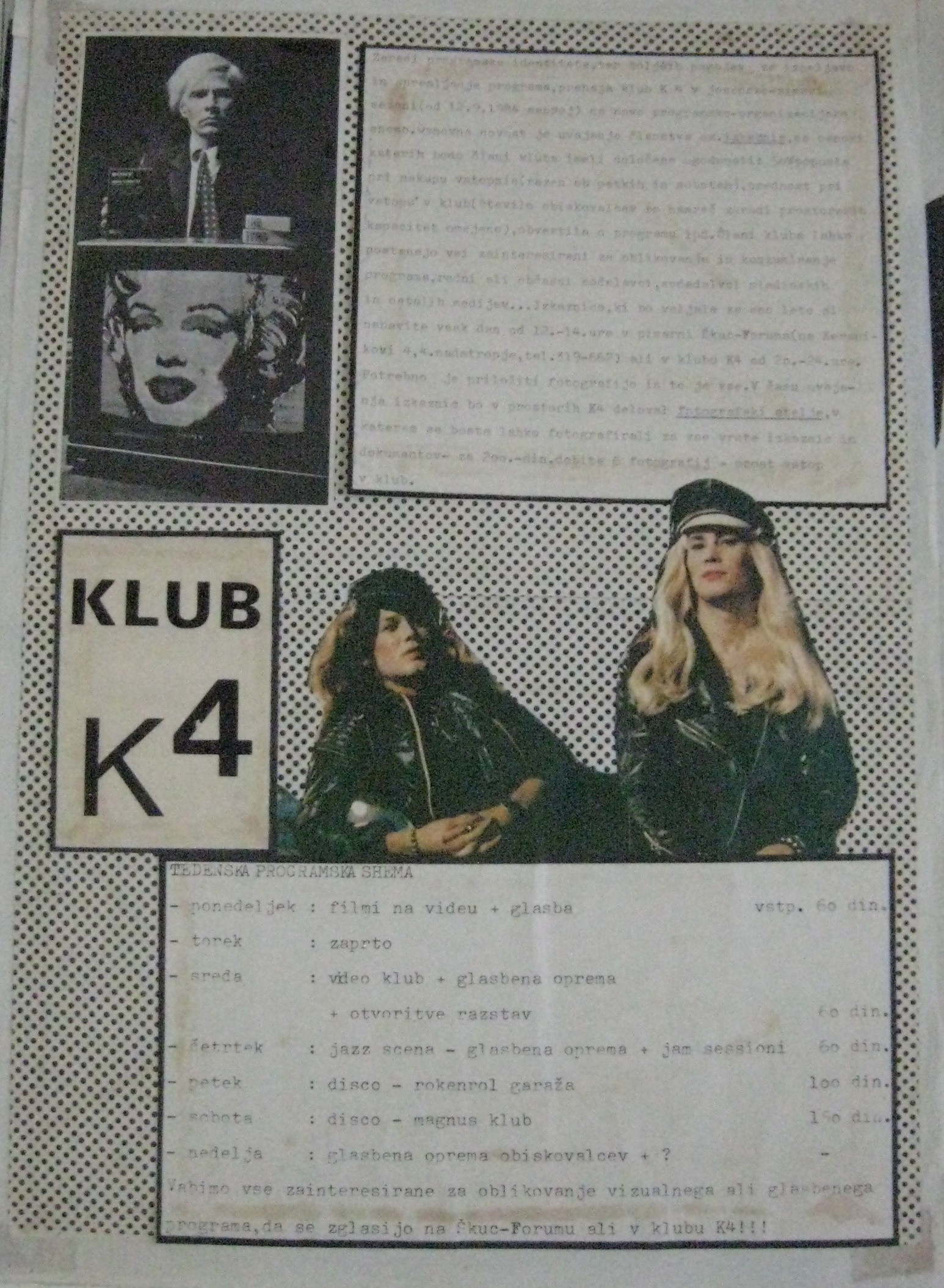

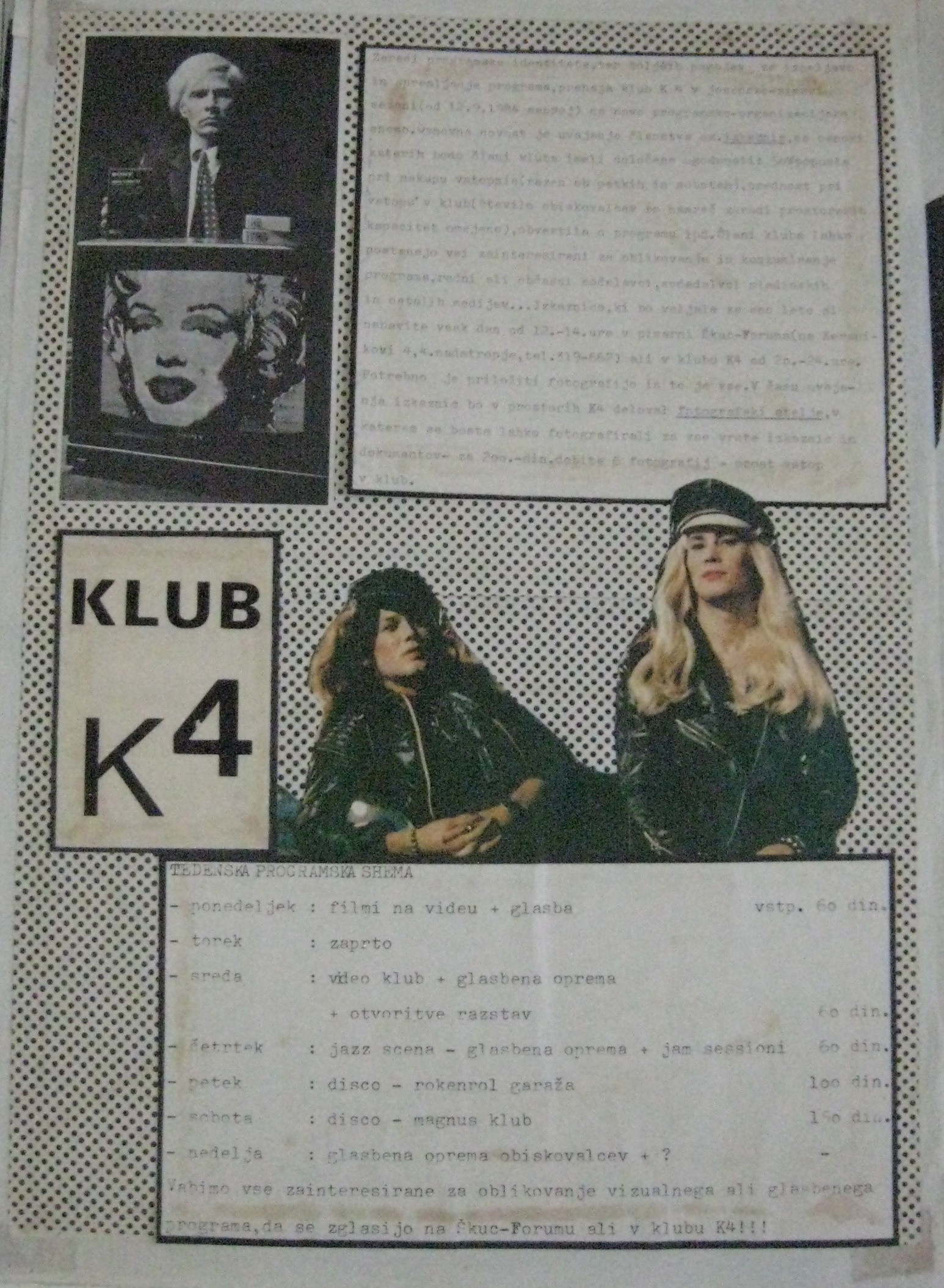

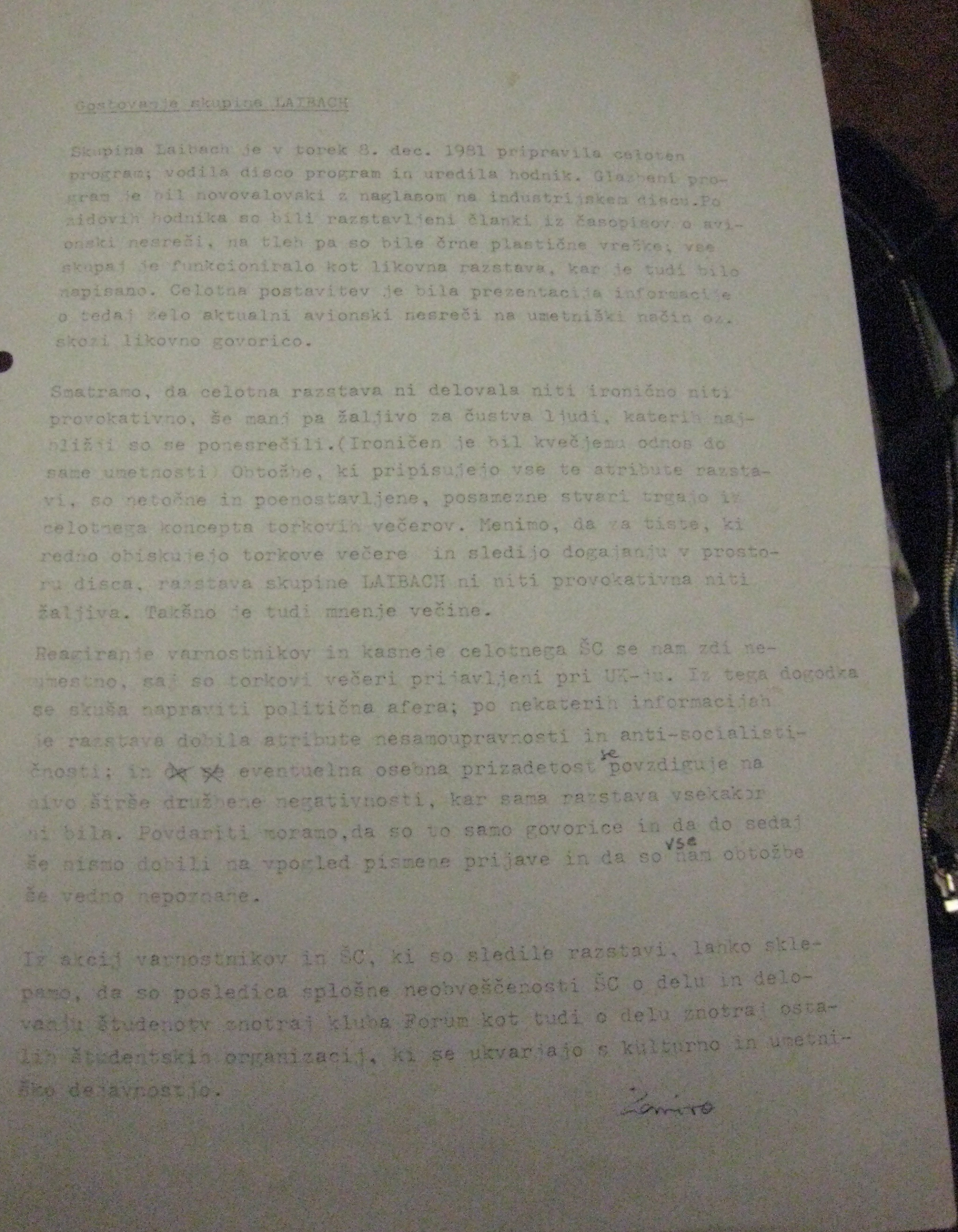

The FV 112/15 Group Collection is a blend of artistic materials representing the time, social movements, and lifestyle of young people in Slovenia in the 1980s. It documents a central part of Ljubljana’s subculture and the alternative youth movement through the work of an amateur theatre group called the FV 112/15 Theatre and through the activities of three alternative clubs. The group cultivated an ironic attitude toward socialism and deconstructed bourgeois stereotypes.

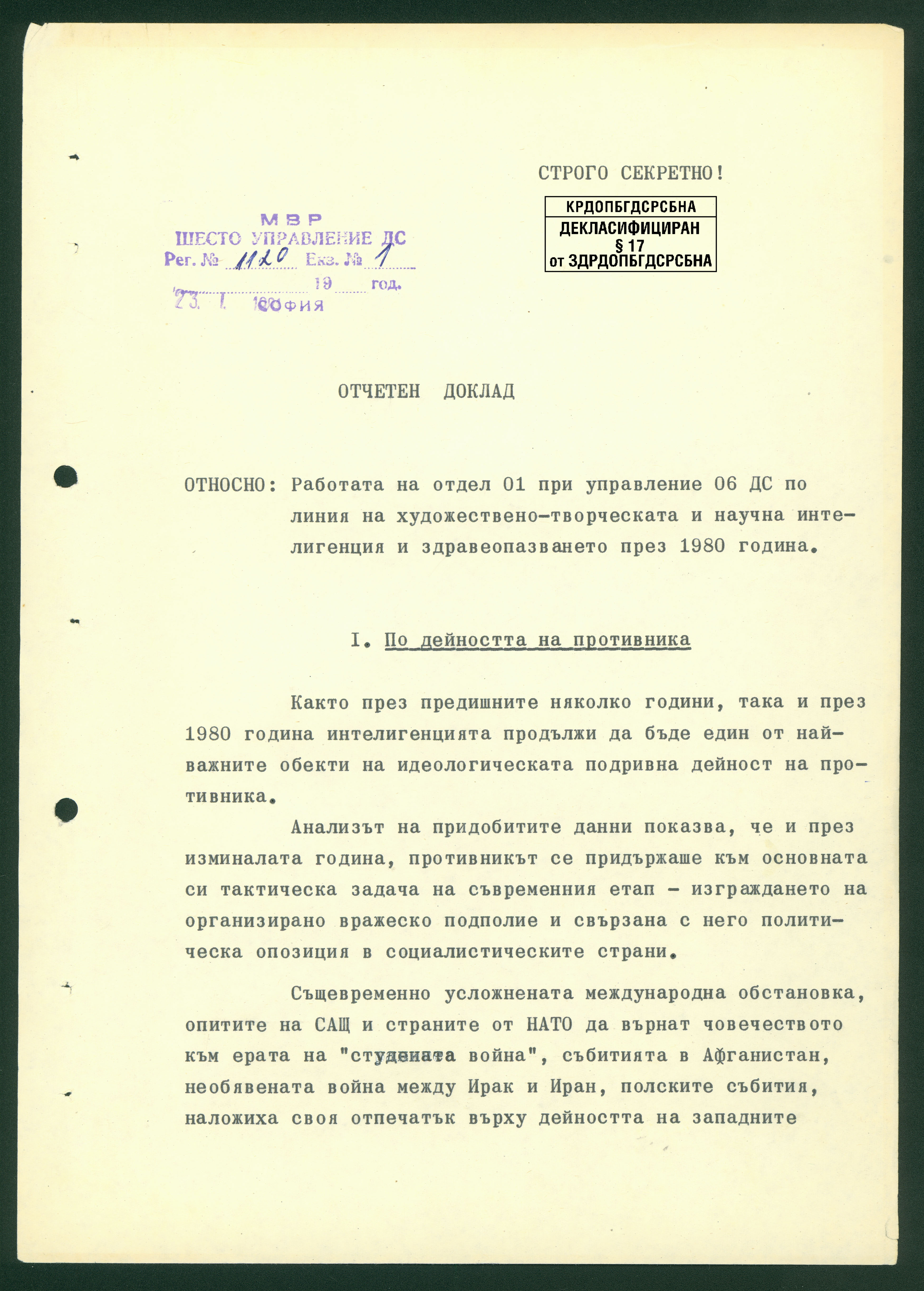

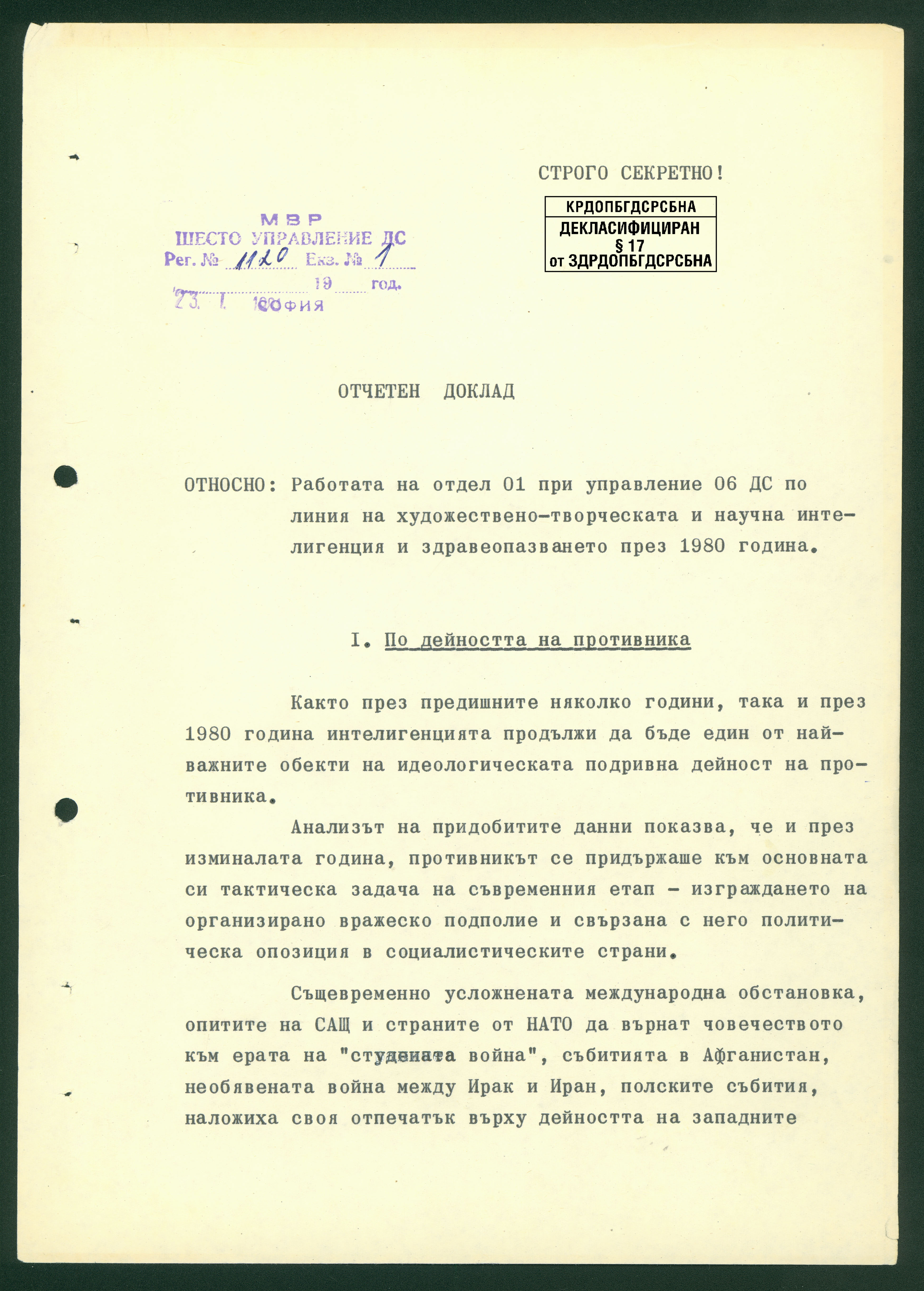

Summary Report about "Work of Department 01 at Division 06, State Security, with respect to the artistic and scientific intelligentsia and healthcare in 1980", Sofia, 23 January 1981. The report summarizes the work of the State Security among the intelligentsia (in arts, the sciences, and the medical profession) in 1980. It states that, as before, intellectual were a prime target of the subversive efforts by enemy forces from abroad. The report highlights the difficulties in the casework of agents. Yet some of the observations succeeded in "infecting their circles" because they had been conducted over long periods. The report, thus, is a good illustration of the concrete work of the state security among the intelligentsia and of its attempts to prevent acts of cultural opposition.

After a few months break, when the journal was coming close to its end, the restart of “World in Move” with its double issue of March–April 1981 seemed to be not just a positive sign of survival, but a real promise of a rebirth. The newly designated chief editor, Ferenc Kulin, together with his very much tried and tested editorial team, managed to get rid of direct censorship from the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League, and was offered another chance by the main cultural commissar, György Aczél himself, “to prove their talents.” No doubt they tried to do their best on the 224 pages of the book-sized double issue.

On the first two pages there was an editorial addressed to readers briefly summing up the recent changes in and around the paper, and drafting further plans for the future. As it was stated, a long decade passed since the start of “World in Move,” and after a prolonged period as a “youth paper,” it was high time to become a forum for adults with full responsibilities. It is true that in two short paragraphs one can be read the obligatory ideological “loyalty statement” of all legally published papers (“engagement with socialism, dialectical and historical materialism,” etc.), but more important is the list of radical claims for free public debates in all fields of life: in politics, culture, arts, literature, science, education, and so on.

These ambitions are well reflected by the content of the double issue: finely written poems, short stories, plays, essays, studies, reviews, and critiques of contemporary books, films, music, and theater performances, experimental art pieces, passionate public debates (on schools and higher education), a series of socially authentic photographs (like teenage kids at rock festivals). The world seemed to be moving dynamically, and the journal “World in Move” did too – at least for a few years to come … until the end of 1983.

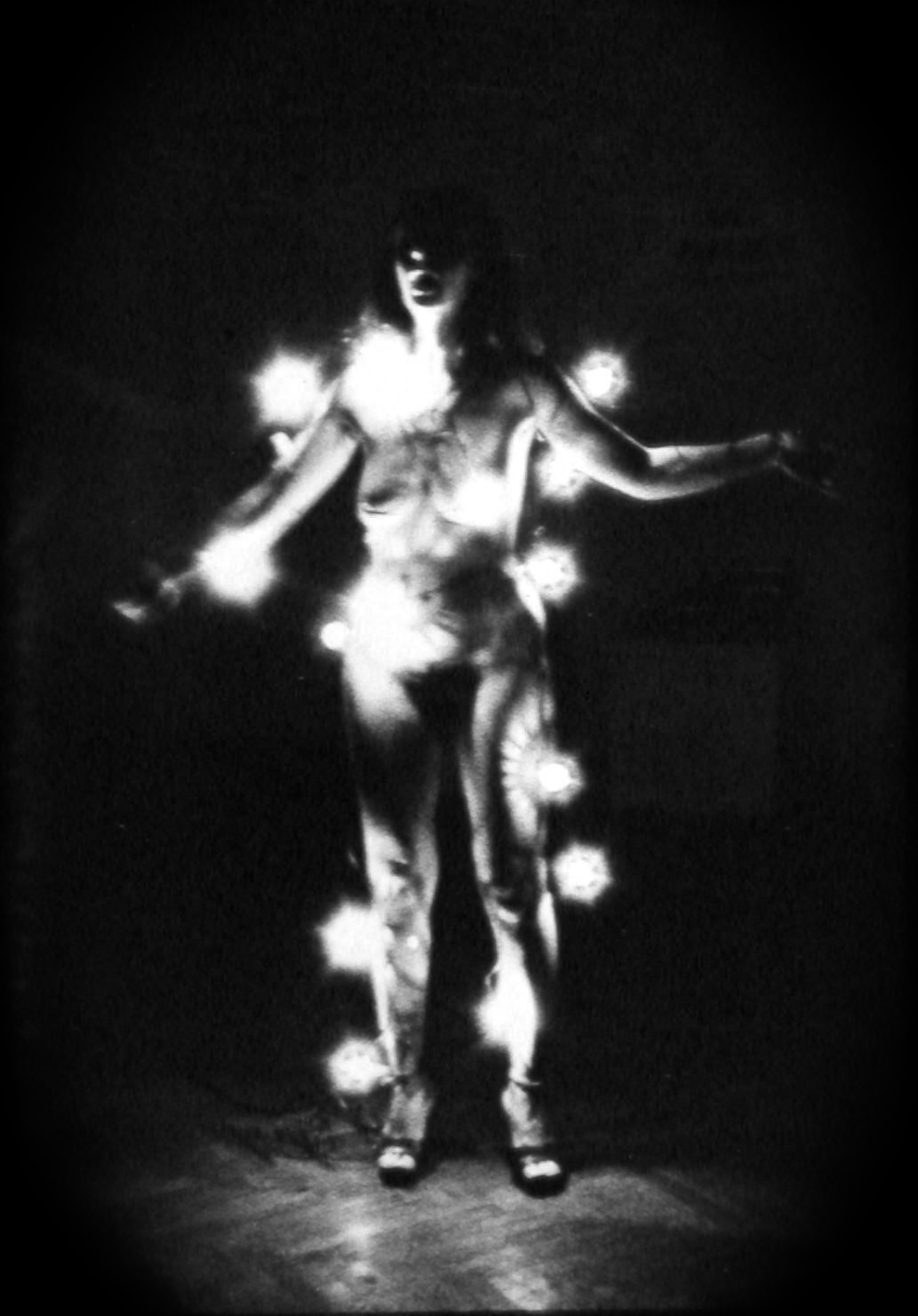

The photo presented Ewa Partum making her performance Stupid Woman in the Dziekanka Workshop, November 20, 1981. The performance was acknowledged as one of the essential pieces of women's art or even feminist art in Poland. Ewa Partum was one of the prominent female artists of the neo-avant-garde in the time of late socialism in Poland, alongside with Natalia LL, Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Izabella Gustowska, Teresa Murak, Zofia Kulik, and Barbara Konopka. Partum exercised the performativity of gender many times, conducting in her works deconstruction of the femininity and features associated with it. The question of gender and femininity was the subject of the Stupid Woman performance as well. On the picture taken by Tomasz Sikorski, naked Ewa Partum is performing with only chains of lights on her body.

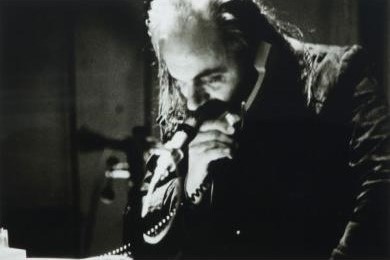

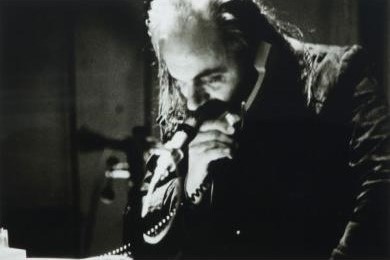

The fourth performance from the Homage to Josip Broz Tito cycle is ˝Telephoning˝ by Tomislav Gotovac. It was staged in the SC Gallery in Belgrade on April 5, 1981, and the photographs of the performance were done by Milisav Mio Vesović and Ognjen Beban. It is the only performance from the Homage Tito cycle that was not staged in Zagreb.

In the last subversive action, Gotovac waited for someone to inform him by the telephone that President Tito had died. With this performance, the artist additionally placed himself in a passive position by waiting for the information to come to him indirectly, not directly as in earlier actions via television, newspapers or radio, for one of his friends, associates or family to indirectly notify him about Tito's death. In this work, Gotovac used subversive activity, in which he did not criticize the regime, but rather encouraged the public and the regime itself to think.

Milan Šimečka made the chess pieces using bread in the prison where he was taken after the capture of the exile literature caravan, which was sent from London by Jan Kavan. Milan Šimečka spent one year in prison and during this period he wrote letters that were preserved and later published in samizdat editions. He also spent some time playing a game of chess using pieces he made from bread that had been given to prisoners.

The Student Newspaper published a photograph of Marijan Molnar dressed as a terrorist/criminal in 1981. With this photograph, which is a part of the "For the Democratization of Art" cycle, Molnar wanted to point to the "dose of terrorism in the field of art” by dressing himself as a terrorist. This means that the external difference is always the internal, that the external constraints pressuring art are always reflected in it, as an inherent (im)possibility to be tamed by the artwork" (Molnar, Marijan. Akcije i ambijenti, Zagreb: Naklada MD, 2002., 161).Suzana Marjanić thinks that with this action, Molnar ˝also expressed his fascination with the anarchist groups of 1970s˝ (Marjanić, Suzana. "Performans i terorizam ili izvedba terorizma." Narodna umjetnost 50, no. 2 (2013), 102-127).

Since the 1960s, Ivan Manolov Petkov – Turkata, who was a civil engineer by profession began drawing as an amateur painter. His paintings are in the style of the dramatic and grotesque visions of the world typical of the works of Pieter Brueghel the Younger (also known as Hell Brueghel) and Hieronymus Bosch as well as of Paul Delvaux and Salvador Dalí. The varieties of surrealism were forbidden since they were particularly dangerous for the regime with the ridiculing of the utopias. At that time, the knowledge that Marxism was an utopia was already present in Bulgaria. The works of Ivan Petkov – Turkata were not allowed to participate in art exhibitions but in 1977 he managed to make an independent exhibition in the hall of Sofstroyproekt – the institute where he worked as an engineering technologist. The exhibition was closed down prematurely.

The State Security put him under surveillance by the code name "The Painter" and kept a record with "materials" – slanders with the purpose of "preventing, neutralizing the enemy activity". Investigated by the State Security, interrogated, eavesdropped and kept under observation, Ivan Petkov ceased making public statements against the regime and began expressing his opinion of the "people's power" through his paintings.

Despite the regular interrogations, denunciations and warnings, Ivan Petkov created influential paintings-metaphors in which his criticism of the regime was surreptitiously expressed. The paintings "Anthropological Excavator" (1981) and "Lobotomy" (1983) are one of his large-scale metaphors of socialism – socialism as antihuman, disabling regime (after lobotomy, man becomes mentally and emotionally paralysed).

Ivan Petkov used mainly oil-paints on canvas or wood but also water-colours and mixed techniques. He experimented with sculpture and decorative art. The painting "Anthropological Excavator" which was property of the painter's inheritors was part of Petkov's independent exhibition "Surrealism in Time of Socialism" (2015, curator Krasimir Iliev) at the Loran Gallery during which it was bought by Angel Gatev.

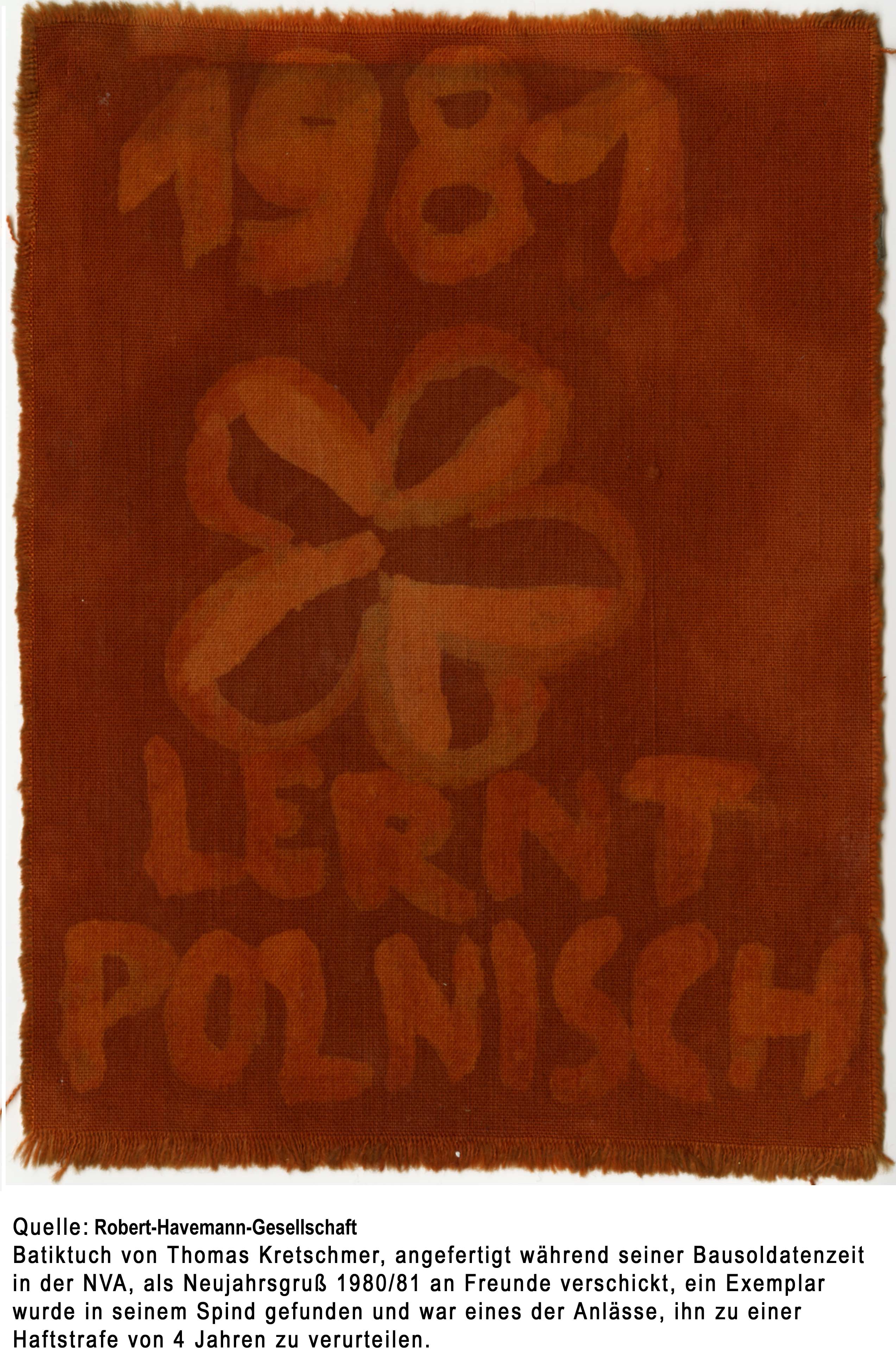

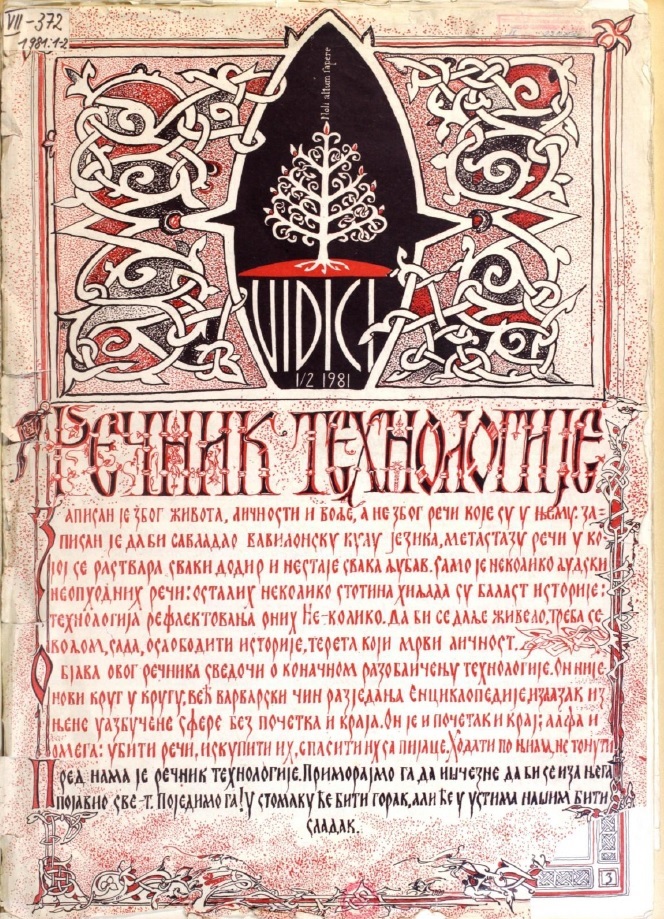

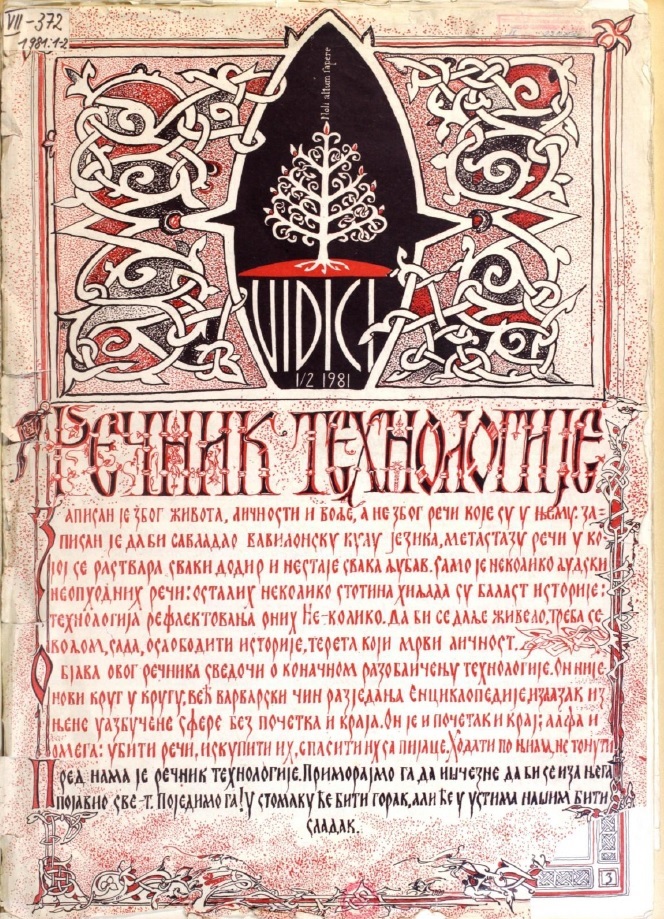

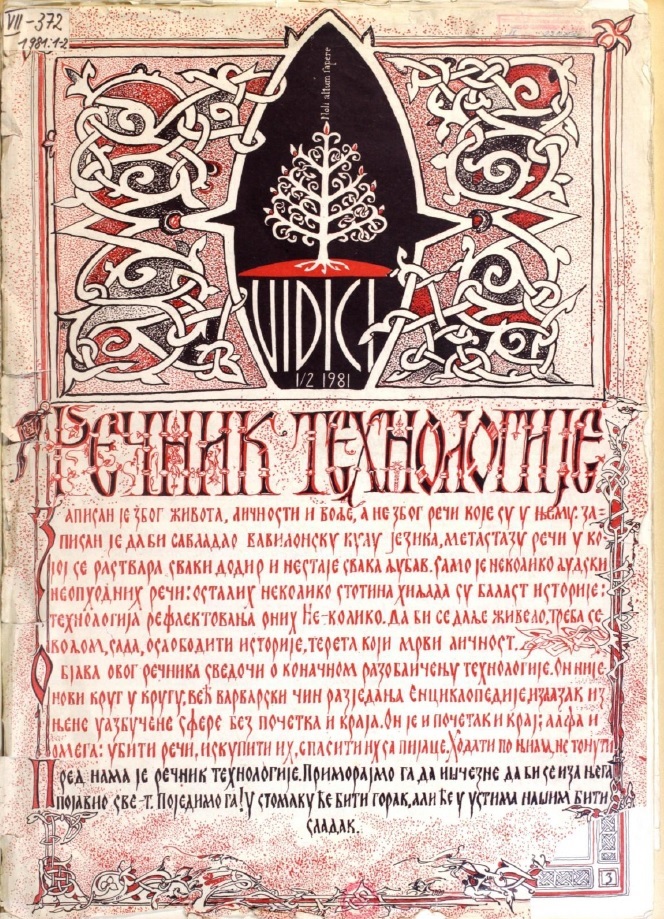

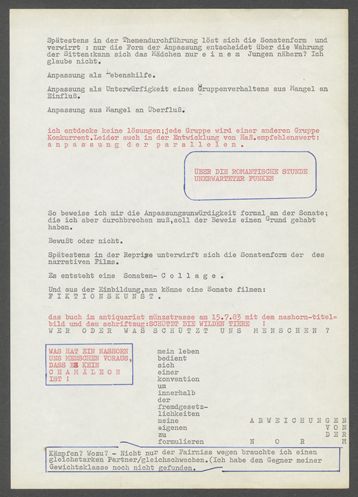

“The Glossary of Technology” is the name for the special issue of “Vidici” that came out in the spring of 1981. It is one of the most significant dissenting publications that directly relied on the then subversive press trends in Czechoslovakia and Poland. “The Glossary of Technology” acquired a great deal of inspiration from the Solidarity Movement, which some of the journalists and editors were in contact with. In contrast to all previous editions, it was modelled on a manuscript from mediaval times with illustrations and using a calligraphic style. It was completely handmade and crafted with old-fashioned technology. Another specificity was that this issue was conceived as a dictionary with carefully selected samples. The manner in which the dictionary looked had a symbolic meaning. It was a protest against the modern technology-based social systems (Z.P. Piroćanac, Nomenclatura Serbica, 2012, 1). The edition had 171 terms on 30 pages. Some of the terms mentioned were: "WILL – unconditionality. The possessor of movement and the only force that can master it. Will realized as life is personality. Will is without conditions, but it is the condition for everything. “Let there be light,” and there was light. (Book of Genesis); DEMOCRACY – equilibrium. A form of medium of society. This is the technology that cannot be eliminated by an individual. The devilish game of democracy is concerned with knowledge and ignorance, crime and punishment, cruelty and kindness ... (Cummings); MASS – indolence. Being the mass does not mean being part of the crowd, but rather being indistinguishable in the same impersonal frequency of consciousness in general. History is required to vanish in the mass, because it has become complete numbness, pure immanence. A direct consequence of the new role of masses organised into a collective ... is barbarism (Berdyaev); MORALS – mirroring, limiting. Morals are laws realized in the medium of society. Only technologists need morality to avoid collision while moving, however the individual does not need it. Morality is acting egoism. Moral judgments belong to a stage of ignorance in which the distinction between what is real and imaginary is lacking …” (Nietzsche).

All this was too confusing for the political authorities who did not know exactly what was behind this coded edition. The edition was banned, and its subversive nature was discussed in front of the University Commitee of the Union of Communists, where an analysis was initially formulated in the party document "Analysis of the Ideological Orientation of the Journals "Vidici" and "Student".” In it we see that it is precisely the "aesopian language" and that it is impossible to understand the text without a "key" or "code", which worried the party most. Eventually, it was concluded that "The Glossary" was anti-humanist and antisocialist-oriented, which was enough of a reason to ban it. Soon afterwards, the party organs launched a media avalanche that lasted for several months, and the highest party officials spoke of the necessity to reckon with the group gathered around "Vidici" and "Student". However, it turned out that the criticism of "The Glossary" was merely a motive for launching a broader backlash against dissident groups after Tito’s death (1980). The subsequent outcome would be the publication of the "White Book" in 1984, by Croatia’s Communist party leaders, which called for an end to the so-called "cultural counter-revolution".

„Blind Chance” is one of the most known films of the Polish cinema of moral anxiety genre. The plot of the film is divided in three equally important parts: three different life stories of a young man (reenacted by Bogusław Linda). Depending on the sheer accident (him getting on the train or missing it), the main character enters different social milieus and constructs differently his biography. Main question of the “Blind Chance” is a reflexion on human agency and ability to shape one’s fate, destiny and inevitable course of events. Film shows in an interesting way the social reality of Poland in the 1970s and the 1980s. Depending on the smallest, the most mundane choices a student could find himself in different social groups: communist party, democratic opposition or politically neutral Academia.

Kieślowski’s film was produced in 1981, but it was not screened until 1987, as it was perceived as “dangerous” by the censorship and the Ministry of Culture and Art. In the National Film Archive we can access the protocol from the pre-release closed screening devoted to “Blind chance”. Some of the participants of the Ministry’s pre-release commission, tried to underline the philosophical and metaphysical value of the film as well as the craftsmanship of the director and the historical value of the oeuvre (the pre-release screening took place only few days after the introduction of Martial Law in Poland). Most of voices in discussion did not perceive the film as a threat to Polish society. Despite of rather mild opinions voiced during the pre-release audition, the “Blind Chance” waited 6 years to be shown publicly in Polish cinemas.

This makes Kieślowski’s „Blind Chance” one of the most known „półkownik” (Polish vernacular world for “films laying on the shelves for years”). The case of Kieślowski’s film shows that even the movies produced with support of the public funding and despite the positive feedback from other filmmakers could be banned from distribution under the excuse of posing a threat. In this sense, even film directors working publicly, could be taken out from the official field of cinema production.

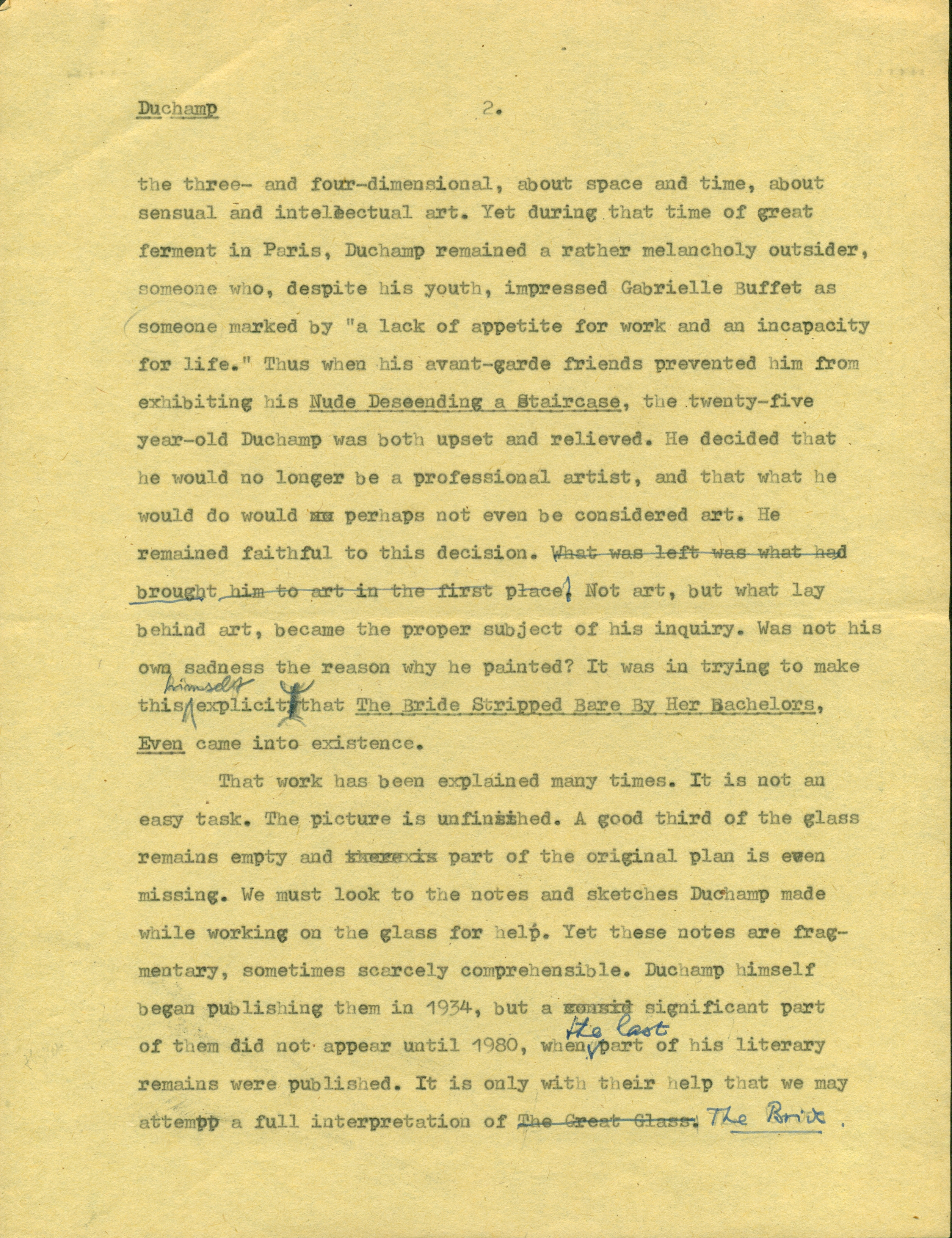

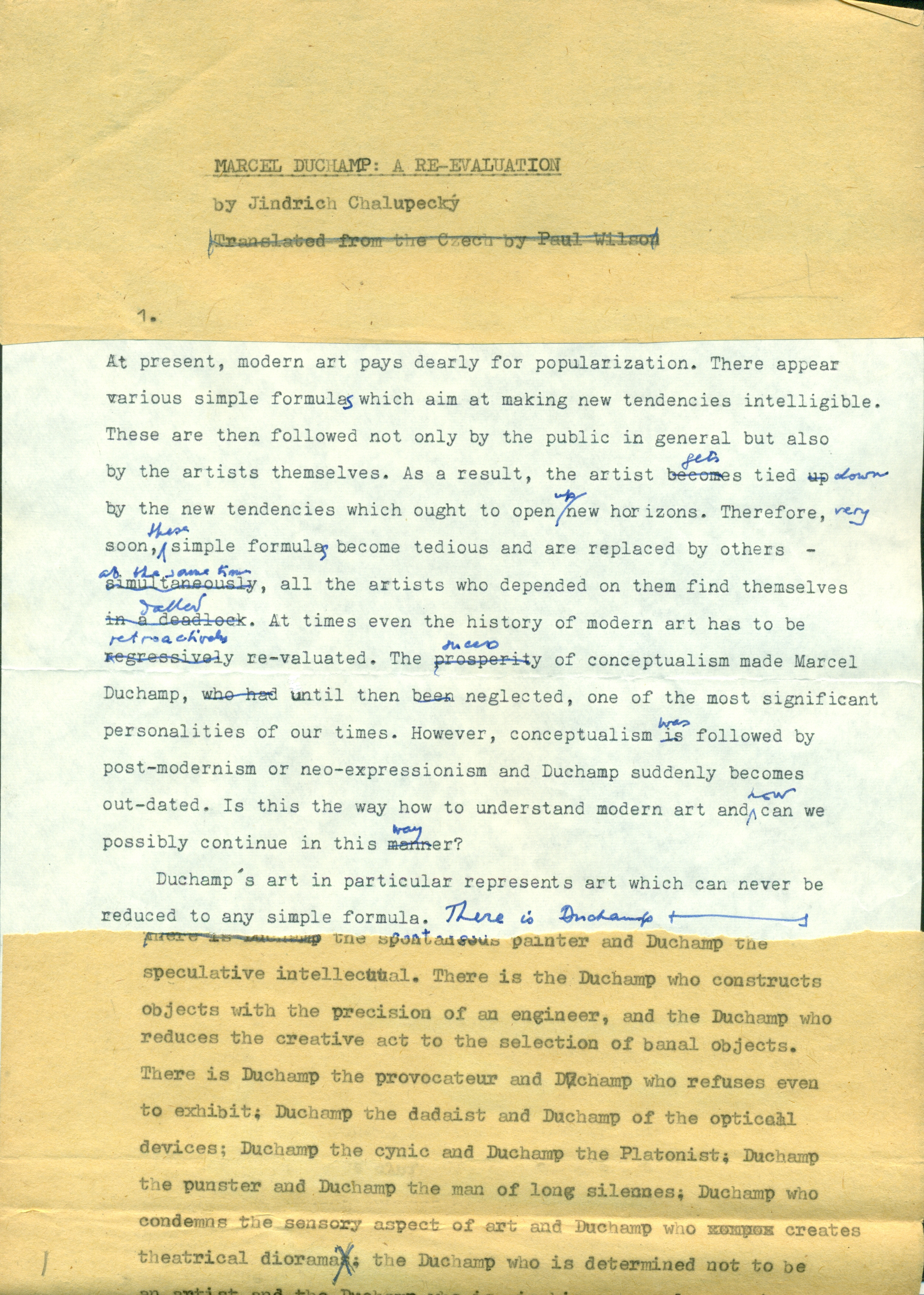

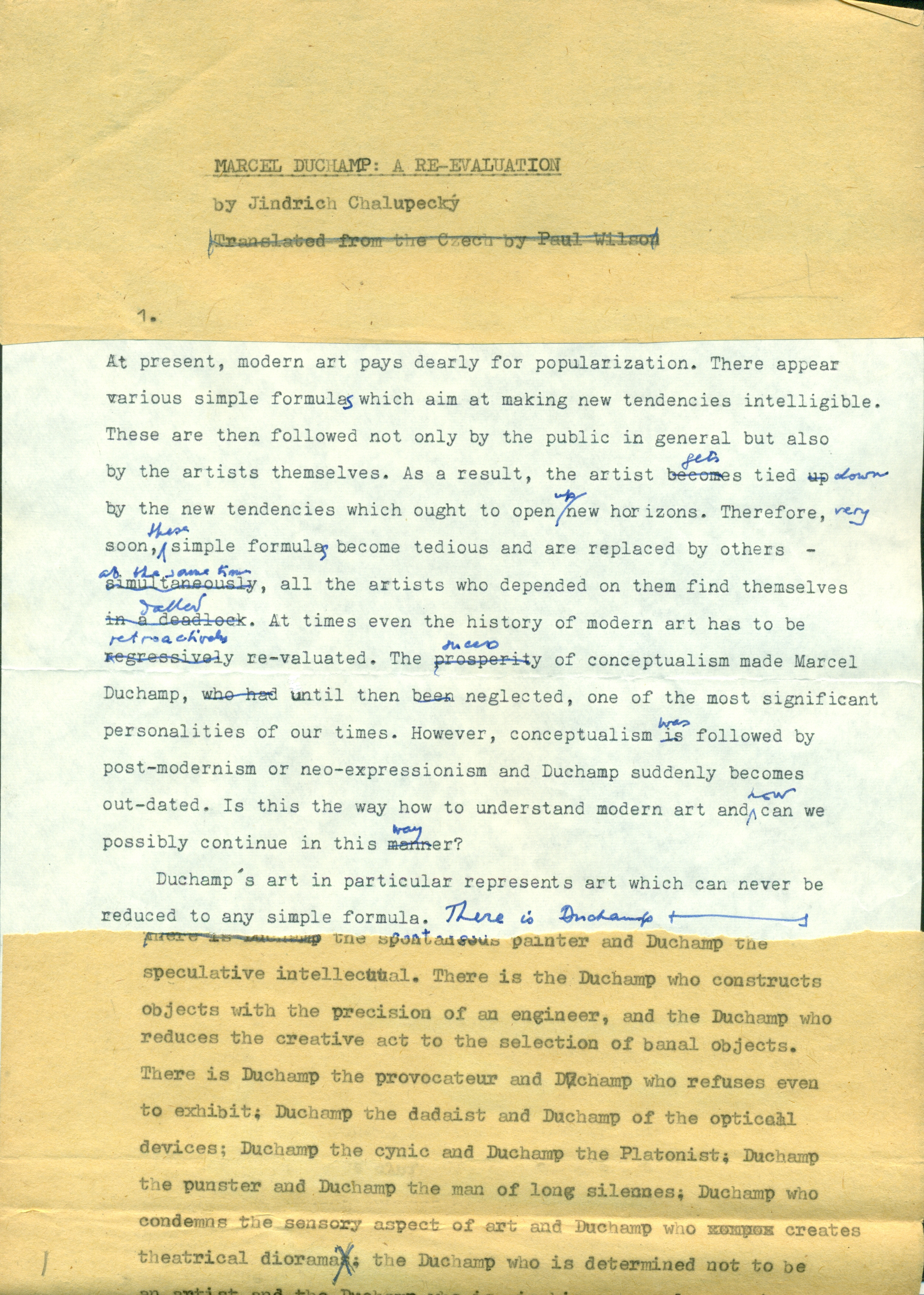

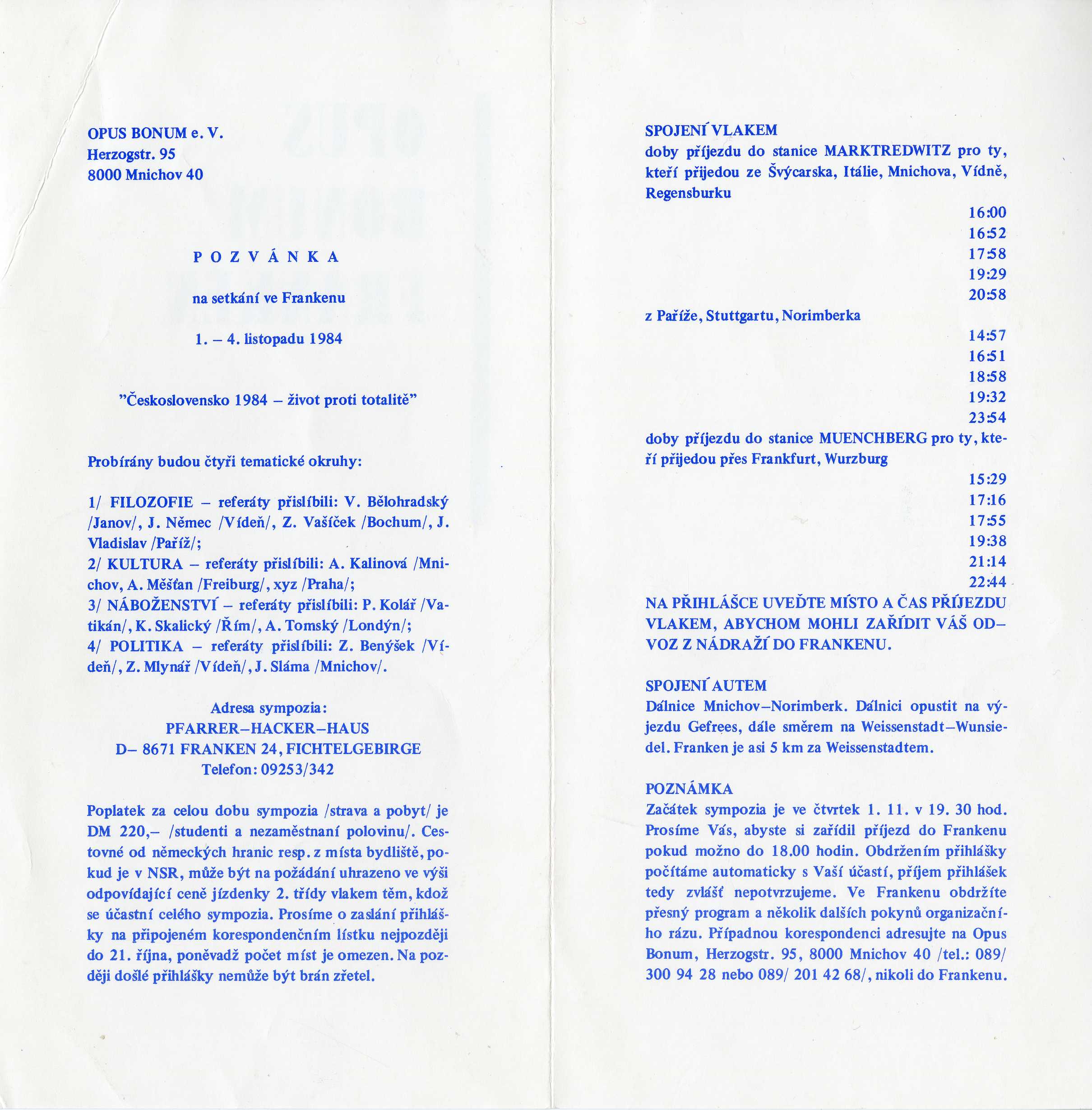

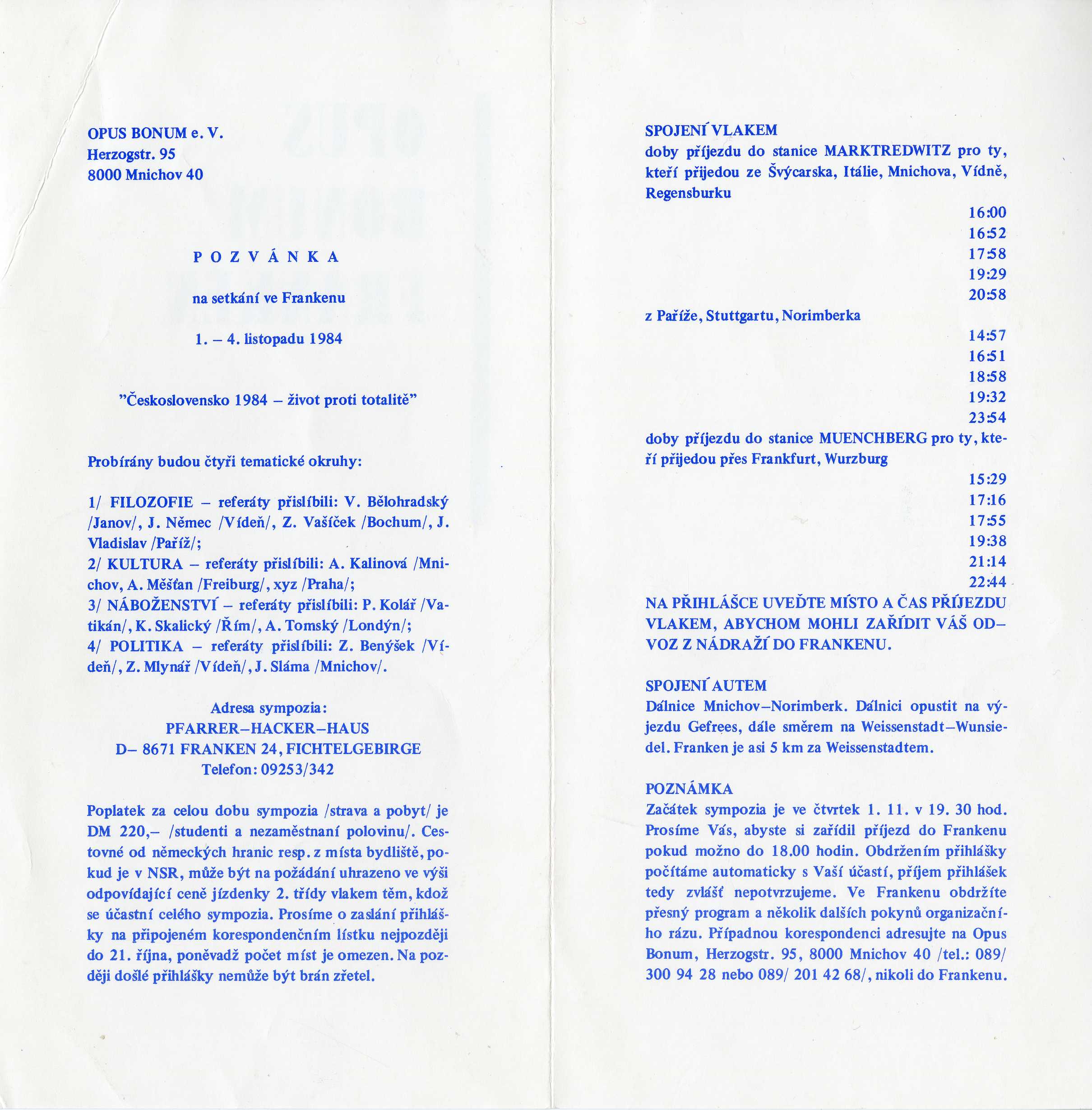

The lay Catholic Association Opus Bonum was founded in 1972 as a community of people caring for the preservation of the values of Czech and Slovak Christian culture. Since 1978, it has been holding symposiums in Bavarian Franken, which grew into unique discussions of various streams of Czechoslovak exile. Opus bonum also engaged in charity activities, organized concerts, exhibitions, literary evenings and published publications that spread through Czechoslovakia. Through its activities, it has always tried to help the anti-communist opposition in Czechoslovakia. After 1989, the documentation centre focused on supporting research on the history of domestic spiritual resistance, opposition movements and civic initiatives, as well as on the history of Czech and Slovak democratic exile.

A solo exhibition by Marijan Molnar was held in the Extended Media Gallery (Gallery PM) in Zagreb. The exhibition named "Common and Special“ lasted from 11 to 15 May 1981 and also included some of the works from the "For the Democratization of Art" cycle. The exhibition was well attended by the city’s cultural circle, and the main youth magazines (Polet and Studentski list) ran positive reviews on the exhibition.

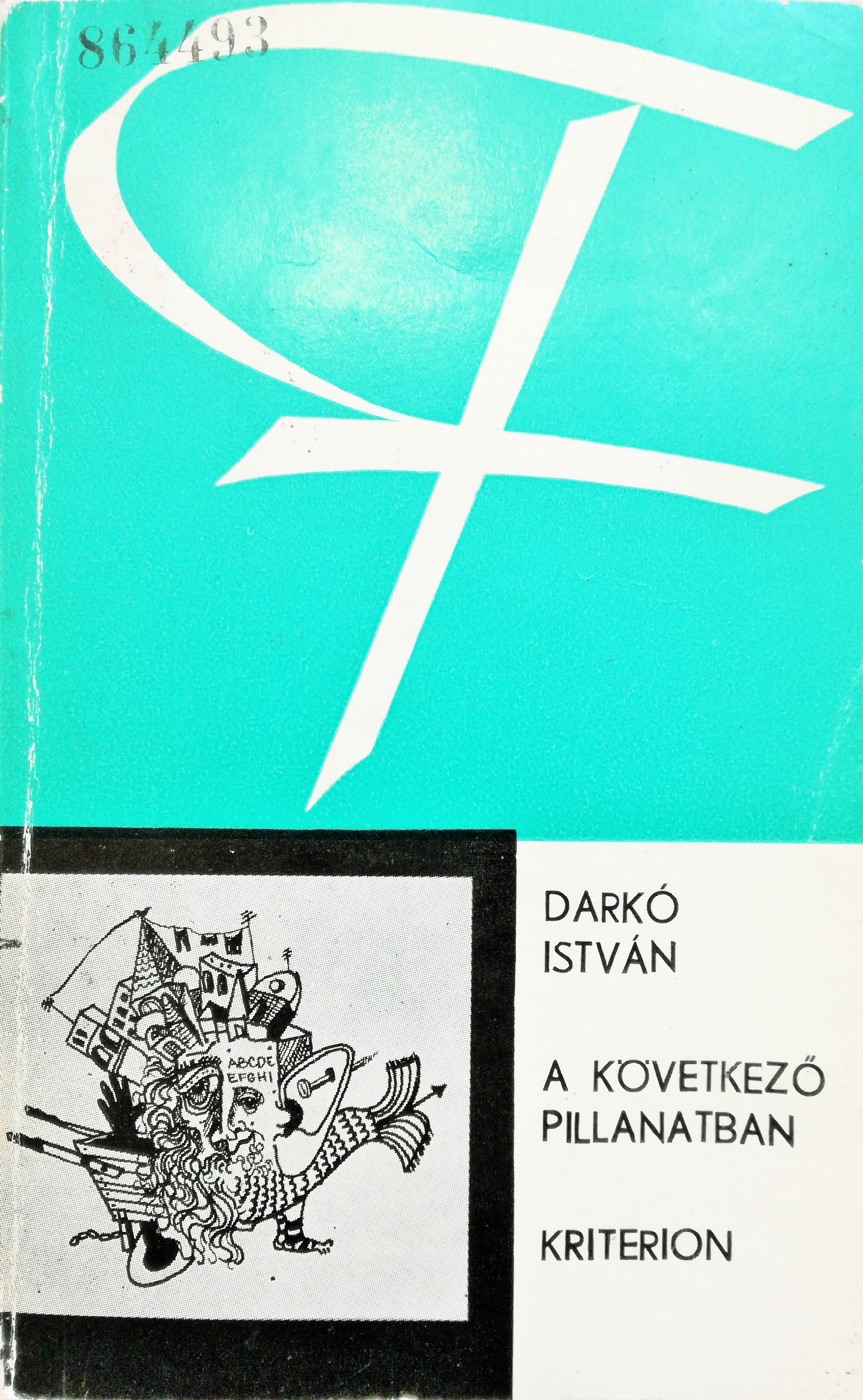

Darkó, István. 1981. A következő pillanatban: Fantasztikus történetek (In the next moment: Fantastic stories). Book

Darkó, István. 1981. A következő pillanatban: Fantasztikus történetek (In the next moment: Fantastic stories). Book

The philosopher Péter Egyed and the poet Géza Szőcs convinced István Darkó to write and to publish his writings in a separate volume. But Darkó's writings did not conform to a regular genre. In his book it is also disturbing that one or two pieces are similar to short stories or narrations but yet are not. In literary terms, this is such a text écriture that it is patterned with some established genres. In those days, text and text literature should have lived its time in Romania too, as in the whole of Europe, but this was an unfortunate environment in which, if one did not adapt to the literary standards, one’s writings were not published. Darkó did not adapt to the current literary standards, because this was not an aim for him as an actor. He wrote down what he wanted, in the way he felt and saw. His writings were often the written modification of a sounding material. In certain cases he may have heard what happened before he could note it down. The writing was born from the sound, and one genre gave him the possibility of another one, but Darkó remained an actor in each genre, as both his tape plays and his writings are performable. In his "city" live "distilled people", who behave amazingly, but with their thoughts, their obsessions they carry the burden of every person. Darkó "plagiarises" many times from his earlier writings: he copies from the programmes of Cat Radio, from the articles of his paper Bendzin, and sometimes from the writings of “Henrik Szénégető” or “Fruléz.” The characters of his fictive world organise their own lives, creating a fictive reality, with a certain deadly content, from which may be understood the true reality, which is thoroughly hidden because of the normality of cowardice. The singularity of his writings lies in the fact that they create a structural fiction with multiple content and layers, which has a kind of hermeneutical relation to the current reality. Darkó never forgets those who are writing the counter story, the cultural history of nastiness, against the forces creating the world order, those who set all kind of traps for the heedless part of humanity, who harass, threaten and chase them. The people of darkness and nastiness cannot be helped to power. Darkó's writings are all allusions to such a utopia, in which the atmosphere and the hopelessness of the depressed existences, the Nothing continuously speaks.

The Forrás (Source) series of the Kriterion Publishing House had an official committee, an editorial council. The usual procedure was to ask for a reference either from them or from other famous writers. Two references had to support a Forrás volume and according to custom the volume editor could ask for references from whoever he wanted. He obviously would not ask for references from anyone he knew would have an unfavorable opinion of the manuscript. Thus Egyed turned to the poet and writer László Csíki and Andor Bajor, because he knew that they understood the message of the author. The two references were obtained, the volume was published, and then came the official standpoint of the editorial council members according to which Egyed had gone beyond the rules and that he had exaggerated or rushed with this project. This was discussed at the consultation organised by Utunk (Our way), the Cluj-based literary, artistic and critical weekly of the Hungarians of Romania. The participants included Zsófia Balla and Géza Szőcs, representing the third Forrás generation, who said that the manuscript had to be published at all means, because it was important, it expressed something that came from their life experiences. They found themselves in Darkó's writing, rather than in other writings that had been published earlier in the Forrás series, boring, grayed, dusty, forgettable. Péter Egyed interprets the expression of cultural resistance, which appeared also in the Romanian press and constitutes a specific genre, in its content as being about an another culture. He claims this because as an editor at Kriterion Publishing House he knew exactly the censorship instructions. He knew very well the sort of cultural products that the Romanian Communist Party expected from authors. He knew the key terms and he corresponded on various matters with the ideological secretaries, who always wrote down what the poem, prose etc. on had to contain. If these were not contained in it, an another culture was obviously born, not one that accorded with the official system of expectations. But the official expectations could not work, because no one was willing to write like a Party official in the 1980s. Specifically, in a situation recalling Cat Radio, in which writing is about nothing other than the fact that everybody is chased and the chasers are also being chased round and round, this could not really be a content corresponding to any official ideological norm. According to Egyed the "opposition" says openly: "not this." Darkó's writing does not go directly against the system, but it says that there is an "Other", which expresses you and which has nothing to do with this system – which says that what you live in is not like that, and pays attention to the fact that you are being chased, that you are near to death. These are the feelings that come over from his text.

The volume was published in a print run of 5,000 copies, an astonishing number from today’s perspective, and created quite a considerable literary subculture. The interpretation of Darkó's writings appeared periodically later in the works of the literary critic Attila Mózes, the man of letters Levente Gyulai, the artistic writer Gábor Martos and the literary historian and poet Ágnes Kata Miklós.

Imre Baász: The Chances of Survival [A megmaradás esélyei/Șansele supraviețuirii], 1981, installation

Imre Baász: The Chances of Survival [A megmaradás esélyei/Șansele supraviețuirii], 1981, installation

The Chances of Survival is the title of the three preparatory graphics and an installation presented on the first Medium exhibition as an installation. The date of the work is very important. In 1981, people from Transylvania had started leaving Romania due to the worsening living standards and the ethnic harassment suffered by people who belonged to the non-Romanian minority groups.

Baász, who has always been against emigration, thematized this process through his central work. The message was personal and universal at the same time. On one hand, by 1981, most of Baász’s friends had left Romania. On the other, the life of a minority society cannot and should not be compared with the life of the majority society, therefore the minorities should not concentrate on blending in .

The main motive of the works was a real-life fascine guarded by a white cage; it also included six photographs and three photocopies all showing the fascines. The installation used a photo taken at the funeral of philosopher Antal Kapusi showing six men. Baász distorted and scrabbled the images of the people who had already left the country.

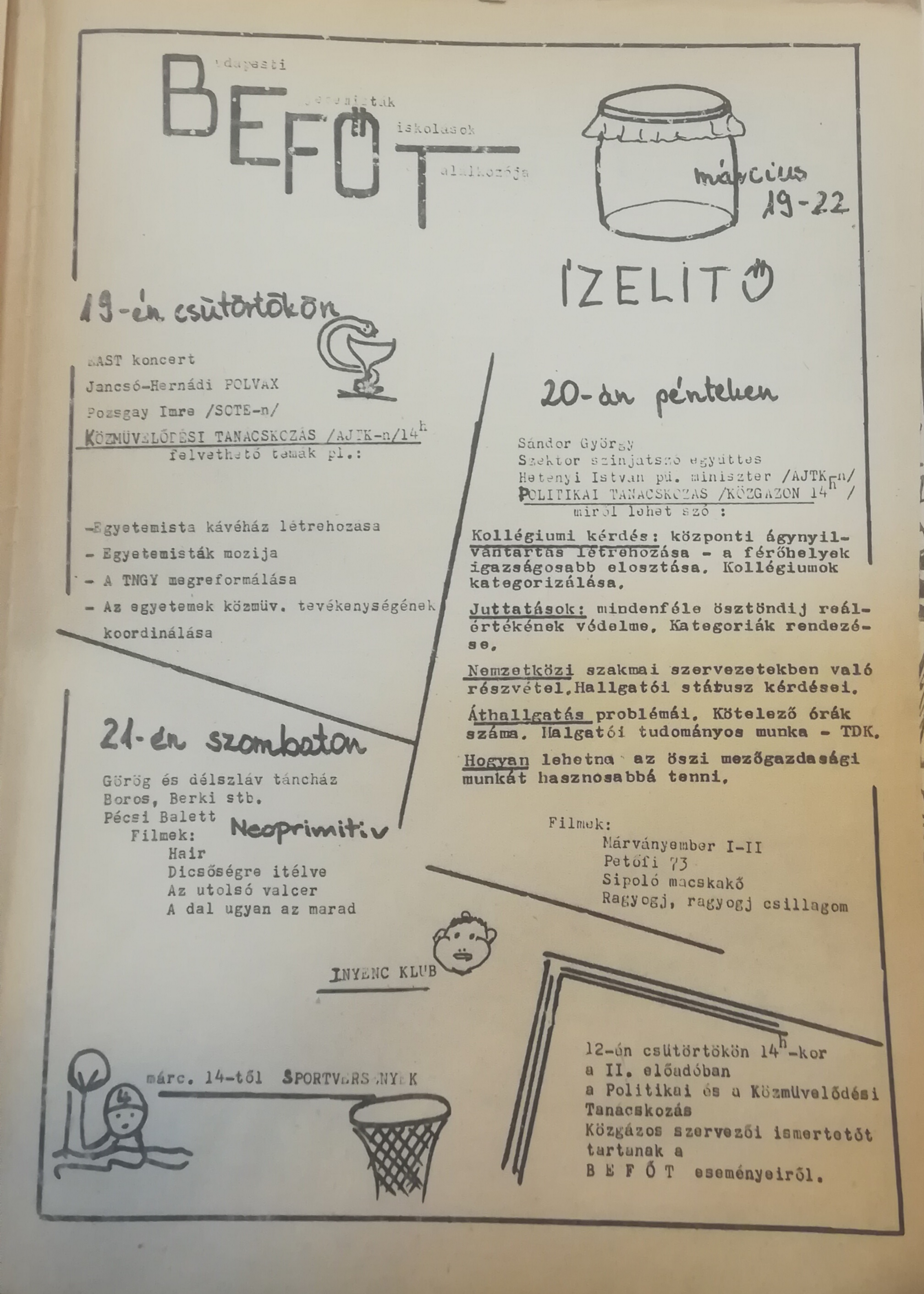

In the issue of the 11th of March 1981, Klub Közlöny informed the readers about the program of the Meeting of Students from Universities and Colleges in Budapest (Budapesti Egyetemisták és Főiskolások Találkozója – BEFŐT). The aim of the event of the 19th–22nd of March, initiated by Gyula Jobbágy, was to organize an independent forum for students of universities. We have information about the Polvax political debate club programs, and the different discussions of issues the students were interested in (colleges, scholarships, cultural activities at universities, etc.). The party leadership misinterpreted this project as an opportunity for opposition students to cooperate together and thus considered this process to be dangerous. In response to BEFŐT, the organizers were regulated, the comments were strictly limited, and the unfolding of the free debate became impossible. Because of this intervention the essence of BEFŐT was lost.

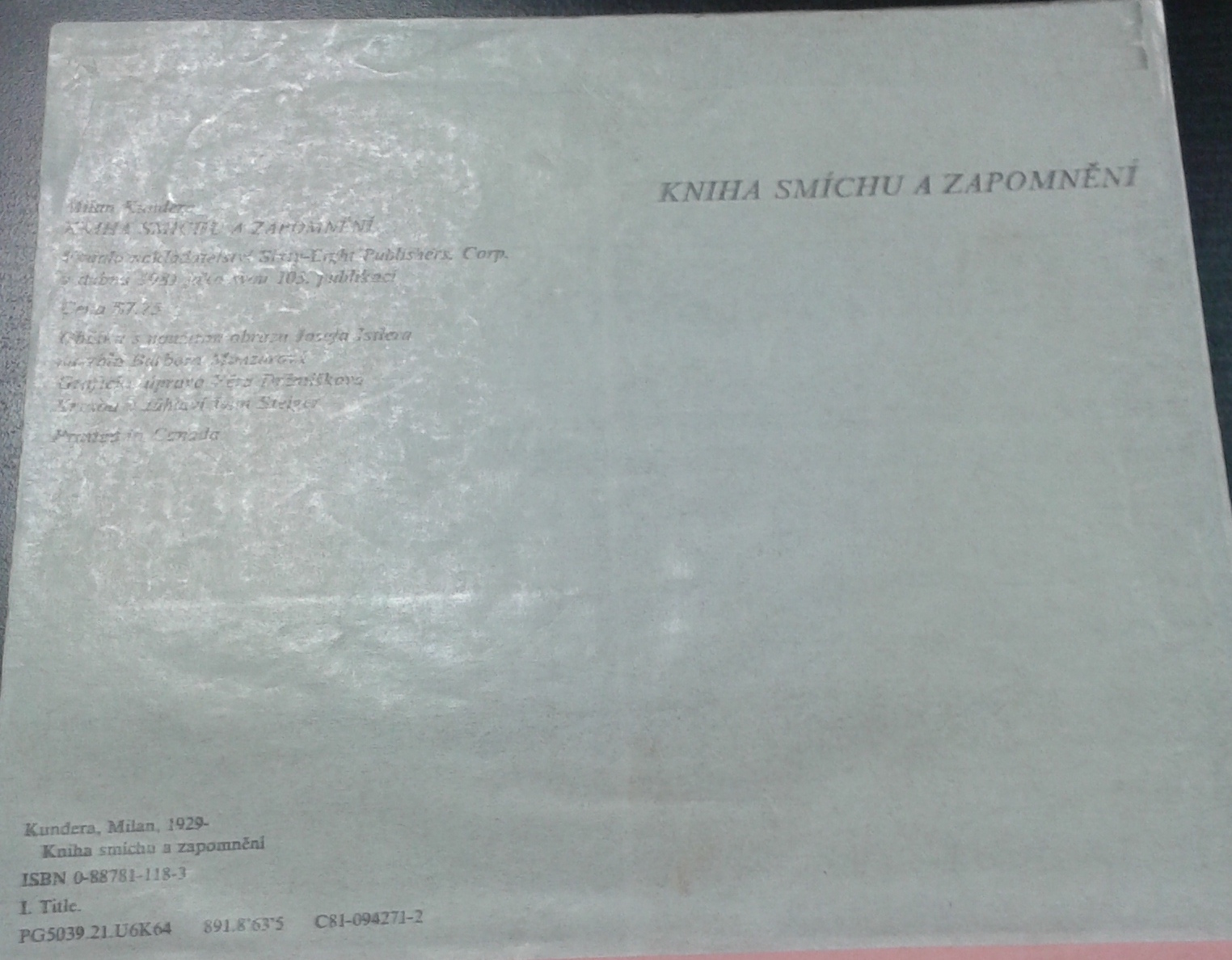

In 1975, Kundera moved to France. There he published The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979) which told of Czech citizens opposing the communist regime in various ways. An unusual mixture of novel, short story collection and author's musings, the book set the tone for his works in exile. Published in Czech (Kniha smíchu a zapomnění) in April 1981 by 68 Publishers Toronto. This book is also a proof that the owner had an active interest in unofficial literature. We do not know when and under what circumstances copy of this book became part of Mr. Šufliarsky´s collection.

Performances or actions from the "For the Democratization of Art" cycle in which the artist spray-painted graffiti in an underpass in Novi Zagreb in 1981. This was the continuation of the cycle which began with the collection of signatures on Republic Square, but it differed from it in its use of a new form of expression: graffiti.

The Nádosy bequest is an exceptional collection of materials documenting the daily work done by a Christian samizdat author and his efforts to establish a network of contacts. It also contains materials concerning the organization of the missionary working group, international communication, and the process of samizdat production.

The performance, or action, from the ''For the Democratization of Art“ cycle, in which the author hung a banner bearing the slogan "For the Democratization of Art" on the SKUC Building in Zagreb in 1981. The work is the continuation of the cycle which started with the collection of signatures on Republic Square and the drawing of graffiti in an underpass. The artist again changed his form of expression and decided to use a banner.

The beginnings of the Video Studio Gdansk are connected to the I National Congress of “Solidarity”, organised in Gdansk in 1981. At first, the independent “Solidarity” filmmakers documented the union’s most important events, however soon the first documentaries were produced. Video Studio Gdansk has been operating for almost 40 years, and its archive today consists of several thousands of video materials. It mostly comprises own videos, created by the Studio: raw footages (of the most important oppositional events, like strikes, clashes, protests), documentaries, reportages, few feature films, and numerous recordings of television theatre, public debates, cultural events, etc.

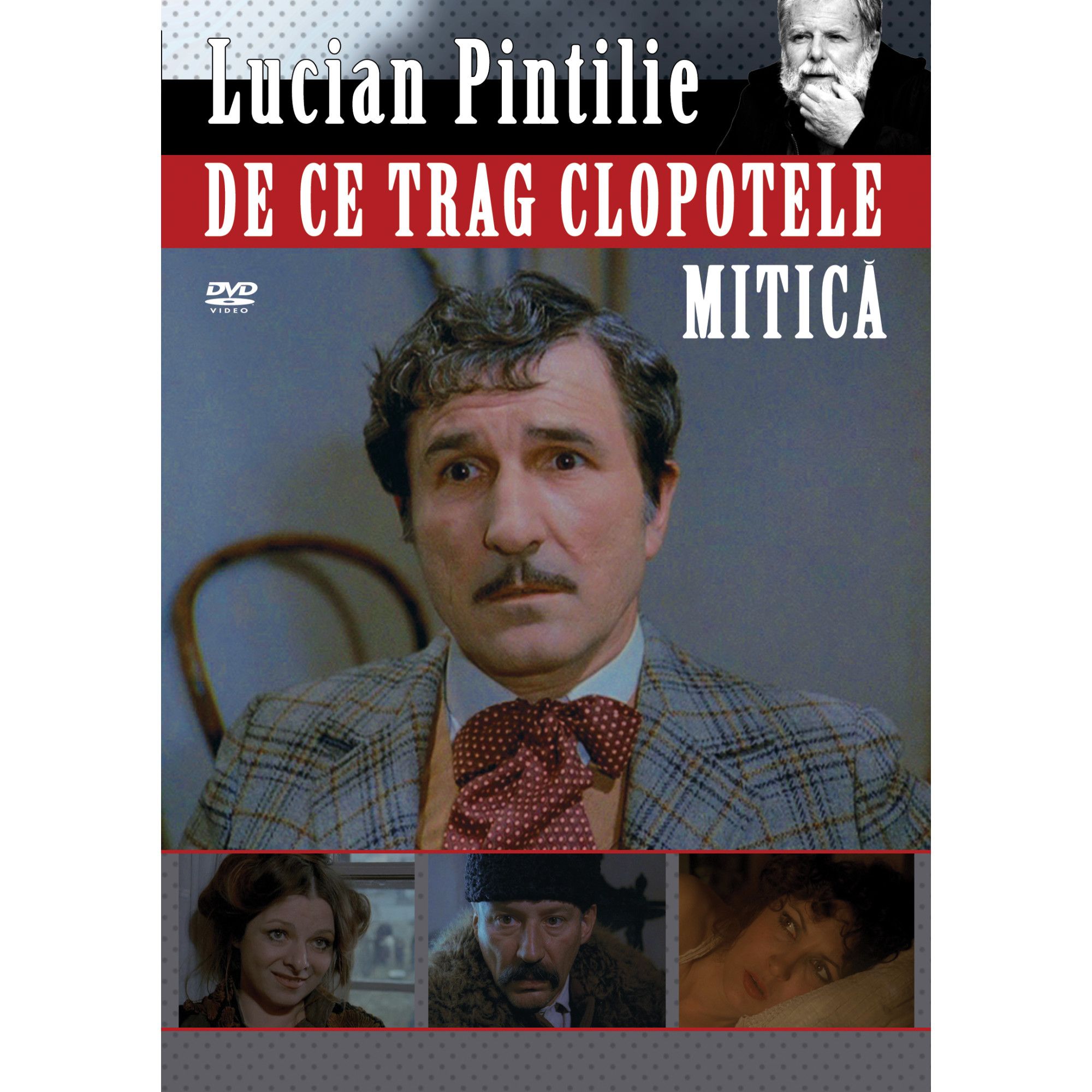

Concerning the censorship of Lucian Pintilie’s film De ce trag clopotele, Mitică? (Why are the bells ringing, Mitică?), November 1981. Report

Concerning the censorship of Lucian Pintilie’s film De ce trag clopotele, Mitică? (Why are the bells ringing, Mitică?), November 1981. Report

Gábor Demszy’s collection contains not only samizdat books and journals but also objects. The ramka (bolting-cloth stretched on a wooden frame) was a tool used in the samizdat printing process and today constitutes an important relic object of this technique.

A Brochure on the founding of the Opus bonum community, which was inherited by Josef Florian, the initiator of modern Christian culture in the Czech lands. The brochure was published by Opus bonum in 1981 and presents its editorial program and an overview of the diverse activities of this organization.

Invitation to the annual exile meeting of the Catholic Catholic Association Opus bonum in Bavarian Franken

Invitation to the annual exile meeting of the Catholic Catholic Association Opus bonum in Bavarian Franken

An Invitation to the annual exile meeting of the Catholic Catholic Association Opus bonum in Bavarian Franken. Thanks to the tolerance of Opus bonum, representatives of various political beliefs regularly attended the meeting. There was a chance for all those who had a say on the subject, from Christians of all denominations to atheists, from conservative thinkers to modernists, from those who came to exile after 1948 to those who came in different waves after 1968. These meetings grew over time in unique discussion clashes within Czechoslovak exile. In George Orwell's year, the symposium was organized under the title Czechoslovakia 1984 - Life Against Totality. At a conference held on from 1 to 4 November 1984, papers from Czechoslovakia were read, among them the contribution of Václav Havel, Six Notes on Culture.

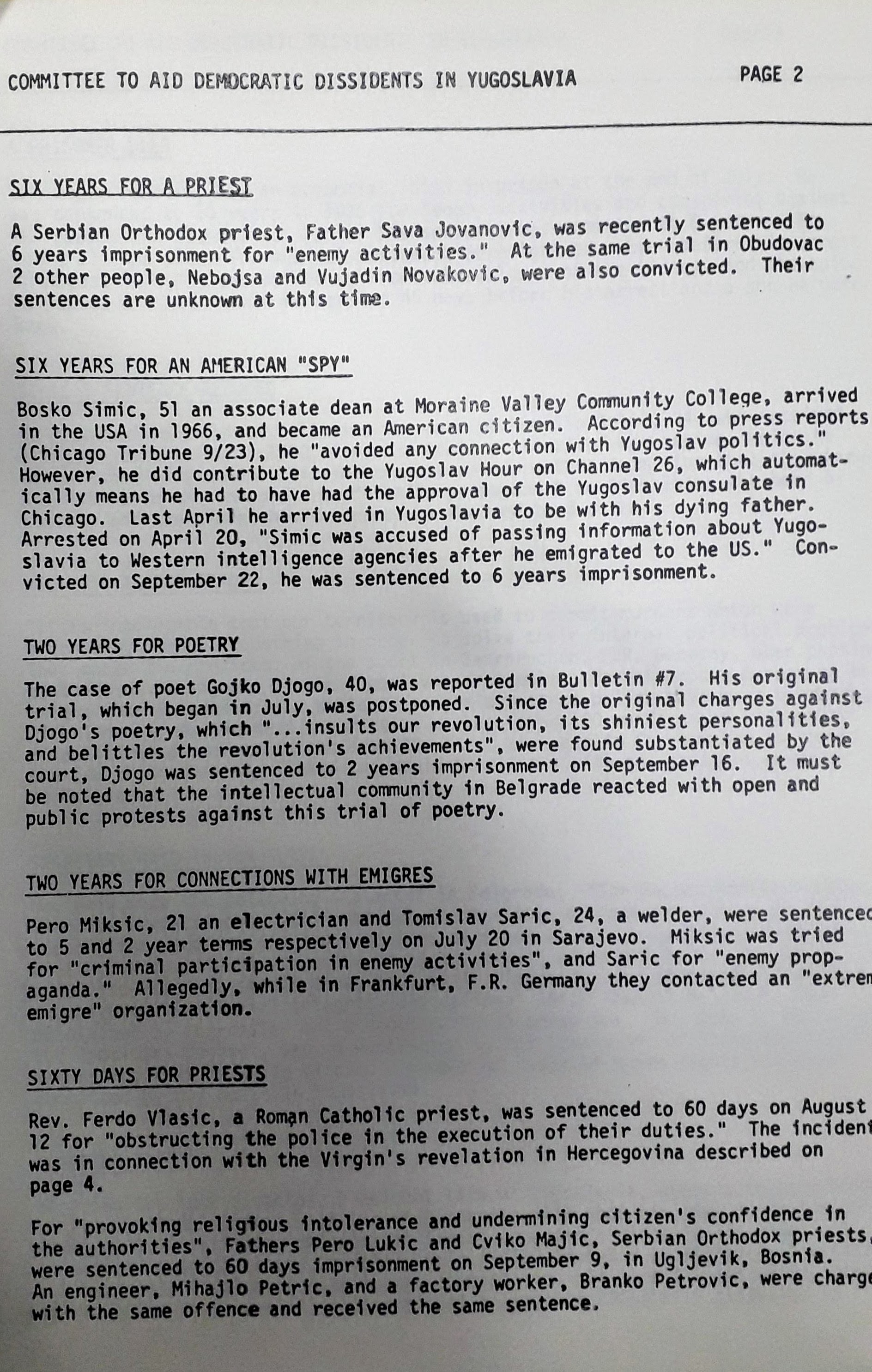

Gojko Đogo was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for publishing a collection of poems entitled Vunena vremena [Woollen Times] in which he “metaphorically alluded to Tito’s rule as one of tyranny, indolence and ignorance” (Dragović-Soso 2002, 54). It was the first time that “poetry was being tried” and thus support for Đogo was considered to be a principled defence of the freedom of literary and artistic creation and brought together intellectuals from across the political spectrum (nationalists, the “New Left”, and liberals).

The Đogo case was significant in that it led to the first institutional base of intellectual activism since the crackdowns of the early 1970s. This is reflected in the formation of the Committee for the Protection of Artistic Freedom at the Association of Serbian Writers in May 1982.

In the first two years of its work, the Committee raised its voice against Đogo’s persecution and imprisonment, the ban of the book Slučaj Đogo – dokumenti [The Case of Đogo - Documents] by Dragan Antić, the ban of the play Golubnjača in Novi Sad, the broadcast Beograde, dobro jutro [Belgrade, Good Morning] by Dušan Radović, the ban of Ljubomir Simović’s collection of poems Istočnice, the sentencing to seven months’ imprisonment of the Dubrovnik poet Milan Milišić, the closure of the Zapis publishing house, the ban on the regular publication of the newspaper Književne novine, the ban of Nebojša Popov’s book Društveni sukobi – izazov sociologiji [Social Conflicts: A Challenge to Sociology], the illegal detention of the writer Borislav Pekić in Belgrade, the ban of Aleksandar Popović’s play Mrešćenje šarana [The Spawn of the Carp] in Pirot, and the ban of Živojin Pavlović’s book Ispljuvak pun krvi [Spit Full of Blood], among others (Kljakić 2015).The performance or action from the "For the Democratization of Art" cycle, in which the artist drew graffiti on a facade in Belgrade in 1981, while on another facade he hung a banner bearing the slogan "For the Democratization of Art". This work was a continuation of the cycle initiated in Zagreb with the collection of signatures on Republic Square, drawing graffiti in an underpass, and hanging banners. In Belgrade, the artist continues with earlier expressive forms - graffiti and a banner.

The Gino-Hahnemann Archive at the Academy of Arts also contains several films. They document simple events and occurrences, but were meticulously prepared and often reflect deep cultural-historical examinations of Kafka, Hölderlin or Michelangelo. As a dramatist and director, Hahnemann created exposés with shooting schedules, gave recommendations regarding camera settings and documented these with still motions, even noting the materials used as well as their costs. The Hahnemann archive at the Academy of Arts contains thirteen such film documentations (spanning 1981-1986). They underline the laborious production of alternative, non-state sanctioned art in the GDR.

The first interviewee of the research collection which later became the Oral History Archives was Jenő Széll (1912–1994), one of the politicians and intellectuals who supported Imre Nagy against the hardliner Stalinist leader Mátyás Rákosi. Széll’s interview was recorded in 1981–1982, and it served later as an example of the method of doing interviews adopted by OHA. Hegedűs B., the interviewer and a close friend of Jenő Széll’s, not only raised questions about Széll’s personal role during the revolution (Széllhad served as the government commissioner of the Hungarian Radio), but also asked about the events of his life before the revolution, his illegal activities in the workers’ movement before 1945, his trial and the years he spent in prison (1957–1963), and his later fate up until 1981. The transcript of the sound recording, which comes to roughly 1.6 million characters, is avaible as part of the holdings of the archive. Later, a video-interview was also done with Széll, and in 2012, his son Péter Széll published a shorter, edited version of the OHA-interview in 100 copies.

Since its publication in 1981, Virgil Ierunca’s book Pitești has been a key work for those interested in studying the extreme forms of repression implemented by the Romanian communist regime during its first years of rule. The book examines the implementation of an “experience of a grim originality” called ‘“re-education” that took place in Pitești prison between December 1949 and August 1952. The idea of re-education was inspired by the theories of the Soviet educator Anton Makarenko (1888–1939). He was a specialist in juvenile delinquency and a partisan of the re-education of young detainees with the help of other detainees of the same age who were already re-educated. The Romanian communist authorities took Makarenko’s ideas onto the next level by making permanent torture the main instrument for the re-education of younger students guilty for having other political sympathies than communist ones.

In his book, Virgil Ierunca describes how the re-education experiment began in Pitești prison at the end of 1949 with the blessing of the then head of the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, Nikolski, and who were the main persons among prisoners involved in implementing the experiment. The book contains a detailed account of the many types of tortures that young detainees had to endure to be become re-educated and describes the last days of those who died because of torture in Pitești prison, based on the accounts of former prisoners who emigrated from Romania. From Ierunca’s point of view, the main purpose of the experiment was the destruction of the personality of the individuals who at the end of their re-education lost their moral values and standards and became “new men.” Consequently, they were not only forced to renounce their families, friends, and religion, but also to became the torturers of their friends or other inmates.

Virgil Ierunca also shows how the re-education was transferred from Pitești to other Romanian jails, such as Târgu-Ocna, Ocnele Mari, and Gherla and how it ended in 1952 when the Romanian authorities blamed their ideological enemy, the Iron Guard and its followers, for the atrocities that had happened in Pitești prison. Commenting on the issue of responsibility, the author mentions that the Romanian authorities and the first prisoners who tortured without being previously tortured were the only ones to blame for the deaths and the destroyed lives in Pitești prison.

The German journalist and writer Jürgen Serke (b. 1938) dealt with persecuted and silenced artists. At the beginning of the 1980s, he was researching a book about life and work of Polish, Russian, East German, and Czechoslovak poets and writers living in exile. Thus, Jürgen Serke, accompanied by photographer Wilfried Bauer and Czech poet in exile, Jiří Gruša, visited Blatný in Ipswich in October 1981. Then, Serke wrote a report about Blatný and his life in exile entitled “Escape to the Madhouse” (Flucht ins Irrenhaus), which was published in the West German magazine Stern in December 1981. The following year, Serke’s book “Expelled Poets” (Die verbannten Dichter), which also included the report about Ivan Blatný, was issued. Serke’s article about Ivan Blatný in Stern found an echo. After its publication, Ivan Blatný received many letters and gifts, mainly from Czechoslovak emigrants. Some people also came to Ipswich to visit Blatný personally. Then, in 1982, British and Norwegian televisions made a documentary film about Ivan Blatný. Hence, Jürgen Serke, or specifically his article, “Escape to the Madhouse”, significantly contributed to the rediscovery of this almost forgotten exiled poet.

The Ivan Blatný Collection at the Museum of Czech Literature contains Blatný’s copy of Serke’s article.

The Dan Petrescu and Thérèse Culianu-Petrescu collection includes representative Western books that offer critical analyses of the communist regimes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, brought semi-clandestinely into Romania and used as alternative sources of intellectual formation. An example of moral resilience in the face of communist dictatorship, this collection illustrates the cultural nonconformism of an informal grouping of young intellectuals known as the Iaşi Group, out of which, at the end of the 1980s, in a period of profound despair, the critical discourse, lucid and courageous, of Dan Petrescu made an impression through the intermediary of the Western mass-media. The story of dissidence in Iaşi, in particular that of Dan Petrescu, was until 1989 that of a confrontation between the truth of critical intellectuals and the lies of dictatorship. The dichotomous story of dissidence during communism turned after the opening of the files of the former Securitate into confrontation between each of the protagonists with the collective past of the group. Preferring marginality to stardom, Dan Petrescu and Thérèse Culianu-Petrescu are among the few heroes who did not lose this status even after the files of the secret police brought to light betrayals and complicities hitherto suspected but unproven.