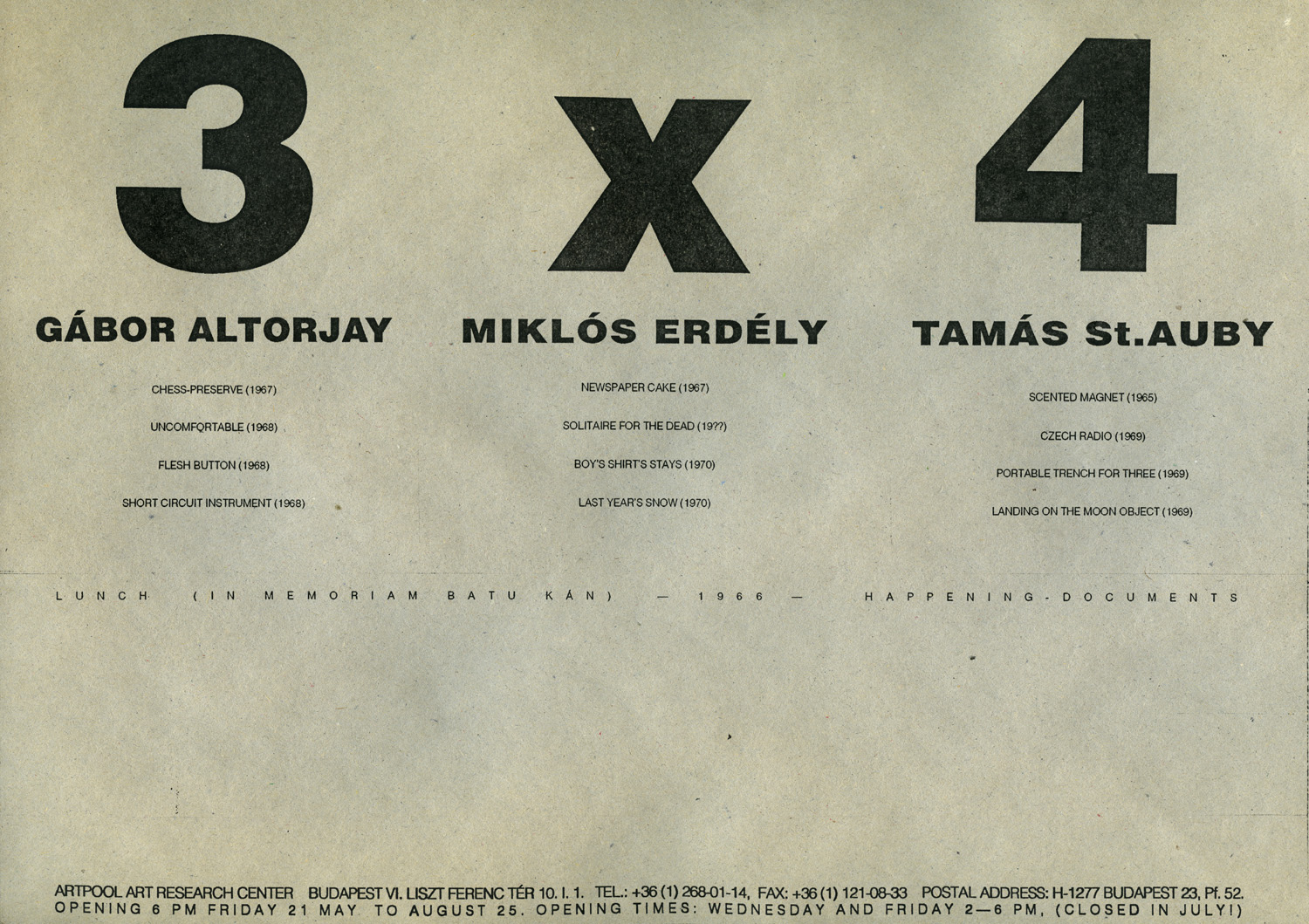

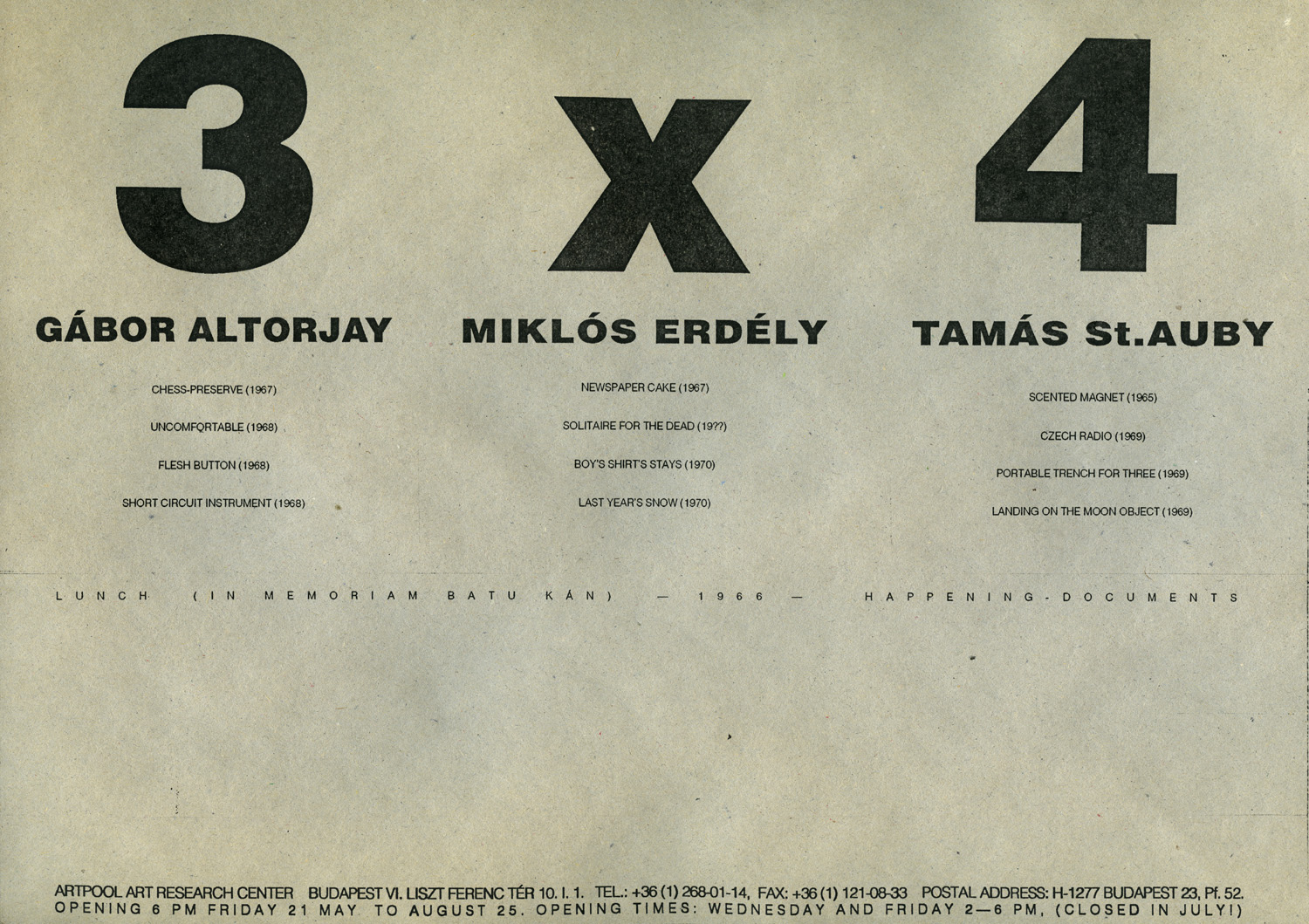

(Miklós Erdély: Newspaper Cake, 3×4, Artpool, Budapest, 1993)

The first realization of Miklós Erdély’s idea of the Newspaper Cake was made by Gábor Altorjay in 1967. The version in the Artpool’s collection was done on the occasion of the exhibition 3×4 in 1993 by the organizers following the original concept. Regarding Erdély’s idea in the 1960s, the “cake” is constructed of round newspaper cut-outs glued to one another and sliced up as a cake. Tamás Szentjóby referred to the cake as a dish that is “eaten by everybody every day,” interpreted as a metaphor, for “stuffing” society with information.http://www.artpool.hu/Fluxus/3x4/Erdely_ujsagtorta_en.htmlThe Collections from the Centre for Czechoslovak Exile Studies contain many unique materials associated with the key figures of Czechoslovak exile. The collections contain archived materials that are related to exile not only in Europe but around the world, including Latin America and Australia.

The National Gallery of Art in Lithuania holds a collection of artworks from the 20th century. The collection includes paintings, sculptures and prints by artists who worked in Soviet Lithuania, as well as by artists who lived abroad. During the postwar period, the style of Socialist Realism was imposed on artists who remained in Lithuania. From the 1960s onwards, the main goals of Lithuanian artists were to preserve the national identity and continue the modernist tradition. With no active or direct links with Western art, artists developed individual versions of Realism, Expressionism, Surrealism, Abstraction, and other tendencies in modern art. Some of these works can be ascribed to the cultural opposition.

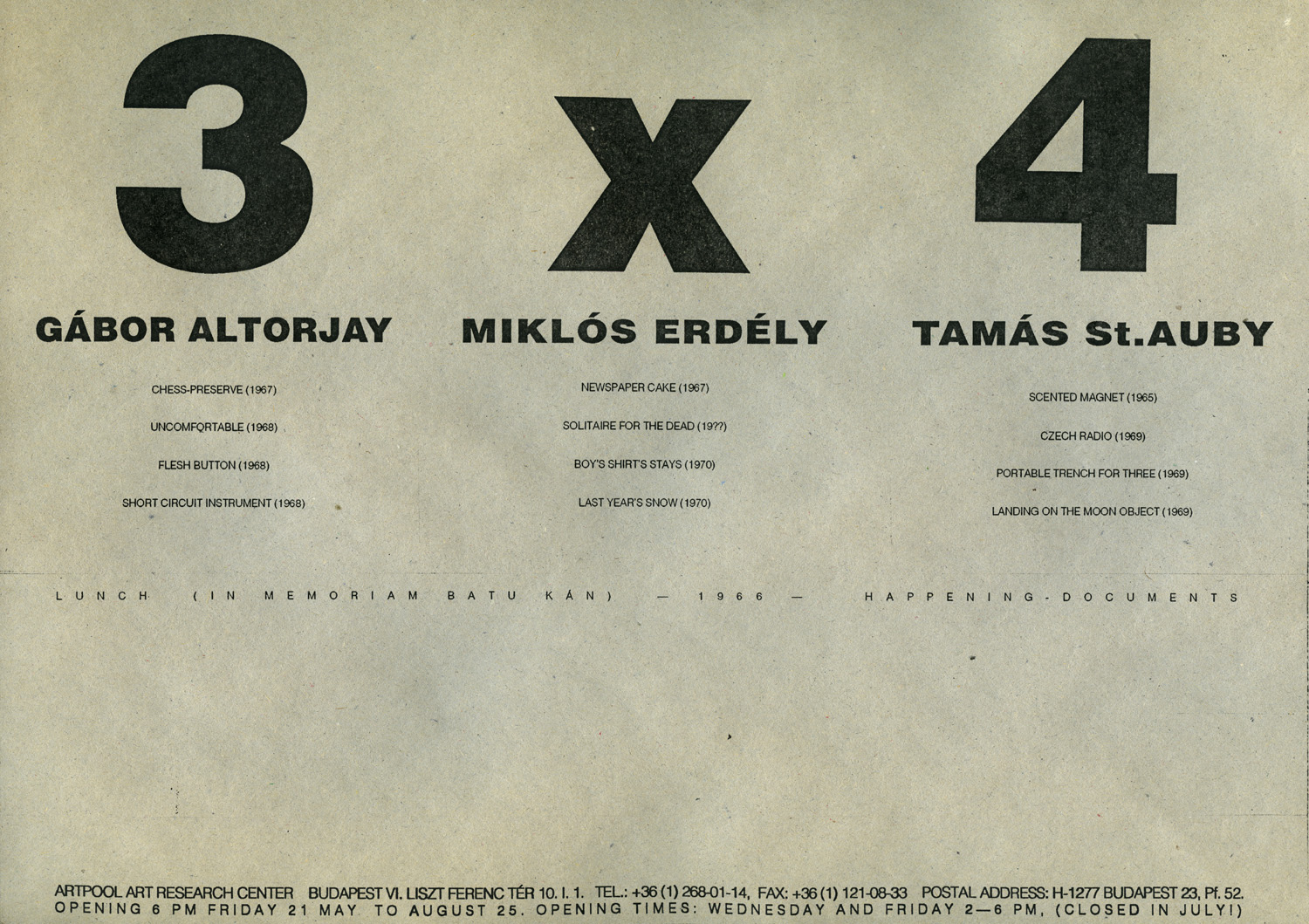

(Artpool Art Research Center, 21 May-25 August, 1993)

At the exhibition of Gábor Altorjay, Miklós Erdély, and Tamás Szentjóby, 12 Fluxus objects were presented from the 1960s. The exhibition also included the screening of the video documentation of the first Hungarian happening with the title The Lunch (In Memoriam Batu Khan), presented by Gábor Altorjay and Tamás Szentjóby on June 25, 1966. Miklós Erdély was the person who suggested the basement of a flat in Budapest as the venue for the happening and also some ideas regarding the happening itself. The works on exhibit included Fluxus objects like Newspaper Cake (1967) and Boy’s Shirt’s Stays (1970) by Miklós Erdély; Chess Preserve (1967) and Uncomfortable (1968) by Gábor Altorjay; as well as Czechoslovakian Radio (1969) and Landing on the Moon (1969).http://www.artpool.hu/Fluxus/3x4/Beke_en.html

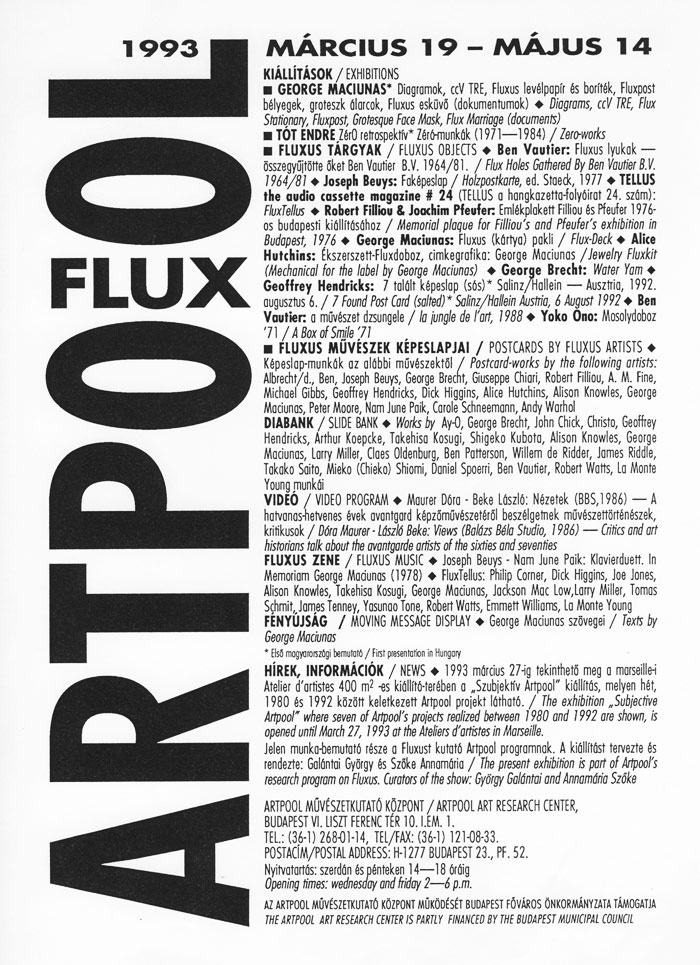

(Artpool Art Research Center, 19 March-14 May, 1993)

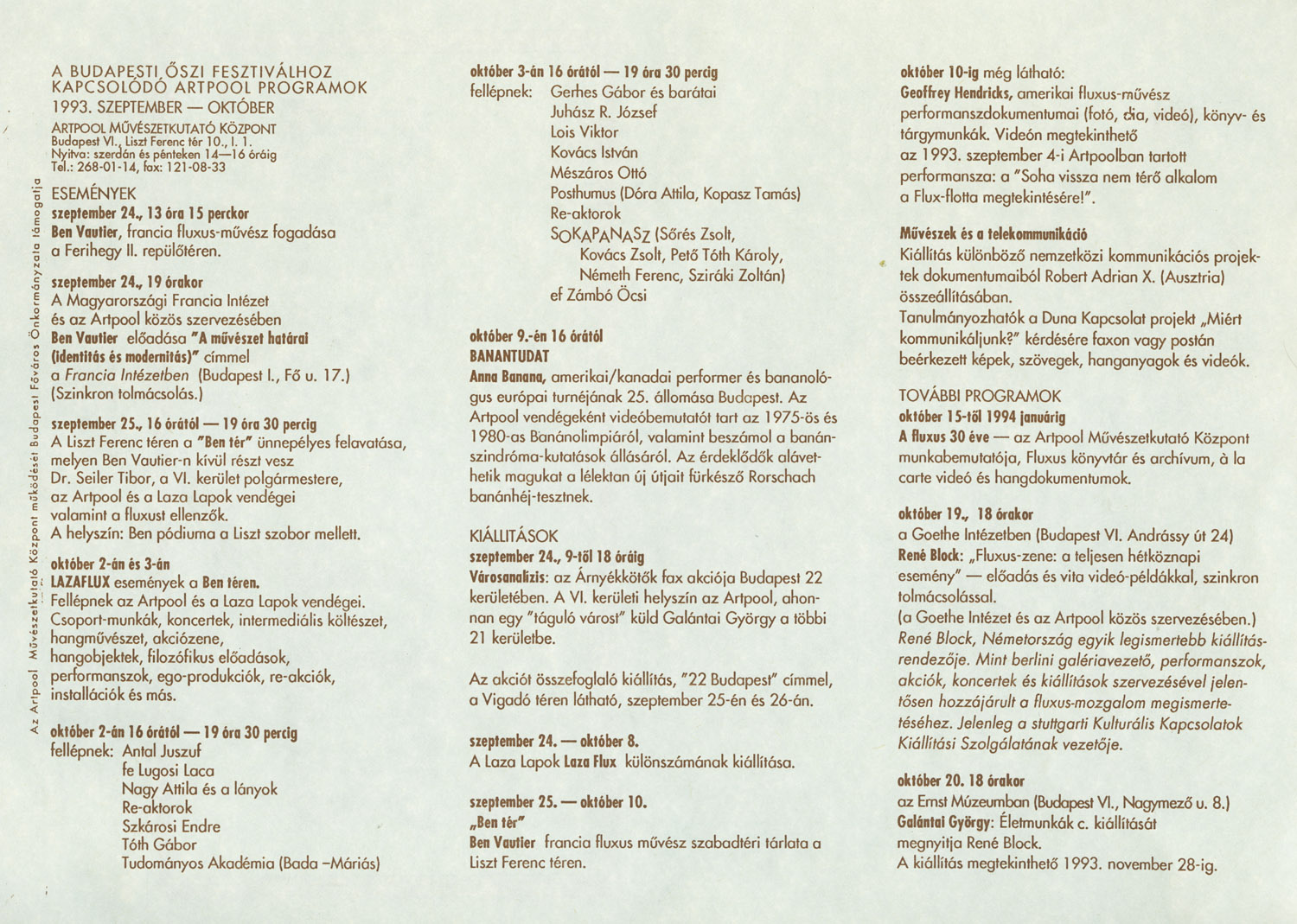

The great scale study exhibition entitled Artpool Flux organized by Artpool included George Maciunas’ first exhibition in Hungary (Diagrams, ccV TRE, Fluxus Writing Paper and Envelope, Fluxpost Stamps, Grotesque Mask, Fluxus Wedding); the retrospective of Endre Tót’s Zer0 works; the presentation of fluxus postcards of Ben Vautier, Joseph Beuys, George Brecht, Robert Filiou, etc.; and the fluxus show entitled Slidebank – with works by Geoffrey Hendricks, Shigeko Kubota, Claes Oldenburg, Daniel Spoerri, La Monte Young, etc. In the frameworks of the Video Program the film Point of views by László Beke and Dóra Maurer was screened; as part of the program Fluxus Music the audience could listen to the Piano Duett. In Memoriam George Maciunas by Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik, and the piece Fluxtellus. On an electronic message display texts of George Maciunas were shown.

http://www.artpool.hu/1993/930319_e.html

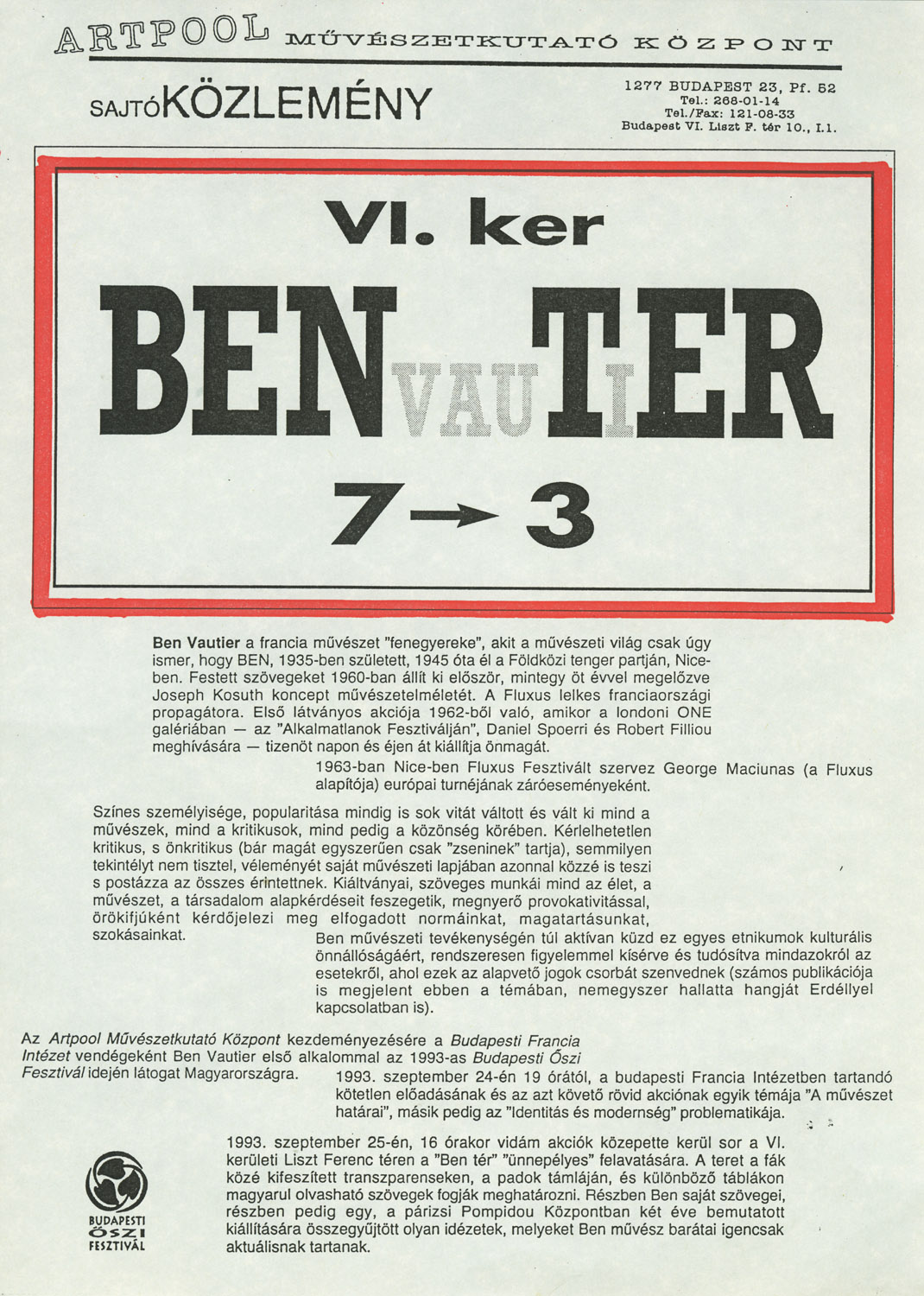

(Liszt Ferenc Square, Budapest, September 25, 1993)

Ben Vautier and György Galántai presented their common project BEN (vauTiER) TÉR within the framework of the Budapest Autumn Festival in September 1993. Vautier visited Budapest at the invitation of Artpool. The title and the basic idea of the exhibition came from the common practices used by the movement of Fluxus, such as word-collage (Georges Maciunas) and letter-exchange (Ray Johnson). Through the project, the Liszt Ferenc square as the location of Artpool Art Research Center turned into “Ben tér” (Ben square) for the time of the event. On giant banners among the trees and on the backrests of the benches, Hungarian translations of statements by Vautier could be read. The artist’s inscriptions appeared on “Ben's podium,” which was set up for the project. The inauguration started with Vautier’s action Tout, rien et n’importe quoi (All, Nothing and Anything). Through the day-long project, the podium and the square turned into the site of several spontaneous Fluxus actions and performances with the participation of the audience through singing, dancing, and discussion. The assistants of the spontaneous event were Júlia Klaniczay and Gábor Tóth. Additional participants included Jonas Mekas, Antal Juszuf, the “Yugoslavian Scholars.”http://www.artpool.hu/1993/930925_e.html

Part of a civic and ethical project with no equivalent in any of the other former communist countries of Europe, the Museum collection of the Sighet Memorial is an extraordinary site of memory, both individual and collective, of Romanian communism seen from the perspective of the victims of the regime. The Museum collection of the Memorial to the Victims of Communism and to the Resistance includes an impressive number of documents, photographs, letters, newspaper collections, books, manuscripts, albums, and various other objects illustrating both the repressive dimension of the communist regime in Romania and the reaction of Romanian society to that regime, in accordance with the vision promoted by the Civic Academy Foundation through the intermediary of the International Centre for Studies into Communism.

Among the manuscripts of Adrian Marino’s works in his collection, his memoirs entitled Viaţa unui om singur (The life of a lonely man) stand out through the virulent criticism of the Romanian literary life of the period 1964–1989. The manuscript is a printed text, in A4 format, containing 633 pages. The posthumous publication of this volume of memoirs in 2010 generated a heated debate in the Romanian press concerning the relationship of the Romanian intellectuals with the communist regime, which attracted special attention to the case of Marino himself. A first draft of his memoirs, which stopped in 1989, was written between February and December 1993. Dissatisfied with this first draft, Marino rewrote the text in the second half of the 1990s, adding the post-1989 period as well. The author relied on his personal archive, especially the correspondence, to reconstitute in detail events that had taken place decades before. Marino’s memoirs represent – beyond the story of the life of an intellectual under communism – a critical analysis of literary life and of the relationship between the intellectual and the authorities in communist Romania. In this respect, Marino criticises the compromises made by a series of Romanian cultural figures during the communist period, for example, the historian and literary critic George Călinescu, and attempts to explain what he calls the “mass collaboration” of Romanian intellectuals. According to Marino, this phenomenon can be explained by the “total lack of tradition and civic consciousness of the liberal democratic-Western type” of the Romanian intellectuals, who are “structurally, organically, and traditionally conformist and obedient,” all the more so in the communist period, when they depended from an economic point of view “wholly on the State” (Manuscript, 71; Marino 2010, 57). This last aspect of the intellectuals’ economic dependence on the institutions of the communist state was analysed by the American anthropologist Katherine Verdery through the concept of “mechanisms of bureaucratic allocation” (Verdery 1991, 94). The “mechanisms of bureaucratic allocation” of resources and the competition among intellectuals for accessing them represented instruments through which the communist authorities co-opted the intellectuals in order to implement certain cultural policies to legitimate their power (Verdery 1991, 94). Trying to escape this mechanism through which intellectuals were turned into instruments, Marino chose not to work in an official cultural institution, explaining this option in his memoirs: “I was and I remain a ‘free man.’ [...] I owe nothing to the communist regime. I was and I have remained foreign to any idea of ‘social career,’ university, academic, etc. I was and I have remained since my release from prison (1963), a complete freelancer, with no ‘employment record,’ not listed on any ‘payroll,’ etc.” (Manuscript, 309; Marino 2010, 254). Thus, Marino tried to avoid the subordination of his intellectual work to the “official culture” (Manuscript, 309; Marino 2010, 254), by which he meant those cultural products created in accordance with the cultural policies of Ceauşescu’s regime. Instead, Marino claimed to be part of the so-called “alternative culture,” by which he understood those cultural products which did not follow the official guidelines, but escaped censorship. (Manuscript, 309; Marino 2010, 254). In fact, Marino`s books received publishing permission from the censorship authorities, and consequently these books were published by state publishing houses. This means that these cultural products were tolerated by the regime, which never ordered the withdrawal of his published books from bookshops or libraries.

The Oral History Collection of the Sighet Memorial contains several thousand testimonies of great relevance for what the Romanian communist regime meant in general and especially for the prison experience of thousands of former political detainees. The distinctiveness of this oral history collection is strictly connected to the recovery and systematic conservation of the memory of those who went through significant traumatic experiences during the communist regime, with the aim of saving from oblivion that part of history which was officially suppressed until 1989, but which emerged spontaneously to the surface immediately after the change of regime.

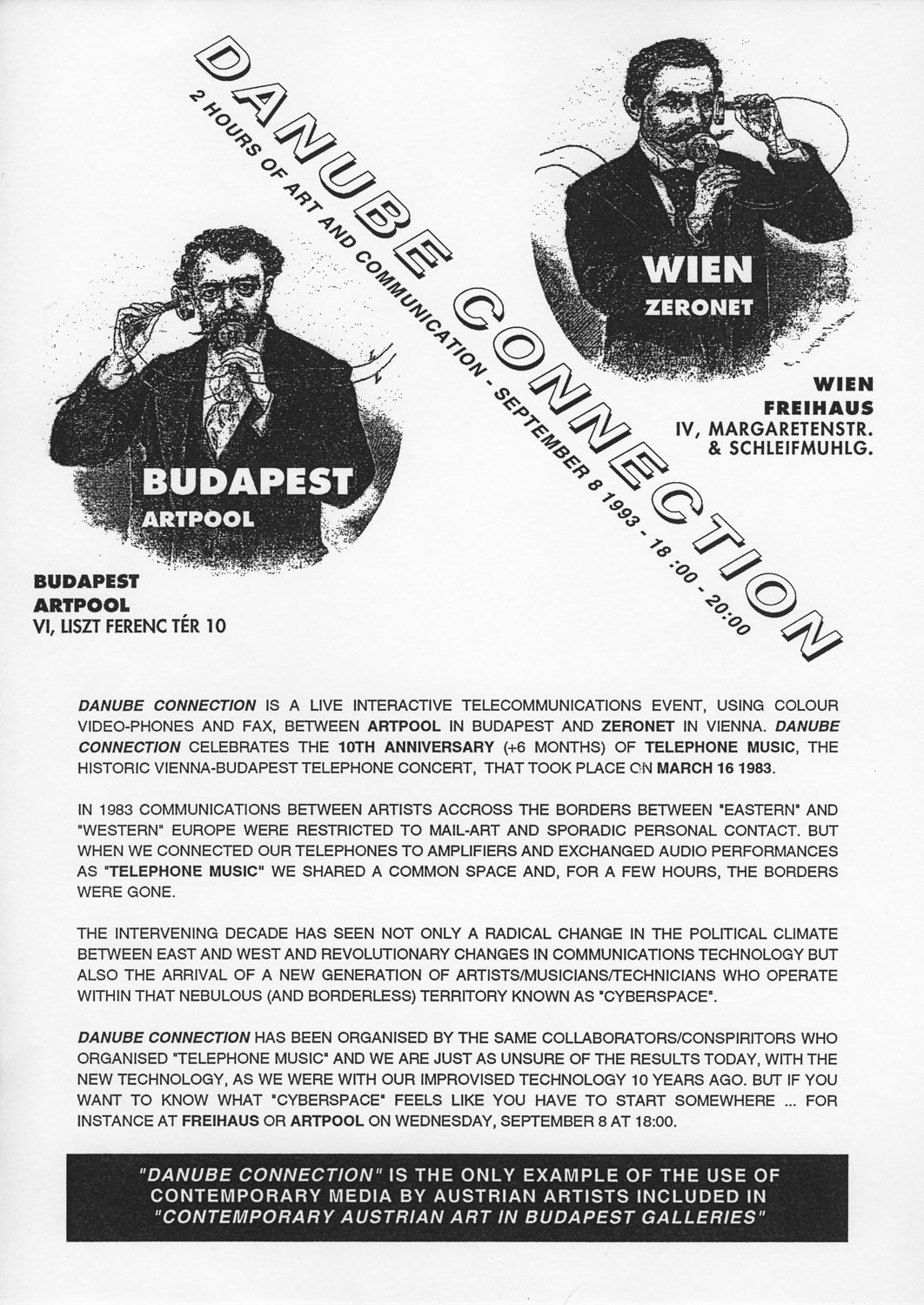

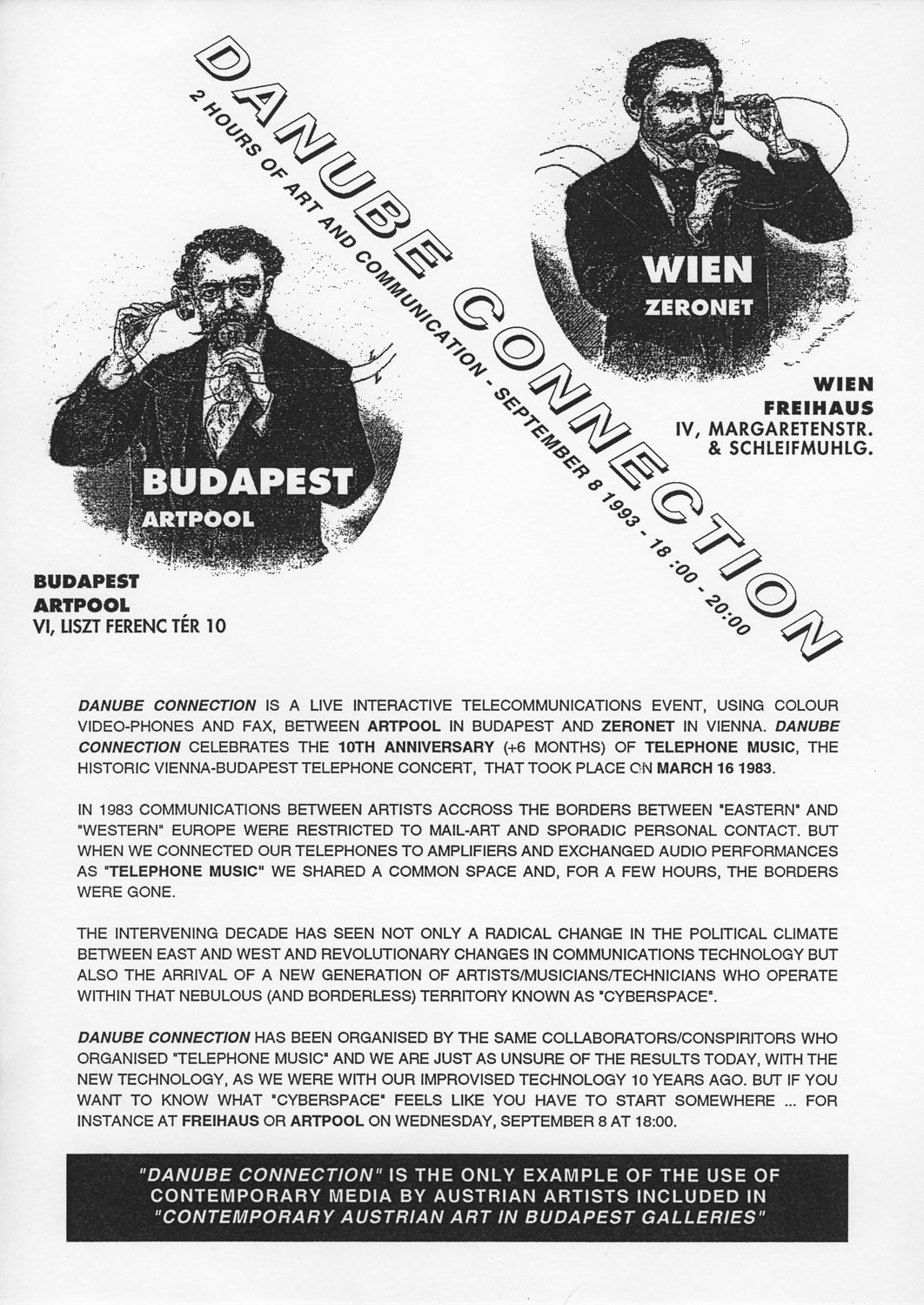

The Danube Connection – electronic communication happening for two telephone lines and a picture-phone: the live low budget interactive telecommunication event between the Freihaus-Kunstlabor in Vienna (with the cooperation of Robert Adrian X) and Artpool Art Research Center in Budapest, took place in September 1993. Materials received via post and fax were integrated spontaneously in the connection. The event was an homage to the telephone concert in 1983. It was organized as part of the Austrian-Hungarian gallery-cooperation project “Playing without borders.” Participants in the live event included Robert Adrian X and Mia Zabelka from Vienna and Júlia Klaniczay, György Galántai, Paul Dutton, János Szirtes, and Endre Szkárosi from Budapest.

The Audiovisual Section of the Libri Prohibiti library contains recordings of non-conformist music and spoken word, underground lectures and seminars. It also contains video-documents and amateur film productions. The unavailability of the original recordings and total content consisting of thousands of exemplars makes the collection unique in the Czech context.