One of the most imposing rooms of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara is dedicated to the tricolour flags that were in the street or in various institutions during the very tense days of December 1989. It houses some fifteen flags, all original. “They are flags that have, in a sense, been to war; people came out to demonstrations with them in the days from 15 to 22 December; some of them were shot at; some were discoloured by the weather on those days; they are important symbolic objects that had very important trajectories for the revolutionary movements of 1989, in those heated and bloody days in Timişoara,” says Gino Rado. The majority have a hole where the communist emblem was removed – the flag with a hole in the middle became one of the emblematic images of the Romanian Revolution of December 1989. Of all these flags, only one is of the Communist Party: it was taken down from the building of the Party Committee in Timişoara. They came to the Memorial as donations over a number of years, mostly in the period 1990–1994.

Norijada is the colloquial name of the celebration day for Zagreb secondary school students, which usually falls on the May 30. On that day, seniors from all around Zagreb are officially entitled to mark the end of their schooling, and "go crazy" (noriti or ludovati) for the last time before setting out for more serious business, preparation for graduation and university studies. Anthropologically speaking, it was a kind of a rite of passage toward adulthood. This ritual – most probably originating in the post-war period – in the classics program secondary school in the late 1980s was especially colourful because the students would wear ancient Roman costumes in order to highlight the orientation of the school. These were typically white togas for boys and luxurious white long dresses for girls. One also had to pay attention to authentic hairstyles and jewellery, because it significantly contributed to the overall impression. On this occasion the school students would act out rather loudly and colourfully.

The standard activities generally transpired as follows: first, the students would gather on the main staircase of their school, and begin singing songs that usually describe different (bad) traits of their teachers, who had to remain quiet for the sake of peace. The ties with their student status were visibly broken, and equality with the adult world, which allowed some degree of criticism, was perhaps the inherent meaning of this procedure. At the end of this event, one of the students, usually the funniest, would read the ‘last testament’ of the departing generation to the younger ones. The testament usually consisted of the ten commandments, which reversed the house rules of the school (for instance, “Never greet a teacher when one passes by or near you,” etc.). The first part of separation was thus finished, and the students would finally leave the school. They went out to the streets to meet students from other schools and display solidarity with them. This was the moment when real Norijada began, and students officially announced their separation from their previous life. On that day the students were allowed to do anything (except commit crimes). They would wander around, or swim in the wishing well and other fountains, or tease chance passers-by. They would usually get dead drunk and smoke heavily, and everybody was invited to do so because everybody was supposed to feel the same way. Moreover, in order to leave some trace of their “crazy” generation, students usually wrote graffiti on walls, citing their class, school and the year of the Norijada.

In May 1989, Dr Sorin Costina decided to sum up on paper the principal steps by which his passion for collecting art had developed. The result of this effort of memory is an eleven-page text, typed single-spaced, in which are mentioned the most important landmarks of an unusual and spectacular passion. “Also in the years 1962 to 1963 I had my first contacts (as Paul Neagu puts it) with the visual, or the visual arts. A first shock, an exhibition from the Dresden Galleries seen at the Museum of the Republic (I still remember the reviews, my favourite magazine in those years: second-rate works and rather weak with the exception of Titian’s Lady in White). For what I was then, it was a great festive event,” recalls Sorin Costina, speaking of one of his first encounters with the visual arts. He places his first encounter with contemporary art two years later: “Finally, my first contacts with contemporary art took place in Iaşi in 1965.” According to his notes, on 16 August 1969 he bought his first picture, The Bridge of the Turk, a scene in the old town of Sibiu by Ferdinand Mazanek. The price was 138 lei. His records of his purchases of items of visual art were kept in detail until 1989. According to this unpublished document, Sorin Costina bought most of the works that today make up his private art collection from galleries and studios in Bucharest. The last sentence of this testimony is particularly relevant for the way in which Sorin Costina conceived his own collection: “The marginalisation of all that is best in Romanian culture explains my ability to approach these figures of great value while unfortunately not rising to their level.” Small extracts from this document (which is also an account of the life of Dr Sorin Costina) have been cited in various texts about Sorin Costina’s life or within several autobiographical texts by the author himself. The text has never been published in its entirety. The manuscript is to be found in Sorin Costina’s private collection.

At the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara may be seen Lorenţ Fecioru’s vest with the holes made by the bullets that killed him and the traces left by their victim’s blood. This object with a profound emotional charge was donated in 1999 by the mother of the hero-martyr. The material traces of the violent death of this young man are symbolic for all the young people who, with the recklessness and courage of youth, took part in the Revolution of 1989. At the same time, the manner in which he met his death is illustrative of the repression that followed in the days immediately after the outbreak of the popular revolt in Timişoara. Along with over 1,000 others, Lorenţ Fecioru is a martyr of the bloody events that led to the change of regime in 1989 and one of those to whom all Romanians are indebted for the freedom that they enjoy today. It is a civic duty of all Romanian citizens to preserve their memory, a duty that the Memorial has taken upon itself to pass on to generations who did not experience the Revolution of 1989.

Lorenţ Fecioru was one of those who, alongside the poet Ion Monoran, took part in the stopping of trams in Maria Square on 16 December. He died in the night of 17–18 December from the effects of a bullet fired by a sniper straight into his heart. In the public documents issued after the Revolution of 1989, it was initially stated that Lorenţ Fecioru was shot on the steps of the Cathedral of Timişoara. The facts, however, are otherwise, albeit equally tragic. Two decades after the tragedy played out, Lorenţ Fecioru’s youngest son related for a national newspaper what actually happened to his father: “My father was shot by a sniper in the night of 17–18 December. In the Securitate files photographs have been found that were taken during the day, when my father and some of his colleagues from work went out into the street and climbed onto tramcars, onto buses. I understand that in the file is written ‘mission accomplished.’ He was on the balcony with his friends that evening, telling them that he had seen when the photographer took pictures of them and that he was afraid to go out onto the balcony. The moment he went out onto the balcony he was shot. I saw the bullet that killed him, because he was shot in the heart and the bullet came out through his back and ricocheted off two walls in the house. His friends took him to the morgue, and by ‘good fortune’ they found a coffin, otherwise he would have been incinerated like the others.” This version is confirmed by researchers at the Memorial to the Revolution. Gino Rado, the vice-president of the Memorial, mentions that Lorenţ Fecioru was on the balcony at his home on Calea Şagului in Timişoara when he was fatally shot. The vest donated by the family of the hero-martyr Lorenţ Fecioru is on the same ground-floor level of the building of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, very close to the corner dedicated to the child-martyr Cristina Lungu.

The tightening control implemented by the communist authorities on the circulation of cultural goods in Romania in the 1980s was strongly felt by Adrian Marino, the author of works in the field of literary history and comparative literature whose documentation could not have been carried out without consulting many books published in the West. After the customs service in communist Romania confiscated certain books sent by his collaborators in the West at the end of the 1980s, Marino wrote to the local and central authorities a series of memoirs containing an elaborate argumentation. Through these memoirs, Marino protested against the abusive confiscation of certain books in foreign languages sent from the West.

One of these typewritten documents, which is today in the Adrian Marino collection, is the memorandum sent to the Central Committee of the PCR on 12 March 1989, in which the author informed the communist authorities about a series of “abuses and illegalities committed during certain postal and customs operations” concerning a parcel sent from Munich on 21 June 1988 (Memoir 1989, 5). The parcel contained four books, one by Nietzsche, two published in the USA about Mircea Eliade, as well as a book by Adrian Marino himself published in France about the French linguist and literary critic René Étiemble. At the same time, upon his entering the country, the customs service had confiscated all the publications he carried with him, among which he mentions books and magazines in French, as well as “a history of Romanian political ideas up to 1876,” In the argumentation of the memoir, Marino questions the “competence” of the customs employees to judge “the content” of the confiscated works (Memorandum 1989, 5). Marino ironically highlights the paradox of the situation: “Can the documentation of a Romanian writer, whose competence has been recognised both in the country and abroad, be stopped by any customs worker, who judging by his handwriting has recently finished learning the alphabet?” (Memorandum 1989, 5). The document concludes with the request that the confiscated volumes be returned to him, and that the abuses be investigated. Aware of the preoccupation of Ceauşescu’s regime for the external image of the country, Marino invokes the fact that these abuses “cast a most unfavorable light on the Romanian customs authorities (including from the foreign tourists who were present at that moment), especially since their working attitude – military, rude and brutal – was and remains unforgivable” (Memorandum 1989, 6). On the one hand, this document illustrates the limitation by the communist authorities of the documentation material obtained from various sources in the West, and, on the other hand, it constitutes an example of opposition to the daily practices of censorship in Romania in the 1980s.

Upon receiving the highest French order of merit for military and civil merits – the National Order of the Legion of Honour (Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur) in 1989, Croatian sociologist Rudi Supek (1913-1993) granted an interview to Radio Zagreb in which he talked about his life and, among other things, about his opposition activities. He was awarded due to his activities as one of the organisers of resistance in the Nazi concentration camp in Buchenwald and due to his contribution to the development of sociology as a science and his cultural work with France. In the interview, he said that five years earlier (1984), he was awarded for his scholarly work, which was, in his opinion, even more important. But that fact was ignored in Yugoslavia at the time. He stated that the authorities did not like him because he insisted on the stance that there is no socialism without democracy. He said that he was a sympathiser and a member of communist parties (CP of Yugoslavia and CP of France) from the mid-1930s to 1948, but that he later did not want to be involved in Stalinist and Comintern-type of parties. He stated that he returned from France to Yugoslavia because for patriotic reasons, although he had much better conditions to continue his academic career abroad, in France, the USA or Canada. He also spoke about the problems of socialist systems in which there is a negative selection of personnel, stating that the monopoly of a single party promotes careerists and mediocrity. According to Supek, the advancement of society, especially in the economy, requires a free democratic political system. He also talked about his engagement in the environmental movement and his book, which had just been published in its third edition. He said that the crisis of socialism was a result of the fact that socialism had remained wedded to the concept of industrial society. He felt it necessary, globally, to transition to a post-industrial society that would not be based on exploitation of nature and humanity itself, to enter into a new type of socialism.

The letter, which reached Voice of America radio station in the autumn of 1989, represents an ample critical analysis of the practice of the personality cult adopted by the Ceauşescu family, a phenomenon which reached the limits of the absurd in Romania in the 1980s. The author, an unidentified Romanian citizen who had emigrated to France in the autumn of 1989, succeeded, before his departure from Romania, in capturing the reactions of people in Iaşi to the official visit of the presidential family on 13–15 September 1989. According to his letter, the “masquerade” began several days before the arrival of the Ceauşescu family. The letter ironically recounts the fact that the preparations for the official visit did not take into consideration the shortage of food and the weather. Thus, during the rehearsals, “small children were dressed in national costumes and kept in the cold or in the rain,” while party agitators went through the city with loudspeakers instructing the population to chant “hurrah!” at the passage of the car with the presidential couple. The agitators also encouraged people through the loudspeakers not to give the president any letters, but to give them to their factory managers. The local elite wanted to avoid a situation in which the “most beloved son of the people,” as the president was called at that time, might be disturbed by the population’s complaints. The author of the letter also analysed the role of the nomenklatura in preserving this personality cult, as well as their abusive behaviour. For example, he noticed that the heads of factories represented “a new class of nomenklatura, with discretionary powers.”

In the end, the letter received by the radio station highlights the population’s general discontentment, which was manifest, on the one hand, through various outlets such as humour, and, on the other hand, through spontaneous acts of revolt. As for the jokes about the Ceauşescu couple, the letter described a discussion in a tramway. One of the people observed with irony that the pigs on exhibition in the town centre were very big, but none were as big as Ceauşescu. The absurd of the situation consists in the fact that the exhibition in question was meant to prove the richness of the country’s agriculture while the population suffered from a severe food shortage. As an act of revolt, the author mentioned that the glass windows of the Moldova general store in Iaşi had been covered with graffiti: “Bring down the dictatorship! Bring down Ceauşescu! Bring down communism!” Offering a wealth of details about the population’s state of mind, the letter is a document reflecting the frustration which dominated Romanian society before the collapse of the regime in December 1989.

Among the very few images that were taken from a high position, Lucian Ionică draws attention to those taken in a central place for the revolutionary events of Timişoara in December 1989: the former Opera Square, now Victory Square. He mentions that he never really felt any serious threat when he tried to take photographs, and that, on the contrary, he experienced a moment of great good fortune and generosity precisely on the occasion of taking these photographs from above. “In my case, the fear I had had that I might encounter hostile reactions proved unfounded. No one bothered me, no one prevented me from taking photographs. On the contrary, for one of the photographs I was even the beneficiary of a combination of favourable circumstances: in Victory Square, to capture that crowd, I couldn’t photograph from ground level. I had to go upstairs in a building. And I went upstairs in the building situated diagonally opposite the Opera Theatre, where at the time there was a milk-bar – now it’s McDonalds – and on its façade, high up, you can still see the marks of bullets from the Revolution. Quite simply, I just knocked on a door, and the gentleman agreed to let me onto his balcony. And from there I took photographs – one of which is among the best known photographs of Opera/Victory Square during the Revolution. I took a few pictures from there.”

Among these photographs mentioned by Lucian Ionică, one in particular, even after such a long time, has a very powerful significance for him: “From the balcony I took a number of photographs, among them one that I would like to see turned into a monument. Of course there would have to be an artist, a sculptor who wanted to do this. There was, and I think there still is an electrical installation there. It’s an installation enclosed in a box, like a 70cm x 70cm square about 2 metres long. Well, on the surface of that there were five people, like a living statue. The image is very powerful, both visually and symbolically. As if people were standing on a pedestal, ordinary people on a pedestal. If a sculpture in realistic style were made from that photograph, it would show, in my opinion, that desire of people both to see and to participate in what was happening there."

The photo made by Tomasz Sikorski in 1989 or 1990 shows the wall of the underground passage under Rozdroże square in Warsaw. The square, located in the center of the city, is a transport junction where Warsaw citizens everyday change a bus. The walls of the underground passage were an attractive space for the graffiti creators who put there their tags and stencil graffiti. That way, the spontaneous, informal graffiti gallery emerged there.On the picture there are visible the stencil graffiti by Towarzystwo Malarzy Pokojowych (Association of Peaceful Painters), for example one with the Superman posture with the face of general Wojciech Jaruzelski, acronym PZPR (Polish United Workers’ Party) on his chest – a token of the affirmative and in the same time waggish attitude toward the ones in power, placed in the same line with the pop culture heroes. Another stencil graffiti depicted general Jaruzelski with a mohawk, dressed as a punk in a leather jacket. There is also a graffiti with characteristic inscription ‘Solidarność’ (Solidarity) and Israel’s flag above it what one can interpret as an anti-Semitic connection of mass union movement with the Jewish influences.

In the view of historian Myroslava Mudrak, “Tabirne” (Billiards) is “an exercise in ironic expression.” “Through pastel tones (usually employed by the symbolists who would describe ethereal themes, suspended dream-like situations, somewhat out of touch with the concrete vividness of reality, where saturated primaries and secondary hues would be used), which tend to create a mood of warmth and intimacy, we have the epitome of the grotesque and decadent (another feature of symbolist art). Typical of this approach is the existential moment—the questioning of “who am I?” “where am I going?” “what’s next for me?” “how did I get here?" Not only are the incarcerated (in the background) facing the agony of this questioning, but even the Cheka members are put in a situation, which is somewhat out of character with their role. In a brief, relaxational moment, they seem to let down their guard to feel the weight of their charge lifted momentarily, yet at the same time, still carrying on, making the viewer aware of the horrible and deadly nature of that charge, visible at the end of their sticks.“

Besides Rudi Supek’s (1913-1993) cultural-oppositional activities as the initiator of the Korčula Summer School and as a member of the Praxis circle of intellectuals, he is also known for his engagement in the environmental movement. This was reflected in his book Ova jedina zemlja: idemo li u katastrofu ili Treću revoluciju? (This only Earth: Are we heading for disaster or the Third Revolution?) published in 1973. Supek was one of the first scholars in Yugoslavia who wanted to warn the public of the growing environmental problems of modern civilisation. This book shows Supek’s divergence from the then Marxist mainstream in Yugoslavia and most leftist philosophers, who insisted that environmental issues were, in fact, a capitalist ploy to diminish the revolutionary potential of the working class. The book critically considered the relationship between states and social systems in the field of ecology, and criticism was focused to socialist systems as well, especially the dominance of the state administrative apparatus (Cifrić 2016: 104). The book was successful, and two new editions were published (in 1978 and 1989). In the foreword to the third edition, Rudi Supek explained that the first edition of his book was greeted with mistrust and scepticism “from both the left and the right”. The most of his leftist fellow philosophers and sociologists told him that he had “fallen for American propaganda,” while others were disappointed because they thought he would write about Croatia and its exploitation in Yugoslavia (Supek 1989a).

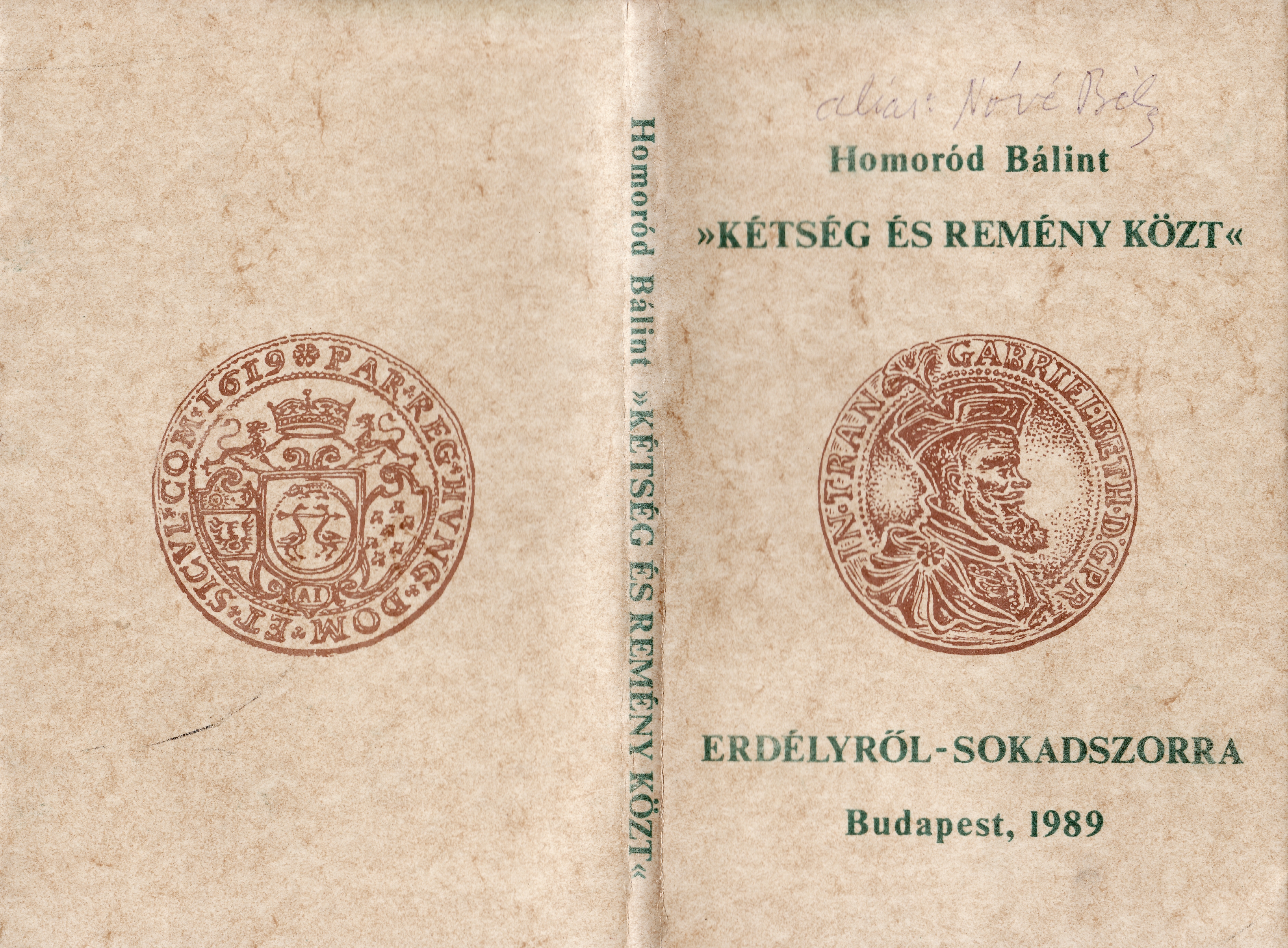

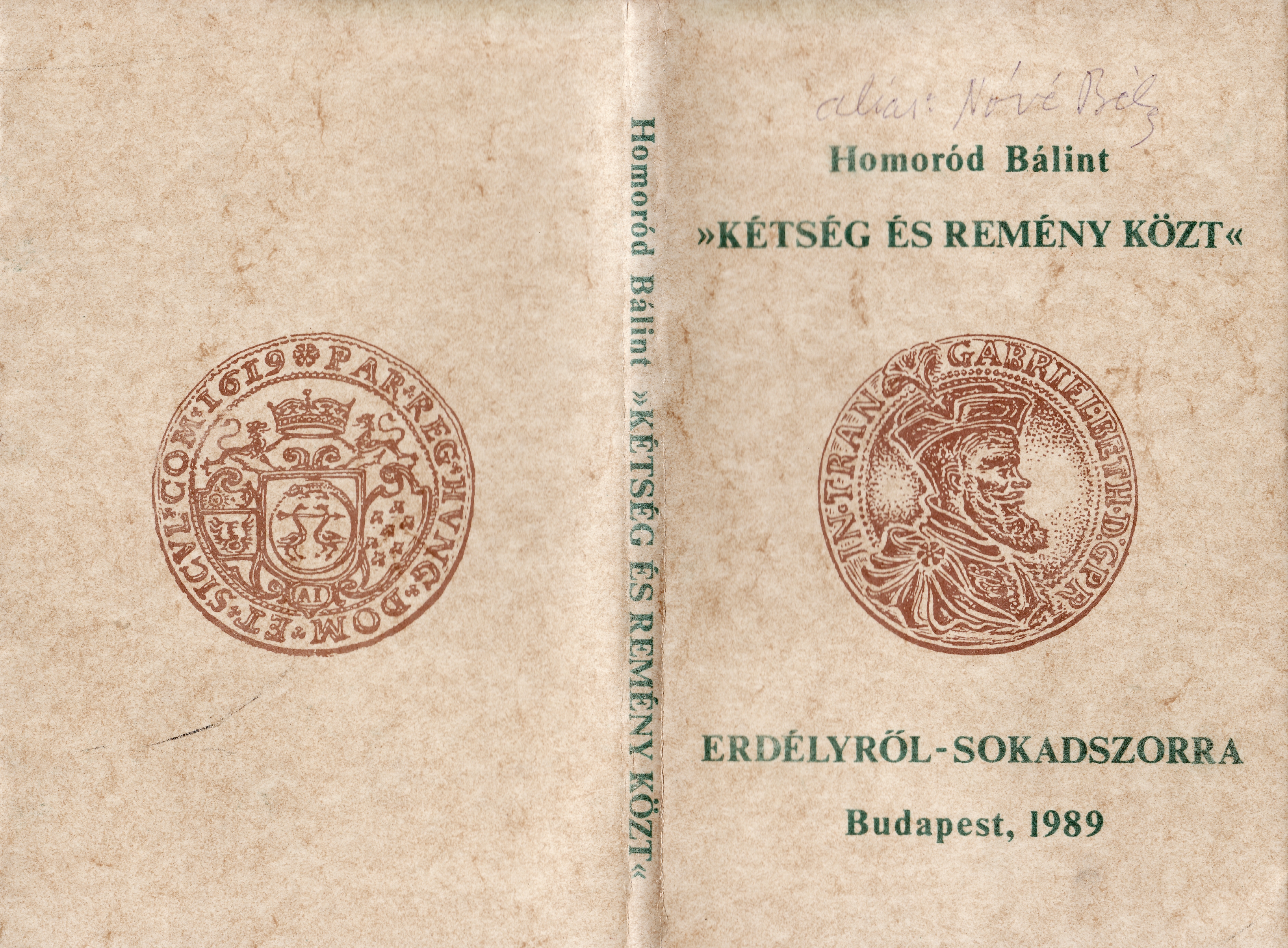

![Homoród, Bálint [Béla Nóvé]. Kétség és remény közt: Erdélyről sokadszorra (Hopes and Doubts: Once Again on Transylvania), 1989. Book](/courage/file/n54992/035.jpg)

Homoród, Bálint [Béla Nóvé]. Kétség és remény közt: Erdélyről sokadszorra (Hopes and Doubts: Once Again on Transylvania), 1989. Book

Homoród, Bálint [Béla Nóvé]. Kétség és remény közt: Erdélyről sokadszorra (Hopes and Doubts: Once Again on Transylvania), 1989. Book

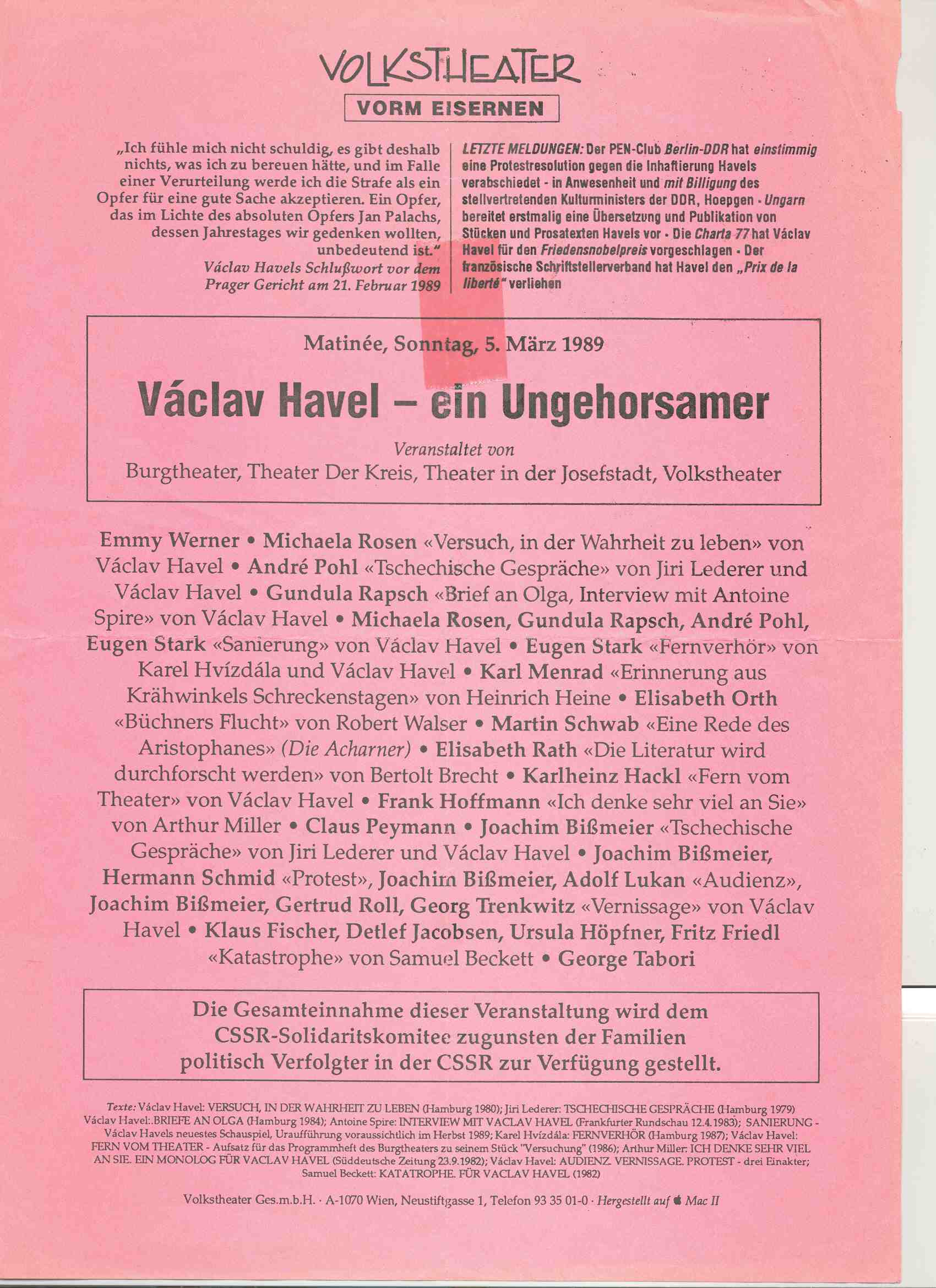

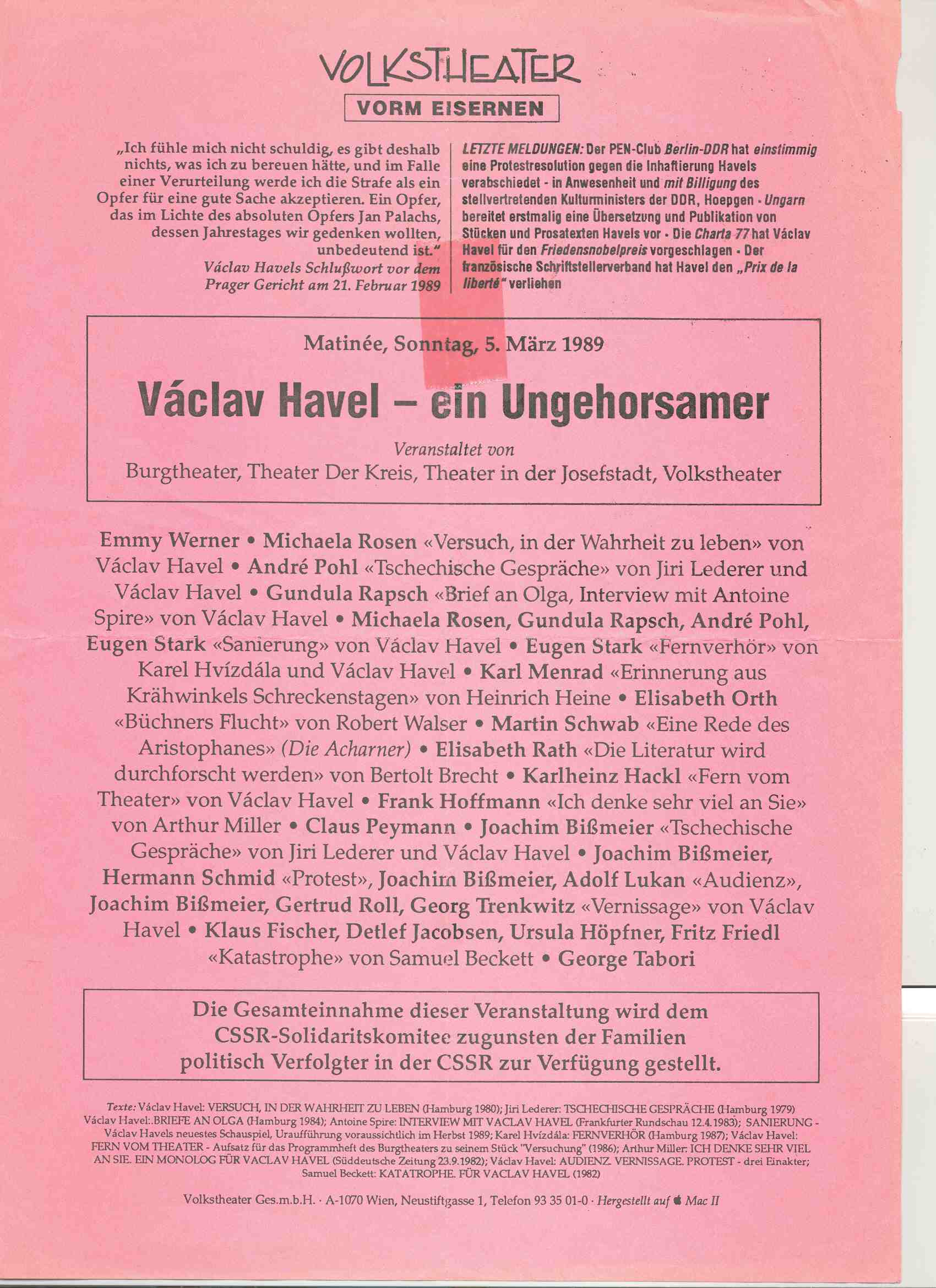

A flyer for a solidarity event held at the Vienna Volkstheater on March 5, 1989, by large Viennese theaters to support Václav Havel. Václav Havel was arrested on January 16 for attending a demonstration during Palach Week, and in February was sentenced to nine months in prison. After his appeal and many foreign protests, the sentence was reduced and Havel was conditionally released in May 1989.

The leaflet shows the interest of the western public in the fate of Václav Havel, the most prominent representative of the Czechoslovak cultural and political opposition.

The flyer was exhibited at the exhibition „Czech Republic. Austria. Divorced - Separated - United / Lower Austria State Exhibition 2009 / State Chateau and City Gallery, Hasičský dům, Telč

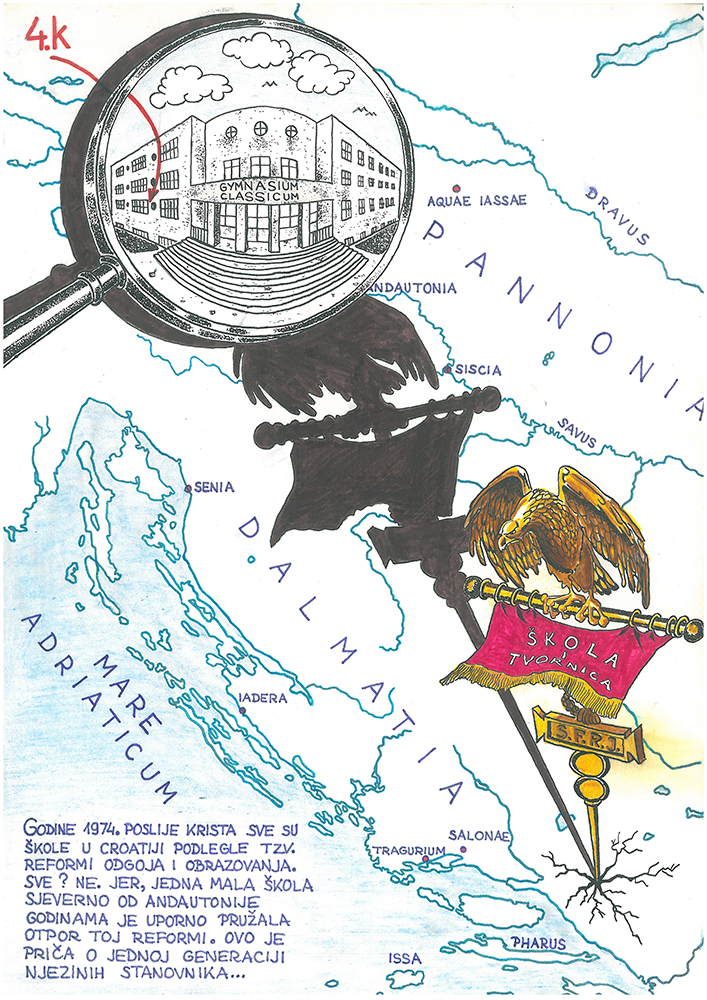

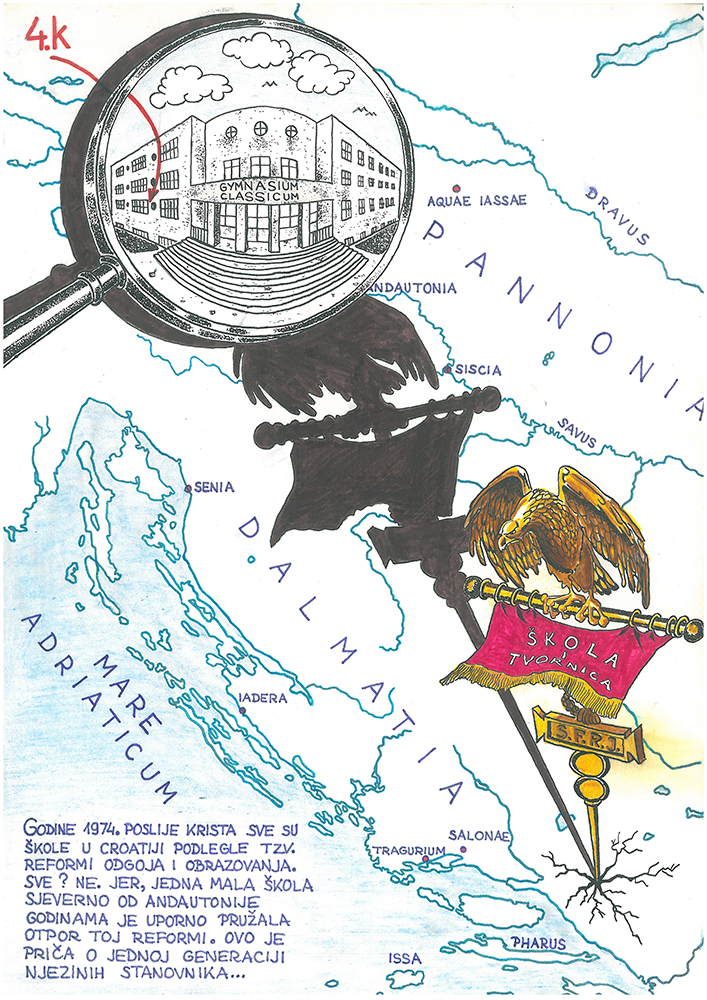

The cover of the classroom samizdat was designed for the matriculation of students from class 4K in 1989. It parodies the exceptional case of the Educational Centre for Languages, which retained the teaching of Latin and Greek despite the Šuvar school reforms by using the very popular comic strip Asterix.

The cartoon paraphrases the first sentences of the popular comic: “In the year 1974 AD, all schools in Croatia were subject to the so-called Education Reform . All? Well, not entirely. One small school north of Andautonia [an ancient Roman town near Zagreb] has been mounting resistance to this reform persistently for years. This is a story about a generation of its dwellers…“

The victorious Roman eagle carries a flag with Šuvar's slogan “School and factory” and beneath it there is a plaque, which instead of the Latin SPQR (senatus populusque Romanus) carries the abbreviation for Yugoslavia, that is, SFRJ (Socijalistička Federativna Republika Jugoslavija).

The last poem in the samizdat is “Don't give up, our Classical School, don't give up, our youth,” which pays a tribute to the school's classical curriculum and its exceptional status (“Oh, our reformed Classical School/Hold on tight!/We know that it's not easy/in this world./In this world of strictly directed heads.”)

The collection of the Archives of the Peace Movement in Ljubljana contains 58 boxes of archival materials accumulated by the activity of the Centre for the Culture of Peace and Non-violence in Ljubljana, as well as the democratic opposition and the forerunner of civil society in the 1980s and 1990s in Slovenia. The collection testifies to peace-making activities of a part of Slovenian society which advocated greater democracy of in Slovene society and citizen involvement in policy-making.

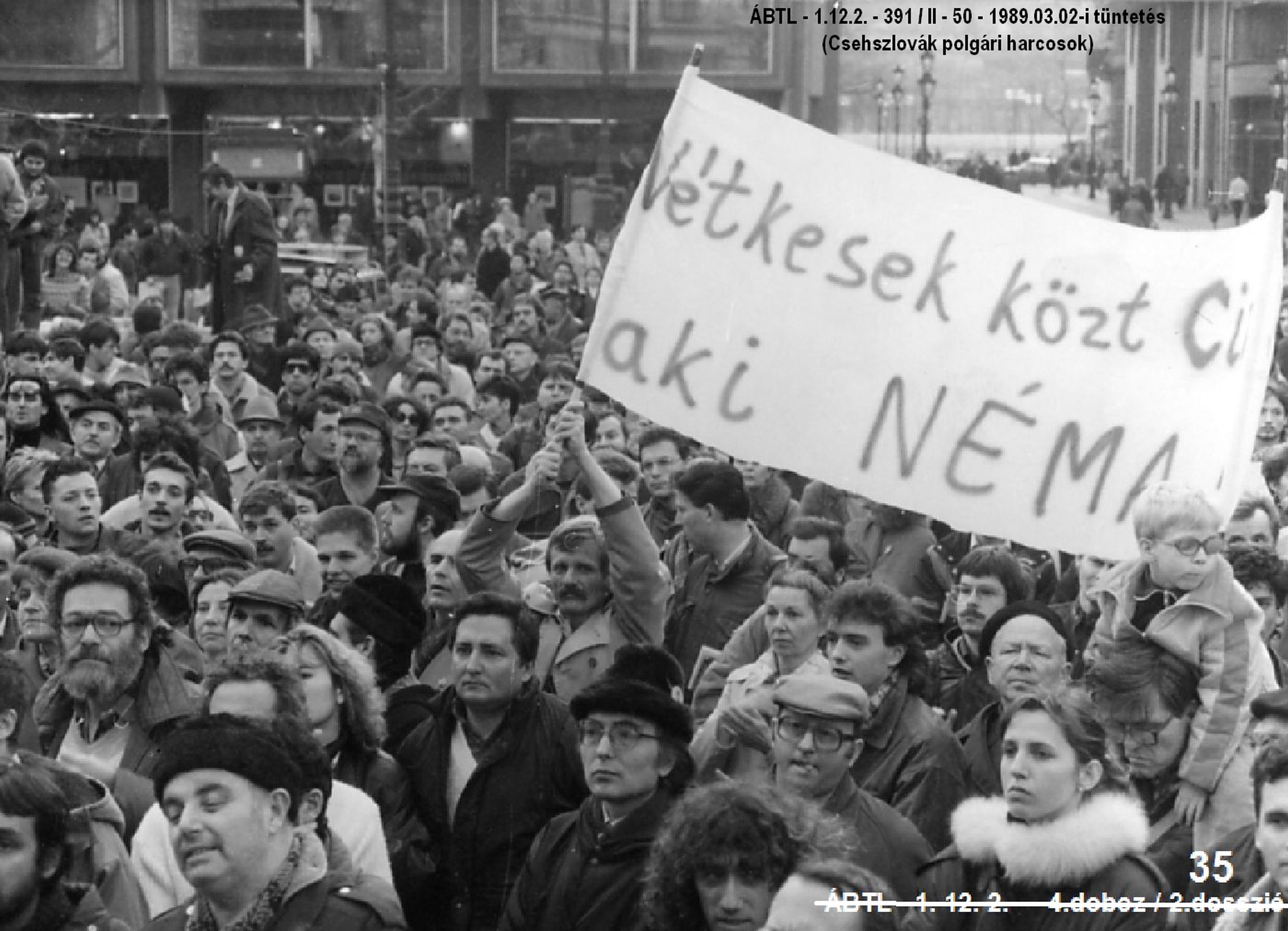

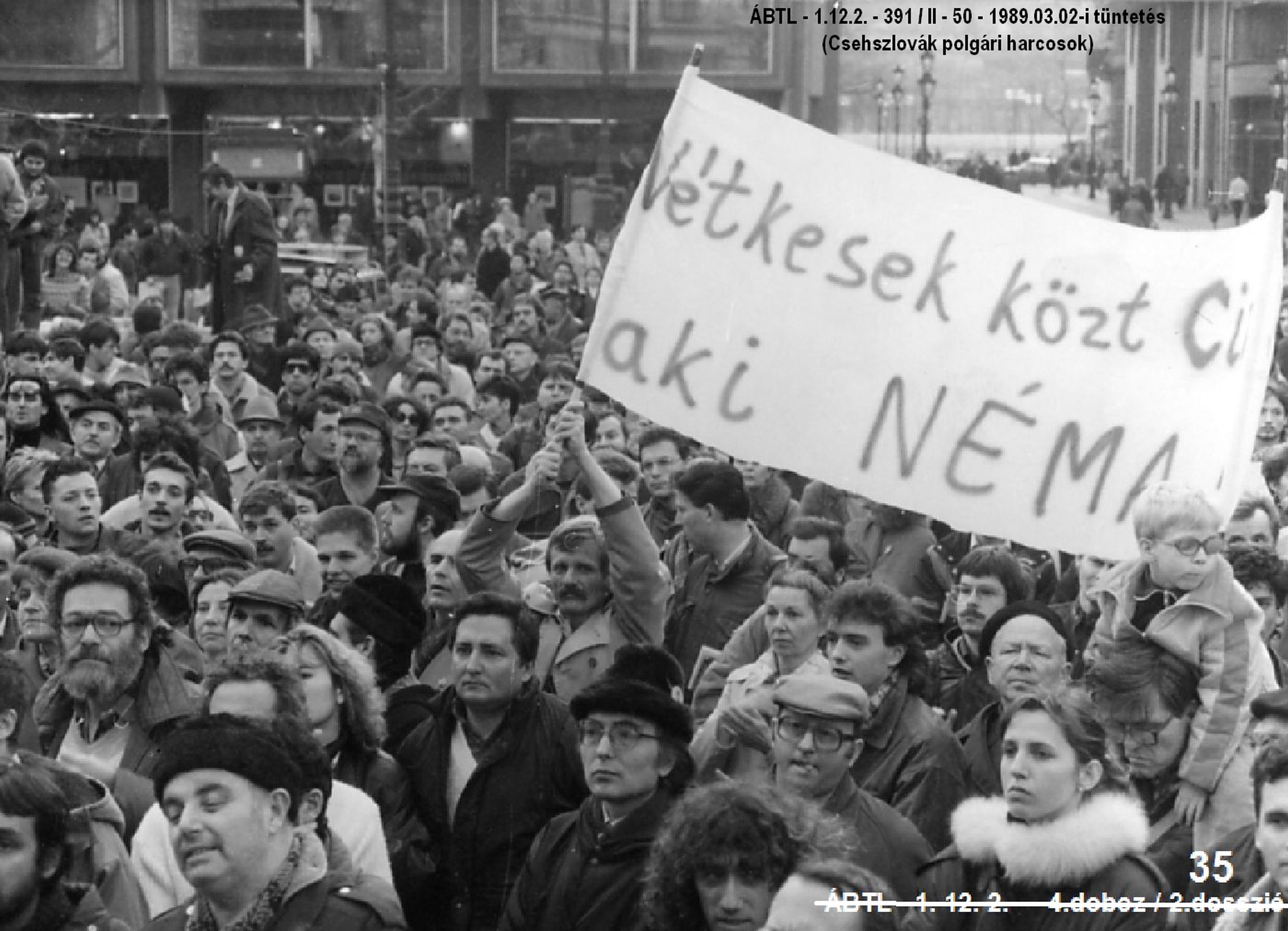

A “Protest against the persistent imprisonment of civil activists,” for example against Vaslav Havel’s arrest, was held on 2 March by numerous alternative organizations and parties. Between 400 and 600 people protested on Vörösmarty Square. One of the photos, one can see a banner with the sentence “Silence is complicity.” This photo was probably taken by István Kurta.

Some of the photographs taken by Lucian Ionică are snapshots of moments of high drama. Among them, those “hard to look at” images from the Paupers’ Cemetery, with the bodies of those killed by the repressive forces of the communist regime, hastily buried by the representatives of those forces, and then disinterred in order to be laid to rest in a fitting manner. There are also in the collection some photographs with portraits of children wounded during the Revolution of December 1989 in Timişoara. They were taken in the Timişoara Children’s Hospital on 24 December. The photographs show the wounded children in bed; the three snapshots include portraits of two boys and a girl. “For a few years after I took those photos I tried to trace the children I had photographed. I couldn’t find them, although I tried repeatedly. In the confusion and the strong emotions of the events back then, I didn’t have the inspiration to make a note of their names. Today I don’t know what has become of them, what they are doing,” says Lucian Ionică, confessing his regret at being unable to follow the story of those whose drama he immortalized in December 1989. “In the Timişoara Revolution, there were a lot of teenagers in the street. However the repressive forces had no compunction about firing at them. They were victims of the Army in the first place. Opening fire on minors is impossible to accept. Of course it is not justified against adults either, but the brutal actions of the soldiers against the children show how faithful those in the forces of repression were to Nicolae Ceauşescu,” is the comment of Gino Rado, the vice-president of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, summing up the tragic consequences of the involvement of forces loyal to the communist regime in the repression of the demonstrators, including minors (Szabo and Rado 2016). According to research carried out at the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, as well as other official statistics documenting the scale of the repression in the city in December 1989, at least six children or adolescents under the age of 18 were killed in this symbolic city of the Romanian Revolution. The youngest hero-martyr was Cristina Lungu; when she was fatally shot in December 1989, she was only two years old.

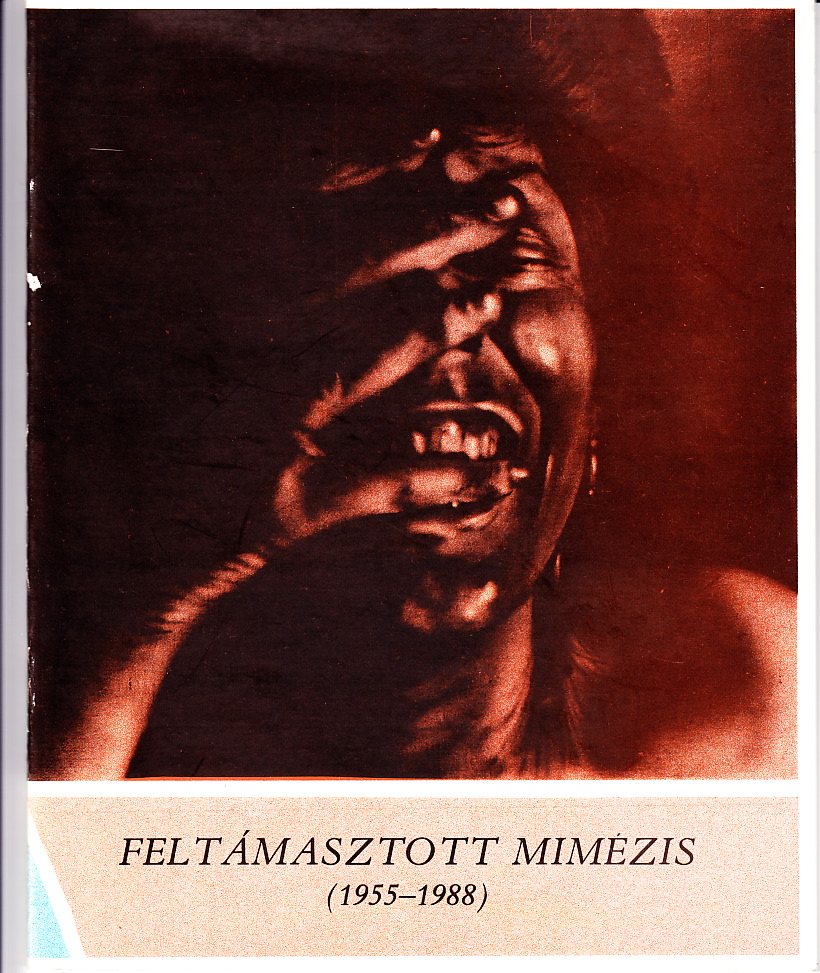

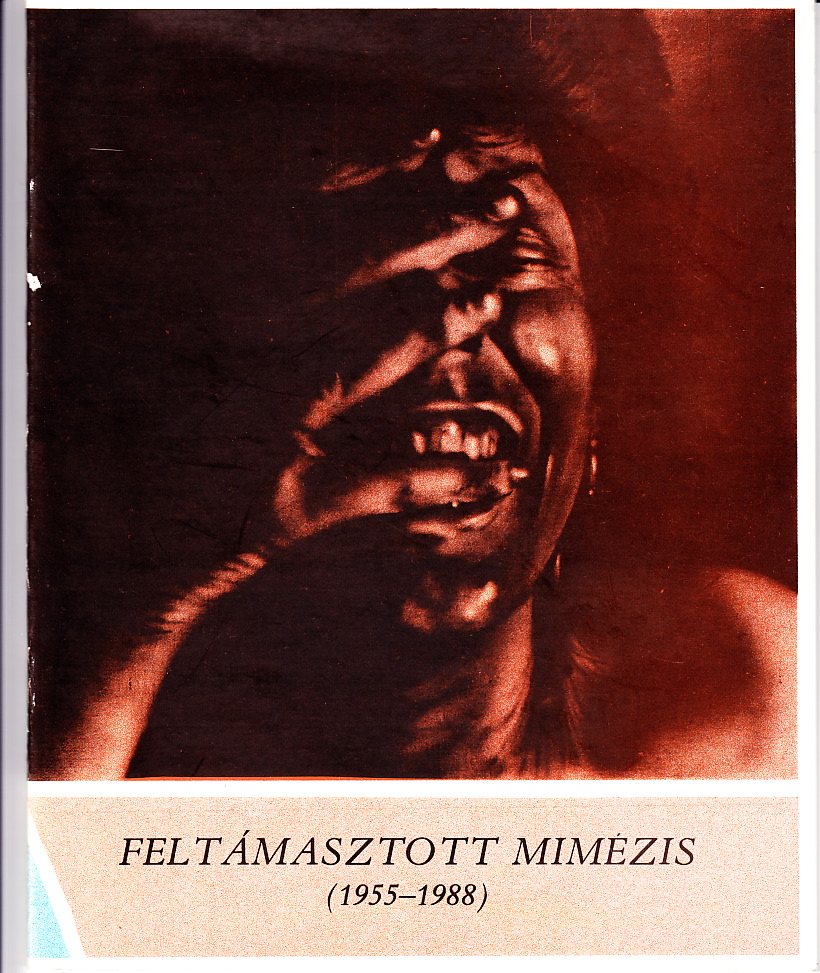

May 21 - June 29, 1989, Greek Church Exhibition Hall, Vác. Opened by Dr. Lajos Németh

As part of the research program on the establishment of the collection, József Bárdosi curated the exhibition entitled Revitalized mimesis (1955-1988), with which he designated the path of collection development in the long run. He selected a figurative works which in some form reflect on the social reality of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

This reflection is formulated on the language of realism understood in quotation marks, informed by critical, conceptual, minimalist, hyperrealist, and radical tendencies. The local types of hyperrealism inverted the original intentions of the movement in order to formulate their political or aesthetic messages.

Artists exhibited: Márton Barabás, Sándor Bernáth(y), Ákos Birkás, Tibor Csenus, Gábor Czene, László Dinnyés, László Fehér, Tamás Gál, László Gyémánt, György Jovián, Ádám Kéri, László Kéri, Imre Kocsis, Gyula Konkoly, György Korga, László Lakner, István Mácsai, György Marosvári, László Méhes, István Pál Nolipa, István Nyári, András Orvos, László Patay, Péter Sarkadi, Ágnes Szakáll, Attila Székelyhidi, Ákos Szabó, Iván Szkok, Zoltán Tardos, Noémi Tamás, Róbert Várady, László Varkoly, Gábor Záborszky, Gábor Zrínyifalvi.

Cristina Lungu was the youngest hero-martyr of the Revolution of December 1989 in Timişoara. When shed died, shot in the heart by one of the bullets fired from the roof of the Research Centre on Calea Girocului, Cristina Lungu was only two and a half years old. She died on Str. Ariş in Timişora, at the crossing with Calea Girocului, in her father’s arms with her mother beside her. Her destiny is symptomatic for the fate of most of the over 1,000 victims of the Romanian Revolution of 1989, who lost their lives not in a direct clash with the apparatus of repression, but because they happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when a stray or ricocheting bullet cut short their lives.

The tragic moment is recounted as follows in one of the books published by the publishing house of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara: “There was a moment of respite, around 10 pm, after intense shooting close by, on Calea Girocului. They came out at the crossing of Str. Negoi with Str. Arieş and Calea Girocului. At a certain moment, Cristina fell. Her father thought she had tripped, because there had been no particular noise. When he picked her up, Doru Lungu noticed that blood was flowing from her mouth. Then he ran with her to the County Emergency Hospital: “And it was only in the morning, about 4 am, that I found out, someone told me, that in fact she had been shot and had died on the spot. I wanted, because someone there had told me, to run quickly to the Morgue to take her, because otherwise I would never be able to get her.” Because he was afraid that her body would disappear for ever in the criminal action of erasing the traces of the repression of the popular revolt, her father was determined to take her from the Morgue, although it would have been almost impossible to bury her officially, because he had no documents. But he did not reach her, because he was given advice to take care and not to put himself in danger, because two people from the Securitate were at the Morgue, carrying out investigations into the deceased. It was only in the afternoon of Thursday 21 December that he managed to recover her body, his good fortune (if one can speak of good fortune in these circumstances) being that she had not been put in the batch that would arrive in Bucharest for incineration.” (Szabo 2014)

On the ground floor of the building of the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişora there is a thematic corner dedicated to this heroine-martyr. Her portrait, donated by her family to the institution in 2001, is covered by a pane of glass pierced in the middle by the impact of a bullet. The pane comes from a shop in the centre of Timişoara, in Opera Square, a place where there were violent exchanges of fire between 17 and 22 December 1989. In connection with the tragic case of this youngest victim of the December 1989 events in Timişoara, the portfolio of the Memorial also contains some testimonies by her parents and information that helps to place Cristina Lungu in both her historical and her family context.

Krzysztof Skiba, ‘Komisariat naszym domem. Pomarańczowa historia’, Warsaw: Narodowe Centrum Kultury, 2015.Tomasz Sikorski, Marcin Rutkiewicz, 'Graffiti w Polsce 1940-2010', Warsaw: carta blanca, 2011.

One of the documents in the Alexandru Călinescu private collection reflects the perspective from which this critical intellectual in Iaşi was regarded by the authorities in the last years of communism, when the dissidents in the city, including Alexandru Călinescu, became radicalised in their attitude towards the Ceaușescu regime. The document was discovered on 23 December 1989, in the cabinet of the person who had been propaganda secretary for Iaşi county up until the previous day, and thus came into the possession of Alexandru Călinescu. It had also been sent, as Alexandru Călinescu recalls, to the then rector of A.I. Cuza University of Iaşi, “so he would work on me, but without success, of course,” he adds. This document was published by the former dissident in 2018 under the suggestive title “My life told by the Securitate,” together with other documents of the same type and an article summarising the context of the last two years of communism in Romania.

The Securitate informative note begins by recalling the intellectual origins of the person in question and emphasising that “he has always manifested a particular interest in entering into relations with foreign citizens of all categories, especially language assistants, diplomats, reporters, journalists, writers, etc., but with many of these he exceeded the official context, […] repeatedly transgressing in a flagrant and ostentatious manner the provisions regulating relations with foreigners.” Because he had “cosmopolitan” ideas and implicitly a “communion of ideas” with some of these foreigners, “he particularised the relations in such a manner that they developed from simple friendship to seriously affecting the interests of the Romanian state,” the document continues. The informative note on Alexandru Călinescu emphasises his role as the leader of the oppositional group around the magazine Dialog: “He has been considered the mentor of a group of young people with literary ambitions, launched by the above-mentioned publication, and has appointed himself a ‘school leader’ of the so-called ‘1980 generation,’ to whom he has passed on his harmful ideas.” The articles published in Dialog under the direction of Alexandru Călinescu by him and his disciples are characterised as being ‚ “of a contestatory character, which has attracted the attention of reactionary circles in the West, who provided them with publicity through the ill-famed radio station Free Europe.” As the leader of the new generation at Dialog, which he directed towards “hostile activities,” Alexandru Călinescu was considered to have “arrived at the threshold of treason,” resulting – according to the note – in no more than a sanction through Party structures with a “vote of blame.” The note goes on to emphasise that the individual in question “has not drawn appropriate conclusions from the measures taken in 1983. Making a mockery of the good advice and disregarding the clemency that was shown in his case, he has continued to maintain the same position, at first more prudently, then more and more openly and ostentatiously.” The document then recounts how Alexandru Călinescu “has gone further down the slope of treason,” by facilitating Dan Petrescu’s and Liviu Cangeopol’s meetings with French journalists to whom they granted interviews “with a particularly hostile content,” and thus becoming “the coordinator from the shadows of the alleged Iaşi dissidence.” Moreover, the document states, Alexandru Călinescu has shown solidarity with the dissidents in Bucharest, who have taken a public position in defence of Mircea Dinescu. The conclusion of the informative note with regard to the individual under surveillance is that “he more and more often exteriorises ideas inciting opposition to the socialist regime in our country, […] letting himself be influenced by what is happening in other socialist countries.” It is interesting to observe the interpretive key in which the Securitate informative note narrates all these real actions of contestation of the regime, as a result of which Alexandru Călinescu had become at the end of the 1980s one of the most heavily surveilled critical intellectuals in Iaşi and indeed in the whole of Romania. In the words of the secret police documents, “by the hostile actions he has carried out, especially in the last two years, […] Alexandru Călinescu has proved [...] that he has crossed the threshold of treason to the country and has become a tool of reactionary circles in the West, through which he has seriously compromised his status as citizen, Party member, and university teacher.” In other words, all that after 1989 became an act of courage was considered an act of treason before 1989.

This typewritten conversation originally would have been published in Pál Diósi’s book about prostitution, This is not a Joyride (1990). Pál Diósi, who originally recorded his conversations on tape and paid for their transcription himself, talked with a man of Jewish origins who received sexual services from a prostitute several times. The editor of Gondolat [Thought] Publishing House believed that if the fact that a Jewish person had paid for sex had been revealed, it would have compromised the Jewry of Budapest, so the interview remained in manuscript form.

The Lucian Ionică private collection is one of the few collections of snapshots taken during the tensest and most feverish days of the Romanian Revolution of December 1989 in the city of Timişoara, the place where the popular revolt against the communist dictatorship first broke out. The photographic documents in this collection preserve the memory both of the dramatic moments before the change of regime and of the days immediately after the fall of Nicolae Ceauşescu, when sudden freedom of expression produced moments no less significant for the recent history of Romania.

Project for supporting democratic organisations, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1989’, 1989. Publication

Project for supporting democratic organisations, In: ’Yearbook of Soros Foundaton–Hungary 1989’, 1989. Publication

The Soros Foundation Hungary project in support of new democratic organizations in 1989–1990

By the spring of 1989, Hungary had managed to halfway through the process of political transition: the political monopoly of the one-party communist system had already been shaken, but civilian society and democratic forces still could not break through the colossal structure of the forty-year-old monolithic regime. There were fewer and fewer legal and political barriers to democratic organizations, and the main obstacles were the lacks of finances and media coverage concerning the awakening society and the political opposition. Independent media channels and organs in the print press which could inform the public efficiently about major political changes were still badly needed in the country. Similarly, there was not adequate public space or office infrastructure for the newly launched local and national movements, proto-parties, organizations, student clubs, trade unions, etc. The accelerated process of forming new parties, together with the beginning of the Roundtable Sessions of the Democratic Opposition and then the Nationwide Negotiations made it clear that the traditional semi-conspiratorial, amateur strategies used by the oppositional forces were wholly insufficient to remove the old monopoly power system.

From the outset, Soros Foundation Hungary (HSF), as the main supporter of independent civilian initiatives, realized that it was time to overtly “underwrite democracy,” to borrow from the title one of the books by Soros. In the spring of 1989, Soros publicly offered a sum of one million US dollars in support of the newly launched democratic organizations. The grand curatory (the main decision-making Advisory Board) discussed the practical details of the planned project at two sessions. The call for applications was then published, and an operative staff was formed in May to manage the project, led by László Sólyom. It included Gábor Fodor, Elemér Hankiss, László Kardos, and a dozen members of the SFH secretariat.

The new support project, as was expected, became extremely popular within a short period of time, and the deadline for the submission of applications was eventually extended six times to eighteen months, with more than double the sum Soros originally had intended to spend on the project. (It proved to be an almost ceaseless rally, which is well reflected in the fact that, as late as October 1990, there was still a package of 25 new applications for support waiting to be assessed, most of them convincing cases with rightful claims.) In 1989, 353 applications were received from various parts of the country. During the first year run of the project, the Advisory Board of the Soros Foundation Hungary approved claims made by 157 applicants and donated a total of 44 million Hungarian forints. It also distributed badly needed office equipment: 49 copy-machines, 26 computers, 12 telefax machines, 6 phone sets with recording machines, and 3 laser printers.

Some of the successful applicants gained support from the Soros Foundation Hungary in 1989–1990:

Nationwide movements, and organizations: League to Abolish Capital Punishment, the Independent Lawyers’ Forum, the International Service for Human Rights, the Asylum Committee, the Press Club for Free Public Speech, the Raoul Wallenberg Society (Budapest-Pécs) Committee for Historical Justice, the Foundation for Aiding the Poor. Trade unions: the League of Independent Democratic Trade Unions, the Trade Union of Employees of Public Collections and Cultural Institutions, the Educators’ Democratic Trade Union, the Solidarity Alliance of Workers’ Trade Unions, the Scientific Workers’ Democratic Trade Union, the Chemical Industry Workers’ Democratic Trade Union. Church organizations: (Lutheran) the Evangelical Youth Association, the Association of Christian Intellectuals, the Ecumenical Fraternal Society of Christians, the Hungarian Protestant Cultural Society. Minority organizations: the Association of Transylvanian Hungarians, the Rákóczi Union, the Hungarian Jewish Cultural Society, the PHRALIPE Independent Gipsy Association, the FII CU NOI Roma Society. Environment Protection: the Danube Circle, the Independent Center for Ecology, the Holocén Society for Nature Protection.

Of the roughly 500 applicants, 201 organizations and organs (printed press, local radio and tv channels) received valuable financial and material help from the Soros Foundation Hungary. The project, the deadline for which was extended six times, lasted until late 1990, and it distributed more than double the originally offered sum, i.e. significantly more than two million USD.

The complete archival collection of the project (applications, letters of support, secretarial reports, minutes of curatory sessions, press clippings, and files of the former secret police) can be found in the OSA-Blinken Archives. The detailed list of the organizations which were given support were also published in the 1989 and 1990 Yearbooks of the Soros Foundation Hungary. See their online version here.

Shortly before his death, the Czech art critic Jindřich Chalupecký decided to sell part of his written legacy to the Museum of Czech Literature. Following his agreement with Marie Krulichová, an employee of the acquisition department of the Literary Archives of the Museum of Czech Literature, he sold his correspondence and some of his friends’ manuscripts to the Museum in the spring of 1989. At that time, the control of the communist regime weakened and the Museum of Czech Literature supported unofficial artists and writers through similar purchases of their documents. The collection of correspondence contained, for example, letters from Czech artists Kurt Gebauer, Eva Kmentová, Jiří Kolář, Karel Nepraš, Zbyněk Sekal or Adriena Šimotová. Chalupecký also corresponded with Canadian translator and writer Paul Wilson, who was expelled from Czechoslovakia in 1977, and with Czech writer and literary historian living in the United States, Milada Součková. The collection of correspondence contained almost 2000 letters. Together with the correspondence, Chalupecký also sold some of his friends’ manuscripts (ca. 750 pages), for example poems of Josef Kainar or Josef Škvorecký, to the Museum. The extent of this part of the Jindřich Chalupecký Collection, sold to the Museum of Czech Literature in 1989, totalled 6 cartons (boxes).

The Jindřich Chalupecký collection was later extended. The majority of materials were given to the Museum by Chalupecký’s wife, poet and translator, Jiřina Hauková, in the 1990s. Some documents became part of the collection later, after Jiřina Hauková’s death in 2005. Nowadays, the collection is stored in 51 carton (boxes).

The Praxis and Korčula Summer School Collection includes significant books and articles by the Praxis thinkers and a complete set of all editions of the journal Praxis. It represents a first-class cultural legacy because it is the most comprehensive collection of the phenomenon, widely recognised not only in (the former) Yugoslavia but also internationally. During the socialist period, philosophers and sociologists of a predominantly Marxist orientation actively participated in the promotion of the culture of critical thought by writing for the journal, and by attending the summer school.

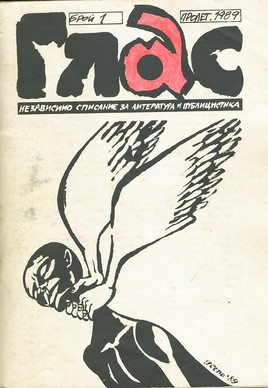

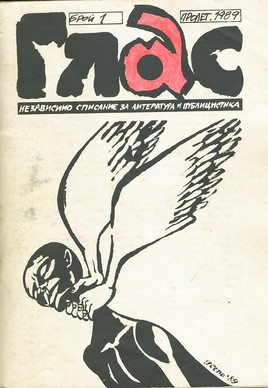

Samizdat magazines appeared in Bulgaria only at the end of the 1980s. Two important Bulgarian samizdat magazines were conceived together, their first issues were published at the same time: "Glas. Nezavisimo spisanie za literatura i publitsistika [Voice. Independent Magazine for Literature and Journalism]" with founder and editor-in-chief Vladimir Levchev and "Most. Almanah za eksperimentalna poezia [Bridge: Almanac for Experimental Poetry]" with founder and chief editor Edvin Sugarev. Both magazines were printed on typewriter and reproduced on xerox at no more than 100-200 copies. The first issue of "Glas [Voice]" was reproduced on documentary photo paper. The artist was Stefan Despodov, who created the covers by hand. The magazine was produced in the bathroom of Vladimir Levchev, which was turned into a photo laboratory.

Vladimir Levchev says: "In the autumn of 1988, the Club for Publicity and Democracy, then known as the Klub za glasnost i preustroystvo [Club for Glasnost and Reconstruction] was organized. At the end of December, enthusiastic about the new developments, Edvin and I spontaneously decided to start a Samizdat magazine. We acted very expeditious. Since then there were two accessible xerox machines in Sofia and they were under surveillance, and there were no computers at all, the 'samizdat' was, of course, a technically difficult task. On Edvin's idea, we bought two-sided photo paper, and using my bathroom for a lab, after a week's work, we produced around 100 counts of two independent magazines, Edvin's 'Most' and 'Bridge'. We photographed each page printed on a typewriter - it was like a hand paved street ... First we thought of making two issues of one magazine so that if we were arrested after the first issue, we would do a second one. But then we switched to two different magazines. After we prepared the issues, we distributed them to friends, famous 'dissidents', people with access to a copy machine at their office, who could made more copies. ... The first issues of the two magazines came out in January 1989.

In January 1989, with Blaga Dimitrova, I signed the letter in support of Petar Manolov and became a member of the Club [for publicity and democracy] and then of 'Ekoglasnost'. A little later, Deutsche Welle, the BBC and Radio Free Europe reported about the magazine, and in the autumn, during the Eko-Forum, Rumyana Uzunova also took an interview with me. I was released from the magazine I worked at at that time, “Narodna Kultura” ['People's Culture'] and fined 500 leva for issuing an unregistered magazine. They called me to the Bulgarian Book and Print Association [i.e. the censorship authority] and I was threatened that if I publish another issue, I will be fined 1,500 levs, and State Security will deal with my case and I will probably go to jail. I did, however, issue another issue - this was during a 'Ekoglasity' subscription […], an eco-forum. No one could even suspect that even on November 10, 1989 Zhivkov would resign. Until 10th of November 1989, I published four issues." (quoted after interview of V. Levchev, Rudnikova 2006)In the first issue of the magazine "Glas [Voice]" the founder Vladimir Levchev - after the introduction ending with the words "It [Bulgaria] yearns for a little publicity, for democracy!" - statet the main objectives of the magazine as “to publish mainly literature, poetry, criticism and essays, which hardly can find a place on the pages of the official jurnals”, as well as of critical texts on ecological, economic and social problems, written by Bulgarian and foreign authors.

Both samizdat magazines cooperated with well-known Bulgarian intellectuals who published their critical views of the regime: the writer-dissidents Blaga Dimitrova, Radoy Ralin, Valeri Petrov, Binyo Ivanov, Dragomir Petrov; the emmigrants Tzvetan Todorov, Atanas Slavov, Tsvetan Marangozov and many other well-known authors parallel to young authors such as Rumen Leonidov, Anni Ilkov, Mirela Ivanova, Virginia Zaharieva, Elisaveta Musakova, Ilko Dimitrov, Hristo Stoyanov, Antoaneta Tzeneva, Boryana Katsarska and other; the critics Aleksandar Kyosev, Mihail Nedelchev, Alexander Yordanov; the philosophers Zhelyu Zhelev (the later president of the country), Ivan Krastev, Kalin Yanakiev and others.

After the fall of the communist regime, "Glas" and "Most" were legalized. Many independent journals appeared, even printing became expensive. The magazine "Glas" remained a literary magazine, the publishing of several issues was sponsored by the Open Society Foundation of George Soros. In 1994, Editor-in-Chief Vladimir Levchev left for the United States. For several years he kept the magazine on the Internet, and in Sofia Rumen Leonidov and Vladimir Trendafilov published several more issues. The last issue of the magazine "Glas" was num. 14/1994.

Today, "Glas" and "Most" magazines are bibliographic rarities. Thanks to the "Free Poetry Society", created in 1990 by Blaga Dimitrova, Vladimir Levchev, Edvin Sugarev and other writers, and re-organized in 2016, all issues of the two magazines are uploaded with free access to the website of their society, www.freepoetrysociety.com.

Antanas Miškinis (1905-1983) was a Lithuanian poet and Soviet political prisoner. He started his creative activity in the mid-1920s. In the mid-1940s, he joined the Lithuanian partisan movement, for which he was convicted and sent to Siberia. While serving his sentence, he wrote romantic poems (psalms). Many of them were copied out or learned by heart by other Lithuanian political prisoners at that time in Siberia. The collection holds psalms and poetry written by Miškinis during his imprisonment from 1948 to 1956.

"Spartakus" was a newspaper of the Federal Trade Union “Freedom” (Zawodowy Związek Federacyjny “Wolność”), founded in Tricity by Zbigniew Stybel – one of the key members of the anarchistic Alternative Society Movement. The Federal Trade Union “Freedom” was founded under state socialism and was the first anarchistic trade union after war. Initially its activity was limited to helping conscientious objectorsdoing civilian service instead of mandatory military training based on conscription. Stybel, who stayed out of the anarchistic centre, noticed that people who managed to get a replacement service, were usual made to do very hard and humiliating jobs. Based on this realization, he had an idea to establish a trade union as an organization which could help people in such situation. With time the activities of FTU “Freedom” were broadened to offering help in other work environments.Unlike other anarchist magazines (like “A Capella”), the “Spartakus” did not have the typical qualities of alternative youth magazines. The editorial board was not eager to use counter-cultural visual extravaganza, and the thematic scope concerned mostly workers’ situation and broader socio-political issues. The magazine’s main goal was to sustain communication between the union and people needing its intervention. Such profile of a newspaper was exceptional in the third-circuit press at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s.

In a letter dated November 11, 1989, Alenka Bizjak addressed the editorial board of Mladina in Ljubljana as a reaction to the article ˝Notice Before Expulsion˝ (Slo. “Opomin pred izključitvijo”) by Vlado Miheljak published in the magazine. In the article, Bizjak and the Greens were accused of "ecofascism." In her letter, Bizjak asked the editorial board of Mladina to publish her response to the charges of "ecofascism" and to the disrespect for the activity of the Greens political party that was founded a few days earlier. Bizjak signed the letter as chairwoman of the Greens of Ljubljana. Bizjak expressed her disagreement with the state of society, which was also manifested in media attacks on the then newly-formed democratic opposition, in the following words: "The basic functioning and engagement of the Greens of Slovenia is primarily directed toward issues of human survival in this poor country of ours and the basic prerequisite for their success is a truly democratic and legal state."

The 3rd issue of “Rewolta” from December 1989 is distinguished by an attractive cover with the portrait of Piotr Kropotkin. Inside one can find texts about e.g. anarchism in USSR, Black Cross activities, having sex in prison, critiques of parliamentary democracy and a biography of Edward Abramowski. Broad thematic scope, brilliance and brave style of “Rewolta’s” authors made this magazine one of the most interesting anarchistic publications of the time of transformation.

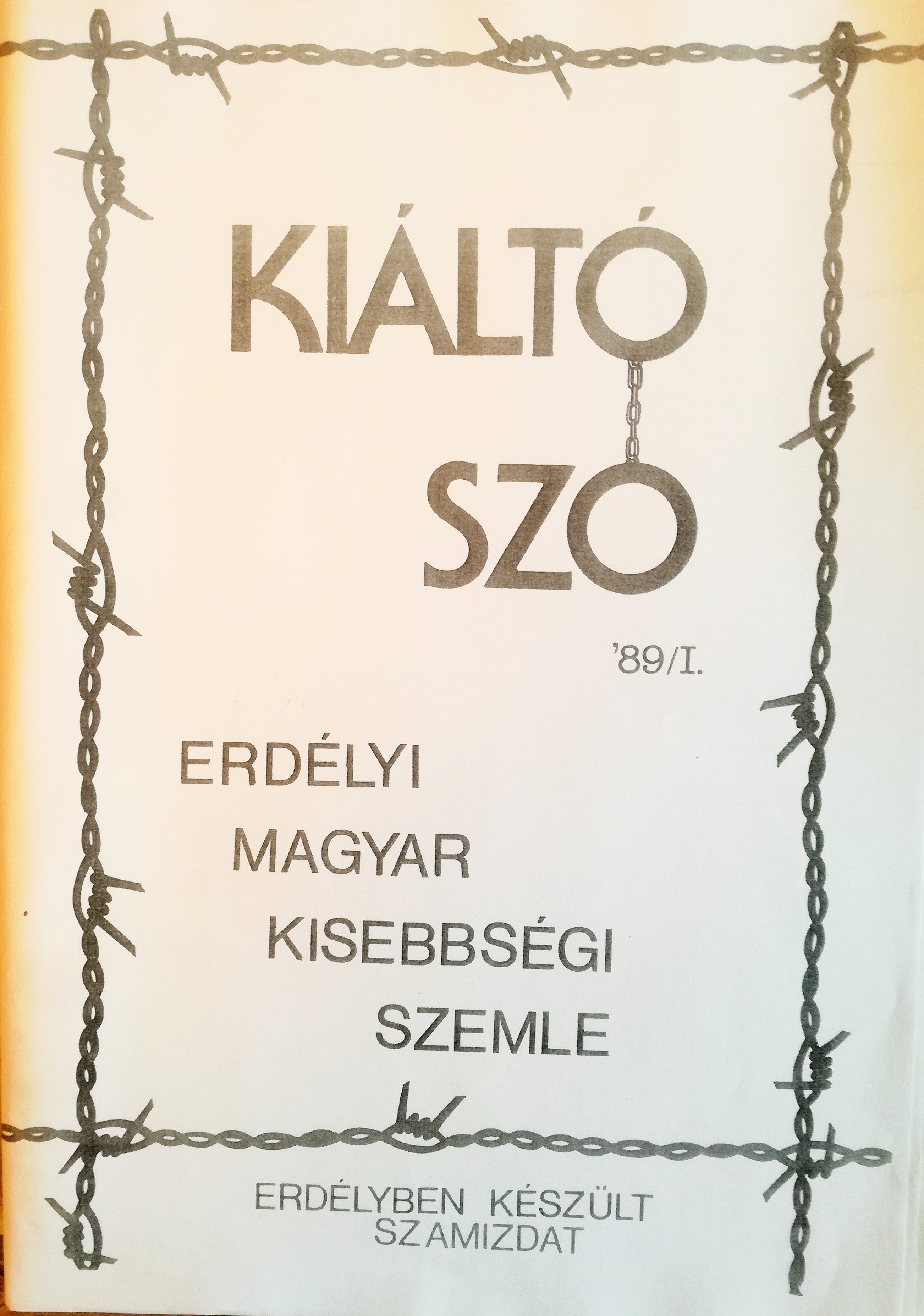

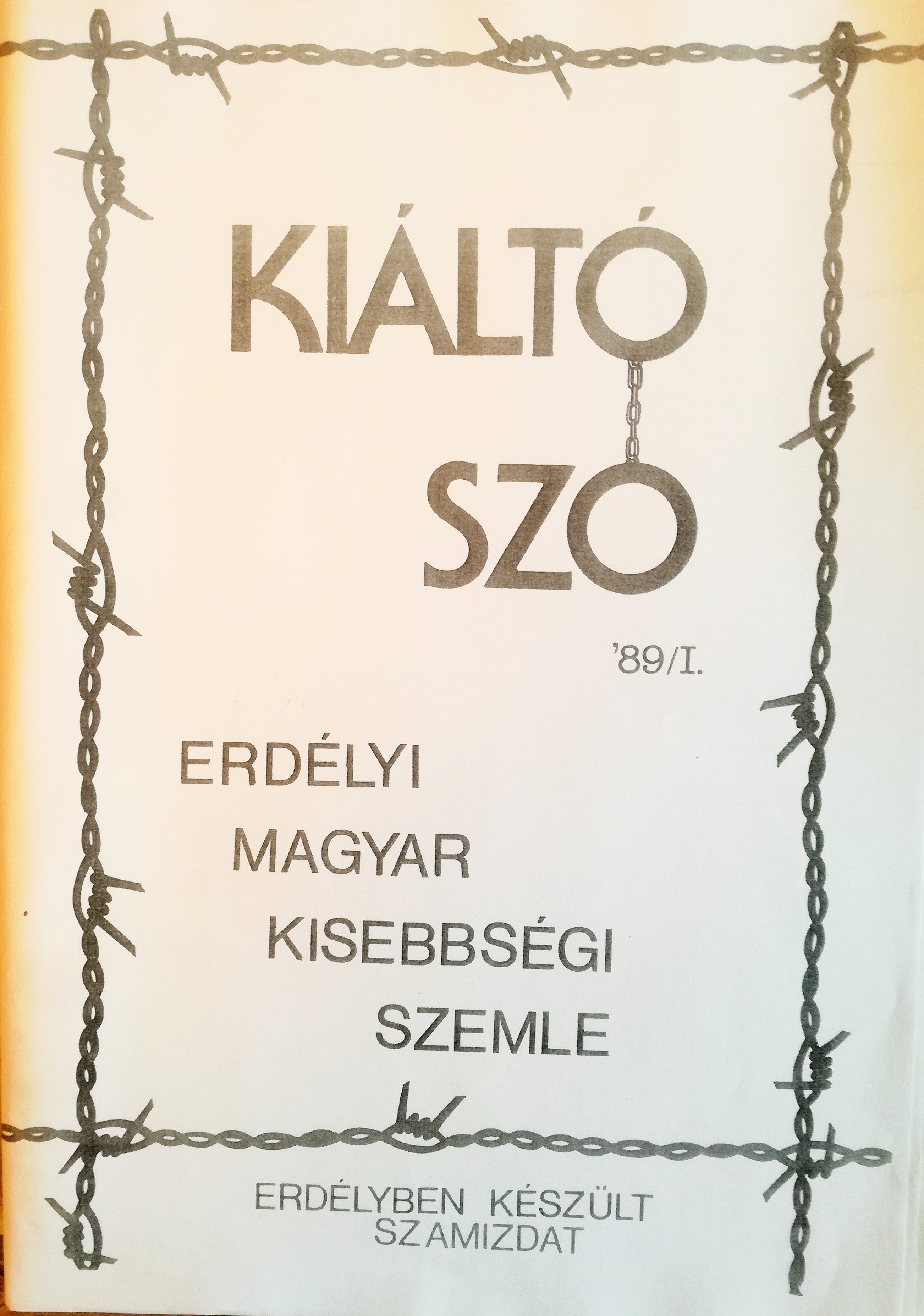

When editing the samizdat the editors realised that they were unable to produce a radical change in their minority situation on their own, since this required a democratic turn within the country. This led to the idea of the community of fate: the discrimination they were subjected to would only cease if the ethnic majority also got rid of the suffocating dictatorship. So there was an overlap between the minorities and those democratic, non-politicising Romanian individuals, who, although they did not feel the minority oppression for themselves, were nonetheless suffering from the lack of democracy. The editors were guided by the conception of finding sympathisers to resonate with their dissatisfaction. Therefore the magazine was partly bilingual. Whenever they felt the need, they not only translated into Hungarian certain important writings of their Romanian fellow ideologists, but also published the Romanian versions of these texts. In the person of Doina Cornea – who counted as an example for her attitude, spirit of sacrifice, and criticism of the system – they found a colleague who at the beginning had not even suspected that she was cooperating with them as they had borrowed several of her declarations without her knowledge, primarily from Radio Free Europe, and corresponded with her in the samizdat.

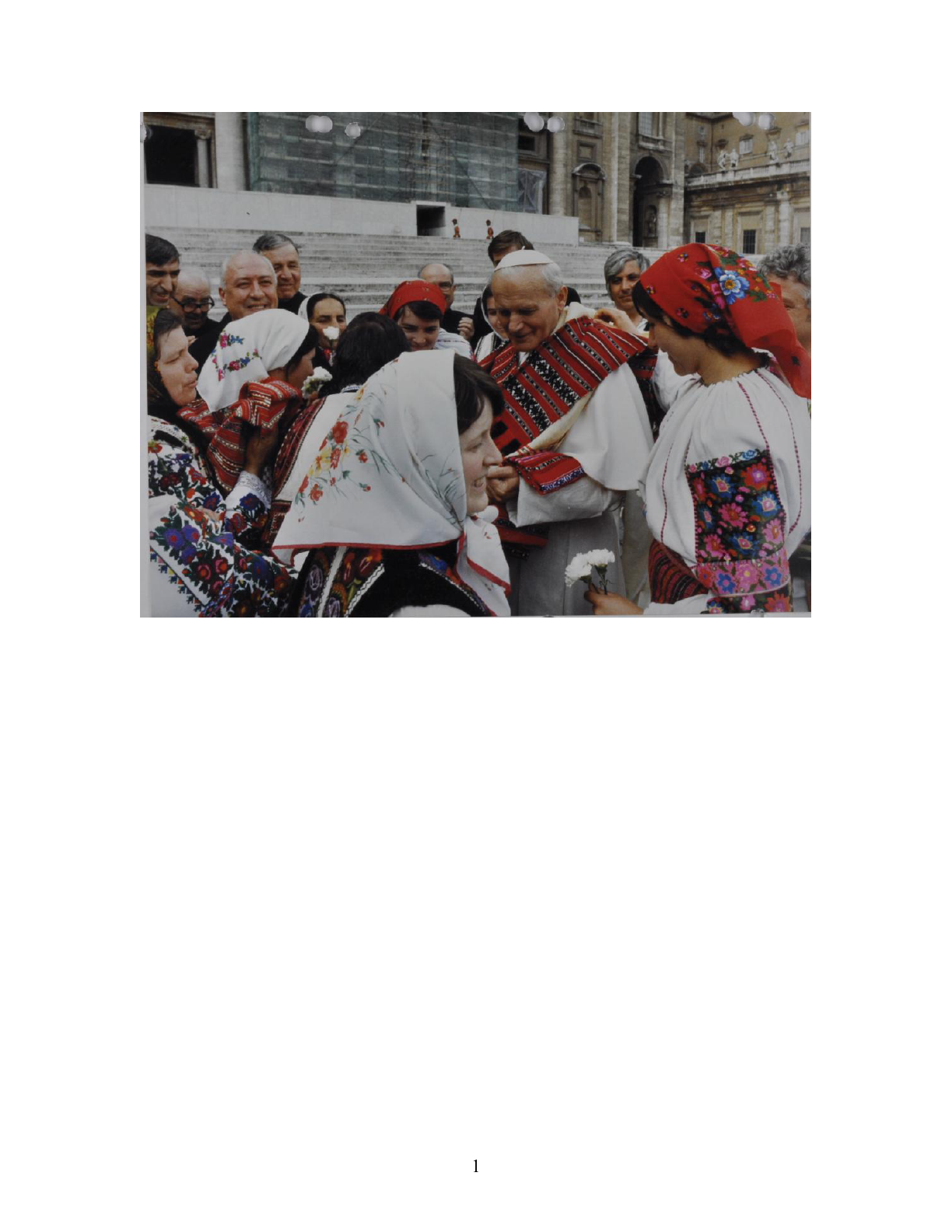

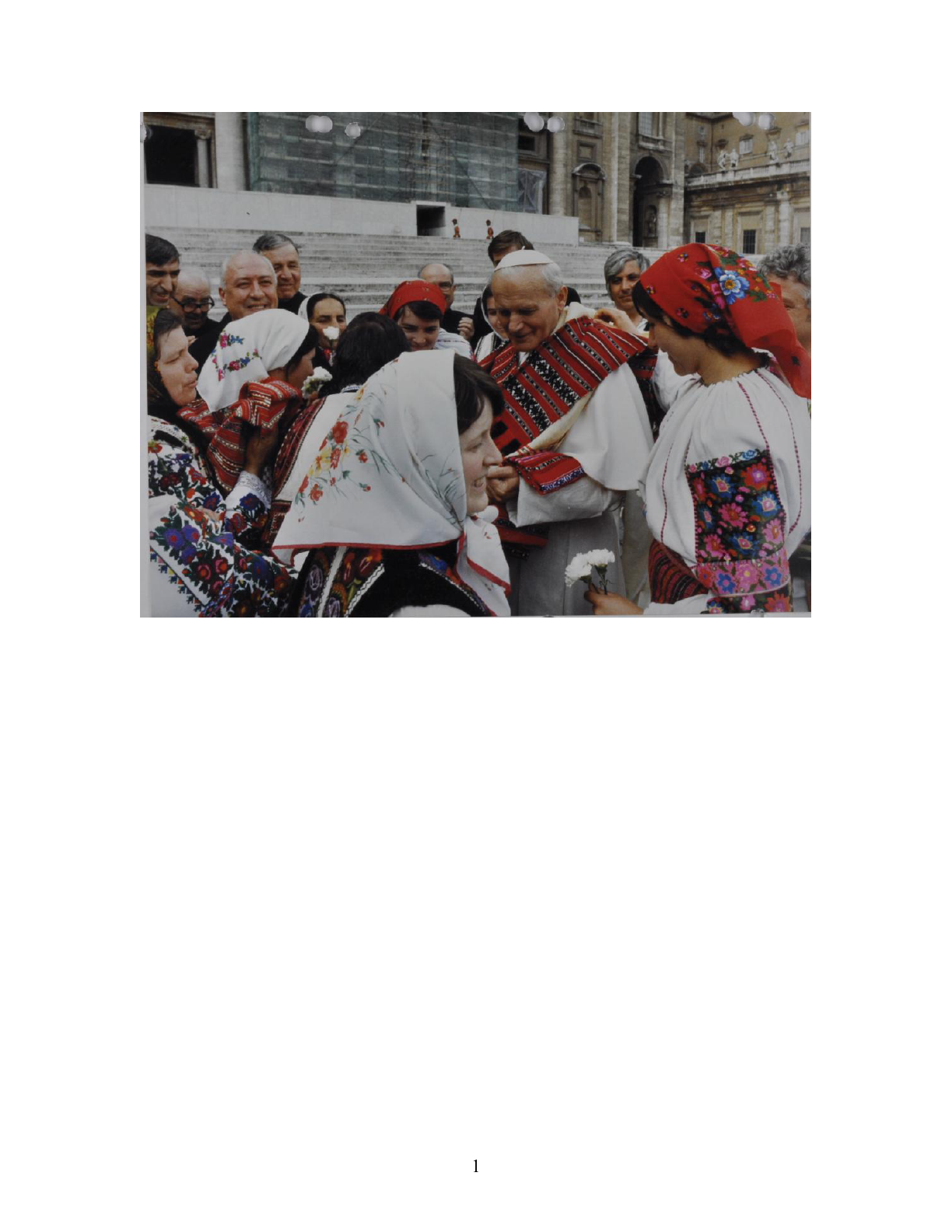

The first step of the Hungarian–Romanian union of efforts was the publication of the leaflet entitled Fraților – Testvérek in the spring of 1988, in which linguist Éva Cs. Gyimesi together with puppeteer, artist, and prose writer Ivan Chelu protested against the potential demolitions of the Transylvanian villages. As a debut of the relationship established with Doina Cornea they first published a real conversation between her and another (unidentified) Romanian intellectual entitled “Találkozás Doina Corneával” (Meeting with Doina Cornea), and then published Cornea’s text entitled “Doina Cornea levele a Szentatyához” (Doina Cornea’s letter to the Holy Father). The views of the editors and those of Cornea had much in common, though the former had certain reservations regarding the way the latter interpreted the contemporary situation. In spite of all this what really mattered was that finally there was a Romanian intellectual with whom they agreed on a number of issues and in certain cases they could confront each other “in a way that was usual among members of the same team when it came to clarifying ideas.” They accepted Cornea’s call for solidarity and unity irrespective of nationality and agreed without reservations upon her encouragement to avoid any form of violence. They were convinced, along with Cornea, that there was an institutional crisis in Romania and that behind this the Securitate was operating everywhere. They were also in agreement that the laws of the country must be abided by and that the same applied to international treaties. However, the editors went further: they believed that this was not enough for the Hungarian minority and that there was a need for basic legal arrangements, which ensured not “socialist” but real democracy, and not only for Hungarians, but also for every Romanian citizen. They agreed with Cornea’s idea of stimulation to action, though they held different views as regards the driving force behind this and what this would mean in practice. They acknowledged that Cornea did not want to be a politician: she was primarily interested in the moral aspect and according to her there was mainly a need for moral renewal, since without that political change was impossible. Nonetheless, the editors wanted to take political action, at least through the medium of the printed word. They doubted that the elimination of the moral recession would lead to the solution of the political crisis. At the same time they accepted the fact that under the given circumstances they all had to serve as witnesses and that this should be followed by action.

Afterwards a dialogue began with Doina Cornea, who by then was a dissident personality known across Europe. The first tone of this dialogue was set by Éva Cs. Gyimesi by means of an open letter, entitled “Nyílt Levél Doina Corneának” (Open letter to Doina Cornea), which was published in both Hungarian and Romanian. The addressee could identify the sender “without a signature” on the basis of the letter’s contents and their shared experiences. In reality this was a one-sided dialogue, in fact the collaborators of the samizdat reflected on several of Doina Cornea’s affirmations, but they did not receive a reply.

In her letter, Gyimesi includes her carefully formulated reservations. The “anonymous” correspondent considers it strange that her addressee does not want to build a closer relationship with the Hungarians on the grounds that her fellow Romanians would accuse her of “having sold herself to strangers.” The question arises: does she refuse to act in an organised way in general or is it them, the “strangers” she avoids joining forces with? Cornea felt deeply hurt because once she had indeed been the victim of a rude offence committed by one person due to her nationality, but Gyimesi warns her: crimes committed by individuals should not constitute a reason for collectively blaming an entire community. For the editors, this was a guiding principle. There were numerous offences committed by Romanians that they were fully aware of and protested against, but they never intended to turn these reprehensions into anti-Romanian acts. This is how they expected to be treated by the other side as well (Doina Cornea included). This was followed by the most essential message conveyed by Gyimesi’s letter which focused on the reconciliation between Hungarians and Romanians in the spirit of the ideology of Transylvanism. Afterwards, the correspondence between the editorial team of Kiáltó Szó and Doina Cornea followed a broader course. In the following editions which failed to be published, a further three epistles sought to further clarify Doina Cornea’s views broadcast by Western radio stations and argued that these views actually complied with the conception of the editorial team. Philipp, Tibor. Krassó György's performance: Renaming the Münnich Ferenc street, Budapest, 1989. Photo

Philipp, Tibor. Krassó György's performance: Renaming the Münnich Ferenc street, Budapest, 1989. Photo

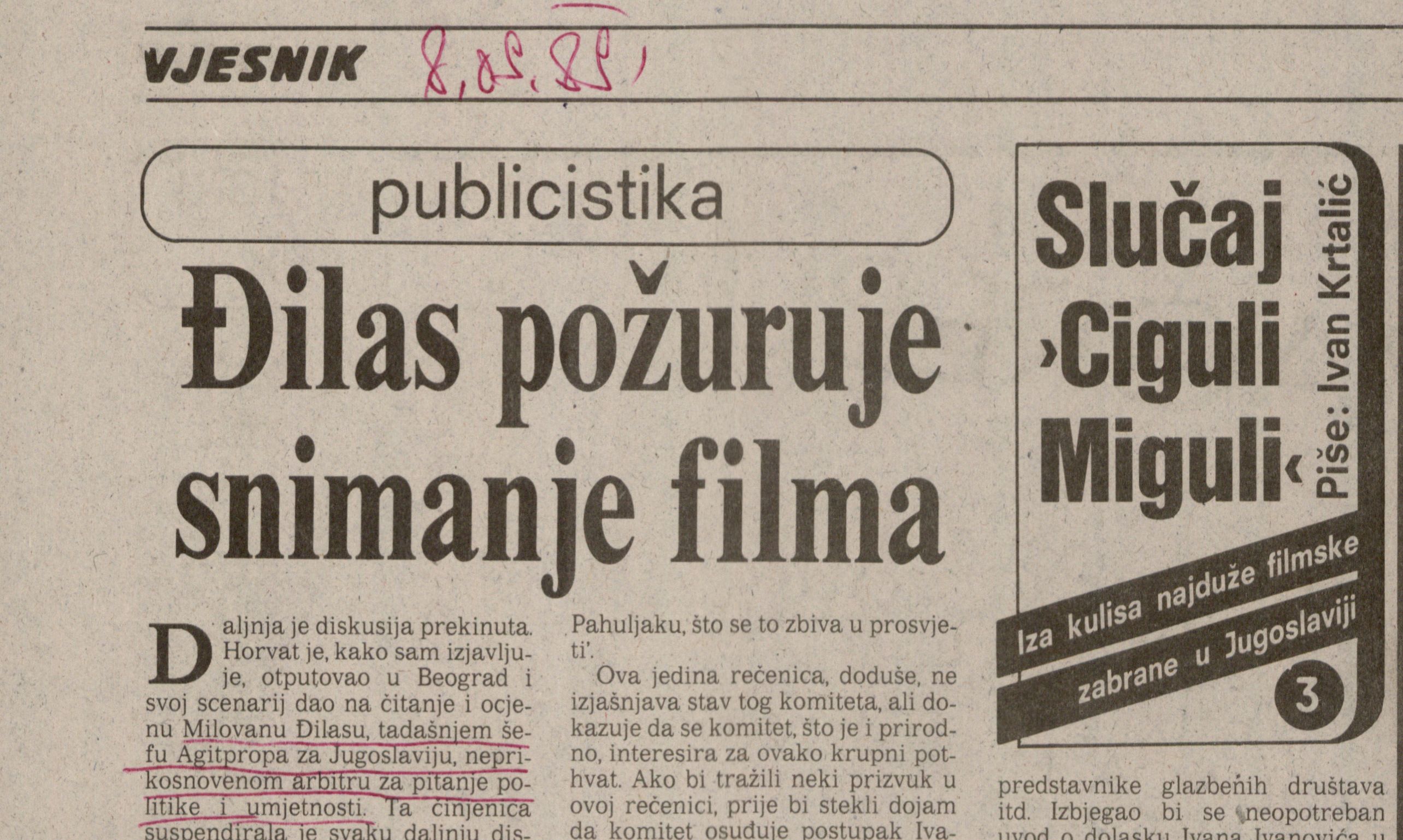

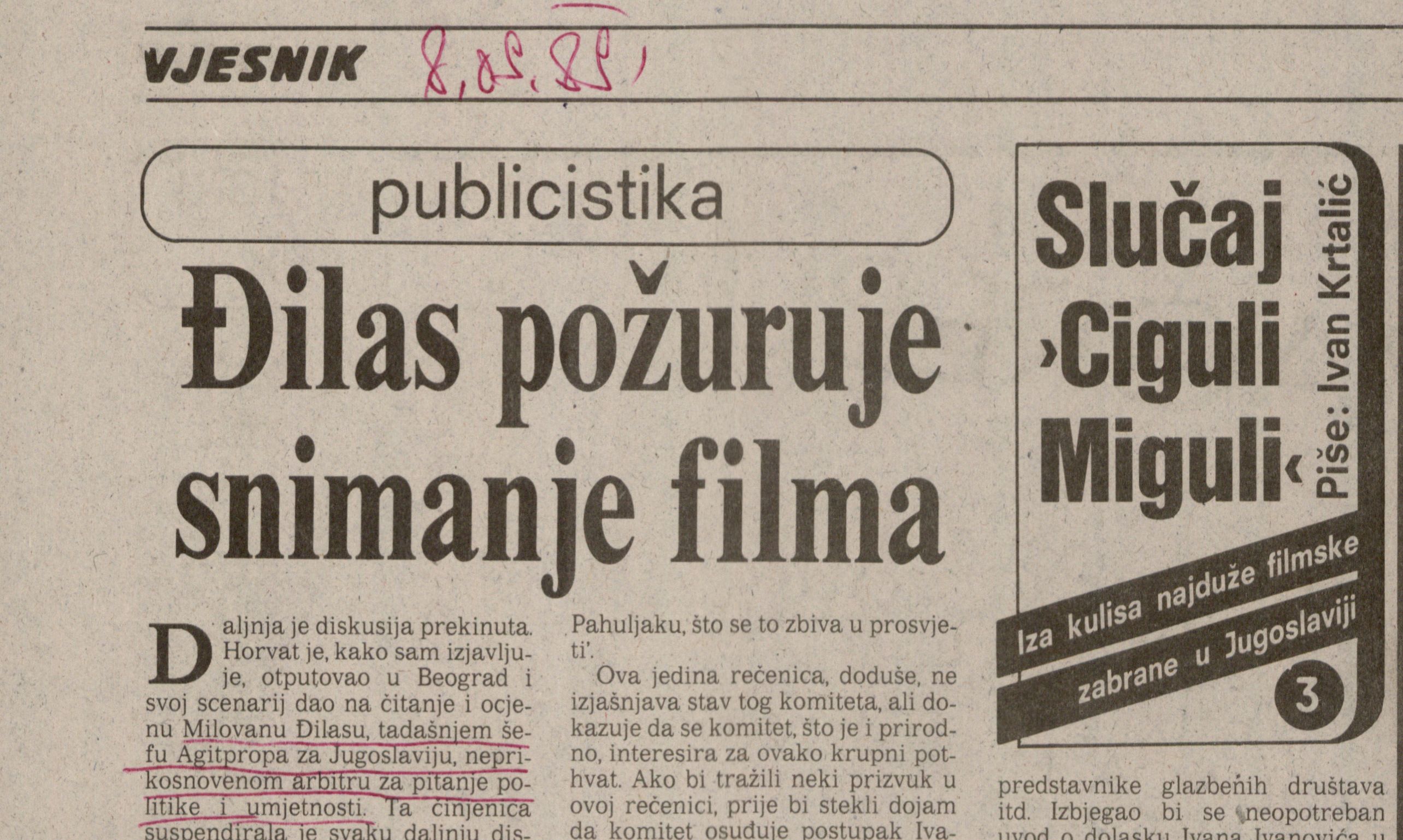

The feature film Ciguli Miguli (1952) by director Branko Marjanović and screenwriter Jože Horvat was the first banned film in socialist Croatia. The film was supposed to be the first post-war socio-political satire. It ridiculed bureaucracies of the Soviet type. However, Party leaders read this satire as antisocialist opposition defying civil traditions. The public viewing license was granted only on April 30, 1977, and in 1989 it was first shown on television. It then attracted great media attention. In 1989, Igor Krtalić wrote a feuilleton on the case of Ciguli MIguli for the newspaper Vjesnik.

Memorandum addressed to Nicolae Ceauşescu, President of the Socialist Republic of Romania, in Romanian, 1989. Manuscript

Memorandum addressed to Nicolae Ceauşescu, President of the Socialist Republic of Romania, in Romanian, 1989. Manuscript

The leadership of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church, acting underground because their Church had been officially dissolved by the communist regime in December 1948, sent a memorandum to Ceauşescu in October 1989, in which they asked that the official status of their Church be restored. After the Greek Catholic Church was dissolved by the communist regime, its hierarchs and hundreds of priests continued to practise their confession clandestinely. This underground religious activity continued until the fall of the communist regime. During the 1980s the leadership of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church launched several initiatives that aimed at regaining official status. In 1989, these initiatives were encouraged by the open debates in the Soviet Union about the fate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which led to the restoration of the latter’s official status in December 1989. In this context, marked by the reforms initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev, the leadership of the Romanian Greek Catholic church asked Ceauşescu that the situation of the Church be discussed at the fourteenth Congress of the Romanian Communist Party, which was planned to take place in November 1989 and that their church regain its official status. In this respect, the Greek Catholic hierarchy invoked the state constitution. Article 30 of the 1965 Constitution stipulated that: “Freedom of conscience is guaranteed to all citizens of the Socialist Republic of Romania” (ACNSAS, FD 69, vol.1, ff. 45–46). In this respect the Greek Catholic hierarchy had the courage to mention the state repression that targeted their Church’s priesthood and parishioners after 1948, but also the harassment affecting Greek Catholic priests and parishioners at the time when the memorandum was drafted. The Securitate managed to confiscate a copy of this document and attached it to a file of the Documentary Fonds in order to illustrate the anti-State activities of the leadership of the Greek Catholic Church. The document was signed by several bishops and vicars: Alexandru Todea, Ioan Ploscaru, Vasile Hossu, Tertulian Langa, and Lucian Mureşan.

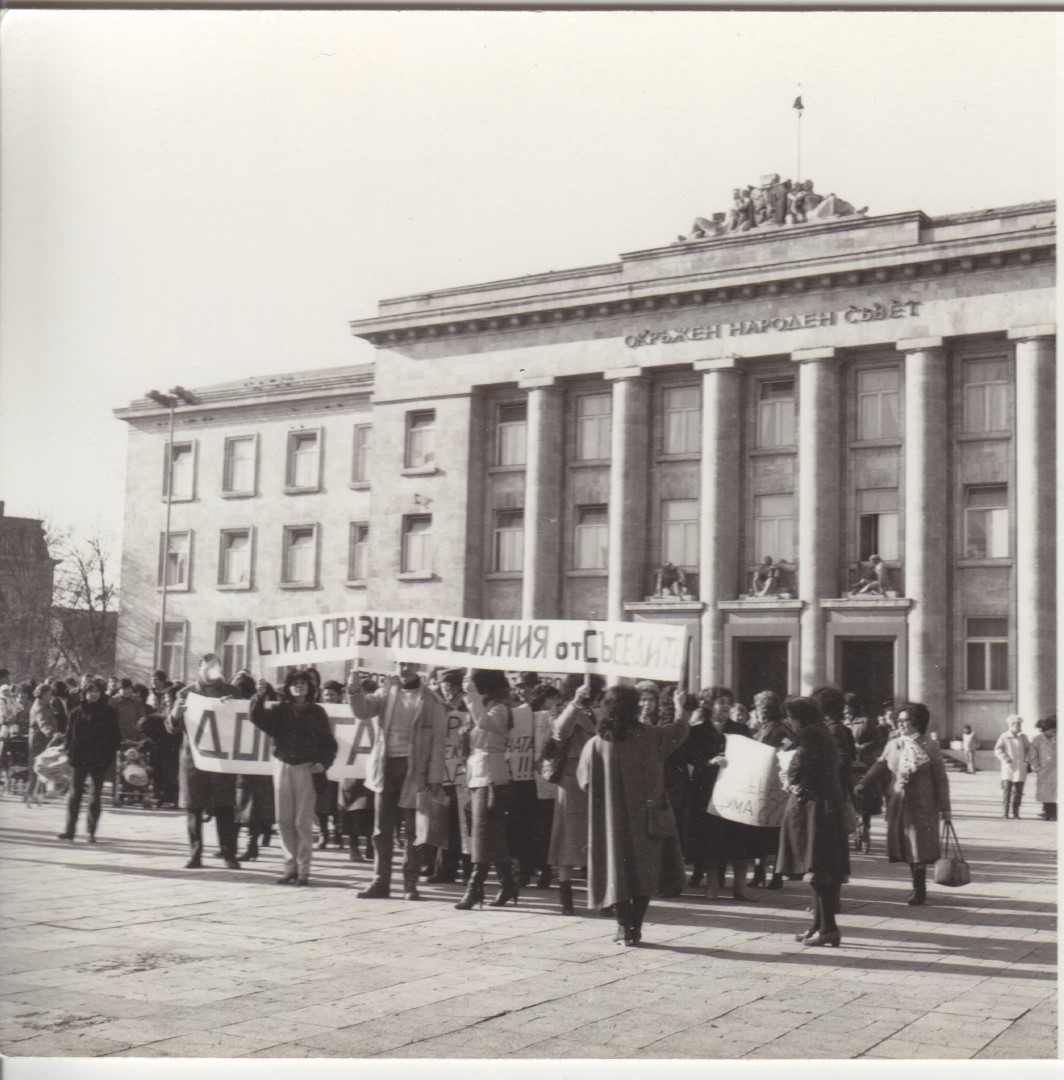

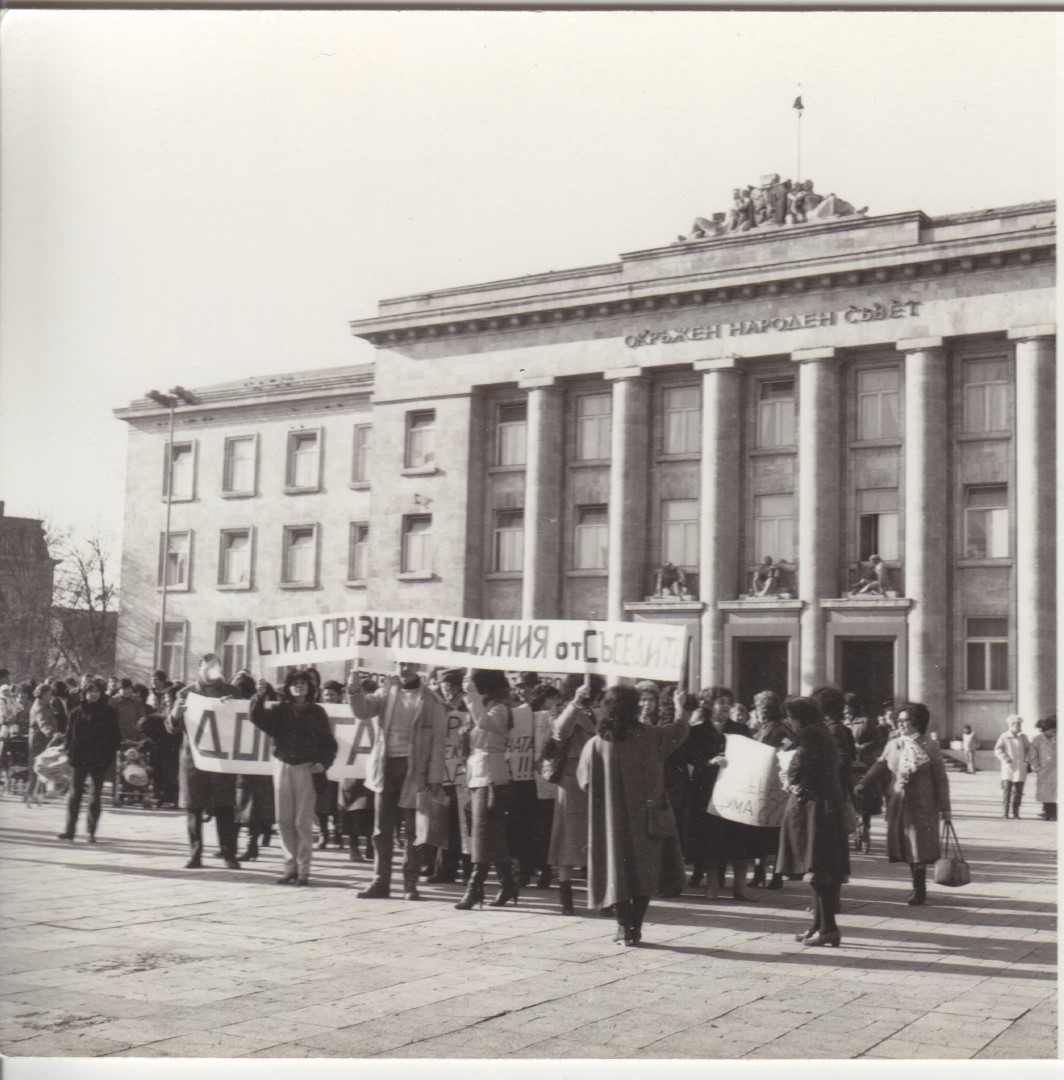

Numerous demonstrations were organized in 1989 in Budapest. Nine of the demonstrations are documented in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security (Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára – ÁBTL). As of January 1989, however, the freedom of assembly was guaranteed by law. The secret police observed and recorded the events by following their earlier reflexes, and they focused on identifying the participants and the banners. The photo collection of street demonstrations is the visual imprint of the actions which were organized by the different civil, artistic, and activist groups and a good source on the ambivalent behavior of the political police in the transitional period before the collapse of the communist system.