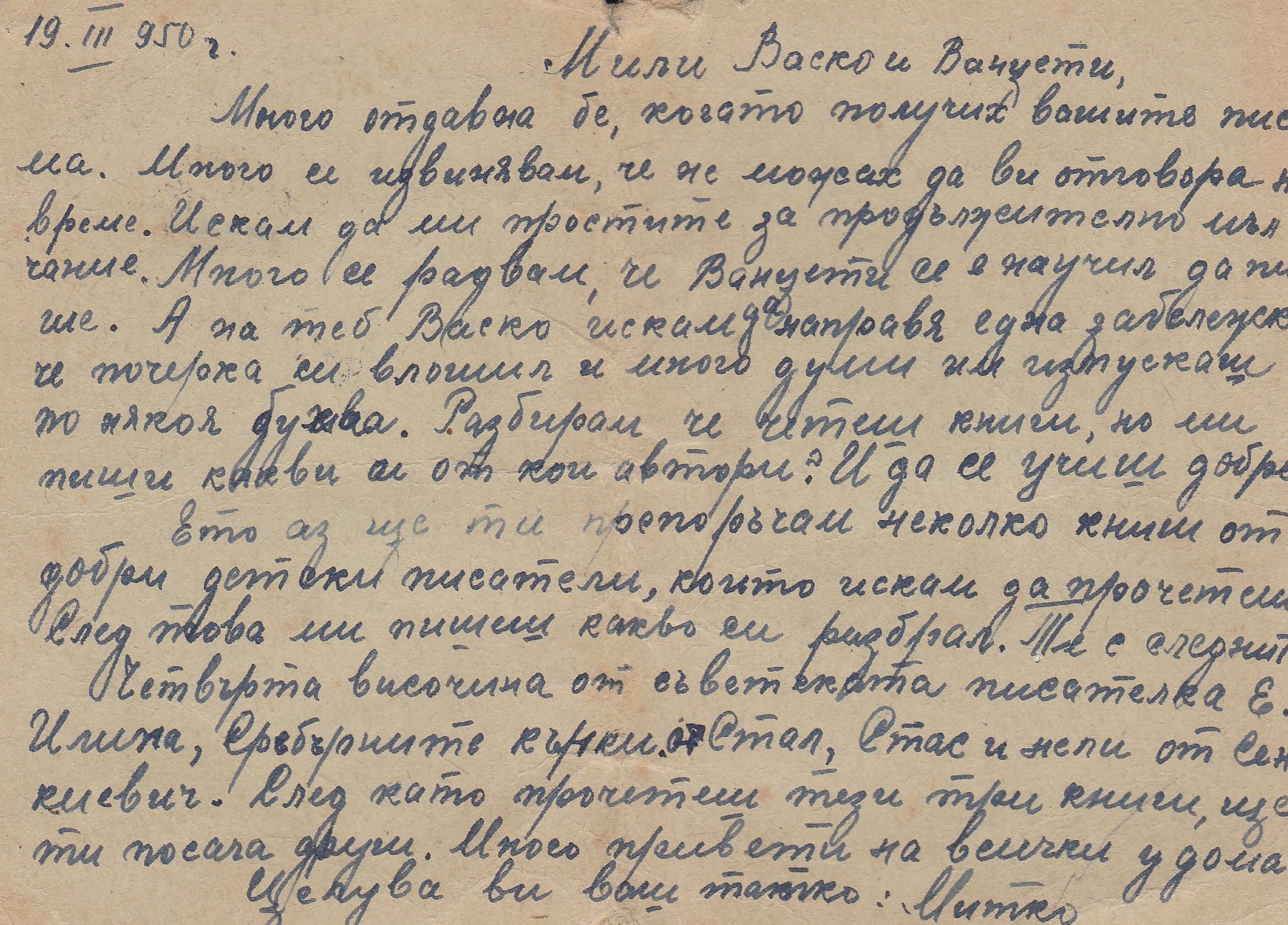

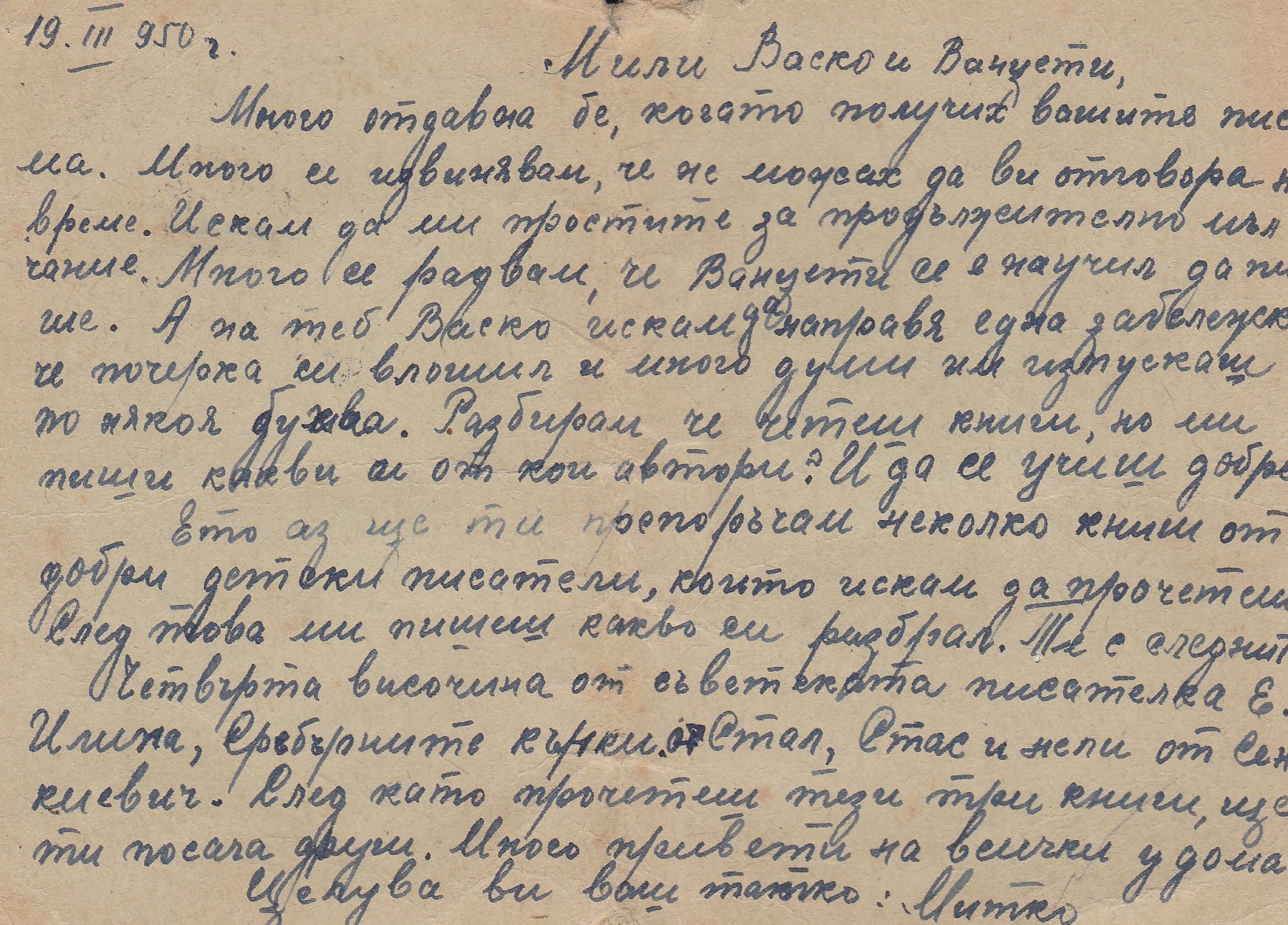

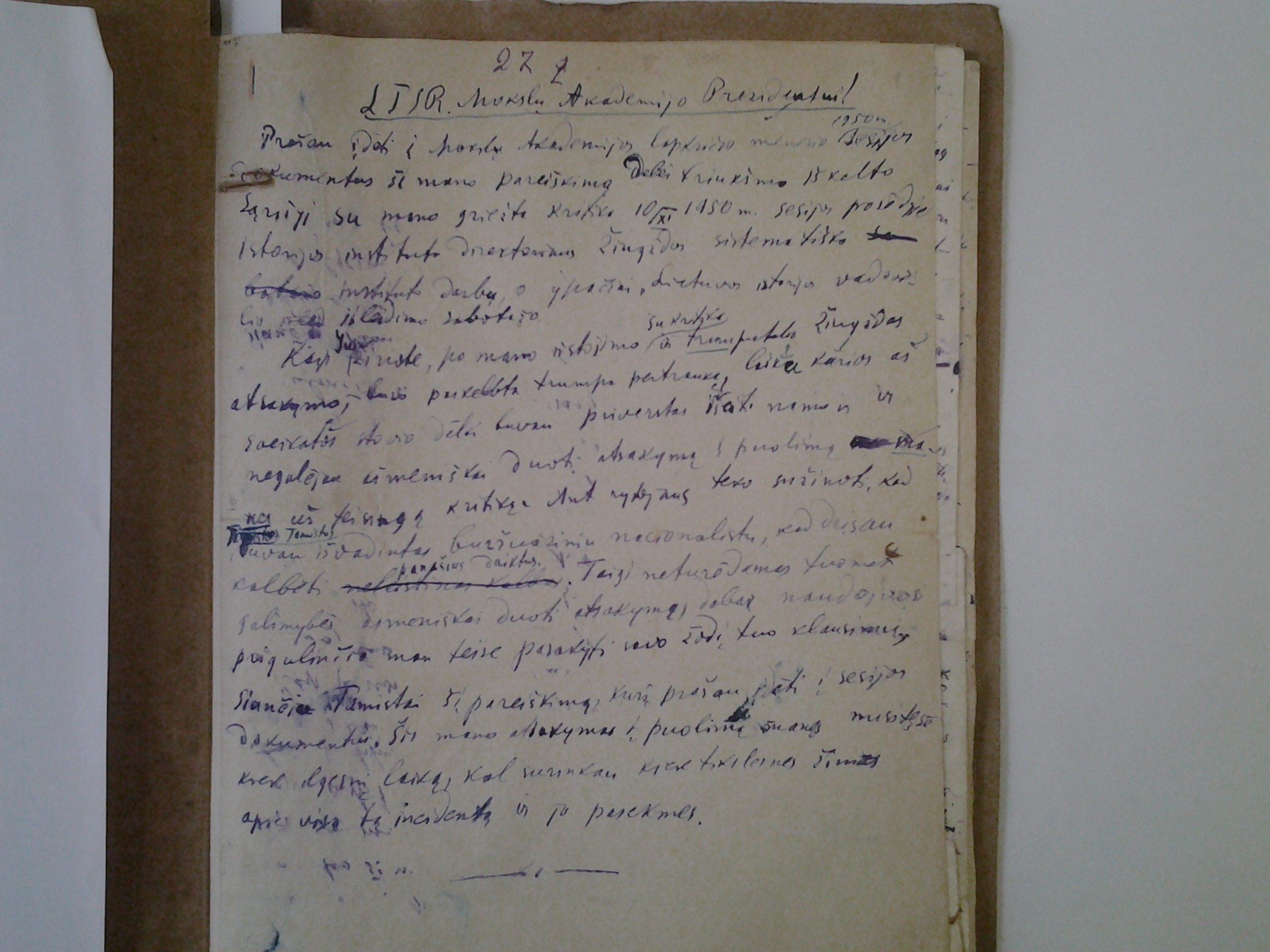

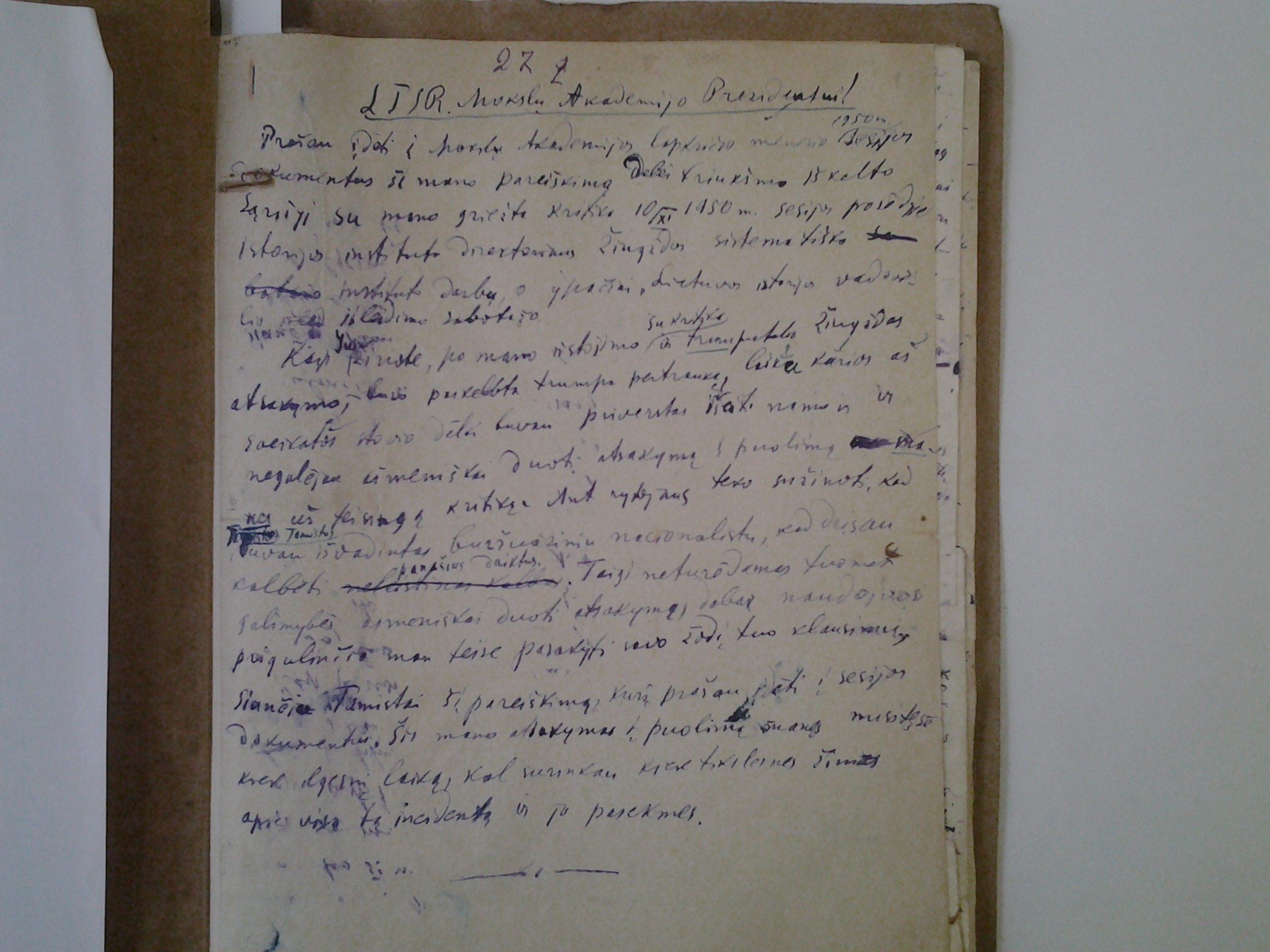

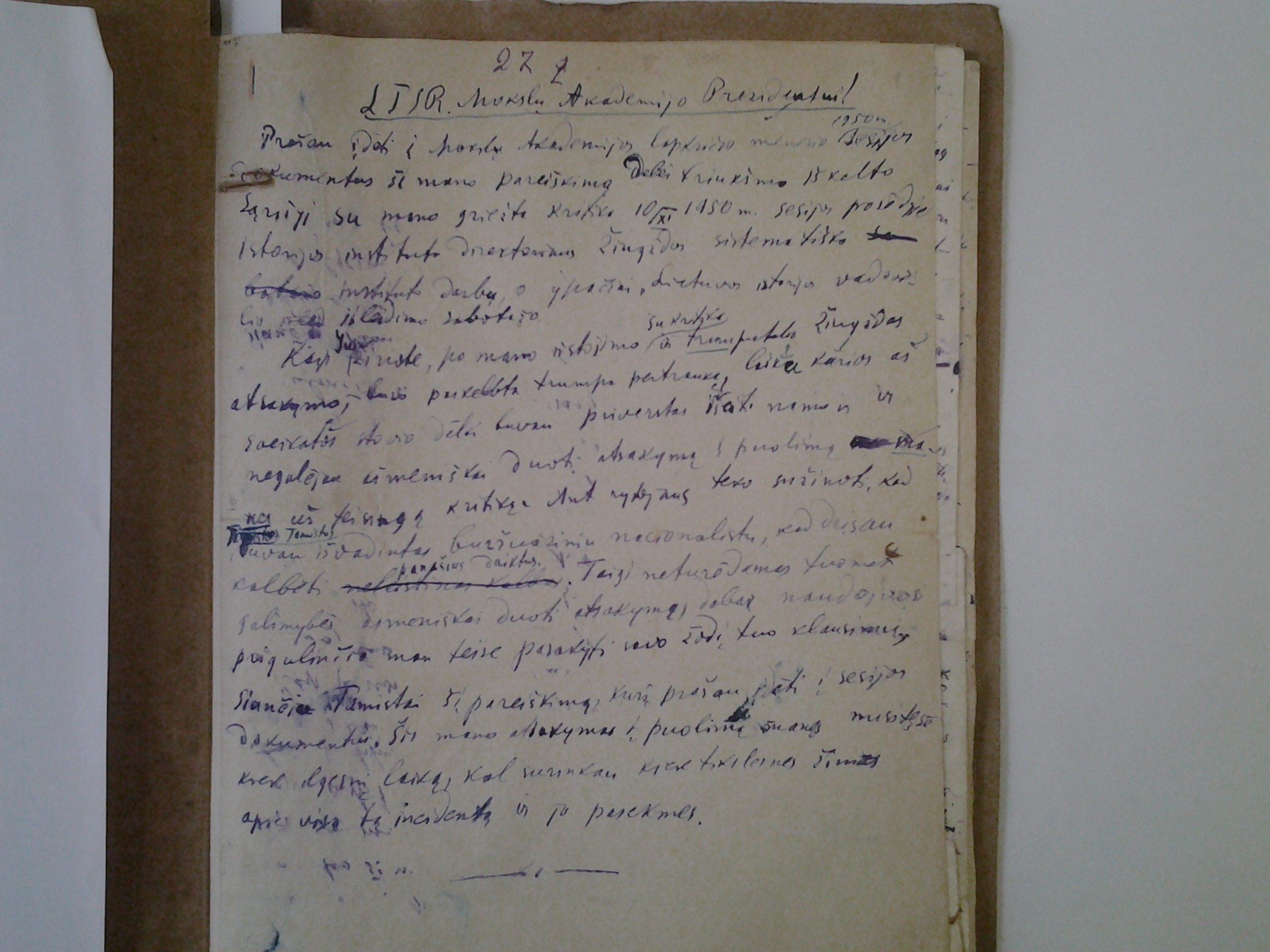

The handwritten letter from Matulaitis to the Academy of Sciences. In the letter, he criticises the Academy and the Institute of History. The letter (written in 1950) reflects very well the situation of Lithuanian historians during the late Stalinist period. Matulaitis, who spoke out about the need to research the history of the Lithuanian nation, came under pressure, was accused of ‘bourgeois nationalism’, and was dismissed from his job.

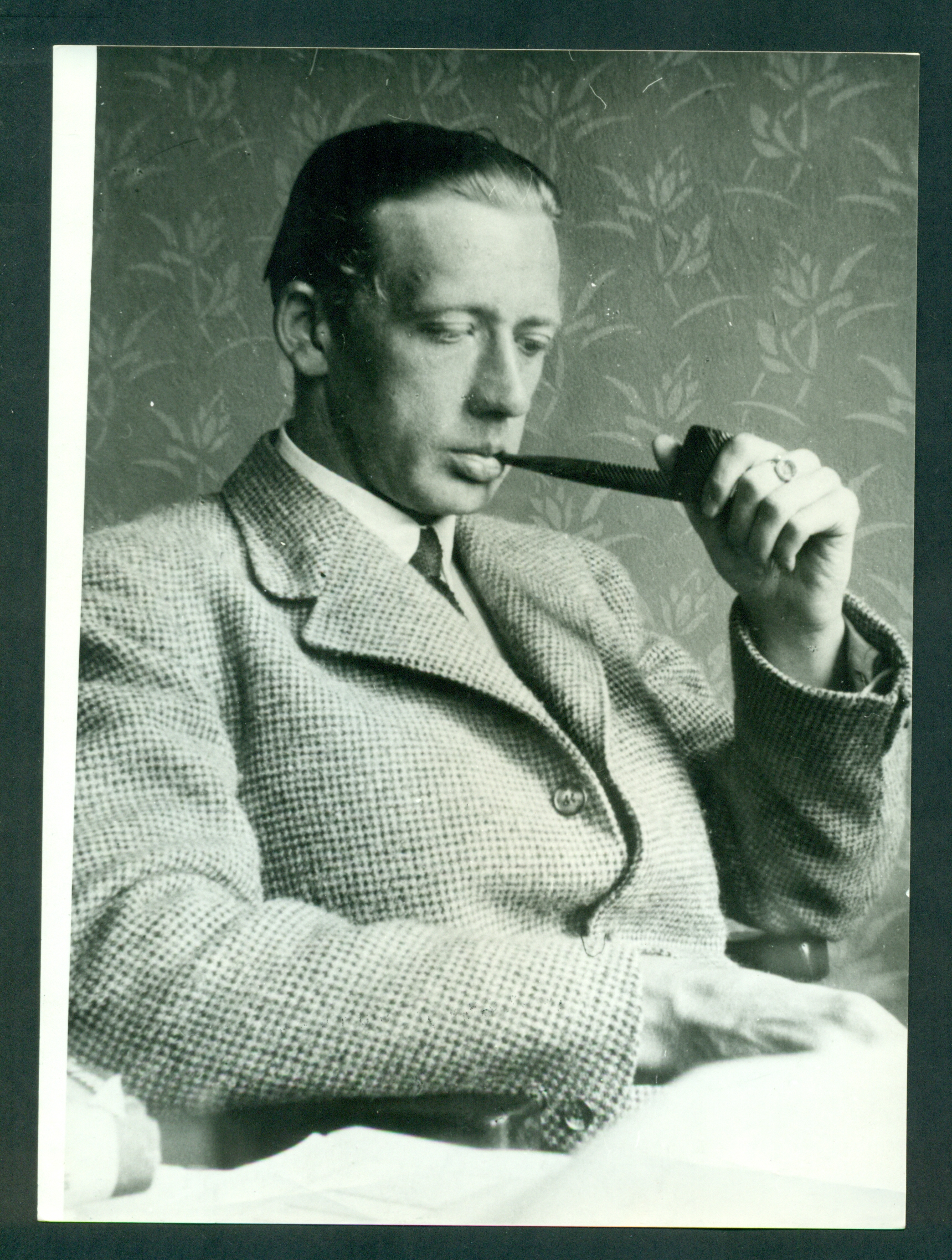

Milan Šimečka (1930-1990) was a Czech and Slovak philosopher, essayist and publicist. He was one of the prominent personalities of the Czechoslovak opposition from 1968. He published in samizdat and exile, and for this he was detained illegally for a year. The collection contains mainly texts and correspondence.

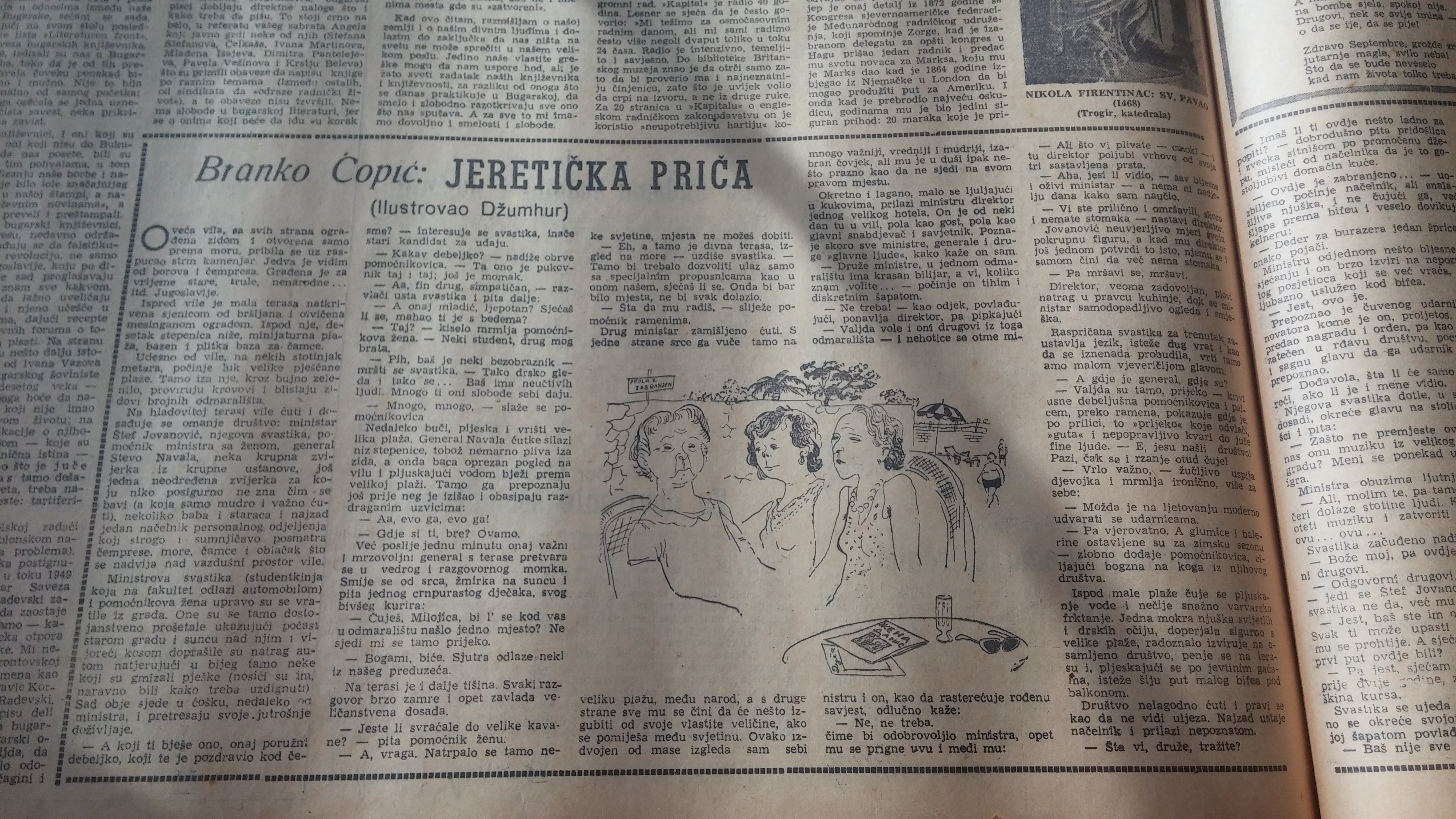

On 22 August 1950, ‘Književne novine’ published a story by Yugoslav writer Branko Ćopić, entitled ‘Jeretičke priče’ [Heretical Tales]. As the title alone suggests, the heresy was to touch on the communist model of government, even through satire. Ćopić targeted his criticism at privileges and the Soviet model of society, which although publicly renounced by the Yugoslav party two years previously, he continued to observe in Yugoslav practice. In the story, which traces a summer day in the life of the privileged ruling class, one criticism follows on the heels of the other: a girl student (a minister’s sister-in-law) drives to the faculty by car, while the deputy minister fantasizes about how marriage could land him a minister’s post and later the job of prime minister. Alongside all of this, the appearance of other figures in the story was also problematic, such as a general and an important personality of whom little is known ‘because he wisely and importantly keeps his silence’, as well as others (R. Petković, 2000, Sudanije Branku Ćopiću [The Show Trial on Branko Ćopić], p. 12–13).

Such a portrayal of Yugoslav society was sufficient to provoke a scandal. Immediately after its publication, a smear campaign was unleashed against Ćopić. The famous writer Skender Kulenović, a good friend of Ćopić’s, accused him of ‘abusing free expression’ in the very next issue of ‘Književne novine’. Others alleged that he was a ‘bourgeois critic’ and was discrediting ‘the tendency of development of our socialist society’ (R. Petković, 2000, p. 20). Thus a wave of criticism was released, culminating in a public declaration by Tito – uncharacteristic for all later cases of the repression of artistic creation in Yugoslavia. At the Third Congress of the Women’s Anti-fascist Front on 29 October 1950, he declared, ‘And what does it mean, when people from a minister, a general and a deputy minister to a shock worker are put into a satire, when it, so to speak, encompasses our whole state leadership and economy. He has taken the whole of society and depicted it from top to bottom as negative (…). We will not permit such a satire and leave it without response. He need not be afraid that we will arrest him for what he has attempted to do. No, we must publicly answer and say once and for all that hostile satire that intends to shatter unity cannot be tolerated among us’ (R. Petković, 2000, p. 23).

Ćopić’s literary legacy, which is kept at SANU, includes the Pismo Veljku [Letter to Veljko] in which Ćopić writes about this case. While he acknowledges that he may have exaggerated in some places, since he wrote the story in a hurry, he considers his course as ‘honourable’ and ‘worthy of a true writer’, and is ‘not ashamed of having taken the path of satire’ (R. Petković, 2000, p. 28). According to a leading Serbian historian, ‘This whole case is significant for the researcher. It illustrates the contradictory nature of the Yugoslav regime with regard to the issue of repression and civil freedom. The existence of informers and their everyday activity is in itself a sign of repression. But on the other hand, the non-existence of serious punishment is an indication of liberalization’ (P. Marković, 1996, Beograd između istoka i zapada [Belgrade between East and West] 1948–1965, p. 178).

Precisely Ćopić is a good example of the dual nature of the Yugoslav system. Thanks to his undoubted revolutionary merit, he succeeded in avoiding more serious repercussions in relation to his personal integrity and writing, though he continued to critically view Yugoslav society through the medium of satire in the following decades.

Invitation card to the Pál Teleki commemorial Celebration organized by the HSAE, Landshut, Austria 2nd April 1950

Invitation card to the Pál Teleki commemorial Celebration organized by the HSAE, Landshut, Austria 2nd April 1950

Invitation poster to the Pál Teleki Commemorative Celebration organized by the HSAE in Landshut, Austria, on April 2, 1950.

The Hungarian émigré scouting movement from its very start expressed high regard for the conservative prime minister Count Pál Teleki, who served as an “honorary scout chief” in the interwar period and was considered a charismatic leader of the Hungarian scouting movement. Teleki’s suicide in April 1941 was regarded as the martyrdom of a great Hungarian patriot and was in fact a desperate protest against Hungary's shameful attack of Yugoslavia as a German ally. Both Catholic and Protestant Church ceremonies commemorated the anniversary of Teleki’s death. In 1947, before the HSAE could gain its full legitimacy as a national scouting association, the émigré scouting movement was named after Count Teleki as was one of the first Hungarian scout troops.

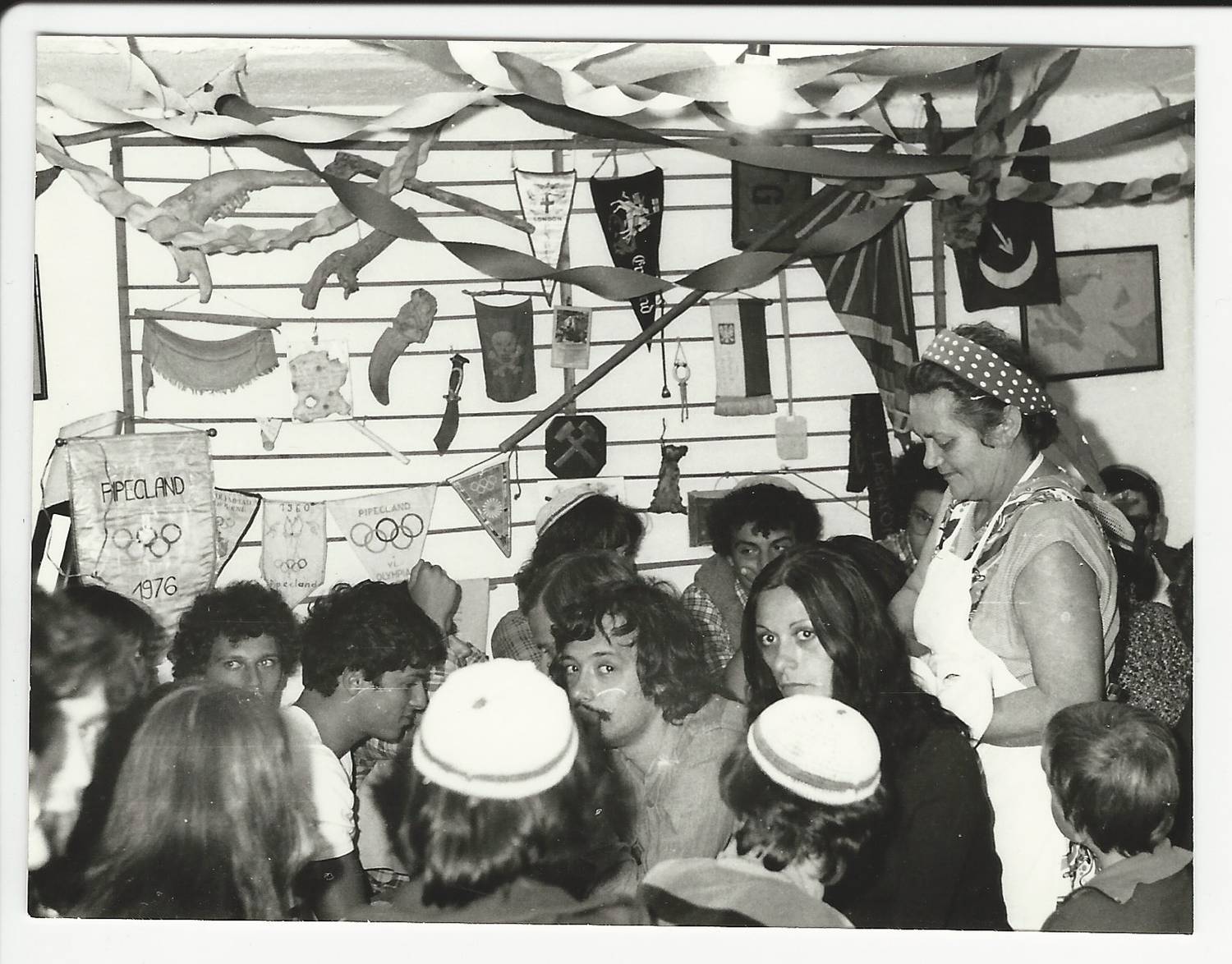

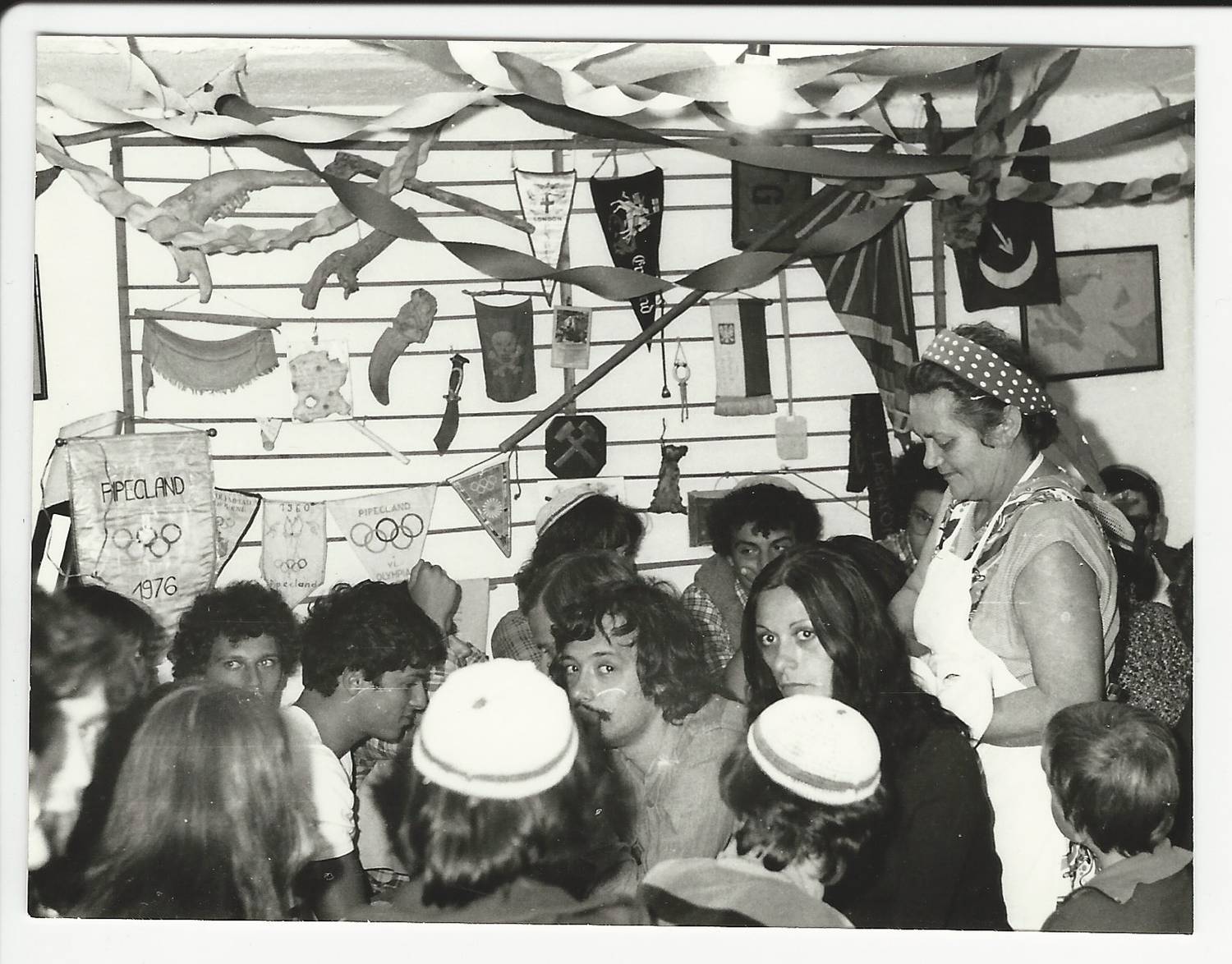

The totem wall was in a strict sense one of the most iconic objects of Bánk. Originally, it served as a clipboard, then gradually it became the totem wall, bearing various kinds of items (used during games) related to important or memorable events. The totem wall also functioned as a reminder by making the past visible to the participants. Initially, the display changed year to year (some of the items were lost), but after a while, it became an untouchable and stable object.

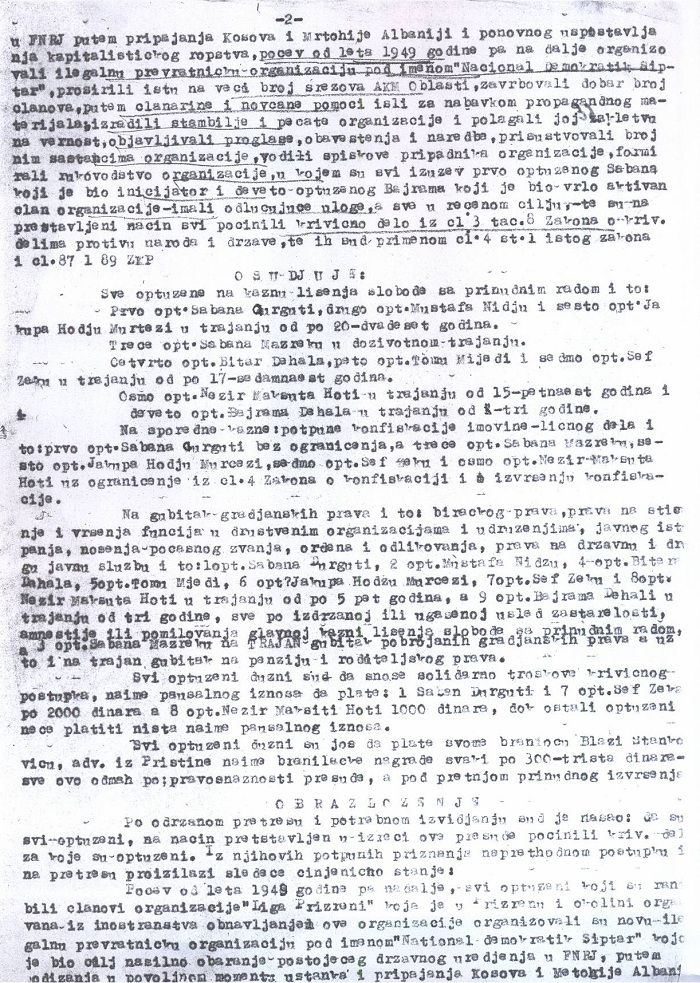

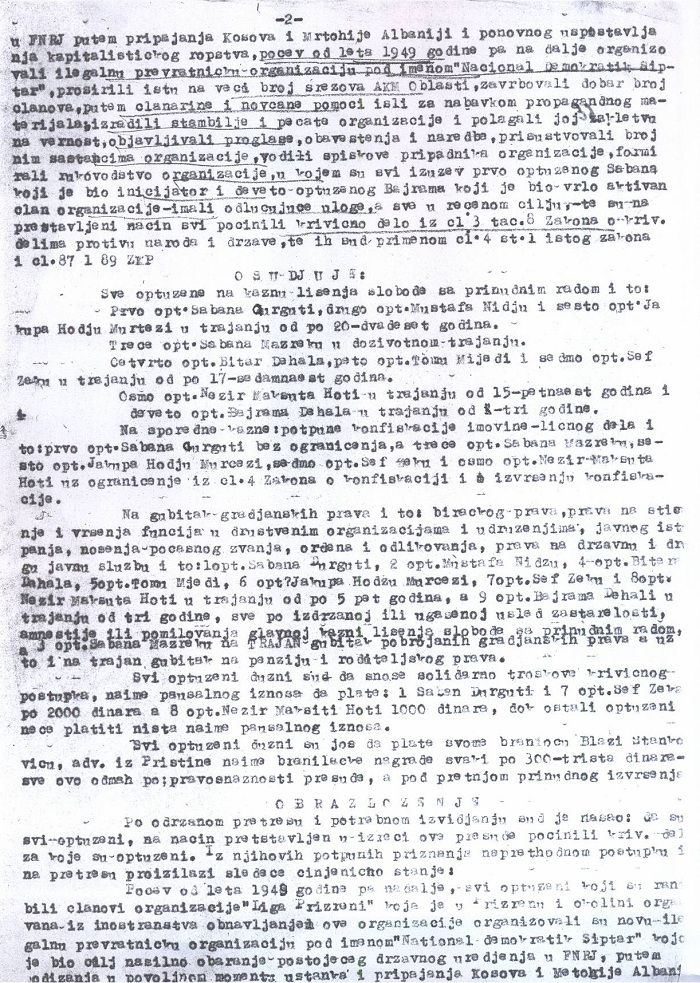

Čengić, Aziz. National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence, 1950. Article

Čengić, Aziz. National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence, 1950. Article

In the issue from 15 December 1950, the Croatian expatriate magazine Hrvatski dom published the article “Nacionalna politika Komunističke partije Jugoslavije u svijetlu borbe hrvatskog naroda za samostalnost” [National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence] by émigré Adil Zulfikarpašić, written under the pseudonym Aziz Čengić. Zulfikarpašić was a friend of Augustin Juretić and his associate until Juretić's death in 1954. It was Zulfikarpašić, together with Msgr. Pavao Jesih, who took over the magazine Hrvatski dom after Juretić’s death. The two of them edited the magazine until the last issue in October 1958.

In the article, Zulfikarpašić (Čengić) described the development of the national policies of the CPY since its establishment after World War I until after World War II, and concluded that "the theory of free nations of Yugoslavia, even with the constitutional right to secession from the union, is a façade – in reality it is rigid centralism carried out from Belgrade through the Central Committee of the CPY (Hrvatski dom, 15 December 1950, 2-3). Zulfikarpašić published a similar article, "Political report on the situation in Yugoslavia," in the newspaper Hrvaska riječ a month later (No 1-2, January-February, 1951). Similar analytical articles dealing with the issues of communist ideology and criticism of the communist government in Yugoslavia were published in Hrvatski dom continually in an attempt to influence the attitude of Western countries and their public opinion of Tito's Yugoslavia.

The manuscript of the article " National policies of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the light of the Croatian people's struggle for independence " is held in the Augustin Juretić Collection at the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome. The collection also contains a printed version of the article published in Hrvatski dom.

Request for instructions on the screening of Soviet movies in Croatian cinemas. 11 December 1950. Archival document

Request for instructions on the screening of Soviet movies in Croatian cinemas. 11 December 1950. Archival document

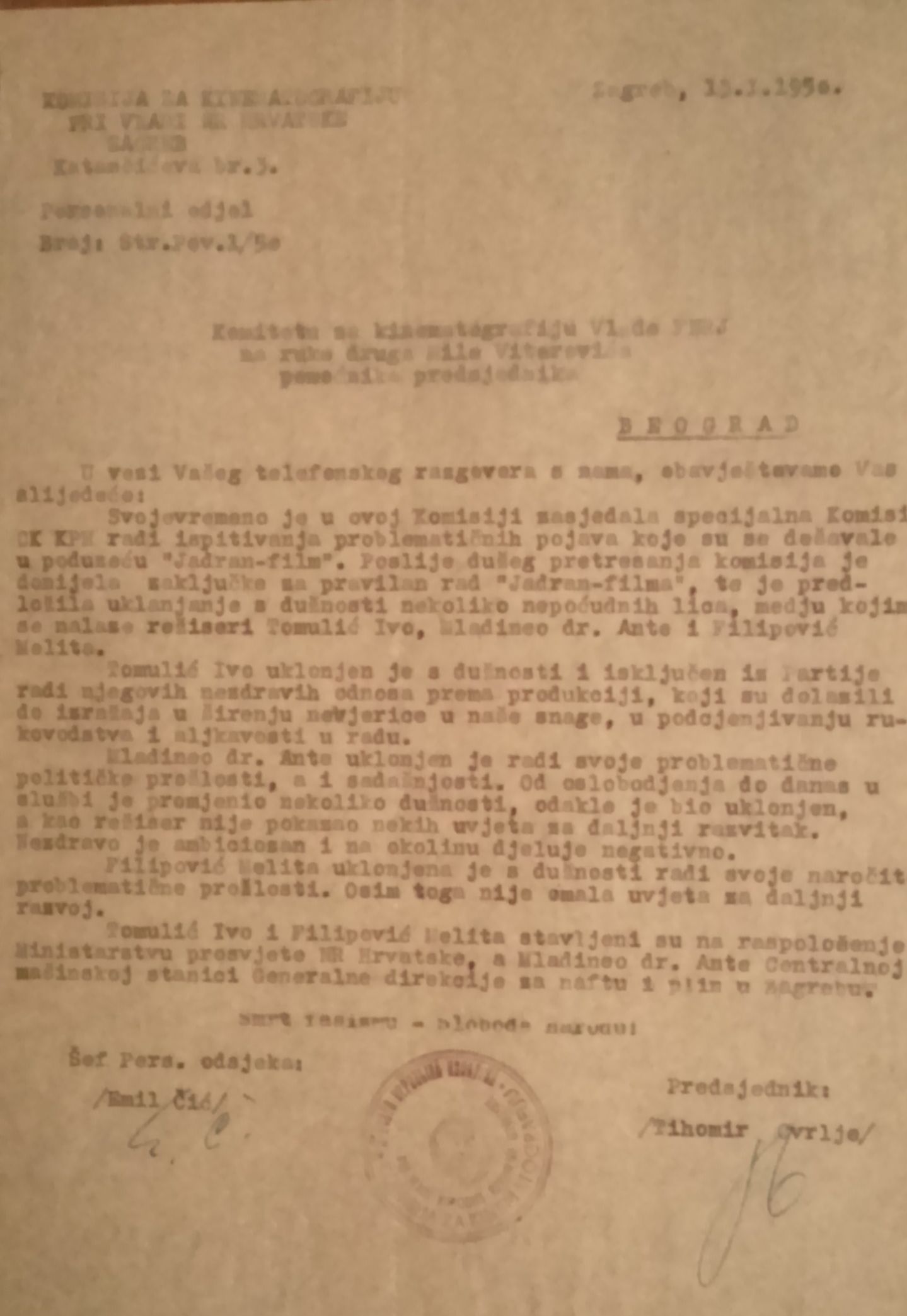

Correspondence between Cinematography Commission of the Government of the People’s Republic of Croatia (PRC) and Cinematography Commission of the Government of Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY) in December 1950 on the screening of Soviet movies in Croatian cinemas, illustrates the control by the Communist Party and state authorities over the import and distribution of films for screening in cinemas, as well as subordination of film repertoires to political and ideological needs.

Films produced in communist Yugoslavia until 1948 were based on the principle of socialist realism inspired by the USSR. The entire film industry developed under the ideological principles which directed the newly established state towards Marxist and socialist cinematography (Lučić 2015, p. 23). Accordingly, cinema repertoires were dominated by films from the USSR, while the influence of movies from Western countries, which were also screened, remained slight. After the Tito-Stalin Split (Yugoslav-Soviet Split) in 1948, Soviet movies stayed on cinema repertoires across Yugoslavia, but with increasing competition from Western, especially American movies (Lučić 2015, p. 71).

In a specific case, the Cinematography Commission informed Cinematography Commission of the Government of the FPRY of findings that film audiences were “protesting against the screening of particular Soviet films,” and that “a certain confusion” was caused by some scenes in domestic documentaries in which photographs of Stalin could be seen. While these film were “approved by the censors, but audiences were protesting against Soviet films,” the Cinematography Commission asked for urgent instructions as to whether it should any Soviet films should be removed from the cinema repertoire, and if so, which ones (HR-HDA-309. CC of the Government of PRC, file st. conf. 32/1950).

Written account of Mērija Grīnberga to the State Control Ministry about circumstances of her firing from the Museum

Written account of Mērija Grīnberga to the State Control Ministry about circumstances of her firing from the Museum

After her return from Czechoslovakia on 10 February 1946, Mērija Grīnberga had to submit several accounts of her journey to the authorities. After she was forced to leave her position as acting head of the Ethnography Department of the Historical Museum, she had to submit an explanation to the Ministry of State Control of the Latvian SSR as to why she did not hand over the collections of the department to her successor, according to the rules. Although Mērija Grīnberga was born in St Petersburg and her spoken Russian was good, her written Russian was a little clumsy, but the draft is written very expressively, and describes in detail the attitude of the museum administration towards the museum collections and her personally. The drafts of the accounts written by Mērija are also interesting because they show how she gradually adopted the ideological language of the Soviet regime.

The modern collection of the Gallery of Szombathely eloquently exemplifies the complex relationship between official culture and the culture of dissent during the socialist period. The genealogy of the collection is inseparable from the conservation of the leftist counter-culture of the Horthy era, especially of the legacy of the left-wing painter Gyula Derkovits, who was born in Szombathely. The collection of artworks was based on the notion of “progress,” and it became increasingly intense in the 1970s, but it only partly followed the socialist canon. It also initiated the emergence of new and critical trends that were in opposition to the official culture politics.

The underground periodical Dzimtene (The Motherland) was published in 1950 and 1951 by Vilis Toms, a member of the Association of Latvian National Partisans (as editor), and Broņislava Martuževa. The periodical was written and copied by hand, because there were no possibilities for printing it. Each of the 11 issues was copied out by Martuževa by hand, up to ten copies. One problem was the distribution of the periodical. Martuževa thought of putting it in the letter boxes of local people. However, some copies were instantly obtained by state security organs. The May 1950 issue of the periodical consists of 16 pages. The cover was made by Pēteris Logins.

The formal authority of the Cinematography Commission of Government of People's Republic of Croatia (PRC) encompassed the administration of cinematography and motion picture distribution in Croatia, the preparation and development of cinematography and motion picture distribution, oversight of state motion picture production and distribution companies, training and specialization of qualified personnel (Narodne novine [Croatia’s official journal], no. 86, 1947). In the performance of such tasks, the Cinematography Commission regularly consulted the Cinematography Commission of the Government of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY) and the Croatian Communist Party’s Agitprop Department and acted on their instructions..

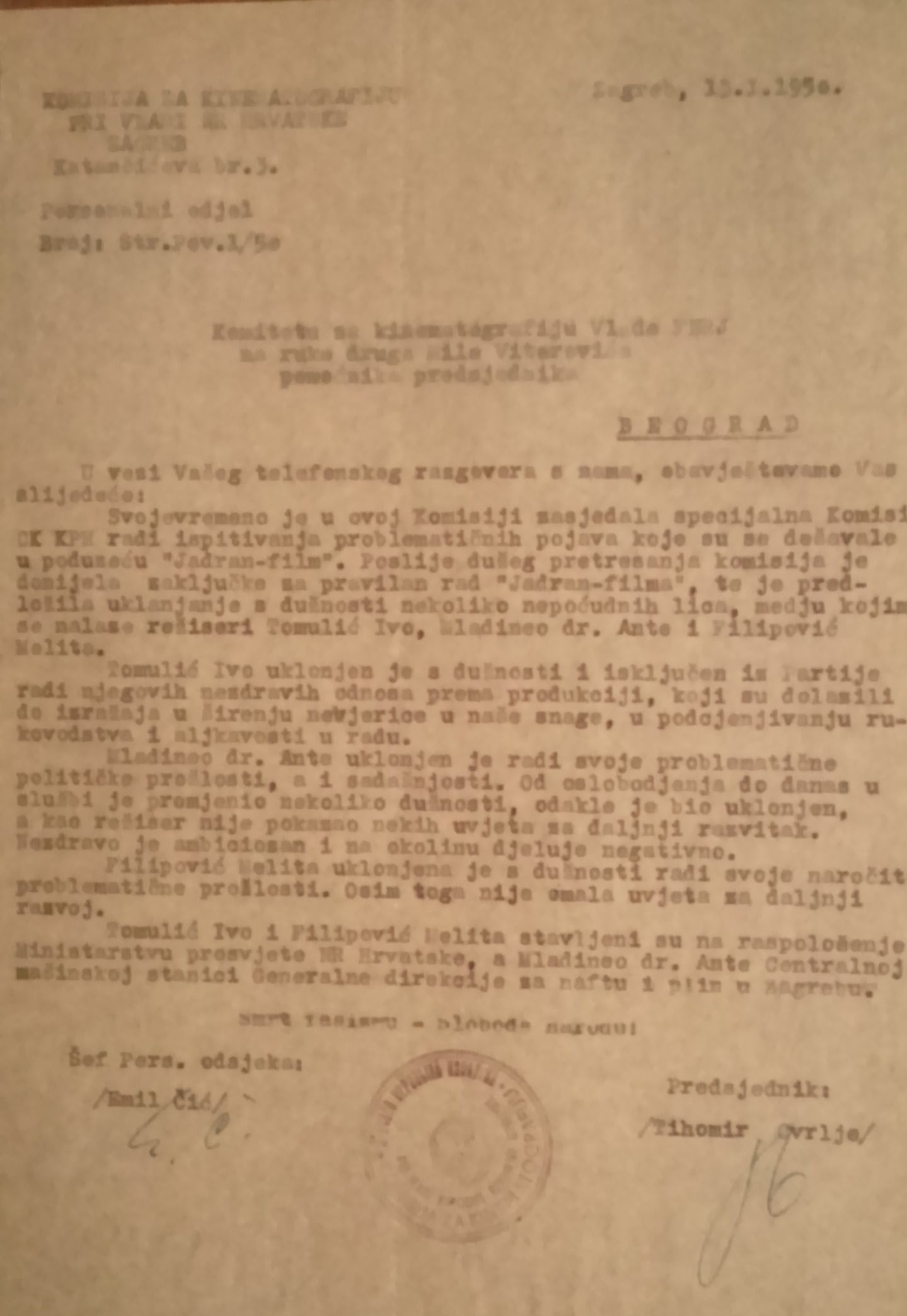

The genuine control exercised by the Communist Party over the Cinematography Commission of the Government of PRC and the companies under its formal jurisdiction is further illustrated by the Commission's report sent on 13 January 1950 to Cinematography Commission of the Government of the FPRY. It describes the results of oversight of Jadran film's activities conducted by a special commission of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia which held session at the Cinematography Commission. A result of that campaign was the dismissal of several “suspect individuals,” including producers Ivo Tomulić, Ante Mladineo and Melita Filipović. They were assessed as unsuitable because of “an unhealthy attitude toward production, which was reflected through the spread of scepticism about the capability of the system, undermining authority and sloppiness in their work,” as well as their “problematic pasts.” Also underscored was their “unhealthy ambition” and negative influence on the working environment, with a lack of potential for further professional development as producers (HR-HDA-309. CC of the Government of PRC, file st. conf. 1/1950).

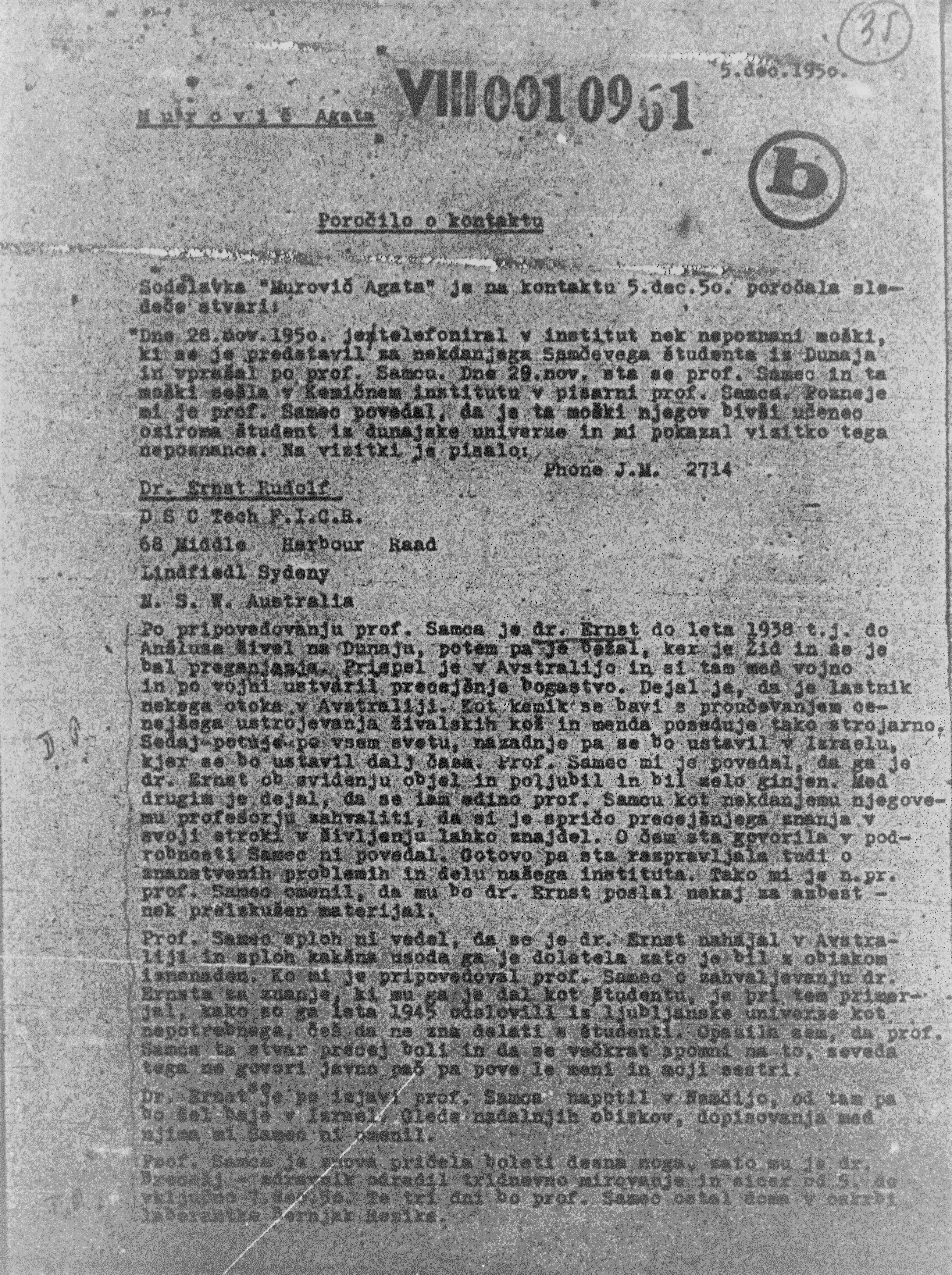

UDB-a captain France Malešič recorded the information obtained by an UDB collaborator with the code name Murovič Agata. At the meeting held on December 5, 1950, the collaborator reported about Maks Samec’s contacts with foreign experts, his health condition and the situation at the institute as well. This was a regular meeting between Malešič and his subordinate that was part of a broad surveillance scheme by the Slovenian branch of secret political police (UDB-a).

Petko Ogoyski - one of the few living artists who survived socialist prisons and labor camps, was an important figure in the Bulgarian cultural opposition against the communist regime. As a member of the Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union-Nikola Petkov (BZNS-Nikola Petkov) and poet/writer, Ogoyski was imprisoned twice (1950-1953 and 1962-1963) by the socialist state for writing “hostile” poems, texts and aphorisms and for “conspiracy”.

The Tower-Museum was established as a private initiative of the family Petko and Yagoda Ogoyski. The exhibition is partly a national and local ethnographic one, including household appliances, costumes, and weapons from the 19th and 20th centuries. At the same time, this was a way to circumvent the censorship of the communist regime. Among the ethnographic materials, Petko Ogoyski kept and preserved evidence from the periods of his imprisonment in six prisons and two forced labour camps; as also notes, books and poems written by him during and after the discharge from prison. The materials of the Tower Museum have been collected by Petko Ogoyski since his first imprisonment in 1950.

The collection of Petko Ogoyski documents the repressions of the socialist state over dissidents and is a valuable source of the forms of asserting political principles and moral positions by intellectuals.

Although it is not officially dated, Muncitor forestier (Forestry Worker) was probably painted in the late 1940s or early 1950s, when its author was trying to adapt his artistic creation to the new cultural policies. From the point of view of the technique used, the painting combines tempera and oil painting on plywood. According to the art historian Radu Popica, the painting Muncitor forestier (Forestry Worker) illustrates the “difficulties” encountered by Mattis-Teutsch in the process of adapting to socialist realism (Popica 2015, 12). The artist tried to combine techniques of his art from the 1930s with the precepts of socialist realism. However, this synthesis, called by the artist “constructive-realism,” failed to convince the authorities (Popica 2015, 13). As has been observed by Dan-Octavian Breaz, although Mattis-Teutsch’s art in the 1930s suggested the “new man” of socialist realism, the modernist techniques used by Mattis-Teutsch were in fact incompatible with socialist realism, because they were unsuitable for the purpose that art was supposed to serve in the new society (Breaz 2013, 124). This explains the negative reception of Mattis-Teutsch’s artistic creation in the 1950s, despite his honest attempts to integrate into the new cultural context.

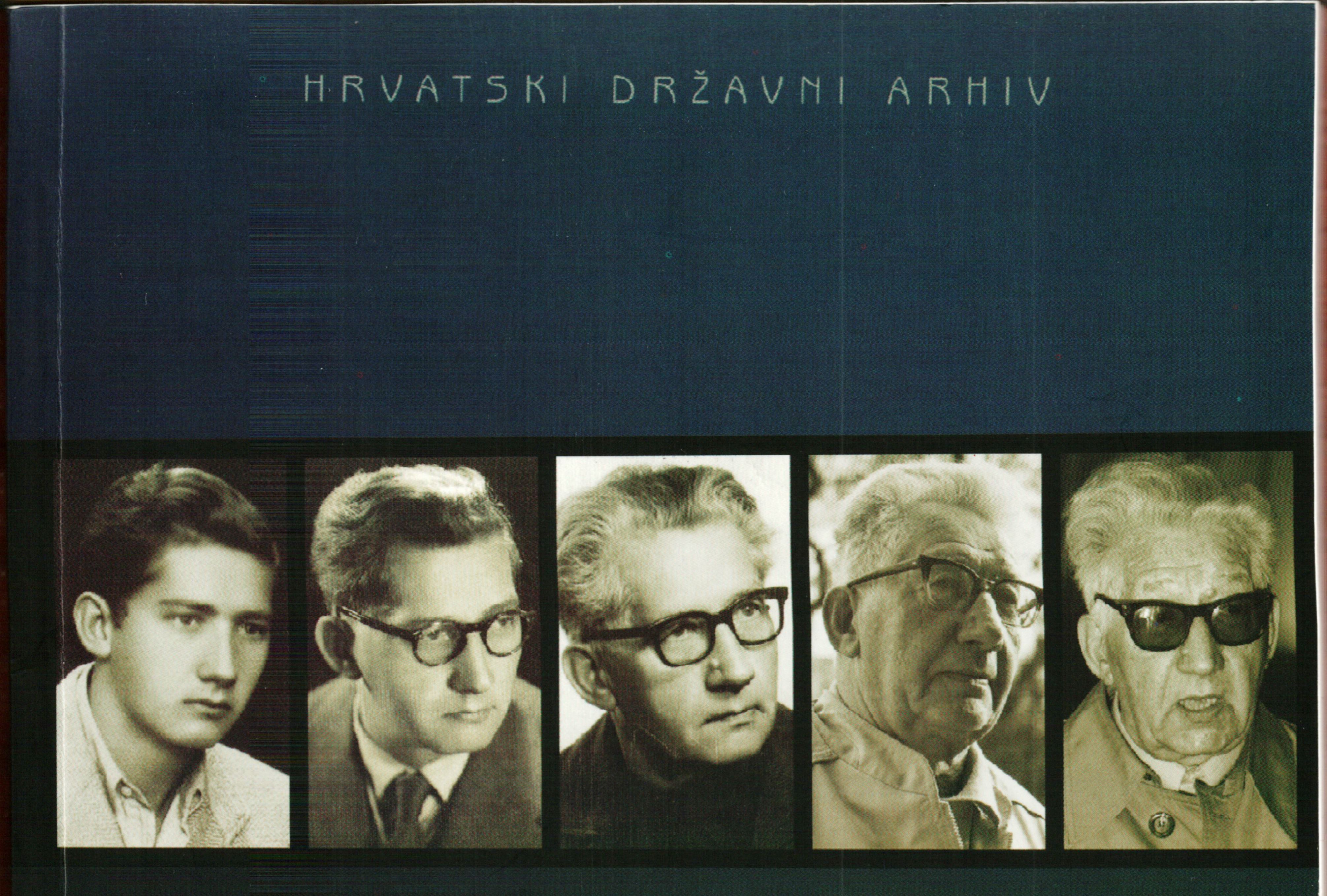

The personal collection of Croatian philosopher and sociologist Rudi Supek contains documents and photographs that testify to Supek's intellectual activity, which had been prevented in some phases of his life. Supek was the editor of two critically-oriented Marxist journals, Pogledi and Praxis, and as one of the main protagonists of the Korčula Summer School of Philosophy, he expressed views that did not align with those promoted by the Communist authorities. Supek's disagreement with the practices of the communist regime stemmed from his understanding of the position of intellectuals in society and his stance that there is no socialism without democracy. This collection also illustrates Supek's work as one of the pioneers of the environmental movement in Yugoslavia.

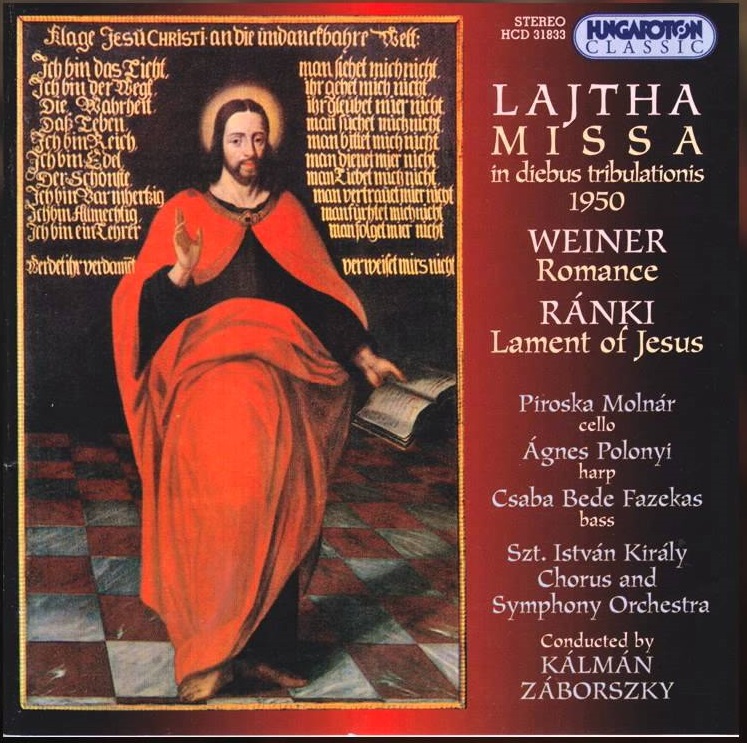

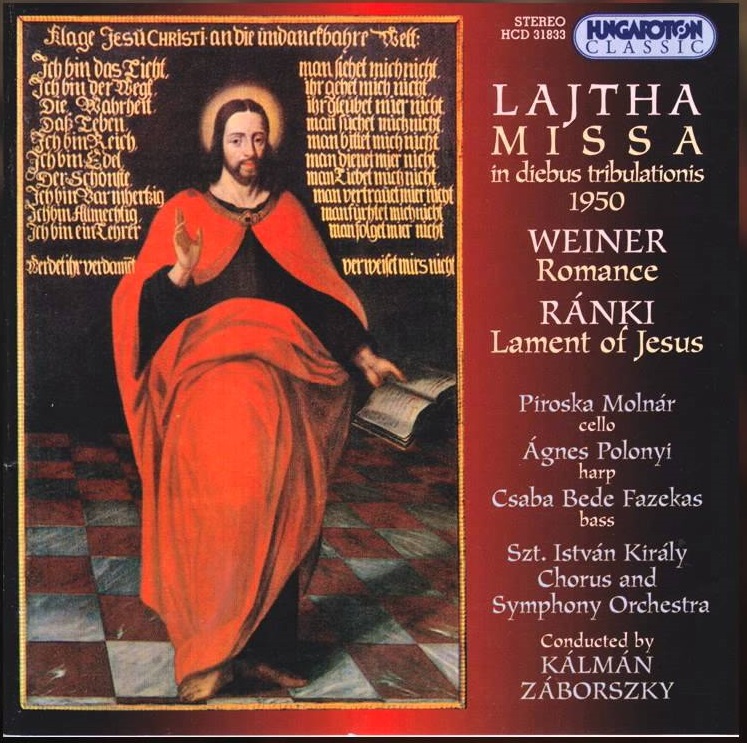

During the Rákosi era, when religious life was oppressed and religious works, choirs, publishers, and institutions were banned, László Lajtha composed Catholic masses in Latin. Before, Lajtha had shown no interest in religious music. His masses are Missa in tono Phrygio – “In diebus tribulationis” Op. 50 (1950), Missa pro choro mixto et organo Op. 54 (1952), and Magnificat, pour Choeur de Femmes et Orgue Op. 60 (1954). – Lajtha dedicated the Magnificat to Margit Tóth, a member of the Lajtha group and Trois Hymnes pour Sainte Vierge, pour Choeur à trois voix de Femmes et Orgue Op. 65 (1958). The Missa in diebus tribulationis op.50. was composed between April to June in 1950. This was not much time, given that Lajtha was composing a mass, so he worked intensively. This period was very hectic in Lajtha’s personal life. In 1948, he returned from London and had to remain in Hungary because he was not given a passport. He was dismissed from all his all positions, and he had to sell his personal belongings to get money. He became lonely. His sons emigrated, and most of his friends lived abroad, in other European countries. Lajtha always highlighted his rejection of socialism. Composing a mass was one of the ways in which he expressed this rejection. His mass was performed first in 1957, when István Vermes, the head of Magyar Radio (Hungarian Radio), decided to present works by composers who were under pressure from the communist regime. Although the cultural policies of the Kádár era were less radical, this kind of masterpiece still stood a good chance of being banned. Magda Kelemen, who knew Lajtha’s work as a composer, proposed changing the mass’s title to Phrygian Mass (Mise fríg hangnemben). This title seemed less explicit as an expression of opposition to the socialist regime. The mass was presented by Magyar Radio in 1957. In 1989, it was performed again, and in the 1990s a performance was recorded on CD.

Juretić, Augustin. “Suština sukoba Kominform – Tito” [The essence of the Cominform conflict – Tito] (Hrvatski dom), 1950. Article

Juretić, Augustin. “Suština sukoba Kominform – Tito” [The essence of the Cominform conflict – Tito] (Hrvatski dom), 1950. Article

The Croatian expatriate magazine Hrvatski dom, edited and published by Augustin Juretić in Switzerland, carried the article "The essence of the Cominform conflict – Tito," in its issue of 15 November 1950. The article is unsigned, and as with most unsigned articles in the magazine, its author is probably Juretić. The article described the essence of the conflict between Tito and Stalin, considering it through the prism of Marxist theory and practice. Juretić concluded that Tito carried out the last communist revolution in the world, which according to Marxist theory made him the leader of the world communist movement, i.e. placed him ahead of Stalin. As a warning to Western leaders, Juretić stated that in the future Tito could become more dangerous than Moscow, and that “the destruction of world communism will required Tito’s destruction as well” (Hrvatski dom, 15 November 1950, 3-6)

The manuscript of the article is held in the Augustin Juretić Collection at the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome. The collection also contains a printed version of the article published in Hrvatski dom.

The letter was drafted in the context of press attacks against and persecution of Hans Otto Roth by the communist authorities after the establishment of the Petru Groza government in March 1945. These measures culminated in July 1948, when Roth was arrested and investigated for political reasons for six months along with other leaders of the German community in Romania involved in managing the General Savings Bank of Sibiu (Hermannstädter Allgemeinen Sparkasse) for his alleged mismanagement. The letter dated May 1950 was addressed to the Lutheran pastor Alfred Herrmann, an old friend who had been persecuted by the Nazi leaders of the German Ethnic Group of Romania for his socialist sympathies. Alfred Herrmann (1888–1962), former first pastor of Bucharest in the period 1937–1946, was one of the supporters of the new communist regime in the Evangelical Church of Augustan Confession of Romania (Weber and Baier 2015, 245). The document represents a critical reply to a series of letters received from Herrmann during 1950. In this letters Herrmann argued that he had supported the new regime because the church needed to embrace the so-called “peace movement” and to involve itself in building the new society. The Fight for Peace Committee was an institution created by the communist regime in Romania in order to enlist clergy of the officially recognised denominations and mobilise them for the achievement of political aims.

To answer the motives invoked by Herrmann, Roth claims that the aim of each Christian should be to oppose the use of violence “in any form.” From this point of view, peace represents an aim that the Church must naturally follow. At the same time, Roth argued against the idea that the Church should support the newly established communist regime because, according to him, the Church should become involved only in those “forms of social organisation” in which “love for our fellow men can truly exist.” He rejects the involvement of the Church in building the “new socialist society” through a subtle critique of the violent methods used by the communist regime to impose it. Ironically, Roth points out to Herrmann that a series of motives invoked by the latter to justify his support for the communist regime were similar to those presented to him several years before by Bishop Staedel, the pastor placed by the Nazis at the head of the Evangelical Church of Augustan Confession of Romania in 1941.

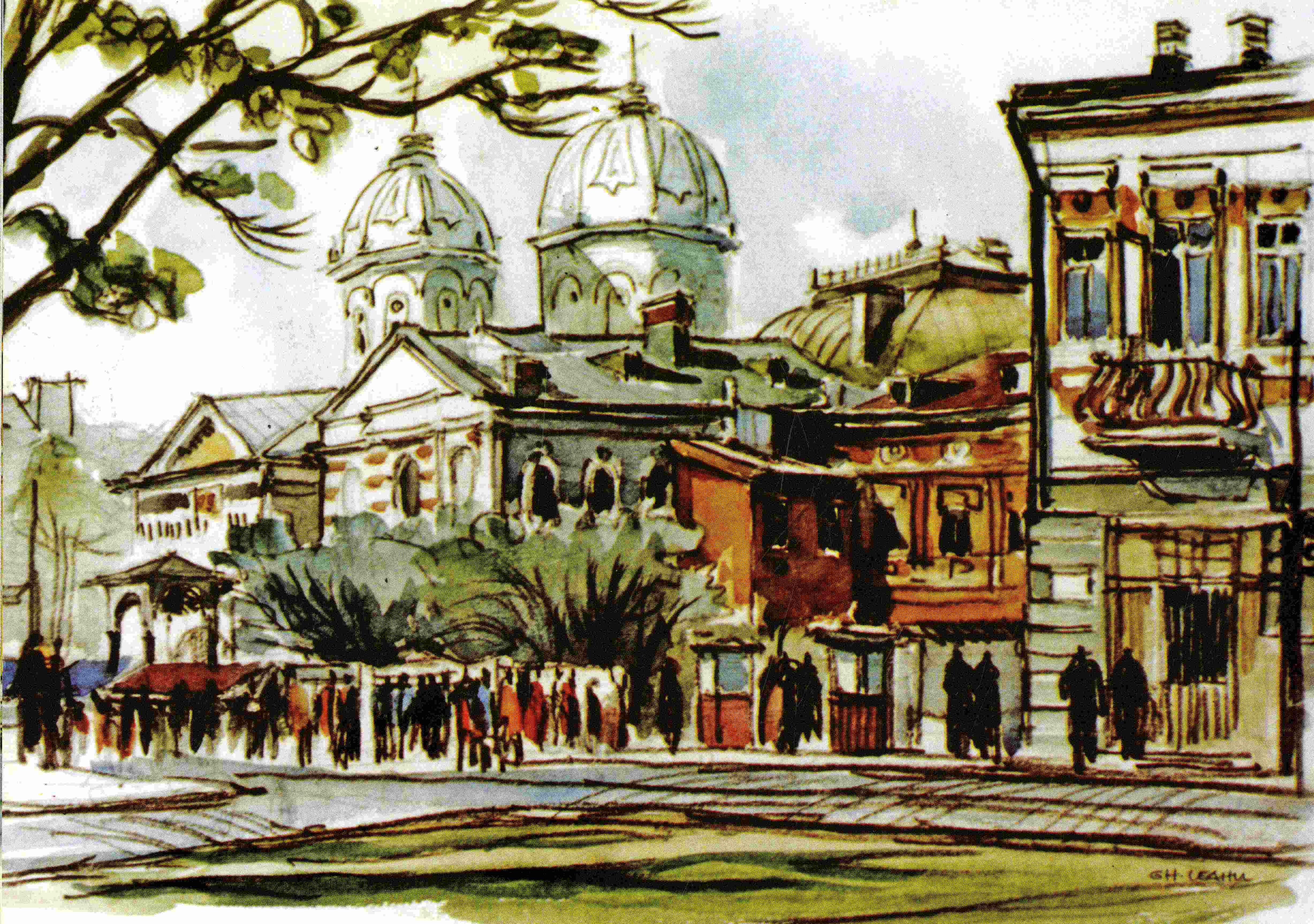

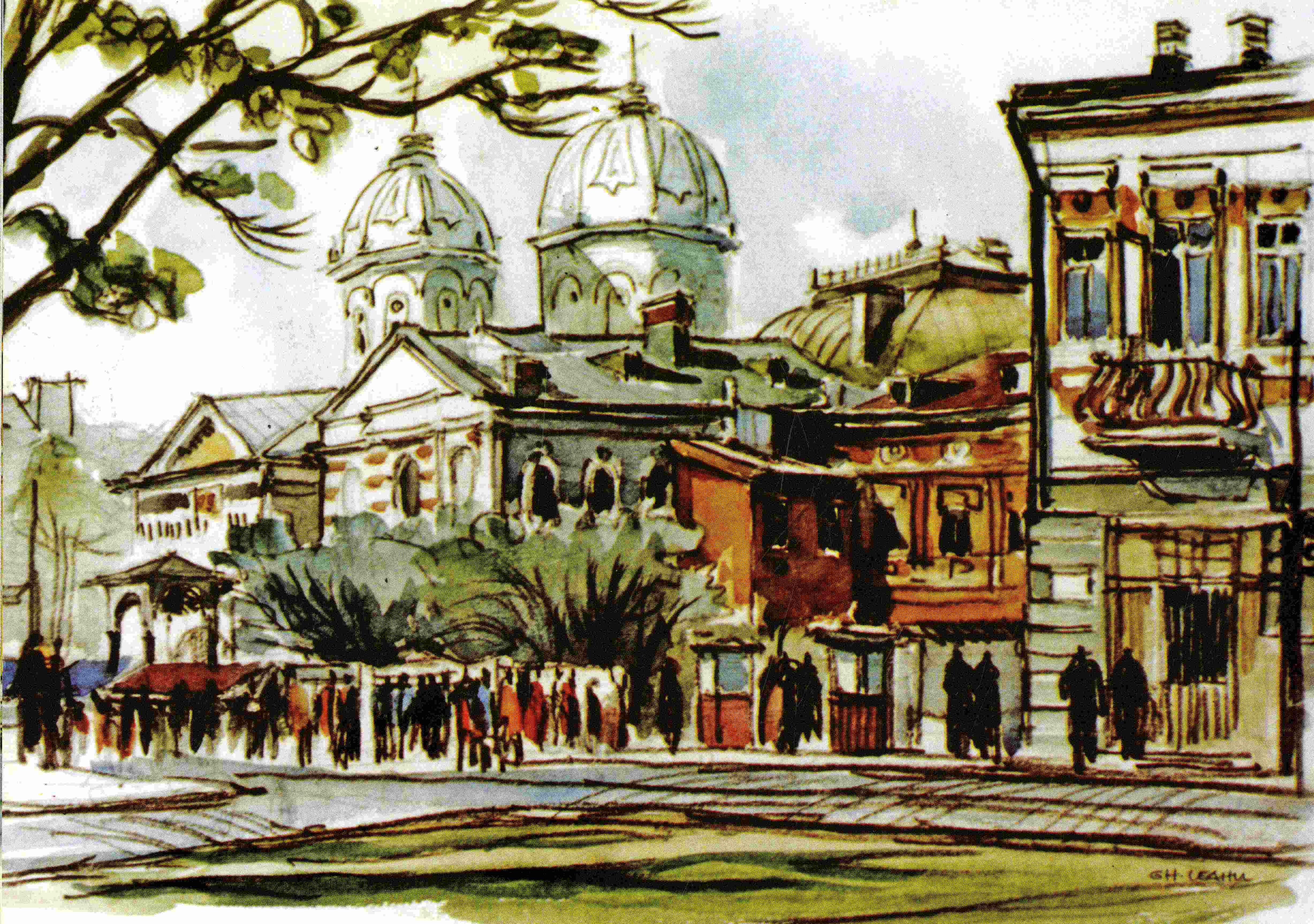

The collection reflects the activity of the architect Gheorghe Leahu, known in Romania for his watercolours representing streets and monuments of Bucharest destroyed as a result of the “urban systematisation” policy of Ceauşescu’s regime. The Gheorghe Leahu Collection includes watercolours, drawings, manuscripts, letters, photographs, and books.