Concepts

- subculture

- punk

- propaganda fanzines

- censorship

- deviances

Competences

Throughout the course and the activities the students should:

- get acquainted with the main spaces of the underground music scene and its representatives in the socialist period, particularly the punk movements

- review the context of the music culture of the period, focusing on their own country

- understand the mechanisms of censorship, banning and surveillance.

- understand the complex interactions between the willingness to conform and being in opposition

- understand the aspirations of the bands, and learn the variations of opposition in the area of music

Attitudes: students should

- be open towards the artistic attitudes towards to music

- be able to analyze the relationship between musicians and power under socialism

- be able to appreciate the autonomy of art and music

- be able to appreciate the forms of opposition against the constraints of the party

Skills: students should

- be able to find information related to punk music life, focusing on their own country

- be able to recognize the characteristics of resistance in the works

- be able to effectively browse the database

by Barbara Hegedüs

Punk

Punk refers to both a music genre and a subcultural (e.g. diverse from the majoritarian culture) movement. Punk emerged around 1975-76 in London and New York, which is when the British group Sex Pistols and the American group Ramones were formed, and when Patti Smith, the “godmother of punk,” who had a deep impact on the Central European scene, had begun her career. The music and the sense of life attached to it became popular primarily among the dissatisfied youth who had been afflicted by the economic crisis and unemployment – they wanted to act out against the institutionalized social, cultural and musical norms. The movement refused popular culture, conservatism, hippism, and proclaimed an anarchistic social order. Anger, nonconformist thought, subversive attitudes and provocative clothing were among it its typical features. Punk music can be characterised by simple structural forms and an aggressive stage behaviour.

Punk in the socialist countries

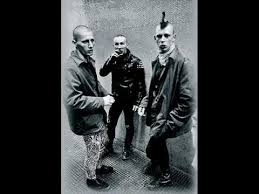

Despite of the precautions of socialist state powers, the movement infiltrated the East and Central European countries at the end of the ’70s and early ’80s. The punk generation had grown up in the socialist system and therefore took its structure for granted. At the same time, they faced a stubborn silence from parents when it came to questions of the past, which only increased their curiosity. Punk youngsters wanted to challenge the existing order – they declined the apolitical attitude of the older generation, declined civil obedience and state control, and were looking for possibilities for a different life. Their provocative clothing, which represented their integrity, followed western trends – they wore ripped clothes, boots and worn leather jackets. A mohawk hairstyle was common, as was a safety pin for jewelry.

From the beginning, authorities saw the threat of “Western hooliganism” in this phenomenon and tried to control it in various ways – they tried to discredit the bands and their fans in the media, while the police held power demonstrations and the concerts were watched by the state security. Informants were also deployed in the bands or in their peripheral environment. If the police considered it necessary, they shut down the concerts, arrested the audience or the band members, or in extreme cases they even brought them to trial, which could result in the musicians going to prison. The provocatively dressed youngsters risked their further education and even their employment – they were exposed to constant harassment in the streets or at school and they were asked for verification of identity at every step.

Bands

Even though the political climate of the ’80s in Central and Eastern Europe was characterized by a general softening, due to the rebellious attitude of the movement, the punk groups were constantly exposed to retaliation. The first groups in Poland were formed in 1978: The Boors, Kryzys, Tilt , Deadlock in Warsaw, and Speedboats in the so-called Tricity (Gdańsk, Sopot, Gdynia), and the Poerocks in Wrocław. Initially Polish punk was tightly connected to neo-avant garde artist groups, student clubs and art galleries, and was less concerned with politics. Punk became a mass movement in Poland from the early ’80s after the introduction of martial law. Several pioneers of the movement emigrated abroad due to the increasing control of the authorities, while Brygada Kryzys (Crisis Brigade) was banned due to the authorities objecting to its name. The Czechoslovakian band FPB used several stage names to confuse the permanent surveillance of the secret police.

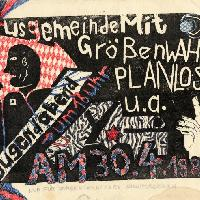

In the GDR, the authorities prioritised the handling of the “punk issue”. The East German secret police, the Stasi, regularly observed and interrogated the musicians, and placed informants among them. The group Planlos (Planless), formed in 1980, was one of the first punk groups in the GDR. Its frontman Michael Boehlke later told of the constant police harassment in several interviews. Schleim-Keim was formed in 1981 and co-operated with other musicians at the recording of the first punk album in the GDR, DDR von unten (GDR from below 1983). The album managed to reach West Germany where it achieved some success, but in the GDR it was only distributed via copied cassette tapes. The Stasi was aware of the production processes, however it interfered only after the album had been completed. Two members of the Schleim-Keim, Klaus and Dieter Ehrlich, were arrested, while Dimitri Hegemann was forbidden to leave the territory of the GDR.

In the GDR, the authorities prioritised the handling of the “punk issue”. The East German secret police, the Stasi, regularly observed and interrogated the musicians, and placed informants among them. The group Planlos (Planless), formed in 1980, was one of the first punk groups in the GDR. Its frontman Michael Boehlke later told of the constant police harassment in several interviews. Schleim-Keim was formed in 1981 and co-operated with other musicians at the recording of the first punk album in the GDR, DDR von unten (GDR from below 1983). The album managed to reach West Germany where it achieved some success, but in the GDR it was only distributed via copied cassette tapes. The Stasi was aware of the production processes, however it interfered only after the album had been completed. Two members of the Schleim-Keim, Klaus and Dieter Ehrlich, were arrested, while Dimitri Hegemann was forbidden to leave the territory of the GDR.

The authorities did not spare L’Attentat (founded in 1983) either. Two members of the group, singer Berndt Stracke and bass player Maik Reichenback were arrested and sentenced to prison. It was revealed only after the regime change that Imad Majid, guitar player of the band, was responsible for the imprisonment of Reichenbach and Stracke, as a non-official employee of the Ministry for State Security.

Within the Soviet Union, punk culture first became popular in Latvia. The first punk group, Akla Zarna (The Blind Gut) was formed in 1985, but in 1987 the band changed the name to Inokentijs Marpls. They, along with other members of the punk movement, were constantly abused by the authorities: a TV program on Inokentijs Marpls was even censored as late as 1989.

The first Yugoslavian punk groups were formed in Slovenia (Pankrti, 1977) and Croatia (Paraf, 1976). Czechoslovakian punk had been launched by the group Extempore, with its 1979 song Libouchec in which Mikoláš Chadima uttered the word “bullshit” from the stage, leading to fury from the socialist authorities who then wanted to imprison him. An Energie G concert was stopped, and the band dissolved due to the constant abuse of the police.

The first Hungarian punk band Spions was formed in 1977, and altogether performed three concerts in Hungary, two of which were shut down, citing technical difficulties. The frontman of the band, Gergely Molnár, who later emigrated to Canada, was under permanent surveillance – his English teacher, for instance, was instructed to overload him with homework in order to prevent him from taking part in subversive activities.

The music of Auróra, a band from Győr, was banned because of its anti-systemic lyrics and they received several official warnings from the authorities. The concerts of the group Vágtázó Halottkémek (VHK) were shut down a number of times, they were under close surveillance, and comprehensive reports were written on them.

Probably the most notorious story was connected to the CPg (Come on Punk Group), a band from Szeged who angered the authorities from the beginning with their radical anti-communist lyrics. During a concert, when the audience ripped a chicken being used as a show element into pieces, the members of CPg were arrested and sentenced to 2 years in prison for incitement. In 1984, members of Közellenség (Public Enemy) from Veszprém followed in their footsteps and were sentenced to prison for truculence and for offences against the state.

In Romania, powerful state control made it difficult for the “harmful” punk subculture to emerge. A few bands were formed in Craiova – Terror Art and Antipro for example – and they were under surveillance from the secret police from the very beginning. Several band members were arrested and some were tortured during interrogation.

In the socialist states, punk musicians could never release a record legally. Russian bands Avtomaticheskiye udovletroriteli and Grazhdanskaya Oborona were not able tot release a single record, despite their popularity. Their home recordings were distributed as samizdats – just like the music of the Bulgarian band Novi Tsvetya, founded in 1979.

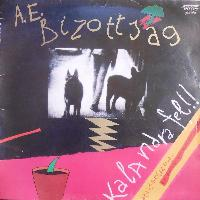

Nevertheless, the more “subtle” versions of punk were eventually legalized by the authorities. The Polish band Tilt, for example, played at official festivals and were able to release a record. The Hungarian group Bizottság (Committee) consisted of artists, and substituted the anger and frustration of punk with elements of humour and the grotesque. They became so popular that they were eventually approved of by the cultural policy of the authorities, although they were forced to make a compromise – they had to change their name due to the dangerous reference (to the Central Committee), which they extended to A. E. Bizottság (A. E. being Albert Einstein).

Nevertheless, the more “subtle” versions of punk were eventually legalized by the authorities. The Polish band Tilt, for example, played at official festivals and were able to release a record. The Hungarian group Bizottság (Committee) consisted of artists, and substituted the anger and frustration of punk with elements of humour and the grotesque. They became so popular that they were eventually approved of by the cultural policy of the authorities, although they were forced to make a compromise – they had to change their name due to the dangerous reference (to the Central Committee), which they extended to A. E. Bizottság (A. E. being Albert Einstein).

By the end of the ’80s, at the time of the perestroika proclaimed by Mikhail Gorbatchev, clashes between the authorities and the artists became rare. This moderation can be illustrated by the success of the Soviet group Zvuki Mu, who played a combination of alternative rock and post-punk, and whose album in 1989 was produced by Brian Eno, former member of Roxy Music.

Punk scenes

Clubs

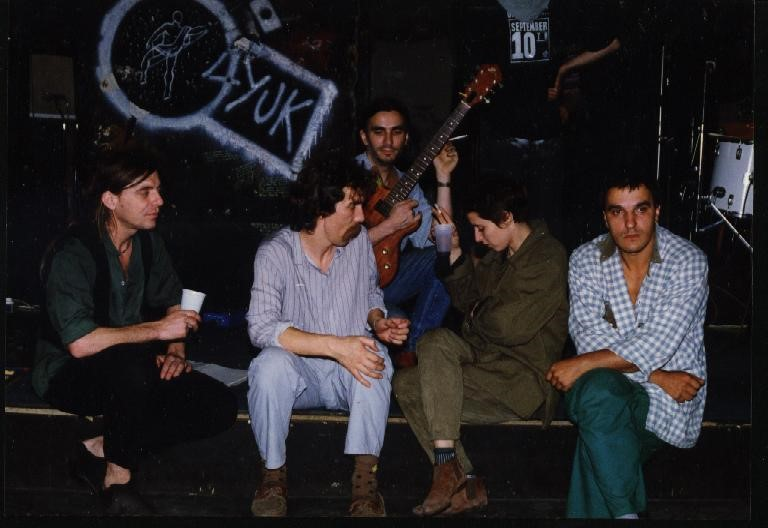

Punk bands of the socialist era were primarily provided with an opportunity to play by alternative clubs. A concert of the British band Raincoats was organized in the Remont Gallery in Warsaw, lead by Henryk Gajewski – it took place on the 1st of April 1978, andis considered to bethe overture of Polish punk. Remont was shut down in 1979, after which Gajewski opened Post Remont, focusing on education and alternative subcultures instead of exhibitions. After Gajewski emigrated, the student club Hybrydy became the primary venue of the Warsaw punk scene.

There were three alternative clubs in Slovenia that accommodated the punk subculture (their story is documented by collection FV 112/15). The Disco Študent / Disco FV (1981-1983), the Šiška Youth Centre (1983-1984), and the Kersnikova 4 (K4) (1984-) all frequently hosted hardcore punk, heavy metal and DJ-nights. These clubs also organized theatre performances by FV 112/15 and shows by the band Borghesia (lead by Neven Korda), who also considered their performances as a type of punk theatre.

In Czechoslovakia, the Prague Jazz Days, organized in May and November of 1979, was the first festival where punk bands were permitted to play, and many new bands formed after being inspired by the festival. At the end of the ‘80s, however, the authorities started a comprehensive attack: unwanted bands were banned and blacklisted and punks were assaulted both by the police and the media. Nevertheless the movement could not be stopped, for further groups had been formed, this time also outside the capital (F.P.B, Visaci Zamek, Plexis, Zóna A stb.).

The Fekete Lyuk (the Black hole) opened in 1988 and was the most significant alternative club in Budapest around the regime change. It became a cult place, even in its own time, for its clientele enjoyed a relatively great freedom, although the presence of the police was constant. The stage of The Fekete Lyuk peacefully accommodated various musical genres – the punk scene had relocated there after the punk club in Kispest was shut down. Bands such as Auróra, VHK, Trottel, Hisztéria and the Bizottság regularly performed at Lyuk.

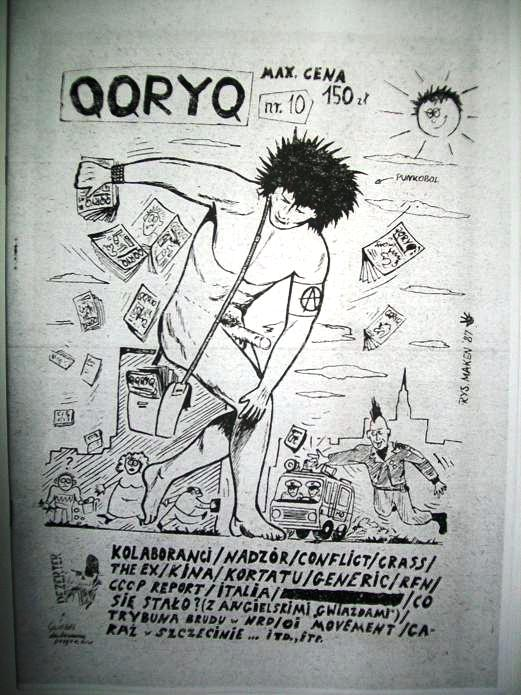

Magazines, fanzines, collections

Fanzines are amateur paper publications produced by literature, music or film fans. The first punk fanzine in Poland, entitled QQRYQ, was started by Piotr ‘Pietie’ Wierbicki in 1985. Its first and second edition were unsuccessful, but 50 copies of the third edition were distributed , and it gained a high number of collaborators, correspondents, distributors and readers. QQRYQ, together with Antena Krzyku from Wroclaw, soon became among the most influential hardcore punk magazines in Poland. Wierbicki also founded a huge private collection, containing cassette tapes, articles and fanzines from the 1980s.

The art album Polski punk 1978-1982 contains photos, fanzines, flyers and notes on the leading figures of the first wave of Polish punk. Polish punk, published in 1000 copies by photographer Anna Dąbrowska-Lyons in 1999, sold out in the blink of an eye. Dabrowska-Lyons plans to publish a second edition in 2018.

The art album Polski punk 1978-1982 contains photos, fanzines, flyers and notes on the leading figures of the first wave of Polish punk. Polish punk, published in 1000 copies by photographer Anna Dąbrowska-Lyons in 1999, sold out in the blink of an eye. Dabrowska-Lyons plans to publish a second edition in 2018.

Substitut in Berlin is the largest archive on the punk subculture in the GDR, founded by Michael Boehlke, a member of the band Planlos. Substitut contains songs, posters, flyers, collections of lyrics, typical punk clothing and paintings.

The Tamás Szőnyei’s Poster Collection includes documents of alternative life in Hungary in the ’80s, particularly the new wave and punk movements.

Documents of punk life from the ebra can also be found in the collection of Ferenc Kálmándy, as well as in the collection of historian Gábor Klaniczay.

The photo collection of Fortepan, containing photo documents of the 20th century, is of great importance, since it provides free access to the photographs. Fortepan possesses a large number of photographs of the everyday life of the underground and of the punk movement.

The photo collection of Fortepan, containing photo documents of the 20th century, is of great importance, since it provides free access to the photographs. Fortepan possesses a large number of photographs of the everyday life of the underground and of the punk movement.

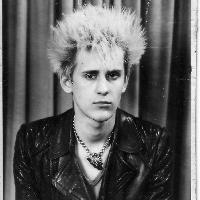

Exhibitions

Journalist and photographer Anna Dabrowska-Lyons was among the most important figures of punk circles in Warsaw. Although, by her own accounts, she was never under surveillance and was never censored, she emigrated to England in 1986. Her portrait photos of the first waves of punk were first exhibited in 1983 in Warsaw.

Dabrowska focused on the expressions of emotion on the faces and of the atmosphere, not on the externalities of these movements.

With the exhibition Fuck 89 in ADA, the alternative cultural centre presented the anarchist-punk movement of Warsaw in the years of transition. The exhibition primarily showed photos, flyers, brochures and fanzines, and was accompanied by concerts, talks, workshops and film projections.

The exhibition Warsaw Punk Pact took place in Leipzig in 2017, and aimed to celebrate the forty years of punk in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. The exhibition was concluded by talks, presentations and film projections.

Exhibition ostPUNK! – too much future was launched in 2005 in Berlin, and was later presented in Dresden and Halle. The scenario of ostPUNK! was written by Michael Boehlke and Henryk Gericke, former singer of the band Leistungsgleichen. A documentary film was produced with the same title in 2007 in collaboration with Carsten Fiebeler, presenting six former punks telling stories of their lives. In March 2018 in Rijeka, an exhibition was organized on the Croatian punk band Paraf. Journalist Velild Dekic had collected several photographs, album covers and other documents on the band. The graffiti made by the band members in 1977 one of the staircases in Rijeka has been proclaimed protected as a cultural relic.

Punks not dead

By the end of the eighties, the raw indignation had calmed down and punk subculture had lost its significance. The movement, however, lives on in Central and Eastern Europe, representing not so much a political, but rather a musical trend, frequently combined with other genres (rock, metal, hardcore, rap).

Exercises: Courage and film festival

Have a look at the first piece of Tamás Szőnyei’s poster collection!

Who was Anna Frank and what did the ‘No future’ slogan represent?

Watch the film Bp underground until the 11th minute and answer the questions!

a.) What was the relation of the authorities to the punk scene of the ‘80s, and how did they relate to the authorities?

b.) What can you learn about the relationship between skinheads and punks?

c.) How can the appearence of the punk groups be characterized?

d.) Who was Péter Erdős, mentioned in the CPg song?

e.) What was the misconception related to the abbreviation CPg? What could have been the reason for that?

In which temporary band did three members of the Bizottság play together? Look up the solution in the COURAGE database!

Prepare a presentation of Fekete Lyuk! Watch the relevant detail from the film Bp Underground (from min 8.)!

What did rebellion through music mean in Romania, with one of the most repressive systems of the socialist bloc? Check the work of Andrei Partoș in the COURAGE database!

True or false? Find the answers in the COURAGE Registry! If the answer is false, find the correct answers.

The exhibition Infernal golden age borrowed its name from a song by the group ETA.

Historian Gábor Klaniczay, who was among the key figures of the opposition, highlighted in a paper that the best moments of Hungarian new wave had not been documented, thus, paradoxically, a more comprehensive documentation on it has been produced by the surveillance of the police and the secret service.

Underground music is underrepresented in the Hungarian Rock Museum.

The anarchy symbol can be found on the flyer of the band Kryzys Romansu.

The anarchy symbol can be found on the flyer of the band Kryzys Romansu.

The short movie I Could live in Africa is about a punk band called Izrael.

At the beginning of a class:

Listen to a punk song (e.g. UMCA by CPg, a concert recording by VHK, Kinderkrieg by L’Attentand, J.M.K.E. – Tere Perestroika), which has been written in a language you don’t know. What does this song say about the state of mind of the authors?

What kind of subcultures do you know of besides punk?

Find out about the exact meaning of ‘anarchy’! Prepare a presentation about it!

What do you think you could rebel against today? Write lyrics about it in a ‘punk mood’! If you can play a musical instrument, write the music for it, too!

Watch the entire Bp Underground! How is punk related to the hardcore style? Find out about it and prepare a Powerpoint presentation!

Have a look at Tamás Urbán’s photos on punks on the Fortepan! Impersonate the people on the pictures! Two people can join them from the viewpoint of a policeman and an outsider (e.g. a person sitting in a car)!