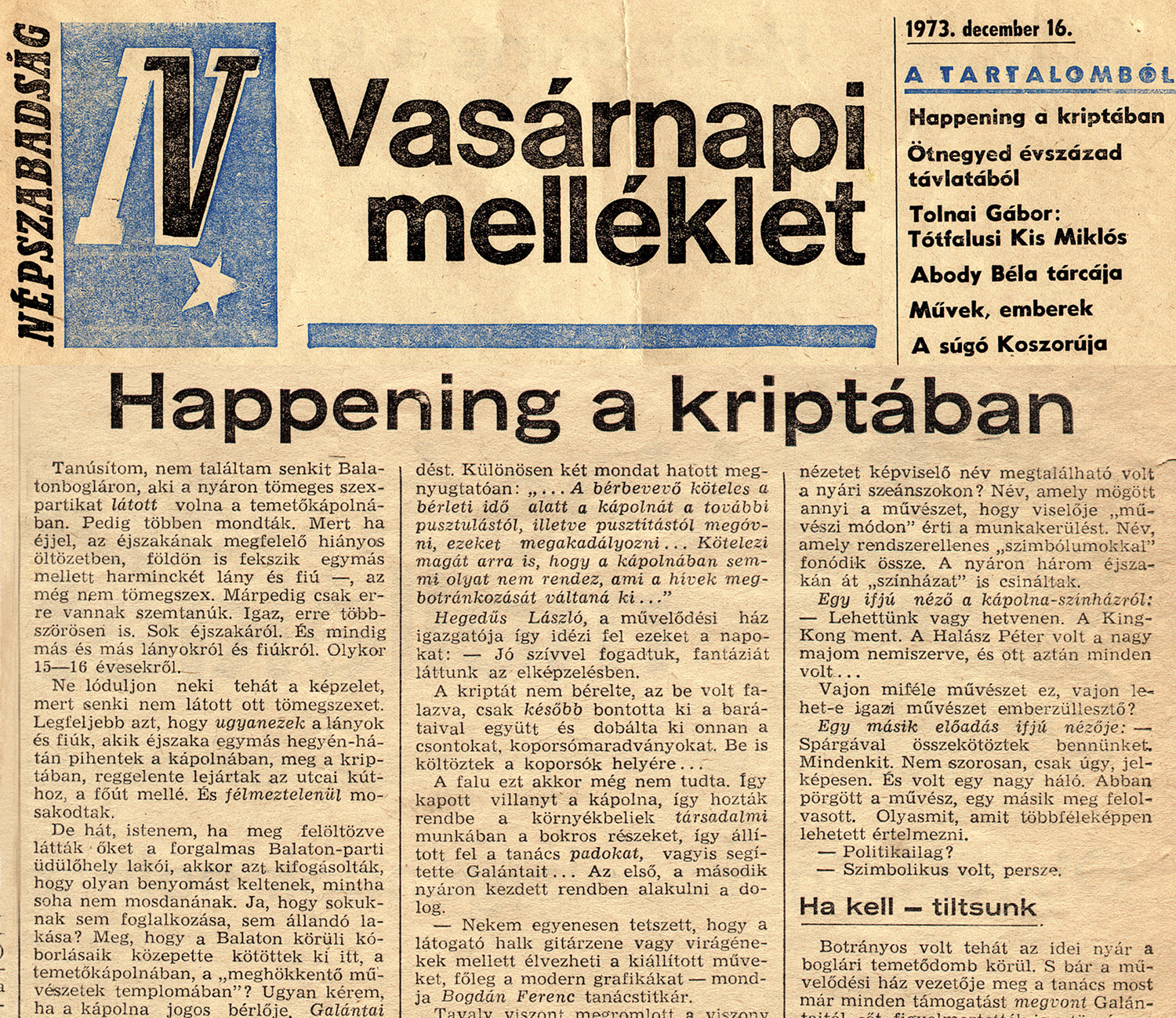

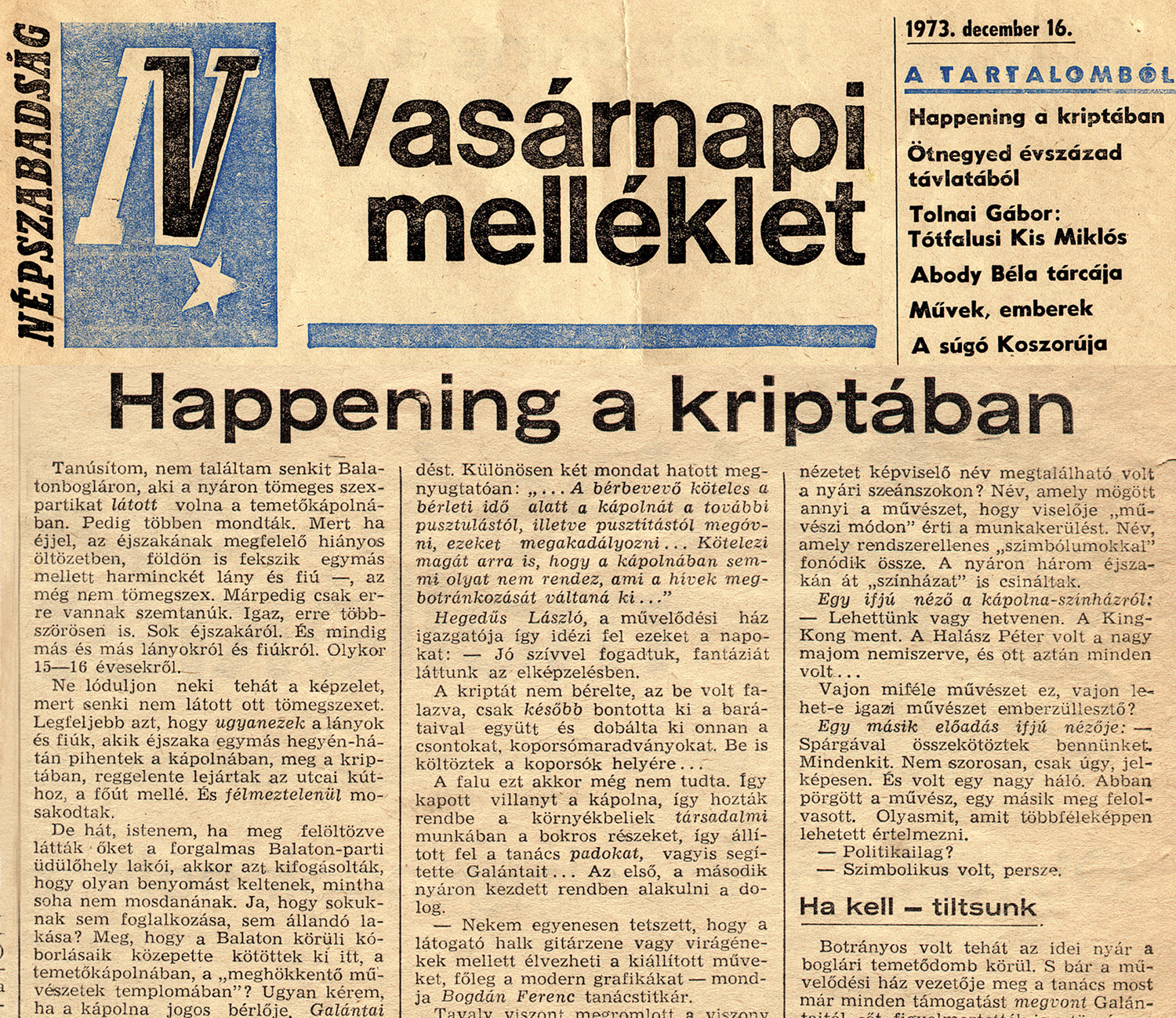

Publication of the article “Happening in the Crypt” by László Szabó, Népszabadság, December 16, 1973.

On December 16, 1973, a full-page article entitled “Happening in the Crypt” was published in the Sunday supplement to the most important daily, the communist Népszabadság [People’s Liberty], discrediting and vilifying György Galántai and the Chapel Studio. The article had been commissioned by the party headquarters and György Aczél. It was written by the editor-in-chief of the criminal column, a man named László Szabó, the country’s “chief police officer” at the time. On the days following the publication of the article, the chief editor of Népszabadság received several letters of protest (e.g. from Tamás Szende, Júlia Vajda, István Eörsi, etc.). These letters were never published or answered. As a consequence of the article with names listed as participants of the Chapel Studio, several artists had to leave the country as emigrants in the following years (György Pór, Péter Halász, Tamás Szentjóby, etc.). Other artists were banned and put on a list, in particular, the initiator, György Galántai.

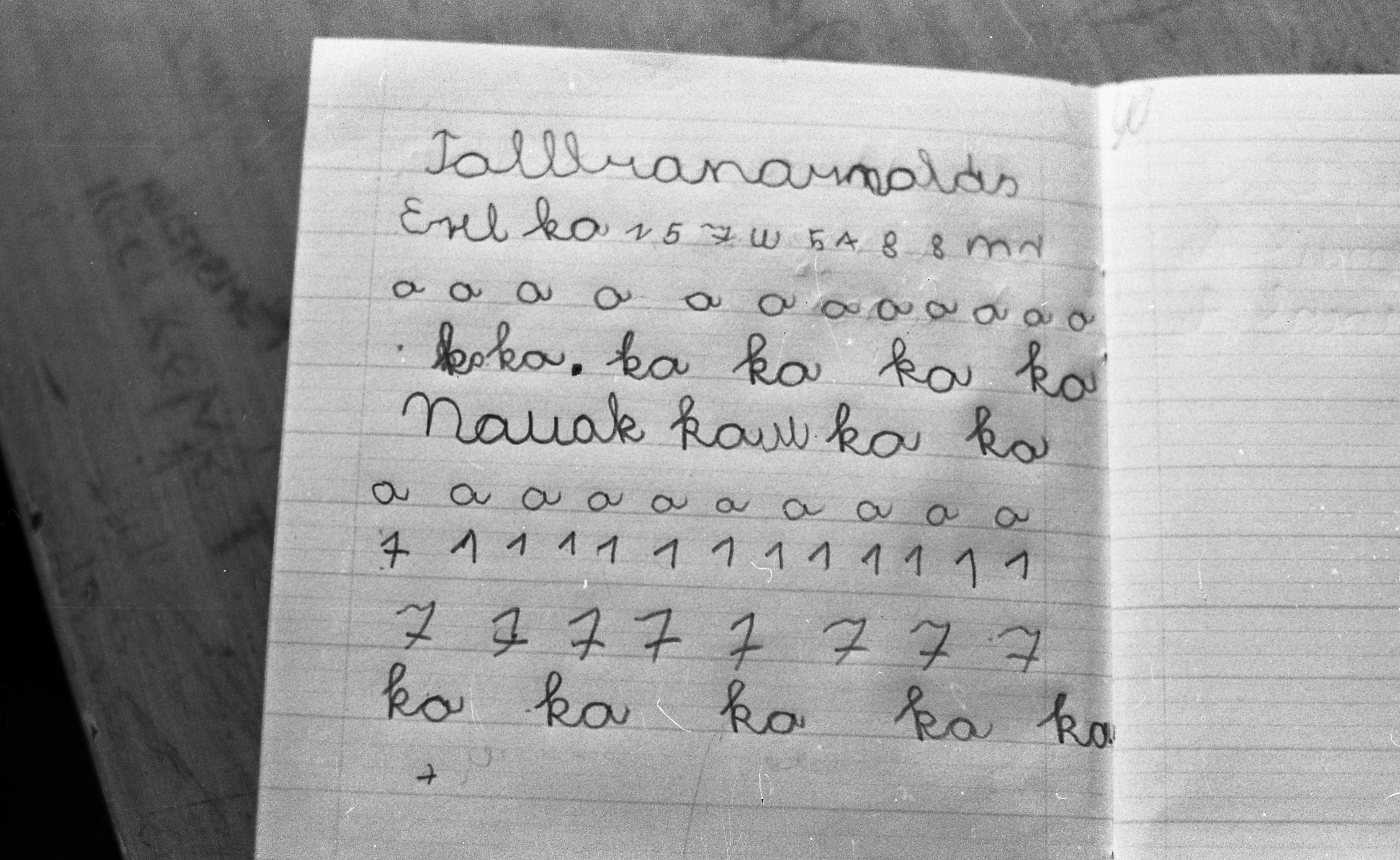

Katalin Ladik’s sound poetry performance The Positions of the Letter O following the screening of O-pus,, July 29, 1973

Katalin Ladik’s performance of an improvisational interpretation of the experimental film O-pus, which she created together with Attila Csernik and Imre Póth in 1972, was held in the Balatonboglár Chapel Studio in 1973. (It was the first sound poetry performance in Hungary.) For the film, Csernik used various forms of the letter “O” printed on a sheet of paper. He also made a bigger “O” cut out of cardboard, which he placed over the letters printed on paper in different variations. The film focused on the connection between the “body” of the letter “O” and parts of the human body. Following the screening of O-pus in Balatonboglár, Ladik was asked by Csernik to sing what she saw in the film. Ladik performed an improvisation, without a score. Csernik’s installation space in the chapel of the large letter “O” complementing the film also became part of the performance.

Newspaper reports on trials for offences of enemy propaganda, Vjesnik and Oslobođenje, 1973. Press clipping

Newspaper reports on trials for offences of enemy propaganda, Vjesnik and Oslobođenje, 1973. Press clipping

The card contains five cut and glued press clippings containing reports on court trials against Dušan Makavejev, the director and producer of the film “W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism”, against Lazar Stojanović, the director and producer of the film “Plastic Jesus”, and against Kosta Čavoški, then an assistant professor at Faculty of Law in Belgrade, sentenced to five months in prison with a two-year suspended sentence, on charges of criticism of the 1971 Yugoslav constitutional amendments.

The film “W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism” from 1971 was banned in the SFRY for 15 years, although it won many awards abroad (Interfilm, international criticism in Berlin, Luis Buñuel Award in Cannes). As further described in the Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography's film lexicon, Makavejev among other things ironically thematized the rigidity of the communist regime, i.e. the conservatism of supposedly advanced socialist societies. The main character Milena, a young Yugoslav communist, also represents feminist attitudes in relation to psychoanalysis and Marxism, while the film’s structure in general relies mostly on the experience of the so-called historical, especially the Soviet, avant-garde.

The film “Plastic Jesus”, directed by Lazar Stojanović, was made in that same year. The film was banned, locked away, and first shown in 1990. Its author was sentenced to prison. Besides its erotic content, the film was banned primarily because of its open criticism of Tito's cult of personality and the Yugoslav regime. This film led to Stojanović’s as inclusion among the directors of the so-called Black Wave, a Yugoslav film movement of the 1960s and early 1970s. It was characterized by criticism of contemporary socialist society, ideology and government and their public presentation, and by realism in the presentation of everyday life versus the official socialist cultural statism which represented reality through the prism of the overall progress and prosperity of Yugoslav socialist society.

Besides those described above, the collection also includes approximately fifty press clippings from the period 1972-1974 that are thematically linked to the crimes of enemy propaganda in artistic production, the crime of production and distribution of pornography, and the crime of impugning the reputation of the state, the highest state officials and institutions. The documents are available for research and copying.

The Sanda Budiș Collection is an important source of documentation for understanding and writing the history of that particular segment of the Romanian exile community which was extremely active in supporting dissidents in the country and in disseminating information about the repressive or aberrant policies of the Ceauşescu regime. In particular, the collection illustrates the actions of the collector and other personalities aimed at putting pressure on the communist authorities in order to give up the project of systematisation of Romanian villages. Also, the documents in this collection reflect the involvement of Romanians abroad in rebuilding democracy in their home country.

Group of Yugoslav Communists. Comparing Nationalism in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia , in Croatian, 1973. Leaflet

Group of Yugoslav Communists. Comparing Nationalism in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia , in Croatian, 1973. Leaflet

This dress belonged to Nadiya Svitlychna, which she wore while imprisoned at a hard labor camp near the village of Barashevo in Mordovia in 1972-1976. This is a cotton summer dress with an embroidered collar drawing on styles seen often as part of Ukrainian national dress. The collar was detachable so it could be quickly removed, because camp administrators had forbidden such adornments. This tradition was started by Ukrainian female political prisoners who had been given 25 year sentences for their involvement with the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. It was form of resistance that affirmed their solidarity with one another and also reasserted their humanity, dignity, and culture. Ukrainian female political prisoners also refused to wear on their chests tags with their camp numbers on them. In her memoir, Svitlynchna notes that she was never put in isolation for these acts, but did spend time in separate cells. Svitlychna also wore this dress after being released from the camps, as the consequences of incarceration often reverberated widely for the inmate of hard labor camps, who struggled to find employment and housing, leaving them precarious and vulnerable.

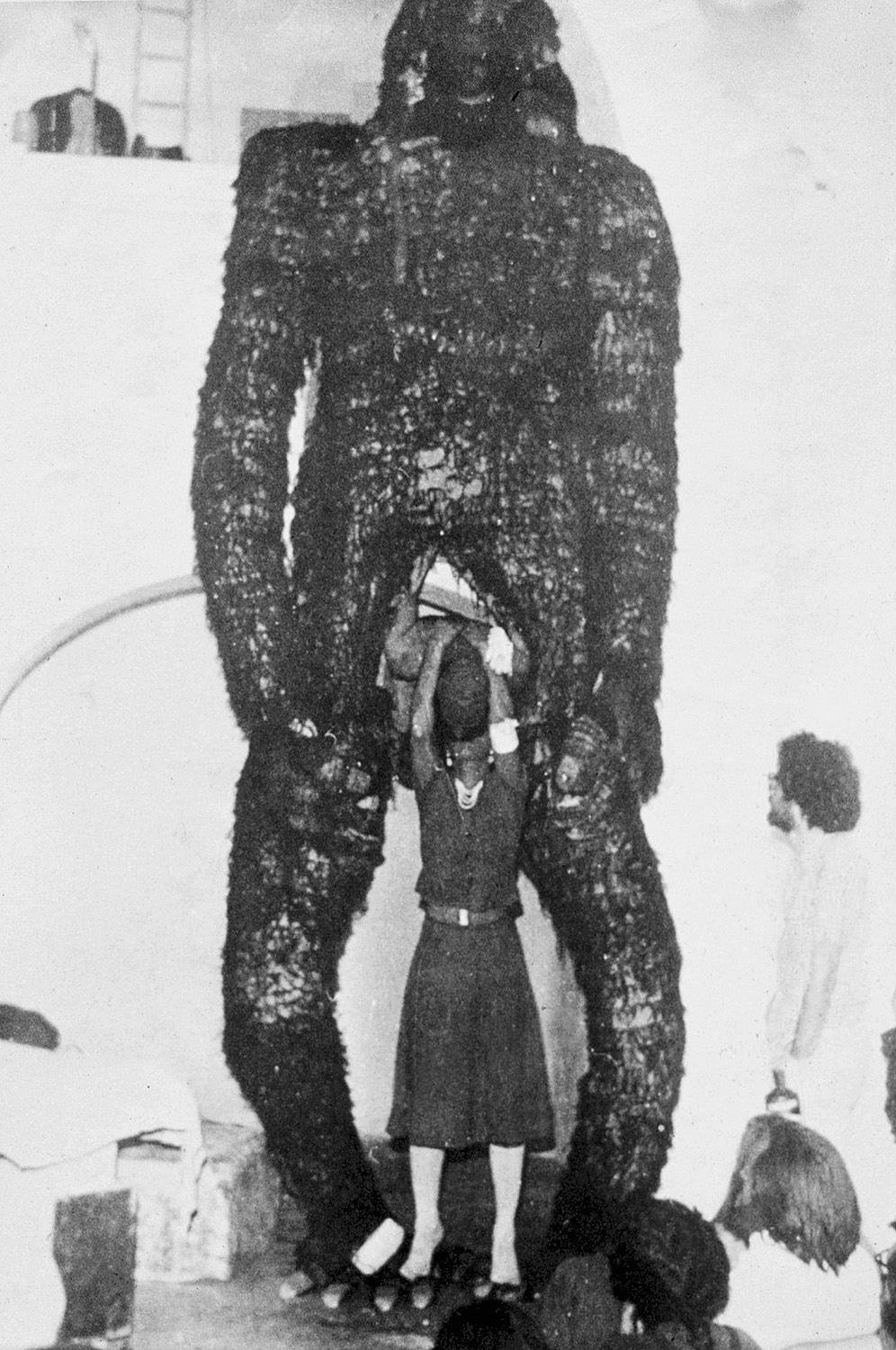

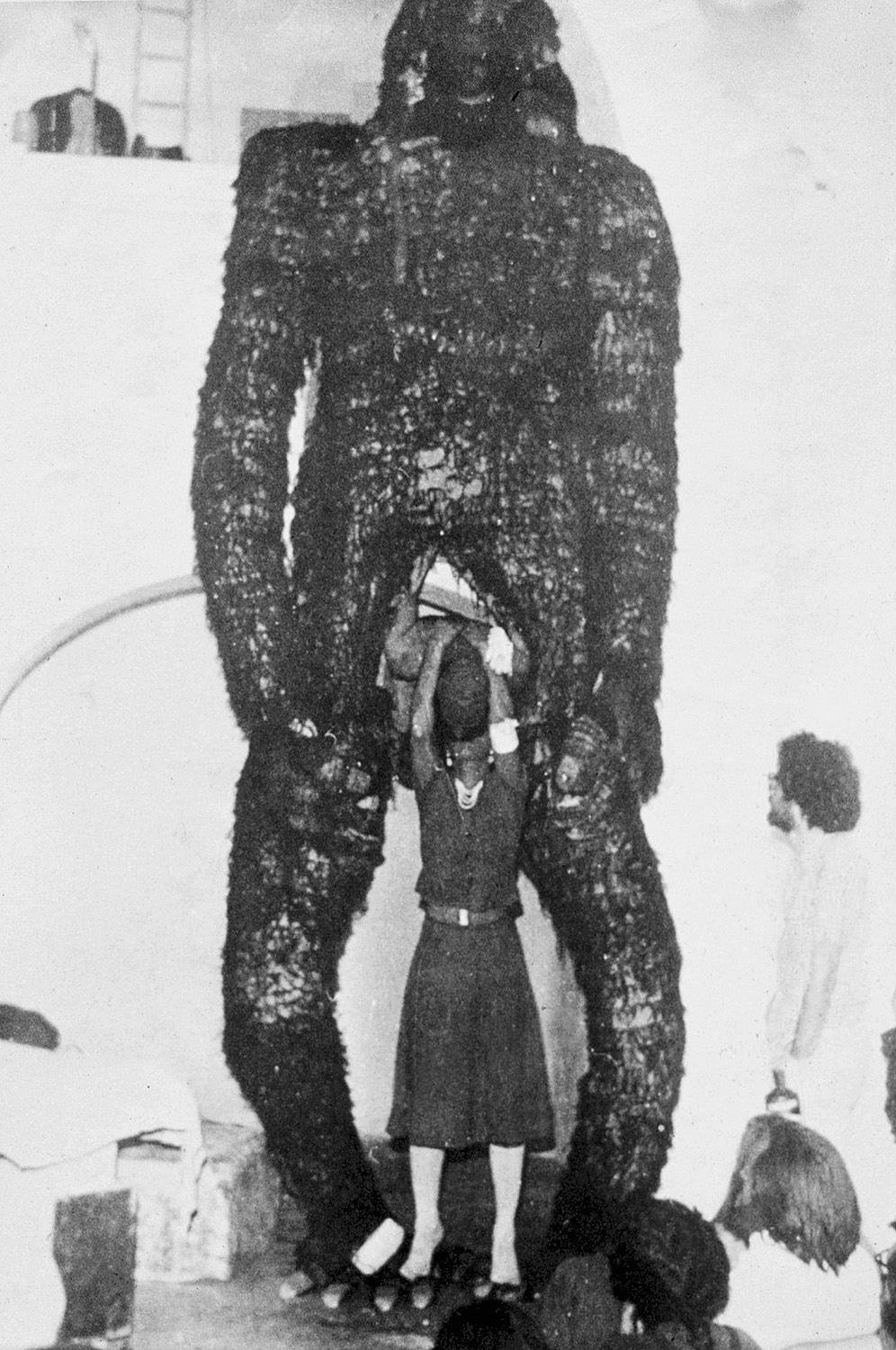

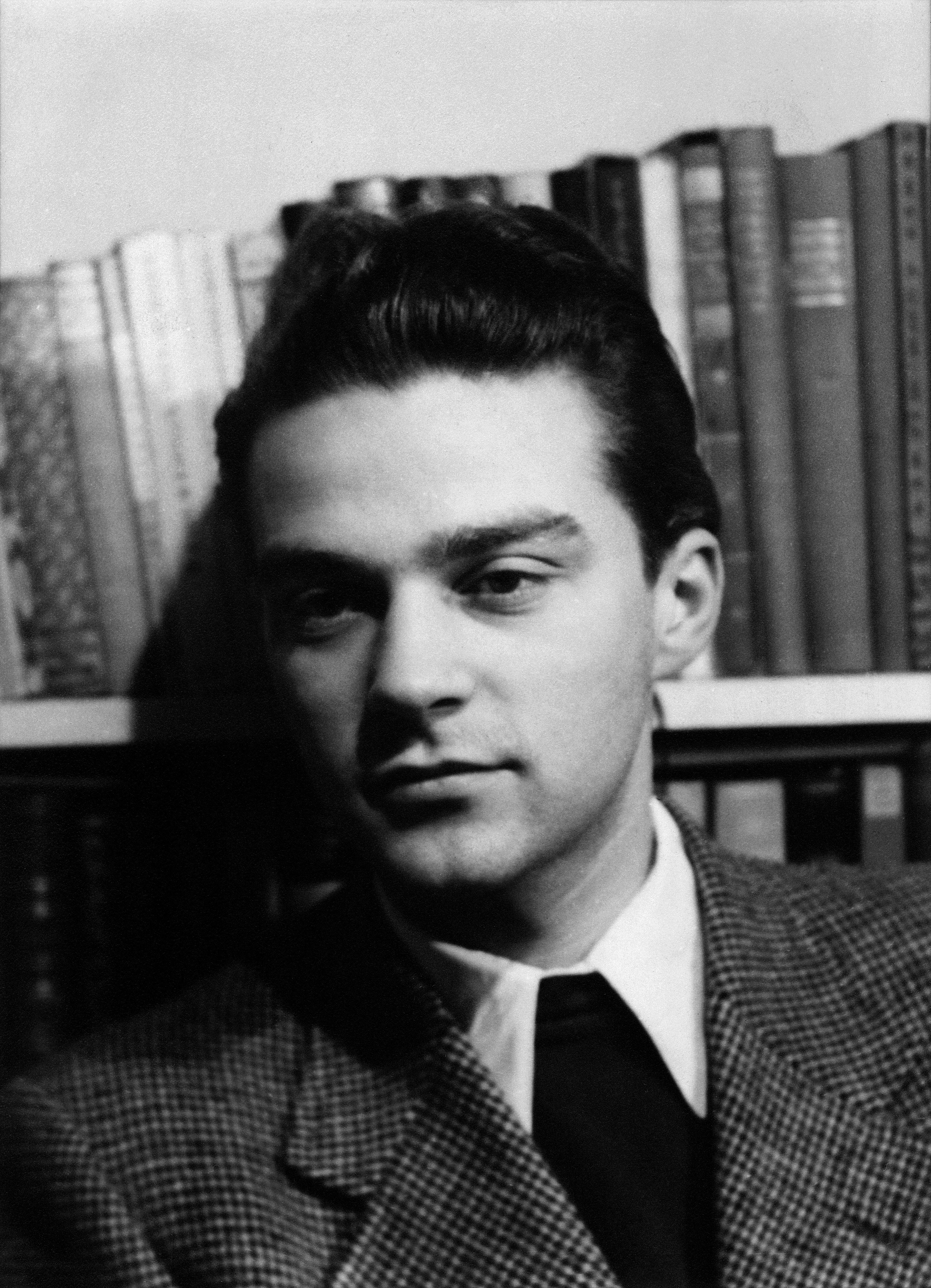

Kassák Theater: King Kong, August 13, 14, 16-18, 1973 (Participants: István Bálint, Péter Breznyik, Éva Buchmüller, Péter Halász, Marianne Kollár, Anna Koós, Miklós Kovács, István Szeghő, Can Togay)

The members of the alternative theater of Péter Halász and Anna Koós visited Balatonboglár for one week in 1973. Their experimental theater pieces King Kong and Play with Birds were both performed in several versions while they were there.

King Kong was a three-day-long play characterized by ritual scenes and elements. The central “character” of the play was King Kong, an enormous hairy monkey as tall as the height of the chapel inside. He welcomed visitors as they arrived. The hidden references to the oppressive regime were encoded in both fabled elements and erotic symbols. Through the transformation of a character (from a man into a woman), the play intended to illustrate the possibility of defeating power. However, after occupying the position of the enemy, the whole procedure restarts from the beginning. Questioning the boundaries of social and personal morality, the theater piece reflected on the oppressive strategies used by organs and institutions of power. It was later performed at the Dohány Street apartment theater.

Exhibition Tükör / Mirror / Spiegel / Miroir, August 5-11, 1973, organized by László Beke

The exhibition was organized by art historian László Beke in 1973. It addressed the theme of the mirror, which had been in the focus of artists for decades and had also been used by avantgarde artists. The exhibition had a double focus in its approach. On the part of the organizer László Beke, it focused on the symbolic meanings of the mirror. On the part of the participating artists, the mirror was regarded as a tool for self-reflection. On a higher level, the mirror as a symbolic object also implied political criticism: mirroring art in a politically compulsory way. The exhibition was the first international mail art exhibition organized in Hungary. Participants: Francis Picabia, Angelo de Aquino, Gábor Attalai, Balázsovics Mihály, András Baranyay, Ben Vautier, Canada Art Writers, Gustave Cerutti, Dalibor Chatrny, Gáyor Tibor, Dóra Maurer, Tom J. Gramse, Klaus Groh, Jerzy Kiernicki, Jiří H. Kocman, Romuald Kutera, Péter Legéndy, János Major, David Mayor, Christian Megert, Anette Messager, Steffen Missmahl, Géza Perneczky, Sándor Pinczehelyi, Martin Schwarz, Jörg Schwarzenberger, Mieko Shiomi, Zdzisław Sosnowski, Petr Stembera, Tamás Szentjóby, Ádám Tábor, Endre Tót, János Tölgyesi, Janos Urban, Jiří Valoch

The photograp presents the spatial form designed by Antoni Starczewski. The form has a shape of a great round shield of 6-meter diameter. On the disk there are set sheet-metal cuts, spreading radiate from the center of the circle. The effect is that the construction evokes the image of a working rotating wheel.Starczewski’s form was built during the First Biennial of Spatial Forms in 1965. The photograph by Tomasz Sikorski was taken in 1973.

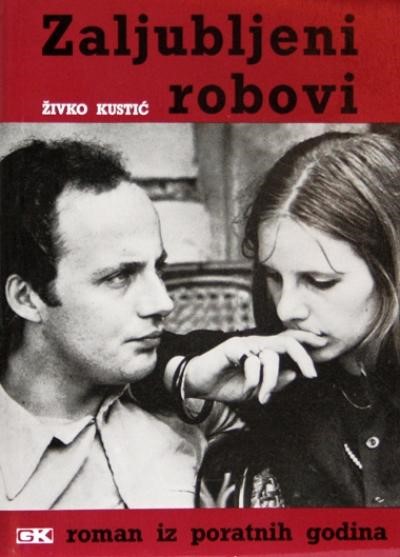

The main sections of this novel contain a plethora of autobiographical elements from Kustić's personal life. For instance, it deals specifically with his marriage to an Orthodox woman, Marica Radenković, and also with his transition from Roman Catholicism to the Greek Catholic Church. This book was Kustić's first and only novel he wrote in his life, which in a wider context examined the life of Catholic believers in a socialist and atheistic society. Kustić demonstrated a religious world which managed to survive within a society that had undergone a socialist revolution.

He pointed out the military and educational system as specific places in which believers had to engage in a struggle against atheism, so the stories from this novel particularly refer to the collision between the religious and atheistic worldview in these social institutions of socialist Yugoslavia. Through his characters, he expresses optimism that the socialist project of society without religion had to fail. That is why one of Kustić's characters says: "I have long been convinced that this entire conflict between religion and atheism, Christianity and Marxism on our soil is pure historical confusion. There are fellow educators who do not see it, who even enjoy this conflict, who are ready to torture, as they do. They know, in fact, that the Church is indestructible, remembering all that we have learned de mortibus persecutorum" (Kustić 1973: 138).

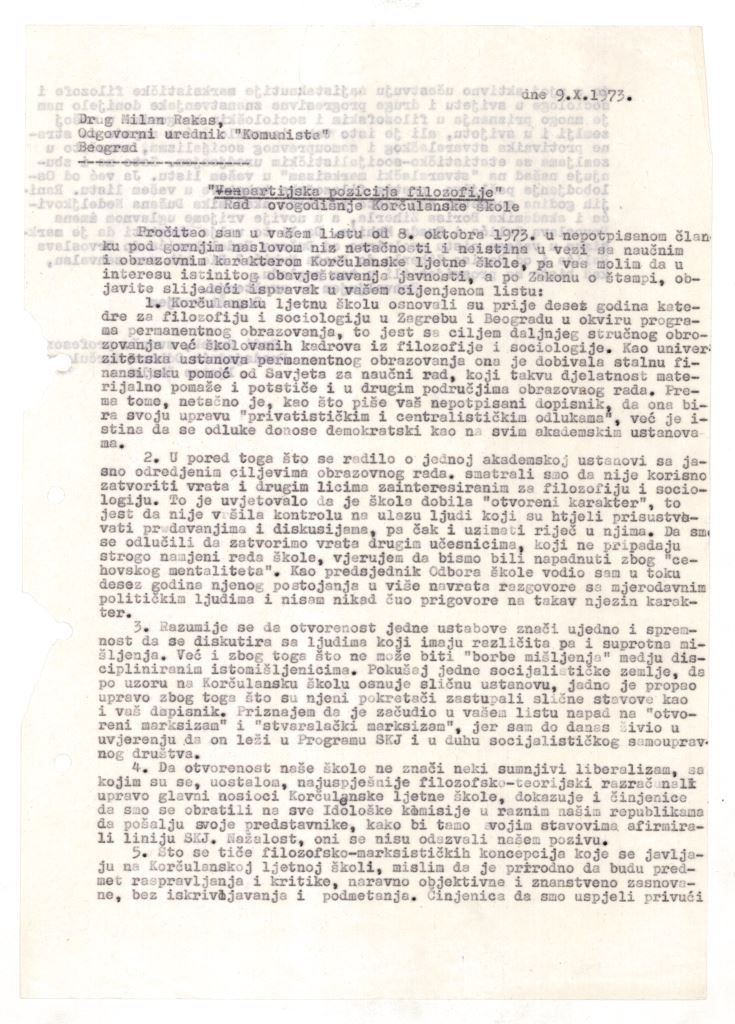

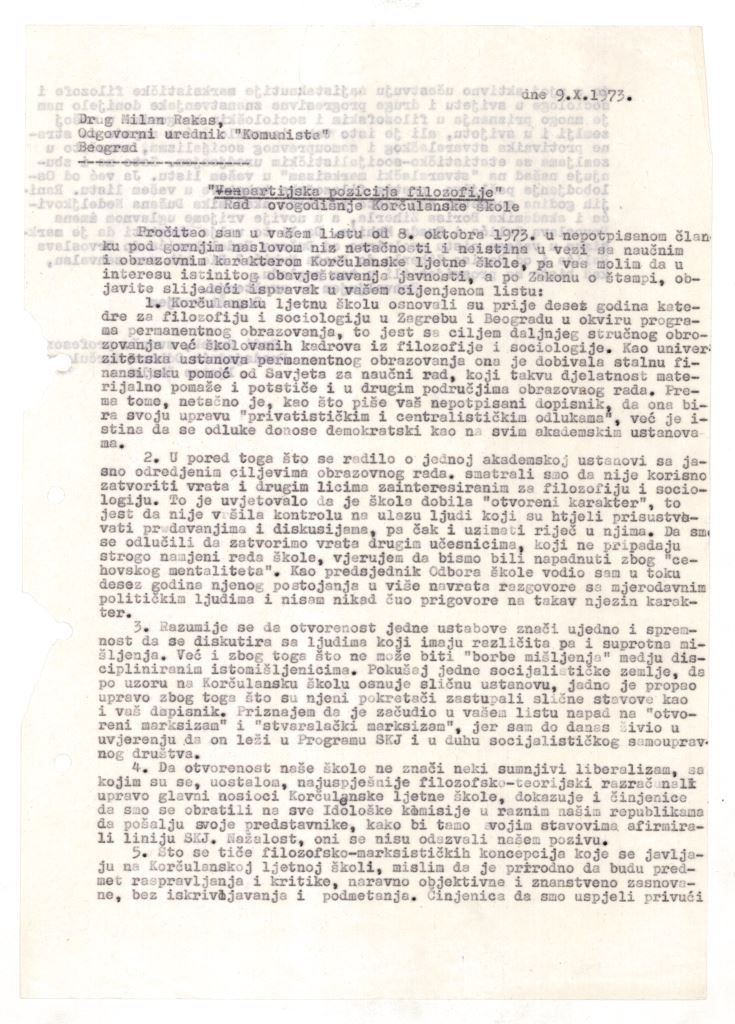

Together with the famous Croatian philosopher Milan Kangrga and other intellectuals, Rudi Supek founded a philosophical school that was held every summer in Korčula from 1963 to 1974. Originally conceived as an academic exercise, the School soon became an international event with free critical discussion on a different subject put to the fore each year. It was a gathering of philosophers and sociologists from all around the world (for example, Erich Fromm, Lucien Goldmann, Henri Lefebvre). However, after a time the ruling state-party structures turned against the School and the intellectuals who were called “praxisovci” (Praxis intellectuals, or Praxis thinkers) (Lešaja 2014, 246). The writing of Komunist, the official newspaper of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY), is an example of the regime's attacks on the Korčula Summer School and the Praxis intellectuals. In 1973, Komunist publicly branded the School as "political opposition" and “philosophy outside of the Party”, alluding to the open character of the School and the participation of foreign intellectuals. Supek responded in a letter addressed to the editor-in-chief of Komunist, Milan Rakas, in which he pointed out, among other things: “It is understood that the open character of an institution means at the same time willingness to discuss with people who have different and opposite opinions. Although it cannot be a 'conflict of opinions' among disciplined minded ones, ... I admit that I was surprised to see an attack on 'open Marxism' and 'creative Marxism' in your publication, because I have lived in the belief that they ['open Marxism' and 'creative Marxism'] are part of the LCY Programme and components of the spirit of self-management.” He also pointed out that the openness of a school does not mean “left-liberalism.”

In 1948, when the Czech poet Ivan Blatný emigrated from Czechoslovakia, the State Security confiscated his property including belongings, such as family photographs, official documents, correspondence and manuscripts of poems. After the investigation of Blatný’s emigration had been closed, these materials were acquired by an employee of the Pedagogical Faculty of the University in Brno, who was in contact with the State Security. He placed these documents in a cupboard at the Department of the Czech Language and Literature, where they remained, unnoticed, for many years. In 1973, when another employee of the Faculty, Jiří Rambousek, had to leave the University because of political reasons, he decided to hide these document in his own apartment. At that time, the building of the Faculty was renovated and Blatný’s documents risked being destroyed or thrown out. These documents were hidden in Rambousek’s flat for nineteen years. In 1993, Ivan Blatný’s materials which were confiscated by the State Security in 1948 were purchased by the Museum of Czech Literature from Blatný’s cousin Jan Šmarda.

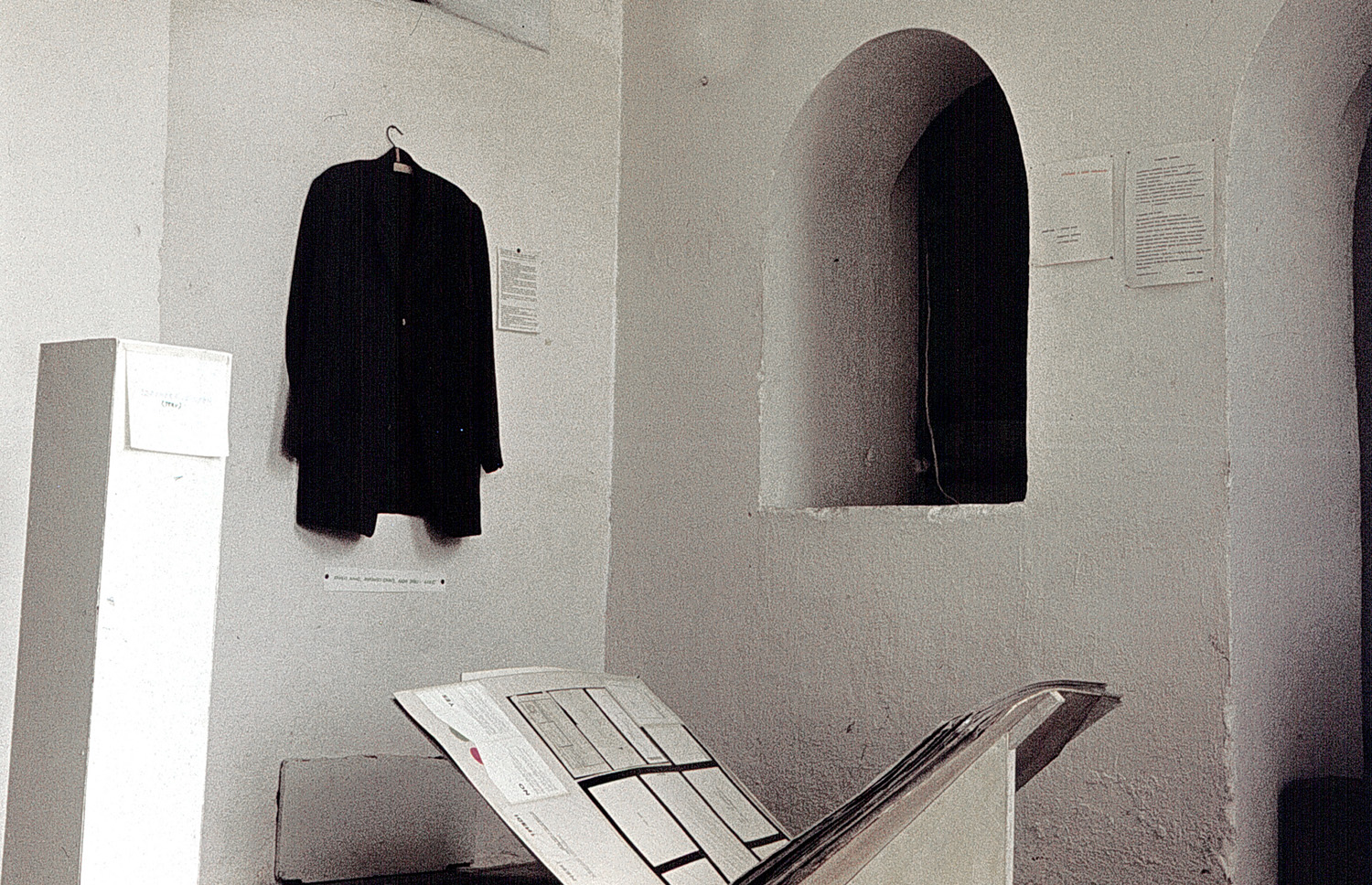

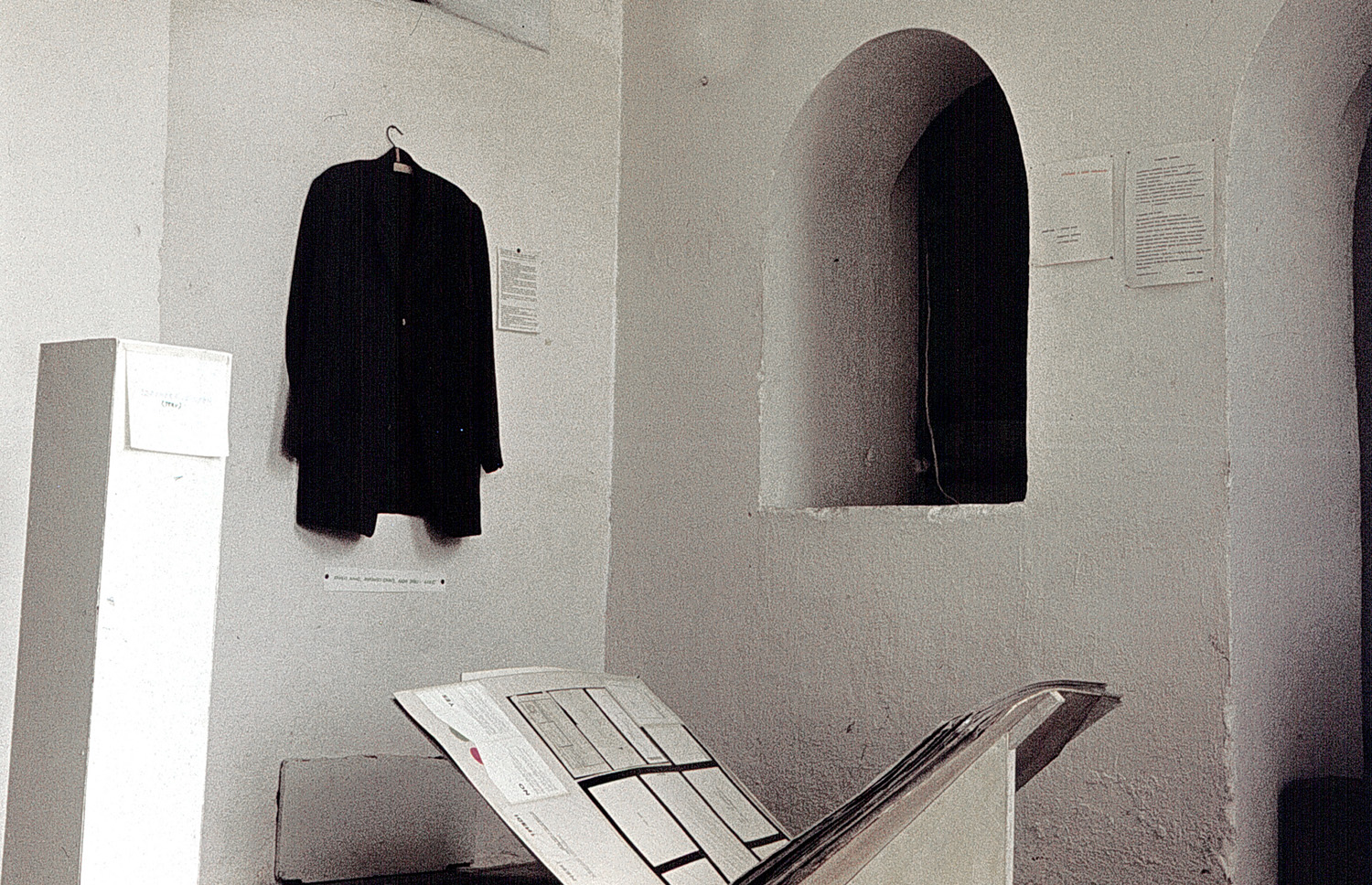

The three artists’ main concept was to problematize the characteristics of avantgarde art by raising the question in the title of their work What is Avantgardism? Can it be considered an avantgarde act that Miklós Erdély, György Jovánovics and János Major exhibited a coat? As they state in the text accompanying János Major’s coat (exhibited on June 24–July 7 1973, together with other artworks by Miklós Erdély, György Jovánovics, János Major), their aim was to liberate the avantgarde from its charges, as it indicated prohibitions from the beginning of its history. The coat considered as a symbol of the bureaucrat referred to the state officials, the only people who came to the Chapel in a coat. Questioning if exhibiting the coat is an avantgarde act is at the same time a concept artwork, as the coat can be considered both a readymade object and the illustration of the idea of the act of exhibiting that. Tamás Szentjóby reconstructed and exhibited the coat in 1995 at the Víziváros Gallery as his own artwork, thereby appropriating the work from his partner contributors and contextualizing the meaning of avantgarde on a new level.

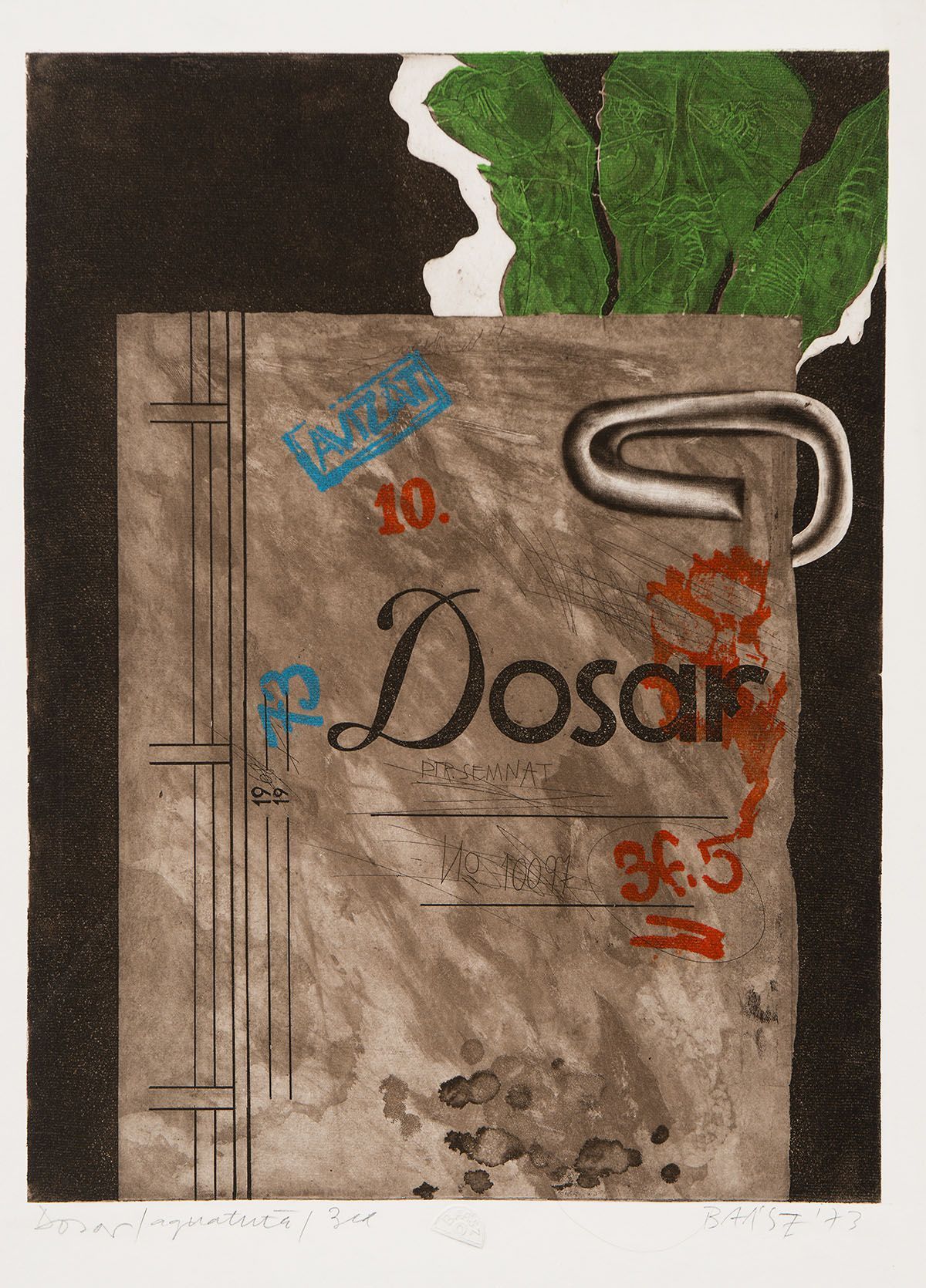

![Imre Baász: File [Dosszié/Dosar], 1973, aquatinta, 45.1x34 cm](/courage/file/n17731/4.+Dosszi%C3%A9.jpg)

Baász almost never chose the actual political situation or oppression specifically as a theme. Even the work entitled File, which depicts the typical layout of the surveillance dossiers made by the Securitate (Departamentul Securității Statului, the secret police of Romania, between 1948 and 1989) to find and target dissidents. The dossier is old, stained, and dirty and the pages are pinned together with a safety pin, which is also one of the key signs of the artist, dominating The Wounds of the Earth series.

The Reformatory School in Aszód has undergone many changes since its foundation in 1884, and a lot has happened between its walls. The institution is still in operation today, having survived two world wars, the communist dictatorship, and even a tragic homicide. In 1973, Tamás Urbán took around 500 touching, shocking, and honest pictures about the lives of the residents of the reformatory school as his graduation project.

He was able to take photographs in the institution because he was working together with Youth Magazine (Ifjúsági Magazin), and he did not have face any particular challenges or have to deal with unusual complications while working on the project, though he visited the institution several times a week for two or three months. As Urbán sees it, this was because of his discrete style, especially when he did reports. He consciously avoided splurge, he brought only the most necessary equipment with him, and he did not force anything. As he recalled in 2015, “Suddenly I was in the community and everything came naturally.” He spent days among the residents, closely observing their everyday lives, including how they worked, played, and took drugs. Urbán maintained contact with a number of the residents of the institution even after he had finished the project. These letters, however, had to be smuggled out.

In 1975, Urbán’s first exhibition was held at the Reformatory School, and it featured the pictures he had taken there. The event was opened by Éva Keleti, one of Urbán’s teachers, but the plan to exhibit the pictures to a larger audience could not be realized: the authorities did not allow the photos to be taken from the institution because of their content. A representative of the ministry who was present for the opening ceremony made this decision clear. The pictures were impounded and the remained at the Reformatory School. While Éva Keleti and others tried to prevail on the authorities to change their decision – (even going as far as György Aczél in the process), they were not successful. Nevertheless, in 1978, Urbán brought this photo series to the first display of the Studio of Young Photographers. Despite the prohibitions, the photos brought him success, both from the audiences and in the profession. As Urbán recalls, because of this photo report, he was accepted into the Association of Hungarian Journalists. The photos taken at the Reformatory School are also the direct antecedents to his major topics of the 1980s: the photo series about prisoners and people on the margins of society, such as drug users.

The photos were recently found again under a broken piano in the Reformatory School by the educators at the institution. After more than forty years, on November 23, 2017, Tamás Urbán’s photo report was again exhibited in Aszód, this time with photos taken by his son, Ádám Urbán. The exhibition, which was entitled “Then and Now,” was opened by Éva Keleti, but this time the photos were not kept under the control of the state, and soon they will be exhibited outside the institution so larger audiences can also see them. While many things have changed since the transition, Urbán’s photographs have not lost their significance.

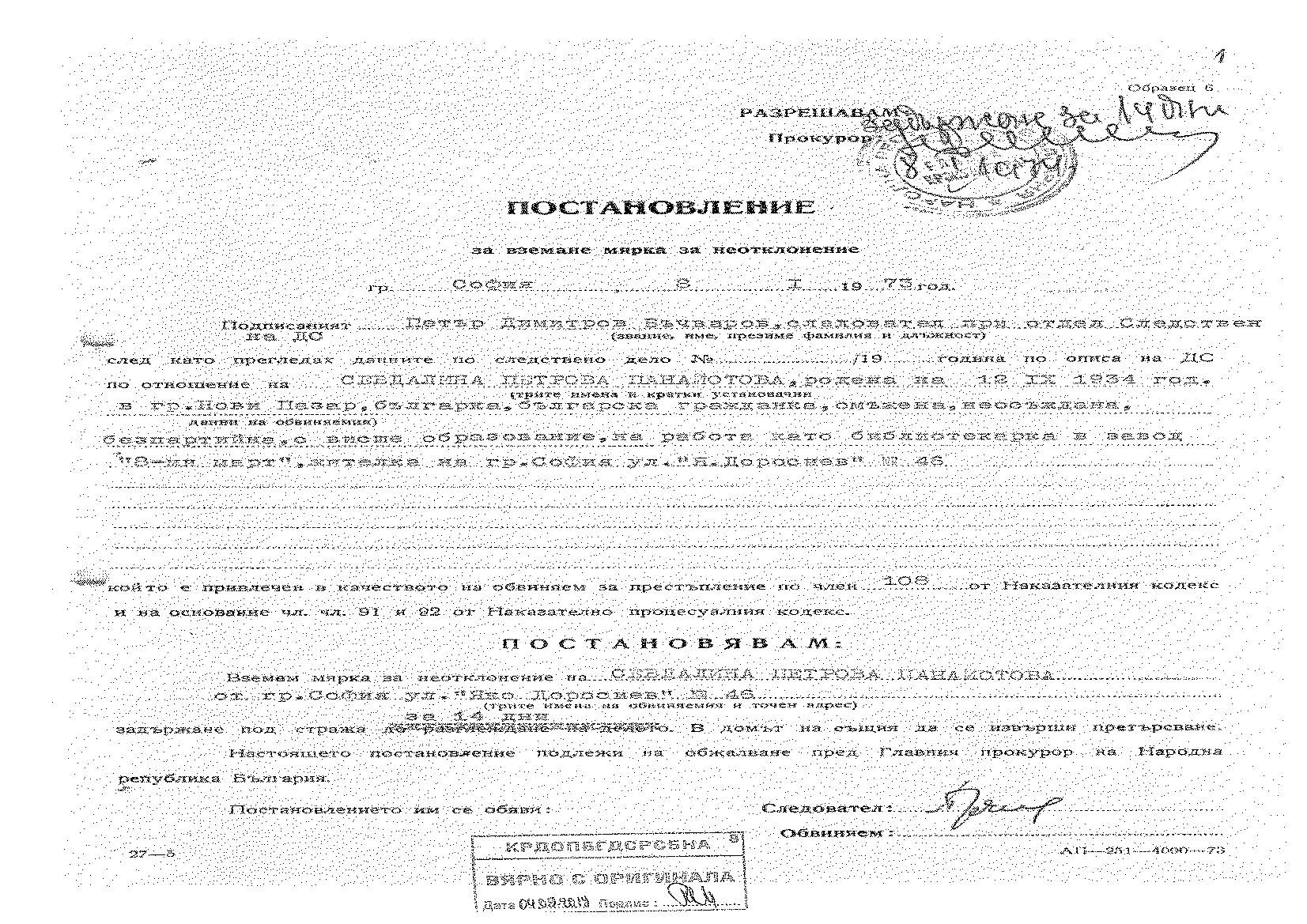

This dossier consists of the State Security file on Sevdalina Panayotova, created in the early 1970s. It shows how the state observed and persecuted critically minded members of the intelligentsia, even when their actions had hardly become public. It is also evidence of dissenters’ strategies to create room for critical thought, based on social networks and private spaces.At the beginning of the 1970s, Sevdalina Panayotova became the center of a group of people with dissident inclinations. The group included former fellow students from Sofia University and colleagues from the March 8 Factory, where she worked as a librarian at that time. They read forbidden literature (such as Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and Cancer Ward, Thomas Mann's A Sketch of My Life, Nikolay Raynov’s Mysticism and Faithlessness, and others), discussed the mistakes of socialism from a philosophical and socio-political point of view, and criticized the nomenklatura and others. Sevdalina Panayotova tried to establish a literary and philosophical workshop in the March 8th Factory and worked out a plan for the topics to be discussed. In parallel, she had two of her closest friends take a survey among their colleagues on Youth and Socialism. The idea was to write a critical account of the situation of Bulgarian youth, which was to be exported to the West (on a ship) and published there. For this purpose, she contacted a sailor from Burgas.

In 1972 the State Security opened a so-called “Terrorist Operational development case” against a close associate of Sevdalina Panayotova, Georgi Konstantinov Georgiev. Georgiev had been "sentenced to death in 1953, commuted into 20 years' imprisonment, as an organizer of a terrorist organization that committed various bombings, including the one in the 'Park of Freedom' on 3 March 1953, at the Stalin's monument..." (according to the State Security file).

Sevdalina Panayotova was then also put under surveillance by State Security. Sevdalina Panayotova and Petar Peev were accused of being anarchists. Some months later, in July 1973, Georgi Konstantinov Georgiev emigrated from Bulgaria. Petar Peev was sentenced in September 1973 to the forced labor camp in Belene for 3 years as “an irrepressible enemy of the people's republic and socially dangerous".

Sevdalina Panayotova was subjected to day-to-day pressure from the State Security including a search of the apartment and a series of interrogations for "reading and disseminating literature directed against the socialist system". State Security accused her of “conversations in which you expressed slanderous information about the public and state system”. In September 1974, she was detained for 14 days as “accused under Art. 108”, i.e. “Anti-government propaganda and agitation, spreading defamatory claims and literature affecting the state and public order”. Further on, the file reads: "It was found that Sevdalina Panayotova did not commit any criminal activity because of which she was released on 18 January [1974]”. However, because of her "bad influence" on the youth, State Security found "it expedient [for her] to be expelled from Sofia". Thus, Sevdalina Panayotova was forced to move with her family to the small town of Chepelare in the Rhodope Mountains. Due to a lack of evidence, her investigation was terminated in the spring of 1974.

All quotations are from the file "Investigation Case No. 6965 Anarchists", Central Archive of the Commission for the Disclosure of Documents and Declaration of Affiliation of Bulgarian Citizens to the State Security and Intelligence Services of the Bulgarian People's Party Army (CRDOPBGDSRSBNA), Arh. No II sl.d. 6965; III raz. 32666r.

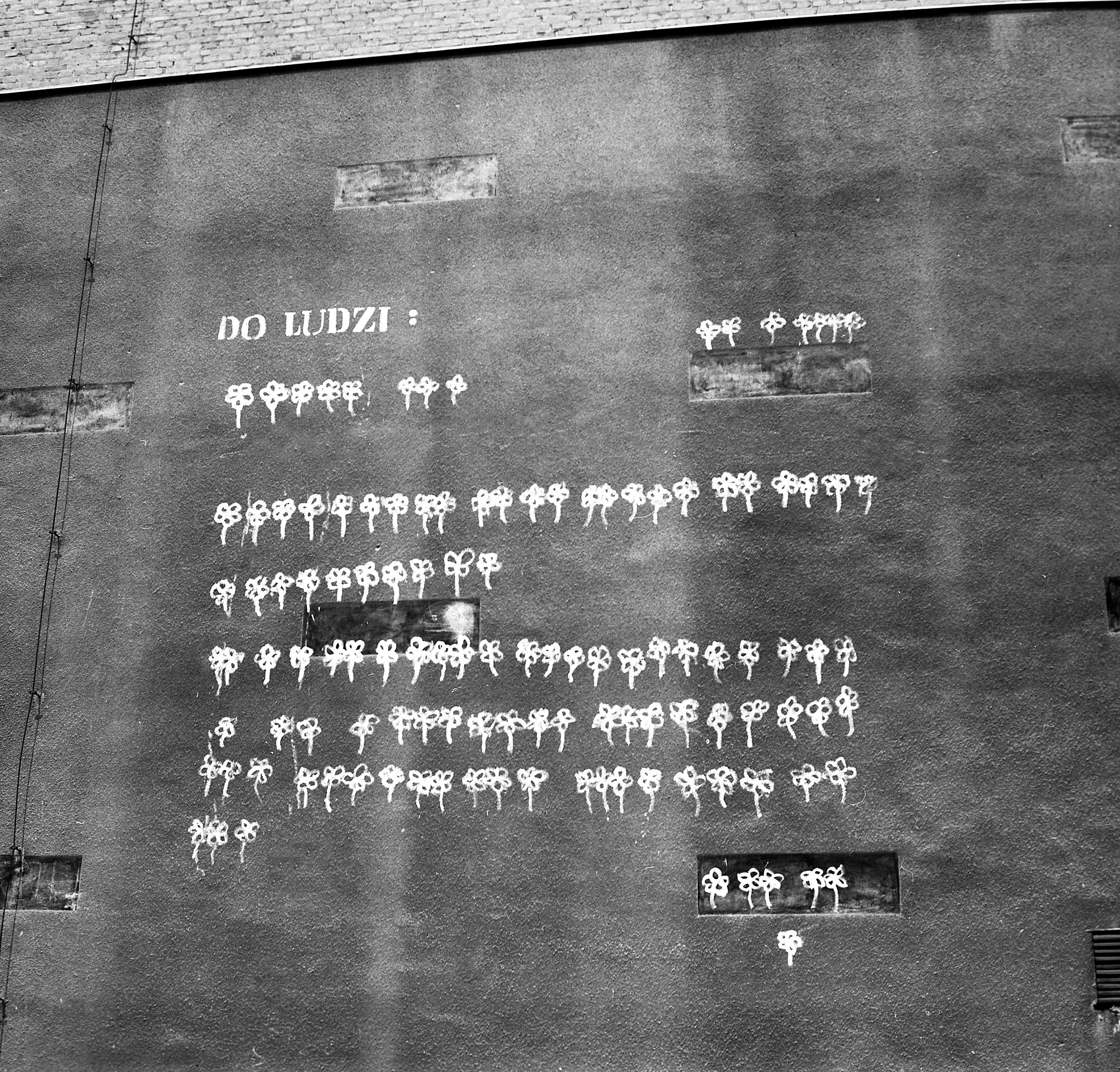

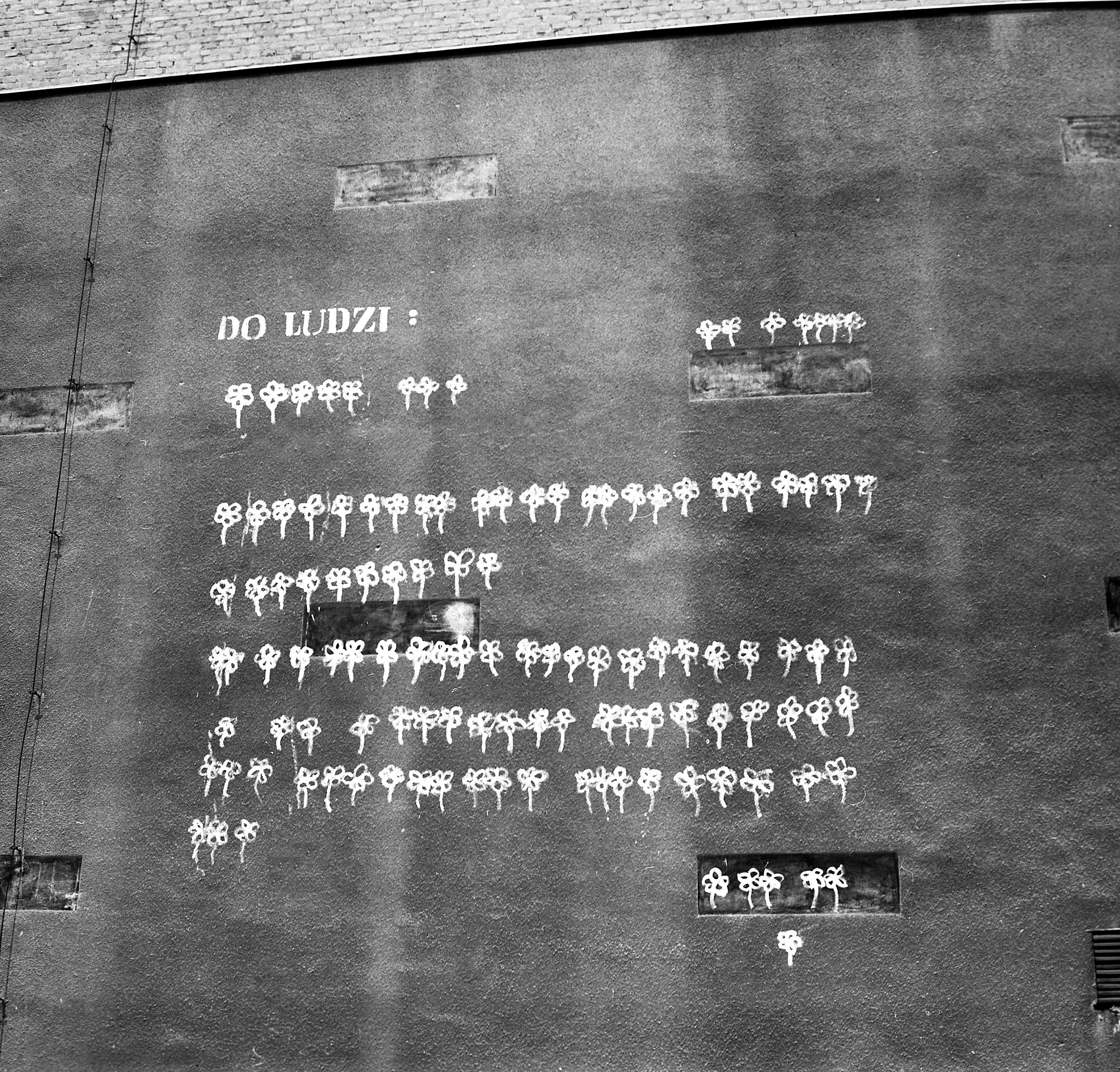

The photo shows probably the first artistic mural in Poland, made by Christian Wabl in 1973, during the Fifth Biennial of Spatial Forms Cinema Laboratory (Kino Laboratorium) in Elbląg. The mural showing "a letter to the people" made of flowers' pictographs instead of letters of the alphabet was painted on the wall of the Mechanical Works Zamech company. Tomasz Sikorski made the photo during the Biennale in 1973.

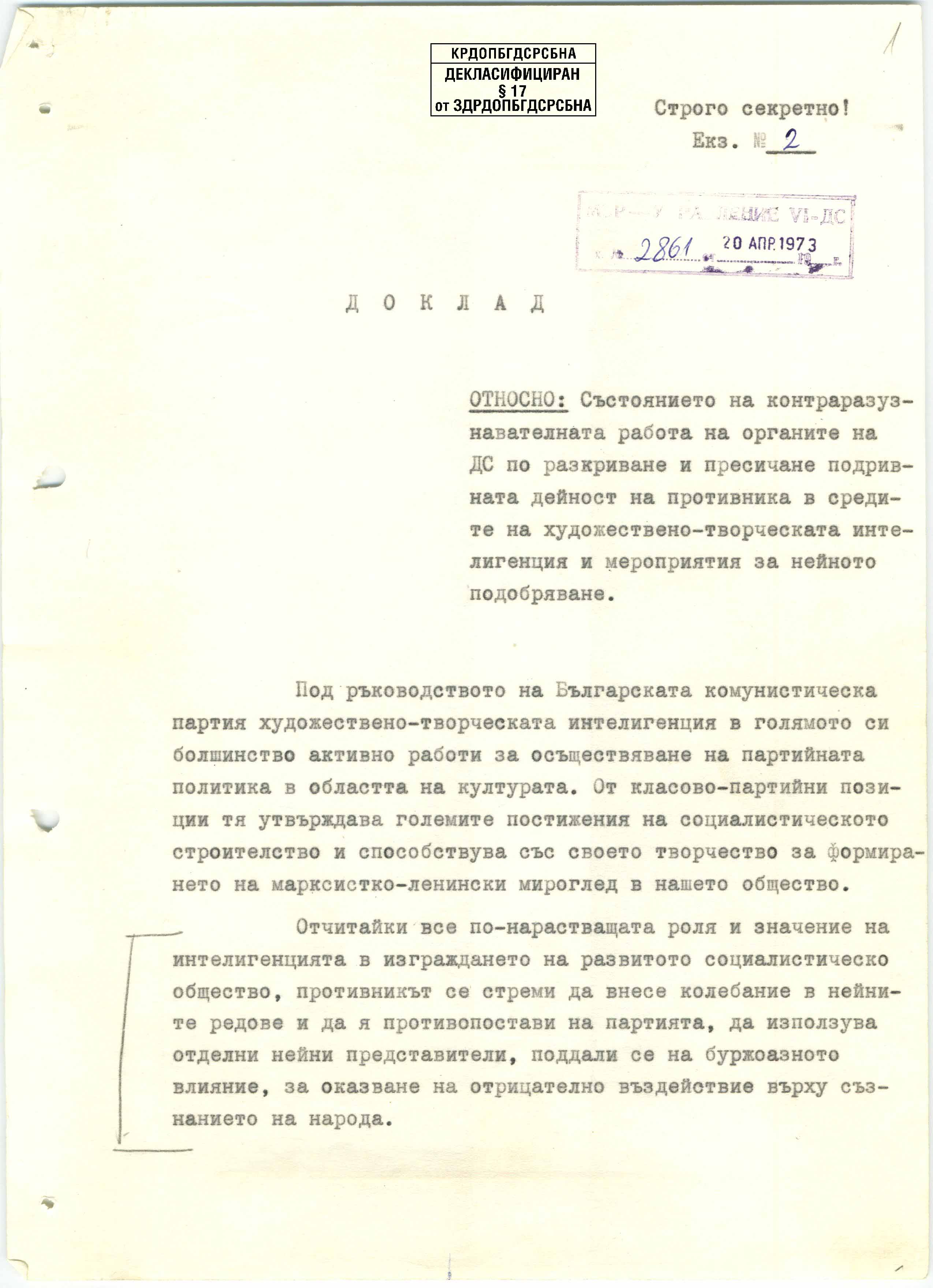

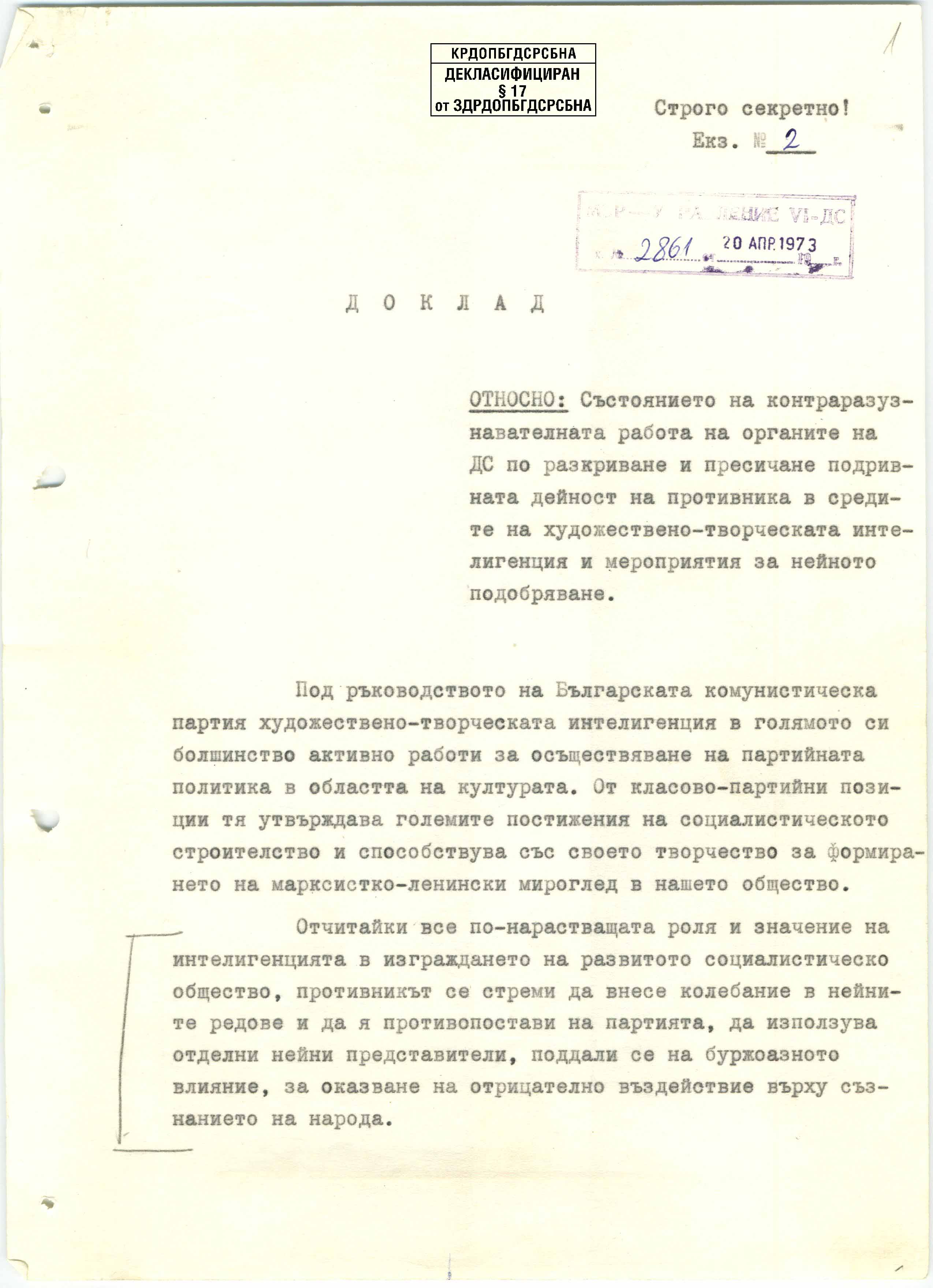

Report "The status of counter-intelligence work of the State Security to unveil and suppress the subversive activities of the enemy among the artistic intelligentsia and measures for its improvement", Sofia, April 20, 1973.

The report presents the state security's vision of how "the enemy" tries to win over wavering members of the artistic intelligentsia (whose majority is said to support and promote the party line). It is reported that among the intelligentsia groups of friends are formed in so called ‘microstructures’ opposing the policies of the party. Typical examples of this are said to be the writers Hristo Ganev, Valeri Petrov, Marko Ganchev, Gotcho Gotchev and Blagoy Dimitrov. The report is a good example for the assessment of the political attitudes of the intelligentsia by the state in the early 1970s, and also of the way how such assessments were rhetorically framed.

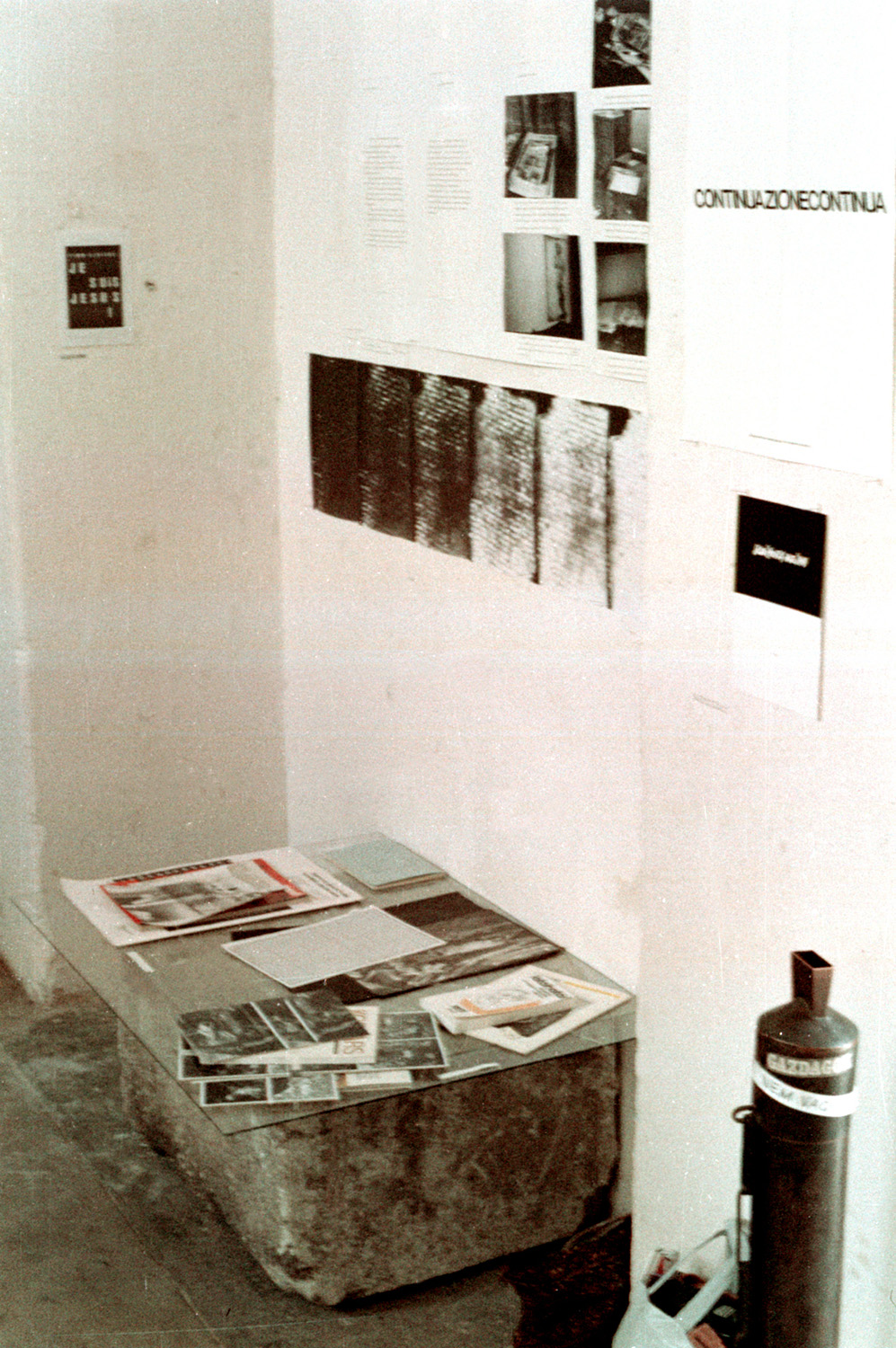

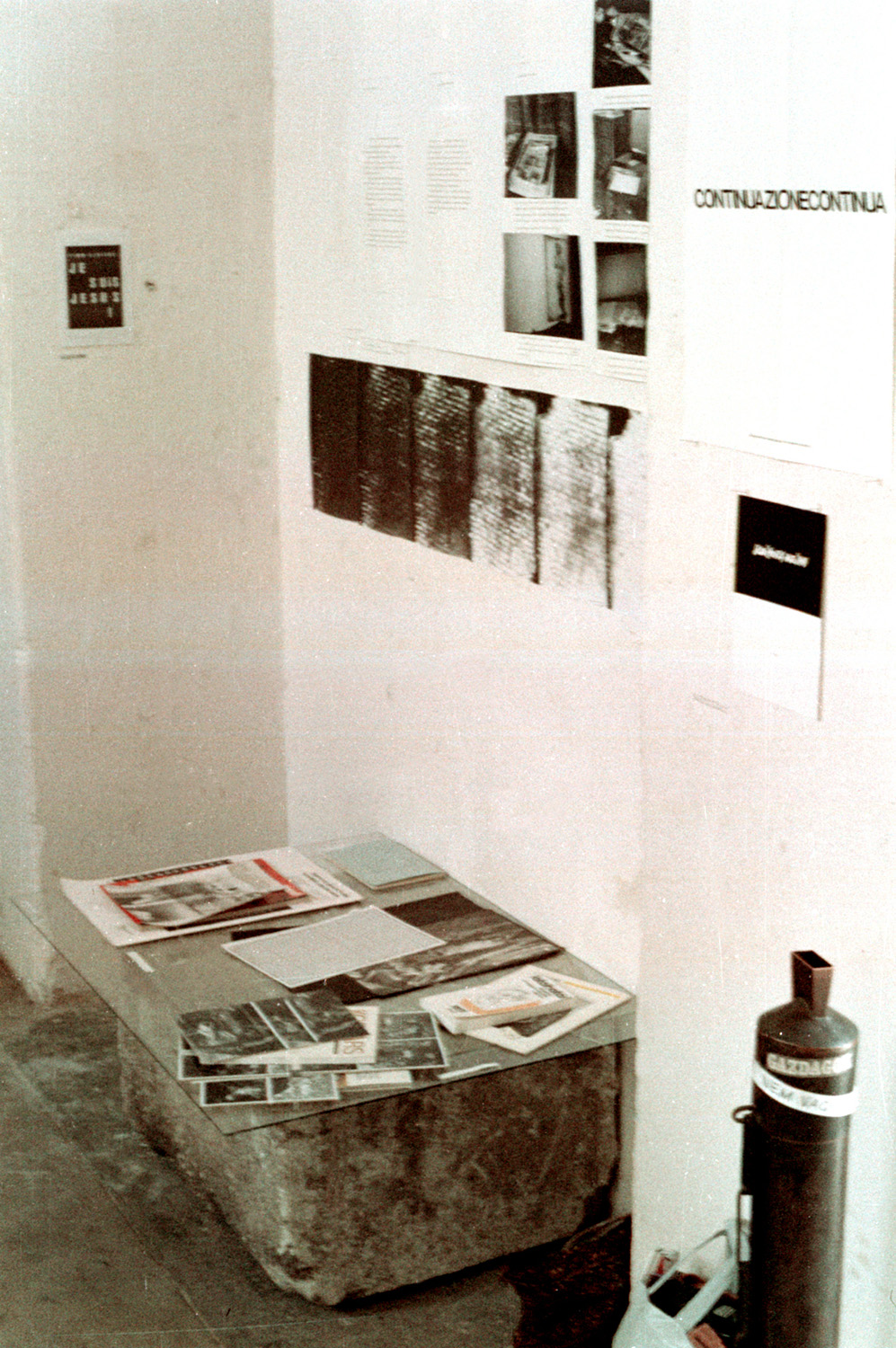

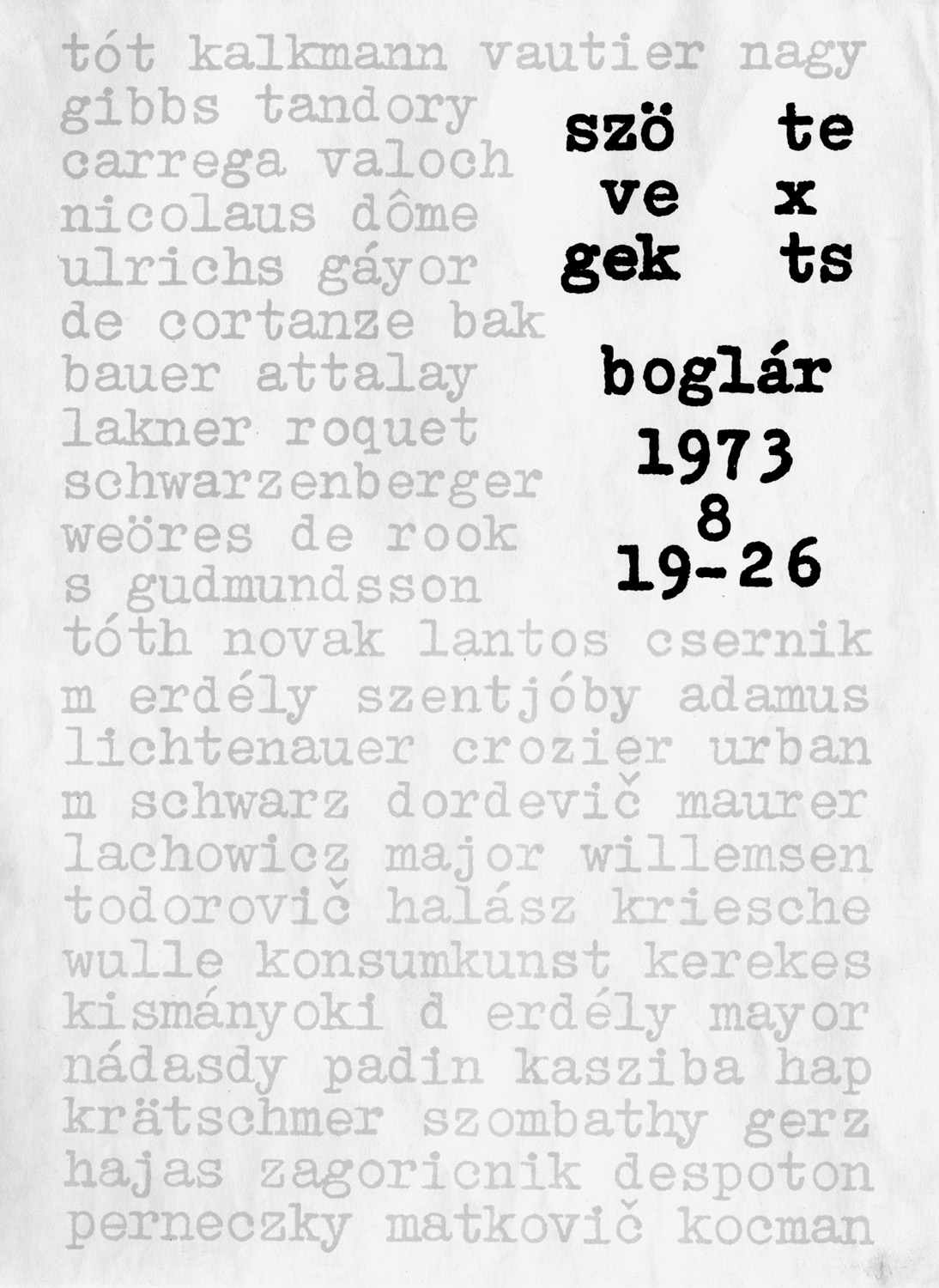

Exhibition Szövegek / Texts, August 19–25, 1973, organized by Dóra Maurer and Gábor Tóth. Conception: Dóra Maurer

Szövegek / Texts was the first international exhibition of visual experimental poetry in Hungary including concrete texts, visual poetry, text-based conceptual artworks, and other poetry related experiments. The conception of the exhibition came from Dóra Maurer who, with the help of Gábor Tóth, has worked on an international collection of text based works for years. The exhibition at Balatonboglár was accompanied by concrete poetry actions, such as Hommage à Tristan Tzara by Dóra Maurer, or Fire/Ice by Tibor Gáyor.

Participants: Gábor Attalai, Imre Bak, Ugo Carrega, Robin Crozier, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Gáyor, Jochen Gerz, Michael Gibbs, Tibor Hajas, H. W. Kalkmann, J. H. Kocman, László Lakner, János Major, Slavko Matkovic´, Dóra Maurer, David Mayor, János Nádasdy, Maurizio Nannucci, Clemente Padin, Géza Perneczky, G. J. De Rook, Tamás Szentjóby, Bálint Szombathy, Miroljub Todorovic´, Endre Tót, Gábor Tóth, Timm Ulrichs, Janos Urban, Jirí Valoch, Ben Vautier, Franci Zagoricnik and others.

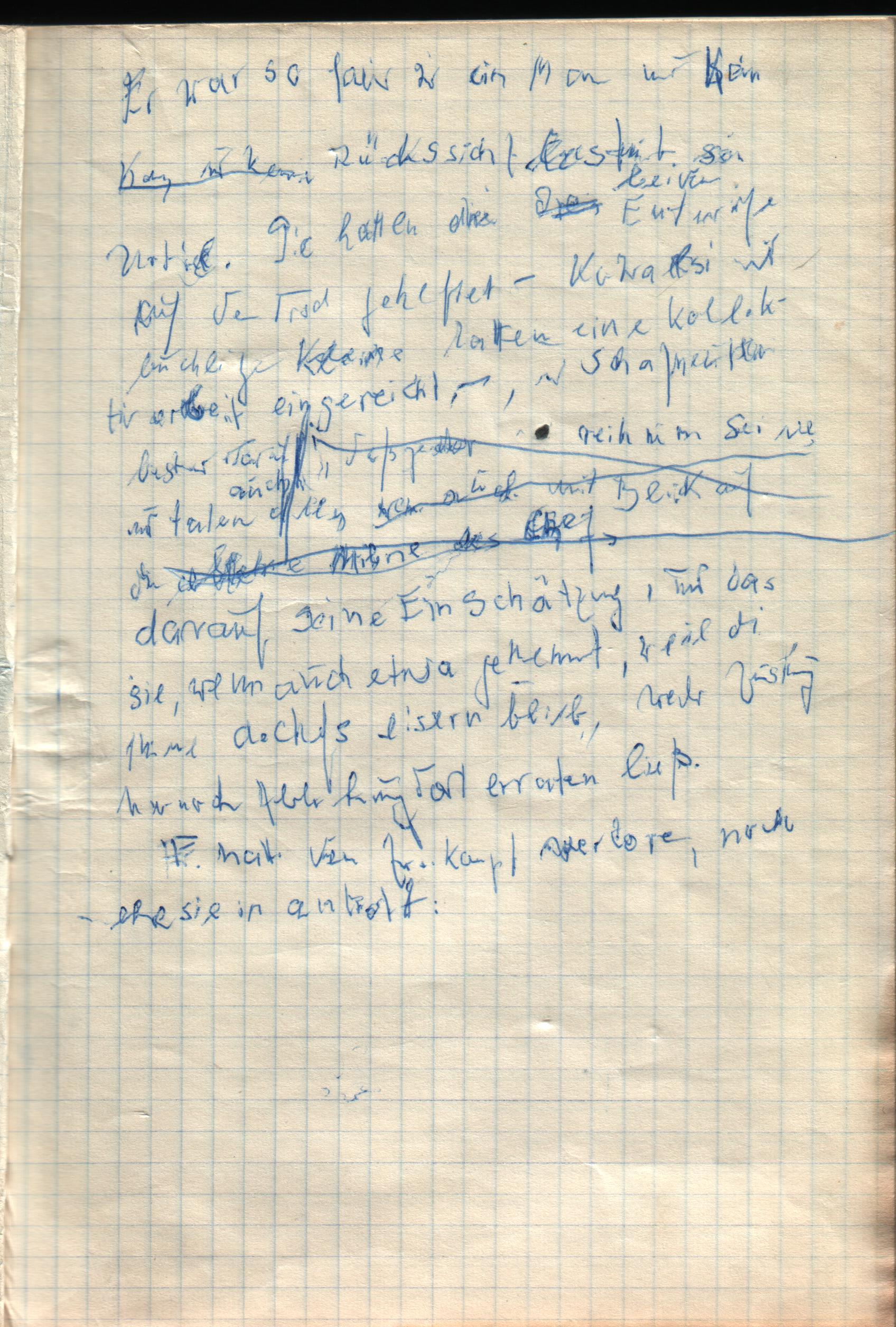

Brigitte Reimann was unable to complete what is regarded as perhaps her most important work, the novel "Franziska Linkerhand“ which details the failure of a jaded, young female architect to embrace socialism. She worked on the novel from 1963 until her death 10 years later in 1973. In 1974 the fragments were published by the Berlin-based New Life publishing house and translated quickly into multiple Eastern European languages. Additionally, the work was licensed for publication in West Germany and adapted for the stage and television. The final page of the original manuscript remained unreleased until the unabridged new edition was published in 1998. [Transcription of the scanned masterpiece] He was only as fair as a man could be

(…) Consideration (…) his judgement. They bound the two drafts on the table – Kowalski and his humpbacked little pal had submitted a collective work -, and Schafheutlin insisted (…) his estimation, that they, although somewhat hampered, since the voice of the boss remained unwavering, revealed no inkling as to whether he approved or rejected the work.

Fr. had lost the duel, before she even entered the competition.

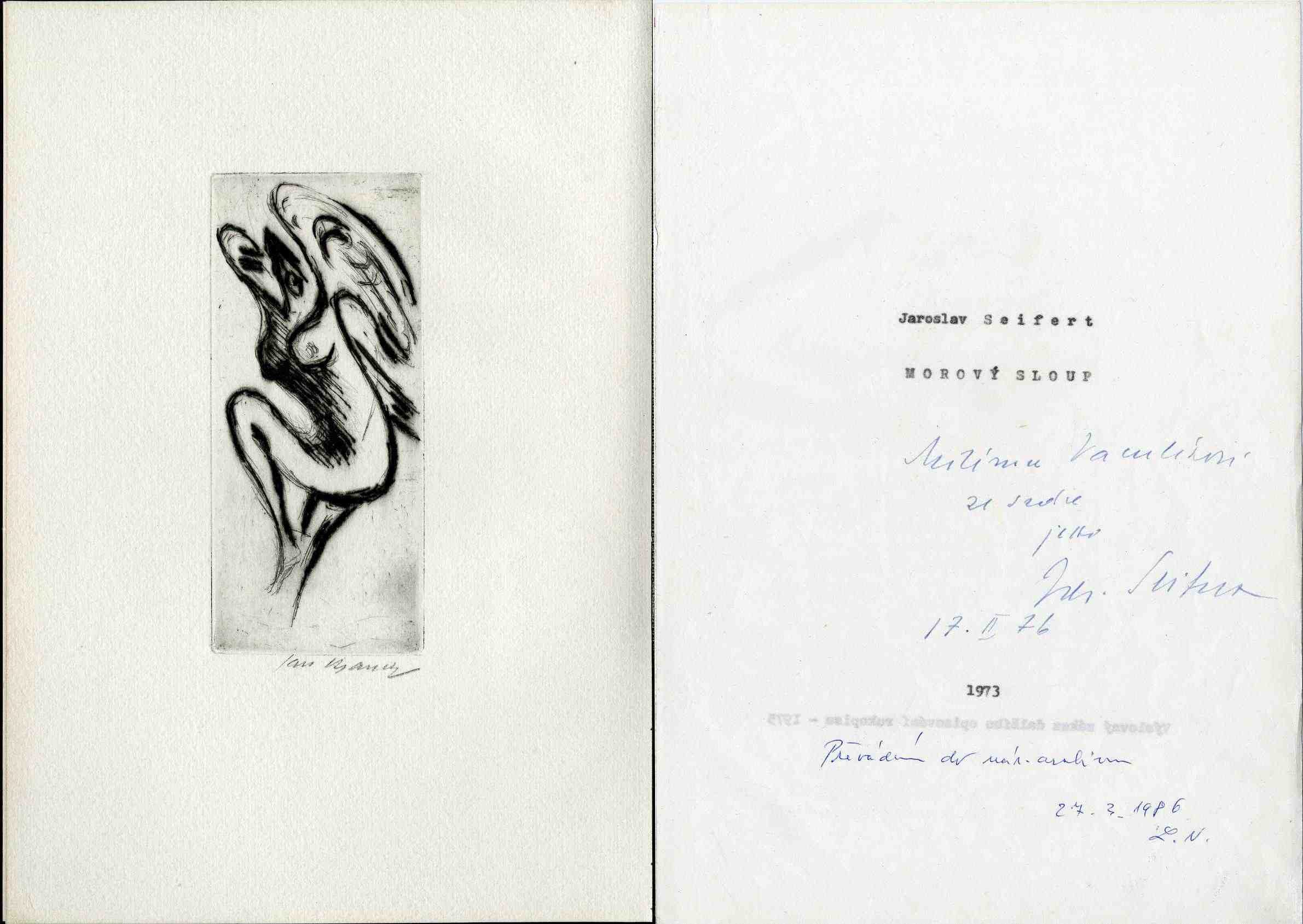

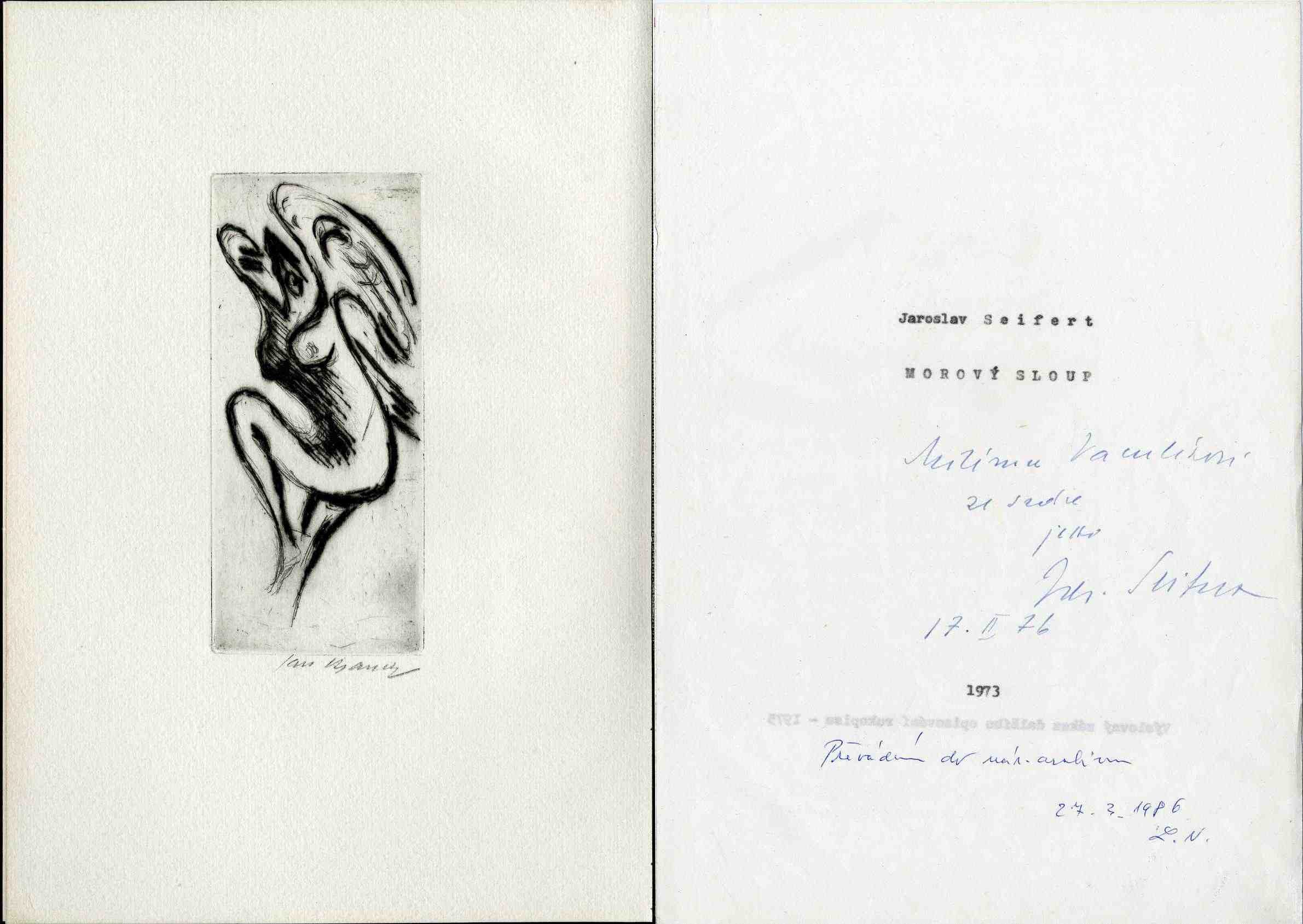

"Morový sloup", a collection of poetry by Jaroslav Seifert, was published in the samizdat edition Edice Petlici in 1973. The book is supplemented with illustrations by Jan Bauch. Inside is the dedication by the author to Ludvík Vaculík, who was the founder and organizer of Edice Petlici. And in 1986 he made another dedication, "Transforming into the National Archives", referring to the newly-exiled Czechoslovak Documentation Center of Independent Literature, founded by historian Vilém Prečan together with other personalities of Czechoslovak exile. In the seventies, the collection was published several times abroad, and in Bohemia for the first time in 1981.