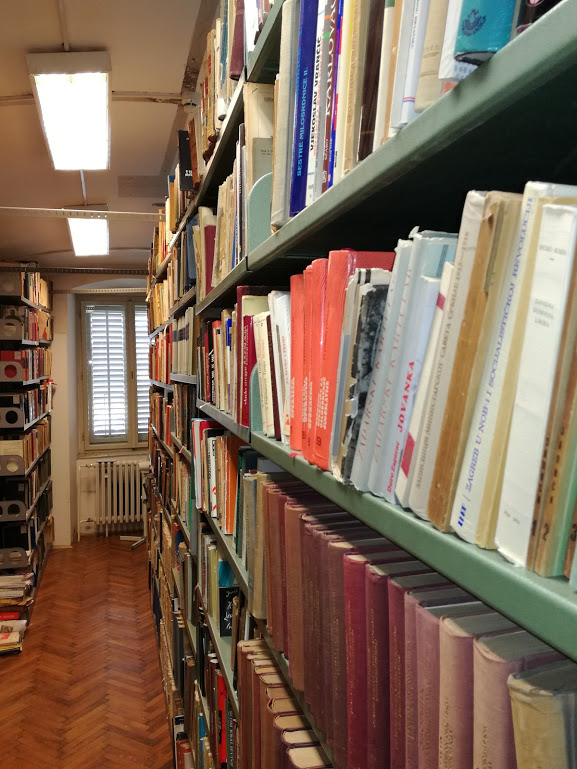

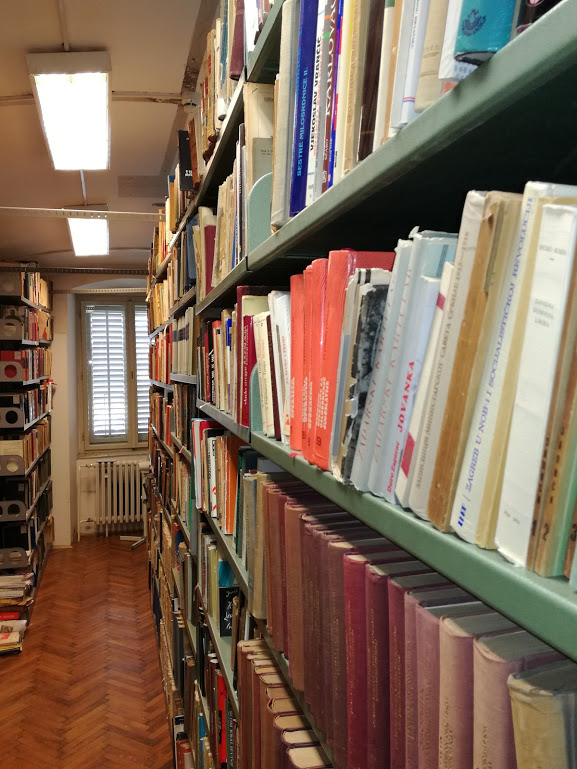

The Collection of Croatian-American historian Jere Jareb (PhD) contains over 4,500 books, magazines and various brochures in Croatian, English, German, Italian and Slovenian. Dr Jareb, who began compiling the collection in the 1950s, donated it to the Croatian Institute of History in 1997. A particularly intriguing part of the collection are the numerous editions of books, magazines and brochures published by Croatian emigrants in the USA who were critical of the communist regime in Croatia and Yugoslavia. Some of these editions are not available anywhere else in Croatia.

The Art Collections of the Museum of Czech Literature contain works of art connected with the literary field (illustrations, visual works by writers, graphics, etc.). The collection has been built from inheritances; a number of works by officially non-approved artists from the period before 1989 are present here.

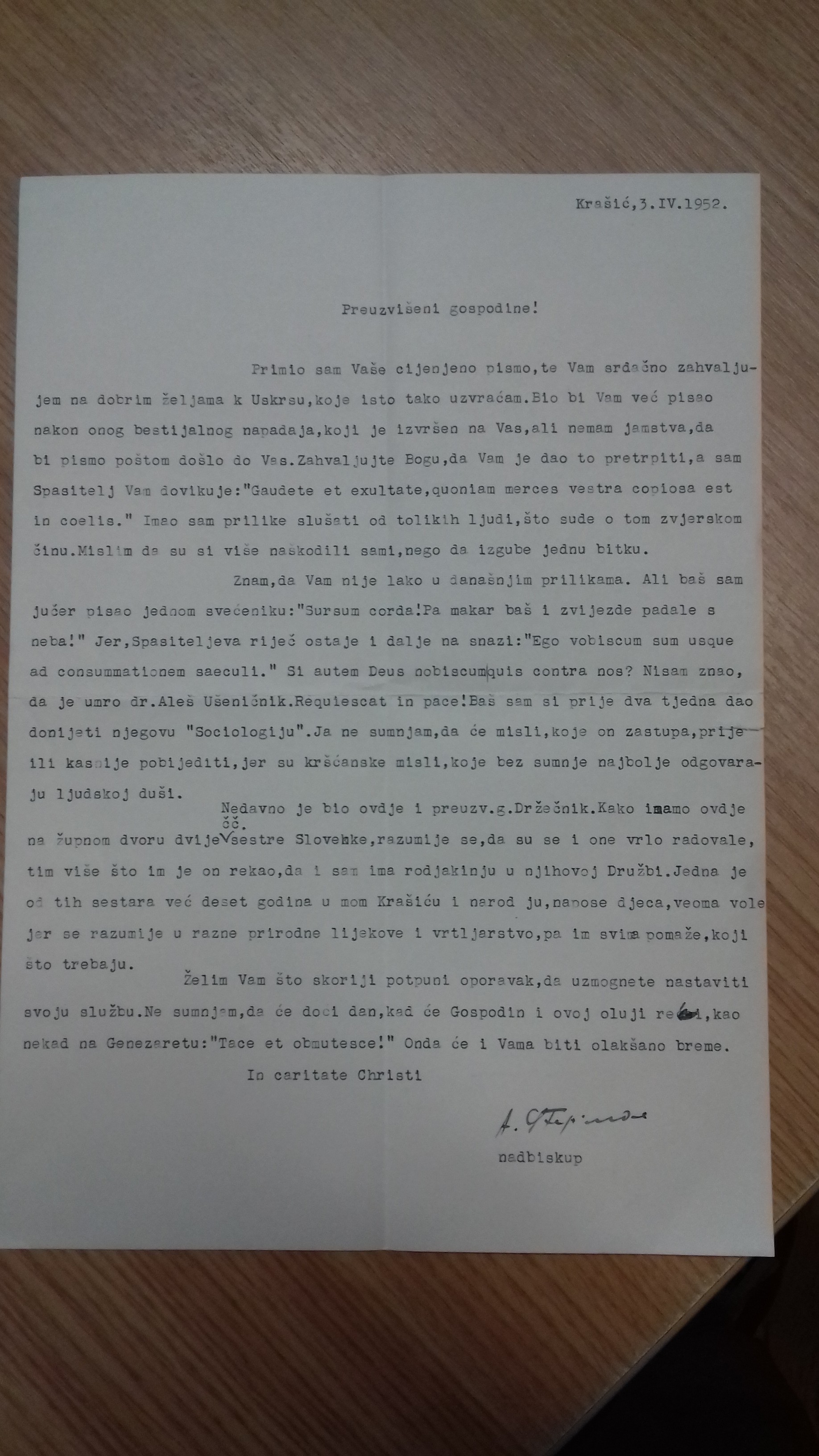

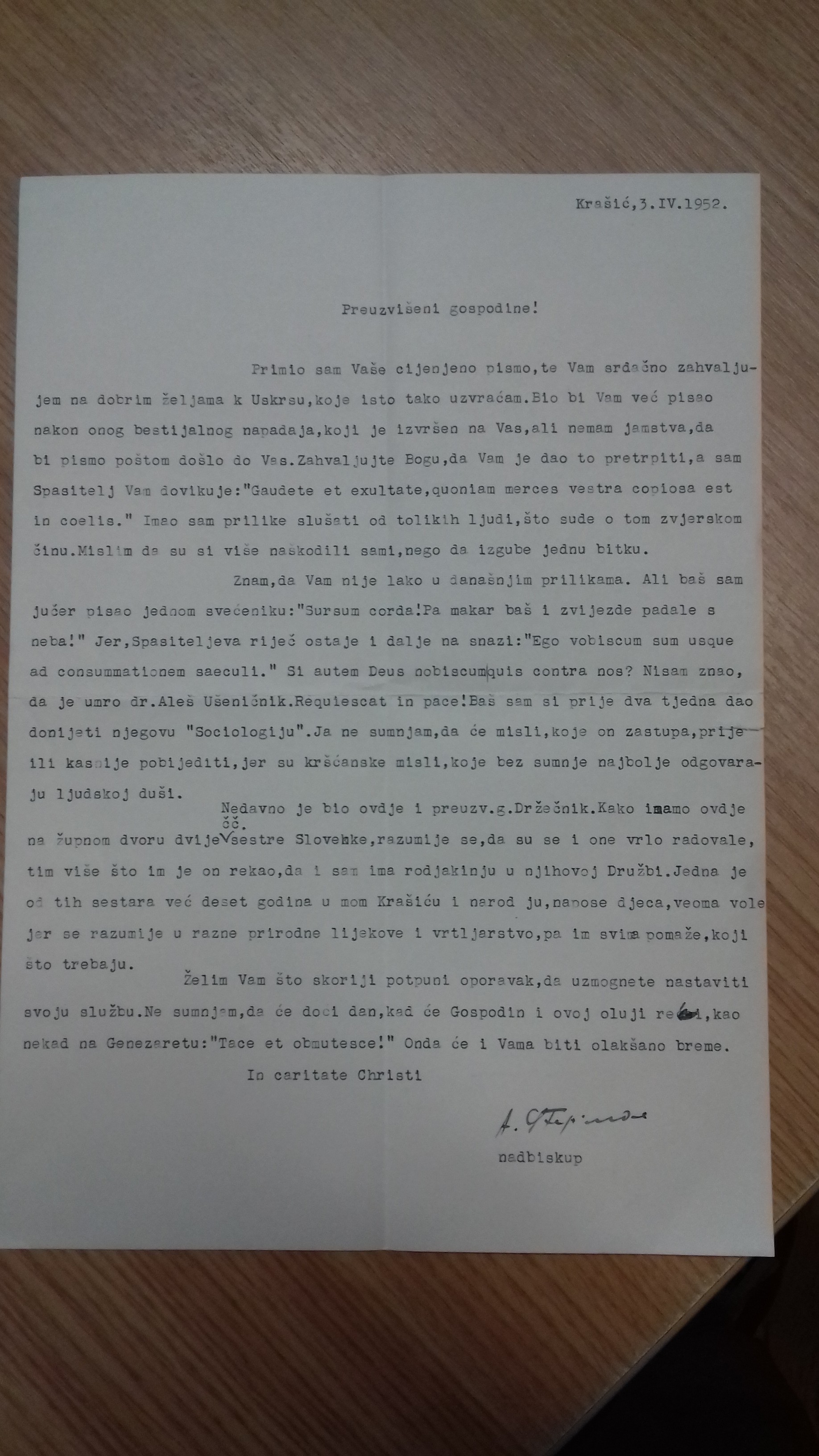

In this letter of April 3, 1952, the archbishop of Zagreb, Alojzije Stepinac (1898-1960), who was at the time under house arrest in Krašić, after being transferred therefrom Lepoglava prison, expressed his sympathy to Bishop Vovk after the brutal attack on him in Novo Mesto which resulted in his burning. Stepinac expressed uncertainty as to whether his first letter had reached Vovk. The archbishop of Zagreb encouraged Bishop Vovk to see the positive effects of such a savage attack on one of its bishops for the Catholic Church and also took the opportunity to comment on various Slovenian people, a sociologist whose work he read, a bishop whose visit he received and nuns who were under his care. The letter reflects the solidarity between the two persecuted men, Stepinac and Vovk, and network they maintained. The letter shows that if the authorities knew about it, the letter would have been confiscated. Now the letter is available to the public and curator of the collection sees it as an example of how a prominent member of opposition to the regime, Stepinac, saw Bishop Vovk as a new symbol of opposition. The letter is preserved in the Anton Vovk Collection, in box number 77. It is freely accessible to the public.

Overview of priests and other officials from all religious communities convicted in Croatia in period 1944-1951, 14 February 1952. Archival document

Overview of priests and other officials from all religious communities convicted in Croatia in period 1944-1951, 14 February 1952. Archival document

The document has 95 pages, it was dated on 14 February 1952 and originally entitled “Overview of priests and other officials from all religious communities, convicted in Croatia in the period 1944-1951.” It is an alphabetical list of 271 priests, seminarians and religious officials convicted in Croatia in that period. For each person, the religious affiliation, type of offence, and the type and place of enforcement of the sentence (execution, strict imprisonment, forced labour, loss of civil rights) are listed.

The opposition activities for which they were convicted were primarily: speeches against the authorities, printing/reproduction of illegal flyers and brochures in private homes, monasteries and other sacral buildings, distribution of such flyers and brochures, and threatening letters to the state authorities. They were also accused of cooperation with the Ustasha regime and the foreign occupiers, espionage, sabotage and assistance to illegal organisations during and in the initial post-war years.

According to data at the end of the document, among the convicted were: 206 Roman Catholic priests, 15 Roman Catholic seminarians, 15 Roman Catholic nuns, 3 Greek Catholic priests, 13 Orthodox priests, 2 Orthodox nuns, 1 Evangelical leader, 2 leaders of the Islamic Religious Community, 7 leaders of Seventh-day Adventist Church and 7 leaders of the Jehovah's Witnesses. As set out below, at the time of writing that report, there were another 70 persons in the penitentiaries in Stara Gradiška, Lepoglava and Slavonska Požega: 57 Roman Catholic priests, 9 Roman Catholic seminarians, 3 Roman Catholic nuns and 1 Orthodox priest.

The document is available for research and copying. It was quoted in the works of several authors (Akmadža 2003, p. 183; Matijević 2007, p. 121).

On 9 March 1952, a grandiose exhibition was opened about the life of the communist leader, Mátyás Rákosi. It was organized on his 60th birthday. The party was held at the Munkásmozgalmi Intézet (Institute of the Labour Movement), in the building that housed the Museum of Ethnography until 2018, and which had previously housed the Supreme Court that sentenced Rákosi to years-long imprisonment in 1937. The exhibition had two parts: an eight-room presentation of Rákosi’s life, and twenty-five rooms of gifts given to Rákosi. These gifts were extraordinary because they showed the new form of Hungarian folk art, in which folk art symbols were mixed with the symbols of socialism. After the exhibition closed, the objects were not inventoried in the collections of the Museum of Ethnography. The museologist ignored them until the 1960–70s. In 2012, the Museum of Ethnography put the folk-art exhibition of the collection on display under the title Rakosi60@neprajz.hu. Curators worked to ensure that this exhibition presented the original objects in a memorial context to reflect the previous conception; they thought it important to show more interpretations of an exhibition that was surrounded by unspoken rejection. Here you can find a list of the exhibited objects: http://rakosi60.blogspot.hu/

The Ukrainian Museum-Archives in Cleveland, OH contains a hidden world-class archival collection amassed over the last century. Founded in 1952 by Ukrainian WWII refugees, the materials document the lives and struggles of multiple generations against communism. The museum-archive took on the mission of preserving Ukrainian culture at a time when it was being destroyed in the Soviet Union, assembling a vast collection of books, periodicals, photographs, ephemera, diplomatic papers and other materials that document a century of struggle. This is a unique institution that spans international borders, but is simultaneously integrated into an urban American neighborhood. The collection is based in Cleveland’s historic Tremont neighborhood and attracts partners like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the National Academy of Sciences in Ukraine, and other institutions interested in digitizing its hidden gems.

Petko Ogoyski in his collection holding the wooden shoe with a secret hiding-place in which his wife, Jagoda, put medicines and a small pencil and so brought them to the forced labor camp in Belene on Persin Island. During the communist period, the materials showing the repressive nature of the communist regime in Bulgaria were hidden at the birthplace of Petko Ogoyski, in the village of Ogoya, located between Sofia and the city of Vratsa. They were openly shown and made known to the public after the political turn in November 1989. After the end of the socialist state, numerous events were organized in which Petko Ogoyski participated and used materials of his collection (s. Events).

The State Security Service paid close attention to the course and conclusions of religious meetings (conferences, councils). The Service prepared reports (information) on such meetings, and in addition to these reports it collected and attached copies of materials originally prepared for and used at such meetings. The Service also interrogated individual participants in the meetings, and drew up reports on that as well.

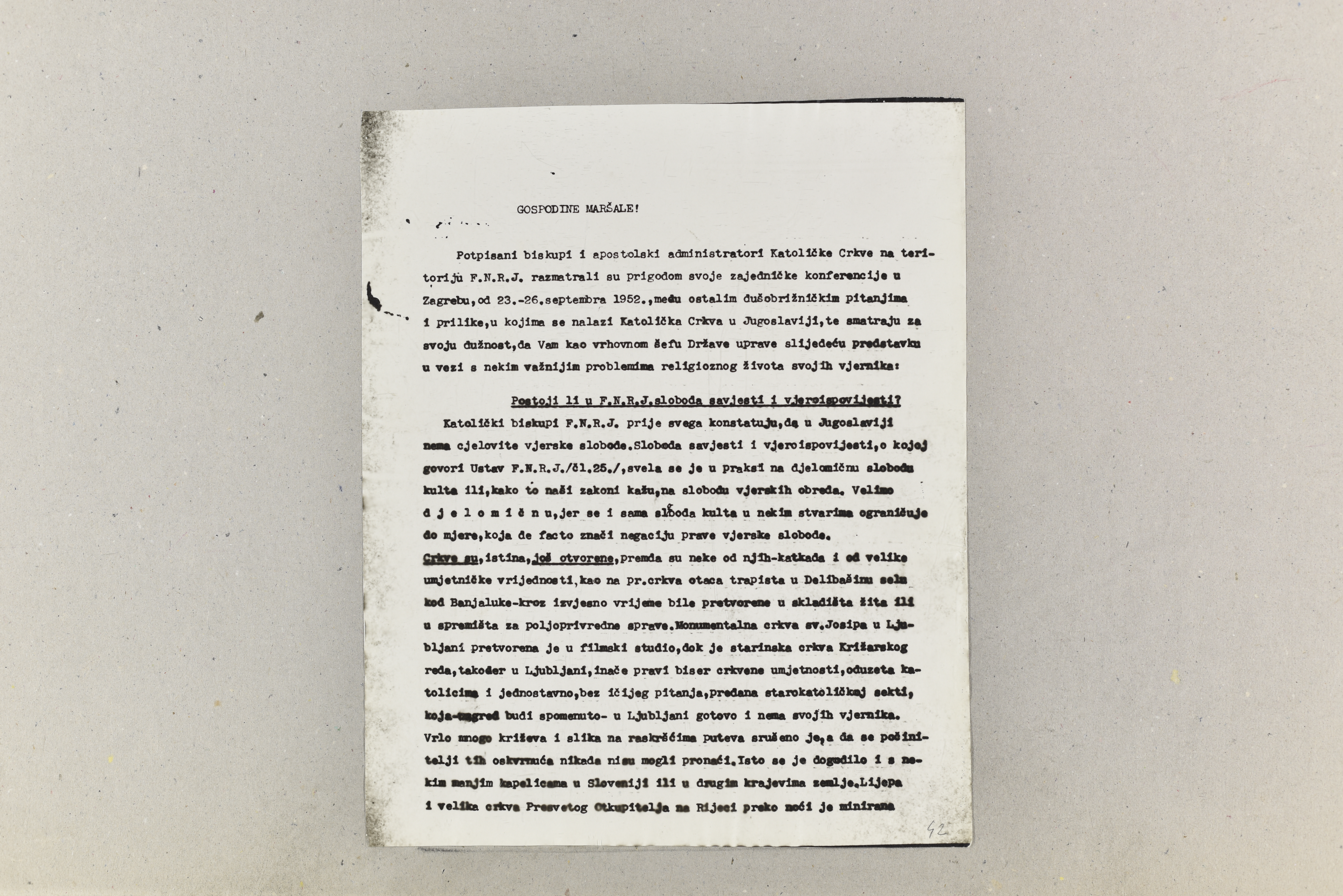

An example of such practices are the documents (approximately 200 pages, code 001/16) on the Conference of Bishops in Zagreb from 22 to 26 September 1952. One of the main topics of the conference was the stance on Roman Catholic clergy associations, whose establishment was encouraged by the communist authorities with the assistance of loyal priests with the intention of breaking Church unity. On the basis of an opinion secretly sought from the Vatican, the bishops adopted a decision to prohibit these clergy associations. This is why the Yugoslav Government submitted a protest note to the Vatican, accusing it of interfering in internal affairs. The elevation of Aloysius Stepinac to the rank of cardinal was cited by the Yugoslav Government as grounds to sever diplomatic ties with the Vatican (Akmadža 2003, p. 171-202).

In addition to an internal report about the conference (conference summary), these documents of the Croatian State Security Service have attached to them the records of interviews with bishops who participated in a conference, transcripts of the conference minutes, working papers and the adopted resolutions. Among them is a copy of petition sent on the last day of the conference from the Yugoslavian Catholic bishops to Josip Broz Tito. In a ten-page document, the bishops criticise state's previous attitude toward the Roman Catholic Church and openly demand favourable treatment. Inter alia, they specify that in Yugoslavia “there is no freedom of conscience and religion, rather the Catholic Church has been denied basic religious freedoms and its vital rights are threatened.” With reference to the aforementioned clergy associations, it was observed that “their role is to break down ecclesiastical discipline and progressively weaken religious life, and not to normalise the relations between the Church and State.” In the conclusion of the petition (“Our final word”) they sought freedom of religious education, Catholic press and religious organisation, as well as unfettered use of the resources necessary for those purposes. In the context of the aforementioned severing of diplomatic ties between Yugoslavia and the Vatican at the end of that year, instead of improving, state policy toward the Catholic Church grew worse. The document is available for research and copying.

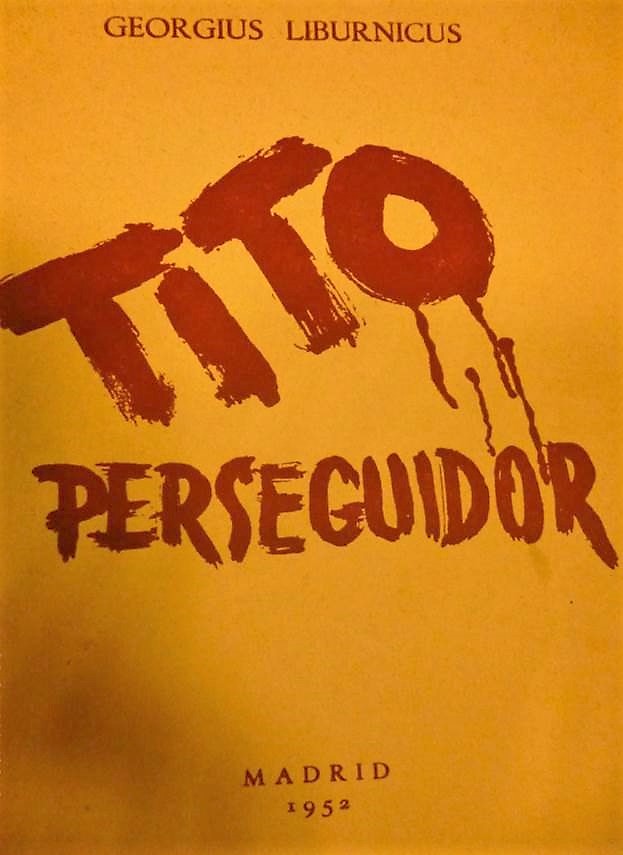

![Liburnicus, Georgius. Tito perseguidor (Tito the Persecutor). Madrid: [s. n.], 1952. Book](/courage/file/n6650/o89.jpg)

Augustin Juretić published the book Tito perseguidor (Tito the Persecutor) under the pseudonym Georgius Liburnicus in 1952, in the early years of socialist Yugoslavia. The year of the publication is even more important as it was a time of change in Yugoslav foreign policy with its turning towards the Western countries. In an effort to normalise relations with the West, Yugoslavia began the partial democratisation of its society and endeavoured to present itself as a society embracing democratic values. Tito the Persecutor confutes this image of Yugoslavia in the Western media, and reveals the true nature of the communist regime, describing the persecution of the Catholic Church and its clergy.

The book can be regarded as providing cultural opposition as its entire content deals with criticism of socialist Yugoslavia. It is written in the Spanish language, one of the world languages, and is thus accessible to a greater number of readers as well as policy makers.