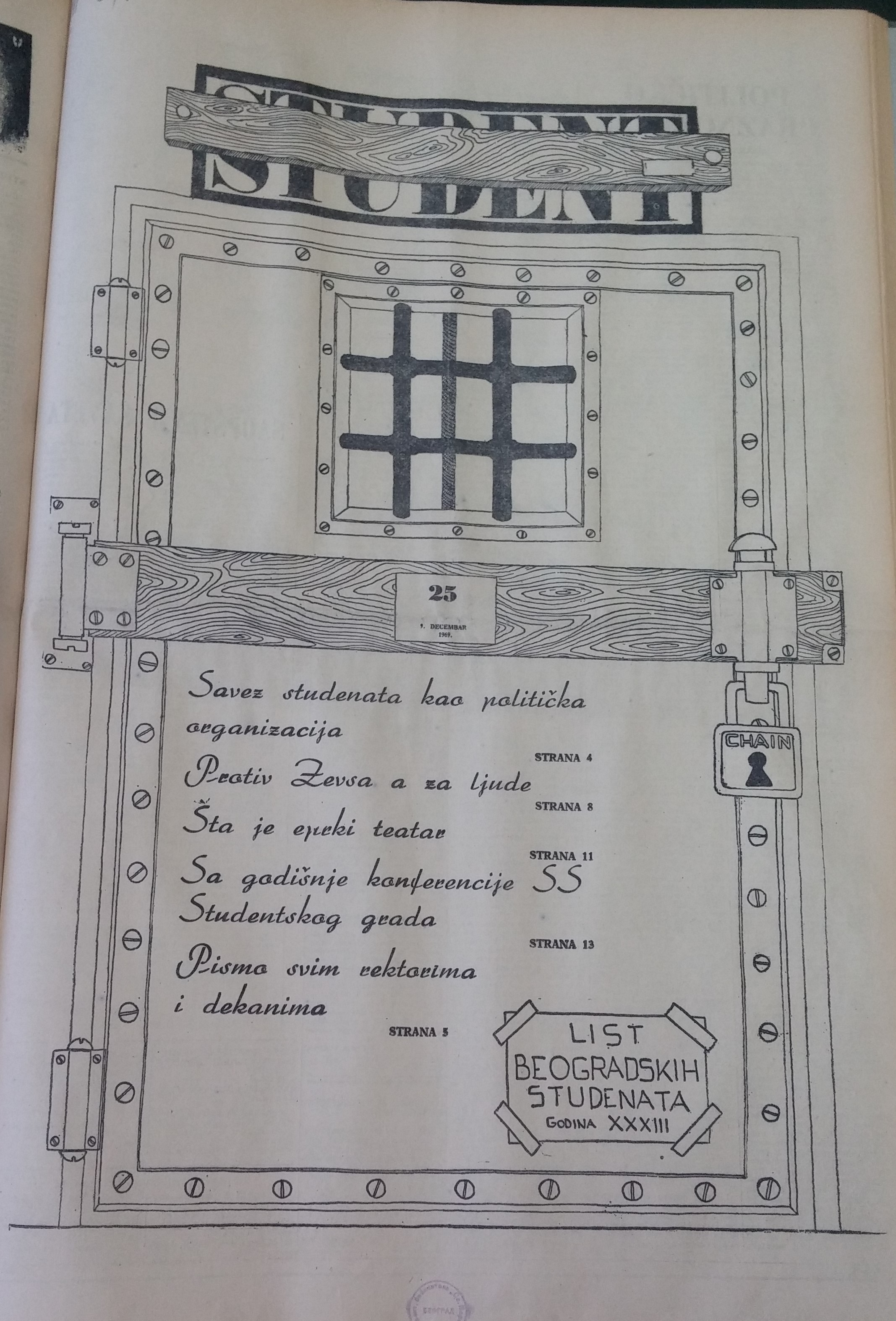

The “Student” magazine, which was often the target of party critique, found itself in a particularly difficult situation at the end of 1969. After the public discussion “Socialism and Culture” at the Philosophical Association of Serbia at the end of November 1969 (29.11.–3.12.), a final attack was launched on the editorial staff at “Student”. In reaction to this attack, issue 25 of 9 December 1969 appeared with the cover page displaying prison bars, while a nailed plank was symbolically printed across the magazine's logo – an image used to signify the closure of a company or business. The magazine's final page showed the illustration of a man in front of prison bars with a sling around his neck – a clear allusion to the pressure the editorial staff was being exposed to. The entire edition abounded with illustrations of torture racks and methods of execution used through history, starting with the gallows to the guillotine. This all predicted the attack anticipated for the middle of December when the city committee of the League of Communists accused the editors of “Student” of wanting to impose their perspective in the form of a monopoly on art and culture, of rejecting the revolutionary role of the League of Communists, of wanting to take over the “baton of the revolution“, while the final charge was related to counter-revolution (I. Moljković, 2008, „Slučaj ‘Student’“, 10).

As expected, the editorial staff was replaced, while the new editors were required to represent the policy promoted by the party as the “third way”, hence action that did not come close to a “position” but was also not “in opposition”. A large number of intellectuals who had defended “Student” in these debates later ended up in prison, which to a significant extent related to their commitment in this case, such as Vladimir Mijanović, Lazar Stojanović, Danilo Udovički, Milan Nikolić, Pavluško Imširovič, and others.