The Declaration on the Name and Status of the Croatian Literary Language was proclaimed by Croatian linguists published in the weekly Telegram on March 17, 1967, with the signatures of eighteen Croatian scholarly and cultural institutions. Croatian linguists and writers gathered around Matica hrvatska and the Association of Writers of Croatia were dissatisfied with published dictionaries and orthographies in which the language, according to the Novi Sad Agreement (1954), was called Serbo-Croatian. In late 1966 and early 1967, they had decided to write an amendment to the new Constitution which was being prepared in the late 1960s. They secretly prepared a text about the name and status of the language that was officially used in the Socialist Republic of Croatia (SRH) as part of the then Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). The text of the Declaration was drafted in Matica hrvatska's premises by a group of academics, literary and cultural workers (Miroslav Brandt, Dalibor Brozović, Radoslav Katičić, Tomislav Ladan, Slavko Mihalić, Slavko Pavešić, Vlatko Pavletić). The Steering Committee of Matica hrvatska approved the content of the Declaration on March 13, 1967, and sent it to other Croatian cultural and academic institutions. In the next few days, the Declaration was signed by a total of eighteen Croatian academic and cultural institutions which directly dealt with the Croatian language, and by a significant number of prominent intellectuals.

The publication of the Declaration was not only a cultural but also a political affair. It had additional weight because of Miroslav Krleža, probably the most prominent left-wing intellectual not only in Croatia but all of Yugoslavia, was one of the intellectuals who signed the document. Despite the fact that the writers of the Declaration were cautious in attempting to avoid any boundaries set by the League of Communists (they used the usual communist phraseology and the style of "self-managing socialism" and the Yugoslav slogan of "fraternity and unity"), the publication of the Declaration triggered strong political reactions and set the repressive apparatus in motion. The Croatian language was a litmus test through which the overall economic, political and cultural subordination of Croatia within Yugoslavia was revealed (Kovačec 2017), and the appearance of the Declaration is considered the practical beginning of the Croatian national movement – the Croatian Spring.

The Matica hrvatska Collection at the Croatian State Archives contains the original document of the Declaration with accompanying materials (the manuscript of the Declaration, multiple typescript versions with and without signatures and stamps, Dalibor Brozović's telegrams, letters of the signatory institutions of the Declaration that give their support to its contents).

This private collection contains the works of the composer Srđan Hofman, from the late 1960s to the present. Hofman is a representative of post-modernism in music, prominent as a composer of electro-acoustic music in Yugoslavia. Because of the nature of his music, the collection includes different media such as notes on Hofman’s compositions, audio recordings of their performances (both in electronic form and on records and tapes), together with the author’s publications and publications by others on his music. As the collection reflects Hofman’s entire oeuvre, we can trace its beginning from the end of 1960s and witness his continuing creative development.

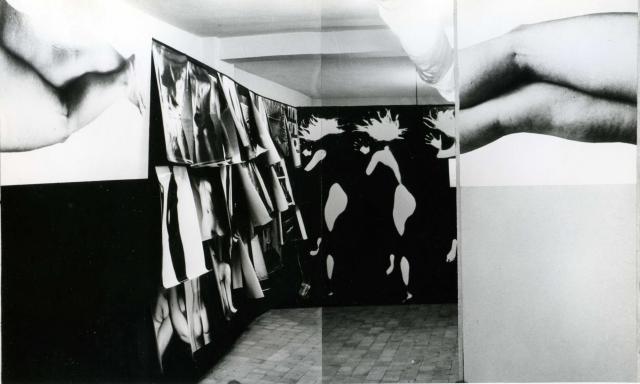

The renowned happening of Tadeusz Kantor took place on the 23rd of August 1967 on a beach in Łazy, near Koszalin in the north of Poland by the Baltic Sea, as a part of periodic plein-air in the nearby Osieki. The most famous element of this happening, the Sea Concert, transpired in the following manner: The audience, composed of beachgoers in their bathing suits were sat on deckchairs arranged in regular rows, so that the first row were partially immersed in the water. In front of them, several meters into the water, a podium with stairs had been erected. Then came a boat, and a tall man in a black tailcoat alighted and entered the podium. The man, facing the sea, and with his back to the audience commenced conducting the waves. The man in the tailcoat was a painter and author of the installations, Edward Krasiński. Tadeusz Kantor directed the entire happening by issuing commands through a speaker. The famous photography was taken by Eustachy Kossakowski. It is currently in possesion of the Artists’ Archives of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. It is probably one of the most often reproduced Polish photographs. Museum of Modern Art reports dozens of requests annually for use for posters, illustrations, book covers, etc..

Source: Teatr niemożliwy. Performatywność w sztuce Pawła Althamera, Tadeusza Kantora, Katarzyny Kozyry, Roberta Kuśmirowskiego i Artura Żmijewskiego, Zachęta i Kunsthalle Wien, Warszawa 2006.

Czerska Karolina, Tadeusz Kantor, „Panoramiczny happening morski”, Culture.pl 2014, http://culture.pl/pl/dzielo/tadeusz-kantor-panoramiczny-happening-morski

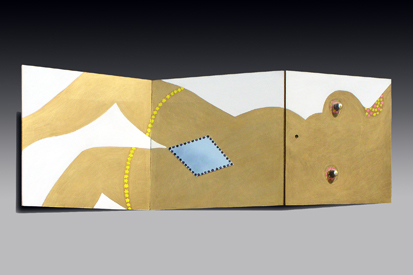

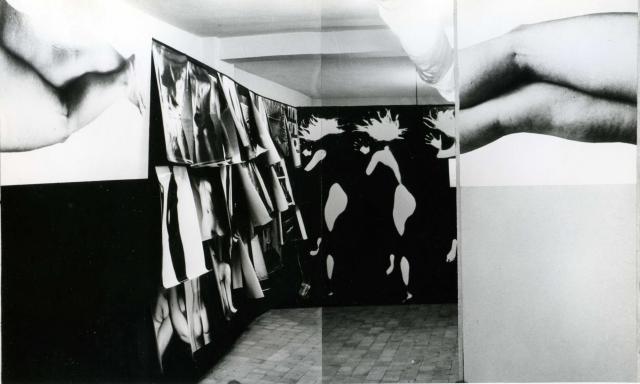

“Let me sink upwards (Waving image),” oil, gumming, mixed media, fiberboard, 305 × 342 cm.

The large format oil painting of Sándor Altorjai, consisting of two panels with adjoining sections of collages and applications: there is a jacket, a hat, a beard, a few old bank notes, and photos fixed on the left panel, and on the right there are plenty of photos, photocopies, and press clippings. The painted parts were made with multiple techniques, with brush, dripping, scratch, overprint, uncovering, one can see even marks of paint applied by feet. Originally a sculptural, shiny waving hand protruded from one of the sleeves of the jacket (in accordance with the subtitle).

The photos were taken during a film shoot with a close friend of the artist, Miklós Erdély, depicting him masked as a “poor Jew,” confronted with texts and press clippings of the period. The photocopy of the author’s identity card, placed in the lower right corner (substituting the sign), deserves special attention, because at that time it was forbidden to reproduce an official document in any form.

The work has an adventurous history. It was intended to be shown first at the yearly exhibition of the Studio of Young Artists in the Ernst Museum in 1967, but an unusually large jury arriving five days prior to the opening judged it inappropriate (along with 69 other artworks). However, this single work could not be carried away immediately due to its size and weight, so it remained in the exhibition space, but was covered with a drape. This way many visitors could see it by moving the drape.

The very same thing happened in 1980, at an exhibition organized after the death of the painter. Just before the opening, a party delegation from the district council descended on the spot and told to the director of the institution that the picture was inappropriate for exhibition due to its ambivalent Jewish aspects. The director called the curator to act accordingly, but he refused to remove the object because of its size and weight. The director then covered the picture with a drape himself, but the audience undraped it several times during the opening event.

According to the consensus of art historian professionals, this image is one of the masterpieces of Hungarian Pop Art. It came into the Contemporary Collection of the Hungarian National Gallery in 1982, where it became a respected item. Currently it is shown in the permanent exhibition. The waving hand reappeared in its place (most likely due to a restoration process), but was still missing in the photo displayed on the website of the collection.

The collection shows the activities of Modris Tenisons’ troupe. In 1966, Modris Tenisons founded the first mime troupe in the Soviet Union. It was made a separate section of the Kaunas National Drama Theatre in 1967. Later, in 1970, it moved to Kaunas Musical Theatre. The troupe was well known for its performances, as well as for creating and living in the Hippie community in Kaunas. After the self-immolation of Romas Kalanta in Kaunas in 1972, and the youth protests against the Soviet regime, Modris Tenisons and his troupe were forced to leave Kaunas Musical Theatre and end their creative work.

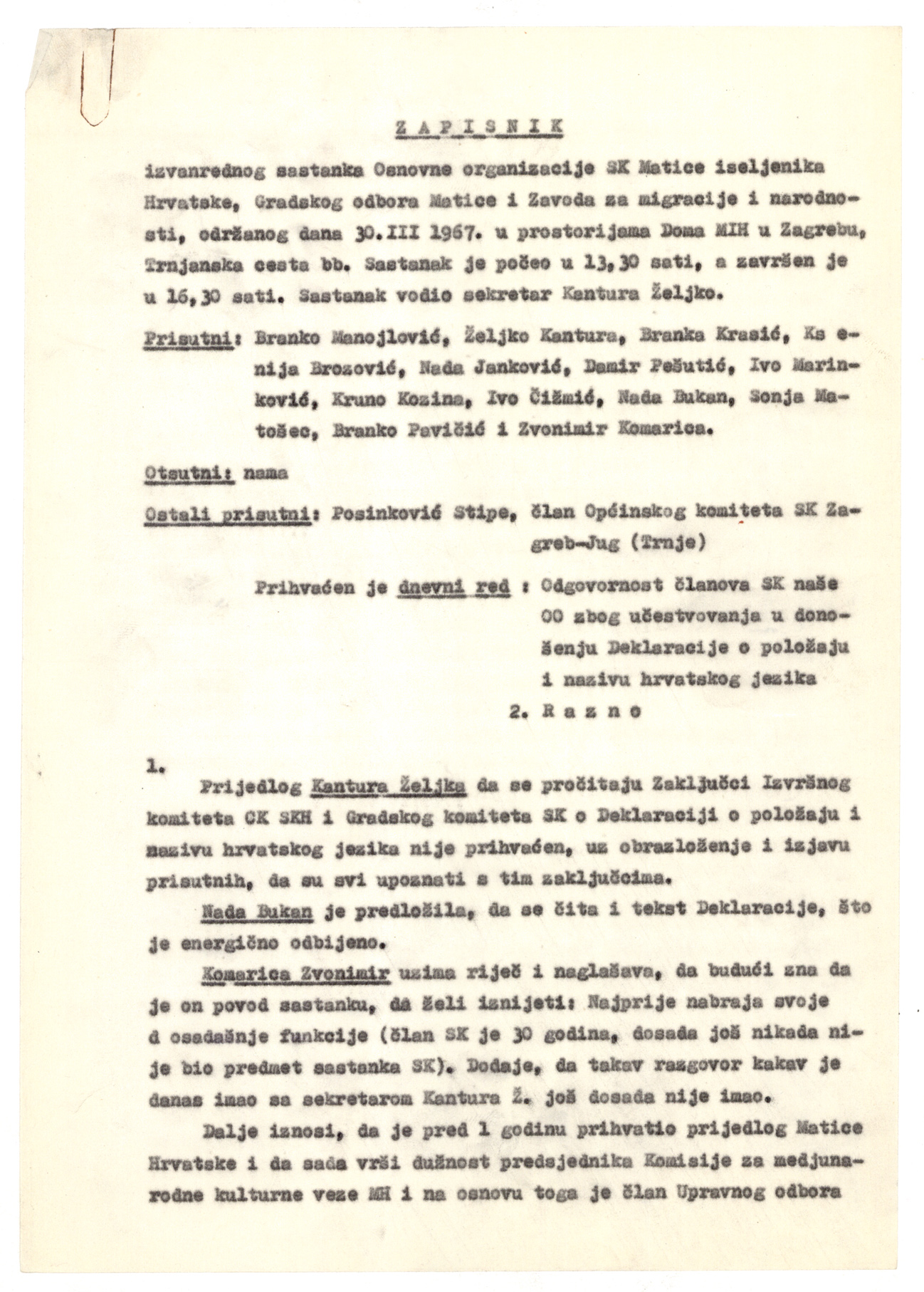

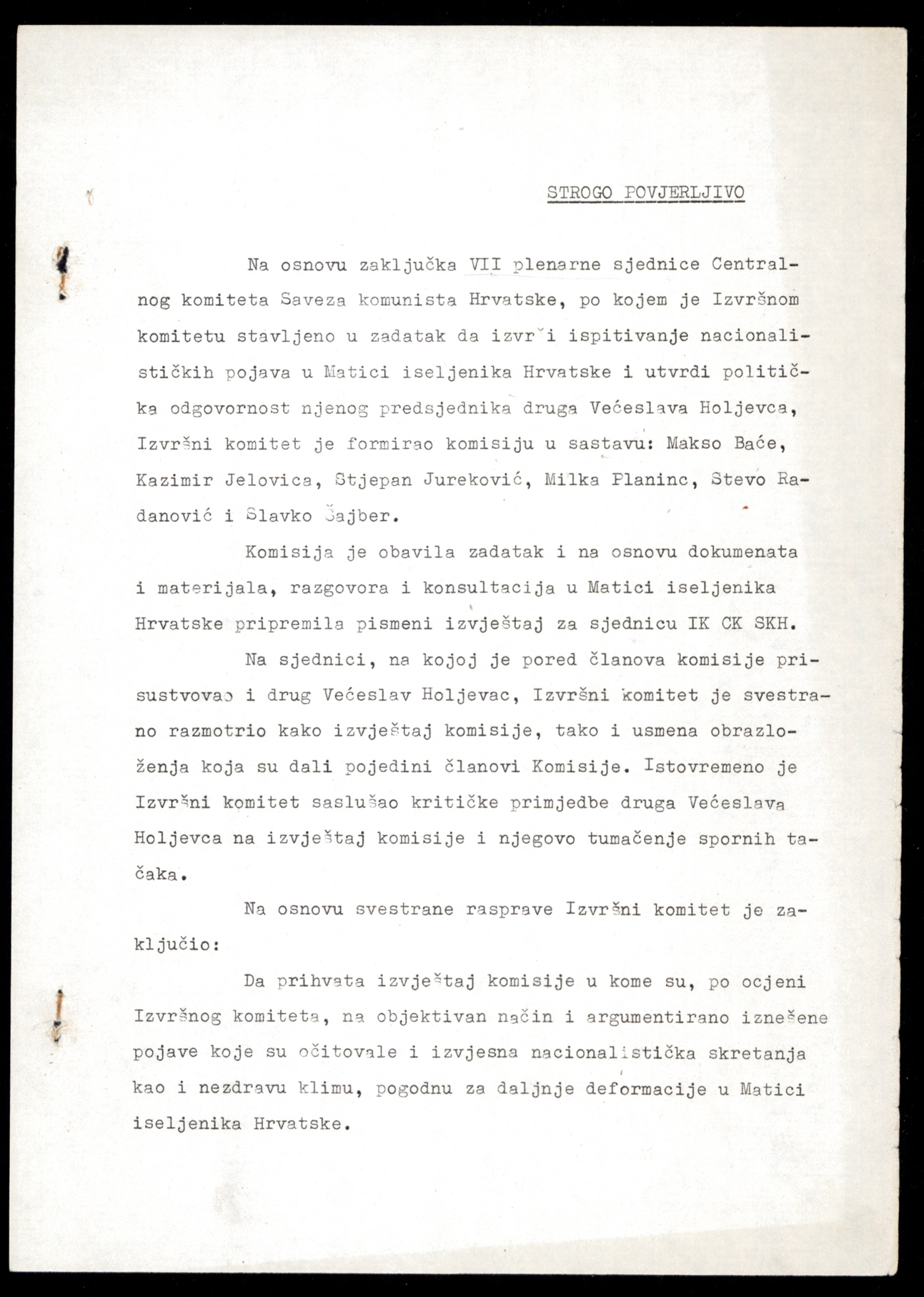

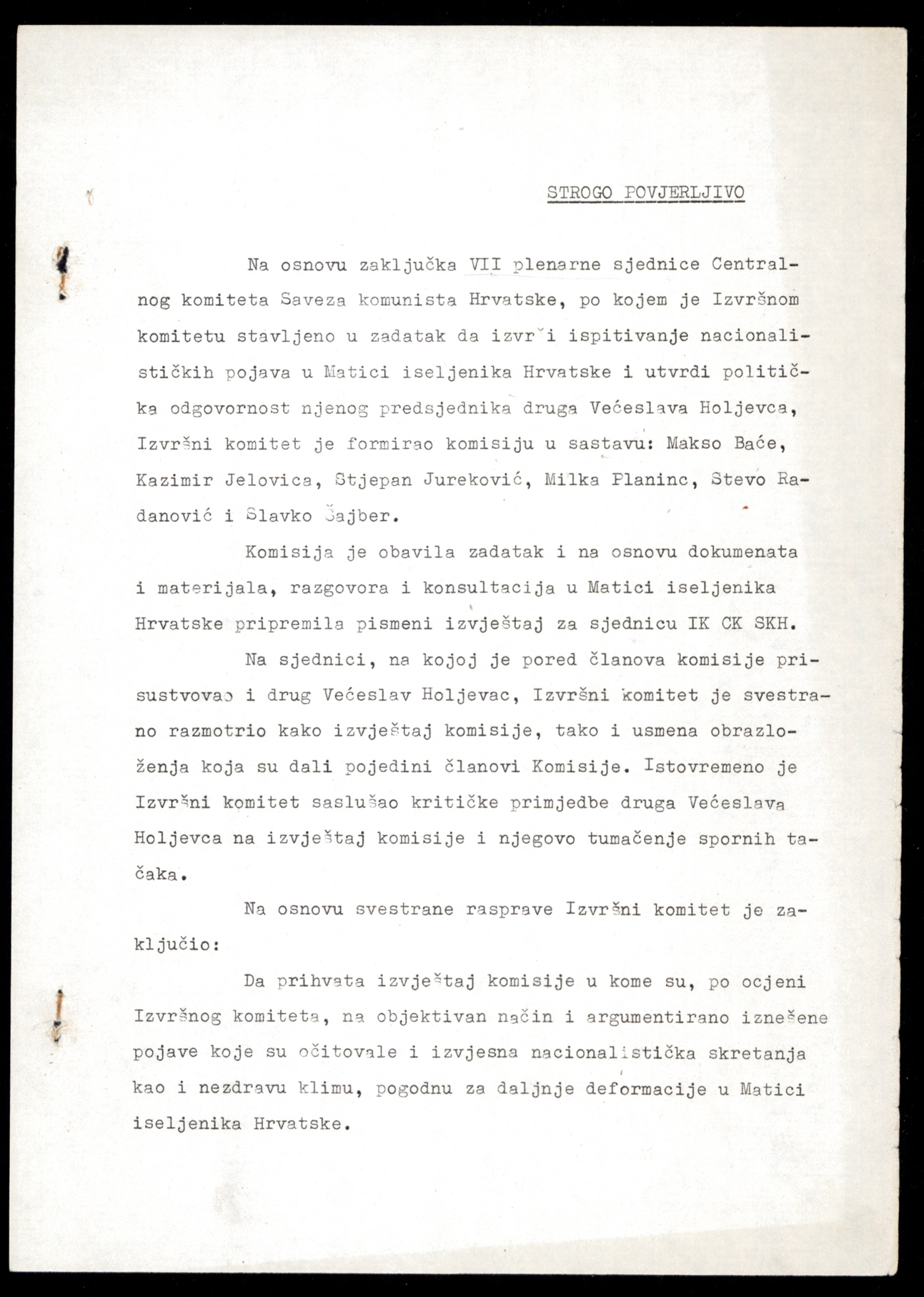

Minutes of the emergency session of organization of the League of Communists in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia, 1967

Minutes of the emergency session of organization of the League of Communists in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia, 1967

The minutes of the meeting of the three parties, convened to determine the responsibilities of Zvonimir Komarica, then director of the Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies, and also the chairman of the Commission on International Cultural Relations of Matica hrvatska (MH) and a member of the MH managing board, regarding the adoption of the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language. Komarica was accused of participating in the debate on the text of the Declaration, and did not publicly dissociate himself nor attempt to prevent its publication. He was then expelled from the League of Communists of Croatia (LCC). The subject of the meeting was also the signing of a letter of support to Ljudevit Jonke, a signatory of the Declaration by members of the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia, Ivan Čizmić and Nada Bukan, for which they were also expelled from the LCC shortly thereafter.

By 1995, the document was, along with the other records of socio-political organisations, a part of the Archive of the Institute of History of the Labour Movement of Croatia/Institute of Contemporary History. That year, in July, it was handed over to the Croatian State Archives (CSA) where it is kept today. The documents are accessible for use without any restrictions.

Alenka Puhar is the author of the first translation of George Orwell's dystopian novel 1984 into Slovenian, and at the same time into the language of any communist country. Puhar translated the novel in 1967 when she was still a student and it had a great influence on her. This was primarily reflected in the fact that the book gives its reader a device for critical thinking, which helped Puhar compare the society in the novel 1984 to Yugoslav society and come to comprehension that they are similar totalitarian systems. This knowledge determined Alenka Puhar’s future professional path.

The collection contains the first printed version of the novel 1984 which was translated in 1967, but does not include Puhar’s manuscript, which she handed in to the publisher. She did not keep the manuscript.

Pavel Doronin started his “anti-Soviet” activities in November 1967, when, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the October Revolution, he produced a short leaflet with a message criticizing the regime and considered “subversive” by the Soviet authorities. The content of this text – Кто Продаёт Свою Совесть / Кто Причиняет Стране Страдания (Who Sells One’s Consciousness / Who Causes Suffering to the Country) – represented an acrostic with the first four letters of each line forming the initials of the Soviet Communist Party – КПСС / CPSU). Thereafter, Doronin constructed seven typeset-stamps in his apartment (each one coinciding with a word of the acrostic), which he then used to print twenty-four leaflets. Doronin spread the leaflets by, on the one hand, distributing six copies throughout Chișinău and, on the other hand, by sending the rest of the leaflets by post to various Soviet institutions, factories, and religious organizations. Another form of expressing his discontent was the drafting of caricatures and letters that he sent to various Soviet newspapers. Thus, in May 1970 Doronin creatively altered an anti-American caricature published in the Soviet journal Krasnaia zvezda (Red Star), the official organ of the Soviet Ministry of Defence, by inserting Breznhev’s portrait instead of the original image of the American president and by writing the initials of Czechoslovakia, Egypt and Vietnam against the background of heavy weapons, initially intended to refer to US war-mongering. Although during the preliminary inquiry the defendant insisted that he only intended to show the discrepancy between the official Soviet rhetoric of peace and the reality of Soviet military involvement abroad, the interpretation that the KGB investigators favoured emphasized the more serious accusation that Doronin in fact viewed the whole foreign policy of the USSR as more aggressive than that of the US. Finally, in a series of letters that he sent to the Soviet central newspapers Pravda and Izvestiia in October 1970, Doronin criticized various sensitive aspects of Soviet official policies and everyday life. Besides several short texts focusing on the ”Jewish question,” he also reacted to the debate around Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s nomination to the Nobel Prize for Literature. Reacting to the writer’s condemnation by the official Soviet press, Doronin wrote: “The journalists of a newspaper that is called Pravda (Truth) should be ashamed of spreading all sorts of baseless calumnies and of mocking a man who deserves only recognition, honour and respect from the Soviet people and all other peoples! And this is happening in a country where everyone is boastfully talking about Man as the main value? After all this, how can one believe in a Socialist future?” In another note he sent to Pravda, referring to a trial of a black marketer (spekuliant), Doronin harshly criticized the corruption and inequality within Soviet society, claiming that some party members were becoming a privileged class of “exploiters” instead of providing worthy examples of honesty and hard work. Despite the occasional, isolated and sporadic character of Doronin’s acts of defiance, this case is a fascinating example of how personal, social and political grievances could combine to stimulate an individual’s critical acumen beyond the limits usually tolerated by the regime. Doronin certainly did not fit the typical image of an anti-Soviet dissident or oppositional figure. However, the authorities took his “ideological deviation” seriously enough to spend considerable efforts in order to investigate his case and to condemn him for his “dangerous” views, despite his “sincere repentance” during the trial.

The Alenka Puhar Collection on the Human Rights Movement in Slovenia/Yugoslavia was mostly created in the 1980s and testifies to the struggle of Slovenian and Yugoslav activists to promote and protect human rights in Yugoslavia. Alenka Puhar was one of the key people in the 1983 campaign to abolish the death penalty in Yugoslavia, and in the organization of mass protests in Ljubljana in 1988 and in the Slovenian spring in the late 1980s. The collection documents the struggle and connections between Slovenian activists and other Yugoslav activists and dissidents who had the common goal of promoting and protecting human rights in Yugoslavia and ultimately the collapse of the communist regime.

A conclusion on the basis of a report submitted by the Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia, 1967

A conclusion on the basis of a report submitted by the Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia, 1967

This is a document containing a conclusion based on investigative actions pertaining to the alleged emergence of nationalism in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia (EFC) from 1964 to 1967, i.e. during the term of Većeslav Holjevac as its president. The Commission has identified incidents that "have manifested a certain nationalistic turn as well as an unhealthy climate, suitable for further deformities in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia-" Holjevac was held the most responsible for this, because of "deeper ideological and political misconceptions about the national issue he is considering outside of the class and social context." Henceforth, Holjevac was forced to resign from membership in the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia (CC LCC), and consequently from the post of president of the EFC. As a concrete fault, the document specifies: the shortcomings of the proposed EFC Charter due to the one-sided orientation on emigrants exclusively of Croatian nationality, then the mitigation of the characterization of two emigrant organizations - the "Croatian Academy" in New York and the "American-Croatian Academic Club" in Cleveland (from those hostile to Yugoslavia, to neutral, cultural organizations) in materials prepared by Secretary I. Marinković. Holjevac was also accused of hesitating to condemn the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language and its signatories, the lack of a reception and non-attendance on Republic Day in 1966, the singing of Croatian songs on New Year’s Eve ("Heavenly Maiden, Queen of the Croats," "Arise, banus"). The accusations included an appeal for help from emigrants during the flood in Zagreb in 1964, because it was addressed to "Croatian emigrants and other Yugoslav citizens on temporary work abroad," as well as putting Franjo Tuđman, Zvonimir Komarica and Ivo Frangeš on the list for the Main Committee (MC) of the EFC, and the rationale for signing a letter of solidarity with Ljudevit Jonke after the official condemnation of the aforementioned Declaration.

Holjevac was additionally found guilty of political aberrations on the nationalist viewpoint because of his disagreement with such assessments and for "ignoring his political responsibility." The Commission therefore instructed the convening of the EFC Extraordinary Assembly because of the changes in the MC and the definition of the EFC’s orientation "in accordance with the policies of our society."

This document is a very clear example of repressive action taken by the CC LCC, i.e., one of its bodies, in terms of cultural policy. Conduct beyond the established ideological line was not allowed and was quickly dealt with, and those involved were punished by the loss of their status in society, functions and often employment, and were placed under surveillance.

By 1995, the document was, along with the other records of socio-political organisations, a part of the Archives of the Institute of History of the Labour Movement of Croatia/Institute of Contemporary History. That year, in July, it was handed over to the Croatian State Archives (CSA), where it is kept today. The documents are accessible for use without any restrictions.

"The Tied Up Balloon", 1967, director Binka Zhelyazkova, script-writer Yordan Radichkov, cameraman Emil Vagenshtayn.

In 1967 Binka Zhelyazkova shot the movie "The Tied Up Balloon" (1967) after the script of Yordan Radichkov based on his short novel of the same name. Zhelyazkova created the film after five years of silence for the bureaucratic apparatus had banned her from shooting after her first two movies from the late 1950s and the early 1960s.

"The Tied Up Balloon" is based on a true story – the breaking off of a military aerostat during World War II which flew over a small Bulgarian village. The villagers decide to chase the balloon in order to make themselves shirts and pants from its silk material. The pursuit of the balloon is rendered by multiple tragicomic situations. Gradually, the villagers forget the initial impulse for the chase of the balloon, forget the feud with the villagers from the neighbouring village with whom they fought for the balloon. In their attempt to reach the balloon they rise in spirit. Finally, the balloon falls on the ground and the men catch it but in that very moment the military police force arrives and in order to save the balloon the villagers let it fly away. However, instead of flying away the balloon makes a turn and tries to fight the soldiers but in the end it is "deadly" shot.

The leitmotif of the film is a running barefoot and speechless girl in white – a peculiar projection of the balloon which flew away towards freedom. Just like the balloon, the girl is running; at times she is hiding from the villagers, at times she is dancing a chain dance with them; in the end, just like the balloon, she is shot by one of the villagers, by one of her own. With this character, Binka Zhelyazkova expressed her own feeling of pursuit, of impasse and as the analysts interpreted it of what would have happened after the shooting of the movie (Станимирова, Братоева).

The film is a modern, stylized cinema reading of Yordan Radichkov's work, a complex mixture of comic and tragic, rich of colourful characters and situations which outline the multilayered Bulgarian national character.

The film is a rebellion against the standards of the socialist art – the conscious breaking of the plot in pieces, the rich metaphors and the pessimistic disharmony in the end of the movie (the death of the girl and the burst of the balloon) define the style of Zhelyazkova and Radichkov as "magic realism". "Long before Kusturica, with her Balkan temper and emotion, she had created in cinema the same "reality striving for the sky" with which he conquered the world." (Станимирова 2012: 243)

The movie was finished in spite of the many bureaucratic obstacles in front of the team. The film participated in the International Cinema Festival "Expo 67" in Montreal and was bought for distribution in Europe and America. Nevertheless, the Bulgarian side recalled the movie, cancelled the contract for its purchase and paid a penalty in dollars. The Bulgarian cinematography refused to let the movie participate at the international cinema festival in Venice. The film was shown for a short period of time at a cinema theatre in order to avoid an official ban. Afterwards, it was taken off the cinema for more than two decades. The party document revealing the attitude of the authorities remained hidden; it wasn't published but sent as a circular letter to all sections – party committees, cultural institutes: "...the recent film of the director Binka Zhelyazkova, "The Tied Up Balloon", causes serious anxiety. The director turned some negative sides of the script into an entire movie concept. The events and characters are developed in the light of pessimism and distrust of man. Contrary to the truth to historical facts, the Bulgarian villagers of the period of World War II are depicted as a half-savage crowd. The movie is a mockery of man, of the human and national dignity, of the historical traditions and the heroic struggles of the Bulgarian nation." (cited after Станимирова 2012: 247-248)

Only in the early 1989, the film was shown at the Berlin International Film Festival in Western Berlin (later called Berlinale).

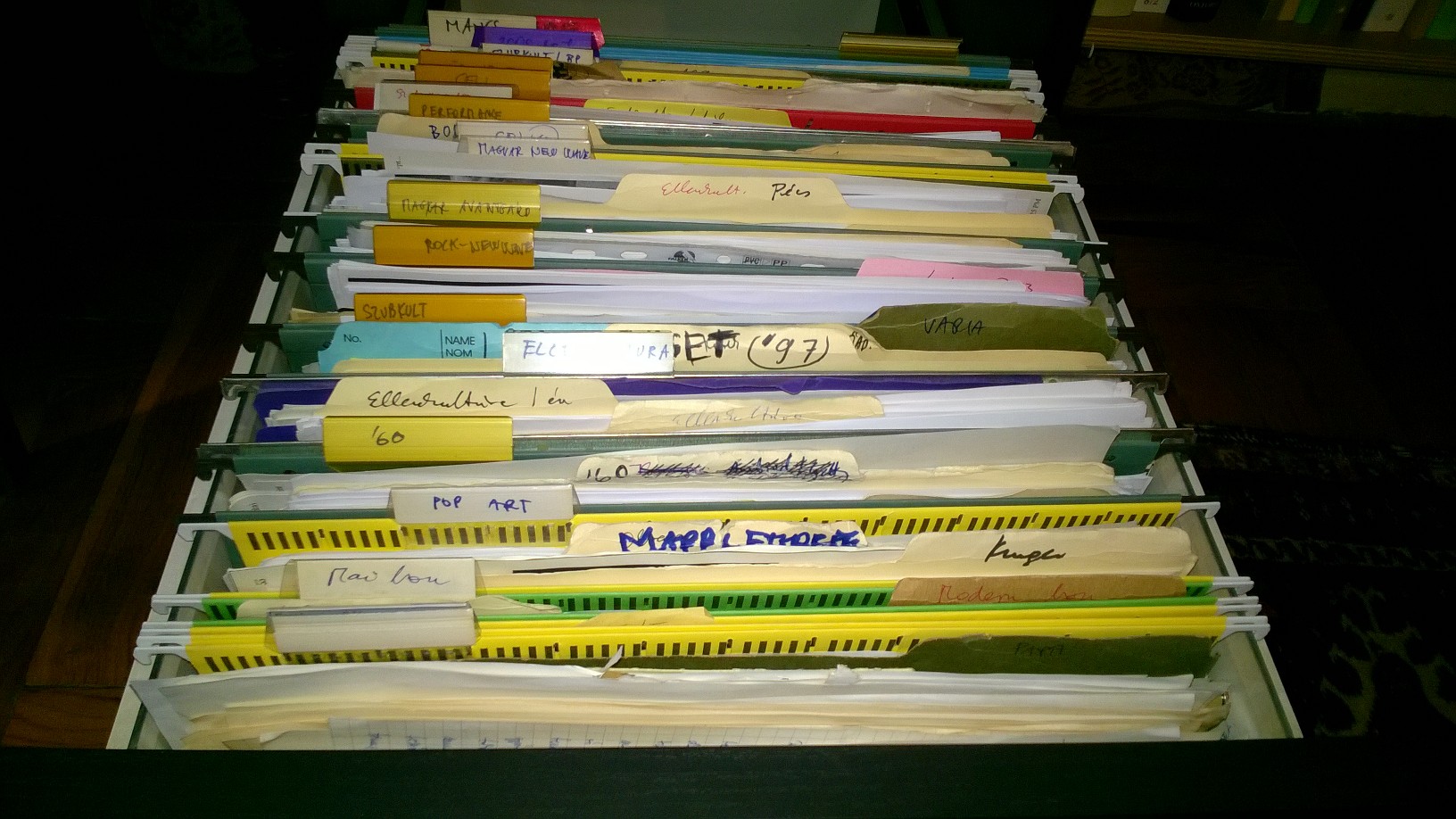

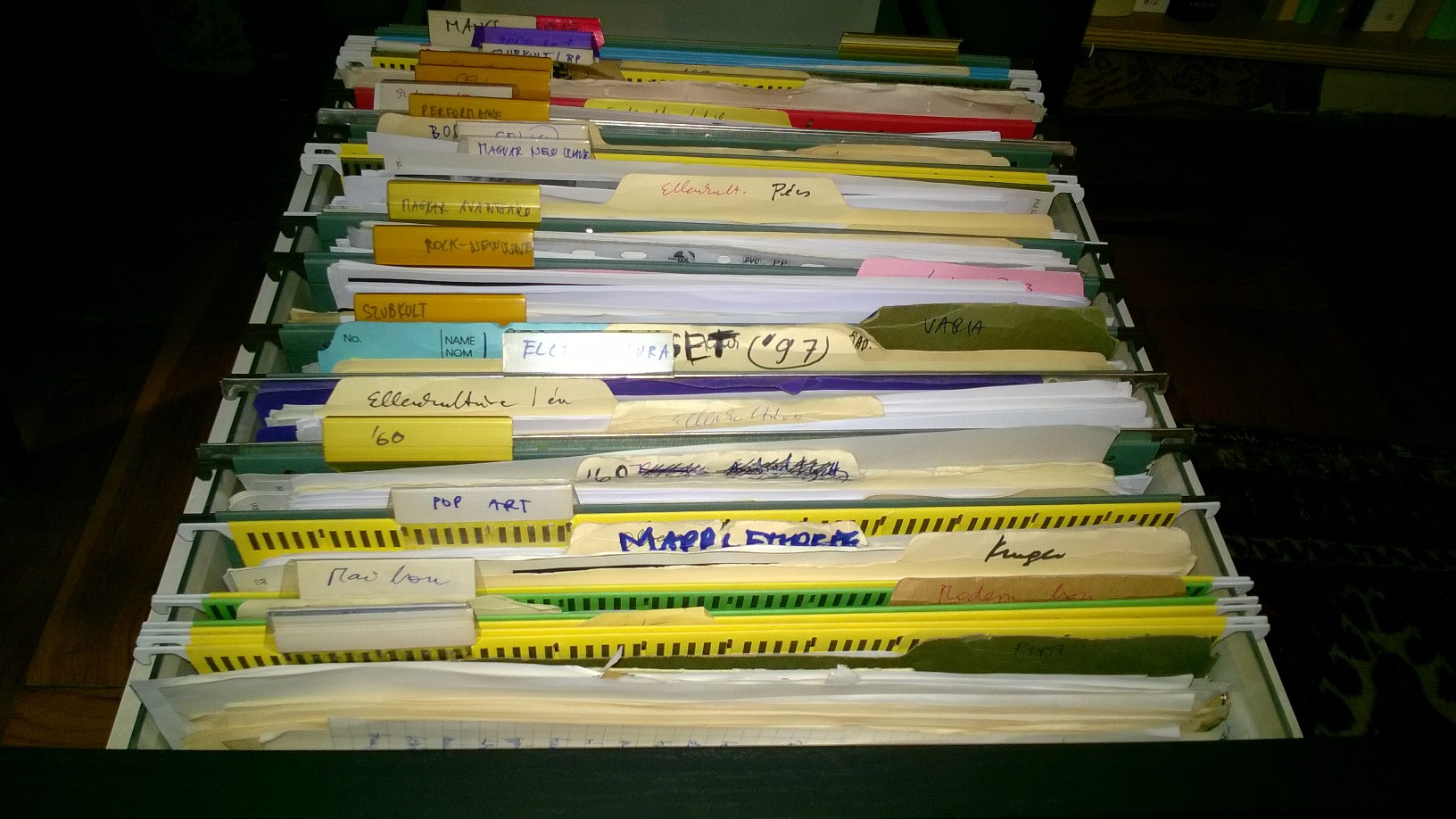

The private collection of historian Gábor Klaniczay (1950-) includes written, visual, and audio sources from the 1970s and 1980s. These sources all concern the alternative, underground cultural trends, art, music performances, and political oppositional movements of the period. The almost entire series of the samizdat publications from Hungary also constitute an important part of the collection, as do the leaflets and posters from his trips to Paris and New York.

On 30 June 1967, Modris Tenisons’ troupe joined the Kaunas National drama Theatre, where it became highly visible and was appreciated by theatre audiences. Documentation about the activities and productions of Tenisons and his troupe starts at this point.

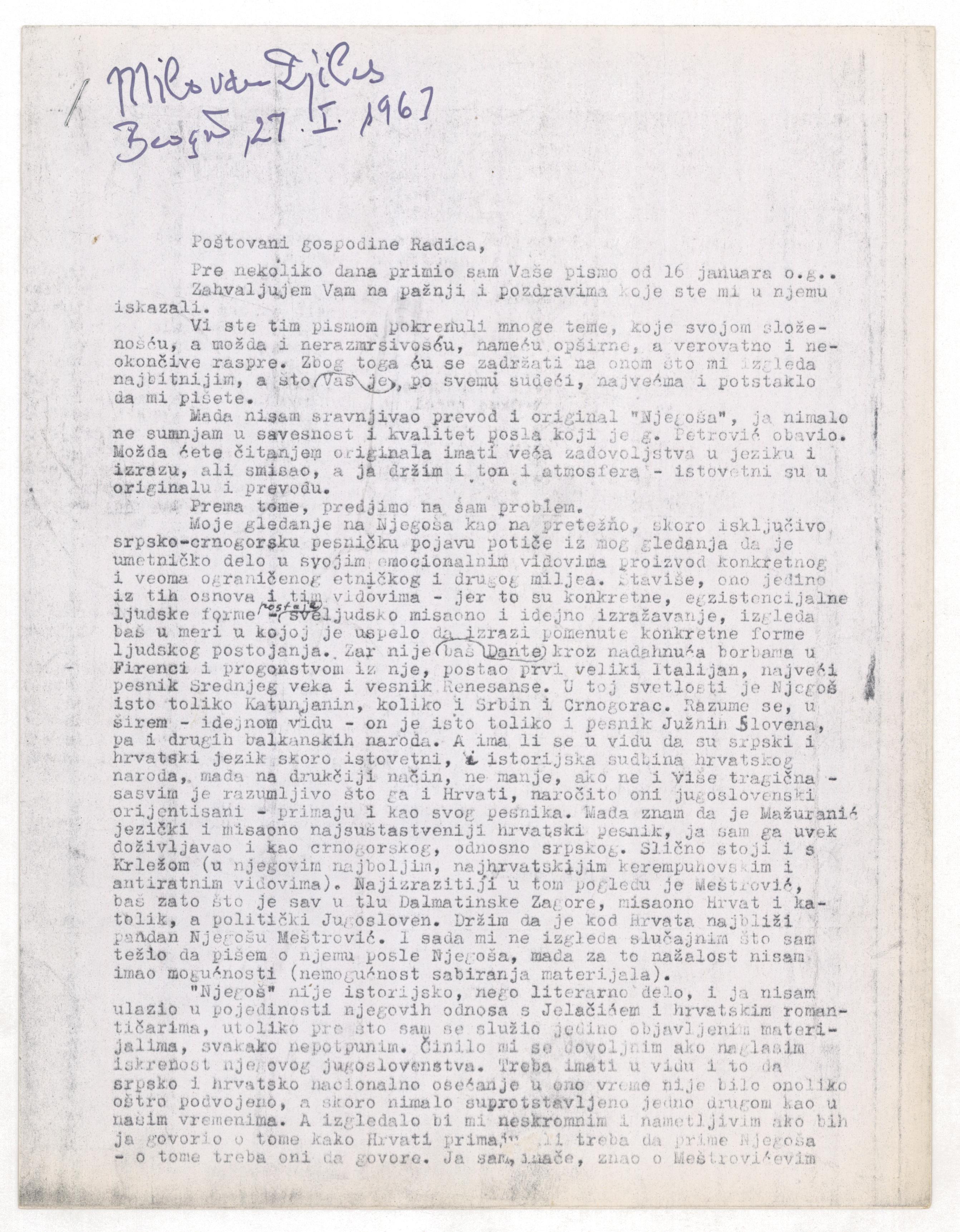

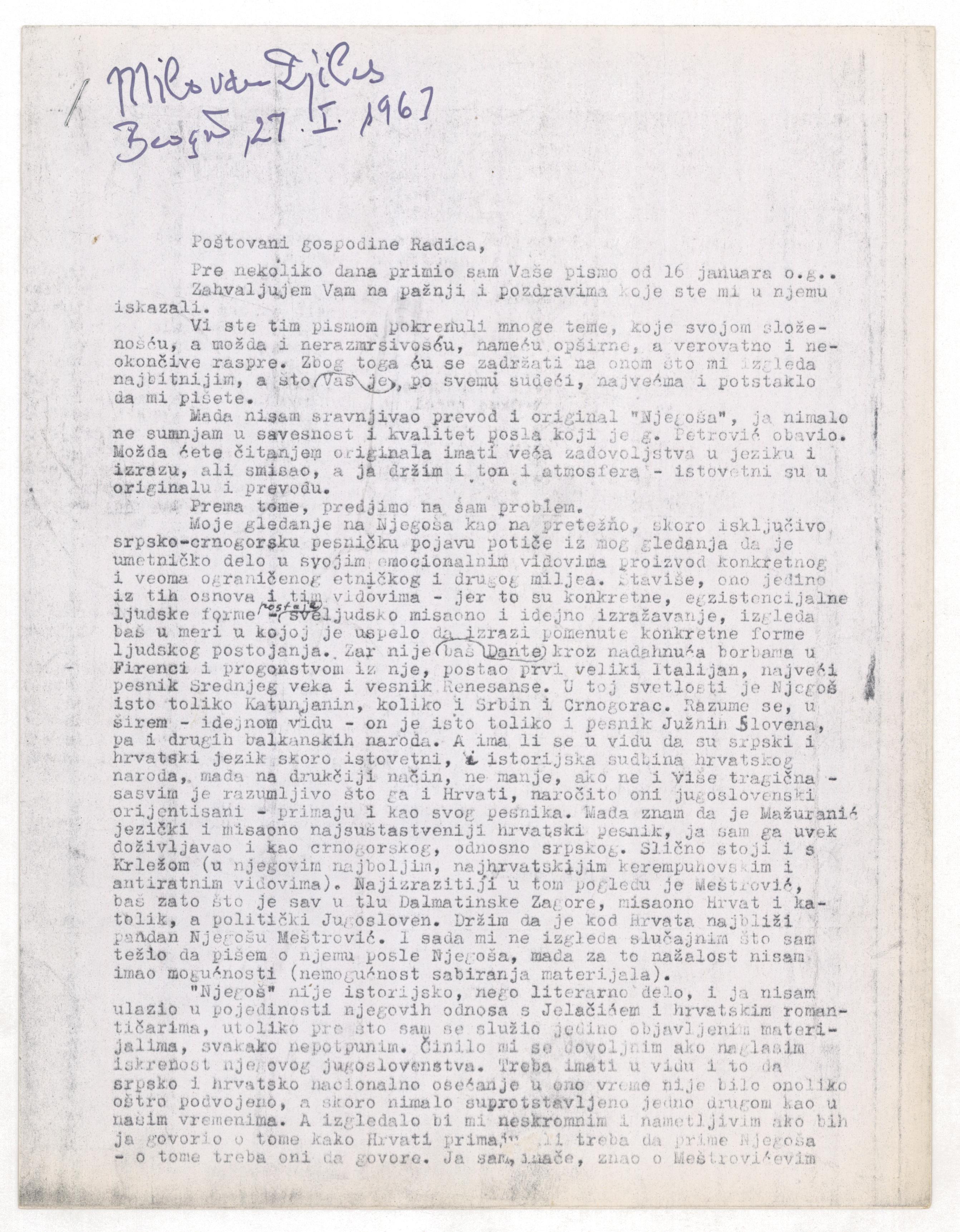

Milovan Đilas’ letter to Bogdan Radica was written in 1967 in Belgrade after Đilas had been released from prison. It was Đilas responding to Radica’s letter on 16 January 1967. The reason for this letter was Đilas' book titled Petar Petrović Njegoš: Poet, Prince, and Bishop published in 1966, in the USA. Their correspondence started after Radica had written about the life of Milovan Đilas and his conversion from a rigid communist to a dissenter. In the letter the first Yugoslav dissenter Milovan Đilas wrote to Bogdan Radica on matters relating to Croatian-Serbian relations, the question of Yugoslavia’s existence and the literary works of Petar Petrović Njegoš. Radica wrote about Đilas in a series of essays and articles in the American reviews and newspapers, more importantly, the article "The Idealism of Milovan Djilas" issued in 1963 in the review The Commentary.

Radica was fascinated how Đilas read Njegoš and how he abandoned Marxist literature, coming back as a traditional writer. So it happened that they both commented in the letter the influencing factors of Njegoš on Croatian and Yugoslav literature. Radica felt that Đilas failed to adequately explain the relationship between Njegoš and the Croats of his time, like Ban Josip Jelačić and Ljudevit Gaj. Nonetheless, Radica pointed out that Njegoš had a great influence on the moral workings and mentality of the Yugoslav communists. In addition, in 1952, he also refers to Đilas' work Legenda o Njegošu (The Legend of Njegoš), in which he postulated that Njegoš’s Russophilia was the cause as to why so many Montenegrins turned to Stalin during the time of the Tito-Stalin conflict in 1948. Radica thought that Đilas' communism could not be understood without looking the culture that was inspired by Njegoš’s works. Therefore, this was clearly the reason why Đilas returned to Njegoš after his fall and break with the Marxist regime in 1954. After all, according to Radica, Đilas' re-reading of Njegoš was an effort to find some intellectual harbourage after abandoning the Party.

Gábor Altorjay’s Fluxus object entitled Chess Preserve was realized as part of the action Chess!! In 1967 (Írószövetség, Budapest, April 12, 1967) – evoking Marcel Duchamp’s passion for chess. The action was accompanied by the following poem:

1. Preserve a set of chess!

2. Put on a dark suit, a white shirt and a tie!

3. Use 250 ml of perfume!

4. Put the chess set on a table in front of you!

5. Put on 3 pairs of rubber gloves!

6. Open the chess set and say out loud: “Chess!” and pour the chess pieces on your own head!

7. Point at the door and shout: “There he goes!”

Around this time, Altorjay was working on other similar “anti-artworks” which recontextualized everyday objects, for instance Short Circuit Instrument (1968) and Uncomfortable (1968). The reconstruction of the Chess Preserve was made by Artpool for the exhibition 3×4 (1993), and it was exhibited in other shows, as well (Impossible Realism, Artpool P60, 2001; Dada and Surrealism / Rearranged Reality, Hungarian National Gallery, 2014).

The Estonian Student Building Brigade collection contains material about the activities of the Estonian Student Building Brigade, a feature of student life in Soviet Estonia. The activities of this organisation are sometimes described as a free space, which is also reflected by this collection. The documents and artefacts show how students used the summer not only for building work but also for provocative entertainment and irritating the authorities. The Estonian Student Building Brigade has a relatively positive image, and is the only remarkable phenomenon from Soviet times which has ever been celebrated since the restoration of independence.

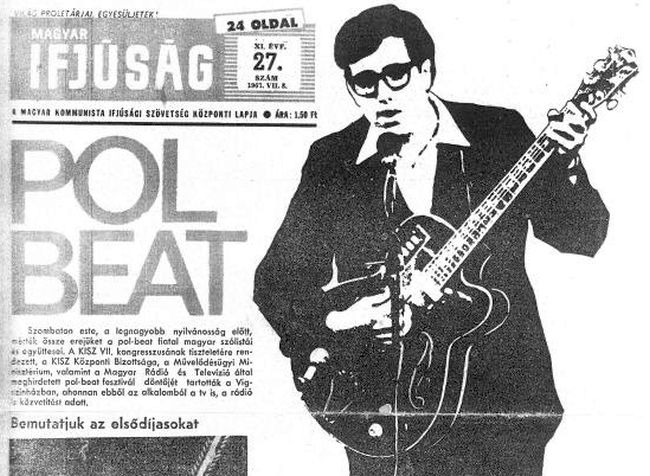

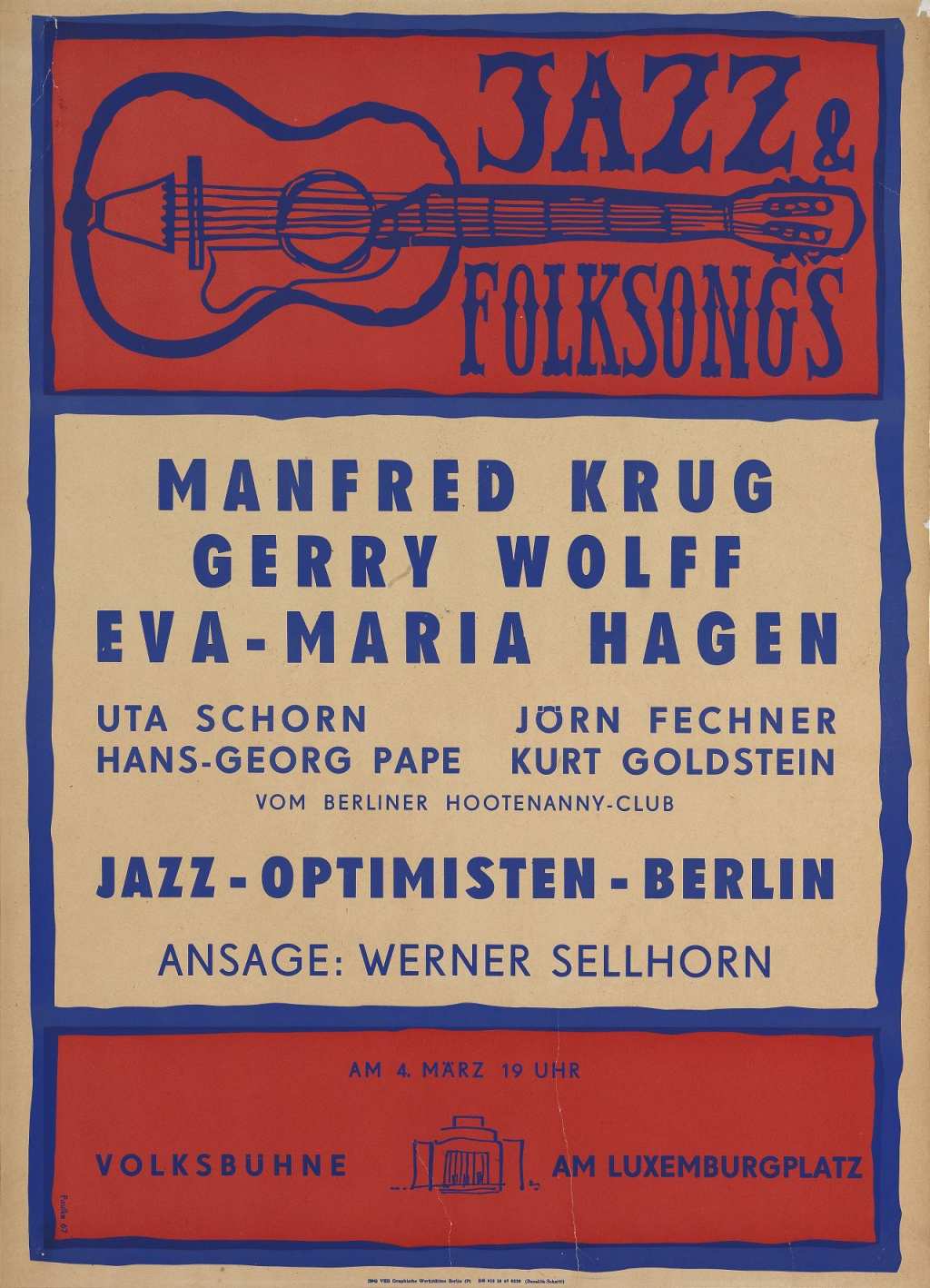

The event was the direct outcome of the anxieties of the political elite. The party and communist youth leaders were worrying about the growing youth interest in popular music. They realized that young people were influenced by rock and roll, the beat movement, and they frequented concerts which rapidly became hit events in socialist Hungary as in the West. The authorities also recognized that these events were more popular, the youth were singing the songs, dancing together, and, thus, these events had bigger emotional effects than political speeches. Accordingly, the political elite expected that youth attitudes could be shaped by the lyrics of popular songs and, therefore, cultural criticism could be avoided. Pol-beat came to Hungary from the West, where young people protested against consumer capitalism, alienation, mass production, and the Vietnam War. The Hungarian term for pol-beat was invented by Tamás Bauer. The protest song from the West (by Bob Dylan, Joan Baez) also became popular in Hungary.

The Vietnam War became the topic of the Hungarian protest songs, as well. This produced strange effects: if Hungarian youth protested against the Vietnam War and, thus, in their songs they reflected upon social problems in the West, they actually could confirm the legitimacy of power and, hence, the Communist Youth Federation supported them. In 1968, at a TV-show “Hello boys, hello girls” [Hallo fiúk, hallo lányok] Imre Antal, the host, called the pol-beat an innovative and useful genre and called on the audience to join the movement.

János Maróthy also supported the movement because he considered pol-beat the folk music of the city. He thought that the pol-beat and protest-song were contemporary revolutionary songs.

As head of the Brukenthal Museum’s ethnography section, which also included the Museum of Folk Technics from 1963, Cornel Irimie, together with other ethnographers and museologists working at the institution, conducted field research on several aspects of peasant culture in villages located in various parts of Transylvania throughout the 1960s. The research concluded with the writing of studies as well as with the acquisition of many icons painted on glass. Both activities contradicted the communist regime’s policy of combating and limiting religious practices in society. In spite of this, Irimie’s leading position within the institution and the authority he enjoyed nationally in the field of ethnology made local authorities turn a blind eye to these activities. Irimie argued that the icons on glass created in monasteries or in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century peasant handicraft centres, which he rescued due to his acquisition policy, were part of the national artistic heritage. In addition, he also took advantage of the relative cultural opening in the first years of the Ceauşescu regime (1965–1971) and published a series of research studies on icons painted on glass.His activities in this respect are reflected in the file entitled Icoane pe sticlă în arta românească (Icons Painted on Glass in Romanian Art) which includes the findings of his field research, drafts of certain scholarly works, and reports on the acquisition of icons painted on glass for the ethnography section of the Brukenthal Museum. A report drawn up by Irimie in July 1967 mentions that, as part of a programme from June–July 1967, a team of museologists, fine artists and photographers from the Brukenthal Museum, led by himself, had visited over 100 Transylvanian localities and acquired 474 icons. This broad field research and icon collection action was the basis for some of Irimie’s studies regarding icons on glass and for papers he presented at international conferences. In these scholarly contributions, Irimie analysed the stages in the development of religious glass painting techniques, created a typology of religious painting centres in Transylvania, and pointed out the kinship between them. Moreover, Irimie also analysed the art of masters who painted icons on glass, emphasising the influences of the Western and Eastern canonical religious painting, as well as the stylistic mark that peasant culture left on these icons. Notable among his publications on this topic is the album Icoane pe sticlă (Icons on Glass) that he published together with Marcela Focșa. It was later translated into English (as Romanian Icons Painted on Glass), French and German.

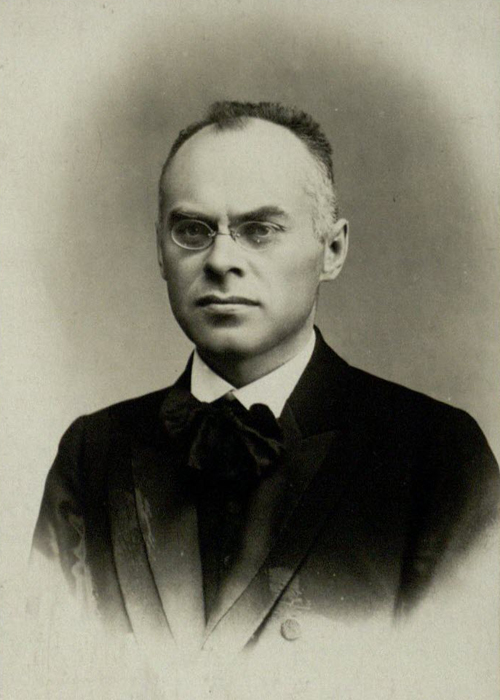

Augustinas Janulaitis was a famous Lithuanian national activist, an active member of the Social Democratic Party, a lawyer and historian. In 1945, he became dean of the Faculty of History at Vilnius University, and later a member of the Academy of Sciences. The Augustinas Janulaitis collection, which is kept in the Wróblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, holds various manuscripts of Janulaitis' work, and documents relating to his career and life in Soviet Lithuania. His letter to the president of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences reflects the difficult situation in 1946, when he was attacked by the Soviet authorities for bourgeois nationalism. To students, he was an example of an intellectual and a scholar of interwar independent Lithuania.