The archival fond of Zhelyu Zhelev (1935-2015) illustrates the life and the intellectual work and political activities one of the most notable Bulgarian dissidents, who after the end of communist rule also became an important political figure. The collection thus contains important documents for the study of the state socialism period, in particular on oppression and opposition, and for the study of the transition to democracy.

The collection contains documents, manuscripts, books, letters and other writings of Zhelyu Zhelev. It also contains documents related to his manifold intellectual and political pursuits, such as minutes of discussions, official correspondence, editorials, book and article reviews, etc. It reveals the development of Zhelyu Zhelev as a scholar (of philosophy) and as a politician – first as a dissident, then as president. At the same time, the collection holds valuable documents on the development of academic institutions in Bulgaria during state socialism.

Zhelev’s academic career is a good illustration of the limits of the hesitant liberalization of cultural life in the late 1950s/60s. As a young scholar Zhelev, who graduated from the Philosophical Faculty of Sofia University in 1958, was supported by professors of the faculty because of his original thinking. However, an article written in 1963 in which he disputed Lenin's ideas on philosophy was blocked from publication. Zhelev (at that time, 28 years of age) reacted by writing personally to party boss Todor Zhivkov. This initiated the state’s surveillance and censorship machinery; from that moment, the State Security Authorities would observe him. Zhelev’s academic dissertation was not accepted, and he was expelled from the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) in 1965. He was even deprived of his right to reside in Sofia, and with his wife Maria Zhelevi had to relocate to the village of Grozden in Burgas region (1966–72).

The collection also reveals the ways how intellectuals who felt pressure by the authorities tried to maintain their creativity and autonomy. Zhelev, for example, managed to publish his central ideas and parts of his dissertation in Bulgaria and also abroad (Germany and Yugoslavia), which earned him recognition in philosophical circles. The collection also shows how the authorities tried to influence intellectuals by providing them with particular attractive positions, which went hand in hand with periodic disincentives if they dissented. Zhelev was allowed to return to Sofia in (1972). He was then allowed to defend his dissertation and began to work as a scholar at the Research Institute for Culture at the Committee for Culture.

However, his book Fascism, which was published by the People's Youth [Narodna mladezh] publishing house in 1982, but written during his internal exile, provoked the government’s furor. In this work, Zhelev analyzed the totalitarian regimes of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Franco Spain. Without directly referring to communism, he presented obvious analogies. Three weeks after publication, State Security ordered its confiscation due to its "lack of a partisan class approach". Zhelev was removed from the Scientific Council of the Research Institute for Culture at the Committee for Culture. Additionally, the department he led was closed by a so-called “reorganization”. However, enough copies (approximately 6000) had been printed, allowing the book to circulate through unofficial channels in Bulgaria and abroad over the following years. The book received a large positive response.

In the following years, Zhelev continued to publish his works in samizdat form. At the same time, he earned the title of Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, although he criticized the aesthetic education programs of the Committee on Culture's in his work.

Around the beginning of 1988, Zhelev organized the first collective dissident actions. He participated in the organization of the Public Committee for the Environmental Protection of Ruse [Obshtestven komitet za ekologichna zashtita na Ruse]; he was co-founder of the Club for Support of Openness and Reconstruction [Klub za podkrepa na glasnostta i preustroystvoto]. He gave numerous interviews for radio stations such as Deutsche Welle, The Voice of America, Radio Free Europe and the BBC. He was among the dissidents who condemned the so-called Revival Process, i.e., the forceful assimilation of Bulgaria’s Turkish minority, which he called "one of the most terrible crimes" of the communist regime.

The collection includes a rich catalogue of materials demonstrating Zhelev’s important contribution to the non-violent transition from communist rule to a democratic multi-party system. In September 1989, Zhelev initiated negotiations between leaders of various informal movements to build a common coalition against the Communist Party. From these talks the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF) emerged in December 1989 as the first anti-communist coalition. Zhelev was unanimously elected its chairman. As chairman of the UDF, Zhelev participated in roundtable negotiations with representatives of the Communist Party about the transition towards parliamentary democracy (January–May 1990). In August 1990, the newly elected parliament elected him president and in January 1992, he became the first president of Bulgaria elected by popular vote. After the end of his presidential mandate (January 1997) he devoted much energy to fostering of regional and international cooperation.

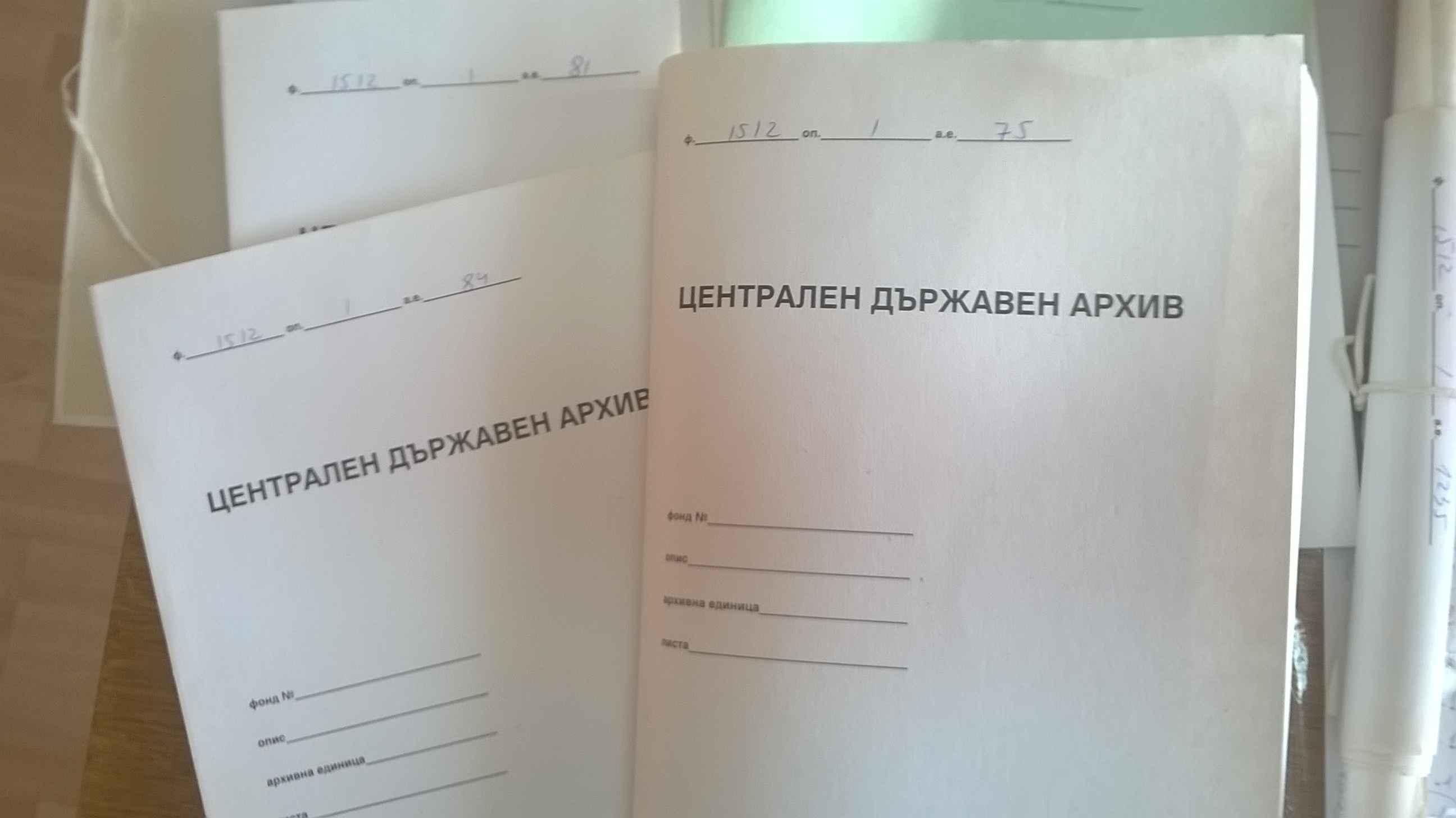

As a scholar, Zhelev was always conscious of the importance of documentation. The basis of the collection, thus, is his personal archive. Zhelev systematically preserved biographical documents, his scientific publications and related reviews, interviews and correspondence relating to his activity as a scholar and a politician, materials from his participation in dissident movements, etc. From 1996 until his death in 2015, the archive was kept by the Dr. Zhelyu Zhelev Foundation. The materials were used by the Foundation for its extensive work in developing national and international dialogue about the socialist past, about the nature of totalitarian rule, and about democracy. After Zhelyu Zhelev’s death, his daughter Stanka Zheleva donated Zhelyu’s personal archive to the Archives State Agency.

The collection is generally used by scholars. The materials in this collection allow one to understand the constant pressure put on scholars during state socialism but also examine the (then) emerging critical scholarly work on the regime. The collection reveals the state’s comprehensive control of scientific work through a centralized and hierarchical system. The collection is important for the study of the emergence of organized dissent in Bulgaria at the end of the 1980s and for the transition period from a communist regime to a democratic society.