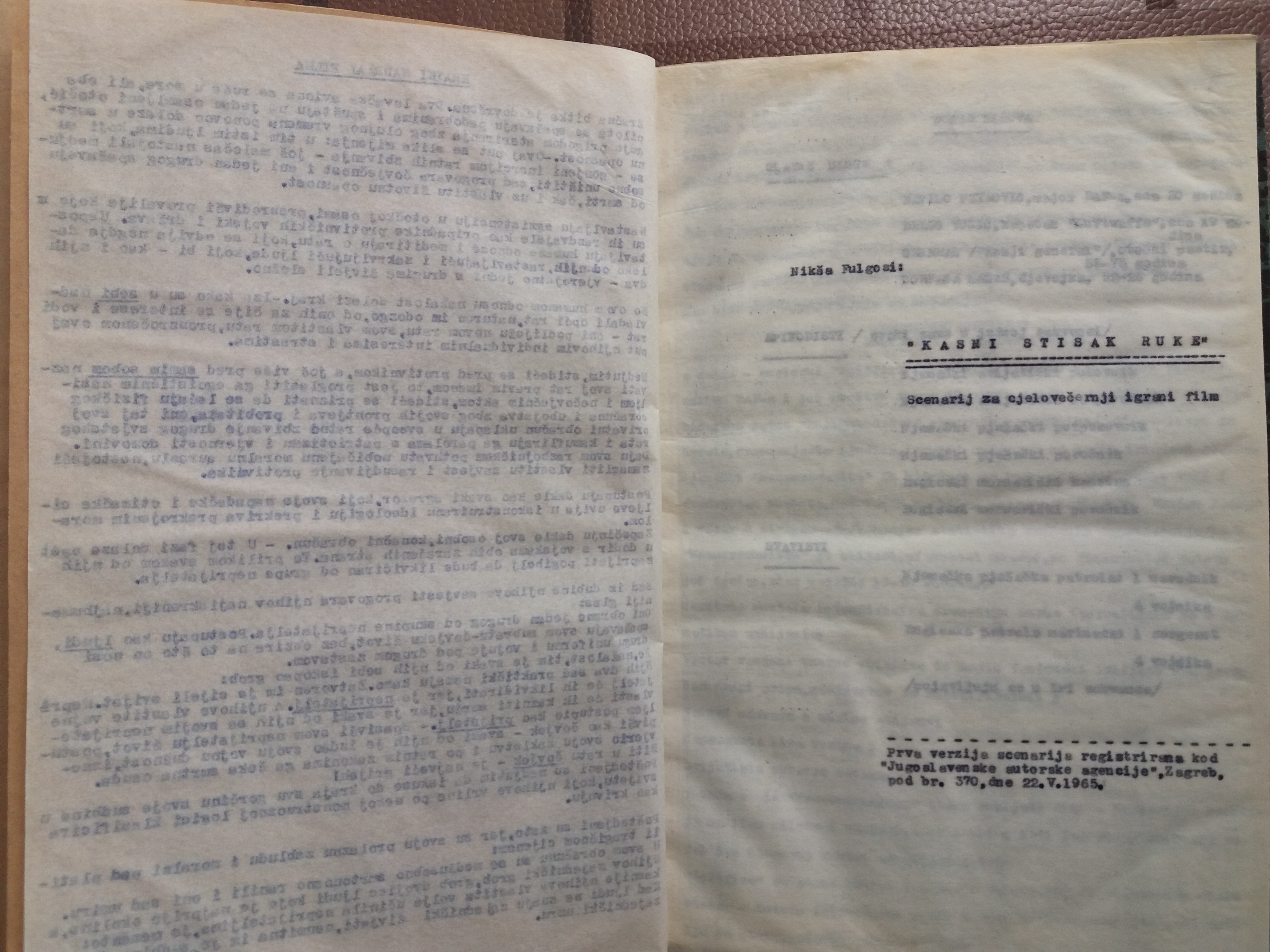

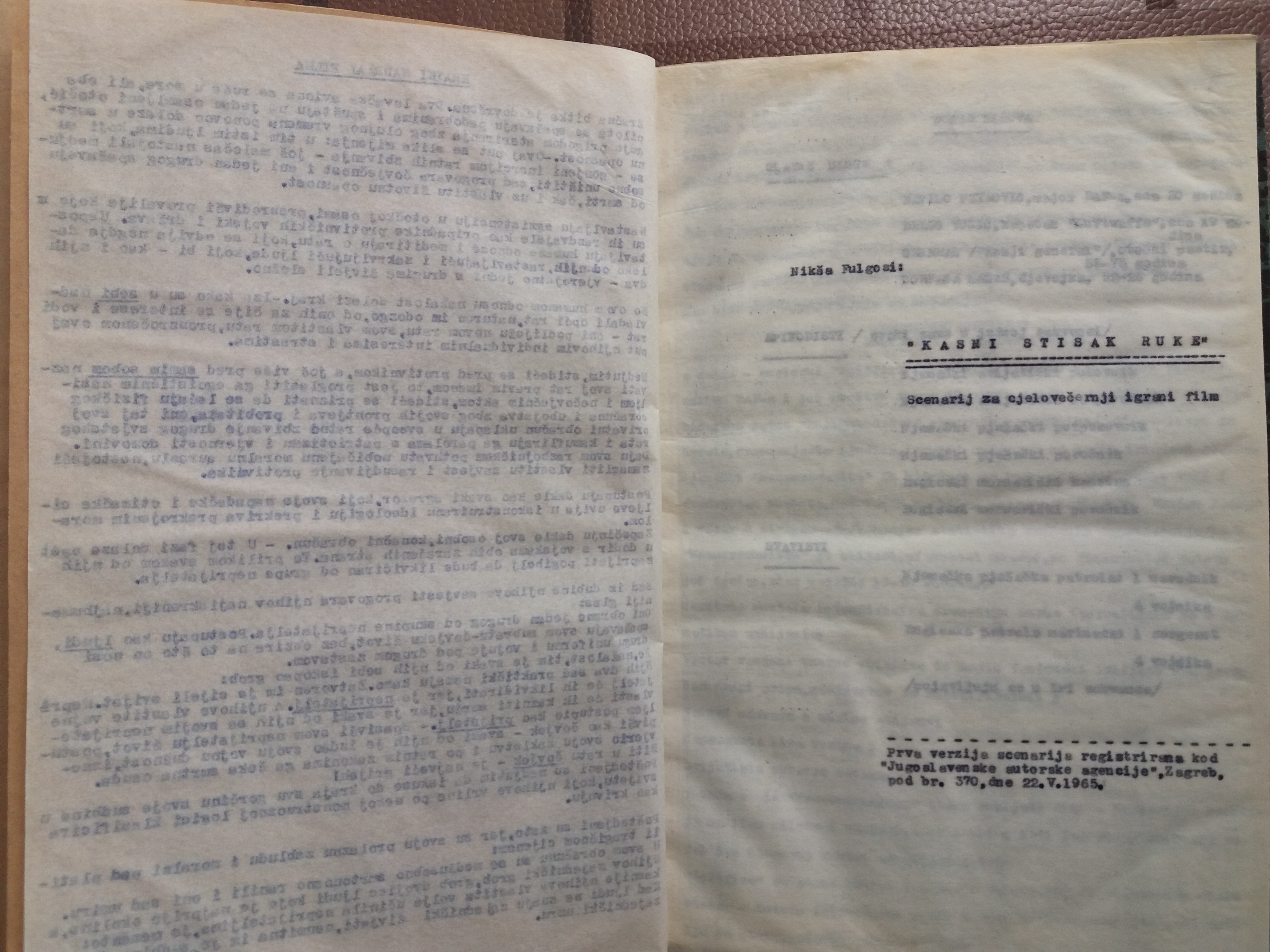

The screenplay for the feature film Kasni stisak ruke (The Late Handshake) from 1965 was the subject of a complex background of human drama based on stories from the Second World War, set in Dalmatia in 1943.

Faced with wartime circumstances and inspired by the universal human aspirations for overcoming the conflict, Fulgosi made a brilliant study of the controversy surrounding the war. However, the film was never made. There is no specific information about the reasons for the screenplay’s rejection. It can be assumed that Fulgosi's unconventional approach and choice of themes had come to the attention of censors as in the case of the making of his first film Mala Jole.

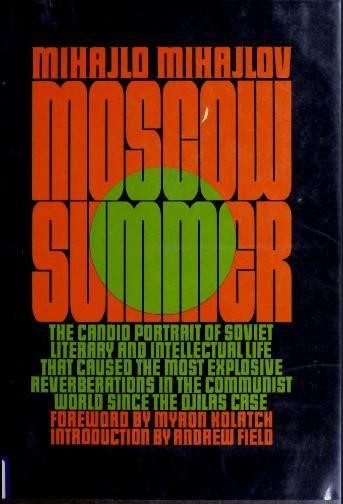

The manuscript of Mihajlov's travels, “Moscow Summer,” written in English is in the box 28. The text was the fruit of Mihajlov's visit to the Soviet Union in the summer months of 1964. Mihajlov supported Nikita Khrushchev's reforms and the program of de-Stalinisation, and he criticized the changes in the Soviet leadership after Kruschev’s fall. This criticism alarmed those in charge of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy, since it could once more undermine Soviet-Yugoslav relations, which had normalized in the mid-1950s.

Referring to the publication of the first two essays of this book, Tito himself called out Mihajlov in February 1965 as a result of pressure from the Soviet ambassador due to his criticism of the new political course following the fall of Khrushchev in the autumn of 1964. Despite censorship of Mihajlov’s essays in Yugoslavia, American politicians and the public were interested in Mihajlov's case precisely because of his stance on the Soviet Union during the political upheavals in the upper echelons of the Soviet party in those years.

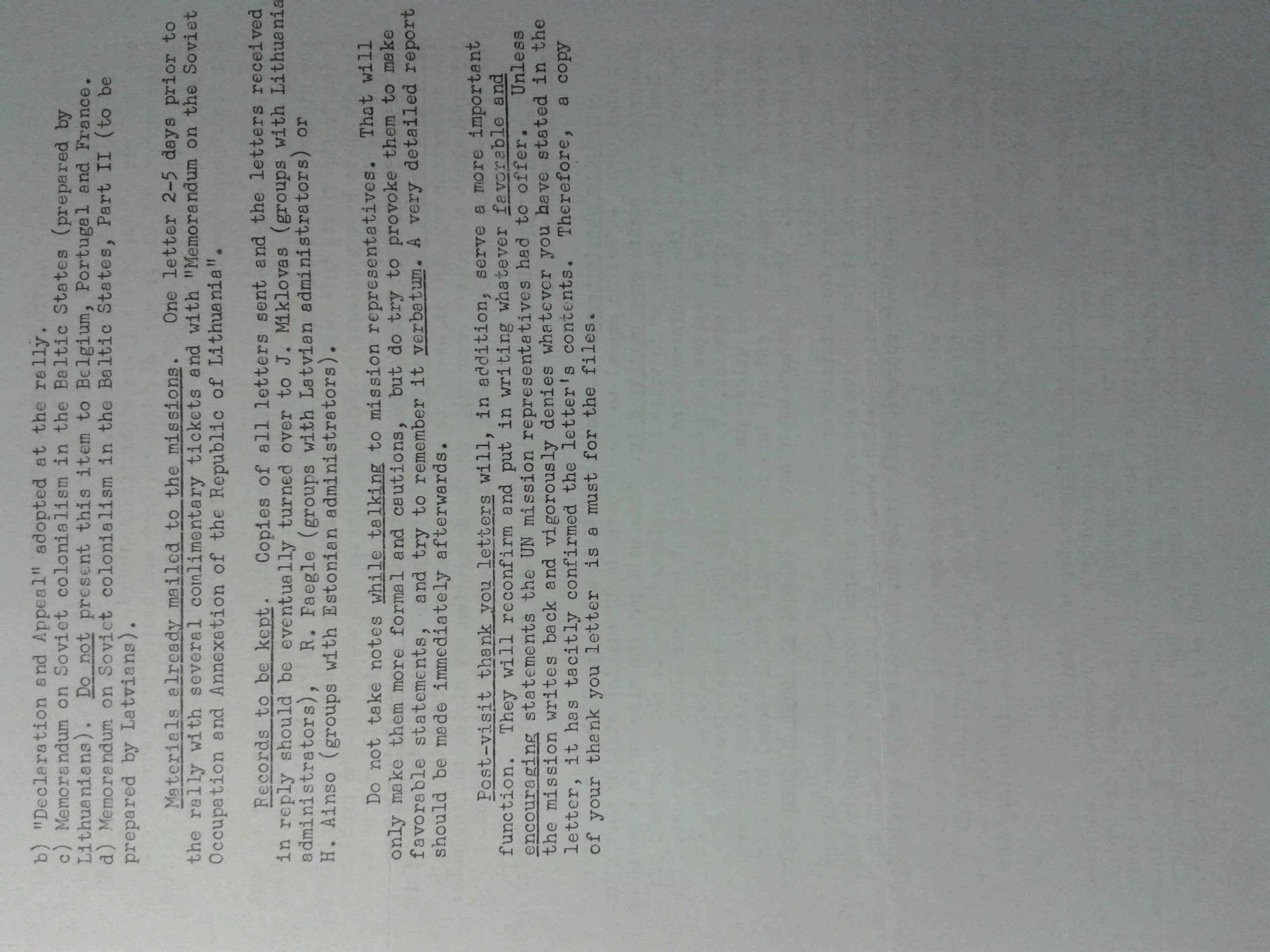

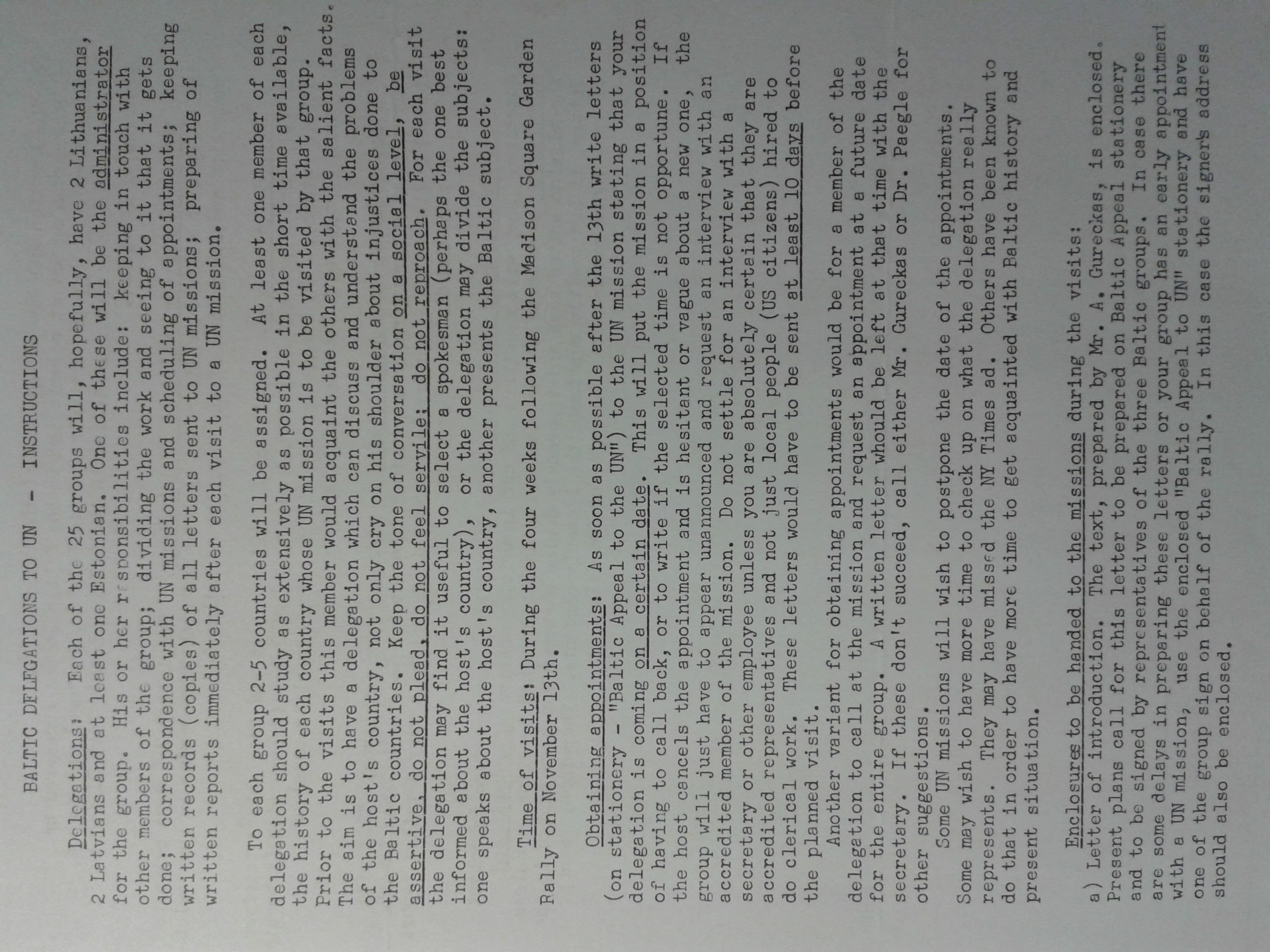

The Baltic Appeal to the United Nations (Batun, formed in 1966) was a pressure group formed by émigré Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians. The organisation grew out of the Baltic Freedom Rally, held on 13 November 1965 with 15,000 participants. The aim of Batun was to bring to the attention of United Nations member states the fact that the three Baltic States had been illegally annexed by the Soviet Union. At the beginning, Batun concentrated on providing printed information on the situation in the Baltic States, and on personal contacts with diplomatic representatives at the UN. In the late 1980s, and throughout 1991, Batun helped to inform Western media, non-governmental organisations and foreign ministries about the situation in the Baltic States, which were moving towards restoring their independence.

The Pugwash Movement Collection testifies to the anti-nuclear and anti-war activities of intellectuals from around the world during the Cold War era. The collection contains books and magazines, including the proceedings from the Pugwash Conferences, which were held every year in different city in the world. It also contains Encyclopaedia moderna, the most important journal for the history of anti-nuclear and peace movements in Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav government mostly did not look favourably upon the activities of the Pugwash movement’s members in Yugoslavia.

Report on hostile activities by religious communities and the State Security Service's countermeasures in 1965, 1965. Archival document

Report on hostile activities by religious communities and the State Security Service's countermeasures in 1965, 1965. Archival document

The cover and content of the Croatian State Security Service's report on enemy activities of religious communities and its countermeasures in 1965. Such multi-annual and annual overviews/reports on the activities of religious communities, with particular focus on their activities, classified as “hostile activities,” were prepared by the Service regularly. The most oft-cited forms of “hostile activity” by religious communities included incitement of ethnic hatred, hostile propaganda and the dissemination of false news, abuse of religion and the church for political purposes, incitement of religious hatred and intolerance, hostile activities against the state through émigré organisations, the émigré and religious press, and influencing workers and émigré communities. Considerable attention was focused on religious publications and foreign travel by religious leaders. The reports also include data on the Service's collaborative network and measures (studies, controls and operational measures) to counter such activities.

In that particular report for the year 1965, the main activities of the Roman Catholic Church were analysed in the context of Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) and the negotiations in the early 1960s between the Vatican and Yugoslavia meant to settle relations between the Yugoslav Government and the Catholic Church, which resulted with the signing of the protocol a year later (25 June 1966).

During 1965, which can be seen in Service's Report, Church-State relations deteriorated. The primary cause was a letter to church members adopted by the assembly of the Conferences of Bishops in Zagreb in May of that year. The Report highlights that its adoption “constitutes an abuse of religion and the Church for political purposes and an attack on the social and political system“ in the country. Another cause was the celebration of the 250th anniversary of Our Lady of Sinj in Sinj on 15 August of that same year. As described by Akmadža, the authorities were irritated with Bishop Franić's circular letters on the occasion of the celebration, in which, when writing about the presence of Cardinal Šeper at the celebration (he became cardinal in that same year), he often emphasised the national character of the celebration and appeared to promote ultra-nationalist tendencies (Akmadža 2004, p. 492). In this vein, in the Report, the Service assessed that it “it recognised the tendency to give Šeper not only the role and status of Church or religious leader, but also the status of national leader.”

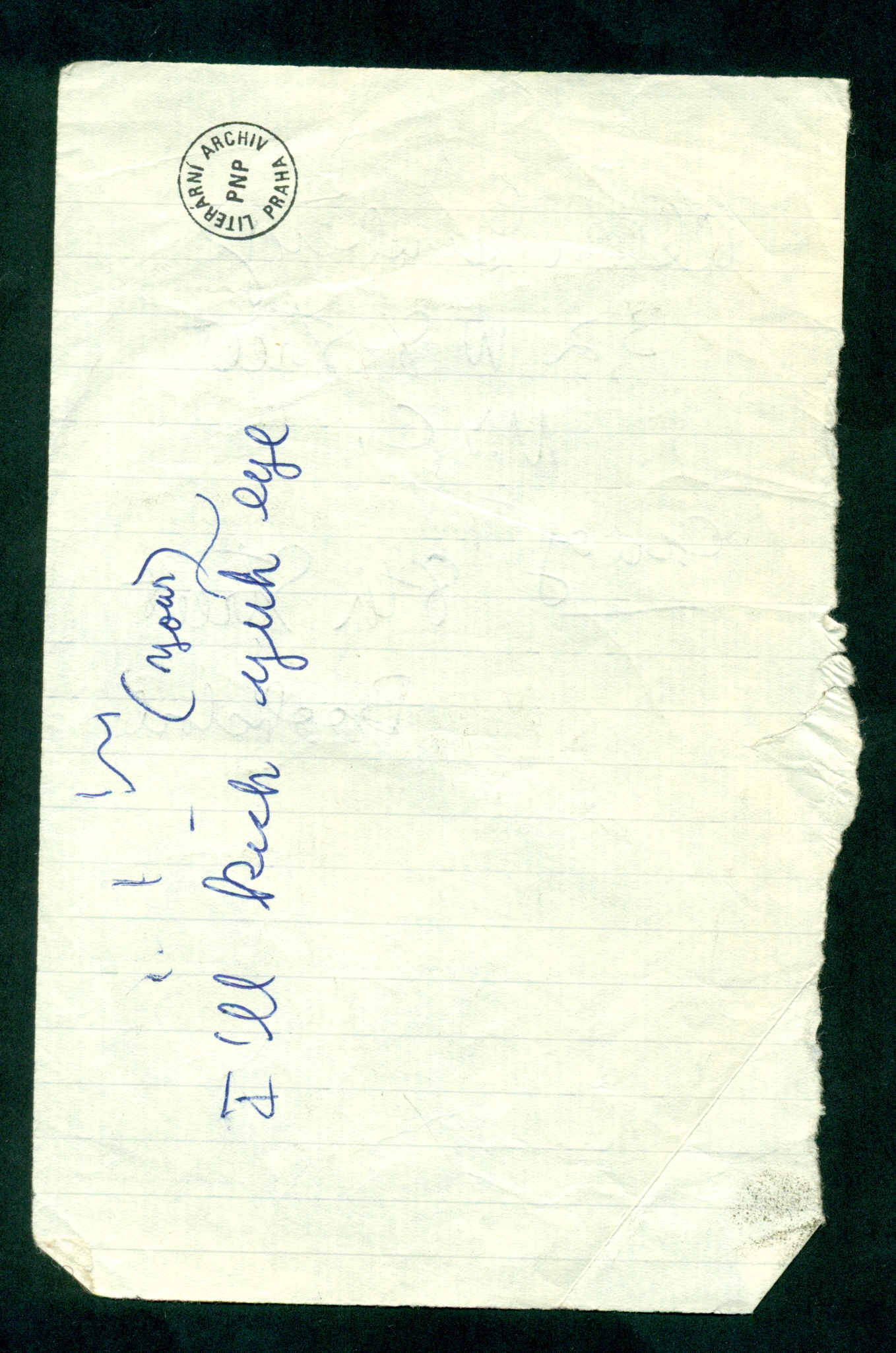

Aleksandar Dyakov is the son of Tsvetan Dyakov, a graduate and doctor of the University of Brussels; he was sentenced by the so-called People's Court and his family was interned. At the early age of thirteen, Aleksandar Dyakov started going into training for boxing at the Slaviya Sports Centre. He was getting on very fast and for several years was a national champion. In 1958, Dyakov graduated in sculpture from the "N. Pavlovich" Higher Institute of Fine Arts, in the class of Mihail Kats. In 1962, he was awarded the first prize at the National Youth Exhibition for the work "Upright Figure (The Little Mason)". The trail of many of his works vanishes and there are many unrealized projects. Aleksandar Dyakov also worked as a painter-producer in a series of movies. In 1978, he played the leading part of a sculptor in the movie "With Love and Tenderness" (directed by Rangel Valchanov, script by Valeri Petrov).

The works of A. Dyakov loaded with powerful messages. In the exhibition "Forms of Resistance", Krasimir Iliev shows two of Dyakov's sculptures – "Spirit and Matter" (1965) and "Corrosion" (1976).

In 1965, while discussing "Spirit and Matter", the opinions of the jury were contradictory and the circumstances demanded to postpone the decision whether to accept the work for the exhibition of the Sofia painters. The idea of the sculptor is as follows: "The spirit is stronger than matter but not because it's almighty. It is capable of overcoming even a monstrous mutilation of the body through the gentle power of beauty which gushes out of its divine nature". After some passionate discussions, "Spirit and Matter" was allowed to participate in the exhibition but by a different name – "War".

In the next years, Aleksandar Dyakov made bold statements in front of high functionaries of the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP): he openly criticized the fact that the country was congested with monuments to hate and violence, with monuments to Bulgarians killed by Bulgarians and to Bulgarians killing Bulgarians; he stressed the fact that this sowed black seed in the souls of people and that their children and grandchildren would gather in a black harvest. The author expressed the same ideas by the sculpture "Corrosion" (1976), showing that the heroic ideals were destructed.

After 1989, Aleksandar Dyakov made the exhibition "20th Century Projects". Among his projects was the one for transformation of the Monument to the Soviet Army in Sofia (Krida Art Gallery, 2001). His retrospective exhibition at Rayko Aleksiev Gallery (2012) consisted only of photographs. There is no monograph dedicated to his work.

Kazys Boruta (1905-1965) was a famous Lithuanian novelist, poet and translator. The Kazys Boruta collection holds various documents: his diaries, correspondence and manuscripts. The documents illustrate the situation of the writer in Soviet Lithuania. The government tried various means to control and restrict the writer’s creative initiatives. During the period of Stalinism, Boruta was arrested, accused of collaborating with bourgeois nationalists, and imprisoned. After he was released, he had problems publishing his work.

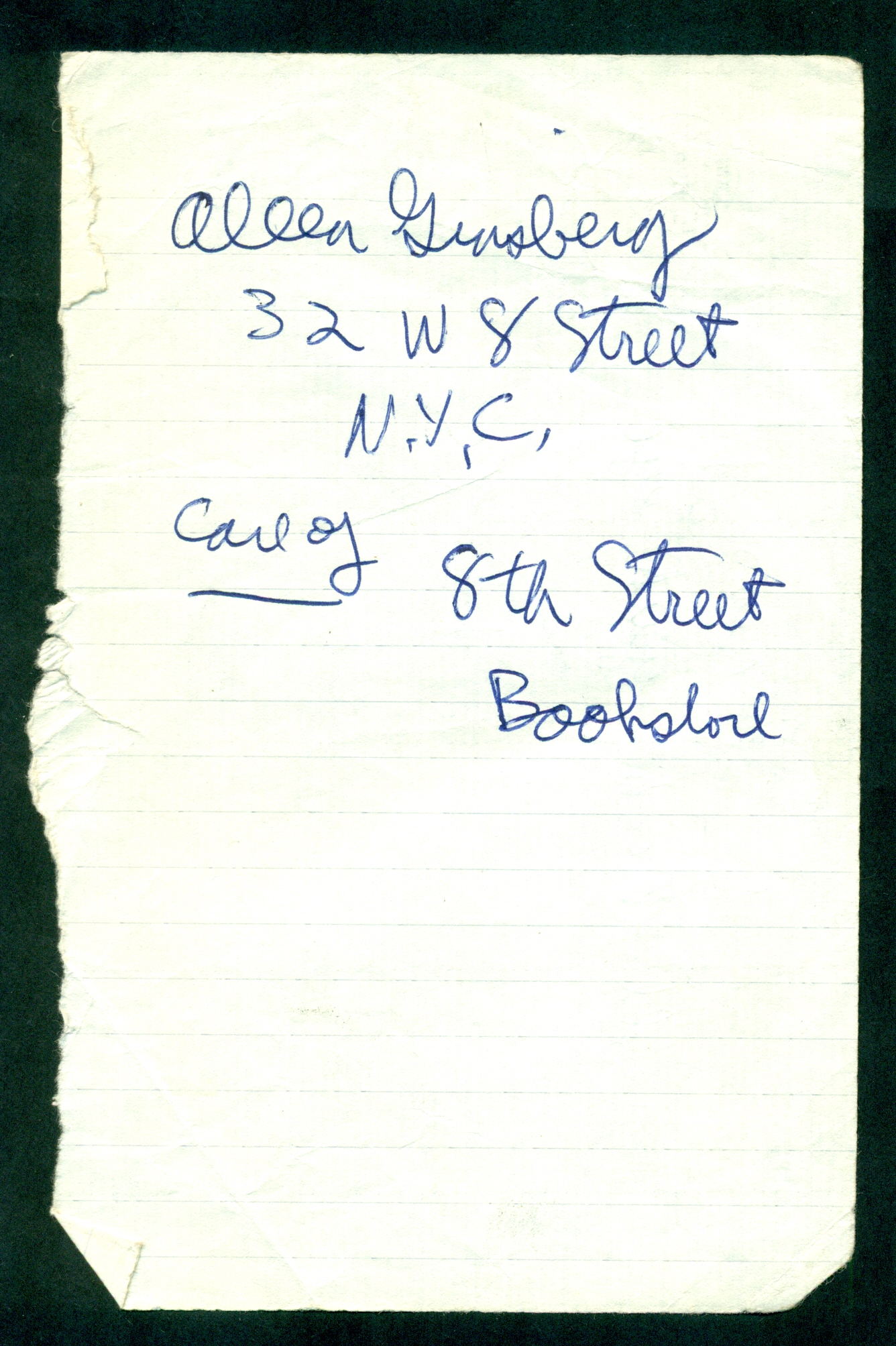

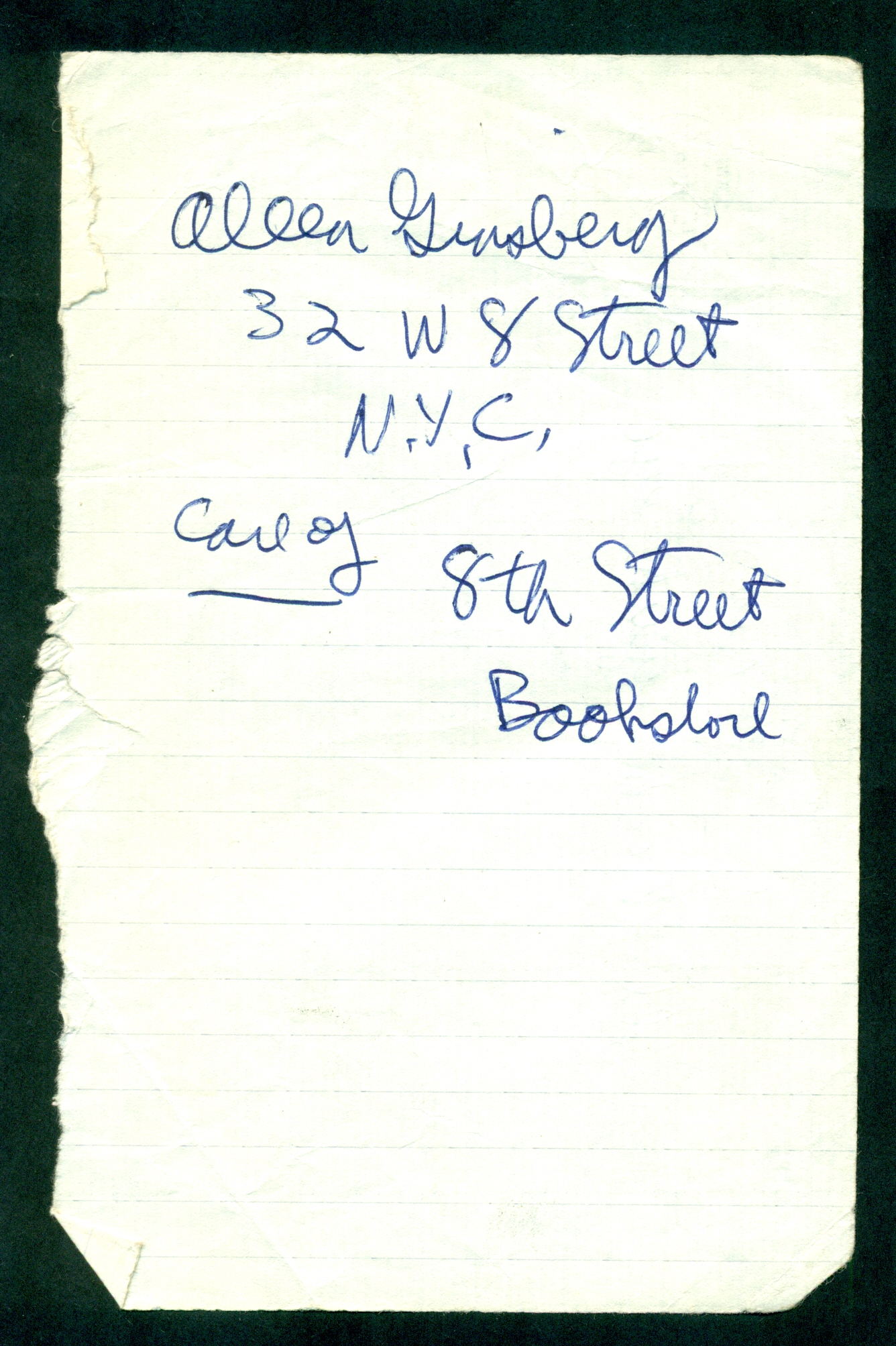

Allen Ginsberg, American poet and leading figure of the Beat Generation, arrived in Prague in February 1965. During his stay in Czechoslovakia, he attended several public readings and discussions. At the beginning of May, during the May celebrations, he was elected by students “The King of May”. However, a week later, he was deported by the State Security to the airport and expelled from the country. Later, Czechoslovak press launched a denigration campaign and accused him of “corrupting the youth”.

The Jindřich Chalupecký Collection at the Museum of Czech Literature contains Ginsberg’s address from 1965 written by Ginsberg himself. This address illustrates Chalupecký’s interest in the American poet and probable contact between them during Ginsberg’s stay in Czechoslovakia in 1965. Moreover, Chalupecký’s name appeared in Ginsberg’s diary that was confiscated by the Czechoslovak State Security.

The personal collection of Milan Knížák (born 1940), a Czech artist, poet and founder of the group Aktual, contains unique books of the events organised by Aktual, one of the sources mapping the life of the provocative artist, the Czechoslovak underground and alternative art of the 1960s.

The painting dates back to the approximately ten-year-long existence of the Zugló Circle, specifically, to the years when its members were influenced by the French abstract expressionism. This period is a brief but important manifestation of Art Informel in Hungary. The trend emphasizing the freedom of expression had special significance in the Hungarian context in the early sixties because it opposed the socialist realist aesthetic principles prescribed by the cultural policy of the Kádár regime. Taking sides with the autonomy of art had a political undertone, which was an important feature not only of the neo-avantgarde endeavours in Hungary but also in other parts of Central and Eastern Europe.

The painting is also important from the perspective of exhibition history because it was displayed at the Zugló Circle's exhibition ÚT – Új Törekvések in 1966, which was banned by the Lectorate of the Fine and Applied Arts immediately after the opening. The exhibition was organized at the airport (MALÉV KISZ Club) and included works by Imre Bak, Pál Deim, Tamás Galambos, Endre Hortobágyi, László Lakner, Sándor Molnár and István Nádler. The unusual site was chosen because it would not have been possible to organize an exhibition at an official venue, especially after the group’s banned exhibition at the Academy’s KISZ Club in 1963.

The private collection of musician, DJ, radio journalist, and educator Attila Koszits is the primary source on rock and underground (especially New Wave) culture of the last half century in Pécs, a city in southern Hungary. The collection contains periodicals, photo documentation, literature of music, bootleg recordings, and music recorded on discs and cassette tapes.

An open letter written in January 1965 by Knuts Skujenieks from the prison camp was addressed to his writer colleagues. He asked them not to keep silent about his fate, because ‘culture does not exist without its carriers, and it is important to fight for them, and not to contribute to their moral and physical annihilation.' The letter is a statement of Skujenieks' civic position, a protest against inertia and the fear in Latvian society. It was perhaps too bold for the political climate of Latvia, because it presented evidence that in prison Skujenieks became spiritually more liberated than his colleagues who enjoyed physical freedom, although it has to be admitted that the spirit of resistance of the younger generation of writers in Latvia in the 1960s was stronger than in the 1970s. Official discussions by the Writers' Union in 1965 and 1968 of the poetry he wrote in Mordovia testify to this.

At the 5th Congress of the Latvian Soviet Writers' Union in December 1965, the younger generation of writers and the more liberal section of the older generation managed to oust from the Union's Executive Board the five most notorious defenders of Socialist Realism and the Communist Party line in literature. A more liberal leadership of the Union was elected. In speeches at the congress, the younger generation of writers spoke out in favor of more creative freedom, against censorship, for the rehabilitation of the pre-Soviet literary heritage, and about the possibilities of getting more information about Latvian exile literature and world literature in general, and protested against the ban on the Jāņi midsummer festival. Although the Latvian Communist Party Central Committee was unhappy with the results of the congress, it had to put up with them. The congress was an important turning point in Latvian literature, and in the history of the Writers' Union, which changed from being an obedient follower of the Communist Party into an organization which was willing and able (although within certain limits) to defend creative freedom and the national culture.

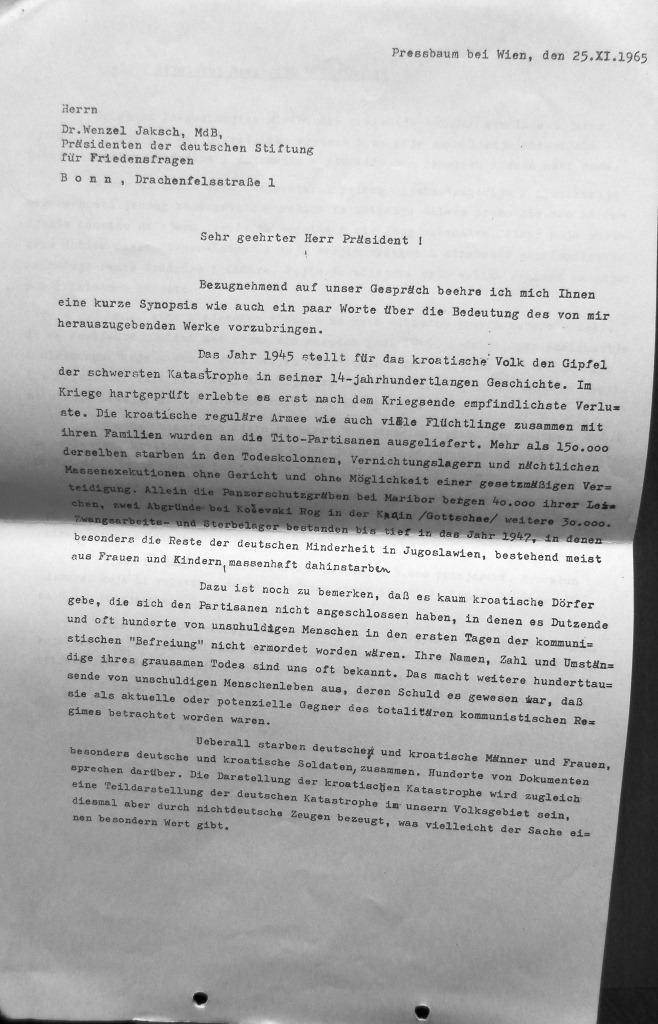

This is a typewriter letter consisting of 2 pages in extended tabloid format. The document was written in German on 25 November 1965, and since the Draganović’s handwritten signature is lacking, we may assume that it is a copy of a letter which Draganović wanted to store in his archives/personal papers. The original of this document is available at the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome, and the copy is in the Croatian State Archives. The material is available for research and copying and is located in registry no. 2, under number 6.2.

The German Social Democratic politician Dr. Wenzel Jaksch (1896-1966), was the president of the German Foundation for European Peace Questions (Deutsche Stiftung für Europäische Friedensfragen). Draganović wrote him a letter in which he explained the need for publishing his book on the Bleiburg tragedy of the Croatian people. Draganović said that the book will contain considerable information about the crimes of the Yugoslav communist regime unknown to the world public. He stated that he planned to publish the book in three languages and he asked for financial support from the German Foundation for European Peace Questions, presided over by Wenzel. The letter testifies that Draganović was in the final stages of preparing his book, which was completely unacceptable to the communist regime in Yugoslavia and whose publication the government sought to prevent. This document is important because it explains the underlying intention of the creator of the Krunoslav Draganovic collection: the publication of a book about the Bleiburg tragedy.

Mykhailyna Khomivna Kotsiubynska and Zina Genyk-Berezovska became acquainted in Kyiv during a visit by the latter to the Ukrainian capital in 1964. They became fast friends, Kotsiubynska’s letters accounting for more than a third of the letters sent to Genyk-Berezovska. The letters are now held and the T.H. Shevchenko Institute of Literature in Kyiv, Ukraine. The entire correspondence is the byproduct of a close female friendship, one that was deep and forged during a difficult time. The three letters sent in 1965 show that these two were under surveillance, as their letters were often lost, or more likely confiscated in transit. Kotsiubynska's letter from July 30, 1965 asks why there has not been any word from Genyk-Berezovska. Kostiubynska was particularly aggrieved because she had sent an important letter in which she wrote among other things about the death of a close relative and Kotsiubynska's adoption of her four-year-old daughter. Genyk-Berezovska wrote back sometime later, prompting Kotsiubynska to write a letter on August 21, 1965, underscoring how important this correspondence was to her and asking Genyk-Berezovska to write more frequently. The letter from September 30, 1965, opens with "Zinochka, my dear bumble bee!" Kotsiubynska asks why she has not heard from Genyk-Berezovska and wonders whether she is ok. Kotsiubynska writes that she misses Genyk-Berezovska greatly, especially given what is happening in Ukraine at this time. In Aesopian language, Kotsiubynska explains that things are not going well and that one of their friends has been arrested. "Things are not fun for us right now. Our friend, who has not written you for so long, will not be able to write you again for some time. And it is not his fault." She also asks whether Genyk-Berezovska received an earlier letter, presumably in order to ascertain whether it might have been intercepted by the state security services. When one reads back letters sent between these two women--especially those written in the late 1960s and early 1970s--one can feel the stresses of not being able to communicate regularly and with any certainty. This weighs heavily on Kotsiubynska, who is also under pressure and surveillance from the authorities. In May 1966, she asks Genyk-Berezovska if she has received a letter from Ivan, referring to Svitlychny, who had been released on April 30, 1966 for being "socially harmless." Apparently, his stature and popularity had been so great and the protests against his arrests so numerous, that the authorities opted to release him. The following year, Kotsiubynska wrote two letters that were only ten days apart--July 5 and july 15. In the first, she tells Genyk-Berezovska that she has been fired from her job and expelled from the Communist party. In the second, she says simply "this year has worn me down completely." Through their correspondence, one senses the immense psychological pressure facing literary scholars and human rights activists in Ukraine at this time, though one would also have to read Genyk Berezovska's responses in order to have the complete picture.

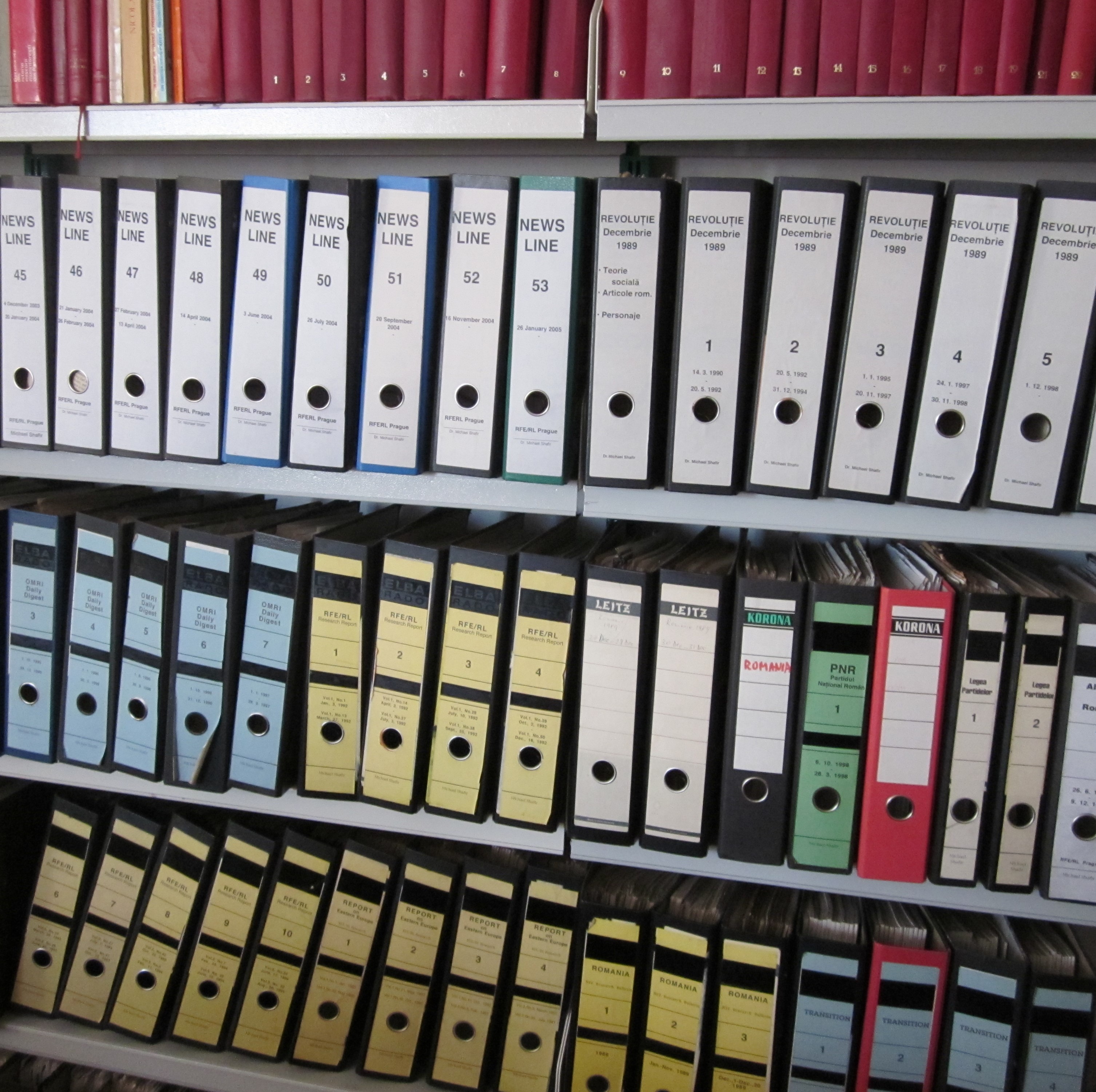

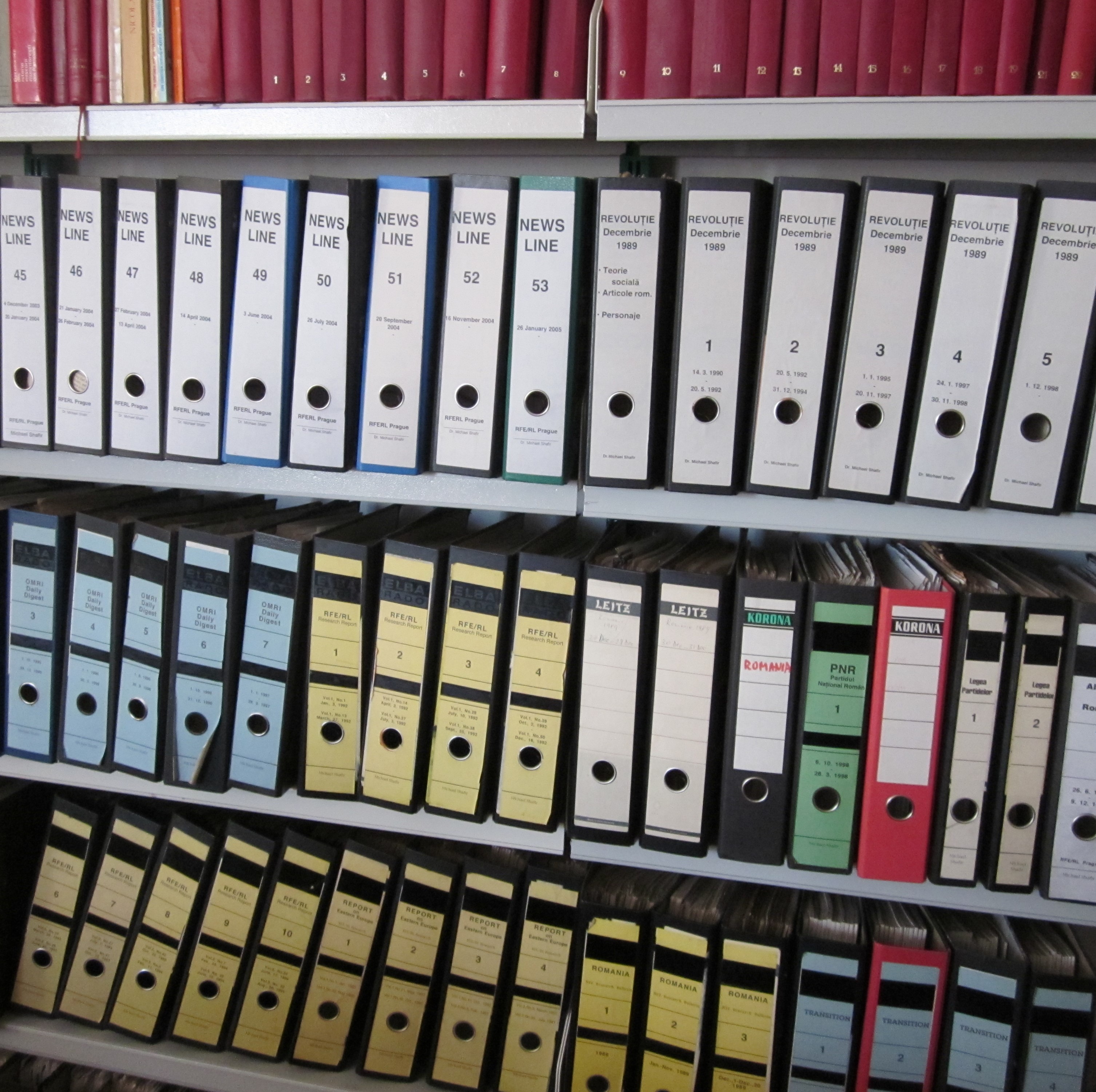

The Michael Shafir Collection represents a significant part of the personal library of its founder, who selected and accumulated items while in exile, in accordance with his academic and professional interest in what was known during the Cold War as East European politics. As he held various positions in Radio Free Europe (RFE), the collection also includes many documents relating to the activity of this institution, most of them from the late 1980s, but also some from the 1990s.

Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie visited Hungary in 1964 and then requested help to create a scientific folk dance collection in Ethiopia. György Martin, who had already engaged in research on folk dances in Hungary, and a colleague, Bálint Sárosi, traveled to Africa to spend two months in Ethiopia between 7 June 1965 and 3 August 1965. The Institute for Cultural Relations supported their trip, and the Ethiopian state helped organize research in the country. The Ethiopian Emperor intended to use the collection for political aims to shore up the legitimacy of the regime. Political goals were combined with academic interest, but there were no academic research groups in Ethiopia which specialized in this topic.

Martin and Sárosi’s collecting trip was successful: they collected material in eight Ethiopian regions (Shoa, Wollo, Tigre, Begemder, Gojjam, Wollega, Kaffa, and Hararge) and in seventeen towns (Debra Berhan, Dessie, Hayk, Wuchale, Wurgesa, Woldya, Kuaram, Makale, Axum, Enda Selassie, Gondar, Debra Markos, Lekempti, Jimma, Harar, Alemaya, and DireDawa). During their trip, they collected many varieties of Ethiopian folk dances, shot 3,000 meters of film, and took more than one hundred photos. They used a magnetic tape recorder to archive music. They also drew maps of their tour. Martin took notes about the circumstances of the collecting work and the characteristics of Ethiopian dances. Although they could not take part in any special event or regular folk dance occasions, they could still add their own observations on the formal elements of Ethiopian folk dances to the existing material in Ethiopian folk dance. This work was useful for Martin, who was always working from comparative perspectives. As Bálint Sárosi recalled, they traveled down long roads in a Land Rover, and even the driver did not know precisely where they were. They used maps and tried to ask local people about the right routes. The people and the leaders of the villages where they collected helped them in their work, and locals often improvised dances. At the end of the trip, they had to submit a report and a list of suggestions for the Ethiopian state. Copies of their collection were handed over to the Ethiopian state, but they was destroyed in the subsequent war.

Benedikt Rejt Gallery and its collection were founded in the 1960s with the aim of collecting contemporary tendencies in visual arts. The gallery kept buying works by progressive artists even after 1968. The Benedikt Rejt Gallery owns a unique collection of constructivist pieces.