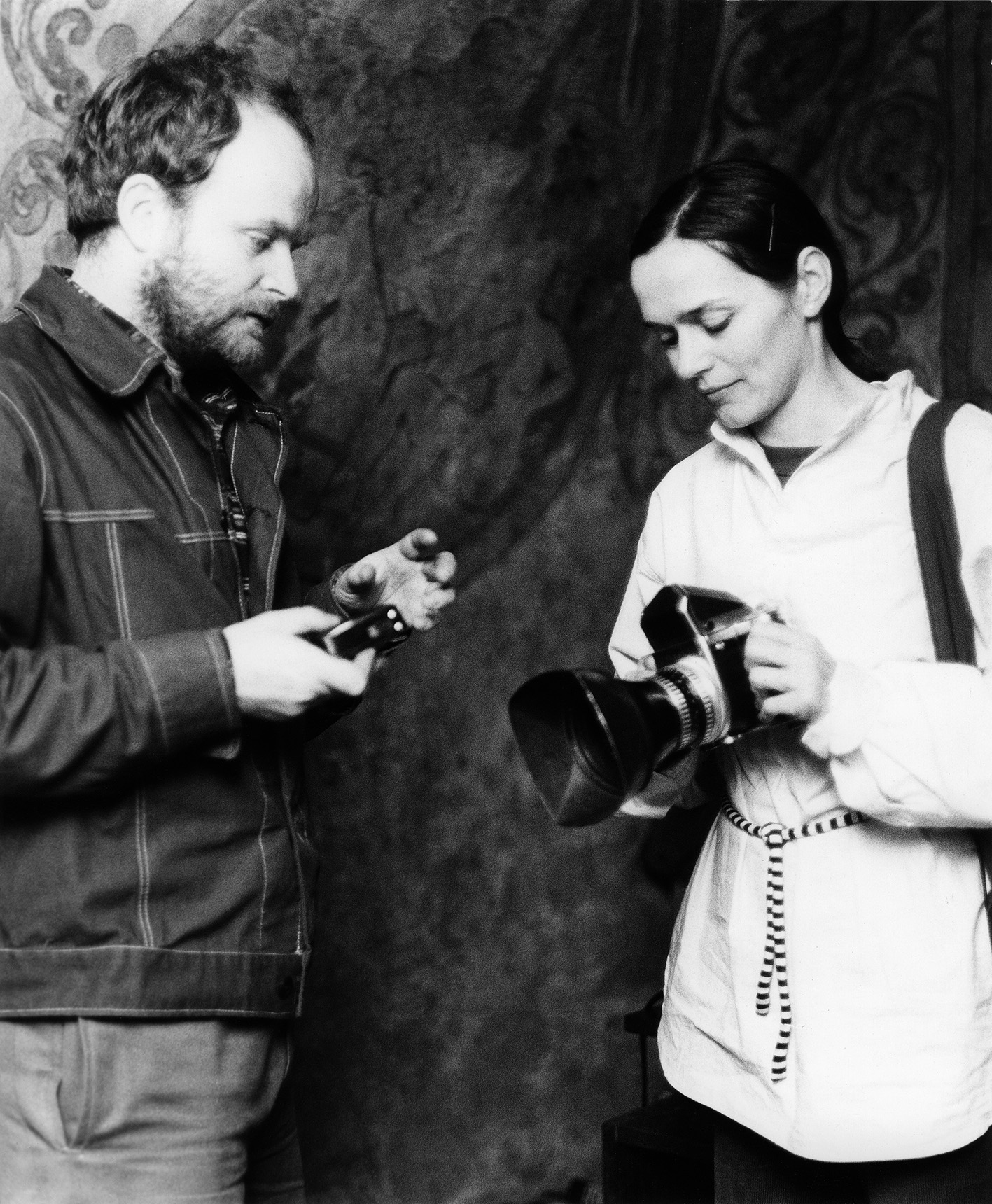

KwieKulik is an artistic duo of Zofia Kulik (born in 1947) and Przemysław Kwiek (born in 1945). In the years 1971-1987 they created process art, performance, and conceptual art, with politically engaged and critical undertones.

Simultaneously, since the late 1960s they regularly documented the artistic life of Poland, focusing on ephemeral phenomena.

Kwiek and Kulik were under particularly deep influence of Oskar Hansen’s theory of Open Form, which stressed the importance of finding a language to comment on or translate visual forms. Hansen proposed terms such as: dynamic and static, light and heavy, open and closed. In this last distinction, the “open” form describes such architecture, that becomes a “background for events”, accentuating the presence of people and their activities in space. „Open form” is indefinite, variable, and it incites collective participation, while bringing forward and setting the framework for individual expression and subjectivity. „Closed” forms, on the other hand, aggressively loom over their vicinity, are difficult to modify, and dominate the people around them. The milieu set around Hansen and Jarnuszkiewicz moved on from discussions on sculpture and architecture to games and conversations, employing exclusively visual means and gestures. They continued those games in plein-air, and eventually on public space. KwieKulik were among the firsts to record on camera these visual games and dialogues. These games could well take place in their private apartment or on the face of a popular actress (Game on an Actress’s Face). Once even the son of the couple, Dobromierz, became a “pawn” in such a visual game (Activities with Dobromierz).

Other notable examples of experimental methods of artistic work pursued by KwieKulik, aside from the visual games, include “interactions” (współdziałania), “provocation with the camera” (prowokowanie kamerą), “interrupted projection” (projekcja przerywana), and “activities for a camera” (działania dokamerowe).

All these terms introduced by KwieKulik described unscripted processual, collective and performative activities which often engaged random passers-by, and which usually left behind a photo or film registration.

They have also elaborated their own form of appropriation art, which they referred to as “parasitic art” or “commentary art”. During art events they composed space arrangements of other artists' sculptures and they made interventions in other artists’ short films (Activities with One-Minute Films).

Clearly Kwiek and Kulik had inclinations for conceptual work, i.e. devising their own repertoire of artistic techniques and their own language to describe art (the Kwiekulik Dictionary was placed in a monumental book summarising their artistic career).

They drew inspiration for their activities from contemporary developments in scientific and theoretical research in cybernetics, IT, miniaturisation, automation, and praxeology (the theory of acting efficiently).

Kwiek and Kulik did not perceive the Party, the organisations it sanctioned, nor the entire state as a hostile regime. On the contrary, they demanded it functioned accordingly to the official, progressive declarations. They expected democratisation, openness, and modernisation, and did not refrain from formulating their requests and criticism in official letters, which they kept sending incessantly. They also used their clashes with institutions in their art.

The artists however came to develop a highly critical opinion regarding the functioning of the institutions of the Polish People's Republic. In their actions, on many occasions they made reference to the material poverty of life in communist Poland, and they used the national flag and the red banner.

The artistic career of Przemysław Kwiek and Zofia Kulik saw two major turns: the appearance of the Neue Wilde movement, which returned to the individualistic, irrational, art for art’s sake ethos, and then the downfall of Polish People's Republic, and the shift in public discourse towards market and conservative values. Both of these phenomena contradicted the vision of doing art and the worldview of the duo. Moreover, they noted that other artists began to pay greater attention to documenting their own art. All this contributed to gradual suppression of their artistic activities

In 1987 Zofia Kulik concluded her artistic collaboration with Kwiek and started her own independent artistic project. She abandoned the open form and performative actions. In a way, her work became the exact reversal of notions and ideas that had represented her activities as a duo. Instead, she began to create “closed forms”, such as photographic collages, which were static objects, “closed” to any interference by others, while visually mimicking the ordered, hierarchical, organised, and ornamental patterns of cathedrals, altars, oriental carpets, and paintings of kings. Her works were created using a technique of multiple film exposure. They were composed of hundreds of photographs of symbols of totalitarian and military violence, as well as male human bodies twisted in a peculiar alphabet of gestures (e.g. The Gorgeousness of the Self). These works gained substantial recognition in the 1990s and were interpreted i.a. from the perspective of feminist theories.

The popularity of Zofia Kulik’s new project rekindled interest in the activities of the duo, as well as in the Archive.

Today Zofia Kulik continues her archiving efforts under the brand of Kulik-KwieKulik Foundation.