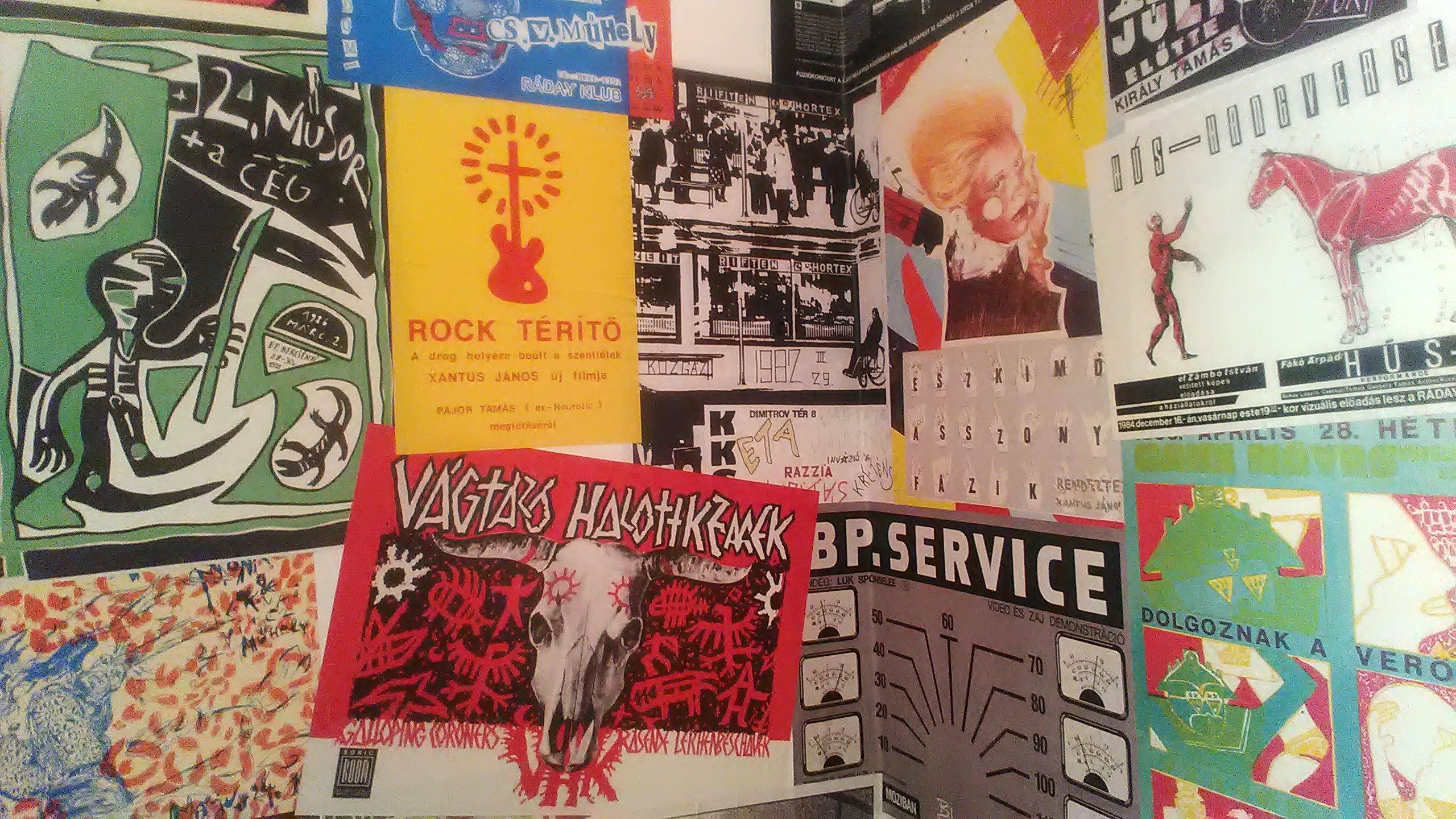

Tamás Szőnyei’s private poster collection documenting the underground music scene of the 1980s is one of the largest of its kind in Hungary. He received the first poster from his brother in his early twenties in 1978, and became fascinated ever since with the visual world of new wave and art punk (these are sometimes synonyms in the Hungarian context). Szőnyei became a journalist of pathbreaking music reviews documenting and commenting on the events of the emerging new wave and punk subculture. Naturally, he was very much present in the underground scene.

In the 1970s and 1980s, posters were a particularly important way—in most cases practically the only—to inform the potential audience of a forthcoming concert. This resulted in a proliferation of posters on the streets, universities, dormitories, and every place where young people were expected to pass by. Most of them were offset prints, though serigraph prints, graphics, and photocopies were also present. It was largely an illegal activity. One needed permission from the state advertisement agency (MAHIR) to post any kind of advertisement, but the majority of these bands (themselves playing without permission) did not have such authorization. The police made photos of placarded underpasses, forwarded these to MAHIR, which then made attempts to fine the bands and the clubs where the concerts took place. The phenomenon was so widespread and the walls were so full of posters of the most various type and size that it was generally not particularly risky to post these during the night, even though the police could technically arrest people for “wild posting.” The monetary punishment, however, could accumulate. The number of posters of the underground scene that the Archive of the Hungarian National Széchényi Library holds are very low, also suggesting that most of these posters were printed illegally. Placarding was most often done by members of the band themselves: their resources were rather limited and the mentioned citations could mean a serious consequences in their professional career.

Szőnyei always held a little scalpel in his pocket: he enriched his collection by taking off the posters from the walls with this handy tool. He also received donated posters, but the majority of the collection is from the streets. He gave up systematic collecting with the evaporation of punk subculture in the early 1990s. Occasionally, he still adds posters or flyers to the collection if the given item’s visual culture resembles that of the 1980s.

The posters are artworks as well as significant sources for historiography because there are few sources from which the history of the Hungarian underground can be reconstructed. There were no official magazines devoted to this subculture, and fanzines were less comprehensive and shorter-lived than their Western counterparts. The magazine Poptika launched by the Communist Youth Organization (KISZ) in 1982 was immediately closed down after publishing its first issue. Part of the editorial board started the independent magazine Polifon in 1985 that covered all music genres, but its permission was rescinded after a couple of issues. The proofreader of Polifon, Sándor Szilágyi, was one of the editors of Beszélő samizdat journal and a well-known representative of the democratic opposition. His name appeared nowhere in the magazine, but it is possible that his involvement was known by the secret police, which might have contributed to the termination of the periodical. It is ironic that one of the most useful sources lacking in the West for documenting the underground music scene, is precisely the reports prepared by the secret police, who developed an interest in the emerging movement from the 1970s. Still, the posters provide a unique insight into the changing landscape of urban youth culture.

Posters were often prepared by the musicians themselves. The actors of the new wave scene were usually active in multiple genres and created hybrid artwork in a decidedly heterogenous style. A certain kind of proud amateurism characterized their music and performances as well, and on the posters refined artistic design was often combined with visual gestures suggesting a homemade character. In punk subculture these posters were indeed prepared most often by unskilled designers. As the art historians Mónika Zombori and Anikó Katona point out, another feature was that the posters tended to undermine the primary purpose of the genre: providing full information on the event. This was not always motivated by purely artistic considerations. Creators of the posters sometimes applied various methods to prevent law enforcement from cancelling or surveilling the events. Posters with information that could be decoded only by fans were by no means rare. For instance, one of the most popular punk bands, VHK (the acronym of Vágtázó Halottkémek, “Galloping Coroners”), that particularly irritated the political police, promoted their concerts under the alias SVIHÁK, making a language game out of the letters V, H, K.

Zombori traces the origins of the new wave posters to the band Spions (founded in 1977) and the poster prepared for their first concert in January 1978 (which appears in the COURAGE Registry as a featured item) as well as the advertisements by the artist and musician Sándor Bernáth(y). Bernáth(y) was also the person behind the revitalized image of the cult band Beatrice. The real inauguration of the new wave, however, happened in 1980, when the popular self-proclaimed punk band Beatrice invited the just formed Bizottság (Committee) to debut at their concert as a supporting act in front of tens of thousands of people. This had a rapid effect on the emerging music scenes, especially the new wave. Significantly, Ifjúsági Magazin (Youth Magazine), the monthly of KISZ addressing teenagers, reported on this event with sympathy.

This happened at a time when KISZ modified its cultural policy and decided to offer official space for some of the new subcultural trends in order to keep developments under control and try to influence more effectively the political views of the youth. Hungaroton, the state-owned music label (that is, the only one allowed), also negotiated with some of the bands on the edge of legality about releasing an album. Hungaroton was in a special position, for it had to respect political requirements, but at the same time make a profit. Therefore it started to support a few new wave bands that were less outspoken and experimental, like KFT, which was even allowed to tour in the West. The official and the underground scenes were not strictly divided. For example, György Soós, Sándor Bernáth(y), András Wahorn, and János Vető, who were among the best poster designers for the alternative bands, also designed album covers for Hungaroton. György Bp. Szabó had a major role in shaping the image of Petőfi Csarnok, one of the most popular concert venues in Budapest. The majority of the bands however had no hope to release an album officially, and their music was distributed only on samizdat tapes. It is no surprise that a song by the band CPg (Come on Punk group) with the title, “Péter Erdős, You Son of a Bitch!” gained popularity in the underground: it referred to Hungaroton’s top manager under late Socialism, who ultimately decided on the fate of musicians’ careers. Members of CPg were imprisoned because of the anti-communist message of their songs performed on stage.

Nonetheless, some of the suppressed bands were noticed in the West. In January 1981, the

New Musical Express magazine devoted a report to the Prague and Budapest nonconformist music scenes. Having heard about this, fans were euphoric. This seemed to be a much more significant success and acknowledgement of their favorite bands than the reported Western popularity of the few darlings of Hungaroton, perceived to be a result of state orchestrated manipulation. Genuine interest by Western representatives of new wave and punk gradually grew in the 1980s, and a couple of albums were released in Western cities by bands who did not have this possibility in Hungary, like the mentioned VHK. Also, more and more Western performers visited Hungary, especially after the Budapest Sportcsarnok opened in 1982. Contacts across the Iron Curtain that avoided strict state control became more frequent, and with the spread of the compact cassettes that were easily copied, music became much more accessible for an Eastern European audience. By the end of the decade, amateur labels appeared and offered self-released cassettes; some even survived the regime change.

The 1990s brought about a significant change not only in politics, but also in terms of concert advertisements. The former posters of A4 and A3 size were replaced either by larger placards or smaller flyers. The latter could be found not on the walls and lampposts anymore, but in art cinemas and pubs, and the former found their way to official advertising surfaces. Their design also changed, and computer graphics became increasingly dominant. As Tamás Szőnyei recently observed in an interview with the Hungarian weekly

HVG, the do-it-yourself attitude of the 1980s is being reborn on the internet, especially on social media sites.