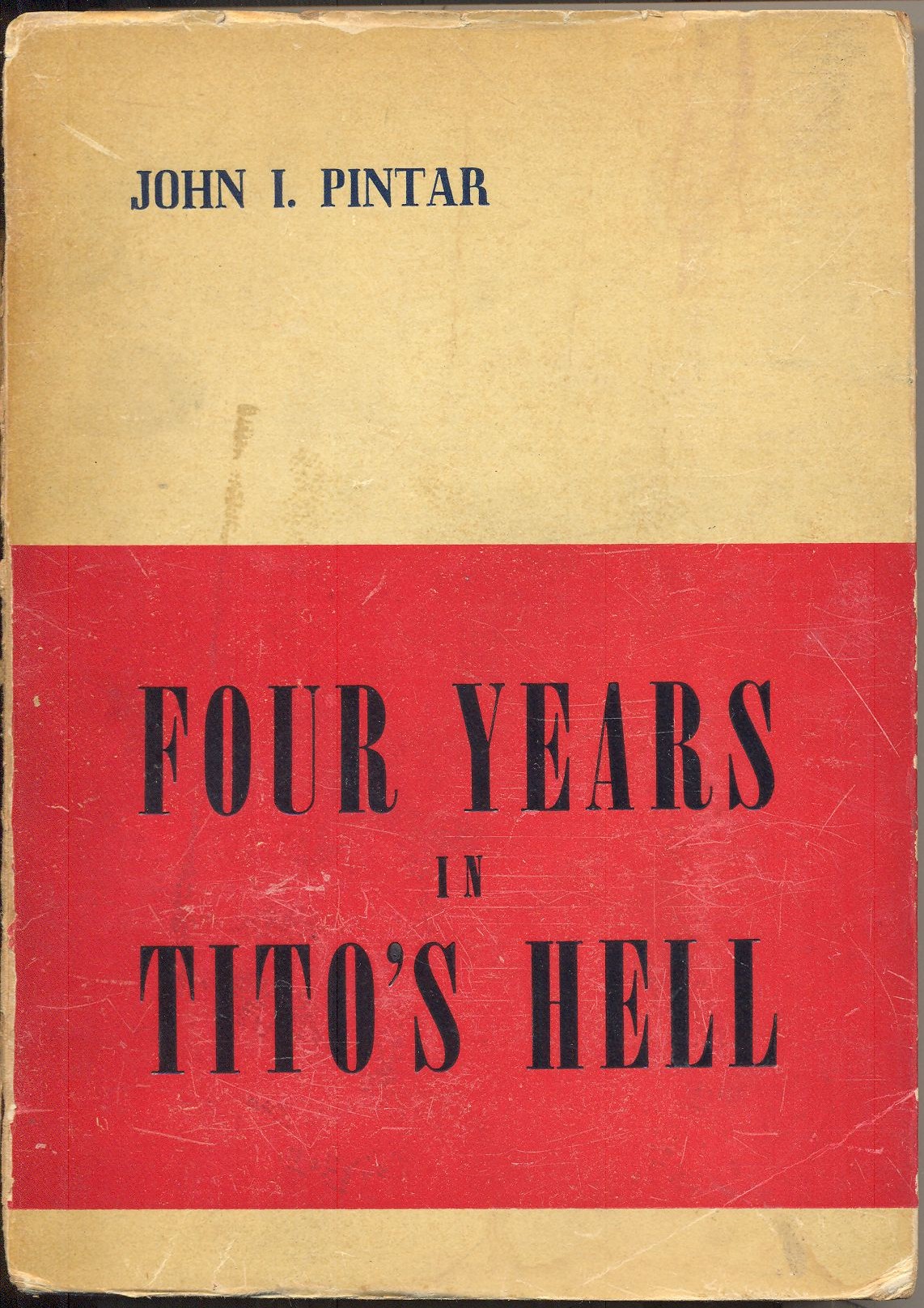

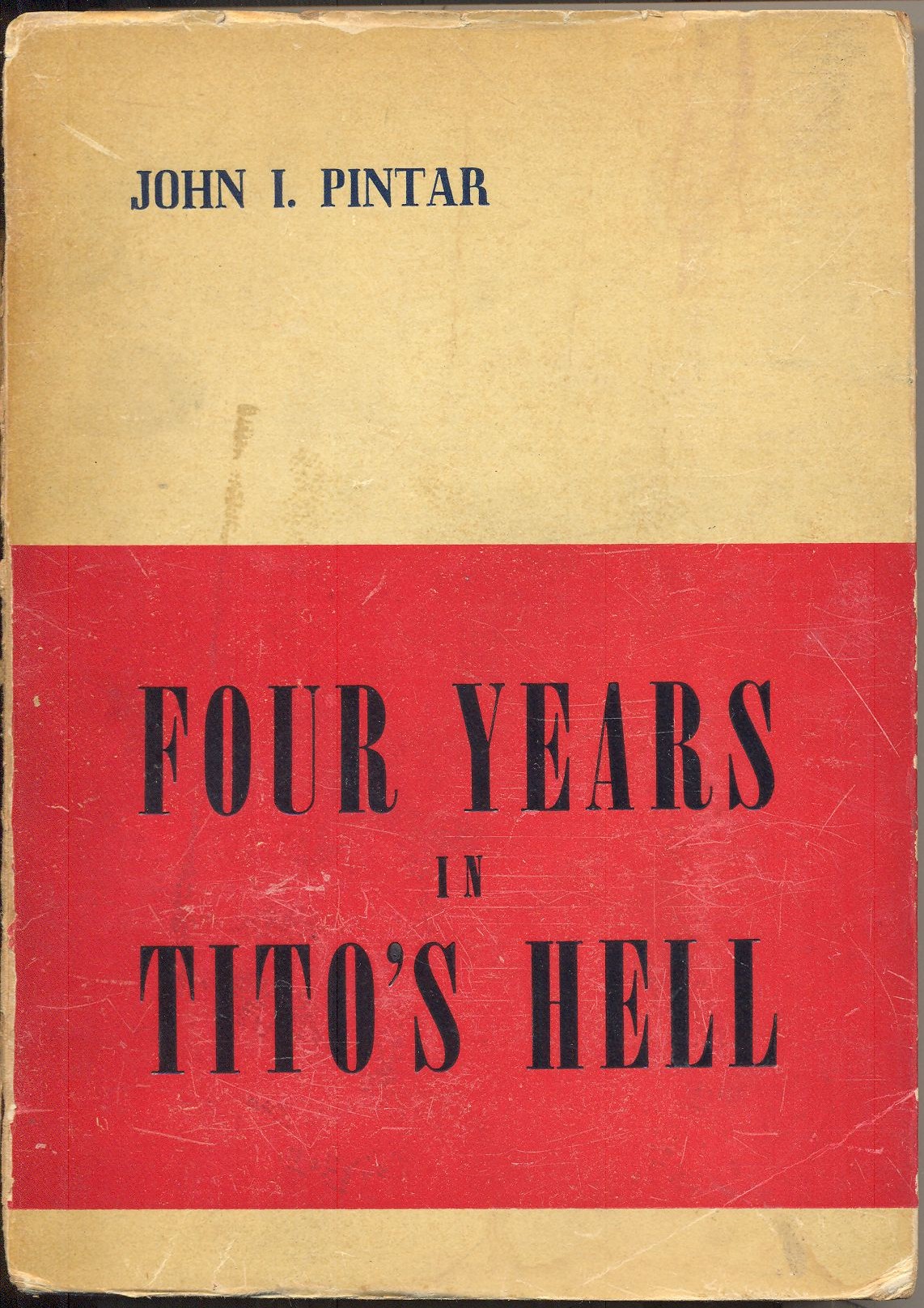

John I. (Ivan) Pintar was an American citizen and entrepreneur who lived and worked in Zagreb since the mid-1930s. After World War Two, the communist regime in Yugoslavia arrested him in the autumn of 1946 and sentenced him to death in early 1947 after a show trial under charges of being an American spy. Thanks to the mediation of US authorities and the US embassy in Belgrade, his sentence was reduced to 20 years in prison with forced labour.

After four years spent in jail in Lepoglava and Srijemska Mitrovica, and after the persistent efforts of the US Department of State and US Ambassador to Belgrade George V. Allen, he was released at the end of 1950 and returned to the United States (New York). He wrote a book on the communist regime and his prison experience. He could not publish the book in Yugoslavia, nor in the United States, as officials in the Yugoslav embassy in Washington obstructed him in his efforts to do so. Certain Yugoslav diplomats even offered him money to hand over the manuscript to prevent its publication. Ljeposav Peranić, a pre-war Croatian immigrant in Argentina, provided help to Pintar and he published his book in Buenos Aires with a print run of 3,000 copies. Pintar dedicated the book to all victims of communism. He served his sentence in Lepoglava prison in 1947, when Zagreb Archbishop Alojzije Stepinac was also imprisoned there. Pintar testified about Stepinac’s imprisonment. In the conclusion of his book, Pintar said: “What I experienced in Tito's Communist State has been repeated in every country which has had the misfortune to come under Communist control” (Pintar 1954, 295). In 1995, the book was also published in Croatian.

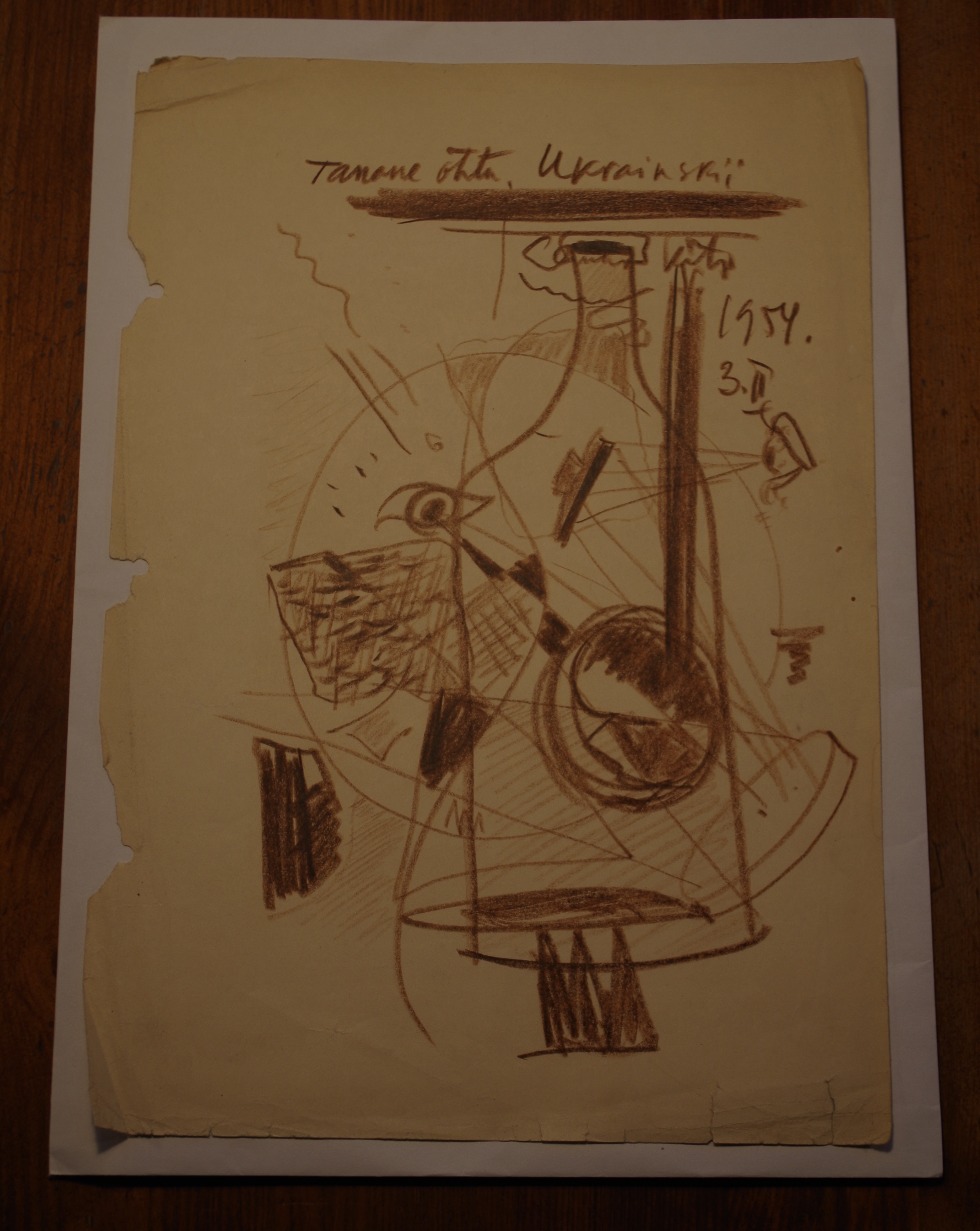

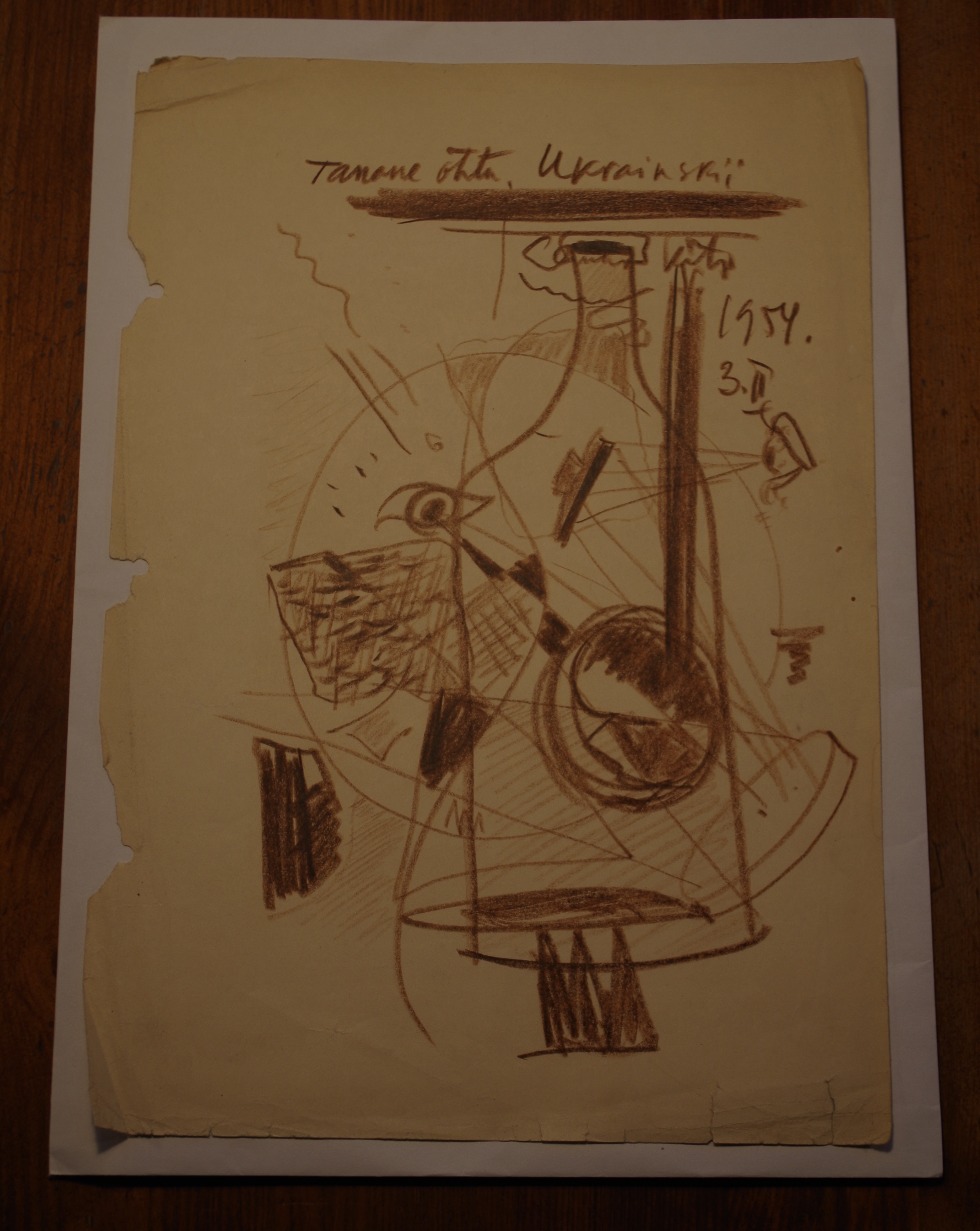

The abstract drawing by Elmar Kits is dated 1954. Kits only showed his abstract work publicly in 1966, when he held a solo exhibition at Tartu Art House. Along with other exhibitions the same year, this exhibition is considered to be one of the most remarkable events in Estonian art history, and ‘the manifestation of modern art and the top event in the 1960s’. The solo exhibition of work by Kits led to a turn in Estonian art life: abstract art, which was criticised before, became more accepted.

Nevertheless, this abstract drawing in the collection of Indrek Hirv is not well known, and it therefore remains unacknowledged. Kits drew it casually as a gift for his friend Louis Pavel, Hirv’s father, during a drinking party in 1954. It is drawn in brown pencil, and the shape of a bottle is recognisable in the picture. The words tänane õhtu. ukrainskii (tonight. ukrainskii) are also written on the drawing, and the date 3 February 1954.

Indrek Hirv considers this work to be a masterpiece in his collection in the context of cultural opposition, because it contrasted clearly with the prevailing Socialist Realism, and anticipated the exhibition that took place over ten years later, and the art reforms in the 1960s in general.

He has also offered this drawing to exhibitions, but it has nevertheless not so far been seen by a wider audience.

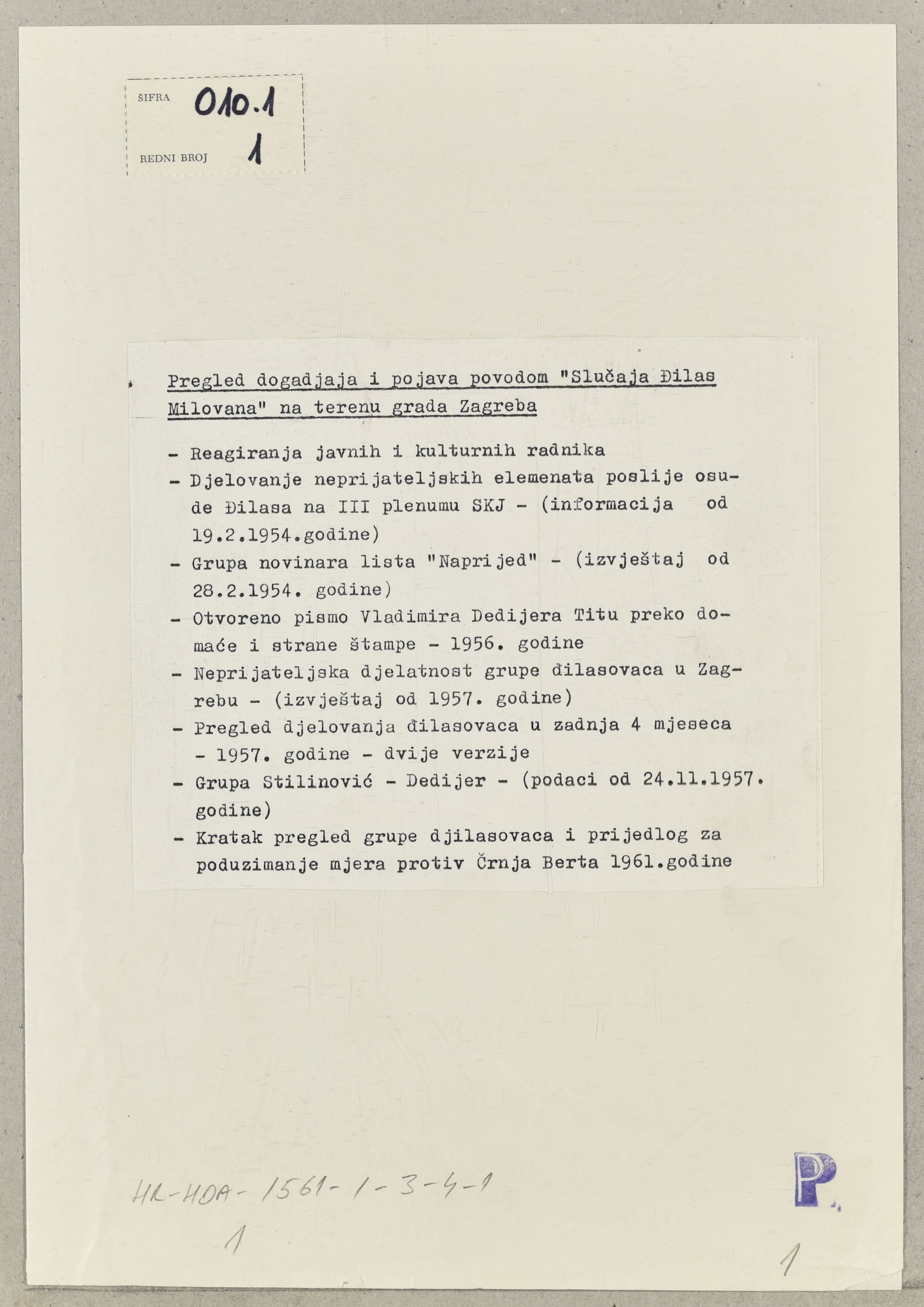

Information of the State Security Service/Zagreb Department on reactions to the Djilas case in Croatia. 19 February 1954. Archival document

Information of the State Security Service/Zagreb Department on reactions to the Djilas case in Croatia. 19 February 1954. Archival document

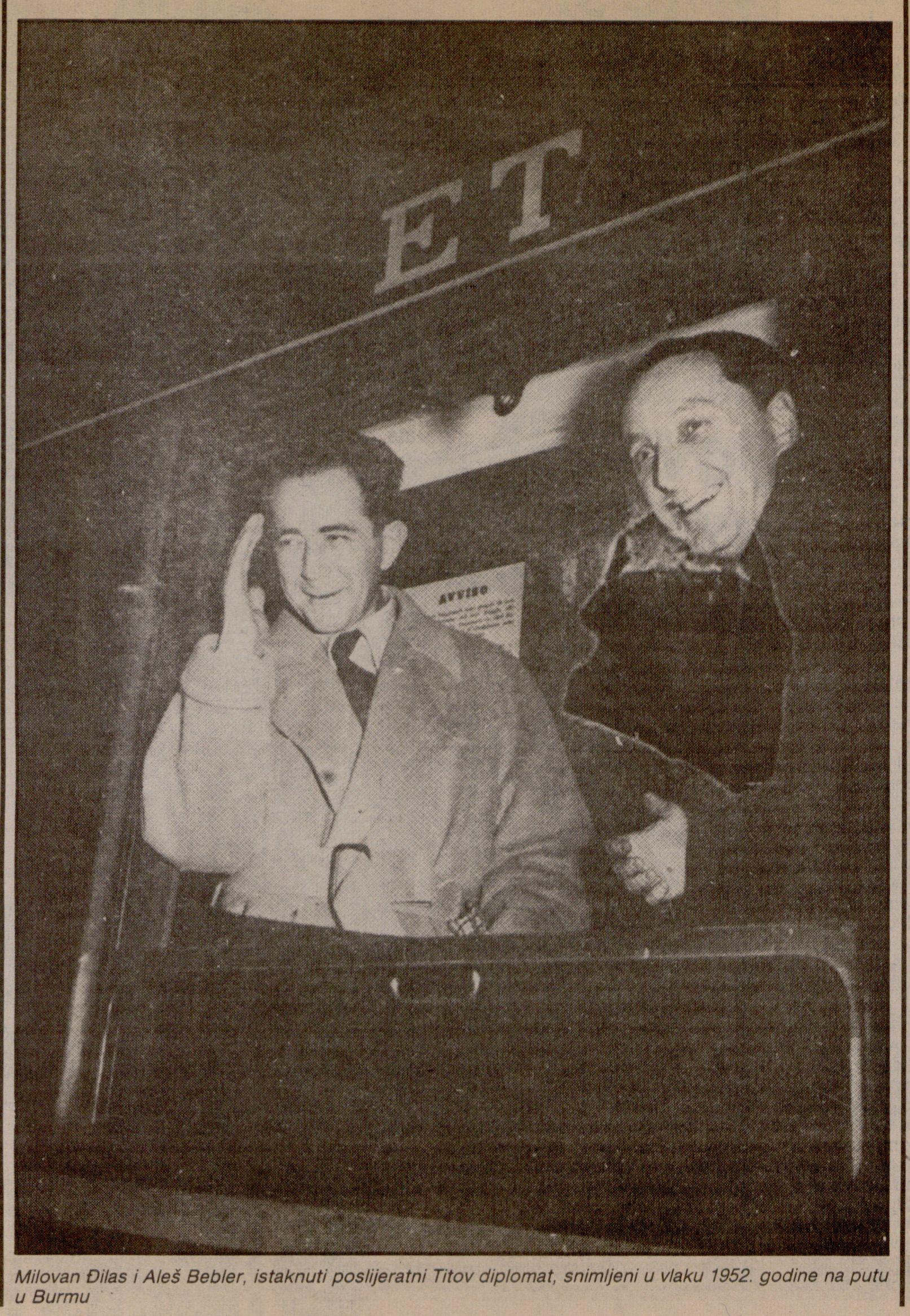

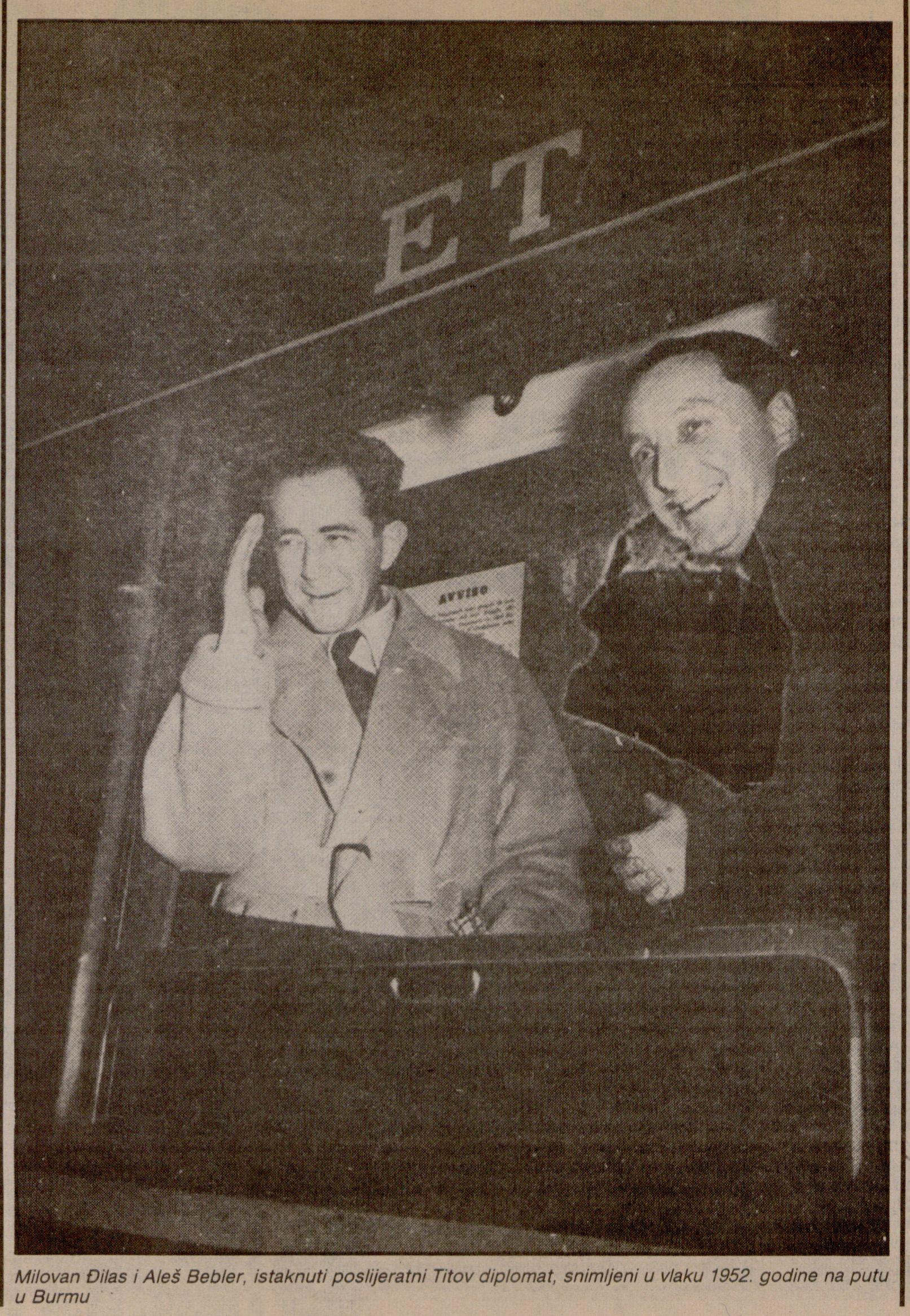

In 1953, Milovan Đilas, a high-ranking member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, published a series of articles on the need for democratization and liberalization of Yugoslav society, which led to his condemnation at Party forums and expulsion from the Party. Yugoslav communist leaders labelled all of those who supported similar ideas Djilasovci, i.e., Djilas supporters (Radelić 2010, p. 56).

The Croatian State Security Service accorded considerable attention to such cases. In an extensive analysis conducted in February 1954, the Department in Zagreb provided an overview of responses to the Djilas case in public and cultural circles, especially among journalists, staff at the University of Zagreb, and groups which were already considered opposition to the communist regime (i.e., persons under surveillance due to the Cominform split, the clergy, members of former non-communist political parties). But, Naprijed's editorial board, led by Dušan Diminić, and many “of their supporters in other newspaper editorial boards (Vjesnik, Vjesnik u srijedu) were specifically singled out, as they had been “adopted anarchist and anti-Marxist positions even before Djilas and his articles, which just encouraged them to go in that directionˮ (HR-HDA-1561. SDS RSUP SRH, code 010.1/1-1). The Croatian State Security Service also described the influence of Djilas supporters, i.e., connections to certain “lobbiesˮ in other parts of Croatia, especially in Istria (Pula, Buzet, Poreč and Pazin). At that time, such “localismˮ was also a serious political label (Spehnjak and Cipek 2007, p. 272).

The document has 18 pages. It is available for research and copying.

The Congress of the MWU held in 1954 seemed an unlikely place for raising controversial issues, while the chairman of the Union, Andrei Lupan, seemed an even more unlikely candidate for that. Lupan’s social and ideological background was irreproachable from the regime’s point of view, while his literary credentials were superior to those of many of his colleagues due to his education in interwar Romania. He generally supported the “Bessarabian” camp within the MWU and contributed to the improved quality of the literary output produced by its members, but his closeness to the regime was also indisputable. This ambiguity characterised Lupan’s entire career, and he was attacked by representatives of the “1960s generation” during the late 1980s for his political opportunism and failure to act on behalf of his colleagues persecuted by the regime (see Masterpiece 2). However, in 1954, just after Stalin’s death and in the as yet uncertain climate of the emerging “thaw,” Lupan openly tackled the issue of the classic literary heritage in one of the first public discussions on this topic. This question was controversial mainly due to the “common literary heritage” that Romanian and “Moldavian” culture shared. In the first post-war years, the Soviet authorities attempted, albeit with less vigour, to continue the “Moldavian” nation-building project launched in the MASSR in the interwar period, which postulated the existence of a separate “Moldavian” nation and culture. This also presupposed the construction of a distinct standard language, as well as the rejection of cultural and literary figures deemed “un-Moldavian” and linked to Romanian “bourgeois nationalism.” However, starting from the mid-1950s, the “common cultural heritage” of “Moldavian” and Romanian culture began to be emphasised by the “Bessarabian” faction. This was in line with other similar cultural battles waged on the Soviet periphery, such as those of the Tajik / Persian and Karelian / Finnish affinities. Still, the issue of “classic heritage” was primarily a stake in the internal struggle within the MWU between the “Bessarabians” and the “Transnistrians,” with the former supporting the partial rehabilitation of the traditional Romanian cultural canon and the latter adamantly opposed to it. The central institutions in Moscow sided with the “Bessarabians,” thus securing their final victory. In his report, Lupan mentions, first, the success of the project aimed at publishing the “classics” (among whom he included figures whose works had already been published, like A. Donici, C. Negruzzi, I. Creangă, C. Stamati, M. Eminescu, but also other prominent writers not yet fully included into the ”Soviet Moldavian” literary canon, e.g., V. Alecsandri, A. Russo, I. Neculce, D. Cantemir, A. Mateevici – all hailing from the historical Moldavian Principality). However, besides the customary criticism of “bourgeois nationalism,” Lupan also openly admitted that “our classic literature is intimately historically connected to Romanian literature,” being “a common treasure for both peoples.” This bold statement, given the context of the era, was supplemented by his criticism of “distortions and lack of clarity” that could result in “erasing our cultural heritage.” Lupan’s reference to writers such as George Coșbuc, Alexandru Vlahuță, and Ioan Slavici (coming from outside the “Moldavian” geographical area) as part of this heritage is especially striking. He harshly criticised an article published earlier in the official newspaper Sovetskaia Moldaviia (Soviet Moldavia), which tried to “appropriate” Eminescu exclusively for “Moldavian” culture, denying the common cultural heritage with Romania. Lupan’s position was clearly approved by the centre, signalling Moscow’s changing attitude in this regard. Lupan contrasted the “national dignity” purportedly fostered by the rehabilitation of the classic heritage to the “cosmopolitanism and [bourgeois] nationalism” reviled by the Soviet regime, but still found that the publication of the classics “will assist in the development of our literature, in solving the most complicated questions of the Moldavian literary language, will contribute to the enrichment and polishing of our language.” Finally, Lupan was clearly advocating the revision of the literary standard according to the model of “classic literature,” i.e., according to the Romanian model (without, of course, stating this explicitly) and condemned excessive “folkloric” influences. All these opinions had hardly been acceptable several years before. In fact, Lupan’s speech indicated a fundamental shift in official policy, which was to culminate with the total “rehabilitation of the classics” and an effective return to the Romanian literary standard in 1957. This case also shows that revisions in cultural policies on the Soviet peripheries, customarily associated with Khrushchev’s Thaw, were in fact initiated immediately after Stalin’s death, in 1954. The combination of local cultural battles with central signals, openly visible in Lupan’s speech, is what makes this example especially interesting. This case also highlights the generational and ideological contrast with the Perestroika period of the 1980s. As the controversy and open conflict between Lupan and Grigore Vieru shows (see Masterpiece 2), although the issues at stake remained similar, their interpretation was starkly different in the two periods. Beyond the similarities in substance, the generational and ideological conflicts of the 1980s signified a new and radical stage in the internal dynamics of the MWU and in its position toward the regime.

The American artist Christo (Christo Vladimirov Javacheff) descends from a Bulgarian industrialist family.

In 1953, he began his studies at the Higher Institute of Fine Arts (HIFA). In 1954, the talented student painted the painting "Rest". That was a time when the theme of "socialist building" established itself as a leading one in art. The representation of the development of heavy industry (factories, reservoirs, highways, works) was a priority. The collectivization (respectively mechanization) of agriculture and livestock breeding was also one of the important topics in propagandist art: portraits of brigade leaders, shock-workers, innovators, team leaders, heroes of labour, eminent front-rankers, labour competitions "running high". The painting of Yavashev lacks a labour enthusiasm – the faces are depressed, the poses express fatigue, the falling horizon dramatizes the feeling of despair (Iliev 2016: 106). The painting was highly criticized by the Rector of the Higher Institute of Fine Arts, Prof. Panayot Panayotov, "because of the colourful clothing and the inclined horizon" (Stefan Javacheff, cited through Iliev 2016: 106). The Rector determined the clear ideological requirements of the Institute: "Our institution of higher education is ideological. It is wrong to think that the good painter, sculptor or applied artist could fulfil the tasks required by the present day regardless of whether he has or has not a socialist view of life, a new vision and attitude toward the world." (Panayotov 1958, cited through Iliev 2016: 106). Thus, the painting was not only criticized but it remained unknown, preserved by the painter's brother.

Christo Javacheff found a way out of the environment that suppressed art by emigrating in 1957. Together with his wife Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon Christo Javacheff became world-known.

After the political changes, the art of Christo Javacheff – Christo slowly won official recognition in Bulgaria. Christo's first significant exhibition was realized not until 2015 at the Sofia City Art Gallery.

The composition "Rest" never left the home of Stefan Javacheff; its reproduction in real size was shown for the first time at the exhibition "Forms of Resistance".

The collection includes Croatian State Security Service's file on the case of first and best known Yugoslav dissident, Milovan Djilas, and its reception in Croatia. During 1953, Djilas published a series of articles in the newspaper Borba on the need for democratization and liberalization of Yugoslav society, which led to his condemnation at Party forums and expulsion from the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. In Croatia, similar ideas were mainly manifested in the weekly Naprijed, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Croatia. It led to open conflict with Party leaders and the suppression of the newspaper, while its journalists were forced to halt their careers in journalism. The collection includes different analysis and reports on operational measures conducted by the Croatian State Security Service against the Naprijed group and other Djilas supporters (Djilasovci) in Croatia until the beginning of 1960s.

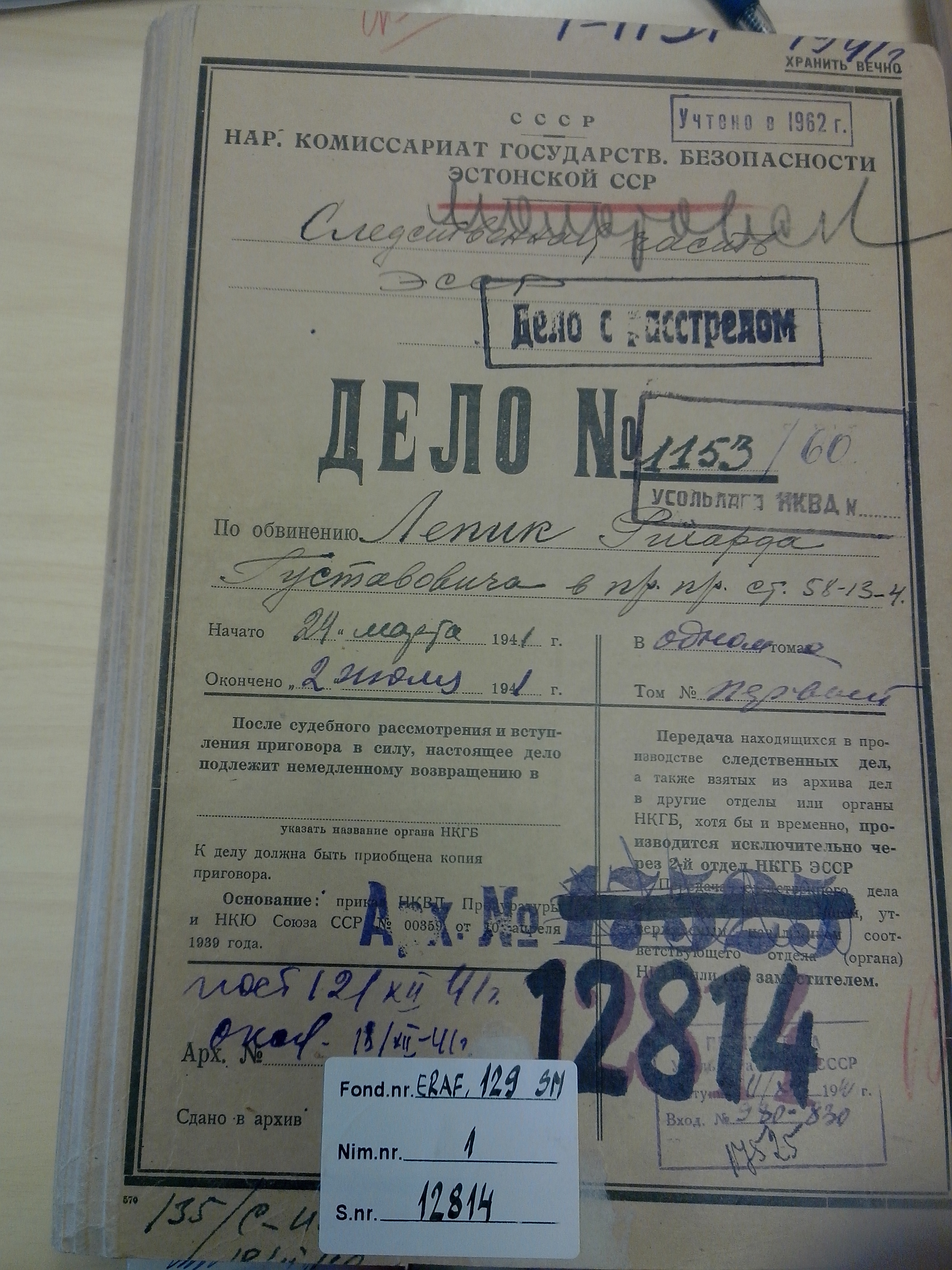

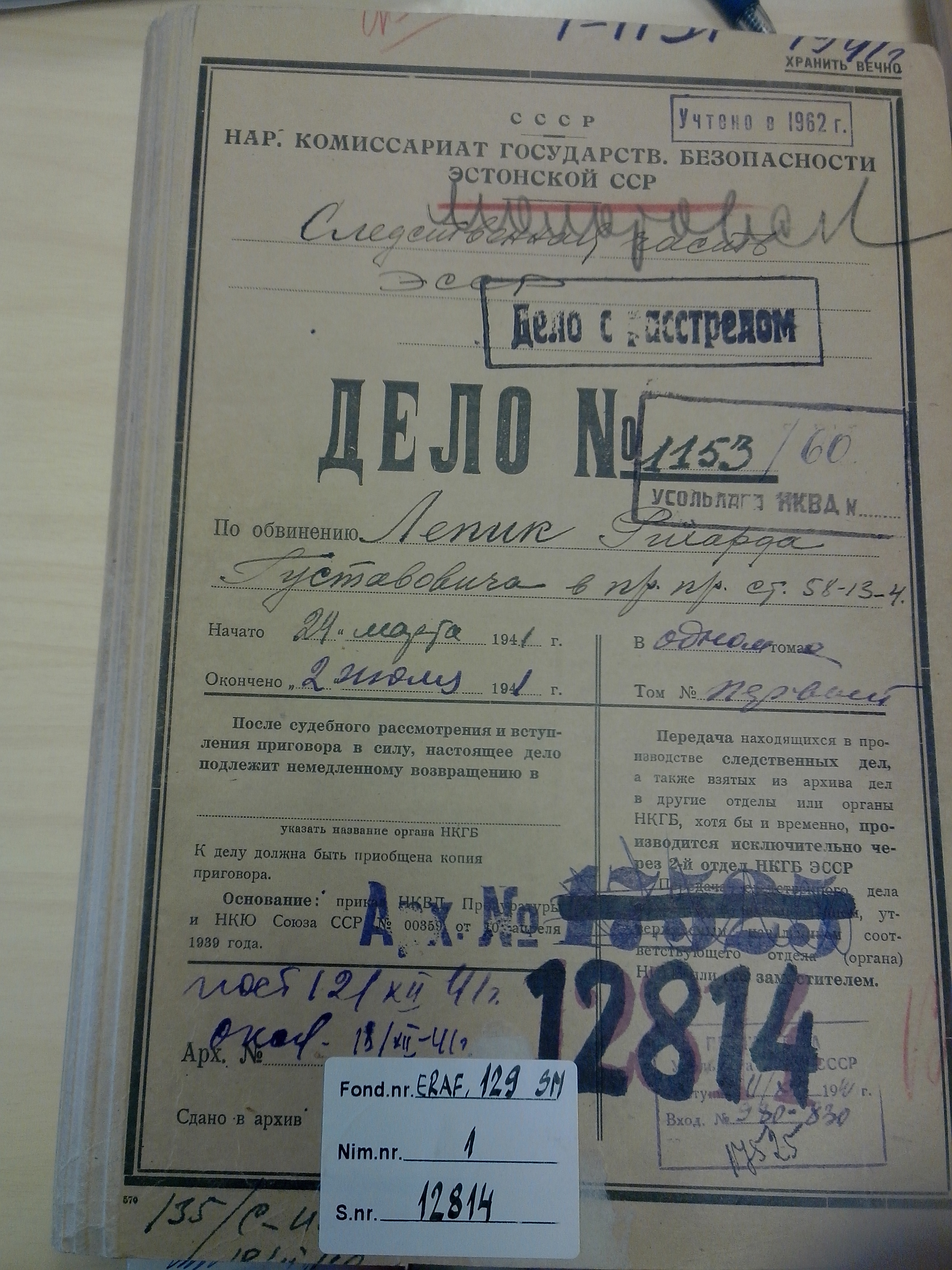

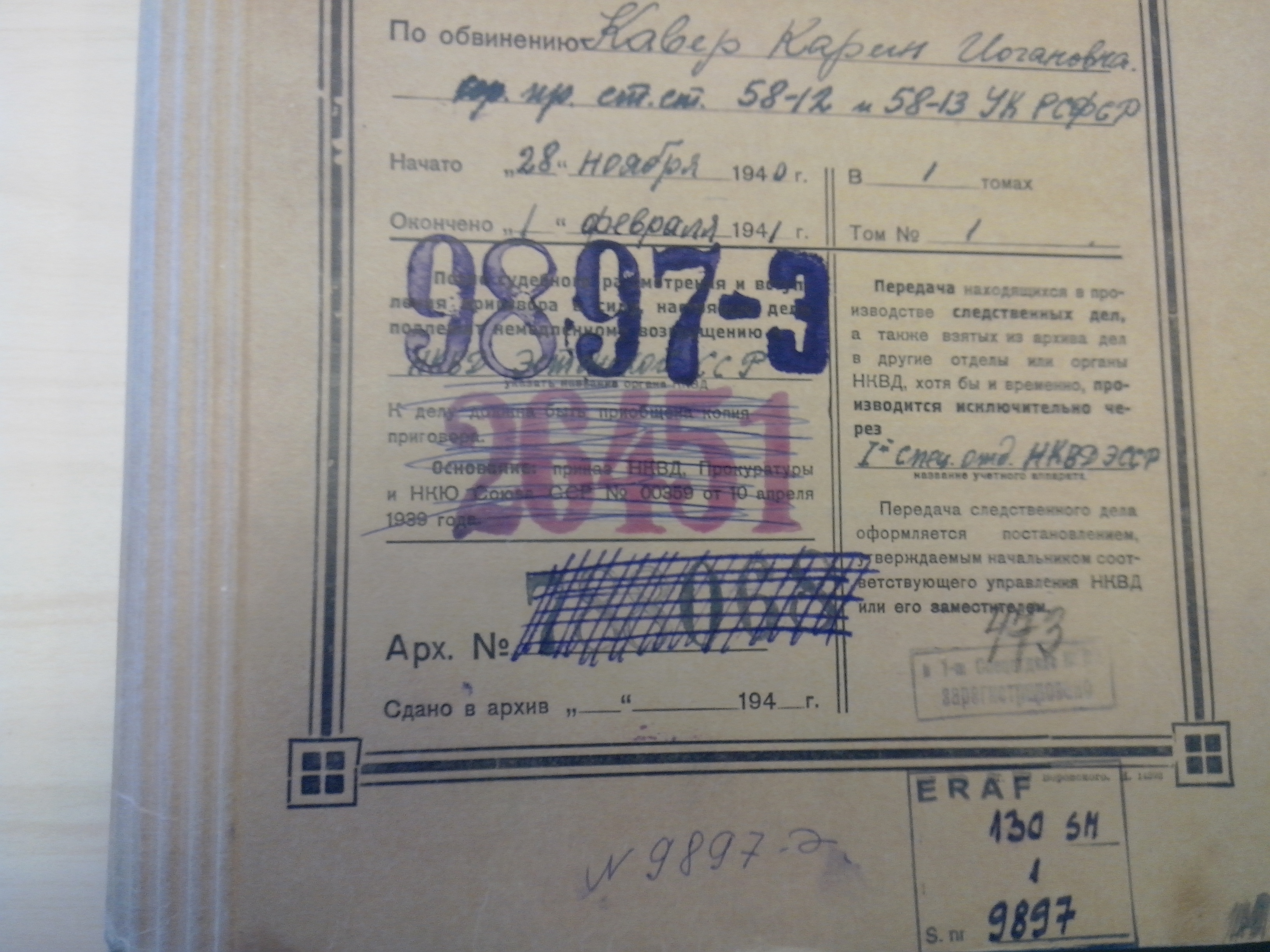

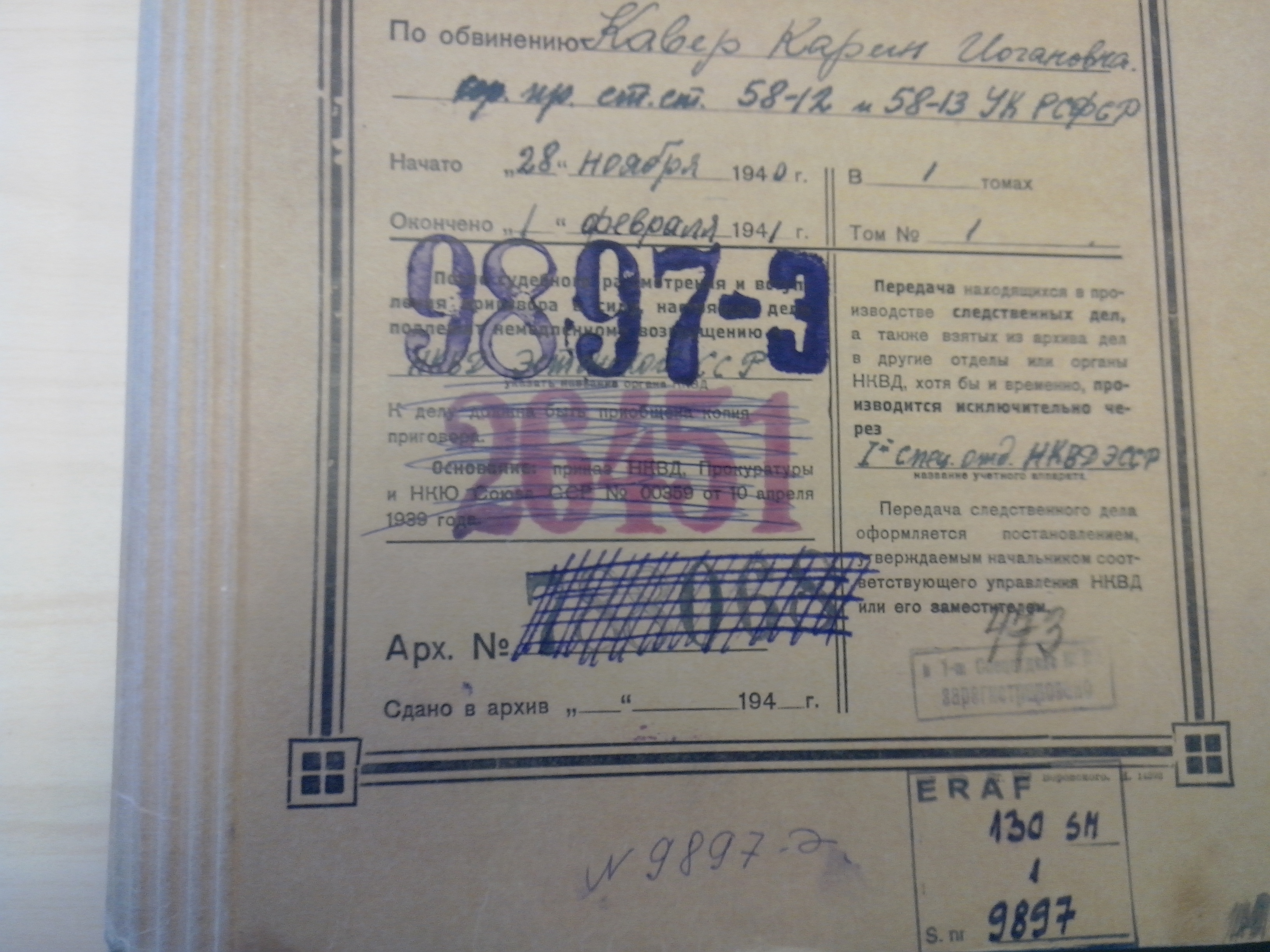

The collection of incomplete investigative files at the National Archives of Estonia is an extensive, though partial, set of investigative files about people who were persecuted during the Soviet period. A significant part of the collection is made up of the files of persecuted cultural figures. The cases included in this collection were still open when the KGB was liquidated in 1991.

The photographies from the Tomislav Peternek collection at the Museum for Contemporary Art in Belgrade document scenes of significant historical protests and conflicts between people and the police in socialist Yugoslavia. In addition to the photographers outstanding faculties in aesthetic terms, the photographies are examples of the modernist current that have intersected with photographic socrealism. The photo from the series "Red University" [Crveni univerzitet] was part of a significant exhibition held at the Belgrade Youth Center [Domu omladine Beograda] right after the end of student protests in Belgrade in 1968 despite the high risk to be threatened by the authorities and the police.

The collection of completed investigative files at the National Archives of Estonia is an extensive set of investigative files about people who were persecuted during the Soviet period. A significant part of the collection is made up of files about persecuted cultural figures. The files in this collection are complete, which means that the interest of the authorities towards a person (or persons) had ended, due to death, rehabilitation or other reasons, and the cases were closed.