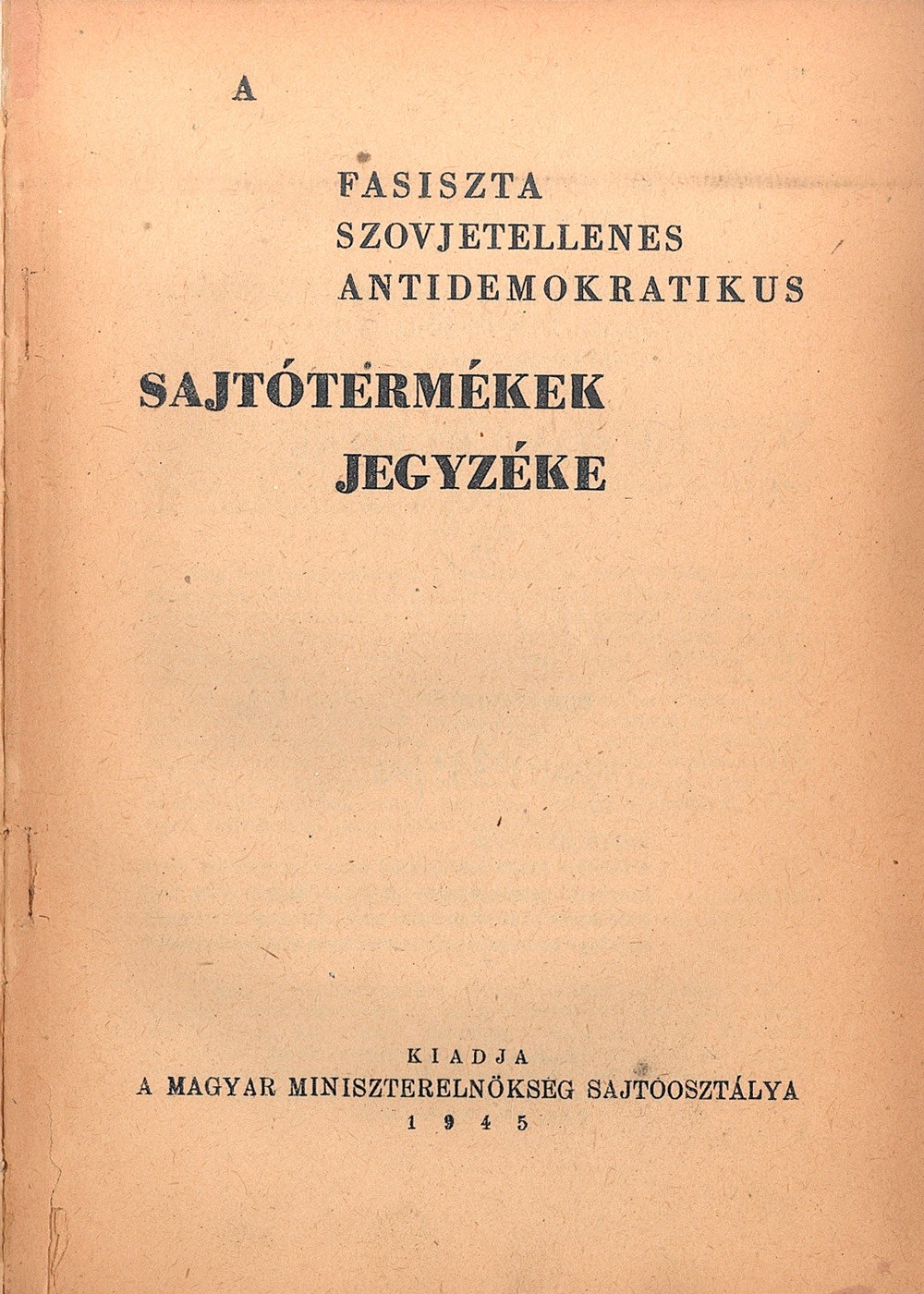

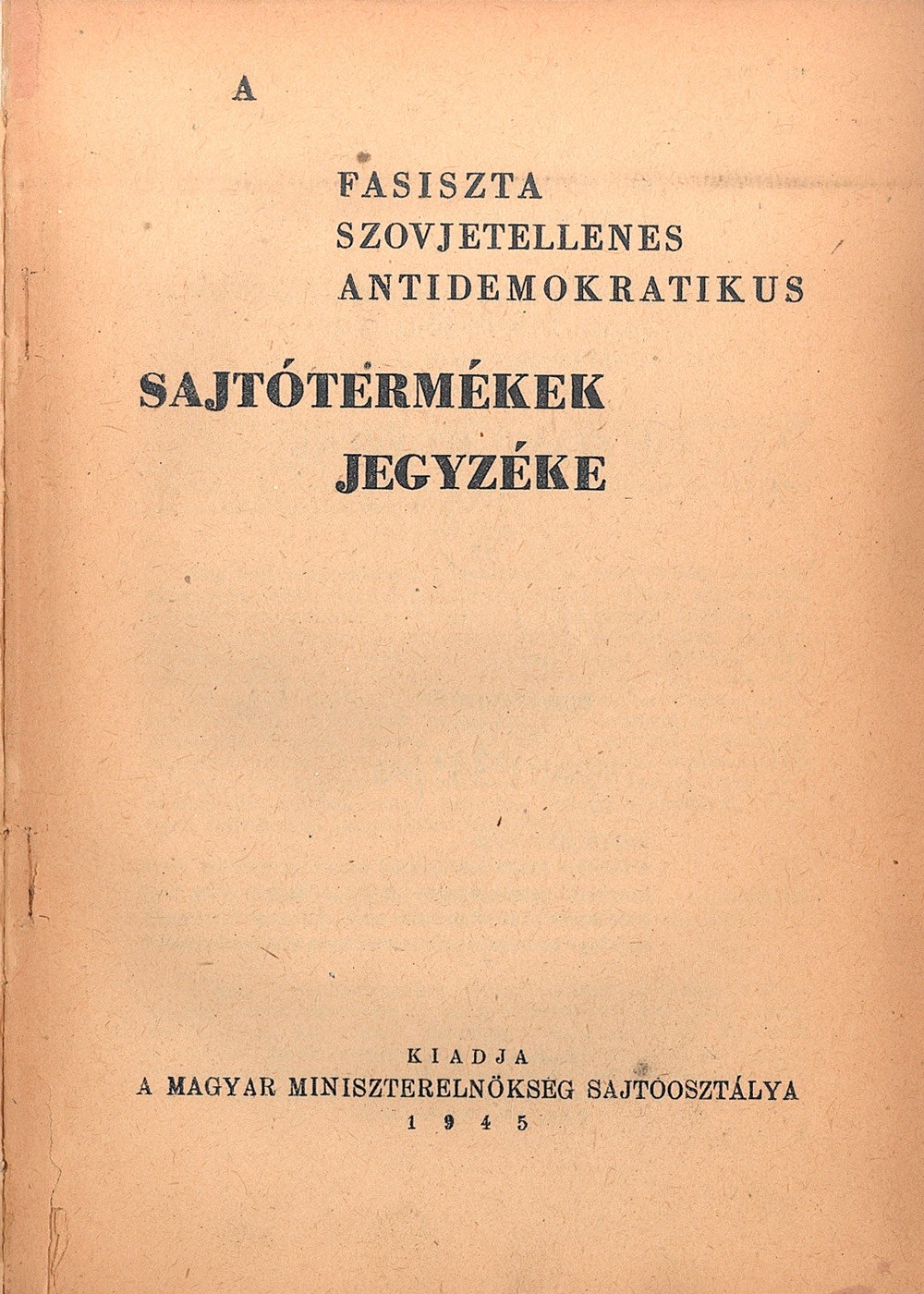

The Closed Stacks Department of the National Széchényi Library (OSZK) was established in 1946. Everything that was not permitted by the censors and could not be part of the public collection of the library was put here. The librarians argued that the task of the national library was to collect every type of publication regardless of its content. The books and journals which were published by Hungarians who fled the country after the Revolution of 1956 added to the number of items. The department became a meeting point for members of the emerging opposition in the 1980s, which created an opportunity to get actual samizdat writings.

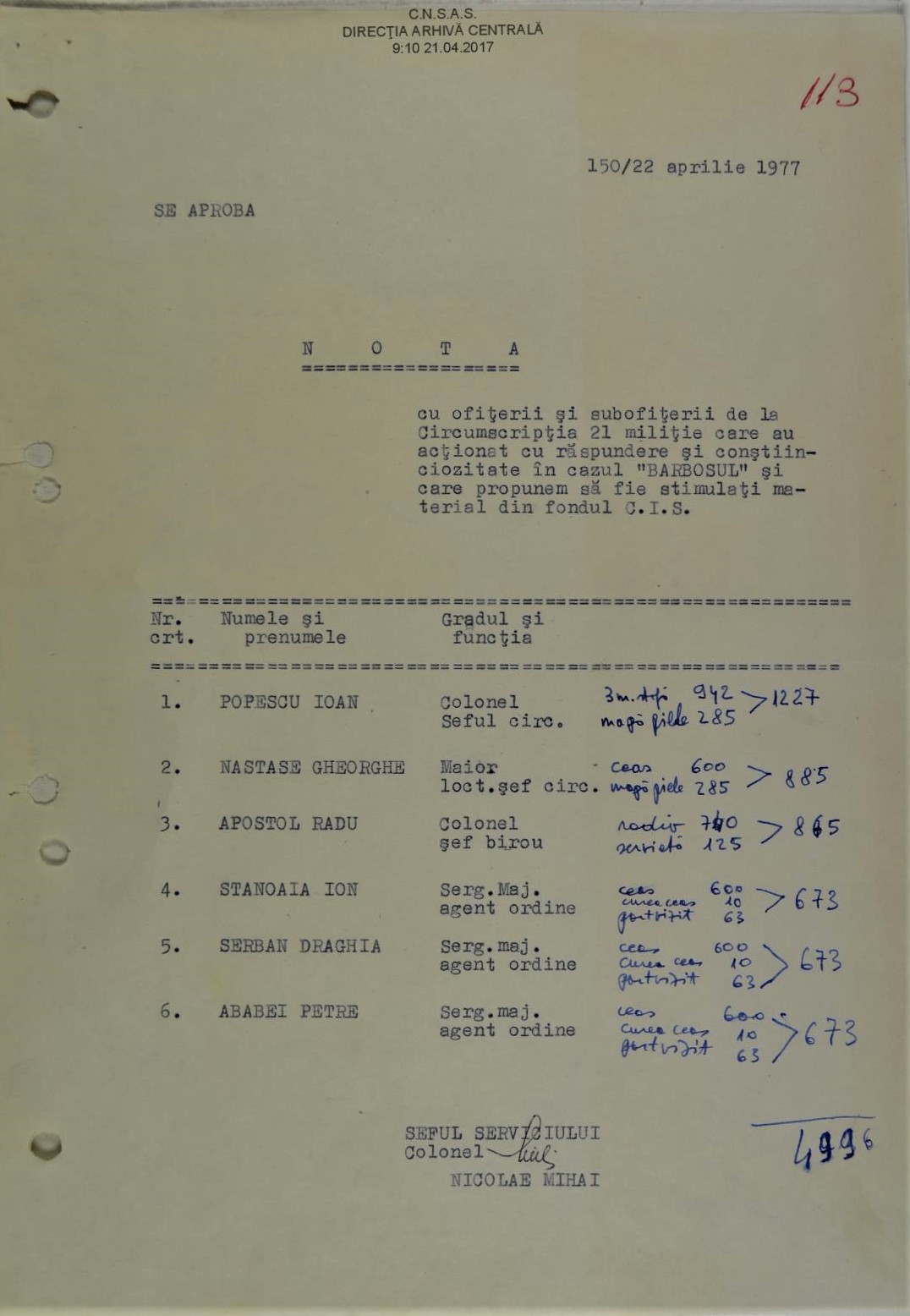

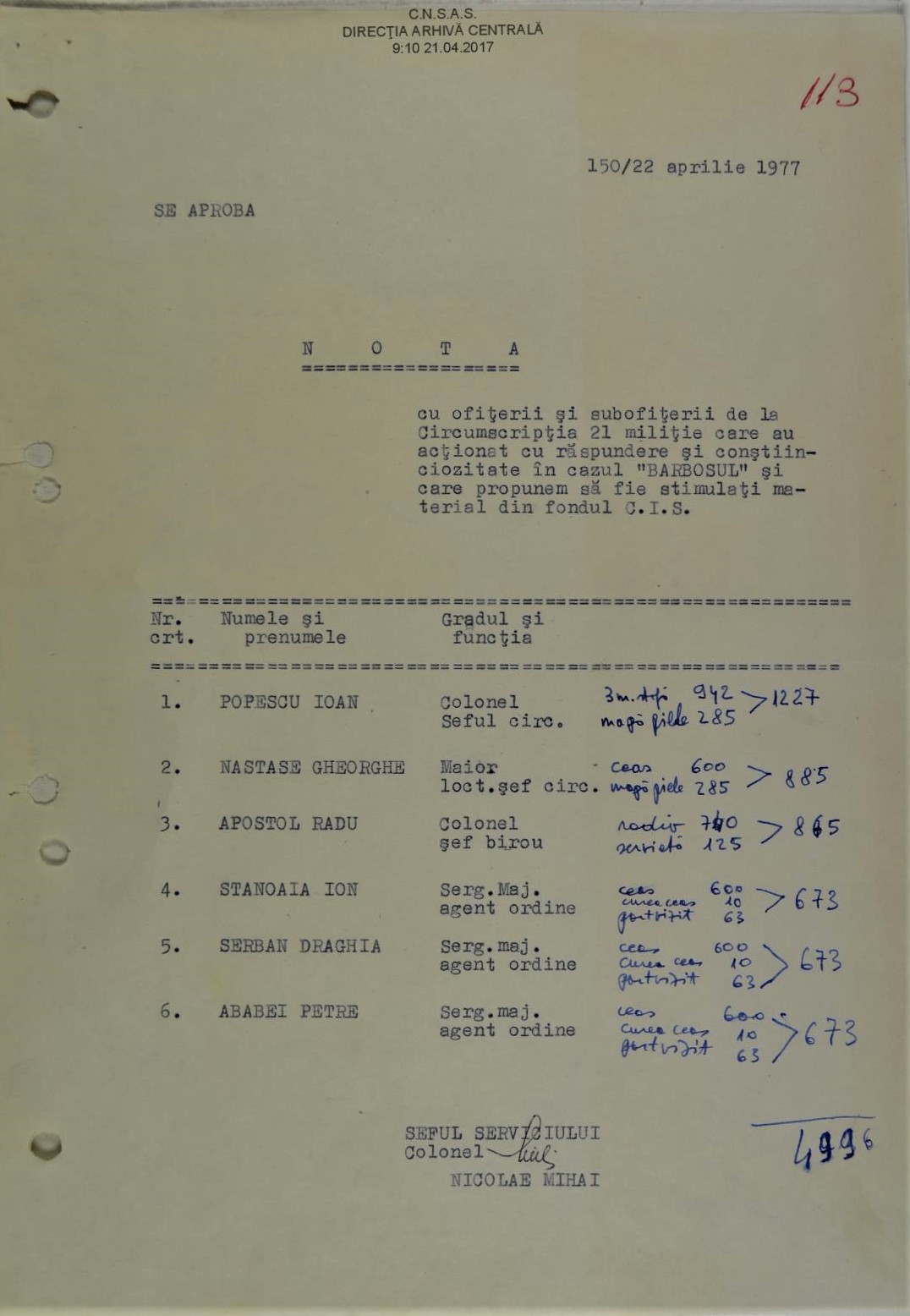

Even Paul Goma has characterised this document as a tragi-comical one. The note contains a list of the Militia officers who were involved in his case, whom the Securitate officers asked their superiors to reward for helping in this mission. The rewards were: 3 metres of cloth and a leather folder for the commander, watches, leather briefcases, leather wallets and radios for the others. Usually, the Securitate rewarded its informers with small amounts of money and some cheap products. They rather preferred to facilitate various services. This note is unusual because this is about rewarding some Militia officers. Besides the amusing aspect regarding the modest level of this reward, the document is relevant for the relation between the secret police, the Securitate, and the Militia, because the money for procuring these items originated from the Securitate’s financial funds. The document qualifies as a masterpiece of the collection especially because of its uniqueness, which can be explained only by considering how unusual was the emergence of the Goma Movement for the Romanian secret police. The Securitate officers faced for the first time the taking shape of a large coherent movement, so they used all possible methods in order to curtail its development. This small document is a rare piece of evidence regarding the subordination of the Militia to the Securitate, which otherwise it is not obvious from the documents in the CNSAS Archives (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/10, f. 113-114).

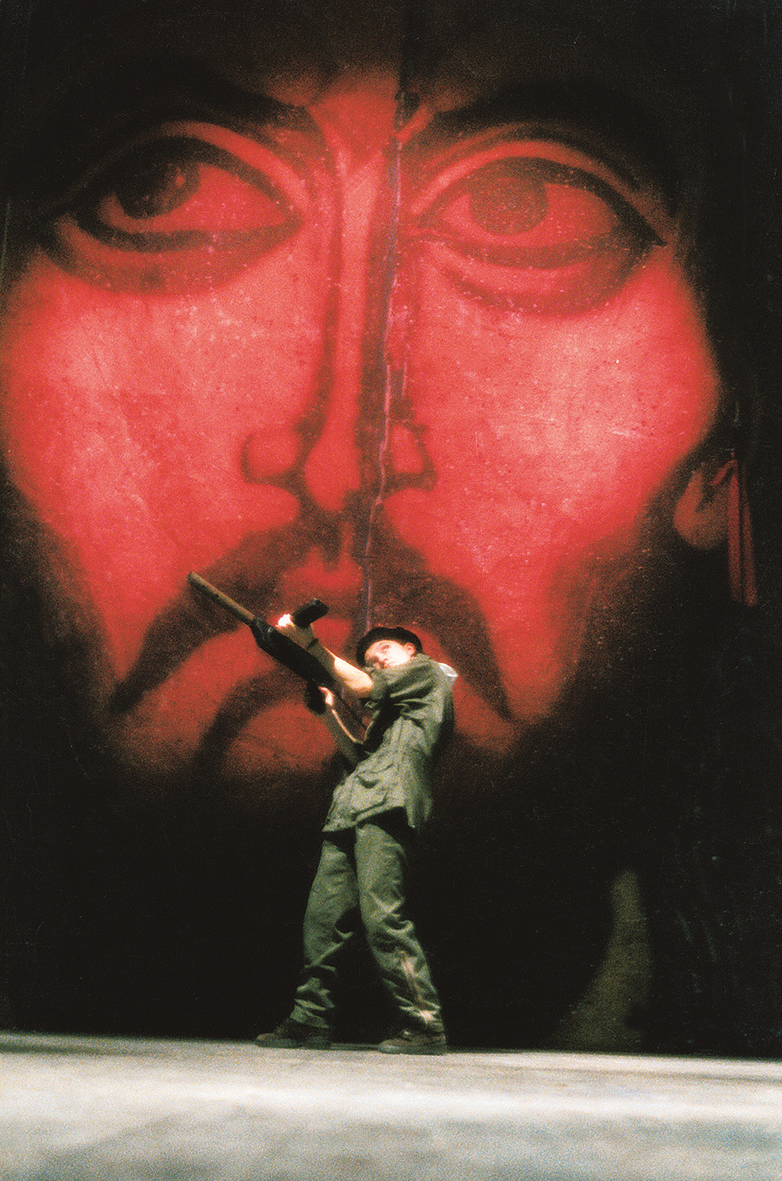

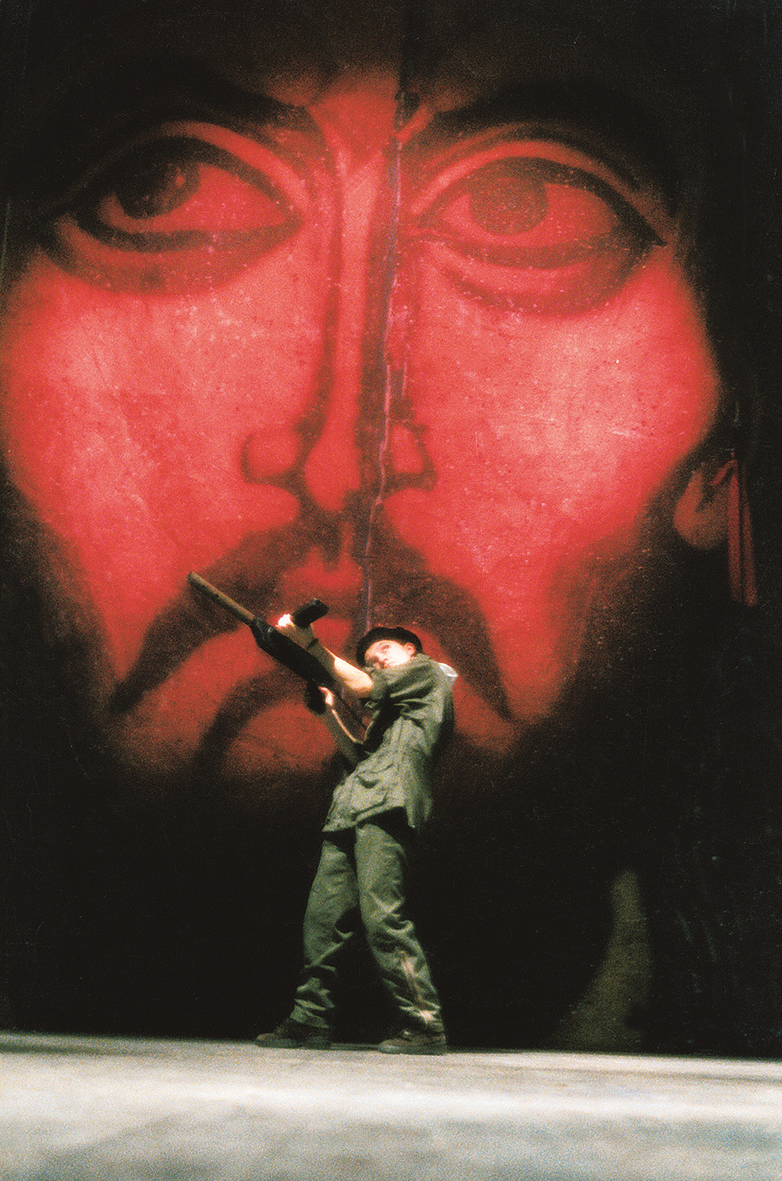

Keston has 69 anti-religious and political propaganda posters, though it remains unknown how the Keston Institute acquired them. Archivist Larisa Seago deduces that they likely came from different sources over time. The poster featured here was created by V. Zharinov in 1977, as part of the set “Razum protiv religii” (or “Together Against Religion”). 40,000 copies were printed. A. Karasev and S. Rezin were the authors of the rhyme used in the image: “Honest people’s sacred duty is to save children from the church’s darkness.” This poster is a reminder of the Soviet state’s foundational atheism and efforts well into the 1970s to dissuade and discourage the life and work of faith communities throughout the USSR.

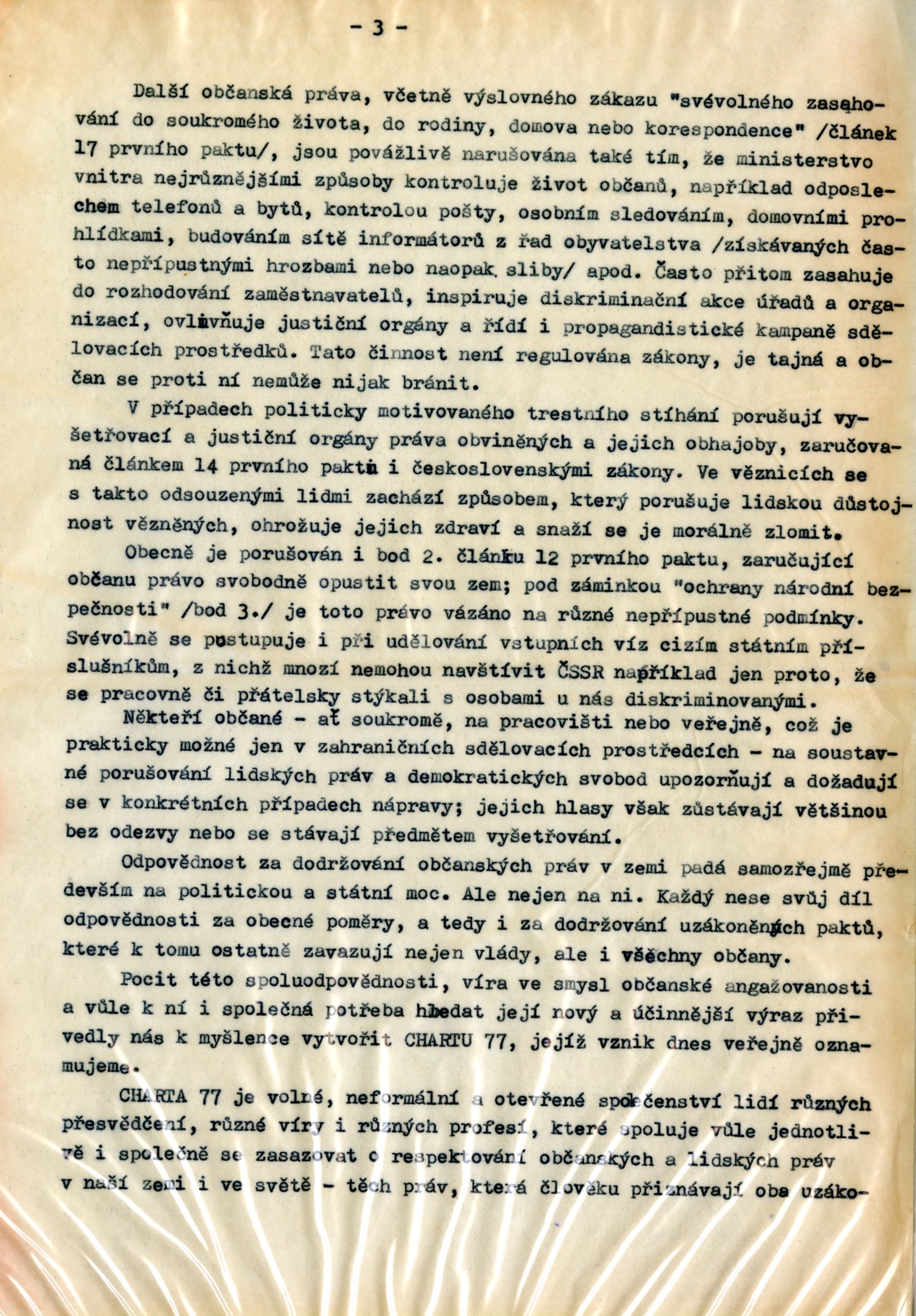

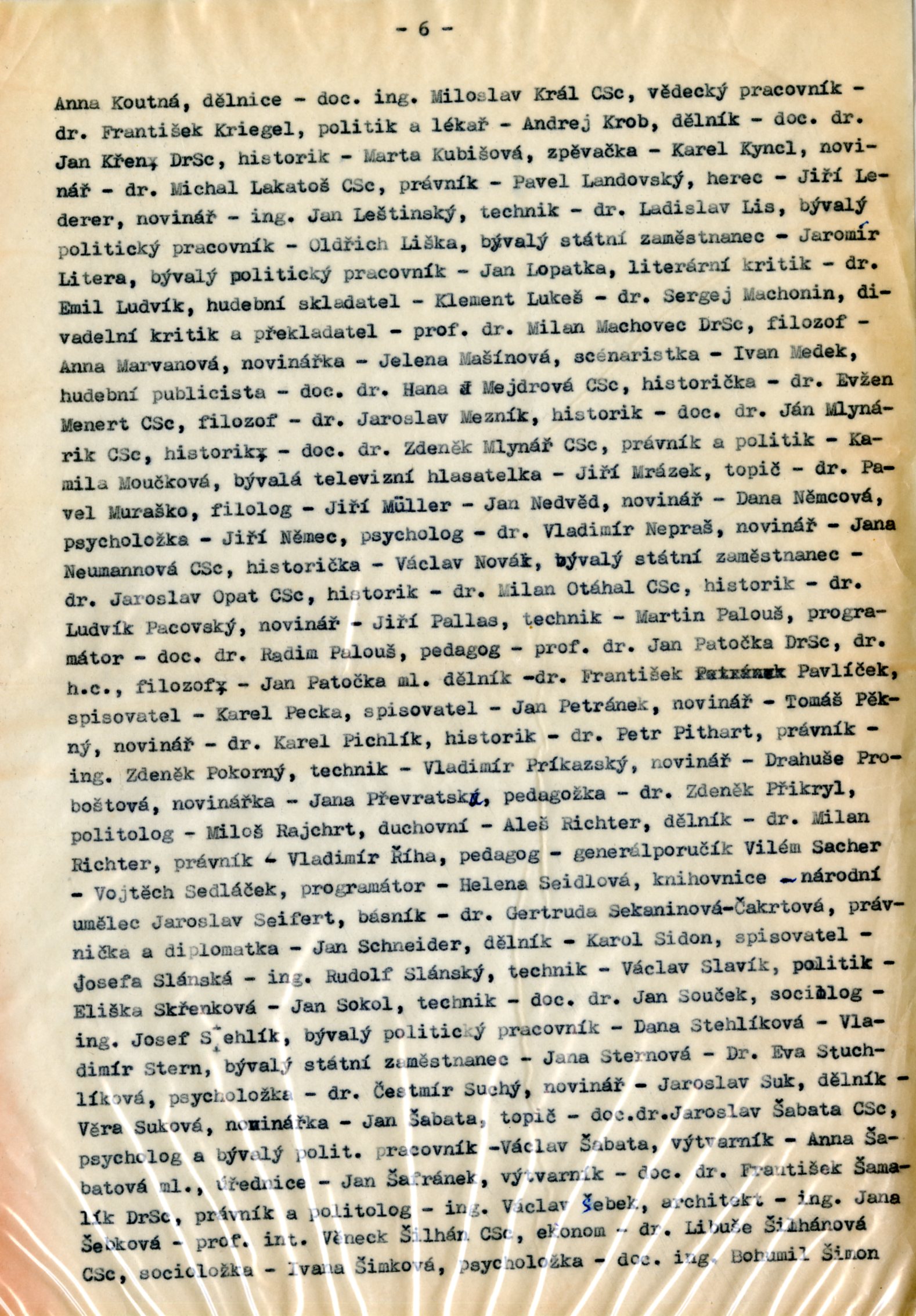

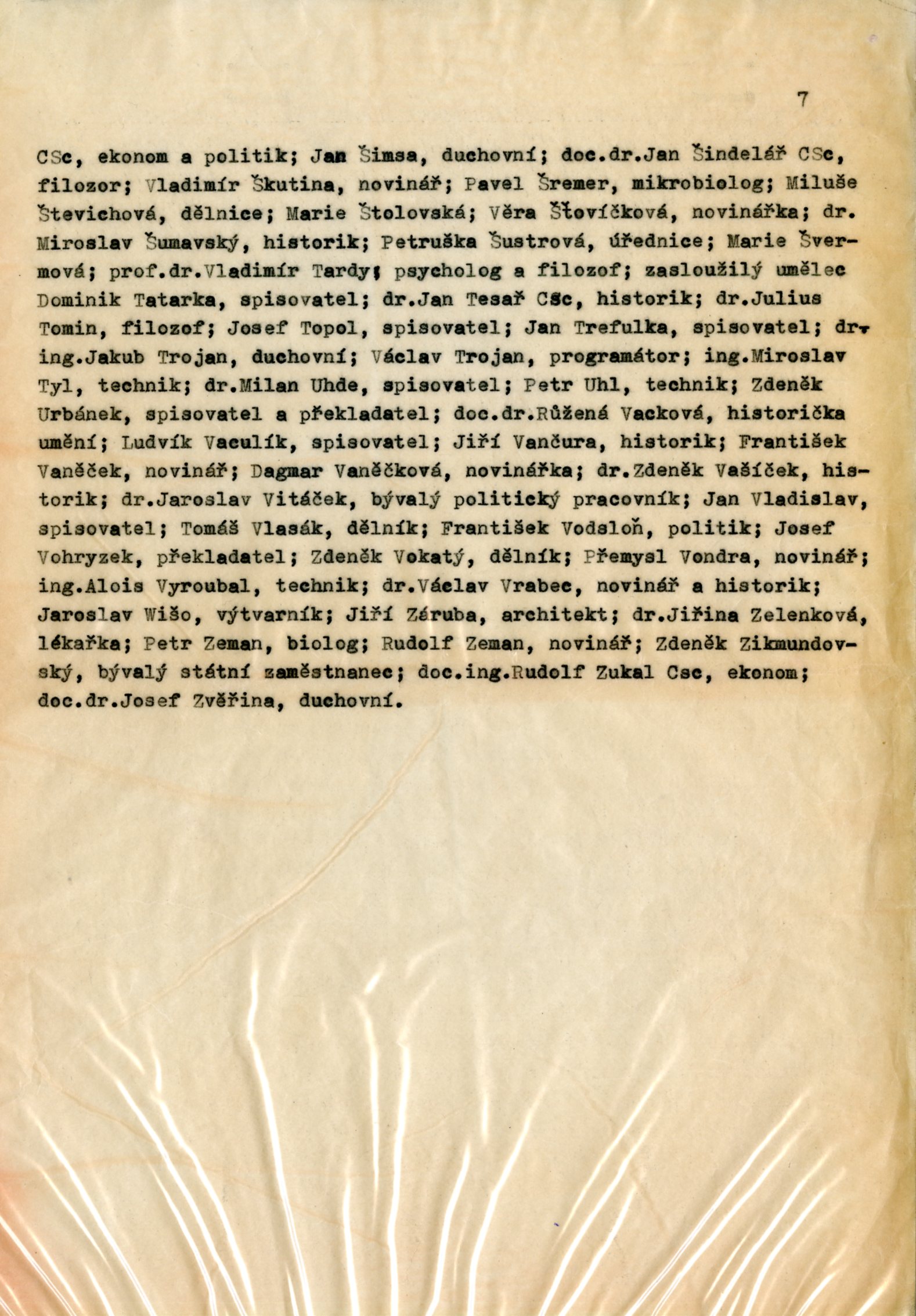

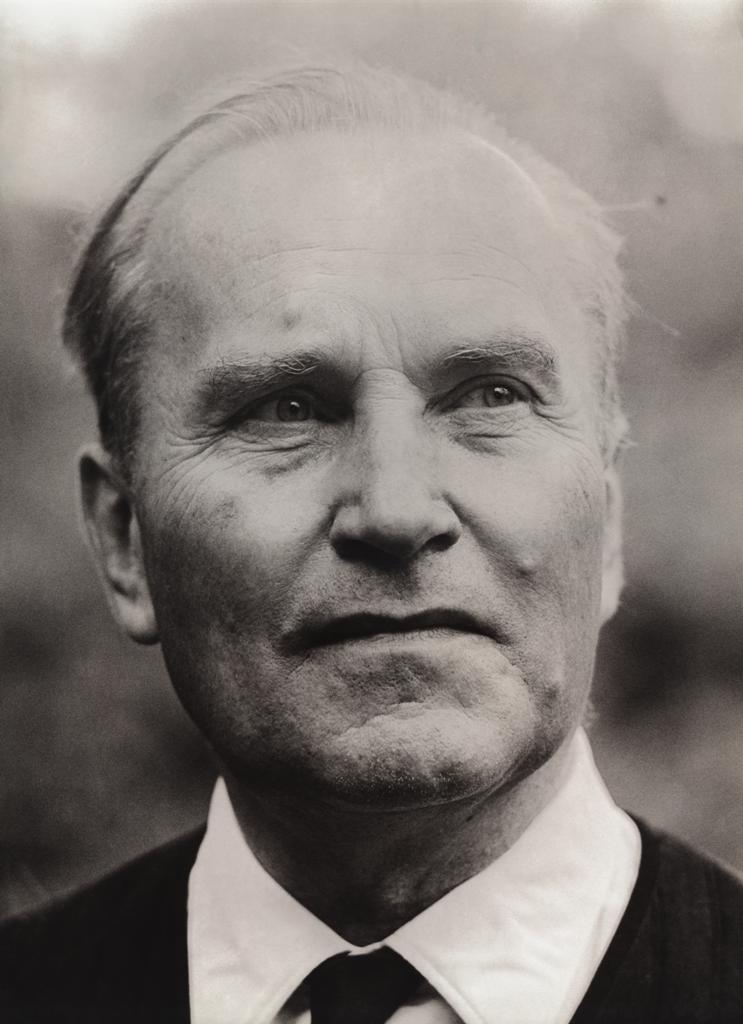

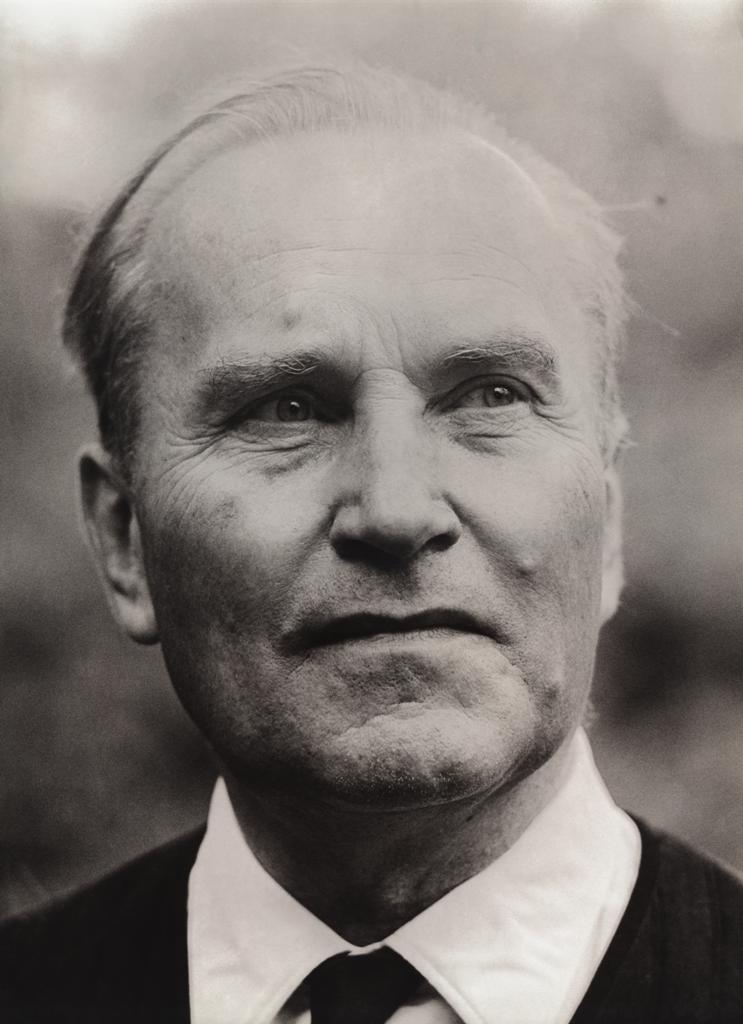

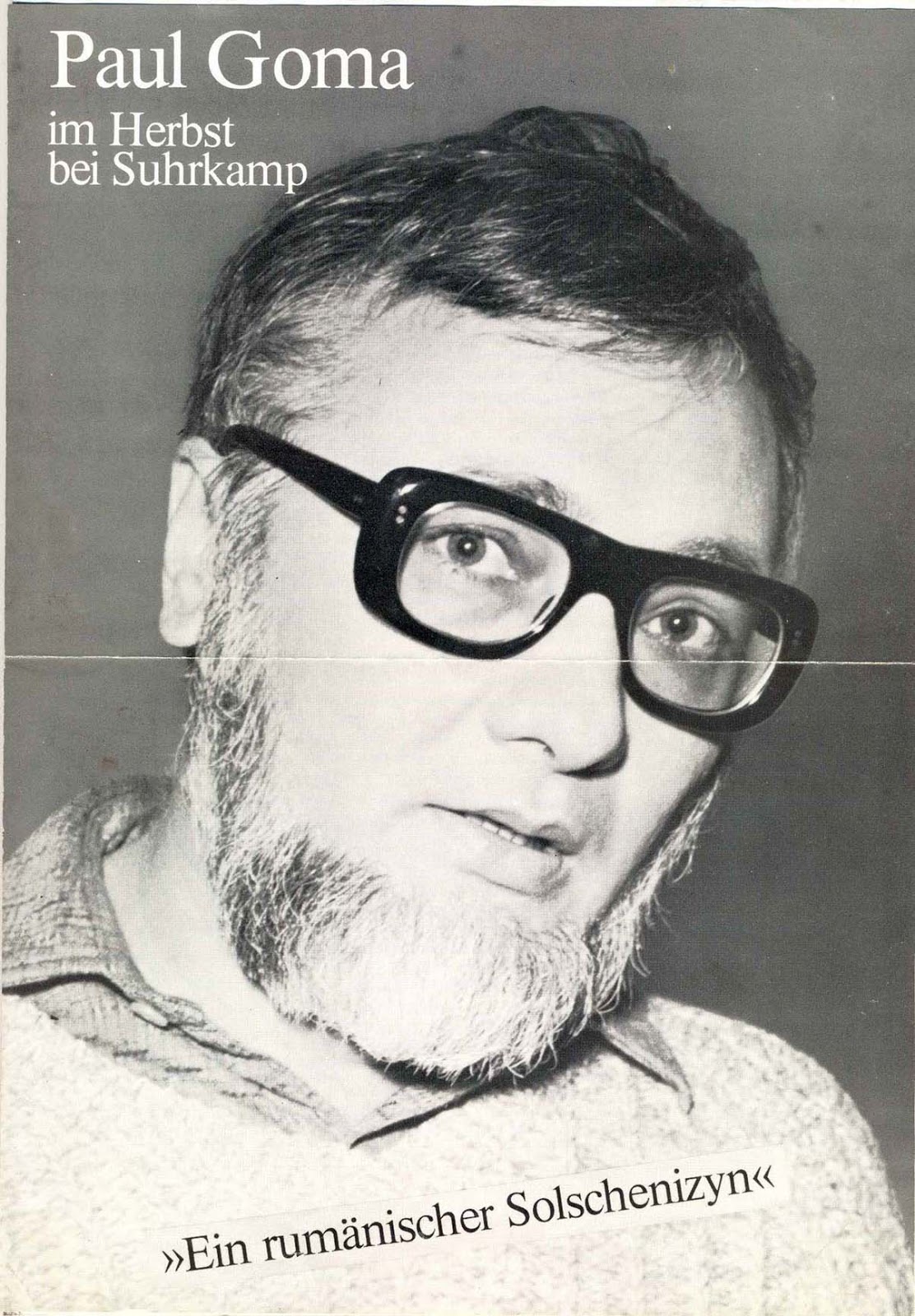

The trigger of the struggle for human rights in this region, which was considered by many analysts a fundamental factor in the collapse of communism in 1989, was the Helsinki Agreements of 1975. The very idea of monitoring human rights abuses, which the Charter 77 grasped from these agreements and promoted until 1989, also inspired Goma and perhaps others in the Soviet bloc. This idea, however, was entirely novel in the countries of East-Central Europe, including Romania. Most individuals in this region lacked the necessary background to fully grasp a problem which was central in Western political thinking, but absent or distorted in local politics even before communism. Nonetheless, due to the transnational travel of ideas, movements for human rights gradually emerged after 1975. In Romania, the ephemeral movement arose around an arid letter addressed to the First Follow-Up Meeting of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), which was to take place in Belgrade beginning in 1977. This letter was initially signed only by Goma, his wife Ana Maria Năvodaru and six other persons: Adalbert Feher, a worker; Erwin Gesswein and Emilia Gesswein, a couple of instrumentalists with the Bucharest Philharmonic Orchestra; Maria Manoliu and Sergiu Manoliu, mother and son, both painters; and Şerban Ştefănescu, a draftsman. However, by the day of Goma's arrest, 192 individuals had endorsed this collective letter of protest. The list of signatures was confiscated from Paul Goma's residence at the moment of his arrest, but he had managed to send it to Radio Free Europe in advance. The lists confiscated by the secret police in 1977 were returned to Paul Goma in 2005. Thus, the document listing all these persons is now part of Paul Goma Private Collection in Paris, but copies can be found in the CNSAS Archives in Bucharest (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7), as the secret police preserved them in Goma’s informative surveillance file, and in the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives in Budapest (OSA/RFE Archives, Romanian Fond, 300/60/5/Box 6, File Dissidents: Paul Goma).

Ivan Blatný (1919–1990), an important Czech poet, lived and died in exile in the United Kingdom after 1948. Upon arrival in the UK, he applied for political asylum and became a “banned” poet in Czechoslovakia as a result of his emigration and openly talking on BBC radio about political pressure against artists in Czechoslovakia. Despite being banned, his work circulated in Czechoslovakia through both samizdat and official printings.

The Ștefan Gane Collection documents in photographs and slides the extent of the demolitions imposed by the so-called systematisation programme in Bucharest following the devastating earthquake of 4 March 1977, which the communist regime used as a pretext for destroying or mutilating numerous historic monuments. The Ștefan Gane Collection is also an important source for understanding and writing the history of that particular segment of the Romanian exile community which was extremely active in disseminating in Western countries information about the aberrant policies of the Ceaușescu regime. In particular, this personal archive illustrates the efforts of the collector and of other personalities from the exile community to stop the systematisation of Bucharest.

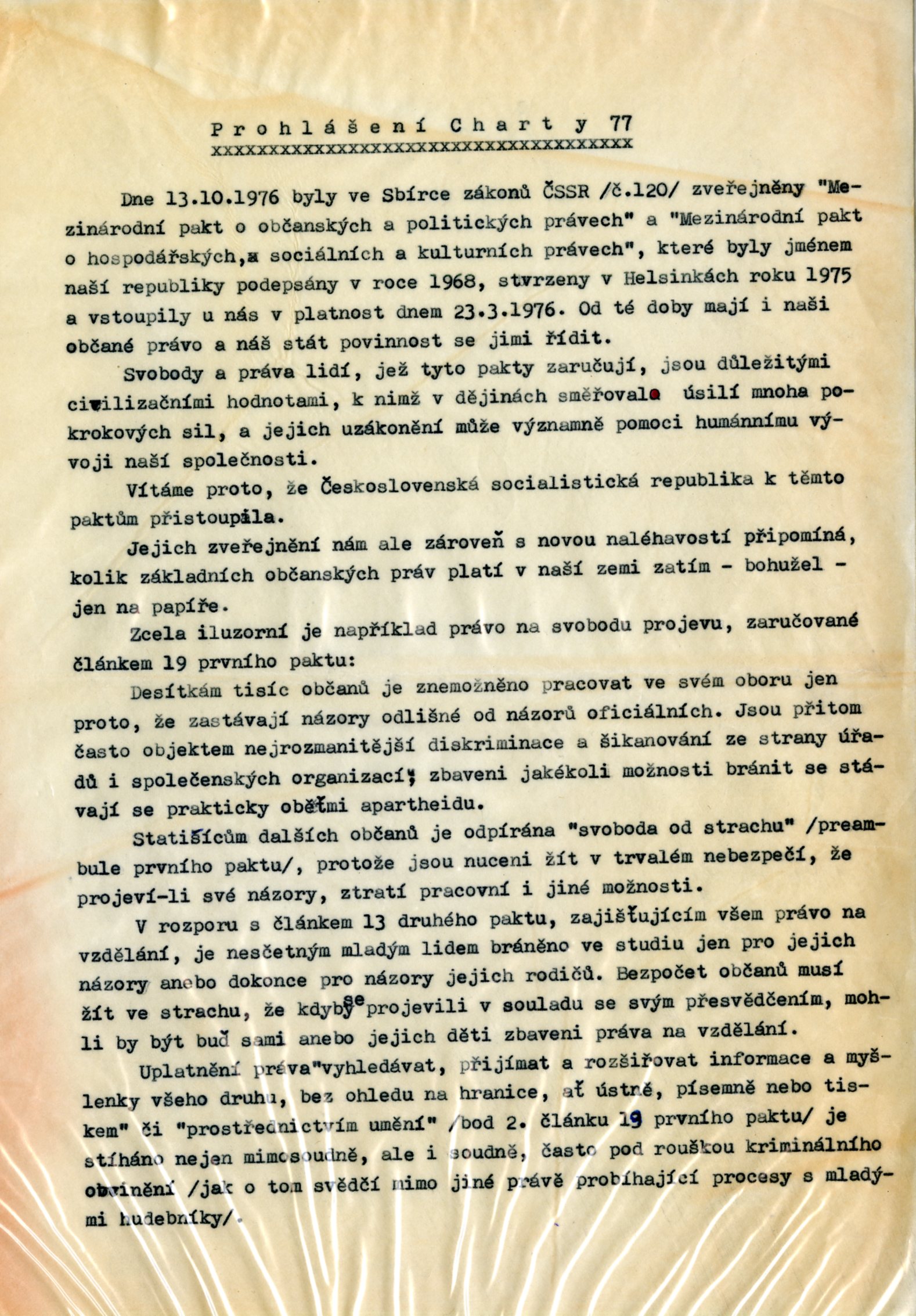

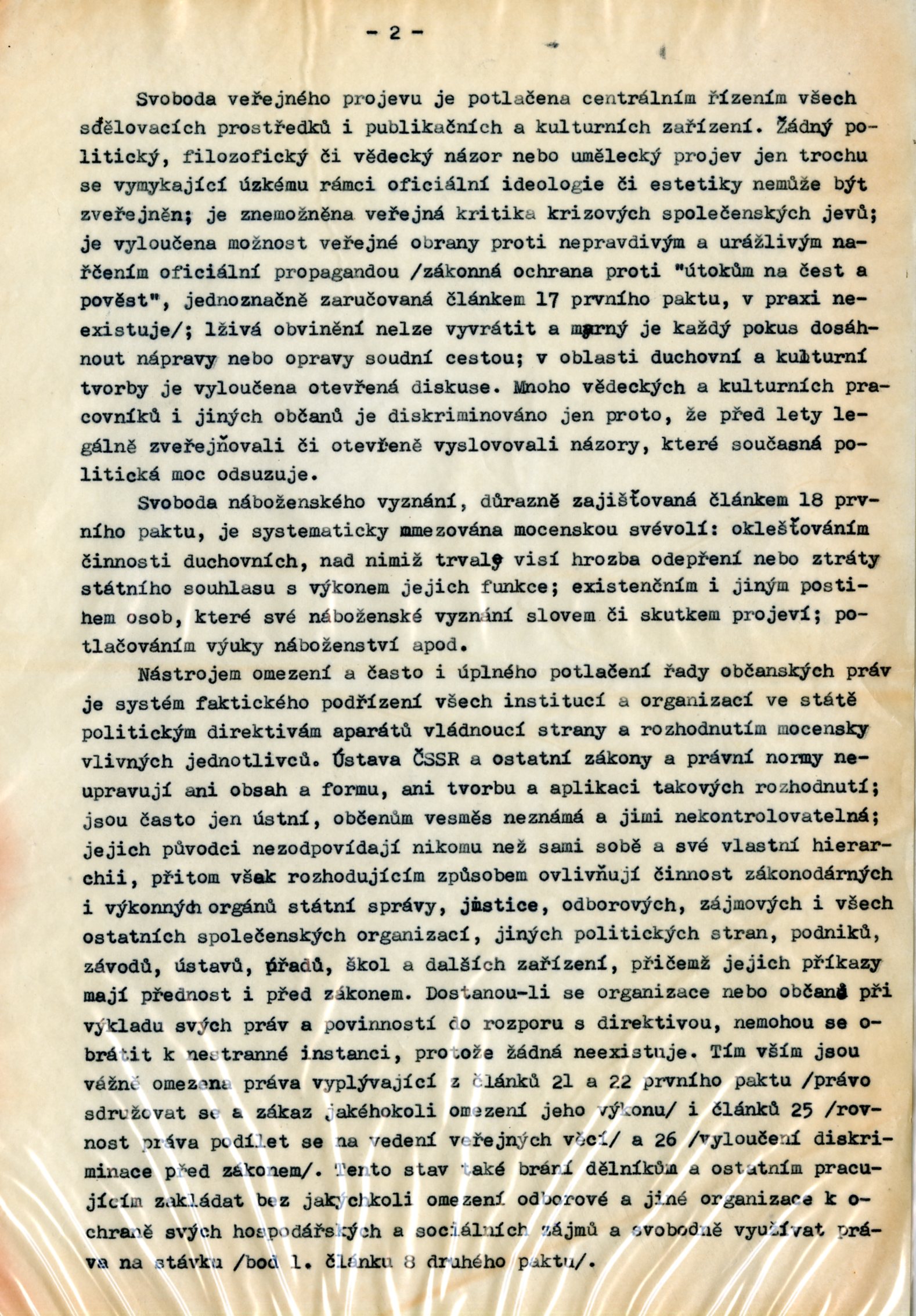

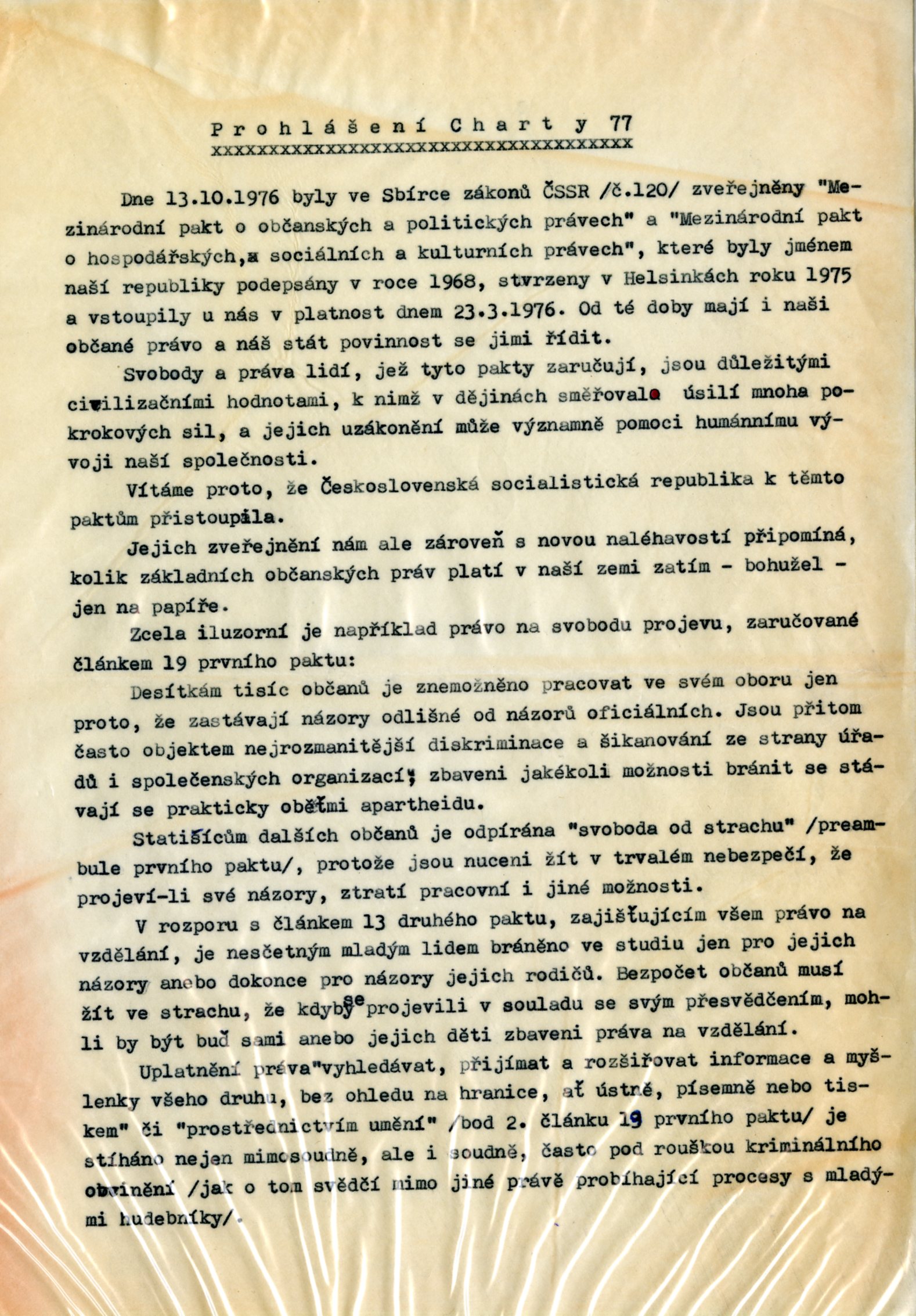

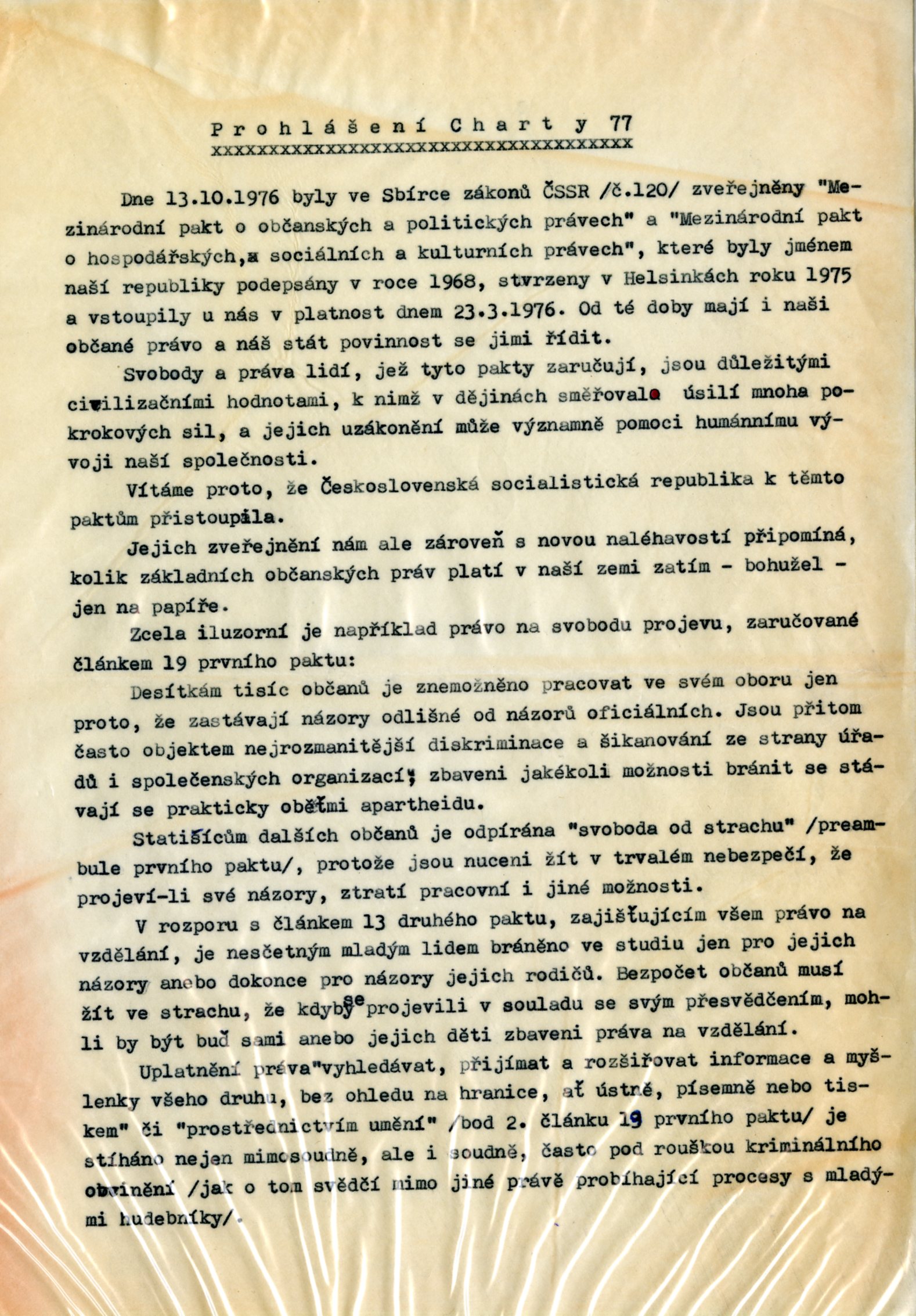

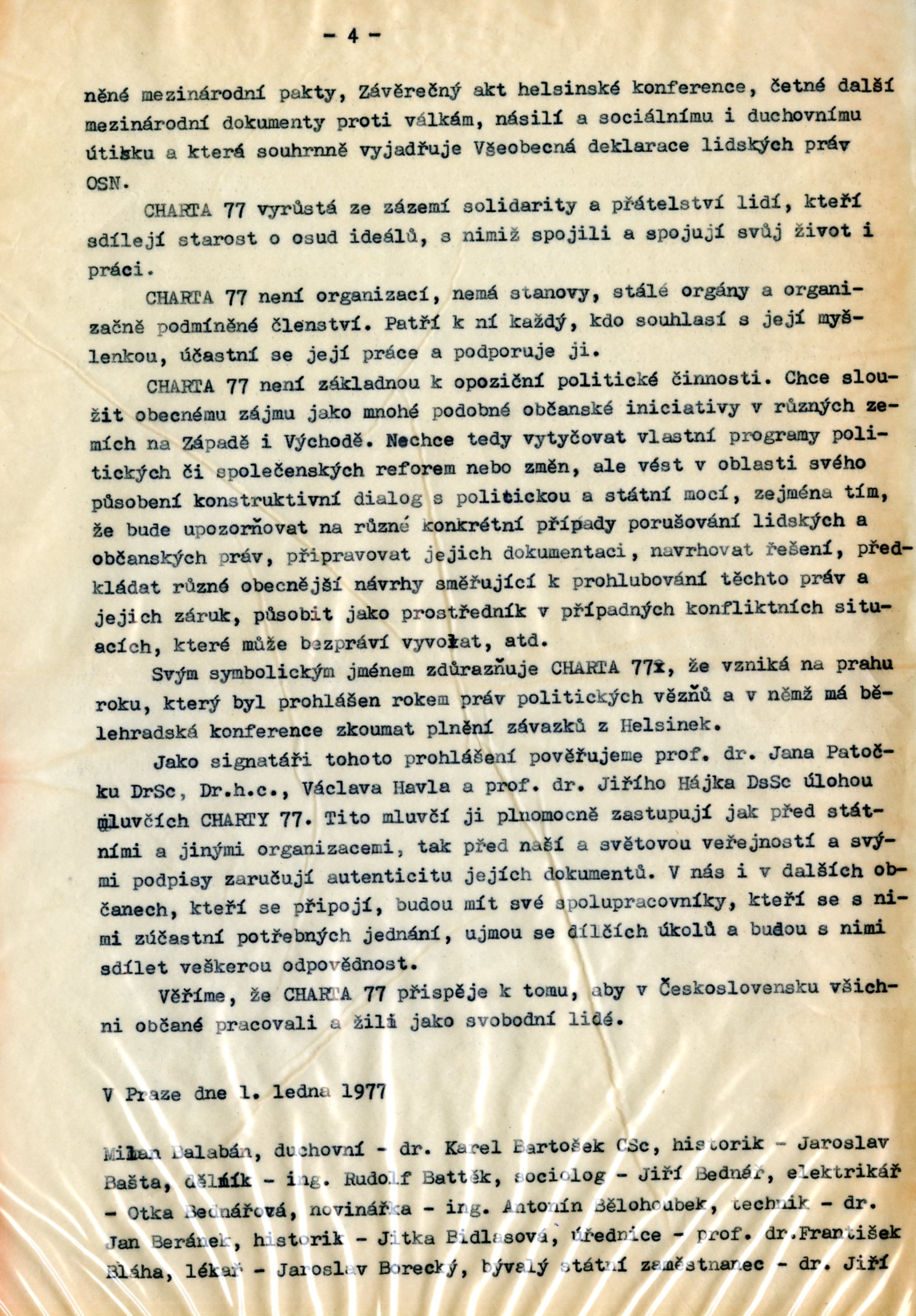

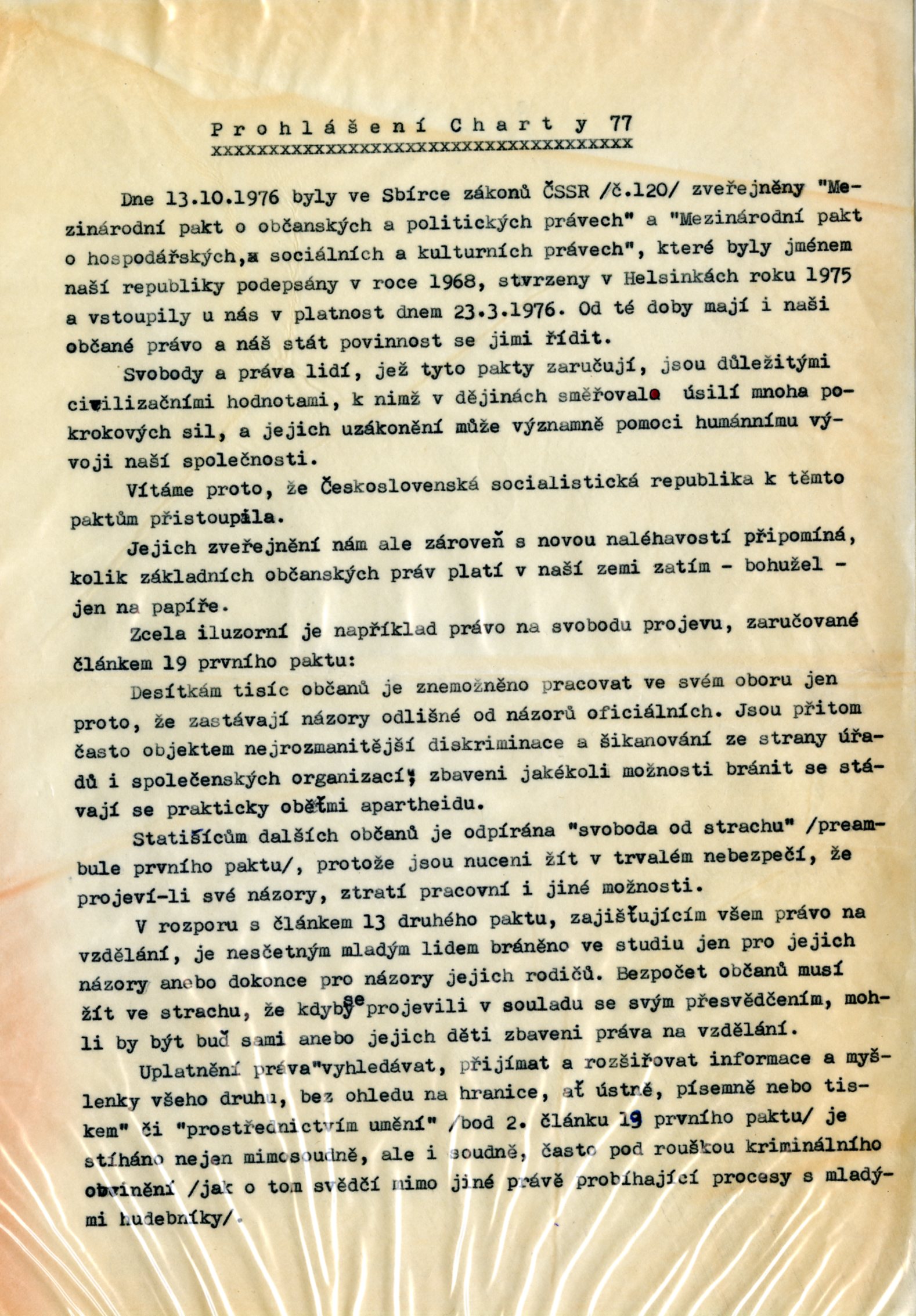

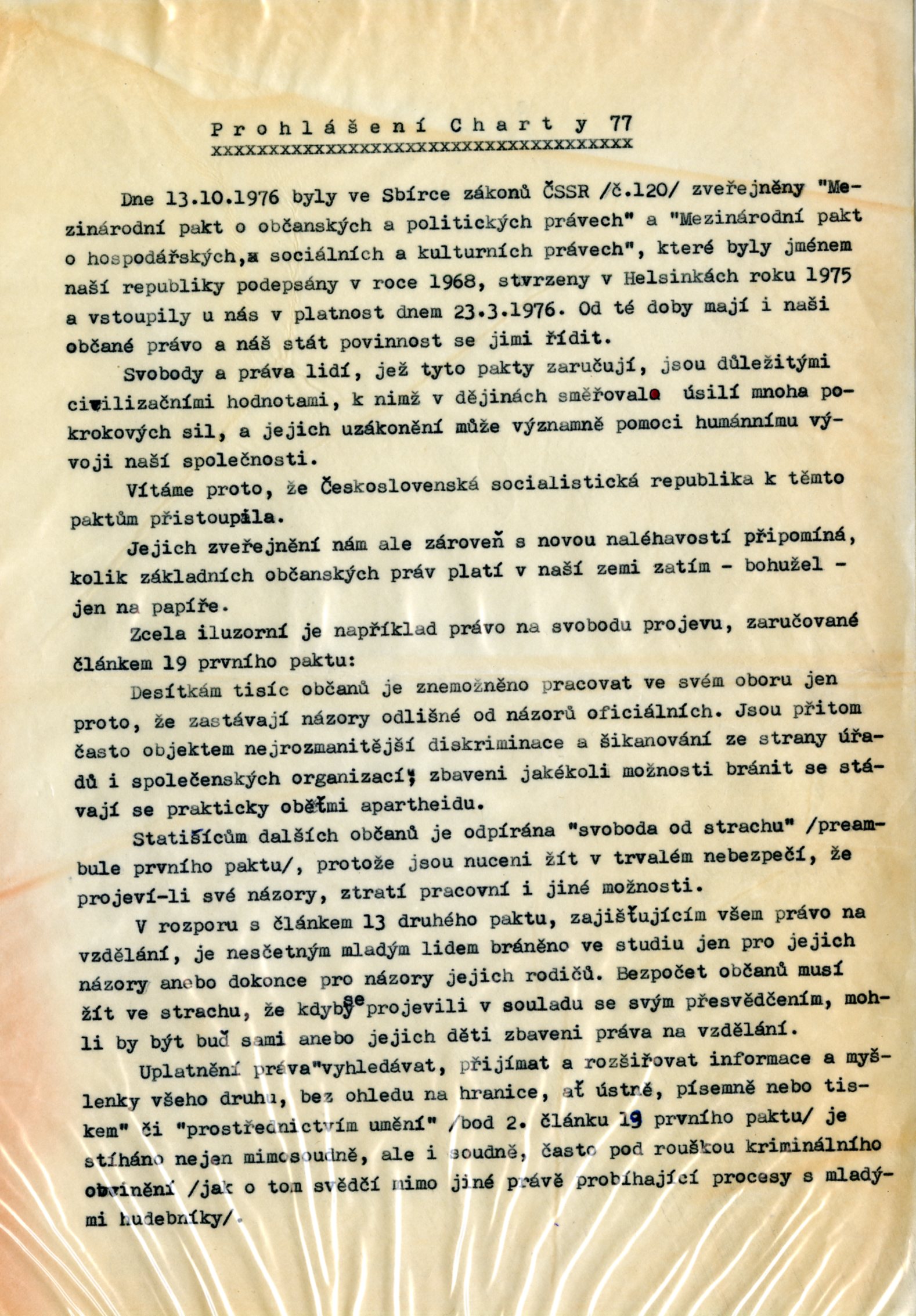

![Charter 77, n. d. [original: 1977]. Print copy](/courage/file/n25624/Charta.jpg)

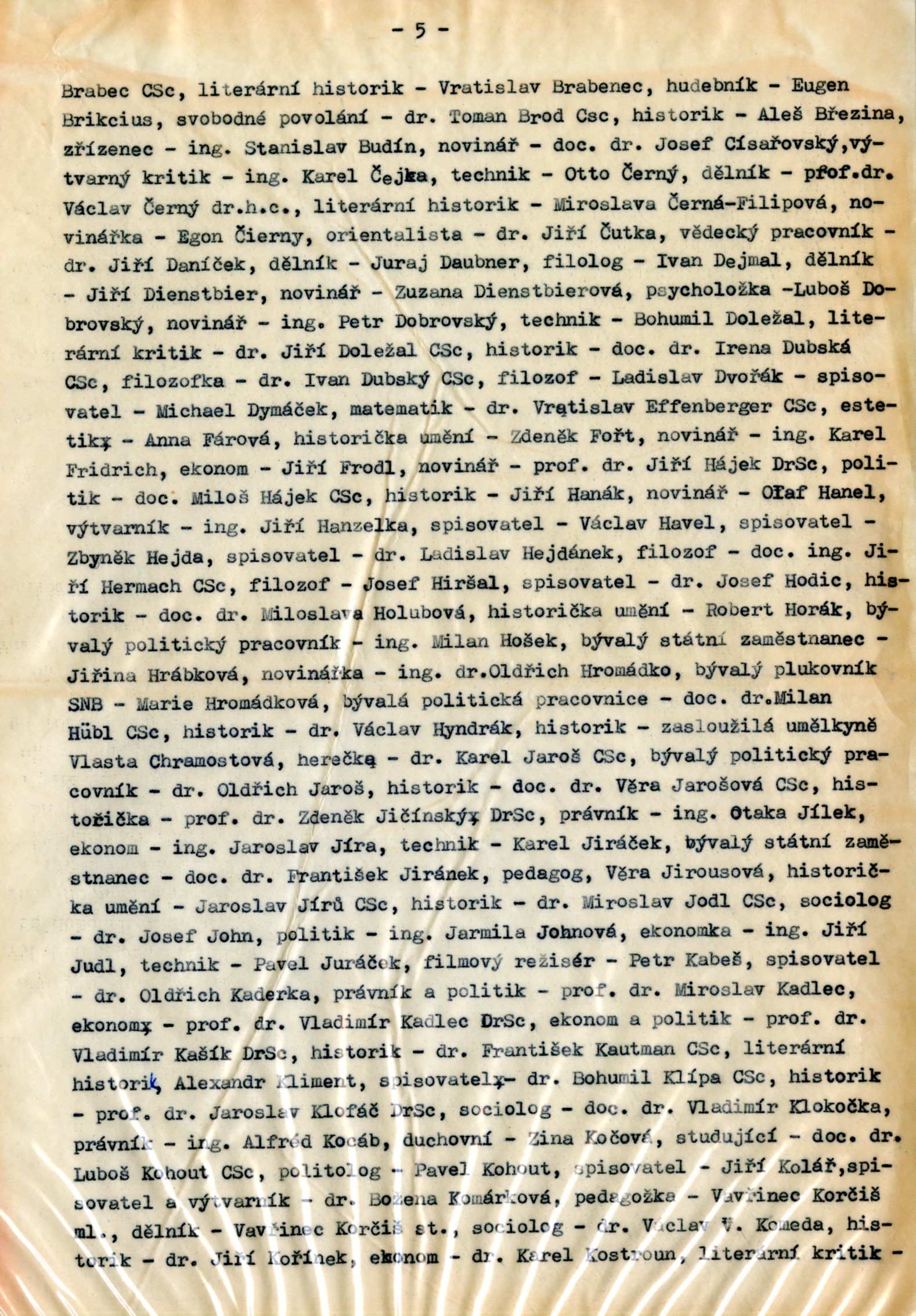

Charter 77 (Charta 77 in Czech and in Slovak) was an informal civic initiative in communist Czechoslovakia from 1976 to 1992, named after the document Charter 77 from January 1977. Founding members and architects were Jiří Němec, Václav Benda, Ladislav Hejdánek, Václav Havel, Jan Patočka, Zdeněk Mlynář, Jiří Hájek, Martin Palouš, and Pavel Kohout. Spreading the text of the document was considered a political crime by the communist regime. After the 1989 Velvet Revolution, many of its members played important roles in Czech and Slovak politics. We do not know when and under what circumstances this copy of Charter 77 Declaration was brought to Mr. Šufliarsky's collection.

The most significant part of the Raţiu–Tilea Archives Collection deals with the political and cultural activities of the Romanian exile community in the West from 1940 to 1989. Some files relating to the Romanian exile community cover only internal organisational issues of Romanian exile associations, while others have been created around an initiative or an event. The file entitled Textele Memorandumului 1977 (The drafts of the 1977 Memorandum) reflects the initiative launched by Ion Raţiu in 1977 to organise in London in the period 1–4 April 1977 a meeting of the committee of the Romanians living in exile. Its main aim was to create a memorandum for protesting against the human rights infringements of the Ceauşescu regime (Fond Raţiu–Tilea/29, 16). Although Raţiu himself had drafted the Memorandum, the official sender of the document was the so-called “Meeting of Romanians in London (1–4 April 1977).” This memorandum was meant to be sent the governments of the states that signed the Helsinki Final Act on the occasion of the CSCE follow-up meeting which took place in Belgrade from 4 October 1977 to 8 March 1978. The file comprises the drafts and the final version of the Memorandum, a letter addressed to the “the signatory Powers” of the Helsinki Final Act to which the Memorandum was annexed, and lists with signatures of those attending the aforementioned meeting in London.

The internal political context of the Eastern Bloc during late 1970s was marked by the emergence of various dissident movements following the breach in the system produced by the provisions of the Helsinki Final Act, which the communist states had signed. Even in Romania, where no significant dissident movement had occurred before, Paul Goma expressed his solidarity with Charter 77 and then launched a human rights movement on this Czechoslovakian model (Petrescu 2013, 80–82). The Goma dissident movement was step by step dismembered by the Securitate and Goma himself was expelled from the country. Although Romania complied poorly with the obligations assumed at Helsinki, the Western powers “overlooked completely Ceauşescu’s internal policy” (Petrescu 2013, 82). Raţiu was among the very few intellectuals in the West during 1970s that tried to reveal Ceauşescu’s skilful policy of manipulating the West by presenting his regime as following an “independent” path in the Soviet bloc in order to obtain various economic and political gains (Raţiu 1975, 36–37).

Being a law graduate, Raţiu understood perfectly the opportunities offered by the stipulations of the Helsinki Final Act when facing the human rights infringements of the Ceauşescu regime. These stipulations had already been invoked by various dissident movements in the Eastern Bloc. Raţiu’s skills in this respect are well illustrated by the complex argumentation developed in the Memorandum. The document entitled: “The Implementation of the Final Act of the Conference on Security & Co-operation in Europe Helsinki, August 1975 by the Government of the Socialist Republic of Romania: Memorandum for the Belgrade Conference, 1977 prepared by Romanians assembled at the Royal Holloway College, University of London, 3 April 1977” was addressed to “the signatory Powers” of the Helsinki Final Act as an appendix to an open letter. In this letter, Raţiu emphasised that “no improvement can be detected in our country in the fields of human rights.”On the contrary the Ceauşescu regime continued to deny “political, civic and religious freedoms” (Fond Raţiu–Tilea/173, 1). The memorandum was structured following the main parts (the so called “baskets”) of the Helsinki Final Act. Concerning the first part of the Helsinki Final Act, Raţiu argued that “the government of the Socialist Republic of Romania ignored” its provisions, “by prohibiting any public or private expression of opposition to the regime,” “by limiting the right of association to the Communist Party and its subsidiary organisations,” “by the political police, which has unlimited power over the population.” In the context of the harsh repressive measures took against the members of the Goma movement, Raţiu stated that “Freedom of Conscience, Freedom of Speech and the Right to hold meetings do not exist” in Ceaușescu’s Romania, “all meetings, marches or demonstrations critical of the regime are prohibited,” and the political opponents “are interned” in psychiatric hospitals (Fond Raţiu–Tilea/173, 18). He also argued the Ceaușescu regime did not respect religious freedom and the members of various cults were “persecuted.” Raţiu himself being a Greek Catholic mentioned that the Greek Catholic Church, which had over 1.7 million followers before 1948, “remains forbidden and its members are deemed to be incorporated into the Greek Orthodox Church” (Fond Raţiu–Tilea/173, 18).

Concerning the second and the third parts of the Helsinki Final Act, Raţiu emphasised that Ceaușescu’s regime used the “the lack of foreign currency” as an “excuse for not implementing other provisions” of the Helsinki act such as the free circulation of people and ideas (Fond Raţiu–Tilea/173, 21). He accused Ceaușescu’s regime that the bureaucratic procedures for obtaining an exit visa had become so complicated and abusive that people had very few chances to travel abroad (Fond Raţiu–Tilea/173, 22), and concluded that: “Travel for personal or professional reasons, out of Romania, has become more difficult after the Helsinki Agreement than before” (Fond Raţiu–Tilea/173, 18).

The file “The Drafts of the 1977 Memorandum” give insights to the creation of one of the most vocal initiative launched in exile by Ion Raţiu. The content of the memorandum speaks out about Raţiu’s life-long commitment to democratic values and his constant criticism directed at the Romanian communist regime in a period when the latter co-opted several cultural personalities of the Romanian exile community by manipulating a nationalist discourse. This initiative exemplifies how the Helsinki Final Act offered tools for those in both East and West assuming a critical stance towards the communist dictatorships, and provided a common ground for their initiatives.

The Basic Declaration of Charter 77 of 1st January 1977 on the Causes of the Origin, Purpose and Targets of Charter 77, which on the Holiday of the Three Kings on January 6th, 1977, the playwright Václav Havel, the actor Pavel Landovský and the writer Ludvík Vaculík were issued to the Office of the Federal Assembly, Czechoslovakia and the Czechoslovak Press Office. On the way to Prague's Dejvice, their chase was ended, and the StB members caught up with them and they were then, detained by state security. The three were released later in the evening, apparently in response to the news which travelled abroad. The published Declaration of Charter 77 had given rise to a number of restrictive measures by the Czechoslovak regime. Its signatories were subjected to a constant persecution of the regime through police surveillance, house searches, job cuts, seizure of passports, detention, physical violence, imprisonment or expulsion from the country.

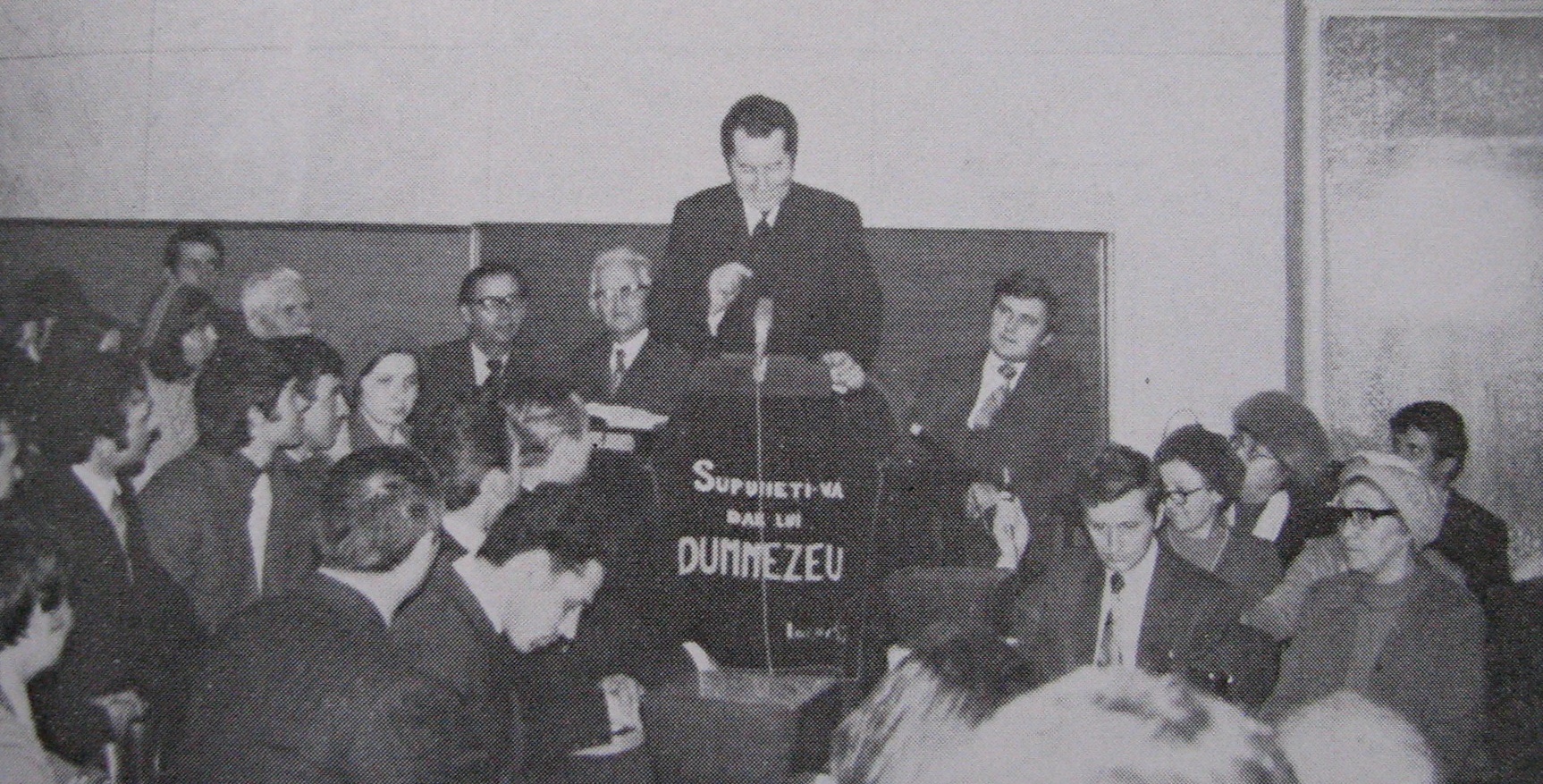

![The Neo-protestant Denominations and Human Rights in [communist] Romania, in Romanian, 1977. Open letter](/courage/file/n41952/Iosif+TON+1977.jpg)

The Neo-protestant Denominations and Human Rights in [communist] Romania, in Romanian, 1977. Open letter

The Neo-protestant Denominations and Human Rights in [communist] Romania, in Romanian, 1977. Open letter

In February–March 1977, the Baptist ministers Iosif Țon, Pavel Nicolescu, Radu Dumitrescu, and Aurelian Popescu, the Pentecostal minister Constantin Caraman and the Christian Evangelical minister Silviu Cioată (a member of the Christian Evangelical Church of Romania – a Plymouth Brethren protestant religious denomination) drafted a letter of protest concerning the infringements of human rights in Romania focused on cases of infringement of religious freedom affecting those religious denominations to which its authors belonged. The letter was sent to several Western embassies and to Radio Free Europe. The latter broadcasted the open letter in April 1977. Due to the criticism of the communist regime expressed in the document, those signing it were arrested and interrogated by the Securitate.

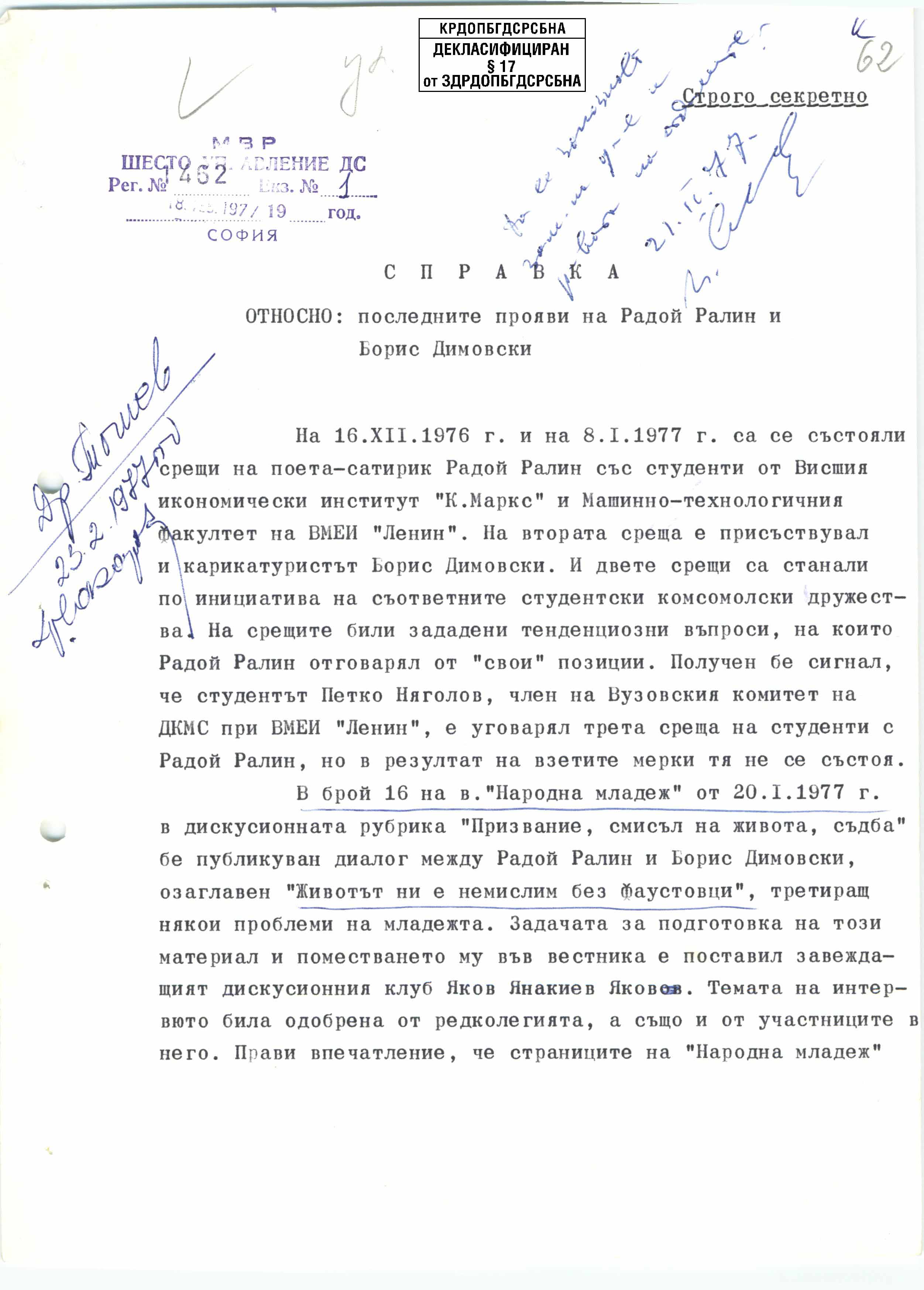

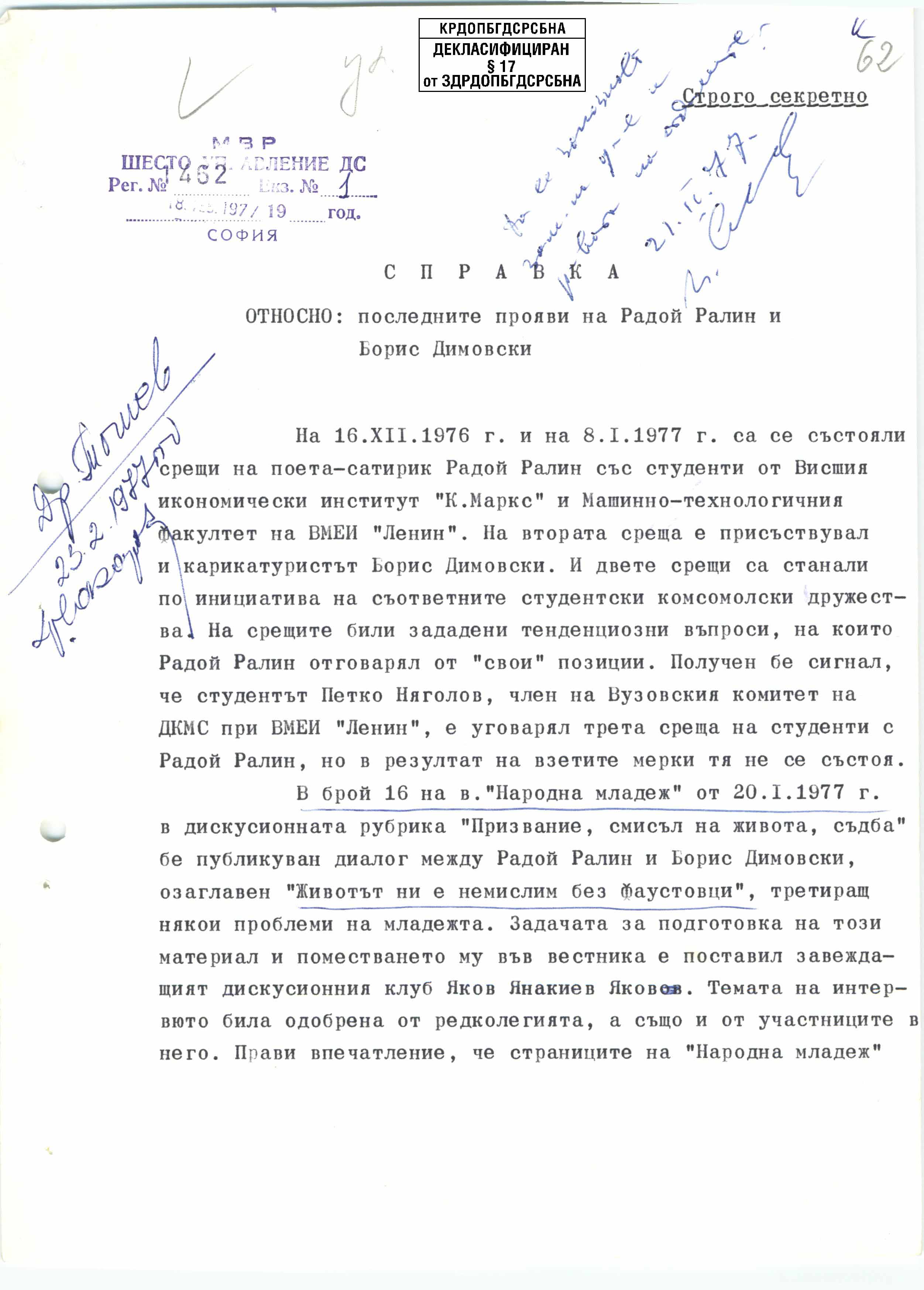

Report about "The last actions of Radoy Ralin and Boris Dimovski", Sofia, February 18, 1977.

This report presents the observation results of two well-known critical cultural figures, the writer Radoy Ralin and the cartoonist Boris Dimovski. Their literary dialogue "Our life is unthinkable without Faust followers", published in the journal "The People's Youth" (Narodna Mladezh) in January 1977, is analyzed by the state security agent. The document relates that the two intellectuals made statements in meetings with students that were ambiguous or of anti-party character. The document is, therefore, a good example of how closely critical intellectuals were surveilled by the state security.

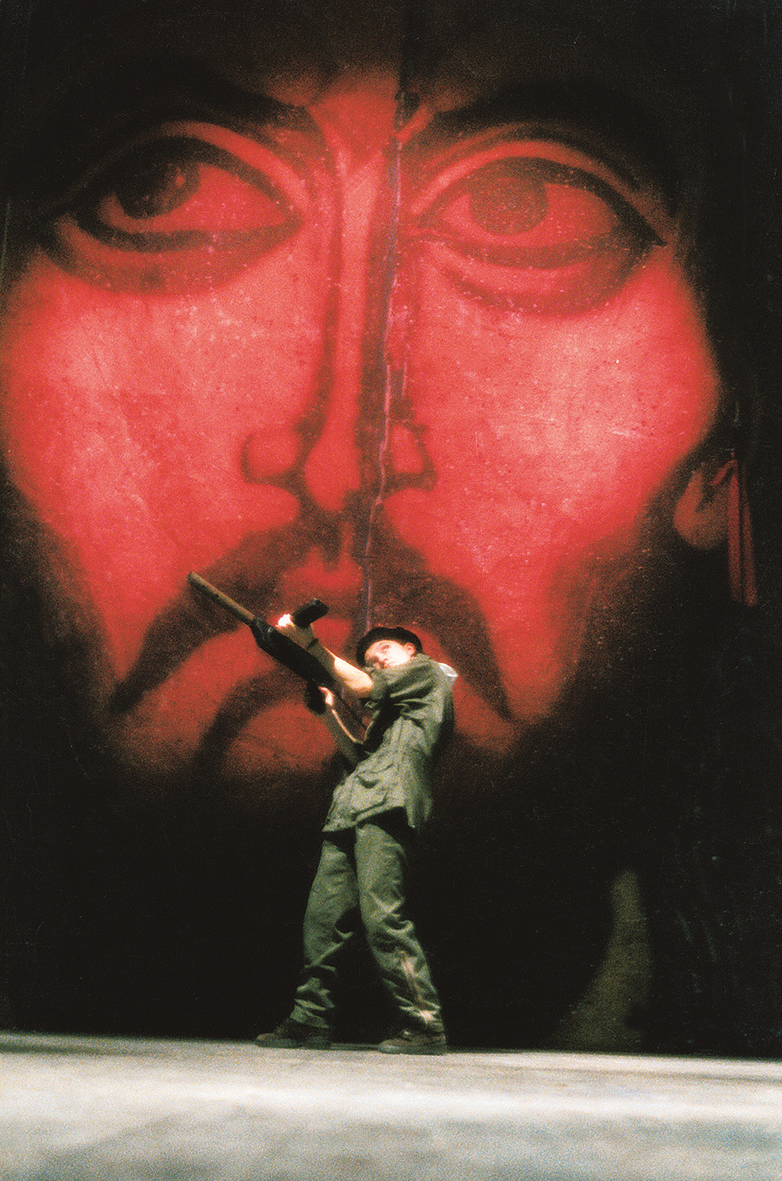

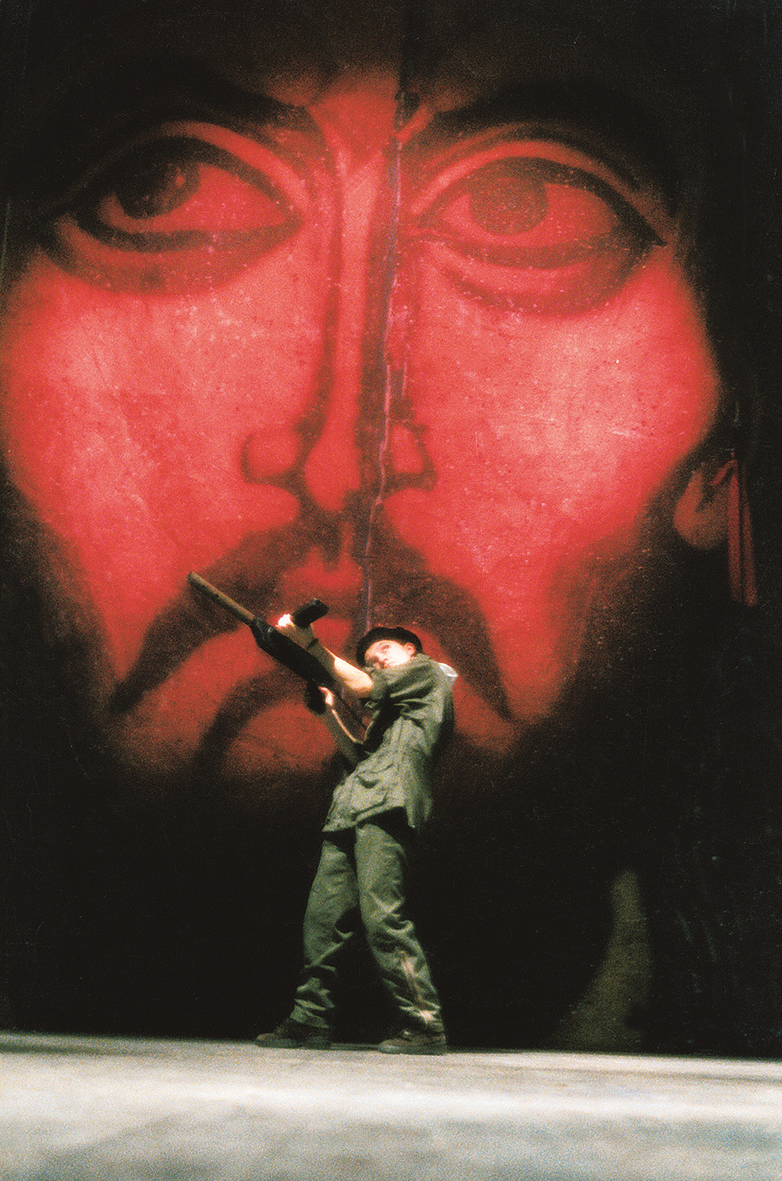

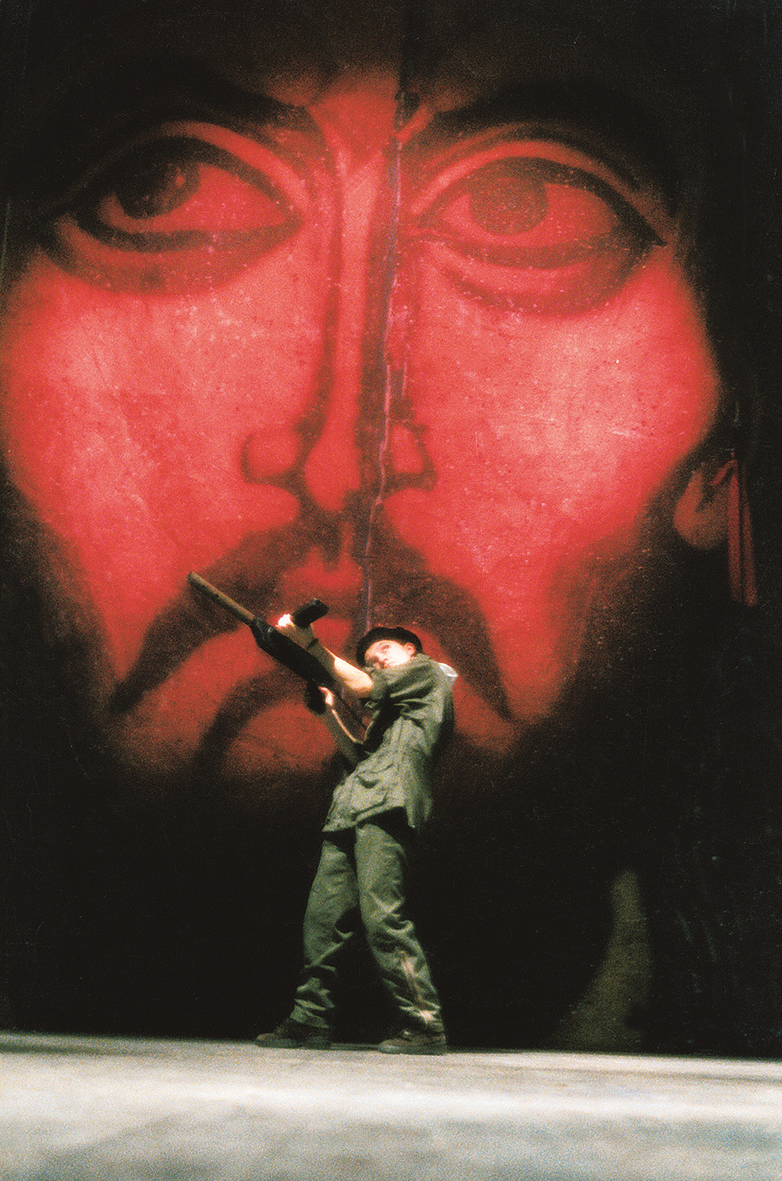

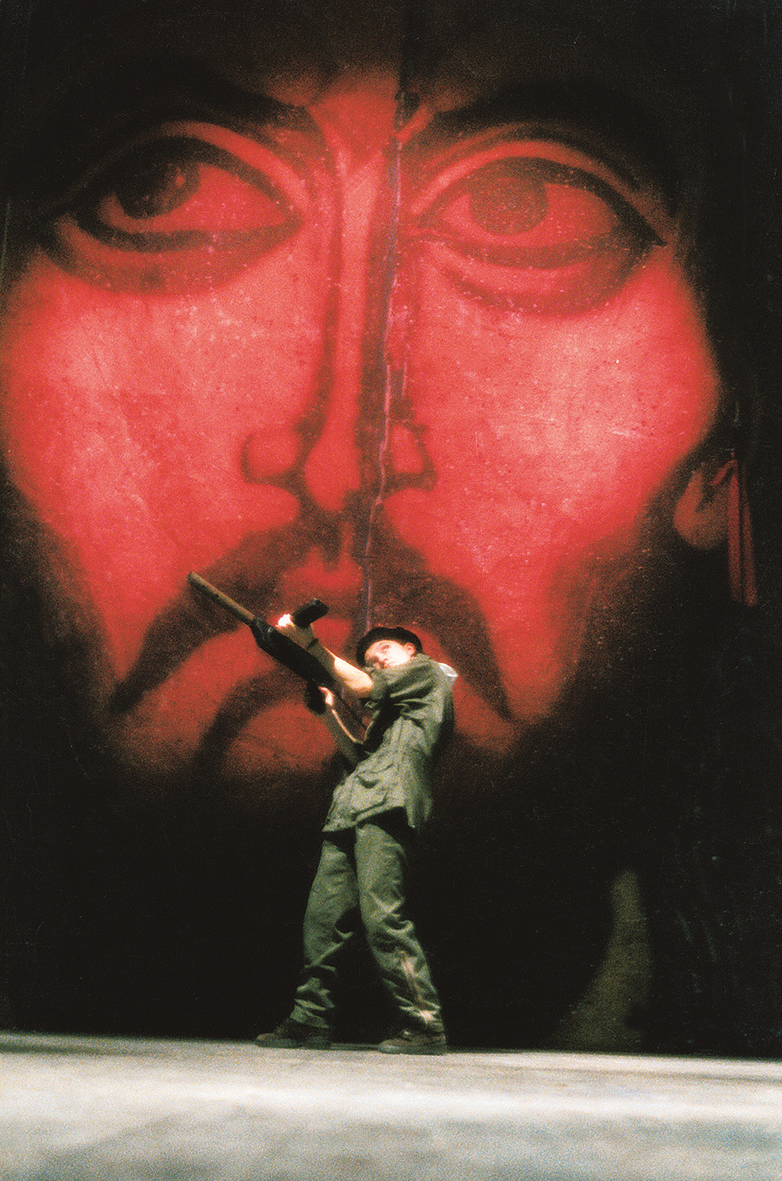

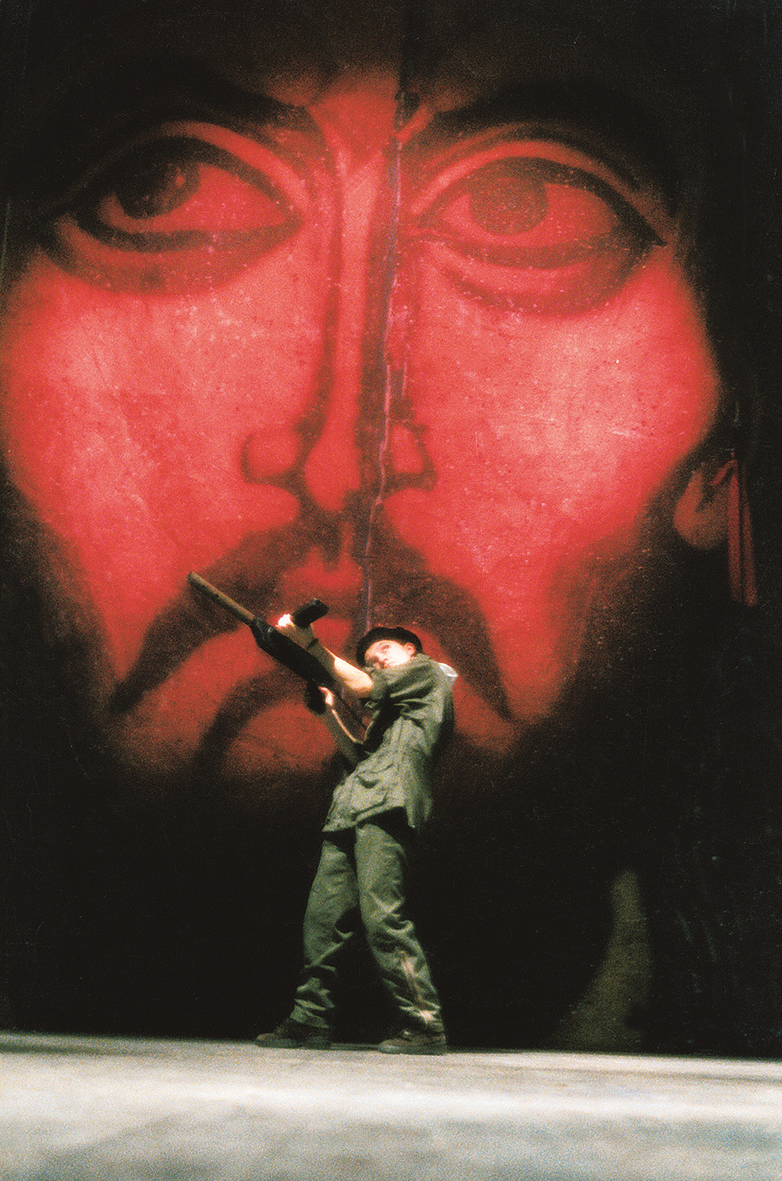

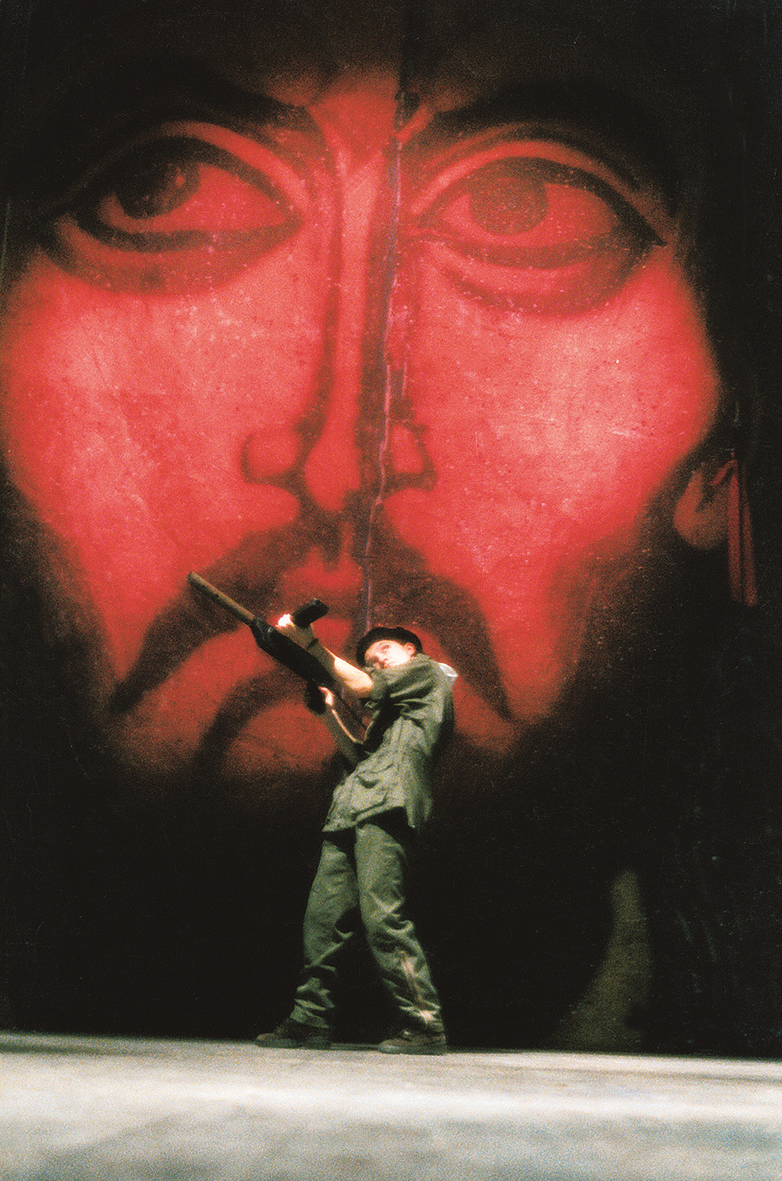

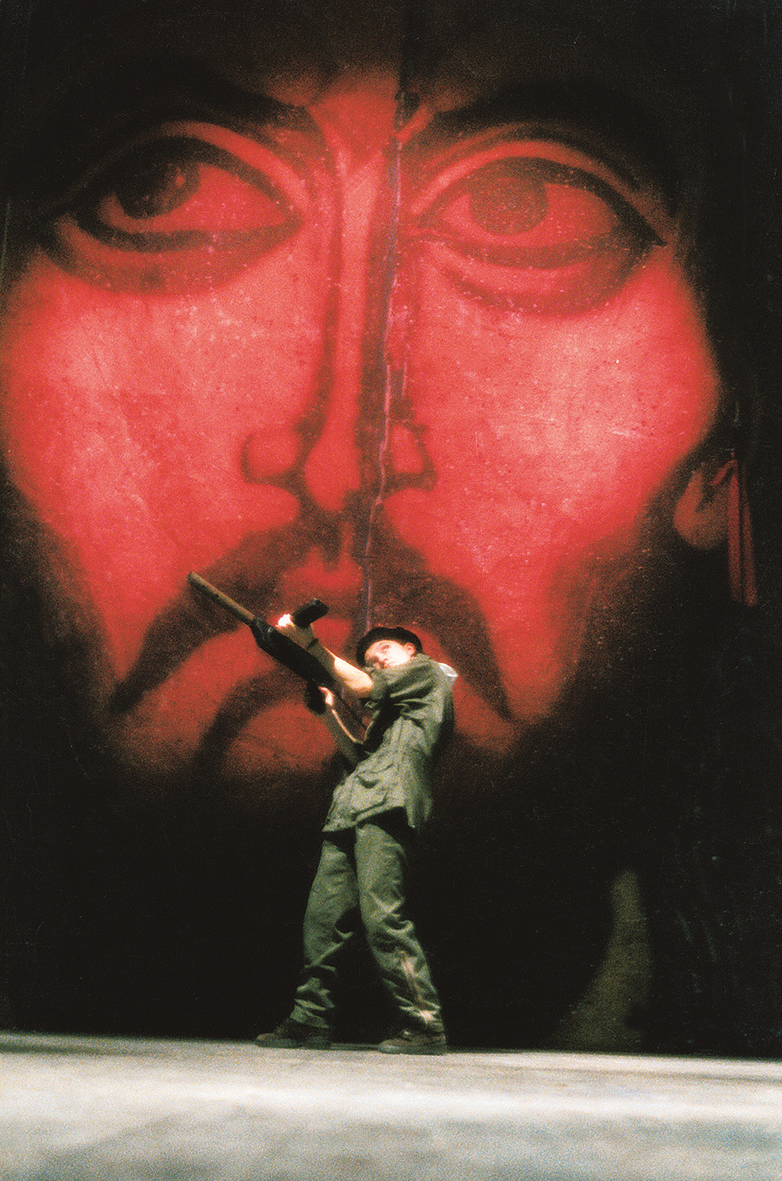

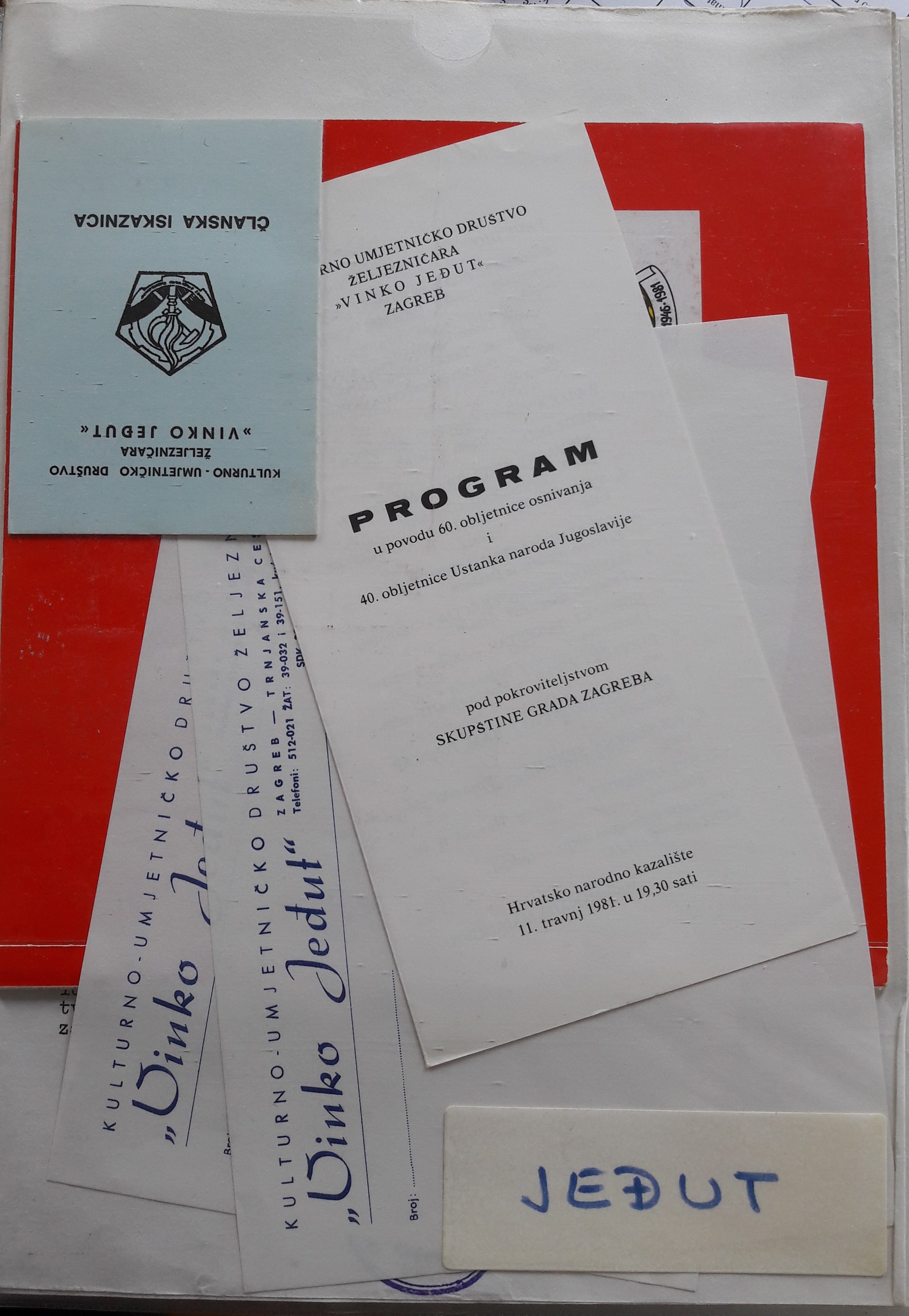

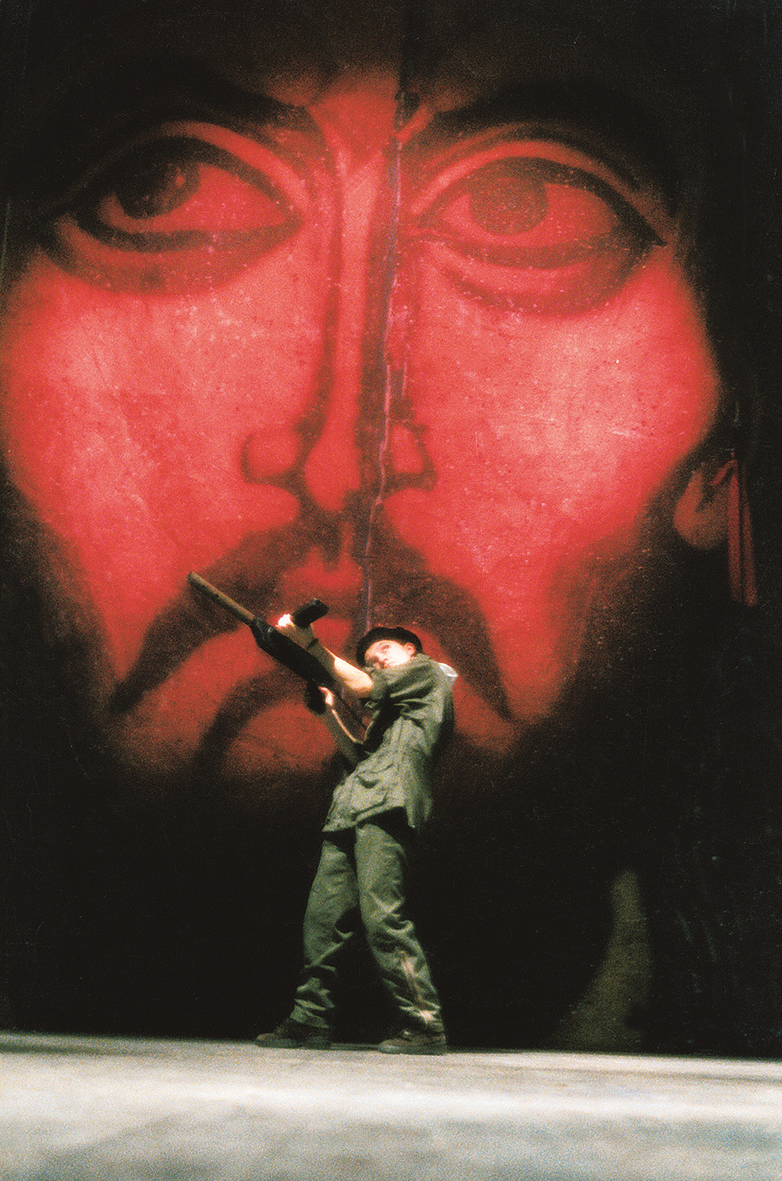

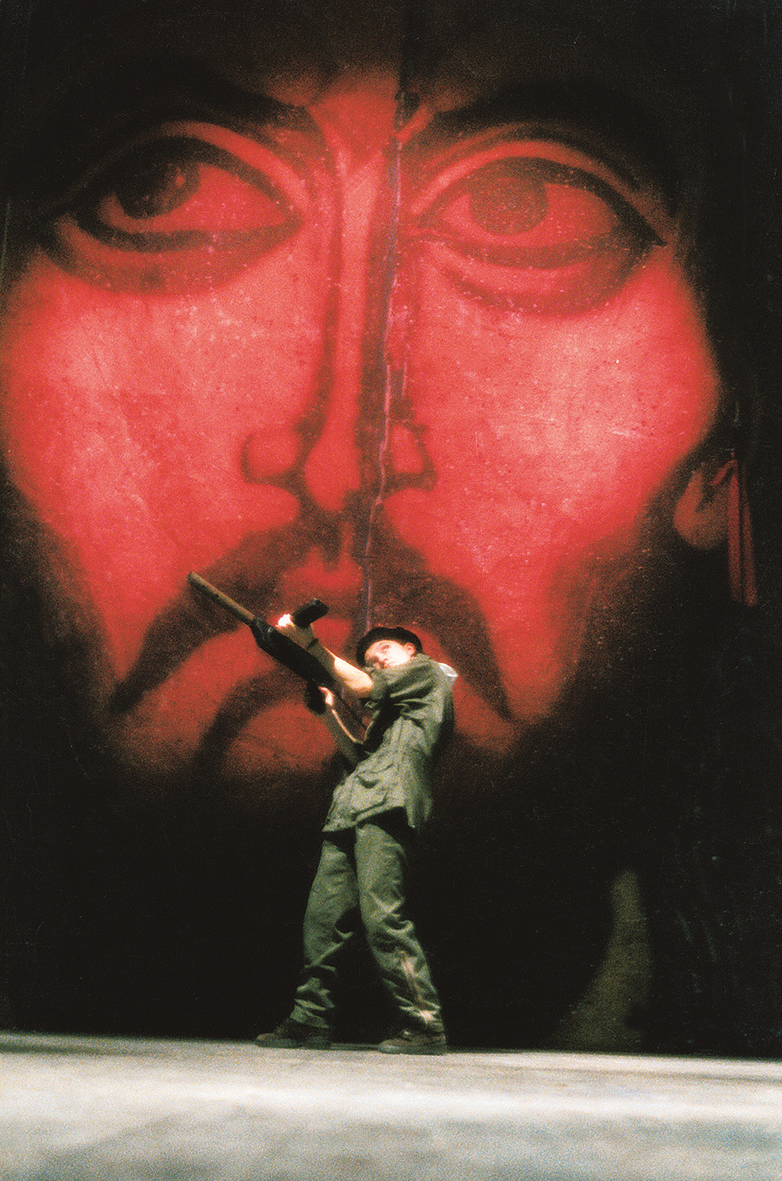

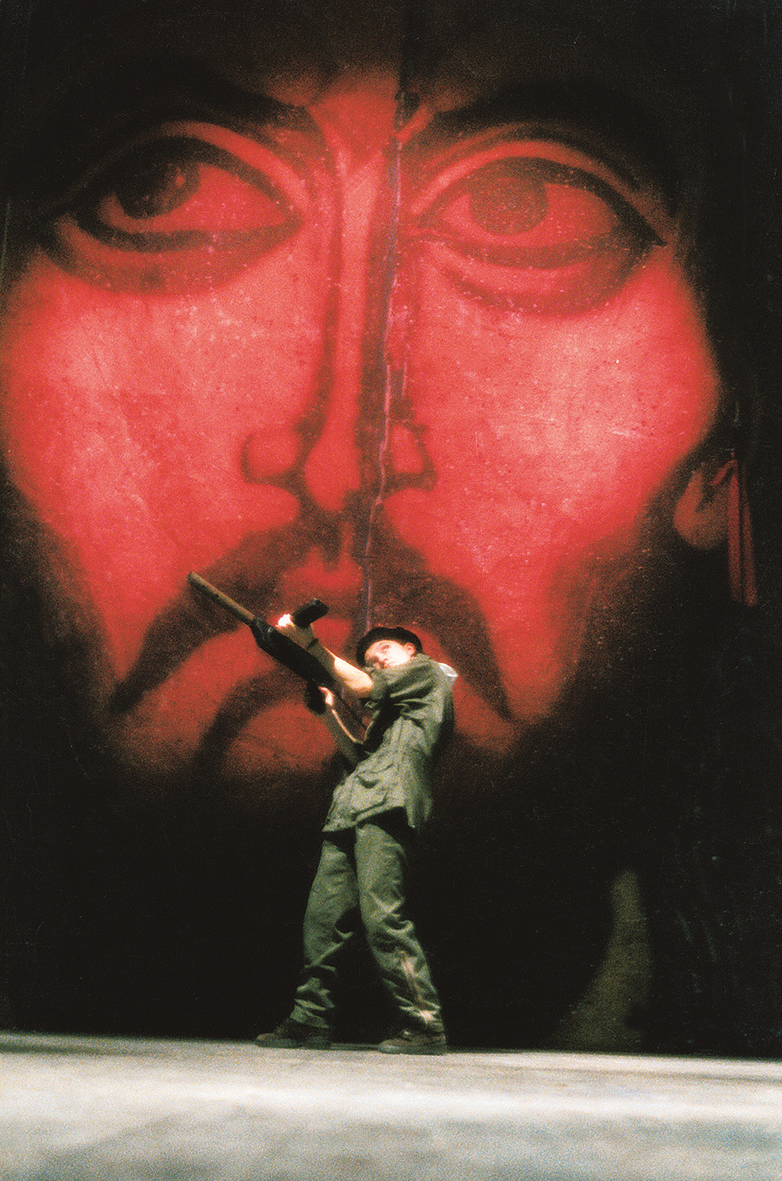

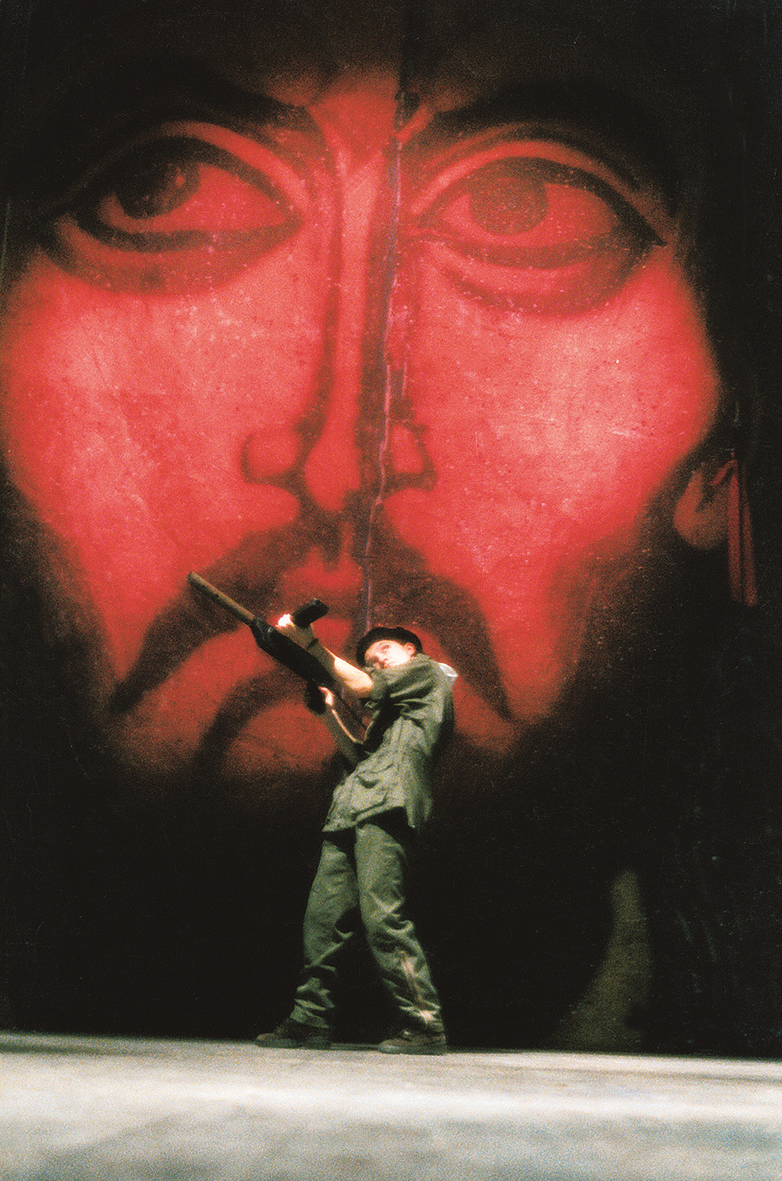

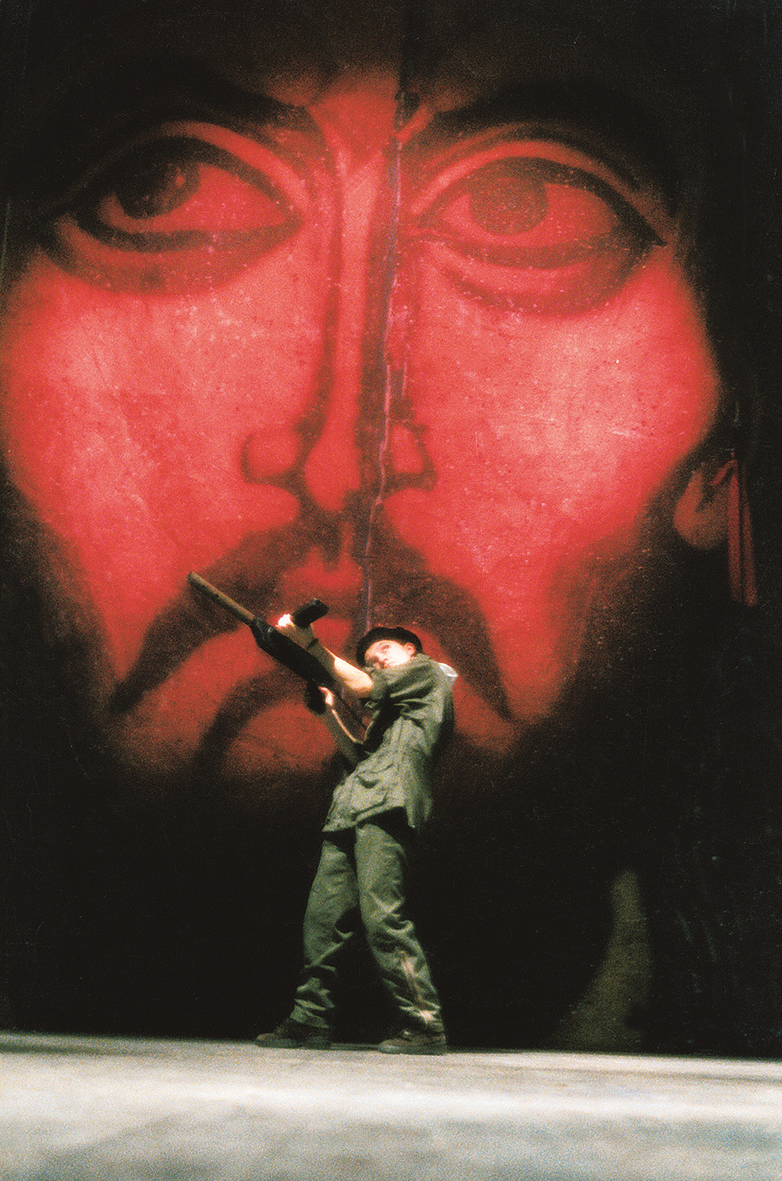

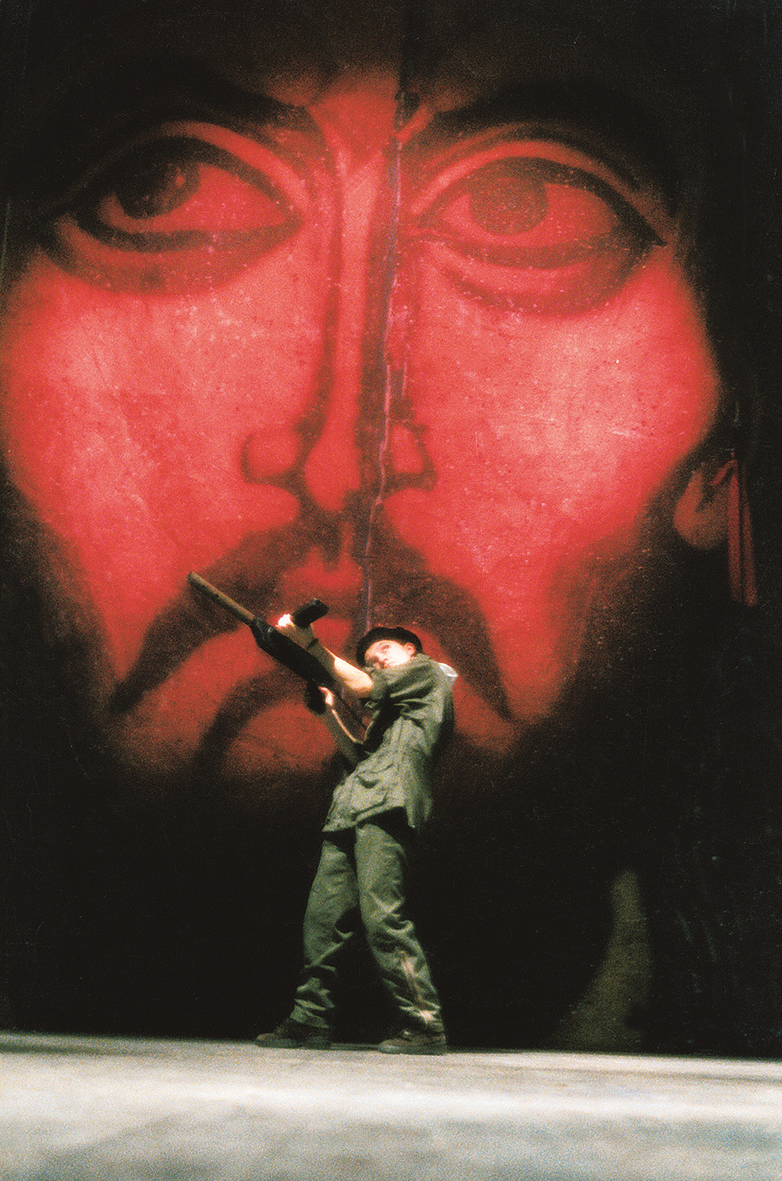

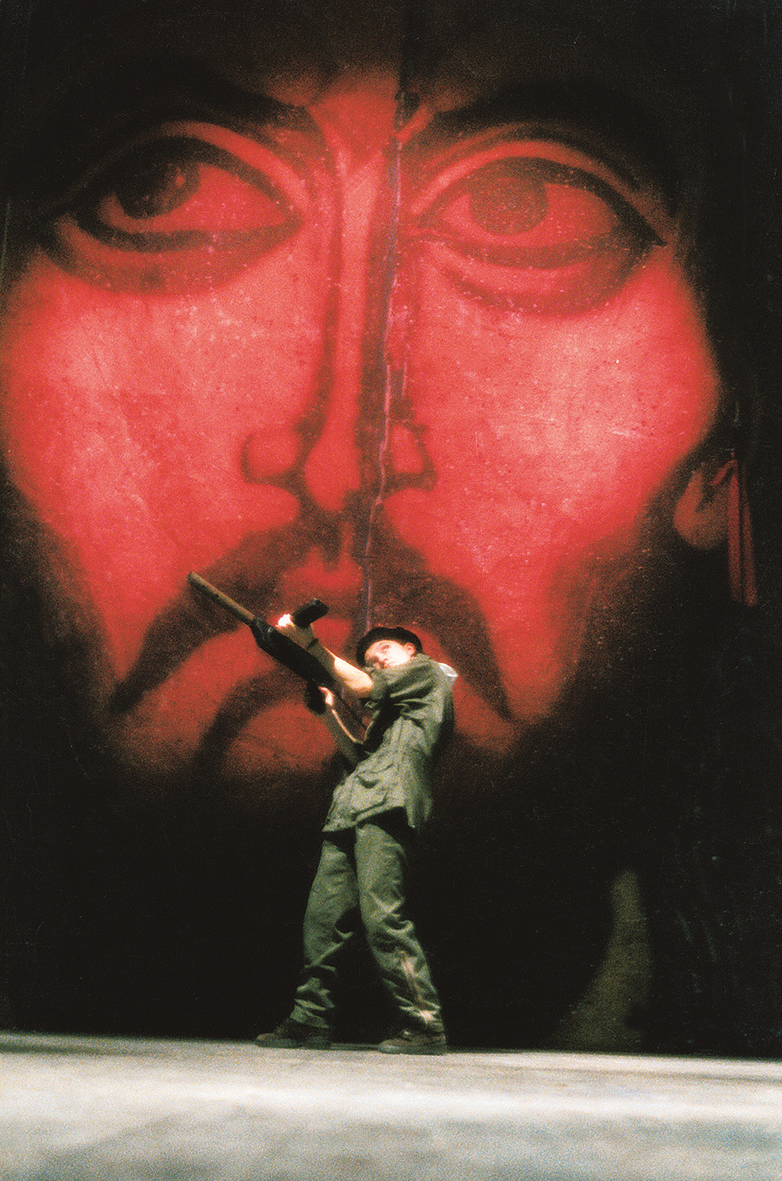

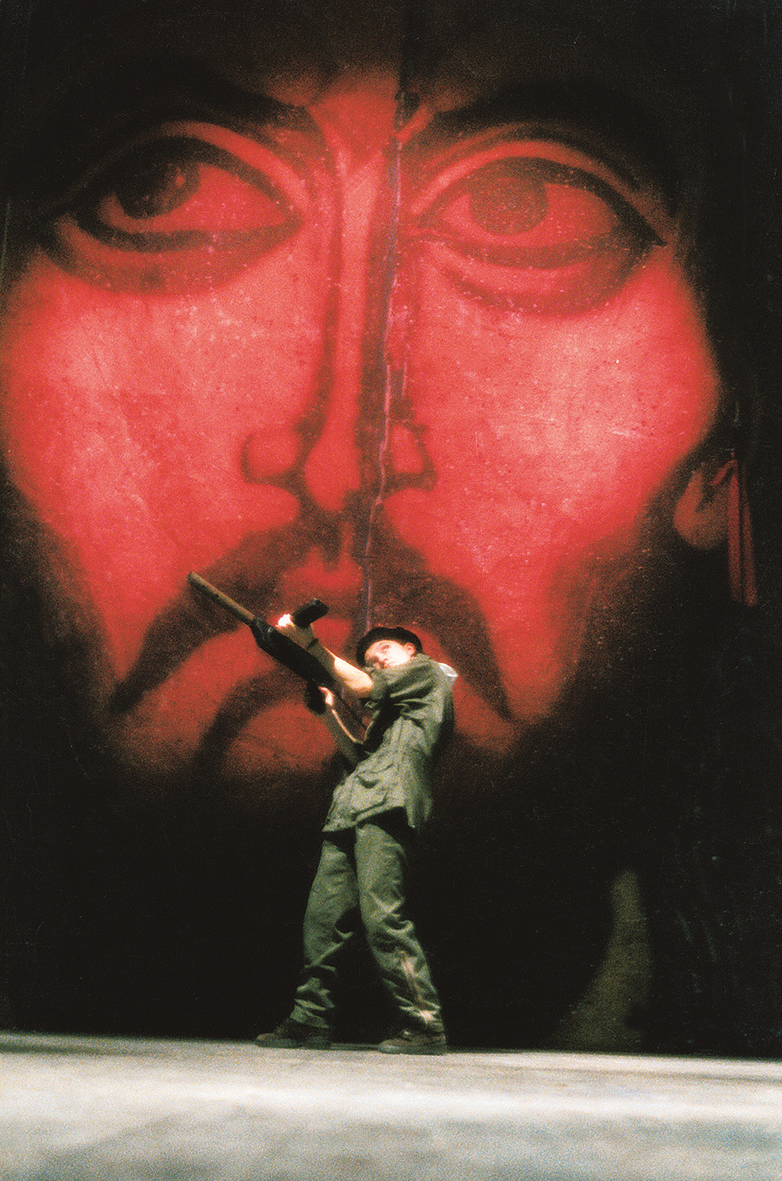

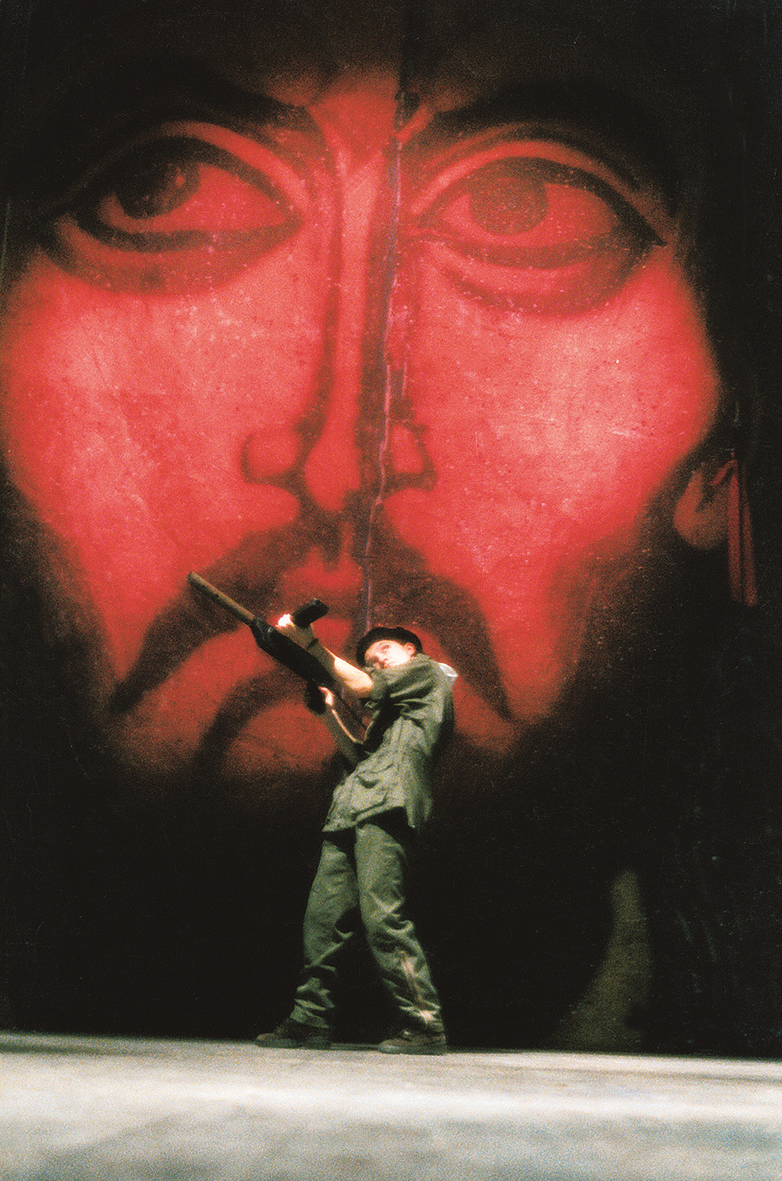

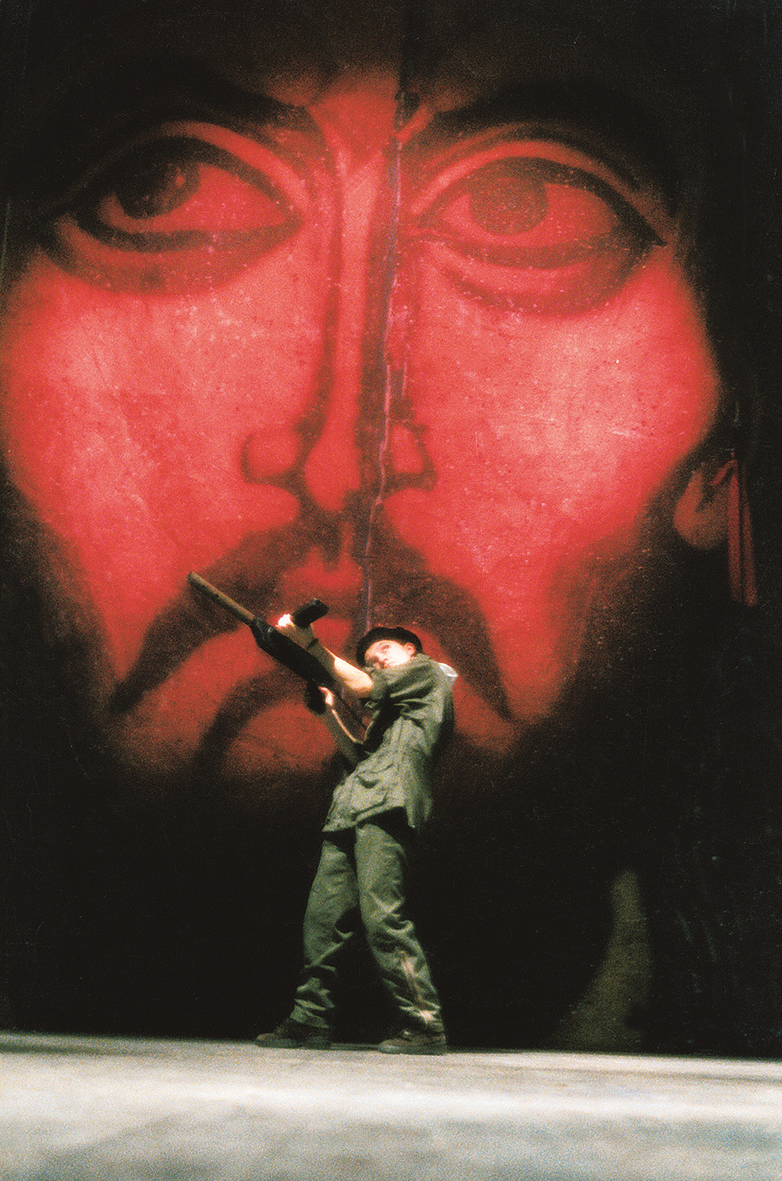

After a three year long rehearsal period, the performance One Day in the Life of Ignac Golob by the theatre company Coccolemocco premiered in 1977. Preparations for the performance took so long, among other things, due to problems with the rehearsal space, which was finally found in the premises of the Society of Amateurs in Culture and Arts Vinko Jeđut. 25 people participated in the show, most of them from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Branko Matan wrote the libretto, Branko Brezovec was in charge of the direction, Tihomir Milovac made the props, Božo Kovačević provided the voice for Ignac, while Mladen Blaić provided the voices for other puppets. The main backbone of the performance were gigantic three-meter tall puppets, designed and made by Jadranka Fatur.

The performance follows the life of a factory worker, Ignac Golob, through a series of images from his everyday life: Ignac at Work, Ignac at Home, Ignac in a Shop, Ignac and the Sun, ... and finally Ignac and Death. The text by Branko Matan was subtitled "morality play on contemporary life," and engages in a dialogue with the book by Wilhelm Reich, Listen, Little Man! The theme of the "little man", unconsciously concealed in all of us, signifies "that model of ‘non-freedom’ which is the only one still needed by the crazed mass production of consumption" (cited from the program booklet), both in capitalism and socialism. Socialism failed to deal with the contradictions and deceptions of banality of everyday life before which the "little man" Ignac Golob, a factory worker, is helpless and ineffective, but primarily lacks responsibility. His diagnosis of the world is "Let it be what needs to be!"

The performance questions the idealized image of Yugoslav socialist society and through the portrait of the "little man" Ignac Golob and its co-responsibility for the social conditions of the society he lives in, it comes to the diagnosis spoken up by an actor on stage: “(...) if an individual lets the world come out of him, then nobody has a chance anymore.” The performance talks about the responsibility of the little man for “the death of all our languages”.

Gordana Vnuk cut the newspaper articles about the show and stored them in her collection, along with the program booklet, tickets for the show, and other documentation related to One Day in the Life of Ignac Golob.

Gordana Vnuk's personal collection contains published and documentary materials about the festival of new theatre Eurokaz, the theatre company Coccolemocco, the international theatre festivals Young People’s Theatre Days and Young People’s Theatre Days of Dubrovnik and the The Society of Amateurs in Culture and Arts Vinko Jeđut at which premises the company was working for some time under the pretext of being its theatre section. Coccolemocco, as a part of independent cultural scene, introduced new elements to the performing arts and a new type of theatre into Croatian and Yugoslav society. Through their selection of themes, the young theatre zealots inaugurated and discussed issues pertaining to Yugoslav leftist practices, relying on the utopian ardour of their generation who chose theatre as a possible mode of responsible and open action along the lines of Brecht and his dialectical method. Such an attitude ultimately lead to negative criticisms from a part of the professional mainstream community.

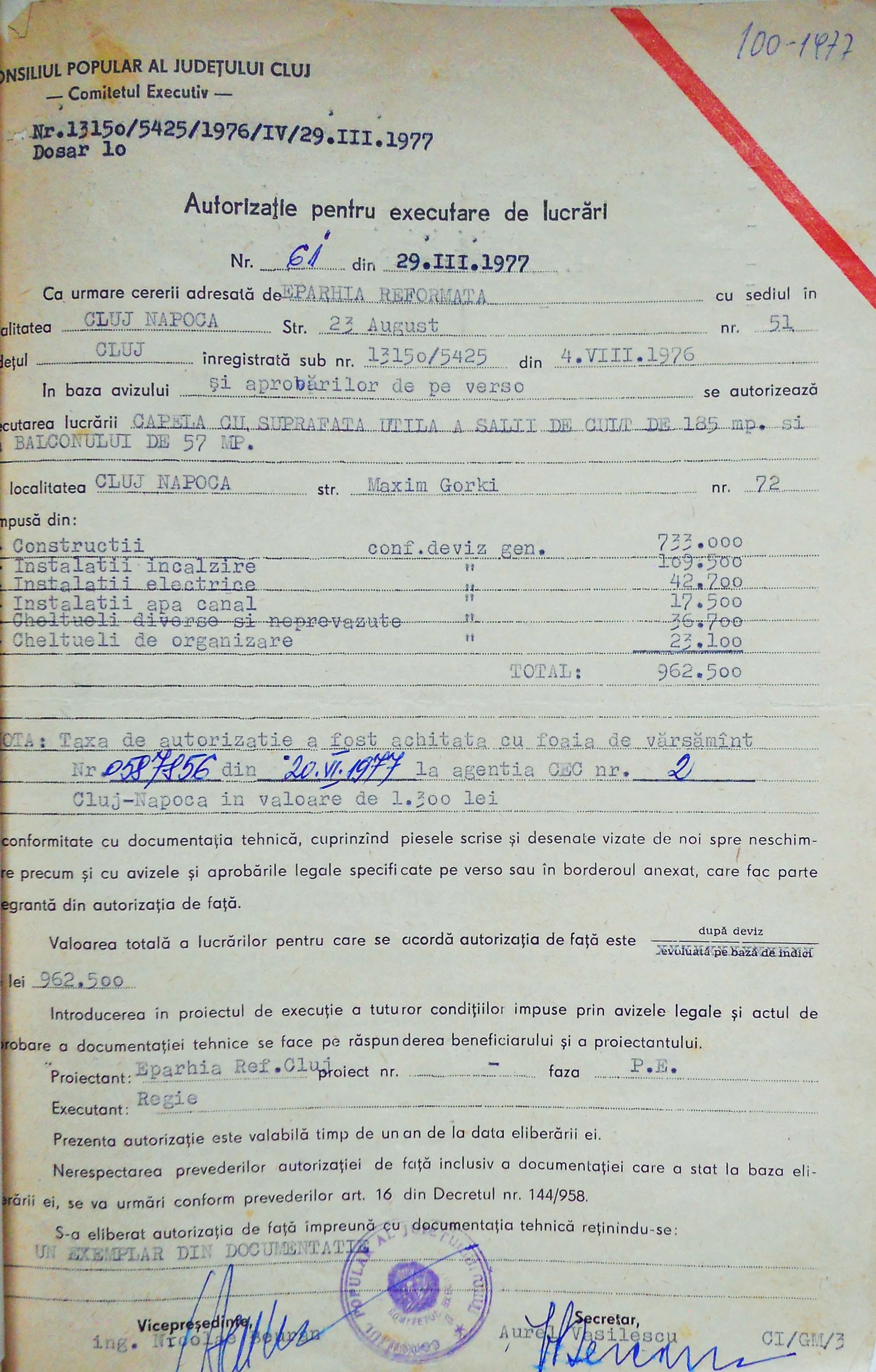

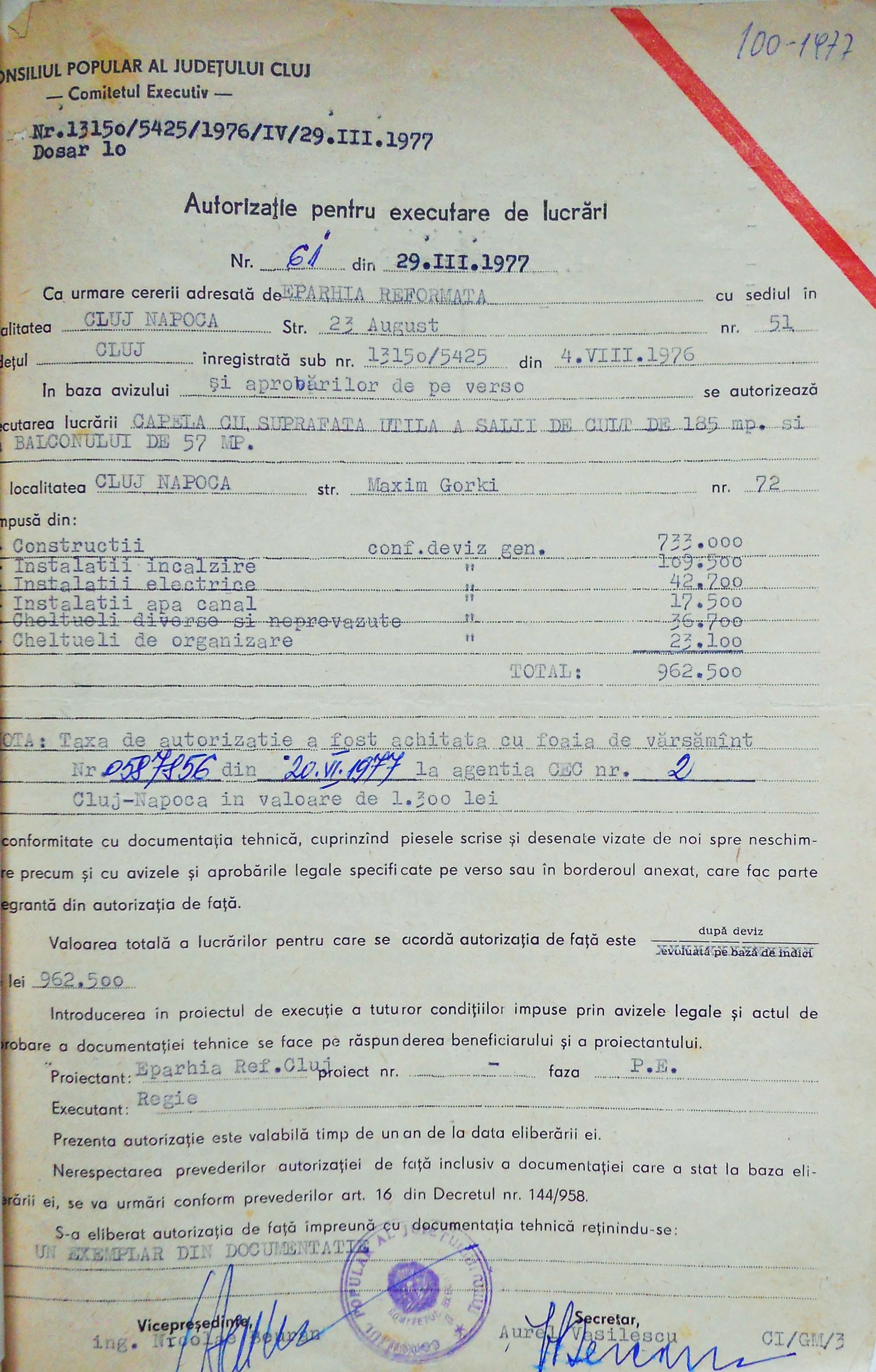

The prelude to the issue of the church building permit of 1977 is at least as interesting as what happened after this. The beginnings of the church construction in Dâmbul Rotund can be related to 14 April 1946, when – on the occasion of the Palm Sunday outdoor church service –, the pastor of Cluj-Hidelve and his church members laid the foundation stone of the Remembrance Church "in front of a large gathering, on the ground of the reformed church of Hidelve, at number 62 Str. Partizan." In 1948 the school–house of prayer was nationalised, but the idea of a church construction was promoted again only in 1956, when, at a presbytery meeting, referring to the construction of the reformed church in the Iris district, Gyula Kis pronounced the request for a church construction for the believers in Dâmbul Rotund. He further explained that the "ground at no. 72 Str. Gorki is perfect for the construction of a church and prayer house" and his proposal for the purchase of the ground was accepted by the presbytery. After the purchase of the ground, they sold the ground on Str. Partizan and moved the foundation stone to the newly purchased ground. According to notes from 1957, the architect Károly Kós drew up plans for a new church, but for unknown reasons these were not used in the end (statement of András Dobri).

The congregation, dreaming of a church and manse, got from 1 April 1969 in the person of János Dobri a pastor, who not only wanted to keep their dream, but also wanted to achieve it. The new pastor considered his primary task to be the construction of the church, as the barrack-building then used for church services had room for only about 120 persons out of a congregation of almost 3,000. Opinions differ concerning the original author of the plans. Different sources name either the building designer dr. Pál Farkas, of Transylvanian origin, but living in Debrecen at that time, or the architect József Finta, born in Cluj and living in Budapest. The plan was adapted by the architect László Nagy in 1969 and Dobri started to organise the church construction works. The Gustav-Adolf-Werk set aside 50,000 deutschmarks for this purpose and the development of the construction work can be followed from 1971 also based on the Securitate agents' reports. In the summer of 1972 Dobri travelled to Bucharest, where he had an audience with János Fazekas, vice-president of the Council of Ministers, who even called in to the debate the head of the Department of Religious Affairs Dumitru Dogaru. But theoretical consent was not followed by action. The approval of the Department of Religious Affairs was subject to the modification of the plans and accompanying documents. Then another impediment arose: the zonal urban plan of the Dâmbul Rotund district had not been drawn-up yet, and consequently patience was required since a building permit could not be obtained before such a plan was issued. One of the officials of the Cluj People’s Council told László Nagy, who was dealing with the case, that even the leaders of the Reformed church did not consider the building of the church to be a priority (ACNSAS, 211500/5).

The seven-year battle with the responsible authorities in Cluj and Bucharest finally ended in success. On 29 March 1977, the Executive Committee of the Cluj County People’s Council issued building permit No. 61, in which they gave their consent to the construction of the "chapel," consisting of a hall of worship of 185 m2 and a gallery of 57 m2 with a total value of 962,500 Romanian lei (KKREL 1977/7, Building permit No. 61). On 24 September 1977, work was begun. It was not only carried out by the members of the congregation of Dâmbul Rotund. Pastors and members of other congregations and theology students helped them, and regardless of their religious and ethnic differences both Hungarians and Romanians, Catholic, Orthodox and Evangelical alike worked here. It was teamwork that meant something important for the people, and showed that even under the communist regime one could obtain little victories. The church constructed largely by voluntary work was finished in 1980 and consecrated on 27 April that year. It was constructed in a time, when the hope that it was possible seemed an illusion. It was named the Church of Hope, because it brought hope to many people in a dark era (statement of Anna Jankó; statement of András Dobri).

According to the original plan the new construction was both church and manse at the same time. The state first granted the building permit only for the construction of the church, which was carried out between 1977 and 1980. Following this they had to wait five more years to start work on the parish building near the church. The obtaining of the new permit was accompanied by difficulties similar to the those experienced with the initial church project. János Dobri began to take steps in May 1982 and they were finally able to start in 1985. With local effort and foreign help the parish building was constructed, including the pastoral residence, prayer room and pastoral office, together with childcare and medical rooms. But this activity was associated with the new pastor András Dobri, who served there from 1 January 1986. The actual completion of the construction is considered to be 18 September 1988, when the second part of the old plan had been carried out as well (Dobri 2014).

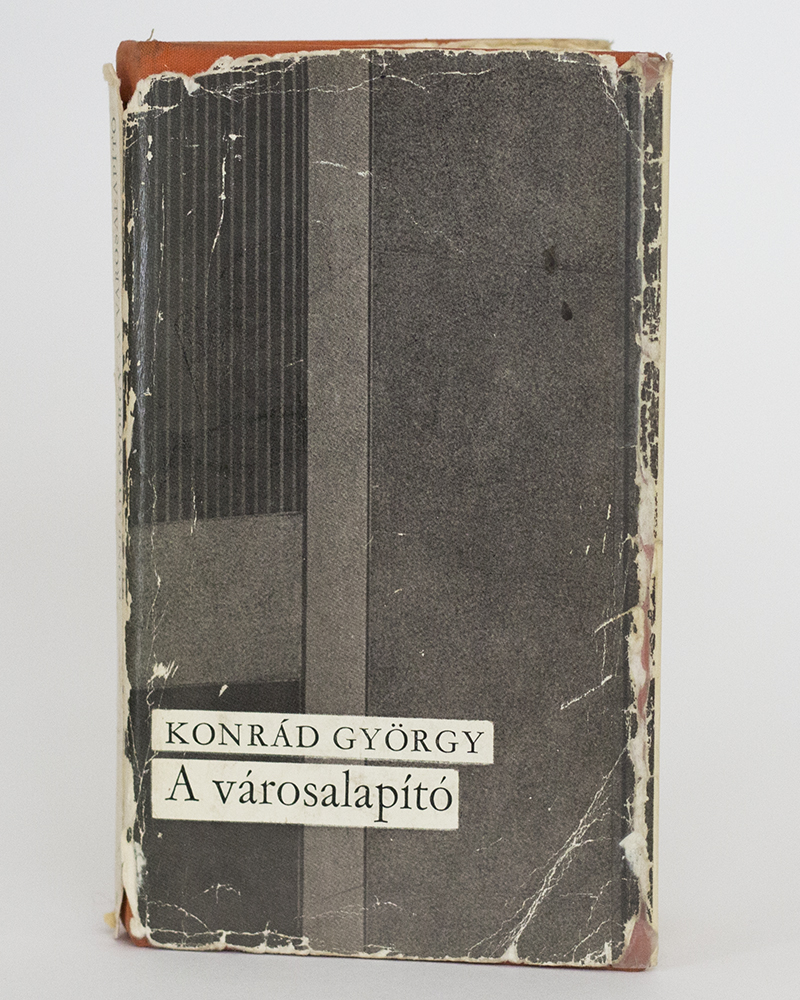

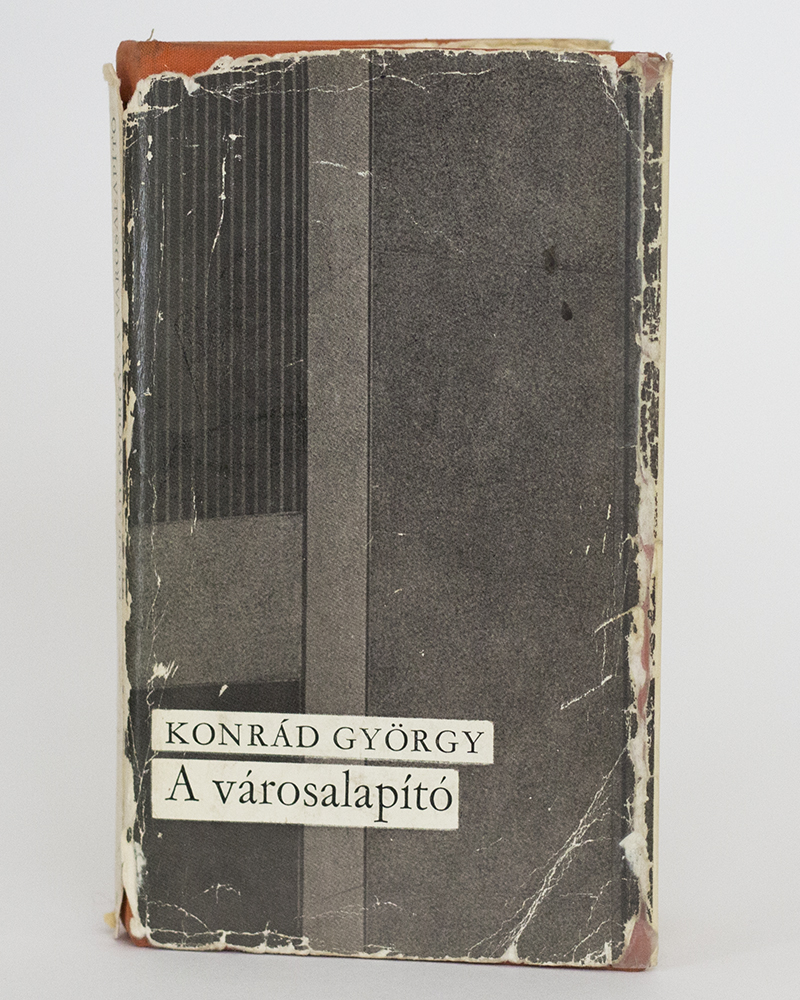

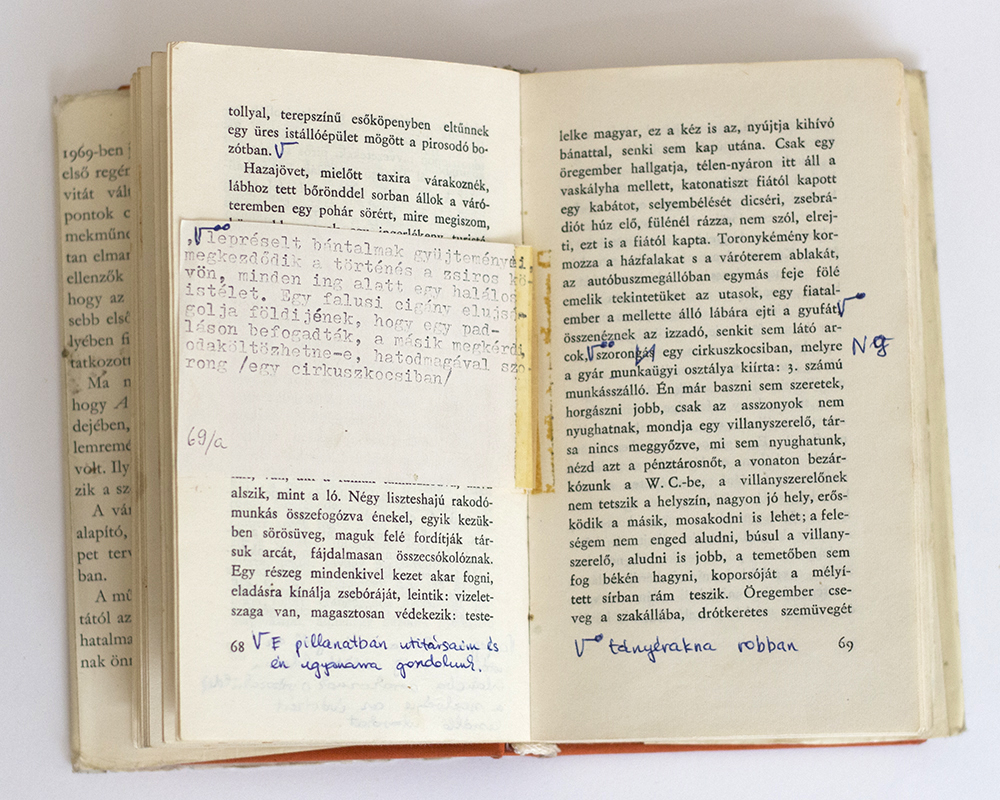

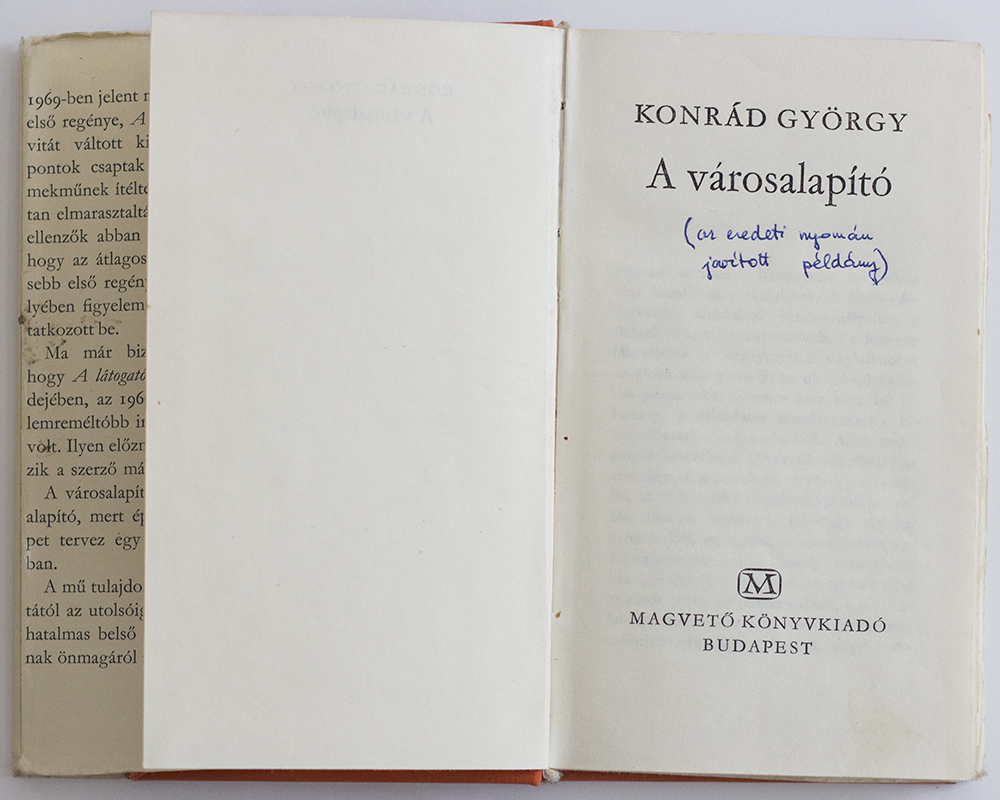

“I write what I write, state publishers publish from me what they want, and I, however, publish my work as I can.” In 1974, György Konrád summarized the functioning of censorship in an interview given to the West German periodical Die Zeit. The dissident author and activist Konrád was regularly persecuted by the state authorities from the early 1970s. His works were either not published or printed only following thorough censuring. His novel, The City-Builder could be published in Hungary in 1977 only with substantial cuts and modifications forced by the censor.Gábor Klaniczay, the young intellectual interested in counter-culture preserved one copy of Konrád’s novel. This book is unique, however: in his own copy, Klaniczay corrected by himself the parts that were cut or modified by the censor. At that time, the original texts of forbidden or censured works were shared in manuscript or homemade copies among oppositional networks. The book displayed here documents both the intention of suppressing culture and the individual act of resisting it.

After the death of the Czech philosopher Jan Patočka in 1977, his students were afraid that his manuscripts would be confiscated by the state police. The fact that Jan Patočka had died at Strahov Hospital was hidden from the public. Ivan Chvatík learned of it from a broadcast by Radio Free Europe. He decided to immediately save Patočkaʼs documents. Ivan Chvatík met Miroslav Petříček on the way to Patočkaʼs house and together they called Jiří Michálek, who owned a car. It turned out that Michálek and Jiří Polívka had had the same idea. They travelled together to Patočkaʼs flat. After initially hesitating, Jan Sokol, the son-in-law of Jan Patočka, finally agreed to give Patočkaʼs writings to Chvatík and his colleagues. Then, Patočkaʼs materials were loaded into the car. The situation seemed dramatic, as an unknown car with men sitting inside was waiting in front of the house, and Chvatík and his collaborators were afraid they were being watched. Nevertheless, nothing unexpected happened and Jiří Polívka were able to safely hide the documents in a secret location.

Thanks to the fact that Patočkaʼs students Chvatík, Polívka, Petříček, and Michálek ran the risk of being uncovered and saved Patočkaʼs manuscripts, almost all of Patočkaʼs work and his personal notes were preserved and could be later published.

Data Sheets on Windmills from Enisala, Dunavăţ, Frecăţei and Mahmudia in Dobrogea, in Romanian. Research: 1965-1977. File

Data Sheets on Windmills from Enisala, Dunavăţ, Frecăţei and Mahmudia in Dobrogea, in Romanian. Research: 1965-1977. File

From 1964 until the end of the 1970s, Hedwig Ulrike Ruşdea, a museologist at the Museum of Folk Technics, conducted multiple pieces of field research on the technology of windmills and on their history and role within rural communities in the region of Dobrogea. In this file, she compiled specification sheets for the researched windmills, notes on the history of artefacts, interviews with former owners, who had been labelled as kulaks (chiaburi in Romanian) by the communist regime because of their owning a windmill, observations on the economic and social role of windmills, analyses of their numeric evolution, photographs of windmills rescued from the villages of Enisala, Dunavăţ, Frecăţei, and Mahmudia in Dobrogea, and reports on the acquisition of these windmills. The information included in this file persuaded the leadership of the Museum to rescue and reassemble the four mills at its open-air exhibition located on the outskirts of Sibiu. The various data gathered in the file are also a valuable historical source on the history of the region's cultural heritage and on the impact on this heritage of the economic and social modernisation policies implemented by the communist regime.

This collection consists primarily of the items confiscated by the Securitate on 1 April 1977, on the occasion of the house search and arrest of the driving force behind an emerging movement in defence of human rights in Romania, Paul Goma, a writer censored in Romania but successful abroad. A particular feature of this collection is that the confiscated items were not destroyed, but were preserved by the Securitate and finally transferred to CNSAS in 2002, from where they were returned to Goma in 2005. Thus, the collection is one of the few which travelled after 1989 from Romania into exile and is now to be found in Paris, where Goma was forced to emigrate a few months after his arrest and the confiscation of the collection.

Charter 77 was an informal Czechoslovak citizens' initiative that criticised state power for the non-recognition of basic civil and human rights, following the movements of the CSSR and their signing of the Final Act at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe on 1st August 1975 in Helsinki.

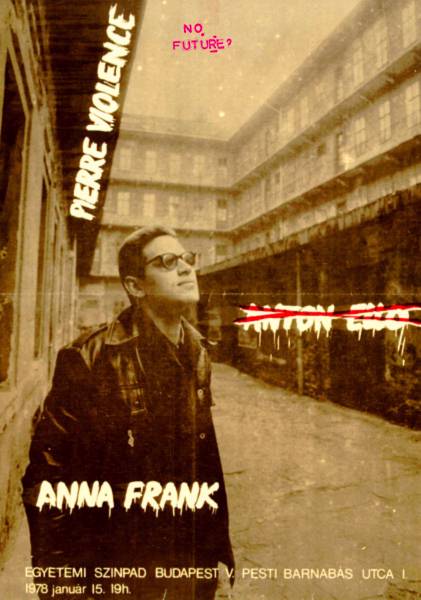

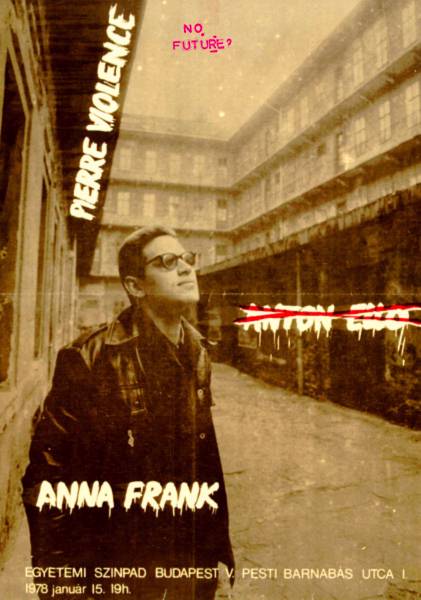

This offset poster represents a significant event both in the history of the Hungarian new wave and in Tamás Szőnyei’s personal story. This was the first item of Szőnyei’s collection. He received it as a present from his painter brother, György Szőnyei. The poster advertised an art-punk act by a certain “Anton Ello” and “Pierre Violence,” who are Gergely Molnár and Péter Hegedűs of the band Spions. They used pseudonyms and their band’s name, Donauer Video Familie (that eventually turned into the not less ironic Spions), was not displayed either. The potential audience would have had little clue of what to expect.

The event was entitled Anne Frank Memorial Evening, and the name Anne Frank appeared on the poster as well. One of the band’s songs was “Anne Frank’s Dream,” which is a violent apocalyptic vision: it is initially about a coercive sexual act with Anne Frank before the Nazis discover her. The text is also open to a variety of figural meanings, one being that the perpetrator is the totalitarian political power itself and listeners of the song are all Anne Franks whose best chance for gratification is to be assaulted before the quickly approaching death. “No future?”—the poster questioned with an homage to the Sex Pistols.

The band Spions had a huge impact on the new wave in Hungary, despite the fact that they could not release an album, and performed no more than two (!) times in Budapest and on one single occasion in the city of Pécs. The band grew out of a lecture series on the history of rock music that was held under the auspices of the Society for Dissemination of Scientific Knowledge (TIT), an institution of public education supervised by the Ministry of Culture. The lecturer was Gergely Molnár, who analyzed texts by Lou Reed, David Bowie, Roxy Music, and the Kraftwerk in an event at the Ganz-Mávag factory, House of Culture in April 1977. The opening and closing acts were songs performed by students of the Music Academy, Péter Hegedűs and György Kurtág Jr. Hegedűs approached Molnár to start a band, and they wrote a bunch of songs together. The event advertised on the poster was their first performance. It happened at the University Stage (Egyetemi Színpad) that was founded in September 1957 by the Loránd Eötvös University of Budapest. The Stage was one of the few official spaces where alternative performing acts and concerts could be held. The proto-Spions was the first art-punk band on this venue. The audience was small, but the songs had a greater impact than they ever imagined. These were formative experiences for such cult bands as Kontroll Csoport, Európa Kiadó, or URH, and their inspirational, witty songs were played throughout the 1980s.

The performance at the University Stage, however, was interrupted by the director of the venue, who went to the stage and explained that the concert had to be cancelled because of “technical reasons.” There is no clear evidence that the disruption was politically motivated, though witnesses say that it did sound bad. Nevertheless, it was made into a political issue by the artists when the next concert was advertised with a poster that used the image of the director of the University Stage interrupting the first performance. The poster contained another direct provocation to the officialdom of the regime. It featured the song “Ungvári Tamás” that bears the name of a famous public intellectual of the Kádár regime as its title. Ungvári was notorious for committing large numbers of factual mistakes in his works, which was noticed by many at the time; but this alone, perhaps, would not have provoked Molnár to devote an entire song to him. But Ungvári also aspired to write on popular music and counterculture with no fewer mistakes: fans, for instance, counted over 3,000 factual mistakes in his bestselling book on The Beatles. Such things, and Ungvári’s antipathy towards the alternative scene, inspired the lines by the Spions: “you mixed up, Tamás / Lennon with Lenin, Tamás / alliteration, Tamás / not politika, Tamás / but poetica, Tamás.”

The Spions provoked the interest of the political police, and there is extensive reporting on Molnár and his circle’s activities in the Historical Archives of the State Security Services (ÁBTL). For instance, Molnár’s private English teacher regularly informed on him, and the agent was instructed to provide a lot of homework for the musician in order to keep him busy and prevent him from “subverting” the system. Extensive practice of verb conjugation paid off well for Molnár: he emigrated to Canada in 1978 and never looked back. Hegedűs also left Hungary, coming back only after the regime change. The memory of the short-lived Spions and their songs, however, remained in the country and inspired an entire generation of new wave artists.

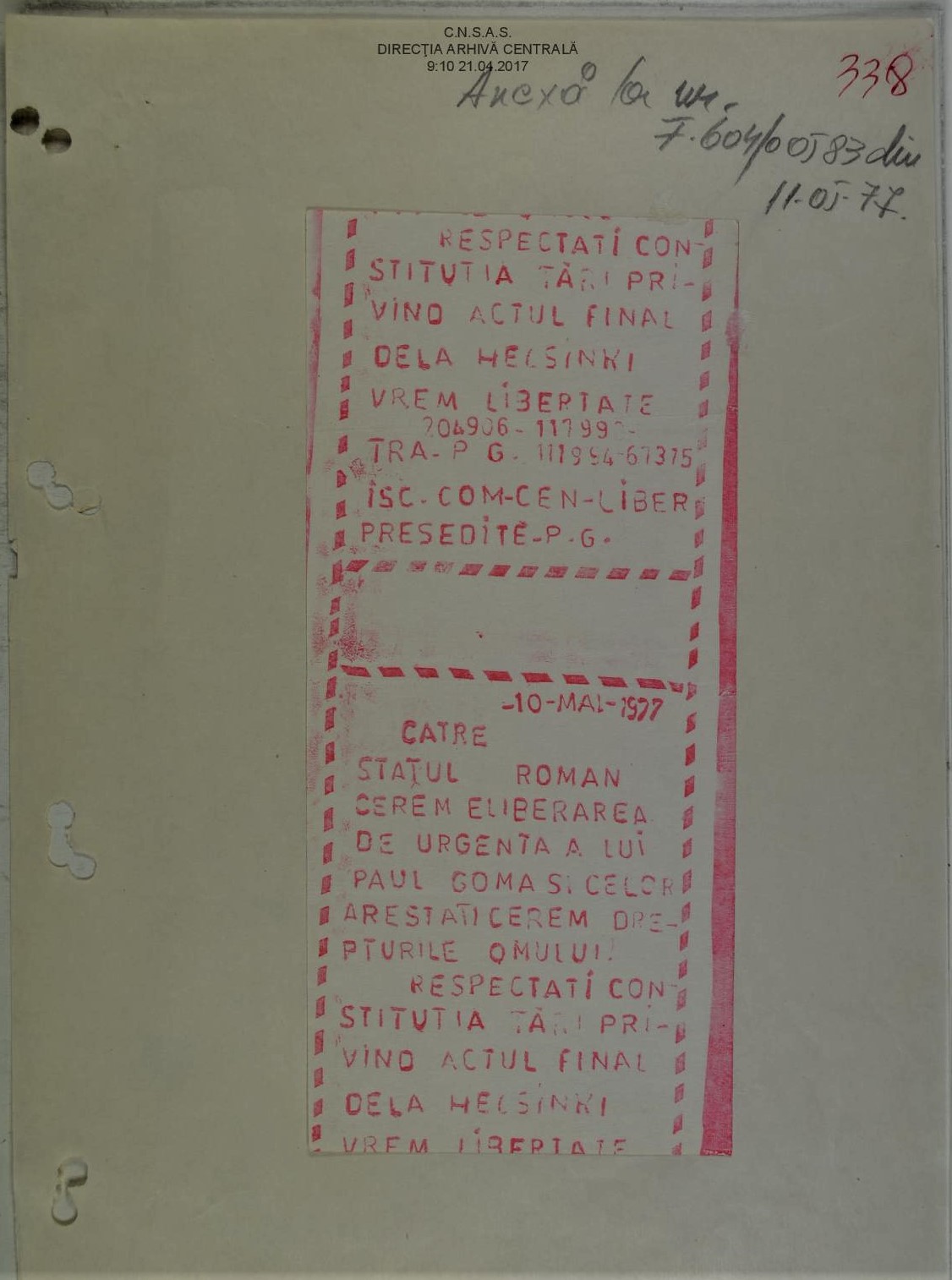

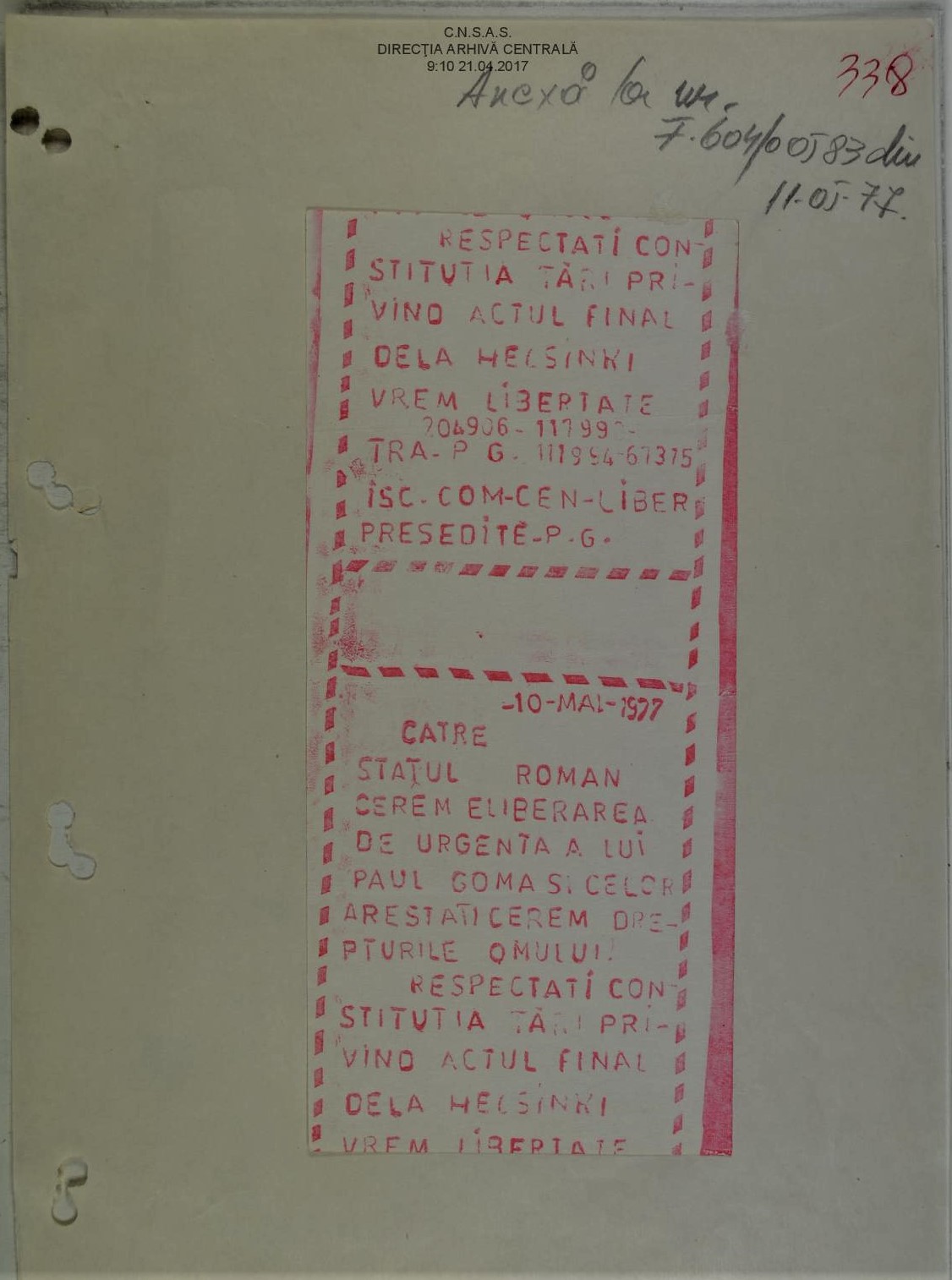

A Securitate report contains information about a bunch of leaflets which were found somewhere near the Timpuri Noi (Modern Times) factory in Bucharest. The Securitate report says that the manifestos were found on 10 May 1977, in fact four days after Goma’s release. However, the date it is not randomly chosen because this was Romania’s National Day before communist rule, which was significant because it symbolised the Royal Family of Romania, which was forced into exile by the communist authorities. The Securitate officers noted that the pieces of paper were found by some workers in a small perimeter, between two factories situated quite close to the city centre. The report states very clearly that manifestos like these were not found in other neighbourhoods or out of the city. The little hand-made manifestos contained the following text: “To the Romanian state: We ask for the release of Paul Goma and those who are under arrest. We ask for respect of Human Rights! Respect the Constitution of Romania in accordance with the Helsinki Final Act. We want freedom!” Two of these leaflets have been preserved in the original in the CNSAS Archives. These leaflets illustrate that the impact of the Goma movement on Romanian society was more significant than the statistics compiled by the Securitate indicate (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/10, f. 337-338).

The informal group of the Six Artists consisted of Raša Todosijević, Era Milivojević, Marina Abramović, Zoran Popović, Neša Paripović and Gergelj Urkom. The work of these artists began with the establishment of the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade in 1971. It lasted to 1973, when each of them started working independently. Their artistic activity was above all a resistance to the existing practice that was being taught in the framework of school programs at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade. They advocated the establishment of a modern approach to the reconstruction and functioning of artistic institutions, as well as to redefining the effects of art. The accent started to be set on the artist as a subject and to his authorial speech, "speech in the first place". The artists began to introduce new media into art (installation, bodybuilding, photography, film, text ...).

Securitate. Plan of Action against Goma and his supporters at RFE and in the Romanian emigration, 17 March 1977

Securitate. Plan of Action against Goma and his supporters at RFE and in the Romanian emigration, 17 March 1977

The Goma Movement Ad-hoc Collection includes numerous plans of action against the individuals involved in supporting the open letter of protest against the violation of human rights in Romania which was to be addressed to the CSCE Follow-Up Conference in Belgrade. Each Securitate informative surveillance file contains periodically updated plans of action, but these usually required only the approval of the high-ranking Securitate officer in charge of the case of the person in question. What is remarkable about this plan of action, which is part of Goma’s personal file, is its endorsement by the highest possible office holders in the Ministry of the Interior, to which the Direction of State Security was directly subordinated in 1977: the plan was countersigned by Nicolae Pleșiță, first deputy minister, and finally approved by Teodor Coman, the minister of the interior himself. Obviously, the hierarchical level of those who endorsed this plan indicates the great importance attached to this case. It is worth noting that the “successful” handling of the Goma Movement, in which Pleșiță involved himself and acted as Goma’s head interrogator, led to his promotion to the rank of lieutenant general in 1977. The same year, he coordinated the repressive measures taken by the regime in the aftermath of the Jiu Valley miners’ strike of August. Pleșiță remains notorious, however, for his actions while head of the Centre for Foreign Intelligence between 1980 and 1984, in particular for the 1982 failed attempt at suppressing Goma while in exile in Paris, and for the 1981 bomb attack on the RFE headquarters in Munich, for which the Securitate seems to have hired the infamous terrorist known as Carlos the Jackal. After 1989, Pleșiță showed no remorse for his misdeeds, and all attempts to hold him legally responsible for these wrongdoings eventually failed.

To return to this particular Securitate plan, its content and date of issuance illustrate that it was just an intermediate stage in the devising of actions meant to disintegrate the emerging movement. Chronologically, the date of issuance, 17 March 1977, is over a month after the open letter of protest against the violation of human rights was made public by Radio Free Europe, and thus it is entitled “plan of action for continuing the actions for annihilating and neutralising the hostile activities which Paul Goma initiated, being instigated and supported by Radio Free Europe and other reactionary centres in the West.” At the same time, it is a plan one step short of Goma’s arrest, which occurred two weeks later, on 1 April 1977. The document includes four separate types of action. The first type consists of the so-called “actions of discouragement, disorientation and intimidation,” which were directed mainly against Goma, but the necessity of tackling his supports separately is also mentioned. This type of action consists mostly of various forms of harassment up to the level of deporting him outside Bucharest in order to seclude him from his channels of communication across the border. These actions of rather soft repression were to be accompanied by attempts bring this problematic episode for the Securitate to a faster and neater end by convincing Goma to either give up or emigrate. The second category of actions included the use of the foreign press and publications in the attempt to compromise Goma and implicitly the movement for human rights initiated by him among the Romanian emigration and the Western audience. The third category referred to actions of counterbalancing the denigrating messages broadcast by Radio Free Europe, which was the radio agency that helped Goma the most. Finally, the fourth category consisted of actions to compromise Goma among the personnel of Western embassies in Bucharest, with the aim of depriving him of his channels of communication with RFE or other members of the exile community (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/6, f. 109-112). All these measures failed, and thus Goma was eventually arrested and brutally interrogated, including by First Deputy Minister Pleșită himself, but liberated approximately a month later, on 6 May 1977, due to the massive protests of the Romanian emigration in Paris, which managed to convince many outstanding personalities to sign a petition for his release. This plan of action testifies to the Securitate practice of spreading calumnious rumours about all those who spoke against the regime in order to defame and isolate them. As Goma himself observes, “a document of great importance for me. (…) I knew that (…) the [calumnious] rumours and gossip (…) were inspired by the Securitate. Now I have the proof that the Securitate was not only inspiring, but also authoring them” (Goma 2005, 397).

At the InterContinental Hotel in Prague on 1 March 1977, Czech philosopher and dissident Jan Patočka met with Max van der Stoel, the Dutch foreign minister, who was at the time on an official visit to Czechoslovakia. The meeting was initiated by the Dutch journalist Dick Verkijk at a time when the Charter 77 signatories were persecuted and silenced by the police. This was the first official meeting of a Charter 77 spokesman with a foreign political representative who recognized Czechoslovak dissent.

Patočka explained in German to the minister and, through a recording, to the international public, that the aim of the Charter 77 was not to fight against the regime, but to demand the observance of the valid constitution and other laws. A day later, President Gustáv Husák called off official talks with the Dutch minister. Jan Patočka was ill at the time and after this meeting he was subjected to days of interrogationby the State Security. Eventually, on 13 March 1977, he died.

This unique sound recording documenting the meeting between Patočka and van der Stoel was made by Dick Verkijk, who initiated and attended the meeting. The recording is stored in the Jan Patočka Archives, which has also decided to make it public and uploaded it to YouTube.

Dick Verkijk played this sound recording during a ceremonial meeting organised on 1 March 2017, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of this event, in InterContinental Hotel in Prague. Several high representatives of the Czech Republic took part at the ceremony, including the Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka and Minister of Foreign Affairs Lubomír Zaorálek. The ceremony was also attended by, among others, the Vice President of the European Commission Frans Timmermans and by the director of the Jan Patočka Archives Ivan Chvatík. Frans Timmermans stated at the ceremony that the activity of the Charter 77 Czech dissident movement had a significant influence on the fall of the Iron Curtain and the end of the Cold War in Europe.

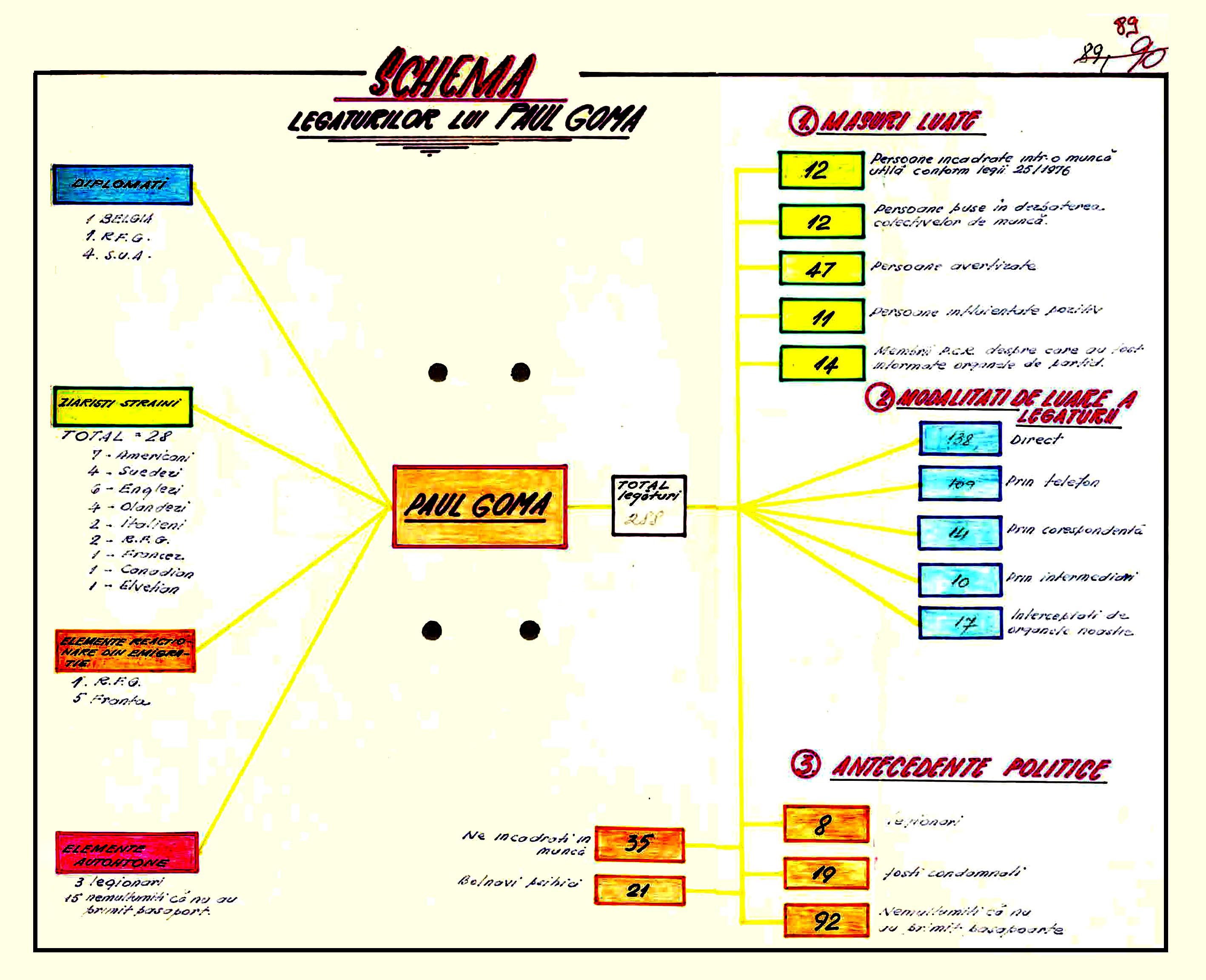

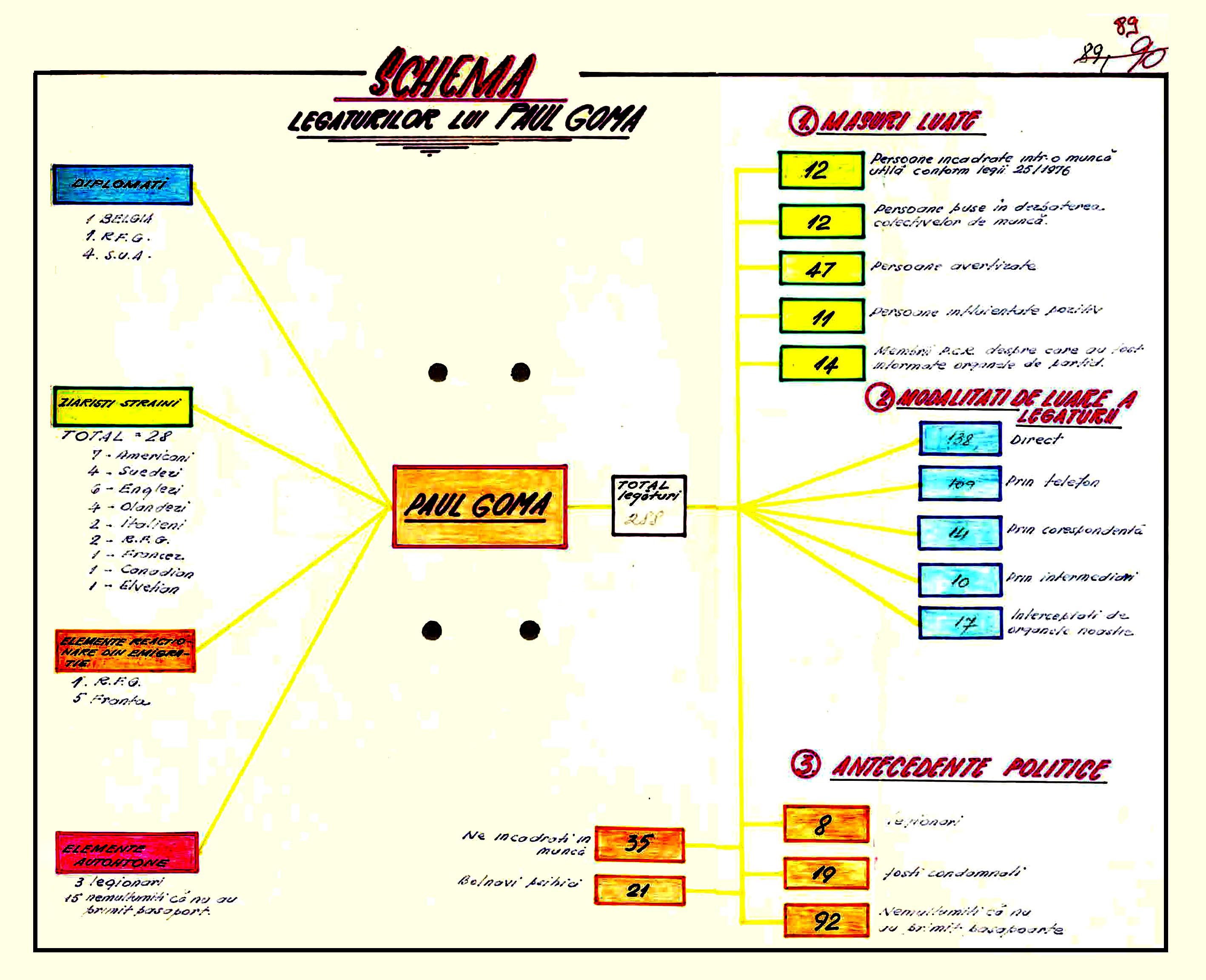

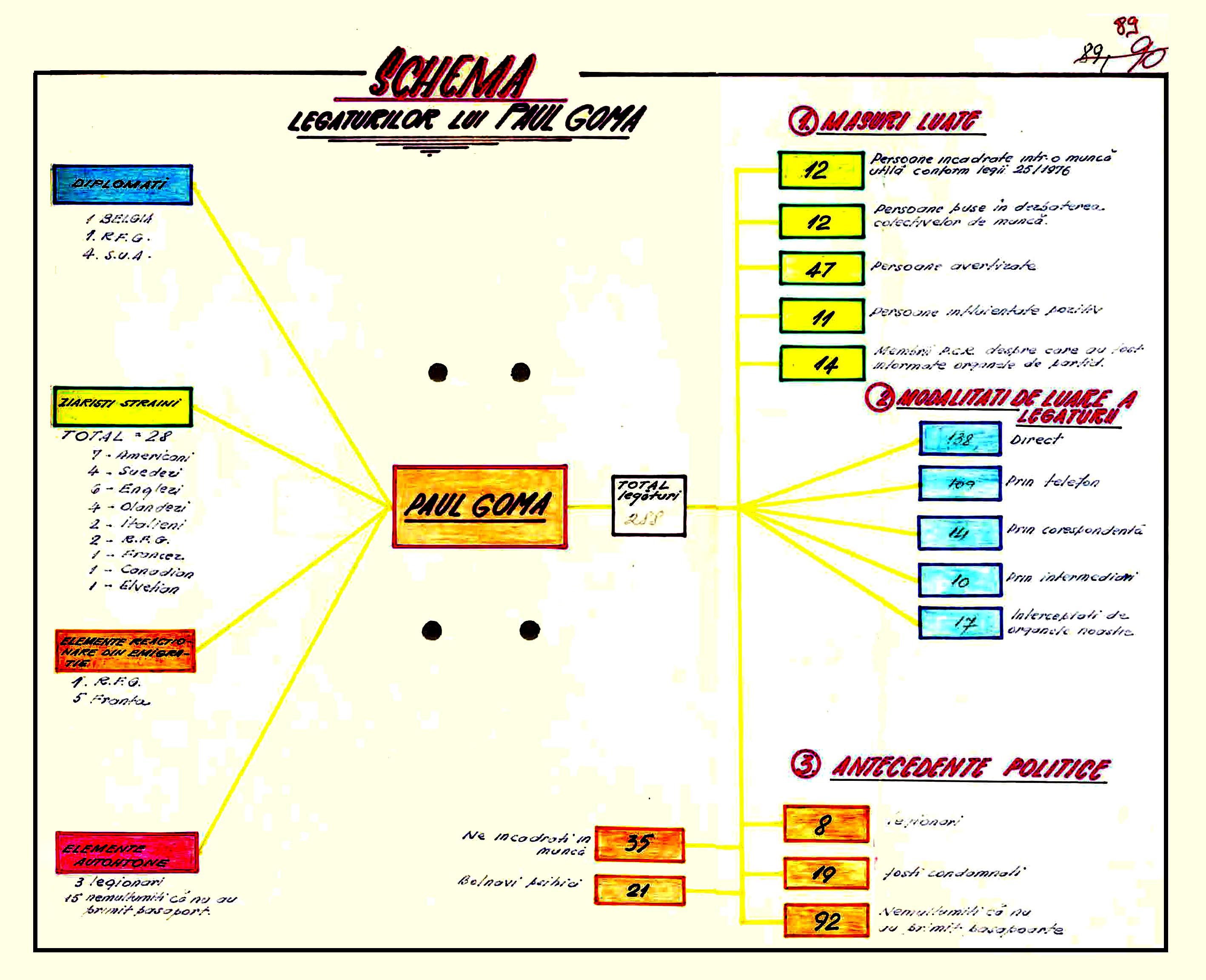

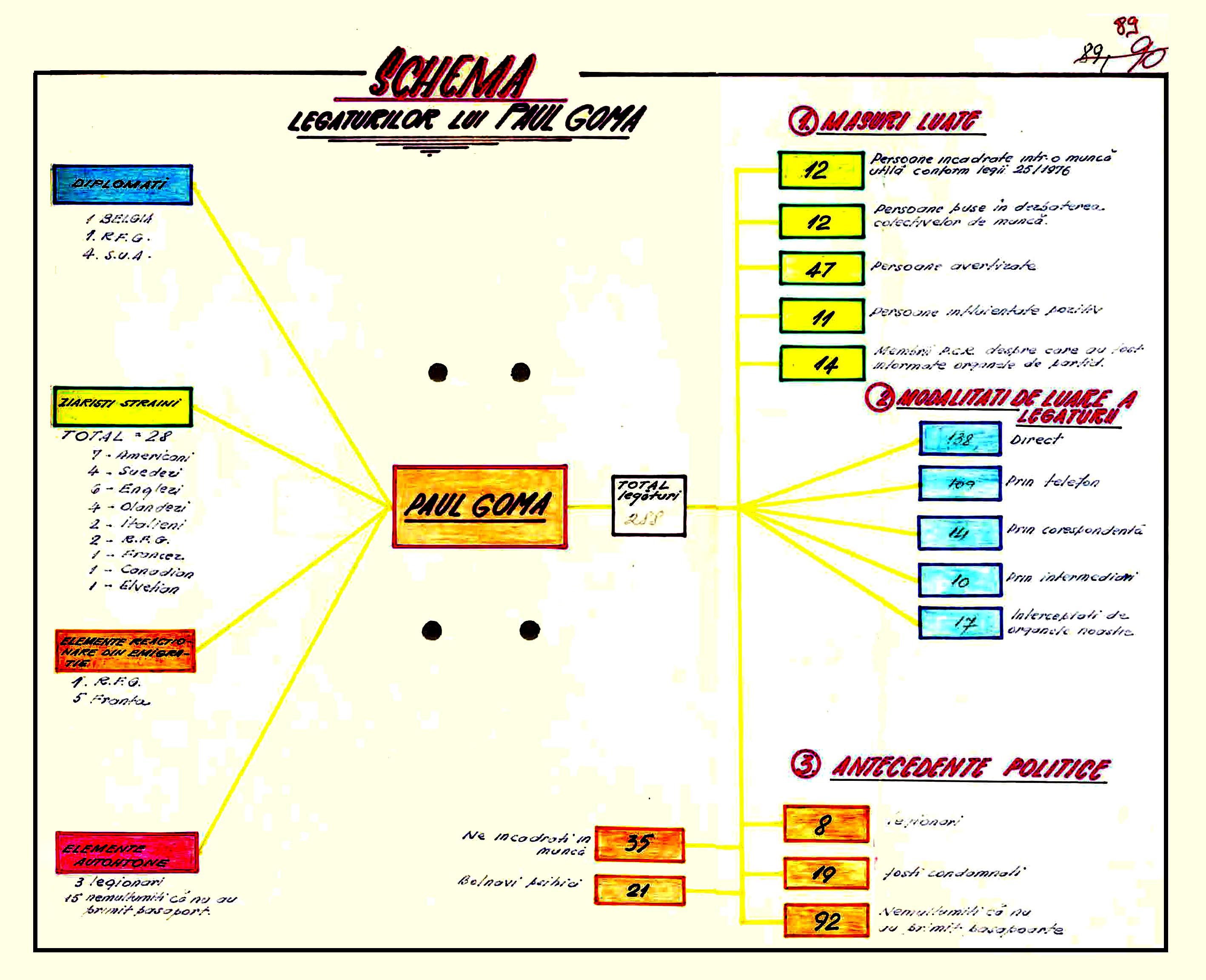

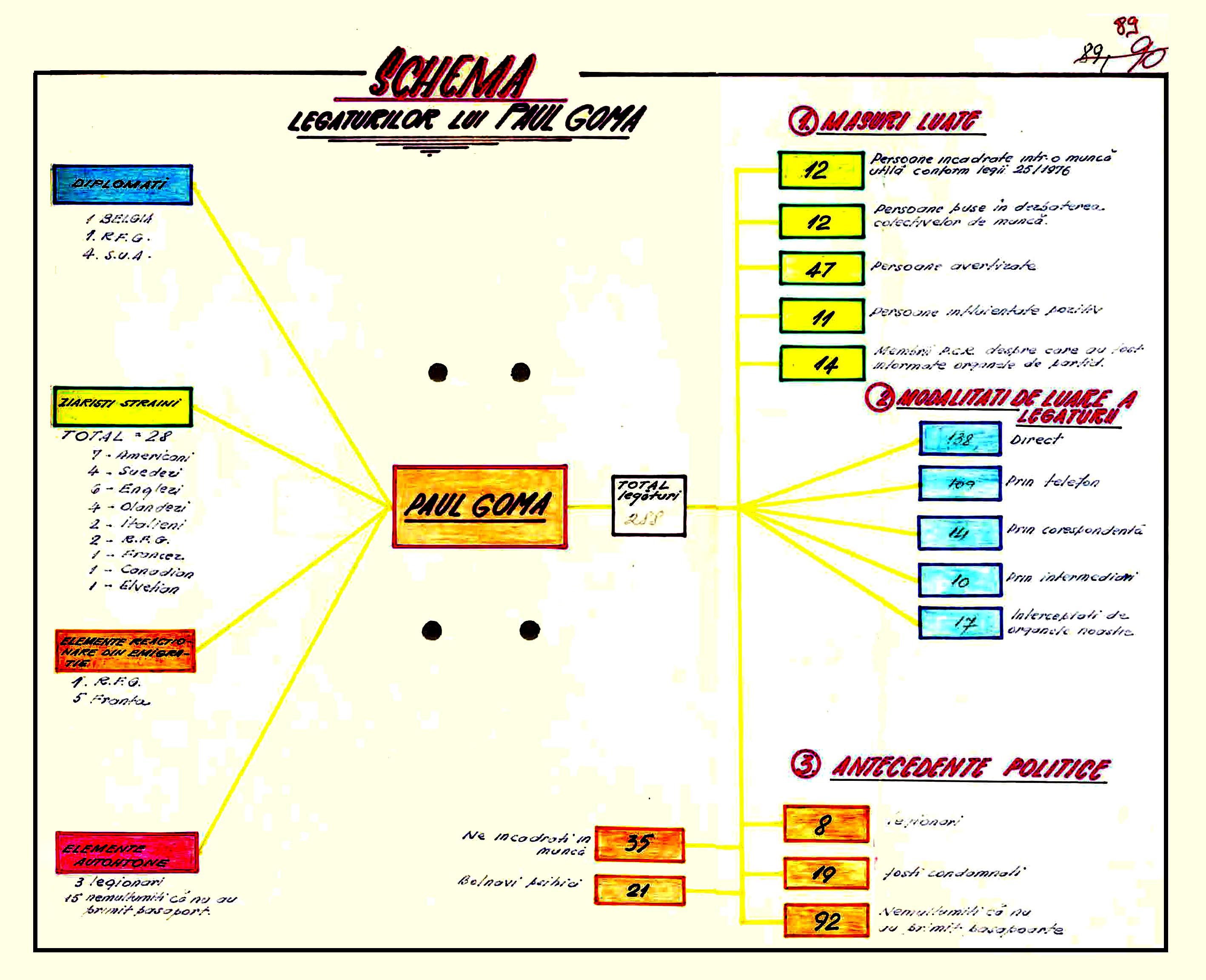

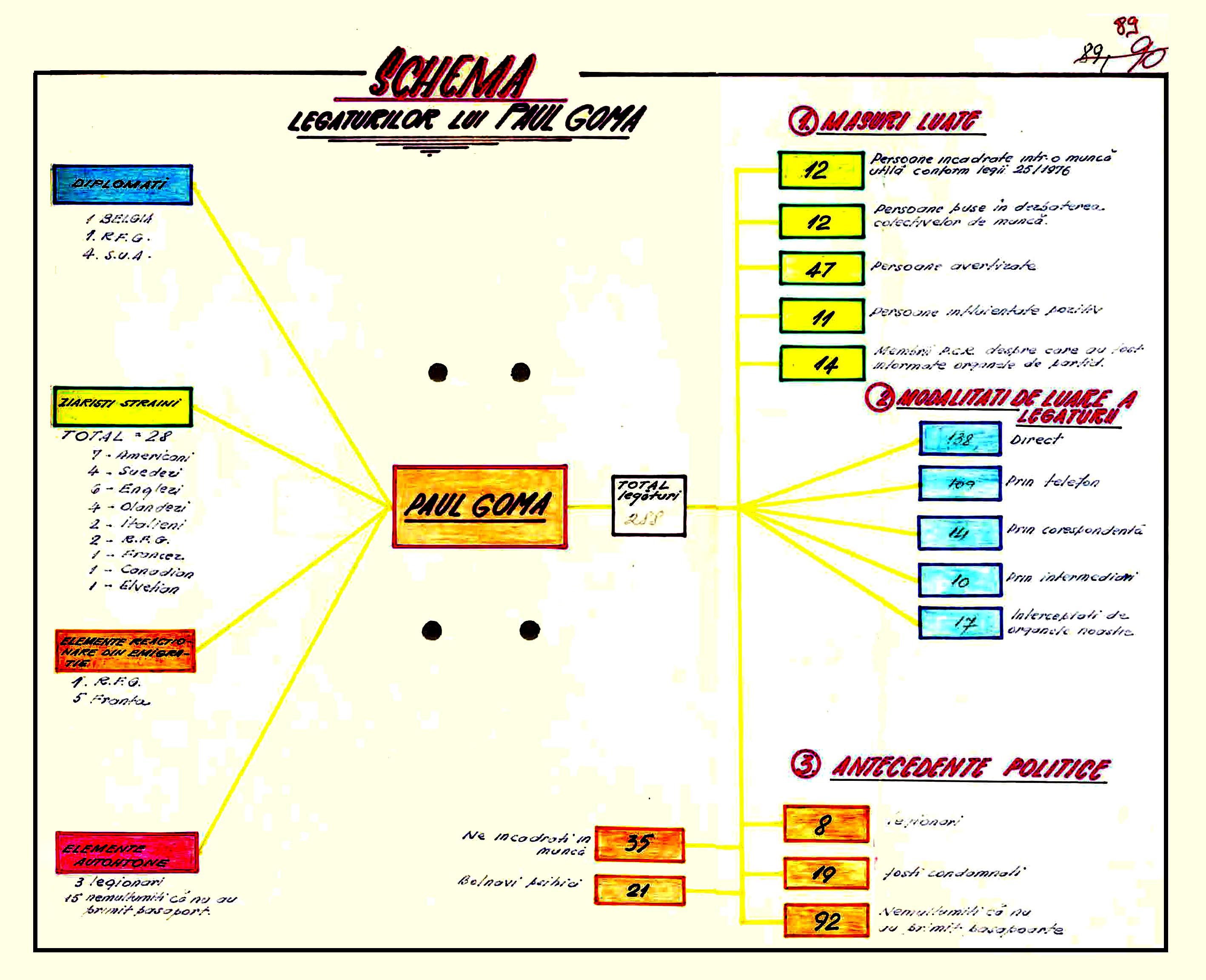

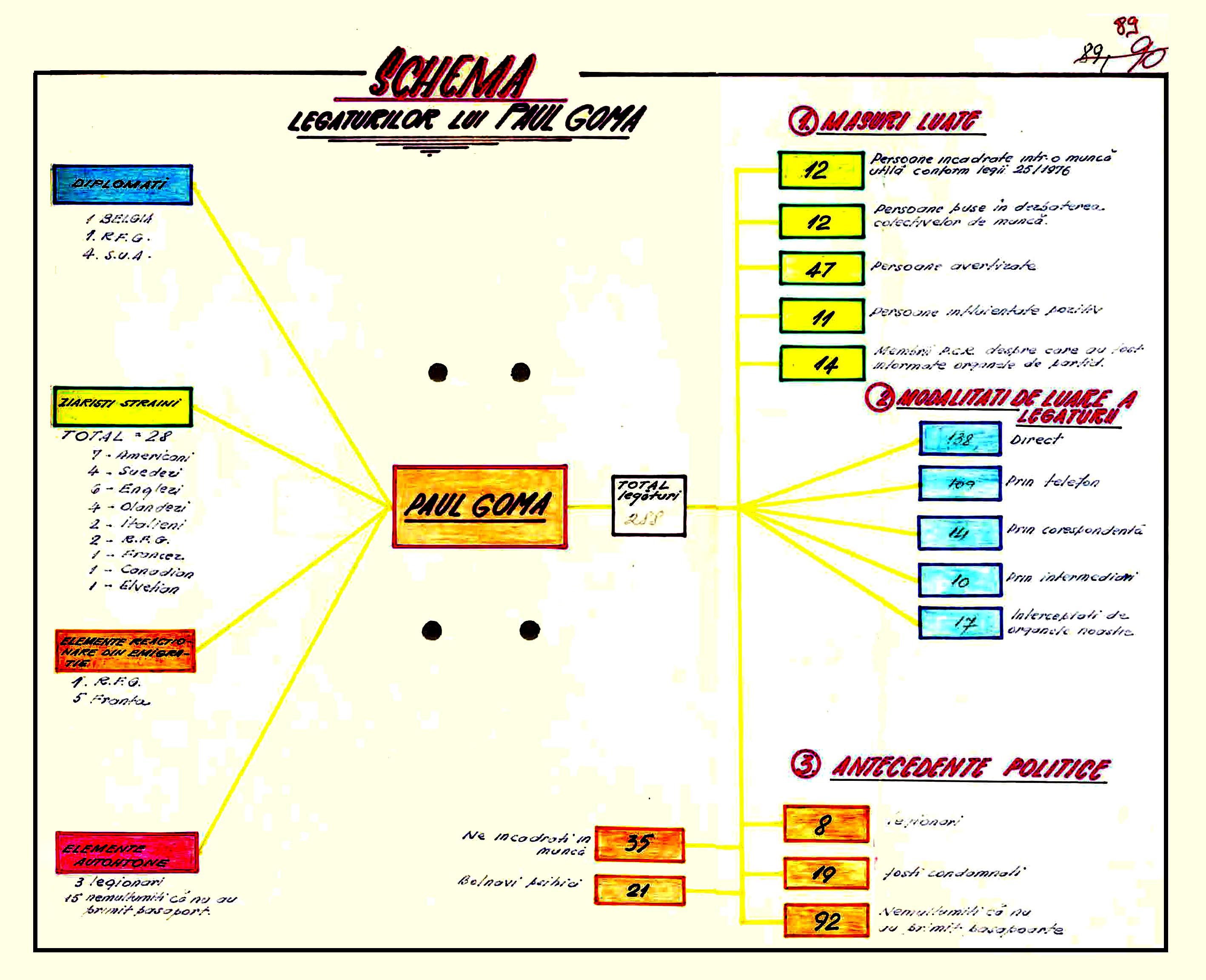

This chart epitomises the typical and efficient method which the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, used against those who attempted to establish networks of dissent in Romania. It seems to have been drafted for the Securitate officers who prepared the operative decision-making process regarding an emerging human rights movement in Romania, inspired by Charter 77. The driving force behind this movement was the writer Paul Goma, who initiated the movement in February 1977 by drafting a collective letter of protest against the violation of human rights in Romanian, which he and more than 200 other individuals eventually endorsed and addressed to the CSCE (Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe) Follow-Up Meeting in Belgrade. It was the first time that the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, had faced such an enormous challenge, and thus it had to react quickly in order to curtail the spread of the movement. In order to counteract this movement, the secret police had to collect in two months complex information about all those involved.

This chart and its annexes epitomise the collection of these complex data in the short time span between 9 February, when the collective letter was first broadcast by Radio Free Europe, and 1 April 1977, the day when the secret police arrested Paul Goma. The first thing one notices about this chart is its resemblance to the drawings made by high school teachers to facilitate a better understanding of a topic. The chart actually highlights Goma’s connections with the internal and external supporters of this movement which at that time constituted a collective action of unprecedented magnitude in communist Romania and implicitly a novel challenge for the Securitate. The chart only contains a schematic representation of Paul Goma’s relations with other persons (schema legăturilor lui Paul Goma). The central field, which features Paul Goma, is connected left and right with two columns of differently coloured fields. The left-hand column seems to represent a typology of individuals whom Goma had contacted in order to send documents relating to the activity of the emerging movement across the border to a Western country. They are divided into four categories: diplomats, foreign journalists, “reactionary elements from the emigration” and “autochthonous elements.” The right-hand column seems to categorise all those who had contacted Goma with the purpose of endorsing the movement. At the time when this chart was drawn, the Securitate had been able to scrutinise only 288 persons out of 430; the number of those identified to date is added in pencil. About these persons, there are three types of information offered: the actions taken (against them), their method of contacting Goma, and their political background (antecedente politice). The complex data collected about all these, which is included in annexes to this chart, included age, ethnicity, profession, education, place of residence and political background, meaning information about previous anti-regime activities.

The chart is an unusual type of document in the archives of the Securitate. Its unique character is directly related to the novelty of the challenge which the Securitate had to confront with Paul Goma’s attempt to establish a Romanian Charter 77. The novelty was twofold: it consisted both in the network established and the ideas expressed by this movement. Such a rapid solidarisation of individuals around a common purpose did not occur in communist Romania either before or after the Goma movement. At the same time, the defence of human rights was a totally alien idea and ideal in the political traditions of Eastern Europe in general, and of Romania in particular, even considering the period before the communist takeover. Thus, this emerging movement which implied the defence of a political idea (and not a material benefit) must have been really puzzling for the Securitate officers, who did their best to grasp the situation and understand the “real” motivations of the individuals protesting for the observance of such an “abstract” issue as human rights. This coloured chart and its annexes testify to the methods used by the Securitate in order to disaggregate a collective action for a common interest, the observance of human rights, into a multitude of individual actions, driven by personal interests and thus easier to break apart. In Goma’s words, “this is the use of statistics in the house of terror” (Goma 2005, 412).

The Goma Movement was a genuine moment of strong mobilisation against the communist regime, but it is canonised in the Romanian national narrative as a one-man collective protest. The overlapping is inevitable, since few of the other proponents were public personalities, while Paul Goma was indeed the driving force behind the short-lived movement. For instance, Goma’s open letters, such as the one he sent personally to the Czech writer Pavel Kohout, a signatory of Charter 77, to express his solidarity or the one he addressed to the secretary general of the Romanian Communist Party, Nicolae Ceaușescu, to ask him to join the movement for human rights in Czechoslovakia, are usually considered the main documents of the Romanian Charter, although they were not collectively endorsed. However, their content is certainly spectacular due to Goma’s talent as a writer, and thus more interesting to quote. Particularly interesting is the open letter to Ceauşescu in which the author makes a comparison between the defiant attitude of the secretary general of the Party in 1968, when he seemed to support the Prague Spring, to the silence of 1977 around Charter 77. In this letter, Goma invites Ceaușescu to follow his initiative of publicly expressing solidarity with the Czechs and Slovaks who have signed Charter 77. Through a much-quoted phrase, Goma drew the attention of his addressee to the simple fact that “in Romania, [only] two people are not afraid of the Securitate, your excellency and myself.” Thus, Ceaușescu, just like himself, was practically free to write to the Charter signatories, Goma’s argument continued. If he does this, all Romanians will be able to overcome their inherent fear of the Securitate and follow his and Goma’s example. As far as Ceaușescu is concerned, Goma underlines, the letter will illustrate “consistency with the declarations of 1968” and the secretary general’s genuine desire to “fight for socialism, democracy and humanity.” At the same time, “Romania will be able to participate in the [Helsinki Follow-Up] Conference in Belgrade with dignity.” The text of this letter is both amusing and mocking; it is illustrative of Goma’s literary talent and it is quoted by most analysts due to the unusual style for an official (though open) letter to Ceaușescu. The letter was preserved by Goma in copy and was confiscated by the secret police in 1977, in the moment of his arrest. It was returned to Paul Goma in 2005. Thus, the letter is now part of Paul Goma Private Collection in Paris, but copies can be found in the CNSAS Archives in Bucharest (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7) and the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives in Budapest (OSA/RFE Archives, Romanian Fond, 300/60/5/Box 6, File Dissidents: Paul Goma).

In the film, the actor roams the city and uses the opportunity to overcome various obstacles that lie before him (walls, fences...). He walks aimlessly. Speed walking, the artist passes though various surroundings. In motion, he marks his own individual path of movement through the city. He jumps across obstacles, representing a symbolic act of defiance and appropriation of the micro-space, of the free subject. This work is a statement on the intertwining of art and an everyday action – walking. In his works, Neša Paripović creates an intimate atmosphere. He did not perform in public. Movement, like the actor's roaming, represents deviation from a stable place in society. The actor conquers the public space precisely through his own private space of action. Rhythmicality is immanent in the work as the rhythmic film shots match the motion of the artist.

The collection illustrates Alojzij Šuštar's theological and pastoral work as a priest and archbishop who led the Catholic Church in the Archdiocese of Ljubljana despite the restrictions on freedom imposed by institutions under the communist government’s control. The Collection includes books, original manuscripts, Šuštar’s published articles and his correspondence and polemics, which demonstrate his critical stance toward Slovenia’s communist regime in the late years of the regime and in the period of transition to democracy.

The Records of the Presbytery Meetings of the Honterus Evangelical Parish in Braşov, 1977–1983, in German. File

The Records of the Presbytery Meetings of the Honterus Evangelical Parish in Braşov, 1977–1983, in German. File

The volume made up of the records of local presbytery meetings in the period from 1977 to 1983 reflects the difficulties faced by the parish of the Honterus Evangelical community in the restoration of the Black Church. Using the 1977 earthquake as a pretext, Ceaușescu dissolved the Directorate for Historic Monuments (Direcţia Monumentelor Istorice) because it had previously been opposed to demolishing the Enei Church in Bucharest, a historic monument from the eighteenth century (Panaitescu 2012, 224). After the dissolution of this institution, which had been responsible for financing and coordinating the restoration of historic monuments, the restoration of the Black Church was interrupted. Because of the complex restoration works which had been started, the church could no longer be used by the community. The record of the presbytery meeting of 27 January 1979 reflects the discussions of this management forum after it was informed by the High Consistory of the Evangelical Church of Romania that the restoration funds granted by the state had been stopped. At this meeting the presbytery members discussed the strategy that the community should adopt. It was decided to draft reports addressed to the authorities underlining the importance of the Black Church, one of the largest Gothic buildings in South–East Europe. Also, the architect Schuller proposed to send the authorities documentation including photographs of the construction scaffolding around the Black Church in order to emphasise the danger for the city’s population of stopping the works (Black Church Archives and Library, Presbyterium Protokolle 24 /1977–1983, 7).After state funding was stopped, the curator Otmar Richter initially requested the financial support of the High Consistory, the management forum of the Evangelical Church of Augustan Confession of Romania. Because the church lacked the financial resources to continue the restoration project from internal sources, it resorted to private donations and obtained the support of the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland (Federal Republic of Germany). Richter visited the board of the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland in the autumn of 1981 and obtained the financial backing to continue the restoration works. The fact that the regime tolerated this initiative can be explained by the importance of economic relations between Romania and the Federal Republic of Germany, but also by the foreign debt crisis which meant the authorities wanted the foreign currency donated by the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland to be spent in Romania and to enter the national budget. In addition to the records of the meetings of the Honterus parish presbytery, this file also includes historical and technical documents drafted by historians and architects concerning the structure of the building and its evolution in time. These documents were used in making decisions about the technical solutions to implement in the restoration process in the period 1981–2000. The documents of the volume describe one of the key moments in the Black Church restoration process, when the radical change of the Ceaușescu regime’s policy concerning historic heritage endangered the local initiative started in the 1930s, whose purpose was to save one of the most important monuments of the historic heritage of the city and of the community. The fact that the Black Church restoration was successfully resumed illustrates the existence of the grey zone of tolerance which local communities could use to promote their own interests, even when these conflicted with the official communist policies.

The Mihnea Berindei Collection comprises a significant part of the founder’s personal archive. These materials were accumulated in exile during the period 1977–1989, when Berindei was actively involved in assisting Romanian dissidents persecuted by the Ceauşescu regime. He was also an important intermediary between the fledgling Romanian opposition movement and the Western press, public opinion, and political establishment, playing a crucial role in publicising and enhancing the visibility of the Romanian case in the West. The major part of Mihnea Berindei’s personal archive is currently stored at the Iași Branch of the Romanian National Archives (Serviciul Județean Iași al Arhivelor Naționale). These papers were donated to the archives in 2013 and 2016. They include a variety of materials relating to communist Romania, the policies of the Ceauşescu regime and various manifestations of Romanian dissent (including cases of specific dissidents). The collection features a rich selection of documents relating to the activity of Radio Free Europe (RFE) during the 1980s, when Berindei was closely associated with the station’s Romanian-language service. The collection also contains a series of materials dealing with Eastern European developments in the 1990s. This is one of the most important private archives concerning communist Romania created in exile. As such, it will be of utmost significance to interested researchers and the wider public.

The Theatre Association „Gardzienice” – the Centre for Theatre Practices was founded as a theatre and a performance group by Włodzimierz Staniewski in a small village Gardzienice near Lublin (Poland) in 1977. Since then, it has become one of the best known examples of experimental theatre, linking musicality, music, performance and close relationship between the artists and the audience. The Theatre, apart from producing new performances, is also very active in the field of artistic education – in 1997 it started the Academy of Theatre Practices, where students from different humanistic fields can develop their animation and performance skills.

Miodrag Mica Popovic (1923-1996) was a painter, art critic, writer and academician. Popovic's lifestyle itself can be described as in cultural opposition to the regime and government that imposed its own ideological forms. Until the end of his life, he clearly demonstrated his incompatibility with the system, which let him stay faithful to the ideal of free thinking and expression. The images from the series the ‘Scenes Painting’ [Slikarstvo prizora] stem from the period between 1968 to 1971. Through that series the artist critized the social and political circumstances in socialist Yugoslavia.