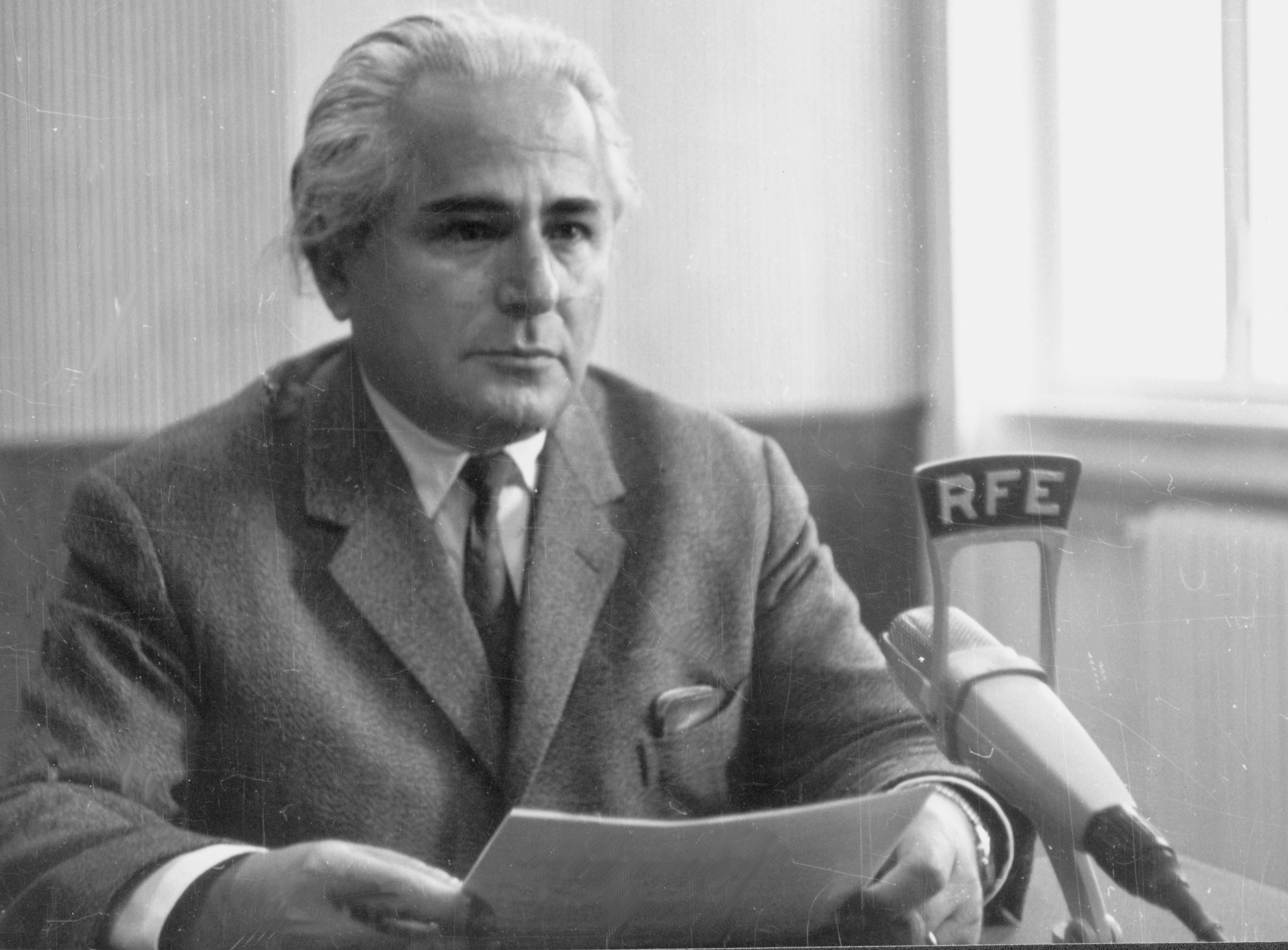

The picture shows Hristo Ognyanov during a Radio Free Europe broadcast. Ognyanov was a long-time contributor to the Bulgarian language program of Radio Free Europe.

One of the programs of Radio Free Europe was called Bulgarian Literature under Communism, which Ognyanov created in 1964 (CSA F. 1264, op. 1, a.e. 289). The featured item contains the program transcripts, totaling about 375 pages. The Ognyanov’s broadcasts provided a broader picture of the development of literature in Bulgaria, while at the same time condemning the restrictions imposed by the government. He specifically presented works from Bulgarian literature and culture that the communist regime had banned in Bulgaria. In the series, Bulgarian Literature under Communism Ognyanov reported on official decisions of the Bulgarian Communist Party and revealed lies in the party’s propaganda.

Vjesnik Newspaper Documentation is an archival collection created in the Vjesnik newspaper publishing enterprise from 1964 to 2006. It includes about twelve million press clippings, organized into six thousand topics and sixty thousand dossiers on public persons. Inter alia, it documents various forms of cultural opposition in the former Yugoslavia, but also in other communist countries in Europe and worldwide.

The sentence in the case of Nicolae Dragoș and his oppositional group was pronounced on 19 September 1964, following a final round of testimonies that the main defendant and his associates provided in court. The main defendants, Nicolae Dragoș and Nikolai Tarnavskii, were accused of “common anti-Soviet views” that prompted them to “create an underground organisation on whose behalf they [intended] to undertake agitation and propaganda activities with the aim of undermining and weakening Soviet power.” Judging by the summary of their actions in the text of the sentence, the two main protagonists and initiators of this group started to discuss concrete plans for spreading their message in the summer of 1962, when the plan to set up a clandestine printing press emerged. It is interesting to note that initially Dragoș planned to print the leaflets a bit later, in 1965 or 1966, after a longer period of preparation, but, “due to the difficulties of provisioning the population with foodstuffs, which emerged throughout the country because of a poor harvest, decided to do this in 1964.” This passage is especially revealing both as a rare admission of real economic problems (albeit in a secret document) and as an indication of a direct stimulus that prompted Dragoș and his collaborators to act when they did. The sentence also carefully summarises the main stages of the organisation’s activity, i.e., the collecting of addresses to which the leaflets were to be sent in several Soviet cities (including Lviv, Minsk, Kiev, Leningrad, Dnepropetrovsk, Rostov-on-Don, Kharkiv, Odessa, Chișinău, etc.) and the recruitment of new members who were entrusted with practical tasks. The sentence also clarifies the structure of the organisation’s core, which seems to have included an inner circle (composed of Dragoș, Tarnavskii, and Cherdyntsev) and an “outer ring” consisting of the other three defendants (Postolachi, Cemârtan and Cucereanu), all of them students at the Institute of Fine Arts whom Dragoș recruited through his brother, Vladimir. The text of the sentence also provides a chronological narrative of the printing and dissemination of the 1,300 leaflets produced by Dragoș and Tarnavskii between February and 15 April 1964. Dragoș’s situation was aggravated by the accusation that, while trying to recruit new members, he “attempted to create the impression that a widespread clandestine organisation purportedly existed,” thus “camouflaging his own role in its founding and in the producing of the anti-Soviet leaflets.” Dragoș and Cherdyntsev were also accused of writing a letter to the First Secretary of the CPSU, Khrushchev, in which they purportedly “articulated calumnies concerning the policy of the communist party, against Soviet democracy” and “threatened the CPSU, on behalf of the clandestine organisation that, if repressive measures were to be applied against the DUS, the latter’s members would respond by similar measures, up to and including organising strikes and public demonstrations.” Several copies of this letter were later confiscated by the KGB from the defendants’ apartments. Given the fact that over 850 leaflets were distributed in various Soviet cities, it is obvious that the Soviet authorities were worried about the potential impact of the organisation and about the extent of its informal network. Despite Dragoș’s insistence that he did not pursue the goal of “undermining Soviet power,” all the defendants were found guilty of distributing anti-Soviet leaflets in which they propagated “vicious calumnies concerning the policy of the party and of the Soviet government, the Soviet state and social order, and the living conditions of the workers in the USSR.” The group was accused of extrapolating from certain particular problematic issues in the economic sphere and the “temporary difficulties” faced by the regime in order to recruit “politically unstable” citizens, mainly from student circles, and to manipulate them so as to achieve the organisation’s “hostile goals.” Consequently, Nicolae Dragoş and Nicolae Tarnavskii were sentenced to seven years in a high security labour camp. Ivan Cherdyntsev and Vasile Postolachi were sentenced to six years in a high security labour camp, while Sergiu Cemârtan and Nicolae Cucereanu received a five-year prison term, under similar conditions. Additionally, Dragoş and Tarnavskii were condemned to three years of prison according to article 81, paragraph 2, of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, for stealing the printing equipment from Tatarbunar. The sentence also included a provision relating to the confiscation of the property belonging to the main defendants. As the latter possessed no significant property, the confiscation measure was suspended. The sentence was annulled in February 1989 by a special decision of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR, by which Dragoş and his co-accused were rehabilitated. However, the additional three-year prison term for stealing the printing equipment was left standing by this court decision. The case of the Democratic Union of Socialists, closely linked to the context of the “thaw,” is emblematic for its openly political focus, its supra-national scope, and the possible parallels to much more significant similar cases in the Soviet Bloc. It is also interesting because of its “transitional” character. Although a direct product of Krushchev’s era, it also foreshadowed some of the topics that would be salient in the “dissident” movement on the Soviet periphery in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

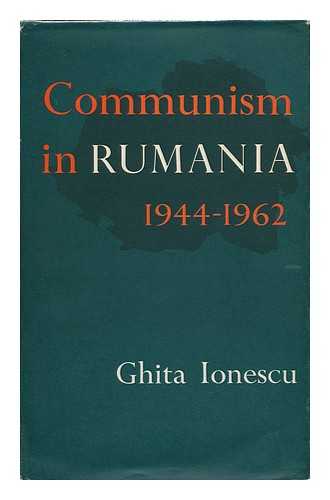

Since the 1960s, Communism in Romania, 1944–1962 has been the classic monograph on the first two decades of postwar Romania, setting the frame for subsequent research on the topic not only in Western academia, but also in post-1989 Romanian historiography. The book was written between 1960 and 1963 (before the relative liberalisation of the late 1960s that allowed Western scholars to conduct field research in Romania). The author therefore had limited access to Romanian sources such as the official press and official statistics, and relied rather on memoirs and various publications of Romanian exiles in the West. However, many of his conclusions are still valid. His life experiences in both interwar Romania and Western exile provided him with deep insights into the key events of the period he was researching. Before 1945, he was well acquainted with some communist Romanian intellectuals, such as Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu, one of Gheorghiu-Dej’s competitors for the leadership of the Party during the period from 1945 to 1948. As a person involved in the political organisations of the Romanian exile, Ionescu had the opportunity to meet people that had held key positions in the period of the communist takeover in Romania (1944–1947) and had managed to escape to the West. He benefitted also from his experience as head of the Romanian service of Radio Free Europe where he had the occasion to access valuable information and to acquire a broader comparative perspective on the communist regime in Romania in its East European context.

As with most Western contributions on the Eastern Bloc of the 1950s and 1960s, the conceptual framework of the book is provided by the theory of totalitarianism. He also approached the communist regime in Romania from a comparative perspective and tried to understand its evolution by paying special attention to Moscow’s strategies in the Eastern Bloc. The book is made up of three parts focusing on three distinct periods of postwar Romania, an introduction dealing with the history of the Communist Party of Romania during the interwar and war period, and conclusions. As the author explains in the preface, the book was structured chronologically because he considered that the turning points in the inner politics of postwar Romania were the results of Cold War shifts and Eastern Bloc disturbances (Ionescu 1964, xvi). Thus, the first part analyses the stages of the Communist takeover in Romania from the instalment of the Groza government in March 1945 to the forced abdication of King Michael in December 1947. The second part deals with key aspects of the sovietisation of Romania, such as the creation of the one-party system, the internal Party purges, the collectivisation of agriculture and the launch of intense industrialisation. The third part of the book covers the period 1956–1962, giving special attention to the effects of de-Stalinisation and the Hungarian Revolution in Romania and to the collectivisation and industrialisation drive of the period 1958–1962 and its impact on Soviet-Romanian political relations.

Communism in Romania, 1944–1962 is not only a comprehensive monograph on a period marked by radical political and social transformations, but also offers original insights into the turning moment of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Ionescu analyses how Gheorghiu-Dej skilfully eluded the de-Stalinisation wave in the mid-1950s and consolidated his position in the Party. He rightly observes the origins of the Romanian split with Moscow in the economic disputes over the greater economic integration of the Eastern Bloc countries into COMECON and predicted in Nicolae Ceauşescu the future winner of the internal competition to succeed Gheorghiu-Dej at the Party’s head.

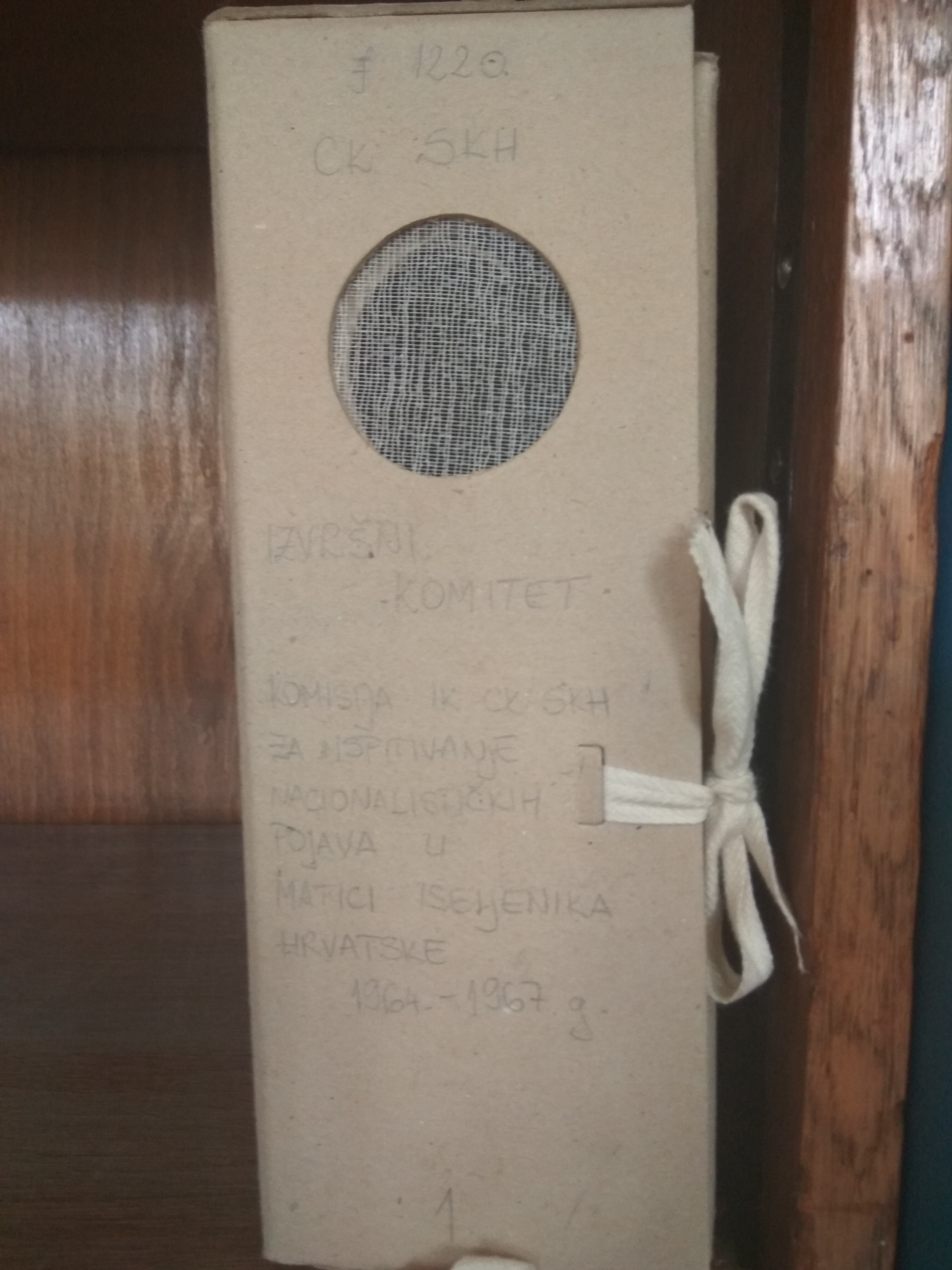

Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia (1964-1967)

Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia (1964-1967)

This thematic collection documents the work of the Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia (EFC) of Executive Council of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia (EC CC LCC), in the period from 1964 to 1967. The commission was established solely to monitor the activities of the EFC's president, Većeslav Holjevac, and some of his associates, who were considered as opposition figures and nationalists. The collection contains documents that explicitly cite examples of oppositional activities in the EFC which testify to the role of the EFC leadership in opposition in the field of culture pertaining to Croatian emigrant communities, as well as the role of CC LCC in their condemnation.

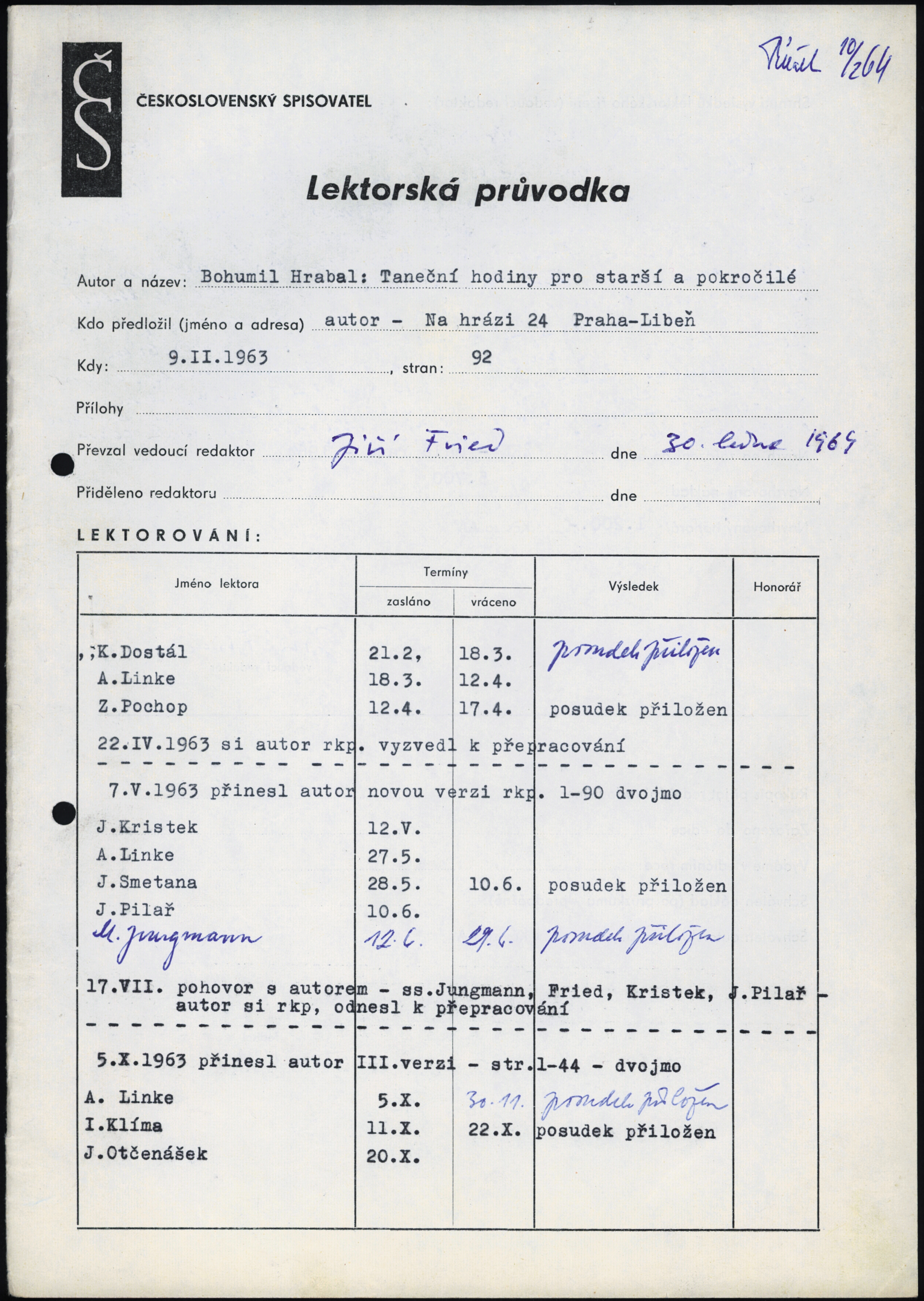

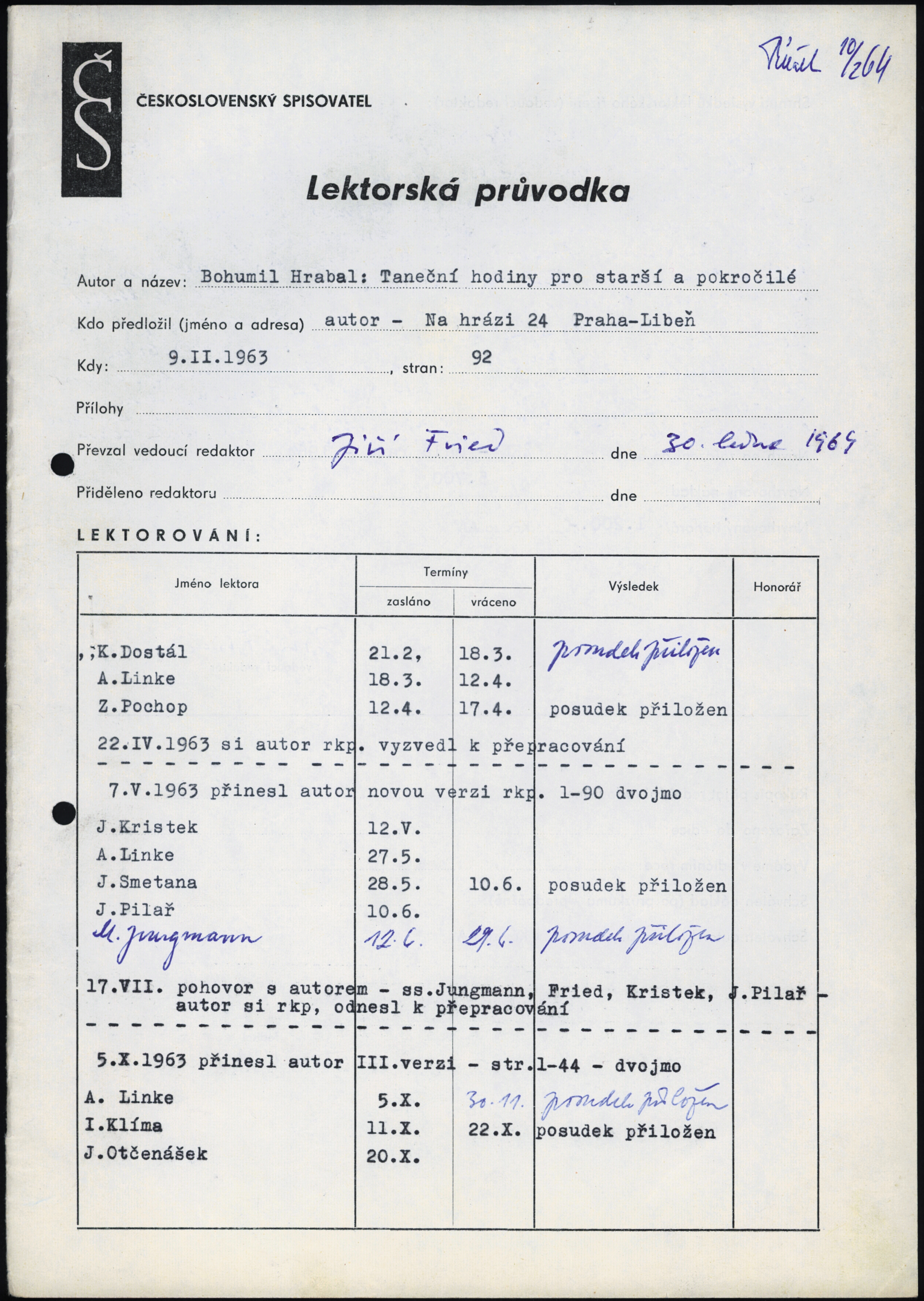

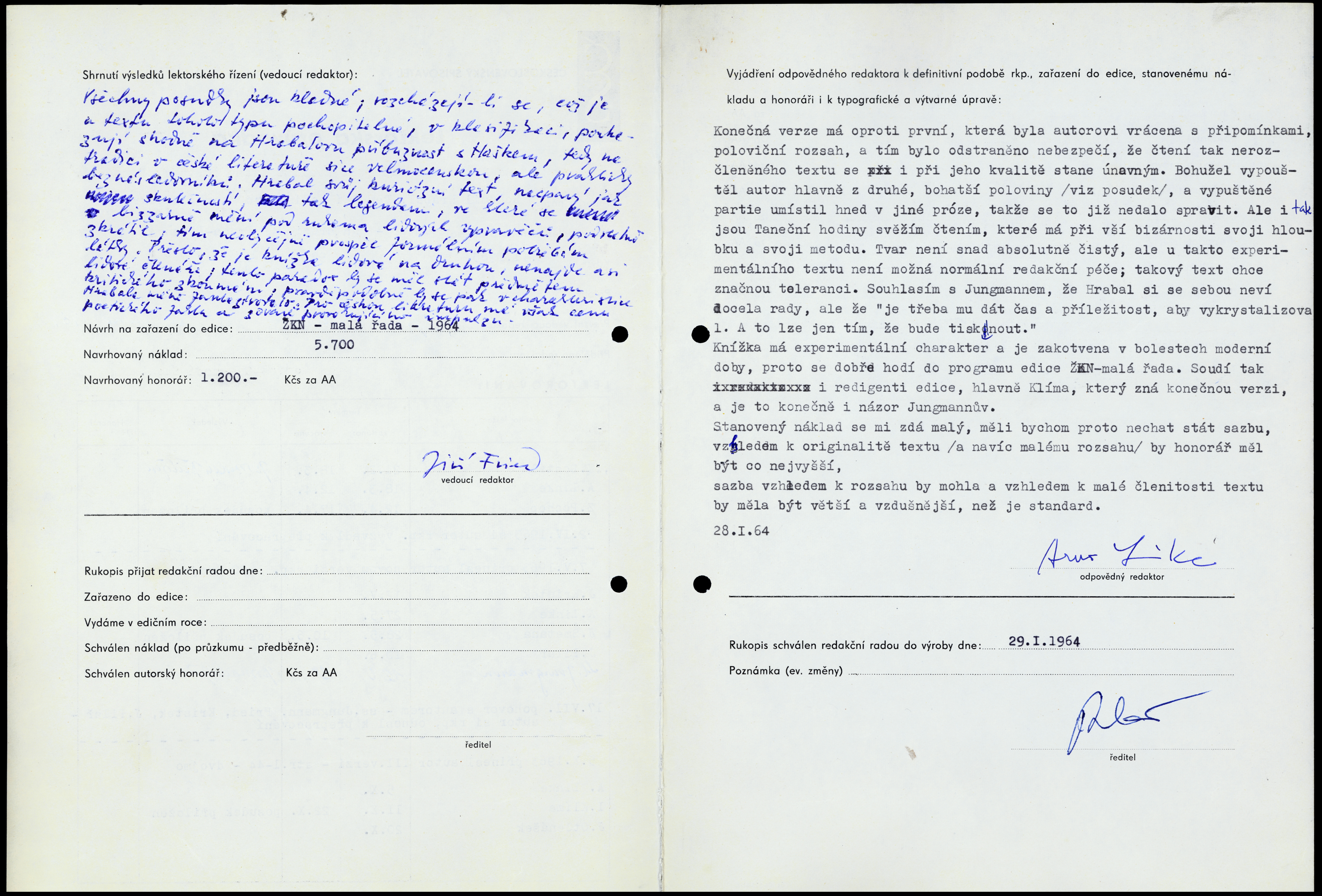

The Czechoslovak Writer Publishing House collection deposited in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature (LA PNP) contains sources documenting the course of review processes, which often led to demands for changes to literary works. This was also the case for the experimental text entitled “Dancing lessons for the advanced in age” (1964) written by the well-known Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal (1914–1997). This text was finally shortened by the author following the reviewers’ requirements. “Dancing lessons for the advanced in age” consists of the only continuous and unfinished sentence representing the monologue of the seventy-year-old uncle Pepin who recalls his past. Other sources stored in the LA PNP documents include the prohibition of Hrabal's collection of short stories “Lark on a String”.

The last, 73rd, issue of bi-weekly newspaper (Literaturni novini" ("Literary News") was published on February 2, 1964, almost three years after its first issue came out on May 24, 1961. Then the newspaper was discontinued by the state because it was declared "harmful and anti-party". In 1961 the head of the Bulgarian communist party, Todor Zhivkov gave his personal permission for the launch of this new literary newspaper in order to show his positive attitude towards intellectuals and to demonstrate the democratization of the artistic sphere. Vassil Akyov was selected as editor-in-chief of the newspaper. He gathered in his team people expelled from the "Narodna mladezh" ("People's Youth"" newspaper for their "anti-party behavior", such as Stefan Prodev and Simeon Vladimirov; the brave satirists Krum Valkov and Radoy Ralin; the then unknown, yet promising writers Ivan Paunovski, Yordan Vassilev and others. Akyov himself had been dismissed as head of the cultural department of the Communist Party's daily newspaper “Rabotnichesko delo" ("Workers deed”).

The new newspaper broke old stereotypes and personality cult clichés both in its graphic design and writing. It presented new books with poetry, fiction and literary criticism; it featured literary works, which had not been allowed to be printed (for example, the newspaper for the first time after September 9, 1944 published poems by the hitherto silenced poet Atanas Dalchev); it developed modern views on publishing and opened a column for young and talented authors; it also opened doors to contemporary Western European literature.

All this predetermined the fate of the newspaper: the newspaper was banned without a scandal through a "silent murder". With the argument "to avoid unnecessary duplication [...], to improve and expand the information ..." the state order to unite "Literaturni novini" with the loyal to the regime weekly "Narodna kultura" ("People's Culture)". Zhivkov personally announced the ban of the newspaper to its staff. According to preserved memories Prodev said: "Comrade Zhivkov, the biggest mistake is to stop a newspaper. Every stopped newspaper remains in the history of a country!" Stefan Prodev and Yordan Vassilev acquired the text of the decision of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party to stop the newspaper and put it on the first page of the last issue - „Message" in black letters in the style of newspaper obituaries.

Although the editor-in-chief and the newspaper's associates were not subjected to repression, the ban on the newspaper functioned as an intimidation of the intelligentsia, imposing narrow frames on acceptable journalistic behavior.

Following his organisation of the wreath-laying ceremony at the statue of Stephen the Great on 11 October 1964, Moroșanu was severely reprimanded and subsequently expelled from the Polytechnic Institute several days later. The expulsion process followed a carefully staged ritual which involved, among other things, a decision of the “student collective” presumably taken from below. This stage was necessary as a formal preliminary step to the official decision signed by the rector. It also served as a confirmation of the loyalty and political reliability of the student body, which acted in solidarity in order to eliminate any “foreign elements” from its midst. A similar strategy was followed in other cases related to accusations of nationalism against Moldavian intellectuals in this period. The decision of the students’ “general meeting” was issued on 14 October 1964. This document is revealing not only due to its contents, but also because of the euphemistic language it used to argue for Moroșanu’s expulsion. After a preliminary report of the secretary of the Institute’s Komsomol cell, the meeting took note of Moroșanu’s “unacceptable behaviour.” This consisted, among other things, in his unmotivated absences, lack of academic discipline and poor performance, displaying of a rude attitude toward the head of department and his colleagues and, most importantly, in his “pernicious assertions concerning different questions related to the economic and cultural development of the republic.” Moroșanu allegedly dismissed, “rudely, incorrectly and with open contempt,” the attempts of his colleagues to point out his mistaken views and behaviour. The euphemism of the document reached its height when Moroșanu was accused of “performing a series of a-political actions” [a veiled reference to the incident at Stephen the Great’s statue] and of “attempting to assemble around himself a group of students, setting this group against the student organisations of the Institute and thus trying to position himself as a spokesman on behalf of Moldavia’s youth.” Moroșanu was also accused of an unhealthy reaction to criticism, “trampling upon” the student newspaper which printed his caricature. Despite his temperamental issues, it is obvious that his political behaviour was the real issue which led to his expulsion. Although the meeting concluded by recommending Moroșanu’s expulsion on the ostensible grounds of his “behaviour, which was incompatible with the rank of a Soviet student” and his “hooligan-like attitude toward the department’s staffand fellow students,” the invocation of his “a-political deeds” shows the limit of tolerance beyond which the Soviet authorities were unwilling to go. The meeting formally requested Moroșanu’s expulsion from the institute, deeming him “unfit to become a Soviet engineer and organiser of production.” Two days later, on 16 October 1964, the rector of the Polytechnic Institute, S. I. Rădăuțanu, signed an order expelling Moroșanu. Significantly, this document reproduced the decision of the student meetingalmost word-for-word, thus underscoring the staged character of the whole affair. However, in the late 1960s, after serving his prison term, Moroșanu succeeded in being readmitted to the Polytechnic Institute after an audience with the Union minister of higher education. This was due to his persistence and to his skilful manipulation of Soviet legislation.

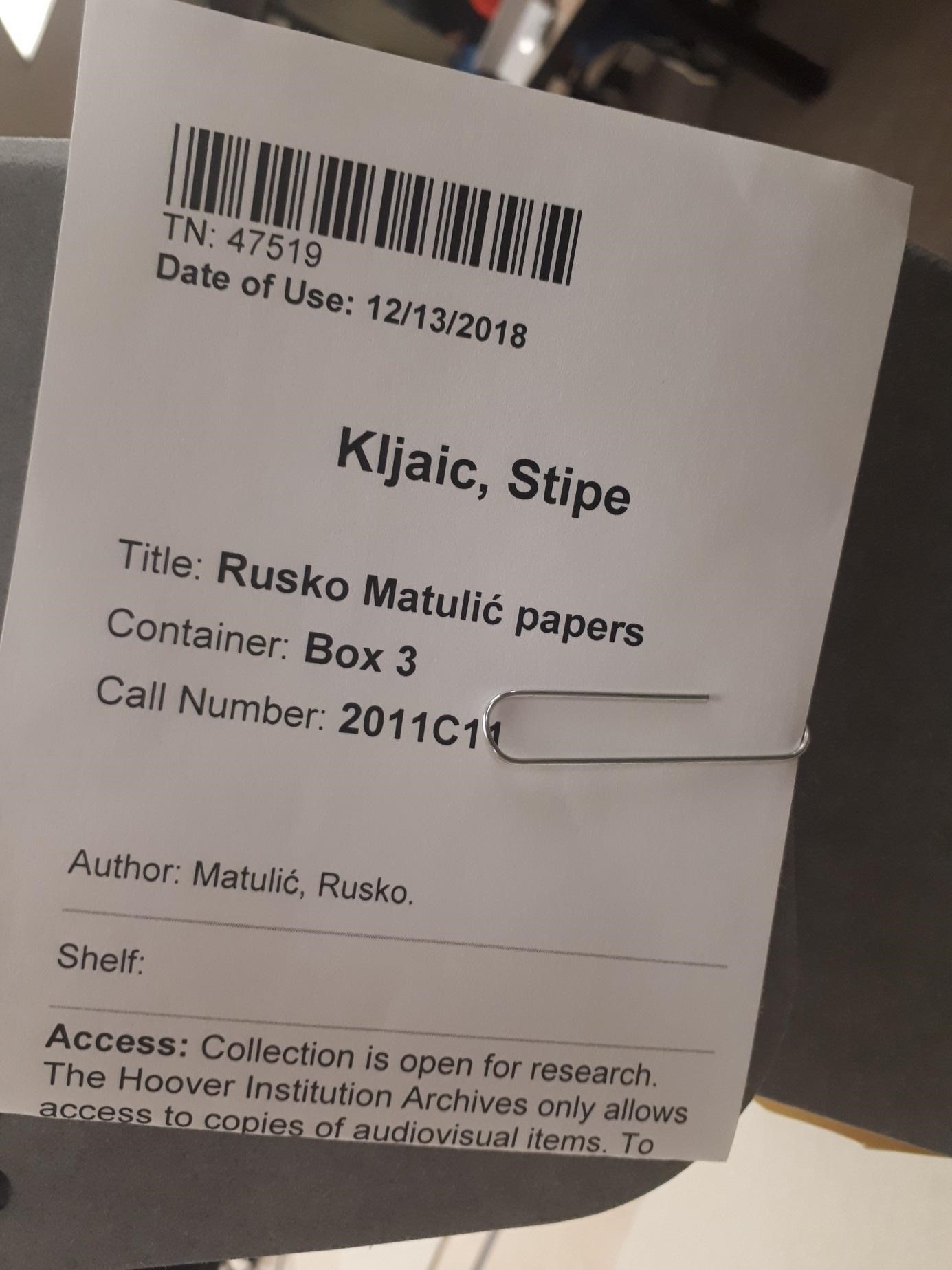

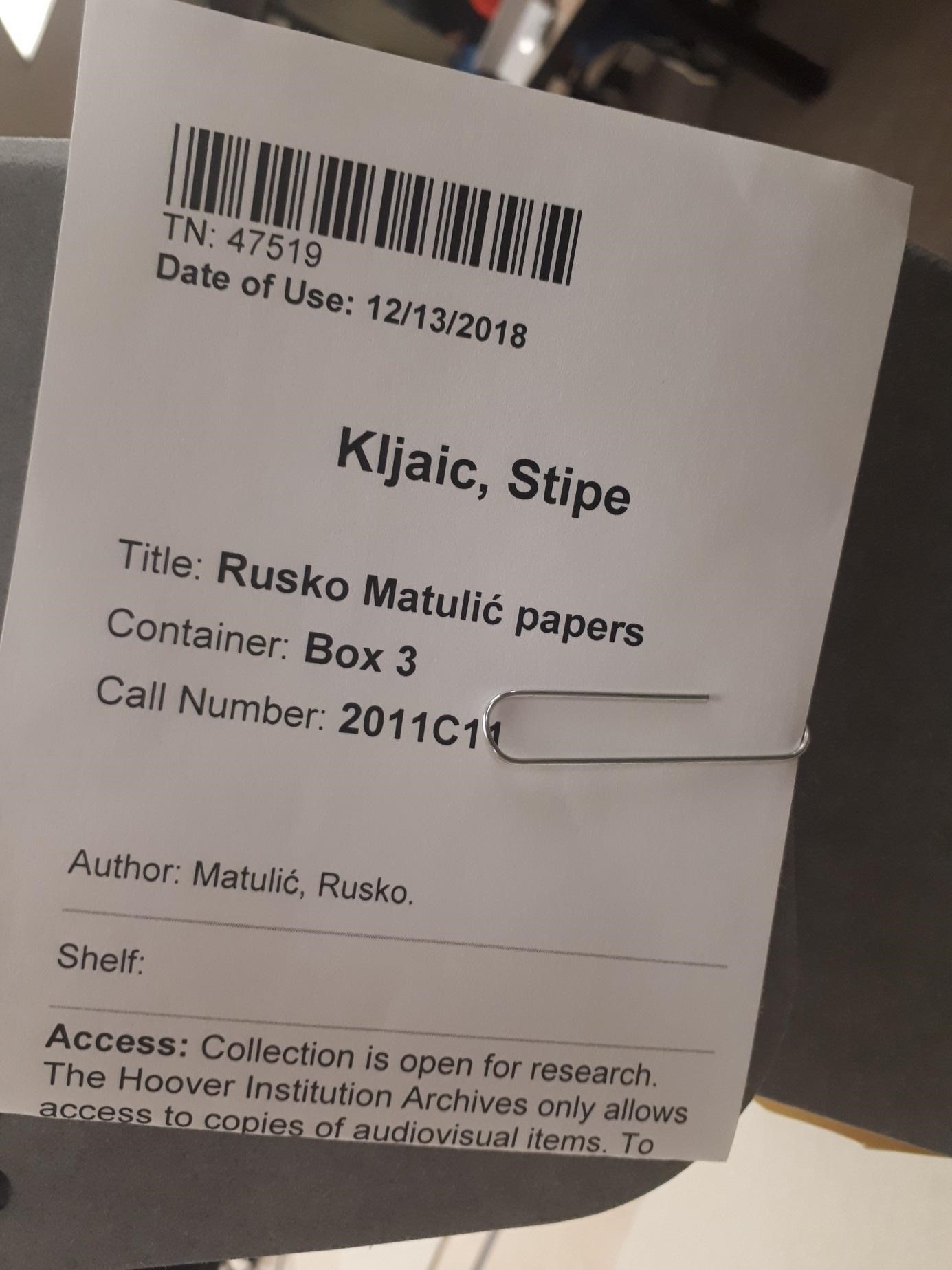

The bequest of Rusko Matulić, an American engineer and writer of Yugoslav origin, is held in the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The collection largely encompasses Matulić's activities as a political émigré in the United States of America, when he mainly dealt with the publication of the bi-monthly bulletin of the Committee Aid to Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia (CADDY). The bulletin and organization acted as a part of the Democratic International, established in New York in 1979. Mihajlo Mihajlov, one of the most prominent Yugoslav dissidents, was a member and the main initiator of launching the CADDY organization and its bulletin. Rusko Matulić was Mihajlov's main collaborator in the overall CADDY project.

The collection illustrates Adrian Marino’s intellectual evolution as a historian and literary critic who chose to pursue his activity outside the institutions controlled by the communist regime. The Marino Collection includes books, original manuscripts, and the author’s correspondence, which reflects a critical perspective on Romanian literary life in the period 1964–1989.

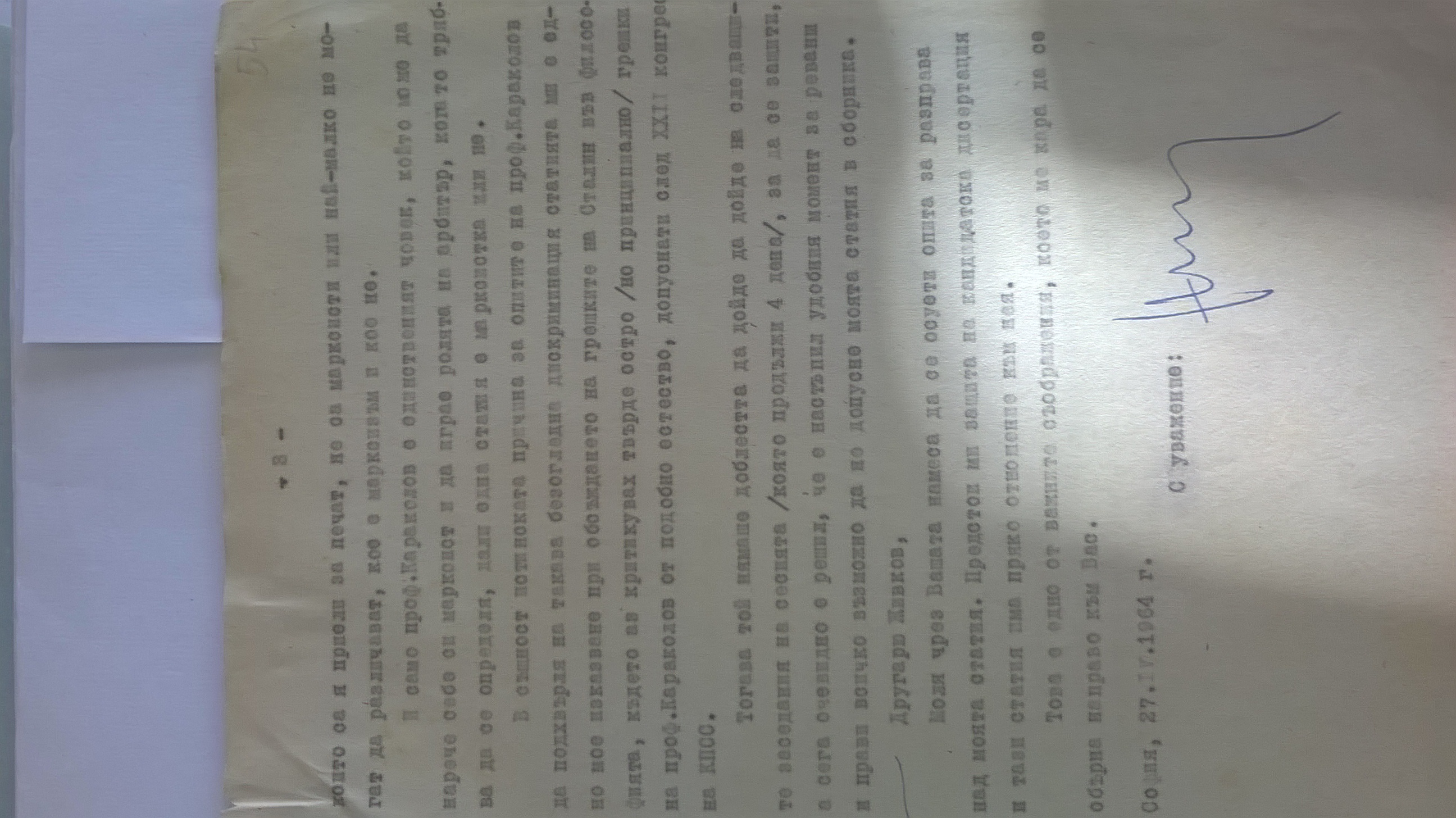

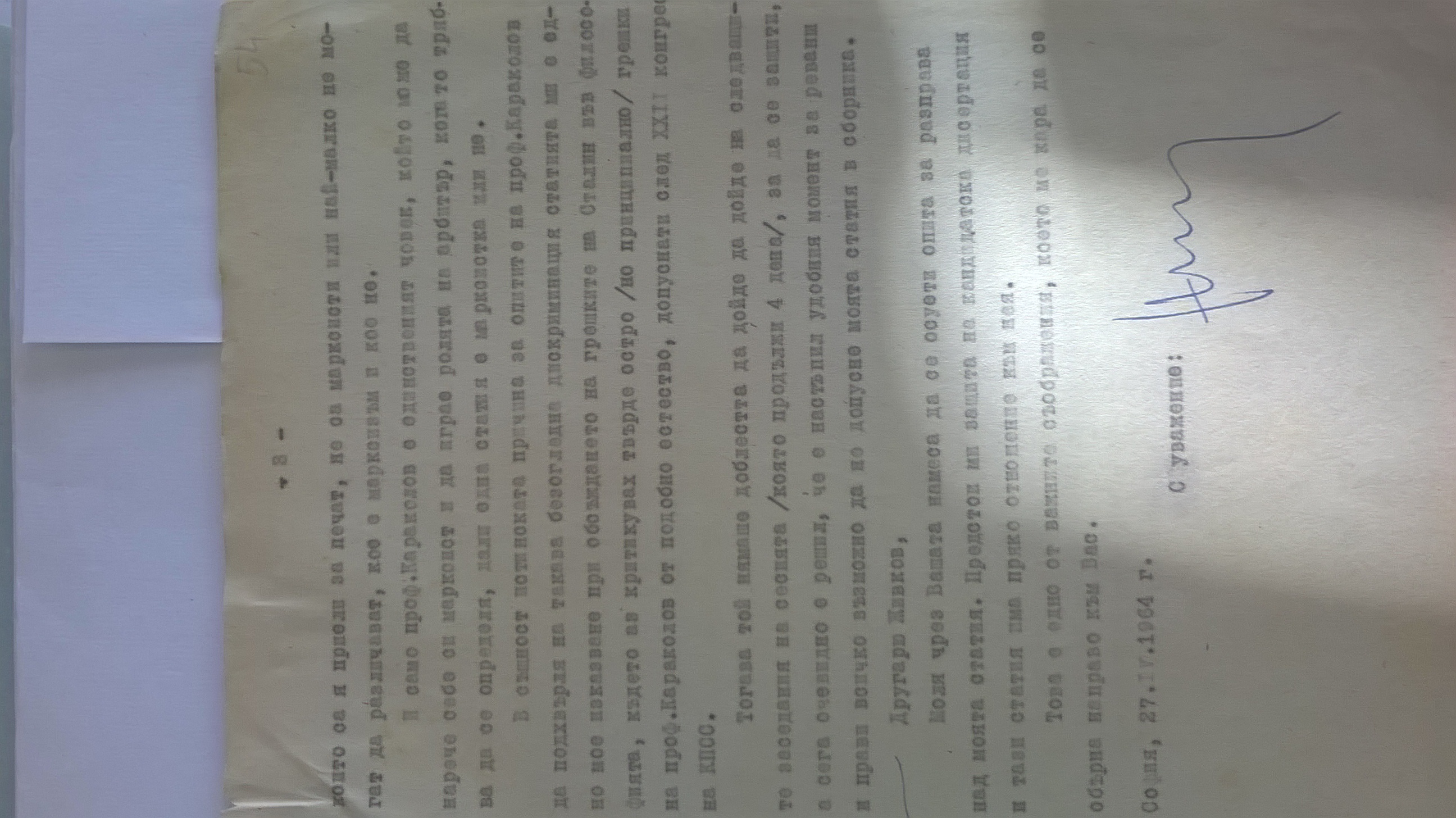

In response, Zhelev wrote to the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party, Todor Zhivkov, and to the President of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Academician L. Krastanov, on 27 April 1964. In his letter he asked "for your intervention to stop the attempt to deal with my article. I'm about to defend my dissertation and this article is a part of it." One month later, he received a response to his appeal by academician Todor Pavlov, honorary chairman of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Director of the Institute of Philosophy, and long-time member of the Presidium of the National Assembly. Pavlov qualified Zhelev's appeal as "an inexcusable misleading of the First Secretary of the Party." He called Zhelev's theses "a retreat from dialectical materialism to Hegel's idealistic system" and ended by urging the PhD student "not to use in future such diversions and not to abuse the time, trust and goodwill of the First Secretary of our Party."

Zhelyu Zhelev's article was not published. On the contrary, this episode became the starting point of near-constant surveillance and periodic repression of Zhelev by the government and the State Security. He was not permitted to defend his dissertation, was expelled from the Party and with his wife was forced to leave Sofia (until 1972).

The documents which make up this featured item show the workings of an independent mind and how an oppressive state responded, as well as demonstrating the means which the government used to silence Zhelev (though unsuccessfully).

Václav Havel started to write visual poetry at the beginning of the 1960s, and in 1964 he created a collection of these poems titled Antikódy (Anticodes). The majority of his visual poems were created before 1969. In the 1970s and 1980s Havel wrote several new poems. His collection Antikódy was published in 1993 and again in 1999. Since then, new poems have been found. In 2013, Laterna Magika (National Theatre in Prague) performed a play based on Havel’s visual poetry. The same year this poetry was published and presented as an exhibition.

Irimie, Cornel. Research on Pastoral Life in the Area of Mărginimea Sibiului, in Romanian,1964. File

Irimie, Cornel. Research on Pastoral Life in the Area of Mărginimea Sibiului, in Romanian,1964. File

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Cornel Irimie, together with museologists, ethnographers, and photographers working at the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu, conducted ethnographic research on the civilisation of the Romanian villages that suffered as a result of forced collectivisation in the period 1949–62. This process dismantled the social structure of the Romanian village and produced great changes in the lifestyle of the peasantry (Kligman and Verdery 2011, 2). An exception to the rule were the shepherd villages that had been less or not at all affected by collectivisation. This is the case of villages in the area of Mărginimea Sibiului, at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains, west of the city of Sibiu.The research conducted by Irimie and his team in this area in the first half of the 1960s reveals the spiritual universe of shepherd communities in communist Romania. Its result was the German-language study “Neue Forschungen zum Hirtenwesen der Rumänen mit einer Darstellung der Mărginimea Sibiului als einer typischen Zone” (New Research on the Pastoral Life of Romanians with the Case Study of Mărginimea Sibiului as a Typical Area) written in December 1964. The study has twenty-nine typewritten pages and is divided into five chapters. The first chapter deals with the history of shepherding in the Romanian space and the biographical references on the topic, the second with the toponyms of shepherd villages in Mărginimea Sibiului and their origins, the third with forms of habitation in the shepherd villages of this area, the fourth with wool-processing techniques, and the fifth with religious beliefs and customs specific to shepherds. Within the latter topic, Irimie analyses the symbolism of the lamb within the religious universe of shepherds, and how this symbolism is present in customs during Easter celebrations. Research on certain religious practices from a sociological and ethnographic perspective, as in this study, was an activity that ran counter to the communist regime’s official policies. The authorities were always careful to describe religious practices in the Romanian rural world in negative terms, calling them reminiscences of rural backwardness.

Galin Malakchiev was born in the family of a cavalry royal officer from Ruse, a circumstance that caused the talented sculptor troubles after the imposing of the communist power. Galin Malakchiev worked as an oxygen-welder at the construction of the St. St. Cyril and Methodius National Library. While doing his military service as a labour service man, he began his studies in architecture. Allowed to enrol in the "N. Pavlovich" Higher Institute of Fine Arts, G. Malakchiev studied one year but repeated it in order to be in Lyubomir Dalchev's class. In 1961, he graduated in sculpture in Dalchev's class.

He created easel and monumental sculptures and established himself as a vanguard sculptor breaking the dogma of the ideological plastic arts typical of that time – heroes with clenched fists carrying flying flags.

In 1964, the sculpture "Harlequin" was part of the National Exhibition of Sculpture and Graphics by the name of "Circus Artist". The rejection of firmness, the hyperbolic elegancy, the delicacy of the figure and its unstable stability all aim at reflection. However, exactly because of this, the sculpture was not only disputed by art critics such as Dimitar Ostoich, Spas Gergov, Veneta Ivanova and Ivan Funev but the author was accused of "formalism", "decorative end in itself" and "subjectivism". The first independent exhibition of Galin Malakchiev was in 1966 but it was closed in just four days. The artist refused to compromise and chose the way of internal emigration.

Accused of "decadence", "abstractionism" and "imitation", Malakchiev left the capital and in 1973 settled together with his wife Tsvetana in the village of Batuliya, near the town of Svoge. There he created some of his most famous works of art but his restricted financial resources limited him to only small sculptures.

In 1982, Malakchiev had an independent exhibition in the building of the UBA. It won him the first prize in easel plastic arts in the name of Marko Markov.

After 1989, there were several exhibitions dedicated to Galin Malakchiev: in 2001 at the Rayko Aleksiev Gallery, in 2009 at the National Gallery and the last one in 2011 at the Sredets Gallery. None of them was accompanied by a study on his creative work. The sculpture "Harlequin", included in the exhibition "Forms of Resistance", is evaluated as "the first total artistic resistance against the socialist realism in sculpture, a revolt not only against its plastic stereotypes but against its nature – the attempt at replacing the divine. [...] The spiritual essence of this creature is completely different; it doesn't feed on Marxist ideology, on party slogans which give birth to cast-iron and granite heroes. Its origins should be found in the divine breath." (Iliev 2016: 141)

So far, there is no monograph published on Galin Malakchiev's work.

![Lešaja, Ante. 2014. Praksis orijentacija, časopis Praxis i Korčulanska ljetna škola [građa] (Praksis Orientation, Journal Praxis and The Korčula Summer School [collection]). Beograd: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, p. 218.](/courage/file/n28836/Prvi+nastup.jpg)

The first public appearance of the entire editorial board of Praxis (Student Centre, Zagreb, end of 1964). From left to right: Rudi Supek, behind him (obscured from view), Branko Bošnjak, Gajo Petrović (editor-in-chief), Danilo Pejović (editor-in-chief), Predrag Vranicki, Milan Kangrga, Danko Grlić; far right (with back turned): the director of the Student Centre, M. Heremić, next to him, Antun Žvan.In the first issue of Praxis in 1964, the first core Praxis group, consisting of Zagreb-based humanist thinkers (philosophers and sociologists), proclaimed the basic platform of the future Praxis critical orientation. In his introduction entitled “Čemu Praxis?” (“Why Praxis?”) Praxis editor-in-chief Gajo Petrović announced the primary origin of the future Praxis orientation: “criticism of all that exists” (the phrase was taken from Karl Marx). This motto served as a principal starting point which generated a decade of criticism by Praxis thinkers; first of all philosophical and sociological analysis dealing with various topics and forms of “everything existing” in the sense of links between freedom and practice (the syntagma “all that exists” combined with criticism provides both an active and social meaning: the truth is verified in practice) This standpoint became the focal point for differentiation and promotion of the culture of dissent among Praxis thinkers and those supporting this orientation, but also among those who disputed it.Considering the promotion of the culture of dissent, which was in opposition to the concept of a single-party system, the editors of Praxis and the leaders of the Korčula Summer School were exposed to government attacks.The photograph, which was owned by Asja Petrović, is located in the Praxis and Korčula Summer School Collection. The photo is also published in the book written by Ante Lešaja (2014).

Report on the work of the Commission on Ideological Work of the CC LCC in the period from the 4th to 5th Congresses of the LCC, 1964

Report on the work of the Commission on Ideological Work of the CC LCC in the period from the 4th to 5th Congresses of the LCC, 1964

The report was dated October 1964, detailing the work of the Commission in the fields of culture, science and the media. It documents ongoing and systematic monitoring and the course of activities in the above-mentioned areas by the Commission through the practice of extended Commission meetings, discussions on prepared materials, as well as personal contacts by members and associates of the Commission with people from specific fields of cultural and scholarly life. In the report, we read numerous reviews and criticisms of cultural activities and the media. For example, the members of the Commission believed that Radio-Zagreb alone "managed to generate for one area the type of associates who will constantly and persistently fight for certain criteria, relationships, definitions and meanings of a specific art form from certain conceptual (clearly socialist) and aesthetic positions." Publishing was considered expensive, criticized for the low circulation of books and the neglect of the literature of Eastern countries, as well as the inadequate work of publishing councils. In film production, it was said that there were very rarely high-quality achievements: the greatest extent is achieved with cartoons of the Zagreb School of Animation, but other films "rarely use their range and conceptual profile to be active participants in performing social functions." The editorials of literary journals were criticized for the lack of understanding of social processes and development, the lack of Marxist criteria, and the presence of national overtones and romantic references to the past. However, the report says that conversations conducted in the Commission, for example with the people from the magazine Telegram, as well as other forms of influence at all levels and on different occasions, have shown that "it can speed up the process of conceptual cleansing with anarchic, pseudo-liberal, petit bourgeois and similar aberrations."