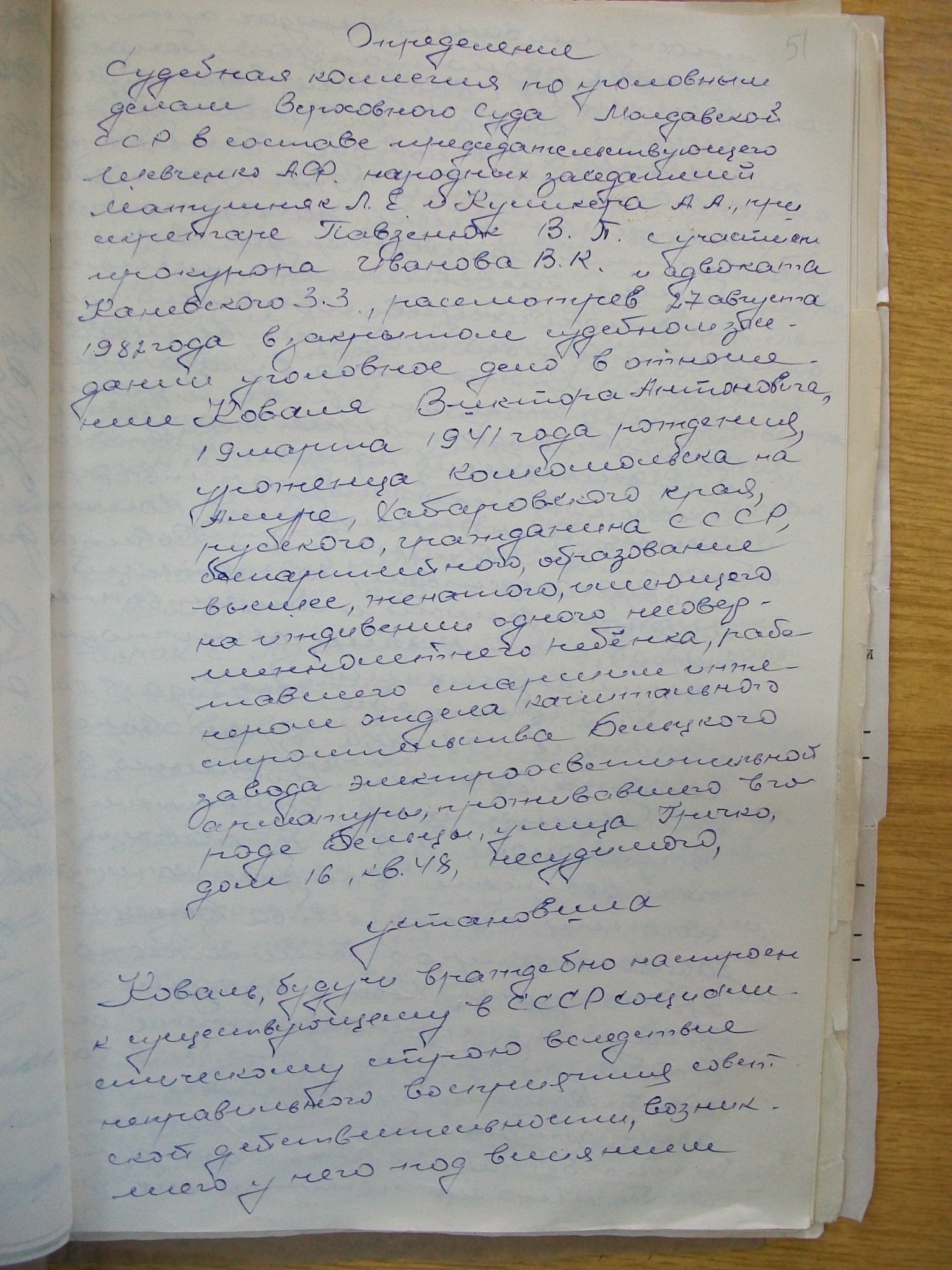

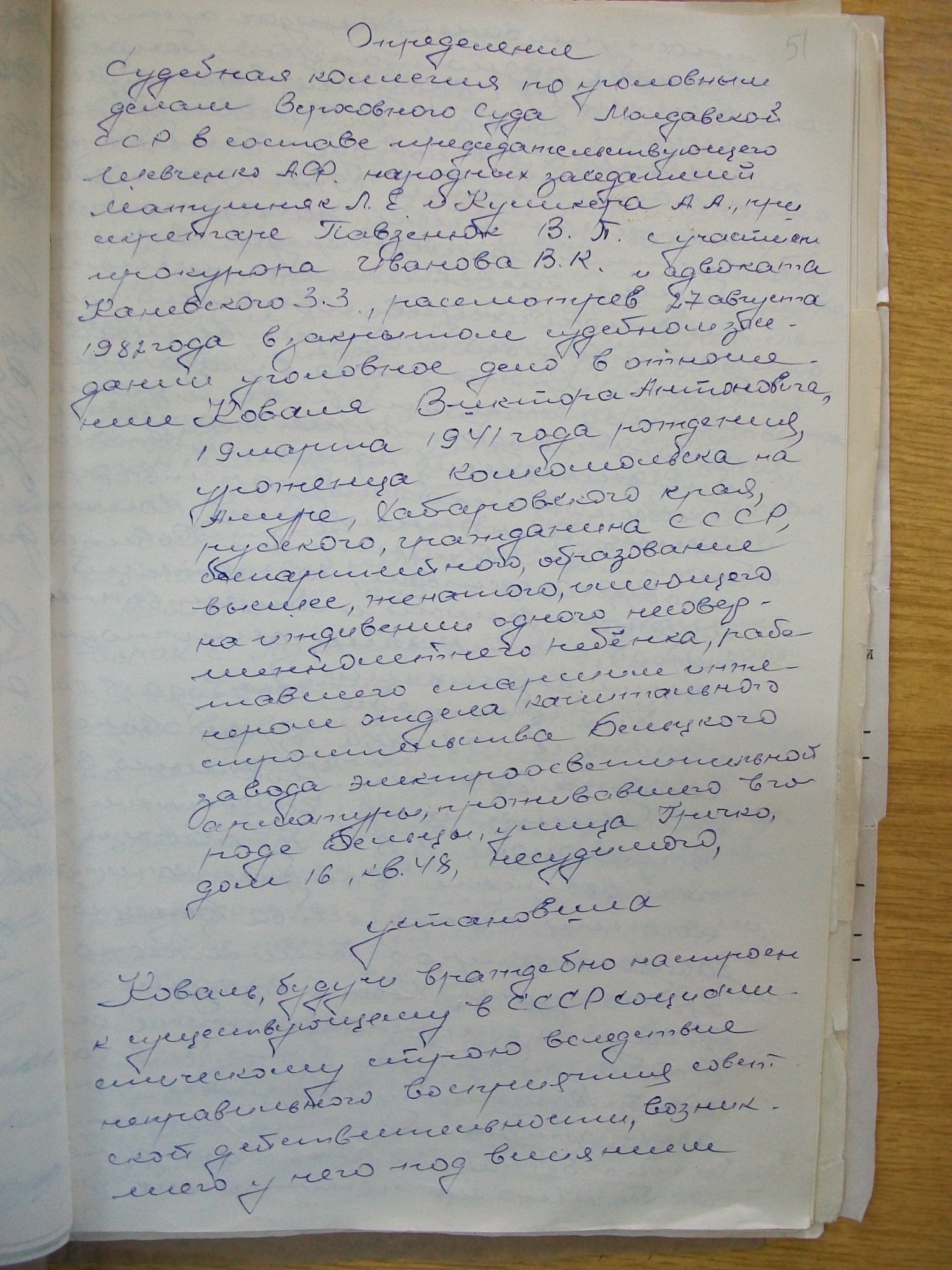

Special Decision (opredelenie) of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR concerning the case of Viktor Koval (in Russian). August 1982

Special Decision (opredelenie) of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR concerning the case of Viktor Koval (in Russian). August 1982

Following Viktor Koval’s trial, on 27 August 1982 the Penal Section of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR issued a special decision (opredelenie) regarding his case. In effect, this document represented a surrogate of the official sentence. Similarly to the usual pattern of such documents, the court emphasised the defendant’s “hostile attitude” towards Soviet power. In Koval’s case this deviant behaviour was purportedly due to his “false perception of Soviet reality,” which was induced by his “listening to the broadcasts of the anti-Soviet radio stations Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, Deutsche Welle, BBC etc.” The document further summarised the defendant’s main anti-regime activities, which he undertook during 1977–1982. These included his criticism of “Soviet democracy,” his refusal to take part in the elections to the Supreme Soviet, his condemnation of the lies and distortions propagated by the Soviet press, his critical attitude toward Soviet foreign policy, in general, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, in particular, and, most importantly, his open support for the Solidarity movement in Poland. The comparison between the Soviet political system and the political structure of Western countries was a constant theme in Koval’s conversations with his colleagues, which was allegedly proven by numerous witness accounts invoked in the document. Koval was also clearly aware that the Soviet state did not guarantee the basic civil rights of its citizens. This constituted another recurrent topic which emerged during the investigation. The authorities were particularly alarmed by Koval’s general critique of the Soviet system as a whole. The material evidence uncovered during searches of Koval’s apartment also contributed to the court’s ruling that the defendant had “committed a socially dangerous act” that fell under the provisions of article 203, part 1, of the Penal Code of the Moldavian SSR (“spreading calumnies and lies aimed at discrediting the Soviet state and social order”). However, based on the conclusions of the psychiatric assessment, the court found that Koval exhibited signs of a mental illness and personality disorder. It therefore declared him mentally unfit and thus exempt from criminal responsibility. He was thus sent to a special psychiatric facility in Dnepropetrovsk (Ukraine) for “forced medical treatment.” Most of Koval’s papers and documents confiscated by the KGB were temporarily kept as a part of his file, while the rest were returned to his wife. This case is one of the most blatant examples of the application of punitive psychology in the MSSR during the late Soviet period. Koval’s political opposition to the regime, although it never transcended the individual level, was perceived as serious enough to warrant harsh repressive measures camouflaged under the “humane” rhetoric of a medical case.

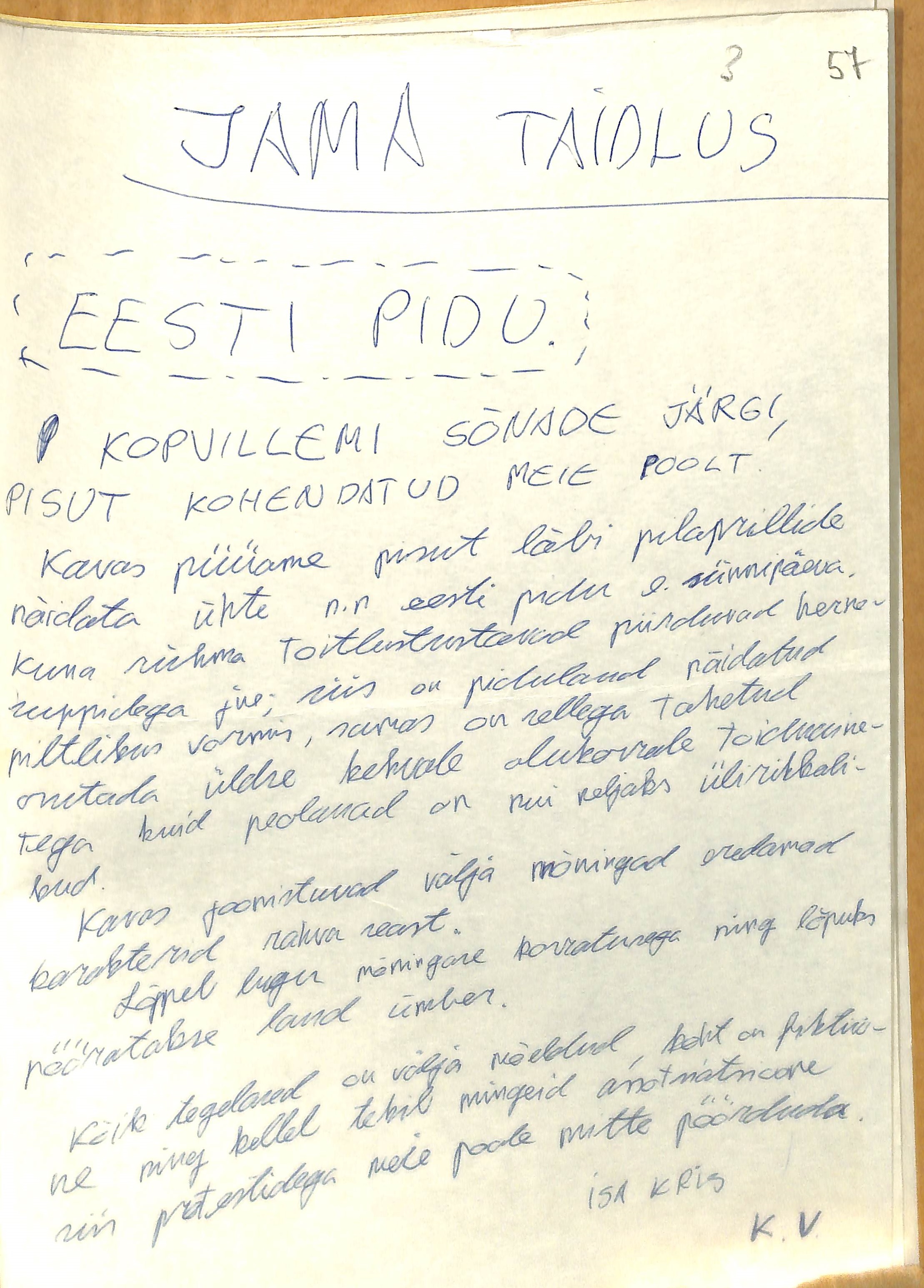

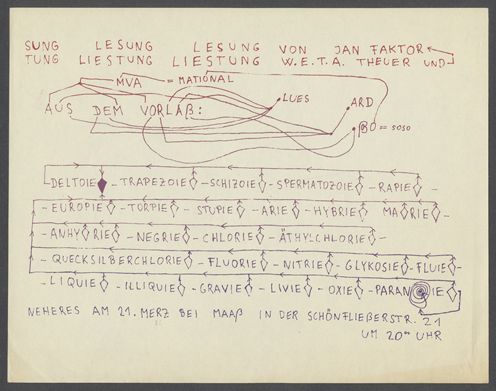

Performances were a common amusement at the Estonian Student Building Brigade (ESBB). This draft was written for a production in 1982 ending a meeting of groups. The title of the production was Eesti Pidu (Estonian Party), and the scenario hints, among other things, at the lack of groceries in Soviet Estonia, which paradoxically did not stop people giving lavish parties. This was made possible by having the right acquaintances, or by using other clever practices. These topics could not be discussed openly, but it was possible to express them during the working summers of the ESBB. Thus, this scenario is a good example of the societal free space which the ESBB offered students.

Normally a climbing harness is made from materials tested according to international (UIAA) standards, light, and very comfortable. However these could not be found in the last decade of communism in Romania. The solution achieved by improvisation by Dragoș Petrescu has the following characteristics: “The climbing harness was a very important part. Precisely because you could never be sure of the object you had improvised, you made a combination of chest harness and seat. Out of worn rope, usually six lengths placed parallel and sewn together with synthetic surgical thread, you made a sort of waistcoat with braces made of tape for blinds, which you wore around your chest and with which you tied yourself into the rope. Initially, mountaineers climbed with only the chest harness, only that they realised that once you were hanging on the rope, the chest harness became very tight; the circulation stopped and that could be fatal. Then they came up with the idea that it was good to have a seat as well as the chest harness. The so-called seat was usually made from strapping for car seatbelts sewn with surgical thread, which looked like a belt with two loops for the feet, into which you fastened yourself together with the chest harness. For the seat, you got hold of various materials. Principally seatbelt strapping. Ideally, we used the seatbelts for Dacia cars, but these were quite expensive. Many ‘got hold of’ one of these straps from the people that worked in the factory in Braşov where they were produced and where the unfinished product was sold illegally by the metre. As a rule, we made ourselves both seat and chest harness.” The original complete harness, composed of chest harness and seat, exists in Dragoş Petrescu’s private collection of improvised gear, but it can no longer be used for climbing as the materials from which it is made have deteriorated.

“Interrogation” is one of the most renowed films directed in Poland after World War II. It is a bold, politically engaged settlement with the Stalinist period in contemporary Polish history. The story is about a young actress (character played by Krystyna Janda) who is arrested by the Security Service and held captive in prison in order to force her to testify about her colleagues. “Interrogation” shows the methods used by Stalinist repression apparatus in order to break ordinary citizens, as well as prisoners’ efforts to preserve dignity and humanity.

The pre-release committee took place in April 1982, in the midst of Martial Law in Poland. As one can see from the committee’s meeting protocols, film critics and representatives of authorities deplored Bugajski’s oeuvre as hateful, false, antisocialist propaganda without any value. By the central decision, the copy of “Interrogation” was sealed and put on the archive’s shelf (this way “Interrogation” became one of the most famous “półkowniki” – the films laying on shelves, without possibility to be shown publicly). Bugajski managed to preserve one copy of his film, which was later screened privately within opposition circles of the "second circuit" (“drugi obieg”). The official premiere of “Interrogation” took place on 13th December 1981 – eight years after introduction of the Martial Law and eight years after the film had been produced. The film was Bugajski’s debut – repressions put on him by authorities, forced him to emigrate from Poland in 1985.

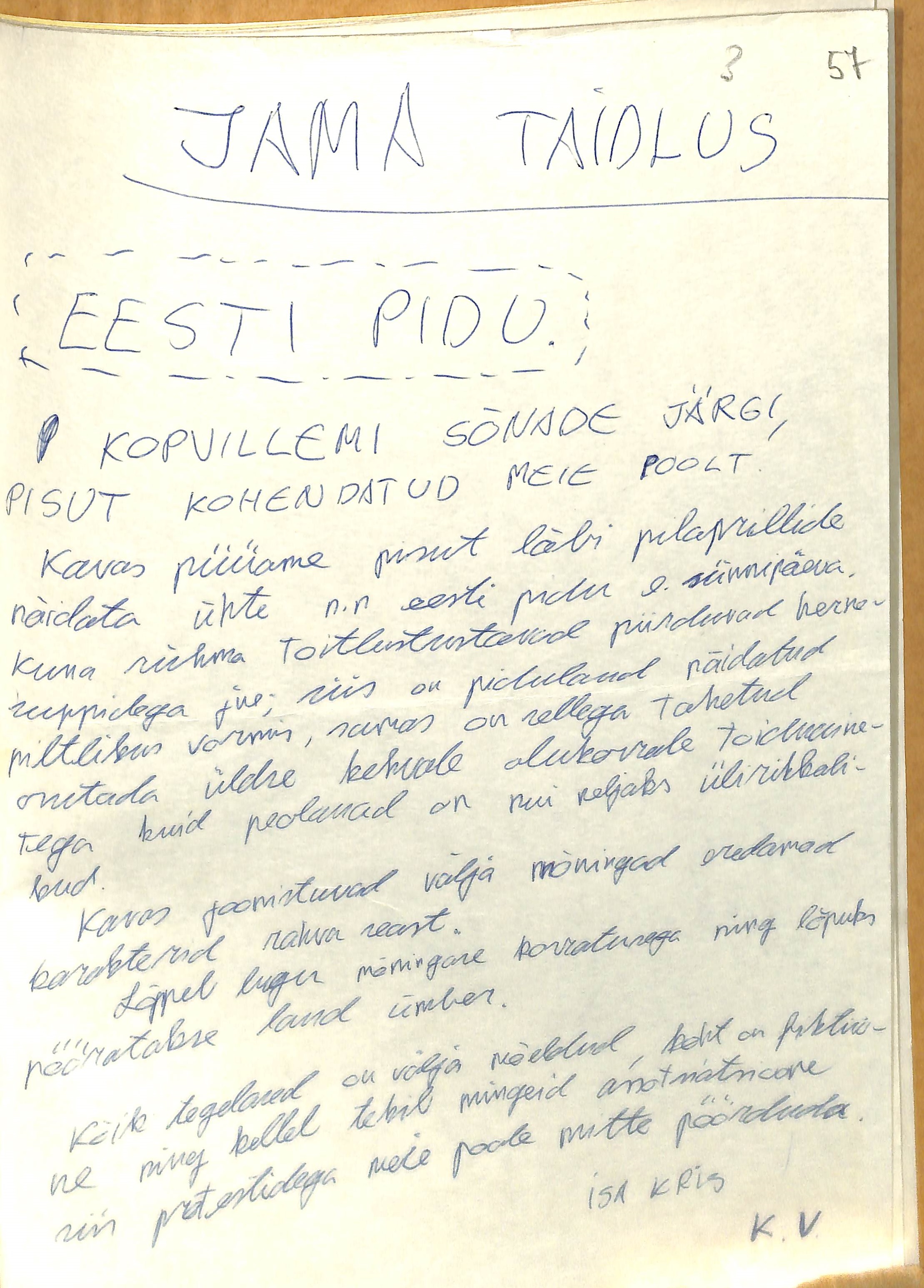

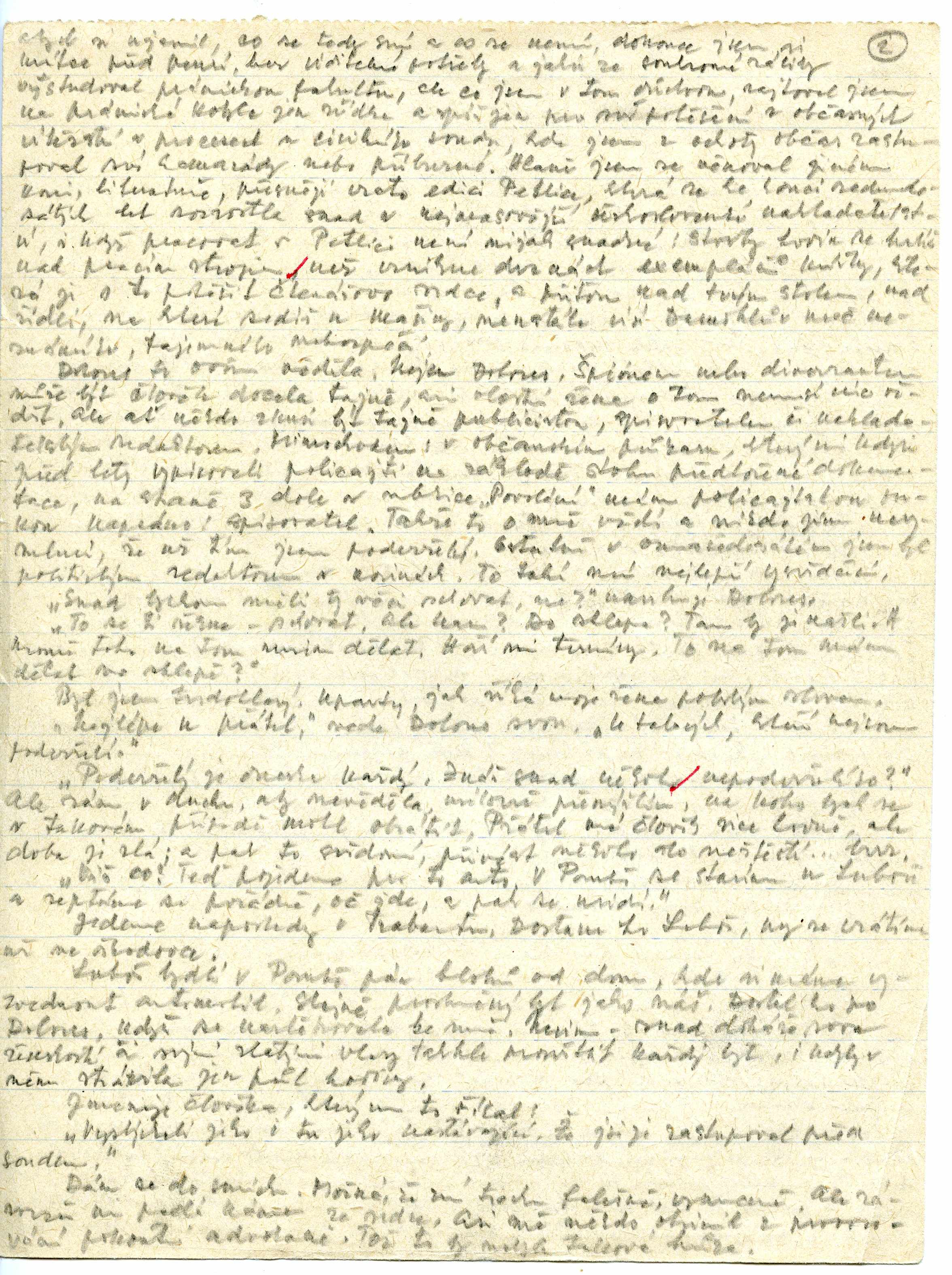

Jaromír Šavrda, a writer, poet, journalist and dissident from Ostrava, was, because of his samizdat activities, twice held in the custodial prison in Ostrava and later imprisoned in Ostrov nad Ohří, first from September 1978 until March 1981 and then from September 1982 until October 1984. During his second stay in prison, Šavrda wrote two books reflecting his experiences as a political prisoner; they depict his personal experiences from police persecution and describe the lives of people that Šavrda met in prison. The first of the books was “Vězeň č. 1260” (The Prisoner No. 1260), written between September and November 1982 and published as samizdat, followed by “Ostrov v souostroví” (The Island in the Archipelago), written by Šavrda between November 1982 and January 1983. After his return from prison, this two texts were published in 1987 as an omnibus called “Přechodné adresy” (The Temporary Addresses), at first in samizdat edition Popelnice and then in edition Expedice. “Přechodné adresy” was first officially published in the 1990s (Ostrava: WMCG 1991, 1993). Both texts were also published separately with original titles in 2009 (Prague: Pulchra, 2009). “Přechodné adresy” (2009) is also a name of a documentary film about Jaromír Šavrda directed by Petra Všelichová.

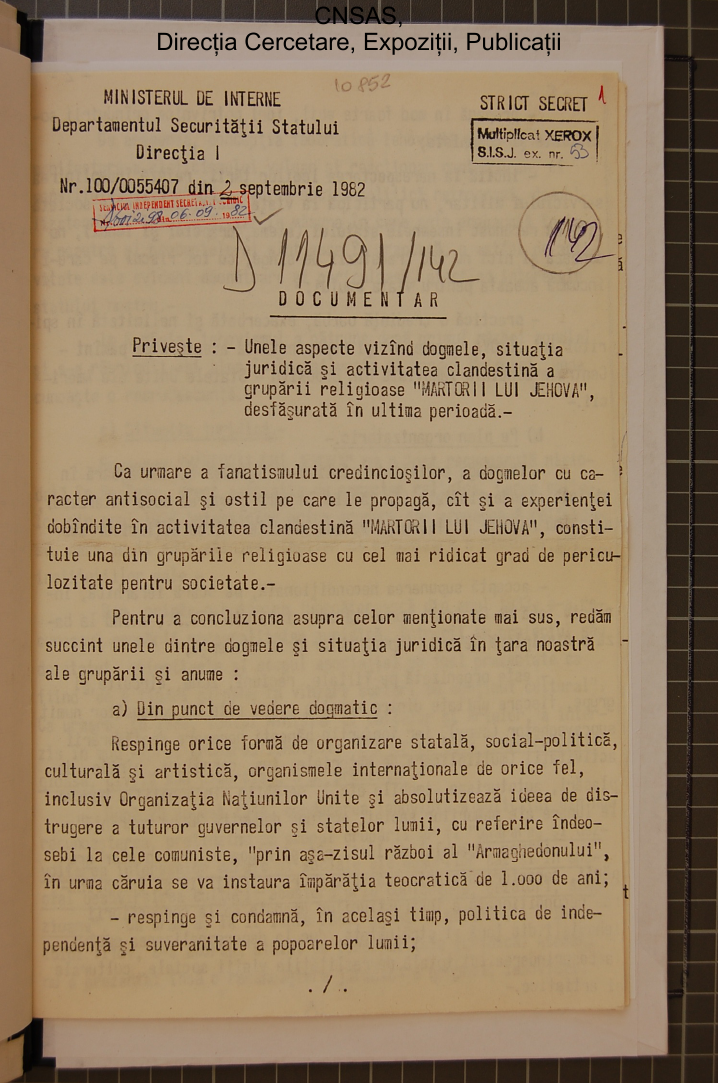

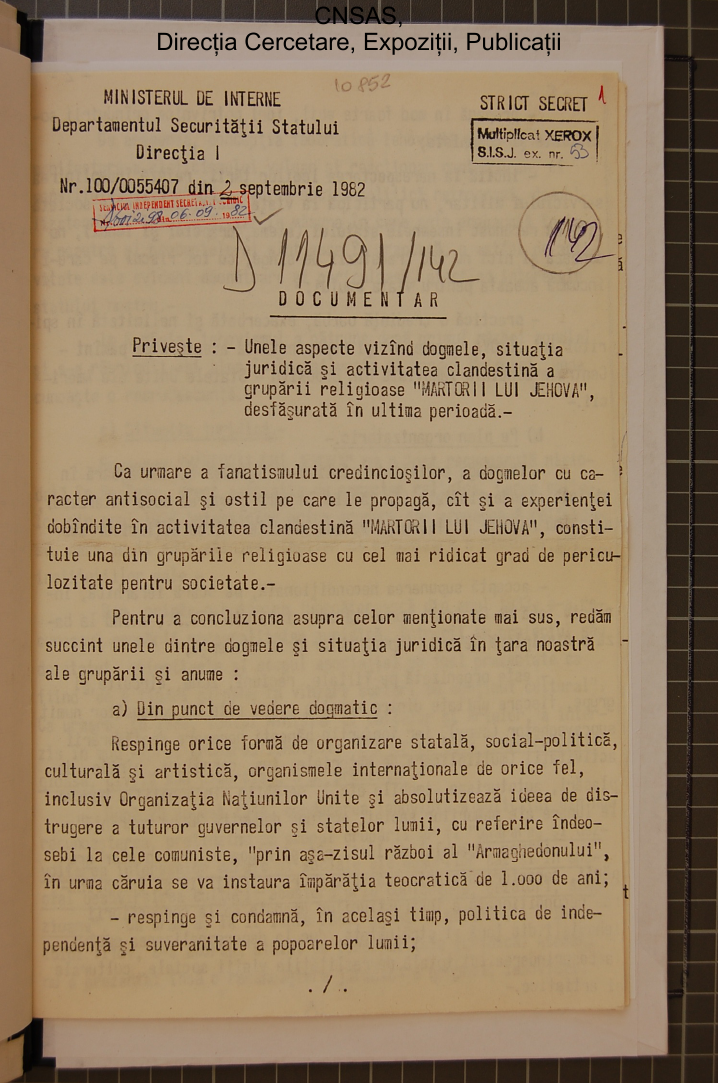

The legal situation and the clandestine activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses religious group, in Romanian, 1982. Report

The legal situation and the clandestine activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses religious group, in Romanian, 1982. Report

The report on “the legal situation and the clandestine activities of the religious group entitled Jehovah’s Witnesses” was drafted by the First Directorate of the Securitate (in charge of gathering information within the country). This report synthesised the evolution of the religious community of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Romania, their legal status during the past and at the time of its issuance, and the policies of the Securitate regarding this religious denomination.

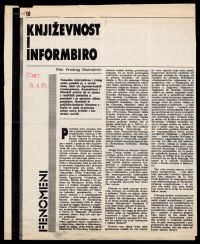

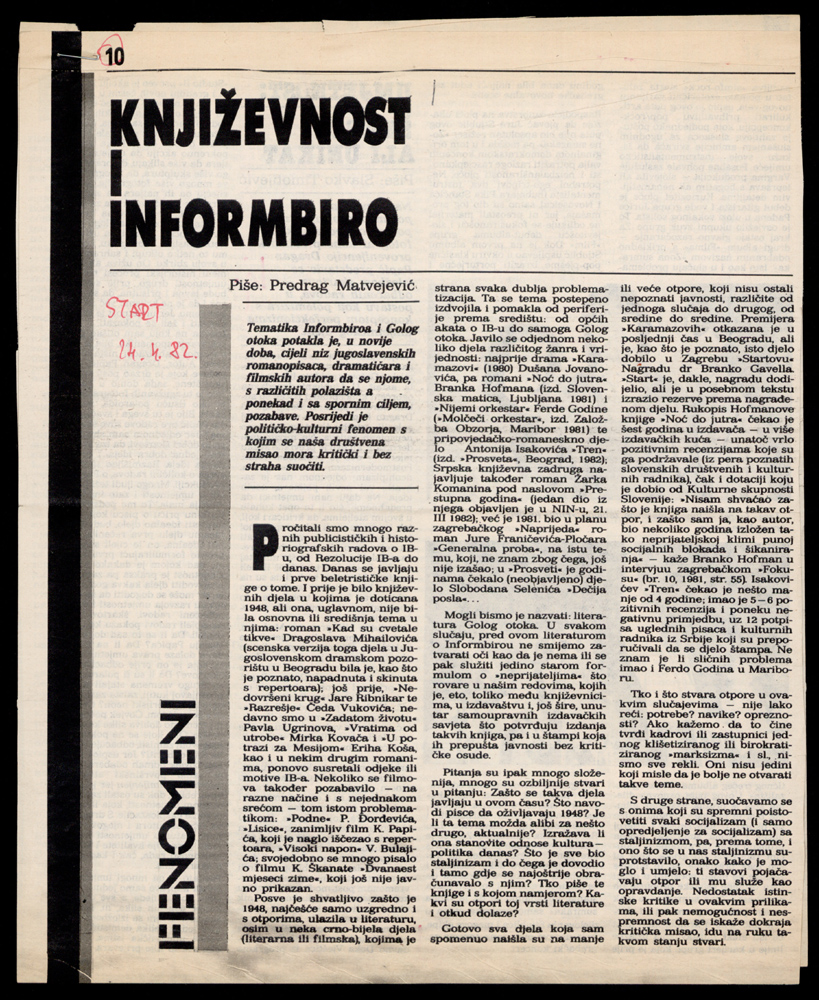

Matvejević, Predrag. Književnost i Informbiro (Literature and Cominform), Start, 1982. Press clipping

Matvejević, Predrag. Književnost i Informbiro (Literature and Cominform), Start, 1982. Press clipping

“Literature and the Cominform” is a newspaper article written by Predrag Matvejević (Mostar, 7 October 1932 – Zagreb, 2 February 2017) in which he critically reviews the breaking of the taboo on the Tito-Stalin Split (Yugoslav-Soviet Split) in 1948 and the Goli otok prison camp, and their analysis in Yugoslav literature, theatre and film in the early 1980s.

The review was published in magazine Start on 24 April 1982. It was founded by newspaper company Vjesnik on 29 January 1969 as a semi-monthly automobile magazine. In the period 1969-1972, when it was edited by Andrinko Krile, such topics were soon left behind, and the magazine focused on interviews about topics avoided in other magazines, and by the mid-1970s it became a magazine that covered politics, culture and the media, to which the most prominent Croatian journalists and intellectuals contributed. Krile was removed from his post as a member of the Croatian Spring, and it was assessed that Start had “succumbed to the base impact of the West and was a part of the Westernisation of Croatia.” According to Božidar Novak, after the Croatian Spring was suppressed, the magazine was rigidly censured, and until the July 1973 it was obliged to pay the so-called “trash tax.” In the period 1973-1980, under editor Sead Saračević, it acquired a new form and journalistic expression. Topics like so-called high culture were added, the works of the world’s top artistic photographers were regularly published, and a prominent place was accorded to feuilletons on political and historical themes. In the period 1980-1987, under editor Mladen Pleše, the magazine focused on new topics such as rock and roll and it highlighted the writings of social analysts and covered sensitive domestic policy topics. This put the magazine in a difficult position, because the political leadership maintained strict watch to ensure that the policy of “With Tito after Tito” was not violated. Political pressure continued when liberal and critical politicians and scholars began to speak in the magazine’s pages. The magazine continued to come out until 22 June 1991.

The article described above, like many other articles published in Start encompassed in the collection, are available for research and copying.

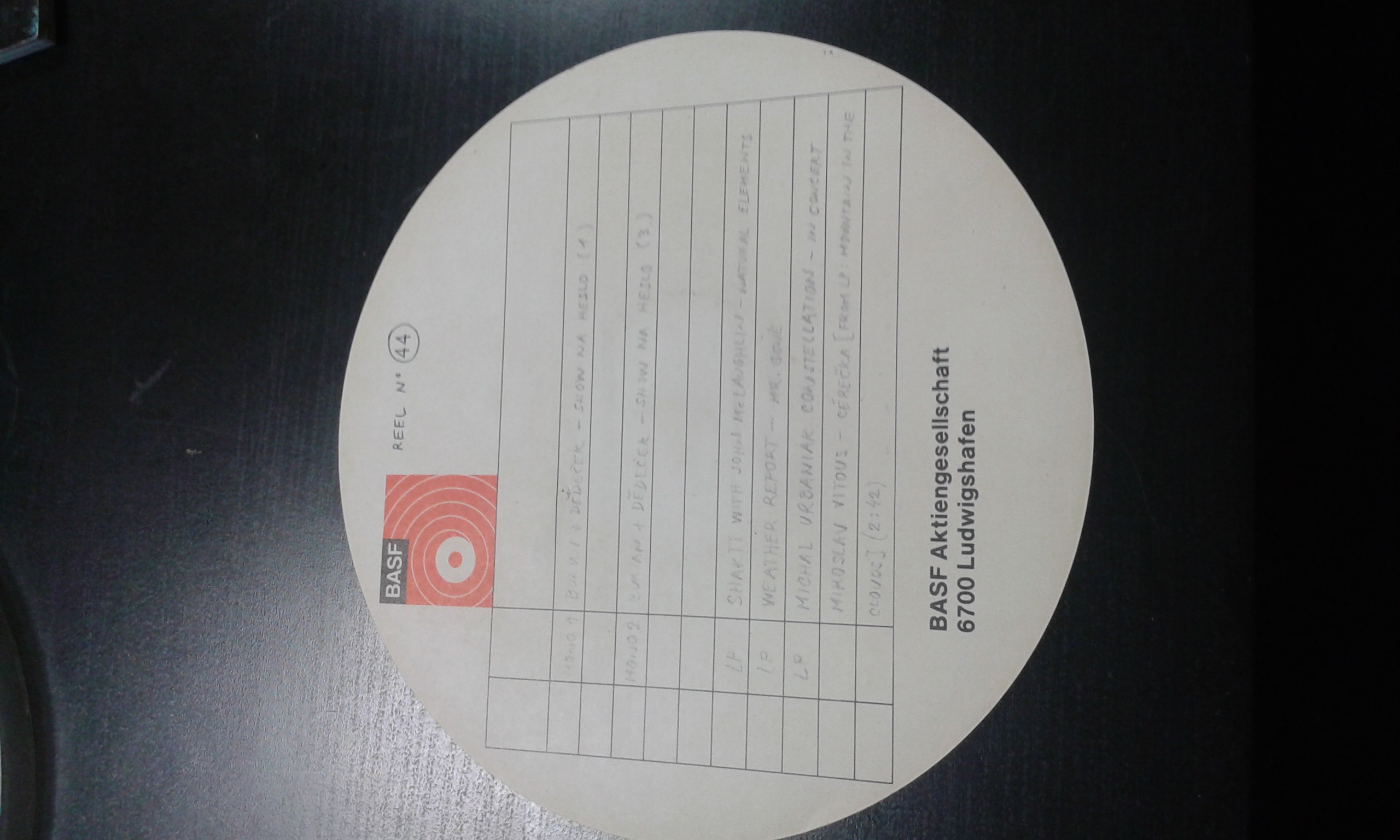

Show na heslo [Show with a Password] a satirical program of Jiří Dědeček and Jan Burian, which they presented at the Mladá Garda student´s dormitory in Bratislava (Slovakia) in 1982. The author of the unique recording is Michal Šufliarsky.Music (voice) recordings: material: tape

Lucrarea Fusta care se găsește în colecția privată a lui Sorin Costina este un ulei pe pânză. Ea este nesemnată și nedatată, dar reprezintă una dintre lucrările foarte cunoscute ale artistului plastic Ion Grigorescu, în acest moment cel mai cunoscut artist român pe plan internațional. Dimensiunile acestei lucrări sunt de 32 cm lățime și 58 de cm înălțime. Pictura a fost achiziționată pe data de 20 aprilie 1982 direct dintr-o expoziție de la Căminul Artei din București și a costat 1.000 de lei. În momentul achiziției, lucrarea nu era înrămată. Actuala sa ramă este realizată dintr-o baghetă de stejar, la sugestia unui alt artist plastic contemporan foarte renumit în România, Paul Gherasim. Lucrarea a fost adusă în locuința colecționarului chiar de către Ion Grigorescu, care în luna iunie a anului 1982 s-a oprit pentru puțin timp la Brad în drumul său către o mănăstire din regiune. Fusta a fost prezentă în cadrul mai multor expoziții tematice sau de autor. Lucrarea ar putea fi încadrată în experimentele vizuale ale artistului cu corpul uman, o temă tabu în perioada comunistă. Această lucrare a fost inclusă în diverse expoziții retrospective despre Ion Grigorescu, dintre care cea mai recentă, din 2018, a fost găzduită de Muzeul Ţării Crișului din Oradea.

This item is a typical announcement of a regular work day of the Noor-Tartu (Young-Tartu) movement. Announcements which were usually placed in educational buildings and hostels were an information channel to recruit people for work days. Anyone who saw an announcement was free to join a work day. The Raadi cemetery, which is mentioned in the announcement, especially its one part – Old St John’s cemetery – was one of the main areas of the work of Noor-Tartu. This announcement itself was simple, and made with the means that were available. However, the announcement is still remarkable due to the big letter K in each corner of the paper. It is a hint at the former name of the movement – Kodulinn (Hometown) – , which was used until the spring of 1981. The movement only changed its name because the Tartu Komsomol organisation deliberately named its new organisation for school students Kodulinn in order to cause confusion. The date on the announcement is Sunday, 28 November, without mentioning the year. However, we can assume that the work day took place, and that the announcement was written, in 1982. At that time, the activity of Noor-Tartu was not obstructed, but in later years these announcements were removed by the authorities, in order to disrupt the work days. The announcement belongs to the core group of the former movement. Like the entire collection, this item has not attracted wider attention, which is also the intention of the current operator of the collection. It is possible that it will be used for research after the collection is given to an institution.

This issue numbers only fourteen pages and comprises the “Introduction” signed by Attila Ara-Kovács and Antal Károly Tóth’s “Memorandum” and “Programme Proposal,” together with a presentation of the contents of the previously published seven issues. At the time of publishing the editors placed their hope in the “inner and activated” resistance of the population and on “the support of Hungary and of the democratic powers of the world,” while expecting repressive actions against themselves. In their effort to change the system “they saw a friend, a supportive partner with sober judgment in everyone who detested tyranny, and especially in the Romanian people.” They stated that they were ready to share their dedication and solidarity with all of their Romanian friends and fellow sufferers in order to regain their common freedom. Moreover, the authors found it important to underline that “this solidarity, this dedication does not convey and bear any hidden intentions.”

The “Memorandum” which was also sent to the participants of the Madrid CSCE Follow-up Conference, takes a stand in favour of the Hungarian minority, providing a brief account of the ethnic policy of Ceaușescu’s regime, the measures aimed at assimilation and as the methods applied to hamper the preservation and development of the Transylvanian Hungarian collective identity. It highlights the concept of second-class citizenship and the lack of possibilities of self-defence, the nonexistence of community interest groups. It pointed out that the chances of changing the situation are most affected by the fact that international conventions fail to take a stand with regard to the collective rights of minorities and that the mode of approach applied in international practice that only considers the point of view of human rights, ignores the values inherent in an ethnic minority, a community marked by rich tradition, particular culture and collective identity. The editors argue that minority values should deserve separate protection in contrast to those of the majority population which enjoy a dominant position. They state that an international effort which tries to protect the rights of minorities without taking into consideration their group character involuntarily places them at the mercy of the majority. In order to change their disenfranchised situation, the editors request that the conventions about to be concluded at the Madrid Conference should include the rights of Transylvanian Hungarians to preserve their values. The “Memorandum” summarises the aspirations of the editors in four paragraphs in which they ask that the Transylvanian Hungarians be allowed the possibility to feel that they are an organic part of the Hungarian nation “and thus all ethnic minorities should be granted equal rights,” that they might preserve their particular collective values and be able to create an organisation to promote their independent interests. They see a guarantee for the enforcement of these rights in the establishment of an impartial international committee.

They annexed a “Programme Proposal” to the “Memorandum,” in which they formulated in detail the most important demands in with of solving the situation of the Transylvanian Hungarians in communist Romania. The six-page document explains that the rights necessary for survival exist merely in theory and underlines the strong discrepancy between the situation depicted in official declarations or speeches and the everyday practice. Under these circumstances, demanding any rights seems an impossible mission. Moreover, the approval of any motion whatsoever is unimaginable without the proper intervention of some influential personality. Based on the assumption that two ethnic groups can only live together side-by-side if they treat each other as equal partners, the editors requested that Hungarians in Romania be granted the possibility “to freely demand the defence of their rights and interests.” They were aware of the improper timing of their demand as “even cultural claims formulated in pretentious language were openly labelled as reclaiming-revisionist.” They were also aware that although the Eastern European situation rendered the chances of seeing such claims solved entirely impossible, the worsening conditions forced them to take action considering that, as they themselves explained: “we cannot afford the luxury of waiting for a miracle to happen if we want to see a change.”

The “Programme Proposal” formulates the “demands” in ten paragraphs that occasionally make necessary the inclusion of several subparagraphs. The first demand repeats the first paragraph of the “Memorandum,” namely, that the Hungarians in Romania should be considered as an organic part of the entire Hungarian nation, and, as Romanian citizens, they should have the right to freely maintain their contacts with the Hungarian People’s Republic “both on an institutional and an individual level.” They also added another nine subparagraphs in which, among others things, they touched on the right to travel freely, the abolition of the regulation concerning the accommodation of foreign friends and of the practice of confiscating Hungarian cultural products at the customs, the right to freely invite Hungarian bands and personalities from the neighbouring countries, and the right of Transylvanians to have access to Hungarian TV channels as well as to books and publications from outside Romania which were in the Hungarian language.

The second “demand” asks for an institutional framework which would allow the cultural autonomy and the preservation of the collective identity of the Hungarian minority in Romania. This demand is detailed in eighteen subparagraphs. They demand that art. 22 of the 1965 Constitution should be completed with the right of minorities to create an interest organisation with an independent media organ, responsible for the administration of Hungarian cultural life and school policy, the control of Hungarian staff policy, the protection of monuments, and the legal remedy for minority grievances. They demand that a stand should be taken officially in favour of recognising minority culture as an organic part of Hungarian culture and not some branch of Romanian culture. They also demand that special departments of minority education should be founded within the Ministry of Education and in the county school inspectorates, and the reintroduction of Hungarian nursery-schools, schools, and universities thus providing the opportunity for all Hungarian children to learn in their mother tongue, with special emphasis on the possibility of learning Romanian history and geography in Hungarian. Furthermore, they demand the enforcement of Law 6/1969 concerning teaching staff status, which stipulates that teachers who have no or only partial knowledge of Hungarian cannot teach Hungarian classes. They take a stand in favour of eliminating the criteria of a compulsory number of pupils in a class, in order to ensure the survival of rural Hungarian schools and ask for the adoption of the Yugoslavian minority Act which permitted the establishment of a school even in case of nine children. They demand that the minority publishing house Kriterion should have an extended sphere of competence and a more solid financial background so that it can perform the tasks ignored by other publishers. It is also stated that that the Hungarian press and Hungarian radio and television programmes should focus on relevant problems of the Hungarian minority. They also demand that the authorities cease to treat Hungarian intellectuals as suspicious elements and put an end to their permanent monitoring and harassment by the secret police for the sole reason that they are Hungarians. The last subparagraph demands real freedom of religion and the internal autonomy of Hungarian churches.

The third demand, detailed in three subparagraphs, calls for the autonomy of regions populated by a Hungarian majority – the so-called Székely (Szekler) Land – together with equitable representation in the government. The fourth point, also structured in three subparagraphs, requests the suspension of the Ceaușescu regime policy of changing the ethnic constitution of historical Transylvania, the Partium, and the Banat. The fifth point, including nine subparagraphs, requests for the Hungarians in Romania the possibility to create and develop their sense of identity, defined both by their past and by their present. The sixth paragraph demands that the free use of the Hungarian language – both formal and informal – should be equally justified in all areas of greater Transylvania which are also inhabited by Hungarians. Subparagraphs three and four formulates the claim that in settlements with mixed population, the teaching of the Hungarian language should be made compulsory in Romanian schools. In addition to this, they demand that such localities be provided with bilingual signs, including the names of settlements, streets, shops, factories, public institutions, museums, and product names.

The seventh point formulates the claim that the Hungarian minority should enjoy equal opportunities of self-fulfilment to the Romanians, and that professional development and the selection of employees should be performed according to qualification and not according to ethnic criteria. The eighth point underlines the need to preserve historical and cultural traditions, whereas paragraph nine refers to the Moldavian Csángós who were a Hungarian-speaking group. This paragraph asked that Csángós be considered also Hungarians, against the practice of the official statistics that considered them Romanians, and that they be allowed to participate in Hungarian cultural life. The tenth paragraph, in compliance with paragraph four of the “Memorandum,” demands that the competence to examine and decide in case of pressing issues concerning the situation of Hungarians in Romania should be assigned to an impartial international committee, comprising both Romanians and Hungarians.

Although the consideration of the interests of the Hungarian minority were a priority in formulating the “demands,” the editors were aware that “their consideration cannot be isolated from the solution of matters of general interest” and that “first and foremost the Romanians should have the competence” to draw international attention to the common issues. The editors did not consider this unusually harsh “measure” to be premature, arguing that, “it is high time the wall of silence were demolished and that the massive and seemingly indestructible practice of injustice and arbitrariness that haunts the entire population of Romania (with the exception of a few) as a nightmare were ultimately [denounced as] responsible for today’s totally catastrophic conditions.” They believed that the programme proposal also served the interests of the Romanians “as lawfulness would implicitly add to their rights.”

The eighth issue of Ellenpontok is the best-known issue of the samizdat to date. The “Memorandum” and “Programme Proposal” that it included are considered to be documents of historical significance, for they represented the most renowned documents of the Hungarian civil opposition in Romania at that time. In the course of time these two documents have been published on more occasions. In Hungary they were published in the well-known samizdat Beszélő, No. 5-6 (December 1982). In France, Párizsi Magyar Füzetek (Hungarian Brochure of Paris), No. 12 (1983) published an article under the title “What’s Happening in Transylvania?” and included the full “Memorandum” and excerpts from the “Programme Proposal.” These documents were also mentioned in the most prestigious papers in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, France, and Britain. Radio Free Europe broadcast the contents of the documents on several occasions, especially during the year 1982. The “Memorandum” and “Programme Proposal” were also included in Géza Szőcs’s volume Az uniformis látogatása (The visit of the uniform), published at the end of 1986 in New York. After the regime change the two documents were published on multiple occasions in the works of Antal Károly Tóth. It speaks for their value and significance that Éva Cseke Gyimesi included both documents in her 2009 volume Szem a láncban: Bevezetés a szekusdossziék hermeneutikájába (Piece in a chain: Introduction to the hermeneutics of Securitate files), “since the memory of these documents has faded and the younger generation know almost nothing about them.”

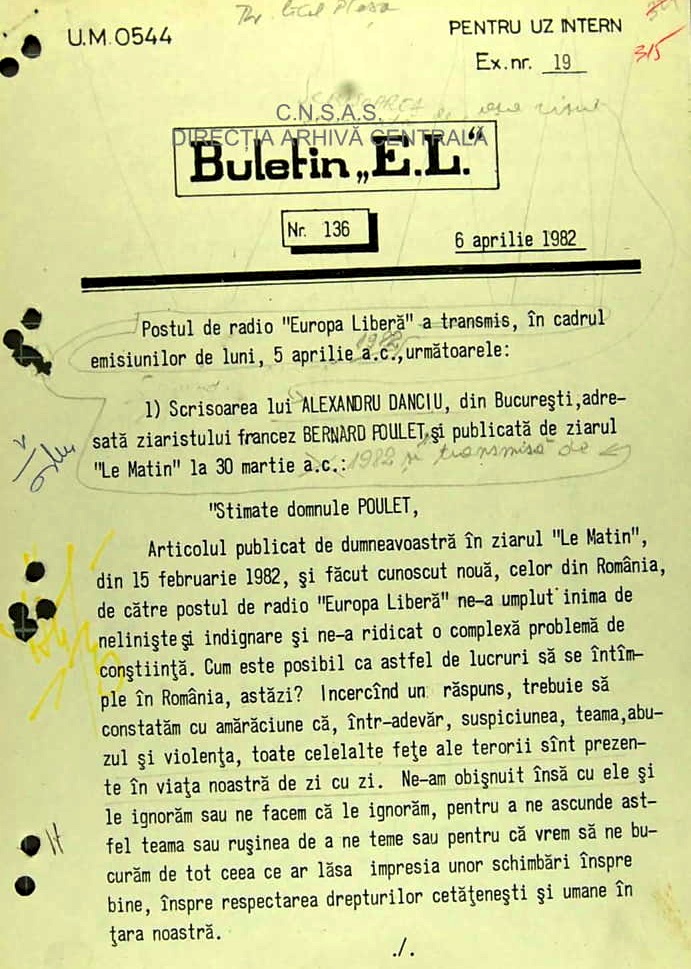

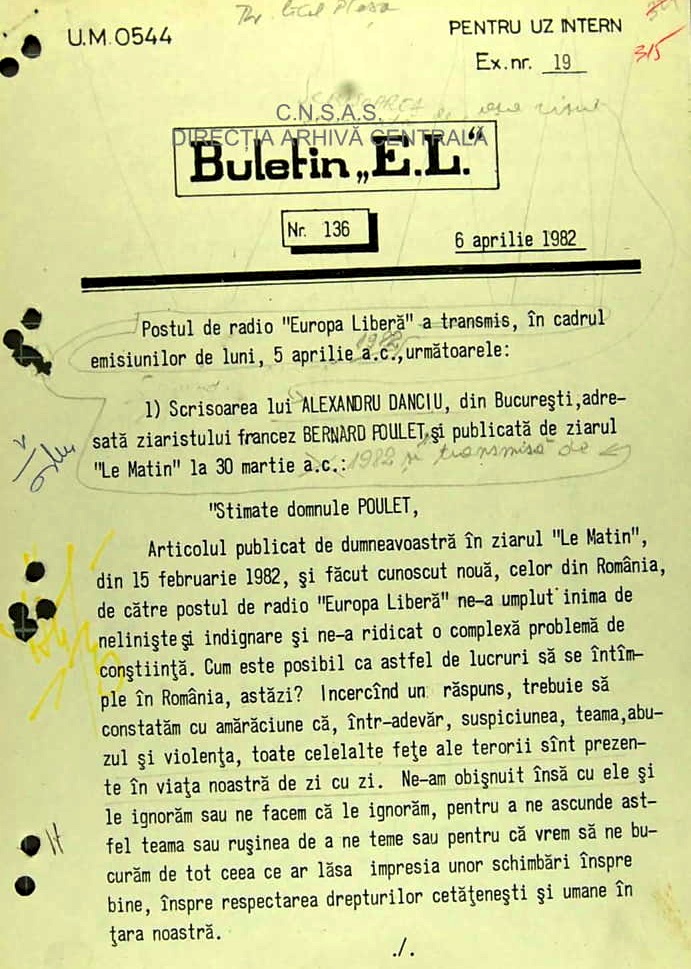

Published on 30 March 1982 by the French daily Le Matin, the article entitled “Le témoignage d’un Tzigane” (The testimony of a Gypsy) was written under the pseudonym “Alexandru Danciu” by Nicolae Gheorghe. A few days later the article was read during one of the broadcasts of Radio Free Europe and it was republished in an issue of L’Alternative magazine the same year. The article was a reply to a contribution of the French journalist, Bernard Poulet, who was attacked and badly beaten when he tried to contact the Romanian dissident Vasile Paraschiv. The official explanation that Poulet got from the authorities was that he had been attack by a group of “Gypsies.” Using as a pretext the false conclusion of the investigation, “Alexandru Danciu” denounced “the methods of the Romanian Securitate to silence political dissidents,” and also “a multilaterally developed prejudice (...) racism against Gypsies.” The latter was used “more and more often by Romanian officials to explain many of the negative developments in the country,” such as the lowering of incomes, the increase in common law offences, and violence against foreigners. In what follows, “Alexandru Danciu” lists the violent methods used by the Militia against the Roma: beatings for “quicker civilising,” home searches and abusive arrests, forced labour on various construction sites, including the Danube–Black Sea Canal, or in agriculture during the summer. After stating that discrimination was part of the daily life of Roma people, Nicolae Gheorghe denounced the refusal of the Romanian communist regime to deal with their serious social problems and to recognise them as national minority. For the authorities, the integration of Roma people into Romanian society was not a viable solution since they saw them “only as a residue of the past, which must disappear through assimilation into the multilaterally developed society.” Most likely Nicolae Gheorghe’s article reached the West with the help of one of his many academic contacts before the Securitate opened an informative surveillance file on him. Its reading at the microphone of Radio Free Europe led to the intensification of the Securitate’s surveillance of Nicolae Gheorghe.

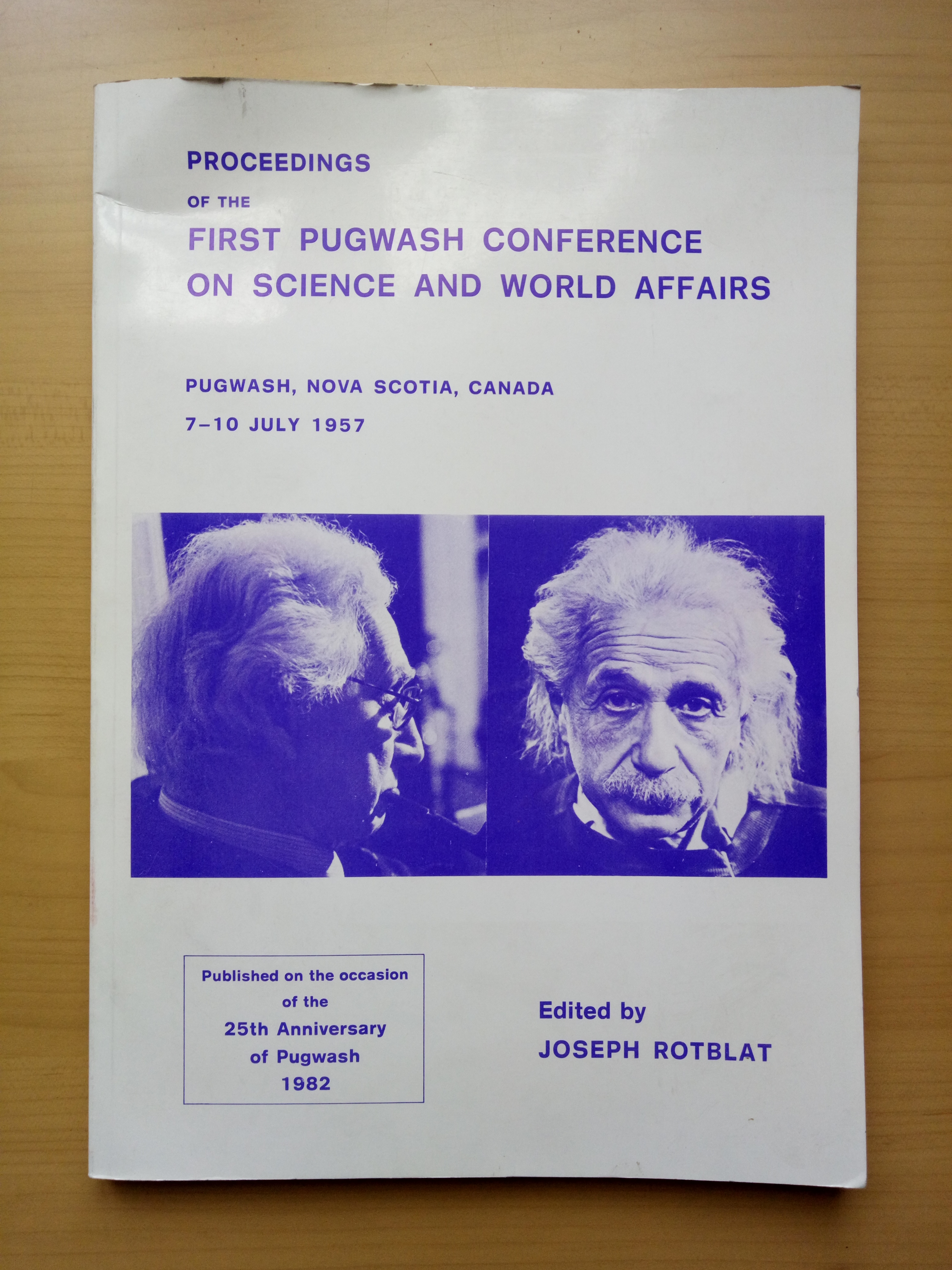

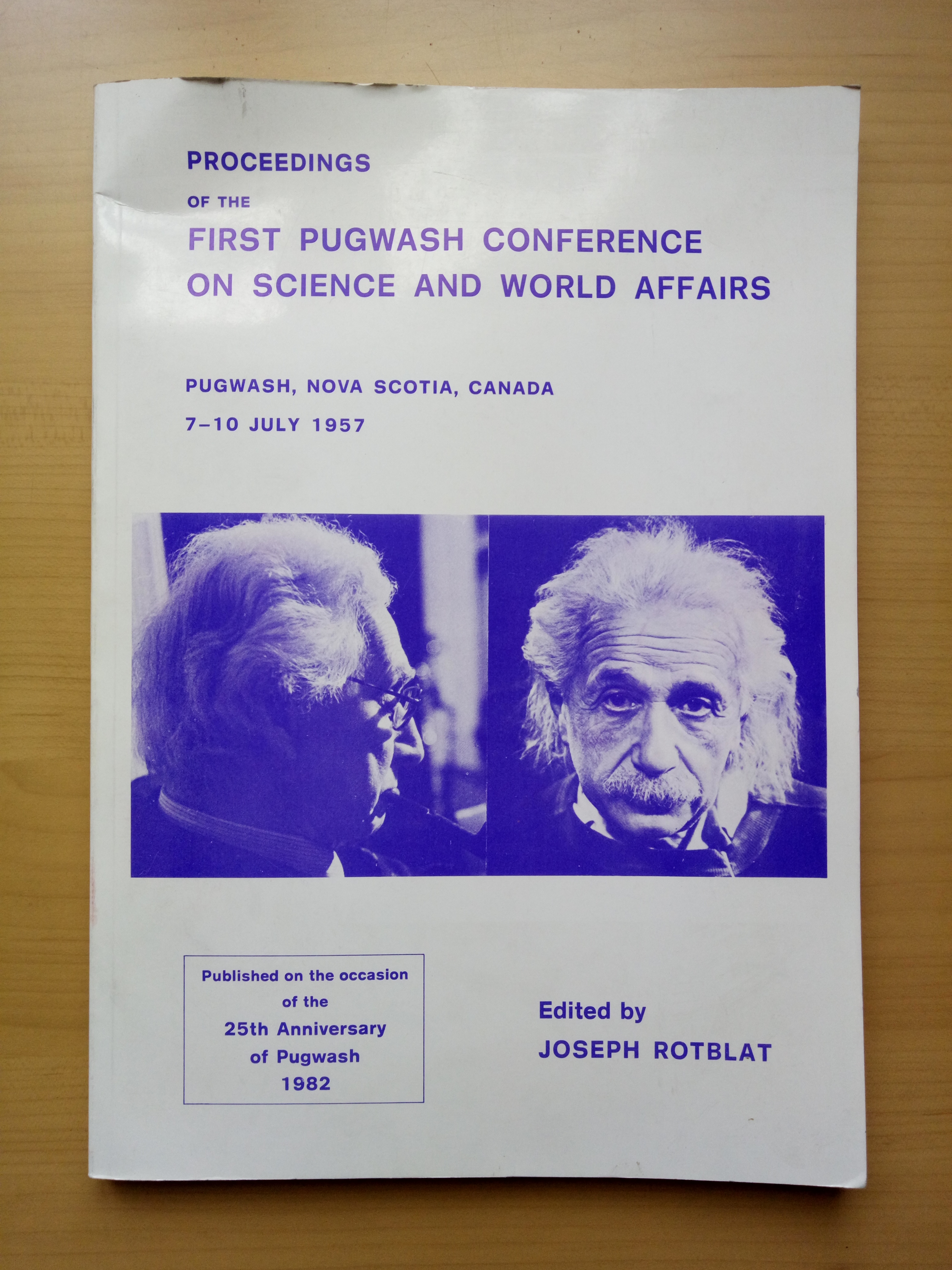

Rotblat, Joseph, ed. Proceeding of the First Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs: Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Canada, 7-10 July 1957, 1982. Book

Rotblat, Joseph, ed. Proceeding of the First Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs: Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Canada, 7-10 July 1957, 1982. Book

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs (popularly called the Pugwash Movement) is an international organisation of scientists and intellectuals who advocate world peace. It has emerged as an international conference on science and global problems, and at the time it was “a significant international factor and channel of communication among scientists,” (Knapp, 1995, 71), primarily discussing the dangers of the development of nuclear weapons.

After each conference, the presented papers were published, but this was not the case with the first conference held in 1957. Only in 1982, on the twenty-fifth anniversary, were the proceedings published with all papers and almost all materials that were then discussed. The first conference was attended by 22 participants (of whom sixteen were physicists, two chemists, one biologist, two physicians and one lawyer) from ten countries (seven from the USA, three from the USSR, three from Japan, two from the United Kingdom, two from Canada, and one each from Australia, Austria, China, France and Poland) (Rotblat 1982, 11).

The first conference ended with a joint warning from scientists from all five countries that had or were developing nuclear weapons that the potential nuclear war would end as a “world catastrophe, with hundreds of millions people killed instantly, and hundreds of millions more dying in the aftermath” (Knapp 2013, 88-89). Croatian scientist Ivan Supek was the first man from Yugoslavia who joined the Pugwash Movement and promoted its ideas. At that time, due to plans on the possibility of developing a nuclear program, the Yugoslav authorities received the ideas of this anti-nuclear movement with scepticism. Thanks to Supek's advocacy, the Yugoslav public became aware of the movement and their activities.

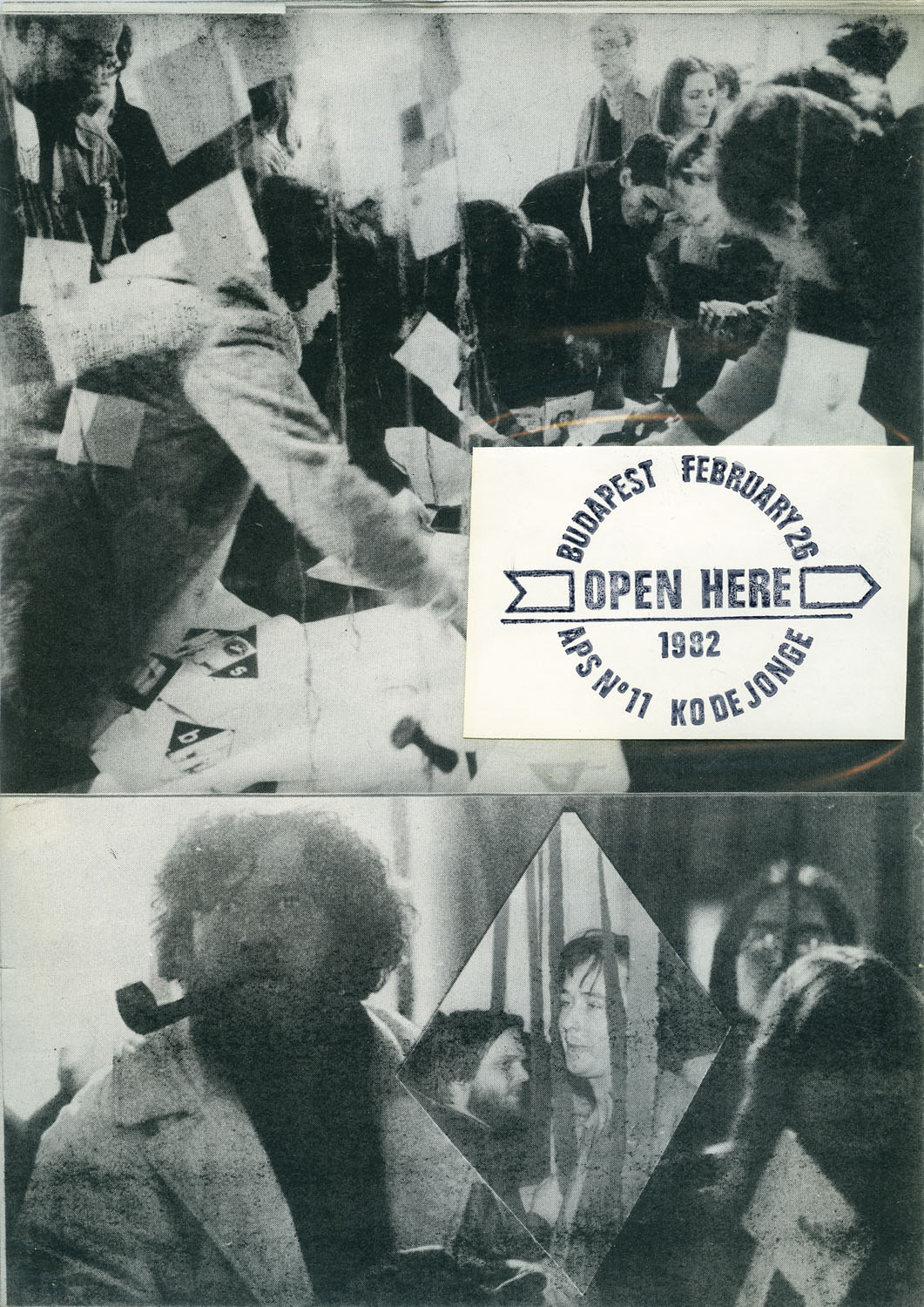

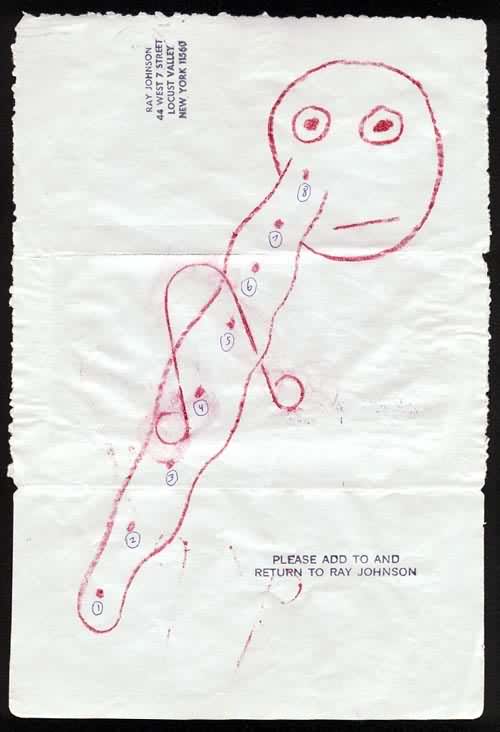

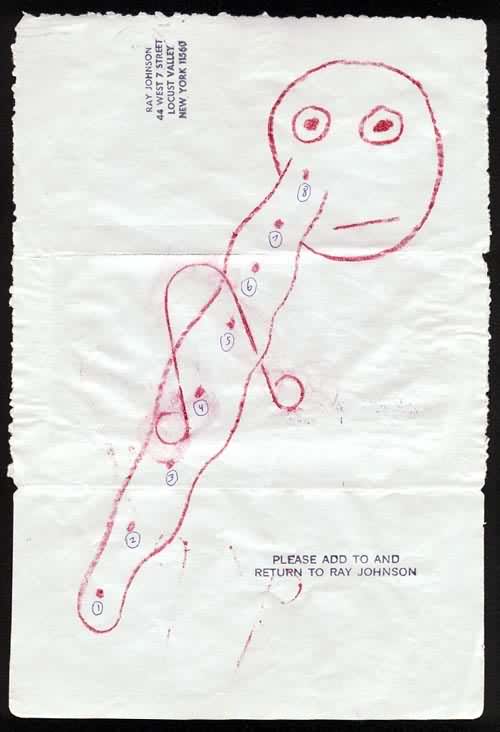

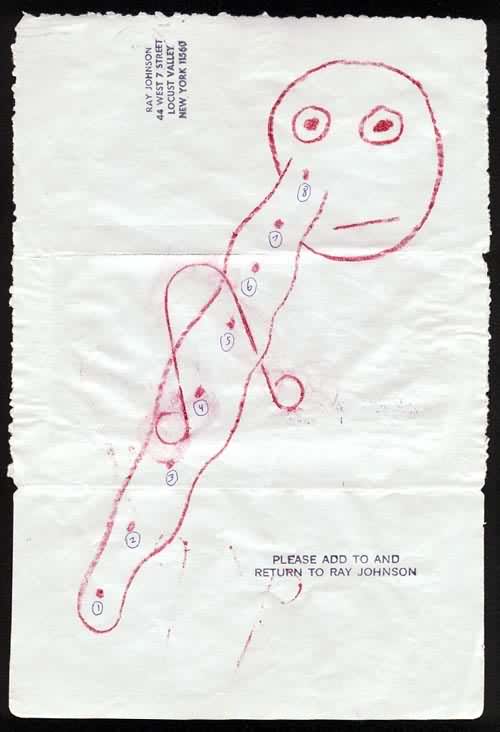

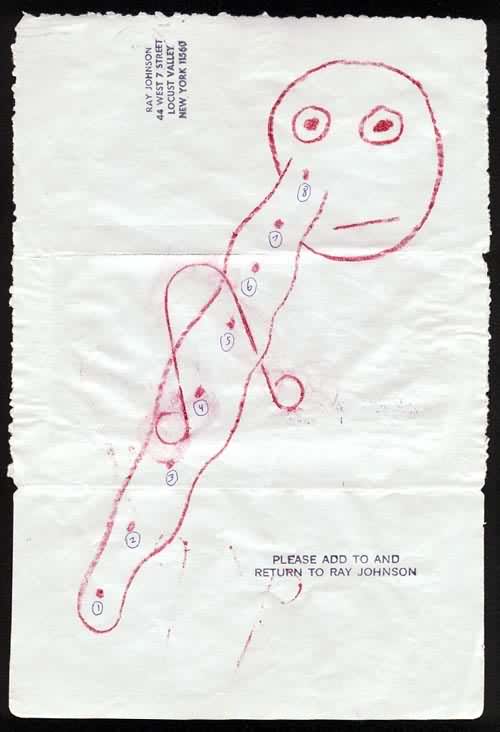

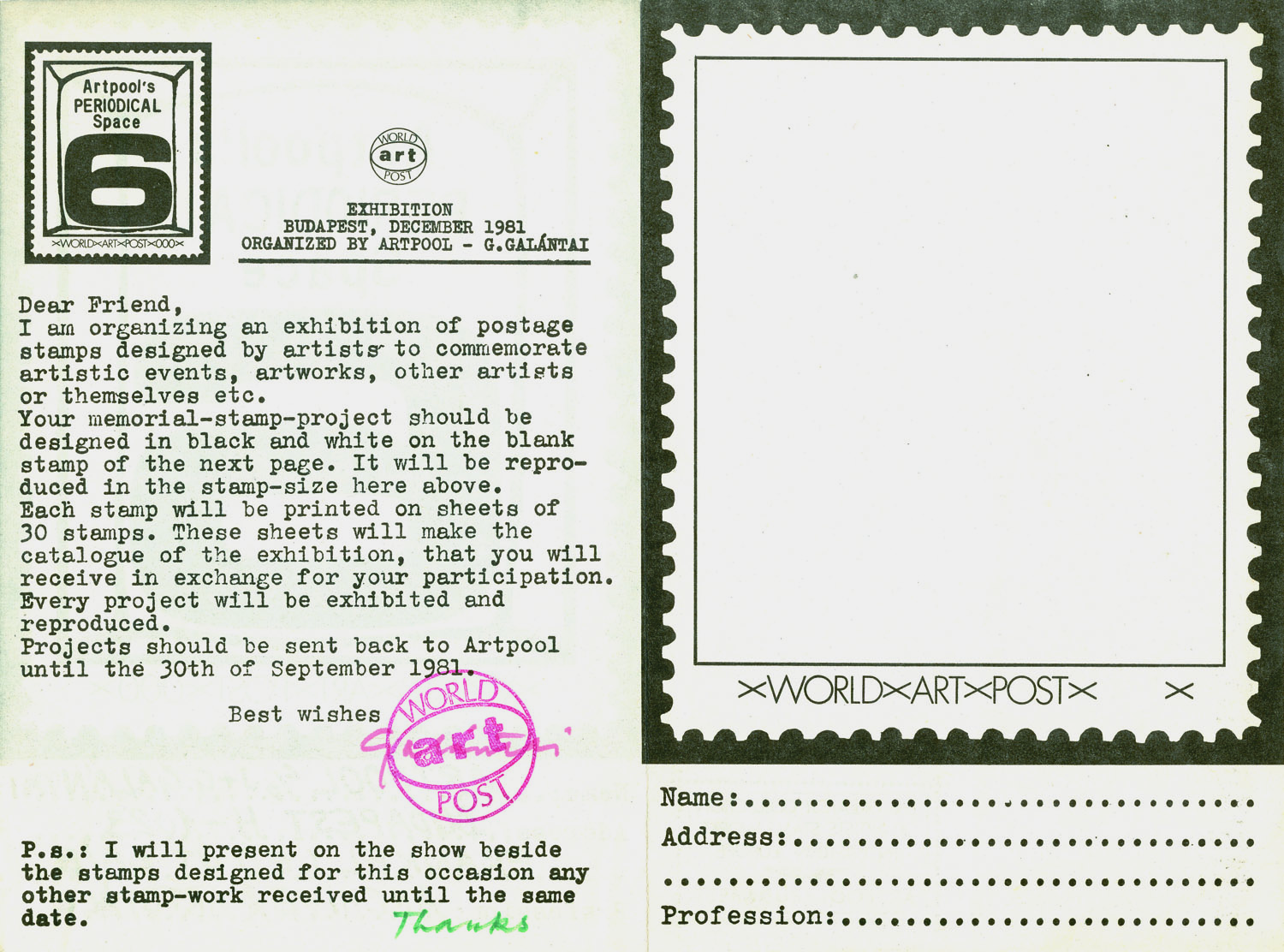

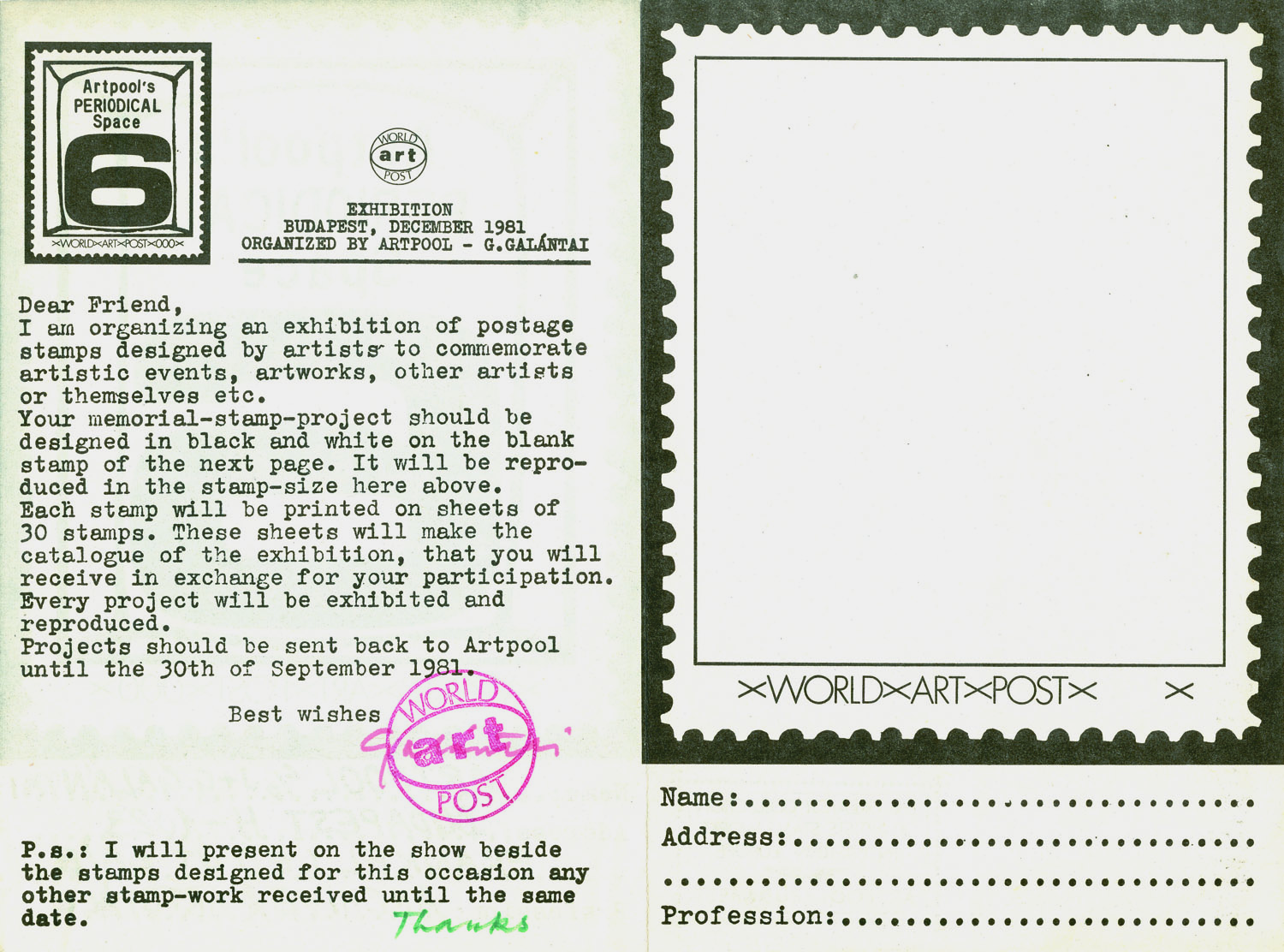

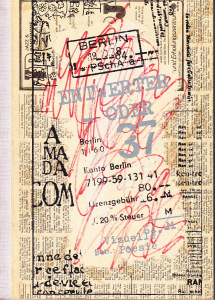

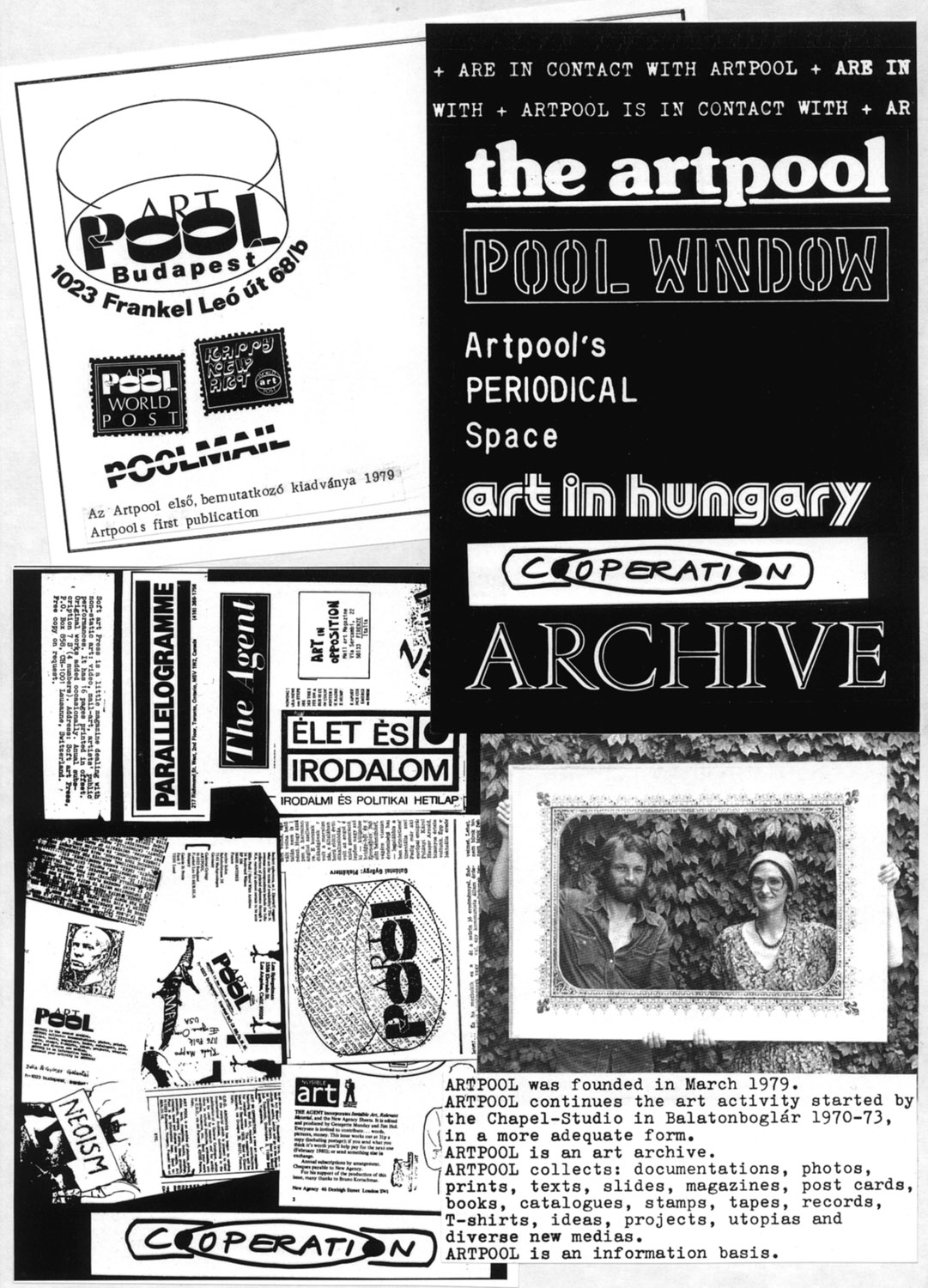

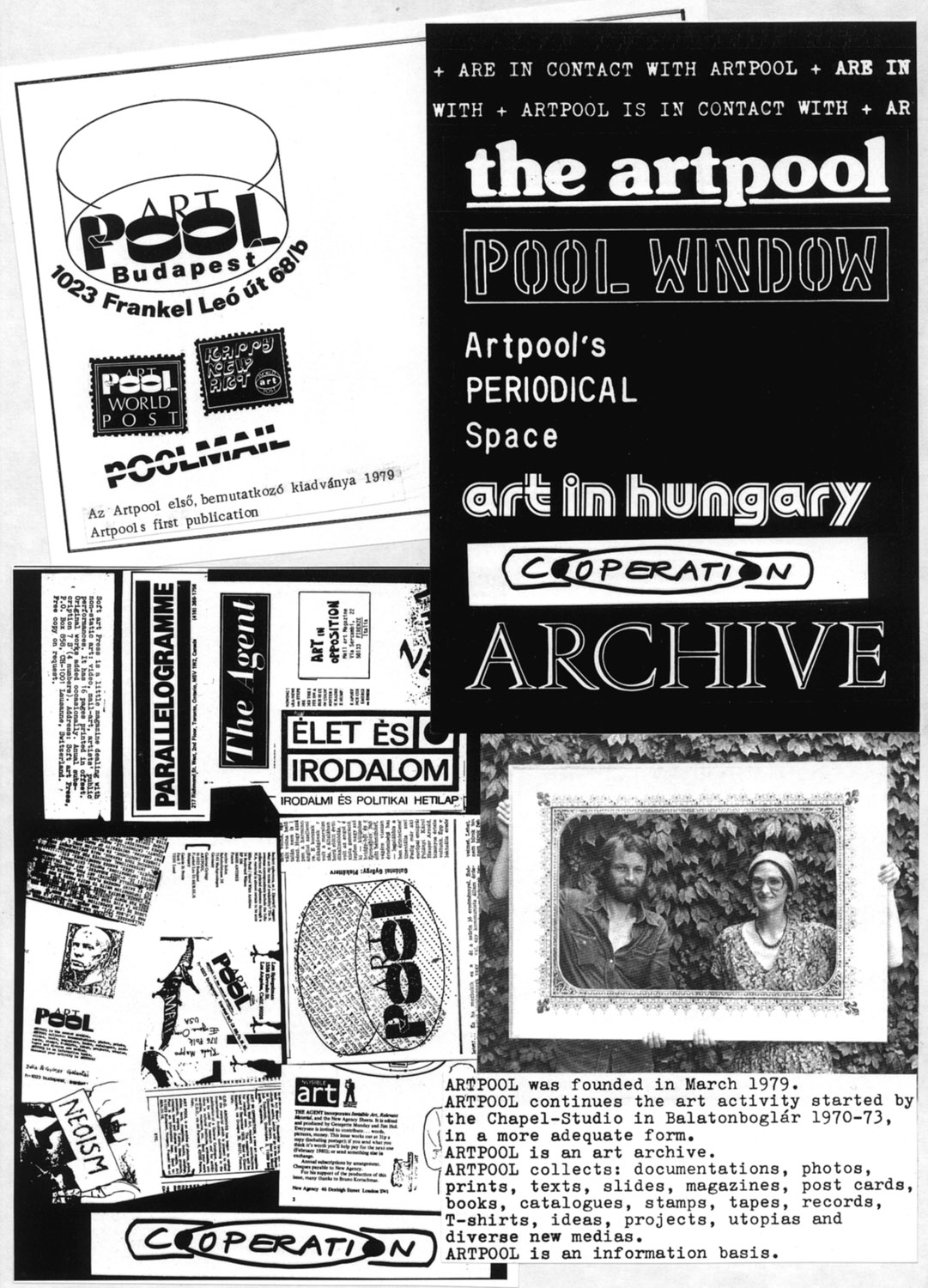

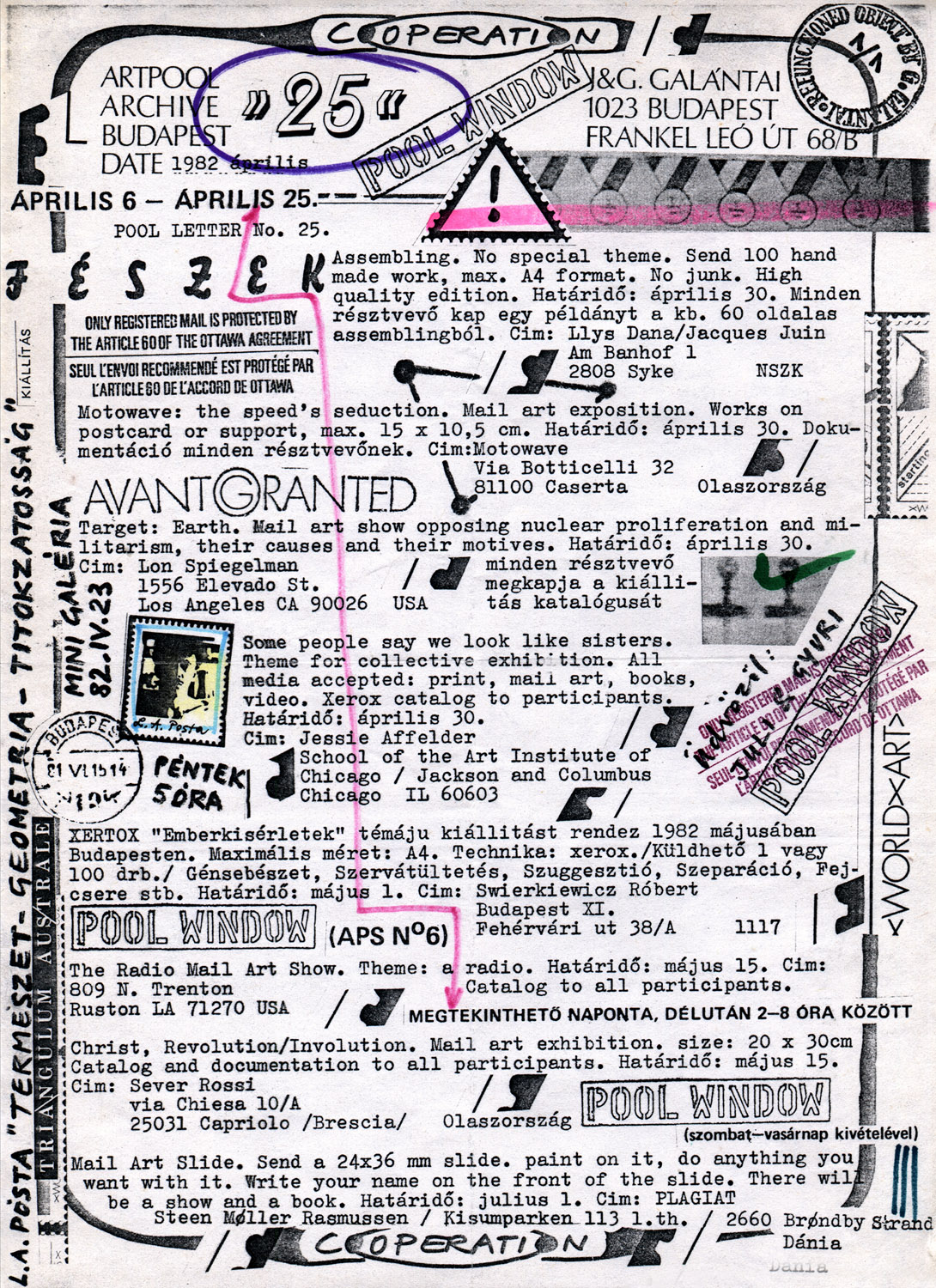

A project based on the extension of the correspondence with Ray Johnson

In July 1979, Artpool got Ray Johnson’s mailing address from Romano Peli in Parma. At first, they didn't get any replies to the letters they sent him.

In 1982, Ginny Lloyd, who knew Johnson personally, was visiting Artpool and found it strange that Ray hadn’t answered the letters. Galántai then decided to make one last try with a postcard action: he made twenty postcard-collages and mailed them one after the other over the course of twenty days.

An answer arrived soon. The first was a “send to” letter with drawings, asking that the person who had received the reply send it to Wally Darnell in Saudi Arabia. The drawing or the letter? The request wasn’t clear to Galántai, so he decided not to deliver the letter passively, but instead to become a part of the action, so he photocopied the drawing.

There were four numbered Fan Club stamps on the drawing with four distinctive “bunnies.” He decided to rearrange them to allow for further additions.

A new decision was made. For the upcoming “Artpool’s Ray Johnson Space,” he decided to invent a background institution, the “Buda Ray University” (modelled on the Buddha University).

Copies were made of the modified drawing and then sent to all of Artpool’s mail connections and then back to Ray Johnson.

October 13, 1982 - Johnson mailed the second drawing with the “add to” stamp on it.

November 3, 1982 - Johnson mailed the third drawing.

December 22, 1982 - A letter arrived referring to the second drawing with the inscription “Thank you for all your communications” and a Dora Maar Fan club stamp. The year came to a close with a letter with a Yoko Ono Bunny stamp.

September 28, 1983 - the fourth drawing’s inscription “Thank you for your” refers to the former letter (after nine months) and continues with “send to Peter Below,” and the drawing: a duck in a cloud with the inscription DUCK CLOSE and with a ballpoint pen OH BOYS ALWAYS THE SAME STYLE.

The Buda Ray University gained more and more participants through the continuous posting of the first four letters. The University published a book in 1985 which contained a selection of the letters which had been received up to that time.

February 13, 1986 - Johnson mailed the fifth drawing “BILL de KOONING'S BICYCLE SEAT,” which arrived enclosed with a catalogue of the Nassau Museum, in exchange for the Ray Johnson Artpool Book.

The fifth drawing was the most successful. Many replies came within a short period of time. There were too many replies to include in a single a book, so Artpool had to use another form of publication: the exhibition.

Artpool’s Ray Johnson Space was shown 14 times in 8 different countries between 1986 and 1993, either as part of other events or sometimes as an independent program.

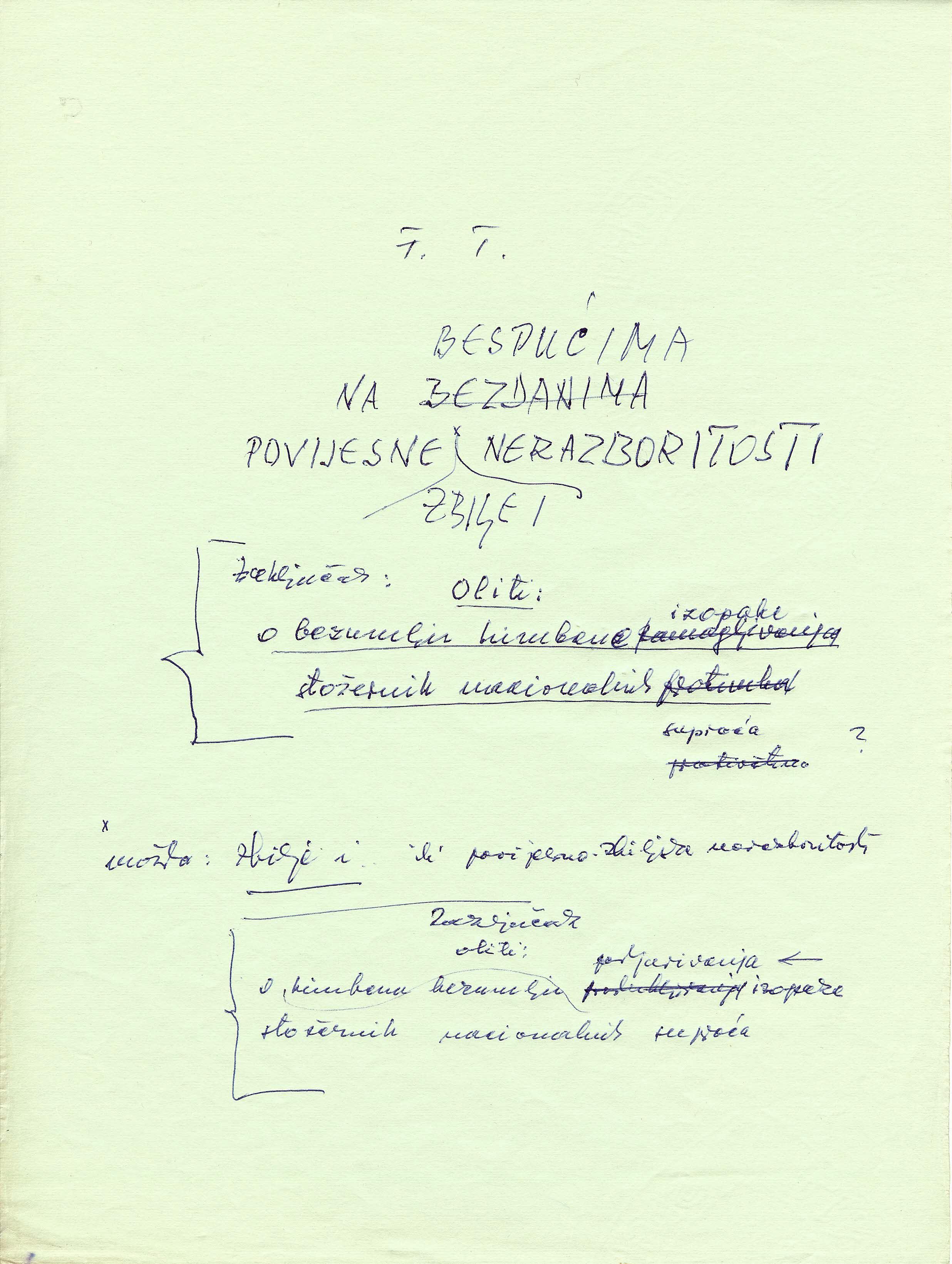

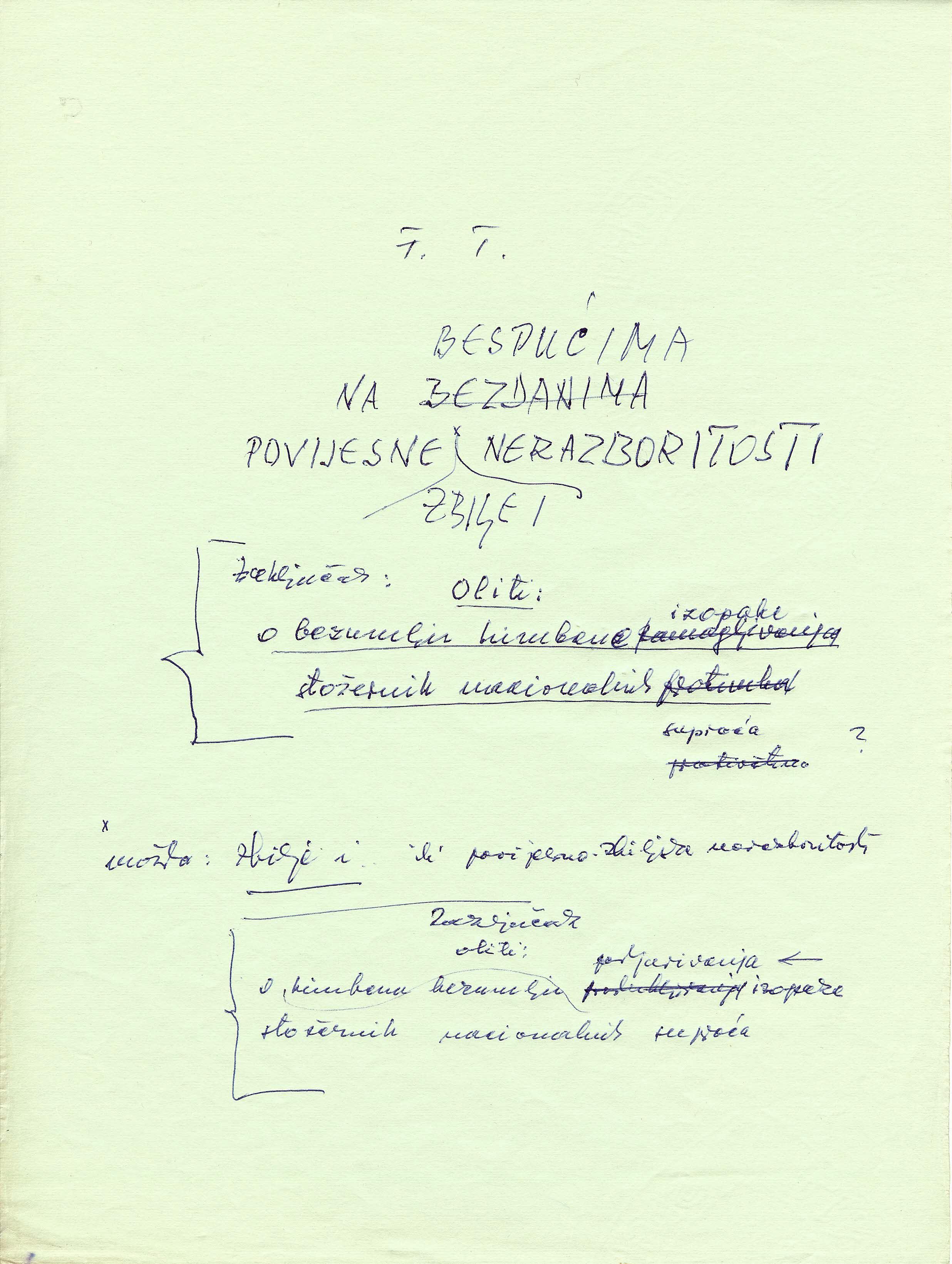

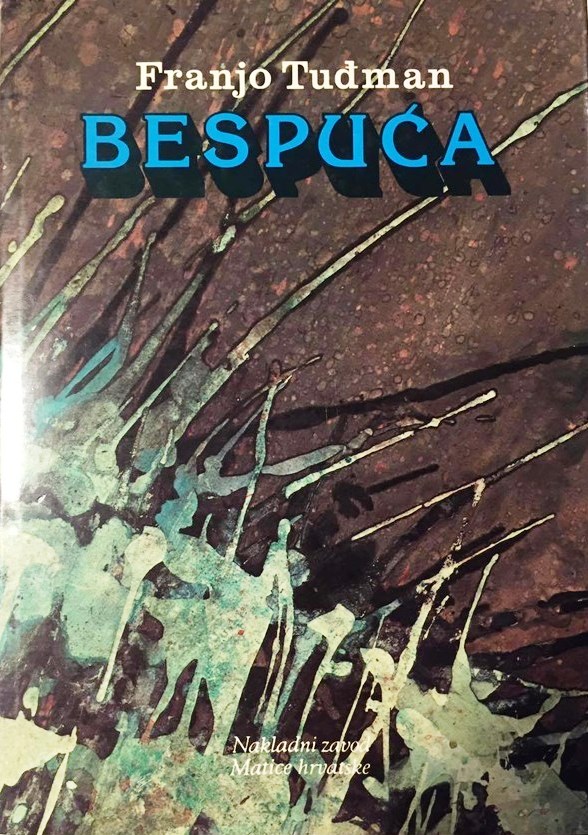

Tuđman, Franjo. Draft of the title page of the book Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy, in Croatian, 1988. Manuscript

Tuđman, Franjo. Draft of the title page of the book Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy, in Croatian, 1988. Manuscript

One of the best known books by Franjo Tuđman, Bespuća povijesne zbiljnosti: rasprava o povijesti i filozofiji zlosilja (Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy) was published in mid-1989, but the manuscript was completed in February 1988. Tuđman unsuccessfully attempted to publish the book in Croatia for a year and a half. Without the approval of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia, it was difficult to find a publisher who would have the courage to publish the book, which dealt with a topic for which Tuđman had been prosecuted by the regime twice. Finally, Marija Peakić-Mikuljan, director of the Matica hrvatska publishing house, took the risk. But even when the book was printed in June 1989, an order from the top of the communist regime in Croatia came not to distribute it. Nevertheless, the unfolding political situation in 1989, in which the political authority of the League of Communists continually declined, opened the way for its distribution.

The focus of the book is the issue of victims of World War II. Tuđman tried to draw attention to the manipulations and forgeries which tended to multiply the numbers of Serbian victims and accuse the whole Croatian nation as genocidal and criminal (Jareb 2011, 305). Tuđman was one of the first historians who encouraged scholarly research into this problem in the mid-1960s. In the book, he also shows how and why his efforts were impeded, and how he was later marginalised and imprisoned. The book represents an outline of his previous research and papers on the issue of victimhood. Tuđman opposed the so-called Jasenovac myth – the one-sided approach and multiplication of the number of casualties, especially of Serbian victims. Tuđman described the origin of the myth which was, in his view, “used (...) as a direct foundation for the theory of the genocidal character of any expression of Croatian identity” (Tuđman 1989, 120). Tuđman exhibited consistency in fighting against unscholarly approaches and exaggeration of the number of victims because he was also critical of the so-called Bleiburg myth. He rejected similar exaggerations of the number of victims killed by the communist authorities in 1945 (the so-called Bleiburg tragedy) that are popular in the Croatian diaspora.

Call for Protest in Support of the “Arrested” Editors of the Romanian Hungarian Samizdat Ellenpontok, in Hungarian, 20 November 1982

Call for Protest in Support of the “Arrested” Editors of the Romanian Hungarian Samizdat Ellenpontok, in Hungarian, 20 November 1982

Apart from the official addressees, the “Call for protest” – also included in the Göteborg collection – was published in the most prestigious samizdat of the Kádár era which addressed the “second public sphere,” Beszélő. The “News” column of issue no. 5–6 (December 1982) published it under the title “Cases of Harassment by Police Forces in Transylvania – A Hungarian Act of Protest.” The same edition of Beszélőalso included the fundamental documents of Ellenpontok no. 8 (October 1982), “Memorandum” and “Programme Proposal.”, while the previous numbers (1–4) were published in detail in issue no. 4 (September 1982) of Beszélő. The “Call for Protest” was signed by seventy-one representatives of the Hungarian opposition of the time – writers, literary historians, historians, editors, economists, lawyers, sociologists, philosophers, philosophy historians, translators, film directors, poets, pianists, architects, linguists, journalists, academicians, actors, public writers, sculptors, biologists, ethnographers, and a three-time Olympic champion.

The Call has the following content: “On 6 and 7 November 1982 Romanian state security personnel arrested several young Hungarian intellectuals in Transylvania. They conducted searches in their homes and confiscated documents relating to the political situation in Hungary and Transylvania. The exact number of persons arrested is not known yet. The following names are known: Attila Ara-Kovács, writer-philosopher, Attila Kertész, actor, Géza Szőcs, poet, and Károly Tóth, teacher. In the course of a week several persons were interrogated, among them being the agricultural engineer Lóránt Kertész and his wife Éva Kertész, Márta Józsa, Éva Bíró, András Keszthelyi, a philosophy student, together with the Tóth couple. Some of them, for instance Géza Szőcs, Károly Tóth, and his wife, were physically abused. After a few days Attila Ara-Kovács and Károly Tóth were released on the condition that they cannot leave the city (Oradea) or their homes. We still have no information regarding the whereabouts of the remarkable poet Géza Szőcs, whose name is known in all Hungarian-speaking territories. Not even his closest relatives and friends know where he is. We have reason to suspect that the political police has still not released him. We make an appeal to everyone: protest!We also call on our Romanian friends: please intervene for the release of Géza Szőcs!This call for protest has been sent by its signatories to the president of the Ministerial Council of the Hungarian People’s Republic, to the directory board of the Union of Hungarian Writers, and to the Hungarian PEN Club.” (Beszélő Összkiadás 1992)

The call for protest is not entirely accurate due to the lack of authentic sources. It is mostly based on rumours and assumptions, and although it abounds in information it remains the instrument of the selected few. The moderate form of the collective enforcement of interests, as expressed through the “media outlets” – the samizdat – is obviously an organised one, aimed at improving the situation of those affected. There are no data regarding the immediate effects of the call for protest in Romania, nor whether the leaders of the MSZMP (Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party) too any immediate steps in order to change the minority policy in Romania. At the same time, the official Hungarian circles reproached “in the course of internal discussions” that the call reached international media outlets sooner than the Hungarian government. In December of 1982 the editorial team of Beszélő categorically denied this, arguing that such accusations only “discredit a fully legitimate civil initiative,” and divert the attention from the real issue, namely, “what’s going on with the Hungarian intellectuals in Romania and what can Hungarian public opinion and the Hungarian state do against the serious violation of minority rights.” (Beszélő Összkiadás 1992).

In a diary entry written in prison on his sixtieth birthday (14 May 1982), Tuđman ponders his life and actions. He looks back on the six decades of his life, remembering his arduous childhood, his participation in the Partisan war between 1941 and 1945, his military and academic career after the war, as well as the prison time he endured due to his struggle for a different interpretation of recent Croatian national history and a better status for the Croatian people in the Yugoslav federation. He asks himself how many years of his life remained and expressed a desire to live until his eightieth birthday, because he would have "seen much from our national destiny, from the world ... And then I would know what will happen to my grandchildren ...". In his reminiscences, he encouraged himself by saying that, despite the troubles he had endured, every unselfish sacrifice “pro patria” was never in vain. He stated that he could go abroad "as a professor, writer, analyst at some institute," but that he did not want to do that because he knew that "the destiny of this nation was to be resolved in the homeland" and that he was prepared to suffer for his beliefs. He points out that he followed an uncertain path in seeking for historical truth and writing about its purpose. Tuđman wrote that he "realised that in political life, and even in life in general, we should have the moral courage to oppose blind currents and muddy torrents, but also sober prudence." He wrote that everything he did was to shed light on the obscured Croatian past to "treat the huge wounds of the past" and “prevent them from deepening.” He believed that he was not alone in this endeavour, mentioning a circle of Croatian intellectuals and politicians (such as the writer Miroslav Krleža, or the former mayor of Zagreb, Većeslav Holjevac, and others cited in pseudonyms). In this diary, he also wrote a sentence which shows that he then became aware of the need to politically fight for freedom: "If you really want freedom – either individual or national – it is worth fighting for it with your own efforts."

This document is available for download in a scanned (pdf) format at the website (prior registration required). It is ten pages long. This diary record is also available in published form in Tuđman 2011b, pp. 261-263.

Tuđman’s diary is handwritten, mostly with a fountain pen, on thin memo-size sheets of paper, on 10,180 pages. Tuđman began writing his diary on the day of his first arrest on 11 January 1972, in prison in Zagreb, and that part of the diary which covered his first imprisonment in 1972 was published in 2003 (Tuđman 2003). The rest of it, which covers the period from the beginning of 1973 until the end of 1989, was published in three volumes in 2011. The first volume covers the period from 1973 to 1978 (Tuđman 2011a), the second from 1979 to 1983 (Tuđman 2011b) and the third from 1984 to the end of 1989 (Tuđman 2011c). Tuđman's widow, Ankica Tuđman, edited these three volumes.

Franjo Tuđman's diary has a turbulent history. It was created in under difficult political conditions because, for the Yugoslav communist regime, even reading the foreign press or writing your own private diary could be deemed sufficient evidence of "hostile activities," for which some individuals (potential adversaries) were prosecuted and sanctioned in political trials. Due to the danger that the diary would fall into the hands of the police, Tuđman did not always fully express his political views, and some persons in the diary were mentioned only by their initials or under pseudonyms. Although the author himself wrote why and under what conditions he wrote the diary, it has not yet been publicly revealed who "smuggled" the diary from prison, how and where it was hidden, stored and kept for many years.

Tuđman's daily notes testify to his personal life, intellectual and moral dilemmas, motives, ambitions and goals. The diary testifies to his understanding of the philosophy of history that contrasted from the reigning Marxist doctrine of "the withering away of the nation" and the postmodern philosophy of "the end of history." Tuđman believed that historical scholarship was inseparable from the achievement of the ideals of human freedom. He felt that the increasing globalisation and integration of the world led to the broader individualisation of nations. For this reason, the primary goal of his activity was a free and sovereign Croatian nation in a community of European states and peoples, with full recognition of human rights. That is why he set forth from the universal values of individual and national freedom as the principles upon which a future Europe could be built.

Besides information on Tuđman's private life, the diary is full of information on events in the last two decades of communist Yugoslavia, and on developments on the global political scene. Particularly interesting is his interpretation of the events around the Croatian Spring as well as the relationships among its participants. After serving his prison sentences, he began to privately associate with other intellectuals who had also suffered consequences after the quelling of the Croatian Spring, primarily with members of Matica hrvatska and the leaders of the defeated liberal wing of the League of Communists of Croatia – Miko Tripalo and Savka Dabčević Kučar. As they usually met on Fridays, in his diary Tuđman referred to these meetings as "Friday banquets." However, according to Tuđman, most of them, primarily Savka Dabčević Kučar and Miko Tripalo, were not prepared for some more decisive action. In response to an offer to Croatian dissidents from an American publisher to write essays on historical, political and economic circumstances and the condition of Croatia, only Tuđman agreed to collaborate. Tuđman wrote in his diary that he "begged" them to accept the offer to write, and, disappointed by their refusal, asked himself "where will this self-satisfaction with the role of the royal opposition lead?" (Tuđman 2011a, 1 October 1975).

Ferenc Kálmándy, a photo artist from the underground milieu in Pécs, was prompted by the Budapest underground rock band Trabant to shoot a photographic series entitled “Too Late to Run Away, Shameful to Stay” in 1982. The composition, which consists of six pictures, captures visually the paradoxical scenery of movement posed by János Vető’s rhymes. The slow, hesitating movement of objects (in reality, people) set on the scene and the halting movement of bodies suggest the absolute futility of the paradox occurrence symbolized in the song or, perhaps, any occurrence, so it represents the rule of melancholic spleen typical of the oeuvre of Trabant. Both running away and staying are reduced to a series of actions which suggests hollowness and superfluity: the blurred movement of the body and human figures symbolize this state and a meaning of life associated with it.

This work reveals Kálmándy’s desire to link his work to contemporary photo art genres and underground cultural scenes. The figures in the photograph are director of cartoons Károly Papp (who at the time worked together with Ferenc Kálmándy for the Gallery of Pécs) and architect János Rauschenberger. Rauschenberger also worked as a stage designer, and he served as the editor of the periodical Bercsényi 28-30 between 1978 and 1980. The journal was the theoretical forum of the Bercsényi Architecture College of the Budapest University of Technology between 1963 and 1988. Alongside articles on architecture, it also published writings on underground music and arts. Its previous issues are available at bercsényi2830.hu.

Étriers (short climbing ladders) are essential technical equipment for a difficult climb that requires artificial means. In Dragoș Petrescu’s private collection of improvised gear, there are three such items, made by working with a rather unusual material: “The lateral elements of the étriers are made from synthetic tape for blinds, sewn with surgical threat, also synthetic, and dyed red and blue with Gallus textile dye. Then the rungs, the second basic component of the étriers, are made from pieces of the wheel rim of a Sputnik (USSR) semi-racing bicycle. However you had to get hold of the bicycle wheel rim. You could have the good fortune, as I did, to have an acquaintance who gave up a bashed wheel that was beyond repair. Once you got the wheel rim, the inner frame, then you cut it to the desired size, carefully smoothed the sharp edges (with a file and sandpaper), and used it for the rungs of the improvised étriers. This wheel rim was made of duralumin and it was suitable for making étrier rungs, which had to be light and strong. Consequently, you were obliged to improvise. Out of one such wheel rim I managed to make two normal étriers and one smaller one,” says Dragoș Petrescu. The improvised étriers are still useable today.

A project based on the extension of the correspondence with Ray Johnson

In July of 1979, Artpool got Ray Johnson's mail address from Romano Peli in Parma. At first, they didn't get any replies to the letters they sent him.

In 1982, Ginny Lloyd, who knew Johnson personally, was visiting Artpool and found it strange that Ray hadn’t answered the letters. Galántai then decided to make one last try with a postcard action: he made twenty postcard-collages and mailed them one after the other over the course of twenty days.

The answer arrived soon, the first “send to” letter with drawings, asking that they send it to Wally Darnell in Saudi Arabia. The drawing or the letter? The request wasn’t clear to him, so he decided not to deliver the letter passively, but instead to become a part of the action, so he photocopied the drawing.

There were four numbered Fan Club stamps on the drawing, with four characteristic “bunnies.” He decided to rearrange them to allow for further additions.

A new decision was made. For the upcoming “Artpool's Ray Johnson Space,” he decided to invent a background institution, the “Buda Ray University” (modelled on the Buddha University).

Copies were made of the modified drawing and then sent first to all of Artpool’s mail connections and then back to Ray Johnson.

October 13, 1982 - Johnson mailed the second drawing with the “add to” stamp on it.

November 3, 1982 - Johnson mailed the third drawing.

December 22, 1982 - A letter arrived, referring to the second drawing with the inscription “Thank you for all your communications” and a Dora Maar Fan club stamp, and finally, a letter with a Yoko Ono Bunny stamp closed the year.

September 28, 1983 - the fourth drawing's inscription “Thank you for yaur” refers to the former letter (after nine months), and continues with “send to Peter Below,” and the drawing: a duck in a cloud with the inscription DUCK CLOSE and with a ball-point pen OH BOYS ALWAYS THE SAME STYLE.

The Buda Ray University gained more and more participants through the continuous posting of the first four letters. The University published a book in 1985 that contained a selection of the letters that had been received up to that time.

February 13, 1986 - Johnson mailed the fifth drawing “BILL de KOONING'S BICYCLE SEAT” which arrived enclosed with a catalogue of the Nassau Museum, in exchange for the Ray Johnson Artpool Book.

The fifth drawing was the most successful. Many replies came within a short period of time. There were too many replies to include in a single a book, so Artpool had to use another form of publication: the exhibition.

The Artpool's Ray Johnson Space was shown 14 times in 8 different countries between 1986 and 1993, either as part of other events or sometimes as an independent program.

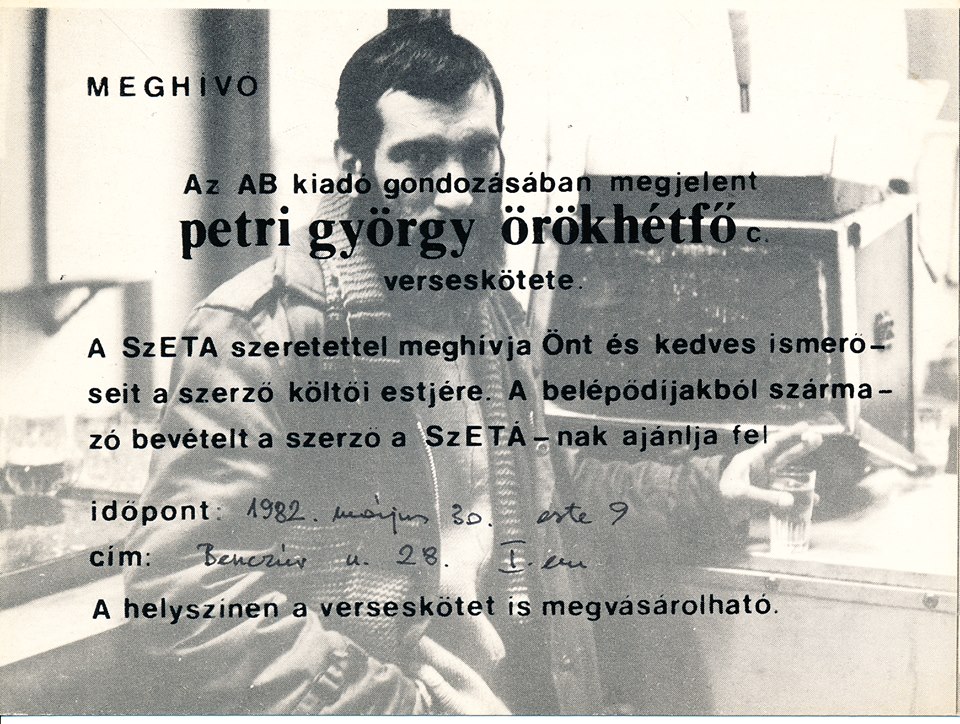

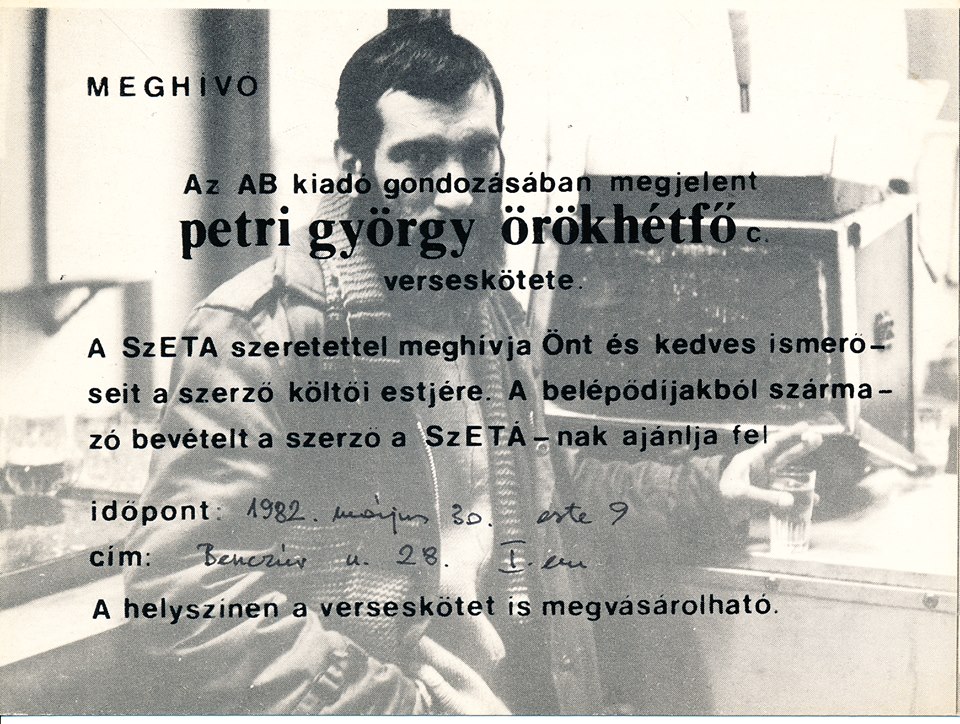

Invitation card to the samizdat book-launch of AB Independent Publisher: 'Ever-Mondays' by György Petri, 1982. Printout

Invitation card to the samizdat book-launch of AB Independent Publisher: 'Ever-Mondays' by György Petri, 1982. Printout

This single page invitation card to the AB Independent Publisher’s poetry book launch of “Ever-Mondays,” by György Petri, on the 30th of May 1982 in Budapest, is a rare and revealing early document of the Hungarian dissident movement.

“Fund for Aiding the Poor” (SZETA) just debuted a year before, and the most influential periodical of Hungarian democratic opposition Beszélő (Speaker), together with the AB Independent Publisher, was established less than half a year later, in late 1981.

In fact, the author himself, poet and philosopher György Petri, was also a founding editor of Beszélő, and an active supporter of SZETA. It was a small miracle when he offered the income from his book sales entirely for the relief activities of SZETA; it was printed on the invitation card that his book, which had been rejected for years by state publishers, would be available uncensored, and could be purchased at the event.

All these reflect upon the engagement of independent actions: the radical claim for both political and cultural freedom together with the still challenging, new activism for social justice and solidarity.

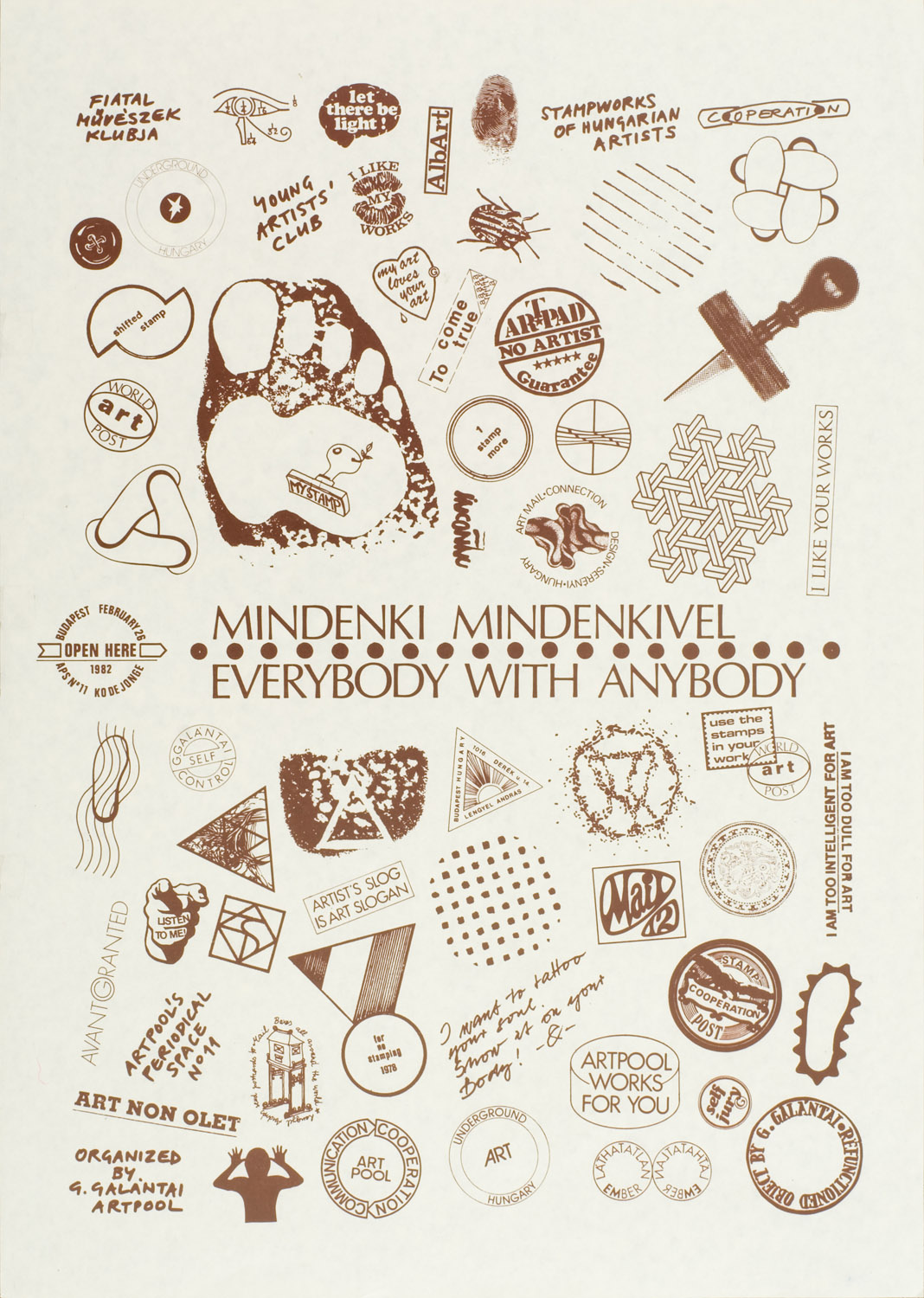

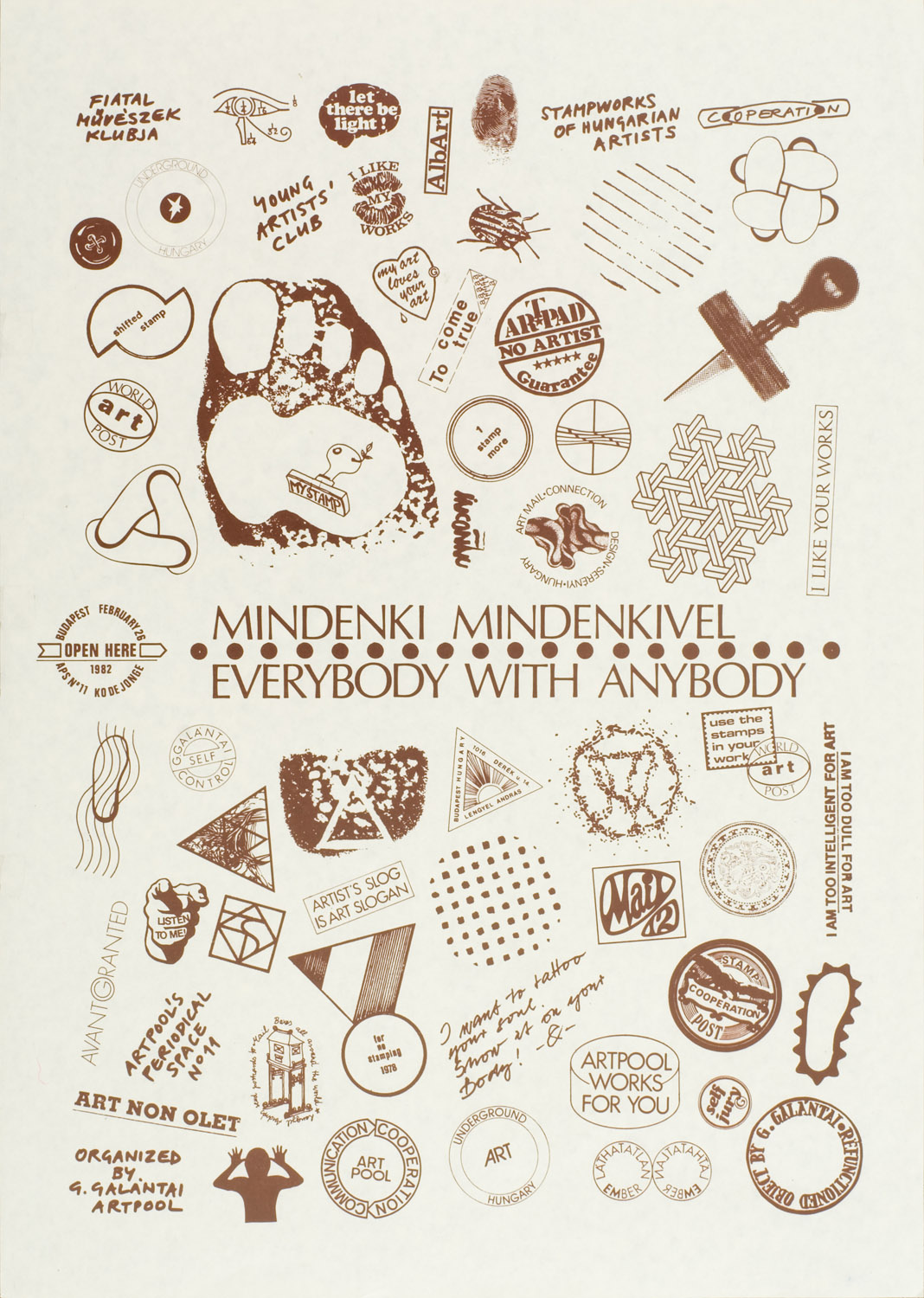

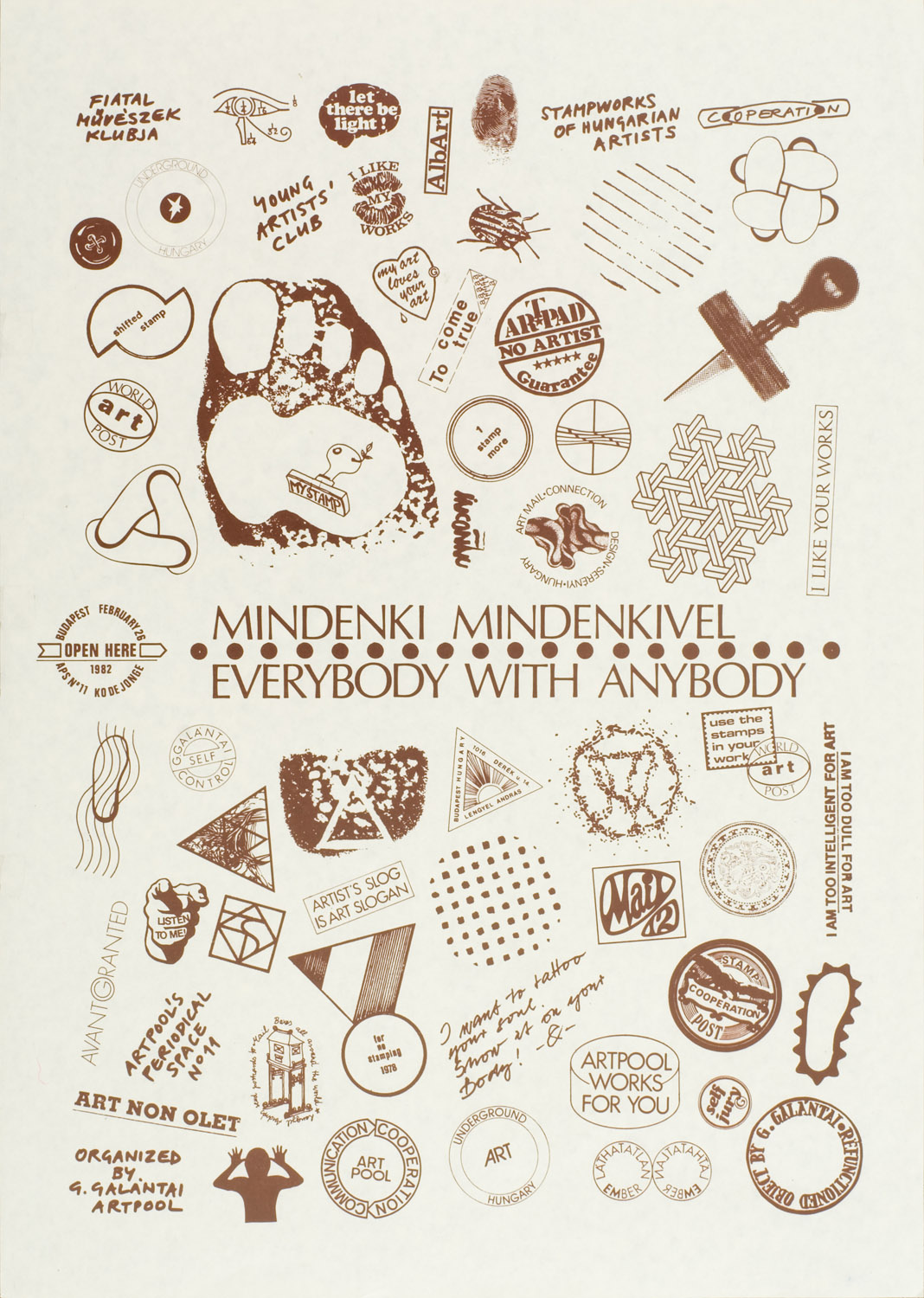

The greater part of the exhibition consisted of the commemorative stamp designs made by 550 artists from 35 countries at the call of György Galántai, who had been organizing the project for two years and thus was establishing Artpool’s artistamp collection. Accompanying the exhibition held at the Fészek Klub, an artists’ book catalogue was published containing related theoretical texts and 27 stamp sheets with the 756 stamp images sent in response to the call.

György Galántai “directed” Stamp Film in the Balázs Béla Stúdió using images from the World Art Post exhibition material. He added soundworks by the networkers. The mainstream periodical Élet és Irodalom published a selection of the Hungarian participants’ stamp designs. The exhibition and the catalogue met with a good international response. During their 1982 Artpool's Art Tour, Galántai and Klaniczay “handed out” copies of the catalogue to their artist colleagues, and they received important publications in exchange. The Canadian pioneer of the artistamp genre, Mike Bidner, contacted Artpool upon purchasing a copy of the catalogue. He invited the Stamp Film for the Artistampex organized by him in Canada, 1984. Before his death, he donated his collection of thousands of artistamps to Artpool.

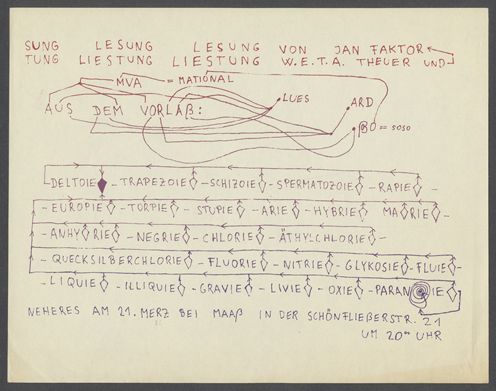

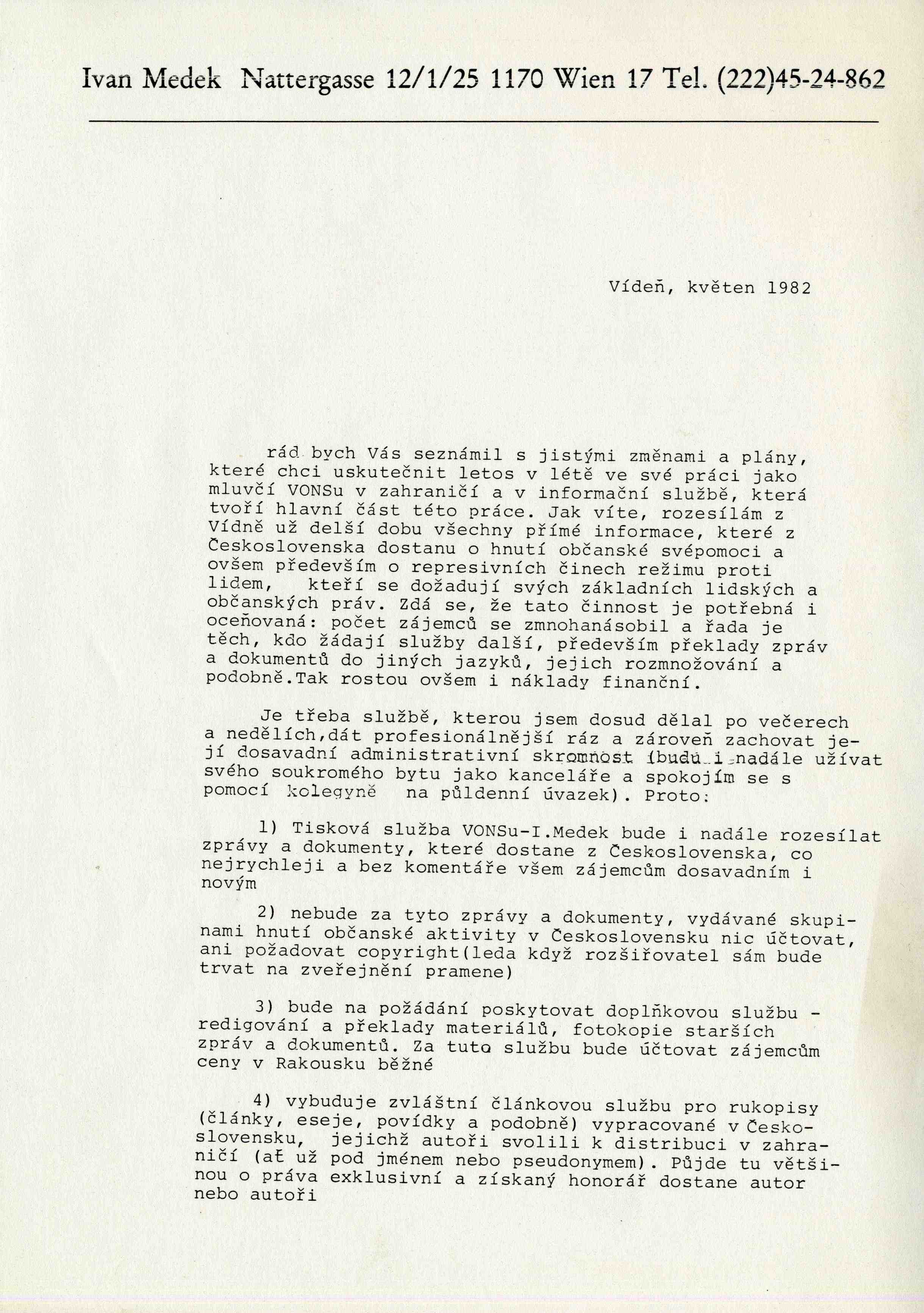

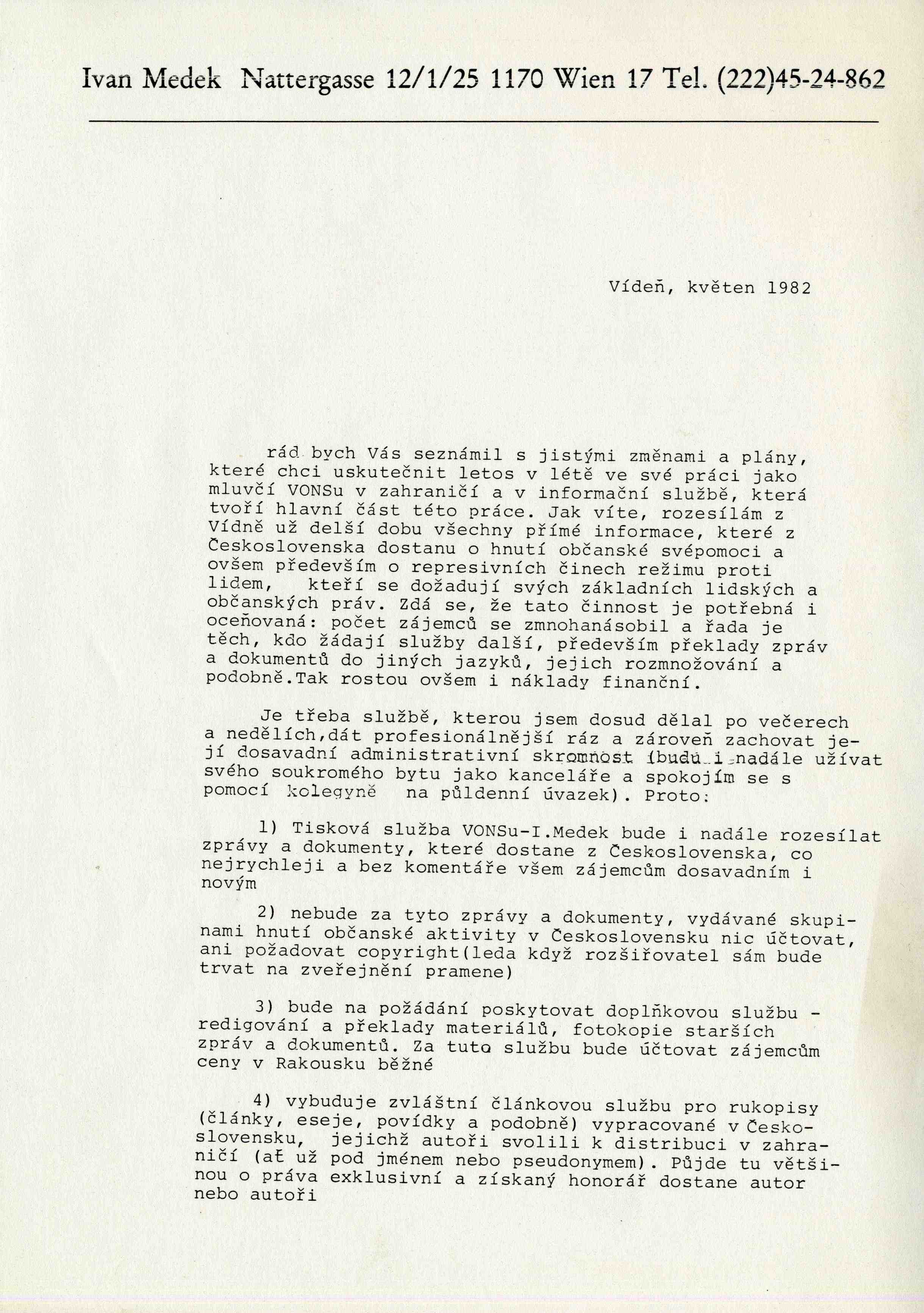

Ivan Medek's letter from May 1982 announcing the establishment of the Press Service in Vienna, through which he circulated up-to-date information from Czechoslovakia, in particular the documents of Charter 77 and the VONS Communication to more than 70 addresses of foreign and exile institutions.

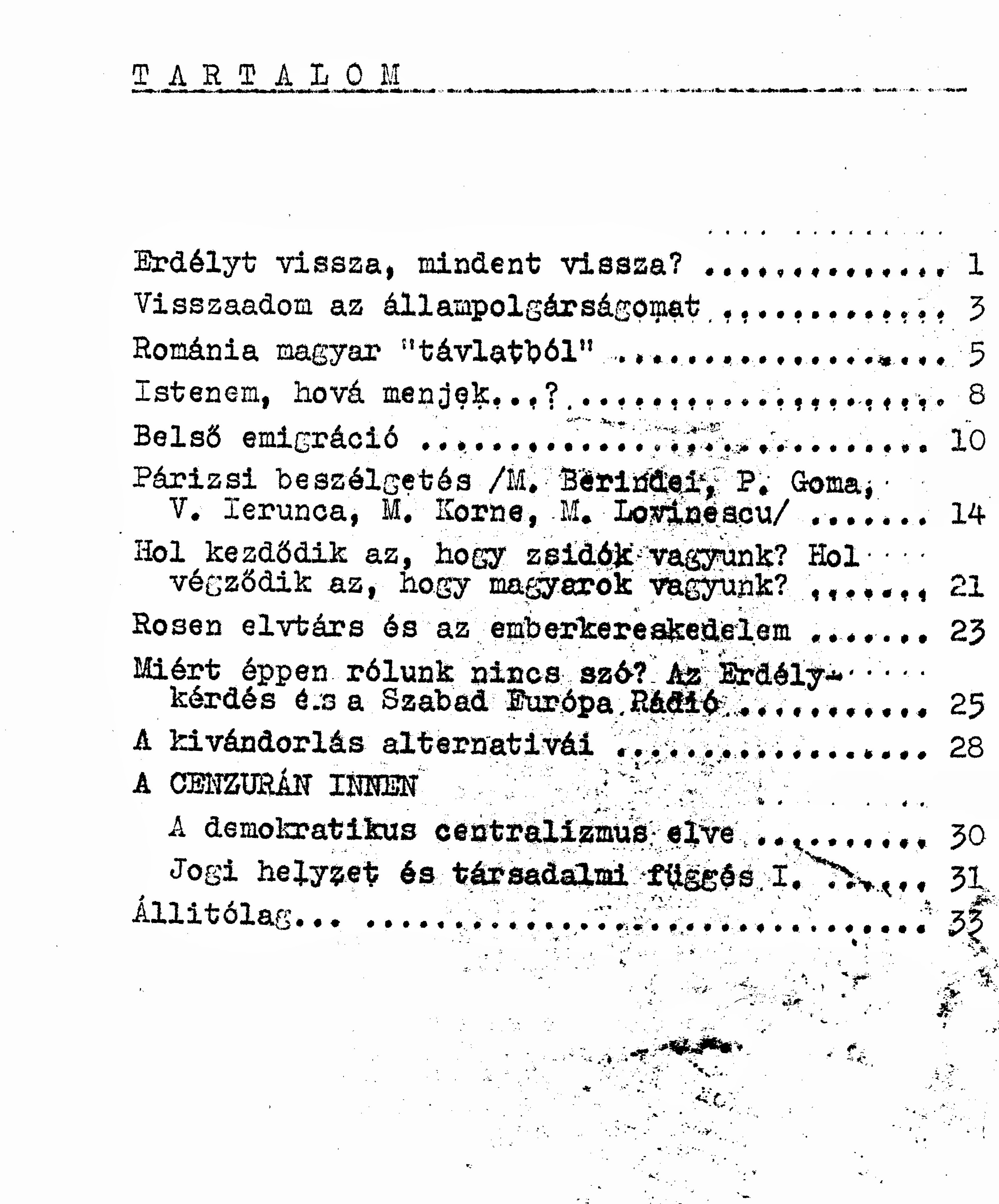

This original copy of the samizdat can be found in the tenth volume of the observation file on Géza Szőcs. Its source was András Keszthelyi, a university student, in whose possession on 8 November 1982 the Cluj-Napoca Securitate found twenty-one copies of the fifth to eighth issues of Ellenpontok, which they confiscated. The seventh issue (September 1982) – considered the most magazine-like – included two articles pertaining to the heading “On this Side of Censorship” and ten other texts. This publication includes the only article written by Géza Szőcs, his two-page text entitled “Transylvania Back, Everything Back?” which, analysising the situation, reaches the conclusion that the editors and distributors have put their lives at risk by founding the first Romanian samizdat paper. Although the column entitled “Documents” is missing, this is compensated for by two texts Attila Ara-Kovács which discuss the situation of Romanian Jews as well as his several articles about the fate of Transylvanian Hungarians. The latter articles discuss the disruption of Hungarian national homogeneity and the mobility restrictions imposed on “internal emigration,” the “city embargo,” the prohibition of commuting, the official modality of emigration to Hungary and defection, in the form of fictitious dialogues. In this context mention must also be made of an article by András Keszthelyi which considers the alternatives to emigration from the point of view of the Romanian Communist system. This edition also includes interviews with Mihnea Berindei, Paul Goma, Virgil Ierunca, Mihai Corne and Monica Lovinescu, published under the title “Parisian Interview,” which had been noted down and translated by Antal Károly Tóth on the basis of a tape recording of the Romanian-language radio programme broadcast by Radio Free Europe. Thematically we may include here another article by Ara-Kovács which tries to offer an answer to the question of when the Hungarian-language broadcast of Radio Free Europe will effectively cease its self-censorship on the Transylvanian issue, The column entitled “On this Side of Censorship” features a fictive story by István Mészáros entitled “The Principle of Democratic Centralism” together with Ara-Kovács’s reasoning regarding the legal status and social dependence of the subject and the citizen. The edition ends with the officially non-publishable newsfeed of the column entitled “Reportedly.”

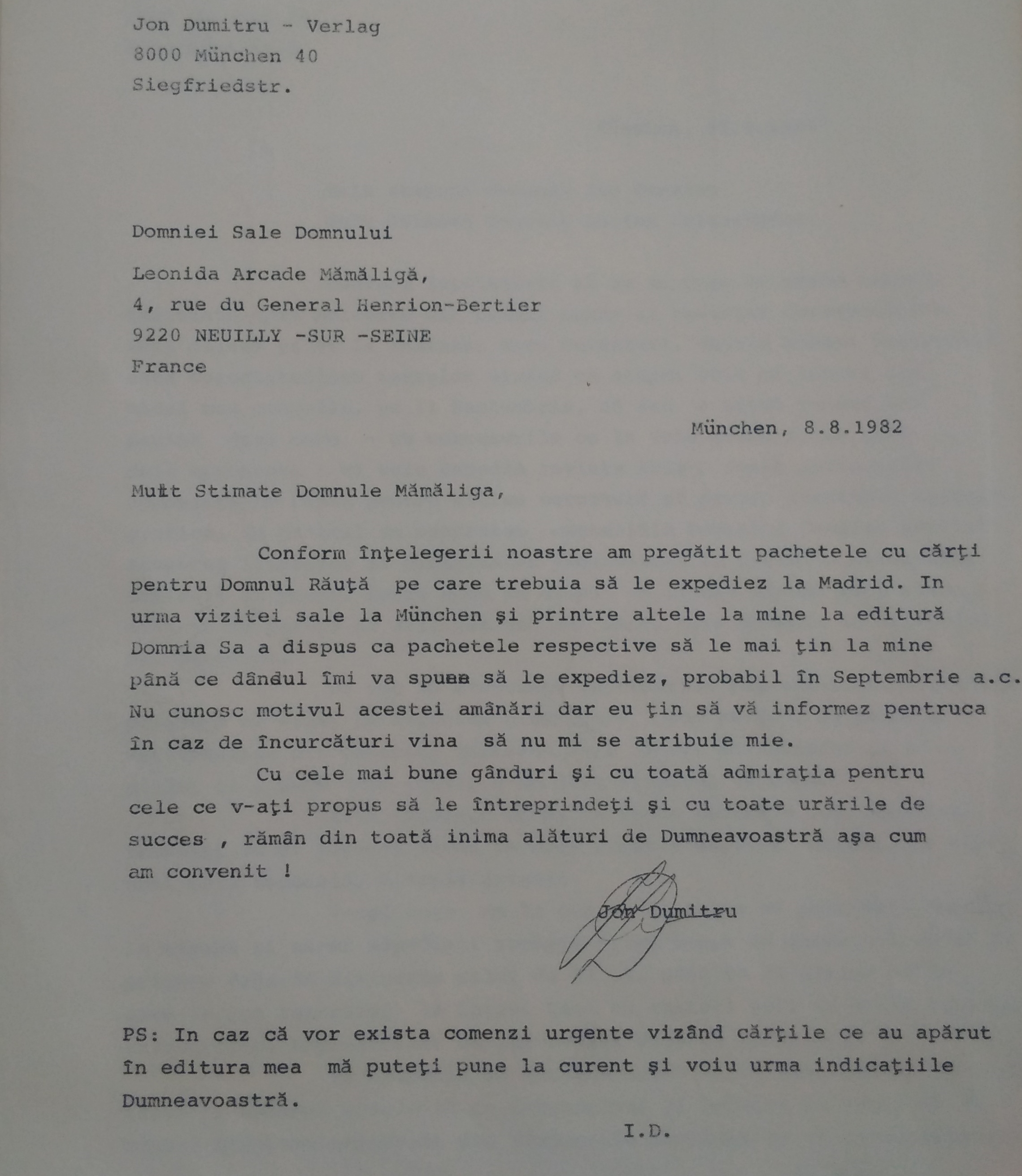

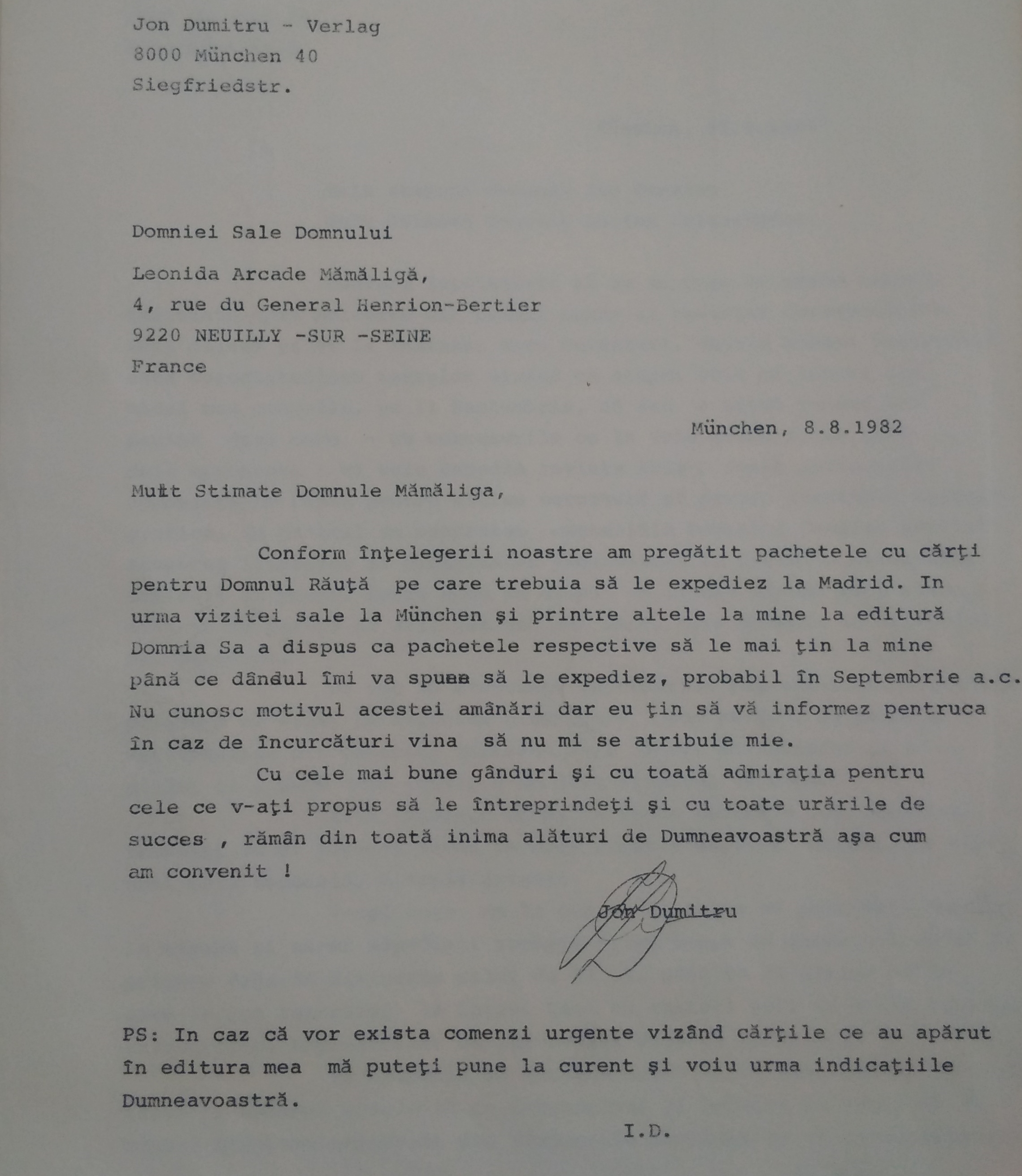

This document contributes to the understanding of the activity of the postwar Romanian exile community in the 1980s, especially regarding the correspondence and interaction between its most active members. During the communist period in Romania, the Romanians of the emigration were in general located at significant distances from each other, being settled on several continents: Europe, North America, South America, Australia, and Africa. The most active of them founded organisations, associations, institutions, institutes, foundations, publications, and publishing houses in their countries of residence. The purposes of their efforts were to: represent the Romanian nation, its democratic values and principles, and to defend its interests until the collapse of the communist regime; to coordinate the activity of Romanians abroad to carry out activities that would help to restore the democratic system in Romania; to represent the exile community within democratic societies and solve its problems; to establish links with Western governments and international organisations; to collaborate with representatives of the other "captive nations" in Central and Eastern Europe to form a common front to unmask and remove communism. Such an approach was also that of Ion Dumitru, a personality of the exile community, who set up in the mid-1960s one of the most important publishing houses of the Romanian emigration. It was founded in Munich, where he settled in 1961, and was officially registered in 1976 as a printing company. The Ion Dumitru Publishing House published over eighty books by exiled Romanians, many of them extremely valuable for national culture and history. To acquire such volumes, the owner of the publishing house, Ion Dumitru, maintained an ample correspondence with those interested. A proof of these relationships is this letter, which Ion Dumitru addressed to Leonid Mămăligă on 8 August 1982. Leonid Mămăligă, who wrote under the name L.M. Arcade , was a personality of the Romanian exile community, in which he made a name for himself, in particular, through the establishment and coordination for more than thirty years (1958–1989) of the Neuilly-sur-Seine Cenacle. The purpose of this cenacle, unique in France during those years of exile, was respond to the need for a Romanian place to offer Romanian intellectuals outside the country the possibility of thematic meetings and discussions. Also, the cenacle represented a platform of expression for Romanian intellectuals in exile, which helped them to keep alive the Romanian identity abroad and to put Romanian culture in communication with that of France. At the same time, the cenacle stimulated the act of creation both in Romanian and in French, by supporting and promoting Romanian writing, as it had its own publishing house, Caietele Inorogului (The unicorn notebooks). As or the subject of the letter that Ion Dumitru addressed to Leonid Mămăligă, in it he talks about sending a package of books published by his publishing house for another well-known Romanian exile, Aurel Răuţă, a professor at the University of Salamanca, Spain. Aurel Răuţă was a notable personality of the exile community because of his publishing activity and the founding, among others, of the Asociația Hyperion (Hyperion Association) in Paris. This was a distribution platform for books by Romanians in exile. In ten years of activity, he distributed to Romanian emigrants more than 10,000 volumes, published at more than 130 publishing houses. The document in the Ion Dumitru Collection in the IICCMER archive is a copy in A4 format.

Lydia Sklevicky approached the "women’s question" primarily from the scholarly but also from the popular science position, and in a way that she was active in the print media and in public forums held in the Yugoslav centres of the new feminist movement - Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana.

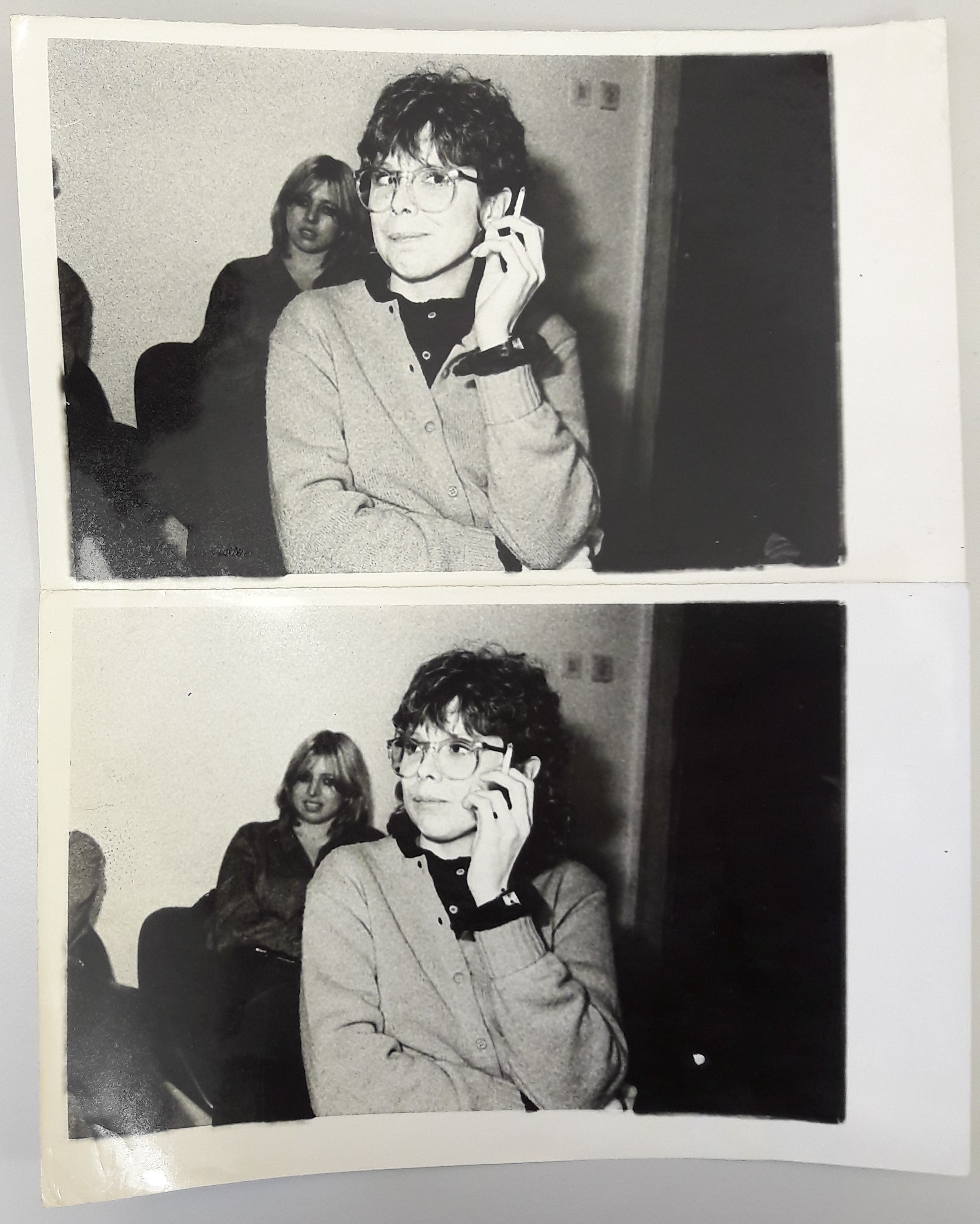

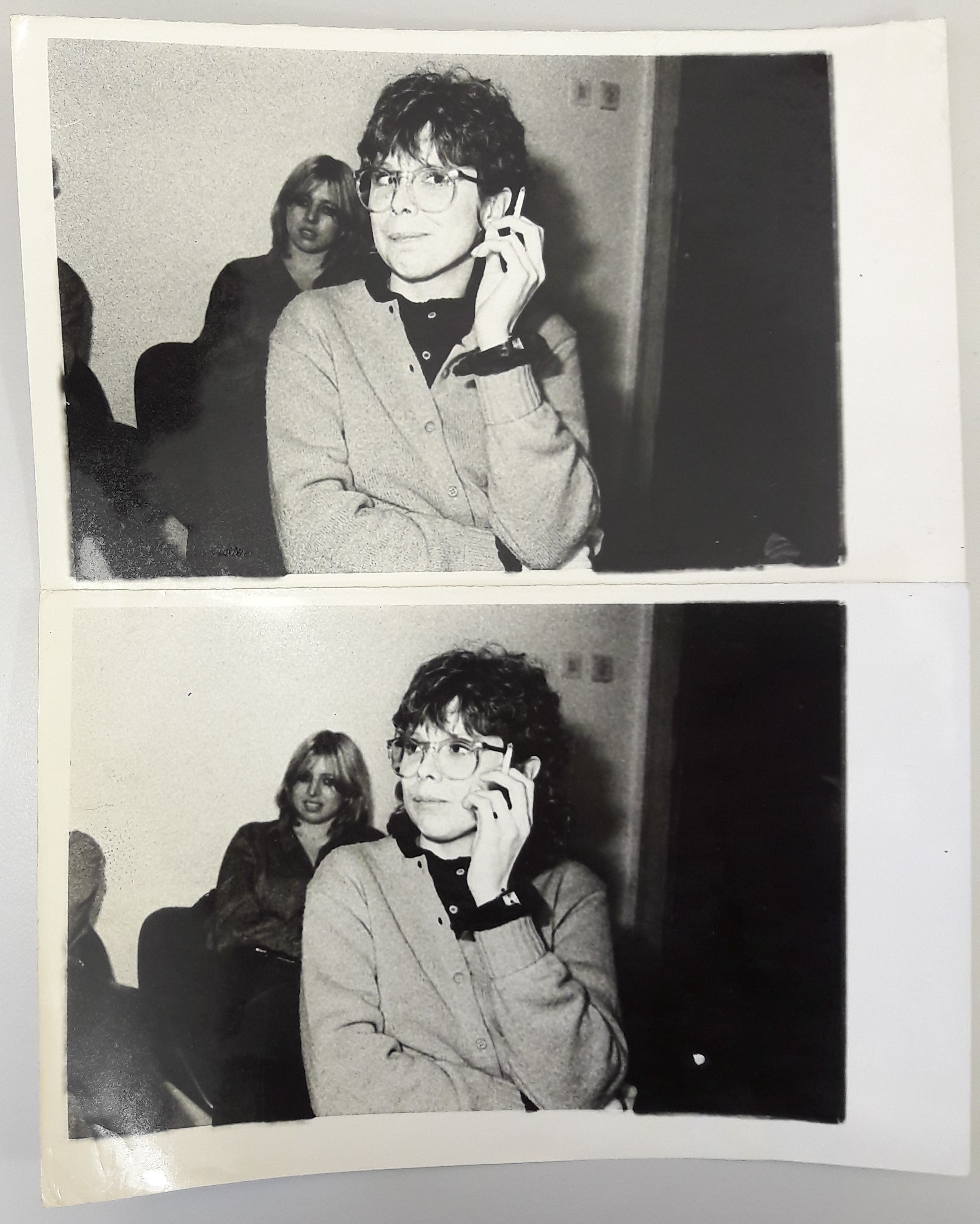

Two photographs of Lydia Sklevicky attending the forum about female/ale relations in the Student Cultural Centre (SKUC) in Belgrade were taken by the photographer Dragan Papić on January 7, 1982, while on January 16, 1982, Belgrade's Omladinski list published an article by Snežana Bogavac, “Satisfied, oppressed women,” which stated that in Yugoslavia there is no serious research into the status of women (because in the scholarly circles this topic is "bypassed and marginalized"), and accordingly forums such as the one in SKUC have no significant impact. Despite the defeatist attitude of the article’s author, Sklevicky continued to advocate, at the forum in Belgrade and in her other work, for the presence of the "women’s question" in the public focus and its concrete resolution in the terms of obtaining the rights guaranteed to the women by the SFRY Constitution.

The two mentioned photographs of Lydia Sklevicky and the article from the Omladinski list are kept in the Sklevicky Feminist Collection.

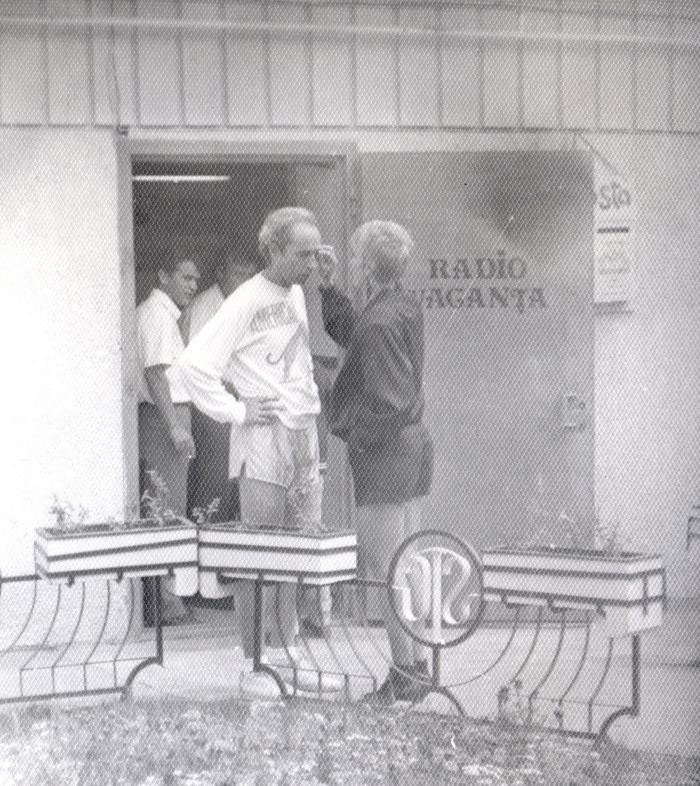

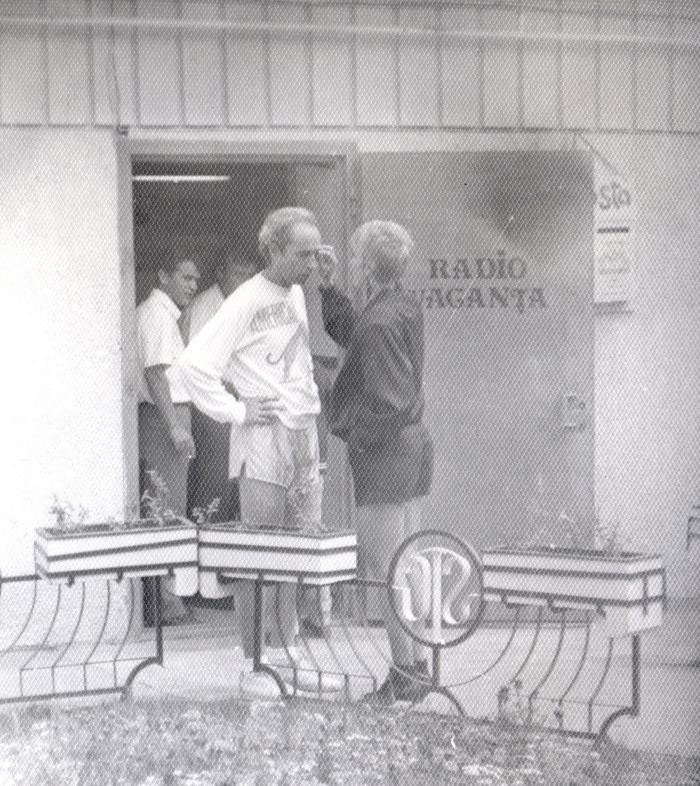

The Andrei Partoş–Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti Private Collection includes photographs, publications, and various documents regarding a seasonal radio station that operated during the summer holiday period in Costineşti, which was officially and popularly considered to be the seaside resort for young people. This radio station and its associated activity in Costineşti was a social phenomenon without any term of comparison in the Romania of the 1980s, an epitome of the alternative culture of the younger generation under later Romanian communism and a formative experience for the generation who supports the democratic consolidation in present-day Romania.

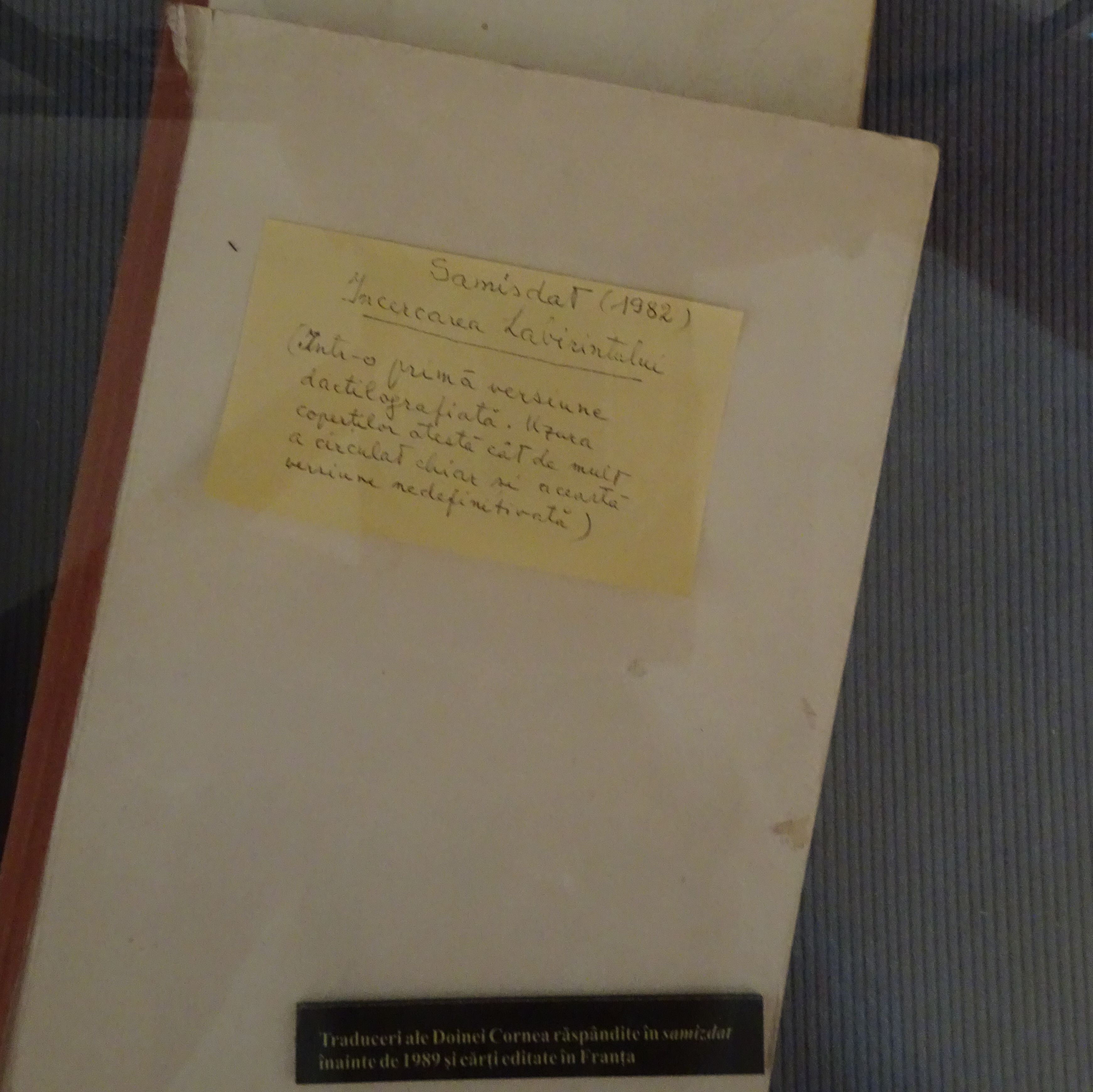

Eliade, Mircea. Ordeal by labyrinth, translation by Doina Cornea (in Romanian), samizdat issue, 1982

Eliade, Mircea. Ordeal by labyrinth, translation by Doina Cornea (in Romanian), samizdat issue, 1982

Mircea Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth: Entretiens avec Claude-Henri Rocquet (Ordeal by labyrinth: Conversations with Claude-Henri Rocquet) is the first book which Doina Cornea translated in 1982 in order to circulate it in communist Romania as a samizdat issue. The book found its way to Romania with the help of Doina Cornea’s daughter, Ariadna Combes, who had earlier taken advantage of a trip to France to emigrate. Using informal channels, she managed to send her mother many books that were not available in Romania. Among them, there was Mircea Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth, which had been published in 1978 (C. Petrescu 2013, 308–309). A former member of a group of very gifted young intellectuals (the so-called generation of 1927), Mircea Eliade was a prolific writer whose political affinities had been with the Iron Guard, the extreme right political movement in interwar Romania. Due to his encyclopaedic erudition, which proved instrumental after his emigration, Eliade later became a renowned historian of religions in the United States and informally the most famous member of the Romanian diaspora. Although the communist regime tried to recuperate Eliade in order to use him as agent of influence in the West, he was still a taboo person as a refugee and former supporter of the Iron Guard.

As a lecturer in French language and literature at the University of Cluj-Napoca, Doina Cornea translated L'Épreuve du labyrinth into Romanian and used it in her classes without any official approval. As she mentioned in the forward of the post-communist edition of her samizdat translation of Eliade’s book, her motivation for selecting it as a teaching material was to offer a role model to her students: “The young reader, who is unfortunately used to certain patterns of thinking, will be amazed from the beginning by the freedom, the openness and the creativity in Eliade’s thinking” (Eliade 1990, 5). This initiative and the letter sent to Radio Free Europe (RFE) in which she criticized the state of education in Romania led to her ousting from the university in the autumn of 1982. Forced into early retirement, Doina Cornea had thus more spare time to use for her dissident activities (C. Petrescu 2013, 308–309).

One of her first dissident actions was to further refine the Romanian translation of Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth and add explanatory notes for a wider readership (Cornea 2006, 73), in order to transform this manuscript into a widely distributed samizdat publication. The process was time consuming and also entailed high personal risks for Doina Cornea. As she remembers, she started to type the translation on very thin pages in order to make up to six copies at once using carbon paper (Cornea 1990). At that time the possession of a typewriter was strictly controlled by the communist regime. Anyone who wanted to have one was legally compelled to obtain an authorisation from the Militia. If permission was granted, the owner had to provide the same Militia with a typeface sample of the machine so that its unique characteristics could be registered. Additionally, a sample of its typing was to be provided at the beginning of every year, and also every time the typewriter was repaired (C. Petrescu 2013, 296-297). This measure allowed the authorities to quickly identify and punish the authors of samizdat publications or other types of presumably hostile writings such as leaflets and letters sent to the Romanian authorities or foreign radio stations. It also served to discourage those people who might nurture the idea of producing and distributing these texts by drastically decreasing their chance of not being identified by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate.

Apart from the high personal risk resulting from her being quickly identifiable from the typeface sample of her typewrite, Doina Cornea’s decision to multiply the translation of Eliade’s book also entailed high financial costs. At that time all photocopying machines were state owned and their use was strictly monitored by the communist authorities, especially by the Securitate. Thus, in addition to the significant cost of multiplying the many pages of the translation, Cornea or those who helped her probably had to buy the goodwill of the operator(s) of the photocopier so that they would turn a blind eye to what was being copied. Because other intellectuals refused to help her, Doina Cornea had to rely on the support of her son and his friends and also on the aid of her former students. All of them gladly made a small monthly contribution to help her pay for the photocopying of the manuscript and they also got involved in the dissemination of its 100 copies (Cornea 1999, 14).

The content of this samizdat, Mircea Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth, is in fact a book-length interview in which the Romanian historian of religions speaks about his early life and his many formative experiences. He talks about his extensive and diverse reading, about his scholarly interests in Oriental studies and especially in the history of religions and mythologies, and about his dissertation in philosophy. A lengthy discussion is given to the meaning of his trip to India, where he learned more about Indian cultures and religions. Following the experience of this spiritual voyage, he wrote some of his well-known literary pieces, such as Maitreyi (published in English translation as Bengal Nights), Nights in Serampore, and Isabel and the Waters of the Devil. Also in India, Eliade admitted that he became interested in politics, and in means (violent and non-violent) of fighting politically against discrimination. Although Mircea Eliade speaks about his time in Romania before his emigration to the West in 1940, he deliberately avoids any mention of his involvement in the activity of the extreme right political party, the Iron Guard. The rest of the book is concerned with his period of exile in Paris and Chicago, and traces step by step his method of research in the history of religions. It aimed not only at rediscovering the archaic roots of the spirituality and the blending of the sacred and the profane in the everyday life, but also at underlining the symbiotic relation between spirituality, freedom, and culture. Consequently, in the context of the book, the labyrinth becomes synonymous for Eliade’s initiatory journey into the realm of spirituality that helped him rediscover the new real, reality, and thus opened a door towards personal freedom, fulfilment and self-knowledge. Related to this, Mircea Eliade underlines the role that intellectuals have or should have in the formation and preservation of national spirituality and explains why their role as guardians of spirituality is even more important under dictatorial regimes such as communist ones (Cornea 1990, 5–6).

Apart from the rationale of providing Romanian readers, especially young readers, with an incentive to work on themselves following Eliade’s example, Doina Cornea’s motives for translating his book-length interview into Romanian also reflect their similar opinions. Like Mircea Eliade, Doina Cornea believed that spirituality (and the rediscovery of religion) was the only way to gain personal freedom. As she pointed out in many of her letters sent to RFE or in the interviews she gave, Cornea considered culture and religion as the best weapons with which to fight against communism and to secure freedom from the constraints and misery of daily life in a non-democratic regime (Cornea 2006; Jurju 2017). The translation and dissemination of the book L'Épreuve du labyrinth as a samizdat reflected Doina Cornea’s decision to serve as a guardian of authentic spirituality for young intellectuals living under a communist regime, thus fulfilling the important role that Mircea Eliade defined in his dialogue with the French writer Claude-Henri Rocquet.

This monotype by Heldur Viires dates from 1982. It is called Army with Banners. Heldur Viires is well known for his skill at monotypes. They are mostly abstract, colourful, and filled with interesting patterns. This print is a good example of his later work, when he had gained extensive skills in the technique.

The Anonymous Mountaineer collection illustrates how a passion for the mountains and for climbing could become a passion for freedom. More precisely, the collection reflects a distinctive type of cultural opposition, practised by those with a passion for the mountains and for climbing. This sport permitted a temporary escape from the routine of life under communism into places where the communist regime effectively ceased to exist. At the same time, in the case of communist Romania there was also a second dimension of opposition, because climbing involved a connection with the parallel economy in order to procure the necessary technical equipment, which was not to be found in shops. The Anonymous Mountaineer collection preserves a great variety of climbing equipment that was either improvised by the owner of the collection or obtained on the black market, where such items were commercialised.

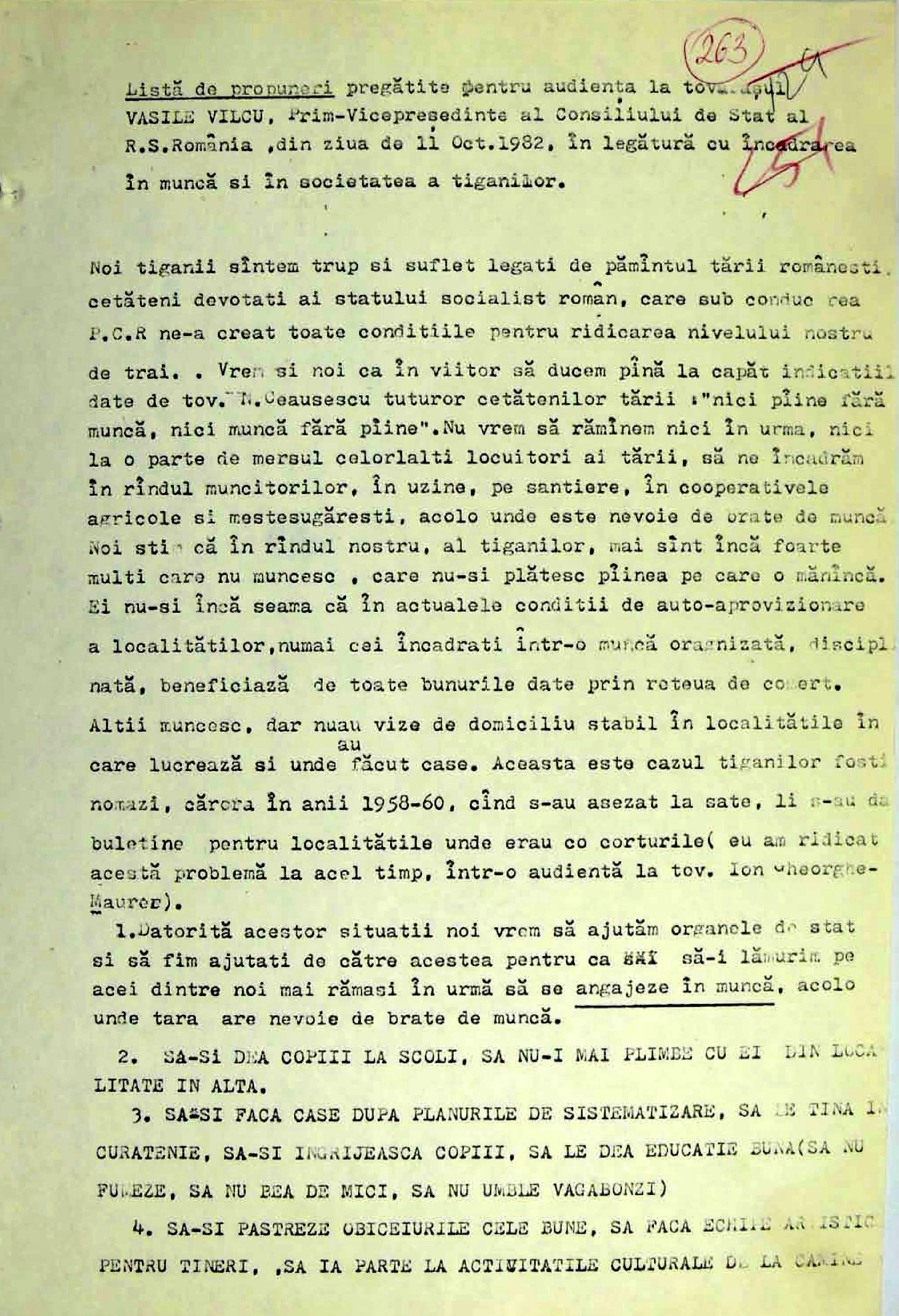

Memorandum of Ion Cioabă and Nicolae Gheorghe to Vasile Vâlcu, prime-vice-president of the State Council of the Socialist Republic of Romania, 11 October 1982

Memorandum of Ion Cioabă and Nicolae Gheorghe to Vasile Vâlcu, prime-vice-president of the State Council of the Socialist Republic of Romania, 11 October 1982

The memorandum signed by Ion Cioabă and Nicolae Gheorghe was presented to Vasile Vâlcu, the prime-vice-president of the State Council of the Socialist Republic of Romania, during an audience on 11 October 1982. It contained a complex list of proposals for “the integration into work and society” of Roma that mirrored faithfully the results of Gheorghe’s research and his ideas about solving their problems.

After stating that “the Gypsies” considered themselves “devoted citizens of the Romanian socialist state, which, under the leadership of the Romanian Communist Party, ensured all the conditions for raising our level of living,” the two signatories raised the question of those nomadic Roma who did not enjoy the benefits of socialist modernisation. For those Roma who continued to live on the edge of poverty due to their nomadic lifestyle, the two Roma leaders devised a complex set of measures that would help them integrate into mainstream society. These included the sedentarisation of Roma by offering them jobs and a place to live, the schooling of Roma children, the participation of Roma people in social, cultural, and educational activities in order for them to learn the rules of living in a society, the observance of their particularities as a minority group, and the creation of a commission to ensure the implementation of these measures and the representation of Roma at the local and central level. Although the memorandum received no answer and the communist regime continued its policy of forced assimilation of Roma, its authors were not prosecuted by the authorities.

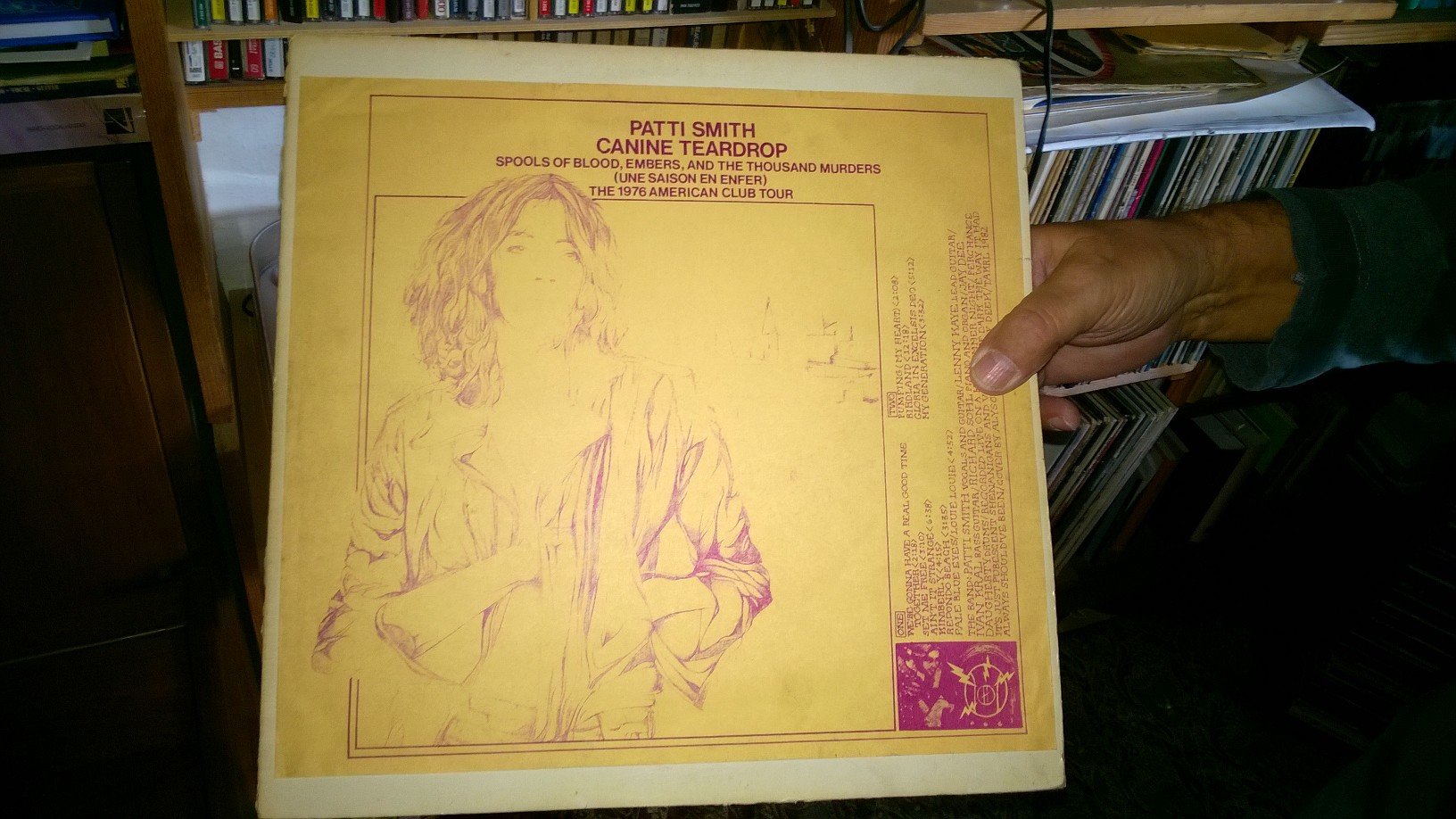

Gábor Klaniczay’s collection of vinyl LPs consists of albums released in the 1970s and 1980s, CDs, and tapes of concerts of music by Hungarian New Wave bands.

These records include some pirated discs, for example, Patti Smith’s Canine Teardrop (1982). This is an important item in Klaniczay’s music collection. He acquired it thanks to his trips abroad and his connections. This LP was banned in Hungary.