The official accusatory act concerning the case of Gheorghe Zgherea (case No. 33/ 023262) was issued on 2 June 1953 by the senior investigator of the Inquiry Section of the Cahul District Directorate of Internal Affairs, Captain Vorobiev, and approved by the Head of the Directorate, Colonel Eliseev, the next day. This document summarised the main “anti-Soviet” activities undertaken by Zgherea, who was labelled an “active participant in the anti-Soviet illegal sect of Inochentists-Archangelists.” The defendant’s “anti-Soviet” activities purportedly began upon his entering the Inochentist community in December 1949 and acquired a systematic character after December 1950, when he became a preacher and “went underground” [pereshel na nelegal’noe polozhenie]. Zgherea was specifically accused of “roaming through the villages of Vulcănești, Strășeni, Kotovsk, and other districts of the Moldavian SSR” and engaging in “systematic anti-Soviet agitation” through “using the religious prejudices of the believers.” He attempted to persuade his peasant audience to “refrain from taking part in the social-political life of the country, to boycott the elections for the institutions of Soviet power, tried to convince the village youth not to join the Komsomol” and appealed to the members of the collective farm not to work in the kolkhoz [on Sundays and religious holidays]. Interestingly enough, the religious thrust of Zgherea’s message was minimised by the authorities. The main emphasis was on the disruptive social and political consequences of the defendant’s and his fellow preachers’ propaganda. Another serious count of indictment referred to Zgherea’s “co-option of new members into the sect,” as well as to his “taking active part in the illegal gatherings of the sect members,” where he presumably spread his anti-Soviet views among those present. The Soviet authorities were alarmed not only by the existence of these “anti-Soviet views” as such, but also by the parallel underground structure of the Inochentists, which represented a direct threat to the stability of the regime in rural areas, still under tenuous central control during the immediate post-war years. According to this document, Zgherea’s “guilt” was confirmed not only by the defendant’s own confession, but also by the witness accounts and testimonies. Apparently, Zgherea had no papers or personal belongings (aside from two photos found during his arrest), thus confirming his marginal and “underground” status. It should be emphasised that Zgherea’s case was only one of several trials against prominent members of the Inochentist community (some of them belonging to Zgherea’s immediate network) which took place in late 1952 and early 1953. Thus, the defendant was only one victim of the concerted campaign of the authorities against the Inochentists, aimed at destroying their clandestine structures throughout the MSSR. This probably explains the very harsh verdicts issued against Zgherea and his co-religionists. As in other similar cases, the accusatory act was later used as the basis for the official sentence in this case.

The collection holds much valuable information on the policy of Lithuanian Communist Party Central Committee towards various manifestations of cultural opposition. The documents also reflect the situation of the Lithuanian intelligentsia, whose main goal was to preserve the Lithuanian cultural heritage. The documents cover the period of liberalisation, i.e. de-Stalinisation, in Soviet Lithuania.

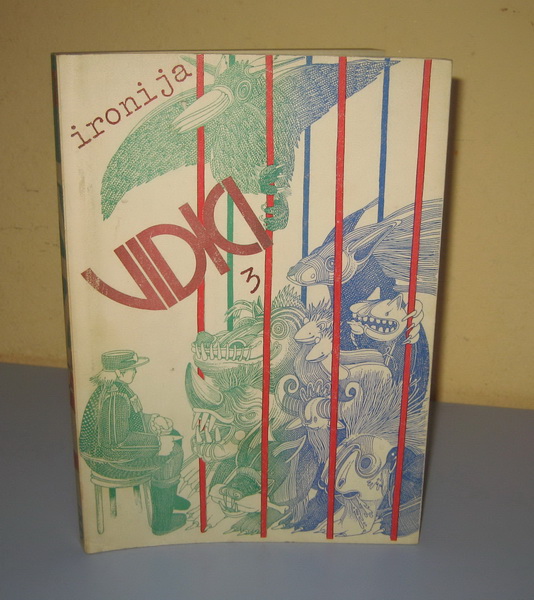

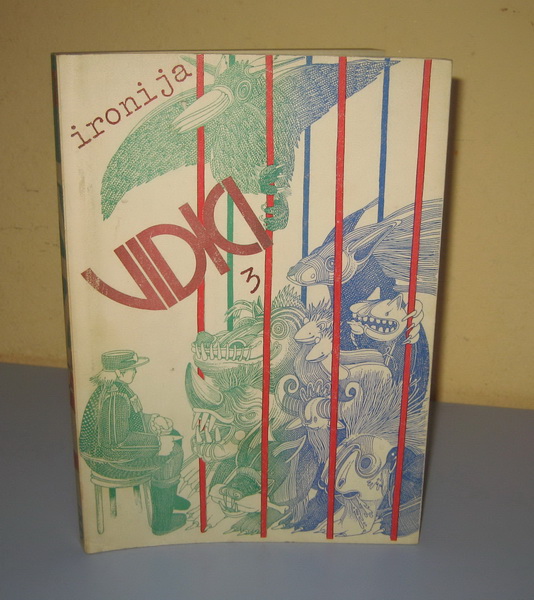

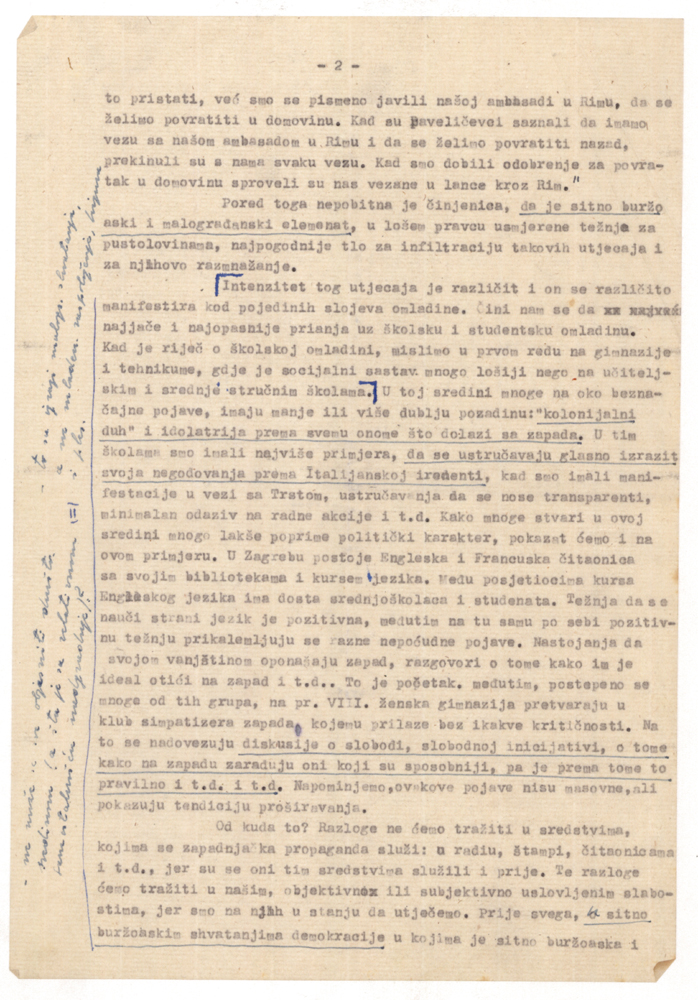

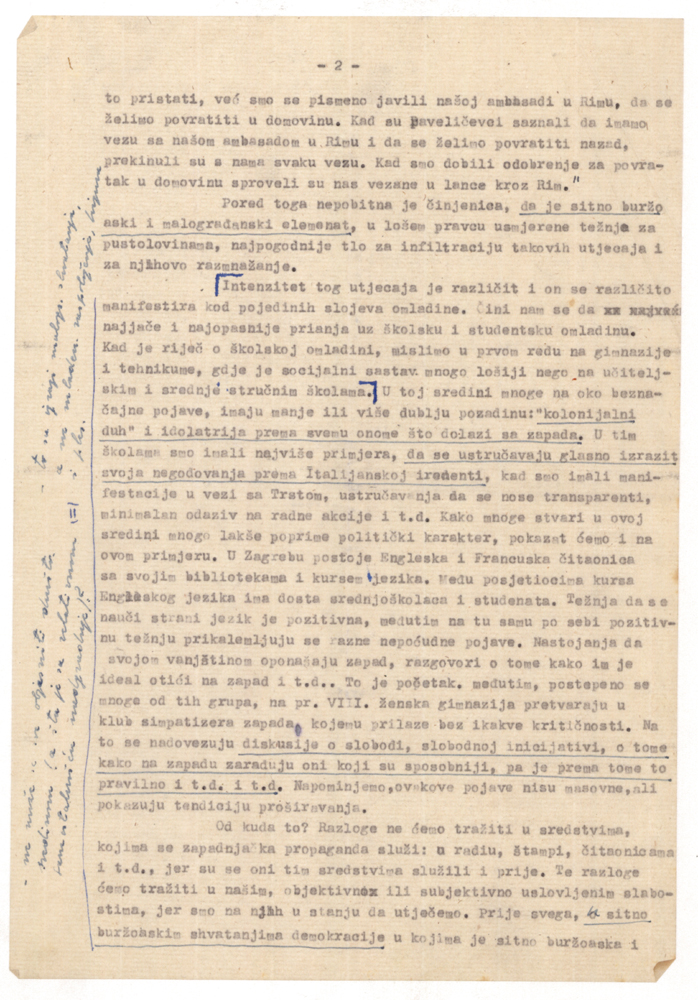

The document is a comprehensive analysis drafted by the People's Youth of Croatia (PYC) which emphasises phenomena considered to be the result of Western culture’s influence on young people. All of the youth activities that the PYC deemed to have been created under the influence of the West were also considered oppositional because they were at odds with the prevailing ideology. The paper lists and analyses the flight of young people to the West as a result of idolatry of the West; dissatisfaction with the regime or economic problems (since legal migration was largely prohibited until the early 1960s); debates about freedom and free initiative that, to the extent they proceeded, especially in Zagreb, were not desirable because they surpassed of the accepted framework; coverage of events in the West by the youth press, especially movie columns (Vie Giovanilli, Horizon, The Revue, The Film Journal), which in the opinion of the PYC was too exaggerated and idealized the Western way of life versus that under socialism; the reading of works by authors who considered the notion of freedom (Camus, Sartre) at the philosophical level; the spread of comics as a typical form of creative expression by Western cultures; the "hip" behaviour of young people (Western clothing and hairstyles, establishing “gangs“), the obsession of the youth with the Wild West and similar phenomena.

This PYC document, along with the records of other so-called socio-political organizations, was until 1995 a part of the Archives of the Institute of History of the Croatian Workers' Movement/Institute of Contemporary History. In July of that year, the archives were handed over to the Croatian State Archives (CSA), where they are kept today.

The archives are regularly used by the researchers for scholarly publications, which was the case for this report as well.

The Central Press Supervision Authority files, stored at the Security Services Archive in Prague, contain materials documenting the control of press and newly issued publications in Czechoslovakia from 1953 to 1968. Examples of censorship with extensive transcriptions from ‘defective’ literary works are very valuable as they include unknown information on the ways authors and editors negotiated with the censors, reveal the origins of the works, provide information on the alterations that were imposed and the existence of text variants, and they even cover prominent authors’ previously unknown works.

Augustinas Gricius’ letter to Justas Paleckis, written in 1953. The Lithuanian writer Augustinas Gricius (1899–1972) informed Paleckis that the gravestones of well-known Lithuanian cultural activists (the composers Stasys Šimkus, Sasnauskas, the writer Kazys Binkis, Professor Jaunius) in Kaunas city cemetery had been destroyed. The graves of Darius and Girėnas (Lithuanian pilots who flew across the Atlantic) were in especially bad condition. Gricius also criticised the Kaunas city authorities, who had shown no interest in preserving the gravestones of famous Lithuanian cultural activists. Augustinas Gricius was a journalist, writer and public figure.