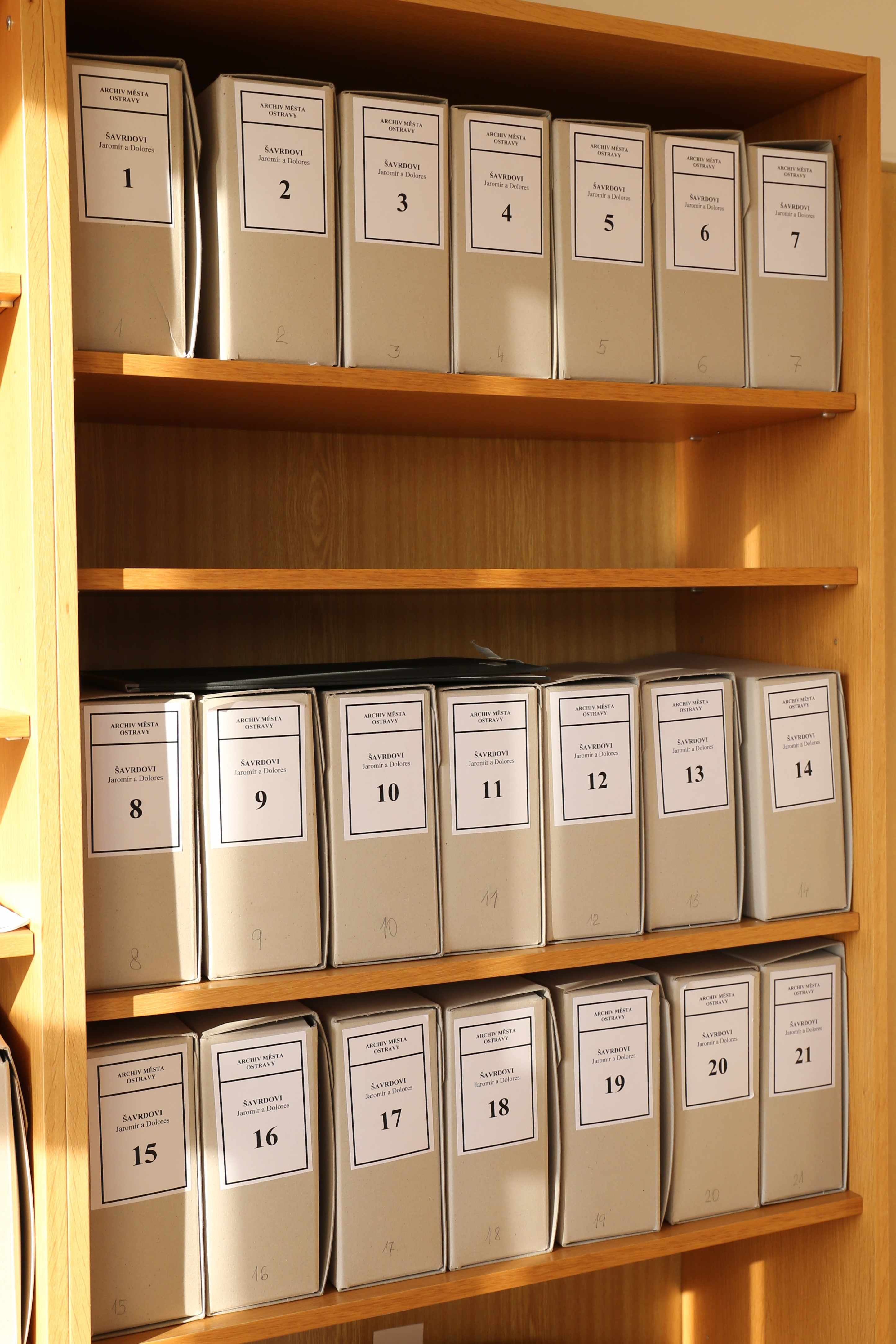

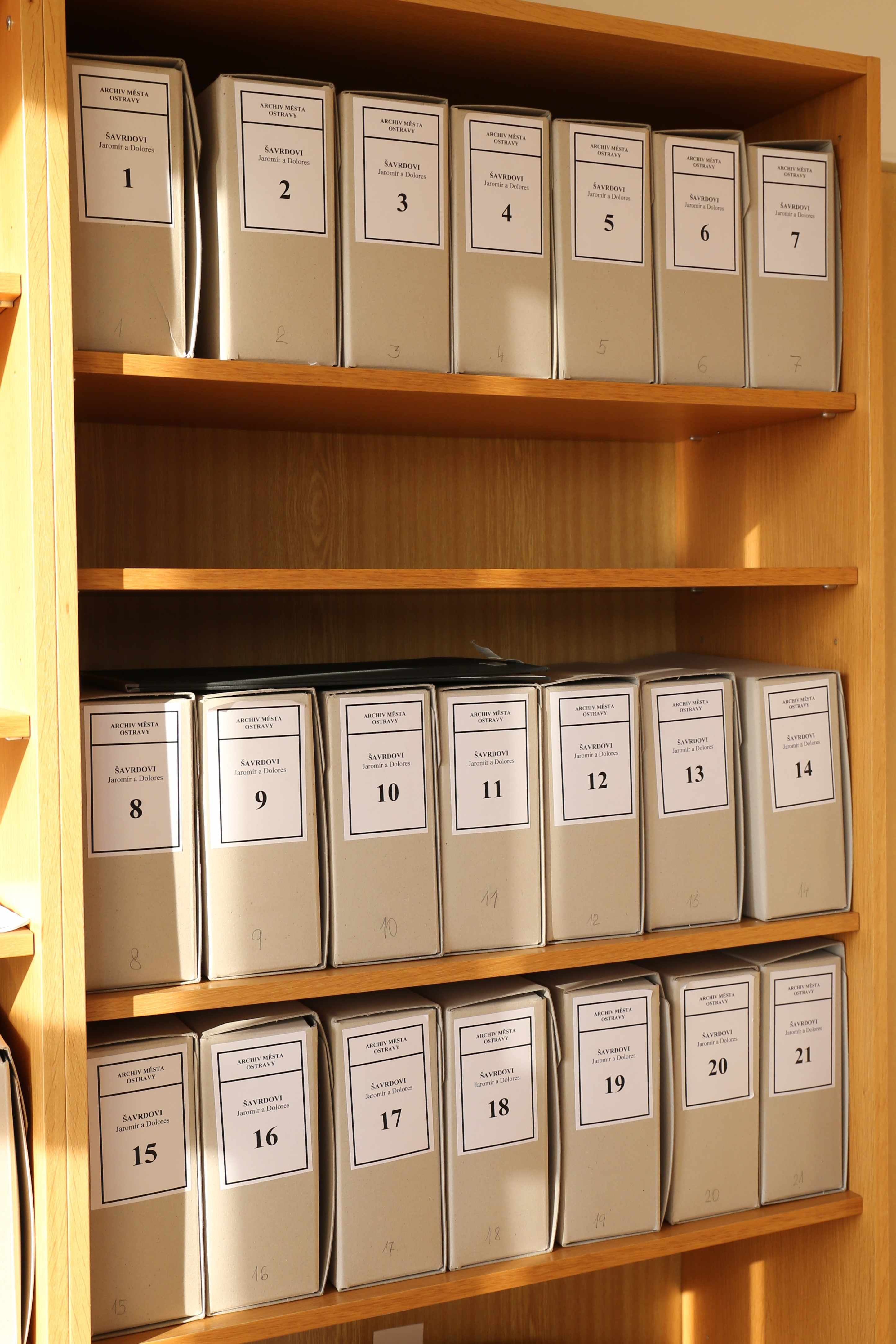

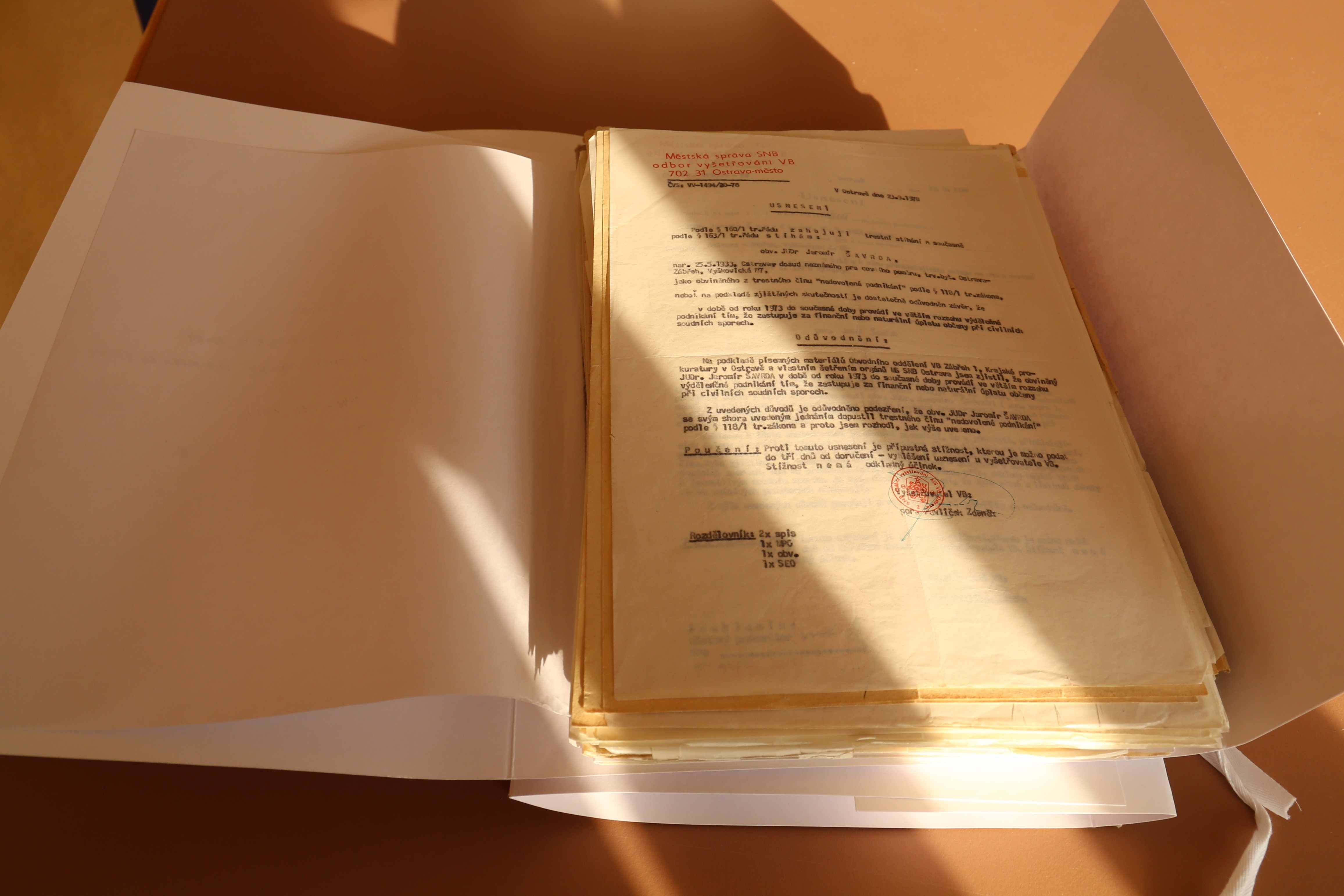

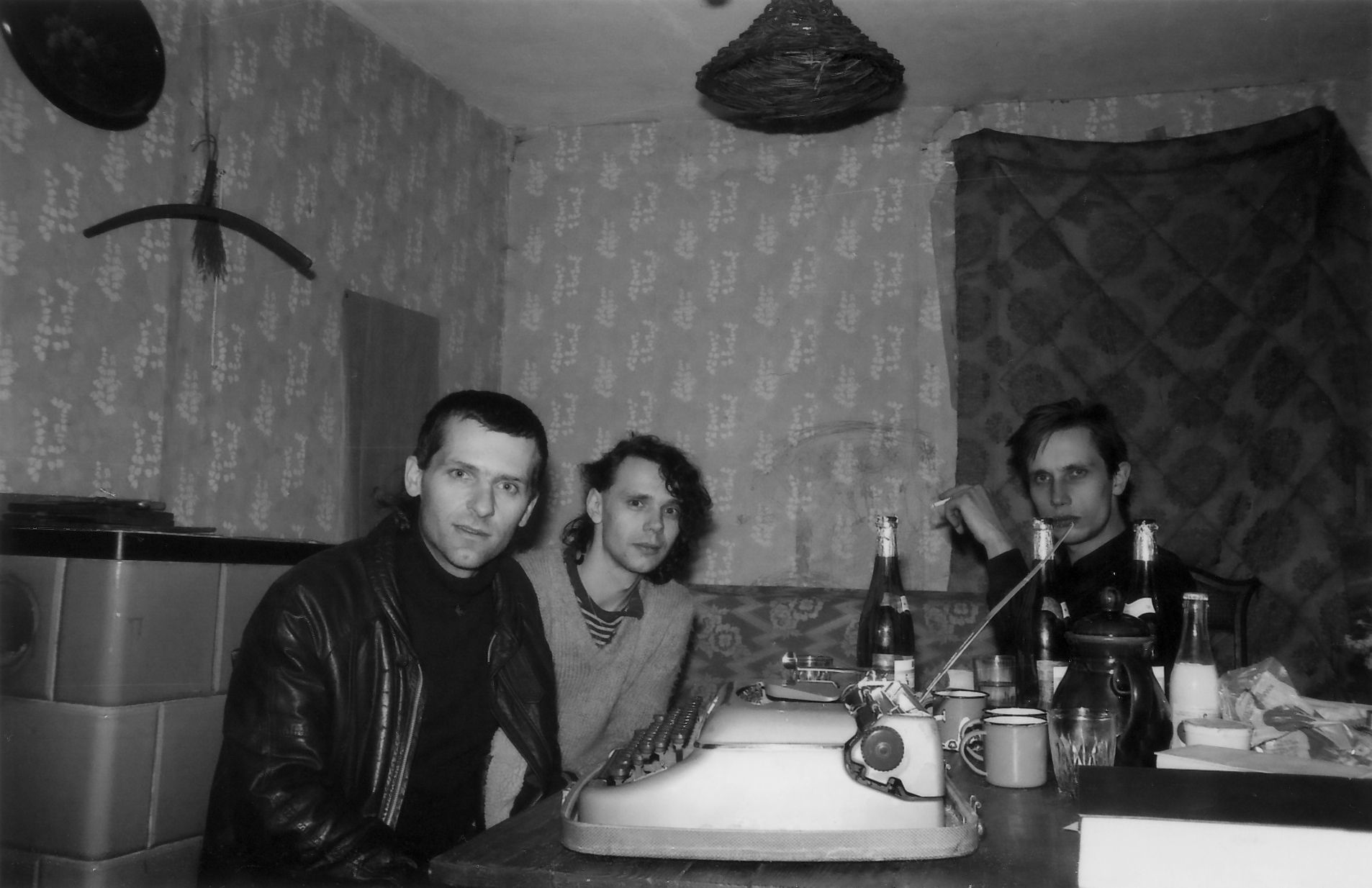

The Jaromír and Dolores Šavrda Collection consists mostly of materials documenting the life and work of Jaromír Šavrda (1933–1988), a Czech journalist, writer, political prisoner and significant representative of dissent in Ostrava. Parts of the collection are, for example, Jaromír Šavrda’s biographical documents, his literary work including poetry written in prison, samizdat editions of his works as well as works written by other authors, manuscripts and typescripts of books and magazines, materials documenting his activities in dissent and his correspondence.

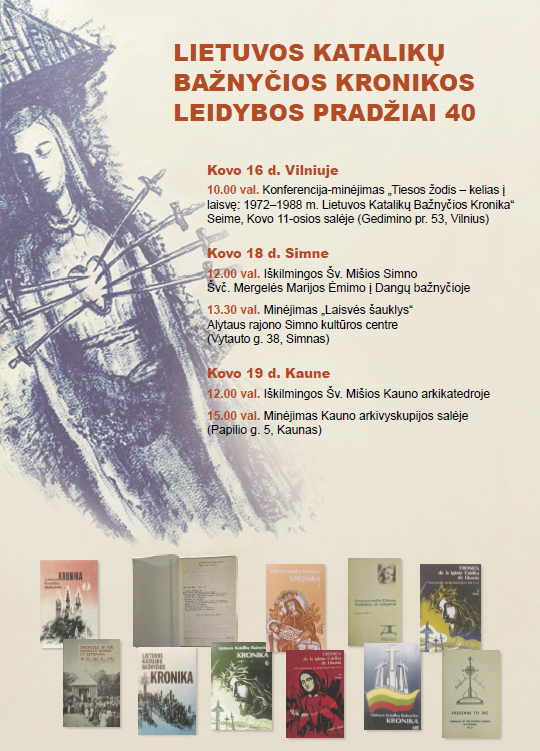

The exhibition ‘Lietuvos Katalikų Bažnyčios Kronikai – 40 metų’ (The 40th Anniversary of The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania) was held on 12-26 March 2012 in the Lithuanian parliament (Seimas). The exhibition was accompanied by the international conference 'Tiesos žodis – kelias į laisvę: Lietuvos Katalikų Bažnyčios Kronika 1972–1988 metais’ (Truth as the Path to Freedom. The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania in the Period 1972-1988), in which historians, politicians and former anti-Soviet dissidents took part. One famous guest at the conference was the well-known Russian human rights activist Sergei Kovalev, a former distributor of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania. The organisers of the exhibition and the conference were the Lithuanian parliament and the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania.

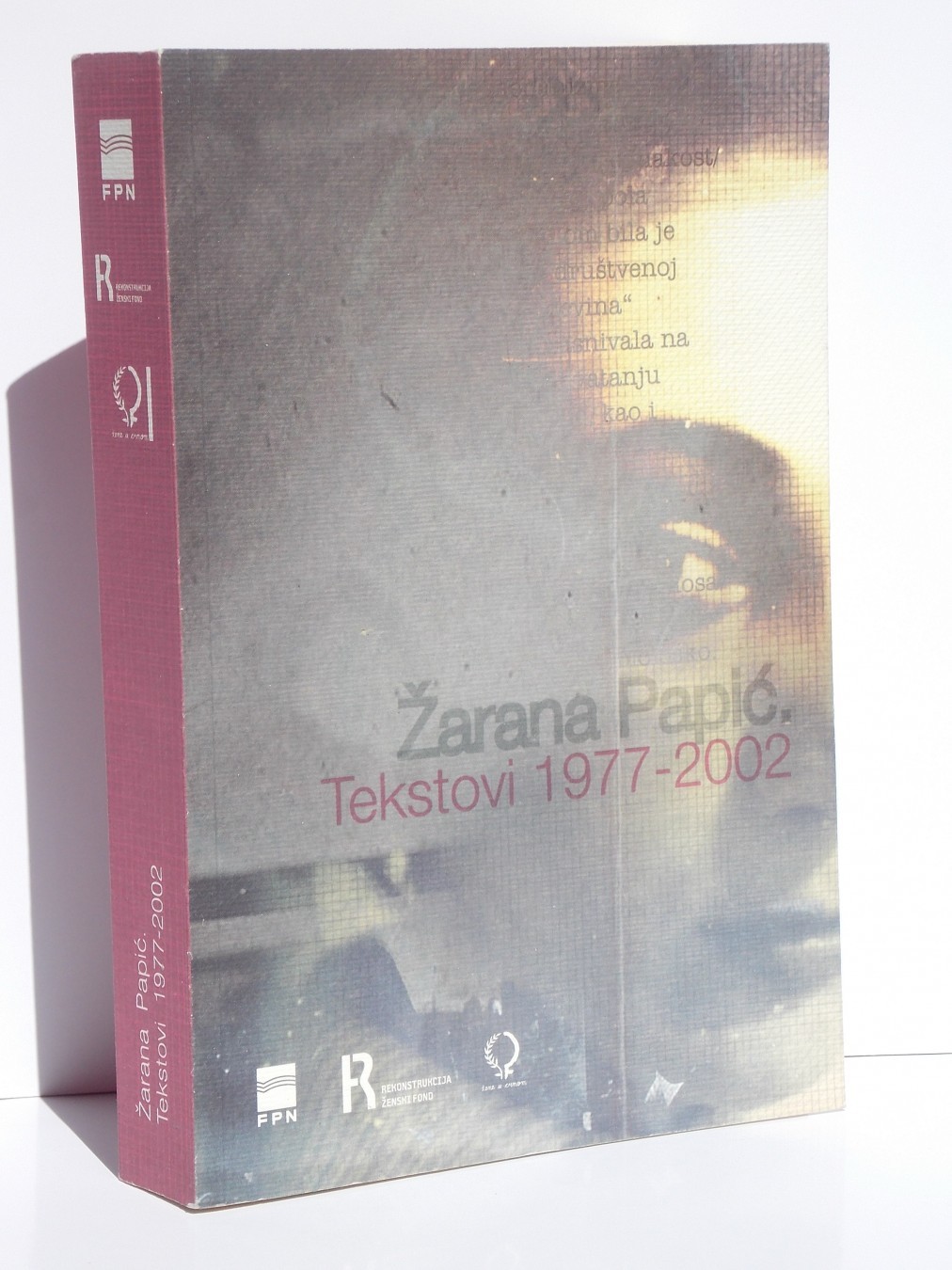

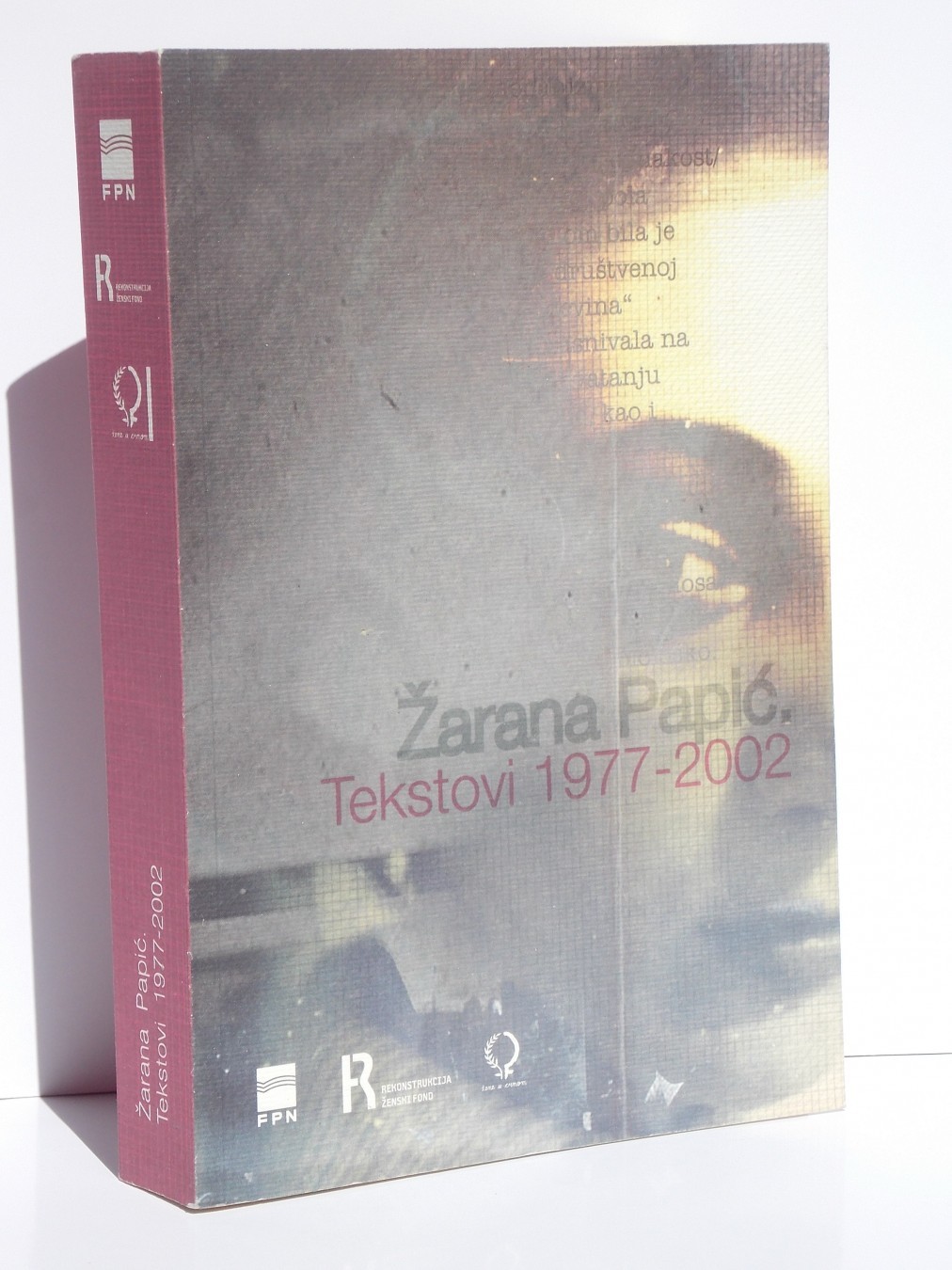

This edited volume of Žarana Papić’s writings between 1977 and 2002 represents the work of Žarana Papić from the start to the end of her research activity. In addition, the editors intended to include a wide range of issues Papić dealt with, as well as how these issues changed throughout the time she worked on them. That is why each text is briefly put into the social and cultural context in which it appeared. This brief introduction can be read as a short summary of her works.

The compilation also includes a complete bibliography of Žarana Papić’s works and two interviews with her. In the bibliography it can be seen that Papić’s texts were published in Serbian, English, German, French, Albanian, Slovak and Norwegian.

This book can be read as a comprehensive chronological representation of Žarana Papić’s theoretical work. It is significant that while reading the selected texts, from the first one in 1972 to the last in 2002, it becomes clear that the texts weave through different histories: the history of feminist movement, history of (Yugoslav/Serbian) sociology and anthropology, and ultimately the history of a fallen political system and its transformation.

Although the context and theoretical interests of Žarana Papić changed, there is a common thread linking all of her texts: the feminist perspective. In this sense this selection can be understood as an attempt to fully present the authentic testimony of a person who was feminist in thought and action and to present the development of feminism in the territory of the former Yugoslavia.

The Jan Hus Educational Foundation's collection presents an extraordinary set of materials documenting the work of a British organisation focusing on the support of the cultural opposition in Czechoslovakia, mainly through the underground university, scholarships, and the publication and translation of forbidden or inaccessible books. The collection was handed over to the Moravian Museum in 2012 after negotiations were made.

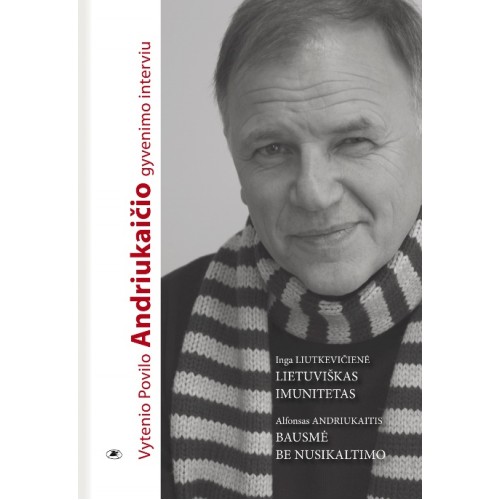

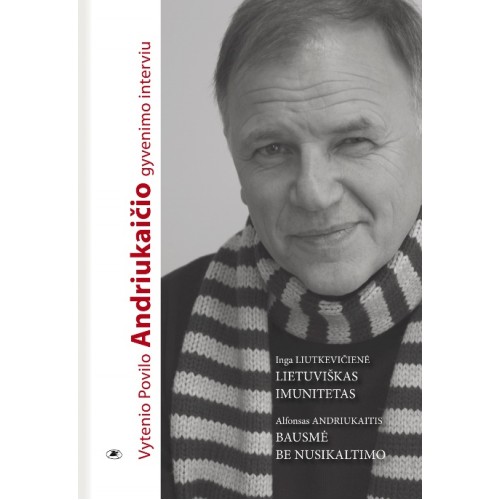

Some interviews with Vytenis Andriukaitis by the journalist Inga Liutkevičienė were published in 2012. The book Lietuviškas Imunitetas. Vytenio Povilo Andriukaičio gyvenimo interviu (Lithuanian Immunity. An Interview about the Life of Vytenis Povilas Andriukaitis) includes interviews about the underground Strazdelis University, and copies and illustrations of documents about it. The whole collection is still not accessible to researchers or society, as it needs to be transferred to institutional (state) archives (Andriukaitis plans to do this in the near future), and making an inventory of the contents of the collection requires a lot of work. Because of this, the book is very useful in understanding the cultural opposition in Lithuania.

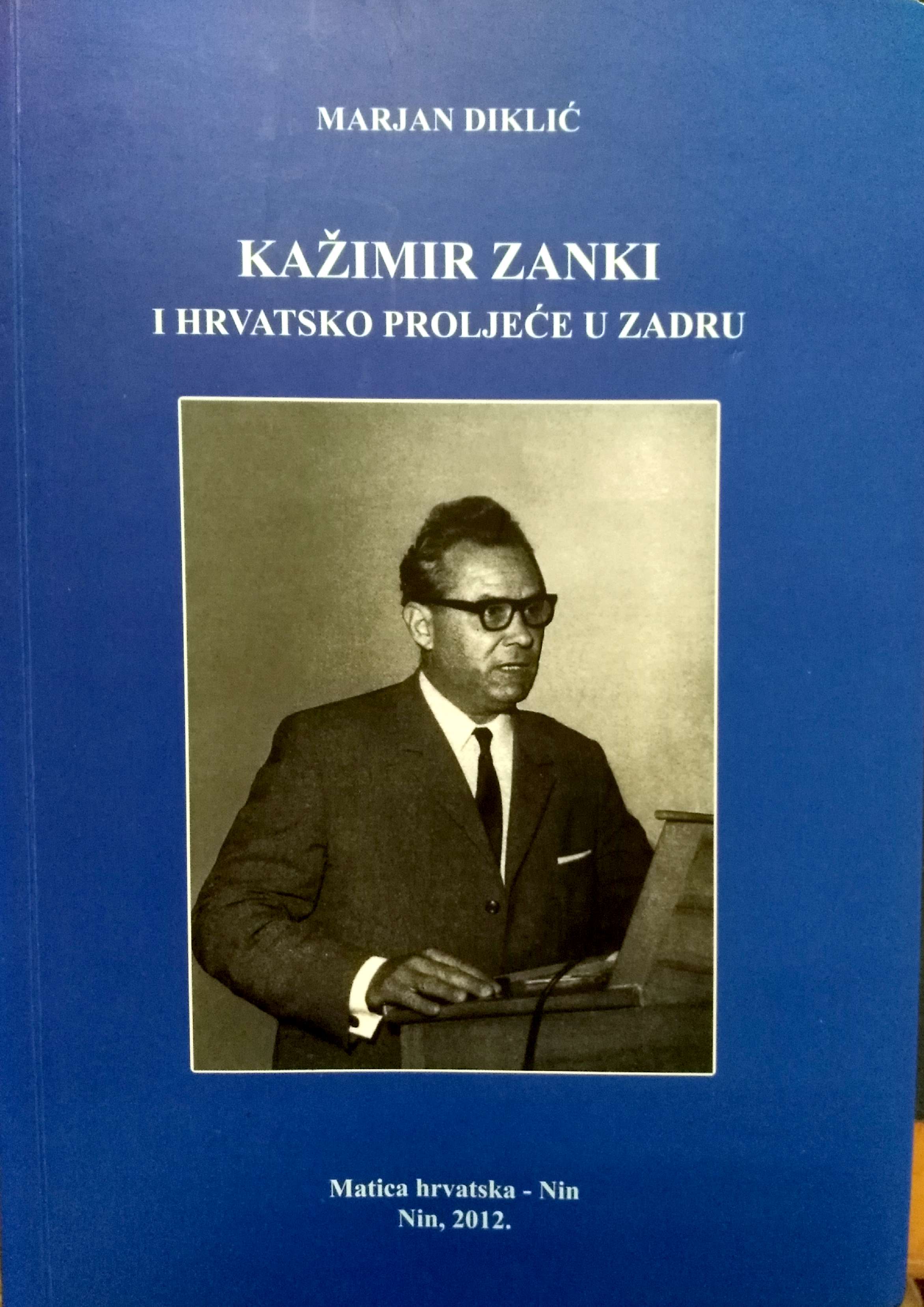

![Publication: Diklić, Marjan. Kažimir Zanki i hrvatsko proljeće u Zadru [Kažimir Zanki and the Croatian Spring in Zadar], 2012. Book](/courage/file/n49091/DIKLI%C4%86-KA%C5%BDIMIR+ZANKI+I+HRVATSKO+PROLJE%C4%86E_1.jpg)

Publication: Diklić, Marjan. Kažimir Zanki i hrvatsko proljeće u Zadru [Kažimir Zanki and the Croatian Spring in Zadar], 2012. Book

Publication: Diklić, Marjan. Kažimir Zanki i hrvatsko proljeće u Zadru [Kažimir Zanki and the Croatian Spring in Zadar], 2012. Book

Marjan Diklić published a book about the Croatian Spring in Zadar in 2012, where "The report of the working group of the Conference of the League of Communists of Croatia - municipality of Zadar" was published for the first time.

The exhibition was organised by CNSAS (Romanian acronym for National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives) at Western University of Timișoara. The event deliberately coincided with the conference 40 Jahre Aktionsgruppe Banat: Akteure und Texte – Mitstreiter und Begleiter (40 years since the creation of Banat Action Group: Actors and texts – supporters and followers), organised by Institute for German Culture and History in South-Eastern Europe (Institut für deutsche Kultur und Geschichte Südosteuropas e.V.), which is affiliated to Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, and Western University of Timișoara. The exhibition displayed old photos of the members of this non-conformist group of Romanian-German writers, manuscripts and publications of the writers of the group, and documents from the surveillance and investigation files issued by the Securitate. The official opening of the exhibition took place on 26 April 2012.

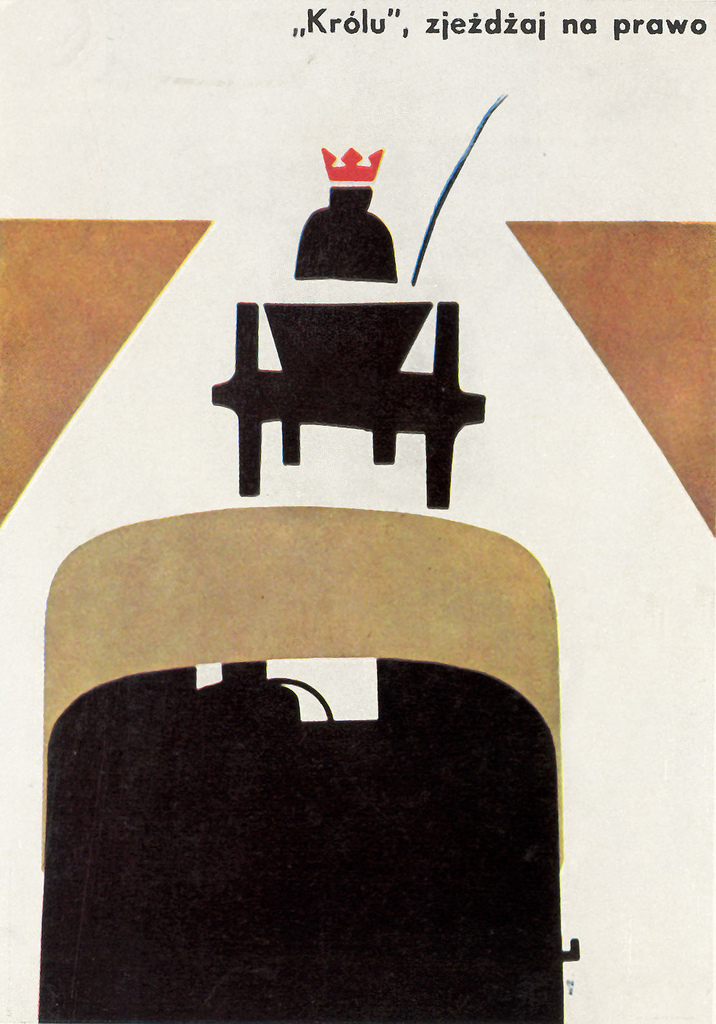

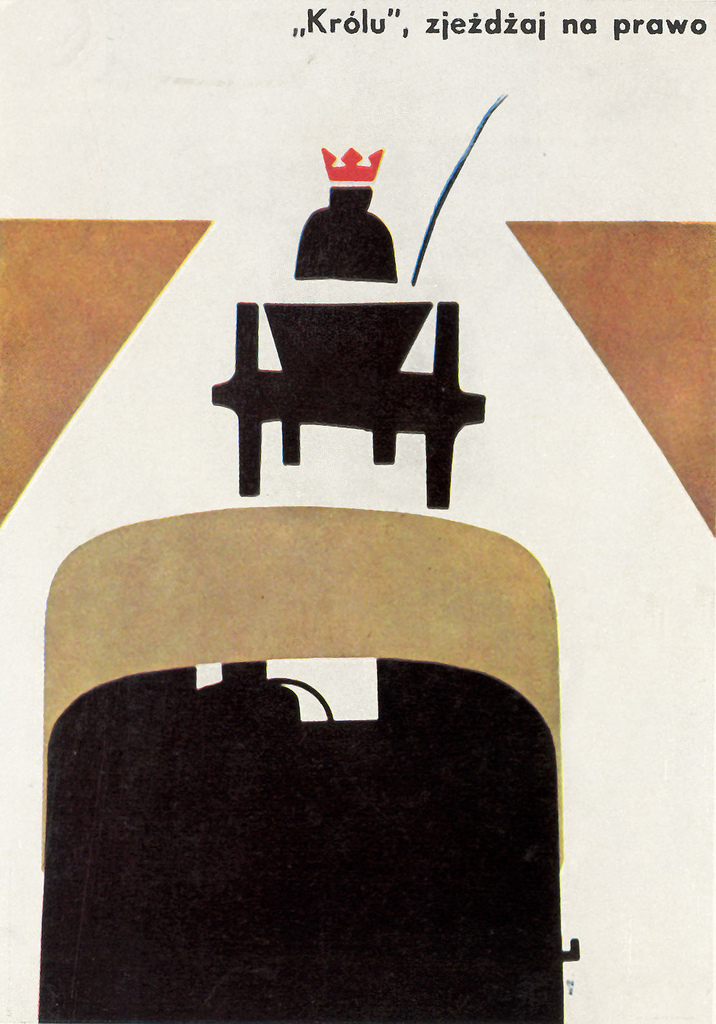

Wojciech Zamecznik's collection represents the early stage of Polish school of poster design. Zamecznik himself has an interesting biography - ex-Auschwitz prisoner, active member of Association of Polish Artists and Designers, who created posters for artistic and political purposes. The collection shows the tension between the official language of socialist posters and private photographs, more intimate and portraying the everyday life.

Karol Radziszewski’s Kisieland is a long-term project that started in 2009. It is a piece documenting encounters of Karol Radziszewski with Ryszard Kisiel. The film is based on Kisiel's private archives and describes the underground queer and avant-garde culture in socialist Poland. It uses different visual representations of queer culture of Polish 1980s. Ryszard Kisiel, a stakeholder of the Queer Archives Institute, took various photographs of queer milieu in dark times of anti-gay campaign "Hiacynth" (1985-86), now Radziszewski stages them as a mean to reconstruct the social history of minority movements, LGBTQ strategies, and artistic avant-garde in martial state Poland.

The masterpiece is one of the founding stones of Polish queer art - it not only shows the roots and genealogies of Polish LGBTQ identity, but also links past experiences with contemporary queer studies' discussion about resistance of minority groups.Kisieland was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw in 2016 to be included in its permanent collection.

Stilinović's retrospective exhibition with the ironic title Zero for Conduct, was held at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb from 30 November 2012 to 3 February 2013. Tihomir Milovac, the curator of the exhibition, came up with the title Zero for Conduct, which refers to the movie of the same name directed by Jean Vigo in the 1930s. Milovac wanted this title to underscore Stilinović's anarchism, the struggle against institutions, and the intractable artistic nature that is strongly present in his work.

The retrospective covers the period from Stilinović's first films in the early 1970s, the early series of photographs of Mayday 1975 to recent photographs such as the Chinese propaganda from 2001. The works from the cycles "Money," "Economy," "Geometry of Cakes,˝ "In Praise of Laziness," "Work is a Disease," and the "Exploitation of the Dead" are presented. The exhibition was well attended by the public, and received good media coverage.

Ferenc Erős’s interview collection includes in-depth interviews with second-generation Holocaust survivors. This project was one of the first which seeks to revive suppressed memories of the Holocaust and the effects of the psychological strategies used to grapple with these memories and the ways in which trauma are transmitted within families.

A three-day conference on the émigré journal The Croatian Review was held in the National and University Library in Zagreb from 13 to 15 December 2012. The occasion was the centenary of the birth of Vinko Nikolić (1912-1997), who was its long-time editor-in-chief. As an accompanying event, there was a small exhibition staged under the title “The Croatian Review 1951-1990” displaying the manuscripts and records from the Vinko Nikolić Papers, which also includes the archive of The Croatian Review and have been held in the Manuscript and Old Book Collection since 1991.

The conference itself had been announced in the media as a very important cultural event, which was co-organised by a number of leading scholarly and cultural institutions such as the Croatian Writers’ Association, Matica hrvatska, the Croatian Language and Literature Department at the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb, the Croatian Institute of History, the Ivo Pilar Institute of Social Sciences, the Croatian Heritage Foundation, and the National and University Library in Zagreb. One of the main goals of the conference was to find an answer to the question about the current attitude toward the valuable diaspora heritage. The main topics of discussion were “Culture and Freedom,” “ A Dialogue with the Homeland,” and “The Diaspora Legacy and Future”.

The participants pointed out that the programme of Croatian Review was visible already in the first issue and was immediately promoted as a “free and independent cultural press” without political preferences (especially totalitarian, because Ante Pavelić’s Ustasha regime had been criticised to the same extent as the Yugoslav communism). The review’s proclaimed mission was to be in service of Croatia and to help the struggle for the state’s independence and cultural unity. These objectives had been achieved when The Croatian Review was brought back to Croatia, which meant the end of the division between the diaspora and homeland literature. However, according to Martina Lončar, who reviewed this conference for Vijenac, the low attendance and numerous cancelled participants convinced the organisers that diaspora literature and heritage had been on the fringe of public interest and that the attitude toward this type of literary heritage had been extremely “superficial and commemorative”. Younger scholars and students were called upon to deal more with the literary achievements of The Croatian Review and of Vinko Nikolić’s “émigré pen .”

Source: Martina Lončar, "Zaboravljena hrvatska književnost", Vijenac, no. 492 (2012). http://www.matica.hr/vijenac/492/zaboravljena-hrvatska-knjizevnost-21589/ (accessed on 8 July 2017)

Since 2012, in cooperation with Artyčok.tv, the Academic Research Center of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (VVP AVU) has released a "Window to the Video Archive" programme with works from the VVP AVU Video Archive. Thus, many videos (video art, films and documentaries) from the Video Archive are accessible online. Material in the section "Window to the Video Archive" presents older works (material dating back to the end of the 20th century), works on the border of video art, film and document, as well as documentary material related to the recent development of Czech and Slovak fine art.Artyčok TV is an online platform for contemporary art, monitoring and co-creating art scene events and related cultural activities. Artyčok TV was created in 2005 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. It’s database of audiovisual material includes exhibitions reports, profiles, and lectures by theorists and artists. The content of Artyčok TV is developer mainly by artists, curators and theoreticians.

A notable event in the history of the Michael Shafir Collection was its donation to the Octavian Goga Cluj County Library, which made this private collection available to a wider public. When Michael Shafir returned to Romania in 2005, he transferred his collection to the Faculty of European Studies of Babeş-Bolyai University, where he was teaching. When he retired, he also removed his collection, in the hope of finding a more appropriate storage space for it After Shafir talked in an interview about his efforts to find a hosting institution for his collection, the head of the Octavian Goga Cluj County Library persuaded him in 2012 to sign a deed of donation. He did not hand his collection over with an index and the collection remains unarchived to this day.

![Velikonja, Nataša and Tatjana Greif. 2012. Lezbična sekcija LL: kronologija 1987-2012 s predzgodovino [Lesbian Section LL: A Chronology 1987-2012]. Ljubljana: ŠKUC.](/courage/file/n23806/LL+25_kronologija.jpg)

Publication: Lezbična sekcija LL: kronologija 1987-2012 s predzgodovino (Lesbian Section LL: A Chronology 1987-2012), 2012. Book

Publication: Lezbična sekcija LL: kronologija 1987-2012 s predzgodovino (Lesbian Section LL: A Chronology 1987-2012), 2012. Book

As a way of commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Lesbian Section ŠKUC LL, Tatjana Greif and Nataša Velikonja co-authored an almost 400-page volume that traces the history of not only ŠKUC LL, but also of lesbian culture, art and the movement in Slovenia in general. The chapter “Lesbians Before the Lesbian Movement” (“Lezbištvo pred lezbičnim gibanjem”) gathers in one place all knowledge available about the lives and work of women who engaged in sexual and/or emotional relationships with other women (mostly prominent intellectuals and artists), from the late 19th century up to the emergence of the lesbian and gay movement in 1984. Also described are the circumstances and some of the situations homosexuals and lesbians faced during socialism, especially at the time when same-sex relations were criminalized in the Criminal Code of Yugoslavia. Furthermore, the book delves in great detail into the 1980s gay and lesbian social life in Slovenia, focusing on the social climate and cultural events that created the conditions for the first gay film festival in socialist Europe that took place in Ljubljana in 1984. The book also recounts the circumstances surrounding the cancellation of the fourth gay film festival, when the authorities exerted pressure on the organizers. The organizers interpreted this pressure and the media attacks to which they were subjected as a direct ban. This event, along with intensive networking with other democratic and civil groups, greatly contributed to the politicization of the emerging LGBT movement and the gradual shift it made from the cultural to the activist sphere (Velikonja and Greif 2012, 73-74). The central and the longest part of the volume chronologically maps ŠKUC LL's activities and development in the period 1987-2012. While researching and writing, Grief and Velikonja heavily relied on archival materials from the Lesbian Library and Archive, reprinting many illustrations and photographs from the collection in the volume itself.

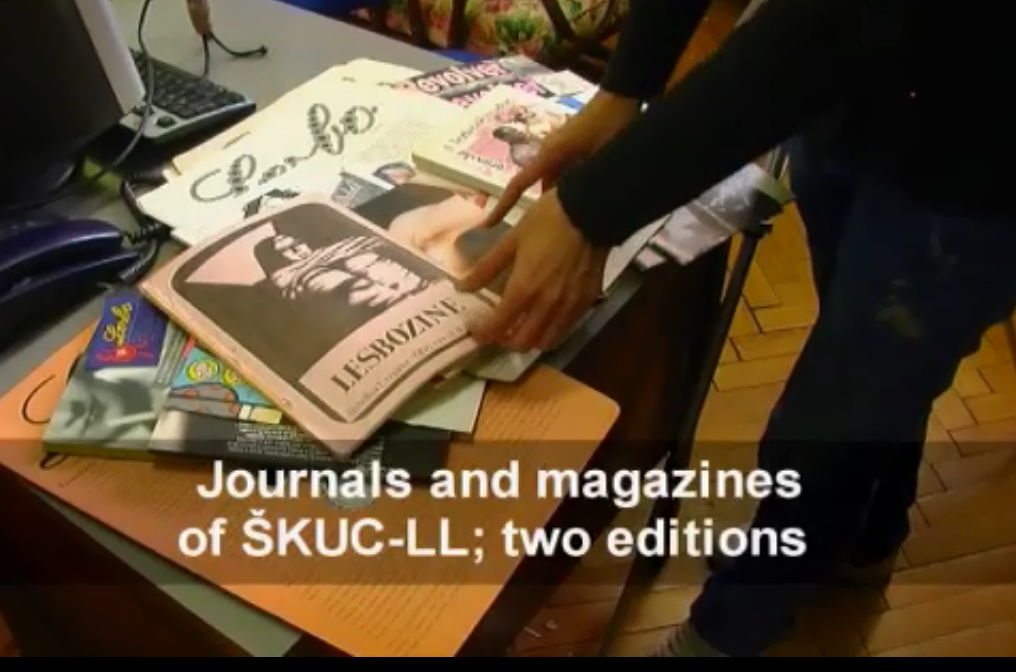

The documentary film Relations. 25 years of the lesbian group ŠKUC-LL (Razmerja. 25 let lezbične sekcije ŠKUC-LL, Ljubljana, 2012, 84 min) was released on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the lesbian organization ŠKUC LL to mark a quarter of a century of the lesbian movement in Slovenia. Through private recollections, interviews and a wealth of documentary video materials, the film Relations traces the history of ŠKUC LL since its foundation until 2012. The film features prominent Slovenian activists and feminists who directly participated in Lesbian Section first public activities in the 1980s, such as Suzana Tratnik, Natasa Sukič, Mojca Dobnikar, Natasa Velikonja and Tatjana Greif. The first part of the film is focused on the lesbian and gay movement that emerged in the 1980s in the Yugoslav socialist context. Media and video materials from Lesbian Library and Archive were extensively used in the film, i.e., the cover of Lesbosine magazine in 1988.

The author and director, Marina Gržinić, a Slovenian philosopher and visual artist, together with co-authors Aina Šmid and Zvonka T Simčič, described Relations on the promotional webpage as follows: “The film presents a variety of processes of marginalization and the struggle for rights by the lesbian and LGBT community in Slovenia and beyond in the former Yugoslavia. It is a struggle for visibility, but also a testimony to the incredible power of the lesbian movement, its artistic and cultural potential, critical discourses and emancipatory politics. The film consists of interviews, documents, art projects, nightlife, political appearances, and critical discourse. The film also talks about Europe, global world capitalism and the status of lesbians today.” (http://grzinic-smid.si/?p=276).

Authors and directors: Marina Gržinić, Aina Šmid, Zvonka T Simčič.

“Academy of Movement. City – field of action” was an exhibition which presented film and visual documentation of the Academy of Movement alternative theatre in the city space, from 1975 to 2011. The event was curated by Wojciech Krukowski, director of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art (1990-2009) and founder of the Academy of Movement. The core part of the exhibition were 16 mm films from hidden camera showing partisan actions of the Academy of Movement in the city space in the 70s and 80s, as well as over 200 photographs from this period.

Donation of the Lovinescu–Ierunca Collection to the Central National Historical Archives in Bucharest

Donation of the Lovinescu–Ierunca Collection to the Central National Historical Archives in Bucharest

Already in the 1990s, Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca decided to donate their impressive collection in Paris to the Romanian state. In 1998 they named as the executors of their will Gabriel Liiceanu and Mihnea Berindei, who were thus entrusted with bringing the collection (composed of books, documents, and vinyl records) to Romania (Lovinescu 2010, 477). After the death of its owners and creators, the collection was divided between Gabriel Liiceanu and Mihnea Berindei. According to the archivists who organised the collection, Claudiu-Victor Turcitu and Laura Ristea, at the beginning of 2012 Mihnea Berindei decided to donate his part to the National Archives of Romania in Bucharest. Besides the 4.2 linear metres of manuscripts, memoirs, and press clippings, Berindei also donated 5.00 linear metres of books, collections of newspapers, and magazines, which were included as part of the library of the Central National Historical Archives in Bucharest. Since 2015, the Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca collection has been open for research at National Central Archives in Bucharest.

Drita (Luri) Vukshinaj was born in Prizren on 10 March, 1954. She graduated from the Technical High School and worked as a floor manager at Progres, a synthetic fiber factory in Prizren. Coming from a non-openly political family, Vukshinaj is a great example to illustrate women’s voices. After injuring her leg at six-years old, there were no options offered to her in Kosovo at the time (1960) except for amputation. Her father, not wanting two women to travel alone, would not allow his wife to accompany Vukshinaj to Skopje to receive better care. When Vukshinaj turned thirteen, and found a treatment option in Belgrade, her father refused to allow her to stay alone at the Belgrade hospital for an extended period of time. When she threatened to jump from the second-floor window, he relented. She managed to receive treatment from a hospital in Belgrade on her own, where she remained for a year despite her father’s hesitations, to be able to improve her walking. Vukshinaj’s father’s fear had less to do with ethnic hostility than with his perception of women as property, who were not permitted to leave the house without an escort. For many adult women in Kosovo, it would have been enough to marry and have children. Though Vukshinaj did these things (She married Akik Vukshinaj, a former political prisoner and engineer, and had three daughters: Fjolla, Filloreta and Sheki), she also became a strong advocate for people with disabilities by working to mobilize patients and provide resources. With her NGO for people with disabilities in Kosovo, Drita Vukshinaj became a lifelong women’s rights and disability rights activist. Drita Vukshinaj died on 9 March, 2016. KOHI interviewed Drita Vukshinaj on 27 July, 2012. The audio file is available in Albanian as well as the transcripts, which is also translated into English and Serbian. In this extract from the English translation of the transcript, Drita remembers her activist work for the disabled:

“I started working with women when I saw in the daily newspaper Rilindja, I think it was in 1994, that a Handikos office for people with disabilities had been opened in Prizren…I found out from the paper where the office was, and went there on my own. [...] At that time, there were 200 disabled persons registered as members. Very few of them were women; they were mostly men. Until after the war, after 1999, we had some activities, such as helping poor women — especially women in villages. We identified where this category of people lived.

In 1999, the office reopened and resumed its work, and so more humanitarian aid began to arrive after the war. At that time, it was a great surprise that […] all these disabled people suddenly appeared. I was one of those who went out day and night. I was out every day. I went out of town, everywhere, but I had never seen those people before. However, because of the humanitarian aid, people began to declare themselves disabled. We had personal contact with them, but I preferred to be with the women. I talked to them, maybe they were of different ages, 40, 50, 60 [sic] years old, and they were from the city, but I had not known or seen them before, and they said that their families did not let them go out of the house and into society. This motivated me to do even more for this group of people. We started registering them throughout the entire Municipality of Prizren, which had a total of 78 villages. Sometimes it happened that we would go to a house and a woman with disabilities lived right next door, but the family living next to her did not know it. So we would not find out unless the other family accepted us into their home. This was one of the greater difficulties that we had. It happened sometimes that we visited a place several times until we convinced the families that these women need to be out in society, needed to be integrated, needed to gain some skills.”