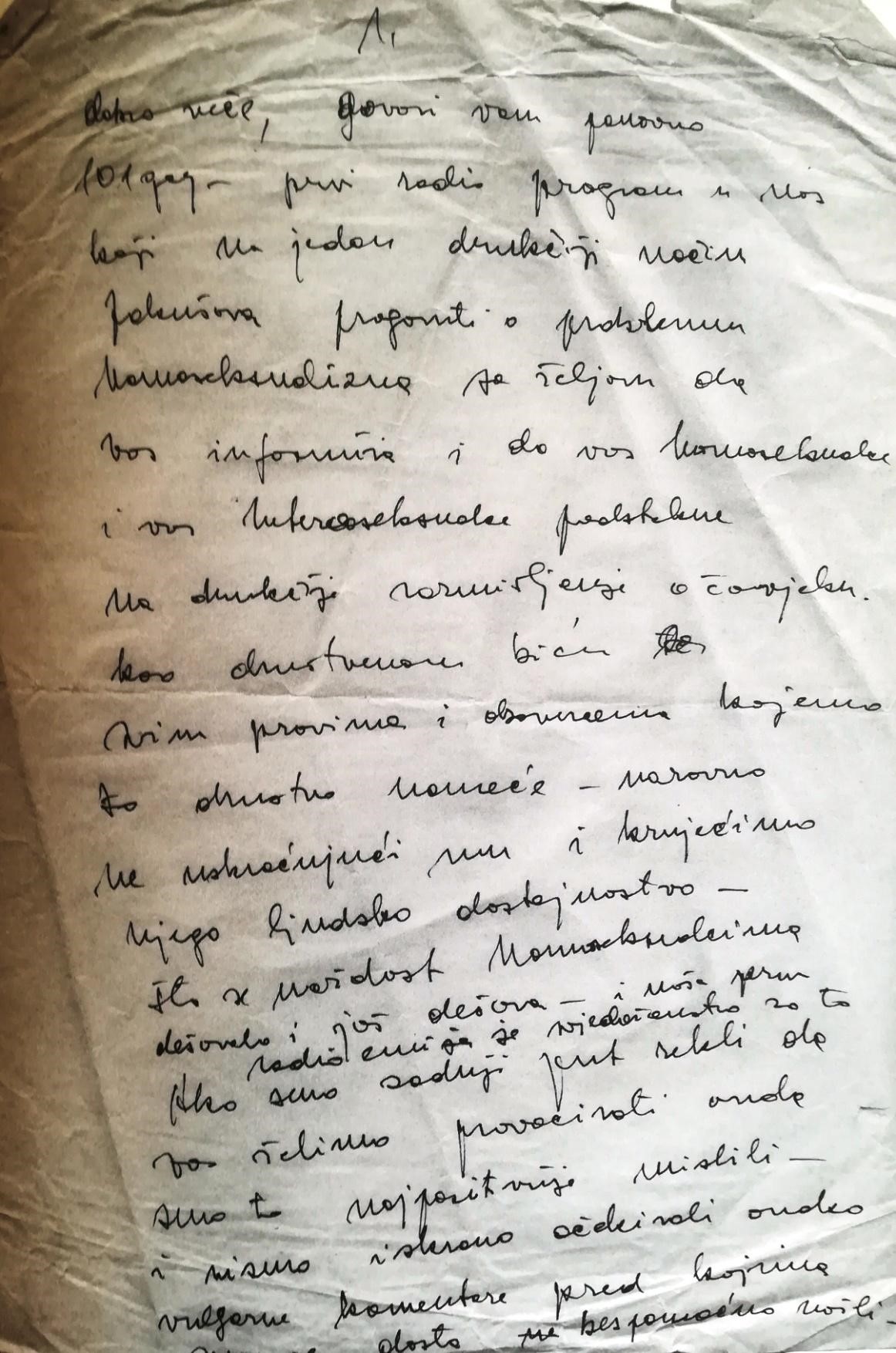

![Marošević, Toni. Notes for “Frigidna utičnica” [The Frigid Socket] radio show. 1984. Manuscript](/courage/file/n9768/Frigidna+uticnica.jpg)

“Frigidna utičnica” [The Frigid Socket] was the first and only radio show dedicated to homosexuality in socialist Yugoslavia. The show, created and hosted by Croatian journalist Toni Marošević, was first aired in the spring of 1984 on Zagreb’s Omladinski radio [Youth Radio, later Radio 101], which in the 1980s was known for stepping out of the official boundaries of socialist journalism. Homosexuality in Yugoslavia was socially mostly unacceptable, almost invisible in the media, and negatively perceived both by most of the population and the ruling Communist Party. Even if it appeared in newspapers and magazines, the topic of homosexuality was usually presented with pity or ridicule (Kuhar 2003). Marošević conceived of “Frigidna utičnica” [The Frigid Socket] as a relaxed, humorous, but also very direct and provocative show, with a simultaneously strong educational component (Bosanac 2013). The first show sparked huge interest and dozens of listener phone calls and comments were aired live. Some were very aggressive, even vulgar, while some expressed support and approval. Also, some negative reviews appeared in the daily press (Tomeković 1984). Even though Marošević was not personally subjected to any sort of pressure from the communist authorities, due to the public controversy the show sparked, the broadcast was cancelled after the fourth week (Dobrović and Bosanac 2007, 233-236). Marošević entrusted his personal bequest to Domino (now part of the History of Homosexuality in Croatia Collection), together with a handwritten note for one of the “Frigidna utičnica” [The Frigid Socket] broadcasts from 1984.

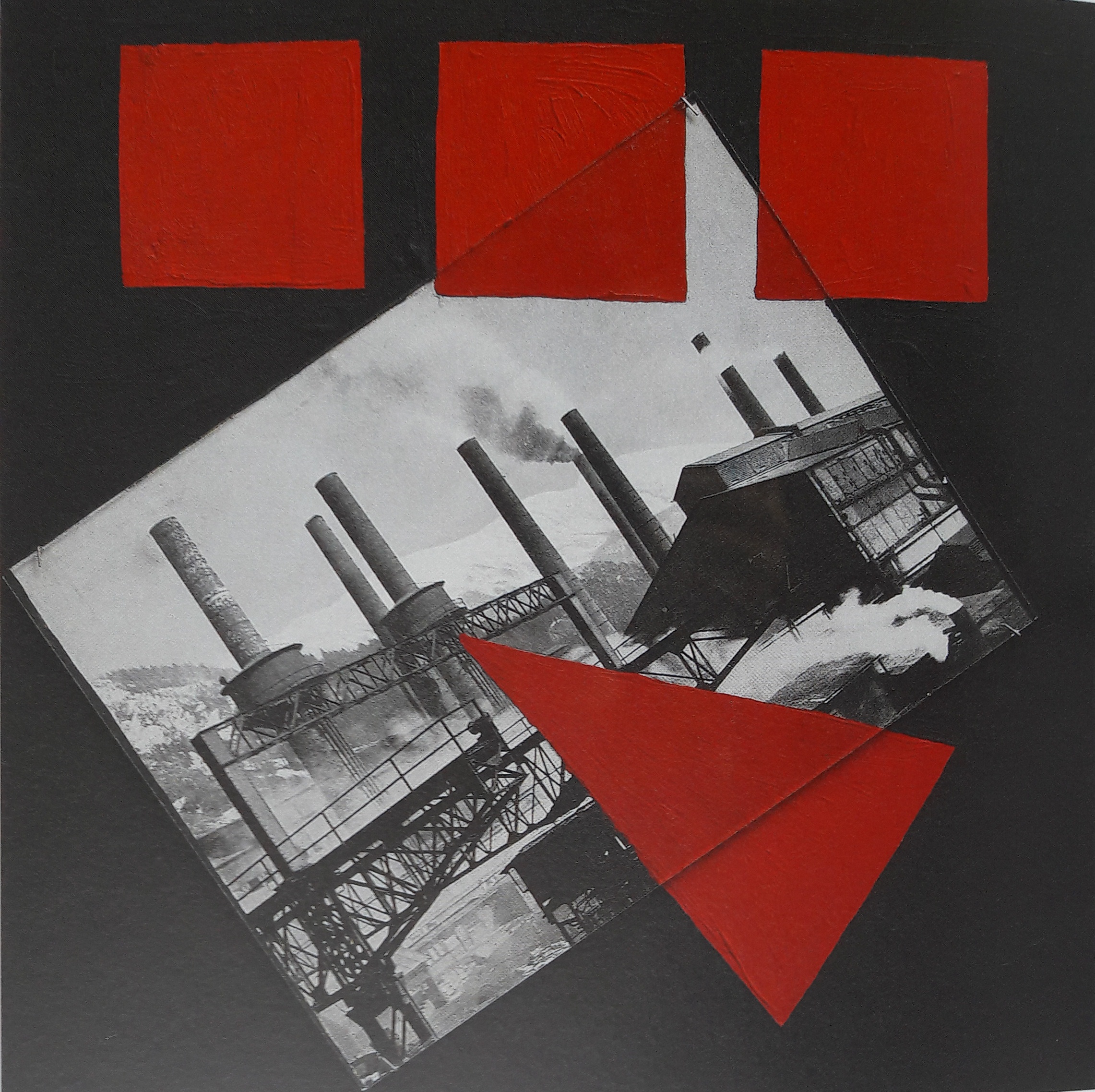

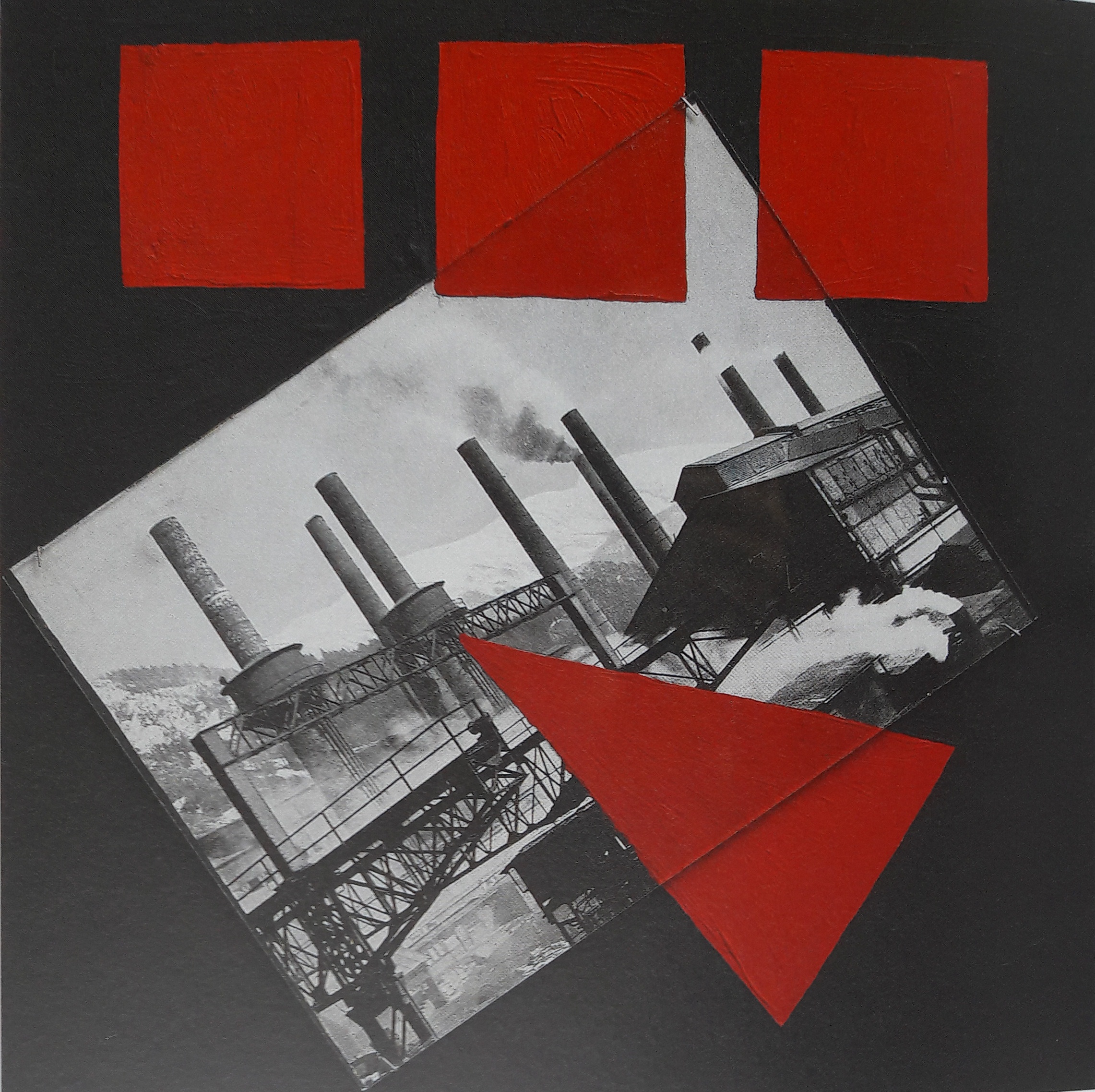

Mladen Stilinović's work showing one of the motifs of early socialism - youth volunteer work campaigns. As part of the "Exploitation of the Dead" cycle, the work criticizes the socialist system, indicating its weariness and hinting at its disintegration.

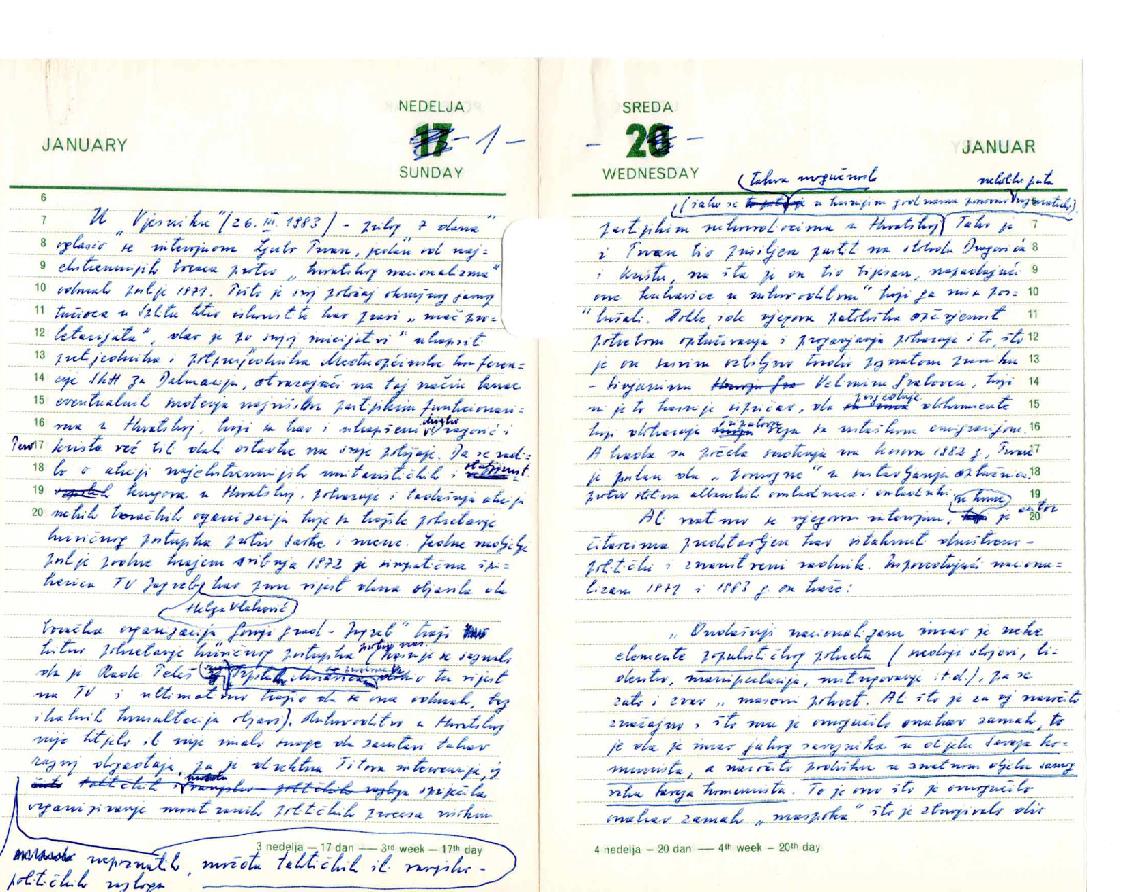

In his manuscripts, Tripalo records the notes of the proportions of the reformist movement, which his opponents called maspok. As one of the leading individuals, considered to be the most prominent public tribune, Tripalo became a chronicler and analyst of this phenomenon. As in the other Tripal annotations, his analytical and critical discourse testifies on the democratic evolution of an important party dissident.

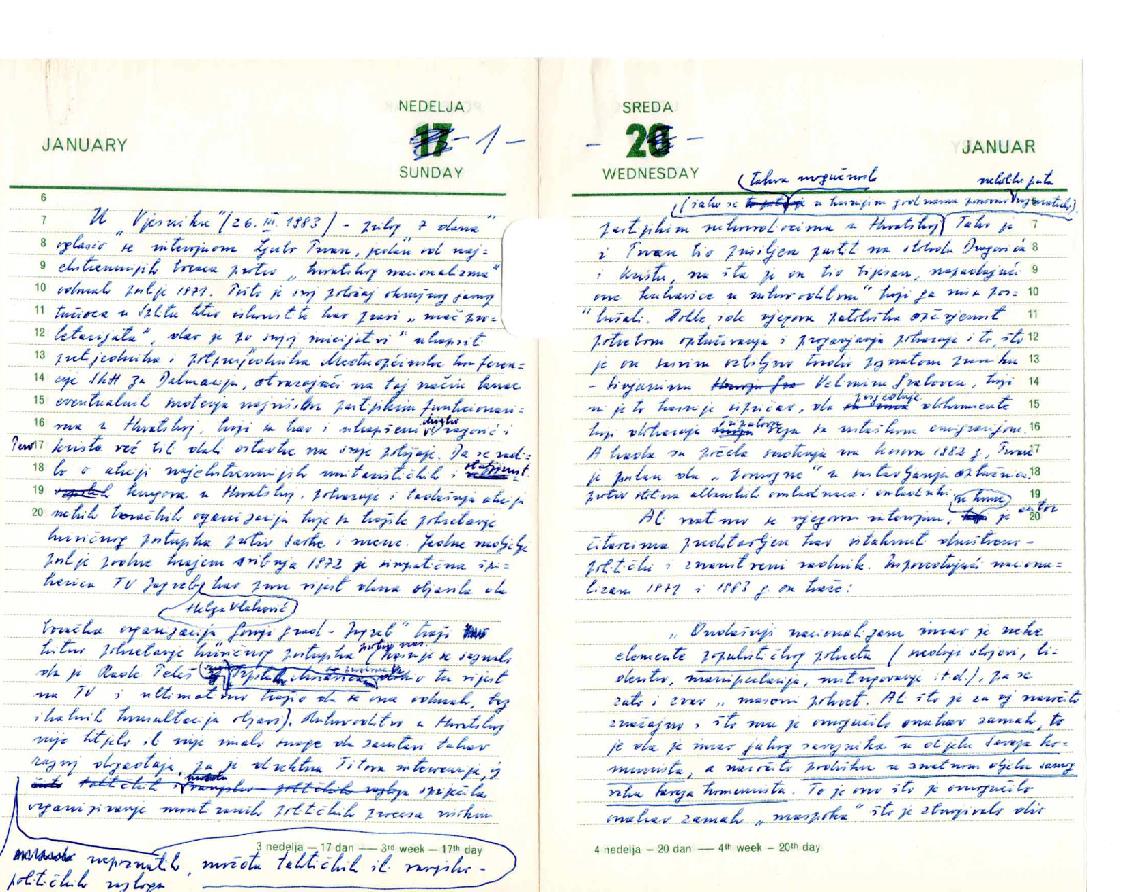

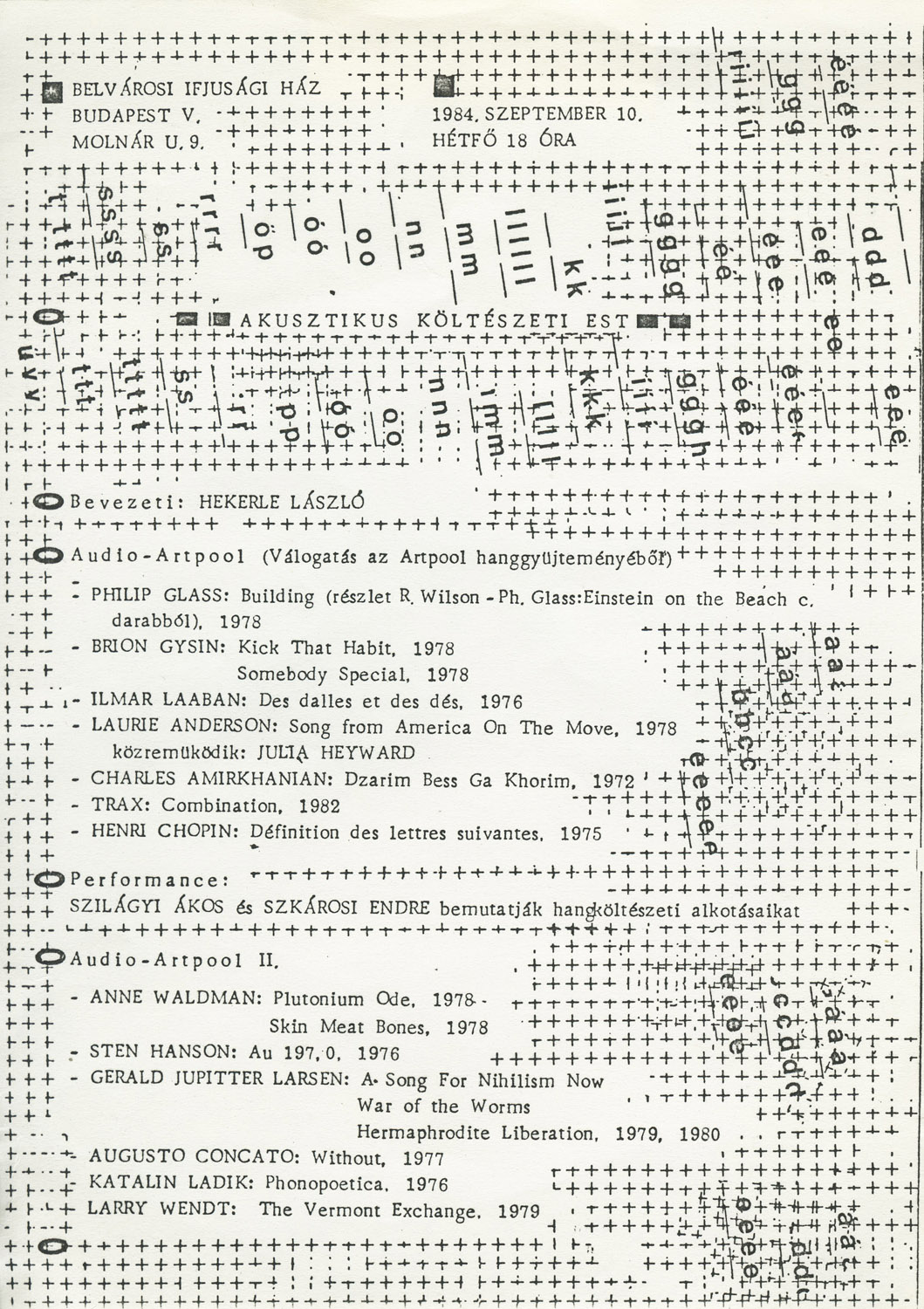

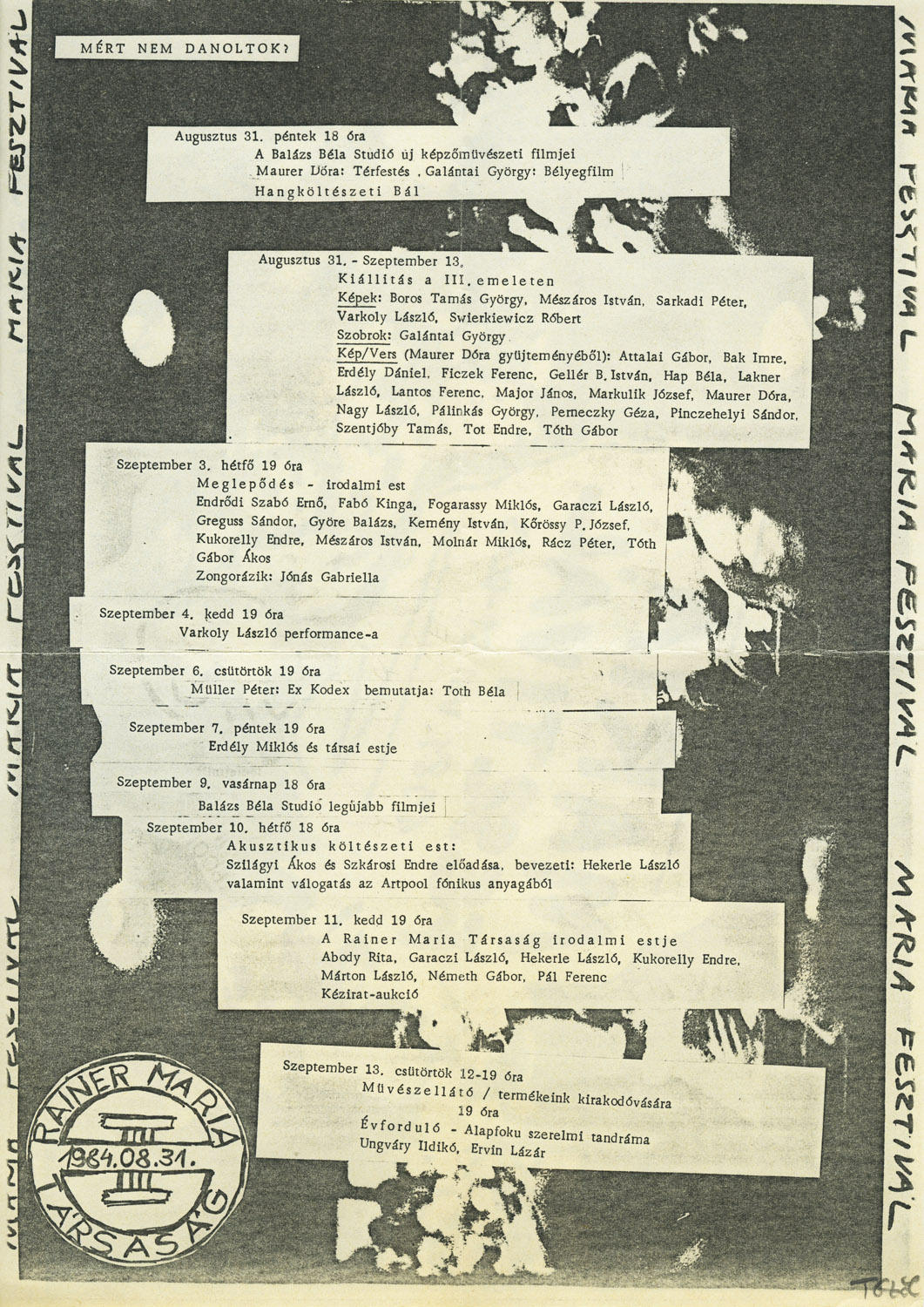

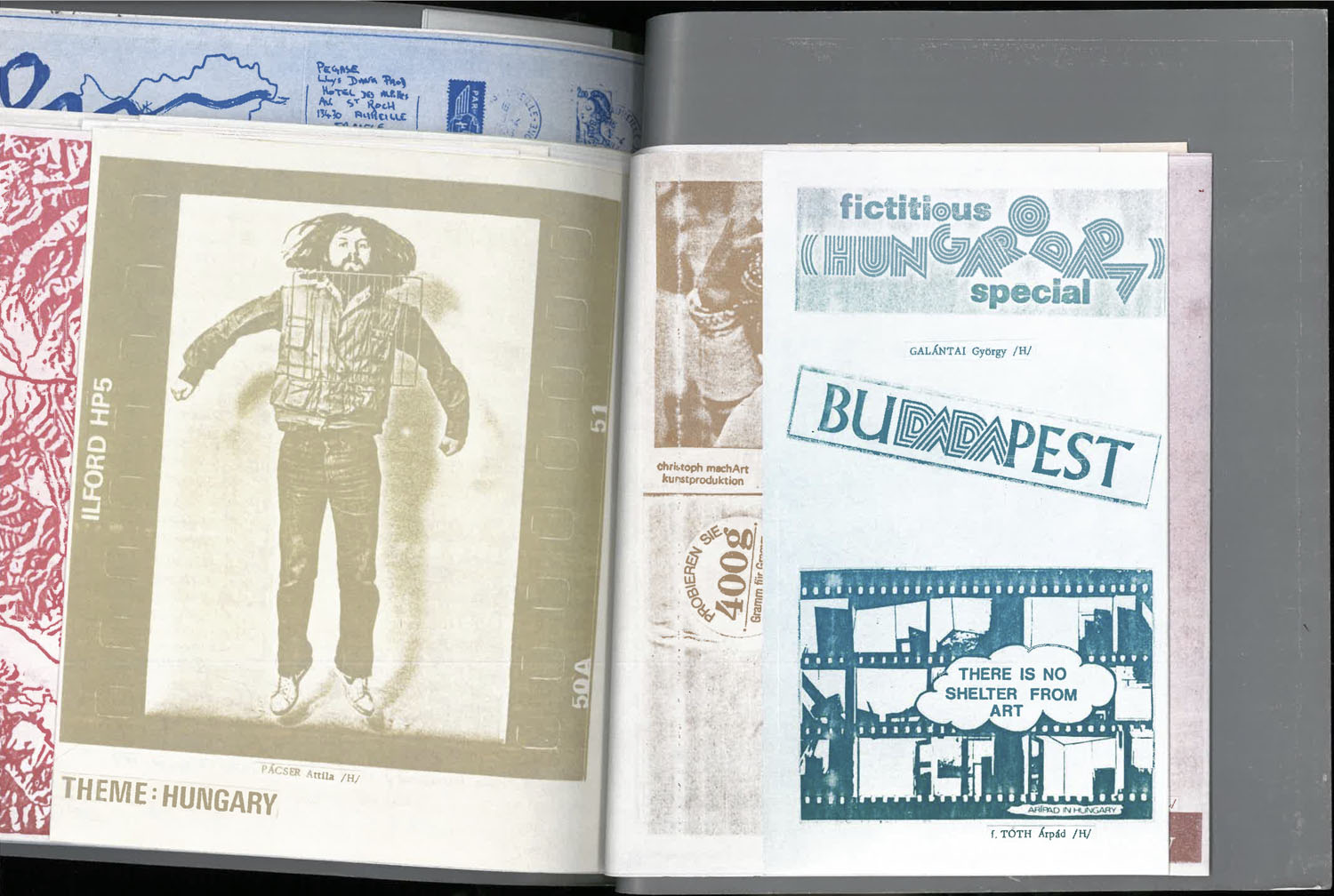

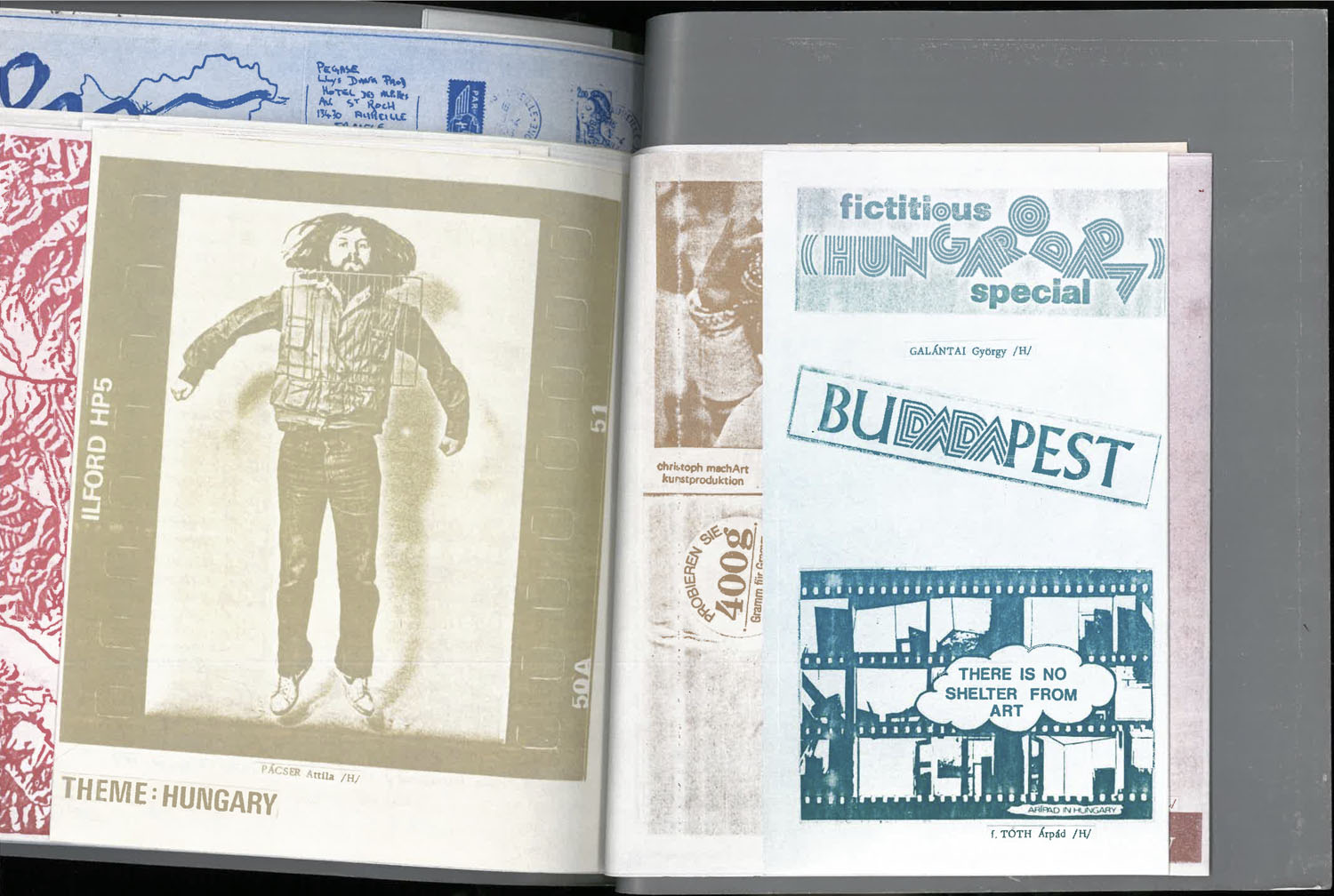

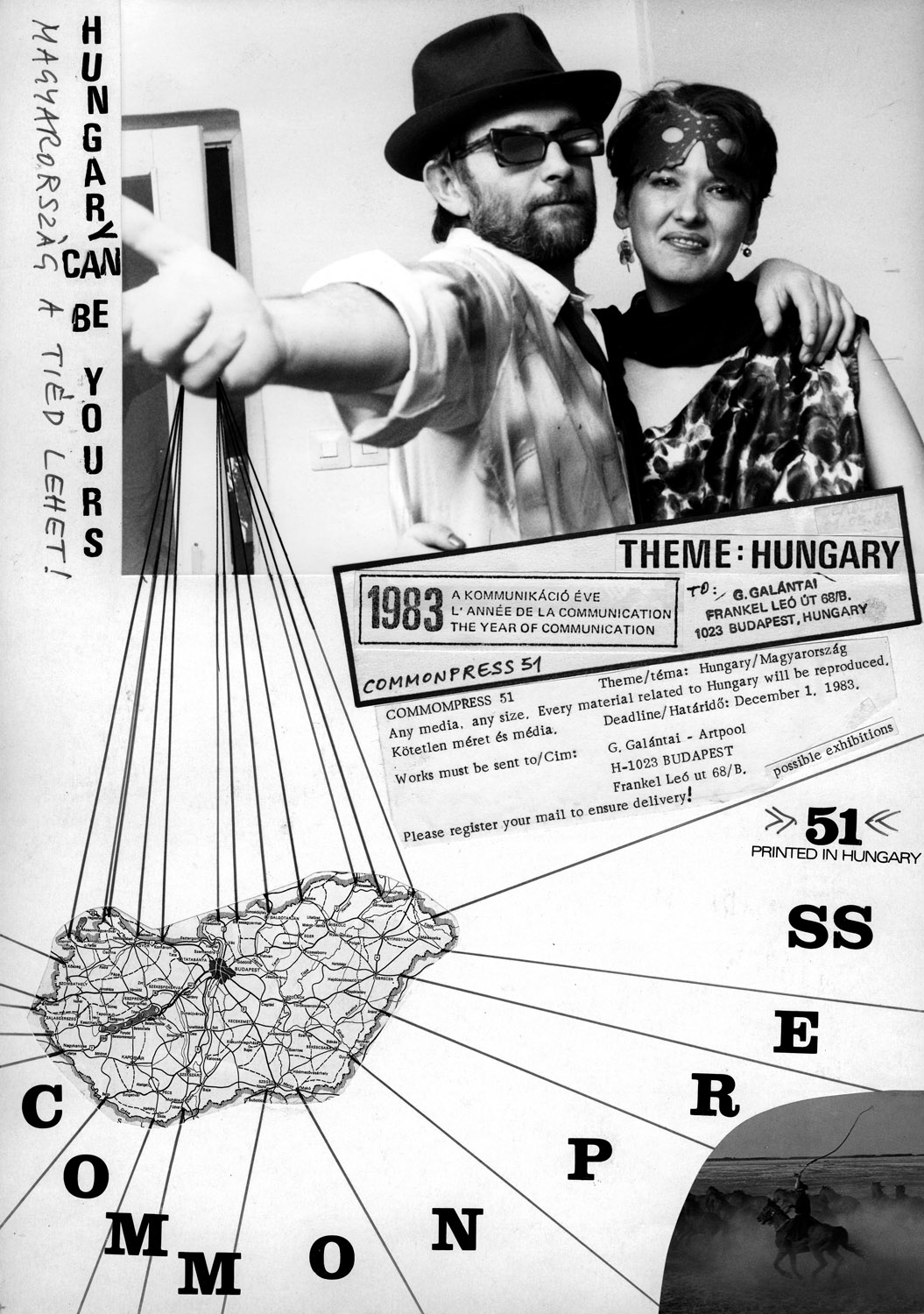

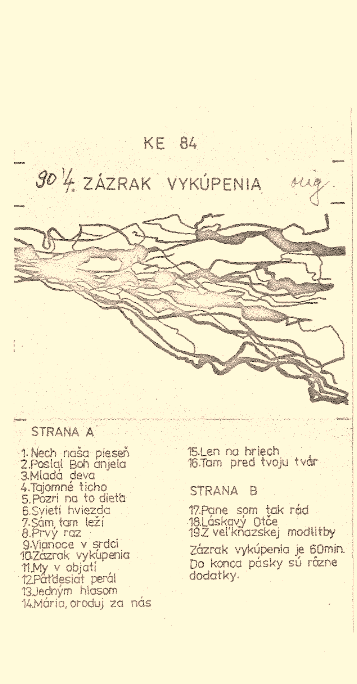

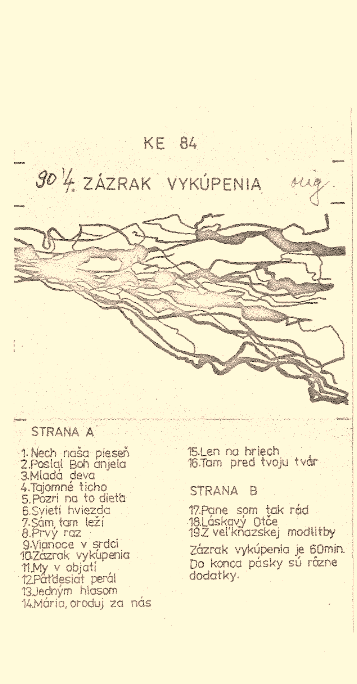

“Miért nem danoltok? – Maria Fesztivál (August 31–13 September 1984, Budapest, Belvárosi Ifjúsági Ház). Balázs Györe, Ákos Szilágyi and Endre Szkárosi took part in the acoustic poetry evening, where a selection from the phonic collection of Artpool was also presented.

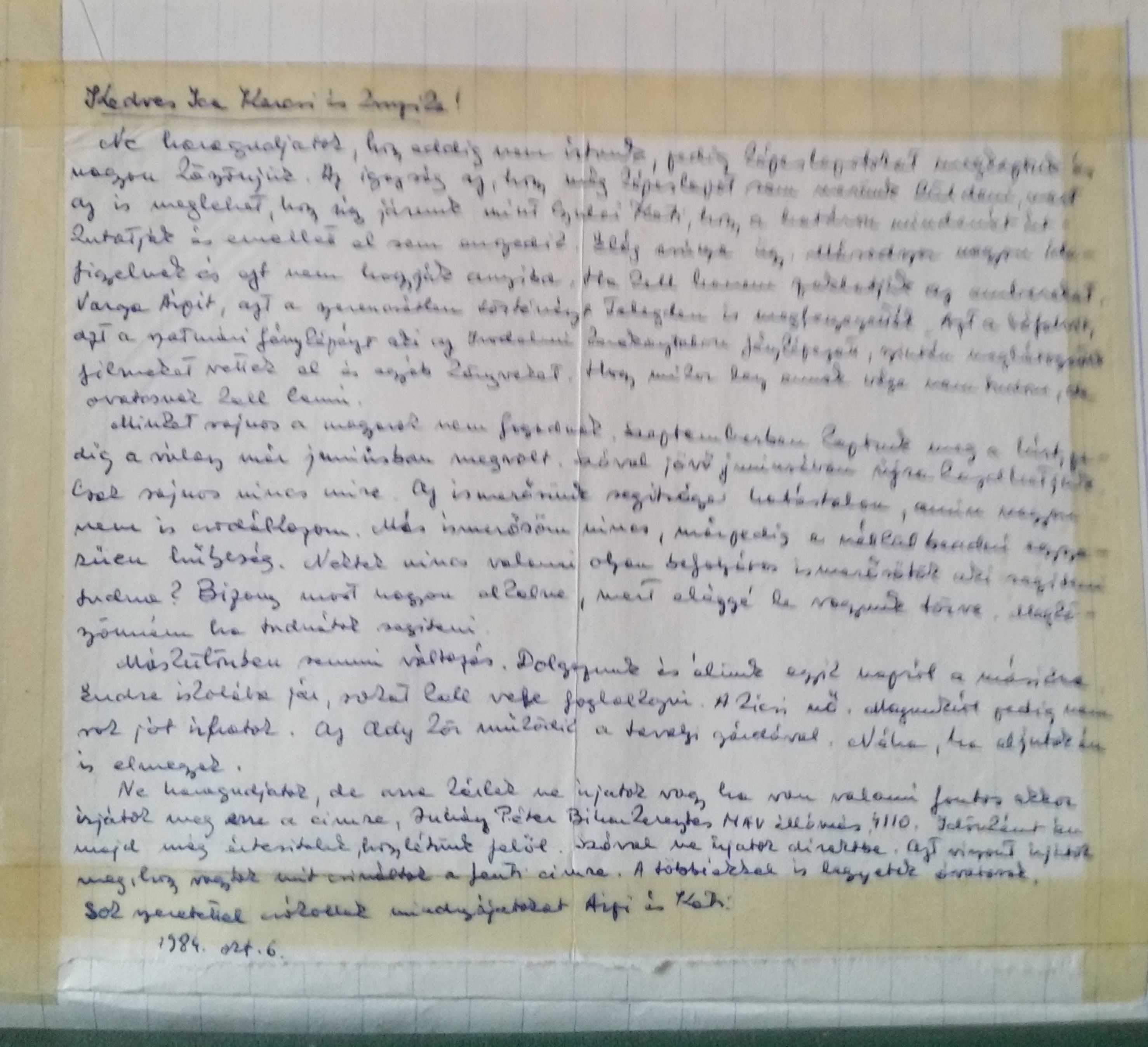

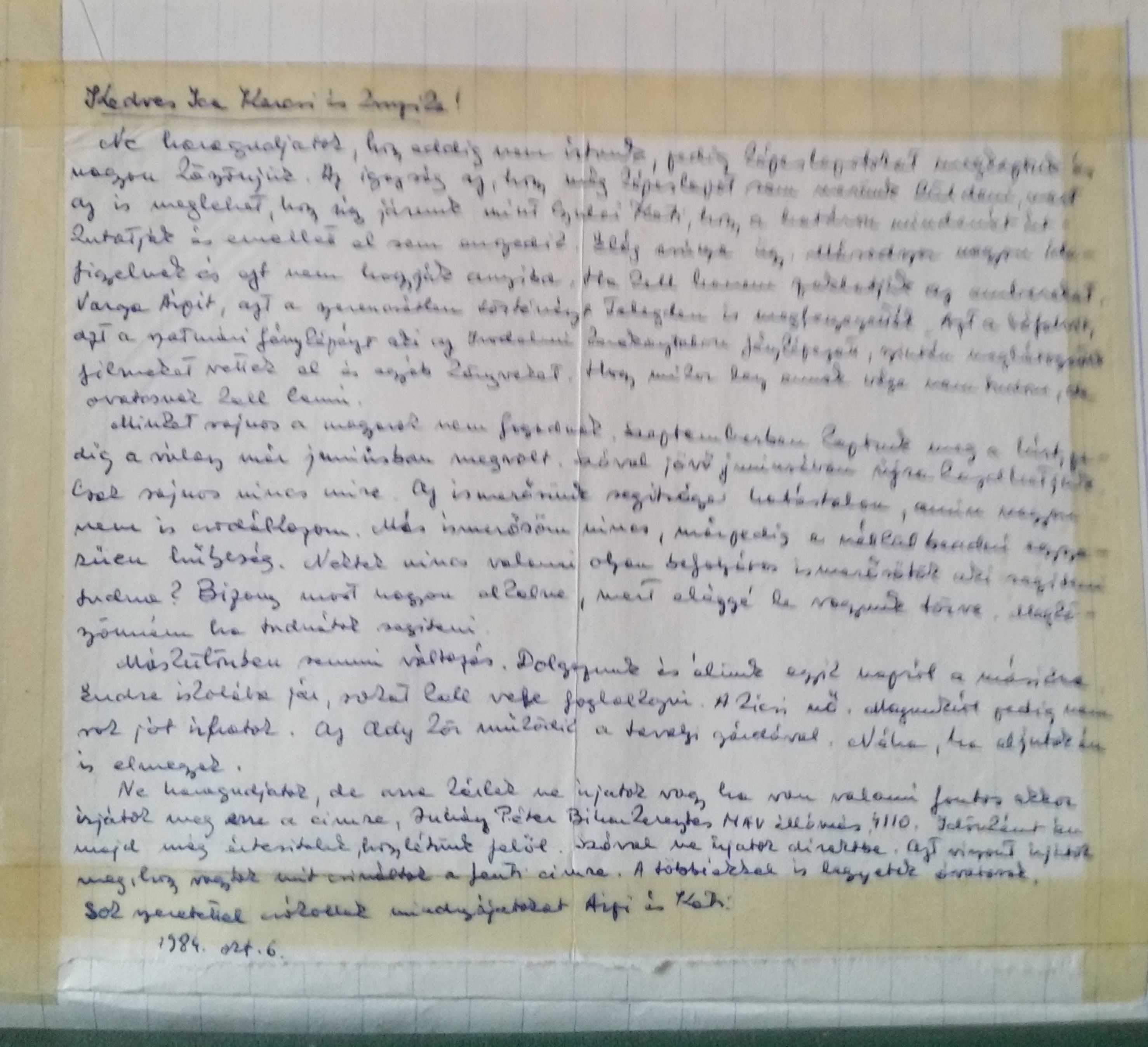

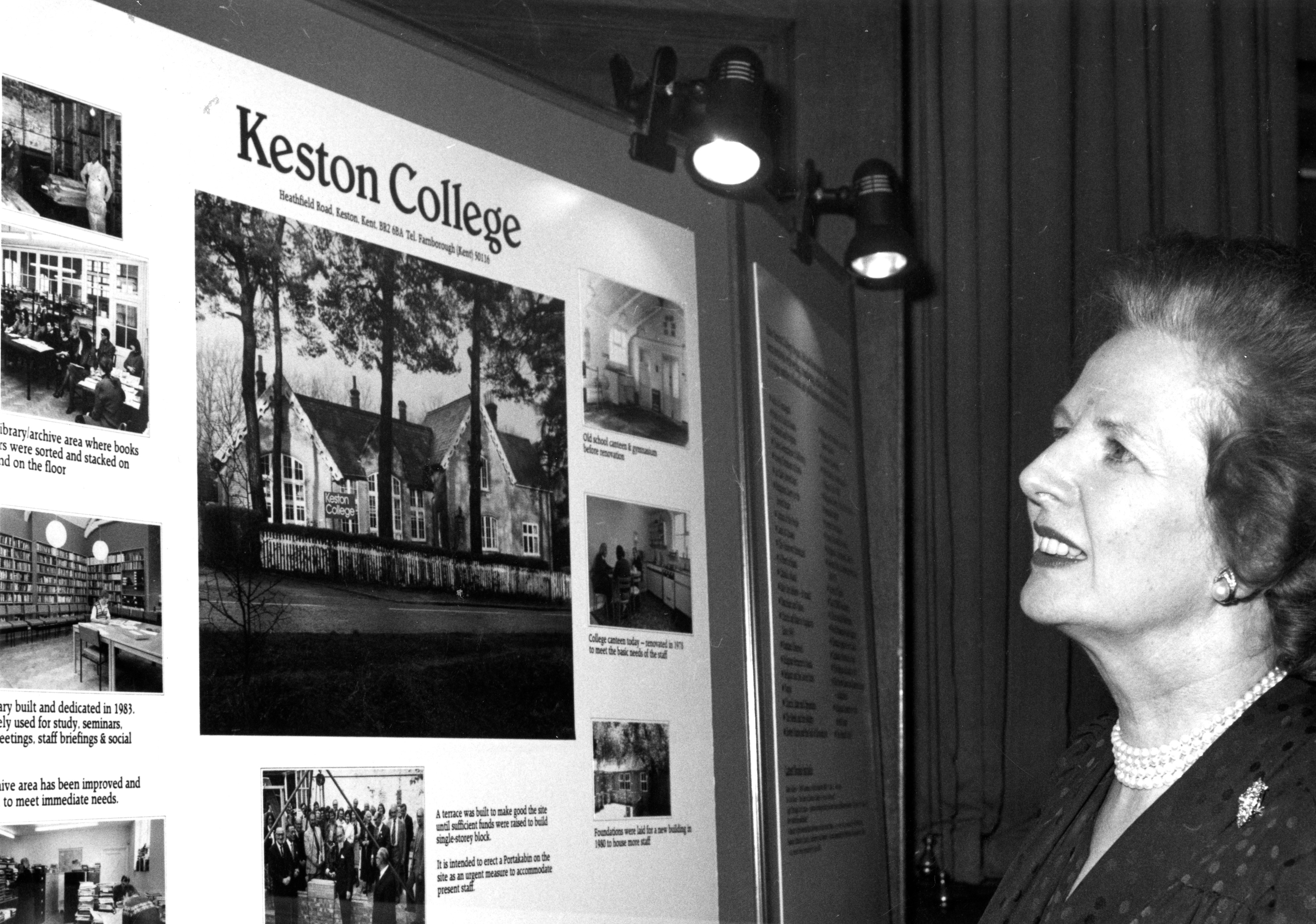

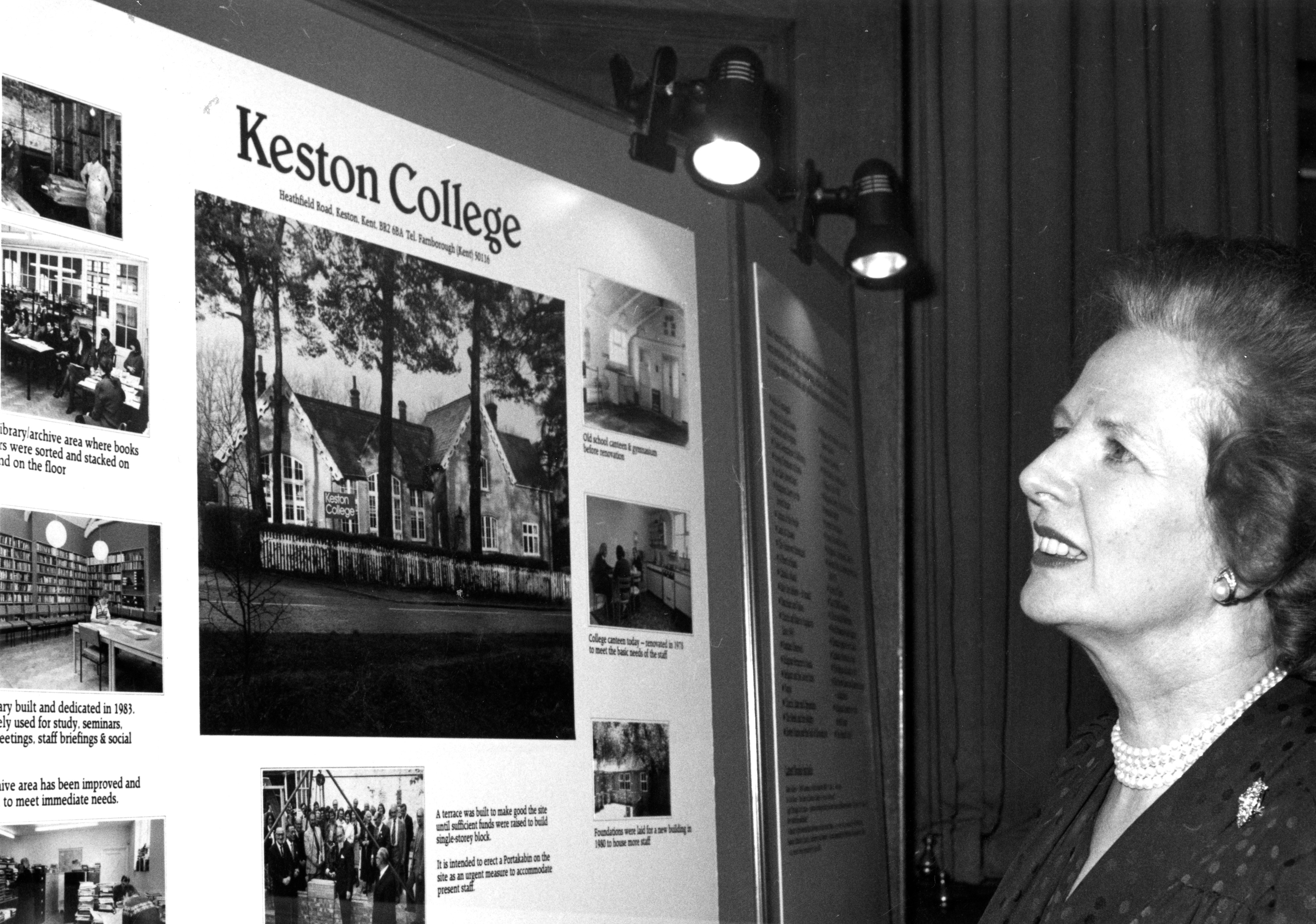

Letter “Smuggled” Across the Romanian-Hungarian Border, in Hungarian, 6 October 1984 (Letter Size: 15 cm x 14cm)

Letter “Smuggled” Across the Romanian-Hungarian Border, in Hungarian, 6 October 1984 (Letter Size: 15 cm x 14cm)

The Ellenpontok – Tóth Private Collection includes several hundred letters dating from that time. Especially interesting are the letters and notes of various shapes and sizes, smuggled primarily across the Romanian–Hungarian border by individuals during the eighties. In that time the relevant Transylvanian events had news value. Measures taken against the Hungarian minority were hardly talked about in the press, so it was essential to spread information to the broader public, partly with the purpose of protecting the victims of such measures, and partly in the hope that the situation of the minority would be improved by drawing the attention to these atrocities occurring under the Romanian communist regime.

This smuggled letter, size 15 cm x 14 cm, was delivered to the Tóth family in October 1984 while they lived in Budapest. The senders were the Spaller couple, old friends of the Tóths living in Oradea. Both Árpád Spaller and his wife Katalin obtained their degrees at Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, in 1970 and 1971 respectively, in special education (health pedagogy) and Romanian language and literature. After graduating they both worked as teachers in Oradea (Spaller and Spaller 2006).

The text of the letter is as follows:

”Dear Ica, Karcsi and Zsuzsika!

Excuse us for not having written so far, although we were glad to receive your postcard. The truth is that we hesitate to even send a postcard for fear we might end up like Kati Gyulai [Gyulai Katalin, verse performer from Oradea (Molnár 1993)], who underwent a thorough customs control only to be refused entry to the country. Quite an unfortunate case. On the other hand, they keep a close eye on us and they mean it seriously. They keep harassing people. Árpi Varga, [Árpád Varga, 1951-1994 (Sipos 1995)], that miserable historian from Tileagd was also threatened. They also showed up in the home of Sófalvi, that photographer from Satu Mare who took photos at the Literary Round Table, and confiscated some of his films and books. We have no idea when this will end but we ought to be cautious.

Unfortunately, we were denied entry to Hungary. We were informed about this in September, although the decision was already made in June. So, we can apply again next June. Unfortunately, we cannot expect much. The help from our acquaintance hasn’t been efficient which doesn’t surprise us. We do not have any other contacts to turn to, so applying under such circumstances is totally pointless. Do you happen to know anyone influential who could help us? To be honest, it would mean a lot to us now, because we are rather disappointed. We would appreciate your help.

Otherwise, everything is the same. We are working and living from one day to the other. Endre attends school, he pretty much needs our assistance. The little one is growing. As for us, not much good news to tell. The Ady Circle is still active with the old members. Sometimes, when we have time, we also attend.

If you don’t mind we need to ask you to stop writing to us, or if there is anything important, address your letter to Péter Juhász [railway worker] Biharkeresztes MÁV station 4110. From time to time, we shall send you news about us. So, please don’t write directly to us. But please let us know how you are in a letter sent to the above address. And please be cautious in the case of the others, too.

With love, Árpi and Kati.

October 6, 1984”.

The letter of the Spaller family perfectly illustrates the fear present in those times, affecting both the public sphere and the everyday life of the individual. People, afraid they might be observed and harassed by the Securitate, in the constant climate of insecurity, chose to be silent, avoiding any form of public manifestation. It also says a lot that the senders of the letter did not give a Romanian address for direct correspondence, but that of the railway station in Biharkeresztes, a Hungarian settlement 6 km from the Hungarian-Romanian border, which is also a border crossing point.

The reasons behind emigration did not require much explanation back then. Beginning with January 1983 it became increasingly difficult to obtain a residence permit from the Hungarian authorities, as the application involved the presentation of a letter of invitation. This seemingly insignificant administrative obstacle – as revealed also in the above letter – could represent an enormous impediment for families who planned to emigrate, though emigration did not prove to be an impossible endeavour on the whole: in 1987 the Spaller family moved to Hungary where they managed to find jobs that suited their qualifications. At present they live in Budapest (Spaller and Spaller 2006).

The machine-read transcript of the audio recorded interviews from the secret meetings which took place in Božena Komárková´s flat, comprised of 42 pages. She discusses her life, reflection of T. G. Masaryk, St. Augustine, relationship to democracy, Christian faith, Socialism and Christianity, church affairs after the Communist coup in 1948, etc. The transcription is crossed out and supplemented by Božená Komárková´s comments. Part of the collection is also the original audio record. This document shows authentic and original views from the meetings and a wide range of views from the prominent figure of Protestant dissent - Božena Komárková.

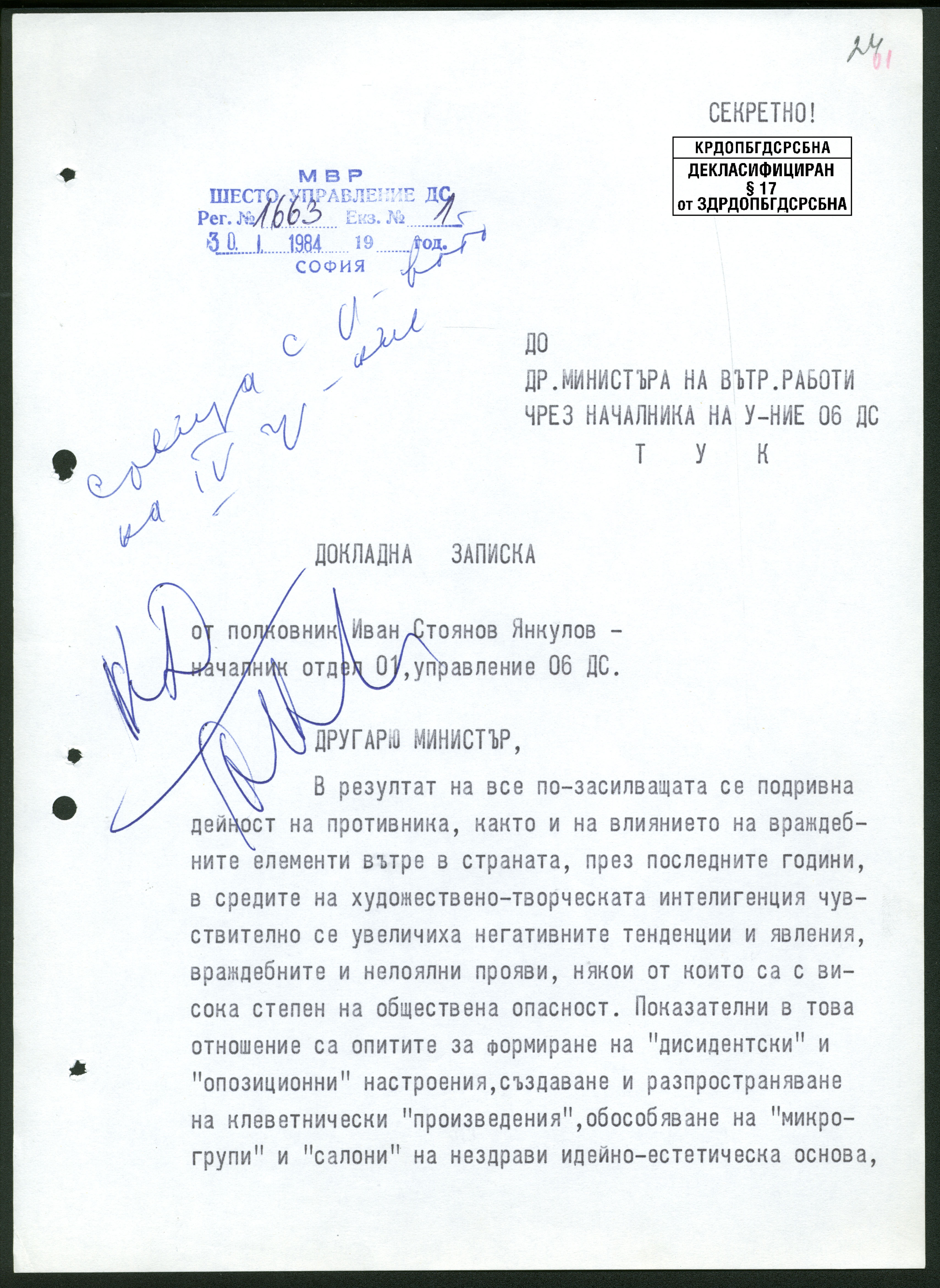

Information about "Prophylactive activity of Division 01, Administration 06 - SS for the period from 1 January 1980 to 30 June 1984", Sofia, 16 August 1984.

The document reveals that during the reporting period, the appointment of more than 200 persons whom the regime considered to be of "enemy origin or standing at unhealthy ideological and aesthetic positions" was declined by the government. Career promotion of 60 persons of these categories was not granted either. The document also talks about the measures and events that the state security identified to improve its "prophylactive work" among the intelligentsia. This document, thus, gives a good idea about the nature of work of the state security against cultural opposition, and how persons deemed illoyal faced significant problems in their careers.

The “Exploitation of the Dead“ Collection by the self-educated neo-avantgarde artist Mladen Stilinović was compiled in socialist Croatia in the period from 1984 to 1990. It is a cycle of paintings dealing with the theme of dispersal or disappearance of symbols, both those widely accepted, such as the Christian cross, as well as the symbols of the Yugoslav socialist period, such as the red star. The author detects changes that affected the socialist system at the symbolic level in the 1980s and puts them in the context of art in a subversive way by using ideological and political reality.

May 1984 Founding contract signed by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Soros Foundation New York

May 1984 Founding contract signed by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Soros Foundation New York

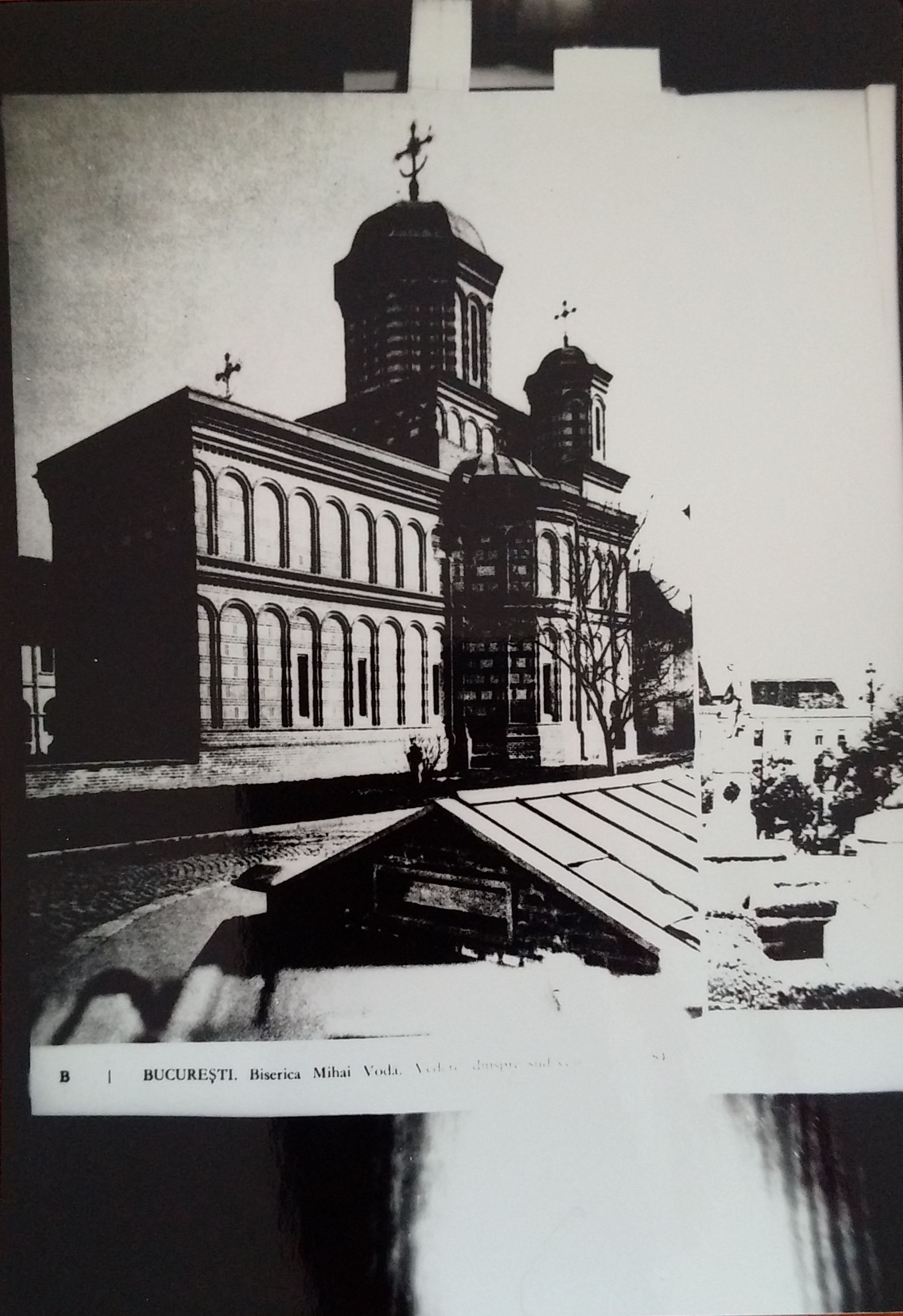

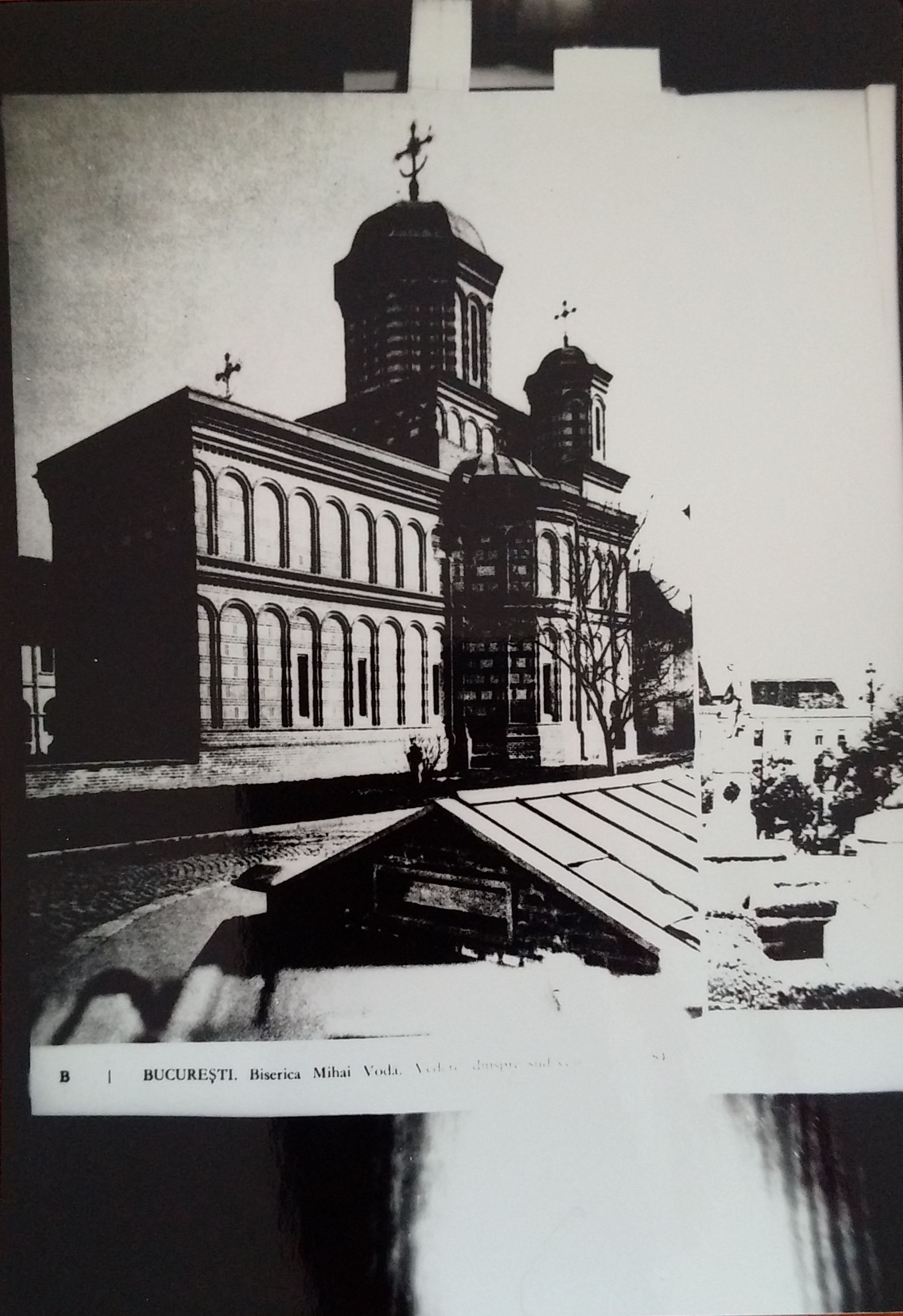

The church of the former Mihai Vodă Monastery is one of the oldest surviving buildings in Bucharest. The monastic complex of which it was part, nowadays partially destroyed, dated from 1594, and had served various purposes over the centuries, including princely residence, military hospital, and medical school. The most important of these was its transformation into the home of the State Archives after the founding and international recognition of the modern Romanian state in 1862. The Mihai Vodă monastery, an emblem of premodern Bucharest, was founded by one of the most important rulers in the pantheon of the national history of the Romanians, Michael the Brave (Mihai Viteazul), whence its name. As ruler of Wallachia in the period 1593–1601, he was the only leader of any of the premodern states existing within the present boundaries of Romania who managed to bring under his military control, “to unify,” for a very short time (1600–1601) a territory approximately corresponding to that of contemporary Romania. For this reason, Michael the Brave has been considered to be a key figure in national history, starting from the early nineteenth century and the first professional attempts to codify that history into a narrative frame. Paradoxically, communist historiography conferred on Michael the Brave an infinitely more important role in national history than he had ever been accorded by historians before the First World War or in the interwar period. Due to the teleological reading of national history that characterised the (re)interpretation of historical materialism in the time of the Ceauşescu regime, Michael the Brave came to be seen as prefiguring the so-called “Union of 1918.” This expression refers to the joining of the historical regions of Austria-Hungary with a majority Romanian population to the Old Kingdom of Romania, which did not in fact happen until after the Peace Treaties of Saint-Germain (1919) and Trianon (1920). This historic moment became fundamental for the national identity of the Romanians following the (re)codification of national history under the direct guidance of the Party and the imposition of this version as representing the “single historical truth” through the intermediary of the documents adopted at the Eleventh Congress of the RCP in 1974. According to this interpretation, Michael the Brave was the first ruler who achieved the union of the Romanians and anticipated by his actions the culminating moment of national history, the “Union of 1918,” which was achieved by popular action from within, the “will of the masses” of Romanians, and not at the negotiating table. This image of Michael the Brave was intensely promoted under the Ceauşescu regime, not only through school textbooks or works of historiography, but much more efficiently through the intermediary of a cinematographic narration: the film Mihai Viteazul (1970), in which the protagonist is played by one of the best loved actors of the communist period, is to date the most viewed Romanian historical film, with over thirteen million viewers, and in third place in an overall ranking of films produced in Romania, with only 1.3 million viewers less than the film that takes first place.

In spite of the special importance of this historical figure in the redefinition and reproduction of national identity under the Ceauşescu regime, the monastery complex that he founded and that had constituted an emblem of pre-modern Bucharest became the victim of the most notorious of the demolitions ordered by the same regime. Due to the elevated position that it occupied in the urban landscape, its site was destined for the House of the People. Consequently, in 1985, the monastery ensemble was demolished, while the church and bell-tower were moved from their original position to make room for the communist architectural ensemble, whose pièce de résistance was to be the House of the People, today home to the Romanian Parliament. Initially scheduled to be demolished (and thus to share the fate of the twenty churches that were demolished between 1977 and 1989), the Mihai Vodă church was saved from destruction at the last minute. The compromise solution was to move it from the hill on which it had been established by Michael the Brave to a new position at the foot of the hill, where it would be hidden by the new apartment blocks that were to be built. As a result of the operation of moving the church down a slope, it was shifted a distance of 289 metres, descending by 6.2 metres. Initially sited on the Mihai Vodă Hill, at what was then Str. Arhivelor no. 2, it is now to be found at Str. Sapienţei no. 4. In the course of this process of radical reconfiguration of the centre of the city of Bucharest, another eight churches were moved in the same way as the Mihai Vodă church. These operations necessitated much inventiveness on the part of the engineers, and so may themselves be counted among the actions of cultural opposition, of finding a way not of directly disobeying the orders received but of moderating their consequences by proposing solutions that would be tolerated. In Alexandru Barnea’s private collection there are three photographs of this church, taken in 1985, a few months before it was moved. They stand as testimony to the policy of remodelling the past that was characteristic of the Ceauşescu regime, which made intense use of national history for the purposes of legitimation, but at the same destroyed all that did not fit the new secularised version of that history. By transforming all national history into a prehistory of the Communist Party, past rulers who had fought for “unity and independence” became precursors of the General Secretary of the Party, who – continuing their model – was trying to pursue a policy of distancing in relation to the Soviet Union. However all that did not fit the atheist vision of the communist regime was condemned to oblivion or even to destruction. Actions such as that of the collector Alexandru Barnea contributed decisively to the preservation of the pre-communist historical memory of the Romanians.

This collection of the Czecho-Slovak poet, novelist, playwright, philosopher and “guru” of the Czechoslovak underground, Egon Bondy (real name Zbyněk Fišer, 1930–2007), consists of sources related to the history of the Czechoslovak literary underground and the left-wing opposition to the communist regime.

The Tóth Private Collection in Göteborg comprises the most comprehensive materials related to Ellenpontok (Counterpoints), the Hungarian-language samizdat publication which gained international reputation in the early 1980s due to its resolute fight for human and minority rights in communist Romania. At the same time, the items resulting from the different stages of the Tóth family’s emigrant life (Hungary, Canada, Sweden), such as official documents, manuscripts, sound recordings, photos, private correspondence, and books on minorities, shed light on the cultural efforts undertaken by the collectors in order to improve the situation of those left behind.

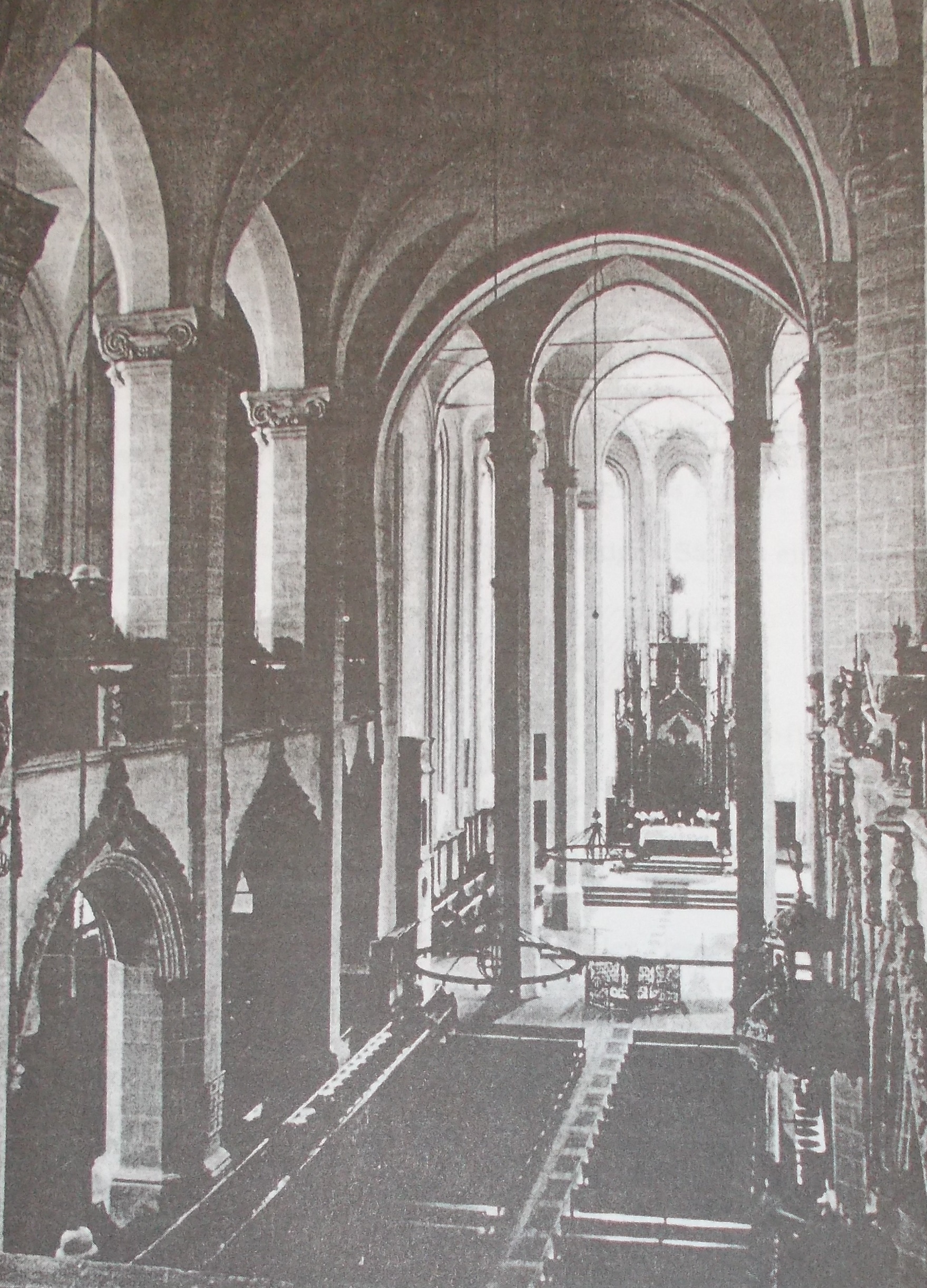

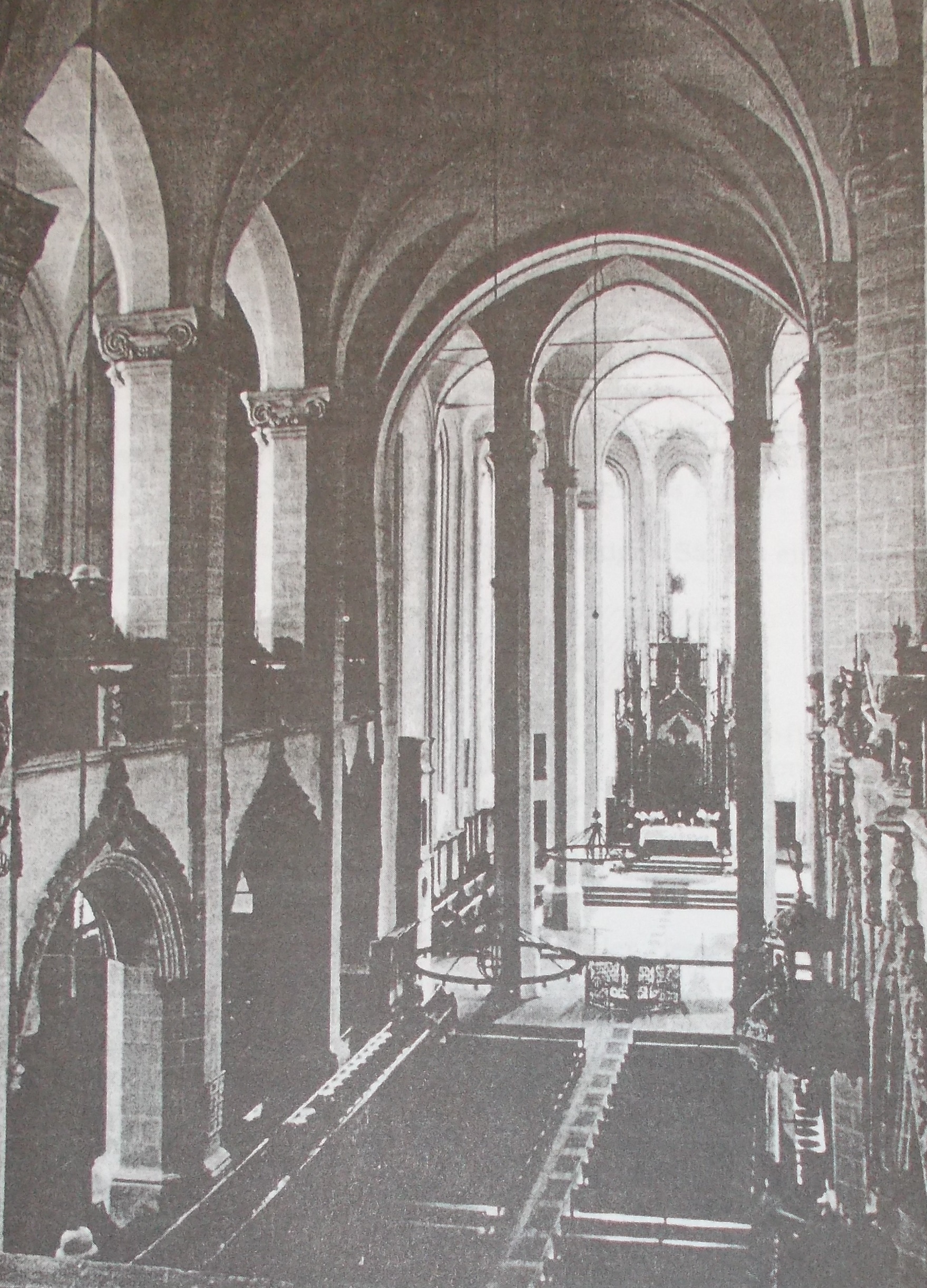

In the period 1981–1984, significant restoration work on the interior of the Black Church took place with the financial help of the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland (Federal Republic of Germany). Due to this work, the Black Church could not be used by its parishioners during this period. On 27 May 1984, the church was re-opened with a festive event and a religious service that marked both the 600th anniversary of the beginning of the construction and the re-inauguration of the Church. The religious service was conducted by Bishop Albert Klein of the Evangelical Church A.C. in Romania. This event represented a significant moment in the history of the Black Church Restoration Ad Hoc Collection due to the fact that it was the occasion for the publication of several articles in the local press popularising the history of the restoration process and its achievements. These articles made use of the documents and photos in the collection preserved within the Black Church archives.

The many letters to be found in Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca’s collection are indisputable evidence of their commitment to using RFE’s broadcasts to protect Romanian dissidents from the abuses and acts of violence organised against them by the communist authorities. An illustrative example of this is the letter that Father Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa sent to Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca in October 1984.

A former political prisoner, Calciu-Dumitreasa was imprisoned again in 1979 after delivering a series of seven sermons for young people the previous year. Through his sermons, Father Calciu-Dumitreasa hoped to strengthen the faith of young people whose Christian spiritual life was threatened by communist atheism and materialism (Petrescu 2013). The letter written by Father Calciu-Dumitreasa describes his situation and the situation of his family after his release from prison (August 1984) due to a huge campaign organised by the Romanian diaspora, and also makes known to the listeners of RFE’s Romanian desk his decision to emigrate.

At the beginning of his message, Calciu-Dumitreasa mentions that while imprisoned he refused any kind of collaboration with the regime. Furthermore, he continued to perform his duty as a priest despite the threats, terror, and beatings he was subjected to by the communist authorities. After his release, Calciu-Dumitreasa has been welcomed by his friends, acquaintances, and former students but to his very great disappointment the Romanian Orthodox Church has decided to strip him of the priesthood. Thus, in his letter he urges the Orthodox Church’s hierarchs to reconsider their position regarding his removal as he has proved to be a faithful defender of Christian values even in the most unfavourable circumstances. Moreover, the Securitate continues to watch each of his movements and its "unbated persistence in hate and malice" means that persecution against him and his family has continued.

In this context, Calciu-Dumitreasa mentions that despite his immense investment of love, faith, and suffering in "our country and Church," he has decided to emigrate due to the harassment his family continues to be subjected to by the Securitate. At the end of his letter, Calciu-Dumitreasa expresses his belief that those who have stood by him in difficult times in Romania will also surrender him with their love into his forced exile.

Mladen Stilinović's work from the "Exploitation of the Dead" cycle, depicting a photograph of one of the typical Party gatherings. The photograph itself, outside the context of Stilinovic's work, would represent visual proof of the Party gathering. But, as a part of his work, it points to the weariness of such gatherings, and thus to the end of the socialist period.

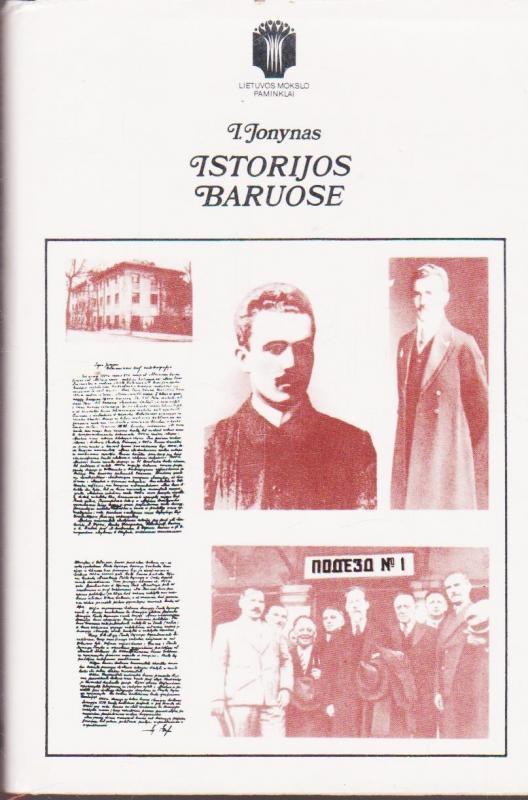

![Publication: Jonynas, Ignas. Istorijos baruose [In the Historical Area], 1984. Book](/courage/file/n30774/Jonynas+Istorijos+baruose.jpg)

A volume of Jonynas’ writings was published in 1984, edited by one of his students, the famous Lithuanian historian Vytautas Merkys. It includes several previously unpublished works: Jonynas’ autobiography, and the article ‘Lithuanian historiography’. It also contains several letters from Jonynas from the interwar period to various foreign historians. Jonynas’ most important work ‘Vytautas’ Household’ was published for the first time in Soviet Lithuania. Practically all the documents were taken from the Jonynas collection.

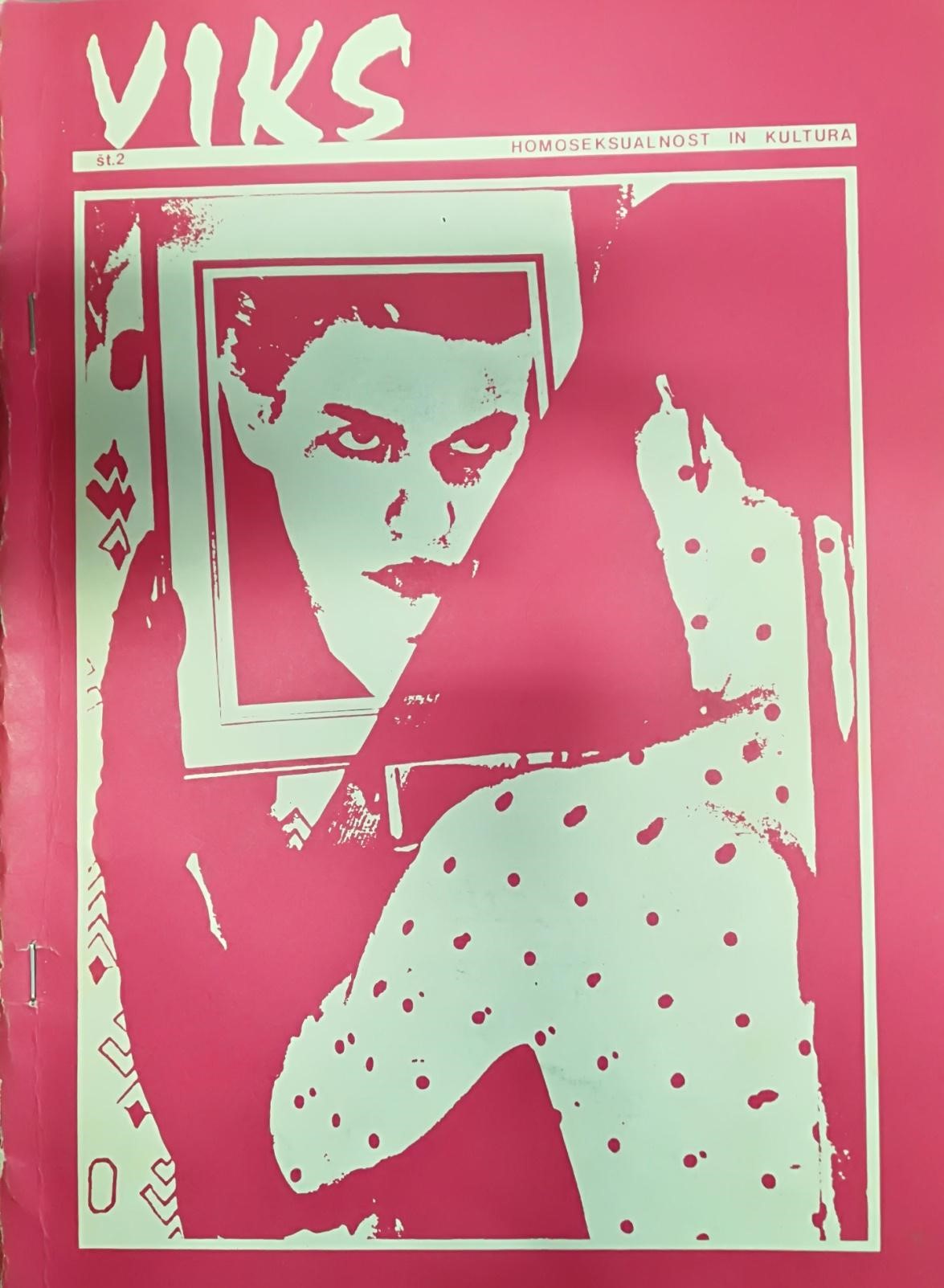

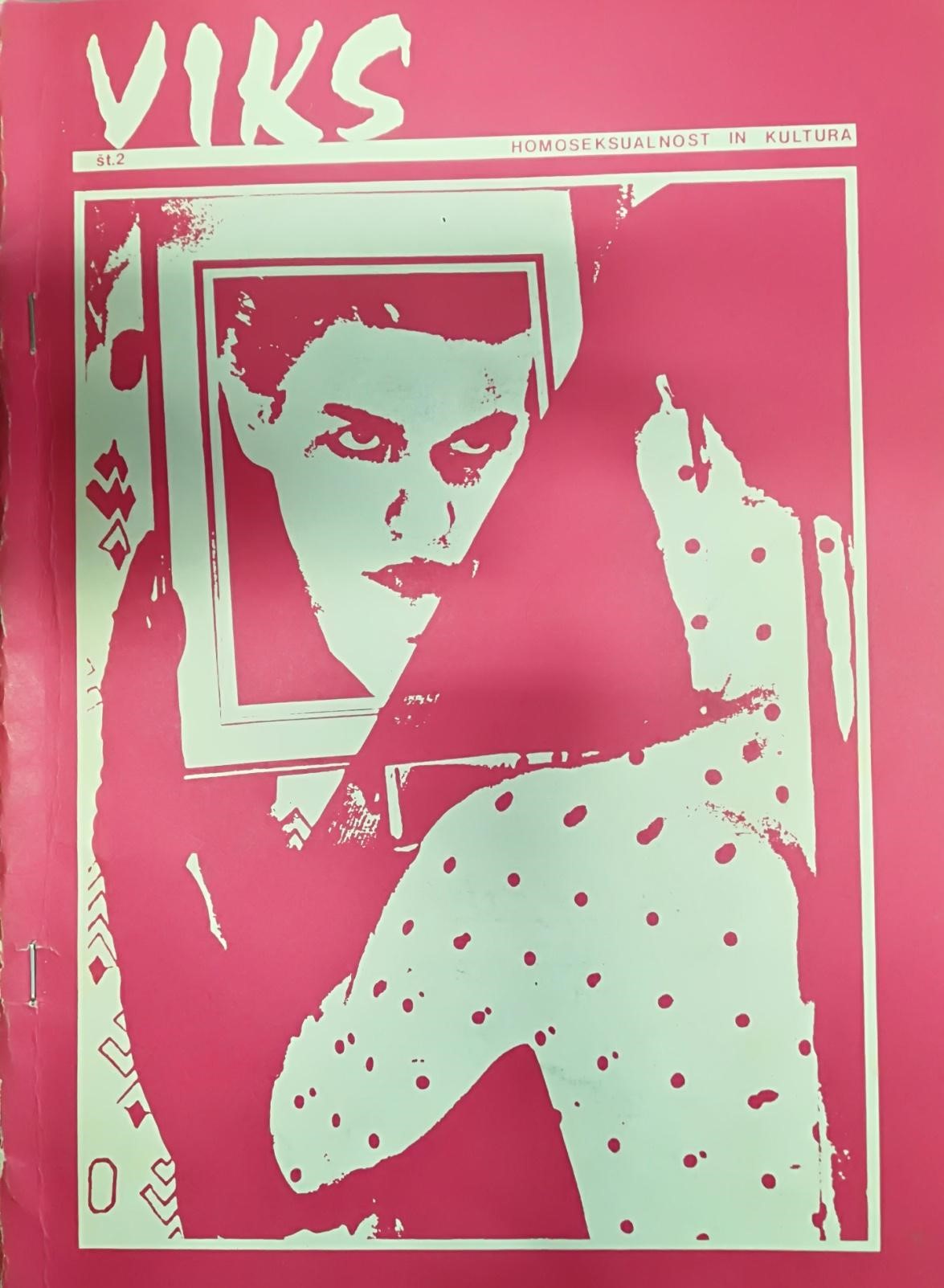

The second issue of the magazine Viks, entitled “Homosexuality and Culture,” came out on April 24, 1984, the opening day of the Magnus Film Festival, the first cultural manifestation dedicated to homosexuality in any socialist country. The magazine was edited by a group of gays and lesbians who gathered around the youth cultural center ŠKUC and organized the festival. This special edition of the magazine was printed in 600 copies and handed to audiences at the festival. It contains 42 pages, and approximately 20 illustrations with contemporary, easily recognizable European gay subcultural motifs. Over the three following decades, this issue of Viks gained a cult status in Slovenian and the post-Yugoslav LGBT community, and was exhibited at events dedicated to the history of homosexuality and the LGBT movement.

Alongside the festival’s program and a schedule of affiliated cultural and club events, in an effort to appeal to the younger generation of Ljubljana’s gays, lesbians and artists, Viks also carried several lengthy programmatic articles and interviews with emancipatory, educational and mobilizing overtones. Thus it aligned itself politically and theoretically with contemporary liberationist, leftist and counter-cultural movements in Slovenia and Western Europe. These texts promote an ideal of freely and openly lived (homo)sexuality. Non-normative sexual practices were viewed as strongly dissident in nature, but not so much against socialism as against patriarchal and traditional forms of sexual and family life.

The article “Pink Love under the Red Stars – Homosexuality under Real Socialism” (“Roza ljubezen pod rdečimi zvezdami – homoseksualizem pod realnim socializmom,” pp. 18-21) delivers a historical overview of the legal and social status of same-sex sexual and emotional relationships in socialist countries. The anonymous author is equally critical of the 20th century discrimination of homosexuality both in western liberal democracies and socialist countries. However, the Stalinist period in the USSR was seen as especially brutal and arduous insofar as it attributed negative political meanings to homosexuality, declaring homosexuals “traitors,” foreign “spies,” decadent bourgeoisie, and enemies of socialism. Soviet homosexuals, the article suggests, were not able to recover from this traumatic period, and were still unable to engage with emancipatory social movements and practices. At the same time, the example of the German Democratic Republic (GDR, known also as East Germany) is held as an example of both positive changes in communist stance on homosexuality, and a way in which, since the late 1970s, a dialogue could take place between the government and gay and lesbian groups.

This photograph from the Ștefan Gane Collection is a testimony to the Ceaușescu regime's policy of transforming the urban landscape and destroying everything that was opposed to its vision. An example of this is the almost total destruction in 1985 of the Mihai Vodă Monastery, of which only the church and the bell tower were preserved and moved to another site down an incline.

The church of the former Mihai Vodă Monastery is an emblem of premodern Bucharest and one of the oldest buildings that have been preserved in Bucharest. Built in 1594, over time it had several destinations, including Princely Residence, Military Hospital, Medical School, and headquarters of the State Archives. It was founded by one of the most important rulers in the Romanians' national history: Mihai Viteazul (Michael the Brave). He was the ruler of Wallachia between 1593 and 1601 and the only leader of one of the premodern states existing in the modern perimeter of modern Romania that unified, for the period 1600–1601, a territory roughly equal to that of today's Romania. Thus Mihai Viteazul was considered from the nineteenth century an important figure in national history. Under the communist regime, historiography of gave Mihai Viteazul a much more important place in national history than he had had before. He was named as the prefigurer of the so-called "Union of 1918". This historical event consisted of the annexation of the historical regions of Austro-Hungary, inhabited mostly by Romanians to the so-called Old Kingdom of Romania and was materialised in the Peace Treaties of Saint-Germain (1919) and Trianon (1920). This image of Mihai Viteazul as anticipator of the “Union of 1918” was strongly promoted under the Ceauşescu regime not only through textbooks and historical works, but also through the historical film Mihai Viteazul, made in 1970.

Despite the overwhelming importance the communist regime granted to Mihai Viteazul, the monastery complex he founded became the most famous victim of the total demolition of Bucharest. The site where it was located, a high position in the urban landscape of the capital, was assigned by the communist authorities to the building that is now home to the Romanian Parliament. In 1985 the monastery was demolished, but not entirely. At the last moment, the church and the bell tower were moved, despite the initial plan that everything should be destroyed. The church was moved to the base of the hill, where it was subsequently hidden by communist buildings. The church was originally located on Mihai Vodă Hill, on the former Archives Street no. 2, and was moved to Sapienţei Street no. 4, where it still stands. This photograph was taken clandestinely by Ștefan Gane a few months before the edifice was moved, and went with him to France in 1985 when he emigrated. The photo in question, which is today in the Ștefan Gane collection, is in the original, 10x15 cm, printed on black and white paper. Today it is an important historical source for understanding and writing a part of Romania's recent history in connection with the project of destruction of the national patrimony practised by the communist regime between 1977 and 1989.

Essay by Dorin Tudoran: Cold or Fear? About the Condition of Today’s Romanian Intellectual (in Romanian). 1984.

Essay by Dorin Tudoran: Cold or Fear? About the Condition of Today’s Romanian Intellectual (in Romanian). 1984.

By late 1983, Dorin Tudoran espoused increasingly radical ideas regarding the total failure and essentially flawed character of the communist system as a whole, which he saw as irredeemable and deeply corrupt. He had already made his views public in 1983 in a series of interviews with various Western press outlets, expressing his conviction that Ceaușescu’s Romania was an absolute dictatorship and seeing the communist system as the main cause of the Romanian people’s material and moral decay. In his essay written in early 1984, Tudoran proposed a complex analysis of the role and situation of intellectuals in communist Romania. Tudoran focused primarily on the causes of his colleagues’ subservience and total submission to the communist regime. He found the roots of this phenomenon in the persecution and déclassement of this stratum by the communist authorities after 1945, comparing them systematically to their peers in Central Europe. Among the factors which generated compliance, Tudoran highlighted the specificity of local political traditions; the terror of the first decade-and-a-half of communism, which led to a mass “moral capitulation” of the intellectuals; their complete reliance on the state for professional survival; and the skilful manipulation of their upward social mobility by the communist authorities. However, Tudoran argued that the compliance of the absolute majority of intellectuals in Romania was, above all, a direct consequence of Ceauşescu’s personal rule and of the Romanian communist system. The essay concluded that Romanian intellectuals had to reassert their responsibility toward the broader society by emulating and following the lead of their predecessors from the generation of 1848, who had succeeded in breaking with the political traditions of subservience to the state and had emancipated themselves by embracing synchronicity with the West. Rejecting the notion of “resistance through culture” as inefficient and outdated, Tudoran pleaded for an alliance with other social groups on the Polish model. In his opinion, this was the only way to limit the abuses of the communist system, as long as total change was still inconceivable. This work, viewed at the time as the most radical text written by a Romanian dissident since Paul Goma, still represents the best and most convincing analysis of the Romanian intellectuals’ plight under communism produced by an “insider.” Mihnea Berindei received a typewritten copy of the original text, in Romanian, which he then forwarded to the editorial board of the journal L’Alternative, recommending it for publication. It was in fact published in French later that year (in two parts, the first in L’Alternative, no. 29, September–October 1984, pp. 42-50, and the second in the following issue). In a special note to the editors, Mihnea Berindei stated: “the text turned out to be longer than required. If possible, I suggest its publication in two parts. If not, I would very much like to […] keep its structure, including the mottos. In other words, at least something from all the chapters should be kept, since the text has a certain structure and ‘strategy.’ Maybe the complete version would be interesting for another periodical, if it is not interesting for the journal that suggested its writing […]. It’s good that the text exists. It could also be printed under another, more attractive title!” This clearly shows Berindei’s personal role in steering the text toward publication and his position of intermediary between authors writing in Romania and the Western public sphere. Despite the apparent initial hesitations of the editorial board, Tudoran’s text had a rather significant impact on the exile community and also prepared the ground for the emergence of similar critiques in the following years. This masterpiece highlights Mihnea Berindei’s contribution to the “journey” of this fundamental text of Romanian dissent toward its target audience in the West.

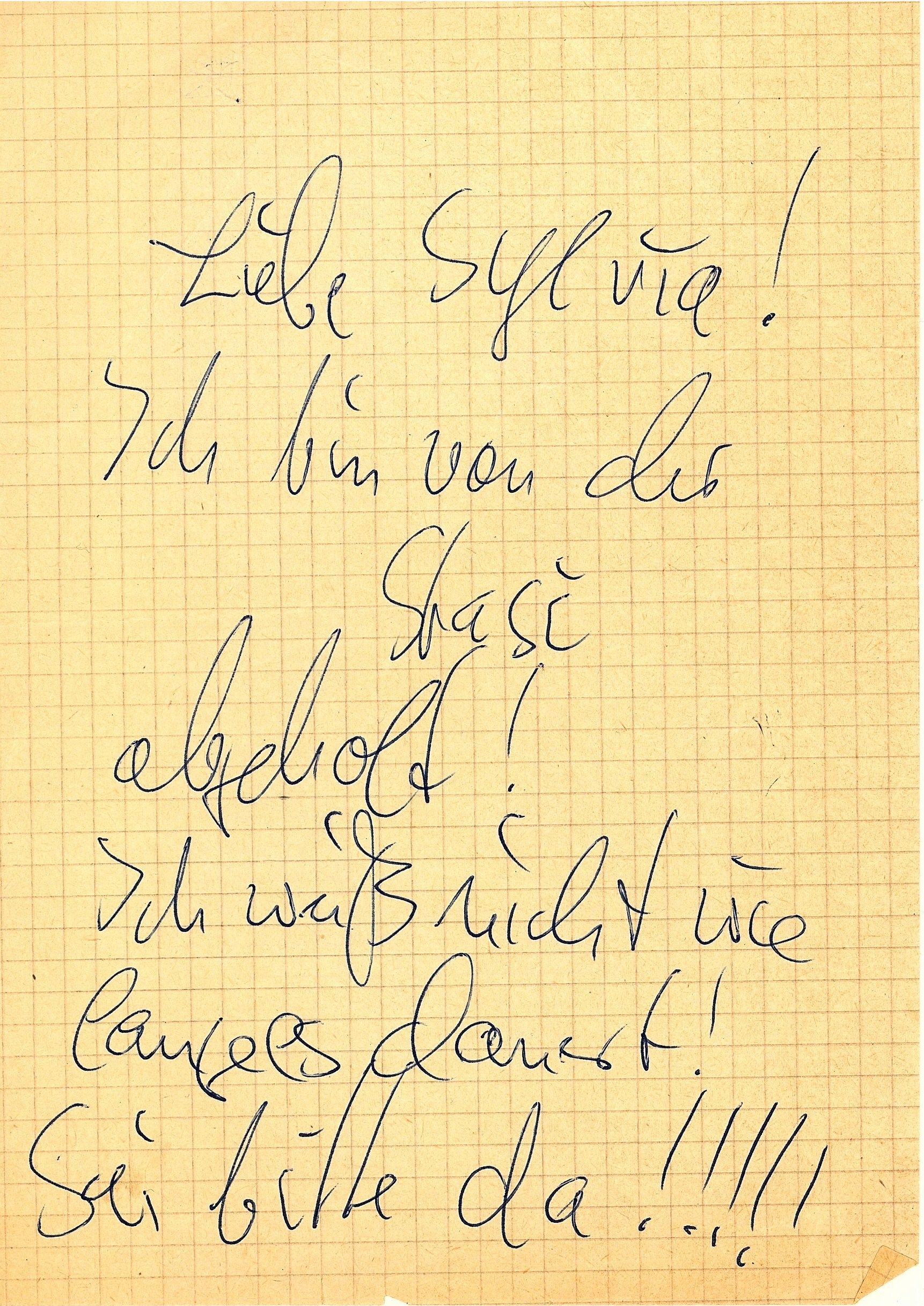

The collection attracted the attention of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who visited the Keston College in 1984. Thatcher attended a reception in Church House, Westminster on April 25, 1984. The photo was taken by Derek Davis, most likely, a hired photographer. According to a Keston News Service report (No. 198, 3 May 1984), this reception was held in order to mark Rev. Michael Bourdeaux’s announcement as the recipient of the 1984 Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion. Sir Sigmund Sternberg and the Bishop of London hosted the event, as chair and co-chair of the newly formed “Friends of Keston College.” 200 distinguished guests were in attendance, among them Margaret Thatcher. She used the opportunity to praise the work of Keston College, noting that she often quoted information provided by Keston in meetings with other heads of government because of its reliability. Margaret Thatcher is associated with the systematic economic policies of neoliberalism that emerged under the Thatcher and Ronald Reagan governments. Neoliberalism confronted the planned economies of Socialist governments throughout the decades in which the Keston Institute was most active. These linkages between the Thatcher government and the Keston College/Institute highlight the intersection of religion and ideology with the politics of neoliberalism and human rights.

The life and work of the painter Ventseslav Terziyski during the period of state socialism are an expression of resistance and standing-up for one's own positions. The paintings of Ventseslav Terziyski are not realistic; they do not create a narrative. His paintings are usually untitled. A lack of figural composition and a storyline is characteristic to his work. Terziyski does not follow established norms, nor does he observe the rules of the perspective. He therefore did not receive recognition during the era of socialism; he was not accepted into the Union of Bulgarian Artists. Terziyski refused to compromise and to take jobs offered to him. He did not participate at exhibitions. He refused to accept any government assignments. He drew on cardboard boxes or any paper he found in the streets and survived only on his paintings, which he sold at low prices to acquaintances. "With his paintings the homes of people from all over the city [Blagoevgrad] are strewn," says Dr. Nurie Muratova from the Balkan Society for Autobiography and Social Communication. The paintings of this original artist became included in an avant-garde exhibition only at the end of the communist regime, in the 11.11.88 exhibition in Blagoevgrad. In the following year, shown the day after the political change on 10 November 1989, a following exhibition was organized by the Union of Bulgarian Artists in Blagoevgrad in which Ventseslav Terziyski participated. The exhibition gained great interest and became a sign of the transition. In 2014, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the political transition, a national exhibition of contemporary art was organized in Blagoevgrad, using the symbolic title 11-11. More than 30 artists from Sofia, Blagoevgrad, Ruse, Plovdiv, Botevgrad and elsewhere participated. Ventseslav Terziyski presented new works; his paintings were included also in other exhibitions, and he has since been making annual solo exhibitions at the American University in Blagoevgrad. Today, Ventseslav Terziyski is among the most established and famous artists not only in Blagoevgrad but also in wider national context.

The Fine Art Archive consists of diverse documents connected to Czech and Slovak art of the twentieth and twenty first century. Catalogues, books, invitations, journals, photography, slides, cuts and other items have been gathered continuously since the mid-1980s.

A work from the "Exploitation of the Dead" cycle showing a large factory complex with chimneys. The picture of the great factory complexes is one of the synonyms for socialism, which was the very reason why Stilinović used it. But shown on a black background and in combination with red geometric figures, it becomes the subject of Stilinović's criticism and indicates the weariness of this socialist symbols.

![Migrating Birds [Vándormadarak/Păsări călătoare], 1984, silkscreen print](/courage/file/n76628/6.+V%C3%A1ndormadarak.jpg)

The bird itself was a central figure in the work of Baász. In the preface to The Bird and the World of Peace [A madár és a béke világa] exhibition catalog from 1986, he explains the usage of the bird’s eternal motive. According to this text, the bird serves as a symbol of the artist’s creative power, of his privilege to rethink, rebuild, but also to rediscover. The wings, present in Baász’s oeuvre even without the body of the bird, are a call for options, open possibilities, freedom.

In the silkscreen print from 1984, we are confronted with two types of bird depictions. First, we can see a flock of real birds with wings heading right, organized, together, in front of a blue background. Second, on the upper left side of the artwork, we can see a more particularized bird, a swallow, with closed wings. If we look closely, we see that it’s not a real animal. It’s only a wind-up toy, which is paralyzed when not activated. Despite all its disadvantages, it’s much bigger than the real birds, and it’s heading in a different direction. This again conjures emigration by drawing a parallel between the migrating birds who make long flights in order to survive the winter and the artist’s acquaintances who left the country in hope of a better future. According to another interpretation, the seven migrating birds symbolize the seven Székely counties clinging to traditional values, while the swallow, who could be interpreted as a representation of the artist, chooses to focus on the future instead of the past.

Like a red line, Ellenpontok divided Géza Szőcs’s life into two: before and after 1982. Choosing to remain in his home country, thus accepting the monitoring by the secret police that this entailed, without a job and facing existential problems, he continued his dissident activity. On 14 July 1984 in the spirit of the traditions established by Ellenpontok, he addressed a fourteen-page petition to the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party in which he advocated the minority rights of Hungarians, and – at that time he alone – of Germans. With the thirteenth Congress of the Party drawing near, which provided the opportunity for publishing guidelines regarding its nationality policy, Szőcs formulates his demands in ten points. In the first point he asks that the Romanian constitution should include not just personal, but also collective ethnic rights – considered a taboo subject even today –, lifting up his voice for the recognition of Hungarians and Germans living in Romania as independent ethnic-historical groups. In addition to the reestablishment of the Ministry of Nationalities which operated between 1944 and 1952, he asks for the elaboration and guarantee of a law on nationalities (ethnic minorities), in accordance with the Nationality Statute of 1945, still in force, the 1946 Nationality Draft Act of the Hungarian People’s Union and the Programme Proposal drawn-up by the editors of Ellenpontok. He asks for public debate with a view to restoring such administrative, institutional and cultural frameworks related to ethnic interests as the former Hungarian Autonomous Region, The Transylvanian Museum Society, the Union of Hungarian Writers in Romania, the Hungarian Music Conservatory in Cluj-Napoca, the network of Hungarian-language schools and the university providing Hungarian-medium education in Cluj-Napoca, etc. He requests the making public of the unification document of the Cluj-based universities, dating from 1959, which stipulated as a principle for the future an obligatory minimum number of Hungarian students and teaching staff as well as the educational framework. He raises the issue of examining subjects such as Hungarian-language film production in Romania, or the extension of the one-hour Hungarian-language television broadcast. The fifth point of the petition is especially daring, since it encourages the compilation and disclosure of lists of Hungarians and Germans living in Romania. Moreover, Szőcs argues in favour of the disclosure of social and economic statistical data concerning the various nationalities. As far as education is concerned, he asks for disclosure of the number and proportion of Hungarian and German university graduates in the period 1945 to 1984, and, in the context of the last 10 years, a full l list of graduates who were declared to be Hungarians or Germans, broken down by higher education institutions. He also asks for the disclosure of statistics regarding secondary schools, by counties and cities. In the seventh point of the petition he asks for the Romanian Communist Party to publicly take a position against the practice of the press which, wrapped in the appearance of semi-officialdom, left room in periodicals or other publications for nationalistic and anti-Semitic manifestations, presenting the historical role of nationalities, especially that of the Hungarian minority, in a one-sided and distorted manner. Szőcs asks that the Party distance itself from the anti-minority policy of the interwar governments and render impossible the revival of this policy; as for preventing the falsification of history and malicious manipulation he sees the solution in the publication of a “White Book” which will contain all the significant documents – both political and cultural – pertaining to Romanian–Hungarian historical coexistence. Szőcs suggests that Romania should initiate at the United Nations the inclusion of an article in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which will explicitly address minority rights, and also bring up the topic of supplementing the convention regarding genocide to include cultural genocide and, ethnocide, including an article about the elaboration of guarantees for rendering this impossible. In support of his requests and suggestions, Szőcs supplies primarily historical data, organised into points A, B, C, D and E. A part of the nationality-related requests touched upon by Szőcs in the spirit of constitutionality, compliance with Lenin’s ethnic principles and democratic freedom of opinion were already included also in the programme proposal of Ellenpontok in one form or another. He justifies his petition by arguing that the “current solution” of the nationality issue does not, for the time being, put an end to the flux of Hungarian and German masses determined to leave the country. “Except for those embracing assimilation,” Szőcs writes, “ethnic minorities at all times and in all places have wanted to enjoy equal rights not just as individuals but also as a group. This is why we demand not just personal rights – which can often prove to be rather vulnerable – but also collective ethnic rights.” “To conclude,” he writes, “I wish to express my appreciation to the Party leadership regarding the fact that they have abandoned the practice of retaliating against the formulation and expression of opinions different from the official point of view by immediately applying physical liquidation or long-term deprivation of liberty. I am fully aware of the fact that in the 1950s I would have had to pay with my freedom or life for similar activities, such as the publication of the illegal magazine entitled Ellenpontok – notwithstanding that this magazine did not attack the existing social order, had no agitating character and did not oppose the nationality policy of the party, either, but only practices and methods that are contrary to the declared principles of this policy.” The petition of July 1984 remained without a reply. Nevertheless, Géza Szőcs continued to use this means to inform the Party leaders about the existence of primarily Hungarian minority claims. On 10 February 1985, Szőcs drew up his proposal regarding the establishment of a world alliance of minorities. “We apply to the UN with the proposal,” he wrote, “that it should lay the foundation of an institutional system under its auspices, the purpose of which is to represent in principle the interests of all the ethnic minorities in the world.” He concluded his proposal, extending over more than one page, with the following lines: “The ethnic minorities living in all parts of the world together represent an enormous majority against any majority taken separately. The Minority International conceived by us could function as a right hand extended as a sign of peace for this majority organised from minorities.” On 15 February 1985, after a personal visit paid by Szőcs, the writer and later emigrant Dorin Tudoran also signed up to the proposal, as did the economist and politician Károly Király on 27 March 1985. On 28 March 1985 Szőcs submitted another petition to the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party. In the sixth and last point of the petition which summed up the new developments, unwelcome from the ethnic point of view, of the months following the first petition, Szőcs asked the Romanian Party and state leadership to present and support at the UN the proposal for the creation of a minority world alliance signed by the three of them and attached to the petition. The service of the petition represented not only an organised action but also a Hungarian-Romanian joint demonstration. This proposal for a world alliance of minorities was presented also in Western countries, but no substantive reverberations resulted.

Video published in December 2016 on the YouTube channel of VLS, 47’ 17”

The material was recorded in February 1984 at the University Stage, Budapest in the third productive period of the band, after the release of their first disc, during the concert entitled Aerobic. The performance was carefully arranged and included first-time performances of new songs, large scale stage design, and costumes painted for the occasion.

The most interesting aspect of the video – beyond its documentary value – lies in the history reflected of its mediality: according to the caption it was shot by a professional television team with three cameras, but it never was broadcasted, as several small characteristics of the material suggest, for example some parts of the image are missing and black blanks have been inserted, while the sound continues.

This YouTube video is most probably the digital version of the once half-cut material: it was abandoned at this stage, when it turned out that permission would not be granted to broadcast it. However, someone archived a copy on VHS. The quality of the image suggests that this tape was digitalized then and published on the internet 32 years after the event.

There are other interesting details: the method of editing songs separately breaks the original span of the concert, some parts were clearly left out; the cameramen sometimes stands in front of the performers; the totals were recorded through the reflecting window of the technician’s cabin, so the stage design is not very prominent.

However, the pillows fixed on the performer’s garb function perfectly. The stage presence of the artists is elemental and provocative. They restart the performance of several songs, and the program is intertwined with various spontaneous actions. Some of the songs sound provocative even today.

The record is a valuable document even in its fragmentary state. Although it shows only an episode from the history of the band, many interesting details of its spirit “come through” for the Hungarian-speaking audience (as there are no subtitles).

Doctor Ivo Banac is one of the most recognized and world-famous Croatian historians. His work is also recognized by his status of professor emeritus at Yale University. His book The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics, first published in 1984 in English and later in Croatian, is one of the best books dealing with the national origins and issues in Yugoslavia. In Tito's Yugoslavia, this problem was swept under the rug, but eventually, due to other reasons as well, it gave way to Slobodan Milošević attacking Croatia, resulting in the war in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Today, it is a cult book and describes the creation of Yugoslavia, explains the roots of the national problem in Yugoslavia and associated political implications. Until 1991, there was a ban on publishing the book in Yugoslavia. The importance of the book lies primarily in the scientific approach by Dr Banac and his abilities to emotionally distance himself from the issues, separating him from the numerous Croatian authors abroad. What makes this book significant is also its availability in English-speaking countries, making it accessible to foreigners and all those interested in issues associated with socialist Yugoslavia.

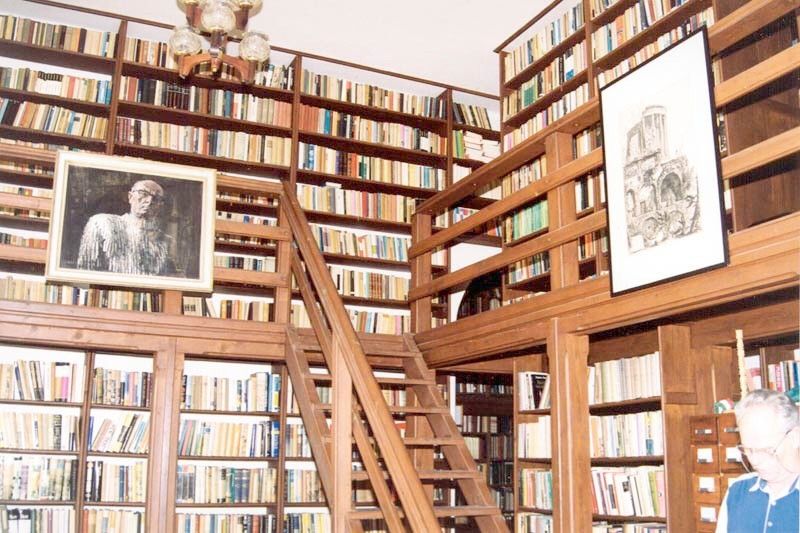

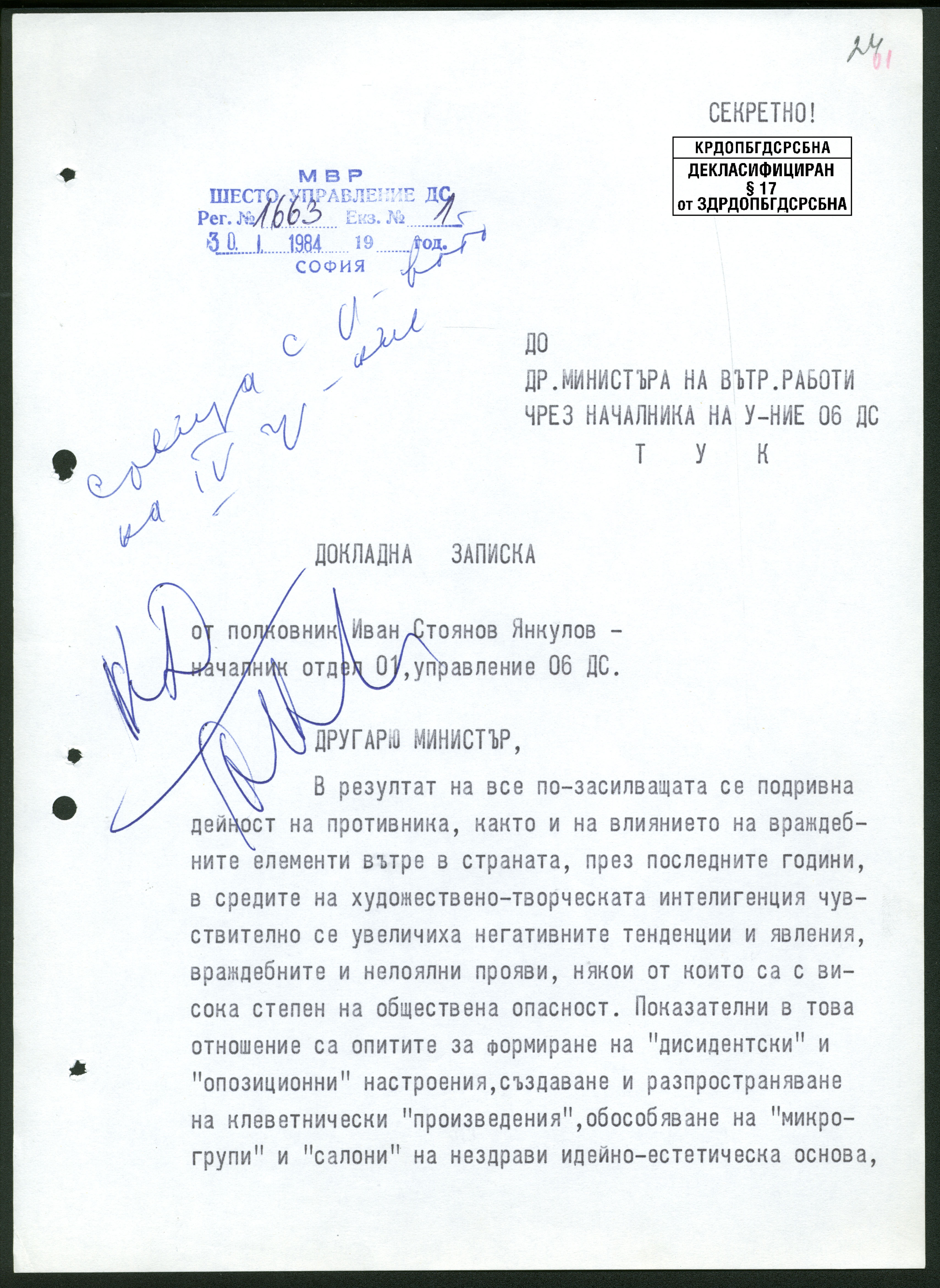

"Report by Ivan Stoyanov Yankulov, Head of Division 01, Section 06 – State Security", Sofia, 30 January 1984, to the Minister of the Interior.

The officer reports about the strengthening of "negative tendencies" to be observed lately among the intelligentsia. These are said to be due the stepped-up afforts of the "enemy" as well as the activities of "hostile elements" inside the country. The report also detailed the problems of the state security's work among the artistic intelligentsia because of their distrust, of their closed way of life or of their high professional or social status. Therefore, it is suggested, the development and monitoring of this category of persons should be carried out by technical means. The document, thus, indicates growing resentment of the regime by the intelligentsia and shows the ways, how the statet security evaluated the effectiveness of its own work.Through colour photographs and slides, the Alexandru Barnea private collection documents the demolitions imposed by the communist regime in the centre of Bucharest following the devastating earthquake of 1977, which served as a pretext for the destruction or mutilation of many historic monuments. The policy of demolishing the architectural and urbanistic heritage has been considered one of the most aberrant and arbitrary measures in the recent history of Romania.