The most interesting part of this file is formed by the political drawings by Lembit Saarts, a friend of painter Heldur Viires. These drawings were used as evidence against the group of artists from Tartu known as the Tartu Circle. Artists from the circle, Valdur Ohakas, Ester Potisepp (later Roode), Henn Roode, Lembit Saarts, Ülo Sooster and Heldur Viires, were accused of anti-Soviet ideas and plots. They were sentenced to 25 years in a prison camp, except Esther Potisepp, who received ten years. Later, all the sentences were reduced to ten years. However, they were freed in 1956, at the beginning of the period of Khrushchev's thaw.

The art historian Juta Kivimäe has stated that this persecution was not actually meant against these particular young artists, but rather to affect indirectly old and influential art teachers and painters, such as Addo Vabbe, Elmar Kits and Johannes Võerahansu.

In this letter Emil Cioran reacts to the news received from his parents who had written to him about the conviction of his brother Aurel Cioran for his involvement in the Legion of the Archangel Michael. He was to spend the following seven years in political prisons. In this context, Emil Cioran approaches in a critical manner the former involvement of them both (he and his brother) in the Legionary Movement. The importance of the text consists in the insights it gives us into the process of critical evaluation of his former allegiance to the Romanian fascist movement. Emil Cioran expresses his disappointment that his brother continued to support the Legion after 1945. He states that this political movement “led only to the unhappiness of its followers” and mentions that he had warned his brother about the possible consequences of his involvement in the Legion. Finally, he ends his argument by saying that: “This is the consequence of an absurd faithfulness.” Nevertheless, Emil Cioran had been a supporter of the Legion at least until 1941. Cioran’s critical evaluation of his former political sympathies was a process that occurred gradually after 1945 (Zarifopol-Johnston, 10). Besides the valuable information to be found in it, the letter has literary value in itself. The literary style characteristic of Emil Cioran is recognisable in some sentences of the letter, such as: “Life is a sinister comedy written by the Devil.” Taking into account the tragic situation of his family, Emil Cioran felt embarrassed to speak about his editorial success in France and he starts the second part of the letter by presenting his news as a consolation for his parents. This news concerned the publication of his first book in French, entitled Précis de décomposition. This book was published at Gallimard Publishing House in 1949 and a year later it received the Rivarol literary award. This part of the letter also reflects the difficulties encountered by a foreign writer in his endeavours to be integrated in the French contemporary literature milieu and to write in a foreign language.

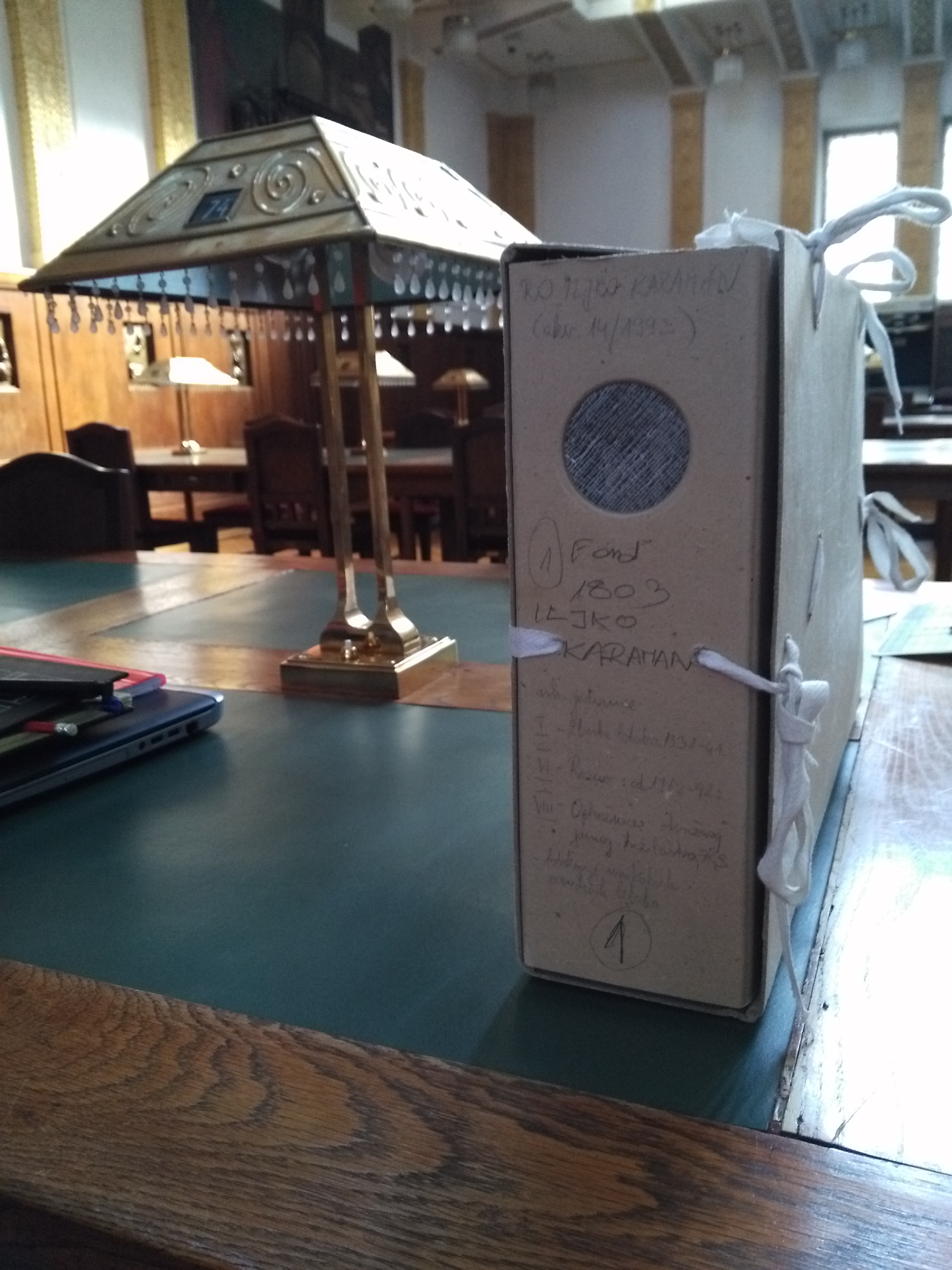

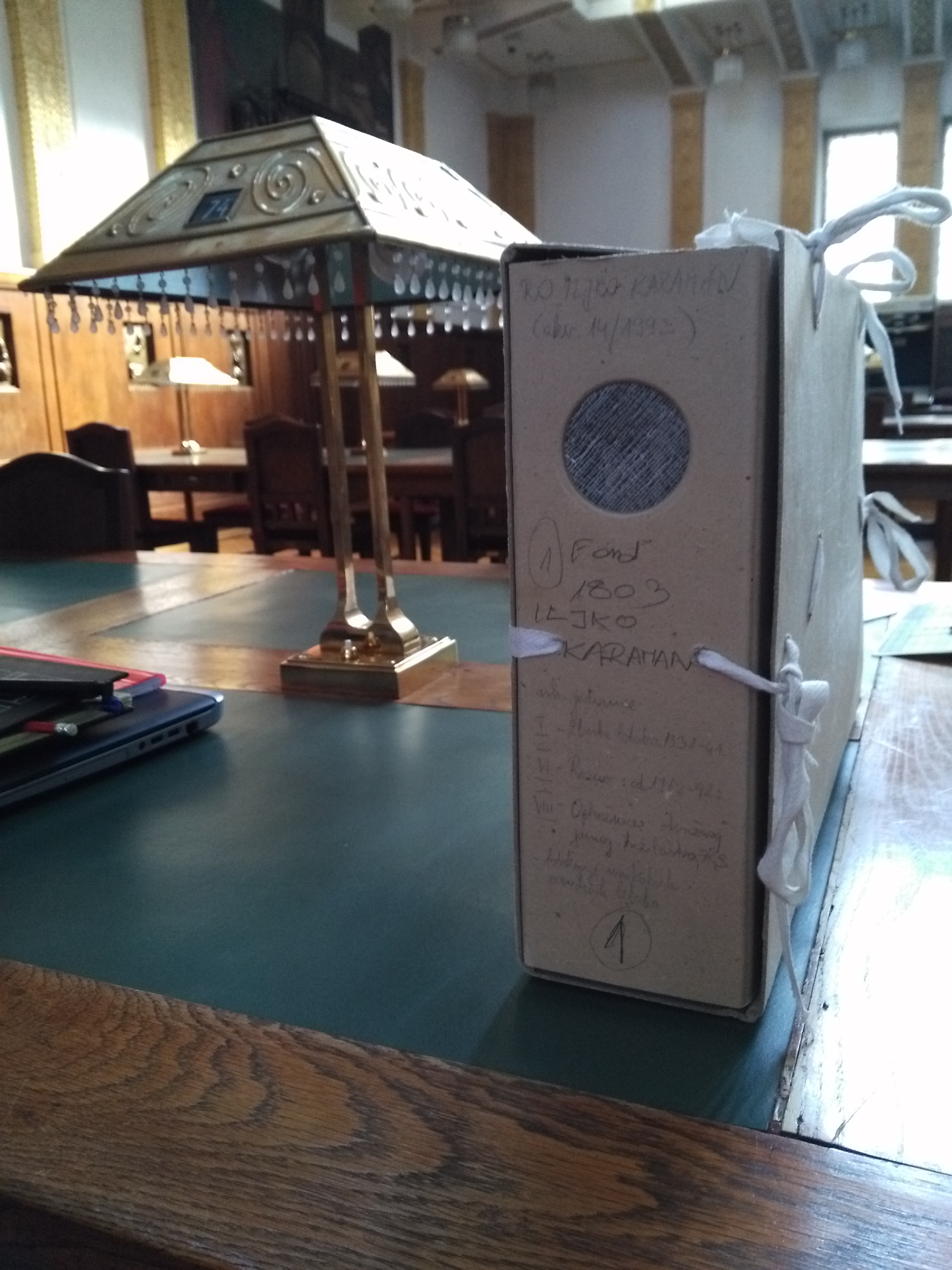

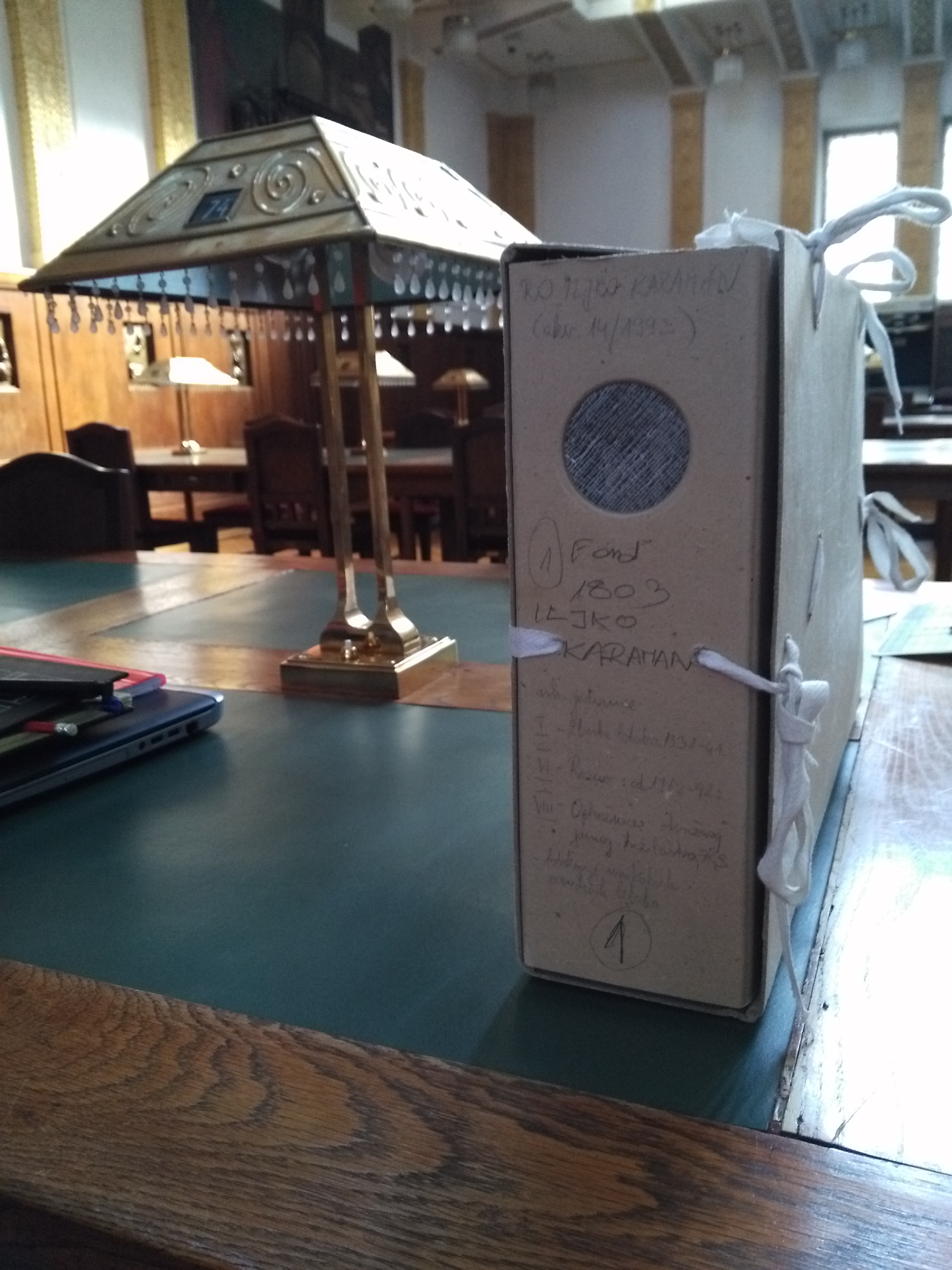

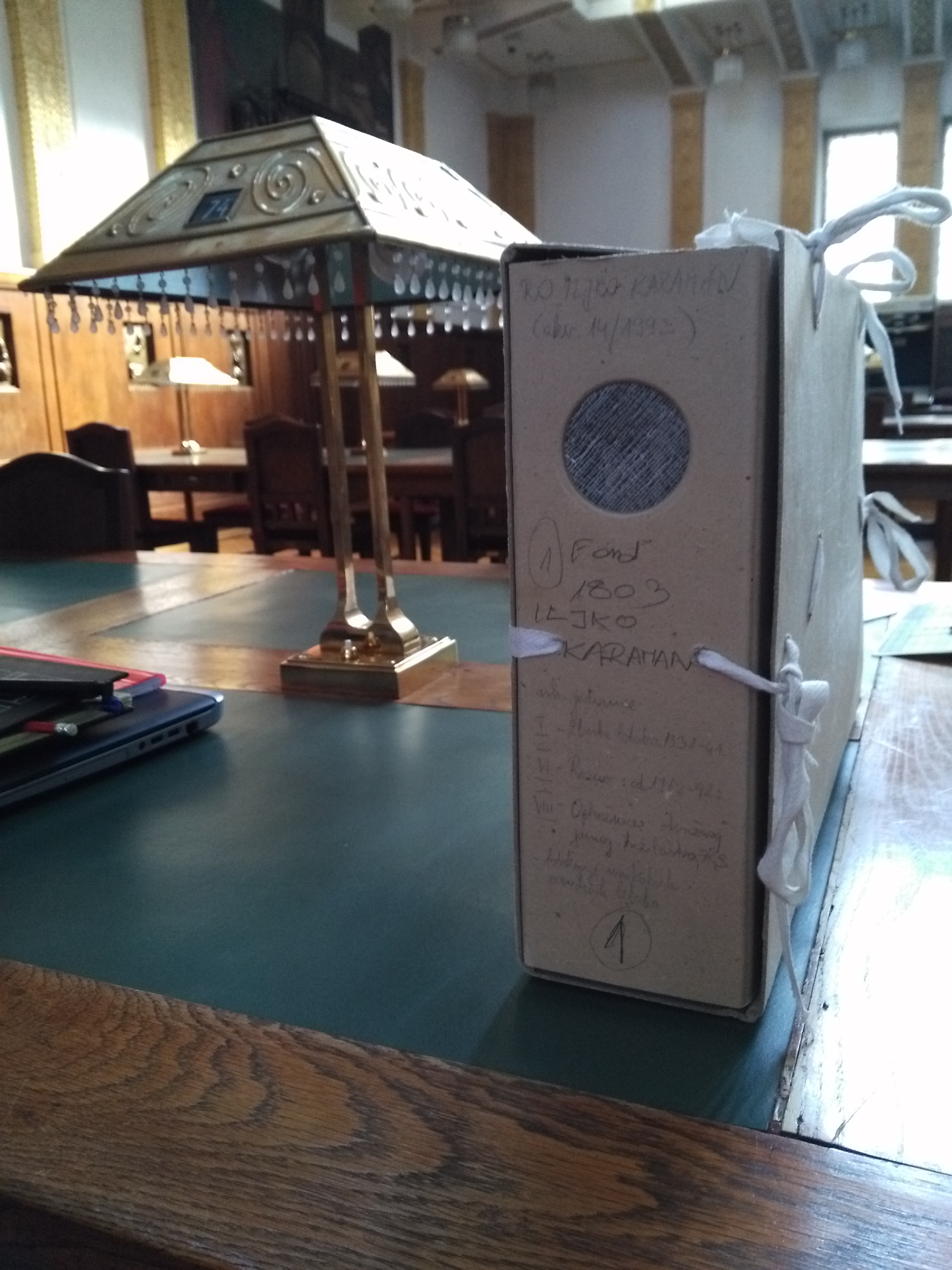

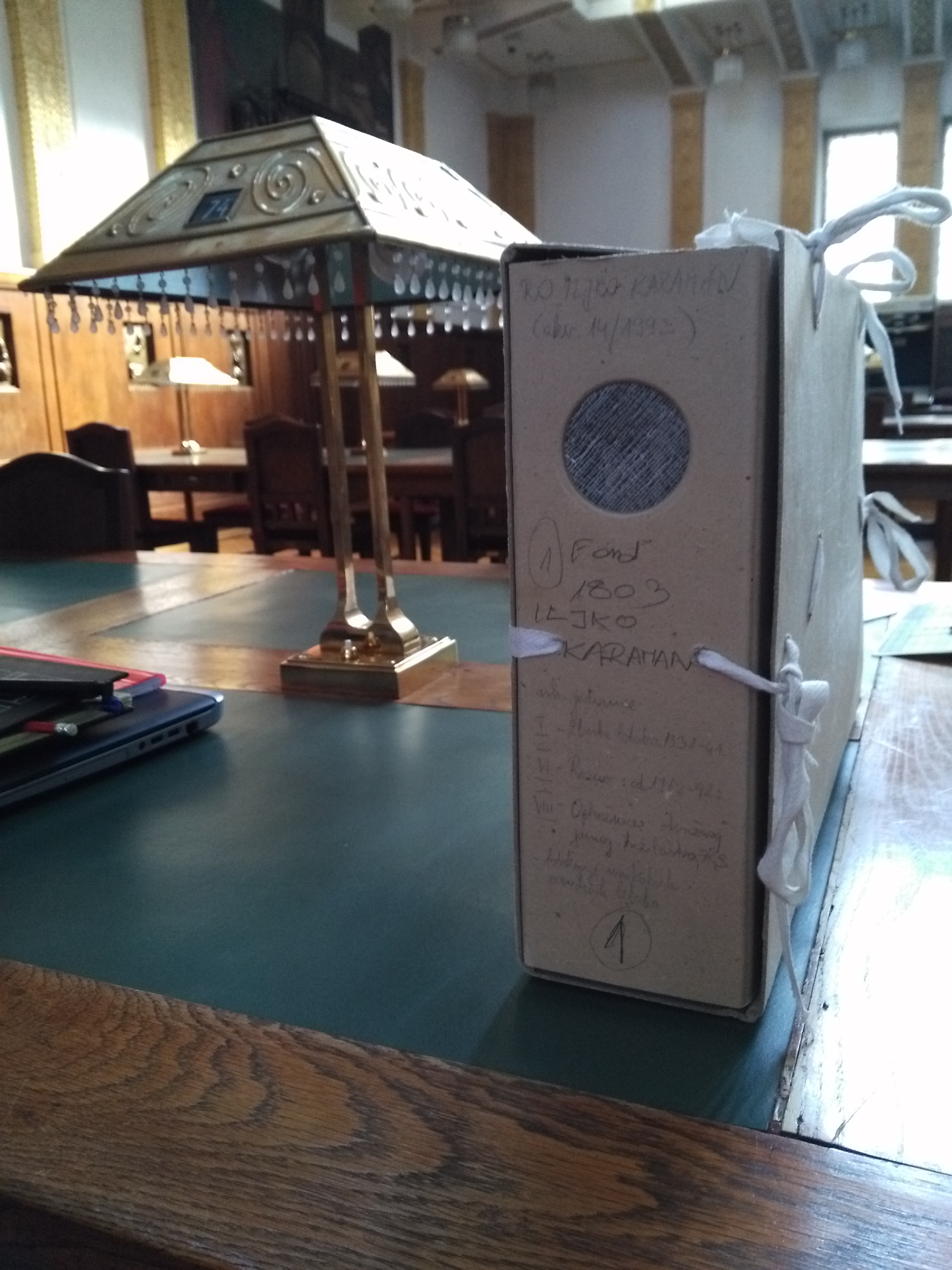

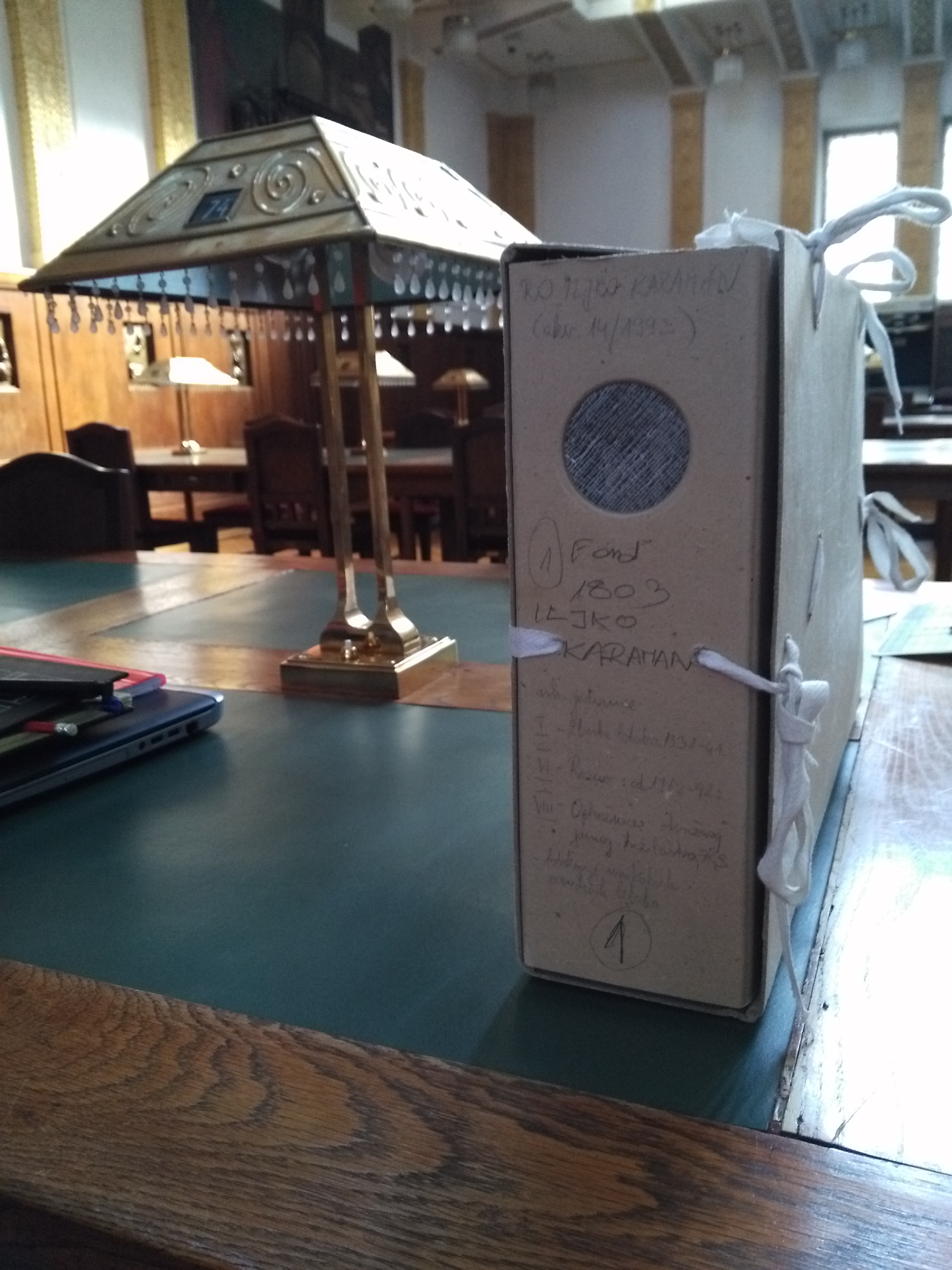

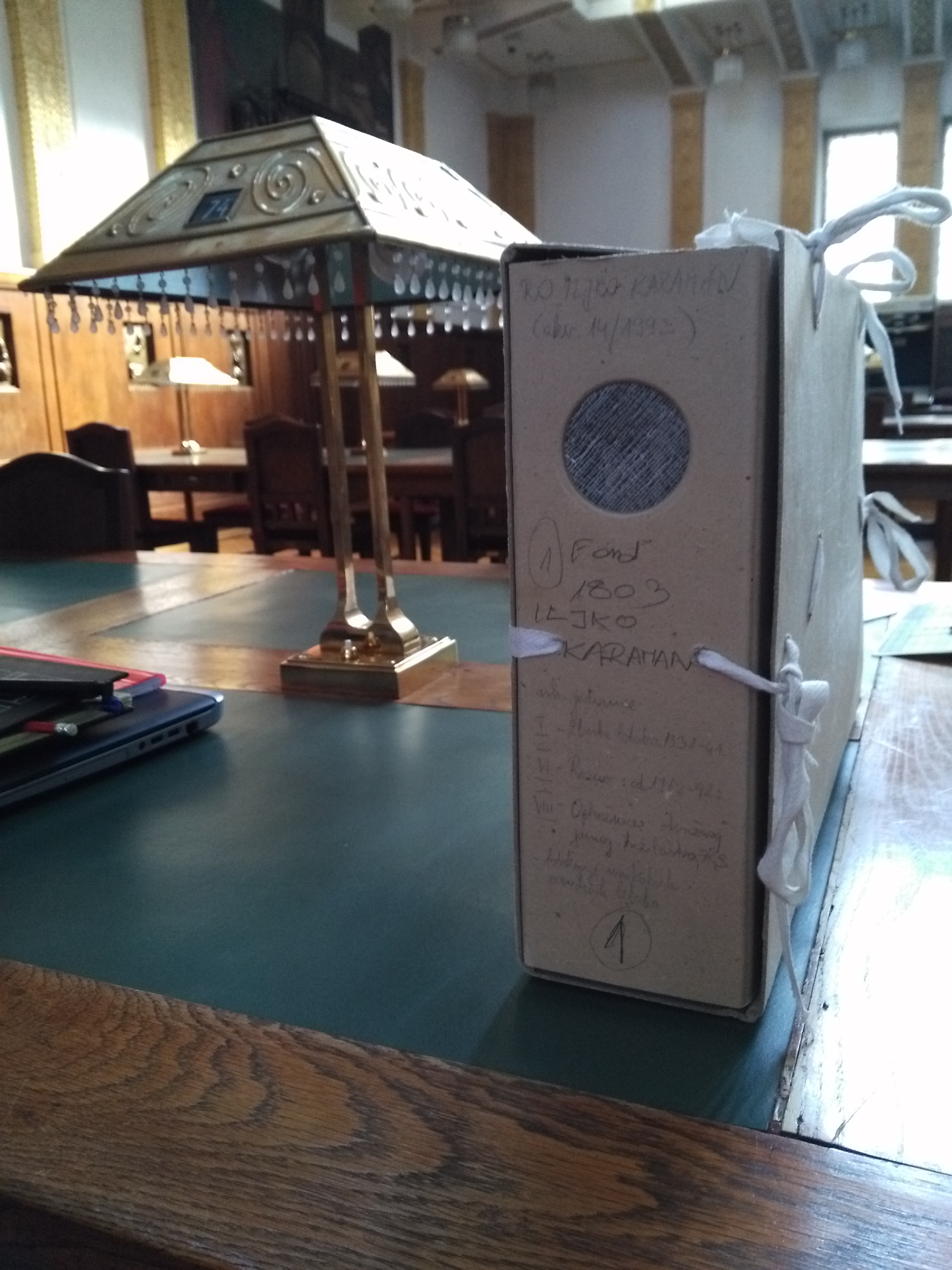

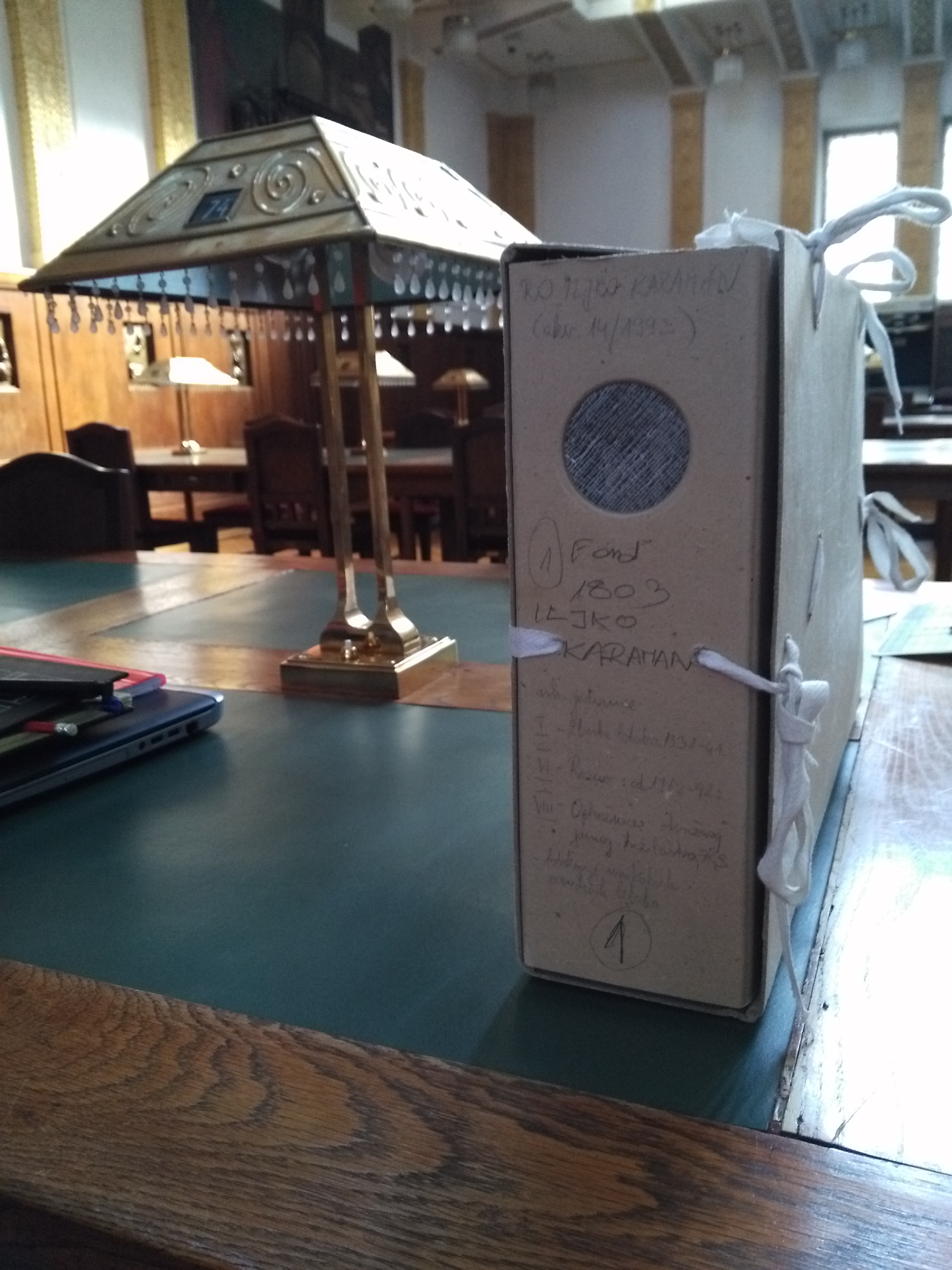

The Iljko Karaman Collection is an archival collection established in 1949 by the Zagreb Deputy Public Prosecutor, Iljko Karaman (1922-2010), who deposited the collection at the Croatian State Archives in 1992. The collection includes unique material related to state censorship practices in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the Independent State of Croatia, the People’s Republic of Croatia and the latter Socialist Republic of Croatia until the 1980s.

The extensive Czechoslovak Writer Publishing House Collection deposited in the Museum of Czech Literature illustrates the publishing activities of one of the most important postwar Czech publishers from its establishment in 1949 until its end in 1997. The materials allow for the reconstruction of the negotiations between authors, editors and publishing managers, and it frequently provides the only evidence of literary works that were never published. This collection provides a picture of censorship in socialist Czechoslovakia and how the publishing industry functioned under a Soviet-style communist dictatorship.

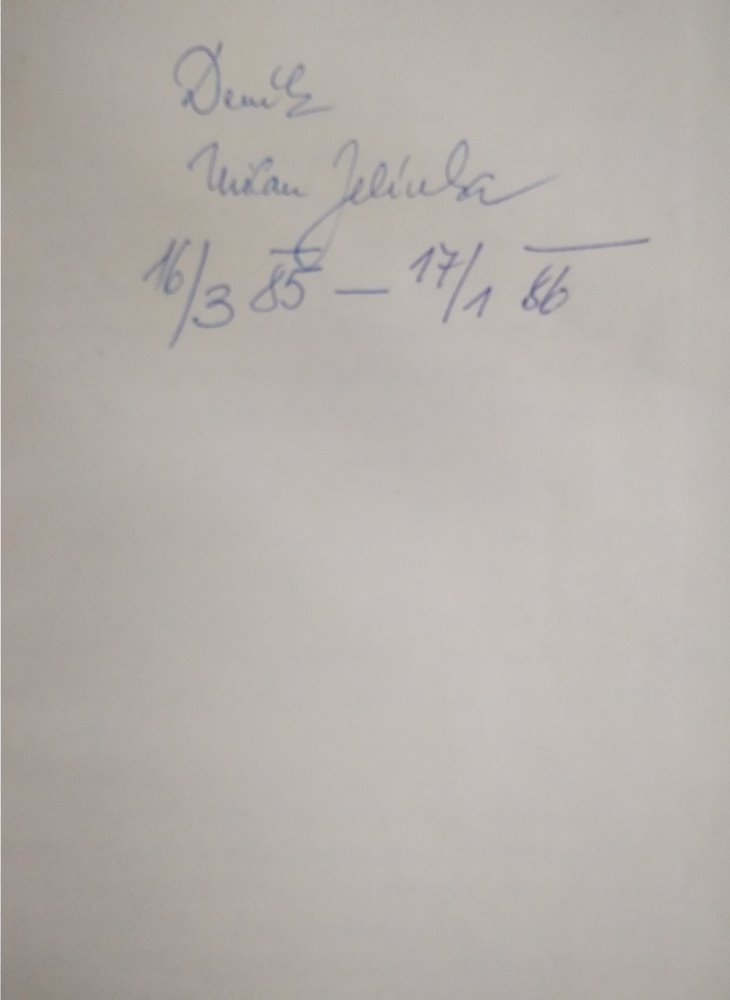

The diaries are presented in the form of separate notebooks which were written by Milan Jelínek over a continuous, yet not daily, period of time. Jelínek recorded his everyday impressions, commenting on current events; a large part of them are summaries and short reviews of the books he read. The diaries prove the mindset of an enthusiastic Communist transformed to a critic, and the disappointment of the social and political development following the Prague Spring. There a also very valuable and non-encrypted, "uncensored" records about the publishing of samizdat titles and the organisation of the underground university within the activities of the Jan Hus Educational Foundation. What is interesting, are also the characteristics of other people from the academic and dissident environment.

The papers of the Council of Free Czechoslovakia were completed in 2006 at the Centre of Czechoslovak Exile Studies. The fund includes 190 cartons of archived materials, which can be found in the council's governing bodies, as well as materials prepared as a basis for negotiations (newspaper clippings, interviews, manuscripts, notes etc.), minutes of meetings and remarks, and of course rich correspondence between members of the council or with exile, governmental and non-governmental organisations. Press releases, statements, and memoranda can also be found in the fund.

On April 21 1949, an UDB-a agent-provocateur was sent to visit Hedy Samec. The agent, who introduced himself as an acquaintance of a German soldier who was in a cordial relationship with Mrs. Samec, had two goals: first, to explore whether Mrs. Samec would be ready to conspire with a suspicious foreign citizen; and, secondly, in the event of an affirmative answer, they wanted to pressure her into becoming an UDB-a informant.

The mission failed because Mrs. Samec immediately informed her husband about the visit, and he reported the incident to the police. The UDB-a found out that Mrs. Samec was too frightened to establish any kind of contact with strangers, so they could not lure her into a trap, but on the other hand, they ascertained some knowledge about Mrs. Samec’s influence on her husband.

During the first decade of the communist regime, the educational system in Romania was fundamentally reformed in accordance with the Education Act of 3 August 1948, which imposed – among other things – the nationalisation of denominational schools. Faced with this difficult situation, the leadership of the Evangelical Church asked pastors to teach confirmation classes in clergy houses, churches, or state schools. Starting from the end of 1948, the local authorities received instructions to obstruct the teaching of any confirmation classes.

In reaction, the leadership of the Evangelical Church sent numerous memorandums to the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Bishop Friedrich Müller did his best to tackle this kind of interdiction, which he had already faced when Episcopal vicar in 1941. At that time, he had opposed the taking-over of denominational schools by the local Nazi organisation, the German Ethnic Group, which controlled the German minority in Romania. The confirmation classes were very important for the Evangelical Church, because without attending these classes, young people could not have been able to pass the confirmation examination and become full members of the religious community. However the state authorities considered the confirmation classes to be a tool for preserving the Church’s influence in society.Particularly interesting is the memorandum sent by the High Consistory of the Evangelic Church A.C. in Romania to the Ministry of Religious Affairs on 28 February 1949. In this memorandum, Bishop Müller criticises the measures taken by the Securitate and Militia against the practice of confirmation classes in the village of Brădeni/Hendorf (Sibiu county). This document is remarkable for the complex theological argumentation concerning the significance of confirmation classes for Evangelical young people. In the first part of the memorandum, Bishop Müller argues that the instructions sent to local Militia stations by the Securitate Directorate of Sibiu violated the laws of the communist state, including the Constitution of 1948 and section 7 of Decree no. 177 of 1948 regarding the activity of religious denominations in Romania. In the latter text, the Bishop explains, it is plainly stated that “denominations are free to organise themselves and practice their religion if these practices do not contradict the Constitution, the security of the state, or public order.” Bishop Müller also emphasises that the banning of confirmation classes violates the basic rights of citizens, which are guaranteed by article 27 of the communist Constitution of 1948. He goes on to invoke the speeches of the minister of education, who had stated in the official newspaper Scânteia that religious denominations were free to teach the principles of their faith to the young generations of their communities. In addition, the minister had alluded to the fact that insults to “religious feelings” helped only the “enemies” of the new regime. Pursuing this official declaration, Bishop Müller ends his argument by saying that “there is no worse insult to religious feelings than banning the religious education [...] of young people.” He thus asks the Ministry of Religious Affairs to urge the leadership of the Securitate to stop the persecution against confirmation classes. In this way, Bishop Müller tried to take advantage of the inconsistencies in the policies of the communist regime, which intended on the one hand to limit the influence of the churches among young people, but on the other, to co-opt the local protestant churches.

Nikola Tanev was a Bulgarian painter who studied at the Paris Academy of Decorative Art. Tanev had 28 independent exhibitions in Bulgaria and 27 exhibitions in various European countries: Berlin, Innsbruck, Mannheim, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg, Leipzig, Stuttgart, Rome, Milano, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Malmö, Warsaw, Prague, Brno, Budapest, Bucharest, Belgrade, Zagreb, Split. He was among the founding members of the Native Art Society. There is no evidence that he was involved in political activities and party and political struggles before 1944. He was not a member of any political party and organization. His elder brother Stefan Tanev (March 15, 1888 – 1952) who was also non-party related was a long-time editor-in-chief of the Utro [Morning] Newspaper (1911 – 1944).

Both brothers were arrested in September 1944 by the so-called "people's democratic power". Stefan Tanev was arrested on September 13, 1944 and sentenced by the so-called People's Court to life imprisonment. In 1952, he died in prison under obscure circumstances. Nikola Tanev was arrested on September 26, 1944 and spent six months in the Central Prison and various buildings adapted for prisons for "political criminals". The intellectuals prevailed among the criminals; there were many painters arrested: Rayko Aleksiev, Aleksandar Bozhinov, Boris Denev, Konstantin Shtarkelov, Aleksandar Dobrinov. After September 9, 1944, the authorities used as a reason for repressions the works of the painters and the reports against them. A joke of the painter Aleksandar Bozhinov from the time he was in jail is preserved: "It is an honour and pleasure to fall among such an intellectual elite! No serious intelligentsia left outside." Tanev as well as the other painters continued their work in the prison; they drew on wrapping paper, on sheets of paper from grocer's books, on accounting forms etc. There are numerous prison sketches, portraits and drawings of the interior of the cells preserved which are of great documentary value.

Nikola Tanev was released from prison in April 1945 with the explanation that he had been imprisoned by mistake. In this period, the painters were openly given propagandist assignments: to approve through their art the "activities of the people's power" and to contribute to the building of socialism. "The period from 1944/1945 to 1955 was extremely important for the development of communism – the socialist realism got its way and the accusations of "formalism" intensified. The "pure landscape" was not in position to solve such tasks thus it was declared unimportant. In documents from the sessions of the art juries one could see the arguments for the rejection of paintings of Nikola Tanev. For example: "The landscape is too relative... This is not an artistic work. I am against its acceptance." (with reference to his painting "Slaveykov Square").

Experiencing the sanctions of the authorities, in order to survive, N. Tanev deliberately decided to take part with his art in the process. However, the differences in relation to Tanev's previous landscapes are significant: the sunny multicolouredness and the jubilant feeling were replaced by distressing autumn and winter pictures; heavy and leaden sky; drizzly; denuded trees; small grey figures. Grey-brown monochromy oppresses everything. A bright example are the miner's compositions of Nikola Tanev. Praised by the state art critique who saw in them a "new stage in his creative work" that approved the "building of socialism" (Божков 1956: 22), these paintings of Tanev show the dark conditions of work in the mines near the town of Pernik which functioned as forced labour places.

In 1949, Nikola Tanev had an apoplectic stroke and two years later – a myocardial infarction. Semi-paralysed, in 1955 he was awarded "honoured painter", a title related to small monthly subsidy which enabled him to take treatments. Nikola Tanev died in 1962.

After the political changes in 1989, the life and work of Nikola Tanev became a subject of many analyses. His art is considered an organic part of the European art but at the same time related to the national way of life.

Until the exhibition "Forms of Resistance" there were no documents published related to Nikola Tanev's stay in prison and there was no connection made between his paintings "Pernik Mines" and the series "Kutsiyan", on the one hand, and his life in prison, on the other hand.

![Croatian State Archives in Zagreb: HR-DAZG-1007-527: “Žalba na presudu Okružnog suda u Zagrebu K 236/949-7” [Appeal letter against Zagreb District Court verdict K 236/949-7], December, 1949.Photo by Franko Dota](/courage/file/n231185/Appeal+letter.jpg)

“I have been sentenced to 6 months in prison for unnatural fornication. I do not believe my behaviour should be punishable by law since it does not constitute a crime. From the most ancient times of human history, among the oldest civilizations, the Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, in the Islamic world, in Japan and China, this ‘unnatural fornication’ had been tolerated. It was only with the emergence of the Catholic Church and its supremacy that this fornication was proclaimed the sin of Sodom, and harshly punished […] Countries that managed to wrest themselves free from Catholic supremacy introduced more tolerant regulation of sexual matters, regarding marriage and even homosexuality. As far as I know, there is not a single modern state that would consider adultery or homosexuality crimes” (HR-DAZG-1007-527: “Žalba [Branka Vujaklije] na presudu Okružnog suda u Zagrebu K 236/949-7”, prosinca 1949. [Appeal (of Branko Vujaklija) against Zagreb District Court verdict K 236/949-7, December, 1949]).

With these words Branko Vujaklija, a 23-year-old theology student and Serbian Orthodox cleric from Zagreb, attempted to convince the Croatian Supreme Court to release him from prison where he was held for “unnatural fornication.”

During his trial, Vujaklija unapologetically declared he was homosexual. He tried to explain to the judge that he was only acting in accord with his “natural sexual instincts,” that his sexual relations were always with consenting adults and never in public, so therefore, Vujaklija argued, he could not have been declared guilty. The judge ignored his arguments, and found his acts extremely immoral (Dota 2017, 94-95). Vujaklija did not give up and wrote an appeal (part of which was quoted earlier). He changed his argument: since he was sentenced as a moral degenerate and a debauched bourgeois, this time Vujaklija himself decided to use ideological arguments as well. He tried to explain to the judges that the contempt towards homosexuality had its origins in the Catholic tradition that should have no place in a new, modern and progressive socialist society. However, his efforts were in vain, and the Supreme Court of Croatia rejected his appeal (Dota 2017, 95).

Both the court sentence and Vujaklija’s appeal were retrieved during Domino’s research, and thus became part of the Collection History of Homosexuality in Croatia. The 1949 verdict, as well as other related documents, including the cited appeal letter, were originally held in the State Archives in Zagreb (DAZG), and are part of the Zagreb County Court Fund (HR-DAZG-1007).

These documents testify to the ideological motivations behind the persecution of homosexuality in the post-revolutionary phase of communist Yugoslavia, but also to the resistance mounted by some sentenced homosexuals against the authorities. Vujaklija was bold and daring enough not only to depict his homosexuality as a completely natural phenomenon, but also to demand his own acquittal and the decriminalization of the same-sex sexual relations in general.