The Folk Dance House Movement as cultural opposition?

The spectrum of those activities, events, and organizations, which supported and resuscitated the folk dance, folk music, folk art or another part of the folk culture, is uniquely broad in Hungary. These activities were an essential part of the Folk Dance House Movement, which started in the 1970s. The Folk Dance House Movement created the “dance house” method to save the most valuable elements of Hungarian folk dance culture. The practice became one of the aspects of the National Register of Best Safeguarding Practices of UNESCO in 2011.

During the socialist era, the Folk Dance House Movement was an alternative opportunity for entertainment, and in some cases it came to be considered “tolerated” or “banned” by the culture policy of the Kádár regime. Béla Halmos documented the movement from the beginning, and he collected folk music and folk dance materials too. First, he had his private archive, and in 1999 the Folk Dance House Archive was created. Like the Folk Dance House Archive, Ferenc Bodor began to collect information in connection with the Nomadic Generation. In the personal bequests of Ferenc Kiss, Sándor Csoóri, László Nagy, Imre Makovecz and others we find valuable information about folk culture under socialism.

Folklorism – The Folk Dance House Movement

The discovery and the reinterpretation of peasant culture (like folk poetry, folk song, folk music, folk dance, folk customs and folk art) and, furthermore, the process of folklorism appeared in the first part of the nineteenth century as the part of national political movements. Folklorism as a form of cultural opposition often was part of the ideology of political, cultural, intellectual changes, as well as a kind of authority used for its actual aims. The antecedents of the Folk Dance House Movement were theories which wanted to use folk culture in contemporary culture. This attitude appeared at the beginning of the twentieth century among the members of the Gödöllő Colony of Artists. They were the earliest Nomadic Generation use parts of peasant culture in different ways than during the nineteenth century. In the interwar period, revisionist movements and the political era used the folk (peasant) culture as an expression of national consciousness. Folk culture appeared on the “stages”: political figures, fashion designers, and artists used and reinterpreted it. On the other hand, there were intellectuals and ethnologists like István Györffy. who wrote about similar methods to the folk dance house movements which were able to teach and use folk culture in different ways than the aforementioned movements.

After 1948, when the political system changed in Hungary, the cultural policy adopted a very different attitude to peasant culture. The government followed Soviet methods and wanted to efface peasant culture. On the other hand, the political era wished to use folk culture as a basis of socialist culture. They established new institutions like the Folk Art Institute in 1951, which was lead by Jenő Széll until 1955. It aimed to collect folk culture artifacts and to teach the new socialist folk culture to the people. Though the institute was established during a time of radical political and cultural change, the staff collected and researched peasant culture as had been done in the 1930 and 1940s, so they used the previous scientific/political methods. The main idols were Zoltán Kodály and István Györffy, so the members of the institutions were also the part of the cultural opposition. In 1956, the name of the institution was changed [Népművelési Intézet], and in 1958, it was closed. In the Népművelési Intézet, László Vásárhelyi and Iván Vitányi also wished to support the professional and scientific research. The Népművelési Intézet and György Aczél, who was responsible for social policy under Kádár, also supported the youth club movements, so the Folk Dance House Movement and the Youth Folk Artist's Studio were in special connection with the government.

The role of the folklore (principally the folk song) in modern culture and the viability of the folk song as a contemporary genre were controversial questions among intellectuals at the end of the 1960s. The members of the Népművelési Intézet also expressed their opinions about these issues. Some of them started to bury the folk songs and thought that the new folklore would be based on beat music, while others supported the theory that the folk song is also famous and had value for the people of the time. The latter opinions were verified by the popular tv shows, “Nyílik a rózsa” [The rose opens] and the “Röpülj, páva!” [Fly peacock].

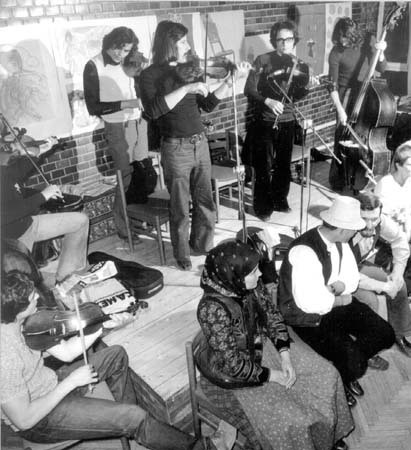

After these antecedents, a group of urban youths discovered the archaic, traditional folk culture and tried to popularize it in the 1970s. One side of this was the Dance House Movement. The main supporter and organizer of the Dance House Movement was György Martin, and in 1972 they organized the first dance house in the Kassák Club. They invited dancers from Szék (or Sic by its Romanian name); the musicians were the recently founded Sebő Group. Originally, this event was private, but given the broad interest with which it was met, the organizers opened the dance houses, so original peasant culture became the part of urban culture.

The other side of this came with the foundation of the Fiatalok Népművészeti Stúdiája, or Studio of Youth Folk Art. It was an interesting group which included musicians and builders, and they called themselves Nomadic Generation, drawing the name from the title of a novel by Sándor Csoóri entitled “Nomad’s Diary” [Nomád Napló]. The members of these groups knew one another, and some of them belonged to both organizations.

This folklorism movement became more and more popular and had a special concept of tradition too. The members of the movement thought of the folk culture in different ways, and they wanted to learn and use the original folk culture which had not been influenced by socialist ideas, motifs etc. In other words, they wanted to restore the voice of tradition. The members of the movement organized film clubs and literary and theatrical lectures, and they liked beat music too, so they sought ways to express critical opinions of the political system. The main characters of the movement were József Zelnik, Sándor Csoóri, Ferenc Sebő, and Béla Halmos. The folklorism and the dance house movement were common identities which constituted a form of cultural resistance to the politics of the era; they were part of a lifestyle. They provided fora for the expression of new opinions and ideas as alternatives to what was seen as vapid mass culture. They also gave new meanings to the words “festival,” “celebration,” and “community.”

Thanks to these movements, members of the younger generations were able to get information about the Hungarian minorities in the neighboring countries. This is why the members of the folklorism and dance house movements were often called nationalists. Sentiments of national belonging and the desire for freedom seemed dangerous in the eyes of power. This is why, beginning in 1974, the regime became to become increasingly intolerant of these movements and began to harass and censor the organizations and individuals in question. The political system tolerated the gatherings where people sang and danced, but the ethnographical, sociological, and political classes were banned, and in a dance house, people were only allowed to dance and play folk music. The journals Tiszatáj [Landscape of Tisza] and Kritika [Criticism] published discussions about the movements.

It is an interesting to ask how the members of the movement thought of themselves. If we consider the interviews which were done with members of Nomadic Generation and people who were somehow connected with the Dance House Movement, we can see that they had many romantic, innovative ideas which ran contrary to the accepted political attitudes of the era. Ferenc Sebő called “it was a sort of romantic revolution.” The connection between the dance houses and the government was a paradox. The distrust was made policy, and constant watch was kept on the participants on the movement. The government often took sanctions. Fortunately, György Aczél and Iván Vitányi supported the movement.

On the other hand, many people did not get passports. This was not extraordinary even in the 1980s. Márta Sebestyén, the famous Hungarian folk singer, was 17 years old in 1974 when she got the Young Master of Folk Art award and was invited to Bulgaria with the Sebő Band. However, she did not travel because she was not given a passport until they had traveled to Russia.

The members of the Folk Dance House Movements were bound up with the oppositional cultural movements. In these groups, mavericks were frequent guests. Those who were called nationalists became members of the Hungarian Democratic Forum, a conservative political party. They were targets of secret observation and were known as “Subások.” They called themselves as “nagy népi hurál” [big folk hural], and they were the regular attendants at dance houses. There are interviews with Sándor Csoóri, Ferenc Kiss, Ferenc Kósa, József Zelnik, Iván Vitányi, Bertalan Andrásfalvy, Imre Makovecz, Marcell Jankovics, Zsuzsanna Erdélyi, Béla Halmos, and the most famous transborder Hungarians like András Sütő, Zoltán Kallós, Árpád Könczei, Péter Gágyor, and Anikó Bodor.

Thanks to the Dance House Movements, Transylvanian folk songs and traditional folk culture became popular among Hungarian intellectuals. From the 1980s, the connection between the movement and cultural opposition was clear.

The oppositionist shade of the dance house movement and of interest in folk music was also clear in the 1980s. One need merely think of the popular and famous “Stephen the King” (István a király) rock opera or other versions of folk songs by the band Muzsikás in 1986. The audience learned how to read between the lines and understood the implied messages of the songs. From the 1980s, folk singers and folk musicians often took part in subversive activities and sand national songs like the so-called Kossuth song together. In March 1989, young people from Veszprém went to the Soviet barrack in Szentkirályszabadja and demanded the withdrawal of Soviet soldiers from the country.

Interviews in Institutional Archives and private collections

Some members of the Folk Dance House Movement and the so-called Nomadic Generation started to collect every document connected with the movements and events. The Folk Dance House Archive, established by Béla Halmos, became the most important of these collections, available in the László Lajtha Folklore Documentation Library and Archives in the Hungarian Heritage House. The bequest of Béla Halmos is part of the Folk Dance House Archive. The bequest of Ferenc Bodor is the other significant bequest and collection with information about the Nomadic Generation. After Ferenc Bodor died, it was moved to the building of Selyemgombolyító, which was a significant site for the dance house movement. The interviews are essential parts of Ferenc Bodor’s bequest.

The circumstances of the format of archives, their goals, and ways in which they can be used

Folk Dance House Archive

Béla Halmos, who was a musician, a folklorist, an organizer, and the head of the urban revival movement, always tried to further the dance house movement. With the Sebő Band and with his wife, Katalin Gyenes, he documented the movement, including important events. He also collected journals, tickets, photo, and posters from the outset. They collected a substantial amount of data and documents over the course of the decades. In 1997, the Dance House Movement celebrated the 25th anniversary of its founding, so Béla Halmos organized a jubilee exhibition using materials from his own collection and collections owned by others (Téka, Méta Band, Béla Kása, Ágoston Bartha, Kálmán Magyar). He also kept the attention of the audience, and he knew that the collection of original folklore and the documentation of the movements and the events was significant. Béla Halmos established the Folk Dance House Archives in 1999 as part of the Hungarian Cultural Institute Folk Art Department, and in 2001, the László Lajtha Folklore Documentation Library and Archives in the Hungarian Heritage House got the collection. The Folk Dance House Archive is based on Béla Halmos’s private collection. The goals of the Folk Dance House Archive were summarized by Béla Halmos in 2000:

The Folk Dance House Archive will be the center of the collections, archives, and research connected with the history of the folk dance house movement. Béla Halmos devised the method of collection, systematization, and documentation. Béla Halmos thought that the digitalization of the collection would be necessary in the future, and he also thought about questions concerning copyright. On the other hand, without any human resources, he could not do systematic collection, but had to rely on occasional opportunities to make additions. Béla Halmos filled this archive with interviews, and the archive was later given the name the Béla Halmos Oral Archives. Here we find interviews and life history interviews with the members of the folk dance house movement. Their memories are remarkable parts of the collection. Béla Halmos started dating and processing these interviews, but his unexpected death brought this work to an end.

The Hungarian Heritage House bought the bequest of Béla Halmos in 2014. It contained folklore collections, manuscripts, photos, interviews, books, and his violin.

The purposes of the interviews and the methods according to which they were done

During the interviews, the interviewers focus on the main parts of the folk dance house movement, but Béla Halmos often concentrated on asking about as much information as he could about daily life, the relationship between culture and policy, and the possibilities folk dance houses had in the 1970 and 1980s. From the interviews, we can see the relations among the members of the folk dance house movement during the 1970 and 1980s. During the interviews, Béla Halmos never talked about his political views. He just asked and listened during the interviews.

Summary

The folk dance house movement as a special Hungarian phenomenon started in 1972. It was a special part of the international club and folk movements of the 1960s. The uprising among youths began in the Soviet countries, similarly to the West. Parts and elements of the Oral History and Folk Dance House Archives are valuable documents which show special viewpoints in the Kádár era and help further a scientific understanding of the history of the folk dance house movement.