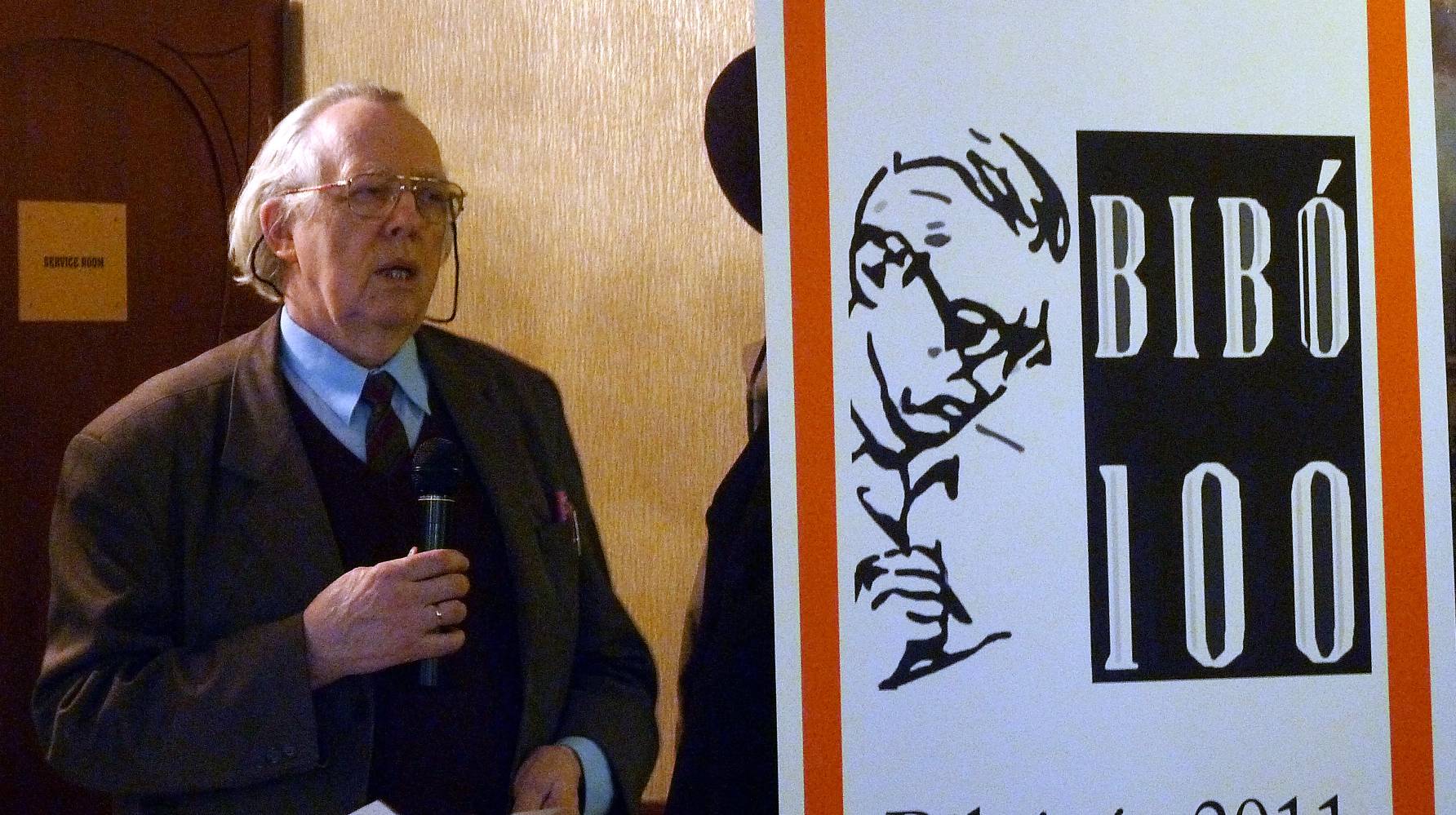

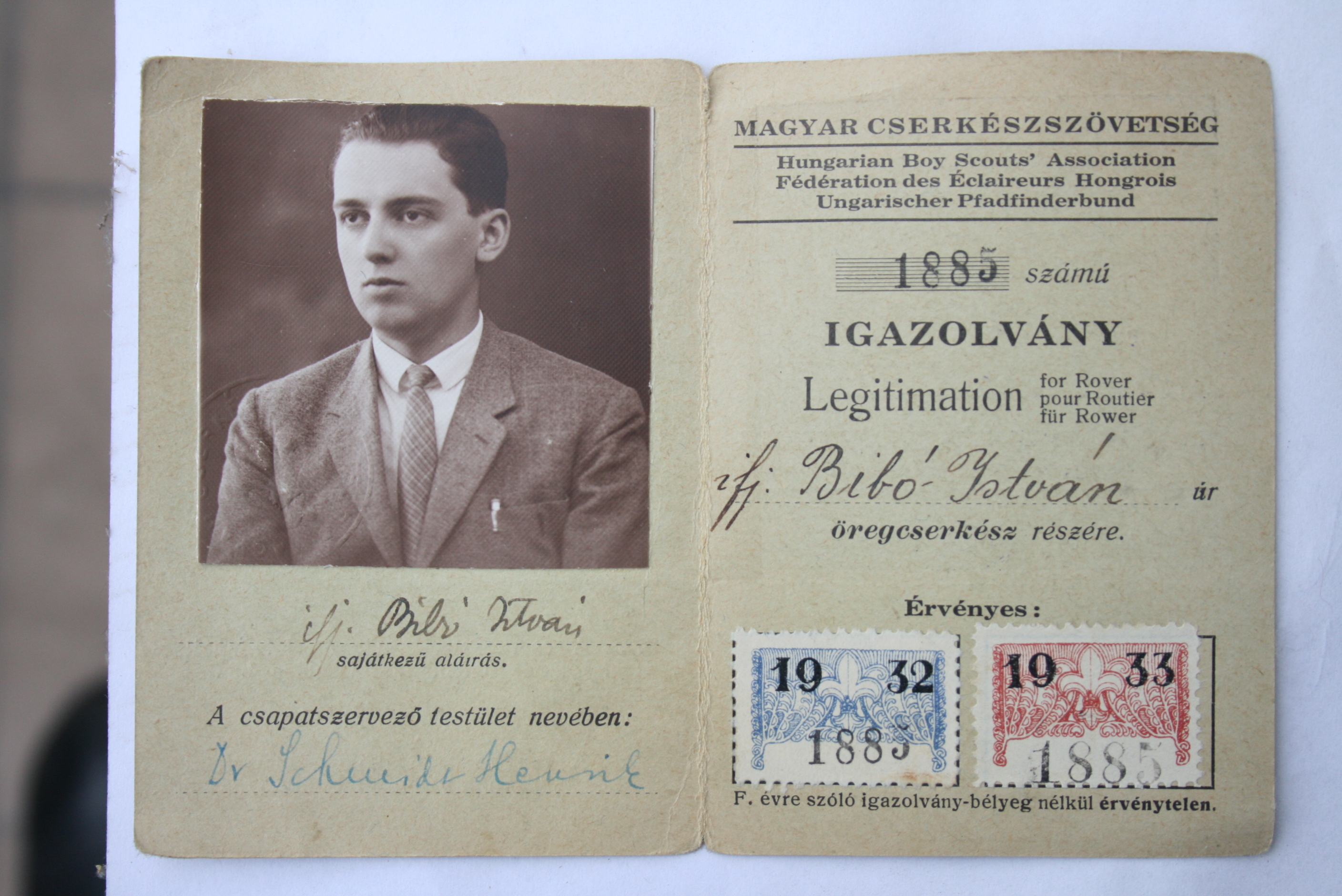

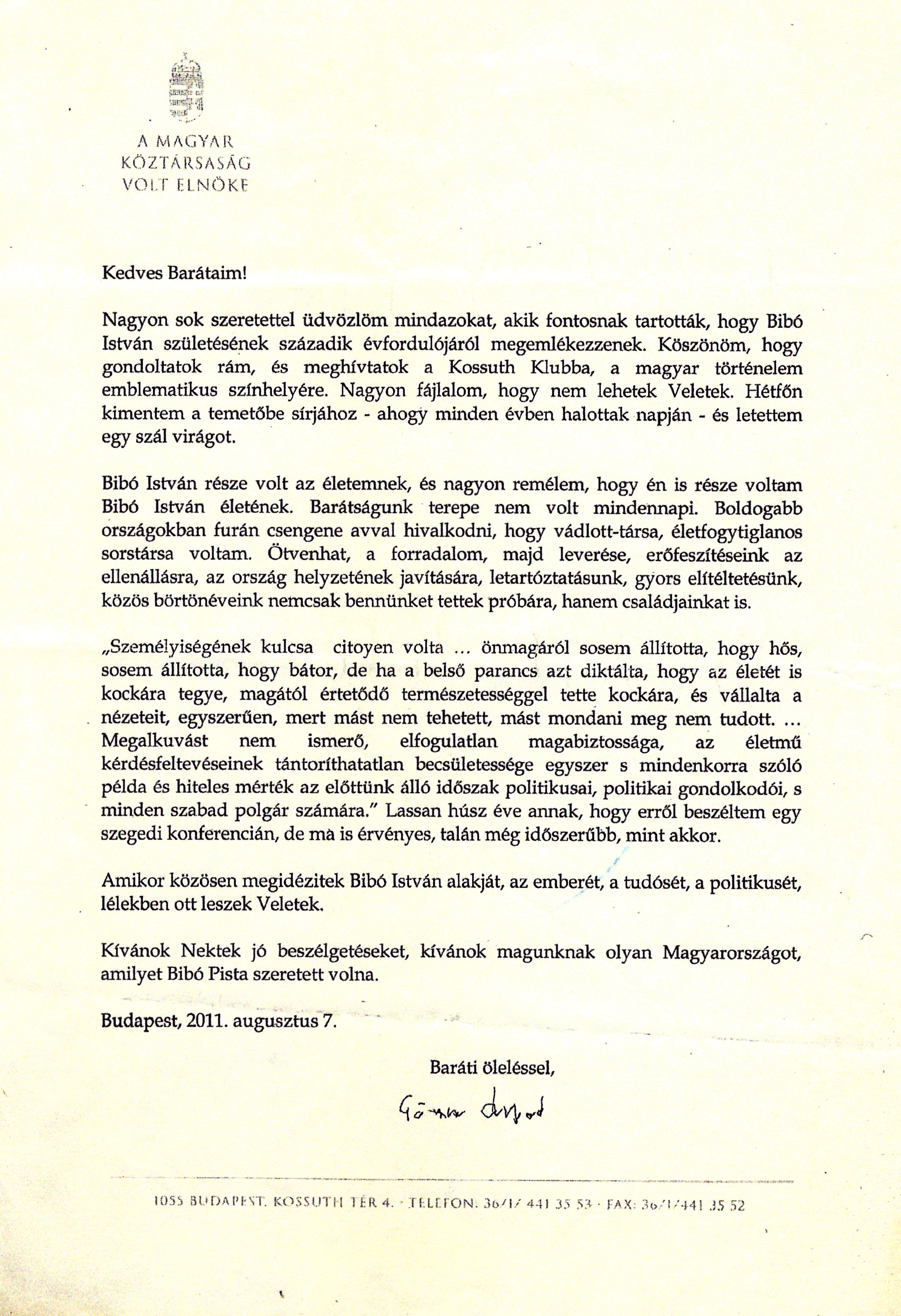

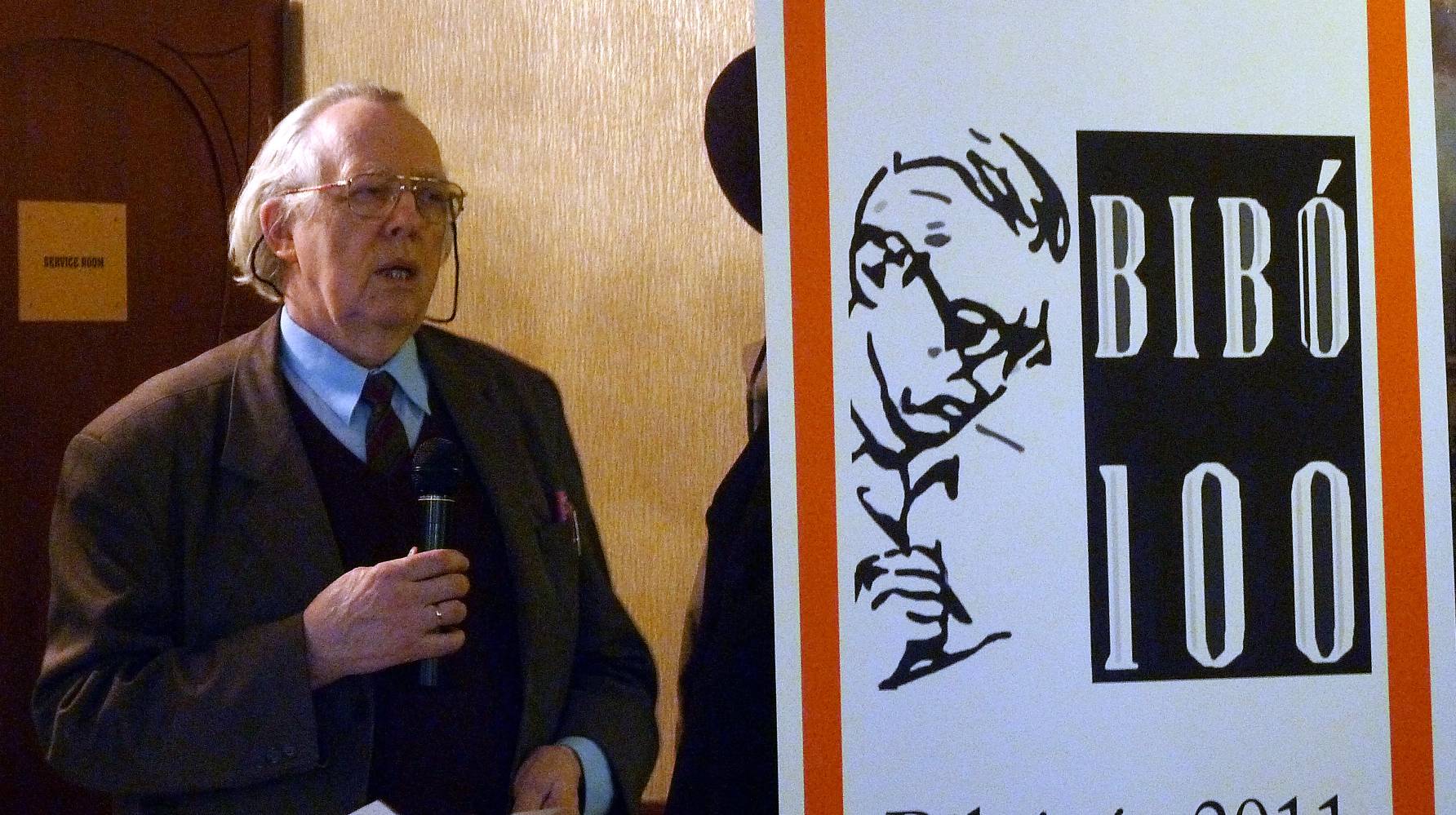

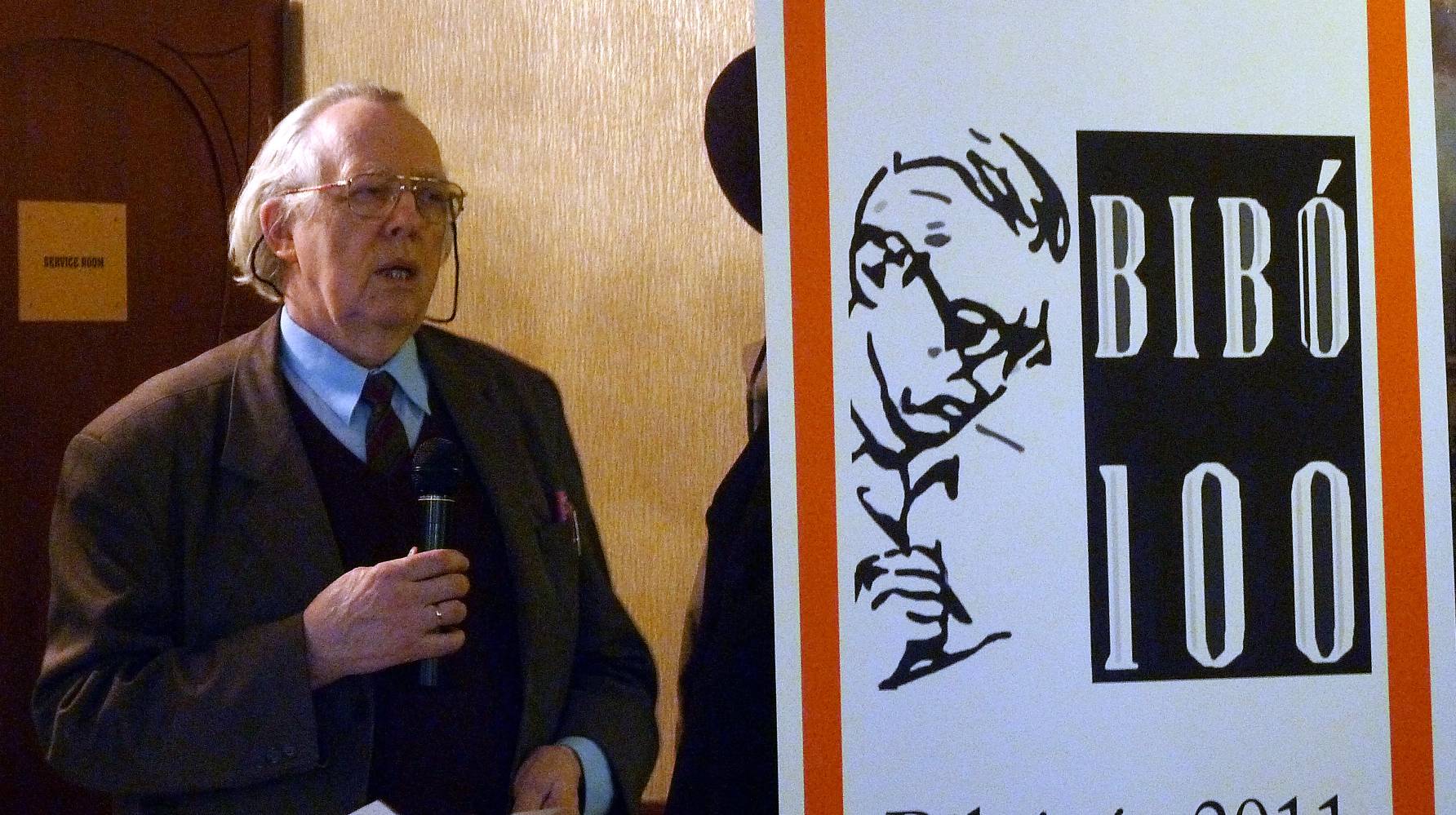

Since the deaths of István Bibó and his wife in Spring 1979, their family bequest has been enlarged with the addition of a large number of memorial items: photos, publications, videos, and other records. Art historian István Bibó Jr., as the main voluntary caretaker of the family collection, himself contributed all these materials fairly creatively, and he devoted a great deal of time and energy to collecting and preserving his father’s legacy. The original family collection by now has been enriched by many new memorial items. Thus, it has become a unique source for research on Bibó’s reception in Hungary and worldwide. Among the memorable events of the four past decades, the centenary of István Bibó's birthday in 2011 was of particular importance. It included several commemorations, workshops, and conferences, and many studies and books were published, interviews were done, films were made, and exhibitions were organized. These materials constitute a distinctive sub-collection of the Bibó bequest. A brief chronicle of the year, an invitation card, a photo, and a conference opening speech held by István Bibó Jr. may well give an air of the “Bibó Memorial Year.”

On May 7, 2011, the Study Centre for National Reconciliation organized a trip to the island of Goli for interested individuals, students, professors and journalists. The purpose of the trip was to familiarize the public with the events that took place on the island of Goli during the period of socialist rule, and the main eyewitness of those events was Andrej Aplenc. Aplenc was detained on Goli as a student on two occasions and as a part of the excursion he talked about life and survival on the island.

The temporary exhibition of the study and library of the journalist, writer, poet and playwright Ladislav Mňačko (1919–1994), which is almost identical to the study in his Prague apartment, was opened on 14 February 2011. Part of this ceremonial opening was a memorial evening “Ladislav Mňačko – Odchody a návraty” (Ladislav Mňačko – Departures and Returns) which was organised by the Museum of Czech Literature, the Slovak Institute in Prague and the Centre for Information on Literature in Bratislava. The exhibition of Mňačko’s study is in the Little Villa of the Museum of Czech Literature on Pelléova Street in Prague 6, and has been owned by the Museum of Czech Literature since 2006. In addition to the permanent exhibition, the villa is used for smaller temporary exhibitions on current topics about literature and cultural, as well as for social events.

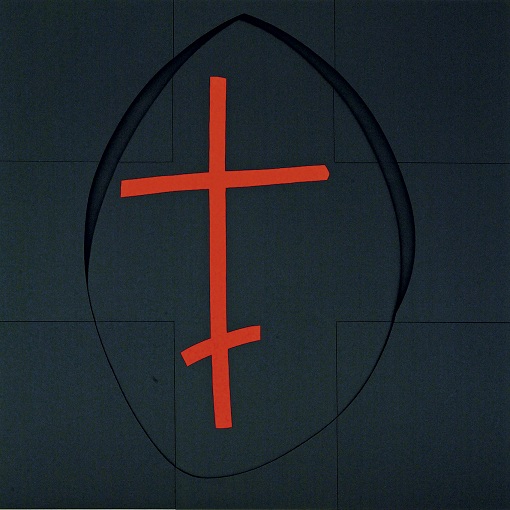

This global insight – to see beyond and more – has intensified over the years. Symbolic things from the past – as in some of the cycles, such as Topographies, Cuts through the civilization, Habitats, Question marks or exclamation points, or Out of town– have been transformed to a synthesising form. It is all derived from the process of his thinking about being. Thus, the vantage point is a subject to change as well. He no longer sees the “world state” through a “universe satellite” within a earthly-universal confrontation.

This new process is signalled first by pyramids and followed by either barrows or graves – Crossed barrows, Graves of suprematism, Graves for Malevich a. o.

Futurism, which together with cubism sparked, among other things, Malevich’s ideas of suprematism, was not only a dynamic time element, but also an idea of the future, despite the fact that Malevich’s elementarism resulted in point zero. The inherent interconnection of Sikora’s interpretations, or paraphrases, is primarily not a matter of form interpretation, but rather a general question on the nature of the future itself. The reflection and interconnection of societal movements and his work cannot be confused for an experience of descriptivism or its formal depiction. Where Sikora perceives objects as a black wall or black holes, it can easily be seen as pessimism, or a different form of an exclamation point if you will. We have advanced but in reality have gone back. In other words, the future does not lie where we have advanced, it has rather been somewhere else.

The stated issues have recently been tackled by Sikora with brilliant polemics. The underlying exhibition’s object is a paraphrase of Malevich’s Black square, reflected within a black cube with barred insights called Malevich’s prison. Inside the cube, Sikora left a formation of mirrors played in a spectacular virtuality which, at the same time, demonstrates the distance between Malevich’s “utopia” and the current virtual world.

ZKM│Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnlologie, Karlsruhe 28 January 2012 – 19 Aug 2012

Akademie der Künste, Hanseatenweg, Berlin 27 October 2011 – 1 January 2012

Curators of the exhibition: Piotr Krajewski (WRO Art Center, Wrocław) and Miklós Peternák (C³ Foundation, Budapest) Initiative, concept: Siegfried Zielinski (Universität der Künste, Berlin)

The event series was a parallel presentation of the oeuvre of "two, somewhat forgotten, but outstanding artists" (as one curator put it), initiated by the Akademie der Künste, Berlin. The exhibition was first presented in Berlin, then in Karlsruhe, later in Wrocław, and finally in Budapest. Although Zbigniew Rybczyński and Gábor Bódy never met, research into the language of film, interest in image-theory, and artistic and technical innovation are common features running parallel through their fifteen-year-body of work. Their artistic gestures were different, but both shared an intensive interest in new technologies, which they used to create "something unseen and unheard".

On the occasion of the event series, the complete video works of Gábor Bódy were published on DVD by C³. His entire catalogue was digitalized and his feature film, Psyché was restored (produced by the Hungarian National Film Fund and Film Archive, with the support of C³ and the Akademie der Künste, Berlin). A great deal of preparatory work preluded the publication of the DVD and video-works: all available tapes were located, different versions were compared, and the highest quality version was chosen and technically adjusted (dropouts, subtitles etc.). The curator described this latter phase as, “to whip into shape a crumpled Tiziano”. The main consideration during restauration was to “not lose anything from the aura of the work”. The DVD did not enter the commercial circuit as the composer of a musical piece used in one video could not be located. Altogether, 200 free copies were printed.

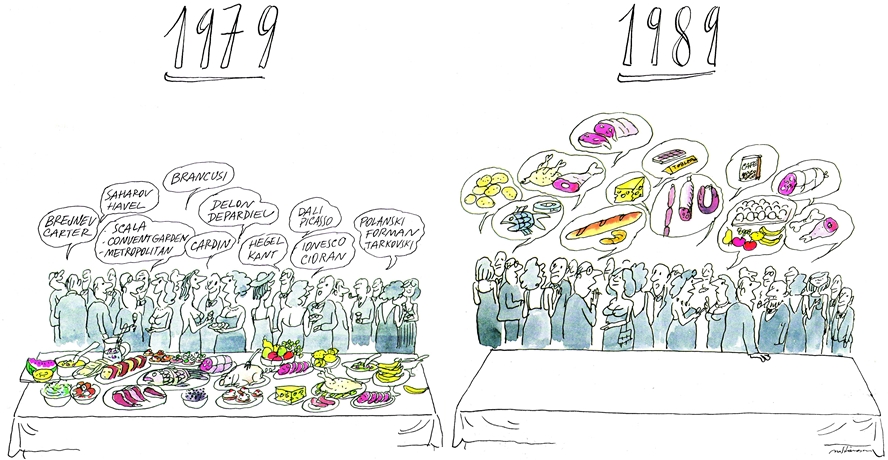

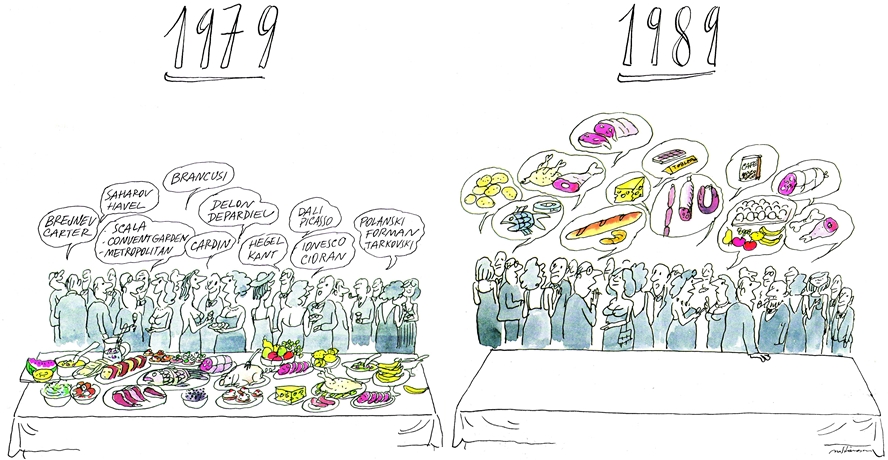

With the support of the Romanian Cultural Institute in Warsaw, Mihai Stănescu exhibited some dozens of his works in the Polish capital in an exhibition entitled “Making fun of the dictatorship: Romania in Mihai Stănescu’s cartoons 1979–1989.” The exhibition was opened on 14 March 2011 and was open to the public until 3 May the same year. The host of this artistic event was the History Meeting House in Warsaw, an important and very active institution for the recovery of the memory of the twentieth century. At the opening, Mihai Stănescu was accompanied by the Polish cartoonist Jacek Frankowski. The presentation of the exhibition for the Polish public contains the following observation: “Executed in an acid and vivid manner, Mihai Stănescu’s cartoons became famous for their harsh satire directed at the communist regime. The Warsaw exhibition includes works from the period 1979–1989, many of which were censored for their extremely transparent allusions to poverty, lack of individual liberties, and other subjects that were taboo at that time.” In the middle of the period of the exhibition, there was also a public showing at the same location of Andrei Ujică’s film The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceauşescu.

Between 6 May and 2 June 2011, an exhibition “Děkujeme vám” (Thank you) was organised by Libri Prohibiti to mark the 60th anniversary of the launch of the Radio Free Europe in 1951. A libretto of the exhibition used pictures as well as recordings stored in the Audiovisual Section of Libri Prohibiti. Recordings of broadcasts of the Czechoslovak edition of Radio Free Europe are also part of the collection. Some examples are the music broadcast by Karel Kryl and legendary radio host and DJ Rozina Jadrná, whose broadcast “Odpoledne s hudbou” (Afternoon with music) became, after its premiere in 1965, one of the most popular broadcasts of the radio station. A similar case is “Vzkazy domovu” (Messages Sent Home), personal messages from emigrants to their relatives and friends in Czechoslovakia, which was also hosted by Jadrná. The exhibition was complemented by audio – edited versions of some well-known broadcasts of the radio station. Olga Kopecká-Valeská, a former deputy director, commented the relocation of the audio archives from Munich to Prague in 1995 and the copies made by Libri Prohibiti. There is a video recording of the event with guests – former listeners or employees of RFE – on the website of Libri Prohibiti.

Szabolcs Vajay’s collection is the bequest of a Hungarian scholar who represented classic European erudition. It also documents the efforts to save a marginalized culture. The collection offers insights into a way of life in exile which is centered around efforts to preserve heritage abroad, a lifestyle which arose in part as a response to political assault on culture.

An international conference of historians, lawyers, political scientists and linguists on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Croatian Spring was held in October 2011 at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. The organisers were the Miko Tripalo Centre for Democracy and Law and the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. Co-organizers: Faculty of Law, University of Zagreb and Faculty of Political Science, University of Zagreb. The conference stressed the Croatian Spring as one of the most important events in the history of socialist Croatia. The event also initiated a critical discourse on the democratisation of contemporary Croatian society as well.

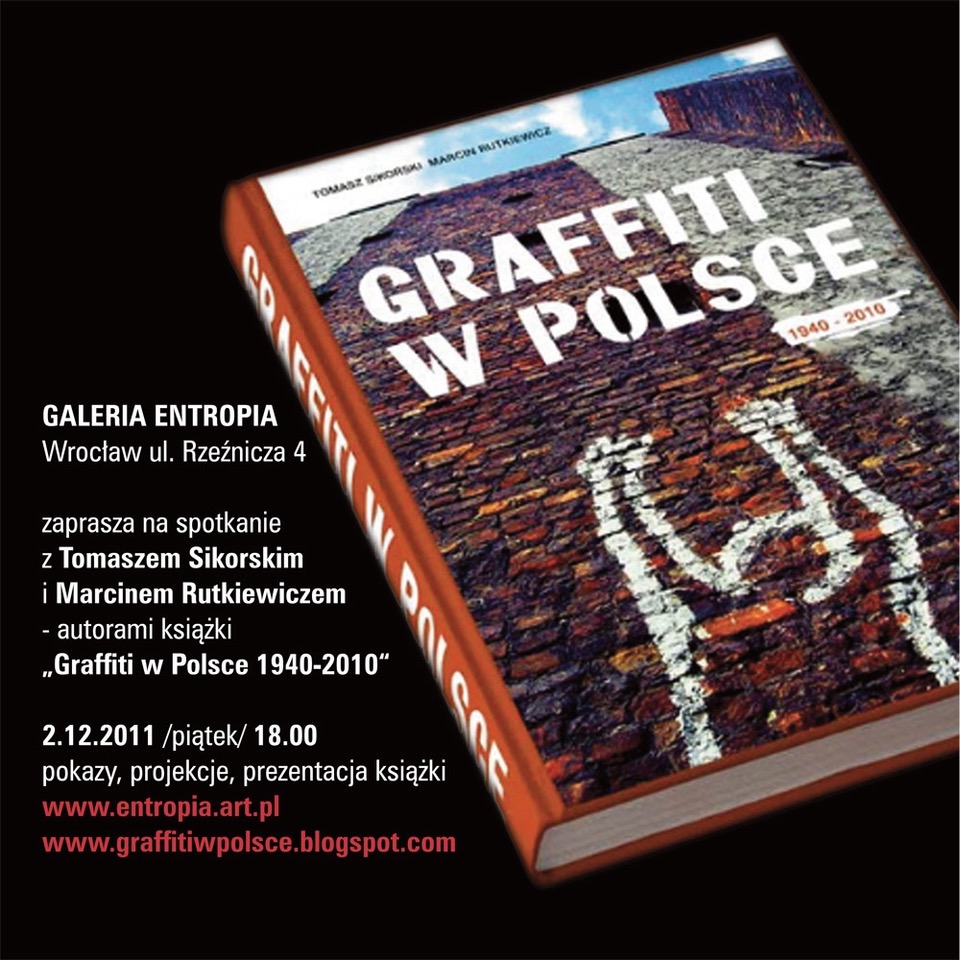

The album Graffiti w Polsce 1940-2010 (Graffiti in Poland 1940-2010), edited by Tomasz Sikorski and Marcin Rutkiewicz and published in 2011, is the widest presentation of the photographies of graffiti from the collection of Tomasz Sikorski. The time frames assumed in the book are justified by the mass action of the resistance through the graphic forms on the streets of Polish cities under the Nazi occupation during the WW2 that could be seen as a breakthrough in the occurrence of the graphic signs in public spaces. The book’s narrative goes on to the 2010 – to the date of the book’s release – enclosing the whole history of the Polish People’s Republic and the first two decades of the democratic Republic of Poland.The main content of the album is divided into parts about the graffiti before and after the 1989 transition. The first part was elaborated by Sikorski, while the second was written by Rutkiewicz. Besides the division based on chronology, the authors applied the thematic distinction on the ‘fighting’ graffiti (openly engaged in political and ideological matters) and ‘artistic’ graffiti. Further chapters were written by Agata Szwedowicz about the graphic diversion under the Nazi occupation, Bartosz Stępień about advertising and propaganda murals under the communism, and Igor Dzierżanowski about the graffiti on the threshold of the 1980s and 1990s. In the publication, there are also a lot of commentaries and recollections made by the graffiti artists.Source:Tomasz Sikorski, Marcin Rutkiewicz, Graffiti w Polsce 1940-2010, Carta Blanca, Warszawa 2011.

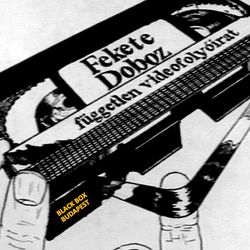

The video periodical Black Box was the first independent film production studio during the last years of communist rule in Hungary. It reported on demonstrations and civilian initiatives that the official media passed over in silence or reported on with disinformation. With its film reports, and portraits distributed in samizdat channels, at the beginning Black Box managed to create the largest film collection documenting the events of the transitional period and the change of political system both in Hungary and in other communist countries.

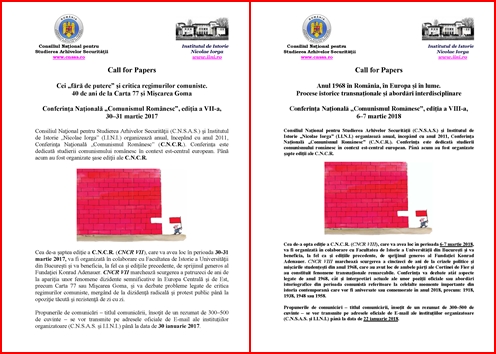

Comunismul românesc (Romanian Communism) is a series of national conferences organised annually in Bucharest each March since 2011. The conference series is a joint project of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archive (CNSAS) and the Nicolae Iorga History Institute of the Romanian Academy, to which the Faculty of History at the University of Bucharest has also contributed since 2016. Its main purpose is to bring together scholars interested in the study of the communist regime in Romania in a regional and wider European context. The initiation of the conference series led to a closer collaboration between CNSAS and the Nicolae Iorga History Institute, which subsequently engaged in the project of digitising the publications related to the history of the Romanian Communist Party that are now part of the Online Collection at CNSAS. Over the years, participants at the conference have approached various aspects of the history of communism in Romania and East-Central Europe, ranging from repression, opposition, and propaganda to everyday life, memory, and post-communist nostalgia. Many of the papers, especially those dealing with repression and the role played by the Securitate, have been based on documents in the CNSAS Online Collection. More importantly, during this series of conferences, participants have made valuable suggestions regarding the types of documents that should be included in the online collection.

On the basis of the“Heiner-Müller-Archive / Transitraum” several exhibitions have already been realized. What is particularly remarkable, are the results of the student seminars, e.g. the exhibition: "Fürs Erste sind wir in der LPG" [For now, we are in the LPG (Agricultural Union of the GDR)], "50 Jahre Heiner Müller" "Die Umsiedlerin oder Das Leben auf dem Lande“ [The Resettlerd or Life in the Countryside]. They were shown at the Heiner-Müller-Archive from 20.10.2011 - 17.11.2011 and took place in cooperation with the foundation of the Academy of Arts (AdK). Also in cooperation with the AdK, Kristin Schulz produced an exhibition, along with the recollections of selected eye-witnesses called: “Ich hätte gern, daß Freunde mich besuchten / Statt des Beamten, der die Steuer eintreibt“[I would prefer friends come visit me / Instead of the public officer collecting taxes]. The "Transitraum" accommodated the exhibition from October 23 to December 18, 2015. In March 2016, the “Internationale Heiner-Müller-Gesellschaft” conducted a “Heiner-Müller-Festival” in The Berlin theatre "Hebbel am Ufer" (HAU). At this event, Kristin Schulz presented the “Heiner Müller-Archiv / Transitraum” under the title "Transitraum goes HAU" as an extravagant temporary exhibition, showing Heiner Müller's relationship to his books.

The donation of Éva Cseke-Gyimesi Collection to BCU Cluj-Napoca (Library of the Institute of Hungarian Literature), 25–26 June 2011/ 30 August 2013

The donation of Éva Cseke-Gyimesi Collection to BCU Cluj-Napoca (Library of the Institute of Hungarian Literature), 25–26 June 2011/ 30 August 2013

The greatest event in the history of the Éva Cseke-Gyimesi Collection was the donation to BCU Cluj-Napoca. The book donation handed over in June 2011 was processed in 2012–2013 by the library of the Institute of Hungarian Literature which is a subsidiary of the Central University Library. The latter is part of the Library of the Faculty of Letters Branch – Section Hungarian Department, which is located on the first floor, in wing A of the Faculty of Letters, and has served the Departments of Hungarian Language and General Linguistics, Hungarian Literature, and Hungarian Ethnography and Anthropology since 1990. The evolution of the book stock of this section of the library of the Faculty of Letters was influenced by the administrative and legal transformations of the departments with Hungarian as the language of teaching. The first inventory register of the library contains the titles of publications acquired in the period between 1902 and 1912. The majority of publications featured in this library come from donations made by various teaching staff members and personalities, but there are also publications bought from private libraries. Thus, in 1941 the private collections of Elemér Császár and Gyula Baross were acquired, both renowned Hungarian literary critics. Consequently, the book stock of this library was enriched by a number of 8,308 volumes, giving a total by the end of 1941 of as many as 12,000. At present this fond constitutes the old stock of the library. Similarly, a part of the book stock of the Hungarian Civic Circle of Sibiu, dissolved in 1944, can be found in this library and at the Romanian-Hungarian section. The library contains 14,812 volumes and 175 titles of periodicals, in addition to the 12,000 volumes in the old stock. Apart from the Gyimesi Éva collection, it is home also to the Zoltán Szabó collection which features 900 books and 25 periodicals (Library of the Faculty of Letters Branch – Section Hungarian Department 2018).

The registration of volumes of the collection donated was carried out under the label Fond Gyimesi Éva. Moreover, the book legacy bearing the sign “Cs. Gyimesi Éva Könyvespolca” (Cs. Gyimesi Éva Bookshelf) was displayed in a visible place in the library hall. The documents, amounting to three boxes, were donated in August 2013 and have not been processed yet. The family have not placed any restrictions on research and have not classified the documents as confidential. It is planned to resort to group work involving students to process this material. These efforts imply the setting up of an inventory list that will allow public access as well so that this part of collection can become available for scholarly research.

In 2011, the Madona Museum of Local History and Art organized the exhibition ‘Elza Rudenāja - 100’, which paid tribute to the creator and first director of the museum. Photographs from this exhibition and an introductory text are displayed on the site of the museum: http://www.madonasmuzejs.lv/par-muzeju/elza-ruden%C4%81ja/elzai-ruden%C4%81jai---100

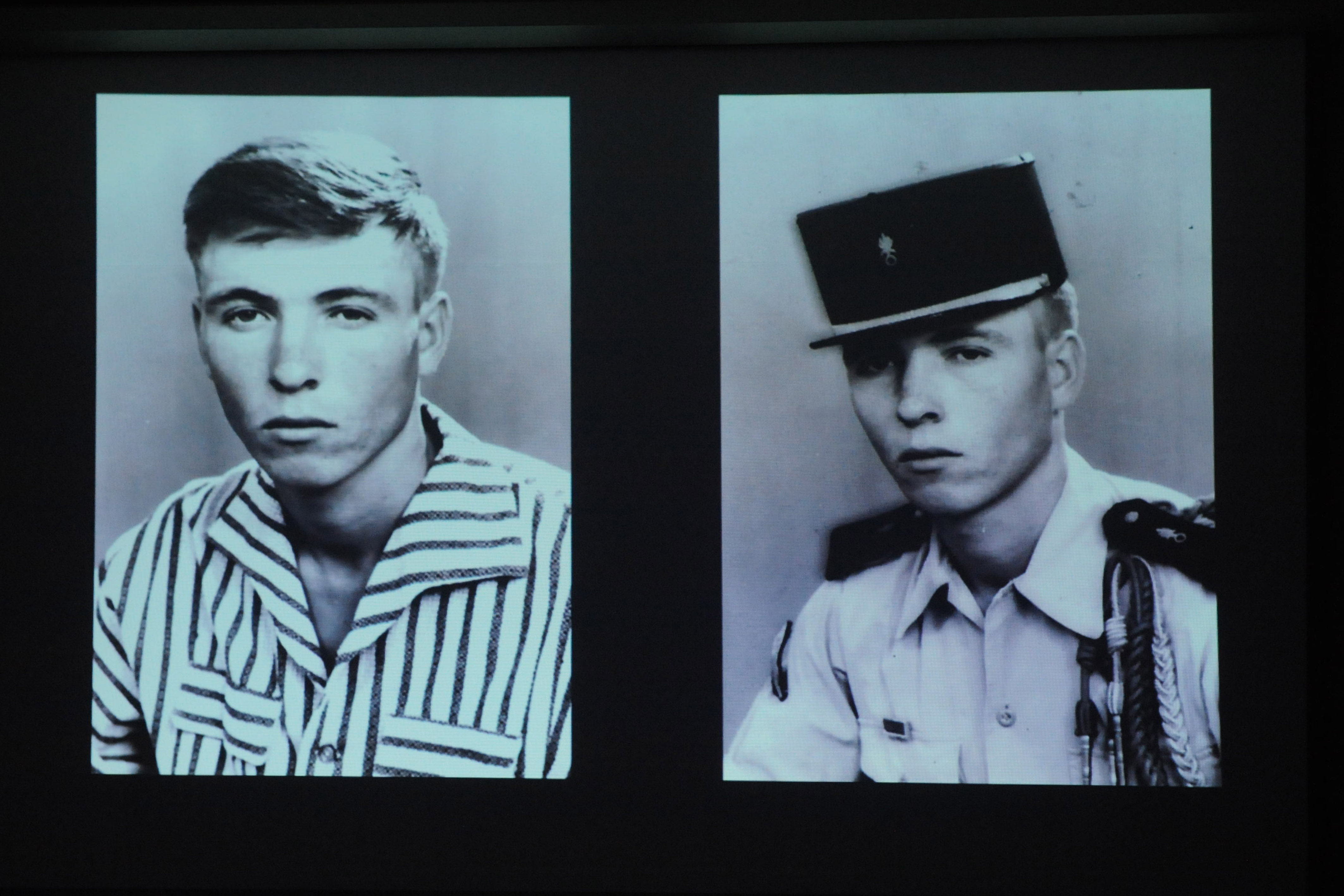

In the autumn 2011, veteran legionnaire and military historian Dr. Tibor Szecskó was the first to return his questionnaire of 50 questions, covering his whole life career. As the main organizer of the Hungarian veterans’ circle in Provence, he was the also one who managed to get many of his comrades involved in their shared memory research work (questionnaires, oral history interviews, memoirs, film shootings, archival research at the Headquarters of the French Foreign Legion in Aubagne, etc.)

He was born in 1939 in the rural town of Gyöngyös, Hungary, as the third and youngest child of a working-class family. His father was a mason working for a state farm. As a second-year student of a vocational school in the autumn of 1956, he took part enthusiastically in local events of the revolution. Together with a friend, they then hitched a ride with a lorry and travelled to Budapest, where they joined the largest group of insurgents at Corvin-köz, and took part in the battles in several parts of the city. In late November, without saying goodbye to his family, he escaped to Austria with other teenage boys. For a few weeks he stayed in the Eisenstadt refugee camp, then he was transported to France and given the status of “réfugier politique.”

As soon as he arrived in the city of Rouen, he signed up at the Legion’s recruitment office, but being only 16 years old, he was rejected. For two years he shared all the misery of the tramps in Lille and Paris, sleeping in the “Draft Hotel” (Hôtel de Curant Air) under bridges, living off of aid for refugees and poorly paid, sporadic work. Hunger and misery pushed him to try his fortune again with the Legion in the autumn of 1958, this time with much success. He was shipped as an 18-year-old recruit from Marseille to Oran, and soon found himself on the military training base of Saida. Another two years passed, and he was promoted to sergeant at the age of 20, and became the training warrant of hundreds of young Hungarian recruits arriving at that time in North Africa. Afterward, as a warrant of the 3rd Infantry Regiment, he also took part in the offensives in the Sahara and Madagascar, was injured twice, and then was commanded to the 1st Cavalry (Warship) Regiment.

After the Algerian war ended in 1962, the main base of the Legion was moved from Sidi-bel-Abbes to the town of Aubagne, South of France, and Szecskó held his new post here at the Headquarters of the Legion. In the 1970s and 1980s, he became the Director of the Museum and the Archives of the French Foreign Legion, and edited its monthly magazine Képi blanc. In the meantime, he received his MA and then PhD degree in history from the University of Montpelier. He finished his military career in 1986 after close to 29 years of service in the Legion; however, he kept active in his field of science and in organizing circles of veteran legionnaires (AALE). He published a number of articles and a dozen books on the history of French Foreign Legion in French, English, and German.

Before 1990, based on rumors fostered by the communist secret police, he, together with his fellow patriots, thought for decades that all active legionnaires had been deprived of their Hungarian citizenship. He became a French citizen in 1974, and lived together with his Spanish-French wife, children, and grandchildren in Aix-en-Provence for half a century. Among his many prizes and decorations, he was most proud of the “Knight of Arts and Literature,” a prestigious French prize established for civilians, that no active military man ever received, except him. Though he felt all through his life a strong homesickness, and managed to preserve his traditional Hungarian patriotism, he never had the chance to return to Hungary after 1956—for a long time due to his political anathema, and then his poor state of health. He passed in Aix-en-Provence in late 2017 following years of struggle with his fatal illness. His parting was not only a painful loss to his family but also to his friends and the Hungarian circle of veteran legionnaires in Provence, of which he had been a devoted organizer for decades.

His straightforward, and emotive answers to his questionnaire lay bare his life career and frame of mind. He also reflected on his feelings toward his native land, the Legion, and his host country. Though his loyalty to the former two seems to remain firm, similarly to his stubborn anticommunism rooted in his early life experience of 1956, he felt much more reserved and often critical of the French public affairs and way of life, as both are lacking “the real” patriotic loyalty and altruism. Thus, keeping alive the regular meetings and traditional community rituals, with their strong 1956 engagement, served to strengthen the Hungarian legionnaires’ moral and cultural resistance.

List of completed veteran questionnaires, 2011–2017

(Place and date of birth, residence in France, and year of completion)

1. A., Domokos (Budapest, 1939) Paris, 2012

2. Bubla, István Miklós (Keszthely, 1936) Paulhan, 2017

3. Huber, Béla (Sopron, 1942) Aubagne, 2012

4. Spátay, János (Budapest, 1943) Puyloubier, 2011

5. Soós, Sándor (Budapest, 1939) Septémes les Vallons, 2012

6. Sorbán, Gyula Elek (Budapest, 1940) Toulon, 2011

7. Szecskó, Tibor (Gyöngyös, 1939) Aix-en-Provence 2017, 2011

8. Morvay, Tamás (Budapest, 1938) Vins sur Caramy, 2012

9. Nemes, Sándor (Szekszárd-Zomba, 1941) Borgo (Corsica), 2011

10. Pápai, Lajos (Öcsöd, 1937) Montrichard, 2014

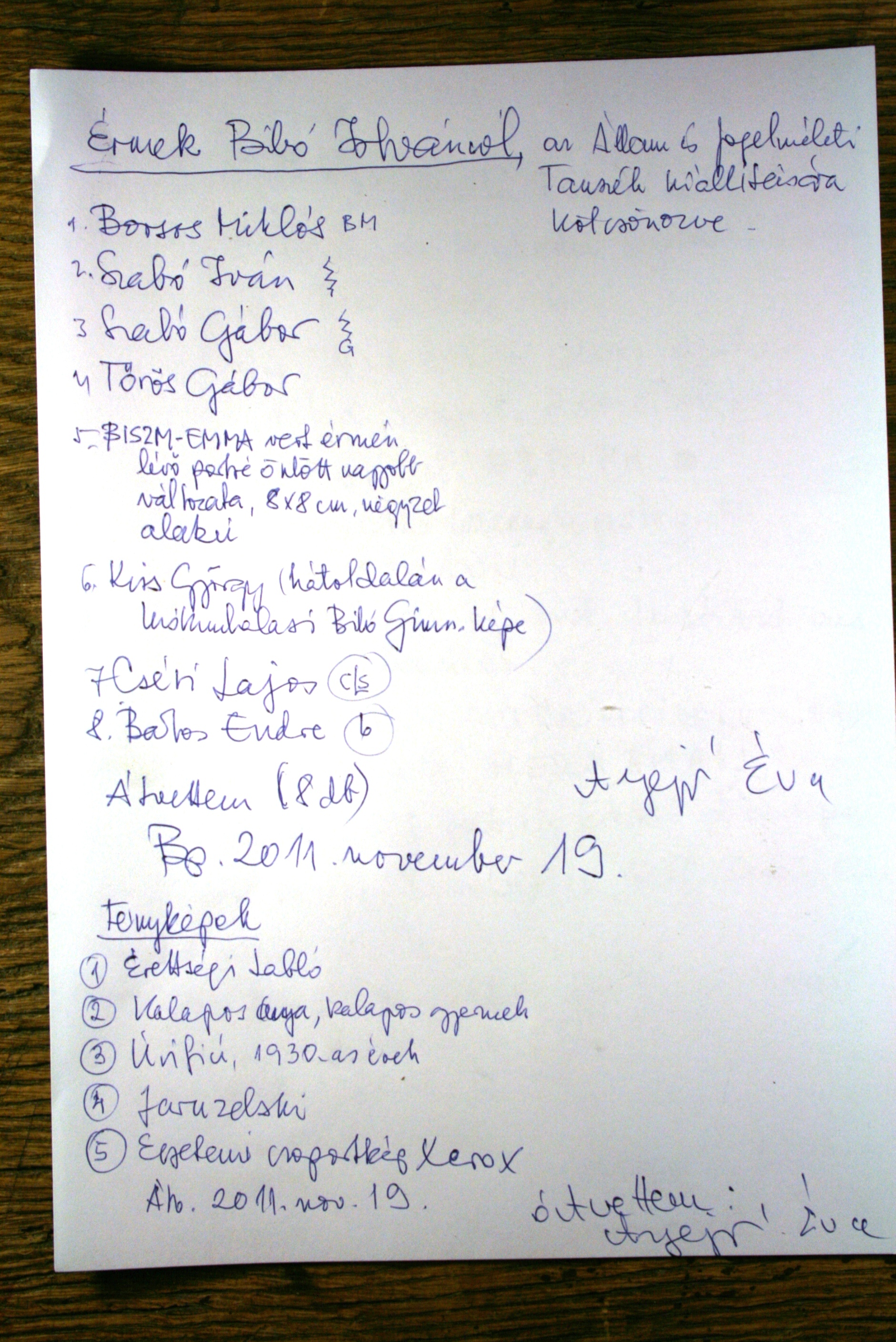

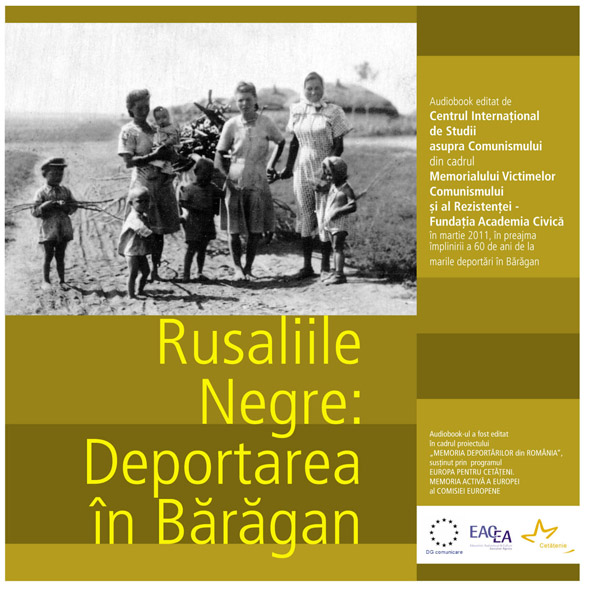

Publication: ICSC. Rusaliile Negre: Deportarea în Bărăgan (Black Whitsunday: Deportation to the Bărăgan), 2011. Audiobook.

Publication: ICSC. Rusaliile Negre: Deportarea în Bărăgan (Black Whitsunday: Deportation to the Bărăgan), 2011. Audiobook.

On the basis of the materials to be found in the oral history archive of the Sighet Memorial, a second audiobook was launched in 2011 under the title Rusaliile Negre: Deportarea în Bărăgan (Black Whitsunday: Deportation to the Bărăgan). The occasion for the launch of the audiobook was the sixtieth anniversary of the massive deportations from the west of Romania, from the border with Yugoslavia, to the Bărăgan, a vast plain in the south of the country, which at that time was almost completely uninhabited, a veritable Siberia in its isolation from the rest of the country and its minimal population density. The title alludes to the fact that this event took place on 17–18 June 1951, on the very day of the feast of Pentecost (Whitsunday), the seventh Sunday after Easter calculated according to the method used by the Orthodox Church. This multimedia document includes twenty extracts from seventeen interviews in the oral history archive of the International Centre for Studies into Communism, part of the Memorial to the Victims of Communism and to the Resistance. The editing was the work of Andreea Cârstea and the musical illustration is by Grigore Leşe. The audiobook was created as part of the project “Memory of the Romanian Deportations,” financed through the European Commission’s programme “Europe for Citizens: European Remembrance.”

Romulus Rusan, who coordinated this project, describes thus the drama experienced by those deported without guilt, without any prior notice, without the possibility of escaping the consequences of this arbitrary action, which targeted all those of whom it was suspected that they might have sympathised with the policies of the communist leader in neighbouring Yugoslavia, Iosip Broz Tito, who was already in open conflict with the leader of the Soviet Union, Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin: “The deportations from the Banat and Mehedinţi in the summer of 1951 were one (the most bestial) of the numerous projects of social purging invented by the communist regime in the Gheorghiu-Dej period, at the height of Soviet domination. Following a plan prepared over three months with diabolical precision, during the night of 17–18 July over 44,000 people were removed from their homes without any prior notice, starting with women and men fit for work and continuing with their families, comprising elderly people up to eighty-five years of age and children of all ages (one of them born just two days before). After a long-drawn-out journey of two weeks, locked in livestock wagons, the deportees were unloaded in a number of railway stations in the Bărăgan, from where trucks carried them to eighteen different points in the deserted steppe. Left to their own devices in the open, under the burning summer sun, they first had to make underground huts, as in a primitive village. In the years that followed they built themselves more presentable houses and brought the virgin soil under cultivation. They thus managed to obtain food for themselves and for their farm animals, overcoming poverty and isolation, surviving like so many Robinson Crusoes of the twentieth century.” The grandparents of one of the authors of the present text were among those hurriedly deported on that dark Whitsunday night, from a village near Timişoara, where they had settled after fleeing from Bessarabia. Leaving behind their house and their belongings for the second time, they were forcible moved to the middle of the Bărăgan, where they arrived with what they had been able to pack quickly and carry with them, where they were given nothing but a door and two windows, so they could make themselves a house of mud and reeds before the coming of winter, where they were forced to reorganise their entire existence in the middle of a deserted plain with almost no sources of water. Their children escaped deportation only because at that moment they were at university in Bucharest. So as not to share the fate of their parents, they falsified their birth certificates, changing their name and Bessarabian place of origin, which had been one of the reasons for the inclusion of their parents in the list of deportees. Romanians from Bessarabia who had taken refuge in Romania at the end of the war to escape the Soviet regime and were implicitly considered by the communist regime in Romania to be anti-Stalinists and potential Titoists, constituted the second largest group among the categories deported to the Bărăgan in June 1951.

The exhibition “Black Whitsunday: The Deportations to the Bărăgan” was first opened at the Dimitrie Gusti National Village Museum, which hosted it in the period 25 March to 25 April 2011. The exhibition then travelled to Timișoara, Drobeta Turnu Severin, Sighet, Sibiu, Berlin, Sindelfingen, Munich, Augsburg, Tübingen, Budapest, and Cluj, before returning to Bucharest, to the Sighet Memorial’s Pemanent Exhibition Space in the Romanian capital. The exhibition’s twenty-eight panels presented themes relating to the forced removal from the Banat of all those who were suspected for various reasons of being adepts of Iosip Broz Tito. The panels relect the following themes: the international context of the Stalin–Tito split, the elaboration of the so-called “dislocation” plan, the compilation of “black lists,” the deportations to the Bărăgan, aspects of daily life in the new settlements – building houses, obtaining water and food, school, work in the fields, funerals – and the use of the area as a place to send released political prisoners into so-called “forced domicile.” The explanatory texts, complemented by hundreds of photographs, maps, and objects, are based on the personal testimonies of those directly involved, recorded and archived by the Civic Academy Foundation. The opening of the exhibition was also the occasion for the launch of an audio-book containing extracts from the recollections preserved in the Oral History Archive of the International Centre for Studies into Communism. The exhibition was part of the project “The Memory of the Romanian Deportations,” financed by the European Commission through the programme “Europe for Citizens: Active Memory of Europe.”