Samizdat from Hungary in the Vera & Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

Location

-

Budapest Arany János utca 32, Hungary 1051

Show on map

Languages

- Hungarian

Website

Name of collection

-

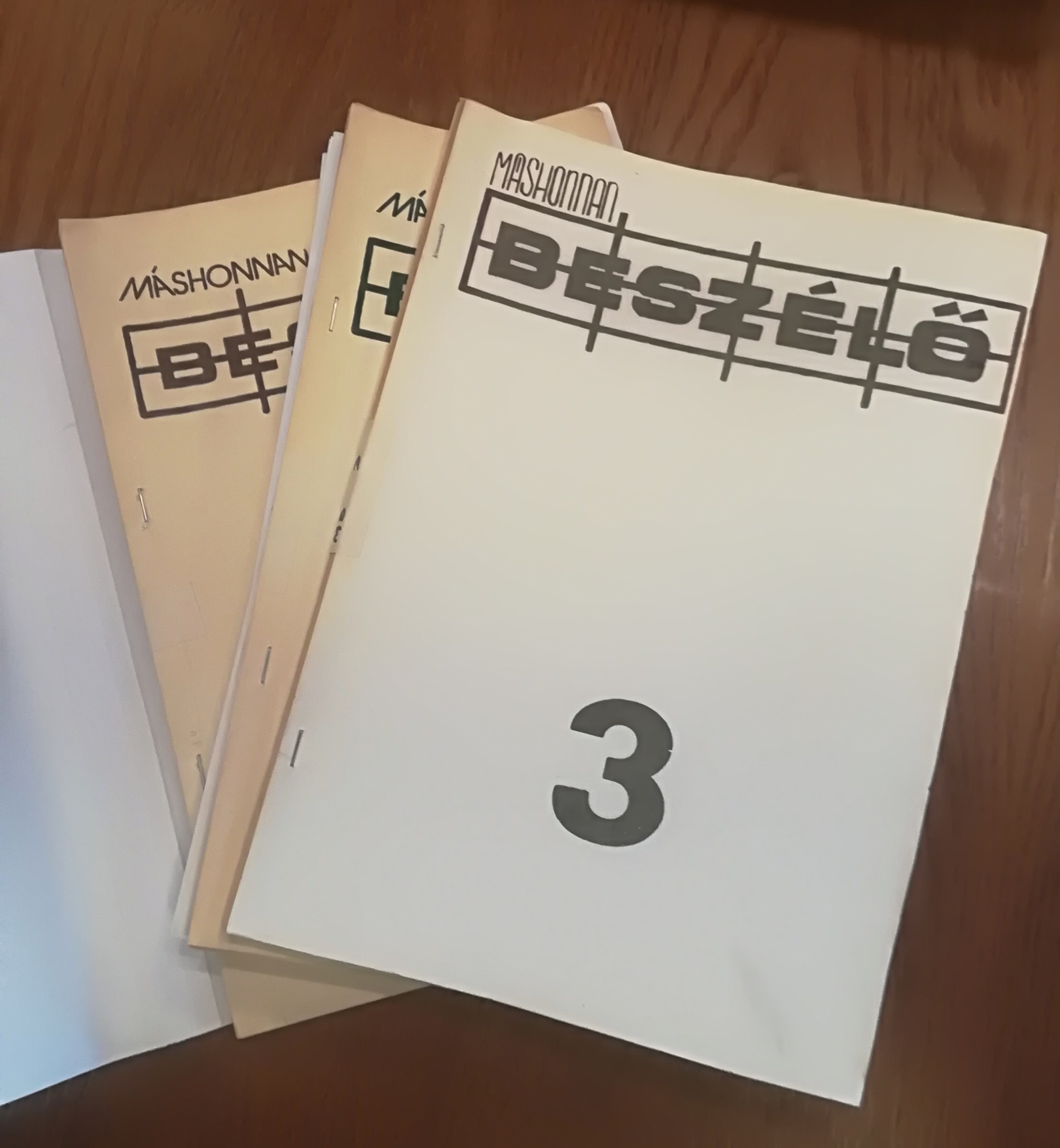

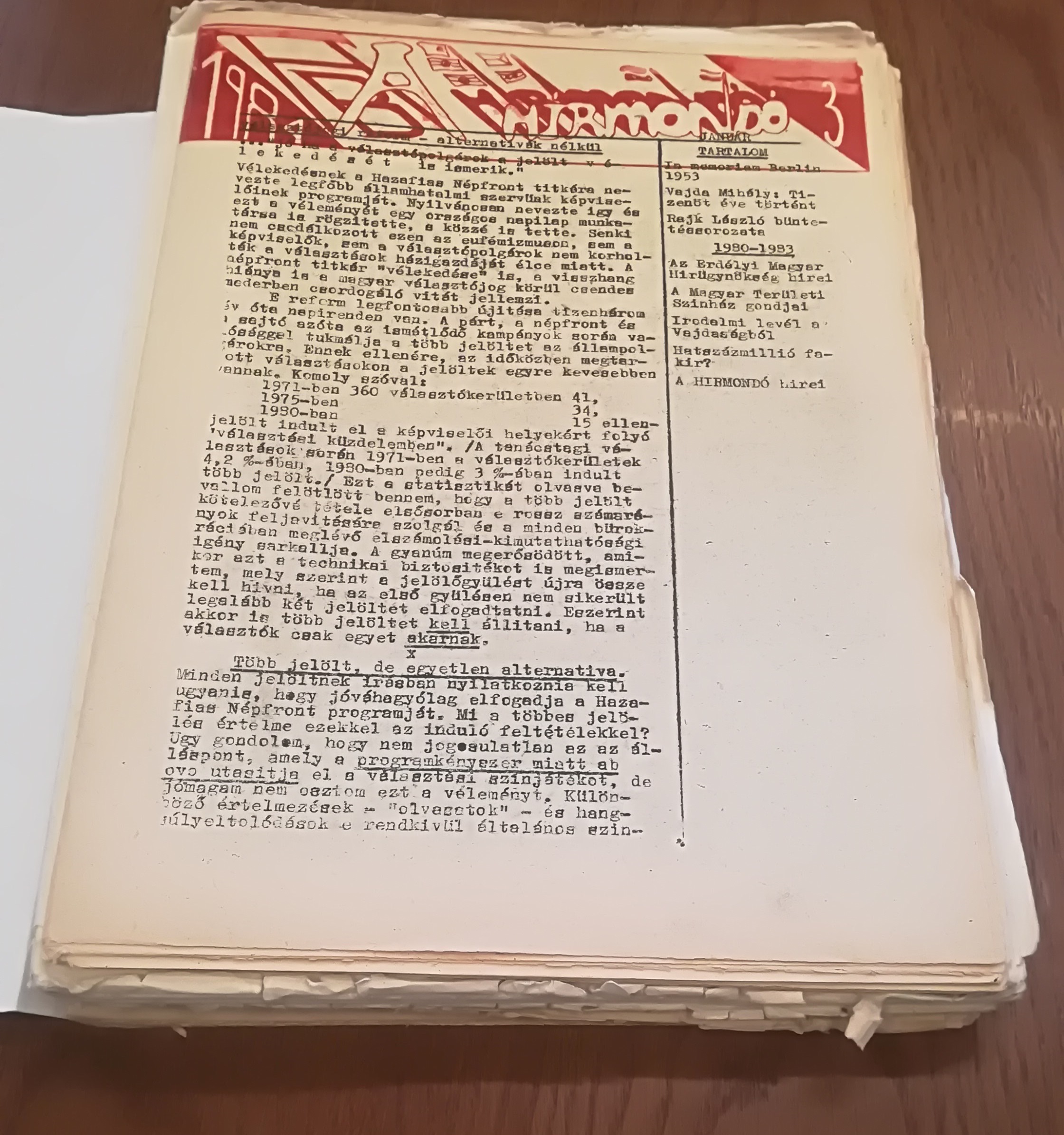

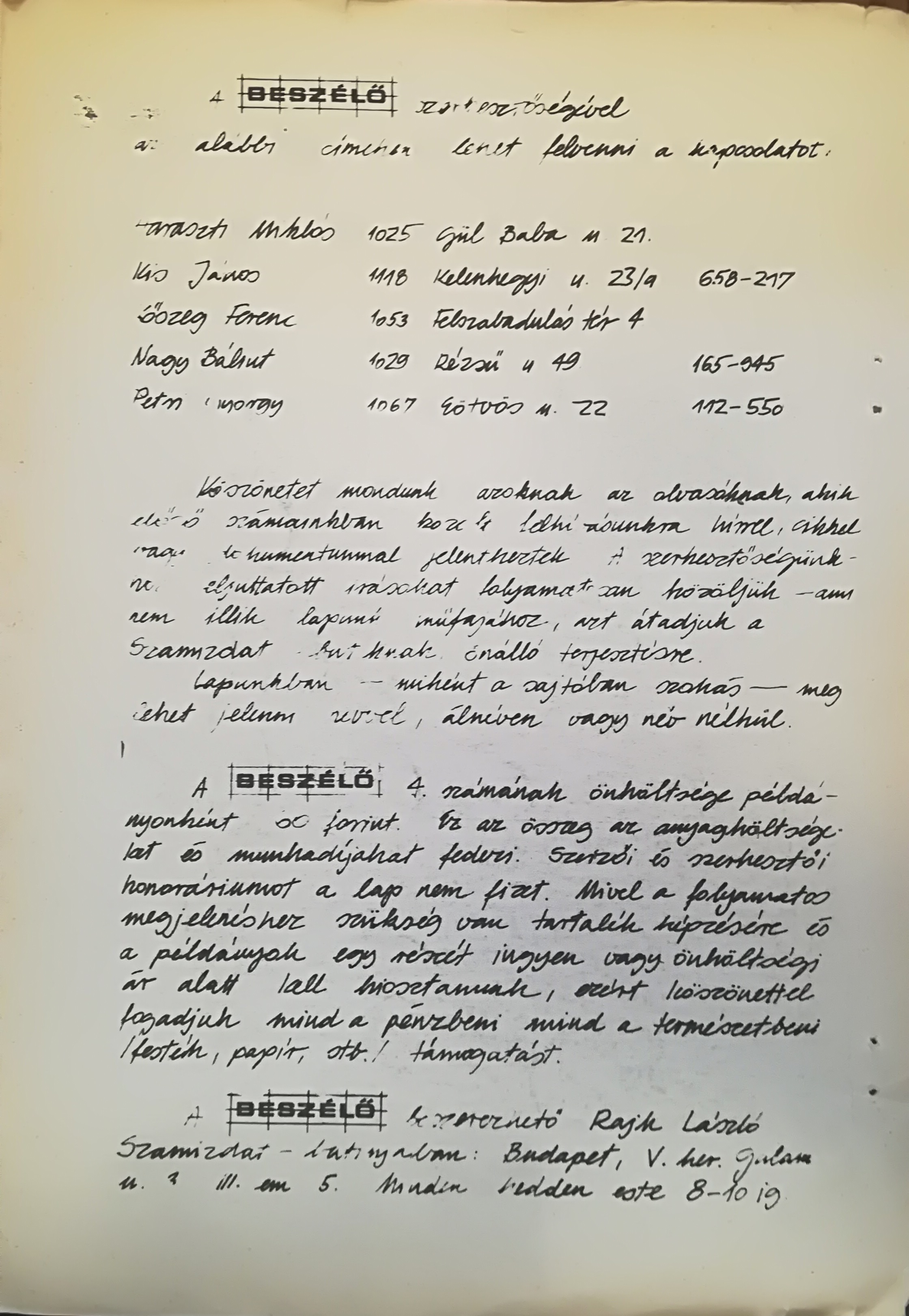

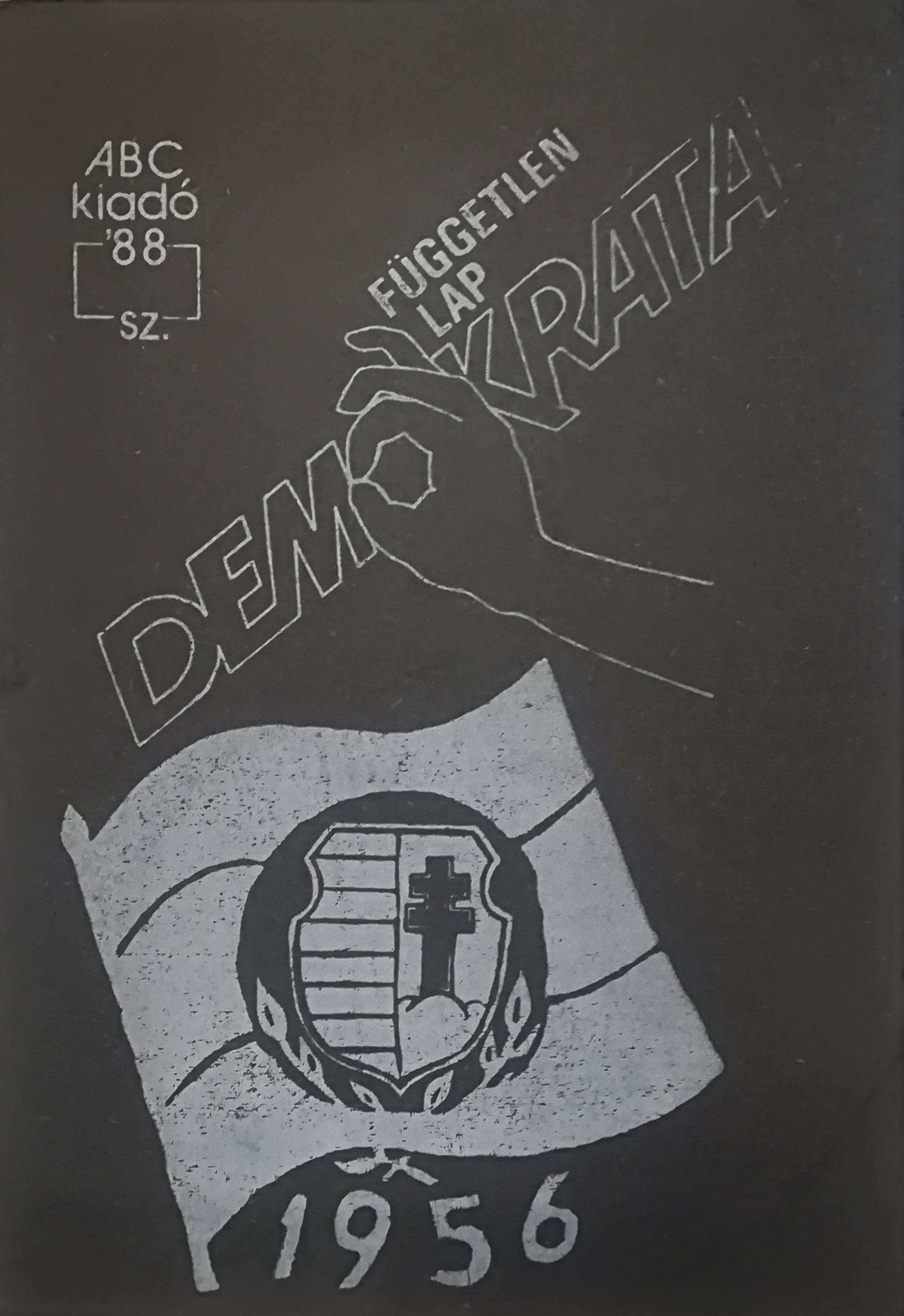

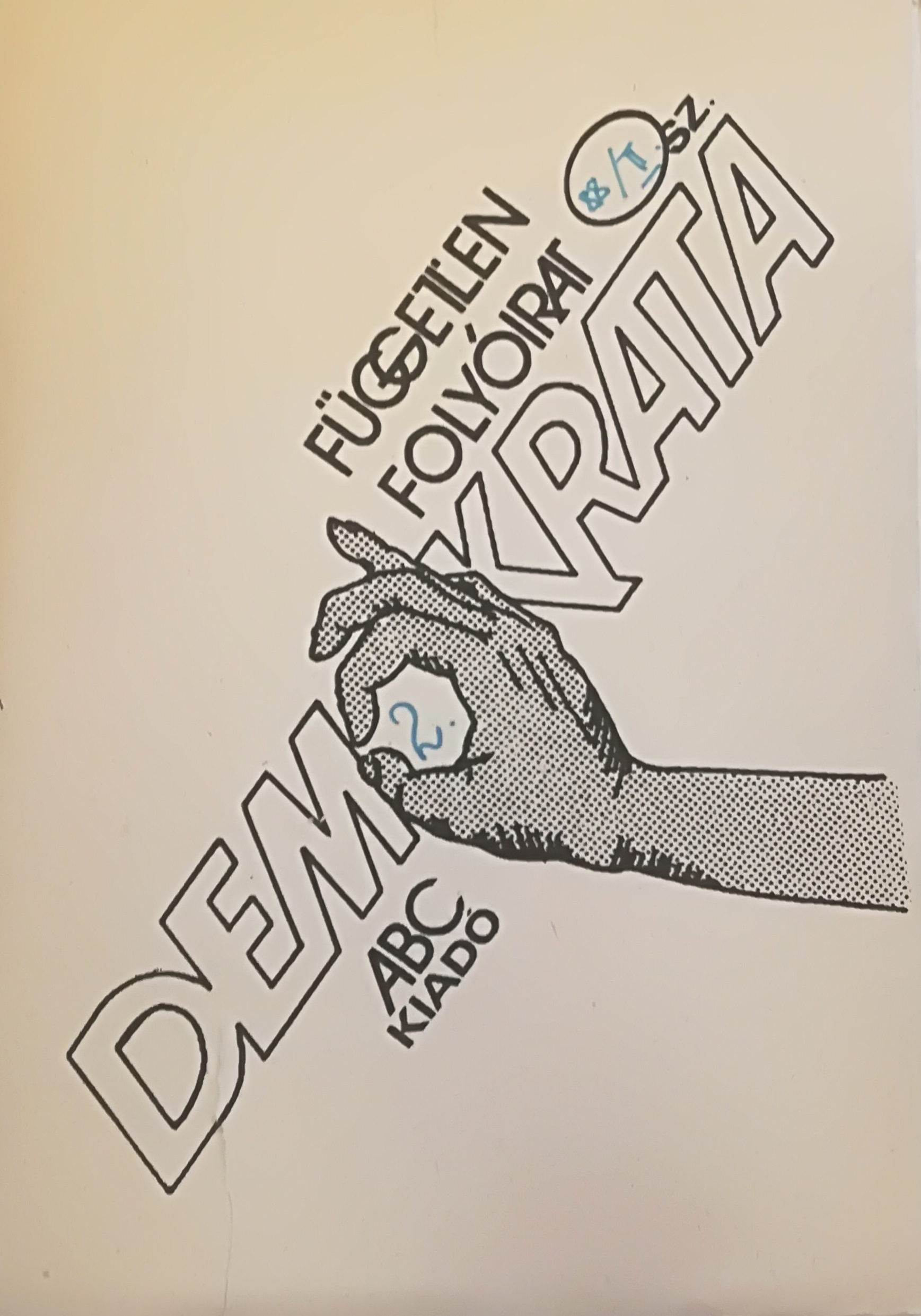

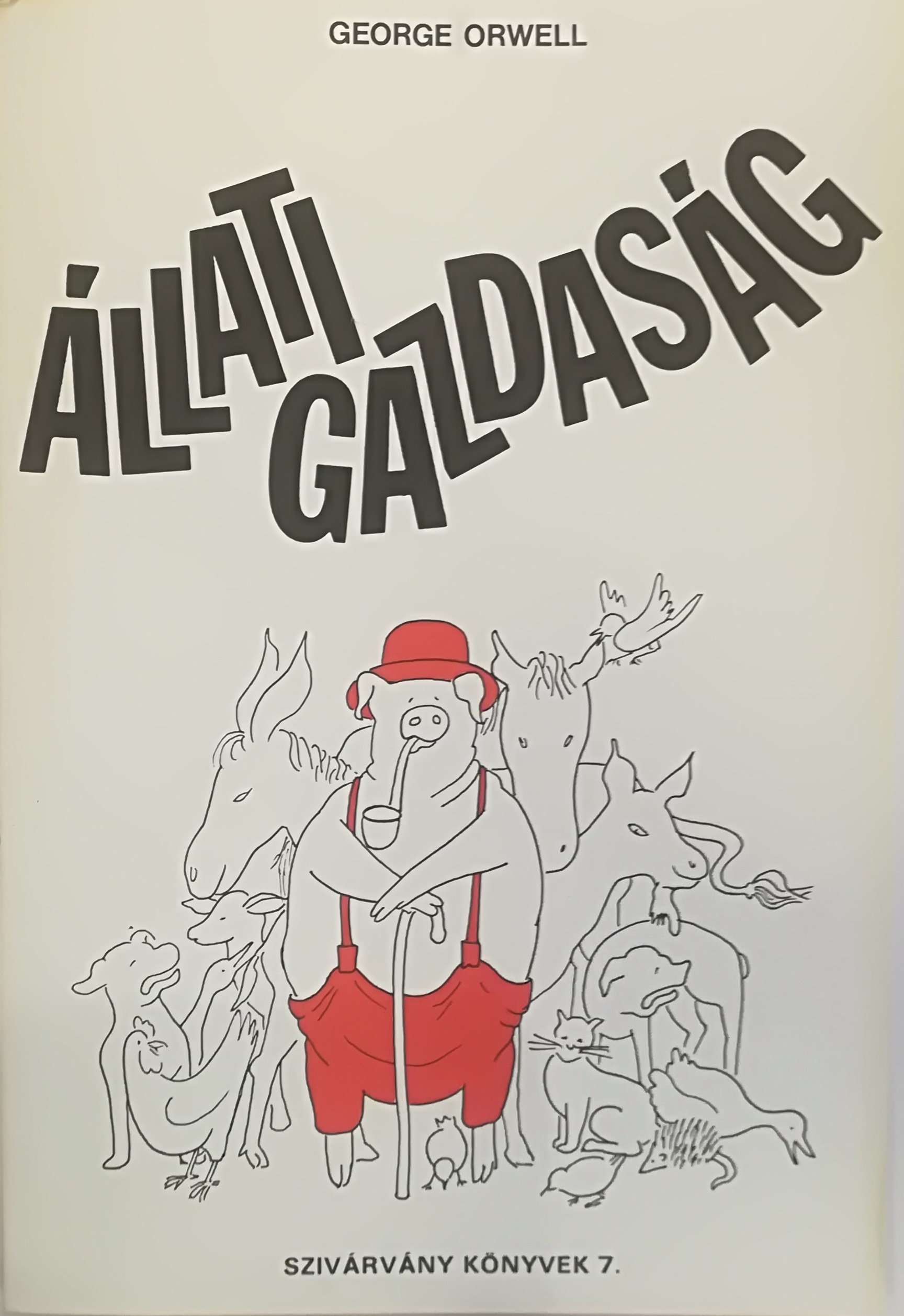

Samizdat Collections in the Vera & Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

Provenance and cultural activities

Description of content

Content

- artifacts: 0-9

- equipment (typewriters, duplicating devices, audio-video equipments, etc.): 0-9

- publications (books, newspapers, articles, press clippings): 100-499

Operator(s)

Owner(s)

Geographical scope of recent operation

- national

Topics

Founder(s)

Date of founding

- 1995

Place of founding

-

Budapest, Hungary

Show on map

Creator(s) of content

Collector(s)

Supporters

Important events in the history of the collection

Featured items

Access type

- visits by appointments

Author(s) of this page

- Huhák, Heléna

References

Mink, András. Interview by Péter Apor and Tamás Scheibner. COURAGE Registry Oral History Collection. July 4, 2017.

Bozóki, András. "A MAGYAR DEMOKRATIKUS ELLENZÉK: ÖNREFLEXIÓ, IDENTITÁS ÉS POLITIKAI

DISKURZUS." Politikatudományi Szemle 19, no. 2 (2010), 7-45. http://www.poltudszemle.hu/szamok/2010_2szam/2010_2_bozoki.pdf.

Kőszeg, Ferenc. "AZ M. O. KIADÓ." Beszélő 1, no. 14 (1985). http://beszelo.c3.hu/cikkek/az-m-o-kiado

Sükösdi, Miklós. "A szamizdat mint tiposzféra. Földalatti nyomtatási kultúra és független politikai kommunikáció a volt szocialista országokban." Médiakutató, 2013, 7-26. http://www.mediakutato.hu/cikk/2013_02_nyar/01_szamizdat_tiposzfera.pdf

Nóvé, Béla. Múltunk, ha szembejön: önkényuralmi emlékeink. Budapest: NORAN LIBRO KIADÓ, 2013.

Demszky, Gábor. Elveszett szabadság: Láthatatlan történeteim. Budapest: Noran Libro Kiadó, 2012.

Csizmadia, Ervin. "A szamizdat szubkultúrája." Budapesti Negyed 1998, no. 4 (Winter 1998). http://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00003/00005/129-172.html

Demszky, Gábor. "A szamizdat mint értékteremtõ műfaj Rajk László művészetében." n.d. http://rajk.info/en/samizdat/demszky-gabor-a-szamizdat.html

"Az OSA Archivum." n.d. http://osaarchivum.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=48&Itemid=133&lang=hu

Tóvári, Judit. "Az OSA (Open Society Archivum) Archívum." In Forráskutatás a világhálón. Eger: Eszterházy Károly Főiskola, 2014. https://www.tankonyvtar.hu/hu/tartalom/tamop412A/2011-0021_17_forraskutatas_a_vilaghalon/adatok.html

Danyi, Gábor. "„Do it today – Tomorrow it may be illegal!” - PSZR elveszett rövidfilmje az illegális nyomtatás folyamatáról." Last modified August 7, 2015. http://www.osaarchivum.org/blog/%E2%80%9EDo-it-today-%E2%80%93-Tomorrow-it-may-be-illegal%E2%80%9D-PSZR-elveszett-r%C3%B6vidfilmje-az-illeg%C3%A1lis-nyomtat%C3%A1s-foMink, András, interview by Scheibner, Tamás, Apor, Péter, July 04, 2017. COURAGE Registry Oral History Collection