As part of Infermental 6, Antonio Muntadas and Hank Bull initiated the Cross-Cultural Television project. In this framework they asked artists from around the world to record materials from local television programs and submit them for compilation with other project materials.

Miklós Peternák, together with László Beke and Gyula Száva, decided to make a Hungarian submission. On 22 November 1986, they used a Betamax recorder (a format since obsolete), provided by Gyula Száva, to record their contribution.

They sat in front of the television all day, waiting for some part of the programing that they liked, and then recorded it. A little more than three hours fit on the Betamax tape. However, it turned out that they had missed the deadline for posting contributions to Vancouver.

Miklós Peternák did not want to waste the work they had invested in the recording, so with the help of a friend in a video studio he edited a shorter, “watchable” version of the tape: they ran the material through a mixer in real time while adding special effects.

The resulting material reflects not only the Hungarian television programming of the time, but also the contemporary technical circumstances characterizing television receivers and video technology. The record—which contains black and white fragments of the program, often ghostly, poppy images, and sometimes even stripes (the image “runs”)—treats these mistakes as esthetical features.

Years later, this idea led to a project called Medium analysis (Watching Television), at the Intermedia department of the Hungarian Academy of Arts. Initially, it was held every other year, then stopped, but rather recently students themselves restarted the series. Today it is a festival-like event throughout the building, with several parallel programs.

There was an intention to organize these events on the original date of the Medium analysis. It later turned out that this date, 22 November is also important in terms of media history, because it was the first time that broadcast television was interrupted, in this case, in order to announce the death of John F. Kennedy (“the birth of breaking news” as Stephen Kovats called it at an analysis session).

The later Göteborg collection of the Tóth family was greatly influenced by the discussions held on the nights of 18–19 and 20–21 September 1986 in Budapest between the former editors of Ellenpontok. During these conversations, which took up two nights, the former editors, Attila Ara-Kovács, Géza Szőcs, Ilona Tóth, and Antal Károly Tóth,discussed the most memorable events relating to the samizdat in retrospect, four years after their occurrences. Antal Károly Tóth, acting as the host and moderator, recorded the conversations on three 90-minute tapes and published the redacted transcript in 2017 in a volume edited together with his wife. The retrospective exchange of ideas, the search for the “truth” encouraged the Tóths to embark on a collecting mission involving the acquisition of materials and various items relating to the samizdat publication.

By giving their testimonies, the participants in these discussions made an attempt at reconstructing history. All of them were members of a minority ethnic group, and thus their personal memories were defined by the collective memories of the group they belonged to, by their common history and their shared destiny. While recalling the cultural events together, the group acted as heritage-creators who freely shaped the events of recent years and weighed the occurrences of the past partly according to momentary conduciveness. They became embedded in the past and applied their former perspective in creating a picture of times gone by. Thus, in the course of these discussions they recollect the events through their own life stories and the destinies of their families, from their rather subjective points of view. They reveal the everyday history of the samizdat from their perspective as participants directly involved, present insiders’ views on the former editorial team and allow a glimpse into their feelings, into the inner world of their opinions, indirectly revealing details that could otherwise not be conveyed to an outsider.

Letter of staff of the Museum of the River Daugava (then Dole History Museum) to editorial office of the "Literatūra un Māksla"

Letter of staff of the Museum of the River Daugava (then Dole History Museum) to editorial office of the "Literatūra un Māksla"

Staff and activists from the Museum of the River Daugava (then the Dole History Museum) were actively involved in the protest campaign against the construction of the Daugavpils hydroelectric station. Collective and individual letters of protest were sent, mainly to the editorial office of the Literatūra un Māksla (Literature and Arts) weekly, which published the article by Dainis Īvāns and Arturs Snips. The Dole History Museum also addressed a letter to this weekly. Signed on 24 November 1986, the letter consists of two pages. It mentions the damage to historic monuments by the construction of the Pļaviņas and Riga hydroelectric stations, and points to the expected damage that would be done by the Daugavpils hydroelectric station.

The document reproduces the report drawn up by two representatives of the communist Militia following the search carried out on 3 December 1986 for the purpose of investigating the possible illegal basis of the collection of art stored in Brad at the home of Dr Sorin Costina. Under Law 18/1968 regarding the control of the provenance of goods not acquired through legal means, the possessions of any physical person could be checked if there were “data or indications,” basically meaning information collected through informers, pointing to “an evident disproportion” between the estimated value of a person’s possessions and the income legally obtained by that person. The text of this minute, drawn up in the wooden language of the communist authorities, does not identify in its conclusions any illegality that might have been found as a result of the search. However it is highly relevant with regard to the manner in which the communist authorities penetrated the private lives of citizens. The document mentions that the search lasted approximately three hours and provides in ten hand-written pages a detailed inventory of all the items found in the Costina family home. It was drawn up in three copies, one of which, in the original, is now in the Costina family archive.

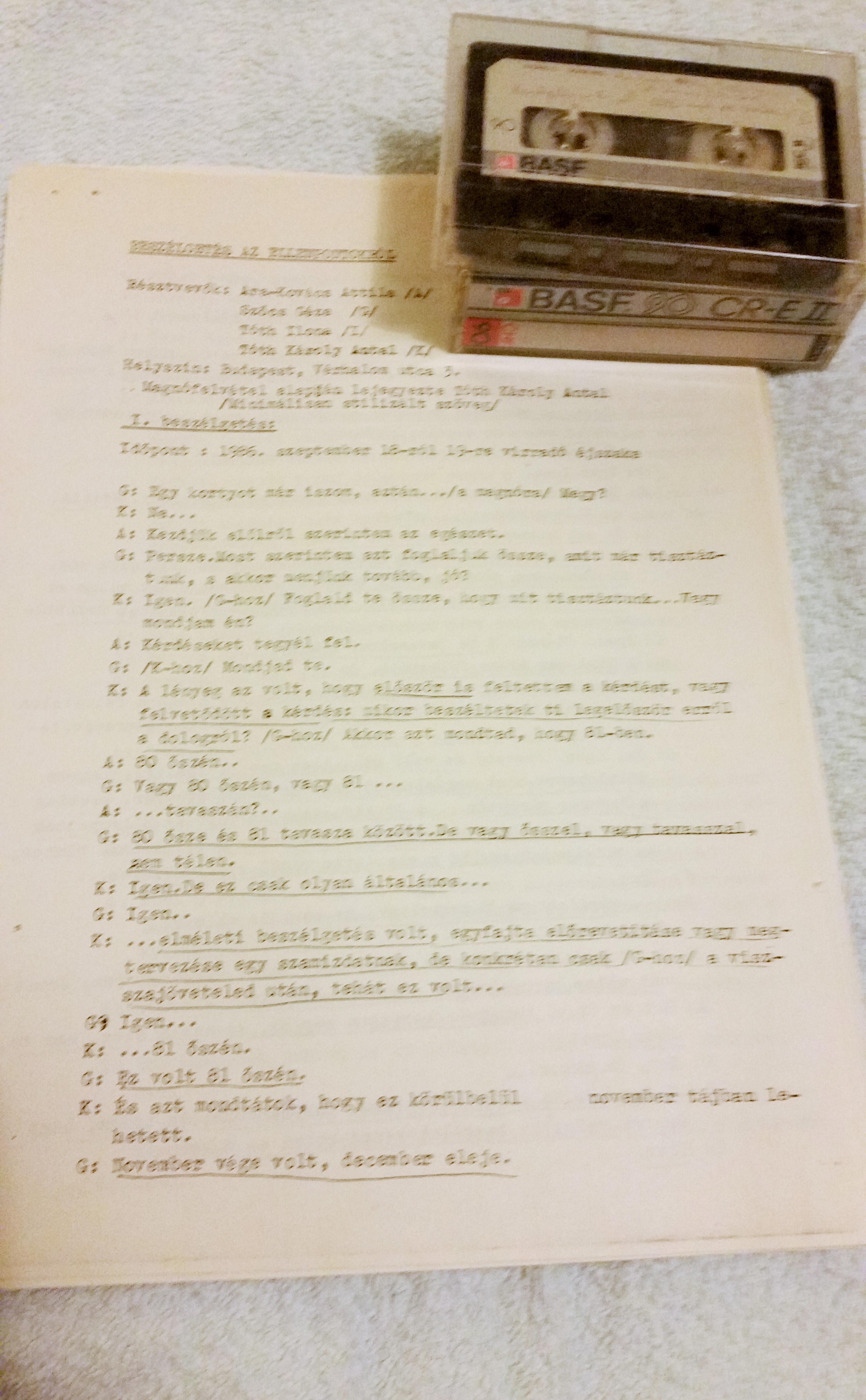

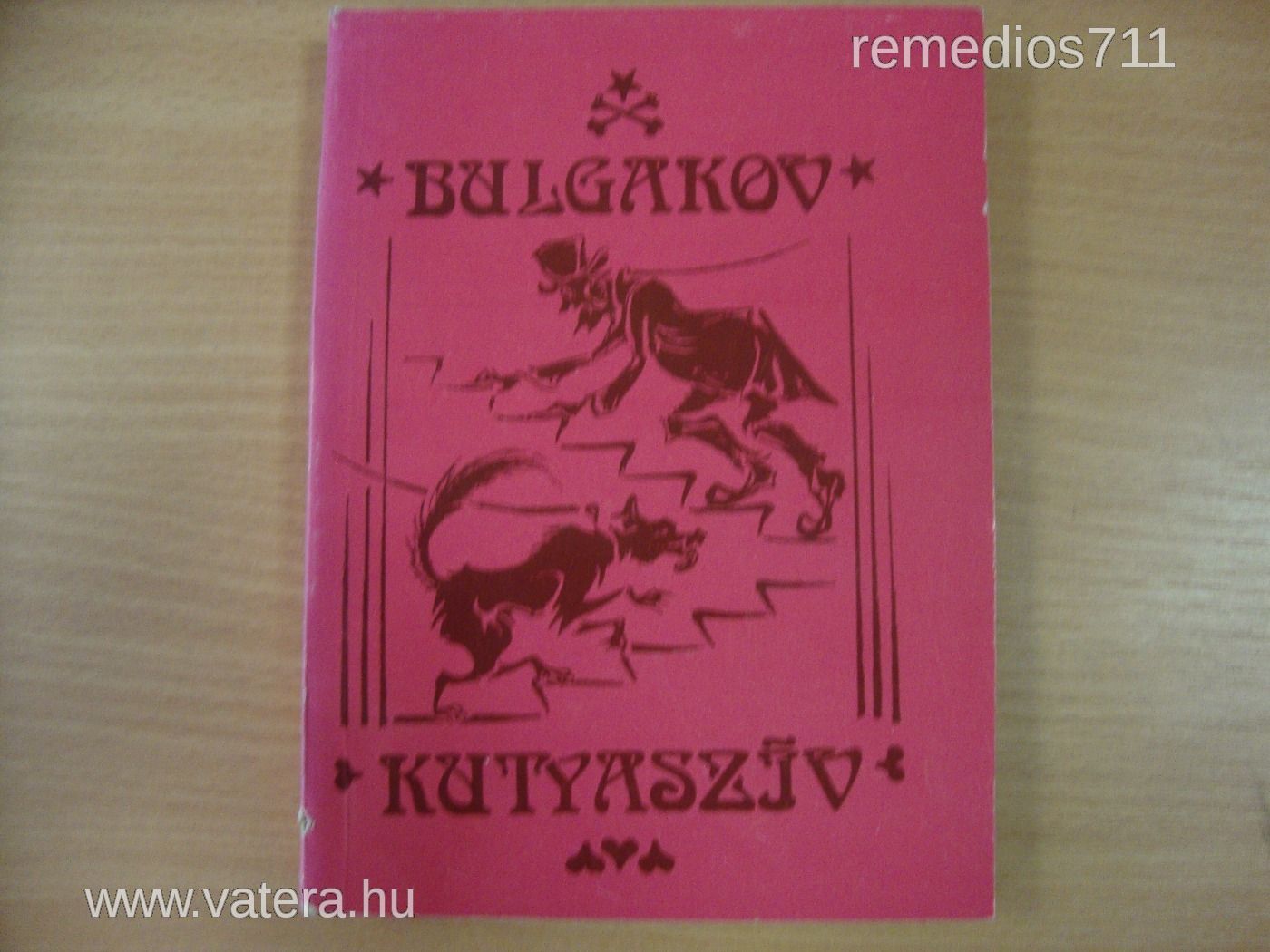

![Publication of book Bulgakov, Mihail. Kutyaszív [Heart of A Dog], 1986.](/courage/file/n136846/bulgakov-kutyasziv-szamizdat-1-magyar-kiadas-fdf9_1_big.jpg)

In January 1986, Katalizátor Iroda published this novel, which was classified as a “prohibited book” at the time. It was produced with the stencil machine of Beszélő, It then became the first book published by Katalizátor Iroda. It was translated by Zsuzsa Hetényi.

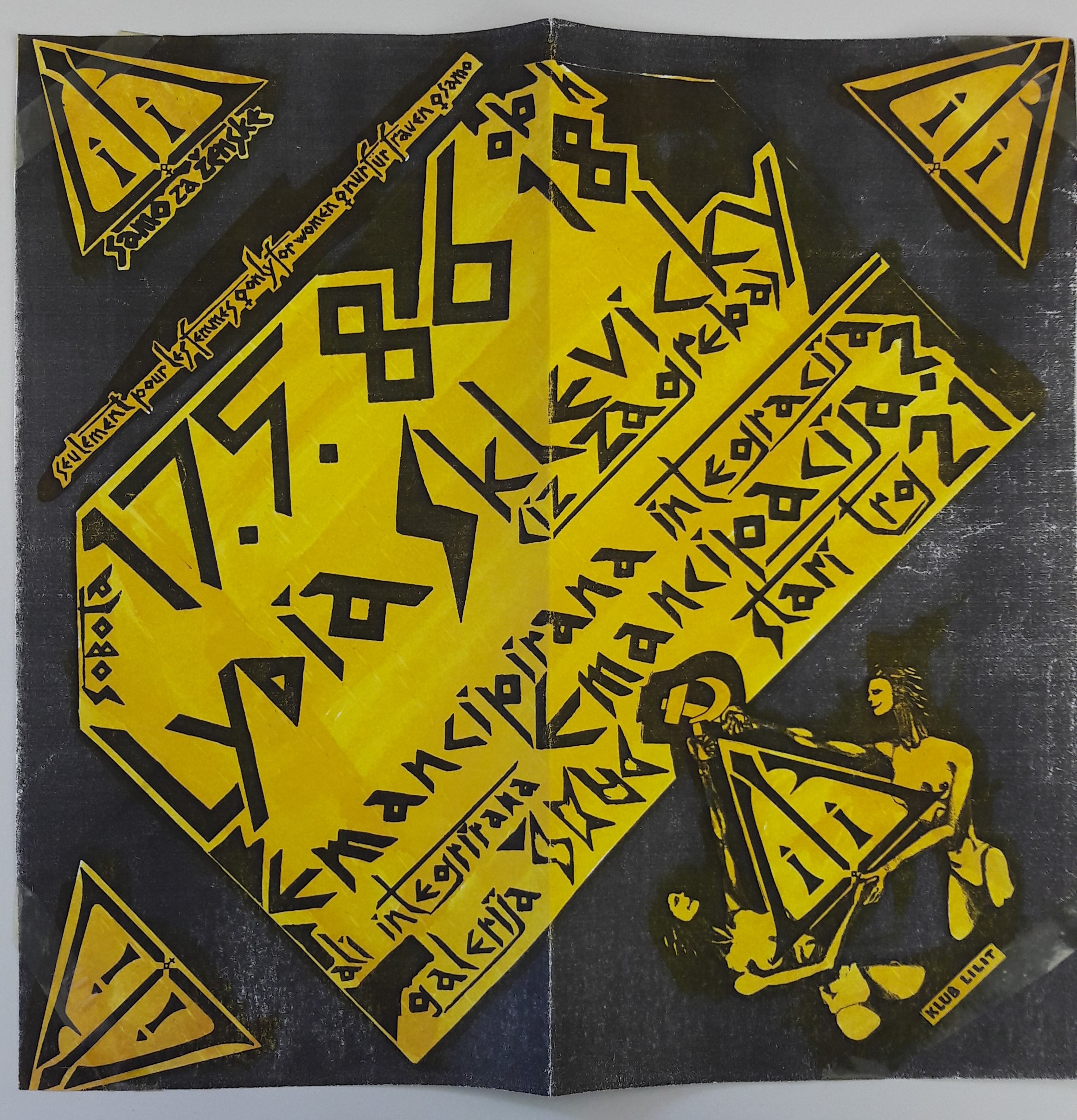

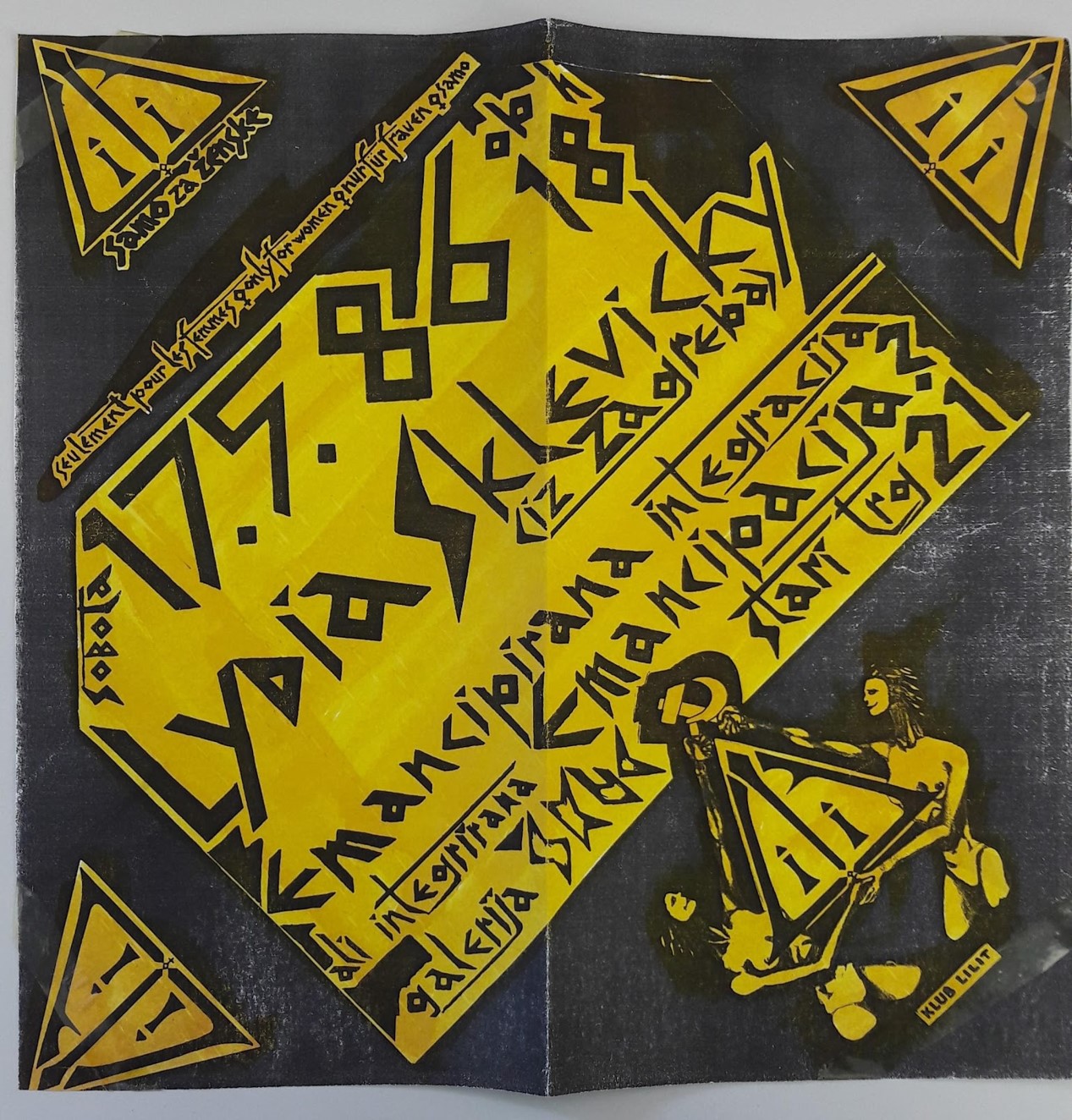

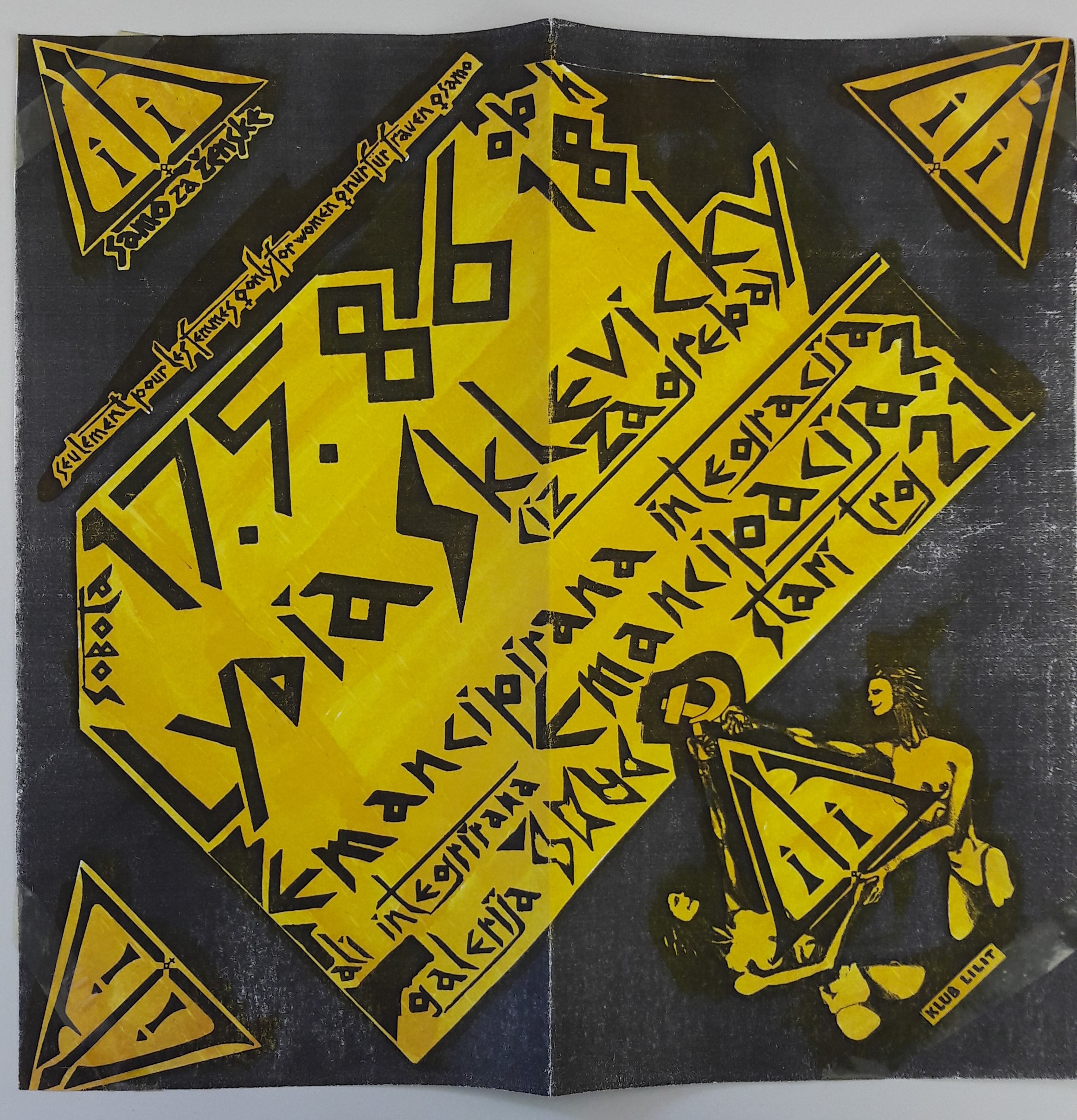

As an engaged feminist Lydia Sklevicky held public presentations in the Yugoslav centres of the new feminist movement, Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana, in which she advocated for the greater presence of the "women’s question" in public and scholarly circles, constantly emphasizing that this question had not been resolved within the Marxist and socialist political order in Yugoslavia.

One of the lectures Sklevicky held was on the topic of "Emancipated Integration or Integrated Emancipation" in the ŠKUC Gallery (Old Square 21) in Ljubljana on Saturday, May 17, 1986. The lecture was organized by the first Slovenian feminist club, Lilit, and the poster for it stated that the lecture was intended strictly for women. The poster is kept in the Sklevicky Feminist Collection.

Cornea, Doina. Regarding the reform of the Romanian educational system (open letter), in Romanian, 1986. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina. Regarding the reform of the Romanian educational system (open letter), in Romanian, 1986. Manuscript

This document drafted in December 1986 is one of a series of open letters sent by Doina Cornea to Nicolae Ceaușescu. A copy of the letter was also sent to Radio Free Europe (RFE) and broadcast in January 1987 (Cornea 2006, 198). As Cornea confessed in her post-1989 interviews, despite the repression and the strict censorship, she tried to think and behave under communism as if living in a free society (Liiceanu 2006, 8–9). She considered that this behaviour was in accordance with her moral values, but also might play a transformative role in a society under dictatorship, because others would be encouraged to follow her example. Her strategy of opening a free dialogue with the authorities also illustrates also the profoundly democratic character of her inner convictions.

The ethical and cultural background of her open letters draws on two main sources: 1. the tradition of the Greek-Catholic Church (of which she was a member), banned by the communist regime in 1948, which functioned underground under communism despite the state repression directed at priests and parish members; 2. the influence exercised by the works of Mircea Eliade and Constantin Noica, both members of the so-called “generation of 1927” (Petrescu 2013, 309). During her teaching activity at the University of Cluj in the late 1970s and early 1980s, she tried to introduce a non-conformist bibliography that promoted different cultural models from those approved by the regime and encouraged free thinking among her students. Due to these attempts she lost her position in the Faculty of Letters in June 1983 (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, ff. 51–52).

If in other open letters she identified among the causes of the general crisis in Ceaușescu’s Romania the decay of cultural and moral values (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 73), in this letter Cornea drafts a plan to solve some of these problems by proposing a reform of the educational system. Thus, she starts her open letter by mentioning the fact that in her opinion some of the main problems of Romanian society under communism (“corruption”, “negligence,” and hypocrisy are caused by the “progressive degradation of the educational system” after 1948. Her criticism targets especially the following aspects of the Romanian educational system during the 1980s: the focus of the state authorities on technical education and the lack of investment in the humanities, the emphasis on memorisation and the failure to encourage critical thinking, and the lack of exigency and the encouraging of mediocrity due to the pressure on teachers from the state authorities (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 73).

She ends her open letter by proposing several measures for a future reform of the educational system: 1. depoliticising education; 2. “reconsidering all curriculums in the disciplines that have suffered deformations caused by the intrusion of the official ideology, such as history, social sciences, literature, and philosophy”; 3. university autonomy; 4. more academic exchanges with foreign universities; 5. reform of teaching methods by paying more attention to “quality” and less to “quantity”; 6. “the re-establishment of those theoretical high-schools transformed into technical secondary schools”; 7. the reintroduction of the humanities in all secondary schools; 8. “the establishment of schools for ethnic minorities in proportion to their percentage in the total population” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 76).

During the home search in November 1987 when the letter was confiscated by the Securitate officers, Doina Cornea was asked to write on the recto side of the first leaf: “I am the author of this text,” and to sign for authentication (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 73). Like other letters confiscated during the home searches, this document was invoked during her interrogations at the Securitate in November and December 1987.

The Marian Zulean personal collection is an illustration of the fact that any act of cultural opposition is dependent on the societal context that generates it. It implicitly highlights the fundamental difference between Romania and other communist states in the last years of the period 1980–1989. The more than 400 newspapers, magazines, brochures and books, originating especially from the Soviet Union in the Gorbachev period, epitomise a reformist political discourse that had become relatively official in the rest of the Soviet bloc, but was considered dangerous by the Romanian Securitate.

Postcard sent by citizens of Western countries to the president of Czechoslovakia demanding the release of imprisoned members of Jazz Section

Postcard sent by citizens of Western countries to the president of Czechoslovakia demanding the release of imprisoned members of Jazz Section

The Jazz Section Collection, now deposited in the National Archives, contains a postcard from 1986 addressed to the Czechoslovak president, Gustáv Husák; the postcard was part of a campaign to release the detained members of the Jazz Section. Similar postcards which were sent by citizens of Western countries led to the earlier release of many political prisoners – members of the Jazz Section – and to lower sentences for others.

The collection contains one copy of the June 1986 issue which escaped shredding, bound together with the other Tiszatáj issues from 1986. Gáspár Nagy’s poem entitled “From a Boy’s Diary,” which generated literary-political scandal, appears on page 10 of the 112 pages. In addition to writings by Gáspár Nagy, the issue also includes poems by Sándor Csoóri, István Kovács, and László Koncsol, an essay by András Sütő, two articles commemorating Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky (who had been born 100 years earlier), and, finally, treatises on segments of László Németh’s literary oeuvre.

Proceedings were launched against the editorial staff and the periodical was suspended due to a poem by Gáspár Nagy in which Nagy alludes to the revolution of 1956 and the moral crisis of the late Kádár-era. Some claim it contains references to János Kádár himself. Kesić, Ante. "Lies and deceptions plus insults and slander". Vjesnik, 9 December 1986. Press clipping

Kesić, Ante. "Lies and deceptions plus insults and slander". Vjesnik, 9 December 1986. Press clipping

Ante Kesić responded to Krsto Papić's "Lies and deceptions" (see the featured item in the "Ivan Aralica Collection") in the text "Lies and deceptions plus insults and slander,” in which he provided counter-arguments to Papić’s statements. Kesić accorded particular attention to accusations on “fabrications” related to his reading of Papić's and Aralica's screenplay for the prospective movie. Kesić criticised the representation of the teacher-training school in Dalmatia and the education of that time. He argued: “They turned the humane school of the new society into a place for venting one’s base instincts and torture. This place was controlled by some hypocrites, careerists, ambitious female students/lovers, who as under-aged girls reign over the school from their fornicatory beds .” Furthermore, he stressed that although the Party was never mentioned, it is nevertheless indirectly represented as a source of evil because the four people who ruled over the school could not position themselves above it, i.e., it is clear that they featured as the Party leadership in disguise. “Could the Party be abrogated by two screenwriters and removed from the historical scene, where it bore all social power? Or to bury it somewhere deep behind the scenes and transform it into an accomplice in crime ?”

Furthermore, Kesić quoted the book A History of the League of the Communists of Yugoslavia (Belgrade: Izdavački centar Komunist, 1985, p. 374) to underscore the positive role of the Party in education during the years of the Cominform crisis (28 June 1948): “In the midst of the conflict with the Cominform … the Communist Party increasingly stressed the importance of a freely developed creative personality. […] the new teaching personnel had to be created by fighting for free ideological development under the conditions of socialist democracy, by expanding the battleground of thought and taking the initiative…” Kesić’s “defence” of the party stressed its democratic qualities in making one’s views known, and that the method of showdowns with those with different views by “lynching” – which is vividly represented in the film – could not be imputed to the Party.

Among other things, Kesić stressed that the Presidency of SUBNOR approved of his assessment “because of the personality of the screenplay writer [referring to Ivan Aralica], who is already politically known to SUBNOR, but now rests in the gentle shadow of literary sunshine.” Thereby he again pointed out the importance of political suitability for literary producers in a socialist society, in which there was no room for its abnegators and in which art and politics operated hand-in-hand in the advanced socialist phase as well.

When the National Legionary State was proclaimed in Romania in September 1940, Ion Raţiu chose to resign from the post he occupied at the Romanian Legation in London and asked for political asylum in the United Kingdom because he did not want to serve the new fascist regime in Bucharest. He became involved in the organisation of the Romanian exile and worked as a journalist specialising in topics related to Romania. In this position he acquired a good knowledge of postwar East European political affairs. Besides radio shows and newspaper articles, his expertise was also materialised in various academic works such as: Policy for the West (1957), Contemporary Romania: Her Place in World Affairs (1975), and Moscow Challenges the World (1986). Although published in 1986, the first draft of the book entitled Moscow Challenges the World was written in the period from 1946 to 1950, when due to health problems Raţiu spent long periods in a sanatorium in Switzerland. Raţiu launched his own business during the late 1950s, and thus for a time invested less effort in continuing his researches. He resumed these academic activities during the 1970s and the opportunity to publish the book in an updated form occurred during mid-1980s. At that moment the intensification of the Cold War during the Reagan administration aroused the interest of the public in contributions concerning the Soviet Union and its foreign policy. The book reflects the theoretical approach to communist regimes marked by the concept of totalitarianism that was dominant in Western academia during late 1940s and 1950s. In its four parts, Raţiu offers a critical overview of the intellectual sources and the main components of the Marxist-Leninist official ideology; he provides an explanation why the 1917 Revolution succeeded in Russia, analyses the strategies and techniques used by Moscow to “export” the revolution, and delivers a complex insight into how the economy works in communist societies and what the social effects of their economic system are. The most relevant contribution of Raţiu’s book to a better knowledge of the Soviet System consists in his analysis of the strategies developed by Moscow of manipulating communists and communist sympathisers abroad in order to reach its goals: “In communist thinking there is no division between domestic and foreign policy. The world is divided vertically into chunks. It is divided horizontally into two layers: the exploiters and the exploited. There is only one ‘nation,’ the proletariat, and one foe, the capitalists and their lackeys. Consequently, the true home of the ‘nation’ is the land where the foe is defeated” (Raţiu 1986, 106). Following this argument, Moscow presented the “defence” of the Soviet Union as “the first duty, therefore, of all communists, whether they live inside Russia or outside it” (Raţiu 1986, 166–168). According to Raţiu’s analysis, these Soviet strategies represented effective tools for influencing public debates in the West and expanding its system of satellite countries in the developing world.

Pope John Paul II. Letter on the 50th anniversary of Franić's priesthood, 1986. Manuscript of letter.

Pope John Paul II. Letter on the 50th anniversary of Franić's priesthood, 1986. Manuscript of letter.

Pope John Paul II sent a letter to Split Archbishop Franić on the 50th anniversary of his ordination as a priest. It is clear that he was quite familiar with Franić's resistance to the atheistic regime and his defence of the Church's rights under the socialist dictatorship. The pope pointed this out in this letter when said that "you have certainly proven your faithfulness and loyalty to this Holy See." According to the pope, Franić's resistance to the communist regime was fruitful in the sense that the Church in Split in the 1980s recorded numerous clerical and religious vocations despite attempts at the de-Christianization of society.

Sociology, along with other social sciences, was under a strong political pressure in the socialist era. After the foundation of the Sociological Research Group (1963), sociologists tried to make room for more autonomous academic activities. “Critical sociology” formed in part because many sociologists refused to legitimize the communist regime through their work. This collection gives insights into this controversial dynamic, i.e. the struggle between scholars on the one hand and political institutions on the other.

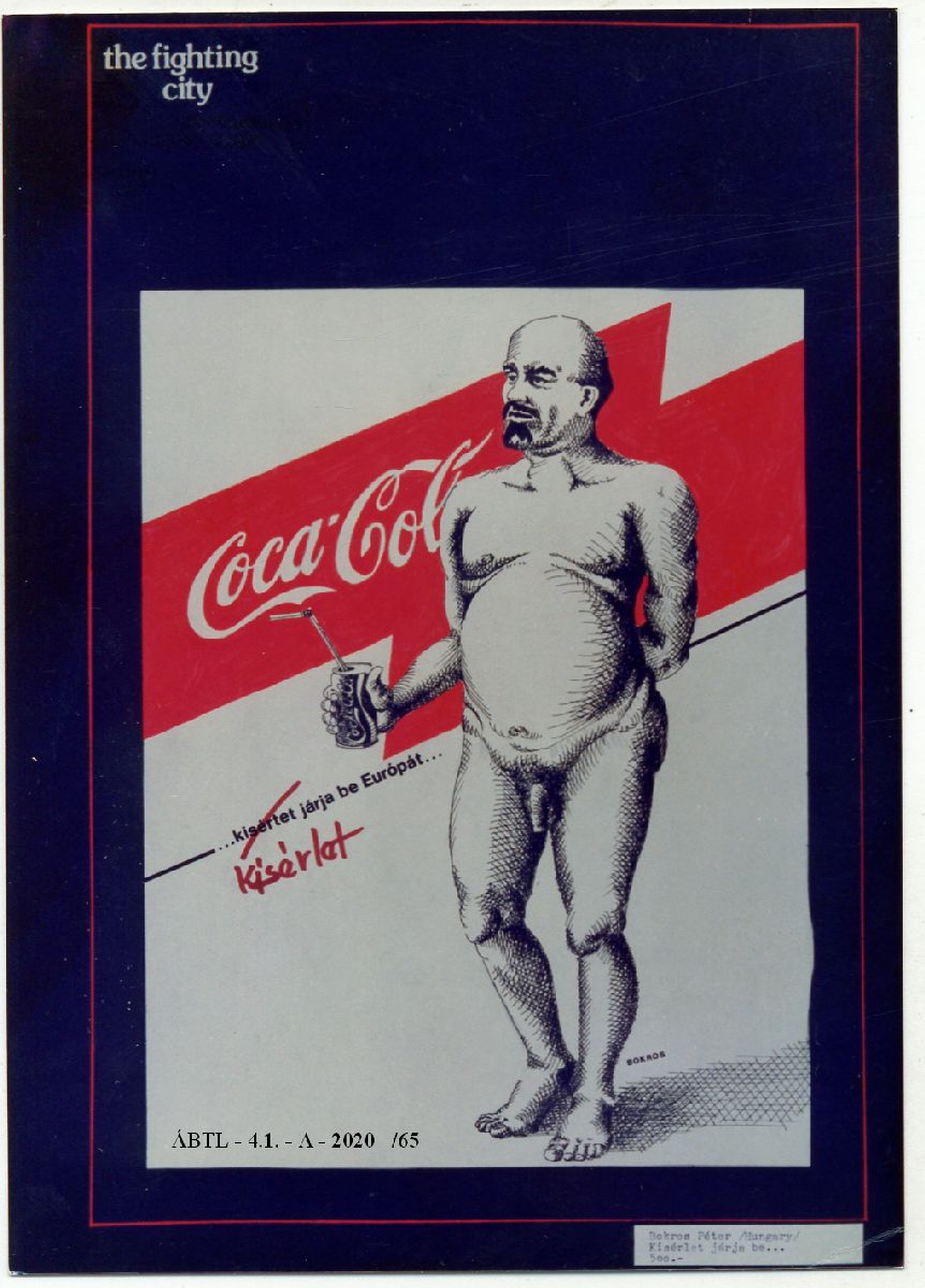

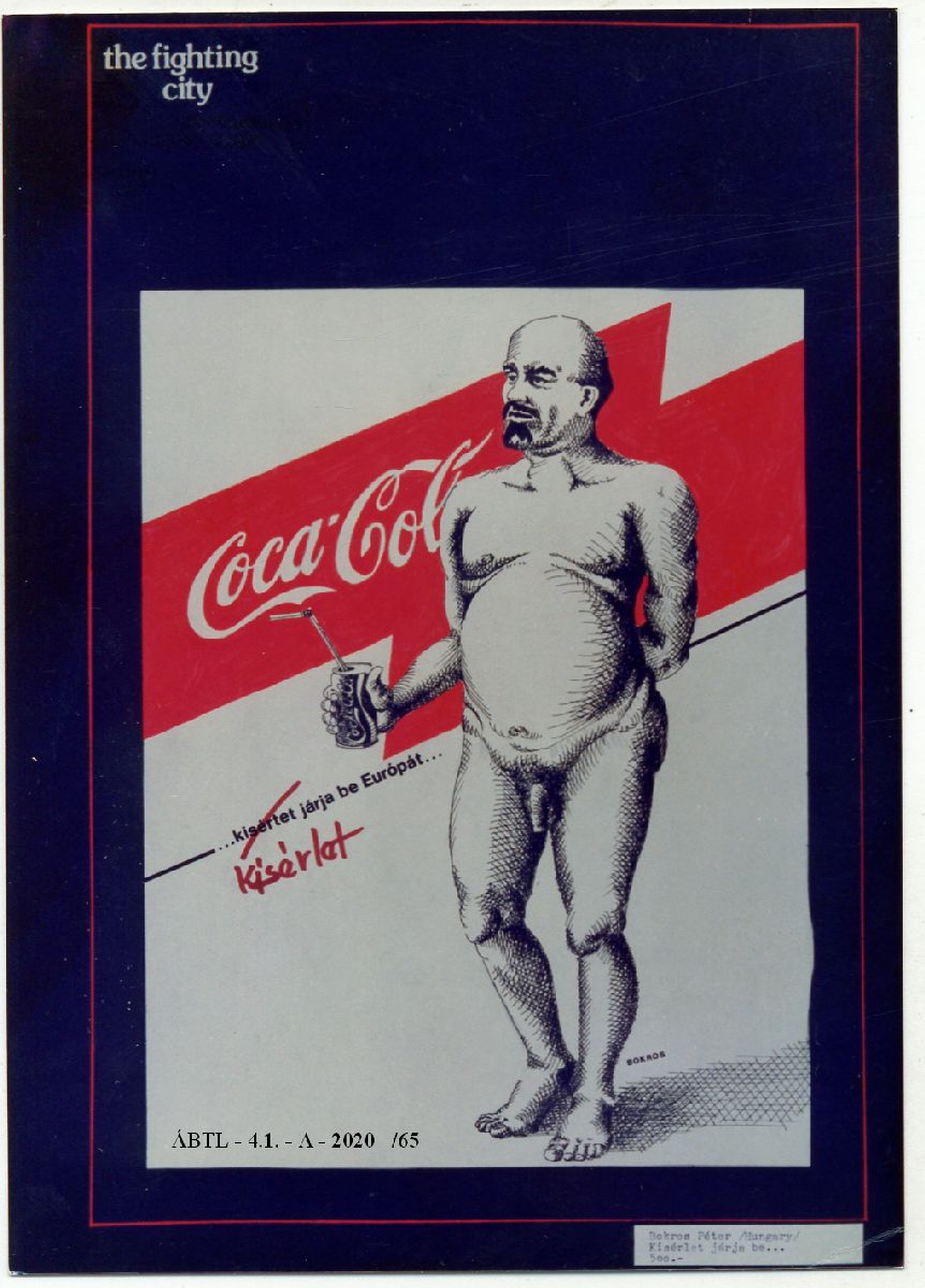

The exhibition entitled “A harcoló város/The Fighting City, 1986” was organized by the amateur artist group Inconnu to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. The police banned the event on the opening day and destroyed the artworks. However, before that, an agent took photos of the compositions. Thus, the secret police itself created, through the act of destruction, a group of sources which is today the single visual trace of the exhibition. This photo collection is kept in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security Forces (Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára – ÁBTL).

The protest campaign against the construction of the Daugavpils hydroelectric station in 1986-1987 was the first issue during perestroika in Latvia to involve the wider public, especially the intelligentsia, and it was the first step on the path that led to the restoration of national independence. This was the first case during the Soviet occupation when the endeavours of the intelligentsia to defend the natural and historical riches of Latvia were successful. The collection consists of material gathered by the staff of the Museum of the River Daugava, and donated to the museum in 1987-1998 by several people who were involved in the 1986-1987 protest campaign, mostly among the protesters, but there is also material provided by their opponents too.

In the case of the screenplay My Uncle’s Legacy, film director Krsto Papić was the main opponent of Ante Kesić and SUBNOR because he sought funding from the council of Jadran Film to make the film. Papić responded to the news that Ante Kesić had interpreted the screenplay for the film at the meeting of the SUBNOR presidency (Vjesnik, 28 November 1986), and asked for the opportunity to give his account of events in the newspaper Vjesnik because Kesić’s view was full of “lies, insinuations and deceptions.”He explained the writing of the screenplay, which he adapted from the novel by Ivan Aralica and named it My Uncle’s Legacy. Since Papić alone carried the project, he asked that all objections and criticisms be addressed to him. Moreover, he sharply criticised Kesić and his “ideologised” reading of the screenplay: “Ante Kesić either did not understand the text or he deceived not only the SUBNOR Presidency as a person of ill will, but also the entire Yugoslav public by means of newspapers and other media with unbelievable fabrications, which he “read” from the screenplay My Uncle’s Legacy. He concluded that this case would end up in court.The press clipping is important because it contains arguments, which Krsto Papić as an exponent of the cultural opposition used against the objections of Ante Kesić. It illustrates the role of public media such as the newspaper company Vjesnik in providing space for such debates. Otherwise, the intervention in the screenplay of the feature film My Uncle’s Legacy was considered as the last attempt of this kind in Yugoslav cinematography before the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1990.

The results of the so-called “rearrangement” operations in the centre of Bucharest was as follows: 5.86 km2 of the historic centre of the city were demolished; 1.66 km2 remained waste ground overgrown with weeds; approximately 20,000 properties were destroyed; over 60,000 families were forced to move; 19 streets were blocked or ceased to exist. The following Orthodox churches were demolished: Enei, Albă Postăvari, Old Spirea, Well of Healing, St. Nicholas Sârbi, Gherghiceni, St. Nicholas Jitniță, Lady Oltea, St. Vineri Hereasca, Olteni, Old St. Spiridon Vechi, Holy Trinity Dudești, and Bradului (Bradu Staicu). The following monasteries were wholly or partially demolished: Cotroceni, Nuns’ Hermitage, Mihai Vodă, Văcărești, Antim, and St. Pantelimon. The following synagogues were demolished: Aizic Ilie, Rezith Doadh, and Malbim. Other historic buildings were also demolished: the Brâncoveanu Hospital, the great covered market in Unification Square, the Mina Minovici Institute of Forensic Medicine, the Yellow Inn, the Republic Stadium, and the Military Museum. Eight churches were translated from their original sites and hidden among apartment blocks: St. John Moși, Schitul Maicilor, Olari, St. Ilie Rahova, Mihai Vodă, St. John Piață, New St. George Capra, Stork’s Nest; so was the synodal building of the Antim Monastery. “The great merit for the translation, and thus saving from demolition, of these monuments is due to the engineer Eugen Iordăchescu of the Project Bucharest Institute,” says Andrei Pandele. This operation of saving cultural heritage that had been destined for destruction indeed called for professionalism on the part of those who conceived it, but also the courage to propose a compromise solution that would have a chance of being accepted by Nicolae Ceaușescu, who was personally supervising the construction of the House of the People.

The image captured by Andrei Pandele illustrates the translation of the church of the Mihai Vodă Monastery, an emblem of pre-modern Bucharest, originally situated on the hill where the Palace of the Parliament – built during the Ceauşescu regime under the name of the House of the People – now stands. The monastery buildings, which surrounded the church and were completely demolished to make way for the House of the People, were the first location of the State Archives after the founding of the modern Romanian state in the nineteenth century. The monastery was founded in 1594 by Michael the Brave, an extremely important figure in the national past, as he is considered the first to have unified, for a short time in 1600–1601, the territories that now make up Romania. In spite of the fact that during the Ceauşescu regime Michael the Brave became even more important in national history than he had been before, the monastery fell prey to the so-called “urban systematisation” programme promoted by the regime. The monastery church was saved from demolition by the operation of translating it, which in this case was one of the most laborious actions of this kind as it required it not only to be slid along a distance of 289 metres, but also lowered by 6.2 metres. Andrei Pandele’s photograph shows the Mihai Vodă church still on the rails used for the translation, already at the foot of the hill, close to its present position, although it is now hidden behind apartment blocks taller than it, which were built after this image was immortalised.

The depiction by Péter Bokros shows the figure of Lenin, naked, with a Coca-Cola in his hand. The subtitle cited an altered version of the first sentence of the communist manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Instead of the original opening sentence of the manifest, the infamous lines “A spectre is haunting Europe,” he wrote “An experiment is haunting Europe.” The graphic was created for the exhibition of Inconnu entitled “A harcoló város/The Fighting City, 1986,” which was a commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution. This artefact, like the other items which were going to be put in display in the exhibition, was confiscated and destroyed by the political police. We know this from the photo documentation made by the secret security forces.

Glavlit documents were transferred to the Lithuanian Central State Archives in 1986. This was related to the decision to create a separate Glavlit fond in the archives (the first transfer of documents was a purely bureaucratic decision). After Glavlit was liquidated in 1990, its documents in the archive were complemented with new documents.

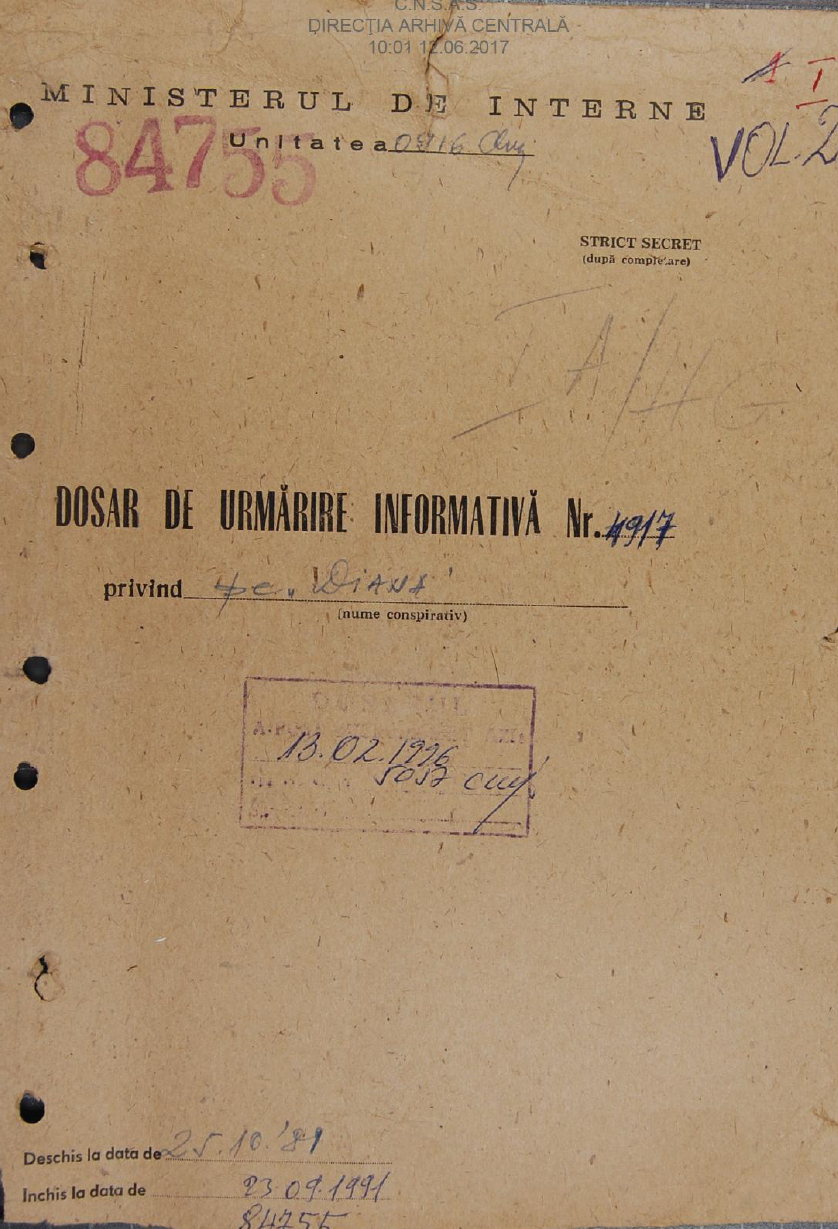

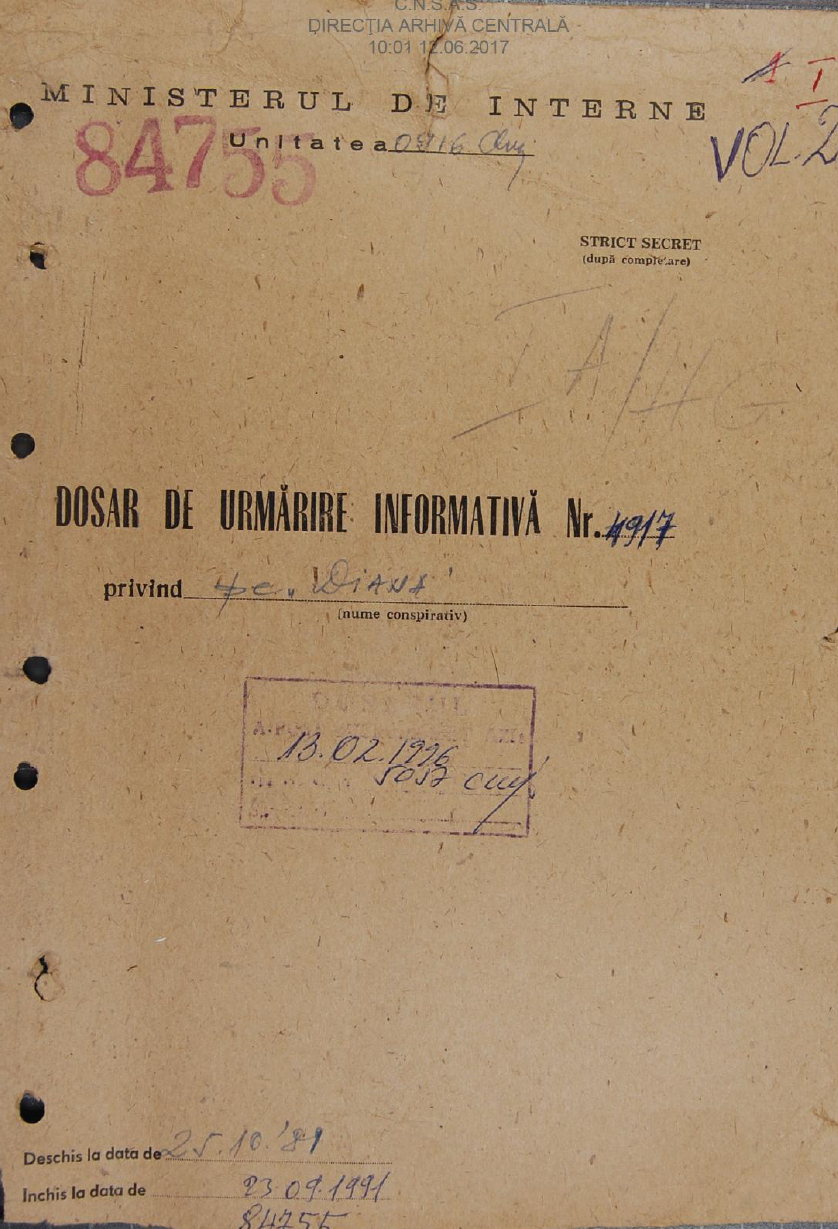

Securitate. Herta Müller’s discussion with a German citizen about her persecutions by the Securitate, 25 July 1986. Report

Securitate. Herta Müller’s discussion with a German citizen about her persecutions by the Securitate, 25 July 1986. Report

The third volume of Herta Müller’s informative surveillance file (dosar de urmărire informativă) contains reports on and transcriptions of the conversations that she had with various persons inside her house. On 25 July 1986, Müller welcomed a German citizen called “Marișca.” The discussion started with the host showing her guest several reviews of her book and other publications by other German writers living in Romania. Herta Müller spoke about the success of her Niederungen (Nadirs) in West Germany and used this episode to describe the persecutions she was subjected to by the Securitate. Müller remembered that as she had turned down the offer to became its informer, the Securitate started to harass her and she lost her job as a translator at an engineering factory in Timișoara. Moreover, she was periodically summoned to the secret police and accused of “social parasitism” and unapproved contacts with foreign citizens. Following a visit to the local Party secretary, Müller received a new job but due to her conflicts with the director of the school, who objected to her wearing trousers during classes, she was removed from her teaching position. Müller also recounted her experience of social and professional marginalisation as she got fired from other jobs because of the intervention of the Securitate, which subjected her to constant physical and psychological abuse.

Copy of a letter from the wives of the arrested members of the Jazz Section to the president of Czechoslovakia, 7 September 1986

Copy of a letter from the wives of the arrested members of the Jazz Section to the president of Czechoslovakia, 7 September 1986

The Jazz Section Collection, now deposited in the National Archive, contains a transcript of a letter sent to the office of the president of the republic by the wives of the imprisoned members of the board of the Jazz Section from 7 September 1986; the transcript was made by Ivan Medek on 9 September 1986 in Vienna. Ivan Medek, a signatory of Charter 77 and a member of the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS), who went into exile in Austria and established a press agency in Vienna, collected information about independent civic initiatives and political trials in Czechoslovakia and the violation of civil and human rights by the communist regime. He sent these messages on to Western organisations interested in human rights’ abuses; they organised campaigns in support of political prisoners and helped exert pressure on leading politicians in countries with totalitarian and authoritarian regimes to release political prisoners and to observe the basic rights of the civilians of their state. It is unclear if the letter to the president had any immediate influence on the fate of the detainees, however, there were several similar campaigns in Western countries that resulted in the release of many of the detained members of the Jazz Section, and much lower sentences were issued than had been proposed.

The novel “The Invalid Siblings” (Invalidní sourozenci) (1974) is one of the most important works by the Czecho-Slovak poet, novelist, playwright, philosopher and “guru” of the Czechoslovak underground, Egon Bondy (real name Zbyněk Fišer, 1930–2007). A manuscript of this dystopian novel, which depicts life around the year 2600 on the last piece of land surrounded by rubbish, was obtained by the Museum of Czech Literature (PNP) in 1986 from the antique bookshop Kniha (Karlova street, Prague 1). At the time, this novel had only been published as a samizdat (1974) and in exile (1981), and had not been officially published in Czechoslovakia. A manuscript of Bondy’s philosophical work “Buddha” (officially published in 1968) was bought by PNP together with “The Invalid Siblings”.

Bulgakov's Heart of a Dog, a satire on the Soviet New Man, was written in 1925 in the Soviet Union, and it was immediately confiscated and banned until as late as 1987. From the 1960s it was circulated in the country in Western editions, but in Hungary very few people had the chance to read the novel. It was not known even among people who had access to sources of clandestine literature under the Kádár regime.

The situation changed a little when the Slovak journal Svetová Literatúra published the novel in Slovak translation in 1978. The Hungarian writer György Spiró thus could read the novel - strangely enough, upon the recommendation of the notorious hard liner cultural journalist, columnist of the party daily, and editor of the journal Szovjet Irodalom [Soviet Literature], Pál E. Fehér. Spiró started to work at the Csiky Gergely Theatre in Kaposvár as a dramaturge in late 1981 (officially from early 1982), and he encouraged the director to adapt it for stage. By then, the professor of Russian Zsuzsa Hetényi had already prepared the translation based on the 1969 Paris edition of the book, which Spiró had lent to her. The initiative nevertheless failed, and the Hungarian translation was put on file in the archive of the Institute of Theatre in Budapest. There was a second attempt to stage it in 1986, but the authorities intervened. The Hungarian translation, however, was published in the same year by one of the smaller samizdat publishers, Katalizátor Iroda.

The publication of the book caused some tensions within dissident circles. The book was brought to Katalizátor Iroda by Ádám Modor, who had until that point been involved in the printing of the samizat journal Beszélő since 1983. The editors of the journal had a rule: no other publication was allowed to be printed on the stencil machine of Beszélő located in the suburban workshop of painter Kitty Márczi. Modor, however, decided to print Heart of a Dog anyway that was noticed by the editors. In March 1986, the editorial team parted company with Modor, who brought the book to Katalizátor Iroda and published it under their brand.

The book did not reveal the identity of the translator. This was at Hetényi's request, because she had small children and did not want to cause any trouble for his father either, who was the Minister of Finance at the time. The publication caught the notice of the political police in January 1987, when one of their agents visited the samizdat shop (boutique) and bought a copy of it. Katalizátor Iroda then became a target of the secret police. In 1988, Heart of a Dog was legally published in Hetényi's translation as Kutyaszív by Európa Publishing House. This version slightly differs from the previous one, for the editor of the Európa version made changes to the manuscript to which the translator did not give her consent. There have been several editions of the text since then, and Hetényi revised the text for every new issue.