The poem’s original title was Szaltószabadság, a neologism difficult to translate (roughly, “Summersault Freedom”). It means “the freedom of flipping in the air,” but it also echoes the word sajtószabadság, which means “freedom of the press.” When the journal Mozgó Világ was launched by the Central Committee of the Communist Youth Organization (KISZ) in December 1975, Nagy’s poem was to appear in the first issue with its original title. However, the censors demanded that it be changed: editor Miklós Veress and the poet choose a line from the poet referring to Korbut.

Grandma Tells a Tale (poplar, acacia, 80x50x37 cm, 1975)

The point of departure of the sculptures of Géza Samu is often an abandoned object of rural origins, which he then reinterprets with sculptural means. Grandma Tells a Tale, a wooden sculpture, is also built around the form of a traditional piece of peasant furniture, a milking stool. This is then augmented with simple, playfully assembled carved forms, thus becoming anthropomorphic and evoking the figure of the grandmother in an emblematic way. The assembly of the elements, which are made out of different types of wood, rewrites the theme in a surprising way, moving away both from folk woodcarving traditions and sculptural conventions and elevating the composition into a dreamy state. The sculpture seems to be traditionalist and experimental at the same time.

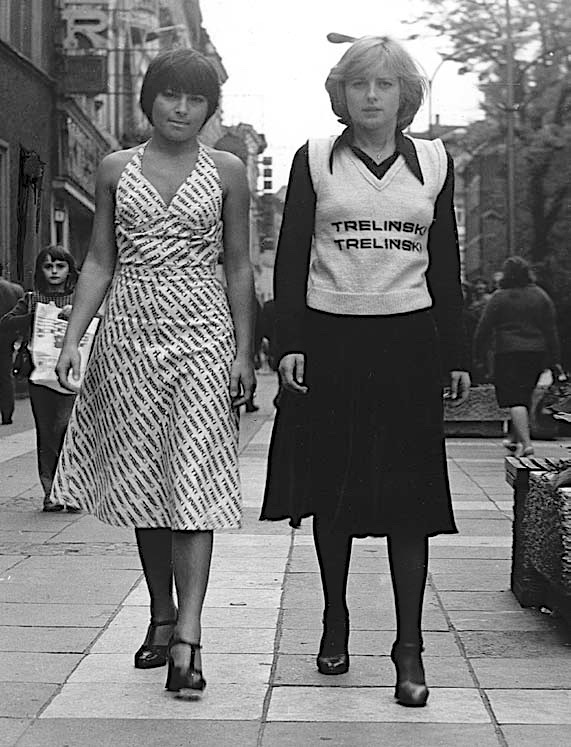

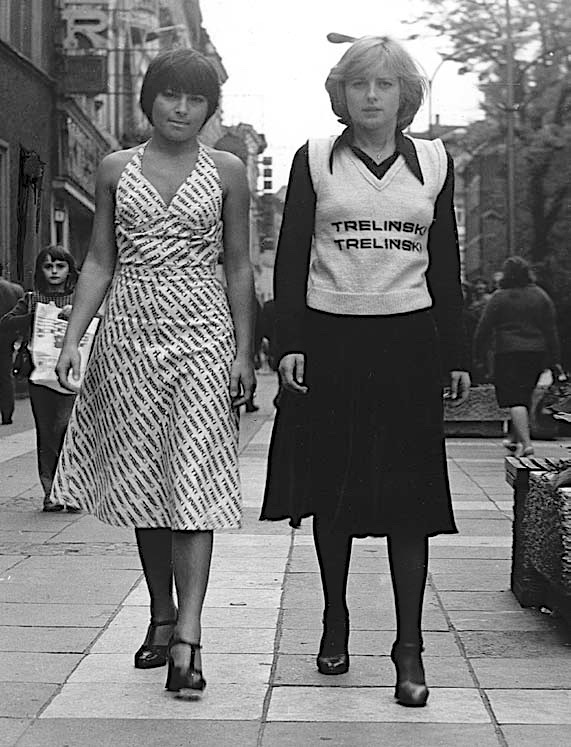

The photography from the Tomasz Sikorski collection presents Clothes – a piece from the cycle Self-tautologies – Nothing about Myself created by Jerzy Treliński in the 1970s. On the photo, there are two women walking the street in Zielona Góra city in 1975. First of them has the dress, while the second – the vest with prints ‘Treliński’. The prints on the clothes were made from the same typographical pattern.Treliński as an artist is for the whole his life associated with the Łódź neo-avantgarde milieu. He combined within his works the inspiration form the conceptualism and Russian constructivism. In the Self-tautologies cycle, he created a lot of objects, from books, posters, and postcards, to clothes and flags, to pencil graffiti and everyday-life objects. All of the items were marked by the creator’s surname, always made as the same graphic sign. That way, signaling his presence, Treliński did not reveal anything about himself, while the sign of his individuality became the commentary to the social reality.Source:Łukasz Guzek, Najbardziej radykalne postawy w ruchu galerii konceptualnych lat siedemdziesiątych. Galeria 80x140 Jerzego Trelińskiego i Galeria A4 Andrzeja Pierzgalskiego [The Most Radical Attitudes Within The Movement Of 'Conceptual Galleries' In The 70s. Jerzy Trelinski's Gallery 80x140 And Andrzej Pierzgalski's Gallery A4], „Sztuka i Dokumentacja”, nr 4/2011, s. 49-68.

During half a century spent in exile (1940–1990), Ion Raţiu manifested a constant interest in the political situation in Romania under both Antonescu and communist dictatorships. His involvement was materialised in various initiatives of organising the Romanian exile in Western Europe or writing about Romanian issues either as a journalist or as a political analist. His writings represent a coherent critical aproach to communist regimes and distinguish themselves through the contributions they make to a complex analysis of Soviet propaganda abroad, especially in the developing countries (such that provided in Moscow Challenges the World), but also through the astute observations on the features of Ceauşescu’s regime in the essay Contemporary Romania: Her Place in World Affairs. This is a critical evaluation of what was perceived at that time in the West as a detachment of the Romanian communist regime from Moscow’s strict control. In the first part of the book, Raţiu provides an overview of the history of the Romanian Communist Party before its coming to power and of the first decade of the communist regime in Romania. In the second part, the author delivers a critical assessment of the “nationalist turn” of Romanian communism during the 1960s and early 1970s. His main hypothesis is that the nationalism of the Romanian communist leaders, especially Gheorghiu-Dej, was not a “genuine” one because the latter had not displayed any nationalist attitudes previously (Raţiu 1975, 31–33). On the contrary, up to the mid-1950s, he was a servile instrument of Soviet policies in Romania. According to Raţiu, the “nationalist turn” makes sense in the context of the conflict with Moscow caused by the changes that the Soviet leaders wanted to impose on COMECON, which would have stopped the industrialisation drive in Romania and transformed it mainly into an exporter of primary commodities and an importer of industrial products. In the third part, Raţiu analyses the evolution of relations between the Soviet Union and Ceauşescu’s Romania during the first part of the 1970s and questions Ceauşescu’s Romania’s “independence” in relation to Moscow. In the last part of the book, Raţiu emphasises that this image of an “independent” Romania in the Eastern Bloc is the result of Ceauşescu’s skilful policies, which have created in the West the illusion that the real tensions of the 1960s have continued. The author argues that simulating conflict with Moscow has became a “profitable business” for Ceauşescu, due to the Western economic support he has obtained with this attitude. Raţiu’s book is one of the first critical assessments that questioned the positive image that Ceauşescu’s regime skilfully created in the West during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Raţiu also provides a complex analysis of the contradictions of Ceauşescu’s regime between its foreign image and its inner ossification in Stalinist political practices: “While maintaining doctrinal purity at home of a strict Stalinist type, the Romanians gradually became the champions of tolerance towards other roads to socialism, and in fact raised this tolerance to the rank of a principle” (Raţiu 1975, 36–37).

The Éva Cseke-Gyimesi Ad-hoc Collection kept by CNSAS contains, besides Securitate files, pieces of evidence regarding the critical approach to the regime inherent in the targeted person’s professional activity, and her struggle against the violation of human rights and for the institutionalisation of minority rights. The collection represents the model story of the Transylvanian Hungarian intellectual observed in the 1970s and 1980s, which exhausts both the meaning of secret police harassment and that of coping with this type of harassment.

Unveiling of the windmill from Beştepe (Dobrogea) at the permanent exhibition of the Museum of Folk Technics, June 1975

Unveiling of the windmill from Beştepe (Dobrogea) at the permanent exhibition of the Museum of Folk Technics, June 1975

The windmill from Beştepe (Northern Dobrogea) is undoubtedly one of the most valuable pieces in the collections of the ASTRA Museum in Sibiu. It reflects the heritage of this province's rural civilisation. It was acquired for the museum by Hedwig Ulrike Ruşdea in 1969, as a result of field research conducted in the area. From 1973 to 1975, Ruşdea oversaw the windmill's reassembly at the museum based on specification sheets prepared during previous field research. The reassembly, carried out by the museum's craftsmen, was partly filmed by the institution's documentary film-maker. In July 1975, it was unveiled in the presence of the director Cornel Irimie and of the local press. Since then, the windmill has been a veritable symbol of the ASTRA Museum, having been used in numerous promotional materials.

Two dolls within which photo-films with the images of Opanas Zalivakha’s paintings was smuggled from Soviet Ukraine to the US

Two dolls within which photo-films with the images of Opanas Zalivakha’s paintings was smuggled from Soviet Ukraine to the US

In their smuggling operations, the Smoloskyp couriers used various ways to obtain and to transport samizdat and other materials of the Ukrainian cultural opposition from Soviet Ukraine. Manuscripts were usually copied as microfilms, hidden in luggages or parcels (in souvenir dolls, busts of Lenin or Shevchenko, etc.). In order to smuggle materials, Smoloskyp agents sometimes used official Canadian Communist delegations that visited Ukraine, as their luggage was checked less thoroughly on the border. Unbeknown to them, Smoloskyp agents attached microfilms to their luggage or talked them into carrying some souvenirs (with microfilms hidden inside).

Nowadays, two doll-containers are displayed on the Smoloskyp permanent exhibition in Kyiv as a symbol of the creative agency of both Ukrainian cultural opposition and Ukrainian diaspora in building hidden communication channels and making the case of the Ukrainian oppositional movement internationally known.

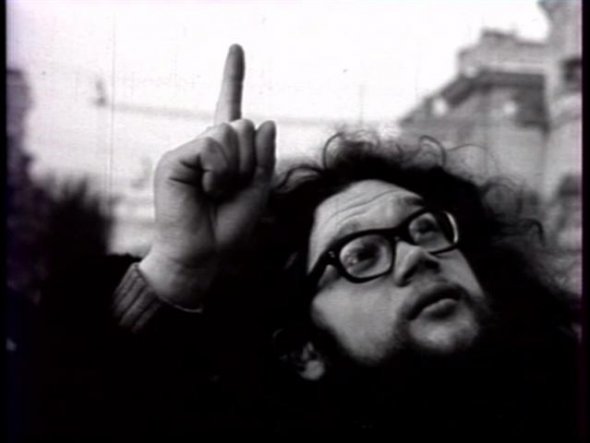

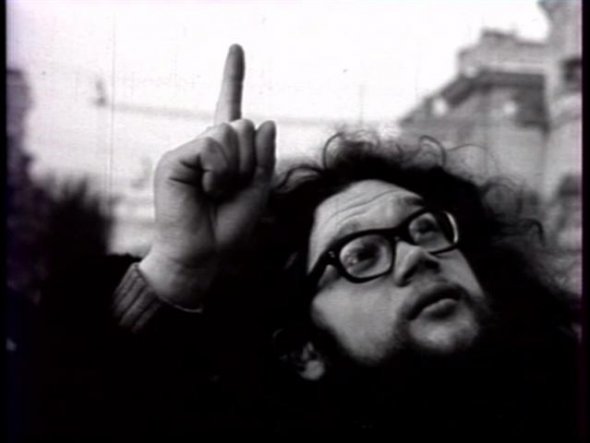

Artūras Barysas-Baras‘ film Tie, kurie nežinote paklauskite tų, kurie žino (Those of you Who don't Know, Ask those Who do) is an avant-garde, 4.5-minute-long silent film made in 1975. The idea of the film could be interpreted as mystical: the action takes place on Cathedral Square, and the main hero points a finger to heaven.

Letter from the Joža Rožanković printing press addressed to the Praxis editorial board, notifying them of the cancellation of printing services, 19 March, 1975.

Letter from the Joža Rožanković printing press addressed to the Praxis editorial board, notifying them of the cancellation of printing services, 19 March, 1975.

The journal Praxis, whose editorial board consisted of Rudi Supek together with Milan Kangrga, Gajo Petrović, Danko Grlić, Ivan Kuvačić, was published from 1964 to 1974, four times a year in the Croatian language. It also had international editions in English, French and German. Intellectuals gathered around the journal advocated for a neo-Marxist approach to philosophy and sociology. Soon this group was called the Praxis intellectuals (Lešaja 2014: 246), and they promoted a social system which would expand the individual's ability to act freely and creatively. From this standpoint, they criticised capitalism and its understanding of human freedoms and rights which, according to them, leads to alienation. But they also criticised the free market elements which were introduced into the economic system of self-management socialism in Yugoslavia in the mid-1960s and certain other aspects of the Yugoslav socialist system which they considered over-bureaucratized. That is why they often came into conflict with the LCY. The journal was repeatedly attacked and censored by the authorities, its financing was blocked, and even though it was not officially banned, its publishing was disabled by “self-management censorship” (Stipčević 2005: 11-12). Namely, the working people of the Joža Rožanković printing company informed the editorial board of their decision not to provide printing services for the journal anymore. The Rudi Supek Personal Papers in the Croatian State Archives (CSA) contain the letter from Franjo Kalapoš, the manager of the printing company, sent in March 1975, notifying the editorial board of Praxis that the self-management bodies and political organisation of the company made the decision that the journal would no longer be printed. The Praxis editorial board then tried to find another printer, but every single one of them refused to print the journal. That is why the already prepared issue of Praxis (6/1974) was never published. According to Gajo Petrović's testimony, “certain forums even told us not to try too hard, as all the presses received the notification and the workers in all of them were quite in agreement regarding the matter” (Lešaja 2014: 286).

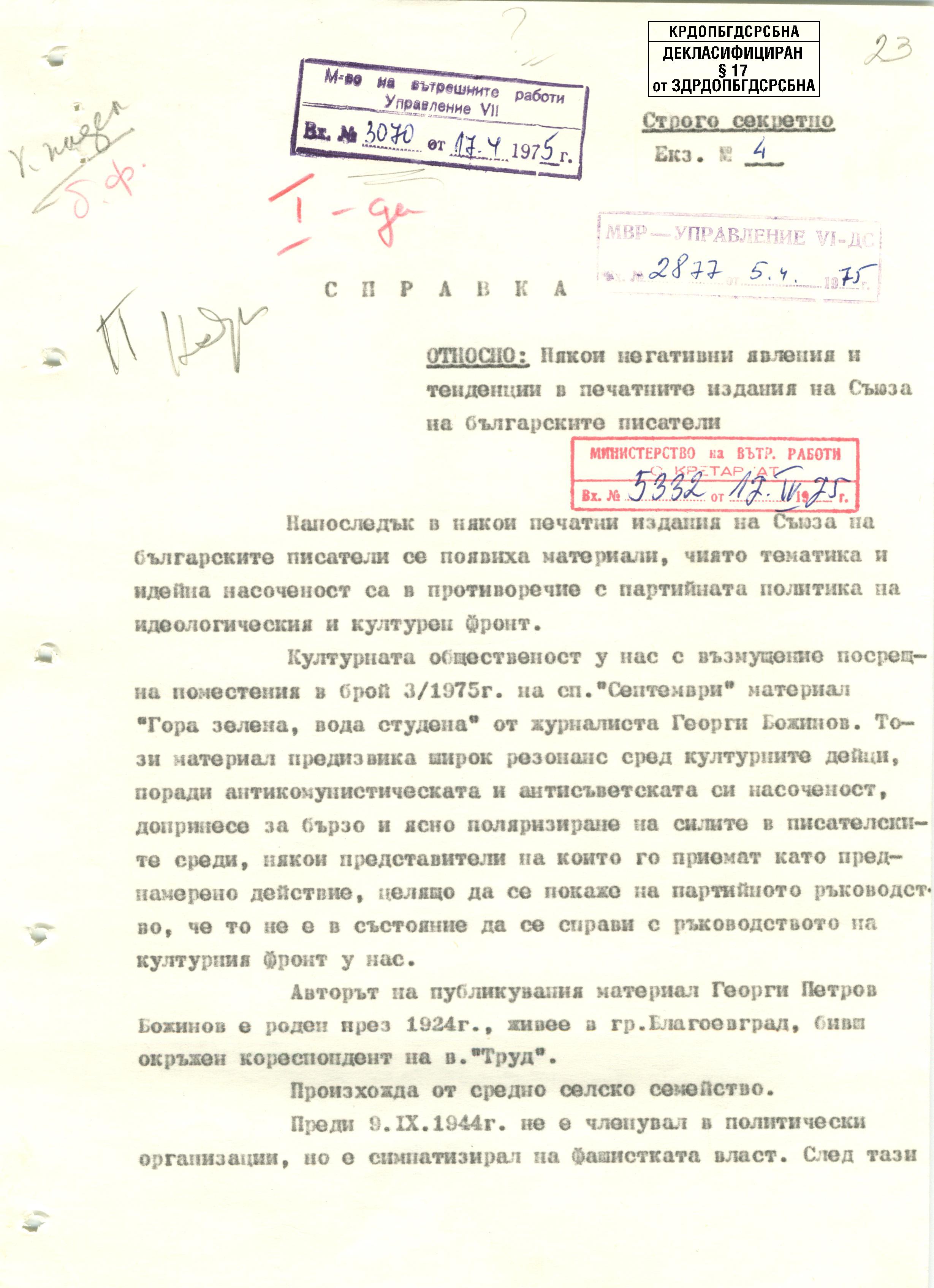

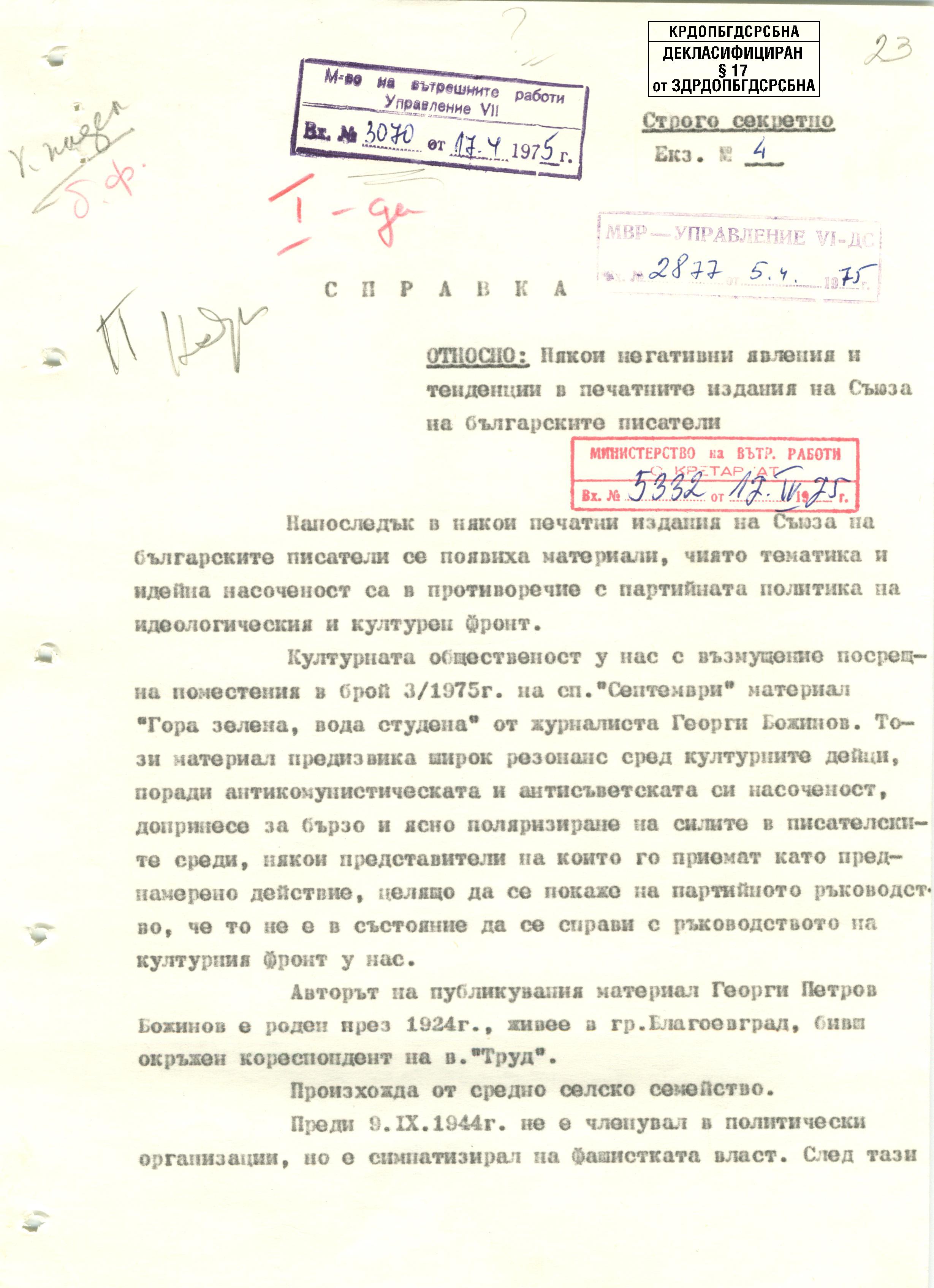

Report about "Some negative manifestations and tendencies in the publications of the Union of Bulgarian Writers", Sofia, April 5, 1975.

The report documents a number of newspapers interviews and items published in periodicals of the Union of Bulgarian Writers or by its members that are said to contradict party policy, for example, because they are allegedly anti-Soviet. The document is a good example of the ways how agents of the state security observed the Union of Bulgarian Writers and the activities of their members, and how the political profile of intellectuals was rendered by them.

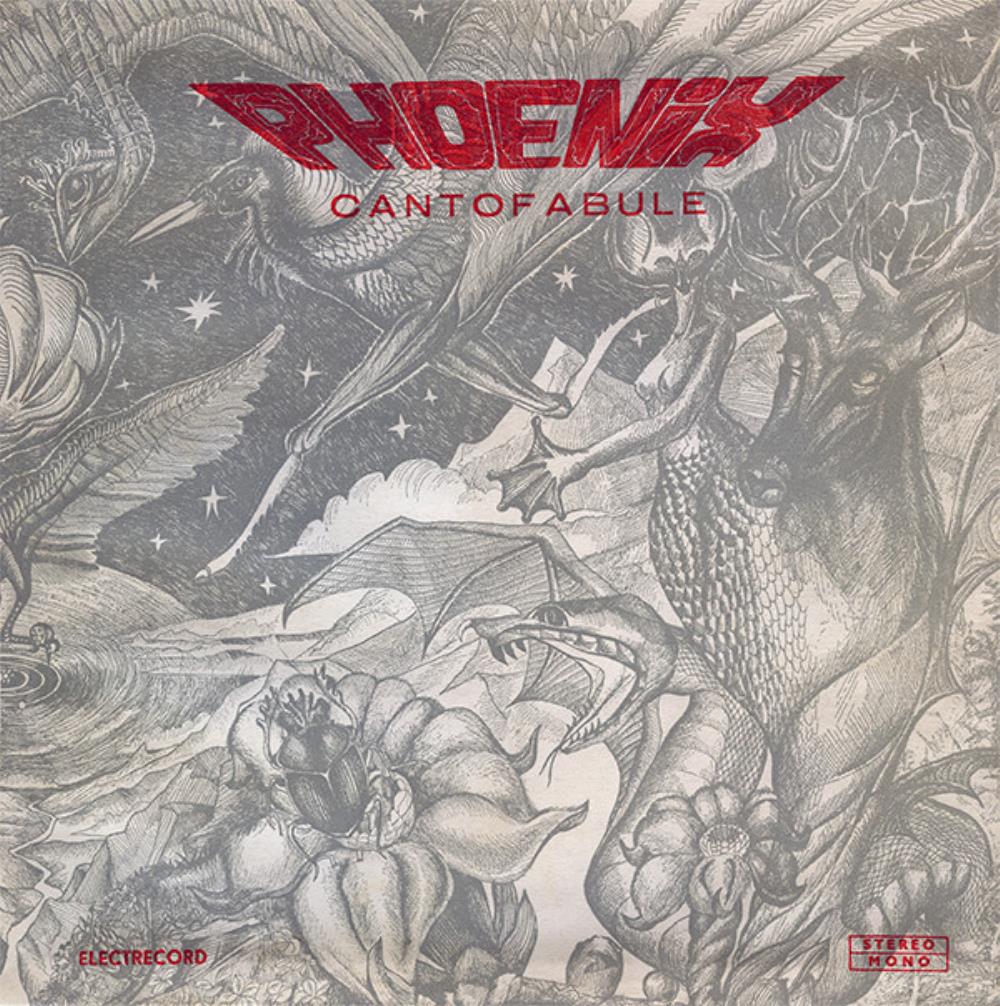

Most specialists and fans of rock music in Romania agree that three albums marked the history of this musical genre under communism: (1) Muguri de fluier (Flute buds) of 1974, an LP by the Timișoara-based band Phoenix; (2) Zalmoxe of 1979, the album by the Bucharest-based band Sfinx, which underwent tedious a three-year process of protracted censorship until its release, although it was named after the famous god of the Dacians, the ancestors of the Romanians who under Ceaușescu’s regime took prominence over the Romans in the myth of common descent; and (3) Cantafabule of 1975 by the same Phoenix. Together with Sfinx, Phoenix was among the most innovative rock bands in communist Romania, and is credited with developing the so-called ethno-rock style. This represented an original synthesis of lyrics inspired from ancestral traditions and pre-Christian folklore with modern sounds specific to progressive and psychedelic rock. More than a decade after their debut, already at the height of their musical career, Phoenix created during the winter of 1974–1975 what remains to this day their masterpiece: the double LP entitled Cantafabule (erroneously printed on the front cover as “Cantofabule”). The lyrics were the work of two very talented poets from Timișoara, Andrei Ujică and Şerban Foarță, who had also collaborated with Phoenix to create their previous hit, Muguri de Fluier. This album, however, was far less oriented towards local sources of inspiration than the previous one, which had highlighted autochthonous pre-modern traditions. For the new album, the two poets took inspiration from Western medieval bestiaries and authored a universal story about a series of mythological creatures, some small and rather innocent, such as the unicorn or the scarab, and others vicious and dangerous, such as the asp and the basilisk. Towards the end of the rock poem, which has fourteen parts, all these fantastic creatures enter into a fierce conflict with each other, which leads to a new beginning. Accordingly, the last piece of the album is dedicated to the fantastic bird of rebirth and eternal return, the phoenix, which gave its name to the band. Phoenix toured entire Romania to stage concerts with this rock poem. During concerts, the members of the band dressed in special costumes to interpret these fantastic animals and used volunteer students to complete the entire gallery of mythological creatures, which were also represented on the cover of the album. Cantafabule was a best-seller of that time, as it seems that half a million copies were sold, according to the estimations of the members of the band. It is from this album that the phrase came which rock fans and the eternal admirers of this band use to greet one another: Fie să renască (Be it reborn). Two years after the release of the album, all the members of the group (except for one) managed to clandestinely cross the border, so all pieces by Phoenix were banned in communist Romania. Yet, the band survived in the collective memory of its fans, while its albums, which became extremely expensive items on the black market, continued to disseminate their music among younger generations who did not have the chance to attend its concerts. The last of the Phoenix albums produced under communism, Cantafabule represents to this day a great achievement due to its original blend of ancestral lyrics and modern music, a genuine masterpiece of rock in Romania.