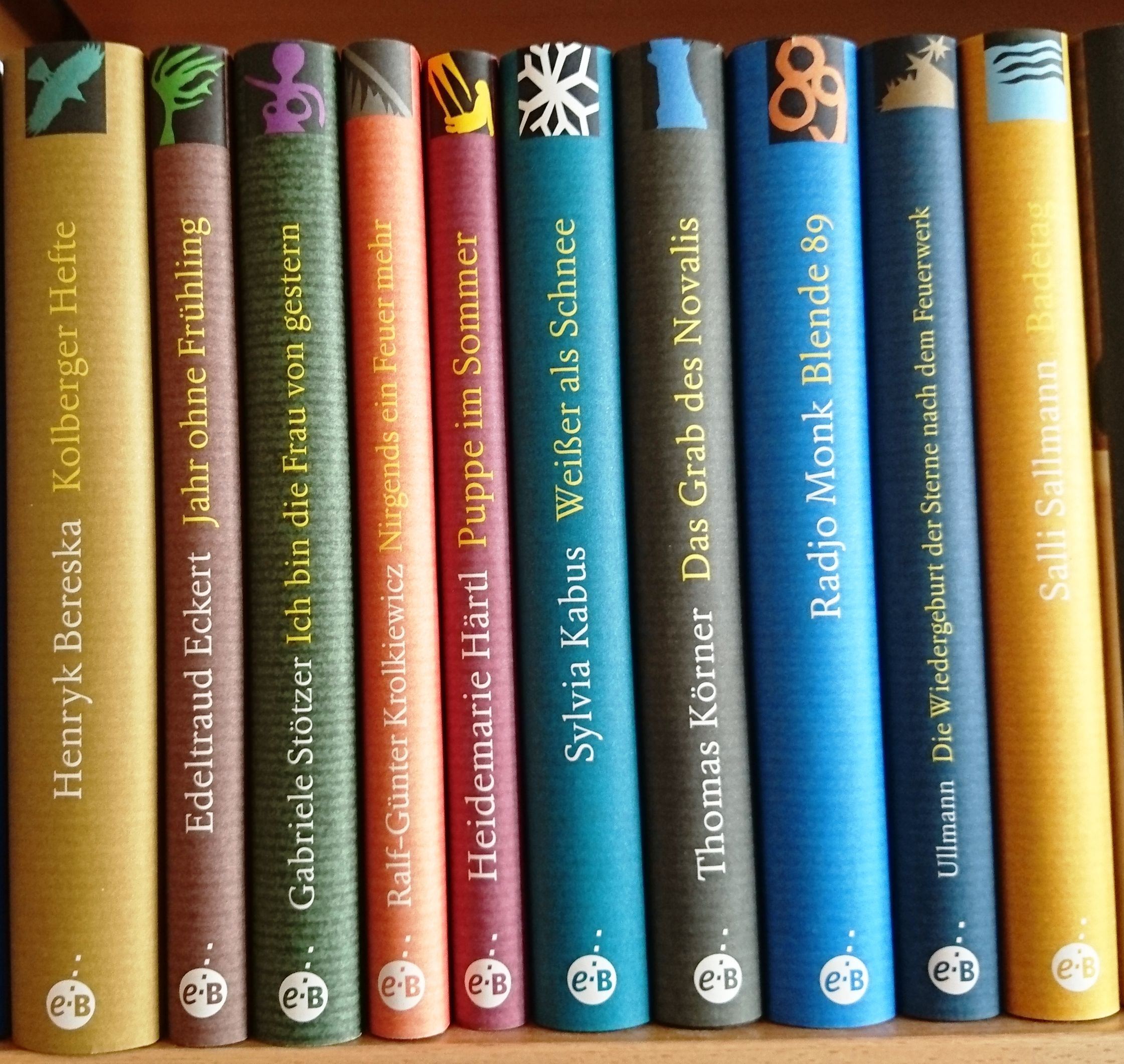

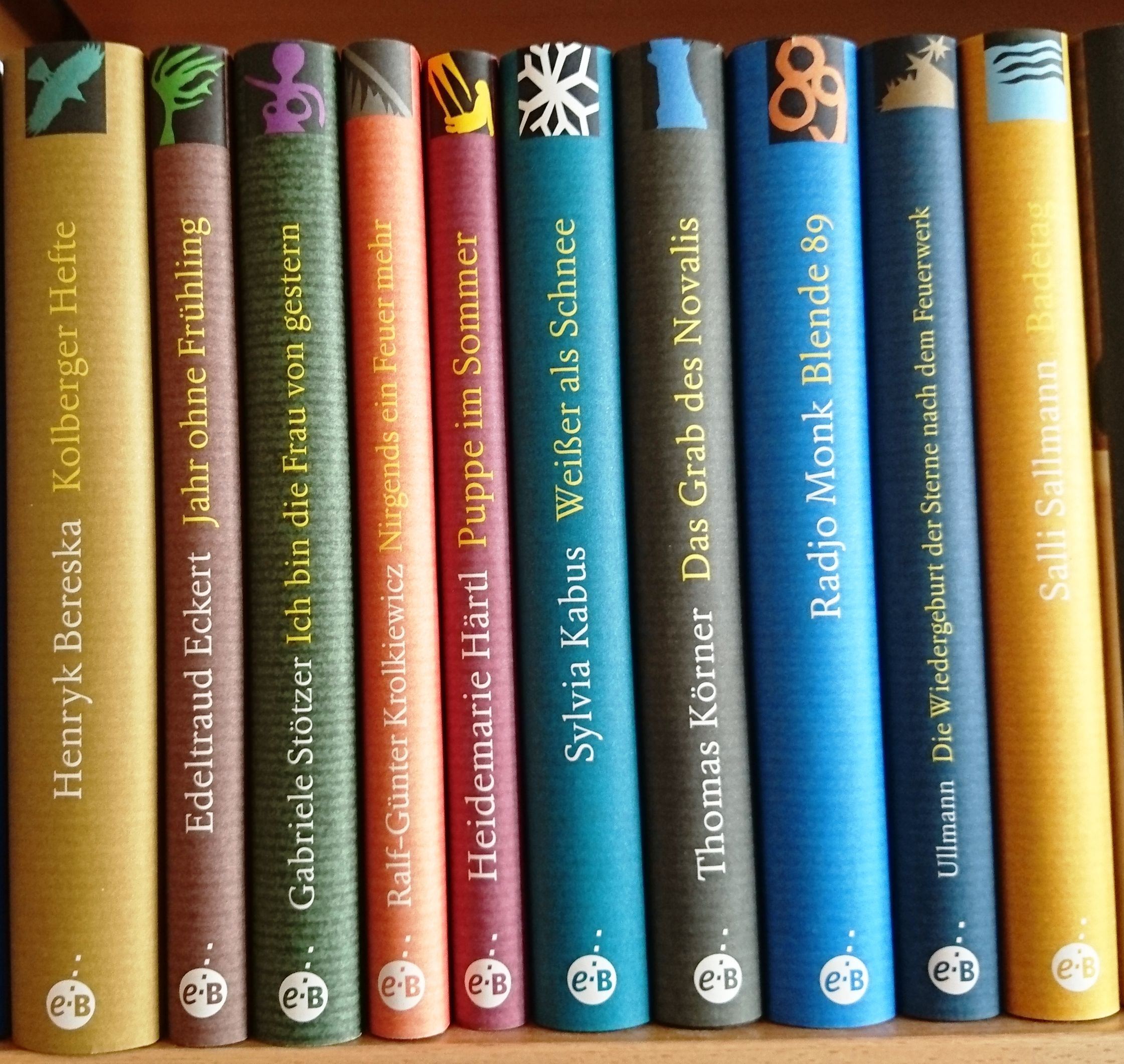

Based on their "Archive of Suppressed Literature in the GDR" and in collaboration with the Büchergilde Gutenberg, Ines Geipel and Joachim Walther initiated the book series "Die verschwiegene Bibliothek" [The reticent library]. From 2005-2008 ten volumes were published with works of the following authors: Henryk Bereska, Edeltraud Eckert, Heidemarie Härtl, Sylvia Kabus, Thomas Körner, Ralf-Günter Krolkiewicz, Radjo Monk, Salli Sallmann, Gabriele Stötzer und Günter Ullmann.

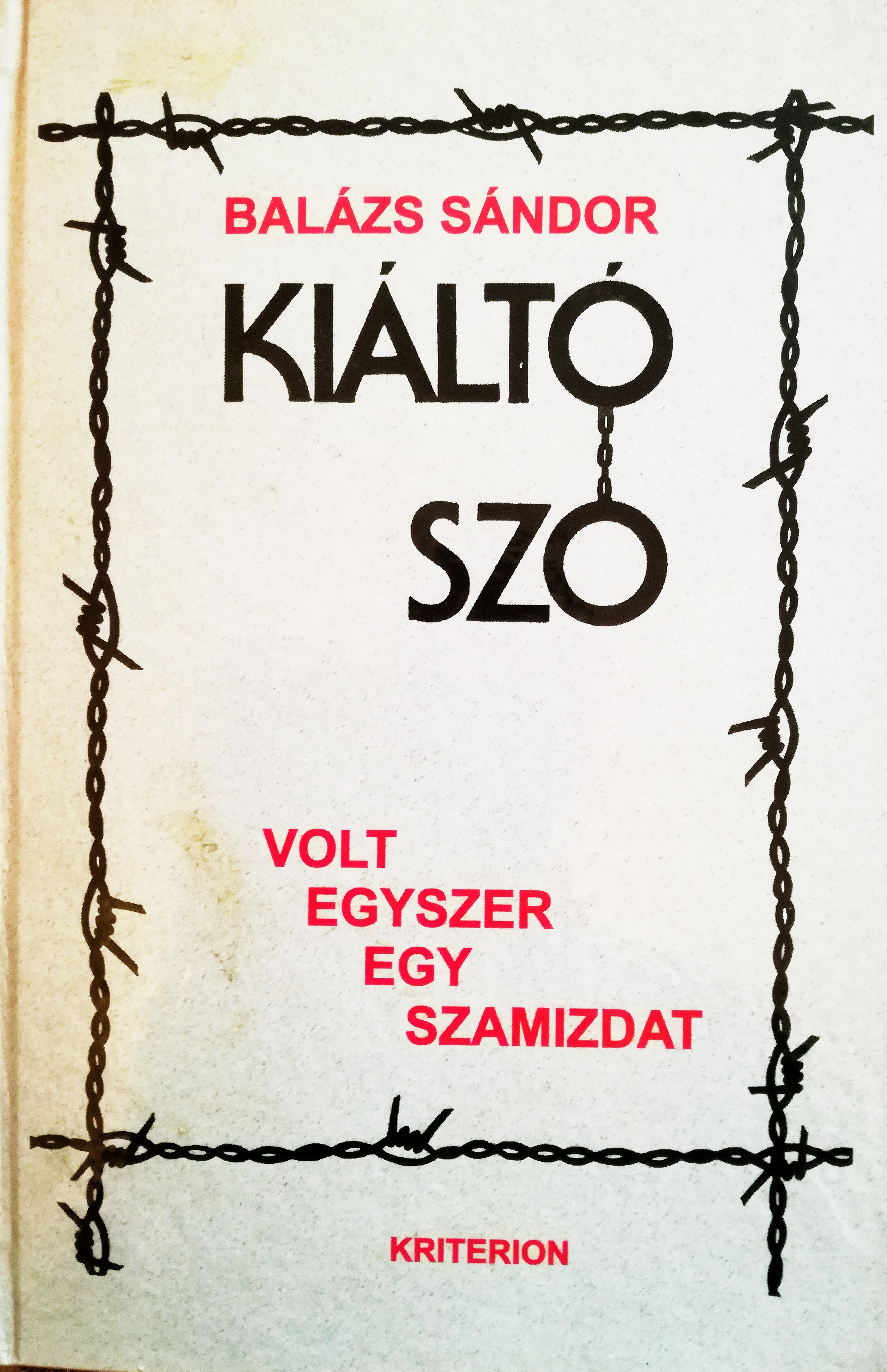

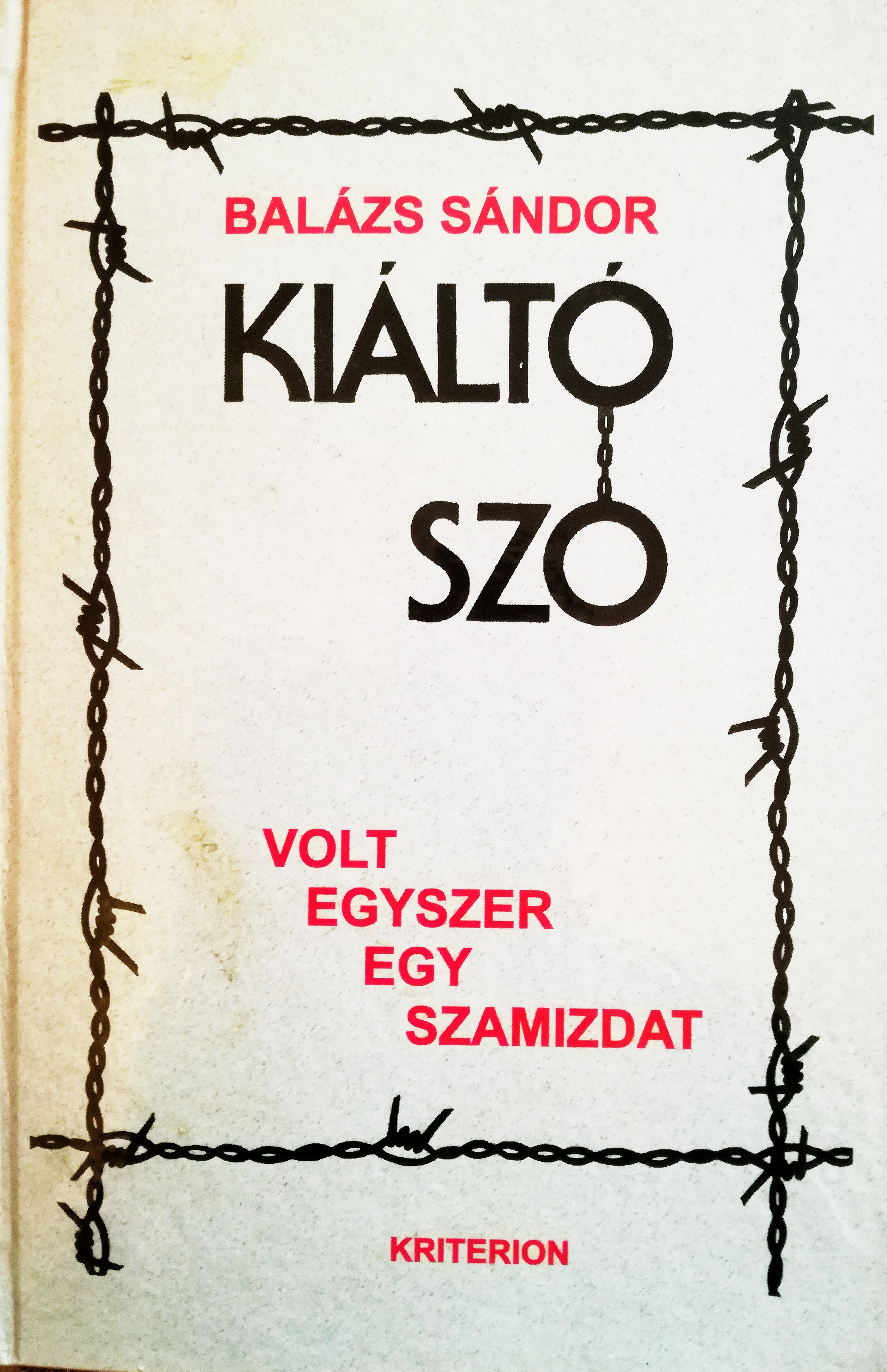

Balázs, Sándor. Kiáltó Szó: Volt egyszer egy szamizdat (Screaming Word: Once There Was a Samizdat), 2005. Book

Balázs, Sándor. Kiáltó Szó: Volt egyszer egy szamizdat (Screaming Word: Once There Was a Samizdat), 2005. Book

Although in 1990, in the heat of the revolution, Sándor Balázs “blew the cover” of the collaborators of the samizdat in the first issue of the Korunk magazine, published two of their writings, and briefly outlined their underground activity, he could not undertake the publication of Kiáltó Szó as a volume for quite a long while. Balázs feared for a long time that he would be accused of illegally introducing printed materials from Hungary, so he decided to make the history of Kiáltó Szó public only when it seemed that the atmosphere had calmed down. For his book Balázs exclusively chose texts that were either included in the two published editions or which were manuscripts in his possession pertaining to the remaining seven issues. He did not publish those writings that had been destined to appear in the Kiáltó Szó samizdat but had been published by his former colleagues in one form or another after 1989. He defines the genre of the book as “a recollection supported by documents,” as this definition includes both the subjective approach to the subject-matter and the commitment to present facts without bias. The volume is divided into two parts. As far as the structure and contents are concerned, the first part is the reflection of the second, entitled Documents, which thematically features, ignoring chronological order, the Kiáltó Szó articles that either appeared in print or were multiplied on a typewriter. In the first part, following the presentation of the samizdat’s genesis, the individual thoughts and explanations attached to the various documents shed light on the basic conception of the editors. The volume presented in the course of 2006 definitely imprinted in public awareness the last significant underground manifestation of Transylvanian Hungarian dissidence.

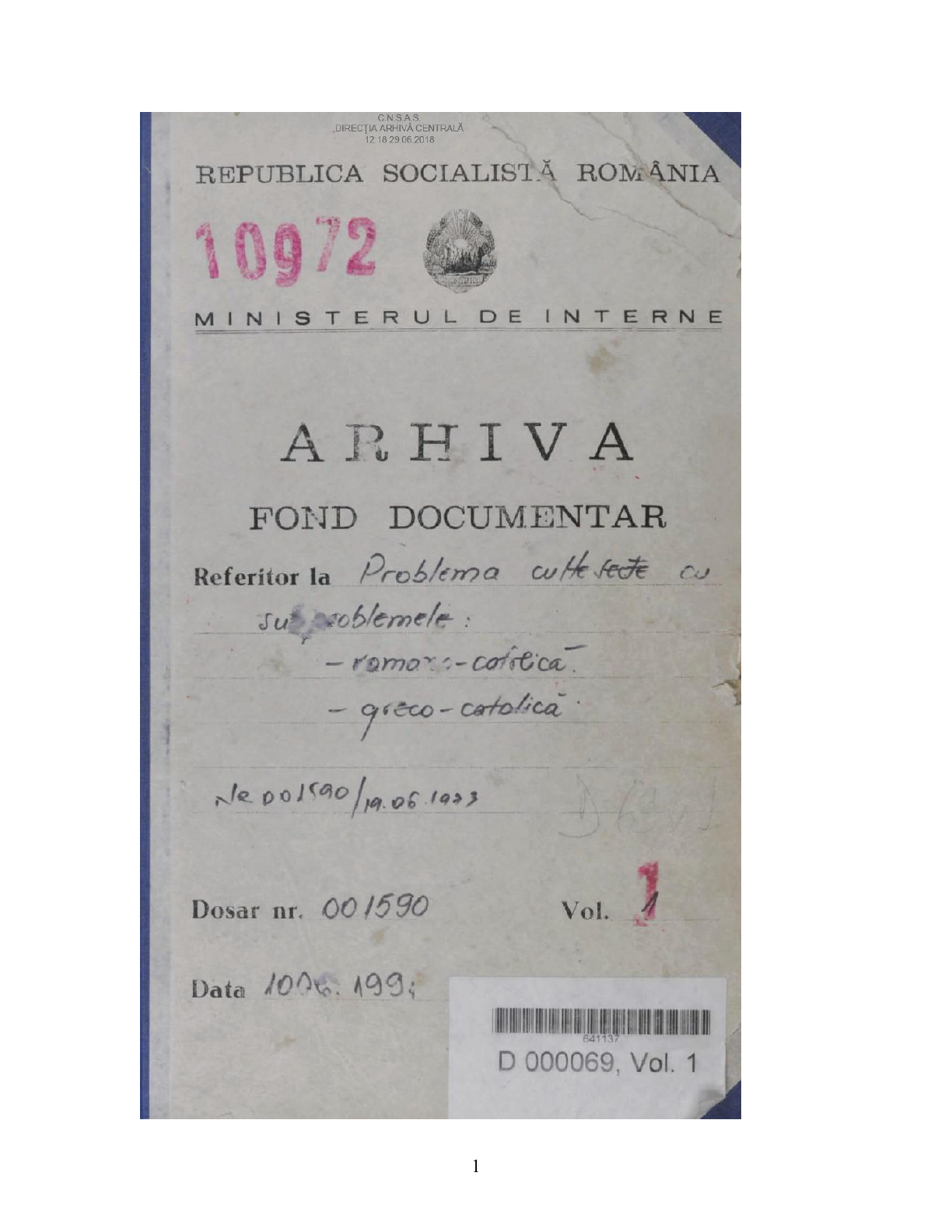

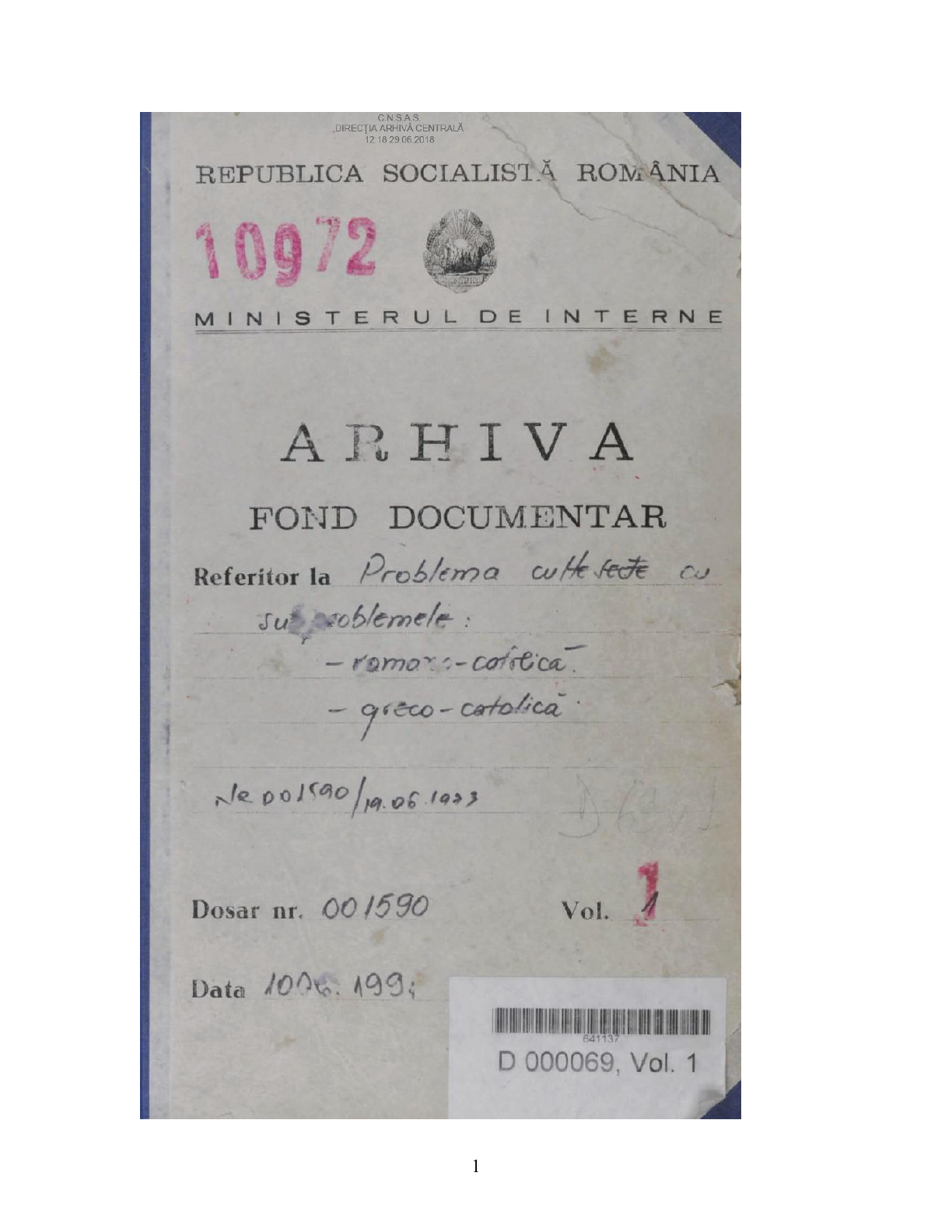

Transfer of the custody of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church Ad-hoc Collection from the SRI to CNSAS

Transfer of the custody of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church Ad-hoc Collection from the SRI to CNSAS

The majority of the files on the Romanian Greek Catholic Church pertaining to the Documentary Fonds were transferred from the Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI) to the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives (Consiliul Național pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securității – CNSAS) between 2005 and 2008. CNSAS is the official authority in Romania in charge of the administration of the Securitate’s archives. The activity of CNSAS is regulated by Law 187/1999 and Governmental Emergency Ordinance (OUG) 24/2008, modified by Law 293/2008. Since this transfer, the files of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church Ad-hoc Collection have been accessed by many academics and students, and also by victims of the communist state’s policies regarding the Romanian Greek Catholic Church.

In 2004, the Museum-Archive joined the International Samizdat Research Association, an informal network of over twenty research institutions and archives, studying and preserving samizdat collections. The ISRA project was organized by the Open Society Archives in Budapest. Among other founding members are Memorial Center (Moscow), and Forschungsstelle Osteuropa (Bremen).

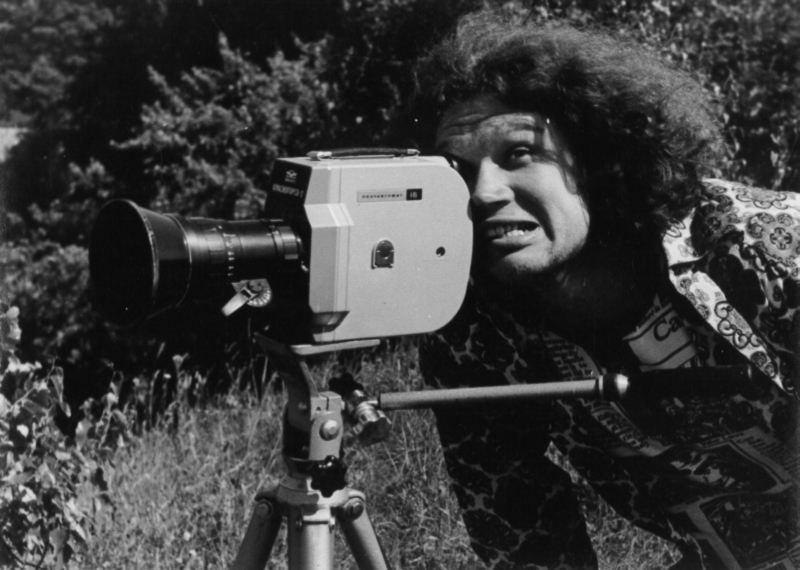

The collection represents filmmakers in Soviet Lithuania who could escape Soviet censorship because they were not professionals, and therefore worked outside official structures. As a consequence, these artists were able to address sensitive social issues, and use avant-garde forms of expression that were forbidden in official contemporary cinematography.

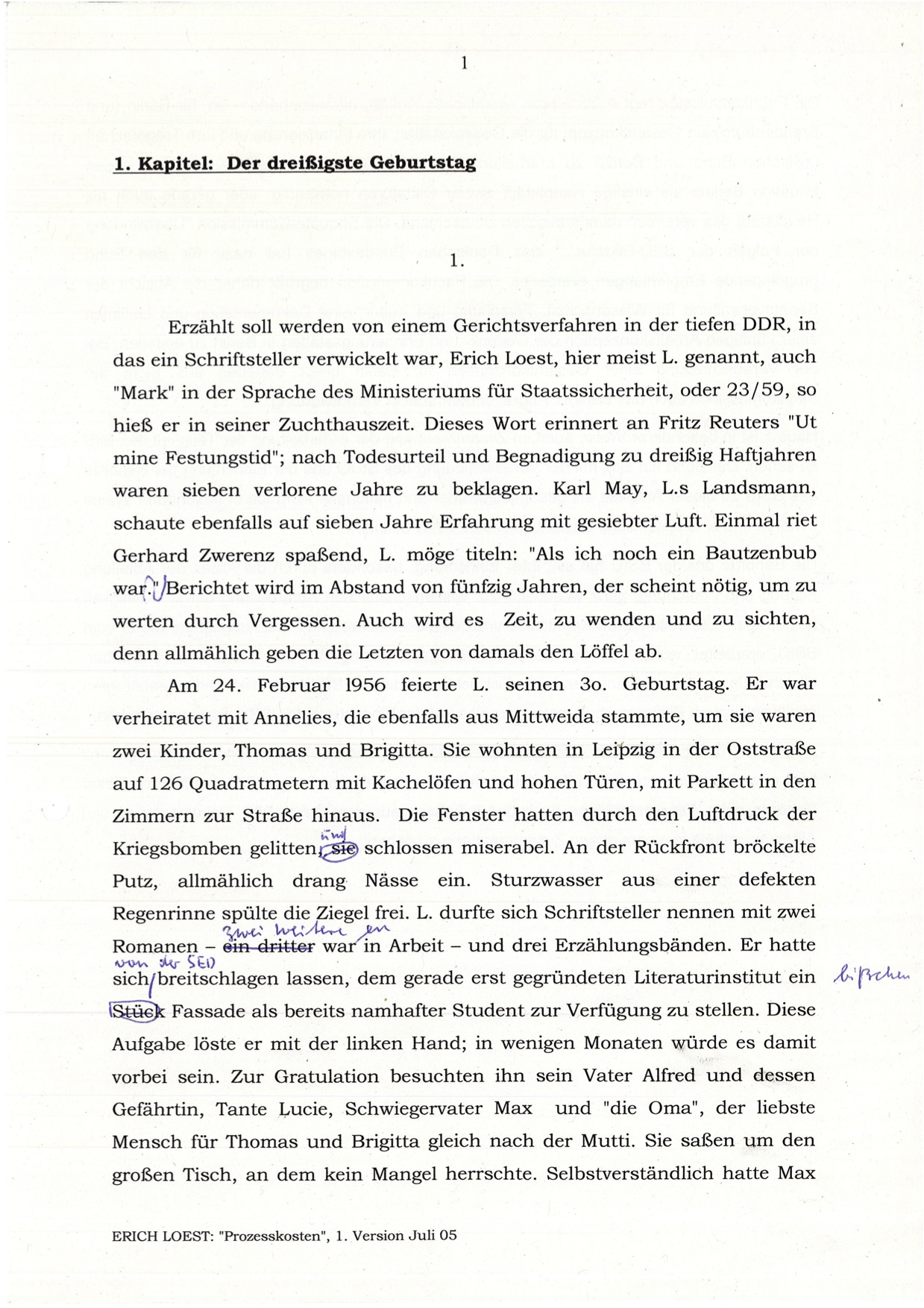

![Hand-notated manuscript of the book Prozesskosten [Legal Costs] (2005)](/courage/file/n117266/manuscript_el.jpg)

The author’s experience in prison is documented in the shocking account Prozesskosten [Legal Costs] (2007), published fifty years after Erich Loest’s release from prison. The archive contains handwritten corrections to the manuscript, presented here in an example.

The Jazz Section (JS) Collection was founded thanks to Karel Mašita, a former member of the section, and was supplemented by materials collected in exile by the historian Vilém Prečan. The collection contains documents which had been created since 1968: e.g. the correspondence regarding the foundation of JS and the first years of its operation, plans for activities, correspondence with authorities, documents regarding supervision and screenings, complaints concerning the attempts by the authorities to dissolve JS, the liquidation of the Union of Musicians and the reaction of the international press to the trials of members of JS.

“If one were to seek a simple answer to the query about the content of the BITEF archives, it would most certainly indicate a sound and profound strife to spring free from a provincial and orchestrated frame of thought and culture, in general. BITEF is the most tangible evidence that in Belgrade, Serbia and Yugoslavia, cultural pluralism and universalism was the weapon for conquering freedom in the world of political monism and political bipolarism.” writes Branka Prpa, the former head of the Belgrade Historical Archives in the web presentation of the book produced for the 40th anniversary of BITEF in 2007.

In 2005, the IAB started to process and classify the BITEF fond according to international standards so that the material until 2004 is very well systematized. A finely and creatively manufactured publication and an exhibition were produced which, according to Prpa, served as “an illustration of the power of cultural dialogue enacted with a non-pretentious definition of new theatrical tendencies.” Jovan Ćirilov wrote the introduction under the titel “testimony”, co-authors under the lead of Prpa were Olga Latinčić, Branka Branković, Svetlana Adžić. The book contains on about 300 pages in Serbian language the founding documents and minutes of the administrative council at the Belgrade authorities, program overviews, extracts (transcripts) from the talks after the performances with directors, actors and intellectuals, extracts from the newsletter that was accompanying every BITEF edition, many photographies, an overview of all the prices awarded and a name registry. It can be read at the Archives of Belgrade.

Producing the book and exhibition was, after the murder of Zoran Djindić in 2003 and the nationalist path reinforced, a kind of cultural resistance too. Prpa almost sentimentally looks back to BITEF’s beginning, when “[t]he petrified structures begun to crumble under the pulling force of the universalistic ideas which inevitably produce cathartic exhilaration with regard to the profanity and banality imposed [afterwards, JN] as a formula based on egotism and egocentrism of the individual and of the nation.”

The forty-fifth anniversary of the formation of the Reformed Congregation of Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund, and the twenty-fifth anniversary of the church construction was in 2005. Just as at the celebration of earlier anniversaries, the church service on 24 April 2005 served for remembrance and reckoning at the same time. Though the population of the congregation had decreased from 2,269 to 1,300, spiritual edification, diaconal work and the education of young people continued. A year earlier, with the help of co-religionists from Heemstede and Haarlem in the Netherlands, the congregation of Dâmbul Rotund had inaugurated a congregation house at Băgara, Cluj county, which served for the spiritual strengthening of the community. During the remembrance there were remembered not only the pastors of the congregation's history and the elders, caretakers and main caretakers, who solicitously loved their church and offered an effective help in the life of the congregation, but also all those, who had participated in the self-empowerment of the congregation and in the construction of the church building, and who, over forty-five years, had served their church by their work, material support and prayers. On the occasion of the anniversary the congregation issued a commemorative booklet with the title “A Kolozsvár–Kerekdombi Református Egyházközség 1960–1980–2005” (The Reformed Congregation of Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund 1960–1980–2005), in which in addition to the construction of the church building they remembered the twenty-five-year history of the choir, and also János Dobri, who played a determining role in the events.

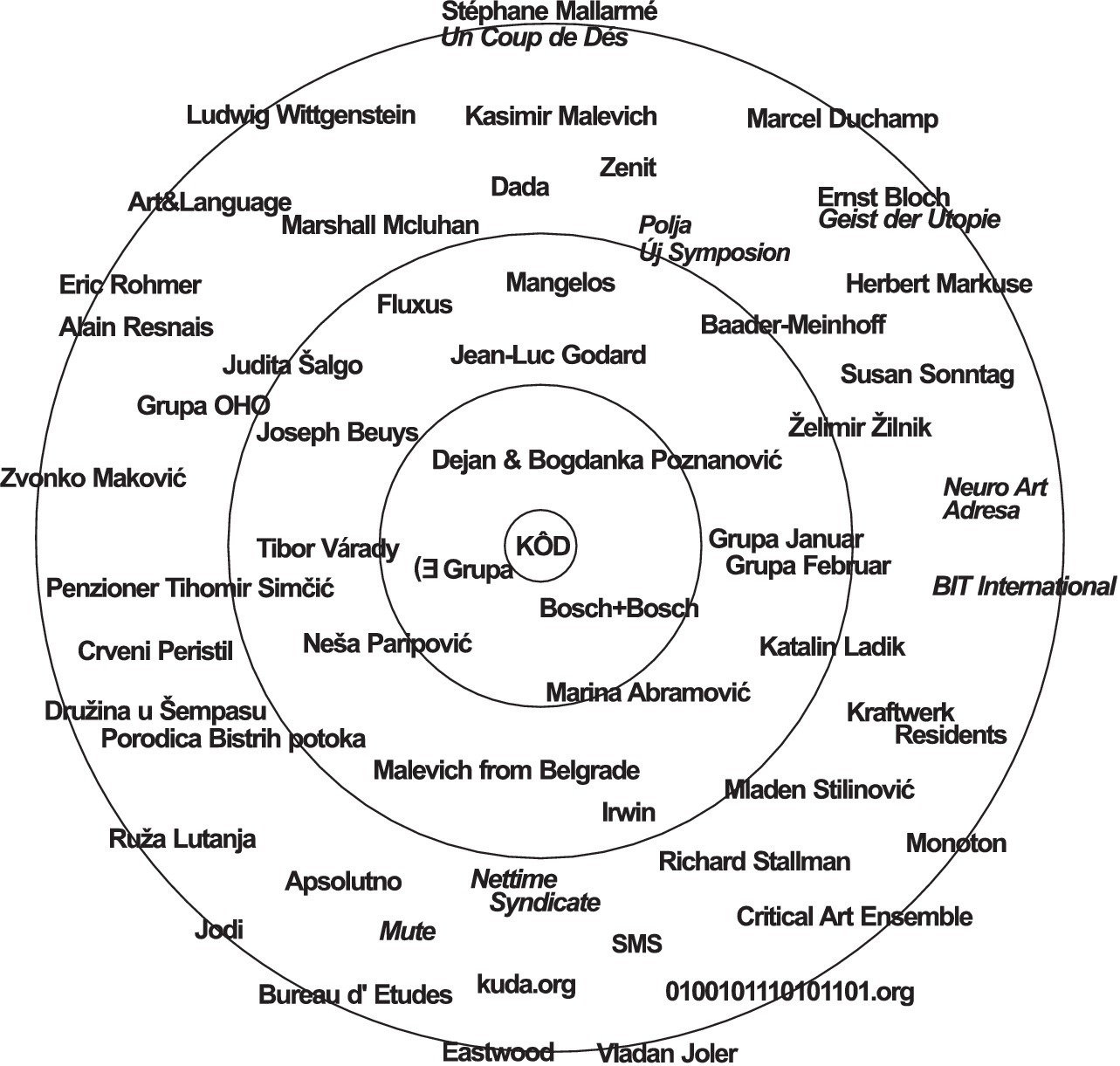

The exhibition Continuous Art Class, The Novi Sad Neo-Avantgarde of the 1960s and 1970s took place at the Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina in Novi Sad from 18 November to 3 December 2005, which included a selection of woks of groups (Ǝ and (Ǝ– KÔD from the period between 1970 and 1972. Some of the relevant political postulates have been presented: “An Open Letter to the Yugoslav Public” as well as “Song about Film” and “Song – Underground Youth Tribune, Novi Sad” which led to the incarceration of the respective authors, Miroslav Mandić and Slavko Bogdanović. There was an introduction by editors Tibor Várady and Vujica Rešin Tucić.

The following works were presented: Early Works (Rani radovi), 1969, Želimir Žilnik; Value-added Tax (Porez na promet), 1970, Slavko Bogdanović / KÔD; Cube (Kocka), 1970, Slobodan Tišma / KÔD; Aesthetics (Estetika), Text 1 (Tekst 1), 1970, Mirko Radojičić / KÔD; (Ǝ Group, 1 / 10, 1971, Communication (Komunikacija), 1971, Vladimir Kopicl, Čedomir Drča, Ana Raković; Information (Informacije), 1971, Slavko Bogdanović; “An Open Letter to the Yugoslav Public” (Otvoreno pismo jugoslovenskoj javnosti), 1971, February Group (Grupa Februar); Contact Art (Kontakt Art), 1971, Bogdanka Poznanović; Inside, outside (Unutra, spolja), 1971, Tibor Várady; NZ,1971, Peđa Vranešević / KÔD; New Arts Snack (Zakuska novih umetnosti), 1971, February Group / Miroslav Mandić; Comics about KÔD group (Strip o grupi KÔD), 1971, Slavko Bogdanović; Feedback letter box, 1971, Bogdanka Poznanović; The End, 1973, Slobodan Tišma, Čedomir Drča; Invisible band (Nevidljivi bend), 1973, Slobodan Tišma, Svetlana Belić, Čedomir Drča, Mirko Radojičić; Invisible Artist (Nevidljivi umetnik), 1973, Examples of invisible art (Primeri nevidljive umetnosti), Repetition (Ponavljanje), 1975, Slobodan Tišma, Čedomir Drča; Phonepoetica,1976, Katalin Ladik.

The following documentary videos were presented (in 8mm format):

Maniac 7001 (Manijak 7001), 1970, Youth Tribune Novi Sad; An Exhibition at the Lavatory (Izložba kod klozeta), 1970, Novi Sad; Action - Heart (Akcija Srce), 1971, Youth Tribune Novi Sad; Rivers, Cubes (Reke, kocke), 1971, Youth Tribune Novi Sad; Performance (Performans), 1974, Futoški Park Novi Sad, 19 P. Čarnojevića Street (Ulica P. Čarnojevića 19), 1973/4, Novi Sad; Riders (Jahači), 1974, Novi Sad; Wood of Souls / Jailor Give Me Water, 1974, Novi Sad.

Related publications, such as essays and magazines, were also presented, for example Adresa; Polja, magazine for art and culture; Új Symposion, Student.

The exhibition hosted artwork of different individuals and groups from that period, included video documentation and reference publications and was realized in wallpaper format. The members of New Media Center_kuda.org from Novi Sad curated the exhibition.

In 2005, CNSAS (Romanian acronym of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives) returned to Paul Goma all the 39 notebooks confiscated from Paul Goma’s home on the occasion of his arrest on 1 April 1977 and later archived in the Confiscated Manuscript Collection at CNSAS. This restitution was based on a post-communist legal framework which aimed at rectifying the wrongdoings of the communist regime. In the case of this restitution, no copies were preserved in the Archives of CNSAS, so today the originals are only to be found in the Paul Goma Private Archive, while copies of the documents that reached Radio Free Europe can also be found in the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives in Budapest. However, many of the documents confiscated from Goma were also preserved in his informative surveillance file, in particular the open letters and the lists of signatures, and thus they are still preserved in the Archives of CNSAS. The Paul Goma Private Collection is truly a special case not only because many of its items are preserved in copies in other repositories, but also because it is one of the few which travelled after 1989 from Romania into exile. The post-communist pattern was rather to bring back to Romania the collections created in exile, so this event in the story of the collection represents an exception to the rule.

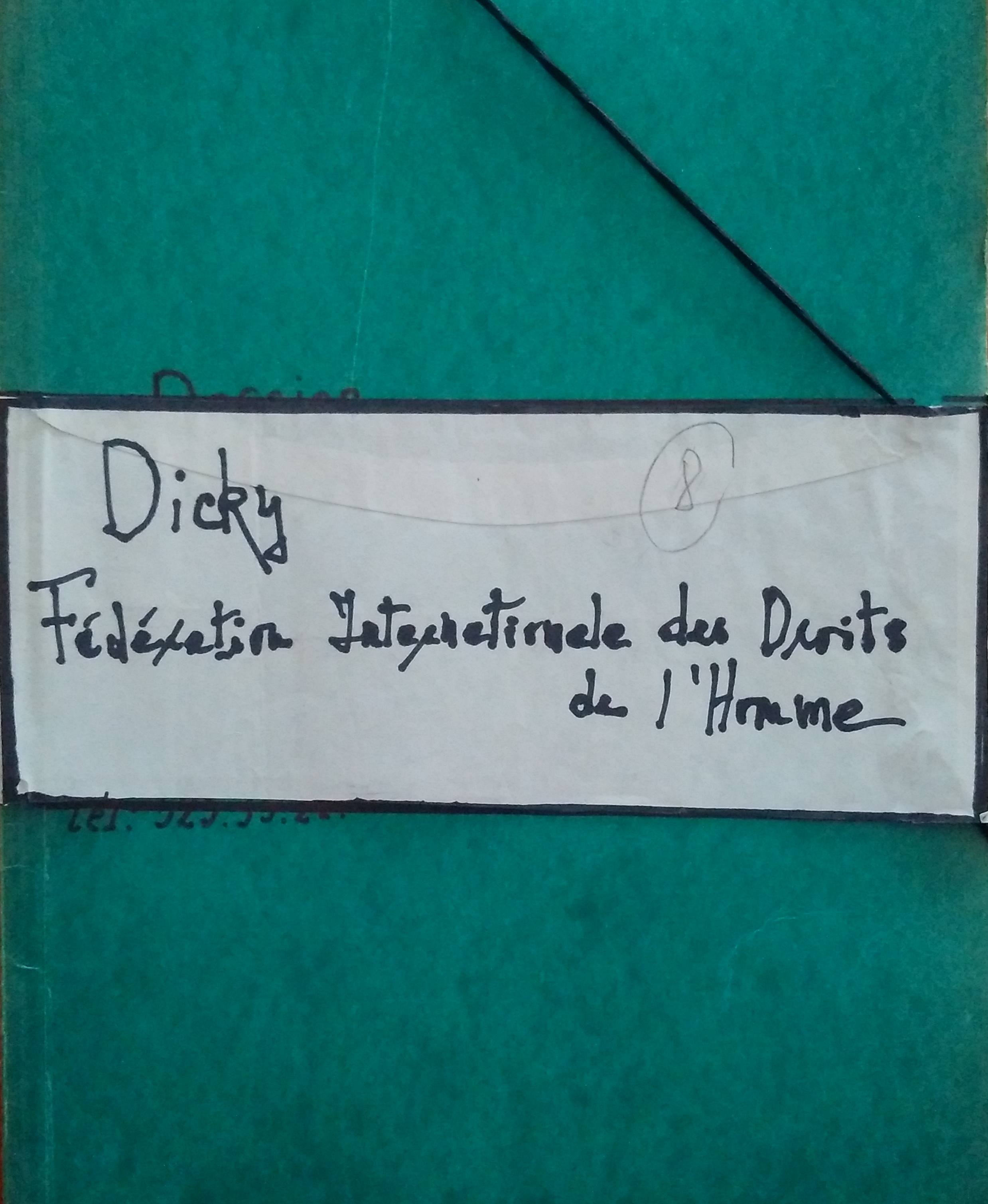

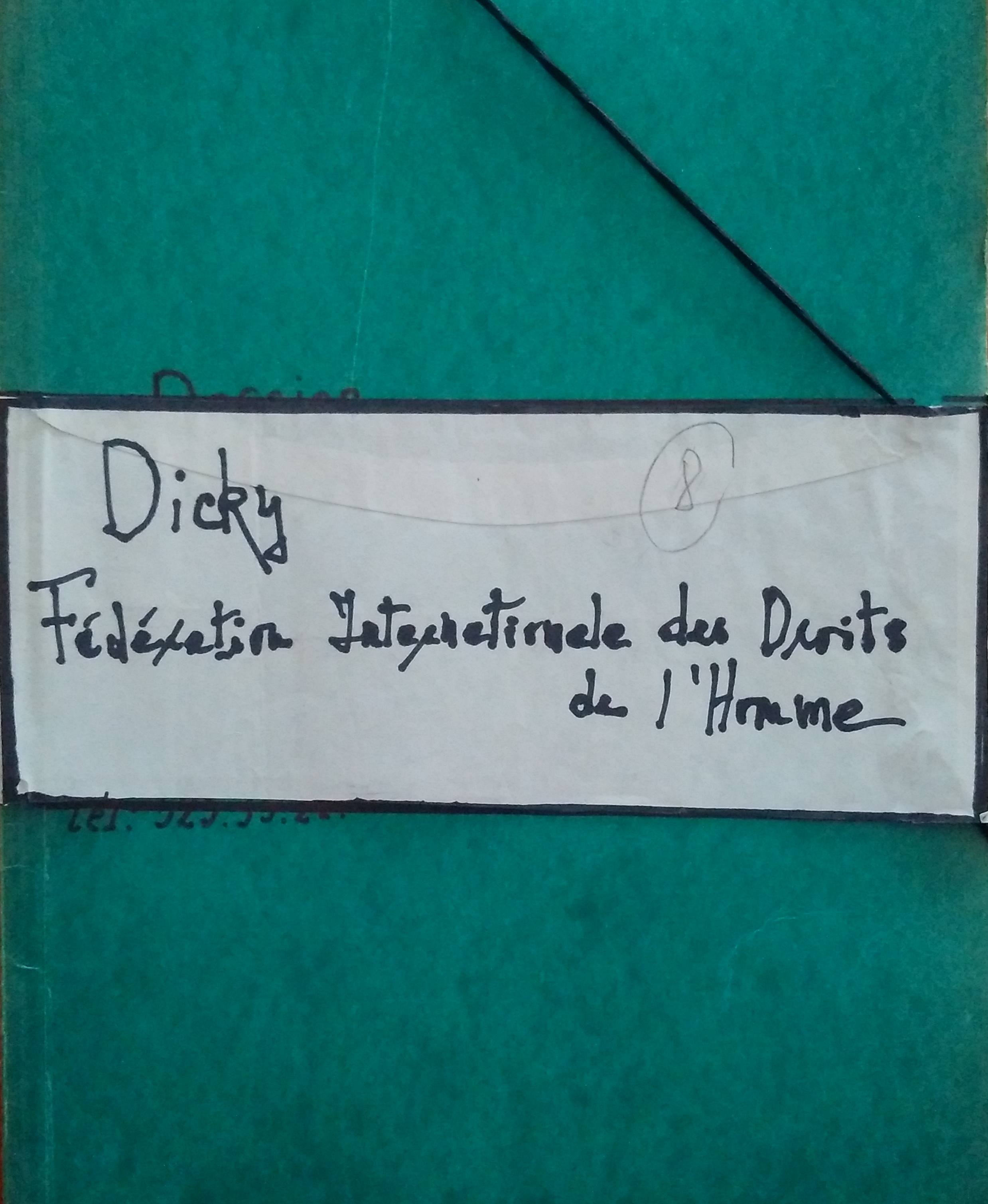

The Sanda Stolojan collection was donated by Sanda Stolojan to the National Institute for the Memory of the Romanian Exile (INMER). This was possible as a result of the Institute's efforts to identify such collections for the purpose of bringing them to Romania and opening them for research. The completion of a full inventory and the opening of the collection for research took place in 2005. On the one hand, the documents in the Sanda Stolojan Collection contribute to the understanding of the history of the Romanian exile community as well as of Romanian–French bilateral relations between 1968 and 1998. On the other hand, this private archive reflects a series of actions taken by the collector and other personalities in exile to stop human rights abuses in communist Romania and the demolitions imposed by the Ceaușescu regime after 1977. At the same time, some of the materials contained in the collection document the way some of the personalities of the Romanian exile contributed to the consolidation of democracy in post-communist Romania.

The exhibition presented the key theme of the 20th century: visual renditions of the concept of the Slovak nation, its beginnings, and the sense of its existence. Its aim was to clarify to what extent various forms of the Slovak myth are merely a romantic anachronism manifesting itself in the modern period or perhaps a manifestation of the crisis of collective identity; it also represents its natural search for identity. This frequently misused subject in history – in fact a complex of themes under the title “Slovak Myth” – is illuminated in the exhibition and in a miscellany of interdisciplinary work. It is a catalogue of a wide range of works including painting, sculpture, drawing, graphic art, photography, new media, and film, but also artefacts of folk culture and historical documents.

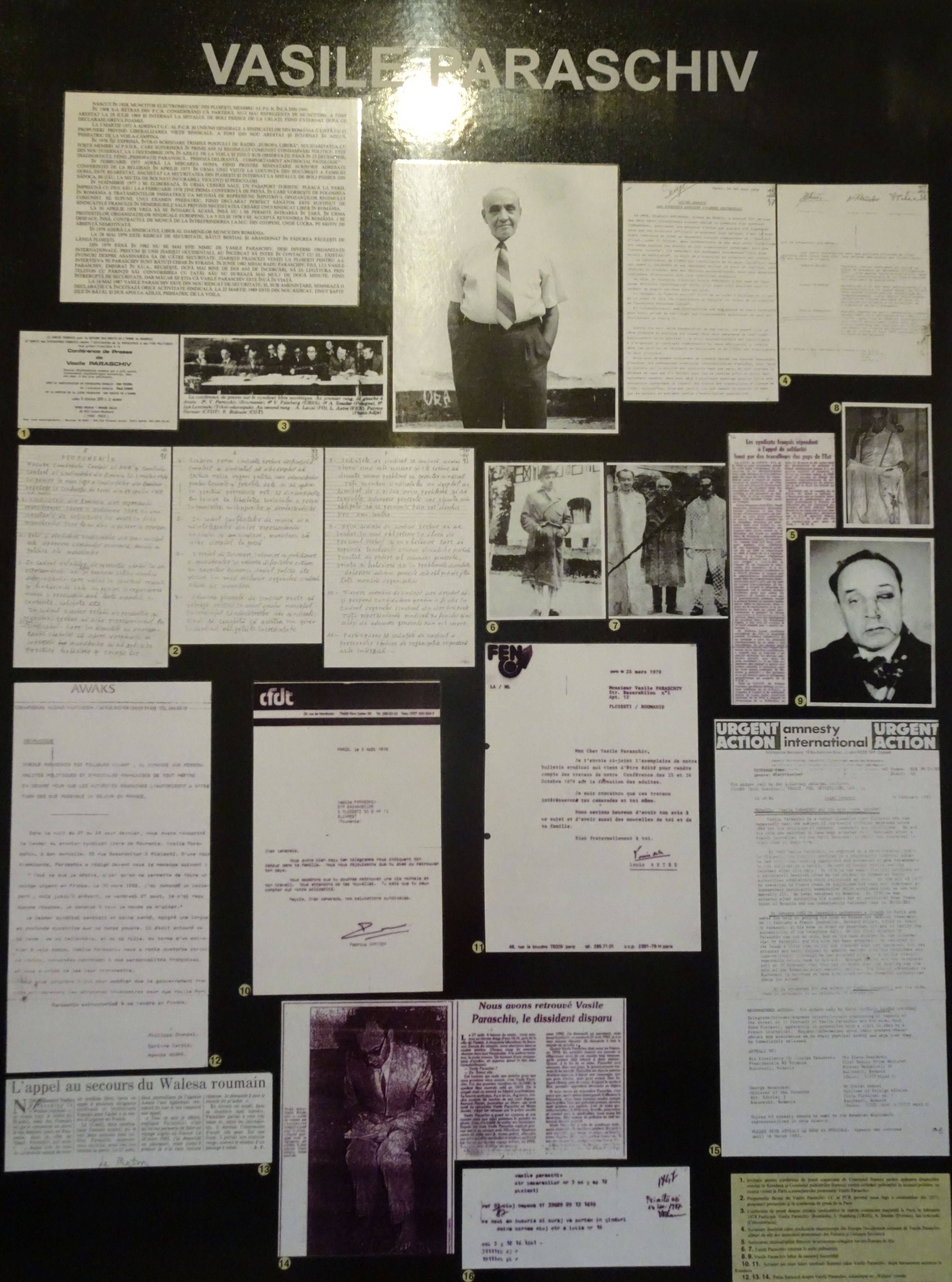

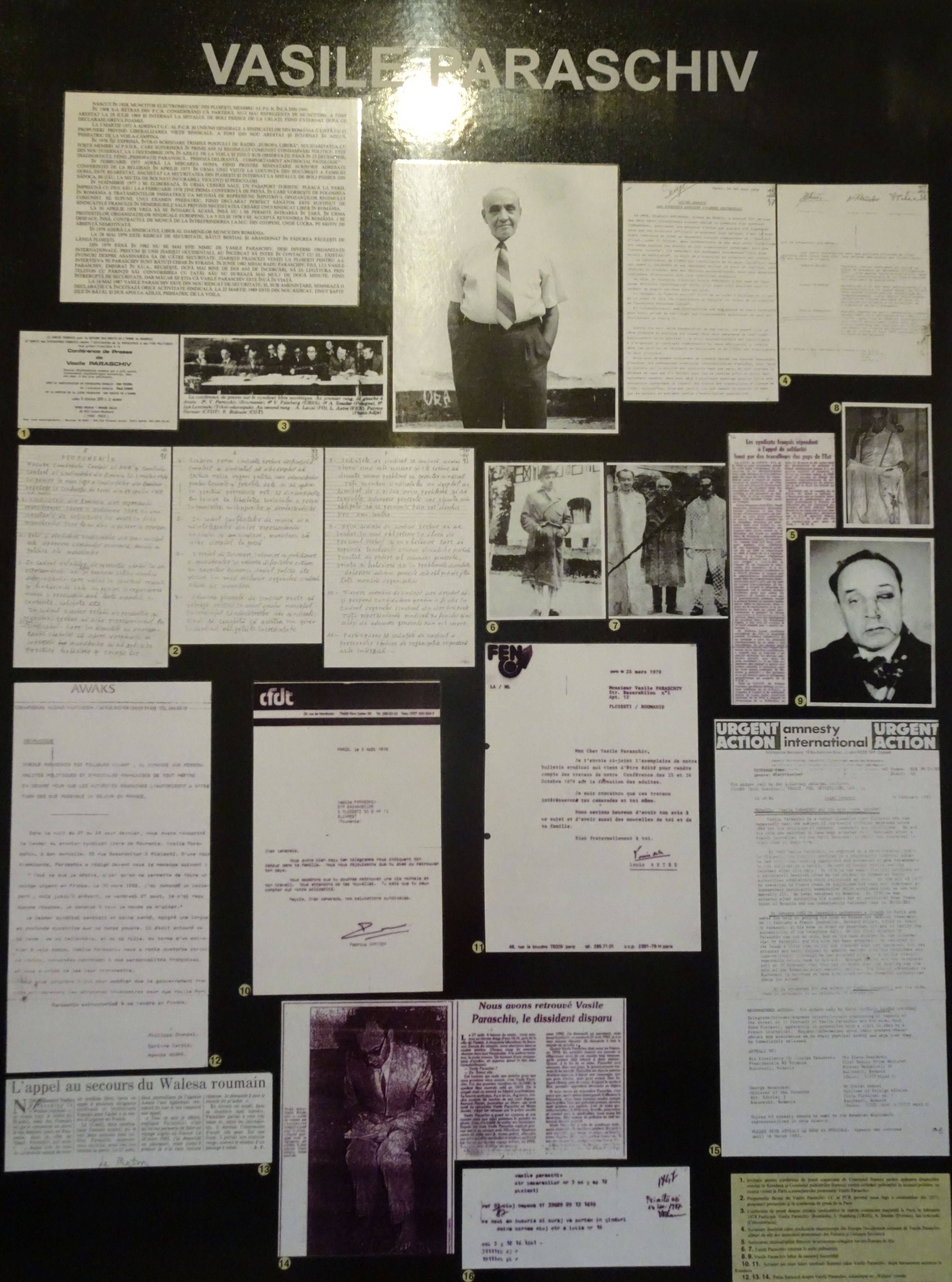

Paraschiv, Vasile, interview by Mihai Chiru, 2005. Transcript, Sighet Memorial – Oral History Collection

Paraschiv, Vasile, interview by Mihai Chiru, 2005. Transcript, Sighet Memorial – Oral History Collection

Vasile Paraschiv’s testimony is filed at number 2164 in the oral history archive of the Sighet Memorial. The interview, whose summary extends to three pages, was taken by Mihai Chiru in 2005 in Piteşti, on the occasion of the symposium “The Piteşti Phenomenon: Re-education by Torture” organised annually by the Association of Former Political Prisoners, the County Museum in Piteşti, and the local authorities in the city, in collaboration with other relevant institutions. This symposium is emblematic for the exceptionalism of communism in Romania: it symbolises the mixing of victims and torturers that was experimented with in several prisons, among them that of Piteşti – the uninterrupted torturing of political prisoners with the help of some of their cellmates, with the aim of completely destroying the personalities of the latter.

Vasile Paraschiv’s testimony was initially stored on a 60-minute Sony audio cassette, but it now also exists in digital format. His testimony sums up the main stages in the violent confrontations that this worker had with the communist state’s apparatus of repression, and the most important episodes in the periods in which he was under political arrest. More precisely, the themes touched on by Vasile Paraschiv in this oral history interview are the following: his renunciation of the status of Romanian Communist Party (PCR) member in November 1968; his public letter of 1971 in favour of the creation of a Free Trade Union; his expression of solidarity with the movement for human rights initiated by Paul Goma in 1977; the refusal of the communist authorities to let him back into Romania on his return from a visit to France in 1978, during which he had given numerous interviews regarding his personal experience of psychiatric repression; and the last years of Romanian communism and his final confrontations with the Ceauşescu regime.

Regarding his experience of psychiatric repression, the most relevant testimony refers to the abuses that he suffered after he adhered to the human rights movement initiated by Paul Goma. “In February 1977, I met the writer Paul Goma, I signed his open letter to the Helsinki follow-up conference at Belgrade, and I was again arrested by the Securitate, who were keeping watch on my home, and taken to the Bucharest Militia, Drumul Taberei district, where they asked me and put pressure on me to give a declaration in which I would retract the signature I had put to Paul Goma’s letter. I refused to do this and for this reason they beat me; they mistreated me until I lost consciousness. For many minutes I was completely knocked out. After midnight I was loaded into a car and taken to the Securitate in Ploieşti, and from there, the next morning, I was again admitted to the Săpoca mental hospital, Buzău county, where I was checked in by the hospital director, Dr Anton Nicolau. Without asking me anything, why I had been brought there, because I was brought by two militiamen in uniform, he gave orders for me to be admitted to Section 2 of the hospital, which was the section for dangerous patients, people who were incurable, were violent, were truly dangerous,” says Vasile Paraschiv in his testimony. He continues with a shocking account of what he experienced during his political detention in the hospital: “If at the Militia in Drumul Taberei, Bucharest, I saw death close up, at Section 6 in Săpoca, Buzău county I saw Hell on earth. Here men and women half naked, with bare breasts, unkempt hair, faces covered with blood, torn dresses, were going round all the time in a state of agitation, the men marching and singing, commanding, some of them songs of grief, others songs of longing – it was a veritable Hell. I forgot to say that in all the other hospitals where I was, at Urlaţi and Voila, no one made me, no one obliged me to follow any kind of treatment; I was just admitted and kept there under observation; no one gave me anything. At the Săpoca Hospital, however, Dr Anton Nicolau, who as an agent of the Securitate obliged me to follow a medical treatment for out-patients. The nurses would put five to seven, maybe more pills in my hand and oblige me to swallow them; I put them in my mouth and then slipped them under my tongue; they gave me a glass of water and I had to open my mouth; I opened my mouth and after that they told me I was free. I went to the lavatory and threw them all down there. I’m convinced, and the doctors can confirm, that if I had swallowed those pills I would have become a real patient and I wouldn’t be here in front of you today. This idea, of putting the pills under my tongue, I’ve wondered how it came to me, and I’ve come to the conclusion that God gave it to me, because otherwise I would be long dead.” Vasile Paraschiv was one of the few direct witnesses of psychiatric repression in Romania, which constituted one of the most barbarous methods of annihilating those who criticised the communist regime, and which was used even after the political detainees were officially released from the prisons in 1964.