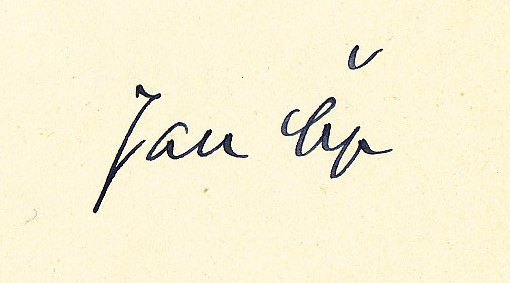

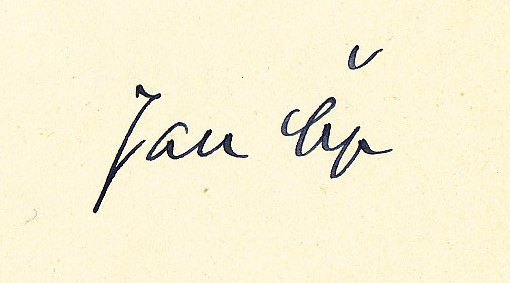

Jan Čep (1902-1974) was one of the most prominent representatives of modern Czech prose. His collection contains his manuscripts of radio reflections, which he wrote for Czechoslovak Radio Free Europe. Through his reflections, he tried to face totalitarianism and spiritually strengthen people "at home".

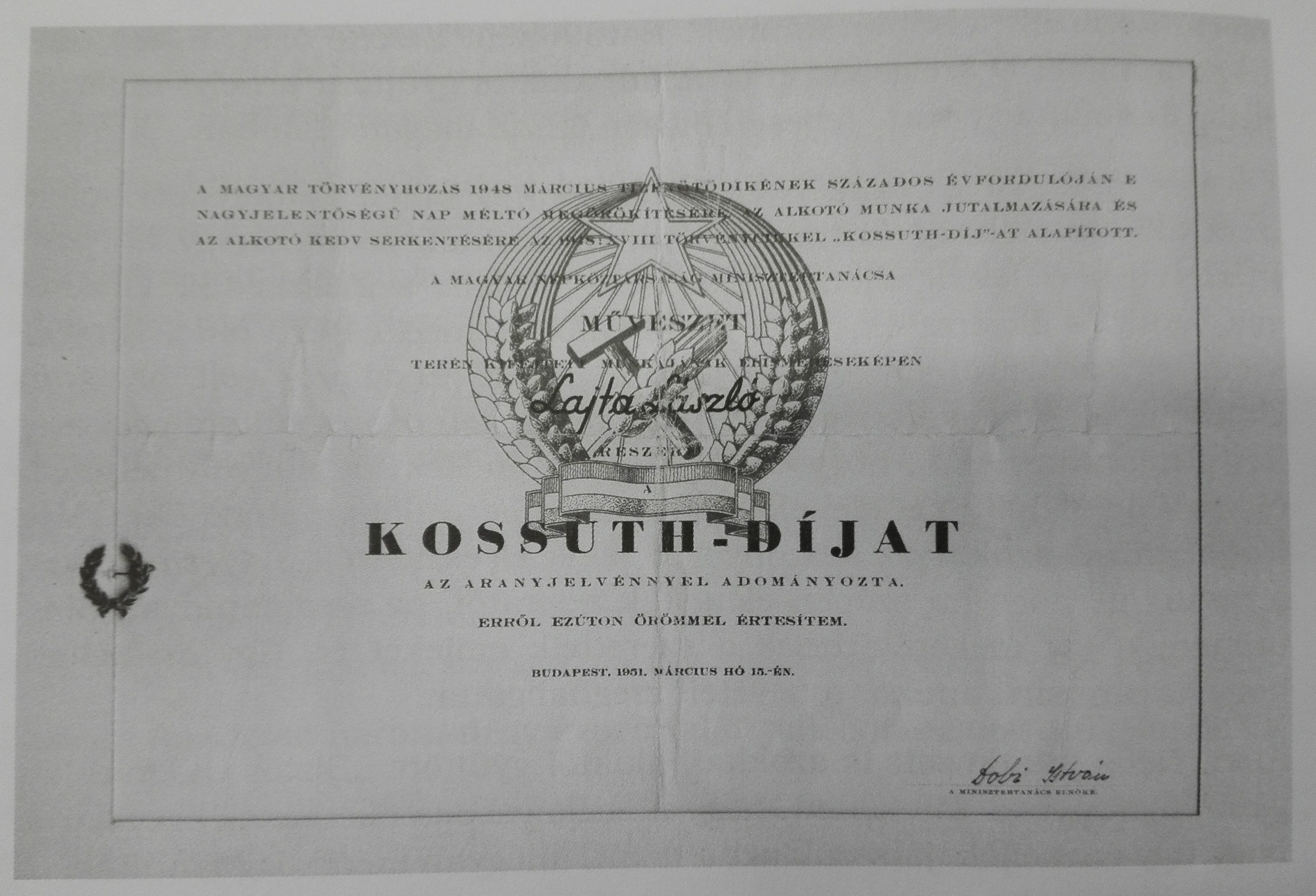

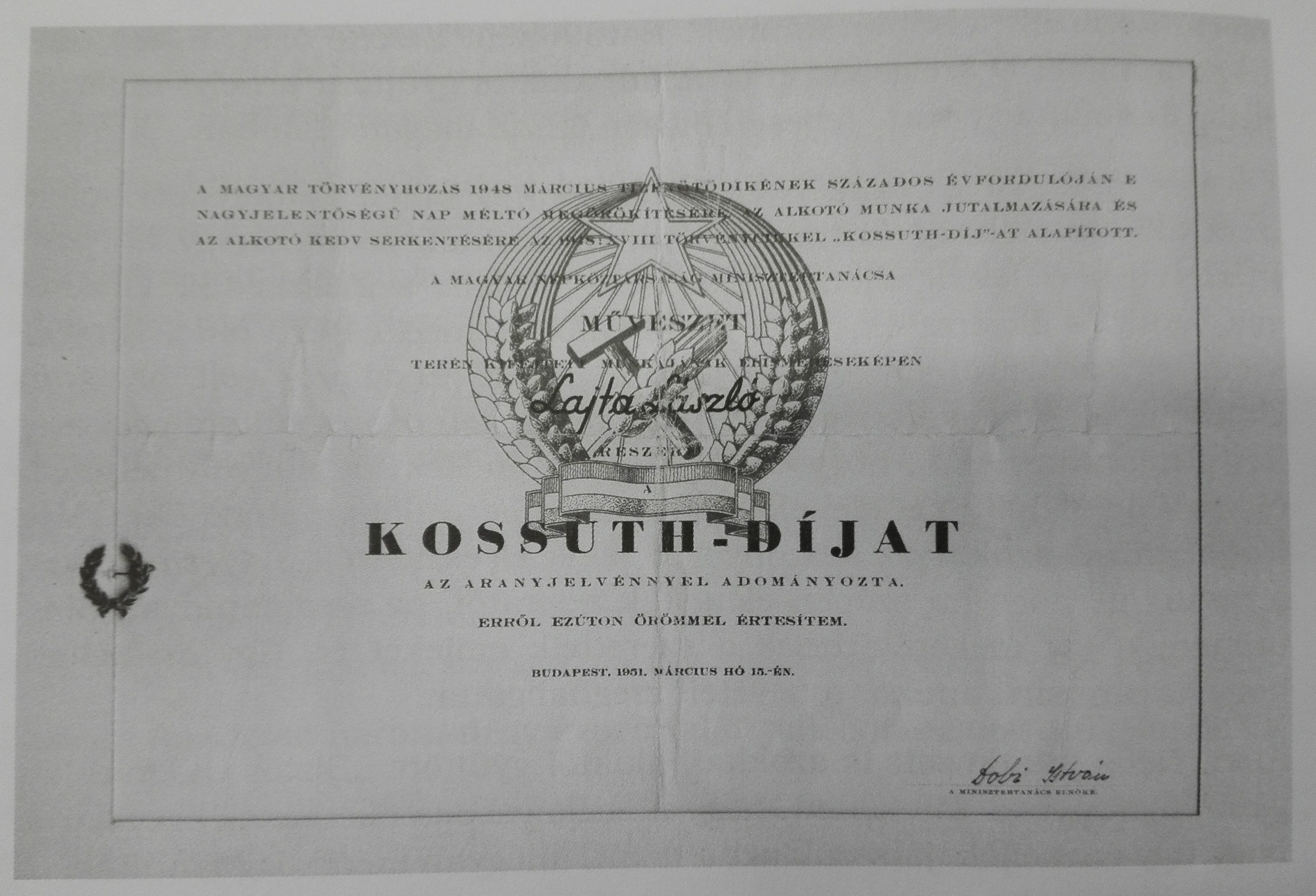

László Lajtha received the national Kossuth Prize for his work as an ethnographer and folk music collector. This gesture did little to offset the fact that in 1948, upon his return from London, the Hungarian government denied him a passport, thereby forcibly keeping him in Hungary where he was blacklisted. He refused any connection with the Communist Party, and had to sell his belongings to make ends meet. Lajtha was a world-famous composer, and without a doubt, it was extraordinary that he was prohibited from traveling. The Kossuth Prize was a symbolic gesture, one that permitted him to travel within the country collecting folk music and songs without allowing him to leave.

Lajtha attended the ceremony but donated the prize money as a protest against the political regime. (The Kossuth Prize, a state-sponsored award in Hungary, was established in 1948 to mark the centenary of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. In 1948, and during the socialist era, the award was given to those with prominent achievement in the fields of science, culture and the arts, as well as in building of socialism.)

This ad-hoc collection consists of the work of Binka Zhelyazkova, an emblematic Bulgarian cinema director, as it is preserved in the Bulgarian National Film Archive, plus related materials. Zhelyazkova was among the first generation of professional Bulgarian cinematographers and one of the first female directors not only in Bulgaria, but in general. The collections informs not only about the work of this notable director but gives also insight into the development of Bulgarian cinema throughout the entire period of state socialism.

The collection comprises the films of Binka Zhelyazkova as well as extensive written materials (film documentation, reviews in the press etc.) and photographs. It outlines the contradictory and dramatic cultural situation in Bulgaria in the second half of the 20th century. The materials exemplify the pressure exerted on artists as well as of their opportunities of resistance and evasion, of maintaing personal and political integrity, and of creating socially engaged, vanguard cinema.

Ferdinand Peroutka, who represented the democratic past of Czechoslovakia, and mainly the First Czechoslovak Republic, became the director of the Czechoslovak section of Radio Free Europe (RFE) in New York on 6 April 1950. The Czechoslovak service of the RFE began its regular broadcasting from Munich on 1 May 1951 with the famous phrase “This is the voice of Free Czechoslovakia, Radio Free Europe.” One of the first speakers was also Ferdinand Peroutka, who stated, besides other things: “One magazine would mean little in a country where freedom reigns. But one free magazine, one radio station in a dictatorial regime – that is a revolution, because such a system is based on the fact that only the government can speak and nobody can answer back, that anyone can be charged, but nobody can defend themselves. However, once even a fraction of freedom enters that rigid and artificial system, from anywhere, once it is again possible to set argument against argument, once it is no longer possible to act without criticism, once there is a place to call untruths into question, then this whole proud system quavers.”

The Literary Archives of the Museum of Czech Literature possesses a mimeograph copy of the typescript of this speech.

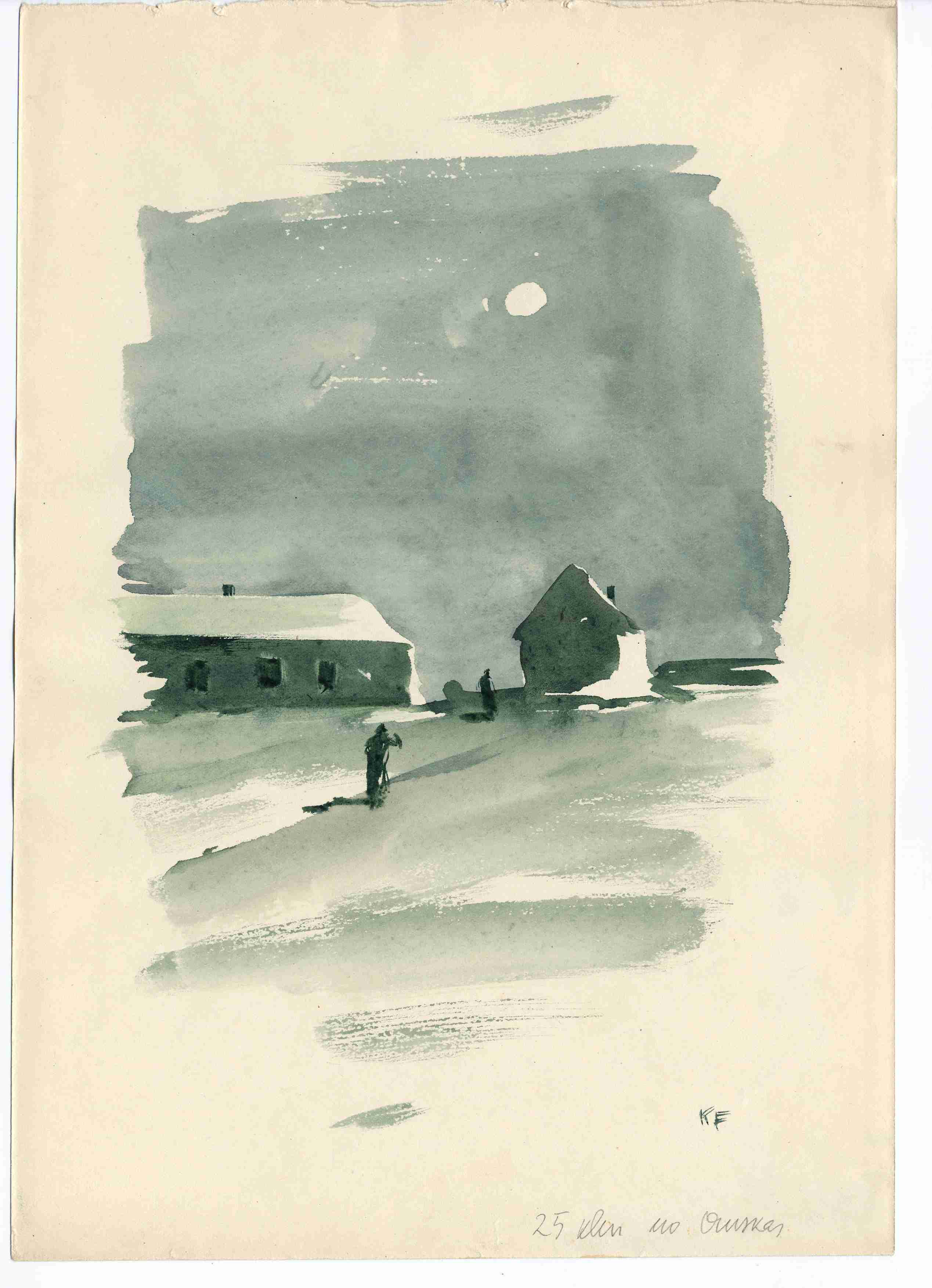

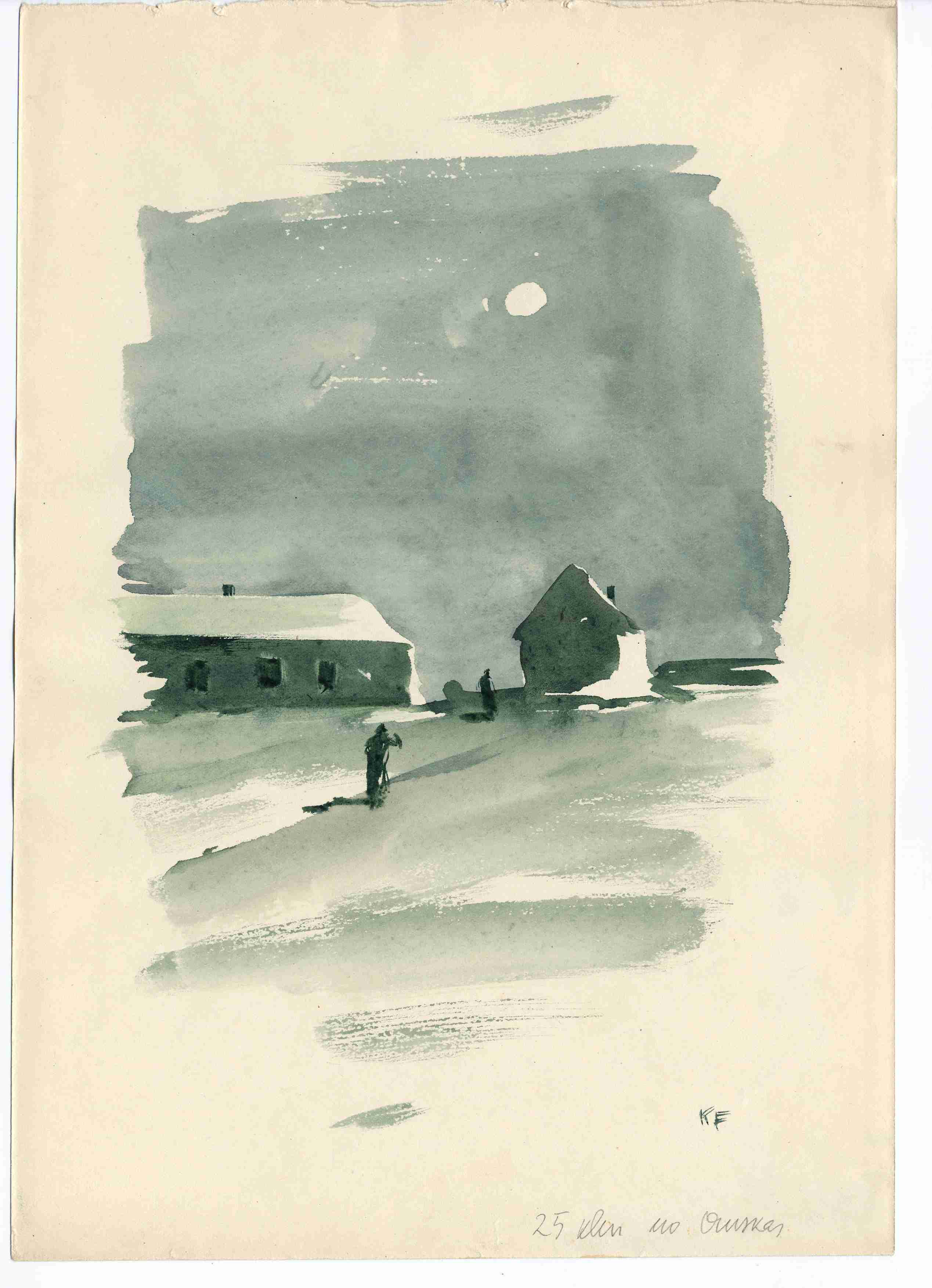

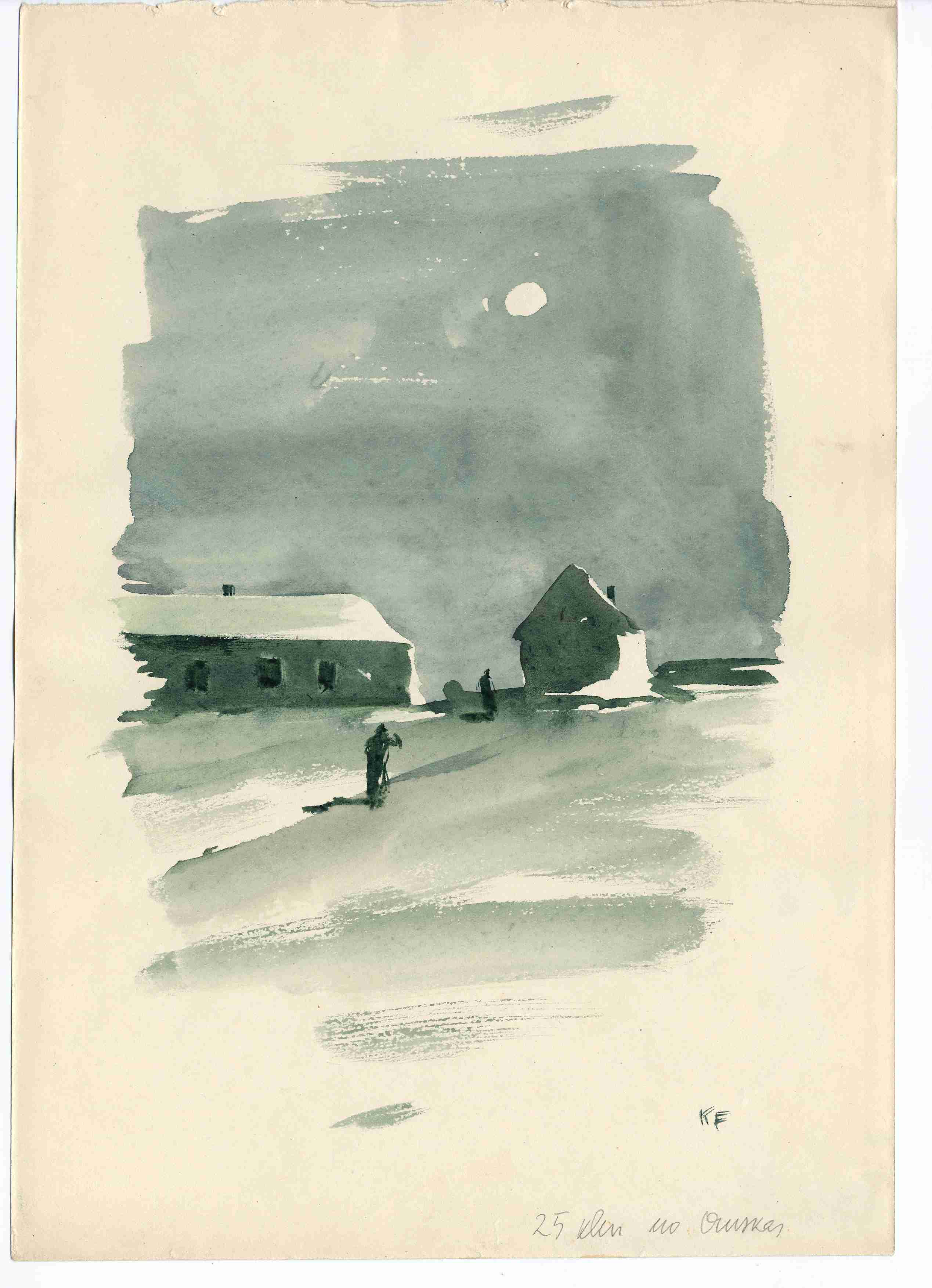

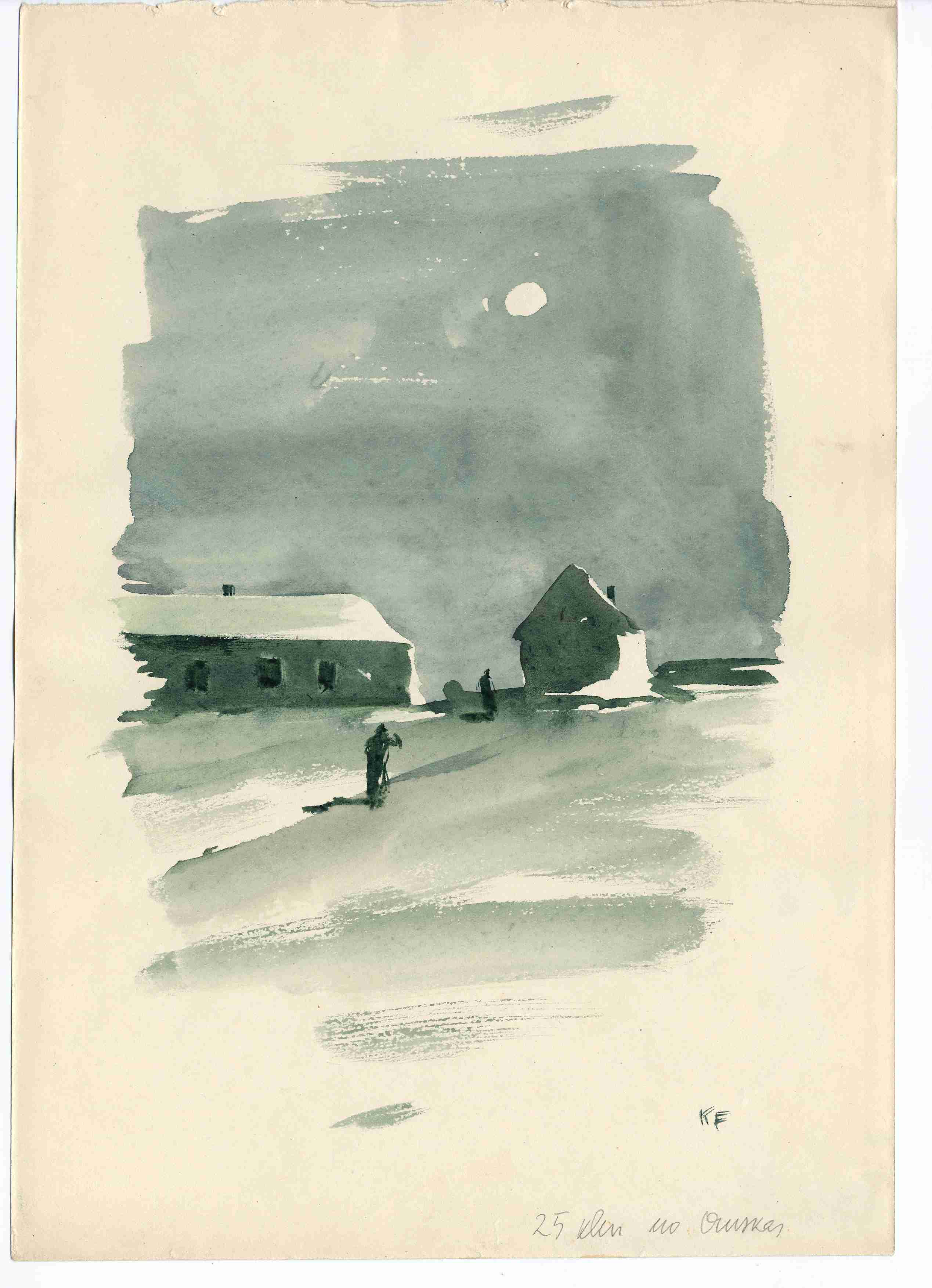

In 1951, a group of 12 people, mainly actors, poets and translators, were arrested and sentenced to between seven and 25 years in prison, for ‘treason to the Motherland’. Although the charges differed in each case, the main charge common to all of them was being a member of an anti-Soviet group, whose main activity was anti-Soviet propaganda, that is, they met more or less regularly between the autumn of 1945 and the spring of 1947, in order to discuss books, plays, etc. Although the defendants claimed that political topics were not discussed at their meetings, they were charged with presenting excerpts from Andre Gide's book Le Retour de L'U.R.S.S. at one of the meetings (not all the defendants participated in this particular meeting). In fact, contrary to the claims of the security structures, there was no organized resistance group. It was a loose framework of intellectuals, who tried to continue the cultural practice of private intellectual exchange that they had been used to in independent Latvia, and that was their main crime in the eyes of the security services. In fact, they were two circles of friends who grouped around the painter Kurts Fridrihsons (1911-1991) and the translator and philologist Maija Silmale (1924-1973). Both were strong personalities, who stood out in the depressing atmosphere of the cultural life of post-Second World War Riga. They had a deep interest and knowledge about French culture, and Western culture in general, and were unable to and did not try to adapt to the new Soviet cultural environment, with its explicitly anti-Western position. Among their friends were other people who loved French culture: the poetess Elza Stērste (1885-1976), the translator and lecturer Ieva Birgere-Lase (1916-2002), and the actress Mirdza Lībiete-Erss (1924-2008). Perhaps, this was why the group was later known as the ‘French group’, although not all the people detained in these cases had a special knowledge of French culture. At the beginning of the 1950s, the persecution of the ‘bourgeois’ and especially social-democratic intelligentsia of independent Latvia reached its peak, and the arrests and sentencing of this group were intended by the security services as a warning to all the Latvian intelligentsia that attempting to exist in parallel with official Soviet culture and keep an orientation towards Western ‘cosmopolitan’ literature and art was a crime. Although the files should be viewed with caution, because they were written in such a manner as to confirm the version of the interrogators, they contain an abundance of material about the mood of the Latvian intelligentsia in the post-Second World War years, the still-existing hope that the independence of Latvia would be restored, the attempts to maintain an intellectual life outside the official constraints, and the attempts to learn about cultural life outside the USSR. Today the ‘French group’ is seen in Latvia as a vivid example of intellectual resistance to the Soviet regime. Material from the criminal files is used by academics and authors of biographical books and articles, and in the preparation of documentaries and television programmes.

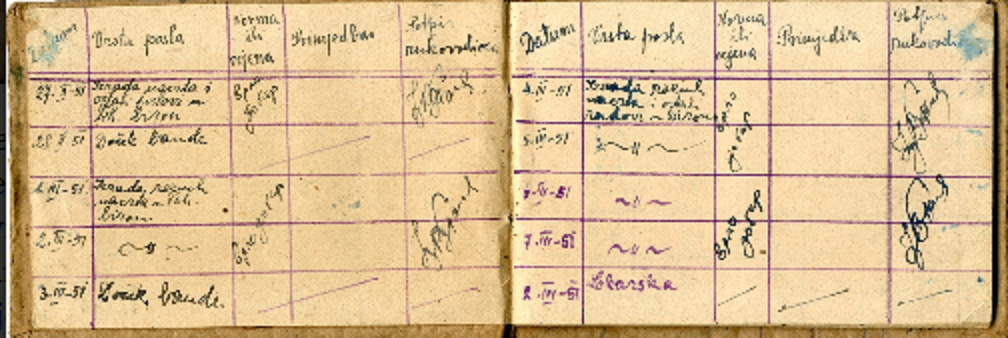

The ‘Inmate Work Log’ is a booklet containing brief notes about the jobs that Grgo Šore, or any other detainee, had to perform on a daily basis during his stay in the prison camp on Goli otok. The entries in the log are dated from February 27 through October 20, 1951. Šore wrote with a pencil and pen, and the log consisted of heading: date, type of work, norm or rating, comment and supervisor’s signature. Queue rules or ratings and supervisor’s signature were completed in Cyrillic by the supervisor, while the comments were left empty. It is evident from the booklet that on Goli otok Šore, apart from heavy physical labour, also worked as a construction technician on the design of industrial facilities and accommodations for inmates (Interview with Dubravka Peić Čaldarović). The document testifies to the torture of inmates in this ideologically motivated camp.