This letter from Juliana Jirousová (then Stritzková) to Ivan Martin Jirous, the key figure of the Czechoslovak underground, from 10 September 1974 is the first of the letters stored in the library Libri Prohibiti. This letter was not sent to prison, unlike the rest of the collection. This is perhaps why it has not yet been published and is unknown to most people. The letter was written before the wedding of I. M. Jirous and J. Stritzková in 1976 and was not the subject of censorship. There is some interesting information about relationships in the underground, friendships, as well as the everyday life which I. M. Jirous and Juliana Stritzková led. In the letter, Stritzková mentioned songs by Karel Soukup (alias Charlie, a Czech underground songwriter), the married couple the Daníčeks (Jiří Daníček was a poet, playwright, script writer, translator and political prisoner. His wife Vlasta, called Amálka in the letter, was Juliana’s best friend), and also about the psychiatric sessions Jirous had to attend.

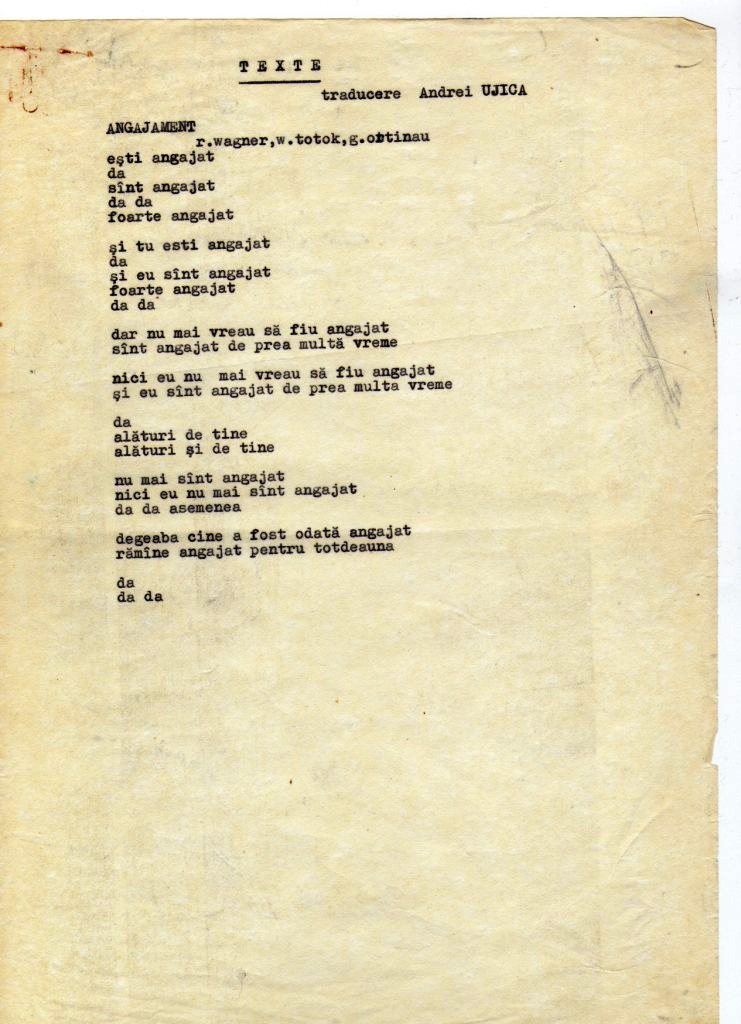

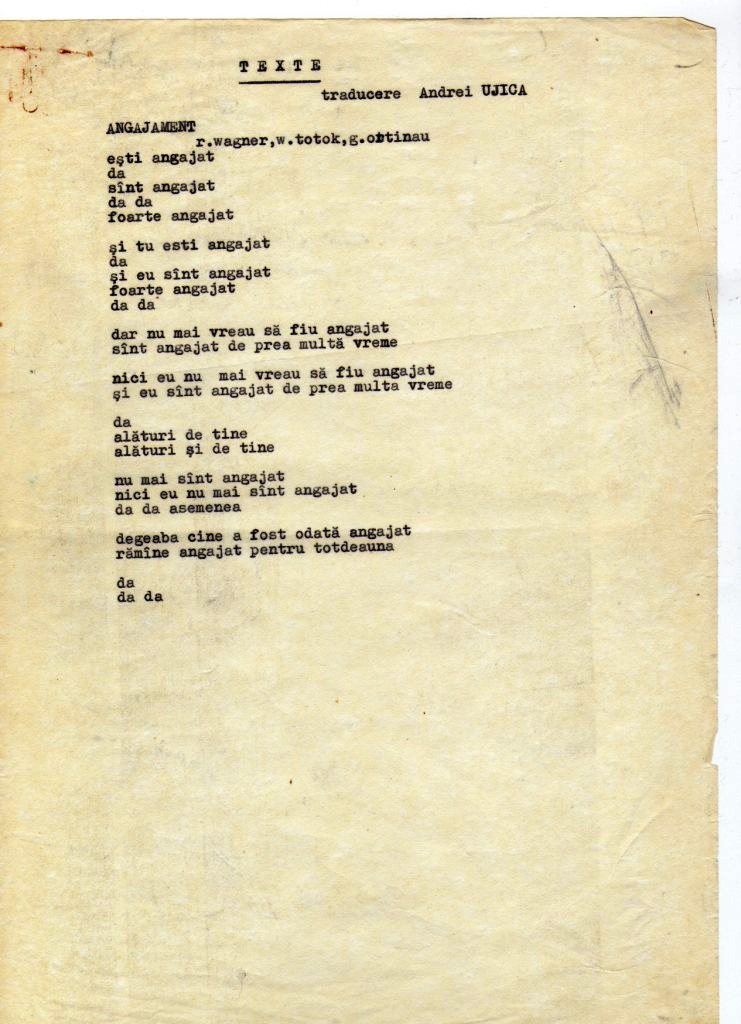

According to the testimony of the Aktionsgruppe Banat members, the poem was the collective work of the entire group, which they assumed and published as such (Totok 2001, 22). The text was sent for publication in Romania in 1974, but the censorship prevented it. It was first published two years later in a changed form in the West German cultural magazine Akzente: Zeitschrift für Literatur (No. 6/1976; Totok 2001, 22–23).

The poem uses wordplays to suggest the omnipresence of coercion in the society they lived in and it represent a subtle critique of the state–citizens relation in Ceaușescu’s Romania. The authors played with the meanings of the German word Engagement which in the poem could be understood both as employment and (ideological) commitment. In the second part of the poem, the authors suggest overtly and ironically the coercive character of the state–citizen relation in the society they lived in and the impossibility of the latter modifying this relation either in ideological or in practical terms:

“I’ve been engaged for too long

I don’t want to be engaged anymore

I have also been engaged too long

yes

with you

also with you

I am no longer engaged

I am not engaged either

yes yes, me neither

in vain, who was once engaged

remains forever engaged.”

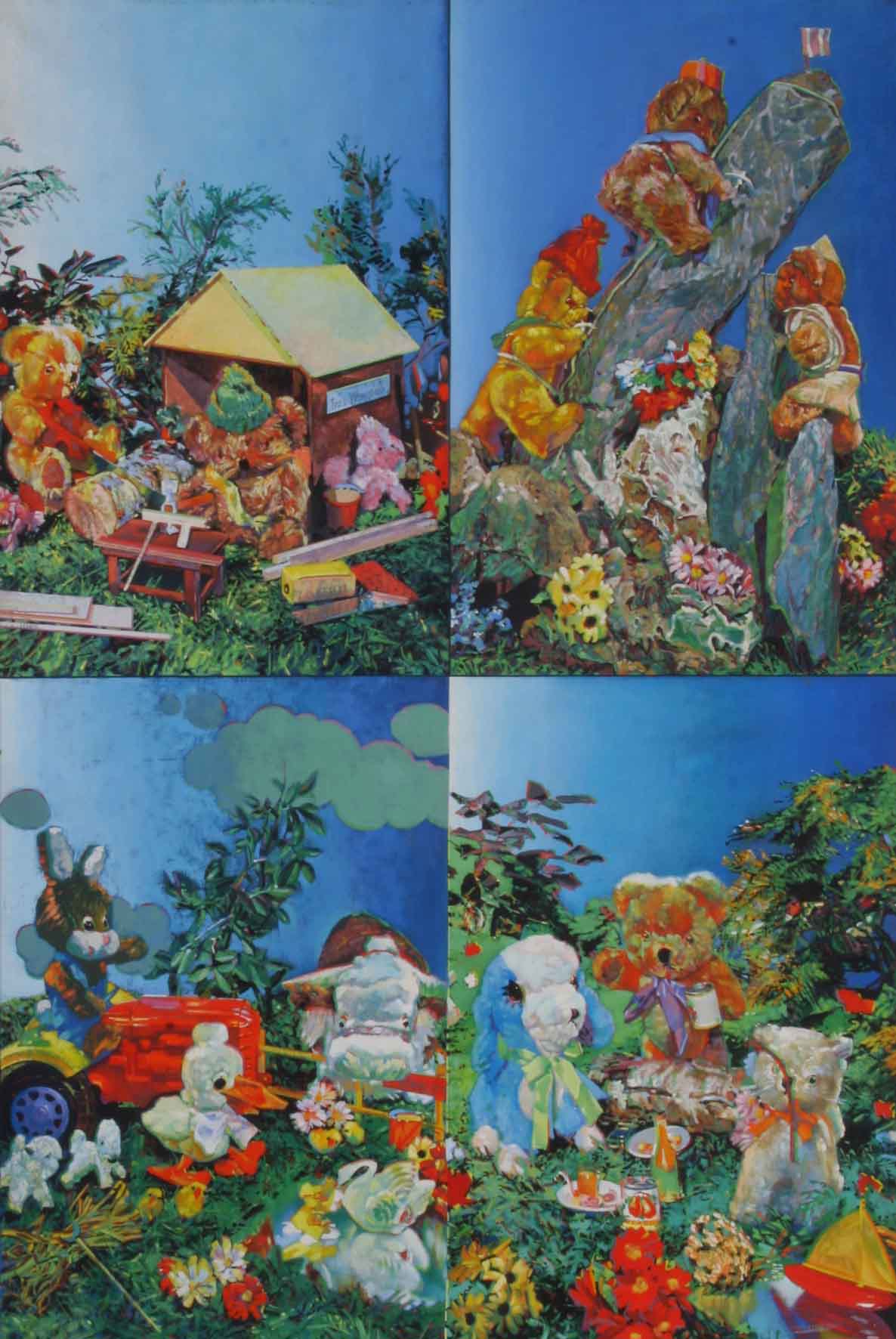

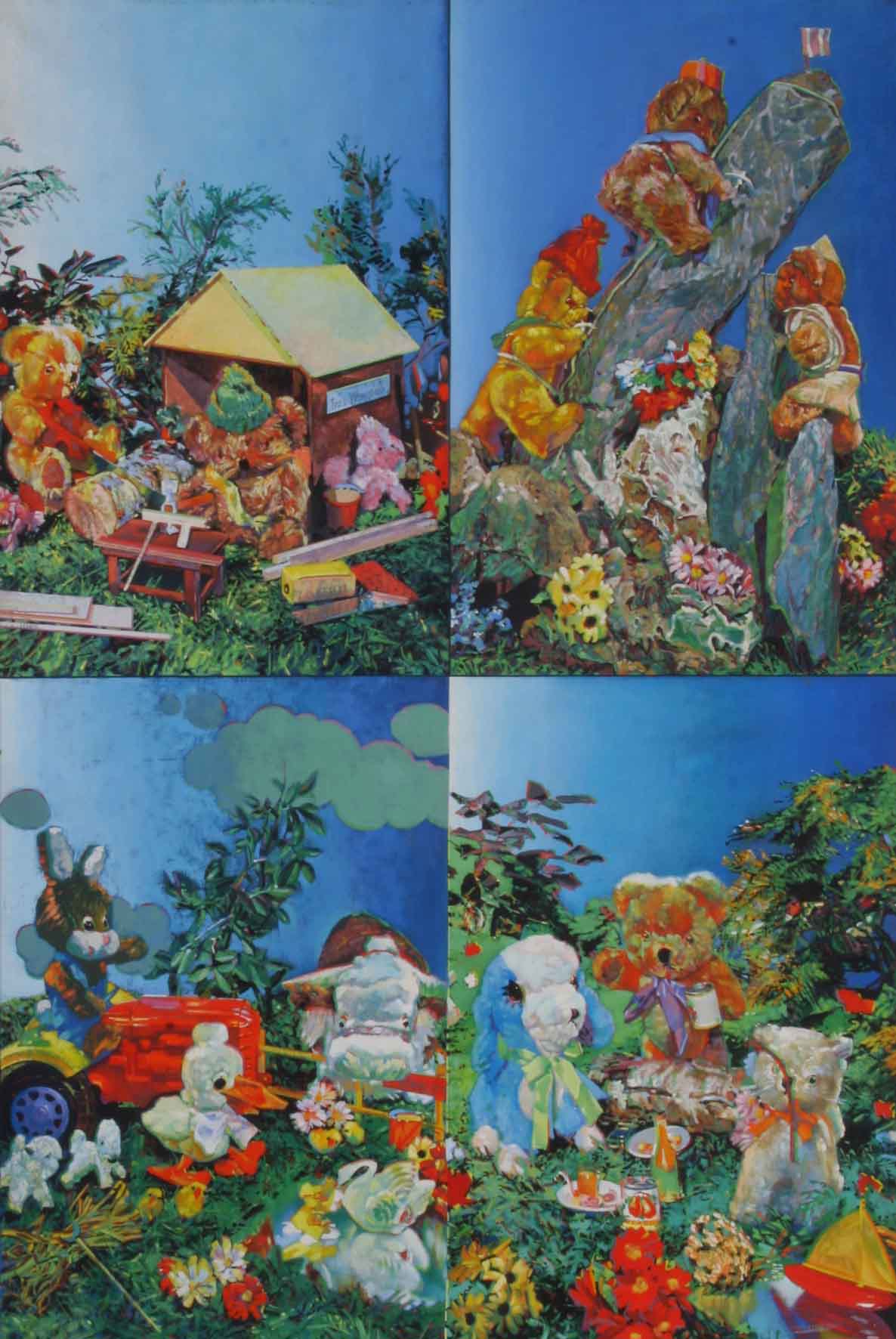

At the beginning of the 1970s, Ákos Birkás was experimenting with critical, grotesque, “bad painting,” targeting purposefully banal subjects. The theme of his work in the collection is four postcards available at the time in Hungary from English import.

On the pictures one sees plush animal toys in everyday situations (sawing, mountain climbing, gathering in a garden, picnicking). The painter juxtaposed the cards in two rows, thus creating a “picture in picture” situation, distancing the viewer from the “cuteness” of the animal toys and making it possible to compare visual analysis of the image promoted for children’s use.

Despite its detached mode of painting, the intention behind this composition is different than the Western photorealist approach of the time (like the works of Franz Gertsch or Chuck Close). In opposition both to learned approaches and official ideology, the painter wanted to map “aesthetic reality,” i.e. to show and analyse the real situation of visuality, and thus make it possible to accept it.

Ivana Tigridová (1925-2008) was a journalist and human rights activist. She was one of the most distinguished personalities of Czechoslovak exile. In Paris, she founded two organisations supporting prisoners and persecuted opponents of the regime in Czechoslovakia and other countries of the Eastern Bloc.

In 1970, when in New York graffiti just was being born, 18 years old Włodzmierz Fruczek made his first works on the walls of Warsaw. Fruczek was a beginning artist working as a decorator in the Fish Central Office. He regularly crossed the district of Warsaw after the war known as the Wild West, located partially on the ghetto area: ruined, filled with debris, rumored to be a dangerous site of criminality and black economy. The landscape of ruins and dead walls must have a strong impact on the young artist who without any project or idea in a few days painted a set of figures on the walls of the buildings of Żelazna, Grzybowska, and Waliców street. The paintings, made with emulsion paint, depicted outlines of human bodies, sometimes only torsos or limbs. Some of the figures stayed calmly, even holding hands but many of them were outstretched in extreme postures. The painting on the photo, made on the wall on Waliców 14, showed the scene of execution and as the only one of the set had a title: Dance of Death. It was a spontaneous, emotional reaction of the artist on the remains of war and Shoah that he was surrounded by.Tomasz Sikorski took his picture about 1974. In his narrative, the Fruczek’s work is a symbolic beginning of the graffiti in Poland, independent from the American patterns of street art, artistically significant, and closely tied to the local history. For that reason, the photography of the Dance of Death opens the story about the post-war artistic graffiti in Poland.Source:Tomasz Sikorski, Marcin Rutkiewicz, Graffiti w Polsce 1940-2010, Carta Blanca, Warszawa 2011.

Ortinau, Gerhard. The street ballad of the ten parts of speech of the traditional grammar, in German, 1974. Manuscript

Ortinau, Gerhard. The street ballad of the ten parts of speech of the traditional grammar, in German, 1974. Manuscript

The poem Die moritat von den 10 wortarten der traditionellen grammatik (sic!) [The street ballad of the ten parts of speech of the traditional grammar] was written by Gerhard Ortinau and published in 1974 in the literary magazine Neue Literatur in a collage of texts created by the young Romanian-German writers from Aktionsgruppe Banat. The poem is made up of three parts entitled: schaltung (lining up), umschaltung (dealigning), gleichschaltung (bringing into line), which depict through metaphors how the political system worked in Ceaușescu’s Romania. Ortinau used in this poem seemingly absurd statements such as: “a pronoun was arrested” and “the adverb was cut off from the newspaper” to suggest practices such as political repression and censorship. The poem ended with a paraphrase, which represents an irony concerning the Ceaușescu’s dictatorship: “Die sprache c’est moi!” (sic!) [The language c’est moi!]. The non-conformist character of the poem can be seen also from the spelling, which avoided the usual capital letters for nouns, specific to the German language.

The publication of this collage of texts, Neue Literatur, was possible due to the relative liberalisation that took place in Romania during the late 1960s and early 1970s. For a short period of time, cultural institutions enjoyed more autonomy in their relation with the political decision-makers and censorship was less strict. In this context, Gerhardt Csejka, one of the editors of Neue Literatur, had a key role in promoting the texts of Aktionsgruppe Banat and helping them to pass the filter of censorship (Iorgulescu 2006, 419–421). The Securitate noticed the hidden message in this text due to the notes provided by informers from the German speaking literary milieu of the Banat, who gave to the secret police a detailed interpretation of its metaphors and word plays. For example, one informer explained to the Securitate officer in a note of September 1974 that the title of the third part of the poem was an allusion to the so-called Gleichschaltung, the process by which the Nazi regime imposed its control on all areas of German society (ACNSAS, I 210 845, vol. 2, 15 verso).

Keston’s information about this image is somewhat limited. The original photo was taken by Friedensstimme, most probably in the year 1974, when a hand-made printing machine like this one was discovered in a house in Latvia and confiscated by the authorities. Four women, workers of the Initsiativniki Publishing House “Christian”, were arrested on October 24, 1974 for being in possession of this printing machine. According to an article published in the Russian journal Vestnik Istiny (No. 2-3, 1977), this kind of printing press could print 400 copies of the gospels during one working day. These Latvian women were Initsiativniki, a dissident wing of the Soviet Baptist community that emerged after a split in the church’s ranks in 1961. According to scholar Julian Birch, this movement was “an interesting and indeed unusual example of cross-national, or State-wide, dissent within the USSR.

Kolike su škare cenzorske (How big are the scissors of censorship), Vjesnik u srijedu (VUS), 1974. Press clipping

Kolike su škare cenzorske (How big are the scissors of censorship), Vjesnik u srijedu (VUS), 1974. Press clipping

This is an interview by conducted by VUS reporter Boris Gaj with Đuro Šmicberger (1922-2006), the chairman of the commission on the control and approval of motion pictures for public screening in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia. Šmicberger talked about the commission’s practices pertaining to the control and authorisation of motion pictures produced in the Slovenian film industry for public screening, as well as the authorisation of foreign films for public screening. Such commissions also existed in other Yugoslav republics. The collection includes about 150 press clippings from the period 1969-1991 which deal with the practices of film censorship, giving examples of blocked films, etc. The documents are available for research and copying.

The novel “The Invalid Siblings” (Invalidní sourozenci, 1974) is one of the most important works by the Czecho-Slovak poet, novelist, playwright, philosopher and “guru” of the Czechoslovak underground, Egon Bondy (real name Zbyněk Fišer, 1930–2007). Marcel Strýko, a Slovak philosopher and dissident, compared the dystopian novel to “a catechism of the Czechoslovak underground”. The novel, which was completed in February 1974, presents a vision of the moral and ecological crisis of a totalitarian society in the distant future. The plot takes place around the year 2600 on the last piece of land surrounded by rubbish. After this last area is also flooded, only the “invalids” (intellectuals, outcasts from totalitarian society, reminiscent of underground dissidents) survive on an improvised raft. The sequel to “The Invalid Siblings” was Bondy’s novel “Afghanistan”, written in 1980. At first “The Invalid Siblings” was published in 1974 as a samizdat volume. The novel was also published in exile by Sixty-Eight Publishers in Toronto in 1981. After 1990, the novel was published several times in (the former) Czechoslovakia. The novel has also been published abroad.

A manuscript of the novel was bought by the Museum of Czech Literature (PNP) in 1986 and is now part of the Egon Bondy collection deposited in the Literary Archive of PNP.

Antanas Sniečkus was the first secretary of the Lithuanian Communist Party from 1936 till his death in 1974. The collection holds many documents, including correspondence with Lithuanian writers, and transcripts of meetings with the intelligentsia (in 1957) which reflect the aspirations and ambitions of the country’s cultural elite to preserve and develop the cultural heritage of the Lithuanian nation. The most interesting documents for the project cover the period of de-Stalinisation in Soviet Lithuania.

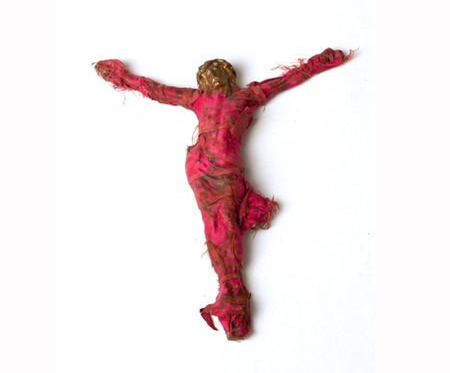

The No Art Collection is a part of the Anti-Museum founded by Vladimir Dodig Trokut. It consists of characteristic avant-garde and post-avant-garde artefacts. The Anti-Museum’s No Art Collection was established during the many years of Trokut’s activity as a member of the informal cultural opposition, which was supported by prominent individuals and public personalities, such as artists and politicians like Koča Popović and Jure Kaštelan.

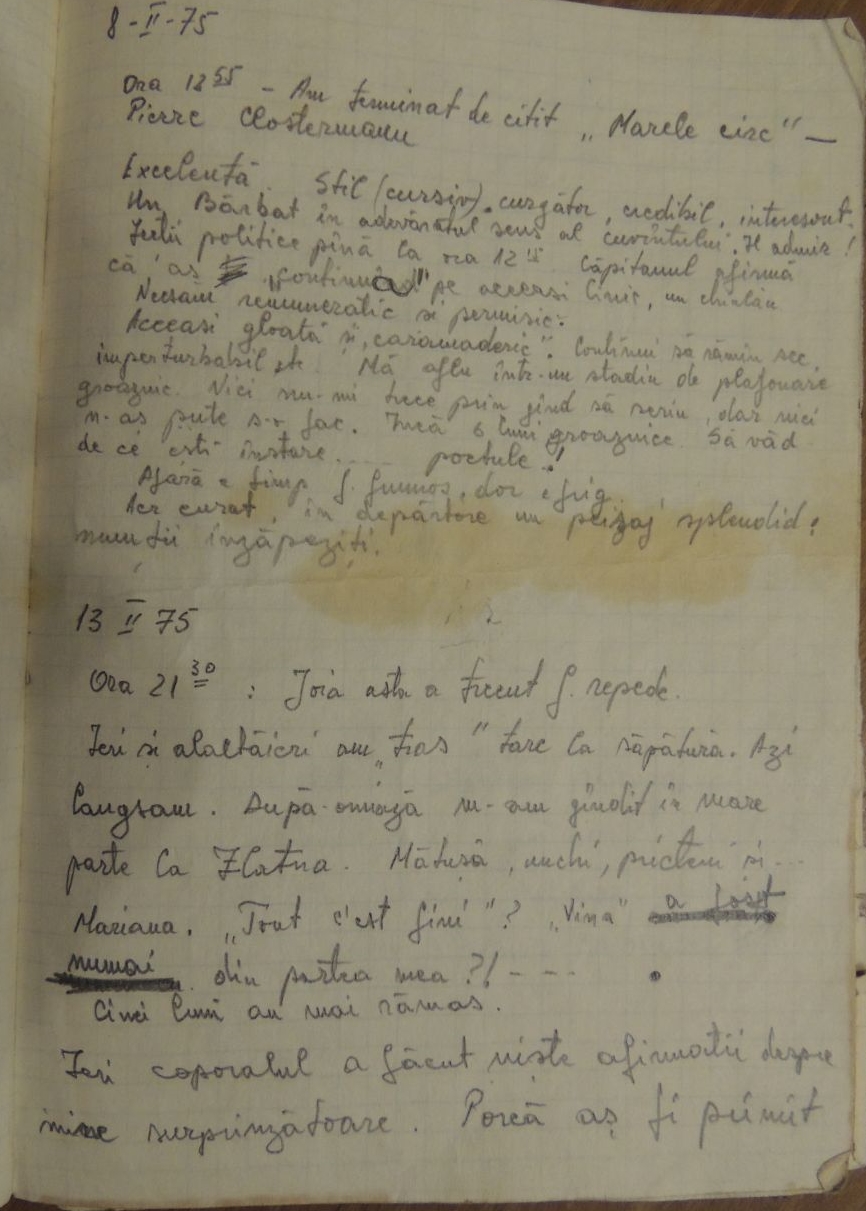

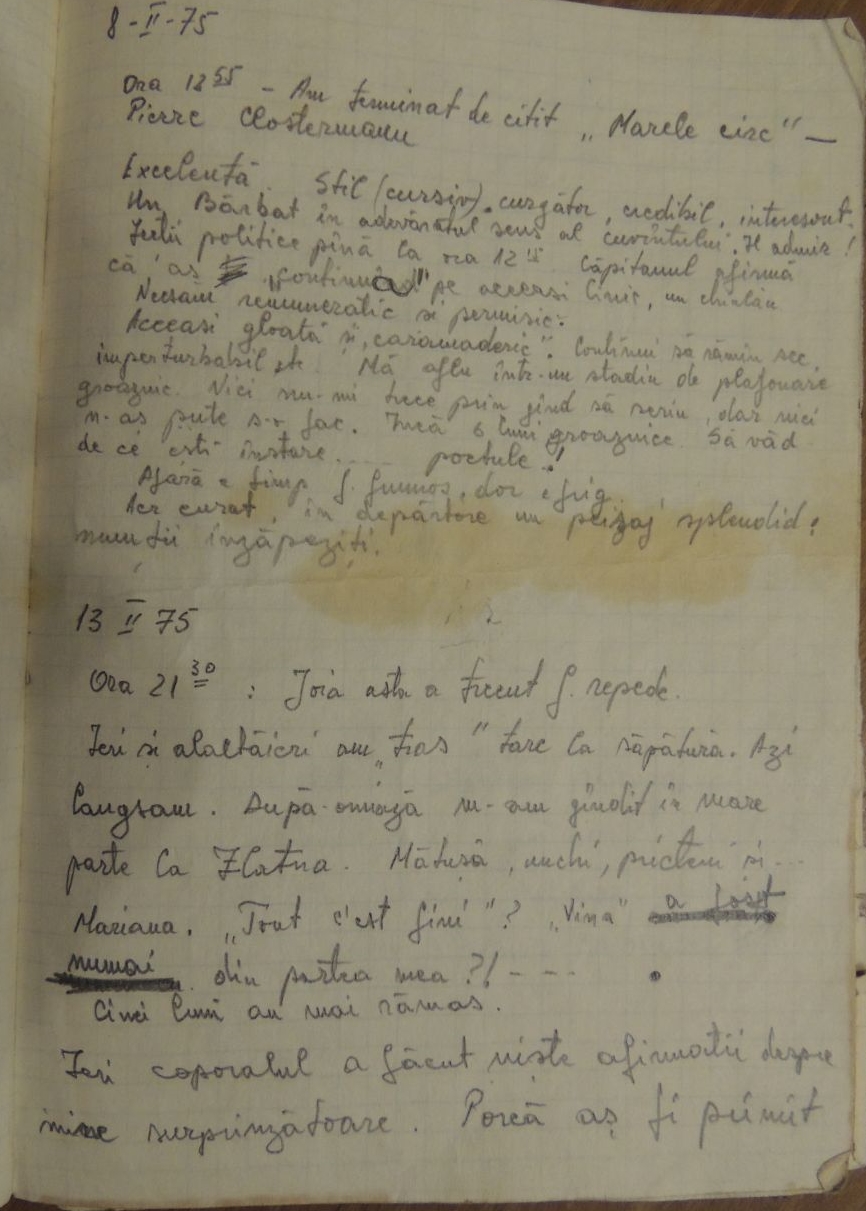

“In the army, the majority of the lower ranks are incompetents. And this in the army of the RSR [Socialist Republic of Romania]! Adolescence made me commit some “follies.” So others think. I don’t. For that reason they’ve brought me here. Military service means pickaxe, shovel, spade. My country needs me, but it despises me. I’m going to do my military service with [common-law] convicts.” This is a short extract from the manuscript that contains Ion Monoran’s army diary. From these few words, the reader may sense the drama experienced by the author when he was forced not only to carry out exhausting work, but also to live among individuals with whom he had nothing in common, and with whom, in normal circumstances, he should never have had to have any dealings.

In 1974 and 1975, Ion Monoran did his military service in special conditions at the Piteşti Petrochemical plant, because he had already been classed as a “hostile element” to the communist regime because of his attempt to flee Romania together with seven classmates when they were in their final year of high school. The harsh experience of doing military service in communist Romania in a special place, together with convicts, is recorded in real time in his diary.

Ion Monoran’s army diary is written by hand and remains unpublished. A few short passages, poeticised, appeared in the volume Eu însumi (I myself). The manuscript consists of approximately thirty pages.

“If only I could flow continually, and not tire, just as the river doesn’t tire,” is one of the last entries in this diary, which records the brutalising experience of an extraordinarily sensitive person confronted with the military service imposed by the communist state and with life alongside common-law convicts.

As the largest national public collection, the Contemporary Collection of the Hungarian National Gallery contains a significant number of Hungarian artworks made between 1945 and today. The acquisition of the collection can be divided into different phases: in certain periods the goal of what type of works to collect shifted in accordance with the actual cultural politics. Since the eighties, they extended the collection backward in time as well, so today they own thousands of pieces which were previously a blind spot due to political reasons, but relevant in terms of cultural opposition. The procurement process is still ongoing.

The Orfeo Group created a rehearsal room in the mansard of their commune in Pilisborosjenő in 1974. This act was motivated in part by an attack launched by the communist cultural political leadership. As a result, the Studio was banned from every community centre in the country. From 1974 to 1976, very intense studio work was organized in this rehearsal room. Lessons were held for the actors in speaking techniques, motion, and theatre practices in the various rooms of the house. It served as a kind of college based on a mentor system, according to Tamás Fodor. In the rehearsal room, they created and performed their 3-act play (The hospital room no. 6., Warren/Militants, Lawn). They held literature evenings and premiers, as well. A select audience of intellectuals, philosophers, and artists visited the house. Today, the rehearsal room is home to the puppets made by Ilona Németh, one of the founding members of Orfeo. This illustrates the continuity between the past and the present.

The photo archive of Goran Pavelić Pipo contains over 15,000 negatives. The photographs are mainly black and white, and on them Pavelić recorded rock concerts and everyday life around the popular Zagreb cafés Zvečka, Blato and Kavkaz in the period from the late 1970s to the late 1980s, also known as the new wave era. His photographs were conceptually and aesthetically opposed to the photographs in the then official press, such as Večernji list, Vjesnik or Borba, and thus represented a kind of cultural opposition. The Pavelić Photo Archive is extremely important to an understanding the phenomenon of the new wave and the contemporary urban scene in socialist Zagreb.

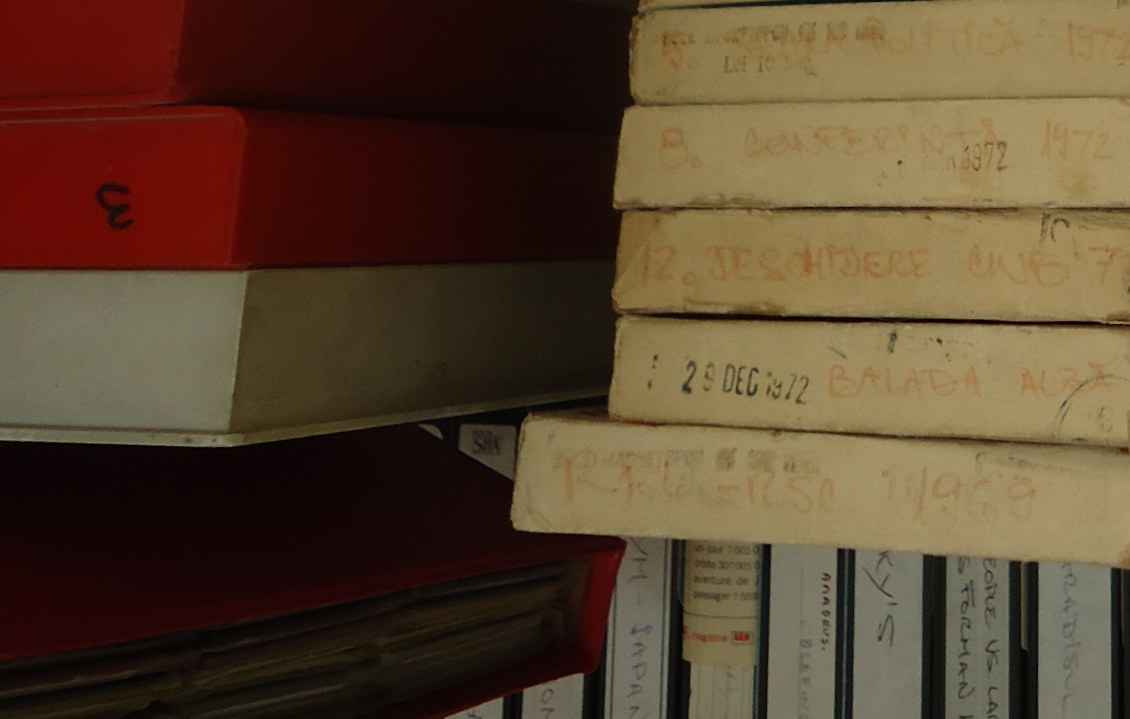

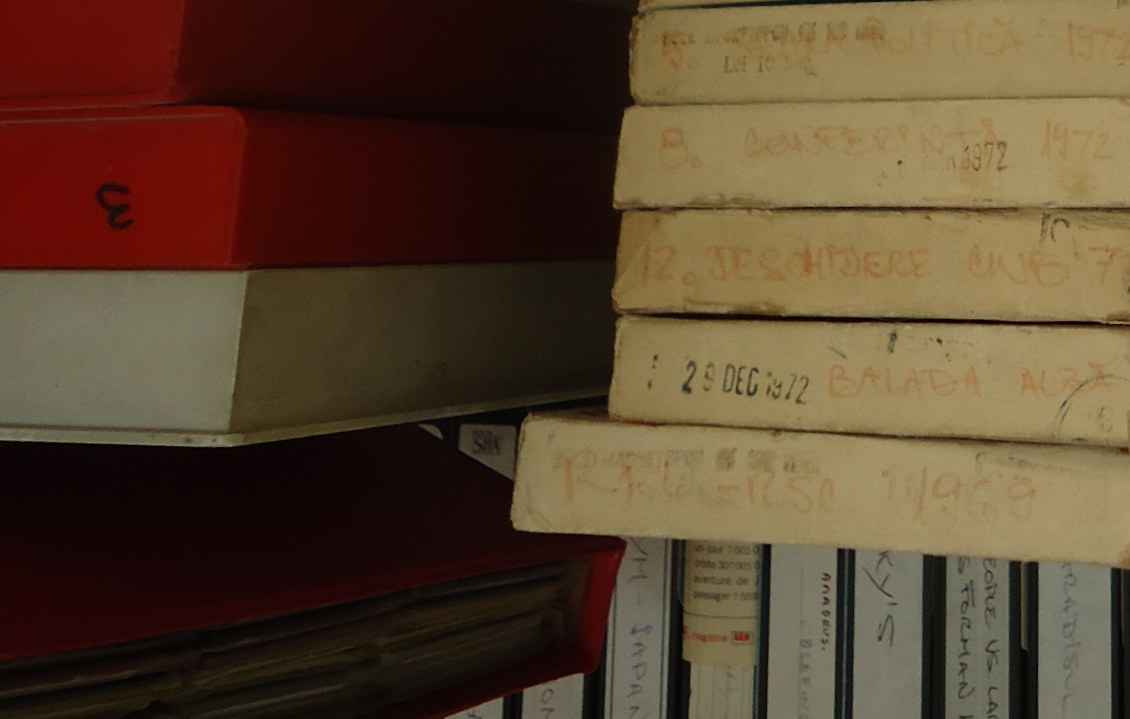

The film Balada albă (The white ballad), winner of two awards in 1974, is in the Mirel Leventer private collection both in its original format, on a roll of film, and in digitized format. The film reconstructs the tragic death of a colleague from the Architecture Faculty during a winter excursion to the mountains. Because the vacation after the first examination session was in February, many students left to walk in the mountains then, even if the weather conditions were not favourable. In the winter of 1973, a group of Architecture students was caught by a blizzard, and the student in question basically sacrificed his life to save the others. It was a death that shook all his colleagues, and some of them paid him posthumous homage through this film. “It is a film that began like a reportage on the funeral of a colleague of ours, in sixth year. Together with some colleagues, he climbed the mountain in very difficult conditions and in saving the others, he met his own end. He was found dead after three days of blizzard; he was completely frozen and was, by a bitter irony of fate, very close to the chalet, on the way back. A terrible tragedy. Without initially thinking that anything in particular would come out of it, out of a sort of inertia, I filmed the funeral; I filmed it on 8 mm. Then I used the scenes in the 16 mm film. I made a screenplay, together with three other colleagues; we climbed the mountain, we repeated the route the following year; we filmed in similar conditions; we put ourselves in danger too. Then I did the editing in our laboratory at the Faculty; I did amateur editing. That was in 1974; the tragedy was in 1973,” recalls Mirel Leventer. The film was shown at two film festivals, and at each it won an award: the National Festival of Student Art in Cluj-Napoca and the Festival of Bucharest Cine-clubs. It was also awarded a prize by the magazine Cinema. The music is by a well known Romanian singer-songwriter, Dorin Liviu Zaharia. He plays the flute and recites a poem written by himself entitled “La trecătoare” (At the crossing), superimposed on an extract from the melancholic piece “Oh Well, Part Two” composed by Peter Green and performed by the then group Fleetwood Mac, who were in vogue at the time. After 1989, the film was projected as part of the Club A evenings.