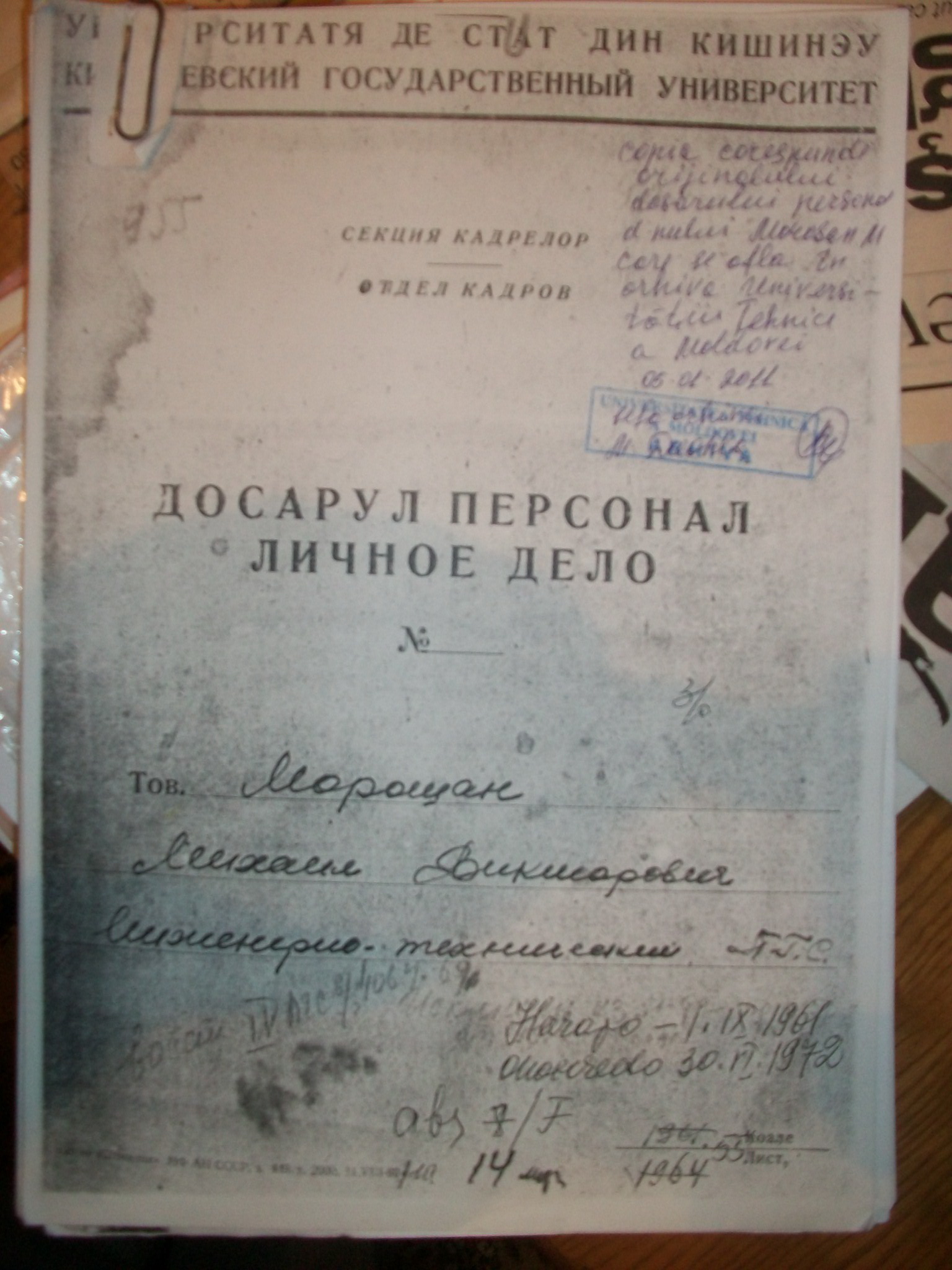

The Mihai Moroșanu Private Collection comprises various materials relating to the anti-regime activity of Mihai Moroșanu, one of the most famous Moldovan dissidents of the Soviet period, well-known for his staunch criticism of the regime and for his strong nationally oriented views. The collection consists of a number of personal files, interviews, photos and judicial materials relating to Moroșanu’s case, spanning the period from the early 1960s to the early 1990s. Due to his uncompromising resistance to the Soviet regime, Moroșanu is one of the very few authentic dissident figures in the Moldovan context.

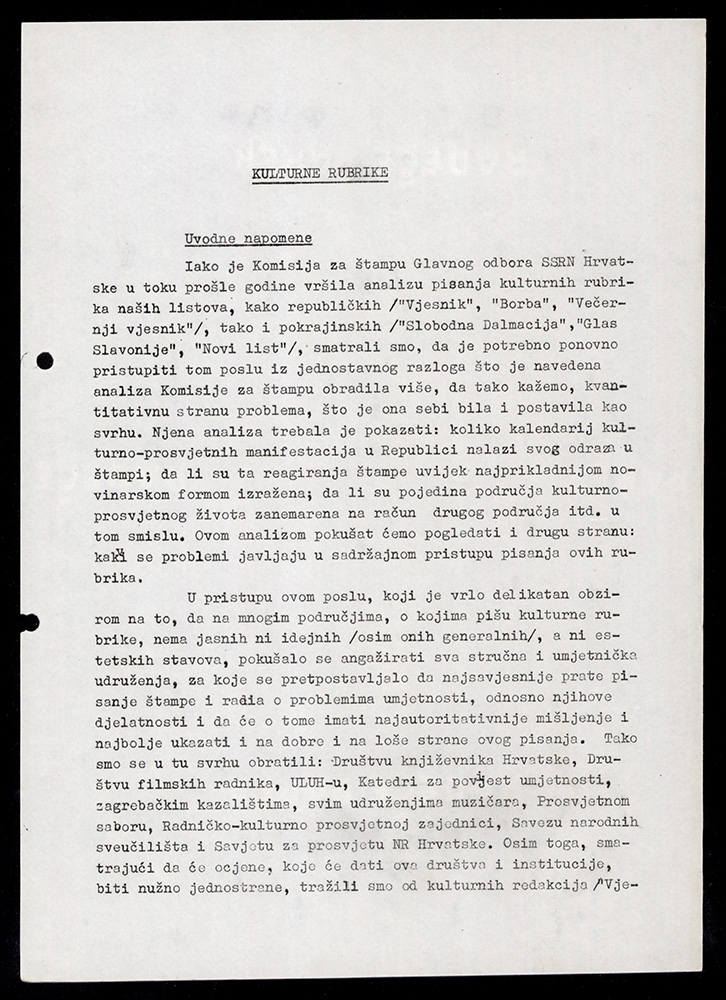

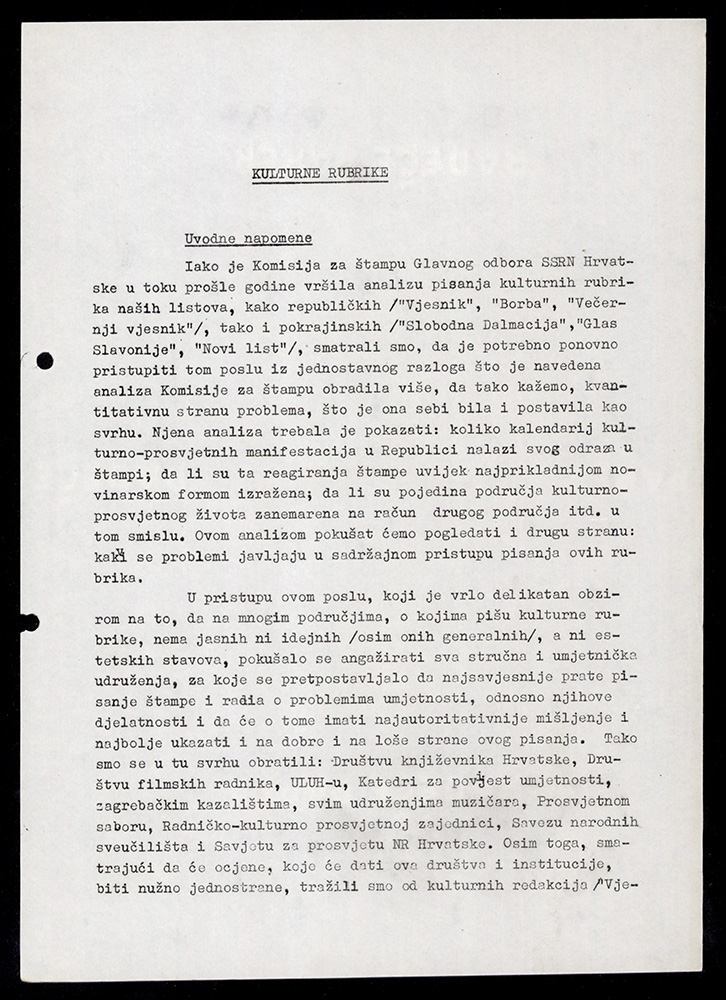

Materials and minutes of the session of the Ideological Commission on the culture sections of daily papers and Radio Zagreb, 1961

Materials and minutes of the session of the Ideological Commission on the culture sections of daily papers and Radio Zagreb, 1961

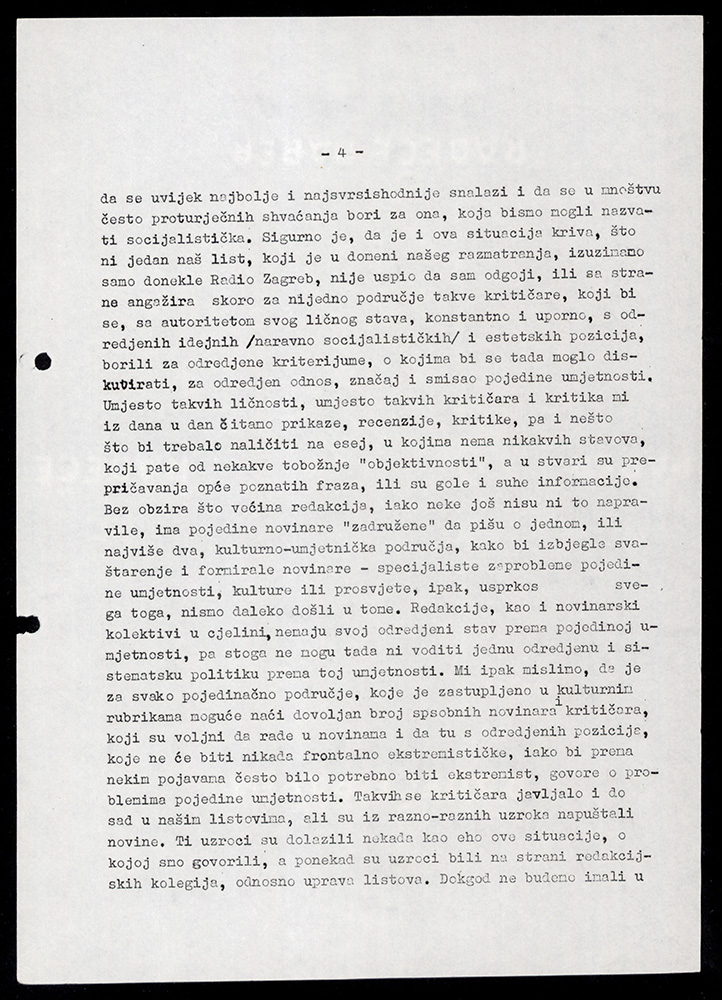

The described materials are an example of the jurisdiction of the Ideological Commission and present its activities in the field of press and radio. In the preparatory materials for the session, a number of daily newspapers (Vjesnik, Borba, Večernji vjesnik, Slobodna Dalmacija, Glas Slavonije, Novi list) were analysed in general and then the coverage and quality of the topics and also the criticisms of theatre, film, literature, fine arts, music, education, adult education and cultural-mass work were specifically examined. The materials were then discussed at the session itself. It is important to note that the session was also attended by writers of the cultural columns of the aforementioned newspapers, thus directly addressing the criticisms and guidelines for future work.

The editorial boards of the newspapers were criticized for considerable ambiguity and vagueness in the field of culture and the arts and were asked to hire journalists specializing in a specific field of the art who would write from the socialist standpoint. Also, the members of the Ideological Commission believed that the press was pro-Western and uncritically served texts from the foreign press (an example after Camus's death, when "the press wrote a great deal, but without the trying to put the writer in his proper place in the literature, and especially given his socio-political position in the life of contemporary France"). Cinema sections were criticized for only transcribing descriptions of foreign films from foreign editions and writing sensationalist pieces about movie stars and movies, indulging the tastes of the widest audience (the blatant adulation for to the film "Some Like It Hot," for example). The Commission wanted the direction of writing to turn more toward achievements in the USSR and India, which the Commission’s members called "advanced directions and attempts" and the "struggle between old and new understandings." Film criticism, it was believed, should first and foremost provide a preliminary ideological rating of the film and take into consideration its social role.

Also, the Censorship Commission hardly permitted a tourist documentary for the domestic market, although not for the overseas because it is " bourgeois and shows our circumstances."

The members of the Commission also had a role as censors, which is shown by the example of Ivan Šibl, who excised a text by Nela Eržišnik from a television magazine because her work was considered "babbling of the most petit bourgeois kind." It should be said that "bourgeois" in the communist view implied a wide range of behaviours that deviated from the proclaimed one and which retained the characteristics communists associated with civil society traditions. That term, in fact, became an insult to whomever it was applied. For example, many things were in principle deemed as expressing the "petit bourgeois mentality": from greetings on the street such as "sir," "gentlemen," "kiss the hands," "m'lady," etc., instead of "comrade," through the use of protection and privilege, "hierarchical gathering," criticisms, servility toward foreigners, corruption and drunkenness, to more severe offenses and crimes.

In literary criticism, there was a call to change the way in which books by domestic authors are covered – so that criticism affectionately welcomes the works of domestic authors just “as it greets a multitude of works an often problematic foreign origin.”. As to art criticism, the view was expressed that genuine art criticism does not exist in the press, but that there were numerous problems: the professional, moral and creative quality of the critics, the ambiguities of aesthetic criteria and the issue of educating the artistic taste of the audience.

Although the document does not mention the persons who did not act in line with the required ideological course, it is an important indicator of the existence of cultural influences and activities in variance with what was accepted and therefore unsuitable for the LCC Ideological Commission, which often criticized them. By 1995, the document was, along with the other records of socio-political organisations, a part of the Archive of the Institute of History of the Labour Movement of Croatia/Institute of Contemporary History. That year, in July, it was turned over to the Croatian State Archives (CSA) where it is kept today. The documents are accessible for use without any restrictions.

Kazys Boruta started keeping a diary in the interwar Republic of Lithuania. He wrote it with intervals practically until his death. Only a very small part of the diary was published during Soviet times, in the last volume of his collected works. In the diary, he wrote very openly about the conflicts with his superiors in the Soviet Lithuanian Writers' Union, and about his relations with the authorities in general. The diary reflects the complicated situation of the rebellious artist in the Soviet regime, who tried to protect his personal and creative autonomy.

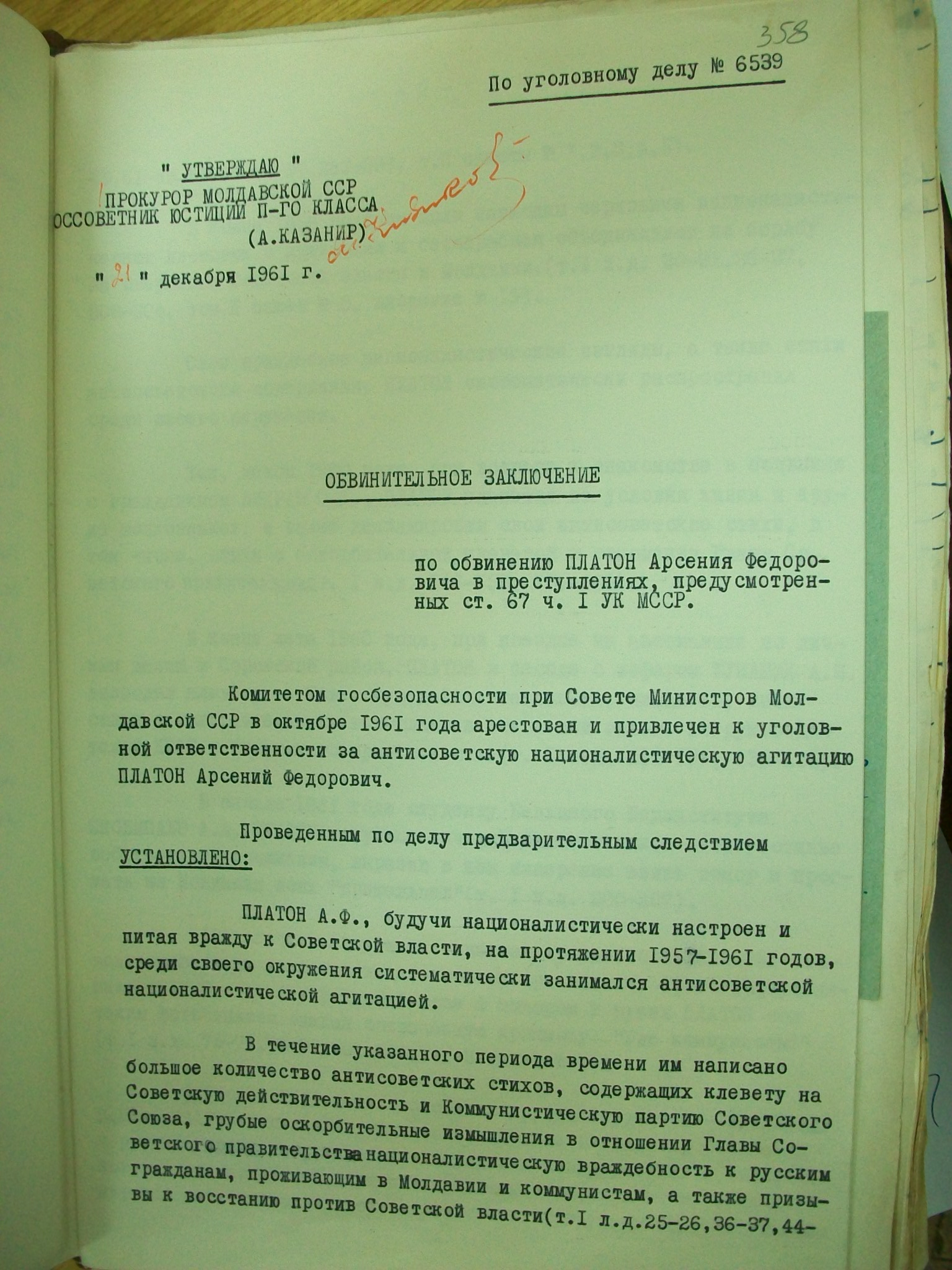

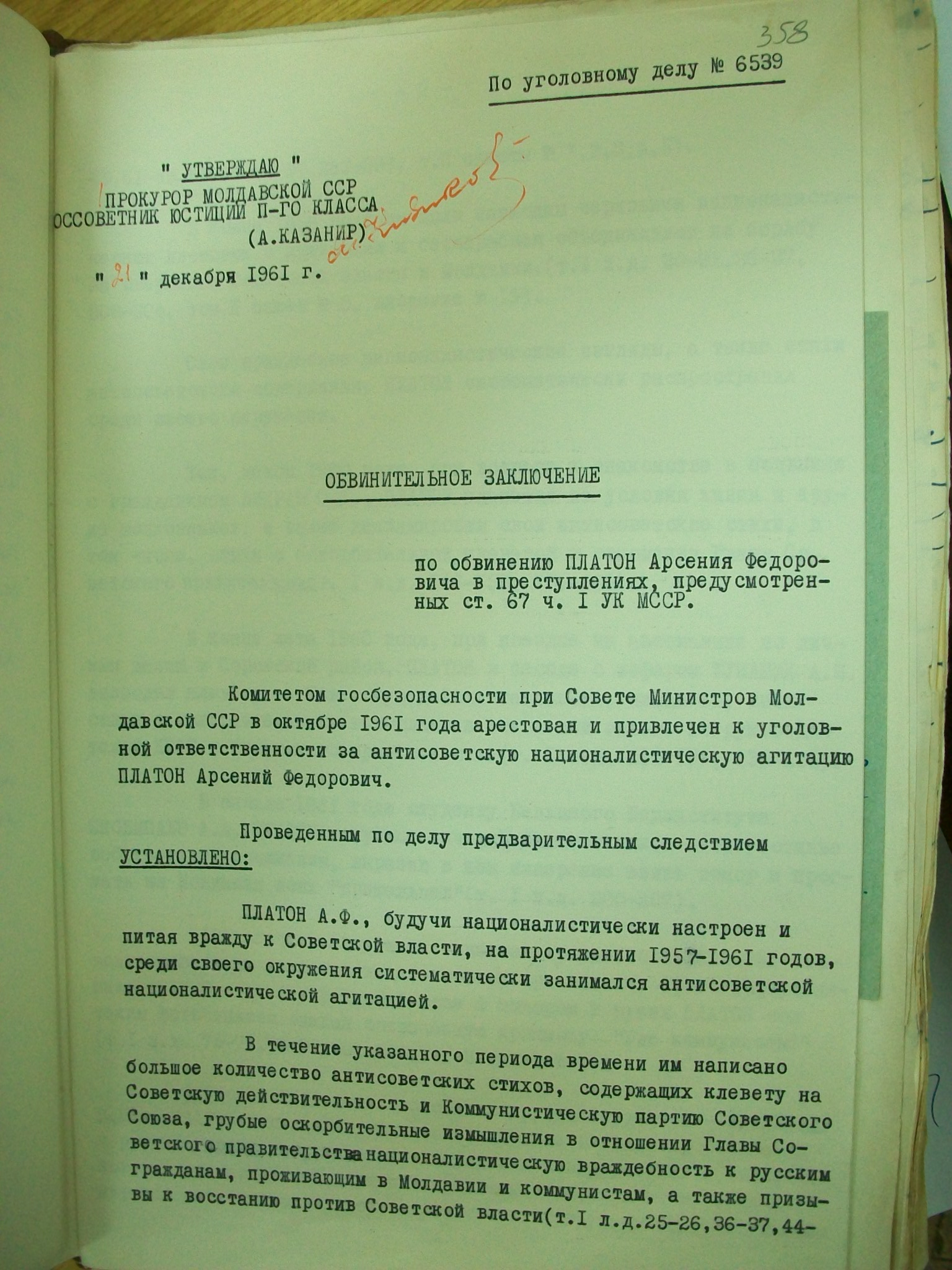

Arsenie Platon. Anti-Soviet Poems and Draft Leaflets. 1959-61. Manuscripts (in Romanian and Russian)

Arsenie Platon. Anti-Soviet Poems and Draft Leaflets. 1959-61. Manuscripts (in Romanian and Russian)

On 18 October 1961, after searching Arsenie Platon’s house, the police and KGB officials in Bălți discovered several notebooks and separate papers that contained various poems written by Platon during the previous several years. This aspiring poet had already published some of his literary productions in local and central periodicals. However, scattered among these texts were around ten poems with clear and occasionally radical anti-Soviet overtones. These poems fell into two broad categories. The first category comprised several texts criticising the social and economic policies of the regime and the chronic shortages of basic consumer goods, contrary to official propaganda (e.g., the short poem Radio, which contrasted the claims to material abundance emphasised by Soviet propaganda with the dire material situation of the ordinary people). The abuses of collective farm managers and the economic discrimination and inequity hidden behind the official façade of equality were additional targets for Platon’s critical acumen (as, for example, in the poem “The Soviet Peasant and the Collective Farm Chairmen” (“Țăranul sovietic și președinții de colhoz”), which mocked the privileges of the latter and extolled the honest but devalued work of the peasants). Some of the other poems (e.g., “Woman is Equal to Man” / “Femeia este egală cu bărbatul”) combined social, economic, and nationally based criticism in a forceful condemnation of the regime, calling for “escape from slavery” and for “burning [the Russian intruders] with fire and flames.” The second category of poems was openly nationalist with a strong anti-Russian thrust, e.g., the poem “A Longing” (“Un dor”), in which the author talked about his dream that he might “rise up, one holy morning, and start the fight / together with my Romanian brothers,/ To get my revenge, for I can no longer bear/ Seeing my Moldavia torn by wild boars.” In several other similar texts, Platon used strong language to refer to the Soviet regime, calling its representatives “red beasts” (fiare roșii) and “accursed butchers” (călăi blestemați). Platon also wrote two drafts of anti-regime proclamations, appealing to his “Bessarabian brothers” – “workers, peasants and intellectuals” – to “combine their forces” into “one single fist” in order to “smite the red beasts.” He also demanded “full freedom” for Moldavia, mentioning the suppression of religion and economic exploitation as the main grievances against the Soviet regime. Platon’s radical language and especially the draft leaflets, which were interpreted by his KGB investigators as highly subversive and potentially dangerous, virtually guaranteed his condemnation for “anti-Soviet propaganda.” The question of Platon’s literary and intellectual sources is particularly interesting. It seems that he was familiar – probably from his primary school years and further reading – with some basic models of classic and interwar Romanian literature, which shaped his vocabulary and references. His literary pursuits probably enhanced his national awareness and provided him with a suitable language to express his discontent with the regime. Although his poems are rather unsophisticated and lack literary value, they provide a fascinating example of an oppositional narrative “from below,” elaborated by a marginal individual seeking literary recognition. The original manuscripts were not destroyed by the KGB staff and are still part of Platon’s case file stored at the SIS Archive.

This ad-hoc collection mainly consists of documents separated from the fonds of judicial files concerning persons subject to political repression during the communist regime which is currently stored in the Archive of the Intelligence and Security Service of the Republic of Moldova (formerly the KGB Archive). It focuses on the case of Arsenie Platon, a person of peasant background and an aspiring poet, who was tried and convicted in 1961 for displaying nationalist views and for conducting “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” among his friends and acquaintances. Platon’s “anti-Soviet” opinions were mostly expressed in a series of poems and short proclamations in which he criticised ethnic discrimination against the Moldavians and called for the overthrow of Soviet power. This case is emblematic for less widely known forms of grassroots cultural opposition, falling under the same broad category as the cases of Gheorghe Muruziuc and Zaharia Doncev. Platon’s file includes no further information about his fate after the end of his prison term.

Patrice Lumumba was the first prime minister of independent Congo and was assassinated in 1961, only 67 days after taking office. This event triggered protests in Belgrade which fast grew into larger clashes between the demonstrators and police. The biggest riot took place at Tašmajdan Park. The police used water cannon against the protestors. Thirty-five protestors, 51 police officers and nine members of the fire brigade were hurt. The demonstrations were mainly organised in front of the Belgian embassy since it was believed that Belgium, the former colonial power in Congo, had orchestrated the murder. The demonstrators took over and ransacked the embassy. These events in front of the Belgian embassy in Belgrade were recorded and documented in the photographs of Tomislav Peternek, at that time a reporter with the newspaper ‘Borba’. The police used the opportunity to confiscate his films, but later returned them.

The Sanda Stolojan Collection is an important source of documentation for understanding and writing the history of that particular segment of the Romanian exile community which was actively involved in the West in unmasking the communist regime in Romania. At the same time, this private archive contributes to an understanding of Romanian–French bilateral relations between 1968 and 1998. In particular, the collection illustrates the activity of the collector and other personalities of the exile aimed at promoting respect for human rights in Romania and stopping the demolitions imposed by the communist authorities as part of Bucharest's systematisation programme, and later at supporting the reconstruction of democracy in their country of origin.

The Ion Dumitru Collection is the richest and most diverse of all the private archives of the Romanian exile community, which makes it indispensable for the study of the history of postwar Romanian exile. The collection is also a fundamental source for documenting and understanding Romania's (domestic and foreign) political, cultural, economic, and social evolution during both the communist and post-communist periods. At the same time, this private archive is a historical source both for understanding how the Bucharest authorities acted to divide the Romanians abroad and to counteract their actions aimed at unmasking the wrondoings of the communist regime between 1948 and 1989 in the West and for how Romanians within the country perceived the emigrant community.

Kljaković, Jozo. Krvavi val: isječci iz suvremenog života [Bloody Wave: Excerpts from Contemporary Life ]. 1961, Book.

Kljaković, Jozo. Krvavi val: isječci iz suvremenog života [Bloody Wave: Excerpts from Contemporary Life ]. 1961, Book.

Kljaković wrote this autobiographical political-utopian novel during his émigré period in Rome. He dealt with the crisis of the ideological focal points of his time through the prism of real and fictitious situations, in which Kljaković stood out in particular by sharply rejecting communist ideology. Kljaković's novel was inspired by the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. For this reason, the central character is named Oskar Csokor, who suffered at communist hands in Hungary in 1956. Likewise, the very title of the novel refers to the emergence and spread of communism as a "bloody wave" that flooded the entire world of its time. The book was banned in the socialist period, so its second edition was only published in Croatia in 2011.

The official accusatory act concerning the case of Arsenie Platon (case No. 6539) was issued by the KGB investigator Captain Sidelnikov on 19 December 1961, when it was approved by the head of the Moldavian KGB, Major General Savchenko. This document was also approved by the Prosecutor General of the Moldavian SSR, A. Kazanir, on 21 December 1961. The accusatory act provided a concise and synthetic narrative of the main “anti-Soviet activities” conducted by the defendant during 1957–1961 and a detailed account of the accusations brought against Platon. The main count of indictment referred to the “anti-Soviet nationalist agitation” that Platon purportedly spread among his network of friends and acquaintances. Concretely, the defendant was accused of the following misdemeanours: “displaying a nationalist orientation and open hostility toward Soviet power, during 1957–61 he systematically conducted anti-Soviet agitation; he wrote and spread poems containing calumnies regarding Soviet reality and the CPSU, rude and insulting attacks against the Head of the Soviet government, as well as anti-Soviet nationalist fabrications, directed against communists and citizens of Russian origin residing in Moldavia; produced drafts of nationalist proclamations with open calls to the Bessarabians to unite in their fight for overthrowing Soviet power in Moldavia; spread among his milieu provocative nationalist fabrications and lies, expressing his discontent with Soviet power and with the presence of Russian people in Moldavia; propagated calumnies against Soviet reality, praising the living conditions during the former Romanian bourgeois regime; publicly read his anti-Soviet poems, which distorted and discredited the Soviet social system and the leaders of the Soviet state.” This fragment is revealing not only for the substance of Platon’s crimes in the eyes of the Soviet authorities, but also for the language and rhetoric used by the regime to categorise and classify various dissident and oppositional actions. It is clear that Platon’s nationalist views, the articulation of his opinions in public, as well as his draft proclamations and the favourable comparison of the Romanian regime to its Soviet counterpart were the most serious aspects of his case, which aggravated his situation further. Platon’s defence strategy, based on his denial of any public impact of his views and the obstinate refusal to confirm the witness accounts that incriminated him, ultimately backfired when the investigators adduced additional evidence and confronted him directly with the witnesses. It seems that his arrest was preceded by a denunciation made by several of his co-workers or fellow patients during his earlier time in the hospital, in the summer of 1961. Although this does not result clearly from his file, it is probable that the KGB had some hints of his suspicious behaviour, which explained the search of his house on 18 October 1961. The accusatory act also carefully traced Platon’s contacts during 1957–1961, emphasising the possible motivations and influences that might clarify his conversion to nationalism and his criticism of the regime. Despite Platon’s acceptance of the substance of the accusation and of his guilt, the accusatory act noted that the defendant’s “anti-Soviet views” were already apparent during his earlier prison term, in 1957, and thus contradicted Platon’s assertion that he only became disenchanted with the regime after 1959, under the influence of his co-worker, Nikolai Emelianov. The textual nature of Platon’s criticism and the possibility of a wider public impact of his views were especially worrying for the authorities. Despite the isolated and spontaneous character of his actions and the failure to prove Platon’s connection to any organised form of opposition, the radicalism of his nationalist rhetoric was enough to convince his KGB investigators of his potential danger. He was indicted according to article 67, part 1, of the Criminal Code of the Moldavian SSR (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda aimed at undermining Soviet power”) and sentenced to three and a half years of prison in a high-security labour correction colony. Following the usual pattern of the Soviet justice system, the sentence repeated almost literally the text of the accusatory act.